* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Marching Notes

Date of first publication: 1929

Author: Ernest La Prade (1899-1969)

Illustrator: Jay

Date first posted: May 11, 2022

Date last updated: May 11, 2022

Faded Page eBook #20220530

This eBook was produced by: Stephen Hutcheson, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

MARCHING NOTES

Books by

ERNEST LA PRADE

ALICE IN ORCHESTRALIA

MARCHING NOTES

COPYRIGHT, 1929

BY DOUBLEDAY, DORAN & COMPANY, INC.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES AT

THE COUNTRY LIFE PRESS

GARDEN CITY, N. Y.

| CONTENTS | ||

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | THE MAJOR | 3 |

| II | THE GREAT STAFF | 19 |

| III | A NICE MESS | 37 |

| IV | RULES AND REGULATIONS | 53 |

| V | BETWEEN THE BARS | 69 |

| VI | ALICE TAKES COMMAND | 91 |

| VII | GUIDEPOSTS | 111 |

| VIII | MUSICAL ARTILLERY | 129 |

| IX | ALICE RECOGNIZES AN OLD ACQUAINTANCE | 145 |

| X | THE GENERAL ARRIVES | 159 |

| XI | THE GENERAL DEPARTS | 179 |

THE MAJOR

Alice had a new piece. Her lesson having been well prepared, her piano teacher had told her that she might begin to study a new composition: the Minuet Number 1 with Trio, by Mozart. Accordingly, on her way home, she had stopped at the music shop to buy a copy of the minuet, and now she was eager to find out what it was like. As soon as she reached home she ran to her piano, placed the new music on its rack, and began to try it over.

She was not a highly accomplished pianist; but considering her age, which was ten years, and the fact that she had been taking lessons for little more than one of those years, she was a rather good sight reader. She had an alert mind, a quick eye, and a good musical ear; and, most important of all, she was tremendously fond of music and worked very hard. She enjoyed practising the piano. Even scales and exercises interested her, and the pieces which she played herself, or heard others play, filled her with delightful, mysterious emotions. They seemed to be trying to tell her something which she could not quite understand but which she felt was exciting or soothing, gay or sad; and she was constantly trying to find out more definitely what their messages meant.

For Alice was both observant and curious. She noticed a great deal of what went on about her, and she always wanted to know the reason for everything. One of the things she had noticed was that certain pieces of music appealed to her much more strongly than others, and she often wondered why they did so. It was not because they were longer or shorter, faster or slower, or louder or softer than the others. That much she was sure of. But, try as she would, she could not discover what it was that made one piece sound “prettier” than another. This new minuet, for instance—what made it so charming? It was really very simple. Already she had learned to play it fairly well.

“Why,” she said to herself, “it’s easy. There’s nothing to it. And yet, there is something to it, after all, because it’s one of the prettiest pieces I’ve ever played. It’s so nice and jolly and—and old-fashioned. It sort of reminds me of something that happened a long time ago—something awfully nice, I’m sure, but I can’t quite remember what it was. I wonder why it sounds so old-fashioned. I wonder why it’s different from any of my other pieces. Pieces all look so much alike—why do they sound so differently? They’re all made up of notes and rests and bars and things, but how are the notes put together to make music? I ought to know that. I can play music; why can’t I compose it?”

She pondered a moment; then her face suddenly brightened.

“P’r’aps I can compose music!” she exclaimed. “I’ve never tried. Maybe if I just play any notes I happen to think of it will be music.”

She poised her hands over the keyboard and then let them fall at random on the keys. The result was a harsh discord.

“Oh, dear!” she cried, “that doesn’t seem to be the way. I s’pose I don’t know enough about it. There’s so much that I don’t know. For instance, how many notes make a piece? And why do some notes sound well together and some not? And when you compose a piece, how do you begin, and what do you do in the middle, and how do you end?”

She leaned back in her chair and gazed in perplexity at the notes of the Mozart minuet. They had suddenly turned into a riddle, which she tried vainly to solve. Why was it that she could read them but hadn’t the least idea how they were written? It was as if she had learned to read words without knowing how to spell even so much as “cat.” That was clearly impossible. Why, then, were notes so different from letters?

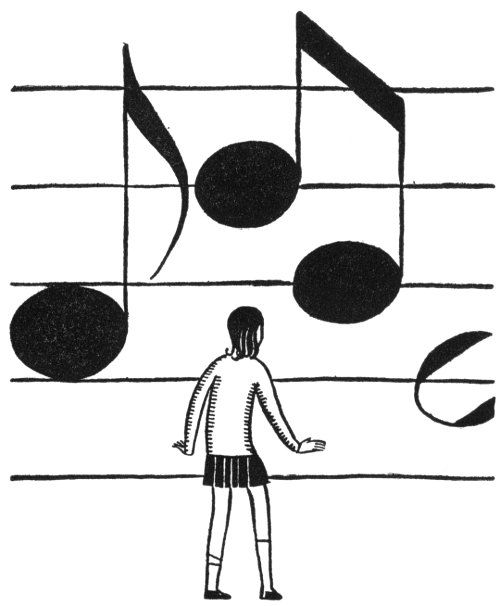

Alice stared hard at the notes, as if hoping that they might tell her the answer to the riddle; but they merely stared stupidly back at her. Suddenly she sat up straight and blinked. Were her eyes playing pranks, or had she really seen a note move from one measure to the next?

“Well, of all the queer——” Alice began, and then stopped, her eyes wide with astonishment. Another note had changed its place on the staff.

“I do believe they’re alive!” she Whispered excitedly. “They are alive—and they’re growing bigger and bigger!”

