* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Nine Lives. A Cat of London in Peace and War

Date of first publication: 1941

Author: Alice Grant Rosman (1887-1961)

Illustrator: Diana Thorne

Date first posted: Oct. 4, 2022

Date last updated: Oct. 4, 2022

Faded Page eBook #20221010

This eBook was produced by: Delphine Lettau, Al Haines, Pat McCoy & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

By Alice Grant Rosman

| THE WINDOW | ||

| VISITORS TO HUGO | ||

| THE YOUNG AND SECRET | ||

| JOCK THE SCOT | ||

| THE SIXTH JOURNEY | ||

| BENEFITS RECEIVED | ||

| PROTECTING MARGOT | ||

| SOMEBODY MUST | ||

| THE SLEEPING CHILD | ||

| MOTHER OF THE BRIDE | ||

| TRUTH TO TELL | ||

| UNFAMILIAR FACES | ||

| WILLIAM’S ROOM | ||

| NINE LIVES |

COPYRIGHT, 1941, BY ALICE GRANT ROSMAN

MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

Van Rees Press • New York

TO

AGNES AND BETTY

CIVIL AMBULANCE-DRIVERS

IN LONDON UNDER FIRE

London,

1941.

CONTENTS

| I | First Meeting | 3 |

| II | A Strong, Silent Cat | 13 |

| III | Return from the Country | 22 |

| IV | He Acquires a High Garden | 30 |

| V | Mice and Men | 41 |

| VI | A Cat Is a Tie | 51 |

| VII | The Rich Train | 59 |

| VIII | A Cat of No Mean City | 75 |

| IX | Interview with a Royal Cat | 89 |

| X | In the Silly Season | 98 |

| XI | He Smiles | 108 |

| XII | Prelude to War | 118 |

| XIII | London Waits | 128 |

| XIV | Empires, Dead and Alive | 140 |

| XV | Lest We Forget | 149 |

| XVI | In the Battle Area | 158 |

| XVII | The Rug that Went to Hospital | 170 |

| XVIII | Noises in the Night | 181 |

| XIX | London Calling | 192 |

| XX | The Backbone of Britain | 201 |

| XXI | “A Military Objective” | 209 |

| XXII | In the Morning | 218 |

| XXIII | V for Victory | 230 |

Nine Lives

s a race cats are not gregarious or co-operative,”

says my encyclopedia, approaching a

serious subject in a properly respectful

manner. Gregarious and co-operative are

adjectives no compiler would use about a nonentity, for

example. If he had said “the cat is an unfriendly beast”

I should have despised the man, but this judicious

handling of the subject at once acknowledges a cat’s

natural reserve and his right to indulge it.

s a race cats are not gregarious or co-operative,”

says my encyclopedia, approaching a

serious subject in a properly respectful

manner. Gregarious and co-operative are

adjectives no compiler would use about a nonentity, for

example. If he had said “the cat is an unfriendly beast”

I should have despised the man, but this judicious

handling of the subject at once acknowledges a cat’s

natural reserve and his right to indulge it.

“The dog has an extraordinarily keen intelligence,” proceeds the same authority, “and more highly developed mental qualities than any other animal.”

Ridiculous! Let us beware of sweeping statements. The man does not know everything. He has never met your cat or mine.

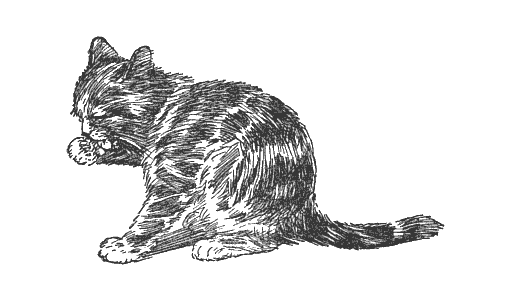

He has never seen Samuel Penguin who, far from “lashing his tail to denote anger” as laid down in the encyclopedia, waves it for pleasure or in response to conversation; who is a fellow of infinite capacity and often seems more dog than cat and sometimes more penguin than either.

This pleasing chameleon has now ruled our household for more than ten years and shown his mettle in peace and war.

This world of total war would have seemed utterly fantastic on that day years ago when we came to the conclusion that life seemed rather unfurnished without a cat.

An old friend, recalling our faraway home where there had been a long succession of animals, brought the matter to a head.

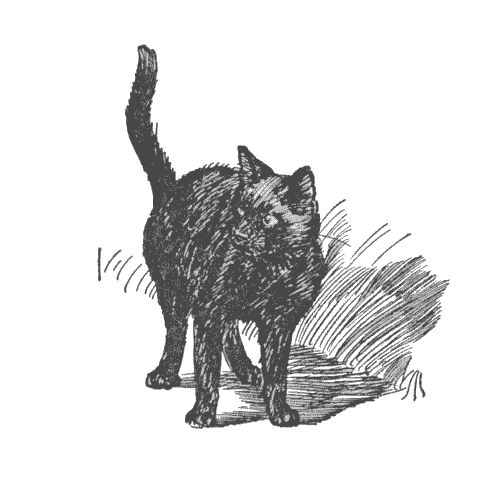

“I did think I should be sure to find a black cat sitting by the fire,” she said, calling to see us in London. “It seems the one thing lacking.”

It was. For some years there had been reasons against it, but now these were gone and we decided to put the matter in hand at once.

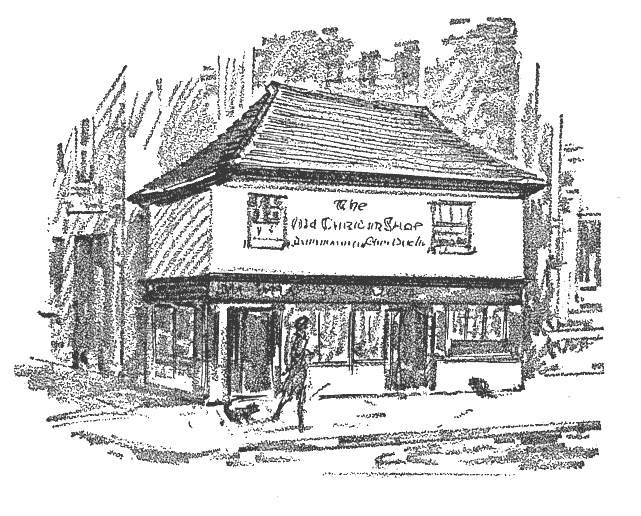

There was an element of the ridiculous in the transaction which followed, and, seen at this distance of time, it seems the fitting prelude to our acquaintance with Sam. In no other way could we have acquired such a cat.

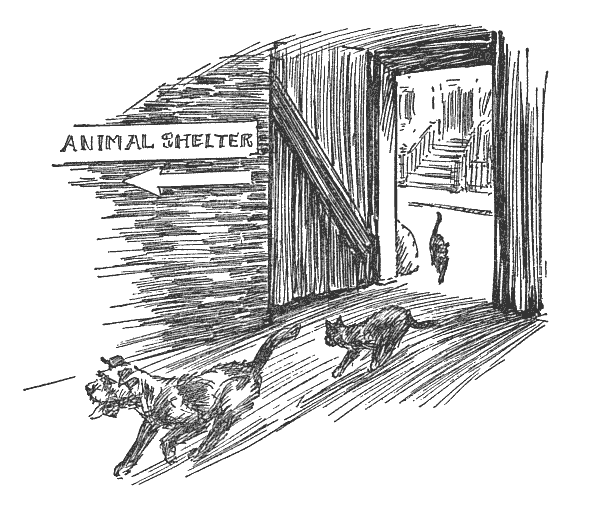

We discarded pet shops as unlikely to supply what we needed. We wanted no curled darling with a long pedigree, but a fellow of character and personality, one orphaned perhaps or lost and consigned to a Cats’ Home.

We knew nothing of such institutions, however, so telephoned the nearest Animal Society to ask for advice.

“Oh, I shouldn’t apply there if I were you,” exclaimed a sympathetic voice at the other end.

“Really?”

“Not on any account.” She was firm about it, though we never discovered why. Perhaps it was a question of professional jealousy. “Now, what kind of cat do you want?” she inquired, in a considering voice.

“A large, ordinary, influential house cat.”

We had come to the right place. The firm young woman was not to be daunted by adjectives or the fact that finding cats for casual strangers was no part of her ordinary routine.

Having asked our address she triumphantly produced the name and telephone number of a member of her Society’s Council living in the neighborhood.

“Ring her up,” she advised kindly. “I am sure she will be able to help you.”

Clearly this was a most amiable organization, which we had chosen by random from the telephone book, and unencumbered with red tape.

We therefore lost no time in getting in touch with Mrs. Cross of the Council—to give her a random name—and she proved as prompt as the Secretary.

“Can you wait a week or ten days?” she asked.

Rather dazed at such unquestioning affability we agreed that we could.

Half an hour later Mrs. Cross was announced and there walked in a delightful looking stranger in early middle age.

“Do forgive me, but I had to come and see the kind of home the cat was going to have,” she said.

We were friends in a moment. Mrs. Cross is like that, amusing, preposterous, and even at times devastating, but with an air that nobody could resist, and while she remained in the district she was a source of continual entertainment to us, even though dogs and not cats were the interest of her life.

One day the family doctor who had brought her into the world called to see her and in the course of conversation she said suddenly:

“By the way, doctor, I have often meant to ask you. Do you believe in vivisection?”

“Certainly, my dear, certainly,” said the old man beaming.

“Oh, you do! Then please leave my house at once,” said the lady firmly. “And never come here again. Our acquaintance is at an end.”

“If you’ll believe me,” she told us, “he actually argued and protested and I almost had to eject him by force.”

After a year or two we suddenly discovered that she had left the neighborhood, but it was not till Christmas that we learned the reason.

“You will probably be surprised to hear I have married again,” she wrote on her card of greeting. “The point was that the brute of a landlord gave me a fortnight to remove my dog or leave the flat.”

It seemed a new and original reason for marriage but I hope it was a success. We lost sight of her, but she remains the kind intermediary who introduced to us the most wonderful cat in the world.

That first day, having looked over our proposed arrangements for his comfort, she told us that he was black and had been discovered—a stray—at an animal shelter and taken home by one of her friends on the Council.

“But she will be willing to part with him because she has four cats already and the Colonel is complaining that he can never find a vacant chair. Cats,” said Mrs. Cross, “are like the ticket agencies. They always have the best seats in the house.”

The circumstances seemed propitious. The stray had been rescued for conscientious reasons and would be no deprivation. The profits in the transaction would be fairly matched, the strange Colonel regaining his chair and we acquiring a cat of the house.

His temporary guardian brought him herself in due course, and he was not merely wearing a smart red leather collar but a silver medal engraved with our name and address. The latter was for his protection rather than our pleasure, of course, to guard him from further adventures in the underworld.

The streets of London are full of self-contained and competent cats, going about their lawful occasions, but we quite lost sight of this as we listened to her warnings on the dangers he might encounter if we let him out. Luckily this is a top flat, which eased her mind a little, and more than ever impressed by the sense of responsibility of this excellent Society, we promised to guard him like diamonds, as the melodramas say.

The new inmate of the house, meanwhile, released from his basket, was taking stock of the premises with natural suspicion, ignoring the company. He retreated before our words of welcome and at last vanished behind the couch, where he sat stolidly, peering out with a noncommittal expression.

A bowl of lunch was ready, fortunately, and his guardian was left to do the honors, as the cat seemed highly temperamental. This had the desired effect, though we were unprepared for his response.

