* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Interplanetary Hunter

Date of first publication: 1937

Author: Arthur K. Barnes (1909-1969)

Date first posted: Aug. 25, 2022

Date last updated: Aug. 25, 2022

Faded Page eBook #20220852

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

This file was produced from images generously made available by Internet Archive/American Libraries.

Tommy stepped outside into the breathlessly hot blinding mist, thick with the stench of rot and decay. Earthly eyes could not penetrate this eternal shroud for more than a hundred feet at a time, even when a wind stirred the stuff up to resemble the churning of a weak solution of dirty milk. Strike grimaced and thoughtlessly filled and lit his pipe.

Thirty seconds later the air was filled with the thin screams and hangings of dozens of the fabulous whiz-bang beetles as they hurtled their armored bodies blindly against the metal walls of the station, attracted by the odor of tobacco. Strike flinched and hurriedly doused the pipe. A man couldn’t even have the solace of a smoke on this damned planet. His life would be endangered by the terrific speed of those whiz-bangs. . . .

From “Venus,” one of the five fascinating adventures in INTERPLANETARY HUNTER.

Interplanetary

Hunter

by Arthur K. Barnes

ACE BOOKS

A Division of Charter Communications Inc.

1120 Avenue of the Americas

New York, N.Y. 10036

INTERPLANETARY HUNTER

Copyright 1956 by Arthur K. Barnes

“Interplanetary Hunter” is based upon

material originally copyrighted by

STANDARD MAGAZINES INC.

1937, 1938, 1940, 1941, and 1946.

An Ace Book.

First Ace printing: September, 1972

Printed in U.S.A.

| CONTENTS | ||

| VENUS | 7 | |

| JUPITER | 41 | |

| NEPTUNE | 79 | |

| ALMUSSEN’S COMET | 114 | |

| SATURN | 178 | |

Day again—one hundred and seventy dragging hours of throttling, humid heat. An interminable period of monotony lived in the eternal mists, swirling with sluggish dankness, enervating, miasmatic, pulsant with the secret whisperings of mephitic life-forms. That accounted for the dull existence of the Venusian trader, safe in the protection of his stilt-legged trading post twenty feet above the spongy earth—but bored to the point of madness.

Tommy Strike stepped out from under the needle-spray antiseptic shower that was the Earthman’s chief defense against the myriad malignant bacterial infections swarming the hothouse that is Venus. He grabbed a towel, made a pass at the lever to turn on the refrigeration unit that preserved them during the hot days, shut off the night heating system and yelled:

“Roy! Awake! Arise! Today’s the great day! The British are coming! Wake up for the event!”

Roy Ransom, Strike’s assistant, staggered into view, rubbing the sleep from his eyes.

“British?” he mumbled. “What British?”

“Why, Gerry Carlyle! The great Carlyle is coming today. In his special ship, with his trained crew, straight from the Interplanetary Zoo in London. The famous ‘Catch-’em-alive’ Carlyle is on his way and we’re the lucky guys chosen to guide him on his expedition to Venus!”

Ransom scratched one thick hairy leg and stepped under the shower with a sour expression. “Ain’t that somethin’?” he inquired.

“You don’t look with favor on Mister Carlyle?” Strike chuckled.

“No, I don’t. I’ve heard all I want to hear about him. Capturing animals from different planets and bringing them back alive to the Zoo in London is all right. I’d like the job myself. But any guy that rates the sickening amount of publicity he does must have something phony about ’im.” He kicked toward the short-wave radio in one corner of the living room.

“Bein’ so close to the sun, we’re lucky if we bring in a couple of Earth programs a day through the interference. An’ it seems to me every damn’ one of ’em has somethin’ about the famous Carlyle. Gerry Carlyle eats Lowden’s Vita-cubes on expedition. Gerry Carlyle smokes germ-free Suaves. Gerry Carlyle drinks refreshin’ Alka-lager. Pfui!

“An’ now we’re ordered to slog around this drippin’ planet for ’im, doin’ all the work of baggin’ a bunch of weird specimens for the yokels t’ gape at, while he gets all the glory back home!”

Tommy Strike laughed good naturedly.

“You’re all bark and not much bite, Roy. You’re just as glad as I am something’s turned up to relieve the monotony.” He brought out his daytime clothes, singlet and trousers of thin rubberized material and the inevitable broad-soled boots for traversing the treacherous soft spots on Venus’s surface.

“Yeah?” retorted Ransom. “I can tell you one thing this visit’ll turn up, an’ that’s trouble. Sure as you’re born, Tommy, that guy’s comin’ here to get two or three Murris—he hopes! An’ you know what that’ll mean!”

Strike’s eyes clouded. There was truth in Ransom’s remarks. Hunting for the strange little creatures called Murris never had resulted in anything but trouble since the day Sidney Murray, co-leader of the first great Venusian exploration party, the Cecil Stanhope-Sidney Murray Expedition, first set eyes upon them.

“Well,” he shrugged, “we can stall until just before he’s ready to leave and have some fun at least. Maybe he’ll listen to reason.”

Ransom snorted in wordless disgust at this fantastic hope.

“Anyhow,” insisted Strike, determined to see the cheerful side, “even if there is any disturbance, it always blows over in a few days. I’m heading for the landing field. They’re just about due.”

Tommy stepped outside into the breathlessly hot blinding mist, thick with the stench of rot and decay. Earthly eyes could not penetrate this eternal shroud for more than a hundred feet at a time, even when a wind stirred the stuff up to resemble the churning of a weak solution of dirty milk. Strike grimaced and thoughtlessly filled and lit his pipe.

Thirty seconds later the air was filled with the thin screams and bangings of dozens of the fabulous whiz-bang beetles as they hurtled their armored bodies blindly against the metal walls of the station, attracted by the odor of tobacco. Strike flinched and hurriedly doused the pipe. A man couldn’t even have the solace of a smoke on this damned planet. His life would be endangered by the terrific speed of those whiz-bangs.

A few steps took him to the safety of the rear of the station, where abandoned calcium carbonate tanks loomed like metal giants in the fog. There was a time when it had been necessary to pump the stuff to the miniature space-port a safe distance away whenever a ship was about to land.

There, sprayed forth from thousands of tiny nozzles high into the air, its tremendous affinity for water carved a clear vertical tunnel in the fog for the approaching spaceship pilot. New telescopic developments, however, rendered the device obsolete.

Strike paced deliberately along the trail that paralleled the ancient pipeline—Earthlings soon learn not to overexert in that atmosphere—and before he had covered half of it his quick ears caught the shrill whine of a spacecraft plunging recklessly into the Venusian air-envelope.

It rose to a nerve-rasping pitch, then dropped sharply away to silence. Presently, sounding curiously muffled and distorted through the clouds, came the noise of opening ports, the clang of metal upon metal, voices. Gerry Carlyle and company had arrived.

He increased his pace somewhat and shortly entered the clearing that served as space-port. He paused to let amazed eyes roam over the unaccustomed sight. Gerry Carlyle’s famous expeditionary ship was an incredible monster of gleaming metal, occupying almost the entire field, towering into the air further than the eye could reach in that atmosphere. Its green glass portholes were glowing weirdly from the ship’s lights as they looked down upon the stranger.

The craft was immense, approaching in size the giant clipper ships that traveled to the furthermost reaches of the System. Strike had never before been so close to a ship of such proportions. He smiled at the sight of the name on her bow—The Ark.

The Ark, of course, was one of the new centrifugal flyers, containing in her stern a centrifuge of unbelievable power with millions of tiny rotors running in blasts of compressed air, generating sufficient energy to hurl the ship through space at tremendous speeds. The equipment of The Ark, too, was the talk of the System.

Carlyle, backed by the resources of the Interplanetary Zoo, had turned the ship into a floating laboratory, with a compartment for the captured specimens arranged to duplicate exactly the life conditions of their native planets. All the newer scientific inventions were included in her operating apparatus—the paralysis ray, anti-gravity, electronic telescope, a dozen other things the trader knew by name only.

His musings were interrupted by the approach of a snappily-uniformed man who saluted, smiling.

“Are you Mr. Strike?” he asked. “I’m sub-pilot Barrows of The Ark and very glad to meet you. Gerry Carlyle will see you at once. We’re anxious to get to work immediately.”

This day was to be one of many surprises for Tommy Strike and perhaps the greatest shock of all came when he stood beside the sloping runway leading into the brightly lighted belly of the ship. For, awaiting him there, one hand outstretched and a cool little smile on her lips, stood the most beautiful girl he had ever seen.

“Mr. Strike,” said Barrows, “this is Miss Gerry Carlyle.”

The trader stared, thunderstruck. In those days of advanced plastic surgery, feminine beauty wasn’t rare but even Strike’s unpracticed eye knew that here was the real thing. No synthetic blonde baby-doll here but a natural beauty untouched by the surgeon’s knife—spun-gold hair, intelligence lighting dark eyes, a hint of passion and temper in the curve of mouth and arch of nostrils. In short, a woman.

But Miss Carlyle’s voice was an ice-water jet to remind the trader of earthside manners.

“You don’t seem enthusiastic over meeting your temporary employer, Mr. Strike. Something wrong about me?” Strike flushed, angry at himself and his own embarrassment. “Oh—oh, no.” He fumbled for words. “That is, I’m surprised that you’re a woman. I—we expected to find a man in—well, in your position. It’s more like a man’s job.”

Sub-pilot Barrows could have warned the trader that this was a touchy point with Gerry Carlyle but he had no chance. The girl drew herself up and spoke coldly.

“There isn’t a man in the business who has done nearly as well as I. Name a half-dozen hunters. Rogers, Camden, Potter—they aren’t in the same class with me. Man’s job? I think you needn’t worry about me, Mr. Strike. You’ll find I’m man enough to face anything this planet has to offer.”

Strike’s eyebrow twitched. An arrogant female, withal. Terrific sense of her own importance, wilful, selfish. He decided he didn’t like her and rather hoped she had come looking for Murris. If so, she would learn one or two bitter lessons.

There followed a five-minute interlude of scurrying about and shouting and unloading, all done to the tune of Gerry Carlyle’s voice, which could crack like a whiplash when issuing commands.

Then Strike found himself leading a small party back to the trading post. Now surprisingly Miss Carlyle showed a flattering attention to him.

First she wished to know about the business of the trading post.

“It isn’t very exciting,” its proprietor told her. “Mostly we sit around being bored stiff, playing cards or fiddling with the bum radio. Several times during a Venusian day our natives bring in a load of some of the medicinal plants we want. Occasionally a rough gem of one kind or another, though Venus is very poor in minerals. The only stone really worth much to be found up here is the emerald.”

“Surely there isn’t enough profit in medicinal plants, considering transportation costs, to persuade a young man like you to bury himself here.” She waved her hand around disparagingly.

