* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

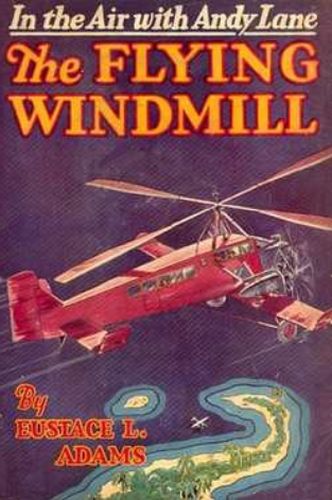

Title: The Flying Windmill

Date of first publication: 1930

Author: Eustace L. Adams (1891-1963)

Illustrator: Seymour xxxxx

Date first posted: Nov. 3, 2022

Date last updated: Nov. 3, 2022

Faded Page eBook #20221103

This eBook was produced by: Stephen Hutcheson, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

“ANDY, THAT’S THE ISLAND ALL RIGHT, BUT THE MONOPLANE HAS BEATEN US TO IT!”

| The Flying Windmill. | Frontispiece (Page 99) |

Copyright, 1930, by

GROSSET & DUNLAP, Inc.

Made in the United States of America

| CONTENTS | ||

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | A Crash on the Road | 1 |

| II | A New Kind of Plane | 18 |

| III | Aboard the “Flying Windmill” | 29 |

| IV | Andy Takes a Vote | 42 |

| V | The Take-off | 50 |

| VI | A Disturbing Message | 62 |

| VII | Southward Bound | 79 |

| VIII | Hook Island | 91 |

| IX | Captured | 100 |

| X | The Tables Are Turned | 111 |

| XI | The Attack | 130 |

| XII | The Hurricane Strikes | 141 |

| XIII | A Sleepless Night | 152 |

| XIV | The Brass-bound Chest | 167 |

| XV | A Fight for Life | 184 |

| XVI | The Treasure | 194 |

| XVII | Sam Makes a Decision | 203 |

THE

FLYING WINDMILL

“Quick, Andy! Look down there!”

Sonny Collins’ voice rose to an excited shriek as he leaned far out over the cockpit and pointed straight down toward the ground.

“Look! Look at those two cars!”

Andy Lane tilted his swift little monoplane far over on one wing and stared down the line of Sonny’s pointing arm. Two cars were racing side by side along a wide ribbon of concrete that turned and twisted between the rolling hills of the countryside. Their speed was terrific. Occupying the full width of the road, they careened around turns at a whirlwind speed that threatened instant destruction to both.

The young pilot watched them for a moment, then cut the throttle of his powerful Apex engine and nosed his ship down in a dive that threatened to rip the silvery wings from her sleek, bullet-shaped body. In that single glance, Andy had seen something that was far more startling than a mere breakneck race between two road hogs. Clinging to the running board of the car which roared along the middle of the road was a man who pointed with one hand toward the driver of the other car. And from something which glistened in the pointing hand there darted a tiny knife-stab of crimson flame.

“He’s shooting, Sonny!” shouted Andy, opening up his engine to give greater speed to the diving plane.

“Oh, Andy!” came Sonny’s voice. “One of them has crashed!”

Andy looked down again just in time to see the car which had been racing on the right side of the road hurtle across the ditch and roll over and over in the field beside the highway. Then it came to a stop and was immediately hidden by a huge cloud of dust. The other car swerved from side to side as its driver jammed on the emergency brake. It skidded to a stop, then began to roll swiftly backward toward the wrecked car.

The pilot in the diving plane scanned the adjacent fields, searching for a landing place. But from horizon to horizon there was no piece of cleared land large enough for his fast little ship. Garden patches, clumps of woods and bowlder-strewn meadows spread for miles in every direction.

“There’s nothing to do but to try the road,” he muttered to himself.

The backing automobile had now come to a stop beside the ditch. Two men leaped from it and ran across the field to the overturned wreck. As Andy leveled out for his dangerous landing, he could see the two men bending over a still, limp figure. Then they rose and dashed at full speed back to their waiting automobile, which immediately got under way and raced up the road at ever-increasing speed.

It was odd, Andy thought, that they had not carried the injured man with them, to take him to the nearest hospital. But he had no time to puzzle out the mystery, for the road was swinging up toward the gliding plane with tremendous speed. On the left side of the concrete surface was a wide ditch, partially filled with water. On the other side was a series of telegraph poles, which offered a barrier as dangerous as a huge picket fence. Dozens of gleaming copper wires drooped from pole to pole, all the way to the horizon ahead. Fortunately the wind was blowing almost straight down the road.

“Watch yourself, Sonny,” yelled Andy. “This may be a crash!”

The song of the wind through wires and struts dwindled to a murmur as Andy lifted the nose of the plane. He headed down toward the edge of the road that was nearest the ditch. For a few heartbreaking seconds it seemed to Sonny that the left wheel must drop over the edge while the other rolled along the smooth highway. The right wing tip almost brushed the telegraph wires. Then, with a quick little sideslip and a skillful kick at the rudder pedal, Andy swung both wheels to the concrete, just on the ragged edge of safety. There was a soft jar as the shock absorbers took up the impact of landing. Then the plane rolled to a stop.

“Whew!” gasped Sonny, his brown eyes very large behind the horn-rimmed glasses. “That took years off my life.”

Andy Lane did not answer. He jerked his safety belt loose and leaped from the cockpit.

“Come on,” he shouted, “let’s see what we can do for this injured man!”

As Andy sped across the wide strip of concrete and headed toward the crumpled wreck of the motor car, his passenger bent over and snapped the safety buckle which secured a tan-and-white collie dog to his special compartment in the cockpit of the plane. The dog whined and wagged his tail, eager to leap to the ground.

“Let’s go, Scotty,” said Sonny, vaulting over the edge of the cockpit.

With a scramble and a leap the famous flying dog jumped to the ground and was off in a brown streak after his master, Andy Lane. Sonny ran after him, dreading what he might see beneath that overturned mass of steel at the end of the two deep ruts in the soft ground.

Andy was bending over the unconscious figure of a man who lay just beside the wreck. With swift fingers the flyer was unbuttoning the man’s coat and shirt. Then he placed his ear close to the bare chest. He nodded in relief.

“He’s breathing, Sonny,” he said, “and his pulse seems strong.”

There was no sign of a wound on the man’s body. Andy lifted his arms and legs, moving them carefully to see if there were any fractures. Then, suddenly, Andy turned to his friend.

“Sonny,” he called, “look inside that car. Maybe there’s another passenger in it or under it.”

Sonny moved hastily to the wreck. What had been a heavy, eight-cylinder sedan was now a twisted, useless thing which would lie out in the weather until it rusted to powder. He peered within the shattered tonneau and crawled under its hood. To his tremendous relief there was no sign that any others had been riding in it when the crash had come.

The collie dog was running this way and that, his nose close to the ground. The soft fur of his neck was ruffled, his long, bushy tail was held rigid. He was growling softly, deep down in his throat. As Sonny emerged from beneath the wreck, Scotty bounded toward the road, barking at the top of his voice, looking down the highway in the direction taken by the two men who had hurried away.

“Sonny,” called Andy, “grab this man’s feet. I’ll take his shoulders. We’ll fly him to the nearest hospital. I can’t find anything the matter with him except for a bump the size of an egg on the back of his head.”

Just as the two began to lift the stranger, his closed eyelids lifted and he gazed about him in astonishment. He stared at Andy and Sonny, then turned his head and looked around at the landscape. His eyes fell on the wreck of his machine. Then he seemed to remember.

“Put me down, please, boys,” he groaned. “I’ll be all right. Put me down.”

Andy and Sonny lowered him again to the ground. The man sat up, shook his head dizzily and then began to feel in the inside pocket of his coat. It was evident that he had not found what he was searching for, because his hands began to dig hastily into one pocket after another.

“It’s gone,” he declared at last, looking at the boys as though he expected them to know all about it.

“That’s too bad, sir,” said Andy, soothingly. “But at least you got out of a bad mess with nothing but a bumped head. That’s something.”

“I might have known they’d get it,” said the man in a discouraged tone. “It would have been easier to have given it to them in the first place.”

“Give whom what?” asked Sonny, curiously.

