* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

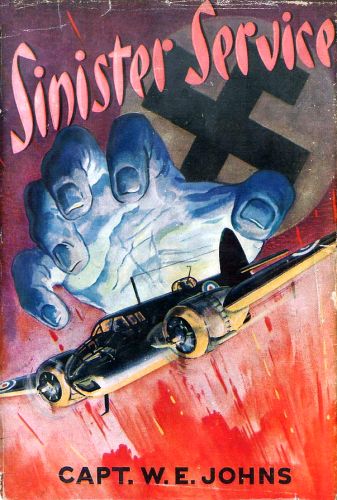

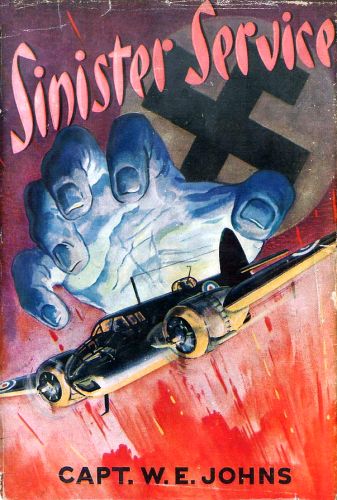

Title: Sinister Service

Date of first publication: 1942

Author: Capt. W. E. (William Earl) Johns (1893-1968)

Date first posted: Dec. 31, 2022

Date last updated: Dec. 31, 2022

Faded Page eBook #20221266

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, akaitharam, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

The Air Adventures of

Major James Bigglesworth

BIGGLES HITS THE TRAIL

BIGGLES FLIES EAST

BIGGLES AND CO.

BIGGLES IN AFRICA

BIGGLES: AIR COMMODORE

BIGGLES FLIES WEST

BIGGLES GOES TO WAR

BIGGLES FLIES SOUTH

BIGGLES FLIES NORTH

BIGGLES IN SPAIN

THE RESCUE FLIGHT

BIGGLES IN THE BALTIC

BIGGLES IN THE SOUTH SEAS

BIGGLES—SECRET AGENT

BIGGLES DEFIES THE SWASTIKA

SPITFIRE PARADE

BIGGLES SEES IT THROUGH

BIGGLES IN THE JUNGLE

BIGGLES: CHARTER PILOT

BIGGLES IN BORNEO

SINISTER SERVICE

THE ADVENTURES OF LANCE LOVELL, COUNTER-ESPIONAGE

OFFICER, TOLD BY HIS BROTHER AND

UNOFFICIAL ASSISTANT, RODNEY LOVELL

Captain W. E. Johns

Illustrated by

Stuart Tresilian

GEOFFREY CUMBERLEGE

OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

Oxford University Press, Amen House, London E.C.4

GLASGOW NEW YORK TORONTO MELBOURNE WELLINGTON

BOMBAY CALCUTTA MADRAS CAPE TOWN

Geoffrey Cumberlege, Publisher to the University

| First published | 1942. |

| Reprinted | 1949. |

PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY M. AND G. BLANCHARD LTD.

| CONTENTS | ||

| Foreword by Rodney Lovell | 7 | |

| PART ONE | ||

| I. | An Interrupted Journey | 17 |

| II. | The Enemy Strikes Back | 27 |

| III. | An Unexpected Meeting | 39 |

| IV. | The Enemy Strikes Again | 51 |

| V. | Walls within Walls | 65 |

| VI. | Warm Work | 76 |

| VII. | Run to Earth | 87 |

| PART TWO | ||

| VIII. | Secret Mission | 101 |

| IX. | The Adventure Begins | 106 |

| X. | Lance gets Busy | 123 |

| XI. | On the Road | 130 |

| XII. | Hamburg | 140 |

| XIII. | Shocks | 148 |

| XIV. | Desperate Work | 157 |

| XV. | Still on the Run | 168 |

| XVI. | A Fight for Life | 175 |

| XVII. | Touch and Go | 182 |

Before I tell you how all this came about—that is, how I came to be in the Secret Service (or, as some call it, the Sinister Service)—I had better tell you a few things about myself, and my brother Lancelot, because this will save a lot of explanation later on. Incidentally, I am afraid there will be a good many I’s in my story, but this cannot be avoided if I am to tell you the part I played myself in these dark adventures.

As you will have seen, my name is Rodney Lovell, with the accent on the last syllable, please—Lovell. I am seventeen years old, tall for my age, and fairly tough from doing a lot of mountain-climbing when I was a kid. You see, I had the misfortune to be born in Germany, where my father was in the Diplomatic Service. He was away a good deal, but we had a nice home at Brengen, in the Black Forest, where there was some good climbing to be had. Lance and I often spent days together in the mountains. We went to school at Brengen, where, naturally, we learned to speak German as well as we spoke English. In the house, of course, we spoke English, but outside we spoke almost entirely in German—for obvious reasons.

Lance is three years older than I am, and so it came about that when I was fifteen he was eighteen, and went off to Oxford to finish his education. But just before this something happened, something which I suppose was responsible for what we are doing now. Lance went crazy on gliding. As you may know, in pre-war days gliding was all the rage in Germany, although what we did not realize then was that it was all part and parcel of a huge scheme for making the youth of Germany air-minded. But that is by the way. Lance took up gliding, and he must have been pretty good at it, for he won several competitions at the Wasserkuppe, where the national and international contests were held.

As a direct result of this he became interested in flying—that is, power-flying, in proper aeroplanes. He told me privately that as soon as he was old enough he was going to join the R.A.F. For the time being he had to be content to join a flying club. He often took me with him into the air, and although I was too young to take my ‘ticket,’ I could soon handle a plane fairly well. Well, to make a long story short, Lance went to Oxford, where he managed to get into the Oxford University Air Squadron. For the next two years I saw him only during vacations. He was still wrapped up in flying.

Then, suddenly, everything seemed to go wrong. Our little world went to pieces.

You may have noticed that calamities seldom come singly, and thus it was with us. Hitler gained control in Germany, and we—that is, my mother and I—often found ourselves in embarrassing positions. Fellows at school, fellows I had known for years, instead of being friendly suddenly became—how shall I say? Well, they became arrogant and vicious. I couldn’t understand it at all, and it made me miserable. One day I saw a small boy being kicked about, and, naturally, I took his part. It turned out that he was a Jew. I didn’t know that, and I can’t say that it would have made any difference if I had, for it wasn’t his fault, and he was a harmless little fellow, anyway. I got some hard kicks for my pains, and after that I was unpopular at school.

As if things weren’t bad enough, on top of this came the news that Lance had crashed, and was in hospital, badly injured. Another fellow, a pupil, had collided with him in the air. I was now seventeen, and in the ordinary way I should soon have followed him to Oxford; but then, to cap all, my father died. He died very suddenly. I have always felt that there was something strange about the manner of his death, for he was on his way to England at the time and was certainly fit enough when he started. So we never saw him again. The Germans said it was pneumonia. It may have been—I don’t know.

My mother packed our things and we returned to England. It was a good thing we did, for the war broke out soon afterwards. My mother took a cottage in Scotland, near her old home, and there Lance, who by this time had been discharged from hospital, came to see us. He was thin and pale, and although he insisted that he was fit, he had obviously been very ill. He walked with a slight limp, which the doctors told him he would have for the rest of his days. But the real tragedy of the crash, from his point of view, was this: he had been turned down, on medical grounds, for the R.A.F. There was nothing he could do about it, and this made him miserable. He went off to London, and soon afterwards wrote to say that he had been successful in getting a job; but he was curiously vague as to what it was. Apparently it was some sort of traveller’s job, for although he had a room in London he was seldom there.

A little later I followed him to London, where, as so many fellows had joined the forces, I was able to get an office job. I wasn’t very happy in it, but it enabled me to keep myself so that I was no longer a financial responsibility to my mother. In any case, I didn’t care about the job because I intended, as soon as I was old enough, to join the R.A.F. as an aircraftman, hoping that pretty soon, owing to my flying experience, I would be able to get my ‘wings.’

I saw Lance occasionally, although I seldom knew where he was or what he was doing. However, he seemed to be getting on very well, for he always had a fair amount of money. What was more important, he was now fit again, although he was still thin and walked with a limp. Sometimes when he came to see me I thought he looked very tired, but as he was sensitive about his health I thought it better not to mention this. Sometimes he gave me a little extra money. Once we went for a run in his car—a powerful Bentley. When I asked him how he had got it, he told me it wasn’t his, really; it belonged to the firm. Which, I subsequently discovered, was true. But he didn’t tell me the name of the ‘firm.’ I asked him how he managed to get petrol for such an extravagant car, but he said in a vague sort of way that he had a friend who fixed him up. This also was true, but I little guessed who the friend was. He wouldn’t talk about himself. Naturally, I was curious, but whenever I brought the subject up he would change it deftly.

