* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Graham's Magazine Vol. XXII No. 1 January 1843

Date of first publication: 1843

Author: George Rex Graham (1813-1894), Editor

Date first posted: Jan. 24, 2023

Date last updated: Jan. 24, 2023

Faded Page eBook #20230138

This eBook was produced by: John Routh & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

GRAHAM’S MAGAZINE.

| Vol. XXII. | PHILADELPHIA: JANUARY 1843. | No. 1. |

| Fiction, Literature, Articles and Reviews | |

| 1. | Autobiography of a Pocket-Handkerchief |

| 2. | The Philosopher and the Fish |

| 3. | The Coquette; Or the Game of Life |

| 4. | Count Potts’ Strategy |

| 5. | How To Tell a Story |

| 6. | The Fatal Mistake |

| 7. | Our Contributors: Literary Women of the United States |

| 8. | Review of New Books |

| 9. | Editor’s Table |

| Illustrations | |

| 1. | The Coquette |

| 2. | The Fatal Mistake |

| 3. | Our Contributors |

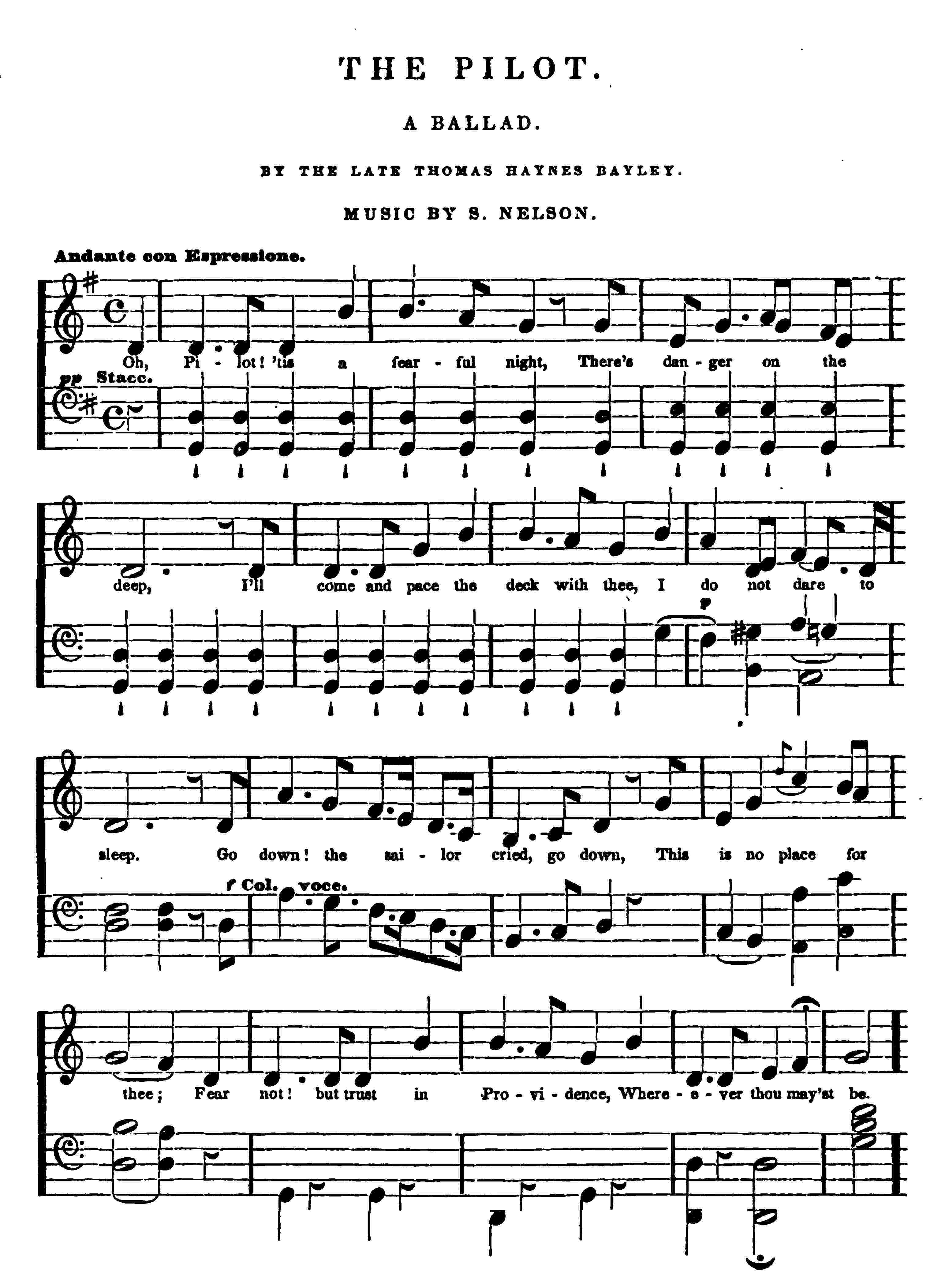

| 4. | The Pilot |

Certain moral philosophers, with a due disdain of the flimsy foundations of human pride, have shown that every man is equally descended from a million of ancestors, within a given number of generations; thereby demonstrating that no prince exists who does not participate in the blood of some beggar, or any beggar who does not share in the blood of princes. Although favored by a strictly vegetable descent myself, the laws of nature have not permitted me to escape from the influence of this common rule. The earliest accounts I possess of my progenitors represent them as a goodly growth of the Linum Usitatissimum, divided into a thousand cotemporaneous plants, singularly well conditioned, and remarkable for an equality that renders the production valuable. In this particular, then, I may be said to enjoy a precedency over the Bourbons themselves, who now govern no less than four different states of Europe, and who have sat on thrones these thousand years.

While our family has followed the general human law in the matter just mentioned, it forms a marked exception to the rule that so absolutely controls all of white blood, on this continent, in what relates to immigration and territorial origin. When the American enters on the history of his ancestors, he is driven, after ten or twelve generations at most, to seek refuge in some country in Europe; whereas exactly the reverse is the case with us, our most remote extraction being American, while our more recent construction and education have taken place in Europe. When I speak of the “earliest accounts I possess of my progenitors,” authentic information is meant only; for, like other races, we have certain dark legends that might possibly carry us back again to the old world in quest of our estates and privileges. But, in writing this history, it has been my determination from the first, to record nothing but settled truths, and to reject everything in the shape of vague report or unauthenticated anecdote. Under these limitations, I have ever considered my family as American by origin, European by emigration, and restored to its paternal soil by the mutations and calculations of industry and trade.

The glorious family of cotemporaneous plants from which I derive my being, grew in a lovely vale of Connecticut, and quite near to the banks of the celebrated river of the same name. This renders us strictly Yankee in our origin, an extraction of which I find all who enjoy it fond of boasting. It is the only subject of self-felicitation with which I am acquainted that men can indulge in, without awakening the envy of their fellow-creatures; from which I infer it is at least innocent, if not commendable.

We have traditions among us of the enjoyments of our predecessors, as they rioted in the fertility of their cis-atlantic field; a happy company of thriving and luxuriant plants. Still, I shall pass them over, merely remarking that a bountiful nature has made such provision for the happiness of all created things as enables each to rejoice in its creation, and to praise, after its fashion and kind, the divine Being to which it owes its existence.

In due time, the field in which my forefathers grew was gathered, the seed winnowed from the chaff and collected in casks, when the whole company was shipped for Ireland. Now occurred one of those chances which decide the fortunes of plants, as well as those of men, giving me a claim to Norman, instead of Milesian descent. The embarkation, or shipment of my progenitors, whichever may be the proper expression, occurred in the height of the last general war, and, for a novelty, it occurred in an English ship. A French privateer captured the vessel on her passage home, the flax-seed was condemned and sold, my ancestors being transferred in a body to the ownership of a certain agriculturist in the neighborhood of Evreux, who dealt largely in such articles. There have been evil disposed vegetables that have seen fit to reproach us with this sale as a stigma on our family history, but I have ever considered it myself as a circumstance of which one has no more reason to be ashamed than a d’Uzès has to blush for the robberies of a baron of the middle ages. Each is an incident in the progress of civilization; the man and the vegetable alike taking the direction pointed out by Providence for the fulfilment of his or its destiny.

