* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

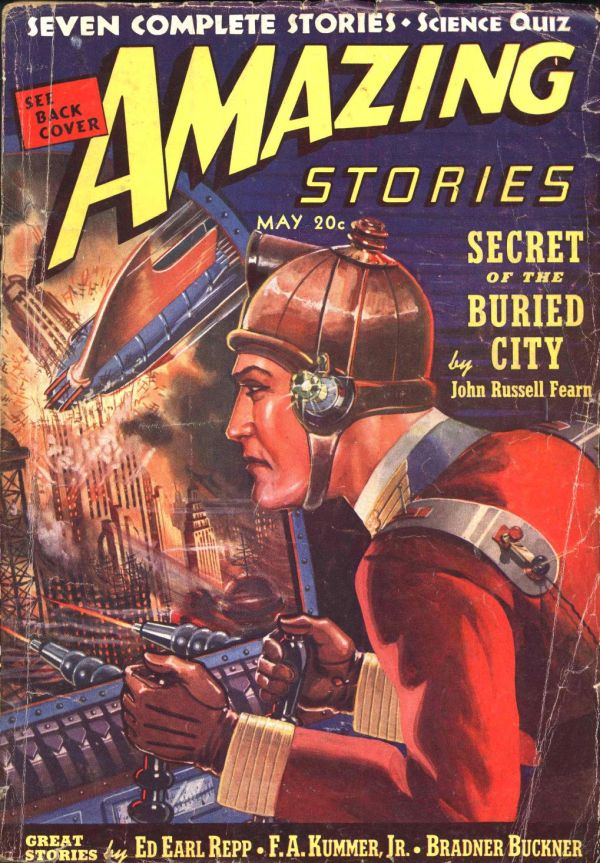

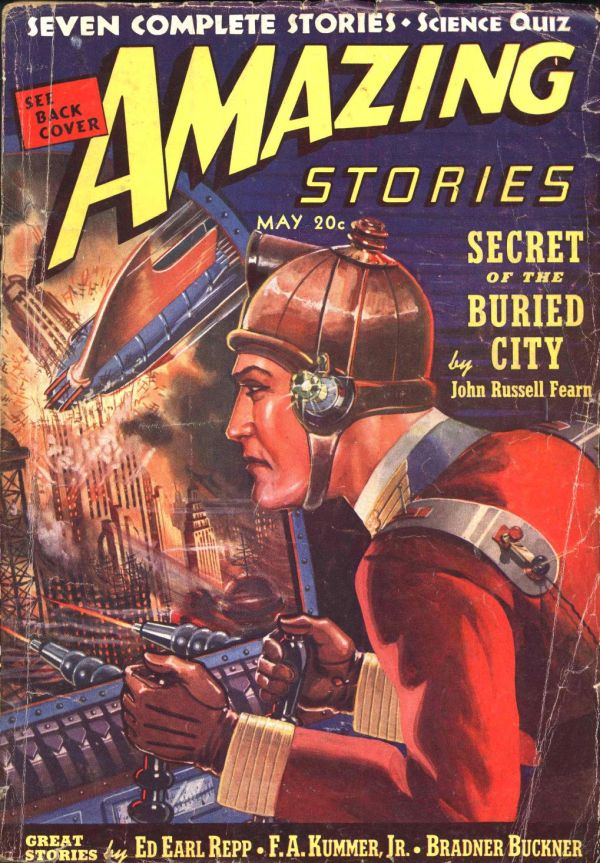

Title: Secret of the Buried City

Date of first publication: 1939

Author: John Russell Fearn (1908-1960)

Date first posted: Feb. 23, 2023

Date last updated: Feb. 23, 2023

Faded Page eBook #20230237

This eBook was produced by: Alex White & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

This file was produced from images generously made available by Internet Archive.

Secret of the Buried City

By

JOHN RUSSELL FEARN

Rodney Marlow found a metal city buried beneath his farm, and in it the secret of an amazing menace.

Rodney Marlow had bought the old farmhouse with its several acres of land with the idea of turning it to profit. He had envisioned fruit and vegetables produced by his expert technical knowledge from the Agricultural College. . . . But the presence of large quantities of old iron under the subsoil rather upset his ideas. In fact, he was distinctly annoyed. Everywhere his shovel touched, wherever his pick drove into sunbaked earth, he encountered more metal. On every portion of his land it was the same, and probably it explained the sickly nature of even the weeds and grass which were unable to form any deep root growth.

“Swell place to sell to a guy!” he growled one morning, pausing in the hot sunshine to mop his face and gaze round with baffled eyes. “Must be an old car dump, or something. . . .”

He meditated for a moment, gazed back at the silent farmhouse, at the lonely country around him—then with sudden savage vigor he whipped up his pick and drove it down with all the force of his young, powerful muscles.

Immediately he jumped back, gasping at the pain stinging through his palms at the terrific rebound. Woefully he stared at his pick; the pointed end had bent considerably under the impact.

“No wonder I got the place cheap,” he muttered, then as the pain in his hands began to subside a puzzled look came into his eyes. Something of his anger changed to wonderment. All the land metalbound? Definitely! He had driven his pick into almost every quarter of it. Perhaps a foot or so of soil, then metal—rusty and incredibly hard.

Slowly he went down on his knees, stared down into the nearest foot deep cavity he had made. Reaching down his arm he hammered on the metal with his knuckles; it gave back a solid, earthy thud.

“Looking for worms?” inquired a quiet, amused voice behind him.

“Huh?” He emerged with a start, straightened his tumbled black hair. A girl in a cool, summery frock was gazing down at him, swinging a large picture hat in her hand. Her blue eyes were still smiling as he hastily stood up.

“Some—something I can do for you?” he asked, rather puzzled. He had imagined himself entirely alone: his last look round the landscape had revealed its emptiness. . . .

“I wondered,” the girl said, “if you could direct me to Middleton? I’ve walked nearly five miles from my home, I should imagine. Once I left the main road I seemed to lose my way,” and she jerked her sunflooded golden head back toward the dusty road leading past the farm.

“I saw you here as I came past, and so—” She stopped, waited prettily, still swinging her hat.

Rod wiped his powerful hands rather uneasily down his trousers. This sudden shattering vision of loveliness in the wilderness was rather too much for his peace of mind.

“Sure I can direct you,” he nodded. “Take the road straight through until you come to fork roads. Turn due left, and keep going.”

“How far is it?”

“About three miles from here.”

The girl sighed. “The car would have to break down this very day! I’ll have no feet left at this rate. You haven’t a car I could borrow?”

“Sorry, no.” Rod shook his head regretfully. “You see, I live alone here, and I’ve no particular use for a car. I walk if I want to get anywhere. But I don’t like to see you having to do it,” he added gallantly. “I suppose a farm-horse wouldn’t be any use?”

“Do I look like an equestrian?” the girl asked dryly.

“Eh? Well—no. But if your mission’s important. . . .”

“Not particularly. A friend asked me to drop over and see her on business. The day is all right, but the distance—! I’d no idea it was so far.” The girl winced, fanned herself with a wisp of lace and glanced down at her dusty shoes.

“I’m Phyllis Bradman,” she volunteered suddenly, and with a certain purposeful movement she took a step back and leaned against the fence, eyeing Rod curiously. He returned the compliment, smiled rather shyly.

“My name’s Rod Marlow,” he said, shaking her slim hand. “I’m sorry you’re put out like this. Guess that if I hadn’t spent all my spare cash on this dump I’d have had a decent car to offer you— Some guy must have taken me for a sucker when he sold me this lot.”

“What’s the matter with it? Something to do with that hole you were peering into?”

“Take a look,” Rod growled, and gently grasped the girl’s arm as she stared down into the cavity. She seemed unaware of his grip as her thoughtful eyes looked down; he for his part found the contact remarkably alluring.

“This metal’s all over the place,” he went on sourly. “Doesn’t seem to be broken at any point, either. I had visions of orchards and vegetables, and instead I get this. Wish I’d stuck in the auto factory now, boring though it was.”

The girl looked at him quickly. Her face was no longer amused; it was serious.

“Do you realize that you may have something here which is far more valuable than orchards or vegetables?”

“Such as?”

“A meteorite, maybe—though I certainly never heard of one landing in this part of the Middle West. Some scientists would give their souls to have what you’ve got buried right in your back garden.”

“They can have it,” Rod grunted moodily. “I’m thinking of the money I’ve lost.”

“You might try and get through the metal,” the girl said hopefully.

