* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

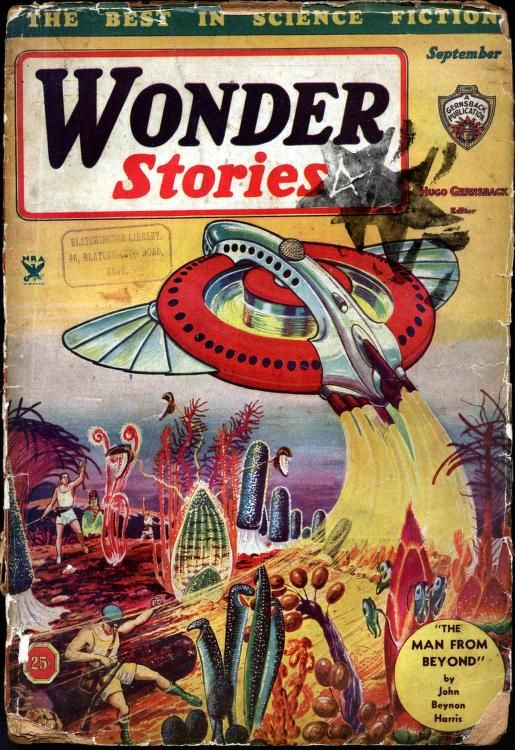

Title: The Man From Beyond

Date of first publication: 1934

Author: John Wyndham (as John Beynon Harris) (1903-1969)

Illustrator: Frank R. Paul (1884-1963)

Date first posted: May 22, 2022

Date last updated: May 22, 2022

Faded Page eBook #20220544

This eBook was produced by: Alex White & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

This file was produced from images generously made available by Internet Archive.

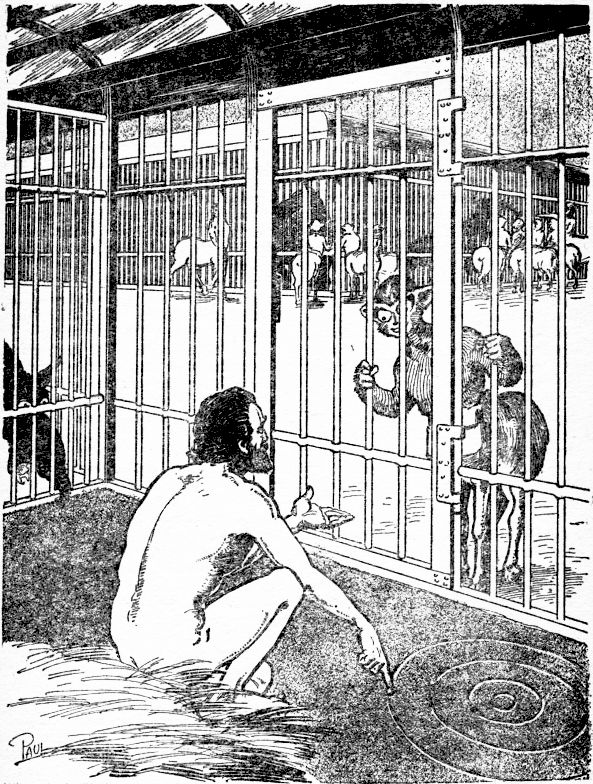

(Illustration by Paul)

It had scrawled a series of queer lines in the dust.

THE MAN FROM BEYOND

Also published under the title The Man From Earth.

By

John Wyndham

Writing under the pseudonym John Beynon Harris.

First published Wonder Stories, September 1934.

Here is a brand new treatment of the interplanetary theme. The writer attempts to bring out a side of human nature that few authors touch upon. Gratz hates mankind because of its evil greed and lust for power. He denounces his own kind to an alien intelligence. And then the tremendous truth is revealed to him . . . .

You will find this tale one success in our drive for distinctly new stories.

One of the greatest sights in Takon[1] these days was the exhibition of discoveries made in the Valley of Dur. In the building erected especially to house them, Takonians and visitors from other cities crowded through the corridors, peering into the barred or glass-fronted cages, observing the contents with awe, interest, or amusement according to their natures. The crowd was formed for the most part of those persons who will flock to any unusual sight, providing it is free or cheap; their eyes dwelt upon the exhibits; their minds were ready to marvel and be superficially impressed, but they had come to be amused and they faintly resented the efforts of the guides to stir them into intelligent interest. One or two, perhaps, studied the cases with real appreciation.

|

All Venusian terms are rendered in their closest English equivalents. |

But if the adults were superficial, the same could not truthfully be said of the children. Every day saw teachers bringing their classes for a practical demonstration of the planet’s prehistoric condition. Even now, Magon, a biology teacher in one of Takon’s leading schools, was having difficulty in restraining his twenty pupils for the arrival of a guide. He had marshaled them beside the entrance, and to keep them from straying, was talking of the Valley of Dur.

“The condition of the Valley was purely fortuitous and it is unique here upon Venus,” he said. “Nothing remotely resembling it has been found, and it is the opinion of the experts that nothing like it exists anywhere else. This exhibition you are going to see is neither a museum nor a zoo, yet it is both.”

His pupils only half attended. They were fidgeting to and fro, casting expectant glances down the row of cage fronts, craning to see over one another’s backs, the more excitable among them occasionally rising on their hind legs for a better view. The passing Takonian citizens regarded their youthful enthusiasm with a mild amusement. Magon smoothed back the silver fur on his head with one hand and continued to talk.

“The creatures you will see belong to all ages of our world. Some are so old that they roamed Venus long before our race appeared. Others are later, contemporaries of those ancestors of ours who in a terrible world were forever scuttling to cover as fast as their six legs could carry them . . . .”

“Six legs, sir?” asked a surprised voice.

Some of the youths in the group sniggered, but Magon explained considerately.

“Yes, Sadul, six legs. Did you not know that our remote ancestors used all six of their limbs to get them along? It took them many thousands of years to turn themselves into quadrupeds, but until they did that, no progress was possible. The fore limbs could not develop such sensitive hands as ours until they were carried clear of the ground.”

“Our ancestors were animals, sir?”

“Well, er—something very much like that.” Magon lowered his voice in order that the ears of passing citizens might not be offended. “But once they got their forelegs off the ground, released from the necessity of carrying their weight, the great change had begun; we were on the upward climb—and we’ve never stopped climbing.”

