* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Pasteur, Knight of the Laboratory

Date of first publication: 1938

Author: Francis E. Benz (1899-1954)

Date first posted: Feb. 11, 2023

Date last updated: Feb. 11, 2023

Faded Page eBook #20230210

This eBook was produced by: Stephen Hutcheson, John Routh & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

Copyright, 1938

By DODD, MEAD AND COMPANY, Inc.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

NO PART OF THIS BOOK MAY BE REPRODUCED IN ANY FORM

WITHOUT PERMISSION IN WRITING FROM THE PUBLISHER

Published, March, 1938

Second printing, September, 1938

Third printing, November, 1938

Fourth printing, May, 1939

Fifth printing, February, 1940

Sixth printing, December, 1941

Seventh printing, May, 1943

Eighth printing, March, 1944

Ninth printing, November, 1946

Tenth printing, October, 1948

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

BY THE VAIL-BALLOU PRESS, INC., BINGHAMTON, N. Y.

Impatiently the horses pawed, rattled their harness, shook their heads in the driving cloud of rain and sleet. Inside the stagecoach, passengers shivered, chilled to the marrow with the damp, October cold. The driver stomped up and down before the Hôtel de la Poste, now soothing the anxious team, now hurrying the porters who strapped the luggage on board.

On the driver’s box—there was no room inside—two boys about fifteen years old huddled under a tarpaulin, trying their best to keep dry and yet wave and talk to their parents who called from under the eaves of the hotel.

One boy smiled as if smiles had always been easy for him, as if he’d never had a care in the world. This happy-go-lucky fellow was Jules Vercel, traveling with Louis Pasteur from their native Arbois to school in Paris.

Though Louis was not the easygoing type, a stranger could have seen he was a real boy. Any of the townspeople of Arbois would have agreed to that. Louis might take his studies a little more seriously than Jules, but he was equally thorough when it came to fishing in the river Cuisance or to the mock battles they staged in the tanyard of Louis’ father.

Right at this moment, Louis Pasteur realized he was going to be homesick. And after that, more homesick. The biting, icy rain clattering on the canvas and nipping at his cheeks was bad enough, but looking around him, realizing he would be traveling for two days from this familiar scene was far worse.

The driver blew his horn. The team gave a preliminary jerk at the coach.

“Good-by, Mother and Father,” cried Louis.

“We’ll be back for Christmas, don’t forget,” yelled Jules.

“Good-by, Louis! Good-by, Jules! Write as soon as you reach Paris,” cried the parents, almost in concert.

“Keep yourselves bundled up good,” added Louis’ mother as the coach started on its journey.

Lurching through the mud puddles, the great coach pulled away. Fighting to keep back the tears, Louis watched the square towers of Arbois and lastly the steeple of his church, in which he had so often attended services, fade into the whipping curtain of sleet and rain. Even the wonders of Paris, his opportunity for an education there, were not enough to silence that aching sense of loss.

Perhaps Louis felt that way at fifteen when boys of our days would not because, in 1838, a good share of a boy’s life was his home life. Moreover, if Louis had stopped to look into the cause of his lonesomeness, he would probably have seen that his parents took even more interest in his future, in his education, than did those of most of the other boys in Arbois. In 1838 a high-school and a college education was only an unfulfilled dream for most boys. Few of the lower classes, especially, had this opportunity. The majority were called into military service or to work just as soon as they were able to carry a musket or swing a hammer. It had been that way for Louis’ father.

Jean Joseph Pasteur, in fact, had followed both the wars and a trade. The trade he had learned was that of his father, grandfather and great-grandfather, tanning hides and skins. He had barely passed his apprenticeship in the tanner’s field when he had been called to serve in the army. Still in his teens, he had fought with the French Army in Spain, in the Peninsular War, during 1812 and 1813. He was one of the bravest men in the brave Third Regiment and because of his courage advanced quickly to the rank of Sergeant-Major and was finally decorated with the Cross of the Legion of Honor by his beloved leader, Napoleon.

As is the case after many a war, it was hard for these soldiers to return from action and adventure to tiresome trades and police supervision in their native villages. For Jean Pasteur, still under twenty-five years old, life had seemed to settle under a dull cloud. The return of Napoleon from Elba was a faint ray of hope that, when it faded, made work in the tanyard at Besançon even more irksome, more discouraging.

With this uninteresting life, Jean Pasteur began to live more and more within himself. His experiences as a soldier had taught him not to whine, not to cry out, no matter how great his injury. They had taught him caution, not to show his emotions, taught him how much he could gain by controlling his facial muscles. Now in Besançon, faced with the problem of hammering out a living, he grew into a steady, quiet, plodding type of man. In the little church at Besançon, however, Pasteur spent many an hour. He loved to go there in the quiet of the evening and pour out his troubles to his God enthroned upon the altar.

He always felt better, he said, after such a visit.

Only once did he allow his emotions to gain the upper hand and that was when an edict issued by the Mayor of Salins ordered all the late soldiers of Napoleon to turn in their swords to a certain place. Pasteur obeyed this order very reluctantly. One day he heard that these weapons were destined for police service and when he recognized his own Sergeant-Major’s saber on a police agent, he could restrain himself no longer. He sprang upon the agent, knocked him down and tore the sword away from him. This action caused quite a commotion in the town. Those on the side of the mayor became very indignant while the former friends and soldiers of Napoleon could hardly restrain their enthusiasm. The mayor was nonplussed. He did not know what to do. He thought that if he punished Pasteur, he would arouse the anger and the ire of the old soldiers of Napoleon who were Pasteur’s friends. So he went to the colonel of a regiment quartered in the town and asked for help. But this officer refused because he understood full well the feelings which motivated Jean Joseph Pasteur and approved of them. As a result Pasteur was allowed to keep his sword.

Again he settled down to his tanner’s trade and soon he came to be known to many of the neighbors as the “old soldier” even at only twenty-five. One person, however, did not call him the “old soldier” and her name was Jeanne Étienette Roqui. She lived just across the river Furieuse from Pasteur’s tannery yard. Often, in the early morning especially, Jean Joseph would watch Jeanne Étienette work in her father’s garden—secretly, he thought. His actions, however, were not unnoticed by the young lady across the river who soon thought that the “old soldier” was not so old after all. It was not long before Pasteur became acquainted with her family that was descended from one of the most ancient plebeian families in France. The acquaintanceship between the two young people soon ripened into love. Pasteur asked for her hand in marriage and was instantly accepted.

The household built from their marriage proved ideal for their children. Father and mother seemed to be made for each other. Jean Joseph’s careful, reserved mode of living balanced perfectly with Jeanne Étienette’s activity, her imagination and enthusiasm. Her love for her husband had much to do with his endless consideration for the children.

Soon after they were married, they moved to Dole and settled down in the Rue des Tanneurs. Here their first daughter was born and four years later, Friday, December 27, 1822, at two o’clock in the morning, Louis Pasteur was born into this world. It was from this humble Catholic household that our Knight of the Laboratory began his crusade for a better world for all children and grown-ups.

At Dole another daughter was born. Shortly afterwards the family packed up and left for Marnoz, where the Pasteur home is still known. On one of its inner doors is a painting by Jean Pasteur that tells the story of his own life, that shows his longing for the army had not disappeared, even though he was proud of his wife and small family. The painting depicts a soldier, clad in an old uniform, leaning on a spade. The ex-soldier, now a peasant farmer, looks up into a gray sky and as he gazes, he dreams of days of glory gone by. He sees the flash of the sun on the eagles of Napoleon, the glitter of cold steel and the tossing of plumes. It seems as if the ex-soldier were waiting for a call from the distant hills, beckoning him back to the former days of glory.

Marnoz, however, did not prove to be a good place for a tannery, so the Pasteur family did not live there long. Louis was not yet old enough to attend school at Marnoz and he remembered very little of his life there. His recollections were confined to his playing near a brook which ran alongside of the Aiglepierre road. His real life began at the house at Arbois, just below the bridge over the Cuisance River.

Fronting on the street, the little house to which the Pasteurs moved had in the rear a tanning yard, with the water close by. In the yard were pits, dug for the preparing of the skins, where Louis and his friends spent a great deal of their playtime.

