* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Biggles at World's End [Biggles #65]

Date of first publication: 1959

Author: W. E. (William Earl) Johns (1893-1968)

Illustrator: Leslie Stead (1899-1966)

Date first posted: March 15, 2023

Date last updated: July 10, 2023

Faded Page eBook #20230329

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

BIGGLES AT WORLD’S END

Biggles of the Air Police has been called upon to fly over many lands, but on this assignment he must not only pit his wits against a formidable opponent but do so in what is acknowledged the most treacherous climate on earth for any type of craft, land, sea or air

BIGGLES

AT WORLD’S END

✹

CAPT. W. E. JOHNS

Illustrated by Leslie Stead

Brockhampton Press

LEICESTER

First published 1959

by Brockhampton Press Ltd,

Market Place, Leicester

Made and printed in Great Britain

by C. Tinling & Co. Ltd,

Liverpool

Text copyright © 1959 by Capt. W. E. Johns

Illustrations copyright © 1959 by Brockhampton Press Ltd

| CONTENTS | ||

| ✹ | ||

| Chapter | page | |

| FOREWORD | 9 | |

| 1 | A MATTER OF HISTORY | 13 |

| 2 | AN UNCIVIL RECEPTION | 24 |

| 3 | DISTURBING NEWS | 35 |

| 4 | A FLIMSY CLUE | 46 |

| 5 | SMOKE | 60 |

| 6 | THE CASTAWAYS | 71 |

| 7 | MR CARTER TELLS HIS TALE | 81 |

| 8 | GONTERMANN SHOWS HIS HAND | 89 |

| 9 | QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS | 100 |

| 10 | THWARTED | 108 |

| 11 | RISKY WORK | 120 |

| 12 | GONTERMANN PULLS A FAST ONE | 130 |

| 13 | THE WEATHER TAKES A HAND | 141 |

| 14 | BATTLE OF WITS | 151 |

| 15 | STALEMATE | 162 |

| 16 | HOW IT ENDED | 173 |

To obviate breaks in the following narrative here are some facts the reader should know about the southernmost tip of the continent of South America which Ferdinand Magellan, the great Portuguese navigator and discoverer of the sixteenth century, named Tierra del Fuego, by reason of the signal fires he saw burning ashore as he made his celebrated and hazardous voyage from the Atlantic to the Pacific through the Strait that bears his name. He was the first man to make the passage.

Before the completion of the Panama Canal in 1920 a ship moving from one ocean to the other had to make the dangerous trip round ‘The Horn’, and a sailor having done this had something to boast about. Between the mainland and the maze of islands that lie south of it runs the Strait discovered by Magellan in 1520, three hundred and fifty miles long and between two and seventeen miles wide. The names of some of the jigsaw pattern of islands and channels speak for themselves: The Furies; Famine Reach; Mount Misery; Desolation Island; Gulf of Sorrows.

Far from being a Land of Fire, this place where the two oceans meet is a land of ice, of savage mountains, gale-lashed cliffs, mighty fjords and terrifying glaciers which crunch and crackle under their weight of ice and cast great masses of it into the sea. In a word, this is the supreme desolation, with the worst climate in the world. Nearly every day of the year it rains, icy rain lashed by furious gales. It is no matter for wonder that much of this inhospitable area has still to be explored. And no wonder this bleak and lonely land has sometimes been called the End of the World. As far as civilization is concerned, it is. Certainly it has been the graveyard of more ships than any other place on earth. One can travel for weeks through the gloomy channels between the islands without seeing any sign of life. Animals are rare, for even in ‘summer’ the ice never entirely disappears. When Magellan went through, his famished crew finished by eating the brine-soaked leather parts of their equipment.

When Charles Darwin, the famous English naturalist, went through the Strait in the ship Beagle, in 1831, he found a few wretched natives, called Alakalufs, eking out a precarious existence on the islands, living on mussels and carrion washed up by the waves. Practically naked, sleeping on the wet ground like animals, always on the move in an endless search for food, he thought they were the lowest type of humanity on earth. Compared with them the Eskimo lived a life of luxury. He wrote: ‘These poor wretches are stunted in growth, their faces hideous, their skins filthy and greasy, their voices discordant and their actions violent.’ He also said: ‘One sight of this dreadful coast is enough to make a man dream for a week of shipwreck, peril and death.’ In his journal we find: ‘The distant channels between the mountains appeared from their gloominess to lead beyond the confines of this world.’

In the Hydrography Records we read: ‘Nowhere does the weather change more quickly or more violently. In no part of the world, the whole year round, is there worse weather. Winter and summer alike, rain, hail, snow and wind are absent only for brief periods. Ice is always present.’

It is not surprising that tourists are rare, although at least there are no flies or mosquitoes. The weather, it seems, is too much even for them!

However, between March and May there may be brief periods of clear skies; and the islands are not entirely destitute of vegetation. There are forests of antarctic birch, pines, willows, moss and lichens.

The territory, both the mainland and the islands, belongs partly to Chile and partly to the Argentine. Magellanes, until recently called Punta Arenas (and as it still appears as such on most maps we shall use that name) is the chief town, with a population of about twenty-five thousand. It is in Chile, and is the most southerly town in the world. It is the centre of the great Patagonian sheep and wool industry. Flocks of forty thousand are not uncommon. This business is chiefly in the hands of a mixed community of Europeans, including British.

With the opening of the Panama Canal the prosperity of Punta Arenas as a store depot and coaling station declined. Fewer ships call now. They nearly all take the shorter and easier route through the Canal.

It was to these inhospitable shores that Biggles was sent on a mission which, while perhaps not resulting in the most spectacular of his adventures, called for more than ordinary skill in airmanship and produced natural hazards that—as he himself put it—were enough to drive any pilot round the bend.

Air Commodore Raymond, chief of the Air Police based on Scotland Yard, leaned back in the chair behind his desk and with the tips of his fingers together regarded his senior operational pilot with the faint smile which Biggles had come to associate with a difficult question and perhaps an even more difficult assignment.

Biggles, who had been sent for, pulled up a chair, sat in it and reached for a cigarette from the box which had been pushed towards him. ‘All right, sir, tell me the worst,’ he requested sadly. ‘I can take it.’

‘How would you like to go on a treasure hunt?’

‘I wouldn’t.’

‘You seem definite about it. Why not?’

‘Because more often than not it means a lot of hard work for nothing.’

‘I see. In that case I’d like to ask you another question. You probably know Erich von Stalhein better than anyone.’

‘I should,’ confirmed Biggles, grimly.

‘If he made a statement supported by nothing but his bare word would you believe him?’

‘Yes.’

‘You would?’

‘Most certainly.’

‘In spite of his record?’

‘If he gave me his word I’d take it in spite of anything. As for his record, mine through German eyes would look just as questionable.’

‘Your confidence in a man whom we know has spent most of his life as a spy would surprise most of the people who know how often you’ve nearly killed each other.’

‘Which means they’re not judges of character. I know von Stalhein. What may be even more to the point, I know his type.’

‘He has on occasion pulled some murky tricks.’

‘So have I if it comes to that, although it could depend on what you mean by murky. It’s all a matter of which side you happen to be on and the methods you’ve been taught to employ.’

‘Well?’

‘Hauptmann von Stalhein is a Prussian, which means that by nature and by training he believes in ruthlessness plus efficiency as the best means of getting what he wants. But that doesn’t make him a liar. As an officer coming from an old military family his pride wouldn’t allow him to sink as low as that, which is why he was bound eventually to come to loggerheads with his late employers on the other side of the Iron Curtain whose clocks are set to tick on lies and hypocrisy. I knew he wouldn’t be able to stomach that for long; in fact I told him so. If he gave me his word I’d accept it, just as he would, I’m sure, accept mine. In that respect our codes are pretty much alike. But what is all this about? Do I understand he’s made a confession of some sort?’

‘Not a confession. Call it a statement.’

‘Voluntarily?’

‘Yes.’

‘He came to this country on the understanding that he wouldn’t be asked to rat on his previous associates. That, considering what they did to him, is a fair indication of the sort of man he is.’

‘He hasn’t ratted on anyone. What he told us came out of the blue. He just thought we might be interested.’

‘Are we?’

‘We most certainly are.’

‘Nothing to do with the Iron Curtain?’

‘Possibly indirectly, but that’s only surmise. Actually, as the information he has given us dates back to the first world war it’s really a matter of history.’

‘Does this in some way hook up with me?’

‘It might. Or let us say you might be involved. That’s for you to decide.’

Biggles nodded sombrely. ‘Ah! Now we’re getting there. Carry on, sir. What’s the job?’

‘It’s a long story, but you’ll have to be patient and listen if you’re to get a grasp on the set-up. Help yourself to cigarettes.’

‘Thanks. Where do we go?’

‘To one of the few parts of the world over which you have not, so far I know, flown. Tell me. Do you remember a German battleship that made front page news for some time in 1914-15?’

‘The Emden?’

