* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

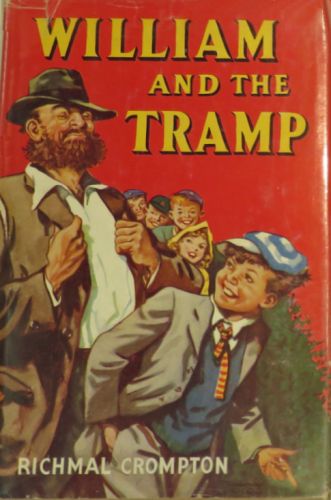

Title: William and the Tramp

Date of first publication: 1952

Author: Richmal Crompton Lamburn (as Richmal Crompton) (1890-1969)

Illustrator: Thomas Henry Fisher (as Thomas Henry) (1879-1962)

Date first posted: Nov. 6, 2022

Date last updated: Nov. 6, 2022

Faded Page eBook #20221109

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

| By the Same Author | |

| (1) | JUST WILLIAM |

| (2) | MORE WILLIAM |

| (3) | WILLIAM AGAIN |

| (4) | WILLIAM—THE FOURTH |

| (5) | STILL—WILLIAM |

| (6) | WILLIAM—THE CONQUEROR |

| (7) | WILLIAM—THE OUTLAW |

| (8) | WILLIAM—IN TROUBLE |

| (9) | WILLIAM—THE GOOD |

| (10) | WILLIAM |

| (11) | WILLIAM—THE BAD |

| (12) | WILLIAM’S HAPPY DAYS |

| (13) | WILLIAM’S CROWDED HOURS |

| (14) | WILLIAM—THE PIRATE |

| (15) | WILLIAM—THE REBEL |

| (16) | WILLIAM—THE GANGSTER |

| (17) | WILLIAM—THE DETECTIVE |

| (18) | SWEET WILLIAM |

| (19) | WILLIAM—THE SHOWMAN |

| (20) | WILLIAM—THE DICTATOR |

| (21) | WILLIAM AND A.R.P. |

| (22) | WILLIAM AND THE EVACUEES |

| (23) | WILLIAM DOES HIS BIT |

| (24) | WILLIAM CARRIES ON |

| (25) | WILLIAM AND THE BRAINS TRUST |

| (26) | JUST WILLIAM’S LUCK |

| (27) | WILLIAM—THE BOLD |

| (28) | WILLIAM AND THE TRAMP |

| (29) | WILLIAM AND THE MOON ROCKET |

| (30) | WILLIAM AND THE SPACE ANIMAL |

| (31) | WILLIAM’S TELEVISION SHOW |

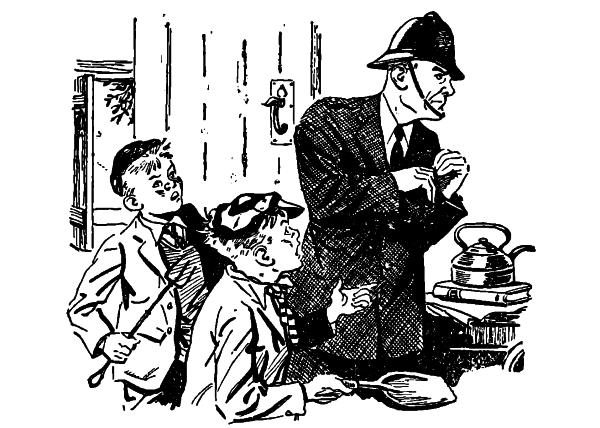

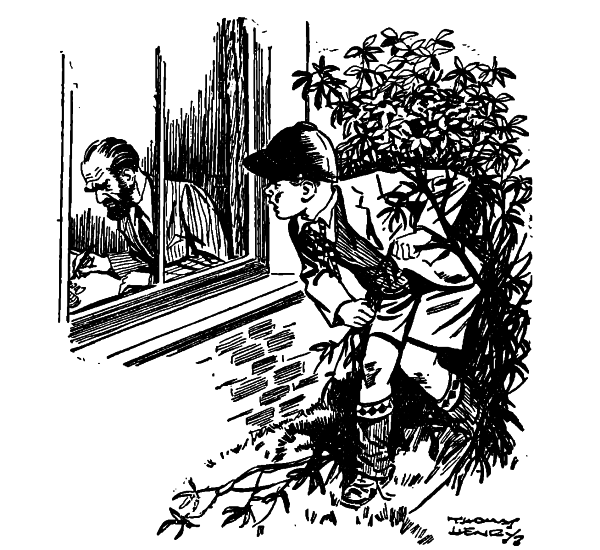

“IS HE STILL THERE?” ASKED ARCHIE IN A HOARSE WHISPER. WILLIAM AND GINGER LOOKED CAUTIOUSLY OUT OF THE WINDOW.

WILLIAM AND THE

TRAMP

BY

RICHMAL CROMPTON

ILLUSTRATED BY

THOMAS HENRY

LONDON

GEORGE NEWNES LIMITED

TOWER HOUSE, SOUTHAMPTON STREET

STRAND, W.C. 2

© RICHMAL CROMPTON LAMBURN

| First Published | 1952 |

| Second Impression | 1952 |

| Third Impression | 1954 |

| Fourth Impression | 1956 |

| Fifth Impression | 1959 |

Printed in Great Britain by

Wyman & Sons, Ltd., London, Fakenham and Reading

| CONTENTS | ||

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | William and the Tramp | 9 |

| II. | William Meets the Professor | 46 |

| III. | William Beats the Record | 84 |

| IV. | William and the Returned Traveller | 118 |

| V. | William and the Haunted Cottage | 145 |

| VI. | William and the Pets’ Club | 173 |

| VII. | William’s Secret Society | 209 |

| VIII. | Archie Has a Party | 231 |

“William, do stop messing about with your food,” said Mrs. Brown.

“I’m not messing,” said William with dignity. “I’m pretending that that pea on the top of that pile of potato’s me on the top of a mountain, an’ I’ve gotter get down an’ there’s this precipice here an’ this swamp here an’——”

“Hurry up with your lunch and stop talking, dear,” said Mrs. Brown.

“Yes, but listen,” said William earnestly. “If I try to come down by this path I’ll as likely as not fall into the precipice, an’ if I come down by the other path I’ll fall into the swamp. Look! You can see it’s a swamp ’cause——”

“William!” said Mr. Brown.

William relapsed into silence, contemplated his mountain scene with frowning perplexity for some moments, then, tiring of the problem and realising that everyone else had nearly finished, demolished mountain top, precipice and swamp in one gigantic landslide and dealt with the results in a summary if inelegant fashion.

So deeply absorbed was he in this work of demolition that it was some time before his mind was free to listen to the conversation going on around him.

“Don’t be back late from golf, dear,” his mother was saying. “Remember, we’re going to the Botts’ this evening.”

“The Botts’?” said Mr. Brown, in pained surprise.

“Yes, don’t you remember? A Mr. Bumbleby is coming to speak to the Literary Society to-morrow and he’s arriving to-day and spending the night with the Botts, and Mrs. Bott has asked everyone in to meet him this evening.”

“Bumbleby?” said Mr. Brown. “Never heard of the chap. Didn’t even know they knew anyone of that ridiculous name.”

“They don’t exactly know him, dear,” said Mrs. Brown. “Actually, they’ve never even seen him, I believe, but Mr. Bott’s the President of the Literary Society——”

“He provides all their funds, so he has to be,” put in Robert.

“And they like to put up the speaker,” said Ethel, “and invite a select circle of their friends to show him off to. I’m only going because I enjoy watching Mrs. Bott being refained.”

“This Bumbleby’s a well-known literary figure,” said Robert. “He’s travelled all over the world and he published a book last spring that made quite a stir.”

“I hate listening to speeches,” said Mr. Brown irritably.

“He’s not going to make a speech,” said Ethel. “He’s just going to eat the Bott food and meet the Bott friends and answer any questions the Bott friends may like to ask him. Mrs. Bott told me that it was to be all quite irregular. I think she meant informal.”

“I’m afraid we’ll have to go, dear,” said Mrs. Brown firmly. “She’s most anxious for everyone to be there. She’s even asked William.”

Ethel groaned, Robert said “Good Lord!” and William hastily swallowed the remains of his landscape before entering into a spirited defence of his manners and appearance—a defence that proved beyond dispute the desirability of his presence at any social function.

He had arranged to meet the Outlaws at the old barn after lunch, but it began to rain and Mrs. Brown said that he must stay indoors till it stopped. William did not believe in wasting time. The Outlaws were organising a show that was to take place at some indefinite date when enough “turns” had been prepared, so William decided to fill in the interval by practising his tight-rope act. He had never actually practised it yet. He had merely enjoyed glorious mental visions of himself walking with airy nonchalance at a dizzy height with crowds of cheering spectators far below. The only practical step he had taken towards the materialisation of this vision was the appropriation of a length of clothes line from his mother’s washing basket. He stood now with the rope in his hand, his brows drawn together in frowning concentration, his eyes roving speculatively round the room. Then, with the air of a general marshalling his forces, he tied one end to the door handle, stretched the rope across the room, and tied the other end to the top handle of his chest of drawers. Having done that, he stood on his bed, bowed low to the imaginary crowds, spat on his hands and stepped on to the rope. The resultant crash brought the entire household out into the hall.

“Are you hurt, dear?” said Mrs. Brown, in a voice of tender concern.

“What on earth are you up to now, William?” said Mr. Brown, in a voice that held concern but little tenderness. “Come down here at once.”

William’s dishevelled figure appeared on the landing and began to make its way slowly downstairs. His face wore the vacant expression with which he was wont to meet the concerted attacks of his family.

“I’ve not hurt myself an’ I’ve not done any harm,” he said, forestalling the inevitable queries and accusations. “Not any real harm, I mean. The handle came off the chest of drawers, but I bet it must’ve been loose to start with. Well, I bet real tight-rope walkers have somethin’ on their feet to make ’em stick. They must have. Glue or somethin’. Well, I’m jolly good at balancin’, but I went right over at once, so——”

“Be quiet, William,” said Mr. Brown, who knew that William’s eloquence, if not checked at its source, could grow to an overwhelming torrent. “Why don’t you try to help instead of playing these fool tricks?”

“Yes, but listen,” protested William. “I was tryin’ to help. I mean, if I learnt to be a real acrobat I’d be able to earn my livin’ an’ you wouldn’t have to pay any more money for me. They earn pounds an’ pounds, do real acrobats, an’ I bet they’ve all gotter start same as I did with a rope in their bedrooms, an’——”

“Be quiet, William,” roared Mr. Brown, stemming the torrent as best he could. “I don’t want to hear any more about it. You’ve damaged your chest of drawers and you’ll have no more pocket money till it’s paid for.”

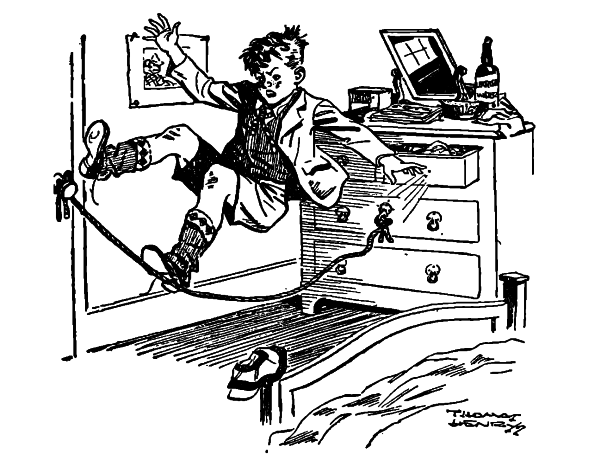

WILLIAM STEPPED FROM THE FOOT OF THE BED ON TO THE ROPE.

“All right,” said William, who had expected this, adding, without much hope, “I’ll mend it for nothin’ for you if you like. I bet I could with a few nails and a hammer.”

“No, William,” said Mrs. Brown, who knew by experience what wholesale destruction could be wrought by William with a few nails and a hammer.