Indoors, Louis passed many hours working with his crayons. He attracted the attention of educated people in the village with his pictures and was called the “artist.” It was nice to have their praise, but he liked better the grudging compliments of his father, who always tried not to spoil him.

At the primary school and the school that resembles our grade school, Louis couldn’t be any too proud of his lessons. He was not quick to learn; everything had to be studied thoroughly before he could recite it. He never affirmed anything unless he was certain of it. But going over the pages so often made him interested in them, as well as able to keep up in his class.

The primary schools in those days differed from the grade schools as we know them today. The pupils were divided into groups and over each group there was what was called a “monitor.” This monitor was one of the brightest and smartest pupils of the group. Louis, many times, longed to be a monitor but he was just an average student. When the schoolmaster, M. Renaud, would go from group to group selecting monitors, Louis would look up at him with his big eyes that showed clearly his earnest desire to be allowed to act as monitor, but the schoolmaster never gave Louis the chance he longed for. The monitor acted in this way. When the time came for the reading lesson he would read a sentence and then the entire class would spell aloud the words in the sentence in a sort of singsong manner.

Even though Louis’ father was no student, he made it his business to know educated men and to have them at his house. He made a point of increasing his own knowledge so that he could help Louis with his school work. He wanted the boy to earn his living with his brain rather than with his hands.

To Louis it seemed the natural thing to study thoroughly and to take his lessons seriously. His father and mother gave up much, worked day and night to provide for his schooling. They were always interested in what he learned. All their visitors, including the village priest, a doctor, a philosopher and the headmaster of the school, M. Romanet, asked him about his lessons. How could he expect to answer their questions if he didn’t study?

But outside of school hours, Louis did not spend all his time with his books. One of his greatest delights and joys was to go fishing. Many times he and his youthful comrades would go on fishing parties up the Cuisance River. Jules Vercel especially was a very good fisherman and Louis delighted to go on expeditions with him. They never came home empty-handed.

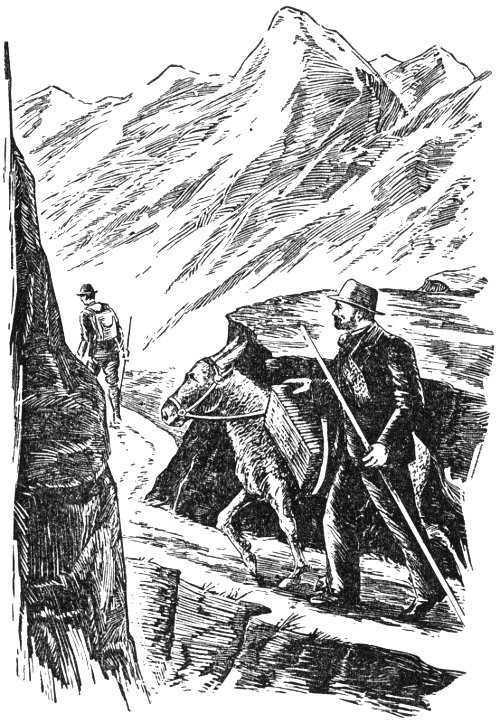

Again, Louis and his playmates enjoyed going on long hikes through the woods, especially through the wooded heights above the wide plain, toward the town of Dole, where they would explore the ruins of the Vadans Tower, an old fortress rich in historical interest and which reminded them of the glory of heroic days.

In fact, all the citizens of Arbois were very proud of their local history. They considered themselves intensely patriotic and were inclined to boast not a little of their importance. Louis, whose patriotism in later life was second only to his love for God and his suffering fellowman, must have absorbed some of his feeling of patriotism from the citizens of Arbois. Yet Louis and his playmates were more interested as boys in the past history of Arbois than in its present.

For instance, in April, 1834, the Republic was proclaimed at Lyons. The citizens of Arbois rose up in arms against this government as soon as the news was brought to them. Louis and his friends watched the arrival from Besançon of two hundred grenadiers, four squadrons of light cavalry and a small battery of artillery, sent to pacify the Arboisians. This did not affect Louis half so much as some of the old stories concerning the bravery of the citizens of Arbois, especially the story concerning the siege of the city under Henry IV when Arboisians held out for three whole days against the besieging army of twenty-five thousand men. Stories of this sort worked upon his lively imagination and when he and his playmates were wandering through the woods, they would act out again and again some of the stories they had heard concerning the bravery of the Arboisians. These stories inculcated that intense patriotism which ever marked the life of our Knight of the Laboratory.

As Louis grew older, M. Romanet, the headmaster of Arbois College, began taking him on walks. Louis liked the master. He treated you like an equal instead of like a child. For instance, there was that Sunday afternoon when they strolled down the road toward Besançon that led between the green, vine-planted hills. To the left, on a tree-clad hill, the relic of the Vadans Tower seemed to throw a thrilling serenity upon the Sabbath quiet. It was like a picture out of a book, except that M. Romanet’s voice made it a reality.

“What are you going to do when you finish the middle school, Louis?” he was asking.

“I don’t know,” Louis replied. “Father wants me to go to the college at Besançon and come back to teach at Arbois when I’m through there.”

“How old are you now, my boy?”

“Almost fifteen.”

“Have you ever heard of the École Normale?”

“A little. Why?”

“Well, they have much more to offer you there than at Besançon. You have to be a Bachelor of Science or Letters to enter, but you’ll be better off in the end.”

“But Paris is two days’ journey away. And it would cost much to go there.”

“I know. But the École Normale is the place for you to go. Take my advice, Louis. You are a true scholar. You know how to study. And you’ll be a real man—not a drudge—besides. France and the world of knowledge need men like that.”

The more Louis thought about the École Normale, the more he wanted to go there. Yet his father regretfully vetoed the idea. The boy was too young to be so far from home. And the expense was too great.

M. Romanet kept the subject alive in the Pasteur household, but it was Captain Barbier, a soldier who spent his leave with the Pasteur family, who settled the issue.

“And how is the boy?” he asked of Louis before the Pasteurs at dinner.

“Very fine, sir,” Louis returned respectfully.

“I hear you do well in school?”

“Very well,” M. Pasteur put in. “M. Romanet, his headmaster, says Louis is a fine student. I am very proud of him. It was my ambition to give him a hunger for learning. He is to be a teacher.”

“Where will he get his degree?”

“M. Romanet wishes he could attend the École Normale in Paris. But the entrance requirements for the École, I understand, are quite severe and a special preparation is necessary. Few schools are equipped to give a boy this preliminary training. Unless one would send his son to a preparatory school in Paris, the chances of qualifying are extremely slim. I feel that I cannot afford to send him to Paris, nor feel safe in letting him go so far from home.”

“Too bad. I can understand your feelings.”

“Yes. But the boy can do very well with a degree from Besançon. That is much to be thankful—”

“But wait—” the captain broke in.

“Yes?” Louis’ hopes rose, his face lighted, as did his father’s.

“I am stationed at Paris. I seldom leave. I could keep an eye on the boy. He doesn’t look like a mischief-maker.”

“But the cost?” the two Pasteur faces fell again.

“Simple. In the Latin Quarter, in the Impasse des Feuillantines, is a preparatory school run by a M. Barbet. He often takes boys from the country at half tuition.”

Could this be true? Was he, Louis Pasteur, really going to Paris and later to the École Normale? Louis turned wishing eyes on his father.

“Can you make arrangements with M. Barbet to admit Louis?”

“Very likely. I will contact him as soon as I return.”

It seemed years before the letter from Captain Barbier arrived with the news that M. Barbet would accept Louis if he came to Paris. The boy looked from his mother to his father, trying to read their decision. No word was spoken for more than sixty seconds. Then Mme. Pasteur rose to her feet, crossed to Louis, laid a friendly arm around his neck.

“We will hate to see you go, Louis,” she said slowly. “But we want to give you everything you need to face the world. That is our duty to God and to you. I know your father wants you to go.”

“Yes,” Jean Pasteur finally nodded. “I do.”

