* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Leaders of the French Revolution

Date of first publication: 1929

Author: J. M. (James Mathew) Thompson (1878-1956)

Date first posted: Sep. 5, 2022

Date last updated: Sep. 5, 2022

Faded Page eBook #20220914

This eBook was produced by: John Routh, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

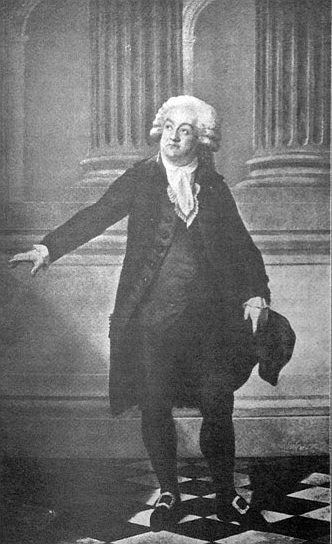

SIEYÈS

as a Member of the Directory

from a coloured engraving in the Hennin Collection

LEADERS

OF THE FRENCH

REVOLUTION

By J. M. THOMPSON

HARPER COLOPHON BOOKS

HARPER & ROW, PUBLISHERS

NEW YORK

This book was originally published in 1929 by Basil Blackwell and Mott Ltd., London, and is here reprinted by arrangement.

First HARPER COLOPHON edition published in 1967 by Harper & Row, Publishers, Incorporated, 49 East 33rd Street, New York, New York. 10016

| CONTENTS | |

| INTRODUCTION | ix |

| SIEYÈS | 1 |

| MIRABEAU | 17 |

| LAFAYETTE | 41 |

| BRISSOT | 67 |

| LOUVET | 91 |

| DANTON | 113 |

| FABRE D’ÉGLANTINE | 135 |

| MARAT | 163 |

| SAINT JUST | 187 |

| ROBESPIERRE | 213 |

| DUMOURIEZ | 245 |

| INDEX | 269 |

| PORTRAITS | |||

| SIEYÈS | Frontispiece | ||

| MIRABEAU | Facing | page | 18 |

| LAFAYETTE | „ | „ | 42 |

| BRISSOT | „ | „ | 68 |

| LOUVET | „ | „ | 92 |

| DANTON | „ | „ | 114 |

| FABRE D’ÉGLANTINE | „ | „ | 136 |

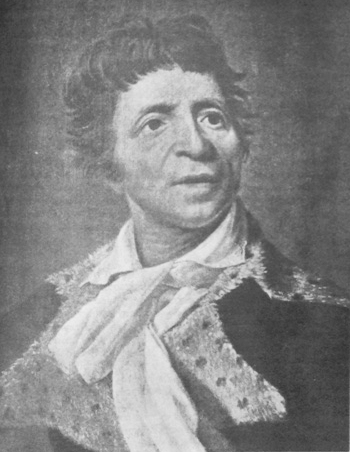

| MARAT | „ | „ | 164 |

| SAINT JUST | „ | „ | 188 |

| ROBESPIERRE | „ | „ | 214 |

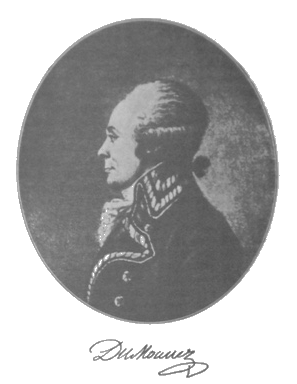

| DUMOURIEZ | „ | „ | 246 |

Acknowledgements are due to those who have kindly allowed the use of the above portraits: To John Rivers, Esq., who lent for reproduction his print of Louvet; to Messrs. Thomas Nelson & Sons, Ltd., for Sieyès, Mirabeau, and Marat; to Herbert Jenkins, Ltd., for St. Just; to Albin Michel for Robespierre; to Messrs. Hachette for Dumouriez and Danton; and to La Librairie de l’Humanité for Fabre d’Églantine.

When, in 1895-9, in the course of his Lectures on the French Revolution, Lord Acton spoke of the mass of new material which had been published during the last thirty years, he went on to say, ‘In a few years all these publications will be completed, and all will be known that ever can be known.’ Thirty more years have passed, and the end seems to be as far off as ever. New material is still being published, and imperfect judgements are still being expressed. There are few signs yet of ‘that golden age’ in which ‘our historians will be sincere, and our history certain.’

Probably the historian will never know enough to make his history certain. His business is to reconstruct past facts as accurately as he can by selecting and arranging the most important pieces of evidence from the tangle of information put before him. For this he needs experience, judgement, and imagination: the disciplined imagination of the detective, not the freely creative imagination of the poet or artist. He will consider which accounts of an event depend upon eye-witness, and which upon hearsay; which were written down at the time, and which long afterwards. He will balance private letters against public speeches as evidence of a man’s real opinions. He will learn how far to discount polemical or propagandist pamphlets, and when to suspect memoir-writers of malice or special pleading. He will remember how few public men, in the revolutionary and Napoleonic era, failed to find a place in Eymery’s Dictionnaire des Girouettes, or gallery of political weathercocks. In all these things the French Revolution, by the very richness of its materials, is a fascinating field for historical study.

History cannot be certain: but the historian can be sincere. He may not discover truth, but he must always be a truth-seeker. Here the French Revolution is a warning, as well as an opportunity. For it is notorious that, from Lescène des Maison’s Histoire de la Révolution en France, published (in April, 1789) a month before the Revolution began, to the latest controversies of Mathiez and Lenôtre, the study of the French Revolution has been perverted by the spirit of political partisanship. To the group of historians who came under the influence of 1830 and 1848 the republicanism of 1791-4 seemed almost divine: but they could not agree as to its Messiah: Lamartine chose Vergniaud; Louis Blanc, Robespierre; Michelet, Danton; and Villiaumé, Jean Paul Marat. To Lamartine all that was good in those years perished with the Girondins: to Louis Blanc regeneration began with their fall: to Michelet the whole Revolution was an inspired mass-movement, which it was blasphemous as well as unpatriotic to criticize. The scientific study of the evidence, which Carlyle might have undertaken, if he had not been ‘scared from the British Museum by an offender who sneezed in the Reading Room,’ was begun by Tocqueville in France, and Sybel in Germany. It has been taken up again during the last thirty years by Sorel, Aulard, Mathiez, and many more. But the subject has still too many bearings on modern French history to be treated in a quite impartial spirit. Bougeart was imprisoned for four months, and his book Marat confiscated by the police in 1860. Vermorel’s Introduction to his edition of Marat’s works (1869) was a violent political attack on Gambetta, who had coupled his hero (one might have thought it a compliment) with Cæsar, as a demagogue and an anti-democrat. Forty years ago Aulard was shot at, after a professorial lecture, by a member of the audience who disagreed with his conclusions. To-day he is decried as a ‘Dantonist’ by a new school of avowed ‘Robespierrists,’ whose spokesman is Mathiez; whilst both denounce the Royalist apologies of Bainville, and the œuvres de vulgarisation of Lenôtre.

An English writer on the Revolution is in no danger of assassination. But he may well be troubled by the difficulty of treating a subject that rouses such passions impartially, and of finding an Ariadne’s thread to guide him out of the labyrinth. The plan adopted in the chapters which follow is to study the Revolution through a series of representative Revolutionists; to describe their part in it, and to interpret it through their experience. If there is some risk of repetition in this method, there is less danger of looking at the many-sided structure of the Revolution from only one or two angles. We soon find how different were the antecedents and the capacities of the men whom the Revolution attracted and used; how many currents of thought flowed into its flood; and how impossible it is to include all its aspects or ideas within the scope of an epigram, or the terms of a definition. ‘Leaders,’ we call them; but indeed they were led—or rather, swept off their feet, and carried along by a movement which they were powerless to control.

It will perhaps help towards a consecutive view of the Revolution if we preface the separate studies which follow with a short sketch of the background common to them all. Let us imagine the Revolution as a great drama in five acts. Here is the plot.

The Prologue is placed in the first fifteen years of the reign of Louis XVI, from 1774 to 1789, when every attempt to avert the results of a century’s misrule, bankruptcy, and class war, is blocked by class privilege, vested interests, and a king who has no mind or will of his own.

