* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

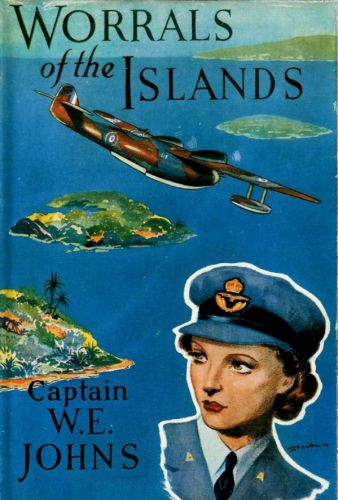

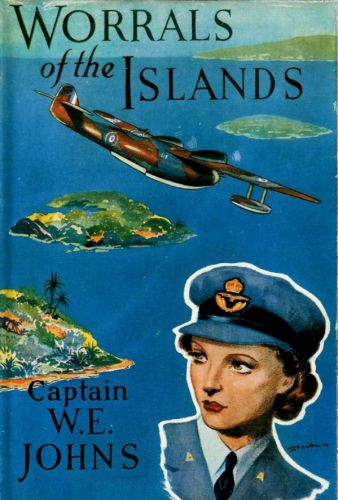

Title: Worrals of the Islands--A Story of the War in the Pacific

Date of first publication: 1945

Author: Capt. W. E. (William Earl) Johns (1893-1968)

Illustrator: Leslie Stead (1899-1966)

Date first posted: Nov. 19, 2022

Date last updated: Dec. 1, 2022

Faded Page eBook #20221134

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, akaitharam, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

Holding up her hands, palms forward, to show that they did not hold a weapon. (p. 74)

WORRALS

OF THE ISLANDS

A Story of the

War in the Pacific

by

Captain

W.E. JOHNS

Pictures by Stead

HODDER & STOUGHTON LTD.

LONDON

First printed, October, 1945

Made and Printed in Great Britain for Hodder & Stoughton, Limited, London

by Wyman & Sons Limited, London, Reading and Fakenham

| CONTENTS | ||

| PAGE | ||

| I. | A SIGN FROM THE PAST | 7 |

| II. | MEET BILLY MAGUIRE | 21 |

| III. | INGLES ISLAND | 34 |

| IV. | “ONE AIRCRAFT FAILED TO RETURN” | 43 |

| V. | A VISIT AND A VISITOR | 57 |

| VI. | WORRALS TAKES A CHANCE | 70 |

| VII. | WHAT HAPPENED AT MAITAL | 81 |

| VIII. | A STAB IN THE BACK | 94 |

| IX. | FRECKS HAS A BUSY DAY | 107 |

| X. | INTO ACTION | 116 |

| XI. | WORRALS TAKES A PRISONER | 130 |

| XII. | PAM TELLS HER TALE | 144 |

| XIII. | HIGH SPEED SORTIE | 158 |

| XIV. | VISIBILITY ZERO | 172 |

| XV. | BLITZED | 183 |

| ILLUSTRATIONS | ||

| Holding up her hands, palms forward, to show that they did not hold a weapon. (p. 74) | Front | |

| “Help. Nine British girls . . . alive . . . island . . . south-east Singapore. . . . Reward this man.” (p. 11) | 32 | |

| “Are you Billy Maguire?” queried Worrals. (p. 29) | 33 | |

| What she had taken to be a mangrove branch thrown up by the tide, moved. (p. 41) | 48 | |

| Worrals looked. “You’re right,” she agreed. “I think it’s trying to attract our attention.” (p. 48) | 49 | |

| Worrals took a compass bearing of the direction indicated. (p. 58) | 96 | |

| In a few minutes the canoe, freshly provisioned, was moving at a steady pace through the blue water. (p. 93) | 97 | |

| “It’ll be all right as long as they don’t come ashore, but if they do. . . .” (p. 105) | 112 | |

| It was a hat, dirty and sodden with sea water; a blue, tricorn hat. (p. 109) | 113 | |

| Worrals standing in the canoe waving, at imminent risk of capsizing it. (p. 111) | 144 | |

| One of them was a tall, powerfully-built fellow. (p. 135) | 145 | |

| Her finger tightened on the trigger. (p. 138) | 160 | |

| The distance between the two aircraft closed swiftly. There came a glittering streak of tracer. (p. 155) | 161 | |

A slight fall of snow had covered the airfield with a thin, untidy mantle, and a mass of indigo cloud piling up on the northern horizon gave promise of more to come. Squadron Officer Joan Worralson, W.A.A.F., regarded it for a moment with disfavour; then, leaving the Spitfire, which she had just landed, in the hands of mechanics who had run out to meet it, with her flying kit over her arm she made her way towards her quarter. But in passing Station Headquarters a hail brought her to a halt, to wait for her friend and comrade of the skyways. Flight Officer Betty Lovell, more commonly called “Frecks.”

Frecks jerked an apprehensive thumb in the direction of the clouds. “Hello, Worrals. You just about made it,” she remarked, “The Old Man was getting in a flap for fear you got tangled up in the snowflakes.”

Worrals received this information without emotion. “What does he think I am—one of the Babes in the Wood?” she inquired coldly. “He’s got two flights up topsides, but does he worry about them? No. Why not? Because they’re being coaxed through the cumulus by pilots in pants. Men! They can take care of themselves, but we’re poor little waifs who can’t be trusted to find a way home unless the sun is shining. Fiddlesticks to him.” Worrals’ voice was crisp with sarcasm.

“He means well, poor brute,” murmured Frecks condescendingly. “The old damsel-in-distress stuff dies hard in some of these whiskered warriors.”

“Is that what you came to tell me?” asked Worrals.

“No. Guess who’s here?”

“Santa Claus?”

“Don’t be a fool. It’s Marcus.”

“Marcus?”

“Squadron Leader Yorke, of Air Intelligence, no less.”

Disapproval clouded Worrals’ eyes. “If I were you,” she advised, “I wouldn’t be so free and easy with Christian names. To call a man by his first name is to put all sorts of conceited notions in his head. What does he want?”

“He wants to see you.”

“What about?”

“Search me. He thinks you’re the cat’s whisker, but apparently I’m only a loose hair on the end of its tail. Anyway, he said he’d wait for you. You’d better come. The Old Man’s blowing down his nose as it is—you know how he gets when Intelligence rolls up with a bright idea.”

“What a nuisance men are,” sighed Worrals. “I’m panting for a cup of tea.”

“He’s got tea waiting in the office.”

“That’s different,” declared Worrals, and walked on towards the building.

“Ha! Managed to get back, I see,” greeted the C.O., Wing Commander McNavish, D.S.O.

“Considering I’ve always managed to get back, so far, sir, I don’t see why you need give Squadron Leader Yorke the impression that I’ve done something astonishing,” returned Worrals curtly.

“Some men are finding the new Spitfire a bit of a handful, my gal,” explained the C.O.

“That must be because they’re ham-fisted,” averred Worrals. “With me, she practically flies herself.”

Squadron Leader Yorke, after a quick, amused glance from one to the other, played peacemaker. “Hello, Worrals,” he interposed with a friendly smile.

Worrals considered him with affected suspicion before dropping her flying kit on the floor and reaching for the tea-pot. “What glad tidings have you brought from the seats of the mighty?” she inquired.

The Squadron Leader looked pained. “Now what have I done?” he asked plaintively.

“Nothing—yet. But I’m getting clairvoyant where men are concerned. You haven’t come here to ask me if I’d like a spot of leave, or anything like that. Am I right?”

“Dead right,” admitted Yorke wanly. “Leave was the last thing I had in mind.”

Worrals smiled. “Brave man—he dares to tell the truth. All right, I’ll forgive you. I’ve been dodging snowstorms for the last hour and I found them rather tiresome. I shall feel better when I’ve had a cup of tea. Break it gently, though.” She sipped hot tea with a relish she made no attempt to conceal.

The Squadron Leader picked up a scrap of paper that lay on the desk. It was a photograph that appeared to have been torn roughly from corner to corner. The larger part was missing.

“Do you know this girl?” he asked quietly.

Worrals’ expression changed in a flash as she took the mutilated portrait. “Yes,” she answered in a curious voice. “I know her. Frecks knows her, too—or rather, knew her. She’s Julia Carson. We were at the training depôt together. She was killed at Singapore when the Japs crashed in—or at any rate, she’s been missing ever since. It upset me when I heard about it. She was a grand kid . . . the life and soul of the party. Came from Birmingham, I believe.” Worrals raised her eyes. “Why do you show this to me? Where did it come from, anyway? It looks as though it’s been in a battle.”

