* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Gimlet Lends A Hand

Date of first publication: 1949

Author: Capt. W. E. (William Earl) Johns (1893-1968)

Illustrator: Leslie Stead (1899-1966)

Date first posted: Apr. 1, 2023

Date last updated: Apr. 1, 2023

Faded Page eBook #20230403

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, akaitharam, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

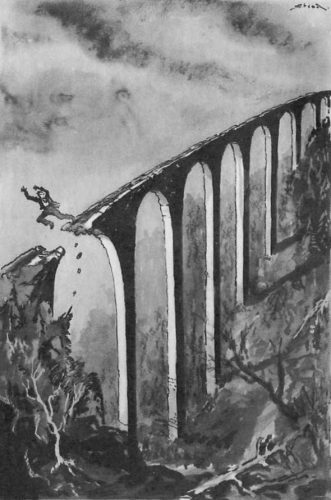

Taking a deep breath, he jumped across the gap

GIMLET

LENDS A HAND

A “King of the Commandos” Adventure

By

Captain W. E. JOHNS

Illustrated

By

LESLIE STEAD

Published by

THE BROCKHAMPTON PRESS, LTD.,

LEICESTER

The characters in this book are entirely imaginary,

and have no relation to any living person.

First printed, 1949

Made and Printed in Great Britain by C. Tinling & Co., Ltd.,

Liverpool, London, and Prescot.

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | SOME OLD FRIENDS MEET | 9 |

| II | A TRAGEDY OF RICHES | 22 |

| III | CUB TAKES A JOB | 35 |

| IV | A TOWN THAT TIME FORGOT | 44 |

| V | A WHIFF OF SMOKE | 59 |

| VI | MONEY TALKS | 69 |

| VII | MONEY TALKS AGAIN | 79 |

| VIII | THE SCENT WARMS UP | 92 |

| IX | CUB GETS A SHOCK | 103 |

| X | AN EERIE RECONNAISSANCE | 115 |

| XI | MONEY FOR NOTHING | 129 |

| XII | THE PASSAGE OF THE STYX | 140 |

| XIII | GIMLET TAKES OVER | 153 |

| XIV | INTO THE DEPTHS | 164 |

| XV | TRAPPER PULLS HIS WEIGHT | 173 |

| XVI | BUTTONED UP | 186 |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| I | Taking a deep breath, he jumped across the gap | Front. |

| PAGE | ||

| II | In every alley hung a strange indefinable smell of corruption and decay | 54 |

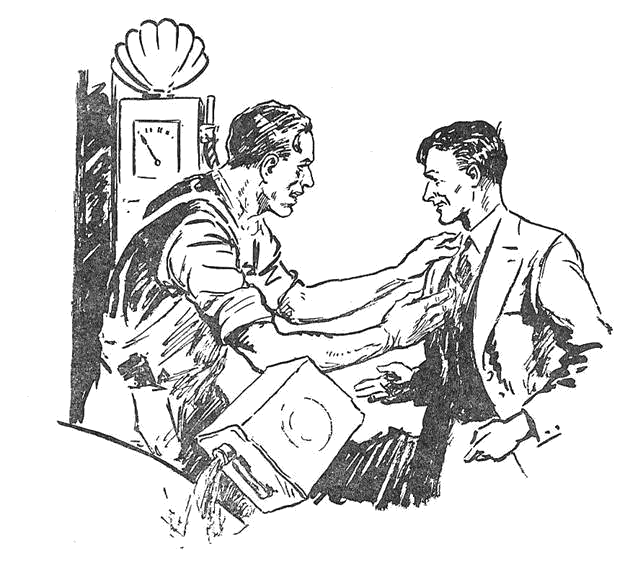

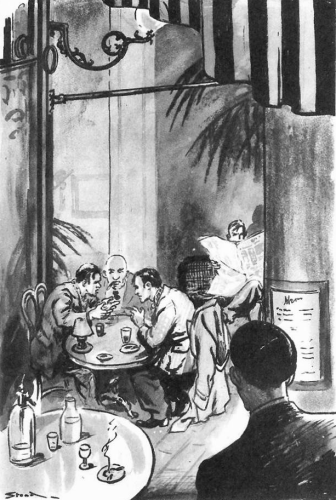

| III | Three men sat together in earnest conversation | 112 |

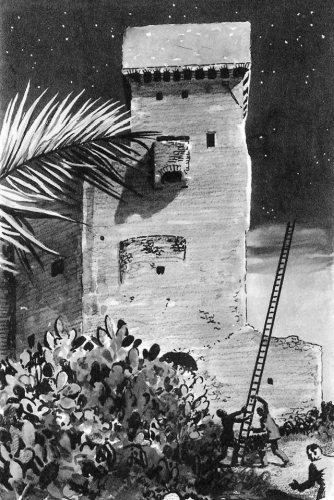

| IV | “All clear,” said Cub. “Get her up” | 128 |

Nigel Norman Peters, commonly called “Cub” by his comrades of the commando unit known as “King’s Kittens,” walked briskly down the Old Kent Road, London S.E. He walked briskly, with a spring in his stride, for, appropriately, there was a smell of spring in the air in spite of the mixed odours normally to be encountered on the south side of the river. As he walked, dodging pedestrians, perambulators and piles of country produce being unloaded from their respective trucks, he scanned the names above the shops and business premises like a man who knows what he is looking for yet is doubtful of its precise location.

His quest did not take him far, and he came to a halt before a garage in the forefront of which a big, broad-shouldered, fresh-complexioned man, in oil-stained overalls, whistled softly through his teeth as from a battered can he filled the radiator of a Ford V8 that had seen better days. Cub watched him for a moment, a smile of recognition, and perhaps some slight amusement, lifting the corners of his mouth. Then he spoke. “Hello, Copper, you big stiff,” he greeted with the easy familiarity of long-standing friendship.

The man addressed swung round, the exclamation of surprise that rose to his lips being drowned in a spontaneous shout of welcome that made several passers-by look round in mild alarm. Unconscious or unconcerned by this he tossed aside the can regardless of its splashing contents and with a good-natured grin lighting his face held out an enormous hand. “Blimy! What do yer know?” he cried, in a rich Cockney accent. “If this ain’t a treat and a narf. How are yer, chum?”

“Fine,” answered Cub, wincing as he disengaged the hand that engulfed his own. “Go easy on that handshake of yours or you’ll break somebody’s arm one day,” he warned. “How’s yourself?”

“Oh, not so dusty, mate,” replied Copper cheerfully. Turning his face to the garage he shouted: “Hi! Trapper! Look who’s ’ere.”

A second man, looking puzzled, appeared from the rear of the building, a man as unlike the one who had called as could be imagined. He was dark and lean. A wisp of black moustache adorned his upper lip. A scar that seared his cheek broke into creases as he, too, flashed a smile of recognition, showing two rows of perfect teeth.

“Tiens!” he cried delightedly. “If it isn’t our own Cub come to see us.”[1]

[1] These comrades, who will be known to many readers, are more fully described in King of the Commandos.

Cub looked around. “How’s the business going?” he inquired.

Copper’s face clouded. “How’s it going?” he echoed. “If you ask me I’d say it’s pretty well gone. You can’t run a joint like this on free air and water. We were going to sell petrol, but we can’t get no petrol to sell. Same with tyres, same with spare parts, same with everything. I tell yer straight, old pal, if there comes another perishing war the government can fight it themselves as far as I’m concerned. It ’ud make yer sick. They dish yer out with medals but what’s the use of ’em? I can’t live on brass. When I ask fer a little drop of petrol what do they give me? Forms—forms—forms. I’m sick of forms. I never did ’ave any time for ’em. When they wanted us ter go out and do some dirty work they didn’t dish out no forms then—no bloomin’ fear. What say you Trapper, old pal?”

Trapper shrugged his shoulders. “I told you,” he said simply.

“All right, all right, don’t rub it in,” growled Copper. To Cub, he went on: “We run this old car as a private hire job, but as I was a sayin’ ter Trapper just now, the old cow drinks too much juice.” He sighed. “Give me the old days. ’Ere terday and gone termorrer. That’s the stuff. What say you, Trapper?”

“Tch! Every time.”

“Let’s go into the office and ’ave a chin-wag,” suggested Copper.

“Don’t tell me you’ve got an office?” scoffed Cub.

Copper frowned. “Of course we’ve got an office. This is a business. At least, that was the idea.”

They went through into a little room littered with wrapping paper, forms, oily rags and accessories of the motor trade. “Watch where you’re sittin’, chum,” warned Copper, “there may be a drop of oil about and I wouldn’t like ter spoil that smart walkin’-out kit of yours. What are you doin’ yourself? Last time you wrote you said you was helpin’ your Dad run your place as a farm.”

“Like you, we had an idea,” returned Cub gloomily. “And like you, we were swamped with forms. We’re giving up.”

“I’ll tell yer what’s wrong with this country,” announced Copper earnestly. “There’s too many people tellin’ too many people what ter do, and what they can’t do.”

“I think you’ve got something there,” agreed Cub. “But let’s not talk about that.”

