* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Secret of the Moon Treasure

Date of first publication: 1940

Author: John Russell Fearn (as Thornton Ayre) (1908-1960)

Date first posted: Sep. 7, 2022

Date last updated: Sep. 7, 2022

Faded Page eBook #20220920

This eBook was produced by: Alex White & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

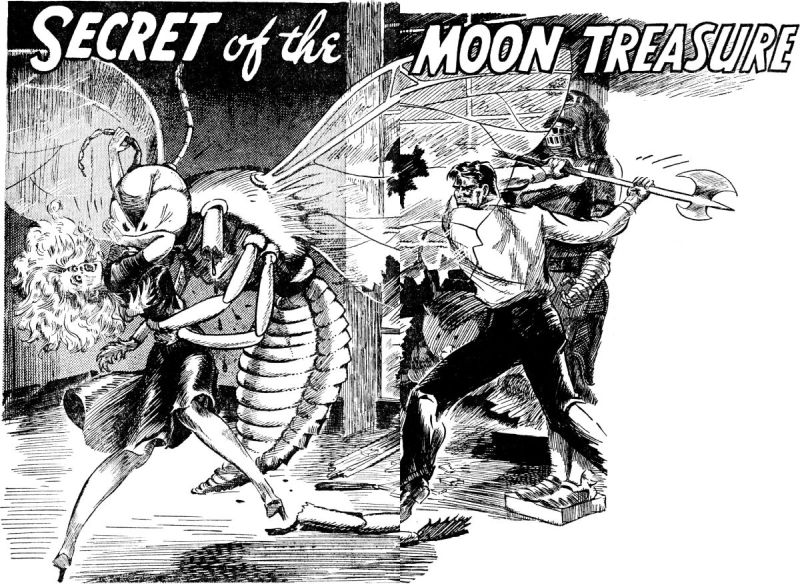

My ancient axe sheared off one of the monster’s legs and I swung again, madly

Secret of the MOON TREASURE

By

John Russell Fearn

Writing under the pseudonym Thornton Ayre.

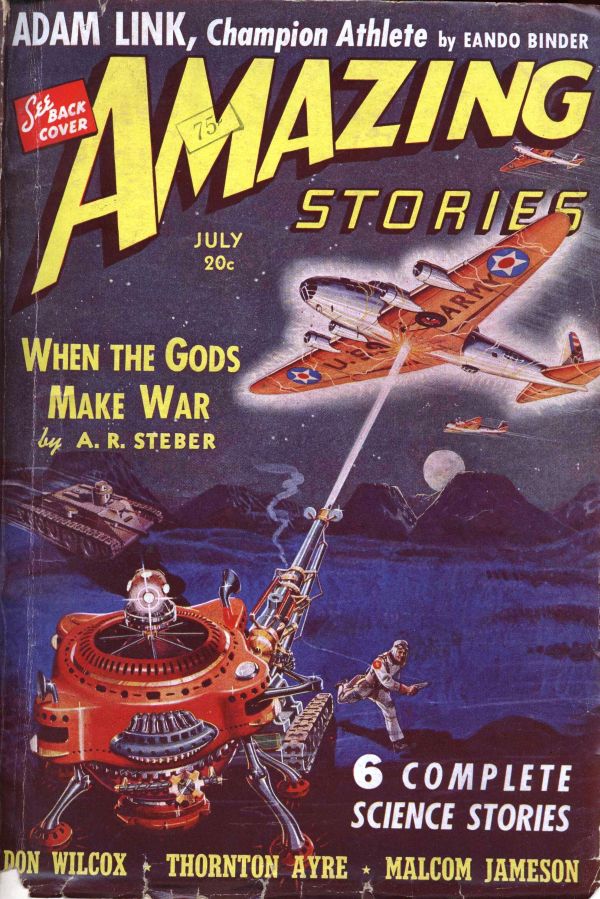

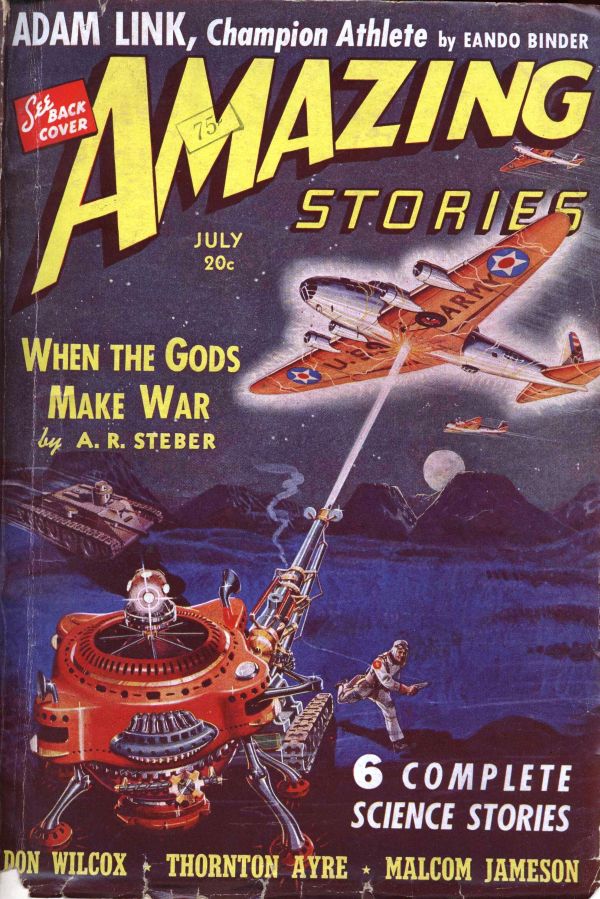

First published Amazing Stories, July 1940.

What strange treasure from the moon could be so important as to warrant wholesale murder over possession of a worthless-looking weed?

“Well, you don’t believe me, do you?”

Dr. Coratti was off on another of his tantrums. In fact, ever since he’d gotten back from man’s first trip to the moon, the gray-haired, nervous inventor had been anything but a prize package.

“Now father, you mustn’t say such things. Of course we believe you,” said Beryl, his tall, dark, amazingly calm and collected daughter.

“Yes, father, we don’t doubt for a minute that you discovered a great secret on the moon.”

That was Lucy, his younger daughter. Lucy is blond and pert, and besides she’s my wife, and I ought to know.

Dr. Coratti, however, was not mollified. He threw his napkin on the dinner table.

“And you, Curt Fowley,” he demanded, “what do you, as an attorney, think?”

I tried to be diplomatic. “Dad,” I said, “as long as it is a discovery on which you haven’t filed claim, there’s a possibility that the criminals you’re worrying about may steal it from you.”

“Steal, fiddlesticks!” Coratti snorted. “Nobody’s going to steal anything from me!” And he got up in a huff and strode from the room. Headed for his laboratory outside, we knew. The laboratory where none of us was welcome.

Well, Coratti didn’t show up the rest of the evening, so we three just sat around the lounge and watched a teleplay from New York; that is, when we were not wondering what the hell had got into the cantankerous inventor. The estate was not the sort of place to make one cheerful, either: old-fashioned, rambling, true enough, but there was too much gray paint on the buildings, too somber an overtone that hung over everything.

The laboratory was a large barnlike building, a kind of hangar for experimental and constructional purposes—there Coratti had built his rocket ship. A river curled about the far end of broad acres.

The only inhabitants of the place, outside Dr. Coratti and Beryl, were the Butsons, manservant and housekeeper—a couple of hard-bitten old devils who had passed their golden wedding in service.

It was around ten-thirty when Lucy, who had been uneasy all evening, said she was going to find out what her old man was doing. In five minutes she was back, hurriedly, swinging the lounge door wide. Her cheeks were flushed, her eyes bright with alarm.

“Dad—in the laboratory!” she gasped out. “He’s dead! Dead . . .”

Beryl and I jumped up. I caught Lucy tightly.

“Wait a minute! Take it easy! He can’t be dead; it isn’t—”

“He is dead!” she shouted hysterically. “Lying there on the floor—Oh, Curt, it’s horrible . . .”

With my arm still about her we went outside. Beryl went ahead of us. She stood staring at Dr. Coratti’s sprawling form on the laboratory floor when Lucy and I came in.

“Yes,” Beryl said quietly. “He is dead.”

I still could not believe it. I tested the pulse, but there was not the slightest flicker; nor any respiration. I turned the doctor over gently and stared at his ashen face and fixed, staring eyes. His mouth was twisted into a sardonic grin, as though he had contemplated something grimly amusing as his last mortal act.

Thereafter I had my hands full. Lucy was utterly inconsolable, weeping and shuddering by turns. Coratti had understood her sensitive nature better than anyone else, and they had always been close. Beryl was different. The event had shocked her, it was true, but she was calm enough. While I tried to convince Lucy there was nothing we could do about it, Beryl went in and phoned for the doctor.

