* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Gimlet's Oriental Quest

Date of first publication: 1948

Author: Capt. W. E. (William Earl) Johns (1893-1968)

Illustrator: Leslie Stead

Date first posted: Feb. 12, 2023

Date last updated: Feb. 12, 2023

Faded Page eBook #20230212

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, akaitharam, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

“Keep still everybody,” said Gimlet

GIMLET’S

ORIENTAL QUEST

A “King of the Commandos” Adventure

By

CAPTAIN W. E. JOHNS

Published by

THE BROCKHAMPTON PRESS, LTD., LEICESTER

in association with Hodder & Stoughton, Ltd.

The characters in this book are entirely imaginary,

and have no relation to any living person.

First printed 1948

Made and Printed in Great Britain by C. Tinling & Co., Ltd.,

Liverpool, London, and Prescot.

| CONTENTS | ||

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | HIGHLAND INTERLUDE | 9 |

| II. | EXPLANATIONS | 25 |

| III. | CUB MAKES A FRIEND | 35 |

| IV. | THE RIVER TAKES A HAND | 47 |

| V. | WATERY WORK | 59 |

| VI. | STRANGE REVELATIONS | 71 |

| VII. | TUANIK SHOWS HIS HAND | 87 |

| VIII. | GIMLET TAKES OVER | 100 |

| IX. | AT THE LITTLE LOTUS FLOWER | 110 |

| X. | COPPER TAKES A TURN | 125 |

| XI. | A NIGHT TO REMEMBER | 138 |

| XII. | SINISTER DEVELOPMENTS | 150 |

| XIII. | WHEN THIEVES FALL OUT | 166 |

| XIV. | TIGER FODDER | 178 |

| LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS | ||

| “Keep still everybody,” said Gimlet | Front. | |

| PAGE | ||

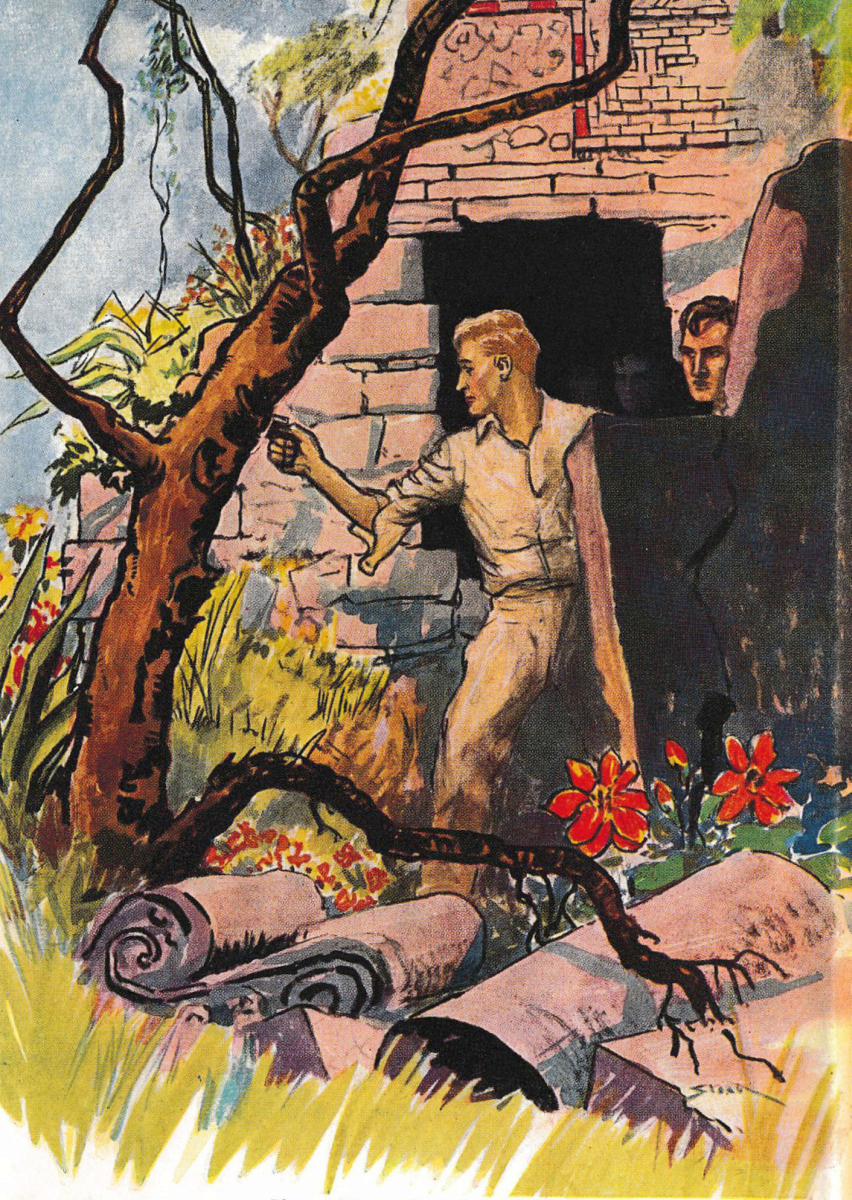

| “There’s something on, and it’s no’ a fush.” | 37 | |

| In a moment the tree was going down the river | 57 | |

| He dropped on his knees and felt the hole | 68 | |

| Very quietly he opened the door and looked in | 94 | |

| “I’ll just slip in to make sure.” | 117 | |

| Copper was prepared for almost anything, but not for elephants | 128 | |

| “That, I imagine, was the temple gates.” | 156 | |

| “Boys, this is it.” | 174 | |

The day was hot. An August sun, with the sky to itself and its zenith passed, loitered lazily along its timeless track towards the towering contours of the Cromdale Hills, already purple with heather, their feet in the hurrying waters of the River Carglas, new-born in the shrinking snows of Ben Macdhui. In short, the day, even as cloudless days go in the crystal atmosphere of the Scottish Highlands, was perfect—perfect, that is, for everyone except those who plied their fishing rods along the river’s rockbound banks in the hope of tempting a salmon to its doom.

Nigel Norman Peters, sometime known as “Cub” to the rank and file of the commando unit called “King’s Kittens”, had given it up. No fish, not even the foolish one that is said to linger in every river, could be expected to rise under such a sun and in water so clear that the shadow of the line fell across the bed of the stream like a hawser. But he was satisfied just to sit and watch the living water. It was enough. The capture of a fish was a desirable but not essential complement to happiness. So, with rod and gaff lying beside the wrappings of a sandwich lunch, he reclined within the shade of an alder and from under the brim of his hat watched the water swirling past, foaming as it dodged the boulders that sought to check its headlong rush to the sea. Silver gleamed as a fish jumped, on its way to the spawning beds at the headwaters of the river. Cub watched it jump again in the neck of the pool, yawned, and refusing to be tempted into futile action, stretched five feet eight inches of lithe figure a little lower into grass that had never known a scythe. This, he pondered pensively, was the thing everyone was talking about, Peace—the thing distraught politicians were tearing about the world looking for. The silly fellows were looking in the wrong place. They were looking in the cities. Good. The longer they looked in the wrong place the longer would peace prevail in the few places where it was still to be found. This, undoubtedly, was one of the best of them—or so he thought.

The sun dawdled on, thrusting minutes gently into the past. He did not trouble to count them. There were more to come. It was a pity, he soliloquised, that his old comrades, “Copper” Colson and “Trapper” Troublay, were not there to enjoy it with him. They should have been, but Trapper had gone home to Canada to see his folks, and while Copper was expected to arrive at any moment he had been delayed on account of his mother, who at the moment of their departure had fallen sick. Thus, the little shooting and fishing party which their old C.O., Captain “Gimlet” King, had arranged for them at Strathcarglas, his Highland sporting lodge, had come unstuck. At Gimlet’s suggestion, when he had got in touch with him on the telephone to tell him what had happened, he had come on alone to await the arrival of Copper, and possibly Gimlet himself. And this he had done, only to find on arrival at the lodge that the caretaker and his wife, apparently through some misunderstanding, had gone on their annual visit to Edinburgh. This information he had gathered at the local post office. Even then the chapter of accidents was not finished. The local tavern, the Strathcarglas Arms, which had figured so dramatically in his first visit to the lodge, was still shut, as no new tenant for it had yet been found.[1] As a result of these unfortunate circumstances, rather than return home Cub had gone to the nearest village, Auchrory, and there, in the Fishers Arms Hotel, installed himself pending the return of the caretaker to the lodge, or the arrival of the other members of the party. He had been there for the best part of a week, most of which time he had spent in the vain pursuit of a salmon, using rods and tackle lent to him by Macnaughton, the hotel proprietor. The weather, so he had been informed, was against him, and this had proved to be only too true in spite of the fact that the river at this point was both deeper and wider than it was higher up, where it ran close to Gimlet’s lodge. It was the same river. Still, the lack of co-operation on the part of the fish didn’t really worry him; he was content merely to be in such restful surroundings.