“Sit up, Samuel Penguin,” she said, standing before him, bowl in hand.

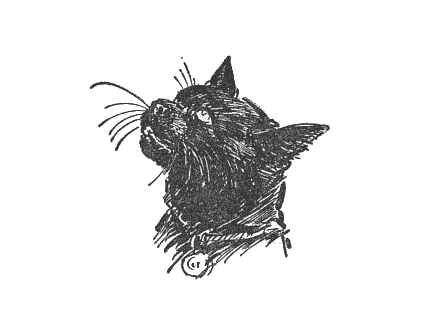

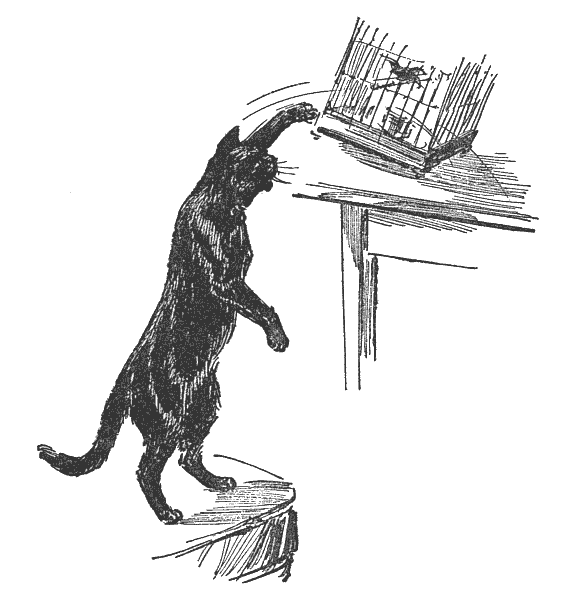

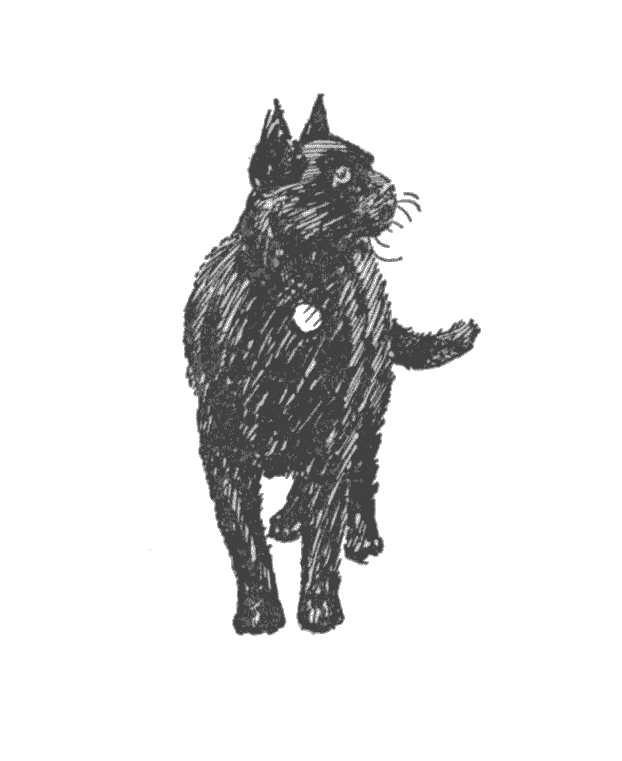

The creature rose to his hind legs, dangling his forepaws like fins in a balancing manner. With his small, neat head and shining satin figure he was a penguin almost to the life.

“How can you bear to part with him?” we exclaimed.

She laughed.

“Sam,” she said, “you are a success.”

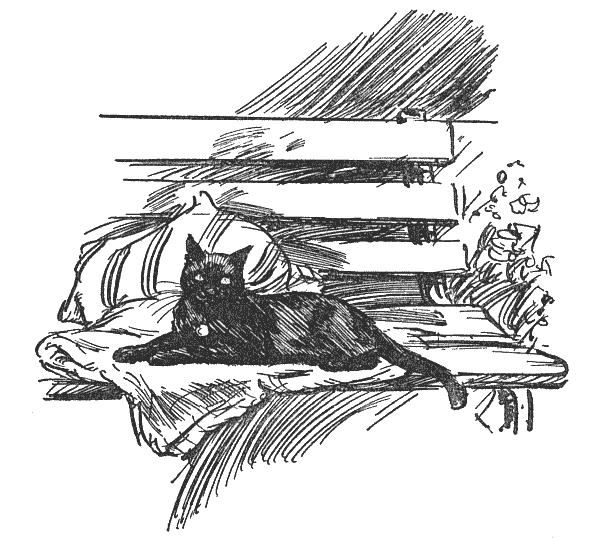

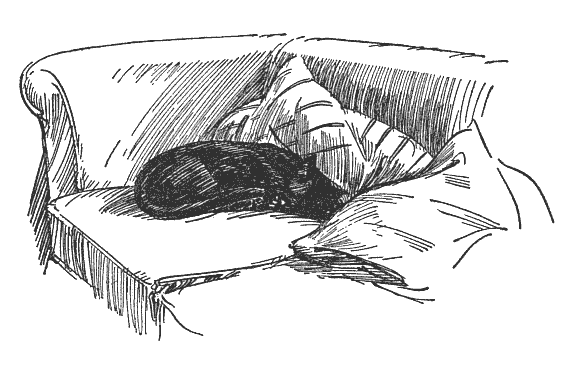

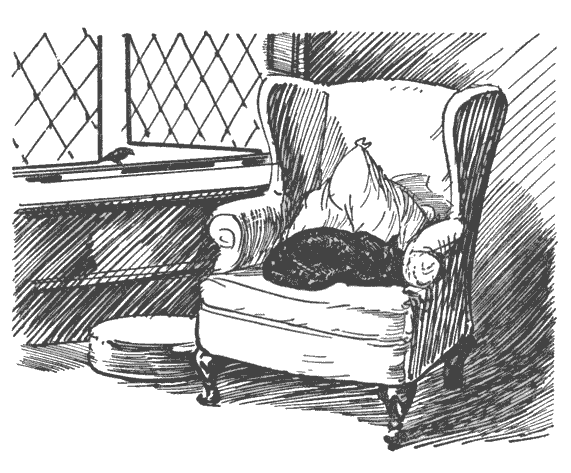

On this May morning in the London of 1941 he lies spread out in an easy chair, sleeping the sleep of the just. Has he not sent some of his breakfast to a Persian colleague who was bombed from his home last week, and so done his bit for England, Home, and Beauty? What cat could do more?

A burst of spring sunshine breaks through the clouds and Samuel Penguin expresses his appreciation in the usual way, rolling over on one ear, then dropping to sleep again, all his form stretched out to the warm rays.

The barrage balloons, a myriad of silver fishes far overhead, descend as the sky clears and float half way, and “George,” the nearest, turns in the breeze and bows politely. Seen at this angle he is no longer a fish but a prize ram with a horned nose. And now he is coming down after all, panting with hunger you would say, to lie like a fainting elephant under the ministering hands of his crew.

George almost looks in at our windows, yet when, in the winter of 1939, we went to find his resting place, we searched in vain for hours. Some of the households under his protection had thought of the men who serve him, far from their homes at Christmas, doing this important work, yet perhaps forgotten because unseen. A Christmas cake with almond icing, rich, fruity and homemade, was the first production, then mince pies, nuts, games, cards, biscuits, chocolate, sweets, cigarettes, and hand-knitted socks. George, it seemed, was popular, and contributions came rolling in, even the little shops adding their quota as the news went round.

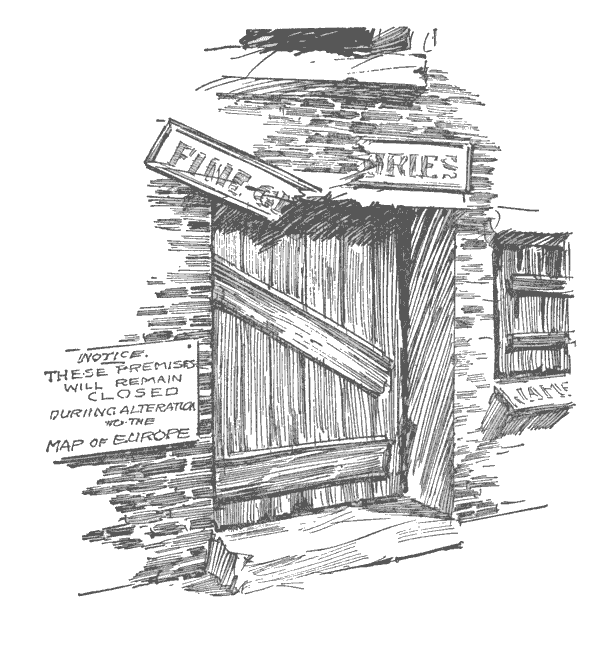

It was an icy day when some of us set out in search of George’s habitat. The postman did not know the address, or the passersby. We ruled out the police, who might have thought we were seeking military information, and it was the coal man who finally led us to the wooden door.

A sentry, in tin hat and Air Force blue, opened it a few inches and looked out suspiciously.

“May we come in?” we asked.

“No,” said the sentry.

The corporal in charge thought otherwise, however, and we were invited into the mess room, already garlanded for Christmas and with a brave fire at each end.

Outside in a desolation of frozen mud lay George, tucked under his tarpaulin on which snow had been falling intermittently since dawn, but not one of the men wore his overcoat, and their cheeks were glowing.

They felt fine, they said.

Things have developed since those days (for we still sometimes knock at the wooden door, when some suitable gift has come into our hands). The crew have built better quarters and made themselves a garden. A cat has taken charge of the crew. He basks on a ground sheet, directing operations when weather permits, otherwise sleeps by the mess room fire, they say.

Like Samuel he wears a white disc, denoting that he has been registered by Narpac—National Air Raid Precautions for Animals, so that if the worst should befall, he will not be left injured, homeless, or neglected.

News has just come up that Fluff the Persian is very ill and would not touch his breakfast. He belongs to a work-woman whose little home was bombed out the other night and who is accommodated nearby for the moment with her family. As soon as she finds new quarters the authorities will provide for the furnishing.

Fluff, the canary, the eight-day clock, and her youngest daughter’s best hat were rescued at the height of the raid. It was a bad night and even Sam was exhausted afterwards for days and only woke from his dreams to eat.

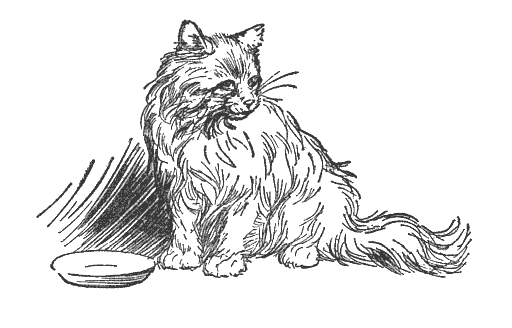

The smoke-gray Persian with orange eyes is the idol of his family and has not the stamina of S. Penguin.

Taken to the Animal First Aid Post where hundreds of his fellows have found shelter and care, he fretted for his friends and his familiar place and would not be persuaded to eat. Expert opinion called it shock and ordered warmth, care, and food if he could be persuaded to take it.

They have him in their room now, and perhaps the canary and the eight-day clock will comfort him as he lies in his blanket, hearing the voices he knows. Four saucers surround him, milk, meat, water, and fish.

