* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Alice in Orchestralia

Date of first publication: 1941

Author: Ernest La Prade (1889-1969)

Illustrator: Carroll C. Snell (1893-1958)

Date first posted: September 16, 2022

Date last updated: September 16, 2022

Faded Page eBook #20220941

This eBook was produced by: Stephen Hutcheson, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

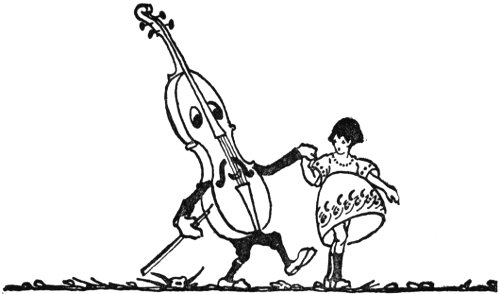

ONE OF THE MANY AMUSING DRAWINGS DONE BY CARROLL SNELL FOR “ALICE IN ORCHESTRALIA”

Do you know that a short underground ride on the “tuba” will bring you to Fiddladelphia, the capital of Orchestralia?

At any rate, that’s how Alice got there in Ernest La Prade’s book, ALICE IN ORCHESTRALIA.

Mr. La Prade, formerly a violinist in the New York Symphony Orchestra, has contrived to put an amazing amount of information about music into the pages of this amusing story.

WALTER DAMROSCH, former conductor of the New York Symphony Orchestra, says of the book:

“Alice in Orchestralia is but another Alice in Wonderland, for the author takes us in delightful fashion into the heart of that most wondrous land of all—the land of music.”

Alice is to be envied, for there is hardly anything about a modern symphony orchestra—its make up, its functions, its manner of speaking that universal language of human emotions—that she does not learn through the pages of this book. And it is all done in such a beguiling way that one might swear it had been written by the whimsical and immortal author of the original Alice in Wonderland.

“I am glad that this work was written by an American, and I am proud that he is also a member of my orchestra.”

If you’re at all interested in music, you’ll find this book the most ingenious and delightful published in many a day.

Preceded by her trumpeters and surrounded by her guard, rode Titania, Queen of the Fairies

A L I C E

IN ORCHESTRALIA

BY

ERNEST LA PRADE

FOREWORD BY

WALTER DAMROSCH

Illustrated by Carroll C. Snell

GARDEN CITY NEW YORK

DOUBLEDAY, DORAN & COMPANY, INC.

1941

COPYRIGHT, 1925, BY DOUBLEDAY, PAGE & COMPANY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES AT THE COUNTRY LIFE PRESS, GARDEN CITY, N. Y.

TO

MY MOTHER

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The author gratefully acknowledges his indebtedness to Miss Katharine Young, for many years identified with the New York Symphony Society’s Concerts for Young People, at whose suggestion this little work was undertaken and whose aid and encouragement have been invaluable.

FOREWORD

“Alice in Orchestralia” is but another “Alice in Wonderland,” for the author takes us in delightful fashion into the heart of that most wondrous land of all—the land of music.

Alice is to be envied, for there is hardly anything about a modern symphony orchestra—its make up, its functions, its manner of speaking that universal language of human emotions—that she does not learn through the pages of this book. And it is all done in such a beguiling way that one might swear that it had been written by the whimsical and immortal author of the original “Alice in Wonderland.”

I am glad that this work was written by an American, and am proud that he is also a member of my orchestra. I prophesy for this book a wide distribution wherever the English tongue is spoken and the love for music prevails.

Walter Damrosch.

| CONTENTS | ||

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | The Brass Tunnel | 1 |

| II. | A Strange Journey | 14 |

| III. | A Topsy-Turvy Rehearsal | 24 |

| IV. | A Quartet Out of Tune | 39 |

| V. | A Tea Party in Panopolis | 57 |

| VI. | The Brassydale Band | 75 |

| VII. | Alice Inspects the Artillery | 99 |

| VIII. | A Concert in Orchestralia | 110 |

| APPENDIX | ||

| The Orchestra | 127 | |

| The Strings | 128 | |

| The Wood-Wind | 134 | |

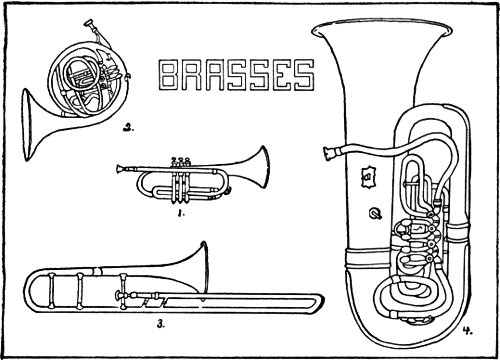

| The Brasses | 139 | |

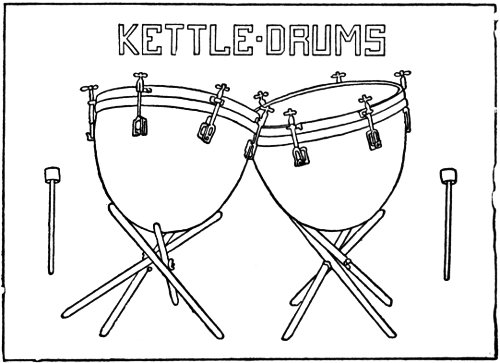

| The Percussion Instruments | 142 | |

| The Orchestra and Its Builders | 147 | |

| Typical Programs of Concerts for Children and Concerts for Young People | 166 | |

| LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS | ||

| Preceded by her trumpeters and surrounded by her guard, rode Titiana, Queen of the Fairies | Frontispiece | |

| FACING PAGE | ||

| “It’s no use going there,” he said | 78 | |

| APPENDIX ILLUSTRATIONS | ||

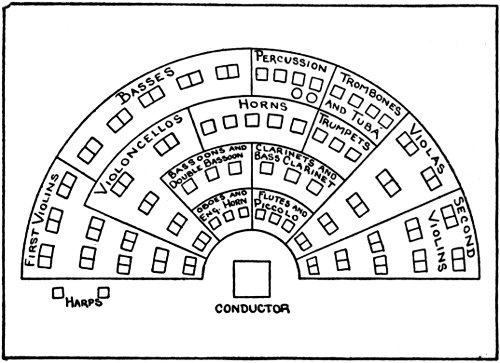

| Usual Seating Plan in a Symphony Orchestra | 127 | |

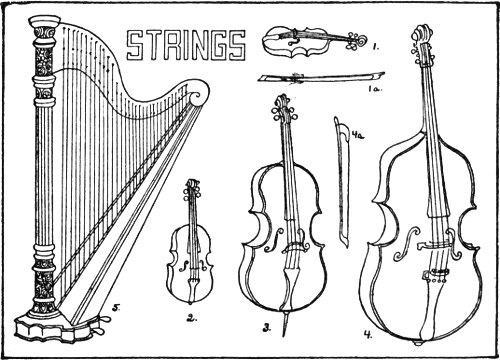

| The Strings | 129 | |

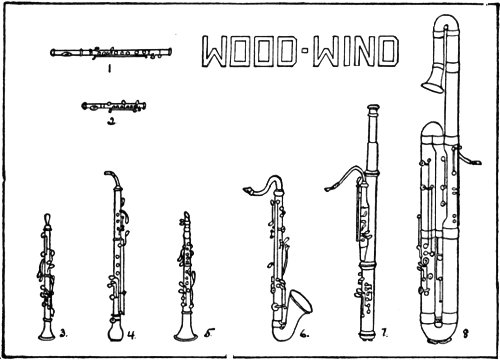

| The Wood-Wind | 134 | |

| The Brasses | 139 | |

| The Kettledrums | 143 | |

ALICE IN ORCHESTRALIA

lice leaned over the railing of

the box and gazed, fascinated, at

the broad stage below her. It

was filled with gentlemen all

dressed exactly alike in tail coats

and striped trousers, and seated

in half-circles so that they all faced toward a

little raised platform which stood at the center

of the front edge of the stage. Round the platform

was a brass railing, and behind the platform

was a kind of desk made of beautifully

carved wood. It was not the platform, however,

nor the desk—nor even the gentlemen in tail

coats—that interested Alice, but the strange-looking

objects which the gentlemen held in

their hands or between their knees, or which

stood upon the floor beside them. These peculiar

objects were of many different shapes and

sizes, and there were so many of them that Alice

was quite bewildered. Some were long and

thin, some were short and fat, some seemed to

be made of wood, some of silver, and some of

brass, and each one seemed to be busily engaged

in making a different kind of noise, for there

rose from the stage a most extraordinary jumble

of sounds. Alice was surprised, for she knew

that the queer-looking objects were supposed to

be musical instruments, and the sounds they

were making did not sound at all like music.

lice leaned over the railing of

the box and gazed, fascinated, at

the broad stage below her. It

was filled with gentlemen all

dressed exactly alike in tail coats

and striped trousers, and seated

in half-circles so that they all faced toward a

little raised platform which stood at the center

of the front edge of the stage. Round the platform

was a brass railing, and behind the platform

was a kind of desk made of beautifully

carved wood. It was not the platform, however,

nor the desk—nor even the gentlemen in tail

coats—that interested Alice, but the strange-looking

objects which the gentlemen held in

their hands or between their knees, or which

stood upon the floor beside them. These peculiar

objects were of many different shapes and

sizes, and there were so many of them that Alice

was quite bewildered. Some were long and

thin, some were short and fat, some seemed to

be made of wood, some of silver, and some of

brass, and each one seemed to be busily engaged

in making a different kind of noise, for there

rose from the stage a most extraordinary jumble

of sounds. Alice was surprised, for she knew

that the queer-looking objects were supposed to

be musical instruments, and the sounds they

were making did not sound at all like music.

