* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Biggles Defends the Desert

Date of first publication: 1942

Author: Capt. W. E. (William Earl) Johns (1893-1968)

Illustrator: Leslie Stead

Date first posted: Dec. 26, 2022

Date last updated: Dec. 16, 2023

Faded Page eBook #20221258

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

BIGGLES BOOKS

PUBLISHED IN THIS EDITION

First World War:

Biggles Learns to Fly

Biggles Flies East

Biggles the Camels are Coming

Biggles of the Fighter Squadron

Second World War:

Biggles Defies the Swastika

Biggles Delivers the Goods

Biggles Defends the Desert

Biggles Fails to Return

See here

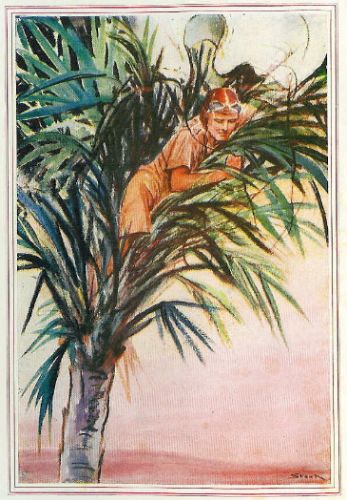

“I sat in the top of the palm like a caterpillar in a cabbage, listening to the nazis talking underneath.”

BIGGLES

DEFENDS the

DESERT

Captain W.E. Johns

RED FOX

BIGGLES DEFENDS THE DESERT

First published in Great Britain as Biggles Sweeps the Desert

by Hodder and Stoughton 1942

| Contents | ||

| 1 | A Desert Rendezvous | 9 |

| 2 | Desert Patrol | 20 |

| 3 | What Happened to Ginger | 33 |

| 4 | Shadows in the Night | 45 |

| 5 | The Decoy | 59 |

| 6 | Biggles Strikes Again | 70 |

| 7 | Events at the Oasis | 83 |

| 8 | A Desperate Venture | 92 |

| 9 | A Perilous Passage | 107 |

| 10 | The Haboob | 120 |

| 11 | Happenings at Salima | 128 |

| 12 | The Enemy Strikes Again | 136 |

| 13 | Biggles Takes His Turn | 148 |

| 14 | The Storm Breaks | 158 |

| 15 | Abandoned | 168 |

| 16 | The Battle of Salima | 183 |

| 17 | The Last Round | 196 |

To the

CADETS OF THE AIR TRAINING

CORPS

many of whom will soon be carrying on

the Biggles tradition, as those already

in the Service carried it during the

Battle of Britain, and are still ‘Venturing

Adventure’ above the near and

distant corners of the earth.

The word ‘Hun’ used in this book was the generic term for anything belonging to the German enemy. It was used in a familiar sense, rather than derogatory. Witness the fact that in the R.F.C. a hun was also a pupil at a flying training school.

W.E.J.

So slowly as to be almost imperceptible the stars began to fade. The flickering rays of another day swept up from the eastern horizon and shed a mysterious twilight over the desert that rolled away on all sides as far as the eye could see. Silence reigned, the tense expectant hush that precedes the dawn, as if all living things were waiting, watching, holding their breath.

Suddenly a beam of light, tinged with crimson, began to paint the sky with pink, and simultaneously, as though it were a signal, from the north-east came the deep, vibrant drone of aircraft. Six specks appeared, growing swiftly larger, and soon resolved themselves into Spitfires[1] flying in Vee formation.

[1] Legendary single-seat RAF fighter from World War Two armed with guns or a cannon.

From the cockpit of the leading machine Squadron Leader Bigglesworth, better known in the R.A.F. as Biggles, surveyed the wilderness that lay beneath, a desolate, barren expanse of pebbly clay and sand, sometimes flat, sometimes rippling, dotted with camel-thorn bushes, and sometimes broken by long rolling dunes that cast curious blue-grey shadows.

The rim of the sun, glowing like molten metal, showed above the horizon. With it came the dawn-wind, and almost at once the aircraft began to rise and fall, slowly, like ships riding an invisible swell. The sky turned to the colour of polished steel, and the desert to streaming gold, yet still the planes roared on. Once Biggles toyed with the flap of his radio transmitter, but remembering his own order for wireless silence, allowed it to fall back. Instead, he glanced at his reflector to make sure that the machines behind him were still in place.

The rocking of the planes became more noticeable as the sun climbed up and began its weary toil across the heavens, driving its glittering lances into a waterless chaos of rock and sand, sand and rock, and still more sand. But Biggles was looking at the watch on his instrument panel now more often, and the frown of concentration that lined his forehead dissolved as an oasis came into view, a little island of palms, as lonely as an atoll in a tropic sea. His hand moved to the throttle, and as the defiant roar of the aircraft dropped to a deep-throated growl, its sleek nose tilted downwards. Soon the six machines were circling low over the nodding palms, from which now appeared half a dozen men in khaki shirts and shorts, and wide-brimmed sun helmets.

Biggles landed first, and taxied swiftly towards them. The others followed in turn, and in a short while had joined the leading machine, which had trundled on into a narrow aisle that had been cleared between the trees.

Biggles jumped down swiftly, stretched his cramped limbs, and spoke to a flight-sergeant who, having saluted, stood waiting; and an observer would have noted from their manner that each enjoyed the confidence of the other, a confidence that springs from years of association—and, incidentally, one that is peculiar to the commissioned and non-commissioned ranks of British military forces. Amounting to comradeship and sympathetic understanding, the original backbone of discipline was in no way relaxed, a paradoxical state of affairs that has ever been a source of wonder to other European nations. The N.C.O.[2] was, in fact, Flight-Sergeant Smythe, who had been Biggles’ fitter on more than one desperate enterprise in civil as well as military aviation.

[2] Non-Commissioned Officer e.g. a Sergeant or a Corporal.

‘Is everything all right, flight-sergeant?’ inquired Biggles.

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Did the stores arrive as arranged?’

‘Yes, sir. Flight-Lieutenant Mackail brought most of the stuff over in the Whitley[3]. He has flown the machine back to Karga. He told me to say that everything is okay there, and he will be on hand if you want him.’

[3] A long-range night bomber with a crew of five.

Biggles nodded. ‘Good. Get the machines under cover. Fit dust sheets over the engines and spread the camouflage nets. Send some fellows out to smooth our wheel tracks with palm fronds. I hope they understand that no one is to set foot outside the oasis without orders?’

‘Yes, sir. I’ve told them about the risks of getting lost in the dunes.’

‘That’s right; moreover, we don’t want footprints left about. Is there some coffee going?’

‘Yes, sir. I’ve put up the officers’ mess[4] tent near the spring. It’s a little farther on, in the middle of the palms.’

[4] The place where the officers meet for eating and relaxing together.

‘Did you bring that boy of yours with you?’

‘Yes, he’s here, sir. He’s got the radio fixed up, and someone is always on duty, day and night, listening.’

‘What about petrol?’

‘It’s all here, sir, in the usual four-gallon cans. I didn’t dump it all in one place. I had half a dozen pits dug, in different parts of the oasis—in case of accidents.’

‘Good work, flight-sergeant. I’ll have another word with you later.’

As the flight-sergeant moved off Biggles turned to the five officers who were standing by. ‘Let’s go and get some breakfast,’ he suggested. ‘I’ll tell you what this is all about.’

In the mess tent, over coffee and a cigarette, he considered his pilots reflectively. There was Flight-Lieutenant Algy Lacey, Flight-Lieutenant Lord Bertie Lissie, and Flying-Officers Ginger Hebblethwaite, Tug Carrington, and Tex O’Hara, all of whom had fought under him during the Battle of Britain.

‘All right, you fellows,’ he said at last. ‘Let’s get down to business. No doubt you are all wondering why the dickens we have come to a sun-baked, out-of-the-way spot like this, and I congratulate you on your restraint for not asking questions while we were on our way. My orders were definite. I was not allowed to tell anyone our destination until we were installed at Salima Oasis, which, for your information, is the name of this particular clump of long-necked cabbages that in this part of the world pass for trees. Even now, all I can tell you about our position is that it is somewhere near the junction of the Sudan, Libya, and French Equatorial Africa[5].’ Biggles broke off to sip his coffee.

[5] Now Chad.

