* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: The Holiday and Other Stories

Date of first publication: 1870

Author: Oscar Pletsch (1830-1888)

Illustrator: Oscar Pletsch (1830-1888)

Date first posted: Sep. 15, 2022

Date last updated: Sep. 15, 2022

Faded Page eBook #20220943

This eBook was produced by: Marcia Brooks, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

THE HOLIDAY,

AND OTHER STORIES,

FOR YOUNGEST READERS.

With more than One Hundred Illustrations

BY

OSCAR PLETSCH, HARRISON WEIR, HAMMATT BILLINGS, AND OTHERS.

BOSTON:

JOHN L. SHOREY, No. 13, WASHINGTON STREET.

NICHOLS & HALL, No. 43, WASHINGTON STREET.

1870.

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1869, by

JOHN L. SHOREY,

in the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the District of Massachusetts.

Electrotyped and Printed by Rand, Avery, & Frye, Boston.

| IN PROSE. | ||

| Page. | ||

| The Holiday. By Uncle John. | 1 | |

| Letters from Dolls. | 6 | |

| Winding the Clock. (Pletsch) | 9 | |

| The Doll’s Bonnet. By G. T. Brown. | 11 | |

| The Poppy. | 12 | |

| The Bluebirds’ House. By Charlie’s Mamma. | 18 | |

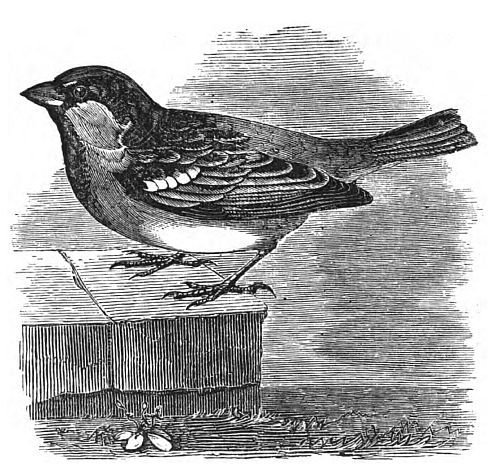

| The European House-Sparrow. | 19 | |

| Charles Reading the Bible. | 21 | |

| Story of Robin Redbreast. By W. O. C. | 23 | |

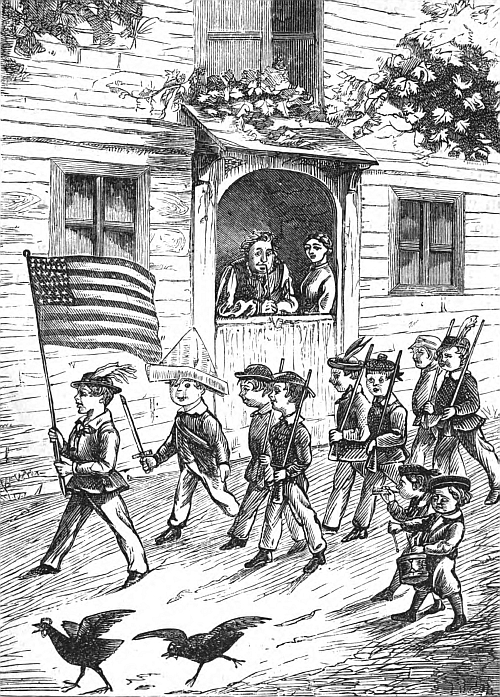

| The Fourth of July. By Alfred Selwyn. | 24 | |

| The Elephant and the Bridge. By Trottie’s Aunt. | 26 | |

| Henry’s Happy Day. By Emily Carter. (Pletsch) | 27 | |

| The Little Boy’s Mistake. By Uncle Charles. | 30 | |

| The Words of Christ. | 32 | |

| Charlotte Cutting Bread. | 33 | |

| Bessie’s Temptation. | 36 | |

| Edwin makes himself Useful. | 39 | |

| The Cat and the Chicken. | 42 | |

| Playing at Icebergs. | 45 | |

| The Donkeys. | 47 | |

| Lizzie and her Chicks. By W. O. C. | 48 | |

| More Scared than Hurt. By Emily Carter. | 49 | |

| How the Cat was Lost and Found. By Trottie’s Aunt. | 53 | |

| The Horse that called a Doctor. | 55 | |

| Which is the Prettier Doll? (Pletsch) | 57 | |

| Frank learns to walk. | 59 | |

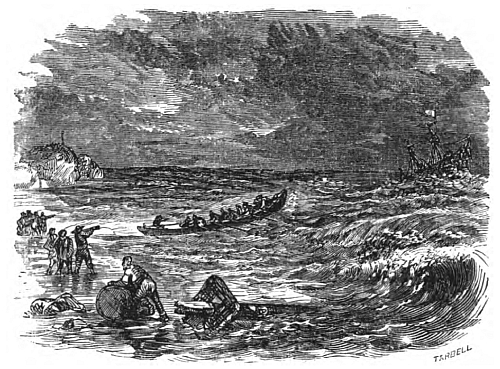

| The Life-Boat. | 61 | |

| Ellen’s Bunch of Grapes. | 64 | |

| Lucian and his Cousin. | 65 | |

| The Ship in the Ice. | 69 | |

| Alfred’s Mishap. (Froment) | 71 | |

| About Grip. By Trottie’s Aunt. | 75 | |

| Charles and his Dog. (Weir) | 77 | |

| “Don’t do that, naughty Sheep”. | 81 | |

| Minnie’s Gift. By Acorn. | 83 | |

| Emma’s Pets. | 85 | |

| May’s Little Pinky. | 87 | |

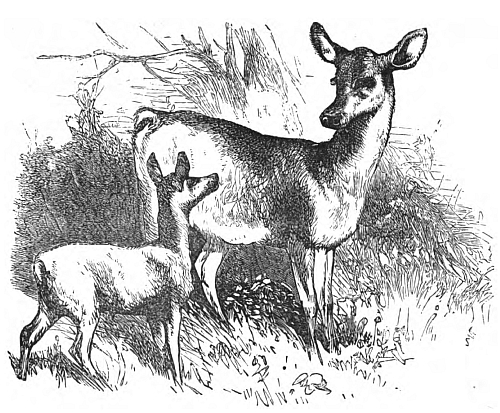

| The Deer and the Fawn. | 91 | |

| Aunt Helen. By Frank. | 94 | |

| Our Woodpecker. By W. O. C. | 95 | |

| How Johnny lost his Supper. | 97 | |

| Margaret’s Story. | 101 | |

| How a Dog, &c. By Trottie’s Aunt. | 104 | |

| Rain in the Woods. | 107 | |

| Fanny and her Pets. | 109 | |

| The Wheelbarrow, a tragedy, with seven designs by Frolich. | 113 | |

| Arthur’s New Ship. | 118 | |

| Lucy and her Chicks. By W. O. C. | 120 | |

| Holding the Skein. (Pletsch) | 121 | |

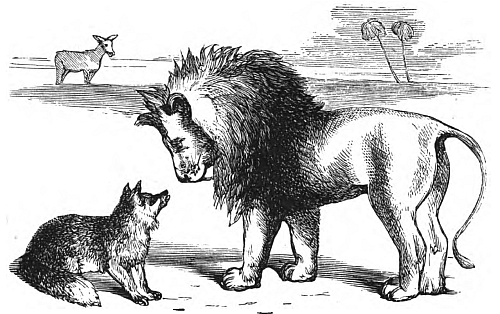

| The Donkey, Fox, and Lion. | 123 | |

| Letter from an Injured Person. | 125 | |

| The Severe Schoolmaster. | 128 | |

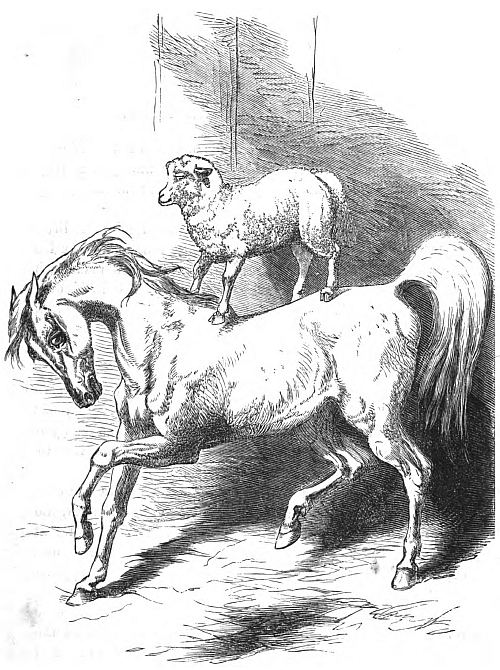

| The Horse and the Lamb. | 129 | |

| Baby is Awake. (Pletsch) | 132 | |

| The Two Cakes. | 134 | |

| Story of Little Benjamin. | 137 | |

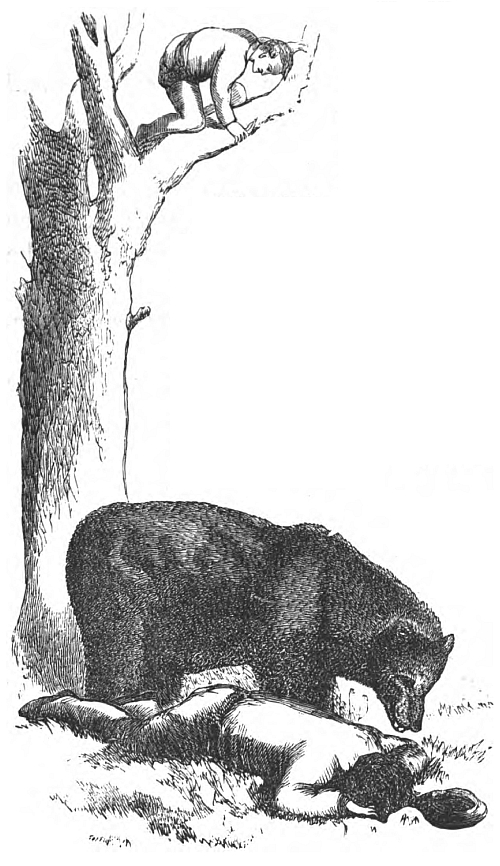

| The Two Travellers. | 140 | |

| Brownie’s Kittens. | 141 | |

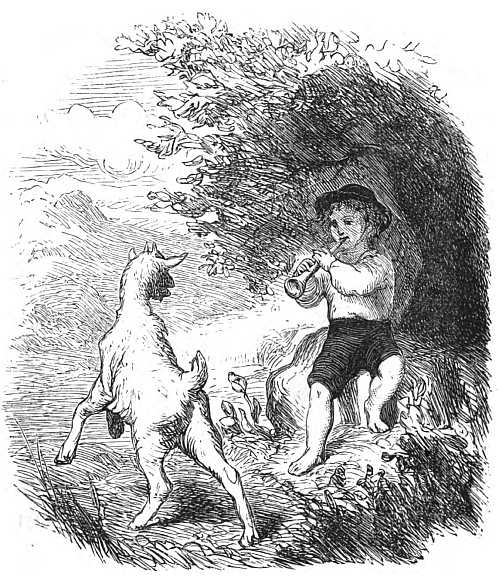

| Max and his Kid. (With seven illustrations by L. Frolich) | 145 | |

| A True Incident. | 151 | |

| Mary and the Birds. By W. O. C. | 152 | |

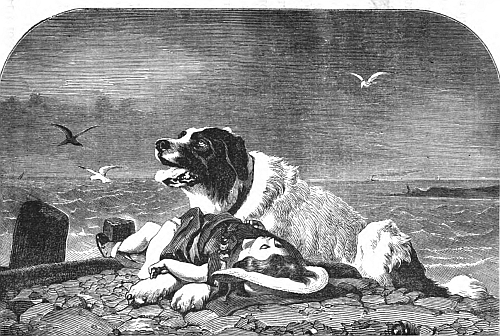

| Saved. | 153 | |

| Can Kites be of Use. | 157 | |

| Grandmother has come. | 161 | |

| Tea and Coffee. | 165 | |

| The Ride to Boston. | 167 | |

| The Big Snow-Ball. | 168 | |

| Sleepy Time. | 169 | |

| About Minnie. | 172 | |

| Little Anna’s Pictures. By W. O. C. | 173 | |

| Making a Way through the Ice. | 174 | |

| Susan as a Greek Girl. | 177 | |

| The Dogs in the Barn-yard. | 181 | |

| “A Merry Christmas, Grandpa!” | 186 | |

| IN VERSE. | ||

| Page. | ||

| A Child’s Fancy. By A. | 4 | |

| The Test. By Mrs. A. M. Wells. | 8 | |

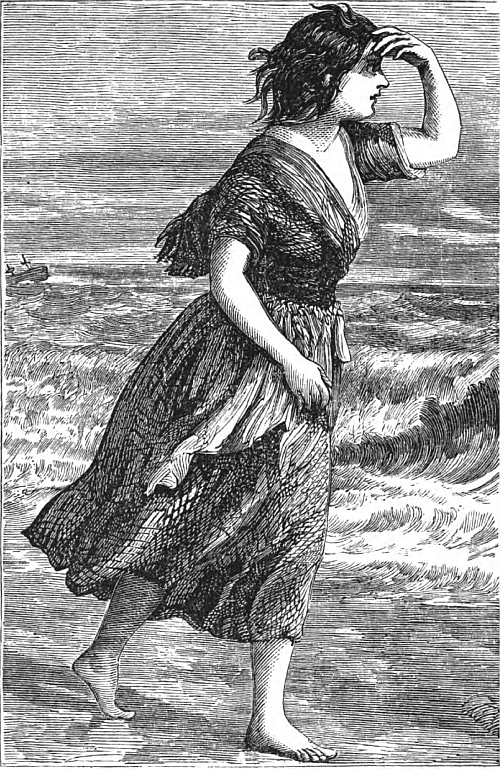

| The Fisherman’s Wife. By A. | 13 | |

| Morning. By A. | 15 | |

| The House of Cards. By Ida Fay. | 16 | |

| The Flying-Fish. | 31 | |

| The Children’s Song. By Emily Carter. | 41 | |

| Wishing. By William Allingham. | 44 | |

| Who’ll buy Baby? By Aunt Clara. | 52 | |

| The Boy and Butterfly. | 56 | |

| Eddie’s Good-Night Hymn. | 63 | |

| All for the Best. | 68 | |

| Evening. By A. | 79 | |

| Nora’s Hymn. By Emily Carter. | 80 | |

| Kitty Gray. By Aunt Clara. | 89 | |

| Wishes. By Mrs. Harrington. | 90 | |

| The Toad. By Marian Douglas. | 92 | |

| Sisters in the Bower. (Pletsch) | 93 | |

| Jack and the Sparrow. | 100 | |

| Deaf and Dumb. By A. | 106 | |

| Who stole the Eggs? | 111 | |

| Evening Hymn. | 124 | |

| Corn. | 124 | |

| By the Cradle. By Emily Carter. | 133 | |

| The Rain. By Gerda Fay. | 136 | |

| Autumn Days. By Emily Carter. | 143 | |

| Shun Bad Company. By Aunt Clara. | 144 | |

| Four Years Old. By Fannie Benedict. | 159 | |

| The Crow. By Emily Carter. | 160 | |

| Mother’s Good-Night. | 166 | |

| My Winter Friend. By M. Douglas. | 171 | |

| The Call of Samuel. | 176 | |

| The Concert. | 180 | |

| Beautiful Things. | 185 | |

I should like to take you, one of these fine summer days, to a place that I know on the seacoast. It is not a great many miles from the city; but there are woods and hills, and all the sights and sounds of the country, around you.

In the midst of them is a charming little cottage. From the front windows of the cottage, you catch a glimpse of the ocean through the pine-trees; and within a stone’s-throw you have rocks and coves, and sandy beaches, and all the sights and sounds of the sea.

This cottage is the summer home of my Cousin Annie. She thinks there is no place in the world like it, and is as happy there as the day is long.

But to-day she is having a nicer time than ever; for her brother Charles has come home for a holiday. Charles is a tall, manly boy, about fifteen years old.

When he comes down to the seashore, he likes to throw off his city clothes, and put on a loose sailor-dress. I think he has been out in a boat this morning; and I dare say he has brought home a good mess of fish. But he is going to spend the rest of the day with Annie.

