* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Lilac Time

Date of first publication: 1928

Author: Guy Fowler (1893-1966)

Illustrator: From the Colleen Moore-George Fitzmaurice Photoplay—A First National Picture

Date first posted: Oct. 28, 2022

Date last updated: Oct. 28, 2022

Faded Page eBook #20221055

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, Pat McCoy & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

A First National Picture. Lilac Time.

LOVE CAME WITH PERFECT UNDERSTANDING.

LILAC TIME

BY

GUY FOWLER

NOVELIZED FROM THE SCREEN

PLAY ADAPTED BY WILLIS GOLDBECK

FROM THE STAGE PRODUCTION

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS FROM THE

COLLEEN MOORE-GEORGE FITZMAURICE

PHOTOPLAY—A FIRST NATIONAL PICTURE

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS NEW YORK

Copyright, 1928, by

GROSSET & DUNLAP, Inc.

Made in the United States of America

To

COLLEEN MOORE

Who, as Jeannine in ‘Lilac Time,’

revives so poignantly the indomitable

spirit of France in the dark

days of War.

G.F.

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | An Eagle Falls | 1 |

| II | Jeannine Berthelot | 15 |

| III | The Toast | 27 |

| IV | Jeannine’s Revenge | 41 |

| V | Trial Flight | 54 |

| VI | Flying Orders | 68 |

| VII | The Infant Matures | 80 |

| VIII | Understanding | 94 |

| IX | Contact! | 109 |

| X | The Highest Courage | 123 |

| XI | Meanwhile—Berle Le Bois | 137 |

| XII | The Red Wins | 151 |

| XIII | Temptation | 165 |

| XIV | Friends on the Road | 180 |

| XV | Barriers | 195 |

| XVI | Dijon | 208 |

| XVII | Fortitude | 222 |

| XVIII | Lilacs | 236 |

| XIX | Awakening | 250 |

| XX | Together | 264 |

| Addendum | 272 |

LILAC TIME

Time had been gentle with the village of Berle Le Bois. The cobblestones were smooth and rounded, worn by the feet of generations. Old wine filled ancient casks in the cool deep cellars of the cottages and the village was a place of laughter and song and simple living.

The sunlight of France had tinted the cottages honey-colored. With the same divine artistry it had touched the faces of the people until their skins were brown and polished as the leaves in autumn. And always, of course, the sun brought royal purple to the grapes.

But swiftly, in the passage of a single day in 1914, Time ceased to caress the village with a kindly hand. Song and laughter suddenly were silenced, or, if they sounded at all, it was with the plaintive note of futility. The Berle Le Bois of other days passed into oblivion. Something grim and brooding descended upon the village and the passing of Time came to be an ordeal to every living thing.

It was so with Jeannine. Like all the others, she, too, waited for the next hour, dimly wondering what new suffering it would bring. She paused now, in her arranging of the long table in the low ceiled dining room, to gaze at her mother, bent over the stove in the kitchen beyond. Mme. Berthelot was thinking of the simmering food with one side of her mind. But with the other, that part which lay deep and set the stern lines in her face, she was concerned with other things.

“The sun is good today,” Jeannine ventured. “Perhaps they will all return.”

“Perhaps,” her mother said moodily. “They may be saved for another day.”

A swift shadow passed over the dark eyes of the girl like a fleeting cloud before the sun. It had been like that when her father, Pierre, the peaceful one, responded to the call in 1914.

“It will be nothing,” Jeannine had cried gayly. “In a week it will be over.”

Then had her mother looked at her strangely, with a slow half smile.

“Do not be too sure.”

How well now she remembered the meager hysteric news of Verdun. Then the brief unemotional message from the War Office that Mme. Berthelot anticipated before she read.

“They shall not pass,” was the inscription over the great picture of Clemenceau, that now looked down from the wall of the dining room over the fireplace. But Pierre, the peaceful, had passed.

Jeannine turned to Grandpère Julien, whose face was like leather drawn taut across his bones. He sat deep in his chair, his knees covered beneath a rusty army coat, relic of the Franco-Prussian war. Grandpère knew of battle. To be sure, did he not return, paralyzed though he was? From a great distance came the growling rumble that forever sounded, until one ceased to hear it altogether.

“Do you hear the guns Grandpère?” she asked.

The ancient man peered at her without moving his head.

“Eh, it is not war,” he spoke scornfully. “There are too many miles between the men. Gas!” A brief flame lighted his eyes. “They are mathematicians, not soldiers!”

Jeannine set down the plates and cups and walked to the door. Her movements were lithe and sure. Life pulsed in her slim strong body as it glowed in her slumberous eyes. She leaned against the door frame, gazing into the distant western sky. A single plane hung in space, so high that the song of its motor was lost. For a moment she watched it, a speck against the edge of a lofty cloud, and saw that it was moving swiftly as it passed across the expanse of fluffy white.

As she lowered her gaze, Jeannine looked down to the stone doorstep, worn like a saucer by the tread of the Berthelots. Yet, surviving Time and the generations of passing feet, there remained the legend that had been carved there—the legend of the clan, perhaps before the Berthelots were peasants. It might, possibly, have been copied from an escutcheon. It was a brief sentence in French; “Love cannot die.”

Never, since she could remember, had Jeannine understood the inscription, nor had any one taken the trouble to explain it. On the contrary, all things die. Or so she had been taught. A movement across the road caught her attention and she looked up to see a man emerge from the pine barracks. He grinned broadly and waved a careless hand. His red face was smirched with grease and he wore the baggy cover-alls of a mechanic in the British army.

Jeannine smiled and the man accepted it as a signal. He strode across the road towards her.

“ ’Tis loike th’ sunshine t’ see ye smile, it is,” he said, pausing before her, his legs spread wide, his big hands thrust into the pockets of his jumpers.

Jeannine, like all the remaining Berthelots, had learned enough of soldier jargon to comprehend the language from across the English channel. She knew, too, that when O’Rourke paid compliments it was for a purpose.

“You have much dirt.” She continued to smile as she gazed at his greasy uniform, then at the marks on his face.

“Sure, an’ it’s ashamed Oi am,” O’Rourke told her quickly. “It was me intintion t’ wash up, but whin Oi seen yez standin’ here it was an inspiration, it was. So Oi come roight over.”

“You beg for something now,” she answered wisely.

The Irishman grinned, revealing tobacco stained teeth.

“ ’Tis not beggin’, Miss Jeannine, Oi am, but askin’ a favor.”

Mme. Berthelot appeared suddenly behind Jeannine’s shoulder. O’Rourke bowed and sobered instantly, as he gazed innocently into her steady gray eyes.

“Good mornin’, Madam. Oi was sayin’ to your daughter as how yez could do me th’ bit av a favor.”

Mme. Berthelot was silent. O’Rourke shifted and continued.

“As yez know, av course, we’ve drawn no pay since—well, ma’am, ’twas so long ago Oi’ve forgotten. An’ Oi was wonderin’ if a bit av fresh bread an’ a bottle av wine could be put on tick, Oi was. Just this once, ma’am, an’ no more. Oi could smell th’ bread a-bakin’ clean over in the hangar, ma’am.”

How many loaves of bread and how many bottles of wine Mme. Berthelot had “put on tick” for O’Rourke was a thing beyond her recollection. Her gray eyes grew warm for an instant and she turned silently back into the cottage. In a moment she was again at the door with a loaf of golden brown bread in one hand, the slim green bottle in the other.

O’Rourke met her on the sill with hands out-stretched.

“Oi’ll remimber yez till th’ crack o’ doom, Oi will,” he said gladly. “An’ whin the pay comes——”

Mme. Berthelot waved him off and she came as near to a smile as she ever did.

Jeannine was smiling openly. Her face grew suddenly sober and she spoke to the mechanic with a little catch in her voice.

“Mike, when will they come home?”

O’Rourke looked at her swiftly, then gazed into the sky. Over his shoulder, Jeannine could see the lettering on the barracks—Thirteenth Flight, 22nd Wing, R.A.F.—and the insignia, two machine guns crossed, with an eagle roosting between them.

“Well now, Miss, ye niver can tell about thim lads. As long as there’s a Heinie aloft they’ll shtay, av course. But Oi’m expectin’ thim any minute now, Miss. Th’ whole bunch av thim took off just after dawn, they did.”

Jeannine nodded and turned back into the house. O’Rourke wheeled to start across the road. At that moment the adjutant stepped from the barracks door. With frantic haste, O’Rourke gripped both the bread and the bottle in one hand, held it behind him and whipped the other into a smart salute. The adjutant gazed at him for a lingering second and returned the salute. As he strode away his lips twitched beneath his gray military moustache.

The noonday sun cast its soft radiance into the dining room where Jeannine resumed her preparations. As she arranged the plates and the silver, she counted half aloud.

“Seven,” she said softly to herself, in French. “Today, with the sunshine, there must be seven. There were seven last night.”

Her eyes wandered up to the walls and traveled among the curious objects that were tacked there. Bits of torn canvas, showing the black insignia of the Iron Cross, were everywhere, with holes through which she could see the walls.

There were, too, broken propeller blades, bits of bullet scarred fuselage and squares of canvas which bore the insignia of Richthofen’s flying circus. But strangest of all, was the display on the aged sideboard and it was to this which Jeannine looked now with tragic eyes. Half a dozen bottles of wine stood first and on a shelf which extended the width of the sideboard, were a number of broken champagne glasses. For the most part, their slender bases were intact. In nearly every instance the glass itself was broken to ragged sawtooth edges.

It seemed to Jeannine, as she gazed at this display, that Time itself dragged by on pinions that were wounded and might, at any moment, crash into eternity. Dimly, she wondered if tonight the flight commander would silently raise a brimming glass, pour its contents on the floor and smash the slim goblet as a signal that he, to whom the toast was drunk, would drink no more to his fellows. Each broken glass was for a shattered boy shot down in flight.