‘As most of you know,’ he continued, ‘a fair amount of traffic, both British and American, is passing from the West Coast of Africa to the Middle East. Most of it is airborne, and it is that with which we are concerned. This oasis happens to lie practically on the air route between the West Coast and Egypt. Over this route is being flown urgent stores, dispatches, important Government officials travelling between home and the eastern battlefields, and occasionally senior officers. It is quicker than the sea route, and—until lately—a lot safer. The route is about two thousand miles long, and the machines that fly it are fitted with long-range tanks to make the run in one hop. We are sitting about midway between the western and eastern termini—which means that we are a thousand miles from either end. For a time, after the route was established, everything went smoothly, but lately a number of machines have unaccountably failed to arrive at their destinations. They disappeared somewhere on the route. No one knows what became of them.’ Biggles lit a fresh cigarette.

‘Our job,’ he resumed, ‘is to find out what happened to them, and that doesn’t just mean looking for them—or what remains of them. There is a mystery about it. Had one machine, or even two, disappeared, we might reasonably suppose that the pilot lost his way, or was forced down by structural failure or weather conditions; but during the past month no fewer than seven machines have failed to get through, and the Higher Command—rightly, I think—cannot accept the view that these disappearances are to be accounted for by normal flying risks. They believe—and I agree with them—that the machines were intercepted by hostile aircraft. After all, there would be nothing remarkable in that. It would be optimistic to suppose that an important air route like this could operate indefinitely without word of it reaching the ears of the enemy. Naturally, they would do their utmost to prevent the machines from getting through. There is no proof that such a thing is happening, but it is a possibility—I might say probability.’

Here Algy interposed. ‘Suppose enemy machines are cutting in on the route; surely it’s a long trip down to here from the enemy-occupied aerodromes in North Africa?’

‘You’ve put your finger on something there,’ agreed Biggles. ‘My personal opinion is that the Nazis, or Italians[6], have detailed a squadron or a special unit to take up its position near the route in order to patrol it and destroy any Allied machine it meets. You will now realise why we are here. The machines that fly over this route must go through, and our job is to see that they go through. If an enemy squadron is operating down here, then we must find it and wipe it out of the sky. They will get an unpleasant surprise when they discover that someone else is playing their own game. At the moment we hold the important element of surprise. Assuming that enemy aircraft are operating in this district, they do not know we are here, and I am anxious that they should not know. That’s why I forbade the use of radio on the way. Ears are listening everywhere, even in the desert. One message intercepted by the enemy might be enough to give our game away, and even enable him to locate us. Well, that briefly is the general line-up, but there are a few points that I must raise.’ Biggles paused to pour himself another cup of coffee.

[6] From 1940 to 1943 the Italians, under the fascist dictator Mussolini, formed an alliance with Hitler and joined in the battle against Britain and her allies.

‘We are out here in the blue absolutely on our own, to do as we like, a free-lance unit. The rest of the squadron is at Karga Oasis, nearer to the Nile. I sent them there to be in reserve, as well as to form a connecting link with the Air Officer Commanding Middle East. I thought six of us here should be enough. Spare machines, stores and replacements are at Karga; they include a Whitley, converted into a freight carrier, for transport purposes. There is also a Defiant[7]. I thought a two-seater might be useful on occasion, and the Air Ministry very kindly allowed me to make my own arrangements. Angus Mackail is in charge at Karga. He has with him Taffy Hughes, Ferocity Ferris and Harcourt. Flight-Sergeant Smythe is here, as you saw, with a section of good mechanics to look after us. That son of his, young Corporal Roy Smythe, who did so well with us up in the Baltic[8], is in charge of the radio, which, however, will be used only for receiving signals.’

[7] British two-seater fighter carrying a rear gunner in a four-gun turret. It had no forward-firing guns.

[8] See Biggles in the Baltic.

Biggles finished his coffee.

‘The first thing I want to impress upon you all is this,’ he continued. ‘We are in the desert—never forget that. To get lost is to perish miserably from thirst. The sun is your worst enemy, as it is the enemy of every living creature in the desert. The sun dries your body. While you can drink you can make up for the loss of moisture, but the moment you are denied water thirst has you by the throat. Twenty-four hours at the outside—less in the open sand—is as long as you could hope to survive without a drink, and death from thirst is not an ending one would choose. Every machine will therefore carry a special desert-box, with food, water, and anti-thirst tablets, in case of a forced landing. No one will move without a water-bottle. That’s an order. If you break that order, any of you, you won’t have to answer to me; as sure as fate the sun will turn on you and shrivel you up like an autumn leaf. Don’t ever say that I haven’t warned you. And, believe it or not, it is the easiest thing in the world to get lost. On the ground, you could get hopelessly lost within a mile of the oasis. As far as possible we shall operate in pairs, so that one can watch the other; but there will, of course, be times when we shan’t be able to do that. There’s another reason why I don’t want people to wander about outside the oasis. Footprints and wheel tracks show up in the sand, and we don’t want to advertise our presence to the enemy. If they discover us we shall soon know about it; we shall have callers, but instead of leaving visiting cards they’ll leave bombs. Everyone will wear a sun helmet. Keep in the shade as far as possible. Expose yourself, and the sun will blister the skin off you; the glare will sear your eyeballs and the heat will get on your nerves till you think you’re going crazy. Apart from the sun, we have another enemy in the haboob, or sandstorm. Algy and Ginger have been in the desert before, and they know what it means, but the rest of you are new to it—that’s why I’m going to some trouble right away to make sure that you understand what you are up against. That’s all for the moment, unless anyone has any questions to ask?’

‘Can I ask one, old warrior?’ put in Bertie.

‘Certainly.’

‘Assuming that the jolly old Boche[9] is polluting the atmosphere along our route, is there any reason why he should choose this particular area—if you see what I mean?’

[9] Slang: derogatory term for the Germans.

‘Yes. If he operated at either end of the line his machines would probably be seen. It seemed to me that he would be likely to aim for somewhere near the middle, because not only is the country uninhabited, but it happens to be the nearest point to German-controlled North Africa—at any rate to Libya, where there is a German army.’

‘Yes—of course—absolutely,’ muttered Bertie. ‘Silly ass question, what?’

‘Not at all,’ answered Biggles. ‘Well, that’s all for the moment. We’ll have a rest, but everyone will remain on the alert ready to take off at a moment’s notice. I’ve arranged for a code message to be radioed when the next transport machine leaves the West Coast for Egypt, or vice versa. Naturally, machines operate both ways over the route. Until we get such a signal we will confine our efforts to reconnaissance, noting the landmarks—such as they are. There is at least one good one. The caravan route, the old slave trail, as old as the desert itself, passes fairly close, running due north and south. All the same, the only safe plan in desert country is to fly by compass. Reconnaissance may reveal some of the lost aircraft, or the remains of them.’

‘Say, chief, what about Arabs?’ inquired Tex. ‘Are we likely to meet any, and, if so, what are they like?’

‘To tell the truth, I’m not sure about that,’ Biggles admitted. ‘There are wandering bands of Toureg—those are the boys who wear blue veils over their faces—all over the desert. They are tough if they don’t like you. Our best policy is to leave them alone in the hope that they’ll leave us alone—hark! What’s that?’

There was a brief attentive silence as everyone jumped up and stood in a listening attitude. But the matter was not long in doubt. An aircraft was approaching.

‘Keep under cover, everybody,’ snapped Biggles, and running to the door of the tent, without going out, looked up. For a full minute he stood there, while the roar of the aircraft, after rising in crescendo, began to fade away. There was a curious expression on his face as he turned back to the others, who were watching him expectantly.

‘Now we know better how we stand,’ he said quietly. ‘That was a Messerschmitt 109[10]. He was only cruising, so I imagine he was on patrol. It would be waste of time trying to overtake him—no doubt we’ll meet him another day. I don’t think he spotted anything to arouse his suspicions or he would have altered course—perhaps come low and circled. I’m glad he came along, because the incident demonstrates how careful we must be. Had anyone been standing outside the fringe of palms he would have been spotted.’

[10] German plane often abbreviated to ME. The main German single-seat fighter of World War Two.

‘But sooner or later we shall be seen on patrol,’ Ginger pointed out.

That may be so,’ agreed Biggles, ‘but to be seen in the air won’t provide a clue to our base. This is not the only oasis in the desert. Well, that’s all. We’ll have a look round the district when we’ve fixed up our quarters.’

Over early morning tea the following day Biggles planned the first operation.