Even Sir Samuel Penguin could not ask for more.

t is hard to believe that the Sam of today, who

lifts his head at the sound of the Air Raid Siren

and glances from one to the other of us to see

if anything is going to be done about it, is the

same cat who for many months looked us over and

went his own way, revealing nothing.

t is hard to believe that the Sam of today, who

lifts his head at the sound of the Air Raid Siren

and glances from one to the other of us to see

if anything is going to be done about it, is the

same cat who for many months looked us over and

went his own way, revealing nothing.

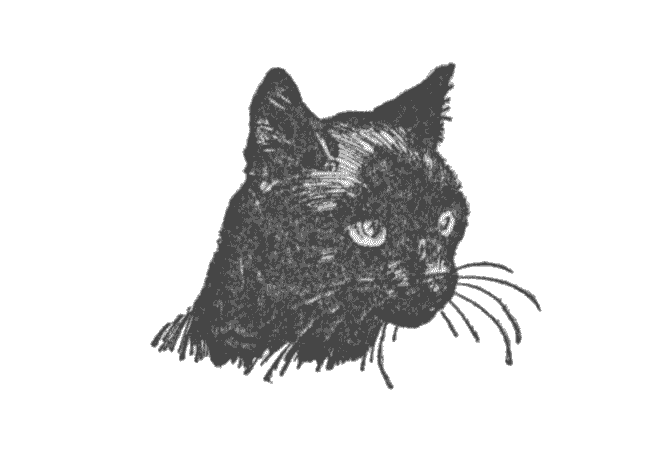

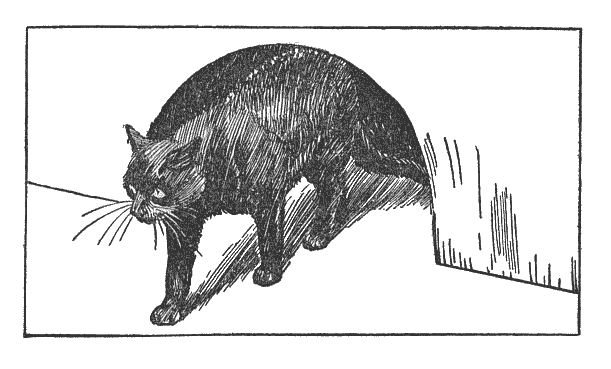

One might imagine he sensed the fact that we had each secretly been a little disappointed in his appearance, except that he was far too impersonal to be suspected of any interest in the matter.

Though we did not put the heresy into words at the time, we agreed later that he was not quite the cat we had hoped him to be; he was too long and thin; he was an odd-looking cat with none of the debonair charm of his predecessors in the family.

There used to be a theory when we were children that to attach a cat to a new home you must thoroughly butter his paws, the idea being that by the time he had licked them clean again, he would have forgotten his old address and settle down contentedly. This is of course a libel on a cat’s memory and mental attainments. If he stayed it must have been because he liked the butter or had no fault to find with his new surroundings.

There was no necessity to try this or any other experiment on Sam because he accepted the situation and saw his guardian depart without making any attempt to escape. His manner, however, lacked enthusiasm, and when he could at last be persuaded to sit on the hearthrug by the fire he did so with shoulders hunched and with none of that pleasant abandon of the comfortable cat.

“Don’t you like the place, Sam?”

No answer. He stared ahead of him at a world of lost delights we could not see and where no alien voice could reach him.

Carried to my bed that first night, he sat there in the same unyielding manner and had not attempted to move when I fell asleep. Next morning he had vanished. We called and searched for half an hour without avail, until suddenly a black head appeared over the top of my wardrobe.

This walled fortress could have been reached only by way of the dressing table, the mantelpiece, and a flying leap, unless the cat had wings, yet nothing had been knocked over or disarranged.

“He must be a witch’s cat,” we decided. “Better go and lock up the broomsticks. We shall have to be careful.”

It required a ladder to bring him back to earth, for he sat there stubbornly, watching our efforts to entice him with gold, unwinking eyes.

He was in fact ungregarious and non-co-operative, and, having revealed his hiding place, he never went there again.

It was not a good beginning, but we made excuses for him, for he had his virtues. His manners were above suspicion, and in the kitchen it was reported that he could be left with fish, flesh, or fowl, and he would not dream of touching it unless invited. Nothing would induce him to come in to meals and ask for food. It might be that too much discipline in early youth had soured the cat, we thought, and tried to coax him with saucers of milk and cream. It was no use; he turned his back and marched off, and we soon discovered that he drank nothing whatever.

In fact, like the good young man he neither drank nor swore.

When after a month or two he had still never been heard to make a sound of any kind we came to the conclusion that he must be dumb, but his late guardian denied it. She revealed, however, that he had never been a cat of the first consequence in her house, where she had had her favorite and the cook another. This did not suggest a very intimate knowledge of his disabilities, and it seemed likely there was something wrong with his vocal chords.

We tried a little gentle massage, but he still retreated before all advances, and if too much pressed he would retire to a distance, aloof and proud, or stand on his hind legs and impatiently push open the door. When it was shut he would rattle the handle at first from the floor and then sitting on the nearest chair, eyes dark with indignation, hitting out at it with a long arm.

After all, the cat was clever and entertaining, and what more could anybody ask? As we grew accustomed to his looks we began to find graces in them as we forget the plainness of a human friend.

His fur was of the finest, and he was always beautifully groomed. Visitors began to remark his magnificent and shining coat and make fun of his oddities, for he would sit looking them in the face with a steady and most uncatlike gaze, his small forepaws neatly together, head up, sides sleek, and a ridge of upstanding fur neatly tracing his spine.

This peculiarity puzzled everybody. It was as though his coat had been put on back to front, or as one critic disrespectfully suggested:

“Sam, I regret to say you have an incompetent furrier.”

Presently we discovered that he could think, in spite of those who like to declare that animals have instincts but nothing more.

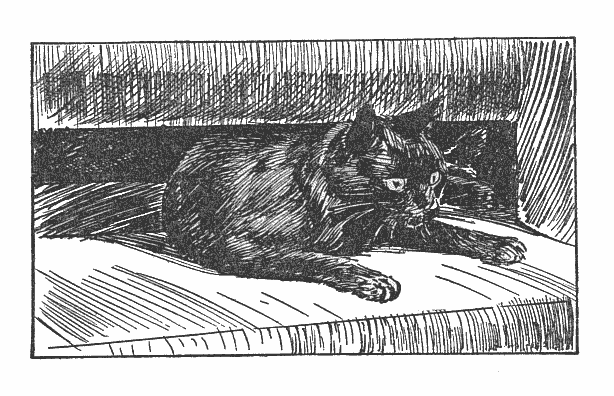

He would stroll in looking for a resting place and examine every chair and couch with a considering air. Often he would discard them all and make off down the passage, looking into the bedrooms, one by one, pausing a moment to make up his mind and then going on again until the perfect place was discovered. He would take no advice and cared for no preparations. If followed he would retire indignantly.

He learned all the ways of the household and how to use them to his own advantage. When a shrill whistle announced that stores were on the way up in the service lift you would see him racing, a black streak, for the kitchen. We had been advised that a diet of raw steak was the proper food for a cat of his color, and this may have been a pleasing change for Samuel Penguin, who certainly thrived on it and began to fill out, now there were no longer four rivals to compete with him for the meal. Soon we were amused to notice a change in his tactics.

Ethel in the kitchen liked his company and left the dividing door ajar on the ground that the rattling of handles was liable to fuss her when she was at work. Now when the whistle blew Sam would cock his ears and listen for further developments. He had soon discovered that other things besides his dinner came up in the lift and learned to distinguish one thud from another as they were transferred to the table. Resounding bangs or the rolling of fruit and vegetables were of no interest to a cat. A soft thud and rustle of paper announced that the butcher had done his duty and it was worth while to get up and have a look.

The strict training of his youth still held, however. He would sit on a chair and watch the parcel opened with dignity and self-restraint, never venturing to touch it until invited.

“No one could ever call him a greedy cat,” defended Ethel, showing us the bowl with one piece of meat uneaten. “He always does that—what my granny used to call leaving something on your plate for Mary Manners.”

In time his interest in parcels, thanks to Ethel’s indulgence of the fancy, began to include anything we brought in from town. He would rise on his hind legs, paws spreading until his curiosity was satisfied, and, when the wrapping was large enough, sit in it and wash his shining nose.

It was at least something that he made no complaint of our hospitality and had begun even to tolerate conversation, but still obstinately he held his tongue, a strong, silent cat who neither meowed nor purred.

The sun has passed from his chair, and Samuel Penguin has just drawn attention to the fact by a sound between a cough and a grunt, hinting that he would like to be moved back into the glow, thank you.

Oh, yes, he was deceiving us all those months for some reason best known to himself. His vocal chords are in excellent order, and he often has much to say to his intimates though still reserved in general company.

However, he has long mastered the establishment, whereas ten years ago we were on our trial, and he cared little who came or went.

To say the least of it this was unflattering and we told him so. We boasted of the charms and attainments of his predecessors in the family.

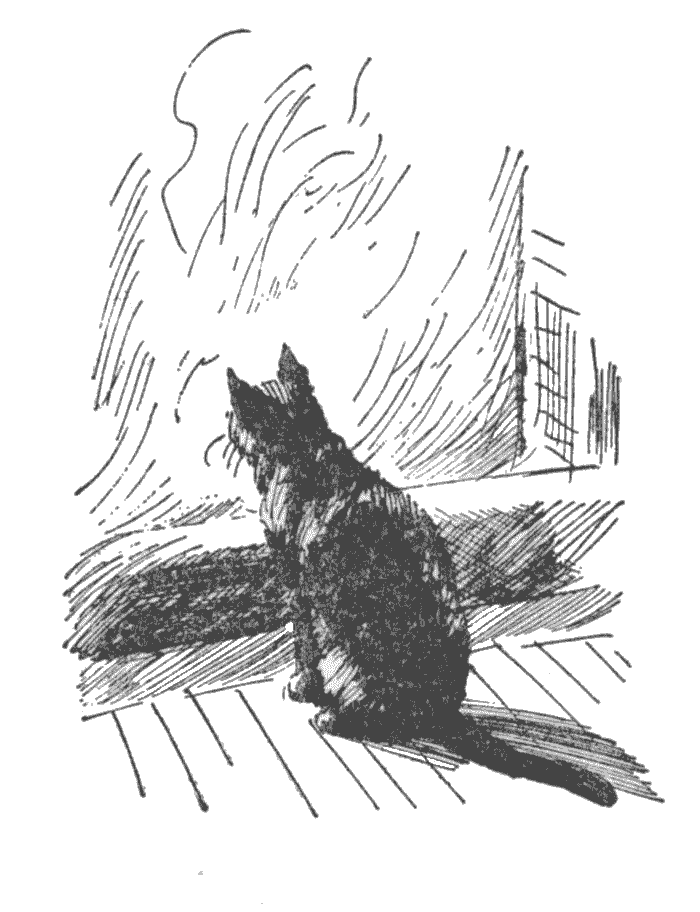

Sam turned his back on these puling reminiscences or mounted a chair by the window and, paws on sill, looked down on the passersby. Pigeons wheeled across from one tall building to another out of the wind to settle in galleried rows for the night. The cars and taxis running past had yellow eyes like his own, and they twinkled back at him through the gathering mist. He seemed to like them.

By day when the weather grew milder, he would spend hours sitting aloft on the stone coping of a little balcony set in an angle of the wall, but one morning just before breakfast he was missed and we called him in vain. Every nook and corner was searched, and the coping was so wide that nobody thought of its danger.