The man’s eyes looked at the two boys as though he had not seen them before. They were honest blue eyes, a little confused now, and surveyed the features of Andy and Sonny with the greatest care. Then, suddenly, they turned to the road and saw Andy’s airplane there. Once again the man studied the faces which looked down at him.

“I know who you are,” he said at last. “You’re the famous flyer, Andy Lane.” He turned to Sonny. “And you are the young radio operator, Sonny Collins.”

The boys smiled and nodded. They were not surprised that they should have been recognized. Indeed, it was exceedingly difficult for them to go anywhere, nowadays, without having someone whisper their names and thus start a procession of curious people who would follow the two young heroes around until they dodged into some building to escape.

“Yes,” nodded the man, thoughtfully, “I’ve seen your pictures in the news reels so often I feel as though I’d met you both a dozen times.” He fell silent and there was something in his expression that kept the boys from speaking. He seemed to be wrestling with a serious problem. At last his face cleared. “Listen, I have a very queer story to tell you. Sit down here for a few minutes. You won’t be wasting your time.”

Andy was astonished at the man’s request. But he sat down on the grass and Sonny took his place beside him. A cold, wet muzzle pushed itself into Andy’s hand and Scotty crouched close beside his master, his large brown eyes fixed upon the face of the stranger.

“Now I know I can’t be wrong,” smiled the man. “That’s Scotty, the dog who has flown on all your great adventures. All right, now, listen to me. I haven’t told anyone in the world, with one exception, what I’m going to tell you now. And the only reason I’m telling you is that you are Andy Lane, the boy who is known all over the world for his honesty, courage and ability.”

Andy’s face became pink, but he held his peace. Sonny was unkind enough to nudge the older boy with his elbow, which did not increase Andy’s peace of mind. He always became red when people started to praise him.

“Another reason I’m telling you this,” continued the man, “is that I know you have both made so much money out of prizes and rewards that another million wouldn’t worry you very much.”

Andy sat upright in astonishment. A stranger, sitting out here in the countryside, discussing a million dollars! Had the man’s bump affected his brain? But Andy was too courteous to ask.

“The men who shot at me and caused my car to careen into the field here,” said the man, quietly, “have just robbed me of something that is worth more than a million dollars.”

Sonny’s eyes grew large and round. He glanced toward his friend, but Andy was sitting quietly, studying the stranger’s face.

“Yes, more than a million dollars. No one knows how much more. Maybe two or three millions. Tell me, you boys, have you ever heard of Blackbeard?”

“Sure,” said Sonny, immediately. “When I was a very little kid I used to read about him in Grimm’s Fairy Tales.”

“That’s Bluebeard, ivory head,” laughed Andy. “Do you mean Blackbeard, the pirate?”

“Yes.”

“I’ve heard of him,” nodded Andy. “He did a lot of rough work on our Southern coast and down in the Caribbean, didn’t he?”

“Yes. And those two thieves have just stolen a plan showing Where he buried a lot of his loot.”

Sonny whistled. Andy’s expression did not change.

“That’s a hard one to believe, isn’t it?” asked the man, looking at Andy. The boy nodded. “All right. Now that it’s gone, I can’t prove it to you. You’ll have to take my word for it. Listen; six months ago I was searching through some old things in a trunk that belonged to my grandfather. He was a sea captain, who owned and sailed a clipper ship out of Salem in the China trade. I found an old notebook, faded, discolored and dog-eared. It contained a number of his accounts. Upon one of the pages was a notation that he had befriended a seaman named Thomas Catlin who was sick and broke in Shanghai. The man died and left my grandfather a map which he claimed showed an island in the Bahamas where Blackbeard had buried some of his loot.”

“Why didn’t your grandfather go and try to dig it up?” asked Andy, practically.

“He intended to. But he was lost at sea on his next trip to China. My father was a plain business man. He wasn’t much interested in Grandfather’s things and, so far as I know, never went through the Captain’s trunk. I discovered the notebook and was interested. When I saw the map I began to make inquiries. I found that Blackbeard actually did operate in the Caribbean and that it is thought he buried treasure in several places in the West Indies.”

“How did those men happen to steal your map?” Andy asked. “Did they just hold you up and take everything you had, or were they after the map itself?”

“They were after the map. And they got it. I never saw the two before, but I know whom they were working for. I went to a man to get him to form a small party to go down there after the treasure. I didn’t have the money and I knew that I would not be able to go myself, so I trusted him too far. He double-crossed me. Now he’ll go down there and dig up the treasure himself and instead of getting a fifty-fifty split, he’ll get it all.”

“Why can’t you go down there yourself?” asked Andy.

“I’ll tell you honestly,” answered the man looking straight at the flyer. “I don’t know whether there’s any treasure there or not. Most of those wild treasure stories turn out to be false alarms. I have a wife who is an invalid. I cannot leave her. I know that a treasure hunt might take months and months. I would rather lose a treasure that may not be there at all than be away from my wife for even a week.”

Andy’s eyes took on a sparkle of excitement. He had not taken the man seriously until he had said that it was quite possible that the treasure did not exist. If the thing had been a swindle of some kind, the man would never have admitted even the possibility of error.

“Why are you telling us this?” Andy asked, quietly.

“I want you to find that treasure for me,” said the man. “If I didn’t know all about you, you can bet that I’d never have told you. But I know that you will keep your word. I want you to fly down to the Bahamas and look for that gold. If you find it you can have two-thirds of it. The other third will be mine because I am the only one who knows where it is.” Then he added, with a very worried expression, “That isn’t true. I’m not the only one who knows about it. Henry Brewer’s two thugs know about it and he’ll know about it as soon as that car gets back to New York. And just as soon as Brewer can charter a boat he’ll be down there digging it up. That’s why I want you to fly—to beat him to it.”

Andy remembered the man who had stood on the running board, shooting at this man who sat there before him now. Men did not shoot at each other for nothing. Nor did they wreck big cars for the fun of it. This was not just a silly story, to be forgotten in the next moment.

“If those fellows have gotten away with your map, Mr.——”

“Briggs.”

“—Mr. Briggs, how will you know where the treasure is?”

“I’ve studied it for six months!” exclaimed Mr. Briggs earnestly. “I’ve memorized every line. I could draw it so accurately that you’d never know it from the original. I always kept the old notebook in the safe so that I couldn’t lose it. I had an engagement with this man Brewer to show him the map. I got it out of the safe and was taking it to him when his men stole it from me.”

“Why don’t you have him arrested?” asked Sonny.

“Don’t worry,” said the other with a hard laugh, “he will have hidden it away somewhere and I wouldn’t be able to prove a thing.”

“Tell you what we’ll do,” said Andy with sudden decision. “We’ll take you back to New York and we’ll think the thing over. Maybe we’ll talk it over with some of the boys. If we decide we’d like to take it on, you can give us the rest of the dope then. How’s that?”

“Fine!” agreed Mr. Briggs, but he seemed more than a little disappointed that the famous young flyers had not accepted his proposition at once.

Andy and Sonny helped him to his feet and took him to the Apex monoplane. In less than five minutes they were zooming into the air and banking around toward the flying field at Mineola.

It was not quite daybreak on the following morning when Andy, Sonny and the mascot, Scotty, slid down to the broad landing field at Mineola. The gray shadows were chasing each other across the mile-long expanse of turf. The mammoth factory of the Apex Aeroplane and Motor Corporation, which stood at one edge of the field, was already bathed in the first pink lights of the sunrise, yet despite the fact that the regular work would not begin for nearly three hours, one whole end of the building blazed with electric lights.

Andy taxied his air yacht over the grass to the lighted end of the factory and cut the engine. He yawned, stretched and rubbed the sleep out of his eyes.

“How do you manage to be so wakeful at this hour of the morning, Sonny?” he demanded, throwing one leg over the edge of the cockpit.

“It’s a gift, like being able to wiggle your ears,” the slim, bespectacled youth told him gravely.

“Then I’ll never acquire your gift,” laughed the other, dropping to the ground. “The only time I can stay awake at daybreak is when I’m doing my trick at the wheel on a long flight. Then I get used to it, somehow. Come on, let’s go in. By all the lights in the factory it looks as though the Flying Windmill was ready to hop off.”

Sonny unhooked Scotty’s safety belt and tossed him over the side of the cockpit. The dog squirmed in the air like a cat, landed on all fours and bounded across the grass toward his master, barking and nipping at the famous flyer’s legs as though he knew that something very unusual were afoot.

