* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: The Monkey and The Tiger

Date of first publication: 1965

Author: Robert Hans van Gulik (1910-1967)

Illustrator: Robert Hans van Gulik

Date first posted: Nov. 10, 2022

Date last updated: Jan. 21, 2023

Faded Page eBook #20221117

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, Pat McCoy & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

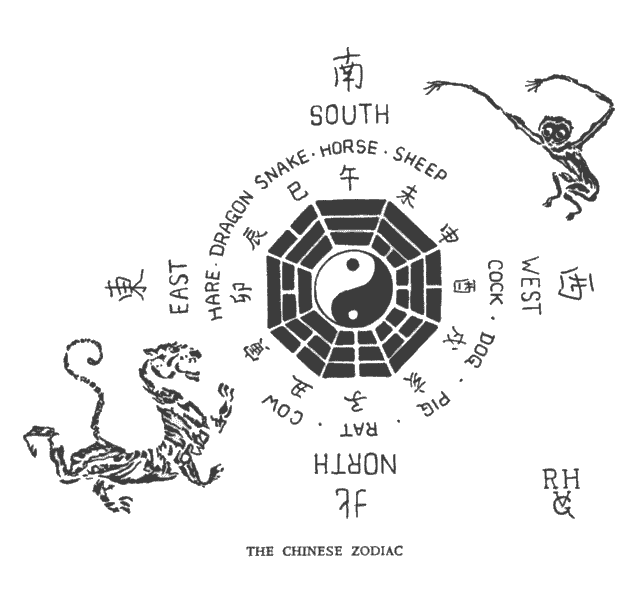

In the accompanying Chinese zodiac—always represented with the south at the top—the images of the Monkey and the Tiger indicate their correct position; the other animals are represented by their cyclical signs only. The complete set, known as the ‘Twelve Branches of Heaven’, consists of 1 Rat (Aries), 2 Cow (Taurus), 3 Tiger (Gemini), 4 Hare (Cancer), 5 Dragon (Leo), 6 Serpent (Virgo), 7 Horse (Libra), 8 Sheep (Scorpio), 9 Monkey (Sagittarius), 10 Cock (Capricorn), 11 Dog (Aquarius) and 12 Pig (Pisces). This series also indicates the 24 hours of a natural day: the Rat 11-1 a.m., the Cow 1-3 a.m., etc.

A second cyclical series (not depicted here) consists of the ‘Ten Stems of Earth’, which represents also the Five Elements and the Five Planets, viz. I chia, II yi (both wood and Jupiter), III ping, IV ting (fire and Mars), V mou, VI chi (earth and Saturn), VII keng, VIII hsin (metal and Venus), IX Jen, X kuei (water and Mercury). The twelve ‘branches’, combined with the ten ‘stems’, form a sexagenary cycle: I-1, II-2, III-3, IV-4, V-5, VI-6, VII-7, VIII-8, IX-9, X-10, I-11, II-12, III-1, IV-2 and so on till X-12. This cycle of sixty double signs is the basis of Chinese chronology. Six cycles indicate the 360 days of a tropical year and the twelve lunar months, and also the years themselves in an ever-repeating series of sixty—‘A cycle of Cathay’! The year 1900 was VII-1, a year of the Rat, and we are living now in the cycle that began in 1924 with the year of the Rat I-1; this particular cycle ends in 1984. The current year, 1965, is II-6, a year of the Serpent, 1966 will be III-7, a year of the Horse.

The octagonal design in the centre of the zodiac is explained in the Postscript.