Plants have sensations as well as animals. The latter, however, have no consciousness anterior to their physical births, and very little, indeed, for some time afterwards; whereas a different law prevails as respects us; our mental conformation being such as to enable us to refer our moral existence to a period that embraces the experience, reasoning and sentiments of several generations. As respects logical inductions, for instance, the linum usitatissimum draws as largely on the intellectual acquisitions of the various epochs that belonged to the three or four parent stems which preceded it, as on its own. In a word, that accumulated knowledge which man inherits by means of books, imparted and transmitted information, schools, colleges, and universities, we obtain through more subtle agencies that are incorporated with our organic construction, and which form a species of hereditary mesmerism; a vegetable clairvoyance that enables us to see with the eyes, hear with the ears, and digest with the understandings of our predecessors.

Some of the happiest moments of my moral existence were thus obtained, while our family was growing in the fields of Normandy. It happened that a distinguished astronomer selected a beautiful seat, that was placed on the very margin of our position, as a favorite spot for his observations and discourses; from a recollection of the latter of which, in particular, I still derive indescribable satisfaction. It seems us only yesterday—it is in fact fourteen long, long years—that I heard him thus holding forth to his pupils, explaining the marvels of the illimitable void, and rendering clear to my understanding the vast distance that exists between the Being that created all things and the works of his hands. To those who live in the narrow circle of human interests and human feelings, there ever exists, unheeded, almost unnoticed, before their very eyes, the most humbling proofs of their own comparative insignificance in the scale of creation, which, in the midst of their admitted mastery over the earth and all it contains, it would be well for them to consider, if they would obtain just views of what they are and what they were intended to be.

I think I can still hear this learned and devout man—for his soul was filled with devotion of the dread Being that could hold a universe in subjection to his will—dwelling with delight on all the discoveries among the heavenly bodies, that the recent improvements in science and mechanics have enabled the astronomers to make. Fortunately, he gave his discourses somewhat of the progressive character of lectures, leading his listeners on, as it might be step by step, in a way to render all easy to the commonest understanding. Thus it was, I first got accurate notions of the almost inconceivable magnitude of space, to which, indeed, it is probable there are no more positive limits than there are a beginning and an end to eternity! Can these wonders be, I thought—and how pitiful in those who affect to reduce all things to the level of their own powers of comprehension, and their own experience in practice! Let them exercise their sublime and boasted reason, I said to myself, in endeavoring to comprehend infinity in any thing, and we will note the result! If it be in space, we shall find them setting bounds to their illimitable void, until ashamed of the feebleness of their first effort, it is renewed, again and again, only to furnish new proofs of the insufficiency of any of earth, even to bring within the compass of their imaginations truths that all their experiments, inductions, evidence and revelations compel them to admit.

“The moon has no atmosphere,” said our astronomer one day, “and if inhabited at all, it must be by beings constructed altogether differently from ourselves. Nothing that has life, either animal or vegetable as we know them, can exist without air, and it follows that nothing having life, according to our views of it, can exist in the moon:—or, if any thing having life do exist there, it must be under such modifications of all our known facts, as to amount to something like other principles of being. One side of that planet feels the genial warmth of the sun for a fortnight, while the other is for the same period without it,” he continued. “That which feels the sun must be a day, of a heat so intense as to render it insupportable to us, while the opposite side, on which the rays of the sun do not fall, must be masses of ice, if water exist there to be congealed. But the moon has no seas, so far as we can ascertain; its surface representing one of strictly volcanic origin, the mountains being numerous to a wonderful degree. Our instruments enable us to perceive craters, with the inner cones so common to all our own volcanoes, giving reason to believe in the activity of innumerable burning hills at some remote period. It is scarcely necessary to say, that nothing we know could live in the moon under these rapid and extreme transitions of heat and cold, to say nothing of the want of atmospheric air.” I listened to this with wonder, and learned to be satisfied with my station. Of what moment was it to me, in filling the destiny of the linum usitatissimum, whether I grew in a soil a little more or a little less fertile; whether my fibres attained the extremest fineness known to the manufacturer, or fell a little short of this excellence. I was but a speck among a myriad of other things produced by the hand of the Creator, and all to conduce to his own wise ends and unequaled glory. It was my duty to live my time, to be content, and to proclaim the praise of God within the sphere assigned to me. Could men or plants but once elevate their thoughts to the vast scale of creation, it would teach them their own insignificance so plainly, would so unerringly make manifest the futility of complaints, and the immense disparity between time and eternity, as to render the useful lesson of contentment as inevitable as it is important.

I remember that our astronomer, one day, spoke of the nature and magnitude of the sun. The manner that he chose to render clear to the imagination of his hearers some just notions of its size, though so familiar to astronomers, produced a deep and unexpected impression on me. “Our instruments,” he said, “are now so perfect and powerful, as to enable us to ascertain many facts of the deepest interest, with near approaches to positive accuracy. The moon being the heavenly body much the nearest to us, of course we see farther into its secrets than into those of any other planet. We have calculated its distance from us at 237,000 miles. Of course by doubling this distance, and adding to it the diameter of the earth, we get the diameter of the circle, or orbit, in which the moon moves around the earth. In other words the diameter of this orbit is about 480,000 miles. Now could the sun be brought in contact with this orbit, and had the latter solidity to mark its circumference, it would be found that this circumference would include but a little more than half the surface of one side of the sun, the diameter of which orb is calculated to be 882,000 miles! The sun is one million three hundred and eighty-four thousand four hundred and seventy-two times larger than the earth. Of the substance of the sun it is not so easy to speak. Still it is thought, though it is not certain, that we occasionally see the actual surface of this orb, an advantage we do not possess as respects any other of the heavenly bodies, with the exception of the moon and Mars. The light and warmth of the sun probably exist in its atmosphere, and the spots which are so often seen on this bright orb, are supposed to be glimpses of the solid mass of the sun itself, that are occasionally obtained through openings in this atmosphere. At all events, this is the more consistent way of accounting for the appearance of these spots. You will get a better idea of the magnitude of the sidereal system, however, by remembering that, in comparison with it, the distances of our entire solar system are as mere specks. Thus, while our own change of positions is known to embrace an orbit of about 200,000,000 of miles, it is nevertheless so trifling as to produce no apparent change of position in thousands of the fixed stars that are believed to be the suns of other systems. Some conjecture even that all these suns, with their several systems, our own included, revolve around a common centre that is invisible to us, but which is the actual throne of God; the comets that we note and measure being heavenly messengers, as it might be, constantly passing from one of these families of worlds to another.”

I remember that one of the astronomer’s pupils asked certain explanations here, touching the planets that it was thought, or rather known, that we could actually see, and those of which the true surfaces were believed to be concealed from us. “I have told you,” answered the man of science, “that they are the Moon, Mars and the Sun. Both Venus and Mercury are nearer to us than Mars, but their relative proximities to the sun have some such effect on their surfaces, as placing an object near a strong light is known to have on its appearance. We are dazzled, to speak popularly, and cannot distinguish minutely. With Mars it is different. If this planet has any atmosphere at all, it is one of no great density, and its orbit being without our own, we can easily trace on its surface the outlines of seas and continents. It is even supposed that the tinge of the latter is that of reddish sand-stone, like much of that known in our own world, but more decided in tint, while two brilliant white spots, at its poles, are thought to be light reflected from the snows of those regions, rendered more conspicuous, or disappearing, as they first emerge from a twelvemonths’ winter, or melt in a summer of equal duration.”