“Andy, did you decide about the treasure hunt?” asked Sonny, catching up with the older boy.

“No, and I hardly slept a wink thinking about it,” confessed Andy. “It sounds just too wild to be true. I don’t dare tell Sam and Joe and the rest about it. They’d think we had lost our minds. It would be a wonderful stunt, though, if we could dig up all that buried gold and whether we found it or not, we’d have a wonderful time looking for it.”

Sonny looked very disappointed.

“If it weren’t for the work on the Flying Windmill,” continued Andy, “I’d be tempted to fly down to Hook Island and see if Mr. Briggs is as foolish as he sounds. But this new plane is just about the most important thing the Apex Company has tackled in a long time. I’m drawing down a perfectly crazy salary for being vice president and consulting engineer and I really ought to do something about earning it. I don’t see how I can get away.”

Sonny opened his mouth as if to argue, but they had reached the factory door and there was no time. Andy led the way as they entered a huge, hangar-like room which occupied one entire end of the building. At first glance the great room seemed absolutely filled with airplanes of every kind and description. All of them were complete and ready to go, for this was the delivery room where finished jobs were rolled from the main part of the factory when they were ready for their flying tests.

At one end of the vast hall were a whole brood of tiny, vicious-looking Army scouts, which were snuggled under the wing of a tremendous biplane that looked large enough to carry a dozen of the smaller ships within her cabin. She bore a famous name on her huge cabin, for this was the great Apex No. 1,[1] which had carried Andy Lane and his daring crew on the first of their many record-breaking flights. Andy looked at her and repressed a desire to step over to her and to pat her weather-stained fuselage. Had it not been for that first great flight, in which he and his crew had remained in the air for fifteen days and nights without touching wheels to the ground, the Apex factory might still be little larger than the one-story shed it had been before orders began to pour in as a result of the flight. Yes, that ship had sold more Apex motors and Apex planes than all the salesmen of the organization combined.

|

See “Fifteen Days in the Air.” |

Amphibians were there, too, looking very odd with their boat-shaped hulls and wheels which projected awkwardly from their sides. Over in one corner stood a mammoth bomber, built for the Navy from the designs of an Apex flying boat in which Andy and his pals had won the great race around the world.[2]

|

See “Racing Around the World.” |

They looked very ghostly, these silent ships, which waited to take their turn in the air under the master hands of Apex test pilots. But Andy loved every one of them. They were, to his eyes, more beautiful than any painting which ever hung in a gallery.

“Look,” exclaimed Sonny, clutching his friend’s muscular arm, “they’re opening the doors and rolling the Flying Windmill out!”

The two boys hastened their steps. Just inside the barn-like doors which opened on to the flying field, there was a scene of the greatest activity. A dozen mechanics were swarming over an extraordinary-looking plane while a tiny tractor tugged at her, dragging her out of the building. Even Andy, who had watched the plane being built, could never look at her without surprise, for she resembled no ship that had ever before taken the air on anything but a short experimental flight.

Her fuselage and undercarriage looked something like an ordinary tri-motor cabin plane, but there was where all resemblance ceased. Her lower wing, if such it could be called, consisted merely of two struts projecting from her hull, and at the end of the struts were two ailerons which, in their shape, looked like overgrown tennis rackets. The stabilizer, near the tail, was bent upward at each end, looking as though careless mechanics had tried to lift the stern of the ship by pulling up on the tips and, in so doing, had bent them hopelessly.

But the oddest thing about the entire plane was the thing which took the place of the top wing. It looked for all the world like a mammoth, four-bladed fan fastened to the cabin roof by a four-legged support. The blades of the fan were tremendously long. The forward blade projected far out beyond the bow, the rear almost to the tail. The other two extended out to each side almost as far as an ordinary wing tip.

“Every time I look at that thing,” laughed Sonny, “it seems funnier and funnier!”

A very fat man who, in his loose suit of coveralls, looked almost like a Teddy bear, walked slowly after the rolling plane, surveying its queer lines with no little disgust. Andy and Sonny walked up to him and slapped him on the back.

“What’s the matter, Sam Allen?” smiled Andy. “You look as though you had eaten something that didn’t agree with you.”

“Everything I eat agrees with me!” retorted the chief mechanic of the Apex factory. “But if that plane doesn’t give me the heebie jeebies, nothing ever will. Last night I dreamed about it in my sleep and I got so upset I fell out of bed!”

Sonny and Andy roared with delight. When the first one-man autogyro had been tested out at the Apex field several months ago, Sam had taken an instant dislike to it. The sight of the rapidly whirling blades made him dizzy, he said. He wanted to throw a dozen eggs into them to see what would happen. Beyond that, he was not interested. He refused to show his astonishment at the marvelous flying of the thing and had protested vigorously when Andy had recommended that the Apex Company buy the patents and construct a large model, with three engines and sufficient cabin room to hold a dozen passengers.

But nobody had taken the fat mechanic seriously. Everybody, from the president of the company down to the smallest grease boy, knew that Sam Allen always fussed about everything new. But his fussing did not prevent Sam from pitching in and working like a Trojan on the construction of the bigger ship. To have watched him working upon its three great Apex engines, one would never have known that the plane had not been constructed according to his own plans.

“Look at the way those fan blades droop,” complained Sam. “They look all limp and tired.”

“They’ll straighten out when they start revolving,” said Andy.

“I know it,” nodded Sam. “But they look discouraged, just as though they were too feeble to start turning.”

Andy was forced to admit that the windmill atop the cabin did not look right. The four long blades were fastened to the shaft at the center by a universal joint, or hinge, which permitted them to droop limply when at rest. He knew that when they started to turn, they would straighten out as rigidly as a stone at the end of a whirling string. It was this very flexibility that permitted the blades to automatically adjust themselves to bumps in the air when in flight. But it did look odd, to say the least.

“I suppose we’ve got to test the silly thing now,” said Sam, as they walked out on the field.

“You don’t have to go,” Andy reminded him. “We can get one of the other mechanics to watch the motors.”

“Just let me see you go up without me, Andy Lane!” roared Sam. “I’ve been up in crazier things than that and you know it. Why, after riding in a flaming rocket plane all over the face of the earth that thing looks safer than a hospital bed.”[3]

|

See “On the Wings of Flame.” |

“All right, Sam,” agreed Andy, who had known all along that Sam would never consent to being left on the ground. “Is Joe Lamson here?”

“You bet. We’ve been here all night working on the last-minute odds and ends. Joe’s in the cockpit right now tracing the lead wires.”

“How soon can we start?” asked Sonny.

Sam stooped suddenly, with amazing speed for one so fat. He swept Scotty into the crook of his left arm and proceeded to ruffle his soft fur.

“Hello, you flying pooch,” he said. “You’re getting almost too big to be a mascot any longer. You eat too much and there’s only room for one big eater aboard Apex ships. And that’s me, hound.”

Scotty squirmed around in Sam’s huge arms, trying to lick his face. But Sam held him tightly, despite the dog’s long, awkward legs and body. The two were fast friends. The dog remembered the pounds and pounds of tender meat that Sam had given him on long flights, while the mechanic remembered a number of occasions when Scotty’s watchful eyes and ears had saved Apex crews from disaster.[4]

|

See “Over the Polar Ice.” |

The plane had come to a stop now, at the edge of the field. The tractor had waddled back into the factory hangar. The mechanics, having nothing else to do, were idly swabbing the plane’s gleaming sides with white cotton rags. Everything was ready.

The mechanic, the two boys and the dog stepped to the side of the great ship, mounted a short stepladder and entered the main cabin.

“Gee, this looks small, compared to the fifty-passenger transatlantic Apex,”[5] murmured Sonny.

|

See “Pirates of the Air.” |

“Yes, but it’s as big as most of the twenty-passenger planes that are in use on the transcontinental air routes,” Andy reminded him. “Let’s give her a final inspection before we start the engines.”

He walked along a narrow corridor toward the bow and entered the control room, or pilot’s room.

