* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: What I Have Seen and Heard

Date of first publication: 1925

Author: J. G. (John Gordon) Swift MacNeill (1849-1926)

Date first posted: Jan. 21, 2023

Date last updated: Jan. 21, 2023

Faded Page eBook #20230134

This eBook was produced by: Mardi Desjardins, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

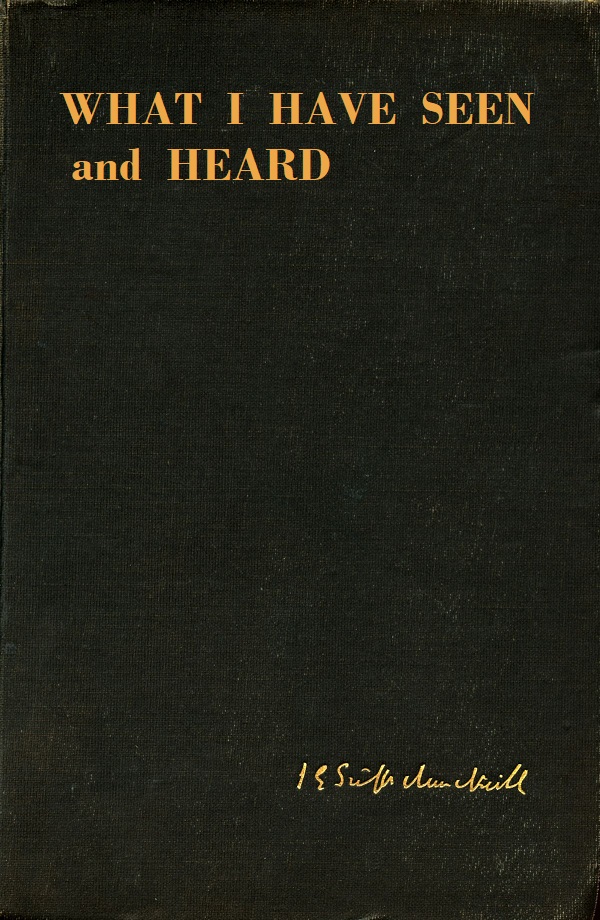

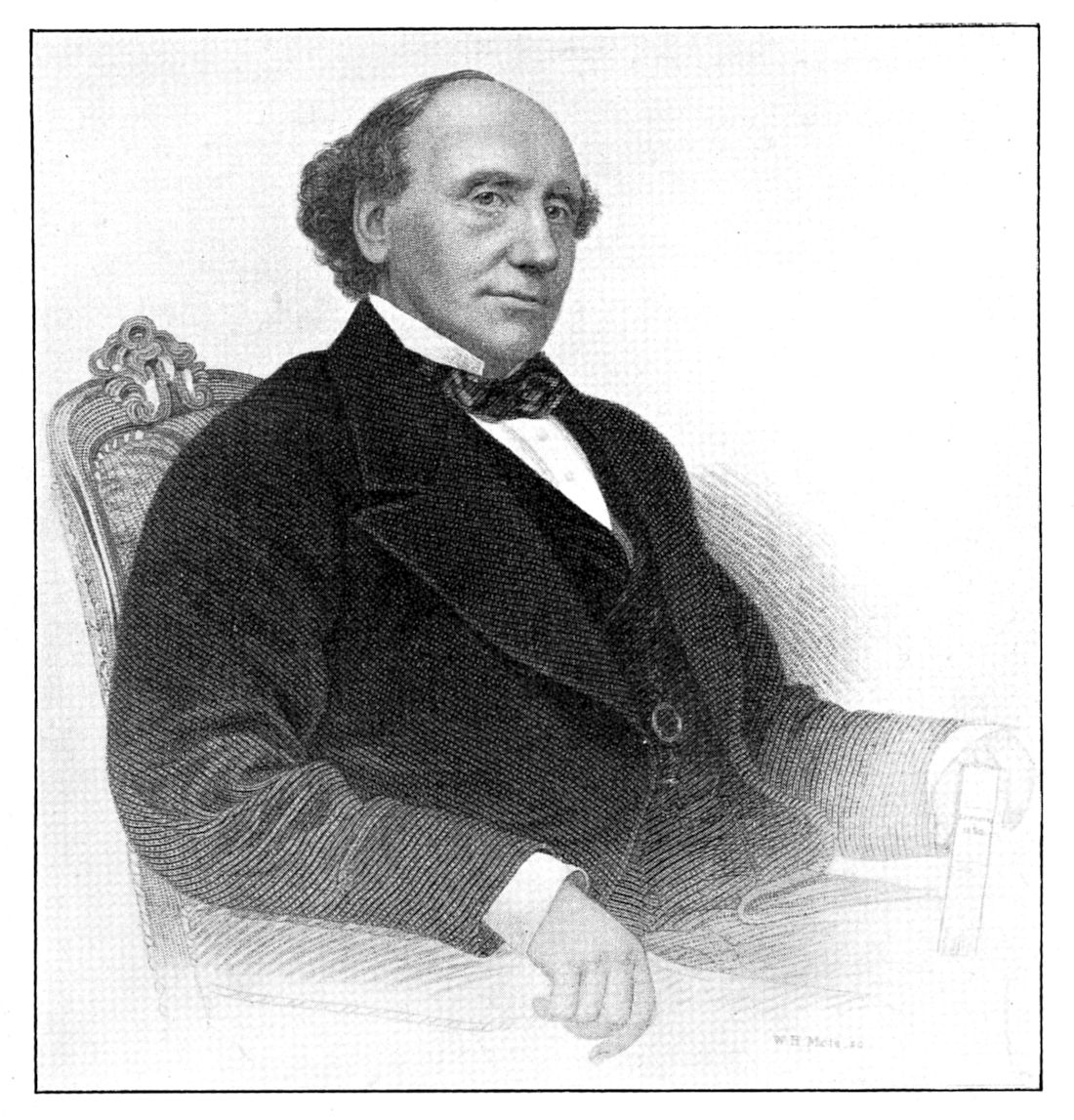

Frontispiece]

J. G. Swift MacNeill.

Photograph by Lafayette, Dublin.

What I Have Seen

and Heard ‐ ‐ ‐ by

J. G. Swift MacNeill

With Fourteen Illustrations

Arrowsmith :: London :: W.C.1

First published in 1925

Printed by J. W. Arrowsmith Ltd.

11 Quay Street & 12 Small Street, Bristol

I Dedicate This Book

to

My Sister

Mary Colpoys Deane MacNeill

| Contents | ||

| PAGE | ||

| Foreword | 13 | |

| PART I: DUBLIN | ||

| Chapter I. Of My Earliest Years | 17 | |

| Lord Fisher. My father. Lord Seaton. Lady Seaton. Mr. John Egan. My mother. | ||

| Chapter II. Of Links with the Eighteenth Century | 23 | |

| Dean Swift. Mr. Deane Swift. Theophilus Swift. Sir Jonah Barrington. Lord Chief Justice Lefroy. Mr. Justice Lawson. Mr. Ellis. My grandparents. Mr. Thomas Parnell. | ||

| Chapter III. Of the Days of My Childhood | 31 | |

| Lord Justice FitzGibbon. Lord Edward FitzGerald. Thomas Moore. Terence Bellew MacManus. Sir Benjamin Guinness. Mr. Arthur Guinness. Mr. Gladstone. Mr. Cecil Rhodes. Mr. Edward Houston Caulfield. Mr. Justice Keogh. Rt. Hon. Edward Litton. Mr. O’Connell. Lord Chancellor Napier. Mr. Anthony Lefroy. Dr. Ball. Dr. Webb. Mr. (Baron) Dowse. | ||

| PART II: DUBLIN AND OXFORD | ||

| Chapter I. Of Trinity College | 55 | |

| Dr. Ingram. Dr. Mahaffy. Mr. Blennerhassett. Rev. Thomas Gray. Rev. Thomas Stack. | ||

| Chapter II. Of a Dean and Some Oxford Professors | 63 | |

| Dr. Liddell. Mr. Lecky. “Lewis Carroll.” Dr. Pusey. Canon Heurtley. Canon Liddon. Bishop Samuel Wilberforce. Mr. Sidney James Owen. Dean Kitchen. Bishop Edward Stuart Talbot. Bishop Stubbs. Mr. Goldwin Smith. Professor Freeman. Mr. J. A. Froude. Right Hon. Montague Bernard. Mr. Charles Neate. Viscount Bryce. Dr. Jowett. Rev. George Washbourne West. Rev. Thomas Fowler. Primate Alexander. | ||

| Chapter III. Of Mr. Ruskin and Miss La Touche | 79 | |

| Chapter IV. Of Some Undergraduates | 84 | |

| Lord Rosebery. H.R.H. Prince Leopold. Mr. Asquith. Judge Atherley Jones. Sir Alfred Hopkinson. Mr. Burdett-Coutts. The O’Mahony. Lord Coleridge. Sir Ellis Ashmead Bartlett. Mr. Frederick York Powell. Mr. Lawrence Irving. Mr. Fisher. Mr. Grant Allen. Cardinal Manning. Archbishop Whately. Lord Curzon. Archbishop Thomson. | ||

| Chapter V. Of the Oxford Union | 94 | |

| Bishop Creighton. Bishop Copleston. Mr. Christopher Redington. Mr. Edwin Harrison. Bishop J. C. Ryle. Sir William Harcourt. Mr. J. R. Green. Archdeacon Sinclair. Mr. Herbert Richards. Professor A. W. Verrall. Sir Perceval Lawrence. Professor Courtney Kenny. Mr. Gilbert Talbot. Mr. Gordon Butler. Cardinal Manning. Earl Stanhope. Lord Chief Justice Coleridge. Bishop Wilberforce. Sir Robert Mowbray. Sir John Mowbray. Lord Charnwood. Mr. Arthur Magee. Lord Hugh Cecil. | ||

| PART III: DUBLIN AND WESTMINSTER | ||

| Chapter I. Of the Tragic Ending of Great Careers | 107 | |

| Sir John B. Karslake. Right Hon. Frederick Shaw. Mr. Justice Keogh. Mr. A. M. Sullivan. Mr. Disraeli. | ||

| Chapter II. Of the Founder of the Home Government Association | 118 | |

| Chapter III. Of Nepotism and its Consequences | 125 | |

| Rev. J. A. Galbraith. Rev. Samuel Haughton. Lord Chancellor Cairns. Mr. Gerald FitzGibbon. Mr. Alexander Miller. Mr. Edward Gibson (Lord Ashbourne). Mr. David Plunket (Lord Rathmore). Mr. Gerald FitzGibbon. Mr. Justice Burton. “Alphabet Smith.” Lord Randolph Churchill. Chief Baron Palles. Sir Charles Lewis. Mr. Joseph Biggar. | ||

| Chapter IV. Of the Old Irish Leaders | 137 | |

| Mr. O’Neill Daunt. Rev. Thomas Wilson. Mr. O’Connell. Mr. Lecky. The O’Gorman Mahon. Mr. Parnell. Captain O’Shea. Mr. John Martin. Mrs. Parnell. Bishop Pakenham Walsh. | ||

| Chapter V. Of Certain Famous Lawyers | 149 | |

| Lord Chief Justice Whiteside. Lord Chancellor Napier. Mr. Justice James O’Brien. Lord Fitzgerald. Mr. (Baron) Fitzgerald. Lord Chief Justice May. Lord Justice Barry. Mr. Denis Caulfield Heron. Dr. Webb. Lord Justice Christian. Lord O’Hagan. Lord Ashbourne. Mr. Justice O’Hagan. Judge Charles Kelly. Mr. Justice Lawson. Mr. Edmund Dwyer Gray. Mr. Francis Macdonagh. Serjeant Armstrong. (Serjeant) Sir Colman O’Loghlen. Mr. Thomas De Moleyns. Mr. Justice William O’Brien. Mr. (Baron) Dowse. Vice-Chancellor Chatterton. Lord Hemphill. Lord Chancellor Walker. | ||

| Chapter VI. Of my Contemporaries at the Bar | 188 | |

| Lord Justice J. F. Moriarty. Lord Carson. Lord Chief Justice Peter O’Brien. Mr. T. M. Healy. Sir William Johnson. Mr. John Redmond. Mr. William Redmond. Mr. Gladstone. Mr. John Bright. Mr. Joseph Chamberlain. | ||

| PART IV: WESTMINSTER | ||

| Chapter I. Of Speakers of the house of Commons | 209 | |

| Mr. Speaker Peel. Mr. Joseph Chamberlain. Mr. T. M. Healy. Mr. Speaker Gully. Mr. Courtney. Mr. Dillon. Mrs. Gully. Mr. Speaker Lowther. Mrs. Lowther. | ||

| Chapter II. Of Great Men and Great Causes | 224 | |

| Mr. John Redmond. Viscount Goschen. Mr. Labouchere. Sir Carne Rasch. Mr. Herbert Robertson. Lieut.-General Laurie. The Earl of Midleton. Sir John Kennaway. Lord Avebury. Mr. Bromley Davenport. Mr. W. H. Smith. Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman. Sir James Craig. Lord Charles Beresford. Mr. Gladstone. Sir Lewis Pelly. Lady Campbell-Bannerman. | ||

| Chapter III. Of Mr. Gladstone | 243 | |

| Chapter IV. Of Mr. Joseph Chamberlain | 253 | |

| Mr. Chamberlain. Mr. Winston Churchill. Mr. T. M. Healy. The Duke of Devonshire. Mr. Cecil Rhodes. Mr. Thomas. | ||

| Chapter V. Of Two Visits to Africa | 259 | |

| Mr. Cecil Rhodes. General Gordon. Dr. Jameson. Miss Olive Schreiner. Mr. Parnell. | ||

| Chapter VI. Of Some Cabinet Ministers | 270 | |

| Sir William Harcourt. Mr. Speaker Peel. Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman. Mr. Warmington. Lord Rosebery. Mr. Gladstone. Mr. “Lulu” Harcourt. Sir Henry Seymour King. Mr. Walter Long. Mr. Augustine Birrell. Mr. Robert George Arbuthnot. | ||