“Perhaps,” thought Alice, “they are having a sort of musical Caucus race—the kind of race in which everyone starts when he pleases, and runs in any direction he pleases, and leaves off when he pleases—and everybody wins a prize.”

Alice, you should know, was not the same little girl who fell down the rabbit hole and had all those exciting adventures with the Dodo and the Duchess and other remarkable people, but she had read all about that other Alice and was rather proud that she had the same name as the little girl in the story. She was sure that they must be distantly related—third or fourth cousins, perhaps—and she wished that she too might fall down a rabbit hole or get through a looking-glass into Wonderland. Indeed, she was confident that some day she would find her way into that delightful country, so she kept her eyes open for likely-looking mirrors and rabbit holes, and was ready to follow the very first white rabbit she saw with a watch and a waistcoat.

To-day Alice’s mother had brought her to hear her first symphony concert, and she was very much excited about it. She was fond of music and took the greatest interest in her piano lessons—she practised an hour every day—but she had never seen or heard a symphony orchestra until this moment. The number and variety of the instruments astonished her, and she wondered whether they could possibly all play at once without getting mixed up. She wished she knew the names of all of them, and how they were played, and what sort of sound each one made. Her seat was almost directly over the right-hand side of the stage, so that she could see them all quite plainly, and she began to try to pick out the ones that she did know.

“There,” she said to herself, “are the violins.” (She recognized them because her brother Hugh had a violin on which he had recently begun to take lessons.) “But what a lot of them there are! Dozens and dozens! Why, they reach right across the stage in a double row—and there are lots more behind them. And those big things at the back that look like giant violins are the bass viols—I know that. Oh! and there’s a trombone—and another—and another. Three of them! I know them by the way they slide in and out. They look as if they went right down the men’s throats. I wonder if they do. Now, let me see, are there any more that I know?” She looked carefully at all the instruments, but there were no others whose names she was sure of. One she thought might be a flute, and there were several, of different shapes and sizes, which she supposed were horns; but she was not at all certain.

One enormous instrument particularly fascinated Alice. It was made of gleaming brass and looked like a huge snake all coiled up with its mouth wide open. It was almost underneath the box in which Alice sat, and for a moment she had the unpleasant feeling that it had opened its great mouth in order to swallow her, as a boa constrictor swallows a sheep. She soon realized however, that such a notion was absurd.

“Of course it isn’t really a boa constrictor,” she told herself, “because it’s made of brass—and besides, its mouth is really more like a funnel. It certainly looks big enough to swallow me; but if it did,” she went on, smiling at the idea, “it would most likely choke to death, because its throat gets smaller and smaller all the way down to its tail. Now, I wonder where its throat ends and its tail begins?”

That was an extremely difficult question to answer, and Alice was still pondering over it when her speculations were interrupted by a loud clapping of hands. Looking up she saw a very elegantly dressed gentleman, also in a tail coat and striped trousers, who had just come through a door at the back of the stage. Making his way to the little platform with the brass railing, he mounted upon it and smiled and bowed to the audience. Then, turning round toward the orchestra, he rapped upon the desk with a little white stick, waited until everybody was quite still, and then gave the signal to the orchestra to begin to play.

Glancing at her programme, Alice was delighted to find that the first number was Mendelssohn’s Overture to “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.”

“Oh, how jolly!” she exclaimed to herself. “I wonder if there will be anything in it about Bottom and Puck and the other fairies!” For Alice was well acquainted with the charming people of Shakespeare’s fairy play. She had not only read about them in Lamb’s “Tales from Shakespeare,” but she had also seen the play performed, only the summer before, by a company of actors who had visited her school. So she leaned over the railing and listened very attentively.

At the first sound of the mysterious magic chords with which the overture begins, a spell seemed to fall upon the vast auditorium. The stage was changed, as if by a wave of Titania’s fairy wand, into a lovely forest glade surrounded by giant oaks and flooded with silvery moonlight. For a moment all was still; not a leaf rustled, not a cricket chirped. Then, suddenly, came a sound of pattering feet, tinkling elfin laughter, and faintly, in the distance, a fanfare of tiny trumpets. Titania and her court were approaching. Nearer and nearer they came, until finally, with a lively fanfare from the fairy trumpets, the procession appeared in the moonlight and marched gaily round the glade. Preceded by her trumpeters and surrounded by her guard, who were armed with lances of sharpest spike-rush, rode Titania, Queen of the Fairies. Her chariot was a moon-flower drawn by six spirited fireflies; on her brow sparkled a diadem of tiny stars, and in her hand she held a shining wand.

With great pomp and ceremony the procession circled the glade and drew up at one side, and instantly a company of elfin dancers appeared before it and began to perform an entrancing ballet. Round and round they twirled, now in couples, now in groups, now joining hands in one great circle which revolved so swiftly that it made one dizzy to watch it. Again they would leap into the air and go whirling madly about among the tree-tops, their little wings humming like bumblebees and their laughter tinkling like silver bells.

All at once they were gone, and for a little while the glade was empty. Then from the depths of the forest came a loud and harsh “Hee-haw!” and into the moonlight strode a most extraordinary creature. It had the body of a man, dressed in a leather jacket and short breeches, but its head was the grave and solemn head of an ass. Alice recognized him at once: he was Bottom the weaver. He walked up and down the glade in a very pompous manner and attempted to sing a song, but he must have had a very bad cold in his head, for his voice was dreadfully hoarse and gruff.

When he had finished his song Bottom lay down upon a grassy bank and fell fast asleep, and he had hardly begun to snore when a very lively little elf all dressed in red came leaping and somersaulting down the glade, snatched off the ass’s head and darted away into the forest, leaving Bottom’s own head in its proper place on his shoulders. Then all Bottom’s friends—Peter Quince the carpenter, Snout the tinker, Starveling, Snug, and Flute—came out of the wood and wakened Bottom, and the whole company joined in a jolly and extremely comical dance. They danced themselves away at last, and then back came all the fairies—Queen Titania with King Oberon, followed by Puck and Peaseblossom and Mustardseed and all the rest—tripping, dancing, singing, and laughing as merrily as before.

But soon the first faint blush of dawn appeared. The night was nearly over, and, as no well-brought-up fairy ever stays out after daybreak, away they flitted to their homes in acorn cups and rosebuds, to sleep until the stars should wake again. And as they vanished the enchanted glade slowly faded away, the trees changed back into bass viols and the grassy banks into gentlemen in tail coats. The spell was ended.

Everybody applauded heartily. The conductor bowed with great dignity and went away through the door at the back of the stage; but as the applause continued he came back again and bowed once more and waved his hand at the orchestra, and all the gentlemen in tail coats stood up and looked very solemn. Alice did not applaud. She sat quite still and stared hard at the stage, hoping that the fairies would reappear; but it was no use—they refused to show themselves again. Presently Alice’s mother leaned forward and said:

“How did you like it, dear?”

Alice turned round, her eyes bright with excitement. “Oh, Mother!” she exclaimed, “wasn’t it wonderful! I saw Puck and Titania and Bottom and—and all, just as plain as could be!”

“Did you really?” said her mother. “Why, it must have been almost as good as seeing the play.”

“It was better,” Alice declared, emphatically, “lots better; because in the play the fairies were just grown-up people dressed like fairies, and these were real ones—little tiny ones, like the fairies in story books, with hats made out of buttercups and frocks made out of daffodils. Puck had wings exactly like a dragon fly’s.”

“How charming he must have looked!” said her mother.

“Didn’t you see him too?” Alice inquired.

Her mother shook her head. “I’m afraid my eyes are not so sharp as yours,” she said. “But I heard him quite clearly.”