“Hello, Andy!” came a quiet voice from a grave-faced, calm-eyed young man who, on his hands and knees, was engaged in examining the braided wire control leads. This was Joe Lamson, who, as chief test pilot for the factory, had been co-pilot on all of the record-breaking hops made by Andy and his crew. He was nearly ten years older than Andy Lane, and, because of his marvelous flying ability, his knowledge of navigation and his all-round dependability, he had been a tower of strength in every emergency. When the control wheel was in Joe Lamson’s capable hands, the ship was as safe as any plane could ever be.

“She’s ready to hop off,” said Joe, rising, and surveying the room with his serious, level gray eyes. “She’s a funny-looking crock, but I think she’ll surprise us by doing more different stunts than any other plane ever did before.”

There was a hollow groan from Sam.

“I don’t want planes to do stunts,” he said sourly. “I like them to fly fast and straight. That’s all.”

And with that, Sam put Scotty down on the floor and retreated to the rear of the cabins to examine some mechanical contrivance that he thought might need his attention.

“If you couldn’t see that windmill blade sticking forward above our heads,” said Andy, “you’d never know that this wasn’t an ordinary ship.”

He glanced at the two comfortable chairs placed behind the dual control wheels, at the familiar groups of instruments, gauges and dials on the instrument board in front of the wheels and at all the other gleaming and polished things within the compact little room. He glanced out of the non-shatterable glass windows that formed three walls and the roof. Yes, it looked very much like the control room of any other tri-motored ship of her size, except that the familiar expanse of top wing outside was replaced by the four awkward-looking blades of the rotating windmill above.

“Let’s go and look at the radio room,” suggested Sonny.

Leaving Joe to continue his last-minute inspection, Andy and Sonny walked back through the corridor. The first door to the right led into a tiny cabin, completely furnished with a folding berth, a desk, dresser and chairs. This was the captain’s sleeping room and office. Andy’s eyes shone with pride as he looked at it. This comfortable little room was to be his during all the long and short experimental flights of the big new ship. He was going to fly again, to hurtle through the skies, to fight storms, and to spend days and nights with Sonny and Sam and Joe, with whom he had already shared such marvelous adventures. That was life. Nothing could be more fun. The next cabin was Sonny’s radio room, where the boy had already spent hours on end installing a small but very efficient sending and receiving set. Andy knew that the lad would spend every spare moment in this room, his ear phones clamped on his head, his slim, nervous fingers twirling the dials. Good little Sonny! Despite the four years’ difference in their ages, the two had been friends for many, many years. And because Sonny was one of the most expert radio amateurs in the entire world, he had acted as radio operator on most of the long flights taken by Apex ships. His familiar call letters had been heard by friends of the ether in nearly every country in the world. His messages from Apex ships had been relayed to Mineola from all four corners of the globe. No, Andy could not imagine starting on a flight without Sonny at the sending key.

Next came a cabin which would be shared by Joe and Sam in their off-duty hours. There were two berths, an upper and a lower, with furnishings as comfortable as those in Andy’s own cabin. On previous flights, the crews had been larger. An assistant mechanic and another pilot had been carried. But since the Flying Windmill was not intended for anything but comparatively short experimental flights, she had been designed to accommodate a crew of four in comfort rather than extra men who would have to be crowded into her capacious fuselage.

Beyond this room was a large, bright cabin which extended the full width of the ship. This was the combination living and dining room. It was furnished with wicker chairs and tables, all gayly painted and making the place look more like a comfortably furnished sun porch than the cabin of an airplane. The chairs were upholstered in red and black chintzes. All the wicker work was lacquered a vivid red. The balsa-wood paneling of the walls was enameled in a deep shade of ivory. Wall brackets and a frosted dome in the ceiling were still lighted, although the morning sun was now flooding the field outside with its brilliance. Andy snapped off the switches.

“It’s certainly a pleasant room, Sonny,” he said. “We’ll have some good times here while we’re finding out whether it will pay to build these ships in commercial quantities.”

In an alcove at the rear of the living cabin was a completely equipped kitchenette. A three-burner electric stove, an electric refrigerator and wall racks of gleaming pots and pans made the little place look extremely efficient.

“I’ll bet Sam has the time of his life here,” laughed Andy. “Look, he’s put in his provisions already, even though he doesn’t know whether we’ll decide to make a long hop today or not! Here’s salt, pepper, sugar, flour, vegetables—you might have known that Sam would take care not to miss a meal!”

“You never said a truer word, Andy!” came Sam’s hearty voice from the door. “If there’s anything in the world that gives me an attack of the twitches, it’s not knowing when I’m going to get my next meal. So when I heard you say that if a short hop was successful we might make a long one, I thought I’d stock up. I haven’t forgotten a thing. And by the way, Andy, what do you say to a little breakfast when we get up in the air? It’s so long since I’ve cooked a meal in a ship that I crave to throw some things into a frying pan and smell them sizzling.”

“Great idea,” applauded Andy. “But in the meanwhile, let’s be taking off. If we wait much longer, the newspaper men will be clustering around and we won’t be able to avoid them.”

“We are ready right now,” declared Sam.

“Good. Let’s go. Everybody get parachutes on. Remember that this is a test flight.”

They all climbed into their clumsy parachute harnesses and went to their stations. Sonny, taking Scotty with him, went into his office, impatient for the ship to leave the ground so that he might unreel his antenna wire. Sam, an open-mouthed bag of tools around his neck, stood by the door. If trouble developed with any one of the three engines, he had but to step out to one of a series of three catwalks which led to the engines. Thus, as on all the other great Apex flights, he would be able to adjust, and even repair, any of his engines while in flight.

Joe was already in his pilot’s seat. Andy took his place beside him. They had each taken lessons in flying these strange autogyros, but they were aware that a ship three times as large as the one they had learned on might act very differently in the air.

Andy pressed the starter switches and all three engines began to click and whir. First one, then another, burst into life, back-fired and popped for a moment, then began to run sweetly, roaring and muttering in turn as Andy opened and closed the throttle.

The pilot pulled a little lever not unlike the gear shift on a motor car, which connected the center engine to the shaft of the windmill. Slowly at first, then faster and faster, the three great vanes began to rotate. Andy watched them carefully. When they were whirling sufficiently fast, he disconnected the center engine. He waved to the little group of mechanics on the ground. They scattered. He pushed forward on the throttle, just as though he were starting for the take off in an ordinary plane. The great fabric of the ship trembled. She rolled slowly ahead over the grass. But hardly had she begun to move when Andy pulled back on the control wheel. Instantly the fat rubber tires of the landing wheel left the ground. The bow rose and the Flying Windmill began to climb at an angle that would have thrown an ordinary ship into an instant stall. But she did not hesitate. Up, up, she climbed at an astonishing speed.

Andy’s heart beat fast. This ship’s actions were so contrary to those of the planes which he had flown so many thousands of miles that he was tempted time and time again to nose down lest she stall and slip into a tail spin. But she climbed steadily, her three engines roaring.

The altimeter read two thousand feet when Andy leveled her out. Then she began to pick up forward speed. Now she handled exactly like any other ship. Except for the flashing arc of the whirling vanes overhead, he would never have known that he was handling an autogyro. The speed indicator crept forward to one hundred and twenty-five miles an hour. Then to one hundred and fifty. That seemed to be her top speed in still air.

Around and around the great flying field she flew, while Andy became accustomed to the feel of her controls. Then he cut the engines and, instead of nosing down into a glide, he held the wheel back against his chest. Instinctively he and Joe braced themselves for a tail spin. Instead, the great ship began to settle down gradually, slowly, in an almost vertical descent. Andy held her there, marveling, and watched the altimeter drop to fifteen hundred, one thousand and then five hundred, with practically no forward speed.

At five hundred feet he opened the three engines so that they ran at about a third of their full power. There was still not sufficient forward speed to keep the plane from descending, but she moved slowly ahead, settling gradually. At last they were within fifty feet of the landing field. Andy opened the motors a little more. The air-speed meter now showed only thirty miles an hour, yet the plane was flying evenly, holding her altitude. She seemed to almost float along over the ground.

They were approaching the edge of the field. The Apex factory loomed up ahead of them, its tall smokestack far above the altitude at which the ship was flying. Andy gave the engines a bit more gas, pulled back on the wheel and the great plane rose like a balloon over the towering stacks.

Joe Lamson, who had been sitting perfectly rigid during the first few moments of the remarkable flight, whooped with delight.

“I never saw anything like it in my life!” he laughed. “Why, we could have landed her right on the roof!”

“You take her,” grinned Andy.

