* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

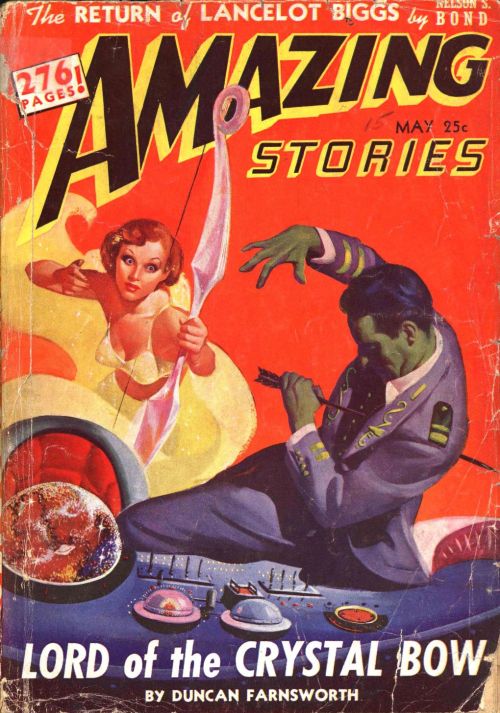

Title: Arctic God

Date of first publication: 1942

Author: John Russell Fearn (as Frank Jones) (1908-1960)

Date first posted: Sep. 26, 2022

Date last updated: Sep. 26, 2022

Faded Page eBook #20220959

This eBook was produced by: Alex White & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

This file was produced from images generously made available by Internet Archive/American Libraries.

Arctic God

By

John Russell Fearn

Writing under the pseudonym Frank Jones.

First published Amazing Stories, May 1942.

How could an English village be here in the frozen north? And what was the arctic god they feared so much?

“Say, ever hear of this range on maps or things?”

Jerry Marsden pulled off his helmet, rubbed his aching bearded face and drew a breath of the lung-cutting air.

Sid’s face emerged from the furs too—bewhiskered, beefy. He gave a puzzled frown.

“Nope.” Jerry looked round in the gloom: the weak Polar daylight was very near masked to twilight by the storm. “I’ve not the remotest idea where we are. And that’s kind of funny, come to think of it! We started this Expedition to find and claim new territory, then we have to lose our Omnibus and find the new territory on foot!”

He looked again at the gaunt, rocky interior of the cave then toward the tunnel that loomed back of it. Sid caught his thought.

“We might as well see where it takes us. Can’t do much on the outside until the storm blows itself out anyway. Come on.”

They made their way carefully along the rocky vista. The further they went and left behind the polar hell the warmer the air seemed to get. Jerry’s pedometer said they’d covered nearly two miles before the tunnel ended, and by this time the warmth was so oppressive they had to start pulling off their furs.

“Queer?” Sid looked his question, then stared at the barrier wall in the light of his torch.

“Volcanic activity probably,” Jerry replied. “Right now I’d give my life—what it’s worth!—to see what’s beyond this wall. First we get an unknown mountain range, then a natural tunnel through it—But what’s beyond that?”

“More tunnel and more storm I expect. We can try and find out.”

Discarding their furs completely they set to work to pull away the mass of boulders and stones that blocked the passage. The more they worked the more evident it seemed that volcanic subsidence had created the barrier. But there was not a great deal of it. At the end of an hour’s heavy manual labor Jerry pulled clear a block of pumice-rock that allowed a pure, clear ray of light to shine through.

“Say, it’s daylight!” Sid looked amazed. “I thought the storm had blanked that completely!”

“Storm or no storm, it’s still daylight,” Jerry said briefly. “Anyway, we’re on the other side of the range by now and the storm may not be raging here— Come on, give me a hand. This gets interesting.”

They redoubled their efforts, clawing and pulling, at last managed to scramble through the gap they had made. Then they sank down to a sitting position, astounded at what they beheld. It was like looking down into a medieval paradise. . . .

They were high up on a completely encircling range of mountains. At the mountain summits frothed and fumed atmospheric vapors from the streaming cold of the Arctic: there was an incessant dull rumble of thunder as heat and cold locked in combat.

But down here in the cup made by the range was a great sweeping fertile valley, dazzling with flowers and pasture land. It reached right to the edges of a quaint town that looked like something lifted wholesale from the Middle Ages of England. There were thatched roofs, cobbled streets, overhanging gables, little mullioned windows—

Over it all a blue sky. The sun was hidden by its low angle and the further barrier of the mountains—otherwise the air was warm and springlike, the wind a gentle caress.

Sid said finally, “Maybe we’re dead?”

“Dead nothing!” Jerry growled. “This valley is volcanic, hence the warmth. It’s shut off from the Arctic waste—an immensely fertile stretch all by itself. But I’ll be damned if I can figure out this little colony. Looks as though a chunk of England sideslipped in Time or something. . . . Better go see what they’ve got. Maybe quaff a measure of mead,” he finished, grinning through his bearded lips.

They set off together down the mountain slope. It was a longer descent than they had expected. The flowers, when they reached them, turned out to be conventional daisies, buttercups, and dandelions . . . Far away in the distance were cattle—perfectly normal sheep and cows, even horses. Once they glimpsed a pair of oxen yoked together and led by a man in curiously old-fashioned costume.

“I still think we’re dead,” Sid muttered, as they went on knee-high through the grass. “Such peace and quiet as this can’t exist in polar ice—Maybe it’s Utopia!” His eyes gleamed at that. Then he pointed quickly. “Take a look! Men and women right out of ‘Pilgrim’s Progress’!”

Jerry grinned as he saw what he meant. Men and women were clearly in view now they had touched the outskirts of the town. They all wore the quaint Puritanlike garb of early England. The men wore billowy-sleeved shirts, jerkins, and tight breeches; the women tight-bodiced dresses with flowing skirts and, here and there, a conical hat. There were a few children—very few, Jerry noticed.