Alice was disappointed. It seemed to her that anyone should have been able to see the fairies—they were so plainly visible to her. But she said nothing more about it, and presently became interested again in looking at the various instruments of the orchestra. The one which looked like a brass boa constrictor still reared its enormous funnel-shaped mouth almost underneath Alice’s seat. It seemed to yawn invitingly, as much as to say: “Won’t you drop in for a moment? There’s plenty of room—I’m sure you’d find it very comfortable and cozy.”

“That’s all very well,” Alice thought, “but how should I get out again? Of course, if I were like the Alice in the story I could eat a little cake or a bit of mushroom or something and grow smaller and smaller until I was small enough to crawl right through and out at the end of its tail. That would be fun. I wouldn’t be any bigger than a fairy when I got out. I wonder if the fairies would let me come and dance with them? They might think I was a fairy too—only I shouldn’t have any wings. I wonder if there are any fairies without wings. Of course, I might borrow some from a bumblebee or a butterfly or a moth. I think I should like a moth’s wings best—they’re so soft and downy.”

It was a delightful idea, and Alice would very likely have gone on thinking about it until, in her imagination, she had got herself fitted out with a pair of wings of the most fashionable design, been crowned queen of the fairies, and had a row with Oberon into the bargain; but just then the conductor reappeared and prepared to begin the next number.

Looking again at her programme Alice learned that the next number was a “Symphony in C,” by Schubert; but as she did not know what a “symphony” was she was little wiser than before. It proved, however, to be very agreeable to listen to. Its lovely melodies and warm, rich harmonies seemed to caress and lull Alice into a state of delicious dreaminess, and leaning back in her chair she closed her eyes in order to enjoy more fully this delightful sensation. She felt as if she were sitting in a swing which swayed gently to and fro in the shade of a spreading oak tree, while a gentle summer breeze fanned her cheeks and softly tousled her hair. The air was warm and drowsy, full of the scent of new-mown hay and the hum of bees, and Alice thought she would like to sit there with her eyes closed and dream daydreams for hours and hours. So she was rather annoyed when she heard a voice calling her name.

“Oh, dear!” she said to herself, “just when I was feeling so nice and comfy! Now I wonder who it can be that wants me.”

The voice was very faint and far away, so Alice sat quite still with her eyes closed, thinking that she might have been mistaken. She was not mistaken, however, for soon she heard the voice again, faintly but quite distinctly, calling, “Alice! Alice!” So with a sigh she opened her eyes and sat up—and then she opened her mouth as well, and stared, and rubbed her eyes, and stared again; for what she saw was most surprising. Just in front of her was a high green hill, in the side of which was a circular opening like the entrance to a tunnel. Evidently it was a very long tunnel, for though Alice was looking directly into it she could not see the other end; and what seemed still more remarkable was that it appeared to be made entirely of polished brass. Alice was wondering how many barrels of brass polish it took to keep the tunnel so bright and shiny, and thinking that she shouldn’t particularly care to have the job of polishing it every week, when she became aware that the voice was still calling her name, and that the sound undoubtedly came from inside the tunnel.

“Well,” she said, aloud, “I’m sure I don’t know who they are or what they want, but I s’pose I’d better go and find out.” So she jumped out of the swing and went skipping down the long brass tunnel.

n and on went Alice, sometimes

walking, sometimes skipping

merrily as she hummed a

tune to herself. There was nothing

at all to see in the tunnel, and

after a time she began to think

that she must have come a very long way. However,

she seemed no nearer the end of the tunnel

than when she had started: and when she looked

behind her, expecting to see the round spot of

daylight at the entrance, it had disappeared.

n and on went Alice, sometimes

walking, sometimes skipping

merrily as she hummed a

tune to herself. There was nothing

at all to see in the tunnel, and

after a time she began to think

that she must have come a very long way. However,

she seemed no nearer the end of the tunnel

than when she had started: and when she looked

behind her, expecting to see the round spot of

daylight at the entrance, it had disappeared.

“Well,” she said, surprised, “that’s queer. I must have come round a bend without noticing it. This is certainly the longest tunnel I ever heard of, but there must be an end to it somewhere, so I may as well keep on walking,” and on she went once more, humming her cheerful little tune.

The curved brass walls of the tunnel gleamed and shone so brightly that presently it occurred to Alice to wonder where the light came from which was reflected with such brilliance by the polished metal. She saw no electric bulbs or gas jets, and she couldn’t understand why the tunnel was not quite dark inside, like those she had passed through on railroad trains.

“I s’pose,” she decided, after puzzling over the question for some time—“I s’pose that one day some sunbeams must have wandered in here by mistake, and then they got lost and couldn’t find the way out. Oh, dear! What if I should get lost and never find my way out?”

She felt just a wee bit frightened and had begun to walk faster when, all at once, she turned a sharp bend and came to the end of the tunnel. But instead of coming out into the open air, as she had expected, she found herself in a long hall with a vaulted roof, at either end of which was the entrance to another tunnel like the one through which she had come. The floor of the hall was level, but down the middle of it was a wide gap about four feet deep with two shiny rails running along the bottom. Alice concluded that she must be in a railway station—although she had never before seen a railway station made entirely of brass—and she had hardly come to that conclusion when a train, also made entirely of brass, without a locomotive, slid noiselessly out of one of the tunnels and came to a stop. Instantly all the doors opened, apparently of their own accord, and a faint, muffled voice which seemed to come from everywhere at once said, “All aboard—watch-a-door!”

Without stopping to think that she hadn’t the least idea where it would take her, Alice got into one of the cars, the doors closed, and away went the train down the tunnel. Alice sat down and looked about her. Except for herself the car she was in was quite empty, and as far as she could see she was the only person in the entire train. She had never heard of a train without any passengers or even a conductor. “But,” she thought, “maybe it’s a good thing there isn’t any conductor, since I haven’t got a ticket. He might put me off the train—and I’m sure I’m tired enough of walking.”

Just then, the queer, muffled voice which she had heard as she got into the train called out something that sounded like “Neckstar oofty ooftree!” The voice sounded so near that Alice jumped. She looked all about her but could see no one, and she was beginning to feel a bit uneasy when the train stopped at another station, the doors all opened as before, and the voice said again, “All aboard—watch-a-door!” This time Alice was ready for it, and discovered that it came from a sort of tin trumpet over her head. She decided that it must be some kind of talking machine, and wondered how it knew what to say and when to say it. Meanwhile the train had started again, and after a few moments the voice in the trumpet spoke again: “Neckstar oofty ooftree!”

“It’s rather hard to understand,” thought Alice. “I s’pose ‘neckstar’ means ‘next stop,’ and the rest of it must be the name of the station—something street, very likely. How anybody can tell which station is which I’m sure I don’t know, because all the names sound exactly alike. But the stations all look exactly alike too, so p’r’aps it doesn’t make much difference which one you get out at.”

On went the train, through mile after mile of shining brass tunnel, stopping now and then at stations whose names all sounded like “oofty ooftree.” As nobody ever got either into the train or out of it, and as nothing exciting had happened for a long while, Alice began to grow restless. She had nearly made up her mind to get out, herself, at the next station, when suddenly the train shot out of the tunnel into dazzling sunlight. Alice looked eagerly out of the window and saw that she was travelling through a very beautiful country. On either side of the railway spread lovely green meadows full of daisies and buttercups, while in the distance were rolling hills covered with trees. Here and there she saw a tiny house, painted white, with green blinds and a red roof, and all overgrown with ivy.

“Last stop—All out!” said the voice in the trumpet, quite distinctly this time. Alice obediently stepped out upon the station platform, and she had no sooner done so than the doors closed again and the train dashed off in the direction from which it had come.

Alice looked all about her, hoping to see somebody to whom she might speak, for there were a great many questions she wanted to ask. But there was not a living creature in sight; the station was as deserted as the train had been.

“Well,” thought Alice, “this is certainly the loneliest place I ever saw. But maybe it’s Sunday, and everybody’s at church—or p’r’aps this is one of those countries where all the people take naps after luncheon. Anyhow, I may as well walk about a bit and see what the village is like; and I might meet somebody to talk to.” There was a door near the center of the platform which looked as if it might lead to the street, and Alice had just started toward it when she was startled by a loud rumbling sound close beside her. The only object on the station platform was a curiously shaped trunk which looked somewhat like an enormous bottle with a long neck, only it was square instead of round. It stood on end with its back against the wall, and it was rather more than twice as tall as Alice. She examined the trunk with curiosity, wondering what on earth could be inside it, and whether the sound she had heard could possibly have proceeded from it. The sound was repeated, louder, deeper, more rumbling than before. There could be no doubt about it: it did come from the trunk. And, stranger even than that, it sounded remarkably like a snore. In fact, it was a snore—an immense, ear-filling, ground-shaking giant of a snore, but unmistakably a snore. It grew gradually louder, rising and falling in regular waves of sound, and then suddenly it broke off with a choke and a snort, and was followed by a violent pounding on the inside of the trunk. Then an incredibly deep bass voice shouted angrily, “Let me out! Open the door, I say, and let me out!”