“It has,” answered Yorke drily. “I learned from the Record Office that you were on the same training course as Section Officer Julia Carson, so I ran down to confirm that it was her.”

“What led you to suppose it was her?”

“Her name is on the back—but I’ll talk about that in a minute.”

“Why come to me?” queried Worrals. “Why not consult her parents?”

“Because at the moment it would be a cruel thing to raise hopes that might never mature.”

“What do you mean?”

The Squadron Leader took out a tobacco pouch and filled his pipe pensively, “There is a chance that Julia Carson may be alive,” he announced. “Sit down and I’ll tell you why we think so.”

“This promises to be interesting,” murmured Worrals, as she and Frecks pulled up chairs.

“It may strike you as slightly fantastic,” asserted the Intelligence Officer.

Worrals reached for her tea cup. “Go ahead,” she invited.

“Julia Carson disappeared with several thousand other people when Singapore fell,” began Yorke. “With a few exceptions we don’t know what happened to these unlucky men and women. We may never know. If you read the papers you will have seen that we have time and time again pressed the Japanese government, through an intermediary power, to submit a list of prisoners in their hands; but for reasons known only to themselves they have ignored the request. So much for Singapore. It is a fact that Julia Carson was there until the finish. She was offered a chance to get out in a British Overseas Airways flying-boat, and accepted; but at the last minute she gave up her seat to an old lady, the mother of a planter.”

“She would,” interposed Worrals softly.

“It’s a long jump to the second part of the story,” continued Yorke. “About three months ago a British flying-boat pilot, on patrol over the Timor Sea, investigating what at first he took to be a piece of wreckage, made it out to be a canoe, with someone in it. The sea was calm, so he landed. There was one occupant in the canoe—or the remains of what had once been a man; a native. He was dead, and judging from the state of the body he had been dead for some time. In the ordinary course of things there would have been nothing remarkable about this; such little human tragedies are not uncommon in the Pacific. But investigation revealed that this man was, or had been, the bearer of a message. Around his neck, suspended by a shoelace, was a piece of tin—to be precise, the lid of a fruit-can. Through it, by means of perforations, had been punched a message, a message just about as grim as one can imagine. Here it is; you may read it for yourself.” Squadron Leader Yorke took from his wallet a disc of thin, rust-stained metal, about four inches in diameter.

Worrals held it up to the light, so that the tiny holes could be more clearly seen, and read aloud, slowly: “Help. Nine British girls . . . alive . . . island . . . south-east Singapore. . . . Reward this man.”

In dead silence Worrals handed the disc back to the Squadron Leader, who continued: “That was not all. We now come to a tragedy within a tragedy. Thrust through the native’s mop of hair was a piece of bamboo—a tube, so to speak. In passing, I may say that it is customary for many islanders to carry their primitive possessions in this way. The bamboo had been sealed with clay at both ends, to keep secure what it contained. Inside, tightly rolled, was that photograph. It had been used in lieu of paper, for on the back, in pencil, a message had been written. Julia had brains. She sent the message in duplicate. It seems likely that the photograph was the original message; then, realising that it might not survive a long journey in an open boat, she contrived an alternative which was pretty certain to endure—the tin lid. But by the very nature of it the message had to be brief. It may be supposed that the message on the photograph was more comprehensive, more explicit; in fact, we know it was. But only about a third of it reached us. By a lamentable mischance the clay seals defeated their object, for inside the bamboo was a small beetle. Whether it was already there when the photograph was put in, or whether it crawled in just before the tube was sealed, we don’t know. It may have been a tiny grub at the time. But it was there. It couldn’t escape, and it grew to maturity in its prison. The creature had to eat to keep itself alive. There was only one thing available. The photograph. For just how long it ate the paper we do not know, but it managed to get through about two thirds of it. So, unfortunately, the vital part of the message is missing, and can never be recovered.”

“What ghastly luck,” muttered Frecks.

Yorke nodded. “It boils down to this. As it stands, the photo tells us little more than the metal disc. It is obvious that there was a list of names of all the girls in the party, but with the exception of one surname, none remains, although, ironically, we can see the services to which the girls belonged—four members of the W.A.A.F., two of the A.T.S., two W.R.N.S., and a member of Queen Alexandra’s Royal Nursing Service. The most vital part of the message, which might have given us a clue to the position of the island, has gone. So has the date on which the message was written—except the year, 1943, which doesn’t help us much. Apparently the girls were wrecked. A period of time is mentioned, but all that remains is the one word ‘weeks,’ and we have no idea to what that refers. It may have been the time interval between leaving Singapore and the wreck of the boat. That information would have been useful, but it has gone, and guessing won’t help us. In short, for any practical purpose the photo is no more use than the tin. All we know for certain from these pathetic relics is that the girls left Singapore in a boat. We don’t know where they went, or where they are.”

“What about the nationality of the native?” queried Worrals. “Didn’t that tell you something?”

“Not a thing,” was the reply. “The pilot who found the canoe could only say that the body looked like that of a typical islander. He himself came from Perth, in south-west Australia, and had no experience of the islands. In any case, the body was too far gone in decomposition for any tribal marks, paint or tattooing, to be observed. For the same reason he couldn’t bring the body home.”

“No indication of why the man died?”

“Practically none. There was no water in the boat, so he may have died of thirst. But let me finish. The enquiry which we at once set on foot produced the following meagre, yet intensely interesting, information. First, we have the evidence of a nursing sister named Worton—one of the lucky ones who escaped the enemy bombs and got away when surrender became inevitable. She was taken to Ceylon and is now in this country. We have questioned everyone who got back. Sister Worton states that on the evening of the capitulation, one of her nurses, Pamela Deacon, came hurrying to her to say that a friend of hers, a girl in the W.R.N.S., was going to try to get a party of girls away in a small boat. Could she go with her? Sister Worton said yes. Everything was at sixes and sevens and it was a case of everyone for himself. She never saw Nurse Deacon again, but, thinking the matter over, she recalled that Pamela was friendly with a Wren named Angela Wishart. Both are on the list of missing. This evidence is of importance because it proves that a party of girls did intend to escape by boat, even if they did not succeed in doing so. It begins to look now as if they did get away. There were plenty of small craft available. The R.A.F. had its own sailing club there. The girls may have taken one of these boats, or a naval or R.A.F. power-boat. We think a sailing craft was used, for this reason. On her application for enlistment form, Angela Wishart made a note in the qualifications column that she had had experience with small sailing craft. It may have been for that reason that she was accepted in the category of boat’s crew. We feel that Angela would probably choose a sail boat; first, because she knew how to handle one, and secondly, because there is practically no limit to how far such a craft can travel, whereas the range of a power-boat is governed by the amount of fuel in its tank. We get another link-up when we find that Angela Wishart, besides knowing Nurse Deacon, was often seen with Section Officer Julia Carson, of the W.A.A.F. These three girls, then, knew each other, and it would be the most natural thing in the world if they tried to get away together.” The Squadron Leader relit his pipe, which had gone out.

“The only other evidence we have,” he resumed, “was provided by a pilot of British Overseas Airways who was engaged in transporting government records from Singapore to Australia. He reports that on the day after the base surrendered he saw a small sailing craft well out to sea on a south-easterly course. This has been confirmed by the captain of a Dutch tanker, who made a note in his log-book. This shows that two days later, the same, or a similar craft, tacking under mains’l and mizzen, made signals to him at a position roughly a hundred miles south-east of where it was seen by the air pilot. He couldn’t alter course, however, because his ship had been attacked and was in a sinking condition. It did, in fact, sink, but the crew was picked up by a British destroyer. The captain saved his log. That is all the evidence a searching enquiry has produced, but it fits very well, and suggests, if it does not actually prove, that at least one small boat got away. It may, or may not, have been the one taken by the girls.”

“What a story,” breathed Frecks.

“It certainly is,” agreed Yorke. “Now let us try to reconstruct the incident as it may have happened. When the defence of Singapore collapsed a lot of people tried to escape falling into Japanese hands by any means they could discover. A girl, a Wren named Angela Wishart, gets together a party of girls and sets sail in a small boat, which takes up a south-easterly course. It holds that course for at least three days, and we may suppose that it was making for Australia. Had it been making for India, the only other British territory within striking distance, it would have headed north-west. The first question is, how far did the boat get before it was wrecked—assuming it was wrecked—causing the girls to take refuge on an island?”