| Chapter VII. Of People in High Places | 278 | |

| Sir Henry Fowler. Sir Frank Lockwood. Queen Victoria. Mr. Samuel Young. The Duke of Argyle. Bishop Wilberforce. The Earl of Stamford. Mr. Asquith. Mr. Gulland. Lord Stamfordham. | ||

| Chapter VIII. Of Tragedy and Comedy | 286 | |

| Lord Randolph Churchill. Lord Kitchener. Mr. Wallace. Dr. Tanner. Mr. Speaker Peel. Mr. Balfour. Lord Courtney. Lord Charles Beresford. Captain Wedgwood Benn. Sir John Rigby. Sir Trout Bartley. | ||

| Chapter IX. Of the Fate of Mr. Parnell | 298 | |

| Mr. Parnell. Mr. Sexton. Mr. J. F. X. O’Brien. Eugene O’Kelly. Mr. O’Hanlon. Mr. William Redmond. Mr. T. M. Healy. | ||

| Chapter X. Of Three Great Parliamentarians | 302 | |

| Mr. Labouchere. Mr. Michael Davitt. Sir Dunbar Plunket Barton. Mr. W. H. Lecky. Mr. T. M. Healy. Mrs. Lecky. | ||

| Index | 313 | |

| Illustrations | ||

| J. G. Swift MacNeill | FRONTISPIECE | |

| Photograph by Lafayette, Dublin. | ||

| FACING | ||

| PAGE | ||

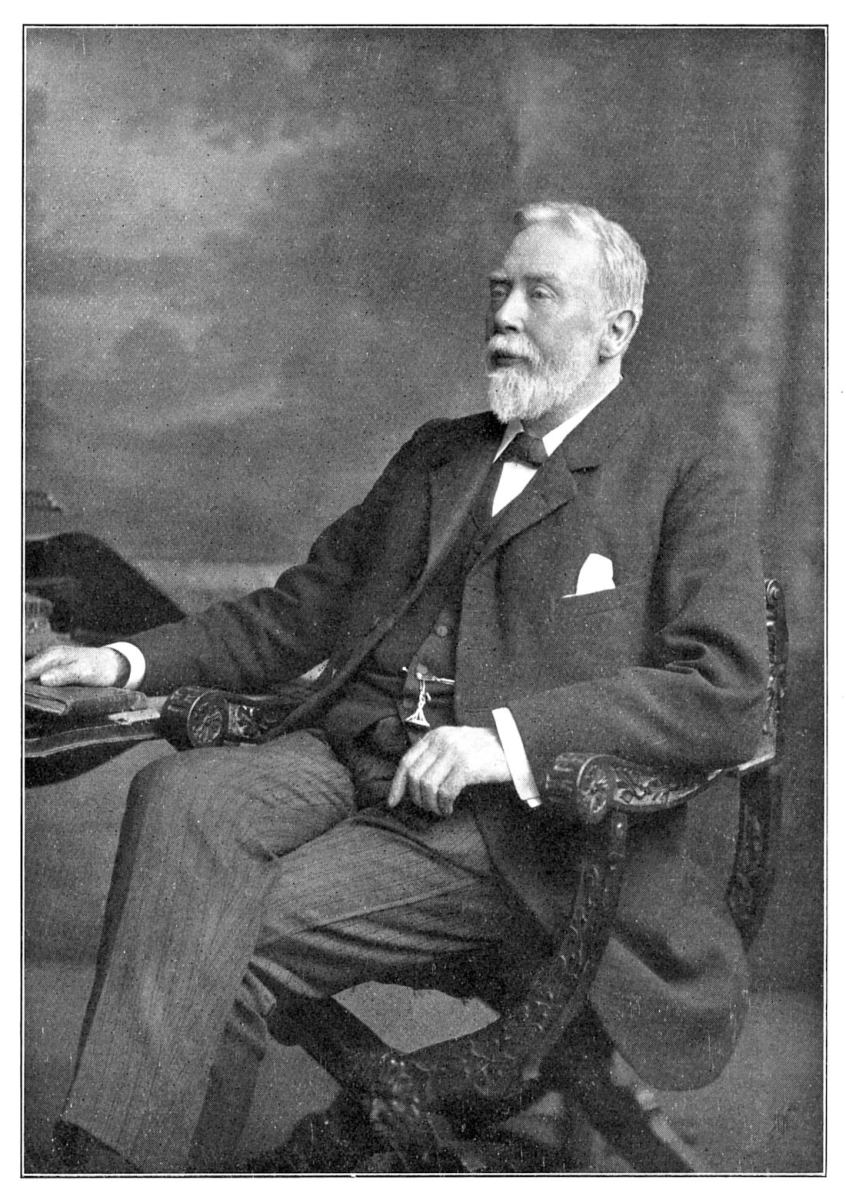

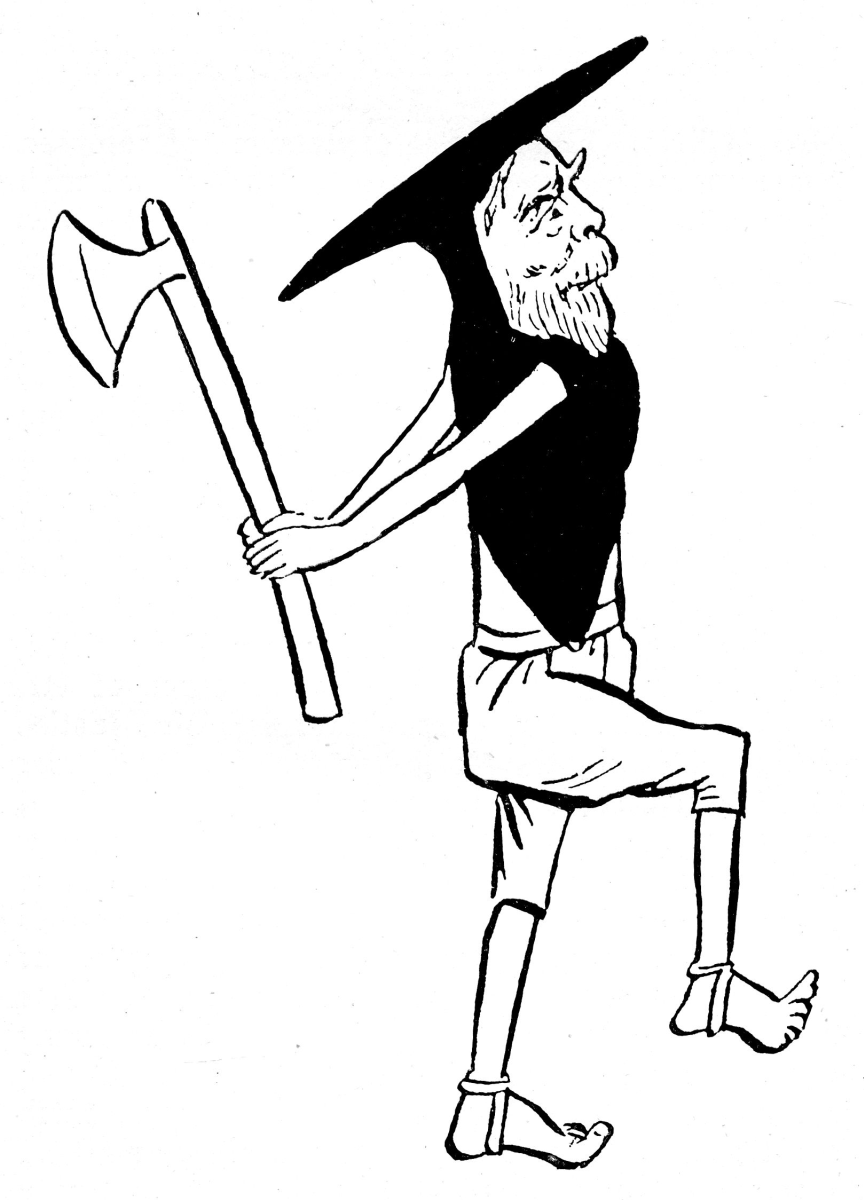