[1] See Gimlet Comes Home

He was dozing when the crack of a twig lifted his eyes from the river to the far bank a little way down stream, the direction from which the sound had come. Behind the rocks that held the river in its bed the bank was closely fringed with weeping birches, their leaves forming a pale green curtain between the water and a stand of conifers that occupied with stiff precision the lower part of the hill beyond. His interest was perfunctory, even slightly resentful. He thought, and hoped, that the intruder would reveal itself to be a roe deer, and his interest quickened when he saw that it was a man—not so much on that account as because the invader was dressed in a style unusual for the Highlands, where tweeds are the more general rule. The dark lounge suit he wore looked as out of place as would flannels at a funeral. Nor was the manner of his approach in accord with the scene. He came running, running hard, dodging through the trees; and as he ran he looked about him wildly, snatching frequent glances over his shoulder, at no small risk of collision with one of the many obstructions that beset his path. And this undignified haste was all the more remarkable because the man was well advanced in years, as a grey, close-trimmed beard attested.

With a deepening frown of wonderment Cub watched the runner swerve towards an ancient birch which, standing within the spate area, had fallen aslant under its load of lichen. The man’s hand went hurriedly to his pocket and came out holding an object too small for Cub to identify. This he thrust into what was apparently a fork, or hole, in the tree, although Cub could not see it. This done, he crouched for a moment, breathing heavily, staring back along his track, so that for the first time his face was clearly revealed, chalk white against a background of sombre shadow. The attitude lasted only for a moment, but it was long enough for the expression of stark, unbridled fear, to be photographed indelibly on Cub’s brain. Then, still following the river, he ran on, and was quickly lost to sight in the dappled shadows. The noise of his hasty passage died away and the brae resumed its former serenity.

Cub stirred slightly, wondering what this strange behaviour signified. The man he had seen was not entirely a stranger; he had seen him once before, for he was lodging in the hotel; but as to who he was and what his name and business might be, he knew nothing. He only knew that he was not a fisherman and that he had a son, a quiet, reserved sort of lad of about fifteen. There his interest, such as it was, ended.

It did not occur to Cub that the singular scene he had just witnessed was only half played out; and he was about to get up when the sounds that had at first disturbed him were repeated in greater volume. There was a crashing in the undergrowth and two men of middle age, complete strangers this time, burst into view, following the course taken by the forerunner. Like him they were inappropriately dressed for the time and place. Both wore lounge suits of dark material, one navy blue and the other brown. The man in the blue suit wore—of all the unseasonable head-dresses he could have chosen for a Highland glen—a bowler hat. Moreover, he appeared to be a coloured man of some sort.

The two men did not stop, or even pause, but panting heavily, as if unused to vigorous exercise, looking about them they ran on, jumping over the smaller rocks and ducking under branches that impeded their progress.

In half a minute they were out of sight.

Again Cub sank back, staring, now, in thoughtful deliberation, for the drama he had witnessed had passed the stage of being merely odd. It seemed to justify serious contemplation, a form of mental exercise he knew how to employ. The outstanding factors were evident. The old man had been running away from the two who followed in hot pursuit, presumably to obtain possession of the object which the fugitive in his extremity had hidden in the tree. It was still there. Presently, if he succeeded in giving his pursuers the slip, he would no doubt return and recover it. Cub waited.

He waited until the sun dipped behind the trees so that the far side of the pool was cast prematurely to the shadows. This was the moment to which he had been looking forward, for now a fish might “take”; but his natural curiosity had been aroused, so making his way to the shallow tail of the pool he waded over and walked along to the leaning tree. As he expected, there was a hole in it, a cavity about six inches in diameter level with his shoulder. He inserted a hand, but the hollow within was deep and he could not reach the bottom. He smiled faintly as, perceiving that the withdrawal of the object was likely to be less simple than its insertion, he visualised the old man’s dilemma when he returned.

Still pondering the incident he returned to his gear, shouldered bag, gaff and rod, and walked slowly back to the hotel for supper.

He looked into the lounge in passing, ostensibly to exchange notes with any other fisherman already home, but really to see if the bearded man had returned. He was not there. But his son was. The boy was seated in a chair that commanded a view of the road up which anyone returning from the river must come. Two strangers had arrived. He recognised them at once. They were the two men he had seen by the river. They were sitting together at the far end of the room, whisky on a small table between them. Their eyes, however, were on the boy.

Cub went out. In the hall he encountered Ina, the waitress. “Oh, Ina, what’s the name of the old boy with the grey beard who came a few days ago?” he inquired casually.

“You must mean Doctor Lander.”

“And the young chap with him?”

“That’s his son.”

“Ah, that’s what I thought. How long are they staying?”

“I don’t know. I don’t think they booked for any particular time.”

“I see—thanks, Ina.” Cub passed on. He had his bath but did not change, for he had a notion to go out again.

When he came down the lounge was full and the talk was all of fishing—or rather, the futility of it in such conditions. In this debate three people took no part. One was the boy, who still sat as before, staring down the road. His eyes, Cub noted, were now clouded with anxiety. The others were the two men he had seen on the river bank. They sat alone in a corner. Occasionally one spoke in a tone too low to be overheard. Covertly they watched the boy, who gave no sign that he was aware of it. Cub watched the road, the boy, and the men, until the gong went for supper. There was a general stir, but the boy did not move.

Cub hesitated, uncertain how to act. The boy’s worried expression made him feel uncomfortable. He wanted to tell him that he had seen his father by the river, and warn him that the men were watching him—as he was sure they were; but a natural reluctance to intrude into what, after all, was not his affair, restrained him. The boy’s manner, too, he felt, did not encourage friendly overtures. So when presently the two strangers walked through to the dining-room he followed them in.

As Ina served his soup he asked her quietly if the newcomers had booked rooms. She told him that they had, but she did not know for how long. They were not fishers. Their names were Mr. Smith and Mr. Gray, both from the South. Mr. Gray was the one in the brown suit. Yes, they had arrived by road, in their own car.

Cub went through the meal with his attention divided between the door and the strangers, at the same time calling himself a fool for wasting time in speculation over a matter that did not concern him. The boy did not come in. He was, Cub supposed, still waiting for his father. Remembering the white, frightened face, an uneasy feeling grew on him that the old man would not come—unless he was engaged in the recovery of the object he had deposited in the tree, which would certainly be a lengthy operation.

Cub continued to speculate. It was the fact that Smith and Gray had left the river that he did not like. It suggested that they had achieved their purpose, whatever it might be. Nor did he like the look of them, although that, as he realised, might be a consequence of their suspicious behaviour.

Smith was the older. He was a man of between forty-five and fifty, robustly built, going bald in front, with a bland, self-confident manner; but his lips were thick, and his expression hard, and for all his benign indifference to his surroundings, his eyes, very dark and set wide apart, were never still. His nose was flat, as if it had been broken at some time and had had the bone taken out of it. There was a curious scar on his right cheekbone, the shape of a dog’s hind leg. But it was the colour of his skin that puzzled Cub most. It was a sort of dirty greyish green, as if the man had a tincture of negro blood in his veins. Gray was an altogether different type. He was a smallish man of perhaps thirty, black-haired, sleek, and immaculate. A stiff white collar and a diamond ring on the third finger of his right hand were conspicuous, as was the corner of a crimson silk handkerchief that had been arranged to show in the outside breast pocket of a tight-fitting jacket. It was evident at once that he was not a European. His skin was the sallow, olive brown of the Eurasian, while prominent cheek bones and flattish features suggested Mongolian ancestry. Like his companion, he was hard to place, but somewhere, thought Cub, an ancestor had made contact with the Far East. In business he might have been anything, but it was not easy to image the sort of business that could have brought him to Glencarglas. Clearly, he had not come for sport, as did most people from the South.