In some sort of market place, jammed with fruit stalls, oxen, shouting men and bargaining women, Jerry came to a halt with Sid right beside him. There was an instant flurry among the populace at the presence of two strangers—bearded, dirty, heavily armed. Some ran to shelter in the heavily gabled houses, which in spite of their design appeared to be composed of still comparatively new material. Others of the people stood their ground, waited doubtfully.

Jerry made a vague welcoming gesture with his arm.

“Hi ya, folks! Any idea where we are? What place is this, anyway?”

The people looked at each other. An old man wagged his gray head doubtfully.

“ ’Tis strangers thou art,” he breathed. “Only by witchcraft couldst thou have come hither.’ ”

“Huh?” Jerry stared at Sid, then gave a grunt. “Witchcraft my foot! We walked it—pounding, pounding, through the snow-ways beyond this mountain range— Dammit, isn’t anybody going to give us a welcome?” he went on impatiently. “We don’t want to hurt you. All we ask is food, a chance to rest, and—and a shave.”

At that a girl edged her way from the crowd and looked at Jerry critically; then at Sid. She was very slight, possibly twenty-two, dressed in the simple Puritan style. Her flaxen hair reached nearly to her waist. Her face was oval, delicately flushed; her eyes gray and bright with intelligence.

“Perchance I—I canst help thee,” she said, coming forward and dropping a little curtsy. “I—er—“—she glanced nervously at her frowning fellow townsfolk—“I can help thee because my father is the town cryer. He knoweth much—”

She caught Jerry’s hand in impulsive quickness. “Come quickly, I beg of thee!”

“Yeah—yeah sure,” Jerry agreed, surprised; and with Sid beside him they all three pushed through the gawping people to a tavern further up the street.

It was an ale-house of the pure old fashioned sort, full of oaken cross beams, rough wood tables, brass ornaments, hide-backed chairs . . . The windows were cross-patterned in diamond-mullion.

“Please tarry,” the girl smiled, waving to chairs, then she went hurrying off to other parts of the tavern.

“Where’d they get this ‘thee’ and thou stuff?” Sid demanded, sitting down and scratching his head. “Looks like we sidetracked ourselves someplace and finished up in medieval England. If that’s wrong how did this place get here?”

“Take a look,” Jerry said in response, and jerked his head. The populace was peering through the windows now, muttering and talking. They were in the doorway too, tramping on each others’ toes to get a better look—

Then suddenly the girl and a massive stomached man appeared—presumably her father. He took a look at the people, slammed the door in their faces and bolted it, clamped shutters across the window, then lit massive candles to relieve the gloom. He turned, red-faced, genial, massive armed, a huge apron round his immense middle.

“Marry, but thou art strangers indeed!” he exclaimed, staring at them. “And a comely crop of beard too—” He broke off as the girl nudged him, seemed to remember something. “I am Robert the Robust,” he explained. “Town cryer to his most Excellent Majesty Ethelbert the Red—and in spare time, forsooth, keeper of this tavern. Here ist mine only one—Hesther. But—” he frowned—“whom wouldst thou be?”

Jerry hesitated. “We’re polar explorers. Tell you what you do, Robert—bring us something to eat and drink and we’ll tell you the whole story. There’s plenty to it—both sides.”

“So be it—but thou talkest in strange vein—”

“We’ve nothing on you, pal,” Jerry said; then as the rotund one went off with a mystified look he added to the girl, “Look, Hesther, what goes on? We don’t know anything about this setup, see? We’re from the outer world—New York. Ever heard of it?”

She shook her flaxen head, watched as Jerry eased off his accoutrements. “I knoweth only the England whence we came but a year or so ago.”

“Year or so?” Jerry looked at her sharply.

She seated herself. “Of a truth. The storm brought us hither and we wert lost. We slept. Then the Great God of the Mountain gaveth us life, and peace, and brought us hence. . . .”

“But—but—” Jerry got a grip on himself. “Listen, you belong to an England that went phut some four centuries back at least— When did this valley come into being? Anyway, who’s the Great God?”

“None knoweth.” There was reverent awe in her gray eyes. “He giveth life as he willeth it. None hath seen him—but he liveth. Far up yonder mountain.”

“Gold in them thar hills, pal,” Sid grinned.

Jerry relaxed. “Your witness,” he sighed.

“Repeating the question, when did this valley come into being?” Sid demanded.

“Three years ago perchance. We buildeth it ourselves when the Great God of the Mountain sent us hither—”

The landlord suddenly returned, planked down plates loaded with wholesome fare and two tankards of foaming ale.

“This on the house?” Jerry inquired briefly. “We’ve no money to pay for it see—unless you’ll take American money.”

“American money? What badinage is this? No money—”

“Father, it were better to let them tarry,” the girl broke in urgently. “They are not of us. They cometh from the outer world—from one York—”

“New York!” Jerry growled, wiring into the food. “Deal of difference! We came through a tunnel into this valley and we want to know what it’s all about. Listen, Robert, your daughter says you left England in a storm a year or so back. . . .”

“Tis true,” the landlord acknowledged. “We calleth this valley ‘Little England’ after the country we left. We set out for unknown parts as settlers with many children and many a head of cattle. Storm struck us. We wert driven into Polar ice and went to sleep. About three years ago the Great God of the Mountain waketh us and gave to us this valley. We buildeth our homes . . . everything.”

“A moment,” Jerry said quickly. “What ship was it you sailed in? From England I mean?”

