* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: The Enid Blyton Holiday Book

Date of first publication: 1946

Author: Enid Blyton, (1897-1968)

Date first posted: February 13, 2023

Date last updated: February 13, 2023

Faded Page eBook #20230203

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, Ruth Haines & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

This file was produced from images generously made available by Internet Archive/American Libraries.

THE

HOLIDAY BOOK

LONDON

SAMPSON LOW, MARSTON & CO., LTD.

MADE AND PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY PURNELL

AND SONS, LTD., PAULTON (SOMERSET) AND LONDON

| Contents | ||

| Chapter Name / | ||

| Originally appeared in | Illustrated by | PAGE |

| The Pixie in the Pond | Sylvia Ismay Venus (1896 - 2000) | 7 |

| Story: Sunny Stories No. 40 Oct 15, 1937 | ||

| She Wouldn’t Believe It | Eileen A. Soper (1905 - 1990) | 12 |

| Story: Sunny Stories No. 123 May 19, 1939 | ||

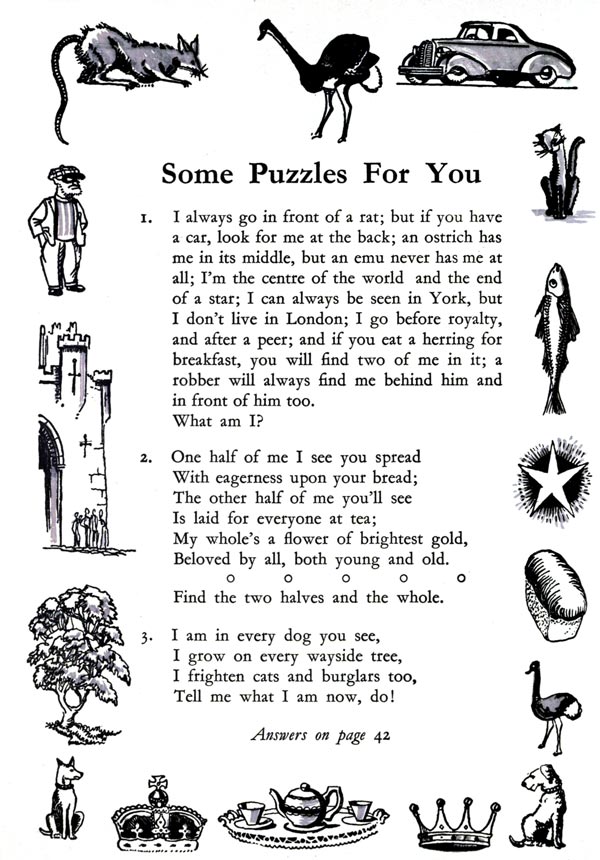

| Some Puzzles for You | Edward Jeffrey (1898 - 1978) | 16 |

| The Golliwog Who Listened | Eileen A. Soper (1905 - 1990) | 17 |

| Story: Sunny Stories No. 126 Jun 9, 1939 | ||

| Slip-Around’s Wishing Wand | Edward Jeffrey (1898 - 1978) | 23 |

| Story: Sunny Stories No. 108 Feb 3, 1939 | ||

| The Bumble-bee and the Rabbit | Eileen A. Soper (1905 - 1990) | 30 |

| Story: Sunny Stories No. 97 Nov 18, 1938 | ||

| Green-Eyes’ Mistake | Edward Jeffrey (1898 - 1978) | 33 |

| Story: Sunny Stories for Little Folks No.247 Oct 1936 | ||

| The Tale of Lanky-Panky | Eileen A. Soper (1905 - 1990) | 43 |

| Story: Sunny Stories No. 96 Nov 11, 1938 | ||

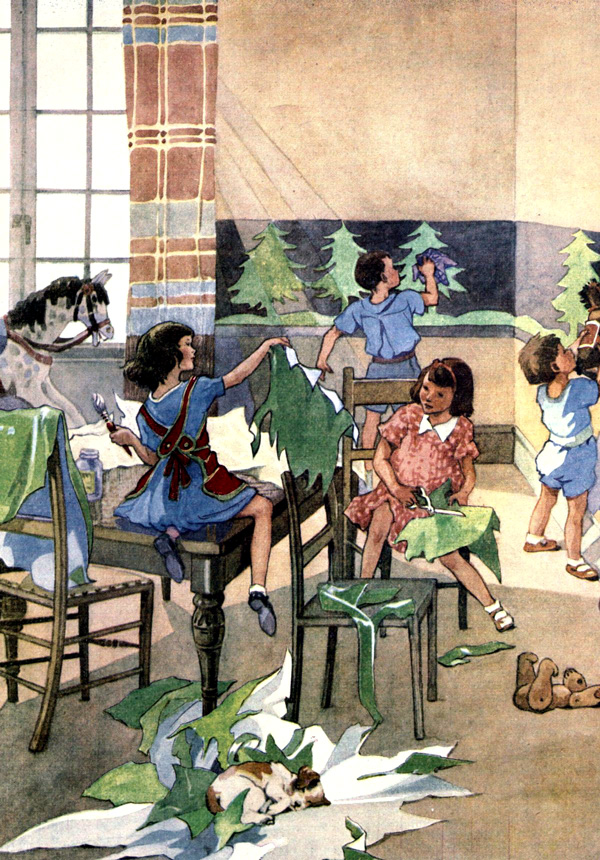

| Bobby the Cow-Boy | Kathleen Mary Gell (1913 - 1997) | 49 |

| Story: Sunny Stories No. 130 Jul 7, 1939 | ||

| The Cockalorum Bird | W.E. Narraway (1915 - 1979) | 53 |

| Story: Sunny Stories for Little Folks No.229 Jan 1936 | ||

| The Magic Shell | W.E. Narraway (1915 - 1979) | 65 |

| Story: Sunny Stories No. 87 Sep 9, 1938 | ||

| The Greedy Little Sparrow | Eileen A. Soper (1905 - 1990) | 68 |

| Story: Sunny Stories No. 74 Jun 10, 1938 | ||

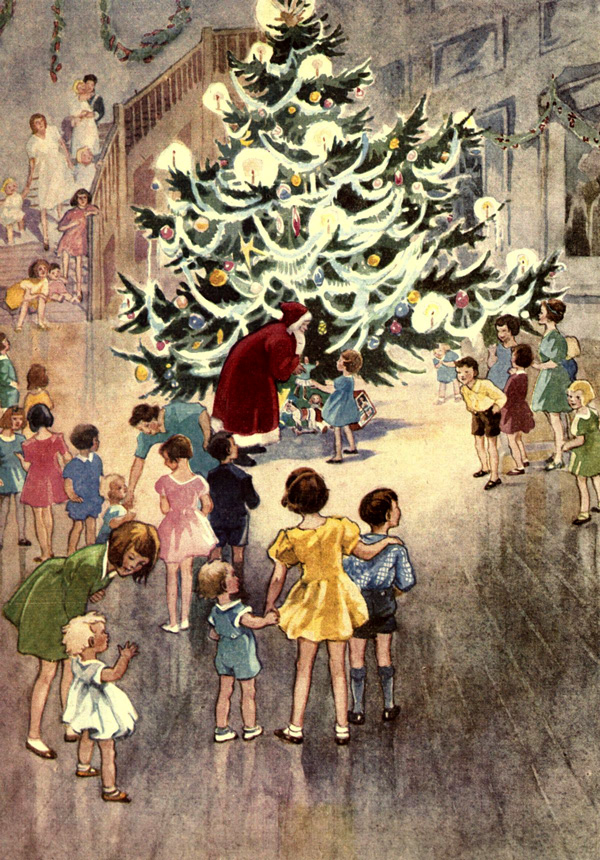

| Play—Here Comes Santa Claus | ✯ uncredited | 72 |

| Play: Specially Written | ||

| Our Own Christmas Crackers | ✯ uncredited | 80 |

| The Pig that Went to Market | Norman Meredith (1909 - 2005) | 81 |

| Story: Sunny Stories for Little Folks No. 242 Jul 1936 | ||

| The Funny Old Dragon | Eileen A. Soper (1905 - 1990) | 92 |

| Story: Sunny Stories No. 104 Jan 6, 1939 | ||

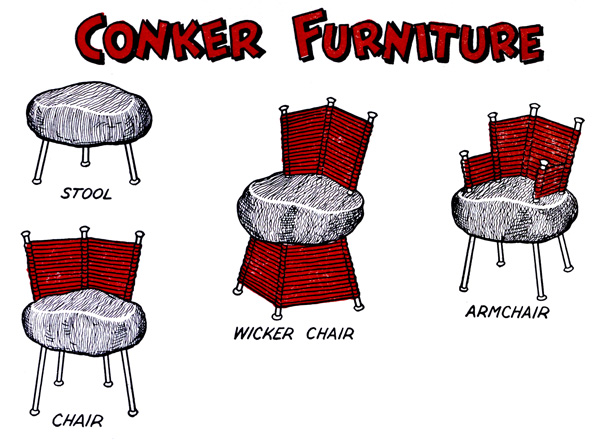

| Conker Furniture | ✯ uncredited | 96 |

| The Mouse that Lost His Whiskers | Edward Jeffrey (1898 - 1978) | 97 |

| Story: Sunny Stories for Little Folks No. 227 Dec 1935 | ||

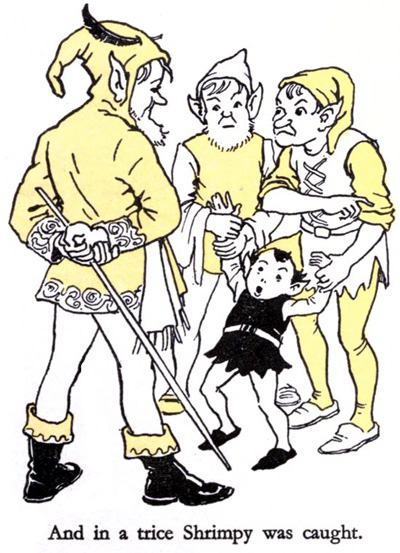

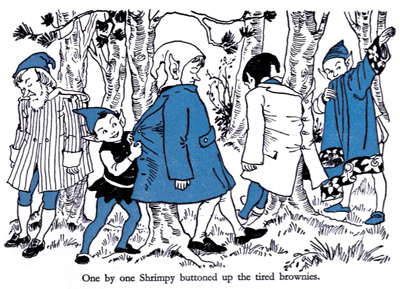

| Tig, the Brownie Robber | ✯ uncredited | 106 |

| Story: Sunny Stories No. 124 May 26, 1939 | ||

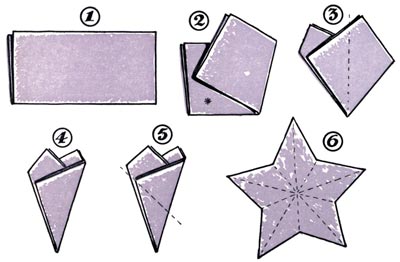

| Stars for the Christmas Tree | ✯ uncredited | 112 |

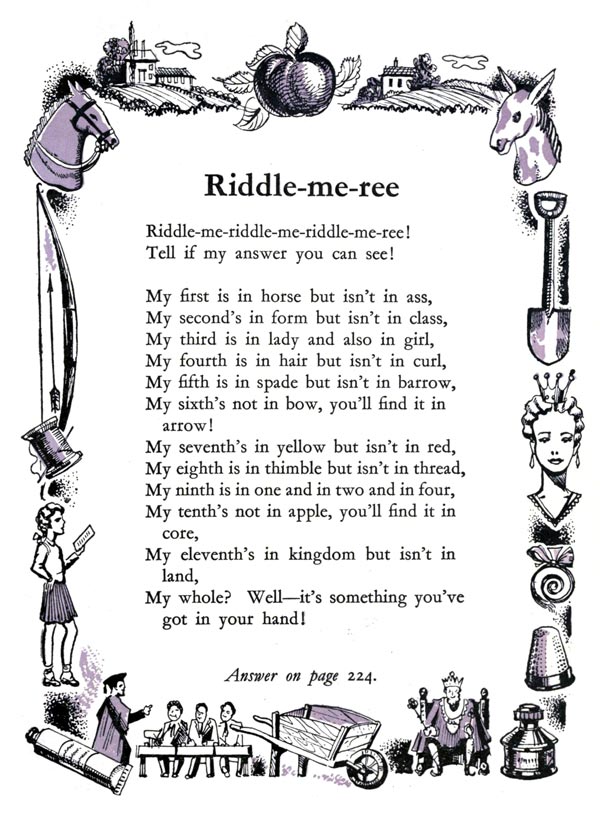

| Riddle-me-ree | ✯ uncredited | 113 |

| The Firework Goblins | Edward Jeffrey (1898 - 1978) | 114 |

| Story: Sunny Stories No. 94 Oct 28, 1938 | ||

| The Magic Sweet Shop | Kathleen M. Gell (1913 - 1997) | 119 |

| Story: Sunny Stories for Little Folks No. 194 Jul 1934 | ||

| Beware of the Snake | uncredited | 129 |

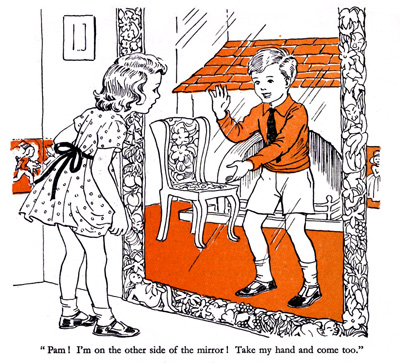

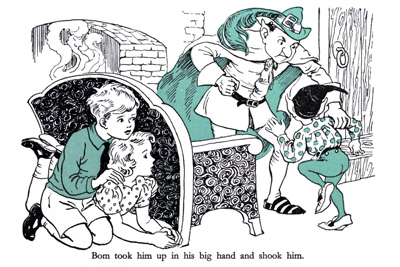

| The Goblin Looking-Glass | ✯ uncredited | 130 |

| Story: Sunny Stories for Little Folks No. 176 Oct 1933 | ||

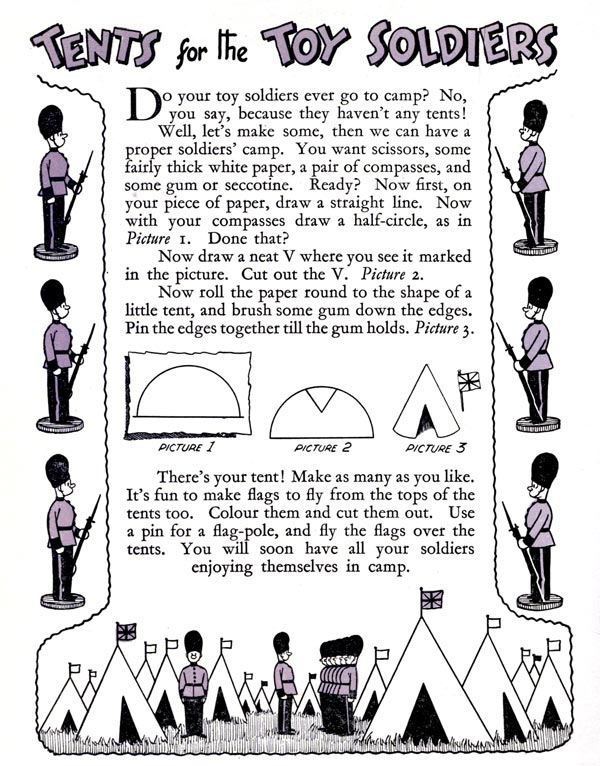

| Tents for the Toy Soldiers | ✯ uncredited | 144 |

| The Tale of Bubble and Squeak | Mary K. Lee | 145 |

| Story: Sunny Stories No. 41 Oct 22, 1937 | ||

| Mr. Snifty’s Dustbin | Eileen A. Soper (1905 - 1990) | 153 |

| Story: Sunny Stories No. 76 Jun 24, 1938 | ||

| Good Gracious, Bruiny | Grace Lodge (1893 - 1975) | 157 |

| Story: Sunny Stories No. 89 Sep 23, 1938 | ||

| The Tale of Mr. Busybody | Sylvia Ismay Venus (1896 - 2000) | 161 |

| Story: Sunny Stories for Little Folks No. 226 Nov 1935 | ||

| The Rat, the Dormouse and the Robin | Eileen A. Soper (1905 - 1990) | 172 |

| Story: Sunny Stories No. 115 Mar 24, 1939 | ||

| A Novel Easter Card | 176 | |

| Little Mr. Woffles | Eileen A. Soper (1905 - 1990) | 177 |

| Story: Sunny Stories for Little Folks No. 200 Oct 1934 | ||

| Oh, Mister Crosspatch! | Edward Jeffrey (1898 - 1978) | 188 |

| Story: Sunny Stories No. 122 May 12, 1939 | ||

| How Clever You Are | ✯ uncredited | 193 |

| In the Heart of the Wood | ✯ uncredited | 194 |

| The Christmas Tree Pig | Edward Jeffrey (1898 - 1978) | 205 |

| Story: Sunny Stories No. 102 Dec 23, 1938 | ||

| Rain in Toytown | Edward Jeffrey (1898 - 1978) | 209 |

| Story: Sunny Stories for Little Folks No. 250 Nov 1936 | ||

| The Bit of Magic Paper | ✯ uncredited | 220 |

| Story: Sunny Stories No. 95 Nov 4, 1938 | ||

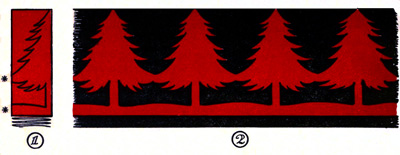

| A Frieze of Christmas Trees | ✯ uncredited | 224 |

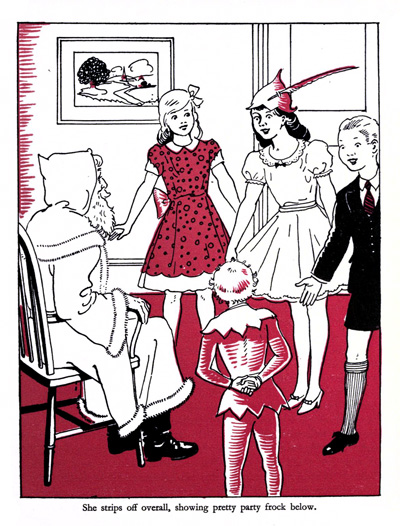

| Pinkity’s Party Frock | ✯ uncredited | 225 |

| Story: Sunny Stories No. 91 Oct 7, 1938 | ||