Copper selected a crushed cigarette from an oily packet. “And what brings you to Old Smoky?” he asked. “You didn’t come special ter see us, I’ll bet.”

“I wouldn’t come to London without coming to see you,” protested Cub. “Look at me now. I’ve come straight from the station—couldn’t get here fast enough.”

“Good fer you, old pal,” said Copper warmly.

“As a matter of fact, I’ve had a letter from Gimlet,” stated Cub.

“What’s ’e got ter say? All huntin’ and shootin’, I’ll bet.”

Cub took an envelope from his pocket and extracted the single sheet of paper it contained. “No. He’s in town. He wrote from the Ritz.”

“What does ’e say?”

“He simply says, ‘What about it?’ ”

“Go on.”

“That’s all.”

“What d’you mean—that’s all?”

“What I say.”

“Wot’s ’e talkin’ about? Wot about it? Wot about wot?”

“I’ll tell you if you’ll give me a chance,” complained Cub. “Stuck on the letter was an advertisement cut out of a newspaper. I’ll read it to you. Listen to this.” He read aloud:

“ ‘£10,000 is offered for the services of a man accustomed to living dangerously. Must be physically fit, prepared to go anywhere, possess a high degree of initiative and able to furnish highest references concerning moral character. Familiarity with lethal weapons and ability to speak colloquial French are essential qualifications. Apply in first instance to Box 4791.’ ”

“Blimy! ’E don’t want much,” snorted Copper.

“I reckon you’d expect something for ten thousand pounds,” returned Cub.

“Ten thousand quid would be better than a poke in the eye with a dirty oil can,” admitted Copper. “Still, I reckon the bloke who takes on that job can say goodbye ter mother.”

“I imagine Gimlet spotted the advertisement and thought it might interest me.”

“Meanin’ that ’e reckons you’re the bloke for the job, eh?”

“Either that, or it was his idea of a joke.”

“Ten thousand quid don’t sound like no joke ter me,” declared Copper. “Sounds more like a beautiful dream. If the queue fer that job don’t cause a traffic jam I don’t know wot will.”

“I don’t think so,” disputed Cub. “Remember the essential qualifications. The ability to speak French like a native will stump most people, I imagine.”

“ ’Ave you bin after the job?”

“I wrote to the box number.”

“Wot ’appened?”

“I had a reply. That’s what brought me to town.”

“Who is this guy with all the dough and where does ’e live?”

“I’ve no idea,” admitted Cub. “All I got was a typewritten note with no address. It simply says that if I wish to present myself as a candidate for the post I must go and sit alone on a seat on the west side of Leicester Square, today, at eleven-thirty precisely. A Daimler car, registered number VLX 4321, will draw up. I am to get in the back seat and shut my eyes. The driver will do the rest.”

“I’ll bet ’e will,” sneered Copper. “What ’ave yer got ter shut yer eyes for?”

“Presumably so that I can’t see where I’m going.”

“Don’t make me laugh. You won’t see, chum, but you’ll feel, I’ll bet my boots,” asserted Copper. “I’d say you’ve got ter shut yer peepers so that yer won’t see the bloke who beats yer over the dome with a short length of gas pipe before ’e picks yer pockets. Are you goin’ ter do it?”

“Of course.”

“You must be balmy,” declared Copper. “Never mind livin’ dangerously. You go fer this job, chum, and you’re liable ter die dangerously. Why not take a runnin’ jump in front of the next ’bus and save yerself the sweat of goin’ ter Leicester Square?”

“I think you’re wrong,” argued Cub.

“Well, you’ll see. I tell yer mate, the job stinks. Take my rip and ferget it. Let’s go round to the Cat and Sparrer and ’ave a nice friendly game of darts.”

Cub shook his head. “Not for me. I’m going to see this through. It’s the most interesting thing that’s happened to me since we went East.”[2]

[2] See Gimlet’s Oriental Quest.

“Okay, ’ave it yer own way,” sighed Copper. “To me it looks like bein’ a sad endin’ to a bright young life. What say you, Trapper? Am I right?”

Trapper clicked his tongue. “Tch. Every time.”

“I’ve got an old friend in my pocket if anyone starts any rough stuff,” said Cub meaningly.

Copper grinned. “That little Mauser?”

Cub nodded.

“You ain’t fergotten ’ow ter use it?”

“Not likely. I’ve been practising on the stoats that raid our chickens. But I shall have to push along now or I shall be late.”

“We’re comin’ with you,” decided Copper suddenly.

“Oh no you’re not.”

“Why not?”

“Because if three men instead of one turned up that would be the end of it. The letter said I was to go alone.”

Copper scratched his head. “All right. We’ll run you up ter Leicester Square any old how.”

“Fair enough,” agreed Cub. “But when you’ve dropped me you keep out of the way. If the driver of the Daimler suspects that he’s being followed that’ll put paid to the whole show.”

“You mean we’ve got ter sit and do nothin’ while you go off on yer own and start playin’ at livin’ dangerously?”

“You’re going to put me down where I tell you in Leicester Square,” replied Cub firmly. “You stay there, and when I’ve had my interview I’ll come back and tell you all about it.”

“Do we get a share in the ten thousand?”

“I haven’t got it yet.”

“True enough,” agreed Copper. “Is that okay with you, Trapper?”

“Okay with me.”

“Then let’s trundle along to Leicester Square,” said Copper, returning to the Ford on which he had been working. He got in and took the wheel. Trapper got in behind with Cub.

It was a close thing, the result of a traffic jam, much to Cub’s agitation; but in the end the vehicle pulled up at the rendezvous with a minute to spare. Cub got out just short of the actual meeting place and walked towards it without a backward glance. His eyes switched from the number plate of one passing car to another, and dead on time he saw the Daimler coming. It pulled into the kerb. He glanced at the driver, but little could be seen of him as his cap was pulled down and his collar turned up. Goggles covered his eyes.

Behaving as if the car belonged to him Cub got in, sat down and closed his eyes. Instantly the car began to move. Whatever the outcome, he thought, his strange adventure had begun. The temptation to open his eyes was almost unbearable, but he resisted it, for he had a feeling that the driver would be watching him closely in his reflector. He tried to follow from memory the direction of the car, but soon gave it up. It was one of those things, he decided, that might be possible in theory, but not in practice. He could only settle down to wait for the end of the journey.

It came sooner than he expected—after about ten minutes, as near as he could judge; but he realised of course that in that time the car might be anywhere between Marble Arch and the Mansion House. His pulses quickened as the car came slowly to a standstill. He heard the door being opened and knew that the driver was looking at him. It was an uncomfortable feeling, and it struck him that now, if Copper’s warnings were justified, the blow would come. Instead, a voice said quietly, “Keep your eyes closed, please. You have done well so far—in fact, you are the first to survive the ordeal.”

Cub made a mental note that he was not the first applicant.

“Take my arm,” ordered the voice.

Cub felt an arm, and took it. He groped his way out of the Daimler. The arm drew him across what his feet told him was a pavement.

“Up three steps,” said the voice.

Cub obeyed. A door was unlocked. He walked forward and it was closed behind him.

“All right. You can look now,” said the voice.

With a sigh of relief Cub opened his eyes and saw that he was in a well-furnished hall—the hall, judging from its size and appointments, of a mansion. However, he thought quickly, there was nothing surprising about this, considering the sum of money offered by the advertiser. He looked at the man who had brought him in, and who was now divesting himself of his outdoor clothes. The scrutiny told him little. He judged the subject of his inspection to be about thirty years of age. Dressed in a dark lounge suit and wearing glasses the man might have been a clerk holding a responsible job.

Before Cub could notice details his companion said: “Put your cap on the stand and come this way.”

Holding his cap, Cub was moving to obey, when the man turned in a flash and rapped out: “Stick ’em up!” A small revolver had appeared in his hand.

Now, to say that Cub expected this, or anything of the sort, would be going too far; but from the very nature of what he was doing he was prepared for anything to happen, and his nerves and muscles were braced in subconscious anticipation. He had been taught, in the most deadly school of all, to think fast and act at the same time. That he did both was largely automatic. Continuing without a moment’s pause the movement he had started he slashed his cap in the face of his aggressor, side-stepped and jumped forward simultaneously. His left hand closed on the wrist that held the weapon, forcing it up. His left foot slipped between the man’s legs so that as he threw his weight forward the man went over backwards. Cub fell on him. With scant ceremony he twisted the wrist, wringing a cry of pain from his adversary and causing his fingers to open. Another moment and Cub was on his feet, had kicked the gun clear, snatched it up, and holding the man covered, backed to the nearest wall, his eyes alert for fresh dangers. He began to edge towards the door.

His muscles tensed again when a voice, quite near, said quietly: “Very good.”

Then a door opened and an old man walked into the hall. He seemed slightly amused. Looking at the one now picking himself up from the floor, speaking with a slight American drawl he went on: “I’m sorry, Linton, but it was your own idea you know. I hope he hasn’t hurt you. Don’t ever turn gangster—you’re much too slow.” To Cub, completely ignoring the revolver pointing at him, he continued: “Come this way, young man. Linton is my confidential secretary. He meant no harm. Give him back his gun. He was acting under my instructions.”