I admired him tremendously. I always did. In fact, I think most fellows do admire their elder brothers. In Lance I had something to look up to, for he was a grand chap and we had always been such pals. He was absolutely fearless, and would take any risk in the most casual sort of way. If he hadn’t been so thin he would have been really handsome. When anything amused him he had a funny trick of smiling with his eyes, but he seldom laughed out loud. I put this down to the effects of the crash. I’m afraid I got very fed-up during the intervals he was away, for sometimes he would disappear for weeks on end. It was, I think, for this reason that he suggested I gave up my cheap diggings and used his rooms in Jermyn Street—to keep the bed aired, as he put it.

When the first dim suspicion entered my mind that he was in the Secret Service I do not know. The idea did not come suddenly, in the manner of a brainwave. It seemed to develop slowly, but once the thought had crystallized in my mind I felt that this was the answer to his mysterious behaviour. I determined to challenge him the next time I saw him.

About a week later, one Friday evening, he arrived home looking more tired than usual. I put my question to him, but he laughed it off without giving me a direct answer.

‘What put that extraordinary idea into your head?’ he chaffed me—but I noticed that his keen grey eyes were not smiling.

‘I’ve been putting two and two together,’ I told him. ‘You speak German like a Nazi, you know Germany inside out, and you can drive any sort of vehicle—including aeroplanes. These accomplishments would, I imagine, be very useful to a man in the Intelligence Service—particularly at a time like this.’

‘My dear Rod,’ he replied, in a bantering tone of voice, ‘may I remind you that you speak German, you know Germany, and you can fly aeroplanes, but you’re not in the Intelligence Service.’ He always called me Rod—short for Rodney.

‘That may be so, but you’re three years older than I am,’ I parried.

He laughed and clapped me on the shoulder. ‘Forget it,’ he said.

‘All right,’ I agreed reluctantly. ‘Are we going out to dinner?’

He shook his head. ‘Sorry, old boy, I can’t—not to-night. I shall have to be drifting along now.’

I was bitterly disappointed. ‘What? Going off again already?’ I cried. ‘Where are you going?’ I demanded.

Lance shrugged his shoulders. ‘Matter of fact, I’ve been doing rather a lot of work lately and I’m a bit run down. I’ve got a day or two off. It’s a bit stuffy in London and the sirens get on my nerves, so I thought of running down to the New Forest for a spot of fresh air.’

‘Doing what?’

‘Oh—just hiking.’

‘In that case,’ I said evenly, ‘there’s no reason why I shouldn’t come with you.’

He looked up sharply. ‘What about your job?’

‘I don’t go back until Monday morning. If it comes to that, I shouldn’t care if I never went back at all.’

‘Why, that’s fine,’ Lance astonished me by saying. ‘Come along, old boy, by all means. It will be like old times, you and I, tramping through the forest.’

‘Do you really mean that?’ I shouted delightedly.

‘Of course. I’ve got the Bentley outside. Put your pyjamas and a toothbrush in a bag and we’ll push off right away. We’ll find an inn somewhere to park for the night.’

At that moment the sirens wailed.

‘There goes Old Gloomy,’ he observed. ‘Come on, let’s get off before the bombs start banging.’

In half an hour we were on our way. Little did I dream where our journey was to end. For that night my adventures began, adventures which, I think you will agree, would satisfy the wildest craving for excitement. Now I’ll get on with the story.

It must have been about nine o’clock, and we were just on the fringe of the New Forest, when a girl crashed out of the bushes and stumbled on the road not twenty yards in front of our dimmed headlight. Lance was keeping a sharp look-out for stray forest ponies, but even so, I wouldn’t have given much for her chance, for the Bentley was fairly lapping up the miles. The girl, seeing us bearing down on her, threw up her arms as if she had lost her head. She looked like losing her life.

Even now I don’t know how Lance stopped the car in time. His arms and legs seemed to jerk like a steel spring that snaps across the middle; the car tried to hunch itself; the brakes screeched; the tyres, on locked wheels, bit into the macadam with the rasping wail of a circular saw. We stopped with a jerk that threw me forward against the instrument panel. By the time I had recovered myself the girl was groping her way towards the door. She seemed to be crazy.

Lance pushed open the door on his side. ‘What the dickens do you think you’re playing at?’ he demanded crisply.

The girl didn’t answer at once. After a glance over her shoulder, swift and apprehensive, she had the nerve to try to get into the car.

But Lance wasn’t having it. ‘Not so fast, young lady,’ he said curtly. ‘What’s the idea?’

‘Help me—help me—you must help me.’

The words fairly shot out of the girl’s mouth, like bullets pouring from a machine-gun. It was obvious that she was very badly scared—or pretended to be.

‘Take it easy—take it easy. What’s the trouble?’ asked Lance.

‘Two men are after me.’

‘Two, eh?’ I saw Lance’s sharply cut features relax into a ghost of a smile. I don’t think he believed her. I didn’t—I don’t know why.

‘If it’s a lift you want, why not say so?’ went on Lance reproachfully. ‘Why all this dramatic——’

He got no farther. There was a crashing of undergrowth and two men charged out of the bushes. They pulled up dead when they saw the car.

Lance got out with alacrity and the girl dived into the seat he had just vacated. I got out quietly my side and walked round to the back of the car. I don’t think the men saw me.

After a brief pause they came on, walking slowly up to the car. The beam of Lance’s pocket-torch stabbed the gloom and revealed their faces in yellow spotlight.

‘Lost something?’ he inquired coldly.

Frankly, I don’t quite know what my feelings were at this moment. I was rather annoyed at being stopped, and I may have been rather alarmed. Vaguely, at the back of my mind, I started thinking about fifth-columnists, and parachutists, and about people’s cars being stolen. It seemed to be a funny business. But when I saw the faces of the two men I felt that there might be something in the girl’s story after all. They weren’t exactly toughs in the accepted sense of the word, but they were the sort of fellows ordinary men instinctively distrust. One was heavily jowled, with overhung eyebrows and a dour expression; the corners of his mouth were turned down at an aggressive angle. The other was taller, hatchet-faced, alert; the brim of his hat was well down over his eyes. Both were fairly well dressed. Neither answered Lance’s question, so he spoke to them again.

‘What’s all this about?’ he said tersely.

‘Look out!’ I fairly yelled the words, and at the same time dived at the nearest man.

He had taken a quick step forward with his arm raised, and I saw a revolver in his hand. I caught it coming down and landed him a crisp jab in the ribs that made him grunt. The gun went off, singeing my hair and temporarily blinding me. I didn’t see the second man, but I felt him; he landed on my back like a sack of flour.

A brisk two minutes followed—a hazy two minutes. I have no clear recollection of the details, because, for one thing, it was dark. I nearly hit Lance by mistake, but throwing the fellow off my back, I grabbed the arm of the chap with the gun and gave it a twist that made him curse. The gun clattered on the hard road. He snatched at it, but I gave him a kick that sent him sprawling forward on his face. Having no time to pick up the gun, I caught it with the toe of my shoe and sent it farther down the road. Before I could get back one fellow was already climbing through the hedge. A moment later his companion broke away from Lance and followed him. I ran to the gun, snatched it up, and started after them, but Lance shouted to me to get back in the car.

I got in beside him, and noticed that the girl had managed to get into the back seat. The car shot forward and raced for about a couple of hundred yards. Then Lance stood on the brake and stopped again. He took the weapon from my hand and examined it in the light of the instrument board.

‘Mauser,’ he said softly, in a queer tone of voice.

Then he turned to the girl.

‘Were those friends of yours?’

‘Don’t be absurd,’ she returned sharply.

Lance shrugged his shoulders in a way that told me that he was not entirely convinced, ‘What was the idea?’

‘Do you really want to know?’

‘I most certainly do,’ answered Lance in a brittle voice. ‘In fact, if you haven’t a good explanation to offer I’m going to take you to the nearest police station.’

‘All right,’ said the girl without hesitation. ‘I’m sorry I had to stop you, but—well, I bit off a bit more than I could chew. I’m grateful to you for getting me out of a mess. I live quite close. If you would care to run me home I’ll tell you all about it. Or, if you prefer, take me to the police station and I’ll make a statement.’

Lance hesitated, but only for a moment, ‘Where do you live?’

‘Back down the road about a mile, then turn left. Two hundred yards along and you’ll see a drive on your right. Turn in there.’

‘Very well. But make no mistake, young lady,’ said Lance evenly, ‘if there’s any nonsense somebody is liable to be hurt. It happens that I, too, have a pistol in my pocket.’

I may say that this was the first I knew about Lance carrying a weapon. Anyway, without another word he turned the car, took the turning and ran up a longish drive between silver birches to a pretty old cottage. He pulled up outside the door, and I saw his eyes make a quick reconnaissance. Not a light showed anywhere, although this, of course, was only to be expected on account of the black-out. All the same, even in a house that has been blacked-out one can usually see a faint chink of light somewhere if one looks hard enough.