This is an odd building with stone ornaments here and there and balconies tucked at different points on different floors, as though the architect had detested uniformity and determined to give every flat its own individual character.

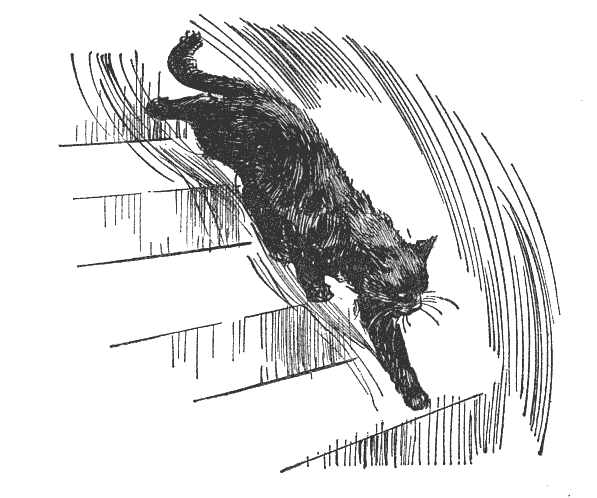

The plan has its virtues, not the least among them that it saved the life (or one life) of Samuel Penguin. He must have leapt after a bird on to a ledge and slipped, for we discovered him at last on another balcony, twenty feet below.

A rescue party brought him back, whole but subdued, and for days he walked like a cat on hot bricks. His paws were very sore and his relieved family waited on him hand and foot as he slept off the nerve strain of his perilous adventure. A small piece of liver was ordered with his steak as likely to tempt the appetite of the invalid; a little cream was offered in a particularly attractive saucer. Eiderdowns were put down for his bed. He accepted the first and last, but turned from the cream with distaste. Nothing would induce him to drink.

“It will oil your works, Sam, and help you to purr.”

He had no intention of purring or taking anyone’s advice. Yet perhaps he listened though he gave no sign. Who can say?

“You are beautiful but not very gracious, Sam,” said the head of the house between indignation and amusement. “Why will you never sit on my knee?”

A day came when he got up and sat there one whole long afternoon, as though he alone of any of us knew that it was the last chance he would ever have.

arkness fell upon Sammy Penguin’s family,

and we who were left decided to go away

from London to the country for a little

while taking the cat of the house with us.

arkness fell upon Sammy Penguin’s family,

and we who were left decided to go away

from London to the country for a little

while taking the cat of the house with us.

We bought a red leather lead to match his collar and a traveling-basket, dubiously displaying them before him. His response was better than we could have hoped, for he leapt into the basket and promptly went to sleep.

Having the railway compartment to ourselves next day, we set him free and he stood with his forepaws on the window ledge gazing out with evident interest. He even accompanied us to the restaurant car for luncheon and ignored in a dignified manner the advances of fellow travelers and the familiarity of the waiter’s “Well, puss, what can I do for you?”

Puss indeed! Never in his life has Samuel Penguin responded to this childish form of address.

The hotel had not been warned to expect a cat visitor but the reception clerk was a reasonable man.

“If we take dogs, why not cats?” he said.

Superstition may have played its part in Sam’s cordial reception. The hotel was newly opened and the cat was black. What better omen for a prosperous season? His collar hid the fact which even we had been slow to discover, that he wore a neat white tie, but no harm was done. He became not merely a welcome but also a popular guest.

This was some of the most beautiful country in England, deeply wooded hills and flowering valleys ringed by old cities rich in history. It was now early summer, hard perhaps for a cat not to be out and free in a world full of bird song and deep grass. Yet Samuel Penguin showed no disposition to escape to these delights but would sit by the window which looked towards Bredon, enjoying the sun and the flash of passing wings, or move to the dressing table, to sniff with obvious delight the flowers brought in to us from friendly gardens.

“The cat is esthetic,” we said, but quickly learned better.

As soon as we fastened his lead and led him out of doors, he raced for the lawn, in search of the salad which every cat requires. Never having owned a purely indoor cat before, we had not realized the need. He passed the larkspurs, delphiniums, and roses, which had seemed to charm him, without a glance and eagerly cropped the coarse grass, sneezing from time to time as it tickled his whiskers.

This refreshment over he was ready to go indoors, walking with great dignity, tail aloft, and retire for a bath and a sleep.

He was soon a familiar resident. The porters knew him; the head waiter gave us counsel about his diet; chambermaids from upper floors came down to our room to entertain him when we were out; the manager made inquiries as to his health and comfort.

At night he slept in his basket, rising at dawn to push aside the window curtains and look out at the new day.

Then “half-term” came at the public school in the town, and early in the morning parties of tall lads invaded the hotel to breakfast with visiting parents. Somehow Sam eluded us and slipped downstairs to the vestibule. There we found him, blandly sitting in the center of a concourse of boys.

We should have expected him to run for his life, and we should have expected them to be self-conscious, but not a bit of it. They addressed him, showed him off, and introduced him to assembling parents.

They said to us: “Your cat is the talk of the place. Is it true he has been seen walking on a lead in the public gardens?”

It was not true, but it didn’t matter. Sam was a success and he knew it. His silken coat glowed in the morning sunshine; his eyes turned in rather smug approval from one young lord of creation to another. This was his world and we were nowhere.

We began to suspect that in the past of which he could not tell us the Penguin had been a man’s cat.

What then had become of the monster? Had he basely deserted his good companion and left him to fend for himself, or died perhaps, forgetting to provide for his orphaned cat?

The wiseacres tell us cats care only for places and nothing whatever for their human friends, but Sam, in an acquaintance of years, has disproved all theories, and still faithfully he is the friend of man.

There is an alternative explanation, of course, for we soon discovered that if caught up, however gently from behind, he would turn and fight like a demon. Had he, in that tragic past, been stolen, carried away, and then escaped from his captor far from home; stolen to be sold to the vivisectionists perhaps, or to some lesser villain dealing in hides and skins? I had a friend once who used to take pleasure in reading me the daily advertisements—“damaged house cat, one and eleven pence.”

There are scores of well authenticated instances in which cats, moved to a distance, have returned to the old address, finding their way across strange country and tramping incredible miles.

We once met an even more remarkable traveler. He was a cosmopolitan cat who regularly went round the world in an ocean liner, waited on by a steward in an officer’s cabin. When the ship touched port he liked to go ashore with the rest of the passengers and would hurry down the gangway ahead of them.

One night in Bombay he was late returning and, alas, the liner sailed without him. His friends on board were loud in their lamentations, believing him lost forever. The traveler cat, however, knew his way about. He was no tyro. He simply boarded the next ship of the line, sailed home in her to Tilbury, stepped ashore and crossed the docks.

There in her familiar berth was his own vessel getting ready for sea again. He walked up the gangway and into the officer’s cabin.

Samuel Penguin, an individualist, seemed quite indifferent to his change of residence, and never during his six months in London had he shown any disposition to run away. Yet, when our stay in the country came to an end and we returned home by road, he exhibited the greatest excitement whenever we entered a town. Otherwise he sat humped in his corner with an air of dejection or fidgeted from seat to seat.

The passing fields and little woods, the flowering hedgerows, and even the birds meant nothing to him. It was evident that he was no country cat, but a man about town.

At length the tiresome journey was over and the car drew up before our block of flats. Directly the door opened he jumped out and raced for the lift, as though he had never lived anywhere else in his life.

Stranger still, quite suddenly that night he purred to us!

He was not dumb; he had been shamming, looking us over with natural suspicion. For two years he had been moved here, there, and everywhere—from some life we could not guess to the comparative haven of an animals’ shelter; from there to the Colonel’s house where four more favored cats were already in possession; and then to our flat and finally to a hotel in the country. What could a reasonable cat think of these perpetual changes? No sooner had he become accustomed to one habitation than he was thrust out, a stranger, into the world again.

Returning to the familiar flat perhaps restored his sense of security, and so he broke his long and determined silence and blissfully sang himself to sleep.

Or was it just that the daily salad had oiled his works? Discussing this knotty point we saw that somehow and from somewhere, now we were back in town, we must find time to fetch him grass.

It is not to be supposed that he threw off all reserve and unbent completely, but he was now the cat in possession.

When friends came to stay he would bustle after them and survey the luggage as it was unpacked like one making an inventory. While the window cleaner did his work he would follow him from room to room and sit watching until it was done, like a suspicious housewife. The man was one of his satellites but this made no difference; and when anyone moved a piece of furniture he showed real agitation. (That wretched first owner surely must have deserted the cat.)

Slowly we began to see that in some ways he was more dog than cat. He walked, for instance, with his tail aloft like a banner and waving a little at the tip; and when the hall door bell rang, he would point his ears and rush to see who was there.

On the other hand it cannot be said that he was hospitable after nightfall. He liked early hours, and after ten p.m. would begin to give visitors a hint that it was time to depart. At first he stared them out of countenance, and if this had no effect would try physical means, leaping on the chair arms and at last tearing madly about the flat until the door was shut in his face. No sooner did they make a move than he was still again and would pompously see them to the lift like an early Victorian papa who meant to have no nonsense.

He slept at night on somebody’s bed or easy chair that autumn, but by and by when all was still except for the passing of late cars on the road, or the whistle of a distant train, he would get up and march about on his own affairs. By day his steps were soundless, but now he positively tramped, so that one of us, waking, would call out to the other: “What is the matter? Can’t you sleep?”

This peculiarity at last gave us the clue to Samuel Penguin’s difference from other cats we had known. In spite of his black coat and golden eyes he was largely Siamese. The original Puss-in-Boots an expert has called these curious and lovely creatures from their habit of striding heavily about in the dead of night. We should have known it from his small delicate head and doggy way and the exquisite texture of his fur.

We were grateful that the meow had been omitted from Sam’s attainments, at least in the ancestral minor key. The distressing voice of the Siamese is the only drawback to a brilliant cat. Whether the ridge down Samuel’s spine is another inheritance we have never discovered, but the clear proof of his mixed descent was to come with the years, and he wears it now with pride.

NEWS BULLETIN: Fluff, the Persian, has licked a little butter from his mistress’s finger. In a case of life and death rations cannot be considered.

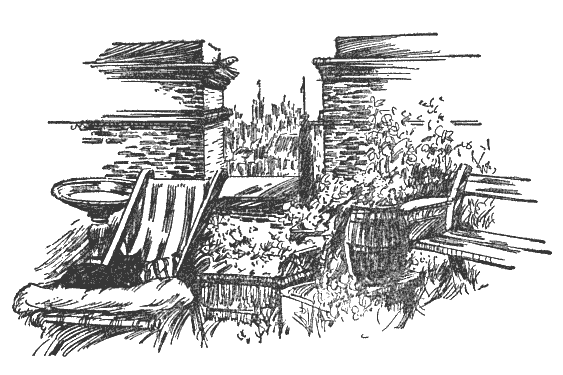

t was a great moment for the cat of the house

when a member of his family who possesses

“green fingers” decided to have a roof garden.

It was to be in tubs and boxes, but the place was

there to her hand with a delightful view over the roofs

of London to the distant Surrey Hills. There was even

an iron fence and gate for privacy and walls east and

west to stay the wind. Best of all there were innumerable

posts against which a cat could rub his person and

many hideouts where he could lurk in secret, to persuade

his distracted friends that he was lost to them

forever.

t was a great moment for the cat of the house

when a member of his family who possesses

“green fingers” decided to have a roof garden.

