* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Graham's Magazine Vol. XXII No. 5 May 1843

Date of first publication: 1843

Author: George Rex Graham (1813-1894), Editor

Date first posted: Mar. 7, 2023

Date last updated: Mar. 7, 2023

Faded Page eBook #20230314

This eBook was produced by: John Routh & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

GRAHAM’S MAGAZINE.

| Vol. XXII. | PHILADELPHIA: MAY 1843. | No. 5. |

| Fiction, Literature and Articles | |

| 1. | Oliver Hazard Perry |

| 2. | The Pillow of Roses |

| 3. | Henry Wadsworth Longfellow: With a Portrait |

| 4. | The Twin-Sisters: a Leaf From the Journal of an Antiquarian |

| 5. | The Heir of Fleetwood |

| 6. | Review of New Books |

| Illustrations | |

| 1. | Little Red-Ridinghood |

| 2. | The Love Letter |

| 3. | The Family Outing |

The family of Perry has now been American for near two centuries. The first of the name on this side of the Atlantic, was a native of Devonshire, who emigrated to the new world about the middle of the seventeenth century, settling at Plymouth, in Massachusetts. Being of the sect of Friends, however, this residence proved to be as unfavorable to the indulgence of his peculiar religious opinions, as that from which he had so lately migrated in his native island, and he was induced to go deeper into the wilderness. He finally established himself, accompanied by others of his persuasion, on Narragansett Bay, at a place called South Kingston. Here Edmund Perry, for so was the emigrant called, acquired a landed property of some extent, from the Indians, and by fair purchase, which has continued in the possession of his descendants down to our own time.

From Edmund Perry was descended, in the fourth generation, Christopher Raymond Perry, the father of the subject of this memoir, who was born in 1761. This gentleman chose to follow the sea. After serving for some time in private armed vessels of war, during the Revolution, he turned to the merchant service for employment when peace was made, being at that time a very young man, as is seen by the date of his birth. In the course of one of his early voyages, Mr. Perry met with a passenger of the name of Sarah Alexander, a lady of Irish birth, but of Scotch extraction, whom he married, in the year 1781. The fruits of this union were a family of sons, most, if not all of whom have been in the naval service of the country, and of daughters, one of whom, at least, is now the widow of an officer of rank. From this marriage, indeed, have been probably derived more officers of the navy, than from any other one connection, that of the family of Nicholson excepted. The lady who so soon found herself a wife and a mother, in the country of her adoption, proved a valuable acquisition to her new relatives, and left a strong and useful impression on most of those who have derived their existence from her.

The first child of the marriage between Christopher Raymond Perry and Sarah Alexander, was the subject of this memoir. He was called Oliver Hazard, after an ancestor of that name who had died just previously to his birth, as well as after an uncle of the same appellation, who had been recently lost at sea. Oliver Hazard Perry was born on the 20th of August, 1785. The early years of the child were distinguished by no unusual occurrences. He was kept at school, at different places, but principally in the vicinity of the residences of his own family. The armaments against France, however, induced a sudden and material increase of the naval force of the country; and in June, 1798, Christopher Raymond Perry, the father of Oliver, received an appointment as a captain in the new marine. Capt. Perry’s commission placed him the eighth on the list of officers of his rank, but there being no ship of a suitable size for him to take, he was directed to superintend the construction of a vessel that was soon after laid down, at Warren, in his native State. On this occasion, Capt. Perry, accompanied by his wife, removed to Warren, leaving the household in charge of their eldest son, then a boy of only thirteen. This may be said to have been Oliver Perry’s first command, and it is the tradition of the family that he acquitted himself of these novel duties with great prudence, kindness and impartiality. It was certainly a high trust to repose in a boy of his tender years, and proves the complete confidence his parents had in his discretion, temper and good sense. At this period of his life, as indeed he continued to be to a much later day, the youth was obliging, active and of singularly prepossessing appearance; and is said to have been an object of great interest within the limited circle of his acquaintance.

Capt. Perry’s vessel was a small frigate, that was very appropriately named the General Greene. She appears on the registers of the department as a vessel of 645 tons, and rating as a 24. In the journals of the day, however, she is oftener called a 32, which was about the number of guns she actually carried, while her rate would have properly made her a 28. This ship was not ready to sail until the spring of the year 1799. By this time her captain’s eldest son had resolved to enter on a career similar to that of his father’s, and, having some time previously announced his wishes, a warrant was issued to him as a midshipman. Perry’s appointment was dated April 7th, 1799, and made one of a small batch which occurred about that time, generally with intervals of a day between each warrant, and which contained the names of Trippe, Robert Henly, Joseph Bainbridge, Noel Cox, &c., &c.

Soon after Perry joined his father’s ship, or about the middle of May, the General Greene sailed to join the force in the West Indies. Capt. Perry was directed to proceed to the Havana, and to look after the trade in that quarter, as “well as that which passes down the straits of Bahama to the Spanish main.” After remaining a few weeks on her station, the yellow fever broke out in the ship, and she returned to Newport about the close of the month of July. In this short cruise Perry was first initiated in his sea service, and it is a singular circumstance that it was marked by the appearance of that dire disease by which he was, himself, subsequently lost to the country.

By bringing his ship North, Capt. Perry soon purified her, and she sailed again, for the same station, a few weeks later. Thence she went off St. Domingo, to cruise against Rigaud’s barges, which committed many and sanguinary outrages; his orders directing him to circumnavigate the whole island of St. Domingo. While employed on this service, the General Greene found several of the brigand’s light craft at anchor under the protection of some batteries. The ship stood in, and anchoring, a warm cannonade commenced. In about half an hour the batteries were silenced, as was supposed with some loss, but a vessel which had the appearance of a French frigate heaving in sight in the offing, Capt. Perry lifted his anchor, and went out to meet her, without taking possession of his conquests. The stranger proved to be a French built vessel, that had changed masters; being, at the time, in the English navy.

The General Greene next went off Jaquemel to assist Toussaint to reduce the place. The ship is said to have been very serviceable on this duty, and to have had her full share in the success which attended the expedition. In all this service, Perry was present, of course, though in the subordinate station of a young midshipman. It was the commencement of his career, and no doubt had an influence in giving him useful opinions of duty, and in favorably forming his character.

The General Greene was placed under the particular command of Com. Talbot, by special orders from the department, of the date of Sept. 3d, 1799, but did not fall in with that officer until April of the following year, when Capt. Perry reached Cape François, the point from which he had sailed to make the circuit of the island. Here the latter officer was directed to proceed to the mouth of the Mississippi, and receive on board Gen. Wilkinson and family; that officer being then at the head of the army. The frigate arrived off the Balize about the 20th of the month, and sailed again for Newport on the 10th of May. An act of spirit manifested by the elder Perry, on his return home from the Balize, is recorded to his credit, and as affording a proof of the school in which his gallant son was educated. The Gen. Greene had taken an American brig under convoy that was bound into the Havana. Off the latter port, an English two-decked ship fired a shot ahead of the brig to bring her to. Capt. Perry directing his convoy to disregard the signal, and the wind being light, the Englishman sent a boat in chase of the brig. When sufficiently near, the Gen. Greene fired a shot ahead of the boat, as a hint to go no closer. The boat now came alongside of the frigate, and the two-decker closed at the same time, when the latter demanded the reason of the Gen. Greene’s shot. The answer was that it had been fired to prevent the boat from boarding a vessel under her convoy. The English officer, who must have known that this reply, which manifested far more spirit in the year 1800 than it would to-day, was in strict conformity with maritime usage, had the prudence not to persist, and the honor of the American flag was vindicated. This circumstance, taken in connection with a few others of a similar character, which occurred about the same time, had a strong influence in elevating the reputation of the infant navy, and in erasing an unfavorable impression that had been made by the impressment of five men, two years earlier, from on board the Baltimore, 20.

The crew of the Gen. Greene were paid off, as usual, at the end of the year; or, soon after her second return to Newport. Capt. Perry was continued in command of the ship, however, and orders were sent to prepare her for another cruise; but the negotiations for peace assuming a favorable aspect, the orders were countermanded, and the ship was carried to Washington and laid up. The peace-establishment law reduced the list of captains from twenty-eight to nine, and, as Captain Perry was not one of those retained, he retired from service, with Talbot, Sever, the elder Decatur, Tingey, Little, Geddes, Robinson, and others. His son Oliver, however, belonged to the one hundred and fifty midshipmen that the law directed to be retained, and his fortunes were cast for life in the service.

Young Perry was left on shore, to pursue his studies, from the time the Gen. Greene returned from her second cruise, until the spring of the year 1802, when he was ordered to join the Adams, 28, Capt. Campbell, which ship was then fitting for the Mediterranean station. This frigate, known to the navy by the sobriquet of the little Adams, was a vessel a hundred tons smaller than the General Greene, but was deemed one of the fastest ships the country had sent into the West Indies, during the late contest. Her present commander was an officer of gentleman-like habits and opinions, and well suited to inspire young men with the manners and maxims appropriate to their caste. The ship also enjoyed the advantage of possessing a thorough practical seaman in her first lieutenant, the late Com. Hull, who, a short time before, had filled the same station on board the Constitution, 44, Com. Talbot.