Once again she turned to the table and counted the plates. Either there would be a gay, reckless youth at each place in a little while, or on the sideboard yonder there would be another shattered goblet, perhaps more. Jeannine moved swiftly toward the door and her anxious eyes again sought the cloud-flecked sky. In the kitchen Mme. Berthelot continued about her duties with monotonous, unhalting certainty. Mme. Berthelot had seen so much of war.

Jeannine strained her ears for the staccato song of the pursuit planes. She was accustomed to this trick, as one becomes in a roaring mill, quite capable of distinguishing a certain sound above all others.

Faintly at first, she heard it. Her eyes narrowed as she faced the brilliant sky. A plane aloft over Berle Le Bois was no indication that the Thirteenth was returning. Jeannine watched the heavens, sweeping them with her gaze from one end of the horizon to the other. The sound increased in volume until she knew there would be more than a single ship.

Presently, out of the west they appeared in formation. They were flying high, probably at the altitude at which they had crossed the lines, dodging Archies, too far aloft for the machine guns. Jeannine waited until she could count the formation. In the lead, at the junction of the flying V, was the flight commander. That would be Major Russell. Then in their proper order, came the others, three on either side.

Jeannine turned and signalled to her mother.

“They are coming,” she called, and there was laughter in her voice. “Seven of them.”

Grandpère Julien nodded in his chair and at the sound of her glad cry, he started.

“Seven today,” he cackled. “Tomorrow—who knows?”

Jeannine ran out into the garden to watch the sky. Beside the cottage lilacs bloomed and the air was sweet with them. She stood in the winding path that skirted the bushes and counted again as the seven planes swung into a wide circle, dropping in easy spirals. As they swung into the wind for a landing, the girl darted between two lilac bushes to halt before a niche built in the masonry. A statue of Joan of Arc looked back at her with granite tranquillity.

Jeannine crossed herself and her lips moved, although she spoke scarcely above a whisper. Her prayer was in her native tongue.

“Saint Joan,” she breathed, and a faint smile curved her lips, “thank you for bringing them all home safely this day.”

The hum of the motors had, by now, increased to a drone. The flight commander already had turned the nose of his ship to earth and she could see the round form of his head as he leaned out to peer below. Suddenly, he straightened out above the field and came to a three point landing, then taxied gently to the hangars. In swift succession then, the others plunged and flattened out on quivering wings.

As Major Russell climbed down and removed his helmet, Jeannine approached the field from the road. Anxiously, she studied his young face, smeared with the oil that spurts back in a plunge. Russell ran bronzed fingers through his shaggy hair and gazed upward towards his flight, now spread out fanwise for landing. Youth was in his face and his carriage, but too, there was the drawn expression of nerve strain, the weariness in his narrowed eyes of constant searching for the enemy.

The second plane landed neatly and rolled up beside the Major. A cheerful youngster climbed stiffly from the cockpit and reached for a cigaret.

“Heinie was hot this morning, eh, Major?” he remarked casually.

Russell smiled and nodded.

“Everything all right with you?” he asked in turn.

The youth shrugged and jerked his cigaret toward the wings of his ship.

“I’ll need a patch or two,” he replied.

The third plane came to earth and a boy stepped out, a boy unbelievably young.

“The Infant seems to have been stung.” The man beside Russell sent a swift, comprehensive gaze along the fuselage of the boy’s plane. The Major strode over to greet his protégé.

“All O.K., Rogers?”

The Infant, as he was known in the squadron, raised eyes that yet bore the horror of the morning. His face twitched and the slim hand that clutched his helmet and goggles quivered.

“All fit, sir. Except—” he turned expressively to gaze at the row of holes drilled in the side of his plane like the even line of ports in a ship. He steadied himself against the fuselage.

“Lucky,” said the Major, turning to watch the fourth chaser bound across the field. Jeannine had approached them until she stood within earshot, watching each landing, her eyes glowing happily at their nearness. Two more came down and the pilots sought the feel of ground beneath their feet without delay.

The seventh ship straightened off into the wind and as it sped past them flying low, Jeannine and the men saw its pilot slouched in his seat, apparently at nonchalant ease. Suddenly, the left wing dipped and the plane seemed to quiver before it turned. Then, with awful slowness, it pancaked down, whirled grotesquely and crashed.

Even as the nose of the ship bit into the earth, sending up a spray of dirt, men ran out to the field. Jeannine, oblivious of regulations, followed them, stifling a scream as she ran.

Before the first of them ranged beside the wreck, a slim figure was crawling slowly from the shattered cockpit. He was clear of the plane when they reached him, sitting up on the ground, with his arms braced behind him for support. A ghastly smile greeted them and the boy shook his head to fling the blood from his eyes. A field mechanic kneeled beside him, offering his shoulder. In another moment, Major Russell was peering into the boy’s eyes.

“We didn’t even know they nicked you, Harley.” In the Major’s voice was a note of bewildered amazement, as though he had been the victim of some ghastly practical joke. His eyes went to the walls of the plane and new wonder came into them as he saw the holes studded in the fabric.

Harley coughed and spat blood. As the paroxysm ceased, he smiled again.

“He—he got over me—somehow,” said the boy. “I’m—awfully sorry, Major. Feel—rotten about it——”

Stretcher bearers came on at the double quick. Jeannine leaned back against the body of the wrecked plane, forcing the tears from her eyes, fighting to choke down the sobs. She saw them lift young Harley to the stretcher and watched them strangely as they came toward her bearing their burden.

Harley’s eyes were wide open. He recognized her and raised his hand. The stretcher bearers paused.

“I remembered how you counted us off every day,” he smiled wanly. “So—I—I came home.”

She took his hand in her own and leaned over him, smiling to distract his attention from the tears that would not down. It was not a new thing for her, this merciful deception, the hopeful words that sprang from a hopeless heart. Jeannine had comforted them before.

Looking into Harley’s eyes that were glazed in pain, she recognized the shadow that hovered there. She had come to know now, that when they writhed and groaned, the chances were they would live. But when, as now, they lay quietly and smiled, they had made their final flight.

“You mus’ not talk, petit,” she told him softly. “Jus’ rest. You go now to—what you call him—blighty. For long rest. An’ you come back all well again.”

Even as she voiced the words Jeannine knew that Harley, in his coma, understood. These fliers sensed death instinctively and scorned it, played hide-and-go-seek with it among the clouds, laughing in harmony with the wild singing of the wind in their rigging. Time was whipped into faster rhythm by the staccato beating of their mighty engines and if that were not fast enough there were the machine guns and the swift hammerings of their brave hearts.

The drums of ancient wars were slow and paced. A clock ticking the seconds seemed to loiter behind in the race of time. Life, to such as Harley, was lived more furiously and death must speed its hand to tag them.

The stretcher-bearers hurried on and Jeannine’s last glimpse of Harley’s face was to photograph his dying smile on the retina of her memory. The men moved off alone, or in little groups. Death might not slacken the momentum of their days and nights. There were holes in the wings to be patched, engines to be attuned for the next dawn. Between these victories of death such times as this were merely interludes.

Young as she was, the girl had come into a strange understanding with the men of the Thirteenth and through them, perhaps, with all of mankind. She had been a child when they first came, bare legged, brown from the sun that gave the purple to the grapes and the tint of honey to the stones of the cottages there.

She recalled those early days now, as she stood alone.

Pierre, the peaceful one, her father, had gone out even before the fliers came. But somehow, then, life had not been terrible and the war was a glorious thing. They laughed and there was singing among them at night. That was before Mme. Berthelot had become what now she was, a woman of ice who thawed only on rare occasions.

Then, the news of Pierre’s death! That had been the first shadow. It was then that the fliers had suddenly become more friendly. Instead of laughing at her forever, they talked to her kindly and seemed to accept her. For Jeannine, strict military discipline went by the boards. They had smiled and turned away when she defied the orders of a sergeant mechanic. They had done the same when she ignored the edict of a pompous officer of the general staff.

“The little devil will have her own way anyhow.”

They had said that and shrugged.

So it was that Jeannine became the mascot of the Thirteenth Flight. Major Russell called her the guardian angel. That, of course, was foolish, she thought, because she was nothing like an angel. Strange, too, that in the same breath, he would say she was a little devil. At first she had pondered over that a great deal.

If she were to be their guardian angel, she decided at length, it would be necessary to comfort them always and forever to obey their least command. It would also require a measure of dignity and certainly a vast amount of self control. As an angel, Jeannine argued with herself in those first days, it would be out of character for her to steal into the hangars when the men were working on the planes. It was against orders.

Likewise, it would be improper for her to play humorous pranks on the fliers as she did often. It was so droll to watch them, for instance, when she donned a suit of greasy overalls and insisted on examining odd parts of the engines. Or, when she found a can of brown paint and searched carefully for a stone of the proper size and shape, painting it to exactly resemble a cruller which she heated in Mother Berthelot’s oven.

“Phwat th’ divil!” Sergeant O’Rourke, the mechanic, had dropped it and the expression on his face could still send her into a rapture of laughter when she recalled it.

No, Jeannine had decided. It would not do to be the guardian angel. As the little devil of the Thirteenth she was free to do as she pleased. Devils disregarded rules. Of course, they were punished sometimes, but she had already come to know that the fliers were marvelously tolerant.

There were times, though, when she took the other rôle. They became more frequent as the war continued. She learned to wrap neat, clean white bandages over minor wounds. And there was none who could sew more swiftly, or more willingly. From her mother, even before the fliers came, Jeannine had learned the art of cookery, so that her services were as much in demand in the kitchen as elsewhere.

In her rôle as the little devil, however, she found the greatest satisfaction. It was far more amusing. For instance, by slipping quietly around the cottage, unseen by Mme. Berthelot, she could disappear into the dank, cold cellar. Far in the rear, stored in bins underneath the ground, was wine. Row upon row of bottles and casks.

In return for a bottle of wine she could play in the hangars for a whole morning. The mechanics told her so frequently. So often, in fact, that Mme. Berthelot put a huge padlock on the cellar door with her own strong hands.