“T’was the good ship Springflower—”

“Springflower!” Jerry twirled. “Listen, Sid, that ship is on the official list of mysteriously vanished ships—ranking with the Kobenhavn and Cyclops for mystical disappearance . . . Lemme think! The Springflower sailed from England with a party of some thousand colonists aboard in June, 1542! Not sure of the month, but I know it was that year . . . Holy Cats, these must be the survivors!”

“Descendants, you mean,” Sid snapped. “How do you figure they lived in the odd four centuries between?”

Hesther caught the implication of the argument for she said,

“Nay, not descendants. We—a thousand strong—art the original people who left England . . .”

“This has got me licked,” Jerry muttered. “Just what happened in the four centuries in between?”

“Mebbe the Old Man of the Mountain,” Sid mused.

Jerry looked up again. “Nobody’s seen this Mountain God of yours—How do you know there is a God?”

“Tis there for all to see,” the landlord shrugged. “At times yon mountain range bursts with fire and from it there steppeth but more numbers of our people from the Springflower. One by one the great God of the Mountain is returning to us all those who wert aboard that ship. In time, perchance, we shall be all here . . .”

“Something screwy somewhere all right,” Jerry sighed, going on with his meal. Then presently, “When do the mountain fireworks start again? Any chance of seeing anything?”

“Of a truth!” Hesther broke in excitedly. “Even this day it ist time for yon mountain to bring us more people—”

“To day? How’d you reckon days with six months of continuous light this time of year?”

“We measureth by the candle,” she smiled. “I canst show thee this mountain if thou art desirous—”

“It’s a deal,” Jerry nodded grimly. “And later, Robert the Robust, I’ll borrow something to slice these whiskers.”

Robert nodded, then asked, “Wouldst thou not care for an audience with Ethelbert the Red himself?”

“Can he tell us any more than you have?”

“Nay—”

“Oke, then we’ll leave Ethelred the Bert to his crown of glory and look into this for ourselves. Listen, you folks ever heard of radio?”

“Radio?” Hesther repeated the word in unaccustomed wonder. “What ist?”

“Or electricity, or atoms?” Jerry persisted. “Or explosives, stars, the universe?”

“Daughter, he talketh of devil’s tools,” Robert breathed.

Jerry compressed his lips. “Just as I figured. You folks don’t know the first rudiments of modern science. You never heard of movies or talking pictures or television, either?”

Father and daughter shook their heads mystifiedly. Jerry nodded, lifted up his portable radio and switched on the receiver portion.

“This may interest you,” he said briefly. “Later, when we’ve looked into the puzzle of this place we’ll call aid—Right now”—he tuned the dial—“you’re listening to a short wave station from that New York I told you about. We call it twenty nine meter band.”

Hesther jumped back nervously and caught her equally astounded father’s arm as the radio burst into sudden life. The announcer spoke briefly. Swing music began to come over the air, entirely free of all static jamming or atmospherics.

“Witchcraft!” the landlord panted, eyes popping. “Devil’s witchcraft!”

Hesther however, her first shock over, looked at the radio more closely, her keen gray eyes studying it intently.

“Listen to it and hear what goes on in the great big world outside here,” Jerry smiled. “Call in the rest of the folks . . . Now, Robert the Robust, your razor— And afterwards, Sweet Nell of Old Drury, we’ll be with you to take a look at the Old Man of the Mountain himself.”

Cleaned up and shaved, fresh for the unexpected course their Polar expedition had taken, Jerry and Sid walked with the girl between them to a grassy knoll she chose facing the opposite side of the mountain range perhaps a couple of miles away.

She seated herself and waited solemnly, gray eyes fixed steadily on the cliff face, hair blown back gently by the breeze.

“Anybody ever tell you you got looks?” Jerry murmured.

“Nay . . . Have I?” She even colored slightly.

“Plenty. Get you in New York in modern duds and you’d knock the socialities for a loop— We’ll skip that for the moment though. Tell me, how’d you get the wood to build this town of yours? And the tools?”

“They wert here—awaiting us. The God attendeth to everything. As to the wood— There wert a forest here, waiting to be hewn.”

“Hm-m. And everybody, you included, just sort of came here—? Just like that!” Jerry snapped his fingers.

“Yea.” The girl looked reflective. “I remember falling asleep aboard the Springflower. There wast dreadful cold. Then—then I woke, here in this valley. My father wert with me, and one other whom we knew. So . . . we joined yonder community in the town.”

“Somewhere,” Jerry said, “it begins to look as though four centuries have skidaddled. The medieval world has gone, Hesther. Today, beyond here, it is a world of radio, flying machines, wars, chaos, economic revolutions— Machine Age gone mad. Understand?”

“Nay,” she said, innocently. “But I believe thee— The radio, as you call it. Black magic indeed!”

“Yeah. Yeah, sure . . .” Jerry cocked a hopeless eye on Sid: then suddenly the girl caught each of their arms tightly, nodded her flaxen head. “Behold!” she cried.

Following her gaze they were just in time to see a sudden blaze of light in the distant mountain, for all the world like a giant flashlight. A cloud of white smoke puffed upwards and drifted away on the warm breeze. As it cleared, some four people merged into view, mere dots against the mountain. They were motionless for a while then began to move slowly down towards the town.

“Well I’ll be twice damned!” Sid exploded. “It’s as good as a stage illusion!”

“We’re going to look into this,” Jerry said curtly, jumping up. “It’s no supernatural setup, I’ll wager. Come on.”

“ ’Tis folly to question the God of the—” Hesther broke off as Jerry swung on her.

“You don’t have to come, Hes, if you don’t want. But we’re going to take a look . . . It’d help if you’d show us the way, at least.”

She hesitated, then that bright light of youthful intelligence came again to her gray eyes. Definitely she was a girl who loved something out of the ordinary.

“Sobeit,” she said briefly. “Come.”