Joe took the controls and began to duplicate the stunts that Andy had tried. At last he cut the engines when the ship was over the middle of the field. The revolving vanes kept on whirling as the upward rising air passed the slowly descending plane. Slowly, steadily, she sank, while Joe held the control wheel hard back. The field seemed to float up toward them, growing closer and closer with each passing instant. The watching spectators mushroomed in size as the plane settled. Then, at last, the tail skid touched the ground. The strange craft sat down like a tired hen, her wheels striking with a bump. But there she was, after a vertical descent!

Joe grinned at Andy and opened the throttles again. Once more the queer-looking ship began to climb almost straight in the air. Joe made a motion as if to turn the controls over to Andy, but the boy shook his head.

“I’m satisfied with her, Joe,” he said. “I’d go anywhere in her.”

“So would I,” agreed the pilot.

“Now let’s just fly around for a couple of hours to be sure that there aren’t any defects in her which flying will bring out. Then we’ll take her to the factory, make our report and decide what to do next.”

“If that’s the case,” broke in Sam, appearing in the control room, “why don’t we try to chew something?”

“Hungry Sam wants to eat at every pause in the conversation,” laughed Andy. “Well, it isn’t a bad idea at that. Tell you what let’s do, Sam. I have an idea that I want to pop at you. This control room is big enough so that we can all squeeze into it at the same time if Sam doesn’t breathe too hard. Bring your breakfasts in on a tray, Sam. We’ll eat them out here where we can see how the plane behaves and talk over our plan at the same time.”

“Fair enough,” beamed Sam.

“How would you birds like to go hunting for a couple of million dollars’ treasure?” asked Andy, when all four flyers had squeezed into the control room to eat a delicious breakfast of fried eggs, broiled bacon, toast and coffee.

Sam balanced a cup on his knees, reached over and placed his finger around Andy’s sun-bronzed wrist.

“His pulse seems all right,” he said gravely, “but he sounds feverish.”

“I’m not feverish,” declared Andy, working the control wheel with one hand and using his fork with the other. “I have a map in my pocket which is supposed to show an island in the Bahama group where a million or two dollars in gold is buried.”

“Let’s go and dig it up,” said Joe, quietly.

“If you are heading for there now,” said Sam in an alarmed voice, “I’m going to open the cabin door, place my finger in the release ring of my parachute and let you all come and kiss me good-by before I jump. Of all the wild-eyed, addle-pated, dumb Dora ideas I’ve ever heard, this beats all! We’re flyers, not gold diggers. We all have more money than we know what to do with and now we have to go hunting for more.”

He stopped, with his mouth opening and closing like a trout’s, and looked toward Sonny for moral support. But the youngster, who was in on Andy’s secret, merely looked at the mechanic and grinned. Joe was devoting himself to capturing the last of a bit of egg that seemed on the point of slipping off the edge of his plate.

“Treasure hunting,” moaned the pessimistic Sam. “If that isn’t just another word for trouble, I’m a flat-footed kiwi! Listen, did you ever read Treasure Island, or any of the other books about hunting for buried gold?”

“So you really can read, after all, Sam?” asked Joe, innocently.

“Listen, rubber-face,” retorted Sam, “it’s all right for you to sit there and make those wheezes, but you don’t know what it’s all about. Did you ever read about a treasure-digging party that wasn’t chased all over the vacant lot by a lot of bloodthirsty natives, or pirates, or something, with daggers and guns and everything? No, sir, if we want trouble, we can find it some other way.”

“When do we start, Andy?” asked Joe, paying not the slightest attention to Sam’s bleats.

“Well, the folks at the factory want us to take this ship off on a cruise, so that we can test her out thoroughly away from the public’s eye. Mr. Avery, the president of the company, suggested that we take her up to Canada somewhere and play around with her a couple of weeks until we know her inside out and are able to make recommendations for improving her in case it is decided to build more like her.”

“Brrrr,” shivered Sam. “It’s September and the weather is getting cold up there now. I never did like cold weather. Remember the last time we were up there? I nearly——”

“Now what I had in mind,” continued Andy, not listening to Sam, “was that we make our test flight to the south instead of north. We’ll follow the most direct route to Miami, hop over to the Bahamas and find this island. Then we’ll take a few days’ vacation while we’re digging. If we find the money, all right. If we don’t, we’ve had a nice time.”

“Sounds good to me,” replied Joe. “Tell us what the treasure is all about.”

Andy told them briefly of the stirring events connected With the crashing of the racing motor car and the strange tale told by the man, Briggs. He told them how Briggs had drawn a sketch from memory, showing the shape of the island and the supposed location of the treasure. He warned them that the man’s memory might not be accurate and that they might not even find the island, to say nothing of the treasure itself. He also mentioned the possibility of another searching party appearing on the island and finding the treasure.

“So that’s why I thought of starting right away,” he concluded, “to beat them to the job. They could have taken the train south last night, you know. In that case they’d be in Miami to-morrow morning. They could charter a boat and be at this Hook Island place to-morrow night or the next morning at the latest. So if we’re going into it at all, we’d better step on the gas.”

“But we’d need some time to get things together,” objected Sam. “It’ll be hot down there, you know. We’ll need light clothes, a two weeks’ supply of food——”

“Why all the food?” demanded Sonny.

“Because most of those islands are uninhabited and have no more things to eat on them than you’ll find on top of the South Pole. Besides, we’ll have to have picks and shovels, maybe a couple of sticks of dynamite, ropes and—oh, lots and lots of things.”

“And a couple of automatic pistols,” added Joe, firmly. “I hear that our old friend Brewster has escaped from jail in London and while that bird is loose, I don’t start any long flights without a gun or two.”

“Right you are, Joe,” agreed Andy. “I’ve been shot at enough by that crook without being able to shoot back.”

For an instant they were all silent, gazing down on the gently rolling hills of Long Island, as they thought of the number of times their paths had crossed with Herbert Brewster. Time after time, their enemy had caused them untold troubles and had done his best to kill them. The man was a wonderful flyer, daring and unscrupulous. Ever since Apex ships began to make record-breaking trips, Brewster’s ambition had been to cause them disaster, for he had never forgotten that Andy Lane and Sonny Collins had exposed his dishonesty and caused all honest men to shun him. It had been Andy and his companions who had finally forced Brewster, the air pirate, down at sea, where he had fallen into the hands of the British Government.[6] And now he had escaped from prison! Andy shivered, as though a cloud had passed over the sun.

|

See “The Mysterious Monoplane.” |

“Well, let’s take a vote now. If we’re going after that treasure, I’d like to start this very afternoon. We have most of the equipment we used for flying over the tropics in our ’round-the-world race. It’s all in storage at the factory. We can draw the tools and things out of stock at the plant. We can load up the food supplies in an hour’s time. I’m sure I can get Mr. Avery to permit us to go. So let’s vote on it. Who’d like to go?”

“Me!” shouted Sonny, so loudly that Scotty, who had just fallen asleep, jumped up and barked in excitement.

“Good,” smiled Andy. “I have two recruits, Sonny and Scotty.”

“I’m in,” declared Joe.

“Between you all, you’ve crowned me Queen of the May,” mourned Sam. “You know I won’t let you fly off without me. It would spoil your luck. You’d have forced landings every three-and-a-half miles. Your gas tanks would leak and you’d find your food all spoiled in the lockers. You’d break out with the seven-year itch and——”

“That’s enough!” roared Andy. “Are you with us or not?”

“Why, of course,” answered Sam, “and you knew it all the time!”

“Great stuff! All right, then, it’s all decided. We’ll go back to the factory now. There’s no danger in a little hop to the Bahamas, so I’ll just jump into my own plane, dash home to say good-by to Mother and Dad and we’ll be off as soon as possible. Joe and Sam can check over the plane and Sonny can attend to the buying of the food.”

“Yes,” agreed Sonny. “My father is in California, so I won’t be able to say good-by to him. I might as well work as loaf.”

“Yow!” exclaimed Joe, breaking into one of his rare smiles. “So we’re off again, eh, fellows? Well, well, that’s great! As long as we fly with Andy, there’s always something doing.”

They turned back toward the factory in the highest of spirits. Had any of them realized what dangers were awaiting them on a sun-drenched island of the Caribbean, they might have hesitated in making their decision so promptly!

