* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

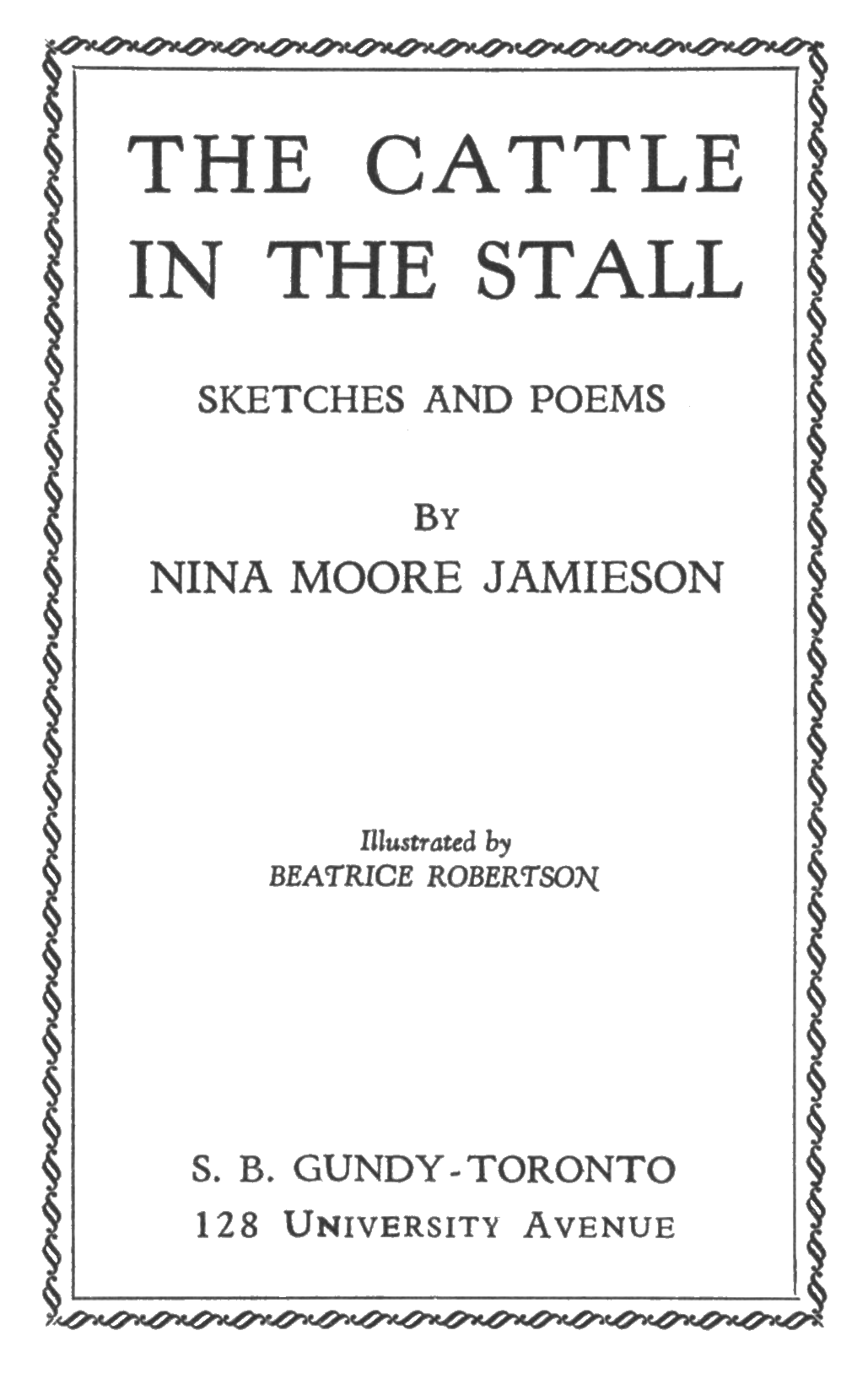

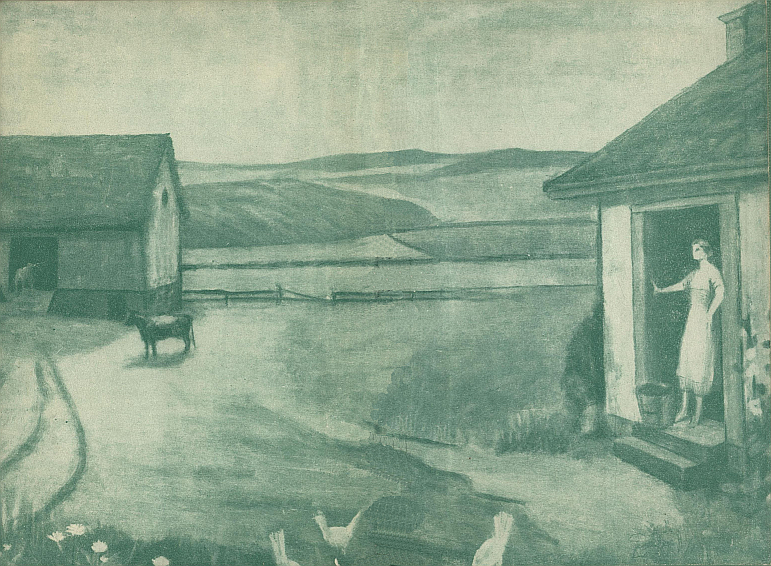

Title: The Cattle in the Stall

Subtitle: Sketches and Poems

Date of first publication: 1932

Author: Nina Moore Jamieson (1885-1932)

Illustrator: Beatrice Robertson (1879-1962)

Date first posted: July 17, 2022

Date last updated: July 17, 2022

Faded Page eBook #20220730

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, Pat McCoy & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

Copyright, Canada, 1932

Printed in Canada

T. H. BEST PRINTING CO., LIMITED

TORONTO, ONT.

CONTENTS

| PAGE | |

| FOREWORD | v |

| THE CATTLE IN THE STALL | vii |

| ASSISTING THE FIRST ROBIN | 1 |

| THE SPRING IS IN THE COUNTRY | 9 |

| THE HIGHWAY IN OUR MIDST | 11 |

| A BENCH IN THE PARK | 17 |

| THE MINIATURE | 26 |

| THE EARLY HEN GETS THE BROILERS | 27 |

| MUD | 32 |

| THE PASSING OF THE PIONEER | 38 |

| THE WINDS OF SPRING | 44 |

| LOVE TRIUMPHANT | 49 |

| THE SOCIAL CUP OF TEA | 51 |

| THAT FIRST DOMINION DAY | 57 |

| SAP’S RUNNING | 63 |

| THE INTERESTING COW | 69 |

| NOVEMBER | 76 |

| OLD COUNTRY CHURCH | 78 |

| HEAT | 84 |

| THE ROMANCE OF FENCES | 90 |

| THE CYCLE OF THE WHEAT | 97 |

| ROSES FROM THORNS | 102 |

| THE QUILTING | 103 |

| WHEN WAGONS WERE IT | 111 |

| SOFT WATER | 115 |

| THE COUNTRY STORE | 120 |

| THE DARNING BASKET | 125 |

| FREEDOM | 130 |

| MRS. SNODDY’S DIET | 131 |

| MAKING SOAP | 137 |

| FROM A HILLTOP | 145 |

| SHINING ’EM UP FOR THE BIG FALL FAIR | 150 |

| WHEN CRISP OCTOBER CHILLS THE AIR | 155 |

| THANKSGIVING | 161 |

| JOHNNY’S SO LONG AT THE FAIR | 167 |

| THE STORM | 174 |

| SIGNS OF COLD WEATHER | 179 |

| WHITE FROST | 185 |

| LITTLE COUNTRY FAIRS | 187 |

| THE VILLAGE BEGINS ITS DAY | 189 |

| THE STORMY DAY | 195 |

| THE VILLAGE STREET | 201 |

| THE SCHOOL-MEETIN’ | 210 |

| TO THE MUSIC OF SLEIGH BELLS | 214 |

| ACCORDING TO THE BOOK | 220 |

| DAWN | 226 |

| FINIS | 227 |

Her own serene and courageous “Finis”, which concludes this volume of her collected work, reveals more clearly than any formal foreword the essential character of Nina Moore Jamieson. So we need speak only of the environment of her childhood and later life—details that all who study an author’s work desire to know. She was an April maid, born in 1885, while her parents were staying with relations in Hollywood, Ireland, and spent some years as child and girl in the village of Cookstown, South Simcoe, where her father, W. F. Moore, was principal of the Public School. Later, the family moved to Dundas when Mr. Moore received the appointment as principal of the Public School there. She herself, followed her father’s profession, teaching first at Red Bay, in Bruce County, where she gathered the material for her novel, “The Hickory Stick”; then at Rosser, Manitoba, after taking a course at the Winnipeg Normal School; and finally, came back to Ontario and taught the school at Westover in Wentworth County.