“Heart failure,” the medico said, when he’d finished his examination. “Not at all uncommon in a man of fifty-eight; happens suddenly. I’d say he had been undergoing tremendous strain of some sort . . . Well, I guess we all have these things to face. Good night.”

But the conviction of foul play persisted with me. I even went around the laboratory hangar outside to look for footprints, but of course there were none. When I got back to the hangar, Beryl had gone but Lucy was still there, seated on a chair, her tear-misted eyes gazing blankly in front of her.

“Well, did you find anything?” she asked in an absent voice.

“Find anything?” I pretended innocence. “Such as?”

“You went to look for signs of an attack, didn’t you?” she demanded, getting to her feet. “Didn’t you?” She caught my arm tightly.

I admitted it, and looked at her taut face. It was not grief-stricken now but set and hard.

“He was alone all evening,” Lucy went on. “Curt, it’s sheer nonsense to think that he died, just like that! Father was thin and nervous, yes; but he was wiry, used to strain and— Well, maybe he was right, after all. Maybe those criminals he worried about did steal his secret! Maybe they did kill him!”

I put my arm around her. “Take it easy, child. If something’s up, we’ll get to the bottom of it.”

Heart failure or murder, I wasn’t going to let my wife get hysterical. Particularly when Coratti’s corpse on a table, over which Beryl had temporarily thrown a sheet, stood out like a sore thumb.

So I tried to show concern and poked into this and that, not that it meant much to me, as I’m not much of a scientist. The hangar was stocked with endless jars of chemicals, machinery, electrical equipment, and at the far end there was even a botanical section. Lucy joined me at that point, and we stood looking in puzzled silence at a soil bed full of remarkably strange plants. Funny thing was, they were all dead.

“Queer,” Lucy observed, frowning. “I never knew Dad was interested in plants. Unless—unless he brought them back with him from the moon,” she added quickly. “That may be it.”

I looked at them closely. They looked as plants do when transplanted during hot sunshine. The soil around them was pretty loose.

“Your guess is as good as any,” I sighed. “Unattractive looking plants, too—rather like cactus. Don’t seem to be of much use.”

So that was that.

On the whole we passed a pretty bad night, but at least Lucy was calmer and more composed the following morning. I was prepared to give all the help I could to the funeral when an early phone call put a stop to my intentions. I was needed immediately in the city on legal business.

Ten minutes later I was in my car headed back to town. The law is a remorseless machine, and it kept me tied to a stuffy courtroom for more than three days before I was able to finish the case. I went to our city apartment to get my bag before heading out to the country again, when the telephone rang.

To my surprise Beryl’s voice came over the receiver—but it did not sound like the Beryl I knew. She was hurried, excited.

“Curt? Thank goodness I’ve got you at last! I’ve tried before—”

I interrupted her. “Anything happened? Lucy all right?”

“Yes, yes—she’s all right. Listen, Curt—this is urgent! I’ve just found something among Dad’s effects which explains that great secret he talked about. I don’t like being in the country here with Lucy and having this secret around. We might be attacked—criminals, I mean. Are you coming back or shall we drive in?”

“I’ll be right with you,” I said. “Meanwhile, hold tight.”

It was an hour later that evening when I swept into the driveway of the old estate and pulled up with a shriek of brakes. I had only just got out of the car when I distinctly heard a revolver shot—and then another from somewhere in the rear of the old place. In another moment I was running under the trees along the shale path to the expanse of grounds at the rear.

I was just in time to see three heavily muffled figures go racing across the sweep of lawn in the starlight, to vanish in the direction of the hangar.

“Curt! Curt, is that you?”

I twirled around as I realized it was Beryl’s voice, full of anguish, half choking.

Running through the shadowy dark I found her at last, sprawled helplessly on the floor between the open French windows. She was trying to raise herself. I caught her in my arms, lifted her head and shoulders, and she coughed thickly. In the starlight I saw her light-colored dress was darkly stained across her left breast.

“Curt. . . . listen. I haven’t much time.” She plucked at my sleeve with a quivering hand. “They shot me . . . twice. The secret . . .”

“What is the secret?” I panted. “Beryl—in God’s name—”

I raised her higher, and blood flecked her lips for a moment.

“The—the weeds . . .” She sighed; then with a tremor she relaxed and her head fell back.

I knelt there, too stupefied to move. Beryl was dead, shot by those damned—well, shot by whom?

I looked up sharply at a sudden blasting roar through the night; followed with my eyes a cream of sparks climbing into the darkened sky. Dr. Coratti’s rocket ship, obviously driven by the murderers of Beryl!

The killers had gone off into space in the only rocket ship known to Earthmen, and the secret of its motive power—as far as I knew—was locked in the dead brain of Dr. Coratti.

It took me several seconds to gather my wits. Then I lifted Beryl’s dead body to the library divan and switched on the lights. There was a scene of infinite disorder. Chairs were overturned, rugs rumpled, papers scattered wholesale. It was obvious Beryl had made a desperate fight for her life.

After a while I got Butson and his wife to come in. The two caretakers seemed too appalled to speak when they saw Beryl’s corpse and the blood on her dress. And when they did, they couldn’t tell me anything.

“That’s a big help,” I snapped. “Well, where is my wife all this time?”

“She went out, Mr. Fowley, for a walk—about two hours ago, it’ll be, by now.”

So, naturally, that made me even more jittery.

Lucy had not returned by the time the police came. There was the coroner, one or two plainclothes men, and a shrewd-eyed little man who introduced himself as Inspector Davison. His questions brought forth nothing more than I had already learned. The coroner laconically observed that Beryl had died from bullet wounds through chest and stomach. After that he left, bag in hand.

By then I was all set to explode. I can stand just so much complacence, and then I blow up. I would have, in fact, if Lucy hadn’t come in just then through the open French windows.

She stood blinking, obviously dazzled by the light and confused by the presence of the police. I looked at her quickly. She was dressed in her fur coat and little hat, but she had rubber ankle boots on. They were stained to the tops with yellow mud, still moist.

“Curt—” She came over to me quickly. “Curt, what has happened here? What are these—”

She stopped, her hand going in horror to her throat as she caught sight of Beryl’s dead body still on the divan. She collapsed right there in my arms, and we had to spend about ten minutes bringing her round again.

I had to explain everything as gently as I could. She listened, taking it all in, and closed her eyes once or twice in horror.

The inspector got on the job then. “Where did you go, Mrs. Fowley? I’d like to know, if you don’t mind.”

“Why, I went for a walk by the river,” Lucy said. “I felt I wanted to clear up my mind a bit, after the funeral.” She stopped and thrust out her rubber-booted feet. “I suppose you want proof of what I say? Well, there it is. The river tow-path is covered with yellow mud like this.”

Inspector Davison nodded slowly, his keen little eyes studying her face. For that matter, I was studying it too. Something had happened to Lucy since I had left her three days before. She seemed now to be laboring under a tremendous strain. Being accustomed to her every mood, I could sense it clearly.

Davison pondered a moment, then he turned away abruptly and signaled one of his men to accompany him. They went out of the room and started an investigation outside again.

“Lucy,” I whispered. “Lucy, dearest, what’s wrong? What’s happened to you since I saw you last? You’re different—so different!”

She looked at me directly then, and though her tongue again gave denials I saw terror—yes, terror—and with it a certain stubbornness in those blue eyes of hers.

“You’re being silly, Curt,” she said rather sharply, getting to her feet. “What I want to know is what did Beryl find out that she was so anxious to tell you? When I left her she was reading. The minute my back was turned, she must have started snooping again.”

“Snooping? Oh, you mean going through your father’s papers and effects. . . .”

I turned as the inspector came in again.

“Tell me, Mr. Fowley, have you any idea what those weeds are in the laboratory? Was your father a botanist, Mrs. Fowley?”

“We believe they are probably lunar plants,” I answered him quietly. “But what possible connection could they have with the murder?”

“An investigation has many angles,” Davison said. “I’ll have a botanist here to look these plants over and classify them, if possible. In the meantime you will both stay on hand here. I shall leave men around the house on twenty-four hour duty.”

So again, that was that.

Two nights after Beryl’s funeral things began with a vengeance! Lucy and I had gone to bed about midnight, and I must have fallen asleep immediately. But I was awakened suddenly by a strange rushing sound, accompanied by an unearthly wailing as from a dungeon of damned souls.

I stiffened, listening, awakening by degrees to awareness. There was not just a single cry but many of them—remote, unearthly. I sat up quickly and twisted around; then I got my second shock. Lucy had gone! I groped for the light switch, but before I found it I heard the dry leathery beat of giant wings momentarily against the great window of the bedroom.

Forgetting all about lights, I floundered out of bed and tore back the curtains. The night was a wild one, with a moon nearly at her last quarter riding the ragged deeps. It was an incredible sight I saw then. Some five or six things with mighty batlike wings outspread—and bodies similar to those of an ant—paraded across my vision. Ants with bats’ wings! What the hell was this?