The first Act opens with the summoning of the States-General in May, 1789. The Commons, who represent the mass of the nation, together with a part of Convocation (the clergy) and of the House of Lords (the Bishops and Peers), form themselves into a National or Constituent Assembly, and refuse to be dissolved until they have control of taxation, and a Constitution under which the King is the legal Executive, and not the arbitrary ruler, of the Sovereign People. This first Act ends with the fall of the Bastille in July, and the transference of the King from Versailles to Paris in October, 1789.

The second Act covers the main legislative work of the Revolution—the reconstruction of France, of its crown, Church, parliament, and administration—which was carried through by the Constituent Assembly between October, 1789, and June, 1791. Throughout this period the character of the Revolution was changing: national enthusiasm was giving place to parliamentary compromise and party intrigue; patriots were becoming politicians, quarrelling about policies, and competing for power; the interests of Paris began to dominate the Assembly, at the expense of those of the provinces; the discussion of Church affairs added fresh bitterness to political issues; and it grew increasingly apparent that the King was both unwilling and incompetent to play his part as a constitutional monarch. This second Act ends with the King’s ill-advised and disastrous flight to Varennes, on June 21, 1791, which gave a new trend to the whole Revolution.

The third Act, which runs from June 21, 1791, to August 10, 1792, sees the working out of these new influences—republicanism, springing from Varennes; democracy, the protest of the working classes against their disfranchisement by the bourgeois Assembly; war-fever, stimulated by the disloyalty of the emigrants; the struggle between conservatives and radicals (Feuillants and Brissotins) for control of the Government; and growing exasperation at the certain obstruction and suspected treachery of the Court. At last all these combustibles explode in the ‘Second Revolution’ of August 10, 1792, the sack of the Tuileries, and the suspension of the King.

Act IV is the struggle between the Girondin party, which dominates the Convention of September, 1792, and the growing forces outside Parliament—the Commune of Paris and the Jacobin Club. The main issues are the conduct of the war, the fate of the King, the treatment of the clergy, and the regulation of food and wages. The Girondin leaders gradually show their inability to rule, and lose the confidence of the country. They are overthrown by the coup d’état, or ‘third revolution,’ of May 31 to June 2, 1793.

The fifth and last Act of the Revolution runs from June 1793, to July, 1794, and is the story of the rise and fall of the Jacobin Committee Government—the régime of the Terror. It is cut in two by the fall of Danton in April, 1794, and ends with the fall of Robespierre on July 28, the same year.

There remains an Epilogue to the drama—the anti-Jacobin reaction of Thermidor, and the last days of the Convention, 1794, down to its final dissolution in October, 1795.

During the six years of this revolutionary drama there must have been at least a hundred men who played large enough parts, and left a clear enough impression on the records of the time, to repay historical study—over fifty, for instance, figure as speakers alone in Aulard’s volumes on the Orators of the three Assemblies. Few of them were great men, but they lived under the microscope of great times, which gave to their most insignificant qualities portentous proportions. Perhaps, too, their age and country, which subjected them to no standardized education, or compulsory service, or industrial discipline, perhaps the general disuse of law and order to which the generation before the Revolution had grown accustomed, perhaps the cult of Rousseau’s natural man, encouraged a peculiar variety and extravagance of character. Whatever the cause, there are few periods in history so rich in personalities as the years 1789-95.

Of the eleven men chosen for study, one (Mirabeau) died in the middle of the second act of the drama, and one (Louvet) during the epilogue; one (Brissot) was executed, and another (Marat) was murdered, at the end of the fourth act; two (Danton and Fabre) were put to death in the middle, and two more (Robespierre and St. Just) at the end of the fifth. Three only (Sieyès, Lafayette, and Dumouriez) survived the Revolution, and lived to see its cynical apotheosis in the Napoleonic Empire. But to all of them the Revolution was an overwhelming experience. What did they do in it? What did they think of it? Let us see.

SIEYÈS

EMMANUEL JOSEPH SIEYÈS

| 1748 | May 3, born at Fréjus. |

| 1773 | Ordained priest. |

| 1775 | Secretary to Lubersac, Bishop of Tréguier. |

| 1787 | Member of Provincial Assembly of Orléans. |

| 1788 | Vues sur les moyens d’exécution dont les représentans de la France pourront disposer en 1789. |

| Essai sur les privilèges. | |

| 1789 | Qu’est-ce que le Tiers-État? |

| Délibérations à prendre dans les Assemblées. | |

| Elected deputy to States-General by Tiers-État of Paris. | |

| Reconnaissance et exposition raisonnée des droits de l’homme et du citoyen. | |

| Quelques idées de constitution applicables à la ville de Paris. | |

| 1790 | Projet de loi contre les délits, etc. |

| Projet d’un décret provisoire sur le clergé. | |

| Aperçu d’une nouvelle organisation de la justice, etc. | |

| 1791 | Déclaration volontaire aux patriotes, etc. |

| 1792 | Elected deputy to the Convention for Département of Sarthe. |

| 1793 | Journal d’instruction sociale. |

| 1795 | Notice sur la vie de Sieyès. |

| 1799 | Director, then Consul. |

| 1836 | Died at Paris, æt. 88. |

AUTHORITIES:

Qu’est-ce que le Tiers-État, ed. Champion (Paris, 1888).

St. Beuve, Causeries de Lundi, Vol. 5.

Clapham. The Abbé Sieyès (London, 1908).

Visitors to Paris between 1830 and 1836 were able to see many material relics of the French Revolution and of the Napoleonic régime, which have since been swept away in the attempt to make the city safe for bureaucracy, by depriving the mob of sites for barricades. Even more interesting than the streets and buildings of Old Paris were the figures of the few men who, having played a leading part in the great and dangerous days of 1789-95, were still living on under the dull, safe rule of that repentant Jacobin, Louis Philippe. One of these survivors might occasionally be seen driving out in his carriage, or walking stiffly along from his house in the Faubourg St. Honoré—‘a small, thin, thoughtful man, with grey hair, a grave smile, and a courteous manner,’ carrying his stick ‘held out from both his hands crossed behind his back.’ His sharp, clever features reminded scholars of the portraits of Erasmus. If he spoke, his voice was still musical, rather weak and indistinct, but charming. But he did not speak often, or easily. It was known that he had refused to write his memoirs, and was unwilling to talk of what he remembered. Had he not always been reputed a philosopher—oracular, austere, and a little cynical? Besides, people remembered what he had been through. They thought him another Daniel delivered from the burning fiery furnace; the hair of his head had been singed, the smell of fire had passed upon him; and they drew back a little from his touch. They were proud, but rather afraid, of Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès.

He had been born as long ago—and how much longer it must have seemed to them—as 1748, when Louis XV was still bien aimé, but when the disastrous peace of Aix-la-Chapelle first brought home to popular opinion the incompetence of his government, and the failure of his arms; and when the early publications of the Rationalist school were sowing those dragons’ teeth which had since produced so unexpected a harvest.

Young Sieyès was a victim of piety and middle-class parents. He wanted to go into the artillery, or the mining engineers, but was forced into the Church. ‘Behold him thus’ at the age of fourteen ‘decidedly sequestered from all reasonable human society’ (the account is his own, but the language is that of his eighteenth-century translator); ‘ignorant, like every scholar of his age, having neither seen, heard, nor understood anything, and chained to the centre of a sphere which was to be instead of the universe to him. . . . In a situation so contrary to his natural disposition it is not extraordinary that he should have contracted a sort of savage melancholy, accompanied with the most Stoic indifference as to his person and his future situation. He was destined to bid farewell to happiness; he was out of nature; the love of study only could claim him.’

No one can pass through ten years of seminary life without acquiring, however unwillingly, a clerical stamp. The regular, irresponsible life, the hours of silence for study or prayer, the habit of reciting Offices, and the obligation to self-examination and confession, turn the mind inwards, and give the character a meditative tone, which may, indeed, fit a man for great ends, but will indispose him to pursue them by ordinary means. Sieyès ‘probably may, in his solitude, have formed his mind to the love of truth and justice, and even to the knowledge of man, which is often confounded with the knowledge of men.’ ‘The leading passion in his mind’ (so he describes himself in middle life) ‘is the love of truth. . . . He is not content when he enters into a subject, until he has examined it to the bottom, and analysed all its parts, and afterwards put it together.’ This scientific thoroughness, this philosophical search for unity, he carried, not (as his teachers intended) into theology, but into the study of Locke, the anatomist of the mind; of Condillac, who thought that experience contained nothing but what it received from outside; and of Bonnet, ‘the first careful student of the psychology of the severed worm.’ As a result he remained all his life a political vivisectionist. Every book that he read, and every experiment that he made, confirmed his belief in reason, progress, paternal government, and the rule of law. Every influence strengthened his dislike for the Church, the Parlements and all other privileged and obstructive bodies. By the time that he became a priest he had (as he claims) ‘succeeded in dismissing from his mind every notion or sentiment of a superstitious nature’; and his tutors reported to his bishop that, ‘though he might turn him into a gentlemanlike cultured canon, yet he was by no means fitted for the Ministry of the Church.’