William looked out of the window.

“I say!” he said eagerly. “It’s stopped rainin’. May I go out?”

“Yes,” said Mr. Brown, Mrs. Brown, Robert and Ethel, in a chorus of heartfelt assent.

It had begun to rain again by the time he reached the old barn—a steady downpour that was discovering the many weak places in the roof, and sending trickles of varying amplitude on to the ground beneath. The three other Outlaws were already assembled there. Ginger held a cardboard box and was anxiously watching its occupant—a guinea-pig curled up on a bed of cotton wool. Douglas was practising handsprings and had already transferred to his person a large part of the mud that formed the floor of the ramshackle edifice. Henry was making unsuccessful efforts to climb the wall. Ever since they had begun to use the old barn as a meeting place, Henry had had a theory that, if he could get up to the roof, he would be able to swing himself right over from one side to the other by the wooden beam that spanned it. So far he had not been able to climb more than a yard or two up the wall. . . .

“I bet if I carved footholes all the way——” he was saying, as he picked himself up for the tenth time that afternoon.

“Hello, William,” said Ginger. “I don’t think he’ll be able to learn any tricks, after all. He doesn’t seem any better. . . .”

William gazed solicitously at the invalid.

“It’s your own fault,” he said sternly. “You shouldn’t have given him that tonic of your mother’s.”

“It did my mother good.”

“Well, she’s not a guinea-pig, you idiot.”

“It said on the bottle that it invig’rated the whole system, so I thought it’d help him do his tricks.”

“It seems to have uninvig’rated him, all right. We’d better let him sleep it off.”

At that moment Henry fell down once more, this time on the top of Douglas, whose handsprings had taken him into the neighbourhood of the wall, and the ensuing scuffle landed the two of them into the puddle that had formed under the largest hole in the roof. There they brought their scuffle to a satisfactory conclusion and sat up, looking at William.

“About this show,” said Henry breathlessly. “Have you started practisin’ your tight-rope walkin’ yet?”

“Well, sort of,” said William evasively. “It’s a jolly sight more diff’cult than what it looks, but I bet it only needs a bit more practice. I could have gone on practisin’ to-night, if the handle hadn’t come off, an’ if I hadn’t to go to that ole thing at the Botts’.”

“Gosh, yes!” groaned Ginger. “I’ve got to go to it, too.”

“So’ve I,” groaned Douglas.

“So’ve I,” groaned Henry. “My mother’s jolly lucky, not bein’ able to go to it.”

“Why can’t she?” said William.

“She’s gone up to London to a meetin’, an’ she can’t get back in time.”

“What sort of a meetin’?”

“It’s a meetin’ about gettin’ holiday homes for poor ole people what have never had a holiday.”

“What!” said William, aghast. “Never had a holiday!”

“No. They’re tryin’ to get houses for these poor old people to have holidays in, an’ they say that everybody ought to help.”

“Gosh! I should jus’ think so,” said William earnestly. “Gosh! Jus’ think of it! Never had a holiday!”

“Well, there’s nothin’ we can do about it,” said Henry.

“I bet there is,” said William. “I bet if we look round we can find somethin’ to do about it.”

At this point a small figure in a mackintosh, with a sou’wester perched on its curls, appeared in the open doorway.

“Can I come in, pleathe, William?” said Violet Elizabeth humbly.

William looked at her warily. He always distrusted Violet Elizabeth’s humility.

“No, you can’t,” he said shortly.

Violet Elizabeth stepped into the barn with a radiant smile.

“But I’ve come,” she said.

“Then you can go away again,” said William. “We’re busy.”

“I’ll be buthy, too,” said Violet Elizabeth serenely. “I like bein’ buthy.”

“Then you can go and be busy somewhere else,” said William.

“But I don’t want to be buthy thomewhere elthe,” said Violet Elizabeth. “I’d rather be buthy with you. What are you buthy doin’?”

They looked at her helplessly. She had selected one of the drier spots on the ground and had seated herself cross-legged, with the air of one prepared to make an indefinite stay.

“Well, now,” said William, shifting his position so that his back was turned on the intruder and trying, without success, to ignore her presence, “about these poor people without holidays. We’ve gotter do somethin’ about it.”

“What can we do?” said Ginger. “It’s big houses they want an’ ours are too small.”

Reluctantly they turned to Violet Elizabeth.

“There’s yours,” said William. “There’s heaps of room in The Hall.”

“Yeth, there ith,” agreed Violet Elizabeth complacently. “We’ve got ten bedroomth and a garath and a coal thed. Ith a lovely coal thed. Ith got little windowth like a little houthe and a little door that lockth.”

“Ten bedrooms!” said William. “Then you oughter take some of these poor people into it for a holiday.”

“I bet we could get the whole lot into it if we packed ’em tight,” said Ginger.

“No, you couldn’t,” said Henry. “It’s somethin’ to do with carbon peroxide.”

“Well, thereth the greenhouth and the garden frame,” said Violet Elizabeth, pleased to find herself the centre of the discussion and anxious to prolong it as far as possible. “You could get two people in the garden frame if they didn’t mind being a bit thquathed up. And one could thleep in the wheelbarrow in the tool thed. Ith quite comfy. I’ve tried it.”

“Oh, shut up,” said William impatiently. “You’ll be sayin’ next that we could get one or two in the rain-tub if they didn’t mind gettin’ a bit wet. It’s bedrooms they want, not garden frames an’ wheelbarrows.”

“I don’t think Mummy would let them have bedroomth,” said Violet Elizabeth doubtfully. “Thomeone athked her oneth and thee thaid thee liked to keep herthelf to herthelf, and Daddy thaid that an Englithmanth houthe wath hith cathle.”

“That’s rot,” said Henry. “A house isn’t a castle. A castle’s got a thing like a sort of frill on the top and holes to pour boiling oil from.”

“Ith got a balcony,” said Violet Elizabeth. “You could pour boiling oil from that if you liked.”

“I wish you’d all shut up talkin’ an’ talkin’,” said William sternly. “What we’ve gotter do is to find some poor people an’ get ’em into Violet Elizabeth’s house for a holiday.”

“I bet her mother wouldn’t let them stay,” said Douglas.

“I don’t think she could turn ’em out,” said Henry, assuming his air of omniscience. “It’s the lor that if people are axshully in a house, you can’t turn ’em out. My mother knows someone that’s got someone in her house an’ can’t turn ’em out. Even the p’lice can’t turn ’em out.”

“My Mummy’ll thend for the poleeth,” said Violet Elizabeth, with a smile of blissful anticipation, “and we’ll pour boiling oil on them from the balcony. I’ve got a bottle of cod-liver oil we could uthe. Won’t it be fun!”

“I wish you’d shut up talkin’ an’ wastin’ time,” said William, frowning round at the company. “We’ll never get anythin’ done at this rate. What we’ve gotter do first of all is to go round to Violet Elizabeth’s house an’ see how many poor people without holidays we can get into it. Are your mother an’ father at home, Violet Elizabeth?”

“No,” said Violet Elizabeth. “Mummy’th gone to London, and Daddy’th at the offith, but they’ll be coming back early ’cauthe we’ve got Mithter Bumbleby coming to dinner and there’th a party afterwardth.”

“Don’t we know that!” groaned William. “We’re all supposed to be comin’ to it.”

“It’ll be a nithe party, William,” said Violet Elizabeth. “There’th going to be thauthage rollth.”

“We’ll need ’em,” said William succinctly. “Well, come on. It’s stopped rainin’.”

It was just as they were approaching the Hall that they saw the bearded, tousled man sitting by the side of the ditch eating something out of a piece of grimy newspaper. He was ragged and dirty, but he wore his rags and dirt with a jaunty air, undaunted, as it seemed, even by the raindrops that dripped steadily upon him from the tree above. The four stood in a little group, watching him.

“He looks poor,” whispered William.

“He looks a bit like Mr. Rose,” said Violet Elizabeth, remembering a tramp who had made free with her mother’s possessions last summer.

“No, he doesn’t,” said William. “He’s got more hair an’ more beard an’ a nicer face. I think he’s jus’ a poor person what wants a holiday.”

“All right. Go on. Ask him,” said Ginger.

“All right. I’m goin’ to,” said William. “I’m jus’ thinkin’ out what to say.”

He hesitated a few more moments, then stepped forward and cleared his throat.

“G’d afternoon,” he said.

The tramp looked up from his meal.

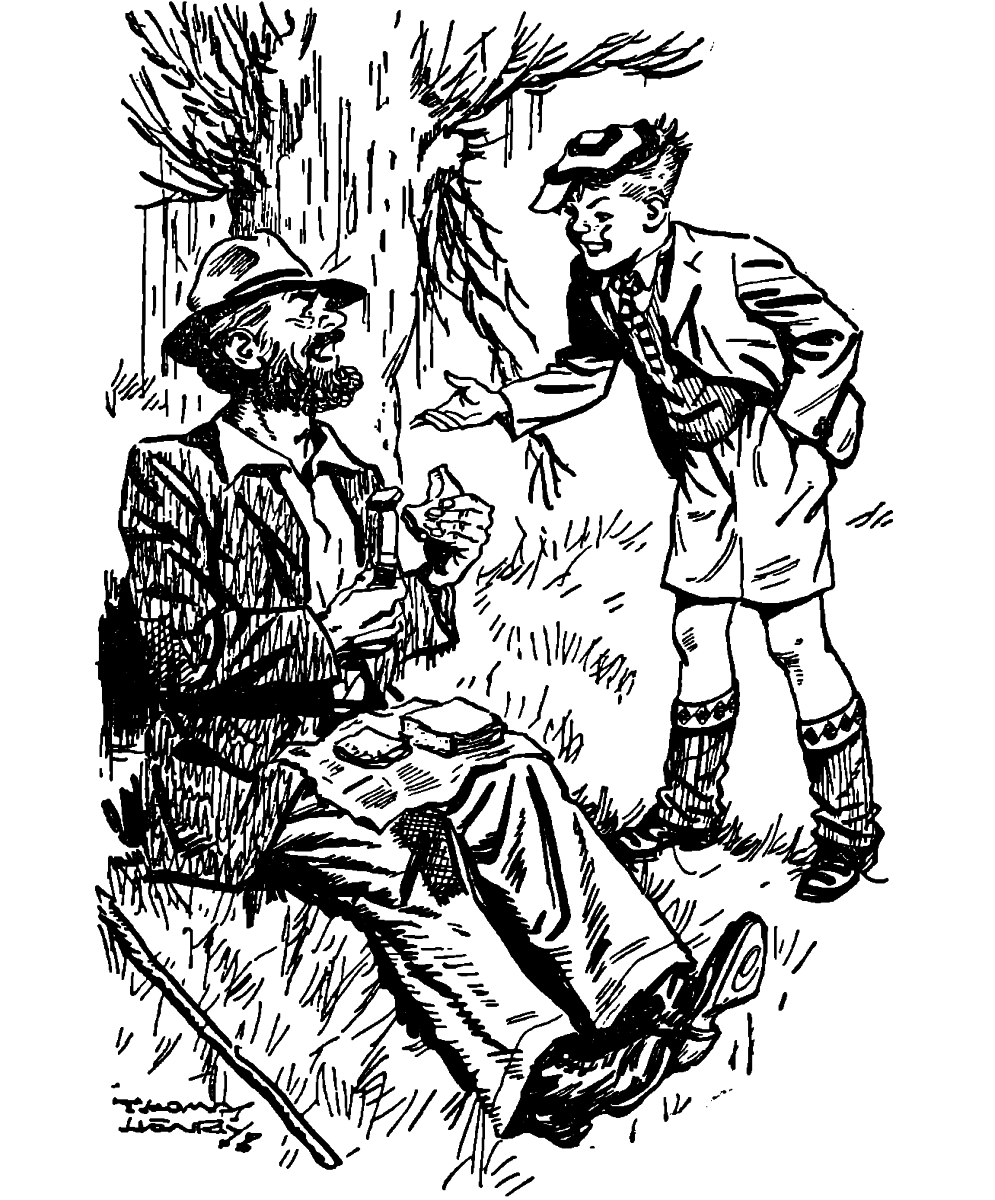

“HAVE YOU EVER HAD A HOLIDAY?” ASKED WILLIAM.