‘Nobody at home, eh?’ murmured Lance.

‘No; since my maid went into munition work I live here alone. I have a daily woman to look after the place, but at the moment she’s sick.’

‘Funny sort of place for a girl to live—alone, isn’t it?’

‘I don’t live here all the time,’ explained the girl. ‘During the week I work in London, but this house happened to be mine—it was left to me by my father—so I come down for week-ends.’

Lance helped her out of the car.

‘Are you coming in?’ she inquired.

‘Certainly,’ replied Lance smoothly.

She opened the door with a latchkey and we followed her in. A match flared. She lit a candle and went through into a sitting-room, where an oil-lamp soon made things considerably brighter.

Glancing round the room I saw that it was comfortably, even tastefully, furnished. Then I had another look at our new acquaintance. She was, I judged, not more than twenty, dark, good-looking rather than pretty, with steady brown eyes. She was neatly dressed in tweeds with flat-heeled walking shoes.

She looked at us appraisingly for a moment. ‘Would you like a cup of coffee?’

‘That’s not a bad idea,’ answered Lance.

She disappeared for a few minutes and then came back with a tray.

‘Do you take sugar, Mr ——?’ Her eyes caught mine and asked a question.

‘My name’s Lovell,’ I told her. ‘Rodney Lovell. This is my brother, Lancelot.’

‘Mine’s Ashton-Harcourt—Julia to my friends. Make yourselves at home. It’s a bit chilly—I’ll light the fire.’

Lance caught my eye and smiled faintly. Presently we were gathered round the fire, quite a snug little party.

‘And now, how about the story?’ suggested Lance.

Julia regarded him thoughtfully for a moment. ‘I’m afraid you won’t believe it,’ she said dubiously.

‘Suppose you tell us—and leave us to judge?’

Julia still looked doubtful. ‘I suppose you’ll think I’m crazy if I say that those two men were spies?’

Lance considered her sceptically. ‘You haven’t by any chance been reading——’

She interrupted him. ‘If you’re going to start talking like that I won’t say another word. Please get the idea out of your head that because I’m a girl I’m a fool.’

‘No such idea was in my head,’ protested Lance. ‘How about going on with the story?’

‘Very well. Then I repeat, unless I’m right off my course, those two men were spies.’

Lance raised his eyebrows. ‘You use an expression that has a familiar ring—being off your course. Was that just a figure of speech or does it imply that you’re a sailor—or an air pilot?’

Julia laughed. ‘That was rather clever of you. Yes, I’ve flown quite a lot. I hold the “B” licence.’

‘Good,’ I put in. ‘We all talk the same language. We’ve done a bit of flying.’

‘Why, that’s splendid,’ declared Julia. ‘It should make things a lot easier to explain. It’s a longish tale, but I’ll cut out the details and give you the main facts.’

‘Go ahead,’ invited Lance.

‘I’ve been flying for about two years,’ went on Julia. ‘The war, of course, put an end to it. I’ve never owned my own machine—that is, not a power-machine—but I once had a sailplane. To be quite frank, I found flying a bit expensive, so I took up gliding at the London Gliding Club, and did quite a bit of cross-country work. I mention this because it has a direct bearing on what happened to-night. About a month ago I was sitting here, just about this time, when I heard a noise that puzzled me not a little. A glider doesn’t make much noise, but it does make a little, and, to anyone who has flown one, it is unmistakable. The noise I heard was the soft whine of a sailplane coming in very low. The weather was much like it is to-night, moonlight, just a little wind—perfect for soaring. I know what a sailplane sounds like, you needn’t doubt that, and believe it or not, I distinctly heard one go over. Naturally, I ran out and looked up, but I couldn’t see anything; not that I expected to; you know as well as I do that you can’t see a machine very far away, at night, unless it carries navigation lights.’

Julia filled up our coffee-cups.

‘Well, I came in and let it go at that,’ she resumed. ‘A week later, about the same time, I heard the same noise. That got me guessing—seriously. Who could it be? There hasn’t been any gliding since the war started, and people don’t glide at night, anyway. Well, I thought about the problem for some time, and the more I thought the more I became convinced that something funny was going on. Laugh if you like, but you can’t say that the theory I’m going to put forward isn’t possible. The Germans have some of the finest glider pilots in the world, and it suddenly struck me that there was no reason why a power pilot shouldn’t tow a glider to within striking distance of the coast. The glider pilot could then cast off and go anywhere he wanted to—always assuming that he knew the country. I remembered that the year before the war a team of star German sailplane pilots came over here. They stayed at Dunstable, and did quite a lot of gliding. They seemed rather partial to the New Forest—they said they always kept away from built-up areas because of the risk of an emergency landing. You see what I’m getting at?’

‘Go on,’ said Lance quietly. ‘You’re doing fine.’

‘Thanks. Very well, it is beyond dispute that German pilots could come over here if they wanted to, without anyone being the wiser. Sailplanes have a certain advantage over power planes in that they are silent—or comparatively so. Last week we had an ideal night for gliding, so I sat outside and waited. Just before midnight I distinctly heard a glider go over. I should say it was about a couple of hundred feet up. It was heading south. The hum of it told me that the pilot was losing height, as if he intended coming down. I followed the sound, but, of course, I couldn’t keep up with it. I was left far behind.’

‘So you don’t know whether it landed or not?’ Lance put the question.

‘I didn’t see it.’

‘But if a machine came over and landed, could it get off again?’ I asked.

‘Certainly,’ answered Julia. ‘A car could tow it off. For years at Dunstable we used a car for towing off. You simply jack up the rear wheels and use the power to run a winch.’

Lance nodded. ‘That’s right.’

‘Of course,’ continued Julia, ‘the glider needn’t necessarily want to get off again. Its mission might be to bring something over, or somebody—a spy, for instance. But this is only surmise. I wanted facts, so to-night, being an ideal night for gliding, I decided to try to get them.’

‘Did you tell the police about your suspicions?’ queried Lance.

Julia’s lip curled. ‘The police!’ she said scornfully. ‘Of course I went to the police—and a lot of thanks I got. They thought I was a crazy woman with a spy complex. In desperation I wrote a report on the whole thing and sent it to the Ministry of Home Security. What happened? Nothing. It’s true I got a brief note of acknowledgement, but it wasn’t very encouraging.’

‘How about finishing the story?’ suggested Lance.

‘Yes, let’s stick to the facts. To-night I decided to do a bit of spy-catching on my own account, but, as you saw, I made a mess of it. They nearly caught me. I started early and walked to an open piece of country about three miles from here—the direction in which the machine seemed to be heading when I heard it. Sure enough I heard it coming, and started to follow the sound. But I didn’t get far. I collided with two men who, if their actions were anything to go by, were also waiting for the aircraft. They came after me and I ran for my life. I’d no weapon of any sort. Luckily, I know every inch of the country, so I made for the nearest road and managed to race them to it. You know the rest. I saw your car coming and made a dive for it. Believe me, the matter was urgent, for the men were close behind. You saved the situation—at least, as far as I am concerned.’

‘Yes, it rather looks that way,’ acknowledged Lance thoughtfully. ‘What are you going to do next?’

‘Nothing,’ answered Julia shortly. ‘I’ve had enough. I’m not going to make a bigger fool of myself trying to get the police interested. What can I do?’

Lance caught my eye. Then he turned to Julia. ‘Suppose we all have a go at trying to locate this mysterious glider?’

Julia sprang to her feet. ‘Now we’re getting somewhere,’ she declared enthusiastically. ‘What a joke it would be if we could teach these professional spy-catchers their business.’

Lance nodded. ‘Yes, it would be a joke, wouldn’t it?’ he agreed softly. ‘As a matter of fact——’

He broke off, and I jumped up as there came an unmistakable sound outside. A car-starter had whirred. Julia made a dash for the window, but Lance was after her in a flash. He caught her by the arm and pulled her back.

‘Put the light out,’ he snapped, and ran to the door.

Julia evidently obeyed his order, for as we got to the door the room was plunged into darkness.

‘Confound it,’ muttered Lance viciously.

The red tail-light of our car was just disappearing round a bend in the drive.

As the tail-light faded Lance turned quickly to our hostess.

‘Have you got a car?’

‘Yes—but no petrol.’

‘None?’

‘Not a drop. The tank’s dry.’

‘How far away is the nearest garage or petrol pump?’ asked Lance tersely.

‘The nearest is in the village—Lyndenham. It’s about three miles.’

A telephone stood on a writing bureau. Lance walked over to it and picked up the receiver. He wobbled the call-arm up and down. Not a sound came from it. ‘Dead,’ he said succinctly. ‘They must have cut the wire. How far away is the nearest call-box?’

‘There isn’t one nearer than Lyndenham.’

‘What a nuisance. Who’s your nearest neighbour?’