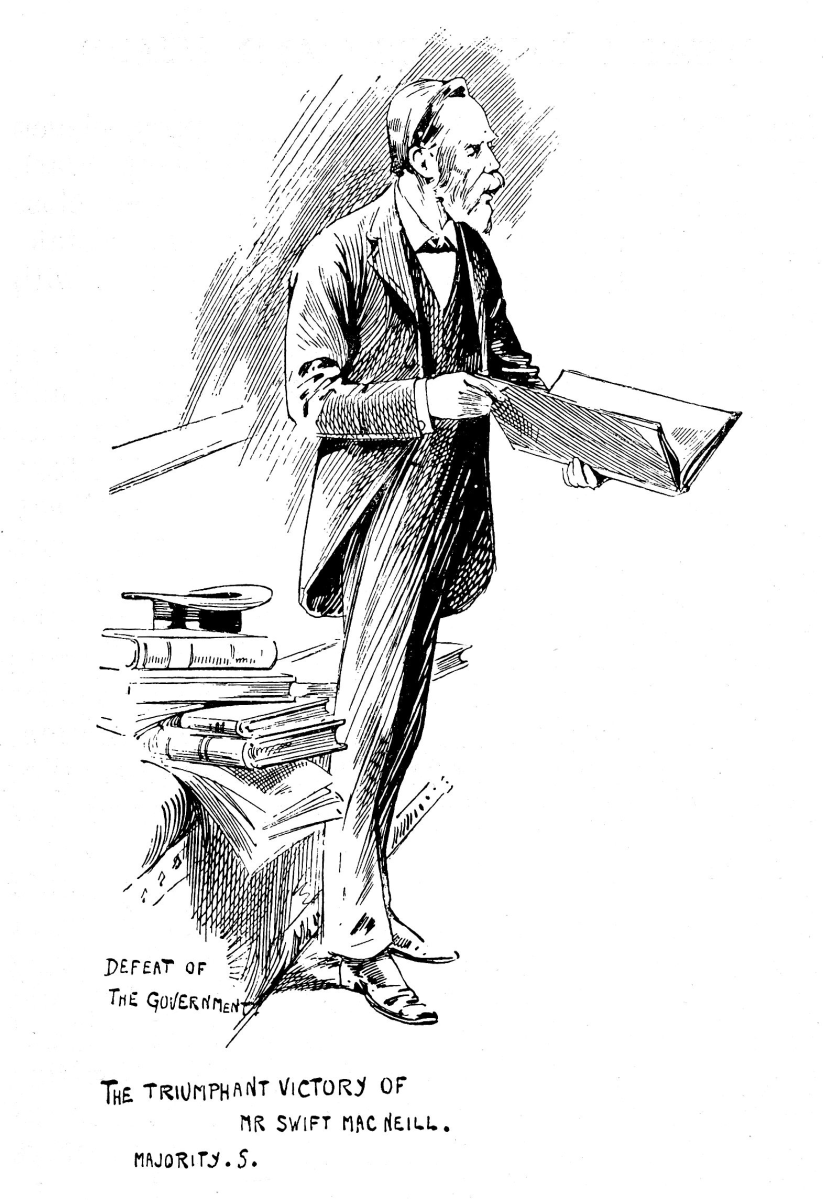

| J. G. Swift MacNeill “on the war path” | 18 | |

| Cartoon by “Spy.” By courtesy of the Proprietors of Vanity Fair. | ||

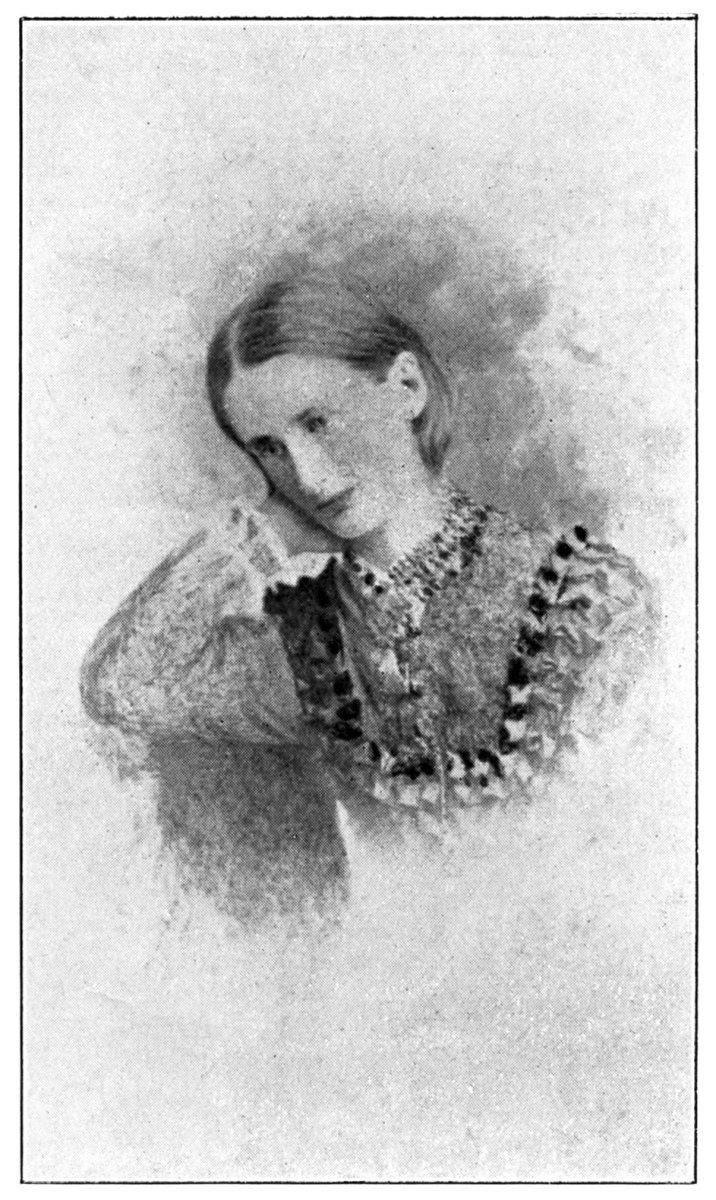

| Miss Rose Lucy La Touche | 80 | |

| From a photograph, hand-coloured by Miss La Touche. | ||

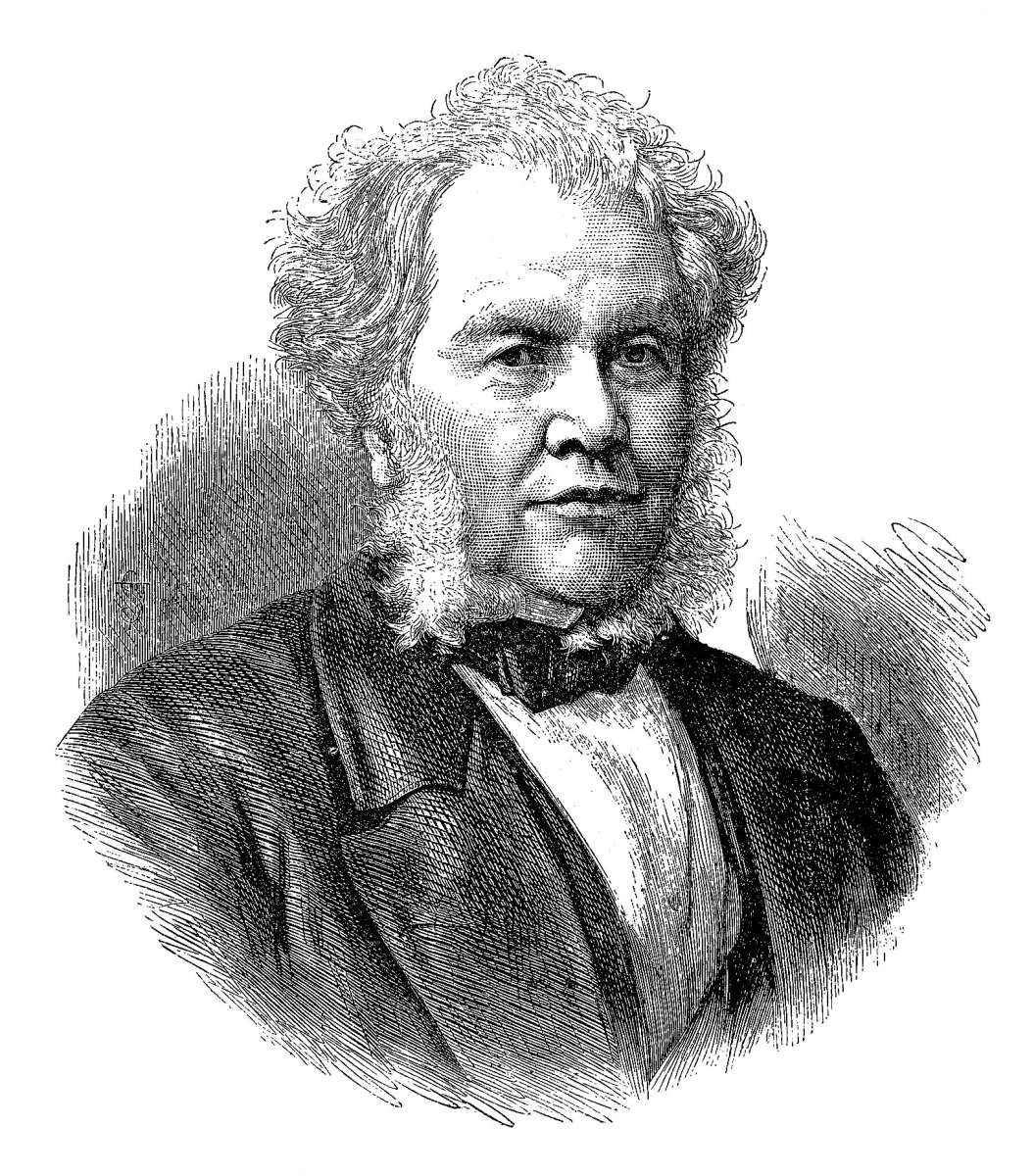

| Mr. Isaac Butt | 118 | |

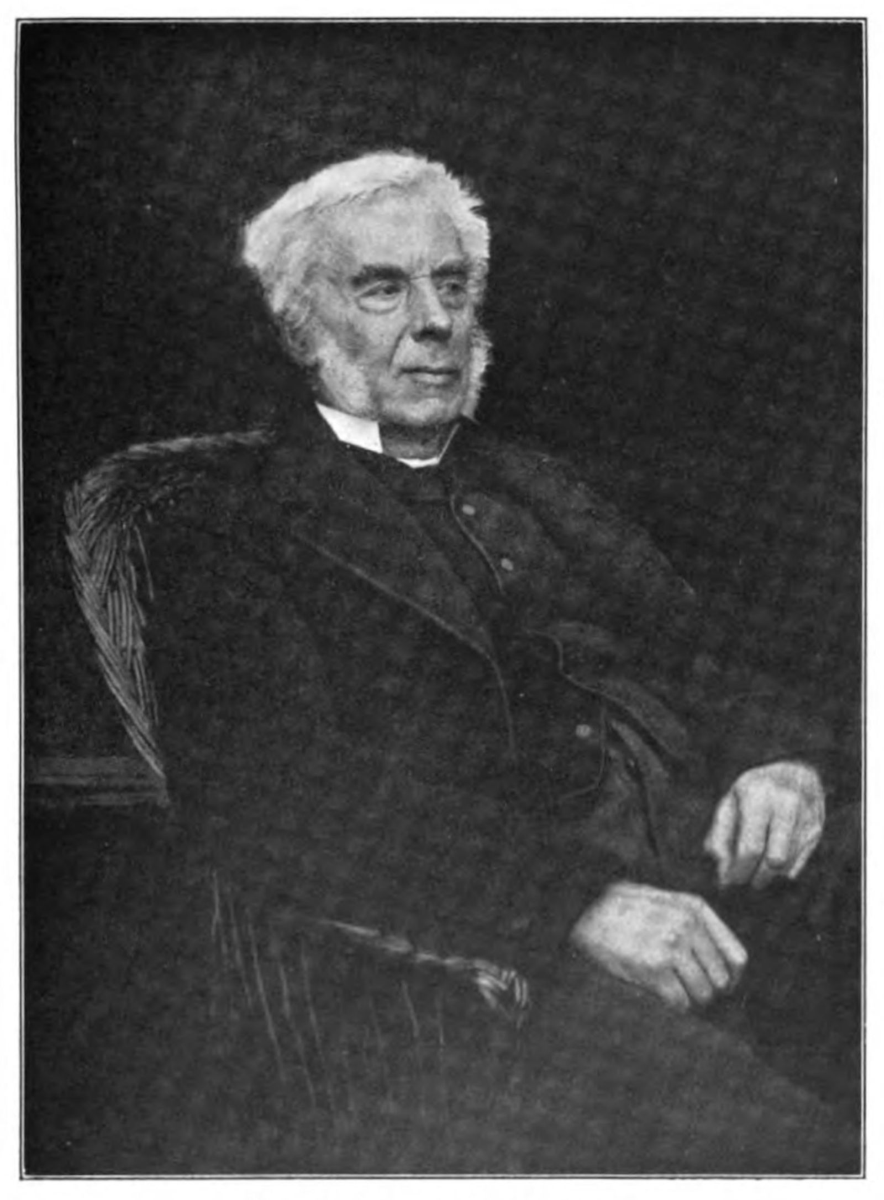

| Mr. W. J. O’Neill Daunt | 138 | |

| By courtesy of Messrs. T. Fisher Unwin Ltd. | ||

| Mr. Parnell | 146 | |

| By courtesy of The Graphic. | ||

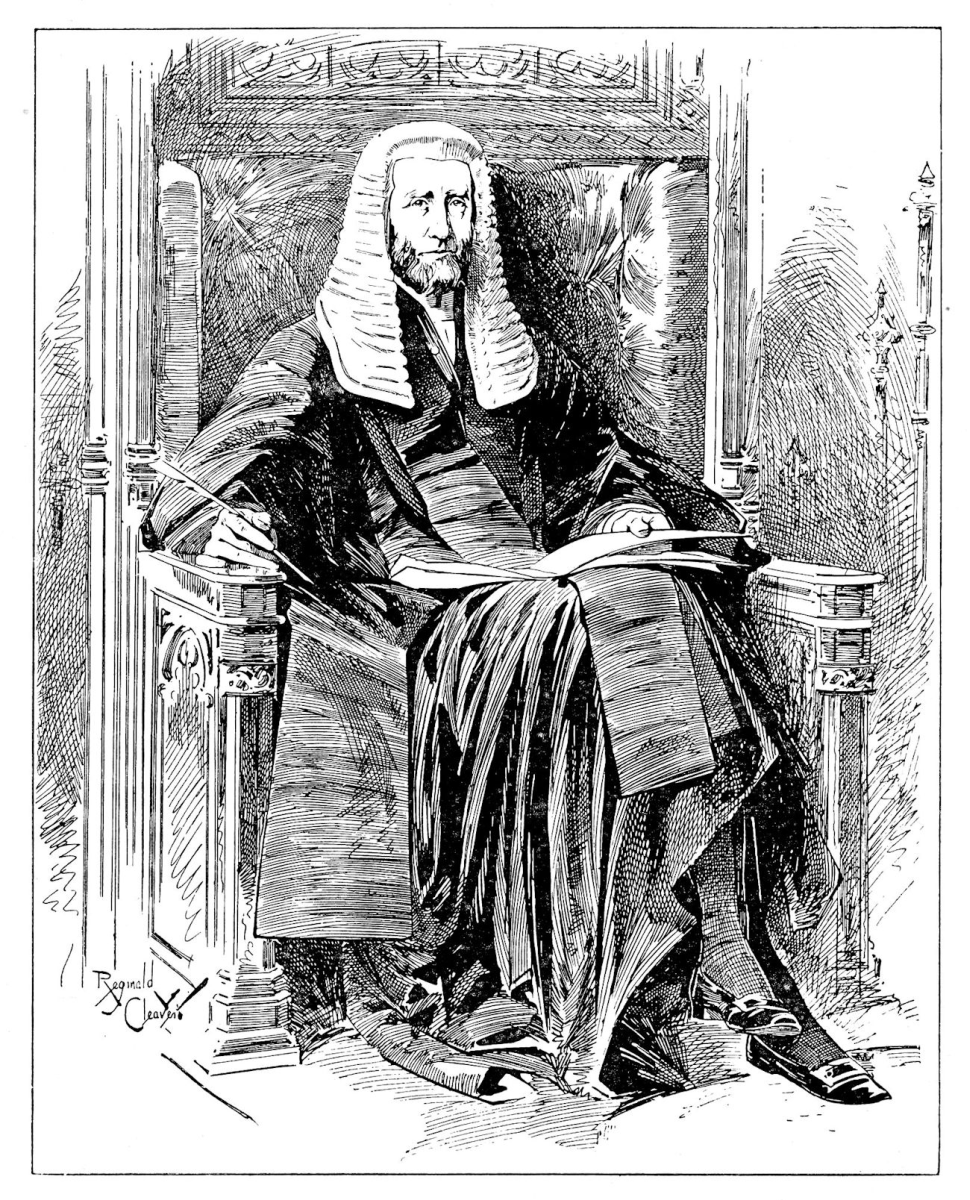

| Lord Chief Justice Whiteside | 150 | |

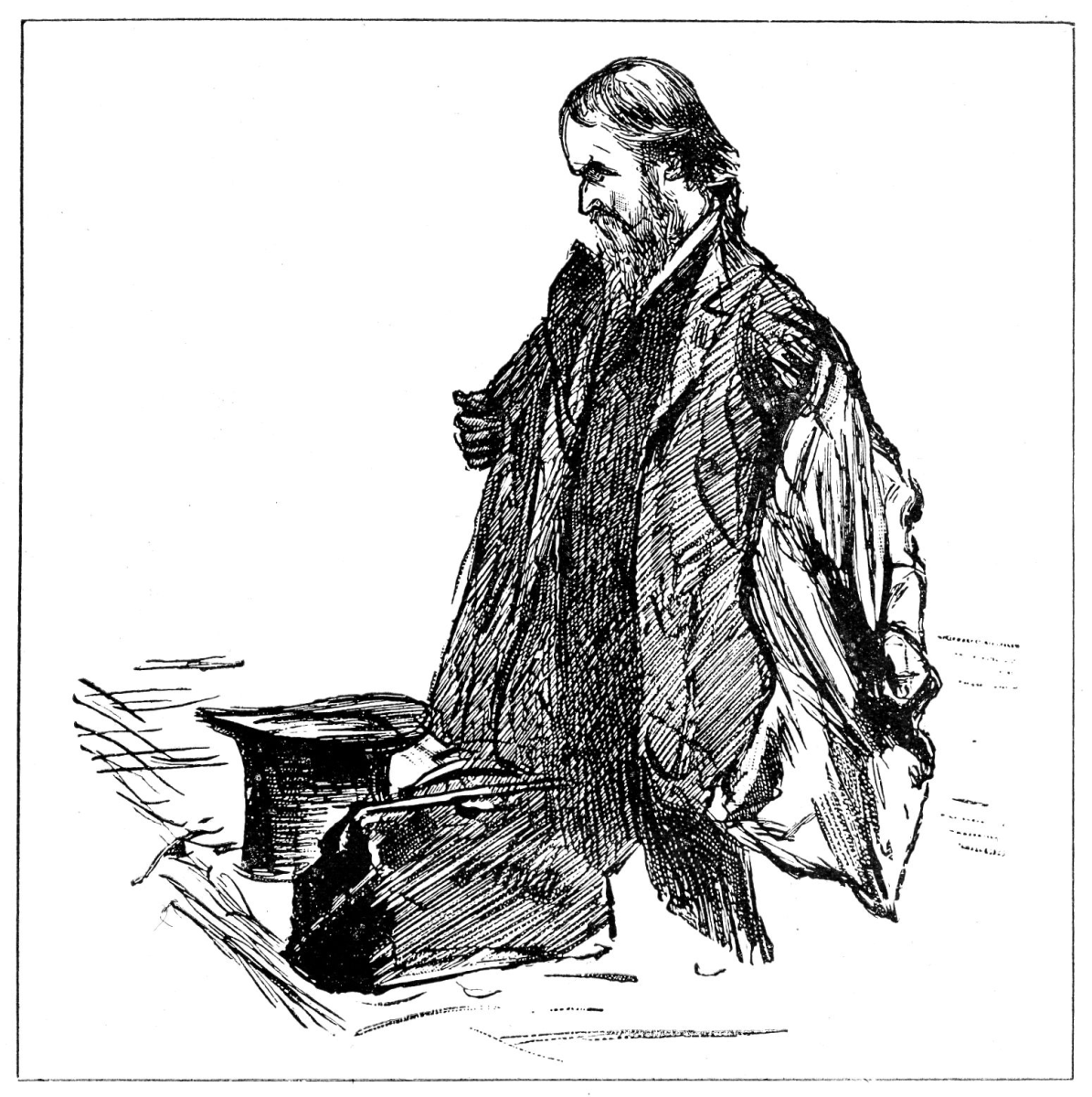

| The Irish Foot Soldier (J. G. Swift MacNeill) | 202 | |

| By courtesy of the Executors of Sir F. C. Gould and Messrs. T. Fisher Unwin Ltd. | ||

| Mr. Speaker Peel | 212 | |

| By courtesy of The Graphic. | ||

| “The minority who opposed the Statute met with ridicule and gibes” | 236 | |

| By courtesy of the Executors of Sir F. C. Gould and The London Express Newspaper Ltd. | ||