‘No signal has come in, so as far as we know at the moment we have no aircraft flying over the route,’ he remarked. ‘That gives us a chance to have a look round. I don’t expect enemy opposition; if there is any it will be accidental, and for that reason we needn’t operate in force. It would be better, I think, if we started off by making a thorough reconnaissance of the entire district, or as much of it as lies within the effective range of our machines—say, a couple of hundred miles east and west along the actual route, and the district north and south. Keep a sharp look-out for wheel tracks, or any other signs of the missing machines. Algy, take Carrington with you and do the eastern section. Fly on a parallel course a few miles apart; that will enable you to cover more ground; only use radio in case of really desperate emergency. Bertie, you make a survey of the northern sector. Don’t go looking for trouble. There are one or two oases about up there, but you’d better keep away from them—we don’t want to be seen if it can be avoided; information travels fast, even in the sands. Tex, you fly south, but don’t go too far. I don’t think you’ll see much except sand. Everyone had better fly high—you can see an immense distance in this clear air. I’ll take Ginger and do the western run. All being well we’ll meet here again in two hours and compare notes. That’s all, unless anyone has any questions?’

No questions were asked, so in a few minutes the engines were started and the six machines taxied out to the open desert for the take-off. Algy and Tug Carrington took off first, and climbing steeply disappeared into the eastern sky. Bertie and Tex followed, heading north and south, respectively.

Biggles spoke to Flight-Sergeant Smyth, who was standing by. ‘Remember to smooth out our wheel tracks as soon as we’re off,’ he said. Then he called to Ginger: ‘All right, let’s get away. Make a careful note of anything that will serve as a landmark. The course is due west. We’ll fly parallel some distance apart. If you see anything suspicious, or worth investigating, come across to me and wave—I’ll follow you back to it. I shall keep you in sight; in the same way, you watch me. Let’s go.’

The machines were soon in the air, heading west, with the oasis, a tiny island in an ocean of sand, receding astern. At fifteen thousand feet Biggles levelled out, and with a wave to his partner, turned a few points towards the south. Ginger moved north until the other machine was a mere speck in the sky, when he came back to his original westerly course. Throttling back to cruising speed he settled down to survey the landscape.

At first, all he could see was an endless expanse of sand, difficult to look at on account of the glare, stretching away to the infinite distance, colourless and without outline. Nowhere was there rest for the eye. There was no definite configuration, no scene to remember, nothing to break the eternal monotony of sand except occasional patches of camel-thorn, or small outcrops of what appeared to be grey rock. Over this picture of utter desolation hung an atmosphere of brooding, overwhelming solitude. Overhead, from a sky of gleaming steel, the sun struck down with bars of white heat, causing the rarefied air to quiver and the machine to rock as though in protest.

Ginger had flown over such forbidding territory before, but even so he was not immune from the feeling of depression it creates. Assailed by a sense of loneliness, as though he alone was left in a world that had died, he was glad that the other machine was there to remind him that this was not the case. Pulling down his smoked glasses over his eyes to offset the glare he flew on, subjecting the ground, methodically, section by section, to a close scrutiny. For some time it revealed nothing, but then a strange scar appeared, a trampled line of sand that came up from the south, to disappear again in the shimmering heat of the northern horizon. He soon realised what it was. The litter of tiny white gleaming objects that accompanied the trail he knew must be bones, human bones and camel bones, polished by years of sun and wind-blown sand. ‘So that’s the old caravan road, the ancient slave trail,’ he mused. ‘Poor devils.’ It was an outstanding landmark, and he made careful note of it.

Some time later, on the fringe of an area furrowed by mightily curving dunes, as if a stormy ocean had suddenly been frozen, he saw another heap of bones—or, rather, an area of several square yards littered with them. Clearly, it marked the spot where a caravan, having left the trail, had met its fate, or perhaps had been wiped out by those fierce nomads of the desert, the veiled Toureg. Ginger marked down the spot, which formed another useful landmark in an area where landmarks were rare. He made a note of the time, to fix its position in relation to the oasis. This done, he glanced across at Biggles’s machine, and having satisfied himself that it was there, still on its course, he went on, and soon afterwards came to the fringe of country broken by more extensive outcrops of rock, between which the camel-thorn grew in thick clumps, which suggested that although the country was still a wilderness there might be water deep down in the earth. Shortly afterwards Biggles came close and flew across his nose, waving the signal for return.

On the return journey the two machines for the most part flew together, although occasionally Biggles made a brief sortie, sometimes to the north and sometimes to the south. In this way they returned to the oasis, after what, to Ginger, had been a singularly uneventful flight. Landing, they taxied in to find that the other machines were already home. The pilots were waiting in the mess tent.

Biggles took them in turn, starting with Algy.

‘See anything?’ he asked crisply.

Algy shook his head. ‘Not a thing.’

‘What about you, Bertie?’

‘I saw plenty of sand, but nothing else.’

Tex and Tug made similar negative reports.

Biggles rubbed his chin thoughtfully. ‘We didn’t see anything, either, except the old caravan route,’ he said slowly. ‘I was hoping we should find one of the missing machines so that by examination we might discover what forced it down. Between us we must have covered thousands of square miles of country. I don’t understand it. To-morrow we’ll try north-east and north-west—perhaps one of those districts will reveal something. If we draw blank again, I shall begin to think that my calculations were at fault. It isn’t as though we were flying over wooded country; if the missing machines came down in this area we are bound to see them. It’s very odd. If they didn’t land, where did they go? Why did they leave the route? They certainly didn’t land on it, or not in the four hundred miles of it which we’ve covered this morning.’

‘They might have got off their course,’ suggested Algy.

‘I could believe that one might, but I’m dashed if I can imagine seven machines making the same mistake.’

‘We may find them all in the same sector, one of the areas we haven’t covered yet,’ put in Ginger.

‘If we do it will puzzle me still more,’ declared Biggles. ‘It will raise the question, why did seven machines leave the route at practically the same spot? Don’t ask me to believe that the Higher Command would choose for a job like this pilots who are incapable of flying a simple compass course. In fact, I know they didn’t, because Fred Gillson was flying one of the machines, a Rapide of British Overseas Airways, and he was a master pilot. No, there’s something queer about this, something I don’t understand. We’ll have a spot of lunch, and perhaps do another patrol this evening.’

Biggles looked sharply at the tent entrance as Flight-Sergeant Smyth appeared. ‘Yes, flight-sergeant, what is it?’ he asked.

‘A signal, sir, just in. I’ve decoded it.’ The flight-sergeant passed a slip of paper.

Biggles looked at it. ‘Good,’ he said. ‘This may give us a line. One of our machines, a Dragon[11], wearing the identification letters GB-ZXL, left the West Coast at seven this morning. It must be well on its way by now, and should pass over here inside a couple of hours. General Demaurice is among the passengers; he’s coming out to take over a contingent of the Free French[12], so there will be trouble if the machine doesn’t get through. We can escort it through this area. Ginger, come with me. We’ll go to meet it. We’ll take the same course as we did this morning, although we may have to fly a bit farther apart so that it won’t slip by without our spotting it. Don’t go far from the route, though. Algy, you stand by with Bertie; when you hear the Dragon coming, whether we are with it or not, take off and escort it over the eastern sector as far as your petrol will allow you to go. Flight-Sergeant, you stand by the radio in case another message comes through. Come on, Ginger, we’ve no time to lose.’

[11] De Havilland Dragon, a twin-engined transport biplane.

[12] French troops still fighting against Germany and Italy after the occupation of France in 1940. They were led by General de Gaulle and the Free French Government operating in exile in London.

In a few minutes the two machines were in the air again, climbing steeply for height and taking precisely the same course as they had taken earlier in the day except that Ginger went slightly farther to the north, and Biggles to the south, an arrangement which enabled the two machines to watch the air, not only on the exact route, but for several miles on either side of it, in case the Dragon should have deviated slightly from its compass course.

As he flew, Biggles kept his eyes on the atmosphere ahead for the oncoming machine. Occasionally, for the first half-hour, he saw Ginger in the distance, but from then on he saw no more of him. This did not perturb him, for it was now about noon, and although it could not be seen he knew that the usual deceptive heat-haze was affecting visibility.

Time passed, but still there was no sign of the Dragon, and Biggles’ anxiety increased with each passing minute. Where could the machine be? He made fresh mental calculations, which only proved that his earlier ones had been right. If the Dragon had kept on its course at its normal cruising speed he should have met it before this.

When an hour had passed he knew beyond all shadow of doubt that one of two things must have happened. Either the Dragon had slipped past him in the haze, or, for some reason unknown, it had not reached the area of his patrol. He realised that there was a chance that Ginger had picked it up, and turned back to escort it, a possibility that was to some extent confirmed by the fact that there was no sign of Ginger’s machine.