Rod stared at her. “Say, why are you so interested in the stuff?” he demanded. “And where would be the sense in just digging through a lot of iron? Think of the time it would take! The season would be finished by then—”

“Listen!” The girl spoke so imperiously that he promptly subsided. “I’m no scientist in the professional sense, but I do know a thing or two about the things they go crazy over. If there is an enormous, hitherto unfound, meteor right here on this land of yours you’ll more than get your money back from the Scientific Association. On the other hand, if it’s only a great sheet of metal, perhaps from the foundations of some old building, you’ll soon find how deep it is after drilling through it. If you come to soil after an inch or so it is an old foundation: if not, then it’s a meteor.”

Rod rubbed his chin thoughtfully. “Maybe you’ve got something there. I’m beginning to think it’s lucky you chanced along as you did—”

“Have you an acetylene torch, or an electric arc welder?”

“I guess not.”

“Right!” With sudden activity the girl put on her hat; it framed her sensitive, intelligent face in a lacy halo. “Leave this to me, Mr. Marlow. I’ve got to go into town anyway, and while I’m there I’ll buy an electric welder from Markinson’s. They’re big electrical people.”

“But—but I can’t afford things like that!” Rod objected. “Hang it all, Miss Bradman, I—”

“Forget it!” she laughed, moving away. “We’re both in on this. Science is a pet fad of mine, anyway. I’ll be back sometime this afternoon—and don’t be surprised if I’ve bought a car in the interval!”

She moved to the fence opening and out into the dusty road, leaving Rod staring blankly after her. He had known girls in his time, none of them very impressive—but this one positively took his breath away. Her calm decisions, her beauty, her manifest intelligence—

“Gosh,” he whispered, and looked at her slim, retreating figure striding actively away through the sunshine.

He turned to look back at the hole—then once more to the road. But the girl was no longer there!

Dumbfounded, he raced to the rail of the enclosure and stared along the great dusty expanse leading to Middleton. There was not a single corner where the girl could have hidden herself, and yet—

“Gosh!” Rod gulped again. He wondered if he had had a touch of sunstroke. But surely a girl like that could not have been a delusion? If so, he was willing to have more of them. He went slowly back to the hole. The girl’s footprints were still visible in the loose soil.

Rod hardly knew how the time passed afterward. Repeatedly, memory of the girl returned to him; it even put him off his dinner. Most of the time he was outside, shoveling away a good clear area from the hole.

Then, toward midafternoon, he looked up with sudden expectancy at the sound of distant roaring. Screwing his eyes against the sunshine he discerned a long trail of dust whirling up the road; something merged out of it—a fast roadster. It stopped at the fence opening with a scream of tires.

“Hallo there!” Phyllis Bradman waved her arm cheerfully, climbed swiftly out of the car and came tripping across to where Rod was standing.

He eyed her rather dubiously, glanced across at the auto.

“Then you did buy one?”

She nodded. “I can always do with two, and money is no consideration so far as I am concerned. I brought an electric welder along with me, too. You’ll have to carry it, though.”

“O.K.” Rod strode across to the roadster, surveyed its smooth lines enviously, then hauled the heavy welding instrument from the big rumble seat. The girl came up behind him as he lowered it into the shallow hole he had dug.

“I can’t begin to thank you—” he began, but she waved her hand indifferently.

“Skip that. Point is, can you work the thing?”

“Sure; it’s on the same design as the welders we used in the auto factory. Only wants connecting to the power socket. . . .”

He picked up the surplus flex and carried it back to the plug and socket just inside the farmhouse door. Then he returned and switched the instrument on, took the pair of blue goggles the girl pulled from her handbag. Silently she slipped a pair over her own eyes.

“Funny thing,” he murmured, as he tested the savagely bright flame. “I could have sworn something queer happened to you when you left me this morning. When I looked for you down the road you had vanished. Where the deuce did you go?”

“Only on and on,” she sighed. “The furthest three miles I ever struck. There’s a dip in the road a bit further along, though; and since I stooped to adjust my shoes that’s why I probably was out of sight.”

“Yeah—maybe.” But Rod’s voice had no ring of conviction. Innocently though the girl regarded him, calmly though she explained away the mystery, Rod knew that his eyes had not deceived him. Deep rooted inside him was a growing wonder.

Motionless, they both watched the biting core of incandescence from the welder eat steadily into the metal amidst a shower of sparks. Minutes passed, and still it bored steadily downward.

“If this is the floor of an old building it must have been a bank,” Rod growled at last. “We’ve penetrated a foot of metal already, and still going.”

“If it is a meteor, it might be solid,” the girl observed. “Anyway, go right ahead and we’ll see what happens.”

He nodded, continued his activities—then five minutes later he glanced up triumphantly.

“It’s through! The metal’s about two feet thick and as tough as the devil. Won’t be long now.”

With a new enthusiasm he cut a line, formed it gradually into a square, then as the last piece fused away he thudded heavily on the metal with his boot. The section gave way and vanished below. The sound of incredibly far distant echoes floated upward.

Whipping off his goggles he stared at the girl with amazed eyes. Taking off her own glasses she returned his look, peered at the black square. It framed an absolute, ebony dark.

Regardless of the soil and dirt the girl went on her knees beside Rod. Together they peered down. At last their eyes met once more.

“No meteor could be this thick,” Rod muttered. “You heard the echo from that fallen metal plate? It sounded miles away. . . .”

He relapsed into thought for several moments, then suddenly snapped his fingers.

“Got it!” Scrambling to his feet he went over to the farm and returned with an enormous coil of strong rope, together with an electric torch. He flashed the beam swiftly in the opening, but it failed to reveal anything beyond black, empty space. In silence he tied it to the rope, lowered it down and watched intently. Only when the rope was nearly at its extremity—one hundred and fifty feet—did the torch alight on something solid. What its exact nature was was not distinguishable.

“Smells dank,” Phyllis said, sniffing.

“But what the dickens is it?” Rod demanded, hauling the torch back again. “Can’t be a disused mine. . . .”

He meditated briefly, then shrugged. “Guess there’s only way to find out, and that’s go down!”

“But—but suppose something happens?” the girl asked anxiously.

“Have to chance that. We can’t leave this hole here and not know what it’s all about, can we?”

Rod thrust the torch in his hip pocket, fastened one end of the rope securely to the car axle and dropped the other end into the hole.

“Wait here until I come up again,” he said to the girl, and she nodded slowly, watching anxiously as he lowered himself into the hole, gradually vanished from her sight. Lying face downwards she squinted into the dark.

Rod could see her head and shoulders above him as he descended. She grew more remote. He swung in emptiness, the rope sliding gradually through his hands and past his scissored legs. Pausing once, he tugged out his torch and waved it around. Darkness. He sank lower. The hole above became a square star with the girl’s head still outlined against it—

Suddenly his feet were scraping something solid. It felt like metal. Gingerly he released the rope and edged forward, tugging at his torch as he did so. But the torch jammed in his hip pocket. He tugged at it furiously, then before he realized what had happened his left foot plunged into emptiness and he went flying into space. It was impossible to save himself. He seemed to fall for infinite miles, landed at last with a stinging pain through his head. Weakly he collapsed, stunned with the impact.

Gradually, from the mists of oblivion, he became aware of sounds—rustling, metallic sounds, like joints moving in oiled sockets. For a time he lay with his eyes closed, almost devoid of all sensation, save profound bewilderment. The memory of his fall and blow on the head was still in his mind.

The noises seemed to grow stronger. His nostrils drew in the sweetish, sickly odor of powerful antiseptics; he heard the gurgle of water, the clink of glass striking glass. . .

Wearily he opened his eyes, lay gazing in blank wonderment at a shadowless flood of light contrived from somewhere in a metal ceiling above him. His first impression, which he just as quickly dispelled, was that he was in some kind of hospital. But the instruments around him were ahead of those in any hospital, despite the advanced surgery of this year 1967. Further, the objects moving about so gently and putting their instruments away were not living beings, but robots. Three of them—perfectly fashioned creatures of metal, even with strong resemblance to human beings in outline and face, but just the same still mechanical.

Rod sat up with a jerk as the full significance of everything dawned upon him. He winced at the stinging pain in his head. Everything rushed back to memory—the fall, the hole through the metal—Was this, then, the inside of the metal mystery? Through the windows of this particularly replete place he could distinguish other buildings, low built, and floodlit, stretching away for perhaps two miles then ending in blank darkness.

Phyllis Bradman? What had happened to her? Was she still waiting above? Shakily he got off the low built bed.