“Good afternoon, young ’un,” he said easily. “An’ wot can I do fer you?”

“Well,” said William, “we were wonderin’—er—I mean, we were thinkin’—er—I mean—— Well, have you ever had a holiday?”

The tramp cut off a piece of crust with a villainous-looking knife and chewed it thoughtfully.

“Not ter my knowledge, young ’un,” he said at last.

“Would you—would you like one?” said William tentatively.

The tramp cut off a piece of mouldy cheese rind, surveyed it without enthusiasm and threw it into the ditch.

“That depends on circs, young ’un,” he said. “It depends on wot sort of an ’oliday an fer ’ow long an’ various other things too noomerous to mention. At this ’ere precise moment you finds me hempty within an’ wet without, so the prospect of a refuge from the elements, as the poets say, is not unwelcome.”

“He’th too big for the garden frame, William,” said Violet Elizabeth, “unleth he had hith head thticking out of the top.”

“Oh, shut up about the garden frame,” said William. “It’s a bedroom he’s goin’ to have, not a garden frame. Look here,” he went on, turning to the tramp, “if you like to come along with us, we’ll find you a place for a holiday, an’ you’ll get a jolly good dinner there, too.”

“I don’t think Mummy’th going to like him much, William,” said Violet Elizabeth. “I think thee’th going to think he’th common.”

“Never mind that,” said William. “He’s poor an’ that’s all that matters.”

The tramp had risen from the grass and was adjusting his shabby coat around him.

“Lead on, young ’un,” he said. “Never yet did Marmaduke Mehitavel refuse the challenge of fate.”

“Is that your name?” said William, impressed.

The tramp winked at him.

“One of ’em, young ’un,” he said.

“Have you got alibis—I mean aliases?” said Ginger eagerly.

“Plenty o’ both,” said the tramp with a wink.

“Leth call him Mithter Marmaduke,” suggested Violet Elizabeth. “Ith a nithe name and ith eathier to thay than the other. Are you hungry, Mithter Marmaduke? I know there’th chicken for dinner.”

The tramp raised his nose and sniffed the air rapturously.

“Lead me there, little lady,” he said. “Lead me there.”

“Let’s go through the hole in the hedge,” said William. “That’s the way we gen’rally go into Violet Elizabeth’s garden.”

He led the way and the others followed, Douglas bringing up the rear.

“I think all this is jolly dangerous,” he said. “I shouldn’t be surprised if we ended up by gettin’ into a row. We did that time we found homes for people.”

“Well, this is different,” said William. “Holidays is diff’rent from homes, an’ anyway Henry’s mother said we ought to do it so it can’t be wrong.”

In the shrubbery they stopped to consider the situation. Mr. Marmaduke lounged against a tree and watched them with an air of philosophic detachment. He took an old clay pipe from one pocket, a box of matches and some stray pieces of tobacco from another and began to smoke.

William gazed through the trees at the impressive masonry of the Hall. “Who’s in this afternoon, Violet Elizabeth?”

“Nobody’th in now,” said Violet Elizabeth. “Cook’th thuppothed to be in, but thee ran out of cloveth for the bread thauthe, tho thee’th gone to the village to get thome. An’ the garage key fith the kitchen door, tho I can get in all right.”

“Good!” said William, assuming his commander-in-chief manner, brows knit, face set and stern. “Now, the rest of you stay here with Mr. Marmaduke, an’ Violet Elizabeth an’ me’ll go ’n’ look round the bedrooms an’ find a nice one for him. . . . Come on, Violet Elizabeth. We’ve gotter be quick or your mother’ll be back before we’ve finished. You don’t mind stayin’ here, do you, Mr. Marmaduke, while we find a room for you?”

“Any place hunder the sky is ’ome to Harchibald Mortimer,” said Mr. Marmaduke amiably.

“Is that another of ’em, Mr. Marmaduke?” said Ginger.

“That’s another of ’em, young ’un,” said Mr. Marmaduke.

William stood in the middle of the bedroom and looked round appreciatively.

“This is the nicest,” he said. “He can have this.”

“Oh, but, William,” protested Violet Elizabeth, “thith ith Mithter Bumbleby’th room. Why can’t Mithter Marmaduke have one of the otherth?”

“I don’t like the others,” said William. “Their beds aren’t made an’ they haven’t got flowers an’ tablecloths an’ things.”

“Well, thath becauthe they’ve got thith one ready for Mithter Bumbleby.”

“There’s a nice fire here, too,” said William. “I don’t see why this ole Mr. Bumbleby should have it. He’s not a poor person what wants a holiday.”

The argument seemed unanswerable, so Violet Elizabeth contented herself by saying: “But what will Mithter Bumbleby do, William?”

“I dunno,” said William, knitting his brows into their most complicated pattern. “We’ve gotter think about that. It all needs a bit of plannin’, of course. What time is he comin’?”

“I’m not thure, William. I know he’th being here for dinner, ’cauthe Mummy thaid thee wath going to have a thlap-up dinner for him with chicken and a thoufflée.”

“Well, let’s go an’ fetch him up to see his bedroom, anyway,” said William.

As they reached the hall, the kitchen door opened and Ginger entered.

“I say!” he said. “How much longer are you goin’ to be? He’s gettin’ tired of waitin’.”

At that moment the telephone bell rang. “I’ll anther it,” said Violet Elizabeth, taking up the receiver. “I can anther a telephone ath well ath a grown-up.”

William and Ginger could gather little from her conversation, which seemed to consist chiefly of “Yeth, Mithter Bumbleby,” but at last she put down the receiver and turned to them, beaming triumphantly.

“He’th not coming to-night. He’th jutht finithed giving a lecture at the plathe where he ith and the trainth to Hadley don’t fit in, tho he’th thtaying where he ith till to-morrow morning. He told me to tell Mummy. Ith lovely, ithn’t it? Mithter Marmaduke can have hith room now.”

“I bet your mother’ll turn him out when she finds him,” said Ginger.

The complicated pattern of William’s brow unravelled itself. His face shone with the light that heralded one of his ideas.

“Tell you what!” he said. “I know what we’ll do. Why shouldn’t Mr. Marmaduke pretend to be this ole Mr. Bumbleby? No one’s seen this ole Mr. Bumbleby, an’ I bet Mr. Marmaduke could talk as well as him. He seems jolly good at talkin’. Anyway, we promised him a nice dinner an’ a holiday, an’ we’ve gotter give it him.”

“No one would think he was a real lecturer—not with those clothes,” objected Ginger.

“Why shouldn’t people with holes in their clothes give lectures?” said William.

“I don’t know,” said Ginger, “but they don’t.”

“I know what we’ll do,” said Violet Elizabeth excitedly. “Daddy put some clotheth out for Mummy’th jumble thale an’ they’re all in a pile in the bocthroom. They’re much better than Mr. Marmaduke’th clotheth, an’ Daddy’ll never remember them. I’ll borrow Daddy’th rathor for him, too, and a collar and tie.”

“Yes, that’s a jolly good idea,” said William judicially.

“But what about his dinner?” said Ginger. “Your father an’ mother’ll smell a rat if he has dinner with them. I ’spect, with him bein’ used to picnics, his table manners are diff’rent from other people’s.”

“He could send a message that he wants to have dinner in his room ’cause he’s tired,” suggested William. “I bet people do get jolly tired lecturin’.”

“But what about this party afterwards?” said Ginger. “They’re all goin’ to ask him questions. I was in the post office this mornin’ an’ Gen’ral Moult an’ Colonel Pomeroy were talkin’ about it. Gen’ral Moult said he was goin’ to ask him questions about South Africa.”

“Well, that’s all right,” said William. “You know what Gen’ral Moult is. All he wants to do is to talk about South Africa himself. He’ll go on for hours an’ hours, spoutin’ this ole book he’s writin’.”

“Yes,” said Ginger, “but Colonel Pomeroy said he was goin’ to ask him how the rope trick was done. In this book of his, Mr. Bumbleby said he’d found out how it was done.”

“What’s a rope trick?” said William.

“Ith it the thame ath cath cradle?” asked Violet Elizabeth.

“No,” said Ginger, “it’s a boy what climbs down a rope he hasn’t climbed up or up a rope he hasn’t climbed down—I forget which.”

“I bet it’s climbin’ down a rope he hasn’t climbed up,” said William, “an’ I bet I could do it all right. It’d make a jolly good acrobatic trick for our show, too. I don’t s’pose they’ll let me do any more tight-rope walkin’ at home, so this’ll come in jolly useful. An’ I’ve got the rope.”

The kitchen door opened again, and Henry and Douglas looked in.

“I say!” said Douglas. “Are you never comin’?”

“We’re jus’ gettin’ it fixed up,” said William. “We won’t be a minute now. Where are you havin’ this party to-night, Violet Elizabeth?”

“In the garden room,” said Violet Elizabeth. “The fire in the library smoketh an’ the drawin’-room carpet’th jutht been cleaned, tho Mummy doethn’t want people trampling over it in muddy thoeth. Bethideth, thee’th only jutht had the conthervatory turned into a garden room, tho thee wanth people to thee it.”

“Gosh! That’s all right, then,” said William. “It’s got a skylight window, hasn’t it?”

“Yeth,” said Violet Elizabeth. “It hath.”

“Well, then, I could take up my rope an’ wait up there by the skylight till I hear them talkin’ about the rope trick, an’ then I could let down the rope an’ climb down an’ they’d think it was the real rope trick ’cause they hadn’t seen me go up.”

“I still think we’re goin’ to end up by gettin’ into a row,” said Douglas, apprehensively.

“Well, it doesn’t matter if we do,” said Ginger. “It’ll have been worth it.”

“An’ we’ll have given him a good dinner an’ a holiday same as we promised,” said William. “We can look out for somewhere else for him to-morrow, when Mr. Bumbleby’s here. Come on now back to the shrub’ry.”

At first they thought that Mr. Marmaduke had grown tired of waiting and had continued his leisurely career of vagabondage, but he soon came strolling back through the bushes, completely at his ease.

“Jus’ takin’ a look round,” he explained. “I’m of a naturally curious turn of mind.”

“Now listen,” said William earnestly. “We’ve got this good dinner an’ bed, but you’ve gotter pretend to be Mr. Bumbleby.”

Mr. Marmaduke did not seem to be at all perturbed by this.

“Anythin’ to oblige, young ’un,” he said. “One halias is the same ter me as another. A citizen of the bloomin’ world, that’s what I am.”

“An’ will you put on some clothes that Violet Elizabeth’s goin’ to get for you?”

Mr. Marmaduke looked down at his bedraggled garments.

“I got a mind above clothes, same as the lilies of the field,” he said, “but, as you may ’ave observed, a change can ’ardly be for the worse.”

“An’ then,” said William, “when you’ve had this dinner we’re goin’ to fix up for you, will you come down an’ talk about travels to people?”

“Wot travels?” said Mr. Marmaduke, with a shade of pardonable perplexity in his voice.

“Any travels. I mean, if people ask you about South Africa, I suppose you can make somethin’ up?”

“You suppose right, young ’un,” said Mr. Marmaduke, his equanimity restored. “Never-at-a-loss, that’s me second name. Talked meself into more situations an’ out o’ more situations than hany other man in Hengland.”

“That’s all right, then,” said William. “I expect it seems a bit funny to you, but, you see——”

Mr. Marmaduke waved a horny, unmanicured hand.

“Why waste time in hexplanations, young ’un?” he said. “Take each step as it comes, that’s my rule. The hunexpected’s the very sauce of life, as the poet says. There ain’t no hemergency in the bloomin’ hencyclopaedia that Horatio Grimble ain’t equal to.”

“Is that another of ’em, Mr. Marmaduke?” said Ginger.

“That’s another of ’em, young ’un,” said Mr. Marmaduke.