The bustle of getting ready was twice as exciting when Louis learned that his friend, Jules Vercel, was also going to Paris and would travel with him. The boys’ families were in constant discussion as to what to pack for their sons, what stage should be taken, what everything would cost. Sometimes the excitement was interrupted by a moment of thinking how empty their homes would be without the two lads, but there was little time for regrets until the endless minutes before the stage left.

Then instead of a promising student worthy of traveling to Paris, Louis’ father and mother saw only a scared boy, wet and cold, wishing he could get off the stage and run back home—and staying on the seat because of the hidden spark, the unquestioning fate that was to carry him along.

Louis was thoroughly cold and miserable. But he wouldn’t quit.

“Wanta go home?” he mumbled under his breath to Jules.

“Do you?” Jules tried to taunt between chattering teeth.

“The Knights of Arbois never went home licked, did they?” Louis demanded. “Well, I’m going to ride into Paris with my banners flying.”

Louis, though his face did not betray him, failed to live up to his resolve. He did not ride into Paris with banners flying. All the way to the city, even when they stopped in Dole, or Sens, or Fontainebleau to change horses, he couldn’t tear his mind away from Arbois. When they rumbled onto the streets of Paris, when Louis got his first glimpse of this great city with its huge buildings of stone, its crowded streets, men hurrying on mysterious errands, actually dodging horses’ hoofs in their mad haste and, in contrast, the lolling crowds contentedly sipping their coffee at the sidewalk cafés, he was not impressed. He wished, instead, he were plowing into the streets of Arbois.

Soon after their arrival at the hotel-station in Paris, where they were met by a representative of M. Barbet’s school, the boys got their first look at their new home. It was not very impressive, situated in the crowded Latin Quarter among rundown tenement houses. They were assigned to a small cell-like room which already had another occupant. Three to a room was the rule at M. Barbet’s.

Louis wondered where the classrooms were and was soon told that the students attended classes at the Lycée St. Louis or at the Sorbonne. M. Barbet’s school was a place where students lived and studied only. There were no actual classes except for private tutoring.

Every night in the dormitory on the Impasse des Feuillantines was as bad as the first one. Louis could not sleep, could not forget his home, even tried reciting poetry to lull himself into rest.

Attending classes at the Lycée St. Louis was no better. In spite of his willingness, his intense interest in the studies, he couldn’t concentrate. “If only I could get a whiff of the tannery yard,” he told Jules Vercel, “I feel I should be cured.”

Even the kindness of M. Barbet, who understood his plight, seemed to do no good. Louis knew he was not doing his lessons properly, and was ashamed of himself because of that fact. But M. Barbet would try to interest him, try to draw him out. Finally the master realized the matter had come to the point where Louis’ health was showing the results of the sleepless nights.

Louis hated himself for being homesick when the rest of the boys seemed to get along after the first few days. He did not realize he had been blessed with parents who had shared his life far more than most parents. He took it for granted that all parents were chums of their children.

Louis could not sleep, could not forget his home.

One morning, after Louis had been at school for almost a month, a messenger called him from class. Listless with loss of sleep and skimped meals, he walked down the street to the café on the corner where the messenger had instructed him to present himself.

The room seemed deserted. He walked farther in toward the rear of the place, where some of the tables were in shadow. Suddenly a smile burst across his face as he ran to a corner table.

“Father! Father!” he cried again and again, as he threw his arms around the welcome figure.

M. Pasteur patted his son’s shoulder shyly.

“You are glad to see me, Louis?” he asked softly.

“I wish I could tell you how glad!”

“I know, my son. I was almost as young as you when I went to Spain for the war,” the father said quietly.

“But why are you here? Did you come to see me? How is everyone at home?”

“Everyone is all right at home. I came to take you back. Come, let us go and pack your things. M. Barbet wrote me about you.”

Without another word M. Pasteur led his son out of the café and went with him to help gather up his things. The school was behind them before any of Louis’ friends returned from class.

Shyness kept Louis from mentioning the matter, but he murmured a prayer of thanks for having so kind a father. He wished there were some way to tell him how grand he had been not to ask any questions, not to raise the issue of going back home or staying in Paris. His father had understood he couldn’t stay and had told him to pack for the trip home without even trying to coax him to remain.

Louis hated having to admit defeat, but this one bad break wasn’t going to ruin the rest of his life. He was determined to make up for lost time. Back to school in Arbois he went, to earn more prizes than he could carry home at the end of the term.

During that year, he did not show his disappointment at the failure of the Paris trip, but, like his father after the Spanish War, he turned more within himself, invented his own solitary amusements. He took to his crayons again and won praise for his drawings throughout Arbois. Gladly, he undertook portraits of anybody who asked for one, finally climaxing his achievements with a picture of the mayor. The compliments of this official, coming at the end of the school year when Headmaster Romanet praised him for his success in graduating from the Arbois school, strengthened Louis’ courage, his determination that he should make another try for the École Normale.

Rather than go to Paris for his preparation, Louis decided with M. Pasteur that the best way would be to attend the Royal College in near-by Besançon. Their plan proved to be thoroughly successful. Louis found himself under a philosophy master named M. Daunas who took the same friendly interest in his progress and his pleasures as had M. Romanet in Arbois and M. Barbet in Paris. M. Daunas was a graduate of the École Normale and told Louis of all he would find there, the learning and the living. Louis’ desire to enter this great school, founded by Napoleon in 1808, grew stronger with each of those talks.

The science master, M. Darlay, however, did not share M. Daunas’ interest in the young man’s career. During a certain class, Pasteur became so interested in Darlay’s explanations that he forgot his usual shyness and repeatedly interrupted the lecture with questions.

Becoming annoyed and embarrassed, M. Darlay exclaimed: “Who is teaching this class, M. Pasteur, you or I? It is my province to ask questions, not yours!”

“I’m sorry,” said Louis.

Nevertheless, Louis’ interest in science was born at the Royal College. He forgot outside amusements, even drawing, in his hungry desire for more knowledge of science. For the first time, Louis’ thorough, searching habits of study were swept ahead by a burning enthusiasm. At the end of the term, his highest grade was in science.

In a letter home, he spoke of giving up drawing, though one of his pictures had been placed in an exhibit.

“All this does not lead to the École Normale,” he wrote. “I prefer a first place at college to ten thousand praises in the course of conversation.”

But Louis Pasteur was not sacrificing his hobby and his leisure-hour pleasures to become a dry professor, buried in a dusty library. He visualized himself as slowly buckling on his armor to fight for a better world of science. Just as the knights of old left King Arthur’s Round Table, armed with Faith and Courage and Strength, to battle a dragon in a murky cave, or as the Knight Crusaders mounted their steeds with the cry “God Wills It” on their lips and in their hearts, he was preparing himself to ride into the unknown darkness of science to battle for a healthier and better world.

It was in 1840, when he was eighteen years old, that Louis won his degree of Bachelor of Letters.

Toward the end of the summer holidays, from the headmaster of the Royal College at Besançon came an offer of work as preparation master for the younger students while he continued at the school his own work on higher mathematics, in preparation for the École Normale. He would be allowed a small salary and free room and board.

He accepted and went.

By this time, the boy had grown into a man. Living away from home, working on a subject that was too exciting to leave, he merely had to keep on with his consistent effort to succeed as a tutor. His students liked him and consequently did well in their studies. In a letter written about this time to his sisters, he stated in very serious words the way that he worked.

To will is a great thing . . . for Action and Work usually follow Will, and almost always Work is followed by success. Will opens the door to success both brilliant and happy; Work passes these doors, and at the end of the journey Success comes to crown one’s efforts.

These are profound words for a young student of eighteen, but Louis had faced much in his eighteen years. He had discovered that to earn what one wanted, to be successful in life, one had to work and work hard. Then having done one’s best, to trust in God.

Louis passed on this advice to his sisters, for he thought a great deal of them. He truly loved them and was anxious to instill in them ambitions equal to his own. The strong tie of love that bound him to them was probably a family trait inherited from his mother. She was a Roqui, and that ancient plebeian family was noted for the ties of love that bound its members together. In fact “to love like a Roqui” was almost a proverb in France.