Cub tried to put a prosaic complexion on the scene he had witnessed by the river, and failed. The more he thought about the incident the more evident it became that he owed it to the boy to tell him about it. He was still waiting. He was obviously worried and anxious. He would have to be told eventually, anyway, if his father did not return. Indeed, thought Cub, he might—although he jibbed at the idea—have to tell the village constable. He could not forget the old man’s face. Obviously, he was—or thought he was—in danger. There was no doubt whatever about that. If his pursuers were now watching the boy it seemed more than likely that he was in for trouble, too. The more Cub thought, the closer loomed the shadow of a tragedy. He wanted no truck with tragedy. He was on holiday, and he had promised himself a couple of hours at the sea-trout, after the sun was down.

He tried to work the thing out logically. The two strangers had been chasing the old man with a definite purpose. The relentlessness of their pursuit made that abundantly clear. They wanted something. The old man knew he was being followed, and he knew what the men wanted. It was reasonable to suppose that it was the object he had hidden in the tree. Either they had caught him, or they had not. If they had not, then he would have come home for supper. If they had caught him—well, anything might have happened. The pursuers, not finding what they sought on the person of their quarry, would demand to be told what he had done with it. If he had confessed that he had hidden it in the tree they would collect the object and in all probability depart. If he had refused the information they might suppose that he had left the thing at home, in which case they would make for the hotel to search his room. The fact that they had come to the hotel, therefore, suggested that so far they had been unsuccessful in their quest. If they knew about the son they might think he had it, or know where it was. If this reasoning was correct, their next step would be to visit the old man’s room—assuming they knew he would not be in it. Failing in this, they would turn their attention to the boy. The least Cub thought he could do was warn him, to put him on his guard. Should the lad resent his interference or ignore the warning—well, that was his affair. He, Cub, would have discharged his responsibility, such as it was. He would then go after the sea-trout. It was the sort of evening that promised sport.

When coffee was brought he picked up his cup and took it through to the lounge. He had to pass close to Smith and Gray. They took no notice of him—not that there was any reason why they should if they had not seen him by the river. He found the boy in the same chair, still watching the road. There was no one else in the room.

For the first time Cub looked at him closely. The boy, he thought, apart from looking worried, seemed thin and listless, as if he might have been recovering from an illness. He looked lonely, too, sitting there with no one to speak to. These things awoke in Cub a sudden sympathy, a feeling that he ought to help him. But he also wanted to go fishing. There might, he decided, be time for both. He took the plunge. Addressing the boy he said: “Forgive me for butting in, but are you waiting for your father?”

The boy started and looked up, brows knit, eyes questioning. “Yes, I am—why?” he replied in a quick nervous voice.

“I wondered—I saw him by the river this afternoon,” explained Cub awkwardly, assailed suddenly by the idea that he might be making a melodrama out of a simple domestic occurrence.

“He told me he was only going for a short walk,” the boy prompted, in a voice crisp with anxiety. “He said he wouldn’t be long.”

“You are—sort of worried about him?”

A brief pause. “Yes.”

Cub thrust his hands in his pockets to cover a queer feeling of embarrassment. “Look here,” he went on, “I know it’s no business of mine, but was your father in any sort of danger when he went out? I have a reason for asking. Don’t answer if you don’t want to.”

The colour drained slowly from the boy’s face. He moistened his lips. “Why do you ask that?”

“I saw something going on that struck me as a trifle odd. Was he?”

“Yes.”

Cub smiled lugubriously. “I was afraid you were going to say that.”

The boy’s eyes darkened with apprehension. “Something has happened. What is it?”

This was going farther and faster than Cub had intended—at least at this juncture; but having started he had to go on. “I don’t want to start a flap, but I think you ought to know that those two queer-looking types who arrived today are watching you.”

The boy stared. “Watching me?”

“ ’Fraid so.”

“Never mind me, what about my father?” the boy asked sharply. “Where is he?”

“I don’t know,” returned Cub truthfully. “I saw him this afternoon by the river. He seemed to be in the dickens of a hurry, and . . .”

“Go on.”

“He was being followed.”

“By these two men?”

“Yes. They didn’t spot me under the trees on the other bank. I wouldn’t let them see that you know. In fact, perhaps we had better not talk here. They’ll be in at any moment. I’m going out for a couple of hours after sea-trout. Your father may come back in that time. If he doesn’t—well, you’ll see me come in. I’ll tell you what I saw this afternoon.”

“It must have been serious for you to mention it,” observed the boy shrewdly.

“True enough,” admitted Cub. “However—but we’d better not talk here. I’ll see you when I come home, unless, of course, your father comes back, in which case the thing won’t arise. Where shall we meet?”

“My father has a bed-sitting room here—perhaps that would do?”

“What’s the number?”

“Twenty-one. My bedroom is next to it—number twenty.”

Cub nodded. “We’ll leave it like that then.”

Smith and Gray came in as he went out.

Picking up his rod Cub walked to the bottom end of his beat, the best part of two miles, crossed the bridge that spanned the river at that point, and then made his way up to the scene of the incident that still occupied his mind. By the time he had reached the hollow tree the sun was far down behind the hills, but the afterglow persisted, varnishing the river’s unbroken surfaces with carmine, blue and gold. The rocks were still warm. The sun-soaked air had not lost its heat and midges flirted joyously with death as they waltzed above the small brown trout in the tail of the pool. The only sounds were the plaintive calls of a pair of sandpipers and the murmur of water spilling over rock and stone.

He looked up and down the river. There was no one in sight. He looked at the tree which, he had good reason to believe, held the secret of the strange events of the afternoon. Nothing had changed. Moving quickly he took a fishing lead from his pocket, pressed it over the fly at the end of his cast, inserted it into the hole and allowed it to run to the bottom. Then, taking the gut between finger and thumb at the point where it vanished into the hole, he withdrew the lead and with his eye measured the distance between it and his hand—a simple operation that told him that the base of the hollow was nearly five feet below the level of the hole. The object that he had seen dropped in was still there, he decided, for short of cutting down or mutilating the tree it was hard to see how it could be retrieved. Even if the hole was enlarged it would still be impossible to reach the bottom. A quick glance up and down the river revealed that he was still alone, so removing the lead from the fly he made a cast upon the broad surface of the pool. But he was preoccupied, and when a fish rose he struck too soon, and missed it.

With a muttered “dash it” at his carelessness, he reeled in, stood for a moment undecided, and then walked slowly up the river bank. As he walked his eyes explored the undergrowth, furtively, as if he was afraid of what he might find. In the solemn hush of the gloaming the atmosphere of tragedy seemed more tangible than it had been in the bright light of day.

He reached the next pool with his fears unrealised. It lay in deepest shadow, black and smooth, a veritable sink of mystery where the water made uncouth sucking noises as it scoured unseen holes and cavities below the summer level. Local lore asserted that this was the resort of water kelpies. They called it, aptly, the Witches Pool.

Cub advanced a pace and stared down into the pot—the deep hole usually to be found in such pools, the result of scouring during the winter spates. He could see nothing but a vague reflection of the trees behind him. Not that he expected to see anything. The water was too deep, a full twenty feet as he knew well, for he had fished there before. On rare occasions when the water was dead low and without a ripple it was just possible to see the bottom, a chaos of great boulders flung in by centuries of high water following the melting of the winter snow. Even in such conditions it was only possible to probe the depths in early morning, when the sun was on the other side.

A salmon, travelling leisurely, came swirling into the pool. From force of habit he watched for it to show again. Ten seconds later it shot high into the air from the centre of the pot, to fall back with a splash in a shower of spray. The air seemed to turn a shade cooler as Cub realised that this was no casual jump, but the startled leap of a badly-frightened fish. There was a broad ripple as the silver streak sped on up the river. It jumped again in the neck of the pool, still travelling fast. He did not see it again.

He was still pondering the strange behaviour of the fish when a silky voice behind him inquired, “Any luck?”

At the unexpected sound Cub’s nerves twitched, betraying,—although until that moment he was unaware of it—the taut condition of his nerves. He turned. It was the coffee-coloured man—Gray. With smoke curling from a cigarette held loosely in the corner of his mouth he was leaning against a tree.

Cub’s first thought was, how well the voice went with the face. The language used was English, without a trace of accent, but the dulcet tone employed was as foreign to the scene as would have been a peacock on the heather. “No, I can’t find a fish,” he answered carelessly. “I think I’ll pack up.”

“Lovely evening.”

“Beautiful.”

“Nice spot, this.”

“Delightful.”

“Is it a good place for catching fish?”