These ten years of theological training were followed by ten years more of ecclesiastical business. Under the patronage of Lubersac, bishop first of Tréguier, and then of Chartres, Sieyès saw clerical and aristocratic society from inside, and got first-hand knowledge of administration. He carried his scientific habits into his new life. ‘I thought myself,’ he says, ‘a traveller amongst an unknown people, whose manners required to be studied.’ A confirmed student, he distrusted instinct all his life as a guide to truth, and was in danger of missing surface facts (which often contained the clue to what he wanted) in the search for underlying principles. ‘What a pity,’ said a lady of him, ‘that that so amiable a man should have wanted to be so profound!’ He also lacked, for he deliberately put it aside, the historical point of view. Politics he regarded as the science ‘not of what is, but of what ought to be.’ ‘To judge the present by the past,’ he said, ‘is to judge the known by the unknown.’ But can anyone know the present? Is it not the peculiar advantage of history that we can isolate and study a piece of the past, hopeful of arriving at the truth about it, and confident that it will turn out to be extraordinarily like some piece of the present which we cannot study because we cannot detach it from its surroundings?

Sieyès was saved from some of the results of this mistake by the clearness with which he saw the relationship between philosophy and statesmanship. ‘So long as the philosopher does not go outside the bounds of truth, he must never be accused of going too far. His function is to fix the political end, and he cannot do that until he has arrived there. If he were to stop halfway, and raise his standard there, he might merely mislead. On the other hand, the duty of the administrator is to adapt his advance to the nature of the ground. The philosopher does not know where he is, unless he has reached his goal; the administrator, unless he sees where the goal is, does not know where he is going.’ Sieyès put these words at the head of his most famous pamphlet, and made them the guide of his career. He was that unusual person, the philosopher who is not afraid of going too far.

His seminary mind was further corrected by his seminary character. Trained to look for absolute worth, and finding more beauty in music than in a woman’s eyes (it is said he never noticed their colour), he formed few friendships, disliked most of the men with whom he worked during the Revolution, and had no affection for the crowd—though there is no need to believe Napoleon’s story of his refusing to say Mass for the canaille. On the other hand, when he went as his bishop’s representative to the Estates of Brittany, ‘nothing could exceed the indignation he brought from this assembly against the shameful oppression in which the noblesse held the unhappy third estate of the people’; and as one of the twelve clerical representatives at the Provincial Assembly of Orléans, studying questions of taxation, agriculture, commerce, and poor relief, he soon found himself standing with another scientifically minded deputy, Lavoisier, for a policy of radical reform. ‘What a social order that must be,’ he often complained, ‘when the permanence of the fourteenth century is fixed in the midst of the progress of the eighteenth!’ This humane sympathy for the wrongs of the poor reinforced his philosophic impatience with a chaotic society and an impotent government, and threw him, as enthusiastically as his donnish temperament permitted, into the Revolution. So he became Mirabeau’s acknowledged master, the reputed inspirer of Robespierre, and the constitutional architect of Bonapartism.

As the 1780’s went on, without any real progress towards reform; when every demand of the poor seemed to be blocked by privilege and prescriptive right, and every good intention of the King to be headed off by a reactionary Court; Sieyès was attracted, like many of his contemporaries, by the idea of emigration to a land where it was supposed that there was no Court, no privilege, and no poverty. He had saved up nearly 50,000 livres, and was upon the point of sailing to America, when the political storm burst, and he faced, willingly enough, the greatest opportunity that a philosopher ever had of putting his principles into practice.

In 1788 Necker announced that the States-General would meet early in the next year, and invited public discussion of the situation. The Press was flooded with pamphlets. Sieyès, who had reached his fortieth year without breaking his philosophic silence, was moved to write, and found that he had the gift of lucid expression. His two first pamphlets did not catch popular attention, but the third, issued in January, 1789, with the clever title, Qu’est-ce que le Tiers-État?, at once made history; for it made the National Assembly, and was (says Lord Acton) ‘as rich in consequences as the Ninety-five Theses of Wittenberg.’ In the famous debate of June 15-16, which decided that there should be a revolution, most of the talking was done by Mirabeau, but most of the ideas came from Sieyès’ pamphlet. It was in the course of these sessions that Arthur Young heard Sieyès speak ‘ungracefully and ineloquently, but logically,’ and noted his ‘remarkable physiognomy, and quick rolling eye.’ And from this moment, though his voice was weak, and his manner cold, he was always attended to. Mirabeau’s ‘There is then one man in France!’, and the series of letters in which he addresses Sieyès as ‘Mon maître,’ show that his better-known tribute in June, 1790, was sincere. Sieyès’ calculated audacity—Mounier says that the Tennis Court oath was devised to block his bolder suggestion of an appeal to Paris—and his gift for finding the mot juste for every phase of the Revolution—‘Gentlemen (on June 23rd), do you not feel that you are to-day all that you were yesterday?’—gave him a popular as well as a parliamentary reputation. And, so long as there was work that he could do, he would do it—in July backing Mirabeau’s protest against the summoning of troops to Paris, and hitting upon the idea of the National Guard; in August helping to reject a doctrine of representation which would have stopped the work of the Assembly; and in September laying the foundation for those new administrative divisions of France which became the basis of national unity. But his uncompromising mind was not made for the give and take of political life. He was too honest, and too indifferent as to what people might think of him, to join in the scramble for power, or in the manœuvres of party politics. His sense of justice was offended by the provisions of the Civil Constitution of the Clergy. ‘They want to be free,’ he said, ‘but they know not how to be fair.’ And with this epigram he went back to his books.

During 1790 he was less seen in the House than at the ‘ ’89 Club,’ which he had helped Condorcet to found, for ‘the study and application of the social art’—Sieyès’ usual name for his favourite science—or at the ‘Cercle Social,’ which published the Bouche de Fer, or at Brissot’s ‘Amis des Noirs.’ But in June, 1790, on the anniversary of his first political exploit, he was elected, rather unwillingly, President of the Assembly and of the Jacobin Club. He was, indeed, recognized by now as the foremost political thinker of the Revolution—a revolutionist, because he believed in the right of the people to revolt against oppression; a monarchist, because he thought monarchy the best security for freedom; and a democrat, because he held by the ultimate sovereignty of the people. But, as he agreed with Voltaire that the tyranny of many might well be worse than the tyranny of one, he stood not only for a limited monarchy, but also for a limited democracy—for the disfranchisement of the poor, for indirect election, and for a system of filling up vacancies in the House without an appeal to the country. Safety from oppression, he always maintained, lay in a balance of power, and all his constitutions resembled those piled-up figures and brackets of algebraical formulæ, which are apt to end, in the right-hand margin, with ‘= 0.’

The first set-back in Sieyès’ career came in 1791. When Mirabeau died on April 2, those friends of the King who had been trying to mould his mercurial policy, and who had for the last ten months purchased Mirabeau’s advice, looked about for a successor. Governeur Morris had urged Talleyrand to play the part of Mark Antony. But only Sieyès had the necessary reputation for honesty, courage, and clear-headedness. He was known to be discontented with the new leaders and the recent developments of the Revolution. La Marck, the faithful servant of an unfaithful master, Montmorin, a weak but willing minister, and Cabanis, Mirabeau’s doctor, fresh from his deathbed, believed that the ‘master’ might consent to carry on the work of his disciple—might write, at least, another of his famous pamphlets in favour of what they called ‘the revision of the Constitution.’ Sieyès, sounded by Cabanis, consented, on condition that the King showed his intention ‘to put himself decidedly and irrevocably at the head of the Revolution,’ and to form a new and competent Ministry. But in truth he can have had little hope either that these conditions would be fulfilled—he knew the King too well—or that any number of pamphlets, in the summer of 1791, could save the monarchy. For at this very moment the stupid and ineffective King was outwitting them all, and preparing a stroke destined to bring many of his opponents, with himself, to the scaffold. While Sieyès was collecting signatures for his ‘Voluntary Declaration’ of June 17—it was, in effect, a ballon d’essai for his revision policy—Louis was preparing disguises and false passports for his flight to Varennes. When he was brought back a prisoner on the 25th, Sieyès’ policy was wrecked. After two letters to the Moniteur declaring for monarchy against the republicanism of Thomas Paine and his friends, he retired into that philosophic silence from which he had emerged three years before. The first part of his career was over.

