* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

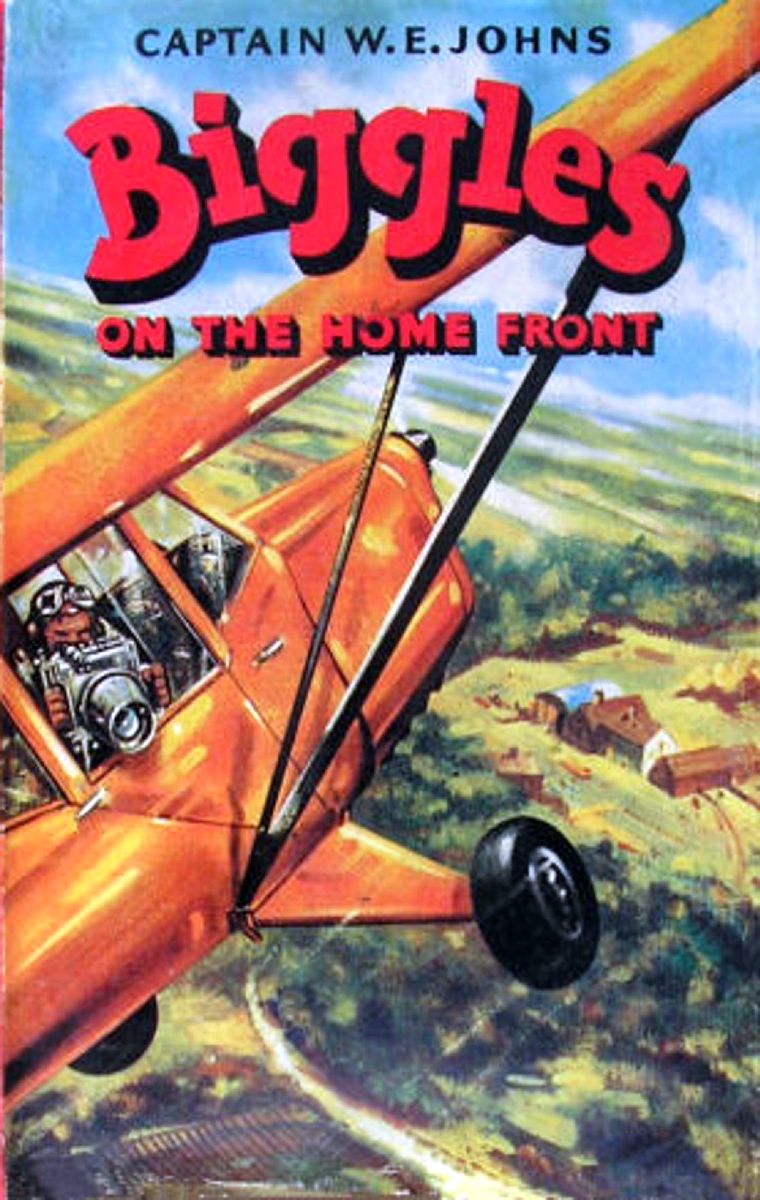

Title: Biggles on the Home Front

Date of first publication: 1957

Author: Capt. W. E. (William Earl) Johns (1893-1968)

Illustrator: Leslie Stead (1899-1966)

Date first posted: June 5, 2022

Date last updated: Sep. 26, 2023

Faded Page eBook #20220604

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, akaitharam, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

BIGGLES ON THE HOME FRONT

An adventure of Biggles and his Air Police Pilots

in and around London

Inspector Gaskin of the C.I.D., worried by

a crop of jewel robberies in London, knew

very well what difficulties crooks were up

against when it came to disposing of stolen

gems. Yet those who might have pulled

these recent jobs were certainly getting big

money for their loot. “They’re spending

it like it dropped from heaven,” he told

Biggles. “Where are they getting it from?”

ON THE HOME FRONT

by

CAPTAIN W. E. JOHNS

With illustrations by Stead

HODDER AND STOUGHTON

THE CHARACTERS IN THIS BOOK ARE ENTIRELY

IMAGINARY AND BEAR NO RELATION TO ANY

LIVING PERSON

First Printed 1957

MADE AND PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN FOR

HODDER AND STOUGHTON LIMITED, LONDON

BY C. TINLING AND CO., LTD., LIVERPOOL, LONDON

AND PRESCOT

| CONTENTS | ||

| Chapter | Page | |

| I. | INSPECTOR GASKIN CALLS | 9 |

| II. | THE BAIT | 25 |

| III. | WHEELS WITHIN WHEELS | 41 |

| IV. | GIVE AND TAKE | 52 |

| V. | A DAY IN THE COUNTRY | 65 |

| VI. | A DANGEROUS ENCOUNTER | 76 |

| VII. | ACCIDENT OR MURDER? | 87 |

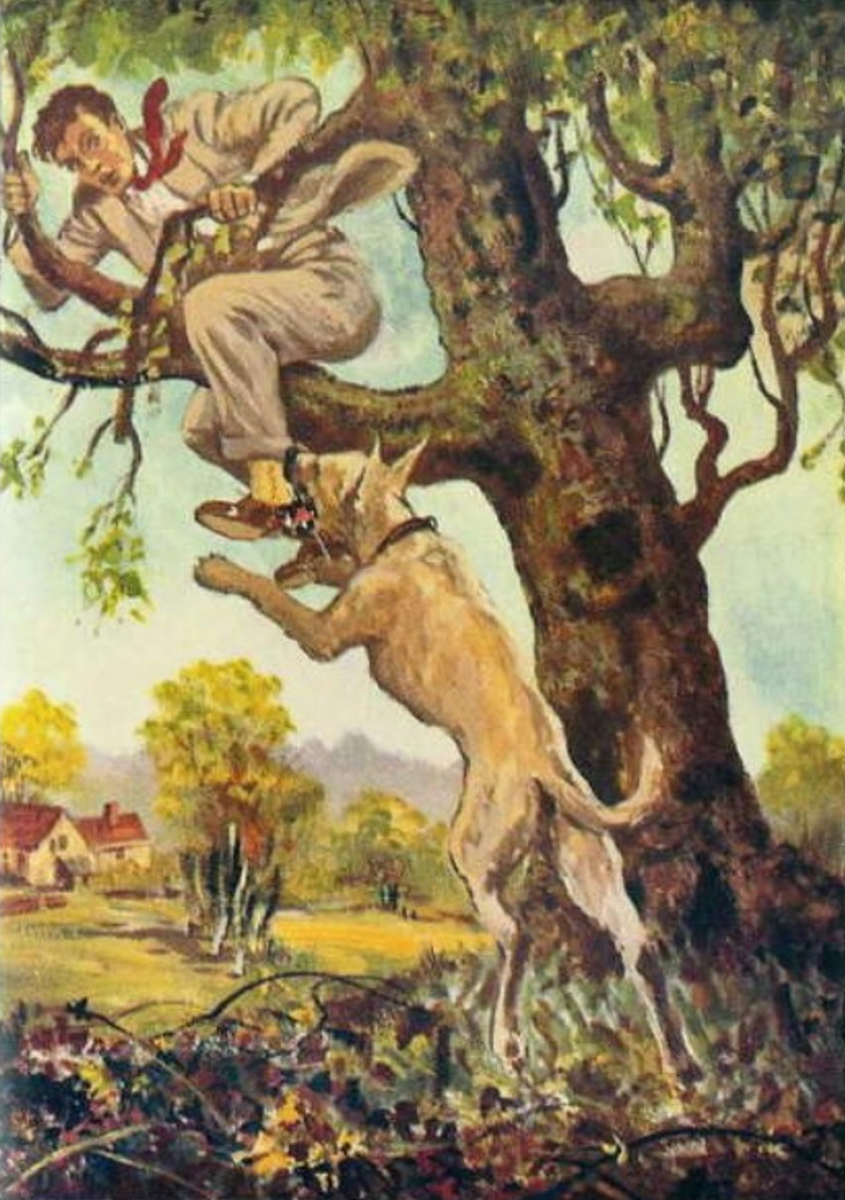

| VIII. | BERTIE CLIMBS A TREE | 99 |

| IX. | ALGY SPEAKS HIS MIND | 109 |

| X. | LAXTER MAKES A PROPOSITION | 122 |

| XI. | NEWS FOR INSPECTOR GASKIN | 134 |

| XII. | THE TRAP | 145 |

| XIII. | NEW MOVES | 159 |

| XIV. | WEARY WORK | 169 |

| XV. | THE END OF THE TRAIL | 178 |

As the door of the Air Police Operations Room opened Biggles glanced up from the map which, with his police pilots, he was studying in connection with some recently published aircraft endurance ranges.

“Hello, Inspector,” he greeted cheerfully, as the burly, dark-suited figure of Inspector Gaskin, of the Criminal Investigation Department, New Scotland Yard, advanced slowly into the office. “Take a pew.”

“Thanks,” grunted the detective.

“What’s on your mind?” inquired Biggles. “You look like a man who’s lost half a crown and found a penny.”

“I feel,” answered the square-faced police officer, heavily, as he dropped into the chair that Ginger pulled out for him, “like a man who’s just seen his last quid go down the drain.”

Biggles smiled. “On a fine spring day like this? Never mind. Another one’ll turn up. It’ll all come right in the end.”

“It doesn’t look that way to me at present,” asserted Gaskin, lugubriously.

“What’s the headache?”

“If I knew the answer to that mebbe I could handle it.” Producing a well-smoked pipe the Inspector began with great deliberation to fill it.

“Handle what?” asked Biggles.

“Don’t you ever read the papers?”

“When I have time.”

“If you did,” rejoined the detective, “you might have noticed that over the past few months the Yard has had enough smacks in the eye to give anyone doing my job a permanent squint.”

“From what direction did these smacks come?”

“From several directions, but all jewel robberies. Big stuff. Fifteen thousand quids’ worth from one house; ten thousand from another; five thousand from a block of flats in Mayfair, and a tray of rings worth a couple of thousand from a shop in Bond Street. Close on a hundred thousand pounds’ worth altogether, and we haven’t a clue as to where it’s gone, much less recovered any of it. It still goes on. I lie awake o’ nights wondering where the next crack’ll come from. The Insurance Companies are beginning to squeal.”

Biggles grimaced. “I’m not surprised. How’s it being done? I mean, what’s the particular method?”