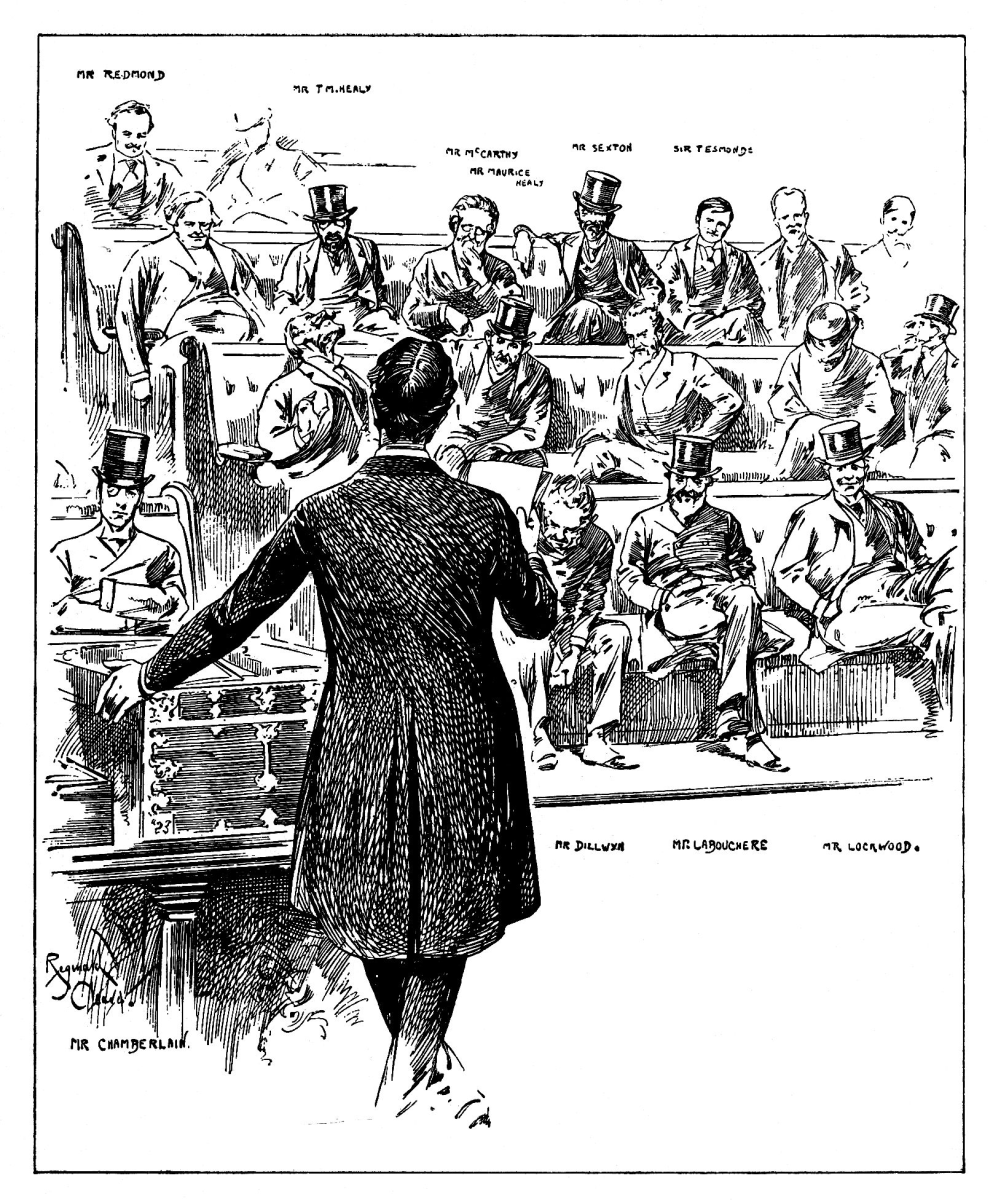

| “On March 11th, 1892, I moved that the votes of three members be disallowed” | 238 | |

| By courtesy of The Graphic. | ||

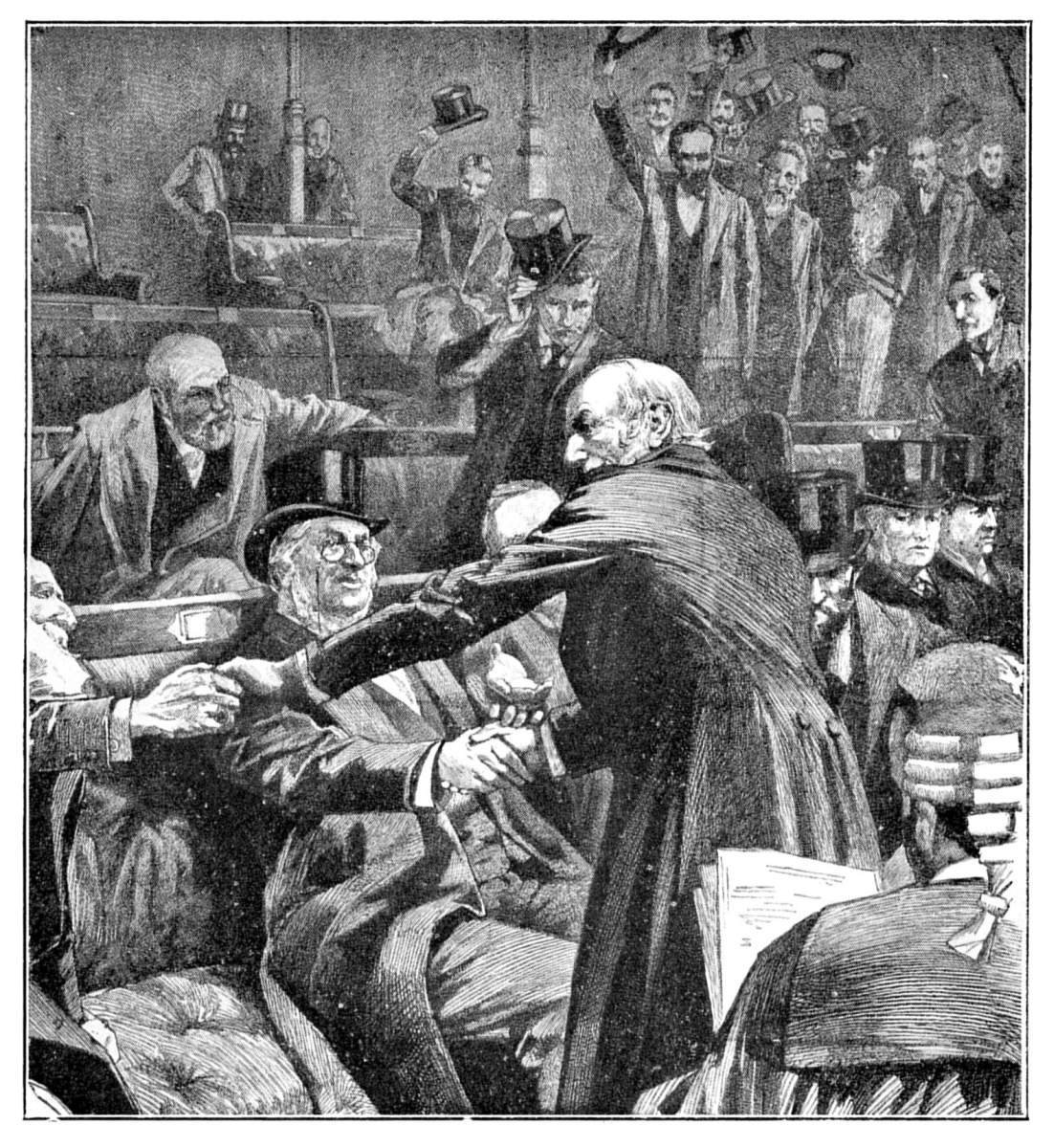

| Mr. Gladstone welcomed by Sir William Harcourt and cheered by the Irish members | 246 | |

| By courtesy of The Graphic. | ||

| Mr. Balfour amuses the Irish members | 288 | |

| By courtesy of The Graphic. | ||

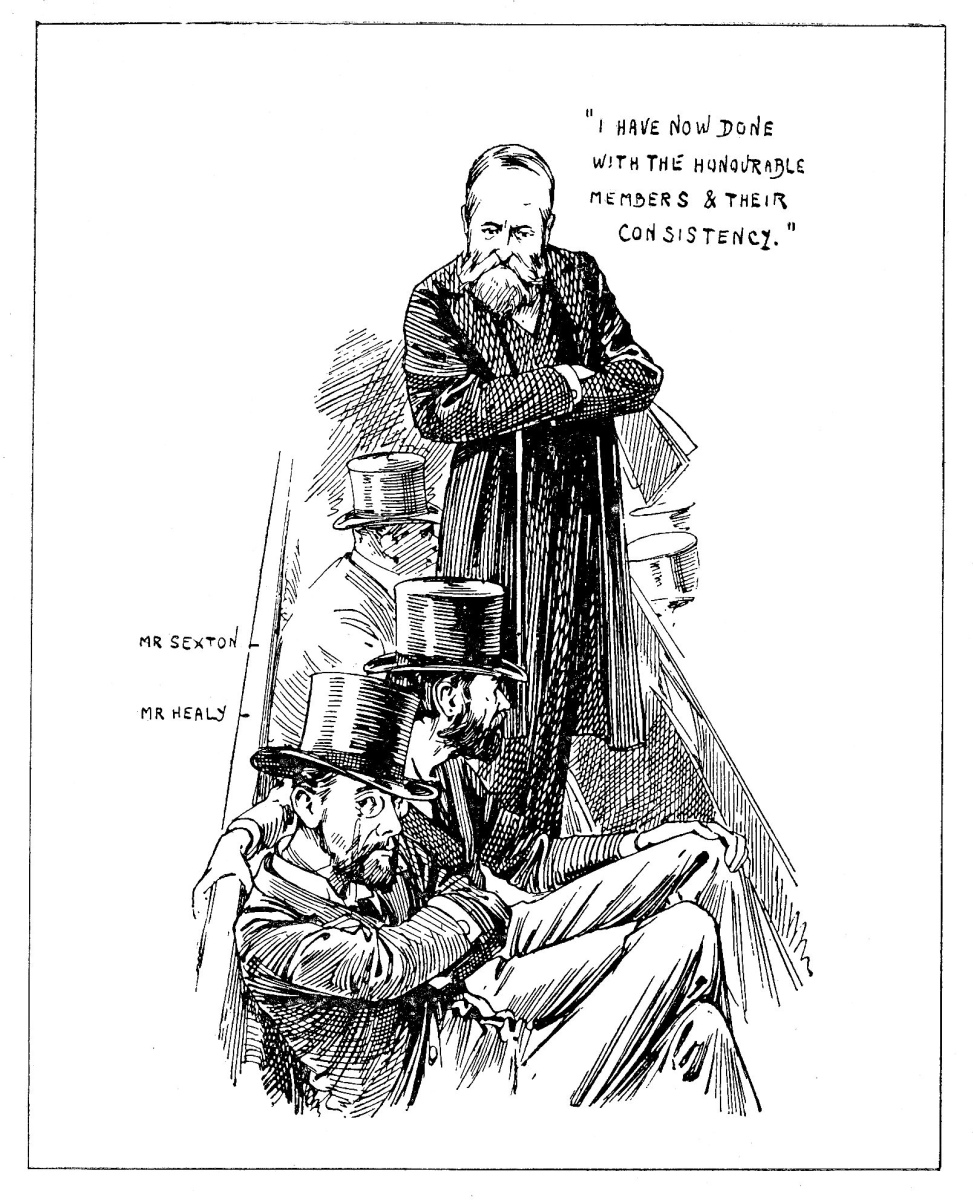

| “The bond of cohesion was broken” | 300 | |

| By courtesy of The Graphic. | ||

Foreword

I have been so frequently requested to write my reminiscences that I have at length consented to make the somewhat considerable effort necessary to place on record the details of a number of incidents, selected out of an innumerable crowd of anecdotes which rush upon my mind. But I desire to impress on everyone who does me the honour of reading these pages that I am not writing an autobiography, but am simply recording my recollections of men and matters of interest as I have acquired them in the course of a long and somewhat strenuous life.

I anticipate the criticism that these stories are too often related in the first person singular. I am, however, in large measure stating what I have seen and heard; and I may perhaps also advance in excuse the suggestion that in giving full rein to the personal equation I am, at least in this one respect, following in the footsteps of recent Prime Ministers.

J. G. SWIFT MACNEILL.

Part I

DUBLIN

Lord Fisher. My father. Lord Seaton. Lady Seaton. Mr. John Egan. My mother.