During the next three years, from July, 1791, to July, 1794, the happiest man was the man who had no history. When they asked Sieyès afterwards what he had done during this period, when Paris passed through all the experiences of insurrection and massacre, of war at home and abroad, of poverty, famine, and the guillotine, he answered simply, ‘J’ai vécu’—‘I survived.’ It would, indeed, be a gross exaggeration of the Terror to suppose that life was at any time unsafe for those who lived quietly, kept out of politics, and did not correspond with Royalist refugees. The life of Paris went on much as usual. The quarrels of Jacobin and Girondin were viewed with increasing indifference. The cafés and theatres were crowded, as the carts passed to and from the guillotine. In a population of three-quarters of a million few felt themselves in danger of proscription; and there were priests and aristocrats who came untouched out of the Terror. But, as revolutionary opinion moved on from stage to stage; as the Liberals of 1789 became the Conservatives of 1791, the Liberals of 1791 the Conservatives of 1792, and the Liberals of 1793 the Conservatives of 1794; when Mirabeau, buried in the Panthéon as a patriot of 1791, was disinterred to make room for Marat, the patriot of 1794; when the Girondin leaders, who headed a national war in 1791-2, were executed as traitors in 1793; when Danton, twice the saviour of his country in 1792-3, was put to death as a counter-revolutionary in 1794; when accusations of incivisme became the common coin of party politics, and there was no appeal from an arbitrary tribunal except to a despotic committee; when patriotism took on the character of a fanatical religion, and was ready to sacrifice every affection on the altar of the country—then it required an extreme degree either of indifference or of courage to take a prominent part in public life. These conditions, too, arose gradually, thus enticing their victims on with the fascination of playing with fire, till they were involved in disasters which they could hardly have foreseen; and it was not only the stupidest, but also the finest characters which were the most likely to succumb.

Sieyès had no mind to be a martyr, and took unheroic precautions to keep out of sight. During the autumn of 1791 he lived outside Paris; by the end of July, 1792, he was sixty leagues away; and he took no part in the events of August 10. He only came back in September because he was elected, against his will, a member of the Convention—an honour that it seemed less dangerous to accept than to decline. But the period which followed was the most inglorious of his life, for it was spent in avoiding responsibility, and in evading the logical consequences of his own past. He gave up the attempt to instruct his contemporaries, and even the belief that they were worth instructing. ‘Woe to the teacher!’ he writes. ‘Men want to be pleased, and will let you flatter them; but they will not put up with education.’ ‘Let us hold our tongues’ became his refrain. A member of the Constitutional Committee, and none more fit to direct it, he contributed hardly anything to the Constitution of 1793. A member of the Committee of General Defence, he drafted a single report on the Ministry of War. He voted in as few words as possible for the death of the King, whom he had been ready to serve eighteen months before. He made no protest against the proscription of the Girondin leaders, with whom he had been on friendly terms the previous year. Only on the safe Committee of Education he found congenial work, and did it well, drawing up a comprehensive scheme for primary and secondary schools on curiously modern lines, and a plan for semi-religious festivals, such as ‘a feast of animals’ and ‘a feast of the visible universe,’ which seems to have inspired Robespierre’s better known Religion of the Supreme Being. He never sank lower than when he spoke in the Convention on November 11, 1793, in support of the anti-clerical demonstrations of the ‘Feast of Reason.’ ‘Are you not astonished,’ wrote an old English acquaintance, Sir Samuel Romilly, ‘to see Sieyès in all this, standing up in the midst of his fellow-murderers, and claiming applause for his having so long ago thought like a philosopher? Ill as I long thought of him, I did not imagine him capable of such degradation.’ To make himself doubly secure, Sieyès gave his clerical stipend of 1,000 livres as a subscription to the national treasury. The rest is silence, and the drawn blinds of the house in the rue St. Honoré. But there exists a copy of some verses recommending the quiet life, by the side of which Sieyès has jotted down, to relieve his mind, classical quotations appropriate to the Terror: ‘Jusque datum sceleri’ (crime was punished), ‘‘Ruit irrevocabile vulgus’ (the mob has the bit in its teeth), and the like; together with a scrap of paper containing some caustic remarks on a meeting (as it seems) of the Committee of Public Safety, and on a speaker who can hardly be other than Robespierre. Once only, on the eve of Thermidor, he was delated to the Jacobin Club, and saved—he was fond of telling the story—by his cobbler, who said that he was no politician, and lived among his books: ‘I mend his boots, and I can answer for him.’

The fall of Robespierre in July, 1794, and the destruction of the Paris commune, did not end the Terror so completely as is sometimes supposed, and the political weather of Thermidor remained treacherous for weak constitutions. Sieyès need no longer draw down his blinds as the tumbrils went past, or suffer from ‘sinister dreams’ in which (as Dumont suggested) ‘he saw his head rolling on his own carpet.’ He accepted a place on the Committee of Legislation, and even sat, most unwillingly, on the Commission of Inquiry that transported some of the remaining Terrorists. But it was not until March, 1795, that his return to public life, cleverly prepared by the autobiographical pamphlet, Notice sur la vie de Sieyès, was signalled by his appearance on the reconstituted Committee of Public Safety. Here at last ‘the artist of human affairs had half Europe for his canvas,’ and everything that he designed had a ready sale. On March 8 he asked for the reinstatement of the Girondist members, and it was agreed. On March 21 he carried through the House at a single sitting a coercive law against Jacobins and Royalists. In May he concluded a treaty with Holland. On July 4 he introduced an elaborate specimen of his political algebra, which became the Constitution of 1795. Three times he helped the Convention to victory over the forces of disorder, and it was he who, according to the account that Napoleon dictated to Gourgaud, called upon the future Emperor, on the thirteenth Vendémiaire, to save the country by his genius and by his guns.

At this time Sieyès was forty-six, and still had nearly half his life to live. His later career under the Directory and Consulate—as a member of the Five Hundred, as Director, Plenipotentiary, Consul, and Senator—made European history. More and more silent under the Empire—the silences of Sieyès were barometer readings, showing the weight of the political atmosphere—and for fifteen years an exile under the Restoration, he returned to Paris in 1830 for the last six years of his life—a legendary figure, a faded relic of an age that seemed almost as far away as the days of Louis XV. What were his thoughts at the end of it all? ‘Were it not curious to know,’ writes Carlyle in 1834, ‘how Sieyès in these days (for he is said to be still alive) looks out on all that Constitutional masonry, through the rheumy soberness of extreme age? Might we hope, still with the old irrefragable transcendentalism?’ St. Beuve, who had an opportunity of reading a mass of Sieyès’ still unpublished correspondence, was struck by the contrast between the adulatory tones in which he was addressed, by all manner of people, during the time of his power, and his own unbroken distrust and dislike of human nature. ‘I detest society,’ he wrote at this time, ‘because no one in society believes in moral goodness. . . . Talk to them of intrigue, and they will understand; but spend a lifetime in working for their happiness, and they will merely wonder whether you are worth including in one of their villainous cliques.’ Not that he was unequal to the party struggle. ‘While they cheat me by lying, I cheat them back,’ he said, ‘by telling the truth.’ But he was utterly disillusioned. Like Danton, but in more donnish language, he would have said, ‘I am sick of men.’ He had not only been disgusted by his company during the Revolution; he had also been frightened. When, in 1832, his mind was weakened by illness, he told his valet: ‘If M. Robespierre calls, I am not at home.’ He is said to have cried out in his dreams, ‘Eloignez de moi cet infâme!’

Yet he deserved to have, and doubtless enjoyed, prouder and pleasanter thoughts. Never designed by nature for the Church, he had yet performed the ‘priestlike task’ of baptizing and burying the Revolution. For Sieyès created the National Assembly, and was the first Frenchman (so he claims) to cry ‘Vive la Nation’; and yet it was he who, only ten years later, wrapped dead and dishonoured liberty in the Constitution of Brumaire, and laid it in a Bonapartist grave.