“Smash and grab, using stolen cars, and climbers[1].”

[1] Slang for cat burglars.

“That must mean there’s more than one gang at it.”

“At least two parties, but not necessarily gangs. The climbers and flat raiders may work alone; but, of course, it needs a gang of three or four to work a smash-and-grab racket.”

Biggles looked puzzled. “But what’s gone wrong? I thought you could identify these specialists by their methods.”

“So we can, more or less, but lately they’ve been particularly fly, almost as if someone has been giving them a tip or two. It’s no use suspecting if you can’t lay hands on evidence to prove.”

Biggles reached for a cigarette. “Well, all I can say is, I’m glad this angle of crime isn’t up my street.”

“You don’t know how lucky you are,” rejoined Gaskin bitterly. “I know you have some big jobs to handle, but with you they mostly happen only once. My brand of crooks may not be such big game as yours, but I have them with me always. It’s a war that never ends. From time to time I take prisoners but there are always others on the outside. And by the time I’ve got those rounded up those who were inside are out again.”

Biggles smiled. “It must be tough. But carry on. Get it off your chest if it’ll ease the pain.” He eyed Gaskin shrewdly. “Or had you a better reason than that for coming up the stairs to tell me about it?”

“I thought you might have one of those brainwaves——”

“Now, wait a minute,” broke in Biggles. “You’re the professional sleuth. You’ve been at it for what—thirty years?”

“Thirty-two.”

“That, aside from aviation, must make me look like an amateur.”

“I have an idea aviation might come into this.”

“I see,” said Biggles, slowly. “That’s different.”

“It’s only a hunch, with nothing to back it up.”

“No matter. Even a hunch has to start from somewhere. Go ahead.”

“It’d mean explaining the whole set-up of how my sort of crooks work.”

“That’s all right. It so happens we’re not pushed for time, and I’m always willing to learn. You’ve an idea. Out with it. I’m listening.”

“I’ve come to the conclusion there’s a new man in the business.”

“A new man. But surely he wouldn’t mix smash and grab with climbing drainpipes. The two things don’t go together.”

“They might if there was one set of brains behind ’em. That’s the only answer I can arrive at to account for this sudden burst of activity in the so-called underworld. It’s my guess that the trouble is at the receiving end. There’s a new man on the job and he’s paying fair prices.”

Biggles frowned. “I don’t quite understand what you’re getting at. By receiver I take it you mean the man who receives the stolen goods, commonly known as a fence.”

“You’ve got it.”

“But is the fence all that important?”

“He’s the most important man in crime, and he’s also the hardest to catch. You’ve got to catch him with the goods on him, or be able to prove that he’s had the goods and knew the stuff was stolen. And that takes some doing.”

“So I can imagine,” nodded Biggles.

“You see,” went on the Inspector, relighting his pipe, which had gone out, “we often get a squeak from the underworld about a job, either before or after it’s been pulled off. Forget what you’ve heard about honour among thieves. There isn’t any. One crook will put in a whisper about another, or one gang will double-cross another gang if they think it’s to their advantage. Or may be out of revenge. But it’s almost an unwritten law that a crook must never shop a fence.”

“Why? Why should a fence be sort of sacred?”

“Because, don’t you see, if crooks shopped him they’d be cutting their own throats. How would they dispose of their swag? They seldom know the value of the stuff they pinch; but the fence knows. It’s his job to know. He makes his own price, and as far as the thief is concerned it’s a matter of take it or leave it. As the crook is usually short of money, he takes it. It may surprise you to know that a crook is lucky to get even a quarter of the value of the stuff he pinches. Ten per cent is more usual. Which means that for a thousand quids’ worth of sparklers he gets a hundred. And even out of that he may have codgers, and other people, to pay.”

“That’s a lovely word—codger,” put in Bertie Lissie. “What’s a codger?”

“The underworld name for a watcher. The curse of that is, a crook tries to get youngsters to do it because they’re less likely to arouse suspicion. These silly kids stick their necks out for a quid or two and so take the first step on the road to Dartmoor; because it’s only a question of time before they find themselves involved in bigger jobs. Then there may be the car thief to pay, too, in case one’s necessary for a quick getaway.”

“Why not use his own?” queried Ginger.

“Because we should spot it. The crook prefers a stolen one. That’s done by a specialist who knows how to start any make of car. For ten pounds he’ll provide anything from a sports car to a van and park it where you want it. For smash-and-grab raids the car thief will fix a tow-bar and a chain with a hook on it for tearing down shutters and steel grilles over jewellers’ windows.”

“Very interesting,” murmured Biggles. “But let’s get back to the receiver, the fence, if that’s the man you want.”

The Inspector resumed. “As I was saying, the thief has to take what he can get for the loot. Imagine the feelings of a crook who has risked a five years’ sentence to get a parcel of gems. The fence gives him, say, a couple of hundred quid for ’em. The next day the crook reads in the newspapers that they were worth three thousand. What can he do about it? Nothing. Knowing he’ll be under suspicion he daren’t keep the stuff on him for a moment longer than is necessary.”

“Do these crooks ever go back to the fence and say they’ve been cheated?”

“If they do the fence has the answers ready, and they’re not unreasonable. He argues the stuff is hot—red hot—and if it should be found in his possession he’s likely to get ten years. Again, receiving is a long-term business. He may have to keep the stuff for months, maybe years, waiting for the fuss to die down before he tries to sell it. Of course, he may recover part of his outlay by taking the gems out of their settings and melting down the gold. That’s easily disposed of. But he has to be more careful with the stones even if they’re re-cut, because there’s always a chance that an expert will recognize them.”

“You make it sound as if jewel stealing is poor business.”

“It is. I know crooks who could make more money by going straight, but some queer bug in their brains won’t let ’em.”

“All right. Let’s get down to brass tacks. What do you think has happened to set off this spate of robberies?”

“I’ve told you. I believe we have a new type of fence to deal with, one who’s prepared to pay better prices. The crooks I know who might have pulled these recent jobs have all got money. They’re spending it like it dropped from heaven. Where are they getting it from?”

Biggles shrugged. “Don’t ask me. How can this new fence, assuming there is one, afford to pay more than the old hands?”

“I can see only one answer to that. He’s got a safer and quicker way of unloading the stuff. I’m as certain as I sit here that it’s going to the Continent, or some of it would have been traced by now. And if you ask me how, I’ll tell you.”

“How?”

“It’s being flown out.”

“Ah!” breathed Biggles. “Now I see what you’re driving at. You think I might be able to help you to find this fly guy?”

“Could the stuff be flown out of the country?”

“Probably,” admitted Biggles, frankly. “In fact, it has been done.”

“By the regular services?”

“Not as far as I know. I can’t imagine a crook, knowing that all ports are watched within minutes of a crime being discovered, trying to get through Customs with hot jewels in his pocket, even if he had a passport, which is unlikely.”

“This new fence may not be known to the police.”

“No matter. Any man or woman spotted going through Customs more often than the currency allowance permits soon comes under suspicion. If this man you have in mind is doing that it’s only a question of time before they cop him.”

“What about a private aeroplane?”

“That could be the answer,” conceded Biggles. “Air smuggling goes on all the time in Europe, where it’s only a few minutes’ job to slip a load of contraband across a frontier. A privately-owned machine in the hands of a capable pilot can cock a snoot at official airports.”

“And are you telling me there’s no way of stopping that?”

“If there is, no one has yet thought of it. Just think for a minute. If, during the war, with thousands of men on the watch, equipped with radio, radar, searchlights, guns and all the rest of it, machines could slip through on secret missions, dropping anything from spies to provisions, and even landing, without being caught, how much easier must it be now without such obstacles? In those days failure meant death, without any argument. Yet men, and women, were willing to take a chance. Today, the worst a sky sneak has to fear is a short prison sentence. We keep an eye open always for unofficial air traffic, but I can’t watch the coast, east and west, day and night, from Land’s End to John o’ Groats. I’ve neither the staff nor the machines to do it, and if I had I wouldn’t guarantee to stop such a racket, should one start.”

“I’ve an idea one has already started,” growled the Inspector.

“You’re thinking in terms of a fence with an aircraft?”

“Or a fence with a pilot on his pay-roll.”

“Assuming that is so, wouldn’t it be easier for you to locate him on the ground, since he would of necessity be in contact with your pet jewel thieves? Watch them and they should lead you to him. I imagine you know them by sight, and where they spend their spare time.”

“Of course. But the trouble about that is, they know me. The old lags know everyone in my Department by their Christian names. That’s all part of their business. They can spot a cop as quick as a teenage girl can spot a film star. When I show my face in the Barnstaple Arms, commonly known as the Barn, in Soho, where a lot of ’em hang out—and I often look in to see who’s around—they gather round me like I was a rich uncle and argue as to who’s going to buy me a drink.”

Biggles smiled. “They must love you.”

“Yes, as much as an old mouse loves the house-cat.”

“What’s the idea?”

“Oh, mebbe it’s just to let me see they haven’t forgotten me. Mebbe it’s a front to cover up their nervousness, to let me see they’re behaving themselves. More likely it’s just bravado, swank, to kid themselves they’re not afraid of me.”

“But they are.”

“You bet your life they are, particularly when they have something on their minds and they know I’m on the war path. Then it’s a battle between their vanity and their fear of the law.”

“Why do they congregate at that particular pub?”

“They’ve got to congregate somewhere to keep in touch, to get the latest news in their line of business. Birds of a feather . . . you know. The Barn is as good as anywhere, I suppose, and it’s central. Anyway, they have to go out some time; they can’t sit indoors all the while. Of course,” concluded the Inspector meaningly, “as you don’t normally come in contact with ’em they wouldn’t know you.”

“Neither would I know them,” Biggles pointed out. “And I’m not pining to know ’em. These dirty birds are your pigeons, and as far as I’m concerned you can keep them.”

“You’d soon get to know ’em if you had a look at their mugs in our Rogues Gallery,” argued the Inspector. “We’ve photos of all of ’em, ugly, plain and handsome.”

“Purely as a matter of interest tell me this,” requested Biggles. “How do crooks usually pass their stuff to a fence? I mean, do they go to his house, or shop, if he has one?”