| Shadows on the Wall | ✯ uncredited | 229 |

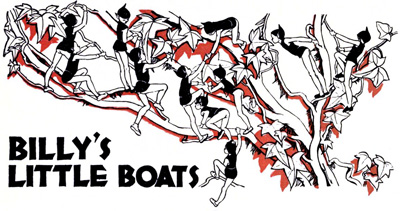

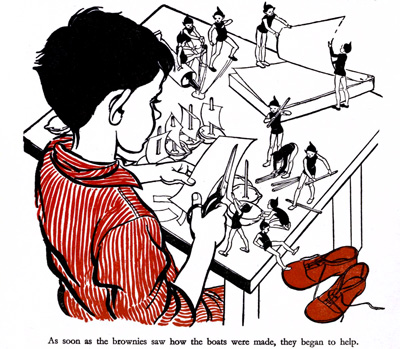

| Billy’s Little Boats | ✯ uncredited | 230 |

| Story: Sunny Stories No. 96 Nov 11, 1938 | ||

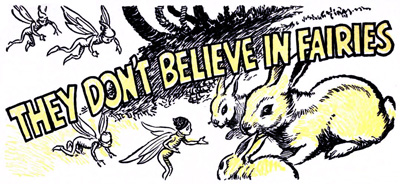

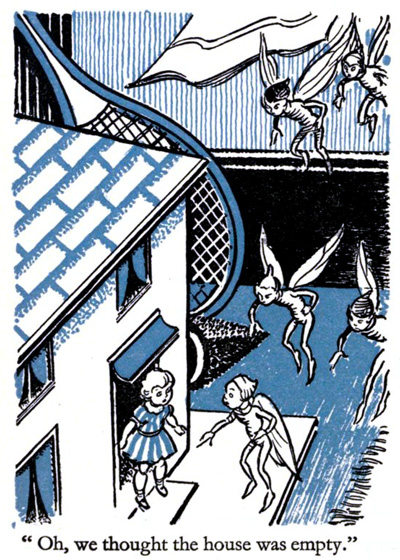

| They Don’t Believe in Fairies | ✯ uncredited | 235 |

| Story: Sunny Stories No. 100 Dec 9, 1938 | ||

| Summer Holidays | ✯ uncredited | 240 |

| Poem: Specially Written | ||

| The Tale of Chuckle and Pip | Mary K. Lee | 241 |

| Story: Sunny Stories No. 127 Jun 16, 1939 | ||

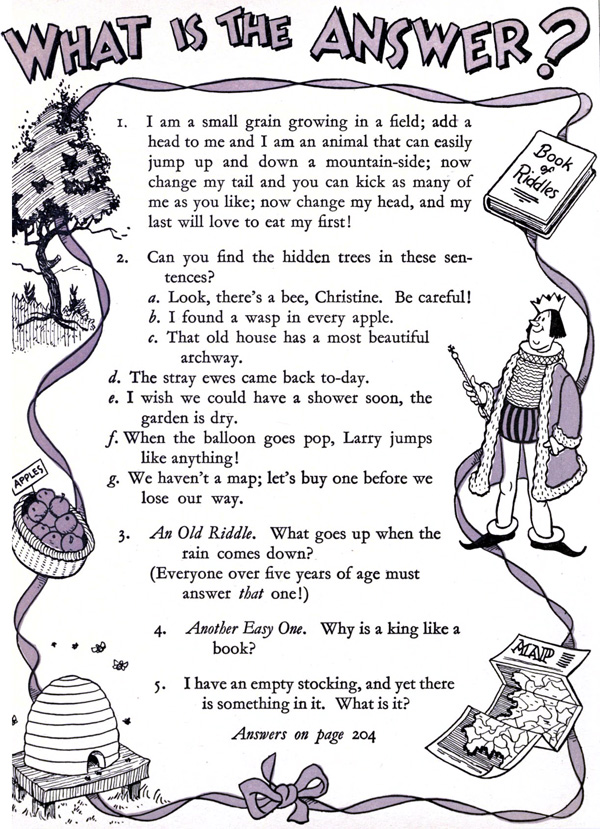

| What is the Answer? | ✯ uncredited | 248 |

| Big-Hands and Nobbly | ✯ uncredited | 249 |

| Story: Sunny Stories for Little Folks No. 241 Jul 1936 | ||

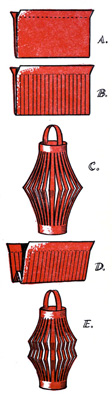

| Let’s Make Some Lanterns for Xmas | ✯ uncredited | 257 |

| Joey’s Lost Key | Edward Jeffrey (1898 - 1978) | 258 |

| Story: Sunny Stories No. 131 Jul 14, 1939 | ||

| The Top that Ran Away | ✯ uncredited | 263 |

| Story: Sunny Stories No. 76 Jun 24, 1938 | ||

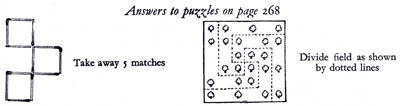

| Can You Do These? | ✯ uncredited | 268 |

| The Christmas-Tree Fairy | Kathleen M. Gell (1913 - 1997) | 269 |

| Story: Sunny Stories No. 46 Nov 26, 1937 | ||

| A Little Weather Girl | ✯ uncredited | 273 |

| The Tiresome Brownie | Gail Brown | 274 |

| Story: Sunny Stories No. 133 Jul 28, 1939 | ||

| The Poor Old Teddy | Edward Jeffrey (1898 - 1978) | 278 |

| Story: Sunny Stories No. 40 Oct 15, 1937 | ||

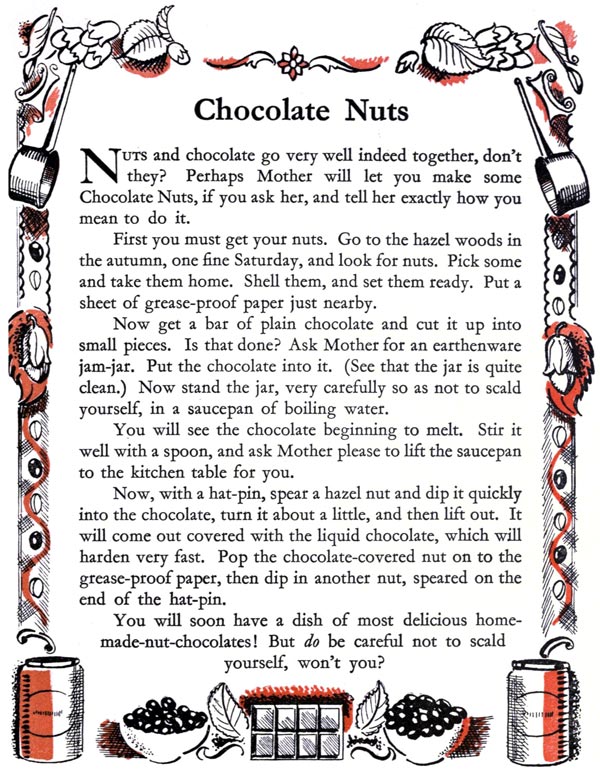

| Chocolate Nuts | ✯ uncredited | 283 |

| The Twiddley-Hen’s Egg | Norman Meredith (1909 - 2005) | 284 |

| Story: Sunny Stories No. 84 Aug 19, 1937 | ||

| Cover Art: | Hilda Boswell (1903 - 1976) | |

| Colour Plates: | Grace Lodge (1893 - 1975) | |

The name of Illustrator and where the story originally appeared have been added to the original table of contents. Illustrations that are in the public domain under Canadian law as at 2022 have been included in the eBook and are indicated by ✯ . All other illustrations are still under copyright so cannot yet be included.

Once upon a time there was a small pixie called Whistle. You can guess why he had that name—he was always whistling merrily! He lived with his mother and father in a little toadstool house not far from a big pond. It was a lonely house, for no other pixies lived near, and as white ducks swam on the pond there were no frogs or toads for Whistle to play with.

“I’m very lonely, Mother,” Whistle said, a dozen times a day. “I wish I could play with the field-mice. They want to show me their tunnels under the roots of the oak tree.”

“No, Whistle,” said his mother firmly. “The last time you went to see a mouse’s nest you got lost underground, and I had to pay three moles to go and look for you. You are not to play with field-mice.”

“Well, can I play with the hedgehog then?” asked Whistle. “He is a good fellow for running about with me in the fields.”

“Certainly not!” said his mother. “His prickles would tear your nice clothes to pieces. Now run out and play by yourself, Whistle, and don’t worry me any more.”

So Whistle went out by himself, looking very gloomy. It was dull having to play by himself, very dull. He shook his head when Tiny the field-mouse ran up to him and squeaked to him to come and play. He didn’t go near the hedgehog when he saw him in the ditch. Whistle was an obedient little pixie.

He ran off to the pond. He liked to watch the big dragon-flies there. They were nearly as big as he was.

It was whilst he was watching the dragon-flies that he saw a merry little head poking out of the water nearby, watching the dragon-flies too! Whistle stared in surprise. He didn’t know there was anybody else near, and here was a little pixie in the pond—a pixie about as small as himself, too!

“Hallo!” said Whistle. “Who are you?”

“I’m Splash, the water-pixie,” said the little fellow, climbing out of the water and sitting beside Whistle. “I live in the pond with my father and mother. We only came last week. I didn’t think there was any one for me to play with, and now I’ve found you. What luck!”

“Oh, Splash, I’m so pleased!” said Whistle. “My name is Whistle. We can play together every day. What shall we play at?”

“Come into the water and I’ll teach you to swim,” said Splash.

“But what about my clothes?” said Whistle. “They’ll get wet.”

“Well, they’ll dry, won’t they?” said Splash. “Come along! Mind that mud!”

But dear me, Whistle was so anxious to get into the water that he floundered right into the mud, and you should have seen how he looked! He was black from head to foot!

“Oh dear!” said Whistle, in dismay. “Look at that! I’d better get out and dry myself, and then see if the mud will brush off. Come and sit by me, Splash, and I’ll teach you to whistle.”

So Splash sat by Whistle in the sun, and the pixie taught his friend to whistle loudly. By the time the dinner-hour came, Splash could whistle like a blackbird! Whistle’s clothes were dry, but the mud wouldn’t brush off. It stuck to his clothes, and was all over his face and hands too. The two pixies said good-bye, and each ran off to his dinner.