The Pasteur household was based on two loves—love for each other and love for God. Louis showed his love for his sisters in many ways. When he was at home he would help them prepare their lessons in the evening before the father gave the signal for night prayers. He would accompany them to church for Mass, as well as join them in picnics up the river.

One evening, Josephine, Louis’ favorite sister, broke the silence with, “I simply cannot study any longer. This grammar lesson is so hard.”

“Let me help you,” said her brother, as he came to her side and placed an arm around her. “See, this is the way to parse that sentence.

“You know it is very difficult to be patient sometimes,” he continued, “but obstacles can be overcome by work and when one becomes accustomed to work, one can no longer live without it. Someday, Josephine, you will find that out.”

His letters to his sisters from the Royal College at Besançon contained many similar admonitions and as a rule he would end his letters to them with, “Love each other as I love you.” His love for his sisters led him on one occasion to offer his salary from the Royal College to help toward their education.

At Besançon Louis Pasteur met a young man who became his lifelong friend. Charles Chappuis, the son of a notary of St. Vit, was also preparing for the École Normale but specialized in literature rather than in science. The two young men, both striving for the famous school, were soon constant companions. On their long walks together in their leisure hours, they would talk of both books and chemistry. Pasteur was as fond of books as the literary student. Chappuis felt almost as much interest in the laboratory.

Charles was the first real friend Louis had ever had in school. He was thoroughly happy when they were together, exchanging confidences, talking about things Louis had always been too shy to speak of to anyone outside of his family. They talked of Arbois and St. Vit, of their parents, their ambitions. Before the year was out, they were as close as brothers.

Pasteur also gained in Chappuis a leader whose good influence appeared throughout his life. He found a joy in literature that balanced his own passion for chemistry and physics. Through Chappuis, he avoided letting his mind slip into a narrow, intolerant rut by keeping it alive through the teachings of God and man.

At the end of the year, Charles went to Paris for his final preparation for the École Normale. Louis wanted desperately to go, but his father thought it better for him to stay. Probably he was afraid of a repetition of the painful failure of Louis’ last trip to Paris.

A letter from Chappuis in Paris made Louis even more anxious to go. Charles missed him. What good times they could have! Perhaps they could study together!

But, “Next year,” was M. Pasteur’s brief answer to all his son’s arguments.

So, back again at Besançon, Louis threw himself day and night into his studies, trying to forget the absence of his good friend. Still working as preparation master and student, he took extra lessons in mathematics. For a while he considered taking, along with the École Normale examination, the tests for another great school, the École Polytechnique. He even wrote Chappuis about his idea.

I shall try this year for both schools [he said in a letter to his friend]. I do not know whether I am right or wrong in doing so. One thing tells me I am wrong; it is the idea that we might be parted; and when I think of that, I believe that I cannot possibly be admitted this year into the École Polytechnique.

Chappuis replied, like the unselfish friend that he was:

You know your tastes. Think of the present and also of the future. You must think of yourself; it is your own fate you have to direct. There is more glitter on one side; on the other the gentle, quiet life of a professor, a trifle monotonous perhaps, but full of pleasure for him who knows how to enjoy it. You, too, appreciated it formerly, and I learned to do so when we thought we should both go the same way. At any rate, go where you think you will be happy and sometimes think of me.

Either Charles’ letter or the study of mathematics cured the young Knight of the Laboratory of the Polytechnique. In fact, he said of mathematics after an exhausting day of study: “One ends by having nothing but figures, formulas and geometrical forms before one’s eyes. . . . On Thursday I went out and I read a charming story, which, much to my astonishment, made me weep. I had not done such a thing in years. Such is life.”

Also, Pasteur realized the Normale examinations would be plenty to manage without preparing for those of the other school. He had talked with a friend of Chappuis who had lately entered the Normale at the head of the class—but who still trembled when he mentioned the examinations he had taken.

“Were those examinations difficult!” exclaimed this friend to Pasteur in answer to a question the latter had asked. “You know you have to pass one written and one oral examination in every subject.”

“Were the written tests very hard?” questioned Louis further.

“Well, they were difficult enough, but at least you had time to think, but those orals! Just imagine walking into a room, standing in front of a table. Opposite you are the examiners, stern-faced and sour-looking. You almost think that you had committed a crime and that these men were the judges with the power to sentence you to life imprisonment. Then the questioning begins and with your knees knocking together you stammer out your first answer. Believe me, I don’t care to go through that again.”

And at Besançon Louis had ample proof that the going would be anything but easy when he faced the test on August 13, 1842.

If I do not pass this year [he had written to his father] I think I should do well to go to Paris for a year. After talking to some who have taken the examinations, I can see now what advantage there is in giving two years to mathematics; everything becomes clearer and easier.

But he goes on:

Of all our class students who tried this year for the École Polytechnique and the École Normale, not a single one has passed, not even the best of them, a student who had already done one year’s mathematics at Lyons.

Louis once received a first in physics and was twice second in the class, but his average grades were no more brilliant than they had been. The fate of his classmates in the examinations for the Normale, classmates whom he considered better than himself, made the day of the examinations look as black as a thundercloud.

The examiners, the students, everything in the room on that fateful day seemed to upset him. This test meant so much. Whether he could enter the École this year or must spend another year in study. Whether he could live up to the hopes of his parents, who had sacrificed so much for his education. Whether he was really to be successful in life.

When he left the hall, after the final examination, he had no idea whether he had passed or failed. One minute he was convinced he would sweep through with flying colors. Another he feared dismal failure.

Thirteen endless days dragged by. Would those judges never tell him the results?

Then the long-awaited answer came. Louis Pasteur had passed his examinations. But unfortunately the young scientist’s grades were not all that he had hoped. Out of a class of twenty-two, he stood fifteenth.

He was declared admissible to the École Normale. But even with this ambition finally gained, he was not satisfied. He had passed less brilliantly than he had for his Bachelor of Letters degree. His grade in chemistry was only mediocre. He decided to prepare for another year before entering the school.

So, the following October, five years after his first trip to Paris, Louis Pasteur boarded the stage with Chappuis for a year’s study at the school of M. Barbet. But now he did not come to M. Barbet as a forlorn lad. He had grown up. He was more sure of himself. He came as a tall young man, full of energy, ambition and enthusiasm for his work. His school fees were reduced to one-third of the regular charges. In return he was to teach younger pupils mathematics from six to seven each morning.

Though he did not have the privacy of his own room as he had at Besançon, he did have Chappuis and the opportunity for far better instruction than at the old school.

Do not be anxious about my health and work [he admonished in a letter to his parents]. I need hardly get up till 5:45, you see it is not so very early.

My Thursdays I shall spend in a neighboring library with Chappuis, who has four free hours on that day. On Sundays, we shall take a stroll and work a little together. . . . I also shall read some literary works. Surely you now know that I am not homesick this time.

Though all his classes at the Lycée St. Louis were of great interest to him, Louis Pasteur was most impressed by the lectures at the Sorbonne by M. Dumas, and there again saw reason after reason why his own life should be devoted to science. In December Louis wrote:

At the Sorbonne, I attend the lectures of M. Dumas, a celebrated chemist. You cannot imagine the crowds of people that come to these lectures. The room is immense, and always quite filled. We have to be there half an hour before the lecture is scheduled to begin to get a good place, just as if you were going to a theater; there is also a great deal of applause; there are always six or seven hundred people present.

At one of these lectures, Dumas conducted an experiment solidifying carbonic acid. For this he needed a handkerchief or a cloth to collect the snow resulting from the solidification, so he asked, “Has anyone here a handkerchief?”

In a moment Louis bounded onto the platform, offering his handkerchief for the experiment. Dumas instructed him to hold it in such a way as to collect the snow as the carbonic acid solidified. After the demonstration, Louis carefully folded the handkerchief and kept it for years as a precious relic.

It was not long before Louis had made himself so useful at M. Barbet’s that he was excused from paying even his one-third tuition. But he kept a close record of all his expenses. His father insisted that he dine with Chappuis on Thursdays and Sundays, though Louis would have preferred not to spend the money. As it was, he always held these meals at the Palais Royal to less than fifty cents on every occasion.