Perceiving that he was already running his petrol supply to fine limits Biggles turned for home, and in doing so had a good look at the ground. Instantly his nerves tingled with shock as he found himself staring at a wide outcrop of rock which he had not seen on his earlier flight, although had the rock been there he could not have failed to notice it. How could such a state of affairs have come about? There was only one answer to that question. He was not flying over the same course as he had flown earlier in the day. But according to his compass he was flying over the same course; he had never deviated more than a mile or two from it, a negligible distance in a country of such immense size.

Biggles thought swiftly. Obviously, something was wrong. He could not believe that his compass was at fault because compasses rarely go wrong, and, moreover, he had boxed[13] it carefully before starting for the oasis. Yet if his compass was right, how did he come to be flying over country that he had never seen before? This was a problem for which he could find no answer. The sun was of very little use to help him fix his position for it was practically overhead, so he took the only course left open to him, which was to climb higher in the hope of picking up a landmark which he had noted on his first flight.

[13] Boxing a compass involves correctly calibrating the compass to suit each fully-equipped aircraft.

By this time he was flying back over his course, or as near to it as he could judge without relying on his compass, but even so, it was not until he had climbed to twenty thousand feet that, with genuine relief, he saw, far away to the south-east, the caravan road. How it came to be where it was, or how he came to be so far away from it, he could not imagine. For the moment he was content to make for it, and from it get a rough idea of his position. The road ran due north and south. By cutting across it at right angles he would at least be on an easterly course, which was the one he desired to take him back to the oasis. And so it worked out. Half an hour later the oasis came into sight, and soon afterwards he was on the ground, shouting urgently for Algy as he jumped down.

Algy, and the others, came out at a run.

‘Have you seen the Dragon?’ asked Biggles crisply.

‘Not a sign of it,’ answered Algy. ‘We’ve been standing here waiting for it ever since you took off.’

Biggles moistened his sun-dried lips. ‘Ginger is back, of course?’

‘No,’ declared Algy, alarm in his voice. ‘We haven’t seen anything of him.’

Biggles stared. ‘This is serious,’ he said. ‘I cut my petrol pretty fine. If Ginger isn’t back inside ten minutes he’ll be out of juice.’

‘What can have happened to him—it isn’t like him to do anything daft,’ put in Tex.

‘I’ve got an idea what’s happened to him,’ answered Biggles grimly. ‘Let’s get into the shade and I’ll tell you. Flight-Sergeant, check up my compass will you, and report to me in the mess tent.’

‘An extraordinary thing happened to me this morning,’ went on Biggles, when the officers had assembled in the tent. ‘I lost my way, or rather, my compass took me to one place this morning, and at noon, although it registered the same course, to a different place. I ended up miles north of where I thought I was.’

‘Your compass must be out of order—if you see what I mean,’ remarked Bertie.

‘Obviously,’ returned Biggles.

At that moment the flight-sergeant appeared in the doorway. ‘Your compass is in perfect order, sir,’ he said.

‘Are you sure?’ Biggles’ voice was pitched high with incredulity.

‘Certain, sir, I checked it myself.’

For a few seconds Biggles looked astounded; then the light of understanding dawned in his eyes. ‘By thunder!’ he cried. ‘I’ve got it! Someone is putting a magnetic beam up, to distort compass needles. It’s been done before. It was put up to-day to upset the Dragon and take the pilot off his course. I’ll bet he was lured off his course in the same direction as the other seven. Ginger and I ran into the beam and our compasses were affected at the same time. That’s why I went astray. Now the beam is off, my compass is okay again.’

‘If the beam has been turned off we can assume that the Dragon is a casualty,’ put in Algy slowly.

Biggles drew a deep breath. ‘I’m afraid you’re right, but I’m not thinking only of that. If this compass business is really happening it introduces another new factor.’

‘What do you mean?’

See here

“I’ve got an idea what’s happened to him,” said Biggles grimly. “Flight-sergeant, check up my compass, wil you, and report to me in the mess tent.”

‘Look at it like this. Early this morning there was no interference. A machine then left the West Coast. Shortly afterwards the magnetic influence was switched on. That’s too much like clockwork to be accidental. It looks as if the Messerschmitts don’t have to patrol; they know where and when they can find an aircraft on the route. They couldn’t know that unless someone, somewhere, is tipping them off, probably with a shortwave radio. A person doing that needn’t necessarily be at the terminus—he might be anywhere along the route. There is this about it. I now have a pretty good idea of the direction in which the missing machines disappeared—I can judge that from the error of my own compass. We shall probably find Ginger in the same locality, unless he discovered in time what was happening and tried to get back. There’s just a chance that he landed to look at something, although I don’t think that’s likely. After I’ve had a bite of lunch I shall have to go out and look for him.’

‘Alone?’ queried Algy.

‘Yes,’ answered Biggles shortly. ‘I don’t feel like risking too many machines until we know for certain what is happening, and therefore what to expect. Someone will have to stay here to carry on in case I don’t come back, which is always on the boards.’

‘Why not let me go?’ suggested Algy.

‘No.’ Biggles was definite. ‘I’ve been out in that direction and you haven’t.’

‘Where shall we look for you, if for any reason you don’t get back?’

Biggles thought for a moment. ‘I fancy Ginger is somewhere in the area north-west from here, between a hundred and two hundred miles distant. Your best plan would be to fly due west until you come to the caravan road; cross it, and then turn north. That’s the way I shall go. You’ll see a big outcrop of rock. I don’t know how far it stretches—I didn’t wait to see; but that, as near as I can tell you, is where I expect to find Ginger. If I’m not back in two hours you’ll know I’m down, but give me until to-morrow morning before you start a search because I might land voluntarily, for some reason or other. I might have to go down to Ginger if I see him on the ground, or possibly the Dragon, although I shall await official confirmation that it has failed to arrive before I organize a serious search for it.’ Biggles turned to Flight-Sergeant Smyth who was still waiting for instructions. ‘Get my machine refuelled,’ he ordered. ‘Tell the mess waiter he can serve lunch. That’s all.’

Over lunch, a frugal affair of bully beef, biscuits, tinned peaches and coffee, the matter was discussed in all its aspects, without any new light being thrown on the mystery. Ginger failed to put in an appearance. When, at four o’clock, there was still no sign of him, Biggles took off and headed west. The sun, long past its zenith, was sinking in the same direction.

Reaching the broken country beyond the caravan road Biggles turned sharply north, to find that the rocks grew bolder, sometimes running up to small, jagged hills, with gullies filled with drift sand between them. This sand he eyed with deep suspicion, for experience had taught him its peculiar properties. In some places, he knew, the grains of sand would have packed down like concrete, hard enough to carry a heavy vehicle; in other places it would be as soft as liquid mud, a death trap to any vehicle that tried to cross it—a phenomenon due to the force and direction of the wind when the sand was deposited. Barren and desolate, worse country would have been hard to imagine, and Biggles had to fly low in order to distinguish details.

He was following a smooth, sandy gully, hemmed in by gaunt, sun-scorched rocks, rising in places to a fair height, when he came suddenly upon the object of his quest. There, in the middle of the gully, stood the Spitfire, apparently undamaged, and abandoned. There was no sign of movement. The airscrew was stationary.

Biggles was amazed. Although he was looking for the aircraft, and expected to find it, he had not supposed that he would discover it in such peculiar circumstances. He would not have been surprised to find that it had crashed, nor would he have been astonished had Ginger been standing beside it. What he could not understand was why, if the machine was in order, as it appeared to be, it had been abandoned. The sand seemed to be firm enough, judging from the shallow wheel tracks.

With the fear of soft sand still in his mind he did not land at once, but circled the stationary machine at a height of not more than fifty feet, to make sure that the wheels were fully visible—that they had not sunk into the sand. Satisfied that they had not, he landed, and taxied to the deserted aircraft.

Jumping down from his own machine he ran over to it. He had a horror that he might find Ginger dead, or seriously hurt, in the cockpit, but it was empty. For a moment he started at it blankly, not knowing what to think. He could not find a bullet hole, or a mark of any sort, to account for the landing. The petrol gauge revealed that the tank was still half full. He even tried the engine, and finding it in perfect order, switched off again. Standing up, he surveyed the sterile landscape around him.

‘Ginger!’ he shouted. And then again, ‘Hi, Ginger!’ But there was no reply. Silence, the silence of death, took possession of the melancholy scene.