The late Lord Fisher once said to me, after question-time in the House of Commons: “Mr. MacNeill, you are a damned good fighter! I wish to God I had had you with me in the Navy.”

In view of this tribute, at which I was naturally flattered, it may perhaps seem appropriate that my earliest reminiscence should be of the first of the many controversies in which I have taken part. It occurred when I was four years old.

During the summer of 1853, while being taken by steamboat from Limerick down the River Shannon to the County Clare, the home of my mother’s family, I made friends with a spaniel. Suddenly, owing to the extreme heat, the dog had a fit. Naturally, I was terrified at the sight, but my fear quickly changed to horror when I saw the owner of the dog take out a penknife and proceed to relieve its pain by bleeding it. It was useless for anyone to tell me that he was doing the dog good: I was convinced that he was treating it most cruelly, and I attacked the kindly gentleman with great fury, hitting, kicking and screaming, and praying that the dear, good God would send him to hell.[1]

I recollect that on the homeward journey, in the same year, we missed the steamer to Limerick by a few minutes at Kilrush. I perfectly remember the tears of vexation and disappointment in my mother’s eyes at this upsetting of our arrangements. But happy for us was this set-back! If we had caught the steamer we should, in the ordinary course, have been passengers in the train which was wrecked in collision at Sallins, a few miles from Dublin: one of the worst railway accidents of the nineteenth century.[2]

My father,[3] during these earliest years of my life, was Curate of St. James’s Church, Dublin. LORD SEATON The parish was, for the most part, an extremely poor one, and its requirements made great demands on the time, patience and energy of both my father and my mother. They, however, gave freely of all, living in simple fashion and being always ready to offer their help where it could do good. And in so doing they set an example which soon brought other workers to their assistance.

J. G. Swift MacNeill “on the war path!”

Cartoon by “Spy.” By courtesy of the Proprietors of “Vanity Fair.”

In the parish, stands the Royal Hospital, Kilmainham, which was, until recent changes, a home for army pensioners, like the Chelsea Hospital in London. It was also the official residence of the Commander of the Forces in Ireland. When my father was at St. James’s the Commander of the Forces was Lord Seaton.[4] He was a charming and kindly old gentleman of splendid physique. I remember my delight at seeing him on horseback with his staff at the reviews in the Phoenix Park. But it was not until many years afterwards that I realised that in him I had seen and known a maker of history—for he had been the military secretary of Sir John Moore and one of the pall-bearers at his funeral at Corunna in 1809, a distinguished commander in the Peninsular War, the originator and leader of the decisive movement of the 52nd Light Infantry at Waterloo, and at a later period the Military Governor of Canada during a crisis in which it became manifest that the establishment of responsible government is the way of salvation for the British Empire.

Lady Seaton, the daughter of an English clergyman, was very anxious to take part in parish work, and had charge of a class of little boys, of whom I was one, in the Sunday School. This was held in the Grand Jury Room of the Court House of Kilmainham,[5] just outside the Royal Hospital. Lady Seaton was, I thought, a lady born to command: MY MOTHER her manner though gracious savoured of the stern. Once when she had directed the class to repeat a verse in Holy Scripture, which she had read out, she asked me why I had not a Bible. I told her that I could not read. “How is that?” she inquired. I told her, certainly not by way of complaint, but simply as a matter of fact, that my mother[6] had never taught me to read. I remember the dear old lady’s reply: “Your mother, my dear, must have had the very best of good reasons for what she did.”

In truth, so it was. I am one of the few persons since (in Lord Brougham’s words) “the school-master is abroad” who have perfect recollections of being illiterate. I was seven years old before I knew the letters of the alphabet. My parents had been advised by doctors not to teach me on the ground of what was termed my “precocity,” and my recovering from an attack of scarlatina was said to have been due to the fact that my little brain was not so susceptible to inflammation as it would have been had it been exercised. However this may be, when at last I began to learn, the task of teaching me seemed all but hopeless. I was not, I think, deficient in intelligence: I knew the Biblical stories: The Swiss Family Robinson and Robinson Crusoe, which were read to me by my mother, I think I had by heart. But to the work of learning to read I was wholly unequal. The drudgery of it was intolerable, and I am certain that to this day I should be an illiterate if it were not for the patience and devotion of my mother in teaching me. There is no patience like that of a mother, and nothing but the solicitude of mine would have enabled her to succeed in teaching me to read, although when that had been accomplished my subsequent progress in education was smooth and even rapid.

[1] I did not then know the less circuitous form for the expression of that amiable prayer, which Bishop Wilberforce once asked a layman to say for him when soup had been spilt on his episcopal apron.

[2] The recollection of not a few disappointments which, like this, have been blessings in disguise, and of several providential escapes from sudden and terrible forms of death, has done much to assuage calamities of life which at first seemed too great for human endurance. These escapes I ascribe to the guardianship of God’s ministering angels, in whose power I as firmly believe as did John Wesley.

[3] My father, the Rev. John Gordon Swift MacNeill, M.A., Trinity College, Dublin, was the only son of Gordon MacNeill, a descendant of the last John MacNeill, Laird of Barra, an island in the Hebrides. My grandfather, Gordon MacNeill, graduated in Trinity College, Dublin, obtained a commission in the 77th Regiment, and served with distinction in the Walcheren Expedition, but was compelled to retire with captain’s rank through ill-health brought on by low fever contracted in the Netherlands. He was a man of some literary taste, and was on intimate terms with Grattan and Curran. He wrote several plays, which were acted with considerable success, the most popular being entitled “Changes and Chances,” in which Macready, the celebrated actor, appeared in the principal part as “Major Forrester.”

[4] Better known, perhaps, as Sir John Colborne.

[5] Kilmainham Court House closely adjoins Kilmainham Jail, notorious for the imprisonment of Robert Emmet, the insurrectionary leader who was executed in 1803, and for the imprisonment as “suspects” of Mr. Parnell and other Irish Nationalists in October, 1881. It was, moreover, the scene of the incident known as the “Kilmainham Treaty.” From within its walls the “No Rent” manifesto was issued, and in Kilmainham in 1883 were executed the men convicted of the assassination of Lord F. Cavendish and Mr. Burke. The name of Kilmainham is also associated with that of Mr. John Egan, K.C., who was Chairman and Recorder of that Court in 1799. While in straitened circumstances he was offered a judgeship if he would vote, in the Irish House of Commons, for the Union, dismissal being threatened if he ventured to oppose the measure. When the vote was taken, the Ayes numbered 106 and the Noes 111. Egan, coming to the tellers as the last of the Noes to be counted, shouted at the top of his voice: “I am one hundred and eleven. Ireland for ever and damn Kilmainham!” When Egan died his entire fortune consisted of three shillings, found on his mantelpiece. Had all acted with his honourable bluntness and “damned the consequences” the Irish Parliament would never have been destroyed. In the words of a bagatelle published after his death:

“Let no man arraign him

That knows to save the realm he damned Kilmainham.”

[6] My mother was Susan Colpoys Tweedy, daughter of the Rev. Henry Tweedy, M.A., Trinity College, Dublin, who, having served as Cornet and Lieutenant in the 7th Dragoon Guards, in which he was known as “Handsome Tweedy,” entered into Holy Orders. My grandfather died as Curate of New Ross in his thirty-second year. My mother, who was only six years old when her father died, used to describe him as “an angel of goodness”—a description most truly applicable to herself.

Dean Swift. Mr. Deane Swift. Theophilus Swift. Sir Jonah Barrington. Lord Chief Justice Thomas Lefroy. Mr. Justice Lawson. Mr. Ellis. My grandparents. Mr. Thomas Parnell.

My great-grandfather Godwin Swift, who was born in 1740, frequently related an anecdote to his children (of whom my father’s mother, Anna Maria Swift, was one), who in turn repeated it to me. One day, when he was about four years old, he was brought into the drawing-room of his father’s home and placed on the knee of an old gentleman. As he sat there, gazing with childish interest into the face above him, his father impressively told him never to forget that he had sat on the knee of a great man. There is little doubt that the great man was Dean Swift, who died in 1745. My great-grandfather’s father and Dean Swift were first cousins and on terms of great affection and intimacy.

I remember that in my sixth or seventh year I met an old gentleman, who was tall and very intellectual looking, very refined and courteous. He was dressed in a swallowtail coat, with the frill that characterised the morning dress of the end of the eighteenth and the beginning of the nineteenth centuries, and I recollect being much impressed by a massive seal hanging on a black silk ribbon from his vest. He was a first cousin of my great-grandfather Swift, and bore the name of Deane Swift, after an ancestor, Admiral Deane the Regicide. This Mr. Deane Swift had been one of the foremost leaders of the United Irishmen and a powerful assailant of the Government as a pamphleteer in the insurrectionary movement of 1798. His name appears in the list of proscribed persons in the Fugitive Act of 1798. While in hiding near Dublin Castle he had a narrow escape from detection and arrest, which in his case would have meant trial by court martial for high treason, certain conviction and death. He was walking in disguise through the streets, when an officer grew suspicious of his identity and to test him hissed in his ear as he passed, “Deane Swift.” With great presence of mind he passed on without giving the slightest sign that the words had any meaning for him, and so escaped.

Mr. Deane Swift’s father, Theophilus Swift, was celebrated in his day for scholarship, eccentricity, pungency as a pamphleteer, and passionate attachment to the Crown, the last being a subject on which there was no possibility of agreement with his son, although divergence of views on public matters did not interfere with their attachment for one another.

After the duel of the Duke of York with Colonel Lennox[1] in 1789 Theophilus Swift sent a challenge THEOPHILUS SWIFT to Colonel Lennox for having the arrogance to fire at the King’s son. They met, and Swift was very dangerously wounded. Eventually he recovered, and many years later, in 1807, when Colonel Lennox had become Duke of Richmond and Lord-Lieutenant of Ireland, he attended the first Viceregal Levée. Making a pun, he humorously reminded the new Lord-Lieutenant of the duel. “When last I had the honour of waiting on your Grace,” he said, “I received better entertainment, for on that occasion your Grace gave me a ball.” The Duke smiled. “Then,” he said, “the least I can do now is to give you a brace of balls.” And he instructed his comptroller to send out immediately the invitations for two festivities in Swift’s honour.

While practising at the English Bar Theophilus Swift achieved notoriety by appearing as counsel for Renwick Williams, commonly known as “The Monster,” who was accused and convicted of stabbing women indiscriminately in the streets. The crime was so detestable that several gentlemen of the Bar had refused to undertake the defence—a duty which Swift accepted, vindicating his action in a very able pamphlet.

After Swift left the English Bar to look after his property in Ireland he became defendant in one of the most curious prosecutions for libel ever instituted. One of the Fellows of Trinity College, Dublin, had dared “to dub his son[2] a blockhead, to stab both the fame and fortune of an ingenuous but modest youth”; while another had disparaged his proficiency in Latin verse by saying publicly “that Latin verse was nothing but a knack.” Theophilus removed his son from Dublin to Oxford and issued a pamphlet entitled, “Animadversions on the Fellows of Trinity College, Dublin,” in which, amongst other things, he denounced the Fellows for marrying against an express statute of the University. He was prosecuted for criminal libel, convicted, and sentenced to twelve months’ imprisonment. A Dr. Burrowes, subsequently Dean of Cork, against whom Swift in his pamphlet had been particularly caustic, published a defence of the Fellows, in which he in his turn cast aspersions on Swift. For this Burrowes was prosecuted, convicted, and sentenced to six months’ imprisonment. He was then actually placed in the same cell in the Dublin Newgate as Theophilus Swift, and in this very extraordinary situation the two enemies established a warm friendship!

These trials, which took place in 1794, created a very great sensation in Dublin. Sir Jonah Barrington, who was one of the counsel for Swift, has placed on record a capital score made off him while he was cross-examining one of the college witnesses. “I examined,” he writes, “the most learned man in the whole University, Dr. Barrett, a little, greasy-looking, round-faced Vice-Provost. He knew nothing on earth save books and guineas, never went out of the college, held but little CHIEF JUSTICE LEFROY intercourse with men and none at all with women. I worked at him unsuccessfully for more than an hour. Not one decisive sentence could I get him to pronounce. At length he grew tired of me, and I thought to conciliate him by telling him that his father had christened me. ‘Indeed?’ he exclaimed. ‘I did not know that you were a Christian.’ ”

I have some few further recollections which form links with the eighteenth century, and these I may give here, although to do so removes them from their chronological position in these reminiscences.

Early in 1866 I saw presiding over the Court of Queen’s Bench in Dublin the Right Hon. Thomas Lefroy, who was then still retaining his office as Chief Justice of Ireland, although in his ninetieth year. His appearance can best be described as “mummified,” and, his eyes being closely shut, he seemed entirely unconscious of his surroundings. My old friend, the late Lord Morris and Killanin, who nearly twenty years afterwards was himself Lord Chief Justice, was pleading in Court. Suddenly the apparently inert judge opened his eyes, and in a clear voice put a question to counsel which showed him to be mentally alert, with a full grasp of the bearings of the argument.

In the previous year the Lord Chief Justice had exhibited such extreme physical feebleness while trying a murder case that Mr. Lawson (afterwards Mr. Justice Lawson), then the Attorney-General, was compelled to place before him the curial portions of the death sentence, written in large hand, and actually to stand beside him on the Bench, dictating and prompting, while the aged judge repeated word after word.

Needless to say, the Chief Justice’s retention of his office in these circumstances was considered a public scandal, and it was openly stated that his reason for so doing was a desire that a Tory Government, rather than the Whig Government which was then in power, should have the appointment of his successor. It was also stated, though probably with more humour than truth, that the Chief Justice’s son, Mr. Anthony Lefroy, who was at the time one of the Members for Dublin University, had already applied for exemption from service on Committees in the House of Commons—on the ground of increasing years. It is, of course, impossible to say whether rumour was correct in her interpretation of the Chief Justice’s motive in retaining his office, but the fact remains that directly the Whig Government fell and the Tories came into power his resignation was tendered, and he retired to enjoy an honourable old age.