“Is that so?” replied Cub slowly. “Well, if those are a sample of your orders I don’t like them. I’ll keep the gun.”

“It isn’t loaded,” remarked the old man casually.

“This one is,” returned Cub grimly, switching the weapon to his left hand and whipping out his Mauser.

“Splendid,” complimented the old man calmly. “I guess you’ve used a gun before.”

“This time you’ve guessed right,” Cub told him.

“Have you a police permit to carry that one?”

“I have.”

“For what purpose?”

“Killing vermin—and vermin covers a wide field.”

“Quite so,” was the response. “Come into the library. I’d like a word with you. You can come too, Linton.” The old man turned back towards the door of the room from which he had emerged, and from which, apparently, he had been watching Cub’s arrival.

Cub hesitated. “All right,” he agreed. “But no more tricks. I warn you that if I have to pull this trigger, one of you, perhaps both, will need an ambulance. I don’t like tricks—with guns. That’s how accidents happen.”

The old man looked round. He was smiling faintly. “Do you never miss?”

“Not very often.”

“I’ll take you up on that,” said the old man sharply. He pointed to a full length painting of a man in old-fashioned clothes that occupied part of the wall at the far end of the hall. “See if you can hit that,” he invited.

Cub’s eyebrows went up. “Are you kidding?”

“No.”

“I shall spoil the picture.”

“It’s of no great value.”

Cub shrugged. “It’s your property. Where would you like the holes?”

“Anywhere, as long as you hit the target.”

“One through the head, say, and one through the heart?” suggested Cub.

“You can have as many shots as you like.”

“I’m not emptying my gun while I’m in here, if that’s your idea?” said Cub curtly. “Two shots should be enough.”

He jerked up the Mauser. It spat twice, the shots following closely. A trail of tiny sparks leapt the length of the hall and a faint blue reek of cordite smoke marked the direction of the bullets. Then the muzzle of the gun returned to the old man as he walked the length of the hall to examine the target.

“Remarkable,” said the old man. “Remarkable,” he said again. “I thought from your letter that your age might be against you, but for one of your years you seem singularly well able to take care of yourself. Where did you learn to shoot like that, young man?”

“That,” answered Cub, “is my business.” He was still not quite satisfied that this strange business was straight and above-board.

The old man fired another question, this time speaking in French. “If you can speak French as well as you shoot you may be the man I’m looking for.”

Cub answered in the same language. “Then the sooner you put up your proposition, monsieur, the sooner we shall know if we are wasting each other’s time.”

The old man smiled and nodded approvingly. “Better and better,” he murmured. “Come into the library, Mr. Peters.”

Cub followed his prospective employer into a room in which dignity was the dominant factor. He noticed that the blinds were drawn and the lights on.

“You can put your gun away; you won’t need it while you’re here,” said the old man.

Sincerity rang true in the voice, and this, with the old man’s air of calm assurance, dispersed such fears as Cub still entertained. Rather sheepishly he slipped into his pocket an instrument that seemed as out of place as a Bren gun in a nursery.

His host indicated a chair. “Sit down and make yourself comfortable,” he invited. “I shall have quite a lot to say. You’d better stay too, Linton, in case I need you.”

Cub sat down.

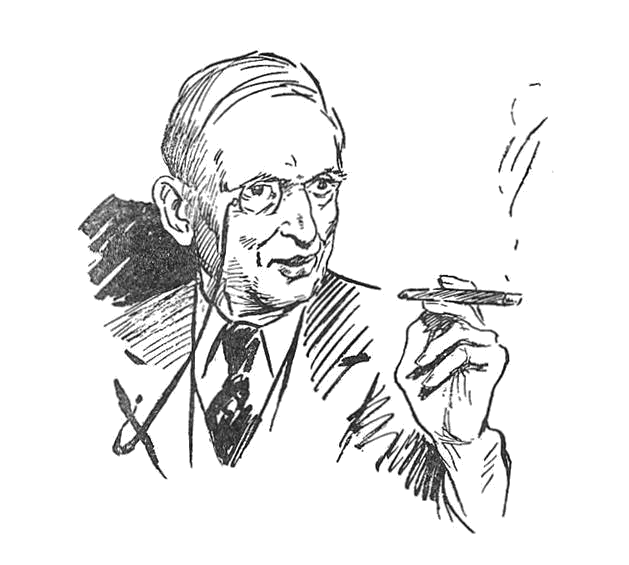

It was with respect and curiosity that Cub now had an opportunity of observing closely for the first time the man whom he felt sure had inserted the advertisement, for what purpose remained to be revealed.

He saw a man whom he judged to be about sixty years of age, of frail physique, with a long, thin, clean-shaven face on which ill health or worry had graven many lines. A high intelligent forehead ended in sparse white hair, neatly parted on one side. The chin was square, and the lips of a rather large mouth, pressed together, hinted at determination and strength of character. But these features were secondary to the eyes which, light grey in colour, held in them a penetrating quality which created in Cub an uneasy feeling that the man was looking into him rather than at him. Yet in some curious way, opposed to his general expression of hardness, was one of sadness, as if he had suffered some great grief. For the rest, he was simply but expensively dressed. A gold rimmed monocle depended from a black silk cord over a white silk shirt. Cub was well aware that history has proved over and over again that first impressions are deceptive, but he decided there and then that if this man was anything but entirely trustworthy he would never again rely on his own opinion.

During the period of this inspection he had himself, he knew, been closely scrutinised, and when the first question came, a perfectly natural one, he found it not easy to answer.

“What exactly brought you here?” inquired the old man. “Tell the truth. Be sure that if you don’t I shall know it.”

This Cub could well believe. “Your invitation,” he countered.

“Yes, of course. But why did you answer the advertisement?”

“I don’t know exactly,” replied Cub slowly.

“Was it that you hoped to make an easy ten thousand pounds?”

“Partly, I suppose, but not entirely. May I say curiosity, combined with the fact that I seemed to hold the qualifications demanded, which were somewhat unusual?”

“How did you come to see the advertisement? Were you looking for a job?”

“No. It was sent to me by a friend.”

“Who was this friend? Believe me, these questions are not without purpose.”

Cub hesitated.

“If you would rather not answer my questions you have only to say so and we will consider the interview closed.”

Cub made up his mind quickly. He had no secrets to hide. “The cutting was sent to me by my old commanding officer, Captain King, of the commandos.”

“Why did he send the clipping to you in particular?”

“I haven’t seen him to ask him,” replied Cub frankly. “During the war we had some pretty hectic adventures together so presumably he thought I would be interested.”

“In the money?”

“No. I don’t particularly need money. I have as much as I want and my father is quite well off.”

“Who and what is your father?”

“Colonel Peters. A soldier. He commanded a battalion of the regular army during the war. He is now on the Retired List.”

“Does he know about you coming here?”

“Yes. He promised to vouch for me should it be necessary. He knows I’m capable of taking care of myself.”

“Where did you learn to shoot as you do? Surely that is an unusual accomplishment for a fellow of your age?”

“I learned to shoot in the same place where I learned French—in France during the war.”

“You weren’t old enough to be in the war.”

“Officially I was not, in the early days. But the circumstances were unusual and my case was made a special enlistment.”

The old man’s eyebrows went up. “In a commando unit?”

“Yes.”

“Disgraceful. What were these circumstances?”

“It involves a story, but I will tell it briefly,” answered Cub. “At the time of the evacuation at Dunkirk I was at school. Hearing from a returning soldier that my father was on the beach, wounded, I stowed myself away on a boat to get to him. I didn’t find him and eventually got left behind in enemy territory. I got in with some French boys and we did all the mischief we could. One day I got mixed up in a commando raid and was brought home. By that time I knew every inch of northern France, and the enemy’s positions. That’s why I was taken on. Afterwards I often went to France on special missions with Captain King and two particular friends. I was demobilised at the end of the war.”

“Incredible,” murmured the old man. “A boy of your age engaged in such work. You must know what it is to live dangerously!”

Cub smiled. “Looking back I suppose it was pretty dangerous.”

“Are you quite fit?”

“Perfectly, as far as I know.”

“You don’t mind where you go?”

“I’d rather like to see France again.”

“I said nothing about France.”

“No. But you would hardly stipulate a knowledge of French if you were looking for someone to go to any other country.”

The old man’s face softened. “Quite right,” he agreed. “What about your moral character?”

Cub looked uncomfortable. “To tell the truth, sir, I’ve never considered it,” he admitted. “I wasn’t too good at school, and then five years of war didn’t give me much chance to find out what I really was. I’ve never been tempted to do anything underhand so I can’t really say what I’d do if I was. You’d better ask my father or Captain King about that.”

“I see. I imagine you’ve never really wanted anything you couldn’t have?”

“That’s about it.”

“But you’d like ten thousand pounds?”

“I’d take it if it was offered to me, if I thought I’d earned it. Why not? You offered it. I didn’t ask for it.”