“Yes, it’s a good place when conditions are right,” acknowledged Cub.

“Pretty deep, eh?”

“Very deep.”

“How deep would you say?”

“Twenty feet or so.”

“Do many people come fishing here?”

“Quite a few.” Cub shouldered his rod. “Well, I’ll be getting along. Goodnight.”

“Goodnight.”

Without a backward glance Cub walked slowly to the bridge, and on towards the hotel. What, he wondered, was Gray doing there at that hour?

He met only one person on the way home, a smallish, red-whiskered man of cheerful expression who was strolling hands in pockets towards the river. He knew him by sight and reputation, as did everyone who fished the Carglas. It was Sandy Macrae, the one man in the village who somehow could always manage to get a fish. On this occasion he carried no rod, having been warned off the water for employing methods not approved by the Fishery Board. In other words, as a poacher Sandy was renowned from Speyside to Deeside. If anyone wanted a fish he could always get one from Sandy—or Sandy, if he had not one or two at home in the bath, would soon get him one. Rumour said he kept a rod hidden on the river bank.

The poacher smiled and raised a respectful hand in greeting. “Any luck, sir?” he inquired in passing.

“Not today,” returned Cub. “I’m afraid the fish won’t take until we get a change in the weather.”

“Aye, I’d think that,” agreed Sandy carelessly, as if the question of whether or not the fish would take was a matter of minor importance—which, as far as he was concerned, it was. “There was a bonny fush in the Witches Pot th’ morning,” he volunteered.

Cub nodded. “He’s probably on his way up the river by now.”

Sandy considered the sky. “Aye. There’s rain a’coming,” he opined.

“I may find one tomorrow,” said Cub as he walked on.

As he approached the hotel he looked at his watch. It was eleven o’clock. He had been out just two hours.

Because the lights were on and the blinds not drawn Cub could see into the lounge as he approached the front door. None of the people in whom he was interested was there. Passing the lounge door, therefore, he went in search of Jean, the chambermaid. From her he learned that Smith’s room was number fourteen, and Gray’s next to it. Both were on the first floor—the same floor as the rooms occupied by himself and the Landers. Gray he had left at the river, but he spent a minute looking for Smith, because he wanted to know where he was. Not finding him in the bar he went upstairs, using the staff staircase, which reached the first floor opposite number fourteen. The door was ajar. The light was not on, but he could hear someone, presumably Smith, moving about.

Proceeding along the corridor he halted at number twenty-one and without knocking turned the handle. The door yielded to his pressure so he looked in. The room was in semi-darkness, and in the half-light he could just make out the slim figure of the boy he had come to see silhouetted against the open window. “I didn’t knock because Smith’s door is open; I think he’s inside, and I didn’t want him to hear me,” he explained.

“He’s still watching me,” stated the boy calmly.

“That’s what I thought. Has your father come back?”

“No. Did you see nothing of him at the river?”

“Not a sign, but Gray was there, near the place where I saw him this afternoon.”

“Won’t you sit down? You were going to tell me what happened.”

Cub closed the door quietly and pulled up a chair. “By the way, my name’s Peters—Nigel Peters. My friends call me Cub.”

“Mine’s Lander—Tony Lander.”

Cub smiled. “Good. Now we’re all set. You know, Tony, this is all very difficult,” he went on with some reluctance. “I still feel that I’m butting in on something that doesn’t really concern me . . . but I thought I’d better tell you what I know.”

“It’s very kind of you,” Tony assured him. “I’m only glad that somebody knows something of my father’s movements. You see, I’m afraid he may never come back—now.” He spoke without emotion.

“Oh, it may not be as bad as that,” protested Cub, somewhat startled by this frank admission.

Tony shook his head, slowly. “I’ve been expecting this for some time,” he announced wearily. “Now it’s happened. Tell me what you saw. Then you’d better go, and for your own good forget all about it. There’s no need for you to become involved.”

“Don’t worry about me,” said Cub confidently. “I can take care of myself—or I should be able to by now.”

“You may think so,” returned Tony earnestly. “But this may be something bigger and far more dangerous than you imagine. Please tell me what you saw. Speak quietly in case Smith comes along to listen outside the door.”

“All right,” agreed Cub. “It won’t take long. I was fishing the home beat this afternoon. The fish weren’t taking so I packed up and lay under a tree. About half past four your father appeared on the opposite bank. He was running, and he seemed—well, pretty badly scared. He ran on and that was the last I saw of him. A minute or two later these fellows Smith and Gray appeared. They also were running, obviously chasing your father. That’s all. They disappeared in the same direction. I didn’t see any of them again. I should have thought nothing of it if your father hadn’t looked so upset.”

“He had reason to be,” said Tony slowly. “Where exactly did this happen?”

“Just below what they call the Witches Pool.”

“Did you go back there tonight?”

“Yes.”

“And you saw nothing?”

“Nothing of interest.”

“Did you look—for my father?”

“Er—yes. ’Matter of fact, I did. I was by the pool when Gray came along.”

“What was he doing?”

“Nothing in particular as far as I could see. He came up behind me, quietly.”

“Did he say anything?”

“He spoke about fishing—asked me if fishermen often went there, and wanted to know how deep the water was.”

“You’re sure he didn’t see you this afternoon?”

“I’m pretty certain of it.”

There was a brief silence. “What I don’t understand is why these men are still hanging about,” Tony went on. “If they’ve got what they came for why haven’t they gone?”

“Perhaps they haven’t got what they came for.”

“If they overtook my father they must surely have got it. He always carried in his pocket the thing they wanted.”

“So that was what the fuss was about? They wanted something your father had, eh?”

“Yes.”

“He knew that?”

“Yes.”

“Then why on earth did he carry it about with him? Why not pop it into the bank, or somewhere equally safe?”

“I don’t know.”

“But you knew all about this?”

“Of course. We, my father and I, have lived under a shadow for some time, moving from place to place, trying to give these people the slip. But sooner or later they found us. As you see, they even found us here, within a day or two of our arrival.”

Cub considered Tony curiously. “May I ask what this thing is these men are after?”

“You may, but I can’t answer.”

“Can’t?”

“I don’t know what it is—or was.”

“You don’t know!” Cub’s voice rose with astonishment.

“My father never told me. I only know that although he went in fear of his life he wouldn’t part with it.”

Cub thought for a moment. “But I don’t quite understand. I thought you didn’t know these men, Smith and Gray. Now I gather they’ve been after you for some time?”

“I knew somebody was after us, but I didn’t know who. This is the first time I’ve seen these two men. My father may or may not have recognised them, but he must have realised that he was being followed. What puzzles me is why they are still here.”

“They’re here because they haven’t got what they came for,” declared Cub.

Tony’s eyebrows went up. “You speak as if you were sure of that?”

“I’ve reason to think it,” said Cub. “You see, Tony, while your father was running I saw him stop to hide something. That could only have been the thing which, from what you tell me, these fellows were after.”

“Then you know where it is?”

“I think so.”

“Where is it?”

“I’d rather not tell you.”

“Why?”

“Because if you don’t know—well, you don’t know, and neither threats nor anything else could get the information out of you. It’s safer for you not to know. Nobody but you knows that I know. For the moment, at any rate, it’s better that things should stay that way. Of course, if you insist. . . .”

Speaking slowly and seriously Tony broke in. “You’d better forget where the thing is, forget the whole business, or you may find yourself in the position that my father and I have suffered.”

Cub smiled. “I’ll think about it. Meanwhile, the pressing question is, what are you going to do about your father?”

“What can I do?”

Cub shrugged. “Frankly, I don’t know. It’s a bit early to talk about bringing in the police, although if the thing’s as serious as you say you may have to go to them. But I don’t think there’s much point in starting a search at this time of night.”

“If my father was alive he’d have returned by now,” said Tony heavily.

“He may still come.”

“I don’t think so, now, after what you’ve told me. They caught him. If there’s nothing more we can do we might as well go to bed. It’s getting late.”

The worried frown in Cub’s forehead deepened. “I’m afraid you may have a spot of trouble with these fellows who call themselves Smith and Gray—which, by the way, strike me as being convenient names. We can reckon they’ll still try to get what they came for. If they haven’t already done so, it’s a pretty safe bet that their next shot will be at this room. When that fails they’ll be after you.”

Tony lifted a shoulder. “What does it matter? I almost wish they could find what they want, and then perhaps they’d clear off.”