Annie has had her morning bath, and her stroll on the beach. Little Freddy, the pet of the family, has been with her, and has been having a grand time picking up stones and shells, and digging wells in the sand.

And now they have all come together up on the high, grassy point, which they call the “Look-out,” to enjoy the sea-breeze. Little tired Freddy has gone fast asleep in his sister’s lap. Charles kneels beside her, and, with spy-glass in hand, is taking a view of the ocean, and pointing out all that there is to be seen.

Now, if any of my little readers who live far back in the country, on the mountains or the prairies, would like to look at the ocean, they cannot do better than to fancy that they are sitting by Annie’s side.

The wide, open sea is before you. It is a warm, sunny day; but the sea-breeze keeps you cool. With every breath of the pure, salt air, you seem to take in new life.

You hear the waves rolling and breaking on the beach, and dashing and gurgling among the rocks. You see sail after sail dotting the waters far as the eye can reach. Listen now, and Charles will tell us something about them.

“There is a large ship,” he says, “at anchor in the bay. She must be a man-of-war; but she is so far away, that I can hardly make her out. I see three or four fishing-vessels coming in. I see three brigs and any number of schooners.

“One of them, I think, is a pilot-boat. And there is a large vessel coming in. She must be an emigrant-ship. Yes: her deck is filled with people.”

“Oh! let me look at her,” said Annie. “How glad they must be to see the land!”

Charles hands her the spy-glass, and she takes a long look through it All of a sudden she exclaims, “Why! Charles, I do believe I see the sea-serpent!”

“Nonsense!” says Charles, taking back the glass. “It is only a school of porpoises.”

Then we have a good laugh at Annie’s mistake.

And here we will end our trip to the seaside.

Uncle John.

O little flowers! you love me so,

You could not do without me;

O little birds that come and go!

You sing sweet songs about me;

O little moss! observed by few,

That round the tree is creeping,

You like my head to rest on you

When I am idly sleeping.

O rushes by the river-side!

You bow when I come near you;

O fish! you leap about with pride,

Because you think I hear you;

O river! you shine clear and bright,

To tempt me to look in you;

O water-lilies pure and white!

You hope that I shall win you.

O pretty things! you love me so,

I see I must not leave you:

You’d find it very dull, I know—

I should not like to grieve you.

Don’t wrinkle up, you silly moss;

My flowers, you need not shiver;

My little buds, don’t look so cross;

Don’t talk so loud, my river.

I’m telling you I will not go;

It’s foolish to feel slighted;

It’s rude to interrupt me so:

You ought to be delighted.

Ah! now you’re growing good, I see,

Though anger is beguiling:

The pretty blossoms nod at me;

I see a robin smiling.

And I will make a promise, dears,

That will content you, may be,—

I’ll love you through the happy years,

Till I’m a nice old lady.

True love (like yours and mine), they say,

Can never think of ceasing,

But year by year, and day by day,

Keeps steadily increasing.

A.

A plate of apples was passed round to a group of children. There was a fine red apple at the top, which a little girl took. “How greedy you are!” said her next neighbor, “to take the largest. I meant to take that myself.”

FROM LUCY’S DOLL.

I am Lucy’s doll. I think my name must be Dolly; for I never heard Lucy call me any thing else, and she has had me ever since she was two years old. Now she is six.

When I first came here to live, I think that Lucy could not have known how weak I was; for she was not careful of me, and one day she let me fall to the floor, and I broke one of my ankles. Ever since that, I have not been able to walk without limping.

Lucy is older now, and takes more care of me. The only time she treats me as I do not like to have her is when her “Nursery” comes. Just as quick as she sees it in her papa’s hand, she lays me flat on my back on the table; and there I have to lie, with nothing but the ceiling to look at, till she is tired of reading,—and that is not soon.

Once she did let me sit in her lap; and then I saw beautiful pictures, and I wished I could read what it said about them. I know it was something nice, for Lucy looked pleased. But dolls cannot read. Is it not too bad?

I send you a copy of my photograph. I am in Lucy’s arms, you see, and have my bonnet on. I shall say nothing of Sarah’s doll; for I don’t like her, she is so proud.

If you print this letter, I will write you another, and tell you of a dreadful accident that happened to me soon after I broke my ankle.

Thekla.

FROM SARAH’S DOLL.

I am Sarah’s doll, and I am larger and handsomer than the pert thing that belongs to Lucy. I have a blue silk dress, trimmed with red ribbons; I have purple shoes; and my hair is black and thick, and I am to have it done up behind in a bunch one of these days.

I do not have a broken ankle, like some folks. Oh, no! Sarah thinks too much of me to let me fall, and break my limbs. She has a nice trunk, in which she lays me away when she is not playing with me. It is dark there, which I do not like; but then no dust can get on my nice silk.

Sarah has a black doll whose name is Flora. She is my slave. I can beat her as much as I like; that is, if Sarah will help me, for I cannot lift my arm without Sarah’s help.

Sarah’s brother Tom is a bad boy. One day he took me, and tied me face to face with black Flora. I thought I should have fainted. Another time, he tied a piece of twine round my feet, and hung me, with my head down, on the knob of the door. He says I am a proud thing, and so he likes to play tricks on me.

I do not care for books or pictures. All I care for is dress. If I am dressed well, and my cheeks are red, I am as happy as a doll can be. But I do not like to see Lucy’s doll dressed as well as I am.

Now, I am told there are some little girls who are just like me in these things. They do not care for books or pictures. All they care for is dress; and they do not like to see other little girls with dresses as fine as their own. If you do not want to have people say of you, “She is silly as a doll,” you must try and not be like me in these things.