“But just a minute,” put in Worrals. “I think you’re taking rather a lot for granted. Speaking from memory, Australia is about two thousand miles from Singapore. The nearest point of India is nearly as far. I doubt if the girls had such an ambitious—not to say dangerous—project in mind. Let us put ourselves in their position. Personally, I should have set a course for the nearest port still in Allied hands, hoping to be picked up on the way. The main thing would be to get out of Singapore before the Japs arrived. Sumatra and Java had not then been occupied by the Japs, so it seems to me more likely that the girls would try to reach one of the big Dutch ports, like Batavia. Of course, when they discovered that the Japs were there ahead of them, they would have to keep on. A lot of refugees, including natives, were on the move, and the girls might have got the news from them. What I really mean is, I doubt if the girls originally set out for Australia, although that may have been their ultimate objective.”

“You may be right,” agreed Yorke.

“They would certainly not start without a map,” averred Worrals. “But it seems unlikely that they would manage to get hold of instruments for deep-sea navigation. Such instruments would not be in a small sailing boat normally used for pleasure cruising in and around the harbour. Without instruments they would soon be lost, so when they went ashore it is unlikely that they knew just where they were. They may have encountered storms. In short, after they were seen by the Dutch captain anything could have happened to them. As far as I can see, the position where the canoe was found, with the dead native, means nothing at all. You say he had been dead for a long time. With no one to control it the canoe might have drifted hundreds of miles from its original course.”

“I quite agree,” admitted Yorke. “Let us assume that these desperate girls just tried to get as far from Singapore as they could, calling at the islands for food. Eventually the boat was wrecked. Where? We have no idea. And when I tell you that there are, in these seas, some ten thousand islands, large and small, you begin to see what a hopeless task it is to look for them. It would be easier to find a button on a shingle beach.”

“But you have looked for them?” put in Worrals quickly.

“Of course. For three months we have been making regular reconnaissance flights. Apart from that, Allied aircraft operating in the zone have been asked to keep a look-out. All this has been without result. As the islands are nearly all covered with jungle it is difficult to see anything through it. Smoke has been seen, but that may mean nothing. There are Japanese on many of the islands, as well as natives. It does really seem a hopeless proposition, particularly when the time factor is taken into consideration.”

“What exactly do you mean by that?” asked Worrals.

“I mean, anything can have happened since the girls were cast away, or since they despatched their message. They may have died from hunger, or fever. They may have been rounded up by Japanese patrols. They may have been captured by hostile natives. Admittedly, most of the natives are reasonably tame—or they were, at the outbreak of war. But they used to be a pretty wild lot, and since the white man’s restraining influence has been absent for a long time, they might have lapsed into their bad old habits—one of which was cannibalism. Again, Japanese aggression may have made them savage. But this is all surmise. When we come down to brass tacks, this is the position. The girls may no longer be on the island. They may not even be alive. If they are alive, still on their island, it might be any one of at least a thousand which they would have to pass on a passage to Australia. They might be on Borneo, which embraces two hundred and forty thousand square miles; Sumatra, a hundred and sixty-four thousand square miles; Java, forty-six thousand square miles—to name three of the largest. I doubt if they could have reached New Guinea. They might be a thousand miles away, on Timor, which covers twenty-six thousand square miles, or on a mere atoll stuck somewhere in the Flores Sea. The more one thinks about it, the more futile does a search become.”

“You’re not likely to find them by sitting at home,” Worrals pointed out, with some asperity. “You may be sure that those girls, having sent their S.O.S., and knowing that this government doesn’t ignore such signals, are waiting confidently for someone to rescue them. No matter how hopeless it seems the search must go on. It mustn’t stop while there is a chance, however remote, that they may be alive. We—and when I say we I mean the services to which the girls belonged—owe them that.” Worrals warmed up. “Don’t you see, the belief that help is on the way will keep them alive, and fighting? If they ever learned that you had chucked up the sponge they’d die of heartbreak and shame—and so would I.”

“We’ve done everything possible, and we shall carry on,” asserted Yorke.

“From the way you spoke just now it doesn’t sound like that to me,” declared Worrals. “I have an uncomfortable feeling that this search has been conducted in a haphazard sort of way. It needs a personal interest behind it.”

“What can we do?” cried Yorke. “The islands are in Japanese hands. To search every island would be a tremendous undertaking, requiring thousands of men—even without Japanese interference.”

“All right, then, put thousands of men on it, and be dashed to the Japanese.”

“That’s impossible,” snapped Yorke. “We can’t spare the men—not thousands of men.”

“Very well, then put someone on the job who has the spirit to say, I will find these girls—and mean it; someone who will tackle the thing with method, comb the whole area systematically.”

“That’s all very well, but where are we going to find such a man?” demanded the squadron leader.

“Why a man, necessarily?”

“What do you mean?”

“Why not a woman? She would understand more clearly than you evidently do how these girls must be feeling.”

“Rubbish!” exploded Wing Commander McNavish.

“I take exception to that remark, sir,” said Worrals, with a frosty light in her eyes.

“Wars aren’t for women,” growled the C.O.

“If you said they shouldn’t be I’d agree with you,” rapped out Worrals. “Who started the war, anyway? Men. Take a look at the world and see what a nice mess men have made of it. No wonder they had to appeal to women to help them out.”

The C.O. moved uncomfortably. “I was thinking about certain jobs,” he countered.

“What jobs?” flared Worrals. “As far as I know there’s only one job in this war that hasn’t been done by women. I’ve never heard of a girl commanding a battleship—but maybe that’s only because there are more spare admirals than ships.”

“Here, I say,” broke in Yorke. “This is getting a bit hot.”

“You asked for it,” muttered Frecks.

Yorke looked at Worrals. “Do you mean that you’ll take over this search?”

“You’ve been a long time arriving at that simple fact, but it’s just what I do mean,” confirmed Worrals.

“Pah! The gal’s out of her mind,” snorted the C.O.

“You’ve said that before, sir, and there are times when I’m inclined to agree with you,” replied Worrals, with dangerous calm. “Then I remember what a lot more fun I get than the chairborne division,[1] and I’m not so sure of it. Being utterly sane must be dreadfully dull.”

[1] Air Force slang. A play on the word airborne, meaning those who work in offices, as opposed to those who fly.

“All right—all right. If that’s how you feel about it let’s get down to brass tacks,” suggested the squadron leader nervously. “I don’t suppose for a moment the A.O.C. will let you go, but——”

“Won’t he,” broke in Worrals hotly. “Won’t he? You wait and see.”

The C.O. snorted. “Ha! What do you think you are—a wizard?”

“No,” replied Worrals evenly, “just a prophet.”

The little town of Darwin, in the Northern Territory of Australia, crouched on its forked peninsular under the fierce bars of white heat flung down by the tropic sun. Tall coconut palms, regardless, threw feathery crowns high into the air, far above the twisted limbs of ancient tamarind and banyan trees; above the pink and white perfumed flowers of frangipani, scarlet poinciana, trailing purple bougainvillea, blood-red hibiscus, canary yellow cascara, and the golden bells of alamander. Among the branches fluttered butterflies, finches and parakeets of brilliant plumage, watched by jewel-eyed lizards. Along the curving beach, where the blue combers of the Timor and Arafura Seas roll in, a million sandpipers moved about among the crawling hermit crabs.

Regardless, too, of the heat, for the war had crept uncomfortably close, men and women went about their business urgently—government officials, in spotless white; cattlemen in wide sombreros; sea-bronzed men from the pearling luggers; airmen in blue; stalwart Malays; fuzzy-haired Fijians; swarthy Philippines; Chinese in baggy trousers, carrying sunshades; black boys, half naked, often incongruous on bicycles, and others that make up Darwin’s cosmopolitan population.

Three miles away, in the room that had been allotted to them at the airfield, Worrals and Frecks, shirt-sleeved, studied a map that more than covered the table.

Worrals’ assertion in the field of prophecy turned out to be correct, although she had only managed to get her way after a long tussle with the Air Officer Commanding, who—not without some justification—declared that the undertaking was so hazardous that he would think twice before allowing anyone to attempt it. However, Worrals had countered every argument, and in the end had managed to get his reluctant approval. Once this had been settled every facility was put at her disposal, with the result that five weeks later she and Frecks arrived in Australia. They had been in Darwin for a week, and they had not been idle.