It was to be in tubs and boxes, but the place was

there to her hand with a delightful view over the roofs

of London to the distant Surrey Hills. There was even

an iron fence and gate for privacy and walls east and

west to stay the wind. Best of all there were innumerable

posts against which a cat could rub his person and

many hideouts where he could lurk in secret, to persuade

his distracted friends that he was lost to them

forever.

Directly breakfast was over, it became his practice to follow the gardener like a shadow, and soon if anyone mentioned the word roof, he would race to the door.

“The cat understands English,” she exclaimed. “If he can spell we are done.”

Fortunately in this particular his education had been neglected and from then on certain words had to be spelled in the presence of our precocious beast.

The little garden was an experiment, but to the onlooker it seemed that everything grew for green fingers. People possessed of these useful attributes seem to need no garden hints. They simply thrust something into the earth and presently there is a bush or a budding flower.

Sticks put into a pot of daffodils by the florist to prop the blooms, burst into leaf when in the presence of such fingers and next thing they have developed into a privet hedge or bush of laurel.

On the small balcony we have a spreading chestnut tree four feet high which was once a nut in the gardener’s hands; and in these days of war when money should not be spent on merely decorative plants, it glows with beauty for our refreshment through the open door.

Our neighbors opposite are growing tomatoes “for victory” on their window ledges, but we can go one better than that. The roof garden has become a vegetable plot in miniature, and even the window boxes round the balcony are green with young carrot tops in place of the tulips which usually delight us.

Last summer an enterprising firm grew lettuces in pots in Regent Street, but the gardener beat even that curious record with excellent runner beans as well as the humbler vegetables, all grown on a London rooftop.

That first year the soil she bought was so rich that even the pansies tried to grow into trees, and asters, pinks, and carnations flourished between the tubs of ornamental shrubs.

Around this block of flats and others close by an army of pigeons had for years led a more or less unmolested existence. They slept on the narrow ridges of stonework under our windows and woke us every morning with a murmur of cooing song. Sam was often discovered balancing on the back of a chair and gazing out at this attractive noise, opening his mouth in what should have been a meow if he had not decided early in life that meowing is simply not done.

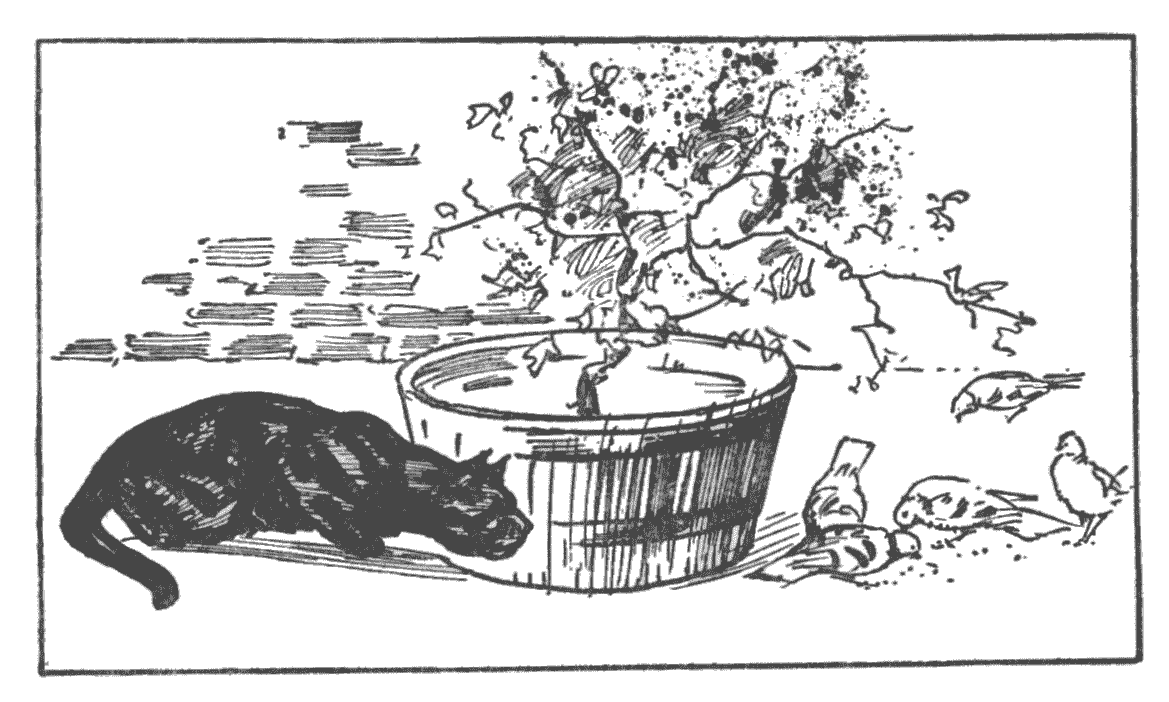

He was strictly ordered not to touch the birds and, understanding “No, Sam” perfectly well, has never once in a long life transgressed since his fall from the balcony. The cynical may argue that he has never been hungry, which is true, and there was an “incident,” as the communiqués say, but it ended happily. An odd noise was heard in the drawing-room and pulling out a couch beneath a corner window, we found a young pigeon, fluttering and terrified, at one end of it and Sam, hardly less astonished, at the other. He had done it no harm and was praised accordingly, while the young visitor was restored to its mother.

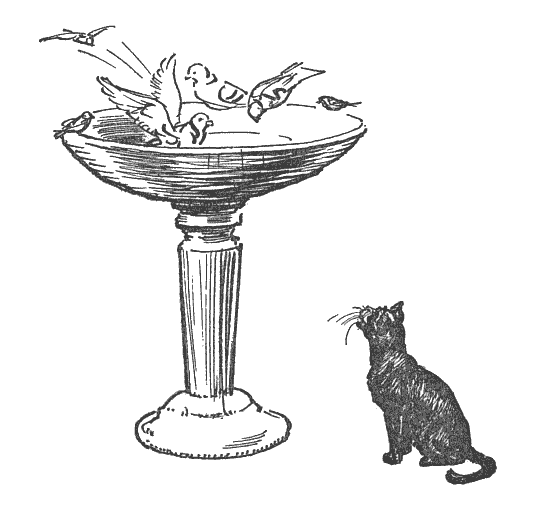

Naturally the installation of a bird bath and feeding bowl for the birds on the roof garden soon attracted the pigeons, as well as starlings, sparrows, and other small fry. It was not only a humanitarian gesture. The gardener meant to give them no excuse to eat her young shoots and you would think the pigeons knew it by the way they clamor when the bowl is empty.

The London pigeons, however, are the most pampered of birds. Who has not seen them fluttering down in battalions in Trafalgar Square, to sit on the heads, shoulders and even hands of strangers with crumbs and grain to give them? Ours, moreover, were living a double life, had we but known it, for they had a friend and protector who walked down the road every morning to scatter seed for their breakfast.

It is credibly reported that they not only expected this good friend, but kept a lookout bird to give due warning as soon as he turned the corner.

Meanwhile, the deceitful creatures, feigning hunger, moved at ease among us, almost beneath our feet, and, more surprising, Samuel Penguin’s.

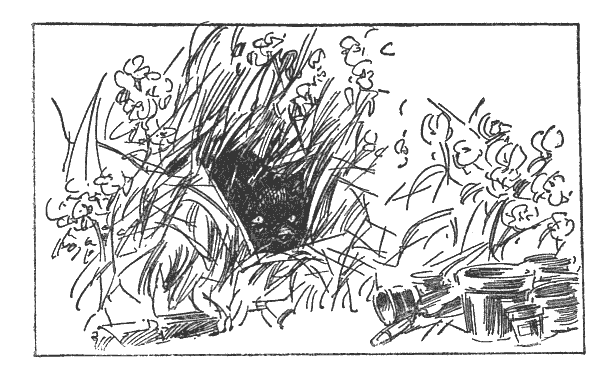

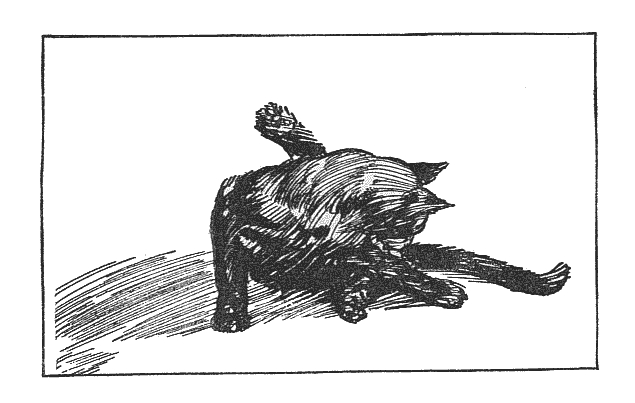

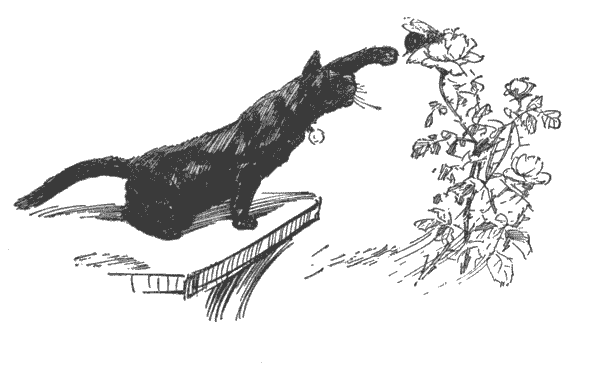

This was the life for him. He would stalk them silently crouching between the tubs, or leap into the middle of the party and stand there as though astonished at their fluttering and indignant retreat, and, when called to order, lie on his stomach with the most innocent expression imaginable. What, he seemed to ask, was all the fuss about? He wasn’t doing anything.

He discovered a narrow ledge below the parapet and here he would lie watching, with narrowed golden eyes, the moving clouds or perhaps the distant spires of the City.

For all we know he may be a direct descendant on his mother’s side of that fine fellow who, six hundred years ago, followed young Dick Whittington to the metropolis and helped to found his fortunes. It was at the foot of Highgate Hill not many miles to the north of us that Dick sat discouraged on a stone by the wayside with his bundle over his shoulder and his cat beside him and heard the pealing of Bow Bells:

“Turn again, Whittington,

Thrice Lord Mayor of London.”

A little wind from the southeast carried the message distinctly, and the cat (if I know anything) arose and stretched and wound himself round his master’s legs.

So doubly advised Dick turned again, pushing down the country road with his friend at his heels. Perhaps he passed this very spot, a sunny English meadow, starred with daisies, and found before he reached the City a stream where he could drink and wash away the stains of travel to make a good impression; and the wise cat with the same end in view carefully groomed his whiskers.

There is a sinister silence in my reference books about this illustrious predecessor of Samuel Penguin. One goes so far as to say the origin of the Whittington legend is lost in the mists of time. This is “fifth-column” work, undoubtedly, by some brute who would banish from the world all magical or pleasant things.

For let us look at the facts. There must have been thousands of Lord Mayors since, good citizens all, to have attained that high position, but which of them do we remember, as we remember Dick?

Highgate is a suburb now. London has reached out and gathered it into the fold. And there, at the foot of the hill, carefully railed for all the world to see, is the very stone, commemorating the fact that here, with his cat, rested in 1341 (shall we say?) the poor apprentice who was to become Sir Richard Whittington, thrice Lord Mayor of London and benefactor of the City.

Obviously Bow Bells and the cat between them did the whole thing.

Besides the birds, the growing plants were a source of constant delight. Sam went from box to box, sniffing the different entrancing smells and finding blades of grass to eat.