“Well,” said William doubtfully. “It ought to be all right. There’s no reason why it shouldn’t be all right. We’ll take you up to this bedroom now.”

Then, headed by William, the strange procession went up the stairs to Mr. Bumbleby’s room.

Mrs. Bott’s “garden room” suggested a suburban drawing-room transplanted into the heart of a tropical jungle. Heavily upholstered settees and arm-chairs stood about in nests of palm trees and flowering shrubs. Creepers festooned the glass walls, and plants of various kinds straggled from the roof. Carpets covered the floor, and the whole was illuminated by a torch held aloft in the hands of a marble female who had formed part of the Italian garden before Mrs. Bott had had it transformed into a tangled mass of sweetbriar and chilly stone seats described by the gardening expert who had transformed it as an Olde English Pleasaunce Garden.

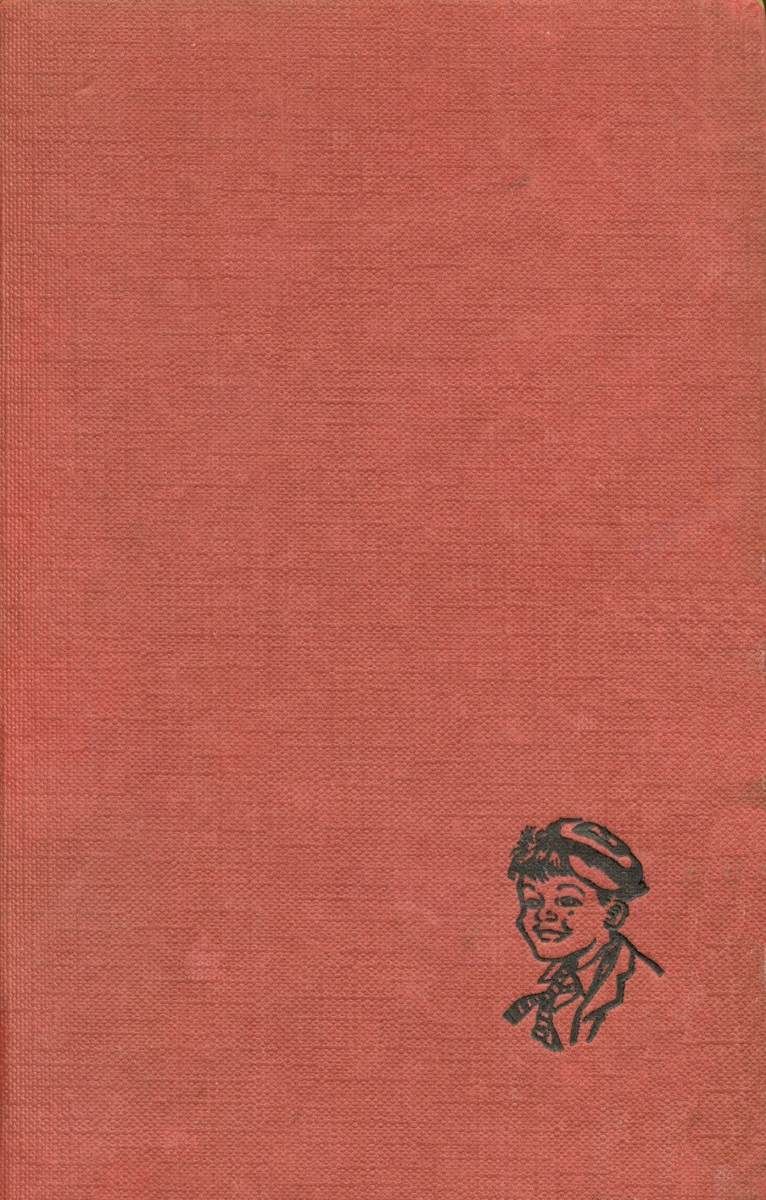

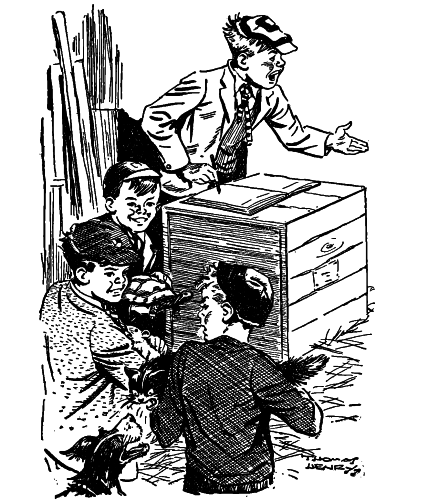

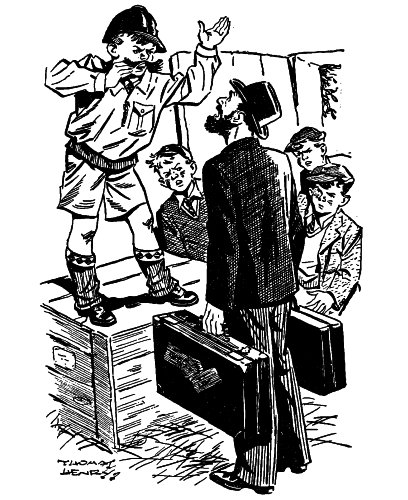

HEADED BY WILLIAM THE PROCESSION WENT UP THE STAIRS.

Mrs. Bott, her mauve satin bosom overlaid with sequins and her cockney accent with a careful if unconvincing veneer of refinement, moved about this scene of tropical luxuriance, greeting her guests.

“Sow glad to see you, General Moult! Sow good of you to come!”

General Moult wore an air of abstraction. He had spent the last few days preparing the questions about South Africa that he intended to ask Mr. Bumbleby, and had managed to incorporate into them the bulk of his Boer War diaries.

“I’m very much looking forward to meeting Mr. Bumbleby,” he said. “I have several questions that I should like to ask him.” He glanced round the room. “He’s arrived, I suppose?”

“Ow, yes, ’e’s arrived all right,” said Mrs. Bott. “But, to tell you the truth, I ’aven’t seen ’im myself yet. I bin up to London for a bit o’ shoppin’ an’ when I got back ’e’d come. A bit earlier than what we expected. But Violet Elizabeth received ’im an’ took ’im up to ’is room. A proper good little ’ostess she was, an’ all. ’E’d bin lecturin’ all week an’ ’e was that tired ’e sent a message ’e’d like ’is dinner in ’is room an’ not to be disturbed. Gettin’ ’is notes ready, I suppose, an’ collectin’ ’is thoughts an’ what not. Them clever people need a lot of time to themselves, you know, to rest their brains in. I always say that people like you an’ me’s got a lot to be thankful for—not bein’ brainy.”

“Quite,” said the General, rather coldly.

“ ’E said in this message ’e’d be down at nine o’clock exact. . . . Ow, there’s Colonel Pomeroy. Sow glad to see you, Colonel Pomeroy! Sow good of you to come!”

“Not at all, not at all,” said the Colonel. “Delightful of you to ask me. It’s the rope trick I want to ask about. Mr. Bumbleby says in his book that he has discovered how it is done. Now when I was in India in 1903——”

“The rope trick’s nothing to what some of the witch doctors in South Africa could do,” said General Moult. “I remember when I was there in 1899——”

Mrs. Bott disentangled herself from one of the straggling plants and passed on to her other guests.

“Sow glad to see you, Miss Milton! . . . Sow good of you to come! . . . Ow, there’s Mrs. Brown. An’ Mr. Brown. An’ Robert an’ Ethel. Sow good of you all to come!”

“Very good of you to ask us,” said Mr. Brown, with such lack of enthusiasm in his voice that Mrs. Brown hastily broke in with: “How charming you’ve made this room, Mrs. Bott!”

“Yes, I’ve always wanted a garding room,” said Mrs. Bott. “I think Nacher’s sow beautiful, don’t you. . . . Now I ’ope you’ve brought William along. A real eddication, I always think, for children to listen to someone with brains same as this ’ere Mr. Bumbleby. I’m lettin’ Vi’let Elizabeth stay up for it. Ever so excited, she is, about it. I don’t think you’d find many children of ’er age so keen on ’earin’ about travels as what she seems to be. I always said that child ’ad brains if only you could find ’em.”

“William’s been to tea with Ginger,” said Mrs. Brown. “I expect he’ll be coming along with the Merridews.”

Mrs. Bott turned her devastating hostess’s smile upon the Vicar.

“Ow, Mr. Monks, sow glad to see you! Sow good of you to come!”

“Not at all, not at all,” said Mr. Monks, throwing a quick glance round the room and greeting his parishioners with a series of brisk nods. “I’m very anxious to meet Mr. Bumbleby. A strange eccentric character, I’ve heard, who has slept in—er—doss houses and mingled with tramps and criminals in order to get some of his material. By the way, speaking of tramps, that reminds me, Mrs. Bott, that a very doubtful character has been seen hanging about the village to-day. I believe it’s the same man who broke into the Vicarage last year. If so, he’s only just out of prison. . . . I saw your man Tonks cleaning the car as I passed the garage, and I took the liberty of telling him to keep an eye on the grounds this evening.”

“That’s ever so good of you, Mr. Monks. I do so ’ate doubtful characters. . . . D’you hear that, Botty?”

Mr. Bott, who was wandering about in the background—short, stout and perspiring—explaining to anyone who would listen to him that these do’s were not much in his line, but the missis said they ought to do their dooty by the commoonity, brightened visibly at the prospect of a little diversion and said: “Yes, love, I ’ear.”

“Well, mind you keep a look-out for him. . . . Ow, good evenin’, Mrs. Merridew. Sow glad to see you! Sow good of you to come! Do them boys good to be somewhere where they’ve got to sit still and listen fer a change. . . . Where’s William Brown?”

Ginger raised an expressionless face.

“He’s comin’ along later, Mrs. Bott.”

“Not tryin’ to get out of it, is ’e?” said Mrs. Bott grimly.

“Oh, no,” said Ginger. “He’s not tryin’ to get out of it.”

He made his way quietly to the door that led into the garden, where Violet Elizabeth was standing—a vision of infantile innocence in a white party frock with a blue sash.

“Where’s Mr. Marmaduke?” he whispered anxiously.

“He’th upthairth. He thaid he’d come down at nine o’clock. He’th enjoyed hith dinner. It wath very thlap-up. . . . If he dothn’t come down, I’ll go up and fetch him. He wath lying on hith bed when I went in latht. I hope he hathn’t gone to thleep. Where’th William and the otherth?”

“William’s up on the roof gettin’ his rope trick ready, an’ Henry’s helpin’ him, an’ Douglas is comin’ on later. His mother made him go back to wash his face again ’cause he’d left some of it out. I’m stayin’ down here to catch hold of the end of the rope when William lets it down, an’—— Gosh! There he is!”

For Mr. Marmaduke was entering the room by the other door. He had changed into Mr. Bott’s discarded suit. It was a little too short and hung loosely on his figure, but his appearance on the whole betrayed only such negligence as might be attributed to the absent-mindedness of genius. He had put on Mr. Bott’s shirt, shoes, collar and tie. He had washed his face and had evidently passed a casual comb through his hair and beard. It was clear that he was by no means overawed by his surroundings. Even Mr. Bott’s sober city suit and decorous tie could not quite quell his air of jaunty insouciance.

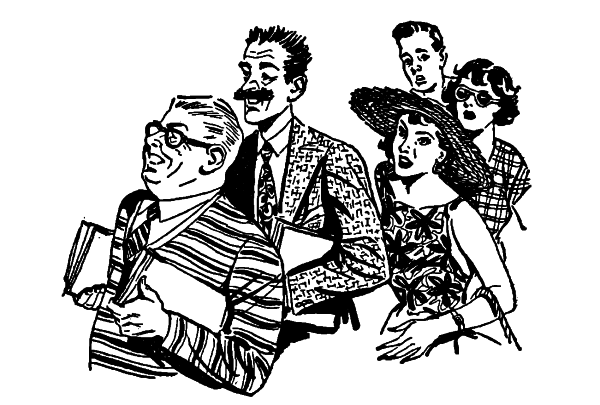

“OW, THERE YOU ARE, MR. BUMBLEBY,” SAID MRS. BOTT. “SOW PLEASED TO SEE YOU!”