He looked around at the circle of eager-eyed, silver-furred faces about him. His eyes dwelt a moment on the slender tentacles which had developed from stubby toes on the fore-feet. There was something magical in evolution, something glorious in the fact that he and his race were the crown of progress. It was a very wonderful thing to have done, to have changed from a shaggy, six-footed beast to a creature who stood proudly upon four, the whole front part of its body raised to the perpendicular to support a head which looked out proudly and unashamed at the world. Admittedly, several of his class appeared to have neglected their coats in a way which was scarcely a credit to the race—the silver fur was muddied and rumpled, but then, boys will be boys; no doubt they would trim better and brush better as they grew older.

“The Valley of Dur—” he began again, but at that moment the guide arrived.

“The party from the school, sir?”

“Yes.”

“This way, please. Do they understand about the Valley, sir?” he added.

“Most of them,” Magon admitted. “But it might be as well—”

“Certainly.”

The guide broke into a high speed recitation which he had evidently made many times before.

“The Valley of Dur may be called a unique phenomenon. At some remote date in the planet’s history, certain internal gases combined in a way yet imperfectly understood and issued forth through cracks in the crust at this place, and at this place only.

“The mixture had two properties. It not only anaesthetized, but it also preserved indefinitely. The result was to produce a form of suspended animation. Everything that was in the Valley of Dur has remained as it was when the gas first broke out; everything which has entered the Valley since has remained there imperishably. There is no apparent limit to the length of time that this preservation may continue.

“Among the ancients, the place was regarded with superstitious fear, and though in more recent times many attempts have been made to explore it, none were successful until a year ago when a mask which would withstand the gas was at last devised. It was then discovered that the animals and plants in the Valley were not petrified as had hitherto been believed, but could, by means of certain treatment, be revived. Such are the specimens you are about to see: the flora and fauna of a million years ago—yet alive today.”

He paused opposite the first case.

“Here we have a glimpse of the carboniferous era—the tree ferns and giant mosses thriving in a specially prepared atmosphere, continuing the lives which were suspended when Venus was very young. We hope to be able to grow more specimens from the spores of these. And here,” he passed to the next case, “we see the beginning of one of Nature’s most graceful experiments—the earliest form of flower.”

His audience stared in dutiful attention at the large, white blossoms which confronted them. They were not very interesting; fauna has a far greater appeal to the adolescent mind than does flora. A mighty roar caused the building to tremble; eyes were switched from the magnolia-like blossoms to glance up the passage in anticipatory excitement. Attention to the guide became even more perfunctory. Only Magon, to the exasperation of his pupils, thought it fit to ask a few questions. At last, however, the preliminary botanical cases were left behind, and they came to the first of the cages.

Behind the bars, a reptilian creature, which might have been described as a biped, had its tail not played so great a part in supporting it, was hurrying tirelessly and without purpose to and fro, glaring at as much of the world as it could from intense, small eyes. Every now and then it would throw back its head and utter a kind of strangled shriek. It was an unattractive creature covered with a grey-green hide, very smooth; its contours were almost stream-lined, but managed to appear clumsy. In it, as in so many of the earlier forms, one seemed to feel that Nature was getting her hand in for the real job. She had already learned to model after a crude fashion when she made this running dinosaur, but her sense of proportion was not good and she lacked the deftness necessary to produce the finer bits of modeling which she later achieved. She could not, one felt, even had she wanted, have then produced fur or feathers to clothe the creature’s nakedness.

“This,” said the guide, waving a proprietorial hand, “is what we call Struthiomimus, one of the running dinosaurs capable of traveling at high speed, which it does for purposes of defense, not attack, being a vegetarian.”

There was a slight pause while his listeners sorted out the involved sentence.

“You mean that it runs away?” asked a voice.

“Yes.”

They all looked a little disappointed, a trifle contemptuous of the unfortunate, unhappy Struthiomimus. They wanted stronger meat. They longed to see (behind bars) those ancient monsters which had been lords of the world, whose rumbling bellows had sent Struthiomimus and the rest scuttling for cover. The guide continued in his own good time.

“The next is a fine specimen of Hesperornis, the toothed bird. This creature, filling a place between the Archeopteryx and the modern bird is particularly interesting—”

But the class did not agree. As they filed slowly on past cage after cage, it was noticeable that their own opinions and that of the guide seldom coincided. The more majestic and terrifying reptiles he dismissed with a curt: “These are of little interest, being sterile branches of the main stem of evolution: Nature’s failures.”

They came at length to a small cage occupied by a solitary curious creature which stood erect upon two legs though it appeared to be designed to use four.

“This,” said the guide, “is one of our most puzzling finds. We have not yet been able to classify it into any known category. There has been such a rush that the specialists have not as yet had time to accord it the attention it deserves. Obviously, it comes from an advanced date, for it bears some fur, though this is localized in patches, notably on the head and face. It is particularly adept upon two feet, which points to a long line of development. And yet, for all we know of it, the creature might have occurred fully developed and without any evolution—though of course you will realize that such a thing could not possibly happen. Among the other odd facts which our preliminary observation has revealed, is that although its teeth are indisputably those of a herbivore, it has carnivorous tastes—altogether a most puzzling creature. We hope to find others before the examination of the Valley is ended.”

The creature raised its head and looked at them from sullen eyes. Its mouth opened, but instead of the expected bellow, there came from it a stream of clattering gibberish which it accompanied with curious motions of its fore-limbs.

The interest of some of the class was at last aroused. Here was a real mystery about which the experts could as yet claim to know little more than themselves. The young Sadul, for instance, was far more intrigued by it than he had been by those monsters with the polysyllabic names. He drew closer to the bars, observing it intently. The creature’s eyes met his own and held them; more queer jabber issued from its mouth. It advanced to the front of the cage, coming quite near to him. Sadul held his ground; it did not look dangerous. With one foot it smoothed the soil of the floor, and then squatted down to scrabble in the dirt.

“What’s it doing?” asked someone.

“Probably scratching for something to eat,” suggested another.

Sadul continued to watch with interest.

When the guide moved the party on, he contrived to remain behind unnoticed. He was untroubled by the presence of other spectators since most of them had gravitated to watch the larger reptiles feed. After a while, the creature rose to its feet again and extended one paw towards the ground. It had scrawled a series of queer lines in the dust. They made neither pattern nor picture; they did not seem to mean anything, yet there was something regular about them.