“There’s profit all right.” Strike shrugged. “The drugs distilled from some of the Venusian growths are plenty valuable. And then there’s the adventure angle.” He smiled wryly.

“Plenty of young bucks are willing to sign a three-year contract for the thrills of living on Venus—if they don’t know anything about it beforehand. But it does take an awful lot of stuff to bring a freighter our way. We seldom see a ship more often than three or four Earth-months apart.”

“What in the world—or in Venus are those?” She directed his attention to the thousands of fungi now springing up through moist soil with almost visible movement. They were shaped somewhat like the human body and so pale that they might be a host of tiny corpses rising from their graves.

The trader grimaced. He had never liked those things. They reminded him constantly that battle and destruction were the watchwords in this hellhole, where the fang of every creature was turned upon its neighbor and even the plants had poisoned thorns while the flowers gave off noxious gases to snare the unwary.

“Fungi mostly,” he answered. “They grow and propagate amazingly fast. Many of the smaller life-forms here exist only a single day—they are born, live and die in one hundred and seventy hours. Naturally their life cycle is speeded up. In a few hours all these puffballs will begin popping at once to spread their spores around. It’s a funny sight.

“During the long night, of course, the spores lie dormant. And most of the larger creatures hibernate from the intense cold. Our night life up here is nil. This is strictly a nine-o’clock planet.”

She sniffed noting what all newcomers to Venus learn. Although the view is a drab almost colorless one, an incredible multiplicity of odors assails the nostrils—sweet, sharp, musklike, pungent, spicy, with many unfamiliar olfactory sensations to boot.

Strike explained. On Earth flowering plants are fertilized by the passage of insects from one bloom to another, they develop petals of vivid colors to attract bees and butterflies and other insects. But on Venus, where perpetual mist renders impotent any appeal to sight, plants have adapted themselves to appeal to the sense of smell, therefore give off all sorts of enticing odors.

So it went, question and answer, the pleasant business of getting acquainted, until the all-too-short walk to the station was over. But Strike was not deceived by the girl’s sudden change of attitude.

He knew that an interplanetary hunter of Gerry Carlyle’s experience would certainly have read up on Venus before ever coming there. And he suspected she knew the answers already to every question she asked.

She must have noticed Strike’s disapproving eyebrow during the first moments of their meeting and had deliberately set out to ingratiate herself to promote harmony during her brief stay on the cloudy planet. The trader was willing to be friendly but he looked upon the girl with caution and distaste. Her aggressiveness was not to his taste.

Gerry Carlyle was decidedly a woman of action.

“No time to waste,” she declared incisively as they reached the post. “Earth and Venus are nearing conjunction and I want to be ready to take off as soon after that date as possible.

“I’ve no wish to hang around in space waiting for Earth to catch up to us with a cargo of weird specimens raising hades in the hold. If you’ve no objections, Mr. Strike, we’ll make our first foray at once.”

Strike nodded, staring at this disturbing girl, who could be one instant so warm and friendly, the next imperious and dominating.

“Sure,” he agreed. “Be with you in a moment.”

He ran up the metal stairway to where Roy Ransom’s face hung over the porch rail like an amazed bearded balloon and the two vanished into the house. Strike returned shortly with a tiny two-way radio.

“Ransom sends out a radio beam for us to travel on. I tell him which way to turn it in case we deviate from a straight line. It’s the only possible way to cover any distance in this murk.” He adjusted a single earphone, slipped receiver and broadcaster unit into a capacious pocket.

Next he insisted on painting the insides of everyone’s nostrils with a tarry aromatic substance.

“Germ-killer,” he smiled. “For each dangerous animal on this planet there are a hundred vicious bacteria to knock off an Earthman in twenty hours. I guess that finishes the preliminaries. Shall we go? I ought to warn you that the sense of hearing is well developed up here, so it’ll help if you move as quietly as possible.”

“One moment.” Gerry Carlyle’s cool voice struck in abruptly. “I want two things thoroughly understood. First, I’m the sole leader of this party and what I say goes.” She smiled with icy sweetness. “No complaints, of course, Mr. Strike, but it’s just as well to forestall future misunderstandings.

“Secondly, you must know that the main object of this expedition is to catch one or more Murris and return with them alive. We’ll take a number of other interesting specimens, of course, but the Murri is our real goal.”

She looked around challengingly, as if expecting a dissenting reaction. And she was not disappointed. Strike glanced up at the porch to exchange a significant look with Ransom.

When he smiled wryly, Gerry Carlyle’s temper flared.

“What is the mystery about this Murri, anyhow? Everywhere I go, on Venus, back on Earth among members of my own profession, if the word Murri is mentioned everyone scowls and tries to change the subject. Why?”

No one answered. The Carlyle party shifted uneasily, their boots making shucking sounds. Presently Strike offered, “The fact is, you’ll never take back a Murri alive. But you wouldn’t believe me if I told you the reason, Miss Carlyle. I—”

“Why not? What’s the matter with them? Is their presence fatal to a human in some way?”

“Oh, no.”

“Are they so rare or so shy they can’t be found?”

“No, I think I can find you some before you take off.”

“Then are they so delicate they can’t stand the trip? If so, I can tell you we’ve done everything to make hold number three an exact duplicate of living conditions here.”

“No, it isn’t that either,” the trader sighed.

“Then what is it?” she cried. “Why all the evasions and secretive looks? You’re acting just like Hank Rogers when I caught him one day in the Explorers’ Club.

“He came up here awhile back to get a good Murri specimen. But he returned empty-handed. I asked him why, and he refused to tell me. Actually acted embarrassed about something. What’s it all about?”

Tommy Strike shook his head firmly.

“It can’t be explained, Miss Carlyle. It’s just something you’ll find out for yourself.”

And on that note of dissatisfaction the party struck off through the mist. The half-dozen men from The Ark were surprised to find the going comparatively easy.

Although the great amount of water on Venus would presuppose profuse jungle growth, there is insufficient sunlight to support much more than the tallest varieties of trees, which shoot hundreds of feet up into the curtain of the mist, their broad-bladed leaves spread wide to treasure every stray sunbeam that filters through.

Undergrowth, which is confined to a sprawling, cactuslike shrub with poisonous spines and to a great many species of drably flowering plants with innumerable odors and perfumes, is laid out almost geometrically in order to catch the diluted sunshine without interference from the occasionally lonely trees.

“The main danger in travel,” as Strike explained, “is in losing the radio beam. Sometimes we have to circle a bog and we’ve got to be pretty careful not to let the signal fade.”

The party, with Strike and Gerry Carlyle in the lead, hadn’t been five minutes away from the station when the restless quiet was shattered by a terrific grunting and coughing like that of a thousand hogs at feeding time. The noise was intermittent, rumbling for a few seconds somewhere ahead, then stopping abruptly to be succeeded by slopping and smacking sounds.

The entire party paused for an instant at that blast of strange thunder. Startled by the sound out of nowhere.

The trader grinned. “Shovel-mouth,” he explained. “Not very dangerous.”

Gerry Carlyle glanced at her guide catching his implication. “We prefer ’em dangerous, as a matter of fact. Though I hardly expected to find anything interesting this close to—er—civilization.”

Strike grinned at the thrust and a little prickle of excitement crawled up his spine as he watched the Carlyle party slip into their smooth routine. The girl’s crisp commands detailed one man to remain with the bulky equipment. Two more loaded a pair of cathode-bolt guns, baby cannons beside the pistol the trader carried for emergencies.

Two of the others, including the girl, selected weapons resembling the old-fashioned rifles—now to be seen only in museums. Barrows was to work the camera.

“Allen,” Gerry snapped, “you circle around to the left. Kranz to the right. As usual, hold your fire unless it’s absolutely necessary to prevent the specimen’s escape. We’ll give you three minutes to get into position.”

The two flankers were already moving off into the mist when Strike woke up.

“Wait!” he cracked out. “Come back here. No one must get out of visual touch with me! It’s too easy to get permanently lost. Sounds carry far, naturally, but it’s impossible for an untrained ear to tell which direction they’re coming from in this fog.”

Gerry Carlyle’s eyes flashed in momentary anger as her commands were countermanded but the plan of action was amended to permit the two flankers to remain within sight of the main body.

Strike had thought that Miss Carlyle’s assistants were rather a colorless lot, stooges automatically going through letter-perfect roles, and wondered if they’d be any good if they found themselves suddenly without a leader. But when the party spread out with military precision for the stalk Tommy Strike had to admit to himself that he had never witnessed a more competent movement.

Not a single unnatural sound broke the quiet. Not a stick snapped, not a fungus squelched beneath an incautious heel. Even the sucking noises from marshy spots were missing. In sixty seconds they slipped into a little clearing and stood gazing with professional curiosity at the doomed shovel-mouth.