Soon the gardener provided him with his own salad box, to which was presently added a larger one containing his private lawn. To shade him from the wind she planted a border of michaelmas daisies round it and here he would lie stretched at his ease, peering through the forest of daisy stems at the visiting birds or enjoying the warmth of the sun.

Then, turning, we would find he had gone, over the roof perhaps to the strange and exciting territory of the other block, or swift as an arrow down the stairs to slip in at any available open door. All his suspicions of the human kind had gradually worn away. He approached these strange households affably as one certain of welcome, examined their rooms one by one, and, if he liked the place, went to sleep in the laundry basket or under the bed. Half the time they didn’t see him come in and he was only found after long and frantic searching. We bought him a bell for his collar, and this helped a little, but with all this coming and going he had become a marked cat. The workmen were on excellent terms with him, and he would sit among their trestles and paste as they redecorated an empty flat, yet return spotless and immaculate as ever.

The porter would ring the bell, Sam under his arm, or perhaps to say:

“Have you lost him, Madam? Because I hear he was seen passing the time of day with the coal man at the entrance door.”

The porter had a cat of his own. Moreover, he has served the tenants here for more than half a century. He saw the place built in his boyhood, when flats in London were new and rare and these were known in the Victorian manner as “suites.” Many of the stage celebrities of the time came to live in them (for flat dwelling was probably considered rather Bohemian in those days), and he knew them all. He saw the place altered and brought up to date, gas succeeded by electricity, box-rooms below give place to furnaces for central heating, the nearby mews change to a garage.

“You won’t find such doors nowadays,” he says, fingering the fine-grained wood which defies draughts and noise. “Nor such sound walls.”

I believe he looks upon the new blocks springing up with their vast vestibules and poky rooms as a vulgar mushroom growth, all very well in their way, but not at all suitable to “my tenants.”

He remembers when the last toll bars up the road were swept away, because a famous lord of the time missed his train to the country; and from the roof garden he will point out the charming curved back windows in what was once a duke’s town house. The drawing-room still has its fine painted ceiling, he says. “Ah! those were the days.”

The ducal family owns much of the property in the neighborhood and to that we owe the pleasant space of grass and trees visible from our windows and serving no other purpose than to add grace to a London street.

There are trees too, rising above the housetops, and the delicate spire of a church containing a reredos painted by Burne-Jones to the memory of Christina Rossetti. The Rossettis lived in the neighborhood long ago, the father having come to England from Italy, a political refugee, as men who love freedom have come throughout the centuries and as they are coming now.

Not more than a hundred yards away Sir John Millais painted some of his most famous pictures, and round the corner the great Siddons had a country house and garden.

Samuel Penguin, caring for none of these things, nevertheless seemed to enjoy the view.

“Perhaps,” said the gardener, watching him with his forepaws on the sill, “he wants to exercise his catty privilege of looking at a King.” If so he had a grand stand view, for often the royal car drove by without any other fuss or ceremony than an extra policeman here and there to keep the traffic moving. Seeing these, people would gather in little groups in the street to wave and raise a cheer.

And today when we hear of the dictators’ armored trains scuttling about Europe, bristling with machine guns and bodyguards, we smile and hum the latest popular song:

“The King is still in London town

Like Mr. Jones and Mr. Brown.”

We bought a sundial, a garden seat, and a hammock shelter with a waterproof cover to shut out the wind and rain.

Samuel Penguin preferred to occupy the shelter in solitary state, except in hot summer nights when his lawn grew chilly and he would curl up between us rather than be banished indoors.

By day the view contained too many roofs and chimneypots in the foreground, but with dusk it became mysterious and enchanting. Southward suddenly the face of Big Ben seemed to be hanging like a friendly lantern in the sky and the massed roofs melted into pools and bridges and towers and the masts of phantom ships on a phantom river, and here and there a floodlit building like a ghostly windjammer added to the illusion of a city new and strange, and everywhere a myriad of twinkling lights threaded and girdled the scene.

Remembering the brilliant skies of southern latitudes, we were always sorry that London seemed to have few stars, but this was an illusion. They were there and waiting for the dark nights to come. Charles’s Wain, Orion’s Belt, and the Pleiades keep watch with the Fire-Spotter, the Air Raid Warden, and the Home Guard above the darkened city, symbol that the little lights of man, though dimmed, shall burn again.

By November the garden shelter had to be dismantled and packed away lest the winter gales should hurl it into the road, for even in mild weather we had found it necessary to clamp it securely to the iron railing.

Gusts of wind would billow the canvas covers as if it were a ship at sea, parting at the same time the fur of an indignant cat in all directions.

Once an open tin of green paint set down on a newspaper was lifted into the air and sent careering over the face of the building to the pavement eight stories below where it missed by only a few yards a Rolls Royce standing at the curb and a passing pedestrian.

The tragicomedy of the lost hat on another occasion was due to a summer breeze. Inevitably it was a favorite hat, and the gardener, coming in from town, had forgotten to change it before going on the roof.

In a moment it was gone. Moreover, the lift was in use by one of those slow and stolid people who seem doomed to appear in moments of emergency and clog the wheels of progress. By the time she reached the street there was no sign of the hat. It had, however, been seen.

A passing minx had picked it up from the pavement, put it on her head, examined the effect in a neighboring window and coolly walked off with it.

MEMO: Perhaps a little grass from Sam’s salad box might be good for Fluff the invalid.

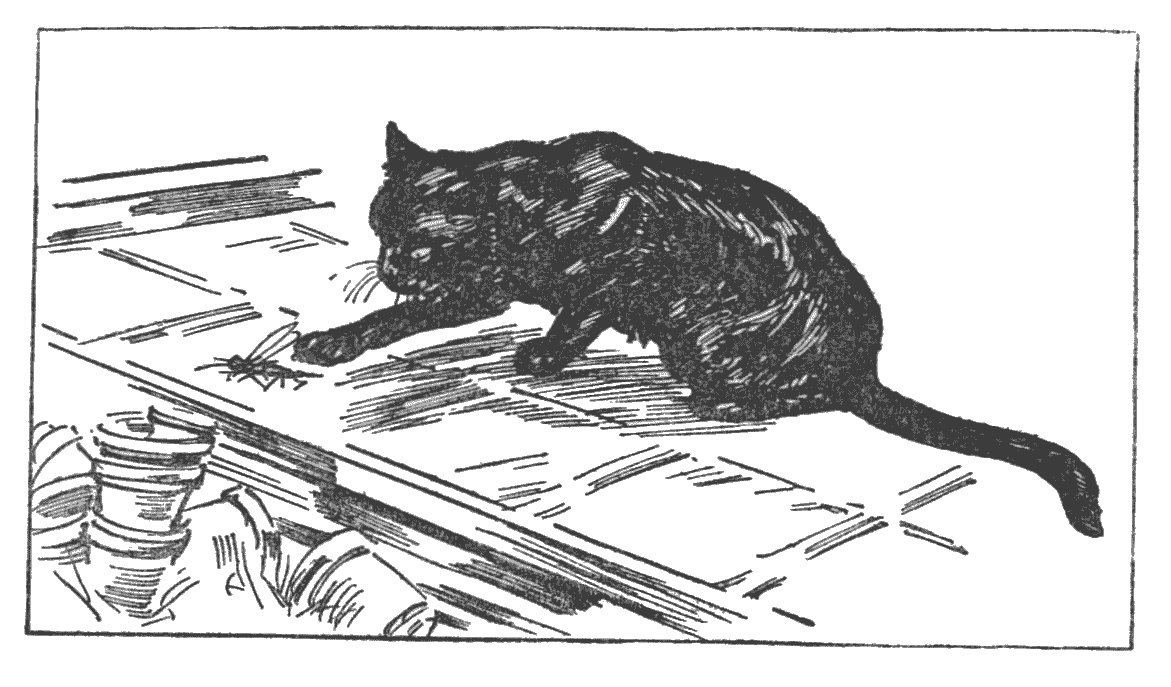

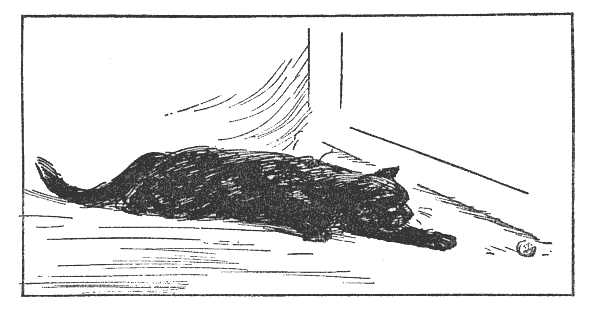

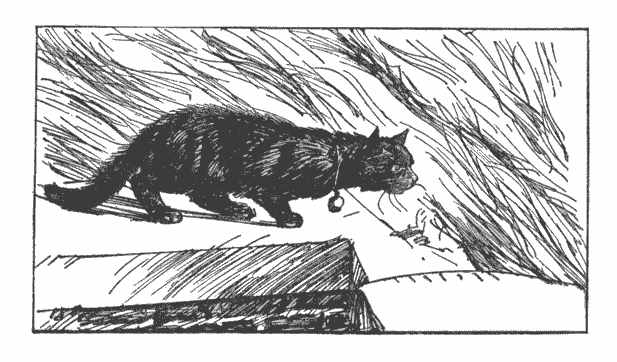

amuel Penguin is no mousekeeper. As far as

we are aware he has never seen a mouse in

real life, though it is possible that his reputation

as a hunter may have kept such visitors

away from our premises. These things must get about

in the underworld, or how should a mouse survive?

amuel Penguin is no mousekeeper. As far as

we are aware he has never seen a mouse in

real life, though it is possible that his reputation

as a hunter may have kept such visitors

away from our premises. These things must get about

in the underworld, or how should a mouse survive?

Sam’s friends, anxious to bring him a present, tried every kind of toy mouse in vain for some time. Like Queen Victoria on a celebrated occasion, he was not amused.

He had attached himself to a doctor neighbor of ours, so much so that when this man came in for a game of bridge, Sam would sit a whole evening on the arm of his chair watching his play like an expert, and then offer to accompany him home.

As a slight return for these attentions, no doubt, the doctor brought him a clock-work mouse. This was a success, though I believe it was less its mousiness which attracted him than the delectable noises it made. He liked to hear it wound up and would then knock it over in order to listen to the works running down. Though it has long vanished from the scene, he remembers this attractive sound and attends all clock-winding occasions with an alert and hopeful air.

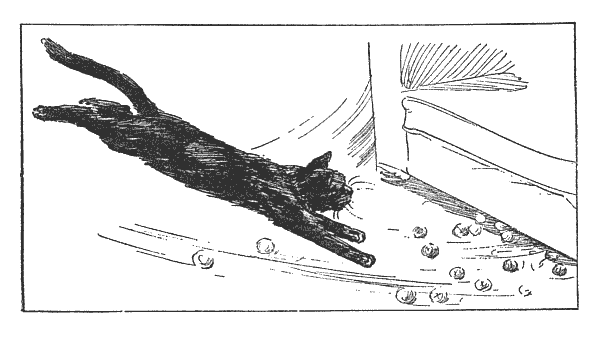

An American visitor, having met Samuel, kindly sent him one Christmas a different mouse—a soft affair filled with catnip. This caused him intense excitement. Sam the Silent actually muttered with joy, half growl, half gurgle, clasped it to his heart, tossed it in the air to catch it again and after a hilarious morning dropped to sleep with it under his arm.