The old man nodded. “Quite right my boy, so I did. What I meant was, you’ve no desire to get rich quick?”

“I’m not panting to be a millionaire.”

“Few would if they knew what it involved.”

“You speak as if you know.”

“I do.”

“Are you a millionaire?”

“Many times over.”

“It hasn’t brought you happiness.”

“Why do you say that?”

“You wouldn’t be looking for a gunman if you had nothing on your mind,” asserted Cub.

The old man looked at his secretary and smiled sadly. “He keeps pace with an argument very well, doesn’t he?”

“Any more questions, sir?” asked Cub.

“Yes—one,” was the answer. “Would you take the job I have to offer if I offered it to you?”

Cub shook his head. “Not without first knowing what you’d expect me to do.”

“Ten thousand pounds is a lot of money.”

“I set my liberty at a higher figure.”

“I see. You think I might want you to break the law?”

“I suspect it. Ten thousand is more than any straight job is worth.”

“It seemed a not unreasonable sum for a man to weigh in the balance against his life.”

Cub smiled. “I risked mine every day for nearly five years for a lot less.”

“Yes, but then you had a cause to fight for. Now you have none.”

“Why not let me be the judge of that?” suggested Cub.

The old man leaned back and put his finger tips together. He regarded Cub thoughtfully for a full minute. Then he said: “My instinct tells me that you are a fellow to be trusted. If my instinct, which has never yet let me down in my dealings with men, is no longer a factor on which I can rely, then what little life remains for me to live will be a sorry business indeed. I’m going to take you into my confidence. If you fail to respect it you will do an old man a grave injury, and cost a young one his life.”

“What you tell me, sir, will go no further without your permission,” declared Cub.

“What exactly do you mean by that? Can’t you keep a secret to yourself?”

“I could, if it were absolutely necessary. But in case there should be any doubt in what you are going to tell me I might wish to consult my father, or my old C.O., who are two of the bravest and straightest men I’ve ever met or am ever likely to meet.”

“That’s fair,” agreed the old man. “I will modify the word secret to include those in whose loyalty and integrity you have absolute faith. Now let us get on. Does the name Rudolf K. Vanderskell mean anything to you?”

“Not a thing.”

The old man glanced again at his secretary, this time with a twinkle in his eye. “Such is fame,” he murmured whimsically. Turning back to Cub he explained: “Rudolf Vanderskell is the richest man in the world today.”

“Where does he come into this?” inquired Cub.

“Right here. I’m Rudolf Vanderskell.”

“It doesn’t sound like a British name.”

“It isn’t. I’m an American citizen.”

“Couldn’t you find the man you want in America?”

“Probably, but the difficulty was to find him without the matter being given publicity. It would have been impossible to advertise without the name of the advertiser becoming known, and once it was known to my enemies my object would have been defeated at the outset. Not only would my project have collapsed, but the result would have been disastrous. I’m too well-known in my own country. That’s why I came here. But more of this presently. Now listen carefully to what I’m going to tell you, for it is the kernel of the very hard nut which you will have to crack if, having heard my story, you enter my service.”

“I’m listening, sir,” said Cub, wondering what was coming.

“It is our misfortune, yours and mine, to live in a tragic age,” continued the millionaire. “Every country, every race, every creed, is striving for supremacy as never before in history. In this scramble for power individual members of every class are striving to outsmart their fellows. Some, by their ability and their industry, have achieved their ambition by fair means. Others, through lack of these qualities, have failed, and in their rage and envy of their more fortunate fellows now wage underground warfare against civilized society. Wherefore law and order has gone by the board. I am, let us admit, one of those who have been outstandingly successful, and for that reason alone am singled out for persecution. Now, one of the most brutal weapons employed by the failures is known as kidnapping. Everyone has heard of it, but few realise the mental anguish it inflicts on those against whom it is directed—which is, of course, why it is used. I know, for I have more than once been the victim. The first time was fifteen years ago when my small daughter Anne was taken. I, foolishly perhaps, informed the police, not supposing seriously that the kidnappers would resort to the extreme measures that were threatened should I take such a course. I was wrong. My child, a baby of two, was never seen again. No doubt she was murdered; but it is the uncertainty of not knowing her fate that has taken the joy out of my life. From this dreadful shock my wife never fully recovered. Before she died she gave me a son. He is now fourteen, and as you will readily imagine, has from birth been a constant anxiety, although everything in my power was done to protect him. Ten days ago he disappeared from the private school at which he was being educated. The following day I received a letter demanding a million dollars as the price of his release. I was given three weeks in which to pay.”

“If you have so much money why not pay?” suggested Cub.

The millionaire smiled wanly. “I would, willingly, if I thought the ransom would achieve its purpose. It would not. I have no guarantee that my son would be released; and if he was, what is there to prevent a repetition of the crime? Be sure that the scoundrels who hold him would not abandon readily such a source of easy money. If I got him back it would not be practicable for us both to spend the rest of our lives in hiding. Others have tried and it doesn’t work. Yet it is equally certain that if I do not pay my son will be murdered.”

Cub stared, aghast. “Do you mean to say that this sort of thing goes on all the time?”

“It does.”

“I haven’t seen anything about it in the papers.”

“You wouldn’t. The thing is kept quiet for fear of further reprisals. For that same reason I dare not inform the police. In any case they would be powerless to do anything. The crooks would know at once, for they work in gangs; they use bribes, and their ramifications are extensive. To inform the police, or the press, would be simply to sign my son’s death warrant.”

“These villains must be worse than the devil himself,” declared Cub.

“They are. Certainly they are not to be judged by our standards. Nothing is too mean, too low, too brutal for them. They know my lips are sealed. No one knows my miserable secret—except Linton here. I live in dread that it should become known, for that would be the end of my son. You may think that my method of bringing you here was unnecessarily melodramatic. Now, perhaps, you will understand. I may be watched even here, although I hope that I have succeeded in giving my persecutors the slip. I was in New York when the abduction occurred. To do anything there was out of the question. My only chance of saving my son lay, first of all, in escaping from enemy surveillance. With the details of how I achieved this I need not trouble you. Let it suffice that I slipped away like a thief in disguise and crossed the Atlantic in a specially chartered airplane.”

“Why did you choose England?” asked Cub curiously.

“One reason was to be nearer to my son.”

Cub looked surprised. “Then you know where he is?”

“Within a mile or two, I think.”

“How on earth did you learn that?”

“As part of my precautions I had made provision for it. I was always aware of the danger and took every possible measure to be forearmed. I even went to the length of having myself and my family tattooed with a small identification mark for recognition purposes, for the guidance of the police should doubt arise—by which I mean should a body be found, or mutilation be inflicted, as sometimes happens in this dastardly form of crime. The mark, by the way, is a small blue Maltese cross, which is part of the original coat of arms of my family, on the upper part of the left arm. My son has it. I mention it because circumstance might arise in which you would need some definite proof of identification.”

Cub stared. “Am I to understand that this kidnapping is a regular racket? I mean, have other people lost their children too?”

“Certainly some have. Probably more than is generally supposed, because as I said just now, the lips of parents are sealed for fear of bringing the vengeance of the gangsters on their helpless children. But let me continue. As soon as my son was old enough to understand the cloud under which he lived I thought it expedient to explain the danger to him. We made a plan. I must tell you that part of the horrible technique of kidnapping is to persuade or force the victim to write to his parents imploring them in heartrending terms to secure his release from his unhappy condition by complying with his captor’s orders. Such a letter in the victim’s own handwriting also serves the purpose of confirming that he is still alive—otherwise the wretched parents would have no guarantee that he had not already been murdered. It is all part of the wicked plot and I knew it. My son has written such a letter to me, but because we made provision for it he was able by a simple code to convey to me a message which must have escaped observation. The letter, by the way, was directed to my home in New York, which suggests that my enemies suppose me still to be there. I was expecting it, and had made arrangements for it to be flown at once to me here. Unfortunately the code that we arranged had of necessity to be one that could be employed anywhere, easily, without a key, and without such signs or symbols as would betray it instantly; and for that reason only a word or two could be conveyed. Our code consisted of leaving certain letters in the words of the context disjointed. That is to say, in the continuous flow of writing certain letters would have an almost imperceptible gap between them. Thus, for instance, if one wanted to convey the letter H, and the word help occurred in the text, there would be a tiny break in the writing between the first letter and the last three. When all these letters are strung together they form a word, or a sequence of words. As it happened, the letter my son was invited or compelled to write was a very short one, so short that he was able to convey to me only a single word. That word was the name of a place, and you can imagine what it meant to me. It told me at least how hopeless without it would have been any search for my son.”

“And this place,” queried Cub, “is in France?”

“Perfectly correct.”

“And you are looking for someone to try to rescue him?”

“Yes.”

“And you think that is worth ten thousand pounds?”

“Not necessarily. Success would be worth, to me, a great deal more, obviously. To have offered less might not have produced the sort of man I needed. To have offered more could hardly have failed to attract more attention than I considered advisable. The press might have picked on it. They have a way of ferreting things out. They would have traced it to me, and the resultant publicity would have destroyed my object and my boy as well.”