‘I don’t know,’ answered Julia. ‘It’s a farmhouse standing back from the road nearly half a mile away. It changed hands just before war broke out. The purchaser wanted to buy this cottage at the same time—at least, a man came to see me about it—but I wouldn’t sell.’

‘Hm.’ Lance thought for a moment. ‘Look here,’ he said quietly, ‘I’m no alarmist, but I’ve got a feeling that we’re in a tight spot. Those men who attacked you must have followed us here—or watched the car lights from a distance. Now they’ve taken my car, but it’s pretty certain they didn’t take it merely because they wanted it. They took it to isolate us here. If we go out we may run into something unpleasant—that is, if we simply walk down the drive. We shall have to think of something better than that.’ Lance went over to a sideboard, and in the light of his torch examined the contents. He brought a bottle back with him. It was labelled brandy. ‘Do you happen to have another bottle of this stuff?’ he asked Julia.

‘I think so,’ she answered. ‘In fact, I believe there are two or three in the cellar. They belonged to my father. I always keep one up here in case of accidents.’

‘Please go and fetch all you have.’

Julia went out, and presently came back with another bottle. ‘This is the only one I can find,’ she said.

Lance stood the two bottles together. ‘It should be enough. Where’s the garage?’

‘Just outside the front door, on the left.’

‘Is there an inside door—I mean, can you get into the garage without going outside?’

‘No, but there’s a side door opposite the back door. The garage used to be a garden shed until I converted it by knocking out one end and putting double doors in.’

‘Let’s go and have a look at it.’

Julia led the way to the kitchen. Through the window over the sink we could see a rectangular building. The side door showed up black in the starlight.

‘What’s the make of your car?’ asked Lance.

‘It’s a Vauxhall twelve.’

‘Apart from petrol, as far as you know, there’s nothing wrong with it?’

‘Oh no, it’s in perfect order.’

‘Fine.’ Lance moved towards the door.

‘Just a minute—what are you going to do?’

‘For a start, get out of here. As I’ve already said, I think it would be dangerous to walk out, although I wouldn’t take such a serious view if we didn’t know for certain that these people we’re up against carry firearms. That Mauser tells an ugly story. To start with, it’s German. People don’t carry that sort of gun for bluff—it’s too heavy and it’s too efficient. I intend, therefore, to drive the car out and make for the village.’

Understanding leapt into Julia’s eyes. ‘Using brandy for fuel instead of petrol?’

‘That’s my idea. If I may say so, you keep pace with the situation very well.’

‘Thanks. And when we get to the village—what then?’

‘You can go to the local inn; or, if you prefer, to the village constable, and ask for protection.’

‘That’s considerate of you,’ returned Julia, a hint of sarcasm in her tone. ‘And what are you going to do while I tell my story to a cynical police officer?’

‘Take a stroll round the forest and try to find this glider.’

‘Oh no, you’re not,’ declared Julia emphatically. ‘Not without me. Please remember this is my affair.’

‘It may be your funeral. This is serious—more serious than you may suppose. We’re at war, don’t forget.’

‘I’m not likely to forget it,’ retorted Julia. ‘If you go wandering about the forest it’s more likely to be your funeral than mine. I know every inch of the country. Without me you’d be floundering about like a mosquito in a thunderstorm.’

Lance shrugged his shoulders. ‘All right, if that’s how you feel about it.’

‘It is. This is the first real excitement I’ve had since the war started. But let’s not argue. Let’s get clear of the house. I’ll get my coat.’

We went back to the sitting-room, saw that the fire was safe and got the brandy. Julia fetched her coat; then we went back to the kitchen. Lance opened the back door an inch and listened, but everything was quiet—or seemed to be.

‘Stay where you are until I give you the all-clear,’ he whispered.

With the two bottles under his left arm, and his gun in his right hand, he crept through the door and stood flattened against the house wall near a rain-water tank. I watched the garden and the drive. Nothing stirred. Lance glided across to the garage like a ghost; there was a faint click as he lifted the latch and disappeared inside. Still there was no sign of opposition, and I began to wonder if we weren’t going to a lot of unnecessary trouble after all.

There was a delay of about five minutes while Lance was putting the brandy in the tank—at least, I assumed that was what he was doing.

‘Your brother seems to be rather good at this sort of thing,’ whispered Julia in my ear.

I smiled in the darkness. ‘He is.’ Actually, I had been doing some fast thinking, and I was more than ever convinced that either directly or indirectly he was in the Intelligence or Counter-Espionage Service.

Presently his shadowy figure appeared in the opposite doorway. He whistled softly.

‘Over you go,’ I told Julia.

As she went across to the garage I distinctly heard a twig crack somewhere among the trees that lined the drive, but I could see nothing. I closed the door, locked it, and then went over. Lance was waiting.

‘Good,’ he said quietly. ‘I’ll drive. Julia, you get in the back seat. Rod, you’ll have to open the garage doors. I doubt if you’ll be able to do it without making a certain amount of noise, so speed is the great thing. Once you start, go right on whatever happens. Never mind about closing them. The instant the doors are wide enough for me to get through hop into the seat next to me as fast as you can. Here’s the Mauser. Keep it handy. As you open the garage doors I shall start the engine. If anything happens I shall make a rush for it.’

I went to the doors and investigated the lock to make sure that there should be no hitch once I started opening them. It was an ordinary Yale lock which, of course, I could open from the inside. There were bolts top and bottom, but they were already drawn.

‘All ready,’ I said, and turning the lock pushed the doors wide open—or tried to. One of them stuck half-way. I put my weight against it and shoved. The bottom scrunched on the gravel drive with a noise that settled any further question of silent tactics. I heard the car start up behind me. Simultaneously a shot smashed through the door—a glancing blow that sent splinters flying. I made a dive for the car. It was already on the move. I fell into my seat, slammed the door and wound down the window. Two yellow flashes close to each other leapt towards us from behind a rhododendron bush. I let drive at it, firing as fast as I could pull the trigger. Something hit the bonnet of the car with a metallic whang.

‘Get on the floor, Julia,’ snapped Lance, and we sped down the drive. Several shots were fired, and at least two bullets hit the car, but they did no serious damage. Swinging into the main road, we nearly collided with a big saloon that was just slowing up. Our wheels rasped on the macadam as we swerved past it. Lance tore on down the road.

‘Watch that car behind us, Rod,’ he said evenly.

I floundered over into the back seat and looked through the rear window. The car was following us.

‘It’s coming,’ I said.

‘How much lead have we got?’

‘About a hundred yards.’

‘It’s a Buick, so it’ll have speed of us; use your gun when it starts to draw up.’

‘You bet I will,’ I grated, and bashed the glass out of the window with the butt end of my gun.

‘Hey—go steady with my car,’ protested Julia.

‘I’ll buy you a new one,’ I promised, and took a long shot at the pursuing car, just to let the driver know what to expect if he tried to get too close.

We raced on down the road, doing about fifty miles an hour. The Buick made a spurt and started overhauling us, so I opened fire, taking careful aim, whereupon the car dropped back. Evidently the driver didn’t like the situation.

‘The village is half a mile, ahead,’ called Julia.

I watched the Buick. Presently a head appeared above the rim of the sunshine roof; a moment later a gun spat and I caught the faint whistle of a bullet. For the next two or three minutes I gave shot for shot, and then we ran into the village. It was, of course, in utter darkness on account of the black-out; no doubt it would have been dark at that hour, anyway.

Lance turned a corner. A yard yawned on our left. He ran into it, flicked off the lights and stopped the engine. Five seconds later the Buick tore past.

‘I don’t think they saw us,’ I said.

‘They’d hardly have the nerve to start a pitched battle in the middle of a village, I imagine,’ murmured Lance. He got out, walked as far as the main road, and came back. ‘I don’t see them,’ he said. ‘They must have gone right on.’

‘And where do we go from here?’ I inquired.

Lance thought for a moment. ‘Now that they think we’ve bolted I think our best plan is to fix Julia up somewhere and then go back to the house. They’d hardly expect us to——’

‘I like that,’ broke in Julia. ‘You’re not fixing me up anywhere. I’m in this as much as you are—more, in fact, since I started it, and it happens to be my house.’

‘Have it your own way,’ agreed Lance. ‘Don’t think I’m trying to get rid of you. My suggestion was dictated by common prudence. Perhaps my idea that girls should not be exposed to danger is antiquated.’

‘It passed out of fashion with crinolines,’ murmured Julia smoothly. ‘If you’re satisfied that we’ve thrown the enemy off the trail let’s go back to the cottage by all means.’

Lance said no more. He cruised quietly back up the road and brought the car to a stop a hundred yards or so short of the drive.

‘I think a reconnaissance would be advisable,’ he suggested. ‘You watch the car, Rod.’

‘Just a minute,’ I put in. ‘What was the idea of coming straight back here? Why didn’t you get some petrol while you were in the village?’