Then she met Norman Jamieson of Beverly Township, married into farm life and became the mother of four—two sons and two daughters. Her mother once said, of this gifted daughter who was also so utterly simple in all her ways, “She was unfailingly cheerful, full of calm serenity and responsive kindness, qualities which her maternal grandfather had in a marked degree.” She gave with a lavish heart.

During the Great War her poems attracted the attention of the editor of the Mail and Empire and he persuaded her to write sketches of the life she knew for that paper. To the Mail and to the Star Weekly, to which she also contributed articles, the editors of this volume tender their grateful thanks for permission to use material taken from their files. In these writings and in her articles for various farm journals, Mrs. Jamieson won her way not only into the hearts of her readers of all classes, but into the ranks of Canadian literature.

I hold no place of high import

Where roars the thronging mart—

One of the little ones of earth

I do my humble part.

With fork and pail and stable broom

As evening shadows fall

In common tasks I tend for Him

The cattle in the stall!

I love the knotted dark along

The heavy, rough-beamed roof,

The cleanly crackle of the straw

Beneath the shifted hoof;

The woven chorus of content

That drones from wall to wall—

Because I love, for His dear sake

The cattle in the stall.

For since of old a stable knew

That wondrous Baby’s birth,

Methinks He loves the cattle best

Of all the beasts of earth.

Their kind eyes gave Him welcome there—

They heard His first, faint call!—

Oh, proud am I to tend for Him

The cattle in the stall!

Now comes once more the glorious night,

Christmas of the year!

They watch in reverence and awe

The miracle draw near.

The Child divine is born again—

His love is over all—

It rests in benediction on

The cattle in the stall!

The old white cat, Tom, lay along the top rail of the fence and yawned in the gay sunshine. His coat was immaculate, for he had polished himself from stem to stern, above and below decks, abeam and abaft. (The boy has just been reading one of W. H. G. Kingsley’s sea stories—hence the vocabulary! A few weeks ago it was Mexican cowboy stuff, and “loco” and “lariat” and “Gringo” had the floor). He regarded with scorn two busy white hens which scratched and gossiped industriously a few yards away. Foolish creatures, to spend so much energy hunting grubs, when they might bask idly in the warmth, as he did, confident that someone would provide plenty of food, presently!

Tom did not know that his attitude had any significance, but it had. Far more certain than the appearance of the first robin, the cat’s first sunbath is a forecast of Spring. He let his strong, nervous claws sink idly into the rail, and suddenly the pull on his tense muscles roused all the old hunting instincts. His back arched . . . his tail lashed softly . . . he sniffed the air suspiciously. Somewhere field mice cowered . . . somewhere nests were in prospect, tiny bird babies, tender to his wicked old teeth—Ah! Spring! Spring! That is the time for a cat to be alive!

The old wagon that stood behind the drive house, hidden in a snowdrift all Winter, with only one wheel-rim showing out, emerged triumphantly under the thrust of the suddenly fervent sun last week. The wagon knows it is time for wagons to be on the job—and there it is, ready for business! The trough at which the noisy geese fed in December, disappeared when February kicked up so many storms and commotions. I saw it this morning, and it looked like an old friend. It still held chopstuff from the last feeding—and the geese were at it, as though they had never left it!

Jakie, the goat, has hardly been outside the stable all winter. He has a very keen regard for himself, that goat, and believes his self-respect requires one thing of him, only—that he shall taste every horse’s hay and oats, to make sure it is first-class, and nibble samples from every cow’s manger, and fill up his odd corners from the chop box when it is open, and jam his strong, beautifully curved horns into the bran bags until the bran comes out, if he cannot find one that has been left handy for him.

When I see him patter elegantly across the stable yard, his slender, springy white legs twinkling under the bulging affluence of his fringed white body, and lean to scratch meditatively against a tree trunk, I know the season has turned the corner, Jakie is a good weather prophet.

He expects to use that tree steadily, or he would never have started at it!

You know that little rhyme of Stevenson’s:

“In Winter, I get up at night,

And dress by yellow candle-light.

In Summer, just the other way,

I have to go to bed by day!”

I do hate this dressing by yellow candle-light. It always gives me an up-all-night feeling, though it may be actually seven o’clock by the real time. But these mornings, when John starts the household on its daily run about six, the sun is just making magic in the East, twisting the rainbow’s tail, and squeezing the juice out of Aurora Borealis. Our bedroom window faces the way it should face—out towards his habitation—and above the black fringe of the cedars his streamers run across the sky.

There is a delicacy, a transparency in the nameless colors that slide and ripple before him. No wonder ancient peoples worshipped the sun, seeing no further than his majesty and splendor! It is worth the effort of getting up in the morning, just to see frail hues lighten and grow to a great shifting glory of beauty and promise in the Eastern sky. What if they do fade almost immediately? What if their ashes are dull and cold as the sun springs from them bright and confident? To-morrow’s dawn will see the miracle renewed.

Something in the heart of the cedars is changing. Their tarnished and dingy coats have felt the touch of the conjuror’s hand, and a vague, responsive green awakens, elusive as an ectoplasm. I see the sturdy nubs of my crocuses poking up in the sod, where yesterday grey ice ruled. Presently there may be a back-fire in the shape of hail or sleet storm, but what about it? Those determined little javelins thrusting their way from beneath snow and congealed leaves, flout the power of dying Winter.

Last night, John and I walked over to call on a neighbor—an old man with a rich store of recollections of other days. I had a pencil and notebook in my pocket, and wore the boy’s barn rubbers over my slippers, because ordinary low rubbers would have stuck traitorously in the mud at the second step. John took our invaluable gasoline lantern in his hand to show us the best places to step, and forth we went, into the still starlight, the lantern casting hobgoblin shadows at our feet.

We went across the fields, following the fences, where the drifts still had a backbone, and held us up. There was the little temporary pond beloved by the geese, who are wild with delight to get open water after the long frosts of Winter. They rush down there as soon as the big white egg has been laid in the nest, and the uproar they raise is deafening! We skirted it carefully, clinging to the rails of the snake fence, for the ice at the edge was unreliable. Then on along the sod, stumbling occasionally into a furrow in a slippery place. My broad, ungainly rubbers were heavy on my feet, but gave me a substantial foundation in the yielding, half-frozen soil.

After a while we came to the fence surrounding the bush, and when we had climbed it, and gone a short distance, I stood still, and let John go on ahead with his intrusive lantern. The night was so very beautiful! The stars shone so benevolently, so jovially, from the utter deepness of sky. The great trees, solitary or in groups, shadowy in the gloom, with their outreaching arms that blotted out the little twinkling lights of heaven, were so friendly, so filled with strength and the promise of new life!

A bush is delightful at any time, and particularly in Winter, when the snow grasps it about the knees, and smothers its darkness under soft fluffs of white, but it is a bit of fairyland on a mild night in Spring. I could almost think I heard the sweet sap hurrying up from the roots of the maples to receive its blessing out of the clean, cold air. Listening intently, I did hear the softest thrilling undertone—the very voice and melody of Spring.

But John could not hear them. He declared I was mistaken. Perhaps I was—it is early yet for them. But I did see a mosquito or two, lately, and on sunny days flies dance in the warmth at the south side of the house. Ah, that sun! It shows up every shabby spot in the carpet, and causes a regular riot in the mind of the housewife. New wallpaper—new paint—new rugs! The Spring sun, prying mercilessly into every corner, makes the old stuff look so utterly dissipated that its case is hopeless.

You could tell the season by the youngsters. Without warning, they became suddenly infected with the craze for skipping. Pat-pat! The little slippers go incessantly to the beat of the old rope. They have robbed their handsleigh of its pulling rope, and have begged various good bits from their father—and at times, have slaughtered my indoor clothesline for their futile purposes. At all hours, in all places, they skip. Betty milks her cow at night, and takes the rope from Madge, giving her milk stool in place of it. Then she skips while Madge milks. The cows do not mind. Dear me, I wonder what the cows would mind!

It is nothing new to go into the stable and see a large black and white cow lying down comfortably, chewing her cud—and a youngster stretched out at ease along her back.

It is the time of year for a change—in diet, clothing and environment. I like to slide out, if only for a day, or a few hours, “to mingle with the Universe, and feel what I can ne’er express, yet cannot all conceal,” as Byron has it. There is no guilt on my conscience when I elope with myself and leave the farm and the housework, and the milking with complete serenity. No use to go away with my body, and leave my mind back there fretting about dinner dishes and the gathering of the eggs. I go away all together, and come back that way. It is a holiday.