Oh dear! How cross Whistle’s mother was when she saw his clothes! “You bad, naughty pixie!” she scolded. “You have been in the pond. Take off your clothes at once. You must have a hot bath.”

“Oh, Mother, don’t be angry with me,” begged Whistle. “I have found a friend to play with. It is a water-pixie called Splash!”

“Indeed!” said his mother, pouring hot water into the tin bath. “Well, just remember this, Whistle—you are not to play with water-pixies at all! You will only get muddy and wet, and I won’t have it!”

“But, Mother!” cried Whistle, in dismay, “I do so like Splash! He is so nice. He wanted to teach me to swim.”

“You’ll drown before you learn to swim in that weedy pond,” said his mother. “Now remember, Whistle, I forbid you to play with that water-pixie.”

Whistle said no more. He knew it was no use, but he was very sad. It was hard to find a friend, and then not to be allowed to keep him.

That afternoon, Whistle stole down to the pond. Splash was there, sitting in a swing he had made of bent reed. He was whistling away, having a lovely time, eagerly waiting for Whistle.

“What’s the matter?” he cried, when he saw the pixie’s gloomy face.

“Mother was very cross about my muddy suit, and says I mustn’t play with you,” said Whistle sadly. “So I came to tell you. After this I shan’t come down to the pond, because if I do I might see you and play with you, and I don’t want to upset my mother.”

“Oh, bother!” said Splash, in dismay. “Just as we have found one another so nicely. It’s too bad!”

“Good-bye, Splash,” said Whistle. “I’m very, very sorry, but I must go.”

Off he ran home; and just as he got there he met his father, who called to him.

“Whistle! How would you like to go for a sail on the pond this afternoon? I’ve got a fine little boat here that used to belong to a child.”

“Ooh, how lovely!” said Whistle, looking at the toy boat, which was leaning up against the side of the toadstool house and was even bigger than the house itself!

“Mother! Where are you?” called Whistle, in excitement. “Are you coming for a sail too?”

“Yes!” said his mother. So in a short time the little family set off to the pond, Whistle and his father carrying the ship, and his mother running behind. They set the boat on the water, and then they all got in.

It was a windy day. The wind filled the little white sail and the ship blew into the middle of the pond. What fun it was! Whistle’s father guided the boat along and Whistle leaned over to look for fish. He saw a big one, and leaned so far over that he lost his balance! Splash! Into the water he went head-first!

“Oh! Oh! Save him! He can’t swim!” cried Whistle’s mother in dismay. “Oh, Whistle, Whistle! Quick, turn the boat about and save Whistle!”

But just then the wind blew so hard that the ship simply tore across the pond and left Whistle struggling in the water. Poor little pixie—he couldn’t swim, and he was in great trouble.

But suddenly up swam Splash, the water-pixie. He had watched the boat setting sail, and had kept by it all the way, though the others hadn’t seen him. As soon as he saw his friend fall into the water he swam up to him, and catching hold of him under the arms, he swam with him to the boat.

“Oh, you brave little fellow!” said Whistle’s father, as he pulled the two of them into the boat. “You have saved Whistle! He might have drowned! Who are you?”

“I am Splash, the water-pixie,” said Splash. “I live in the pond. I would very much like to be friends with Whistle and teach him to swim. He has taught me to whistle like a blackbird, and my mother is very pleased. I should like to do something for him in return.”

“Oh, you are the bravest little pixie I have ever seen!” cried Whistle’s mother, as she sat hugging Whistle to her. “Please be friends with Whistle. He must certainly learn to swim. I will make him a little bathing suit, and then it won’t matter if he gets wet or muddy.”

“Oh, Mother, how lovely!” cried Whistle, in delight. “I told Splash this afternoon that I could never see him again, and I said good-bye to him, because you said I wasn’t to play with him—and now he is to be my friend after all!”

“You deserve it, for you’re a good, obedient little pixie,” said his father. “Now you’d better bring your friend home to tea with you, if Mother has enough cake!”

“Oh yes, I made treacle buns this morning,” said Whistle’s mother, “and there is some new blackberry jam too. Ask your mother if you can come, Splash!”

Splash jumped into the water and swam to his cosy little home in the reeds. In a moment or two, three pixies popped their heads out of the water—for Splash had brought his father and mother.

“Thank you for the invitation,” said Splash’s pretty little pixie-mother. “He will be most delighted to come. I am just going to brush his hair. Perhaps you will all come to tea with us to-morrow? We should love to have you.”

So all the pixies became friends, and now Splash and Whistle play together all day long, and Whistle can swim just as well as Splash can; and as for Splash’s whistling, well you should just hear it! The two pixies sound like a cage full of canaries!

There was once a very old, very proud doll. Her name was Florrie, and she belonged to Katie. She was proud because she had belonged to Katie’s mother when she was a little girl—so you can guess that Florrie was very old indeed.