You must love books and pictures. You must care for many other things besides dress. You must like to see your friends dressed as well as you are, and must not feel envy if they are dressed better. Envy is a bad, bad feeling: you must drive it out of your heart, and leave it to dolls.

Sarah’s Doll.

FROM FLORA.

There is no truth in the story that I am a slave. I am no such thing. I am as good as Sarah’s doll; and, if she beats me, I can beat her if Sarah will only help me.

When I am dressed up, I am very handsome. It is true, I am kept in the kitchen, and do not take tea with the two lady dolls. The hair on my head was got from an old mattress, and my eyes are made out of blue beads. But I know quite as much as the two lady dolls do, and can write just as good a letter.

Flora.

Buttercups, every one

Bright, like a summer sun,

Looking and smiling so bonny,

Some of you come with me—

Something I want to see,

Want to find out, about Johnny.

If I can slip you in

Close under Johnny’s chin;

If you can there shine clearly;

Though he may own it not,

We shall the truth have got,—

Johnny loves butter too dearly.

Chasing the dragon-fly,

Johnny, with shout and cry,

Tramples the fair fields over;

While I string lilac-bells,

Or, in the grassy dells,

Hunt for the four-leaved clover.

Stirring you through and through,

How the winds play with you,

Putting you all in a flutter!

Tell me, O buttercup!

Through the grass looking up,

Tell me, Does Johnny love butter?

Mrs. A. M. Wells.

While my mother winds the clock, I hold the watch to my ear. “Tick, tick, tick,” it says; for it is a real silver watch, and keeps time. My Aunt Alice gave it to me. My name is Alice too; and I was named after my aunt.

I will tell you how she came to give me the watch. She said that she had an old watch that once belonged to her grandfather, who was, of course, my great-grandfather.

“Now, Alice,” said my aunt, “if you will learn to tell the time of day, you shall have the watch.” So I learnt to tell all the figures on the watch,—1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12. Then I learnt what the short hand of the watch meant, and what the long hand meant.

Then I got my mother to explain to me all about it; and, after a week’s practice, I could tell the time of day quite well.

So I called on my Aunt Alice, and said, “Now, aunt, if you please, I will take that old silver watch that once belonged to my great-grandfather.”

“What! you haven’t learned already to tell the time of day, have you?” cried my aunt.

“Just try me,” said I. So my aunt led me to the clock, and pointed to it; and I said at once, without a pause, “It is seven minutes past three o’clock.”

“You are right, little girl,” said my aunt. “The watch is yours. It does not keep very good time now. It loses about ten minutes a day. But, if you will take care of it, I will send it to the watchmaker’s, and have it cleaned and fixed.”

This my aunt did, when she found that I took good care of the watch; and now every day I hang the watch up on a nail by the side of my bed. It keeps good time, and I have learnt to wind it up every day myself. My mother says I am a small girl to own a watch, and that mine is rather a big one for a lady: but I love it because it once belonged to my great-grandfather; and he, I am told, was a good man.

Alice.

Little Helen is three years old. One day, she was tired of playing with her dishes: her blocks would not make houses; and her doll was “naughty,” she said. So she came, and laid her curly head on my knee.

“Please take me up, mamma. Tell me a story.”

“What shall I tell Helen about?” I said, as I let her “cuddle up cosey” in my lap.

“Tell me about when you were a little girl.”

So this is the story I told my darling:—

“When I was a little girl like you, only larger, my Aunt Mary brought me a doll,—a great doll, with a head made of wood, so that I could not break it if I let it fall on the floor.

“This doll had blue eyes and very red cheeks. She was nicely dressed, just like a grown-up lady. But, what pleased me most, she had a bonnet,—a real bonnet made of straw, with a blue ribbon round it. She was a fine doll indeed; and I loved her very much: her name was Lucy.

“We had a little dog then: his name was Carlo. He was quite a young dog; and he would jump about and play, just as the kitten plays with you. One day, my mother took me to spend the day at my grandma’s house.

“I left my doll on a great box in the corner of the kitchen; and Carlo was left at home too. We were gone all day. When we came back, I ran to find my dear doll, my pretty Lucy. And where do you think she was?”

Then little Helen opened her eyes very wide, and said, “Where?”

“Why, she was on the floor; and her pretty bonnet was all crushed and torn! Carlo had jumped up in a chair, and then on the box; and he had taken my Lucy by the head, and with his sharp teeth had pulled off the nice straw bonnet, trampled on it, and torn it all in pieces. It was quite spoiled.”

“Then what did you do? Did you cry?” asked Helen.

“Yes, I cried very much. Then I ran after Carlo; and I caught him by the hair, and held him fast, and raised my fist to pound him as hard as ever I could, and punish him for touching my doll.

“But my mother would not let me do so to poor Carlo. She said it was my fault for leaving my doll on the box. Carlo did not mean any harm: he did not know any better. I ought to have put my doll in my play-house.”

“Tell me about your play-house, mamma.”

But I saw that my little Helen’s eyes were very sleepy; so I said, “Not now, my darling. Some other time you shall hear about the play-house.”

G. T. Brown.

Edwin found a bright-red flower in the wheat-field, and brought it home to his mother. “What can it be? Is it a lily?” he asked.

“No,” said his mother. “It is a poppy.”

“I do not like the smell of it,” said he. “It is not so sweet as a rose or as a pink.”

“No: this is a flower from which a poisonous drug, called opium, is made. A very small bit of opium would put you to sleep, and a large piece would kill you.”

The wind bloweth wildly: she stands on the shore;

She shudders to hear it, and will evermore.

The rush of the waves, as they rose and they fell,

Evermore to her fancy will sound like a knell.

“When, mother, dear mother, will father return?

His supper is ready, the sticks brightly burn;

His chair is beside them, with dry shoes and coat:

I’m longing to kiss him—oh I where is the boat?

“Why does he not come with his fish on his arm?

He must want his supper; he cannot be warm.

I’ll stroke his cold cheek, with his wet hair I’ll play:

I want so to kiss him—oh! why does he stay?”

Unheeding the voice of that prattler, she stood

To watch the wild war of the tempest and flood.

One little black speck in the distance doth float:

’Tis her world, ’tis her life, ’tis her fisherman’s boat!

Her poor heart beats madly ’twixt hope and despair:

She watches his boat with a wild, glassy stare.

Ah! ’tis hid beneath torrents of silvery spray:

Ah! ’tis buried in chasms that yawn for their prey.

Over mountains of horrible waves it is tost:

It is far, it is near, it is safe—it is lost!

The proud waves of ocean, unheeding, rush on;

But alas for the little black speck—it is gone!

Oh! weep for the fisherman’s boat, but weep more

For the desolate woman who stands on the shore:

She flies to her home with a shrill cry of pain,—

To that home where her loved one may come not again.

All night she sits speechless, her child weeping near;

But no sob shakes her bosom, her eye feels no tear:

In heart-broken, motionless, stupid despair,

She sits gazing on—at his coat and his chair.

Hark! a click of the latch—a hand opens the door—

’Tis a step—her heart leaps—’tis his step on the floor:

He stands there before her all dripping and wet;

But his smile and his kiss have warm life in them yet.

He is here, he is safe, though his boat is a wreck:

He sinks in his chair, while her arms clasp his neck;

And a sweet little voice in his ear whispers this:

“Do kiss me, dear father, I long for a kiss!”

A.

How pleasant is the morning!

How innocent and bright!

How pretty and surprising

To see the sun uprising,

A ball of golden light;

While sleepy twilight melts away,

And the delicious summer day

Succeeds the silent night!

How pleasant is the morning!

The flowers begin to shine:

No longer idly dozing,

Their happy eyes, unclosing,

Look laughing into mine.

I watch them open one by one,

Bidding good-morning to the sun

By many a pretty sign.

How pleasant is the morning!

Bright earth and dewy sky

Delicious tears are weeping,

And rivulets are leaping,

And breezes flutter by;

And birds and flowers and trees and grass,

And changeful shadows as they pass,

Enchant the eager eye.

How pleasant is the morning!

How bountiful is He

Who made delight a duty,

And filled the earth with beauty,

And gave us eyes to see!

Rejoice, O happy world, rejoice!

And raise to Him thy glad, glad voice,

Childhood serene and free!

A.

See the card-house, little one!

Is it not amazing fun?

Open wide your bright blue eyes!

High and higher it will rise.

Ah, it falls! a breath of air

Overthrows the fab′ric fair:

Now, dear boy, what shall we do?

Arthur cries, “Why, build anew!”

Right, my boy! we’ll try again:

You shall do like wiser men,—

Keep on trying, brave and true,

Never fear to build anew.

When, a lad, to school you go,

Should you fail your task to know,

Do not then as idlers do,

But cheer up, and build anew.

When, a grown-up man, you try

Some good work to build up high,

Should it fall, and you fall too,

Why, get up and build anew.

If we try to do our best,

We to God may leave the rest;

And, should failure here pursue,

We in heaven may build anew.

Ida Fay.

“THE HOUSE OF CARDS.”

I want to tell you a short story about some birds. It is a true story about Mr. and Mrs. Bluebird.

I have a friend who is very fond of all kinds of pets, and, most of all, of birds; and she loves so much to watch them, that she has put two little bird-houses in the trees near her window.

Here, every year, a pair of bluebirds come to make their home for the summer. My friend likes very much to watch them, as they fly round so busily, getting food for their little ones, and, when the warm weather comes, teaching them to fly.

So, very early every spring, my friend has the gardener clean out the houses, and make them quite nice, and ready for the little birds. But this spring, she was busy about other things; and it was so cold and chilly, she scarcely thought of the birds.

But one morning, as she was sitting by her window, she heard a great twittering and fluttering in the old maple-tree. It was Mr. and Mrs. Bluebird, and they were in some trouble.

Mrs. Bluebird would go into the house and look round; and then she would come out and talk away to Mr. Bluebird; and then he would go in, and they would both come out, and chatter and scold.

Then they examined the other house; but it did not suit them any better. They said, just as plainly as birds could, that they would not do their own house-cleaning; and then they flew off.

My friend was very much amused; but she felt sorry too, for the disappointed little birds; so she had the houses all put in good order that very day.

The next morning she was much pleased to see the little birds back again. No doubt they were glad to find their house so nicely cleaned and put in order. They went to work happily and cheerfully to build their nest, and then to go to house-keeping for the summer.

Don’t you think they were funny little bluebirds?

Charlie’s Mamma.