In both those acts he did well by his country, and did so because he was human enough to forget, for the moment, that he was a philosopher, and to allow the need of the moment to override his reasoned theories. Napoleon was right, as usual, when he remarked, of Brumaire, ‘It may have distressed Sieyès to find me a stumbling-block in the way of his metaphysical ideas; but he came to realize the necessity that somebody should govern, and he preferred me to anyone else.’ Sieyès’ weakness was, as with so many people, the quality upon which he most prided himself—his philosophic detachment. He may not have said, as Dumont asserts, ‘The science of government is one that I think I have mastered’; though Governeur Morris, who met him at dinner, says that he talked very confidently on the subject, ‘turning up his nose at everything said or written about it before him,’ and we have Lord Brougham’s story of how at Brussels, in 1817, Sieyès provided him, unasked, with a complete policy for the English parliamentary Opposition: but he certainly believed that politics is a science whose principles are capable of reasoned exposition, and an art by which they can be expressed in laws and institutions; and it never ceased to distress him when men rejected his philosophy, or when, in practice, his principles did not work. ‘The influence of reason,’ he wrote sadly, ‘is a phenomenon which few men are able to appreciate. The love of humanity, the desire for a perfect society, and the passionate attachment of the upright mind to objects of such grandeur as these, are beyond their moral reach: they cannot believe in them. They do not even understand that political science (l’art social) can win the attention and rouse the enthusiasm of artists in philosophy just as the musician, the painter, and the architect are absorbed by the charm of painting, the taste for beautiful buildings, or the search for perfect harmony.’ Such was Sieyès’ faith; and, to practise it, he withdrew into the solitude which is at the centre of every man’s heart who worships beauty or truth. It must have been, during those last years, a very empty place. All Sieyès’ powers, like those which he had balanced in his Constitutions, had cancelled out. ‘My sight, my hearing, my memory, and my speech,’ he told his friends, ‘have all gone. I have become a pure negation.’

‘There were no religious rites at his funeral,’ writes his biographer, ‘but they praised him over his grave. A plain little classical structure, a sort of shrine, marks the spot in Père Lachaise. Another generation has placed in the shrine symbols of the religion that he rejected, and of the Church that he despised. No public monument has ever been built to his memory, and no party in France looks back on his career with pride.’ The Royalists could never forgive him for becoming a Revolutionary, or the clericals for renouncing his Orders. The men of 1789 hated him as a republican, and the republicans who opposed Napoleon hated him as a renegade. Mounier said that ‘If you took off the mask of metaphysics with which he loved to hide his inner thought, you found a soul devoured by jealousy and covetousness.’ Mallet du Pan described him, more shortly, as ‘Catiline in a clerical collar.’ But Talleyrand and Carnot, two of the ablest of his contemporaries, maintained that France owed to him three inestimable boons—the National Assembly, the National Guard, and the Departmental System—and called him ‘the most representative man of his age.’ It is a true epitaph, and does him honour.

MIRABEAU

HONORÉ GABRIEL RIQUETI, COMTE DE MIRABEAU

| 1749 | March 9, born at Bignon. |

| 1767 | Cavalry commission. |

| 1772 | Married Marie Émilie de Marignane. |

| Essai sur le despotisme. | |

| 1775 | Affair with ‘Sophie’ de Monnier. |

| Avis aux Hessois. | |

| 1777 | Le Lecteur y mettra titre. |

| Imprisonment at Vincennes till 1780. | |

| 1782 | Des lettres de cachet. |

| 1784-5 Visit to England. | |

| 1786-7 Two visits to Prussia. | |

| 1787 | Dénonciation de l’agiotage. |

| 1788 | De la monarchie prussienne. |

| 1789 | Histoire secrète de la cour de Berlin. |

| Manifeste à la nation provençale. | |

| Avis au peuple marseillais. | |

| Elected deputy to States-General by Tiers-État of Aix. | |

| 1791 | April 2, died at Paris, æt. 42. |

AUTHORITIES:

Œuvres, ed. Lumet (3 vols., 1911 and 1921).

Correspondance entre le comte de Mirabeau et le comte de La Marck.

Dumont, Souvenirs sur Mirabeau, with Macaulay’s review in Miscellaneous Writings, Vol. 2.

Barthou, Mirabeau (1913).

MIRABEAU

from a painting by Couderc at Versailles

There is an extreme contrast between the revolutionary careers of Mirabeau and of Sieyès. If Sieyès revolved round the central fire, and was only a little scorched by it at one point of his orbit, Mirabeau, trailing clouds of infamy, plunged into it, and was consumed. None of the men whom we are to consider played a shorter part in the drama of the Revolution, or a more forcible one. If the term ‘leader’ has any application during the period, it is to Mirabeau. If Mirabeau was not great, no one was, till Napoleon.

Honoré Gabriel Riqueti was born at Bignon, near Nemours, on March 9, 1749. He came of a heroic stock, and was an almost fabulous infant; for he is said to have been born with two teeth, to have beaten his nurse at the age of three, and to have shown in early childhood that excess of vitality which drove most of his family to the extremes either of virtue or of vice. It was so to the end. In his last illness the doctor used to ask after the state of his hair: if he was better, it stood stiff and curly; if he was worse, it lay soft and flat on his head.

Mirabeau’s great-grandfather had entertained Louis XIV, and been made a Marquis for it: his grandfather had been so badly wounded at Cassano—‘that was the battle,’ he used to say, ‘in which I lost my life’—that he went about ever afterwards with his right arm in a sling, and his head supported by a silver stock. One uncle had fought at Dettingen and Fontenoy, and had served the sister of Frederick the Great. Another, after a distinguished career in the Navy, achieved a colonial governorship, and barely missed the Ministry of Marine. His father, the Marquis, after a dissipated youth in the army, had settled down as a philosophic farmer, and written books full of new-fangled ideas on taxation and social reform, which earned him (from the people) the title of ‘The Friend of Men,’ and (from the Government) compulsory rustication to the village where Honoré was born.

The boy grew up true to the family type—pugnacious, amorous, adventurous, with a passion for learning and a passion for creating. Like the young Napoleon, the young Mirabeau read books in barracks, and meditated a work on Corsica. With a face disfigured by smallpox, but with charming manners and a head full of ideas, he learnt to quarrel with his family, and to make friends with every stranger he met. ‘It was impossible to know him,’ said Dumont, ‘and not to be fascinated by his talents and engaging manners.’ Married to an unattractive heiress at twenty-three, he soon ran into debt, broke with his wife, and found himself in prison. Here his energy of mind forced an outlet in a treatise on salt-mines, and an essay on despotism; and his physical vitality in a love affair with ‘Sophie’ de Monnier, the misunderstood wife of a neighbouring nobleman. Flying with Sophie to Holland, he found himself convicted of the crime of abduction, sentenced in absentia to lose his head (the execution was carried out in effigy), and brought back to imprisonment at Vincennes.

Vincennes was to Mirabeau what Küstrin had been to Frederick the Great. It did not alter his character, but turned it in a new direction. It did not teach him to discipline his bodily desires—that was a lesson he never learned—but it gave him mental ambitions which disputed their supremacy. His lower nature had monopolized him; now it held only half the field. During the whole time of his imprisonment he wrote furiously. But whereas he began by producing works of sentimental rhetoric and impropriety, such as the Letters to Sophie, and Ma Conversion, he ended with the Des lettres de cachet, a learned and eloquent attack on the prison system under which he was suffering. And when he was free again, though his name got fresh notoriety from three scandalous law-suits, and though he deserted Sophie for Mme de Nehra, and Mme de Nehra for Mme Lejay, yet he impressed those who met him, and who were not disposed to overlook his moral faults, as a man of honour and high ideals. This is particularly true of the friends he made during a visit to England in 1784-5. ‘I had such frequent opportunities of seeing him at this time,’ writes Sir Samuel Romilly, a witness of the highest repute, ‘and afterwards at a much more important period of his life, that I think his character was well known to me. I doubt whether it has been so well known to the world, and I am convinced that a great injustice has been done him. . . . His vanity was certainly excessive, but I have no doubt that, in his public conduct as well as in his writings, he was desirous of doing good, that his ambition was of the noblest kind, and that he proposed to himself the noblest ends.’ Mirabeau was, indeed, in his happiest mood during this visit to England. He spent most of the time in London, seeing the usual sights, meeting the right people, and putting on paper his opinions about everything and everybody. Feeling melancholy one day, because his mistress was absent, he went the round of the London hospitals, and was moved by what he saw to draw up some very sensible suggestions for reform, especially in the treatment of children. He was interested in Parliament, and took particular note of the rules of procedure in the Commons, which he afterwards tried in vain to introduce into the National Assembly. He also had a close and not entirely pleasant experience of English justice, when he sued his secretary, Hardy, for the theft of some of his clothes and papers. After a careful hearing Hardy was acquitted; but the judge said that the prosecution was justified; and Mirabeau was so impressed with the working of the jury system that he never ceased to urge its adoption in his own country. Once he visited Oxford, and wrote that ‘Nature seemed to have formed this asylum expressly for the delightful enjoyment of study for the active tranquillity of letters and arts. . . . In the streets,’ he reports, ‘you scarcely see anyone save professors and students wearing black gowns and scarfs, and on their heads a square, flat cap—the kind of tuft which is in the middle looking like a nail that has been driven through this little black board into their learned heads.’