‘Because it would have taken time, and I wanted to get back here quickly,’ replied Lance. ‘If the enemy suppose that we’ve left the house they may come along to have a look at it—and I’m anxious to have a look at them. In any case, I don’t want to start a fuss in the village if it can be avoided. We can get petrol in the morning. Frankly, I only went to the village to get Julia to a place of safety, but since she has decided to stay with us I must act as if I were alone. There are more aspects to this affair than either of you realize—yet.’

With this cryptic remark Lance stepped on to the grass verge and disappeared among the silver birches. He was away about a quarter of an hour.

‘It’s all clear—as far as one can make out in the dark,’ he said when he came back. ‘All the same, keep your eyes open in case there are any sharpshooters lurking in the bushes.’

He drove the car up the drive. Nothing happened. We put it in the garage, closed the doors, and then stood still for a minute or two, listening. Everything seemed quiet enough, an oppressive sort of silence after what had happened. Nevertheless, I wasn’t convinced that the fellows into whose business we had crashed, whatever it might be, would be content to let it go at that. I couldn’t get the Mauser out of my mind, for, as Lance had remarked, it’s an ugly weapon, favoured only by people in ugly business.

We went across to the kitchen and listened again. It’s easy to get nervy in such circumstances. In an empty house absolute quiet is as ominous as sound.

‘It seems to be all right. Let’s go in,’ I suggested.

We stood for a moment or two in the kitchen, and I was just moving along the corridor towards the sitting-room when Lance spoke.

‘I don’t remember a clock here in the kitchen, when we stood here a little while ago.’

Julia answered: ‘There isn’t one.’

Lance’s manner became tense. His torch split the darkness. ‘Julia, open the back door,’ he said sharply, as, with the beam of light, he explored the furniture.

The only sound was a faint tick-tock . . . tick-tock. My pulses increased their tempo. The light came to rest on a low cupboard. Lance opened it. It was filled with pots and pans. Near by was the fireplace—an old-fashioned kitchen-range. Lance opened the oven door. Instantly the tick-tock became more definite. He knelt, snatched something out of the oven, and went through the door with a rush. I heard him running and raced after him. I could just see his silhouette twisting through the trees of a small orchard. I saw his arm go up, and heard something fall with a thud on the grass. Instantly there was a sheet of flame, an explosion, and a blast of air that knocked me over backwards.

As I picked myself up I saw Lance doing the same thing.

‘Great Scott!’ I gasped. ‘That was a bit hot. Our friends certainly have all the equipment.’

‘Yes,’ said Lance quietly. ‘Let’s get back to the house.’

We walked back and found Julia picking up pieces of shattered glass and putting them into the sink. ‘What on earth was that?’ she asked in a shaken voice.

‘Just a squib our enemies left behind for a souvenir,’ returned Lance grimly. ‘If we hadn’t discovered it the house would have gone up, and we should have gone up with it. Everyone would have supposed that the house had been hit by a bomb dropped by enemy aircraft. There’s an alert on, don’t forget. Close the door, Rod.’ He led the way to the sitting-room.

‘Shall I light the lamp?’ asked Julia.

‘No, but be ready to do so if I say the word. Let’s sit down and be quiet—I fancy we may have visitors. I can’t help feeling that that bang will excite curiosity, and if the fellow who slipped the bomb in the oven comes back and finds the house still standing he’ll want to know why.’

This seemed to be a reasonable assumption, so I said nothing. Silence fell. Nobody spoke. Minutes went by. Then I heard a car coming—heard it turn into the drive. There was nothing furtive about its approach. It stopped. A door slammed. Footsteps crunched on the gravel and halted outside the front door. Knuckles rapped sharply.

‘Behave normally, Julia,’ whispered Lance. ‘Light the lamp, answer the door, and ask him in—whoever it is. Rod, keep your gun handy but out of sight.’

I must say that Julia didn’t lack nerve. She lit the lamp. Then quite calmly she went to the door and opened it.

‘Yes, who’s there?’ she asked evenly.

‘Sorry to trouble you,’ came a cheerful, casual voice. ‘I thought I heard an explosion somewhere about here, so I’m investigating.’

‘Come in,’ invited Julia.

A man walked into the room, and my taut nerves collapsed like a pricked balloon. It was a constable—or rather a special constable. He was a big, florid-looking man of about fifty, fresh-complexioned, with a fair moustache. He carried his uniform cap in his hand, and smiled affably when he saw us sitting there.

Julia turned to us with well-simulated nonchalance. ‘Did you hear any sort of explosion?’ she asked naïvely.

Lance shook his head. ‘No, I haven’t heard a sound. Why, what’s wrong, officer?’

‘I was on my beat and I thought I heard an explosion in this direction. Funny you didn’t hear it.’

‘Very odd,’ agreed Lance. ‘We were sitting here having a chat before going to bed.’ He glanced at his wrist-watch. ‘As a matter of fact I didn’t realize it was so late.’

‘In that case I won’t keep you up,’ announced our visitor. ‘Sorry to trouble you, but we’re all on our toes, you know, with one thing and another.’

‘Yes, I expect you are,’ murmured Lance, in a queer tone of voice.

He showed the officer to the door, waited until the car had driven off and then came back. His face was expressionless.

‘What do you make of that?’ I asked.

‘Nothing—except that special constables in this part of the world seem to be very keen on their job.’

‘But surely you don’t think——’

‘As a matter of fact, I’m doing a lot of thinking,’ interrupted Lance. He turned to Julia. ‘We can’t do anything more until morning, so I think you might as well go to bed. We’ll stay here, taking turns to keep guard—just in case.’

‘I suppose I might as well,’ agreed Julia, lighting a candle. At the door she turned. ‘Glad to have met you—it’s been quite fun, hasn’t it?’

Lance nodded, ‘So far,’ he agreed cautiously. ‘But don’t make any mistake. This business isn’t over yet, and we’re skating on thin ice.’

Julia hesitated. ‘Just one question. Do you think these people are fifth-columnists, or something?’

Lance took a cigarette thoughtfully from his case. ‘It’s a bit too early to say. But we shall find out. Good night.’

As soon as Julia had gone I turned questioning eyes to my brother. ‘It looks as if we’re on the track of something.’

‘Definitely. Julia was right. Something queer is going on, and unless I’m mistaken it’s serious. I don’t like her being here, but it’s a bit difficult to get rid of her without being brutal about it. I’m not altogether happy about you being here, if it comes to that. We’re playing a dangerous game, and we shall have to watch our step.’

‘There’s one thing in our favour,’ I pointed out. ‘These people, whoever they are, don’t know us. They’ll probably think we’re just a trio of inquisitive fools, easily scared off.’

Lance stared at the dying fire. ‘You always were an optimist, Rod, old boy,’ he remarked. ‘You appear to have overlooked the fact that they’ve pinched my car, that our suitcases were in it, and that in our suitcases are clothes. In the pocket of my spare jacket there were some letters I intended answering at the first opportunity. They will reveal my identity.’

‘Just what do you mean by that?’ I asked sharply.

Lance hesitated. Then he looked at me squarely. ‘For heaven’s sake never mention it, but your guess about the work I’ve been doing was right. I’m in the Counter-Espionage Service.’

I drew a deep breath. ‘I see,’ I said slowly, for want of something better to say. ‘And you think these people may know of you?’

‘If they do, they’ll be after me,’ returned Lance slowly. ‘But we’ll talk about this to-morrow. Try to get some sleep. I’ll keep guard.’

We were on the move early the following morning after an uneventful night. Julia came down and got breakfast and we all gave a hand clearing up. Lance said little. He seemed to be doing some profound thinking. But as soon as we had finished our work he put on his coat and picked up his hat.

‘Let’s take a stroll,’ he suggested. ‘Julia, perhaps you would be kind enough to lead us to the open space where you ran into those two men last night?’

‘Is it safe, do you think?’

‘Frankly, I don’t think it is, but, after all, this is England, and I doubt if any gang would have the nerve to shoot three people in broad daylight. If our friends of last night are as clever as I think they must be, they’ll try guile rather than gunshots now that they’ve had time to think things over. Remember, they haven’t seen us yet—at least, not properly; and if they are going to shoot every hiker in the forest the place will soon look like a battlefield. Come on, let’s go—it’s after nine. We’ll lock up and take the key.’

The forest looked just the same as usual, so much so that I found it not easy to believe that the events of the previous night had really happened. We met one or two people and a party on horseback, but nobody suspicious, and an hour’s stroll brought us to an open area of several acres. There were others, similar, in the locality, but none as large. For the most part the country was rough, with gorse, heather, and occasional groups of trees. We didn’t stop walking. We just strolled on, but our eyes were busy—not that there was anything out of the ordinary to look at. On the far side of the piece of ground which we suspected was being used by the mysterious gliders, behind a thick belt of Scotch firs, rose the time-mellowed chimneys of a Tudor house of some size.