COPYRIGHT © 1965 ROBERT H. VAN GULIK

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOG CARD NUMBER 66-16691

ILLUSTRATIONS

| The Morning of the Monkey | |

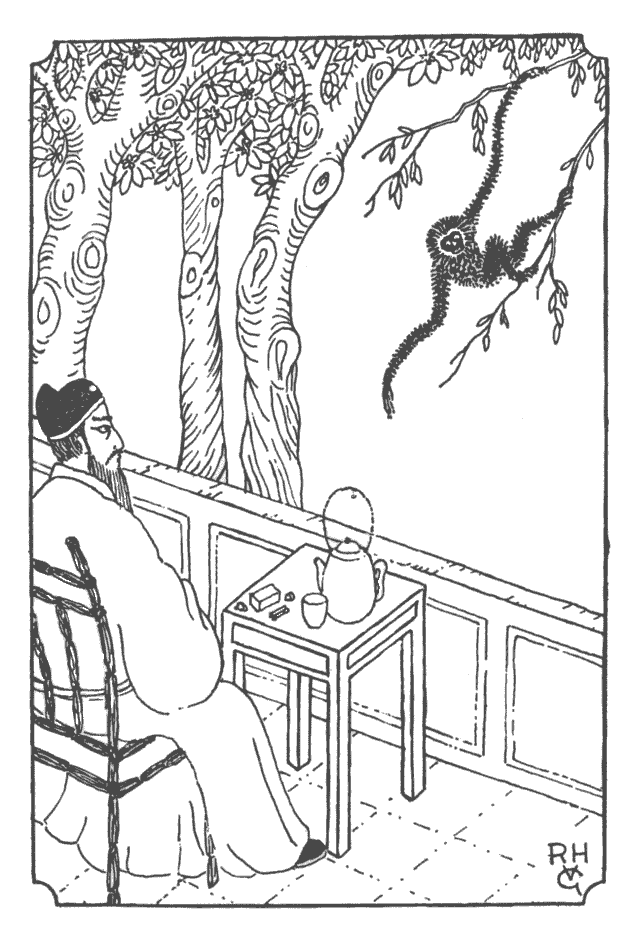

| Judge Dee saw that the gibbon was watching him | 5 |

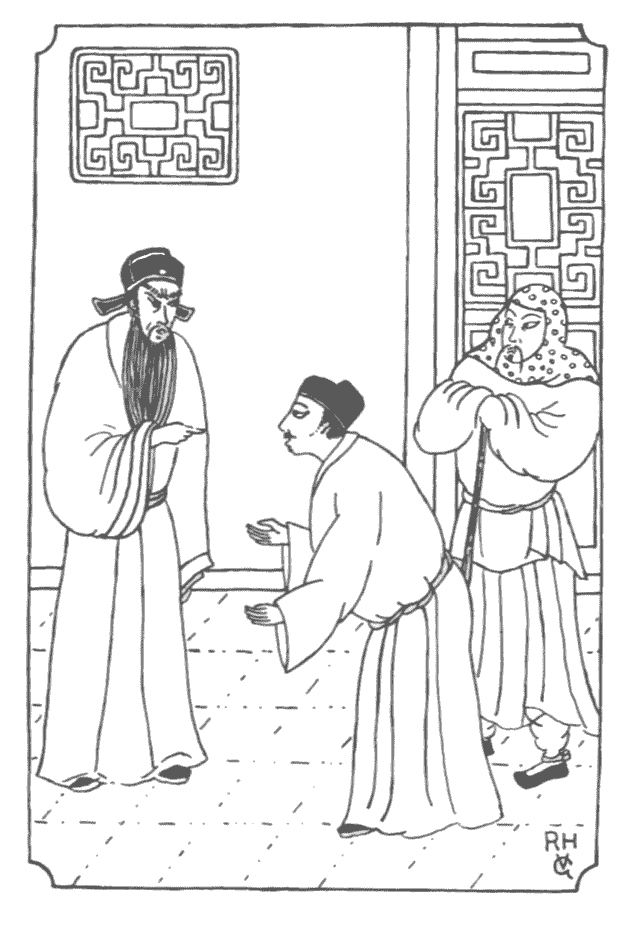

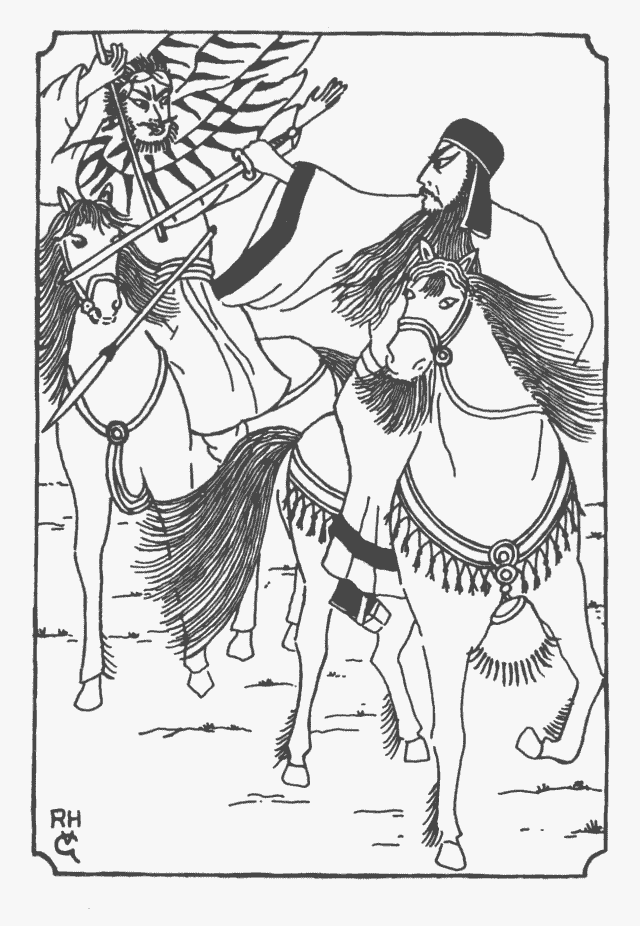

| ‘I am not yet through with you, Mr Leng!’ | 27 |

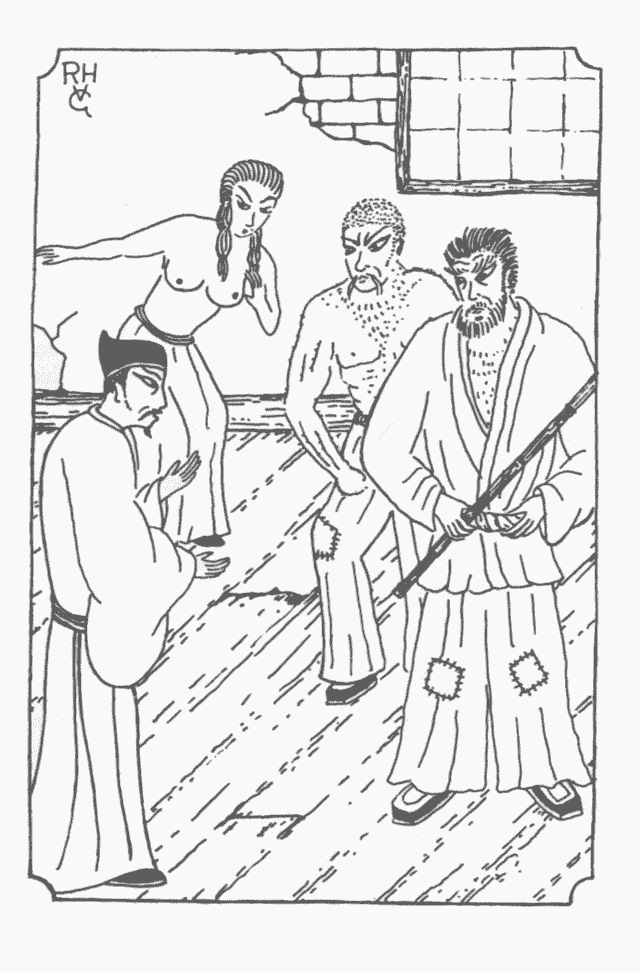

| ‘It’s a very private matter,’ Tao Gan said | 35 |

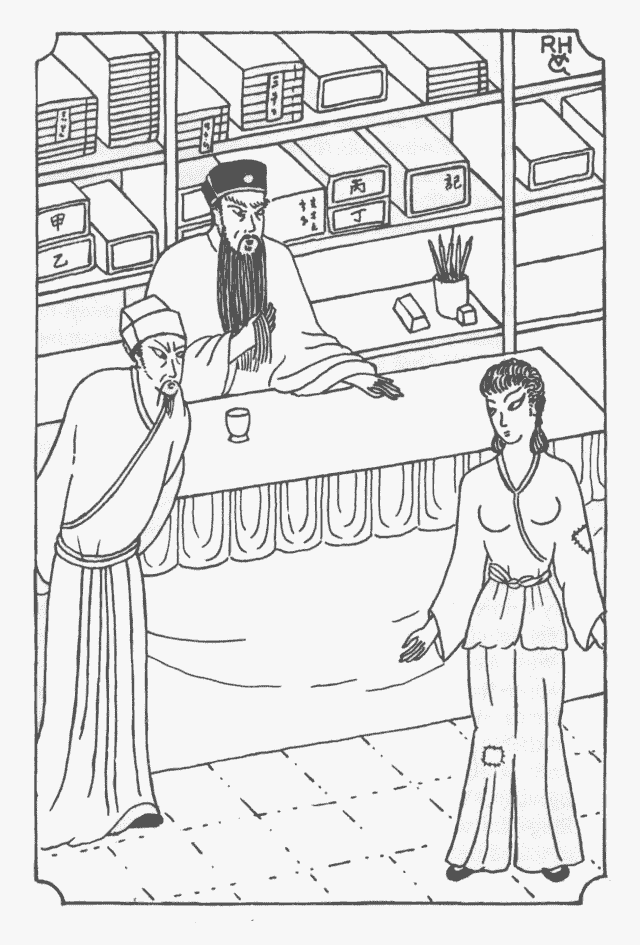

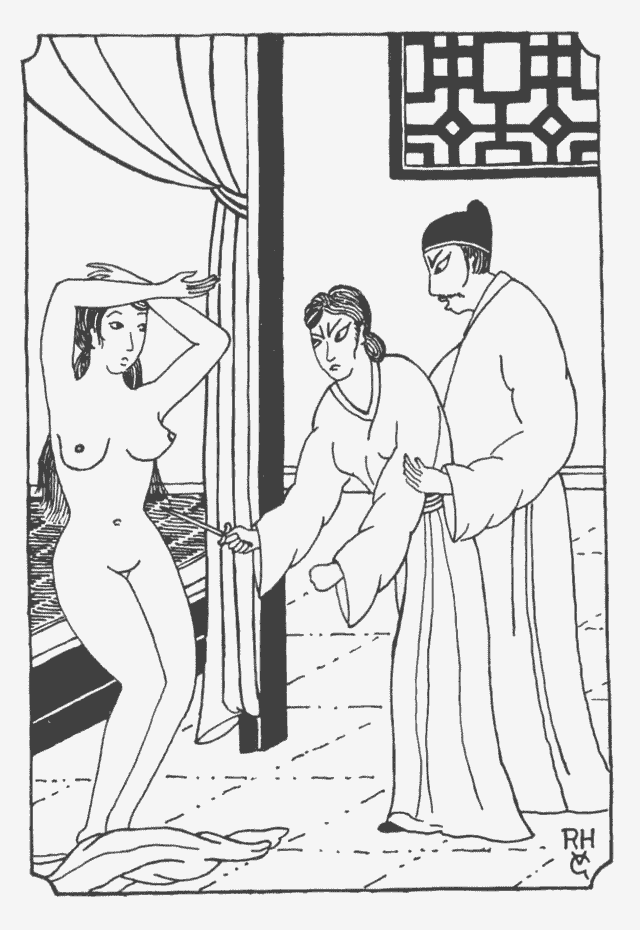

| ‘Well,’ she said, ‘I have done nothing wrong’ | 51 |

| The Night of the Tiger | |

| Judge Dee caught the spear on his sword | 77 |

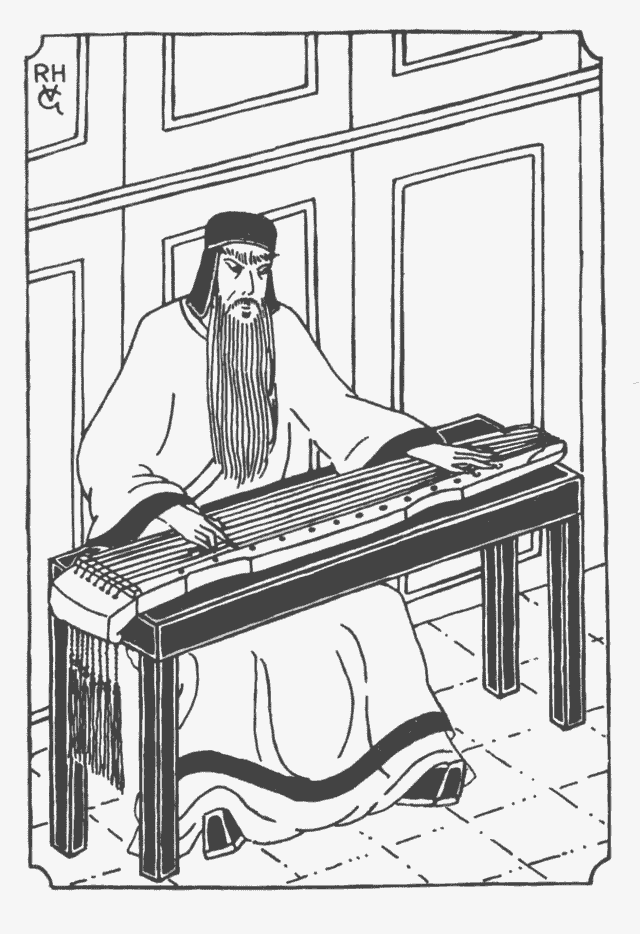

| He pulled the silk strings in succession | 113 |

| Suddenly the judge had the feeling that he was not alone | 119 |

| ‘I grabbed her and shouted at her to stop . . .’ | 137 |

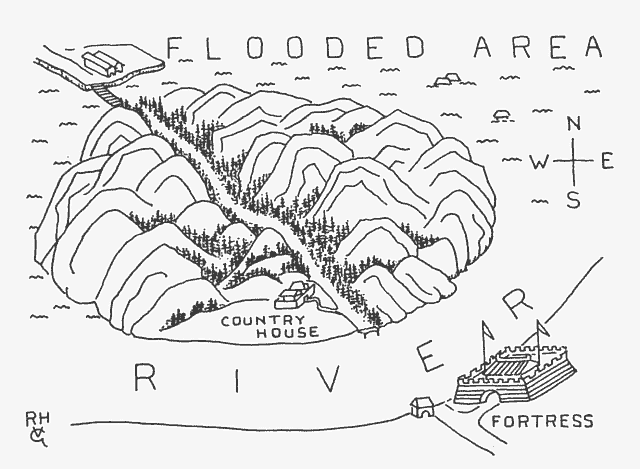

| A sketchmap of the flooded area appears on page 85 | |

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

Note that in Chinese the surname—here printed in capitals—precedes the personal name

| The Morning of the Monkey: | |

| Judge DEE | magistrate of Han-yuan, in a.d. 666 |

| TAO Gan | one of his lieutenants |

| WANG | a pharmacist |

| LENG | a pawnbroker |

| SENG Kiu | a vagabond |

| Miss SENG | his sister |

| CHANG | another vagabond |

| The Night of the Tiger: | |

| Judge DEE | travelling from Pei-chow to the capital, in a.d. 676. |

| MIN Liang | a wealthy landowner |

| MIN Kee-yü | his daughter |

| Mr MIN | his younger brother, a tea merchant |

| YEN Yuan | bailiff of the Min estate |

| LIAO | the steward |

| Aster | a maidservant |

THE MORNING OF THE MONKEY

Dedicated to the memory of my good friend the gibbon, Bubu, died at Port Dickson, Malaya, 12 July 1962.

Judge Dee was enjoying the cool summer morning in the open gallery built along the rear of his official residence. He had just finished breakfast inside with his family, and now was having his tea there all alone, as had become his fixed habit during the year he had been serving as magistrate of the lake district Han-yuan.[1] He had drawn his rattan armchair close to the carved marble balustrade. Slowly stroking his long black beard, he gazed up contentedly at the tall trees and dense undergrowth covering the mountain slope that rose directly in front of the gallery like a protecting wall of cool verdure. From it came the busy twitter of small birds, and the murmur of the cascade farther along. It was a pity, he thought, that these relaxed moments of peaceful enjoyment were so brief. Presently he would have to go to the chancery in the front section of the tribunal compound, and have a look at the official correspondence that had come in.

[1] It was here that Judge Dee solved the Chinese Lake Murders, London, Michael Joseph, 1960.

Suddenly there was the sound of rustling leaves and breaking twigs. Two furry black shapes came rushing through the tree-tops, swinging from branch to branch by their long, thin arms, and leaving a rain of falling leaves in their wake. The judge looked after the gibbons with a smile. He never tired of admiring their lithe grace as they came speeding past. Shy as they were, the gibbons living on the mountain slope had become accustomed to that solitary figure sitting there every morning. Sometimes one of them would stop for one brief moment and deftly catch the banana Judge Dee threw at him.