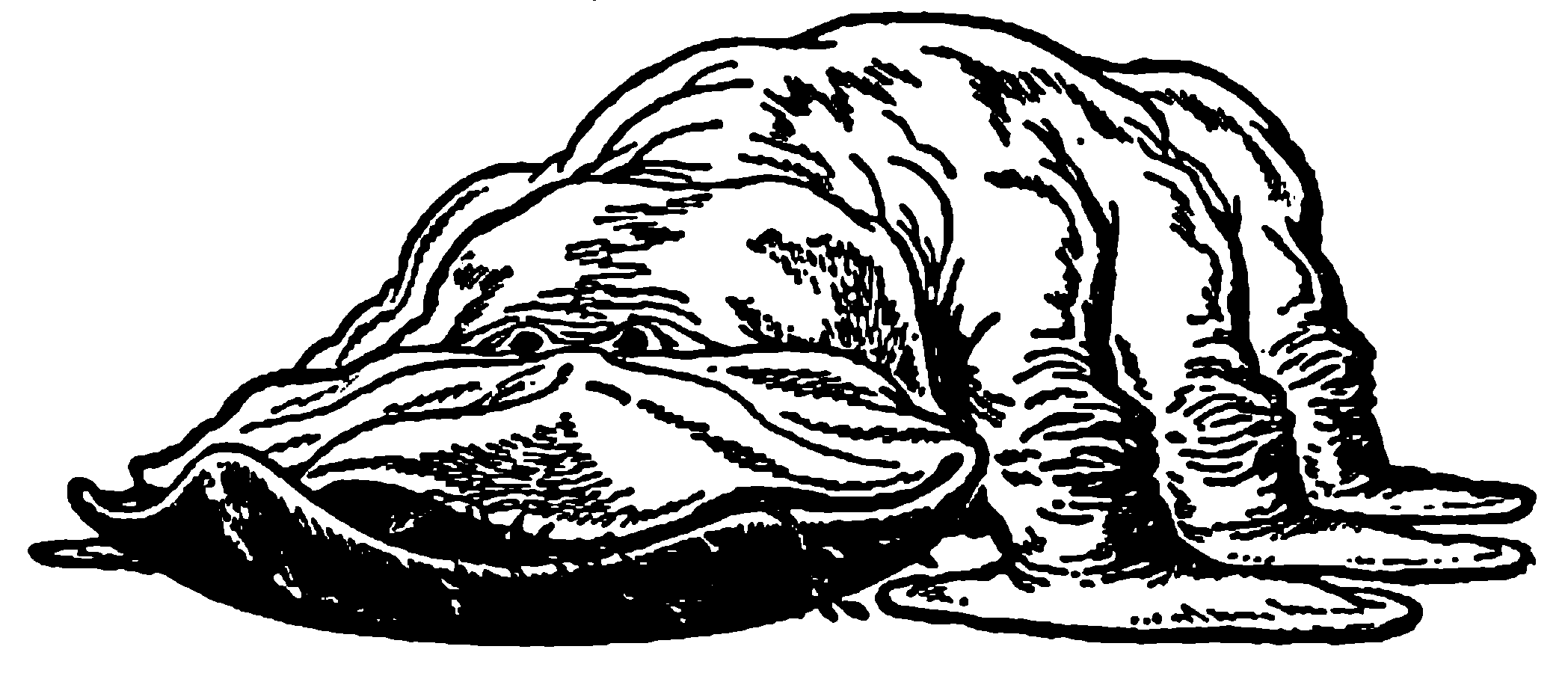

The creature was worth a second look. Fifty feet long and nearly twenty feet wide, it had three pairs of squat powerful legs ending in enormously spatulate discs. Its hide was a thick, tough gray stuff that gleamed dully with a wet slickness in the half light.

But the most surprising feature was the creature’s head which, instead of tapering to a point, broadened into a mammoth snout extending several feet horizontally from mouth-corner to mouth-corner. Flattened against the ground it had a ludicrous similarity to a fan-tail vacuum cleaner attachment.

The shovel-mouth stared at the party disinterestedly out of muddy eyes, then lowered his head and waddled across the clearing. Its mouth plowed up a wide shallow furrow as it ate indiscriminately the numerous fungi, low-lying bushes, sticks and mud.

“Herbivorous,” Strike murmured. “Its main article of diet is fungus growths but it takes so much for a meal that the creature has to spend most of its waking hours eating everything it can get its mouth on.”

Evidently the animal had been dining for some time, for the clearing looked as if a drunken farmer had been trying to plow it up. Gerry signaled, and her men moved into position like soldiers. She slipped up on the creature’s blind side and aimed her curious rifle at the soft, inner portion of the shovel-mouth’s leg.

Plop! The beast jerked, nipped at the wound momentarily, then continued to feed. Twenty seconds later it reeled dizzily about and fell to the ground, unconscious.

Just like that—simple, efficient, no fuss at all. Tommy Strike felt a sense of anticlimax.

“What a disappointment,” he said ruefully. “I expected a terrific battle and a lot of excitement with maybe one or two of us half killed for the sake of the movies!”

“With Mr. Strike heroically rescuing Gerry Carlyle from the jaws of death?” The girl smiled as the trader winced. “Sorry, but this is a business, Mr. Strike, and I find it pays to play safe and sane and preserve my men intact.”

“I value them too much to risk their lives for the sake of a bunch of cheap thrill seekers back home. No. We have excitement and adventure only when someone makes a mistake. Carlyle parties make a minimum of mistakes.”

That was the arrogant and cocksure Gerry Carlyle speaking and Strike did not try to dispute her. “I suppose you used a sort of hypodermic bullet in that rifle of yours. But I thought you’d be using more scientific weapons than that. It seems sort of—sort of primitive.”

The girl smiled.

“I know. You’re wondering about the anesthetic gases. Or the wonderful new paralysis ray. Well, there’re a lot of inventions that work fine under controlled lab conditions that are flops in the field.

“The paralysis ray is just a toy, totally impracticable. It’s unreliable because each species of animal requires a different amount of the ray to subdue him and we seldom have time to fool around experimenting in my work.

“It may also prove fatal if the victim gets too much of a jolt. As for knockout gas, it necessitates the hunters wearing masks and it is difficult to control in the proper dosages—between unconsciousness and death.”

Strike nodded understanding and turned to be surprised by the activity behind him. While he and the girl talked the party had prepared the motionless shovel-mouth for transportation back to The Ark. Broad bands of bluish metal had been fastened around legs and neck and the men had even managed to slide two or three underneath the huge body and encircle it.

Wires led from each piece of metal to a common source, a compact boxlike affair vaguely resembling a battery case with two dials on its face. A throw of a switch energized the metal and gradually the mighty bulk of the shovel-mouth rose from the ground. It hung in the air, suspended like a grotesque toy balloon. To tow it back to the ship would be a simple matter.

“Anti-gravity,” explained the girl. “We give the metal banks a gravity charge of slightly more than one. Like repelling magnetic charges, they rise from the ground and carry the animal with them.”

The equipment-bearer simply lashed a rope round his waist to pull the shovel-mouth along behind and the party resumed the hunt.

“I think,” said Gerry Carlyle, “that we’re too likely to bump into something without warning in this mist. If you’ll bring out the electronic telescope, Mr. Barrows—”

Barrows at once produced one of the most interesting gadgets that Strike had yet seen, a portable model of the apparatus used on all the modern centrifugal flyers. It consisted of a power unit carried by one of the men, and a long glass tube to be carried by the observer.

The front of it presented a convex surface covered with photoelectric material, to the electron streams of all kinds of light, from ultra-violet to infra-red.

As the light particles entered the tube, they passed through a series of three electrostatic fields for focusing, and then through another field for magnification. At the rear of the tube they struck a fluorescent screen and reproduced the image. Looking through the baby telescope gave the impression of gazing down a tunnel in the mist for as far as the eye could reach.

By keeping in constant touch with Ransom at the post, who kept the beam moving slowly around like the spoke of a wheel, Strike enabled the party to move laterally.

Through the telescope they picked up many of the smaller and shyer life-forms not ordinarily seen—lizards, crawling shapes, crablike forms, even two or three of the scaly man-things native to Venus, slithering silently through the fog with sulky expressions on their not-too-intelligent fishlike faces.

Strike and Gerry became so interested in watching this teeming life through the ’scope that they walked into real danger.

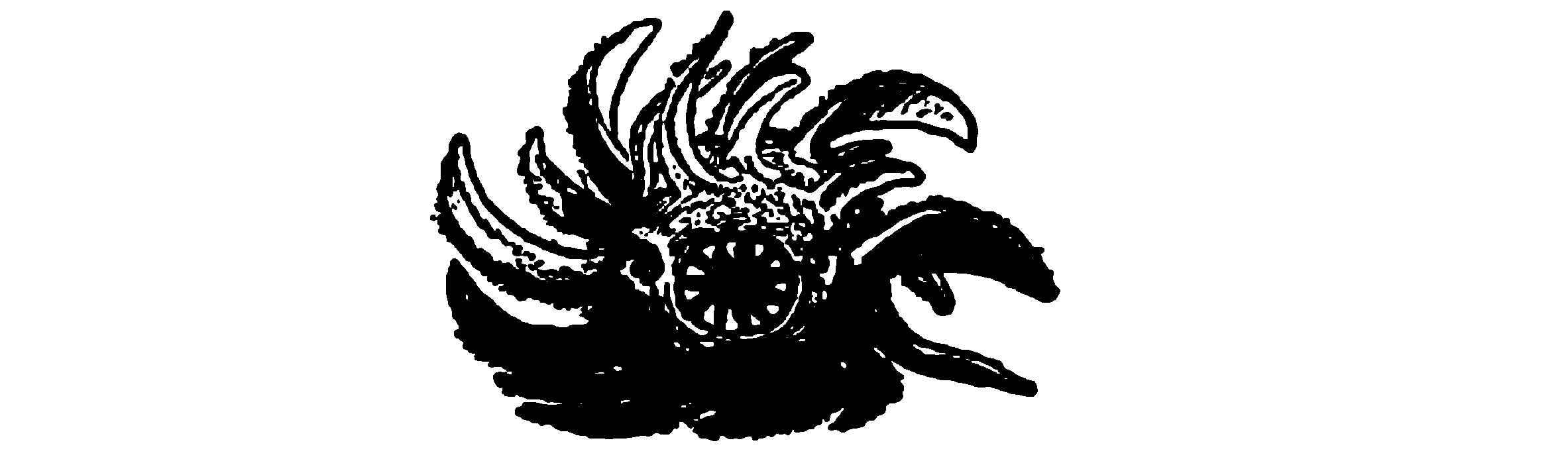

Without warning a rushing sound filled the air at their left, and a round gray ball rolled swiftly into view. It crossed their path dead ahead—propelling itself with dozens of stout cilia sprouting indiscriminately from all sides—then paused abruptly.

The miniature forest of arms waved delicately and exploringly in the air as if trying to locate the source of a new disturbance. Then the fantastic thing rushed unerringly at the Carlyle party.

All the hunters leaped for cover and let the juggernaut roll past. It stopped a few yards beyond with another waving of cilia, as if listening intently. Gerry pumped a hypodermic bullet at it, but the charge ripped glancingly off the armourlike lorica.

“Rotifer,” said Strike shortly. “Something like the tiny animalcules back on Earth, magnified many times and adapted for land travel. Venus is largely aqueous and was even more so at one time. Much of its terrestrial life developed from life-forms originally dwelling in the water—”

He stepped aside again casually as the rotifer rumbled by. “They have their uses, though. That half-hidden mouth of theirs takes in everything it contacts. They’re the scavengers of this planet. We call ’em Venusian buzzards.”

The party scattered for a third time as the blind devourer sought to catch them once more. Barrows looked appealingly at his leader.

“They may have their uses,” admitted the sub-pilot, “but this baby’ll be a nuisance if we have to spend the rest of the trip dodging him.”

There was truth in that, so the rotifer was despatched with a cathode bolt. But as they crowded around to examine this curious bit of protoplasmic phenomena, a shrill scream as shocking as the shriek of a wounded horse tore through from the upper air. They swiveled about to gaze upon the most terrifying of all products of Venusian vertebrate evolution.

Fully fifty feet the monster towered into the midst, standing upright on two massive legs reminiscent of the extinct terrestrial Tyrannosaurus rex. A set of short forelegs were equipped with hideously lethal claws. The head was long and narrow resembling a wolf’s snout, with large ears and slavering fangs.

Everything about the nightmare creature was constructed for efficient annihilation, particularly of those animals who mistakenly sought safety in the tops of the tall trees.