The Adams sailed from Newport, June 10th, 1802, and arrived at Gibraltar about the middle of July, where she found Com. Morris, in the Chesapeake, 38, who sent her up as far as Malaga with a convoy. On her return from this duty, the ship was left below to watch a Tripolitan that was then lying at Gibraltar, the remainder of the squadron going aloft. Here the Adams passed the winter, cruising in the Straits much of the time; a duty that the young men in her found irksome, beyond a question, but which they also must have found highly instructive, as nothing so much familiarizes officers to manœuvering, as handling a ship in narrow waters, and with the land constantly aboard. One of the favorite traditions of the service relates to the steady and cool manner in which Hull worked the Adams while employed on this duty, the ship being in great danger of going ashore on the rocks. Six or eight months of such service is equal, in the way of experience, to two or three years of running from port to port, in as straight lines as can be made; or of making sail in good weather, and of reducing it in bad. The Adams must have commenced her blockade of the Tripolitan about the 21st July, 1802, the day Com. Morris sailed, and remained actively engaged on this duty until relieved by the squadron, which did not reach the rock until the 23d March, 1803; this makes a period of eight months and two days. Apart from the instruction which an ambitious youth like Perry must have been conscious of obtaining under such circumstances, this blockade contained an event which is always an epoch in the life of a young officer. Perry was a favorite with his captain, and being studious, attentive to his duties, sedate and considerate beyond his years, and of a person and manner to set off all these qualities to advantage, that officer gave him an acting appointment as a lieutenant. To enhance the gift, Capt. Campbell made out his orders on the young man’s birth-day. This was transferring young Perry from the steerage to the ward-room the day he was seventeen, one of the very few instances of promotions so young, that have occurred in the American navy.[1] As this promotion took place on the 21st August, 1803, and Perry’s warrant was dated April 7th, 1799, it follows that, in addition to his youth, he got this important step when he had been in the service less than four years and five months.

As soon as the squadron came down to Gibraltar, the Adams was sent aloft again with a convoy. As the ship touched at many different ports on the North shore, our young lieutenant had various occasions to visit places at which she stopped, and to store his mind with the pleasing and useful information with which that region abounds, probably, more than any other portion of the globe. There is little doubt that one of the reasons why the American marine early obtained a thirst for a knowledge that is not uniformly connected with the pursuits of seamen, and a taste which perhaps was above the level of that of the gentlemen of the country, was owing to the circumstance that the wars with Barbary called its officers so much, at the most critical period of its existence, into that quarter of Europe. Travelers to the old world were then extremely rare, and the American who, forty years ago, could converse, as an eye witness, of the marvels of the Mediterranean; who had seen the remains of Carthage, or the glories of Constantinople; who had visited the Coliseum, or was familiar with the affluence of Naples, was, nine times in ten, in some way or other, connected with the Navy.

In May, the Adams, in company with the rest of the squadron, appeared before Tripoli, but no service of importance occurred in which there is any evidence that Perry participated. Soon after, Com. Morris left the coast, and his ships separated. The Adams cruised along the South shore, rejoining the squadron at Gibraltar. This gave Perry an opportunity of seeing some of the towns of Barbary. At Gibraltar, the Commodore took the Adams, in person, she being the ship which he had first commanded in the service, and came home in her, Capt. Campbell going to the John Adams, but taking no officers with him.

Perry reached America in the Adams, in November, 1803. His cruise had lasted eighteen months; much of the time the vessel being actually under her canvass. This was, in every respect, a most important piece of service to the young man, and probably laid the principal foundation of his professional character, besides contributing largely to his information and manners as a man. On his return, he is said to have devoted himself earnestly to the studies peculiar to his calling, and to have made laudable efforts to do credit to himself in his new rank. The young officers, however, who made the Mediterranean cruise in 1802 and 1803, were unfortunate as to the time of their service. The following season, or that of the summer of 1804, was the eventful period of the Tripolitan war, and this was the moment when accident left Perry ashore, devoting himself to useful pursuits, it is true, but removing him from those scenes of active warfare in which he was so well qualified to become distinguished. From the close of November, 1803, until the summer of 1804, Perry was on furlough, and at home. One cannot know this, without regretting that a young officer of his peculiar fitness for the service which then occurred before Tripoli, should not have had it in his power to have been with Preble.

In May, or June, of the latter year, however, Lt. Perry received orders to join the Constellation, at Washington, then fitting for the Mediterranean, again, under his old commander and friend, Capt. Campbell. The ship sailed in July, and on the 10th of September, or six days after the explosion of the Intrepid, and just as the last shot had virtually, if not actually, been fired at the town, she appeared off Tripoli, the President, 44, Com. S. Barron, in company. The Constellation was subsequently employed near Derne, in sustaining the operations of Gen. Eaton, but her size rendered her of no great use on that coast.

Among the vessels off Derne was the Nautilus, 14, the schooner of the lamented Somers, and being in want of a first lieutenant, Capt. Campbell ordered Perry to join her in that capacity. Perry was now in his twenty-first year, and had been about six years in the navy. He had made himself a very good seaman, and was accounted a particularly efficient deck-officer. His acquirements were suited to his profession, his manners good and considerate, his appearance unusually pleasing, his steadiness of character such as to awaken confidence, and his mind, if not of an unusually high order, was sufficient to command respect. The new situation in which he was placed, was one to put his professional qualities to the test, and he acquitted himself, notwithstanding his youth, with credit.

Perry remained in the Nautilus till the autumn of 1805, when Com. Rodgers gave him an order to join the Constitution, as one of his own lieutenants. As this officer was very rigid in his exactions of duty, and particularly fastidious in the choice of subordinates, it was a compliment, though no sinecure, to be thus selected, and there can be no question that it was an advantage to one disposed to do his whole duty to serve under his immediate eye. In this ship Perry remained until the autumn of the succeeding year, when he went to the Essex as second lieutenant, following the Commodore, who was about to return home, where they arrived in October.

Perry had now acquired his profession, and obtained respectable rank. At this period of his life, he was known as one of the more promising young officers of the service, and had his full proportion of friends in all the grades of the navy. He was employed in superintending the building and equipment of gun-boats, soon after his arrival at home, and this was the period of his life when he is said to have formed the attachment, which, a few years later, produced a union with the lady he married. After seeing the gun-boats equipped, he was attached to them, for some years, with the command of a division. This disagreeable service, however, finally ended. After superintending the construction of a second batch, for these useless craft were literally put into the water in flotillas, in 1808, he was appointed in April, 1809, to his first proper command. The vessel he got was a schooner, called The Revenge, which had been bought into the service, and which proved to be a very respectable cruiser of her class; her armament consisting of fourteen short and light guns. His predecessor in this schooner was Jacob Jones, who had been one of the oldest lieutenants, if not the very oldest lieutenant in the navy, at the time he commanded her. As Perry had many seniors on the list, his selection for this command is another proof of the estimation in which he was held by his superiors.

The Revenge had been introduced into the navy more as a despatch-boat than as a regular cruiser, but she was subsequently put into the coast squadron, and was in that situation when Perry took her. After passing the summer of 1809, and the winter of 1809-10, in this duty, cruising most of the time on the Northern and Eastern coast, Perry was ordered to take his vessel to Washington for repairs, in April of the latter year. From this place the Revenge sailed on the 20th of May, for the Southern coast, where she was to be stationed. While thus employed, two occasions occurred to enable Perry to prove the spirit by which he was animated, and, on both of which, he acquitted himself with credit. The first was the seizure of an American vessel that had been run away with by her master, an Englishman by birth, who had put her under English colors, as English built. This vessel was lying in the Spanish waters, off Amelia Island, and two small English cruisers were at anchor near her. The Spanish authorities consented to the seizure, which was made by the Revenge, sustained by three gun-boats, and the vessel brought off in the presence of the two English cruisers. It is impossible to say whether the English officers were, or were not apprised of the true circumstances of the case, or how far they were willing to see justice done; but the spirit of Perry is not affected by these facts, as he proceeded in total ignorance of what might be their determination. While carrying his prize off to sea, an English sloop of war was met, the captain of which sent a boat with a request that the commander of the Revenge would come on board and explain his character. The occurrence between the Leopard and the Chesapeake was then fresh, and the utmost feeling existed in the service on the subject of British aggressions. Perry refused to quit his vessel, and prepared for hostilities. His plan was to throw all hands on board his expected foe, and to trust the chances to a hand-to-hand struggle. The Revenge was well manned, and so judicious and cool were his arrangements, that the probability of success was far from hopeless. The desperate resort to force, however, was avoided by the discretion of the English officer, who did not press his demand.

In August, 1810, the Revenge returned North, and was stationed on the coast in the vicinity of Newport. On the 8th of January, 1811, this schooner was unfortunately wrecked on Watch Hill Reef, though many of her effects were saved through the activity of her commander and his people, aided by boats from the squadron then lying in the Thames. This accident was to be attributed to the influence of the tides in thick weather, but the blame, if blame there was, fell solely on the coast pilot, who was in charge at the time. It was one of those occurrences, however, to which all seamen are liable, and which it surpasses human means to foresee or prevent, while the duty on which the vessel was employed was performed. Perry’s conduct, on this occasion, was highly spoken of at the time, and he at least gained in the estimation of the service by an event which, perhaps, tries a commander’s true qualities and reputation as much as any other which can occur to him. A court, consisting of Com. Hull, Lieut, now Com. Morris, and Lieut, the late Capt. Ludlow, fully acquitted Perry of all blame, while it extolled his coolness and judgment. By this accident Perry lost a command, which he had held about twenty-one months.