At first, Alice was too much astonished to move, but as the pounding and shouting continued she collected her wits and decided that something must be done. The trunk, she saw, was fortunately not locked, but the lid was held down by two clasps, one near the bottom and the other near the top. The bottom clasp she undid without difficulty, but the upper one was quite out of her reach; however, by climbing upon a bench, she managed to reach the upper clasp and unfasten it. As she did so the lid of the trunk flew open and out lurched a huge corpulent and evidently indignant bass viol.

Alice almost fell off the bench in her astonishment, for never before had she seen, or even heard of, a bass viol such as this one. It had legs and arms and a mouth and two very prominent eyes, all of which it proceeded at once to exercise, very much to Alice’s alarm. Stalking up to her it glared at her with its round, staring eyes, brandished its fist under her nose and roared at her like an angry bull.

“Now, then!” it bellowed, “what do you mean by it, eh? Shutting me up in there and nearly smothering me to death! What do you mean by it?—that’s what I should like to know!”

“Excuse me,” Alice stammered, frightened, “I—I didn’t shut you up; I only—I let you out. You see,” she explained, “I only came by the last train, and I didn’t know you were in there until I heard you sno—I mean, shouting.”

The Bass Viol stopped brandishing its fist and regarded her suspiciously. Then it said, apparently somewhat mollified: “Well, I suppose it was those naughty Ukulele boys—they’re always up to mischief. Just wait till I catch them!” Then it added gruffly: “I’m much obliged to you, I’m sure.”

“You’re quite welcome,” said Alice, politely. The Bass Viol’s manner was so much less menacing that she was no longer frightened, and her curiosity promptly got the better of her.

“Excuse me,” she said, “but would you mind telling me how you came to be in that trunk?”

“It’s not a trunk,” growled the Bass Viol; “it’s a bed—a new one, just sent from the factory. I got in it to see if it fitted, and it was so comfortable that I must have dozed off for a moment. And then I suppose those kids came along and shut me in. Just wait till I lay my hands on ’em—they’re a disgrace to the town! I don’t see why they’re allowed to live in a place like Fiddladelphia.”

“Oh!” said Alice, “is this Philadelphia? Why, I’ve been here before. But somehow it doesn’t look quite the same——”

“I said Fiddladelphia, not Philadelphia,” the Bass Viol interrupted. “It’s not the same at all. Philadelphia is in Pennsylvania, unless I’ve forgotten my geography, and Fiddladelphia is the capital of Orchestralia.”

“I see,” said Alice, rather doubtfully. “I’m afraid I don’t remember my geography very well. I think I’ve heard of Orchestralia—it sounds familiar—but I’m not quite sure. Is it a new country that’s just been discovered?”

“No and yes,” replied the Bass Viol. “That is, it’s not a new country—in fact, it’s a very old one—but you’ve just discovered it; and there are millions of people who have not discovered it yet, though it’s much more widely known to-day than it was a few years ago. By the way, how did you say you got here?”

“I came in a funny sort of train that ran most of the way in a brass tunnel,” said Alice. “I think it must have been the Tube.”

“You mean the Tuba,” the Bass Viol corrected her. “That’s the way most of them come.”

“Are there any more people here?” Alice inquired. “I mean—regular people—like me?”

“Oh, very likely,” replied the Bass Viol. “You’re the first one I’ve seen to-day, but we have quite a lot of visitors nowadays. I suppose you’d like to look around a bit now that you’re here?”

“Oh, I should love to!” Alice exclaimed; “only I’m afraid I might lose my way.”

“That’s all right,” said the Bass Viol, reassuringly. “I’ll show you around myself. Come along, we’d better not waste any time.”

Its ill-temper had quite disappeared, and it beamed upon Alice with such fatherly benevolence that she did not hesitate to take the hand it held out to her as it led the way out of the station and into the village of Fiddladelphia.

lice and the Bass Viol emerged

from the station and started

across a beautiful little park

full of shrubbery and of ornamental

flower beds laid out in the

form of graceful musical signs.

There were staves and clefs and various kinds

of notes, and in the center of the park on a little

knoll was an entire piece of music composed of

growing flowers of different colors. Alice was

staring at it and wondering what the tune might

be, when the Bass Viol said, as if reading her

thoughts:

lice and the Bass Viol emerged

from the station and started

across a beautiful little park

full of shrubbery and of ornamental

flower beds laid out in the

form of graceful musical signs.

There were staves and clefs and various kinds

of notes, and in the center of the park on a little

knoll was an entire piece of music composed of

growing flowers of different colors. Alice was

staring at it and wondering what the tune might

be, when the Bass Viol said, as if reading her

thoughts:

“I wonder if you recognize the tune?”

“I’m afraid I don’t,” Alice admitted, “though there’s something familiar about it. I’m not very good at reading music; but I could play it on the piano,” she added confidently.

“What a funny idea!” exclaimed the Bass Viol. “You might just as well say that you couldn’t read print but that you could play it on the typewriter. I shouldn’t call that being able to read, would you?”

“Why, n—no,” said Alice, “I s’pose not.”

“Well, music is like print—either you can read it or you can’t. Now, I’m sure you can read that piece of music if you try. Come, I’ll give you the first note: Do”—he sang the tone in what was for him a high falsetto voice. “Now, what’s the next one?”

“Re,” sang Alice promptly.

“Right; and the next?”

“Mi.”

“Right again. Now go ahead and sing the whole tune. You’ll find it’s not at all difficult once you know how to go about it.”

Thus encouraged, Alice began, and was surprised at the ease with which she sang the piece through from the beginning to end.

“Not bad,” said the Bass Viol when she had finished. “You have a very good ear, and not a bad tone for a wind instrument.”

“Why, the very idea!” Alice protested. “I’m not a wind instrument.”

“Oh, aren’t you?” said the Bass Viol, rather sarcastically. “Then what kind of an instrument do you call yourself? You certainly aren’t a stringed instrument.”

“I’m not an instrument at all,” Alice declared indignantly. “I’m a—I’m a human being.”

“You may be whatever you like in your own country,” said the Bass Viol, “but here you’re an instrument. Everybody is.”

Alice was silent for a moment. She was a little offended. Then an idea occurred to her and her face brightened.

“Is that why they call this country Orchestralia?” she asked.

“Naturally; because all the instruments of the orchestra live here.”

“Oh, goody!” cried Alice. “And can I see them all, and will you tell me their names and all about them?”

“I will introduce you to them—then you can ask them all the questions you like about themselves.”

“I hope they won’t mind,” said Alice, “there are so many things I want to know. Do you mind answering questions?”

“Not at all,” said the Bass Viol, once more in a good humor. “You may ask me as many as you please.”

“Then I may as well begin now,” said Alice, “because there are going to be lots and lots of them. First of all, can all the instruments that live here walk and talk just as you can?”

“Yes, indeed,” the Bass Viol assured her.

“Then why don’t they do it in—in my country?”

“Well, you see, it isn’t necessary. In your country there is always somebody to carry us about, and plenty of people like yourself to do the talking. So we just let you do the walking and the talking for us while we make music for you. That’s fair, isn’t it?”

Alice admitted that it seemed so. By this time they had left the park and were walking down a shady winding road between rows of little houses set in the middle of delightful gardens. Some of the houses were of red brick, some of soft gray stone, some of cream-colored plaster with dark oak beams; some had red roofs, some green, and some had roofs in which many colors were blended in a rich pattern like that of a Persian rug. Most of the houses were covered with vines and creepers which seemed almost to be part of them.

“Pretty, isn’t it?” remarked the Bass Viol, waving its hand toward the houses and gardens.

“I never saw anything so lovely!” said Alice. “It’s all so—so restful! Everything seems to match.”

“That’s just it—it’s harmonious. Harmony is our motto here. That’s why it’s such a pleasant country to live in.”

“Is it always as quiet as this?” Alice inquired. “I haven’t seen anybody yet but you. Where are all the other people—I mean instruments?”

“Oh,” said the Bass Viol, “they’re all at the rehearsal. We’re on our way there now, so you’ll soon see them—all the fiddles, that is; the others don’t live in Fiddladelphia, except a few of the lower-class stringed instruments, such as the guitars and mandolins and those pesky ukuleles, who hang about the outskirts of the village. By rights they ought not to be here at all; they’re not members of the orchestra. But it seems impossible to keep out the undesirable element, even in Orchestralia.”