It was true: the notes had come to life and were growing up at an amazing rate. Already they were nearly as tall as Alice herself; and the lines and spaces of the staff had grown longer and longer and wider and wider, until they had turned into a great flight of stairs which stretched away on either side as far as Alice could see. The bottom step was black, the next one white, the third black, and so on, up to the topmost step, which was black. Alice counted the steps and found that there were nineteen in all. Above the top step she could see nothing but sky, while at the bottom of the stairs the ground sloped sharply down to where she was standing—for she was no longer seated at her piano. The piano, the chair, and all the familiar objects of her room had vanished, and she found herself in a strange country which appeared to be covered with snow. However, as she didn’t feel the least bit cold she concluded that it must be some new kind of snow that was warm and never melted, even in summer. There was nothing of interest to be seen anywhere except on the stairs, where the notes, now grown taller than Alice, were moving up and down and from side to side in a bewildering manner. Alice was staring at them, wondering what they could be doing, when she was startled by the sound of a low, rich voice speaking close to her ear.

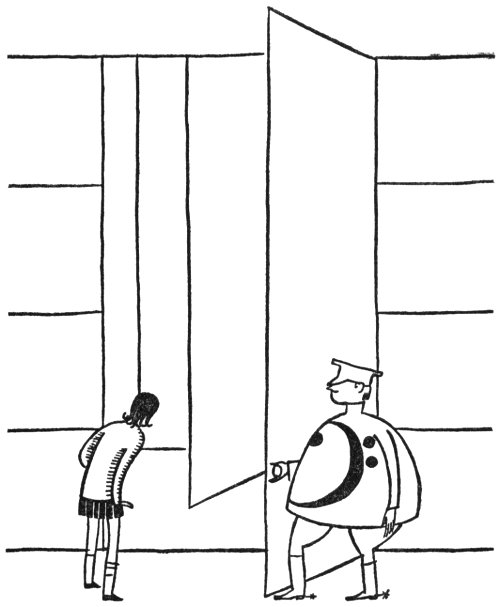

“Pardon me,” said the voice, “would you mind standing aside? I have orders to place a Low C just here.”

Alice turned quickly to see who it was that had spoken. To her surprise there seemed to be nothing near except a large bass clef suspended in midair at about the height of her own head. It appeared so unreasonable that a bass clef should be endowed with the power of speech that Alice thought her ears must have deceived her. She was not left long in doubt, however, for the voice spoke again.

“I’m very sorry to disturb you,” it said, “but I really must beg you to stand a little farther down the hill. My orders, you know . . .”

“Oh, excuse me,” said Alice. “I didn’t mean to get in your way, but at first I—I didn’t see you.”

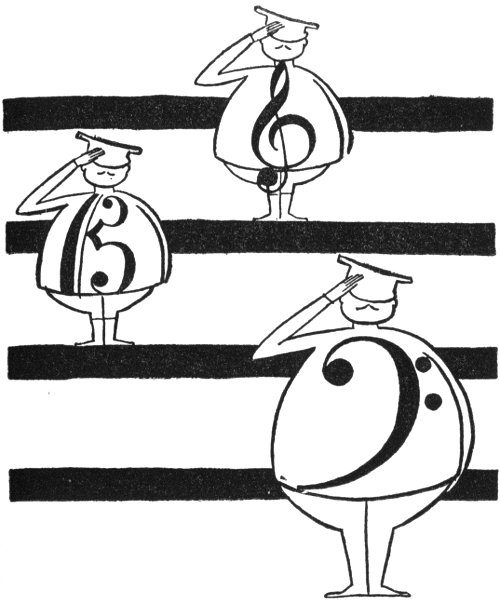

As a matter of fact she was not sure that she saw the person who had addressed her even now. But as she stared harder and harder she thought she could just make out the figure of a queer-looking man, rather short and stout, and dressed all in white. His face too was white—even his hair was white. The only thing about him which was not white was the large bass clef embroidered in black on the breast of his tunic, or blouse, which seemed to be of a military cut. The rest of him was so exactly the color of the surrounding landscape that it was almost impossible to see him. He seemed to realize Alice’s difficulty, for he said kindly:

“You will be able to see me better when your eyes have become accustomed to the glare. In such a white country as this the light is dazzling to human eyes. But, in the meanwhile, may I remind you that you are still standing just where I have to place the Low C?”

“I beg your pardon!” Alice exclaimed, blushing and moving hastily aside. “I was trying so hard to see you that I quite forgot——”

“Please don’t mention it,” said the Bass Clef courteously. “I hate to be so persistent, but the General, you know, is very exacting, and if we don’t carry out his orders without delay we are likely to be court-martialed.”

“I s’pose that must be very unpleasant,” said Alice. “I hope he won’t court—won’t do it to you. Does it hurt much?”

“Sometimes it’s rather painful,” the Bass Clef admitted. “No soldier enjoys being court-martialed; but he’s not apt to be if he does his duty properly.”

Alice was just about to ask what it was like to be court-martialed, for she had only the haziest notion of what the word meant; but at that moment she noticed that on the spot where she had been standing, at the foot of the great flight of stairs, four short steps—two black and two white—had appeared as if by magic. The Bass Clef barked a command:

“Corporal Crotchet, take your post!”

Instantly a quarter note detached himself from the throng on the stairs, ran down to the flight of four short steps that had just appeared, and stood stiffly at attention on the black step at the bottom. Alice stared at him for a moment, perplexed. There was something queer about him. In a moment she saw what it was and began to laugh. The note was standing on his head.

“Why does he stand upside down?” Alice asked the Bass Clef.

“Merely for the sake of neatness,” he replied. “You see, according to regulations, his head must be on the step—or, as you call it, the Line or Space of the Staff—which he is ordered to occupy. If he stood right side up, with his head on the lowest step, his body—I believe you call it ‘Stem’—would extend far down below the Staff. That would look untidy; and soldiers, you know, are always very neat and orderly. Therefore, as a rule, when a note is assigned to a step below the middle of the Staff he stands on his head; and when his place is above the middle he stands right side up.”