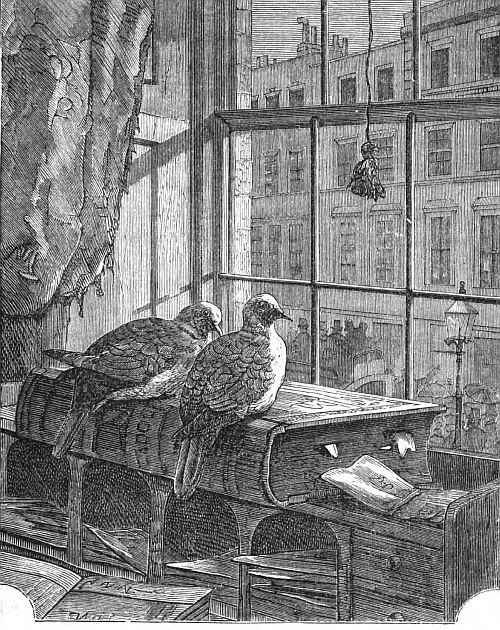

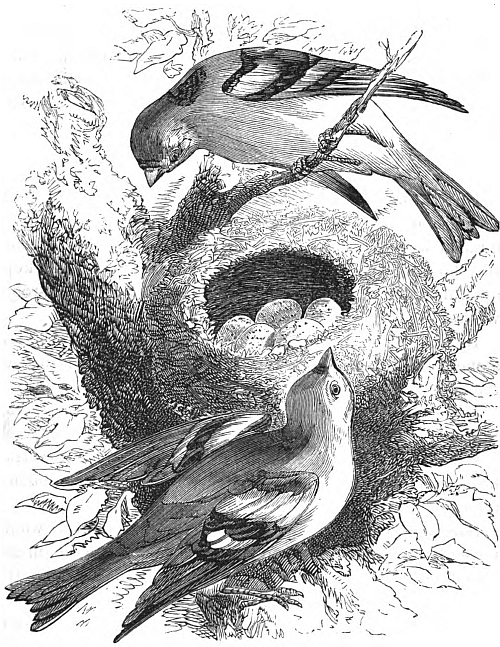

Here is a picture of the little bird that has lately been brought to our country, where it now begins to increase in numbers. In New York, a great many may be seen in the Central Park, and other parts of the city.

These birds were brought here because it was thought they would free the trees of the worms that do so much hurt to the leaves. How many caterpillars do you think a pair of these sparrows will eat in a week? They will eat four thousand.

But I am sorry to say that some bad stories are told of this bird. It is said he will plague the farmers badly by stealing their grain; that he is a sad thief. In England, boys are sometimes hired by the day to scare him from the wheat-fields.

“How fortunate that you have none of our house-sparrows in America!” said an Englishman, not long ago, to a friend of mine. But these sparrows are now here; and they increase so fast, that, in a few years, we shall have a plenty of them. They have been let loose in the Public Garden in Boston.

I hope they will behave better than some folks seem to expect. The house-sparrow is a pretty little bird, as you see. It likes to stay near houses and barns, and to fly over the new-mown hay. The children love it because it is so tame.

It is said that already, in two seasons, this little bird has done much good in the cities of New York, Newark, and Brooklyn. It has cleared the shade-trees of the insects which were such a pest. It is a hardy bird, and stands our cold winters quite well.

After he is fed, he likes a good frolic. In New York, you may see children feeding these sparrows. A favorite sport with the children is to throw up a feather into the air, and then to see these little birds fly after it, each striving to catch it and bear it off to his nest.

Uncle Charles.

Charles Ray is six years old. He can read to the folks from the good book. He likes to read, and he likes to play too.

But he does not like to play in school. No: while he is in school he minds his task; for he does not want to be a dunce when he grows up.

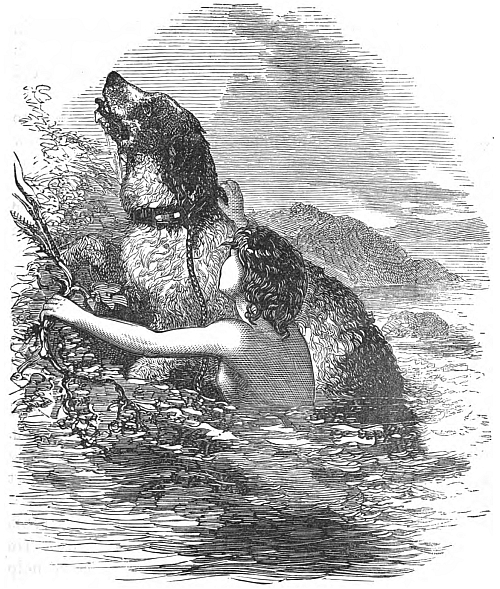

Charles went to the seaside in June; and, while there, he went in to swim. But he did not go in with-out a man to take care of him.

The man tied a rope un-der Charles’s arms; and, when Charles got be-yond his depth, the man would pull him back to the shore. But for this, Charles might have sunk.

There was a large black dog, who went in with him one day; and then Charles had a fine time. He would stand on the beach, and throw a stick as far as he could; and the dog would plunge in and swim for it, and bring it back.

Then a horse was brought down to the beach; and Charles rode on his back in-to the sea, till the waves were up to the little boy’s knees. Then the horse swam, and Charles thought it was fine fun.

This is Robin Redbreast, with his little bare feet. He sits and sings all day long, up in the top of the maple-tree.

Robin Redbreast found a string on a little rose-bush down by the door-step. He took it in his bill, and away he flew.

This is the way Robin Redbreast looked when he pulled the string from the rose-bush.

Robin Redbreast built a curious nest. He put in little sticks and straws, and then wove it together with strings.

This is Lady Redbreast, sitting on her three little light blue eggs, in her little soft nest.

Here are the three young robins that peeped all their little soft heads out of the nest one fine spring morning. Mary saw them, and counted them.

W. O. C.

Little Daisy’s mother was trying to explain to her the meaning of a smile. “Oh, yes, I know,” said the child: “it is the whisper of a laugh.”

Come to the window, Susan, quickly! Get your handkerchief ready to wave. Here come the soldiers marching down the hill. This is Capt. Robert’s company of light infantry. They are out in honor of the Fourth of July.

Capt. Robert is a very able officer. He is six years of age. He is very proud of his troops. He raised the company himself, and drilled them in his father’s back yard. This is their first public parade.

Look at that tall trooper with the flag! Is he the captain? Oh, no! he is a model soldier; but he is not the captain. You may know Capt. Robert by his cocked hat and his sword. Don’t you hear him giving the word of command? What are you laughing at, Susan?

Just look now at the band! There’s a trumpeter for you, who blows with his whole soul. Were ever drumsticks handled better? What a fine thing is martial music!

There, they have all passed by. But I will give you their line of march, and you may run round the corner and see them again. Perhaps you would like to follow them. After the parade is over, they are to have a lunch of gingerbread and lemonade at their headquarters in Capt. Robert’s back yard. I dare say there will be some fine speeches. I should like to be there; but I suppose none but military men will be admitted.

Alfred Selwyn.

“THE FOURTH OF JULY.”

“Take care, take care! that chair will not bear you: you will fall!”

Crash, crash, crash! Down goes the chair, with poor little Trottie on it!

“There! Did I not tell you you would fall? Get up, and do not cry. You are not hurt.”

“But what made the chair give way and break?”

“It is old and weak. If you had done as you were bid, you would not have had a fall at all. You are not as wise as an el′e-phant was, of whom I could tell you.”

“Why, what did he do? Tell me of the elephant.”

“He took care to do as he was bid. One day, when he had a great load on his back, he came to a bridge which had just been put up; and the man who drove him did not know if the bridge might not be too weak to bear so great a weight.

“So the man said to the elephant, ‘Take care, Tim! I do not know if this bridge will bear you.’

“When Tim heard this, he went slow,—oh, quite slow!—and he put one great foot down on the bridge, and pressed hard, to try if the bridge would bear his weight.

“And when he found that the bridge did not so much as crack, then he put his two fore-feet on the bridge, and pressed hard, and gave a great stamp with his feet.

“But the bridge did not so much as shake. So then Tim turned to the man who drove him, and gave him a look which said as plain as words, ‘It is all right: I may cross this bridge.’ And so he did, and got quite safe to the other side.”

“I wish I had been as wise as Tim.”

“So do I; for then you would not have tried to get up on a chair not strong enough to bear your weight.”

Trottie’s Aunt.

“I have had such a happy day, mother!” said little Henry, as he lay on his bed, after he had said his prayers, and was ready to go to sleep.

“Now tell me what you have done,” said his mother.

“Well, first I got up at six o’clock, and went to the barn, and saw Tim milk the cows. Then I came in to breakfast; and you and father each gave me a kiss.”

“I will give you another, my dear little boy,” said Henry’s mother. “Go on with your story.”

“Then, mother, you gave me some corn; and Ida and I went to the door, and called the chickens, and I fed them. There was one queer thing that made us laugh.”

“What was that, Henry?”

“Why, while our two little puppies were playing at fighting, and one was going to jump down on the other, the old rooster, who seemed to think they were having a real fight, came up, and tried to part them. Then the mother of the puppies began to growl and bark; but she could not get out of her kennel to bite the rooster. How we did laugh!”

“What more happened to my little son?”

“Then I went to school with Ida; and my teacher said she should give me a reward of merit next week. There was no school in the afternoon; so we went to the fields, and I had a good time playing in the hay while the men were raking it.”

“But what did you do with the two cents I gave you?” asked Henry’s mother.

“I am coming to that by and by, mother,” said Henry. “After we had played in the hay, I thought I would go with Ida, and buy some candy. Just then, an old, old woman came along, who looked so poor, that I said to Ida, ‘I will give one of these two cents to this poor woman.’ ”

“But why did you not give her both?” asked Henry’s mother.

“You naughty mother! You know all about it. Ida has told you. I did give the poor woman both the cents,” said Henry, kissing his mamma.

“Well, sir, go on with your story.”

“As we passed through the field, mother, I saw a little bird on the ground. It had fallen from its nest in a bush. So I picked it up, and put it back in its nest; and then I thought how happy the mother-bird would be, and that helped to make me happy too.

“We stopped at a field where a man was reaping wheat; and he told us where we could find some nice ripe blackberries. Well, we went and picked some of the nicest blackberries you ever saw; and, if we had had a basket, we would have brought some home for you and papa.

“As we came home by the pond, we saw an old hen and some little ducks; and I said to Ida—I said to Ida—and Ida said to me—said—Ida—ducks—hen—swim—little ducks—so—Ida—ducks—old hen—and so”—

Little Henry, who, while speaking these words, was half-asleep, now fell fast asleep. I am much afraid we shall never learn the end of his story. I wish he had not fallen asleep before he told us what he said to Ida, and what Ida said to him, and what the old hen did when she saw the little ducks in the water. I would like to know all about it. Would not you?

Emily Carter.

“What is the matter, my young friend?” asked a lady of little William Scott, who seemed to be quite vexed about something. “What have you in your hand?”

“It is a flower,” said the little boy. “I asked a girl I met the name of it; and she mocked me.”

“Why, what did she say, William?”

“Instead of telling me the name of the flower, she kept laughing at me, and saying Sweet William. Now, what is the name of the flower?”

“Sweet William,” said the lady.