Now the other toys in the nursery wanted to be friends with Florrie—but Florrie thought herself far too grown-up and grand to bother with young toys like the smiling sailor-doll, the blue teddy-bear, the golden-haired doll, and the pretty Snow-White with her black hair.

“If you speak to me you must call me Madam,” she told the toys. “And pray don’t disturb me at night with your chatter and play. Be as quiet as you can.”

The toys giggled. They thought Florrie was very funny. She had a big china head with brown hair, rather tangled. Her dress, which was of blue silk spotted with yellow, came to her feet, and she wore brown kid shoes with laces. A pink sash was tied round her waist.

“She’s so old-fashioned!” whispered the toys to one another. “She won’t play or laugh—she just goes for lonely walks round the nursery by herself. I wonder what she’s made of—rubber, do you think?”

Nobody knew. The golden-haired doll was made of rubber and could be bathed. Snow-White had a pink velvet body, very soft and cuddlesome. They couldn’t think what Florrie was made of.

Well, she was stuffed with sawdust, just as all old dolls were! But she didn’t tell anyone this, for she felt a little ashamed of it. She went each night for her long walks round the nursery, and turned up her china nose at any toy she met.

And then one night the teddy-bear saw a curious thing. He noticed that wherever Florrie went she left a thin trail of something behind her. Whatever could it be?

He went to look at it. It seemed like thick yellow dust to him. He did not know what sawdust was, for he had never seen any. Could it be some powder that Florrie used?

He called the other toys and told them about it. They watched Florrie, and saw that it was quite true. She did leave a little trail of dust behind her wherever she went!

Florrie didn’t notice it, of course. You can’t see much when your nose is in the air. But soon the toys began to notice something else too.

“Florrie’s getting thinner!” whispered the teddy-bear to Snow-White. “Isn’t it strange?”

Snow-White looked at Florrie. “So she is!” said the doll. “I wonder why.”

“I think I know!” said the sailor-doll. “That dust we keep finding here and there is what she’s stuffed with. She’s leaking! She’ll soon be gone to nothing!”

“How dreadful!” said the golden-haired doll. “I’m made of rubber, so I can’t leak. What will happen to Florrie?”

“She’ll just leak till she’s empty and then she won’t have a body at all,” said the bear. “Well, let her, the stuck-up thing!”

But Snow-White was kind-hearted. “We must warn Florrie,” she said. So she went up to the big old doll and spoke to her timidly. “Please, Madam,” she said, “I’ve something to say.”

“Then say it quickly,” said Florrie, in her grandest voice.

“We think you’re leaking,” said Snow-White. “Don’t you think you’d better not walk about any more? You might leak away to nothing.”

Florrie was very angry. “Leaking!” she cried. “I don’t believe it! It’s just a horrid trick of yours to stop me taking my evening walks. Don’t let me hear another word!”

Well, Snow-White couldn’t do anything. She and the other toys watched Florrie walking about, leaving her trail of sawdust everywhere as usual, and they wondered how soon all her sawdust would be gone.

Now the little hole that had come in Florrie’s back suddenly got very much bigger—and one evening such a heap of sawdust trickled out that really there was hardly any of poor Florrie left except her head and her clothes and the pink covering that used to hold in the sawdust. So she crumpled up on the carpet, and lay there all alone! The toys were upset, but before they could do anything the door opened and in walked Katie’s mother!

Of course she saw Florrie on the floor and she picked her up. She saw the sawdust, and she knew what had happened.

“Oh, poor Florrie!” she said. “You’re leaking! I’ll have to get you a nice new body. Sawdust is out of fashion now!”

So she took Florrie away, and the toys didn’t see her for two weeks. When she came back she was quite different! The toy-man had given her a nice fat velvet body, with baby legs and feet. Her long dress didn’t fit her any more, so Mother had made her a woollen frock and a bonnet. She looked sweet!

The toys quickly cooked a few buns on the little stove, and held a party to welcome Florrie back. She was so pleased. The toys in the toy-shop had laughed at her for being old-fashioned, and had called her “Madam Sawdust.” It was lovely to be back in the nursery, where the toys made a fuss of her.

“I’m so glad to see you all,” said Florrie. “I’m sorry I was silly and stuck-up before. I’m half new and half old now, so I feel quite different. I’d like to join in your games and be friends.”

“You shall, Florrie!” cried every one; and you should just see them each night, having a lovely time with Florrie. Everybody is pleased that Florrie is so different—except one person.

Katie’s mother is quite sad when she sees Florrie. “I wish you were the old Florrie!” she says. “I don’t seem to know you now! I loved you best when you were filled with sawdust!”

But Katie likes Florrie better now that she is more cuddlesome, so Florrie is really very happy!

Once upon a time there was a lovely nursery where all kinds of toys lived happily together. The golliwog lived in the toy-cupboard with the soldiers, the bricks, the balls and the games. The fairy doll, who was very pretty indeed, lived in the dolls’ house, and thought herself very grand.

Then there were other dolls, who lived on the big window-seat with the animals. Not one of the dolls was so pretty as the fairy doll, but one of them was very clever.

This was a small doll dressed as a nurse. She really did know a lot of things. She could nurse people very well, and if any of the toys hurt themselves, or got broken, or were ill, she always knew exactly what to do.

The golliwog loved the fairy doll. He thought she was the prettiest doll he had ever seen, and he did wish she would let him live in the dolls’ house with her, because there was plenty of room. But she wouldn’t.

“I’ll go for walks with you, and I’ll go out to tea with you, and I’ll share your sweets—but I don’t want anyone living in my house!” said the fairy doll.

So the golliwog had to be content with giving the fairy doll nearly all his sweets, and with taking her out to tea in the little toy tea-shop whenever he could.

One day the nurse doll began to speak to all the toys around in her gentle voice.

“Toys,” she said, “I think it would be a good thing if I taught you all some of the things I know. Some day I shall be an old toy, and perhaps the children will give me away. Then you will not have me to nurse you and mend you. But if I tell you all I know, and you learn it well, you will be able to look after each other.”

The toys thought this was a very good idea. “We’ll all come and listen to you each night!” they said; but the fairy doll sulked.

“Who wants to listen to the dull things that that silly old nurse doll tells?” she said to the golliwog. “Don’t listen to her, Golly. Come for a walk with me instead. Let’s go and visit the rocking-horse and ask him for a ride.”

“I will, after I’ve heard what the nurse doll has to say to-night,” said Golly.

That made the fairy doll very angry indeed. She always liked to have her own way, and she walked off in a rage, her pretty little nose stuck up in the air, and her pretty little feet stamping loudly!

The golliwog sighed—but he went to join the ring that sat round the clever little nurse doll.

That night she told them what to do with cuts and scratches, and she showed them her little bottle of brown iodine. “Always wash a cut or a scratch,” she said, “and then dab it with the stuff out of this bottle. Then your cuts will never go bad, but will heal up quickly. Don’t forget, will you?”

The toys promised not to. They ran off to play.

The golliwog went to find the fairy doll, but the naughty little thing had locked herself in the dolls’ house, and she wouldn’t come out. The golliwog was sad. But all the same he went to listen to the nurse doll’s lesson the next night too, although the fairy doll said she would never go out to tea with him again if he did.

“But, fairy doll, it’s important that we should know how to look after ourselves and after each other too,” he said. “Don’t you think you ought to come? You might learn something that would be very useful to you one day.”

“Pooh!” said the fairy doll rudely, and she actually threw a brick at the golliwog. It didn’t hit him but he felt very hurt, all the same.

That night the nurse doll explained how to treat a cold. “It is best to go to bed at once,” she said, “and to keep very warm and have a hot drink. Then the cold will go away quickly; but if you are silly and won’t go to bed, you will be very ill. Now will you all remember that?”

The toys said they would, and the nurse doll made them tell her what she had told them the night before.

“Good!” she said. “You are learning your lessons well! Come again to-morrow. I have something very important to teach you.”

So they all went again the next night, and she told them about sunstroke. “You must always wear a hat that shades the back of your neck when you go out into the hot sun,” she said. “If you don’t, you will get sunstroke, and be ill. This is a very important thing to remember. I saw you, wooden soldier, going about in the blazing sun last summer without even your helmet on. Don’t do it again.”

“What should we have to do with the soldier if he did get sunstroke?” asked the golliwog, who liked to know everything he could.

“We should have to put him straight to bed in as dark a room as possible,” said the nurse doll. “That’s all for to-night, my dears. Come again to-morrow.”

The next night the toys went again, and this time the nurse doll told them what to do if anyone got on fire.

“You know,” she said, “sometimes people play with matches, or go too near the fire, and their clothes catch alight. Now listen carefully and I will tell you what to do. If you see anyone alight, you must quickly get a rug or a thick blanket and wrap it so tightly round them that the flames can’t burn any more and so they go out. That is the best thing to do. Then put them to bed, keep them very warm, give them some hot milk, and call the doctor. Now can you remember all that?”

Some of the toys couldn’t, so the nurse doll said it all over again. The golliwog had a good memory and he soon knew it all. He went to find the fairy doll, after the lesson was over, for he thought that really she would be interested to hear what the nurse doll had taught them that night.

But the fairy doll was still sulking, though she was really getting a bit tired of being so silly.

“Go away!” she said. “I’m tired of seeing you go to the nurse doll’s silly lessons every night when you might be playing with me. You are very horrid.”

“But, fairy doll, the lessons may be so useful,” said the golliwog. “Think now—I know what to do if anyone cuts or scratches himself; I know what to do for sunstroke; I know what to do for a cold; and I even know what to do if anyone gets on fire!”

“Pooh!” said the fairy doll, banging her front-door shut. “Who wants to know dull things like that!”

The golliwog went away and played sadly with the clockwork mouse, who pretended that he had a cold and wanted the golly to nurse him. The golliwog loved the fairy doll very much, but he couldn’t help thinking she was behaving in a horrid, unkind manner.

The next night was terribly cold—so cold that the nurse doll said there wouldn’t be any lesson.

“You had better all cuddle up to one another and keep each other warm,” she said. “Jack Frost is about to-night, ready to pinch our fingers and toes!”

The golliwog went to the dolls’ house to ask if the fairy doll would come out and sit on the shelf with him, so that he could warm her. But she wouldn’t open the door.

“I’m going to light my fire in the kitchen!” she called. “I shall be nice and warm then. You wouldn’t come with me the last four evenings when I asked you to, so I shan’t come with you now!”

“Oh, fairy doll, don’t be so silly!” begged the golliwog, shouting through the letter-box. “Let me light the fire for you, and get it going properly. Then I will sit with you in the kitchen and talk, because there is no lesson to-night.”

But the fairy doll wouldn’t open the door. She took down the matches and struck one. It went out. She struck another—and the lighted head flew off, and fell on to her gauzy frock.

And, oh dear, oh dear! the pretty frock caught fire at once and blazed up. The fairy doll was on fire! She screamed. “Help! Help! I’m on fire! Oh, help, help!”

The golliwog looked in at the kitchen window, horrified. He saw the fairy doll alight. He threw up the window and jumped in, trying to remember what the nurse doll had taught him.

“I must wrap her round in a blanket or a rug!” thought the golliwog. He looked round the room. There was no blanket—but on the floor was a hearth-rug. The golly caught it up and ran to the doll. He wrapped it all round her as tightly as he could, smothering the flames and putting them out.