Oh, the Spring is in the country! Don’t you hear the warm rain falling,

As it falls on green wheat fields, with their faces to the sky?

Oh, the Spring is in the country! Don’t you hear it calling, calling?

But here in squalid city streets, how desolate am I!

I know the sunny corners where the dandelions are peeping—

Ah, dearer far their homely face than fairest hot-house flower.

For it’s Springtime in the country—and I cannot see for weeping—

Heart-homesick for the little farm, and childhood’s happy hour.

I think I see the old stump fence, decked with the grapevine tender,

The long, green lane, the deep, dim bush, the bare old hill, I know

Are lovely now, and calm and still, and fresh with Springtime splendour.

And longing fills the heart of me, to bid me rise and go!

Alas!

The dear wee home below the hill, has now another master.

The black-ridged fields, the shouldering hill, the maples waving high,

Are mine no more forever—and my tears fall fast and faster.

For here in crowded city streets, how desolate am I!

Away back in the Winter certain mysterious strangers were taking all sorts of liberties with our road. One day when I myself was travelling to Toronto in a big truck, several head of cattle careening along behind, I experienced a great thrill in having to turn out for surveyors who were squinting importantly along their little squinters that they lay on top of tripods for that very purpose. Immediately the great question arose to agitate our existence—Just which way was the highway supposed to come through?

I understand it was deeply discussed in the harness shop, the barber shop, the blacksmith shop, the garage and the fire hall. Some mournful prophets opined it would cut off somewhere near Troy, angle over towards the Governor’s Road, catch it somewhere south of here, in the “clay”, and so proceed onwards to Brantford and lesser places, ignoring us completely. That would eliminate the hills and winds that we have felt to be part of the beauty of the road, and besides, it was supposed to be a shorter way.

We could hardly believe all that. To think that a highway would be built to relieve the Hamilton-Galt line on the north and the Hamilton-Brantford road to the south—and miss this village! Passing by on the other side of Lynden we could easily understand. Not that we have a word to say against Lynden, you know. Probably it can’t help itself—being on such friendly terms with Copetown and Jerseyville and Orkney may have cramped its style—but this village, that has been saving itself so long just for this highway, to be defrauded so cold-bloodedly!

We refused to accept the verdict, and see—in a few days out comes our Brantford paper with the joyful news that the highway has to pass right through our village, and so on, arriving duly in London. For this highway is one of the longest streets in the world, behold you—Dundas Street, running from Toronto to London! A nice thing if it failed to come this way when it had the chance!

The paper, to be sure, neglected to state just what road it would follow through the village. Naturally we jumped to the conclusion that it would use the streets already here—entering at the east end, where is first the residence of the man who keeps goats, where the sign says “Welcome—speed limit 20 miles”.

Next is one of our very handsome churches, its comfortable red a picture among the trees and shrubs for which our village has such a name. Then in swift succession—even at twenty miles an hour—the local butcher, the Hydro man, the minister and the doctor on one side of the street, with the postman, the undertaker, the barber, the transport man, the foundry, the reeve, and so on down the list of our foremost citizens, on the other. John said he thought of buying the vacant corner next the foundry and holding it for a service station. He could pump gas, Edwin could look after repairs, the girls could sell gum and pop, and I could keep the books.

I always did want to scoop out wads of ice cream into those nice little cones—but the project died when I was appointed bookkeeper. Why, I can’t even keep track of a dictionary, let alone day books and double entry books and so on. Fortunately we did no more than speculate about it—for soon the news spread that the highway was to bend south with unconsidered suddenness—and it might have missed our service station.

They tell us now that it is to cut in at the back of the bake shop, which doubtless will blossom out in scarlet paint with black and purple trimmings, and become “Ye Olde Bunne Shoppe”. Highways have shed a lot of final “e’s” along their path!

It will emerge somewhere about the dark and devious aftermath of the post-office, completely ignoring our village cafe—locally described as a “calf”—and all our nice row of enterprising stores. Doesn’t this look like something queer in the Government? Why should it take a spite at our noble emporiums of trade? Why, down our front street it is possible to buy black strap molasses in bulk—and can that be done in the whole city of Toronto? I trow not! Just take in a great half-gallon sealer and get it filled—for about half a dollar! And we have cheese in this village that is real cheese—none of this meek stuff that has to wear tinfoil to keep itself from getting tainted by a bunch of lettuce or something equally powerful. This cheese of ours is of such a proper, nippy nature that I understand it eats the edge off the knife used for cutting it!

It is enough to make the town fathers feel like resigning to think that such a thing could be—to eliminate our cherished front street for the sake of saving a few rods to the motoring public. Saving! Look what they’ll miss! When people come into a place like this they want to see it all, of course. They want to see all that they can see, at twenty miles an hour. There is the old watering trough in front of Jackson’s Wagon Works—if they are lucky they will see old Dan himself lighting one of his famous long cigars that the barber buys specially for him, though they make him twist his face into knots before he can get them going, and he finds all sorts of fault with them all the time he is working on them.

There has been a rumor to the effect that the road is to go right through the wagon works! Then, missing our existing streets, it will flounder about in what we call New Ontario, and find itself once more when it gets near our two schools. A lot of good that would do. How could any teacher instruct a class in anything—from the phonic system all the way to the extremities of chemistry and physics, when the landscape is thronged with road gangs and the whiff of tar comes in the window?

Here we are, well situated between Toronto and London—and a pleasant change from either.

And there is our Memorial Hall—and our bowling green—and our skating rink—oh, well. We know how we’ll vote, next time, if the Government does not make a proper business of putting this highway through our village.

About the hardest day’s work I can tackle, is a day in the city. There is always a rush and scurry to get away, leaving the house tidy and the necessary chores done. And then there is the hustle and turmoil of the city, the crowded streets, the noise and confusion, the hot wearisome pavements, the supercilious salespeople, and the utter impossibility of getting what one really wants.

Usually I shop at home, with a mail-order catalogue and a pencil, and have fair comfort. But the catalogue has its limitations. I can’t buy boots that way, nor hats, nor dishes. It was dishes the last time—and boots. Threshing time is coming and my semi-porcelain has become very semi. The heavy hand of time has left me plenty of saucers, two very large platters, a great soup ladle—and precious little else.

I decided to buy the dishes first, and if I had any money left, I would celebrate with boots. So we went down to the city the other Saturday and I pursued my ideal of a dinner set, diligently. And found it, several times. But on each occasion a glimpse at the price tag brought me up short, with shocked conviction that the exchequer wouldn’t stand it. I wanted a plain, unobtrusive set, neat but not gaudy, with good-sized cups that would fit one on top of the other with plenty of vegetable dishes and bowls and all that sort of thing. And I didn’t care a snap for cream jug and sugar basin to match, nor for a teapot with a twisted spout and a groggy handle.

All this I might have had for the price of a yearling calf or a pair of fat pigs. But alas! My little butter and egg money and the revenue from my early chickens, which had seemed such a worthy sum when I counted it before leaving home—withered in my hands as I timidly compared it with the price of the dishes that attracted me.

Long since I had dropped all thought of boots. Boots! A joke—in the same day with such financial cruising as the buying of dishes! I compromised at last, on open stock, and felt as dissatisfied as one deserves to be who compromises. Then I went and sat down in the little park that nestles right in the very heart of the busy city; sat there and waited for John.

Now, John has an insatiable passion for getting his hair cut. He can’t go to town without seeking out a barber and instructing him to do his worst. Why is it, I wonder? Are all men like that? What is their notion for getting themselves all-but-scalped on every possible occasion? These and other idle thoughts occurred to me. For it was market day, and the city was full of sun-burned farmers, all yearning to slip away from their women-folk and spend their hard-earned coin for an unavailing hair-cut.

Meanwhile, I sat on a green-painted bench and looked at the old fountain, as it splashed its unwearied spray into the wide basin. And there was the time-honored statue of good old Queen Victoria, with its shield and flag and silent carved lions. Further down, stood the bronze replica of Sir John A., forever posing in front of the post-office. People came and went, and no one paid any more attention to me than to those silent statues. Presently two women sat down near me.

“Oh, dear—that old car!” said one, fanning her elderly countenance with an advertisement of housefurnishing bargains. “You never can get it when you want it. There should be better service right here in the heart of the city.”

“How did you enjoy your summer cottage?” asked the other, arranging a number of small parcels in her shopping bag.

“Oh, my dear!” said the fanner, with emphatic impressiveness. “Such a time! We were there, right on the lake shore all July—just perishing with cold! Wearing sweater coats, crowding around the stove—absolutely perishing—perishing! And Harry’s people came; first one sister and her children, then the other sister and her husband and little boy. It soon counts up, let me tell you—boarding two or three extra at a place like that!”