Mr. Ronald Avery, president of the Apex Aeroplane and Motor Corporation, stared at his nineteen-year-old vice president in astonishment.

“What’s the idea of the mystery, Andy?” he asked. “You know well enough that you may fly anywhere you want to. But suppose something should happen to you? How would we know where to start looking for you?”

“I’d be tickled to death to tell you where we were going, Mr. Avery,” Andy assured him, “except that we gave the man our word of honor that nobody should know except the crew of the plane who were actually to take part in the flight. It will not be a dangerous flight. It is over civilization for the most part and we have a water jump of less than one hundred and fifty miles. So you see you needn’t worry about us at all. We’ll be back within a couple of weeks. We have the radio, you know, and if anything happens to us we can always send a message to you. But if you have the slightest worry about the safety of the Flying Windmill, we can borrow one of the old ships.”

“No,” said Mr. Avery. “I’d rather you took the autogyro for a real test. If she proves to be a type we want to manufacture, I’d like the shake-down cruise to be made at once.”

He fell silent for a moment, then rose and placed his hand on Andy’s shoulder.

“Go ahead, son,” he said. “Get in touch with me by radio as soon as you can. I know you boys will be able to take care of yourselves. You’ve proved that a dozen times. Go ahead and go treasure hunting if you’ll enjoy it. It will be a good vacation for you, anyway, and you all need one.”

Ten minutes later, Andy was standing in the main cabin of the Flying Windmill. Sonny, Joe and Sam were crowded around him, waiting anxiously to hear Mr. Avery’s decision.

“It’s all right, gang,” said Andy. “Mr. Avery says we can use this ship. How soon can we be ready?”

Joe looked at his watch.

“It is three o’clock now,” he said. “We can take off in an hour.”

“Fine!” grinned Andy. “The sooner the better.”

They all fell to work at top speed. After many long trips in Apex ships, each knew what to do. Sam checked his motors and gathered together a tremendous array of spare parts, tools, and odds and ends for use in repairing any possible damage to the ship. Sonny and Andy made themselves responsible for general supplies and provisions. With the assistance of workmen from the factory, they loaded into the plane sufficient foodstuffs to last two weeks. They ransacked the storerooms of the factory, where were kept clothing, utensils and flying equipment purchased for previous long flights. They found plenty of tropical clothing from the kits used on the ’round-the-world flight. They found pickaxes, shovels and ropes from the lockers in which the equipment was stored after their return from the magnificent flight over the South Pole. They found and tested a collapsible rubber rowboat which they had carried on many of their trips over the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. They were like two small boys rummaging through a pile of Christmas presents, laughing and shouting as they found things that might be of use to them, stopping to remind each other of stirring adventures of which they were reminded by various pieces of equipment.

“I just can’t believe that the old gang is hopping again, Andy,” exclaimed Sonny, joyfully. “I can’t help wishing, though, that it was another flight around the world, or another jump to Europe instead of just to a little island not far from the Florida coast line!”

“Yes, there’s something about flying a hundred miles an hour and going on and on,” agreed Andy. “There’s a terrific thrill to watching strange countries slide under your wings, and looking down on funny little towns and queer people. I hope this long-distance flying of ours won’t spoil us for ever staying at home.”

“I wouldn’t care if it did,” declared the youngster. “The oftener we start long flights, the better I’ll like it.”

“In the meantime,” said Andy, recalling the boy to his task, “how’s that check list? Have we everything now that it calls for?”

“Every single thing and all in the proper lockers, too.”

“Well, then, our job is about over. As soon as Joe and Sam finish their jobs, we’ll be ready to go.”

They found Joe carefully inspecting every bolt, nut, cutter pin and rivet in the fuselage, undercarriage and rotating vanes.

“Did you put your artillery aboard, Joe?” asked Andy.

“Yes, sir!” said Joe. “An automatic apiece and plenty of ammunition. I’d have taken a machine gun along, too, if you fellows hadn’t loaded the ship all up with stuff.”

“You’re getting bloodthirsty,” laughed Andy.

“No. Just careful. I’m tired of having birds shoot at me and not be able to do something more than to blow kisses at them.”

Sam clambered down from a stepladder. He was covered with grease and engine oil from head to foot, but he looked absolutely happy.

“What do you say, Andy?” he said. “The motors are just itching to start.”

“So am I,” agreed the young captain. “Let’s go.”

He whistled to Scotty, who had been dozing in the shadow of the plane. The pup scrambled to his feet, yawned lustily and jumped into the open door of the cabin.

“He knows his place,” commented Andy. Then, turning to a motorcycle policeman who stood near, he said, “We’re ready to go now, officer.”

With a tremendous popping of his engine, the policeman roared across the field. Behind long ropes which were stretched on each side of the landing space, great crowds had already assembled to see their national hero take off. Nobody knew how the news had leaked out, but there had been headlines in the early afternoon editions of the New York papers stating that Andy Lane and his famous crew were tuning up a machine for an immediate take-off. That had been enough. By motor car, bus and train, people had hastened to the field. The police were well prepared for their coming and, remembering occasions when the crowd had broken through the lines and swarmed over the field, extra details of men were on duty, walking up and down the lines and watching carefully for the first sign of a stampede.

Newspaper reporters crowded about the four flyers. Andy was shaking hands with the factory workers who, by their care and hard labor, had made the success of the strange plane possible. The reporters were eager to know where Andy was going, what had been the results of the first test of the great autogyro, how many days he expected to be away and anything else that he cared to make public. Andy liked the reporters. They had always been very kind to him and, in no small measure, had been responsible for his tremendous popularity. But he could not give them any advance information concerning the flight that was about to start. He and his companions posed willingly for the motion pictures. He even made a short speech into the “talkie” microphone. Then he turned to Mr. Avery, who had been waiting for a last-minute word with him.

“Off again, Mr. Avery,” he smiled.

“Yes, Andy,” said the older man. “I don’t mind telling you that I’m more than a little worried. I have a hunch that this flight isn’t going to be as simple as you believe. So be very careful, my boy, and don’t play your luck too hard. Have a good vacation and don’t take any chances that you can avoid. Send me a radio every now and then to tell me how you are getting along. Good-by!”

He shook Andy’s hand vigorously and turned away. The young pilot waved to the crowds and entered the cabin, closing the door behind him. For an instant he stood very still in the big cabin, remembering other times when he had said good-by to the crowds and had set off on a record-breaking flight. What a thrill there was in starting away, not knowing what adventures might befall before their return to this same field! His eye suddenly fell upon an object which he had not noticed in the cabin upon his last inspection. Fastened in a conspicuous place against the wall was an ominous-looking holster. And from the open mouth of the holster projected the ugly black handle of a heavy service automatic. Andy looked at it very thoughtfully. It seemed to remind him that somewhere in the world was an enemy, a desperate man who would risk everything in an effort to do him harm. Then Andy shrugged his broad shoulders. Most people had many enemies, he reflected. So far as he knew, he had none, except for Herbert Brewster and his few companions. Surely the world was large enough to hold both Andy and Brewster!

He heard the engines as they kicked over under the impulse of their starters. He walked forward into the control room. Sam, very awkward-looking with his parachute pack dangling behind him, was watching the windmill as it slowly gathered speed under the drive of the center engine. Joe, behind the wheel, was just sitting there, waiting patiently, calmly, for the vanes to gather sufficient speed for the take-off. Andy took the seat beside him. The rotor whirled faster and faster until at length it could only be seen as a glittering, spinning arc over the glass roof of the pilot room. Sam nodded his contentment at the behavior of the engines and walked to the door, ready for any emergency.

“Disconnect the engine drive to the blades,” directed Andy. “The wind blast from the propellers will keep them spinning now.”

Joe jerked at the lever. The windmill still whirled at a tremendous speed. Andy grasped the control wheel and pushed the throttles wide open. The engines thundered. The plane lurched ahead. The nose rose. The front wheels left the ground. The heavy ship was climbing almost straight into the air.

“What a ship!” exclaimed Andy. “I just can’t get used to her climbing like this!”

As the people on the ground and the hangars and the mighty expanse of the Apex factory shrank in size, the landscape beneath the plane expanded. A glint of blue in the east became a vast sheet of water, extending on and on until, in a blur of haze, it merged with the sky itself. On the west, Long Island Sound appeared. It seemed very large at first. Then it contracted as the plane rose until it appeared to be nothing more than a wide river separating Long Island from the Connecticut shore. Beyond the Sound, the orderly hills stretched back until they, too, were lost in the haze.