With the assistance of Australian Headquarters Intelligence, through the medium of a cheerful and hardworking flight-lieutenant named Dan Lynch, their plans had been brought almost to completion. The first task had been to find the aircraft best suited to their purpose, and after a long discussion the choice had been made. The machine selected was an amphibious flying-boat of the Scud type, which embodied most of the features desirable, if not essential, for the work on hand. As most of the flying would be over water a marine aircraft was the first demand; but, as Worrals pointed out, the occasion might arise when a beach landing would be called for—as, for example, if the castaways were found. Hence, the ideal aircraft was one that could land on, and take off from, both land and water. Several amphibious types available in Australia were considered, but in the end the Scud, a civil transport twin-engined flying-boat, modified to meet military requirements as a submarine chaser, had been decided on. In the civil version there were seats for eight passengers, not counting the crew. Worrals had the seats taken out. Not only were they so much dead weight, but they would be in the way of the fuel and stores she proposed carrying in lieu of passengers. These stores could now run up to half a ton, if necessary. If the castaways were found they would be happy enough to squat on the floor, averred Worrals. Other modifications for anti-submarine work had been the mounting of twin cannon firing forward, and for defence, the installation of a dorsal gun turret, also with twin guns. Worrals stated frankly that she hoped these would never be needed; she had no intention of engaging in combat if it could be avoided, but she was prepared to defend her aircraft should it be attacked. For which reason, after debating the question, a supply of ammunition was requisitioned. As Frecks said, as the guns were fitted they might as well take some shells; they would not be in the way, even if they were never used. Other equipment included radio, a rifle, two automatics, binoculars and a signalling pistol. As an afterthought Worrals added a light automatic gun—a Sten gun, to be precise—observing that it might be useful to scare natives should they prove hostile, in the event of a forced landing. The upper surfaces of the aircraft had been camouflaged in shades of blue and green.

Worrals’ plan was simple. Using Darwin as a permanent base, the Scud would make reconnaissance flights over the islands, working on a definite system. The nearest was Timor, about four hundred miles distant. From Timor they were strung out like a chain all the way to Singapore, two thousand miles distant. To systemise the search, the map, an Admiralty chart, had been roughly squared into a number of divisions, each one bearing a letter. Worrals intended dealing with one letter at a time, surveying each island in that area before passing on to the next. The first letter had not yet been decided on. The factor which caused Worrals most concern was the distance of open sea that lay between them and their hunting grounds. This would be anything from four to five hundred miles at the eastern end, to four times that distance as they worked westward. It was apparent that flying to and fro would occupy a great deal of time, and the endurance range of the aircraft would set a limit to the time they would be able to spend over the objective when they reached it. Then again, Darwin was the Australian base nearest to the enemy. Worrals, of course, had chosen it for that very reason. But this cut two ways. Enemy aircraft, both bomber and photographic reconnaissance machines, often flew to Darwin. With the Scud operating from that base it seemed likely that in its comings and goings, sooner or later it would run into hostile planes. It was this problem which Worrals and Frecks were now discussing.

“If we could establish a base somewhere among the islands it would save an awful lot of time beetling backwards and forwards,” remarked Frecks. “We should be able to cover the squares about six times as fast.”

“Quite so,” agreed Worrals. “But the idea of sitting down in an area occupied by enemy troops, patrolled by enemy warships and flown over by enemy aircraft, strikes me as being a somewhat rash proceeding.” She tapped the chart thoughtfully with her compasses. “Still, if we could get nearer it would be worth a risk,” she went on. “I wonder if there is a place where we could hide up when we were not in the air? We could carry enough stuff in the empty cabin to last us a week or ten days at a stretch.”

“What we really need is a guy who knows these islands,” opined Frecks. “I mean a man who really knows them, knows all the creeks and coves and corners. Apart from anything else he might be able to give us some useful tips.”

Worrals looked up. “You know, Frecks, I think you’ve got something there. Why didn’t you think of it sooner? I wonder if there is such a man available?”

“We could put an advertisement in the local paper,” suggested Frecks.

“And tell the Japanese what we intend doing?” queried Worrals sarcastically. “Have a heart! Let’s ask Dan Lynch. He’ll know of such a man, if anyone does. It’s got to be someone we can trust to keep his mouth shut. Call Dan on the ’phone and ask him to step over.”

Frecks complied, and presently Dan came in.

“How’s it going?” he asked brightly. “Nearly ready to move off?”

“Almost,” answered Worrals. “The machine flies nicely. I gave her quite an airing this morning, to get the feel of everything. All being well we ought to be able to move off first thing to-morrow morning.”

“If you get away before piccaninny daylight—that’s what our natives call the first streak of dawn—you would reduce your chances of being spotted by the enemy, if he’s about.” Dan’s expression became serious. “No offence meant, but it seems all wrong to let a coupla girls like you loose on a job like this. There’s a lot of water out there, you know.” He inclined his head towards the ocean. “Are we running short of men, or something?”

Worrals held out her hands. “See anything wrong with these?”

Dan looked surprised. “Why—er—no.”

Worrals pointed to her eyes. “Or these?”

Dan grinned. “I’d say not.”

“Then what leads you to suppose that you, or any other man, can navigate the Scud through the atmosphere better than I can?”

“I wasn’t thinking about that, exactly,” protested Dan, “I was thinking of what might happen if you ran into a bunch of Zeros and caught a packet.”

“I can answer that,” replied Worrals evenly. “We should hit the drink[2] just as hard—no more, no less—as if a couple of rugged males were on board. The sharks would probably find us a bit tenderer, that’s all.”

[2] R.A.F. slang, meaning the sea, or any expanse of water.

“But suppose the Japs catch you alive?”

Worrals shook her head, slowly, smiling faintly. “Don’t worry, big boy; that won’t happen. There will always be one bullet left in my gun. But isn’t the conversation getting a trifle morbid? Moreover, we’re wasting time.” She explained the factor that had been the subject of debate. “What I’m anxious to know is,” she concluded, “do you by any chance know of a man who knows these islands inside-out, one who might be able to tell us of a little cove where we could lie doggo between sorties, so save rushing to and fro every day? Bear in mind that we should be in the air most of the time, and only use the mooring after dusk, when there wouldn’t be much chance of our being spotted. Even if we didn’t actually stay, it would be useful to know of such a place should we find it necessary to do some running repairs.”

“Yes, I know just the man,” stated Dan. “I could name half a dozen if it came to that. But the man I have in mind has already given us a lot of useful information. He owns a lugger, and has spent most of his life among the islands, trading, pearling and beachcombing generally.”

“Is he handy?”

“Right here, in Darwin.”

“What’s his name?”

“Billy Maguire.”

“Where does he live? We’ve got to step into the town to collect a few things. We could call on him at the same time.”

“If he isn’t on a bender, you’ll——”

“On a what?”

“A bender. That’s what we call a spree in this part of the world. As I was saying, if he isn’t having fun and games ashore you’ll find him on his lugger, Annie, in the harbour.”

“Is he reliable?”

“One hundred per cent., lady. Mind you, he’s tough. We don’t raise sissies, in these parts.”

“The tougher the better.”

“And his adjectives, when anything upsets him, are not the sort you’d hand round in a Sunday school.”

“I don’t care two hoots about that as long as he knows his stuff,” declared Worrals.

“I’m warning you, he calls a spade a spade.”

“No use calling a spade a shovel at a time like this, Dan.”

“Okay—as long as you know. Go and call on Billy. Tell him I sent you. Is that all?”

“That’s all, Dan, thanks.”

“Let me know how you go on.” With a wave Dan turned to go. At the door he looked back over his shoulder. “Don’t forget, you’ve only got three weeks to the wet.”

“To the what?” asked Frecks, frowning.

“The wet.” Dan smiled. “We’ve only two seasons here, the dry and the wet. The wet arrives in December with the monsoon, and runs on to March. We look forward to it because it’s cooler. But it rains. And when I say it rains I mean it rains. In our three months of wet we get more water slung down on us than you get at home in three years. When you see it you’ll know what I mean. You won’t do much flying while it’s on. The wet starts in three weeks, if it’s on time, so get busy—and don’t get caught out.”

“Thanks for the tip, Dan,” called Worrals. “Can we have transport to the town?”

“Help yourself to a jeep from the car-park.” Dan departed.

Worrals reached for her tunic and cap. “Let’s go and see Billy Maguire,” she suggested.

A quarter of an hour later they were walking across the gangplank of the Annie, a lugger of uncertain age but with a definite aroma.

“She stinks,” remarked Frecks.

“So would you, gal, if you’d carried as much dead fish as she has,” boomed a voice, so close, so vibrant, that Frecks started.