“A whip!” yelled Strike, turning to the cathode-gun carriers, sudden apprehension stabbing him deep. “It’s a whip! Let him have it, quick!”

The men looked uncertainly to Gerry Carlyle, who promptly countermanded the order.

“Not so fast. I want this one alive. They’ve nothing like him in London.”

She flipped up her rifle, fired at a likely spot. Strike groaned as the monstrous whip squealed shrilly again and again, staring down at the tiny Earthlings from fiery eyes.

Then from that wolfish snout uncurled an amazing fifty-foot length of razor-edged tongue, like that of a terran anteater. Straight at Gerry Carlyle it lashed out, cracking sharply. Strike’s rush caught the girl from behind sprawling her on the spongy earth.

“Curl up in a ball,” he yelled in her ear, “so it can’t get any purchase with that tongue!”

Gerry obeyed and Strike turned to warn the others as the whip swished over the girl’s ducking head.

“Scatter!” he cried. “Don’t—”

But too late. That coiling sweep of flesh rope struck Barrows glancingly across the head, shearing off the lobe of one ear. Blood spurted as the sub-pilot staggered away, one hand to his face.

The rest of the bearers darted alertly away in all directions, seeking the shelter of the fog. But the man who was burdened with the heavy equipment paused momentarily to shed himself of it. It cost him his life. Straight and sure that incredible tongue snaked out to wind itself around the man’s twisting form. Instantly he shot into the air toward the gaping fanged jaws.

The fellow struggled, screaming. In vain. One arm was pinioned. He hadn’t a chance to defend himself. Before his surprised companions could bring their guns to bear on the whip, there was a swift crunch, a hideous splattering of crimson stuff bright and horrible against the drab background, and it was all over. The expeditionary force was reduced by one.

All possibility of rescue being gone, the reserve gunners lowered their deadly guns and allowed the hunters to go about the job of subduing the monster.

Little snapping reports sounded in rapid succession—three, four, five.

And presently the whip reeled like a tower in an earthquake. It swayed. A few wavering steps described a short half circle. Then quietly it flopped awkwardly down and passed into insensibility.

Strike stood upright and pulled Gerry to her feet. He wiped cold sweat from his brow.

“Whew! That was too close for comfort!”

The girl brushed herself off and stared the trader in the eye. “Hereafter, Mr. Strike, please remember that in a real emergency such as this, one of our cardinal rules is every man for himself. The principle of throwing away two lives in a futile effort to save one is not encouraged among us. No more heroics, if you please!”

Strike’s face flamed. No one likes to be bawled out when he’s expecting warm gratitude. But even more Strike was angry at the apparent callousness.

“Then you don’t think much of your assistants,” he snapped, looking significantly at the bloody muzzle of the whip.

No emotion disturbed the serenity of the girl’s face.

“On the contrary. I regret Blair’s passing very much. He was a well-trained and valuable man. But he can be replaced.”

“Good God, woman!” cried Strike. “Haven’t you any feelings. A friend of yours has just been done to death horribly on an alien planet, far from his home and family. And you—” He stopped, suddenly ashamed of his outburst of sentiment.

Gerry said simply, “We never sign on family men.”

Then she turned her back on Strike and snapped orders to prepare the whip for transportation back to The Ark. But in the last tiny instant as she turned away Strike glimpsed something in her eye which provided him with sudden and complete revelation.

It explained at once the reason for Gerry Carlyle’s shell of impersonal reserve and callousness. She was a woman walking in a man’s world, speaking man’s language, using man’s tools.

As a constant companion of men she had to train herself to live their life, meet them on their own terms. To command their respect she felt she had no right to use the natural endowments—her charm and beauty—that nature intended her to use for that purpose.

Indeed, she dared not use them, for fear of the consequences. To give way to feminine emotion would be, she feared, to lose her domination over her male subordinates. She was, in short, that most pathetic of beings—a woman who dared not be a woman.

All this Tommy Strike guessed and his feelings toward Gerry Carlyle began to change from dislike to pity and perhaps to something warmer. For he was certain he had seen real tears—unshed.

The succeeding days passed swiftly as specimen after weird specimen was subdued and carried to the rapidly filling hold of The Ark.

Strike’s only worry was the ever-approaching hour when he must produce a Murri or face Gerry’s wrath. And although he knew it was coming, still the demand arrived too suddenly for him on the morning of the sixth day.

“Mr. Strike.” Not once had the girl dropped her shield of formality. “I’ve been pretty patient with your repeated sidetracking of my request for a Murri. But our visit here is almost over. We leave in forty-eight hours. To remain grounded during a Venusian night would mean a tiresome and dangerous journey home. Come on—no more stalling.”

Strike looked at the girl. “What if I refuse?”

Gerry smiled glacially. “Your company would hear about it at once. You were ordered to assist us in every way, you know.”

The trader nodded, shrugged.

“All right. Just a second while I—”

The rest of his sentence was lost in a clatter of footsteps as Ransom came down the metal stairs with a curious piece of apparatus in his hands.

“Thought you’d be needing this, Tommy,” he said significantly with a disgusted glance at the girl.

“Yeah, I sure do.” Strike fitted the contrivance to his body by shoulder straps.

“Now what?” Gerry wanted to know. “Do you need special equipment to find a Murri? What’s that contraption for, anyhow?”

Strike was willing to explain.

“The power unit of this ‘contraption’ consists of a vacuum-tube oscillator and amplifier and the receiver unit of an inductance bridge and vacuum-tube amplifier. There’s also a set of headphones”—he held them up in classroom style—“and an exploring coil.”

“The bridge is energized by a sinusoidal current, brought to balance by appropriate resistance and inductance controls. If a conductive body comes within the artificially created magnetic field of the coil, eddy currents set up in the conductive mass will reduce the effective inductance of the exploring coil, serving to unbalance the bridge. This condition is indicated in the headphones—”

“Stop! Stop!” Gerry covered her ears with her hands. “I know an ore-finding doodle-bug when I see one! I just wanted to know why you’re carrying it with you now.”

“Oh, for protection.”

“Protection against what?”

“The natives.”

Gerry stared. “Natives. Those scaly, fish-faced things that skulk around just out of sight in the fog? Why, those timid little creatures wouldn’t hurt us—they couldn’t. Besides, how’ll your doodle-bug protect us against them?”

“Why, they’re very clever at hiding in the mist and this metal indicator will reveal their presence if they get too close. You see, all the natives in this sector wear gold teeth!”

Someone tittered and Gerry flushed. “If you please, Mr. Strike, let’s stick to business and keep the conversation on an intellectual plane. A good joke has its place but—”

“That’s no joke,” Strike said with a touch of bitterness. “It’s a fact. Ever since Murray made his first trip to Venus the natives have gone for gold teeth in a big way. They took Murray for a god, you know, and emulated him in many ways.

“He had several gold teeth, relics of childhood dentistry, so the natives promptly scraped up some of the cheaply impure gold that’s found around here and made caps for their teeth. As for their not hurting us, Miss Carlyle that remains to be seen.”

“It has always meant trouble when one of you animal-catchers tries to mess around with the Murris. You’ll understand me better in a few minutes.” He shrugged and twitched his eyebrows. “I’m just being prepared.”

“Rats! Mystery, generalities, trouble—but no explanations! Your evasive hints of reasons not to touch the Murris just fascinate me all the more. I wouldn’t drop the hunt now for all the radium on Callisto!”

“All right,” Strike capitulated curtly. “Let’s go.” He struck off straight through the mist as if knowing exactly where he meant to go. In five minutes he halted before a mighty cycad peppered with twelve-inch holes which housed a colony of at least fifty of the famous Murris.

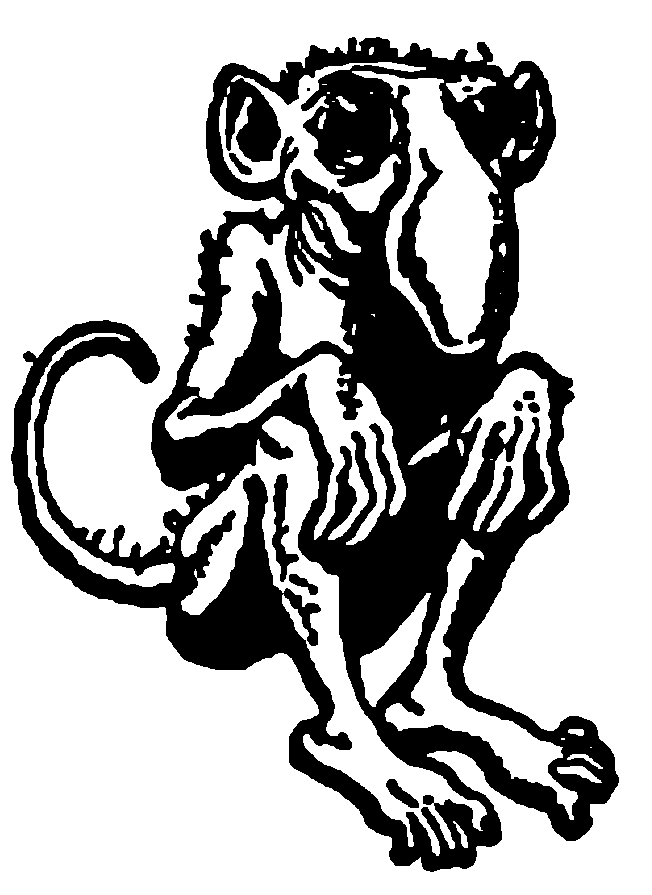

“There you are,” said Strike with resignation. “Pseudo-simia Murri.”

Gerry completely forgot to be indignant at Strike’s holdout. She was swept away in a gale of merriment that overcame the party at sight of the strange creatures.

Perhaps half of the colony were in constant motion, scrambling round and round the huge bole of the tree, up and down, popping in and out of their holes, out along the mighty frondlike branches and back frantically. The others simply sat watching in solemn indifference, occasionally opening their pouting lips to ask sorrowfully—“Murri? Murri? Murri?”

They were well named. Though soft and grayish-brown, with scanty hair growth on their backs, their size and antics did resemble terrestrial simians. With their tremendous nasal development, they looked much like the Proboscis monkey.

And this very de Bergerac beak of a nose made their name even more appropriate, for Sidney Murray, Stanhope’s co-explorer, was famous throughout the System for having the hugest and ugliest nose extant.

The Pseudo-simia Murri colony presented to the eyes of the fascinated watchers a hundred facial replicas of Sidney Murray, spinning and dancing fantastically around the tree.

“Oh!” gasped Gerry finally, wiping laughter’s tears from her cheeks. “Oh, but this is wonderful! Who—who named them?”

Strike looked solemnly at her. “Murray himself named ’em. He has quite a sense of humor.”