One other incident may be mentioned, for the light it throws on a curious side of Mirabeau’s character. It is a letter to Romilly, who was out of town at the moment, describing a dispute between himself and Gibbon at Lord Lansdowne’s house in London. Now, Mirabeau was very fond of provoking arguments, and did not mind what he said—on one occasion he was so rude to Wilkes that only the latter’s tact prevented an open quarrel. But this particular scene cannot have taken place, because Gibbon was at that time in Switzerland. Romilly, who reports the incident, does not know what to make of it. But it squares with an unscrupulousness, a lack of moral sense in certain matters, of which there were other examples in Mirabeau’s conduct at this time.

For as soon as he left England he plunged back into his quarrelsome past, and was immersed in political pamphleteering. ‘I have travelled 300 leagues,’ he writes to Romilly on his return to Paris, ‘composed, printed, struck off, and stitched 2,000 copies of 300 pages each. . . . This book (it was a work on banking, inspired by Clavière) has been written, printed in a foreign country, brought back and got ready for distribution, all in less than five weeks. My journey, somewhat rapid, as you see, was in a country where the slightest thing which had betrayed me would have sent me to the gallows or the stake.’ There followed, at great pressure, four more treatises on finance; two visits to Berlin, during the second of which—a semi-official mission—he sent home seventy despatches in six months, and composed a full-length work on the Prussian monarchy; and an attack on Calonne, under the guise of a treatise on stock-jobbing, which got him an enemy as well as a reputation. It was in this atmosphere of irritation and overwork that Mirabeau committed three literary crimes which it is particularly hard to forgive, because they had so strong a motive in money, and so little excuse in passion. He published as a posthumous work of Turgot a memoir of Dupont’s on Provincial Assemblies which he had already sold to Calonne as a composition of his own. He printed, as an attack upon Necker, and at a time when he was asking for pecuniary help from Necker’s Government, a number of private letters. And, under the catch-title of A Secret History of the Court of Berlin, he published to all the world the confidential despatches which he had supplied to the Foreign Office during his mission to Prussia. This last scandal occurred in January, 1789, and came close to wrecking his career. He sank so low as to be ‘cut’ by Talleyrand. He was only saved by the outbreak of the Revolution.

How did Mirabeau appear to the world at the opening of his political career? This is how he struck an observer at a smart dinner-party at Versailles. ‘He had a tall, square, heavy figure. The abnormally large size of his head was exaggerated by a mass of curled and powdered hair. He wore evening dress with enormous buttons of coloured stone; and the buckles of his shoes were equally large. His whole costume was noticeable for an exaggerated fashionableness which was hardly in the taste of the best society. His features were disfigured by the marks of smallpox. He had a reserved expression, but his eyes were full of fire. Trying to be polite, he bowed too low, and his first words were pretentious and rather tasteless compliments. In a word, he had neither the manner nor the speech of the company in which he found himself.’ His birth was as good as any of theirs; but in his Bohemian life he had unlearnt the ways of the West End.

What character did he commonly bear? That of a man without moral scruples, who would stick at nothing to make money, or to win a woman; a quarrelsome, conceited fellow, with a loud voice and an overbearing manner; an aristocrat who dressed like an actor, and could not be trusted to behave like a gentleman; but endowed with a magnetic force of body and mind which conquered or charmed by mere proximity; and with a knowledge of the world, and a power of mastering affairs, which were without rival among his contemporaries. His scarred face was the symbol of his scarred character: but as the one could not be overlooked in society, so neither could the other fail to fix its mark upon the world.

But Mirabeau would have to live down his past, and to conquer a host of suspicions and prejudices; he would have to make his own career by sheer ability and perseverance. It would not be easy, and he knew it. ‘It is a proud and difficult task,’ he wrote during the first days of the Assembly, ‘that I have undertaken to achieve a career of public service without courting any political party, and without worshipping the idol of the hour; with no weapon but reason and truth—those, and those alone, the objects of my friendship and respect, their enemies my enemies; and recognizing no king but conscience, and no judge but time. So be it! Perhaps I shall fall in the enterprise, but at least I shall not retreat.’

Mirabeau, with his reputation, could not hope to sit in the States-General as a representative of the Noblesse. But, under the convenient rule that allowed members of the other Orders to sit for the Commons, he appealed to his own people in the south—the Manifeste à la nation provençale and the Avis au peuple marseillais were part of his electioneering campaign—and was elected by the Third Estate both of Aix and of Marseilles. He chose to sit for Aix, and set out for Versailles.

Here he at once plunged into the dangerous situation created by the dual struggle between the Lords and Commons, the Parliament and the Crown. Each section of the Lords—that is, the representatives of the Clergy and the Noblesse—claimed to verify their mandates, to discuss the matters mentioned in the King’s speech, and to vote upon them, alone. The Commons claimed that, as they had been given the same number of representatives as the nobility and clergy taken together, the old division into three Houses no longer held good; all three must verify together, and vote together, that is, by head; and until the Lords agreed to this course, the Commons would refuse to do any business at all. Meanwhile, the Crown, which had summoned Parliament in order to raise money, and was prepared to bribe it with a programme of moderate reform, found itself encumbered with three debating societies, each busy about its own grievances, and threatened by a rising tide of opinion in favour of the Commons. Soon it was no longer a question of moderate reform, but of a new Constitution: obstruction was passing into rebellion, and rebellion into revolution.

How did Mirabeau react to this situation? He was a Royalist, but one who believed that the authority of the Crown should rest on the sovereignty of the people. He thought monarchy the most efficient as well as the most congenial form of government for his country; but he considered that it would be more effective and more popular if limited by a frank recognition of the rights of Parliament and the people—if it were no longer arbitrary, but constitutional. He saw the danger of missing the opportunity for such a settlement. ‘I tremble for the royal authority,’ he had written to Montmorin as early as December, 1788, ‘which was never so necessary as at a moment when it is on the verge of ruin. There was never a crisis more full of embarrassment, or offering more pretexts for licence. Never was the coalition of the privileged Orders more threatening for the King, or more formidable to the nation. No National Assembly ever threatened to be so stormy as that which will decide the fate of the monarchy, and which is gathering in such haste, and with so much mutual distrust.’ He soon came to the conclusion that the King’s advisers were incompetent to deal with the situation. ‘If Necker had had an ounce of talent he could have secured 60 millions’ worth of taxes and 150 millions’ worth of loans within a week, and the next day have dissolved the Assembly. If he had a shred of character, his position would be unassailable: he would be marching by our side, instead of deserting our cause, which is also his own; he would play Richelieu’s part with the Court, and regenerate the nation.’

This leadership, which Necker let slip, Mirabeau was to grasp, and to make his own. It seemed, indeed, at first, very unlikely that he would succeed. ‘In every company, of every rank,’ reports Arthur Young, ‘you hear of the Comte de Mirabeau’s talents; that he is one of the first pens in France, and the first orator; and yet that he could not carry, from confidence, six votes on any question in the States.’ But every incident during the summer of 1789 strengthened his hold on the House, and his repute with the people—June 17, when he helped Sieyès to turn the Commons into the National Assembly; June 23, when, in the name of the Assembly, he defied the King’s representative—‘Go and tell those who sent you that we are here by the will of the people, and that we cannot be moved hence save by force of bayonets!’; July 15, when he demanded the withdrawal of the troops that were menacing the Assembly; August 10, when, having been absent on the famous night of the 4th, he supported the suppression of clerical tithes; September 24, when he championed Necker’s financial proposals; and October 30, when he made a great speech on the confiscation of the property of the Church. ‘It is no good pretending,’ said Malouet, ‘that Mirabeau was not the mainspring of power in the National Assembly. His great quality was courage, which added strength to his talents, directed their employment, and developed their force. Whatever his moral reputation may have been, when circumstances brought him to the front he grew in stature, he redeemed his character, and then his genius rose to the summit of courage and virtue.’