“Well, I should say so! But people never think of that. Have you left the cottage?”

“Oh, yes; gave it up at the end of a month. And here’s August, so unbearably hot! I’m just going to take Ruth and Helen out to their Uncle Peter’s, in the country. Harry can stay at his mother’s—she lives down on John Street, not far from the office. You know Peter, don’t you—Harry’s oldest brother?”

“Yes—I think so.”

“Well, we are going up there. Of course, it’s awfully quiet, but the children can wear their old clothes and tear about all they like. I have no bother with them there. It’s such a relief. . . . And Annie has four of her own. . . . She doesn’t mind another one or two——”

“Oh, there’s our car now!” interrupted her companion. “Come on!”

They arose and hurried to the corner and I sighed with relief as I watched them trotting away on their high heels. Their frail blouses revealed a prosperous elaborateness of embroidered camisoles. One had a wrist watch; the other ear-rings and a string of near-pearls. They roused in me a most unreasonable hostility.

Next came a man, and a little girl about the size of the twins. The man had a newspaper, in which he became absorbed as soon as he sat down. The child had an idea of her own, and proceeded to follow it out.

“Daddy—daddy!” she thumped him on the knee. “Daddy!”

“Huh,” he said enquiringly, still deep in his paper.

“Daddy—I want some ice cream! I want some ice cream, daddy!”

This sort of thing lasted for some time. Daddy said no, first emphatically then peevishly, and at last eruptively. I watched with interest, for the twins try all these schemes, too. At last, he yielded. If his no had meant no, there would have been no importunity. The youngster snatched the coin from his reluctant hand, skipped across among the traffic, and presently returned with her ice-cream cone.

It vanished. Then the fun began again. She thumped him on the knee once more. “Daddy!” she said in her childish treble. “Daddy, I want——”

“Oh my goodness!” exploded daddy, “Come on out of here. You’re forever wanting something—I haven’t a minute’s quiet.”

So they disappeared in the crowd, and even as they went I became aware of a very sweet, rather plaintive voice just behind me.

“O Willy!” said the clear tones, “Aren’t you tired?”

“No,” answered Willy, and his voice indicated a small alert young man. “Of course, the city always makes me weary, but I’m not played out. I know somebody that is, though!”

“Yes,” she agreed, and I’m sure she smiled as she said it. “I’m tired. I’ve tramped around through the stores, and I’ve spent all my money, and oh, Willy, I’ve only got about half what I want!”

I held my breath. What would Willy say? Would that plea meet an unkindly response? If so—I felt my knuckles tighten. A man can be so miserly mean when a woman asks for money! But Willy, bless his heart, rose nobly to the occasion.

“You’d better get what you want, now you’re here,” he said, in a most matter-of-fact way. “Or if you’re tired, let me get it. What is it you want?”

“I must get the flannel,” said she, in a low tone. Flannel? said I to myself. Flannel in August? But she went on, rather hurriedly. “I think I had better get it myself. O Willy, all this? No—I’ll only need about half of it. . . . You’re awfully good to me!”

“I intend to be . . . just that,” said Willy gently. “Come on!”

So they also went, and left me feeling very cheerful and glad. I had to think of a man in our neighborhood who went to town with his wife, and when they got there he said to her:—“I suppose you want some money?”—and he gave her a quarter. Men like that, thank heaven, are rare enough to be remarkable. And presently a man came and sat down beside me and took off his hat. It was John.

“How do you like my hair-cut?” said he, blandly.

“Oh, John, your brains fairly show!” I said aghast, for truly it was the closest cut I’ve seen in a long time. He only smiled and put his hat on again.

“Got everything you want?”

“No,” said I, and then with inspiration, added, “but I’ve spent all my money!”

“You always do,” said John, crushingly. But he reached to his pocket, and brought out the shabbiest pocket-book in Ontario, “I guess I can stand a modest touch. How much do you want?”

“I don’t want any,” I said, “I just wanted to see what you would say.”

“Oh!” said John, staring, “Well, ask me if I’m ready to go home, and see what I’ll say to that!”

So I asked him and we went accordingly. And by the time I get enough money saved up for the kind of boots I want, his hair will have achieved sufficient growth to merit another hair-cut. I shall patronize the green iron bench again, while I wait for him. It is the most interesting spot in the city. I expect to get the plot for a novel next time I spend an hour there.

I loved you once—but that was long ago.

And do I love you now? I cannot tell,

My heart is dead—this only do I know—

I loved you once and loved you passing well.

Then mists were rainbows where they touched your head;

The clouds were sunshine, and the throbbing air

Breathed but your name upon the hours that sped.

And life was light and music everywhere.

I loved you once—but fires grow dim and cold,

And time can dull, thank God, the fiercest pain;

I loved you once—my eyes are growing old—

Love never can come back to me again!

There is a clucking hen in the hen house—a real one, full of business, determined to hatch, and telling all about it on the least provocation. When we go in to gather the fruitful egg, she remonstrates. She camps on her chosen nest, and it is nothing to her when the other hens hop in alongside and all crowded as they are, deposit a nice warm egg for her to appropriate. If you have never seen a hen cadge eggs, you should! She quietly hoists herself, and with a swift, easy squirm, a twist of the wing, a cuddling of the body, she draws that egg under her. It is her egg, now—who can identify an egg? The furtive hostility in her eye shows what she thinks of the rest of us. She has important work on hand, and she implies that other folks are great time wasters, running around making a noise, not knowing enough to sit down quietly with a good clutch of eggs and keep them warm.

You might think the business of setting hens and raising chickens was one glad sweet song, wherein the amiable hen laid eggs, and hatched them into lovely chickens without a hitch in the program. Or in up-to-date places, the unfailing incubator turned them out. Well—I hesitate to hurt the feelings of an incubator, so let us just hint that even an incubator has its ups and downs. One of our busy neighbors once sent fifty eggs to a custom incubator to get them hatched, writing, “Dinny” carefully on each. But she had only five chicks for the lot. She had washed some of the eggs to make them look nice—and thus ruined them for life. Some were no good anyway, and some met bad luck. But after she had paid her five cents an egg to the incubator man, she figured that her five chicks cost too much.

Where poultry raising is a business, incubators are used, though I believe one poultry king has hens to help out the mechanical contrivances. But with most of us, the hens are a side line—something for the women folks to make a bit of money out of—and therefore carried on with the makeshift devices that are woman’s portion. An orange crate does for two hens; eggs of uniform size and shape and freshness are preferred. A layer of moist earth in the bottom of the box, then clover chaff or fine straw, then one egg—just one egg at first to try the hen. It is a thrilling moment when she is shown her nice nest, and one draws back, waiting to see what she will do with it!

I always try them at night. They are ready to pitch camp then, anyway, and they are more mellow than in the morning. So I put the hen into her separate compartment just about dark, and never get over the thrill of watching how she acts. She may perch uncertainly on the edge of the box, looking doubtfully at its contents, aware that they are none of her choosing, yet unable to resist the lure, the promise of the nice brown egg cuddling down in the straw. Tentatively she lowers herself into the nest—it feels good—clean, comfortable, just her fit! The egg is snug below her warm breast—ah, this is the life!

She shuts her eyes in ecstasy. I go stealthily and get the rest of the setting, and slide them down beside her. She arises to look very fierce at this disturbance, and pecks at me viciously with her sharp beak. But as she sees the smooth eggs coming, she lifts a wing here, heaves herself there, until all are nicely covered. Oh, the silly hen knows what she does know, and knows it well!

After syrup-making time, comes the season when in most of our country kitchens, you may find a covered box or basket behind the stove, from which arise the small cheeps of young chickens. Sometimes a quart sealer full of warm water is wrapped in a bit of an old flannel shirt and set in the corner of this domicile, and the tiny creatures will fairly stand in piles on each other to get the heat of it to their poor little bodies. For the eggs do not all hatch at once—some will be twenty-four hours behind the others, and if you leave the first arrivals in the nest all that time, they will straggle out of it, or the hen will step on them—awkward thing!—or she may take a notion to go abroad with her first production and leave the possibilities to their fate. The alert farm lady forestalls this by taking away the wee fellows as soon as she hears them toot, and putting them out to pasture in the warmth of the kitchen.

So you see, a clucking hen opens up great vistas, in which we see ourselves the proud owners of ample flocks of plump broilers.

The frost has come out of the ground times without number since it first went in last Fall, and each emergence has been a sore trial. Not that it really hurts our feelings to have old Jack Frost act in this capricious way—Pshaw! Not a bit. But he’s such a villainous bootlegger—he carries so much of the wet goods about him that we like to see him safely tied up in his proper place.