“I see,” said Alice. “So the notes are really soldiers?”

“Of course—and good soldiers, too. They always obey orders.”

Alice gazed curiously at the Bass Clef. She could see him quite well now, and she noticed that, besides his military-looking blouse, he wore a jaunty cap, a belt with a strap over his right shoulder, riding breeches, and white boots with spurs.

“Are you a soldier too?” Alice inquired.

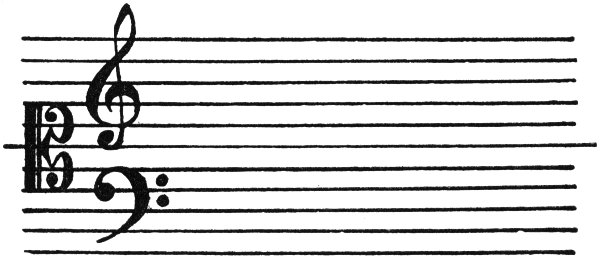

“Naturally,” said the Bass Clef, drawing himself up proudly. “I am a staff officer with the rank of major, and I exercise command over the lower half of the Great Staff. The upper half, you know, is under the command of my friend Major Treble Clef. Then there’s another staff officer, Major C-Clef, who controls the middle portion of the Great Staff; but he’s nearly always on leave of absence nowadays. Except when we are engaged in a campaign for the viola, the ’cello, the bassoon, or the trombone, he generally delegates his authority either to Major Treble Clef or to me, or else he divides it between us, as in campaigns for the piano.”

Alice looked confused. “I’m afraid I don’t quite understand,” she said. “What do you mean by ‘campaign’?”

“The same thing you mean by ‘composition,’ ” the Bass Clef replied. “If you’d ever taken part in one, as we have, you’d realize that ‘campaign’ is the only word that correctly describes it. But human beings seem to have a mania for calling things by stupid and inaccurate names. What possible reason, for instance, can there be for calling our Great Stairs the ‘Great Staff,’ and its steps ‘lines and spaces’? A ‘staff’ is a ‘stick,’ or, in the army, a board of officers; and lines and spaces have nothing to do with steps.”

Alice felt that the Bass Clef was not entirely just in his criticism of human beings.

“But,” she pointed out, “in my country they are lines and spaces. I s’pose that’s because they’re easier to print.”

“It’s just your stinginess,” grumbled the Bass Clef. “Instead of providing us with nice roomy stairs to maneuver on, you print us on flat pieces of paper and shut us up in books. It’s very inconsiderate.”

“I’m sorry,” said Alice. “I—I don’t think we ever s’posed you minded. Besides, if you took up as much space in my country as you do here, nobody would play you, because they’d have to walk miles and miles to read one piece.”

Apparently the Bass Clef had not thought of that. “Well, perhaps you’re right,” he conceded. “But I do wish you’d call things by their proper names. Anybody can see that this is really a flight of stairs; but since you insist on calling it the ‘Great Staff’ we have to call it by the same name, to avoid still more confusion.”

“What do you mean by ‘Great Staff’?” Alice inquired. “I know what the Treble Staff and the Bass Staff are, but I’ve never heard of a ‘Great Staff.’ ”

“Fancy that!” exclaimed the Bass Clef. “Then it’s high time you learned about it, if you ever expect to read music.”

“But I can read music,” Alice protested. “My teacher says I read very well—for my age.”

The Bass Clef looked politely skeptical, and Alice added:

“Anyhow, I’d be very much obliged if you’d explain about the Great Staff—if you have time.”

The Bass Clef glanced at his wrist watch. “Very well,” he said. “I can spare a few minutes. But first I must dismiss these troops.”

He beckoned to two handsome young officers

who were standing near by. As they approached,

Alice saw that one of them wore on his White

tunic the fraction  , while the other had the

word “Allegro” embroidered in black letters

across his breast.

, while the other had the

word “Allegro” embroidered in black letters

across his breast.

They halted in front of the Bass Clef and saluted.

“The battalion is dismissed,” said the Bass Clef.

The two officers saluted again, about-faced, and barked some words which Alice did not understand. However, the notes seemed to understand them, for they promptly formed a column of squads and marched off along the stairs.

“These gentlemen,” said the Bass Clef, “are my aides, Lieutenant Rhythm and Lieutenant Tempo. Charming fellows, both of them, and really indispensable. They direct the actual movements of all our troops. Now, if you’ll just step up here with me I’ll show you what we mean by the ‘Great Staff.’ ”

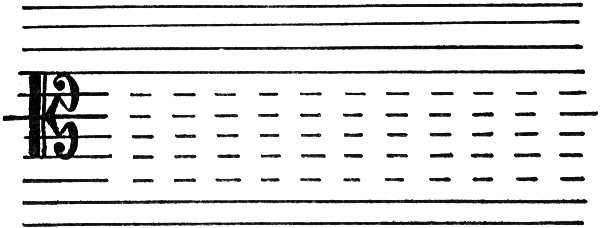

THE GREAT STAFF

The Bass Clef led Alice up the stairs. Halfway to the top they came to a very broad white step which formed a kind of landing. Here the Bass Clef paused and asked abruptly:

“Do you know where we are?”

Alice looked up the stairs, then down.

“Why, we seem to be about halfway between the top and the bottom,” she replied.

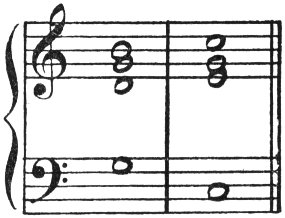

“Exactly,” said the Bass Clef. “We are on the middle step which separates the Bass Staff from the Treble Staff.”