A man appeared at the head of the companion-way. Worrals was prepared for something unusual, but not for what she saw. Frecks clutched Worrals’ arm as from the companion emerged the biggest man she had ever seen. It was not only his height, which could not have been less than six and a half feet, but his vast bulk, his width across the shoulders, that took her breath away. Here, in fact, was a veritable giant. And a skin-tight singlet, the only garment he wore above a belted waist, merely served to emphasize the girth of his enormous torso. Not that he was fat. Never in her life had Frecks seen such muscles. His arms, with their bulging biceps, terrified yet fascinated her. His age might have been anything between forty and sixty-five, for the lower part of his face was lost in a tangle of black beard. A mop of curly hair of the same colour crowned his head. Between the two, dark eyes, eyes with a steady, searching look, from under bushy brows surveyed the girls with frank curiosity blended with tolerant amusement.

“Are you Billy Maguire?” queried Worrals.

The giant took a short clay pipe from between his lips and spat overboard. “That’s me. What can I do for yer?” he boomed, with disconcerting candour.

“We’d like a word with you—Dan Lynch sent us,” answered Worrals.

“Oh. So you know Dan, do yer? Let’s go below.”

The girls followed him to the cabin; and here Frecks had another shock. She expected something in the nature of a pigsty; instead of which everything was shipshape and spotless, although the strange pungent reek was more pronounced.

“It’s the dugong oil,” explained Billy, hearing Frecks sniff. “You don’t notice it after a time. Sit down and make yourselves at home. Drink?” He reached for a square bottle.

“Thanks, but we never drink between tea and dinner,” explained Worrals.

“You won’t mind if I have one?”

“Not in the least.”

Billy poured himself a generous measure and sat down. “Now, what do you want to know? If it’s anything to do with these Japanese rats, I’m your man.” He started to say something else, but checked himself.

Worrals smiled. “Go ahead and swear if it’ll help you to feel better.”

Billy frowned. “Who told you I swore, eh? Dan?”

Worrals nodded.

Billy tapped the table with a great gnarled finger. “You go back and tell him I never swear in front of ladies. Maybe he reckons he’s the only gentleman in the Territory.”

“I’ll tell him,” promised Worrals, and opening her chart on the table told the story of the castaways, concluding with the question that was the real object of her visit.

“I’d say there ain’t no call for you to keep tackin’ backwards and forwards,” said Billy. He had followed the story with keen interest and appeared to grasp instantly the problems involved. “Where did you reckon on makin’ a start?”

Worrals pointed to the square lettered D. “Somewhere near Sunda. It’s the island nearest to the spot where the canoe was found.”

“Well, there’s plenty of snug anchorages round there; the thing is to choose the best, and at the same time one that the Japs won’t be likely to use,” said Billy. “It’s my opinion that there ain’t so many Japs as our people seem to think there are. Work it out for yourself. Why, to put even a handful of men on every island they’d need millions. Course, you’ll find Japs on all the big islands, but I reckon you won’t find many on the little ’uns, though no doubt they cruise round them once in a while. Seein’ I’ve spent me life amongst the islands, there ain’t much I don’t know about ’em. I’d say the berth for you is Ingles Island—no, t’aint no use lookin’ for the name on the map; t’aint there. They’ve found names for most nearly every lump of rock that sticks out of the sea, but not every one. Most people in these parts have heard of Ingles Island, though it’s only a small ’un. No one had found a name for Ingles Island, so we just naturally call it that.”

“Why, naturally?”

“On account of Ingles. Maybe you, being a stranger, never heard of him? Ingles was a writer, one of these fellers who fill up the newspapers. Some years ago he turns up here full of a tale about a sailor named Robinson Crusoe, who got stuck on an island for years. He wants to do likewise, so he can write a story about it. So he arranges with old Tom Bunce, skipper of the lugger Opal, to drop him on an uninhabited island, and pick him up on his way back. ’Bout six weeks he reckoned it would be. Tom drops him. Coming back he piles the Opal on a reef near Bali, with the result that it’s six months, not six weeks, afore he calls for Mr. Ingles. And by that time Ingles had had enough. More than enough. He was wilder than the wildest man on Borneo. Clean out of his mind, he was.”

“What a terrible story,” murmured Frecks.

“I ain’t saying it’s a place I should choose for a holiday,” went on Bill. “But I’ve never found much wrong with Ingles island, and I’ve anchored in the lagoon there scores of times. It’s no better and no worse than most of the smaller islands. It ought to suit you. ’Course, it’s only a little place, but there’s some high ground in the middle which even the biggest seas couldn’t get near. There’s a lagoon, pretty near land-locked, and plenty of mangrove trees for cover. Barin’ a Jap patrol boat comin’ in I reckon anyone could stay there for years without being noticed. There’s even a billabong.”

“Sounds the very place,” declared Worrals. “But what’s a billabong?”

“Where have you bin all your life that you don’t know what a billabong is? You’d know if you lived in these parts. Either we have too much water or not enough. A billabong’s a water-hole—fresh water. You’ll need water, maybe.”

Worrals smiled. “It would be useful. We wash occasionally.”

“When yer run in the lagoon you’ll see a spit of sand—if it ain’t been washed away by a big sea. You’ll find the water about a couple of hundred yards to the south-east. There’s nuts, too—nuts and crabs. If there hadn’t been, I reckon Ingles would have starved. You can always make do on nuts and crabs—I have, many a time.”

“I hope we never have to,” murmured Frecks.

“How do I get to this island?” asked Worrals.

“If you’ll foller my sailin’ directions you can’t miss it,” answered Billy. “T’aint so very big, but you’ll know it the minute you claps eyes on it, ’cause it’s shaped like a pair o’ boxin’ gloves. Here, I’ll show you.”

The next ten minutes were occupied with sheer navigation, at the end of which time Worrals, with a compass course worked out, expressed herself satisfied.

“Thanks a heap, Billy,” she said. “You’ve told us just what we wanted to know.”

“When you aimin’ to weigh anchor?”

“Early to-morrow morning.”

“Well, good luck to you.” Billy held out an enormous hand.

The girls shook it in turn.

“If anything goes wrong, send me a signal on your wireless and I’ll slip across to pick you up,” promised Billy, as they reached the deck.

Worrals looked surprised. “So you’ve got wireless?”

Billy spat into the sea. “Course I’ve got wireless. Ladies like to be up-to-date, don’t they? Annie’s my best gel. The other sort let you down—but not Annie, bless ’er. Last year I made her a present of an auxiliary motor. Not that I’ve much time for engines, mind you. I’ll own they’re useful for getting around the islands, and for picking up dugong.”

“Help. Nine British girls . . . alive . . . island . . . south-east Singapore. Reward this man.” (p. 11)

“Are you Billy Maguire?” queried Worrals. (p. 29)

“And what, may I ask, is dugong?” inquired Frecks curiously.

Billy answered: “Fancy you not knowing that. The dugong is a sea animal what lives in these waters—half-way between a cow and a seal. Carries plenty of fat, and fat means oil. Oil’s money these days. When you’re on Ingles, if you hear a noise like a ghost moaning you’ll know there’s a dugong around. There’s nothing to be scared of, though. Make’s good eating if you’re stuck for grub, too.”

“I’ll remember it,” promised Frecks.

Billy turned to Worrals. “And you’ll be comin’ back every ten days, you reckon?”

“Every fortnight at the outside.”

“Look in and see me when you’re passin’, to let me know how you go on.”

“We will,” agreed Worrals, as they walked across the gangplank. Reaching the wharf the girls turned and waved.

Billy raised a gigantic paw. “Watch out for the scalies!” he called.

“What do you suppose he meant by that?” asked Frecks, as they climbed into the jeep.

“Goodness only knows.”

“Ought we to go back to ask him?”

Worrals thought for a moment. “I don’t think it matters. We can ask Dan when we get back to the station. He’ll know. I’m glad we met Billy. I like him. He’s what I call a man. He says what he thinks and no beating about the bush—the sort of man you could rely on if you were in a jam. I’d bet my clothing coupons that his heart’s as big as the rest of him.”

Lavender-tinted dawn was creeping into the sky when the Scud arrived over its objective. As Billy Maguire had said, there was no mistaking Ingles Island. His description of its shape was apt. Floating, it seemed, on a sea as tranquil as a bowl of milk, was a gigantic pair of boxing-gloves, joined together at the “wrist” end by a coral causeway. Between the twin islands—for there were really two, linked by coral—almost land-locked by the “thumbs,” nestled the lagoon, oval in shape, perhaps six acres in extent, its placid surface reflecting with the fidelity of a mirror the sombre mangroves which in places fringed the shore. The rest was mostly rock, or coral. There was no beach, except at one point where a tongue of storm-powdered coral splayed out into the water from some rising ground, forming a natural slipway and providing a foothold for a small colony of coconut palms. The sun was not yet up, but away to the north a jagged ridge, like a row of broken teeth, marked the course of the larger islands of the group—the islands that comprised square D of Worrals’ map.