When he was quite sure they were out, he unwrapped the poor, sobbing fairy doll. He carried her gently to bed and gave her hot-water bottles. He wrapped her in a blanket he had warmed by the fire, and he gave her a drink of hot milk. Soon the nurse doll arrived—for the golly had shouted for her to come—and very soon she had bandaged the fairy doll well, and everything was all right.

“Golly, I am proud of you,” said the nurse doll, when she went. “You remembered everything I told you. You saved the fairy doll’s life. She has been very foolish, for she would not come to my lessons—but you were wise.”

The fairy doll was so grateful to the golliwog. She slipped her hand into his black one and blinked up at him with tearful eyes.

“I’m sorry I was silly and unkind and rude,” she said. “I am ashamed of it now. Please forgive me, Golly. You were right to go to the lessons and I was wrong not to. If you hadn’t gone, and hadn’t learnt what to do, you wouldn’t have known how to save me and I would have been burnt. Please forgive me.”

“Of course I forgive you, fairy doll,” said the kindly golliwog. “But do remember that if you are stupid you get punished for it sooner or later. I think you had better let me come and live in the dolls’ house with you, and teach you to be wise. I can look after you then, and see that nothing happens to you.”

So he had his way after all, and now he lives in the dolls’ house with the pretty fairy doll, who is quite better, and very much nicer. Wasn’t it a good thing the golly learnt his lessons well? Perhaps you will remember his lessons too, and maybe one day they will come in useful to you!

Once upon a time there was a great magician called Wise-one. He was a good magician as well as a great one, and was always trying to find spells that would make people happy and good.

But this was very difficult. He had made a spell to make people happy—but not good as well. And he had found a spell that would make them good—but not happy too. It wasn’t any use being one without the other.

Now one day he found a marvellous way of mixing these two spells together—but he hadn’t got just one thing he needed.

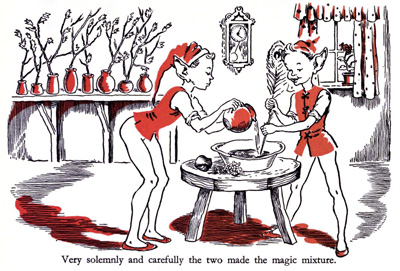

“If only I had a daisy that had opened by moonlight, I believe I could just do it!” said Wise-one, as he stirred round a great silvery mixture in his magic bowl. “But whoever heard of a moonlight daisy? I never did!”

Now just at that moment, who should peep into his window but Slip-Around the brownie. When he heard what Wise-one was saying, his eyes shone.

“Wise-one, I can get a daisy that has opened in the moonlight,” he said.

“What!” cried Wise-one, in delight. “You can! Well, there’s a full moon to-night—pick it for me and bring it here.”

“What will you give me if I do?” asked Slip-Around.

“Oh, anything you like!” said Wise-one.

“Well, will you give me your wishing-wand?” asked Slip-Around, at once.

“How do you know anything about my wishing-wand?” said Wise-one.

“Oh, I slip around and hear things, you know,” said the brownie, grinning.

“You hear too much,” grumbled Wise-one. “Well, as I said you could have anything, you can have that—but only if you bring me the daisy!”

Slip-Around ran off. He meant to play a trick on the magician! He didn’t know where any daisies were that opened in the moonlight—but he knew how to make a daisy stay open!

He picked a fine wide-open daisy, with petals that were pink-tipped underneath. He got his glue-pot and set it on the fire. When the glue was ready he took the daisy in his left hand and a very fine paint-brush in his right.

Then, very daintily and carefully Slip-Around glued the petals together so that they could not shut. He put the daisy into water when it was finished and looked at it proudly. Ah! That would trick Wise-one all right! He would get the wishing-wand from him—and then what a fine time he would have!

When night came the daisy tried to shut its petals—but it could not, no matter how it tried, for the glue held them stiffly out together. So, instead of curling them gently over its round yellow head, the daisy had to stay wide open.

Slip-Around looked at it and grinned. He waited till the moon was up, and then went to Wise-one’s cottage with the wide-open daisy. The magician cried out in surprise and took the daisy eagerly. He put it into water.

“Good!” he said. “I’ll use that to-morrow—it’s just what I want for my spell.”

“Can I have the wishing-wand, please?” said Slip-Around slyly. He didn’t mean to go away without that!

Wise-one unlocked a cupboard and took out a shining silvery wand with a golden sun on the end of it. He gave it to Slip-Around.

“Use it wisely,” he said, “or you will be sorry!”

Slip-Around didn’t even say thank-you! He snatched the wand, and ran off at once. He had got a wishing-wand! Fancy that! A real wishing-wand that would grant any wish he wanted!

He danced into his moonlit village, shouting and singing, “Oh, I’ve got a wishing-wand, a wishing-wand, a wishing-wand!”

People woke up. They came to their windows and looked out.

“Be quiet, please!” called Higgle, the chief man of the village. “What do you mean by coming shouting like this in the middle of the night!”

“Pooh to you!” shouted Slip-Around rudely. “Do you see my wishing-wand? I got it from Wise-one!”

Nobody believed him. But all the same they leaned out of their windows and listened. Higgle got very cross.

“Go home!” he shouted to Slip-Around. “Be quiet—or I’ll have you punished in the morning!”

“Oh no, you won’t!” cried Slip-Around boastfully. “I can wish you away to the moon if I want to! I know what I will do—I’ll wish for an elephant to come and trample on the flowers in your silly front garden! Elephant! Come!”

Then, to every one’s immense astonishment an elephant appeared round the corner of the street in the moonlight and began to walk over Higgle’s lovely flowers. How angry he was!

Soon the folk of the village were all out in the street, in dressing-gowns and coats. They watched the elephant.

“That is very wrong of you,” said Dame Toddle to Slip-Around.

“Don’t interfere with me!” said the brownie grandly. “How would you like a giraffe to ride on, Dame Toddle? Ha ha! Good idea! Giraffe, come and give Dame Toddle a ride!”

At once a giraffe appeared and put the astonished old woman on its back. Then very solemnly it took her trotting up and down the street. She clung to its neck in fright. Slip-Around laughed and laughed.

“This is fun!” he said, looking round at everybody. “Ha ha—you didn’t think I really had a wishing-wand, did you! Now where’s Nibby—he scolded me the other day. Oh, there you are, Nibby! Would you like a bear to play with?”

“No, thank you,” said Nibby at once.

“Well, you can have one,” said Slip-Around. “Bear, come and play with Nibby!”

Up came a big brown bear and tried to make poor Nibby play with it. Nibby didn’t like it at all. When the bear pushed him in play, he fell right over.

“Now just stop this nonsense,” said Mister Skinny, stepping up to Slip-Around firmly. “If you don’t, I shall go to Wise-one to-morrow and tell him the bad things you have done with the wishing-wand.”

“Ho ho!—by that time I shall have wished Wise-one away to the end of the world!” said Slip-Around. “You won’t find him in his cottage! No—he’ll be gone. And I shall wish myself riches and power and the biggest castle in the land. And I’ve a good mind to make you come and scrub all the floors, Mister Skinny!”

“Hrrrrumph!” said the elephant, and walked into the next-door garden to tramp on the flowers there. It was Mister Skinny’s. He gave a yell of rage.

“Mister Skinny, I don’t like yells in my ear,” said Slip-Around. “You yell like a donkey braying. I’ll give you donkey’s ears! There! How funny you look!”

Mister Skinny put his hands to his head. Yes—he now had donkey’s ears growing there. He turned pale with fright. Every one began to look afraid. It seemed to be quite true that Slip-Around had a real wishing-wand. What a dangerous thing for a brownie like him to have!

The little folk tried to slip away unseen, back to their houses. But Slip-Around was enjoying himself too much to let them go.

“Stop!” he said. “If you don’t stay where you are, I’ll give you all donkey’s ears—yes, and donkey’s tails too!”

Every one stopped at once. Slip-Around caught sight of Mister Pineapple the greengrocer. “Ha!” said the brownie, “wasn’t it you that gave me a slap the other day?”

“Yes,” said Mister Pineapple bravely. “I caught you taking one of my apples, and you deserved to be slapped.”

“Well, I wish that every now and again a nice ripe tomato shall fall on your head and burst,” said Slip-Around. And immediately from the air a large ripe tomato fell on to the top of Mister Pineapple’s head and burst with a loud, squishy sound. Mister Pineapple wiped the tomato-juice out of his eyes. Almost at once another tomato fell on him. He looked up in horror, and moved away—but a third tomato fell from the sky and got him neatly on the top of his head.

Slip-Around began to laugh. He laughed and he laughed. He looked at the great elephant, and laughed. He looked at poor Dame Toddle still riding on the giraffe, and laughed. He looked at Nibby trying to get away from the big playful brown bear, and laughed. He laughed at Skinny’s donkey-ears. In fact, he laughed so much and so loudly that he didn’t hear some one coming quickly down the street. He didn’t see some one creep up behind him and snatch at the wishing-wand!

“Oooh!” said Slip-Around, startled. “Give me back my wand—or I’ll wish you at the bottom of the village pond!”

Then he began to tremble—for who was standing there, frowning and angry, but Wise-one, the great magician himself!

“You wicked brownie!” said Wise-one sternly. “You gave me a daisy whose petals were glued open so that it couldn’t shut—not a real moonlight daisy. I have spoilt my wonderful spell. You have no right to the wishing-wand. I shall take it back with me.”

“Oh, why didn’t I wish you to the end of the world when I had the chance!” wailed Slip-Around. “Why didn’t I wish for riches—and power—and a castle—instead of playing about with elephants and giraffes and things!”

“Great magician!” cried Mister Skinny, kneeling down before Wise-one. “Don’t go yet. Look what Slip-Around has wished for! Take these things away from us!”

Wise-one looked around in astonishment and saw the bear and the elephant and the giraffe, and the donkey’s ears on poor Skinny’s head, and the ripe tomatoes that kept falling, squish, on to Mister Pineapple.

“I’ll remove them from you,” he said to the listening people, “but I’ll give them to Slip-Around. He will perhaps enjoy them!”

He waved the wand and wished. The elephant at once went to Slip-Around’s garden and trampled his best lettuces. The giraffe let Dame Toddle get off and went into Slip-Around’s house, where he chewed the lampshade that hung over the ceiling light. The bear romped over to the frightened brownie and knocked him down with a playful push.

The donkey’s ears flew from Mister Skinny to Slip-Around—and lo and behold! the ripe tomatoes began to drop down on the surprised brownie, one after the other, till he was quite covered in tomato-juice!

“You’ve got what you wished for other people,” said Wise-one with a laugh. “Good-night, every one. Go back to bed.”

They all went home and got into bed, wondering at the night’s strange happenings. They were soon asleep—all except Slip-Around. He had the elephant, the giraffe, and the nuisance of a bear in his cottage with him—and it was terribly crowded! His donkey-ears twitched, and he had to wipe tomato off his head every minute. How unhappy he was!

Poor Slip-Around! He had to sleep under an umbrella at last, and the giraffe ate up the tomatoes that fell down plop! The elephant snored like a thunderstorm, and the bear nibbled the brownie’s toes for a joke. It was all most unpleasant. And somehow I think that Slip-Around won’t try to cheat any one again! What do you think?