I could have listened forever to this astronomer, whose lectures so profoundly taught lessons of humility to the created, and which were so replete with silent eulogies on the power of the Creator! What was it to me whether I were a modest plant, of half a cubit in stature, or the proudest oak of the forest—man or vegetable? My duty was clearly to glorify the dread Being who had produced all these marvels, and to fulfill my time in worship, praise and contentment. It mattered not whether my impressions were derived through organs called ears, and were communicated by others called those of speech, or whether each function was performed by means of sensations and agencies too subtle to be detected by ordinary means. It was enough for me that I heard and understood, and felt the goodness and glory of God. I may say that my first great lessons in true philosophy were obtained in these lectures, where I learned to distinguish between the finite and infinite, ceasing to envy any, while I inclined to worship one. The benevolence of Providence is extended to all its creatures, each receiving it in a mode adapted to its own powers of improvement. My destiny being toward a communion with man—or rather with woman—I have ever looked upon these silent communications with the astronomer as so much preparatory schooling, in order that my mind might be prepared for its own avenir, and not be blinded by an undue appreciation of the importance of its future associates. I know there are those who will sneer at the supposition of a pocket-handkerchief’s possessing any mind, or esprit, at all; but let such have patience and read on, when I hope it will be in my power to demonstrate their error.

It is scarcely necessary to dwell on the scenes which occurred between the time I first sprang from the earth and that in which I was “pulled.” The latter was a melancholy day for me, however, arriving prematurely as regarded my vegetable state, since it was early determined that I was to be spun into threads of unusual fineness. I will only say, here, that my youth was a period of innocent pleasures, during which my chief delight was to exhibit my simple but beautiful flowers, in honor of the hand that gave them birth.

At the proper season, the whole field was laid low, when a scene of hurry and confusion succeeded, to which I find it exceedingly painful to turn in memory. The “rotting” was the most humiliating part of the process which followed, though, in our case, this was done in clear running water, and the “crackling” the most uncomfortable. Happily, we were spared the anguish which ordinarily accompanies breaking on the wheel, though we could not be said to have entirely escaped from all its parade. Innocence was our shield, and while we endured some of the disgrace that attaches to mere forms, we had that consolation of which no cruelty or device can deprive the unoffending. Our sorrows were not heightened by the consciousness of undeserving.

There is a period, which occurred between the time of being “hatcheled” and that of being “woven,” that it exceeds my powers to delineate. All around me seemed to be in a state of inextricable confusion, out of which order finally appeared in the shape of a piece of cambric, of a quality that brought the workmen far and near to visit it. We were a single family of only twelve, in this rare fabric, among which I remember that I occupied the seventh place in the order of arrangement, and of course in the order of seniority also. When properly folded, end bestowed in a comfortable covering, our time passed pleasantly enough, being removed from all disagreeable sights and smells, and lodged in a place of great security, and indeed of honor, men seldom failing to bestow this attention on their valuables.

It is out of my power to say precisely how long we remained in this passive state in the hands of the manufacturer. It was some weeks, however, if not months; during which our chief communications were on the chances of our future fortunes. Some of our number were ambitious, and would hear to nothing but the probability, nay, the certainty, of our being purchased, as soon as our arrival in Paris should be made known, by the king, in person, and presented to the dauphine, then the first lady in France. The virtues of the Duchesse d’Angoulême were properly appreciated by some of us, while I discovered that others entertained for her any feelings but those of veneration and respect. This diversity of opinion, on a subject of which one would think none of us very well qualified to be judges, was owing to a circumstance of such every-day occurrence as almost to supersede the necessity of telling it, though the narrative would be rendered more complete by an explanation.

It happened, while we lay in the bleaching grounds, that one half of the piece extended into a part of the field that came under the management of a legitimist, while the other invaded the dominions of a liberal. Neither of these persons had any concern with us, we being under the special superintendence of the head workman, but it was impossible, altogether impossible, to escape the consequences of our locales. While the legitimist read nothing but the Moniteur, the liberal read nothing but Le Temps, a journal then recently established, in the supposed interests of human freedom. Each of these individuals got a paper at a certain hour, which he read with as much manner as he could command, and with singular perseverance as related to the difficulties to be overcome, to a clientele of bleachers, who reasoned as he reasoned, swore by his oaths, and finally arrived at all his conclusions. The liberals had the best of it as to numbers, and possibly as to wit, the Moniteur possessing the dullness of official dignity under all the dynasties and ministries that have governed France since its establishment. My business, however, is with the effect produced on the pocket-handkerchiefs, and not with that produced on the laborers. The two extremes were regular côtés gauches and côtés droits. In other words, all at the right end of the piece became devoted Bourbonists, devoutly believing that princes, who were daily mentioned with so much reverence and respect, could be nothing else but perfect; while the opposite extreme were disposed to think that nothing good could come of Nazareth. In this way, four of our number became decided politicians, not only entertaining a sovereign contempt for the sides they respectively opposed, but beginning to feel sensations approaching to hatred for each other.

The reader will readily understand that these feelings lessened toward the centre of the piece, acquiring most intensity at the extremes. I may be said, myself, to have belonged to the centre gauche, that being my accidental position in the fabric, where it was a natural consequence to obtain sentiments of this shade. It will be seen, in the end, how permanent were these early impressions, and how far it is worth while for mere pocket-handkerchiefs to throw away their time, and permit their feelings to become excited concerning interests that they are certainly not destined to control, and about which, under the most favorable circumstances, they seldom obtain other than very questionable information.

It followed from this state of feeling, that the notion we were about to fall into the hands of the unfortunate daughter of Louis XVI. excited considerable commotion and disgust among us. Though very moderate in my political antipathies and predilections, I confess to some excitement in my own case, declaring that if royalty was to be my lot, I would prefer not to ascend any higher on the scale than to become the property of that excellent princess, Amélie, who then presided in the Palais Royal, the daughter and sister of a king, but with as little prospects as desires of becoming a queen in her own person. This wish of mine was treated as groveling, and even worse than republican, by the côté droit of our piece, while the côté gauche sneered at it as manifesting a sneaking regard for station without the spirit to avow it. Roth were mistaken, however; no unworthy sentiments entering into my decision. Accident had made me acquainted with the virtues of this estimable woman, and I felt assured that she would treat even a pocket-handkerchief kindly. This early opinion has been confirmed by her deportment under very trying and unexpected events. I wish, as I believe she wishes herself, she had never been a queen.

All our family did not aspire as high as royalty. Some looked forward to the glories of a banker’s daughter’s trousseau,—we all understood that our price would be too high for any of the old nobility—while some even fancied that the happiness of traveling in company was reserved for us before we should be called regularly to enter on the duties of life. As we were so closely connected, and on the whole were affectionate as became brothers and sisters, it was the common wish that we might not be separated, but go together into the same wardrobe, let it be foreign or domestic, that of prince or plebeian. There were a few among us who spoke of the Duchesse de Berri as our future mistress; but the notion prevailed that we should so soon pass into the hands of a femme de chambre, as to render the selection little desirable. In the end we wisely and philosophically determined to await the result with patience, well knowing that we were altogether in the hands of caprice and fashion.

At length the happy moment arrived when we were to quit the warehouse of the manufacturer. Let what would happen, this was a source of joy, inasmuch as we all knew that we could only vegetate while we continued where we then were, and that too without experiencing the delights of our former position, with good roots in the earth, a genial sun shedding its warmth upon our bosoms, and balmy airs fanning our cheeks. We loved change, too, like other people, and had probably seen enough of vegetation, whether figurative or real, to satisfy us. Our departure from Picardie took place in June, 1830, and we reached Paris on the first day of the succeeding month. We went through the formalities of the custom-houses, or barrières, the same day, and the next morning we were all transferred to a celebrated shop that dealt in articles of our genus. Most of the goods were sent on drays to the magazin, but our reputation having preceded us, we were honored with a fiacre, making the journey between the Douane and the shop on the knee of a confidential commissionaire.