“Say, where the hell am I?” he demanded hoarsely, staring at the nearest robot.

The thing turned, moved slowly toward him. Then it spoke in a metallic voice—strangely enough in English.

“You are Rodney Marlow?” It was more a statement than a question.

“Yeah, sure I am, but who the devil are you? How did I get into this place, anyway?”

“You came near here of your own accord, through the opening you made in our roof. Evidently the outer surface of our buried sphere and city has pushed its way very close to your soil surface. However, that is beside the point. Nothing has lived here for tens of thousands of years. It has all been preserved. Your coming released hidden switches, started things moving again. . . .”

The thing paused for a moment, then the words from its open mouth orifice resumed.

“You stunned yourself when you fell from the steps. In fact you cut your head rather severely. An operation soon restored you to normalcy.”

Rod gaped in amazement. He could not find the words to express the questions teeming through his brain. All he could do was stand and listen as the robot went on.

“Only as time passes will you begin to appreciate the truth about this underworld—the reason why I speak to you in your own language, why I am a mere machine. The forces motivating my words cannot, as yet, be understood by you. You will only grasp that when you behold those who sleep in another part of this city. I am their spokesman. Time revealed to us, Rodney Marlow, that you would be the savior of your people—that is, the savior of those people who deserve to be saved. . . .”

“How long have I been here? What place is this?” Rod demanded.

“You have been here some three hours. This place is the last habitation of former man—civilization which existed before yours. We retired here before the threat of a vast cosmic disturbance, a disturbance which is about to be repeated. The last men and women of this race still live, but sleep. In due time, Rodney Marlow, you will revive them—but first you have the more urgent task of saving those of your own humanity who deserve to be saved. Certain things must be revealed to you . . . Come!”

Rod obeyed the command dutifully, following the robot from the amazingly efficient surgery into an adjoining building. Its size was enormous; the machines it housed positively breathtaking in their implication. In startled wonderment he gazed around him.

“Be seated, and watch!” the creature commanded, motioning to a stool.

Again Rod obeyed without question, and curious instruments were attached to his head and body. The hidden lights in the great place expired and his gaze transferred itself to a whitely glowing screen. In bewilderment he stared at the vision of a great city, perfectly architectured, reproduced in flawless color. He heard its sounds, smelled its smells, seemed actually present. Tall, slender spires reached to a sky that was curious muddy yellow. Suddenly a large ship—was it a space ship?—crashed headlong into a giant building, crumbling it in ruin to the ground below, with a terrific roar of destruction. Then the view slowly lowered to a well planned street, and there Rod received another shock.

Instead of the activity of busy human beings such as he had expected, he saw instead sub-human looking creatures moving to and fro, the tattered rags of clothing clinging around them. Some of them turned on each other even as he watched, fighting with demoniacal fury. All around on the ground lay dead and decomposing bodies, litter and uncleaned filth.

Again the view changed, swept over seas that contained rotting, drifting ships, over cities that were naught but crumbling skeletons of their original selves. Everywhere, whatever view was shown, revealed destruction and decay of an advanced order.

Then the lights came up again and the screen blanked. The hidden projector ceased its soft whirring. The sounds died out.

“You have seen a movie film of an age long past,” the robot explained. “There are of course many other records, but the one you have seen embraces the main facts. The last civilization reached the very peak of magnificence, then save for the few who managed to escape into this artificial underworld, progress ended.

“The earth during its spatial journey ran into the midst of a cloud of meteoric dust, so enormous in extent ten years elapsed before it was traversed. Though it was not dense enough to entirely block solar radiation, it was dense enough to be collected by and dispersed through earth’s atmosphere, stopping a great deal of heat from reaching the surface and also preventing the flow of several other vital radiations.

“Pre-eminent among the sun’s radiations is the one producing mitogenesis.[1]

|

Mitogenesis is absorbed and given forth by the cells of all living things, but it is so obscure that no instrument can detect it—though it is definitely there, as your experiments in America, Russia, and England have proven. One way to prove its presence is to expose yeast cells for a certain time to the radiation from other living germs: definite life actions result. The radiation goes through quartz, but not through glass, proving it is basically a chemical effect, and chemical fermentation is of course the basis of all life.—Gerald Herd’s “Science & Life.” |

“This solar radiation is responsible for evolution. When the cloud came, the radiation was cut off and evolution stopped. In fact it did more than that; mankind atavized, slid backward down the ladder he had so laboriously climbed. If that seems a strange thing to your mind, remember that a dead body does not just stay dead—it starts to decompose, back into the very elements from which it was born.

“So it was, in a different sense, with human beings. They began to atavize. There were wars, crime, man fought against man. Cities crumbled. Everything in the world save this refuge made by the intellectuals, was wiped out. Man went back to the caveman of the Glacial Age, which in itself was produced by the solar heat blockage. Then the warmth and radiation returned. Man started to ascend once more, right up to his present status—which is still far below the peak we attained.

“And now that same cloud threatens again: only a matter of days separates it from humanity. It will be your task to save as many of your people as you can.”

Rod said nothing. Actually he was wondering how the metal walls of this buried city, which had survived geological changes for such a vast span of time, had succumbed to the attack of an ordinary electric welder. Somehow, it didn’t make sense.

“Why didn’t you escape into space?” he asked at length. “You understood space travel?”

“Certainly, but there was not a world we could go to. None of the planets in the system can safely support life, and the chance of finding a world in the outer deeps was too grave a risk. So we preferred to come below and insulate this one spot of Earth against all chances of atavism. Scientifically we duplicated the missing solar wavelength for our own use, but of course it could only be done on a small scale.”

“And you say I am to herd my own people down here?”

“Those who are intelligent, who form the nucleus of your world’s science and progress—yes.”

“Even assuming I can manage it,” Rod said slowly, “how shall I know how to carry on when I take over down here? All this is so much mystery to me. I’m not a scientist; my knowledge is by no means great. You spoke of some sleepers; what possible chance have I of understanding their motives and aims? How to revive them?”

“That will be revealed to you.” The robot turned aside with another command. “Follow me!”

Rod walked pensively between the grouped machines, halted presently before a device which looked horribly suggestive of an electric chair. Rather doubtfully he obeyed the order to sit within it. Fear gripped him as the lights went out again, save for the dull glow of six red bulbs on a switchboard to the left of him. He heard the soft whir of machinery, then a click— Something moved gently out of the dark and stopped before him, came to life as a glowing rectangle filled with vague, phantasmal shapes.

They represented nothing understandable, but as he watched them, with an hypnotic fixity which he could not by any effort break down, he could feel his mind, his grip on things tangible, beginning to slip. He lost contact with his surroundings; the whole world was a darkness filled with crawling, incredible shapes that, somehow, did something to his mind.

Tremendous ideas began to drift into his brain. He saw hitherto unknown explanations for electricity, gravitation, and other riddles of physics. Engineering and mathematics; those too he fully grasped in their real significance. It was as though knowledge was being poured into him, and strangely enough he retained it all.

When at last he became aware of his surroundings once more his brain was burning with conceptions.

“You believe now that you will understand when the time comes?” the robot asked slowly.

“Everything,” Rod muttered. “Granting, that is, that I can get people to believe me.”

“That is your task, and you will accomplish it.”

“Yeah . . . That’s right.” Rod stood in deep thought for a moment, then he looked up quickly. “Well, I’ve got to be moving,” he said. “I left a young lady up on the surface. She’ll be thinking I’m dead, or something. How do I reach the shaft I came down?”

The robot motioned to the open doorway. “When you go through that exit turn left and keep going until you come to steps. Go up them. Your shaft is almost immediately above their summit. You had the misfortune to slip as you landed. . . .”

Rod turned, cast one look back at the robot as it stood motionless against the wall of the vast laboratory, then he walked out into the soft glowing light of the city. Quietly he walked up the wide street, gazed around on the squat but solidly made dwellings. He came at last to the steps—dozens of them, reaching upward to a remote square star which he knew was the hole he had burned.

Thoughtfully he began to ascend, the city dropping lower and lower behind him. The glow illumined his path. His mind was still in a turmoil. Ideas were falling over themselves—

At a sudden sound he looked up sharply. A long way above him on the steps was Phyllis Bradman herself, coming swiftly down toward him.

“Mr. Marlow! Rod!” she gasped thankfully, and her voice echoed in the great emptiness. “Oh, thank goodness. . . .”

Rod hurried to meet her. Breathless, she finally joined him, nearly fell into his arms.