‘You’re right, Julia; there’s plenty of room here for a glider pilot to get in,’ observed Lance. ‘Naturally, we could hardly expect them to leave machines lying about. Who lives over there in the big house—do you know?’

‘I’ve no idea,’ returned Julia. ‘To tell the truth, I don’t know anybody about here.’

‘If there’s a house, there should be a road near it.’

‘There is. It’s about two hundred yards away on our left. It passes that house.’

‘Then let’s investigate.’

We walked over to the road, a typical forest highway, and followed it until we came to a gate hung on brick, ball-topped pillars, behind which a moss-grown gravel drive meandered between thickets of rhododendron, yew, and laurel towards the house. A labourer, or a gardener, was sweeping up wind-blown leaves.

‘Garthstone Manor,’ murmured Lance, reading the name carved on one of the pillars. ‘Let’s call and ask them if they’ve seen anything of our dog.’

‘Dog?’ Julia stared.

Lance smiled faintly. ‘Yes, our little fox-terrier; we’ve lost him, and we’re most upset about it. We must have an excuse, and that, I think, is as good as any.’

Julia nodded. ‘I understand.’

We went up the drive. The gardener looked up quickly when he heard our footsteps and asked us what we wanted. He was a nondescript sort of fellow. Lance told him we were looking for a dog. The man said it hadn’t come that way, whereupon Lance told him he was wrong, for he had just caught sight of it in the bushes. Without giving the man a chance to reply he walked on towards the house, whistling and calling ‘Bongo! Bongo!’ . . . ‘Dash it, he’s gone again,’ he said loudly when we were right up against the house.

The front door opened and a man came out, and as my eyes found his face I experienced a mild shock. For a moment I couldn’t recall where I had seen him before—then I remembered. It was our special constable caller of the previous night. But now he was in tweeds, a bag of golf clubs hanging from his shoulder. He raised his eyebrows when he saw us.

‘Good morning,’ he called cheerfully. ‘Is this a return visit?’

‘No; as a matter of fact I didn’t even know you lived here,’ answered Lance truthfully. ‘We’re chasing our dog. He went off after a rabbit, and the last we saw of him he was tearing through your shrubbery.’

‘I haven’t seen him.’ The man was frankness itself. ‘Look round by all means. No doubt he’ll turn up—they usually do. Perhaps you’d care to come in and have some refreshment while you’re waiting?’

‘That’s very kind of you,’ returned Lance warmly. ‘By the way, my name’s Lovell. This is Miss Ashton-Harcourt—and my brother.’

‘My name’s Smith—a nice easy name to remember.’ Our new acquaintance raised his hat. ‘Come in.’

We followed him into a well-furnished library, where he offered us hospitality. I don’t know about the others, but I felt a trifle embarrassed.

‘Did you succeed in locating the explosion last night?’ inquired Lance casually, strolling over to a window. It was half-open, and overlooked the outbuildings, shrubberies, and gardens usually to be found round a house of this size. In an open space a bonfire was smouldering; judging by the charred area it had evidently been a large one.

‘No, I can’t make it out at all,’ answered Smith readily. ‘Most disappointing. It’s a dull business, you know, this wandering about half the night. Nothing ever happens here. Still, it’s up to everyone to do his bit.’

‘Quite,’ said Lance vaguely, catching my eye as he turned away from the window.

I stiffened, trying to keep my expression under control, for I knew why Lance had turned away. A slant of wind had eddied the taint of the bonfire into the room, and it had an unusual odour. One doesn’t forget smells, and I had encountered that smell before. It was dope, aeroplane dope—that is to say, doped fabric.

Smith crossed over and closed the window. ‘Phew,’ he sniffed, wrinkling his nose. ‘Why must these confounded gardeners be continually lighting fires?’

‘They’re a trying tribe,’ laughed Lance. ‘Well, we mustn’t keep you from your game any longer,’ he went on. ‘I wonder where that dog went? It was kind of you to ask us in.’

‘Not a bit. Look in again some other time. I can’t ask you to stay to lunch because I’ve got a date at the golf club.’

We all strolled down to the drive. ‘Thanks again, and good-bye,’ said Lance.

‘It’s been a pleasure,’ returned our host.

We walked back towards the gate, whistling and making a pretence of looking for the imaginary dog. Not until we were back on the main road did Lance refer to our visit.

‘So that’s Mr Smith,’ he remarked thoughtfully.

‘What a nice fellow,’ observed Julia.

‘Charming,’ returned Lance drily. ‘Will this road take us home if we keep on it?’

‘Yes, it’s the road you were on last night when I stopped your car.’

‘Are there any more houses about?’

‘Only a public-house—it’s just round the next bend. I don’t think there are any other houses for miles. My cottage is probably the nearest.’

‘It’s rather early to go home; suppose we call at the tavern?’ suggested Lance.

‘I don’t want anything to drink,’ said Julia.

‘Neither do I,’ answered Lance. ‘But we can’t very well go into a public-house without having a drink—and I must have a look at this place. Ah! Here comes the postman. Perhaps he can give us some information.’

The deliverer of letters had just come round a corner on a push-bike. Lance stopped him.

‘Am I right in supposing that a Mr Smith lives at Garthstone Manor?’

‘Yes, he does,’ was the rather blunt answer.

‘I wonder if it is the same Mr Smith whom I used to know in America—Mr P. J. Smith?’

‘How should I know?’

‘I thought he might get some letters from America.’

‘He never gets any letters at all,’ declared the postman surprisingly, and he continued on his way.

Lance made a little grimace. ‘How very odd,’ he murmured, half to himself. ‘But here’s the tavern—the Rockham Arms. Let’s go in.’

The public-house was just opening. It wasn’t a very inviting place. There was nothing friendly or picturesque about it. It was just one of those red-brick houses that only succeed in looking dull. Inside, the rooms smelt disgustingly of stale beer and sawdust. It gave me the impression of not being a popular place, for which, I imagined, the landlord was largely responsible, for he was altogether the wrong sort of man to run a country hotel. He was youngish, about thirty-five, with deep-set eyes of peculiar intensity. They had an almost fanatical gleam, an impression that was aggravated by a mop of long, unkempt hair. I had a vague feeling that I had seen his face before, but couldn’t remember where. He gave us no cheerful greeting, but just stood waiting behind the bar.

We ordered our drinks.

‘I hear you’ve got a new neighbour up at the Manor,’ remarked Lance casually to the landlord.

‘What do you mean—new? He’s bin here a couple of years,’ answered the landlord in a surly voice.

‘I understand he’s a special constable?’ went on Lance.

‘I don’t know nuthin’ about him,’ was the churlish response.

Lance shrugged his shoulders. ‘All right, you needn’t be so bad-tempered about it. I was only trying to be agreeable.’

We were in the place about ten minutes, during which time nobody else came in. Then we walked on down the road.

‘Keep going—I’ll overtake you,’ said Lance quietly, when we had gone only a little way. Turning, I saw him scouting among the bushes at the back of the inn. He soon caught up with us.

‘Well, we don’t seem to be making much progress,’ complained Julia in a disappointed voice.

‘On the contrary we’re doing very well,’ answered Lance. ‘I suggest that we go back to the cottage, get the car, and go into Lyndenham for lunch. We’ll get some petrol at the same time.’

It sounded a good idea, so it was agreed.

We had nearly reached the drive when a car came along behind us travelling at high speed. I heard it coming, but paid no particular attention to it, for there seemed to be no reason why I should. Admittedly, there was no footpath, but I supposed that the driver could see us, and there was plenty of room for him to get by. Lance, who was on the outside, glanced over his shoulder. Instantly his hand flashed to his pocket. At the same time, with his left hand, he gave me a violent shove, and I took a header into the ditch with Julia on top of me. I could see Lance clinging to the hedge. The car swished past within a foot of us.

Furious, I scrambled up and tried to get its number, but if there was one it was smothered with mud. It tore on down the road and disappeared. The whole thing had happened in a few seconds.

Fortunately the ditch was dry. I got back on the road and helped Julia out; she was pale, and gave us her opinion of the crazy driver as she straightened her hat. Suddenly she stopped and stared at Lance as though a thought had struck her.

‘Good heavens! I believe that was done on purpose,’ she said breathlessly.

‘It could hardly have been an accident,’ replied Lance. ‘I had a feeling something of the sort was going to happen.’

‘Why?’ I demanded.

‘Surely you recognized the car?’

‘Great Scott! Of course. It was your Bentley!’

Lance nodded. ‘It was. Had it knocked us down no doubt the driver would have turned the car over on top of us and left it there. The police would have drawn their own conclusions after the publican had told them that we had called there, and that would have been that. I warned you that we were playing a dangerous game. Come on.’

We hurried on to the cottage.

‘Do you happen to have a telephone directory?’ Lance asked Julia, as soon as we were inside.