There was once a large round bumble-bee who flew from flower to flower on the sunny hillside. His coat was velvety and his hum was loud. He was a beautiful bee, and very happy.

One day he flew into a spider’s web. The spider crouched under a leaf, fearful of going near the bee and hoping that he would free himself. The spider did not like either bees or wasps in her web. Sometimes, if the wasp or bee was small, she cut the web around them so that they dropped to the ground and crawled away to clean their wings. But she did not like to go near this great bumble-bee.

The bee was afraid. He did not like the feel of the sticky web around his wings. He tried to fly away—but he flew into more of the web, and soon he could not work his wings at all.

The spider watched. Suppose the bee could not get away? He would soon tire himself out and then she could kill him. She stayed under her leaf, watching with all her eight eyes.

A sandy rabbit, hearing the anxious buzz made by the bee, ran up to see what the fuss was about. He was astonished to see the bee caught in the web. The bee saw him and called to him.

“Help me, rabbit! I am caught here! If you could break the web for me I should drop to the ground and be able to clean my wings and fly. Please help me!” The rabbit went closer. He lifted his paw and broke the web. The bee fell to the ground. He cleaned his wings carefully and spoke to the kind little rabbit.

“You are good,” he said. “I am only a little thing and may never be able to repay you for your kindness, but I thank you with all my heart!”

The rabbit laughed. “It was nothing,” he said. “As for repaying me, that you can never do, little bee. You are so small and I am so big—a tiny creature like you cannot help a rabbit. I do not want to be repaid. Fly off in peace.”

The bee soon flew off with a loud buzz. The rabbit went back to his play. The spider carefully mended her web, and hoped she would catch no more bees.

The days went by. The bee was careful to look out for webs, and did not go near them. The sandy rabbit played happily about the hillside.

He didn’t know that a red fox was watching him each morning, hoping that he would go near to the bush under which he was hiding—then the fox would pounce out, and the rabbit would be caught!

The sandy rabbit did not know that any fox was near. He and his friends played merrily each evening and morning. And one morning he went near to the fox’s bush.

The fox lay still. He hardly breathed. He kept his eyes on the fat little sandy rabbit. He looked round. No one was near to help him. The rabbit’s father and mother had gone down their holes. The shepherd-boy was not yet up. There was no one to save the little rabbit.

A large bumble-bee came sailing by, up early because the sun was warm. He settled on a late blackberry flower to get the honey. The flower was not far from the fox. In alarm the bee suddenly saw the fox’s sharp eyes looking at him.

He flew up into the air, wondering why the fox was hiding. He took a look round and then saw his friend, the sandy rabbit, playing very near—oh, much too near that thick blackberry bush!

“The fox is waiting to catch the rabbit!” thought the bee, in fear. “How can I save him? He was so kind to me!”

He saw the fox stiffen ready to pounce. Straightway the bee flew down to the sharp nose of the red fox. He dug his sting into the fox’s nose and then flew off in a hurry.

The fox barked in pain as the bee stung him, and swung his head from side to side, rustling the bush. The sandy rabbit heard—and in a trice he was off to his hole, his little white bobtail bobbing up and down as he went, a danger-signal to all the other rabbits there.

“Fox!” he cried, “redfox!”

The fox knew it was no good waiting any longer. He would never catch the rabbit now that he knew his hiding-place. He slunk off, furiously angry with the bee. But the little bee was pleased. “I am only small,” he hummed, “but I can do a kind turn as well as anybody else. You did not know I should save your life one day, rabbit, when you saved mine! Little creatures can often do big things.”

The bumble-bee was quite right, wasn’t he!

Green-eyes was a large black cat with the biggest, greenest eyes you can imagine. He belonged to the witch Tiptap, and, like all witch’s cats, he had to help her with her spells.

Green-eyes had an easy life, for he had nothing to do except come when the witch called him, and help her to stir her magic bowl, or sit patiently inside a magic ring whilst she muttered queer spells. He had plenty of good food—fish, milk and sometimes, cream.

He loved cream, and thought he didn’t get enough of it.

“I ought to have cream each day,” he said to himself. “I am a hardworking witch-cat, and I think my mistress should buy me at least three pennyworth of good rich cream each day. But no—she gets it once a week, and that’s all. Mean creature.”

“What is the matter, Green-eyes?” asked the witch who saw the cat sulking in the corner.

“I think you should buy me more cream,” said the cat gloomily.

“Nonsense!” said the witch, sharply. “How dare you talk like that, Green-eyes. You have a fine life with me—no mice to catch, nothing to do except to give me a little help sometimes. I am really ashamed of you.”

Green-eyes twitched his fine whiskers and did not dare to say another word. But he thought a great deal. He wished and wished he could make Tiptap give him more cream, but he could not see how to do it. And then one day he had an idea.

Tiptap called him to help her with a spell. It was a strange piece of magic she was doing. She took a broken piece of china and put it into her big magic bowl. She called Green-eyes to stir it and he did so. Then Tiptap muttered the enchanted words, and the tiny piece of china grew slowly into a beautiful little milk-jug. The witch took it out of the bowl and set it on the table.

She sent Green-eyes for a lemon from the larder. From the lemon she took a little piece of peel and one pip. These she dropped into the jug.

“Pour lemonade, little jug,” she commanded. And then, to Green-eyes’ surprise, the small jug lifted itself into the air and poured lemonade into a glass that the witch had put near. Green-eyes looked into the jug in amazement. There was no lemonade there—only the pip and the bit of lemon skin hopping about. And yet the lemonade certainly came from the jug.

“This is a fine enchanted jug,” said Tiptap, pleased. “I shall sell it to the wizard to-morrow. He is coming to call on me.”

She drank the lemonade herself, and said it was very good. Then she took a tea-leaf from her tea-caddy, a grain of sugar, and a spot of milk and put them in the jug, first taking out the pip and lemon skin.

“Pour tea, little jug,” she said. And at once the jug tilted itself up and poured out a steaming hot cup of tea. There was just the right amount of milk in, and of sugar too. Green-eyes tasted some that Tiptap poured for him into a saucer, so he knew.

“I shall be able to sell that jug for twenty golden pounds,” said Tiptap, pleased. She set the jug on the dresser and went to wash her hands.

“I am going out to tea this afternoon, Green-eyes,” she said. “You must keep house for me. Sit by the fire and listen for the door-bell in case anyone comes.”

Now as soon as Tiptap had gone, Green-eyes thought of a fine idea. If he took that jug for himself, and hid it somewhere, he could make it pour out cream for him whenever he wanted some! Oh, what a fine idea.

“But where shall I hide the jug?” wondered Green-eyes. “I know. I will hide it behind the bath in the bathroom upstairs. I can take my dish up there, and no one will ever know. Ho, ho. I’ll have cream now whenever I want it.”

The naughty cat first of all took his dish upstairs and put it behind the bath, then he went to fetch the jug. It was difficult for him to reach, but he managed it. He pushed a chair to the dresser, jumped up on it, leapt on to the dresser, and took the jug-handle in his mouth. Then, very carefully, he jumped down to the floor again and ran upstairs with the jug. The next thing to get was a drop of cream. But was there any in the larder? Green-eyes didn’t think so. Down he ran again and went to the larder.

He stood up with his front paws on the shelf and sniffed round. No—there was no cream—but wait a minute—there was a bowl of milk there, and on the top of it was a layer of cream, for the milk was very rich.

“Good,” thought Green-eyes, pleased. He took a spoon and scraped off a drop of cream. Then upstairs he went once more, and emptied the spot of cream into the magic jug.

There it was, at the bottom of the jug. Green-eyes felt excited. He spoke to the jug.

“Pour cream, little jug,” he said. At once the jug tilted itself up, and a steady stream of rich cream fell into the bowl. Green-eyes licked it up as fast as it poured in.

And just at that very moment, the door-bell rang.

“It’s only the washing come back,” said Green-eyes to himself. “I’ll just pop downstairs and get it, and then hurry back here. The bowl will be full again by then.”

So, leaving the jug still pouring cream steadily into his bowl, Green-eyes ran down the stairs at top speed. He opened the front door, thinking to see the girl who brought back the washing—but instead he saw the wizard who often came to pay a call on Witch Tiptap.

“Is your mistress in?” asked the wizard, walking into the hall.

“No, sir, she is out to tea,” said Green-eyes.

“Well—what a nuisance,” said the wizard. “I want to write a letter. Where’s the paper and ink?”

“In here, sir,” said Green-eyes, running before the wizard into the little parlour. “You will find all you want here.”

He was just running upstairs when the wizard called him.

“Ho, Green-eyes. There is no ink in the inkstand.”

Green-eyes did not dare to keep the wizard waiting, for he had a very hot temper. So down he ran, and tore into the kitchen to get the big ink-bottle. He filled the inkstand, and went off again. But he was only half-way up the stairs when the wizard shouted for him again.

“What do you want to keep running off like that for? Come here. The nib in this pen is rusty.”

“Tails and whiskers, that cream will be running over,” said Green-eyes in a panic. “What a mess it will make. I’ll have to clear it up before Tiptap comes home.”

He ran to the kitchen drawer and got out the box of nibs that he knew was kept there. He chose one, and gave it to the wizard. Then off he went again, running upstairs.

But before he could reach the bathroom the wizard called him again.

“Green-eyes! Green-eyes! Bless us all, why does that cat disappear like this? Doesn’t he like my company? Green-eyes, will you come here? There are no envelopes at all. How can I write a letter without an envelope to put it in?”

Poor Green-eyes. He fled downstairs again, and found the angry wizard some envelopes. He was just going to slip out of the door once more when the wizard looked at him sternly.

“Why do you keep running off like that?” he asked. “Have you something so important to do?”

“N-n-n-n-n-no,” stammered Green-eyes, not knowing quite what to say.

“Then stay here,” said the wizard, beginning to write his letter. “I’m tired of calling you whenever I want anything. Sit down in that chair where I can see you, and don’t disturb me by running upstairs again.”

Green-eyes sat meekly down in the chair. Presently the wizard became interested in his letter, and his head bent so low that his nose almost touched the paper. Green-eyes felt quite sure he could not see him—so, very quietly, he slid out of the chair, crept out of the door on velvet paws, and shot up the stairs as if a hundred dogs were after him.

And just outside the bathroom door he saw something that made his heart sink down into his paws! Cream was leaking out under the door!

“The bowl has overflowed, and the cream is all over the floor!” thought poor Green-eyes. “Oh, my! What shall I do? I simply must go into the bathroom and stop that jug.”

“Green-eyes! Green-eyes! Bless me if that cat hasn’t done his disappearing trick again!” suddenly shouted the wizard from downstairs.

Green-eyes was so startled that he fell over, rolled to the top of the stairs, lost his balance there and fell headlong down to the bottom. The wizard rushed out of the parlour when he heard the noise, and stood in amazement when he saw Green-eyes rolling down the stairs.

“Is this a new sort of game you are playing, Green-eyes?” asked the wizard. “A poor sort of game, I should think! You must be covered with bruises! I want a stamp for my letter. Come and get me one, and then, stars and moon, if you move out of my sight again, I’ll turn your whiskers into snakes!”

Green-eyes shook and shivered. He got the wizard a stamp and then sat down meekly in his chair again. This time the wizard kept a sharp eye on him.