“You’re alive!” she cried, her eyes searching his face. “When I heard no sounds or anything from you I slid down the rope myself to see what had happened. I found these steps, guessed that you had fallen over the flat summit at their apex. I—I think they’re intended as a sort of observational pyramid of steps, or something, and the hole you made happened to come right over them. I saw that city, all aglow, then— Well, I got scared. I didn’t dare to call anybody here, and I didn’t dare to visit the city either, so I just waited. It—it seemed hours.”

Her rush and tumble of words stopped abruptly. Her eager eyes still studied him.

“What happened?” she demanded quickly. “Is it a real city?”

“Kind of—a refuge from the long dead past,” Rod answered quietly. “Thanks a lot for coming down after me; I really appreciate it.”

“Can I go down there?” she insisted.

“Wouldn’t do any good if you did; I can tell you everything. Besides, there isn’t time. I’ve got a lot to do.”

“You mean bring scientists and other people?”

“Among other things, yes. You can see the place then.”

He took her arm decisively and they returned slowly up the monstrous flight. Certainly the steps looked as though they were intended as a lookout post over the city. Far away in the distance another pyramid reared in similar fashion.

“You’re different, somehow,” the girl said suddenly.

“Am I?” Rod smiled faintly. “I guess some of the things I saw down there were enough to make any guy feel different. . . .”

They fell silent again, presently gained the still dangling rope. Up above the pale evening sky was visible in the rectangular hole. Rod stepped forward, and at the same instant the glow from the city expired; the darkness of the tomb descended.

“Must be some kind of automatic switch in this platform which stops and starts things,” he commented. “Last time I started the city going; this time I’ve closed it down. I half wonder if I’m not dreaming the whole darned thing. . . .”

Seizing the rope he began to ease himself up it.

“I’ll go first,” he said briefly. “When I call fasten it round your waist and I’ll haul you up.”

“All right—but hurry up! It frightens me down here in the dark.”

Rod went up steadily, hand over hand, at last reached the surface. In a few minutes he had the girl beside him again. They stood looking at each other in the approaching sunset.

“Queer, isn’t it, the things we’ve done since morning?” Phyllis said at last, smiling.

“So many things,” he murmured, then as briefly as possible he told her all that had happened to him in the underworld. She listened in wondering silence.

“But—but why should you be chosen of all the people in the world?” she asked finally. “How did they know you’d arrive?”

“That I don’t know; had something to do with time. Anyhow, I’ve things to do, and I start in tomorrow.”

“Would you mind very much if I helped you?”

“Nothing I’d like better. . . .”

Their eyes met steadily, then with mute accord they moved to the girl’s car.

“I shall hardly sleep tonight for thinking about all this,” she said, slipping into the driving seat. “I’ve got something to live for at last; something interesting.”

“But for you it would never have started anyway,” Rod smiled. “You got the right hunch all right. Well, see you in the morning?”

“Early,” she promised, then switched on the engine and engaged the first gear. Rod stood watching in silence as the car moved away through the haze of dust.

A sense of perplexity transiently settled on him. Queer how easily she seemed to fit into the whole picture. He had never known a girl with so much interest in science. Or was it more than science? She had needed plenty of nerve to follow him down into that hole. He turned back toward the hole, gathered some boarding from the outhouse and roughly covered it up. Then he went inside the farmhouse and scraped together a solitary meal. He slept badly that night.

Rod had hardly finished his breakfast the following morning before Phyllis arrived, pushing the door gently open and standing silhouetted attractively against the sunshine.

“Can I come in?”

“Right in!” Rod rose to welcome her, pulled up a chair and poured out an extra cup of coffee.

“Just what,” she asked slowly, “do you intend to do? You say that humanity is threatened with atavism. Suppose nobody believes you?”

Rod’s jaw set doggedly. “They’ll have to believe me! Scientists aren’t fools. I’ll show them this underground place—that ought to convince them, surely. Then I’ll outline the plan of escape. Matter of fact I’m planning to head for New York this morning. You’d better come with me as a very material witness.”

“I’ll do more than that; I’ll take you in the car. But say, have you decided yet on whom you ought to contact?”

“Matter of fact, no.” Rod frowned. “I figured on doing that when I arrived in the city. I’m not well up on big scientists. I was going to look through ‘Who’s Who’.”

“There’s no need for that. The man you want is Doctor Ashley Gore. He’s President of the Scientific Association, and as such is in a position to contact all the big scientists you’re likely to need.”

It was late afternoon by the time they reached New York—nor did they find it easy to gain admission to the President of the Scientific Association. However, after considerable cajoling and stressing of urgency on Rod’s part, they managed it, were shown into the great man’s luxurious office.

Dr. Ashley Gore looked up from his desk with some impatience; it was close on time for him to leave. In appearance he was massive shouldered, faultlessly dressed, with the face of a prize bulldog and a startling bald head. Rather perfunctorily he waved to chairs.

“I sincerely hope you have something of real importance to discuss, Mr.—er—Marlow,” he said briefly, glancing at Rod’s card. “I’m a very busy man, you know.”

“So am I,” Rod answered tartly. “I thought you might be interested to learn that humanity is facing destruction, and that I have the means to save it.”

“Another inventor, eh?” Gore smiled acidly.

“I’m not an inventor. I’m merely offering succor to those people in the world who are considered essential to progress. That’s all. Disaster definitely threatens every living being any day.”

“Indeed!” Gore lay back in his chair, eyes half closed.

“All you have to do is to see the place wherein you can be saved; I will direct all other operations.”

“You will direct!” Gore echoed in amazement, sitting upright. “Your modesty astounds me, sir! What exact position do you hold, may I ask?”

Rod gestured irritably. “Does it matter? Actually, I’m a farmer, but—”

“A farmer!” Gore shot to his feet with a purpling face. “A farmer! And you have the termerity to come here and talk of matters scientific? Of death for the human race? Do you realize—”

“I realize that if you’ll instruct astronomers to examine space they’ll find an approaching cosmic cloud!” Rod broke in hotly. “It will be here any day. The earth may take ten years or so to go through it, and at the end of that time, whatever is left of humanity without protection, will have gone back to the caveman stage. Human beings will be atavized, fighting each other in the ruins of a one time civilization—probably in the midst of a second Glacial Epoch by the cutting off of solar warmth. . . .”

Gore’s expression changed a little. He glanced at the girl, then back to Rod.

“I by no means believe your full story, young man,” he said slowly, “but it does so happen that one thing is in your favor. Recent reports from astronomers, which of course pass through me, have revealed a strange haze in space blurring some of the stars. In fact several plates have been made and studied, but no man as yet has arrived at the real truth.”

Rod shrugged. “Well, there you are. I’ve given you the truth. All I need is your further cooperation. Out at Middleton, one of the newer Middle West towns, is a buried city, right under my own farm. Down there are all the necessities for protecting chosen people from approaching disaster.”

“That is correct, Doctor,” put in Phyllis quietly. “I’ve seen it myself.”

“The least you can do is see for yourself before you start to condemn,” Rod commented.

“Hmmm. . .” Gore stroked his chins then glanced at his diary. “Sunday tomorrow—no engagements,” he murmured. “I could manage it at that. I have to admit that the curious coincidence of facts has aroused my interest, even though I feel there is no real danger. If, of course, you prove all you have said, I will have every scientist in the land investigating your claim.”

Rod got to his feet actively. “Now you’re talking, Doctor. I’ll prove everything, never fear. Suppose we say tomorrow at nine in the morning? I’ll be at the Regent Hotel. We’ll drive over to my place.”

“I’ll bring my own car,” Gore responded. “I have to return to New York remember. Nine o’clock it is.”

Dr. Gore not only brought himself the following morning, but also three other men—lean, gray haired experts of the scientific fraternity. Their manner was vaguely interested, but professionally doubtful. Evidently Gore had sensed something worth while in Rod’s observations and was prepared to take a chance.

Throughout the day the two cars continued their whirlwind journey to Middleton, with only one short break for a tabloid lunch. It was nearing seven o’clock when they regained Rod’s solitary farm. He paused only long enough to provide refreshments all around, then set out into the enclosure with Phyllis at his side and the men behind him.

Eagerly he threw aside the loose boards, removed the last one with a triumphant flourish.

“There you are gentlemen—”

He broke off in dumbfounded amazement, staring blankly as though he could not credit his senses.

The hole was no longer there! The metal, yes—but it was as solid and unscratched as though never before revealed.

“What the hell—?” Rod jumped down into the shallow pit and rubbed frantically at the grayness. No joint, no seam—no hole.

“Is this what you were—er—talking about?” Gore asked with awful solemnity.