I have a very perfect recollection of a Mr. Ellis, whose daughter married a first cousin of my mother’s. When I saw him in the late fifties of the last century he was more than ninety years old, but in full possession of his intellectual faculties. His son, an eminent doctor in Dublin, attained his hundredth year. In 1798 Mr. Ellis was staying at Killybegs, ANNE ARMSTRONG one of the principal towns in the Division of Donegal, which I, a century later, represented in the House of Commons. While at Killybegs Mr. Ellis saw in the offing a ship which he took to be a British man-of-war, and he set out in a small sailing-boat to visit it. But the ship proved to be French, and Mr. Ellis was kept as a prisoner. The ship was subsequently captured in the English Channel by a vessel of the British Fleet, and Mr. Ellis, although in reality an ultra-loyalist, was believed by the British commander to be a disaffected Irishman in the service of the enemy. It was only the earnest entreaties of the commander of the French ship, who solemnly pledged his word of honour as to the truth of Mr. Ellis’s story, that saved him from instant death.

Probably the longest-lived person that I have met was a woman of the peasant class, Anne Armstrong, who, when I saw her at Milton Malbay, County Clare, in 1897, was in her one-hundredth-and-fifteenth year. Parish records show clearly that she spent upwards of ninety years in Milton Malbay, and was already married when she came there. She distinctly remembered the time of the Insurrection of 1798, and was able to point out a seaside lodge rented in the second decade of the nineteenth century by my grandparents when my mother and her brothers and sisters were little children.

My maternal grandmother, Mary Delahunty, daughter and co-heiress of Thomas Delahunty, of Ballyorta, County Clare, was fifteen years old when the Union was carried, and had a lively recollection of the sensation it produced. When she grew up she often heard it condemned by members of the old Irish Parliament, with many of whom she became on intimate terms.[3] In her later years in Dublin one of her greatest friends was Mr. Thomas Parnell, a great uncle of the Irish Parliamentary leader and the youngest son of Sir John Parnell, the Irish Chancellor of the Exchequer, who, like Mr. James FitzGerald, the Prime Serjeant, was dismissed from office for refusing to support the Union proposals. Mr. Thomas Parnell, like my grandmother, was much given to good works, and was a fervent member of the Evangelical party in the Irish Established Church. My grandmother and he conversed for the most part on religious topics, but there were frequent references to the days of their youth and to the Irish Parliament and Irish Parliamentarians whom they had known and to whom they were related. I think it was these references, which I so frequently heard in my boyhood, that first turned my interests towards Irish parliamentary and political history.

[1] Colonel Lennox was formidable as a duellist. The Duke of York narrowly escaped, the bullet of his adversary actually carrying away one of his curls.

[2] The Deane Swift whom I met in later years.

[3] A first cousin of my grandmother was the wife of the Earl of Charlemont, the Leader of the Irish Volunteer movement; another first cousin was the wife of Sir Lucius O’Brien, M.P., a determined opponent of the Union.

Lord Justice FitzGibbon. Lord Edward FitzGerald. Thomas Moore. Terence Bellew MacManus. Sir Benjamin Guinness. Mr. Arthur Guinness. Mr. Gladstone. Mr. Cecil Rhodes. Mr. Edward Houston Caulfield. Mr. Justice Keogh. Right Hon. Edward Litton. Mr. O’Connell. Lord Chancellor Napier. Mr. Anthony Lefroy. Dr. Ball. Dr. Webb. Mr. (Baron) Dowse.

The Crimean War is to me not a mere historical term, but a matter of reality. Our house in Dublin overlooked the King’s Bridge Railway Terminus, and I have a perfect recollection of the Scots Greys leaving the city for embarkation at Cork on their way to the front. The regiment was attired, of course, not in the khaki worn on active service in the present day, but in magnificent scarlet uniforms, just as they appear in Lady Butler’s great picture of an earlier period, “Scotland For Ever.” They were escorted by the bands of other cavalry regiments and were cheered with great enthusiasm. My mother held me up in her arms to view the pageant, which filled me with delight. I turned round and saw the tears streaming copiously down my mother’s cheeks, and my joy was quickly turned to grief. The abrupt transition in feeling has indelibly impressed the incident on my memory, in the form of a picture for which I am thankful, as I have thereby a perfect memory of my mother’s face and figure as a young woman, in a time of life at which I have no likeness of her.

I was sent when nine years old to a private school in Dublin, Bective House Seminary, the Headmaster of which was the Rev. J. Lardner Burke, LL.D., a former scholar of Trinity College, Dublin. I was fairly good at my lessons, and enjoyed my life. The school at that time was one of the best, if not indeed the best, in Dublin, and was famous for the number of its former pupils who had had distinguished careers in the University. The house is a very magnificent one, No. 2 North Great George’s Street.[1]

My home was upwards of two miles from the school, to which I used to go by omnibus in the morning, returning on foot in the afternoon. While walking home one afternoon I was prevented from passing Trinity College by a very large crowd in which were mingled cavalry and mounted policemen. I was told that there was a disturbance, and that as traffic was suspended I must go home by another way. This was on March 12th, 1858, on the occasion of the public entry into the city of the Earl of Eglinton and Winton as Lord-Lieutenant in succession to the Earl of Carlisle, who had retired owing to the resignation of the Palmerston Ministry. The disturbance began with a number of students throwing squibs and crackers from within the MY SCHOOL DAYS rails of the college, with the result that the horses of the cavalry and police became restive. An attempt forcibly to remove those who were responsible for this dangerous method of celebration was met by stone-throwing, and very quickly the affair developed into a fierce riot. Colonel Browne, the Commissioner of Police, read the Riot Act, and then cleared the space between the college and the front railing by a charge of mounted police, in which some very serious blows were exchanged, although there were fortunately no fatal results.[2]

Nearly fifty years later, at an opening meeting of the Trinity College Historical Society, I heard the late Lord Justice FitzGibbon tell, in the presence of Dr. Chadwick, the Bishop of Derry, the story of their valiant deeds as combatants on that occasion. “Who would think,” he asked, “on looking at the Bishop now, that he would have done his best to drag a policeman from his horse, while I held the reins and narrowly escaped a blow from a policeman’s baton?”

As I have said, I was returning from North Great George’s Street when I came upon the scene of this riot. I note as a somewhat curious coincidence that it was in the very same house, where at the time I happened to be visiting Mr. John Dillon, that more than half a century later I heard the news of the outbreak of the insurrection of April, 1916, and that my subsequent walk home again took me past Trinity College, although on this occasion I went into the College in search of protection.

In 1858 my father accepted the Curacy of St. Catherine’s Parish, Dublin, which he held for nearly twenty years, declining several offers of preferment in England and Ireland.[3]

St. Catherine’s Parish, like St. James’s, is among the poorest in Dublin. It is, however, associated with many historic events. Lord Edward FitzGerald, the leader of the insurrection in 1798,[4] was arrested in a house in Thomas Street, the principal street in the parish, and there, until the building was TERENCE BELLEW MACMANUS altered in 1860, some stains on the floor of one of the rooms were exhibited as marks of the blood shed on that occasion.

Because of its historical associations, Thomas Street was always selected as a portion of the route of political processions through Dublin, and it was customary for the crowd to uncover as it passed in front of St. Catherine’s Church as a tribute to the memory of Robert Emmet, the leader of the insurrectionary movement of 1803, who was executed on that spot. The first of these demonstrations that I witnessed was the funeral of Terence Bellew MacManus, on Sunday, November 10th, 1861, but naturally I, a child of twelve, had little knowledge of the significance of that procession of fifty thousand men.[5]

Guinness’s Brewery was in St. Catherine’s Parish, and I remember well Sir Benjamin Guinness, the father of Lord Ardilaun and Lord Iveagh. He was a medium-sized man of a kindly, benevolent expression, with a manner which seemed an unconscious imitation of the old style. He seldom came to St. Catherine’s Church, except on the occasion of services in aid of charities, but he took the heartiest interest in the welfare of the poorer people. He spoke with great affection of my father and mother and of their work among the poor of the parish, very many of whom, of course, worked at his brewery. My mother took particular interest in this work, instituting fathers’ and mothers’ meetings in the school-house; and I remember Sir Benjamin once saying to her: “You are equal to at least five ordinary clergymen.”

Guinness’s was then a very great institution, although I doubt if it had attained to a tenth of its present size and importance. The brewery originally belonged to a family named Rainsford, a name still preserved in Rainsford Street in that neighbourhood. It was purchased for a very small sum by Sir Benjamin’s grandfather, and then attained great prosperity in the time of his father, Mr. Arthur Guinness (whom O’Connell called “that miserable old apostate,” because he had opposed him at the Dublin election of 1836). This prosperity was the direct result of the first attempt to carry out the system subsequently known as boycotting. Guinness’s porter was boycotted throughout Ireland, and the immediate diminution in its consumption led Arthur Guinness, a man of much resource, to open out the trade with the Dominions, which MR. GLADSTONE by the present day has made the brewery one of the greatest business concerns in the world.

Sir Benjamin Guinness, who succeeded his father, was also exceptionally able in administration, and under his control the well-laid foundations of the business were much strengthened. He was, as I have said, a man of great personal charm and genuine amiability, as well as of real public munificence. He it was who restored St. Patrick’s Cathedral when it was practically falling into ruin, an act undoubtedly to the credit and benefit of the City of Dublin, and one which might have been spared the jests which were levelled at the idea of the restoration of a cathedral with money obtained in the drink trade. Many of these jibes were ill-natured; but it must be admitted that they were not without wit. I remember one to the effect that the preacher at the opening service after the restoration would be bound in all propriety to take the text of his sermon from the “He-brews.”

This reference to St. Patrick’s Cathedral leads me to record that it was there that I first saw Mr. Gladstone, whom in all his greatness I was destined for many years to hear and admire in the House of Commons, and of whose notice of myself I have always been proud. While paying a short visit to Ireland in the autumn of 1877 Mr. Gladstone attended a Sunday afternoon’s service in the Cathedral. It was known that he intended to be present, and an immense congregation came to see the author of the Disestablishment and Dis-endowment of the Irish Church, then a comparatively recent fact, in that Church’s principal place of worship. It was on this occasion that I witnessed the only instance I have seen of “pulpit-fright.” The canon in residence, over-awed, apparently, by one member of his vast audience, paused in his discourse, lost the thread of his ideas, and finally brought his address to an abrupt close. Having regard to the fact that the preacher was speaking as the ambassador of the King of Kings, such a display of nervousness at the presence of a mere man, however great and learned, would surely seem unaccountable; yet it undoubtedly occurred. It was a painful and disconcerting incident, and no one appeared more grieved at it than Mr. Gladstone himself, who showed that sympathy and pity which so invariably characterised him, even in the case of those who were his bitterest opponents.

The residents in St. Catherine’s Parish were humble people, a few Protestants in the midst of a large Roman Catholic population. They were good and kindly and grateful for kindness shown to them, and, not being blessed with a very ample share of this world’s goods, were prone to set their hearts on things above. Yet, poor as they were, unknown to them lay many treasures in their homes, for I have seen impoverished rooms in Dublin in those early years which contained exquisite specimens of furniture by Adams, Sheraton and Chippendale. The worth of these articles was then unrecognised; but in later days the treasure was MR. CECIL RHODES discovered by the furniture dealers, by whom vast profits must have been made by their purchase and re-sale. Many years after that period I was the guest of Mr. Rhodes in his lovely residence, Groot Sheen, near Rondebosh, a suburb of Cape Town, and I was unable to refrain from expressing admiration at the wonderful furniture of the library and reception rooms. Mr. Rhodes told me that the greater number of those articles of furniture came from Dublin. “Why,” I said, “I did not think you were ever in Dublin.” “Nor was I,” he replied, “but one of my brothers was A.D.C. to Lord Londonderry when he was Lord-Lieutenant, and I told him to buy up all the old Dublin furniture he could and not mind the price.” I thought as I looked at those exquisite pieces of furniture, then thoroughly restored and renovated, that I may have been renewing my acquaintance with some of the very chairs and tables and cabinets that I had seen in vastly different circumstances in St. Catherine’s Parish.

In the whole of that parish there had been during my father’s curacy but one other man who, in the vulgar acceptation of the term, would be reckoned as of the estate of a gentleman. This was Mr. Edward Houston Caulfield, the grandfather of the present Lord Charlemont. Beginning life with ample fortune, he fell as a young man into pecuniary embarrassment and was pitchforked by his influential political friends into the position of Governor of the Dublin Marshalsea, the Debtors’ Prison, which stood within St. Catherine’s Parish. Naturally, Mr. Caulfield became a leading figure in the neighbourhood, and no parochial meeting was deemed complete without him. He was a man of very aristocratic presence and charming manners: moreover, he knew everyone who was worth knowing in Dublin society. His home was presided over by his sister-in-law, a Miss Geale,[6] his wife having died long before I, as a little boy, first came to know him.

Mr. Caulfield and his daughter and Miss Geale were on terms of the greatest intimacy and friendship with my father and mother, whom they greatly amused and interested with their accounts of the life of society, especially in Dublin Castle, the stories having a poignancy of their own in their contrast with the simple life of doing good amongst the poor to which my parents had absolutely devoted themselves.

Mr. Caulfield was, of course, a Tory of Tories, and he was seldom more happy than when he found gentlemen of his own social position among the prisoners in his charge in the Marshalsea; he would then show them the greatest courtesy and kindness, frequently inviting them as guests to his own table.

I have already said that Mr. Caulfield was almost MR. CAULFIELD an invariable attendant at the parish meetings; but though his presence was regarded as essential, he took little part in the proceedings, beyond uttering a few obvious generalities to which no one paid particular attention. On one occasion, however, he won an oratorical triumph which made him a hero for the moment throughout the parish. The Disestablishment of the Irish Church aroused his keen indignation, and he attended a meeting of protest and addressed an audience largely composed of young men and women, shop assistants and factory workers. His remarks received scant attention until he broached a subject which procured him a hearing and even enabled one to appreciate the “greater silence” with which St. Paul was heard when he spoke in the Hebrew tongue. He was glad, he said, to see so many young men and women at the meeting. These meetings were useful for introductions; these introductions led to acquaintanceship, then to friendship, then not infrequently to marriage, and then to children; so that we should soon have springing up amongst us a race of young Protestants to defend our beloved Church from spoliation and Papal aggression! These sentiments, uttered in all seriousness by a dignified, middle-aged gentleman, were received with shrieks of laughter and a deafening applause, amid which the speaker resumed his seat in obvious, but puzzled, embarrassment.