“If you know the name of the place where your boy is, a rescue shouldn’t be very difficult,” observed Cub. “With some loyal friends I’ve tackled bigger jobs.”

“I’m glad to hear it, but don’t make the initial mistake of supposing that this one is easy,” said Mr. Vanderskell. “The men to whom you will find yourself opposed are murderers by nature and killers by profession. During the war everyone who wore a Nazi uniform was your enemy. You could recognise him on sight. This is a very different proposition.” The millionaire looked hard at Cub. “Well, by now you will have a pretty good idea of what I have in mind, and the sort of man who will be needed to earn the reward—and come back alive to collect it. Do you wish me to continue? If you think the job is too dangerous you’re at liberty to withdraw.”

A ghost of a smile crossed Cub’s face. “I should be very disappointed if you stopped now,” he said.

“Very well,” agreed Mr. Vanderskell. “Before we go on suppose we have a little refreshment? Linton, order some coffee, please.”

“Have you any idea of who these kidnappers are?” inquired Cub presently.

“I have no proof,” replied Mr. Vanderskell. “But since the most notorious gangster boss who has specialised in this sort of crime has recently disappeared from his usual hang-out, it might be assumed that he organised the abduction of my son. If that is so it is probable that he and his confederates are now this side of the Atlantic, because the place where I am instructed to pay over the ransom money is Paris—in an obscure little restaurant to be precise.”

“Why Paris, I wonder?” murmured Cub.

“In the first place, I imagine, because the gangsters would not be so well-known there as in New York, where for all they know the police might be looking for them or setting a trap for them. Secondly, if they were caught in America they would go to the electric chair, because in an effort to stop this dreadful racket the death penalty is in force. I’m not a vindictive man, but I’m bound to say that no fate could be too bad for these villains.”

“Do you know the names of any of them?” asked Cub.

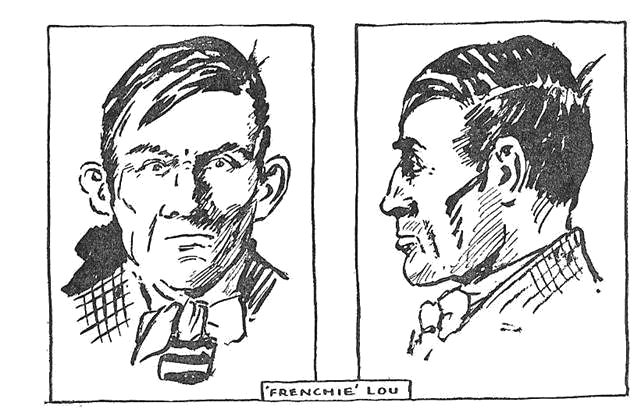

“The most notorious gangster in the United States at the moment, America’s Public Enemy Number One, rejoices in the unpleasant nickname of Joe the Snout. Why, nobody seems to know. Nor does anyone seem to know his proper name. He must be exceptionally cunning, for not even the police know him by sight. As far as they know he has never been in custody,—which is not to say that he has no criminal record under another name. His first lieutenant is a man long known to the police as Frenchie Lou. The police believe that his real name is Louis Zaban.”

“Zaban doesn’t sound very French to me.”

“It isn’t certain that he is French by birth; but he must have been in France in his youth, for he was convicted there on a charge of murder and sent to the penal settlement on Devil’s Island. He escaped, got to South America, turned north and started a new life of crime in New Orleans. Since he must be able to speak French fluently no doubt he is back in France at the moment, with forged identification papers. Another star turn in this gang of crooks is known to the underworld as Slinky. They love nicknames, these people; and of course, they serve as camouflage for their real names.”

“Have you any photographs of these men?” asked Cub.

“Only one of Frenchie Lou—an official police photo. The others, as I said, have never yet been caught. This is Frenchie Lou. You may care to have a look at him.” Mr. Vanderskell took out a notebook, found a photograph and passed it over.

There were, as usual with police photographs, two portraits, one full face and the other profile. Cub found himself looking at a small, swarthy, crafty face, with narrow, furtive eyes and a cruel, thin-lipped mouth. The ears, he noted, stood out from the head—so often a bad sign. He would never have guessed the nationality of the man. He might have been a half-breed from the Levant, or one of the multiple breeds to be found on the waterfront of every Mediterranean port.

He handed back the photograph. “A nasty-looking piece of work,” he observed.

“He is,” asserted the millionaire.

“What is the Christian name of your son, sir?” asked Cub.

“John. I call him Johnny.”

Cub stared at the carpet for a little while. Then he looked up. “If you think I am a suitable person, sir, I’d like to have a shot at finding Johnny and bringing him home. I don’t care about the reward, but I’d be glad if you’d pay my expenses.”

Mr. Vanderskell smiled. “No—no. If you enter my service you will accept the salary I offered. As far as I am concerned the amount is immaterial. The man who brings my son to me can have an open cheque. At a time like this money ceases to have any importance.”

“Then you are satisfied to take me on?”

“I wouldn’t have told you what I have had I decided otherwise,” answered Mr. Vanderskell drily. “You have eleven days in which to work.”

“And if I fail?” asked Cub nervously.

Mr. Vanderskell shrugged his shoulders. “Your failure would probably result in the death of my son, although that, of course, is likely to happen anyway, so there would be no need for you to reproach yourself on that account. If I hear nothing from you I shall go to Paris at the appointed time with the ransom money in my pocket, that being the one remaining hope of saving my son.”

“If I fail it won’t be for want of trying on my part,” stated Cub.

“I believe that,” said Mr. Vanderskell simply.

“What shall I do for money in France?” inquired Cub. “You know the currency regulations here.”

“That is all arranged. Once in France you can draw all the money you want from an address which I will give you. Any more questions?”

“There’s just one thing, sir,” said Cub dubiously. “In France, during the war, I worked in a team of four, which included Captain King. We had a rule, all or none, which meant that no one came back without the others. That in turn meant that the strings holding us together were pretty tight; and it was this team work which, looking back, I can see so often brought us through. Without any silly heroics, each knew that the others would give their lives without the slightest hesitation if by this a situation could be saved. The effect of this was something which would be hard to describe in so many words; but without talking about it we all knew it, and if I can use the expression, gloried in it. Such comradeship is a wonderful thing.”

The millionaire smiled at Cub’s enthusiasm. “Well?”

“Would you mind, if I thought it would make for success, if I brought these men into this?”

“You can do what you like as long as you keep silent about what you are doing. Quite apart from what the effect of careless talk would have on me your own safety would be put in jeopardy. The men you are up against, and there will be several of them in it, are playing for a big stake—a million dollars, plus their liberty. If once they suspect what you are doing your chances of life will be very small indeed.”

“Believe me, sir, one of the things we learned during the war was to keep our mouths shut.”

“Very well. Go ahead and do your best.”

“One thing I shall have to know is the name of this place in France mentioned by your son in his letter.”

“Of course. The word he gave me was Vallonceau.”

Cub shook his head. “I’ve never heard of it.”

“Few people have probably, apart from tourists and historians. Vallonceau is a dead little town, little more than a village, in the mountains of Provence, in the southeast corner of France. I’d never heard of it either, but as you may suppose, I wasted no time gathering all the information about it that books could provide. Naturally, I daren’t risk being seen near the place myself.”

“What do you mean by ‘dead’?” asked Cub curiously. “Uninhabited?”

“Not altogether. Some of the old families still cling to the place, but it would hardly be the choice of people unaccustomed to living in such conditions. Vallonceau is one of those hilltop villages of old Provence that enjoyed their heyday in medieval times. There are quite a number of them in the region—Cagnes, Eze, Gorbio, among others. Although it is hard to believe today, at one time Vallonceau was a centre of art, poetry, and those wandering musicians known as troubadours. Since the late Middle Ages, when men found it was no longer necessary to perch themselves in mountains behind defensive walls, these places have all been in decline, slowly dying in the sun. Today they are grim reminders of another age, of something that has gone for ever. Originally, of course, they were really fortresses, with the houses of the poorer sorts clustering around the feet of a castle for protection from the vandals who century after century ravaged the Mediterranean coasts.”

“How big is this place?” asked Cub.

“It has a population of only a few hundreds. According to the guide books, those who make a study of these things assert that the site of Vallonceau has been a human habitation ever since men left caves to live in buildings fashioned by themselves. The story is told by the old grey stones of the buildings that remain. Inscriptions on them tell us that Vallonceau was there when the ancient Greeks occupied the land. Later, the Romans fortified the place as a garrison town. They built, as usual, an enormous open-air theatre for the entertainment of their troops and an aqueduct to ensure an ample supply of fresh water for their baths. Both are still there. You will see them. Although the village stands in a commanding position atop a hill it is girdled by a massive wall through which there is only one entrance.”

“I hope it served its purpose,” murmured Cub.