Rod looked up dazedly in the doctor’s cold eyes. The expressions on the other scientists’ faces were grim and bitter. Only Phyllis looked sympathetic, though baffled.

“There was a hole!” Rod gasped hoarsely. “The entrance to the underworld. Isn’t that so, Phyllis?”

“Of course!” She looked anxiously at the scientists. “That’s absolutely true, gentlemen.”

Gore turned suddenly. “Come, gentlemen! I think we have wasted time enough: forgive me for wasting your time on an absurd hoax. As for you two, you haven’t heard the last of this—”

“But wait a minute!” Rod shouted, leaping up and clutching the scientist’s arm. “I’ll prove it yet. I’ve got an electric welder in the house. I don’t know how this metal got recovered, but I can soon bore through again. Wait a minute, please.”

Grudgingly, Gore agreed, watched in silence as Rod brought out the equipment and started to work with savage vigor. Minutes passed and searing flame blazed steadily at the metal.

Five minutes . . . ten minutes. The scientists grew restless. Their eyes were twitching from the glare. Phyllis bit her underlip uncertainly. Rod could only gaze through his goggles, unable to swallow the devastating fact that the metal was not even heated, let alone cut!

Baffled, he finally switched off, tugged off his glasses.

“I—I don’t understand it,” he groaned, coming to Gore’s side. “Last time I cut through it in a moment, and—”

“I—I think,” Gore broke in coldly, “we have wasted time enough.”

“But hang it, can’t you see for yourself that the metal is unusual when even this flame won’t go through it?”

“We did not come here to inspect peculiar metals that open and reseal without reason,” Gore retorted acidly. “We came to see an underground city which could be taken as proof of your statements. As it is, there’s nothing more to be said. Good evening to you, sir—and you, young lady!”

Stupefied, Rod watched them go, climb into their car. He only began to come to himself when the dust had settled behind them.

“Phyllis, what on earth’s gone wrong?” he demanded helplessly. “Can you account for it? While we’ve been away in New York somebody has resealed the hole—possibly one of the robots from the city below. But why? And why doesn’t this damned welder cut through it as it did before?”

He regarded the apparatus disgustedly. Phyllis shook her blonde head.

“I’m afraid I don’t know, Rod—unless the opening was secured with a metal far tougher than the other stuff. Perhaps the presence of other people isn’t wanted below. . . .”

Rod rubbed his head in bewilderment. “But why not? Why on earth should my only chance of proving myself right be stopped? Oh, I don’t know! What, for instance, do I do now? I’m sunk!”

The girl considered for a moment. Finally, she said, “I thought you said that while you were down there you were taught all manner of scientific things? Several electrical and engineering secrets among others?”

“Correct. So what?”

“Use your knowledge, of course. Never mind why the hole was sealed up; we’ll probably solve that mystery later. Point right now is to discover why this welder didn’t work this time—or if it comes to that you might try another part of the ground. Perhaps all the metal isn’t the same—may only be this resealed portion we can’t cut. Try it, before we go any further.”

“O.K.”

In a moment or two Rod had obtained pick and shovel and dug another small hole some distance off. Confidently, he set to work again with the welder, but the answer was the same. It failed to make the least impression.

“Then all the metal’s alike,” the girl mused. “The only solution is to find something that will go through it. That’s where your knowledge comes in. I’ll help you if I can, but don’t expect too much.”

“But—”

“Now don’t start protesting! Come into the house and get to work. There must be something you can devise: use your knowledge. It’s the only way you’ll find a permanent key to this underworld, or even an explanation of the mystery, for that matter.”

Rod stared at her for a moment, then snapped his fingers.

“You’re right!” His expression changed a little; he regarded her curiously. “Say, you’re helping me a lot, aren’t you?” he asked slowly. “Why do you do it? Have you some special interest in all this, or something?”

She shrugged. “Consider the circumstances, Rod! I happened in on this right at the beginning. It involves world issues. Can you expect any girl with the normal desire for adventure to drop out right now? Not on your life! I’ve got to see how you make out. Now come on. . . .”

She led the way into the farmhouse, switched on the light. It was already nearing twilight. Without a word she went across to the bureau and found writing pad and pencil. She pulled up a chair purposefully.

“Now—concentrate!” she ordered briefly, pointing to the chair.

The girl’s steady blue eyes were strangely compelling. The oblique rays from the light threw them into curious relief—deep blue irises and large black pupils.

“Gosh, Phyllis, you’re beautiful!” Rod whispered, studying her.

She gestured impatiently. “Oh, never mind that! I’m here to watch you work. Get started!”

He nodded quietly and took up the pencil. It seemed odd to him, but the moment he concentrated the transferred genius from the underworld suddenly leaped into his conscious mind. He forgot all about himself and his surroundings, was only aware of the figuring and computing he performed on that sheet of paper.

Then another sheet—and another. Hour after hour he worked on, without eyestrain, without fatigue, plunging into the midst of the most complicated mathematics, of which, before the underworld venture, he had not even had the slightest knowledge.

Beyond doubt, he was a man inspired. When at last he put his pencil down he realized he was stiff with cramp. His head ached a little, too. He glanced at his watch and gave a whistle: it was 2:30 a. m.

“Gosh!” he whispered. “Nearly six hours solid concentration . . . but I’ve got it! I’ve got it! Electrical energy of a certain wavelength will break down that metal. It will break down any matter in the universe. But how did I ever come to know that?”

He shrugged, sat staring at the mathematical solution he had worked out. He felt like a man who has composed a masterful oratorio in his sleep. Yawning, he turned, then gave a start.

Phyllis was lying on the couch, fast asleep, her traveling coat tossed over her.

Silently Rod crossed over to her, looked down at her perfect features. Uncomfortably he glanced toward the closed door. Strong ideas of conventions were still in his mind.

“Oh, hell!” he growled at last. “The world’s going to change, anyway. What difference does this make?”

He drew the coat further over her, switched off the light, then tiptoed to his own room and flung himself on the bed.

Rod awoke again to the tempting odor of frying ham and eggs. He dressed hastily and strode into the kitchen to find Phyllis in the act of pouring boiling water into the coffee pot. She glanced up with a smile of welcome.

“Just beaten me to it!” she said regretfully. “Thought I’d have everything ready.”

“You know,” Rod muttered, sitting down, “this is all wrong. You were here all last night, and that makes me look a regular heel—”

“Skip that and tell me what you found out,” the girl interrupted briefly. “I’m not interested in what people think. Did you solve the problem?”

“Yeah, I solved it.” Rod looked pensively at the ham and egg under his nose. “But in solving it I came up against something of a mystery. You see, an electrical wavelength, produced by incorporating the right amount of coils and resistances, will cut through any form of matter—not because of the heat it generates but because of the vibration, which shatters molecular clusters asunder. I could, with the necessary recoiling and electrical odds and ends, transform that welder of ours into the right instrument, and it wouldn’t take me more than an hour. But why in Heaven’s name did it cut through the stuff the other day and yet not yesterday? It is just as though it incorporated my special wavelength on the first occasion, but not afterward.”

The girl nodded, stirring her coffee. “There may be another explanation. For instance, on the first occasion it was ordinary metal and collapsed under ordinary means. But after you had been below, the robots—probably by electrical means—toughened the molecular resistance of the metal in every direction, so that it could not be pierced again. That was why it didn’t work the second time. Maybe they did it to test you, knowing that you had the knowledge to devise a means of entry if you wanted.”

“Maybe you’re right,” Rod admitted, shrugging. “Funny how easily I solved the problem. Came just like that!” He snapped his fingers.

Rod finished his breakfast and pushed the plate away. Actively he got to his feet.

“Now there’s work to be done. I want some special wire and electric stuff from Markinson’s. I’m going to convert that welder of ours. Maybe I can borrow your car?”

“You can do more than that,” the girl replied quietly. “I’ll drive you there and, I gather, you’ll need money?”

“Huh? Lord, yes! I’d forgotten.”

“Leave that to me. Now let’s go.”

Once they both returned to the farm, around dinner time, Rod spent most of the afternoon pulling the welder’s insides to pieces and refitting it with the gadgets he had bought. He worked with a skill that inwardly amazed him, knew every detail of what he did, had a perfect knowledge of the position of every screw and every piece of wire. By the time he had finished the whole converted interior fitted neatly into position. Smiling with satisfaction he fastened up the exterior case, then plugged in the socket.

“We’re ready!” he announced, as the girl glanced inquiringly at him. “Now let’s see if my reasoning’s O.K.”