“Sense of humor! Oh, it’s colossal!” She took a deep breath. “What a sensation a dozen of these cute little butterballs will make in London. What a prize!”

“You haven’t got them in London yet,” Strike pointed out, keeping one uneasy eye on the indicator of his “doodle-bug.”

“If you think anything’s going to stop me now you don’t yet know Gerry Carlyle.” Again she was the arrogant, self-willed expedition commander.

They moved up to the cycad and examined the Murris at close quarters. They were quite tame. The close inspection revealed three facts of interest. The first was the presence of a short, prehensile tail equipped with a vicious-appearing sting near the tip.

“Only a weak defensive mechanism,” Strike explained, “as Murris live almost exclusively on the datelike fruits of the tree they live in. The sting’s no worse than a beesting.” He extended one knotty forearm, showing a small pockmark where he had once been stung.

The second was the large brown eyes possessed by the Murri, which stared at the intruders unblinkingly with a heart-wringing, hypnotic expression of sorrow.

“They look as if they’d seen all the trouble and woe in the Universe,” Barrows said. “Makes me feel like a louse to take them away from their home!”

The third was a heap of strangely incongruous junk piled at the base of the big tree. There were cheap clocks, gewgaws, matches, children’s fireworks, odds and ends.

“Offerings by the natives,” explained Strike. “That’s the legal tender up here. Medicinal weeds and rough gems in exchange for—those things.” He gestured at the pile of trash. “Anything fire-producing is especially valuable. The Murri is the native’s god—because of his resemblance to Sidney Murray, the First God.”

There was more laughter, but subdued this time as the party realized that removing one or more Murris would be to commit Venusian sacrilege.

“I see now what you meant by ‘causing trouble,’ ” Gerry said. “But it can’t be too much for you to handle. It’s happened before, I assume, and always blew over. These primitives—if that’s your only reason for dissuading us to capture a few—”

“That’s not the only reason.” But Strike would explain no further.

“More mystery!” Gerry snorted and supervised the setup of a big net under one of the longer overhanging branches.

Then two well-directed shots snapped the limb and catapulted a half-dozen astonished Murris into the net. With incredible agility most of them bounced into the air and scrambled to safety. But one was caught in the tricky meshes. The ends of the net were quickly folded together to form a bag.

“Got him!” exulted Gerry. “Why, that was easy!”

“Sure. But he isn’t in London Zoo yet nor even back to the ship.”

Gerry gave Strike a withering look, then peered into the net. The Murri lay quiescent, staring up with enormously round-eyed amazement.

“Murri-murri-murri?”

Gerry laughed again at this fantastic miniature of the great Murray, mumbling earnestly to himself. “Back to The Ark, boys,” she cried. “We’ll have a lot of fun with this little dickens!”

The party turned to retrace its steps and then trouble broke out for fair. When the Murri had been removed about ten yards from its home tree a violent fit of trembling seized him. He screamed shrilly two or three times and from the Murri tree came a hideous shrieking clamor in response.

The little captive burst into a flurry of wild activity, struggling with unbelievable fury to escape. He twisted, clawed, spat, bit. As the carriers bore him inevitably further away from his home he seemed to go absolutely mad, stinging himself repeatedly with barbed tail in an outburst of insane terror.

After a series of heart-rending cries of despair he gave a final frenzied outburst that ended with a gout of pale straw-colored blood from his mouth.

The entire party stopped to stare appalled at the little creature. Gerry Carlyle’s shell of reserve was punctured. She looked badly shaken. It was some moments before she could force herself to open the net and examine the quiet little body.

“Dead,” she pronounced though everyone knew it. “Internal hemorrhage. Burst a blood vessel.”

Strike answered her bewildered glance with melancholy triumph.

“Agoraphobia. Murris are the most pronounced agoraphobes in the System. They spend their whole lives on and around the particular tree in which they’re born. Take ’em a few yards away and they have a nervous breakdown ending in convulsion and death.”

He indicated the dead body in the net. “I could have told you but you wouldn’t have believed me. You’d have come to find out for yourself anyhow.”

Gerry shook herself like a fluffy dog that has just received an unexpected ice-water shower.

“So that’s what you meant when you said I’d never bring one back alive, is it?”

“Partly.”

“Partly! You mean there’s something else queer about these—”

Strike nodded gloomily. “You’ll find out before long. I know what you’re going to do. Capture another. Cut off his tail so he can’t sting himself. Tie him up like a Christmas package so he can’t move hand or foot. Anything to keep him from killing himself by struggling. Right?”

“Right!” Gerry determined.

“Rogers tried all that when he was here, yet he failed.”

“And so?”

The trader shrugged. “So you’ll fail, too. But don’t let me stop—”

“You won’t stop me, Mr. Strike. Don’t ever think it.”

Together with Kranz, the girl rigged up two makeshift straightjackets to hold the captive Murris rigidly unmoving. Meanwhile, the other hunters spread the big net again and shot down another branchful of the curious Murris. The healthiest pair were quickly strapped up tightly and the party left to the accompaniment of a terrific yapping and hissing and yammering from the survivors of the colony.

Strike and Ransom spent the remainder of the lingering Venusian day resting from their exertions. Activity in that vicious climate quickly sapped the most rugged strength and Strike particularly felt that he had been drained of all energy.

As the light imperceptibly faded Ransom suggested, “I guess The Ark will be leaving soon. Now’s the best time for ’em to take off. Conjunction.”

Strike shook his head.

“No. That tough little Carlyle is over there in her ship learning a mighty bitter lesson. She won’t leave now. She won’t leave for some time,” he predicted. “Wait and see.”

But only to himself did he admit that he wanted badly to see that incredible girl again.

Strike was right. As the absolute darkness of Venusian night dragged its black cloak over the trading post light footsteps ran up the stairs outside. Knuckles beat on the metal door which Ransom opened. Gerry Carlyle pushed in.

“Mr. Strike,” she said and there was a worried crease between her eyes, “neither of the Murris will eat. We can’t force anything down their throats. And if we free them they immediately have one of those terrible fits!”

The trader shrugged. “So why come to me?”

“Can’t you suggest anything to do? They’ll starve themselves to death. And dead Murris have no market value. I’ve sworn I wouldn’t return without at least one healthy Murri, so you’ve got to help me!”

“Nobody can do anything. You’ll never take them back alive. I told you that before. Presently you’ll believe it. If there’s any mercy in you you’ll return those two to their home while they’re well.”

Gerry’s eyes flashed blue fire.

“I’m trying to be merciful without compromising my conscience. If humanly possible I’m taking those Murris home alive. Now—if you’ll only help—we’re going to try feeding through a stomach tube. If that fails, with injections. I thought you’d be able to help us in the food selection.

“It’s hopeless. Rogers tried that too. When you take a Murri away from its home he undergoes such a nervous shock that his metabolism goes haywire. He just can’t assimilate anything.”

Gerry went away furious but was back within twenty-four hours. She was beginning to show the strain. Her hair was awry, her eyes blood-shot from lack of sleep.

“Strike,” she begged, “can’t you suggest anything? They’re growing thinner by the hour. You can see them waste away. If you’ve been holding something back just to—to discipline me I’ll say, ‘Uncle.’ Only please—”

Strike seized the chance to turn the knife in the wound.

“You flatter yourself if you think I’d sacrifice even a couple of Murris for the sake of softening you a little.”

But the thrust missed its mark. Gerry was lost within herself, absorbed in her battle to bend two insignificant caricatures to her will. “Drat them!” she flared. “They’re doing this to spite me. But I’ll make them live. I’ll make them live!”

Forty-eight hours later she was back again, hanging frantically to Strike’s sturdy arm. The Murris’ silent martyrdom had broken her completely. She was a nervous wreck.

“Tommy,” she wailed. “I can’t stand it any longer. They just sit there, so helpless, so frail, without a sound, and stare at me. Those pathetic brown eyes follow me wherever I go.

“They—they’re mesmerizing me. I see them in darkness—I see them in my dreams when I manage to get to sleep. It’s pitiful—and horrible. Even the crew goes around now with silent accusation in their faces. I can’t stand it.”

Strike’s heart went out to this bewildered girl, needing a man’s comfort but not knowing how to get it.

“You see now why Rogers and the others wouldn’t talk about their experience with the Murris? Why I said you wouldn’t believe me even if I told you?”

“Yes. I understand. Rogers was ashamed to admit what he thought was a weakness. Embarrassed to have anyone think a funny little Venusian monkey could soften him up by just staring at him with those hypnotic brown eyes.

“I—I sent the boys out to find that tree and dig it up whole, Murris and all to transport back to earth. I thought that might solve the difficulty. But I see now it wouldn’t.”

“What!” Strike roared in sudden apprehension. The fools! Not content with stealing the natives’ local gods, now they intended to desecrate the whole shrine! “Out there in the darkness? It’s suicide!”

The trader leaped for his furs and heating pads, dressing quickly for a sortie into the bitter Venusian night. Gerry looked surprised.

“How do you mean? Are they in danger?”

“The natives have brought nothing here for trading in the last seventy hours,” he returned grimly. “That means trouble. Plenty!”

“But surely they’re not out at night! The temperature—”

“Doesn’t affect them. They evolved from an aqueous life-form and like it cold. Fewer natural dangers for them at night too.”

He strapped on the gold-detector and radio receiver, strode for the door. “You stay here. Roy! Get the beam working!” He seized a light and barged out.

Gerry’s mouth thinned out as she slipped her fur cape over her head and determinedly followed Strike down the stairway. There was a brief argument ending with the trader’s angry capitulation.

“We can’t debate it now. At least make yourself useful. Carry this.” He handed her the powerful searchlight and they moved off together.

A new world was revealed in the gleaming swath of the light, everything covered with a thick frost, utterly lifeless and still. Each breath was a chill knife in their lungs. In the intense quiet they heard the faint sounds of the work party hard at the task of removing the Murri tree.

A quick run brought them to the clearing. Stationary lights made a ring about the workers, who had already fastened anti-gravity plates to the tree and were loosening the frozen soil. Strike’s voice rang out.

“Stop work, men! Grab your tools and beat it back—” He paused. The needle on the detector’s dial was jerking spasmodically.

“Quick!” yelled Strike. “The natives are close by! Run for it!”

But the work party, blinded by the lights, gaped stupidly about and called out questions. Strike ran at them, shouting furiously, but his words were lost as he witnessed an incredible sight. One by one the members of the digging party were falling, wriggling and twisting amazingly.

One of them thrust his feet straight into the air and made grotesque walking motions. Another dug his face into the dirt trying to walk right down through the earth. The only one remaining upright turned round and round in tight little circles like a pirouetting ice-skater.

“Good heavens!” cried Gerry unsteadily. “What’s wrong with them?”