But it was at this moment, when it seemed that he might become master of the Assembly, and mould the Revolution into the shape he desired, that his career received a fatal set-back, and the Revolution experienced an aberration from which it never recovered. This was the decree of November 9, which laid it down that no member of the Assembly could be also a minister of the Crown. The decree was passed by a snap vote on a side-issue. But it would not have been reversed by longer consideration; for it represented a general conviction that there could be no honest alliance between Parliament and the Crown, as well as a particular suspicion that if Mirabeau were a Minister, he would soon be a Dictator too. The objection to Ministers as liaison officers between Parliament and the Crown rested partly on the theoretical division between the legislative and executive functions of government which Montesquieu had made an axiom of French political science, and partly on the belief engrained by sad experience that the King’s Ministry was a stronghold of arbitrary government, and an enemy of the people. The feeling about Mirabeau was not merely that he had shown—as, for instance, in his support of the royal veto—a tendency to exalt the power of the Crown at the expense of that of the people, but also that he took too much upon himself, and that his manner was increasingly dictatorial. ‘Mirabeau has lost ground in the Assembly,’ wrote Dumont in December, ‘whether from the intrigues of his enemies, or from the torrents of libels poured forth against him, or from the continual faults into which he is drawn by his impetuous disposition, his rage for domination, and that impatient ambition which has been its own betrayer. The idea of seeing him a Minister could not be endured.’ There was also a more definite suspicion—a suspicion, in fact, well grounded—that he was being consulted by the King’s friends, and was giving them his paid advice. Under all these circumstances it is not surprising that a body of men who had just shaken off one yoke should be fearful of falling under another, or that the jealousies and resentments roused by Mirabeau’s domineering personality should have expressed themselves in a veto on his Ministry. Nevertheless, the decree was a serious mistake. It forced Mirabeau to make a secret treaty instead of an open alliance with the King; and it rendered almost impossible any close or friendly co-operation between the Assembly which framed laws and the Ministers who executed them. It was through this gap between legislation and administration that the governing power of the Revolution gradually leaked away.

Mirabeau, we have said, was already in consultation with the Court, as to the possibility of saving the executive power of the Crown; for in this, more and more, he saw the one hope of saving the country. On October 15 he had sent to the Comte de Provence a memorandum based on the events of October 5-6; and on June 1, 1790, began that series of fifty ‘Notes’ to the Court which form the nucleus of the Correspondance entre le comte de Mirabeau et le comte de La Marck—one of the most interesting and important collections of political documents ever published.

What is the policy that Mirabeau suggests? The essence of it is there from the first, in the memorandum of October 15, 1789. The King has been brought from Versailles to Paris, and is shut up in the Tuileries. The Assembly has followed him, and is debating under the eyes of the Paris mob. Is the King free? No. He cannot leave Paris. He is exposed to all the commotions of the capital, at a time when winter is coming on, with its special dangers of poverty and famine. What will the city be like in three months’ time? ‘Certainly a hospital, perhaps a theatre of horrors.’ There is the added danger of a struggle, perhaps a civil war, between Paris and the provinces, where the commercial and agricultural constituencies are already showing their resentment at the extent to which the financial interests of the capital dominate the Assembly. This is a point to which Mirabeau returns more than once in the correspondence; and it is important, because it shows that the main cause of the later quarrel between the Jacobins and the Girondins was present from the earliest days of the Revolution. Mirabeau, with his insistence on the ‘profound immorality’ of Paris, its ‘disdain of landed property, and its insatiable desire to overturn and annex and plunder everything,’ was, in effect, the first ‘federalist.’ In the face of all these difficulties the King has no competent Ministers, no money in the Treasury, and no support in public opinion; while the Assembly grows day by day more unpopular. What is Mirabeau’s remedy? He would have the King retire from Paris to one of the provincial capitals—Rouen would be the best, because it is loyal, rich, populous, and well-situated for organizing the north-western provinces—and from thence appeal against the Assembly to the whole nation, in the name of ‘the peace and safety of the State, and the indivisibility of King and people.’ This plan Mirabeau never gave up—though in the constantly shifting events of the next eighteen months he enlarged it and varied it in several directions. It always seemed to him the most effective way for the King to assert his freedom, and to recover his executive power.

It was in May, 1790, that Mirabeau was definitely approached by Mercy d’Argenteau and La Marck on behalf of the Court, and that, in return for a monthly stipend, and the ultimate payment of his debts, he undertook to advise the King, and to work for him in the Assembly on the lines that he had already laid down. Is it necessary to defend Mirabeau for making this bargain? He was, as always, in need of money. His only marketable possession, besides his wits, was his library, of which some fifty or sixty volumes were, he tells us, ‘of special beauty and rarity,’ and which we can understand his not wishing to sell. And though he kept his books, and sold his services, yet he did not sell his conscience: for the policy which, at any rate for the present, he prescribed to the Court was the same policy which he would in any case have recommended in the Assembly. Perhaps no member of the House, except Robespierre, would have refused the offer; and it was jealousy that sharpened their suspicion of the bribe. But later, as we shall see, the situation changed, and a bargain that it would have been wiser and honester never to make involved both parties to it in treachery to their country.

Mirabeau’s first concern was for allies. Montmorin, Mercy, and La Marck were zealous, but of no political weight. He had given up expecting anything from Necker, who faded away early in September, 1790. But perhaps he might make an ally of Lafayette—that stiff, stupid man, who lived on his reputation as a friend of Washington, and fancied himself a second Cromwell, because he was the King’s warder and commander of the National Guard. Mirabeau twice appealed for his support in the early summer of 1790. Outlining the dangers which threatened the State, and the divided condition of public opinion, he urged that ‘if it were impossible to reunite men through opinions, it might still be possible to reunite opinions through men.’ When reasoning failed to move Lafayette, he tried flattery. The situation, he said, had passed beyond the means of the old diplomacy. Neither wit, nor memory, nor social qualities can avail; no conceivable committee can help us now; only ‘organized thought, the inspirations of genius, and the omnipotence of character.’ ‘Oh, M. de Lafayette!’ he cries, ‘Richelieu was Richelieu for the Court against the nation; and though he did much harm to public liberty, yet he did the monarchy a tolerable amount of good. Be another Richelieu, with the Court, and for the nation; and you will restore the monarchy at the same time as you enlarge and consolidate public freedom. But (he goes on) Richelieu had his Capucin Father Joseph; and unless you too have your Éminence grise you will ruin yourself without saving us. Your qualities and mine are complementary.’ But Lafayette was too priggish to co-operate with a man of no moral reputation, and too conceited to abandon that glorious isolation in which, as Mirabeau told him, he lived ‘entirely surrounded by himself.’ Nearly a year later a final attempt was made by Emmery to bring the two together on a basis of ‘public peace and social order’; but it too failed. Mirabeau’s disappointment is evident in the attacks on Lafayette contained in the Notes of June 1 and 20.

Meanwhile the political situation was rapidly changing. The Constitution of 1791 was taking shape, and the King must determine his attitude towards it. In Mirabeau’s third Note, written on July 3, the day of his only interview with the Court, he does not withdraw from his view as to the necessity of strengthening the executive power of the Crown, but he tries to show the King how much stronger in many ways his position is under the new régime than it was under the old. ‘Before the Revolution the King’s authority was incomplete, because it had no legal basis; inadequate, because it rested on compulsion rather than opinion; and uncertain, because it could be overturned by a revolution which was always imminent. The King had to consult the interests of the nobility, to negotiate with the clergy, to bargain with the Parlements, and to load the Court with favours.’ His legislative power did not help him to rule; his power of taxation made him unpopular; and he got the blame for the arbitrary rule of his Ministers. Now these obstacles have been swept away. ‘In the course of a single year liberty has triumphed over more prejudices that obstructed the royal power, crushed more enemies of the throne, and secured more sacrifices for the national welfare, than the royal authority could possibly have done in several centuries.’ The one effective weapon the King had, and the one he must never lose, is control of the administration. ‘To administer is to govern, and to govern is to reign: that is the whole matter.’ And the secret of administration is to have public opinion on your side.