She broke into a tripping run through the thick grass, Jerry and Sid close behind her. With long accustomedness she found a beaten trail through the flowers, went across a rubbly slope, turned into a direct path leading to the desired spot on the mountain side— Then suddenly she stumbled and fell headlong, hands outthrust to save herself. Her fingers struck a terrific blow against an upjutting chunk of rock.

“Hesther! Hes, are you hurt—?”

Horrified, expecting to see her right hand cut to the bone, Jerry dropped beside her with his handkerchief already out. He gathered her up, and she gave a faint smile.

“Nay, I am not hurt . . . See!” Her hand, as she stretched it out, was only slightly red from the impact but otherwise not even grazed. “I am never hurt,” she went on, as Jerry helped to her feet. “None of us is ever hurt. Perchance that ist strange? Truly, when in England we wert often hurt—But not here.”

“Funny? It’s incredible!” Jerry exploded. “Let me look again!”

Again he turned her hand over, then he felt the stone. It was as rough as a barnacle. The first presentiment of the incredible drove across his brain. He looked at the girl queerly.

“Have any of you folks ever died since appearing in this valley?”

“Nay.”

“Ever been ill? Any of you cut or injured yourselves?”

“Nay— But I have said, it was not always thus. Before the sleep on the Springflower—”

“Yeah—you told me. Hm-m!” Jerry cocked a significant eye on Sid, then shrugged. “Okay, let’s keep going.”

They went on again with the girl to the front. Falling back a little way Jerry said briefly.

“This joint piles up mystery on mystery, Sid. First we get folks who come back to life after four hundred years—then we find out their flesh is so tough a blow can’t even graze it. And a girl’s at that!”

“A few of these folks would be an asset in a front line of infantry,” Sid commented. “Maybe the Old Man again . . .”

They fell into puzzled silence, following the girl’s slender form. She stopped at last on a narrow ledge and pointed to a smoke-blackened fissure on the sheer mountain wall.

“This ist the spot,” she pronounced. “Listen! Thou canst hear the roar of the God himself!”

They stood still for a moment or two and quite distinctly to their ears came the sound of deep internal rumbling, rather like the roar of a tremendous wind. Jerry frowned, studied the fissure carefully. It was jagged, a rough oval which traced out a massive piece of rock.

“Naturally pivoted rock,” he said slowly. “At intervals, I’d say, some inner pressure must swing it round and leave an opening—Like Old Faithful—always works dead to time. You are sure these folks of yours turn up at regular intervals, Hes?”

“Of a certainty!”

“Then I am right. Some bright guy on the other side of this range is playing games—and it seems to me we’d better see what he’s up to—”

“Look here!” Sid exclaimed, on his knees. “Here’s a black mass of discharged magnesium, and leading back from it two thin grooves in the soil— Looks to me as though a magnesium charge was fixed here and fired by electric wires. Then the wires were withdrawn. Happened a lot of times too to judge from the smoke-black on that rock. These valley folks know nothing of explosives, even less of magnesium, so it looks supernatural— We’ve got something, Jerry!”

Jerry nodded, then to the girl’s alarm threw his weight against the jagged line of black that marked the pivoted rock’s edge. He stood back with gleaming eyes as it budged slightly.

“We don’t have to wait for volcanic force to shift it: we can do it ourselves—enough to get through anyway. Come on!”

“This ist madness!” Hesther cried in anguish. “To probe too far into the secrets of the God—”

“We know what we’re about, Hes,” Jerry said briefly, patting her arm affectionately. “Tell you what—skip off back home and we’ll join you later. Right now we’ve got tough work ahead.”

“But I—I—” It was clear her adventurous spirit was torn between superstitious fear and the desire to explore. Fear won. She held back nervously, sat down. “I wilt wait,” she said seriously.

“Oke. Okay, Sid—push with all your power!”

They flung their united strength on the rock and it turned slowly, enough to give them ingress anyway. Jerry pulled out his torch and flashed the beam down the tunnel ahead. From walls and floor spurted puffs of steam.

“Volcanic is right,” Jerry commented, moving along. “And some guy with a hundred percent brain knows how to turn it to account . . . Take it easy!” he finished suddenly, catching Sid’s arm.

The tunnel had ended at a mighty pit in the depths of which they beheld a volcanic heart of fire. Heat of overpowering force beat up and around them, set their bodies streaming. Clinging to each other they edged their way along the ledge that overhung the hell-crater, only breathed freely again when they got to the tunnel’s continuation beyond it.

“Obviously our unknown playmate figures that pit will keep the folks away,” Sid remarked. “Guess he’s not far wrong, either. But they must come up the tunnel in the first place to appear in the valley. Wonder how they got the nerve? There are old folks in the community too—”

He broke off. The tunnel had right-angled suddenly and brought them into daylight streaming through an open cave hole in the mountain side . . .

But they were not facing an Arctic waste but another valley, warm and temperate as the one they had left. A broad swift flowing river passed through its center, and along its nearer bank sprawled a long, roughly constructed wooden building not unlike a military barracks. The valley was rockier than its neighbor and possessed no flowers.

Then there was something else the two saw as they went down the mountain slope. Something was moored in the river alongside the wooden building . . . A submarine!

“Now I know we’ve got something!” Jerry snapped, lips tight.

Their journey down towards the riverside sheds took them past several newly made excavations on the way. Jerry halted and surveyed the first one as they passed it: it was full of metallic veins which spelt something to his eye immediately.

“Wow, take a look!” he whistled. “That’s a gold vein of amazing richness unless I’m mistaken— That’s silver higher up! Good God, this valley’s an absolute crucible of wealth . . .”

They hurried on again, past further excavations which gave obvious yields of bitumen, bauxite, copper, zinc, lead . . . a veritable storehouse such as any nation would give its soul to own.