The altimeter indicated that the Flying Windmill had reached twelve thousand feet. Andy cut the engines down to cruising speed and headed the ship to the south. New York, looking like a toy city beneath the smoke which drifted across it from the factories on the Jersey Meadows, slipped slowly under the fuselage. Crisscrossed by ruler-straight streets and avenues, its lofty buildings foreshortened by altitude, it seemed impossible that six million people lived within its far-flung boundaries.

Then the Flying Windmill was over the marshes, cut into irregular slices by the network of railways which left the banks of the Hudson River, leaped across meandering rivers, dived through tunnels and finally disappeared, heading north, west and south.

“Well, we’re off,” said Andy, turning the controls over to Joe.

Joe looked at him and smiled contentedly. He slouched deeply into the seat cushions and steered easily, his level gray eyes glancing from horizon to compass and back to the horizon again.

“Yes, old-timer,” he said, “we’re off and I’m glad of it. What do you want to do, follow the coast line south or steer a straight compass course?”

“We’ll shoot straight for Washington and Richmond. You know the way that far. It’ll be getting dark about then and we’ll set a compass course for Jacksonville. From there south we’ll follow the coast line. It’ll be easy to follow the Dixie Highway from town to town.”

“Good,” nodded Joe, briefly. “This is the life!”

As Andy walked back through the corridor leading to the living cabin, he hesitated at Sonny’s radio room. He looked in. There was the boy, sitting at his instruments, as much at home as though the ship had been in the air for days instead of minutes. The fact that it was an entirely new type of plane, capable of accomplishing extraordinary feats of flying, meant not a thing to Sonny. They were flying and his beloved sets were operating to his entire satisfaction. That was all that mattered. He had complete faith in any Apex ship and when Andy was in command, Sonny just could not imagine anything happening to it that would make him leave his post. He looked up and saw Andy.

“The set is wonderful!” he declared happily. “On the short waves, I’ve been able to exchange messages with an amateur in St. Louis and when I turn into the broadcasting range I can hear someone giving a lecture in Cleveland. When it gets dark we ought to at least double our range. By the way, how is the ship flying?”

“Like a Zeppelin.”

“It’s the steadiest plane we’ve ever flown in,” declared Sonny. “I can tell that because my sending key doesn’t seem to jump out from under my hand.”

“That’s on account of the windmill,” explained Andy. “You see, each of the blades is hinged separately on the shaft and can adjust itself automatically to the bumps in the air.”

“What time will we get to Miami?” asked the boy.

“We’re just loafing along now, taking things very easy. We’ll pass over Miami just before daybreak. We plan to leave the coast of Florida about the time it begins to grow light.”

“Are we going to need more gas? If we are, I’d better radio to one of the airports at Miami to have a crew ready.”

“No. We have plenty of gas and oil to take us to Hook Island and halfway back to New York. We don’t want to let people know where we are until we’ve found the treasure or have learned that it is all an April Fool joke. That’s one of the reasons why I wanted to make our southward hop in the darkness. This ship is so funny-looking that about a million people would notice it and all the newspapers in the country would carry schedules of our trip. On our way home, it won’t matter.”

Scotty, who was sound asleep on Sonny’s berth, opened one brown eye and lifted a single soft ear. For a few minutes he lay there, wondering if his master were going to do anything that might be interesting to a dog. At last he decided that he might have to sit up all night to keep the pilot company, so he went back to sleep.

Andy turned away from the radio room and strolled into the living cabin. It was bright and cheerful back there. The sun was setting fast, but the room was brilliantly lighted and seemed very home-like. The insulation which lined the walls shut out most of the sound of the three powerful engines and Andy could hear the sound of happy whistling from the direction of the little kitchen.

“Hey, Andy,” came Sam’s jovial voice. “If you haven’t anything better to do, you might help me peel some of these Irish steaks!”

“I might have known that you’d start to cook just as soon as the wheels left the ground,” laughed Andy.

Sam, with a white apron tied around his generous stomach, was busily engaged in peeling potatoes and slicing them into neat little cubes for frying. He was a perfect picture of contentment as he worked there. A sizzling frying pan was fastened on the top of the electric stove. On the aluminum shelf of the kitchen cabinet was a fat, luscious steak.

“We’re going to eat to-night, young man,” said Sam, gravely. “I’ve been thinking for the past hour or two what would happen to us if one of those blades on the windmill should break, or something. We’d come down like a rock. So when I got to worrying about that, I knew we’d have to eat a good meal to take our minds off our troubles.”

“No one’s mind is troubled except yours,” retorted Andy. “Just think how much better off we are in a night flight in this autogyro than in an ordinary plane. If the engines should stop on the old Apex ships, we’d just have to nose down for a landing at a hundred miles an hour in the dark, with a twenty-to-one chance of a complete washout. In this crock, all we’d have to do would be to pull her nose back and we’d settle down for a landing that wouldn’t break an egg.”

“Yeah, and suppose we were to land smack on a church steeple?”

“You win!” laughed Andy. “So you can fix as big a meal as you wish. You would, anyway!”

Just as the Flying Windmill was flying over the millions of electric lights that stared up from the streets and buildings of Washington, Sam announced dinner.

Joe, who was still at the controls, volunteered to eat later. Andy, Sonny and Sam sat down at the table, while Scotty lay down on the floor beside his master, watching his friends expectantly and hoping that they might not forget that a big, healthy dog is hungry most of the time. The reading table had been covered with a white cloth. The chinaware and silver was all in its proper place and gleamed brightly in the light from the wall brackets. Sam had changed to a clean suit of coveralls and had wet his hair and plastered it back until his head was as smooth as a billiard ball.

“We certainly lead a rough life on these trips!” he chuckled. “I ask you if we could have a better meal, or have one more nicely served, if we were at the Ritz?”

“That’s one of the things that makes our long flights a lot of fun instead of a tiresome chore,” asserted Andy. “We know how to settle down and take life easily and comfortably while we can. If we do that when things are going smoothly, we’re able to stand the hard knocks when things go wrong.”

“I could burst right out crying when I see the expression on that dog’s face!” declared Sam.

Before Sonny could move, Sam reached out his fork, speared Sonny’s cut of meat and flipped it toward Scotty.

“Here, pooch,” he called.

Scotty’s brown eyes opened wide. He caught the flying bit of meat in mid-flight, closed his jaws with a snap and swallowed without an effort. Then he blinked and looked up at Sam, licking his chops.

When the fat mechanic turned back to the table, Sonny was contentedly eating the piece of meat which had once been Sam’s, while Andy was carving some leathery, gristly meat to replace Sam’s portion.

Neither Sonny nor Andy made the slightest comment. Sam opened his mouth to protest at the toughness of the piece that Andy was silently putting on his plate, then closed it again.

“Wonderful, tender steak,” murmured Sonny, serenely.

“Best I ever tasted,” agreed Andy, soberly.

Sam said nothing. The joke was on him. He sawed lustily at his piece, then chewed a long, long time, his round, moon-shaped face very woe-begone.

They attacked the fried potatoes heartily, ate a huge slice of apple pie apiece, then sat back, all very comfortable and happy.

It was pitch dark outside when Andy made his way forward to relieve Joe at the wheel. The soft glow from the instrument board was the only light in the control room. It was reflected on the calm, quiet face of the pilot, who sat at his ease, steering almost automatically. Stars filled the sky, seeming to be within reaching distance as they flickered in the black background of the night. Overhead were the four swiftly whirling blades of the rotating vanes, whose arc glittered redly as it mirrored the flames from the three exhaust pipes of the engines.

Andy slipped into the dual control seat and took over the controls. Joe yawned, stretched, then snapped on a tiny light over the chart board which was fastened directly in front of the pilots’ seats.

“Heading straight for Jacksonville, Andy,” he said. “Those reflections in the sky to the east are from Richmond. On our compass course we pass the town about forty miles to the westward. We’ll hit the coast line at Savannah. The plane’s flying like a million dollars.”

“Better hurry in for dinner before it gets cold and before Sam gets hungry again. Give him half a chance and he’ll start eating all over again.”