Just bring him out of the ground and see what happens in no time. The winter roads go juicy and bottomless; the milk truck plows great furrows in them, where the ransomed waters frolic merrily and muddily. Cars are stranded by hill and dale, and honest old wagons that never learned to stall, pitch and roll towards the ditches most fearfully.

Mud! There was mud when Noah beached the ark, but he made so little comment on it that we conclude he was used to it. Mud is made of the dust of the earth, even as you and I, yet how snobbishly we frown upon it! Only children love it, and glory in paddling wet-footedly in it, or moulding it into ancient, child-loved shapes.

A dog or a cat will make choice footing, picking out the soundest, dryest path, but the average child will strike straight for the very depths of it. Why, I wonder? Why do the feet go down with such a joyous plop!—and why are little girls every bit as delighted with feet of clay as little boys?

I never long for cement sidewalks except in mud season, and we have had so much of that this year that I’m deadly weary of it. Such rain, such gloom, such an outraging of the housewifely instinct for clean floors! Each night it rains, and I lie and listen to the wasteful drip from the eaves. The cistern is full—I have to let that glorious soft water go into the ground.

And each morning as I go about my work there is a heaviness, a pressure as if locks and bars held me in. It is only the horror of the mud, however, that restrains me. Otherwise I would like to go and run up and down the lawn, and climb the old cherry tree, and swing on the swing, and jaunt away down to the bush with John for a load of wood, and race the dog to the orchard and back! Yes—just like that!

Spring is in the air, you know, and it doth work like madness in the brain. Spring is in the air—but alas, mud is on the ground, and not even the most temperamental housewife on the concession would dream of yielding to the wild, sweet urging of the wonderful new voice in the air, when that yielding would involve such a spattering and daubing as would undoubtedly come to her from it.

The kitchen floor—well, most people have imagination, so let us imagine it isn’t muddy this weather. Let us pretend there are no wet boots nightly at the back of the stove in a more or less irregular row by the wood-box. Let us tell each other that we dreamed about the sad calamity that befell the twins when they filled their pockets with eggs, and then, being hand in hand and very merry, splashed gaily into a puddle out by the drive house—and fell down in it! The mangled remains of seven eggs and six eggs make only thirteen eggs, and doubtless the dog felt happy about it, when those coat pockets were emptied into his dish. Also, without doubt, the hens will lay more to-morrow.

Let us also weave a little fiction about the semi-swamped twins, who were pretty damp with tears above and puddles below, and had to retire from the scene modestly while some of their essential garments were put through the course of the law. Were they in any way depressed by the accident? Oh, my friends, twins are not like that! They do not depress.

It is largely due to their efforts that I have so much land on my kitchen floor. I reckon that they have carried in the most of a bushel of fine, brown earth in the course of the last few months. Dry earth is not so bad—it sweeps up, but oh, when it is moistened, it sticks like porridge.

There is a task for John when the roads dry a little, but I greatly fear he will be too busy at something else then to heed my injunctions. We have a very good gravel pit on the road down by the orchard, and some day if you chance along, you may espy (at least I hope you will) a determined-looking farmer, which is John, and his equally determined-looking wife, which is me (or I, at your choice). And we will have the grey horses and the old wagon, and the gravel will be catching it! A few loads of it around the buildings, make an unbelievable improvement!

Mud is depressing. The endless fight against it is on a par with the world’s struggle against wickedness. It seems unconquerable, yet who would calmly sit down and endure its disgraceful sway, simply because of the hopelessness of mastering it finally? Our whole career as housewives, is measured by our ability to cope with uncleanness. That idea helps me a lot when the sight of the smeary floors would lead me to sigh. The whole upward strain of this old world is towards purity, mental, moral, physical, spiritual, international, political—and its success depends on the individual.

That is why mud is so depressing—that is why one cannot be mentally serene amidst sordidness and dirt, for physical daintiness must underlie all other kinds. That is why beauty is so refreshing, so very wonderful and exhilarating to the tired soul. That is why, I do believe, these beautiful hyacinths of mine are filling the whole house with fragrance, and the power of their loveliness. Dirt may be discouraging on the kitchen floor, but to them it is a necessity. They lift themselves up from it, strong and inspiring. Dirt—it is only matter in the wrong place, after all, and with them, it has been placed aright.

Oh, it is muddy enough, but yet I would not want to miss these days of my life, though they are gloomy and wearying. There is always something pleasant and delightful to be found, even if it is no more than the little new chickens that arrived yesterday in a damp and dismal world. They are soft, little black masses with yellow crowns on their heads, and the hen is full of fretful jealousy. They are enough to make one forget the weather!

And I have a bulb in the window, here, tall and green, with a flower coming—I’m sure it is a daffodil, though candidly I don’t know yet. To-morrow will tell. Meanwhile I must go back to my warfare with the broom and dustpan, for though I do not claim to be a model housekeeper, there are limits—yes indeed, there are!

“How natural he looks! How peaceful!”

Neighbors looked down at him as he lay in his last sleep, and spoke softly, as though in fear of waking him, though all of us knew no human voice had power to pierce that slumber. But oh, I moved away, and stood at the window, where so often he had stood, in homesick weariness. Cars hummed and droned in the busy streets; a motorcycle or two raved past; the street cars shrieked and clanged only a block away, and at the Salvation Army barracks, just around the corner, exuberant music exploited itself. He had been a stranger in a strange land, amidst all this uproar and bustle.

“How natural he looks!” they said—but they were wrong. In that setting he could never be at home. Yet for many years he had looked forward to the day when he could leave the heavy toil of farming and settle down in a pleasant little town house and spend the evening of his days leisurely and comfortably. He had forgotten how the roots take hold—and his had taken hold miles away, on the rolling hills and valleys of the old homestead.

So when he and his life-partner moved away to their town home they found something terribly lacking, though everything was convenient, and just what they had desired. There was water on tap in the kitchen, but oh, how flat and flavorless it seemed, and oh, how he longed, when sickness seized him, for a drink of water from the heart of the rocks, back on the old farm!

Many a time, as he stood at this very window, looking out on this same noisy street, the eyes of his mind saw the young wheat on the upland, green and sturdy after the Spring rains. Or he visioned the plodding team and the moist furrow, and longed for the feeling of the plow lines over his shoulders.

His hands are thin now, and laid across his still heart. Their work is done, yet the evidence of their labor endures. Many a day he toiled strongly, clearing his land from bush, stumping it, picking off the stones, building fences, draining wet fields, making roads and raising what crops he could, meantime.

He, who had been glad to work with oxen, lived to see tractors snorting upon his acres. He who had been proud to drive in a lumber wagon, would journey to his last resting place in a motor hearse. He who had walked miles through night and storm for a doctor when sickness first struck his own home in the early days had, at the last, the care of a medical man summoned by telephone, armed with hypodermics, X-ray instruments and all the strange, wonderful, yet futile trappings of the profession.

There were beautiful flowers about his casket—white, fragrant and waxen, but what would he have said to them if he could have seen them, I wonder? I remember a Spring day at home when he came walking up through the orchard, which was a mass of bloom, and he stopped and looked at it with utter enjoyment.

“Nothing to equal that ever came out of a hot-house,” he said. “Apple blossoms, white clover and lilacs—they beat ’em all every way!”

. . . . The time came at last. The house was full of people—old friends, who had come to bid their dead comrade farewell, men with hard, rough hands and toil-bent shoulders, whose weatherbeaten countenances advertised their calling. And the young town minister stood forth in the midst of them to speak. He spoke nicely, comfortingly, encouraged by the presence of townspeople, who had come to know the pioneer during his time among them, and had wished to pay their last respects at this hour.

But how could they know him as we knew him? What knowledge had they of the long, honest days of ungrudging labor which he gave for the improvement of a corner of this country of ours. His work, and the thoroughness with which he performed it, helped to create the solidity of our present-day prosperity. He practised no slipshod methods—what was done by his hands or under his direction possessed thoroughness and durability.

He kept the weeds cut in his fence corners, and along the road side—a small thing, perhaps, yet characteristic of the man. These old men are dropping away from us, and much of their history dies with them, untold, for they deem it hardly worth telling. Of course, they did the things that had to be done seventy or seventy-five years ago, but they did them unconscious of any remarkable quality in the circumstance. Their matter-of-fact attitude towards the necessary drudgery of existence and progress is one that we might study with advantage in these days of softer living and easier ways.

The pioneer was typical of his generation in that he did not seek to evade the hard tasks that lay in his path. I have heard him tell about the days he and other old-timers put in with their teams, scraping the school yard, drawing soil over the knobs of rock to make it level and beautiful, or hauling away stumps and debris. The time was given freely in those days; now, nothing is done about the school unless there is good pay for it.