Again the leaves rustled. Now another gibbon came into sight. He moved slowly, using only one long arm and his hand-like feet. He was carrying a small object in his left hand. The gibbon halted in front of the gallery and, perched on a lower branch, darted an inquisitive look at the judge from his round, brown eyes. Now Judge Dee saw what the animal had in his left hand: it was a golden ring with a large, sparkling green stone. He knew that gibbons often snatch small objects that catch their fancy, but also that their interest is short-lived, especially if they find they can’t eat what they have picked up. If he couldn’t make the gibbon drop the ring then and there, he would throw it away somewhere in the forest, and the owner would never recover it.

Since the judge had no fruit at hand to distract the gibbon’s attention from the ring, he quickly took his tinderbox from his sleeve and began to arrange its contents on the tea-table, carefully examining and sniffing at each object. He saw out of the corner of his eye that the gibbon was watching him. Soon he let the ring drop, swung himself down to the lowest branch and remained hanging there by his long, spidery arms, following Judge Dee’s every gesture with eager interest. The judge noticed that a few blades of straw were sticking to the gibbon’s black fur. He couldn’t hold the fickle animal’s attention for long. The gibbon called out a friendly ‘Wak wak!’ then swung itself up onto a higher branch, and disappeared among the green leaves.

JUDGE DEE SAW THAT THE GIBBON WAS WATCHING HIM

Judge Dee stepped over the balustrade and down onto the moss-covered boulders that lined the foot of the mountain slope. Soon he had spotted the glittering ring. He picked it up and climbed back onto the gallery. A closer examination proved that it was rather large, evidently a man’s ring. It consisted of two intertwined dragons of solid gold, and the emerald was unusually big and of excellent quality. The owner would be glad to get this valuable antique specimen back. Just when he was about to put the ring away in his sleeve, his eye fell on a few rust-brown spots on its inside. Creasing his bushy eyebrows, he brought the ring closer. The stains looked uncommonly like dried blood.

He turned round and clapped his hands. When his old house steward came shuffling out to the gallery, he asked:

‘What houses stand on the mountain slope over there, steward?’

‘There are none, sir. The slope is much too steep, and covered entirely by the dense forest. There are several villas on top of the ridge, though.’

‘Yes, I remember having seen those summer villas. Do you happen to know who is living there?’

‘Well, sir, the pawnbroker Leng, for instance. And also Wang, the pharmacist.’

‘Leng I don’t know. And Wang, you say? I suppose you mean the owner of the large pharmacy in the market-place, opposite the Temple of Confucius? A small, dapper fellow, always looking rather worried?’

‘Yes indeed, sir. He has good reasons to look worried, too, sir. His business isn’t going very well this year, I heard. And his only son is mentally defective. He’ll be twenty next year, and still he can neither read nor write. I don’t know what is to become of a boy like that. . . .’

Judge Dee nodded absent-mindedly. The villas on the ridge were out, for gibbons are too shy to venture into an inhabited area. He could have picked it up, of course, in a quiet corner of a large garden up there. But even then he would have thrown it away long before he had traversed the forest and arrived at the foot of the slope. The gibbon must have found the ring much farther down.

He dismissed the steward and had another look at the ring. The glitter of the emerald seemed to have become dull suddenly, it had become a sombre eye that fixed him with a mournful stare. Annoyed at his discomfiture, he quickly put it back into his sleeve. He would issue a public notice describing the ring, and then the owner would soon present himself at the tribunal and that would be the end of it. He went inside, and walked through his residence to his front garden, and from there on to the large central courtyard of the tribunal compound.

It was fairly cool there, for the big buildings surrounding the yard protected it from the morning sun. The headman of the constables was inspecting the equipment of a dozen of his men, lined up in the centre of the courtyard. All sprang to attention when they saw the magistrate approaching. Judge Dee was about to walk past them, on to the chancery over on the other side, when a sudden thought made him halt in his steps. He asked the headman:

‘Do you know of any inhabited place in the forest on the mountain slope, behind my residence?’

‘No, Your Honour, there are no houses, as far as I know. Half-way up there is a hut, though. A small log-cabin, formerly used by a woodcutter. It has been standing empty for a long time now.’ Then he added importantly: ‘Vagabonds often stay there for the night, sir. That’s why I go up there regularly. Just to see that they make no mischief.’

This might fit. In a deserted hut, half-way up the slope . . .

‘What do you call regularly?’ he asked sharply.

‘Well, I mean to say . . . once every five or six weeks, sir. I . . .’

‘I don’t call that regularly!’ the judge interrupted him curtly. ‘I expect you to . . .’ He broke off in mid-sentence. This wouldn’t do. A vague, uneasy feeling oughtn’t to make him lose his temper. It must be the savoury sitting heavily on his stomach that had spoilt his pleasant, relaxed mood. He shouldn’t take meat with the morning rice . . . He resumed, in a more friendly manner:

‘How far is that hut from here, headman?’

‘A quarter of an hour’s walk, sir. On the narrow footpath that leads up the slope.’

‘Right. Call Tao Gan here!’

The headman ran to the chancery. He came back with a gaunt, elderly man, clad in a long robe of faded brown cotton and with a high square cap of black gauze on his head. He had a long, melancholy face with a drooping moustache and a wispy chinbeard, and three long hairs waxed from the wart on his left cheek. When Tao Gan had wished his chief a good morning, Judge Dee took his assistant to the corner of the yard. He showed him the ring and told him how he had got it. ‘You notice the dried blood sticking to it. Probably the owner cut his hand when taking a walk in the forest. He took the ring off before washing his hand in the brook, and then the gibbon snatched it. Since it is quite a valuable piece, and since we have still an hour before the morning session begins, we’ll go up there and have a look. Perhaps the owner is still wandering about searching for his ring. Were there any important letters by the morning courier?’

Tao Gan’s long, sallow face fell as he replied:

‘There was a brief note from Chiang-pei, from our Sergeant Hoong, sir. He reports that Ma Joong and Chiao Tai haven’t yet succeeded in discovering a clue.’

Judge Dee frowned. Sergeant Hoong and his two other lieutenants had left for the neighbouring district of Chiang-pei two days before, in order to assist Judge Dee’s colleague there who was working on a difficult case with ramifications in his own district. ‘Well,’ he said with a sigh, ‘let’s go. A brisk walk will do us good!’ He beckoned the headman and told him to accompany them with two constables.

They left the tribunal compound by the back door, and, a little way along the narrow mud road, the headman took a footpath that led up into the forest.

The path rose gradually in a zig-zag pattern but it was still a stiff climb. They met nobody and the only sound they heard was the twittering of the birds, high up in the tree-tops. After about a quarter of an hour the headman halted and pointed at a cluster of tall trees farther up.

‘There it is, sir!’ he announced.

Soon they found themselves in a small clearing surrounded by high oak trees. In the rear stood a small log-cabin with a mossy thatched roof. The door was closed, the only window shuttered. In front stood a chopping-block made of an old tree trunk; beside it was a heap of straw. It was still as the grave; the place seemed completely deserted.

Judge Dee walked through the tall, wet grass and pulled the door open. In the semi-dark interior he saw a deal table with two footstools, and against the back wall a bare plank-bed. On the floor in front lay the still figure of a man, clad in a jacket and trousers of faded blue cloth. His jaw was sagging, his glazed eyes wide open.

The judge quickly turned round and ordered the headman to open the shutters. Then he and Tao Gan squatted down by the side of the prone figure. It was an elderly man, thin but rather tall. He had a broad, regular face with a grey moustache and a short, neatly-trimmed goatee. The grey hair on top of the head was a mass of clotted blood. The right hand was folded over the breast, the left stretched out, close against the side of the body. Judge Dee tried to lift the arm but found it had stiffened completely. ‘Must have died late last night!’ he muttered.

‘What happened to his left hand, sir?’ Tao Gan asked.

Four fingers had been cut off just at the last joint, leaving only blood-covered stumps. Only the thumb was intact.

The judge studied the sunburnt, mutilated hand carefully.

‘Do you see that narrow band of white skin round the index, Tao Gan? Its irregular outline corresponds to that of the intertwined dragons of the emerald ring. My hunch was right. This is the owner, and he was murdered.’ He got up and told the headman, ‘Let your men carry the corpse outside!’

While the two constables were dragging the dead man away, Judge Dee and Tao Gan quickly searched the hut. The floor, the table and the two stools were covered by a thick layer of dust, but the plank-bed had been cleaned very thoroughly. They did not see a single bloodstain. Pointing at the many confused footprints in the dust on the floor, Tao Gan remarked:

‘Evidently a number of people were about here last night. This print here would seem to be left by a small, pointed woman’s shoe. And that there by a man’s shoe, and a very big one too!’

The judge nodded. He studied the floor a while, then said: ‘I don’t see any traces of the body having been dragged across the floor, so it must have been carried inside. They neatly cleaned the plank-bed. Then, instead of putting the body there, they deposited it on the floor! Strange affair! Well, let’s have a second look at the corpse.’

Outside Judge Dee pointed at the heap of straw and resumed:

‘Everything fits, Tao Gan. I noticed a few blades of straw clinging to the gibbon’s fur. When the body was being carried to the hut, the ring slipped from the stump of the left index and fell into the straw. When the gibbon passed by here early this morning, his sharp eyes spotted the glittering object among the straw, and he picked it up. It took us a quarter of an hour to come here along the winding path, but as the crow flies it’s but a short distance from here to the trees at the foot of the slope, behind my house. It took the gibbon very little time to rush down through the tree-tops.’

Tao Gan stooped and examined the chopping-block.

‘There are no traces of blood here, sir. And the four cut-off fingers are nowhere to be seen.’

‘Evidently the man was mutilated and murdered somewhere else,’ the judge said. ‘His dead body was carried up here afterwards.’

‘Then the murderer must have been a hefty fellow, sir. It isn’t an easy job to carry a body all the way up here. Unless the murderer had assistance, of course.’

‘Search him!’

As Tao Gan began to go through the dead man’s clothes, Judge Dee carefully examined the head. He thought that the skull must have been bashed in from behind, with a fairly small but heavy instrument, probably an iron hammer. Then he studied the intact right hand. The palm and the inside of the fingers were rather horny, but the nails were fairly long and well-kept.

‘There’s absolutely nothing, sir!’ Tao Gan exclaimed as he righted himself. ‘Not even a handkerchief! The murderer must have taken away everything that could have led to the identification of his victim.’