On the 5th May, 1811, Perry was married to Elizabeth Champlain Mason, of Rhode Island, the lady to whom he had now been attached since the commencement of the year, 1807, and to whom he had been affianced for most of the intervening time. At the time of his marriage, Perry was in his twenty-sixth year, and his bride was about twenty. Not long after, he was promoted to the rank of master and commander. Perry obtained this step when he had not been quite fourteen years in service, and at the age of twenty-six. This was a fair rate of preferment, and one that would be observed even at the present time, with a proper division of the grades, and a judicious restriction on the appointment of midshipmen, a class of officers that ought never to be so numerous as to allow of idleness on shore, and which, in time of peace, should be so limited as to give them full employment when at sea.

The declaration of war, in 1812, found Perry in command of a division of gun-boats on the Newport station. This being a duty in which the chance of seeing any important service was very trifling, his first and natural desire was to get to sea in a sloop of war. Most of the vessels of this class, which the navy then possessed, however, were commanded by his seniors in rank, and those that were not, accident had put in the hands of officers whom it would have been ungracious to supersede. Anxious to be in a more active scene, in the course of the winter of 1812-13, he made an offer to serve on the Lakes. This offer was accepted, and in February, 1813, he was ordered to report to Com. Chauncey, at Sackett’s Harbor, and to take with him such of the officers and men of his flotilla as were suited to the contemplated service.

Perry met his commanding officer at Albany, on the 28th February, and together they set out for the Harbor, which place they reacted on the 3d of March. Here Perry remained until the 16th, when he was ordered to Lake Erie, with instructions to superintend the equipment of a force on those waters. On the 27th, he arrived at the port of Presque Isle, or Erie, and immediately urged on the work, which had been already commenced. There is a portion of military duty that figures but little in histories and gazettes, but which is frequently the most arduous of any on which an officer can be employed. To this class of service belong the preparations that are limited by insufficient means, the procuring of supplies, and contending with the difficulties of hurried levies, undisciplined men, and imperfect equipments. These were the great embarrassments with which Washington had to contend in the war of the Revolution, and his conquests over them entitle him to more credit than he might have obtained for a dozen victories.

As respects the state of the Northern frontier during the last war, the reader of history is not apt fully to appreciate all the obstacles that were to be overcome in conducting the most important operations. In 1813, with very immaterial exceptions, the whole lake frontier, on the American side of those inland waters, was little different from a wilderness. The few roads which communicated with the older parts of the country, were scarcely more than avenues cut through the forests, and not always these, while the streams that it was indispensable to navigate were often obstructed by rapids and even falls, frequently filled with drift wood, and rarely aided by locks, or other similar inventions. Supplies usually had to be brought from the Atlantic towns, and most of the artisans were transported from the sea coast, into those distant wilds. Against the difficulties of this nature Perry had now to contend, and he exerted himself to the utmost. At different periods he received reinforcements of officers and men, and in the course of the spring all of his vessels were got into the water. Still a great deal remained to be done; stores, guns, munitions of war, and, to a certain extent, crews having yet to be assembled.

While thus employed, Perry received the welcome intelligence that the squadron and army below were about to make a descent on Fort George. This enterprise had been contemplated for some time, and Commodore Chauncey had promised to give our young commander the charge of the seamen that were to land. No sooner did he get the information that the expedition was about to take place than he left Erie, in a four-oared boat, on a dark and squally night, and after a laborious passage of twenty-four hours he reached Buffalo. The British batteries were then passed in the same boat, as it descended the Niagara river. It had a narrow escape from a party of the enemy stationed on Grand Island. This party compelled Perry to land, when he proceeded on foot. A horse was finally procured from a common, by the seamen of his boat, a bridle was made out of a rope, a saddle without girth, stirrup or crupper was found, and in this style Perry reached the American camp. Here better equipments were given him, and by the evening of the twenty-fifth he got on board the Madison, 24, in which ship Com. Chauncey’s pennant was then flying.

Chauncey gave his visiter a warm reception. There was a scarcity of officers of rank on the lakes, and Perry had obtained a reputation for zeal and conduct that would be apt to render his presence acceptable on the eve of an important enterprise. When he got on board the ship he found the officers of the squadron assembled to receive their orders, and a general welcome met him. The next morning the commodore went to reconnoitre the enemy’s batteries, taking Perry with him, in the Lady of the Lake. Arrangements were then made for the descent.

It would not be easy to write a better description of the appearance of the fleet, as it advanced to the attack on this occasion, than has been simply but graphically given by Perry himself, in one of his published letters. “The ship was under way,” he says, “with a light breeze from the Eastward, quite fair for us; a thick mist hanging over Newark and Fort George, the sun breaking forth in the East, the vessels all under way, the lake covered with several hundred large boats, filled with soldiers, horses and artillery, advancing toward the enemy, altogether formed one of the grandest spectacles I ever witnessed.” It had been decided that a body of seamen were to be landed, under the immediate orders of Perry, but some irregularity existing in the movements of the brigades, his duties took a more extended range. As the boats pulled toward the shore, Perry saw that the soldiers, who rowed their own boats, were getting too far to leeward, for the wind had freshened; and, pointing out the circumstance to the commodore, he was desired to put them on the right course. Pulling toward the advance, Perry fortified his authority by requesting Col. Scott, who led the troops in front, to join him, and together they proceeded on the duty, which was successfully and very opportunely performed. Col. Scott now rejoined his command, and Perry pulled on board the schooner that was nearest in, covering the debarkation. Here the lookout aloft informed him that the British were advancing toward the lake, in force. Aware that the Americans did not expect such a meeting on the shore, Perry now pulled down the whole line to reach Col. Scott, and apprise him of the resistance he was to meet with. Before he could reach that point, however, the British appeared on the bank and gave a volley. This unexpected attack checked the advance but a moment; the boats being within fifty yards of the beach at the time, were soon on it, and the troops landed. Perry now went on board the Hamilton, a schooner of 9 guns, which vessel maintained a heavy fire of grape and canister on the enemy. Other vessels aided, and the troops forming, rushed up and carried the bank. At this moment, Maj. Gen. Lewis, who was to command in chief on shore, reached the schooner, reconnoitered the ground, and then landed, Perry following him. Throughout all this affair, the latter manifested great temper, the utmost coolness, and a zeal which was certain to carry him into the scenes of danger. Commodore Chauncey mentioned his services honorably in his despatches.

The Americans now had command of the Niagara, and Chauncey profited by it to get several small vessels, that had been bought for the service, but which still lay at Black Rock, past the position of the enemy, and up the current into Lake Erie. Perry superintended this service in person, which was immensely laborious, but was successfully performed. This was clearing the way for assembling all the force on Lake Erie, at a single point, and he sailed from Buffalo for Erie about the middle of June. At this time the command of the lake was with the enemy, and it was a great point to collect all the American vessels, in order to make head against him. This was now done, the enemy actually heaving in sight off their port as the last of the Americans arrived.

The English had long maintained a naval force on the great lakes, which was termed the provincial marine. The vessels were employed for the general purposes of a maritime police for transporting troops, and for conveying supplies. By their means the communications were kept up with the different military posts of the interior, and the command of those inland waters was, at need, effectually secured. The Americans had not imitated this policy. On the upper lakes, however, they kept a brig, which was found almost indispensable to convey the stores needed at the more distant stations, and particularly in the intercourse with the Indians in their vicinity. This brig belonged to the war department, however, and not to the navy. For some years previously to the war she had been commanded by a gentleman of the name of Brevoort, who was then an officer in the 1st Infantry. This brig was called the Adams, and she mounted a few guns. She had fallen into the hands of the enemy at the capture of Michigan, had her name changed to that of Detroit, had been cut out from under Fort Erie the previous autumn by the Americans, and destroyed. This produced the necessity of creating an entirely new force, leaving the command of the lake with the enemy until that object could be effected.

In the face of a thousand obstacles Perry succeeded in getting his vessels ready to go out by the early part of August, though he was still greatly in want of officers and of men, particularly of seamen. Capt. Barclay, who commanded the enemy, lay off the port watching him, however, and there existed a serious obstacle in a bar, which extended some distance into the lake. To cross this bar in the presence of the English would have been extremely hazardous, when, fortunately, the latter unexpectedly disappeared, in the Northern board. It is said that Capt. Barclay had accepted an invitation to dine on the Canada shore, and that he passed over with this intention, probably deceived by his spies as to the state of preparation of the Americans. A reinforcement of men was certainly expected from below, and, if acquainted with this fact, the English officer may very well have supposed that his opponent would wait for it.

It was of a Sunday afternoon when Perry commenced his movements; a day and an hour when the measure was probably least expected. To cross the bar it was necessary to lift the larger vessels on camels, and the work required not only great labor, but much time. It was attended with delays and embarrassments, nor was it entirely effected before the British re-appeared. Some distant firing between them and a few of the American small vessels succeeded, but with little or no damage on either side.