“No wonder some bright baby wants to keep this place bottled up,” Sid commented finally. “We’ll just see how much legal right he—or they—have to it.”

For safety’s sake they drew their guns as they neared the sheds. At close quarters it was revealed that there were not many sheds—but one exceptionally long one, a sectional building of the type common in the outer world . . .

From the center doorway as they approached it a tubby figure in soiled white ducks suddenly emerged, battered Panama-hat pushed on the back of his head of gray hair. He was a big man, his figure belied somewhat by his babyish face. It was weather beaten, dissolute of mouth. The eyes were blue and rather vague.

“This is really quite unexpected,” he remarked, in perfect English. “Quite unexpected. Strangers are rare in my little habitat.” He straightened suddenly and saluted. “Captain Bilton at your service.”

“What navy?” Jerry asked briefly.

“Navy? My dear sir, I belong to no Navy. I am a scientist . . . a very great scientist! I am the master of life and death!”

“Yeah?” Jerry looked unconvinced. “I’m Jeremy Marsden of the Marsden Arctic Expedition: this is my colleague Sid Calvert. Our traveling unit was lost and we’re the sole survivors. We got into the adjoining valley by accident.”

“Really? How unfortunate . . .” Bilton’s expression did not change, but his eyes wandered to the leveled revolvers. Then he smiled. “Come inside, won’t you? I am forgetting my manners.”

They followed into a fairly large and sparsely furnished living room. The furniture comprised mainly steel tubing chairs and a metal portable table, obviously from the submarine. Oddly enough the table was already laid for three people. There were fruits, canned meat, bread, and a light wine. Also cutlery, again presumably from the submarine.

“Modest, but serviceable,” Bilton shrugged. “Sit down, won’t you? And I assure you, Mr. Marsden, there is no need for you to keep pointing that revolver at me. I am quite harmless—really.”

“Apparently,” Jerry said, thrusting his gun away and sitting down, “you knew we were coming? Table all laid.”

The Captain gave his babyish smile. “I saw you up on the valley side—through my telescope, so I decided to prepare a little welcome. Eat, my friends. The fruit is all from the woods atop this valley.”

He picked up an apple, bit into it with schoolboyish delight, then leaned back lazily and champed his flabby jowls.

“I’ll skip the eats and come to the point,” Jerry said briefly. “You are in possession of an exceptionally rich valley here. How come? Did you get here by accident or what?”

“Decidedly an accident,” Bilton said imperturbably. “I came originally to explore the Pole— The recent Bilton Expedition, if you recall? A trick of the current carried me under the mountain range into here. I stopped, to look around.”

“I don’t remember your Expedition or anything about it,” Jerry said bluntly. “What happened to your crew? You can’t drive a submarine single-handed.”

“The poor fellows died . . .” Bilton spat out a piece of apple skin casually. “Poor unhappy boys!” he sighed. “Little by little they found this lonely place getting too much for them and their reason snapped . . . One by one they went. I was the only one who kept sane, so naturally I did the merciful thing and shot them, also one by one. At last, only I was left.”

“And being the only one left you then set about convincing the innocents in the next valley that you are a God, eh? Why?”

Bilton beamed. “Why not?” He got to his feet, still munching his apple. “Suppose I show you exactly? Come with me . . .”

Jerry and Sid followed their host from the living room through a doorway that led into a long, well stocked laboratory. So well stocked indeed that Jerry found himself wondering how on earth Bilton had gotten all the stuff together, especially if he had come by accident.

Bilton’s next words helped a little to clear the puzzle.

“As you’ll know, for Polar exploration I needed a submarine fitted with all manner of apparatus. Most of it was machine-tool stuff which I have since utilized to make necessary instruments. The valley is rich in every conceivable element and raw material. The river works my turbogenerator: I have an electric blast furnace. In other words, a little scientific town all on my own . . . Quaint, isn’t it?”

Jerry and Sid glanced at each other. Bilton went on with his apple languidly.

“I don’t doubt you’ve seen some of my excavations,” he said. “I intend to advise the proper quarter in America when I can get out of this damned landlocked valley. Until then, I shall continue to experiment . . . As to the people in the other valley, that is matter of biological science. Know anything of it?”

“Try us out,” Jerry suggested briefly.

“Well, as I said I arrived here by accident—but as I was pushed through an underground stream in the outer ice I saw an ancient ship buried, virtually locked, in the ice. Possibly it had been there for centuries, overwhelmed, the people still on its decks, the cattle still in their pens—frozen, encompassed, solid . . . You know, it is a fact that life can be preserved in ice indefinitely—even for generations.”

Jerry’s eyes gleamed. “Yeah, I know. Go on.”

“I thought little of the incident at the time, but as my men died and I became lonely I wanted company. One day I recalled the statement of Darwin that life itself probably began in the Arctic—that right here, in this very spot, might exist the catalytic elements necessary to beget life. I had already found the valley to be immensely fertile in its yield of raw material—but there were also other elements unclassified by civilized science. Suppose among these elements there existed in practical form the chemical reagents which Darwin had once theorized . . .? I found such an element.”

Bilton nodded his straw-hatted head to a bottle on the shelf, half full of deep green liquid.

“I call it Biltonis,” he said fatuously. “It exists in a mineral element and is Element 87, one of our missing numbers in the Periodic Table. No wonder, since it has been here all the time . . . It can be ground down, pulverized, and made into a potent liquid. When absorbed into the human system—or any organic system for that matter—it has the effect of super-adrenalin. It stimulates the heart first, then as it sweeps on through the bloodstream it checks the normal effects of cell-breakdown—ketabolism—and instead builds up the epithelial cells to granite toughness. Life is not extended, but mortality is reduced by the comparative imperviousness to injury. Even bloodless amputation is possible because of the instant coagulation of blood at the severed points.”