‘No. A sister ship. The Dresden.’

Biggles shook his head. ‘If I knew the name I’ve forgotten it. It means nothing to me.’

‘In that case I shall have to refresh your memory. You must remember the sea battle of Coronel, off the coast of Chile, where a German squadron under Admiral Graf von Spee gave us a nasty smack in the eye by wiping out an inferior British fleet under Admiral Cradock.’

Biggles nodded. ‘That rings a bell. And shortly afterwards von Spee’s lot was wiped out at the Battle of the Falkland Islands. Von Spee went there to mop up our naval base and coaling station at Port Stanley. He found some of our boys in blue waiting for him. Right?’

‘Correct. The Admiralty had anticipated the move and rushed out two of our latest battleships, the Invincible and Inflexible. Actually they would have arrived too late had not von Spee stopped to fill his coal bunkers from a British collier. The coal had to be man-handled and it took him three days. That’s the luck of war. When he got to the Falklands he found, as you say, the boys in blue waiting. Outgunned and outclassed for speed he hadn’t a hope. His fleet was blown out of the water with the exception of one ship, the Dresden, which managed to get away by having the good fortune to find a bank of fog. Even so, with the Navy hunting for her she hadn’t much hope of getting back to Germany, wherefore her captain dived into the labyrinth of islands round Tierra del Fuego, and there remained in hiding for three months in spite of the efforts of our ships to find her. We knew she was there.’

‘Did they ever find her?’

‘Not while she was there, which should give you an idea of what a fantastic maze of islands and creeks and narrow channels it is. Eventually shortage of stores, particularly coal, caused her to leave. She slipped out and managed to reach Juan Fernandez, in the Pacific—Robinson Crusoe’s island—before our cruisers, Kent and Glasgow, caught up with her. Then it was all over bar the shouting. That was the end of the last German warship left on the high seas.’

‘Very interesting,’ murmured Biggles. ‘But what has this to do with me?’

‘I’m coming to that if you’ll bear with me a little longer. It was known that the Dresden had sunk some British merchant shipping although not as much as the more famous Emden, which was sunk in the Cocos Islands by the Sydney. What was not known at the time, and is not generally known even now, was that one of the merchant ships sunk by Captain Ludecke of the Dresden was the Wyndham Star, out of Fremantle, Australia, bound for England with a valuable cargo under her hatches. Captain Ludecke couldn’t have known that. What he really wanted was her coal, he having no other means of refuelling except from ships at sea. The question was, had he found and taken the more valuable stuff? Nothing was said about it and it has always been the general belief that he didn’t find it.’

‘What exactly was this valuable cargo?’ interposed Biggles.

‘About a ton and a half of bar gold and nearly half a ton of platinum from the Australian mines.’

A slightly supercilious smile crept over Biggles’ face. ‘Now I get the drift. Would I guess right if I said it now turns out that the Dresden did in fact lift the boodle?’

The Air Commodore returned the smile. ‘You would. You might also guess, without putting any great strain on your brain, what he did with it. He knew his chances of getting home were remote. In fact, his chances of survival were about the same as an ice-cream dropped in a bucket of boiling water. So rather than take the risk of the gold falling back into our hands what did he do with it?’

‘He hid it.’

‘Right again. I see you’re keeping pace with the story. During his enforced stay in the uncharted channels round the islands of Tierra del Fuego he unloaded the stuff. It may well be that he hoped, when Germany had won the war, to retrieve it; but things didn’t work out that way. That gold, of course, is our property—if it is still there and can be found.’

‘And this, I take it, is the fascinating piece of information von Stalhein has handed you.’

‘Yes.’

‘It’s not known definitely that the gold is still where Captain Ludecke put it?’

‘Von Stalhein has never heard of its recovery and he’d be in a position to know if it had ever reached Germany.’

‘How did he learn about this, anyway?’

‘The story was told to him in the first place by an officer of the Dresden who survived. His luck was in, for having been wounded in the Falklands battle he had been put ashore at Juan Fernandez. From his sick bed he watched the Dresden shot to pieces. After the war von Stalhein lost touch with this officer, but quite recently he learned that he was one of the many still being held prisoner by the Russians. He tried to make contact with him but failed. It has now occurred to him that this officer, in order to secure his release, might tell the Russians about the gold. Indeed, just before he himself was thrown into prison he heard a whisper of an expedition being fitted out to fetch some gold from somewhere, and he thinks it may be a part of the same story.’

‘What made von Stalhein decide to tell us about this?’

‘As you know, since he has been here we have kept the wolf from his door by giving him translation work to do; so he may have spilled the beans out of some spirit of gratitude. From the casual way he mentioned the business he didn’t attach any particular importance to it. The thing being outside politics he said he felt free to speak.’ The Air Commodore smiled. ‘What he actually said was, “Bigglesworth might like to know about this. It offers a job that might be right up his street”.’

‘Very kind of him, I’m sure,’ said Biggles, cynically. ‘Did he ask for any reward for this captivating piece of information?’

‘No. But he may have hoped that if the gold was recovered he’d get something out of it.’

‘Does he know exactly where the gold was hidden?’

‘No. He was given only a rough description of the place.’

‘Why wasn’t he told the precise spot?’

‘For the simple reason that having been weaving about in uncharted channels not much wider than his ship Captain Ludecke himself had only a rough idea of where he was. It’s doubtful if he would ever have found his way out had it not been for a German ex-sailor who happened to be working in Punta Arenas and knew those storm-torn waters.’

Biggles nodded. ‘I see. Well, what does all this add up to? Are you suggesting that I go to this ungodly spot in the wild hope of finding myself tripping over a pile of yellow ingots?’

‘Not exactly.’

‘I should think not. Surely this is a job for the Navy. What would I do with two tons of metal if I did find it? Put it in an aircraft and knock the bottom out of it?’

‘Just a minute. There’s no need to get in a flap.’

‘I’m not getting in a flap; but if half a dozen cruisers couldn’t find the Dresden in this uncomfortable glory hole what chance would I have of finding a few lumps of gold probably tucked in a hole in the ground?’

‘It isn’t intended you should look for the gold—anyhow, in the first place. The first thing would be to ascertain if a Russian ship is already there on the same job. I admit that our cruisers couldn’t find the Dresden, but they were looking with a limited view, from sea level. A search from the air would be a very different matter.’

‘I’ll grant you that,’ agreed Biggles.

‘There is also the question of speed. It wouldn’t take you long to get there. It may be a case of the early bird catching the golden worm.’

‘So the idea is, I go down and park myself amongst the ice and snow and rocks to watch that no one uncovers the cache before one of our ships gets there?’

‘That, broadly speaking, is the scheme.’

‘How do I get there?’

‘Fly down the eastern seaboard of South America. There’s an air route all the way with landing grounds when you get there, even on Tierra del Fuego itself. You’ll find them shown on the latest maps.’

‘And what excuse do I give for flying the length of Argentina? People are getting sticky about foreign aircraft waffling about over their territory.’

‘It isn’t like you to be stuck for an excuse.’

‘To say I was going to Cape Horn merely for a joy ride would, I suspect, produce only a long coarse laugh. I’m not pining to see the inside of a South American gaol.’

‘All right. In case you were unable to think of a reasonable excuse I’ve turned up a genuine reason for the trip. Some months ago an English botanist named Carter, under the patronage of the Royal Horticultural Society, went with a friend to the islands to collect specimens of the flora. Nothing has been heard of them since they left Punta Arenas in a small craft which they hired there as the best way—indeed, the only way—of getting about. Foolishly, you may think, they went off without taking with them a local man who knew his way around. It would not be unreasonable if we sent an aircraft down to look for them, or find out, if possible, what has become of them.’

Biggles nodded, but without enthusiasm. ‘As you say, that sounds fair enough. I take it I could be provided with an official document to prove that my purpose in this outlandish place was to find these two crazy plant collectors?’

‘Of course. In fact, while you’re on the spot you might as well have a shot at that, although they’re probably dead by now.’

‘Clubbed to death to make a dinner for the local natives?’

‘That’s most unlikely,’ answered the Air Commodore, apparently taking the remark seriously. ‘There are some natives, not many, and one of them once told a story of how, when food ran out, they knocked the old women on the head and ate them. But that was some time ago. I doubt if they’re cannibals to-day, even if they ever were.’

‘I hope you’re right,’ returned Biggles. ‘I’ve thought of many ways I might end my career but never in a cooking-pot.’ He got up.

‘Well, what about it?’ queried the Air Commodore.

‘I’ll go and have a look at the map, get the thing sized up, and let you know what I think.’

‘All right. But don’t be too long about it,’ requested the Air Commodore.

At the door Biggles turned. ‘By the way, sir. Should this project materialize what aircraft would I use?’

The question seemed to cause surprise. ‘What’s wrong with the machine you usually take on these missions? That old amphibian, the Sea Otter.’