Great was the satisfaction of our little party as we first drove along through the streets of this capital of Europe—the centre of fashion and the abode of elegance. Our natures had adapted themselves to circumstances, and we no longer pined for the luxuries of the linum usitatissimum, but were ready to enter into all the pleasures of our now existence; which we well understood was to be one of pure parade, for no handkerchief of our quality was ever employed on any of the more menial offices of the profession. We might occasionally brush a lady’s cheek, or conceal a blush or a smile, but the usitatissimum had been left behind us in the fields. The fiacre stopped at the door of a celebrated perfumer, and the commissionaire, deeming us of too much value to be left on a carriage seat, took us in her hand while she negotiated a small affair with its mistress. This was our introduction to the pleasant association of sweet odors, with which it was to be our fortune to enjoy in future the most delicate and judicious communion. We knew very well that things of this sort were considered vulgar, unless of the purest quality and used with the tact of good society; but still it was permitted to sprinkle a very little lavender, or exquisite eau de cologne, on a pocket-handkerchief. The odor of these two scents, therefore, appeared quite natural to us, and as Madame Savon never allowed any perfume, or articles (as these things are technically termed) of inferior quality to pollute her shop, we had no scruples about inhaling the delightful fragrance that breathed in the place. Désirée, the commissionaire, could not depart without permitting her friend, Madame Savon, to feast her eyes on the treasure in her own hands. The handkerchiefs were unfolded, amidst a hundred dieux! ciels! and dames! Our fineness and beauty were extolled in a manner that was perfectly gratifying to the self-esteem of the whole family. Madame Savon imagined that even her perfumes would be more fragrant in such company, and she insisted on letting one drop—a single drop—of her eau de cologne fall on the beautiful texture. I was the happy handkerchief that was thus favored, and long did I riot in that delightful odor, which was just strong enough to fill the air with sensations, rather than impressions, of all that is sweet and womanly in the female wardrobe.

Notwithstanding this accidental introduction to one of the nicest distinctions of good society, and the general exhilaration that prevailed in our party, I was far from being perfectly happy. To own the truth, I had left my heart in Picardie. I do not say I was in love; I am far from certain that there is any precedent for a pocket-handkerchief’s being in love at all, and I am quite sure that the sensations I experienced were different from those I have since had frequent occasion to hear described. The circumstances which called them forth were as follows:

The manufactory in which our family was fabricated was formerly known as the Château de la Rocheaimard, and had been the property of the Vicomte de la Rocheaimard previously to the revolution that overturned the throne of Louis XVI. The vicomte and his wife joined the royalists at Coblentz, and the former, with his only son, Adrien de la Rocheaimard or the Chevalier de la Rocheaimard, as he was usually termed, had joined the allies in their attempted invasion on the soil of France. The vicomte, a marechal du camp, had fallen in battle, but the son escaped, and passed his youth in exile; marrying, a few years later, a cousin whose fortunes were at as low an ebb as his own. One child, Adrienne, was the sole issue of this marriage, having been born in the year 1810. Both the parents died before the restoration, leaving the little girl to the care of her pious grandmother, la vicomtesse, who survived, in a feeble old age, to descant on the former grandeur of her house, and to sigh, in common with so many others, for le bon vieux temps. At the restoration, there was some difficulty in establishing the right of the de la Rocheaimards to their share of the indemnity; a difficulty I never heard explained, but which was probably owing to the circumstance that there was no one in particular to interest themselves in the matter, but an old woman of sixty-five and a little girl of four. Such appellants, unsupported by money, interest, or power, seldom make out a very strong case for reparation of any sort, in this righteous world of ours, and had it not been for the goodness of the dauphine it is probable that the vicomtesse and her grand-daughter would have been reduced to downright beggary. But the daughter of the late king got intelligence of the necessities of the two descendants of crusaders, and a pension of two thousand francs a year was granted, en attendant.

Four hundred dollars a year does not appear a large sum, even to the nouveaux riches of America, but it sufficed to give Adrienne and her grandmother a comfortable, and even a respectable subsistence in the provinces. It was impossible for them to inhabit the château, now converted into a workshop and filled with machinery, but lodgings were procured in its immediate vicinity. Here Madame de la Rocheaimard whiled away the close of a varied and troubled life; if not in absolute peace, still not in absolute misery, while her grand-daughter grew into young womanhood, a miracle of goodness and pious devotion to her sole surviving parent. The strength of the family tie in France, and its comparative weakness in America, have been the subjects of frequent comment among travelers. I do not know that all which has been said is rigidly just, but I am inclined to think that much of it is, and, as I am now writing to Americans, and of French people, I see no particular reason why the fact should be concealed. Respect for years, deference to the authors of their being, and submission to parental authority are inculcated equally by the morals and the laws of France. The conseilles de famille is a beautiful and wise provision of the national code, and aids greatly in maintaining that system of patriarchal rule which lies at the foundation of the whole social structure. Alas! in the ease of the excellent Adrienne, this conseille de famille was easily assembled, and possessed perfect unanimity. The wars, the guillotine and exile had reduced it to two, one of which was despotic in her government, so far as theory was concerned at least; possibly, at times, a little so in practice. Still Adrienne, on the whole, grew up tolerably happy. She was taught most that is suitable for a gentlewoman, without being crammed with superfluous accomplishments, and, aided by the good curé, a man who remembered her grandfather, had both polished and stored her mind. Her manners were of the excellent tone that distinguished the good society of Paris before the revolution, being natural, quiet, simple and considerate. She seldom laughed, I fear; but her smiles were sweetness and benevolence itself.

The bleaching grounds of our manufactory were in the old park of the château. Thither Mad. de la Rocheaimard was fond of coming in the fine mornings of June, for many of the roses and lovely Persian lilacs that once abounded there still remained. I first saw Adrienne in one of these visits, the quality of our little family circle attracting her attention. One of the bleachers, indeed, was an old servant of the vicomte’s, and it was a source of pleasure to him to point out any thing to the ladies that he thought might prove interesting. This was the man who so diligently read the Moniteur, giving a religious credence to all it contained. He fancied no hand so worthy to hold fabrics of such exquisite fineness as that of Mademoiselle Adrienne, and it was through his assiduity that I had the honor of being first placed within the gentle pressure of her beautiful little fingers. This occurred about a month before our departure for Paris.

Adrienne de la Rocheaimard was then just twenty. Her beauty was of a character that is not common in France; but which, when it does exist, is nowhere surpassed. She was slight and delicate in person, of fair hair and complexion, and with the meekest and most dove-like blue eyes I ever saw in a female face. Her smile, too, was of so winning and gentle a nature, as to announce a disposition pregnant with all the affections. Still it was well understood that Adrienne was not likely to marry, her birth raising her above all intentions of connecting her ancient name with mere gold, while her poverty placed an almost insuperable barrier between her and most of the impoverished young men of rank whom she occasionally saw. Even the power of the dauphine was not sufficient to provide Adrienne de la Rocheaimard with a suitable husband. But of this the charming girl never thought; she lived more for her grandmother than for herself, and so long as that venerated relative, almost the only one that remained to her on earth, did not suffer or repine, she herself could be comparatively happy.

“Dans le bon vieux temps,” said the vicomtesse, examining me through her spectacles, and addressing Georges, who stood, hat in hand, to hearken to her wisdom; “dans le bon vieux temps, mon ami, the ladies of the château did not want for these things. There were six dozen in my corbeille, that were almost as fine as this; as for the trousseau, I believe it had twice the number, but very little inferior.”

“I remember that madame,” Georges always gave his old mistress this title of honor, “kept many of the beautiful garments of her trousseau untouched, down to the melancholy period of the revolution.”

“It has been a mine of wealth to me, Georges, in behalf of that dear child. You may remember that this trousseau was kept in the old armoire, on the right hand side of the little door of my dressing-room—”

“Madame la Vicomtesse will have the goodness to pardon me—it was on the left hand side of the room—Monsieur’s medals were kept in the opposite armoire.”

“Our good Georges is right, Adrienne!—he has a memory! Your grandfather insisted on keeping his medals in my dressing-room, as he says. Well, Monsieur Georges, left or right, there I left the remains of my trousseau when I fled from France, and there I found it untouched on my return. The manufactory had saved the château, and the manufacturers had spared my wardrobe. Its sale, and its materials, have done much toward rendering that dear child respectable and well clad, since our return.”