“Mon Dieu,” she exclaimed, “you’d think we had an enemy flight on our hands, the way they make free with the wine.”

After that, Jeannine had to be more careful. She entered the cellar by the stairs from the kitchen, only when her mother was elsewhere. Once she had to remain in the cellar half an afternoon before it was possible to escape with a bottle of wine.

These were the happy, carefree memories. There were others of another sort, many of them. As with Harley this morning. From the first day Jeannine had counted the planes as they took off in the early sunlight, and recounted them when they returned.

She had watched seven of them glinting in the dawn and waited, wide-eyed and trembling, when only three came home. She had seen them speeding up to meet double their number on occasion, of the fleet black planes of the Germans. They had fought below the clouds and above, and yet deep in the rolling mist of them where they were lost to sight completely.

There was the morning of the bombing raid when only Major Russell and two others were on the field with ships available. The great, heavily laden planes of the Germans came over at ten thousand feet. They were two-seaters, each with a pilot and an observer. Before they came over Berle Le Bois the first of the planes loosed his bombs and they fell in a curve.

They struck on the field, but too far out to cause great damage. And before the air was clear of smoke and particles of dirt, Russell and his companions were off the ground, pushing up in a steep climb. Five bombers there were then and they swung in a wide circle behind their leader as he roared back toward the German lines with his engine wide open.

Jeannine had watched the chaser planes climb up, a thousand feet in fifty seconds. Ten minutes later, Russell and his aides were over the bombers, diving with their engines on. She recoiled as a black bombing plane burst into flame, turned over slowly and plunged down like a meteor, leaving behind it a thin tail of smoke. Before the three returned, one other German fell.

The people of Berle Le Bois, gathered in the cobbled street and at the public square, cheered till their throats ached, half maddened in their excitement. Jeannine, more privileged than the rest, ran out upon the field before the hangars as the three ships of the Thirteenth circled once and glided to their landing.

Curiously, still shivering from the strain of watching, she saw the Major and his men climb down stiffly from their cockpits and walk around their ships, slowly, examining the bullet holes.

“Jeannine, I thought you were told to keep off the field.”

Russell had turned on her and his face yet was grim and hard, with something of the expression that held over from the fighting aloft.

“Oh, I am ver’ sorr-e-e. It was that I forgot, Monsieur.”

“Well, don’t forget again. Now leg it out of this.”

Crestfallen, she went back to the cottage.

“The little devil,” Russell remarked to his companions. “Some day she’ll get in the way of a propeller and there’ll be the hell to pay.”

But later, when they came into the cottage, this same gruff, war-bitten young officer had spoken over his shoulder.

“Some more of that pudding, Jeannine. I’ll take you out to see the ships after we eat. What do you say?”

Always it had been like that, so that in the course of time she had come to reign over the flight like an impetuous young queen. The war, so Mme. Berthelot proclaimed frequently, had spoiled her. Certainly in the days before the soldiers came, Jeannine had usurped no authority in her own household.

“It is these English aviators,” said Mme. Berthelot, with conviction. “They let you have your way too much. They are hard enough in other respects. I alone know how to handle you, Jeannine. It is not for nothing that I have known the Berthelots all my life.”

“Were not the Berthelots good people?” the child had asked.

Then, slow amusement lighted on her mother’s face.

“Yes, they were good people, child. And your father was the best of them all. Remember that.”

That puzzled her. Now, with her more mature mind, the same problem often caused her to ponder deeply in the quiet of her garden. Pierre, her father, had been the best of all the Berthelots. Yet it was he who had been chosen to die in the flower of his manhood. To be sure, he had gone to his reward, but was there not something to be gained here on earth? Must one always die to come into his own?

The fliers joked about death and went up to face it laughing. Yet, she had seen the expressions on their faces when they were unaware of her. Men could not look like that and welcome this thing they seemed to fear so little. She had, too, watched the faces of some of them when death already lay chill upon them, and it was not a pleasant sight.

Her reflections were interrupted by the approach of Major Russell. From his face she knew that Harley had gone. His first words confirmed her thought.

“Another one, Jeannine.”

“You have seen him?”

Russell nodded. “He went out easily, thank God. He seemed to be in no great pain.”

“Tell me, Monsieur, what did he say?”

“Nothing. Toward the last. When he was still fully conscious, he just cursed.”

“The Germans?”

“No. It wasn’t that. Just his damnable luck—the war.”

She had heard so many of them do that. Even the French soldiers, though they were so much more bitter toward the enemy.

“Always they blame the war when they are dying,” she said now, with a hint of resentment. “Why is it not the Germans? Are they not the cause of it all? Bah, they have always wanted to tramp their heels on France.”

Russell returned her gaze curiously. He was finding a new side of this joyous child and it rather surprised him. Yet, he disagreed with her.

“The Germans say that about France and England,” he told her. “But just the same, Jeannine, when they die, they curse at war. You see, it isn’t the German people we’re fighting at all, petite. It’s their government. And we’re fighting that because it is the sort of government which makes war.”

He paused to watch her somber eyes as she strove to analyze.

“Do you remember when Hutchinson died last week?” His abrupt inquiry shattered her train of thought.

“Oui, oui, Major. Did I not stand beside him in the sun?”

“Well then, you ought to understand, Jeannine. Don’t you recall how he praised the German who shot him down? Said he was a first rate gentleman.”

She remembered the strained voice of Hutchinson, the look of admiring awe on his face.

“Hutchinson was helpless,” Russell continued. “The fellow could have sent him down in flames. Instead, he put a bullet in him.”

She looked up at him wonderingly.

“You—you mean that it was a good thing to do? That Hutchinson was glad?”

“Certainly. The German couldn’t have done him a greater favor at that moment.”

Jeannine seemed to shrink within herself. Her eyes sought the ground and dull pain burned in her heart as she recalled Hutchinson’s dying words.

“Gad, it was sporting of him, y’ know. He smiled at me when he turned his Vickers loose. He—he—could have—plugged the—engine so easily.”

She spread her hands in an expressive gesture at her sides.

“I cannot understand, Monsieur Major. War—he is something I cannot understand. You—all of them—you do not understand either.”

“That is the real answer, I suppose.” He nodded solemnly and watched her as she turned away. “Don’t think too much about it, Jeannine. You’ll live to see it over with.”

Jeannine returned slowly to the cottage. She walked unnoticed in advance of the flyers and the mechanics who were talking in subdued tones. In her sloe eyes grief gave way before a sullen anger and her heart beat rapidly, whipping her rage into flame. They were so young, these boys. Younger even, than she, some of them, and they came here only to die.

Entering the dining room, Jeannine removed a plate and the utensils from one of the seven places, then pushed the chair against the wall. She reached out for the wine glass, but drew back and a little shudder passed through her body as she remembered. She moved into the kitchen where her mother glanced up from expressionless eyes.

“How many?” asked the older woman, listlessly.

Jeannine did not reply. Instead, she set the plate and the silverware on a tray. Mme. Berthelot nodded and went back to her oven. There would be larger portions now, for the six who remained.

From his chair in the corner by the window, Grandpère Julien eyed the girl as she re-entered the room. In silence he had seen her take away the plate and in silence now he waited for her to speak. Jeannine said nothing.

“It is not war,” the old man shrilled, in his voice a note of violence. “Little boys shot down from kites in the sky.”

His gleaming eyes beneath their shaggy brows raised to a rusted musket hanging on a peg in the wall. The sunlight glinted dully on the time-stained bayonet. Jeannine followed his gaze and for an instant there was in the youth of her face, and the age of his, a bitter resemblance.

She turned away at the sound of tramping feet and from the kitchen watched the men who came in through the open door. Major Russell was first, looking older than when he had landed. The others followed him silently. The Major seated himself immediately and the others took their places. In turn they glanced at the vacant expanse of checkered table cloth where Harley had been accustomed to eat, then looked quickly away.

“Anyone see Von Richthofen today?”

Walker, a veteran of twenty-two, with fifteen enemy planes to his credit, spoke carelessly, hoping by so doing to break the strain.

There was a moment’s silence while they eyed him inquiringly.

“You’re jolly well right we didn’t,” said Rogers, the Infant, with obviously false cheerfulness. “You don’t see that devil and live to tell about it.”

“It was a red Fokker that got over Harley,” said Major Russell quietly. “I thought the kid got away from him.”

Several of the men nodded in corroboration and again six pairs of eyes subconsciously sought the vacant place at the table. In all the enemy flying force there was but one red ship, brilliant as a scarlet tanager, so that all who flew might read the challenge of its pilot, the chivalrous and deadly Von Richthofen.

Jeannine, in the kitchen, listened to the tense silence that followed the Major’s words. Hot tears burned in her eyes and a sob wracked in her throat. Mme. Berthelot looked at her daughter curiously, and her grim, chiseled features softened.

Suddenly Jeannine seized a brown paper sack that lay on the table. With skillful hands she folded it to resemble the fatigue cap of the flying corps. With a slender finger she touched the soot on the oven door and drew a quick smear above her lips, a travesty on the moustache affected by some of the younger pilots. Then, taking up a long handled warming pan, she placed it across her shoulder as though it were a gun and began a queer little dance on the sanded floor of the kitchen.

Mme. Berthelot reached out strong hands and clutched the girl’s arm.

“Have you gone mad?” she demanded. “Come to yourself.”

Tears fell down across Jeannine’s cheeks and she choked back a sob.

“Can’t you see?” she cried, in a voice tinged with hysteria. “Can’t you see?” she repeated. “I must play the fool. I must make them laugh—and forget.”

She laughed wildly and spun away on dancing feet, whirling into the room to the amazement of the men at the table. They stared at her uncomprehendingly and there was no laughter on their lips or in their eyes. As she danced Jeannine sang gay little songs of France, a verse of one, the chorus of another, searching all the while the cynical faces of the pilots. Major Russell alone permitted a shadowy smile to cross his face.

Jeannine realized that she had failed. She pirouetted in a last attempt and, as she whirled, her eyes fell upon the champagne bottles on the sideboard. She paused in her weird dance and began to pile them on her arm.