Joe laughed and left the room. Scotty came in, sniffed about for a few seconds, then scrambled into the seat that Joe had just vacated. He pawed and scratched at the cushions as though he were making a bed out of hay. Then he collapsed into the seat and went promptly to sleep. Andy reached over and stroked his soft fur. He was good company, just being there. Andy remembered other watches of the night when Scotty had silently stood duty with his master. Nights over the inhospitable Atlantic Ocean when the leaping waves seemed to be reaching up hungrily for the frail flying boat which challenged them; nights over the oven-like desert of Arabia, where a forced landing would have meant instant death in a crash, or a slower, but no less certain death at the hands of the hostile tribesmen; nights over the desolate ice mountains of the South Pole, while blizzards threatened to plunge the Apex down to destruction; nights in the control room of a flaming rocket plane, headed at incredible speeds toward the jungles of the Amazon. What adventures they had had together! And if luck held, they’d have many, many more adventures before they made their last landing together.

It was good to sit there in the control room, steering the great plane through the quiet, starlit night. The lighted faces of the dials on the instrument board were the faces of friends who were helping him to guide his ship and to keep her safe in her steady course through the skies. They almost talked to him, telling him that the engines were functioning perfectly; that the ship was upon an even keel; that the temperature within and without the hull was constant and comfortable: that she was headed in the proper direction. And when anything went wrong, these instruments would give him their messages of warning so that he might instantly take steps to correct the trouble or to bring the plane down to a landing in the darkness.

Little clusters of lights slipped beneath the hull. He checked-them off on the chart. Tiny, sleepy villages nestled in the hills, unaware of the strange air monster which hurtled past overhead. Bright pin points of lights crawled along over highways as motor cars sped along between towns. But so swiftly did the Flying Windmill pass them that they seemed not to move at all.

The eastern sky began to glow redly, as though a whole city were afire beyond the horizon. Then the topmost edge of a full moon began to crawl into the sky, looking like a partly cooled ball of molten steel. Its rays illuminated the entire landscape below. Silver hills cast black shadows toward the west. Long, winding rivers shimmered like streams of mercury. The earth, which had been invisible in the darkness, now looked like a strange, new world. Andy stared down at it, never tired of its ever-changing picture.

“We like this sort of thing pretty well, don’t we, Scotty?” murmured the young pilot.

But the collie, who had been busily chasing a cat in his dreams, did not hear.

A beam of white light flashed against the outside of the control room windows. Andy, startled for the moment, stared at it. Then, as the circle of whiteness swiveled toward the bow engine, he knew it to be the faithful Sam, walking out on the catwalk which led along the side of the fuselage to the engine bed. He could see the fat mechanic now, stepping carefully on the narrow platform, his belt hooked onto a rod so that he could use both hands on the engine. For this trip he had invented a new method of greasing the rocker arms, having fashioned flexible leads which led down from each to a convenient spot at the side of the motor. Here Sam halted and produced a pressure grease gun from his open-mouthed tool bag. By inserting its nozzle in the openings of the flexible leads, he was able to lubricate each of the rocker arms in its turn without having to climb all over the engine. This done, he flashed his searchlight on the motor, tested one part after another with screw driver and pliers and, at length, made his way back to the fuselage. Then the searchlight focused on the port wing engine. Completely disregarding the thousands of feet of black void between himself and the ground below, Sam swarmed over the gangway, or catwalk, which led out to this engine and devoted a full fifteen minutes to tending it. The starboard engine came in for its share of his painstaking attention. Then, much to Andy’s relief, he saw the dark figure make its way back toward the cabin door. The boy was always glad when Sam had finished his job on the motors. Of course, he knew that the heavy leather safety strap had been tested and tested again. But there was always the chance that it might fail and in this case, no power in the world could save Sam, for he would not wear his parachute when on that job, saying that it got in his way.

“Oh, boy!” exclaimed Sam, entering the dark control room. “I’m sure glad we’re going south instead of north! There’s a breeze out there that would blow all the hair off a cat’s back. But it was nice and warm and that’s something to be thankful for. Every time I think of some of the cold weather I’ve babied the engines in, I begin to shiver till the fillings start to drop out of my teeth.”

“Well, hold your jaws together then,” Andy advised him. “You’d better turn in now. You’ll be wanting to look at the engines again sometime after midnight, so get a shut-eye while you can.”

At that moment, Sonny entered the room and handed Andy a penciled memorandum. Andy switched on the light over the chart board, read it and then sat silent for a moment, glancing at the note and then at the chart. Sam yawned loudly and turned toward the door. Andy stopped him.

“Better not turn in for a few minutes, Sam,” he said gravely. “Sonny, ask Joe to come out here, will you?”

Sonny disappeared. He was back in a moment with Joe. The pilot glanced at the moonlit earth, then at the instrument board, after which he looked at Andy’s thoughtful face.

“What’s up, old-timer?” he asked, quietly.

“I want to read a weather report that Sonny just got over the radio. Listen to this: ‘Advisory from Washington, D. C. A tropical disturbance of considerable intensity has been reported central a few miles south of Santiago, Cuba, moving slowly northward.’ ”

“Well, what about it?” asked Sam.

“That is the Weather Bureau’s way of saying that one of the West Indian hurricanes is brewing,” said Joe in his calm, even voice.

“That’s why I called everybody together,” replied Andy. “If it is a hurricane, it may sweep over the very spot that we’re headed for. The Bahamas have been hit again and again by hurricanes, the last time as recently as eleven months ago. The point now is, do you fellows want to fly straight down into what may be the path of one of those storms?”

“Sure,” said Sam, promptly. “It may just be a rumor, after all. Someone told me that the people on the east coast of Florida spent half their time in the fall months dodging hurricanes that don’t develop.”

“And the ones they don’t dodge come along and smack them right in the eye,” added Joe.

“Here’s my bright thought for the night,” spoke up Sonny. “Last fall I was tuned in on one of the Florida broadcasting stations when they were expecting a hurricane. When it began to sweep north of Cuba and toward the Bahamas, they went on the air with reports every half hour. It seemed that the center of these storms moves very slowly, so anyone who wants to can get out of the way before it breaks. Now why not keep on with the hop in hopes the whole thing will peter out, as those scares usually do. If we listen to all the warnings, we can beat it in ten minutes’ notice and be in New York before it hits the island we’re going to.”

“Atta boy, Sonny,” yelped Sam. “We’ve never turned back from a flight yet, so why start now?”

“It’s mighty easy not to be afraid of something you don’t know anything about,” cautioned Joe.

“Well, what’s your vote?” Andy asked him.

“I vote to go on,” replied Joe, unhesitatingly. “But I think Sonny better keep the phones glued pretty close to his ears.”

“That’s three votes to go on with the flight,” said Andy, slowly. “So I’ll make the motion unanimous.”

“Good!” approved Sam. “I’ll keep the old engines perking as long as this spinning top thing of ours will hold us up.”

And so the Flying Windmill headed southward through the night, heading directly toward a far-distant storm which had already sunk a score of fishing boats, a schooner and a little coasting steamer which was not equipped with wireless.

The Flying Windmill had roared over countless miles of swamp land, where glittering water reflected the moonlight through tangles of cypress and oak. It would have been a ghastly place for a forced landing and Andy breathed a sigh of relief when he saw, far ahead in the distance, a reflection in the sky which he knew must be Savannah, Georgia. He pressed a button, causing a bell to ring in Joe’s cabin. A few minutes later, the co-pilot entered, ready to take his shift at the controls.

“Flying beautifully, Joe,” Andy told him. “I’ve cut out the bow engine. We’re cruising with the port and starboard engines throttled down to two-thirds speed. We have a tail wind behind us. The air-speed meter shows seventy-five miles an hour. The wind must be boosting us on another twenty-five, because as near as I can figure it from checking the towns on the chart, we’re logging a steady one hundred miles an hour. Here’s Savannah, just ahead of us. I’ll turn in now.”

Joe stared down at the swamps.

“Pretty bad country,” he observed. “And it extends all the way to Jacksonville, too. Might as well shoot straight for the Florida line. It will take us just over the ocean but I’d as soon put this boat down in the surf as in this jungle. At least we could swim for shore without having to push alligators and snakes out of our way.”

“Fair enough,” agreed Andy. “Call me in four hours. We should be well down the Florida east coast by that time.”