‘We do have the ring, however,’ the judge observed. ‘He had doubtless planned to take that too. When he found it missing, he must have realized that it fell off the mutilated hand somewhere on the way here. He probably searched for it with a lantern, but in vain.’ He turned to the headman, who was chewing on a toothpick with a bored look, and asked curtly: ‘Ever seen this man before?’

The headman sprang to attention.

‘No, Your Honour. Never!’ He cast a questioning look at the two constables. When they shook their heads, he added: ‘Must be a vagabond from up-country, sir.’

‘Tell your men to make a stretcher from a couple of thick branches and take the body to the tribunal. Let the clerks and the rest of the court personnel file past it, and see whether any of them knows the man. After you have warned the coroner, go to Mr Wang’s pharmacy in the market-place, and ask him to come and see me in my office.’

While walking downhill Tao Gan asked curiously:

‘Do you think that pharmacist knows more about this, sir?’

‘Oh no. But it had just occurred to me that the dead body might as well have been carried down as up hill! Therefore I want to ask Wang whether there was a fight among vagabonds or other riff-raff on the ridge last night. At the same time I want to ask him who else is living there, beside himself and that pawnbroker Leng. Heaven, my robe is caught!’

As Tao Gan was prying loose the thorny branch, Judge Dee went on: ‘The dead man’s dress points to a labourer or an artisan, but he has the face of an intellectual. And his sunburnt and calloused but well-kept hand suggests an educated man of means, who likes to live outdoors. I conclude that he was a man of means from the fact that he possessed that expensive emerald ring.’

Tao Gan remained silent the rest of the way. When they had arrived at the mud road, however, he said slowly:

‘I don’t think that the expensive ring proves that the man was rich, sir. Vagrant crooks are very superstitious as a rule. They will often hang on to a piece of stolen jewellery, just because they believe it brings them good luck.’

‘Quite. Well, I’ll go and change now, for I am wet all over. You’ll find me presently, in my private office.’

After Judge Dee had taken a bath and changed into his ceremonial robe of green brocade, he had just time for one cup of tea. Then Tao Gan helped him to put the black winged judge’s cap on his head, and they went together to the court-hall, adjoining Judge Dee’s private office. Only a few routine matters came up, so the judge could rap his gavel and close the session after only half an hour. Back in his private office, he seated himself behind his large writing-desk, pushed the pile of official documents aside and placed the emerald ring before him. Then he took his folding fan from his sleeve and said, pointing with it at the ring:

‘A queer case, Tao Gan! What could those cut-off fingers mean? That the murderer tortured his victim prior to killing him, in order to make him tell something? Or did he cut the fingers off after the murder, because they bore some mark or other that might prove the dead man’s identity?’

Tao Gan did not reply at once. He poured a cup of hot tea for the judge, then sat down again on the stool in front of the desk and began, slowly pulling at the three long hairs that sprouted from his left cheek:

‘Since the four fingers seem to have been cut off together with one blow, I think your second supposition is right, sir. According to our headman, that deserted hut was often used by vagabonds. Now, many of those vagrant ruffians are organized in regular gangs or secret brotherhoods. Every prospective member must swear an oath of allegiance to the leader of the gang and, as proof of his sincerity and his courage, himself solemnly cut off the tip of his left little finger. If this is indeed a gang murder, then the killers may well have hacked off the four fingers in order to conceal the mutilation of the little finger, and thus destroy an important clue to the background of the crime.’

Judge Dee tapped his fan on the desk.

‘Excellent reasoning, Tao Gan. Let’s start by assuming that you are right. In that case . . .’

There was a knock on the door. The coroner came in and respectfully greeted the judge. He placed a filled-out official form on the desk and said:

‘This is my autopsy report, Your Honour. I have written in all details, except the name, of course. The deceased must have been about fifty years old, and he was apparently in good health. I didn’t find either any bodily defects, or larger birthmarks or scars. There were no bruises or other signs of violence. He was killed by one blow on the back of his head, presumably from an iron hammer, small but heavy. Four fingers of the left hand have been chopped off, either directly before or after the murder. He must have been killed late last night.’

The coroner scratched his head, then resumed somewhat diffidently:

‘I must confess that I am rather puzzled by those missing fingers, sir. I could not make out how exactly they were cut off. The bones of the remaining stumps are not crushed, the flesh along the cuts is not bruised, and the skin shows no ragged ends. The hand must have been spread out on a flat surface, then all four fingers chopped off at the same time by one blow of some heavy, razor-edged cutting tool. If it had been done with a large axe, or a two-handed sword, one would never have obtained that perfectly straight, clean cut. I really don’t know what to think!’

Judge Dee glanced through the report. Looking up, he asked the coroner:

‘What about his feet?’

‘Their condition pointed to a tramp, sir. Callosities in the usual places, and torn toenails. The feet of a man who walks a great deal, often barefooted.’

‘I see. Did anybody recognize him?’

‘No sir. I was present while the personnel of the tribunal filed past the dead body. Nobody had ever seen him before.’

‘Thank you. You may go.’

The headman, who had been waiting in the corridor till the interview was over, now came in and reported that Mr Wang, the pharmacist, had arrived.

Judge Dee closed his fan. ‘Show him in!’ he ordered the headman.

The pharmacist was a small, dapper man with a slight stoop, very neatly dressed in a robe of black silk and square black cap. He had a pale, rather reserved face, marked by a jet-black moustache and goatee. After he had made his bow, Judge Dee told him affably:

‘Do sit down, Mr Wang! We are not in the tribunal here. I am sorry to disturb you, but I need some information on the situation up on the ridge. During the daytime you are always in your shop in the market-place, of course, but I assume that you pass the evening and night in your mountain villa?’

‘Yes indeed, Your Honour,’ Wang replied in a cultured, measured voice. ‘It’s much cooler up there than here in town, this time of year.’

‘Precisely. I heard that some ruffians created a disturbance up there last night.’

‘No, everything was quiet last night, sir. It is true that all kinds of tramps and other riff-raff are about there. They pass the night in the forest, because they are afraid to enter the city at a late hour when the nightwatch might arrest them. The presence of those scoundrels is the only drawback of that otherwise most desirable neighbourhood. Sometimes we hear them shout and quarrel on the road, but all the villas there, including mine, have a high outer wall, so we need not be afraid of attempts at robbery, and we just ignore them.’

‘I would appreciate it if you would also ask your servants, Mr Wang. The disturbance may not have taken place on the highway, but behind your house, in the wood.’

‘I can inform Your Honour now that they haven’t seen or heard anything. I was at home the entire evening, and none of us went out. You might ask Mr Leng, the pawnbroker, sir. He lives next door, and he . . . he keeps rather irregular hours.’

‘Who else is living there, Mr Wang?’

‘At the moment nobody, sir. There are three more villas, but those belong to wealthy merchants from the capital who come for their summer holiday only. All three are standing empty now.’

‘I see. Well, thanks very much, Mr Wang. Would you mind going to the mortuary with the headman? I want you to have a look at the dead body of a vagabond, and let me know whether you have seen him in your neighbourhood lately.’

After the pharmacist had taken his leave with a low bow, Tao Gan said:

‘We must also reckon with the possibility that the man was murdered here in town, sir. In a winehouse or in a low-class brothel.’

Judge Dee shook his head.

‘If that had been the case, Tao Gan, they would have hidden the body under the floor, or thrown it in a dry well. They would never have dared take the risk of conveying it to the mountain slope, for then they would have been obliged to pass close by this tribunal.’ He took the ring from his sleeve again and handed it to Tao Gan. ‘When the coroner came in, I was just about to ask you to go down into the town and show this ring around in the small pawnshops there. You can do so now. You needn’t worry about the routine of the chancery, Tao Gan! I shall take care of that, this morning.’

He dismissed his lieutenant with an encouraging smile, then he began to sort out the official correspondence that had come in that morning. He had the dossiers he needed fetched from the archives, and set to work. He was disturbed only once, when the headman came in to report that Mr Wang had viewed the body and stated that he did not recognize the dead tramp.

At noon the judge sent for a tray with rice gruel and salted vegetables and ate at his desk, attended upon by one of the chancery clerks. While sipping a cup of strong tea he went over in his mind the case of the murdered vagabond. He slowly shook his head. Although the facts that had come to light thus far pointed to a gang murder, he was still groping for another approach. He had to admit, however, that his doubts rested on flimsy grounds: just his impression that the dead man had not been a tramp, but an educated, intelligent man, and of a strong character. He decided that for the time being he would not communicate his indecision to his lieutenant. Tao Gan had been in his service only ten months, and he was so eager that the judge felt reluctant to discourage him by questioning the validity of his theory about the significance of the missing four fingers. And it would be very wrong to teach him to go by hunches rather than by facts!

With a sigh Judge Dee set his teacup down and pulled a bulky dossier towards him. It contained all the papers relating to the smuggling case in the neighbouring district of Chiang-pei. Four days before, the military police had surprised three men who were trying to get two boxes across the river that formed the boundary between the two districts. The men had fled into the woods of Chiang-pei, leaving the boxes behind. They proved to be crammed with small packages containing gold and silver dust, camphor, mercury, and ginseng—the costly medicinal root imported from Korea—and all these goods were subject to a heavy road-tax. Since the seizure had taken place in Chiang-pei, the case concerned Judge Dee’s colleague, the magistrate of that district. But he happened to be short-handed and had requested Judge Dee’s assistance. The judge had agreed at once, all the more readily since he suspected that the smugglers had accomplices in his own district. He had sent his trusted old adviser Sergeant Hoong to Chiang-pei, together with his two lieutenants Ma Joong and Chiao Tai. They had established their headquarters in the military guardpost, at the bridge that crossed the boundary river.

The judge took the sketchmap of the region from the file, and studied it intently. Ma Joong and Chiao Tai had scoured the woods with the military police, and interrogated the peasants living in the fields beyond, without discovering a single clue. It was an awkward affair, for the higher authorities always took a grave view of evasion of the road-taxes. The Prefect, the direct superior of Judge Dee and his colleague of Chiang-pei, had sent the latter a peremptory note, stating that he expected quick results. He had added that the matter was urgent, for the large amount and the high cost of the contraband proved that it had not been an incidental attempt by local smugglers. They must have a powerful organization behind them that directed the operations. The three smugglers were only important in so far as they could give a lead to the identity of their principal. The metropolitan authorities suspected that a leading financier in the capital was the ringleader. If this master-criminal was not tracked down, the smuggling would continue.

Shaking his head the judge poured himself another cup of tea.

Tao Gan came back to the market-place dog-tired and in a very bad temper. In the hot and smelly quarter behind the fishmarket down town, he had visited no less than six pawnshops and made exhaustive enquiries in a number of small gold and silver shops, and also in a few disreputable hostels and dosshouses. Nobody had ever seen an emerald ring with two entwined dragons, nor heard about a gang fight in or outside the city.