As I watched, they circled against the moon like something out of prehistoric times. They climbed up, flew down to the grounds, circled with their ungodly cries.

I snapped out of my trance and blundered for dressing gown and slippers, shouting Lucy’s name as I did so. There was no response. As I made for the door, I noticed her gown and slippers were absent too.

Then came a different sound—that of smashing glass and a sudden desperate scream, clearly Lucy’s. The noise seemed to come from the library downstairs. I went down the stairs like a madman, missed the bottom step and crashed my length in the hall. Up again in a flash I whipped up a medieval ax from the hall armory and charged into the library.

The light was full on, and I was paralyzed with shock for a second at what I saw. Lucy was fighting desperately with threshing arms and legs against the mighty pincered forelegs of a monstrosity that was now more antlike than ever. It had obviously crashed right through the glass of the French windows to make its attack.

In that second of horror I absorbed the things outlined. The mighty membranous wings, folded now like a cape, enormous eyes, pincered forelegs and powerfully jointed legs behind, leveled its armored body upward. It reared far above my wife, bending her slender body backward with spine-cracking force. Lucy gave a gasping scream and struggled with renewed desperation, screaming huskily.

I whirled my battle-ax then with blind fury, slashed clean through the leg that crushed around Lucy’s back. She sank senseless to the carpet, a watery ichor[1] from the thing drenching her torn gown and nightdress. I struck again, and again, the ax blade flashing in each sweep.

|

Ichor—a pungent, watery substance akin to the life-fluid.—Ed. |

I am pretty powerful and I worked to good effect, insane fury helping me plenty. I caught the thing in a vital spot at last, struck it a blow in its underparts which sent it flapping in blind agony through the broken window. It rose unsteadily, sank down, then was caught by its hideous companions. They went sailing off into the ragged sky.

Drenched in sweat, I dropped my ax with a clatter and wheeled back into the room. I heard revolver shots as I did so. I was examining Lucy for injuries when two of the plainclothes men supposedly on guard burst in. One of them was named Lewis, I remembered.

“What in hell happened here?” he demanded, staring with wide eyes.

“We nearly got killed, that’s all,” I retorted, heaving Lucy’s collapsed weight into my arms. “Where the hell were you?”

“On the grounds, of course. We saw those things flying around, but we figured somebody would come out of the house to meet them. Then we heard the glass smash. Never reckoned one of the damned things had come in and—”

“All right, all right,” I growled. “Take a look around. That blasted thing half killed my wife.”

“But what were they?” Lewis scratched his head. “Looked like bats or something— Hello, what’s this?” He looked beyond the severed ant leg on the carpet and picked up a book.

I glanced at it. It was Jules Verne’s “A Trip to the Moon,” oddly enough.

“I dunno,” I grunted, shifting Lucy more securely in my grip. “Tell Butson and his wife to come up to the bedroom, will you? They’re around some place; I heard them as I came down here. Better have your men look around the grounds for some explanation for all this.”

“Yeah. You bet!”

With the help of the Butsons it took me ten minutes to get Lucy to her senses again. She wasn’t injured, thank heaven, beyond a few scratches and heavy bruises which bandages and ointment could take care of. She lay staring at me in vague wonder when she opened her eyes, then a look of appalled horror came to her face as she suddenly remembered.

“You’re all right, dearest,” I murmured thankfully, gripping her cold hands. “They’ve gone—whatever they were.”

“I didn’t even have a chance . . . I couldn’t sleep, so I went down to get a book—”

“Verne’s ‘Trip to the Moon’?” I put in briefly.

“Yes . . . I dropped it, I suppose. I heard what I thought was the wind rising—then the glass suddenly smashed in, and—”

“Wait!” I interrupted her quickly. “The curtains were not drawn and the light was on? The creatures could have seen you from the outside?”

“Yes, I suppose they could.”

“Hm-m. They must have had a reason for that attack, and I’ll find out what it is if I stay here forever!”

I thought for a moment, an odd idea chasing around my brain. Presently I asked her,

“What possessed you to read Verne’s ‘To the Moon’, anyway?”

Lucy shrugged. “Why not? It’s a good yarn—but my main reason was to pass the time in seeing how far Verne had anticipated Dad’s rocket-traveling secret.”

“But—but you don’t know your father’s secret of rocket travel.”

“What gave you that idea? Of course I know it! He told it to me and to Beryl when he discovered it—but he told us to let it go no further. So we did as he asked. Matter of fact, the duplicate plans are in the laboratory safe. Beryl came across them just after Dad was put in the mausoleum.”

That made me flush. “Holding out on me, huh?”

Lucy ignored that. “Why would you say they attacked me?” she asked irritably.

“I don’t know,” I answered slowly. “Those flying things were not of this world; I’m sure of that. Maybe they were Selenites.”[2]

|

Selenites—Moon people.—Ed. |

“Selenites!”

“I’m going to find out what I can,” I said briefly. I turned to Butson and his wife. “You two can go now, thanks. You’ll be safe enough while I’m gone, Lucy. I’ll be on the grounds within earshot, and I’ll see if anything unusual happens.”

She nodded and relaxed. I scrambled into a few clothes, a hat and overcoat, then went outside and caught up with the plainclothes men snooping around under the trees.

“Anything?” I asked Lewis.

“Nope—except for queer bird footmarks where that thing landed near the French window. Nothing else.”

“The things came from the moon; I’ll swear to it,” I muttered. “They must be able to cross space somehow. I figured there might be somebody on the grounds directing them or something. We’ll keep on looking, anyway.”

“Okay. Maybe you’ve got something there.”

But it did not seem that I had. We wandered around for half an hour or more, flashing our torches at intervals. The estate covered a pretty wide area of ground, and it took us a considerable time to zigzag about. It was as we were slowly returning toward the house that Lewis caught my arm tightly. Immediately we all became still.

Through the thick undergrowth we could see a dim figure crouching down in a more open part of the grounds. The waning moonlight was quite inadequate to reveal him clearly—if it was a he. It had no shape, so heavily was it muffled up. The figure seemed to be on its knees, burrowing steadily into the earth, and using a torch very cautiously at intervals.

“On him!” rapped out Lewis suddenly—and we plunged forward.

But something happened. The unknown jumped up, whirled around, and fired something that sent a fine spray toward us. I caught a glimpse of the figure’s face—long, thin, pallid. Then it seemed as though the earth closed in on me from every side . . .

The next thing I knew, somebody was chafing my wrists. I stared dazedly upward in the reflected light of a torch, to see Lucy’s anxious face bending over mine. Behind her, less distinct, were Lewis and his men.

“Lucy!” I cried. “How did you get here? Ouch, my head!”

I got up dizzily, running my eye over her. She was fully dressed now, or appeared to be. Anyway, she had bundled on her fur coat, scarf and little hat.

Lewis said rather grimly, “She revived us, too.”

“What’s the meaning of this?” I asked her shortly. “I thought I left you in your room.”

“Sure you did—two and a half hours ago! I got worried at the lapse of time. I came to look for you, found you and these men out cold, so I rushed in the house to get some brandy and revive you.”

I looked at her steadily. I had noticed something peculiar. The flashlight shining into her face had failed to make the pupils of her eyes contract. They were wide, gaping pools of black, with a tiny little rim of blue around them.

“What are you staring at, Curt?” she asked suddenly.

“Your eyes. Looks as though you’re—drugged.”

“Oh, that! I took some sleeping tablets to settle my nerves, but they didn’t seem to have much effect—especially when I was worrying about you. But Curt, never mind me! What happened to you, and these men?”

“We were attacked, and somebody has got a mighty powerful scientific weapon with which to defend himself. It ejects a paralyzing fluid. It put us out like lights—” I gestured suddenly. “Let’s get inside. We can do no more out here until daylight. You boys sticking around out here?” I asked them.

“Yeah.” Lewis retorted. “Maybe we’ll find out what that guy was digging for.”

Lucy looked vaguely surprised at this last remark, but I caught her arm and led her into the house, back to the bedroom again. First thing I did was check up on the box containing the sleeping tablets. There were two short, certainly. I distinctly remembered there had been half a dozen, because I’d intended buying more. Now there were only four.

“Curt, don’t you believe me?” Lucy asked quietly, watching me.

I turned to her sharply. She had pulled off her fur coat now, to reveal that she was still in her rent and torn night clothing.

“It’s getting so that I don’t know whom to believe!” I retorted. “I’ve no reason to doubt you—yet I felt I ought to check up. Beats me why two tablets of this strength haven’t even made you sleepy!”

“They have—now,” she said wearily, throwing herself on the bed. “My fears for you kept me awake before— Curt! Curt, dearest!”

She gripped my arm and pulled me down to a sitting position on the bed.