“Only in exceptional circumstances. It’d be too dangerous. More likely contact would be made over the ’phone in a harmless-sounding conversation. But a meet is made, a meet in crooks’ language being an appointment. Both parties arrive dead on time, to the tick. The stuff changes hands and the whole transaction is over in a couple of seconds. I’ve seen stuff passed by a man on the pavement to another in a car without the car stopping. Knowing they might be tailed, which means shadowed, by a police car, they waste no time in idle chatter.”

Biggles thought for a moment. “I get the drift of your idea,” he said, stubbing his cigarette. “But this is outside the range of my official duties.”

“It could be inside if aviation came into it,” contended the detective.

“Agreed. But how are we to find out if aviation does come into the picture?”

“That’s up to you. You’re the flyer.”

“Let’s get to the point,” returned Biggles. “I don’t want to appear unco-operative, particularly as on more than one occasion you’ve helped us. Without promising anything, what exactly do you suggest I do?”

“Well, what I was thinking was this. If you drifted into the Barn once in a while, and stood near the crooks who by that time you’d know by sight, you might hear an odd word dropped that would give you a line. There’s just a chance you might spot one of ’em talking to a man you’ve known at some time or other in the aviation business.”

“I’d call that a pretty remote chance.”

“No harm would be done by having a look round.”

“I suppose not. All the same, I can’t imagine any crook being so daft as to talk in a public bar.”

“You’d be surprised. It’s amazing how rumours travel in the underworld. I don’t know how crooks get to know what they do know. Anyway, I’m certain these jobs are being pulled off by professionals. I know their methods. You’re bound to see some of ’em in the Barn. All you have to do is keep your ears open.”

“Maybe I can think of something more likely than that to produce results,” said Biggles.

“I was hoping you would,” admitted Gaskin, frankly. “But you be careful what you get up to. If they get a sniff of why you’re there you might meet with an accident on the way home.”

“Does the landlord of this pub know he harbours crooks?”

“Probably. But as long as they behave themselves, and they usually do, that’s no concern of his. His business is to serve drinks to people who are sober and can pay for ’em. The customers aren’t all crooks. It’s a perfectly respectable house. Stands at the corner of Greek Street and Landal Square. Now how about casting an eye over some of the photographs I have downstairs?”

“Lead on,” invited Biggles. “You’d better come too,” he told the others, “in case you have to come looking for me.”

They all followed Inspector Gaskin to the photographic department of the Criminal Record Office where are kept for reference the portraits of all criminals known to the police. Actually their work had taken them there before, but the records they had sought on those occasions were different.

The next hour was spent studying the faces, full-face view and profile, of jewel thieves, particularly those known to frequent the Barn and those who Gaskin suspected to have been concerned with the recent robberies. He gave the nicknames by which they were known in the underworld as well as their real names.

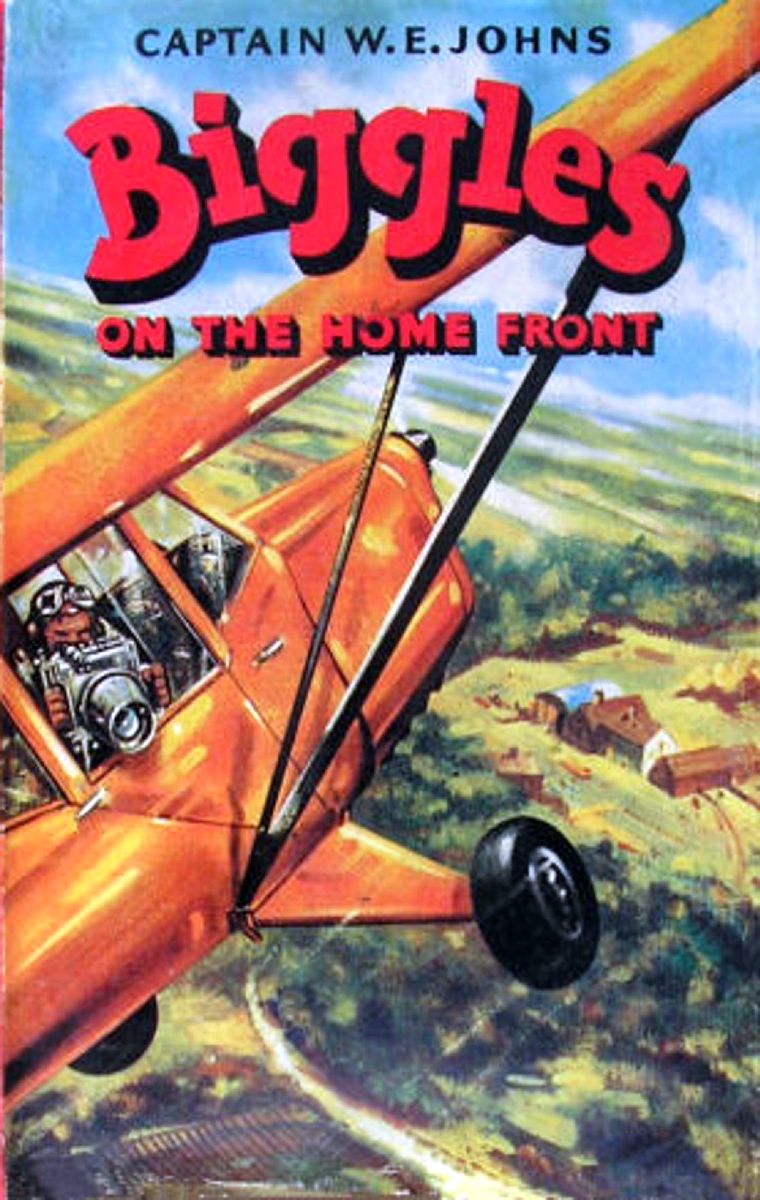

“Here’s a smash-and-grab team,” he said, producing the photographs. “A pretty bunch. They’ve all done time. Darkie Brown, Sid the Sailor and Bruiser Lee. Darkie Brown is the driver—and can he drive! Mind you, it’s always a stolen car, so he doesn’t care if he smashes it, or any other car for that matter. They’re all experts in their way, up to every trick. And here’s the bright boy who gets ’em the car. Toni the Needle. Italian by birth. Gets his name I believe from a nasty habit of carrying a stiletto.” The Inspector turned to another page.

“This lout with the dead-pan expression is Dusty Brace,” he went on. “He used to carry knuckledusters, and still may for all I know. A dangerous type. His department is picking pockets. Works the bus queues in the West End when the theatres close. I’ve popped him in several times. The trouble is they don’t keep him locked up long enough. He’ll never be anything but a thief. He must have been born one, for he once boasted to me he was pinching pennies out of his mother’s purse almost as soon as he could walk. Nasty piece of work. Anyone catching him in the act, I mean a harmless civilian, is liable to get a bunch of steel knuckles in the face.”

“I’ll remember him,” said Biggles. “Are any of these types known to carry guns?”

“A few. Not many. The old hands know where that leads to, but some of the youngsters who’ve spent too much time at the cinema think it’s smart, the silly little fools. Here’s one who used to carry a gun, Mike Sullivan. He’s spent most of his life in prison. You’d think he’d get sick of it. Nice feller, you might suppose, glancing at him. But take a look at those eyes. A real bad ’un. He’ll kill somebody one day. He’s just finished five years for armed robbery and swears he’ll never go back; which I take it to mean anyone trying to arrest him can expect trouble. He started as a codger for an old lag who died recently in gaol.”

“What’s his line now?” asked Biggles.

“Burglary. Cheap stuff, mostly. Robs his own class. He hob-nobs with Dusty Brace. You’ll see ’em both at the Barn.” The Inspector turned to another photograph.

“Now here’s a very different type,” he continued. “They call him Swell Noble so you can guess how he got his name. He was at Oxford, supposed to be studying law, when he first took a fancy to diamonds. Don’t ask me why. He’s a cat-burglar, and a fair masterpiece at it. He’d climb the face of a blank wall to get to a window. He once told me he’d climbed every college tower in Oxford, for fun. Said night-climbing over buildings was a regular sport there.”

“So I believe, but that doesn’t make students cat-burglars. Is Noble in prison now?”

“No, but I fancy he should be. I don’t know anyone else who could have reached the window of that last Mayfair job. As you see, they come from all classes. Here’s another who went to one of the expensive public schools. Augustus Norman. Gus for short. Good-looking chap. He and another feller named Stony Stoneways, who went to the same school, used to work together. The big blocks of luxury flats were their meat. Being smartly-dressed and well-spoken they could get past the hall porter. They knew who occupied the flats and would wait until the selected victim went out. Up they’d go. Knock on the door. No answer. They’d let themselves in with a master key.”

“Suppose somebody was at home?” queried Ginger.

“Easy. They’d called to test the telephone or make some such excuse. They’d say they were sorry—must have come to the wrong number. Gus’s pal, Stony Stoneways, tackled a job on his own. We happened to be watching him and nailed him with the stuff on him. He’s in Pentonville at the moment, with another two years to serve.”

“I shall never understand why men of that sort take to crime,” averred Biggles.

“Must have a crooked streak in their make-up. There was no need for Swell to go off the rails. His father was well off. When he died, broken-hearted, he left all his money to charity. That’s all the good Swell did himself by trying to be a smart guy.”

“I take it these crooks know each other?”

“More or less. They drift naturally into cliques, according to class and the sort of jobs they do. They get to know each other in gaol, no doubt, if not before. I’ve seen Swell and Stony and Gus, talking together in the Barn, comparing notes, although to see ’em you wouldn’t guess what they were talking about. But crooks, like other people, have to talk to somebody, and they turn to those with whom they have something in common.”

The Inspector went on to show them some portraits of receivers, past and present. Most of them were serving prison sentences. They were all ordinary-looking men who might have been met in any street. There was nothing to hint at their unlawful occupations, which, said Gaskin, made them subject to severe penalties, for without them there would be no market for stolen goods, and therefore no purpose in that sort of crime.

“I think that’s about enough to go on with,” said Biggles at last. “Let’s go. This place depresses me.”

“That may be, but these records ain’t kept for fun,” answered Gaskin. “The public must be protected and these are part of our defences. Let me know what you decide to do and how you get on.”

“I will,” promised Biggles, and led the way back to his own quarters.

“This is a new line for us,” remarked Algy, as he closed the door.

“Yes, and I don’t think much of it,” returned Biggles. “Maybe I was weak to allow Gaskin to talk me into what is really his job, but what else could I do? I suppose we should be flattered that he has asked us to lend a hand. Anyway, there is just a chance that aviation may come into it.”