“Apparently it did not, for Vallonceau has been burnt, sacked, destroyed and rebuilt over and over again. In the fifth century it was taken by the Visigoths, and the eighth century by the Saracens. The Burgundians threw the place down and it was again torn to pieces in the religious wars of the Albigenses. From century to century its narrow streets have been slippery with blood, and echoed to the groans of the dying. Yet with all that, in the Middle Ages it was still a place of importance. Charles of Anjou built a château there, which still stands although it was sacked at the time of the French Revolution. It is now private property. But to us its history is only of interest on account of the buildings that remain, for in one of them, unless I am right off the track, my son is a prisoner. Today the place is quite poor and is visited only by tourists. There are two hotels. One, the Hostelrie du Château, dates from the thirteenth century. The other, much larger, is modern, comparatively speaking. That is to say, it is only two or three hundred years old. But it is given three stars in the guide book for the accommodation it provides, so it must be pretty comfortable. But there is no need for me to enlarge on these details. I have said enough to give you an idea of what to expect. Take one of these guide books with you when you go. It includes a plan of the place which should help you to find your way about when you get there.”

“What strikes me as so extraordinary,” said Cub thoughtfully, “is why the kidnappers should choose such a place as a hide-out. There must have been a reason for it.”

“They are hoping to collect the ransom money in France,” reminded Mr. Vanderskell.

“But why France in particular?”

“I imagine the reason for that was because there would be no risk of passing dollar bills—at least, there would be less risk than in America. Gangsters are well aware that their greatest peril lies in disposing of the money they acquire. The numbers of the notes may have been taken by the police, and so traced back to them. Everyone in Europe needs dollars, and in the black market no questions would be asked about where they came from.”

“Even so, why Vallonceau?” said Cub slowly. “Why not keep the boy in Paris? I feel there must have been a reason for taking him to Provence. There must be a hook-up there, somewhere. If I could put my finger on that . . . but I needn’t go into that now, sir. Will you be here when I get back?”

“I hope so.”

“Where am I, anyway?” inquired Cub, remembering suddenly that he did not know.

“You’ll see when you go out,” replied Mr. Vanderskell, smiling. “Linton will show you the way.” He held out a hand. “Goodbye for now. See me again before you go and we will settle financial details, and so on. Once you get to France don’t attempt to get in touch with me unless you have succeeded, or failed, in what you are going to do. The enemy is watchful, and he has eyes everywhere. Good luck. I shall pray for your success.”

The secretary took Cub to the door.

Cub looked out and smiled to himself as he went down a short flight of steps into Park Lane. Hailing a cruising taxi he ordered, “Leicester Square.”

He found Copper and Trapper still waiting, and somewhat out of patience at his long absence.

Copper eyed him almost belligerently. “Well,” he demanded, “wot ’ave you bin up to?”

“Up to?” echoed Cub. “I’ve been getting myself a job.”

“You mean—you’ve got it?”

“I have.”

“For ten thousand . . . ?” Copper’s voice cracked with incredulity.

“I’ve got the job,” said Cub. “I still have to earn the money. Let’s go somewhere and talk about it.”

The broad, fertile valley of the Rhone lay drowsing under a noonday sun that broadcast heat with a lavish hand from a sky that was sheer lapis lazuli—the sun which has ever drawn a stream of pilgrims from less favoured northern lands. The heavily-loaded Avignon-Vallonceau autobus wheezed and rattled as it made its daily run over the long white ribbon of road that meandered carelessly across the undulating landscape; for the nearest railway being over thirty miles away, the bus was the only regular transport that served its terminus and the scattered farms that lay along its route, a route devoid of shade except for an occasional sprawling olive tree or line of cypresses between endless fields of tawny loam in which vignerons were busy with their precious vines.

Those within the vehicle, mostly women with huge baskets returning from the market in Avignon, sweated profusely as they maintained a steady flow of cheerful conversation in an atmosphere heavy with the pungent reek of garlic. In one of the rear seats sat Cub, his eyes following without interest distant horizons, for he was busy with his thoughts.

Three days had passed since the memorable interview in Park Lane, three busy days, for time was the governing factor in the strange employment to which he was now committed.

It had not taken him long to satisfy the curiosity of his astonished comrades as to the purpose of the advertisement and its subsequent development. The project had there and then been discussed at some length, and it was obvious from the start that Copper and Trapper assumed they would be taking an active part in the operation. To this Cub raised no objection. Indeed, he was only too glad to have their support in a mission in which it seemed more than likely that he would need able and reliable assistance.

He had also confided in his old C.O., Captain “Gimlet” King, half hoping that he would take the lead. He did not like to suggest it, however, and as Gimlet did not offer, the question did not arise. Gimlet merely said that if he, Cub, found himself in difficulties, and would let him know, he would see what could be done about it. In any case, if he could spare the time he might run down later to see how things were going. With this somewhat vague promise Cub had to be content.

Following this, two days had been occupied in making arrangements and dealing with travel formalities in the matter of money, passports and transport. For reasons of mobility, having regard to the isolated situation of their objective, it had been decided to travel by road. As Copper said, they had a car—the Ford, which he knew inside out; with it they would be able to move about freely as circumstances might demand. It was obvious that without their own transport they might find themselves severely handicapped; and so this was agreed.

The question then arose of the advisability of them all arriving in Vallonceau together; for as Cub pointed out, in that case, if the purpose of any one of them was suspected, they would all be suspect; whereas, if it was not realised that they were all in the same party, suspicion might fall on one without affecting the others. In the end it was decided that the party might travel together by road as far as Avignon. They would have to stay a night there, anyhow. Cub would then go on alone on the bus and take a room at the Hotel du Midi, the larger of the two hotels. Copper, who was under the disadvantage of not being able to speak French, would have to go on in the Ford with Trapper. They were to stay at the same hotel without appearing to have any connection with Cub, at any rate in the first instance. Later on it would not matter if they were seen about together, for being of the same nationality it would be only natural that they should get to know each other.

The details settled, the first part of the operation was put into practice. The journey to the South of France had been uneventful, and after a night in the old city of Avignon Cub had gone on alone by bus, having first rung up the hotel to confirm that a room was available. His luggage consisted of a small suitcase, and a haversack, but part of his equipment comprised a sketching outfit, the purpose of which was to provide an excuse for him to sit about and watch any particular building or person. This idea came to him as a result of reading in the guide book that Vallonceau was a popular centre for artists, and a society of poets who made a particular study of the lays sung by troubadours in days gone by. Knowing that the weather was likely to be hot he was lightly clad in an open-necked shirt, grey flannel trousers and tennis shoes. As he had discovered in the war, rubber-soled shoes could have more purposes than mere lightness and comfort.

Just how he was going to proceed when he reached his objective he did not know; it seemed impossible to make any sort of plan until he had at least made a reconnaissance of the place. For which reason he was still deep in thought when he became aware that the bus had left the rolling plains for country of a very different nature. On all sides the ground rose sharply to form hills that were all more or less rugged, with outcrops of grey stone showing through a mantle of thyme and rosemary, the aromatic scent of which was discernible sometimes even in the bus. More than once he noticed a cluster of houses clinging precariously to a hilltop as a swallow’s nest might cling to the side of a house; built of the same material as that on which they stood it was not always easy to determine where the rocks ended and where the houses began. From what he had read he judged Vallonceau to be a similar sort of place on a larger scale, a supposition which presently turned out to be correct.

The bus now entered a gorge, and with steam spurting from its radiator cap toiled noisily up a narrow corniche road that wound in a diminishing spiral to the summit of a hill of some size. Once he caught a glimpse of buildings far above him, on a rocky eminence so steep that he found it hard to believe that any vehicle could reach them. On the other side the hill fell away into a gorge so forbidding that he found it better for his peace of mind not to look too closely into it. Actually, as those who have travelled the region know, there was nothing remarkable about this; but only those accustomed to such roads from birth can regard them with equanimity.

Presently to Cub’s relief a turn brought the bus to a less unnerving prospect, and at the same time drew into view two man-made structures that aroused his astonishment and admiration. One was obviously the Roman amphitheatre referred to in the guide books, an imposing saucer-shaped arena, entirely of stone, with tier upon tier of seats rising in concentric circles in the manner of a modern stadium. Around the top perimeter ran a gangway with a projecting bulwark to prevent spectators falling off the edge to the rocks below as they made their way to their seats. At the lowest level an arched portico was provided for the actors to make their entrances and exits. It all seemed to be in a state of perfect preservation.

The other piece of spectacular masonry was the aqueduct which sprang like a viaduct in a series of arches across an abyss, to carry fresh water to the garrison of the mighty empire that had built it.

The bus made another turn and the frowning portal of the ancient village, a tunnel-like gateway in the wall, came into sight. Through this the bus snorted triumphantly to emerge into the Place de la Republique—as a notice board proclaimed—a broad, flat, gravelled area, that was obviously the terminus of the route since the highway ended there. Beyond it, except for one narrow cobbled way, named, as Cub perceived, the Rue de la Château, no vehicle could pass; at any rate, nothing larger than a wheelbarrow.