He went up the broad stone steps of the Temple of Confucius, crowded with the stalls of street-vendors, and sat down on the bamboo stool in front of the stand of an oilcake hawker. Rubbing his sore legs he reflected sadly that he had failed in the first assignment Judge Dee had given him to carry out alone; for up to now he had always worked together with Ma Joong and Chiao Tai. He had lost this rare chance of proving his mettle! ‘It’s true,’ he told himself, ‘that I lack the physical strength and experience in detecting of my colleagues, but I know as much as they about the ways and byways of the underworld, if not more! Why . . . ?’

‘This place is meant for business, not for taking a gratis rest!’ the cake vendor told him sourly. ‘Besides, your long face keeps other customers away!’

Tao Gan gave him a dirty look and invested five coppers in a handful of oilcakes. Those would have to do for his luncheon for he was a very parsimonious man. Munching the cakes, he let his eyes rove over the market-place. He bestowed an envious look upon the beautiful front of Wang’s pharmacy over on the other side, lavishly decorated with gold lacquer. The tall greystone building next door looked simple but dignified. Over the barred windows hung a small sign-board reading ‘Leng’s Pawnshop’.

‘Vagabonds wouldn’t patronize such a high-class pawnshop,’ Tao Gan muttered. ‘But since I am here anyway, I might as well have a look there too. And Leng has a villa on the ridge. He may have heard or seen something last night.’ He rose and elbowed his way through the market crowd.

About a dozen neatly dressed customers were standing in front of the high counter that ran across the high, spacious room, talking busily with the clerks. In the rear a large, fat man was sitting at a massive desk, working an enormous abacus with his white, podgy hands. He wore a wide grey robe, and a small black cap. Tao Gan reached into his capacious sleeve and handed to the nearest clerk an impressive red visiting-card. It bore in large letters the inscription ‘Kan Tao, antique gold and silver bought and sold’. And in the corner the address: the famous street of jewellers in the capital. This was one of the many faked visiting-cards Tao Gan had used during his long career as a professional swindler; upon entering Judge Dee’s service he had been unable to bring himself to do away with that choice collection.

When the clerk had shown the card to the fat man, he got up at once and came waddling to the counter. His round, haughty face was creased in a friendly smile when he asked:

‘And what can we do for you today, sir?’

‘I just want some confidential information, Mr Leng. A fellow offered me an emerald ring at only one-third of the value. I suspect it has been stolen, and was wondering whether someone might have tried to pawn it here.’

So speaking he took the ring from his sleeve and laid it on the counter.

Leng’s face fell.

‘No,’ he replied curtly, ‘never seen it before.’ Then he snapped at the cross-eyed clerk who was peeping over his shoulder: ‘None of your business!’ To Tao Gan he added: ‘Very sorry I can’t help you, Mr Kan!’ and went back to his desk.

The cross-eyed clerk winked at Tao Gan and pointed with his chin at the door. Tao Gan nodded and went outside. Seeing the red-marble bench in the porch of Wang’s pharmacy next door, he sat there to wait.

Through the open window he watched with interest what was going on inside. Two shop assistants were turning pills between wooden disks, another was slicing a thick medicinal root on an iron chopping-board by means of the huge cleaver attached to it by a hinge. Two of their colleagues were sorting out dried centipedes and spiders; Tao Gan knew that these substances, pounded in a mortar together with the exuviae of cicadas and then dissolved in warm wine, made an excellent cough medicine.

Suddenly he heard footsteps. The cross-eyed clerk came up to him and sat down by his side.

‘That thick-skulled boss of mine didn’t recognize you,’ the clerk said with a self-satisfied smirk, ‘but I placed you at once! I remember clearly having seen you in the tribunal, sitting at the table of the clerks!’

‘Come to the point!’ Tao Gan told him crossly.

‘The point is that the fat bastard lied, my dear friend! He had seen that ring before. Had it in his hands, at the counter.’

‘Well, well. He has forgotten all about it, I suppose.’

‘Not on your life! That ring was brought to us two days ago, by a damned good-looking girl. Just as I was going to ask her whether she wanted to pawn it, the boss comes up and pushes me away. He is always after pretty young women, the old goat! Well, I watched them, but I couldn’t hear what they were whispering about. Finally the wench picks up the ring again, and off she went.’

‘What kind of a woman was she?’

‘Not a lady, that I can tell you! Dressed in a patched blue jacket and trousers, like a scullery maid. Holy heaven, if I were rich I wouldn’t mind having a maid like that about the house, not a bit! Wasn’t she a stunner! Anyway, my boss is a crook, I tell you. He’s mixed up in all kinds of shady deals, and he also cheats with his taxes.’

‘You don’t seem very fond of your boss.’

‘You should know how he’s sweating us! And he and that snooty son of his keep their eyes on me and my colleagues all the time, fat chance we have to make any money on the side!’ The clerk heaved a deep sigh, then resumed, business-like: ‘If the tribunal pays me ten coppers a day, I shall collect evidence on his tax evasion. For the information I gave you just now, twenty-five coppers will do.’

Tao Gan rose and patted the other’s shoulder.

‘Carry on, my boy!’ he told him cheerfully. ‘Then you’ll also become a big fat bully in due time, working an enormous abacus.’ Then he added sternly: ‘If I need you I’ll send for you. Good-bye!’

The disappointed clerk scurried back to the pawn shop. Tao Gan followed him at a more sedate pace. Inside he rapped on the counter with his bony knuckles and peremptorily beckoned the portly pawnbroker. Showing him his identity document bearing the large red stamp of the tribunal, he told him curtly:

‘You’ll have to come with me to the tribunal, Mr Leng. His Excellency the magistrate wants to see you. No, there is no need to change. That grey dress of yours is very becoming. Hurry up, I don’t have all day!’

They were carried to the tribunal in Leng’s luxurious padded palankeen.

Tao Gan told the pawnbroker to wait in the chancery. Leng let himself down heavily on the bench in the ante-room and at once began to fan himself vigorously with a large silk fan. He jumped up when Tao Gan came to fetch him.

‘What is it all about, sir?’ he asked worriedly.

Tao Gan gave him a pitying look. He was thoroughly enjoying himself.

‘Well,’ he said slowly, ‘I can’t talk about official business, of course. But I’ll say this much: I am glad I am not in your shoes, Mr Leng!’

When the sweating pawnbroker was ushered in by Tao Gan into Judge Dee’s office, and he saw the judge sitting behind his desk, he fell onto his knees and began to knock his forehead on the floor.

‘You may skip the formalities, Mr Leng!’ Judge Dee told him coldly. ‘Sit down and listen! It is my duty to warn you that if you don’t answer my questions truthfully, I shall have to interrogate you in court. Speak up, where were you last night?’

‘Merciful Heaven! So it is just as I feared!’ the fat man exclaimed. ‘It was just that I had had a few drops too much, Excellency! I swear it! When I was closing up, my old friend Chu the goldsmith dropped in and invited me to have a drink in the winehouse on the corner. We had two jugs, sir! At the most! I was still steady on my legs. The old man told you that, I suppose?’

Judge Dee nodded. He didn’t have the faintest idea what the excited man was talking about. If Leng had said he was at home the previous night the judge had planned to ask him whether there had been a commotion on the ridge, and then he would have confronted him with his lying about the emerald ring. Now he told him curtly: ‘I want to hear everything again, from your own mouth!’

‘Well, after I had taken leave of my friend Chu, Excellency, I told my palankeen bearers to carry me up to my villa on the ridge. When we were rounding the corner of your tribunal here, a band of young rascals, grown-up guttersnipes, began to jeer at me. As a rule I don’t pay any attention to that kind of thing, but . . . well, as I said, I was. . . Anyway, I got angry and told my bearers to put the palankeen down and teach the scum a lesson. Then suddenly that old vagabond appears. He kicks against my palankeen and starts calling me a dirty tyrant. Well, I mean a man in my position can’t take that lying down! I step from my palankeen and I give the old scoundrel a push. Just a push, Excellency. He falls down, and remains lying there on his back.’

The pawnbroker produced a large silk handkerchief and rubbed his moist face.

‘Did his head bleed?’ the judge asked.

‘Bleed? Of course not, sir! He fell on to the soft shoulder of the mud road. But I should’ve had a good look, of course, to see whether he was all right. However, those young hoodlums began to shout again, so I jumped in my palankeen and told the bearers to carry me away. It was only when I was about half-way up the road to the ridge, and when the evening breeze had cooled my head a bit, that I realized that the old tramp might have had a heart attack. So I stepped out and told the bearers that I would walk a bit and that they could go on ahead to the villa. Then I walked downhill, back to the place of the quarrel. But . . .’

‘Why didn’t you simply tell your chair-bearers to take you back there?’ Judge Dee interrupted.

The pawnbroker looked embarrassed.

‘Well, sir, you know what those coolies are nowadays. If that tramp had really fallen ill, I wouldn’t want my bearers to know that, you see. Those impudent rascals aren’t beyond trying a bit of blackmail. . . . Anyway, when I came to the street corner here, the old tramp was nowhere to be seen. A hawker told me that the old scoundrel had scrambled up again shortly after I had left. He had said some very bad things about me, then he took the road to the ridge, as chipper as can be!’

‘I see. What did you do next?’

‘I? Oh, I rented a chair, and was carried home. But the incident had upset my stomach, and when I descended in front of my gate, I suddenly became very ill. Fortunately Mr Wang and his son were just coming back from a walk, and his son carried me inside. Strong as an ox, that boy is. Well, then I went straight to bed.’ He again mopped his face before he concluded: ‘I fully realized that I shouldn’t have laid hands on that old vagabond, Excellency. And now he has lodged a complaint, of course. Well, I am prepared to pay any indemnity, within reason, of course, and . . .’

Judge Dee had risen.

‘Come with me, Mr Leng,’ he said evenly. ‘I want to show you something.’

The judge left the office, followed by Tao Gan and the bewildered pawnbroker. In the courtyard the judge told the headman to take them to the mortuary in the gatehouse. He led them to a musty room, bare except for a deal table on trestles, covered with a reed mat. The judge lifted up the end of the mat, and asked:

‘Do you know this man, Mr Leng?’

After one look at the old tramp’s face, Leng shouted:

‘He is dead! Holy Heaven, I killed him!’

He fell on his knees and wailed: ‘Mercy, Excellency, have mercy! It was an accident, I swear it! I . . .’