“If you asked my opinion, old boy,” put in Bertie, “I’d say the whole disgusting business stinks.”

“Crime in any form stinks,” said Biggles, evenly, as he went back to his desk.

It was on the afternoon of the third day following the illuminating discussion on jewel thieves that Ginger walked into Biggles’ office with a peculiar smile on his face.

“Has Inspector Gaskin been here?” he inquired.

“No,” answered Biggles. “Why?”

“If I’m any good as a prophet you’ll soon be hearing from him.”

“About what?”

“There’s been another jewel robbery.”

“How do you know?”

“It’s in the paper.” Ginger held up an early edition of the Evening News.

“Was this job done in Portman Square, by any chance?” asked Biggles.

Ginger’s eyebrows went up. “Yes! How did you know?”

“Somebody took a handbag from a car parked outside the house of Lady Fenton, maybe.”

“Er—yes.”

“The handbag contained some jewels, the most important of which was a magnificent emerald pendant. Right?”

Ginger tossed the paper aside. “I thought I was bringing you news. I see you know all about it.”

“So I should.”

“Why?”

Biggles smiled. “Because I organized it.”

“You what?”

“You heard me.”

“What’s the big idea?”

“Use your head. For what purpose would I be likely to rig a job like that?”

“You didn’t tell me you were going to do it.”

“I didn’t know myself until last night, after you’d gone home. Gaskin dropped in with his Press Relations Officer and he fixed it all up.”

“Fixed! Do you mean the entire story is phoney?”

“Practically. As far as I know there is no Lady Fenton. There was no car. There was no handbag. There isn’t even an emerald, but I have a very good imitation of one in a genuine gold setting—three dolphins pursuing each other, head to tail. The fish are appropriate.”

“I take it this is some sort of bait?”

“Quite right.”

“You’re hoping to hook a crook?”

“I shall be satisfied if I can get one interested. Just standing around in the Barn waiting for something to happen seemed to me a pretty futile approach so I decided to dangle a bait in the hope of speeding things up. Put it like this. I want to make contact with one or more of these crooks who meet at the Barn. It’s hardly likely that one of them would speak to me, a stranger, without some inducement. I shall have to kick off, and, as I see it, the quickest way to get the ball rolling is to let it be known to the wide boys that I’m in the same line of business as themselves. Even then it may be some time before I get the information I’m really after—the name of a reliable fence. I can’t ask outright. That would be too crude. I’m hoping that someone will tell me what I want to know. Maybe just drop a hint. Whatever I do will mean taking a chance so I decided last night to try this way first. If it doesn’t work, well, Gaskin can’t say I didn’t try. I had to have a bait, and the bait had to be something valuable; valuable enough to interest the sort of receiver who, Gaskin believes, is buying the proceeds of these recent robberies. How could I explain how I came to be in possession of an important jewel unless one had been stolen?” Biggles smiled. “Well, now one has been stolen and the crooks will read about it. I have the swag, and they will soon know that, too.”

“Where did you get the fake emerald?”

“I bought it from a pawnbroker—an unredeemed pledge. He’d had it for years, he said. Here it is—or part of it.” Biggles opened a draw of his desk and took out a circular gold mount with a hollow centre, the cavity being formed by three fish.

“Where’s the stone?” asked Ginger.

“I prised it out.” Biggles produced from a waistcoat pocket what appeared to be a fine emerald.

“Why did you take the stone out?”

“Because although the mount is gold, the stone, as I have told you, is a fake—a very good fake, mind you. It might pass for the real thing with some people but of course it wouldn’t fool an expert. The mount should be enough for my purpose—at all events, as the opening move. A description of the jewel has been issued, and it will be supposed, I hope, that if I have the mount I also have the stone. I would have preferred a genuine emerald, but obviously that was out of the question. A real stone of this size would cost thousands, and I might lose it. In fact, if things go well that’s more than likely. The pawnbroker told me he thought the thing was probably a copy of an original jewel. Anyway, it’ll have to do.”

“And what exactly are you going to do with it?”

“Well, as I say, I didn’t think much of Gaskin’s scheme of just standing around in the Barn waiting for someone to let something slip out. That would be too chancey. We might have played that game for weeks to no purpose and I’ve something better to do. If, sooner or later, it meant offering a bait, I’d rather do it as a stranger, not as someone who has made a habit of drinking in the Barn. That’s why I shall go straight ahead with my scheme.”

“I see,” returned Ginger, slowly. “You’re reckoning on the crooks reading about the robbery.”

“They can hardly fail to notice it.”

“Very well. Then what?”

“Having a professional interest they should wonder who did the job, and how it was done. After listening for a whisper in the underworld without hearing anything they’ll conclude that it was the work of an amateur, possibly someone who had been given the tip by an employee in the house. The staffs of big houses are constantly offered bribes for information about where the valuables are kept. Chauffeurs are offered large sums to leave car doors unlocked—when there’s something valuable inside. Anyway, in this case I’m the amateur who did the job.”

“Yes, but are the crooks to know that?”

“I shall take steps to let them know, in the hope that in due course the information will reach the ears of the man we are after—if he in fact exists. The receiver who pays good prices.”

“You’re going to the Barn?”

“Yes.”

“Am I coming with you?”

Biggles grinned. “In view of what Gaskin said about codgers it might be a good idea if I had one.”

“What about Algy and Bertie? Are they in on this?”

“They’ve already started on it from a different angle, which is to check up on all cross country flights, particularly night flights, made over the last couple of months by privately-owned light planes, whether the flight was made by the owner himself or a pilot employed by him. There should be no difficulty. It’s a routine job, but it’ll take time. I’ve been intending to do that for some time, anyway. I’m not so optimistic as to hope for a direct hook-up between aviation and the Barn, or any other rendezvous of the underworld; but we have to start somewhere. If this private-owner angle fails we’ll have a look at the regular air services.”

“To me, the snag about all this is, we haven’t a particle of evidence that stolen goods are leaving the country, much less that air transport is being used.”

“Gaskin’s a wise bird or he wouldn’t be where he is. If he has a hunch it’s worth riding. I’d say it’s rather more than a hunch. It’s more a matter of elimination. Having been at the game for thirty years he knows all the usual tricks and methods for disposing of stolen property. He’s explored them all without finding a clue and that has led him to the belief that he’s up against something new. What has happened to all this stuff that has been pinched lately? Someone knows. The fact that Gaskin’s narks have failed to pick up a word about it means that this new receiver, and there must be a receiver somewhere, has kept the lid tight on his own security. That in turn suggests he’s no common thief. This chap has brains.”

“If there is a chap,” put in Ginger dubiously.

“There must be,” declared Biggles. “One thing we can bank on is this: these crooks who stole the stuff are not walking about with it in their pockets. They’ve sold it, which is why they’re well supplied with money at the moment. Well, there it is. We’ll have a look at the air angle. When I’m satisfied that flying doesn’t come into it I shall tell Gaskin so and leave him to work things out for himself. Our job here begins and ends with aviation and I’ve no intention of being side-tracked into the ordinary work of the Yard, about which we know little. Gaskin would neither want nor expect that. We’ll begin tonight by seeing in the flesh some of these crooked customers at the Barn. I shall, in fact, be one of them, having just come out of Pentonville.”

“Why Pentonville?”

“That’s where Stony Stoneways is doing time.”

“What about it?”

“His public school pal, Gus Norman, is free, and may be at the Barn. We shall see. What I do there will depend on what happens, so all you can do is take your cue from me. I’ve arranged with Gaskin, should I find it necessary to get in touch with him without going to the Yard, that for the purpose of this operation my name will be Ted Walls. Don’t forget that and call me Biggles, in case my name means anything to them. You can keep your own. It’s as good as any.”

“What time is zero hour?”

“About nine.”

“Do we go as we are?”

“More or less. To look prosperous wouldn’t fit with my act so we’ll wear our oldest clothes, and shirts that aren’t too clean. There’s one thing we shall have to do before we go to the Barn.”

“What’s that?”

“Find ourselves lodgings. If we draw blank we can go home, but in case we do make a contact we ought to have somewhere to go when we leave the Barn. We might be followed.”

“Followed? By whom?”

“I don’t know. But we may arouse some curiosity, and it would hardly do to be seen going home to a rather expensive flat in Mount Street. That might arouse too much curiosity, particularly if it was learned that the occupants of the flat worked at Scotland Yard. These jewel thieves may not have heard of me, but they’ll soon find out who I am if I’m seen going into the Yard. We’ll take a couple of old suitcases with our small kit and book rooms at one of those cheap little hotels in Gillingham Street, near Victoria.”

“Does Gaskin know about this set-up?”

“Of course. I told you he helped me to fix it.”

“Who else?”

“Algy and Bertie. That’s all. I asked Gaskin to keep it to himself. Let’s go and have a cup of tea.”