Biggles came back, frowning. ‘Have a heart, sir. There’s nothing wrong with it—yet. That old flying tea chest has served us well and I wouldn’t say a word against her; but she can’t go on for ever, and if she let me down because I asked her to do too much I would only have myself to blame. Apart from the distance, from what you’ve told me about this objective it wouldn’t be a jolly place to have a serious breakdown.’

‘What about the Sunderland you took out to Oratovoa not long ago?’[A]

|

See Biggles on Mystery Island. |

‘She’s a bit on the big side for easy handling in enclosed waters and she takes a fair bit of room to get off. Why do we always have to borrow from the Air Ministry, anyway? If the government wants an Air Police section they’ll have to provide it with equipment. What am I supposed to do—grow feathers? Surely it’s time they gave us a nice new flying machine for long-range work, something a bit more up to date than the obsolete crates we’re expected to aviate.’

‘What do you want—a jet?’

‘Of what use would a jet be to me, the places I have to go and sometimes get down on? I couldn’t expect always to find a mile-long concrete runway waiting for me.’

‘What have you in mind?’

‘A handy all-purpose job, say a five- or six-seater, with a couple of piston engines of proved reliability. Not too many gadgets. I still prefer to fly by the seat of my pants whenever it’s possible.’

‘I’ll see what I can do about it,’ promised the Air Commodore.

‘I’m not complaining,’ went on Biggles. ‘But as you know, my job doesn’t consist of making easy operational fights from one airfield to another with a staff of mechanics at each end. If the government wants an efficient service it’s about time they spent some money on it.’

The Air Commodore agreed. ‘As a matter of fact I heard the other day of a private venture job that should be about your weight. It’s a prototype and may come on the market. It passed its tests and would have gone into production for the RAF had there not been a change of policy.’

‘Do you mean the machine they named the Gadfly?’

‘Yes.’

‘I read about it. From the accommodation and performance figures it should suit us fine.’

‘I’ll make inquiries.’

‘Thank you, sir.’ Biggles went out.

Biggles yawned. ‘We shouldn’t be long now, and I shan’t be sorry when we get there,’ he remarked to Ginger, who was sitting next to him at the controls of the Gadfly. ‘That’s the snag of these long-distance shows,’ he went on. ‘When things go wrong they’re a pain in the neck. When everything goes right they become so confoundedly boring.’

‘We can’t have it both ways,’ returned Ginger, tritely.

‘On the contrary that’s just what we do get,’ argued Biggles. ‘I doubt if there’s a duller way of passing a day than sitting in an aircraft hour after hour doing nothing. Good weather sends you to sleep; bad weather gets you worried.’

‘At least we have a comfortable machine in which to do nothing,’ Ginger pointed out.

With that the casual conversation fizzled out. The plane droned on, heading south-west, thrusting the air behind it at ten thousand feet under a sky of cerulean blue flecked with wisps of wind-torn cirrus cloud.

Nearly a month had elapsed since ‘Operation Recovery’, to give the project its official name, had been discussed in the London headquarters; but it had been a period of activity, for Biggles had learned from experience that the success or failure of a long-distance flight depended as much on ground work before the start as the actual flying. Wherefore everyone engaged, and this was Biggles’ entire staff, knew all there was to know and had made himself familiar with the objective as far as this was possible from maps, charts, Admiralty Instructions and the Meteorological Handbook on the locality.

In the matter of a new machine the Air Commodore had been as good, if not better, than his word. In view of the urgency and importance of the proposed mission, within three days authority had been obtained for the purchase of the Gadfly. Biggles had then put the machine through its acceptance trials, and being satisfied took delivery, with the result that it was now officially on the strength of the Air Police. After that, with the route already mapped, documents prepared and preparations complete, the Gadfly was soon airborne on its first operation.

Actually, in appearance the machine bore little resemblance to the insect after which it had been named. It was an all-metal, high wing gull-shaped cantilever monoplane amphibian flying-boat of aluminium-alloy construction with twin thousand horse-power engines, horizontally opposed, installed in the wing. It had accommodation for two pilots, radio and navigation cabins, and seating capacity for six passengers. The endurance range was fifteen hundred miles, but an extra tank which had been fitted at Biggles’ request gave it another five hundred. Side floats were attached to the wing by a single streamlined strut. Three-blade constant speed airscrews, retractable landing gear and hydraulic wheel brakes made up an aircraft that was easy to handle and promised to do efficiently any job within the capability of its performance. Biggles would have preferred a wooden hull, holding the view that this was less liable to be holed in the event of collision with an underwater obstruction. However, as he remarked, they couldn’t have everything, and on the whole he was well satisfied with his new equipment. One thing in its favour was, being new, spare parts were available for both the airframe and the power units. So far the machine had lived up to expectations.

Biggles had taken the old route across the Atlantic, from Dakar in West Africa to Natal in Brazil. Thereafter the trunk line down South America had been followed via Rio de Janeiro, Montevideo, Buenos Aires, Bahia Blanca and Santa Cruz. After that the air had become progressively cooler as they approached Rio Gallegos, which had been their last port of call. The weather had been fine all the way, and as they were now in the month of April, in the southern summer, it might be expected to continue.

There had in fact been no trouble of any sort, technical or political, the documents with which Biggles had been provided smoothing the way in the matter of fuel, food and sleeping accommodation at each airport where a night had been spent. There had been no night flying. As Biggles told the others, Ginger, Bertie and Algy, they were not in all that hurry.

Perhaps the most important paper he carried, after the carnet which enabled him to buy fuel and oil on credit, was the one which related to the alleged purpose of the flight. This was to make a search for the missing botanists, Mr Carter and his companion, a man named, it had been ascertained by the Air Commodore, Barlow. Both were middle-aged men with experience of plant collecting in the Andes, but had never before been so far south. No further information had come in about them and the Society that had sponsored their trip was happy about the rescue flight, as they assumed it to be. Biggles had of course every intention of looking for the missing men while he was on the spot, as a sideline to his real purpose for being there.

As far as this was concerned there was so little to go on that in his heart Biggles had not much hope of success. He had seen von Stalhein at his London flat, but all his old enemy could tell him was this: the cache was on the north side of a small island from the top of which, between two cone-shaped hills, it was possible, looking south-east, to see Mount Sarmiento, 7,200 feet, and beyond it, in line, the tip of Mount Italia, 7,700 feet. All this did was to indicate that the cache was in one of the channels towards the far end of the Magellan Strait, nearer the Pacific than the Atlantic ocean. Whether or not the spot had been marked von Stalhein did not know. Nothing could have been more vague, for as Biggles pointed out, there was no suggestion of distance. The two mountains named might be anything from ten to fifty miles from the island where the gold had been unloaded.

‘All we have to do, old boy, is to trot up all the bally hills until we find the one from which we can spot the jolly old mountains lined up, if you see what I mean,’ Bertie had remarked, cheerfully.

‘You can do the trotting,’ Biggles had told him. ‘I’m nothing for mountains, anywhere or at any time.’

‘I’d make a small bet that we shall never need a spade or shovel,’ Algy had offered.

On the way south there had been some curiosity by customs officials about a spade, shovel and crow-bar, which Biggles had included in the equipment. In reply to questions about the purpose for which these tools were intended he pointed out that should the missing botanists be found dead they would have to be buried, and he would prefer not to scratch a grave with his bare hands. This turned into a grim joke what might have caused embarrassment, for the real purpose of the tools was an entirely different matter. Biggles himself was doubtful if they would be needed, but he thought it advisable to be prepared. As he said to the others, they might have to do some digging, and they would look silly if they had nothing with which to make a hole.

Incidentally, their small-arms, pistols and a rifle, they were allowed to keep as they were in transit. Knowing the import of firearms was forbidden in the countries through which they would have to pass they had declared them to the Customs officers, and this correct procedure had, as so often happens, paid off. They were merely requested not to use them except in the unlikely event of being attacked by man or beast. They would have to show them on their way home to prove that they had not been sold in the country concerned.

Biggles’ final instructions had been simple and explicit. Should the cache be located all he had to do was make a signal home when a ship would be sent out to collect the bullion. It would of course be too heavy for the aircraft to carry, and in any case its transportation by air would almost certainly lead to political difficulties. They would have to wait for the ship to arrive in order to point out the spot. Should a foreign ship or party be observed obviously conducting a search a prearranged signal was also to be sent to the Air Commodore.

The Gadfly was now on the last leg of its long journey to Punta Arenas, where Biggles hoped to establish a base from which to make survey flights over the neighbouring land masses and the tortuous channels between them.

Here it should be explained that Tierra del Fuego, the large island that forms the tip of the South American continent, is divided into two parts, the eastern half belonging to Argentina and the western half to Chile. Each country has its own terminal airport, the Argentine air route (which Biggles had so far followed) ending at Rio Grande on the actual island of Tierra del Fuego. Punta Arenas is on the Chilean mainland, on the north side of the Magellan Strait, but Biggles had purposed using it for two reasons, the first being because it was by far the nearer to the area he proposed to search, and the second because Rio Grande, being on the open Atlantic coast, is more exposed to the fury of the gales for which these waters are notorious. In effect, this meant that when he landed he would be on Chilean soil for the first time. After taking off from Rio Gallegos he had for a little while been over Argentina, but having crossed the frontier he was now flying over Chilean territory. It was only a short run, a matter of a hundred and fifty miles, to Punta Arenas, the ultimate objective.