“Tell me if you feel you badly want to go and fall down the stairs again, won’t you?” he said, licking the stamp. “What an extraordinary cat you are! I wouldn’t keep you for five minutes, if I were Witch Tiptap! You haven’t any manners at all! Grrrrrrrr!”

He growled so much like a dog that Green-eyes shook like a jelly, and looked round to see where the dog was. The wizard laughed.

“And now, perhaps, you will get me Tiptap’s morning newspaper and let me have a look at it,” he said. “It is raining and I shall have to wait here till it stops.”

Oh dear, oh dear, this was worse and worse! How long was the wizard going to stay? Green-eyes felt very miserable. If only he hadn’t meddled with that jug!

He fetched the newspaper, and, on his way, he glanced up the stairs. To his horror he saw that the cream was dripping from the top step to the next one! It had run out on to the landing and was now going to roll slowly down the stairs.

“Sit down again,” said the wizard. “I am not going to have you popping in and out of the room. It is most upsetting.”

So Green-eyes sat down. Presently a soft dripping sound was heard. The wizard pricked up his ears.

“What’s that noise?” he said.

“P-p-p-perhaps it’s the k-k-k-kitchen tap dripping,” stammered Green-eyes, not knowing what to say.

“Go and turn it off then,” said the wizard. “A dripping noise annoys me.”

Green-eyes shot out of the door, meaning to go upstairs and get the magic jug—but the wizard heard him going upstairs and roared at him.

“Does your kitchen tap live upstairs? Go into the kitchen and turn it off!”

So Green-eyes went sadly to the kitchen—but, of course, the tap was not dripping. Then he went back to the parlour and once more sat down.

The dripping noise went on. The wizard heard it and looked at Green-eyes.

“Was the kitchen tap dripping?” he asked.

“No, it wasn’t,” said Green-eyes. “P-p-p-perhaps it’s the kettle b-b-boiling over on the stove!”

“Go and see,” ordered the wizard. Green-eyes went, and outside the door he paused. Yes—he would tiptoe up the stairs and see if he could do it without being heard. But the wizard had ears like a hare and he shouted at once.

“Don’t you know your way to the kitchen?”

And Green-eyes sighed and went into the kitchen—but, of course, there was no kettle boiling over. He went back, looking very miserable—for he had seen that the cream had now dripped to the bottom step! The stairs were running with the rich yellow cream—what a mess!

“I can still hear that dripping noise,” said the wizard crossly. “But I suppose it must be the rain.”

Green-eyes said nothing—and then he saw something that made his fur stand up on end! Cream was creeping in under the door! Yes—it really was. It had spread over the hall and had made its way to the parlour. Green-eyes looked at it and didn’t know what to do. So he sat there and just said nothing at all.

The wizard read his newspaper, keeping an eye on Green-eyes all the time. Presently the cream reached his big feet. The wizard shuffled them about, and the cream swirled round. Green-eyes began to shiver with fright.

The cream grew deeper and the wizard felt that his feet were cold. He looked down—and when he saw the cream all round him, he jumped to his feet in fright and astonishment.

“What is all this!” he roared. “What is it? Why, it is cream! Is this a joke, you wicked cat? You have been behaving strangely all the afternoon—creeping away—falling down the stairs—and now comes this cream into the room! What have you been doing?”

“Oh, sir, forgive me!” wept the frightened cat. “I stole a magic jug of Tiptap’s just before you came in, and took it up to the bathroom to hide it. Just as I made it pour cream into my bowl, the bell rang—and you came. I haven’t been able to go upstairs to get the jug and stop it from pouring out cream—and so the cream has come downstairs, and spread everywhere! Oh, whatever shall I do?”

The wizard looked at the cat, and then at the cream. Then he began to laugh. What a laugh! It shook all the ornaments on the mantelpiece!

“Well, it certainly has its funny side,” he said. “First of all, go upstairs and stop the jug pouring out cream. Then come down again.”

Green-eyes waded out of the room through the cream, and up the stairs. He waded to the bathroom, and sure enough, there was the little magic jug, still pouring away for all it was worth!

Green-eyes put out his paw and caught hold of it. He shook it twice, as he had seen the witch do, and it stopped pouring at once. Green-eyes went downstairs again with the jug.

“Oh, so that’s the jug, is it?” said the wizard. “I’ll get Tiptap to sell it to me. Now, Green-eyes, set to work, please. I don’t like my boots all messy like this. Lick them clean. You like cream, don’t you? Well, this will be a treat for you! My word, you’ll have enough cream to last you a year!”

Green-eyes licked the cream off the wizard’s boots. It tasted dreadful, mixed with boot-polish. Then the wizard said good-bye, took his letter with him, and went out of the door, still laughing.

But poor Green-eyes was left to clear up the creamy mess before his mistress came back! How he worked, poor thing! He found a mop and a broom, and took the biggest pail. Then he began to clean up the cream—and in the middle of his work Tiptap came back!

She stood in the kitchen and looked into the hall and up the stairs. She guessed at once what had happened. But Green-eyes confessed too, and soon Tiptap knew everything.

“You are a very naughty, silly, stupid cat,” she said sternly. “I have a good mind to turn you into a mouse for a month.”

“Oh, no, mistress, not that!” cried Green-eyes at once. “I might be caught by a cat!”

“You probably would,” said the witch, severely. “And I’m not sure it wouldn’t serve you right. But you are sometimes useful to me, so I will not do that. Collect all the cream into pails, dishes and bowls, Green-eyes, and you shall have it every day until it is used up. Magic must not be wasted—and you seem so fond of cream that I am sure you will enjoy it!”

Poor Green-eyes! He worked hard all the rest of the day, collecting the cream into dishes and pails. There were four pails full, and seven dishes, so you can guess what a lot there was. Green-eyes had to wash all the floors, and clean up the stair-carpet too. He was very tired when he had finished. He went to the larder to get himself some milk—but Tiptap stopped him.

“No, Green-eyes,” she said. “Milk is not good enough for you, is it! You must have cream! You may have a dish of the cream.”

“But I don’t want it. I’ve turned against cream, somehow,” said Green-eyes.

“Oh, I can’t have it wasted,” said Tiptap at once. “You must have the cream, my dear cat, or nothing at all.”

So Green-eyes lapped up a dish of the cream—but oh, how he hated it! Then he went to bed. He dreamed of cream and the dishes too, standing in a row on the kitchen floor! It made him feel ill to see them.

The cream turned sour—but still Green-eyes had to lap it, for Tiptap meant to teach him a lesson. He groaned and grumbled—but not until he said that never again would he take anything that wasn’t his, did Tiptap forgive him.

“Well, if you really mean that, I’ll forgive you,” she said. “You need not finish up the cream. Go and empty it away, for it really smells dreadful now. Let this be a lesson to you, Green-eyes. I will say no more about it.”

She kept her word—but, oh dear, whenever the wizard came to see Tiptap, how he teased Green-eyes!

“What’s that dripping noise?” he would say. “Oho, Green-eyes, have you ever heard that dripping noise again? When are you coming to tea with me? I’ll have CREAM for a treat. Would you like that? What! You don’t like cream? Well, well, well, what a surprising cat you are!”

Then Green-eyes would slip away to a corner, and remember the dreadful cream-day—and from that day to this he has been a good and honest little cat. So perhaps it wasn’t a bad thing after all!

Answers of puzzles on page 16

1. The Letter R.

2. Butter-cup.

3. Bark.

Once upon a time there was a great upset in the land of Twiddle because Someone had stolen the Queen’s silver tea-service!

“Yes, it’s all gone!” wept the Queen. “My lovely silver teapot! My lovely silver hot-water jug! My lovely sugar-basin and milk-jug—and my perfectly beautiful silver tray!”

“Who stole it?” cried every one. But nobody knew.

“It was kept locked up in the tall cupboard,” said the Queen, “and it was on the very topmost shelf. Nobody could have reached it unless they had a ladder—or were very, very tall!”

Now among those who were listening were the five clever imps. When they heard the Queen say that the thief must have had a ladder—or have been very tall—they all pricked up their pointed ears at once.

“Ha! Did you hear that?” said Tuppy. “The Queen said someone tall!”

“What about Mr. Spindle-Shanks the new wizard, who has come to live in the big house on the hill?” said Higgle.

“He’s tall enough for anything!” said Pop.

“I guess he’s the thief!” said Snippy. “I saw him round here last night when it was dark.”

“Then we’ll go to his house and get back the stolen tea-service,” said Pip.

“Don’t be silly,” said the Queen, drying her eyes. “You know quite well that if you five clever imps go walking up to Mr. Spindle-Shanks’ door he’ll guess you’ve come for the tea-service, and he’ll turn you into teaspoons to go with the teapot, or something horrid like that!”

“True,” said Tuppy.

“Something in that!” said Higgle.

“Have to think hard about this,” said Pop.

“Or we’ll find ourselves in the soup,” said Snippy.

“Well, I’ve got an idea!” said Pip.

“WHAT?” cried every one in a hurry.

“Listen!” said Pip. “I happen to know that the wizard would be glad to have a servant—someone as tall as himself, who can lay his table properly—he has a very high table you know—and hang up his clothes for him on his very high hooks. Things like that.”

“Well, that doesn’t seem to me to help us at all,” said Tuppy. “We aren’t tall—we are very small and round!”

“Ah, wait!” said Pip. “I haven’t got to my idea yet. What about us getting a very long coat that buttons from top to bottom, and standing on top of each other’s shoulders, five in a high row—buttoning the coat round us, and saying we are one big tall servant?”

“What a joke!” said Pop, and he laughed.

“Who’s going to be the top one, the one with his head out at the top?” asked Tuppy.

“You are,” said Pip. “You’re the cleverest. We others will be holding on hard to each other, five imps altogether, each holding on to each other’s legs! I hope we don’t wobble!”

“But what’s the sense of us going like that?” said Snippy.

“Oh, how stupid you are, Snip!” said Pip. “Don’t you see—as soon as the wizard gets out of our way we’ll split up into five goblins again, take the teapot, the hot-water jug, the milk-jug, the sugar-basin, and the tray—one each—and scurry off!”

“Splendid!” said Tuppy. “Come on—I’m longing to begin!”

The imps borrowed a very long coat from a small giant they knew. Then Pip stood on Pop’s shoulders. That was two of them. Then Snippy climbed up to Pip’s shoulders and stood there, with Pip holding his legs tightly. Then Higgle, with the help of a chair, stood up on Snippy’s shoulders—and last of all Tuppy climbed up on to Higgle’s shoulders.

There they were, all five of them, standing on one another’s shoulders, almost touching the ceiling! Somehow or other they got the long coat round them, and then buttoned it up. It just reached Pop’s ankles, and buttoned nicely round Tuppy’s neck at the top.

They got out of the door with difficulty. Pip began to giggle. “Sh!” said Tuppy, at the top. “No giggling down below there. You’re supposed to be my knees, Pip. Knees don’t giggle!”

Snippy began to laugh too, then, but Tuppy scolded him hard. “Snippy! You are supposed to be my tummy. Be quiet! We are no longer five imps, but one long, thin servant, and our name is—is—is . . .”

“Lanky-Panky,” said Snippy suddenly. Everyone laughed.