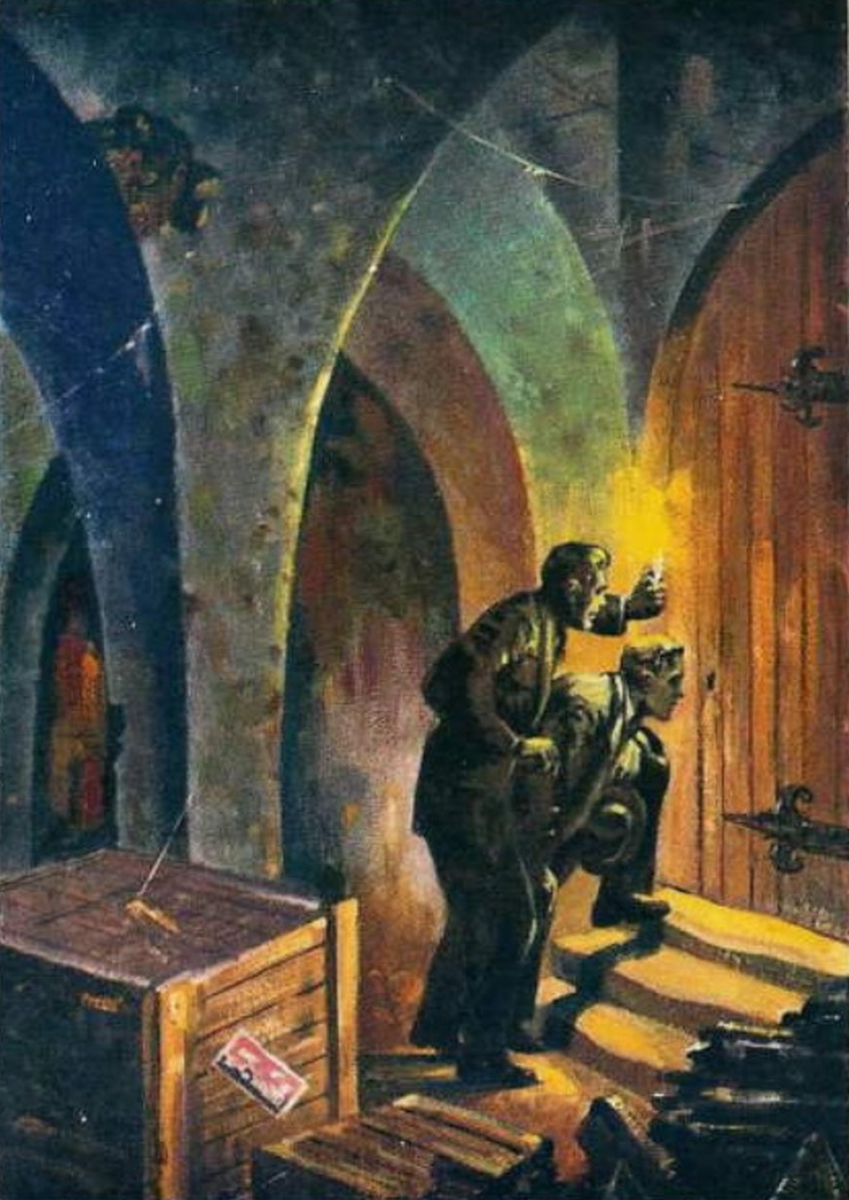

At eight-thirty that evening, Biggles and Ginger, looking somewhat shabby, left Mount Street in a taxi bound for Gillingham Street, where, without difficulty they were able to book two single adjoining rooms in the Clefton, one of the cheapest of the several small hotels such as are always to be found near big railway stations. Then, leaving their suitcases, they walked to Victoria Street, from where a bus took them to within easy distance of their objective. They soon found it, for it was an establishment of some size, certainly a lot larger than Ginger expected. It was a modern type of building, having, as they learned, been rebuilt between the wars, and wore that appearance of prosperity that suggests efficient management.

Pushing open the swing doors of the saloon bar they were greeted by warm, smoke-laden air, a babble of voices and the clink of glass, for as Ginger observed, the place was well patronised. Having provided themselves with drinks at the long bar, where two or three women were serving under the eye of the landlord, they took them to a vacant seat, and from behind one of the customary small tables surveyed the scene.

Presently his roving eye picked out the gun-carrying Mike Sullivan . . .

Broadly speaking the customers were all unknown to Ginger, as was to be expected, for he was out of his usual element; but it was not long before he spotted Swell Noble, leaning against the bar talking to Gus Norman. Presently his roving eye picked out the gun-carrying Mike Sullivan, sitting by himself with a glass in front of him. Soon afterwards, however, Toni the Needle came in and joined him. Heads together they were quickly engrossed in earnest conversation.

Ginger watched all this with a sort of morbid interest. He had encountered quite a number of criminals in his time, but not this sort, and it struck him as extraordinary that these men were apparently content to sit night after night in such a place—when they were not in prison—talking and drinking. That, evidently, was their way of life, for there they were.

“You might try to hear what those fellows are talking about,” suggested Biggles, indicating with a glance Sullivan and the Italian.

Ginger drifted over casually and sat down near them; but they stopped talking at once, although they gave no indication that they had noticed him. After a little while, perceiving that he was serving no useful purpose, he got up and strolled away. But by the time he had rejoined Biggles the two men were talking again, Toni emphasising his points with eloquent gestures that revealed his Southern temperament.

“Nothing doing, eh,” murmured Biggles.

“Not a word. They shut up like oysters when I arrived within earshot.”

“That doesn’t surprise me. With Gaskin’s men always keeping a watchful eye on them they don’t talk in the hearing of people they don’t know. Now you see why I had to devise a scheme to put their minds at rest about us. Only if they think we’re crooks are they likely to talk in front of us.”

For some time they sat and watched while customers came and went, but they saw no one who, as far as they knew, was remotely concerned with aviation. From time to time Swell Noble’s eyes, always restless, went round the room, not so much as if he might be looking for any particular person but rather as a sort of check-up on who was there. Thus did he, thought Ginger, betray the nervous watchfulness behind his pose of easy nonchalance. Slim, of medium height, clean-shaven, with regular features and the figure of an athlete, immaculate in a dark suit, it was not easy to believe that he was what Gaskin had declared him to be; a cat-burglar, a man who had been to prison, a criminal with a record at Scotland Yard.

Gus Norman, to whom he was talking as he leaned against the bar, was a rather different type, although he still had about him that indefinable something, a sort of poise, a confidence in himself, that marks the man of higher education. He was in the early twenties, carelessly dressed in grey flannel trousers, a check sports jacket and suede shoes. He wore his fair hair rather long, and carried plenty of flesh without being actually fat. He could have been called good-looking in a rather effeminate way. From time to time when he caught sight of himself in the mirror on the opposite side of the bar he smoothed his hair in a manner that suggested a trace of conceit in his nature. Was vanity his real trouble? wondered Ginger.

Ginger was still pondering the problem of why such a man should choose deliberately a life of crime when Swell finished his drink and departed, leaving Norman alone.

“Okay,” said Biggles, softly, to Ginger. “I don’t want to spend all night here. Let’s see if we can start something. Don’t look surprised at anything I say.”

He got up, and followed by Ginger joined Norman at the bar. “I believe you’re Gus Norman,” he said, evenly.

Norman’s eyes switched round. “And if I were, what of it?” he returned, curtly, yet in a well-spoken tone of voice.

“You were described to me by a certain party known to both of us. He said I would probably find you here.”

“Well?”

“You’re a friend of Stony Stoneways.”

“I don’t know anyone of that name,” replied Norman, coldly.

Biggles made a gesture of apology. “Sorry. If you don’t know Stony you’re not the man I’m looking for.” He turned away.

Norman caught him by the sleeve. “Just a minute. What about this fellow Stony?”

“I saw him recently. I have a message.”

“Where did you see him?”

“We happened to be in the same—er—hotel.”

“What was the message?”

“It was for a man named Norman.”

“I’m Norman.”

“The message was to say you might be seeing him sooner than you expect.”

Not a muscle of Norman’s face moved. “I see,” he said, slowly. “Anything else?”

“That’s all, except that he did mention it might be worth my while to make contact with you.”

“For what reason?”

Biggles smiled wanly. “I gather he thought you might—er—put me wise.”

“As—for instance?”

“You might know somebody who could do with this.” Holding it in the palm of his hand Biggles gave Norman a glimpse of the gold mount.

Norman’s face remained expressionless. “I wouldn’t know what to do with that,” he said, his eyes flashing round the room.

“Okay. It was just an idea.”

“Where’s the rest of it?”

“What do you mean?”

Norman’s hard eyes met Biggles’ squarely. “You know what I mean. Still, forget it. I’m not interested.”

“Sorry,” said Biggles. “I was only doing what Stony suggested.” He went back to his seat.

“He didn’t bite,” breathed Ginger.

“You wouldn’t know, with a man like that,” replied Biggles. “He has to watch his foot every time he puts it down. The thing is, he knows, or he thinks he knows, who lifted Lady Fenton’s emerald. He recognised the mount or he wouldn’t have asked what I’d done with the rest of it. And if he knows, other people will soon know. That’s all I want for the moment. I’ve planted a seed. All we can do now is wait to see if it bears fruit.”

After a little while Norman finished his drink, and without so much as a glance at them, went out.

“I wonder where he’s going,” murmured Ginger.

“Home, probably,” replied Biggles.

“We might as well go home ourselves,” suggested Ginger.

“Don’t be impatient,” answered Biggles. “There’s just a chance that my seed might start to sprout. You can’t rush these things.”

Half an hour passed. Nothing happened. It was now nearly closing time, and Biggles had just announced his intention of moving off when the swing doors opened and Norman came back. He went straight to the bar and ordered a drink.

“Now what?” said Ginger softly.

“Sit still.”

Five minutes later Swell Noble came in. He joined Norman at the bar. Norman said something. Noble half glanced round.

“I think we’ve got a bite,” said Biggles. “At all events, Norman has just pointed us out to Swell.”

Then, to Ginger’s surprise, Noble came over and sat near them.

“I hear you’ve been talking to a friend of mine,” he said cheerfully.

“Who do you mean?”

“Stony Stoneways.”

“Oh, you mean——”

“Ssh. Not so loud.” Noble’s eyes went round the room meaningly. “I’ve never seen you here before, Mr.——?”

“Walls. Ted Walls. I’ve never been here before,” stated Biggles, truthfully.

“Did you come here simply to give that message to Gus Norman?”

“Not entirely.”

“That’s what I thought.” A ghost of a smile crossed Noble’s face. “Have you still got it?”

“Got what?”

“Don’t quibble. It wastes time. The thing you showed Gus.”

“Yes.”

“Let’s have a look at it.”

Biggles passed the mount.

Swell looked at it and handed it back. “Where’s the rest of it? The piece that matters.”

“Where the rats can’t get at it.”

“You’ve still got it?”

“I have.”

Swell looked horrified. “Do you mean you’ve got it on you?”

“Yes.”

“Then take my tip and get rid of it as soon as you can.” Swell started to get up. “I wouldn’t walk about, in here of all places, with that thing in my pocket. You’re dangerous company. Too dangerous for me.” And with that, to Ginger’s surprise and disappointment, Swell rejoined Norman at the bar.

After a quick drink, and a few words spoken in an undertone, they went out together.

Biggles waited for a minute or two and then he, too, prepared to leave. “That’ll do for tonight,” he decided. “No use trying to do too much at once. Let’s go.”

They went out and walked to Shaftesbury Avenue, where, at a bus stop, Biggles lit a cigarette. “Don’t look round but I think we’re being followed,” he said, softly.

Their bus came in. They boarded it, as did another man at the last moment, as the bus began to move. They went on top. He went inside.

“Is that the man?” asked Ginger.