Ahead now appeared a wide stretch of water which he knew must be the famous Magellan Strait, and the purple smudge behind it, the coast of Tierra del Fuego. He made a remark to Ginger to that effect, at the same time retarding the throttle to drop off some altitude.

To Ginger the difference in the temperature was already noticeable even in the cockpit, the more so no doubt because the Gadfly had come straight down from the tropical north. He surveyed the terrain below with interest, and while what he saw may have been impressive it was not conducive to peace of mind in view of what had to be done. Although he had spent some time before the start making himself acquainted with the territory, as far as this was possible from books, in reality it looked even worse than he had imagined. Indeed, what he saw filled him with misgivings, if not alarm; and the idea of looking for anything in such a chaos struck him as being futile. He could well appreciate why the Dresden had not been found.

From two thousand feet the place looked like what it had been called, and in fact was: the end of the earth. An apparently endless accumulation of rocks, water and snow, flung down without any sort of order. Peaks and ridges of rock, some high and some low but all black and forbidding except where they were streaked with snow, cut everywhere into a sombre sky. On the water, white areas that could only mean ice, had been piled up by the pressure of wind into many bays and creeks. Mist hung like cotton wool in valleys. To the east, where the Strait broadened into the Atlantic, waves were leaping to a tremendous height as they fought the stubborn land with savage and relentless fury. Even the vegetation that had secured a foothold on some of the lower slopes looked grim and repellent.

‘Not too hot, old boy,’ said Bertie, putting his head into the cockpit. ‘Glad I brought my winter woollies.’

‘You’ll need ’em,’ Biggles told him, briefly.

The Gadfly went on losing height slowly, and presently, having followed the northern shore of the Strait, picked up the town of Punta Arenas and, conspicuous from its flat area, and the buildings on it, the airfield. A small air liner carrying Chilean registration letters stood near them.

Biggles made a landing on muddy ground, taxied on to the buildings and switched off. ‘Well, we’re here, anyway,’ he said. ‘Mind your p’s and q’s, everyone. You all know the drill. Whatever happens we must keep on good terms with these people or we shall have wasted our time coming here.’

‘What are you going to do?’ asked Algy.

‘We’ll check in and make known why we’re here, for a start. After that we’ll go into the town, and having found lodgings, ask if there’s any recent news of Carter and Barlow, the botanists.’

‘I don’t know about botanists. They must be fanatics to come to a place like this to look for buttercups and daisies, and what have you,’ muttered Ginger.

‘It’s all a matter of taste,’ returned Biggles. ‘Some people would rather find a new flower than a gold mine. Let’s get out and stretch our legs. I prefer sitting to standing, but one can have too much of it. Let’s hope someone here speaks English.’

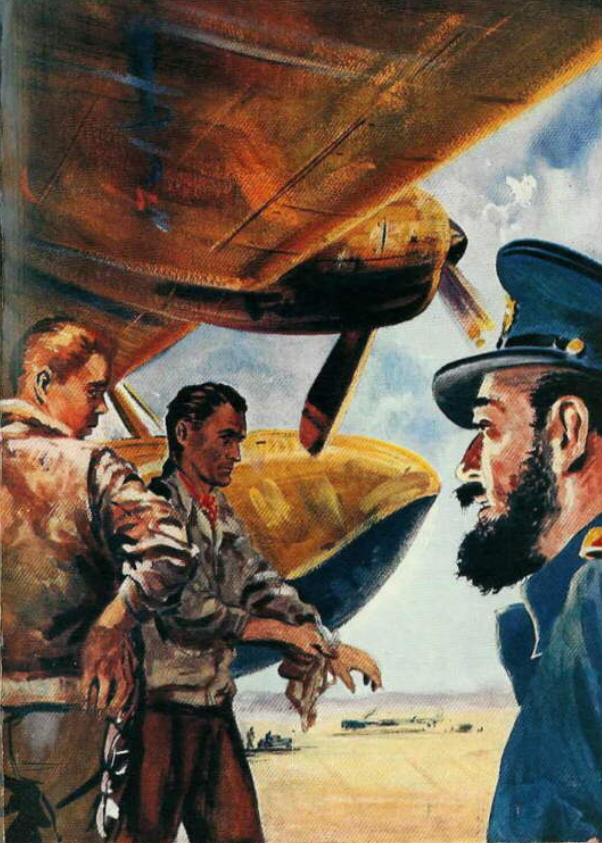

Having got out, as they walked towards what appeared to be the central office a man emerged and strode purposefully to meet them; and before many words had been spoken Ginger perceived they had struck officialdom in the place where it was least to be desired. Indeed, even before the man spoke he saw from his truculent expression and a pompous manner that they were regarded with disfavour. A powerfully built type of perhaps fifty years of age, he wore a faded dark blue uniform. His eyes, under shaggy iron-grey brows, were the colour of ice, and as cold. An untrimmed beard, well streaked with grey, created an impression that he had once been a seaman. Between his teeth he held a curly pipe with a large bowl. He certainly did not look Latin, neither Chilean nor an Argentine, as was the case with a much younger man, also in uniform, who followed at a respectful distance.

The older man spoke. ‘You are British,’ he said, in good English, although the way he said it had the ring of a challenge.

To Ginger it seemed the question was unnecessary in view of the registration marks on the Gadfly.

‘We are,’ acknowledged Biggles.

‘Huh.’ There was a wealth of meaning in the ejaculation. ‘You can’t leave your machine here,’ went on the official, curtly.

Biggles looked surprised. ‘Why not?’

‘You will be in the way of this one which is soon to leave.’ The man indicated the liner.

‘I’m sorry,’ said Biggles. ‘Where would you like me to put it?’

‘Over there.’ The man pointed.

By this time Ginger had realized that they were out of luck. The awkward nature of the official was all too evident, for the liner had ample room to manœuvre for its take-off. Why the man should take this attitude was not so clear.

They all waited while Biggles walked back to the Gadfly, and having moved it to the position ordered, returned.

‘You stay long time?’ was the next question, put harshly by the official.

‘Perhaps. I’m not sure about that,’ answered Biggles.

‘Why you come here?’

‘I was on my way to your office to tell you. Are you the manager here?’

‘Yes.’

‘Good,’ said Biggles, imperturbably. ‘I have in my pocket a letter signed by the Chilean Secretary in London requesting the co-operation of Chilean officials in this country. Would you like to see it?’

The man’s aggressive manner abated somewhat. ‘Presently. What you do?’

‘I have come to make a search for two missing English plant collectors.’

The airport manager smiled unpleasantly. ‘You waste your time. They are dead.’

‘Have their bodies been found?’

‘No.’

‘Then how do you know they are dead?’

‘How can they be alive?’

‘That is what I’ve come to find out.’

The man nodded. ‘We will talk in my office. But first the Customs.’ Turning, he gave an order to his assistant, in his own language, to search the machine. Ginger knew enough Spanish to understand that.

‘Si, Señor Gontermann,’ acknowledged the young man respectfully. He was evidently the assistant manager, and had charge of Customs arrangements.

‘We shall of course obey your orders while we are here,’ said Biggles, evenly.

As they followed the manager to his office Biggles said softly to the others: ‘Pity about this. I’m afraid we’ve struck an unpleasant customer.’

‘What’s biting him?’ asked Algy, indignantly.

Biggles shook his head. ‘I wouldn’t know. If you asked me to make a guess I’d say, from his name, he’s a German, or of German parentage. He’s got a chip on his shoulder about something. Something to do with the war, maybe. Anyway, he has the say-so here, so keep civil tongues in your heads, no matter how he behaves, or we might as well go home—that’s if he’d let us.’

The pilots and crew of the liner came out followed by half a dozen or so passengers.

Having watched it take off and take up a course north-west they followed the manager to his office.

There is no need to narrate in detail the conversation, most of it argument, that went on for more than an hour in the airport manager’s office. While Gontermann did not exceed his official duties he was as difficult as was possible for a man in such a position to be. But, as Biggles said afterwards, he might have been worse had it not been for the letter provided by the Chilean office in London, which he showed with the rest of his credentials. Incidentally, as he was travelling purely as a civilian there was, of course, no mention of his association with the police of Great Britain.