Once in the lake, incomplete as were his crews and his equipments, Perry was decidedly superior to the enemy, who had not yet brought their principal vessel, the Detroit, into their squadron. Under the circumstances, therefore, he wisely determined to bring on an action if possible without any unnecessary delay. Getting under way with his vessels, he went off Long Point in search of the enemy, but failing to find them, as they had gone into Malden to join their new ship, he returned to the anchorage off Erie. Here he received the welcome intelligence that a party of seamen was on its way to join him, from the lower squadron. This reinforcement arrived a day or two later. It was under the orders of Capt. Elliott, who had just been promoted to the rank of master and commander.

As soon as possible, after the arrival of the party from below, the squadron sailed again in quest of the enemy. After communicating with the army above, and ineffectually chasing a British cruiser, it went into Put In Bay, a haven among some islands that lie in the vicinity of Malden, and was favorably placed for watching the enemy. The malady common to these waters in the Fall of the year, had attacked the crew, and Perry himself was soon included among those on the doctor’s list. His case was a very severe one, and to render the matter more grave, all three of the medical officers of the squadron were taken ill also. This was a critical situation to be in, in the face of the enemy, and the more especially, as the vessels were still short of their complements. The latter difficulty, however, was in part remedied, by receiving a hundred volunteers from the army. While lying in this port, the men were exercised in boats, it being Perry’s intention to make an attack on the enemy in that manner, should the latter fail to come out.

Early in September, Perry had so far recovered as to quit his cabin. He now went off Malden to reconnoitre, and to invite the British to meet him. After manœuvering about the head of the lake for a few days, the Americans returned to Put In Bay, on the 6th of September. It would seem Perry received an intimation at Sandusky, that it was the enemy’s intention to come out and engage him, as he was short of provisions, and felt the immediate necessity of opening a communication with his supplies. Subsequent intelligence has confirmed this report, and it is now known that the battle which was fought a few days later was actually owing to this circumstance.

As Perry now fully expected that the English would at least attempt to force a passage toward Long Point, he made his final preparations for a general battle. At a meeting of some of his officers, on the evening of the 9th September, it was determined, at all events, to go out next day, and attack the enemy at anchor, should it be necessary. In order, however, that the reader may have a clear idea of the forces of the respective parties in the approaching action, as well as of their distinctive characters, it is now necessary to give lists of the two squadrons, from the best authorities it has been in our power to consult. The vessels under the command of Capt. Perry, and which were present on the morning of the 10th of September, 1813, were as follows; the Ohio, Mr. Dobbins, having been sent down the lake on duty, a few days before, viz.

| Guns | Metal | |

| Lawrence, Capt. Perry | 20 | 2 lg. 12s, 18 32lb. carronades. |

| Niagara, Capt. Elliott | 20 | 2 lg. 12s, 18 32lb. carronades. |

| Caledonia, Lieut. Turner | 3 | 2 long 24s, 1 32lb. carronade. |

| Ariel, Lieut. Packett | 4 | 4 12s. |

| Somers, Mr. Almy | 2 | 1 long 24, 1 32lb. carronade. |

| Porcupine, Mr. Senatt | 1 | 1 long 39. |

| Scorpion, Mr. Champlin | 2 | 1 long 24, 1 32lb. carronade. |

| Tigress, Lieut. Conklin | 1 | 1 long 32. |

| Trippe, Lieut. Holdup | 1 | 1 long 32. |

| -- | ||

| Total number of guns | 54 |

It is proper to add that all the guns of all the American vessels, with the exception of those of the Lawrence and the Niagara, were on pivots, and could be used together. The vessels which carried them, however, were without bulwarks, and their crews were exposed to even musketry in a close action. Of these vessels, the Lawrence, Niagara and Caledonia were brigs; the Trippe was a sloop; and the remainder were schooners.

The force of the British has been variously stated, as to the metal, though all the accounts agree as to the vessels and the number of the guns.[2] No American statement of the English metal has ever been officially made, but one was appended to Capt. Barclay’s report of the engagement, which should be taken as substantially correct, though a few of its less important details have been questioned by some of the American officers, but not, so far as we have been able to ascertain, on grounds sufficient to render their own recollections certain. The English vessels were as follows, their force being, as stated by Capt. Barclay—

Detroit, Capt. Barclay, 19 guns; 2 long 24s, 1 long 18 on pivot, 6 long 12s, 8 long 9s, 1 24lb. carronade, 1 18lb. do.

Queen Charlotte, Capt. Finnie, 17 guns; 1 long 12 on pivot, 2 long 9s, 14 24lb. carronades.

Lady Prevost, Lieut. Buchan, 13 guns; 1 long 9 on pivot, 2 long 6s, 10 12lb. carronades.

Hunter, Lieut. Bignall, 10 guns; 4 long 6s, 2 long 4s, 2 long 2s, 2 12lb. carronades.

Little Belt, 3 guns; 1 long 12 on pivot, 2 long 6s.

Chippewa, Mr. Campbell, 1 long 9 on pivot.

Total number of guns 63.

On the morning of the 10th September, the British squadron was seen in the offing, and the American vessels got under way, and went out to meet it. The wind, at first, was unfavorable, but so determined was Perry to engage, that he decided to give the enemy the weather-gage, a very important advantage with the armament he possessed, should it become necessary. A shift of wind, however, brought him out into the lake to windward, and left him every prospect of engaging in a manner more desirable to himself.

The enemy had hove-to, on the larboard tack, in a compact line ahead, with the wind at South-East. This brought his vessels’ heads nearly, or quite, as high as S.S. West. He had placed the Chippewa in his van, with the Detroit, Barclay’s own vessel, next to her. Then followed the Hunter, Queen Charlotte, Lady Prevost, and Little Belt, in the manner named. Perry had issued his order of battle some time previously, but finding that the enemy did not form his line as he had anticipated, he determined to make a corresponding change in his own plan. Originally, it had been intended that the Niagara should lead the American line, in the expectation that the Queen Charlotte would lead that of the English; but finding the Detroit ahead of the latter vessel, it became necessary to place the Lawrence ahead of the Niagara, in order to bring the two commanding vessels fairly along side of each other. As there was an essential difference of force between the two English ships, the Detroit being a vessel at least a fourth larger and every way heavier than the Queen Charlotte, this prompt decision to stick to his own chosen adversary is strongly indicative of the chivalry of Perry’s character, for many an officer would not have thought this accidental change on the part of his enemy a sufficient reason for changing his own order of battle on the eve of engaging. Calling the leading vessels near him, however, and learning from Capt. Brevoort, of the army, and late of the brig Adamps, who was then serving on board the Niagara as a marine officer, the names of the different British vessels, Capt. Perry communicated his orders for the Lawrence and Niagara to change places in the contemplated line, a departure from his former plan which would bring him more fairly abreast of the Detroit.

At this moment, the Lawrence, Niagara, Caledonia, Ariel and Scorpion were all up, and near each other, but the Trippe, Tigress, Somers and Porcupine were still a considerable distance astern. All of these small craft but the Porcupine had been merchant vessels, purchased into the service and strengthened; alterations that were necessary to enable them to bear their metal, but which were not likely to improve whatever sailing qualities they might possess.

It was now past ten, and the leading vessels manœuvered to get into their stations, in obedience to the orders just received. This brought the Scorpion a short distance ahead, and to windward of the Lawrence, and the Ariel a little more on that brig’s weather bow, but in advance. Then came the Lawrence herself, leading the main line, the two schooners just mentioned being directed to keep to windward of her; the Caledonia, the Niagara, the Tigress, the Somers, the Porcupine and the Trippe. The prescribed distance that was to be maintained between the different vessels was half a cable’s length.

The Americans were now astern and to windward of their enemies, the latter still lying gallantly with their topsails aback, in waiting for them to come down. Perry brought the wind abeam, in the Lawrence, and edged away for a position abreast of the Detroit, the Caledonia and Niagara following in their stations. The two schooners ahead were also well placed, though the Ariel appears to have soon got more on the Lawrence’s beam than the order of battle had directed. All these vessels, however, were in as good order as circumstances allowed, and Perry determined to close, without waiting for the four gun-vessels astern to come up.

The wind had been light and variable throughout the early part of the morning, and it still continued light, though sufficiently steady. It is stated to have been about a two-knot breeze when the American van bore up to engage. As they must have been fully two miles from the enemy at this time, it, of course, would have required an hour to have brought them up fairly along side of the British vessels, most of the way under fire. The Lawrence was yet a long distance from the English when the Detroit threw a twenty-four pound shot at her. When this gun was fired, the weight of the direct testimony that has appeared in the case, and the attendant circumstances, would show that the interval between the heads of the two lines was nearer two than one mile. Perry now showed his signal to engage, as the vessels came up, each against her designated opponent, in the prescribed order of battle. The object of this signal was to direct the different commanders to engage as soon as they could do so with effect; to preserve their stations in the line; and to direct their fire at such particular vessels of the British as had been pointed out to them severally in previous orders. Soon after an order was passed astern, by trumpet, for the different vessels to close up to the prescribed distance of half a cable’s length from each other. This was the last order that Perry issued that day from the Lawrence to any vessel of the fleet, his own brig excepted. It was intended principally for the schooners in the rear, most of which were still a considerable distance astern. The Caledonia and Niagara were accurately in their stations, and at long gun-shot from the enemy. A deliberate fire now opened on the part of their enemy, which was returned from the long gun of the Scorpion, and soon after from the long guns of the other leading American vessels, though not with much apparent effect on either side. The first gun is stated to have been fired at a quarter before twelve. About noon, finding that the Lawrence was beginning to suffer, Perry ordered her carronades to be tried, but it was found that the brig was still too distant for the shot to tell. He now set his topgallant-sail and edged away more for the enemy, suffering considerably from the fire of the long guns of the Detroit in particular.