“He came out of the pub by a different exit at the same time as we did, so if he isn’t tailing us it must be a coincidence. If he gets off when we do it’ll look less like a coincidence. If that happens pretend not to notice.”

They left the bus at the top of the Vauxhall Bridge Road to walk the short distance to Gillingham Street. The man who had boarded it with them dropped off at the same stop, a few seconds after them, as the conductor rang his bell for the driver to proceed.

“I think that clinches it,” said Biggles, as they walked on. “On no account look round. It seems at if someone is interested in us so our time in the tavern wasn’t wasted.”

“What’s his idea?”

“Maybe just wants to see where we hang out. That suits me, because it suggests that we may have a visitor. After all, an emerald worth three thousand pounds would be a nice piece of fruit for anyone to pick up.”

They turned into Gillingham Street, and presently, into the dingy hall of their hotel. From inside they saw the man who had left the bus with them walk past on the opposite side of the road.

They went up the threadbare-carpeted stairs to Biggles’ room.

“So far so good,” said Biggles, as he closed the door. “They know we have an emerald and they know where we live.”

“What’s the next move?”

“We’ll leave that to them. There’s one thing I must do, though, and that’s drop a line to Algy to let him know where we are, in case he gets worried. We may be here for a day or two. I’d better let Gaskin know at the same time. For obvious reasons we daren’t go near the Yard ourselves, now that we know someone is interested in our movements. I think we might as well turn in.”

The following morning, shortly after Ginger had returned from posting the letters to Algy and Inspector Gaskin and was having a cup of tea with Biggles in his room, the voice of the woman who ran the hotel was heard shouting up the stairs: “Mr. Walls! You’re wanted on the ’phone.”

Biggles turned startled eyes to Ginger’s face. “By gosh! Somebody’s smartly off the mark. Who on earth can it be? Nobody, officially, knows we’re here.”

“It must be either Noble or Norman,” declared Ginger.

“I didn’t give them my address! But it can only be to do with what happened last night.”

They went down to the tiny hall where the telephone shared a small table with a dusty aspidistra. Biggles picked up the instrument. “Hello, yes, who’s that?” he called.

“Is that you, Walls?” came the reply.

“Yes. Walls here,” confirmed Biggles, his expression changing as he recognized the voice. To Ginger he said in a quick astonished tone, “It’s Gaskin.” He went on, into the ’phone, “How did you know I was here?”

“Never mind that. Can you be overheard?” inquired the detective, cautiously.

“No. We’re alone,” Biggles told him.

“All right. I thought I’d better let you know you started something last night. The word has gone round that you pulled the Portman Square job. It has even reached me.” Gaskin chuckled. “I had to pay for that information, too, to make the thing look natural. I told you how fast that sort of news travels through the class of people you’re dealing with. You’re being tailed, so be careful where you go and what you do. Thought I’d better tip you off.”

“Thanks,” acknowledged Biggles. “I’ve just sent you a note to tell you where we were.”

“You needn’t have bothered. Do you think I’d let you barge into that dump without keeping an eye on you?”

“I saw someone behind us as we came home.”

“You didn’t see my man. He was behind the man who was tailing you. The feller you saw was Greeky Stavros. You needn’t worry about him. He’s just a cheap spiv who does odd jobs like that for the bigger boys. He wouldn’t be interested himself so somebody must have put him on to you. Watch how you go. With that thing in your pocket—they know you’ve got it—you might run into a cosh, so keep out of dark corners. That’s all. Anything you want to say?”

“I’d better not talk from here,” said Biggles. “I gather you know what happened last night.”

“I’ve a pretty good idea. Looks as though your scheme clicked. Let me know if I can help.”

“I will. Thanks a lot. Good-bye.” Biggles hung up.

“That was decent of him,” averred Ginger, who had managed to hear the conversation by putting an ear by the instrument.

Biggles looked at him with a curious expression on his face. “It seems we’re already in deeper water than we knew. The fact is, I suppose, being new to this particular stretch of dirty water we were almost certain to get out of our depth. There’s more to it than I thought. It shook me for a moment that our friend should so soon know where we were; but that, to him I imagine, would be just simple routine. We’re learning a thing or two about Gaskin’s regular line of country. I wonder who went to the trouble of having us shadowed.”

“It must have been either Noble or Norman.”

“As you say. But I can’t think why they should bother. They didn’t strike me as that sort.”

They returned to Biggles’ room to finish their morning tea, but hardly had they done so than they heard the ’phone ring again, and the manageress shout: “Mr. Walls! ’Phone.”

Biggles sprang up. “Stiffen the crows! What now? Good thing we didn’t reckon on a quiet morning.”

They returned to the telephone, Biggles holding the receiver so that they could both hear the conversation. “Walls here,” he announced. “Who’s that?”

The man at the other end ignored the question and he wasted no time in preamble. “You were trying to sell something last night,” he stated crisply.

“Quite right.”

“Still got it?”

“Yes.”

“Still want to get rid of it?”

“I’d feel more comfortable without it.”

“I’d believe that,” sneered the voice. “I’ll give you two quid for it.”

“It’s worth ten, by weight.”

“Two.”

“Make it four.”

“Split the difference and say three. That’s the top.”

“Okay,” agreed Biggles. “You coming here for it?”

“Not on your life.”

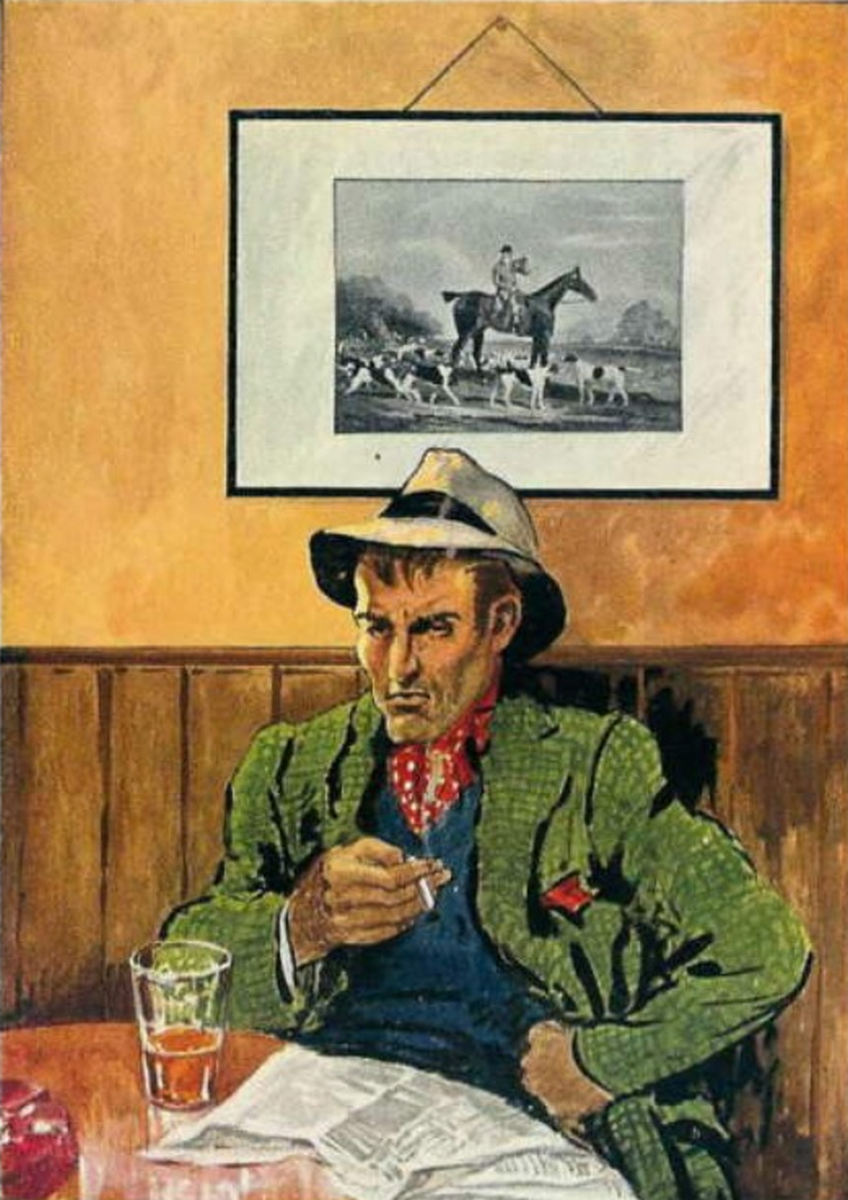

“All right. Where’s the meet?” inquired Biggles, dropping into underworld slang.

“Five to eleven. On the dot. Under the big platform clock at Victoria.”

“I’ll be there.”

“Carry Picture Post in your left hand showing the word Post.”

“Right.”

“And wrap the thing in a bit of newspaper.”

“I get it.”

“One last thing. I take it you’ve still got the missing bit—the thing that was in the middle?”

“Yes.”

“Okay. Be seeing you.” The speaker hung up with a bang.

Biggles turned to Ginger. “As I said just now, we’re learning. Things are moving faster, a lot faster, than I anticipated. We shall have to watch it or we’ll be run off our feet. I’m not sure that hasn’t already happened.”

They went back to Biggles’ room.

“Are you going to part with that piece of gold?” inquired Ginger, after he had closed the door.

“I didn’t really want to but it seems as if I shall have to,” answered Biggles. “It’d look queer now if I refused.”

“What do you make of all this?”

Biggles thought for a moment. “First, we’re dealing with a man who doesn’t know us by sight, because if he did this Picture Post set-up wouldn’t be necessary. That rules out Noble and Norman. He may be a small-time man who’s heard a whisper of what I’ve got. I mean the mount, not what he called the missing bit. Still, that he mentioned the missing bit at all suggests that he has an interest in it. I’ll tell you another thing. The fact that he let me spring him a pound for the mount means he was anxious to buy.”

“Why the mount and not the emerald?”

“I’d say the answer to that is somebody wants to check up that this really is Lady Fenton’s pendant before opening negotiations for the stone. That three-dolphin design is unusual, and would be sufficient proof. When the check has been made someone will be after the stone. That’s how it looks to me.”

“By back-tracking that call we might find out who it was who rang up.”

“Not a hope. It’s a thousand to one it came from a public call box.”