‘Yes.’

‘Would you mind looking up Smith’s number.’

She did so, and marked the place with her finger.

‘Lyndenham, 431,’ murmured Lance.

‘How on earth did you know that?’ cried Julia in amazement. She hadn’t mentioned the number.

‘I didn’t—but I suspected it. I’m afraid I rather overdid things at the tavern, and the bare mention of Smith’s name put the landlord on his guard. Of course, I wasn’t to know.’

‘Know what?’ I demanded.

‘That he was a friend of Smith’s. The inn was on the telephone. As soon as we went out the landlord rang up the Manor. I thought he might—that’s why I went back. I heard him give the number, but couldn’t catch the conversation. It rather looks as if Smith is the man we’re after. We’ve got to be very careful.’

Julia stared at Lance in astonishment. ‘What on earth gave you that idea?’

Lance lit a cigarette. ‘Several things,’ he answered. ‘In the first place, it’s unusual for gardeners to accost people when making a call. Then, Smith was too affable—people are not so free with their hospitality in these hard times. Finally, to clinch matters, there was the bonfire. Not even gardeners build a bonfire of that size so close to a house—anyway, not in war-time. The fire was still smouldering; therefore it had been made recently. When I caught the stink of burning cellulose dope, such as is used on aeroplane fabric, it seemed a safe guess that Mr Smith was a friend of the mysterious glider. You smelt the dope, too, didn’t you, Rod?’

‘Yes, I did,’ I answered. ‘And wasn’t Smith in a hurry to close the window!’

‘In such a hurry that it suggested a guilty conscience. I had no suspicion about the inn until I saw the landlord, and the state of the place. The inside was so filthy that it would certainly discourage customers—which, I fancy, was the intention. I suppose, Rod, you didn’t recognize the landlord?’

‘No, but his face was vaguely familiar. I had a feeling that I’d seen it in a newspaper.’

‘You probably have. The gentleman is Mr Henry Lothman, the disgruntled Bolshevik agitator, who got six months in prison not long ago for uttering threats against the Prime Minister. He’s a nasty piece of work.’

‘By Jove! You’re right!’ I cried. ‘What a memory you’ve got.’

‘A face like that isn’t easily forgotten,’ said Lance seriously. ‘I imagine anyone on the wrong side of the law would find him a ready and willing tool. Unless I’m very much mistaken he’s working for Smith. I’m afraid they realize that we suspect them—in fact, the car incident proves it. They won’t take their eyes off us after this. Frankly, I think that if there happened to be only one of us they’d make no bones about straightforward murder, but three people together are a more difficult proposition. Still, I’ve no doubt they’ll do it if they can—as they’ve just demonstrated.’

‘I wonder if Smith is really a special constable?’ conjectured Julia.

‘Ah! That’s something we don’t know, but we’ll find out. The first question we must ask ourselves is, are we going to stay here or would it be wiser to look for new quarters?’

‘I hate the idea of being driven out of my own house,’ protested Julia. ‘Suppose we stay here for the time being; if it gets too dangerous we can always move to an hotel.’

Lance nodded. ‘Very well, we’ll try it. Before we do anything else we’d better run into Lyndenham and get some lunch. I’ll get the tank filled with petrol at the same time.’

‘How? My ration-book’s empty.’

‘Mine isn’t,’ murmured Lance, smiling faintly. ‘To-night we’ll have a closer look at Mr Smith’s establishment.’

We locked the house, got the car out, and went on to Lyndenham.

‘Isn’t it time you told the police about your car being stolen?’ queried Julia.

‘I don’t think so,’ answered Lance. ‘With all due respect to them, at this juncture the local police might complicate things.’

Lance brought the car to a stop outside the one decent hotel in Lyndenham, one popular with tourists in the summer. He told me to take Julia in and order lunch—he’d join us presently. He had a ’phone call to make. With that he walked away.

Julia and I went into the hotel. There were a number of men in the lounge, and the first one I saw was Mr Smith, chatting with a small group. He nodded to us when he saw us, and asked us to join him in a drink, but I said we were taking lunch and went on through to the dining-room, where we waited until Lance arrived about a quarter of an hour later. He pulled up a chair and sat down.

‘I’ve managed to get the tank filled,’ he told us.

Julia raised her eyebrows. ‘Filled, eh? Are you a magician, or a friend of the Ministry of Supply?’ she asked sarcastically.

‘Just a friend of the Minister of Transport,’ returned Lance humorously. ‘By the way, I have ascertained that Mr Smith is not only a special constable but he’s captain of the local force. He’s lived at the Manor for just over two years; it doesn’t belong to him; he took it furnished, on lease. Incidentally, Julia, you may be interested to know that it was Mr Smith, or rather an agent acting for him, who tried to buy your cottage. Evidently he was anxious to keep the district to himself—which he could have done of course by buying the few dwelling-houses that existed. Ah, here is the gentleman.’

The door of the dining-room opened and Mr Smith came in, followed by three other men. I recognized two of them at once. So, I could see, did Lance. They were the men who had attacked Julia on the road when she had stopped our car. Smith chose a table for four near a window overlooking the street and ordered food.

‘Well, they’re not going to spoil my lunch,’ declared Julia emphatically. ‘I’m hungry.’

‘You can take your time,’ replied Lance. ‘We’re in no great hurry.’

An hour passed. We had finished our coffee. Smith and his companions had also finished their lunch; but they sat on, talking in low tones. They rarely looked in our direction, but it was soon obvious that they were killing time waiting for us to make a move. Lance countered this by ordering more coffee, a move which told the party at the other table that we could play a waiting game, too. Smith said something to the others, got up and came across to us. He addressed Lance.

‘Are you thinking of staying long in these parts?’ he inquired casually.

‘Why?’ parried Lance blandly.

‘I thought you might care for a round of golf some time.’

‘What a pity we didn’t bring our clubs,’ murmured Lance. ‘As a matter of fact, we are leaving almost at once. Miss Harcourt is thinking of closing the cottage; she thinks it’s a bit—er—lonely, with a war on.’

‘I think she’s wise,’ returned Smith suavely. ‘I hear that the burglars are taking advantage of the black-out.’

‘Exactly. That’s what we’ve told her.’

Smith nodded. ‘Well, good-bye if we don’t meet again.’

‘We may run into each other some time,’ smiled Lance. ‘The world’s a small place.’

Smith returned to his party. Presently they all got up and went out, but Lance made no move.

‘What are you waiting for?’ I asked.

‘A message—I think this is it,’ answered Lance.

A man had entered the dining-room; he glanced around and then, seeing that we were the only people in the room, came over to us.

‘Mr Lovell?’ he queried.

‘Yes,’ said Lance. ‘Thanks.’ He took the letter the man held out to him.

‘Any answer, sir?’ questioned the newcomer.

‘I’ll tell you in a moment.’ Lance ripped open the letter. ‘By the way, how did you get down here?’

‘By road, sir.’

‘In a police car?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Hm—pity.’ Lance read the letter. ‘All right, there’s no answer,’ he said, and the man departed.

I could see that Julia was not a little puzzled by all this—and so was I, for that matter.

‘What’s going on?’ inquired Julia curiously.

Lance threw me a sidelong glance, then looked at her gravely.

‘I happen to have a friend at Scotland Yard,’ he explained. ‘I rang him up just before lunch and asked him if he could tell me anything about Smith. Unfortunately the messenger came down in a police car and Smith may have seen it as he went out. If he did, it will confirm his suspicions about us, and we can look out for trouble.’

‘You certainly have some useful friends,’ remarked Julia. ‘Why not get this pal of yours at Scotland Yard to send some men down and surround the forest? Then, when the mysterious glider pilot comes again they could nab him.’

Lance shook his head. ‘They might get the pilot, in which case they would probably scare the rest of the gang. That isn’t enough. We’ve got to find out who’s behind this business, and how far the organization extends, before we talk about arresting anyone.’

‘Well, what are we going to do next?’ asked Julia. ‘Do you really want me to leave the cottage?’

‘Yes. It’s getting dangerous—as Smith hinted, and he wasn’t joking. You fetch what things you need and we’ll find an hotel somewhere. My friend at Scotland Yard wants me to ring him up just before five, and it must be nearly that now. I’ll go and call him. Rod, you stay here with Julia. I shan’t be long—say, about twenty minutes.’

As soon as he had gone Julia got up. ‘Look here, I’ll tell you what. To save time I’ll slip back to the cottage and get the few things I need. I can be back inside twenty minutes. We shall save time that way. I mean, it won’t be necessary for us to go back to the cottage after your brother has finished ’phoning.’

I hesitated. ‘All right,’ I agreed reluctantly. ‘It’s still daylight, so I don’t think you should take any harm.’

‘I’ll watch it,’ smiled Julia, and away she went.