Ginger, out over the desert, like Biggles devoted most of his attention to the sky ahead, hoping to see the oncoming Dragon. Also like his leader, he had no reason to suppose that his compass was not functioning perfectly. It was not until he happened to glance at his watch, on the instrument panel, and then at the ground below, that the first dim suspicion that something was wrong entered his head. He looked down fully expecting to see the scattered heap of white bones that he had noted on his previous flight. It was a conspicuous landmark, and according to the time shown by his watch it should not merely have been in sight, but underneath him. There was no sign of any bones. Moreover, the terrain looked strange—not that he paid a great deal of attention to this because the desert was so much alike that he felt he might easily be mistaken. Yet where were the bones? He could see the ground for many miles in every direction, but there was nothing remotely resembling a heap of bones.

He happened to be wearing his wrist watch, so his next move was to check it with the watch on the instrument board. Both watches registered the same time, which puzzled him still more, for as he had flown over the same course, at the same speed, for the same length of time as before, the bones, he thought, must be there.

He slipped off five thousand feet of height and studied the ground closely. There were no bones, and the conviction grew on him that he had never seen that particular stretch of wilderness before. There were too many rocks. Over his starboard bow there was an absolute jumble of them, biggish rocks, too. Such faith had he in his instruments that not for an instant did he suspect the truth—that his compass was out of order. After all, there was no reason why he should suspect such a thing. He looked across to the left. He could see no sign of Biggles’ machine, but noted that the heat-haze was exceptionally bad. The heat, even in his cockpit, was terrific.

Concerned, but not in any way alarmed, he flew on, and as he flew he made a careful reconnaissance of the grey rocks on his right. At one point, far away, something flashed. Pushing up his sun goggles he saw a quivering point of white light among the rocks. Only three things, he knew, could flash like that in the desert. One was water, another, polished metal, and the other, glass. He knew it could not be water or there would be vegetation, probably palms. He did not think it could be metal because the only metal likely to be in such a place was a weapon of some sort, carried by an Arab, in which case the point of light would not be constant. That left only glass. It looked like glass. He had seen plenty of broken glass winking at him in districts where there were human beings. Indeed, in Egypt he had seen Biggles follow a trail by such points of light, the flashes there being made by empty bottles thrown away by thirsty travellers.

His curiosity aroused he turned towards the object. He realized that this was taking him farther away from Biggles, but he thought he was justified. In any case, he expected no difficulty in returning to Biggles after he had ascertained what it was that could flash in a place where such a thing was hardly to be expected. Putting his nose down, both for speed and in order to lose more height, he raced towards the spot, and in five minutes was circling low over it.

He had only to look once to see what it was. Piled up against the base of a low but sheer face of rock, was an aircraft. The flashing light had been caused by its shattered windscreen. There was no sign of life, and although he flew low over it several times trying to make out the registration letters, he could not, because both wings and fuselage were crumpled. Nor could he be sure of the type. The only letter he could read was G, which told him that the aircraft was a British civil plane, evidently one of the missing machines which Biggles was so anxious to locate. A ghastly thought struck him. Could it be the Dragon they were out to escort? Were they too late after all? Were there, in that crumpled cabin, injured men, perhaps dying of thirst?

This possibility threw his brain into a turmoil. What ought he to do? Was he justified in calling Biggles on the radio? He wasn’t sure. He knew Biggles was most anxious that the radio should not be used if it could possibly be avoided. Should he try to find Biggles? Even if he succeeded, he had no way of conveying the information he possessed. Biggles would probably return to the base, and it would be hours before they could get back. Ginger did, in fact, turn towards the south, and fly a little way, hoping to see Biggles; but then it struck him that he might not be able to find the crashed machine again; it would certainly be no easy matter, lying as it did in a shapeless wilderness of rock.

Worried, Ginger swung round and raced back to the wreck. He could see clearly what had happened. Behind the rock there was a small, fairly level area of sand. Wheel tracks showed that the pilot had tried to get down on it, but had been unable to pull up before colliding head-on with the cliff. Had the sand area been larger Ginger would have felt inclined to risk a landing; but the area was too small; if a comparatively slow commercial machine could not get in, what chance had he, in a Spitfire? It struck him that the pilot must have been hard pressed to attempt a landing in such a place. But uppermost in his mind was the horror that someone might still be alive in the wreck, too badly injured to move. It made the thought of flying away abhorrent to him. Clearly, at all costs—and he was well aware of the risks—he must try to get down to satisfy himself that the machine was really abandoned.

Climbing a little, and circling, he soon found what he sought—a long, level area of sand. It was not entirely what he would have wished, for it had length without breadth, forming, as it were, the base of a long, rock-girt gully. But still, he reflected, there was no wind to fix the direction of landing, so he had the full length of the gully to get in. His greatest fear was that the sand might be soft enough to clog his wheels and pitch him on his nose, or failing that, prevent him from getting off again. There was no way of determining this from the air; it was a risk he would have to take, and he prepared to take it.

First he took the precaution of noting carefully the direction of the crash in relation to the gully, for they were about five hundred yards apart; then, lining up with his landing ground, he cut the engine and glided down. To do him justice, he was fully aware of the risks he was taking, but he thought the circumstances justified them. Concentrating absolutely on his perilous task, he flattened out, held off as long as he dare, and then—holding his breath in his anxiety—he allowed the machine to settle down. His mouth went dry as the wheels touched, but an instant later he was breathing freely again as the Spitfire ran on to a perfectly smooth landing, finishing its run almost in the middle of the gully.

Switching off his engine, he jumped down and stood for a moment stretching his cramped muscles while he regarded the scene around him. His first impression was one of heat. It was appalling, as though he had landed in an oven. The air, the sand and the rock all quivered as the sun’s fierce lances struck into them. The second thing was the silence, an unimaginable silence, a silence so profound that every sound he made was magnified a hundredfold. There was not a sign of life—not an insect, not a blade of grass. Even the hardy camel-thorn had found the spot detestable.

In such a place a man would soon lose his reason, thought Ginger, as, after throwing off his jacket, which he found unbearable, he walked quickly in the direction of the wreck. When he had gone about a hundred yards he remembered Biggles’ order about not moving without a water-bottle, and he hesitated in his stride, undecided whether to return to the machine for it or to go on without it. He decided to go on. After all, he mused, it was only a short distance to the wreck, and he would be back at his own machine in a few minutes. Nothing could happen in that time. It was not as though he were going on a journey. Thus he thought, naturally, perhaps, but in acting as he did he broke the first rule of desert travel.

It did not take him long to reach the machine. He approached it with misgivings, afraid of what the cabin might hold. While still a short distance away he saw that it was not the Dragon, but a similar type, a Rapide[14], carrying the registration letters G—VDH. The crash had been a bad one, the forward part of the aircraft having been badly buckled, and consequently he breathed a sigh of relief when he found the cabin empty. But three of the passengers, or crew, had not gone far. Close at hand were three heaps of sand, side by side, obviously graves, but there was no mark to show who the victims were. Ginger considered the pathetic heaps gloomily before returning to the machine. There was nothing in it of interest. There was no luggage. Even the pilot and engine log-books had been taken from their usual compartment in the cockpit. Further examination revealed the reason why the machine had attempted to land. Across the nose, and also through the tail, were unmistakable bullet holes, and Ginger’s face set in hard lines when he realized that the defenceless machine had been shot down. A number of questions automatically arose. In the first place, why was the machine so far off its track? For off its compass course it most certainly was. Enemy aircraft must have done the shooting, but where were the surviving passengers? Had they buried their dead and then set off on a hopeless march towards civilization?

[14] De Havilland Dragon Rapide, a twin-engined biplane.

Ginger found the answers to some of these questions in the sand. The sand on the graves had been patted smooth by a spade, or similar implement. Such a tool would not be carried by the aircraft. The absence of footprints leading away from the crash puzzled him, but he soon found a clue which solved that particular problem. A set of wheel tracks told the story. A wheeled vehicle, keeping close to the face of the low cliff, had come almost to the crash. It had turned, and then gone away in the direction from which it had come—that is, towards the north.

The tragic story was now fairly plain to read. The machine, which for some unexplained reason had got off its course, had been shot down. The pilot, or pilots, responsible for shooting it down had informed their base, noting the spot where the crash had occurred, with the result that a vehicle had been sent out to examine it. Three passengers had perished. Their enemies had buried them and taken the survivors away. That was all, and as far as Ginger was concerned it was enough. The sooner Biggles knew about his discovery the better. In any case, he was already finding the heat more than he could comfortably bear. Pondering on the tragedy, he set off on the return journey to the Spitfire.