“I’ll not stay here to be laughed at,” said William. “I’ll go home and tell my mother.”

“Good-by, then, Sweet William,” cried the lady laughing, as William ran off, ready to weep with vexation.

As soon as he got into the house, he went to his mother, and, holding up the flower, said, “Mother, please tell me the name of this flower.”

“Sweet William,” said his mother.

“I’m not sweet. I feel angry; I’m ready to cry,” said William. “Why do you all plague me so to-day? When I ask the name of the flower, everybody says, Sweet William. I do not like to have people joke me. I will not be laughed at.”

And, as he said these words, William frowned, and threw his cap on the floor.

“Pick up your cap, and come to me,” said his mother.

William obeyed; but a tear glittered on his cheek.

“Now take down your dictionary, and look at the word sweet.”

William looked, and said, “I have found it.”

“Now glance down the column, and read the words that begin with sweet.”

So William read, sweet-bread, sweet-brier, sweeten, sweetmeat, sweetness; but here he stopped, blushed, and hung down his head.

The line at which he stopped was this: “Sweet William, the name of several species of pink, of the genus Dianthus.”

“Please do not laugh at me,” said William, as he saw a smile on his mother’s face. And then he added, “Yes, you may laugh at me. I deserve to be laughed at. And I must run and beg pardon of the girl and the lady who answered my question; for I was rude to them both.”

We must not take offence till we are sure that people mean to give it by what they say. William was quickly forgiven by the girl and the lady, with whom he had been foolishly vexed.

Uncle Charles.

Out of the water into the light

I leap for a moment, then drop out of sight.

They call me a flying-fish; but I’ve no wing,

Nor can I mount freely like robins, and sing.

The shark and the dolphin, they try and they try

To catch me and eat, but too nimble am I;

For when they come near me, and think I’m their prey,

Up, up, I spring quick, and get out of their way.

Uncle Charles.

Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow: they toil not, neither do they spin; and yet I say unto you, That even Solomon in all his glory was not arrayed like one of these.—Matt. vi. 28.

CHARLOTTE CUTTING BREAD AND BUTTER FOR THE CHILDREN.

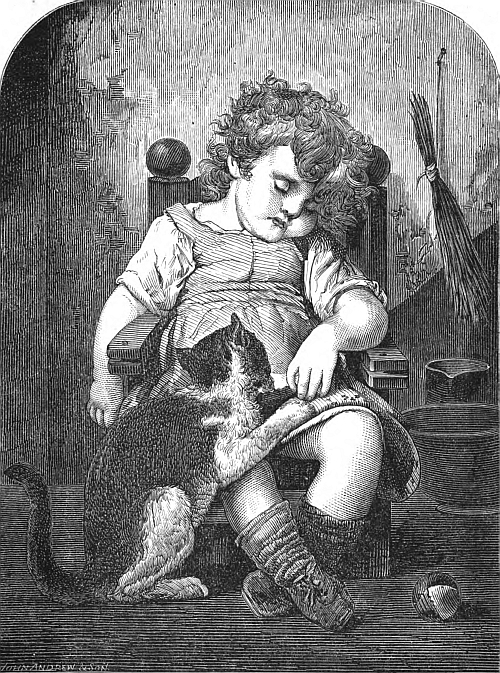

Char′lotte is bus′y cut′ting bread and but′ter for the chil′dren. I want you to look at the pict′ure, and stud′y it well.

Charles, James, Ma′ry, and Ar′thur stand in front of Char′lotte, wait′ing for the slice she is cut′ting. Ma′ry has her arm round Ar′thur, who is look′ing up ea′ger-ly; for he is hun′gry. James, too, feels that he would like a piece of bread. But Ma′ry is quite will′ing to wait.

Lit′tle Paul sits fast′ened in the high-chair, and holds a piece of bread to his mouth with both hands. He has kicked his shoes and one of his stock′ings off from his feet; for he is still not much more than a ba′by.

On the floor I see a whip, a doll, and a wood′en horse; and the old black cat sits qui′et-ly by. I think she must have been fed, or she would not sit so still while there is some′thing to eat in hand.

But, ah! what is that boy a-bout, who stands be-hind Char′lotte, where she can′not see him? That is Rob′ert; and I am sor′ry to say he is tak′ing a bunch of cher′ries out of a plate with-out ask′ing leave.

That is not right. The cher′ries are put there for all the chil′dren; and Rob′ert ought to wait till Char′lotte is read′y to di-vide them. We must not be greed′y. We must not take what does not be-long to us.

Char′lotte is a good sis′ter. The dear moth′er of these chil′dren is dead; and Char′lotte helps her fa′ther to take care of them. She keeps a lit′tle school for them in the big par′lor, and there teach′es them to read and write.

On a mild day in June, while the chil′dren were at their studies in the school-room, a lit′tle bird flew in at the o′pen win′dow, and fell in′to Char′lotte’s lap. It was a young king′bird, and had been chased by a hawk.

Char′lotte took it in her hand, and fed it, and made it tame; so that now it will rest on her head and play with her. Some-times, when she is at work, it will come and take the thread from her hand, and fly off.

Char′lotte is so kind to birds that they love her dear′ly. She has taught them to come to her in the gar′den. They will come and light on her hand, and feed from it. They sing sweet songs when she is by; for they seem to know that she is their friend.

Uncle Charles.

Two hens and a rooster. Is he not a fine, large bird? See his long feathers.

Little Bessie was just six years old; but, young as she was, she was a great com′fort to her fa′ther and moth′er. Shall I tell you why? Well, it was be-cause she was as good as she was pret′ty. If they told her not to do such or such a thing, she would mind what they said to her.

One Sat′ur-day af-ter-noon, her moth′er, who was go′ing out to call on a sick la′dy, said to Bessie, “Now, my dear, I want you to stay at home while I am a-way. Do not go out of the yard.”

“I will stay and keep house,” said Bessie. And then her moth′er gave her a kiss, and left her.

It was a bright, mild day. The birds sang sweetly; and the smell of new-mown grass came from the fields. Bessie felt quite hap′py as she sat on the steps of the front door with her kit′ten in her arms.

But she had not sat there long when she heard the voices of chil′dren com′ing near. She looked up, and there, outside the gate, stood two of her little school′mates.

“O Bessie!” said one of them, “we are go′ing to have a nice time, and you must come with us.”

“What are you go′ing to do?” asked Bessie.

“We are go′ing to pick some ber′ries, and then we are go′ing to take them home; and Clara says she will ask her moth′er to let us have the doll’s tea-set to play with; and we will have the ber′ries for sup′per. Will you come too?”

“Yes, I will come,” said Bessie: “but wait till I take Kitty into the house; for, if I leave her here, some bad boy may come a-long and steal her, or some big dog may scare her.”

So Bessie took her kitten into the house, then came out, and ran to the gate; when all at once she thought of what her moth′er had said to her.

“O Clara! and O Lucy!” said the little girl, “I must not go with you after all.”

“Why, Bessie! you just told us you would go.”

“I know it, and I do want to go so much! But, when I spoke, I for-got that I told mam-ma I would not go out of the yard.”

And the big tears stood in Bessie’s eyes.

“We shall not be gone long; and your moth′er need nev′er know of it,” said Clara.

Poor little Bessie stood there with her hand on the gate. She thought of the nice walk through the fields, and how sweet the ber′ries would taste: but then, had she not told her moth′er she would not go a-way from the house; and was it right for her to break her prom′ise?

“I cannot, I will not, go,” said Bessie; “but, if you will stop and play with me till moth′er comes back, I feel sure she will let me go with you then.”

“No, no! we want to go now,” said Clara and Lucy; and off they ran, leaving Bessie with her hand on the gate.

Bessie watched them till they were out of sight, and then she took a seat on the step. She thought of the nice time they would have among the ripe ber′ries, and she sighed just a little at the thought.

Then she went into the house, and played with Kitty, and tried to make Kitty look at the pictures in her book; but Kitty would have liked much more to look at a good sau′cer of milk.

All at once Bessie saw her mother coming up the street So she ran out of the house, and bound′ed through the gate, to meet her and take her by the hand.

“Has my little girl been good?” asked her mother.

“Yes, mam-ma; but I came near to being naugh′ty,—oh, so very near! Clara and Lucy came for me to go and pick ber′ries with them; and I was go′ing, when all at once I thought of what you had told me.”

“You are a good child, Bessie,” said her moth′er; “and here is an or′ange that I bought for you.”

Bessie felt very hap′py that night. Can you tell me why? It was be-cause she had kept her word to her moth′er. How sad she would have been if she had not done so! Be true to your par′ents, my dear little friends. Nev′er, oh, nev′er, try to de-ceive them!

F. P. S.

Edwin is not three years old; but he likes to be of use. When the snow is on the ground, he will put on his greatcoat, and take his little shovel, and help the men shovel off the snow.

When the warm days of June have come, and the men begin to mow the grass, Edwin will take a rake and try to spread the grass, so that the sun may dry it, and make it into hay.

He likes to take a stick and drive the cows home to the barn-yard. The other day he tried to milk one of the cows; but he found it too hard work for so small a boy.

Then he thought to himself, “I can go up in the hay-mow, and see if the old hens have laid any eggs there.” So up he went, and he looked here, and he looked there, in the hay, till he caught sight of a white hen sitting on her nest.

“Get up from there, old hen!” said he, “and let me see if you have laid an egg.” The white hen did not like to get up; but Edwin made her do so. She scolded him well; but it was of no use. To his great joy, he found four eggs in her nest.

Then he went to another part of the hay-mow, and there he found a black hen sitting. He drove her off, and found five eggs, white and warm, in the nest. So he put them in his apron with the others, and ran to take them to his mother.

But, ah! he ran too fast His foot slipped, he fell! and the eggs rolled out, and were broken on the floor of the barn. The hens flew off as fast as they could go; and the old rooster turned his back on him, and walked away cackling, as if he meant to say, “You are a bad little boy to come and drive off the hens.”

But Edwin was not a bad little boy, though he sometimes fell into mischief in trying to do too much. His mother forgave him for breaking the eggs; and now, when he goes to the barn in search of eggs, he takes a small basket, and puts them in that.

Ida Fay.

Come, we will our voices raise

In a grateful song of praise;

Children, come and join my song:

Praise and prayer to God belong.

Heavenly Father, oh! impart

Truth and love to every heart.

Though the earth and sky are his,

He our loving Father is;

Though all Nature owns his reign,

He will not our gift disdain.

Heavenly Father, oh! impart

Truth and love to every heart.

We are young, and we are frail;

Soon our mortal strength must fail:

Let us find, O holy One!

Light and peace in Christ thy Son.

Heavenly Father, oh! impart

Truth and love to every heart.

Emily Carter.

A TRUE STORY.

Mrs. Holden had an old hen which had only one little chicken. This little chicken was very feeble, and went peeping about in quite a pitiful way. When Mrs. Holden was in the kitchen one day, and saw the old hen clucking around the doorstep with one chicken, she said to her girl Ann, “I don’t think it is of any use to raise that one chicken. I will give it to the cat.”