Sadul looked blankly at them and then back to the face of the creature. It made a quick movement towards the scrawls. Sadul continued to stare blankly. It advanced, smoothed out the ground once more with its foot, and began to scrabble again. Sadul wondered whether or not he should move on. He ought, he knew, to have kept with the rest; Magon might be nasty about it. Well, he’d stay just long enough to see what the creature was doing this time . . . .

It stood back and pointed again. Sadul was amazed. In the dirt was a drawing of a Takonian such as himself. The creature was pointing first to himself and then back to the drawing . . . .

Sadul grew excited. He had made a discovery? What was this creature which could draw? He had never heard of such a thing. His first impulse was to run after the rest and tell them, but he hesitated, and curiosity got the better of him. Rather doubtfully, he opened the bag at his side and drew out his writing tablet and stylus. The creature excitedly thrust both paws through the bars for them, and sat down scratching experimentally with the wrong end of the stylus. Sadul corrected it, and then leaned close to the bars, watching over its shoulder.

First the creature made a round mark in the middle of the tablet, then it pointed up. Sadul looked at the ceiling, but quite failed to see anything remarkable there. The creature shook its head impatiently. About the mark it drew a circle with a small spot on the circumference; outside that another circle with a similar spot, and then a third. Still Sadul could see no meaning.

Beside the spot on the second circle the creature drew a small sketch of a Takonian; beside the spot on the third, a creature like itself. Sadul followed intently. It was trying very hard to convey something, but for the life of him, he could not see what it was. Again a paw pointed up at the light globe, then the fore-limbs were held wide apart. The light . . . . an enormous light . . . . Suddenly Sadul got it—the sun; the sun—and the planets! He nearly choked with excitement. Reaching between the bars, he grabbed his tablet and ran off up the corridor in search of his party. The man in the cage watched him go, and as his shouts diminished in the distance, he smiled his first smile for a very long time.

Goin, the lecturer in phonetics, wandered into the study of his friend Dagul, the anthropologist in the University of Takon. Dagul, who was getting on in years as the grizzling of his silver fur testified, looked up with a frown of irritation at the interruption. It faded at the sight of Goin, and he welcomed him.

“Sorry,” he apologized. “I think I’m a bit overworked. This Dur business gives such masses of material that I can’t leave it alone.”

“If you’re too busy—?”

“No, no. Come along in. Glad to throw it off for a time.”

They crossed to a low divan where they squatted, folding their four legs beneath them. Dagul offered refreshment.

“Well, did you get this Earth creature’s story?” he asked.

Goin produced a packet of thin tablets from a satchel.

“Yes, we got it—in the end. I’ve had all my assistants and brightest students working on it, but it’s not been easy, even so. They seem to have been further advanced in physical science than we are. That made parts of it only roughly translatable, but I think you’ll be able to follow it. A pretty sort of villain this Gratz makes himself out to be—and he’s not much ashamed of it.”

“You can’t be a good villain if you are ashamed.”

“I suppose not, but it’s made me think. Earth seems to have been a rotten planet.”

“Worse than Venus?” asked Dagul bitterly.

Goin hesitated. “Yes, I think so, according to his account—but probably that’s only because it was further developed. We’re going the same way: graft, vested interests, private traders without morals, politicians without consciences. I thought they only existed here; but they had them on Earth—the whole stinking circus. Maybe they had them on Mars, too, if we only knew.”

“I wonder?” Dagul sat for some moments in contemplation. “You mean that on Earth there was just an exaggerated form of the mess we’re in?”

“Exactly. Makes you wonder if life isn’t a disease after all—a kind of corruption which attacks dying planets; growing more and more vicious in the higher forms. And as for intelligence . . . .”

“Intelligence,” said Dagul, “is a complete snare and delusion—I came to that conclusion long ago. Without it, you are wiped out; with it, you wipe out one another, and eventually yourself.”

Goin grinned. Dagul’s hobby-horses were much ridden steeds.

“The instinct of self-protection—” he began.

“—is another delusion, as far as the race is concerned,” Dagul finished for him. “Individuals may protect themselves, but it is characteristic of an intelligent race to try continually by bigger and better methods to wipe itself out. Speaking dispassionately, I should say that it’s a very good thing, too. Of all the wasteful, destructive, pointless . . . .”

Goin let him have his say. Experience told him that it was useless to attempt to stem the flood. At length, there came a pause and he thrust forward his packet of tablets.

“Here’s the story. I’m afraid it’ll encourage your pessimism. The man, Gratz, is a self-confessed murderer, for one thing.”

“Why should he confess?”

“It’s all there. Says he wants to warn us against Earth.”

Dagul smiled slightly. “Then you’ve not told him?”

“No, not yet.”

Dagul reached for the topmost tablet, and began to read:

I, Morgan Gratz of the planet Earth, am writing this as a warning to the inhabitants of Venus. Have nothing to do with Earth if you can help it—but if you must, be careful. Above all, I warn you to have no dealings with the two greatest companies of Earth. If you do, you will come to hate Earth and her people as I do—you will come to think of her, as I do, as the plague spot of the universe. Sooner or later, emissaries will come. Representatives of either Metallic Industries or International Chemicals will attempt to open negotiations. Do not listen to them. However honeyed their words or smooth their phrases, distrust them, for they will be liars and the servants of liars. If you do trust them, you will live to regret it, and your children will regret it and curse you. Read this and see how they treated me, Morgan Gratz.

My story is best started from the moment when I was shown into the Directors’ Room in the huge building which houses the executive of Metallic Industries. The secretary closed the tall double doors behind me and announced my name:

“Gratz, sir.”

Nine men seated about a glass-topped table turned their eyes upon me simultaneously, but I kept my gaze on the chairman who topped the long table.

“Good morning, Mr. Drakin,” I said.

“Morning, Gratz. You have not met our other directors, I think?”

I looked along the row of faces. Several I recognized from photographs in the illustrated papers; others I was able to identify, for I had heard them described and knew that they would be present. There is no mystery about the directors of Metallic Industries Incorporated. Among them are several of the world’s richest men, and to be mounted upon such pinnacles of wealth means continual exposure to the floodlights of publicity. Not only was I familiar with their appearances, but in common with most, I was fairly conversant with their histories. I made no comment, so the chairman continued.

“I have received your reports, Gratz, and I am pleased to say that they are model documents—clear and concise—a little too clear, I must own, for my peace of mind. In fact, I confess to apprehend and, in my opinion, the time has come for decisive measures. However, before I suggest the steps to be taken, I would like you to repeat the gist of your reports for the benefit of my fellow directors.”