“Please don’t keep looking at me like this, as though as though you think I have something to do with all this. It’s as bad for me as it is for you. Just what are you thinking?”

“Just that whoever it was on the grounds is probably the murderer of your father,” I replied slowly.

Lucy looked at me steadily for a moment, then she gave a little sigh and relaxed. Her eyelids drooped, and in a moment she dropped into slumber.

Of course sleep is the easiest thing in the world to imitate, and had she wanted— Damn my suspicions! I got up, cursed myself for ever daring to suspect her at all.

I did not go back to bed. I finished dressing and spent the rest of the time until daylight seated in a chair, smoking and thinking.

I could see from Lucy’s expression at breakfast that she resented my suspicions of the night, so I said little that would recall the matter to her mind.

Toward mid-morning we got a diversion, for Inspector Davison returned with a florid-faced, white-haired individual in immaculate attire, whom he introduced as Dr. Henry Stanson, an eminent botanist.

“Took me some time to locate the doctor,” the inspector explained. “We’ll go right down to the laboratory, if you don’t mind.”

I followed them leisurely, with Lucy looking after me rather wonderingly. In the lab I found Stanson on his knees, peering at the plants. Finally he yanked one out, jabbed a needle in the still moist root and extracted a quantity of sap. Getting up, he narrowed his eyes over globules of moisture which he tested in his portable equipment.

“What are they? New sort of dock[3] leaves?” I asked interestedly.

|

Dock leaves—leaves similar to those of buckwheat.—Ed. |

The white head shook briefly. “This isn’t a plant that has grown on this world. It isn’t even a tropical one. In these days, they are all classified from pole to pole. This stuff”—he raised the glass phial—“is concentrated drug of some kind. A tremendously powerful sedative, I’d say. I guess bromides would be seltzer water by comparison.”

“Fatal?” Davison asked keenly.

Stanson mused. “Well, that depends. I can’t find out much from these few details. I’ll have to check over in my laboratory.”

“Inspector,” I said quietly, “would you object very much if I accompanied you and Dr. Stanson to his laboratory? I’d like to see what his tests reveal.”

He looked surprised. “Why no, there’s nothing against that. You evidently don’t think your wife will be in further danger, then? From flying monsters?” he asked grimly.

“Oh, so you know about them?” I demanded.

“My men told me everything when I arrived. Most interesting sidelight. However, I think there is little chance of any danger during the daytime. We’ll be getting along to the car. Join us when you’re ready.”

I hurried back to Lucy. She gave me a rather chilly glance.

“I’ve got to go back to the city with the inspector,” I said briefly. “Just some routine questioning, you know. I’ll be back later.”

She got to her feet. “Curt, are you sure that is the reason you are going?”

“Eh? But of course—”

“Or is it to build up some filthy suspicion against me?” she blazed. “Do you think I’m blind, that I can’t see you suspect me of some rotten intrigue somewhere? You take the simplest little thing and twist it into a guilty motive to—”

“Lucy!” I caught her tightly. “Lucy, I never said anything yet to make you blow up like that! It’s your own conscience that’s doing it, not anything I’ve done! I’m simply following every lead I can to clear up this mess. Please understand that!”

“Then it’s not questioning you’re going for?”

“No,” I admitted quietly. “I’m going to get an analysis of those laboratory weeds . . . See you later.”

I left her with that, sat in morose silence between Stanson and the inspector as we drove into town. Matter of fact, the thing that had propelled me on this errand had been the botanist’s reference to drugs. I was still haunted by the memory of Lucy’s eyes the previous night. And she was hiding something: her latest uncalled-for outburst made me reasonably sure of it. Pretty damnable business, to have to suspect one’s own wife!

We lunched and then went to Stanson’s private laboratory at the Botanical Institute. He took about two hours making all his experiments, testing the sap on a white mouse from the adjoining experimental annex. At the end of it all, the inspector and I were still interested, but puzzled.

“Well, Doctor, how are we fixed?” Davison asked, his eye on the clock.

Stanson sighed. “I’ve got as far as I can. This sap, if we could only get it in large quantities, would present the medical profession with a most useful addition. It is a drug, as I said before, and reacts strongly on the nervous system according to the amount given.

“In extreme amounts it could kill. In other varying amounts, it might produce effects ranging from complete insensibility to pain, to a complete control over the nervous system. As some drugs can either benefit or kill—adrenalin, for example—so can this one, according to quantity.”

“Insensibility to pain, eh?” the inspector mused. “That wouldn’t be an addition to medical science. We’ve got drugs already that do that.”

“I know—that is only one of the effects, as I pointed out. The real usefulness would come in its ability to control the nervous system. If this drug were injected in given quantity into the bloodstream, a man could, say, control his nerves so accurately as to make his hair stand on end, move his eyes independently of one another, perspire or shiver at will, change the color of his eye pigment, alter his heartbeats—why, there’s no end to what he could do.”

“Hm-m,” the inspector muttered. “This is possibly the secret which was stolen from Dr. Coratti when he was murdered. Also, it is possible that Coratti brought the weeds originally from the moon.”

“I’m sure he did,” I said. “And it is possible that criminals would like to know where they could get more of these weeds. They could start a racket in medicine unparalleled in history, besides the things they could do with them themselves. They might even be able to change their appearance after a dose of the drug.”

“Quite possible,” admitted Stanson.

I said no more, for an astounding thought had stolen across my brain. Lucy had been drugged. Sleeping tablets? Quite possibly; but just as possibly—weed extract.

We had been attacked on the grounds and Lucy had revived us, stressing worry as to my whereabouts as her reason for being in the grounds at all. The indeterminable figure burrowing in the soil? Shapeless fur coat? Could Lucy have had the time to leave the bedroom after I’d left her? Sure—we’d wandered around for an hour and a half. But why would she have left the bedroom? And was it she, anyway . . .

“Something struck you?”

The inspector’s voice broke my meditations. I looked at Stanson.

“Suppose,” I said, “these plants were normal and strong. They could not give off their sap without its being extracted, could they?”

“Certainly they could. Look at the needles on the leaves. They would sting in the style of a common nettle. There are two possible reasons why these plants died—one, because they failed to take root properly; or else because so much sap was taken out of them by somebody. The latter theory seems the more likely.”

“Well, thanks a lot,” the inspector said finally. “We’ve got to be getting along. Send in your account to headquarters, will you, Doctor? You satisfied, Mr. Fowley?”

“I guess so,” I nodded. “Doesn’t seem we’ve gotten very far, though.”

I think I threw Inspector Davison off the scent there. I wanted to reason this out for myself, before getting Lucy in a possible jam. So I effected an air of bewilderment over the whole proceedings as Davison accompanied me in the car back to the Coratti estate. He saw me inside and then departed about his business.

I walked into the lounge, slapping the newspaper I’d bought in town carelessly against my leg. Lucy tossed down her book and eyed me levelly.

“Well, did they ask you many questions?”

“I found out about the plants, anyway,” I retorted. “They’re able to produce change in a human body. For instance, you or I could change into something else under the influence of their sap.”

“So that’s what you’re thinking!” she said bitterly. “You think I drugged myself with plant sap, eh? That’s what you thought last night, too! You believe it was I who attacked you in the grounds!”

“Perhaps you’ve some idea who else it could have been?” I demanded. “Think how all this looks to me! Why don’t you come out into the open and explain things before I find them out for myself?”

“I suppose,” she asked dryly, “I shot Beryl, too.”

“I know you didn’t. I saw other people do that— But you do know something!” I caught her shoulders, forced her to her feet. “You little fool, Lucy, can’t you remember for a minute that I’m your husband, that I’m willing to go through anything to help you if need be?”

Her lips set. “I don’t want your help, Curt—and I resent your beastly suspicions. Anyway, the whole thing’s idiotic. You’re trying to suggest that under the influence of drug I can change myself like—like a chameleon . . .”

“Maybe. The figure that attacked could have been you—and so could its face, for that matter.”

“Oh, you’re impossible!”

She swung away, flushing, and stood gazing out of the window at the man standing idly about the grounds. I hesitated, about to say something to her. Then I shrugged and snatched up the paper I’d brought, and glanced through it for the first time.

The headlines smote me immediately:

MYSTERY CRIME RING AT WORK

I read the column with a frown. Though it was possibly miles apart from the mystery in which I was involved, it had nevertheless a reminiscent scientific tang about it. At my silence Lucy turned, came over and read over my shoulder. She was interested enough to repeat the column in a low voice.

The rapid development of a new criminal organization is causing police much concern. There are distinct evidences of a racket being waged against big industrialists. By some curious process of an undoubtedly scientific nature, the criminal behind the activity is able to learn the innermost secrets of big industries, which he then sells to commercial rivals.

Such a system is bound in time to undermine several big firms whose names are household words in this country. As yet the authorities cannot understand how the criminal is able to learn secrets which are inside four walls, or how he is able to find out what takes place at secret board meetings. A new style of radio detection is suspected, but has yet to be proved.