Mr. Caulfield’s zeal for matters on which he held strong opinions at times exceeded the bounds of prudence. At the General Election of 1868 Sir Arthur Guinness (afterwards Lord Ardilaun) and Mr. David Plunket (afterwards Lord Rathmore) were Conservative candidates in the Church interest for the City of Dublin, then a two-member constituency. Sir Arthur was returned with a Radical colleague, but on an election petition, tried by Mr. Justice Keogh, he was unseated on the ground of bribery committed without his knowledge by his agents. During the trial of the election petition it was proved that Mr. Caulfield had allowed several of the Marshalsea prisoners to leave his custody in order to vote for the Conservative candidates: on a pledge, which was honourably observed by them, that they would return to the prison. This proceeding was certainly questionable. Mr. Justice Keogh, whose own conduct in Parliamentary elections had been a subject of scathing stricture, asked Mr. Caulfield why he placed such reliance on these gentlemen. “I would,” he said, turning to the Judge, “rely on their word of honour just as much as I would rely on yours.” The Judge flared up and threatened to commit him for contempt. Mr. Caulfield looked him straight in the face and expressed astonishment at his words conveying any offence, which was absolutely unintended. “I simply said,” he declared, “that I had implicit trust in these gentlemen, that I trusted their word just as much as I would trust yours. What higher tribute could I give them or you?”

The learned Judge, who in the course of a stormy, JUDGE KEOGH political career had been accused of public falsehood by eminent personages (amongst them being Lord Mayo, who had been Chief Secretary for Ireland and was then Governor-General for India), again attacked Mr. Caulfield. He reserved, however, his final philippic for the delivery of his judgment, when he expressed himself in language that created a great sensation and aroused much sympathy with Mr. Caulfield.

Later, Mr. Caulfield’s daughter, then a very young and attractive girl, had an amusing encounter with Judge Keogh, which she subsequently related to me with great glee. She recognised the Judge, with whom she was personally unacquainted, at an evening party in Dublin Castle, and, remembering her father’s treatment at his hands, she determined, as she afterwards put it, “to teach him a lesson.” At supper she contrived to sit close to her victim, and then, turning to a young officer who sat next to her, asked in a voice loud enough for the Judge to hear: “Do you know Judge Keogh?” The officer was unacquainted with Dublin celebrities, and replied that he did not. “Do you?” he asked, saying, naturally enough, exactly what he was required to say. “Oh, no,” replied the girl, “I should be very sorry to know him.” “Why so?” said her friend. “Who is this Judge Keogh and what has he been doing?” “Oh,” she answered, “have you not read that vulgar judgment of his the other day? He ought to be kicked off the Bench.” Keogh, who had been attracted by the mention of his own name, had of course been listening. Eventually he quite forgot himself, and in accents of great irritation he exclaimed, “I am obliged to you.” Miss Caulfield looked at him in surprise, and preserved that maidenly silence which is expected of young ladies when they are addressed by someone to whom they have not been introduced.

I think that to the Caulfields, to whose conversation with my father and mother I was admitted, I owe my first acquaintance, however distant, with public affairs; for it was from them that, with all the zest for such gossip of a boy, I first heard of the doings of that set of men and women who called themselves “society” in the gingerbread Court of Dublin Castle. And it was certainly through the Caulfields that I first met, in any real sense of the word, an Irish public man.

This was the Right Hon. Edward Litton. To-day that name is entirely unknown, and it does not find a place in any biographical dictionary with which I am acquainted; yet in his own generation Mr. Litton occupied a very considerable position in public life. When I first saw him he was well on in the seventies and the holder of an office long since abolished—that of Master in Chancery. At the Irish Bar he had been a leader both in the Equity and the Common Law Courts, and was regarded as a very adroit and subtle cross-examiner and a powerful and impressive speaker. He had often encountered O’Connell in the Courts and was MASTER LITTON considered to be fully able to hold his own in conflict with the Liberator.

Mr. Litton was a Protestant, and in the forties of the last century he was returned to the House of Commons in the Orange interest for the Borough of Coleraine. Unfortunately, like many other lawyers, he did not gain any success in Parliament equal to that which he had had at the Bar. His first speech, an elaborate attack on the policy of O’Connell, savoured too strongly of nisi prius, and was extremely rhetorical in style. O’Connell chose to refuse to take it seriously. When the House was better acquainted with the new Member, he declared, they would put the same value on his utterances as he did himself; and then, in a grossly disorderly aside which did not reach the Speaker’s official ear, but was heard in every other part of the House, he exclaimed as if to himself: “Ah, good old Ned!”

Mr. Litton was high-minded, resolute and a hater of compromise, with the result that he was disliked by Sir Robert Peel, then the Leader of the Tory Party: he was too true-hearted—Peel would probably have said “quite too violent”—to commend himself to that somewhat shuffling statesman. Consequently, he was passed over as a candidate for a law officership. It was said that he would have received a judgeship if he had abstained from voting on one particular occasion, but so far from abstaining he spoke and voted against the Government. Eventually he was appointed a Master in Chancery, a position admittedly below his deserts, and although he was frequently mentioned as being in the running for vacancies in high judicial offices, such as the Lord Chancellorship and the Mastership of the Rolls, none of these ever fell to him.

Master Litton (to give him his correct title) was kind enough to notice me and to condescend to be my friend, and some of the most delightful hours of my life were spent in his company, listening to his conversation and to his anecdotes of men and things. His eldest son, the Rev. Edward Arthur Litton, had a very distinguished career at Oxford, but, to the Master’s horror, developed decidedly Radical tendencies and even expressed opinions in favour of Irish Church Disestablishment. This appeared such unspeakable heresy to the Master that, when offered a baronetcy, he refused it on the ground that it would be inherited by a “damned Radical.”

The Master had a great respect and affection for my dear parents, and this admiration led him to draw pointed contrasts between my father’s character and those of certain bishops—“Episcopal puppets,” as he termed them.

On one occasion, when my father was dangerously ill, Master Litton wished for a consultation, and when my mother refused to question the skill of the doctor in attendance, he entirely lost his temper with her, accusing her of “damned obstinacy.” My father recovered without alteration in his medical advice, and no one was more delighted than Master LORD CHANCELLOR NAPIER Litton. But my mother, horrified at the Master’s levity of manner and tendency to profane language, began to fear that, notwithstanding all his goodness of heart, he failed to attain the Christian standard. In a little book which she called her “Book of Remembrance” she was accustomed to write the names of the persons whom she mentioned every day in her prayers, and, speaking very seriously to the Master, she told him that his name was in the list. He replied, with an admirable affectation of seriousness, “How can I ever requite such devotion, of which I am wholly unworthy?”

The Master was a prime favourite in the legal profession, although, as was natural for a man of such high honour and sensitive temperament, at times he formed strong dislikes. In particular he had a most contemptuous aversion for Lord Chancellor Napier. This lawyer, as Mr. Joseph Napier, had acquired a great reputation for piety by addressing Young Men’s Christian Associations and cultivating the affections of the Irish clergy at missionary and other religious meetings. Yet his genuineness was more than once in question. His manner was, to use a vulgar expression, “gushing” in the extreme. He invariably shook with both hands even men whose names he could not remember, and without doubt he would have made a fortune on any stage in the part of “Mr. Chadband.” Despite—or possibly in consequence of—this manner, he was generally regarded as a lying, deceitful, double-faced hypocrite, with a profession of religion which was altogether false. Indeed, he went by the name of “Holy Joe.” Needless to say, the frivolity and brusqueness of Master Litton were a sore trial to this good man, and on one occasion at least they came into almost violent collision.

During Mr. Napier’s Chancellorship a puisne judgeship became vacant. The Irish Attorney-General did not desire it, and it was understood that the Solicitor-General was not to have the offer of it. In these circumstances Master Litton applied for the position both to the Lord-Lieutenant[7] and to the Lord Chancellor. From each he received a most favourable and sympathetic reply, that of Lord Chancellor Napier being especially cordial in its tone. Yet the appointment was conferred elsewhere. The Master was naturally mystified at this result, until he received a letter from the Lord-Lieutenant to the effect that the opposition of the Lord Chancellor to Litton’s appointment had been so strong and vehement that much against his will and with great pain and regret he had been compelled to yield to it. The next morning on his way down to Court the Master called on Napier and was shown into his study. The Lord Chancellor rose, put out both hands to Master Litton and, with a semblance of intense emotion, tears filling his eyes, said, “My dear Litton, I did my very best, and I have failed. It was not my fault. I am indeed LORD CHANCELLOR NAPIER grieved.” Litton looked at him steadily, and then produced and read the letter of the Lord-Lieutenant. “Holy Joe” was stricken dumb, and Litton left the room, turning at the door to say: “Lord Chancellor though you are, you are none the less a damned liar and a damned blackguard! Good morning.”

It was in this period of my life, in 1865, when I was sixteen years old, that I first attended a gathering of a political character. My father took me to the examination hall of Trinity College to hear the proposing and seconding of candidates for election to Parliament as Members for Dublin University. The candidates included Mr. Whiteside (afterwards Lord Chief Justice of Ireland), Mr. Anthony Lefroy (the son of the Lord Chief Justice Lefroy of whom I have already spoken), and Dr. Ball, Q.C. (afterwards Lord Chancellor).

The top of the hall, in which the proceedings took place, was separated from the remaining portion by a strong wooden barrier designed to prevent the incursions of the students, who, however, remained as spectators and were able to interpolate into the speeches remarks often as witty as they were offensive. An archdeacon who referred to notes written on sermon paper while he was proposing Mr. Lefroy was caustically asked to put up his sermon and preach, for once, extempore. A reference to Mr. Lefroy’s father produced the suggestion: “Tell us something about his grandfather,” a sally which was greeted with yells of immoderate laughter, the reference being to the supposed illegitimacy of the Lord Chief Justice.

The ablest speech made that day, I thought, was that of Dr. Ball, who, amid a running fire of interruptions, denounced Toryism and eulogised Liberal principles, declaring, with a vehemence that might almost be regarded as an anticipation of the doctrines of Bolshevism, that the time had come for the complete abolition of the present unbearable state of affairs. Dr. Ball’s subsequent political career after this outburst is not without interest. At that election, standing as Radical candidate, he was defeated. But at the very next General Election, only three years later, he stood as Tory Attorney-General and was elected; and eventually, still remaining a Tory, he became Lord Chancellor.[8]

Dr. Ball’s variation of principles was the subject, some years later, of an excellent joke made at his expense by Mr. Dowse[9] when Attorney-General for Ireland. At question-time in the House of Commons Dr. Ball pressed Mr. Dowse to give the exact date of some incident. Mr. Dowse assumed a reluctance. Dr. Ball was still more insistent, and then Mr. Dowse seized the opportunity he had designedly made. “I DR. BALL cannot give the right hon. gentleman the exact date,” he said, “but I will give him the best approximation I can. It was between the time when he contested Trinity College as a Radical and was defeated and the time when he contested Trinity College as a Tory and was elected.”

[1] Formerly the residence of Sir John Parnell and now that of Mr. John Dillon.

[2] The riot is depicted in a painting which hangs in the Common Room of the Fellows of Trinity College.

[3] He finally became Chaplain of the Richmond Bridewell, Dublin.

[4] Thomas Moore, the poet, was asked by Lord John Russell, nearly half a century later, not to write—or if he wrote, not to publish—a life of Lord Edward FitzGerald, since its publication would arouse angry passions which then were not yet dead. Moore disregarded the advice and published his work. He subsequently complained that although he sent presentation copies of it to the members of Lord Edward’s family the receipt of them was never acknowledged. I am in a position to know, however, that one of these copies, if not acknowledged, was at least carefully perused. Some years ago the late Mr. Daniel Browne, K.C., a County Court Judge, told me that he had purchased in a second-hand bookshop in Dublin the copy presented to Lord Edward’s daughter, Lady Campbell. On the margins were careful annotations in Lady Campbell’s writing, and on one page was a very clever drawing of the dagger with which Lord Edward defended himself while trying to escape from arrest. There was also a note in which Lady Campbell related that the Duke of Wellington told her that the Government were very well aware of Lord Edward’s places of concealment and could have arrested him at any moment, had they not preferred to give him the opportunity of leaving the country. His persistence in remaining in Ireland, however, finally left them with no alternative but to order his arrest.

[5] Terence Bellew MacManus had been one of the leaders of the Irish insurrectionary movement of 1848, and had died in exile at San Francisco in 1861. The suggestion was made that his body should find sepulture in the country of his birth from which he had for so long been outcast. The idea was received with enthusiasm. The cortège was attended by delegates from every American city, and the delegates returned with a knowledge of the strength and intensity of the Fenian Movement in Ireland. To the MacManus funeral may be attributed the powerful support subsequently accorded by Irish Americans to the Fenian organisation in the troublous period of 1865-1868.

The project was at one time seriously entertained of making the MacManus demonstration the signal for an outbreak in Ireland which would have involved the country in civil war.

[6] The daughters of Mr. Piers Geale were all ladies of great beauty. This Miss Geale was the only one of them who remained single, the others making such brilliant marriages that Mr. Geale’s home in Dublin came to be known as “the House of Peers.”

[7] In England puisne judgeships are filled on the recommendation of the Lord Chancellor alone. In Ireland they were Government appointments.

[8] Dr. Webb, Fellow of Trinity College, who was a Radical candidate opposing Dr. Ball on this occasion, was very merry over Dr. Ball’s inconsistency, terming him “the ambi-dexter hand-ball.” Yet subsequently Dr. Webb himself made the same change, unsuccessfully contesting a constituency in the Tory interest, and eventually accepting an Irish County Court judgeship from a Tory Government.

[9] Afterwards a Baron of the Irish Court of Exchequer.

Part II

DUBLIN and OXFORD

Dr. Ingram. Dr. Mahaffy. Mr. Blennerhassett. Rev. Thomas Gray. Rev. Thomas Stack.