The room Louis occupied at M. Barbet’s Boarding School became quite chilly during the winter months, making it extremely difficult to study properly. One day he said to Chappuis, “Let’s go out and look at some small stoves. I think I’ll buy one for my room.”

After pricing the stoves, Louis decided it would be cheaper to rent one for a few months. “After all,” he said to his friend, “I only need it for a few months.” Continuing their shopping expedition, they next purchased some wood.

Then Louis thought of something else he needed. The study table in his room bore on its top surface the carved initials of many previous occupants, making it extremely difficult to write properly.

“I think I’ll buy a cloth to cover my table,” he said to Chappuis. But after pricing table cloths in various stores the two shoppers found them to be quite expensive.

“Let’s try one more store,” said Chappuis. “Perhaps this little place here has one on sale.”

The two young men entered the store.

“Have you any cheap table cloths for sale?” asked Louis of the shopkeeper.

“Oh yes,” he answered. “See this beautiful red one? It is only fifty cents.”

The two shoppers thought it to be a bargain and purchased it. Arriving at the school, the stove was set up and soon a fire was kindled. Then Louis opened the package containing the table cloth. Carefully he prepared to spread it on the table top. Suddenly his face fell and a look of dismay swept over his features—the table cloth was full of holes. So much for his bargaining powers!

Most of Louis’ time went into hard work. When he took his second examination for the École Normale, he stood fourth in his class. So, not long before his twenty-first birthday, Louis Pasteur was eligible to enter the École Normale. He had achieved the ambition for which he had struggled so long.

After a short time at Arbois, he reported to the École Normale before any other students arrived. Now he stood like a knight on the edge of the lists. To him the air of destitution of the place, the crumbling walls of this decrepit annex of the Louis Le Grand College represented all he could ask for in life. Here he could enter the contest of Science in earnest. He was no longer a schoolboy, he was a man being trained as a scientist and a teacher.

His forehead was already broad, his nose wide at the nostrils. His eyes showed no signs of wavering as he scanned the building. Every feature was a fighting feature, his face the face of a man increasingly sure of himself. He had come far. And that square chin showed he was going farther. There was strength in his step, faith in himself shining from his whole being as he marched into the École Normale.

At this school, Louis had little free time, but the bulk of those few hours were spent in the library or in the Sorbonne laboratory. His father constantly wrote Chappuis, asking him not to let Louis work too much, and the good friend did his best to get young Pasteur to give up his studies at least occasionally. Louis’ burning enthusiasm for science, for experiments and for studying the lives of great scientists made it impossible to tear him away for long from his test tubes or books.

Finally Chappuis took up a waiting game. He would sit on a stool in the laboratory and wait patiently while Louis worked, saying nothing. After half an hour of this, Pasteur would agree impatiently, “Well, let us go for a walk.” But they would go right on into talk of philosophy and chemistry or of their classes and the laboratory, just as if they weren’t on an outing.

One afternoon in the Luxembourg Gardens, Louis mentioned the subject that was to bring him his first prominence in the world of physics and chemistry.

“Charles,” Louis was saying, “I have been doing a great deal of thinking about racemic—or some call it paratartaric—acid. One day, in the library, I came across an article on this subject and it has interested me ever since. A manufacturer in Alsace, M. Kestner, discovered some by chance when he was making tartaric acid. Now he cannot make it again, though he’s tried often enough. I’ve been wondering if I could find out why.”

“I don’t know, Louis. Possibly,” Chappuis replied, his mind on philosophy lectures.

“It would be hard. Mitscherlich, the German chemist, and Biot, the physicist, have both studied on it and can come to no conclusion.”

“Perhaps not, then.”

“You see, if you take polarized light, light going straight in one direction, and direct it into a solution of tartaric acid, the solution bends the direction of light, but, in paratartaric acid, the light goes through without bending.”

“But what does it matter whether the light bends or not?”

“A great deal. Since all kinds of crystals, all kinds of chemicals, react differently to polarized light, you can often distinguish between them by these bending reactions. When you put solutions of sugar in a polariscope under polarized light, they bend the light to the right, just as does tartaric acid. Essences of turpentine or quinine bend the plane of polarized light to the left.”

“And what good does that do?”

“By making use of it, you can tell just what different elements are contained in certain materials. It would have a great business value and also be useful in a medical way.”

Louis did not realize how accurately he had prophesied. Not many years later the saccharimeter, built on the principle of polarized light and crystals, was being used by manufacturers to discover the quantity of pure sugar contained in commercial brown sugar and by physiologists in following cases of diabetes.

Soon after Louis came to the École Normale, he was made an honorary member of the Arbois College faculty. His old master, M. Romanet, often read Louis’ letters to the senior class. The following summer M. Romanet asked Louis to give a few talks to the students of Arbois College. These lectures, as M. Romanet requested, were summaries of some of the talks Louis had heard at the Sorbonne and at the École Normale. Truly Louis was already the pride of Arbois and especially of his old headmaster who had encouraged him in his early school days.

Louis’ curiosity about changing matter from one form to another was a key to his endless interest in his work. In one of the lectures he attended, the method of obtaining phosphorus was described, but lack of time prevented a laboratory demonstration being made.

Louis satisfied his curiosity by going out, buying a handful of bones and burning them. Very carefully reducing them to a fine ash, he treated the ash with sulphuric acid and proudly extracted about sixty grams of phosphorus that he displayed on a shelf in his room.

His friends teased him about being a “laboratory pillar.” Some did get ahead of him in class work while he spent his time on what they thought was his puttering. But out of the fourteen candidates in the final examination for a professorship in September, 1846, Louis was third of the four that passed. And his results in physics and chemistry brought the jury’s recommendation, “He will make an excellent professor.”

All students of the École Normale, after passing their examination for professorship, had to spend ten years in teaching. This was a government rule. Louis was now eligible to be appointed a teacher whenever the Government wished to do so. And it was not long before the appointment came. It was for a small place, Ardeche. But Balard, Pasteur’s chemistry master, took him into his own laboratory as an assistant and so managed to rescue him from being shipped away at once to the little town as a teacher. The master had every confidence in a brilliant future for Louis and refused to have him buried in a village just when instruction in Paris was most valuable.

Louis, in turn, was devoted to Balard. He was deeply grateful for Balard’s good turn. He could ask for little more than to work under this chemist who had become famous at the age of twenty-four for his discovery of bromin.

A strange, poetic, yet erudite young man came into Balard’s laboratory toward the end of that year. His name was Auguste Laurent, a former professor of the Bordeaux faculty who was both a poet and a scientist. He would not say definitely how he came to leave Bordeaux. Perhaps he did not get along with the heads of the college or, as he remarked, he simply wished to live in Paris. Nevertheless, he was well known in the scientific world and was a correspondent of the Academy of Scientists.

Laurent exerted a great influence on Louis’ future. He was another in the chain of great men who were impressed by the young Knight of the Laboratory and shared their wide knowledge with him, instilled in him some of their own enthusiasm.

This romantic man of facts had made his name by proving the theory of molecular substitution, stated by Louis’ chemistry master, Dumas, back in 1834, which announced that “chlorine possesses the singular power of seizing upon the hydrogen in certain substances, and of taking its place, atom by atom.”

Talking to a friend, Louis had a much more simple explanation of the theory. The two were chatting of Laurent and Dumas.

“It’s a real experience to study under Laurent,” Louis said. “He’s just asked me to help him in some of his experiments.”

“How will that help your work?”

“Oh, the practical laboratory training will help a great deal, but his theory of molecular substitution might help me in my study of crystals.”

“What’s that theory all about? Sounds pretty complex to me. Molecular substitution is a big phrase.”

“Oh, that’s very simple. Just imagine that a molecule, a globe of a compound, is a monument of stones, with each atom of an element as one stone. The theory of molecular substitution merely proves that you can take these stones of one element out of the monument one by one and replace them with stones or atoms of another element.”

“And these stones or atoms will fit in and make just as solid a monument as before?”

“That’s it.”

“You’re smarter than I thought.”