“Why is it so much broader than the others?” Alice inquired.

“To make music easier to read. Once there were three steps where this single broad step now is—two white steps with a black one between them. That black step was Middle C, so called because it was exactly in the middle of the Great Staff. It is also the C nearest the middle of the piano keyboard, as you probably know.”

Alice nodded her head, and the Bass Clef continued:

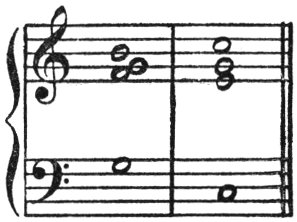

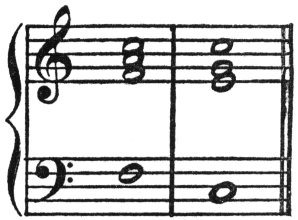

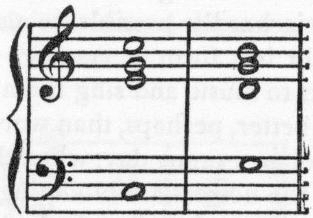

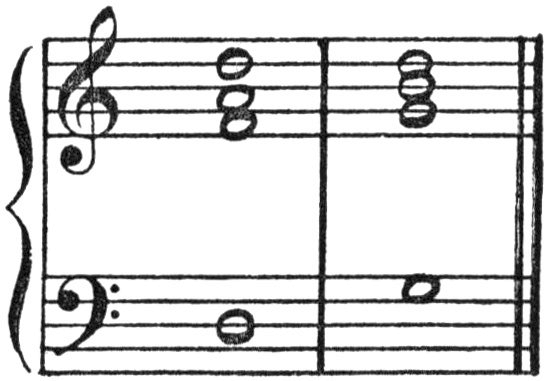

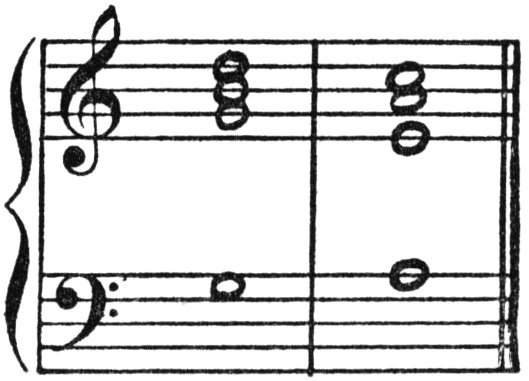

“Now, to avoid confusion, as I said before, we shall call the black steps ‘Lines’ and the white steps ‘Spaces.’ The Great Staff, then, formerly consisted of twenty-one steps—eleven lines and ten spaces—all so much alike that it was often hard to tell exactly which step a note was on without stopping to count up from the bottom or down from the top. For that reason we decided to leave out the middle black step entirely, thus dividing the Great Staff into two staves of nine steps each—five Lines and four Spaces—which makes it easier to tell where you are at a glance.”

“I see,” said Alice; “but what became of Middle C?”

“Why, he merely lost his permanent post and became what we call a ‘leger-step.’ That is, whenever he’s on duty he has a little private step of his own, just long enough for the note to stand on. When he’s acting under my orders his step is placed just above the Bass Staff, with one space between; when he’s serving under Major Treble Clef his step is placed in a similar manner just below the Treble Staff. Is that clear?”

“Ye-es,” said Alice, a trifle doubtfully; “but——”

“Then I’d better give you a demonstration,” said the Bass Clef. He blew a shrill blast on a whistle, and instantly a little soldier with a Sharp on the breast of his tunic came running along the stairs.

“This,” said the Bass Clef, “is Private Accidental, Captain Key’s orderly. He’s a very useful soldier; in fact, we could hardly get along without him.”

“What does he do?” Alice inquired.

“You’ll see him at work later on,” said the Bass Clef. “That will be better than having me explain his duties.”

The soldier, having arrived within a few paces of the Major, halted and saluted.

“Orderly,” said the Bass Clef, “ask Major C-Clef and Major Treble Clef to be good enough to step this way; and have Sergeant Semibreve report to me with a fatigue detail.”

“Yes, sir,” said the orderly, and dashed away to execute his orders. As he turned, Alice saw that on his back he wore a Flat.

A moment later two officers appeared, walking along the stairs toward Alice and her friend. In general appearance they both resembled the Bass Clef, for they were rather short and stout and wore white uniforms with boots and spurs; but the signs on their breasts were different. One of the newcomers had on his tunic an emblem somewhat like the symbol “&,” which Alice knew to be a treble clef. The other, however, wore a sign that was new to her. She had never seen anything quite like it before, though it looked somewhat like a large and ornate letter B.

The three officers saluted each other courteously, after which the Bass Clef presented his colleagues to Alice with due ceremony.

“Gentlemen,” he said, “I should like you to meet a young friend of mine who is interested in our country and our profession.”

The two officers saluted and then bowed, and Alice curtsied.

“I’ve undertaken to explain to her,” the Bass Clef continued, “the precise nature of our duties, and I’ve taken the liberty of calling on you to assist me in demonstrating some of their more complex phases.”

The two officers declared that they were happy to be of service.

“Among other things,” the Bass Clef went on, “I propose to show her, as clearly as possible, how the spheres of our authority fit together and, in certain cases, overlap. The first thing, of course, is to restore the Great Staff. Ah, I see that Sergeant Semibreve has arrived with his detail. Sergeant, have your men restore the Middle C.”