They marched outside to the original pit and jumped down. They donned their goggles, then Rod snapped in the switch of the apparatus and directed the savagely bright beam at the metal. Instantly there was a shower of sparks: a thin, dark line began to appear in the midst of the flare.

“I was right!” he panted. “It does work! It’s going through. . . .” He watched for a moment or two longer, then turned sharply to the girl. “We’re going below when I’ve finished. Garage your car, then get my other torch from the bureau. Bring some provisions and see the farm’s locked up. O. K.?”

“Check!” the girl nodded quickly, and scrambled away.

By the time she had returned with the necessities Rod was triumphantly kicking away the metal square he had burned away. It vanished, was followed by an echoing clang from below.

He welded a metal ring beside the hole and fastened the rope lying nearby.

“Guess you’d better go first this time,” he said, turning to the girl. “You know what to expect, and I’ll follow right after you with the stuff. Here, take the torch. Ready?”

She nodded quickly, and he noosed the rope under her arms. Then bracing it twice round his arm he began to gently lower her into the cavity. At the limit of the rope her faint shout floated up.

“All right! Come on!”

First he lowered the provisions down to her, then slid down gently to her side. As they began to move the metropolis below came suddenly into life. Rod waved his torch beam on the floor, following a long sunken line of metal which had formerly escaped his notice.

“So that’s it!” he ejaculated. “Something like traffic signals. Pass one way over it and you light the city up like switching on a pianola: go the other way and you put it out. I wonder how it happens to be under the very spot we came through?”

“Maybe dozens of them, so we just couldn’t miss,” the girl commented.

For a moment they stood gazing down the infinity of steps; then they slowly began to descend, neither of them speaking. From this high standpoint the city was clearly visible. It spread for perhaps two square miles under the earth—solid and impregnable, housed in its globe of metal, air conditioned by hidden connections to the surface. Again Rod found himself wondering why the metal had been made so impregnable, why he had been stopped in proving his point to the scientists.

They came at last to the first building; the doors had been automatically swung open. Rod recognized it immediately as the laboratory in which he had received his knowledge. The only difference this time was that there were no robots in sight. Everything was quiet.

At last Rod spoke.

“Well, what do we do?”

“Explore,” the girl replied, without hesitation. “Once we have assessed this city’s resources we may be able to decide what to do. Come on. . . .”

They made their tour slowly and thoroughly. Scientific achievements reared on every side, incorporating machinery of every possible use and description, most of which, Rod inwardly realized, he fully understood, thanks to the genius that had been conferred upon him.

The biggest surprise of all came when they entered an enormous domed place resembling a great mausoleum. On every hand, lying full length in six-foot-long glass cases were motionless men and women, lightly clad, hands folded on their breasts. Altogether, Rod counted one hundred and ninety nine cases; the two hundredth, at the far end of the hall was empty.

“These must be the sleepers,” he observed, turning to the girl. “In a darned good state of preservation, too. Later, I suppose, I’ll have to revive them.”

Phyllis nodded slowly. “When you’re absolutely sure of the right method—not before. You might finish them off for good, otherwise.”

“Yeah. . . .” Rod’s eyes wandered to the last empty case and he frowned. “Queer,” he muttered, then shrugging his shoulders he led the way out of the place, returned across the main square to the laboratory.

For another hour they both wandered around, until at last Rod found a magnificently equipped radio-television instrument. With unerring skill, using once again his conferred knowledge, he set the complicated controls into action, started the generators. Almost immediately the screen, using absolutely perfect lifelike color, came into life. The loud speaker twanged noisily, then settled down.

“At least we’re in touch with the world,” he commented briefly, then he hesitated over switching off as the announcer’s worried face and alarmed words arrested attention.

“. . . nor have we any idea what is causing it, but it is an undoubted fact that a crime wave of unprecedented proportions seems to have been launched on America, Britain and Europe, commencing some time after noon today. Murder, rape and theft are sweeping all three countries; there are not enough detectives or police available to tackle the sin flood. Full details are not yet available. It can only be assumed that agents in each country have fixed a given hour and a given day to launch mass terror.”

Rod switched off, stood in silence with lips compressed. The girl laid a hand on his arm.

“It’s—it’s started!” she breathed. “Must have begun just after we came below here. The first signs of atavism. In that case the cosmic cloud itself ought to be visible. Sky was clear when we came down here. . . .”

Rod slowly nodded, then struck with a sudden thought he switched on the televisor apart from the radio. His first study was of the sky. It was muddy yellow in shade, as though dense overhead fog was reigning. The sun’s rays straggled weakly through it. He made observations of different parts of the world. Everywhere the color was the same.

“It’s begun all right,” he muttered; then switching back to New York’s main streets he surveyed in silence the scenes of obvious disorder, the mass rioting, the altercations between police and civilians, the general first collapse of normal law and order.

“Anyway,” Rod muttered, switching off, “we’re safe enough down here. This place produces synthetic radiations to take the place of the lost ones. Machinery must be somewhere around here . . .” He looked round quickly. He did not stop to wonder how he knew which machine was the right one; it came to him quite naturally. Thoughtfully he switched it on, stood listening to its beating purr.

“That makes us O. K.,” he said slowly, “but I still don’t like the idea of men and women turning against each other as they are doing. If only I’d have been able to prove my point to Gore this place would have been a haven.”

“For everybody?” the girl asked pointedly. “No, Rod—only those that are worth saving. You said that yourself.”

“Yes, but how does one discriminate?” he demanded.

“I’m not sure . . . yet,” the girl answered slowly. “One thing is very certain, in my opinion. The whereabouts of this place must never be discovered by the masses at large; we’d be invaded. Even though we can beat anybody off with the apparatus around us, the intruders might do irreparable damage to the machinery first.”

“So long as that hole remains in the roof anybody can get in,” Rod reflected. “And that gives me an idea! I’m going to find out from that damned robot exactly why this place was resealed. The thing must be around here somewhere.”

He turned swiftly and headed to the opposite end of the place. After some searching he found the robot standing against a corner. At his command it moved forward. Sharply he questioned it, but it gave no answers, remained perfectly mute.

Baffled, Rod desisted. “You know,” he said slowly to the girl, “there’s something infernally queer about this. Last time this robot and two others were working of their own accord, but this time only my voice stirs it into action. What stimulated it on the last occasion? I don’t see how it could start off on its own. It looks to me as though there’s some mysterious conspiracy afoot to prevent me knowing why this place was resealed.”

“Maybe, but you got in just the same,” Phyllis pointed out. “The thing right now is to set to work and find out how to refill that hole with metal.”

Rod nodded slowly, ideas once more turning over in his mind.

“Molecules of free air are only that way because of the spaces between them,” he muttered. “Condense them, lessen the spaces, and we get a thin solid. Condense them still further and we get a strong solid. Add more molecules and atomic basis and we get—”

“The metal of which this guardian globe is composed?”

“Exactly. I’m going to work that out.”

Rod moved quickly to the nearest table, pressed a switch, and an automatic calculating device shot from a concealed well. He experienced no wonder at the fact; instinctively he knew it ought to be there. He spoke steadily into the machine, gave the basis of his ideas, then waited as the mathematical interior of the thing clicked and whizzed persistently, building up a formula. In half an hour it was finished, complete to the tiniest detail.

“Wish I’d had one of these at school,” he grinned, taking up the metal sheet. “Let’s get busy. . . .”

He walked across to a self contained force-generating instrument, perched on three massive, wheeled legs. Seizing it, he pushed it through the doorway, aimed the sights on the far distant dim square that marked the opening to the upper world. With the girl right behind him he made quick adjustments to the multiple controls, carefully directed the highly polished, queerly designed lens.

“This thing generates force waves of infinite range, from constructive to destructive,” he explained briefly. “Etherial agitation, if you like the term better. Anyway, electrical charges, following exactly the formula given here, will stream into that gap and condense the molecular paths of the air together, add other molecules into the spaces which are left. Result will finally be seamlessly joined indestructible metal—same thing we came up against. . . .”

He prepared to close the master switch—then suddenly Phyllis grabbed his arm frantically and gave a shout.

“Wait a minute! Wait, Rod! There’s somebody up there, unless my eyes are playing tricks with me!”

Rod stared at the distant opening, his hands dropping to his sides. A figure was certainly in view, commencing to slide down the still dangling rope. Rod’s face set grimly as he watched.

“So we’re being invaded already, eh?” he demanded savagely. “O. K., I’ll show him!”