“Give them wine. Let them drown their memories.” The thought registered and repeated itself and, as she turned, one bottle slipped and fell. She stooped to retrieve it and another went down. She bent again and now, when she least expected it, the strain was broken and the men burst into laughter at her serious efforts.

Major Russell was the first to her aid and between them they got the bottles safely on the table. The ripple of merriment still sounded in throaty chuckles as the Major chose a single bottle. Jeannine stepped back against the sideboard and waited. With a great deal of care Russell drew the cork and in a single movement each man was on his feet. Jeannine accepted the bottle and, moving slowly around the table, filled each glass to the brim. Presently, she stood before the goblet at Harley’s place. For just an instant her lips quivered and the hand that poured the wine was trembling.

Jeannine stepped back to the wall, biting her lip until it paled. Major Russell raised his glass and the men of his command responded gravely. Their young faces were set in grim lines and into the eyes of all but one there came the hard light of controlled emotion. The Infant alone revealed to his mates the stark horror that was his. His face was gray and his firm boyish lips were drawn like a slit as he gripped himself in anticipation of the Major’s toast.

Russell looked down the length of the table into the eyes of each man. As he spoke there crept into his voice a sinister note, cold as the wind that whipped through the wires above the lines, deadly as the whine of a bullet, relentless as the ripping of canvas on the wing.

“To our comrade in hell,” he said.

Slowly he put the glass to his lips and drained it. The others, with the exception of the Infant again, did likewise, but Rogers gulped and choked as though the bubbling liquid were hot lead. Unconsciously, Jeannine pressed against the wall, one small hand held over her lips as if to crush back the cry of protest that came from her heart.

Russell set down his glass and, leaning over the table, reached for the goblet at the vacant place. Mockingly, like a man half mad with grief that must not be shown, he raised it above his head, tilting the brim so that the wine fell upon the table slowly as blood drips from a mortal wound. In a moment which seemed like eternity the goblet was empty. Gripping it at the base, the Major crushed the bowl of the glass against the table, then turned abruptly and set it beside its shattered mates on the sideboard.

Jeannine, with horror in her eyes, found herself counting those ragged goblets in the dead silence. She knew there had been eleven, yet she recounted them slowly. Someone coughed and his flying mates started nervously.

“They say the thirteenth is lucky,” remarked Martin, who liked to gamble, and his sardonic laugh lacked mirth.

The Major was back at his place. His Sphinx-like face turned to Rogers.

“Hop over to headquarters, Infant. I’ll give you a requisition for another man . . . you can tell them another pin has been bowled over,” he added, smiling bitterly.

When the unrelished meal was ended the men returned to their quarters, each to his own duty, glad to be left alone that he might recuperate his shattered nerves. Jeannine, when her chores were done, went to the hangars, lured by the sound of motors under test, forever curious about the fleet planes that had come to be so much a part of her life.

An oath rolled over an Irish tongue and exploded with a familiar brogue, so that she paused before Hangar No. 3. Gazing up toward the source of the oath she found Mike O’Rourke on a platform, beside him a Cockney mechanic from Cheapside in London. The latter clutched a collection of tools in either hand and O’Rourke was calling for them at frequent intervals.

“Whativer did yez do in London?” Mike was demanding. “Oi asked yez for a monkey wrench an’ Oi git a claw hammer.”

“Hi was a gentleman in ladies’ dress goods, hif ye must knaow,” replied the Cockney, a diminutive lad whose eyes and mind were as foggy as his native London.

Mike paused in his work to gaze at his companion with fine scorn.

“In ladies’ dress goods, was it? Well, by th’ saints, ’tis where yez b’long this minute, petticoats an’ all. An’ by th’ way, whin yez address me say ‘sir.’ ”

The Cockney bridled and his falsetto protest came shrilly to Jeannine.

“Hi sir my soo-perior officers an’ you aren’t.”

Again the big mechanic gazed at him from his greater height.

“Do yez see this?” he asked, dropping a heavy thumb on a great blot of grease on his tunic. “Well, that’s me chevrons. An’ as fer bein’ yer soo-perior, mind this.” Mike lifted a brawny fist and held it just beneath the Cockney’s pointed nose.

“Yes sir,” said the little man from Cheapside.

Jeannine, momentarily forgetful of tragedy, was restraining her laughter with difficulty. She saw that the Cockney was woefully unhappy and a sudden inspiration sent her into the hangar just beneath the platform. O’Rourke, busy over the motor of a plane, was unable to see her. She signalled to the Cockney, who presently understood.

A heap of greasy overalls lay on the floor near a tank of petrol. Jeannine donned a suit and in the next moment was climbing up to the platform behind O’Rourke. He was peering into the bowels of the engine and now and then demanded a tool from the Cockney.

Deftly, Jeannine took the instruments from the little man and he climbed quietly down to the floor, glad to be relieved of an odious task. Mike straightened and without turning about, barked an order.

“Now, Petticoats, hand me th’ propeller yonder.”

The propeller lay beside her. For a moment she struggled with it, even managed to raise it from the platform floor. Mike, growling about the delay, turned sharply and faced her. His bushy red brows arched as his sea-blue eyes widened.

“Well, how in th’—what are yez doin’ here? Oi’ve warned you toime an’ agin no wimmin is allowed in here. ’Tis aginst orders.”

Jeannine, smeared with oil, breathing rapidly from her exertions, smiled back at him.

“But M-Mike,” she laughed, “you told me I could help some time. You—you even promised I could grind valves.”

Mike scowled down into the hangar, searching for the Cockney.

“Yez better learn to fly,” he roared into the semi-gloom. “If ye shtay on th’ ground Oi’ll get ye sooner or later, Oi will.”

When he again faced Jeannine his red face beamed in a wide grin and he spread his massive hands in a gesture of helplessness.

“If the Major comes it’ll cost me a month’s pay, it will,” he told her. “But if ye can’t do better’n that Englishman, Oi’m a liar.”

And so was it that Jeannine remained to work beside O’Rourke, who pretended with great sincerity that she was the best helper any mechanic ever had in His Majesty’s service. As she worked her way insidiously into his good graces, Jeannine evolved yet another scheme of amusement.

“Could I sit in the pilot’s seat?” she asked presently, when the propeller was in place.

He shook his head determinedly. “ ’Tis aginst th’ regulations.”

“But Mike, no one would know.”

He studied her for a moment with eyes that twinkled.

“Well, Oi might be bribed,” he admitted. “A bottle av good red wine might make me forgetful, as th’ sayin’ is.”

With a glad little laugh, Jeannine climbed down from the platform and ran from the hangar. Unnoticed by Mme. Berthelot, she descended to the cellar beneath the cottage, where the pungent bouquet of old wine hung heavily on the cool air. Directly, she was out again in the sunlight with the bottle thrust beneath her blouse. As she hurried across the road and out upon the field, the roar of a motor sounded overhead. She paused to scan the blue expanse of the late afternoon sky.

In a moment she found the plane and her breath caught as the motor idled and the ship turned lazily in a spectacular wing-over. The man aloft straightened out then and went into a steep climb, which as suddenly was checked for a tail spin. The adjutant, standing nearby in a group of officers, watched the stunting plane with practiced eye.

“He’s probably our replacement,” he suggested. “He seems to handle his ship decently enough.”

“We’ll know better after a show across the lines,” said a pilot, cynically.

The newly arrived plane had straightened now and was sweeping down in a long oblique dive, like an eagle plunging for his prey.

Jeannine started along beside the edge of the field, her mind divided between two desires. She had remained unnoticed in her baggy uniform. Now, it was a choice of hurrying on to the hangar where Mike awaited his wine, or of chancing detection while she watched the landing of this new pilot from headquarters. As it happened, she had no choice in the matter.

The gray plane suddenly straightened off over the field and the pilot cut the motor. To the flying men there it was obvious that he intended to bring up before the headquarters shed with a flourish. But to Jeannine, his maneuver was a surprise that brought with it a hideous rush of terror.

He eased the plane into a side-slip to reduce his speed, righted her sharply and came down directly on the edge of the field, racing upon Jeannine as she stood transfixed in her fright. It happened so suddenly that realization did not come to her until too late. She saw the pilot lean far out of his cockpit and wave at her in a signal to run. Yet still she stood in the path of the whirling propeller, as a frightened bird stands motionless, hypnotized, before the approach of a python.

The pilot bent low in his seat and reached for the stick. Without an instant’s hesitation he pulled his ship over in a sharp angle. One wing tilted down and Jeannine closed her eyes as the wind from the speeding plane swept into her face. As she opened them again, the little chaser ploughed its nose into the field and the tail came up. There was the sound of ripping canvas and splintered wood, as the plane came to an inglorious halt.

Ignoring the officers and mechanics who were running toward him, the pilot leaped lightly from the cockpit. He walked rapidly back to the edge of the field where Jeannine stood dazed. She saw the set of his lean jaws, the cold flame in his eyes as he approached. Dimly, she heard his voice, clipped and even.

“Damn you,” he said, “you should know better.”

In a movement so swift that she scarcely saw it, his hand struck out and the palm crashed smartly against her cheek. She went down from the force of the blow like a leaf before a sudden puff of wind.

“As a mechanic,” the young man continued bitterly, “you’re a beastly failure.”

He gazed down and instantly his mouth fell open in a startled expression of bewilderment. Jeannine’s greasy cap had been knocked from her head and her thick brown hair lay in clusters about her brow. She was pressing one hand to the red mark on her cheek and her eyes were sparkling with tears.

“Good Lord,” exclaimed the officer, bending over her, “I—I didn’t know——”

Captain Philip Blythe, R.F.C., became abject in his apologies and he was infinitely tender as he attempted to raise Jeannine from the ground. She eluded his arms and sprang to her feet. For a ridiculous instant, the tall young officer of His Majesty’s flying force was kneeling before the girl of France. She stamped one slim foot and her little hands clenched before his astonished face.

“You are one beeg bum,” she exclaimed, in her own version of the queen’s English.