He had gone about halfway when he heard a sound that caused him to pull up short. It was the drone of an aircraft, still a long way off, but approaching, and the shrill whine of it told him that it was running on full throttle. At first he assumed, naturally, that it was Biggles, but as he stood listening his expression became one of mixed astonishment and alarm. There was more than one aircraft—or at any rate more than one engine. Then, as he stood staring in the direction of the sound, there came another, one that turned his lips dry with apprehension. It was the vicious grunt of multiple machine guns.

He dived for cover, for he was standing in the open and did not want to be seen, as a Dragon suddenly took shape in the haze. It was flying low, running tail up on full throttle and turning from side to side as the pilot tried desperately to escape the fire of three fighters that kept him close company. It did not need the swastikas that decorated them to tell Ginger what they were. Their shape was enough. They were Messerschmitts.

As soon as he realized what was happening he threw discretion to the winds and raced like a madman towards his Spitfire, but before he had gone fifty yards he knew he would be too late. The one-sided running fight had swept over him, and a jagged escarpment hid it from view. The machine-gunning ended abruptly, and the roar of engines seemed suddenly to diminish in volume.

Although he could not see, Ginger could visualize the picture. The British pilot, realizing the futility of trying to escape from its attackers, was trying to land, and so save the lives of his passengers. It was the only sensible thing to do.

And then, as Ginger stood staring white-faced in the direction in which the machines had disappeared, came a sound which, once heard, is never forgotten. It was the splintering crackle of a crashing aeroplane. The distance he judged to be not more than four or five miles away.

For a few seconds the drone of the Messerschmitts continued, as, no doubt, they circled round the remains of the Dragon; then the sound faded swiftly, and silence once more settled over the desert.

Now Ginger did what was perhaps a natural thing, but a foolish one—as he realized later. Acting on the spur of the moment, without stopping to think, he dashed up the rock escarpment which hid the tragedy from view. Panting and gasping, for the heat of the rock was terrific, he reached the top, only to discover that another ridge, not more than a hundred yards away, still hid what he was so anxious to see. So upset was he that he was only subconsciously aware of the blinding heat as he ran on to the ridge, again to discover that an even higher ridge was in front of him.

He pulled up short, suddenly aware of the folly of what he was doing. Already he was hot, thirsty and exhausted from emotion and violent movement in such an atmosphere. He realized that he had been foolish to leave the Spitfire without his water-bottle. He needed a drink—badly. He could not see the Spitfire from where he stood, but he knew where it was—or thought he did—and made a bee-line towards the spot.

For a time he walked confidently, and it was only when he found himself face to face with a curiously shaped mass of rock that he experienced his first twinge of uneasiness. He knew that he had never seen that particular rock before; it was too striking to be overlooked. Still, he was not alarmed, but simply annoyed with himself for carelessness which resulted in a loss of valuable time.

Turning slightly towards a rock which he thought he recognized, he walked on, only to discover that he had been mistaken. It was not the rock he had supposed. He began to hurry now, keeping a sharp look-out for something that he could recognize. But there was nothing, and irritation began to give way to fear. Fragments of Biggles’ warning drifted into his memory, such pieces as ‘shrivelling like an autumn leaf.’

He had been following a shallow valley between the rocks, and it now struck him that if he climbed one of the highest rocks he ought to be able to see his machine or the crashed Rapide. Choosing an eminence, he clambered to the summit—not without difficulty, for it was hot enough to burn his hands. The sight that met his eyes horrified him. On all sides stretched a wilderness of rock and sand, colourless, shapeless, hideous in its utter lifelessness.

He discovered that his mouth had turned bricky dry, and for once he nearly gave way to panic. No experience in the air had ever filled him with such fear. His legs seemed to go weak under him. Slowly, for he was terrified now of hurting himself and thus making his plight worse, he descended the rock and ran to the next one, which he thought was a trifle higher. Looking round frantically, he was faced with the same scene as before. It all looked alike. Rock and sand . . . sand and rock, more sand, more rock.

Running, he began to retrace his footsteps—or so he thought—to the escarpment, and was presently overjoyed to find his own footprints in the soft sand. He followed them confidently, feeling sure that they would take him back to the crash. Instead they brought him back to the same place. He had walked in a circle. With growing horror in his heart he realized that he was lost, and he stood still for a moment to get control of his racing brain.

Bitterly now he repented his rash behaviour—not that it did any good. The silence really frightened him. It was something beyond the imagination. It seemed to beat in his ears. A falling pebble made a noise like an avalanche. He trudged on through a never-altering world. All he could see was rock and sand, except, above him, a dome of burnished steel. Time passed; how long he did not know. He was not concerned with time. All he wanted was the Spitfire, and the water that was in his water-bottle. The idea of water was fast becoming a mania. Very soon it was torture. Several times he climbed rocks, but they were all too low to give him a clear view. The loneliness and the silence became unbearable, and he began to shout for the sake of hearing a human voice. He could no longer look at the sky; it had become the open door of a furnace. He put his hands on his head, which was beginning to ache. He no longer perspired, for the searing heat snatched away any moisture as soon as it was formed. He felt that his body was being dried up—as Biggles had said—like a shrivelled leaf.

Hopelessness took him in its grip. He knew he was wandering in circles, but he had ceased to care. All he wanted to do was drink. His skin began to smart. His feet were on fire. His tongue was like a piece of dried leather in his mouth. Sand gritted between his teeth. The rocks began to sway, to recede, then rush at him. Rock and sand. It was always the same. A white haze began to close in on him. Presently it turned orange. He didn’t care. He didn’t care about anything. He could only think of one thing—water.

He walked on, muttering. The rocks became monsters, marching beside him. He shouted to scare them away, but they took no notice. He saw Biggles sitting on one, but when he got to it it was only another rock. Beyond, he saw a line of blue water, with little flecks of white light dancing on it. It was so blue that it dazzled him. Shouting, he ran towards it, but it was always the same distance away, and it took his reeling brain some little time to realize that it was not there. He began to laugh. What did it matter which way he went? All ways were the same in this cauldron. More monsters were coming towards him. He rushed at them and beat at them with his fists. He saw blood on his knuckles, but he felt no pain. The sky turned red. Everything turned red. The sand seemed to be laughing at him. He hated it, and in his rage he knelt down and thumped it. It only laughed all the louder. The voice sounded very real. He tried to shout, but he could only croak.

Suddenly Ginger became conscious that he was drinking; that water, cool, refreshing water, was splashing on his face. He knew, of course, that it wasn’t true, but he didn’t mind that. It was the most wonderful sensation he had ever known, and he only wanted it to go on for ever. His great fear was that it would stop; and, surely enough, it did stop. Opening his eyes, he found himself gazing into the concerned face of his leader.

‘All right, take it easy,’ said Biggles.

‘You were—just about—in time,’ gasped Ginger.

‘And you, my lad, have had better luck than you deserve.’ Compassion faded suddenly from Biggles’ face; the muscles of his jaws tightened. ‘I seem to remember making an order about all ranks carrying water-bottles,’ he said in a voice as brittle as cracking ice. ‘If we were within striking distance of a service depôt I’d put you under close arrest for breaking orders. As it is, if you feel able to move, we’d better see about getting out of this sun-smitten dustbin. It will be dark before we get back as it is.’

Ginger staggered to his feet. ‘Sorry, sir,’ he said contritely.

‘So you thundering well ought to be,’ returned Biggles grimly. ‘Why did you land in the first place?’

‘I saw a crashed aircraft, and came down to see if there was anyone in it.’

Biggles started. ‘A crash? Where?’

Ginger shrugged his shoulders helplessly. ‘I don’t know, but it can’t be far away. Do you know where my machine is?’

‘Yes, I landed by it. I saw it from some way off and went straight to it.’

‘That’s probably why you didn’t see the crash; it’s lying close up against a cliff. It’s a Rapide. It was the flash of broken glass that took me to it. Somehow I’d got off my course.’

‘I can’t blame you for that,’ answered Biggles. ‘I had the same experience. Magnetic interference was put up to affect our compasses—or rather to affect the compass of the Dragon.’