Cub looked pained. “Here, I say, I wouldn’t take that view. No fear! I’m all for making life difficult for the blighters.”

“If they come to me asking questions I shall tell them that I know nothing.”

“They may not believe you.”

“They can please themselves about that.”

“They may search your room. There are no locks on any of the doors here—or rather, they don’t work.”

“Mine has a catch on the inside.”

“That may be all right when you’re in your room, but it’s no use when you go out.”

“They won’t find anything.”

“All right, if that’s how you feel about it. If they try any rough stuff I hope you’ll let me know?”

“Thanks. Really, I’m desperately worried, and in need of help, but I don’t see what anyone can do. If. . . .” Tony broke off as footsteps padding down the passage ended outside the door. His eyes met Cub’s, questioningly.

Cub laid a finger on his lips. Rising, he walked quickly but softly to the wardrobe and stood in the narrow cavity that occurred between one end of it and the wall. He could not see the door but he heard it open.

A voice, a man’s voice, with a husky American accent, said: “Sorry, kid. Must have made a mistake. These doors are all alike in the dark.” The door closed. Footsteps retreated.

Cub stepped out. “That, I think, was Smith.”

“Yes.”

“You see what I mean? That was no mistake. He came to have a look round. I’m afraid it’s a bad sign.”

“In what way?”

“Well—er——” Cub hesitated.

“Go on.”

“He must have known your father wasn’t here. He expected to find the room empty.”

“I’d already realised that. He seemed a bit surprised to find me here.”

“He may have assumed that you would be in your room.”

Tony stared through the open window at the forbidding silhouette of the Cromdale Hills. When he spoke again his voice was tremulous for the first time. “My father is somewhere out there,” he breathed. “It’s awful to know that, yet do nothing about it—but what can I do?”

“I’ll go and have another look round if you like.”

“It’s no use—you know that; thanks all the same. We can only wait to see what happens.”

There was a sudden and unusual burst of activity in the village square below. A man jumped off a bicycle allowing it to fall with a crash. He called something to someone.

Cub looked out of the window, but the light was too dim for him to see distinctly the cause of the disturbance. He observed that the usual crowd of idlers outside the post office had broken up and had strung out behind the stalwart form of Peter Ross, the local policeman, who was walking with unaccustomed briskness towards a man who came running from the direction of the river. It was Sandy Macrae, and he faltered as he ran like a man who has travelled in haste and is nearly at the end of his endurance.

Cub turned back into the room. Remembering that he had seen the poacher obviously bound for the river he had an uncomfortable suspicion of what had happened; but he did not voice it. He simply said: “I’ll be moving off now. You had better go to your room. If you need me send a message—or come along to my room if you like.”

“Thanks,” answered Tony simply.

Cub went out and down the stairs. By the time he had reached the badly lighted hall a little group had collected just inside the front door. Macnaughton, the proprietor of the hotel, was trying to keep others out. The central figures of the group were Ross the policeman and Macrae the poacher.

“All right; don’t make such an infernal noise, Macrae. I’ll get my car out,” said Macnaughton.

Cub joined the party. “What’s the trouble?” he inquired.

Macnaughton turned a harassed face. “This is a nice business,” he rapped out petulantly. “Right in the middle of the season, too. There’s been an accident—one of the guests.”

“Which one?”

“It sounds like Doctor Lander from the description. That rascally poacher was at his old games on my water and snatched a bigger fish than he bargained for. He dragged something to the top of the Witches Pool and saw a face staring at him.”

Cub moistened his lips. “What did he do?”

Macnaughton sneered. “Dropped everything and bolted. The body is still in the river with his hooks in it. I’m going down with Ross to fetch it. Don’t tell the others. They’ll have to know in the morning, but it won’t sound so bad in daylight.”

“If it’s Lander, what about his son? He’ll have to know.”

“As soon as we’re sure I’ll send Mrs. Fraser up to tell him.” Mrs. Fraser was the manageress.

“What are you going to do with the body?”

“There’s a mortuary at the back of the police station.”

“Would you like me to come along and give a hand?”

“Come if you like. What was the old man doing by the river—he doesn’t fish?” Macnaughton strode away, muttering.

Someone had given the poacher a dram of whisky. The glass rattled against his teeth. “I was just having one cast,” he spluttered. “Just one, ye ken, for a wee beastie, . . .”

Cub followed Macnaughton. He was not surprised, but this dramatic confirmation of his fears shook him. He saw again the white frightened face and the sinister pool. He saw other things too, with disconcerting clarity. An accident, Macnaughton had said, and that was what it would look like. That was what everyone would think. Only he knew the truth. There was no doubt in his mind about the body being that of Doctor Lander. In his agitation he nearly told the policeman so, nearly told him what he had seen, but checked himself in time. He might suspect, but he could prove nothing. He could not even prove that Smith and Gray had been near the river, should they deny it. He would, he decided, have to think, and think hard, before he did anything.

Ross beckoned to Sandy Macrae. “Come away,” he ordered curtly. “I want you.”

Cub climbed into the back of Macnaughton’s car.

It did not take the car long to reach the place where the road came nearest to the river, which, as it happened, was immediately above the Witches Pool. In fact, it was the steep brae at that spot that caused the river to swerve, and in doing so scour out the deep “pot.” Leaving the car at the side of the road the investigators scrambled down the brae, with Macrae, who clearly had no love for the task on hand, still muttering under his breath about daft people from the South who fell in the river and spoilt the “fushin’.”

If the pool had looked dark and forbidding in the light of day, in the eerie lingering dusk, with all sounds of bird life hushed, it looked positively evil; and the sullen hiss and gurgle of the water did nothing to brighten the picture. No wonder, thought Cub, the local people had given the place a sinister reputation. If there were such things as water kelpies this would surely be their headquarters.

However, he had little time to dwell on such disturbing fancies, for the policeman, as if as anxious as Macrae to be gone, was already busy on the gruesome duty that had brought him out. He went to Macrae’s rod, still lying where it had been dropped in the poacher’s panic flight, and picking it up, wound in the line until it was taut. When this had been done it could be seen that the line entered the water close under the bank at the edge of the pot. The constable raised the point of the rod and put some strain on it. The rod bent, but as the line remained fast he put it down and took the line in his hands. Advancing to the edge of the water he began to pull, and then, slowly, the line began to come towards him. Hand over hand he drew it in. “There’s something on, and it’s no’ a fush,” he said in a curious voice. “Stand by to grab it when it shows. If the hooks come away we’ll be here all night.”

Cub stepped forward. During the war he had looked on death too often to be afraid of it. He knew that now, as then, it was from the living that he had most to fear. Macnaughton joined him, but the poacher backed away, making noises in his throat.

At last a dark heavy object broke the inky surface of the stream. Both Cub and Macnaughton dropped on their knees and reached out. Cub’s fingers sank into the soft material of the garment.

“Up with him,” grunted Macnaughton.

Cub heaved, and a moment later a human body, the body of a man, lay on the bank, with water trickling from drenched clothes back into the river.

Macnaughton turned the body over. “Aye, it’s Lander,” he said in a hushed voice as he straightened himself.

Cub drew a deep breath as his worst fears were realised. Tony would never see his father again.

The policeman examined the body as far as this was possible in the light of his torch. “He had a nasty crack on the forehead,” said he. “Struck his head on a rock when he fell, na’doot. Knocked himself oot. That’s why he went to the bottom, I’m thinkin’. Young Mackenzie from yon farm did the same thing two years back, ye ken, Mac? Puir mon. Ach, well; let’s get him up the brae to the car.”

From these remarks it was evident to Cub that no thought of foul play had entered the head of anyone but himself. After all, he mused, why should it? The tragedy had all the appearances of an accident, one of those simple accidents which are by no means uncommon in the wilder districts of the Highlands. Had he not been a witness of the suspicious events on the river bank during the afternoon, he, too, would have assumed that the man had died as the result of an accident. He said nothing, deciding quickly that this was neither the time nor place to disillusion the other members of the party. One word in front of the poacher and the whole village would be talking of murder before the night was out.

Not without difficulty the limp body was carried up the brae to the car. Nothing more was said. Macnaughton drove the car back to the village. He stopped outside Macrae’s cottage to let him get off.

“I’ll be seein’ ye in the mornin’,” the policeman told him curtly.

Macnaughton drove on and stopped again outside the hotel to let Cub dismount. There was nothing more he could do. The car went on to the police station with its grim burden.