The Sergeant, a round, fat note without a stem, whom Alice recognized as a whole note, was in charge of a squad of eight privates. These were eighth notes, and they looked so comical, with their little tails sticking out stiffly behind, that Alice could not help smiling at them. However, she soon forgot the drollness of their appearance as she became absorbed in watching what they were doing. For at a word from the Sergeant they had set to work with astonishing energy, and in less time than it takes to tell it they had removed a long section of the broad middle step, replacing it with three steps of the ordinary size, one white, the next black, and the third white. The Great Staff now appeared as the Bass Clef had described it—that is, it consisted of an unbroken series of twenty-one steps, alternately black and white.

“Now, gentlemen,” said the Bass Clef, “let us take our stations.”

He walked a few paces to the left, descended to the fourth Line from the bottom, and halted. The other two placed themselves directly above him, the C-Clef on the sixth Line and the Treble Clef on the eighth.

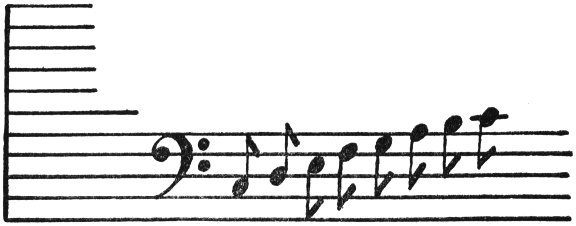

“You will see now,” said the Bass Clef to Alice, “how we define the parts of the Great Staff on which our notes operate. As you already know, I suppose, each of us controls a Staff of nine steps—five Lines and four Spaces—together with as many leger-steps as we may need. Now, my Staff comprises the nine lowest steps of the Great Staff. Therefore, when you see a five-Line Staff with a bass clef at the beginning, you know that the notes appearing on it represent the lowest tones of the scale—those that fit the compass of a bass voice. Just a moment and I’ll make that clearer. Sergeant, clear the field for the Bass!”

The squads of eighth notes scurried about, lifting out sections of the upper steps and carrying them away. When they had finished, all the steps above the ninth, for a distance of several yards, had disappeared, leaving the nine lowest ones presided over by the Bass Clef.

“Why,” said Alice, “it looks just like the left-hand part in piano music—only, there aren’t any notes on it.”

“That is easily remedied,” the Bass Clef assured her. “Sergeant, have your squad take Scale Formation Number 1.”

The Sergeant said something that sounded to Alice like three snorts and a sneeze, whereupon the eighth notes promptly ranged themselves in a diagonal line leading up the Staff from left to right, one note on each step. The first note stood on the second Space from the bottom, while the last two notes occupied short leger-steps above the Staff.

“Do you recognize that formation?” the Bass Clef demanded.

“Yes,” said Alice. “It’s the scale of C. Shall I sing it for you?”

The Bass Clef smiled. “I’m afraid you can’t.”

“Why, of course I can!” cried Alice. “Just listen—I’ll prove it:

“Do, Re, Mi, Fa, Sol, La, Si, Do.”

Her voice was musical and very high, and she sang the tones of the scale in perfect tune. But the Bass Clef chuckled, and Alice flushed.

“What’s the matter?” she demanded. “Wasn’t that right?”

“Relatively, yes,” said the Bass Clef, “but not absolutely. You sang a very good scale of C, but it wasn’t this one. Yours was in the treble range, two octaves higher.”

“Oh, well,” said Alice a bit sulkily, “it’s all the same.”

“That is a very thoughtless remark,” said the Bass Clef reprovingly. “How can it be the same? Bass is bass and treble is treble. If that were not the case I should lose my job, and so would a lot of others—the majority of your piano keys, for instance. Tell me, how many octaves has your piano keyboard?”

“Seven,” said Alice promptly.

“And a quarter,” the Bass Clef added. “Now, then, does the lowest octave sound the same as the highest?”

“Oh, no,” said Alice.

“Do the tones of any octave sound exactly like the tones of any other?”

Alice had to admit that they did not. “But what am I to do,” she asked, “if I want to sing music that’s written in the bass? I can’t sing such low notes.”

“Nor can anyone else,” said the Bass Clef curtly. “Notes can’t be sung, any more than letters can be spoken. They are merely the symbols that represent musical sounds, just as letters are symbols that represent words. You can read notes, but what you sing are tones. Now, I wonder whether you know exactly what a note does represent?”

“Why, it shows what note—I mean, what tone—you’re s’posed to sing or play.”

“Are you sure?” The Bass Clef’s voice was ironic. He pointed to a spot out on the bare white plain below the Staff, where a lone sentry—a sixteenth note with two tails—was slowly pacing up and down.

“Do you see that note out there? Well, what tone does he represent to you—a high one or a low one?”

Alice was stumped.

“I—I can’t tell,” she admitted.

“Why not?” demanded the Bass Clef.

“Because there aren’t any Lines or Spaces.”

“There you are!” cried the Bass Clef triumphantly. “That proves that a note does not represent pitch—that is, the position of a tone up or down the scale. He only indicates a definite pitch when you place him on the Staff; so it’s really the Lines and Spaces of the Staff that show you which tone of the scale you are to sing or play. However, there is something that the note does show you, whether he’s on or off the Staff. Do you know what that is?”

Alice considered the question for a moment; then her face brightened.

“I know!” she cried. “He shows how long the tone is s’posed to last.”

“Right,” said the Bass Clef. “You’ve got it straight at last. I hope you won’t forget it. And now I think we’ve kept the other majors waiting long enough while we’ve been arguing. Let’s ask them to give us a demonstration of their duties. Major Treble Clef, will you take command?”

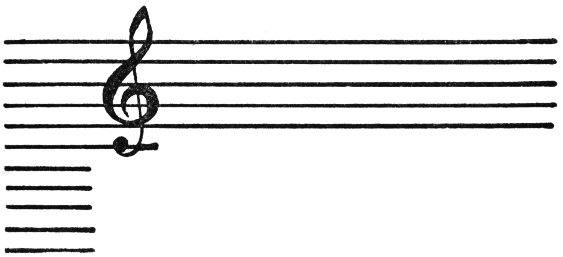

“Certainly,” said the Treble Clef in a high, sweet voice. “Sergeant, clear the field for the Treble.”