Whether Gontermann behaved in this churlish fashion with every visiting aircraft, or whether it was simply because they were British, there was as yet no means of knowing. Gontermann knew about the missing botanists but made it clear from his manner that he couldn’t care less about them. However, he agreed to allow them to use the airfield for the purpose of their search, stipulating that they were not to take aerial photographs. He gave no reason for this, possibly because there wasn’t one, for national security could hardly come into the picture. The truth of the matter was, Ginger suspected, permission to use the airfield was only granted because it could not very well be refused, the travellers and their aircraft being in order according to International Aviation Regulations. It was used by few machines other than the regular service of the LAN (Linea Aerea Nacional) the government-owned company which operated from Santiago, the capital, in the north.

There was trouble about the weapons they carried. Biggles knew there would be. Gontermann wanted to impound them. He would, he said with studied politeness, give them a receipt for them and release them on their departure. Biggles argued that they had been allowed to pass through Brazilian and Argentine airports, and while he did not expect to use them he would feel safer for some sort of protection. In the event of mechanical trouble with the aircraft they might have to shoot something for food. In the end Gontermann said he would allow them to keep the guns provided import duty was paid on them. To this Biggles agreed.

There was another argument about the digging tools, the existence of which was reported by the young Chilean under-manager and Customs officer when he presented his list of contents. Biggles pointed out that should they find the dead bodies of the missing men they would have to bury them. He also said that as it was unlikely they would be able to see the bodies from the air they would make landings if suitable places could be found; in which case, should the machine become bogged, they would need tools to free it. Gontermann was obviously suspicious, and declared that as the visitors had not applied for a prospector’s licence they were forbidden to explore for minerals. However, again he conceded the point, the reason being that there was no law against the importation of such tools.

The matter of their stay being settled, in an atmosphere that was anything but pleasant the party broke up, Gontermann getting into his car without another word and driving off towards the town.

Biggles breathed a sigh of relief and turned to the young Chilean officer who had watched the proceedings with an expression that suggested sympathy for the visitors. ‘Is he always as difficult as that?’ he asked, in Spanish.

The officer, smiling sadly, replied in English. ‘It depends.’

‘On what?’

‘The nationality of the visitors.’

‘Meaning he doesn’t like Englishmen?’

‘That’s right.’

‘He’s a German, isn’t he?’

‘No, he’s a Chilean, but his father, who married a local woman, was a German sailor who had served in the Imperial German Navy.’

‘Perhaps that explains it.’

‘He’s a difficult man for anyone to get on with. He is much alone and spends all his spare time sailing in a little yacht which he keeps in the town. But don’t worry. The staff here are good fellows and they’ll give you service. They don’t like him, either. He is what you would call a bit of a bully. You were unlucky to arrive to-day. He only came because it was the day for the big machine you saw to come.’

‘Will he be here to-morrow?’

‘I think not. I expect he will go sailing.’

‘What’s his Christian name?’

‘Hugo.’

‘And yours, if I may ask?’

‘Juan Vendez, I am always on duty, not that there is much to do. Few people come here, sometimes a prospector or a salesman, but mostly agents for wool and mutton. For the outward journey it may be an official going home on leave or a man who has had enough of the place going back to his own country.’

‘How is it that you speak English so well?’ inquired Biggles, curiously.

‘I lived in England for a year, also France and Germany, to learn the languages necessary for my work. This is an international port, you know, with many foreigners.’

‘Do you like the place?’

‘No. I come from the north where it is warm; but everyone in the Customs and Excise Service must take a turn of duty here because this is not a popular station and no one would volunteer for it.’

‘I can believe that,’ murmured Ginger.

‘I have only a few months left to do, then I return to Santiago.’

‘Tell me, how can I get to the town?’ asked Biggles. ‘Is there a regular conveyance of any sort?’

‘No. With so few passengers such a service wouldn’t pay. One or two taxis may come out to meet incoming machines on the days they are due to arrive. I could telephone your hotel and they would send a car out for you.’

‘We haven’t fixed up anywhere yet.’

‘It doesn’t matter. I shall be going home presently and will take you in the car I use to go to and fro.’

‘Can you recommend an hotel—not too expensive?’

‘I know the very place that should suit you. It is small but clean, and is run by a woman from Scotland whose husband came here to farm sheep but was killed in an accident.’

‘That sounds like our cup of tea,’ said Biggles. ‘Thank you. That’s very kind of you. By the way, do you know anything about the two English plant collectors who came here, went off in a boat and did not return?’

‘I only know what was common gossip at the time. The matter is now forgotten. It is assumed they are dead. The man you should see is Mr Scott, a ship’s chandler near the new mole. Well, they still call it new although it was built in 1927. He will know as much as anyone because it was he who hired out the boat. Naturally, he was not pleased at losing it.’

‘We’ll go and see him,’ said Biggles.

Presently the amiable young officer drove them to the town, and while the absence of trees gave the place a somewhat forlorn aspect Ginger found the streets surprisingly clean with many excellent shops on both sides of the broad main thoroughfare. There was a uniformity about the houses and he saw no large ones.

Vendez dropped them off at the hotel he had suggested, and there they were made welcome and provided with the accommodation they needed by a buxom and rather severe lady who had not lost her native accent. Very soon they were being served in a spotless dining-room with man-sized beef steaks, which met with general approval, for the keen atmosphere had given them all an appetite. Afterwards, over coffee and a cigarette, Biggles fell quiet.

‘What’s on your mind?’ asked Algy, after a while.

‘I’m thinking about this fellow Gontermann,’ answered Biggles, pensively. ‘We shall have to watch our step with him. He’d only need an excuse to start trouble. Frankly, I find myself wondering if his father had any connexion with the Dresden when she was hiding hereabouts. This man we saw this morning would know all about that affair and it might account for his dislike not only of us but of all Englishmen.’

‘In other words, old boy, you think he may be suffering from the same complaint that caused dear Erich to get all worked up about the British?’ guessed Bertie.

‘Something of the sort. But the reason doesn’t really matter. He dislikes us, and we shall do well to remember that.’

‘I was thinking farther than that,’ put in Ginger. ‘Could this passion for sailing, as Vendez told us, have anything to do with the Dresden?’

‘In what way?’

‘He may, or his father may, have heard a whisper about the bullion the Dresden was carrying; in which case he might be looking for it.’

‘I suppose that’s possible.’

‘If I’m right, he wouldn’t take kindly to the idea of other people, which means ourselves, prowling about the islands for any reason whatsoever. Apart from the gold, we might wonder what he was doing. Is that why he was so disagreeable this morning?’

Biggles drew on his cigarette. ‘Could be. We should soon know if you’re right.’

‘Are we doing any more flying to-day?’ asked Algy.

‘No. We need a day off. I think the first thing is to have a word with this Mr Scott who hired Carter and Barlow their boat. If anyone has any ideas of what may have happened to them he should be the man. Let’s walk along.’ Biggles got up.

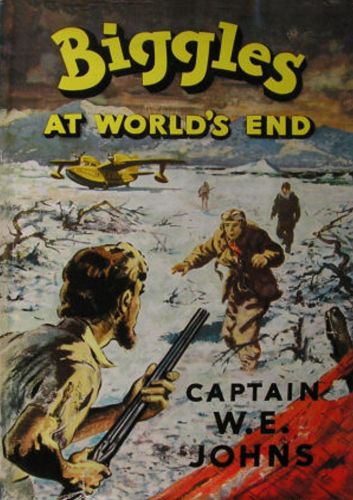

Without any great difficulty they found the ship’s chandler’s establishment with its masses of cordage and the reek of tar. It was, as Vendez had told them, near the mole, where two rust-streaked refrigerator ships, one of them flying the Red Ensign, were busy loading from an extensive freezing plant innumerable carcases of frozen mutton. The odd thought struck Ginger that he might one day, after he had arrived home, find himself eating a chop from one of those same dead sheep.

The ship’s chandler’s establishment was near the mole (page 40)

They went into the shop and made themselves known to the proprietor whose accent again revealed the land of his birth. Having explained what they had come to do Biggles asked Mr Scott if he could give him any information that would assist them in their search.

Mr Scott soon made it clear that this was a sore subject with him, although he was willing to tell them as much as he knew. The two men, he assured them, must have been out of their minds, and he must have been out of his mind to let them have his boat, a ten-ton ketch named the Seaspray, fitted with a small Petter engine. He had suggested they took a pilot with them but they declined on account of the extra expense. They had said they were both experienced yachtsmen and had no fear of not being able to handle the boat. To handle sail at the Isle of Wight was one thing, declared Mr Scott, bitterly; to handle it here was another matter altogether. However, as the men were dead he wouldn’t say unkind things about them.

‘Why are you so sure they must be dead?’ asked Biggles, although as a matter of fact he was of the same opinion.

‘How could they be alive?’ was the reply. ‘They haven’t come back. They had stores for a month, or six weeks at the outside. They couldn’t live on nothing but sea birds even if they had any means of catching them. There’s nothing else except mussels, and there aren’t too many of them.’

‘They didn’t give you any idea of where they were going?’

‘None at all. I doubt if they knew themselves. They just said they were going to cruise among the islands. The weather was fair at the time. They said if it got bad they’d come back.’

‘And did it get bad?’