The Caledonia, the Lawrence’s second astern, was a prize brig, that had been built for burthen, rather than for sailing, having originally been in the employment of the Northwest Company. Although her gallant commander, Lieut. Turner, pressed down with her as fast as he could, the Lawrence reached ahead of her some distance, and consequently became the principal object of the British fire; which she was, as yet, unable to return with more than her two long twelves; the larboard bow gun having been shifted over for that purpose. The Scorpion, Ariel, Caledonia and Niagara, however, were now firing with their long guns, also, carronades being still next to useless. The latter brig, though under short canvass, was kept in her station astern of the Caledonia, only by watching her sails, occasionally bracing her main-topsail sharp aback, in order to prevent running into her second ahead. As the incidents of this battle have led to a painful and protracted controversy, which no biographical notice of Perry can altogether overlook, it may be well to add, here, that the facts just stated are proved by testimony that has never been questioned, and that they appear to us to relate to the only circumstance in the management of the Niagara, on the 10th of September, that is at all worthy of the consideration of an intelligent critic. At the proper moment, this circumstance shall receive our comments.

It will be remembered that each of the American vessels had received an order to direct her fire at a particular adversary in the British line. This was done to prevent confusion, and was the more necessary, as the Americans had nine vessels to the enemy’s six. On the other hand, the English, waiting the attack, had to take such opponents as offered. In consequence of these orders, the Niagara, which brig had also shifted over a long twelve, directed the fire of her two chase guns at the Queen Charlotte, and the Caledonia engaged the Hunter, the vessel pointed out to her for that purpose; leaving the Lawrence, supported by the Ariel and Scorpion, to sustain the cannonading of the Detroit, supported by the Chippewa, as well as to bear the available fire of all the vessels in the stern of the English line, as, in leading down, she passed ahead to her station abreast of her proper adversary. Making a comparison of the aggregate batteries of the five vessels thus engaged at long shot, or before carronades were fully available, we get on the part of the Americans, one 24 and six 12s, or seven guns in all, to oppose to one 24, one 18, three 12s, and five 9 pounders, all long guns. This is estimating all the known available long guns of the Ariel, Scorpion and Lawrence, and the batteries of the Chippewa and the Detroit, as given by Captain Barclay in his published official letter, which, as respects these vessels, is probably minutely accurate; though it is proper to add that an American officer who subsequently had good opportunities for knowing the fact, thinks that the Chippewa’s gun was a 12 pounder. Although the disparity between 7 and 10 guns is material, as is the difference between 96 and 123lbs. of metal, they do not seem sufficient to account for the great disparity of the injury that was sustained by the Lawrence, more especially in the commencement of the action. We are left then to look for the explanation in some additional causes.

It is known that one of the Ariel’s 12s burst early in the day. This would at once bring the comparison of the guns and metal, as between the five leading vessels, down to 6 to 10 of the first, and 84 to 123 of the last. But we have seen that both the Lawrence and Niagara shifted each a larboard bow gun over to the starboard side, a course that almost any commander would be likely to adopt under the circumstances of the action. It is not probable that the Detroit, commencing her fire at so great a distance, with the certainty that it must be some time before her enemy could get within reach of his short guns, neglected to bring her most available pieces into battery also. Admitting this to have been done, there would be a very different result in the figures. The Detroit fought ten guns in broadside, and she had an armament that would permit her to bring to bear on the Lawrence, at one time, two 21s, one 18, six 12s and one 9 pounder. This would leave the comparison between the guns as 6 are to 11, and between the metal as 84 are to 147. Nor is this all. The Hunter lay close to the Detroit, and as the vessel which assailed her was still at long shot, it is probable that she also brought the heaviest of her guns into broadside, and used them against the nearest vessel; more particularly as her guns were light, and would be much the most useful in such a mode of firing.

But other circumstances conspired to sacrifice the Lawrence. Finding that he was suffering heavily, and that he had got nearly abreast of the Detroit, Perry furled his topgallant-sail, hauled up his foresail and rounded to, opening with his carronades. The distance from the enemy at which this was done, as well as the length of time after the commencement of the fire, have given rise to contradictory statements. The distance, Perry himself, in his official letter, says was “within canister shot,” a term too vague, to give any accurate notion that can be used in a critical analysis of the facts of the engagement. A canister shot, thrown from a heavy gun, would probably kill at a mile; though seamen are not apt to apply the term to so great a range. Still they use all such phrases as “yard-arm and yard-arm,” “musket-shot,” “canister-shot,” and “pistol-shot” very vaguely; one applying a term to a distance twice as great as would be understood by another. The distance from the English line, at which the Lawrence backed her topsail, has been placed by some as far as half a mile, and by others as near as 300 yards. It was probably between the two, nearer to the last than to the first; though the brig, as she became crippled aloft, and so long as there was any wind, must have been slowly drifting nearer her enemies.

On the supposition that there was a two-knot breeze the whole time, that the action commenced when the Lawrence was a mile and a half from the enemy, and that she went within a quarter of a mile of the British line, she could not have backed her topsail until after she had been under fire considerably more than a half an hour. This was a period quite sufficient to cause her to suffer heavily, under the peculiar circumstances of the case.

The effect of a cannonade is always to deaden, or even “to kill,” as it is technically termed by seamen, a light wind. Counteracting forces neutralize each other, and the constant explosions from guns, repel the currents of the atmosphere. This difficulty came to increase the critical nature of the Lawrence’s situation, the wind falling to something very near, if not absolutely to a flat calm. This fact, which is material to a right understanding of the events of the day, is unanswerably shown in the following manner.

The fact that the gun-boats had been kept astern by the lightness of the wind, is mentioned by Perry, himself, in his official account of the battle. He also says, “at half past two, the wind springing up, Capt. Elliot was enabled to bring his vessel, the Niagara, gallantly into close action,” leaving the unavoidable inference that a want of wind prevailed at an earlier period of the engagement. Several officers testify that it fell nearly calm, while no one denies it. One officer says it became “perfectly calm,” and others go near to substantiate this statement. There is a physical fact, however, that disposes of this point more satisfactorily than can ever be done by the power of memories, or the value of opinions. Both Perry and his sailing master say that the Lawrence was perfectly unmanageable for a considerable time. This period, a rigid construction of Perry’s language would make two hours; and by the most liberal that can be given to that of the master, must have been considerably more than one hour. It is physically impossible that a vessel, with her sails loose, should not drift a quarter of a mile, in an hour, had there been even a two-knot breeze. The want of this drift, which would have carried the Lawrence directly down into the English line had it existed, effectually shows, then, that there must have been a considerable period of the action, in which there was little or no wind, and corroborates the direct testimony that has been given on this point.[3]

Previously, however, to its falling calm, or nearly so, and about the time the Lawrence backed her topsail, a change occurred in the British line. The Queen Charlotte had an armament of three long guns, the heaviest of which is stated by Capt. Barclay to have been a 12 pounder, on a pivot, and fourteen 24lb. carronades. The latter guns were shorter than common, and, of course, were useless when the ordinary American 32lb. guns of this class could not be served. For some reason, which has not been quite satisfactorily explained, this ship shifted her berth, after the engagement had lasted some time, filling her topsail, passing the Hunter, and closing with the Detroit, under her lee. Shortly after, however, she regained the line, directly astern of the commanding British vessel. The enemy’s line being in very compact order, and the distance but trifling, the Queen Charlotte was enabled to effect this in a few minutes, there still being a little wind. The Detroit probably drew ahead to enable her to regain a proper position.

This evolution on the part of the Queen Charlotte has been differently accounted for. At the time it was made the Niagara was engaging her sufficiently near to do execution with her long twelves, and, at the moment, it was the opinion on board that brig, that she had driven her opponent out of the line. As the Queen Charlotte opened on the Lawrence with her carronades, as soon as she got into her new position, a more plausible motive was that she had shifted her berth, in order to bring her short guns into efficient use. The letter of Capt. Barclay, however, gives a more probable solution to this manœuvre, than either of the foregoing conjectures. He says that Capt. Finnis, of the Queen Charlotte, was killed soon after the commencement of the action, and that her first lieutenant was shortly after struck senseless by a splinter. These two casualties threw the command of the vessel on a provincial officer of the name of Irvine. This part of Capt. Barclay’s letter is not English, and has doubtless been altered a little in printing. Enough remains, however, to show, that he attaches to the loss of the two officers mentioned, serious consequences; and in a connection that alludes to this change of position, since he speaks of the prospect of its leaving him the Niagara also to engage. From the fact that the Queen Charlotte first went under the lee of the Detroit, so close as to induce the Americans to think she was foul of the quarter of that ship, a position into which she never would have been carried had the motive been merely to get nearer to the Lawrence, or farther from the Niagara, we infer that the provincial officer, finding himself unexpectedly in his novel situation, went so near to the Detroit to report his casualties and to ask for orders, and that he regained the line in obedience to instructions from Capt. Barclay in person.