When I hear people say of any undertaking—“It cannot be done”—when last I saw him, with closed eyes and folded hands, but as we knew him in other years, when he used to come stepping with slow dignity down the lane to have a word with us on the events of the day. Many a time I have heard him say: “A man can do anything he honestly tries to do—if only he doesn’t get discouraged too soon.” And, thinking of the hardships and difficulties of his own life, it seems that his words held truth.

It is dangerous for a man to labor too hard, physically, for it makes him prone to mental apathy. When the body is continually weary, the mind has small chance for growth. This fact has often led me to marvel that our pioneer, though a man whose days were claimed by toil, yet retained a broad and kindly attitude of understanding and appreciation. He could talk without gossiping, and could argue without recrimination.

But now it is all over. He and others like him, go down to the silent grave, and because they failed to advertise themselves, their work will soon be forgotten. He was a man of deeds—honest, friendly deeds; he built well and faithfully. Canada is better to-day because of his straight-forward years, and his example of up-rightness.

There is a wind to-day—the wild sweet wind of Spring. It comes in circles—it meets one around every corner, high and boisterous. It is the cleansing wind, cold and strong, before which we scurry, after which we labor to complete the work unceremoniously begun.

For it is such a meddlesome thing! Who would have noticed that pile of papers, browned by exposure to the weather, matted with dampness, mouldy and heavy? With unwearying fingers, the wind has turned them over, loosened their hold on each other, crisped them, given them weapons of noise and individuality, and sent them forth to taunt us. Flap! Flutter! Across lawns just waking to new green beauty, against fences where fresh paint clasps them close, the careless wind chases them.

Which means that our native love of order drives us to go after them, gather them together, and burn them. Because of the wilful impetuosity of the wind, we dare not burn them immediately upon collecting them, so we cram them into a sack, and wait for a quiet hour.

It is just as well, for while we wait more come along. There are piles of leaves from last Fall, that have been banked moistily in corners, or in soggy masses under trees, or tucked away beside the verandah steps. All at once these find themselves released, and they scurry lightly on the crest of the sudden gusts, and let themselves down very conspicuously where the anxious housewife will see that they also must be burned. So into the bag they go, along with the protesting papers.

The wind can do little with such items as old boots and rubbers—and while we are at it, can anyone explain how these treasures come to be scattered about the way they are in the Spring? Certainly they were not out on the lawn last Fall, or ranged along the cellar windows, or lying negligently among the lilacs. Nobody goes outdoors in Winter and removes foot-coverings in snowdrifts. The things weren’t there in the Fall—but they certainly are there now, and if the dog didn’t look so unbelievably innocent over it, we’d never think of suspecting him. But he has them to account for, as well as the great bones, well-gnawed and antiquated looking, that surround his chosen sunning spot.

How one average dog can accumulate such immense and unattractive bones of all varieties rather puzzles his owner. What does he intend to do with them? Keep them in sight, as though they were diplomas to his prowess? They also will burn—but oh, what a sickening smoke they do send forth! Far, worse than the boots and rubbers!

When the wind dies down, about evening, and a cool dampness comes across the world, and a frail slice of a moon hangs in the thin blue of the sky, and away down the hill frogs begin to talk—then let us have a bonfire. Years may witness that we are growing old, but there is still hope of our undying youth while we can thrill to a bonfire.

I really grudge having one in daylight—it does not mean half as much. Daylight bonfires are eminently practical and sensible and sanitary and all the rest of it. But night-time bonfires are exciting, with their leaping of flames and surging of shadows, with their sudden gusts of gay sparks to rush upwards and slowly subside into blackness, with their mystery and risk and glare.

After the orchard has been trimmed, there are piles of brush that soon dry out. There are masses of cedar ends from the hedge. There are tangles of old vines, and perhaps some bits of splintery planks from the stable floor. All fine fuel! Out on the face of a furrowed hill the pile is set, the match applied. A night to remember long!

In course of time even the ashes of it will disappear! For the team will come along, and the plough pass over the wide grey patch, and turn deep down all traces of the burning. It has to be carefully done, however, for fear of hidden nails and sharp ends of metal, and bits of broken glass that may have been among the debris. Horses’ feet invariably find such things! . . . . What is there about this wind to make one restless? Why does it bring queer broken thoughts of tall trees bending on a mountain side—white water springing down the face of ancient rocks—ageless waves climbing a stubborn shore? It stirs the responsive wanderlust that lurks in every one of us! Any person could be a gipsy—in the Spring!

Well for us, that bonds of custom hold us fast! A man may feel the tug of yearning for wild spaces and the smell of camp-fires—but who is to know of it but himself as he follows the team down the long dark furrow? The earth turns over in moist obedience. Far overhead wild birds challenge the season. Away on the horizon a fine plume of smoke tells of busy factories, noisy machines.

Sometimes—when there is wind tearing madly abroad in the sunny day, and Spring fever seems to hold us fast—it seems as if we were becoming too civilized altogether. It seems as if we should be out dancing with the dry leaves and the greening shrubs!

Instead of which we hold ourselves in, carefully, for fear of what the neighbors would say! At least, they can’t say anything damaging about a bonfire—and we’re going to have a beauty, to-night!

Dear arms, that held me in the bitter pain—

Dear heart, that beat so warmly to my own—

Dear eyes, and shall I meet your glance again?

I am alone—alone!

You were my all, in those bright, happy days.

You are my all, wherever you may be—

The sun will add new radiance to his rays

When you come back to me!

Lips bid farewell, and hand withdraws from hand,

But hearts cling close, in anguish or in bliss,

Though you be far, in some war-weary land,

I cherish still your kiss!

You are my all—your honor is my pride!

You are my all—and though you come to me

Broken and wounded, yet, dear, by your side

My happiness shall be!

Dear one, you gave me joy of all the world,

Gave me so much, such treasure is my store,

Having your love, your love with kisses pearled,

How can I ask for more?

Yet this I feel, and know it to be true—

While love endures, and memory holds your kiss,

Not life nor death can sever me from you.

Love bridges the abyss!

This is the busy time for farm women. Not simply because of the chickens that are foaming out of the colony houses and slithering down the little runways like surplus suds on a washday; not because of the many pairs of lace curtains that Spring inquisition stretches on the rack, out in the sunshine of the front lawn, where their pristine stiffness returns to them a hundred-fold, thanks to much starch and taut stretchers; not even because of gardens where weeds grow so much faster and stronger than anything else, until the hoe becomes a deadly tyrant, and there is no more room on the hands for blisters; not for any one of these reasons, nor even for all together is this such a very strenuous season for farm women.

It is because of the meetings.

There will be lawn socials and strawberry festivals and garden parties and Sunday school picnics—and for everything its own particular committee meeting. But of all societies the Women’s Institute surely leads in the number and amplitude of its gatherings. It has the start of church societies because it takes in the women no matter what church they belong to—no matter whether they dodge ladies’ aid and women’s missionary bands. Moreover, it has the support of the Government, being under the Department of Agriculture, and therefore secure as far as backing is concerned.

Each Summer delegates are sent out to visit the various branches and deliver addresses. The branches have no responsibility except to entertain the delegate and deliver her to her next speaking-place. That does not sound like much, and it really isn’t much—but oh, what a buzz it causes.

About this time the women’s missionary society is having its returned missionary to speak on an afternoon—and as all the W.M.S. belongs to the institute as well, it means that we dare not have missionaries and delegates too close together. We MUST get our housework done, in betweenwhiles!

Anybody will entertain the lady—but on second thoughts what about our housecleaning? Some of us have the spare bedroom all torn up; some of us have no curtains up yet; some of us have June weddings weighing on our shoulders; some of us have babies that are teething, and that cry in the night; and some of us are bespoke for visitors. So there you are—who will have the delegate overnight and to meals?

And who will trot her along to the next stop? In the good old days, we used to hitch the team to the democrat, and dad and mother and a daughter and daughter-in-law or two went along and took her to her destination and cheerfully heard her give her address for the second time. Now, it is some brave lady with a car who takes all chances of a flat tire on a remote concession, or a broken axle (from too many stout women in the back seat), or a shortage of gas halfway between here and there. She will courageously venture forth to convey Mrs. Delegate to her appointed place.

Now it is the biggest mistake you ever made if you think of country women as too busy to enjoy life. Quite the contrary. I do not think we run any risk of falling into despondency because of our dull lives. On the other hand, we are in some danger of becoming double-chinned and undeniably portly from the effects of all these meetings.

For every meeting has its inevitable refreshments to wind up with. I am not going to describe what we have—but you will know, when you drive through the country, and see the church door or the school door ajar and hear the voices of women within, that after the meeting there will be refreshments. If your car has to break down anywhere, let it be convenient to one of these places!