This Note is not a piece of special pleading, but a true and statesmanlike view of the facts. Much of what Louis was struggling to keep had ceased to be worth having, and much of what he was refusing to accept would make his position stronger. It was not too late to sever his connection with the party of reaction, to appeal to the loyal mass of the people, and to take his place as a patriot King at the head of the Revolution. By loyally accepting the Constitution he might get the power to revise it, and to regain fuller executive control.

In a later Note, Mirabeau returns to this subject, and outlines his revised Constitution. ‘Royalty hereditary in the Bourbon dynasty; a permanent legislative body elected periodically, and limited to the function of law-making; the executive power centralized and extended so as to be supreme over everything that concerns the administration of the kingdom, the execution of the laws, and the command of the army, the legislative body to have sole control of taxation; the country to be re-divided; free justice, liberty of the Press, responsibility of Ministers; sale of the Crown and Church estates; a Civil List; and the abolition of class distinctions, privileges, exemptions from taxation, feudalism, the Parlements, aristocratic and clerical corporations, pays d’état, and provincial bodies—that (he says) is what I mean by the basis of the Constitution.’

Now, up to about the middle of the summer of 1790 there was a reasonable hope that this programme might be realized, and Mirabeau’s suggestions for realizing it contained nothing inconsistent with patriotism, or with his rôle as a parliamentary leader. But from about the time of the sixteenth Note (August 13) there is a noticeable change of tone, as though the situation had grown too urgent for moderate remedies, and as though more drastic measures were required. What had happened? No specifically new disease had appeared, but an aggravation of the symptoms already present. Perhaps Mirabeau’s interview with the King and Queen on July 3, deeply as it affected his feelings—Madame Campan says that, as he kissed the Queen’s hand upon leaving, he exclaimed, ‘Madame, the monarchy is saved!’—yet convinced him, upon cool reflection, that they could never play the part that he had assigned to them. Already, six months before, he had broken out into complaints of the Court: ‘What wool-gatherers they are! what bunglers! how cowardly! how reckless! what a grotesque mixture of old ideas and new projects, of petty scruples and childish whims, of willing this and nilling that (volontés et nolontés), of abortive loves and hates!’ He had, perhaps, hoped against hope that this impression was wrong: now he knew that it was right. There were other reasons for urgency. Winter was once more in sight, with its added dangers. The Nootka Sound crisis had brought home the risk of foreign war. Provincial discontent had come to a head at Marseilles. The financial situation was desperate. There was growing discontent with the Assembly, whose legislation met with opposition from vested interests all over the country. The Civil Constitution of the clergy, and the clerical oath, were soon to bring about schism and civil war. It was, no doubt, the consciousness of these dangers that led to a new rapprochement between Mirabeau and the Court early in December, when a coalition was talked of, to include Talon, Duquesnoy, and Barnave, but not Lafayette, and when Mirabeau came away from an interview with Montmorin convinced of his sincere attachment to the royal cause, and determined to support him with all his power.

What does Mirabeau now propose? What is his new policy? The organization of a royal army, or at least of certain units under officers of proved Royalism—a beginning to be made with the Swiss and German regiments: the influencing of public opinion by a Royalist paper: the undermining of Lafayette’s position, not only by inducing him to undertake the editorship of this paper (which will then be a failure), and to make proposals for a Constitution (which will be laughed out of the House), but also by encouraging conflicts between the Paris mob and the National Guard: the appointment of new Ministers, Mirabeau’s nominees, or the supervision of the present Ministers by friends of the Court: and the embarrassment of the Assembly by all kinds of Parliamentary manœuvres, such as encouraging the clergy to refuse the oath, and the Assembly to enforce it, or bringing up needlessly controversial matters. The last part of this policy was embodied in the long forty-seventh Note—a pacquet, Mirabeau calls it, and it fills nearly 100 pages of print—which rehearses the obstacles to be overcome, the remedies to be applied, and the means to be adopted to this end. The obstacles are the King’s weakness, the unpopularity of the Queen, the Paris mob, the National Guard, and the difficulty of counting upon any support in the Assembly. The remedy is to accept what is good in the Constitution, and to work for the revision of what is bad. The means to be employed are to ruin the credit of the present Assembly, and to carry a policy of revision in the body that takes its place. This will involve influencing the electorate; passing a measure to prevent the re-election of the present deputies, or at least to limit their re-election to their place of birth (this was directed against Jacobin ‘carpet-baggers’); forming a revisionist party in the House by flattering or bribing prominent members for their support; forming a special organization to capture Paris opinion through its deputies, journalists, and officials; and keeping up a correspondence with travelling agents in the provinces. There will, in short, be three ateliers, or offices, one dealing with the Assembly, one with Paris, and one with the provinces. Mirabeau’s draft of the scheme even includes specimen reports on the state of public opinion, model questionnaires for the provincial agents, and a weekly time-table of meetings between Montmorin (the head of the organization) and his various subordinates.

Now, apart from the over-elaborateness of this plan, and the way in which some of its parts neutralize others, it includes certain features which, to say the least, can hardly be called either patriotic or statesmanlike. The schemes for tampering with the army, for discrediting the National Guard, for bringing the Assembly into contempt, and for buying support for the revisionist party, are such as a dishonest man might adopt, if he were sure that they would succeed, and succeed quickly; but no honest man would have anything to do with them. It can hardly be denied that, so far as he worked on these lines, Mirabeau, during the last six months of his life, was disloyal both to Parliament and to the country. And how, in the light of these proposals, can we think well of his statesmanship? The policy was adroit enough. It was based on an intimate knowledge of the situation. It took men and things for what they were. But it could not succeed quickly. And in the meantime it was playing upon the nerves of the Revolution. It was a policy which might win a point, but not the game; and it would discredit the winner. La Marck was not far wrong when he complained that it was the sort of plan which could only have been carried out by Cardinal de Retz.

In any case the scheme miscarried. The Atelier de Police under Talon and Sémonville bought up a journalist or two, and sent in a few reports of doubtful value. There is one bulletin from Duquesnoy, describing the tactics employed to form a revisionist party in the House. But Mercy and La Marck from the first regarded the plan as unworkable. Mirabeau was not satisfied with his agents, and allowed himself to abuse Duquesnoy. And the King and Queen, while pretending to play their part—as, for instance, in the démarche to the Assembly on February 4—were already secretly planning a quite different move, and one contrary to all the advice that Mirabeau had given them—the flight to Varennes.

Meanwhile Mirabeau’s position in the House was growing more and more difficult. If he had been sure of the support of the King and the Ministers he might have taken a stronger line in the Assembly. If he had commanded the confidence of the Assembly he might have dictated a policy to the Court. But ‘the ambiguous conduct of the Court—its weakness when it ought to make a stand, its stubbornness when it ought to yield, its inaction when it ought to act’—gave the Assembly a power that it would not otherwise have possessed, whilst it compromised at every turn Mirabeau’s own attempts to save it. An incident which happened in November showed what he might expect. The Paris mob sacked the house of de Castries, while the National Guard looked on. This was just such an opportunity as Mirabeau had foreseen for discrediting Lafayette, and he made a point of defending the rioters in the House. But the only result of Lafayette’s public failure was to drive him into the arms of the Court, where Mirabeau’s defence of mob rule was misunderstood, and effectually alienated the King and Queen. ‘He is quite out of favour at the Tuileries,’ writes La Marck, ‘where they are tired of his incurable mania for pursuing popularity’—this at the very moment when Montmorin was forming his coalition, and when Mirabeau was preparing to draw up his forty-seventh Note. In November, indeed, as a result of the Castries affair, Mirabeau was popular with the crowd, and in January he was for the first time elected President of the Assembly. But it was becoming increasingly difficult to walk the political tight-rope.

As his political embarrassments grew, so did his bodily ailments. Already, a year ago, his sight had troubled him, and he had been speaking four or five times a day in the House with a bandage over his eyes. In October he had written that ‘the Assembly, the Jacobins, and his eyes had pretty well killed him.’ Now (January, 1791) his sight is worse, and he is undergoing treatment for it. Overwork and the unhealthy atmosphere of the Manège are breaking up a constitution weakened by years of exertion and excess. But he will go on working to the end.