Whatever was the motive for changing the Queen Charlotte’s position in the British line, the effect on the Lawrence was the same. Her fire was added to that of the Detroit, which ship appeared to direct all her guns at the leading American brig, alone. Indeed, there was a period in this part of the action, during which most, if not all of the guns of the Detroit, the Queen Charlotte, and Hunter, were aimed at this one vessel. Perry appears to have been of opinion that it was a premeditated plan, on the part of the enemy, to destroy the commanding American vessel. It is true, that the Ariel, Scorpion, Caledonia and Niagara, from a few minutes after the commencement of the action, were firing at the English ships, but that the latter disregarded them, in the main, would appear from the little loss the three small American vessels sustained, in particular. The Caledonia and Niagara, moreover, were still too distant to render their assistance of much effect. About this time, however, the gun-boats astern got near enough to use their heavy guns, though most of them were yet a long way off. The Somers would seem to have engaged a short time before the others.

At length, Capt. Elliott finding himself kept astern by the bad sailing of the Caledonia, and his own brig so near as again to be under the necessity of bracing her topsail aback, to prevent going into her, determined to assume the responsibility of changing the line of battle, and to pass the Caledonia. He accordingly hailed the latter, and directed that brig to put her helm up and let the Niagara pass ahead. As this order was obeyed, the Niagara filled and drew slowly ahead, continuing to approach the Lawrence as fast as the air would allow. This change did not take place, however, until the Lawrence had suffered so heavily as to render her substantially a beaten ship.

The evidence that has been given on the details is so contradictory and confused, as to render it exceedingly difficult to say whether the comparative calm of which we have spoken occurred before or after this change in the relative positions of the Lawrence and Caledonia. Some wind there must have been, at this time, or the Niagara could not have passed. As the wind had been light and baffling most of the day, it is even probable that there may have been intervals in it, to reconcile in some measure these apparent contradictions, and which will explain the inconsistencies. After the Niagara had passed her second ahead, to do which she had made sail, she continued to approach the Lawrence in a greater or less degree of movement, as there may have been more or less wind, until she had got near enough to the heavier vessels of the enemy to open on them with her carronades; always keeping in the Lawrence’s wake. The Caledonia, having pivot guns, and being now nearly or quite abeam of the Hunter, the vessel she had been directed to engage, kept off more, and was slowly, drawing nearer to the enemy’s line. The gun-vessels astern were closing, too, though not in any order, using their sweeps, and throwing the shot of their long heavy guns, principally 32 pounders, quite to the head of the British line; beginning to tell effectually in the combat.

As the wind was so light, and the movements of all the vessels had been so slow, much time was consumed in these several changes. The Lawrence had now been under fire more than two hours, and, being almost the sole aim of the headmost English ships, she was dismantled. Her decks were covered with killed and wounded, and every gun but one in her starboard battery was dismounted, either by shot or its own recoil. At this moment, or at about half past two, agreeably to Perry’s official letter, the wind sprung up and produced a general change among the vessels. One of its first effects was to set the Lawrence, perfectly unmanageable as she was, astern and to leeward, or to cause her to drop, as it has been described by Capt. Barclay, while the enemy appear to have filled, and to commence drawing ahead. The Lady Prevost, which had been in the rear of the British line, passed to leeward and ahead, under the published plea of having had her rudder injured, but probably suffering from the heavy metal of the American gun-vessels as they came nearer. An intention existed on the part of Capt. Barclay to get his vessels round, in order to bring fresh broadsides to bear. The larboard battery of the Detroit by this time was nearly useless, many of the guns having lost even their trucks, and, as usually happens in a long cannonade, the pieces that had been used were getting to be unserviceable, from one cause or another.

At this moment the Niagara passed the Lawrence to windward, and then kept off toward the head of the enemy’s line, which was slowly drawing more toward the Southward and Westward. In order to do this, she set topgallant-sails and brought the wind abaft the beam. The Caledonia also followed the enemy, passing inside the Lawrence, having got nearer to the enemy, at that moment, than any other American vessel. As soon as Perry perceived that his own brig was dropping, and that the battle was passing ahead of him, he got into a boat, taking with him a young brother, a midshipman of the Lawrence, and pulled after the Niagara, then a short distance ahead of him. When he reached the latter brig, he found her from three to five hundred yards to windward of the principal force of the enemy, and nearly abreast of the Detroit, that ship, the Queen Charlotte and the Lady Prevost being now quite near each other, and probably two cables’ length to the Southward and Westward; or that distance nearly ahead of the Lawrence, and about as far from the enemy’s line as the latter brig had been lying for the last hour.[4]

Perry now had a few words of explanation with Capt. Elliott, when the latter officer volunteered to go in the boat, and bring down the gun-vessels, which were still astern, and a good deal scattered. As this was doing precisely what Perry wished to have done, Capt. Elliott proceeded on this duty immediately, leaving his own brig, to which he did not return until after the engagement had terminated. Perry now backed the main-topsail of the Niagara, being fairly abeam of his enemy, and showed the signal for close action. After waiting a few minutes for the different vessels to answer and to close, the latter of which they were now doing fast as the wind continued to increase, he bore up, bringing the wind on the starboard quarter of the Niagara, and stood down upon the enemy, passing directly through his line. Capt. Barclay, with a view of getting his fresh broadsides to bear, was in the act of attempting to ware, as the Niagara approached, but his vessel being much crippled aloft, and the Queen Charlotte being badly handled, the latter ship got foul of the Detroit, on her starboard quarter. At this critical instant, the Niagara had passed the commanding British vessel’s bow, and coming to the wind on the starboard tack, lay raking the two ships of the enemy, at close quarters, and with fatal effect. By this time, the gun-vessels under Capt. Elliott, had closed to windward of the enemy, the Caledonia in company, and the raking cross-fire soon compelled the enemy to haul down their colors. The Detroit, Queen Charlotte, Lady Prevost and Hunter struck under this fire, being in the mêlée of vessels; but the Chippewa and Little Belt made sail and endeavored to escape to leeward. They were followed by the Scorpion and Trippe, which vessels came up with them in about an hour, and firing a shot or two into them, they both submitted. The Lawrence had struck her flag also, soon after Perry quitted her.

Such, in its outline, appears to have been the picture presented by a battle that has given rise to more controversy than all the other naval combats of the republic united. We are quite aware that by rejecting all the testimony that has been given on one side of the disputed points, and by exaggerating and mutilating that which has been given on the other, a different representation might be made of some of the incidents; but, on comparing one portion of the evidence with another, selecting in all instances that which in the nature of things should be best, and bringing the whole within the laws of physics and probabilities, we believe that no other result, in the main, can be reached, than the one which has been given. To return more particularly to our subject.

Perry had manifested the best spirit, and the most indomitable resolution not to be overcome, throughout the trying scenes of this eventful day. Just before the action commenced he coolly prepared his public letters, to be thrown overboard in the event of misfortune, glanced his eyes over those which he had received from his wife, and then tore them. He appeared fully sensible of the magnitude of the stake which was at issue, remarking to one of his officers, who possessed his confidence, that this day was the most important of his life. In a word, it was not possible for a commander to go into action in a better frame of mind, and his conduct in this particular might well serve for an example to all who find themselves similarly circumstanced. The possibility of defeat appears not to have been lost sight of, but it in no degree impaired the determination to contend for victory. The situation of the Lawrence was most critical, the slaughter on board her being terrible, and yet no man read discouragement in his countenance. The survivors all unite in saying that he did not manifest even the anxiety he must have felt at the ominous appearance of things. The Lawrence was effectually a beaten ship an hour before she struck; but Perry felt the vast importance of keeping the colors of the commanding vessel flying to the last moment; and the instant an opportunity presented itself to redeem the seemingly waning fortunes of the day, he seized it with promptitude, carrying off the victory not only in triumph, but apparently against all the accidents and chances which, for a time, menaced him with defeat.