Mrs. Bott swept up to him, bridling with pride and pleasure.

“Ow, there you are, Mr. Bumbleby. Sow pleased to see you! Sow good of you to come! A real honour, I can assure you. Sorry I wasn’t ’ere to receive you, but my little girl did it for me, I ’ear. I do ’ope you’re rested an’ all by now. Well, I won’t go introdoocin’ everyone an’ stringin’ off names what I don’t expect you’ll ever remember, but these are all our kind friends an’ neighbours what have come to ’ear what you ’ave to say. Will you sit at this ’ere table, Mr. Bumbleby, an’ the others can shoot questions at you from where they’re sittin’, like. . . .”

Mr. Marmaduke took his seat at the table and swept an unabashed glance round the room.

“Evenin’, all,” he said.

“Rather a rough diamond,” whispered Mr. Monks to Colonel Pomeroy.

“Yes,” said Colonel Pomeroy. “Some of those writing chaps are . . . Hello! The General’s wasting no time.”

For General Moult had risen to his feet and taken a sheaf of notes from his pockets. An audible groan went round the room.

“I should like, sir,” said General Moult, ignoring the groan, “to ask you a few questions about South Africa, which I understand you to have visited recently. I have not been there myself since the time of the Boer War, and I expect there have been many changes during the interval. I went out in 1899 and . . .”

Ginger felt himself grabbed by the arm from behind.

“Come out,” whispered Douglas urgently. “Come out quick. Somethin’s happened.”

Ginger rose and crept quietly out into the night through the garden door, followed by Violet Elizabeth.

“What’s the matter?” he said, when they reached the safe shelter of the shrubbery.

“The real one’s come,” said Douglas.

“What?”

“The real one’s come,” repeated Douglas.

“He—he can’t have,” gasped Ginger.

“Well, he has. I was comin’ out of our house an’ I ran into him an’ he asked me the way to the Hall.”

“He thaid the trainth were impothible,” said Violet Elizabeth. “He thaid tho on the telephone.”

“I know,” said Douglas, “but a friend who was comin’ this way brought him along in his car an’ dropped him at the cross-roads. He’s walkin’ from the cross-roads now, an’ he’ll be here any minute. I ran across the fields to get here first. What’re we goin’ to do? We mus’ tell William quick.”

“We can’t do that,” said Ginger. “William’s up on the roof gettin’ his rope trick ready. We can’t shout to him or everyone’d hear. We’ve gotter do somethin’ ourselves.”

“What can we do?” said Douglas.

“Leth pour boiling oil on him, thall we?” said Violet Elizabeth brightly. “It wouldn’t take any time at all to boil up my bottle of cod-liver oil.”

“Be quiet, Violet Elizabeth,” said Ginger sternly. “Now listen. This Mr. Marmaduke is our friend an’ it’s our fault he’s here, so we’ve gotter hold Mr. Bumbleby at bay till we’ve warned Mr. Marmaduke of danger.”

“How can we?” said Douglas.

“Oh, shut up sayin’ ‘how can we’,” said Ginger, adopting William’s manner together with his position as leader. “We’ve got to. I gotter sort of plan comin’ to me if only you’d stop talkin’ an’ let me think. . . . Let’s see . . . Your coal shed’s the other side of the shrubbery, isn’t it, Violet Elizabeth?”

“Yeth,” said Violet Elizabeth. “Why?”

“Never mind. It’s to do with this plan that’s comin’ to me. Let’s go to the gate an’ meet him.”

“I thtill think it would be nither to pour boiling oil on him,” said Violet Elizabeth wistfully.

Together the three walked down the drive. . . . The night was dark, and it was only by the sound of his footsteps that they knew Mr. Bumbleby was approaching. Ginger planted himself firmly in the middle of the drive, with Douglas on one side of him and Violet Elizabeth on the other. Mr. Bumbleby, hurrying blindly along, gave an exclamation of annoyance as he walked into them.

“What on earth——?” he said irritably.

“Good evening, sir,” said Ginger.

“Good evening, good evening,” snapped Mr. Bumbleby. “This is the Hall, isn’t it?”

“Yes,” said Ginger blandly.

“Well, I’m expected here. My name’s Bumbleby. I’d no idea it was so far from the cross-roads. And it’s so dark I’ve nearly been in the ditch several times. Most annoying!”

“Yes, it is dark, isn’t it?” said Ginger. “We—we’ve come to show you the way.”

“I’m afraid I’m late,” said Mr. Bumbleby, “but I didn’t expect to be able to get here at all to-night. Did Mrs. Bott put off her—er—gathering?”

“No,” said Ginger. “They’re all in the garden room.”

“Sorry to have kept them waiting like this. Where is the garden room? I’d better go straight there.”

“This way,” said Ginger.

He began to lead Mr. Bumbleby along a small path through the shrubbery. The other two followed. Mr. Bumbleby allowed himself to be led along the small path, making noises suggestive of annoyance and impatience as he stumbled into various obstacles.

“I ought to have brought my torch. I can’t see a thing. I nearly fell over something then. . . . Where on earth are we going? Where is this garden room?”

They had reached the other side of the shrubbery.

“Here we are,” said Ginger, opening the door of the coal shed.

“What? Where?” sputtered Mr. Bumbleby, who had just tripped over an uneven piece of ground. “I can’t see a thing. I——”

“Straight in, sir,” said Ginger respectfully.

Mr. Bumbleby never knew whether he stepped into the coal shed of his own accord or whether he was gently propelled into it by the three children. All he knew was that he found himself inside and heard a key being turned in the lock.

“There!” said Ginger, with a sigh of relief. “We’ve got him at bay, all right. Now we’ve gotter go an’ warn Mr. Marmaduke quick.”

Followed by the sound of banging on the door and cries of “Let me out,” the three made their way back to the garden room. There they found the situation more or less unchanged. General Moult was still on his feet, discoursing on South Africa and ignoring the growing signs of restiveness in his audience. He was, in fact, so much accustomed to growing signs of restiveness in an audience that he never even noticed them.

“In 1900,” he was saying, as they entered and took their seats, “came the Relief of Mafeking. I was present myself at that historic occasion, and I remember . . .”

His voice droned on.

Ginger and Douglas made determined efforts to attract Mr. Marmaduke’s attention, but Mr. Marmaduke’s attention was past attracting. He had succumbed to the after-effects of a large dinner and the soporific influence of the General’s voice, and was slumped in his chair, hands in pockets, eyes closed. Ginger fidgeted and coughed, but everyone round him was fidgeting and coughing. He stood up and made signs, but no one noticed him except Mr. Monks, who whispered sharply: “Sit down, my boy, and try to be patient, like the rest of us.”

“Thall I thout ‘Fire!’?” said Violet Elizabeth in a resonant undertone.

“No,” said Ginger.

Miss Milton and Mrs. Monks had been exchanging glances for some time, and now both had reached a point where they could stand it no longer. With a brisk movement Miss Milton rose to her feet.

“Excuse me, General, but don’t you think it’s time you allowed Mr. Bumbleby to tell us something of modern conditions in South Africa?”

General Moult looked surprised and a little hurt by the interruption.

“Certainly, Miss Milton, certainly. I was merely giving a short résumé of conditions as I remember them myself.”

Miss Milton snorted eloquently, and the General sat down with an air of offended dignity.

“Now, Mr. Bumbleby,” said Miss Milton, “perhaps you’ll tell us how far conditions have changed in recent years.”

The clear incisive notes of Miss Milton’s voice dispelled the mists of sleep that had been gathering round the guest of honour. He rose to his feet and surveyed his audience with unruffled calm.

“Well, that’s a question that takes a lot of answering,” he said. “Conditions ’ave changed in some ways an’ not in others. Wot I mean ter say is——”

It was at that moment that Tonks, the chauffeur, appeared in the open doorway, holding a blackened, dishevelled figure by the neck.

“What’s this, Tonks?” said Mr. Bott, trying to look severe but secretly delighted that the hoped-for diversion had actually happened.

“I got that doubtful character Mr. Monks warned me of, sir,” said Tonks. “Proper desp’rate, ’e is, too.”

“This is an outrage,” sputtered Mr. Bumbleby.

“Caught ’im climbin’ out of the coal shed winder,” said Tonks. “Bin ’idin’ up there, I’ll be bound, till ’e thought you was all safe inside ’ere.”

“I repeat, an outrage,” shouted Mr. Bumbleby.

“Go an’ ring up the police, Botty, quick!” said Mrs. Bott. She turned to Mr. Monks. “ ’E is that desp’rate character you warned us of, isn’t he?”

Mr. Monks adjusted his spectacles and inspected the dishevelled figure that was wriggling ineffectually in Tonks’s firm grasp.

“As far as I can see beneath his covering of coal dust and grime,” said Mr. Monks, “he most certainly is.”

“Murder us as soon as look at us, ’e would,” said Mrs. Bott. “You can tell it by ’is face.”

Ginger and Douglas watched helplessly and in silence. The situation had got so far beyond them that there was nothing to do but watch helplessly and in silence.

“You’ll pay for this,” choked Mr. Bumbleby. “My name’s Bumbleby. I’m a fellow of the Royal Geographical Society. I was asked here to lecture——”

“You’ll have to think up a better excuse than that, my good man,” said Miss Milton sternly. “Mr. Bumbleby’s here. Mr. Bumbleby——”

They all turned to look at the chair in which, a few minutes before, the guest of honour had been sitting. It was empty.

“Mr. Bumbleby’s gone,” said someone.

There was a short, tense silence, broken by General Moult.

“Good Lord!” he said. “So has my watch.”

“And mine,” said Mr. Monks.

“Botty, me diamond brooch’s gone,” screamed Mrs. Bott.

It was clear that in the confusion caused by the entrance of Tonks and his captive, Mr. Marmaduke had passed swiftly through the crowd, using his light feet and lighter fingers to their best advantage as he did so.

The Brown family, who had not been in the path of the departing guest, had escaped spoliation. They gathered together, congratulating each other.

“And it’s quite a refreshing change,” said Mr. Brown, “to be present at a contretemps in which William can have had no hand.”

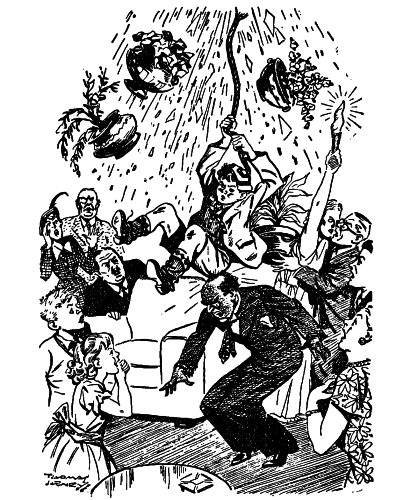

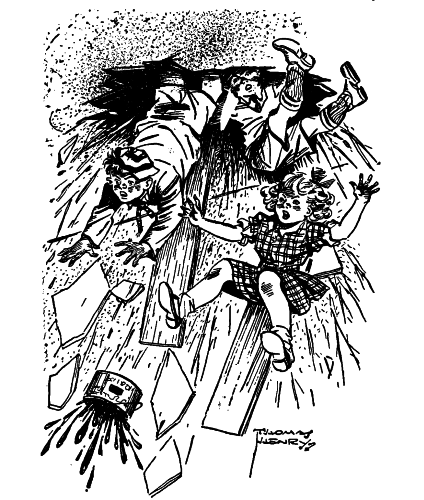

WILLIAM WAS PRECIPITATED ON TO THE HEAD OF THE UNFORTUNATE MR. BUMBLEBY.

“Yes,” agreed Mrs. Brown complacently. “He isn’t even here.”

Above the uproar rose General Moult’s booming voice.

“I say, Pomeroy, he evidently knows a trick worth two of the rope trick.”