The passage out had been uneventful. Most of it had been made in windless starlight. Keeping low, flying by dead reckoning, Worrals had made her landfall without difficulty. Nothing had been seen, not even a piece of floating wreckage. As Frecks had remarked, it seemed impossible that there could be so much water with nothing on it.

After a final searching scrutiny of sea and sky Worrals throttled back, made a circuit of the island as she lost height, and then, scattering clouds of sea birds, put the Scud down on the lagoon so that its run took it near the fringe of coral sand. She lowered her wheels, and a burst of throttle carried the aircraft on to dry land. She cut the engines. Movement stopped. Silence returned.

“Well, here we are,” she announced. “Let’s get busy.”

Frecks pointed at the beach, where an army of crabs, such crabs as she had never seen before, with long waving antennae and ridiculous stilt-like legs, marched up and down with military precision, making a curious clicking noise.

“Did you ever see so many crabs in your life?” she cried.

Worrals smiled. “Funny little fellers, aren’t they? Come on. Let’s have a look round. I want to get the machine out of sight before broad daylight in case an odd Jap pilot comes along.”

It had been decided that the morning should be devoted to making a thorough inspection of the island, so that in the event of trouble they would know just what lay about them. But Worrals’ immediate concern was to find a place where the aircraft could be parked without being seen either from the open sea or from the air. This would determine the site of the camp, and the dump—that is, for the half-ton of petrol, oil and stores, which at present occupied the cabin, but would have to be taken out so that they could sleep in the machine. This arrangement saved the pitching of a tent. In any case, Worrals had no intention of carrying this load about with her; that was the whole point of using the island as a temporary base.

A short walk up the spit of coral sand provided Worrals with the answer to her first problem. The sand quickly petered out in a depression that merged into a mangrove swamp, but dry ground persisted far enough under the trees to suit her purpose.

“Billy was right,” she declared. “This is an ideal place. We’ll run the machine up right away. Here, I don’t think it could be seen either from the sea or the lagoon. An aircraft would have to fly pretty low for the pilot to see through the branches of these mangroves. According to Billy, the water-hole should be somewhere over there.” She indicated with an inclination of her head some higher ground not far away.

“That looks like a track,” said Frecks, pointing. “Don’t tell me there’s someone here.”

“It’s probably the path made by Ingles, in his travels between the water-hole and the lagoon,” returned Worrals. “I imagine it was round the lagoon that he caught his crabs and collected coconuts.”

A short walk practically confirmed this. The water-hole was smaller than Worrals expected, being nothing more than a shallow well with the sides built up with pieces of rock, carefully fitted together.

“Yes, this must be Ingles’ work,” she observed. “The poor chap had plenty of time to spare. I’d hate to be stuck here for any length of time.”

“That reminds me of something,” said Frecks. “We forgot to ask Dan what Billy meant by scalies.”

“So we did,” confessed Worrals. “No matter. If it is anything unpleasant no doubt we shall soon find it—or it’ll find us. Come on; let’s get the machine snug and the stores unloaded. We’ve less time to waste than Ingles had. After that, I want to make a tour of the lagoon, to check the depth of the water. We should look silly if we tore the keel off the boat on a lump of coral—and I believe that isn’t very hard to do. If coral will rip the bottom out of a ship, I fancy it would make short work of a flying-boat.”

The next two hours they worked with hardly a pause. The Scud, scattering the crabs, was run up into its arboreal hangar. The petrol, oil and stores were unloaded, and stacked neatly on a bed of sand a short distance away. This done, a spirit lamp, which made no smoke, provided heat for the preparation of a late breakfast.

One package of stores had been left in the aircraft. This was Frecks’ idea. It consisted of a waterproof bag containing a small but carefully prepared selection of articles. She had pointed out that it was not beyond the bounds of possibility that if the castaways were found, they would be hiding in some place where an immediate landing was out of the question. Yet they might be in a bad way for food and restoratives. So into the bag had been put a supply of concentrated foods, some medical stores, a signalling pistol and a note of encouragement. Attached to the bag was a small parachute. Thus, it could be dropped to provide temporary relief until such time as arrangements could be made for rescue.

“You know,” remarked Frecks, as she sipped her coffee, “this place doesn’t line up with my idea of a South Sea island. There’s something grim, something sinister about it. It’s too harsh. Where are all the beautiful flowers, and birds and butterflies one reads about? I haven’t noticed any. As for that mangrove swamp, it stinks. I can smell it from here.”

“This is a search party, not a natural history class,” reminded Worrals. “It suits me. We shall have to take care we don’t collide with those birds,” she added, nodding to where clouds of sea birds, wing to wing, were returning to their feeding grounds. “We’ll have a look round—hark!”

From far away to the north came the steady drone of aircraft.

Worrals walked to the edge of the trees, and without going out, looked up. Frecks joined her. And there for some minutes they stood, while an irregular cluster of specks in the sky gradually took shape.

“Twelve Mitsubishi army bombers, with an escort of Zero fighters,” murmured Worrals. “Flying at between ten and twelve thousand, for a guess. From the course they’re on I’d say they’re bound for Darwin. This is the sort of thing we must expect; it’s no use kidding ourselves because we’re on a desert island that the sky is our own.”

They watched while the hostile aircraft droned on, and finally faded into the blue.

“Let’s have a walk round,” suggested Worrals.

“Okay. We’ll get the guns.”

“Guns?” queried Worrals. “What are you going to shoot—crabs?”

“You never know,” returned Frecks. “Anyhow, I feel happier with a shooting-iron. I don’t feel so lonely.”

“All right,” agreed Worrals. “We’ve got the guns, so I suppose we may as well carry them.”

They returned to the Scud. Having loaded the automatics, they pocketed them, and made their way across a bleak area, devoid of vegetation except for a short, wiry, sword-grass, to the highest point of the island—a mound of loose rock perhaps forty feet above the level of the lagoon and a quarter of a mile from it. Here they found poignant reminders of the unlucky journalist, Mr. Ingles—a rough bough-shelter supported by large pieces of rock, a litter of sea shells, coconut husks, and, close at hand, a heap of driftwood piled in the manner of a bonfire. It had never been lighted. Altogether it was a depressing spectacle in a lonely scene.

“I don’t wonder that Ingles went off his rocker,” remarked Frecks. “A week here, alone, and I should have the screaming heeby-jeebies. It’s clear to me that desert islands aren’t all they’re made out to be, I imagine Ingles called this spot Lookout Hill.”

“It’s as good a name as any,” returned Worrals.

From the elevation it was possible to judge the size of the island. It was smaller than it had appeared to be from the air, perhaps two miles by three, although from the indentations of the coastline in no place was it possible to get more than a quarter of a mile from the sea. Two thirds of the land was covered by melancholy-looking mangroves; they almost entirely concealed the far part of the island, where, running down into the sea, they made it impossible to tell just where the land ended and the water began. Worrals retraced her steps to the lagoon, and from a little rocky promontory surveyed the aquamarine depths in a check for shallow water or obstructions.

“It looks so beautiful I could throw myself into it,” remarked Frecks.

“Look again, and maybe you’ll think twice about that,” retorted Worrals.

Frecks looked, bending forward, and then pursed her lips in a low whistle. There was no need to say anything.

The lagoon, with its fascinating hues of turquoise, emerald and violet, was a thing of beauty; but its denizens were not—or not all of them. And there were many. The water was alive with marine creatures. There were myriads of fish the size of sardines, flashing like quicksilver as they turned over to feed. There were fish of all colours and shapes, some small, some running up to thirty or forty pounds. There was a blue fish, wearing on a lizard-like face a sardonic grin. Sea-snakes, striped and mottled, wriggled. Lower in the water moved small, goggle-eyed cuttlefish, their tentacles waving dreamily. Barnacles and sea-urchins festooned the coral, over which crawled little octopuses, sometimes squirting brown ink, multitudes of star-fish, and lobsters, and crabs the size of dinner plates. Worrals nudged Frecks as, following a sudden scattering, into the picture cruised a fifteen foot shark, the embodiment of grace and latent power.

“No,” said Frecks quietly, “I don’t think I shall bathe.”

Worrals walked on, completed her survey of the lagoon, and then turned to the rough causeway that linked the two halves of the island. It was about a hundred yards long, and between ten and thirty feet in its varying width, sinking slightly in the middle. Closer inspection revealed it to be dead, colourless coral, pitted with holes, around which thousands of big blue crabs sat basking in the sun. They disappeared with surprising speed at the approach of the intruders who, reaching the far side without mishap, were brought to a halt by a barrier of mangroves, standing up out of the water on a tangle of exposed roots.