“Yes—that’s quite a good name,” said Tuppy. “We are Lanky-Panky, and we are going to ask if we can be the Wizard Spindle-Shanks’ servant. Now—not a word more!”

“Hope I don’t suddenly get the hiccups!” said Pip. “I do sometimes.”

“Knees don’t get hiccups!” snapped Tuppy. “Be quiet, I tell you!”

The strange and curious person called Lanky-Panky walked unsteadily up the hill to the big house where the wizard lived. Tuppy could reach the knocker quite nicely, for it was just level with his head. He knocked.

“Who’s there!” called a voice.

“Lanky-Panky, who has come to seek work,” called Tuppy.

The wizard opened the door and stared in surprise at the long person in the buttoned-up coat. “Dear me!” he said. “So you are Lanky-Panky—well, you are certainly lanky enough! I want a tall servant who can reach up to my pegs and tables. Come in.”

Lanky-Panky stepped in. Tuppy, at the top, looked round the kitchen. It seemed rather dirty.

“Yes,” said Spindle-Shanks. “It is dirty. But before you do any cleaning, you can get my tea.”

“Yes, sir,” said Tuppy, feeling excited. Perhaps the wizard would use the stolen tea-service! That would be fine.

The wizard sat down and took up a book. “The kettle’s boiling,” he said. “Get on with my tea.”

The curious-looking Lanky-Panky began to get the tea. There was a china teapot and hot-water jug on the dresser, but look as he might, Tuppy could see no silver one.

“Excuse me, please, sir,” he said politely. “But I can’t find your silver tea-things.”

“Use the china service!” snapped the wizard.

“Good gracious, sir! Hasn’t a powerful wizard like you got a silver one?” said Tuppy, in a voice of great surprise.

“Yes—I have!” said Spindle-Shanks, “and I’ll show it to you, to make your mouth water! Then I’ll hide it away again, where you can’t get it if you wanted to.”

He opened a cupboard and there before Tuppy’s astonished eyes shone the stolen tea-service on its beautiful tray.

“Ha!” said the wizard. “That makes you stare, doesn’t it? Well, my dear Lanky-Panky, I am going to put this beautiful tea-service where you can’t possibly get it! I am going to put it into this tiny cupboard down here—right at the back—far out of reach—so that a great, tall person like you cannot possibly squeeze himself in to get out such a precious thing.”

“No, sir, no one as tall as I am could possibly get into that tiny cupboard,” said Lanky-Panky, in a rather queer voice. “Only a very tiny person could get in there.”

“And as I never let a tiny person into my house, the tea-service will be safe,” said Spindle-Shanks, with a laugh. “Now, is my tea ready?”

It was. The wizard ate and drank noisily. Lanky-Panky ate a little himself. Tuppy managed to pass a cake to each of the imps without the wizard seeing, but it was quite impossible to give them anything to drink!

That night, when the wizard was asleep, Lanky-Panky unbuttoned his coat and broke up into five little imps. Each one stole to the tiny cupboard. Tuppy opened it. He went in quite easily and brought out the teapot. Snippy went in and fetched the hot-water jug. Pip got the milk-jug. Pop got the sugar-basin, and Higgle carried the big, heavy tray.

They managed to open the kitchen door. Then one by one they stole out—but as they crossed the yard Higgle dropped the tray!

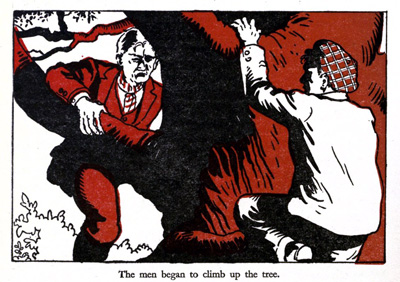

Crash! It made such a noise! It awoke the wizard, who leapt out of bed at once. He saw the open door of the cupboard—he saw the open door of the kitchen—he spied five imps running down the hill in the moonlight.

“Imps!” he cried. “Imps! How did they get in? Did Lanky-Panky let them in? Lanky-Panky, where are you? Come here at once, Lanky-Panky!”

But Lanky-Panky didn’t come.

“Lanky-Panky has disappeared!” he said. “The imps have killed him! I shall complain to the King!”

The Queen was delighted to get back her tea-service.

When the wizard came striding to see the King and to complain of Lanky-Panky’s disappearance, the five clever imps, who were there, began to laugh and laugh.

“Would you like to see Lanky-Panky again?” they asked the surprised wizard. “Well, watch!”

Then, one by one they jumped up on each other’s shoulders, borrowed a big coat from the King and buttoned it round them.

“Here’s old Lanky-Panky!” they cried, and ran at Spindle-Shanks. “Catch the wizard, someone, for it was he who stole the Queen’s things, though he doesn’t know we knew it and that we took them back to her!”

So Spindle-Shanks was caught and punished. As for Lanky-Panky, he sometimes appears again, just for fun. I wish I could see him, don’t you?

Bobby had a book all about cowboys. It had pictures in it, showing the cowboys galloping about on their horses and lassoing all sorts of animals. It was very exciting.

“I shall be a cowboy when I grow up,” said Bobby. “I think I had better practise now. I can play at lassoing things with a rope. And perhaps Farmer Straws will let me ride his little pony sometimes.”

But Farmer Straws wouldn’t. “No,” he said. “I’m not going to have any little scamps riding my quiet old Ladybird. You keep out of my fields, Bobby!”

Bobby was disappointed. It was difficult to be a cowboy and not have a horse.

“I shall ride on the swing-gate instead!” he said. So he climbed up on to the big swing-gate, tied his reins to the gate-post, and galloped there. Sometimes the wind swung the gate open and shut, and then it was great fun.

Mother gave Bobby the old clothes-line for a rope to practise lassoing with. He was very pleased.

But the other children laughed at him. “Bobby the cowboy!” they said. “Ha, look at him, riding on the gate for a horse, and driving the post! And look at his lasso—it’s just an old clothes-line!”

Bobby didn’t like being laughed at, but he was a plucky boy, and he wouldn’t give up just because somebody laughed at him. He climbed up on to the gate once more and clicked to his horse-post!

And how he practised lassoing! He knew how to make a slip-knot at the end of his rope. He knew how to gather the rope into loops and send it spinning through the air, unwinding as it went. But it was very difficult to make the end loop drop over the thing he was aiming at!

“Bobby tries to lasso the gate-post and he nearly catches a cow!” laughed the other children, watching. “Bobby, try to lasso Rover the farm-dog—you’ll find you’ve caught the pig instead!”

Now it is very difficult to go on doing something when people laugh all the time—but Bobby wouldn’t give up. No; he meant to learn lassoing properly—and at last he managed it! It was wonderful to see him aim at a lamp-post and see the loop drop neatly over the lamp and slither down to the foot of the post!

“What use is it, anyhow?” mocked Harry, a big boy, who was the son of Mr. Straws the farmer. “It’s all right if you really live out in the Wild West country and have to lasso horses and cows, but what’s the use of lassoing lamp-posts?”

“Oh, you never know when anything may come in useful,” said Bobby.

Now one day all the children went down to the river to play. Harry took his baby sister with him, a little girl in a push-chair. She was strapped in safely so that she couldn’t fall out. Kenneth, Elsie, Winnie and Tom went too, carrying their boats and balls. They meant to have great fun.

Harry put the baby girl some way back from the river and told her to go to sleep. Then he went off to sail his boat with the others. After that they went away into the nearby field to play ball.

Now the wind began to blow hard, and it blew the baby-girl’s pram along. It blew it down the gentle slope that led to the river, and the little girl screamed.

The farmer, who was working not far off, heard the scream and looked up. When he saw his baby girl in the push-chair, running by itself to the river, he gave a great shout. He began to run.

The children heard the scream and the shout, and they were filled with horror when they saw the baby-girl going in the push-chair to the river.

“She’ll fall in!” shouted Harry. “Quick! Run!”

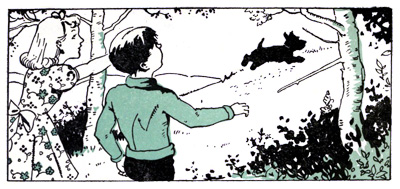

Everybody ran, but it looked as if no one would get there in time. But wait a minute—what is Bobby doing? He has stopped—he has undone the lasso-rope he keeps tied around him. He takes it and loops it quickly—and now it is flying through the air!

Whish! It dropped neatly round the handle of the push-chair, just as it had reached the river-bank. Bobby pulled the rope tightly, and the loop gripped the handle fast. Bobby pulled again.

The push-chair stopped, and then ran safely backwards up the bank, away from the river. The farmer caught the handle and pulled it farther back. He undid the strap and took out his frightened little girl.

All the children ran up, pale and scared. “Is Baby all right?” asked Harry.

“Yes,” said the farmer. “Thanks to Cowboy Bobby! That was a wonderful throw of yours, Bobby! You’re a real cowboy!”

All the children stared at Bobby in wonder. So Bobby had been right—his lassoing had come in useful after all! What a good thing he hadn’t given it up when they had laughed at him!

“Bobby, you can ride my pony Ladybird whenever you like,” said Farmer Straws. “If you want to be a cowboy, you shall!”

“Hurrah!” yelled Bobby, and he ran to find Ladybird at once. My goodness, he was soon galloping round the field, for all the world like a real live cowboy!

But the next day was better still, for Mrs. Straws went to town and bought a proper cowboy set—shaggy trousers, leather belt, red shirt, and cowboy hat.

Don’t be afraid if you hear a wild shout from Farmer Straws’ field when you go near! You will see a fierce cowboy galloping on a pony, his lasso whirling through the air, the pony’s hoofs thundering on the grass. It’s only Bobby—but he looks like a real cowboy now!

Once upon a time there were two children called Benny and Sarah. They lived in a nice house with their father and mother, and they went to school from Monday to Friday, just as you do.

They were rather quarrelsome children, and they were not at all kind to animals.

Rover the dog hated them, for they trod on his toes and pulled his tail. Tibby the cat ran away when they came, in case her tail should be pulled too, or her fur stroked roughly the wrong way. Even the birds in the garden flew off as soon as Benny and Sarah came out, for they were afraid of having stones thrown at them.

Their mother didn’t like to see them unkind, but though she scolded them, and often read them stories of animals and their friends it didn’t seem to make any difference. And one day—ah, something very strange happened to Benny and Sarah!

Every spring the two children used to go out bird-nesting although they knew that their mother had forbidden them to. They pretended to her that they were going to look for primroses, and it is true that they always brought back a bunch—but they brought back something else too!

Packed away in a box of cotton-wool in Benny’s pocket were eggs! Yes, birds’ eggs of all kinds, from the pretty sky-blue ones belonging to the little brown hedge-sparrow, to the reddish-brown ones of the friendly robin. There were thrushes’ eggs, too, and blackbirds’, and sometimes a chaffinch’s egg taken from its neat and mossy nest.

When they got home the children blew the eggs empty and hid them away on an old shelf in the dark summer-house. They had a box there, full of eggs—dozens of them, often five or six of the same kind. Nobody knew but themselves. Many, many birds had been frightened and made unhappy by the two children, but Benny and Sarah cared nothing for that!

Now one day they set off as usual, carrying their lunch in a satchel.

“Good-bye, Mother!” they called, “We are going to look for violets and primroses!”