If you see a pleasant home with a stretch of lawn in front, shrubs and flowers to frame it, and cars of all ages and conditions crowding buggies and democrats in the lane and stable yard, and if you have a little courage and a little interest in your fellow-women, just halt a bit, and attend the meeting. You will find a plain and ordinary woman in charge of it—that is the charm of it! The president does not have to be brilliant nor imposing nor awfully clever. She will probably be quite nervous, and make a good many blunders, that the city woman, if experienced and professional in the business of office-holding, would never make.

But that does not matter a button. A blundering president is really much better for a society than an expert one—she forces the members to come to her aid, and share her responsibility! Besides, there is no particular damage a president can do, no matter how she blunders!

Sometimes the menfolks frown when they have to give up the “light driver” on a day when they wanted it on the cultivator. Sometimes the hired man scowls because the missus is late getting home, and he has to milk the cows she usually handles. Sometimes the youngsters lament when the lovely cake with whipped cream or cherries on it is whisked off to a meeting instead of gracing the home table. Sometimes the baby is naughty, and whoops up his war cry in the full tide of affairs, when the secretary is reading the minutes of last meeting, or the imported delegate is giving her talk. Or he may make a snatch at the tray when it passes, and shower the whole works with cream and sugar. But who minds a baby or two? Let them come, bless their hearts. We are not of much account if we can’t stand something from them.

So, between five and six, these lovely afternoons, you may see the women on their homeward way. The plates or parcels they carry are very negligently wrapped—their work is done. Two or three large ladies in a little old democrat, with a youngster or two tucked in at the back on a shawl that is to save their “good” clothes from the dusty floor; a basket or so, a fat baby and his inevitable satchel; a big umbrella which was originally brought to afford shelter from the beaming sun, but is more inclined to poke its patrons in the back of the neck, pluck off their cherished hair nets, or wallow down so low that the horse is hidden; a horse of the safe variety, guaranteed to pay no attention to feminine driving, however whimsical, but to plod decently home at supper time—a horse that will suffer his bridle to afflict his ear most grievously, yet preserve his calmness—a horse that will not shy, nor balk, nor run away, nor kick, nor bite, nor lie down in harness—in short an institute horse—all these you may spy and interpret along the roads these days.

It really is not so very long ago—quite within the lifetime of many whom we knew. What did they tell us about it? One of the mistakes we make is to let people with their wealth of reminiscence slip away, so that the little intimate stories of earlier days in this land of ours are lost, and only the bare, statistical bones of history remain.

In 1867 nobody dreamed of the network of highways we now have in this province. It is hard to dream highways when surrounded by bush almost impenetrable in its vastness and wildness. In Southern Ontario there were roads—corduroy, plank, mud, stone, clay—and very good roads they were, too, as many an old-timer will bear witness.

People did not go very far from home, then. It was possible to be quite lost within a few miles of it. Country children could grow to manhood and womanhood and never see a train or the smoke of a factory, or know what coal looked like, or taste an orange or banana. Young men with whiskers thought it no shame to attend school and learn what they could. Bare feet were the usual warm weather wear, except for state occasions in the life of youth.

You ought to hear Dan Jackson tell about the good old days. He remembers—he has all sorts of quaint and whimsical bits of stories to tell to the interested listener—and, he is the lad that can tell them, too. John and I spent the evening with him and Mrs. Jackson, and it was hard to believe, as one looked about that beautiful house that he had been the barefoot country boy he described himself, when Confederation was new.

He played us some of the old jigs on his violin—didn’t you know he was one of the enthusiasts responsible for reviving the old-time fiddling that has become so popular again of recent years?—and then he laid down the bow with a sigh, declaring his fingers were too stiff to play. “But I always did love to get music out of anything,” he admitted, “even when I was a kid. . . . We had lots of fun, then, though children to-day would think it a bare life. . . . And it was a bare life—that is why we enjoyed our fun so thoroughly! We couldn’t afford to be too particular about it. Why, I remember the first Dominion Day—lived in Rockton then—did you know the Khan—Bob Kernighan? Yes, yes, of course you did!”

His glance roamed about the room—at the grate, rosily warm under its mantel of gleaming oak—at the hardwood floor laid in a pattern of his own contriving (I’m going to steal it from him, some day!)—at the soft lights, the evidences of taste and beauty, as though finding it difficult to reconcile the modern present with the picture of the past he was recalling.

“Well, we heard some sort of rumor about great doings in Dundas on the First of July. Didn’t know just what it might be, but some of us figured we’d go and see. Soldiers—bands playing—fireworks—a great adventure, mind you, to make such a journey—it took a lot of courage, though it is not really many miles from Rockton to Dundas.

“There was Bob—the Khan, you know—and Emmerson, and me—and some more, and we went. How? Why, walked, of course? Walking was the chief way of getting anywhere, then. Nobody ever died from excessive walking. It was a hot day, too, and we about gave up. But we kept on, encouraging each other, and at last, when we got so we could see down into the valley and get a glimpse of red coats and hear a faint note of a bugle, nothing could have stopped us.

“We got a drink at the spring—you know where it runs out of the mountain below Fisher’s, there? And my, how hungry we began to be! Had never thought about that when we came away. But the more we thought about it the worse we felt, so we hunted through our pockets and we scraped up eighteen cents among us. There was a bake-shop down in the town—I forget who owned it. We must have been great looking customers going in and asking for bread. It was five cents a loaf. ‘Is this all you’ve got boys?’ the man asked us—and when we told him it was and where we came from and all, he let us have four loaves. But when we got out the town boys were waiting for us, knowing by the tufts of hair sticking up through the roofs of our hats and by our home-made trousers and shirts and all that we were country lads.

“They tried to take our bread away and finally stoned us up under the railroad bridge and forbade us to come back. So we hung round above the town all day up along the Peak, and the sides of the mountain—and you know old John Devan’s toll gate up the road? Old John Devan and his toll gate—gone how many years?

“That was the first time I ever saw a sky rocket. I think there was some sort of sham fight that day, too. But presently it began to get dark, and”—his voice was surprised, as though this was a new point to him, “do you know, I got homesick! Yes, sir, homesick! But the rest wouldn’t go. So I struck off alone, scared—blubbering too, I daresay. And I was lost. Had to ask the way to Rockton. Pretty soon a democrat came along and I ran behind it, holding on. Soon I pulled myself up and in, and of course, fell fast asleep in a minute.

“Next thing I knew somebody was looking at me with a light. I had gone all the way home with the democrat to a farm away beyond my own home. Mrs. McMullen—what puddings and pies she could make! Had a dog-churn—such a place for a boy to go—I had often been there. Well, she sent her husband to take me right back home, as the swamp lay between—and ghosts were very real in my young days.”

“And the other boys?”

“Oh, they did not get home until two or three next morning. Bob’s mother kept him chained to a post for two weeks after it—I took my licking, just as I had expected to. I wouldn’t have missed it for any licking—who would?”

Get the sap buckets ready! Hunt up the spiles and scour the rust off them! See that the big, black iron kettles, that came over with the pioneer generation from Ireland, are clean and sound! For maple syrup time is coming nearer, and who wants to miss it? Maybe we do not aspire to the modern evaporator and the scientific rules of the commercial producer—maybe we just make a few gallons for our own use. Anyway, the time is approaching, and there is delight in the very thought!

For day by day, as the sun strengthens, winter is forced to relax his cruel grip on the world. Hidden water trickles with a delicate voice under cover of ice and snow so honeycombed and spongy that they fall back, here and there, to betray its presence. In the still languor of noon, steam rises from roofs and fence rails damp and black and fragrant. Even in northward-looking places icicles fade rapidly, their steady drip-drip a monotone to all the voices of the day.

Unsuspected flies appear out of nowhere. They know sap is ready to run and will presently provide them a sweetness! And the maples, vaguely aware of their sudden importance, tremble with the weight of the rich burden they carry! Thrifty housewives, inspecting the dark, leafless trunk and branches, rejoice to think of the coming of the syrup—and sigh to admit the work it entails!

But the children have no sighs! Rushing home from school to shout the glad news, “Sap’s runnin’! Hey, sap’s runnin’!” they cannot have patience to wait for slow adult feet, but fling off again, down the lane to the clump of maples at the turn, to hang their own pails carefully and hopefully below the gashes their own eager hands can rive in the tree. And the small harvest, brought daily into the farm kitchen, is handled for them by that person who manages to conduct a dozen enterprises daily with fair success. She boils it until the maple flavor is well established and then she turns it efficiently into a syrup of proper heaviness by merely adding brown sugar!