Alice couldn’t help thinking that her amiable guide must be just a wee bit snobbish, and she wondered if life in this extraordinary country was, after all, as perfectly harmonious as the Bass Viol had claimed. However, she said nothing about it, and presently her thoughts went racing off on another tack.

“You said,” she reminded the Bass Viol, “that only fiddles lived in Fiddladelphia; but you’re not a fiddle, are you?”

“Of course I’m a fiddle,” it declared, proudly.

“But,” Alice persisted, “I thought ‘fiddle’ was only another name for a violin.”

“Not at all,” said the Bass Viol. “ ‘Fiddle’ means a stringed instrument played with a bow. We all belong to the fiddle, or viol, family. The violin is merely one member of it—and the smallest one, at that. But here we are at the Conservatory, where we hold our rehearsals. Now you shall see all my brothers and nephews and cousins.”

They had arrived at a very large and beautiful building all of white stone, with a row of tall columns across the front. Mounting a flight of broad stone steps they passed through a magnificent marble entrance hall and into a large auditorium. On the stage a small group of instruments were assembled, and many others sat about in different parts of the hall, but there were plenty of vacant seats.

“Let us go right down to the front,” said the Bass Viol, “so that you can see plainly. We can hear perfectly in any part of the hall—the acoustics are so good.”

“Acoustics?” said Alice. “What are they?”

“Why, acoustics are—ahem!—acoustics, you see—— Well, it’s rather difficult to explain, but they’re the things that make music or speaking sound well in a hall.”

“What do they look like?” Alice inquired. The name suggested something with horns and four legs, but she saw nothing of that description in the auditorium.

“Oh, you can’t see them. They’re only spaces and proportions and—and all that sort of thing,” the Bass Viol explained, rather lamely. “As a matter of fact, nobody knows exactly what they are; but if music sounds well in a place you say that place has good acoustics, and if it doesn’t sound well you say the place has bad acoustics. Does that make it clear?”

Alice thought it was still rather confusing, but as it didn’t seem to be so very important she merely nodded her head and dismissed the matter from her mind.

By this time they had reached the front of the auditorium and taken seats near the center of the stage, from which point Alice could see the performers quite plainly. There were four of them: three small fiddles and one which was about half the size of Alice’s friend, the Bass Viol. They seemed to be having a consultation about the music they were going to play, but in a moment they all went to the rear of the stage where a row of tall, narrow cupboards stood against the wall. Each fiddle opened a cupboard and took from it what appeared to be a man dressed in a tail coat and striped trousers.

“Look! Look!” cried Alice, excitedly. “They keep human beings shut up in those little closets!”

“They’re not human beings,” the Bass Viol corrected her, “they’re only musicians.”

“Only musicians?” said Alice, puzzled. “Aren’t musicians human beings?”

“Well, at any rate, these are not,” said the Bass Viol. “They’re only mechanical dummies that we use for making music.”

“Can’t you make music without them?” Alice asked.

“Certainly not,” said the Bass Viol. “In your country a fiddler can’t make music without a fiddle to play on, can he? Well, we can’t make music without a fiddler to play on us. So we all have our fiddlers, just as your fiddlers all have their fiddles; and we keep them in boxes, just as your violinists keep their instruments.”

“Well,” said Alice, “I s’pose that’s fair; but somehow it seems all topsy-turvy.”

“You’ll soon get used to the idea,” said the Bass Viol, reassuringly. “Things always seem more or less topsy-turvy when you first visit a strange land.”

Having led their mechanical players to the front of the stage and seated them so that they faced each other, two on the left and two on the right, the fiddles then placed their bows in the players’ right hands and their necks in the players’ left hands. At a word from one of the small fiddles, who seemed to be the leader, they all sprang to their positions—the small fiddles underneath their players’ chins, the large fiddle between its player’s knees—and the automatic musicians promptly began to play.

“These four instruments constitute what is called a string quartet,” said the Bass Viol, speaking in a whisper in order not to disturb anybody. “I suppose you know them all?”

“Why,” said Alice, also in a whisper, “I don’t know the big one’s name, but the three small ones are violins.”

“Wrong,” said the Bass Viol; “only two of them are violins—those in front. The one back there at the left is a viola. He’s an older brother of the violins and looks very much like them for he’s the same shape and has four strings, just as they have; but if you look more closely you’ll see that he’s a little larger, and if you listen very carefully you’ll hear that his voice is a little deeper and has rather a sad quality. The big fellow facing the viola is a violoncello, but all his friends call him ’Cello for short.”

“I suppose,” said Alice, “that ‘violincello’ means a big violin.”

“Wrong again,” the Bass Viol corrected her; “it’s ‘violoncello,’ not ‘violincello.’ Now let’s get these names all straight in our minds: ‘viola’ is Italian for ‘viol’ or ‘fiddle,’ and ‘violin’ means ‘little viol.’ Now my name in Italian is ‘violone,’ which means ‘biggest viol’; and ‘violoncello’ really means ‘little violone.’ ”

“I see,” said Alice; “it’s all clear now—only I thought your name was ‘bass viol.’ ”

“So it is. You see, I have several names. In Italy they call me ‘violone’ or ‘contrabasso,’ and in your country ‘bass viol’ or ‘double bass.’ But most people call me simply ‘bass,’ because it’s easier to say. And now we’d better stop talking and listen to the music. It’s a quartet by Mozart—one of his best.”

It was indeed exquisite music, and Alice marveled that the four automatons—mere pieces of machinery—could produce such lovely sounds, even with the aid of four fine instruments. It was not like the music of the full orchestra—not so loud and rich; but it made up for that by its purity and delicacy. Alice listened attentively throughout the performance of the quartet, but when it was finished she was ready with a lot of new questions.

“Why,” she demanded of her friend the Bass, “do they have different kinds of fiddles in a quartet? Why not four violins or four violas or four violoncellos?”

“Ah,” said the Bass, “we have instruments of different sizes partly in order to give variety of tone color and partly in order to increase the compass of the quartet. Do you know what ‘compass’ means?”

Alice shook her head.

“ ‘Compass,’ ” explained the Bass, “means the number of tones, from the lowest to the highest, that an instrument or a group of instruments can produce. Now the piano can produce all the notes of the scale—over seven octaves—but the orchestral instruments have much smaller compasses. So in order to produce the entire scale we have to combine several instruments of different sizes, the smaller ones playing the high notes, the larger ones the low notes. For, as a general rule, the larger an instrument is, the lower its pitch.”

“No wonder you have such a deep voice!” Alice exclaimed, gazing with new interest at the enormous bulk of the Bass.

“My voice is the lowest of all, except the double bassoon and bass tuba,” he said proudly. “I can sing the lowest E on the piano. But I haven’t finished explaining about the compass of the string quartet. The violin, as you probably know, can play as high as the highest notes on the piano, but it can’t go lower than the G below Middle C. Do you know what Middle C is?”

“Oh, yes,” said Alice. “It’s the white key just to the left of the two black keys just to the left of the keyhole.”

The Bass chuckled. “I see you know how to find it. Well, then, the viola can’t go as high as the violin, but it can go five tones lower—to the C an octave below Middle C; and the ’cello can go an octave below the viola. So between them they have a compass of six octaves—and with a scale of six octaves you can make a lot of music. Of course, for orchestral work you need a still larger scale, and a very strong bass besides; that’s where I come in. I can go nearly an octave lower than the ’cello, and my low tones are fuller and heavier, too, so that’s why I’m one of the most important instruments in the orchestra.” The Bass sat up very straight and certainly looked extremely important.

Alice was duly impressed, but her mind was still teeming with questions.

“Why,” she inquired, “are there two violins in a quartet? I should think one would be enough, since there’s only one viola and one ’cello.”

“Well,” said the Bass, “in the first place, if there were only one violin it wouldn’t be a quartet—it would be a trio; and a trio isn’t so satisfactory as a quartet, partly because most music is written in four-part harmony, and partly because the tone of the ’cello is stronger than the tone of the violin. So we have two violins, a first violin and a second violin, to keep the balance.”

“What’s the difference between a first violin and a second violin?” Alice asked. “They look exactly alike.”

“So they are,” said the Bass. “The only difference is that the first violin usually plays higher than the second. Do you go to church?”

The question was so unexpected that Alice was a little disconcerted. “Wh—why, yes—of course,” she stammered.

“Then you’ve probably heard a vocal quartet—a quartet of singers—two women and two men.”

“Yes, indeed,” said Alice. “We have a quartet choir at our church every Sunday.”

“And do you know which voice sings the highest part?”

“The soprano.”

“And the next highest?”

“The alto.”

“And the next?”

“The tenor.”

“And the lowest?”

“The bass.”