“No,” Louis returned, “I have more to learn than I can in a lifetime.”

But it was to Chappuis that he really expressed his delight at working with Laurent, finishing with his usual down-to-earth statements.

“Even if the work should lead to no results worth publishing,” he wrote to his friend, “it will be most useful to me to do practical work for several months with such an experienced chemist.”

His work with Laurent did provide a chance for a closer study of his beloved crystals before their collaboration ended when the master was elevated to an assistantship to Dumas at the Sorbonne. Louis turned his greatest efforts then to his theses for his doctor’s degree.

These two papers, dedicated to his father and mother, bore frightening titles but really dealt with the physics and chemistry of the crystals he had studied ever since his talk with Chappuis about the effect of polarized light on racemic acid and the tartrates.

For physics, his essay was a Study of Phenomena Relative to the Rotary Polarization of Liquids; for chemistry, Researches into the Saturation Capacity of Arsenious Acid. A Study of the Arsenites of Potash, Soda and Ammonia. But, these big words were light labor for him. He wrote to Chappuis that he had only scratched the surface.

“In physics,” he wrote, “I shall only present a program of some researches that I mean to undertake next year, and that I merely indicate in my essay.”

Louis was not so interested in an actual diploma to be framed as he was in the actual work that was also his absorbing hobby. Nevertheless, he was not exactly calm when he presented the essays to the judges and returned home to await their decision.

Louis read and defended his essays on August 23, 1847, and although they were not enthusiastically received by the judges, yet he was successful in his presentation. But the doctor’s degree was only a milepost at which Louis Pasteur did not pause. He had had a letter from his father saying: “We cannot judge of your essays, but our satisfaction is no less great. As to a doctor’s degree, I was far from hoping as much; all my ambition was satisfied with the license to teach.”

After receiving his degree, the newly made doctor visited his home for a short vacation. He was accorded a loving reception by his parents and sisters who were somewhat overawed by the academic distinctions heaped upon their son and brother. The same greeting was accorded him by his old schoolmaster, M. Romanet, and by his old chums of boyhood days, Vercel, Charrière and Conlon.

But it was impossible for Louis to keep away for long from his crucibles and retorts. So back again to Paris and the laboratory. On March 20, Louis read a portion of his paper, Researches on Dimorphism, a study of crystals, to the Academy of Sciences, and received their approbation, even though the study’s big words had been too stiff for M. Romanet at Arbois.

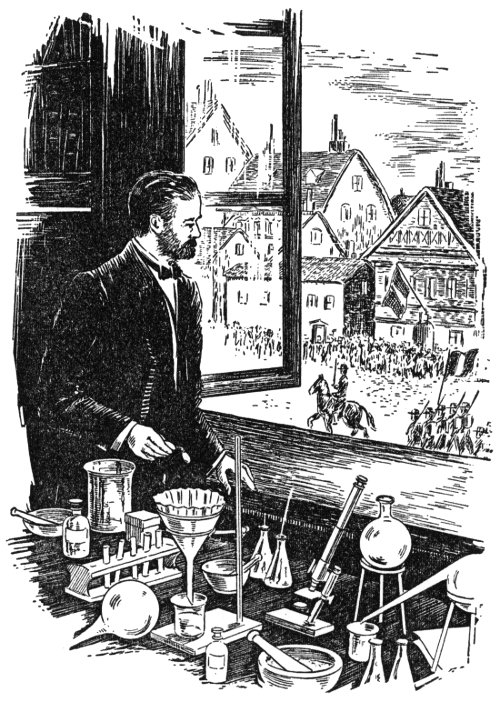

During the early part of 1848 a revolution flamed up in Paris which caused the abdication of the French king, Louis Philippe. Paris was in an uproar and Pasteur, thrilled by the magic ideas of liberty, equality and fraternity, his mind and heart moved by the brilliant writings of Lamartine, the poet of the revolution, had visions of an ideal republic. He enlisted in the National Guard, a city militia intended to guard municipal liberties, founded in 1789, and whose first colonel was General Lafayette of American Revolutionary fame.

Having enlisted with many of his fellow students, Louis wrote to his parents:

I am writing from the Orleans Railway Station where, as a member of the National Guard, I am stationed. A great and ideal doctrine is now being unfolded before our eyes. If it were required I should courageously fight for the holy and sacred cause of the Republic.

One day, returning from his station, Louis saw a crowd gathered around a kind of altar which bore the inscription Autel de la Patrie. One of the bystanders informed him that the altar was erected so that citizens might place donations on it for the cause of the new republic. Pasteur hastened to the École Normale, gathered all his savings, amounting to one hundred and fifty francs, and donated them to the republic.

Telling his father about his action, he received hearty approval. His father advised him to publish his donation in the journal La Nationale as a gift to the republic “by the son of an old soldier of the Empire, Louis Pasteur of the École Normale.”

Still, though patriotism was in the air, though Louis’ mind was filled with his duty to France and her people, he had time to think of his crystals. Anybody might have laughed at him for wasting time on the shapes of tiny pieces of chemicals, but he felt he was on the trail of a discovery that would mean much to chemistry. In those days, he did not know these bits of matter would lay the foundation for discoveries that would improve the health and lengthen the lives of mankind. He did not realize at this time that he would be the first to apply crystallography, the study of the shapes of crystals, to medicine and surgery, as well as to give it a greater importance in the field of chemistry.

But he had reached one conclusion about the tartrate crystals, from which he was trying to find the source of racemic acid. It was common knowledge that the tartrates bent a beam of polarized light to the right, while the paratartaric or racemic acid did not disturb the beam. It was also common knowledge that crystals of the tartrates had many-sided shapes and were dissymmetrical—that is, they were similar in a mirror reflection. Their faces, or facets, were reflected in a mirror just as a left-hand glove reflects as a right-hand one and vice versa.

Louis Pasteur had hoped to prove that the entire crystals of the paratartrate had a different shape from the tartaric crystals, since they did not bend polarized light, and that, for this reason, the outside shape of the crystal would tell how the crystal would react to polarized light.

Eagerly, he studied the crystals of the paratartrates on the bench before him. Would they be symmetrical instead of dissymmetrical? Would they be different in shape from the tartaric crystals?

Slowly he paced up and down before the bench, finally coming back to the microscope. “I should not give up this easily,” he muttered to himself, placing other crystals of paratartrate on the slide.

“Hmmm,” Pasteur peered tensely into the eyepiece. “Yes, it must be. Yes, those two there are left-hand crystals, their faces inclined to the left. And here are more right-hand ones, with faces inclining to the right. Yet a solution of these crystals does not bend light in the polariscope.”

Then the young scientist paused again. An idea, a brilliant light, was bursting through his mind. His heart beat wildly. His whole body trembled. Left-hand crystals bent light to the left in the polariscope. Right-hand crystals bent it to the right. Could it be possible—could this fact be the reason why polarized rays were not affected by this combination of left and right crystals?

Carefully he picked over the crystals again, sorting them. The only way to prove his idea was by experiment. Mitscherlich had not mentioned finding right and left faces in his paratartrates. Perhaps this was the key to the whole matter. But he must take his time, leave no chance for a mistake.

Pasteur inspected each of the paratartaric crystals thoroughly. Every one that turned to the left he placed in one pile. Every one that turned to the right, he placed in another pile.

With shaking fingers, he counted the little bits of paratartrate, made sure there was an equal number in each pile.

“Now the solution,” he spoke to himself, dissolving one of the sets of crystals in a certain quantity of water.

Now into the polariscope.

Louis’ confidence grew as he made the first test. Yes, the solution of right-hand crystals turned the beam to the right, and with the left-hand crystals, the beam was diverted to the left.

Pasteur paused to take a deep breath. Here hung the success or failure of his experiment. This test could bring him fame or it might be just another failure. The scientist proceeded to mix the two solutions. In his heart was a faith that all would be for the best. One failure would be just another stepping stone to the success that must come sooner or later, if he kept working for it. He gave the two liquids ample time to combine thoroughly.