‘You’ll be given an opportunity to explain when you are standing trial,’ Judge Dee told him coldly. ‘Now we’ll go back to my office, for I am not yet through with you, Mr Leng. Not by a long shot!’

Back in his private office the judge sat down behind his desk and motioned Tao Gan to take the stool in front. Leng was not invited to be seated so he had to remain standing there, under the watchful eye of the headman.

Judge Dee silently studied him for a while, slowly caressing his long sidewhiskers. Then he sat up, took the emerald ring from his sleeve and asked:

‘Why did you tell my assistant that you had never seen this ring before?’

Leng stared at the ring with raised eyebrows. He did not seem much disturbed by Judge Dee’s sudden question.

‘I couldn’t have known that this gentleman belonged to the tribunal, could I, sir?’ he asked, annoyed. ‘Otherwise I would have told him, of course. But the ring reminded me of a rather unpleasant experience, and I didn’t feel like discussing that with a complete stranger.’

‘All right. Now tell me who that young woman was.’

Leng shrugged his round shoulders.

‘I really couldn’t tell you, sir! She was dressed rather poorly, and she belonged to a band of vagabonds for the tip of her little finger was missing. But a good-looking wench. Very good-looking, I must say. Well, she puts the ring on the table and asks what it’s worth. It’s a nice antique piece, as you can see for yourself, sir, worth about six silver pieces. Ten, perhaps, to a collector. So I tell her, “I can let you have here and now one good shining silver piece if you want to pawn it, and two if you sell it outright.” Business is business, isn’t it? Even if your customer happens to be a pretty piece of goods. But does she take my offer? No sir! She snatches the ring from my hands, snaps “Not for sale!” and off she goes. And that was the last I saw of her.’

‘I heard a quite different story,’ Judge Dee said dryly. ‘Speak up, what were you two whispering about?’

Leng’s face turned red.

‘I AM NOT YET THROUGH WITH YOU, MR LENG!’

‘So my clerks, those good-for-nothings, have been spying on me again! Well, then you’ll understand how awkward it was, sir. I asked her only because I thought that such a good-looking girl from up-country, all alone in this town . . . well, that she might meet the wrong people, and . . .’

Judge Dee hit his fist on the table.

‘Don’t stand there twaddling, man! Tell me exactly what you said!’

‘Well,’ Leng replied with a sheepish look, ‘I proposed that we should meet later in a tea-house near by, and . . . and I patted her hand a bit, just to assure her I meant well, you know. The wench suddenly flew into a rage, said that if I didn’t stop bothering her, she would call her brother who was waiting outside. Then . . . then she rushed off.’

‘Quite. Headman, put this man under lock and key. The charge is manslaughter.’

The headman grabbed the protesting pawnbroker and took him outside.

‘Pour me another cup of tea, Tao Gan,’ Judge Dee said. ‘A curious story! And did you notice the discrepancy between Leng’s account of his meeting with the girl and that given by the clerk?’

‘I did, sir!’ Tao Gan said eagerly. ‘That wretched clerk said nothing about their having a quarrel at the counter. According to him they held a whispered conversation. I think that in fact the girl accepted Leng’s proposal, sir. The quarrel Leng spoke of occurred afterwards, in the house of assignation. And that is why Leng murdered the old tramp!’

Judge Dee, who had been slowly sipping his tea, now put his cup down. Leaning back in his chair, he said:

‘Develop your theory further, Tao Gan!’

‘Well, this time Leng’s philandering led to serious trouble! For the girl, her brother and the old tramp belonged to one and the same organized gang; the girl was their call bird. As soon as Leng had arrived in the house of assignation and began to make up to the girl, she shouted that he was assaulting her—the old, familiar trick. Her brother and the old tramp came rushing inside, and demanded money. Leng succeeded in escaping. When he was on his way to the ridge, however, the old tramp waylaid him and tried to make Leng pay up by making a scene in the street. Leng’s bearers were beating up the young hoodlums, so they couldn’t hear what Leng and the old man were quarrelling about. Leng silenced the tramp by knocking him down. What do you think of that as a theory, sir?’

‘Plausible, and in perfect accordance with Leng’s character. Continue!’

‘While Leng was being carried up to the ridge he did indeed become worried. Not about the condition of the old tramp, however, but about the other members of the gang. He was afraid that when they found the old tramp, they would come after him to take revenge. When the hawker told Leng that the tramp had taken the road uphill, Leng followed him. About half-way up he struck him down from behind, with a sharp piece of rock, or perhaps the hilt of his dagger.’

Tao Gan paused. When the judge nodded encouragingly, he resumed:

‘It was comparatively easy for Leng, who is a powerful fellow and perfectly familiar with that area, to carry the dead body to the deserted hut. And Leng also had a good reason for cutting off his victim’s fingers, namely to hide the fact that the man was a member of a gang. But as to where and how Leng cut off the fingers, I confess that that is a complete riddle to me, sir.’

Judge Dee sat up straight. Stroking his long black beard, he said with a smile:

‘You did very well indeed. You have a logical mind, and at the same time strong powers of imagination, a combination that’ll go a long way to make you a good investigator! I shall certainly keep your theory in mind. However, its weak point is that it is based entirely on the assumption that the eyewitness account of the clerk regarding the meeting in the pawnshop is absolutely correct. But when I mentioned the discrepancy between the two accounts just now, my intention was to quote it as an example of how little trust can be put in eyewitness accounts. As a matter of fact, it is too early yet to formulate theories, Tao Gan. First we must verify the facts we have, and try to discover additional data.’

Noticing Tao Gan’s crestfallen look, Judge Dee went on quickly:

‘Thanks to your excellent work this afternoon, we now have at our disposal three well-established facts. First, that a beautiful vagabond girl is connected with the ring. Second, that she has a brother; for no matter what really happened, Leng had no earthly reason to invent a brother. And third, that there is a connection between the girl, her brother and the murdered man. Probably they belonged to the same gang, and if so, it probably was a gang from outside this district; for none of our personnel knew the dead man by sight, and Leng thought the girl was from up-country.

‘So now your next step is to locate the girl and her brother. That shouldn’t be too difficult, for a vagabond girl of such striking beauty will attract attention. As a rule the women who join those gangs are cheap prostitutes.’

‘I could ask the Chief of the Beggars, sir! He is a clever old scoundrel, and fairly co-operative.’

‘Yes, that’s a good idea. While you are busy in the town, I shall check Leng’s story. I shall interrogate that rascally clerk of his, his friend the goldsmith Chu, and his chair-bearers. I shall also order the headman to locate one or more of the young hoodlums who jeered at Leng, and the hawker who saw the old man scramble up. Finally I shall ask Mr Wang whether Leng was really dead drunk when he came home. All these routine jobs would be meat and drink to old Hoong, Ma Joong and Chiao Tai, but since they are away I’ll gladly take care of them myself. This work will help to take my mind off that smuggling case that is worrying me considerably. Well, set to work, and success!’

The only occupant of the smelly taproom of the Red Carp was the greybeard who stood behind the high counter. He wore a long, shabby blue gown, and had a greasy black skull cap on his head. His long, wrinkled face was adorned by a ragged moustache and a spiky chinbeard. Staring into the distance he was moodily picking his broken teeth. His busy time would come late in the night, when his beggars gathered there in order to pay him his share of their earnings. The old man looked on silently while Tao Gan poured himself uninvited a cup of wine from the cracked earthenware pot. Then he quickly grabbed the pot, and put it away under the counter.

‘You had quite a busy morning, Mr Tao,’ he croaked. ‘Asking about gang fights, and golden rings.’

Tao Gan nodded. He knew that the greybeard’s omnipresent beggars kept him informed about everything that went on downtown. He put his wine-cup down and said cheerfully:

‘That’s why I got the afternoon off! I was thinking of amusing myself a bit. Not with a professional, mind you. With a free-lance!’

‘Very clever!’ the greybeard commented sourly. ‘So as to turn her in afterwards for practising without a licence. Have your fun gratis, and on top of that a bonus from the tribunal!’

‘What do you take me for? I want a free-lance, and from out of town, because I have to think of my reputation.’

‘Why should you, Mr Tao?’ the Chief of the Beggars asked blandly. ‘Your reputation being what it is?’

Tao Gan decided to let the barbed remark pass. He said pensively:

‘Something young, and pretty. But cheap, mind you!’

‘You’ll have to prove that you’ll appreciate my advice, Mr Tao!’

The greybeard watched Tao Gan as he laboriously counted out five coppers on the counter, but he made no move to take the money. With a deep sigh Tao Gan added five more. Now the old man scooped them up with his claw-like hand.

‘Go to the Inn of the Blue Clouds,’ he muttered. ‘Two streets down, the fourth house on your left. Ask for Seng Kiu. He’s her brother, and he concludes the deals, I am told.’ He gave Tao Gan a thoughtful look, then added with a lop-sided grin: ‘You’ll like Seng Kiu, Mr Tao! A straightforward, open-minded man. And very hospitable. Have a good time, Mr Tao. You really deserve it!’

Tao Gan thanked him and went out.

He walked as quickly as the irregular cobblestones of the narrow alley would allow, for he did not put it beyond the greybeard to send one of his beggars ahead to the inn to warn Seng Kiu that a minion of the law was on his way.

The Inn of the Blue Clouds was a miserable small place, wedged in between the shops of a fishmonger and a vegetable dealer. In the dimly-lit space at the bottom of the narrow staircase a fat man sat dozing in a bamboo chair. Tao Gan poked him hard in his ribs with his thin, bony forefinger and growled:

‘I want Seng Kiu!’

‘You may have him and keep him! Upstairs, second door! Ask him when he’s going to pay the rent!’ When Tao Gan was about to ascend, the man, who had taken in his frail stooping figure, called out: ‘Wait! Have a look at my face!’

Tao Gan saw that his left eye was closed, the cheek swollen and discoloured.

‘That’s Seng Kiu for you!’ the man said. ‘Mean bastard!’

‘How many are they?’

‘Three. Besides Seng Kiu and his sister there’s his friend Chang. Also a mean bastard. There was a fourth, but he has cleared out.’

Tao Gan nodded. While climbing the stairs he reflected with a wry smile that he now knew the reason for the greybeard’s secret amusement. He would get even with that old rascal, some day!

After he had rapped his knuckles vigorously on the door indicated, a raucous voice called out from inside:

‘Tomorrow you’ll get your money, you son of a dog!’