She turned from him and walked with as much dignity as she could command, to a point some ten yards distant.

“But really, you know,” Blythe’s very contrite voice followed her, “I—I’m awfully sorry——”

The girl wheeled swiftly and with deft hands jerked off her suit of greasy overalls. She kicked at the brown heap of it on the ground and this time retreated toward the edge of the field with no further demonstration. There were hot tears of anger in her eyes, but she was careful that no one saw them.

Blythe watched her lithe figure and laughed softly to himself. A motorcycle with a sidecar passenger buckled out across the field and he turned to greet the adjutant who hopped out beside him.

“Are all your mechanics as lively as that one?” he asked, indicating the disappearing Jeannine.

“Not by a damn sight, Captain. You gave her rather a reception, didn’t you?”

Amusement sounded in the adjutant’s chuckle and Blythe flushed.

“D’ye know, old man, I popped her one. I thought it was a boy—so I knocked it out of the way.”

“So we noticed,” laughed the other. “You’ll get a rubbing at mess tonight—striking a girl an’ all.”

“Lord, yes.” Blythe grinned ruefully. “I suppose she’ll spill it everywhere. British officer knocked her down. Brutes an’ all that sort of thing. Good for morale, what?”

“Oh, don’t worry about Jeannine, old man. She’s sporting. You’ll just have to stand for the spoofing.”

He took Blythe’s arm and they started back toward the hangar.

“Good crossing?” asked the adjutant.

The newcomer shrugged. “Fair. My leave was only half in—less, in fact, when the order came to report here.”

A group of officers awaited them at the hangar as they moved up, arm in arm. In the meanwhile, Jeannine had crossed hurriedly to the cottage, half angry, yet amused as she recollected the astonished expression on the face of the British captain.

She started to pass the niche in the gray wall where the little Saint Joan reposed in her seclusion. Moving in behind the shrubbery, Jeannine flung herself down before the shrine. She turned her piquant oil-streaked face upward as she spoke, as though to a near friend, in confidence and with a certain worldly note of revenge.

“Dear Saint Joan,” she began. “He is a flier and I shall always pray for them—even him. Bring him home each evening safe, blessed Saint, and all the others. But let me get even with that one.”

It was at the evening meal that Jeannine’s opportunity came, whether by arrangement with the saint or not being a matter between herself and the silent statue in the garden. The dining room, humble as it was by day, acquired new dignity in the softer glow of candle light. A jug in the center of the long table contained lilacs and their perfume was on the air. The plate and silver gleamed pleasantly, so that war seemed a thing men read of and talked about, rather than a presence in the room.

Jeannine moved through it lightly, touching the flowers, rearranging a plate. She went on into the kitchen. Mme. Berthelot looked up from her stove sharply. A shade of annoyance crossed her somber face.

“Why do you wear your best dress? It is not a Saint’s day.”

Jeannine paused and blank surprise registered in her innocent reply.

“I changed in the dark,” she explained. “It was a mistake. Now, it is too late——” she shrugged and smiled into her mother’s eyes.

The older woman raised her hands in a gesture of futility. There was disbelief in her eyes, but she held her tongue. Mme. Berthelot had long ago given up argument with her daughter.

Jeannine pivoted at the sound of footsteps. Major Russell, with young Blythe beside him entered the dining room. Behind them came the others, gay in the interval of companionship, immaculate in dress uniforms donned especially for the replacement officer just arrived. In their subdued laughter was the echo of merriment over cocktails in their quarters.

Major Russell paused at his place at the end of the table, indicating a chair on his right for Blythe. The others filed in and with informal gayety, each man stood behind his chair, gazing expectantly at the young captain in the position of honor.

“Who was the silly Yankee who said war is hell?” Blythe directed the inquiry to the group and slyly licked his lips.

“General Sherman,” replied Major Russell quickly, “was a man who kept his feet on the ground. I doubt if he ever had a cocktail just before a battle.”

“Of course not,” came from Marshall. “The old gentleman took his whisky neat.”

In the laugh that followed they took their seats as the Major waved a bronzed hand in signal.

“Contact, gentlemen,” he said. “This is in the nature of a flight in gastronomics.”

The door from the kitchen opened to admit Jeannine. She bore an armful of lilacs to be distributed, a spray at a time, before each place. The Major was first to rise, but only by an instant. The others were on their feet, smiling oddly. Blythe rose with them, eyeing his fellows swiftly. He did not, of course, recognize Jeannine in her Saint’s Day gown, nor did he quite understand why a group of officers rose attentively at the approach of a serving girl in a humble billet.

“Bon soir, messieurs.”

She greeted them gayly, flushing in her pleasure at their measured courtesy.

“Captain Blythe,” the major bent in a formal bow, “allow me, sir, to present Mam’selle Berthelot, the guardian angel of the Thirteenth.”

Blythe smiled into Jeannine’s laughing eyes and lowered his handsome head in response to her curtsy.

“The Thirteenth Flight is blessed,” he ventured gallantly.

Jeannine’s eyelids fluttered and in watching them, Blythe failed to catch the amused glances that passed among his fellows. As they again seated themselves he leaned toward the major.

“She’s marvelous, sir,” he said in an undertone. “Really, I didn’t know they came so beautiful in France.”

Jeannine, watching in the mirror, sensed that the stranger had spoken of her. She turned swiftly.

“Monsieur le Capitaine does not remember?” Her voice rang with amusement. “Yet we met in so strange a fashion.”

Blythe gazed up at her, puzzled, a little uneasily.

“Monsieur has the unique honor,” she resumed, still smiling. “He is the only officer who ever struck Jeannine to the ground.”

The newcomer drew back, startled. Recognition came slowly and his lean, wind-driven face flushed as he lowered his eyes. He was boyish when he again faced her, attempting to smile.

“You will forgive me?” he pleaded. “You must understand——”

“Understand,” she repeated. “Of course. Your airplane, he did not knock me down, so—you did, Monsieur.”

The men could no longer control their mirth. Blythe shifted unhappily and grinned. It was the Major who relieved his embarrassment for the moment. Russell drew from his pocket a strip of torn fuselage, bearing part of an enemy insignia. He handed it to Jeannine and she turned swiftly to place it among other trophies on the wall.

As she completed her task, she turned and saluted. It became apparent that this was something of a ceremony. Major Russell voiced a crisp command.

“Attention! About face.”

The fliers stiffened and obeyed.

“Single file to the right—forward—umph!”

As the first marcher came abreast with Jeannine he leaned down and kissed her uptilted lips. The second man did likewise, and all of them until Blythe came up. As he approached she drew back.

“I will save your kiss till you deserve it,” she laughed, and eluded his arms.

He took the rebuff in good spirit and all through the dinner that followed, Jeannine continued to torture him and was aided and abetted by his colleagues at the table.

There was a special dispensation of chicken. It was “Happy” Conway who spoke into Jeannine’s ear as she leaned over him. A golden brown leg lay on the plate which Jeannine set before the major. She deliberately served to the left, cunningly reversing the order so that the fowl came finally to Blythe. He refrained from comment as he received the uninviting extremity. His eyes were cast downward so that he failed to see the malicious gleam in Jeannine’s eyes, and likewise missed the suppressed merriment of his fellows. Conway was innocently sober.

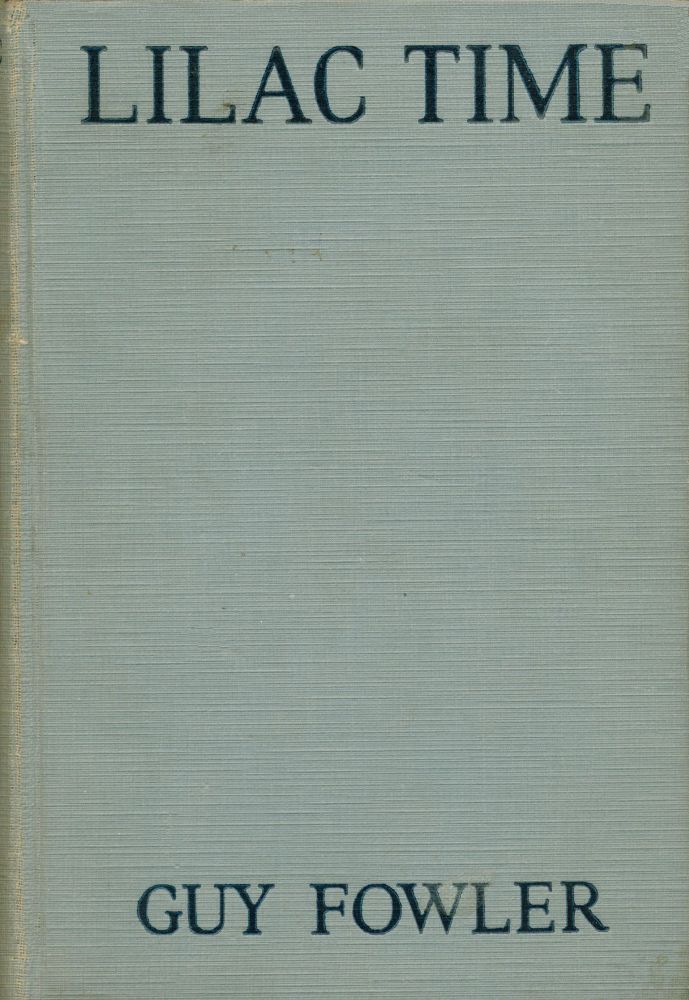

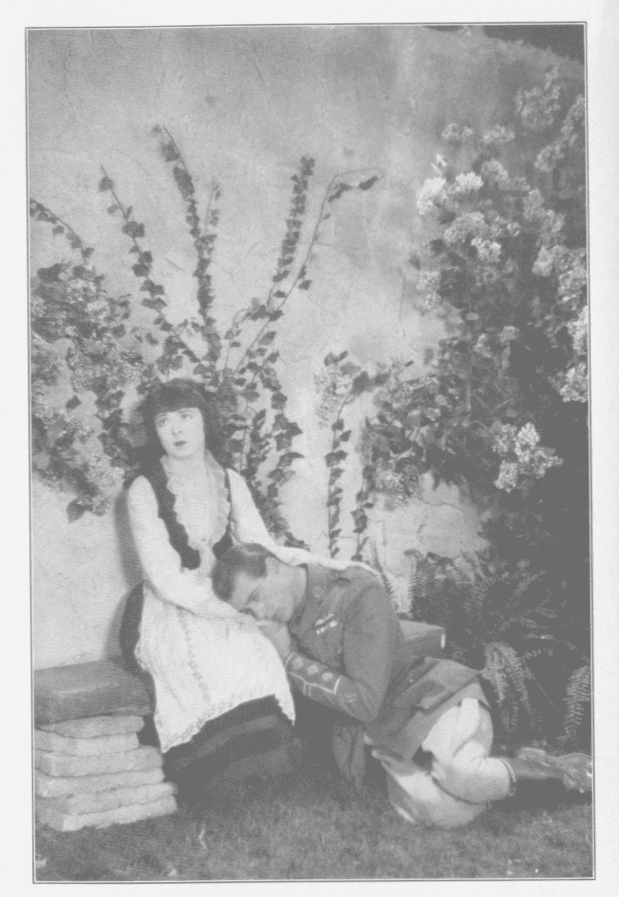

A First National Picture. Lilac Time.