[Conclusion in our next.

|

The writer knows of but two other instances of promotions at so very young an age. One was that of the present Capt. Cooper; and the other, that of the late Lt. Augustus Ludlow, who fell in the Chesapeake. In both these instances, he thinks the gentlemen were a little turned of seventeen. Mr. Cooper, however, got a commission, which was not the case with either Perry or Ludlow. Lawrence must have been made acting when little more than eighteen, and Stewart’s original appointment was made when he was only nineteen. |

|

It is extremely difficult to get the exact truth in details of this nature. With the best intentions men make mistakes, and the historian is obliged to depend on such authority as he can get. The foregoing has been laid before the world by the English, as Capt. Barclay’s official account of his own force. It may have some inaccuracies, but it is doubtless true in the main. A biography of Perry has lately appeared, written by Alexander Slidell Mackenzie, a gentleman who is connected with the family of the late Com. Perry, and who has doubtless enjoyed great advantages in collecting many of his personal facts. To this history the writer is indebted for many of his own details in connection with Perry’s early life and services, but the work is written in too partisan a spirit to be at all relied on in matters relating to the battle of Lake Erie. As respects the force of the two squadrons, for instance, Capt. Mackenzie has fallen into material mistakes even in relation to the American vessels; or not only is the writer greatly misinformed, but the incidental evidence which has appeared in the course of the controversy that has arisen from this battle, is untrue. Thus Capt. Mackenzie puts the force of the Somers at “two long thirty-twos.” Mack. Per. p. 228, vol. I. Now this is contrary to the English official account, contrary to every other American account the writer can get, and contrary to the certificate of Mr. Nichols, who commanded the Somers, after Mr. Almy was sent below. This officer, in explaining the silly story about Capt. Elliott’s dodging a shot, says—“the quarter-gunner at the 32, being about to fire,” &c. This language would not have been used had there been two thirty-twos. Capt. Elliott has more than once distinctly called the 32 a carronade, in speaking of this transaction to the writer, and, as the fact cannot affect any question connected with himself, his testimony is certainly good on such a point. Capt. Mackenzie gives the Scorpion two long guns, whereas the writer believes she had but one; the Caledonia three long guns, when she had but two, &c. &c. It is a fact which would seem to have been generally known to the American squadron, that the third gun of the Caledonia, a 32lb. carronade, was dismounted by its recoil, and fell into the hatchway. Capt. Mackenzie’s account of the British metal, the writer entertains no doubt, is materially inaccurate also, while he will not insist that the one he gives himself, from Capt. Barclay, is rigidly correct. The writer will take this occasion to say that the work of Capt. Mackenzie abounds with errors, though he does not wish to disfigure this biographical notice by detailing them. He refers those who have any curiosity on the subject to his own answer to Mr. Mackenzie’s book, which will shortly be published. |

|

In the battle of Plattsburg Bay, which look place the succeeding year, the wind was so light and battling, that the British anchored before they got as close as they had intended to go. Still, one of their vessels, the Chubb, was crippled, and she drifted into the American line, in the first half hour of the engagement. The distance this vessel actually drifted, under such circumstances, was about as far as that at which Perry engaged the enemy, proving that the latter must also have drifted an equal distance, after he was disabled, had there been any wind. The Chubb, too, was a fore-and-aft vessel, a species of craft that would not have the drift of a square-rigged brig, as her sails would be, and probably were, lowered; nor would they hold as much wind. Capt. Pring, in his official account of this battle, excuses his not cutting the brig Linnet’s cable, after the Constance had struck, and endeavoring to escape, on the ground that his vessel was crippled, and that had he done so, she would have drifted directly into the American line. “The result of doing so (cutting the cable,) must,” he says, “in a few minutes have been her drifting alongside of the enemy’s vessels, close under our lee.” The distance was almost two cables’ length, or 480 yards; 440 yards being a quarter of a mile. Those who believe that Perry engaged the enemy at a less distance than this, increase the probability of his drifting into the British line, had there been any wind. The fact that he did not, is conclusive on the subject of the wind. It should also be remembered that Perry, in saying that the Lawrence was disabled, does not in the least speak figuratively, but literally. His words are “every brace and bowline being shot away, she became unmanageable, notwithstanding the great exertions of the sailing master.” A square rigged vessel, without a brace or bowline, is perfectly unmanageable, as a matter of course. |