When Cub went into the hotel he found that most of the guests had retired for the night. Smith and Gray were still in the lounge, with whisky on one of the small tables between them. Cub did not speak. He went on up the stairs and knocked gently on the door of room twenty. A voice, Tony’s voice, called to him to enter. He went in and closed the door behind him. The light was off, so he switched it on, and found Tony, still fully dressed, sitting on his bed. He drew a deep breath, not relishing the task which he had taken upon himself. But the boy would have to be told the truth sometime, and in the circumstances, in view of what he knew, he decided that he was probably the best person to break the evil tidings.

Tony’s eyes were on his face, open wide, asking a question. “Well?” he whispered.

Cub squared himself. “I’m sorry, Tony, but I shall have to ask you to brace yourself for bad news,” he said quietly.

“They’ve found my father?”

“Yes.”

“He is—dead?”

A brief pause. “Yes.”

Tony held himself well in hand. Only his head seemed to drop a little. “I knew it,” he said in a quite steady voice. “Don’t ask me how I knew, but I knew. Perhaps it was because I’ve been expecting this, dreading it, for months; so it isn’t such a shock as you may think. Oh, why did my father have to behave as he did—why—why—why?” The boy rolled over and buried his face in the pillow.

“That’s something we may never know,” answered Cub gently, sitting on the bed and putting a hand on the boy’s shoulder. “But it’s happened, and it will have to be faced.”

“Where did they find him?” came in a muffled voice.

“In the river.”

“They’ll think it was an accident, of course?”

“Of course. There’s no reason why they should think anything else. No doubt it was made to look like an accident. Only we know—it wasn’t.”

Tony sat up abruptly. “My father was murdered!” He forced the words out through his teeth.

“Yes, I think he was,” agreed Cub frankly. “If he wasn’t actually killed by those two men then his death was certainly brought about by his efforts to escape from them. Tell me: did your father carry a weapon of any sort?”

“I don’t think so. He wasn’t that sort of man. Don’t misunderstand me, though. He wasn’t a coward. He simply tried to keep clear of trouble. That’s why we were always on the move.”

“Have you seen anything of Smith or Gray since I left you?”

“No. I haven’t been downstairs. Are they still in the hotel?”

“Yes. They’re in the lounge, drinking.”

“Then I’ll——” Tony sprang up.

Cub put out a restraining hand. “Take it easy, laddie,” he said softly. “I know how you feel, but you won’t do any good at this moment by blurting out what you know. We’ve nothing against these men; nothing, that is, which in court——”

“But you saw them——”

“What I saw amounted to very little,” asserted Cub. “What did I see? I saw Smith and Gray on the river bank. That could easily be explained. After all, everyone here goes to the river. And they weren’t even at the place where your father’s body was found. I was down at the river myself, if it comes to that. No. The best thing for the time being is to let everyone think it was an accident. Pretend to believe that yourself, as I shall.”

“And let these murderers escape?”

“I didn’t say that. What I said was, let us lead them to think that we accept the accident theory. That may put them off their guard. It won’t be easy for you, I know, but you must try. Once they have an inkling that you suspect the truth, either they’ll disappear, in which case we might never find them again, or they’ll kill you, too. We’ll bring them to the gallows all in good time, never fear. You can’t commit murder and get away with it.”

“But how will we ever prove anything if we don’t speak up now?”

Cub shook his head. “I don’t know. All I know is, our best chance is to keep our mouths shut. Don’t worry. I’ll help you—and I have some useful friends who will help us both.”

“But what can you do?” went on Tony wearily. “You haven’t a clue, and I can’t see how you’ll ever get one now.”

“I’m not so sure about that,” returned Cub. “What about this object your father hid? That may tell us something to put us on the right track. Only I know where it is. Smith and Gray want it. That’s why they came here in the first place and that’s why they’re still here. They expected to find it on your father, that’s pretty certain, otherwise there would have been no point in killing him. But he had got rid of it, so the murderers committed their crime for nothing, which must have made them pretty sick. All the same, they must know it isn’t far away, so the chances are they’ll stay here until they do find it. They’ll stay in this hotel because there’s nowhere else for them to go. There is this about it: if these scoundrels were prepared to commit murder to get the thing then it must be either very valuable or important.”

Tony nodded. “I shall have to stay here myself if it comes to that.”

“I’m not so sure,” returned Cub. “I have a friend who has a house not far away, and if it suited us we could go there. We might go, anyway. We’ll see. For the present it suits me to be here, so that I can keep an eye on Smith and Gray. Tomorrow I shall recover the thing your father hid in the tree. Surely that will tell us something. You say you’ve no idea at all what it could be?”

“No, but I fancy it must be something to do with Siam. My father’s manner seemed to change from the time we left there.”

Cub stared. “From where?”

“Siam. It was called Thailand at one time. I was born there. Perhaps that’s why I’m such a feeble-looking specimen. I had fever pretty badly. My mother died of it. She’s buried in the jungle near our bungalow.”

“What was your father doing in Siam?” asked Cub curiously.

“He was in practice as a doctor. I don’t know how he came to go there in the first place, but he built up a very good practice, with people of the country, some of whom are very rich, as well as Europeans. When the Jap invasion came we had to bolt, of course. My father said we would make for Singapore, but we left it too late. Everything was in hopeless confusion. We ran out of petrol, and I don’t know what would have happened if we hadn’t got a lift on a lorry. We had a pretty awful time, and lost everything, of course, as did most people. I suppose we were lucky to get away at all, but we managed to get on a ship which took us to Australia. It’s all a bit vague to me now. After all, I was only a kid then.”

Cub smiled, wondering what Tony thought he was now.

“Eventually we got back to England, and we seem to have been drifting about ever since,” concluded Tony.

“Why didn’t your father settle down somewhere?”

“He didn’t talk much, but I think he always hoped to get back to Siam, where we were known. After all, my mother is buried there. My father was never the same after she died.”

“Why didn’t he go straight back after the war was over?”

“I don’t know. He seemed strange, as if he was afraid of something. Twice he booked our passages, once by air and once by sea, and cancelled them at the last moment.”

“Hm.” Cub pondered Tony’s words. “That doesn’t throw much light on the mystery, except. . . .” He looked up. “Come to think of it, one of these men, Gray, looks as if he might have Siamese blood in him. He’s got a good dose of the Orient in him, anyway.”

Tony nodded. “I noticed that.”

“He could be a Siamese—of sorts.”

“Easily. He’s probably a half-breed—there are thousands of them, all sorts of mixtures.”

“You’ve never seen him before?”

“No. What I’m wondering is, what he’ll do next.”

“I think I can tell you what the pair of them will do,” returned Cub slowly. “First, they’ll search your father’s room. That won’t do any harm because I’m pretty sure the thing they’re looking for isn’t there. Next, they’ll try your room. If that fails, as it will, they’ll start asking you questions, thinking you might have been in your father’s confidence. If they do try that tell them nothing—not a word. If they start threatening you—well, I shan’t be far away. It might be as well if they didn’t see us too much together. They’ll think you’re alone in the world now, and that’s where they’ll be wrong. But I’m afraid we shall have to be practical. How are you off for money?”

“I haven’t any.”

“None?”

“None at all. I don’t think my father was very well off, but he gave me any money I needed—not that I wanted much. He paid all the bills.”

Cub smiled. “Well, we needn’t worry about that. I’ve got a bit. You just carry on. I’ll speak to Macnaughton and make things right with him until your father’s will is proved—if he made one. Do you know if your father had a lawyer in this country? If he had, you’d better get in touch with him.”

“Yes. He went to see him once. I went with him. I don’t know what it was about because I was left in the waiting room.”

“Where was this?”

“In London. The name of the firm, I remember, was Hawkins & Co., in Staple Court.”

Cub nodded. “You must send them a wire in the morning. If it’s any sort of a firm at all they’ll provide you with money until your father’s estate is settled. Your father must have had some money, in which case the lawyers will know about it. They’ll get in touch with his bank, and so on. You can leave that to them.”

“All right.”

“No doubt the police will hand over to you any money or valuables your father happened to have on him. You’ll have to answer any questions they ask you, of course, but that will be mostly concerned with identity, I imagine. Say nothing about what I’ve told you.”

Tony looked at Cub with tears in his eyes for the first time. “I don’t see why you should do all this for me. It will spoil your holiday. You didn’t even know my father.”