I had come prepared for this request and was able to reply without hesitation.

“When it first became known to Mr. Drakin that International Chemicals proposed to build a ship for the navigation of space, he approached me and put forward certain propositions. I, as an employee of International Chemicals, and being concerned in the work in question, was to keep him posted and to hand on as much information, technical and otherwise, as I could collect without arousing suspicion. Moreover, I was to find out the purpose for which International Chemicals intended to use her. I have carried out the first part of my orders to the chairman’s satisfaction, but it is only in the last week that I have been able to discover her destination.”

I paused. There was a stir among the listeners. Several leaned forward with increased interest.

“Well,” demanded a thin, predatory-faced man on the chairman’s right, “what is it?”

“The intention of the company,” I said, “is to send their ship, which they call the Nuntia, to Venus.”

They stared at me. Save for Drakin to whom this was not news, they appeared dumb-founded. The cadaverous-looking man was the first to find his voice.

“Nonsense!” he cried. “Preposterous! Never heard of such a thing. What proof have you of this ridiculous statement?”

I looked at him coldly.

“I have no proof. A spy rarely has. You must take my word for it.”

“Absurd. Fantastic nonsense. You stand there and seriously expect us to believe on your own, unsupported statement that I. C. intends to send this machine to Venus? The moon would be unlikely enough. Either they have been fooling you or you must be raving mad. I never heard of such rubbish. Venus, indeed!”

I regarded the man. I liked neither his face nor his manners.

“Mr. Ball sees fit to challenge my report,” I said. “This, gentlemen, will scarcely surprise you, for you must know as well as I that Mr. Ball has been completely impervious to all new ideas for the past forty years.”

The emaciated Mr. Ball goggled while several of the others hid smiles. It was rarely that his millions did not extract sycophancy, but I was in a strong position.

“Insolence,” he spluttered at last. “Damned insolence. Mr. Chairman, I demand that this man—”

“Mr. Ball,” interrupted the other coldly. “You will please to control yourself. The fact that Gratz is here at all is a sign not only that I believe him, but that I consider his news to seriously concern us all.”

“Nonsense. If you are going to believe every fairy story that a paid spy—”

“Mr. Ball, I must ask you to leave the conduct of this matter to me. You knew, as we all did, that I. C. were building this ship, and you knew that it was intended for space-travel. Why should you disbelieve the report of its destination? I must insist that you control yourself.”

Mr. Ball subsided, muttering indefinite threats. The chairman turned back to me.

“And the purpose of this expedition?”

I was only able to suggest that it was to establish claims over territories as sources of supplies. He nodded and turned to address the rest.

“You see, gentlemen, what this will mean? It is scarcely necessary to remind you that I. C. are our greatest rivals, our only considerable rivals. The overlapping of our interests is inevitable. Metals and chemicals obviously cannot be expected to keep apart. They are interdependent. It cannot be anything but a fight for survival between the two companies. At present, we are evenly balanced in the matter of raw materials—and probably shall be for years to come. But—and this is the important point—if their ship makes this trip successfully, what will be the results?

“First, of course, they will annex the richest territories on the planet with their raw materials, and later import these materials to Earth. Mind you, this will not take place at once, but make no mistake, it will come as inevitably as tomorrow. Once the trip has been successfully made, the inventors will not rest until they have found a way of carrying freight between the two worlds at economic rates. It may take them ten years to do it, or it may take them a century, but, sooner or later, do it they will.

“And that, gentlemen, will mean the end of Metallic Industries.”

There was a pause during which no one spoke. Drakin looked around to see the effect of his words.

“Gratz has told me,” he continued, “that I. C. is convinced that their ship is capable of the journey. Is that not so?”

“It is,” I confirmed. “They have complete faith in her and so have I.”

Old John Ball’s voice rose again.

“If this is not nonsense, why have we let it go on? Why has I. C. been allowed to build this vessel without interference? What is the good of having a man there who does nothing to hinder the work?” He glared at me.

“You mean?” inquired Drakin.

“I mean that this man has been excellently placed to work sabotage. Why has there been none? It should be simple enough to cause an ‘accidental’ explosion.”

“Very simple,” agreed Drakin. “So simple that I. C. would jump to it at once. Even if there were a genuine accident, they would suspect that we had a hand in it. Then we should have our hands full with an expensive vendetta. Furthermore, I. C. would recommence building with additional precautions, and it is possible that we might not have a man on the inside. I take it that we are all agreed that the Nuntia must fail—but it must not be a suspicious failure. The Nuntia must sail; it is up to us to see that she does not return.

“Gratz has been offered a position aboard her, but has not as yet returned a definite answer. My suggestion is that he should accept the offer with the object of seeing that the Nuntia is lost. The details I can leave to him.”

Drakin went on to elaborate his plan. Directly the Nuntia had left, Metallic Industries would begin work on a space-flyer of their own. As soon as possible, she would follow to Venus. Meanwhile, I, having settled the Nuntia, would await her arrival. In the unlikely event of the planet being found inhabited, I would get on good terms with the natives and endeavor to influence them against I. C. When the second ship arrived, I was to be taken off and brought back to Earth while a party of M. I. men remained to survey and annex territories. On my return, I would be sufficiently rewarded to make me rich for life.

“You will be doing a great work for us,” he concluded, “and we do not forget our servants.” He looked me straight in the eyes as he said it. “Will you do it?”

I hesitated.

“I would like a day or so to think it over.”

“Of course. That is only natural, but as there is not a great deal of time to spare, will you let me have your answer by this time tomorrow? It will give us a chance to make other arrangements in case you refuse.”

“Yes, sir. That will do.”

On that I left them. As to their further deliberations, I can only guess. And my guesses are bitter.

Beyond an idea that it would appear better not to be too eager, I had no reason for putting off my answer. Already I had determined to go—and to wreck the Nuntia. I had waited many years to get in a blow at I. C., and now was my chance. Ever since the death of my parents, I had set my mind on injuring them. Not only had they killed my father by their negligence in a matter of unshielded rays, but they had stolen his inventions and robbed him by prolonged litigation. Enough, you say, to make a man swear revenge. But it was not all. I had to see my mother die in poverty when a few hundred dollars would have saved her life—and all our dollars had gone in fighting I. C.