“So,” I murmured, “we’re not the only folks with a mystery!”

My attempt to be genial was lost on Lucy. She read the column again to herself, compressed her lips.

“What’s the matter? Know something about it?” I asked her bluntly.

“Of course not. I was just thinking that the criminals who shot Beryl and who possibly murdered father might be behind this.”

“Those killers went off into space,” I reminded her briefly. “And a ship like that could not return to any part of Earth without being noticed.”

“But why should they be the only criminals?” Lucy demanded. “The ones that shot Beryl may have been only a section of a larger gang. The other members are possibly the ones who are doing this scientific work of learning secrets; the ones who probably killed father.

“One of them might even have been the person who attacked you in the grounds last night. Remember, he had a paralyzing gun, you said. That proves he was at least a scientist.”

“Yeah—that’s right,” I admitted slowly. I pondered it for a moment, then I made up my mind.

“Lucy, it seems to me that we can never know the truth about all this until we know why those crooks rushed off into space. It is pretty certain that they headed for the moon, and we can only know the answer by going to the moon ourselves!”

“We haven’t a space machine,” Lucy said quickly.

“We can have one. You said yourself there are duplicate plans in the lab.”

She looked startled for a moment. “Why yes, but— Well, how do you even propose to start? Think of the materials we’ll need.”

“Your dad managed it; so can we. We’re not short of money, and I think it’s a good way to get things moving. We may stick here forever otherwise.”

I turned and strode for the door, but to my surprise Lucy caught my arm. The frozen coldness seemed to have gone out of her face. Instead she had become appealing, desperately appealing. It takes a lot of purpose to refuse a woman when they put on an act.

“Curt, I don’t think we should waste time and money doing this. It will take too long, and it can’t achieve any good purpose. Don’t forget the curse that flying to the moon brought to this house, and—”

“Lucy,” I said, “I am ordinarily a patient man. But right now, I crave action!”

I thrust her aside and strode across to the laboratory. The plans were there, sure enough, and the formula for the fuel; but I realized I was not engineer enough to understand them. All I could do was send them to an engineering firm and have them deliver the finished parts in sections. I rang up Inspector Davison and told him of my idea—that it would be better to go after the crooks than wait for them to turn up. He agreed and that was that.

That Lucy did not like any part of the idea I could see full well, though she did not refer to it again. In fact, it was her utter silence that showed me her displeasure so clearly. We sat like a couple of deaf mutes after dinner that evening.

But the radio newscaster snapped us to attention quick enough.

“Reports are coming in from various sections of the country about strange bird life which has appeared in both urban and rural districts.”

The teleplate revealed unmistakable shots of the giant monsters that had attacked Lucy the previous night.

“The birds resemble pterodactyls, prehistoric flying reptiles. Scientists are going to investigate in an effort to classify the creatures. They consider it possible that these birds may have escaped from some corner of the globe which has thus far escaped exploration.”

“So they’re still around!” I breathed, glancing at Lucy’s drawn white face. “Wonder what in heck they’re looking for? We’ve got to keep our eyes peeled.”

She nodded slowly, but whatever she was going to say was cut short by the newscaster’s next words.

“As already announced in earlier bulletins, a new criminal organization has been uncovered in this country. Further investigation has shown that radio devices, at first suspected to be the criminals’ means of learning guarded commercial secrets, are not responsible! In rooms especially guarded and spotted with radio detectors, secrets have still been learned. Meanwhile, the investigation is continuing.”

I switched the radio off. “More I think of this, the more I think you’re right, Lucy,” I muttered. “About the crooks being responsible, I mean. Is it possible that the great secret your dad found is this very one the criminals are using?”

“Possibly,” Lucy frowned, “But I still can’t see why you’re sticking your neck out! Haven’t we had enough grief already?”

Altogether it was tough going thereafter. Nothing seemed to get things going, and my efforts to get Inspector Davison to let us return to town were unavailing.

All I could obtain was permission to go with a plainclothes escort into town, so that I could keep in touch with my legal affairs. This enabled me to become more friendly with Inspector Davison, also. But Davison still withheld permission for Lucy and me to leave the Coratti residence.

“Can’t be done, Fowley,” he said seriously, as I tackled him in his city office. “This case is unique, and you know enough of the law yourself to realize that suspects in a murder which involves scientific implications must be confined to the scene of the murder for a period of six months.

“If nothing happens by then and no culprit is found—if the rocket ship does not return to Earth, that is—you are automatically adjudged innocent, and your wife too. But by then you may have gotten your own space machine finished, and we can do something.”

I nodded resignedly. “Well, there it is. Have you got any leads yet?”

“Not many,” he sighed. “It’s so complex. Your wife is attacked by giant birds; you and my men are attacked by a person with scientific weapons—weapon, anyway. Now I’m inclined to think that there may be a connection between the mystery at the residence and the crime ring that is operating at the moment.”

“So am I,” I said slowly. “I believe that it might be the secret Dr. Coratti discovered, and which was stolen from him after his death.”

“You do?” Davison looked at me keenly. “Do you believe Dr. Coratti died from heart failure?”

“That’s what the medico said,” I answered him steadily.

“Hm-m—If this is Coratti’s secret—this power to look into secret meetings through solid walls—how is it that while they were about it, the criminals only stole that secret, yet left behind the plans for a space ship—plans which you are now using?”

“Plenty of reasons for that,” I said. “The art of probing through walls may not have been in a written plan, nor might the plan have been in the laboratory safe, if there even was such a plan. Again, the criminals did not need the constructional designs of a space ship. They had one already designed—and used it!”

“Hm-m—I see your point. Well, guess the only answer is to fly to the moon, after all. Any progress yet?”

I nodded. “I sent in the plans a week ago and got the first consignment by freight yesterday. I’m going to spend the week-end putting parts together.”

“Good! Sooner you finish the job, the better I’ll like it.”

I left him soon after that. When I got back to the country house Lucy had nothing of moment to report, but at dinner she rather surprised me.

“You mean to go ahead with this insane idea of building a second rocket ship, I suppose?”

“Naturally. One consignment’s here already, isn’t it?”

“Two!” she retorted. “Some electrical machinery was delivered this afternoon. I had the men throw the crates in the hangar.”

“For the daughter of the man who invented space travel, that was damned considerate of you,” I commented dryly.

“It isn’t that—it’s just that I think you’re making a fool of yourself. Then there’s the money involved. And even if you finish the darned ship and get to the moon, how do you know what to look for?”

I smiled grimly. “I’m going to look for weeds.”

“Weeds!” Her blue eyes sharpened.

“Like those in the laboratory,” I went on slowly. “Beryl’s last words to me were something about weeds. We know they came from the moon—and since the crooks went there too, it all adds up. They went to the moon to get the weeds! What the weeds signify, I can find out when I reach there. Understand?”

That same evening I unpacked the crates, and during the next two days—Saturday and Sunday—I worked eighteen hours apiece, welding the plates together with the laboratory’s equipment, gradually getting some sort of shape into the cylindrical object in the hangar cradle.

It was not difficult. The engineers had returned the sectional plans for me to work with. Hardest part was working alone: Lucy did not raise a finger to help me.

But on that Sunday evening, when I was just about all in, Lucy came into the hangar slowly and estimated my progress. I saw her mouth tighten a little.

“Well, don’t you like it?” I asked her bluntly.

“Seems I’ve no say in the matter!”

But nonetheless she went around the section of work I had completed, surveyed the electrical engines, then her gaze wandered to the shelves of chemicals. I thought nothing of that—then. At last she shrugged.

“At least it keeps you out of the house,” she said sourly. “We’re all washed up, Curt, and when we get out of this mess I’m seeing my lawyer about a divorce.”

“Because I’m trying to find out who killed your father and sister, eh?” I asked bitterly. “Hell, that’s gratitude for you!”

“You’re not trying to solve anything!” she blazed back at me. “You are only trying to pin something on me to satisfy your infernal distrust! I never thought you could be such a beast!” And the venom with which she said it made me jump for a moment.

Then she was gone, leaving me scratching my head. I’m telling you, the man who sticks his head out nowadays is a sucker.

When I went into the house an hour later, dog-tired, I found Lucy had gone to bed. I moodily ate the cold supper Butson had left for me, then went upstairs myself. During the day Lucy had seen fit to widen the gap between our twin beds, so that I was now several feet from her. She was sleeping deeply, or else simulating it to avoid conversation.

I got to bed in sullen fury, but I couldn’t keep up the bitterness for long, for my hard work had made me like lead. I must have gone to sleep almost instantly, to be literally shot out of slumber some hours later by something damned close to pandemonium.

I awoke to the roaring and exploding of a giant gun—or so it seemed at first. Then I saw wild and wavering lights flashing through the window. I stumbled out of bed half blind and stared outside. There was no moon, but I was in time to see a monstrous vessel at the end of its journey, cushioning down to the ground on its under jets.