Then began a nightly ritual. Before bedtime Sam would climb to an arm of the couch and sit there expectantly. He was no more the long slim cat of earlier days but a stout fellow with bulging satin sides, but he had not lost his agility. When the mouse was thrown to him he would rise on his haunches and catch it, or using one paw as a bat, launch it back to the “bowler.” Bradman himself—that ace of all cricketers—could not have put more grace into the stroke.

This talent is another Siamese trait, I have been told; also the delicacy of tread which permits Samuel Penguin to walk through the glass or china cupboard without disarranging or breaking anything.

The catnip mouse, alas, wore out, but a favorite friend in New York, learning of the tragedy, sent him a whole box of them and throughout the years he has never forgotten to keep him supplied. So enriched, he has been able to introduce this attractive plaything to certain other favored cats. One Persian gentleman, David Garrick, has earned this attention by sending him each winter when grass is hard to come by (as every house cat knows) a magnificent tin of it growing, tied up with scarlet ribbons.

The man in New York, though seen only at intervals, has a high place in Sam’s regard. After all, they have much in common, a passion for warm rooms, good fires, salads, and a well-groomed appearance. It is true that the man doesn’t wear a white tie and tails in the day time and Sam has no alternative, but he has a quiet voice and knows how to address a cat.

“Dr. Livingstone, I presume,” he said, on meeting Mr. Penguin unexpectedly the first time.

Sam may not have known the reference, but he was visibly impressed by such a respectful salutation.

Moreover, the visitor brought a little music into the house, and the top of the grand piano was a perfect place to lie and enjoy the vibrations. Once when the lid was open for a Beethoven sonata he leapt on the strings in a praiseworthy endeavor to provide orchestral accompaniment, but for the most part he was an excellent audience and would roll over with ecstasy at certain notes in the bass.

One day there arrived from America an enormous box addressed to “Samuel Penguin, Esq.” much to the mystification of the postman, who delivered it with doubt:

“Would it be for you, Miss?”

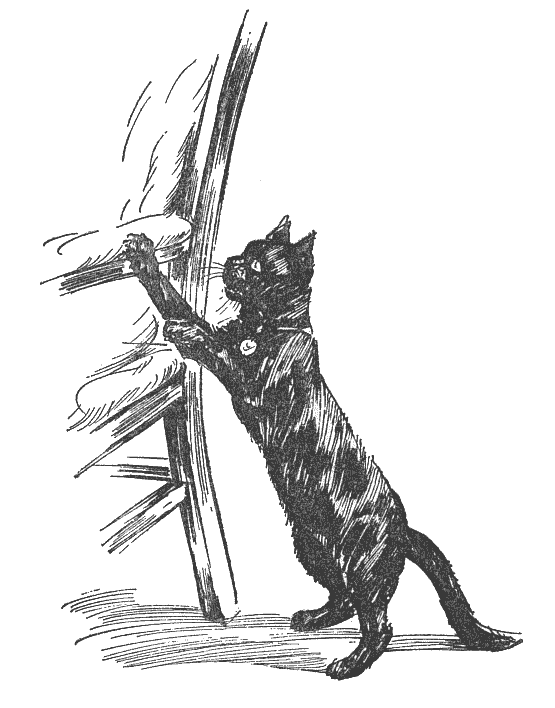

“Oh, yes, it is for the cat of the house.”

The gift proved to be a fine scratching post and I suspect it had a double purpose—to please Sam and to assist a domestic dilemma.

The rascal had reduced one leg of the kitchen table almost to matchwood, and about this time we had learned from an expert that it was sheer brutality to deny your cat somewhere to sharpen his claws. He should have a piece of carpet nailed up firmly somewhere within his reach.

Having bought a yard of stair carpet and nailed it round the table leg however, we had been disappointed. A fig for your experts!

Sam evidently regarded this proceeding as an insult and a reproach. He retreated from the hated thing and washed his hands of it, transferring his attentions instead to the side of a cupboard well out of the public view.

The scratching post was a magnificent affair, not merely covered with carpet, but impregnated with his favorite scent. Our hopes were high, but who really likes a useful present?

Sam enjoyed sniffing it and rubbing his body round it, but scratch the thing? Not he. The box it came in was a different matter,—a brand new bed with masses of fresh tissue paper from foreign parts. He rustled and reveled in it for hours on end.

A wire brush brought to him was a great success, though it was certainly gilding the lily to assist his toilet in this way, when his tongue could do all that was required.

The sharp bristles gave him exquisite pleasure. He rolled, he squirmed, he opened his fingers and closed his eyes, and finally rubbed his teeth on them as the crowning joy of the whole performance, purring loudly. To this day he will follow anyone who produces the brush, demanding service.

Independent still, he went his own way and could not be persuaded, and constantly some new doglike quality was discerned in him.

When given food he disliked or more than he needed he tried to dig up the floor round his plate and bury it. Indeed he carried this peculiarity further and endeavored to hide the signs of his guilt in the same way.

Although he has never once broken anything he did one morning knock over a bowl of flowers while seeking green shoots, and was found in the drawing-room frantically trying to dig up the carpet, pausing from time to time to shake his wet paws.

Our methods of clearing up the wreck did not meet with his approval, and all day long he returned to the place to try again until we concealed the scene of the disaster under a rug.

Doggishly too, he recognized friends from strangers and would come to the door and sit there peering round it, moving his head when any obstacle obscured his view. Friendly invitations to enter were ignored. He was determined to keep his freedom of action and was often disconcerting.

We had an Italian guest one night who announced bluntly:

“Your cat is too fat.”

Samuel, without wasting a moment, climbed on his knee and sat there unhindered throughout the evening. We heard no more criticism of the master of the house.

Italian cats, at least as the tourist knows them, must be among the thinnest in the world; so perhaps our guest’s opinion was quite natural. In a totalitarian country no doubt Sam would have been expected to catch mice for the state.

Another incident of that evening gave us, had we but seen it, a hint of the sinister days ahead. At the time the Fascist régime had not begun its lust for saber rattling at the expense of other people’s territories, and our friends were intelligent, traveled, and charming. Yet when we told them that the gardener called Sam “Pussolini,” owing to his dictatorial ways, one of them exclaimed:

“Oh, hush!”

Hush! It was to be the cry of millions of poor wretches in many countries, in fear of the Gestapo or spying neighbors or servants or corrupted children.

We were astounded, supposing they thought the cat’s nickname almost lese majesté. Instead I daresay it was the inadvertent warning of one who had already seen the beginning of the new tyranny. People in Europe had already vanished from the sight of men for statements hardly less innocent than the gardener’s pun.

Some years later we offered a lift to a stranger stranded on a country road in a torrent of rain, and felt constrained to explain the rather dingy bunch of winter grass we were carrying home to Sam.

The stranger smiled.

“I have lately been feeding eleven starving cats in the English cemetery in Rome, if you happen to know the place,” she said.

We knew it and the headstone to “one whose name was writ in water,” though in truth it was to ring across the world.

Her American husband had been buried there, she said, and it looked so desolate that she had been trying to tidy it up a little, to the incidental comfort of the starving cats.

Sanctions had begun to ruffle the international waters by this time and a nightly broadcast from Rome by a woman who spoke English with an Oxford accent was causing considerable amusement.

Much of her time was spent abusing the foreign press for lying about her country. One paper, she said, had actually dared to say Italy was buying mules for Abyssinia. This was monstrous when she already had 40,000 mules, all of pure Italian breed.

Our new friend agreed that this seemed to be an understatement but said that the atmosphere was not so amusing at close quarters. Things she had seen had induced her to leave the country after a residence of many years, and she gave us some illuminating examples.

“I just couldn’t breathe the air any more,” she said.

All roads lead to Rome, they used to say, but there is only one road now and it echoes to the tread of heavy German feet.

Do Axis visitors trouble to throw their coins into the Trevi Fountain, I wonder?

Does the Gestapo pounce on the urchins of the quarter as they fish the money out? At least it is safe to believe that the cats of Italy grow no fatter, for the locust is over the land.

How fortunate that Samuel Penguin is a free born British cat!

The invalid downstairs may possibly recover. His owner smiles hopefully this morning as she answers inquiries.

Fluff is the apple of her eye, or one of them. The other is her youngest daughter Molly, to whom the Persian belongs.

“He’s ever so well bred,” she says. “We got a paper with him and Molly was given him when she was fourteen. She’s nineteen now and I lay she was anxious about him last night, because she was working, you see. She’s in the War Cabinet.”

No wonder it was necessary to rescue her best hat!

But I suspect her mother was not really suggesting that Molly was Mr. Churchill’s right hand. What with losing her home, nursing her invalid cat and having a daughter clever enough to do night work for the Government, she was a little mixed.

haracter is the essence of a cat, though he

often chooses to conceal it. Posing like the

sphinx at one moment, forepaws neatly together,

he is equally inscrutable, and his

eyes, changing from gold to green, two shining, empty

pools; yet he can respond when it suits his fancy and

convenience.

haracter is the essence of a cat, though he

often chooses to conceal it. Posing like the

sphinx at one moment, forepaws neatly together,

he is equally inscrutable, and his

eyes, changing from gold to green, two shining, empty

pools; yet he can respond when it suits his fancy and

convenience.

Samuel Penguin now followed at the gardeners heels, and his glance, which had at first been a steady stare at each of us in turn, melted at the sound of her voice. When she went out, particularly at night, he sat facing the door with an anxious and expectant air, walked into the hall and back again continually, refusing to go to bed—the man of the house pacing the room and ready to read the riot act about late hours!

It was useless to offer consolation, and at last he would station himself at a point where he could peer round a bookcase at the hall door, his head on one side, listening for the upcoming lift.

He seemed to know by some sixth sense when she was in it and would leap to meet her.

He would leave us for hours at a time but seemed to see no reason why we should be permitted to return the compliment and began to follow us suspiciously when we went to our rooms to change. If, as occasionally happened, we had to leave him alone in the flat, he never failed to make it plain that this was an outrage.

He knew what coats and hats meant and would dog our footsteps to the door, meeting us there when we returned to prove that he had never moved from the spot.

Our ruses to get away unobserved were rarely successful, but one day we slipped out, leaving the radio on for company and came home to find him contentedly listening to a political speech. A man’s voice had not lost its hold upon him.

“George,” said our friend Evelyn to her husband one evening, watching Sam lying with his heels to the blaze, “we ought to have a cat. I want one and so does the cook.”

“No,” said George firmly.

“But why not?”

“Because a cat is a tie.”

“Almost everything in life is a tie if you choose to make it so, including a husband,” retorted Evelyn with spirit, but George merely observed that he should hope so indeed, looking obstinate.

We were all going to a theater and, as luck would have it, met an amusing illustration of the argument. Just in front of us sat a girl in a black satin evening frock, with what appeared to be a black fur over her right shoulder, until it opened its mouth and yawned.

It was a spaniel puppy, very sleepy and comfortable, and Evelyn stroked its silken head.

“He looks very young to be taken out,” she said.

The girl’s escort glanced over his shoulder with an indulgent smile.

“The point is he is too young to be left at home,” he explained confidentially.

They must have smuggled the pup into the stalls under the nose of the management, and we were delighted when he lay perfectly still all the evening and did not make a sound.

“There you see. Ties are what you make them, George.”

“They might have been ejected from the theater,” said George, in the tone of the outraged citizen, who sees someone break a law which he has no desire to break, and get away with it. “Besides a dog is not a cat.”

“How wonderful of you to have noticed that, darling. Then let us have a dog,” suggested Evelyn.

“No.”

“Or a monkey?”

“NO!”