‘Of course it did. It always does. I told them it would. It never stays fair for long. But they were so cocksure of themselves, the poor fools. I should have known better than to let them go.’

‘What do you supposed happened to them?’

‘A score of things could have happened. They might have been swamped, or capsized trying to get ashore somewhere; or maybe crushed flat by growlers. Places like Icy Reach are always full of ’em.’

‘Growlers?’

‘Aye. Lumps of ice the size of a hoose, or larger, that break off the glaciers and fall into the water. That’s always happening. You’ll hear it if you don’t see it.’

‘You know what we’re hoping to do, Mr Scott. Can you give me any advice?’

‘Aye. The same as I gave Carter and Barlow. Go home. You don’t know what you’re taking on.’

‘I can’t do that without making an effort. I was sent here to do a job and if it’s humanly possible I shall do it.’

‘Have it your own way.’

‘Are we likely to see any natives?’

‘Why?’

‘They might be able to give us some information.’

‘You might see some begging-canoe Indians, as we call ’em, in Indian Reach. A few of ’em hang about there hoping passing ships will throw ’em some food. They need it, poor devils, but don’t give ’em anything.’

Biggles looked astonished. ‘Why not?’

‘Because if you do you’ll never get rid of ’em. The women and kids wouldn’t get any of it, anyway. The men would scoff the lot. They’re a dirty, selfish lot.’

‘They’re not dangerous?’

‘They haven’t much chance to be.’

‘If they’re so badly off why don’t they come here?’

‘Scared, I reckon.’

‘Why should they be scared?’

‘That’s an old story. Years ago, when people started raising sheep, the Indians, who had never seen as much food walking about in their lives, started to help themselves to the sheep, with the result that they were hunted like wolves and nearly exterminated. I suppose they haven’t forgotten it.’

‘So that was it. Tell me this. Had your boat, the Seaspray, any distinguishing features that would enable us to recognize her if we happened to find any wreckage?’

‘Not much. She was painted white and had dark red canvas. The fores’l had been patched a bit with a lighter red. She was the only craft here with sails that colour.’

‘One last question. Can you think of any reason why Hugo Gontermann, the airport manager, should have treated us as if we were a gang of crooks when we landed this morning?’

Mr Scott pursed his lips. ‘I don’t know him well. He seems to be a cross-grained fellow by nature. Perhaps because he comes from German stock he has a particular grievance against anybody British. It was before my time, but the story here is his father served in the Dresden, which as you may know, ran in here to hide after the Battle of the Falklands. You’ve heard of that, no doubt. Gontermann’s mother was a local girl and he was born and brought up here. During Hitler’s war he disappeared and someone told me he’d gone to Germany to enlist. It seems he got in the Air Force, and had become a station commander, or something of that sort. Anyhow, when he came back after the war he seemed to know a lot about planes, and that, with his knowledge of the weather and water here, got him the job at the airport. He was the right man for it. He keeps mostly to himself. Goes sailing a lot on his own. He’s a good sailor, and what’s more important, he knows these waters as well as any living man. Some people reckon he was a German spy, but I don’t know anything about that, except his sympathies are German. But that doesn’t make him a spy. You’ll see his boat, Der Wespe, tied up at the wharf.’

‘Thank you Mr Scott. Now I understand, although why he should hold the war against us I don’t know. After all, if his father served in the Dresden he must have helped to send six thousand British blue-jackets to the bottom at Coronel.’

‘Aye. I’d think that way myself.’

‘Is that all you can tell us?’

‘Yes, except don’t trust the weather for five minutes. A squall can come from anywhere. If you stay here you’ll see what I mean.’

As there was nothing more to be said, having thanked the Scot for his assistance Biggles led the way out. ‘So now we know why Gontermann didn’t greet us with a smile,’ he remarked, as they walked on. ‘The fact that his father served in the Dresden is probably a coincidence. As far as I know it was the only German battleship that came here. At all events, it explains how Gontermann happens to be here. If he served in the Luftwaffe he’ll know all there is to know about flying, so we’d better keep that in mind.’

On the way back to the hotel Biggles stopped at a garage and bought, very cheaply, a second-hand and rather dilapidated old Ford car which he said should be good enough to run them to and from the aerodrome.

‘To-morrow,’ he said, as he drove it home, ‘we’ll have a look round from topsides to see if things are as bad as they say they are.’

The following morning found the party at the aerodrome making ready for the first reconnaissance, Biggles going over the machine with meticulous care while the others attended to the topping up of the tanks. The morning air had a nip in it, but the weather was fair, or as fair as could be expected, with a sky mostly blue although some fleecy clouds were being hounded across it by a sharp easterly breeze. To the satisfaction of everyone Gontermann was not there, no regular machines being scheduled to arrive, but Vendez turned up before they had finished and was as helpful as he could be. He told them Gontermann had gone sailing; he had seen his orange-sailed, black-painted boat, Der Wespe, which being translated from the German meant the Wasp—rather appropriately, Ginger thought—making good time down the Strait.

As soon as the Gadfly was in the air, still climbing, Biggles also headed down the Strait, this being the one conspicuous landmark on which they could rely until such time as others could be fixed. There was not a ship of any size in sight, although a small sailing boat, which from its orange sails they took to be Gontermann’s craft, was heading in the same direction as themselves, the course being almost due south. Some distance ahead the Strait took a sharp turn, running north-west to the Pacific.

Biggles took the Gadfly up to ten thousand feet to get a comprehensive view of the entire landscape, and from that altitude it presented a magnificent although somewhat alarming spectacle of a world untouched by human hands. They might, Ginger thought, have been flying over a new planet. Unfortunately the tops of most of the mountains were wreathed in mist—unfortunately because Ginger, who was sitting beside Biggles with the chart on his knees, was relying on these to get his bearings. He had hoped to be able to plot the two with which they were most concerned, Sarmiento and Italia, but that was obviously going to be difficult unless the breeze freshened sufficiently to tear away the curtains that hid them. Occasionally, here or there this did happen, to reveal a giant, glistening white under its blanket of eternal snow, a truly awe-inspiring sight, the more so because he knew that none of these peaks had ever been climbed, and perhaps never would be. They usually occurred in regions marked on his chart inesplorado—unexplored.

He could not see one object to suggest they were still in the land of the living, but one landmark he thought he recognized was the largest of several glaciers that threaded their way through the mountains. This was the great white river of Vergera, composed of enormous masses of ice, ages old, which threw fascinating blue shadows. He could see the splash of the water when huge lumps broke off the moraine to fall into the water below. The bay at the mouth of the glacier was dotted with islands of blue and white ice. There could be no landing there. In fact, he was worried to see what Mr Scott had called ‘growlers’ on many stretches of otherwise open water.

‘What do you think of it?’ asked Biggles.

‘Awful,’ answered Ginger, grimly. ‘We shall never make anything of this.’

‘I must admit I’m inclined to agree with you,’ returned Biggles, cutting the throttle and beginning to lose height.

‘What are you going to do?’

‘Go down to an altitude more in keeping with what we’re supposed to be doing. I’ve lost sight of the Wasp, but at this height Gontermann will be able to see us and he may wonder what we’re doing up here. I doubt if we could pick out St Paul’s Cathedral if it was down there, much less two castaways.’

‘Do you seriously expect to find those two plant hunters?’

‘I’m keeping an open mind about it. Stranger things have happened. One thing you can rely on while we’re here. I’m not taking any short cuts through clouds. Too many of ’em are solid in the middle. I suppose you couldn’t pick out Sarmiento or Italia?’

‘Not a hope. We shall only do that on an absolutely clear day—if such a thing ever happens here. What do you intend to do about it?’

‘We shall have to work to some sort of plan.’

‘How can you make a plan with this sort of stuff underneath you?’

‘The only thing I can think of is to start combing the islands one by one from a low altitude. We’ll start with one we can recognize from its shape. That should give us our bearings. As we finish each one you strike it off on the chart.’

Ginger looked aghast. ‘That would take months, if not years. I can see nothing but islands. There must be thousands.’

‘You’re right. There are thousands. We might, with a little luck, strike the right one. Anyway, can you think of an alternative?’

‘No; unless it’s to locate some natives and ask them if they know anything.’

‘If we see any Indians I shall certainly do that, if we can find anywhere near to land.’

‘According to Mr Scott some usually hang about in their canoes in a stretch of open water called Indian Reach, to beg food from passing ships.’

‘That must be a slow business. I had a good look, in fact that’s why I went up to ten thousand, and I’m pretty sure that at the moment there isn’t a ship of any size in the Strait. That’s one thing we’ve established. I’ll send a cable to the Air Commodore to let him know that.’

‘Right away?’

‘No. Probably in a day or two. We’d better make certain. A ship, even a large one, lying tucked up in one of these narrow channels, would be hard to spot. You’ve got Indian Reach marked on your chart. We might as well go and have a look at it. If the sky should clear we’ll go up again and try to pick out those two mountains. If we can do that and bring them in line they should act as a pointer. If they could be seen looking south-east from the cache, lining them up from the north-west should give us the rough direction.’