I thought the slight color which usually adorned the fair oval cheeks of Adrienne deepened a little at this remark, and I certainly felt a little tremor in the hand which held me; but it could not have been shame, as the sweet girl often alluded to her poverty in a way so simple and natural, as to prove that she had no false feelings on that subject. And why should she? Poverty ordinarily causes no such sensations to those who are conscious of possessing advantages of an order superior to wealth, and surely a well-educated, well-born, virtuous girl need not have blushed because estates were torn from her parents by a political convulsion that had overturned an ancient and powerful throne.

From this time, the charming Adrienne frequently visited the bleaching grounds, always accompanied by her grandmother. The presence of Georges was an excuse, but to watch the improvement in our appearance was the reason. Never before had Adrienne seen a fabric as beautiful as our own, and, as I afterwards discovered, she was laying by a few francs with the intention of purchasing the piece, and of working and ornamenting the handkerchiefs, in order to present them to her benefactress, the dauphine. Mad. de la Rocheaimard was pleased with this project; it was becoming in a de la Rocheaimard; and they soon began to speak of it openly in their visits. Fifteen or twenty napoleons might do it, and the remains of the recovered trousseau would still produce that sum. It is probable this intention would have been carried out, but for a severe illness that attacked the dear girl, during which her life was even despaired of. I had the happiness of hearing of her gradual recovery, however, before we commenced our journey, though no more was said of the purchase. Perhaps it was as well as it was; for, by this time, such a feeling existed in our extreme côté gauche, that it may be questioned if the handkerchiefs of that end of the piece would have behaved themselves in the wardrobe of the dauphine with the discretion and prudence that are expected from every thing around the person of a princess of her exalted rank and excellent character. It is true, none of us understood the questions at issue; but that only made the matter worse; the violence of all dissensions being very generally in proportion to the ignorance and consequent confidence of the disputants.

I could not but remember Adrienne, as the commissionaire laid us down before the eyes of the wife of the head of the firm, in the rue de— —. We were carefully examined, and pronounced “parfaits;” still it was not in the sweet tunes, and with the sweeter smiles of the polished and gentle girl we had left in Picardie. There was a sentiment in her admiration that touched all our hearts, even to the most exaggerated republican among us, for she seemed to go deeper in her examination of merits than the mere texture and price. She saw her offering in our beauty, the benevolence of the dauphine in our softness, her own gratitude in our exquisite fineness, and princely munificence in our delicacy. In a word, she could enter into the sentiment of a pocket-handkerchief. Alas! how different was the estimation in which we were held by Désirée and her employers. With them, it was purely a question of francs, and we had not been in the magazin five minutes, when there was a lively dispute whether we were to be put at a certain number of napoleons, or one napoleon more. A good deal was said about Mad. la Duchesse, and I found it was expected that a certain lady of that rank, one who had enjoyed the extraordinary luck of retaining her fortune, being of an old and historical family, and who was at the head of fashion in the faubourg, would become the purchaser. At all events, it was determined no one should see us until this lady returned to town, she being at the moment at Rosny, with madame, whence she was expected to accompany that princess to Dieppe, to come back to her hotel, in the rue de Bourbon, about the last of October. Here, then, were we doomed to three months of total seclusion in the heart of the gayest capital of Europe. It was useless to repine, and we determined among ourselves to exercise patience in the best manner we could.

Accordingly, we were safely deposited in a particular drawer, along with a few other favorite articles, that, like our family, were reserved for the eyes of certain distinguished but absent customers. These specialités in trade are of frequent occurrence in Paris, and form a pleasant bond of union between the buyer and seller, which gives a particular zest to this sort of commerce, and not unfrequently a particular value to goods. To see that which no one else has seen, and to own that which no one else can own, are equally agreeable, and delightfully exclusive. All minds that do not possess the natural sources of exclusion, are fond of creating them by means of a subordinate and more artificial character.

On the whole, I think we enjoyed our new situation, rather than otherwise. The drawer was never opened, it is true, but that next it was in constant use, and certain crevices beneath the counter enabled us to see a little, and to hear more, of what passed in the magazin. We were in a part of the shop most frequented by ladies, and we overheard a few tête-à-têtes that were not without amusement. These generally related to cancans. Paris is a town in which cancans do not usually flourish, their proper theatre being provincial and trading places, beyond a question; still there are cancans at Paris; for all sorts of persons frequent that centre of civilization. The only difference is, that in the social pictures offered by what are called cities, the cancans are in the strongest light, and in the most conspicuous of the grouping; whereas in Paris they are kept in shadow, and in the background. Still there are cancans at Paris; and cancans we overheard, and precisely in the manner I have related. Did pretty ladies remember that pocket-handkerchiefs have ears, they might possibly have more reserve in the indulgence of this extraordinary propensity.

We had been near a month in the drawer, when I recognized a female voice near us, that I had often heard of late, speaking in a confident and decided tone, and making allusions that showed she belonged to the court. I presume her position there was not of the most exalted kind, yet it was sufficiently so to qualify her, in her own estimation, to talk politics. “Les ordonnances” were in her mouth constantly, and it was easy to perceive that she attached the greatest importance to these ordinances, whatever they were, and fancied a political millennium was near. The shop was frequented less than usual that day; the next it was worse still, in the way of business, and the clerks began to talk loud, also, about les ordonnances. The following morning neither windows nor doors were opened, and we passed a gloomy time of uncertainty and conjecture. There were ominous sounds in the streets. Some of us thought we heard the roar of distant artillery. At length the master and mistress appeared by themselves in the shop; money and papers were secured, and the female was just retiring to an inner room, when she suddenly came back to the counter, opened our drawer, seized us with no very reverent hands, and, the next thing we knew, the whole twelve of us were thrust into a trunk up stairs, and buried in Egyptian darkness. From that moment all traces of what was occurring in the streets of Paris were lost to us. After all, it is not so very disagreeable to be only a pocket-handkerchief in a revolution.

Our imprisonment lasted until the following December. As our feelings had become excited on the questions of the day, as well as those of other irrational beings around us, we might have passed a most uncomfortable time in the trunk, but for one circumstance. So great had been the hurry of our mistress in thus shutting us up, that we had been crammed in in a way to leave it impossible to say which was the côté droit, and which the côté gauche. Thus completely deranged as parties, we took to discussing philosophical matters in general; an occupation well adapted to a situation that required so great an exercise of discretion.

One day, when we least expected so great a change, our mistress came in person, searched several chests, trunks and drawers, and finally discovered us where she had laid us, with her own hands, near four months before. It seems that, in her hurry and fright, she had actually forgotten in what nook we had been concealed. We were smoothed with care, our political order reëstablished, and then we were taken below and restored to the dignity of the select circle in the drawer already mentioned. This was like removing to a fashionable square, or living in a beau quartier of a capital. It was even better than removing from East Broadway into bona fide real, unequaled, league-long, eighty feet wide, Broadway!

We now had an opportunity of learning some of the great events that had recently occurred in France, and which still troubled Europe. The Bourbons were again dethroned, as it was termed, and another Bourbon seated in their place. It would seem il y a Bourbon et Bourbon. The result has since shown that “what is bred in the bone will break out in the flesh.” Commerce was at a stand still; our master passed half his time under arms, as a national guard, in order to keep the revolutionists from revolutionizing the revolution. The great families had laid aside their liveries; some of them their coaches; most of them their arms. Pocket-handkerchiefs of our calibre would be thought decidedly aristocratic; and aristocracy in Paris, just at that moment, was almost in as bad odor as it is in America, where it ranks as an eighth deadly sin, though no one seems to know precisely what it means. In the latter country, an honest development of democracy is certain to be stigmatized as tainted with this crime. No governor would dare to pardon it.

The groans over the state of trade were loud and deep among those who lived by its innocent arts. Still, the holidays were near, and hope revived. If revolutionized Paris would not buy as the jour de l’an approached, Paris must have a new dynasty. The police foresaw this, and it ceased to agitate, in order to bring the republicans into discredit; men must eat, and trade was permitted to revive a little, Alas! how little do they who vote, know why they vote, or they who dye their hands in the blood of their kind, why the deed has been done!