There was a great gray cat under the table, lying in a basket with her three kittens. So Mrs. Holden picked up the poor little chicken, and tossed it into the cat’s basket, looking to see it eaten up.

But, instead of hurting it, the old cat began to lick its little downy feathers just as she did her soft little kittens. And the chicken cuddled down close to the cat, and kept warm.

Mrs. Holden said, “Old Pussy isn’t hungry just now.” But old Pussy had no idea of eating up the chicken, even if she was hungry; and, when food was given to the cat and kittens, the chicken ate some too. So it lived with the cats, and began to grow and thrive; and Mrs. Holden used to take her friends into the kitchen to see the funny sight,—a chicken nestling down among the cats, and the old cat washing it like a kitten.

When Mrs. Puss left her basket, the chicken would jump out, and follow her out of doors and in again.

At last one day, when the chicken got as large as a pigeon, the old cat started out to go hunting. She had got nearly round the house, when she looked round, and saw the chicken following her. Then she turned back, and took it by the neck.

“There,” said Mrs. Holden, “the chicken’s gone now! The old cat has killed it!” But she had not. She carried it back to the basket, and dropped it in. Then she went away.

But she had not got round the house, before the chicken was out and after her again. The old cat heard it, and turned about, and took it by the neck the second time.

“She’ll finish it this time,” said Mrs. Holden. But the cat only carried it back, and dropped it in the basket, and went the same way she did before. In a minute, the chicken was after her. The old cat turned about the third time.

“Now she will surely kill it,” said Mrs. Holden. But she did not She carried it dangling along, and dropped it in the basket, and it staid there that time.

So the chicken lived with the cat after the kittens were given away. She grew to be a very good hen, only she never learned to go to roost like other hens. I do not think all cats would be so kind to a chicken as that cat was: do you?

Harriet F. Woods.

A boy on the back of a cow. Look at them!

Ring-Ting! I wish I were a primrose,

A bright yellow primrose, blowing in the spring!

The stooping boughs above me,

The wandering bee to love me,

The fern and moss to creep across,

And the elm-tree for our king.

Nay, stay! I wish I were an elm-tree,

A great lofty elm-tree, with green leaves gay!

The winds would set them dancing,

The sun and moonshine glance in,

The birds would house among the boughs,

And sweetly to me sing.

Oh, no! I wish I were a robin!—

A robin or a little wren, everywhere to go,

Through forest, field, or garden,

And ask no leave or pardon,

Till winter comes with icy thumbs

To ruffle up our wing.

Well, tell! Where should I fly to?

Where go to sleep in the dark wood or dell?

Before the day was over,

Home comes the little rover,

For mother’s kiss—sweeter this

Than any other thing!

William Allingham.

The Fourth of July was a very hot day,—so hot that we did not feel like walking in the sunshine; so hot that the hens kept in the shade, and the old cat lay down in a cool place in the cellar.

It was voted by the children in our house that we would all stay at home, and have as good a time as we could. It would take me too long to tell you of all our games; but I can tell you of one which seemed to suit the heat of the day quite well.

Little Albert called it “Playing at Icebergs.”

But what is an iceberg? some may ask. You know what ice is? Well, a berg is a great mass or hill of floating ice. Far at the north, where it is very cold, great heaps of ice form along the shores; and in summer they break away, and drift toward the south.

Sometimes these heaps of ice are a mile long and half a mile wide, and as high as the highest house you ever saw. When these bergs are afloat, the ice under water is about eight times more than that above water.

The ship that comes near to these great heaps of ice is in much danger: for, if she should hit them, great splinters of ice might fall and crush her; or, in the night, she might run against an iceberg and be wrecked.

But I must not forget to tell you how we played at icebergs on the Fourth of July. You must know that we have, in one of our upper rooms, a tank which is six feet long by three feet wide. I think that must be quite as large as the table at which you take your meals.

This tank was filled with rain-water; and we were told that we might make little boats out of shingles and paper, and sail them in the tank. This we did; but, as the water was rather warm, my brother Henry ran to the ice-house, and got six large lumps of ice, which he put into the water.

It was then that we began playing at icebergs. First, Albert’s boat ran on an iceberg, and was upset; then, as Mark Winslow’s ship was sailing before a fair wind, down came a great iceberg, and tumbled over on to it, and sank it. The whole cargo, made up of wooden nutmegs, was lost.

We looked at the iceberg to see how much more of it was under water than above. I think I am right in what I have told you on this point. Some men who were in Albert’s boat when it sank were saved, and put on an iceberg; but they must have had a cold time of it there, floating about on ice. Still, as they were made of pewter, ice was much safer for them than fire would have been.

One of these men, who had on a red cap, and carried a gun, fell into the water, and sank to the bottom just like lead. I am glad to say, that, with the aid of a pair of tongs, he was saved. When brought up, he seemed to be quite as hearty as he was before he was drowned. We offered him lemonade, and treated him well.

The ice lasted about half an hour. Then it was found to be nearly all melted; and, as we were nearly all melted likewise, we thought we would go down stairs, and each find as cool a place as he could, and keep fresh for the fireworks in the evening.

Alfred Selwyn.

John has the promise of a little donkey. This little donkey is yet with its mother, and is not quite large enough for John to ride. But John’s father tells him that in four months the little donkey will be quite large enough for him to ride. Will not John have good times then? I think he will.

Here is Biddy with her five little chicks. She had eight chicks at first; but three of them died. They went out in the rain, and took cold. Then I thought that Biddy had better keep in her pen when it rained.

Now these five little chicks have very nice times every day. They scratch in the dirt for worms; and, when a bug flies along, they run after it. If their mother finds any thing for them, she clucks, and tells them to come and get it. When the sun goes down, then the little chicks are all tired. Their little eyes feel sleepy, and they begin to say, “Peep, peep;” which means that they want to go to bed. So the Biddy tucks them all up under her feathers, just as you see in the picture.

Lizzie went out in the morning to feed the chicks, and to give them some drink. They had just waked up, and were peeping out from under their mother’s wing. As soon as Lizzie called them, they all ran out to meet her. They picked up the nice crumbs, and then ran to the dish to drink.

W. O. C.

I know a boy whose name is John Blunt. He is a boy who boasts a good deal. To hear him talk, you would think he was a brave boy,—one who did not fear to walk for miles through a thick wood on a dark night.

But, as you will see, John was bold in his words, but not in his acts. If a small, weak boy came in his way, John would knock off his hat, or try to throw him down; but let the boy be large and strong, and John would take care not to do or say what would tease him.

Once John met a small boy, who, though he was small, was strong and brave; and so, when John said to him, “Come here to me,” this boy, whose name was Charles, said, “If you will ask me in the right way to come, I will come; but I shall not mind you so long as you speak in that tone of voice.”

Then John ran at him to strike him, and throw him down. Charles stood his ground; and, when John put up his arm to strike him, Charles took hold of it so hard, that John cried out with pain, and tried to get a-way.

Then Charles said, “I do not fear you, John Blunt. I do not like to fight; but you may be sure I shall not let you strike me, or throw me down. So now do what you can.” And with these words, Charles let go his arm, and stood up, brave and proud, face to face with the big boy.

“I was in fun,” said John Blunt, who thought it best to walk off, and not to play tricks on Charles. But Charles cried out to him as he went, “Take heed now of what I say, John Blunt: from this time forth, I shall not let you knock off the hats of small boys. If I see you do it, I shall stop you. So look out, and treat small boys well.”

Since that time, John has not been rude to small boys when Charles has been by to see him.

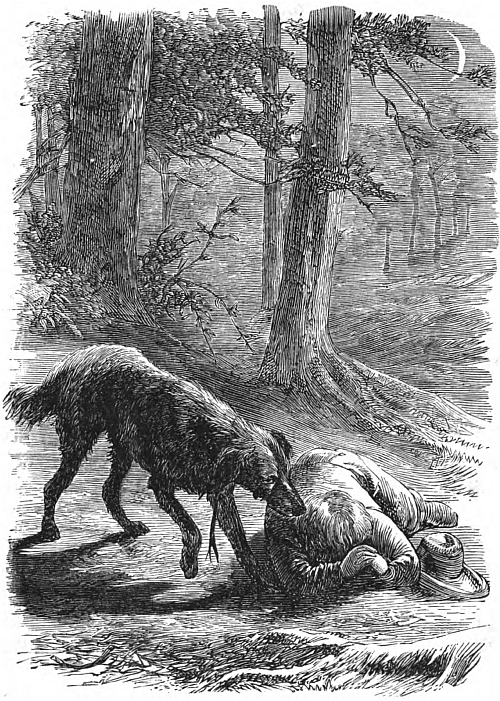

But what I sat down to tell you of now is how John was scared in the grove last week. The sun had set, and the new moon was in the sky, so that it was not quite dark. John had been sent to a place three miles off to get a man to come to mow grass the next day.

John saw some boys at play, and stopped a long while to see them. On his way home, he had to pass through a grove of oak and pine trees. John did not like this. He thought of rob′bers, and he thought of wolves, though no one had ev′er seen a rob′ber or a wolf in that grove.

All at once he heard steps in the dry leaves near by. “Ah! that must be a wolf,” thought John; and he shook with fear. Trot, trot, trot!—near and more near came the sound. “Help, help!” cried John. “Here is a wild beast in the grove. Will no one come to help me?”

In his fear, John fell on the ground, and hid his face with his arms, so that he might not see the grim thing. On it came, near and more near—trot, trot, trot! And now it stands over him; it breathes in his ear; it licks his hand. “Oh, don’t! oh, don’t! Help, help!” cried John.

But no one came; and, as the beast kept on lick′ing his hand, John at last grew so bold as to look up. What did he see? Only old Boz, the miller’s dog! Boz had been tied up all day. At last he broke the rope that held him, and ran out in the grove to have a good time.

How glad John was when he found it was Boz! He made Boz go home with him; for John did not feel quite sure that he might not meet a wolf, and it was well to have a friend in need. John gave Boz some milk and a bone when they got home. Then Boz ran back to the mill, and kept watch there, like a good dog, all night.

Emily Carter.

A baby at auction!

Who wishes to buy?

With small pretty features,

And laughing blue eye.

To those who would purchase,

We’ve only to say,

She’ll furnish you music

By night and by day.

She sings like a robin,

And coos like a dove;

Her heart is o’erflowing

With sweetness and love.

Now, who’ll buy the baby?

She’s fresh as a rose,

With soft dimpled fingers,

And little pink toes.

She cannot be purchased

For silver or gold:

For mother’s love only

Will baby be sold.

No bid for our darling!

Then home we must go;

For no one loves baby

Like mother, I know.

Aunt Clara.

North Andover, Mass.

My friend Miss Jones had a cat to which she gave the name of Buff. One day, when Miss Jones called her, there was no Buff to be found,—no Buff to say, “Mew! mew!” mean′ing, “Here I am!”