Strike seized her about the waist. “Gas! Don’t breathe! The natives get it from one of those devilish Venusian plants. Gets into the nervous system. Localizes in the semi-circular canals. Destroys the sense of balance!” He started back through the mist toward the station.

But with the third step Strike’s world reeled sickeningly about him. He dropped the girl, fighting desperately with outstretched arms for balance. The ground heaved beneath him. Wherever he strove to put his feet it seemed successively to be the sky, the perpendicular bole of a tree, nothingness.

His eyes began to throb intolerably. Terrible nausea shook him and he retched violently several times. He thrashed about so wildly in his efforts to stand upright that his equipment was scattered about the clearing, much of it smashed.

Strike forced himself to lie quietly while the visible world rocked like a storm-lashed ship. He was conscious of the frightened yells of the stricken workmen, a rush of feet, the monosyllabic squeaks and rasps of the Venusians, whose gill-like breathing system filtered out all the poisonous elements of the atmosphere.

Then Gerry’s startled scream knifed his consciousness. Just one outcry, no begging for help. But the sounds of her aimless struggle were plain as she was carried away.

Strike sat up. His smarting eyes took in a confused blur of moving figures. The man who had been standing was down now, a literal pin-cushion, bristling with poison-dipped native spears. Already the body was bloating. None of the others, apparently, were injured. Then a horrid vomiting welled up in Strike’s throat, and he rolled over to be sick again.

But Strike, on the extreme edge of the clearing, had inhaled only a little of the gas. He lay with his face close to the frozen earth, breathing cautiously, testing every lungful for tell-tale odors, then exhaling vigorously.

Gradually the earth slowed its spinning as the stuff worked off. Strike became conscious of a splitting headache as if every nerve-end in his skull were raw and throbbing. But as he took in the scene before him all thought of his own discomfort vanished in a wave of horror. The natives were out for revenge and Gerry Carlyle was their intended victim!

Strike had underestimated the natives’ intelligence. Smarter than he thought, they had recognized somehow in the anti-gravity plates fastened to the tree trunk the greatest threat to the Murris. Further, their sluggish wits had puzzled out cause and effect and had gone unerringly to the control unit with its deadly switch, ready to unleash its power with the touch of a finger.

Gerry lay in a limp bundle on the ground, jerking now and then. About her slim body were clumsily fixed at least a half-dozen of the anti-gravity plates. And the leader of the Venusians was bending over the switch.

Strike started up in a frenzy, yelling. Rubbery knees promptly sent him to the ground again. Not yet. No strength. He whispered a prayer for something to delay that outstretched native finger hovering over the power unit.

Perhaps he would move it the wrong way and—but Strike went cold all over at the thought. He wasn’t sure, but wouldn’t that smash Gerry into a bloody pulp, grind her into a shapeless mess?

Strike began to crawl grimly toward the lighted circle and the pile of weapons belonging to the disarmed work party. It was far, too far. He’d never make it. He paused to be sick again, less violently this time. His head was clearing rapidly but too late. He had to delay things somehow.

Strike’s hand bumped against his pocket, dipped in and swiftly out again holding his pipe. Still half full of tobacco. He snatched out a lighter and applied the flame, sucking vigorously, fighting the giddiness, blowing great clouds of pungent smoke all about him. The pipe dropped from nerveless fingers and he hunched down in a prayerful attitude, hoping, waiting tensely. Had he failed?

Zin-n-ng! Plock! It worked! Strike ducked and curled up into as small a ball as possible. In a split second the air resounded with the shrill whines of hundreds of the tiny whiz-bang beetles, armor-protected against the cold, as they hurtled in a cloud to the source of their favorite scent.

Few flew low enough to hit Strike and those were glancing blows that simply left red welts across his back. He saw perfectly the entire scene as his unwitting allies, the whiz-bangs, stormed into the clearing.

It was as if someone had loosed a series of shotgun charges at the natives. The leader of the Venusians dropped as if cathoded when several of the armored beetles rifled into his most vulnerable spot, the throat.

The natives set up a hideous thin wailing. They ducked. They flailed about them with vigorous futility. Finally they broke and ran wildly away into the dark, dropping even their weapons.

For awhile the whiz-bangs zoomed back and forth across the clearing but eventually they too vanished as Strike’s now-buried pipe gave forth no more enticing scents. Presently Strike stood up, brushed himself off and grinned. This was his moment! Like a conquering hero he strode into the clearing to gaze on the devastation wrought.

The workmen were still prone, sensibly waiting for the effects of the gas to wear off. Gerry leaned like an old rag against the tree, staring with dazed eyes at her deliverer. Her fingers trembled so that Strike had to help her unfasten the anti-gravity plates.

She tried to stand erect but her knees betrayed her and she fell into the trader’s ready embrace. He tried to look stern.

“Well, young lady, I trust you’ve learned two lessons this night. One, that even a Gerry Carlyle can’t always have her way—especially with the Murris. Two, that a mere man, even if only to make an occasional unwanted sacrifice, can sometimes come in pretty handy.”

Gerry became acutely conscious of her position and she tried to free herself with no great earnestness. Strike laughed. She turned a furious crimson and he laughed at her again.

“Simply a vaso-motor disturbance,” she explained frigidly.

“Is that what you call it? I rather like it. I want to see more.” Strike kissed her and Gerry’s vaso-motor system went completely haywire.

From far up in the invisible branches of the Murri tree one of its inhabitants, disturbed by the night’s hullabaloo, leaned out and inquired sleepily through his nose—“Murri? Murri-murri-murri?”

MURRI (MURRIS pl.)

(Pseudo-simia Murri)

Named for the great pioneer explorer Sidney Murray. Murris resemble the Proboscis monkey of Earth; and are a grayish-brown in color with scanty hair growths on their backs. They have large brown eyes and constantly murmur, “Murri-Murri-Murri.”

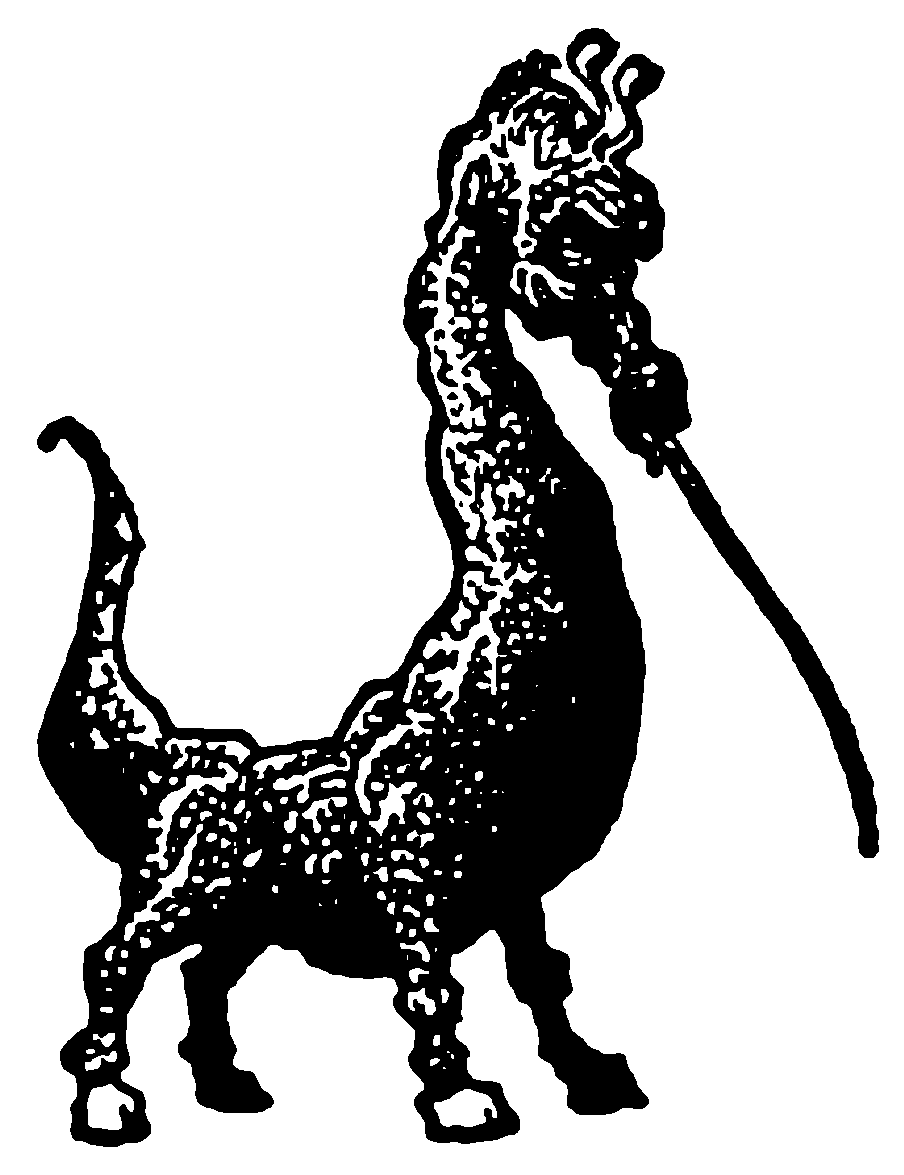

SHOVEL-MOUTH

This monster is fifty feet long and twenty wide, has three pairs of squat powerful legs ending in enormously spatulate discs. It has a tough gray hide. The head is a broad mammoth snout several feet from corner to corner. Herbivorous, it uses its mouth as a scoop and plows through the Venusian marshes scooping up its food.