“Quite right. Now, then, a string quartet is just like a vocal quartet: the first violin is the soprano, the second violin is the alto, the viola’s the tenor, and the ’cello’s the bass. And a symphony orchestra is simply a group of three quartets—a string quartet, a wood-wind quartet, and a brass quartet—with a few extra instruments and a lot of drums and cymbals and things thrown in for good measure. I dare say you thought an orchestra was a frightfully complicated affair, but you see it’s really quite simple.”

“I am beginning to understand it a little better,” Alice confessed. “But there’s lots and lots of it that I still don’t know about; for instance, the wood-wind quartet—what is that?”

“You shall learn all about it in due time,” said the Bass. “But now I want to introduce you to some of the fiddles. They’ve finished their rehearsal, so come along and we’ll interview them before they go home.”

he Bass Viol led Alice through

a door at one side of the auditorium

and down a corridor that

brought them to a room behind

the stage. There they found the

four instruments who had just

finished their rehearsal. They were busily engaged

in removing the powdered rosin that had

accumulated on their strings, carrying on meanwhile

an animated conversation. So absorbed

were they in their own affairs that they did not

see Alice and the Bass Viol enter the room.

he Bass Viol led Alice through

a door at one side of the auditorium

and down a corridor that

brought them to a room behind

the stage. There they found the

four instruments who had just

finished their rehearsal. They were busily engaged

in removing the powdered rosin that had

accumulated on their strings, carrying on meanwhile

an animated conversation. So absorbed

were they in their own affairs that they did not

see Alice and the Bass Viol enter the room.

“Stop here a moment,” whispered the Bass, halting just inside the door. “Do you see that handsome amber-colored violin—the one who is talking to the ’Cello? He is the leader of the quartet and the Principal First Violin of the orchestra. We call him the Concertmaster. Distinguished-looking fiddle, isn’t he?”

“Yes,” Alice agreed; “but he looks rather conceited.”

“Well, perhaps he is,” the Bass chuckled. “You see, he comes of one of the first families of Cremona—the Stradivari—and he’s very proud of it.”

“Cremona?” said Alice. “Where is that?”

“Cremona,” replied the Bass, “is a little town in Italy where all the finest violins come from—the Stradivari, the Amati, the Guarneri, and many others. Now the Second Violin—that modest looking brown one—is not from Cremona: he’s a Tyrolean. He’s a thoroughly good sort—plenty of tone and all that; but he hasn’t got the grand manner of the Cremonese. It’s the same with the Viola; he’s a nice fellow, but not an aristocrat. He claims to be a Gagliano, but the fact of the matter is that his pedigree has been lost, so nobody knows whether he really is or not.”

“Maybe that’s why he’s so sad,” Alice suggested.

The Bass smiled.

“Possibly,” he admitted; “but I’m afraid that doesn’t account for the fact that all the other violas are sad, too. I think sadness must run in the family. Now, it’s different with the ’cellos. They’re nearly always in high spirits, even those who have lost their pedigrees. This one is particularly high-spirited. He’s French—a Vuillaume—and has the true Gallic temperament. He’s well thought of in the community; but, of course, he isn’t a ‘Strad.’ However, I’d better introduce you to them, or they’ll be going home.”

The Bass escorted Alice across the room, and addressed the First Violin.

“Tony,” he said, “allow me to present a young friend of mine who has come to pay us a visit: Mr. Stradivari, Miss—er——”

“Alice,” said that young lady, politely.

The Violin bowed ceremoniously. Although his bearing was proud, his manner was gracious and polished. When he spoke it was with a slight foreign accent and in a remarkably clear and resonant voice—a voice so melodious that he seemed almost to be singing.

“We are honored,” he said gravely. “The young lady is a musician?”

“Not yet,” said Alice, “but I hope to be some day. I’m learning to play the piano.”

“Ah!” said the Violin, “the piano. A useful instrument but veree mechanical—veree. You should learn to play one of us.”

“I should like to, very much,” said Alice timidly; “but I’m afraid it would be awfully difficult. I don’t see how——”

“Excuse me,” the Bass interrupted. “Do you mind if I present these other gentlemen; I’m rather pressed for time. Mr. Stainer, the Second Violin; Mr.—er—Gagliano, our Principal Viola; Mr. Vuillaume, First ’Cello. Gentlemen, Miss Alice.”

The fiddles bowed and Alice curtsied. Ordinarily Alice hated to curtsy; none of the little girls she knew ever did it. But her mother, who was very old-fashioned, had insisted that Alice must learn to curtsy, and now she was rather glad she had, for it seemed just the proper thing to do on this occasion.

“And now,” said the Bass, “I must be off. I’m late for an appointment already, so I’ll just leave the young lady in your charge—you’ll take good care of her, I know. I warn you, she’s a wonder when it comes to asking questions; so be prepared to tell her the stories of your lives. Good-bye—see you later.” So saying, he waddled across the room and disappeared through the door, leaving Alice a trifle ill-at-ease among so many strangers. But the quartet were very kind, and did their best to make her feel at home.

“If you will tell us what it is you would like to know about us,” the First Violin suggested, “we shall be happy to inform you to the best of our ability.”

“Thank you very much,” said Alice; “but, oh, dear! There are so many questions I want to ask that I don’t know where to begin.”

“Then, suppose I begin at the beginning and tell you everything about us that I think would interest you.”

“Oh, yes—please do,” said Alice.

“And if you think of any questions as we go along,” the Violin continued, “don’t hesitate to ask them. That will make it easier for me to tell you just the things you want to know.

“Now, to begin—we are called ‘stringed instruments.’ That is because our tone, or sound, comes from the vibration of strings stretched very tightly over a resonant sound box. Do you know what ‘vibration’ means?”

Alice shook her head doubtfully.

“Then I will try to explain it. Suppose you lie in a hammock and let somebody swing you. You go first to one side, then to the other—right, left; right, left—just like that, don’t you? If the hammock is a big one you swing slowly; if the hammock is a little one, or if it is stretched very tight, you swing faster; and if they push you hard you swing farther to the right and left, don’t you?”

Alice nodded her assent to this proposition.

“All right, then,” the Violin continued, “that is vibration. But it is very slow. Now, can you imagine a hammock swinging from side to side so fast that your eye cannot follow it—three or four hundred times a second?”

Alice’s eyes grew big. “O-oh,” she said, “it would make me dizzy!”

“It would indeed,” said the Violin; “but, of course, no hammocks can swing that fast. However, a violin string is like a hammock—fastened securely at each end, with the middle free to vibrate, or swing from side to side; and that is what happens when you pluck it or draw a bow across it. But because the string is so short and stretched so tight it vibrates very fast—so fast that it makes a sound. Now, the tighter a string is stretched, or the shorter it is, the faster it vibrates; and the faster it vibrates, the higher the sound it gives out.” He plucked his second string. “That,” he said, “is the A above Middle C, and it vibrates four hundred and forty times a second.”

“Why,” said Alice, amazed, “I didn’t know that anything could move as fast as that!”

“Pooh!” said the Violin, “that’s nothing. The next A above this one vibrates twice as fast—eight hundred and eighty times a second, and the A above that one vibrates one thousand seven hundred and sixty times a second. Because each time you go up an octave the number of vibrations is doubled.”

“But how do you play the high notes?” asked Alice.

“By shortening one of the strings—generally the first one, called the E-string—so that it vibrates more rapidly.”

“But I don’t see how you can shorten it,” Alice objected. “It’s fastened tight at both ends.”

“That is true,” said the Strad; “but it can be shortened, just the same. I will show you how.”

He plucked his first string, producing a sharp but musical sound. “That,” he said, “is E—the second E above Middle C. The entire string is now vibrating, from the bridge to this little ridge of wood, which we call the ‘nut,’ at the upper end of the fingerboard. Now, just place the first finger of your left hand on the string here, close to the nut, and press down hard.”

Alice did as she was told, whereupon the Strad again plucked his E-string, this time producing a higher tone than before.

“There,” said the Strad, “you see? That tone is F—a half tone higher than the open string; and you produced it by shortening the string.”

“But I didn’t shorten it,” said Alice; “I only pressed my finger on it.”

The Strad smiled and patiently explained: “Pressing your finger on the string shortens it, to all intents and purposes. It can only vibrate between the bridge and the point where your finger presses it against the fingerboard; so the part of the string that vibrates is shorter—and the rest doesn’t count.”

“Now I understand,” said Alice, greatly interested. “And I suppose that if I press my second finger on the string it will give a still higher note?”

“Exactly,” said the Strad; “your second finger will play G or G-sharp, your third finger A-flat or A, and your fourth finger B-flat or B. If you wish to play higher than that you must slide your hand along the neck to a higher position—that is, nearer the bridge. In that way you can reach all the notes, right up to the end of the fingerboard.”

“Isn’t it very hard to know just where to place your fingers?” Alice inquired. “There doesn’t seem to be anything to guide you.”