Miss Jones looked here, and looked there; and the maids looked, and the men looked: but there was no Buff to mew out, “Here I am! here I am!”

And the day went by, and the night came; but no Buff came with them. And once more the day came, and night came; but no Buff came with them. And so two weeks went by, and no one saw poor Buff.

Then my friend Miss Jones gave Buff up for lost, and said, “My poor cat, I shall see you no more. You were such a fine, nice cat, that I fear some bad man has put you to death for the sake of your soft white fur.”

At this thought, Miss Jones, I am grieved to say, sat down in her arm-chair, and cried.

Now, a day had come when she was to go and stay from home; and the coach was at the door. And, just as Miss Jones was to get in, one of the maids said to her, “You will be cold: you must have your warm cloak.”

“No, no,” said Miss Jones. “My warm cloak is put by where no one but I can get it; and I will not get it now.”

“Then you must not go at all, Miss Jones,” said the maid. “You must not go to take cold and be ill.”

So Miss Jones had to go back to the house to get her cloak; and she went to a room at the top of the house, in which her cloak had been put by. And, as she went in′to the room, she heard a sound of “Mew! mew! mew!” Oh! quite soft and low.

“Hark! That is Buff’s voice. I am sure that is Buff,” thought Miss Jones; and she was like to jump for joy.

And she looked this way, and she looked that, but there was no Buff; and yet Miss Jones was sure that the sound came from Buff. So Miss Jones said, “Buff, Buff, Buff! Where are you, my dear Buff?”

And then there was a soft, low mew, which seemed to come out of the wall, and to say, “Here I am: I am shut in. Pray let me out.”

And Miss Jones went up to the wall; and in it she saw a door, and in the door a lock. So she turned the key of the lock, and the door gave way; and there on the floor was Buff, so thin,—oh! so thin,—that she seemed no more than skin and bones.

Buff could not move, she was so weak; but she looked up at my friend, and said, “Mew! mew! mew!” which meant, “I am so glad, so glad, so glad to see you!”

And Miss Jones took Buff up in her arms, and bore her to a nice warm room, and gave her nice warm new milk: and poor Buff could not lap it at first; but by and by she lapped the milk, and then she did not feel so weak and ill.

In a short time, Buff was well, and could run and jump and play once more; and Miss Jones was right glad to see her fine cat well once more.

“Oh, I am so glad that Buff was found!” said Trottie. “It would have been so sad if Buff had been put to death for the sake of her soft white fur.”

“Yes: it would have been sad. I am glad that Buff was found.”

Trottie’s Aunt.

The story of the horse that went to the blacksmith when his shoe hurt him reminds me of one that went to a doctor of his own accord. It is a true story.

He had been sick several times with the same disease; and a farrier (which means a horse-doctor) had given him medicine that always cured him.

One day, when Old Jack was out at work with other horses, he was taken sick again; and, when no one was near him, he started off, and went to the farrier’s house. It was nearly a mile away.

The man at first supposed the horse’s owner must have come with him; and he looked around in every direction. But, as he did not see any one, he thought the horse was sick, and had come for help.

So the man unharnessed him; and the horse at once lay down, and showed, as plainly as if he could have said it, that he was in pain.

The same remedies that had helped him before were used; and in a little time the horse was better, and was sent home to his master, who had been looking for him.

Horses know a good deal; and, when treated kindly, they grow to love their masters very much. They try to serve you all that is in their power. It is wicked to abuse them.

No person can be truly happy, even in this world, who is not kind to God’s creatures; nor can he be fit to dwell in heaven by and by.

M. O. Johnson.

BOY.

Butterfly, upon the wing,

Pretty, fluttering little thing,

Floating, hovering in the air,—

On what do you live up there?

BUTTERFLY.

Honey-dew, sunshine sweet,

Is the food I have to eat.

The insect gay floated away,

Fearing the boy would mar its joy;

And as it went on glittering wing

Floating, thus it seemed to sing,

“Dear child, it is so bright

In the glad sunlight,

Catch me not, but let me fly:

To-morrow, cold and dead I’ll lie.”

M. E. L.

There were two lit′tle girls. The name of one was Mar′tha; of the oth′er, Ra′chel. They were sis′ters. Mar′tha was the eld′er of the two, and ought to have known bet′ter than to quar′rel: but these lit′tle girls did quar′rel; and what do you think it was a-bout?

I will tell you what it was a-bout. It was a-bout whose doll was the pretvti-er. Ra′chel said, “My doll is the pret′ti-er doll of the two.” And then Mar′tha said, “No, it is not. My lit′tle Flo′ra is much bet′ter look′ing than your fat old Ro′sa.”

Now, Ra′chel did not like to hear her doll called “fat old Ro′sa.” The doll was a pres′ent from her aunt, and Ra′chel set great store by it; and so she said to Mar′tha, “You are a bad girl to call my doll ‘fat and old.’ ”

Mar′tha did not like to be called a bad girl. So she said, “I shall not speak to you till you ask my par′don.” And Ra′chel said, “I shall not ask your par′don.”

And so there they stood, the two sis′ters, each with her doll on her arm, and each feel′ing sulk′y and cross. Just look at them! Now, was it not silly for them to quar′rel a-bout so slight a thing?

Their moth′er came down stairs, and found them stand′ing there, still and speechless. When she learnt what was the mat′ter, she took both the dolls a-way from them, and locked them up, and said, “If the dolls are to be made a cause of strife, they must be put out of the way.”

Mar′tha felt a-shamed; and, af′ter a silence of some min′utes, she went up to Ra′chel, and kissed her, and said, “I ask your par′don if I hurt your feelings.”—“And I am sor′ry that I said what I did,” cried Ra′chel, giving her a kiss in re-turn.

And so the grand quar′rel was made up. The dolls were given back to the chil′dren. Then Mar′tha and Ra′chel put them into their lit′tle car′riage, and went out by the wayside, near the fields, and plucked wild ros′es, but′ter-cups, daisies, and red clo′ver. They had a good time; and I hope they will be too wise to quar′rel more.

Anna Livingston.

Kate says to Frank, “Be brave now, and try to walk. You will not fall if you will but think that you will not fall. Come, do not fear. I will hold my arms wide to catch you if you should fall.”

Frank does not fall. He is more than a year old by one month. He walks to Kate, and she takes him in her arms, and gives him a kiss.

See, his small cart is on the floor; and Kate’s doll is on the floor too. Frank will put the doll in the cart by and by, and push it back and forth. He loves to play; but I hope he will love to learn, too, as he grows up.

In the barn, there is an old black dog whose name is Bob. Bob is good to Frank, and will let Kate put Frank on his back. Then Bob will give him a ride, first to the front gate, then to the grove, and then to the pond.

On the pond, near the shore, there is a boat; and some-times Jane and Frank get in-to the boat and rock it. Bob stands by to see that no harm comes to them. If Frank should fall from the boat, Bob would rush to take care of him; for Bob is a good, strong old dog, and likes to be of use.

It is a sad thing to be at sea, not far from the coast, in a storm. The fear is that the gale, if it comes from the wrong point, will then drive the ship on to the rocks or sands of the shore.

On a day in spring, two years since, the wind blew hard from the north-east; so hard, that the folks in the good ship “John Bright,” which lay not quite four miles from the coast, were in great fear of their lives.

At night, the fog set in with rain; and it was so dark, that the crew did not know how near the shore they were. When the light dawned the next day, they found the ship was near a reef of rocks; and she soon struck on them, and there she lay for some time.

The waves would rush in and lift the ship, and then go back, and let her fall on the sharp, rough rocks; and the folks on board the ship saw, that, if they did not soon have help from the shore, they must be lost in the wild sea, or tossed on the rocks and killed.

But there were brave folks on the shore, who were quick to lend their aid. They drew the life-boat down from the house where it was kept, and then got on board, and went out to the poor ship that lay a wreck on the reef.

A life-boat, you must know, is so made that it can-not well be sunk. It will float on the top of the waves; and, if the waves rush into it, it will still float They can-not sink it.

There were seven brave men in the life-boat that went out to the ship “John Bright.” On board the ship they found, be-sides the crew, three women and a baby. How glad they all were to see the life-boat come to save them!

First the women and the baby were put in the boat; then the men got in, and the boat was rowed back to the shore; and all were saved. The baby did not cry all the time; and the mother said it should be called John Bright, after the good ship that had been lost.

Uncle Charles.

Alice wanted to cut up two oranges so as to divide them equally among seven children. How do you think she did it?

The little boy’s play is over for the day. The busy feet, tired with their running at home and at school, are ready for rest. And now, as he comes to his mother’s side to say his evening prayer, and then give his good-night kiss, dear mamma, stroking his forehead, says, “Eddie has been a good boy to-day: I am sure he has tried to be: and that makes mamma very glad.”

And Aunt Sophie, sitting by, holds up a nice little sheet of note-paper, and says, “Hear what auntie has written for him.”

I am happy, happy, happy,

For I have been good to-day:

While at school I pleased my teacher,

And was gentle in my play.

I have done as mother told me:

I have said no angry word;

For I know that angry children

Are not pleasing to the Lord.

Oh! ’tis pleasant to remember,

When I go to rest at night,

That through all the day, since morning,

I have striven to do right.

And I know that God will hear me

If I ask him every day,

And that his dear love will lead me

In his sweet and pleasant way.

Now may loving angels guard us,

Till the morning’s rosy light

Wakes us from our quiet slumbers:

Darling mother, now good-night!

E. O. P.

The grapes hung purple on the wall. They were Ellen’s grapes. She had raised them from a small vine which now bore one nice bunch, and only one. This she had watched for some weeks.

She had seen the grapes when they were little green dots, no larger than the head of a pin. Day by day, and week by week, they grew and grew till they became quite large, and began to turn purple.

And at last they were ripe, and ready to be plucked. “How nice and sweet they must be!” thought Ellen. “How I would like to eat them all down!”

But she did not eat them. She thought of Mary Draper, a little schoolmate who had been very ill for six weeks, and who, it was feared, would never get well.

Ellen cut the bunch from the stem, put it in a nice basket, and took it to Mary Draper. How glad Mary was! I think it must have helped to make her well; for from that time she grew better, and she is now well enough to go to school. She will never forget Ellen’s kindness.

“How much sweeter it was to do good to Mary than to eat the grapes myself!” thought Ellen.

Alice.