In July, 1866, at the age of seventeen, I matriculated in Trinity College, Dublin, obtaining first place on the first day of the examination. Among the examiners on that occasion were John Kells Ingram and John Pentland Mahaffy, each of whom, in a different way, has since won an undying reputation.

Dr. Ingram, a gentleman of the very widest and most profound erudition, a great historian, a great Greek scholar, and a great exponent of philosophy, was a man of medium size, with hair prematurely grey and wonderfully penetrating bluish-grey eyes. He had a very kindly, reassuring manner, with a quiet and dignified demeanour which invariably commanded respect.

He is best remembered as the author of that immortal national ballad, “The Memory of the Dead,” which is more popularly known from its first line as “Who fears to speak of ’98?” This was written one evening in his rooms at Trinity College some time before he obtained his Fellowship. He was then a young and ardent Irish Nationalist, leaning towards the Young Ireland Movement, which was at that time springing into existence and was destined eventually to destroy the constitutional movement of Mr. O’Connell. Subsequently, however, he took little, if any, part in active political life, and his winning of the Fellowship and consequent devotion to study were the subject of one of Mr. O’Connell’s jibes, that “the bird who once sang so sweetly is now caged and silent in Trinity College.”

It was a matter of general regret amongst those who knew him that Dr. Ingram was not appointed to the Provostship of Trinity College when it became vacant in 1881. But he had not entered into Holy Orders, and indeed it was whispered to his detriment that he held Positivist views which would be unsuitable in the head of a college founded for the advancement of true religion and useful learning. Yet although his failure to reach that office may have caused disappointment to him, he had the consolation of knowing that in the estimate of the world of learning he was the best man for the place. He was emphatically a man of books rather than of action, and a very great ornament to the college in which he was universally beloved and admired.

Dr. Mahaffy, on the other hand, did attain the Provostship, and was in many respects the greatest holder of that office. When I first knew him he was in the late twenties, an athletic-looking, splendidly-built man, with a wealth of bright brown hair and with a marked individuality of manner which DR. MAHAFFY characterised him to his dying day. In conversation with him more than fifty years later, I reminded him that at my first examination, when he came to take up the paper on which I had been writing answers to his questions, I wished to add something more and held on to it; but he pulled it from me, saying with the kindest of smiles, “No, no, this won’t do at all. You must learn to economise your time.” When I reminded him of this, I mentioned that he had given me practically full marks for my paper. “What a mistake I must have made!” was his reply.

Dr. Mahaffy, even when I first knew him, was known as “The General,” because of the wide variety of the subjects which he studied: like Bacon, he had taken all knowledge for his province. He touched nothing in which he did not excel. He has been accused of being a seeker after the great and the highly-placed. In point of fact they sought him much more eagerly than he ever sought them. It is true that he did not suffer fools gladly, and, yielding at times to an astonishing quickness of apprehension and readiness of wit, he said things too good to be forgotten and too true to be forgiven. In commenting once on a certain ungenerous high official who received a large salary intended to defray the expense of frequent entertainments—which, however, were not given—Mahaffy said: “His house was no doubt badly maintained and very dingy: but there were no mice in it.”

Dr. Mahaffy’s greatness as a historian, scholar, divine, antiquarian, and musician have been acknowledged throughout the world; but it is not so generally known that he was a firm believer in supernatural manifestations and had on more than one occasion seen apparitions. He has told me of some of his thrilling experiences of the supernatural.

Despite his nervous sensibilities and a highly-strung temperament, he was a man of great physical courage. On April 24th, 1916, the day of the outbreak of the insurrection to which I have already referred, as I sought sanctuary in Trinity College I saw Dr. Mahaffy in the Provost’s Garden, and he beckoned me to join him. The whole of Dublin was at the moment in uproar. The sound of rifle fire from St. Stephen’s Green could distinctly be heard, the people in the streets were in a state of panic, and no one could tell to what part of the city the terror would next spread. Yet Dr. Mahaffy conversed with me on the situation with perfect quietude of manner. He seemed as he walked up and down the garden to be as calm and free from alarm as if nothing exceptional had been happening, and as if there was nothing to prevent his enjoying studious ease in an academic bower.

I may perhaps record it as a curious coincidence that the late Mr. Rowland Ponsonby Blennerhassett, K.C. and I entered Trinity College on the same day in 1866, and matriculated on the same day in Christ Church, Oxford, in 1868. Mr. Blennerhassett was an undergraduate at Oxford in 1872 when he was elected to Parliament in the Home Rule interest REV. THOMAS GRAY at a by-election in Kerry. This was the last open vote by-election in Ireland, for five months subsequently the Ballot Act received the Royal Assent and the death-blow was given to electoral intimidation. The contest in Kerry was not so much one between the candidates (Mr. Dease and Mr. Blennerhassett) as a struggle between the principles of Whiggery and those of Nationality, and its result made the Home Rule Movement an acknowledged factor in the politics of the United Kingdom.

Until recently the Vice-Provost of Trinity College was the Rev. Thomas Gray, a man little known in the world at large, but loved by every student of the college within the last fifty or sixty years. He died in December, 1924, after these words, which I hoped would meet his eyes, had first been written. At the time of his death he was grey-haired and a nonagenarian. In my time he was a young man with thick, black curly hair. He was a most accomplished scholar and a profound theologian, but his chief repute arose from his extraordinary kindness and sympathy, his constant desire to befriend the students and his readiness to assist them out of scrapes. When Junior Dean, a position to which large disciplinary powers are attached, he controlled the most unruly spirits, not by instilling a fear of fines and penalties, but by arousing in them a genuine dislike of giving him any personal annoyance. Mr. Gray once reminded me that in my student days he saved my life. In an outbreak of rowdyism, in which I was taking my full share, I was bodily seized in order that I might be thrown over the railings of the lawn in one of the college quadrangles. These railings were spiked, and since, needless to say, I was struggling and doing my best to encumber my captors, it is probable that I should have alighted on the railings instead of beyond them and have sustained serious and very likely fatal injuries. Suddenly Mr. Gray walked calmly to the scene, and in a second all thought of rowdyism vanished.[1]

Scholarships in Trinity College, unlike those at Oxford and Cambridge which are conferred as the result of examinations at entrance, are given as the result of an examination held once a year at which students of one, two, three, or even four years’ standing may compete, and are regarded as high academic distinctions. Scholars have the parliamentary franchise of the University, and are regarded in some respects as part of the governing body of the College, whose formal proceedings are described as those of “The Provost, Fellows and Scholars of Trinity College.”

At the scholarship examination in 1868, having won three first honours in Classics in the preceding year, I stood as a candidate among the Senior Freshmen, that being the name given to second-year students. The Fellows of Trinity of fifty years ago, like their successors of the present day, were kind-hearted and considerate, their desire being to make REV. THOMAS STACK the lives of the students in their charge as pleasant as circumstances permitted. In examinations they aimed at the discovery, not of ignorance, but of knowledge. But in any large body of men there are invariably some who fail to conform to the spirit and tone of their associates, and in this instance the exception to the rule of kindness and cordiality was the Rev. Thomas Stack, who, from his ferocious manner at the examinations, was known by the soubriquet of “Stick, Stack, Stuck.” He was a short, pale-faced man whose clerical attire included a monocle, a tie that had once (according to popular legend) been white, and an immense expanse of shirt-front which proclaimed unmistakably that he did not conform to Wesley’s maxim on the relation of cleanliness to godliness. The viva voce portions of scholarship and fellowship examinations were to him so many opportunities for the exhibition of a cowardly brutality towards those temporarily placed in his power. He seemed to come to his task as an inquisitor rather than as an examiner. One of the candidates on this occasion had been deprived of the use of his legs in a riding accident and had to be carried to his place in the hall. With natural sympathy, the other examiners came down from the daïs to save him the trouble and pain of being moved; but Mr. Stack showed no such consideration. He summoned the candidate to come to him, and when the difficulty was explained to him he turned to another of the examiners and said, in a voice loud enough to be heard everywhere in the hall: “Do you know that we have got a cripple here?” Then he walked to the table at which the “cripple” was seated, banged down his books, and said in a loud, rasping tone: “Now, sir, do you see what you have made me do?”

When my own turn arrived I was treated in a manner which would not have been permitted by the Bench in the cross-examination of a perjured witness. I was standing merely to test my strength with a view to winning the scholarship at the next examination, and I was fully prepared for a defeat. But I was not prepared for the treatment meted out to me by Mr. Stack. As it happened, with four of the five examiners I obtained marks that would easily have brought me high up in the list of scholars, and I was afterwards assured by my coach that my answers to Mr. Stack’s questions should have won equally high marks from him; but they did not. Yet it was not his apparent unfairness that affected me, but his demeanour. I left the daïs with a sense of having been subjected to humiliation and outrage and with the feeling that if I went in again for the examination I should be submitting myself to fresh insults. I therefore left Trinity College in the autumn of 1868, and entered Oxford University.

[1] Mr. Gray has since told me that it is because of this incident that the railings of the college lawns are now no longer spiked.

Dean Liddell. Mr. Lecky. “Lewis Carroll.” Dr. Pusey. Canon Heurtley. Canon Liddon. Bishop Samuel Wilberforce. Mr. Sidney James Owen. Dean Kitchen. Bishop Edward Stuart Talbot. Bishop Stubbs. Mr. Goldwin Smith. Professor Freeman. Mr. J. A. Froude. Right. Hon. Montague Bernard. Mr. Charles Neate. Viscount Bryce. Dr. Jowett. Rev. George Washbourne West. Rev. Thomas Fowler. Primate Alexander.

In those days the scholarship examinations of the various Oxford colleges were not held on the same day, and it was the practice for candidates, if they failed at one college, to submit themselves for examination at others until they were successful. I tried first to obtain a Demyship at Magdalen, but failed.[1] The next examination was for exhibitions at Christ Church, and there I obtained a Slade Exhibition in addition to a First Exhibition.

The Dean of Christ Church was then Dr. Liddell, the great lexicographer: an outstanding figure, stern in manner, but kind in heart. He was highly sympathetic in all his relations with the undergraduates, by whom, none the less, he was held in awe for the gravity and austerity of his manner. For my own part I greatly admired and respected him; but I was never at ease in his presence.

On one occasion the Dean was condemning with great severity a good classical scholar who had been plucked at the Little-go through complete ignorance of mathematics. The youth gently murmured in excuse that Mr. Gladstone himself had been plucked at that examination.[2] “Mr. Gladstone,” said the Dean, “came up from Eton with no knowledge of mathematics. It is true that he was plucked in that subject at the Little-go, but he was so much ashamed of himself that he worked at it and eventually obtained a First Class. It is so easy to imitate Mr. Gladstone in his failure: see that you imitate him also in his success.”

I do not think that adequate recognition has ever been paid to Dr. Liddell for his influence in the formation and moulding of the characters of the young men at Christ Church. He was comparable, almost, to Jowett in Balliol, or to Dr. Coffey at the present time in University College, Dublin. He was perhaps at his best in the Cathedral pulpit—a splendid specimen of both physical and intellectual manhood. I remember being present at a friendly undergraduate discussion in college, at which one man, a distant relation of the Dean, said: “I know DEAN LIDDELL him better than any of you, and in my judgment the Dean approaches as nearly as any man, in character and conduct, to the highest Christian ideal.” That was the opinion of one of the Dean’s students given to other students, and is, indeed, a worthy tribute to his greatness.

In Dublin, many years later, I had the happy privilege of meeting the Dean on a footing of greater equality than, of course, had ever been possible in my undergraduate days. He inspired the same feeling of respect, I may say indeed of reverence, in me, in manhood as in boyhood. On one of these days I accompanied the Dean and Mrs. Liddell to a celebrated Dublin photographer’s. Mrs. Liddell begged me to “go and chaff the Dean in order to make him look pleasant in his photograph.” “Chaff the Dean!” I replied. “I could no more chaff him now than I could have done fifteen years ago at Christ Church.”

I was privileged during that visit of the Dean’s to Dublin on more than one occasion to be his guide through the city. I accompanied him and Mrs. Liddell to Dublin Castle, where Sir Bernard Burke, the Ulster King-of-Arms, showed us some of the State papers preserved in the Ward Robe Tower. “Froude and Lecky,” he explained, “both worked here.” “Surely not together?” exclaimed the Dean. “Oh, no,” was the answer. “If they were put here together they would be certain to fight.” Many years later I related this incident in the House of Commons in the presence of Mr. Lecky. He took it very seriously, and interposed, looking unfeignedly grieved, “Mr. Froude and I were never, so far as I am aware, in Dublin at the same time.”

In the Viceregal Court, until recently, forms and ceremonies were observed with a strictness which savoured of the ridiculous. Ladies on leaving the dining-room for the drawing-room made a profound obeisance to the Lord-Lieutenant. The late Lord Londonderry held the Lord-Lieutenancy at that time, and I recollect Mrs. Liddell confiding to me how difficult she found it to refrain from laughter at thus doing homage to one whom she had known as a youth at Christ Church. It was perhaps an anomalous position; yet I do not question that Lord Londonderry could with all sincerity and even with awe have paid a similar compliment to the Dean.

In my undergraduate days, the Rev. C. L. Dodgson, better known by his nom de plume as “Lewis Carroll” and immortalised as the author of Alice in Wonderland, was one of the Students of Christ Church (as the Fellows of that College are called), and a Lecturer in Mathematics. He did not look what he was, one of the wittiest writers in the English language, and the teaching of Euclid seemed more in keeping with his manner as a somewhat serious and austere divine than indulgence in the revels of an unrivalled imagination. His lectures, too, were eminently prosaic and removed toto orbe from the style of the writings which have delighted the world.

Dr. Pusey was in those days one of the Canons DR. PUSEYof Christ Church and Professor of Hebrew. I never had the privilege of meeting him individually, but I remember him as an old gentleman, short in stature, and distinguished always by wearing a skull cap in the Cathedral. He was the preacher of beautiful, simple sermons delivered with a perfect intonation. Towards the close of his discourses the dear old man used to pause to look affectionately on the rows of young men sitting below him, and then would address them in his peroration as “My sons.”