‘Great Scott! I’d almost forgotten,’ declared Ginger. ‘You’re dead right. The Dragon came this way. It was being attacked by three Messerschmitts. They roared right over me, but I reckon they were too concerned with their own affairs to see me. That’s what started my trouble. I heard a machine crash some way off, and instead of returning to my Spitfire I climbed an escarpment to see if I could see the crash. I couldn’t see it, though. It was in going back to my machine that I lost my way.’

Biggles looked amazed at this recital—as he had every reason to. He was silent for a moment.

‘We shall have to get all these facts in line,’ he said presently. ‘Assuming that, like me, you had compass trouble, I came out to look for you. I found your machine and landed by it. I was a bit worried to find you weren’t with it. I was wondering where you could have gone when I heard someone laughing and shouting—’

‘You heard me—from the Spitfires?’

‘Certainly.’

Ginger stared. ‘Then I must have been wandering about close to my machine?’

‘I don’t know about that,’ replied Biggles. ‘All I can tell you is the Spitfires are just behind those rocks on the left—less than a hundred yards away.’

‘Just imagine it,’ said Ginger bitterly. ‘I might have passed out from thirst within a hundred yards of water.’

‘That’s how it happens,’ said Biggles seriously. ‘Don’t say I didn’t warn you. But let’s get to the machines. Thank goodness the heat isn’t quite so fierce now the sun is going down.’

Dusk was, in fact, advancing swiftly across the shimmering waste as the sun sank in a final blaze of crimson glory. There was just time to walk to the Spitfires, make a trip to the crashed Rapide, and return, before complete darkness descended on the wilderness. The heat, as Biggles had remarked, was less fierce; but the atmosphere was stifling as every rock, and every grain of sand, continued to radiate the heat it had absorbed during the day.

Biggles leaned against the fuselage of his machine and lit a cigarette. ‘I don’t feel like taking off in this black-out,’ he told Ginger. ‘Nor do I feel like risking a night flight across the desert with a compass that isn’t entirely to be relied on. We’re in no particular hurry. The moon will be up in an hour, so we may as well wait for it. I’ve some thinking to do, and I can do that as well here as anywhere. Tell me, in which direction was the Dragon flying when you last saw it—presumably the sound of the crash came from the same direction?’

‘Yes,’ answered Ginger. ‘It was over there.’ He pointed to the escarpment, its jagged ridge boldly silhouetted against the starlit heavens. ‘I couldn’t swear how far it was away, because sounds are so deceptive here, but I wouldn’t put it at more than five miles. What are you thinking of doing?’

‘I was wondering if we should try to find it.’

‘Not for me,’ declared Ginger. ‘I’ve had one go at that sort of thing. You got me out of the frying-pan, and I don’t want to fall in it again.’

‘There’s less risk of that at night, when you have stars to guide—Great Scott! What’s that?’

For a little while both Biggles and Ginger stood staring in the direction of the escarpment, beyond which a glowing finger of radiance, straight as a ruler, was moving slowly across the sky.

‘It’s a searchlight,’ declared Ginger.

‘If it is, then it’s a dickens of a long way away,’ returned Biggles. ‘Whatever it is, it’s mobile. Look at the base of it—you can see it moving along the rock . . . that’s queer, it’s stopped now. I think I know what it is. It’s the headlight of a car, deflected upwards.’

‘A car!’ said Ginger incredulously. ‘A car—here—in the desert?’

‘You haven’t forgotten that a car came out to the crashed Rapide—or a vehicle of some sort? It was not one of ours; therefore it must have belonged to the enemy. Whoever shot the Rapide down would report where it had crashed. Unless I’m mistaken, the same thing is happening now. A car is on its way to the crashed Dragon. If it can’t get right up to it, no doubt it will go as close as possible; the people in it can walk the rest of the way. This is an opportunity to learn something definite, and I don’t feel inclined to miss it. Our machines will be safe enough here—unless the car comes this way, which seems unlikely. Anyway, it’s a risk worth taking.’

With Ginger’s water-bottle slung over his shoulder, Biggles started off in a direct line towards the light, which still appeared as a faint, slender beam, like a distant searchlight. From the top of the escarpment a good deal more of it could be seen—the lower part, which descended to a point.

‘No British forces are operating in this district, so whoever is putting that beam up must be an enemy,’ said Biggles thoughtfully, as he stood staring at it.

‘How far away do you think it is?’

‘That’s impossible to tell, because we don’t know the strength of the beam. It might be a weak one fairly close, or a powerful one a long way off. What puzzles me is why it is turned upwards. It can’t be looking for aircraft.’

‘It could be a signal, a signpost, so to speak, for airmen.’

‘Possibly, but unlikely, for there seems to be no reason why enemy aircraft should operate at night.’ Biggles laughed shortly. ‘What a fool I am—the heat must have made me dense. The beam is a signpost, probably a rallying point, for people out in the desert on foot looking for the crashed Dragon. That, I think, is the most likely answer. Let’s go on for a bit; maybe we shall see something. Speak quietly, and make no more noise than you can prevent, because we’re approaching a danger zone, and sound travels a long way in the desert.’

They went on in silence, climbed the ridge that had baffled Ginger, and the one beyond it, which they discovered dropped sheer for about forty feet to a lower level of sand, generously sprinkled with broken rock. In the deceptive starlight they nearly stepped over the edge before they realized how steep was the drop. They went a little way to the right hoping to find a way down, and finding none, tried the left; but the cliff—for they were on the lip of what might best be described as a low cliff—seemed to continue for some distance. There were one or two places where a descent appeared possible, and once Ginger moved forward with that object in mind; but Biggles held him back.

‘I’m not going to risk it,’ he said in a low voice. ‘This desert rock isn’t to be trusted; wind and sun make it friable; if it broke away and let us down with a bump we might hurt ourselves. If we were nearer home I wouldn’t hesitate, but this is no place for even a minor injury—a sprained ankle, for instance. We’re some way from the machines, too. But here comes the moon. Let’s try to get a line on the light; if we can do that we may be able to check up in daylight.’ So saying, Biggles lay flat and using his hands to mask the surrounding scenery, focused his attention on the foot of the beam.

Following his example, Ginger made out what appeared to be three successive ranges of low hills which, from their serrated ridges, were obviously stark rock. The light sprang up from behind the farthest, which he estimated to be not less than twelve miles away. He tried to photograph the silhouette of the rocks in line with the beam on his brain, this being made possible by certain salient features. In the first range there was a mass of rock that took the form of a frog, and behind it a group of four small pinnacles that might have been the spires of a cathedral. These were near enough in line with the beam to fix its position should the light be turned out, and he mentioned this to Biggles, who agreed, but reminded him that when they had first seen the light it had been moving, which proved that it was not constant.

The moon, nearly full, was now clear of the horizon, and cast a pale blue radiance over the wilderness. It was not yet light enough to read a newspaper, as the saying is, but it was possible to see clearly for a considerable distance; and if the lifeless scene had been depressing by day, thought Ginger, it was a hundred times worse at night.

He was about to rise when from somewhere—it was impossible to say how far away—there came a sound, a noise so slight that in the ordinary way it might well have passed unnoticed. It was as though a small piece of rock had struck against another.

Biggles’ hand closed on Ginger’s arm. ‘Don’t move,’ he breathed.

Ginger, his muscles now taut, lay motionless, his eyes probing the direction from which he thought the sound had come, which was on the lower level to the right of where he lay. He stared and stared until the rocks appeared to take shape and move—not an uncommon reaction in darkness when nerves are strained. Moving his head slightly until his mouth was close to Biggles’ ear, he whispered, ‘Perhaps it was a jackal.’

Biggles shook his head. ‘Nothing lives in this sort of desert.’

Another rock clicked, nearer this time, and Biggles hissed a warning.

Staring again at the lower level, Ginger saw that a group of what appeared to be shadows was moving silently towards them. Very soon they took shape, and it was possible to distinguish men and camels. There were six camels carrying riders, and a number of men walking behind them. Two of the camel riders rode side by side a little in advance of the rest of the party. The other four camels moved noiselessly in single file. Magnified by the flat background behind them they were huge, distorted, more like strange spirits of the desert than living creatures. They came on, heading obliquely towards the distant light. When the two leaders were quite close a voice spoke, suddenly, and the sound was so unexpected and so clear that Ginger stiffened with shock. But it was not only the actual sound that shook him; it was the language that the speaker had used.

Speaking in German, he had said in a harsh tone of voice: ‘I’ll tell these young fools of mine to let machines get farther in, in future, before they shoot them down. It’s a good thing you know this country as well as you do, Pallini.’