Cub forced a smile. “That has nothing to do with it. I don’t like murder any more than you do, and anyway, it must have been the hand of Fate that brought me into the affair. You can’t dodge Fate. Strictly speaking I should tell the police what I know, and so I would were I not convinced that it would do more harm than good. In fact, I’m afraid, with all due respect to the police, it would wreck any chance we have of bringing the murderers to book. The police have fixed procedure and they can’t get away from it. The first thing they’d do would be to question Smith and Gray about what they were doing by the river. They’d ask them if they saw your father. The answer to that question would be no. Smith and Gray would simply say they were out for a walk, which would sound reasonable enough. All I could say was, I saw the two men by the river. The result would be, Smith and Gray would vanish, and your life would be in greater danger than ever—to say nothing of mine.”

“You think I am in danger?”

“Yes, I do,” replied Cub seriously. “These men have made it clear that they will stop at nothing to get what they came for. Your real danger will come after they’ve searched these rooms and found nothing. No doubt they’ll search along the river bank, too, to see if your father threw away the thing when they were pursuing him.” Cub got up. “Well, there’s nothing more we can do tonight. You try to get some sleep. I’ll make a plan for tomorrow, I shall probably pretend to be going fishing, and if there’s no one about I’ll have another look at that tree. To get at what is in it will mean sawing the tree down, I’m afraid. However, that shouldn’t be difficult.”

“Can I come with you when you go?”

Cub hesitated. “I don’t see why not,” he decided. “It would be natural, in view of the tragedy, for someone to take an interest in you, and it might as well be me. I’m not much older than you are. If anyone asks about you I shall say I’m taking you out with me, fishing, rather than leave you at the hotel by yourself.”

“What will happen—to my father?”

This was another awkward question for Cub. “He’ll be buried here I suppose, unless you have any special wish in the matter?”

Tony shook his head. “No. What does it matter, now? I shall go to the funeral, of course.”

“I’ll come with you,” promised Cub. “I’ll have a word with the police about it. That’s enough for now. I’ll get along to my room. Come to me there if there’s any trouble.”

“All right. Good night, and thanks again.”

Cub waved and went out. There was no one in the corridor. As he walked along to his room he could hear rain beating on the windows. This was the break in the weather for which he had been hoping, was the thought that passed through his mind; but the fishing would have to wait, he decided. He had something more important to do. That the rain was going to upset his plan was something that did not occur to him.

Deep in thought he undressed and went to bed.

The following morning Cub was up and about before the breakfast gong had sounded. The weather, he was pleased to note, had cleared somewhat; at any rate, it was no longer raining, although low clouds drifting sluggishly among the high hills gave promise of more to come.

His first visit was to the office of the manageress. He told her that Tony was staying on for a bit, and that he would make himself responsible until the boy knew what he was going to do. He then went to the post office and sent telegrams to Gimlet and Copper, wording them in such a way that their real significance would be realised only by the recipients. His next visit was to the police station. No further news was forthcoming except that the Chief Constable was expected. The local doctor had examined Doctor Lander and furnished the death certificate. It was clear from the policeman’s manner that he took it for granted that Doctor Lander had died as the result of an accident, so the rest of the proceedings were merely a matter of form. The few things found in the dead man’s pockets—a few pounds in notes, some small silver, a gold watch and fountain pen—would be handed over to his son in due course.

Preparations would be made for the funeral there, if that was the boy’s wish. Macnaughton had provided evidence of identification. There was nothing for Tony to do. He could see his father if he wished. Cub said he thought he had better not.

By this time the village shop had opened and Cub went in to make two purchases. One was a chopper and the other a hand saw. While he was waiting for change from the note he had tendered Smith came in to buy some cigarettes. He saw the tools at once, as he was bound to, and little guessing the purpose for which they were required, made a silly joking remark about them and their connection with fishing. At the moment Cub was annoyed about this. The last people he wanted to see the tools were Smith and Gray, and it had been his intention to hide them beside the road and pick them up on his way to the river. Thinking fast he turned the occasion to advantage by saying, casually, that the implements were, in a way, connected with his fishing. He had lost some hooks on an overhanging branch, which, to facilitate casting, should have been cut off long ago. As this had not been done he had decided to do it himself. This, he thought, as he left the shop, was reasonable enough. Now, if either of the men saw him on the river bank with the tools, they would know, or think they knew, what he was doing. Otherwise they might have wondered.

On his way back to the hotel he encountered the water bailiff. He had already a slight acquaintance with the man and greeted him with a cheerful good morning.

“Ye’ll no do much good th’ day at the fishing, I’m thinkin’,” said the river guardian in passing.

“Why not?” asked Cub, a trifle surprised.

“She’s a big river,” was the reply. “She fairly comin’ doon after last night’s rain.”

Cub smiled, paying little attention to the remark. That it might affect his programme did not occur to him, although it should have done, as he was to realise later.

Passing on to the hotel he put his purchases in his fishing bag, which hung in the hall, and went in to breakfast. Most of the guests were down by this time. Smith and Gray were there, but Tony had not yet put in an appearance. Everything was the same as usual, except that the customary buzz of cheerful conversation was absent, the natural result of the tragedy of which everyone was now aware. Assailed by a sudden uneasiness Cub was about to go up to Tony’s room in search of him when the boy, looking pale and hollow-eyed, walked in. A rather embarrassing hush fell, out of respect for the bereaved fellow guest.

Cub, looking at the table which Tony had until then shared with his father, saw that only one place had been laid. It was the same at his own table, a table for two, where he sat alone. An idea struck him. Speaking in a normal voice, which in the circumstances was loud enough for the whole room to hear, he said to Tony: “I wonder if you’d care to share my table with me? There’s plenty of room.”

Tony answered: “Thank you. Yes, I’d like to.”

Cub beckoned to the waitress and told her to move Tony’s things to his table, which was soon done.

Again Cub thought he had done a useful piece of work, in that the move had brought them together in such a manner that no one, not even Smith or Gray, could see anything peculiar or significant in it. After that it would not be thought odd if they spent the day together.

Conversation in the room was resumed, but until Smith and Gray went out, as they soon did, Cub said nothing to Tony of the subject that was uppermost in their minds; but as soon as the door had closed behind the two suspected men Cub looked at Tony meaningly and said, in a low voice: “Did you sleep all right—no disturbance, or anything like that?”

“Nothing to speak of,” answered Tony, softly. “I think they searched my father’s room. I could hear them in there, through the wall. It’s very thin. At least, someone was in there and I can’t think who it else could be. I’ve been in, but nothing seems to have been touched.”

“They didn’t try your room?”

“No.”

“They’ll probably do that today, if you go out,” opined Cub.

“Have you any fresh news?” asked Tony.

“No. I’ve spoken to the hotel management, and the police, about you. I’ve told them you’re staying on until your father’s affairs are settled. I don’t think there’s anything for you to do at the moment other than send a wire to your father’s lawyers, as we arranged. Do that as soon as you’ve finished breakfast. Then we’ll go fishing. By the way, I’ve sent wires to my friends in case we should need help.”

“What did you say?”

Cub smiled faintly. “I merely said there were some exceptional fish to be caught. I might not be able to manage alone.”

“Will they understand that?”

“You bet they will.”

Nothing more was said until they went through into the hall. Smith and Gray were there, apparently doing nothing in particular, unless, as Cub suspected, they were watching Tony to see where he went. If they were going to watch him all day, he thought, it was going to be awkward. So he said to Tony, in a voice loud enough to be overheard: “What are you going to do with yourself all day? It won’t do you any good to hang about the hotel. I’m going down to the river. Would you care to come with me?”

Tony looked surprised for a moment. Then, understanding, he answered: “Thanks. But are you sure I won’t be in the way?”

“Not in the least.”

“Then I’ll come.”

“Good enough,” agreed Cub. “I’ll go to the kitchen and get them to put up sandwiches for two. I’ve got a spare flask for tea. You’d better bring a mackintosh. I’ll meet you here in ten minutes.”

“All right. I’m only going to slip over to the post office,” answered Tony.

Smith and Gray went into the lounge, so Cub went off to make arrangements for the picnic lunch.

In ten minutes they met again in the hall. Tony said he was ready.

“Okay, then let’s get off.”

“How far is this place?” asked Tony as they set off down the road.

“About a couple of miles.”

“Where did Smith and Gray go?”