William and Henry, on the roof, had been waiting for this moment. So intent had they been on arranging the rope that the drama enacted immediately below them had escaped their notice. . . . The moment they had been preparing for had arrived. Someone had mentioned the rope trick. . . .

Suddenly the air was rent by a piercing scream from Miss Milton.

“There’s a confederate up on the roof! The window’s opening! A rope’s coming down!”

“Surely,” said Mr. Brown, “something else isn’t going to happen.”

But he was wrong. It was.

Above the babel (for Mr. Bumbleby still had plenty to say and was saying it with pungency and directness) a well-known voice was heard shouting, “Hi! The rope’s breaking. Help!” and William was precipitated on to the head of the unfortunate Mr. Bumbleby, bringing with him a cascade of ferns and flowering plants, and throwing the marble female into the unwilling arms of Mr. Monks.

“Oo, lovely, William!” said Violet Elizabeth, with a cry of rapture. “That’th muth better than boiling oil.”

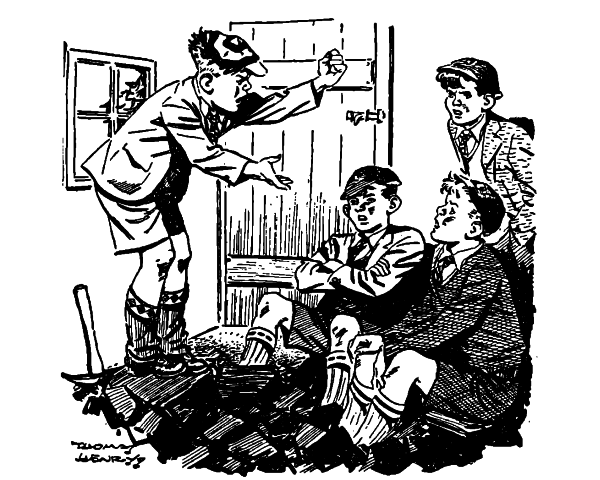

It was a sad and sorry band of Outlaws that assembled the next day in the old barn.

“What did your father say to you when he got you home, William?” said Ginger.

“He didn’t say much,” said William bitterly.

“Neither did mine,” said Ginger, with a short, mirthless laugh. “Didn’t even wait to let me explain.”

“Neither did mine,” said Douglas. “Said I could explain afterwards.”

“Ole Mr. Bumbleby wasn’t too bad when we went to ’pologise, was he?” said William meditatively. “He told us some jolly int’restin’ things about head hunters.”

“An’ ole Mr. Bott wasn’t too bad either, givin’ us half a crown each.”

“Sorry they caught Mr. Marmaduke,” said Ginger. “I hope they don’t send him to prison.”

“I don’t s’pose he’ll mind much,” said William. “He doesn’t seem to mind things. . . . Anyway, the poor ole people without holidays can jolly well stay without holidays now for all I care. They can’t blame me. I’ve done my best for them an’ had no gratitude from anyone.” But William was a boy who lived wholly in the present, and already the stirring events of the previous day were fading into the limbo of the past. “Come on,” he ended. “Let’s go to Crown woods an’ play head hunters.”

William entered the gate with a jaunty swagger, glancing cautiously at the windows of his house, then beckoned to Ginger, Henry and Douglas, who stood hesitating in the road. They entered with a sheepish air. William’s invitation had been given with a nonchalant assurance that had, for the moment, made them believe themselves welcome guests in any home, but the impression faded as they neared the gate, to be replaced by memories of the many occasions on which they had been summarily ejected by Mrs. Brown at tea-time, despite William’s pleas.

“P’raps I’d jus’ better ask her first,” said William, trying to retain his jaunty air. “I’m sure it’ll be all right, but——” He advanced towards the front door, adding hopefully, “She may be out. . . .”

But Mrs. Brown was not out. The front door opened as William approached, and Mrs. Brown, accompanied by Mrs. Monks, Miss Milton, Mrs. Bott and Mrs. Beacon, emerged from it. William remembered that this was the day on which members of the Women’s Institute Committee met at his mother’s house.

“Oh, there you are, dear,” said Mrs. Brown absently. “We’re just going over to the Village Hall to discuss the colour scheme for the decorating. No one else is in, but your tea’s on the dining-room table.”

“Oh—er—I s’pose Ginger an’ Henry an’ Douglas can come to tea,” said William as if a matter almost too trivial to be mentioned had just occurred to him.

Mrs. Brown’s thoughts were obviously elsewhere.

“Yes, dear,” she said vaguely and continued her conversation with the others as she passed him.

“I don’t like that dreary green it was painted the last time it was done.”

“I always think there’s something a bit common about green, anyway,” said Mrs. Bott. “It’s not really a classy colour.”

“What about maroon?” said Mrs. Monks, “or is that too daring?”

Their voices died away in the distance.

“Come on in,” said William, ushering his followers into the house with a lordly gesture. “I said it would be all right. They’re always jolly glad to have anyone I invite to tea.”

Forbearing to remind him of various incidents that clearly disproved this statement, they trooped into the dining-room, where William’s tea was laid. It was limited in quality, but not in quantity. There was a large loaf on a breadboard, a large dish of jam, a large jug of the orange squash that William preferred to tea and a plate of large, if somewhat arid-looking buns.

“ ’S all right, isn’t it?” said William with a touch of modest pride. “I mean, if she’d asked you I ’spect she’d’ve got somethin’ a bit better, but for a tea you’ve not been asked to it’s not bad.”

“Well, you asked us, didn’t you?” said Ginger, stung by the implication that he was ignorant of the rules of polite society. “We’ve got a bit of manners. We don’t go to tea where no one’s asked us. ’Least, not often.”

“Yes, I know I asked you,” said William, “but I wasn’t sure if it’d work. . . . Come on. Let’s get some more plates an’ knives an’ glasses. It’s good jam, too. It’s raspberry. I helped to make it. ’Least, I picked the raspberries for it. . . . ’Least,” after a moment’s thought, “I b’lieve I ate all the ones I picked, but I did acshully mean ’em for jam when I picked ’em. . . . Well, some of the time I did . . . Come on. There’s plates an’ things in the kitchen.”

They stampeded into the kitchen, found the plates, knocked over a clothes horse, precipitating Ethel’s stockings into the hearth, picked them up, shook them perfunctorily to get rid of the coke and replaced them . . . examined the coffee-grinder, played with the idea of putting a piece of firewood through it in order to reduce it to sawdust, decided that they hadn’t time . . . tested the egg-beater on a saucepan of soup that stood on the draining-board, wiped up the resultant mess from the floor as best they could with a duster, then returned to the dining-room and set to work on the tea. For some minutes there was silence. Tea was not an occasion of social relaxation to the Outlaws. Gradually, however, as the more violent pangs of hunger were assuaged, they unbent, and a desultory conversation ensued.

“My father was goin’ on at me again about that hist’ry essay last night,” said William indistinctly, secure in the knowledge that there was no grown-up present to tell him not to talk with his mouth full. “He says he’d have written one if he’d been a boy. Said he enjoyed writin’ hist’ry essays when he was a boy. I bet he didn’t. Well, if he did why doesn’t he go on doin’ it now? There’s nothin’ to stop him. He could write one every Sat’day afternoon ’stead of goin’ to golf.”

He laughed so heartily at this joke that he had to take a deep draught of orange squash in order to recover himself.

“Hubert Lane’s writing one,” said Henry. “He’s got a whole lot of books out of the library and he’s muggin’ them up.”

“He would,” said William scornfully.

“Tryin’ to soap up to ole Golly,” said Douglas, “ ’cause he wants to be asked to the end-of-term party at her school.”

“He’s heard that they’re goin’ to have four diff’rent kinds of ices as well as jelly an’ strawberries.”

“Well, even that wouldn’t make up for havin’ to be p’lite to ole Golly,” said Douglas.

“An’ why’s she got that rotten ole nephew of hers stayin’ with her?” grumbled William. “Messin’ everythin’ up with his ole hist’ry essays!”

“Golly” was Miss Golightly, the head mistress of Rosemount, a large girls’ school on the outskirts of the village. She was a redoubtable lady, and the Outlaws had learnt to confine their intercourse with her to the minimum. At present she had a nephew staying with her, who, after a brilliant scholastic career, had been appointed Professor of History at one of the older universities, and she had chosen to mark the occasion by offering a prize for the best historical essay written by any boy or girl in the village under the age of fourteen—the essays to be judged by her nephew. Not content with that, she had by sheer persistence enlisted the co-operation of Mr. Marks, the head master of the school the Outlaws attended, and he was urging his pupils to enter for the competition, and his pupils’ parents to use what persuasion they could to that end.

“Professor Golightly,” he had said, addressing the school on the subject, “is one of the most distinguished scholars of the age. We cannot let him go away with the impression that our children are devoid of intellectual interests.”

“I don’t see why we shouldn’t,” said William. “I’m jolly well devoid of ’em an’ I don’t know anyone that isn’t.”

“Dunno what good they’d be to us anyway,” said Ginger. “I want to be a juggler when I grow up, an’ a juggler doesn’t need to know any hist’ry.”

“Nor an explorer,” said Henry, who had lately seen the film Scott of the Antarctic.

“Nor a diver,” said William, who had decided to embrace that calling because he wanted to own a frigate and could think of no other means of obtaining one.

“Nor a lion-tamer,” said Douglas, as William reached out for the last bun, divided it into four in a primitive fashion and handed one piece to each of his friends.

“I want to start practising to be a juggler now,” said Ginger. “You can start with quite small things. Spinnin’ pennies an’ things like that. Anyone got a penny?”

William gave a sardonic laugh.

“Yes, we’re likely to have, aren’t we, after goin’ to Hadley Fair yesterday.”

There was a silence, as each was wafted back on a wave of memory to the glorious atmosphere of Hadley Fair . . . the noise and shouting and blaring music . . . the Dodgems and High Flyer and Sky Rocket and Wall of Death . . . the shooting galleries and distorting mirror . . . the bags of peanuts and Monster Humbugs.

“The Wall of Death was the best,” said William. “Gosh! Jus’ think of it!”

Another drugged silence fell as they thought of it. Ginger was the first to emerge. He was a determined sort of boy, tenacious of any idea that had once occurred to him.

“I could try with a plate, if none of you’ve got a penny,” he said.

“Well, you’re not throwin’ any of our plates up in the air,” said William sternly. “They always get broke, ’cause I’ve tried it myself. I asked you to tea, but I didn’t ask you to go smashin’ everythin’ in the house.”

“I’m not goin’ to smash anythin’,” said Ginger. “I’m jus’ goin’ to spin a plate on the table. It can’t do any harm on the table. Well, it can’t, can it?”

“All right,” said William, who was secretly eager for the experiment.

“I’ll be jolly careful,” Ginger assured him. “Look.”

He took up a plate and spun it. It careered across the table and, before anyone could stop it, crashed on to the floor, breaking into three pieces.

“Told you so!” said William. “There you go—smashin’ everythin’ in the house an’ gettin’ me into rows!”

“It’s not everythin’ in the house,” Ginger pointed out. “It’s only one plate an’ I’m sorry an’ there mus’ be somethin’ wrong with it ’cause it ought to’ve jus’ gone on spinnin’ at the same place it started at. They’ve prob’ly made the balance wrong—put too much stuff at one side or somethin’.”

Henry was examining the pieces.

“I bet we could mend it,” he said.

William’s face brightened at the suggestion.

“Yes,” he said. “I know where the glue is. Wait a sec.”

He vanished for a few moments and returned with a small tube.

“You take out this pin at the end,” he said, “then the glue comes out. . . . Well, I’ve taken the pin out, but the glue won’t come.”

“Stick the pin in somewhere else,” suggested Henry.

“Yes, that’s a good idea,” said William. “I’ll stick it in a good lot of places to make sure. . . .” He proceeded to carry out the idea. The glue co-operated with unexpected eagerness. “Gosh! It’s comin’ out everywhere now. Crumbs!”

“It’s all over your suit, William.”