The bus came to a stop beside several vehicles already parked in the place, and proceeded to disgorge its freight. Cub picked up his kit and dismounted leisurely; but his eyes were busy. They ran over the other vehicles—four cars, three of them in the last stages of dilapidation, a decrepit tradesman’s van, a post office vehicle and a small truck which in France is known as a camionnette. There was little else to see. In a corner some youths were playing the ever-popular Provençal game called boules. There was the usual café, with a sun-faded awning, giving shade to several small iron tables and chairs. The only clients were a postman, a policeman and a soldier, who, with shirt collars open and sleeves rolled up, sat together round a bottle of wine. The Hotel du Midi was on the opposite side of the square. Cub walked over to it. A rubicund, shirt-sleeved man met him at the door. “Monsieur Petaires?” he questioned cheerfully, reaching for Cub’s suitcase.

Cub confirmed that he was Mr. Peters.

“This way, monsieur.”

Cub followed the man and was shown to his room, a comfortably furnished chamber which he was glad to note was on the first floor.

“Lunch is ready,” announced the man, who later turned out to be the proprietor, as he departed.

Cub had little to unpack. He disposed his small kit on the dressing table, washed, threw his pyjamas on the bed and went down to the dining room where he enjoyed a good lunch.

The meal gave him an opportunity to observe the other visitors staying at the hotel. There were very few. Apparently, as elsewhere, the petrol shortage had hit the tourist traffic. With mild disappointment he observed that it would not be easy to associate any of those present with his own grim business. There was a man who might have been a commercial traveller. He ate noisily with his napkin tucked into his collar. Two young priests sat together talking in subdued tones. There were two middle-aged women, also together, whose conversation told him they were English school teachers on holiday. There was a grey-haired, scholarly-looking old man, who ate with his eyes on a book propped up in front of him. From the familiar way he spoke to the waiter it was evident that he was either a resident or had been there for some time. Finally, there was a tall, cadaverous, long-haired young man who seemed to have gone out of his way to make himself conspicuous by wearing a bright pink shirt, blue corduroy trousers several sizes too large for him, and flimsy sandals. It was to be revealed very soon that he was, or claimed to be, a poet, engaged on a book of verses in the ancient minstrel style. For the moment he rather embarrassed Cub by the way he smiled at him every time their eyes met.

Presently, through the open window, Cub saw the Ford arrive and pull up in the front of the hotel. Copper and Trapper got out. Their luggage was taken in. Very soon they entered the dining room and sat down together. He took no notice of them.

Finishing his coffee quickly, for he was anxious to be doing something, he went out to make a preliminary inspection of the village, if only, at this stage, to get his bearings.

To his annoyance the pink-shirted young man overtook him at the door. “Excuse me, dear sir,” he said in lisping English, “but you are of the English I think, yes?”

Cub did not dispute it.

“I speak the English with perfection,” went on Pinkshirt.

“What about it?” asked Cub, trying not to show his irritation at this delay.

“I adore the English,” gushed Pinkshirt.

Cub drew a deep breath. “I appreciate your sentiments, monsieur.”

“If I can be of service to you I shall have the honour perhaps—yes?”

Cub nodded. “Thank you,” he said, and would have moved on, but he was not to escape so easily.

“You into the air go out?” inquired Pinkshirt.

“I do,” stated Cub.

“But the heat is formidable. You will suffer from a stroke of the sun.”

“I’ll risk it,” said Cub.

“It would be better to sit now and drink perhaps a pressed lemon. Come, I will read you my verses,” offered Pinkshirt eagerly.

“I am not,” replied Cub shortly, “in the mood for poetry.”

“But what I offer, monsieur, is my own work.”

Cub sighed. He did not want to appear churlish. The fellow obviously meant well, but he had spoken the simple truth when he had stated that he was not in the mood for poetry. “Another time,” he suggested.

“And you will allow me to present you with my book of verse?” questioned Pinkshirt. “It costs only fifty miserable francs,” he added as an afterthought.

“I’ll see you later, monsieur,” said Cub, his patience exhausted.

“Bon. But do not call me monsieur. My name is Leon. Call me Leon.”

“Okay—Leon,” agreed Cub, and turning, walked quickly away. If the fellow persisted in his attentions, he thought, he was going to be a nuisance.

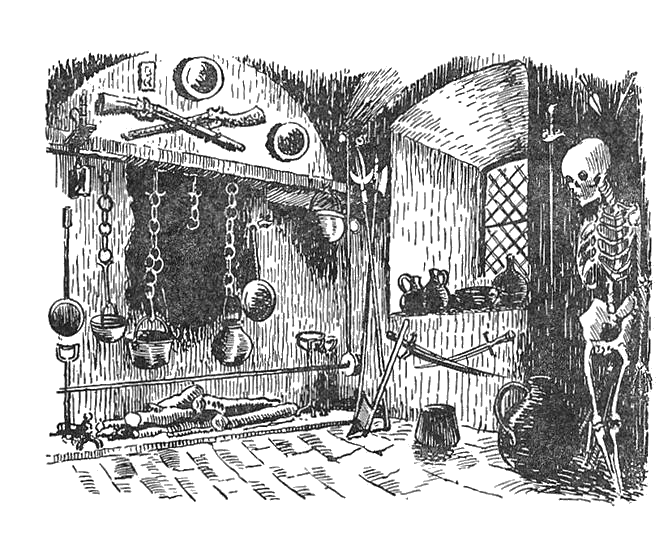

From the guide book Cub had gathered a broad impression of the old village; but even so, what he now saw in reality filled him with amazement. It bore no resemblance to any dwelling place he had ever seen before, or could have imagined. The great age of the place was apparent everywhere. In some strange way, while the rest of the world had moved on, Vallonceau had stood still. Whichever way he turned he was back in the age of men-at-arms, of halberdiers and archers. Enthralled, he walked on slowly, his quest forgotten, except that in a vague way he realised for the first time the difficulties confronting him. He understood now what Mr. Vanderskell had meant by “dead.” It described the place in one word. And the houses, in dying, had leaned wearily against each other, as if weak from a struggle that had for too long been maintained. Not only did the place look dead, thought Cub; it smelt dead. In every narrow alley hung a strange indefinable smell of corruption and decay, of rotting vegetable matter, of goats and manure. It was, decided Cub, the smell of centuries of human habitation. It appalled him, yet, at the same time fascinated him.

There was nothing extraordinary in these reactions. Indeed they were normal. At first sight, any stranger unaccustomed to the medieval villages of Old Provence is at once aware of a feeling of unreality that is at the same time curiously familiar, as if by some magic he has been transported back suddenly through the centuries to a life that he once knew, but had forgotten.

Vallonceau stands, or rather huddles, on a knoll that occurs on the flank of a hill of some size. The local legend is that this knoll was pushed up by a landslide during an earthquake in the distant past. However that may be, the top is not level, but slopes downwards from the château, which stands on a spur at the northern end, to the Place de la Republique, which must at some time have been flattened by hand. Even at first glance it is apparent that the site was chosen and developed with a single object in view—defence. The castle, by no means as large as some, dominates the humble dwellings that seem to cower round it for protection. The whole community is enclosed within a wall some five feet thick, with but a single gateway, so that whichever way one turns in the maze of narrow alleys one is sooner or later brought up by the wall. Approached from within this wall is never more than three or four feet high, so that those inside can loll against it—as they do—to gaze at the impressive scenery beyond. On one side the curious visitor looks down a hundred feet or more into a gorge, on the far lip of which is the amphitheatre. Appearing to connect this with the village is the aqueduct, which is no longer used, but in days gone by ensured an ample supply of water from a spring that gushes out of a neighbouring hill.

On the opposite side of the village the drop is not so deep, a mere thirty feet into the River Gar, which, curling round the parent hill, is in winter a raging torrent, but in summer a bed of sun-bleached stones through which just enough water trickles for the women of the place to use it as a public laundry.

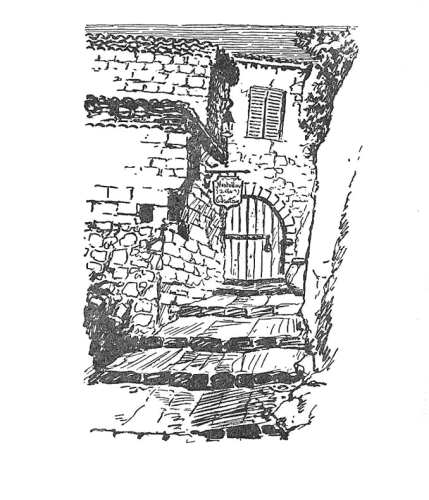

Within the village itself a number of narrow passages, with one exception too narrow for vehicular traffic, wander about in a bewildering fashion. The cobbled street that runs from the Place de la Republique to the castle can boast of only one building of importance, the Hostelrie du Château, outside which a stone bench serves as another reminder of the times in which it was placed there; for its edges are scored and scarred with grooves made by men-at-arms who once sat there to drink their wine and at the same time sharpen their weapons.