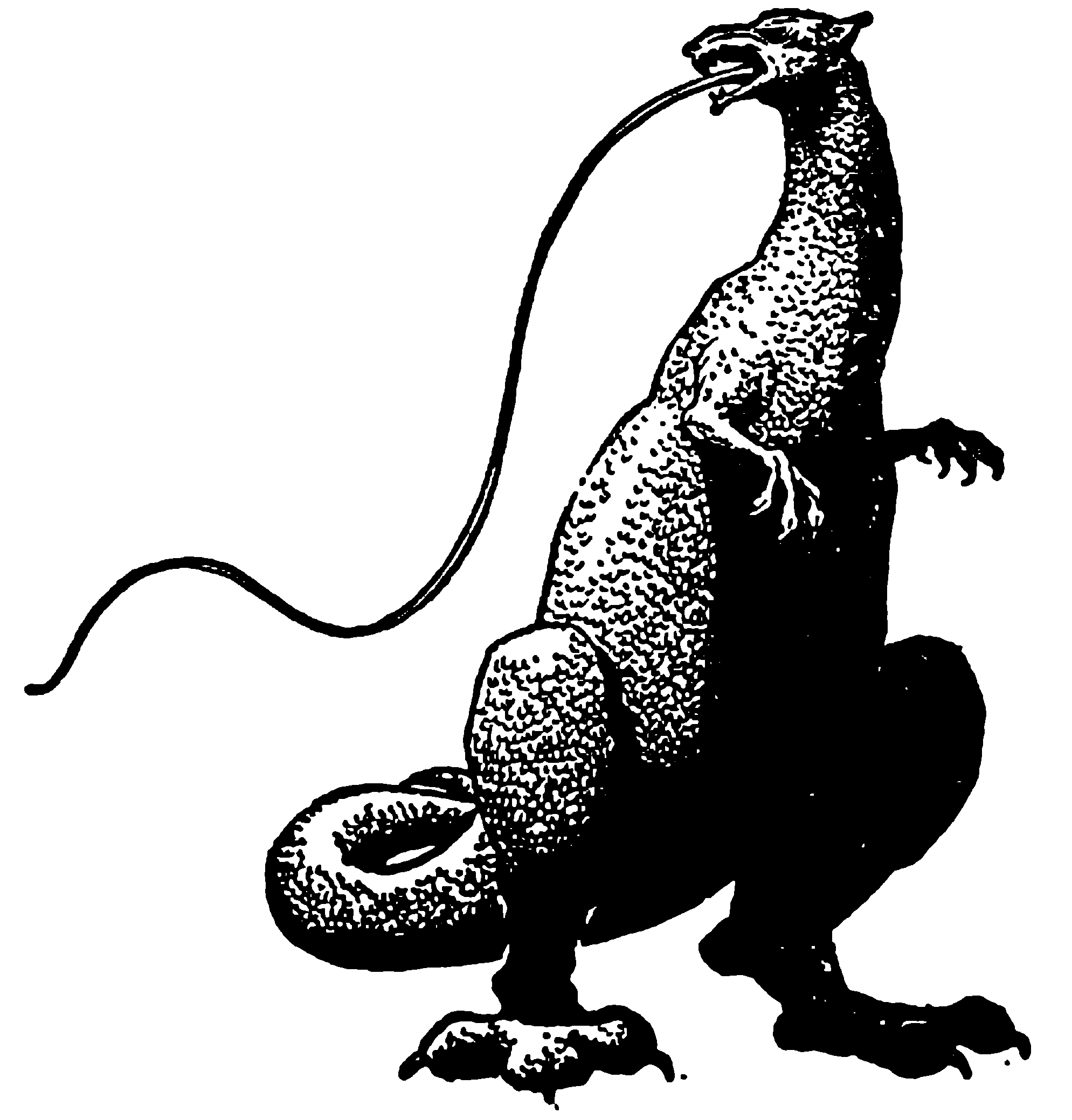

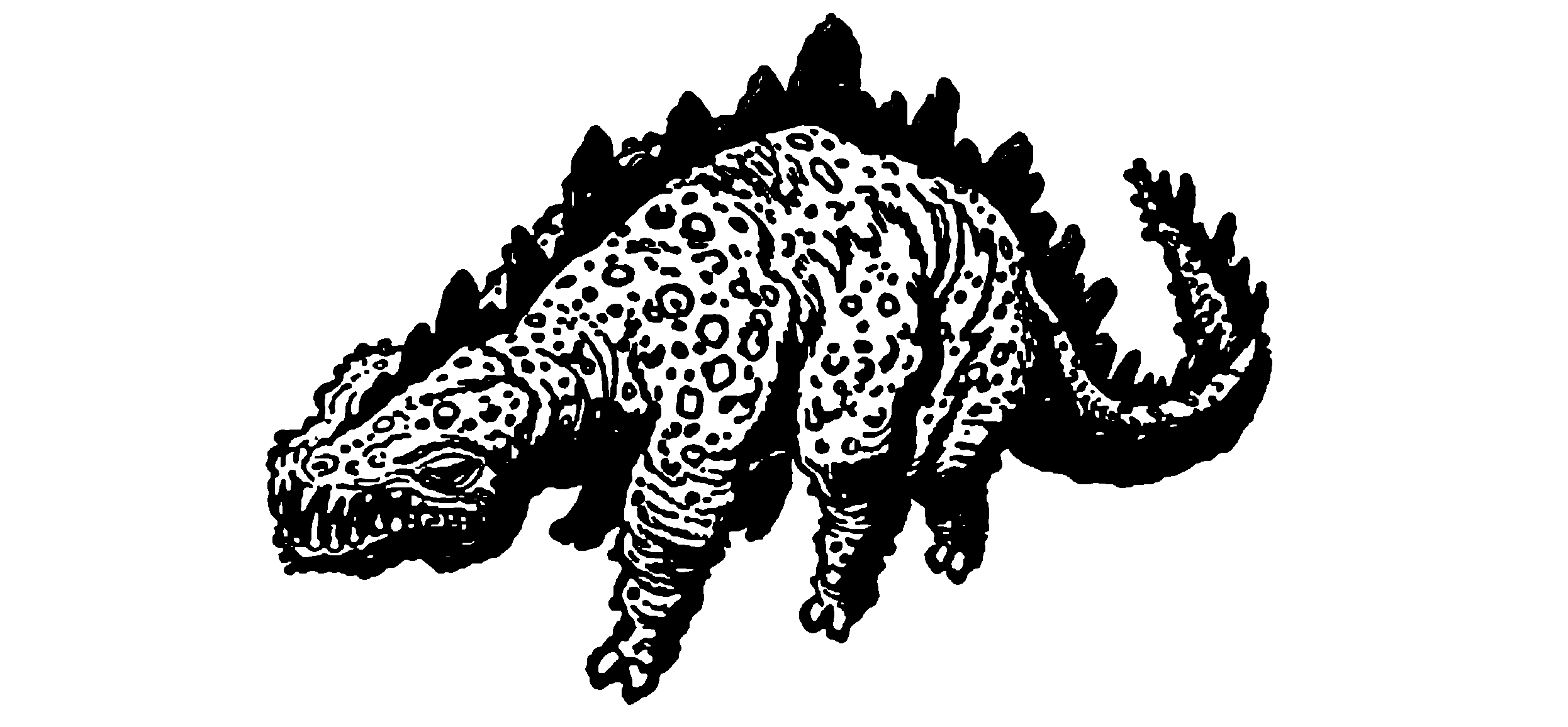

WHIP

This monster towers nearly fifty feet into the air, standing upright on two massive legs. A set of short forelegs equipped with claws and a long narrow wolf-like head, with two large fangs and small ears, describes the most vicious animal on Venus. Its tongue is fifty feet long and razor sharp.

Tommy Strike let out a startled squawk and tried to leap aside. Then suddenly his legs folded limply beneath him, and he fell to the floor.

“Blast it!” he howled at the man behind the desk. “Turn that thing off! You’ve crippled me for life!”

The man behind the desk was past middle age, with rabbit-like eyes peering through thick lenses. On the desk-top before him rested a lead-gray box, the interior of which contained a bewildering array of weird tubes and coils. There was a portable power unit, and a Cameralike lens now focused on Strike’s lower body. The man fumbled for the activating switch, snapped it off.

“Oh—so sorry, Mr. Strike. No harm intended. Just checking my—er—apparatus, seeing that it’s in working order.” Which explained nothing as far as his victim was concerned.

Strike reassured himself that his legs were still sound, then advanced on the older man, who retreated around the desk in alarm with apology very plain on his face.

“I’ve never struck a man as old as you,” Strike said grimly, “but so help me, I’ve a good notion to clip you down!”

It was at times like these when Tommy Strike was led to wonder, privately, if he had been really bright in allowing Gerry to argue him out of the independence of a trader’s life—boring and ill-rewarded as it had often proved to be—to become her second-in-command and the so-called “Captain” of The Ark. Gerry—in one of her rare, very rare, melting moods could certainly wear a fellow down and Tommy had begun to suspect that where Gerry Carlyle was concerned he was sometimes not quite bright—a thought he kept very much to himself. Anyway he had made his bargain—even if it had been when he had been completely dazzled—and he was too stubborn now to admit that he should have waited a little before he mortgaged his future. At any rate—if Gerry thought that he was going to be one of her “yes men,” she was very much mistaken.

Just then the office door slid noiselessly open and all activity was automatically suspended as a girl entered. One with a mind of her own to judge by her firm chin and high-tempered arch of nostril.

Her presence in the office brought an elusive suggestion of far-away places and unfamiliar, romantic things—a breath of the thin, dry wind that combs the deserts of Mars, a faint memory of the spicy scents that throng Venus’s eternal mists.

“Tommy!” Gerry snapped. “That’ll be enough! This is the New York office of the London Interplanetary Zoo, and was not designed for brawling. Now what’s it all about?”

Strike pointed at the visitor.

“This crazy inventor crashed in here with his box full of junk, acting mysterious and refusing to tell me what it’s for. Then all of a sudden he turned the darned thing on me and my legs went out from under me—”

“Oh, my. My, no. Not a crazy inventor. I am Professor Lunde, head of the department of physics at Plymouth University.”

“Oh!” There was a wealth of intolerant scorn in Strike’s voice, and he glanced significantly at Gerry. Lunde was well known as an overly self-important and doddering old fool many years past his prime. He had contributed nothing to advance physical research for ten years, hanging on at Plymouth by virtue of decades-old triumphs.

But, surprisingly, Gerry nodded.

“Sit down, Professor.” Turning to Strike, she explained, “Professor Lunde has been sending me a letter each day for the past week, cryptically reminding me that Rod Shipkey’s broadcast tonight would be of interest to me. Very intriguing.”

Lunde’s cheeks became shiny red apples. “Er—I must apologize for the melodramatic manner in which your attention was solicited. My assistant’s idea, really. Trevelyan is invaluable. Ambitious lad. He felt a woman in your position could not be reached under ordinary circumstances. But my daughter-in-law works for Mr. Shipkey, and, well, we got wind of tonight’s broadcast. I’d rather not explain the purpose of my visit until after you’ve heard Mr. Shipkey, if you please. He’s on now.”

Strike moved across the room to the television set, careful to keep out of range of Lunde’s funny box. He snapped the switch just in time to catch the program highlight.

The image of Rod Shipkey appeared. He spoke with the easy smoothness that characterized this veteran explorer and newsman’s delivery.

“. . . and now for our five-star believe-this-if-you-can of space. Around the largest of our planets, Jupiter, a whole host of satellites of varying sizes are slung in their orbits, tied by the invisible cord of gravity. The closest of these—paradoxically known as Satellite Five because it wasn’t discovered until after some of the larger ones—is a tiny bit of rock less than two hundred miles in diameter. It circles its primary some 112,600 miles away, hurtling like a cannon-ball around Jupiter in less than twelve hours. Incredible to think there might be anything on that barren and useless ball of stone dangerous or even interesting to Man, lord of the Universe.