After that I changed my name, got a job with I. C. and worked—hard. Mine was not going to be a paltry revenge; I was going to work up until I was in a responsible position, one from which my hits could really hurt them. I had allied myself with Metallic Industries because this was their greatest rival, and now I was given a chance to wreck the ship to which they had pinned such faith. I could have done that alone, but it would have meant exile for the rest of my life. Now M. I. had smoothed the way by offering me a passage home.

Yes, I was going to do it. The Nuntia should make one trip and no more . . . .

But I’d like to know just what it was they decided in the Board Room after I had gone . . . .

The Nuntia was two weeks into space, but nobody was very happy about it.

In those two weeks, the party of nine on board had been reduced to seven, and the reduction had not had a good effect upon our morale. As far as I could tell, there was no tangible suspicion afoot; just a feeling that all was not well. Among the hands it was rumored that Hammer and Drafte had gone crazy before they killed themselves. But why had they gone crazy? That was what worried the rest. Was it something to do with the conditions in space; some subtle, unsuspected emanations? Would we all go crazy?

When you are cut off from your kind, you get strange fancies. Imagination gets overheated and you become too credulous. That is what used to happen to sailors on their long voyages in the old windjammers, and it began to happen to our crew out in space. They started to attribute the deaths to uncanny, malign influences in a way which would never have occurred to them on Earth. It gave me some amusement at the time.

First there had been Dale Hammer, the second navigator. Young, a bit wild at home, perhaps, but brilliant at his job, he was proud and overjoyed that he had been chosen for this voyage. He had gone off duty in a cheerful frame of mind. A few hours later he had been found dead in his bunk with a bottle of tablets by his side—one had to take something to insure sleep out here. Everyone agreed that it was understandable, though tragic, that he might take an overdose by mistake. . . .

It was after Ross Drafte’s disappearance that the superstitions had begun to cluster. He was an odd man with an expression which was frequently taciturn and eyes in which burned feverish enthusiasms. A failure might have driven him desperate, but under the circumstances, he had everything to live for. He was the designer of the Nuntia, and she, the dream of his life, was endorsing his every expectation. When we should return to make public the story of our voyage, his would be the name to be glorified through millions of radios, and his the face which would stare from hundreds of newspapers—the conqueror of gravitation. And he had disappeared . . . .

The air pressure graph showed a slight dip at one point and Drafte was no more . . . .

I saw no trace of personal suspicion. No one had even looked askance at me nor, so far as I knew, at anyone else. No one had the least inkling that one man aboard the ship could tell them exactly how those two men had died. There was just the conviction that something queer was afoot.

And now it was time for another.

Ward Govern, the chief engineer, was in the chartroom talking with Captain Tanner. The rest were busy elsewhere. I slipped into Govern’s cabin unobserved. His pistol I found in the drawer where he always kept it, and I slipped it into my pocket. Then I crossed to the other wall and opened the ventilator which communicated with the passage. Finally, after carefully assuring myself that no one was in sight, I left, closing the door behind me.

I had not long to wait. In less than a quarter of an hour I heard the increasing clatter of a pair of magnetic shoes on the steel floor, and the engineer passed cheerfully by on his way to turn in. The general air of misgiving had had less effect upon him than upon anyone else. I heard the door slam behind him. I allowed him a few moments before I moved as quietly to the ventilator as my magnetic soles would allow.

I could see him quite easily. He had removed his shoes and was sitting at a small wall desk, entering up the day’s events in his diary. I thrust the muzzle of the pistol just within the slot of the ventilator, and with the other hand began to make slight scratching noises. It was essential that he should come close to me. There must be a burn or at least powder marks.

The persistent scratching began to worry him. He glanced up in a puzzled fashion and held his head on one side, listening. I went on scratching. He decided to investigate and released the clips which held his weightless body to the chair. Without bothering to put on the magnetic shoes, he pushed himself away from the wall and came floating towards the ventilator. I let him get quite close before I fired.

There was a clatter of running feet mingling with cries of alarm. I dropped the pistol inside my shirt and jumped around the corner, reaching the cabin door just ahead of a pair who came from the other direction. We flung it open and I dashed in. Govern’s body under the impetus of the shot had floated back into the middle of the room. It looked uncanny, lying asprawl in mid-air.

“Quick,” I yelled, “fetch the Captain!”

One of them pelted out of the door. I managed to keep my body between the other and the corpse while I closed the dead fingers around the pistol. A few seconds later everybody had collected about the doorway and the Captain had to push them aside to get in. He examined the body. It was not a pleasant sight. The blood had not yet ceased to flow from the wound in the head, but it did not drip as it would on Earth; instead, it had spurted forth to form into several red spheres which floated freely close beside the corpse. There was no doubt that the shot had been fired at close range. The Captain looked at the outflung hand which gripped the automatic.

“What happened?”

No one seemed to know.

“Who found him?”

“I was here first, sir,” I said. “Just before the others.”

“Anyone with you when you heard the shot?”

“No, sir. I was just walking along the passage—”

“That’s right, sir. We met Gratz running ’round the corner,” somebody supported.

“You didn’t see anyone else about?”

“No, sir.”

“And was it possible, do you think, for anybody to have gotten out of the room unseen between the time of the shot and your arrival?”

“Quite impossible, sir. He would have been bound to walk straight into me or the others—even if there had been time for him to get out of the room.”

“Very well. Please help me with this.” He turned to the other four who were still lingering in a group near the door. “You men get back to work, now.”

Two began to move off, but the other pair, Willis and Trail, both mechanics, held their ground.

“Didn’t you hear me? Get along there.”

Still the two hesitated, then Willis stepped forward and the Captain’s unbelieving ears heard his demand that the Nuntia be turned back.

“You don’t know what you’re saying, man!”

“I do, sir, and so does Trail. There’s something queer about it all. It’s not natural for men to kill themselves like this. Perhaps we’ll be the next. When we signed on, we knew we’d have dangers we could see, but we didn’t reckon with something that makes you go mad and kill yourself. We don’t like it—and we ain’t going on. Turn the ship back.”

“Don’t be a pair of fools. You ought to know that we can’t turn back. What do you think this is—a rowboat? What’s the matter with you?”

The two faces in front of him were set in lines of stolid determination. Willis spoke again.

“We’ve had enough, and that’s flat. It was bad enough when two had gone, but now it’s three. Who’s going to be the next? That’s what I want to know.”

“That’s what we all want to know,” the Captain said, meaningly. “Why are you so anxious to have the ship turned back?”

“Because it’s wrong, unlucky. We don’t want to go crazy even if you do. If you don’t turn her back, we damned well will.”