“And you’re to meet him at five to eleven. Why five to eleven? Why not make it dead on the hour.”

Biggles shrugged. “I wouldn’t know. There may have been a reason for the odd minutes but I wouldn’t waste time trying to guess it.”

“How on earth could he have known your name?”

“The fact that he does tells us something else. Norman or Noble come into this. I told Swell my name in the Barn, but I told no one else. Unless he spread it around, this morning’s development must therefore have started with him.”

“He didn’t strike me as a type who would waste time quibbling over a pound or two.”

“Nor me. It looks as if he might be after the emerald, either on his own account or acting for someone else. Either way he must know where he can dispose of the stone. He knows a receiver, although it doesn’t necessarily follow that it’s the one Gaskin is after. But it could be.”

“It wasn’t Norman on the ’phone?”

“No. Definitely. It was an educated voice but it wasn’t his.”

Ginger agreed.

“This is getting quite an amusing little puzzle,” remarked Biggles, lighting a cigarette.

“I don’t know about amusing,” returned Ginger dubiously. “I have a feeling we’re getting on thin ice.”

Biggles smiled. “The thinner the better. Thin ice means we’re getting somewhere.”

“How about me tailing this chap when you’ve handed him the mount?”

“Not a chance. He’ll anticipate that possibility and see it can’t happen. These crooks live on the jump, as a result of knowing they may be watched. Why do you suppose this meet was made for the middle of a big railway station? Not only will the station be crowded but there are a dozen ways out of it. This fellow may have a car handy, anyway.”

“I could get a car.”

“For it to be any use, the traffic being what it is you’d have to know where he’d parked his. Still, there’s no reason why you shouldn’t watch which way he goes, as far as you can. It wouldn’t do for me to try to follow in case I myself am shadowed.”

“Fair enough,” agreed Ginger. “I’ll do my best.”

“Don’t speak to me afterwards. Make your way back to the hotel. I’ll meet you here. But time’s getting on so we’d better get mobile,” said Biggles, wrapping the gold mount in a scrap of newspaper. “Give me a twenty minutes’ start to get well clear before you come out. You’ll see me standing under the clock at five to eleven sharp. Don’t come too close.”

Biggles arrived at the station, which was only just round the corner, with five minutes to spare, to give himself time to buy the periodical that was to identify him. With it folded as arranged, and the newspaper-wrapped mount in his right hand, he stood by the bookstall until the appointed time and then moved to below the clock.

Although he was prepared for what was to happen he was a trifle taken aback when a slight, dark, smartly-dressed man of about thirty, with a close-clipped strip of moustache on his upper lip, who had been striding along as if on his way to catch a train, stopped abruptly and said in a brittle voice: “Okay. Let’s have it.”

The mount changed hands, as did three tightly folded one-pound notes.

“You staying on at the Clefton?” asked the man tersely.

“For a day or two, anyway,” answered Biggles.

“Right.” The man strode on, leaving Biggles slightly bewildered by the speed at which the transaction had been completed. He lost sight of the man instantly in the milling travellers, and realized that he had caught only a fleeting glimpse of his face. But one vivid impression remained. It was the tie the man was wearing.

Biggles put the notes in his pocket, took a cigarette from his case, lit it and strolled over to the refreshment room where he had a cup of coffee. From first to last he had not seen Ginger. Finishing his coffee he went out and, deep in thought, made his way back to the hotel.

Ginger arrived half an hour later, having, as he said, as a matter of precaution, returned home by the side streets.

“Well, how did you get on?” inquired Biggles.

“How right you were,” answered Ginger. “I hadn’t a hope. I saw the stuff switched, of course, but it was all so quick that I was nearly caught on one foot. The chap walked round the booking office and then left the station by the Continental platform. You know that narrow street. It was choc-a-bloc with cars. For a moment I lost sight of him. Then I spotted him getting in a car and away he went. There wasn’t a taxi handy so that was that.”

“What was the car?”

“A black Mercedes.”

“Get the number?”

“KBX 919. But wait a minute. That wasn’t the end. Talk about learning! I’m learning fast. While I stood there, feeling a bit of a fool, a chap came off the platform and started creating a fuss, saying his car had gone. A policeman came over to see what the fuss was about. The chap pointed to the gap where the Mercedes had been parked and said he had left it there while he went to see his wife off on the boat train.”

Biggles struck himself. “Of course!” he exclaimed. “I must be getting dense.”

“Of course what?”

“The time! Five to eleven. The boat train leaves at eleven. People leave their cars while they see friends off and they don’t come back until the train’s gone. The lad who met me must have marked the car he was going to take and so was all ready for a quick getaway. You did well. This may tell us something.”

“How?”

“Obviously, the fellow who had had his car pinched would give the number to the policeman. The Yard would have that information in a matter of minutes. Another few minutes and every police car on the road would have the number by radio and be on the look-out for it. Of course, the chap who pinched the car would know all about that, so we can assume he hadn’t far to go. As soon as he’d finished with it he’d drop it like a hot brick. That car should have been found by now. Let’s find out where it was picked up. I won’t ring Gaskin from here. Let’s go out to a call box. Someone may be listening and the Yard’s number is too well known.”

They went out to the nearest public telephone. Biggles dialled the Yard, and having got it asked for Gaskin’s extension.

“Walls speaking,” he said, when the Inspector answered. “At ten fifty-five a car numbered KBX 919 was removed without the owner’s consent from Victoria Station, continental side. Has it been found?”

“Just a minute. I’ll find out.”

After a short wait the Inspector came back. “Yes,” he answered. “It was picked up at eleven twenty-five.”

“Where?”

“Against the curb at the west end of Piccadilly, on the Park side, about a hundred yards short of Hyde Park Corner.”

“Thanks. That’s all I wanted to know,” acknowledged Biggles, and hung up.

He turned to Ginger. “That’s even better than I hoped for. It may be that even crooks can slip over little things. You know I don’t trust coincidence, but there are times when it has to be considered. You heard where that car was found?”

“Yes.”

“Do you remember the buildings on the other side of the road?”

“The R.A.F. Club and the Royal Aero Club take up quite a bit of ground. They’re the only two I can recall. One can usually find room to park a car there.”

“I wasn’t thinking so much of parking space as the buildings.”

“The Clubs?”

“Yes.”

“What’s remarkable about that?”

“If the car incident had to be considered alone I’d say nothing. But when I tell you that the man who met me under the clock was wearing an R.A.F. tie you’ll get the drift of the lines on which I’m thinking.”

Ginger’s eyes opened wide. “He might have gone to one of the clubs to meet someone.”

“It’d be reasonable to suppose he’d park the car somewhere near his destination, if only to save walking.”

“Why not try the clubs to see if he’s there?”

“Not likely. He might see me, in which case he’d certainly wonder how a shady character like Ted Walls came to be a member of the club.”

“But you think we may have struck an aviation trail?”

“It seems possible. But don’t forget that such a trail can cut two ways. If, as Gaskin suspects, aviation comes into this jewel racket, we’ve only got to probe deep enough for someone to recognize me. I do my best to avoid publicity, but a lot of people in aviation know me and what I’m doing. It so happened that the fellow I met this morning didn’t know me any more than I knew him; but if he had recognized me we should have needed some nerve to go back to the Barn.”

“If, as you believe, that gold mount is on its way for inspection, the man who wants the emerald may be in the club now. The chap who bought the mount may have gone there to meet him.”

“It could be. But let’s not jump to conclusions. This needs thinking about. For the moment let’s go and have some lunch.”

If, as he averred, Biggles was surprised by the speed at which one incident had followed another, he was soon to learn that these had not come to an end. More were to follow before the day was out.

At nine o’clock he went with Ginger to the Barn, more for something to do, and perhaps with a feeling of curiosity, than for any definite reason. He was expecting to be approached about the emerald but he did not think that would happen at the Barn. More likely a call on the telephone would arrange a ‘meet’, and it was for that he was hoping.

Hardly had they found seats when Gus Norman, who had been standing at the bar, came over to them with a directness which suggested that he had been waiting for their arrival.

“I was hoping you’d turn up,” he began, taking a seat next to Biggles.

“Well, here I am,” returned Biggles. “Go ahead.”

“Have you still got that stone?”

Biggles hesitated.

“Come clean, we know you’ve got it,” said Norman, impatiently.

“Yes. What about it?” replied Biggles.

“If you’ll let me have it I’ll get you the top price for it.”

“Do you mean you want me to part with it without the cash?”

“Yes.”

“Nothing doing. What do you take me for?”

“All right. I’ll give you two hundred for it, spot cash.”

“It’s insured for three thousand.”

“That’s probably over its value. I’m not concerned with insurance.”

“You haven’t even seen it,” argued Biggles. “It may not be the real thing.”

“I’ll take a chance on that.”

Ginger realized that Biggles was being forced into a tight corner. Knowing the stone was a fake he was loath to part with it for fear of repercussions that would reveal him to be as false as the stone. It had never been his intention to sell it. It was to be the lure to take him to the receiver Gaskin was looking for. Norman was a jewel thief, not a receiver.

The conversation continued.

“How much are you going to get for it?” inquired Biggles.

“That’s my business.”

“It’s mine, too. I’m not giving anything away.”

“What do you think you can do with it?” demanded Norman sarcastically. “If you had a market you wouldn’t be walking about with that hot stone in your pocket. Don’t be a fool, Walls. Can’t you see I’m doing you a good turn to take it off you? If it’s found on you it’ll be up the steps for you.”[2]

[2] Up the steps. Crook parlance for the Central Criminal Court, Old Bailey.

“That goes for you, too,” retorted Biggles.

“It won’t be long in my pocket,” declared Norman. “I’m offering you a fair price.”

“And if I don’t take it?”

“You may end up by getting nothing,” asserted Norman, significantly. “A lot of people know you’ve got it.”

“You’re not buying this stone for yourself,” stated Biggles.

“I didn’t say I was.”

“Take me to the man you’re buying it for and I’ll give you a quarter of whatever he pays me.”

There Biggles nearly went too far. Suspicion flashed for a moment in Norman’s eyes. “Nothing doing,” he answered shortly.

Biggles hastened to get on safer ground. “I’ll take five hundred, cash down.”

“I haven’t got that much money on me, but I’ll tell you what I’ll do. You give me the stone. I’ll give you two hundred now, in one-pound notes, and another two hundred when I come back. Make up your mind. There may be a bogey[3] watching us.”