“Very interesting,” Jerry said slowly, glancing at Sid’s keen face. “What happened then?”

Bilton munched reflectively. “Well, as I tell you, I was lonely. I got around to figuring I might try and revive the people preserved in the ice. With Biltonis I might manage it . . . They had merely died from cold and the ice had built up around them, preserving them without harm. I recovered some of them, and the cattle, and injected the fluid into them, using also an artificial respirator to start the heart action. They lived! And the cattle! For an hour after revival however the people were vacant—perfect hypnotic subjects. No doubt due to the shock. I realized I could keep my little secret from them if I sent them into the next Valley. I knew from their vacant droolings they still thought themselves in the Sixteenth Century. So, while they remained capable of being hypnotized I gave them orders in post-hypnotism, which would be obeyed the moment they came to. I told them how to build houses, roads, set themselves up. I even took the tools there myself in readiness for them . . .

“Then,” Bilton chuckled, “I decided to preserve my little secret by building up a seemingly mystical power. After the first ones went to the next valley I sent others to the accompaniment of a magnesium flash. All hocus-pocus of course, but it looks Godlike to those poor innocents. A volcanic pressure opens the mountain and—”

“And hypnotism was the reason why none of those people feared to walk past that boiling crater in the tunnel leading between valleys?” Jerry asked briefly.

“Correct, Mr. Mardsen. The hypnotic subject is never aware of his danger.”

“Hm-m! There are definitely no flies on you, Cap! And how many more have you got to revive yet?”

“No more. The last group went through not so long ago.”

“And you pulled away the wires which fired the magnesium afterwards?” Jerry asked slowly.

“Of course . . .” Bilton threw away his apple-core. “All very simple, you see . . . And, I think, rather wonderful! Ultimately I plan to go and live among these people, spend the rest of my days in paradise, as their God. Happy sentiment, is it not?”

Jerry eyed him. “You seem dead sure there’s no way out of here.”

“Of course I am sure. You cannot get out, and neither can I— Oh you may try to leave by the way you entered, I know—but without a base camp you’d perish. And one cannot even radio for help because radio neither goes nor comes from this spot— Atmospheric disturbance, you understand.”

Sid gave a start. “But we—”

“It boils down,” Jerry interrupted him, “to the fact that you are playing God to a bunch of Puritans, captain?”

“I only desire to live in peace and be their benefactor. Have I not restored them to life, given them a valley, a town, even a king?”

Jerry gave a slow smile and a final glance round the lab. He shrugged.

“Well, it’s been good meeting you,” he said. “Maybe we can help you forget your loneliness now and again?”

“Maybe,” Bilton acknowledged gravely.

“Well—we’ll be getting along. We want to take a thorough look at that other valley—then we’ll probably drop around and see you again. Inevitable I guess—since we’re neighbors until death.”

“You put it very aptly, my friend,” Bilton smiled, then he accompanied them back to the living room door. They left him leaning against the doorway munching another apple, waving his hand now and again as they made their way back to the mountain tunnel.

“Well, any ideas?” Jerry put the question brusquely as they tramped along.

“Darned if I know. Seems to me that that guy’s only one jump ahead of a strait-jacket. Nuts, obviously.”

Jerry’s face was grim. “He’s not nuts, Sid. That’s a pose: at least I think so—to throw us off guard. He’d no doubt have killed us had it not meant that the people in this next valley would have come to look for us and make things awkward for him. No, he’s not insane: he’s damned clever, and scientific too. All that chatter about wanting to be a God was so much bunk to build up the insane angle . . . And besides, he’s proven a liar. He said radio could neither come nor go from here. We know that’s wrong from our own radio—and you, you mug, nearly let the cat out of the bag by telling him we have a radio. The less he knows of that the better.”

“Hm-m,” Sid said, pondering.

“Something else too,” Jerry mused. “He said his submarine crew died of loneliness. What is more likely is that he happened on the place not by accident, but by design— He could have gotten the location of the place from some scientific treatise somewhere, like those approximate positions of Atlantis one often sees. It happened to be right. Once he knew that he still kept his crew beside him to return to civilization for tools and necessities. Then on the second return he killed them all off . . . Naturally there is a way out. I don’t credit his story that there isn’t. Probably under the ice . . .”

“And right here under his control is a wonder-mineral—a perfect medical miracle worth millions to civilized surgery,” Sid muttered. “Cutting without bleeding, hardening of the skin, revival from death . . . But underneath the whole setup is a deeper meaning, which we’ve got to find!”

“You’re telling me!” Jerry retorted. He looked back on the valley from the tunnel ledge. Bilton’s figure had gone now . . .

They turned into the tunnel, made their perilous trip back past the volcanic crater and so to the other valley again. As they pushed the pivot-stone back in place Hesther came up eagerly through the grass.

“Then—then the God didst not destroy thee?” she asked in relief.

“I guess not, Hes.” Jerry smiled faintly. “You been waiting for us all this time?”

“Truly! Prithee, what didst find—?”

Jerry took her arm affectionately. To his inner satisfaction she clung to him eagerly as they went down the valley side.

“We found enough to know, Hes, that you innocent folk in ‘Little England’ here aren’t half so safe as you think. Your God is a man—same as Sid and me. What is more, he’s a scientist.”

“Scientist?” The girl looked up inquiringly. “What ist?”

“I—I mean he makes things—dangerous things, I guess.” Jerry gestured vaguely. “Sid and I are going back later on to look at things more closely. Right now we’re returning to the tavern for a rest.”

Once they reached the tavern they found it jammed with the Puritan men and women listening in awe to a light orchestra from the same short wave station on which Jerry had left the radio. He gave a grin.

“Well, folks, how’d you like it?”