“And yet—believe this if you can!—on Satellite Five there is a strange form of life which has defied all efforts to kill or catalogue it. No man has ever set foot on Satellite Five and returned alive!

“There are three authenticated records of space-masters who, either by choice or force of circumstance, landed their craft on Five. None has ever been heard from again. One of these cases was an expedition especially equipped to take care of itself under any conditions. It was the spaceship and crew of Jan Ebers, famous Dutch hunter of extra-terrestrial life-forms, one of the earliest pioneers in that romantic and dangerous business now epitomized by the greatest of them all—our own Gerry Carlyle.

“What this strange creature, so inimical, may be, we can only conjecture, aided by fragmentary notes of space men who passed briefly in proximity to Satellite Five, and by telescopic observations from Io, the next Jovian satellite outward. These give us a curious picture. Four things we can say about it. The thing is somewhat saurian or wormlike in appearance, low on the evolutionary scale. It seems to be of a sluggish nature, which would be natural considering what a limited supply of energy-building food elements there must be on Five. Not more than one had ever been seen at a given time. And—believe this if you can!—the monster breathes fire! Literally!”

Gerry and Strike exchanged tolerant smiles. They had seen a lot of incredible things, but a fire-breathing monster would require a good deal of seeing to believe.

“. . . have precedent for this phenomena,” Shipkey was saying, “in classic mythology. Cacus, from Vergil’s Aeneid, spouted fire. . . .” Here an attendant stepped into view with an artist’s conception of Cacus, the half-man, half-beast slain by Hercules.

“Well, ladies and gentlemen, time’s a-flyin’. Which is just as well, for there’s not much more we can say about our mysterious fire-demon, the Cacus. Safe it is to say that Man, with his insatiable curiosity, will not long let this remain a mystery. Someone with courage and the proper facilities will dare death once again and tear out the black heart of the secret that shrouds Satellite Five. Indeed, it’s a surprise to me that the inimitable Carlyle has not already done so. Can it possibly be that at last there’s something in the Universe that blonde daredevil hesitates to tackle? Believe that, ladies and gentlemen, if you can!”

The too-handsome announcer with his too-suave voice slipped deftly into focus, saying dulcetly, “This is WZQZ, bringing you Rod Shipkey with the compliments of Tootsie-Tonic, that gentle—” The screen went dead.

Strike looked across at Gerry in surprise.

“I bought one of those gadgets yesterday that automatically turns off the radio when the commercials begin,” she explained. “All right, Professor Lunde. We’ve played ball with you. We’ve granted you an interview, listened to Shipkey. Now let’s have a look at a brass tack or two.”

Lunde hitched himself forward earnestly.

“I have invented a weapon, Miss Carlyle, that will render the monster on Satellite Five helpless!” he proclaimed dramatically. “A paralysis ray!”

Gerry was dubious. She had seen abortive attempts at paralysis rays before.

“What’s the principle?” she asked.

Lunde removed his glasses and used them to tap his fingers and gesture with as he broke into a classroom lecture.

“The transmission of a nerve impulse along the nerve fiber is provided by local electrical currents within the fiber itself. But the transmission of a state of activity from one nerve fiber to another, as happens in the brain when sense organs are stimulated, or from a nerve fiber to a muscle fiber, as happens in voluntary movement, means transmission of excitation from one cell to another.”

“Passage over the junction point between cell is effected by a chemical transmitter, acetylcholine. Every voluntary or involuntary movement is accompanied by the production of minute amounts of acetylcholine at the ends of nerve fibers, and it is through this chemical agent that the muscle is set into action.”

Tommy Strike stirred.

“Old stuff, Doc. Sir Henry Dale and Professor Otto Loewi won the Nobel Prize for physiology and medicine for that discovery sixty—seventy years ago. Nineteen-thirty-six, wasn’t it?”

Lunde seemed vaguely annoyed by this display of erudition.

“Well!” Professor Lunde was resuming. “The acetylcholine is very unstable, and breaks down into other chemicals as soon as its function is completed. There is a disease known as myasthenia gravis, characterized by muscle weakness, in which there is too-rapid destruction of acetylcholine. Now, if a device could be built which would decompose acetylcholine as fast as it is produced within the body—you see? The muscles would be unable to receive nerve impulses, unable to act. Paralysis!”

Lunde now exposed the interior of the leaden-colored box which had caused Strike such distress earlier. The interior showed a bewildering array of tubes and coils, all in miniature; there was also a portable power unit attached. The lens was shutterlike, similar to a camera lens. It appeared extremely simple to operate.

“This, in effect,” went on Professor Lunde in lecture style, “produces a neutron stream. We decided against a stream of electrons, because they lack sufficient momentum; protons, too, can be deflected. But neutrons react with atoms at low energies. And the penetrating neutron blast destroys the acetylcholine by adding to its atomic structure, thus making it so extremely unstable that it breaks itself up at once. It does not harm blood or lymph or bodily tissues because they are essentially stable combinations, whereas acetylcholine is not.”

“Say! That makes sense! And I can testify the blasted outfit sure works! That means we can take a crack at this Cacus jigger on Satellite Five and show Shipkey up for a dope! How about it, Gerry? Let’s go!”

Gerry shook her head.

“Impossible, Tommy, and you know it. I have lecture commitments three weeks ahead, conferences with Kent on the autobiography, business appointments, a hundred and one things to do. No, the Jupiter trip’ll have to wait. Sorry, Tommy. . . .” Then Gerry’s voice turned poisonously sweet. “Besides, I have to run up to Hollywood on the Moon day after tomorrow. Special occasion at the Silver Spacesuit. Henri, the maître d’hôtel, is naming a sandwich after me. A double-decker: hard-boiled egg and ham!”

“Yow!” Strike convulsed with delight, with one wary eye on Gerry as if half expecting a missile. “That’s good. Y’know whose idea that is?”

“Certainly. Nine Planets Pictures runs the Moon as they please, and this is that chimpanzee Von Zorn’s idea of humor. He put Henri up to it. But boy—will I make a speech that’ll singe his ears!”

But Tommy wasn’t to be put off by changing the subject; he was like a small boy at prospect of a fishing trip. “All right; you can’t go. But nobody wants to take my picture or get my autograph. I’m not tied down here. Besides, I’m sick of sitting around. There isn’t a reason in the world why I couldn’t round up the crew and take The Ark myself!”

“I remember the last time you started out alone! On Venus—Remember the lost continent?”

Tommy Strike brushed that aside.

“That was different. This’ll be a cinch with The Ark’s equipment and Lunde’s ray and all the gang—”

“Well—” Gerry was weakening. “Might be arranged. Before we decide on anything definitely, though, there’re three things I’d like to ask Professor Lunde.”

“Yes, Miss Carlyle?”

“First, have you tried your ray on extra-terrestrial animals?”

“Oh, yes, indeed. The curator of the local zoo permitted experiments on several Martian and Venusian specimens. All creatures of our Universe, it seems, transmit nerve impulses with the aid of acetylcholine. Provided this—this Cacus is not a vegetable, I’m sure the ray will work on him, too.”

“All right. Secondly, what’s in this for you? Not money. Even if we found the ray practicable, you couldn’t manufacture it for general distribution because your only market would be hunters like myself who wish to capture live specimens.”

Lunde put on a vague dignity.

“Prestige, miss, is my sole motive. Prestige for Plymouth University and its facility.”

“I see. And now tell me who put you up to this?”

“I beg your pardon?”

“I mean whose idea was it to write me notes about the Shipkey broadcast and so on? You’re just not the type.”

“Er—no. Not entirely my idea. Trevelyan’s, really. He’s my assistant, or did I tell you that before? Smart lad—”

“Very well, Professor Lunde.” Gerry cut the interview off abruptly. “You’ve been very entertaining. My secretary’ll give you a written authorization to install your apparatus in The Ark. We may be able to give it a trial.”

As soon as Lunde had left Gerry immediately snapped open a circuit on the interoffice communicator.

“Barney Galt? You and your partner come right in.”

Two men promptly entered through another door. Galt was tall and lean with a face like a good-natured chow dog. His partner was a nondescript man of middle age. Both were old-time policemen, retired from public duty to act as private investigators for Gerry Carlyle. She wasn’t a girl to bother with bodyguards, but a woman in her position is besieged with all sorts of threats, rackets, fraudulent charities and fantastic schemes; Galt invariably discovered the good among the bad.

“Fellow named Lunde just left here, a little gray-haired chap with a bundle under his arm. Follow him, make a complete check. Don’t interfere with anything he may do; just report anything phony.”

The two detectives saluted casually and left on their unobtrusive mission. Strike snorted.

“Why set those bloodhounds on Lunde’s tail? He’s all right. A bit of an old fool who has stumbled on something good, but too dumb to be anything but honest.”

“Just routine, Tommy. I don’t think there’s anything wrong with Lunde. Just a hunch. If he gets a clean bill of health, you can take The Ark and go.”

“Woman’s intuition again?” Strike spoke with tolerant condescension.

“So what if it is? Tommy, I take lots more precautions than this when I sign the lowliest member of my crew for a dangerous expedition. No doubt Lunde is all he appears, and I know you can take care of yourself, but you can’t blame me for wanting to make sure when it concerns the man I love.”

They grinned at each other.

“Okay, fluff. Snoop around while I rout the crew out of their sinful pleasures and provision the ship. That’ll take several hours; you’ll know by then everything’s on the up and up. Call me as soon as Galt okays Lunde, because Jupiter’s nearing conjunction and I want to take off as soon as possible. ’Bye.”

Events marched swiftly moving inevitably into place the strange pattern that spelled disaster. Tommy Strike was busy over radio and telephone, giving the rallying cry that brought the seasoned veterans of The Ark rushing from all corners, dropping unfinished business or pleasures at once to get to the space-port in time to blast off on another adventurous journey. They’d tell you, those tough space-hounds, that Gerry Carlyle’s expeditions were nothing but iron discipline and hardships with sudden death waiting to pounce on the unwary; but you couldn’t bribe one of them with love or money to give up his berth on the famous ship.

At the landing field itself, under the blazing carbon dioxide lamps, a small man drove up in a surface car, showed an authorization to the guard, passed into the burglar-proof enclosure. He carried a bundle to The Ark, again showed his pass, and went inside. He came out before long empty-handed.

Gerry Carlyle worked without cessation in her office, while outside the city’s lights went out one by one, and the muted torrent of traffic in the canyons of the city street grew thinner and thinner, dwindling away to trickles. Presently a light flashed above the door to the outer office. Someone wanted admittance. Gerry slid a heat-ray pistol into plain sight, then tripped the foot-switch which unlocked the door.

“Come in!” she cried.