A voice answered haltingly in the same language: ‘Yes, Hauptmann[15] von Zoyton, it is a long way again. It was near here that the last machine was brought down. Fortunately I know every inch of the country, but it is always a good thing to have a light to march on. It makes it easier.’

[15] German rank equivalent to Captain.

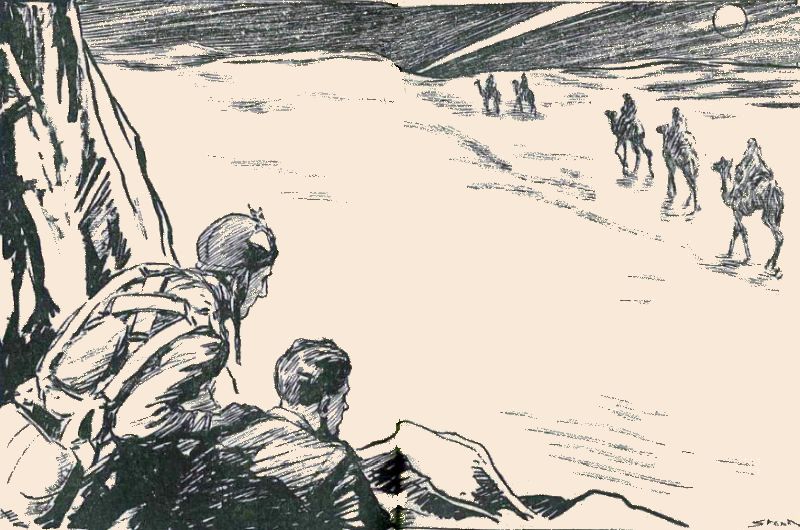

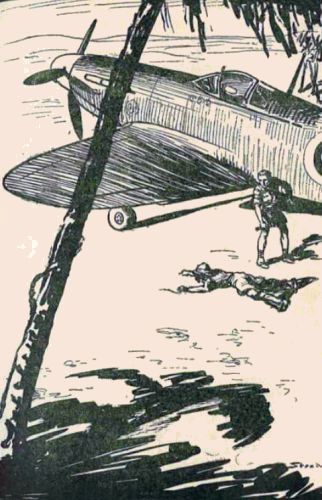

See here

Magnified by the flat background behind them they were huge, distorted, more like strange spirits of the desert than living creatures.

It was now possible to see that both riders wore uniforms, although it was not easy to make out the details. Ginger watched them go past, with the words still ringing in his ears. Then the second part of the caravan drew in line. It comprised, first, the four camels, but this time the riders seemed to have their bodies wrapped in ragged sheets which reached up to their mouths, leaving only the eyes exposed. Rifle barrels projected high above their shoulders. Behind, striding on sandalled feet, were four other men similarly dressed, acting, it seemed, as an escort for five men who walked together in a dejected little group. Four were civilians and the other an officer, a heavily-built man with a square-cut black beard. Ginger caught the flash of gold braid on his sleeves and shoulders. These, too, passed on, and soon the entire caravan had merged as mysteriously as it had appeared into the vague shadows of the nearest range of hills.

Biggles neither moved nor spoke for a good five minutes after the party had disappeared. When he did speak his voice was the merest whisper.

‘Very interesting,’ he murmured. ‘We’re learning quite a lot.’

‘Who did you make them out to be?’ asked Ginger.

‘Of the two fellows in front, one was a German and the other Italian. The Italian, whom the other called Pallini, was probably a local political officer—that would account for his knowing the country. His companion, you will remember, he called von Zoyton. It may not be the same man, but there has been a lot of talk up in the Western Desert about a star-turn pilot named von Zoyton—he commands a Messerschmitt jagdstaffel[16], and has some sort of stunt, a trick turn, they say, that has enabled him to pile up a big score of victories. I’m inclined to think it must be the same chap, sent down here for the express purpose of closing our trans-continental air route. The other mounted fellows, judging by their veils, were Toureg. There were also some Toureg on foot. The five people with them were prisoners, the passengers of the Dragon, on their way, no doubt, to the enemy camp. The beam was put up as a guide.’

[16] A hunting group of German fighter planes. A staffel consisted of twelve planes.

‘You seem very sure of that,’ said Ginger curiously.

‘I’m certain of it,’ declared Biggles. ‘You see, the fellow with the black beard was General Demaurice. I’ve never seen him in the flesh before, but I recognized him from photographs.’

‘Is he an important man?’

‘Very.’

‘Then why didn’t we attempt a rescue? We had the whole outfit stone cold. They had no idea we were here.’

‘All right; don’t get worked up,’ replied Biggles quietly. ‘It was neither the time nor place for a rescue. To start with, they were forty feet below us, and to break our legs by jumping down would have been silly. Suppose we had got the prisoners, what could we have done with them? We couldn’t fly five passengers in two Spits, and they certainly couldn’t have walked to Salima Oasis.’

‘We could have fetched the Whitley from Karga.’

‘Long before we could have got it here the Messerschmitts would have been out looking for us. Don’t suppose I didn’t contemplate a rescue, but it seemed to me one of those occasions when restraint was the better part of valour. Don’t worry, our turn will come. We’re doing fine. We know definitely that enemy machines are operating in the desert, and the approximate direction of their base. The only thing we have to reproach ourselves about is the loss of the Dragon, although now we know the technique that is being employed we ought to be able to prevent such a thing from happening again. Cruising about the desert with a compass that is liable to go gaga at any moment is, I must admit, definitely disconcerting; it means that we shall have to check up constantly on landmarks—such as they are.’

See here

. . . there has been a lot of talk up in the Western Desert about a star-turn pilot named von Zoyton—he commands a Messerschmitt jagdstaffel, and has some sort of stunt, a trick turn, they say, that has enabled him to pile up a big score of victories.

‘How about the Messerschmitts—why aren’t their compasses upset at the same time?’

Biggles thought for a moment. ‘There may be several answers to that,’ he answered slowly. Their compasses may be specially insulated, or it may be they don’t take off until the beam is switched off. The object of the beam seems to be to bring machines flying over the route nearer to the German base, to save the enemy from making long journeys in surface vehicles to the scene of a crash.’

‘Why do they want to visit the crash, anyway?’

To collect any mails or dispatches that are on board.’

‘Of course, I’d forgotten that.’ Ginger stood up. ‘As nothing more is likely to happen to-night we may as well be getting back.’

‘Not so fast,’ answered Biggles. ‘We can’t take off yet, or the noise of our engines will be heard by von Zoyton and his party. We don’t want them to know we’re about. Still, we may as well get back to the machines.’

Biggles got up and led the way back to where the two Spitfires were standing side by side, looking strangely out of place in such a setting. He squatted down on the still warm sand and allowed a full hour to pass before he climbed into his cockpit. As he told Ginger, he had plenty to think about and plans to make. But at length, satisfied that the desert raiders were out of earshot, he started his engine. Ginger did the same. The machines took off together and cruised back to the oasis, which was reached without mishap, to find the others already making arrangements for a search as soon as it was light.

‘Thank goodness you’re back,’ muttered Algy. ‘At the rate we were going there would soon have been no squadron left,’ he continued, inclined to be critical in his relief. ‘What’s going on?’

‘Sit down, and I’ll tell you,’ answered Biggles, and gave the others a concise account of what had happened.

Tug Carrington made a pretence of spitting on his hands. ‘That’s grand,’ he declared, balancing himself on his toes and making feints at imaginary enemies. ‘Now we know where they are we can go over and shoot them up.’

‘Tug, you always were a simple-minded fellow,’ returned Biggles sadly. ‘As you know, I’m all for direct methods when they are possible, but there are certain arguments against your plan that I can’t ignore. To start with, there is no guarantee we should locate the enemy’s base—you can be pretty certain it’s well camouflaged—whereas they would certainly see us. It is, therefore, far more likely that we should merely reveal our presence without serving any useful purpose. When we strike we want to hit the blighters, and hit them hard, and we shall only do that by being sure of our ground. Make no mistake; if von Zoyton is here with his jagdstaffel, we shan’t find them easy meat. They had a reputation in Libya. No, I think the situation calls for stratagem.’ Biggles smiled at Algy. ‘I wonder if we could pull off the old trap trick?’

‘Which one?’ asked Algy, grinning. ‘There were several varieties, if you remember?’

‘The decoy.’

‘We might try it. But what shall we use for bait?’

‘The Whitley.’

‘You must think von Zoyton is a fool. He wouldn’t be tricked by that.’