“So that’s the way it blows, is it? Who’s paying you for this?”

Willis and Trail remained uncomprehending.

“You heard me,” he roared. “Who’s behind you? Who’s out to wreck this trip?”

Willis shook his head. “Nobody’s behind us. We just want to get out of this before we go crazy, too,” he repeated.

“Went crazy, eh?” said the Captain with a sneer. “Well, maybe they did, and then again, maybe they didn’t—and if they didn’t, I’ve got a pretty good idea what happened to them.” He paused. “So you think you’ll scare me into turning back, do you? Well, by God you won’t, you lousy rats. Now get back to your work; I’ll deal with you later.”

But neither Willis nor Trail had any intention of getting back. They came on. Trail was swinging a threatening spanner. I snatched the pistol from the corpse’s hand, and got him in the forehead. It was a lucky shot. Willis checked and tried to stop. I got him, too.

The Captain turned and saw me handling the pistol. The suddenness of the thing had taken him by surprise. I could see that he didn’t know whether to thank me or to blame me for so summary an execution of justice. There was no doubt that the pair had mutinied, and that Trail, at least, had meant murder . . . . Strong and Danver, the two men in the doorway, stared speechlessly. Nine men had sailed in the Nuntia; four now remained . . .

For a time, the Captain said nothing. We waited, looking at the two bodies still swaying eerily, anchored to the floor by their magnetic shoes. At last, the Captain broke the silence.

“It’s going to be hard work for four men,” he said. “But if each of us pulls his weight, we may win through yet. To the two of you, all the engine room work will fall. Gratz, do you know anything of three-dimensional navigation?”

“Very little, sir.”

“Well, you’ll have to learn—and quickly.”

After the business of disposing the bodies through the air-lock was finished, he led me to the navigation room. Half to himself, I heard him murmur:

“I wonder which it was? Trail, I should guess. He’s the type.”

“Beg your pardon, sir?”

“I was wondering which of those two was the murderer.”

“Murderer, sir?” I said.

“Murderer, Gratz. I said it, and I mean it. Surely you didn’t think those deaths were natural.”

“They seemed natural.”

“They were well enough managed, but there was too much coincidence. Somebody was out to wreck this trip and kill us all.”

“I don’t see—”

“Think, man, think,” he interrupted. “Suppose the secret of the Nuntia got out in spite of all our care? There are plenty of people who would want her to fail.”

I flatter myself that I managed my surprise rather well.

“Metallic Industries, you mean?”

“Yes, and others. No one knows what may be the outcome of this voyage. There are a lot of people who find the world very comfortable as it is and would like to keep it so. Suppose they had planted one of those men aboard?”

I shook my head doubtfully.

“It wouldn’t do. It’d be suicide. One man couldn’t get this ship back to Earth.”

“Nevertheless, I’m convinced that either Willis or Trail was planted here to stop us from succeeding.”

The idea that both the men were genuinely scared and wanted only to get back to Earth had never struck him. I saw no reason to let it.

“Anyway,” he added, “we’ve settled with the murdering swine now—at the cost of three good, honest men.”

He took some charts from a drawer.

“Now, come along, Gratz. We must get to work on this navigation. Who knows but that all our lives may soon depend on you.”

“Who, indeed, sir,” I agreed.

Another fortnight passed before the Nuntia at last dipped her nose into the clouds which had always made the nature of Venus’ surface a matter for surmise. By circling the planet several times, Captain Tanner had contrived to reduce our headlong hurtling to a manageable speed. After I had taken a sample of the atmosphere (which proved almost identical with that of Earth), I took my place close beside him, gaining a knowledge of how the ship must be handled in the air. When the clouds closed in on our windows to obscure the universe, we were traveling at a little more than two hundred miles an hour. Despite our extended wings, we required the additional support of vertical rockets.

The Captain dropped cautiously upon a long slant. This, he had told me, would be the most nerve-racking part of the entire trip. There was no telling how far the undersides of the clouds were from the planet’s surface. He could depend on nothing but luck to keep the ship clear of mountains which might lurk unseen in our path. He sat tensely at the control board, peering into the baffling mist, ready at a moment’s notice to change his course, although we both knew that the sight of an obstacle would mean that it was too late. The few minutes we spent in the clouds seemed interminable. My senses drew so taut that it seemed they must snap. And then, when I felt that I could not stand it a moment longer, the vapors thinned, dropped behind and we swept down at last upon a Venusian landscape.

Only it was not a landscape, for in every direction stretched the sea—a grey, miserable waste. Even our relief could not make the scene anything but dreary. Heavy rain drove across the view in thick rods, slashing at the windows and pitting the troubled water. Lead-grey clouds, heavy with unshed moisture seemed to press down like great, gorged sponges which would wipe everything clean. Nowhere was there a darkling line to suggest land; the featureless horizon which we saw dimly through the rain was a watery circle.

The Captain leveled out and continued straight ahead at a height of a few hundred feet above the surface. There was nothing for it but to go on and hope that we should strike land of some kind. For hours we did, and for all the difference it made to the scene, we might have been stationary. It was just a matter of luck. Unknowingly, we must have taken a line on which the open sea lay straight before us for thousands of miles. The rain, the vastness of the ocean and reaction after our journey combined to drive us into depression. Was Venus, we began to ask ourselves, nothing but a sphere of water and clouds? At last I caught a glimpse of a dark speck away to starboard. With visibility so low, I could not be certain what it was. We had all but passed it before I drew the Captain’s attention. Without hesitating, he swerved towards it, and we both fixed our eyes on it and anxiously watched it grow.

As we drew closer, it proved to be a hill of no great size, rising from an island of some five or six square miles. It was not such a spot as one would have chosen for a first landing, but he decided to make it. We were all thoroughly tired of our cramped quarters; a few days of rest and exercise in the open air would put new heart into us.

It would be absurd for an Earthman to describe Venus to Venusians, but there are differences between your district of Takon and that island where we landed which I find very puzzling. Moreover the conditions which I found elsewhere also differ from those which abide here. I know nothing about the latitude of these places, but it seems that they must be very far removed from here to be so unlike. For instance, our island was permanently blanketed beneath thick clouds; one never saw the sun at all, but for all that, the heat was intense and the rain, which seldom ceased, was warm. Here in Takon, on the other hand, you have a climate not unlike that of our temperate regions—occasional clouds, occasional rain, warmth that is not too oppressive. When I look around and observe your plants and trees, I find it hard to believe that they can exist on the same planet with the queer jumble of growths we found on the island. I know nothing of botany, so I can only tell you that I was struck by the quantities of ferns and palms, and the almost entire absence of hard-wooded trees.