“Or a dear gazelle?”

“We shall have nothing,” said George, and he was probably right.

Our “tie,” if you can call him that, was not quite on terms with the kitchen. Ethel’s successor protested her devotion, but he had a way of looking over his shoulder at her with a dubious air as though he could have told a different story. And one day the murder was out. He came running through the dividing door with thunder in his eyes and five floury finger marks on his coat. An unprovoked assault.

“I was only playing with him, Madam,” defended the aggressor.

We hoped there would be no fur in the pie and advised Sam, unnecessarily perhaps, against keeping bad company.

The discovery came at an awkward moment, for we had arranged to go to the South of France for a few weeks and did not care to leave him in hostile hands. Luckily a friend in the country wanted to come up to town, and she was already one of his intimates—that is to say, the kind of acquaintance who did not pounce but understood that a cat prefers to make his own advances. She came to stay therefore and kept us informed of his health and spirits.

For two nights he sat at the hall door from dusk till dawn, incredulous at our base desertion. Then he seemed to give us up for lost and adjusted himself to the new order. Once he frightened his guardian nearly out of her wits by leaping across space from a window to a balcony several yards away, but otherwise he was a perfect host, she said.

When we returned, however, for the first time no Samuel Penguin met us at the door. He was stretched at his ease on a couch in the drawing-room, and there he remained, ignoring our existence. We showed him parcels and rustled paper in vain. He turned his eyes away or stared with contempt and when bedtime came he resisted all invitations and made his own arrangements.

We supposed he had forgotten us, but later events proved otherwise and why after all should cats be more consistent than their human brothers?

That summer we were going on a visit to America, closing the flat and leaving Sam with friends on the other side of London. His whole behavior about this event was entirely different. He superintended our packing arrangements, sat in the trunks, and was full of interest and benevolence. He even made no objection when the shipping people carried the trunks away, though as a rule he treated such visitors with deep suspicion. (The man must have deserted him.)

He had developed an incurable fondness for lying on our clothes; so we packed his basket with a familiar frock and sweater, hoping it would prove a consolation. Poor fools, he was as ready for a holiday as anybody else, and all our consideration was wasted.

In due course we took him by taxi to his new home before joining our ship. He had loathed the drive from the country, but, a true townsman, he seemed to feel this was another matter. He sat up at the window enjoying the streets, the racing traffic, and the river flowing away under Westminster bridge.

His hosts were not strange to him, and he was allowed to go through their flat at once and see how he liked it. The day was one of the hottest in what was to be a record summer, and an oak dining table pushed against a wall, he found, was deliciously cool to the fur.

We found him there fast asleep when the moment came to say good-by and crept away without waking him.

Faithfully by every mail they sent us news of him. He was well, happy, much admired, and the life of the party; he had not run away, been poisoned, or stolen for his fine fur coat. Indeed, he had taken possession, and we had better stay in America for years, because they didn’t want to part with him.

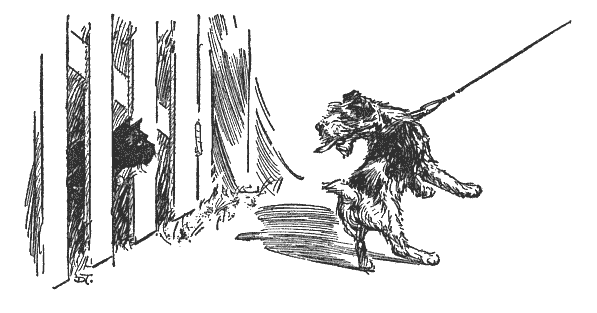

The morning after our return home we hastened to collect the cat of the house from these bandits who had designs upon him, and found him fast asleep in a drawer of the kitchen dresser. This was the cool side of the house, and the weather was still oppressive enough to exhaust any cat, said his hostess in extenuation.

She should have been glad to be rid of him, for in our absence a King Charles’s spaniel had come to stay with her and it was necessary to keep the two visitors apart. Not on Sam’s account. Oh, dear, no. He didn’t mind the dog in the least. She demonstrated as much by bringing in the little spaniel, who whimpered like a child at the sight of its natural enemy. Sam viewed this exhibition with an air of benevolent astonishment.

There was no cold dignity this time. He rode home with us in triumph and went at once to visit all his favorite haunts.

He examined everything that came out of the trunks and sniffed all the foreign smells with evident pleasure. There was a Micky Mouse clock bought for a young friend and we wound it up for his entertainment. He gave it a push but it was too large a mouse for a black fur cat in the height of summer, so he sank to rest in the packing paper.

“Walk on roof, Sam?” said the gardener experimentally.

He leaped up and ran to the front door. It was evident that there was nothing wrong with the memory of the cat of the house.

The garden had been watered though no one would have thought so. The bay trees in their tubs were dead, but here and there a dwarf rose or carnation raised a brave head in welcome; Sam’s lawn was lank and run to seed; the bird bath was dry, the bowl empty, and across the way the pigeons perched in drowsy festoons, seeking the shade. The roof tops seemed a little dizzy in the sun, yet white and cool above the trees of an intervening square rose the lovely towers of Westminster. The hands of Big Ben pointed to six o’clock and his voice boomed the hour with a slow and sonorous precision and a fidelity one could not doubt.

London again, unrivalled still to those who love her, whatever the pleasures and delights behind! Always we have experienced the same sense of enchantment in coming home to her busy, winding streets, her often shabby buildings, her steady voice, which by some strange magic has become for us, born far away, the very rhythm of life.

The gardener doused the thirsty plants, and the water ran into little pools about the roof, leaving damp patches where it was very cooling for a cat to lie.

he cat is a total abstainer.”

he cat is a total abstainer.”

“I beg your pardon,” said the veterinary surgeon.

He was a rosy-cheeked young man and a stranger. We had never had occasion to send for him before, but Samuel Penguin seemed to be out of sorts and wore his ears down like a pair of porch verandahs.

The vet had quickly diagnosed canker, remarking with a nod, as he prepared his lotions:

“Too much rich living. That’s the trouble with him.”

Naturally some defense had to be put up against such a scandalous insinuation; so we told him that, believe it or not, the cat had never once, during a residence of four years with us, been known to drink anything, though offered both milk and water every day. This peculiarity had often worried us, but his medical adviser remained calm.

“That’s all right,” he said. “He knows what he needs.”

He had seized the patient with a firm hand and begun to probe one ear, and Sam assisted the operation, raising his head as the instrument went down, as though indeed he knew. “Nature’s pretty clever,” explained the vet, “and between you and me, the less we interfere with her the better, though it is bad business for me to say it.”

It certainly was, for his fee was little below our own doctor’s. Still he dealt very skillfully with the cat of the house and showed us how to do so ourselves in future, instead of wrapping the whole procedure in mystery.

His work lay largely among horses, but he had also a talking macaw among his patients and had once driven a sick bear in a taxi; “rather an exciting journey,” he said mildly.

The operation completed, he opened Sam’s jaws and examined his teeth with an exclamation of dismay.

“Hullo! I’m afraid you’ll have to come to the surgery and have some of those out,” he said.

“May I be with him?” demanded the gardener suspiciously.

“In the next room, of course,” agreed the vet.

“NO!”

Like two combatants they faced each other over the head of Samuel Penguin, who, now released, had not attempted to move away, but was washing his ears.

“We—ell,” began the vet in a dubious tone. He seemed to realize he was no match for this fanatical family, and becoming aware of the cat still at his feet, he gave him a comical look, between astonishment and amusement.

“You’re a cool customer, I must say. What’s your name?” he asked.

“Sam.”

The hero ceased washing and looked up at the gardener with an air of inquiry. The man laughed.

“Meat, Sam?”

Of course the cat responded to this invitation in the usual way, hurrying to the door, and thereafter there was no more talk of surgeries, as his other talents were reported and discussed.

The young veterinary surgeon had the right touch with cats and understood them. He was to die, alas, in a few years and we have never found his equal. He did not stride in and seize the patient by the scruff of the neck like one of his successors, or address him as “Good Pussy” like the other. Sam loathed both these men in spite of their skill and always retreated at sight of them, but from the first the young vet was a friend.

He even understood our reluctance to let him go to the surgery and after observing Sam for some time and consulting him on the subject, he agreed to bring his instruments to the flat and see what could be done about the teeth. This operation was to clinch the friendship between them.

It was now early winter and we had bought him a dog basket large enough to give him squirming room when he lay before the fire.

He was dozing when the dentist arrived and before he was quite awake his mouth was gently opened for inspection.

After all, the teeth were sound, but covered with acid which must have caused him acute discomfort. Deftly the vet removed great lumps of it before our incredulous eyes, and the patient neither struggled nor made a sound. After that the teeth were scraped and polished and the man stood up.

Sam, released, leant back in his basket and surveyed the operator with glowing eyes. It was the grand climax and quite absurd.

“Walk on roof, Sam?” suggested the vet and was delighted when the hint was taken. It became his regular greeting on future visits for, while the young vet lived, Sam became his prize patient and his sensitive intelligence a source of discussion in veterinary circles.

He had a curious taste in medicine. Once ordered a liniment containing bitter aloes, he liked it so much that he would lick it off the paint brush by which it was supposed to be applied and then ask for more, though he still refused either milk or water.

Years later he had a loose tooth pulled by the “Good Pussy” vet and swore at him fiercely throughout the ceremony, but who can wonder! The creature held him, like a rabbit, by the ears.

It was this last outrage which persuaded us this morning to seek a fresh opinion, for Sam, now getting on in years, is not very well, though he has stood up to the trials of nearly two years of war like a veteran.

We took him to an animal hospital where he sat in the waiting room among dogs of every breed and shade of opinion, sundry other cats and an ancient parrot going blind, who said “Good-by all,” pointedly, at intervals. Horses, mules and donkeys, according to the notice on the gate, were seen in the early afternoon, but I doubt if a whole menagerie would have troubled Sam, who surveyed with interest this new world.

The spotless, air-conditioned room, with rows of well-spaced seats, had the genuine hospital look about it. Men and women in fresh white overalls passed in and out, summoning or releasing patients. Anxious “relatives” received a brief but reassuring smile.

“Animals should be kept apart.”

The warning was painted in good large type on the wall, but except for a Sealyham which clearly wanted to eat an Alsatian, the behavior of the patients was above reproach.

The examination was a great improvement on the pussy vet’s. Samuel is to have a few drops of halibut liver oil daily, a fishy cure which strikes us as distinctly tactful, combining business with pleasure, and to return in a fortnight to report progress.

He and the parrot went to the surgery together but the bird was taken elsewhere for his examination and returned indignantly flapping his wings. The verdict was cataract in one eye, but the second eye was found to be still in good order.

“Did he say anything?” asked the owner rather anxiously.

“Did he not?” returned the vet, grinning.

Sam enjoyed the drive there and back and now wears the pleased and important expression of one who has been seeing life. Moreover, the fee was so small that he will be able to afford his contribution to Animal Day tomorrow.

We shall be out at dawn with thousands of others selling emblems for this cause. The gardener is an Animal Guard, attached to the First Aid Post, and her one male colleague, full of zeal and efficiency, has just delivered our boxes.

His name is David and he walked into the post out of nowhere one day.

“How old do you have to be?” he asked.

“To be an animal guard?” suggested the keeper of the post. “Well, let me see, how old are you?”

“Eleven,” said the applicant firmly.

It seemed a useful age in a busy world, so he was passed for active service and now wears an armlet and a quite unnecessary tin hat, exercises the dogs, runs messages, and is very much the man on the spot.