“Look! It’s goin’ all over the tablecloth. You’re squirtin’ it out too hard.”

“Well, I can’t help it. I’m doin’ my best, aren’t I? . . . Where’s those pieces of plate?”

“Here they are . . . Look out!”

But it was too late. The pieces had slipped from William’s glue-covered fingers and broken into a dozen fragments.

“Well, now what are we goin’ to do?” said William gloomily. “It wasn’t my fault. It was the glue’s. It seemed to go mad all of a sudden.”

“Yes, glue does,” said Henry. “Once I tried to mend a jug I’d broke, an’ it got all over a hyacinth in a pot that was miles away an’ that I hadn’t even touched.”

“Well, we can’t do anythin’ more about it,” said William. “Let’s go to the ole barn.” He suddenly remembered his duty as a host and glanced round the empty table, its emptiness relieved by shining pools and trickles of glue. “Anyone want anythin’ more to eat?” he said, adding simply, “There isn’t anything, anyway, so come on.”

They followed him into the hall. There Douglas, always curious, opened the sitting-room door and peeped inside.

“Gosh!” he said. “They’ve had a good tea.”

The others craned their heads over his shoulder. The room was just as Mrs. Brown and the members of the Women’s Institute committee had left it. Cups and saucers and plates lay about on the tables. The laden cake-stand and tea-waggon stood on the hearthrug. A thoughtful look had come into William’s face.

“Tell you what,” he said. “Let’s clear away an’ wash up. It’ll put my mother in a good temper so’s she won’t mind so much about that plate an’ the glue.”

With an eager murmur of agreement they set to work. Soon everything had been cleared away and the cake plates, still laden with cakes, ranged on the kitchen table.

“What are we goin’ to do with these?” asked Ginger.

“Dunno,” said William, considering them thoughtfully. “We can’t wash them up while they’ve still got cakes an’ things on ’em, can we?”

“I was helpin’ my mother wash up after tea the other day,” said Henry, “an’ there was jus’ one sandwich on one plate an’ she said ‘Eat that up so’s I can wash the plate, dear.’ So I did. You see,” elaborating his explanation, “she wanted to get the food eaten up so’s she could wash the plate.”

They gazed with rising spirits at the tempting array of food.

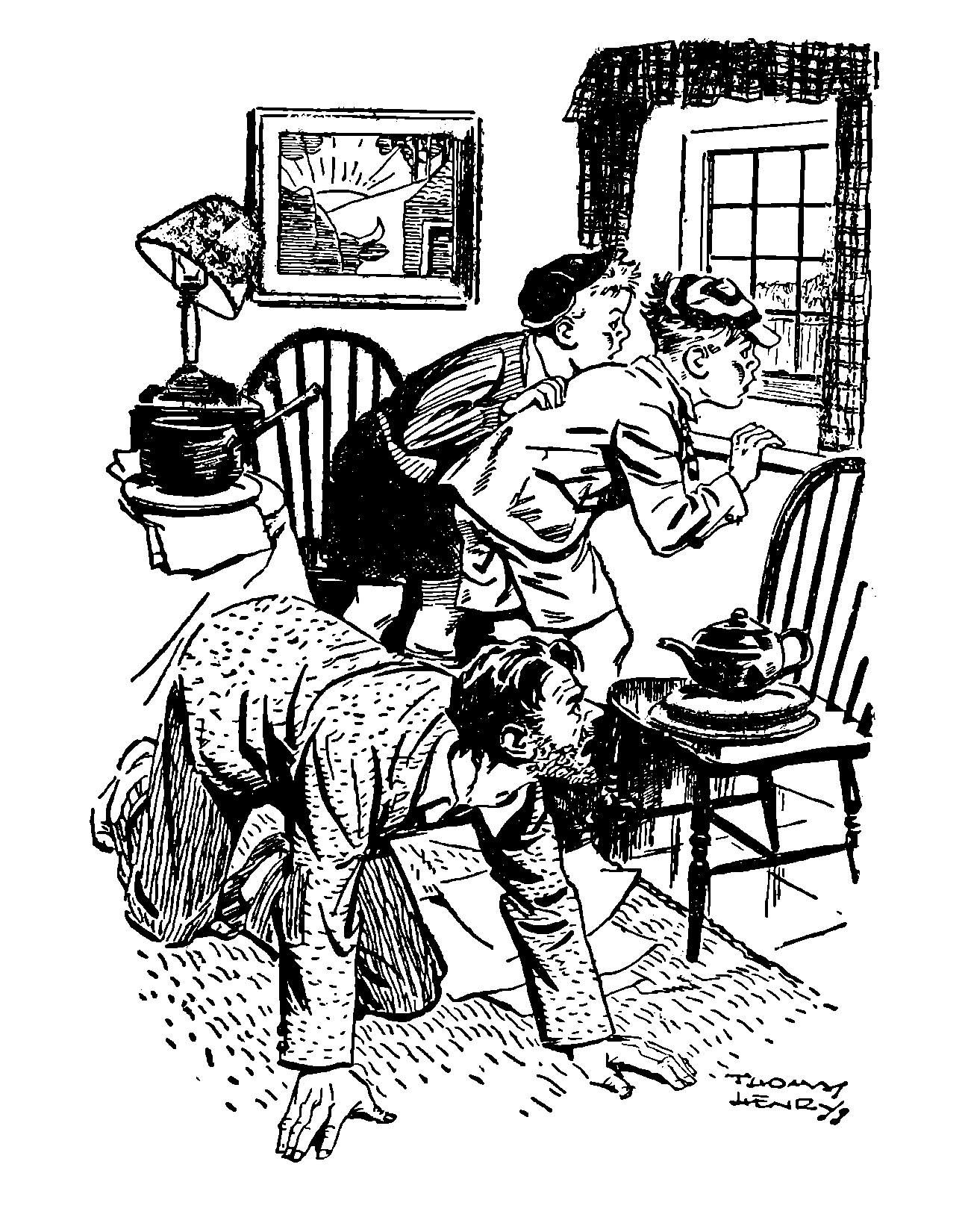

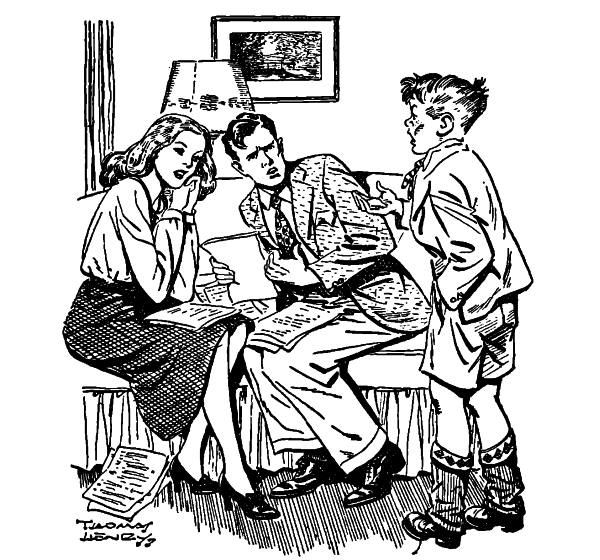

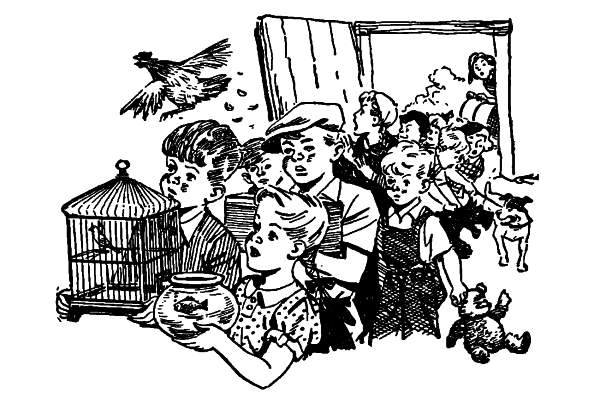

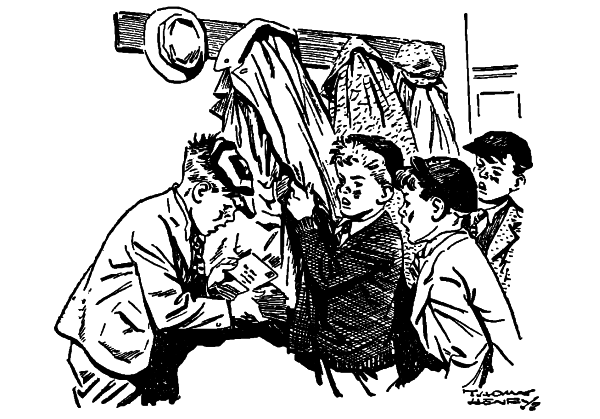

“GOSH!” SAID WILLIAM, “I DON’T KNOW THAT WE OUGHT TO’VE ET UP EVERYTHIN’.”

“Well, there’s jus’ four of those little cakes,” said William, “so, if we each have one, we can wash the plate.”

They munched happily in silence for some time, then Ginger said:

“There’s five of those cookies, so one of us’ll have to have two.”

“No, we needn’t,” said William. “We’ll break it in four an’ have a quarter each. Look! ’S quite easy. They’re jolly fair quarters, aren’t they?”

“Yes,” said three muffled voices.

“That iced cake’s all right,” said Henry. “There’s eight pieces of it so that’s two each.”

The Outlaws were not the first people who, in pursuing the means, had lost sight of the end. The dividing of the food had by this time become an end in itself. The washing-up had faded from their minds. . . .

“Six biscuits . . . That’s one an’ a half each.”

“Two bits of bread an’ butter. I’ll eat ’em.”

“All right. I’ll eat this scone.”

“Look! I’ll cut this bit of currant cake into four. That’s fair, isn’t it?”

“Bags me the slice with the cherry on.”

“No, bags me. . . . All right! Bags me the ginger biscuit.”

“There’s five of these little cakes with nuts on. Let’s draw lots for the odd one.”

“No, let’s toss for it.”

“Well, you can’t, ’cause I’ve eaten it.”

“Look! I’m goin’ to throw this shortcake into the air an’ the one that catches it can have it.”

Hilarity reigned for some minutes, then gradually it died away, and the Outlaws stood gazing at the row of empty cake plates. A look of doubt spread slowly over William’s face, deepening gradually into dismay as he took in the full extent of the devastation.

“Gosh!” he said. “I didn’t mean to eat up everythin’. I dunno that we ought to’ve et up everythin’.”

“Well, we can wash up the plates now,” said Henry, pointing out the one redeeming feature of the situation.

“Y-yes,” said William, “an’ we’d better start doin’ it, too.”

They carried the crockery into the scullery, and William took up his position at the sink.

“Look out!” said Ginger suddenly.

But the warning was too late. Hubert Lane, passing along the road at the back of the house and seeing his enemy neatly framed in the open scullery window, had found the temptation too much for him. He had crept through the gate and taken up a handful of soil . . . and William raised his head to receive the impact of the moist ball full in his face.

“Come on,” he said grimly, flinging down the dishcloth, and the four sped out of the house in pursuit of their foe.

They started off in the wrong direction, thus losing some valuable time, but in the end they found Hubert lurking behind the hedge. William, cheered on by his friends, dragged him into the ditch, rubbed his face in the mud, then let him go. Howls of rage and incoherent threats of vengeance floated back from him as he ran off homewards.

“That ought to teach him,” said William with satisfaction.

Then his satisfaction faded.

“We didn’t do the washin’-up after all, did we?” he said.

“Let’s go back,” said Ginger.

“N-no,” said William. “I don’t think we’d better go back jus’ yet.”

He spoke absently, his brow drawn into a thoughtful frown. Through the memories of a broken plate, a glue-covered tablecloth, a row of cake plates cleared even of crumbs, another memory was looming . . . becoming more and more distinct . . . the memory of his mother saying, “I’ve made enough cakes for two days, then they’ll do for the Parkers as well as the W.I. Committee. Well, they’ll have to, because I’ve used up all my rations.”