“Marry, ’tis witchcraft!” Hesther’s father exclaimed, and a chorus of voices confirmed his assertion.

“No, it’s just—” Jerry started to say, then he broke off and looked at the radio sharply as it crackled violently. It was the sharp crackled burr of electrical interference, repeated at two-second intervals.

“What ist?” asked Hesther in wonder. “Hast the wonder box broken down?”

“What do you make of it, Sid?” Jerry snapped, eyes narrowing.

“No electricity in this town and no static, therefore—”

“Bilton!” Jerry snapped. “Some ultrapowerful electrical machine he’s using. He figures we haven’t got a radio otherwise he wouldn’t be so careless. Damn good thing you didn’t get the chance to spill it out there, Sid. We—”

“Bilton? He is whom?” asked the landlord.

“Your God, my friends! Your Old Man of the Mountain!” Jerry laughed shortly. “He isn’t a God, and this is the Twentieth Century, which breeds scientists like flies. This man revived you by scientific means—witchcraft to you. But he isn’t a spook, or a supernatural being. He’s just a menace—and unless my pal and me do something about it he’s liable to do something unpleasant to all of you in due course. So, best thing you do is trust us and not this God of yours . . . This radio shows he is up to something and once we’ve rested, my pal and I are off to see what it is . . .

“Come on, Sid, time we grabbed some sleep. I’m about all in.”

Three hours later, rested and prepared for anything this time, they took their leave of Hesther once more at the tunnel entrance. Once more the difficult trip past the volcanic crater, and so through to the adjoining valley. Remembering Bilton’s telescope they wormed their way out on their stomachs from the tunnel entrance, used the rocks as shields.

Then suddenly Sid gripped Jerry’s arm.

“Take a look!”

Jerry started at what he saw. Bilton was but half a mile from them, his arms full of various electrical gadgets. He came towards them, stumbling in the stones. They waited breathlessly, gave sighs of relief as he turned suddenly and vanished in one of the countless mountain caves.

“Something up in that cave obviously,” Jerry muttered. “Must be working there—went down to his shack to get some equipment . . .”

He thought for a moment, eased himself up and fingered his gun.

“This is where we break forces, Sid. I’ll follow him up while you go down to his hut place and ransack it. Find out whatever you can that might provide a clue. I’ll keep him away from you somehow. Join you here later.”

“Okay.” Sid went off, keeping the rocks to one side of him.

Jerry got up and moved slowly along to the cave entrance, peered inside. Nothing happened. He crept into the gloom and presently saw ahead of him a flow of steady white light. It resolved itself finally into a string of high-wattage lamps across a cavern roof. Inside the cavern, to his amazement, were lathes, machine tools of every kind, carborundum wheels, grinding implements, metal drills, wire-wound armatures. On one side were completed masses of machinery, bolted up.

In the midst of all this was Bilton himself, at the moment inspecting a furiously working turbine fed by a pounding stream of water volcanic in origin, transmitting its power to the whirling flywheels. He turned at last and went to work on an instrument that sent out flarings of electrical energy. Apparently it was a welder. At any rate it explained to Jerry the curious static behavior of the radio set.

Several times Bilton paused to study a plan—then he went on again. For perhaps half an hour Jerry stood watching, trying to make up his mind what it was all about. Even if he went for Bilton with the revolver there was no guarantee the man would reveal the truth—and that was what really mattered.

The undoubted implication of scientific and electrical power worried Jerry not a little. More than ever he began to fear for those in “Little England”— Then he started violently at a touch on his arm. He swung, relaxed as he saw Sid, his face tense and grim as he looked into the cave.

“Nice setup,” he muttered, then glancing at Jerry sharply, “And I think I know what it’s all about . . . Come outside and I’ll show you.”

They retreated silently into the daylight again, ducked down behind the rocks.

“Well, what?” Jerry demanded.

“I had the free run of that place of his,” Sid said quickly. “I found plenty, but nothing half as important as this plan in his lab. See what you think. I can get it back before he knows anything . . .”

He pulled a roll of parchment from his inside pocket and Jerry frowned as he gazed at it. It showed the Arctic Circle and the northern half of the world. From a spot which was presumably this hidden valley radiated straight lines. The significant thing was that the spot they occupied was dead in the center of the absolute North Pole.

“Say,” he muttered, “these straight lines are given in terms of wavebands . . .”

“I know. That’s the odd part. What else do you see?”

“Plenty,” Jerry snapped. It seems obvious from this that the North Pole is not all ice. The exact North central pole is here, right where we are, and around it—as any scientist knows—are all the swarming currents of Earth itself. The Earth-spin alone draws them here. From this plan it seems obvious that our apple-eating friend intends to build up a massive power station, a simple enough proposition since the valley contains all the raw material to do it with—and his submarine brought all the necessary machine-tools. Seems clear he intends to settle himself here in a spot where nobody in the outer world would suspect anything could even live . . .

“Then,” Jerry mused, “he seems to figure that by using the inexhaustible power of earth’s magnetic energy through a specially designed power house he can use the world’s ether-lanes for a variety of purposes. For one thing he could cripple world radio and radio-telephone by terrific interference. He could cut out airplane motors by the same process. He could even produce electric storms at will anywhere he wanted . . . And none could stop him!”

Sid nodded grimly. “Seems fantastic—but it looks to me like the domination of the world’s power from the Pole, by one man.”

“That’s just what it is!” Jerry retorted.[1] “That’s just what Bilton is doing— But for such a colossal project he’d need more than himself and he’s wiped out his submarine crew—”

|

It was H. N. Dickson, the geographer, who said in his book The World’s Climates and Resources, that if one scientist could ever tap the vast electrical and mineral wealth of the North Pole he could rule the Earth.—Ed. |

Jerry stopped, snapped his fingers. “The people!” he ejaculated. “That’s it! A thousand innocents right under his thumb! Labor! And they won’t know a thing of what’s doing.”