Tao Gan pushed the door open and walked inside. On either side of the bare, dingy room stood a plank-bed. On the one on the right lay a giant of a man, clad in a patched brown jacket and trousers. He had a broad, bloated face, surrounded by a bristling short beard. His hair was bound up with a dirty rag. On the other bed a long, wiry man lay snoring loudly, his muscular arms folded under his closely-cropped head. In front of the window sat a good-looking young woman mending a jacket. She wore only a pair of wide blue trousers, her shapely torso was bare.

‘Maybe I could help with the rent, Seng Kiu,’ Tao Gan said. He pointed with his chin at the girl.

The giant scrambled up. He looked Tao Gan up and down with his small bloodshot eyes, scratching his hairy breast. Tao Gan noticed that the tip of his left little finger was missing. His scrutiny completed, the giant asked gruffly: ‘How much?’

‘Fifty coppers.’

Seng Kiu woke up the other by a kick against his leg that was dangling over the foot of the bed.

‘This kind old gentleman,’ he informed him, ‘wants to lend us fifty coppers, because he likes our faces. The trouble is that I don’t like his!’

‘Take his money and kick him out!’ the girl told her brother. ‘No need to beat him up, the scarecrow is ugly enough as it is!’

The giant swung round to her.

‘None of your business!’ he barked. ‘You shut up and stay shut up! You bungled that affair with Uncle Twan, couldn’t even get that emerald ring of his! Useless slut!’

She came to her feet with amazing speed and kicked him hard against his shins. He promptly gave her a blow to her stomach. She folded double, gasping for air. But that was only a trick, for when he came for her, she quickly thrust her head into his midriff. As he stepped back, she pulled a long hairpin from her coiffure and asked venomously:

‘Want to get that into your gut, dear brother?’

Tao Gan was thinking how he could get these three to the tribunal. Since they probably weren’t very familiar with the city yet, he thought he would manage it.

‘I’ll settle with you later!’ Seng Kiu promised his sister. And to his friend: ‘Grab the bastard, Chang!’

While Chang was keeping Tao Gan’s arms pinned behind his back in an iron grip, Seng Kiu expertly searched him.

‘Yes, only fifty coppers!’ he said with disgust. ‘You hold him while I teach him not to disturb our sleep!’

He took a long bamboo stick from the corner and made to hit Tao Gan on his head. But suddenly he half turned and let the end come down on the behind of his sister, who was bending over her jacket again. She jumped aside with a yell of pain. Her brother bellowed with laughter. But then he had to duck, for she threw the heavy iron scissors at his head.

‘I don’t like interrupting,’ Tao Gan said dryly, ‘but there’s a deal of five silver pieces I wanted to discuss.’

‘IT’S A VERY PRIVATE MATTER,’ TAO GAN SAID

The giant who had been trying to get hold of his sister now let her go. He turned round and asked panting:

‘Five silver pieces, you said?’

‘It’s a very private matter, just between you and me.’

Seng Kiu gave a sign to Chang to let Tao Gan go. The thin man drew the tall ruffian into the corner and told him in a low voice:

‘I don’t care a fig about that sister of yours. It’s my boss who sent me!’

Seng Kiu went pale under his tan.

‘Does the Baker want five silver pieces? Holy Heaven, has he gone mad? How . . . ?’

‘I don’t know any baker,’ Tao Gan said crossly. ‘My boss is a big landowner, a wealthy lecher who pays well for his little amusements. He has got fed up with all those dainty damsels from the Willow Quarter nowadays. Suddenly he wants them buxom and rough-and-ready like. I do the collecting for him. He has heard about your sister, and he has sent me to offer you five silver pieces for having her in the house a couple of days.’

Seng Kiu had been listening with growing astonishment. Now he exclaimed:

‘Are you crazy? There isn’t a woman in the whole wide world who has got something to sell worth that much!’ He thought deeply for a while, creasing his low forehead. Suddenly he burst out: ‘That proposal of yours stinks, brother! I want my sister to keep a whole skin. I am planning to set her up in business, you see? So she gets me a regular income.’

Tao Gan shrugged his narrow shoulders.

‘All right. There are other vagabond girls on the loose. Give me back my fifty coppers, then I’ll say good-bye.’

‘Hey there, not so fast!’ The giant rubbed his face. ‘Five silver pieces! That means living nicely for at least a year, without doing a stroke of work! Well, it doesn’t matter much really whether she’s handled a bit roughly, after all. She can stand a lot, and it’ll cut her down to size, maybe. All right, it’s a deal! But me and Chang are going to see her off. I want to know where and with whom she is staying.’

‘So that you can blackmail my boss later, eh? Nothing doing!’

‘You are lying! You are a buyer for a brothel, you dirty rat!’

‘All right, come with me then and see for yourself. But don’t blame me if my boss gets angry and has his men beat you up. Pay me twenty coppers, that’s my commission.’

After protracted haggling, they agreed on ten coppers. Seng Kiu gave Tao Gan his fifty coppers back, and ten extra. The gaunt man put these in his sleeve with a satisfied smile, for now he had recovered the money he had paid the Chief of the Beggars.

‘The boss of this fellow wants to stand us a drink,’ Seng Kiu told Chang and his sister. ‘Let’s go to his place and hear what he has got to say.’

They went up town by the main road, but then Tao Gan took them through a maze of narrow alleys to the back of a tall greystone compound. As he opened the small iron door with a key he took from his sleeve, Seng Kiu remarked, impressed:

‘Your boss must be rolling in it! Substantial property!’

‘Very substantial,’ Tao Gan agreed. ‘And this is only the back entrance, mind you. You should see the main gate!’ So speaking, he herded them into a long corridor. He carefully relocked the door and said: ‘Just wait here a moment while I go to inform my boss!’

He disappeared round the corner.

After a while the girl exclaimed:

‘I don’t like the smell of this place. Could be a trap!’

Then the headman and six armed guards came tramping round the corner. Chang cursed and groped for his knife.

‘Please attack us!’ the headman told him with a grin, raising his sword. ‘Then we’ll get a bonus for cutting you down!’

‘Leave it, Chang!’ the giant told his friend disgustedly. ‘These bastards are professional murderers. They get paid for killing the poor!’

The girl tried to slip past the headman, but he caught her and soon she also was in chains. They were taken to the jail in the adjoining building.

After Tao Gan had run to the guardhouse and told the headman to arrest two vagabonds and their wench who were waiting near the back door, he went straight to the chancery and asked the senior clerk where he could find Judge Dee.

‘His Excellency is in his office, Mr Tao. Since the noon rice he has interrogated a number of people there. Just when he had let them go, young Mr Leng, the son of the pawnbroker, came and asked to see the judge. He hasn’t come out yet.’

‘What is that youngster doing here? He wasn’t on the list of people the judge wanted to interrogate.’

‘I think he came to find out why his father had been arrested, Mr Tao. It might interest you to know that, before he went inside, he had been asking the guards at the gate all kinds of questions about the dead body that was found this morning in the hut in the forest. You might tell the judge.’

‘Thank you, I will. Those guards are not supposed to hand out information, though!’

The old clerk shrugged his shoulders.

‘They all know young Mr Leng, sir. They often go there towards the end of the month to pawn something or other, and young Leng always gives them a square deal. Besides, since the entire personnel has seen the body, it isn’t much of a secret any more.’

Tao Gan nodded and walked on to Judge Dee’s office.

The judge was sitting behind his desk, now wearing a comfortable robe of thin grey cotton, and with a square black cap on his head. In front of the desk stood a well-built young man of about twenty-five, clad in a neat brown robe and wearing a flat black cap. He had a handsome but rather reserved face.

‘Take a seat!’ Judge Dee told Tao Gan. ‘This is Mr Leng’s eldest son. He is worried about his father’s arrest. I just explained to him that I suspect his father of having taken part in the murder of an old vagrant, and that I shall hear the case at tonight’s session of the court. That’s all I can say, Mr Leng. I have to terminate our interview now, for I have urgent matters to discuss with my lieutenant here.’

‘My father couldn’t possibly have committed a murder last night, sir,’ the youngster said quietly.

Judge Dee raised his eyebrows.

‘Why?’

‘For the simple reason that my father was dead drunk, sir. I myself opened the door when Mr Wang brought him in. My father had passed out, and Mr Wang’s son had to carry him inside.’

‘All right, Mr Leng. I shall keep this point in mind.’

Young Leng made no move to take his leave. He cleared his throat and resumed, rather diffidently this time:

‘I think I have seen the murderers, sir.’

Judge Dee leaned forward in his chair.

‘I want a complete statement about that!’ he said sharply.

‘Well, sir, it is rumoured that the dead body of a tramp was found this morning in a deserted hut in the forest, half-way up the slope. May I ask whether that is correct?’ As the judge nodded, he continued: ‘Last night a bright moon was in the sky and there was a cool evening breeze, so I thought I would take a little walk. I took the footpath behind our house that leads down into the forest. After having passed the second bend, I saw two people some distance ahead of me. I couldn’t see them very well, but one seemed very tall, and he was carrying a heavy load on his shoulders. The other was small, and rather slender. Since all kind of riff-raff often frequents the forest at night, I decided to call off my walk, and went back home. When I heard the rumour about the dead tramp, it occurred to me that the burden the tall person was carrying might well have been the dead body.’

Tao Gan tried to catch Judge Dee’s eye, for Leng’s description fitted exactly Seng Kiu and his sister. But the judge was looking intently at his visitor. Suddenly he said:

‘This means that I can set your father free at once, and arrest you as suspect in his stead! For you have just proved beyond doubt that, whereas your father could not have committed the murder, you yourself had every opportunity!’

The youngster stared dumbfounded at the judge.

‘I didn’t do it!’ he burst out. ‘I can prove it! I have a witness who . . .’

‘Just as I thought! You weren’t alone. A young man like you doesn’t go out for a solitary walk in the forest at night. It’s only when you have reached a riper age that you discover that enjoyment. Speak up, who was the girl?’

‘My mother’s chambermaid,’ the young man replied with a red face. ‘We can’t see much of each other inside the house, of course. So we meet now and then in the hut, down the slope. She can bear out my statement that we went into the forest together, but she can’t give more information about the people I saw, because I was walking ahead and she didn’t see them.’ Giving the judge a shy look he added: ‘We plan to get married, sir. But if my father knew that we . . .’

‘All right. Go to the chancery, and let the senior clerk take down your statement. I shall use it only if absolutely necessary. You may go!’

As the youngster made to take his leave, Tao Gan asked:

‘Could that smaller figure you saw have been a girl?’

Young Leng scratched his head.

‘Well, I couldn’t see them very well, you know. Now that you ask me, however . . . Yes, it might have been a woman, I think.’