Once more the squad of eighth notes set to work, and soon the Staff had been rearranged so that only the nine highest steps were visible, with the Treble Clef in his place at the left-hand end.

“There,” said the Bass Clef, “you have the part of the Great Staff which is used in writing for the soprano voice, the violin, and various other instruments of high pitch; and also, of course, for the right-hand part in piano music. Now, if Major C-Clef will take command, you shall see how his part of the Great Staff is situated in relation to Major Treble Clef’s and mine. I doubt if you are as familiar with his sphere of authority as you are with ours.”

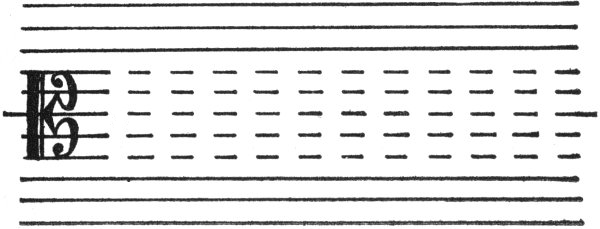

The C-Clef obligingly assumed command and ordered Sergeant Semibreve to restore the Great Staff. As soon as the twenty-one steps were again in their proper places the C-Clef addressed Alice in a full round voice of medium pitch.

“Please notice particularly,” he said, “that my post is on Middle C—the sixth Line of the Great Staff, counting either up or down—and that I always remain on Middle C so long as I am on duty. That’s why my name is C-Clef. Now, I command two different Staves—the Alto Staff and the Tenor Staff—each composed of five Lines and four Spaces; but in the Alto Staff Middle C is the third Line, and in the Tenor Staff it’s the fourth Line. Therefore, if you compare these two Staves, apart from the Great Staff, it looks as if my post were on a different Line in each Staff; but that is an optical illusion, as I shall show you by means of the Dotted Lines. Sergeant, change Lines; Alto, dotted!”

Again the Sergeant snorted and sneezed, and again the eighth notes scurried about in obedience to his commands. Seizing the middle step—the Line on which the C-Clef was standing—they turned it bottom side up. How they accomplished this without upsetting their commanding officer was a mystery to Alice; but they managed it somehow, for there stood the C-Clef, just as before, except that the step he stood on was now black-and-white, so that from a distance it looked indeed like a dotted, or broken, Line. The industrious eighth notes then turned over the two Lines above the middle one and the two below it, so that the five middle Lines of the Great Staff were now dotted.

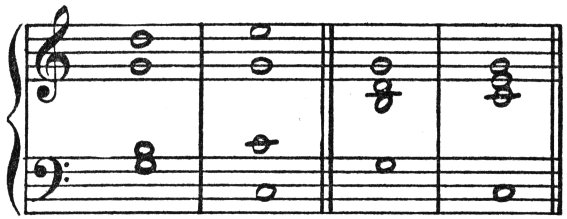

“Now, young lady,” said the C-Clef, “these dotted Lines, with the Spaces between them, constitute the Alto Staff. As you see, its middle Line is Middle C, its two upper Lines are the same as the two lowest Lines of the Treble Staff, and its two lower Lines are the same as the two highest Lines of the Bass Staff.”

“I can see that,” said Alice, “even if it does sound rather complicated. But what I should like to know is what the Alto Staff is good for.”

“Originally,” said the C-Clef, “it was used in writing music for the alto voice and for various instruments whose compass extended about an equal distance above and below Middle C. By writing for such instruments on this Staff you avoided using a lot of leger-steps. Nowadays, however, it is seldom used except in music for the viola, the alto instrument of the ‘string’ family. Nevertheless, you should be familiar with it—and with the Tenor Staff, which I shall show you in a moment—for otherwise you will not be able to read an orchestral score. Now, Sergeant, change Alto to Tenor.”

In a jiffy the topmost dotted Line was changed to black again, and the first black Line below the remaining dotted ones was changed to a dotted Line.

“Here you have the Tenor Staff,” said the C-Clef. “You see, my post is on the fourth line of this Staff; and yet I haven’t budged from Middle C.”

“I understand,” said Alice. “It’s the steps that have changed—not you. But what is the Tenor Staff used for?”

“Formerly it was used in writing for the tenor voice and for instruments of tenor pitch, but now it is employed only in writing for the upper ranges of the ’cello, the bassoon, and the trombone.”

The C-Clef paused and glanced inquiringly at Alice. “Do you think you’ve got the different divisions of the Great Staff clear in your mind now?”

“Yes,” said Alice, “I think I have.”

“Very well, then, it seems to me we’ve had enough discussion of musitary matters for the present. Speaking for myself—I’m hungry; so I propose that we all go and have lunch at the Officers’ Club.”

“Oh!” cried Alice, “that would be nice! I’m hungry too. But please tell me,” she begged, as they started to walk away, “what ‘musitary’ means.”

“It’s a combination of ‘musical’ and ‘military,’ ” the C-Clef explained. “You’ll find it a useful word, because it reminds you that the art of music is like the army—you can’t get far in either without discipline.”

A NICE MESS

Alice and the officers walked briskly along until they came to an opening like the entrance to a cellar, with steps leading downward underneath the Great Staff. Here the C-Clef paused and offered Alice his arm.

“You’ll find it rather dark down below,” he said. “If you don’t know the way it’s somewhat confusing. I think you’d better let me guide you.”