The rocket ship had returned!

“Lucy!” I shouted hoarsely, swinging around and slamming on the light. “Lucy, the rocket’s—”

I stopped dead. Her bed was empty and her clothes had vanished. Confused, I went back to the window, stared out as I scrambled into my pants.

Suddenly I wondered why there was not more action from the boys around the grounds. There was only a momentary blaze of revolvers and then a surprising silence. I frowned, cursed the fact my pants legs were twisted and were holding me up. Savagely I straightened them, grabbed my coat and dashed downstairs. I heard Butson and his wife shouting inquiry as I went.

I raced into the grounds and then brought up sharp, falling back before a sudden monstrous concussion. It hit me like an earthquake, and my dazzled eyes beheld the whole mass of the hangar laboratory going sky-high in one terrific explosion. Flat to the earth I went, my ears ringing. I got up finally to behold a devastating, crackling blaze roaring into the sky, and silhouetted against it were four figures—three men, and a girl, undoubtedly Lucy.

“. . . mercury fulminate!” she was shouting. “I blew it up, I tell you! I—”

“Step on it!” one of the men shouted, and Lucy started to heave forward with them around her.

“Lucy!” I shrieked, leaping up and racing across to them. “Lucy, what’s happened? What’s—”

I got no further than that, for a mist shot suddenly from the air from the nearest man. Part of it missed me, but its inhalation brought me crashing to the ground, there to lie perfectly conscious but unable to move my muscles properly. It was a ghastly sensation chained there to the earth, with my nerves jumping like hell and my eyes following Lucy as she went into the darkness with the men.

Was she going deliberately—or being forced? That was what got me. She had admitted blowing up the hangar with mercury fulminate—and with it my half-made space ship. Then it was I recalled her visit to the hangar and her glance around the shelves. So she had planned to do this thing—planned it to upset my efforts!

I made a mighty effort to break the paralytic spell and failed again. Then I lay still and watched with frozen horror as, through the light of the fire, I saw monstrous antlike birds sweeping down with demoniacal speed, giant wings spread. They missed me—or else took me for dead, just as they ignored the plainclothes men scattered prone about the grounds, obviously victims of the killer’s paralyzing guns.

I saw the birds settle finally at the ship’s open airlock. Their wings folded like giant capes as they waddled inside the ship. Six of them went in one after the other, and came out again with their mighty beaks filled with dead leaves! No—not leaves; weeds! Limp masses of moon-weed! There was definite intelligent purpose in the way they worked.

They gathered up all the weeds they could from inside the ship—and there seemed to be a bushel of them; then they took them over and dropped them in the blaze of the laboratory fire, which was dying down into a smoldering glare.

Evidently satisfied, the birds took to the air again and swept out of sight. I did not need to guess they were following Lucy once more. That settled it for me: I had to break free! I strained and sweated and struggled, and at last felt life coming back into my limbs. I had missed the full impact, anyway.

I got to my feet at last, stumbled to the ship and stared inside it. Firelight through the portholes showed that no weeds remained, but the floor was slippery with crushed sap.

Why the systematic destruction of the weeds? I could not stop to think it out then. Right now Lucy was my sole concern.

Off I went again, stumbling through the undergrowth of the estate, following the direction the birds had taken. I lost sight of them very rapidly but I went on just the same, until I found the trail ended beyond the boundaries of the estate and I was out on the river tow-path.

I did not call for fear of giving my presence away, and I’d no wish for a second shot of that paralyzing fluid. Instead I struck matches and peered at the yellow mud on the tow-path. A recollection of Lucy’s stained boots on the night of Beryl’s murder returned to me. Lucy had spoken the truth then.

There were clear imprints of men’s boots and Lucy’s shoes. Sick with anxiety for what might happen, though the lunar birds were still not in sight, I tracked the footprints until they brought me to a high bank of the river, and beyond it an old boathouse used only in the summertime. There was no sound beyond gurgling water.

I hesitated, then went down to the boathouse. Once I got to it, I froze into attention at the sound of a voice, kept pretty low but nonetheless audible.

“Whether you die or not is of no consequence to us, so get that straight, sweetheart! We can easily chuck you in the river when we’re through, if you don’t come across. If you’re sensible you’ll speak.”

My skin prickled with mounting anger. Yet I had a vague relief too. Lucy was not associated with these mystery men, then: it had only looked that way. Probably they’d had a gun in her back to stop her calling out. Else she’d purposely kept quiet to save anything happening to me.

I crept closer, but I could not get all the conversation because of the noise the river water was making.

“. . . because of ants . . .” I heard that clearly and puzzled over it.

“And what did we get?” the voice went on bitterly. “We got a collection of damned weeds! Sure, they’ll be useful, but it wasn’t what we wanted. Your father had a different secret besides weeds. He knew how to learn secrets without using radio means. We went to the moon to get it and found we’d been tricked, see? We found weeds instead.

“We tapped the wires, heard your sister telling your husband over the phone that she’d found the secret we were looking for—only when we got it from her, it proved to be the wrong secret. But you know the secret we want—so we came back to get it. And you’d better act quick! You know as well as we do that those damned Selenites are here on Earth to avenge the theft of their secrets. So—spill it!”

A lot of things fitted into place in my mind at hearing those words. I edged closer and suddenly caught the pale yellow of a light streaming down a cracked board. I glued my eye to it, and I got a bad shock at what I saw.

The three men were standing in the light of a candle stump—all men whom I could not recognize with their stubbly merciless faces. They looked what they were—space-traveling renegades, with the appalling strain of the void still reflected on their ugly features. In the center of them was Lucy, bound with boat rope to a rickety chair. I could see her as she struggled vainly to free herself, looking up with terrified eyes.

“Well?” demanded the speaker savagely; and I noticed he was smoking. He waited a second or two, then blew the ash from his cigarette and eyed the glowing end thoughtfully. “You got nice eyes—” he murmured significantly.

“How can I speak when I don’t know anything!” Lucy screamed frantically. “I’ve told you over and over! I don’t know the secret you want! I—”

For answer the speaker caught her thick hair and forced her head backward. I saw his cigarette come close.

“You asked for it,” he muttered.

Realizing what he meant, I drew back my fist and drove it with blind fury into the rotten boarding. Then, just as my blow fell and sent blazing pain through my knuckles, I heard the whirring of mighty wings and the stench of reptilian flesh.

Like so many projectiles, three Selenite birds swept suddenly from the heights and slammed with terrific force clean into the roof of the place. I never saw anything like it. Armor-plated, sword-beaked, they went through like bullets.

From inside the boathouse came a desperate scream, and I distinctly saw one of the men go down with a mighty beak impaled right through his body. The candle vanished; mad commotion broke out. I made use of it and slammed my shoulder again and again into the rotten woodwork. It gave at last. I stumbled into the midst of slashing beaks and leathery wings. A pincered foreleg just missed me as I groped my way along.

I found Lucy at last, struggling to get free. My penknife finished the job; and hanging onto her tightly, I yanked her free of the mêlée, half dragged her up the bank to safety. Back to us floated the sound of men dying horribly under the onslaught of the appalling moon-birds.

“Lucy, you all right?” I gripped her tightly, anxiously.

“Yes—yes, I’m all right. Only bruises. Thank God you came when you did—”

“That secret,” I broke in, as I hurried her away through the dark from the hellish spot. “What did they want?”

“I don’t know,” she panted. “I told them that, but they wouldn’t believe it. I think that man was going to blind me with his cigarette . . . They’re fiends, Curt—desperate fiends, blind to everything because the thing they wanted is still beyond them. I guess they chose the boathouse as the safest, nearest place to get to work on me.”

“Guess they won’t any more,” I said grimly. “The birds got ’em for keeps. But Lucy, what is—”

I stopped suddenly. Reaction to the ordeal had caught up with her, and she slumped to the ground and lay motionless. I picked her up and staggered through mud and field back to the house. I was met by the recovered plainclothes men.

“What happened?” Lewis demanded. “What’s been going on?”

I told him in sections as I carried Lucy into the house and up to her room. He stood scratching his head and he gazed at her limp figure.

“Can you beat it? We wait all this time for the rocket to come back, then the guys in it put us to sleep with paralyzing guns. Same way as that other guy did. What the hell was your wife doing down there at the hangar fully dressed, just when those men came?”

“I don’t know and I don’t care, so long as I’ve got her out of their clutches,” I retorted. “But I’ve got one or two ideas to talk over with the inspector. Get him on the phone, will you—and tell him to have some men take a look at the boathouse too. The Butsons are around the house somewhere—send them up here. I’ve got to bring my wife around.”

“Okay.”

In ten minutes, with the Butsons’ help, I’d made Lucy as comfortable as possible, patched up her bruises. A little brandy accomplished the rest.