I waited, feeling that I had been rather foolish to let her go; but it seemed easier than arguing with a strong-willed young woman. All the same, I awaited her return with impatience, and when twenty minutes had passed and she had not come back I began to get worried. Five minutes later Lance walked in. He looked sharply round the dining-room.

‘Where’s Julia?’

‘She’s gone to the cottage to get her kit,’ I explained. ‘She’s coming straight back.’

Lance’s eyes met mine for a moment. He shook his head. ‘You shouldn’t have let her go, Rod. Even now she doesn’t realize how serious this is. How long has she been gone?’

‘Nearly half an hour.’

Lance glanced at the window. Dusk, grey with a promise of frost, was closing in.

‘I’m sorry about this,’ he said tersely. ‘I hope to goodness everything is all right. We may as well start walking to meet her.’

‘Have you had a conversation with Scotland Yard?’ I asked.

‘Yes, I’ve been talking to Inspector Wayne. He knows about me. I’ll tell you about it later. He wants me to carry on. Let’s go.’

We paid the bill and went out. It was nearly dark now, and the place looked grim. A crescent moon hung low in the darkening sky. Having no vehicle—for Julia had, of course, taken the car—we strode on up the road. Not a soul did we see, and we finished by walking all the way to the cottage. It took us only half an hour, for we lengthened our strides as we went on without meeting the car. We fairly ran up the drive.

Julia’s car stood outside the front door, just as one might suppose she would leave it while she went in. There was nobody in the car. The engine was silent. Lance went to the front door. It was unlocked, so we walked in. The house was in darkness. Silence met us on the threshold.

‘Julia!’ called Lance sharply.

There was no reply.

Lance lit the lamp and looked around. Everything seemed to be in order. Nothing had been touched, but of Julia there was no sign. Nor was there anything, apart from the car, to show that she had been there.

‘I was afraid of this,’ muttered Lance.

‘I shouldn’t have let her go,’ I repented bitterly.

‘It’s no use talking about that now. Something’s happened to her, and before we do anything else we’ve got to find her. This is Smith’s work.’

‘Where do you suppose he’s taken her?’

‘To his house, I imagine. At least, I can think of nowhere else.’

‘But would he do that, knowing that we’d be bound to follow?’

‘That may be the very reason why he’d take her there,’ returned Lance drily. ‘I’m afraid we’ve played into his hands. It can’t be helped. Let’s go. We’ll take the car, park it somewhere handy near Garthstone Manor, and explore on foot.’

We put the light out, closed the door, and getting into the car cruised up the road towards the Manor. After the chilly air outside it was comfortably warm in the car. I began to feel drowsy—unusually drowsy.

‘There’s a car following us,’ murmured Lance.

I didn’t care very much. I yawned. ‘Are you sure it’s following us?’

‘I think so. We’ll soon see.’ Lance accelerated and then slowed down. ‘Yes, it’s keeping the same distance behind us.’

I yawned again. ‘Wake me up when we get there.’

Lance’s next words seemed to reach me from a great distance. ‘Rod! Rod! Smash the windscreen.’

The words meant nothing to me. I didn’t want to move. In fact, I couldn’t move. Hazily, as though in a dream, I saw Lance put his hand in his pocket and bring out his gun. Holding it by the muzzle he crashed the butt into the windscreen. Glass shattered. A blast of cold air struck me in the face and I stirred, feeling better, suddenly aware of the danger.

‘What’s happened?’ I gasped.

‘Gas,’ muttered Lance. ‘See if you can get your window open—mine seems to be jammed. They must have turned the exhaust-pipe up into the back of the car.’

I tried to open my window, but it wouldn’t budge.

‘They must have jammed them all,’ snapped Lance. ‘Keep your face near the hole in the windscreen. Lucky I saw you losing consciousness.’

I leaned forward to breathe in gulps of fresh air. Lance did the same.

‘That’s better,’ I announced.

‘Good! The car is still following us. I’m going to behave as if their trick had worked. When they come up with us, lie still as if you were unconscious.’

‘And then what?’

‘It will depend on what they do. Take your cue from me. Ready?’

‘Go ahead.’

By this time I could see that we were not far from the Manor. Lance steadied the pace and began steering an unsteady course to and fro across the road. The swerves became more and more acute. We hit the grass verge, swerved again, then left the road altogether and ran on the open heath on our left. For a minute we bumped over heather and rabbit-holes, keeping more or less parallel with the road, and then, travelling slowly, pushed our radiator into a clump of gorse. The car stopped. Silence fell. I lay still, slumped in my seat—but I kept my eyes open. In the reflector I could see the car behind us slowing down. It stopped with its near wheels on the grass verge less than a dozen yards away. The door opened. Hurrying footsteps swished through the heather. I half dropped my eyelids.

A moment later the door on my side was opened. I heard the one on Lance’s side being opened, too, from which I gathered that we had at least two men to deal with. A torch blazed in my face.

‘They’re unconscious,’ said a voice with a strong foreign accent.

‘They must have guessed something was wrong for they’ve smashed the windscreen,’ answered another. ‘It was too late then, I expect.’

‘What shall we do with them?’ went on the first speaker.

‘Did you bring that bottle of whisky?’

‘Yes.’

‘Take the cork out and throw it on the floor. That will provide evidence that they were both drunk. Then we’ll lock the doors and leave the engine running. That should make sure of them.’

I began to wonder what Lance intended doing, for so far he hadn’t moved. Then an entirely unlooked-for factor altered everything.

Julia’s voice split the crisp air. She screamed only one word. It was ‘Lance!’

The effect on me was like an electric shock. And so, apparently, it was with Lance.

‘Get ’em,’ he snapped, and sprang to life.

I grabbed the man on my side and we went down in a heap. Luckily, he fell underneath, and I drove my knees into his stomach with a force that made him whistle through his teeth. There were several pieces of flint lying about, so I grabbed a piece and banged it down on his head. As he went limp I jumped to my feet and made a dash for the other car, for I could hear the engine revving up.

The driver saw me coming, and by the time I reached the car it was already on the move. The door slammed. I took a flying leap on to the running board and wrenched it open again. The fellow inside tried to kick me off, but I hung on, and we steered a crazy course down the road. I managed to get inside, but by this time the driver had put his foot down and we were travelling at high speed. The car was suddenly familiar, and I recognized our Bentley.

‘Stop,’ I snarled.

The driver cursed. The speedometer was on the seventy-miles-an-hour mark.

I was at a loss to know what to do next, for the driver was clutching the wheel with both hands, and it only needed a jerk one way or the other to cause a bad smash. I glanced over my shoulder, and saw Julia lying in a huddled heap.

‘Are you all right?’ I shouted.

‘Yes, but I’m tied up,’ she answered.

In the next few seconds I thought faster than I had ever thought before. I had no intention of being taken to the Manor where Smith and his gang were probably waiting for us. In sheer desperation I determined to take a risk—it was the only thing I could think of. I shouted to Julia to hunch her knees up to her chin and keep her arms over her face in case we crashed. Then I turned on the driver, feeling really savage. Drawing back my fist, I struck him on the jaw with every ounce of strength that I could muster. His head jerked back and he lost his grip on the wheel; I grabbed it, but at the pace we were travelling I wasn’t quick enough to keep the car on the road. I was reaching over from the left so that the car, when it swerved, went that way. We hit the grass verge with a bang that sent the car into the air. It came down on its off-side wheels, and for a nasty instant I thought we were going to overturn. Then we were on all four wheels, bouncing, bumping and banging over goodness knows what—gorse, bracken, mole-hills and rabbit-holes. We missed a tree by inches. A low-hanging branch scraped us. Julia screamed.

But we were slowing down now. I suppose the driver’s foot had slipped off the accelerator. Failing to find the foot-brake—his legs were in the way—steering with one hand I managed to reach the hand-brake. What happened after that I don’t exactly know. We seemed to go over a precipice. Julia screamed again. I fell in a heap with the driver on top of me. There was a bang and a crash and we stopped dead. Scrambling out of the car, I saw what had happened. We had gone over a steep bank into a sort of gully. Fortunately we had hit it at right angles, otherwise the car must have toppled on its side; as it was, it was standing with its front wheels well up the opposite bank.

‘Are you all right, Julia?’ I gasped.

‘I don’t know—I think so,’ came an unsteady voice. ‘Cut me loose.’

I dragged her out, and with my penknife cut the cords that bound her wrists and ankles.

‘Lance warned you,’ I grunted.

‘All right, I’m not grumbling, am I?’ she protested.

Which was true enough. I helped her to her feet. She staggered for a moment and then steadied herself.

‘What about Willy?’ she inquired.

‘Willy?’

‘The driver—that’s what the others called him. If he isn’t a Hun I never saw one. Take a look at his square head.’

‘Just a minute—don’t talk so much—let me think,’ I muttered. The fact was, I was in a bit of a daze.

‘Where did you leave Lance?’ asked Julia.