[3] Police officer.

“Okay. I’ll take it,” agreed Biggles.

Norman slipped him a wad of notes held together by an elastic band. Biggles handed over the green stone. Norman slipped it in a waistcoat pocket without even looking at it, and without another word walked away. Ginger watched him pass through the swing doors into the street.

“Had I known this was going to happen I’d have arranged for one of Gaskin’s expert tailers to follow him,” muttered Biggles, irritably.

“You didn’t want to part with the stone,” said Ginger.

“Of course not. But what else could I do? I’m afraid I’ve made a bad move.”

“Somebody will soon spot that rock’s a dud.”

“Of course.”

“What are you going to say when Norman throws it back at you?”

“Plead ignorance. I’ll tell him I don’t pretend to be a jewel expert.”

“You’re going to wait for Norman to come back?”

“I don’t think so. We don’t want a scene here. I feel more like going home. Norman will know where to find us. Let’s go.”

As they got up and walked towards the door the man who Gaskin, looking at his photographs, had named Dusty Brace, did the same thing. Reaching the doors together they came into collision.

“Sorry,” said Biggles.

“That’s all right, mate,” said Dusty, and stood aside for them to go first. Which they did. The incident was so trivial that Ginger did not even remark on it as they walked on to the bus stop in Shaftesbury Avenue.

On this occasion, as far as they were aware, they were not followed. In view of what had happened the previous night they watched for the possibility.

They had been talking in Biggles’ room for perhaps half an hour when there came a sharp knock on the door.

“Here we go,” breathed Biggles. “Come in,” he called.

Into the room came Norman and a man they did not know—a tough-looking type. “What’s the idea?” demanded Norman, flinging the imitation emerald on the table.

Biggles feigned astonishment. “What’s wrong?”

“You can keep that bit of green glass.”

“Do—do you mean it’s phoney?” stammered Biggles.

Norman stared hard at Biggles’ face. “Do you mean you didn’t know?”

“I’m no expert.”

“I’ll take your word for it. But that thing’s no use to me. Give me back my two hundred pounds.”

“Certainly,” agreed Biggles, readily, for knowing this probably would happen he was prepared to return the money. Indeed, it would, he realized, cause trouble if he refused. “You don’t think I’d try to hang on to the dough if the thing was phoney, do you?”

“I wouldn’t know,” returned Norman coldly. “Hand over.”

Biggles stood up and put a hand in the trouser pocket in which he had put the wad of notes. His expression changed abruptly. He frowned. Swiftly he went through his other pockets; and when, at the end, he stared at Norman it was clear at least to Ginger that his consternation was genuine.

“It’s gone,” said Biggles, in a voice that sounded slightly dazed.

“What’s gone?” asked Norman, shortly.

“The money you gave me.”

“Don’t try that with me,” rasped Norman, and his companion moved forward threateningly.

Biggles’ eyes narrowed. “Just a minute—don’t get excited,” he said grimly. “I know where that money went.”

“You’d better remember,” prompted Norman, frostily.

“That whizzer[4] Brace has got it.”

[4] Whizzer. Crook slang for pickpocket.

“How did he get it?”

“How do you think? He bumped into me as I was leaving the Barn. I should have guessed that wasn’t an accident. He’s got it.”

“Are you on the level?”

“Of course I’m on the level. I wouldn’t hold out on you over a thing like this.”

“What are you going to do about it?”

“I’ll show you what I’m going to do about it,” rapped out Biggles. “I’m not letting that cheap hook get away with that.”

“What are you going to do?”

“I’m going back to the Barn and make him cough up.” Biggles was really angry.

“I’ll come with you,” said Norman. “Let’s go.”

They all trooped down the stairs and into the street. They had taken only a few paces when Ginger clapped a hand to a pocket and said, “I’ve come without my cigarettes. I’ll catch you up.” He ran back.

The rest walked on, and after waiting for a minute or two at the corner of Vauxhall Bridge Road Biggles managed to stop a taxi, which he held until Ginger rejoined them. “Come on,” he snapped impatiently, when Ginger ran up. “You’re wasting time.”

They all got in the cab. Biggles paid the driver outside the Barn. They all went in. Brace was still there, sitting at a corner table talking to Toni the Needle. Biggles strode straight up to him and held out a hand. “Give it back,” he said softly but succinctly.

“Give what?” inquired Brace coldly. “What are you talking about.”

“Don’t give me that line,” rasped Biggles. “Cough it up.”

“Cough nothing.”

Biggles took a pace nearer. “Listen, Dusty. That money wasn’t mine. You’re going to hand it back, or else. . . .”

“Else what?” sneered the pickpocket.

At this juncture the landlord, who must have seen from the bar that trouble was brewing, bustled up. “We don’t want none of that here,” he said sharply. “What’s the trouble?”

Biggles indicated Brace with a jerk of his thumb. “This cheap skate has lifted out of my pocket a wad that doesn’t belong to me.”

“Give it up, Dusty,” ordered the landlord. “I’ve told you before I won’t stand for that in here.”

“He’s lying,” said Brace.

“You saw me give him the money,” accused Norman.

How the matter would have ended had there been no interruption is a matter for surmise, but at this stage of the proceedings a sudden break in the babble caused all eyes to seek the cause.

Inspector Gaskin had walked in.

After his eyes had made a comprehensive survey of the room he strolled over to the little group of which Biggles was the centre. “What’s going on?” he inquired, casually.

“Nothing much,” answered Biggles. “Just a little argument.”

“What are you doing in here, anyway. This isn’t your usual lay-by.”

“Just having a drink, that’s all. Nothing wrong with that, is there? Why pick on me?”

“Because you looked as if you had something to say,” answered the Inspector, nonchalantly. “What was it?”

Biggles looked at Brace. “Will you tell him or shall I?”

Brace glared. “You squealer,” he spat.

The landlord, apparently concerned more with peace than truth, stepped in. “It was like this,” he explained. “This gentleman dropped some money. This other gentleman picked it up and is arguing about giving it back.”

“We should be able to settle that without any fuss,” said the Inspector, smoothly. He extended a hand to Brace. “Come on, hand it over.”

“But——”

“Don’t argue with me. Where is it?”

Pale with anger or mortification Brace tossed the wad of notes on the table. “I was only foolin’,” he growled.

The Inspector picked up the wad. “Very nice,” he said. “I can understand you wanting to hang on to it, Dusty.” He turned to Biggles. “You seem to have been busy, Walls.”

“No,” protested Biggles, sullenly.

“Where did you get it?”

“I backed a horse, and it won.”

Gaskin smiled sadly. “You always were a good liar, Walls, but I suppose I shall have to take your word for it.” He handed Biggles the wad. “I wouldn’t walk about with that in your pocket, if I were you. Not when Dusty’s around, anyway,” he added, slyly. “Well, I’ll get along.”

“Have a drink, Inspector?” invited the landlord.

“No thanks. Goodnight all.” The Inspector nodded and strolled out with the same assurance as he had entered, whereupon the babble was at once resumed.

Biggles handed the wad to Norman. “You’d better take care of this while I still have it,” he said, cynically.

Norman took the money, and leaving Brace glowering they walked over to the bar. As they reached it a man, a young man, looking somewhat excited, came in hurriedly. Walking quickly to Norman he took him to one side and whispered in his ear.

Norman started. He nodded. A smile spread slowly over his face. He returned to Biggles. “You were right about Stony,” he said softly.

“You mean——?”

“He’s out. Over the wall. So long.” Norman, with the informant who had brought the news, hurried out.

For a second Biggles stood still. Then he turned to Ginger with a grimace. “You heard that?”

“Yes. Stony has broken gaol.”

“That’s a smack in the eye I didn’t expect,” muttered Biggles. “You realize what it means.”

“Of course. Norman will tell Stony he got his message. Stony will deny sending a message and the cat will be out of the bag. Norman will wonder what your game was.”

“And he’ll probably arrive at the right answer.”

“What will he do?”

“He may tackle me about it, in which case it’ll take a bit of explaining. More likely he’ll say nothing. I see two rays of light. One is that the police grab Stony before he can compare notes with his pal Norman. That’s a poor hope because unless I’m mistaken, Norman, knowing where Stony will go into hiding, is already on his way to see him. The other thing that may save us from being marked down as police spies was Gaskin’s attitude towards me when he looked in here. He treated me as if he knew me as a crook. That was a bit of luck.”

“That wasn’t altogether luck,” answered Ginger.

“What do you mean?”

“I asked him to come to the Barn.”

“You what?”

“When I went back to fetch my cigarettes, as I said, I ’phoned him that as there was likely to be a flare-up between you and Brace it might be a good thing if he looked in. His timely arrival wasn’t just a coincidence.”

“So that was why you went back. I knew you must be up to something but I didn’t guess what. Great work. I realized it was asking for trouble to tackle that dirty pickpocket but what else could I do? I had to try to put myself right with Norman. He was bound to discover the stone was a fake and demand his money back. I was prepared for that, and had every intention of returning the notes as the only way of lulling his suspicions that I’d deliberately pulled a fast one on him. It shook me when I put my hand in my pocket and found the money had gone.”

Ginger grinned. “I’ll bet it did.”

“As it happens I needn’t have bothered,” went on Biggles. “If Norman meets Stony our game here will die a sudden death. One way and another I seem to be making a mess of things. You talked a little while ago of being on thin ice. Be prepared for it to break at any moment.”

“Things were going all right till Brace picked your pocket. And it’s sheer bad luck that Stony should choose today to make a break.”

Biggles shook his head. “Things were beginning to slip. That dud stone started it. I was always afraid of that. I may have made a mistake in parting with it. Still, it served its purpose. It has given us at least one important clue.”

“What’s that?”

“The fence Gaskin is looking for is in or near London—or comes to London. At all events, Norman took that stone to a receiver. It was he who spotted it was a dud. If Norman was able to take it to him between the time I gave it to him and the time he threw it back at me it can only mean he hadn’t far to go. The fact that Norman had two hundred pounds in his pocket, ready to pay for the stone, suggests to me that he was sent to the Barn with that object in view. Anyway, we have plenty to think about. There’s nothing more we can do here for the time being so we might as well go home.”

They continued to discuss the situation after they had returned to the hotel, having had a quick meal at a snack bar on the way.

“What’s the next move?” asked Ginger.