Alice thanked him and laid her hand in the crook of his elbow. Then they all entered the opening and started down the steps. Soon it grew dark as pitch, and Alice clung tightly to the C-Clef’s arm for fear of stumbling; but the officers marched right on as if they knew every step of the way. Presently they halted, a door swung open, and Alice found herself once more in broad daylight. At first she was dazzled, but her eyes soon adjusted themselves to the glare, and she saw that she was standing at the edge of a large square field which was covered with short grass and surrounded by a border of trees. The grass was rather peculiar, however, for instead of being green it was white; and the trees too were white, and had snow-white leaves.

“This,” said the C-Clef, “is the Parade Ground—the center of our Musitary Post.”

“My!” Alice exclaimed, “it does look neat. But why is it that everything in your country is white—everything, at least, but the notes, and the Lines of the Great Staff, and the signs you wear on your breasts?”

“Because,” the C-Clef explained, “they are the really important things for you to see. Ordinarily it doesn’t matter whether you see us and the grass and trees of our country or not. In fact, human beings never do see us unless they pay us a visit, as you are doing, and remain long enough for their eyes to get used to the peculiar light. Otherwise, when they see the clef on my breast they think that’s all there is to me. They never guess that the rest of me exists at all; but I don’t mind that. I’m far too busy to worry over such unimportant details. However, now that you are here and your eyes have grown sharper, I shall point out some of the principal features of our post. I think you’ll find them interesting.”

The C-Clef pointed to the farther side of the Parade Ground, where there was a row of long, low houses, all painted white.

“Those,” he said, “are the barracks, where the notes, or enlisted men and noncommissioned officers, live; and on this side of the Parade Ground you see the administration buildings, the commissioned officers’ quarters, and the Officers’ Club. The little square building with a flagstaff in front of it is Post Headquarters, where the Colonel has his office. But there goes mess call. If we don’t hurry we shall be late.”

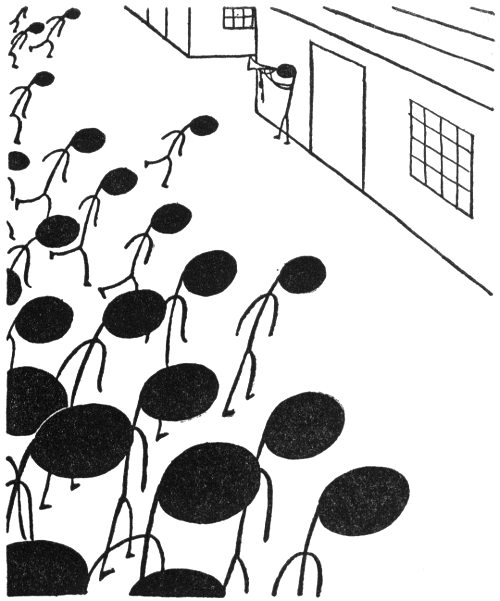

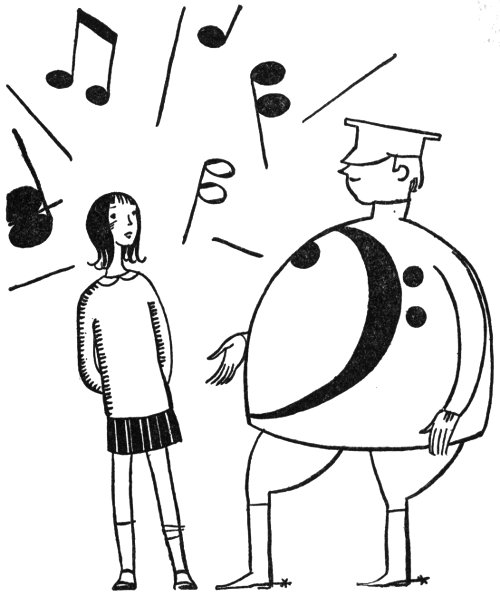

As he spoke, a note who had come out of Headquarters placed a bugle to his lips and blew a melodious call; and immediately the post, which had appeared practically deserted, was filled with a throng of hurrying soldiers. On the farther side of the Parade Ground notes of every description were tumbling out of the barracks and forming in ranks, while on Alice’s side officers came hurrying from every direction toward the large building which had been pointed out to her as the Officers’ Club.

Alice and her three friends also hurried toward the clubhouse and presently found themselves in the dining room—or, as the officers called it, the mess hall. “Mess,” the C-Clef told her, was the army word for “meal.” Alice thought that rather peculiar and wondered whether the lunch would be a messy affair. She had visions of soup spilled on the tablecloth, of greasy dishes and unappetizing food; but her fears were soon dispelled, for the tablecloth proved to be spotless, the dishes clean, and the food excellent—though every bit of it was white, even the meat and vegetables.

There were several other officers, besides the

three majors, at Alice’s table. They were very

polite and took great care to see that she had

everything she wanted, but they seemed a little

shy and embarrassed, conversing among themselves

in low voices, as if they didn’t quite know

what to say to their visitor. Alice was rather glad

of that, for she felt somewhat shy herself; and,

besides, it gave her a chance to look about her

and get a clear impression of the mess hall.

Everything, of course, was white. The floor, the

walls, the ceiling, the tables, the chairs—all were

of the same snowy whiteness. It looked very clean

and cool, but Alice thought it a bit monotonous

and rather too much like a hospital. “However,”

she thought, “I s’pose I’ll get used to it,” and she

began to take stock of her companions at table.

Among them were the two young lieutenants

whom Alice had seen on the Great Staff, and

presently she noticed that one of them, whose

insignia when she had last seen him was the

fraction  , now wore a different emblem; for

on his breast was a large letter C with a line

drawn vertically through it. She was just wondering

what the change meant when, to her astonishment,

the letter C changed to

, now wore a different emblem; for

on his breast was a large letter C with a line

drawn vertically through it. She was just wondering

what the change meant when, to her astonishment,

the letter C changed to  , and then

to

, and then

to  . Nudging the Bass Clef, who sat at her right,

she whispered excitedly:

. Nudging the Bass Clef, who sat at her right,

she whispered excitedly:

“Look—look! What makes him change like that?”