“It is difficult,” the Strad admitted. “It takes a lot of practice; but it can be learned, just as a blind man can learn to find his way about his house—and then, of course, it seems quite easy.”

“Now,” he went on, “I want to explain to you about harmonics. They are very important, because they will help you to understand the wind instruments when you meet them.”

“Suppose you place your finger here on my E-string, exactly halfway between the bridge and the nut—so; and, instead of pressing down hard, merely touch the string lightly.”

Alice did so, and the Strad passed his bow across the string, producing a high flute-like tone, very soft and clear.

“That,” he said, “is a ‘harmonic.’ It is caused by dividing the string into two equal parts with a light touch of your finger which leaves both parts free to vibrate. The tone produced is an octave higher than the open string. Now, if you touch the string at the proper place, it will also vibrate in three, four, or even five, equal sections, producing still higher ‘harmonics’; and as these ‘harmonics’ are very clear and penetrating they are very often used. But I have explained them to you chiefly because, as I said before, they will help you to understand how the wind instruments produce their tones. Now I will tell you something about the bow, which is very important, for a fiddle without a bow would be almost entirely useless. As you have seen, my strings can be plucked with the finger, like those of a guitar or banjo; indeed, they are sometimes played that way in the orchestra—pizzicato, we call it—but that is only for special effects. Most of the time my strings are set in vibration by rubbing them with the hair of a bow, the hair being covered with powdered rosin to increase the friction.

“There are many ways of using the bow. It can be drawn slowly and evenly, so that it produces a long, sustained tone, or it can be moved very rapidly back and forth, in what is called tremolo. It can strike the strings with abrupt hammer-strokes, called martellato; it can dance upon them gracefully in spiccato; it can caress them in smooth, flowing legato passages—and do many other things, too numerous to mention.” The Strad illustrated each method of bowing as he described it, greatly to Alice’s admiration.

“Why, it looks quite easy,” she said; “I believe I could do that.”

“Try,” said the Strad, smiling indulgently as he handed her the bow.

Alice took it and endeavored to imitate the manner in which the Strad had held it, but found, to her dismay, that the light and slender stick of wood seemed to grow suddenly heavy and clumsy in her hand; and when she attempted to draw it across the strings of the fiddle it trembled ludicrously and brought forth only a succession of miserable squeaks. The Strad laughed good-humoredly.

“It’s not so easy as it looks, you see. Now you can appreciate how difficult it is for all the fiddles in an orchestra—fifty or sixty of them—to bow together in perfect unison, as if they were parts of a machine, as they do in all good orchestras.”

“It’s wonderful!” Alice exclaimed. “I don’t see how they ever do it. But tell me—why are there so many fiddles in an orchestra?”

“In order to obtain the proper balance of tone,” replied the Strad. “Our tone is softer and less penetrating than that of the wind instruments, so if there were not a great many of us we would be overpowered by the wood-wind and brasses. In a well-balanced orchestra the ‘strings,’ as we are generally called, outnumber all the other instruments by about two to one—that is, there are about sixty ‘strings’ to about thirty wood-wind, brass, and percussion instruments. So it’s easy to see that we are by far the most important branch of the family.” The Strad drew himself up, a trifle pompously, and Alice said to herself: “There, he is conceited.” Aloud she asked innocently: “Is that what makes you the most important—that there are so many of you?”

“Certainly not!” said the Strad indignantly. “We are the most important because our tone is the most agreeable to listen to, and because we have a greater compass than any other group of instruments and can play more complicated passages. Also we can play longer without getting tired, and we have the greatest range, from very soft to very loud. But perhaps the chief reason is our enormous emotional range—if you understand what that means.”

“I’m afraid I don’t,” said Alice.

“It means,” the Violin explained, “that we can express more different emotions than any other group of instruments. We can be gay; we can be sad; we can laugh; we can weep; we can threaten; we can plead. We can make you think of fairies dancing in the moonlight, or of desolate mountains swept by icy winds; of shepherds guarding their flocks, or of demons riding madly through the night. Of course, no one of us alone can do all this. My duty is usually to play the brilliant or romantic or tender passages. If the composer wants to express sadness he generally gives the principal part to the violas; and if his theme is bold and vigorous, it is most often the ’cellos who play it, while fear and anger are best expressed by the ominous low tones of the basses. The basses, though, can be quite comic at times. They are so big and clumsy that when they attempt rapid, graceful passages the effect is often quite funny. You should hear them imitate elephants dancing the minuet, as they do in ‘The Carnival of the Animals,’ by Saint-Saëns.”

“Oh, I should love to!” said Alice, laughing.

“Now that I come to think of it, you may hear them—this very evening,” said the Strad. “There will be a concert by the full orchestra, and ‘The Carnival of the Animals’ is on the programme. We shall expect you.”

“I shall come, with pleasure,” said Alice. “But,” she added, turning to the Second Violin, who up to this time had remained modestly in the background, “you haven’t told me what you do in the orchestra.”

The Second Violin appeared embarrassed.

“Why, m-my task,” he stammered, “is rather a humble one. Generally all I have to do is to fill in the harmony, or to help my friend here, the First Violin, to carry the melody. Occasionally I have a solo passage, but not very often. As a rule my duties are comparatively unimportant.”

He seemed so modest and unassuming that Alice could not help feeling a little sorry for him.

“I’m sure,” she said, wishing to cheer him up, “that you are just as important as any of the others, even if your part isn’t so—so showy.”

“You’re quite right,” interposed the ’Cello; “this chap’s humility is simply preposterous. He’s as necessary to the orchestra as any of us, but just because he’s called ‘Second Violin’ he thinks he doesn’t amount to a hill of beans. He ought to cultivate a little decent vanity.”

“It wouldn’t be of any use,” said the Viola, gloomily. “If he did he’d only become a first violin, and then where should we be?”

The Strad looked as if he were somewhat nettled by the Viola’s remark, but he apparently decided to ignore it, for presently he smiled, rather haughtily, and said, with the evident intention of changing the subject:

“There is one more point to which we should call the young lady’s attention: I refer to the sordino, or mute.”

He held up, so that Alice could see it, a queer little black object which looked somewhat like a very short comb with only three teeth.

“This,” he explained, “when placed on the bridge of a fiddle, makes its tone sound softer and thinner and rather sad.” As he spoke he fixed the mute upon his own bridge, and instantly his voice sounded more gentle and subdued.

“Oh, I love that!” Alice exclaimed. “Why don’t you use it all the time?”

“Because you would soon grow tired of it, as you do of too much sugar. Besides, it weakens my voice too much; I shouldn’t be able to hold my own against the other instruments.” He removed the mute, and his voice again became strong and clear. “There, that’s better, after all, isn’t it?”

“Well, I s’pose so,” Alice conceded. “But your voice sounded so soft and sweet with the mute.”

“It’s strange,” observed the ’Cello, “how many people like their music soft and sweet. I can’t understand it. Lots of them admire my soft, rich low tones and don’t care at all for my brilliant upper register, which is really the best part of my voice. Their ears are too delicate—they ought to wear ear muffs when they go to a concert.”

“They should, indeed—if there are any ’cellos on the programme,” said the Viola, plaintively. “You really are a noisy lot—always trying to play louder than the rest of the orchestra combined.”

“Oh, shut up!” snapped the ’Cello. “What do you know about it? You haven’t the spirit of an asthmatic mouth organ. If I couldn’t play louder than a whole section of violas, I’d——”

“Gentlemen! Gentlemen!” interposed the Second Violin, “you’re out of tune. Tony, will you give the A?”

The First Violin plucked his second string, and the ’Cello sulkily turned one of the pegs that projected from the sides of his head until his own A-string was in tune with that of the Violin.

“As usual, he’s much too sharp,” grumbled the Viola.

“Well, well,” said the Strad, mollifyingly, “he’s not the only one at fault: you must admit you’re a trifle flat. Now, tune up, and let’s have no more of this discord, or our guest will have a poor opinion of us.”

The Viola did as he was told, and harmony was restored, much to the relief of Alice, who had feared for a moment that the antagonists might come to blows. As they now appeared to be once more on friendly terms, she decided to take her departure, for she was anxious to visit the other instruments while there was still time.

“Thank you very much for all you have told me,” she said to the quartet. “I shall try not to forget it. And now, if you will tell me how to find the place where the wind instruments live, I think I had better go.”

“We are sorry that you can’t stay longer,” said the First Violin, “but we shall hope to see you in the audience this evening. Meanwhile, if you’ll allow me, I shall be happy to see you as far as the next village, where you will find the flutes and clarinets and all their relatives of the wood-wind family. It isn’t far—we can walk there in a few minutes.”