The duchesse had not returned to Paris; neither had she emigrated. Like most of the high nobility, who rightly enough believed that primogeniture and birth were of the last importance to them, she preferred to show her distaste for the present order of things, by which the youngest prince of a numerous family had been put upon the throne of the oldest, by remaining at her château. All expectations of selling us to her were abandoned, and we were thrown fairly into the market, on the great principle of liberty and equality. This was as became a republican reign.

Our prospects were varied daily. The dauphine, madame, and all the de la Rochefoucaulds, de la Trémouilles, de Grammonts, de Rohans, de Crillons, &c. &c., were out of the question. The royal family were in England, the Orleans branch excepted, and the high nobility were very generally on their “high ropes,” or, à bouder. As for the bankers, their reign had not yet fairly commenced. Previously to July, 1830, this estimable class of citizens had not dared to indulge their native tastes for extravagance and parade, the grave dignity and high breeding of a very ancient but impoverished nobility holding them in some restraint; and, then, their fortunes were still uncertain; the funds were not firm, and even the honorable and worthy Jacques Lafitte, a man to ennoble any calling, was shaking in credit. Had we been brought into the market a twelvemonth later, there is no question that we should have been caught up within a week, by the wife or daughter of some of the operatives at the Bourse.

As it was, however, we enjoyed ample leisure for observation and reflection. Again and again were we shown to those who, it was thought, could not fail to yield to our beauty; but no one would purchase. All appeared to eschew aristocracy, even in their pocket-handkerchiefs. The day the fleurs de lys were cut out of the medallions of the treasury, and the king laid down his arms, I thought our mistress would have had the hysterics on our account. Little did she understand human nature, for the nouveaux riches, who are as certain to succeed an old and displaced class of superiors, as hungry flies to follow flies with full bellies, would have been much more apt to run into extravagance and folly, than persons always accustomed to money, and who did not depend on its exhibition for their importance. A day of deliverance, notwithstanding, was at hand, which to me seemed like the bridal of a girl dying to rush into the dissipations of society.

The holidays were over, without there being any material revival of trade, when my deliverance unexpectedly occurred. It was in February, and I do believe our mistress had abandoned the expectation of disposing of us that season, when I heard a gentle voice speaking near the counter, one day, in tones which struck me as familiar. It was a female, of course, and her inquiries were about a piece of cambric handkerchiefs, which she said had been sent to this shop from a manufactory in Picardie. There was nothing of the customary alertness in the manner of our mistress, and, to my surprise, she even showed the customer one or two pieces of much inferior quality, before we were produced. The moment I got into the light, however, I recognized the beautifully turned form and sweet face of Adrienne de la Rocheaimard. The poor girl was paler and thinner than when I had last seen her, doubtless, I thought, the effects of her late illness; but I could not conceal from myself the unpleasant fact that she was much less expensively clad. I say less expensively clad, though the expression is scarcely just, for I had never seen her in attire that could properly be called expensive at all; and, yet, the term mean would be equally inapplicable to her present appearance. It might be better to say that, relieved by a faultless, even a fastidious neatness and grace, there was an air of severe, perhaps of pinched economy in her present attire. This it was that had prevented our mistress from showing her fabrics as fine as we, on the first demand. Still I thought there was a slight flush on the cheek of the poor girl, and a faint smile on her features, as she instantly recognized us for old acquaintances. For one, I own I was delighted at finding her soft fingers again brushing over my own exquisite surface, feeling as if one had been expressly designed for the other. Then Adrienne hesitated; she appeared desirous of speaking, and yet abashed. Her color went and came, until a deep rosy blush settled on each cheek, and her tongue found utterance.

“Would it suit you, madame,” she asked, as if dreading a repulse, “to part with one of these?”

“Your pardon, mademoiselle; handkerchiefs of this quality are seldom sold singly.”

“I feared us much—and yet I have occasion for only one. It is to be worked—if it—”

The words came slowly, and they were spoken with difficulty. At that last uttered, the sound of the sweet girl’s voice died entirely away. I fear it was the dullness of trade, rather than any considerations of benevolence, that induced our mistress to depart from her rule.

“The price of each handkerchief is five and twenty francs, mademoiselle—” she had offered the day before to sell us to the wife of one of the richest agents de change in Paris, at a napoleon a piece—“the price is five and twenty francs, if you take the dozen, but as you appear to wish only one, rather than not oblige you, it may be had for eight and twenty.”

There was a strange mixture of sorrow and delight in the countenance of Adrienne; but she did not hesitate, and, attracted by the odor of the eau de cologne, she instantly pointed me out as the handkerchief she selected. Our mistress passed her scissors between me and my neighbor of the côté gauche, and then she seemed instantly to regret her own precipitation. Before making the final separation from the piece, she delivered herself of her doubts.

“It is worth another franc, mademoiselle,” she said, “to cut a handkerchief from the centre of the piece.”

The pain of Adrienne was now too manifest for concealment. That she ardently desired the handkerchief was beyond dispute, and yet there existed some evident obstacle to her wishes.

“I fear I have not so much money with me, madame,” she said, pale as death, for all sense of shame was lost in intense apprehension. Still her trembling hands did their duty, and her purse was produced. A gold napoleon promised well, but it had no fellow. Seven more francs appeared in single pieces. Then two ten-sous were produced; after which nothing remained but copper. The purse was emptied, and the reticule rummaged, the whole amounting to just twenty-eight francs seven sous.

“I have no more, madame,” said Adrienne, in a faint voice.

The woman, who had been trained in the school of suspicion, looked intently at the other, for an instant, and then she swept the money into her drawer, content with having extorted from this poor girl more than she would have dared to ask of the wife of the agent de change. Adrienne took me up and glided from the shop, as if she feared her dear bought prize would yet be torn from her. I confess my own delight was so great that I did not fully appreciate, at the time, all the hardship of the case. It was enough to be liberated, to get into the fresh air, to be about to fulfill my proper destiny. I was tired of that sort of vegetation in which I neither grew, nor was watered by tears; nor could I see those stars on which I so much doated, and from which I had learned a wisdom so profound. The politics, too, were rendering our family unpleasant; the coté droit was becoming supercilious—it had always been illogical; while the côté gauche was just beginning to discover that it had made a revolution for other people. Then it was happiness itself to be with Adrienne, and when I felt the dear girl pressing me to her heart, by an act of volition of which pocket-handkerchiefs are little suspected, I threw up a fold of my gossamer-like texture, as if the air wafted me, and brushed the first tear of happiness from her eye that she had shed in months.

The reader may be certain that my imagination was all alive to conjecture the circumstances which had brought Adrienne de la Rocheaimard to Paris, and why she had been so assiduous in searching me out, in particular. Could it be that the grateful girl still intended to make her offering to the Duchesse d’Angoulême? Ah! no—that princess was in exile; while her sister was forming weak plots in behalf of her son, which a double treachery was about to defeat. I have already hinted that pocket-handkerchiefs do not receive and communicate ideas, by means of the organs in use among human beings. They possess a clairvoyance that is always available under favorable circumstances. In their case the mesmeritic trance may be said to be ever in existence, while in the performance of their proper functions. It is only while crowded into bales, or thrust into drawers for the vulgar purposes of trade, that this instinct is dormant, a beneficent nature scorning to exercise her benevolence for any but legitimate objects. I now mean legitimacy as connected with cause and effect, and nothing political or dynastic.

By virtue of this power, I had not long been held in the soft hand of Adrienne, or pressed against her beating heart, without becoming the master of all her thoughts, as well as of her various causes of hope and fear. This knowledge did not burst upon me at once, it is true, as is pretended to be the case with certain somnambules, for with me there is no empiricism—every thing proceeds from cause to effect, and a little time, with some progressive steps, was necessary to make me fully acquainted with the whole. The simplest things became the first apparent, and others followed by a species of magnetic induction, which I cannot now stop to explain. When this tale is told, I propose to lecture on the subject, to which all the editors in the country will receive the usual free tickets, when the world cannot fail of knowing quite as much, at least, as these meritorious public servants.