He sighted the projector again, altered the frequency—then he stopped again as a shout reached him.

“Hey, there! Hey! Is that Mr. Marlow? This is Gore!”

Gore! Rod stared blankly at Phyllis, then just for a moment the funny side struck him. The sight of the pompous President of the Scientific Association sliding awkwardly down that rope was certainly worth seeing.

“What the devil brought him back, I wonder?” Rod whispered, waiting; and presently the scientist reached the summit of the vast steps and started to pelt down them at top speed. Breathless, dirty, and perspiring he finally came to a stop, gripped Rod’s arm.

“Is this the place you were trying to tell me about?” he asked wonderingly, gazing around.

“Sure it is, but—” Rod eyed him mystifiedly. “Say, what brought you back, Doctor? I thought you and your associates had given Miss Bradman and me up as hoaxers.”

“We had—at that time.” Gore breathed heavily. “Then, just after dinner time today the most terrible things began to happen in the city. Most people seemed to suddenly lose their sense of reason. Things just went mad. There’s some kind of cosmic cloud in the sky. I thought back on all you had said, remembered your earnestness. You see, the thing I couldn’t understand was not so much why you could not find the hole you had mentioned, but why there should be metal on your land which resisted even a welding flame. That was a point well worth pondering. I decided to give you the benefit of the doubt—came here by plane intending to take another look at the metal. Since the first half of your story had come true, the rest might. Anyway, seeing the horrible things going on in the city I saw no harm in trying. I found the farm locked up; then going to the hole I saw the rope, this lighted city, and— Well, here I am.”

“And only just in time,” Rod said slowly. “I was just on the point of sealing the hole.”

“Evidently,” the girl said slowly, “you are a man of intelligence, Doctor. You reasoned things out for yourself—came right back here to correct your mistakes. I guess that took plenty of pride swallowing in a man of your position. But it’ll pay you; you’ll be safe enough down here with us.”

“But that wasn’t my main reason for coming,” Gore went on anxiously. “Things are getting worse every hour, Mr. Marlow. Surely, amongst all this machinery there must be some way to counteract the atavism which has set in? Save humanity? That’s what you set out to do, isn’t it? What you were chosen for?”

“Not entirely, Doctor. I was chosen to save the deserving of humanity—men and women with intelligence and reason like yours. There is not, so far as I can find, any method here of saving the surface. The cosmic cloud cannot be dispelled by any means we’ve got. All that can be done is to collect down here all those who are worth saving. Only thing is, I’m not quite sure how to discriminate.”

“I am,” Phyllis put in, slowly. “Doctor Gore has provided the answer. He knows all the scientific and intellectual heads of every country. Every scientist and every master brain. That right?”

“Most of them,” Gore acknowledged. “Why?”

“Your task will be to gather them together in the shortest possible time, bring them here. It doesn’t matter how you get them, what methods you use, so long as you succeed. Until you return and bring those whom you think worth having with you, we’ll keep the opening in the roof unsealed. How’s that?”

“Perfect!” declared Rod with enthusiasm. “Matter of fact, that was the idea I had in mind myself. Can you do that, Doc?”

“Without delay,” Gore nodded promptly. “Everything now depends on time. You can rely on me. I’ll get back to New York right away. The plane’s waiting for me.”

“And as you go up the steps,” Rod added, “take care to step over that metal bar at the summit. It’s a switch.”

Gore nodded, turned actively away. In a moment or two he was mounting the steps.

Rod turned slowly to the girl.

“Well, that about settles that. Nothing to do now but wait.”

“I don’t agree with you there, Rod. As I see it, in about ten years the cosmic cloud will have passed and a civilization will remain—buildings, that is. But will it remain? On the last occasion not one brick was left standing on another because of the barbaric destructiveness of atavized humans. Definitely, in this case too, the atavizing people will drift to war and bestial savagery as they sink lower down the scale. Cities will suffer. A world well supplied with arts and treasures will be wantonly destroyed. That isn’t right, particularly when down here there will be expert minds who can take everything over when the cloud passes . . .”

“Well?” Rod looked at the girl curiously.

“You’ve got to devise a means of destroying all those people who try to invade or pillage cities,” she went on grimly. “It’s the only just thing to do. And the only way to do it is to use this force projector on still another wavelength and on a larger scale. Devise a wavelength of destructive power which will pass through solid matter—such as intervening rock, but will disrupt and destroy flesh and blood the instant it strikes it. . . . It can be done.”

“And watch world events through the televisor meantime?”

“Yes. Seems the best course to me.”

“O. K., I’ll get busy—but I’m certainly not going to use such a terrific weapon from underground unless the wanton destruction of surface cities really warrants it. Sounds rather too ruthless to me.”

The girl’s eyebrows rose. “Ruthless? Is that what you think of me?”

“Not of you; only of your plan. You must admit it’s drastic.”

She remained silent, but Rod fancied he detected a curious hardness in her clear blue eyes. In silence he seized the force projector and wheeled it back into the laboratory, settled down to analyze it and work out a wavelength capable of piercing unlimited hard matter yet shattering human structure the moment it was contacted.

As he worked, with the adding machine to aid him, he was aware that Phyllis was watching him in silence. For the first time since he had met her his vague doubts were beginning to crystallize. He had always known the girl was somehow mysterious. Now he was beginning to think she was hard and callous—the last thing he wanted to believe. But there was no gainsaying the fact that since she had come to this underworld all the girlishness had dropped from her. Her whole manner was subtly altering.

Two days passed in the underworld. They were days in which Rod spent nearly all his time working out the final details of a giant force projector, and afterward supervising its rapid erection in a comparatively deserted machine room near the laboratory. Engineering science and tireless robots made short work of a job that would have otherwise been incredibly complicated.

While he was thus engaged the girl spent the time exploring, discovered the synthetic food department and set robots to work on such domestic matters as cooking and attendance. By degrees she unearthed the different places where comfort abounded—long airy lounges, softly lit, immensely roomy sleeping rooms; beds and bedding in perfect repair. There were all clothing requisites, unlimited water and food, automatically controlled air. . . . The place was a super efficiency of preparation, perfectly prepared for an indefinite siege.

It struck Rod that the girl was curiously subdued, and he inwardly blamed himself as the cause. He’d probably gotten her intentions all wrong, anyway.

She spent a lot of time at the radio televisor, intently watching scenes of vast disorder and senseless struggle, listened to the fevered yammerings of radio announcers declaring that war was eminent. Every nation was preparing to fling itself against its neighbor. The whole mad, insane world was drifting under the yellow skies to wholesale slaughter and destruction. Man was falling down the evolutionary ladder with incredible speed.

“It’s easy to see,” Rod commented slowly, as he joined the girl one afternoon, “how the early civilizations fell. Maybe, even, man’s discontent through the ages has been an hereditary relic of that last devolution. At heart he is not all bad—nobody is. What is it makes people bad? Maybe that heritage.”

“Maybe,” Phyllis admitted quietly. “I never thought of it like that before. Whatever it may be, though, the wanton destruction which eradicated early cities from the world must not be repeated. We must stop it, from here—”

She broke off and the question Rod was about to ask was forgotten as they both turned at a sudden sound. A figure came slowly through the doorway, disheveled and weary. It was Doctor Gore. Behind him were evidences of other men and women, all of them worse for wear, expressions crossed between relief and amazement at the vision of the amazing underworld.

“You made it!” Rod cried delightedly and the scientist nodded exhaustedly.

“Yes. The hardest job I ever had—any of us ever had for that matter. Some have come by fast plane, others by road, others walked, but they all arrived. . . .” He turned, waved his arm to the people. “Ladies and gentlemen, meet Mr. Rodney Marlow and Miss Bradman. They will tell you the rest of the story.” Looking at the two again, he added, “There are about two hundred of us altogether—the picked brains of America, England and Europe, in science, politics, engineering, geology, welfare, etcetera. . . .”

“O. K.,” Rod interrupted briefly. “You’ll be well cared for. Phyllis, see that they get a meal, then make accommodation arrangements. I’m going to seal that hole up before any unwanted ones start drifting down.”

The girl nodded and turned away at the head of the weary people. Rod wasted no time sealing the gap. When at last the empty space was closed, with solid, immovable metal he breathed more freely, turned and headed back with the projector to the laboratory. To his surprise, Phyllis was there, seated before the radio. She switched it off and got to her feet as he came in.

“World war has commenced,” she announced steadily.

Rod shrugged. “I expected it— But say, what are you doing here? What about the people?”