As soon as young Leng had gone, Tao Gan began excitedly:

‘Everything is clear now, sir! I . . .’

Judge Dee raised his hand.

‘One moment, Tao Gan. We must deal with this complicated case methodically. I shall first tell you the result of my routine check. First, that clerk of Leng’s is a disgusting specimen. Close questioning proved that, after he had seen the girl place the ring on the counter, Leng told him to make himself scarce. Other customers came in between them, and later he only saw the girl snatch up the ring and go out. The whispering bit he made up, in order to prove that his boss is a lecher. And as to his boss being guilty of tax evasion, he could only quote vague rumours. I dismissed the fellow with the reminder that there’s a law on slander, and sent for the master of the Bankers’ Guild. He told me that Mr Leng is a very wealthy man who likes to do himself well. He is not averse to a bit of double-dealing, and one has to look sharp when doing business with him, but he is careful to keep on the right side of the law. He travels a lot, however, passing much of his time in the neighbouring district of Chiang-pei; and the guildmaster did not, of course, know anything about his activities there. Second, Leng did indeed have a heavy drinking bout with his friend the goldsmith. Third, the headman has located two of the young hoodlums who jeered at Leng. They said that this was obviously the first time Leng had seen the old tramp, and that no girl was mentioned during their quarrel. Leng did push the old man, but he was on his feet again directly after Leng had been carried off in his chair. He stood there cursing Leng for a blasted tyrant, then he walked off. Finally, those boys made one curious remark. They said that the old man didn’t speak like a tramp at all, he used the language of a gentleman. I had planned to ask Mr Wang whether Mr Leng was really drunk when he came home, but after what his son told us just now, that doesn’t seem necessary any more.’

The judge emptied his teacup, then added: ‘Tell me now how it went down town!’

‘I must first tell you, sir, that young Leng questioned the guards thoroughly about the discovery of the body in the hut, prior to seeing you. However, that seems immaterial now, for I have proof that he did not make up the story about the two people he saw in the forest.’

Judge Dee nodded.

‘I didn’t think he was lying. The boy impressed me as very honest. Much better than that father of his!’

‘The people he saw must have been a gangster called Seng Kiu, and his sister—a remarkably beautiful young girl. The Chief of the Beggars directed me to the inn where they were staying, together with another plug-ugly called Chang. There was a fourth man, but he had left. I heard Seng Kiu scolding his sister for having spoiled what he called “the affair of Uncle Twan”, and for having failed to obtain his emerald ring. Evidently that Uncle Twan is our dead tramp. All three are from another district, but they know a gangster boss called the Baker here. I had them locked up in jail, all three of them.’

‘Excellent!’ Judge Dee exclaimed. ‘How did you get them here so quickly?’

‘Oh,’ Tao Gan replied vaguely, ‘I told them a story about easy money to be made here, and they came along gladly. As to my theory about Mr Leng, sir, you were quite right in calling it premature! Leng had nothing to do with the murder. It was pure coincidence that the gangsters crossed his path twice. First when the girl wanted the ring appraised, and the second time when the old tramp took offence at Leng’s high-handed way of dealing with the young hoodlums.’

The judge made no comment. He pensively tugged at his moustache. Suddenly he said:

‘I don’t like coincidences, Tao Gan. I admit they do occur, now and then. But I always begin by distrusting them. By the way, you said that Seng Kiu mentioned a gangster boss called the Baker. Before I interrogate him, I want you to ask our headman what he knows about that man.’

While Tao Gan was gone, the judge poured himself another cup from the tea-basket on his desk. He idly wondered how his lieutenant had managed to get those three gangsters to the tribunal. ‘He was remarkably vague when I asked him,’ he told himself with a wry smile. ‘Probably he has been acting the part of confidence man again—his old trade! Well, as long as it is in a good cause . . .’

Tao Gan came back.

‘The headman knew the Baker quite well by name, sir. But he is not of this town; the scoundrel is a notorious gangster boss in our neighbouring district, Chiang-pei. That means that Seng Kiu is from there too.’

‘And our friend Mr Leng often stays there,’ the judge said slowly. ‘We are getting too many coincidences for my liking, Tao Gan! Well, I shall interrogate those people separately, beginning with Seng Kiu. Tell the headman to take him to the mortuary—without showing him the dead body, of course. I’ll go there presently.’

When Judge Dee came in he saw the tall figure of Seng Kiu standing between two constables, in front of the table on which the corpse was lying, covered by the reed mat. There hung a sickly smell in the bare room. The judge reflected that it wouldn’t do to leave the body there too long, in this hot weather. He folded the mat back and asked Seng Kiu:

‘Do you know this man?’

‘Holy Heaven, that’s him!’ Seng shouted.

Judge Dee folded his arms in his wide sleeves. He spoke harshly:

‘Yes, that’s the dead body of the old man you cruelly did to death.’

The gangster burst out in a string of curses. The constable on his right hit him over his head with his heavy club. ‘Confess!’ he barked at him. The blow didn’t seem to bother the giant much. He just shook his head, then shouted:

‘I didn’t kill him! The old fool was still alive and kicking when he left the inn last night!’

‘Who was he?’

‘A rich fool, called Twan Mou-tsai. Owned a big drugstore, in the capital.’

‘A rich drug dealer? What was his business with you?’

‘He was gone on my sister, the silly old goat! He wanted to join us!’

‘Don’t try to foist your stupid lies on me, my friend!’ Judge Dee said coldly. The constable hit out at Seng Kiu’s head again, but he ducked expertly and blurted out:

‘It’s the truth, I swear it! He was crazy about my sister! Even wanted to pay for being allowed to join us! But my sister, the silly wench, she wouldn’t take one copper from him. And look at the trouble the stubborn little strumpet has got us in now! A murder, if you please!’

Judge Dee smoothed down his long beard. The man was an uncouth brute, but his words bore the hallmark of truth. Seng Kiu interpreted his silence as a sign of doubt, and resumed in a whining voice:

‘Me and my mate, we have never done anything like murder, noble lord! Maybe we took along a stray chicken or a pig here and there, or borrowed a handful of coppers from a traveller—such things will happen when you have to make your living by the road. But we never killed a man, I tell you. And why should I kill Uncle Twan, of all people? I told you he gave me money, didn’t I?’

‘Is your sister a prostitute?’

‘A what?’ Seng Kiu asked suspiciously.

‘A streetwalker.’

‘Oh, that!’ Seng scratched his head, then replied cautiously: ‘Well, to tell you the truth, sir, she is and she isn’t, so to speak. If we need money badly, she may take on a fellow, on occasion. But most of the time she only takes youngsters she fancies, and they get it gratis for nothing. Dead capital, that’s what she is, sir! Wish she were a regular, then she’d bring in some money at least! If you’d kindly tell me, sir, how to go about getting proper papers for her, those things that say she has the right to walk the streets, and . . .’

‘Only answer my questions!’ Judge Dee interrupted him testily. ‘Speak up, when did you begin working for Leng the pawnbroker?’

‘A pawnbroker? Not me, sir! I don’t deal with those bloodsuckers! My boss is Lew the Baker, of Chiang-pei. Lives over the winehouse, near the west gate. He was our boss, that is. We bought ourselves out. Me, Sis and Chang.’

Judge Dee nodded. He knew that, according to the unwritten rules of the underworld, a sworn member of a gang can sever relations with his boss if he pays a certain sum of money, from which his original entrance fee, and his share in the earnings of the gang are deducted. This settling of accounts often gave rise to bitter quarrels.

‘Was everything settled to the satisfaction of both parties?’ he asked.

‘Well, there was a bit of trouble, sir. The Baker tried to rob us, the mean son of a dog! But Uncle Twan, he was a real wizard with figures. He takes a piece of paper, does a bit of reckoning, and proves the Baker is dead wrong. The Baker didn’t like that, but there were a couple of other fellows who had been following the argument, and they all said Uncle Twan was right. So the Baker had to let us go.’

‘I see. Why did you want to leave the Baker’s gang?’

‘Because the Baker was getting too uppety, and because he was taking on jobs we didn’t fancy. Jobs above our station, so to speak. The other day he wanted me and Chang to lend a hand putting two boxes across the boundary. I said no, never. First, if we get caught, we are in for big trouble. Second, the men who did those kind of big jobs for the Baker usually died in accidents afterwards. Accidents will happen, of course. But they happened too often, for my taste.’

The judge gave Tao Gan a significant look.

‘When you and Chang refused, who took on the job?’

‘Ying, Meng and Lau,’ Seng replied promptly.

‘Where are they now?’

Seng passed his thumb across his throat.

‘Just accidents, mind you!’ he said with a grin. But there was a glint of fear in his small eyes.

‘To whom were those two boxes to be delivered?’ the judge asked again.

The gangster shrugged his broad shoulders.

‘Heaven knows! I overheard the Baker telling Ying something about a richard who has a big store in the market-place here. I didn’t ask, it wasn’t my business, the less I knew about it the better. And Uncle Twan said I was dead right.’

‘Where were you last night?’

‘Me? I went with Sis and Chang to the Red Carp, for a bite and a little dice game. Uncle Twan said he’d eat somewhere outside, he didn’t fancy dice games. When we came home at midnight, the old man hadn’t come back. The poor old geezer got his head bashed in! He shouldn’t have gone out alone, in a town he didn’t know!’

Judge Dee took the emerald ring from his sleeve.

‘Do you know this trinket?’ he asked.

‘Of course! That was Uncle Twan’s ring. Had it from his father. “Ask him to give it to you!” I told Sis. But she said no. It’s hard luck, sir, to be cursed with a sister like her!’

‘Take this man back to his cell!’ Judge Dee ordered the headman. ‘Then tell the matron to bring Miss Seng to my office.’

While crossing the courtyard, the judge said excitedly to Tao Gan:

‘You made a very nice haul! This is the first clue we’ve got to the smuggling case! I shall send a special messenger to my colleague in Chiang-pei at once, asking him to arrest the Baker. He will tell who his principal is, and to whom the boxes were to be delivered here. I wouldn’t be astonished if that man turned out to be our friend Leng the pawnbroker! He is a wealthy man with a large store in the market-place, and he visits Chiang-pei regularly.’

‘Do you think that Seng Kiu is really innocent of Twan’s murder, sir? That story told by Leng’s son seemed to fit him and his sister all right.’

‘We shall know more about that when we have discovered the truth about that enigmatic Twan Mou-tsai, Tao Gan. I had the impression that Seng Kiu told us all he knew just now. But there must be many things that Seng does not know! We shall see what his sister has to say.’