JEANNINE, THE SQUADRON’S ADOPTED MASCOT.

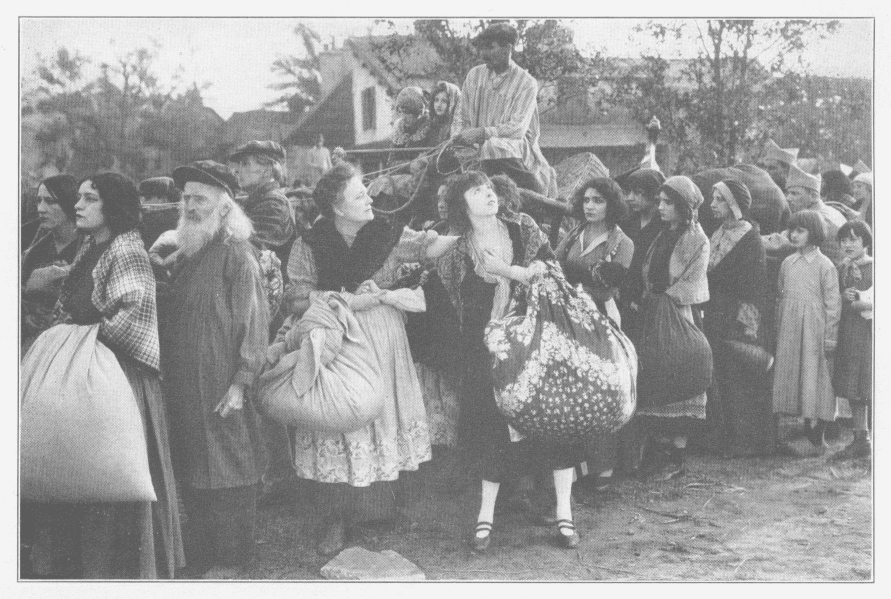

A First National Picture. Lilac Time.

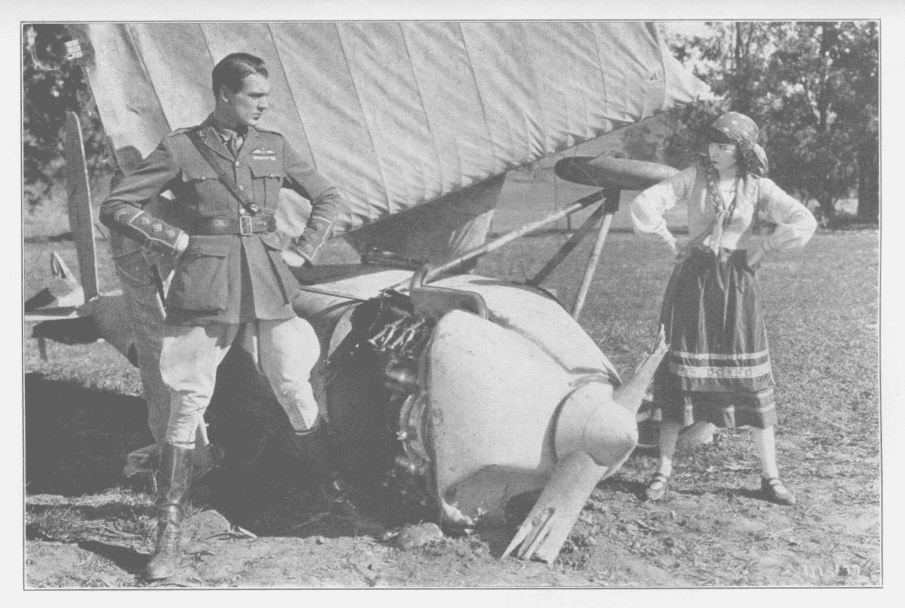

CAPTAIN BLYTHE DISLIKED HAVING HIS MACHINE MADE FUN OF.

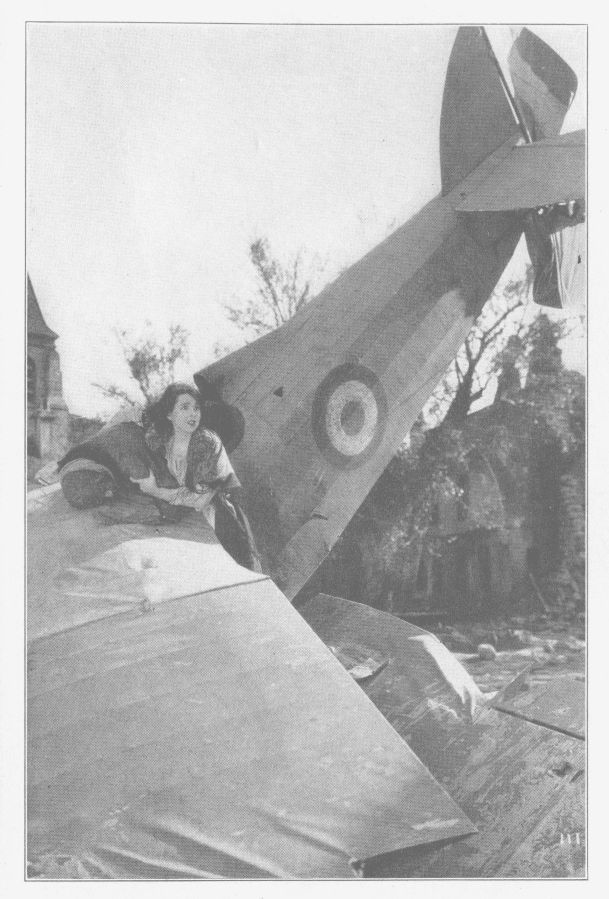

A First National Picture. Lilac Time.

THEY GLARED ACCUSATIONS AT EACH OTHER.

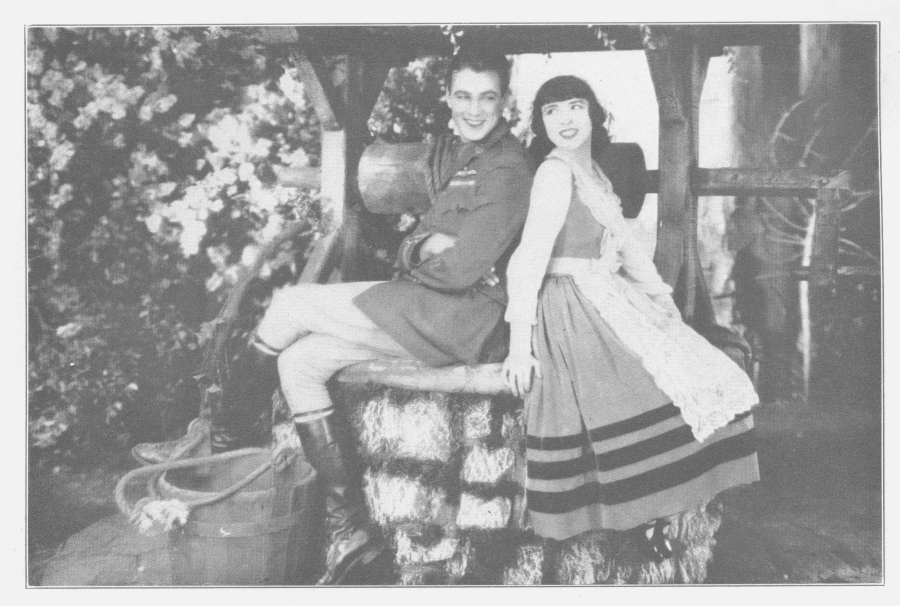

A First National Picture. Lilac Time.

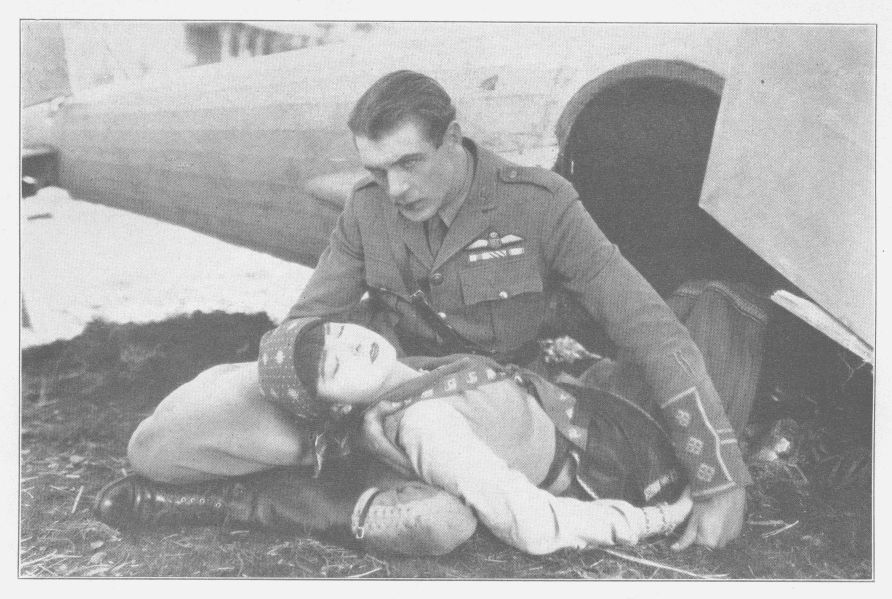

PHILIP THOUGHT SHE WAS DEAD—AND HE WAS AFRAID.