Then for the polariscope. Would the light turn to right or left? Or would the rays pierce through unaffected? Would he know that right and left crystal solutions combined to make a neutral solution? And that the chemical content of crystals could be discovered by their outer shape? Or would he be no closer to knowing the composition of paratartaric acid than before?

His heart thundering against his ribs, he applied the light.

The beam was not turned, shone through without deviation to left or right.

“I have it! I have it!” Louis shouted, rushing out of the laboratory, down the hall.

In the passage he met Bertrand, one of the curators. Wild with excitement, he embraced the official as he would have hugged Chappuis. Babbling, he half carried, half dragged the surprised man out into Luxembourg Gardens.

“Yes, Bertrand, believe me, I have it,” he cheered. “I know the secret of racemic or paratartaric acid—”

“Come, come, the world is not going to explode. Tell me calmly,” the curator laughed, but he was nearly as excited as Louis.

“Well, the acid is made up of right- and left-hand tartaric acids. The right-hand is similar in every way to the natural tartaric acid secured from grapes and combines of its own accord with equal quantities of the left-hand tartaric acid. Since the effect of the two acids on polarized light—the right-hand acid turning the beam to the right and the left-hand turning the beam to the left—is exactly opposite, the two acids balance each other when mixed and the mixture of paratartaric or racemic acid does not turn the light at all. Mitscherlich’s problem is answered.”

“Splendid, my friend.”

Chappuis, unfortunately, was not at the school at the time, but Louis’ exuberant letter gave him all the details.

How often [he said, along with the details of the experiment], how often have I regretted that we both did not take up the same study, that of physical science. We did not understand, did we, we who so often talked of the future? What splendid work we could have done and would be doing now; and what could we not have accomplished united by the same ideas, the same love of science, the same ambition! I would we were twenty with the three years of the École before us!

But only a little more than three weeks later, he had a painful letter to write to his friend. The exuberance was gone, the excitement of his first major discovery. His mother had died within a short time after an attack of apoplexy—before Louis could reach home to see her.

“She passed away in a few hours,” he explained to Charles, “and when I reached home she had already left us. I have asked for a holiday.”

At that moment, Louis’ work was completely suspended. Weeks passed before he again had any zest for life, before he could again take his mind from the tragedy and apply it to science. His parents had been so great a part in his life. He had felt such deep gratitude for the sacrifices they had made to allow him to become a student that the loss of his gay mother was nearly unbearable.

For weeks Louis remained steeped in sorrow. He remembered when he was a little boy, how his mother would pack the lunch baskets for the children to take to school and how she would put in his little basket an extra sweet of some kind. How surprised he would be when he opened his lunch and how he would rush home after school to thank her with a great big hug and kiss. This and many other home scenes Louis reviewed as he was buried in his grief. How he would miss her! It seemed incredible that he would not see her any more.

Years afterwards, when a memorial plate was being placed on the old home at Dole where he was born, Louis said of his mother: “Your enthusiasm, my dear mother, you passed on to me. If I have associated greatness of science with the greatness of country, it was because you instilled these sentiments in me, you inspired me.”

While Louis was at home, Balard, proud of his pupil and assistant, had bragged of his discovery of the constitution of racemic acid in the library of the Institute, where old Academicians would meet to chat. Dumas, Louis’ much-admired chemistry master, listened seriously without a word. Biot, equally revered by Louis as a physicist, had his doubts. He was over seventy-four years old now and found it hard to believe a young man of Pasteur’s age could get to the bottom of a problem that had been too much for an older, much more experienced scientist like Mitscherlich.

Biot did not stop to hear more of Balard’s loud praises. Instead he announced briefly:

“I should like to investigate that young man’s results.”

When Louis returned to Paris, Balard told of Biot’s remarks. Immediately anxious to convince the grand old man of physics, Louis wrote him, asking for an appointment to call.

I shall be pleased to verify your results [Biot’s reply read], if you will communicate them confidentially to me. Please believe in the feelings of interest inspired in me by all young men who work with accuracy and perseverance.

They met in the Collège de France, a school of high studies in Paris where Biot lived. Louis was filled with uncertainty. What if the experiment failed? What if he made some blunder that would spoil this great opportunity to impress one of the greatest scientists in France?

Biot started the proceedings by bringing some paratartaric acid and setting it before Louis. Pasteur could see the old man was putting him to the most rigid test, was not going to allow anything to go unexplained.

“I have most carefully studied it,” the physicist pointed to the solution. “It is absolutely neutral (does not bend the rays) in the presence of polarized light.

“I shall bring you everything,” he went on, as Louis stared at the liquid.

Biot produced doses of soda and ammonia with which to make the crystals from the liquid. He was going to have Louis make those crystals before his very eyes.

When the materials were added to the solution which would produce crystals and the whole was put into a crystallizer, Biot placed it in a far corner of the room where it would not be disturbed.

“I shall let you know when to come back,” he explained to Pasteur, as the younger man passed through the door.

For forty-eight hours, Louis heard nothing from Biot. Certainly those crystals should have started to form by now. He spent those hours that followed in anxious waiting. What if Biot had become displeased with the experiment? Or decided Louis’ experience in laboratory work was not sufficient to make his discovery of the constitution of racemic acid worth taking seriously?

At last the summons came. The eagle-eyed old man again stood over Pasteur’s shoulder during the next step of the demonstration. With great delicacy, Louis drew the finest crystals from the liquid and wiped them absolutely dry.

Would they turn out to be right-hand and left-hand, as they had in his own tests? Fearfully, he looked at each one thoroughly as he dried it. Yes, here were some of the right-hand. And here some of the left-hand. He placed them all on a pile on the bench.

One by one, he drew them out, showed Biot how some of them had right-hand formations, others left-hand. In the process, he separated the two kinds into piles, just as he had in his own tests.

“So you affirm,” said Biot, “that your right-hand crystals will deviate light to the right of the plane of polarization, and your left-hand ones will deviate to the left?”

Louis nodded in confirmation.

“Well, let me do the rest.”

Pasteur left while Biot was to prepare the solutions. In that time, he suffered far more pangs of anxiety than he had on the previous days of waiting. This experiment meant so much. If he could earn the approval of Biot, his future would be well settled. He would be considered seriously by the great men of science throughout France.

If Biot disproved his theory, he would lose ground that would be hard to regain. It would be twice as difficult to get back into this charmed circle of great men after a failure than it had been to climb this far in the first place.

And Biot was hard to please. Like any older man, he was none too willing to have a young doctor barely out of the École teaching him new things about science.

This waiting was agonizing. Why didn’t Biot send for him? Why didn’t he tell him the experiment was a success, instead of keeping him in this awful suspense?

Or had it been a failure?

Almost before the great scientist’s messenger could return, Louis rushed to Biot’s home. His eyes afire with excitement as the scientist first placed in the polarizing apparatus the solution that should bend the beam of light to the left.

Yes! Yes! The light was properly deviated! The experiment was a success!

“My dear boy,” Biot said, taking Louis by the arm, “I have loved Science so much during my life that this touches my very heart.”

Louis was exultant over the success of his discovery. Biot at once suggested they work together, so, with Biot’s help, Louis soon published a paper covering his discovery of the make-up of racemic acid and the effect of polarized light. The title of the study was “Researches on the Relations Which May Exist between Crystalline Form, Chemical Composition, and the Direction of Rotary Power.” Biot gave complete credit to the young man, voicing also the approbation of Dumas, Balard and Regnault.

Biot and Pasteur turned their combined attention to the subject of polarization and began thorough research into its many sides. Here Louis was very happy. He had the chance to eat, sleep and think nothing but Science, day and night. He had the advice and assistance of a skilled and wise man, whose decades of experience were at Louis’ disposal. What more could a young doctor ask?

The shadow of a Government appointment for teaching hung over those happy days, but Louis managed to avoid giving the matter too much thought. After all, the question was out of his hands. When the time came, he would simply have to obey the call. Balard had managed to get him out of one appointment, but, since the Government had trained him at the École Normale for teaching, he must eventually accept a teaching post.

Before a great length of time, he was named to fill a vacancy at the Dijon Lycée. Biot complained that they were in the midst of great work and tried to have the nomination set aside. After much discussion, he succeeded only in having the time set ahead to the fall of the year.