Such a brief description as this, however, can do no more than a little to help the reader to visualise what Cub saw as he sauntered along on his first reconnaissance. No two streets are the same. No two houses are alike. The dwellings, all joined together, follow no conventional shape or size—nor, indeed, any shape known to architecture. The place gives the impression of having been thrown together anyhow rather than built—as in fact may well have been the case. Some of the houses form part of the outer wall, often carrying battlements, bastions and barbicans. Others are wedged in between them. Thus, while one window might overlook the gorge, another looks into its neighbour’s midden. Chimneys project at all angles. On one side of a lane there may be a Gothic arch; on the other, a sinister hole leading apparently nowhere. The monotonous uniform grey is broken only by an occasional crimson splash of geranium or cactus.

Not above half of the houses are occupied. From the door of one a cow regarded Cub with bovine indifference. Another provided a home for some scrawny chickens. Cats were everywhere, emaciated, mangy, furtive-looking beasts that eyed the intruder with suspicion, and fitted well, thought Cub, with their surroundings.

There are no shops. The streets, which are streets in name only, wander aimlessly with no apparent purpose, often doubling back and crossing themselves at higher or lower levels. Some plunge down into darkness and are seen no more. At one point a street becomes a flight of steps that vanishes over the rooftops. There is no order in anything.

In every narrow alley hung a strange indefinable smell of corruption and decay

To Cub the place was a nightmare town, a village in delirium, a place that had died long ago in convulsions. In the days of roistering soldiers and swaggering cavaliers it may have been a bright spot, but now it was a veritable place of mystery and dark deeds.

Of the people who still dwelt in this whimsical conception of a village, the descendants of those who perhaps had helped to build it, little was to be seen. The few that were about were mostly old crones who wore nothing but black; but, as Cub realised, the younger men and women during the daytime would doubtless be working in the fields beyond the wall. Those he saw appeared not to see him; they had, he supposed, become accustomed to tourists gaping at their homes as if they were a race of freaks. They probably resented it, as would anyone, but over a period of time had come to accept it as part of their existence. Where, wondered Cub, in all this frantic medley, was he to start looking for Johnny Vanderskell? The thought depressed him.

After several times finding himself back at his starting place, although how he had got there he did not know, he at length emerged on to an open square in front of the château, a piece of rough, weedy ground, which a signboard, leaning askew, informed him was the Place d’Armes. The site commanded a wonderful view of the country around. On one side stood the castle. A little to the right of it was the last house in the village. It seemed a little better than the rest and boasted a small garden, gay with marigolds, and a vine-shaded terrace. To the left was the village, with the Rue de la Château wandering down to the hotel. Behind, that is to say facing the château, ran the village wall, at this point doubly protected by a hedge of ferocious-looking cacti, with leaves like elongated cabbages terminating in bayonet points.

Cub had a good look at the castle. It appeared to be older than any he had seen in Northern France. It reminded him of a war-scarred old veteran in the last stages of decrepitude, although on one side a sun-scorched growth of ivy did its best to conceal its wounds. At some period, apparently, an attempt had been made at modernisation, for a window in the square tower had been glazed and fitted with a sun blind. The glass was broken and the blind a tattered remnant. There were no windows at ground level. The door was a ponderous-looking affair set well back in a stone archway. On the remains of an iron fence a notice board informed Cub that the price of admission was fifty francs, and that tourists who wished to avail themselves of this privilege should apply to the custodian. A crude hand pointed to the house with the marigolds.

Cub was not yet ready for serious exploration, so he turned his steps homeward. On the way he passed the Hostelrie du Château, and just beyond it a high wall over which hung clusters of ripe oranges. There was a door in the wall, and had it been open he would have looked in. He tried it, but found it locked; and he was turning away when he was a little embarrassed to see an old woman knitting at her open door just opposite. To cover his confusion, for he feared she might think he had designs on the oranges, he asked her if the garden was hers. She told him courteously that it belonged to the Hostelrie. He thanked her and walked on. Reaching the Place de la Republique he was making for his hotel when he saw Copper and Trapper sitting outside the café opposite. There was no one else there so he strolled over and sat at the next table to them.

Copper greeted Cub’s arrival with a peculiar smile. “Been ’avin’ a look round the borough?” he inquired cynically.

Cub said that he had.

“So ’ave I,” stated Copper, meaningly.

“What do you make of it?” asked Cub. “Queer old place isn’t it?”

Copper half closed one eye and regarded Cub narrowly.

“Did you say queer?” He turned to Trapper. “ ’Ark at ’im, chum. ’E calls it queer. It’s queer all right, my oath it is, and not ’arf. If you asked me I’d say it’s a loony-bin. Now I know where the army got the sayin’, round the bend. If this billet ain’t round the bend I’d like ter know wot is. Wot say you, Trapper? Am I right?”

Trapper clicked his tongue. “Tch. Every time.”

Copper looked back at Cub. “Don’t they ’ave no sanitary inspectors in these parts? Why, in London——”

“You’re not in London—or in Paris if it comes to that,” reminded Cub. “And I’m not concerned with public health officials.” He dropped his voice. “What worries me is where we’re going to start looking for what we came here to find.”

Copper selected a bent cigarette from a crushed packet and straightened it carefully. “It ain’t no use lookin’,” he asserted. “They could put a circus in this rabbit warren and we’d never find it. Trapper and me walked in circles till I got dizzy and thought we’d met ourselves comin’ back.”

“Well, we’ve got to do something about it,” asserted Cub with some asperity. “It’s no use sitting here waiting for the boy to come to us.”

“Listen, mate,” said Copper earnestly, “if we start poking about in other folks’ houses it’s likely they’ll want ter know wot we’re lookin’ for—and I wouldn’t blame ’em for that. I should meself.”

The truth of this was so apparent that Cub did not argue. He had been thinking the same thing. In his heart he knew that he had been hoping that they would find some sort of clue waiting for them, someone on whom to fasten suspicion. If there were American gangsters in Vallonceau, he had thought, it would not be difficult to pick them out, if only by their accent. But as far as he could judge from his short inspection the type of man he was looking for was simply not there. At all events, there were no suspicious characters in the hotel, and he could not imagine them residing anywhere else in the district. “All we can do,” he decided, “is stick around keeping our eyes open. We may spot something.”

“And wot if we don’t?”

Cub shrugged. “Then we may have to do a spot of serious spying, starting at the most likely places.”

“To me,” observed Copper, “every house in this lopsided rookery looks a likely place for anythin’. Wot places were you thinkin’ of particular?”

“There’s the castle, for instance. There’s the old hostelry——”

“It’s shut. I tried ter get a drink there.”

“You mean, it’s shut altogether?”

“Fini. That’s wot a bloke told me.”

“There’s the amphitheatre.”

“You could see anyone there a mile off.”

“There might be rooms under it.” Cub spoke without conviction.

Copper shook his head. “It don’t make sense ter me.”

Cub fell silent. Copper’s argument was simple but not to be disputed. Now that they were on the spot the difficulties confronting them stood out much more clearly than they had from a distance.

“Well, we shall just have to sit around and watch,” he decided eventually. Looking up he saw Leon the poet walking across the place towards them, waving a piece of paper. “Oh, for goodness’ sake,” he muttered petulantly. “Look what’s coming.”

Copper looked. “Ha! Pinkshirt! Has ’e had a go at you, too?”

“He has,” answered Cub morosely.

“ ’E’s bin tryin’ ter palm ’is poetry off on us,” muttered Copper. “Wanted ter sell me a book of words fer twenty francs.”

“I’m afraid he’s going to try again,” said Cub.

“If ’e does I’ll chuck ’im over the wall,” stated Copper.

“Getting run in for murder isn’t going to help us,” averred Cub sarcastically. “Better be friendly with the chap,” he advised, as the poet, with a song on his lips, tossing his head to keep his hair out of his eyes, pranced up.

The stony stares that greeted him did not discourage him.

“La, la!” he cried. “What think you of our little town so droll?”

“Nothing,” answered Copper without hesitation.

“Ah, mon ami, that is because you do not comprehend its poetry,” declared Pinkshirt, pulling up a chair to face the tables. “Permit me to explain.”

“I know all the poetry I want,” stated Copper grimly.

“You know poetry! But this is entrancing! Now we are as brothers. What is your favourite poem?”

Copper drew heavily on his cigarette and exhaled slowly. “The boy stood on the burning deck,” he announced.

The poet looked puzzled. “But why?”

“Why wot?”

“Why does he stand on a deck that burns, hein?”

“Because,” answered Copper heavily, “I reckon it was too ’ot ter sit on.”

“Then why does he remain? Tell me that? There was a reason?”

Copper’s expression did not change. “Yes. The reason, accordin’ ter the poem, was because all but ’e ’ad fled.”

“Ha! They were cowards?”

By this time Cub was finding it difficult to keep a straight face.

Copper answered. “If you ask me, chum, they must ’ave bin a lot o’ skunks.”

“So. They drink too much?”

“No. I said skunks, not drunks.”

“What is this skunk? I do not know him.”

“A skunk, chum, is a dirty rat.”

“They were animals?”

“You’ve got it.”

“And there was no boat?”

“Not one.”

“No raft?”