“They’re O. K.—having a meal and a rest. The robots will take care of them. We’ve still got work to do, Rod. Your force projector’s finished, isn’t it? Ready for action?”

“Sure, but we’ve got to wait until we see a deliberate attack on a city before we—”

“We shan’t wait for that,” the girl answered coldly. “Every human being on the surface has got to be destroyed! The Earth, when it clears the cosmic cloud, will start again with a clean sheet, freed forever from the degenerate rabble which has tenanted it too long already.”

Rod stared. “Good Heavens, Phyllis, do you realize what you are saying? It’s world massacre!”

“Oh, don’t be a fool!” Her voice was incredibly hard and commanding. “All the people that are worth while are down here, that’s been seen to. Those who are left above are nothing better than animals, fast on the way to destruction. They’ll kill each other in the end, anyway, but they’ll destroy every useful city and its contents in the doing. I, for one, don’t intend to allow that to happen. Destroy them! They’re nothing but vermin. No brains, no sense, concerned only with their own petty lusts and villainies. . . . If you don’t do it, I will!”

“You!” Rod laughed shortly. “You don’t even know how!”

The girl hesitated a moment, then flashed him a look of biting contempt. Calmly she strode from the laboratory and closed the door. In an instant Rod was after her, caught up to her as she entered the projector room. The giant instrument was standing motionless, ready for instant action. Without so much as a glance to either side Phyllis moved to it, operated the switchboard which Rod had thought was his own especial knowledge, slammed in the switches that started the generators.

Rod saw nothing unusual, but from the graded scale with its quivering needles, from the slow turning of the giant apparatus on its universal bearings, he knew quite well that the girl was controlling the instrument through a slow arc, hurling forth destructive waves clean through the earth, destroying every living thing in the track that reposed on the surface.

Suddenly life surged back into him. He hurled himself forward toward the girl, intent on seizing her and stopping her wholesale destruction of living beings.

“Stand exactly where you are!” she commanded, and to his utter bewilderment a silvered object gleamed suddenly in her hand, whipped with terrific speed from the filmy dress she was still wearing. But this was not the pleasing, generous Phyllis Bradman he had grown to love: it was a cold, calculating woman with a mission to fulfill.

“Make one move toward me until this task is finished and I’ll be forced to destroy you, Rod,” she said slowly. “I beg of you not to make me do it. This weapon is a tiny duplicate of this object here. No flesh and blood can withstand its blast.”

“But, Phyllis, what—? How—?” Rod stopped, too utterly amazed to speak further.

The girl flashed a glance at the meters, at the still slowly turning instrument. Her lips twisted into a grim smile.

“Ask yourself,” she said quietly, “just what good are those left on the surface? What have they ever done? How can a single one of them survive the effects of ever growing atavism? They’ll die, horribly. Maybe spend months in lingering agony from wounds. War—of the vilest kind—will ride the earth and destroy all that has ever been built up, unless those who cause that war are destroyed first! It will be a quicker death for them—a merciful death, for in the end they are bound to meet up with it. The intellectuals, the brains of the world, remain. Down here! The rest will go, leave the earth to be taken over again unscratched. And out of it may grow a better, worthier civilization.”

Vaguely Rod began to see the point of her reasoning. He eyed her steadily.

“In an hour this projector will have encompassed every part of the globe,” she went on quietly, turning away from it. “Since the force beam expands fanwise as it travels, it incorporates an enormous surface area at remoter regions of the world. I have it all reasoned out. Sixty minutes to eliminate a scum that should never have been on the earth anyway—which would never have been had birth been controlled and only intelligence been the permit to life . . .”

“You have it all reasoned out!” Rod whispered. “You have! I thought that was my task. I was chosen to save those that deserved to be saved . . .”

“At my direction, yes,” Phyllis acknowledged quietly.

“What!”

“You’ve known me as Phyllis Bradman,” she went on steadily, moving toward him and putting her weapon slowly away. “That is not my name. Actually, my position is that of a queen, though I am not designated as such. I am the complete ruler of this underworld. My name is Erina . . .”

“I always suspected there was something queer about you,” Rod muttered. “But—but what does it all mean? What are you driving at?”

“I occupied the two hundredth coffin,” she announced calmly. “Let me tell you the whole story. . . . I am the daughter of Saldon Ruj, the former ruler of this underworld—in fact of the whole world before the last atavism set in. When that atavism set in, many enemies were present with us down here. My father was slain. Events so worked out that our only chance of escape from them lay in feigning death by suspended animation, the period of the drug timed to last until mankind should be well on the upward trail again.

“Our enemies presumably slew each other, since no trace of them remained upon my awakening. Because of my position and authority the particular dose I had taken was timed to operate a year ahead of everybody else, so that I could determine in that time what course to take when the others recovered.

“I decided to see the world. I realized from our charts that the next atavism could not be more than a few days away. . . .

“I departed to the surface and took on an apparently ordinary identity. First thing I found was that geological slips had brought out metal underworld remarkably near the surface soil at one spot. Though the metal could not be broken without special knowledge, it was to me, rather disconcerting. The first thing I saw was you investigating the metal. I have to admit, Rod, that you attracted me immensely.”

“Can a woman so clever, so resourceful, be attracted by a mere farmer?” Rod asked bitterly.

“Even a ruler, even a woman who has slept as long as I have, can still love,” she answered steadily. “I was only twenty-two when I went to sleep; physically I am hardly any older even now. I saw the moment I met you that you were no fool, and since part of my scheme included obtaining all the intellectual people I could find, I led you on. Your language was easy; your mind told me everything. . . .”

“Then my discovering the city, all that robot talk, was so much bunk? Even that about me being the savior of mankind?”

“Most of it was true, though I was back of you all the time. The robots, of course, acted and spoke in response to my commands. I personally supervised everything the first time you were down here. It was easy enough, even easier when you accidentally fell and hurt yourself. That gave me time to act.”

“But how did you get down? You met me coming back up the steps!”

“That links up with something else.” The girl smiled mysteriously. “I’ll tell you that later. As you may have guessed, the welder you used on the first occasion was one equipped exactly like the one you used for the final entrance. I arranged that. You found the secret because I hypnotized you into finding it. You were by no means a difficult subject.”

“All those outpourings of genius from that machine? Were they real?”

“In every way. I gave you knowledge of amazing range, all of which is going to be useful to you in building up the new civilization when we take over.”

Rod frowned. “Now I understand why conventions didn’t worry you. Why you had infinite money. Naturally, you manufactured the stuff?”

She nodded slowly, smiling.

“But, Phyllis, it still leaves parts undone. How on earth did you ever reseal that hole when we were away in New York?”

“That was easy enough. I transferred myself from New York to this underworld, performed the act, then returned to New York.”

“What! All in one night! Whose plane did you use?”

“I didn’t use a plane. Do you remember asking me once if I had disappeared while leaving you down the lane?”

“Sure I do. I’ve never forgotten it.”

“It’s a gift, Rod, handed on to me by my father as he died. Even as ordinary rulers hand down certain valuable secrets to their next of kin, so my father handed on to me a supreme scientific achievement of his own discovery—mental control of matter. Mind over matter, if you wish, by which the body is compelled to obey the mind.

“If you remember, the early civilizations used it quite a lot; the Bible records it. If I will myself to a certain place, I am there, just as certain experts in your modern world cause an astral projection to take place. I use my whole body, however. I only behaved normally where necessity compelled it, but where there was no sense in physically wearing myself out, I merely willed myself to a point I was heading for.

“That was how I left this underworld in the first place, how I got to New York and back, how I met you so suddenly, how I disappeared in the lane. I thought, in the lane, that I was out of view, otherwise I would have been more careful.”

“And why did you reseal the hole and make me look such a fool?”

“For a very good reason. When I returned to reseal it I also converted your welder back into a normal one. I wanted only the intelligent men, able to think for themselves. Purposely I made you contact Dr. Gore. I knew that if he found no trace of proof for your statements he’d probably go off in a huff, but if he was really intelligent and scientific he’d finally come back to reconsider the matter of the metal itself. If he didn’t, he wasn’t worth having. My judgment was right, for he turned up. He brought others. That was why I said, save only those that deserve to be saved.”

Rod sighed. “I begin to see. You knew all this would happen on the surface. You got what intelligent residue there was left on earth down here in safety. You destroy the rest before they destroy what intelligence has built up. You intend, when the cloud has passed, to take over the surface, together with those who will awaken in another year. That’s it?”

“Exactly,” she assented quietly.

“And all this you could have done alone,” he whispered. “What need had you of me? An ordinary man?”