“It’s very good of you to take so much trouble,” said Alice; and saying good-bye to the other fiddles she accompanied the Strad out of the auditorium and down the road that led to the home of the wood-wind instruments.

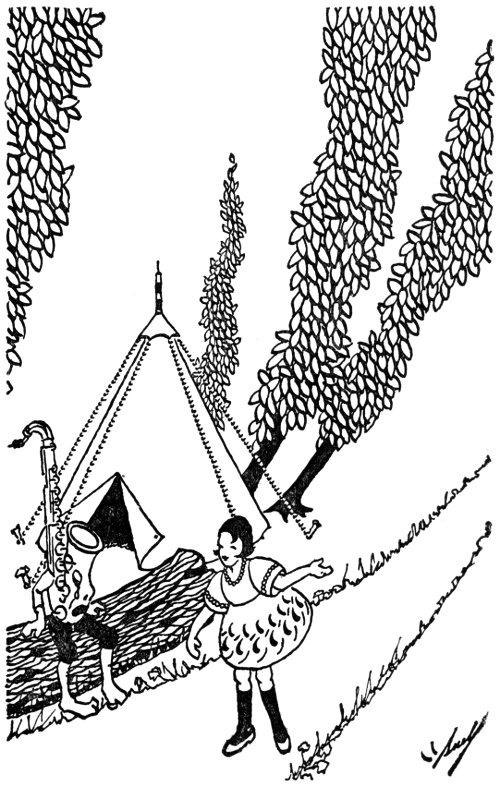

lice and the Violin walked at a

brisk pace and soon had left behind

them the village of Fiddladelphia.

Their way led them

through a pleasant wood of stately

oaks and beeches, from which

they emerged at last upon a grassy common

within view of another village.

lice and the Violin walked at a

brisk pace and soon had left behind

them the village of Fiddladelphia.

Their way led them

through a pleasant wood of stately

oaks and beeches, from which

they emerged at last upon a grassy common

within view of another village.

“There is our destination,” said the Violin: “the village of Panopolis.”

“What a queer name!” Alice exclaimed. “What does it mean?”

“It means ‘The City of Pan.’ Pan, you know, according to the old Greek legend, was a half-god—a jolly sort of chap, with the head and body of a man and the legs and horns of a goat, and he is supposed to have invented the first wind instrument. He fell in love with a beautiful nymph named Syrinx, but she was afraid of his horns and his hoofs and would have nothing to do with him. So Pan changed her into a reed, and then from the reed he made a pipe on which he played the most exquisite music. And as all the wood-wind instruments are supposed to be descended from the pipe of Pan, they regard him as a sort of patron saint of their family, and have named their village in his honor. But here we are at the home of my friend the Oboe. He’s a charming fellow, and takes pleasure in answering questions by the hour—but I ought to warn you that in some ways he’s just a little—er—queer. Nothing serious, of course—perfectly harmless and all that, but—how shall I say?—a trifle eccentric. He has strange notions about pets, and takes great pride in his ancestry, and all that sort of thing. But—well, you shall see.”

They had arrived at a high hedge enclosing a lawn, in the middle of which was a tiny rustic cottage with a thatched roof. Passing through a low lych gate they found themselves in the midst of a large flock of sheep, who stopped grazing and looked at them stupidly. Alice hesitated. The sheep looked harmless enough, but she had never encountered so many of them before, and she wasn’t sure that they mightn’t butt. The Violin reassured her.

“Don’t mind the sheep,” he said; “they’re quite gentle. My friend is so fond of them that he always has a lot of them about. I told you that he had queer notions about pets; but, you see, he comes of a pastoral family—that is, his earliest ancestors were played by shepherds as they tended their flocks—so his fondness for sheep is inherited. He says they make him feel at home. To this day, there’s nothing a thoroughbred oboe likes to play so well as a simple pastoral melody, such as the shepherds of olden times used to improvise to amuse themselves during their long vigils. His voice has a plaintive, wistful quality that makes one think of vast lonely spaces, with no sound but the sighing of the wind in the grasses, and perhaps, far away, a shepherd’s pipe. However, the Oboe can also be gay. He can play the merriest dance tunes and the jolliest songs; and he is also particularly good at Oriental music.”

By this time they had reached the door of the cottage upon which the Violin rapped with his bow. It was opened almost immediately by a queer little instrument about two feet tall, whom the Violin introduced to Alice as the First Oboe. His body consisted of a tube of black wood, about half-an-inch in diameter at the top, but growing gradually larger until at the bottom it flared out into a bell-shaped opening about two inches wide. Down its front, like a row of waistcoat buttons, were six round holes, and attached to it at various points was a complicated system of rods and keys and levers, all made of silver. Projecting from the top of its head, like a feather from its cap, was a slender stem which ended in a sort of wedge-shaped contrivance.

The Oboe welcomed his visitors in a rather thin and nasal voice which reminded Alice of the sounds she herself had often produced with the aid of a comb and a piece of tissue paper. He assured Alice that he would do his best to make her visit both pleasant and instructive, whereupon the Violin left them, to return to Fiddladelphia. Alice lost no time in beginning her quest for knowledge.

“Now, please tell me,” she said, “all about yourself and the other members of your family—how you are played, and what you do in the orchestra, and everything.”

“Well,” said the Oboe, “my family is a large and very ancient one. I can tell you about myself, but I think that the best way for you to learn the characteristics and peculiarities of my relatives is to meet them all personally. Would you like to do that?”

“Oh, yes!” Alice replied with enthusiasm. “That is, if it will not be too much trouble for you.”

“It will be the easiest thing in the world,” the Oboe assured her. “It happens, fortunately, that I have invited them all for tea this afternoon. They will be here shortly, so if you will be good enough to join our party you can make their acquaintance without the least inconvenience to anybody.”

Alice accepted the invitation with thanks.

“Then that’s settled,” said the Oboe. “Now, while we are waiting for the others, I may as well pass the time by telling you something about our respective duties in the orchestra. Shall we sit out on the lawn? It’s very pleasant there—and I like to keep an eye on my sheep.”

The Oboe led the way to a large maple tree in whose shade were several rustic seats, on one of which Alice sat down, while her host reclined as gracefully as his unbending physique permitted on the grass beside her.

“The wood-wind section of the orchestra,” he began, “is composed as a rule of flutes, oboes, clarinets, and bassoons. Together we form a quartet similar to the string quartet, with soprano, alto, tenor, and bass voices. In our quartet the Flute is the soprano, I am the alto, the Clarinet is the tenor, and the Bassoon the bass. But our quartet differs from the string quartet in one important respect: while they have from ten to twenty instruments of each kind—first violins, second violins, violas, and so forth—we have only two or three. The reason for that is that our tone is so peculiar and so penetrating that even a single flute or oboe or clarinet can make itself heard over the whole body of strings.”

“But I thought you said your family was a very large one,” said Alice.

“So I did,” said the Oboe, “but I expressed myself inaccurately. What I meant to say was that our family was one of many branches; for while in numbers the wood-wind instruments are greatly inferior to the strings, there are more different kinds of them. In addition to the four I have named, there are several others which, although they are not regular members of our section, frequently help us out, particularly in the performance of modern compositions. There is, for instance, the Flute’s little brother, the Piccolo; and the Clarinet’s big brother, the Bass Clarinet. And I have a cousin—the English Horn—and a great-uncle—the Double Bassoon. Besides, there are the Bass Flute, the Oboe d’Amore, the Basset Horn and the Double Bass Clarinet—but we see very little of them; they lead a retired life and seldom appear in public.

“Now that you know the names of my relatives,” the Oboe continued, “I shall try to give you an idea of how we are played. All wind instruments, you must know, are alike in one respect: that is, their tone is caused by the vibration of a column of air in a tube, just as the tone of all stringed instruments is caused by the vibration of a string stretched over a resonant box. But wind instruments differ from one another in the means by which their column of air is made to vibrate. In my own case, it is set in motion by the vibration of a ‘reed’ which is held between the player’s lips and through which he blows his breath. A ‘reed’ is simply a narrow strip of cane, shaved down to a very thin edge at one end; but if you will look carefully at my reed”—he pointed to the “feather in his cap”—“you will see that it consists of two strips of cane bound together so that the thin ends are left free to vibrate. For that reason, I am called a ‘double-reed’ instrument. The English horn, bassoon, double bassoon, and oboe d’amore are also double-reed instruments; but the clarinet, bass clarinet, and basset horn have only a single reed which vibrates against a wedge-shaped mouthpiece, while the flute and piccolo have no reed at all. Their air column is set in motion simply by blowing across an opening near one end of the tube.”

The Oboe paused a moment for breath, and Alice took advantage of the opportunity to ask a question. How, she inquired, did one produce all the different tones on a wind instrument—the high ones and the low ones?