“And right now he’s building the machinery for the project in that cave!” Sid cried.

“Yes, I am,” commented a grim voice. “Get up, both of you!”

Bilton was standing right behind them, gun in hand. He was no longer innocent and inane looking. Indeed his eyes were blazing with unholy fire. He snatched the plan savagely from Jerry’s grasp.

“I expected you would return, but hardly so soon!” he snapped. “I intended to block the tunnel the moment I had finished important work on my armatures . . . Well, you’ve been smart enough to piece together my plan—but it won’t avail you anything. You’ve guessed my scheme—electrical domination of the world. Perfectly protected in this valley I can do exactly as I like, can know all that is going on through radio-television. I have agents in the outer world, and I can buy as many more as I need with the gold and silver at my disposal here. Those people I revived shall labor for me . . . By power of destruction I can blackmail the world into whatever I need— And two inquisitive polar explorers shall not stop it!”

Jerry snapped, “Kill us, Bilton, and you’ll darned soon have the rest of the valley people coming in to find out why. Cut them off and you cut off your labor too—”

“I shall blow up the tunnel: it is already mined. Later I shall clear it.” Bilton smiled faintly. “I have it all arranged, you see, and I—”

“Wait!” screamed a girl’s voice suddenly.

It came so abruptly Bilton looked up in surprise, and in that second Jerry hurled out his fist and struck the portly scientist under the jaw, sent him reeling. He got up again immediately but Jerry had him covered.

Hesther came forward hurriedly, and behind her were her father and some of the other valley people. They gazed wonderingly at Bilton.

“You came just in time, Hesther,” Jerry panted. “How’d it happen?”

“We decided to see what really lay beyond the mountain—”

“Damn you, girl!” Bilton blazed, quivering with anger. “You few may have got through, but no more will—I’ll watch it!”

Before the words were hardly out of his mouth he flung himself forward recklessly, arms flung wide. Catching Jerry and Sid violently round the necks he flung them both to earth. Jerry fired, missed: the bullet whanged rock. Stumbling forward Bilton raced for his cave. Jerry whirled round, aimed, fired—

Bilton halted in his tracks, red smearing into sight on his white coated back. He doubled up, stumbled into the cave, and vanished.

“Well, I guess that’s that,” Jerry snapped. “We stepped in and just managed—”

He broke off, twirled with the others as there came a sudden titanic concussion from the tunnel leading to the next valley. Smoke and rocks came belting through the air. The whole mass of the mountain quivered.

Came another explosion—and another, rocking the valley with the reverberation.

“He must have lived long enough to blow the place up anyway,” Sid panted. “Dammit, we took that shot too much for granted— Now he knows he’s sunk he’s blown the whole lot— Take a look!” he yelled.

Hesther clinging to him, scared by the explosions, Jerry stared as a mass of gray viscid substance began to push its way from the blocked tunnel. It was followed by a core of red molten fire.

“That volcanic pit!” Sid shouted. “It’s overflowed or something. Quick! We’ve gotta get out of here . . .”

Even as he spoke the mountain quaked again and dislodged huge boulders that rained thunderously to earth.

“He started a cataclysm,” Jerry muttered, as they backed away. “It can happen easy enough when everything’s made of porous volcanic rock. Shift one rock and the lot comes down. Looks like ‘Little England’ is doomed—and this valley will be a molten quagmire in no time . . . Come on!”

“The submarine?” Sid questioned, as they ran down the mountain slope.

“Yeah—the only chance. We’ve got a makeshift crew. If there’s a way out we’ll find it . . .”

As they raced along that rolling flood of molten stone and lava pursued them. They reached the shed by the river and for a moment Jerry stopped, dashed inside and came out again with the bottle of Biltonis in his arm.

“Might as well,” he said briefly to Sid. “Probably duplicate it in the outer world— Come on, you folks!”

He caught Hesther to him and led the way to the flat deck of the submarine, clattered down into the control room.

“Fuel’s all set,” Sid said briefly, studying the gages. “But how much do you know about driving a sub?”

“Enough to get by,” Jerry retorted, slamming and shutting the conning tower hatch. “Our job will be finding the way out—”

“We can do that all right!” Sid cried. “Look here! A map all laid out! Bilton had everything ready for a quick getaway if it was ever needed.”

Jerry glanced at it, nodded, turned to the baffled Englanders. The wilderness of machinery was something they had never known. None the less they turned to the tasks Jerry assigned them and the engines started up . . .

The submarine stayed on surface until the barrier range was reached—then it submerged. From then on it was a matter of gentle nosing through walls of ice, through the narrowest channel imaginable. Foot by foot—perhaps for hours, perhaps for days . . .

None aboard knew how long it took—but there came a time at last, when the air was fetid and the engines overworked, that the craft rose willingly without obstruction. It bobbed to the surface of the sea.

“We made it!” Sid cried exultantly.

Instantly Jerry flung open the hatch, clambered out on the deck. He stood breathing in gulps of the salt wind.

“Somewhere about two hundred miles off Greenland, as I figure it,” he said. He turned, Hesther clinging to his arm, her father and fellow Englanders staring round them incredulously.

“We’re going to a new world, Hes,” Jerry smiled. “And we’ve got a secret right here that’s going to make us happy and secure . . . Maybe you don’t even mind leaving that Polar prison behind?”

“Mind? Nay! It is as you say—Okay by me!”

“Okay it is!” Jerry grinned. He turned. “Sid, a ship hoving on the horizon— We head towards it. Come on!”

THE END

[The end of Arctic God by John Russell Fearn (as Frank Jones)]