The first fact that I learned, was the very important one that the vicomtesse had lost all her usual means of support by the late revolution, and the consequent exile of the dauphine. This blow, so terrible to the grandmother and her dependent child, had occurred, too, most inopportunely, as to time. A half year’s pension was nearly due at the moment the great change occurred, and the day of payment arrived and passed, leaving these two females literally without twenty francs. Had it not been for the remains of the trousseau, both must have begged, or perished of want. The crisis called for decision, and fortunately the old lady, who had already witnessed so many vicissitudes, had still sufficient energy to direct their proceedings. Paris was the best place in which to dispose of her effects, and thither she and Adrienne came, without a moment’s delay. The shops were first tried, but the shops, in the autumn of 1830, offered indifferent resources for the seller. Valuable effects were there daily sold for a twentieth part of their original cost, and the vicomtesse saw her little stores diminish daily; for the Mont de Piété was obliged to regulate its own proceedings by the received current values of the day. Old age, vexation, and this last most cruel blow, did not fail of effecting that which might have been foreseen. The vicomtesse sunk under this accumulation of misfortunes, and became bed-ridden, helpless, and querulous. Every thing now devolved on the timid, gentle, unpracticed Adrienne. All females of her condition, in countries advanced in civilization like France, look to the resource of imparting a portion of what they themselves have acquired, to others of their own sex, in moments of urgent necessity. The possibility of Adrienne’s being compelled to become a governess, or a companion, had long keen kept in view, but the situation of Mad. de la Rocheaimard forbade any attempt of the sort, for the moment, had the state of the country rendered it at all probable that a situation could have been procured. On this fearful exigency, Adrienne had aroused all her energies, and gone deliberately into the consideration of her circumstances.

Poverty had compelled Mad. de la Rocheaimard to seek the cheapest respectable lodgings she could find on reaching town. In anticipation of a long residence, and, for the consideration of a considerable abatement in price, she had fortunately paid six months’ rent in advance; thus removing from Adrienne the apprehension of having no place in which to cover her head, for some time to come. These lodgings were in an entresol of the Place Royale, a perfectly reputable and private part of the town, and in some respects were highly eligible. Many of the menial offices, too, were to be performed by the wife of the porter, according to the bargain, leaving to poor Adrienne, however, all the care of her grandmother, whose room she seldom quitted, the duties of nurse and cook, and the still more important task of finding the means of subsistence.

For quite a month the poor desolate girl contrived to provide for her grandmother’s necessities, by disposing of the different articles of the trousseau. This store was now nearly exhausted, and she had found a milliner who gave her a miserable pittance for toiling with her needle eight or ten hours each day. Adrienne had not lost a moment, but had begun this system of ill-requited industry long before her money was exhausted. She foresaw that her grandmother must die, and the great object of her present existence was to provide for the few remaining wants of this only relative during the brief time she had yet to live, and to give her decent and Christian burial. Of her own future lot, the poor girl thought as little as possible, though fearful glimpses would obtrude themselves on her uneasy imagination. At first she had employed a physician; but her means could not pay for his visits, nor did the situation of her grandmother render them very necessary. He promised to call occasionally without fee, and, for a short time, he kept his word, but his benevolence soon wearied of performing offices that really were not required. By the end of the month, Adrienne saw him no more.

As long as her daily toil seemed to supply her own little wants, Adrienne was content to watch on, weep on, pray on, in waiting for the moment she so much dreaded; that which was to sever the last tie she appeared to possess on earth. It is true she had a few very distant relatives, but they had emigrated to America, at the commencement of the revolution of 1789, and all traces of them had long been lost. In point of fact, the men were dead, and the females were grandmothers with English names, and were almost ignorant of any such persons as the de la Rocheaimards. From these Adrienne had nothing to expect. To her, they were as beings in another planet. But the trousseau was nearly exhausted, and the stock of ready money was reduced to a single napoleon, and a little change. It was absolutely necessary to decide on some new scheme for a temporary subsistence, and that without delay.

Among the valuables of the trousseau was a piece of exquisite lace, that had never been even worn. The vicomtesse had a pride in looking at it, for it showed the traces of her former wealth and magnificence, and she would never consent to part with it. Adrienne had carried it once to her employer, the milliner, with the intention of disposing of it, but the price offered was so greatly below what she knew to be the true value, that she would not sell it. Her own wardrobe, however, was going fast, nothing disposable remained of her grandmother’s, and this piece of lace must be turned to account in some way. While reflecting on these dire necessities, Adrienne remembered our family. She knew to what shop we had been sent in Paris, and she now determined to purchase one of us, to bestow on the handkerchief selected some of her own beautiful needle work, to trim it with this lace, and, by the sale, to raise a sum sufficient for all her grandmother’s earthly wants.

Generous souls are usually ardent. Their hopes keep pace with their wishes, and, as Adrienne had heard that twenty napoleons were sometimes paid by the wealthy for a single pocket-handkerchief, when thus decorated, she saw a little treasure in reserve, before her mind’s eye.

“I can do the work in two months,” she said to herself, “by taking the time I have used for exercise, and by severe economy; by eating less myself, and working harder, we can make out to live that time on what we have.”

This was the secret of my purchase, and the true reason why this lovely girl had literally expended her last sou in making it. The cost had materially exceeded her expectations, and she could not return home without disposing of some article she had in her reticule, to supply the vacuum left in her purse. There would be nothing ready for the milliner, under two or three days, and there was little in the lodgings to meet the necessities of her grandmother. Adrienne had taken her way along the quays, delighted with her acquisition, and was far from the Mont de Piété before this indispensable duty occurred to her mind. She then began to look about her for a shop in which she might dispose of something for the moment. Luckily she was the mistress of a gold thimble, that had been presented to her by her grandmother, as her very last birth-day present. It was painful for her to part with it, but, as it was to supply the wants of that very parent, the sacrifice cost her less than might otherwise have been the case. Its price had been a napoleon, and a napoleon, just then, was a mint of money in her eyes. Beside, she had a silver thimble at home, and a brass one would do for her work.

Adrienne’s necessities had made her acquainted with several jewellers’ shops. To one of these she now proceeded, and, first observing through the window that no person was in but one of her own sex, the silversmith’s wife, she entered with the greater confidence and alacrity.

“Madame,” she said, in timid tones, for want had not yet made Adrienne bold or coarse, “I have a thimble to dispose of—could you be induced to buy it?”

The woman look the thimble and examined it, weighed it, and submitted its metal to the test of the touchstone. It was a pretty thimble, though small, or it would not have fitted Adrienne’s finger. This fact struck the woman of the shop, and she cast a suspicious glance at Adrienne’s hand, the whiteness and size of which, however, satisfied her that the thimble had not been stolen.

“What do you expect to receive for this thimble, mademoiselle?” asked the woman, coldly.

“It cost a napoleon, madame, and was made expressly for myself.”

“You do not expect to sell it at what it cost?” was the dry answer.

“Perhaps not, madame—I suppose you will look for a profit in selling it again. I wish you to name the price.”

This was said because the delicate ever shrink from affixing a value to the time and services of others. Adrienne was afraid she might unintentionally deprive the woman of a portion of her just gains. The latter understood by the timidity and undecided manner of the applicant, that she had a very unpracticed being to deal with, and she was emboldened to act accordingly. First taking another look at the pretty little hand and fingers, to make certain the thimble might not be reclaimed, when satisfied that it really belonged to her who wished to dispose of it, she ventured to answer.

“In such times as we had before these vile republicans drove all the strangers from Paris, and when our commerce was good,” she said, “I might have offered seven francs and a half for that thimble; but, as things are now, the last sou I can think of giving is five francs.”

“The gold is very good, madame,” Adrienne observed, in a voice half-choked; “they told my grandmother the metal alone was worth thirteen.”

“Perhaps, mademoiselle, they might give that much at the mint, for there they coin money; but, in this shop, no one will give more than five francs for that thimble.”

Had Adrienne been longer in communion with a cold and heartless world, she would not have submitted to this piece of selfish extortion; but, inexperienced, and half frightened by the woman’s manner, she begged the pittance offered as a boon, dropped her thimble, and made a busty retreat. When the poor girl reached the street, she began to reflect on what she had done. Five francs would scarcely support her grandmother a week, with even the wood and wine she had on hand, and she had no more gold thimbles to sacrifice. A heavy sigh broke from her bosom, and tears stood in her eyes. But she was wanted at home, and had not the leisure to reflect fully on her own mistake.