This sort of concoction is not offered for sale—never think that! It would be a breach of the law, for one thing, and a grievous ingratitude for another! . . . . A boy’s mother would not deal with him so. When he works so hard to accumulate all that sap, and resists so manfully the temptation to drink it, he knows she will not fail in her part. And speaking of drinking it—how many a successful and wealthy man to-day looks back across his years of struggle and triumph, to find as one of his happiest memories that simple joy—a long, cool drink of the faintly sweet, indescribably characteristic sap of the maple!

Dusk falling, perhaps—the long, pale shadows creeping across hill and valley—lights shining from the windows—a dog’s voice somewhere—the steady plop-plop of water nearby—a feeling of frost coming with the night—and a faint call from somewhere, “Will—y! Will—y! Supper’s ready! Come!” . . . .

Night, too, holds its glamour in maple syrup time. All day in the bush some one has been going to and fro, collecting the sap from the various trees tapped, drawing it to the great fire, where in the big black kettles it is boiled and boiled, hour after hour. A piece of fat pork, suspended above the cauldron at a calculated height, catches the upheaving liquid as it threatens to foam disastrously over the edge. Oil on the syrup has the proverbially soothing effect, and the syrup retreats within the confines of the kettle once more.

A switch of pine boughs is another discouragement to the ebullient and scalding syrup. Many a kettleful has been soundly whipped into place by this quaint but efficacious method. Old-timers complain that maple syrup to-day lacks something in flavor. It lacks the suavity of the fat pork. It has no trace of the aromatic pungency of the pine bough! Possibly, too, it is without the taste of smoke that sometimes did invade syrup boiled down over the open fire in the heart of the maple bush.

The boiling, when begun, is continued to the finish. And what a lot of time it does take! How vague and slight must be the actual trace of sugar in sap as it comes from the tree! So much moisture to be driven off before color and weight and penetrating sweetness reward. The springing glare of the fire against the silent whiteness of snow—the tall, gaunt trees, stretching upward into the gloom—the silent shape of the dog lying watchful at a safe distance—the recurrent upheaval of the boiling mass—the eddying steam with its characteristic maple fragrance—these make the night of boiling-off one to be remembered long and happily.

It is not likely to be a solitary time. How do the boys and girls of the neighborhood know so definitely when it is to be? Lightly and casually they gather, interested, merry, ready for games that make the night echo with the sound of youthful voices. They know where there will be some syrup left in the kettle for their pleasure—and they know, too, what to do with it.

Unhappily, the splendid hard maples of an earlier generation have been slowly but surely yielding to the pressure of the times. Farms have passed from the hands of those who loved and spared the noble trees, into the brief tenure of men who simply want to snatch from them the swiftest and surest money to be had.

Maple wood is valuable, easily converted into cash. Maple syrup—or hardwood floors? Have we chosen? Or have we simply accepted a decision without questioning its source? Maple syrup is still to be had—of course. But it is no longer a general crop on the majority of farms, as once it was. It has become a novelty to farmers, as to city people. Still, in chimney corners there are old people who can tell us stories about the making of it in other years. And still, rushing excitedly home from school, there are youngsters who have no mind to lose the fun and the enjoyment of it.

Sap’s running! Good news—sap’s running!

“Oh she’s clever, yes, indeed!” said the lady in the tailored suit, most impressively. “Why, she can even make a cow interesting! Anybody that can interest me in a cow——”

“A cow is so-er-commonplace!” said her companion, plump, comfortable-looking in a most expensive coat. “A horse, now—a horse is a noble animal——”

They sat across the table from me the last time I was in town for a day. It was a nice, light, respectable place, where for four bits the white-cap brings you enough to keep you going till the doctor comes. Each of them had a little green teapot about the size of a mucilage bottle, and they had bread-and-butter and frisky salad. They had not interested me in the slightest until their conversation hooked upon the versatile person who had painted a Durham red for them. Then I sat up and looked at them.

Long ago I came to the conclusion that city folk could never be brought into sympathy with actual farm conditions. They don’t feel inclined; it is too much trouble to acquire an understanding of these matters. So it was something of a shock to think that these two unmistakably urban ladies were actually willing to consider the personality of the cow.

Interested. Now what does get a person interested in anything? Not knowledge of it, that’s certain, for I know nothing about airplanes except that I hope in some future existence I may know the glorious thrill of driving one—feeling it rise like a bird, tasting the intoxication of flight, poising, wheeling, dropping with absolute consciousness of power and control.

But a cow—that’s different. Nobody needs to wait until another incarnation to get acquainted with a cow. Her joy-stick is within arm’s length of most of us, and her fuselage is frying in many a homely pan, right now, throughout this fair land. Her propellers make calf’s foot jelly, and bologna and other commercial products. From potted tongue to ox-tail soup, and from the great horn spoon to real leather club bags, the mild and gentle cow assists to the best of her ability. She will live in a field by the side of the road, and be a friend to man, any time except in Winter. Of course, there isn’t much romantic action about a cow. There is no heroic dare-devilry about her to attract the public eye; you don’t see much of her in the movie world. She is no screen star.

Her unpleasant habit of bawling discourteously counts against her. Her manners are undeniably, rather vulgar. She has a way of breathing in one’s face, snuffling with unseemly curiosity, and of course, chewing, chewing, shamelessly and ever-lastingly—oh, she’s vulgar yessir, yessir!

Now what is interesting about all this? I wonder! Of course, cows are about fifty per cent. of the conversation in our happy home, for we are buying or selling them, or milking or feeding them, or concerning ourselves with them or their by-products, for hours out of every day. That’s a commercial interest. Outside of that, cows have a certain attraction for me because they are decent, hard-working citizens, who look to the welfare of their offspring, and mind their own business very consistently. But I couldn’t write a novel about one!

Life must be very barren to people who do not have a wide variety of interests. Goodness me, I like to have lots of roots and branches. I don’t care about crocheting, or tatting, but that is after all, no disgrace. And I never could raise much curiosity on the subject of the after life, or what becomes of the soul after it leaves the body. I’ve had little scoldings for my seeming indifference but it isn’t indifference really. I wouldn’t think of prying into my father’s private papers—though he never told me not to do it, and he does not lock his desk. There are some things one simply doesn’t do.

One night I rode up in the stage with a man who brimmed over with prophecies. He had it figured up that in so many years the end of the world would come. I had to yawn.

“The end of the world will come for me, when my little engine stops running,” I said, unsentimentally. His eyes grew round with horror and he would have thrown up his hands only that he had to balance the groceries that tottered on his inadequate lap.

“But when the Lord comes again——” he protested, getting up plenty of steam for a hot run.

“Now just a minute,” said a stout lady, who was wedged in at the other side of him, and who had been taking in his arguments with both ears. “When I go to town I leave my girl her work to do in the house and mind the baby. And my boy has his chores to do. They know I’m gone and they know I’m coming back. But they have their work to do, and not to be playing with matches and such. They don’t need to come a-running down to the gate, looking for me, or quarrelling about what time they think I’ll be home, or what I’ll bring for them. Nor they don’t need to be trying on my dresses, or wasting the food and the like of that. I don’t lay down too many laws—but I trust them, and I expect them to show judgment.”

It did not end the argument for the futurist gentleman, but it clinched it for me. If the Lord can look after me in this world He can in the next, and there is nobody else who can handle a proposition like that. So ouija boards and Sir Oliver Lodges never cause me to read beyond the headlines. One life at a time is more than I can attend to now and then. As for interfering with those who are at rest—it seems to me a little indecent. We’ll have all eternity to talk to them, so why fret at the brief separation? Why strive to reach across and snatch them back. We love them, and miss them, and we can bring them back in our hearts; the little child who has gone across will come back and pluck the harsh words from our lips and the evil deeds from our hands, if we let it. But to bring that dear one back just for curiosity——

I said I wasn’t interested, but it seems as if I might be if I tried hard enough. A person changes, with time. Take a geranium, and let it stand always the same way, and it grows all to one side. I suppose we grow one-sided too, according to the way the sun shines on us. That is why some of us are so bitter against free trade, and some are so fierce on the subject of tariff—we stand that way towards the light.

It is pleasant to meet with people who are broad-minded, and able to see both sides of a question without getting cross-eyed. I have always been afraid of growing all one way and losing the ability to allow for the other fellow’s point of view.

I wonder if I ever told you about Ziba Fisher’s pigs? He bought a pair of little ones, one Fall, when he was away threshing, and brought them home and put them in an old hen-house, which had an opening in the lower corner of the door about six inches square. That was originally intended to let the hens out—he kept a small kind. Well, Ziba went back to the threshing business again, and left the pigs to his wife’s tender mercies. He was away threshing for eight or ten weeks, and when he came home he found he had a pair of pigs six feet long and six inches in diameter!

Those pigs allowed themselves to be shaped by circumstances. They should be a warning to humanity.

I love to stand upon the hill and watch the night come down