Two days were occupied in minor repairs and necessary adjustments, varied by occasional explorations. These were not pleasure trips, for the rain fell without ceasing, but they served to give us some much-needed exercise and to improve our spirits. On the third day, the Captain proposed an expedition to the top of the central hill, and we agreed to accompany him. We were all to go armed, for though the only animals we had seen were small, timid creatures which scuttled from our approach, there was no telling what we might not encounter in the deeper forest which lay between the hill and the beach where the Nuntia rested.

We assembled shortly after dawn, almost in a state of nudity. Since the heat rendered heavy waterproofs intolerable, we had decided that the less we wore, the better. It would be hard enough work carrying heavy rifles and rucsacks of supplies in such a climate. The Captain shepherded us out into the steady rain, pushed the outer door to behind us and we began our tramp up the beach. We had all but crossed the foreshore scrub which bordered the forest proper when I stopped abruptly.

“Damnation,” I said with some irritation.

“What is it, do you think?” asked the Captain.

“Ammunition,” I told him. “I put it aside ready to pack, and forgot to put it in.”

“Are you sure?”

I hauled the rucsack off my back and looked through the contents. There was no sign of the packet of cartridges he had given me. In order to travel light, we had only a few rounds each. I could not expect the others to share theirs with me in the circumstances. There was only one thing to be done.

“I’ll go back for them. It’ll only take a few seconds,” I said.

The Captain grudgingly consented. He disliked inefficiency, but could not afford to weaken his party by taking a member of it unarmed into possible dangers. I hurried back to the ship, stumbling along through the sand and shingle. As I pulled open the air-lock door, I glanced back. The three, I could dimly see, had reached the edge of the forest and were standing under such shelter as they could find, watching me.

I jumped inside and threw down my rifle and rucsack with a clatter. First I rushed for the engines and turned on the fuel taps, then I made forward to the navigation room. Hurriedly I set the controls as I had been shown, and pulled over the ignition switch. With my fingers above the first bunch of firing keys, I looked once more out of the windows. The Captain was pounding across the beach, followed at a little distance by the others. How he had guessed that there was anything wrong I cannot say; perhaps his glasses had enabled him to see that I was in the control room. Anyway, he meant business . . . .

He passed out of my line of sight, and a moment later I pressed the firing keys. The Nuntia trembled, lurched and began to slither forward across the sand. I saw the other two wave despairing arms. It was impossible to tell whether the Captain had managed to scramble aboard or not. I turned the rising ship towards the sea. Again I looked back, just in time to see the others running towards a form which lay huddled on the sand. Close beside it they stopped and looked up. They shook wild, impotent fists in the direction of my retreating Nuntia.

After a few hours, I began to grow seriously worried. There must be other land on this planet, but I had seen none as yet. I began to have a nasty feeling that it would all end with the Nuntia dropping into the sea, condemning me to eventual death by starvation should I survive the fall. She was not intended to be run single-handed. In order to economize weight, many operations which could easily have been made automatic had been left to manual control with the assumption that there would always be one or more men on engine room duty. The fuel pressure gauge was dangerously low now, but the controls required constant attention, preventing me from getting aft to start the pressure pumps. I toyed with the idea of fixing the controls while I made a dash to the engine room and back, but since it was impossible to find a satisfactory method of holding them, the project had to be abandoned. The only thing I could do was to hold on and hope land would show up before it was too late.

In the nick of time, it did—a rockbound, inhospitable-looking coast, but one which for all its ruggedness was fringed to the very edges of the harsh cliffs with a close-pressed growth of jungle. There was no shore such as we had used for a landing ground on the island. The water swirled and frothed about the cliff-foot as the great breakers dashed themselves with a kind of ponderous futility against the mighty retaining wall. No landing there. Above, the jungle stretched back to the horizon, an undulating, unbroken plain of tree tops. Somewhere there I would have to land, but where?

A few miles in from the coast, the Nuntia settled it for me. The engines stopped with a splutter. I did not attempt to land her. I jumped for one of the spring acceleration hammocks, and trusted that it would stand the shock.

I came out of that rather well. When I examined the wrecked Nuntia, her wings torn off, her nose crumpled like tinfoil, her smooth body now gaping in many places from the force of the impact, I marveled that anyone could sustain only a few bruises (acquired when the hammock mountings had weakened to breaking point) as I did. There was one thing certain in a very problematical future—the Nuntia’s flying days were done. I had carried out Metallic Industries’ instructions to the full, and the telescopes of I. C. would nightly be searching the skies for a ship which would never return.

Despite my predicament (or perhaps because I had not fully appreciated it as yet) I was full of a savage joy. I had struck the first of my revengeful blows at the men who had caused my family such misery . . . . The only shadow across my satisfaction was that they could not know that it was I, and not Fate, who was against them.

It would be tedious to tell in detail of my activities during the next few weeks. There is nothing surprising about them. My efforts to make the Nuntia habitable, my defenses against the larger animals, my cautious hunting expeditions, my search for edible greenstuffs, were such as any other man would have made. They were makeshift and temporary. I did only enough to assure myself of moderate comfort until the Metallic Industries ship should arrive to take me off. So for six months—by the Nuntia’s chronometers—I idled and loafed, and though it may sometimes have crossed my mind that Venus was not altogether a desirable piece of real estate, yet it was in a detached, impersonal way that I regarded my surroundings. It would make a wonderful topic of conversation when I got home. That “when I got home” colored all my thoughts; it was the constant barrier which stood between me and the life about me; this planet might surround me, but it could not touch me as long as the barrier remained in place.

At the end of six months, I began to feel that my time of exile was nearly up. The M. I. ship would be finished by now, and ready to follow the Nuntia’s lead. I waited almost a month longer, seeing her in my mind’s eye falling through space towards me; then it was time for my signal. I had arranged the main searchlight so that it would point vertically upwards to stab its beam into the low clouds, and now I began to switch it on every night as soon as the darkness came, leaving it glaring until near dawn. For the first few nights, I scarcely slept, so certain was I that the ship must be cruising close by in search of me. I used to lie awake watching the dismal sky for the flash of her rockets and straining my ears for their thunder. But this stage did not last long. I consoled myself very reasonably that it might take much searching to find me. But all day, too, I was alert, with smoke rockets ready to be fired the moment I should hear her . . . .