If the lagoon had been a place of beauty the mangrove swamp was a place of slimy horror. The lower parts of the trees themselves were hideous; huge, misshapen, mud-caked boles rising from a tangle of roots that looked like nothing so much as a seething army of grey snakes. Within the maze thus formed, water moved uneasily with many gurglings and suckings. There were other noises, too; stealthy splashings and ploppings.

“I can see as much of that as I want to from here,” murmured Worrals.

Nevertheless, there was a sinister fascination about the place, which gave the impression of belonging to another age, or another world. They watched for some time, trying to see the hidden life that caused the furtive noises.

Suddenly Worrals whirled round. “I’m a fool,” she snapped, pointing to the causeway over which a rising tide was flooding. The lower, middle part was already awash.

She started running, but she did not get far. She pulled up with a jerk when what she had taken to be a mangrove branch thrown up by the tide, moved. A fourteen foot crocodile turned its head and coughed. Ahead, dragging themselves out of the water, were others.

Frecks screamed.

Worrals’ face was pale. “So these are the scalies!” she cried with sudden understanding. “I should have remembered—these waters are stiff with the brutes. We’ve got to get across.”

“No!” Frecks’ voice was shrill with fear. “Let’s go back.”

“I’m not spending the night in that mangrove swamp,” declared Worrals grimly, and taking out her automatic fired at the nearest crocodile.

At the crash of the shot the whole island seemed to come to life. Birds rose in thousands. The causeway heaved as a score or more of mud-coloured bodies rose up and flung themselves into the sea.

“Come on!” yelled Worrals, and firing as she ran, made a dash for the far side.

The crocodiles did not reappear. Nothing else was seen to cause alarm, but Frecks gasped her relief when the passage was made and they stood gazing back from the rising ground above the aircraft. In two minutes the causeway had disappeared from sight as the swirling seas poured over it.

“We were just in time,” observed Worrals, who was still slightly breathless. “I remember Dan telling me that there is a thirty foot rise and fall of tide in these waters.”

“The more I see of this place the less I like it,” said Frecks bitterly. “I don’t think we did anything very clever in coming here.”

“It’s all right. We shall just have to be careful,” replied Worrals. “We’re new to this sort of game, but we should have remembered that there are such things as tides. I think we’ve seen the worst.”

“I sincerely hope so,” answered Frecks fervently. “Obviously it isn’t the place to send children to paddle. Suppose those brutes attack us?”

Worrals shook her head. “I don’t think we need worry about that. The croc. is a devil of a fellow in the water, but according to what I’ve read he’s a coward on land.”

“I hope the book was right,” murmured Frecks dubiously.

They walked on to the camp, which was precisely as they had left it, except that the rising water had crept a little nearer.

“Hark!” said Worrals. She listened for a moment. “Sounds like the Mitsubishis coming back.”

From the cover of a tree they watched the return of the hostile aircraft. “Seven,” counted Worrals. “Looks as though the boys at Darwin have chewed them up a bit. There aren’t as many Zeros as there were, either.”

“Look out!” cried Frecks, and pointed to a bomber that had not previously been noticed because it was much lower than the others, and some distance behind. Slowly losing height, it was at not more than two thousand feet.

“He’s having trouble,” observed Worrals anxiously. “I hope he doesn’t try to land here. If he decides to sit down on Ingles Island we’re in for a brisk time.”

To her great satisfaction the machine did not land, but roared on towards the distant chain of islands. Still, it passed over uncomfortably close.

With a thoughtful expression on her face Worrals watched the enemy aircraft until they disappeared from sight. “See what I mean about keeping the Scud under cover?” she said quietly. “We’ve got to be careful. I doubt if the Japs will do another sortie to-day, so now we’ve got our bearings I suggest we have a spot of lunch and then start work. Every island we cover is one off the list, so the sooner we get mobile the sooner we shall be back in the land where we can step in the water without losing our feet.”

The sun was climbing over its zenith by the time lunch was finished. Preparations were made for instant departure.

“One or two points have occurred to me since those machines went over this morning,” remarked Worrals, as they walked to the Scud. “The first is, we must always be prepared for that sort of thing. Of course, while the machine is parked we shall always hear other aircraft, but once our engines are started up all other sounds will be drowned. I suggest that to prevent any chance of being caught napping, while the motors are running, whoever is not in the cockpit should watch the sky all round. Point two: we should make it a rule that once the machine is moved into the open we should take off as quickly as possible. That again should help to reduce the risk of being spotted.”

“What happens if we are chased?” asked Frecks. “Do we come back here?”

“That’s a knotty problem,” muttered Worrals. “I’ve been thinking about it. We shall be lucky if it doesn’t happen sooner or later. Any Jap fighter could easily overtake us. If we landed here we should give the pilot a sitting target. I think the answer to the question depends upon circumstances. Anyway, I’ll think about it some more. After we get off I’m going to keep low—really low; we shall be more likely to see anyone on the ground, and less likely to be spotted ourselves by a high-flying machine.”

“We shall be more likely to be spotted by Japs on the ground,” Frecks pointed out.

Worrals shrugged. “We can’t have it all ways. Let’s get cracking. I hope the motors will scare those birds off the lagoon. They’re a bit of a menace. Collision with a bird has more than once brought down a machine. You can sit beside me, but if we run into opposition you’ll have to handle the guns. Your job is to watch the sky. I’ll watch the islands.”

The Scud was soon on the lagoon, the roar of its engines sending the birds wheeling away in alarm. Another two minutes and the machine was airborne; being lightly loaded it needed only a short run to “unstick” from the placid water. With the control column forward it flashed over the blue water, and was soon speeding over the face of the ocean, heading north. Once in the air Worrals settled down at a height of not more than twenty feet, which created an impression of tremendous speed. Travelling actually at six miles a minute the Scud needed little time to reach the nearest of the islands, where the search began, and where, to avoid high ground, the aircraft was sometimes compelled to take a little altitude.

Worrals had already decided in her mind on a general line of procedure, although it was subject to modification according to the size of each island. In the case of a small island she would fly straight across the middle, twice, in two directions, and then circumnavigate it by following the beach, doing this twice or three times; how often would depend on how far the land was covered by vegetation. Not for a moment did she imagine that this would be sufficient to enable her to see anyone on the island; but she knew that anyone below would be able to see the Scud, with its British nationality markings. The straight crossings were intended to call attention to their presence. It seemed reasonable to suppose that the castaways, should they be there, would at once make for the beach, or an open space, where they could reveal themselves. She fully expected that in most cases the centre of the island would be covered by trees and bushes, and in this she was not mistaken.

Frecks, for her part, was appalled. As far as she could see, in the short glances she snatched from her sky-watching, there were islands, large and small, to north, east and west. They stretched to the distant horizon. To look at them on the map was one thing; to see them in reality was another. For the first time she realised the magnitude of their task, and her heart sank. Squadron Leader Yorke had been right when he had said that the undertaking was practically hopeless. She did not express her thoughts aloud, however.

Worrals made a mark on her chart, in the letter D, to show that the island had been covered, and then cruised across a narrow channel to the next. It was rather larger, embracing about ten square miles. Another mark on the chart and she went on to the next. There was nothing—nothing, that is, except jungle, scattered coconut palms, and a beach of white coral sand. She perceived that the work was likely to become monotonous.

The fourth island was of considerable extent—about twenty miles long by ten wide. It was a different proposition. Not only was it inhabited, but it was thickly populated with a native population. There was one quite large town and a number of villages. The houses were palm-thatched huts. Out of them, like ants, the people poured, and after one look at the low-flying plane, with wild gesticulations fled to the jungle-clad hills.

“That’s funny behaviour,” said Frecks. “Why do they run away from us?”

The answer was forthcoming, although it was not immediately apparent. Worrals swerved wildly as a cloud of black smoke appeared in front of the Scud. Others followed, and it was soon clear that an enemy ack-ack battery was in action. Worrals jammed the control column forward, and skimming the water banked steeply round a protective headland.

“That’s the answer,” she called. “Those wretched natives are getting wise. They thought we were going to bomb the Japs. Keep your eyes skinned. If there isn’t an enemy landing field here there may be one not far away; if there is, the flak battery will soon be in touch with it. We’ll push along. No use staying. If the Japs are in occupation the girls won’t be there; they’d have been captured long ago. And I don’t think we need bother about the islands in the immediate vicinity.” Still flying low she raced on, and did not resume the search until the big island was a smudge on the skyline.