At length the meal was ended. The young captain rose with studied nonchalance and walked out with the Major, not deigning to turn his head as they passed Jeannine. Out of the room, Russell laughed softly.

“I say, old man, you took it remarkably well,” he congratulated his new subordinate. “Your exit was perfect.”

“The little devil stunted with me quite enough,” laughed Blythe. “She’s a vixen.”

Hours later, when Jeannine and Mme. Berthelot had cleared the table and put away the last of the dishes, night was settled over the earth and the distant rumble of guns sounded from the Loos salient that extended south from La Bassée. Grandpère Julien had long since gone to his bed beneath the roof.

Jeannine moved out into the darkness. For a time she watched the fitful glow low in the western sky and listened to the sound, like the pounding of heavy surf. “Without conscious direction, she drifted among the lilac bushes and came, presently, to the dim statue in the recess. She stood for a moment in silence, then kneeling, spoke softly to the war saint.

“I thank you, blessed Saint, for your goodness. Today, they all came home safely. Tomorrow—may you watch over them again.”

She paused and a faint smile curved her lips. “And I shall forgive Captain Philip, because he flies for France.”

She became suddenly conscious of another presence. Swiftly she rose, her eyes widening. Blythe stood in the shadows. She saw that his face was serious. There was no mockery there and he had heard. They faced one another in silence. She smelled the aroma of the cigaret he tossed aside.

“So, you’ll save no kiss for me?”

Blythe moved forward a single step and took her into his arms. Jeannine did not attempt to retreat. In all her young life she had not felt the strength of a man’s arms about her waist. Not in this manner. She did not struggle when he drew her close and bent over her lips.

His lips met hers warmly, lingering. For a long moment she lay quietly in his arms. When she opened her eyes he was smiling and Jeannine suddenly struggled. She fought with all her strength, but this man from England only held her and continued to smile.

“For that,” he said dreamily, “I shall kiss you again.”

He did, immediately. Against his easy power she was helpless. His laugh maddened her as much as his arms.

“Will you be as strong against the Boche?” she demanded, as he released her.

The smile died on his face. Jeannine realized that her shaft had gone home.

“I’m sorry.” His voice was cold and emotionless now and he stood very tall and straight. “I wanted to apologize,” he went on. “You gave me no chance. Tonight, I—I forgot myself.”

“Forgot,” she repeated. “Always you fliers forget. But not any of them so much as you, Monsieur.”

“But won’t you accept my apology and be friends?” he persisted, gently, his smile returning a little wistfully.

“An’ if I should?”

She had moved out from the lilacs and they were on the path that wound through the garden. There was a softer note in her question and Captain Blythe laughed.

“I think,” he replied slowly, “that I should want to kiss to seal it.”

Jeannine drew herself up to her full height, so that the tip of her head was even with his shoulder. Her eyes flamed into his.

“You—you are one beeg bum.” Her favorite epithet struck him with biting emphasis and in a swift movement she raised herself on her toes and her palm smote him sharply across the cheek.

“There,” she exclaimed, her voice quivering with rage. “You give me one sock—I give you one. Now forget.”

She turned and ran, leaving him standing in the center of the path, tenderly rubbing his flushed cheek. He grinned after her in the darkness.

“Little back-fire,” he muttered.

Blythe wheeled and moved back along the path to the road, then across and on to the hangar. In the gloom of the squat building he stood beside the DeHaviland pusher scout plane that was his while they both lasted. His hand caressed the fuselage as though it were the flank of an animal he loved.

“We’ve got somebody praying for us,” he mused to the plane. “But she hates me like the very devil, old chap.”

Idling beside the ship in the solitary shadows of the hangar, Blythe’s thoughts, like those of every Englishman, wandered back to London and familiar things. He wondered dimly where his honorable father, General Sir Allerton Blythe, would be this night. And in the next moment, he was seeing again the lovely figure of Lady Iris Rankin, who was to be his wife.

Grating his heel on his discarded cigaret, Blythe shrugged and strode out into the night. At the door he paused to study the sky in the west. Low on the horizon it glowed dully and for an interval was black. The sound of the guns reached him faintly on the late breeze. When he swung back toward his quarters, his face was hard and suddenly matured.

He was thinking of dawn and the gray field before the hangars; the ships drawn up in order, with the mechanics testing them again at the last minute. It did not occur to him at all that his DeHaviland might be the one that would not return.

Jeannine’s prayers were answered now each morning as the Thirteenth leveled back across the lines. She would watch them coming in the distance, trying to count as she always had, meeting with difficulty as they dropped from their high ceiling with incredible speed.

From that first flight in the mist of dawn, Captain Blythe had established himself as one of them. Unlike the others, however, he avoided Jeannine and her fiery spirit revolted more each day. Still, to herself, she admitted that the man was born to fly. The way he climbed steeply into the sun, the brilliance of his dazzling plunges toward earth; his nonchalant ease in the cockpit, all these impressed her.

The flight had returned again and the men were scattered about the field, or working in the hangars, studying neat round holes in the wings and fuselage, shrugging when they found one close to the office of their ship. Jeannine started into the field and a sentry blocked her way. She laughed in his face and went on. He turned his back, grinning sheepishly.

She passed around the corner of the hangar to come face to face with the adjutant. He halted, gazing at her sternly. Time and again she had been ordered to keep off the flying field and various sentries had been disciplined in proportion to her infractions. Jeannine smiled and her eyes went to his pleadingly.

From her blouse she withdrew a cruller, fresh from Mme. Berthelot’s oven. He laughed as he accepted it and he too, turned his back while she proceeded on toward the open door of a hangar. Two men were working over a ship, both shapeless in greasy khaki, their faces and hands alike streaked with oil.

She recognized O’Rourke, the mechanic, instantly. It required a second glance to identify in the laboring figure beside him the dignified Captain Blythe. Neither of them marked her approach. She stood for some time watching Blythe up over the engine. As O’Rourke slowly turned the propeller, his superior studied the action of the valves with calculating eyes.

Jeannine had watched a similar procedure many times before, so that the impulse which prompted her at the moment was, in reality, a premeditated thing. She had considered it with O’Rourke as the victim. Now, fired by an intense desire to rouse this calm-eyed flier from England, even in wrath, she awaited her opportunity.

Presently, O’Rourke climbed on the platform beside Blythe.

“Here’s where the damned friction is,” said the Captain. “Look at that valve.”

The Irishman stooped and peered at the defective part. When he straightened, nodding, Blythe bent down and squinted into the little port. Below, awaiting this moment, Jeannine rose on her toes and seized the propeller. Dragging down with her full weight, she pulled the blades over in a sudden turn.

A spurt of blackened oil shot from the valve squarely into Blythe’s eye. He cursed and reached for his handkerchief, blindly. Jeannine’s laugh rang merrily from below as she ran back into the hangar and paused beside the rudder of the plane.

From his commanding position on the platform Mike saw her and glared.

“Get out av here, ye minx,” he bellowed. “How often have Oi told yez ’tis aginst orders? Now move along wit’ yez.”

Blythe, with the oil wiped from his eye, gazed at the girl for a fleeting moment and noted her position. Turning swiftly, he reached into the cockpit and yanked on the rudder bar. The response took Jeannine by surprise. The rudder swung behind her and suddenly a smart blow sent her stumbling. It was exactly as though Blythe had spanked her as he would a mischievous child.

Jeannine righted herself, chagrined. Then, eyeing him ruefully, she laughed.

“Very well, Monsieur,” she cried. “You win again. But some time——”

She turned and ran from the hangar.

“Now that’s over,” said Blythe, quietly, “get those valves in, Mike. Then pull out the chocks and we’ll test her.”

Directly, with Blythe at the controls, O’Rourke kicked out the blocks beneath the wheels and the ship rolled gently out beyond the hangar, the engine idling. On open ground, the wheels again were lightly blocked with planks carelessly flung before them. Blythe climbed from the cockpit to join the mechanic. They were standing attentively, listening to the slow ticking of the motor.

On the opposite side of the plane Jeannine peered curiously into the cockpit. With a hurried glance at the two men who were unaware of her, she climbed into the seat, childishly thrilled. The polished instrument board and the array of instruments held her eager eyes.

There was no warning for the men below. The engine burst into a terrific staccato roar and the ship fairly leaped. Blythe tried for it as the tail swung wickedly past his head, but failed and went sprawling. The mechanic raced out across the field in pursuit as futile as it was ludicrous. Rising, Blythe caught the gleam of wind-whipped hair as Jeannine’s head appeared over the side of the careening DeHaviland.

“Great God,” he cried, “that child—the damned little idiot.”

At the opposite edge of the field a stone fence stretched down across the length of the Berthelot farm. The plane was headed toward it at fifty miles an hour, increasing as it moved. Berthelots long dead had laid each stone, painstakingly and at the cost of infinite labor, taking them from the fields in their arms, depositing each one just so.

As she stared out from the cockpit, Jeannine realized sickeningly, that she was doomed. She had seen enough of wild planes to know how they buckled and plunged when they met an obstruction. She had watched too, as mechanics pulled shapeless, torn bodies from smoking wreckage. Instinctively she began to search wildly with her eyes among the instruments. It was not in her nature to faint, no more than it was to die without attempting to save herself.