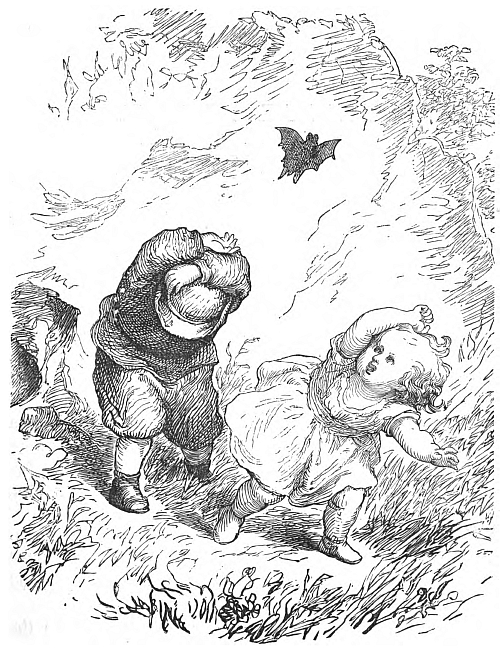

LUCIAN AND HIS COUSIN LILY FRIGHTENED AT A WHAT-IS-IT!

I think I once told you of Lucian and his cous′in Lily,—how Lucian want′ed Lily to go forth with him into the wide world; and how they met some bad boys who tried to take away Lily’s pet lamb (but it was made of wood); and how Lily then cried to go back home.

One fine day, not long after this, they thought they would once more go forth and see the world all by them-selves. So, as soon as they had eat′en their din′ner, they left the house, and went into the wood.

Here it was so pleas′ant, that they sat down on a rock, and watched the birds, as they flew from branch to branch or sang sweet songs on the stone wall near by.

Lily found some bright green moss, and this pleased her a good deal. She found a bay′berry-bush; and the leaves were so sweet to smell of, that she plucked quite a hand′ful. Lucian told her it was also called wax myrtle, and that a nice, fra′grant wax could be made from the ber′ries.

All at once, Lucian cried out, “O Lily! here is some penny-royal.” And then Lily ran to the spot, and they picked as many stalks of this sweet-scented herb as they could car′ry.

But by and by, when they came to a wall where the black-berries grew large and sweet, Lucian and Lily threw away all the sprigs and herbs and flowers they had gath′ered, and be-gan to pick and eat the ber′ries.

“What a good time we are hav′ing!” said Lily.

“Yes,” said Lucian; “but we must not stay here. We must go on till we can find a place where we can pass the night.”

So the chil′dren went on through the wood; and the wood grew thick′er and dark′er; and the little birds stopped sing′ing, all ex-cept the thrush, and that sang sweet′er than ever for a time. But at last the thrush stopped sing′ing too; and then the wood grew so still and dark, that Lily said she would like to go home.

“Now, don’t play the cow′ard again! Be brave this time, do!” said Lucian.

But, as he spoke these words, a strange an′i-mal—an animal he had never seen—flew before his eyes, and made him won′der.

“Oh, dear! What is it? what is it?” cried Lily.

“I don’t know what it is! I never saw such a beast before,” said Lucian.

And then, as it flew once more be-fore his eyes, and brushed his cheek with its wing, Lucian ducked his head, and put up his arms, and ran and screamed as if a wolf were at his heels.

Lily, see′ing that Lucian was so fright′ened, thought it was time for her to be brave; and so, after her first fear, she looked up and saw that the dread′ful what is it was noth′ing but a bat. She had seen a pict′ure of one in a book, and she was sure this was a bat.

So Lily called to Lucian to stop. And then she went to him, and laughed at him, and said, “Who is the cow′ard now?”

Lucian felt some shame when he saw that his cous′in, who was younger than he, and a girl, was the more brave of the two. So he said, “I think we will go home, Lily.”

But this was not so ea′sy. They could not find the path. They sat down on the rock, and cried out, “Help, help!” They did not have to wait long. Old Bob the dog came once more to their aid. He showed them their way home; and there they found the folks just sit′ting down to the tea-table.

I will tell you one of these days what Lucian and his cous′in did a few weeks after this.

Estelle Karr.

What do you suppose the bright little bird,

As through the air he whirls,

Or softly broods in his leafy nest,

Thinks of us boys and girls?

Do you suppose, as the morning light

Steals rosily through the gray,

That he yawns, and says to his sleepy wife,

“Will the children be out to day?

“How queer they look! such a noise they make!

And they run and climb so high!

But they can’t even give one little bird-trill;

And—poor little things!—they can’t fly.”

O little brown bird with shining black eyes!

Nestle close in your soft swinging nest:

We envy you not your gay, careless lives,

For our Father knoweth best.

And he gives to you to pour forth songs

As up through his skies you soar;

But to us he gives immortal souls,

To praise him evermore.

Willie’s Mamma.

Bradford, N. H.

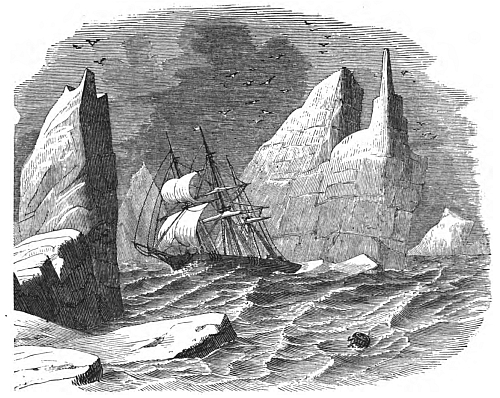

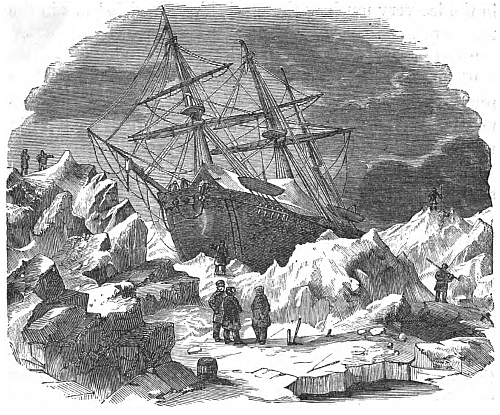

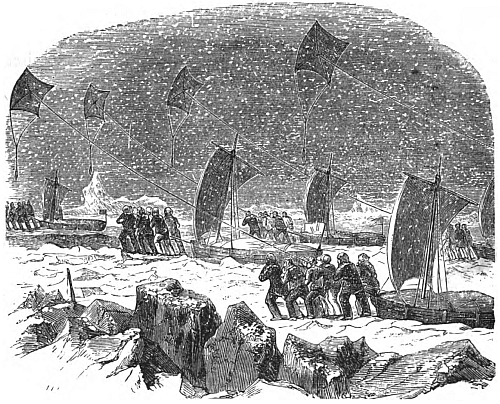

After we had played at ice′bergs by put′ting large lumps of ice in the tank, we went to the ice-house with our ships; and there we talked with Uncle Charles, who had come to get some ice for a pitch′er of lem-on-ade.

“I won′der,” said Albert, “if ships ever get wedged in the ice so that they can′not get out.”

“Give me your ship, and I will tell you,” said Uncle Charles.

He took it, and then, with a hatch′et which he held in his hand, cut a place be-tween two large blocks of ice, and put the ship in it.

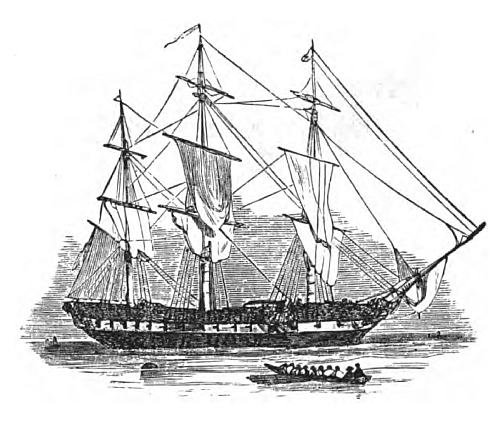

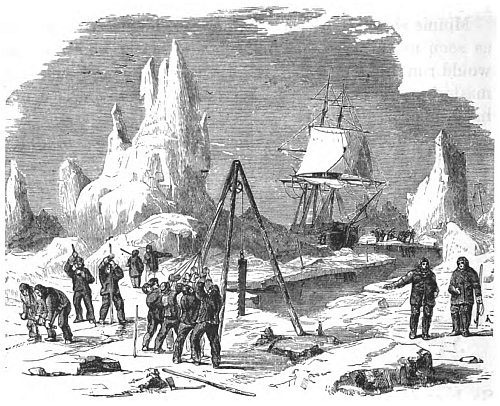

“There!” said Uncle Charles, “your ship is now nipped in the ice very much as the good ship ‘Terrible’ was in the month of Sep-tem′ber, 1836.”

“Tell us a-bout it,” said Albert

“The ‘Terrible’ sailed from England to find a pass′age round the north coast of America. Capt. Ross had the command of the ship. When in Baf′fin’s Bay the ice closed in upon the ship, and she had to stay there ten months.”

“Ten months in the ice! I should not have liked that,” said Albert “What did the men find to do?”

“Well, it was rath′er te′dious for them, I con-fess,” said Uncle Charles. “They could climb about on the ice round the ship, as you may see from this pict′ure, which shows you how the ship lay.”

“But what did they do for things to eat?”

“Oh! they had a good stock of food on board the ship. Some-times they would suc-ceed in shoot′ing a duck. Some-times the sail′ors would play at leap-frog. Sometimes they would act plays. The capt′ain tried hard to keep them cheer′ful.”

“How did they get the ship out from the grip of the ice?”

“The sun helped them out of their scrape. In the month of July, 1837, the ice round the ship melt′ed and broke away; and then the men were so glad, that they gave three cheers. They hoist′ed the sails; and soon the good ship ‘Terrible’ sailed away from the froz′en coast, and got into clear water. On the third of September, she was in sight of the coast of Ireland; and there they were home once more.”

“I hope, when I go to sea,” said Albert, “we shall keep our ship out of the way of ice′bergs and of fields of ice.”

“I hope so too,” said Uncle Charles. “As we sit here by the ice-house on a hot day like this, we get just as much ice as is pleas′ant; but to be jammed in the ice for ten months of one’s life is what I call get′ting too much of a good thing.”

Alfred Selwyn.

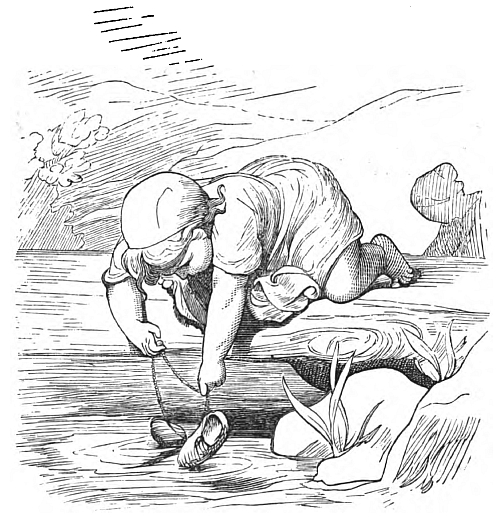

Alfred was a little boy not four years old. He was a good boy most of the time; but he liked to play in the water.

Near the house where he lived, there was a brook; and, at the edge of the brook, there was a little raft tied to the shore.

Sometimes Alfred’s mother would go down to the brook to wash clothes; and Alfred would go with her, and play in the water while she was at work.