“The last I saw of them they were going into the lounge,” replied Cub. “I don’t think they’ll worry us at the moment, although we’d better keep an eye open in case they come to the river. It wouldn’t surprise me if they did. If they do, and happen to speak to us, be careful what you say. Leave the talking to me. On no account must they think we’re looking for the same thing as they are. Our game is to act as if we knew nothing about it. There is this; while it remains where it is they haven’t a hope of finding it.”

“What’s going to happen when they realise that they’ve had their trouble for nothing; when they have to admit to themselves that the thing can’t be found?”

“I don’t know,” answered Cub thoughtfully. “From what you’ve told me about your father being followed there may be someone else in this affair. I mean, Smith and Gray may be acting for somebody. If so, I imagine they’ll get in touch with him and tell him what has happened. Of one thing you may be sure. When all else fails these stiffs will corner you and ask questions. You’ll be their last hope, so don’t go wandering off alone or you may find yourself in serious trouble.”

While this conversation had been taking place they had arrived within sight of the river, although it was still some distance away, and below them, at the bottom of the glen. The sight of it brought a frown to Cub’s forehead, for he realised now what the water bailiff had meant when he spoke of a big river. The river was, in fact in roaring spate, a surging, peat-coloured flood that was carrying all before it. It was far above the level of the previous day, but how much it had actually risen Cub could not yet tell. As a result of the rise the river had of course become much wider.

Tony looked at Cub’s face. “What’s the matter?” he asked, perceiving that something was wrong.

“I’m looking at the river,” answered Cub, in a worried voice. “She’s in a nasty mood. I’m beginning to wonder if we shall get to the tree.” Another thought that passed through his mind was this: If the body of Tony’s father had not by the merest chance been found overnight, it would never have been found. It would have been carried by the flood to the sea, and long before it got there it would have been battered by rocks out of all recognition. He strode on, and did not speak again until they came to the top of the brae above the Witches Pool. There, with mounting dismay, he saw that the high water had so changed the pool that he hardly recognised the place. This was not particularly important because the tree that was his objective was some distance below the pool; but he was afraid that he might find things as bad there. In any case, there could now be no question of wading the river as he had done the previous day, to reach the tree, which was on the opposite bank. Nothing could live a moment in such a raging torrent. They would have to go round by the old stone bridge, more than a mile further on.

As a result of this they were much later arriving at the objective than Cub had estimated—not that it really mattered for they had the whole day before them. By this time it was obvious that he had set himself a difficult task. Not until he actually stood beside the water did he realise the terrible force of the river as it thundered over its bed.

One glance at the tree, when he came within sight of it, and his worst fears were realised. A good three feet of the trunk was under water. What could be seen of the tree rose stiffly from the flood several paces from dry ground, and it was not smooth water, either. It was being flung into leaping turbulence by submerged rocks. There could be no question of wading. And then Cub noticed something else. The tree was now at a considerable angle, leaning under the weight of water. It was clear that any moment might see it wrenched from the bank and carried away.

Cub pointed. “There’s our tree,” he said bitterly. “We can’t get to it. I might as well tell you now. You see that hole, just below the first branch? It was in there that your father put something when he was running along this bank yesterday.” He was too concerned with his predicament to go into further details. “If that water rises another inch the tree will fall and that will be the end of it,” he said grimly. “Believe it or not, yesterday that tree was clear of the water.”

“The water may start to fall now that the rain has stopped,” suggested Tony helpfully.

“The rain may not have stopped on the high ground—that’s where all this water is coming from,” answered Cub. “Anyway, if it rains again we’ve had it. What rotten luck.”

“We’re in no hurry. Let’s wait,” offered Tony.

“That’s all we can do,” returned Cub. “I’ll put my rod together for the look of the thing in case anyone comes along, but they’ll think I’m out of my mind trying to catch a fish with the water in this state. Find a piece of stick and push it into the bank level with the water; that should soon tell us whether it’s rising or falling.”

Tony obeyed while Cub put up his rod. Then it began to rain, not heavily, but the fine drizzle which is generally known as a Scotch mist.

“Well, that’s that,” muttered Cub in a tone of finality, as he put on his mackintosh. “We can’t do anything, so there’s no point in standing here. Let’s get back under the pines; they’ll give us some shelter. We may be here for some time.”

Tony agreed, and they moved back under the thicker trees. Finding a fallen one they sat on it, with nothing better to do than watch the depressing spectacle in front of them. The noise of the rushing waters drowned all other sounds. After a while Cub unstrapped his fishing bag and produced the lunch sandwiches and vacuum flask. “We might as well eat,” he suggested without enthusiasm.

For some minutes they sat under the dripping trees munching their sandwiches without speaking. Then Tony said: “So it was along here that my father came yesterday?”

Cub nodded. “Yes, but it was a different world then. It was too hot to fish and the water was dead low.” He pointed to the far bank. “I was lying over there in the grass when your father appeared, running, a bit lower down. He had no sooner gone than Smith and Gray appeared. They were running, too. That was what made me sit up and take notice. They must have overtaken your father at the Witches Pool—or maybe, having got rid of the thing they were after, he just sat down and waited for them.”

Curiously enough, in his disappointment at not being able to reach the tree Cub had quite forgotten the likelihood of the men, who were the cause of the tragedy, coming that way. He stiffened with surprise, therefore when, a movement catching his eye, he looked up to see them coming along the bank, on the same side as themselves. They were walking slowly, looking at the ground as they came. He laid a hand on Tony’s arm. “S—sh,” he breathed. “Look who’s coming. They’re going over the ground again. Keep quite still. I don’t think they’ll see us—not that it matters much if they do.”

The two men continued to advance, searching the ground thoroughly as they came. From time to time they exchanged remarks, almost shouting above the noise of the water in order to be heard.

Said Gray: “This is a mugs’ game, I tell you.”

“We’ve got to look somewhere, haven’t we?” retorted Smith. “He threw it away, knowing we were after him.”

“I still reckon the boy might have got it.”

“We’ll leave the boss to settle that. He was pretty savage this morning when I told him what had happened.”

Cub glanced at Tony and raised his eyebrows at this piece of information.

The men were by now level with the tree that held the secret for which they sought with such diligence; and, by a curious chance, it chose that very moment to fall. Tony, with a gasp of dismay—drowned fortunately by the noise of the torrent—started up; but Cub dragged him down. “Still!” he hissed. And then, as if to add insult to injury, the tree held apparently by a single root, swung round with the current until it lay flush with the bank—a position which would have suited Cub admirably had the men not been there. As it was, had Gray but known it, he was within a yard of the thing he was at such pains to find.

The men walked on, at a speed which, to Cub, seemed even slower than the pace of the proverbial snail. Their eyes never left the ground, otherwise, had they looked round, they must have seen Cub and Tony sitting there.

With what impatience Cub watched them go can be better imagined than described. No sooner were they swallowed up in the misty rain than he grabbed his bag and made a dash for the tree. He reached it just two seconds too late. The last root snapped, or was torn out of the bank. The tree began to move. Cub made a grab at a branch and was nearly dragged into the water. He had to let go to save himself. In a moment the tree was going down the river, slowly turning over and over as the branches bumped on the river’s rocky bed.

In his anguish Tony groaned.

Said Cub, with a confidence that he certainly did not feel: “No matter; we’ve still got a chance. It won’t go far. It will either get caught up on a rock or in the branches of a low-hanging tree. Let’s follow it.”

Stumbling over slimy boulders, staggering knee deep in boggy sphagnum moss, crashing through fallen trees, Cub forced a way along a bank as wild as only that of a Highland river can be. To make matters worse, the ground was new to him, for he had never fished that particular stretch. For two hundred yards or so he continued the chase, with Tony at his heels, at no small risk of broken bones, if nothing worse. Then the river made a sharp turn and he pulled up with a gesture of impotence. The bank rose sharply in a sheer face of rock against which the water hurled itself with terrifying force, making further progress out of the question.

Borne with other debris on the flood the tree went on, its branches, already mutilated to jagged stumps, rising and falling like arms waving a mocking farewell.

For perhaps a minute Cub stood watching the receding tree, tense with a feeling of frustration. “It’s almost as though the devil himself has a hand in this,” he muttered savagely. “No,” he went on quickly. “I can’t believe after what has happened that the thing was doomed to end this way. It doesn’t make sense. I’m not going to give up now. Our one and only hope of solving this mystery is floating down the river. If we can’t get round that face of rock we shall have to climb it and go down the other side.”

“Anything in that tree must be pretty wet by now,” observed Tony miserably.

“Never mind that. Come on! Up the brae!” Cub’s voice had a clarion note in it.