Lucy was completely conscious by the time Inspector Davison arrived. He nodded to me, then looked at her with a frown.

“What’s all this?” he demanded. “My men outside said something about an attack, a fire—”

I gave him the details as quickly as I could, as Lucy lay there listening.

“How did it happen, Mrs. Fowley, that you were at the laboratory at the very moment those men landed back here?” the inspector snapped.

“Coincidence,” Lucy said quietly. “I didn’t plan it to happen that way, if that’s what you think. I’d blown up the lab when I found they were outside. They asked me what I’d done, so I told them I’d done it with mercury fulminate. They said I’d done it to stop them examining the laboratory. Then they pushed a gun in my back and made me keep quiet.”

“Why did you blow up the laboratory?” Davison asked. “Answer me that.”

“I—I did it to save my husband from getting into danger. I know from what my father told me how space travel can drive a man to madness—and Curt was so dead set on flying to the moon, I considered it my duty to stop him by force. He wouldn’t listen to reason, you see.”

“These men tried to torture you into revealing a secret,” the inspector went on. “What was it? Or do you mean you do not know?”

“I don’t know,” Lucy answered wearily. “I know of it, but nothing about it. All I know the newspapers told me—about seeing through walls. These men thought they were getting the secret from Beryl, but all they got was weeds. So they returned and tried to get it out of me.”

“And the flying horrors are from the moon,” Davison mused. “We can see now, from what you say, Fowley, that they are trying to destroy everybody who has stolen stuff from the moon. They destroyed these criminals because they had brought back weeds from the moon. It is possible they destroyed Dr. Coratti, too. Beryl Coratti died by a bullet, and they tried to get you, Mrs. Fowley, because you are a daughter of Dr. Coratti’s.”

Lucy nodded tiredly. “Guess that’s right.”

“Okay!” Davison perked up a bit. “You get yourself well again, Mrs. Fowley, and leave the rest to us. I’ll see my men keep you safe. I’ve doubled the guard now.”

He motioned to me as Lucy closed her eyes and relaxed. I followed him down to the library. Daylight was peeping through the clouds.

“Fowley,” he said, “do you think—man to man—your wife is telling the truth?”

“I don’t know,” I answered him slowly. “I believe that she blew up the laboratory because she knew that if I went out into space, I would find out a secret which she is trying desperately to conceal. I don’t know what it is, but we’ll find it. Right now, I’ve one or two ideas to put forward.”

“Good! We could do with some original suggestions.”

“Consider this one, then. We were attacked on the grounds by somebody who used a paralyzing gun. In this later attack tonight, paralyzing guns were again used, but by men who had just come back from space! Doesn’t that prove that they alone are not the brains behind this whole set-up?

“It is the one with the first gun, who has been on Earth all the time, that we’ve got to locate. He—or she, for it might be either—is probably the master mind.”

Davison said, “I see your point. And from the style of the gun, it is obviously somebody scientific. But how do we start? Those men who tried to torture your wife are out of the picture—dead, mangled to mincemeat. I looked in the boathouse with my men on the way up here . . . Ghastly sight!

“The only one who still had recognizable features was Joe Calvis, I’d say, a one-time racketeer who escaped prison and was never caught. Well, I don’t see how it all adds up.”

“Some things add up,” I said grimly. “We know that the theft of commercial secrets is somehow connected with this business—and we know Dr. Coratti had a method for getting secrets which he discovered on the moon.

“It is possible that the man who brought about Coratti’s death—or the woman—obtained that secret, and so forestalled the other crooks, Joe Calvis and friends. They, tapping phone wires, thought Beryl had the secret. Maybe she had; but either way, she knew about the weeds as well, and Calvis took that to be the secret.

“Therefore, it is this unknown that attacked us on the first night who caused the death of Coratti. That is the person we want!”

“And you think your wife may know who this person is?” the inspector asked shrewdly.

“It’s possible,” I admitted. Then I went on seriously, “We are dealing with a clever scientist—so we’ve got to be a bit cleverer. Did it ever occur to you, Inspector, that these Selenite things resemble ants?”

“Yeah—so they do.” He looked surprised. “So what? Don’t we know from astronomical data that a Selenite would likely as not look like an ant, since the moon’s interior is pretty much like an anthill on a large scale?”

“Exactly—and therefore, any secret of theirs would like as not be antlike in principle! I heard a reference to ants at the boathouse when those devils had my wife, and from it I gathered enough to think that ants are in this somewhere—earthly ants. Remember, the person who attacked me and your boys that first night was burrowing for something. Could it have been—ants?”

“Well, from what Lewis told me, the guy certainly wasn’t planting radishes,” Davison mused. “Guess we can settle it best by looking at the spot again. Though I don’t see the connection, even now.”

“We may later,” I said. “We know precious little about the real capabilities of an ant. Coratti may have found something out about them. Won’t hurt to investigate.”

Out he went into the fast-waxing daylight to check over the spot. It had been examined before, of course, but with no particular result, since nothing special except footprints had been looked for—and those had been rubbed out. But now, as we prodded around with sticks, we unearthed a veritable anthill. Thousands of the busy little beggars were racing about in all directions on their interminable errands.

The inspector glanced at me grimly. “Guess your hunch was right, Fowley! Do you stop there, or are there more ideas?”

“You bet there are! We’ve got to drag our unknown enemy into the open, since we can’t find out where he is. Ants are highly intelligent, as we know: in their limited sphere they possess the gift of reason, which is supposed to be the prerogative of homo sapiens.”

“Skip the lecture hall and get to cases. They’re intelligent. Right! So what?”

“Suppose,” I said slowly, “they learn the secrets from inside four walls, and hand them on to the criminal?”

He choked. “Huh? Ridiculous, man! Keep your feet on the ground, for God’s sake!”

“I am, though I admit I put that rather badly. Well, I don’t know how these ants do it, but I’m becoming damned sure that they do! And we can find out, too!”

“Well?” He was looking keen again.

“Can you arrange it so that the news of a very big secret meeting of industrialists is given out? Say they are to examine secret plans—say anything, as long as you bait the criminal. Broadcast it far and wide. Can you arrange it?”

“I guess so. What happens then?”

“The meeting takes place, plans are discussed, shown around, secret documents are handed out for reading—all the trimmings. The meeting doesn’t actually signify anything, but it will look to the outer world like the real thing. You will be at that meeting and so will I, if you’ll allow me. When we’re behind locked doors, we’ll see what is happening, and I’ll gamble my soul that there will be ants in the room somewhere.”

Davison rubbed his jaw. “Maybe—but it still sounds impossible to me.”

“That’s the point!” I exclaimed. “It is so damned clever and impossible that it has everybody fooled. Well, we’re going to find out.”

“And suppose there are ants? How do we get to the culprit?”

“Science again,” I grinned. “Ever hear of the Sonagraf?[4]”

|

Sonagraf—an instrument based on the possible outcome in 1970 of today’s scientific instruments for detecting sounds beyond audible range, of which there are vast variety, particularly in the National Laboratories of Physical Research.—Ed. |

“Yeah—ultrasonic detector. We’ve one at the police department.”

“Then you’ll know it can detect sounds beyond audible range, such as the scrape of a match on a box fifty miles away, the crawling of a distant snail, the distinct rapid-fire movement of insect feet. You know that it can blanket every normal sound and detect only the ultrasonic ones beyond audible range?”

“Heck, yes!” Davison looked at me, startled. “I get it! You figure we can get the apparatus tuned to the feet of the ants—follow them and see where they take us?”

I nodded. “Right!”

“Right it is!” he cried. “I’m going back to headquarters right now and make the arrangements. I’ll be back for you the moment I’m all set.”

In the two days that followed, the inspector did not communicate, but the radio gave me enough to know he was on the job. In the news bulletins, Lucy and I heard of new thefts of secrets from industrialists—and also the announcement of a special secret conference of leading industrialists, to be held with every possible “precaution.” It was a masterly bait for a secret-grabbing scientist.

I could not judge Lucy’s reaction to the announcement because, since her ordeal at the boathouse, she seemed listless and disinclined to discuss the matter any further. Frankly I was worried about her. She looked as though mental worry was causing her far more anguish than any physical ailment. In fact, physically she was okay again.

I did not question her because I knew I’d get nowhere, and I arranged with Inspector Davison that he should say he wanted me for questioning again, when he finally arrived to collect me for the secret conference.

Lucy smiled faintly when I told her, said she would be safe enough with so many men on guard. So off I went.

On the way to town the inspector gave me all the details. The conference was all set. Three ultrasonic mobile units were in plain vans outside the building, their detectors geared to the sound vibration of the world of the little.

Since every sound is different, even in ultrasonics, it was no more difficult for the crews to tune in on the distinctive noise of an ant’s feet than for a radio to tune in a given station. All other sounds were wiped out by reason of their vastly different wavelengths and the insulated interior of the mobile unit vans.