‘The trouble is, there are too many confounded mountains,’ grumbled Ginger.

‘As a clue, a couple of mountains are pretty vague,’ conceded Biggles. ‘But there never was a treasure chart yet, that I’ve ever seen or heard of, that wasn’t vague. Where’s this Indian Reach place?’

Ginger studied the chart and gave the direction.

‘Keep your eyes open as we go,’ requested Biggles.

‘For what?’

‘Anything that looks as if it might be interesting. I’ll go down to about five hundred. I daren’t go any lower, but that should enable you to spot anything like the wreck of that ketch the plant hunters were using, or the smoke of a fire, for instance. Tell Algy and Bertie what we’re going to do. They can keep their eyes skinned, too.’

‘This looks like being a long business,’ muttered Ginger, when he returned.

‘I didn’t expect to do it in five minutes. When we’ve been here a month will be soon enough to grouse. We haven’t started yet. Is that straight piece of water in front of us Indian Reach?’

‘It should be, but I wouldn’t swear to anything here. The place isn’t exactly swarming with Indians, anyway. I can’t see one.’

‘Maybe they only show up when a steamer comes through. They’d see it a long way off from the high ground ashore. What’s more important, can you see any growlers?’

‘No, I can’t see any ice at all in the water. As it’s dead calm we should, I think, if there were any.’

‘All right. Then let’s try a landing and see what happens.’

Biggles lined up the aircraft for the longest approach possible and with Ginger holding his breath put it down without any difficulty on water which, protected by the high land around it, was as flat as the proverbial mill pond. He ran on a little way nearer to the rocky shore of the nearest island, switched off and took out his cigarette case.

‘Now we’ve seen what it looks like we might as well relax for a few minutes and talk about it,’ he remarked. ‘Someone might get an idea.’

Bertie came forward. ‘Not much use trying to think of ideas, old boy, when you’re looking for a pin in a bally haystack.’

‘We knew all about the pin and the haystack before we came here,’ Biggles pointed out. ‘So why bring that up? I wish you would all use your heads more and grumble less.’

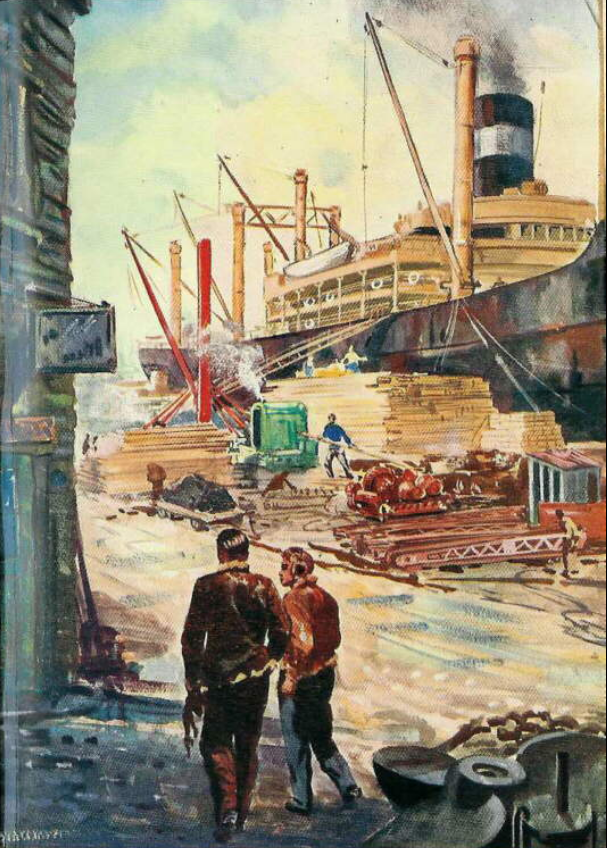

‘I see a canoe coming,’ observed Ginger.

‘From where?’

Ginger pointed. ‘Over there. The people in it must have been picnicking on the rocks—don’t ask me why.’

‘Two men and a kid,’ remarked Algy. ‘What a place to bring a kid.’

‘Maybe it wasn’t brought here,’ returned Biggles. ‘Maybe this is where it lives. I’d say it’s father, mother and child.’

‘People who live in places like this shouldn’t have kids,’ put in Algy.

‘That’s what these people might say if they saw some of our slums,’ said Biggles. ‘I’d wager if you took these people to London they’d be dead inside a month. They obviously know how to live here, but I doubt if they could stand up to the germs, bugs, microbes and what have you, that we have to endure. But here they are. Let’s hope we can find a language we both speak. If they’re in the habit of accosting passing ships that shouldn’t be impossible.’

The canoe, as crazy a little craft as Ginger had ever seen in his life, came alongside. The lower part was a hollowed-out tree-trunk that must have been rotten when it was found. The gunwales were old pieces of flattened tins and the remains of boxes and pieces of fabric thrown up by the sea. These were fastened in place with splinters, fish bones and pieces of wire, in a manner so haphazard that the thing looked as if one wave would knock it to bits.

The canoe came alongside (page 51)

In it was a man, a woman and a small boy, all filthy beyond description. The two adults wore some scraps of sacking tied round their loins. The boy was completely naked. He had no seat, so he simply squatted in three or four inches of icy water which, with a lot of mussel shells, slopped about in the bottom of the canoe. It made Ginger shiver to look at the child. He himself was well wrapped up, and dry, but he was by no means warm. ‘I didn’t know there was anything like this left in the world,’ he muttered.

‘You’ve heard of under-developed people; now you’re looking at some,’ answered Biggles.

‘Some prize specimens, too, I must say,’ put in Algy, disgustedly. ‘Instead of spending millions on rockets why doesn’t somebody do something for these miserable wretches?’

‘The chances are they’ll still be here when civilization has blown itself apart with those same rockets,’ remarked Biggles.

Bertie stepped in. ‘What beats me is how these johnnies manage to live where not even animals will so much as try.’

This conversation was cut short by the man standing up and resting his dirty hands on the side of the aircraft. ‘Tabac—tabac,’ he said, in a coarse voice.

Ginger could hardly believe his ears. It seemed to him that what they all needed was food; yet the man’s first thought was for tobacco—presumably for himself. He remembered what Mr Scott had said when some tins of food were handed out and were put at the feet of the man, not the woman.

Meanwhile Biggles was trying to get into conversation with the man, trying him both in English and in Spanish. It turned out that he knew only a few simple nouns in both languages, having picked them up, probably, from passing ships. But these were not enough to answer the questions Biggles put to him about two white men, alive or dead, who had been cast away. He tried for some time but without result.

‘It’s no use,’ he said at last. ‘We shan’t get anything out of them even if they know anything. All they can think about is food, tobacco and matches.’

‘That’s all I’d be thinking about, too, old boy, if I was paddling that perishing canoe in my pants.’

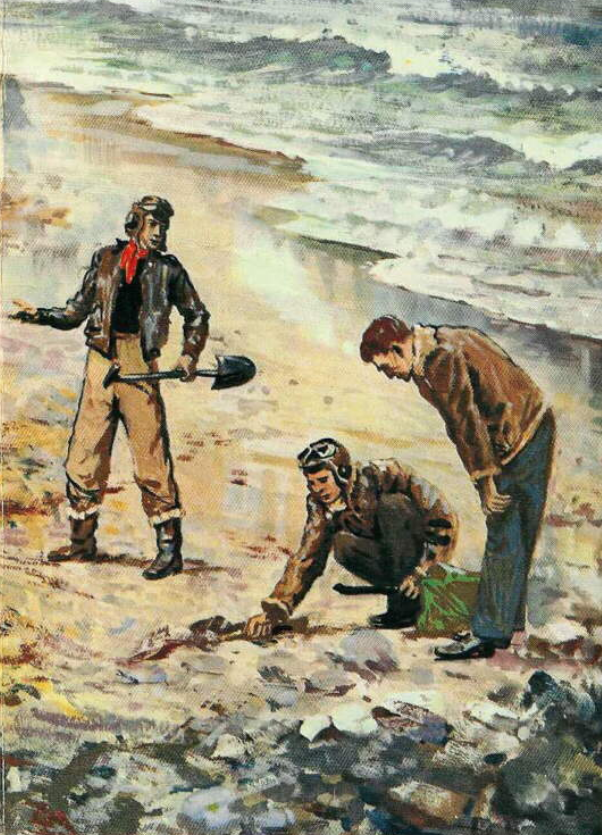

The Indian, having apparently decided that no more tins were forthcoming, pushed off without a word of thanks, and in so doing caused the canoe to swing so that for the first time the far gunwale was revealed.

Ginger caught Biggles by the arm. ‘Stop him,’ he said tersely. ‘Look! The gunwale.’

It was a strip of dark red canvas.

‘That was the colour of the Seaspray’s sails,’ he reminded.