After four months more, my batteries gave out. It is surprising that they lasted so long. As the voltage dropped, so did my hopes. The jungle seemed to creep closer, making ominous bulges in my barrier of detachment. For a number of nights after the filaments had glowed their last, I sat up through the hours of darkness, firing occasional distress rockets in forlorn faith. It was when they were finished that I saw what had occurred. Why I did not think of it before, I cannot tell. But the truth came to me in a flash: Metallic Industries had duped me just as International Chemicals had duped my father . . . .

They had not built—had never intended to build—a space-ship. Why should they, once I. C. had lost theirs? That, I grew convinced, was the decision which had been taken in the Board Room after my withdrawal. They had never intended that I should return . . . . I could see now that they would have found it not only expensive, but dangerous. There would be not only my reward to be paid, but I might blackmail them. In every way it would be more convenient that I should do my work and disappear. And what better method of disappearance could there be than loss upon another planet? The swine . . . .

Those are the methods of Earth—that is the honor of great companies, as you will know to your cost should you have dealings with them. They’ll use you, and then break you . . . .

I must have been nearly crazy for some days after that realization. My fury with my betrayers, my disgust with my own gullibility, the appalling sense of loneliness, and, above all, the eternal drumming of that almost ceaseless rain combined to drive me into a frenzy which stopped only on the brink of suicide.

But in the end, the adaptability of my race began to assert itself. I began to hunt and live off the land about me. I struggled through two bouts of fever and successfully sustained a period of semi-starvation when my food was finished and game was short. For company I had only a pair of six-legged, silver-furred creatures which I had trained. I had found them one day, deserted in a kind of large nest and crying weakly with hunger. Taking them back with me to the Nuntia, I fed them and found them friendly little things. As they grew larger, they began to display remarkable intelligence. Later I christened them Mickey and Minnie (after certain classic film stars at home) and they soon got to know their names.

And now I come to the last and most curious episode which I confess I do not yet understand. It occurred several years after the Nuntia’s landing. A foraging expedition upon which Mickey and Minnie accompanied me, as usual, had taken us into country completely unknown to me. A scarcity of game and a determination not to return empty-handed had caused me to push on farther than usual. At last, at the entrance to a valley, Mickey and Minnie stopped. Nothing I could do would induce them to go on. Moreover, they tried to hold me back, clutching at my legs with their fore-paws. The valley looked a likely place for game, and I shook them off impatiently. They watched me as I went, making little whining noises of protest, but they did not attempt to follow.

For the first quarter of a mile, I saw nothing unusual. Then I had a nasty shock. Some way farther on, an enormous head, reared above the trees, was looking directly at me. It was not like anything I had ever seen before, but thoughts of the giant reptiles jumped to my mind. Tyrannosaur must have had a head not unlike that. I was puzzled as well as scared. Venus could not be still in the age of the giant reptiles . . . . I could not have lived here all this time without seeing something of them before this . . . .

The head did not move; there was no sound. As my first flood of panic abated, it was clear that the animal had not seen me. I took cover and started to move cautiously closer. The valley seemed utterly silent, for I had grown so used to the sounds of rain that my ears scarcely registered them. At two hundred yards, I came within sight of the great head again and decided to risk a shot. I aimed at the right eye and fired.

Nothing happened—the echoes thundered from side to side; nothing else moved. It was uncanny, unnerving. I snatched my glasses. Yes, I had scored a bull, right in the creature’s eye, but . . . . Queer. I decided that I didn’t like the valley a bit, but I made myself go on. There was a curious odor in the air, not unpleasant, yet a little sickly. Quite close to the monster I stopped. He had not budged an inch. Suddenly, behind him, I caught a glimpse of another reptile—smaller, more lizard like, but with teeth and claws that made me sweat. I dropped on one knee and raised the rifle. I had begun to feel an odd swimming sensation inside my head. The world seemed to be tilting about me. My rifle barrel wavered . . . . I could not see clearly. I felt myself begin to fall—I seemed to be falling a long, long way . . . .

When I awoke, it was to see the bars of a cage—

The Revelation

Dagul stopped reading. He knew the rest.

“How long ago, do you think?” he asked.

Goin shrugged his shoulders.

“Heaven knows. A very long time, that’s all we can be sure of. The continual clouds . . . . And did you notice that he claims to have tamed two of our primitive ancestors?—Millions of years.”

“And he warns us against Earth.” Dagul smiled. “It will be a shock for the poor devil. The last of his race—though not, to judge by his own account, a very worthy race. When are you going to tell him?”

“He’s bound to find out soon, so I thought I’d do it this evening. I’ve got permission to take him up to the observatory.”

“Would you mind if I came too?”

“Of course not.”

Gratz was stumbling among unfamiliar syllables as the three climbed the hill to the Observatory of Takon, doing his best to drive home his warnings of the perfidy of Earth and the ways of great companies. He was relieved when both the Takonians assured him that no negotiations were likely to take place.

“Why have we come here?” he asked when they were in the building, and an assistant in obedience to Goin’s orders was adjusting the large telescope.

“We want to show you your planet,” said Dagul.

There was some preliminary difficulty due to differences between the Takonian and the human eye, but before long he was studying a huge, shining disc. A moment later he turned back to the others with a slight smile.

“There’s some mistake. This is our moon.”

“No. It is the Earth,” Goin assured him.

Gratz looked back at the scarred, pitted surface of the planet. For a long time he gazed in silence. It was like the moon, and yet . . . . Despite the craters, despite the desolation, there was a familiar quality. A suggestion of the linked Americas stretching from pole to pole . . . . a bulge which might have been the West African coast . . . . Gratz gazed in silence for a great while. At last he turned away.

“How long?” he asked.

“Some millions of years.”

“I don’t understand. It was only the other day—”

Goin started to explain, but Gratz heard none of it. Like a man dreaming, he walked out of the building. He was seeing again the Earth as she had been; a place of beauty, beautiful in spite of all that man had made her suffer—and now she was dead, a celestial cinder.

Close by the edge of the cliff which held the observatory high above Takon, he paused. He looked out across an alien city in an alien world towards a white point which glittered in the heavens. The Earth which had borne him was dead . . . . Long and silently he gazed. Then, deliberately, with a step which did not falter, he walked over the cliff’s edge . . . .

THE END

[The end of The Man From Beyond by John Wyndham (as John Beynon Harris)]