|

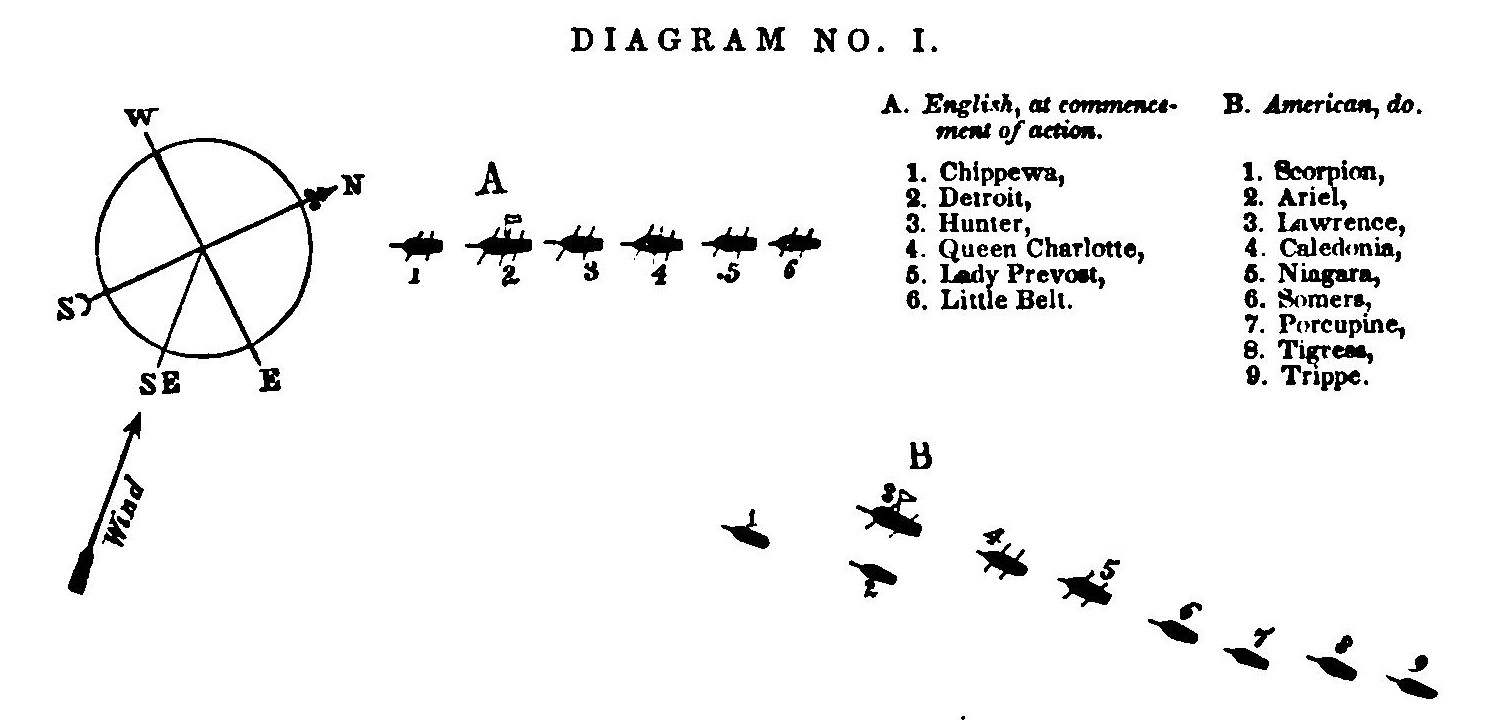

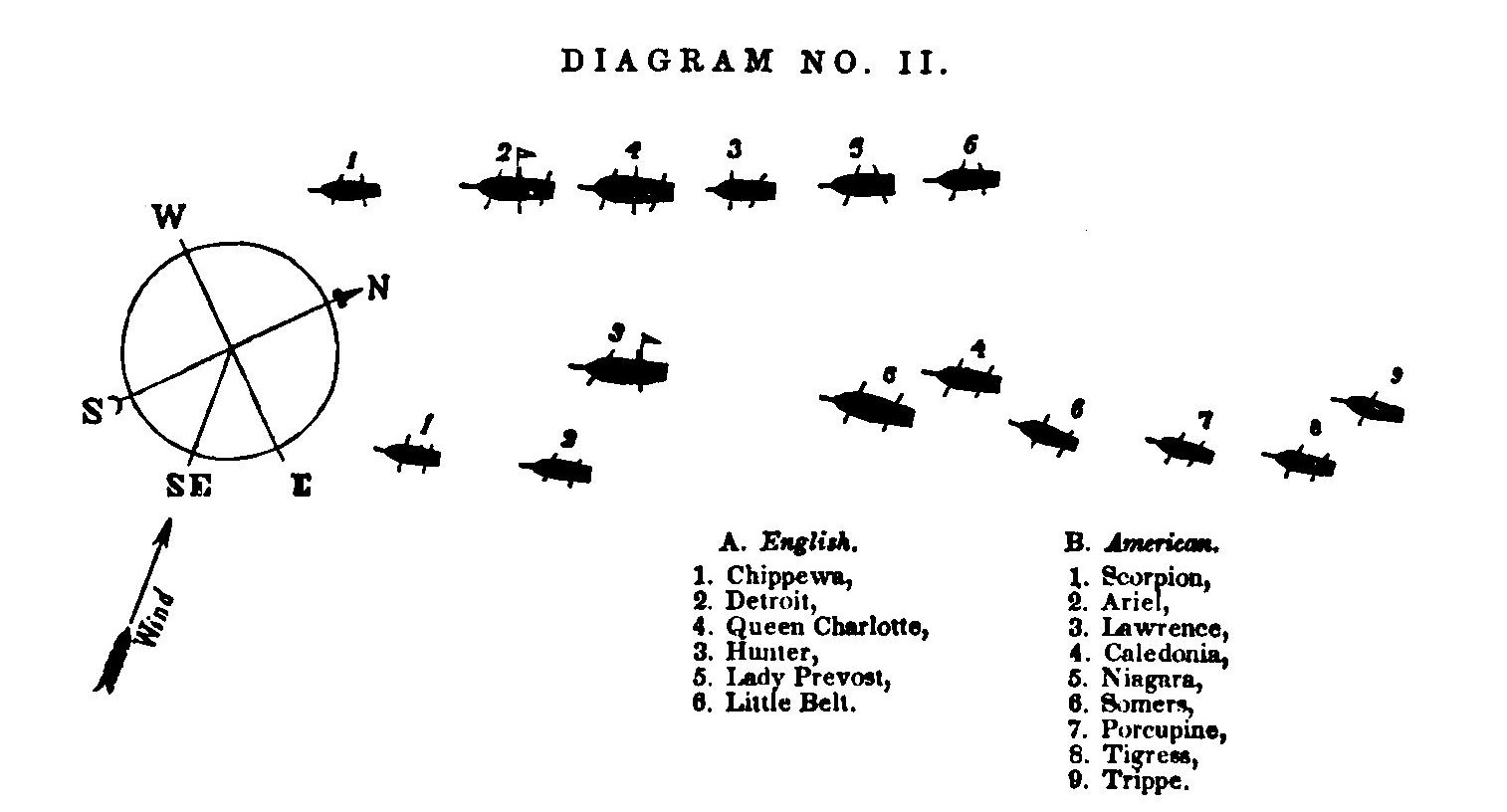

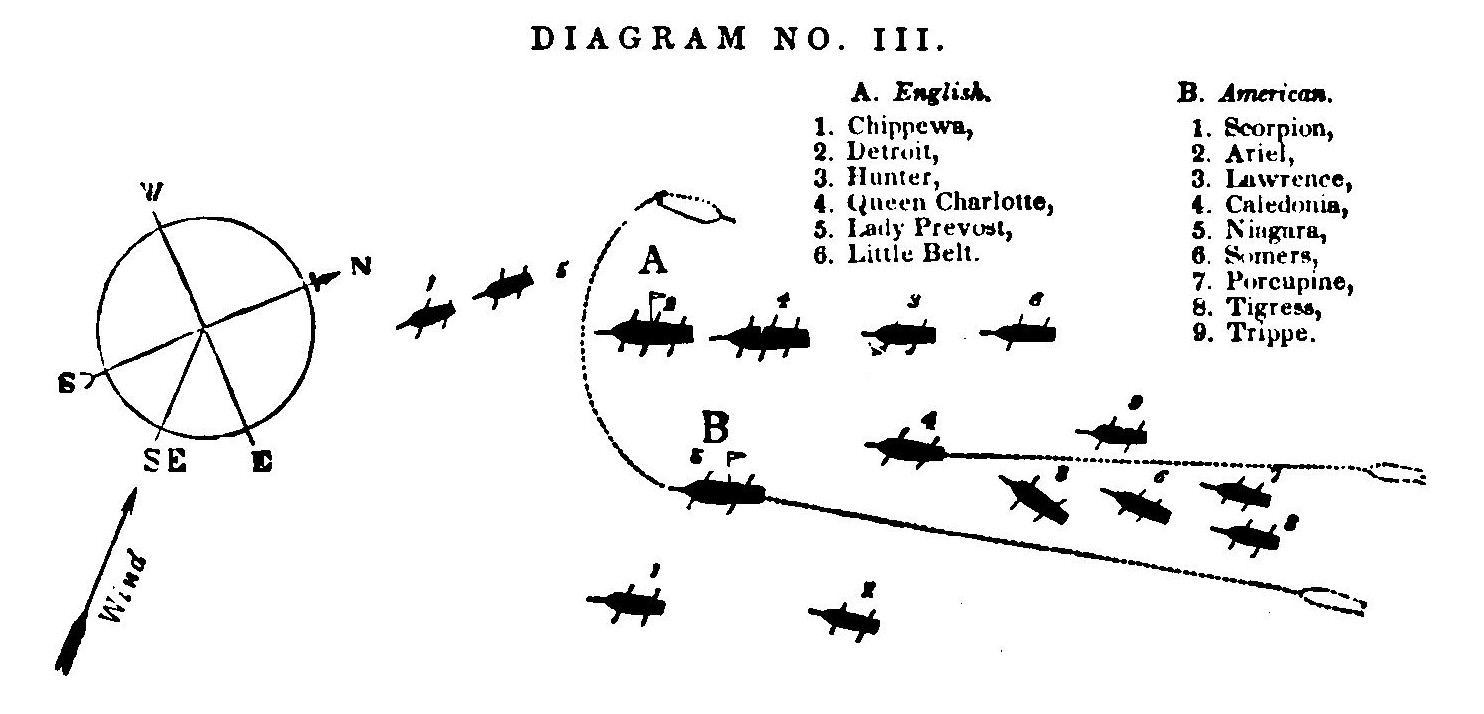

For the easier comprehension of the reader, we give three diagrams, in explanation of what we conceive to have been the positions of the two flotillas, or squadrons, at as many different periods of the battle.

In this diagram, the English are heading about S.S.W., a little off, lying-to; the Americans about S.W. or with the wind abeam. The distances cannot well be represented here, but the render will imagine the leading American vessels to be about a mile from the enemy, and the sternmost more than two. The Lawrence having made sail, is leaving the Caledonia. The witnesses who testify against Capt. Elliott evidently think he ought to have passed the Caledonia, in this stage of the battle, without orders.

In this diagram the Lawrence is lying abreast of the English ships, hove-to; No. 5, the Niagara, has passed No. 4, the Caledonia, and the vessels astern are endeavoring to get down. The distances are not accurate, on account of the small space on which the diagram is drawn, but the intention is to represent the Lawrence at about a quarter of a mile from the enemy, and the Niagara nearly as far astern of her. The Niagara, Caledonia, &c. are all placed a little too far to leeward in this diagram. The four sternmost American vessels, at this period of the action, were probably a mile and a half from the enemy, but making the shot of their long heavy guns tell. At this period of the action it must have been nearly, or quite calm.

This diagram represents No. 3, the Lawrence, as crippled and dropping out of the combat. the English forging ahead. No. 5, the Niagara, has passed ahead, and is abreast of the two English ships, distant from 1000 to 1500 feet; or about as near as the Lawrence ever got. There is no question that this is near the position in which Perry found her, and when he backed her topsail, previously to bearing up. No. 4, the Caledonia, has also passed the Lawrence, and is closing. The other vessels astern are closing also, but their distance was probably greater than represented in the diagram. The precise positions of Nos. 1 and 2, the Scorpion and Ariel, cannot be given at this particular moment; but they were both to windward of the Niagara, as is proved on oath, and denied by no one who was in the battle. On the part of the English some changes had also taken place. The Prevost had gone to leeward and ahead, while the Charlotte had passed the Hunter even in diagram No. 2. The dotted lines from No. 5, Niagara, and No. 4, Caledonia, show the general courses steered by each in passing the Lawrence. Taking this diagram as the starting point, let the reader imagine the English attempting to ware, and their two ships, Nos. 2 and 4, getting foul, while the Niagara, No. 5, (Am.) keeps dead away, passes them, firing at Nos. 1 and 5, Chippewa and Prevost, with her larboard guns, and the two ships with her starboard; then let him suppose the Niagara hauling up on the starboard tack to leeward of the two English ships, raking them, while all the other American vessels close with the English, to windward, and he will get an idea of the closing evolutions of the battle. We have traced a dotted line ahead of the Niagara to show the course she steered, though, as the English kept off also, the combatants ran a greater distance to leeward than is here given. There may not be perfect accuracy in these diagrams, but they must he near the truth. It is also probable that, during the whole action, the English, while lying-to, kept so much off as to continue to draw ahead, in order to protract the engagement at long shot. |

Αεναοι Νεφελαι

Αρθωμεν φανεραι,

Δροσεραν φυσιν ευαγητον,

Πατρος απ᾽ Ωκεανου βαρυαχεος

Υψηλων ορεων κορυφας επι

Δενδροκομους, ινα

Τηλεφανεις σκοπιας αφορωμεθα,

Καρπους τ᾽ αρδομεναν (ιεραν) χθονα.

Aristophanes.

Tum poteris magnas moleis cognocere eorum,

Speluncasque velut maxis pendentibul structas

Cernere.

Lucretius.

Eilende Wolken! Sexler der Lufte!

Wer mit euch wanderte, mit euch schiffte!

Schiller.

Hail! graceful children of the genial sun,

Whose quickening beams evoked your fairy forms

From ocean’s heaving bosom, or the lap

Of silvan lakes or sheen of murmuring streams,

Or green savannas where the moonlit night

Enspheres her brightest galaxy of dews!

Come ye with airy chalices to fill

The wild flowers’ languid eyes with tears of joy—

Come ye to catch the earliest smiles of morn