Occupation is a blessed relief to the miserable. Of all the ingenious modes of torture that have ever been invented, that of solitary confinement is probably the most cruel—the mind feeding on itself with the rapacity of a cormorant, when the conscience quickens its activity and prompts its longings. Happily for Adrienne, she had too many positive cares, to be enabled to waste many minutes either in retrospection, or in endeavors to conjecture the future. Far—far more happily for herself, her conscience was clear, for never had a purer mind, or a gentler spirit dwelt in female breast. Still she could blame her own oversight, and it was days before her self-upbraidings, for thus trifling with what she conceived to be the resources of her beloved grandmother, were driven from her thoughts by the pressure of other and greater ills.

Were I to last a thousand years, and rise to the dignity of being the handkerchief that the Grand Turk is said to toss toward his favorite, I could not forget the interest with which I accompanied Adrienne to the door of her little apartment, in the entresol. She was in the habit of hiring little Nathalie, the porter’s daughter, to remain with her grandmother during her own necessary but brief absences, and this girl was found at the entrance, eager to be relieved.

“Has my grandmother asked for me, Nathalie?” demanded Adrienne, anxiously, the moment they met.

“Non, mademoiselle; madame has done nothing but sleep, and I was getting so tired!”

The sou was given, and the porter’s daughter disappeared, leaving Adrienne alone in the ante-chamber. The furniture of this little apartment was very respectable, for Madame de la Rocheaimard, besides paying a pretty fair rent, had hired it just after the revolution, when the prices had fallen quite half, and the place had, by no means, the appearance of that poverty which actually reigned within. Adrienne went through the ante-chamber, which served also as a salle à manger, and passed a small saloon, into the bed-chamber of her parent. Here her mind was relieved by finding all right. She gave her grandmother some nourishment, inquired tenderly as to her wishes, executed several little necessary offices, and then sat down to work for her own daily bread; every moment being precious to one so situated. I expected to be examined—perhaps caressed, fondled, or praised, but no such attention awaited me. Adrienne had arranged every thing in her own mind, and I was to be produced only at those extra hours in the morning, when she had been accustomed to take exercise in the open air. For the moment I was laid aside, though in a place that enabled me to be a witness of all that occurred. The day passed in patient toil, on the part of the poor girl, the only relief she enjoyed being those moments when she was called on to attend to the wants of her grandmother. A light potage, with a few grapes and bread, composed her dinner; even of these I observed that she laid aside nearly half for the succeeding day; doubts of her having the means of supporting her parent until the handkerchief was completed, beginning to beset her mind. It was these painful and obtrusive doubts that most distressed the dear girl, now, for the expectation of reaping a reward comparatively brilliant, from the ingenious device to repair her means on which she had fallen, was strong within her. Poor child! her misgivings were the overflowings of a tender heart, while her hopes partook of the sanguine character of youth and inexperience!

My turn came the following morning. It was now spring, and this is a season of natural delights at Paris. We were already in April, end the flowers had begun to shed their fragrance on the air, and to brighten the aspect of the public gardens. Mad. de la Rocheaimard usually slept the soundest at this hour, and, hitherto, Adrienne had not hesitated to leave her, while she went herself to the nearest public promenade, to breathe the pure air and to gain strength for the day. In future, she was to deny herself this sweet gratification. It was such a sacrifice, as the innocent and virtuous, and I may add the tasteful, who are cooped up amid the unnatural restraints of a town, will best know how to appreciate. Still it was made without a murmur, though not without a sigh.

When Adrienne laid me on the frame where I was to be ornamented by her own pretty hands, she regarded me with a look of delight, nay, even of affection, that I shall never forget. As yet she felt none of the malign consequences of the self-denial she was about to exert. If not blooming, her cheeks still retained some of their native color, and her eye, thoughtful and even sad, was not yet anxious and sunken. She was pleased with her purchase, and she contemplated prodigies in the way of results. Adrienne was unusually skillful with the needle, and her taste had been so highly cultivated, as to make her a perfect mistress of all the proprieties of patterns. At the time it was thought of making an offering of all our family to the dauphine, the idea of working the handkerchiefs was entertained, and some designs of exquisite beauty and neatness had been prepared. They were not simple, vulgar, unmeaning ornaments, such as the uncultivated seize upon with avidity on account of their florid appearance, but well devised drawings, that were replete with taste and thought, and afforded some apology for the otherwise senseless luxury contemplated, by aiding in refining the imagination, and cultivating the intellect. She had chosen one of the simplest and most beautiful of these designs, intending to transfer it to my face, by means of the needle.

The first stitch was made just as the clocks were striking the hour of five, on the morning of the fourteenth of April, 1831. The last was drawn that day two months, precisely as the same clocks struck twelve. For four hours Adrienne sat bending over her toil, deeply engrossed in the occupation, and fluttering herself with the fruits of her success. I learned much of the excellent child’s true character in these brief hours. Her mind wandered over her hopes and fears, recurring to her other labors, and the prices she received for occupations so wearying and slavish. By the milliner, she was paid merely as a common sewing-girl, though her neatness, skill and taste might well have entitled her to double wages. A franc a day was the usual price for girls of an inferior caste, and out of this they were expected to find their own lodgings and food. But the poor revolution had still a great deal of private misery to answer for, in the way of reduced wages. Those who live on the frivolities of mankind, or, what is the same thing, their luxuries, have two sets of victims to plunder—the consumer, and the real producer, or the operative. This is true where men are employed, but much truer in the case of females. The last are usually so helpless, that they often cling to oppression and wrong, rather than submit to be cast entirely upon the world. The marchande de mode who employed Adrienne was as rusée as a politician who had followed all the tergiversations of Gallic policy, since the year ’89. She was fully aware of what a prize she possessed in the unpracticed girl, and she felt the importance of keeping her in ignorance of her own value. By paying the franc, it might give her assistant premature notions of her own importance; but, by bringing her down to fifteen sous, humility would be inculcated, and the chance of keeping her doubled. This, which would have defeated a bargain with any common couturière, succeeded perfectly with Adrienne. She received her fifteen sous with humble thankfulness, in constant apprehension of losing even that miserable pittance. Nor would her employer consent to let her work by the piece, at which the dear child might have earned at least thirty sous, for she discovered that she had to deal with a person of conscience, and that in no mode could as much be possibly extracted from the assistant, as by confiding to her own honor. At nine each day she was to breakfast. At a quarter past nine, precisely, to commence work for her employer; at one, she had a remission of half an hour; and at six, she became her own mistress.

“I put confidence in you, mademoiselle,” said the marchande de mode, “and leave you to yourself entirely. You will bring home the work as it is finished, and your money will be always ready. Should your grandmother occupy more of your time than common, on any occasion, you can make it up of yourself, by working a little earlier, or a little later; or, once in a while, you can throw in a day, to make up for last time. You would not do as well at piece-work, and I wish to deal generously by you. When certain things are wanted in a hurry, you will not mind working an hour or two beyond time, and I will always find lights with the greatest pleasure. Permit me to advise you to take the intermissions as much as possible for your attentions to your grandmother, who must be attended to properly. Si—the care of our parents is one of our most solemn duties! Adieu, mademoiselle; au revoir!”

This was one of the speeches of the marchande de mode to Adrienne, and the dear girl repeated it in her mind, as she sat at work on me, without the slightest distrust of the heartless selfishness it so ill concealed. On fifteen sous she found she could live without encroaching on the little stock set apart for the support of her grandmother, and she was content. Alas! the poor girl had not entered into any calculation of the expense of lodgings, of fuel, of clothes, of health impaired, and as for any resources for illness or accidents, she was totally without them. Still Adrienne thought herself the obliged party, in times as critical as those which then hung over France, in being permitted to toil for a sum that would barely supply a grisette, accustomed all her life to privations, with the coarsest necessaries.