Once, she half turned and saw men running out in the wake of the ship. Then, bending down in the office, she seized the stick and her feet found the rudder bar. The plane swung sharply around, dragging on one wing that ripped noisily. She had turned completely and now was speeding straight back toward the hangar.

Jeannine’s hand touched a slim lever on the stick. Dimly, she knew that some instrument would kill the engine. She pressed on the trigger and recoiled at the instant response.

She had launched a spray of steel jacketed bullets from the Lewis gun through the propeller field and they sang evilly over the heads of the men who were rushing out from the hangar.

“Down,” shouted Captain Blythe, falling flat and the others followed him to the ground.

He was up instantly as the gun was silenced. The plane came roaring in upon him and he stood like a sprinter, prepared to spring. The others spread out at his signal, each man intent on somehow flinging himself upon the ship as it passed. A single pressure on the switch would end its mad flight. Failure to reach that instrument, they realized with anguish, would bring tragedy far worse than a finish fight above the lines.

Jeannine by now had left the seat and was standing crouched in the cockpit. The ground skimmed beneath her so that she dared not leap. Once more, she gripped the stick and jammed it ahead. She closed her eyes and was only subconsciously aware of the awful crash that brought the earth and sky whirling around her hellishly.

The tail of the DeHaviland rose suddenly and the nose of the ship lifted, then dived and buried itself in the ground. Awkwardly, and, to the stricken men on the field, with terrible deliberation, the great plane turned over, then crashed heavily with the smashed undercarriage uppermost.

Blythe, in advance of the others, was first to reach the wreck. He crawled in madly, tearing at splintered wood and metal with bleeding hands. Thick smoke cleared for an instant as a breeze swept down and he saw the crumpled little figure in the cockpit.

He burrowed feverishly into the débris and only his legs were visible when the others arrived. A dozen pairs of hands lifted the broken ship with infinite care. Men who had become callous at the sight of death turned their eyes away as Blythe slowly backed out, half carrying, half dragging, the unconscious girl. From the road half a mile away a small truck dashed crazily out upon the field, approaching the wreck at breakneck speed.

“Careful, men.” Blythe’s voice was strangely calm. His face was drawn and hard, as it was when he climbed into the sun to jockey for position for life or death with an enemy.

“The engine missed her,” he added, as tender hands relieved him of his burden. “I’m afraid she’s hurt, though, badly.”

The truck pulled up beside them with grinding brakes. Blythe straightened and passed a bleeding hand across his eyes, as though to wipe out some awful vision. He bent quickly over Jeannine, studying her face, then lowered his head to listen for her heart. She stirred in his arms and her eyes opened slowly. A faint smile came to her trembling lips.

“I am so sorr-ee,” she whispered. “I have wreck your beeg plane.”

He drew her closer, so that her head rested against his shoulder and a glad note rang in his voice.

“Damn the ship,” he exclaimed. “You—you are badly hurt?”

Jeannine shuddered and moved weakly against him. Her arm went about his neck and she clung as though in fear, even now, of the fate she had missed. Her face, upturned to his, was very close and pale. She opened her eyes again and Blythe bent his head to kiss her gently on the lips.

Quick color came to her cheeks and she straightened.

“I am—what you call him—shook up,” she said. “I think I am ver’ lucky, Monsieur.”

“Come, we’ll take you home in the truck.” Blythe started to lift her and the men who had watched the brief scene, stooped to aid.

“No, no,” Jeannine told him hurriedly, still with her arm about his shoulder, “I shall walk—no more do I ride today, merci.”

Until then none had marked the swift, silent approach of an army Rolls. As the car halted beside the wreck, a young aide sprang from the driver’s seat and opened the door, standing stiffly at attention. The men in the group saluted sharply, with the exception of Blythe, who yet was handicapped by Jeannine.

A handsome man in the uniform of a general stepped briskly to the ground and turning, assisted an exquisite young woman, charming in her tailored costume of the service at home. With fine deliberation, the man, keen-eyed and erect, spoke pleasantly in an undertone to his companion, and returned the salutes. His eyes, like those of the girl on his arm, went quickly to Blythe.

“What’s the scrape?” he asked abruptly, with a certain familiarity.

Blythe somehow found himself relieved of Jeannine. He saluted smartly and smiled.

“Why, father, just fancy you in this part of the bush.”

General Sir Allerton Blythe smiled grimly. “Yes, yes, quite odd. But see here, young man——”

His glance swept the circle and paused on the girl at his side. Blythe laughed and his tanned jaws reddened as he bowed in mock humility.

“My dear Iris,” he greeted her, “I should have ignored the pater entirely. Another time I will. But there’s been such a devil of a mess—look—” he half turned and indicated the wrecked plane with a gesture.

“That child there,” waving toward Jeannine, “crashed. For a minute we thought——”

He let the sentence die expressively and bent over Lady Iris Rankin’s hand. She laughed softly, forgiving him with the sound. When she spoke it was in the perfectly modulated tone of the gentlewoman, cool as a morning breeze off the English coast.

“Philip, you look as though you might have crashed yourself, dear boy. So glad to see you. Sir Allerton was good enough——”

“Father’s top hole, y’ know. Always doing little things.”

The others had withdrawn unobtrusively, with Jeannine in their midst, proclaiming that she needed no assistance. Yet, she leaned on the wiry arms of two pilots and about her the others moved attentively, still doubting that she had come through so well as she seemed.

Sir Allerton, with the trained diplomacy of a British army officer, already had formed his own conclusions and come to his inevitable decision. Phil had been having an affair with the little French vixen, that much was obvious. It was deuced awkward to come in on it as they had, but of course, Lady Iris would understand. It meant nothing.

“We can only stay for tea,” he put in now. “I’m on an inspection and happened by. Iris had a chance to come over, so we decided to call in. How are you getting on, Phil?”

“First rate, father. The Thirteenth is a splendid outfit. And how goes it with you?”

The white moustached old officer nodded. “So so, Phil. Just so so. There is much to worry about.”

They were walking back toward the car, where the driver and the general’s aide waited rigidly. Philip was describing the recent crash.

“Oh, let’s walk,” suggested Lady Iris. “Where are your quarters, Phil?”

Blythe laughed shortly. “My dear child, I’m not taking you to my quarters. Mme. Berthelot is the only woman in France who makes British rate tea. That’s because we pull her leg for it unmercifully.”

In a few moments they were in the cool low-ceilinged dining room. Lady Alice moved over to the wall to examine the trophies. General Blythe and Philip were talking together of events at headquarters and back in England. Sir Allerton suddenly peered out at his son from beneath his shaggy white brows and his voice lowered.

“So you like the Thirteenth?” he asked and his tone was pitched to carry to the girl. Then, in a subdued growl, he added; “Don’t make an ass of yourself, Phil. Remember who you are.”

Young Blythe gazed levelly back at him and surprise was in his cool, steady eyes.

“Really, father, you’re quite mistaken.”

Lady Iris had come to the old sideboard with its row of broken glasses.

“What do these signify, Phil?” she called gayly. “Unsteady hands?”

“No,” he told her gravely. “No, those are broken hopes, my dear.” He went on then to explain the significance of the display.

She was very subdued when Mme. Berthelot came in from the kitchen bearing a tray. Her hewn face betrayed neither surprise nor humility at the sight of the British general and the lady of rank beside him.

“Mme. Berthelot saves our lives three times a day,” said Philip smiling up at her. “The Thirteenth swears by her.”

The woman set the tray on the table before Lady Iris and her expression softened in a fleeting smile. She made no reply.

“How is Jeannine now?” asked Philip, solicitously.

Mme. Berthelot shrugged. “She is ver’ sorry.”

“But I mean is she all right!” Philip persisted. “Not hurt a bit?”

“A scratch,” replied the woman. “She is—what you pilots say—one ver’ damn fool.”

The general’s deep chuckle mingled with Lady Iris’s musical laugh. Phil grinned appreciatively as Mme. Berthelot wheeled and left the room with no further comment.

“What about this Jeannine, Phil?” Lady Iris spoke lightly. “The darling of the squadron, I suppose?”

“Quite,” he replied, innocently. “She’s a very temperamental youngster playing on the edge of hell. Really, d’ye know, it’s wonderful sometimes, to watch her hovering around waiting for the flight to return. They tell me she counts us every time—and prays for us when we take off. Fancy.”

“Lovely.” Lady Iris was studying him curiously. “I think she’s exquisite.”

General Sir Allerton was sipping his tea with true British appreciation.

As Jeannine moved slowly through the garden in the evening dusk the larks were singing to the dying sun. In the western sky there was a splendor of red and gold and blue, low on the horizon. Facing that magnificence as she had so often seen the fliers do at this hour, she knew that tomorrow would be day of high flight and lofty courage. If she read the signs aright the Thirteenth would rise in the misty dawn to disappear presently over the enemy lines.

Instinctively, she turned in among the lilacs to pause before her shrine. Her prayer was wordless. It was as though the statue in the shadows understood her thoughts, communicating them in turn to the higher power of the saint.

Voices interrupted her, coming from the roadside. A woman’s soft laugh mingled with the heavier voices of men. Jeannine turned and peered between the bushes. The army Rolls was at the gate. Beside it stood Philip, his bronzed face glowing in the evening light. He was smiling into the upturned face of Lady Iris, and Jeannine knew that in a moment he would kiss her. General Sir Allerton was giving clipped directions to his aide.

“It’s been wonderful—even this little glimpse of you.” Philip’s voice drifted back to the shrine.

“I wish I could stay.” Lady Iris leaned a little toward him. “Oh, do be careful, dear boy. This can’t go on much longer——”

Philip’s gay laugh, strong, boyish, reassuring. Then confidently: “They’re breaking now, Iris. Why by Jove, d’ye know, I’d not be surprised at all if we’re out of it before fall.”

Sir Allerton stood silently, his lined face grim with disillusion.

“Good bye, father. Thanks for coming over—and for bringing Iris.”

“Au revoir, my boy. Good luck.”