Louis hated the thought of leaving the Paris laboratory for the town of Dijon, though he reported there properly in the fall. It was tough going, and preparing lessons for his class took almost all his time. His conscientious nature forced him to do the job thoroughly, even though Paris and her laboratories, rather than the classroom, was his native ground. He felt a great responsibility in seeing that his students gained something from their studies and worked endlessly to keep them interested all during the lecture hour. He found performing more experiments kept their attention and made them enjoy his classes, so he turned to this way of teaching.

He taught chemistry to both first- and second-year pupils. The first-year class contained some eighty boys and Pasteur often exclaimed that “it was a mistake not to limit classes to fifty boys at the most. For it is only with great difficulty that I am able to keep their whole-hearted attention toward the end of the lesson.” However, he did solve the problem by multiplying experiments during the last few moments. His second-year class was delightful. It was not large and Pasteur said about them: “They all work and some very intelligently.”

Meanwhile, in Paris, all his friends attempted to arrange some way for him to return, but their efforts did not budge the rules of the Government. Eventually, however, they succeeded in having Louis moved to a somewhat better post at Strassburg, as deputy Professor of Chemistry, where an old school friend, Bertin, was Professor of Physics.

Bertin was glad to welcome Pasteur to the University of Strassburg. “You must live with me,” Bertin said to Pasteur when he arrived on January 15. “I have a house only a short distance from the faculty.”

The Professor of Physics proved to be a fine companion for Pasteur. He had a quick wit and an affectionate heart. His philosophy of life was to accept things as they came and contrasted strongly with Louis’ dynamic energy and ardent ambitions. Bertin often maintained to Pasteur that disappointments were often blessings in disguise. Louis, however, would not agree with him.

“All right,” said Bertin one evening in their home, “I’ll prove it to you.”

“Remember back in 1839 when I was mathematical preparation master at the College of Luxeuil?”

“Yes, I do,” answered Louis.

“Well, I was entitled to two hundred francs a month but I was refused payment. What did I do? Did I kick up a fuss? Oh, no, I quietly resigned. Then I went in for the École Normale examination, entered the school at the head of the list and here I am, Professor of Physics in the Strassburg faculty. If it had not been for that disappointment, I might still be at Luxeuil.”

As Bertin concluded, Pasteur laughed heartily and said, “My friend, you should have been a debater.”

As comfortable as it was at Strassburg, there was one drawback, it was such a long distance from Arbois. Pasteur longed for family life. His suite of rooms at Bertin’s would be large enough to accommodate one of his sisters. He expressed this idea in a letter to his father, who immediately answered, stating: “You say that you will not marry for a long time, that you will request one of your sisters to live with you. I wish this for you and for them. In fact neither of them wishes for a greater happiness than to look after your comfort.”

Louis had no more than received this letter when he was introduced to the new Rector of the Strassburg Academy, M. Laurent, no relative to the scientist of the name. The rector’s home was a meeting place for the members of the faculty, who always found a hearty welcome awaiting them. Bertin accompanied Pasteur on his first visit to Laurent’s home. Duly introduced to Mme. Laurent, he next met the two younger daughters. Then it was that Louis encountered his first distraction from the laboratory. He foresook the brilliant light of his crystals for the brilliant light shining from the dancing eyes of Mlle. Marie Laurent. It was a case of love at first sight for both Louis and Marie. This certainly was odd on Pasteur’s part. Always slow to come to a decision in the world of science, he judged quickly in the world of love. The only explanation for this is that Marie possessed those qualities Louis had always admired. She was pretty, vivacious and gay, yet subdued; modest and yet capable of arousing no ordinary admiration. Pasteur had known her only about two weeks when he sent the following letter to her father:

Monsieur:

A request of the greatest importance to me and to your family is about to be tendered you on my behalf; and I feel it my duty to present to you the following facts, which may aid you in determining your acceptance or refusal.

My father is a tanner in the village of Arbois in Jura, my sisters keep house for him, and help him with his books, taking the place of my mother whom we had the misfortune to lose last May.

My family is in easy circumstances, but without fortune; I value what we possess at about 50,000 francs. As for me, I have long ago decided to give to my sisters the whole of what would be my share. Therefore, I have absolutely no fortune. My only means are good health, ambition and my position at the University.

I left the École Normale two years ago, an agrégé in physical science. I received a Doctor’s degree eighteen months ago, and I have presented to the Academy a few works which have been very well received, especially the last one, a report on which I have the honor to inclose.

This, Monsieur, is my present position. As to the future, unless my tastes should completely change, I shall devote myself entirely to chemical research. I hope to return to Paris when I have acquired some reputation in my scientific works. M. Biot has often advised me to think seriously about the Institute; perhaps I may do so in ten or fifteen years; and after diligent research; but so far this is but a dream, and not the motive which makes me love Science for Science’s sake.

My father himself will come to Strassburg to make this proposal of marriage.

Accept, Monsieur, the assurance of my profound respect and devotion.

p.s.—I was twenty-six on December 27.

This may seem to be a strange letter for a man in love to write to his prospective father-in-law. Never once did Louis mention that he loved Marie. He simply stated his qualifications as a chemist and the fact that he would be a good provider for his future wife. But such was the custom in those days. The fathers of the families decided as to the fitness of the young people to marry.

Louis was in an agony of suspense for weeks, for Marie’s family was on a higher social plane than his own, but M. Laurent finally came to a decision, and Louis’ father and sister, Josephine, traveled to Strassburg. During the period of uncertainty, Louis wrote to Marie’s mother:

“I am afraid that Mlle. Marie may be influenced by early impressions, not favorable to me. I know there is nothing in me to attract a young girl’s fancy. But I do know that those who have known me very well have loved me very much.”

Louis was a little ashamed, too, that his mind and interest was divided between his Marie and his work. “I, who did so love my crystals,” he once remarked in a letter.

But still, on May 29, 1849, when the wedding was about to take place, Louis was missing. Finally he was discovered in his laboratory, deep in an experiment, and brought to the church.

Writing to Chappuis about the wedding, he admitted this was a thoroughly important event in his life. “I believe,” he wrote, “that I shall be very happy. Every quality I could wish for in a wife I find in her. You will say ‘He is in love!’ Yes, but I do not think I exaggerate at all, and my sister Josephine certainly agrees with me.”

After his marriage, Louis’ experiments continued with as much vigor as before—perhaps with greater energy. Mme. Pasteur, graceful and dignified, entered into his researches with great enthusiasm and was often in the laboratory assisting him or at her desk acting as his secretary in preparing the long and detailed notes that he made of each experiment of importance that he wished to report to Biot.

The five years immediately after his marriage were among the happiest of Louis’ entire life. He spent his vacation time in Paris and his teaching time in Strassburg, where he would have worked in the laboratory every minute he was not in the lecture room had not his wife carefully watched his health and insisted that he take at least a reasonable amount of sleep.

Three children, two daughters and a son, were born to the Pasteurs during their stay at Strassburg. Louis Pasteur’s domestic life was truly one of harmony and as yet he had not become famous enough to have his scientific life darkened by bitter controversies. A continual correspondence passed between him and Biot as step by step our knight climbed the ladder of success. Great scientists, like De Senarmont and Regnault began to notice the growing importance of Pasteur’s work, began to perceive in the results of his labors a spark of genius.

When Louis came to Paris in August of 1852 to see Biot, who had become almost a second father to him, the old scientist had prepared a great surprise for him. Biot loved Louis as a son and was ever thinking of the wisest course for him to follow in guiding his future, saving him from more than a few ill-advised steps suggested by more enthusiastic but less sensible admirers.

When Biot knew Louis had arrived in his hotel in the Rue de Tournon, he started on his morning walk around the Luxembourg Gardens and left this note at the hotel:

“Please come to my house tomorrow at 8 a.m., if possible with your products. M. Mitscherlich and M. Rose are coming at 9 to see them.”

Mitscherlich! And Rose, his assistant! Louis was overjoyed. The interview turned out very pleasantly and eventually led to a long crusade for this Knight of the Laboratory.