About an hour later, while they were investigating an attractive cluster of atolls, Frecks let out a yell. “Bandits!”

Following the direction of Frecks’ outstretched finger Worrals saw nine Zeros in a ragged formation, flying high, a few miles to the west. Without a moment’s hesitation she cut the throttle and glided down to land in a convenient lagoon, afterwards taxiing cautiously to the encircling reef. She switched off. The drone of the Japanese aircraft could at once be heard.

“Are you crazy?” demanded Frecks.

“I acted on the spur of the moment,” replied Worrals. “Those Zeros may be looking for us. Sitting here, the Scud should look like a lump of coral from above. We can neither fight nor run away from that bunch, so our only chance is to avoid being seen. It doesn’t mean that we shall always be able to do this. It just happened that we were near an ideal spot for landing.” Worrals spoke without taking her eyes off the enemy machines.

“This is developing into a glorified game of hide and seek,” declared Frecks.

Worrals smiled. “Quite right. And we’re it. Those planes are looking for us all right,” she added. “At any rate, they’re cruising round on no definite course.”

It was twenty minutes before the enemy machines disappeared to the northward.

Worrals glanced at her instrument panel. “I think we’d better be getting back home,” she decided. “We’ve learned something. That big island is one to avoid. Even if we don’t find the girls we look like picking up some useful information for the Higher Command.”

“What about sending a radio signal to Darwin, to bring the boys along to prang that ack-ack battery?” suggested Frecks.

“Not on your life,” answered Worrals. “I’m not using radio unless things are absolutely desperate. The Japs have ears, as well as our people.” Her hand moved towards the starter.

“Just a minute,” said Frecks sharply. “Did you hear something?”

Worrals looked round. “Yes. I thought it was a sea bird.”

“To me it sounded more like a human voice. Listen.”

Presently the sound came again. This time there was no mistake. It was definitely a hail.

“It came from over there,” said Frecks, pointing to a long, low atoll, the nearest point of which was rather more than a quarter of a mile away.

Shading her eyes with her hands, Frecks gazed long and steadily at the atoll. “I can see something,” she asserted. “It looks like a big monkey gone mad . . . just to the left of that fringe of palms.”

Worrals looked. “You’re right,” she agreed. “Whatever it is, I think it’s trying to attract our attention. Just a minute.” She reached for the binoculars and focused them. “It’s a brown man, with a beard, wearing shorts,” she went on. “He’s facing this way, and he’s waving.” She lowered the glasses. “I’m going to taxi over.”

What she had taken to be a mangrove branch, thrown up by the tide, moved. (p. 41)

Worrals looked. “You’re right,” she agreed. “I think he’s trying to attract our attention.” (p. 48)

“Say! Be careful what you’re doing,” said Frecks nervously. “We don’t want a cannibal in the cockpit.”

“You keep your eyes up topsides,” requested Worrals.

After a final scrutiny of the surrounding scene for possible danger she started the motors, an action which had the effect of causing the distant figure to run up and down the beach. The Scud churned the water into foam as it swung round, and then skimmed lightly across the smooth channel that lay between it and its objective.

“It’s a native,” declared Frecks, when they were half way.

“You can’t be sure of that,” answered Worrals. “A white man is soon tanned a nice shade of chestnut in this climate.”

A cable’s length from the white coral beach on which the man was tearing up and down like a creature demented, she cut the throttle, and opening the cockpit cover, stood up. “Hi!” she shouted. “Are you signalling to us?”

The man did not answer. He plunged into the sea and swam strongly towards the aircraft. Worrals waited. Frecks took out her pistol.

“Hi!” shouted Worrals again as the man drew close. “That’s near enough. Who are you?”

She did not expect an answer, and her astonishment was unbounded when the answer came, in rich Cockney English; “Blimy! I thought you were going off without me.”

“For the love of Mike,” gasped Frecks. “He’s British.”

“Eggsactly,” said the swimmer.

“Open the cabin door and let him in,” ordered Worrals.

Frecks obeyed. Dripping water, a strange figure clambered aboard and lay panting on the floor. It was a man. He wore only one garment—a pair of ragged shorts. His skin was the colour of coffee, but his eyes were blue. A tangle of reddish beard covered his chin and a mop of hair of the same tint hung far over his neck. His eyes opened wide as he stared from Worrals to Frecks and back again at Worrals. “Ladybirds!”[3] he cried in a voice of wonder. “I don’t believe it.”

[3] Ladybird—R.A.F. slang for a W.A.A.F. officer.

“Who are you?” demanded Worrals.

“Timms, is the name,” was the reply. “Number 873 Corporal Timms, H.L., R.A.F.—that’s me. Late 906 Squadron, flying Beaufighters. The H stands for ’Enery, but in ’Ammersmith they call me ’Arry.”

“What are doing here?” asked Frecks.

“Nothing—and I’ve had bags of time to do it in,” was the frank answer. “This happens to be the place where I ’it the deck.”

“Ah,” said Worrals softly, suddenly understanding. “Are you alone here?”

“Eggsactly,” said the corporal heavily. “There was two of us—me and Flying Officer Tuke. He’s over there—under the sand.” The corporal pointed to the beach.

“I see,” said Worrals quietly. “Well, we can’t stay here. Is there anything you want to fetch from the island?”

“No, I’m here—that’s all that matters.”

“Hungry?”

“Not particularly; I’ve just had a basin of turtle eggs.”

“All right,” said Worrals. “Make yourself comfortable. We’ll have a talk presently. Shut the door, Frecks.” She turned again to the corporal as an idea struck her. “What’s your service category?”

“Wopag.”[4]

[4] R.A.F. slang, meaning wireless-operator/air gunner. Derived from the initial letters.

“Good. Man the dorsal turret. We’ve some way to go, and there’s a bunch of Zeros nosing round.”

“Ah,” breathed Harry, spitting on his hands. “Zeros. Just what I’ve been waiting for.”

“Well, we’re not waiting for them,” retorted Worrals. “We’ve other things to do.”

She returned to the cockpit, and without further parley took off and headed for Ingles Island. As on the outward journey she kept low. No aircraft of any sort was seen, although she noticed what she took to be a small coastal supply ship steaming between the islands. In less than half an hour, with the setting sun turning the water into streaming gold, the Scud settled lightly on its home lagoon.

“What’s the idea?” cried Harry, with something like consternation in his voice, as Worrals lowered the wheels, ran up into the camp and switched off.

“We’re home,” announced Worrals as she climbed down.

“Home!” The corporal was incredulous—not without reason. “Do you mean I’ve only swopped one island for another? I’m sick of islands. They’re all the same—nothing but water round them.”

“But you’re not alone any longer, and we’ll see that you have plenty to do,” said Frecks, grinning.

“Well, strike me puce!” exclaimed the corporal helplessly.

“Sit down, Harry, and let’s compare notes,” requested Worrals. “First of all, is there anything you want urgently?”

“I could do with a gasper,” declared Harry.

Worrals smiled sympathetically. “Sorry, but we don’t smoke. Bad luck.”

“You ain’t got a razor by any chance?”

“What would we do with a razor?” murmured Frecks.

The corporal received this information with a sad shake of the head, “Eggsactly,” he murmured. “How about some Christian grub? Imagine it; I used to spend quids heaving balls at coconuts on ’Amstead ’Eath. I never want to see another. Coconuts and raw turtle. What a diet!” Harry shuddered.

“Why eat the turtle raw?” asked Frecks.

“Because I’d nothing to light a fire with,” was the simple explanation. “This business of rubbin’ two sticks together don’t work—at least, not with me it don’t, although I’ll own it’s a quick way to take the skin off your ’ands. If I’d had a light I’d have lit a fire the first time you flew over. As it was, all I could do was dance. But you didn’t see me. Was I glad when I saw you go down at the next island!”

“I’ll bet you were,” murmured Frecks.

“Even then I was afraid you’d push off without noticing me,” declared Harry. “I nearly yelled my head off.”

“Tell me this,” put in Worrals. “How long have you been marooned?”

“About four months, as near I can reckon.”

“Have you ever heard anything about any girls being cast away?”

“Girls?” Harry looked amazed. “Good lor’ no! Who’d tell me? I ain’t seen no one. No, that’s a lie. I did see two natives one day, about a couple of months ago, it’d be. They came ashore in a canoe that was falling to bits. I couldn’t talk their lingo and they couldn’t talk mine, so we didn’t get far.”

“Couldn’t they have taken you off?”