The Parkers were coming to tea to-morrow and there would be no cakes for them . . . no rations to make cakes with, even. If his mother had returned from the Village Hall by now, his welcome would be a chilly one. Suddenly his face cleared.

“Tell you what!” he said. “I’ll write that hist’ry essay. They’ve been goin’ on an’ on an’ on at me about writin’ that hist’ry essay, so it ought to put ’em in a good temper if I do.”

“You’ll have to go home to write it,” said Ginger.

“No, I won’t,” said William. “I’ll go’n’ write it in your house. I don’t want to go home for a good long time yet.”

He stooped down, took a cap from the ditch and slipped it on his head, then quickly snatched it off again.

“It’s not mine,” he said. “It’s too big.” He examined the lining. “It’s Hubert Lane’s. Gosh! He must’ve forgot to pick it up. I’ll give it back to him next time I meet him. I’ve no time to bother about it now. Let’s go’n’ write that hist’ry essay.”

He rammed the cap into his pocket and led his band round to Ginger’s house.

Reaching Ginger’s bedroom, they sat on the floor in silent concentration. William had been supplied by Ginger with a piece of crumpled paper and a short stubby pencil. In the anguish of spirit attendant upon mental effort, he had already chewed half the latter away. He sat, staring fixedly in front of him, his brow deeply corrugated.

“Well, come on,” he said at last in a tone of irritation. “Think of somethin’, can’t you?”

“I thought you were goin’ to write it,” said Ginger.

“Well, it’s your fault I’ve got to write it, isn’t it?” said William indignantly. “You started breakin’ plates an’ messin’ about with glue an’ eatin’ up the whole place, an’ if you can’t think of a bit of hist’ry——”

“It was you that squirted the glue out an’ I bet you had as much to eat as anyone,” said Ginger with spirit.

“Well, never mind that,” said Henry pacifically. “Let’s all have a think about hist’ry.”

They had a think about history. Their eyes were glassy, their foreheads furrowed with the effort of it. Douglas broke the silence.

“What about Alfred an’ the cakes?” he said.

“I’m not goin’ to write about him,” said William. “I’m sick of cakes. I’m not goin’ to write about Alfred an’ the cakes or Alfred an’ the glue, so you can shut up about them.”

“What about King Arthur?” said Henry. “He was washed up by the sea.”

“No, that was King John,” said Douglas.

“I’m not writin’ about washin’-up, either,” said William. “If it hadn’t been for ole Hubert Lane we’d have done the washin’-up an’ then p’raps they’d have forgotten about the other things.”

“I bet they wouldn’t,” said Douglas gloomily. “I’ve never known ’em forget anythin’ yet ’cept things you wanted them to remember.”

“Well, that’s not hist’ry, is it?” said Henry. “Let’s get back to hist’ry.”

“There was a man called Clarence once,” said Ginger thoughtfully, “who was killed by a but of something.”

“Of a goat?” suggested Douglas.

“P’raps,” said Ginger vaguely. “I don’t jus’ remember.”

“Well, I’m not goin’ to write about him,” said William. “I’ve been nearly killed by a but of a goat myself. There’s nothin’ historical about it.”

“There’s Victoria,” said Henry thoughtfully.

“That’s a station,” said William.

“It’s a person as well,” said Henry.

“Well, I’m not goin’ to write about that,” said William. “They’d get muddled up, wonderin’ which I was talkin’ about.”

“What about that film we saw?” said Ginger. “Bonnie Prince Charlie.”

William sat up suddenly. His mind went back to thrilling memories of waving swords, swirling kilts, heart-stirring strains. . . .

“Gosh!” he said with interest. “Was he in hist’ry?”

“Yes,” said Henry. “ ’Least, he was pretendin’ to be. That’s why they called him a pretender.”

“I’ll write about him,” said William, taking up his position full length on his stomach on the floor, which was his usual attitude for literary composition. “Now, don’t make a noise, any of you, or I’ll forget what I’m goin’ to put.”

They sat, tense and silent, watching respectfully while William, breathing heavily with the effort of concentration, drew his stumpy pencil over the paper slowly and laboriously—so laboriously that in many places the paper was scored right through.

“There!” he said at last. “I’ve finished it.”

“Read it,” said Ginger eagerly.

William gave a sheepish smile. He was evidently well satisfied by the result of his efforts.

“You can read it,” he said, handing it to them.

They read it. It was an impressive document.

Bony prince charly.

He came bekause they playd skotsh chunes on bag peips he dansed with ladies and fort a battel and fel into a bogg and then there wasent ennything elce to do so he went hoam in a bote.

“It’s jolly good,” said Ginger.

“I don’t know that all the words are spelt right,” said Douglas.

“Yes, they are,” said William, gaining confidence from Douglas’s tone of uncertainty. “I’m a jolly good speller. Sometimes I spell a bit diff’rent from other people, but I b’lieve in—in”—he searched for the word in his mind then finally brought out—“this deformed spellin’ that Parliament’s goin’ to make a lor of.”

Henry was now reading the paper.

“Yes, it’s jolly good,” he said judicially, “but it’s not punctured. It ought to have a comma somewhere.”

“No, it oughtn’t,” said William. “You put in commas to make it sound sense an’, if it sounds sense without commas same as mine does, then it’s all right. I can write sense without commas, so I’m jolly well not goin’ to waste time on ’em.” He took the paper from Henry and put it in his pocket. “I’ve done it anyway, so they oughtn’t to mind so much about the glue an’ things now I’ve shown ’em I’m not devoid of int’lectual int’rests, same as they wanted me to be. What’ll we do now?”

Ginger’s mother solved the problem at this point by calling Ginger down to do his homework and dismissing the other Outlaws.

They parted at the gate, and William began slowly, very slowly, to wend his homeward way. More and more slowly . . . because, the nearer he got to his home, the more vivid became the memory of the presence of glue on the dining-room tablecloth and the absence of cakes on the cake plates in the kitchen and the less effective as a means of atonement seemed the literary composition he carried in his pocket.

It was almost a relief to see Joan coming towards him down the road. Joan was the only little girl whom William admitted to his friendship. She was nine years old, with a round dimpled face and dark hair and eyes. Her father went abroad on frequent business trips, and Joan and her mother generally accompanied him, so that the friendship was never put to any great strain, but at present the family was in England, and Joan was attending Miss Golightly’s school.

“Oh, William,” she said, “I’ve been trying to find you everywhere.”

William gave a self-conscious smirk. He was always flattered by Joan’s interest.

“Oh, well,” he said, “I’ve been havin’ a sort of busy day to-day, but—well, I’m here now.”

There was no answering smile on Joan’s small attractive face.

“I’m in terrible trouble, William, and I want you to help me. You’re the only person in the whole world who can help me.”

The dark eyes were fixed on him beseechingly . . . Joan’s implicit faith in him always went a little to William’s head.

“All right,” he said airily, secretly glad of any undertaking that would delay his return to the bosom of his family. “I’ve got a bit of time now. What is it? Has that pedal come off your bike again?”

“No, William. It’s something much worse than that. It’s—it’s a matter of life and death.”

“Oh,” said William, a little taken aback. “I dunno that I’ve got time enough for that. Things like that take a good long time, you know.”

“Oh, William, you must. You said you would.”

“Well, what is it?” hedged William.

The two began to walk along the road.

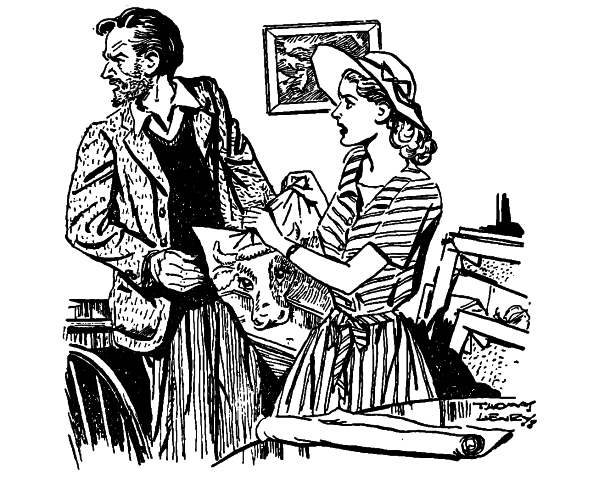

“OH, WILLIAM, I’M SO MISERABLE,” CRIED JOAN, “AND I WANT YOU TO HELP ME.”

“Well, you see, William, it’s Mummy’s birthday to-day, and I’d got her a lovely powder compact for a birthday present and filled it with her favourite powder and I was showing it to Rosemary yesterday in arithmetic and Miss Golightly saw me and took it from me, and she won’t give it back to me. She has a rule that she never gives confiscated things back till the end of the term and she won’t break it. I’ve told her that it’s Mummy’s birthday present, but she still won’t give it me back and I haven’t any money to buy her anything else.”

William considered the problem, frowning.

“But it’s after tea-time,” he said. “Your mother mus’ know by now that you’ve not got a present for her.”

“No, William, she doesn’t. She had to go to London and she won’t be back till half past six, and we thought we wouldn’t start the birthday till she got home. She asked some people in for drinks and she said I could have some friends in, too, at the same time and she said I could ask you and you will come, won’t you, William? We’re going to have a birthday cake and ice cream and meringues and éclairs and lots of lovely things. I’ve been trying to find you all day to ask you. You will come, won’t you, William?”

“Well, it sounds jolly good,” said William, “but——”

“Oh, thank you, William. Hubert Lane keeps trying to get me to ask him, too, but I’m not going to.”

“I should think not!” said William, outraged by the idea.

“But, William, if I haven’t got that powder compact to give her, I shan’t enjoy any of it. William, you will help me, won’t you?”

“Well—er——”

“But, William, you’re so clever. You can do anything. You do the most wonderful things. You’re the most wonderful person I know.”

Again the sheepish smile spread slowly over William’s homely countenance.

“Well . . . I dunno,” he said modestly and gave a self-conscious cough.

“Oh, William, I’m so miserable I don’t know how to bear it.”

Her dark eyes filled with tears.

Beneath William’s rugged exterior there beat a very tender heart. He could never resist tears—Joan’s tears especially.

“All right,” he said. “Don’t worry. I’ll get it back for you. Don’t cry. There’s no need to cry. I’ll get it back for you. I promise I’ll get it back for you.”

The tears vanished from Joan’s eyes. She gave a joyful little jump in the middle of the road.

“Oh, William, I knew you would. I knew how wonderful you were.”

“Y-yes,” agreed William. There was a far-away look in his eye and a feeling of apprehension at his heart. “I dunno quite—I mean, it’s goin’ to be a bit difficult. I mean, I’m not sure——”

“William, you’ve promised, and it’s made me so happy. All the time I was so miserable, I kept saying to myself, It’ll be all right when I’ve found William. William’ll get it for me because he’s so wonderful.”

“Y-yes, I know . . .” said William, torn between a reluctance to dispel this illusion and secret consternation at the thought of the magnitude of the task that he had undertaken, “but—well, I’ve got some rather important things to do to-day. I mean, I’ve not got as much time as what I thought I had at first. I’m—I’m sort of busy with int’lectual int’rests jus’ now, an’ they take a bit of time, do int’lectual int’rests, you know.”

“But, William, you promised.”

“Yes, I know I did. . . . Yes, I’ll do it all right. . . . Yes, I’m not worryin’ about that—not a little thing like that. I’m jus’ wonderin’ how to fit it in. I’m jus’ a bit full up to-day an’——”

“But you’ll do it quickly, won’t you, William? ’Cause Mummy’ll be back soon now. Oh, William, I do love you. I’ll run home now to help get the party ready.” Her voice floated back to him as she danced down the road. “You’ll come early, won’t you, and bring it with you?”

William turned and began to walk slowly in the direction of Rosemount School. His heart sank lower at every step. It never occurred to him to abandon the enterprise—he had definitely undertaken it and somehow or other it must be carried through—but he had an uneasy suspicion that the day’s misfortunes had only just begun.