Biggles shouted to the man to come back, but he took no notice, obviously not understanding.

‘Quick, someone, give me another tin,’ snapped Biggles.

Algy handed him one. He held it up. The man understood that readily enough, and paddled back to collect it. This done Biggles pointed at the piece of red canvas. ‘Where come?’ he asked.

The Indian simply stared back at him with a blank animal face.

‘Where come?’ asked Biggles again. ‘Where find?’

The man looked at Biggles. He looked at the object at which he was pointing. Then at last what he thought was required seemed to penetrate his limited intelligence. Without the slightest hesitation he seized the rag, ripped it off and offered it. ‘Tabac,’ he said.

This of course was not what Biggles wanted. He wanted to know where it had come from. But he took it to save an argument that would obviously be futile. ‘Give him another tin of cigarettes,’ he told Algy.

No sooner had the man taken his reward than he snatched up the piece of wood that served as a paddle and started making for the shore.

‘Wait! Come back,’ shouted Biggles; but he might have saved his breath for all the notice that was taken. ‘Confound the fellow,’ he muttered. ‘Why did he have to be in such an infernal hurry?’ He looked up. ‘I wonder if that was the reason?’ he added.

Above them a dark cloud was racing down the channel, and within a minute it had answered his question when everything was blotted out by driving, slashing, icy rain that whipped the hull of the aircraft as with a thousand canes.

‘I begin to see what Mr Scott meant about the weather,’ shouted Biggles, above the noise. ‘We’ll sit where we are till this has passed.’

‘That Indian knew what was coming,’ said Algy. ‘He may come back when it’s over.’

Biggles shook his head. ‘I doubt it. He’ll make for home and scoff the grub we gave him.’

‘So would I, old boy, every time, if I was as peckish as he looked.’

Biggles picked up the strip of red canvas. ‘If this came from the Seaspray there must be more of it somewhere. I’ll show it to Mr Scott when we get back. He’ll know if it’s his.’

‘If he says it is,’ said Ginger, ‘we can say good-bye to any hope of finding Carter and Barlow.’

No one disputed this.

The squall did not last long. The wind abated. The rain stopped as suddenly as it had begun and it was fair again, the sun shining in a sky of palest eggshell blue. But the cold, which must have been near freezing point, persisted.

‘And to think this is summer here,’ remarked Ginger, rubbing his hands to warm them. ‘What must it be like in winter?’

‘I don’t know, and I don’t want to know,’ answered Biggles. ‘We shan’t be here—I hope. But I do know this,’ he went on. ‘If that rain had been hail, and from the temperature it must have been near it, we’d have had some dents knocked in our upper surfaces. In future I’ll be more careful where I stop. Had the wind come from the opposite quarter it could have blown us on the rocks, and without being able to see a blessed thing we wouldn’t have known which way to go to keep clear of ’em. It was a useful illustration of what can happen here. We might as well move on.’

‘What about that Indian?’ asked Algy.

‘While the storm was on I was thinking about him. I doubt if we shall see him again. I’m by no means sure he was as dumb as he appeared to be. I thought he looked scared for a moment when I pointed to this piece of canvas.’

‘You mean, he knew he had no business to have it?’

‘That would depend on how he came by it. What struck me was, if this is in fact a piece of the Seaspray’s canvas, where’s the rest of it? Even if the boat came to grief the sail would still be in one piece. I have a feeling that greasy-looking wretch in the canoe could tell us.’

Bertie spoke. ‘If he’d found the whole thing one would have thought he’d have made himself a decent pair of pants out of it, with enough over to make his missis a respectable skirt—if you see what I mean.’

‘Let’s see if he’s still about,’ suggested Biggles.

They looked, but the canoe had vanished. The only living creatures in sight were some steamboat ducks which had apparently arrived during the storm. On seeing Ginger’s head appear they raced away across the water at fantastic speed, wings whirling, leaving wakes that might have been made by miniature speedboats.

‘The canoe must have run for shelter,’ decided Biggles. ‘It won’t come back. We might as well press on.’

From the air a truly majestic vista was now presented to their gaze. The wind had torn from the peaks the clouds of mist that had previously concealed them, so that they stood, like sentinels, in all their frozen magnificence, gleaming in the sun.

‘That’s better,’ said Biggles, approvingly. ‘This is our chance to pick out Sarmiento and Italia.’

This now proved to be a simple matter, for looking south across Dawson Island the two mountains were outstanding. The nearer was Sarmiento. Flying on towards it the opportunity was taken to note the shape of the shore lines near it, so that its position could again be determined on future occasions even though it was hidden in cloud. The same procedure was followed with Mount Italia, Biggles flying round while Ginger made notes and sketches on a message pad.

This done, seeing more squalls approaching Biggles headed for home. Long before they were within sight of the airfield the two giants had retired behind their customary cloaks of cloud. On the way they kept a lookout for Gontermann’s boat, but they saw nothing of it.

‘I wonder what Gontermann’s really up to,’ murmured Biggles. ‘I can’t believe he gets any pleasure cruising about on his own in these uncomfortable conditions. But still, one never knows. Some people have queer tastes. I remember the famous Captain Slocum, who amused himself sailing round the world alone in a skiff, came through here, and thundering nearly stayed here. But for a change of wind he’d have had it.’

The Gadfly reached home and landed without incident. After a brief chat with Vendez the party returned to the town in the Ford. Biggles drove straight to the chandler’s establishment where they found Mr Scott at work.

He showed the piece of canvas. ‘Does this mean anything to you?’ he asked.

The Scot did not hesitate. ‘That’s a bit of my canvas,’ he declared. ‘Where did you get it?’

Biggles told him.

‘If that Indian hasn’t got the rest he must know where it is,’ asserted Mr Scott, confirming Biggles’ opinion.

‘Assuming he’s got it, what would he use it for?’

‘To make a portable tent, probably. It’d be the nearest thing to a home that Indian ever had. Usually the best they can do is chuck together a few bits of stick they pick up on the beach. It’s no use them wasting time on anything permanent.’

‘Why not?’

‘Because they must always keep on the move looking for food, mussels on the rocks, or if they’re lucky, a piece of rotten fish. Once the rocks have been cleared from one place they must move on to another, or starve. Queer nobody noticed that piece of canvas before.’

‘It would have meant nothing to anyone who might have seen it. You happened to mention to us that the Seaspray’s sails were dark red.’

‘Gontermann would know that.’

‘He may not have seen the canoe. Even if he did, knowing how he feels about Englishmen he wouldn’t be likely to bother about it.’

‘That’s right. How far does this help you?’

‘I’d say quite a long way,’ replied Biggles. ‘From now on I shall be looking for a red wigwam. There can’t be many about here, and one would show up against either black rock or white snow or ice.’

‘Aye. I’d think that,’ agreed Mr Scott.

As the party returned to the Ford, Biggles said: ‘We’ll go home for lunch. I don’t know about you but I’m ready for mine. I think we’ve done pretty well for our first sortie. At least we have something to look for.’

‘What exactly are we looking for?’ asked Ginger pointedly.

‘What do you mean?’

‘Are we looking for two lost plant hunters or a pile of metal jettisoned by the Dresden?’

‘Both,’ answered Biggles, evenly. ‘I know what we were sent here to find, but we should be a bunch of scabs if, while we’re here, we didn’t try to solve the mystery of the disappearance of two of our own countrymen. What’s a lump of gold, anyway, compared with how the relatives of the missing men must be feeling, waiting day after day for news, hoping against hope. The odds are a thousand to one the men are dead, but that has yet to be proved, and if it should happen that they’ve managed to hang on imagine what a state they must be in. This isn’t the sort of place I’d care to end up.’

Nobody answered.

For the next fortnight, whenever weather conditions made it worth while, Biggles carried on with his task. There were long and short occasions when poor visibility would have made flying not only a waste of time, but dangerous, too. On such days the party stayed at home, Biggles refusing to take risks which he held were not justified by the circumstances.

He had sent a letter to the Air Commodore, by air mail, although he had no more to report than his safe arrival on the spot, the absence of shipping in the Strait except those loading meat at Punta Arenas, and the finding of the piece of red sailcloth which made it almost certain that the botanists’ craft, the Seaspray, had been lost.

They saw Gontermann, always smoking his big bent pipe, at the airfield on days when the regular services were scheduled to arrive from the north, and on the whole his churlish attitude seemed to have relaxed somewhat. Which is not to say he was friendly. Far from it. But at least he did nothing to hinder them, and with that Biggles was satisfied. He told the manager about the piece of sailcloth he had found; indeed, he showed it to him; but this, as was expected, only convinced the German that the plant hunters were dead, drowned in all probability when their ketch had been capsized by one of the all too frequent squalls. He advised them to give up the search. In fact, so insistent was he about this that Biggles began to wonder if there was a reason behind it. Anyhow, he declined to abandon the hunt, arguing that even if the Seaspray had lost its sail, or had been dismasted, it would still have its little auxiliary engine to give it headway.