Altogether, there was something rather fascinating about this excursion into the world of the diminutive . . .

The conference room was on the ground floor of one of New York’s largest administration buildings. Inspector Davison had chosen a conspicuous, well-known place in order to aid the criminal master mind, and the conference was on a ground floor for the convenience of the detector vans.

At the appointed time we were all present—industrialists, the inspector, and myself. Numberless plans and official data and documents were scattered around. I urged Davison to take special note of what the plans were about, so we could recognize them again if we saw them at any time in some other place.

All doors and windows were locked, and the conference began. It signified nothing, but as it proceeded the inspector and I went about the room. Barred doors and windows mean nothing to an ant, anyway . . . Then suddenly I found something. A motionless ant was poised on the window ledge, looking at the conference table.

Davison’s eyes widened unbelievingly as he gazed at it. Then he nodded, and we resumed the search. Altogether we located six of the insects, at different vantage points—overhead, on the level, at a distance. One was even between the two inkwells on the table!

The first part of our problem was solved . . .

The conference broke up thereafter, and we watched the ants gather into a body and pass through the room ventilator to the outside. In the open they were capable of detection. Down we raced to the mobile units and jumped into the first van. The engineers were tensed over their instruments, watching the detectors for direction and giving brief orders to the driver through signal phone.

So began the weirdest trip I have ever known, following scurrying ants—all six of them keeping together, fortunately—through the city in a soundproof van. Not another sound penetrated, except the distinctive tap, tap, scrape, scrape of the ants’ busy little feet.

At times we almost lost them in the detectors; then again we caught up. The journey took us through the back streets of the city and finally out toward open country. I gave a frown as we went on. It was slow going, a crawl—but we were definitely going back toward the Coratti estate! Again I wondered if my original guess about Lucy was right. Surely she was not the guilty genius . . .

It was evening, a thick misty evening, when we lost the sounds completely. Our vans stopped and we all piled out into the mist and gazed around. I recognized the spot after a while. We were about a mile from the estate and half a mile from the river. In fact, we could hear it gurgling in the growing night.

“They went due north, chief—then they must have gone underground, since the sounds stopped,” one of the technicians said.

“Due north? Okay, let’s go!”

We pulled out flashlights and proceeded through the clumpy grass.

We spent plenty of time searching, too—probably an hour and a half, before we came across an almost covered vent that was possibly part of an old sewer system emptying into the river. But it had doors on it now—comparatively new ones, they seemed—and what was more, dried grass was glued onto them to form a perfect camouflage.

Normally, I doubt if anyone could have found the place in ten years . . .

“Locked,” one of the men said, pushing against the doors.

“Wait!” I said quickly, as Inspector Davison raised his gun to fire at the locks. “Wait a minute! Douse your torch a moment. Isn’t that a crack of light?”

It was—but it was only a thin fragment, where our hands had torn away parts of the false grass and the wood had warped with incessant river damp. The inspector peered inside, and a very strange spectacle we beheld.

There was a secret laboratory, not very brightly lit. The hum of a dynamo suggested the river was being used for power. But the devil of it was, we could not see our quarry even now—only the shadow! On the wall of the laboratory an indeterminate shape was busy with something, cast in shapeless silhouette.

Then suddenly everything was dark, and from an angle we could not see there sprang a beam like that from a motion picture projector—except that the beam had a distinct violet tint. Upon a screen near the wall there appeared a “still”—a slide, as it seemed—of a plan, perfectly photographed.

“It’s one of those plans from the conference!” Davison breathed incredulously. “What kind of devil’s witchcraft is this?”

“I’m more interested in finding out who is in there,” I said slowly. “And I believe I can. Listen, Inspector, will you trust me to go back to the house?”

“To find out if it’s your wife?” he asked grimly. “We can break in here and find out for ourselves, can’t we?”

“We can—but this lab is full of chemicals, and I seem to recall an adventure with mercury fulminate. It could happen again. Let me go and see first, Davison. You can stay on guard here and see what else happens.”

“All right. Standish, go with him for—er—protection.”

I did not want the company but I was forced to have it—until I gave Standish the slip in the fog. Then I beat it back to the house. Butson was the first person I encountered.

“My wife? She here?” I demanded.

“No, Mr. Fowley. The men in the grounds have been asking where she is, too. She went up to her room after you went out today; but when I went up to tell her about dinner, I found she was absent. She must have slipped out when this fog came down. I—”

“That’s all I wanted to know,” I said briefly, and tore outside again.

The fog was the very devil. I found that despite my knowledge of the district, I was soon hopelessly lost. Easy enough to get from the river, but the deuce of a job to get back to it. I must have staggered in and around the estate for about thirty minutes before I heard the noise of distant water.

I went forward actively, slipped, and went my length in sloppy mud. I got up and directed my torch downward. I was covered in mud from head to foot—yellow mud!

Yellow mud! A remembrance turned in my brain. I was still some way from the tow-path, yet the stuff was here, too, probably from winter floodings. I went on, searching the way, and presently a square, squat building loomed out of the reek. The Coratti mausoleum—at the far end of the estate.

I stopped again, hesitated, then hurriedly advanced. I hadn’t been quite sure, but now my torch left no doubt about it. The bronze doors of the mausoleum were slightly open! And there were the marks of a woman’s shoes—new and fresh marks—leading right to the doors. But why did none come out?

I blundered into the mausoleum’s silence, flashing my light. The place was quite empty, deadly cold, and the relentless calm of the grave descended upon me. I felt I was a desecrator—but I’d gotten this far and I meant to finish it! I gazed around the walls for a moment, on the sarcophagi[5] of Dr. Coratti and Beryl Coratti in the center of the stone floor, side by side.

|

A sarcophagus is a stone coffin, the word having cropped up quite often in the 1920’s during the great excavations of Egyptian tombs by Howard Carter and others. Generally speaking, a sarcophagus is an ornamental coffin. Being an inventor and well-to-do, it is quite likely that Dr. Coratti was not content with just an ordinary coffin.—Ed. |

Thoughts chased through my brain; strange thoughts. Was it possible that on the night Lucy said she had been on the tow-path, she had really been here? Was it here whence had come the yellow mud on her boots? Again, it was because of her that we had not seen Beryl’s body actually taken to the mausoleum here. Did Lucy have definite reason for wanting it that way?

I felt I was getting near to the truth at last. I cast aside all ideas on the sanctity of the dead, perched my flashlight on a stone and raised the heavy lid of Beryl’s tomb. I only needed to do it for a moment. Beryl lay there, all right—silent, hands folded on her breast, as if asleep . . .

I was feeling a bit unnerved, but I went on. I remarked how much lighter Dr. Coratti’s sarcophagus lid seemed than Beryl’s. It moved easily and I flashed my torch inside the space—but there was no Dr. Coratti there! I dropped the cover back with a gasp, my brain racing at furious speed.

Suddenly I was icy calm. I felt I had the last clue in my grip. I whirled out of the sepulchral, chilly hole and floundered through mud and fog toward the river. At last I came on the group gathered about the trapdoor of the secret underground laboratory.

But the light was flooding forth now, silhouetting a single slender figure in a fur coat, standing at the door with arm upraised. It was Lucy, all right, holding something aloft.

“Take it easy, Fowley!” Inspector Davison shouted as I blundered forward. “This wife of yours has got an explosive in her hand. She threatens to blow up this whole damned laboratory, and the river with it, if we go into this hiding place!”

“I mean it too, Curt!” Lucy shouted, as I came into the fan of light. “You’ve gone quite far enough!”

“Why the devil didn’t you catch her as she came up here?” I demanded.

“Couldn’t. She came from inside the laboratory—”

“From inside . . . !” I stopped, comprehension flashing into my brain.

I swung and vanished in the fog so suddenly that Lucy hardly had time to notice it. Like a madman I floundered up the bank and back again to the mausoleum. Of course! Of course I If she had come from inside the laboratory, there must be a secret way into it—through the mausoleum! Because the footprints outside the tomb were still fresh! And though they went in, they did not come out!

Lucy’s brandishing that explosive—if it was an explosive—was a stall, a stall while Dr. Coratti— Now I saw it! And I proved it a second later, as I heard the clump of running feet in the mud from the direction of the mausoleum.

At the same moment, I heard the leathery beating of wings in the mist and the shrill unearthly cries of the Selenite monsters, which had obviously been at hand somewhere. Evidently they worked by instinct, for their sense of direction was unerring. Their cries, the mist, the running figure, now blended into some eerie nightmare chase—

“Dr. Coratti!” I yelled. “Doctor, the game is up!”

Coratti never had a chance to answer, for at that moment two of the unearthly birds swept into view like projectiles. I threw myself flat—and they missed me! They hurtled straight on and slammed the running, slender figure to the ground. Again and again they dived, while I went sick with horror. Then off they rushed into the mist, screaming their weird triumph.