“Who?” asked the Bass Clef, laying down his knife and fork.

“That lieutenant at the other end of the table. The figures on his breast keep changing.”

“Oh,” said the Bass Clef, “you mean young Rhythm. He is rather a changeable fellow; but that’s nothing against him. His duty, you know, is to stand on the Staff, close beside me, and show how many beats are to be counted to each measure. Therefore, whenever the General orders a change of rhythm the Lieutenant has to change the figures on his breast, which are known as the Rhythm Signature.”

“I see,” said Alice; “but why is he changing them now?”

“Why, that’s his way of blushing. He’s a bashful young chap, and he’s probably embarrassed because you’re looking at him.”

“Oh, I’m sorry!” Alice exclaimed. “I didn’t mean to be rude. I shan’t stare at him any more.”

She turned her eyes to the other side of the table, where the other lieutenant whom she had seen on the Staff was sitting. Hardly had she glanced at him when the word “Allegro” on his breast changed to “Agitato.”

“Oh, dear!” she said, “that one’s blushing too—the one you said was Lieutenant Tempo.”

“So he is,” said the Bass Clef. “He’s as bashful as the other one, and even more changeable. His job is to show how fast or how slowly the General wants the notes to move; and as the General frequently changes his mind on that point Lieutenant Tempo frequently has to change his emblem at a moment’s notice.”

“Are all the officers changeable, like the two lieutenants?” Alice inquired.

“No,” said the Bass Clef; “there’s only one other who changes. That’s the captain sitting there at the right of Lieutenant Rhythm—the moody-looking officer with two Flats on his tunic. His name is Key Signature, but we usually call him Captain Key, to save time. Look!—there he goes. He’s changing now.”

The Captain’s gloomy eyes had begun to sparkle with mirth, and he broke into a hearty laugh. As he did so, Alice saw the two Flats on his breast vanish and a single Sharp appear in their place. She hadn’t the least idea what he was laughing at, but somehow she felt inclined to laugh too.

“Why,” she said, “a moment ago he looked as if he’d lost his last friend, and now he’s as cheerful as he can be.”

“That’s because he has changed from minor to major,” the Bass Clef explained.

Alice looked puzzled. “I thought you said he was a captain.”

“So I did,” said the Bass Clef.

“But how can he be a captain and a major too?”

“He isn’t,” said the Bass Clef.

“But you said——”

The Bass Clef interrupted her impatiently.

“I said that he had changed from minor to major. That meant that his mode had changed. It’s perfectly simple.”

“I s’pose I’m awfully stupid,” Alice apologized, “but it seems all mixed up to me.”

The Bass Clef heaved a sigh.

“Well,” he said, “I’ll try to explain it. You see, the word ‘major’ has several different meanings. As a military term it is the title of an officer next in grade above a captain. In the military sense, I’m a major. But in music ‘major’ means ‘larger’ and refers to the size of an interval or the kind of a mode; and as this is a musitary organization we use the word in both senses—which may be a bit confusing to a civilian, I suppose. However, if you understand the meaning of ‘interval’ and ‘mode,’ I think I can make the rest of it clear.”

“But I’m afraid I don’t,” said Alice.

The Bass Clef shrugged his shoulders.

“There you are!” he exclaimed indignantly. “That shows how little you civilians know about musitary life. Now, you’ve probably been taking piano lessons for three or four years——”

“Oh, no!” Alice broke in; “only one year.”

“That’s quite bad enough,” said the Bass Clef. “As I was about to say, here you’ve been taking piano lessons for a whole year and you haven’t learned what an interval is. It would be just as sensible to try to ride horseback without learning what a saddle was. It’s shocking—that’s what it is. If I were you, as soon as I got home I’d ask my teacher to recommend a good textbook on Musical Theory and Harmony, and I’d set to work and learn all about them.”

“I will,” Alice promised; “but I do wish you’d explain about the interval now.”

“Very well,” the Bass Clef agreed, “I’ll try:

“In music, an interval is the distance, reckoned in steps of the scale, between two tones; and it takes its name from the number of steps it includes. For instance, the interval C—E is called a third, because it includes the three steps C, D, and E. An interval that includes two steps is called a second, one that includes four steps is called a fourth, and so on, up to the octave, which is an interval containing eight steps.

“However, there are intervals that contain the same number of steps and yet are not exactly the same size, owing to the fact that some steps are whole steps and some are half steps. C—E flat, for example, is also a third, because it also includes three steps, but it is actually a half step smaller than the interval C—E. Therefore, in order to distinguish between them we call the larger third ‘major’ and the smaller one ‘minor.’

“Now, the word ‘mode’ means the fashion or manner in which the whole steps and half steps of the scale are arranged. Do you know how many half steps there are in a scale?”

“Oh, yes!” said Alice, eager to prove that she was not entirely ignorant of musitary matters. “There are two of them. The first one comes between E and F, and the second comes between B and C.”

“Well,” said the Bass Clef, “that’s where you find them when your scale is in the key of C major. But if it’s in a different key or in the minor mode the half steps will be found in other places. A scale is in the minor mode when its third tone is a minor third above its first tone. If the third tone is a major third above the first, the scale is in the major mode. For instance, in the scale of C minor the third tone is E flat, and in the scale of C major the third tone is E natural.”

The Bass Clef paused to drop a lump of sugar into his cup of white coffee, which he proceeded to stir meditatively.

“There’s another word,” he resumed presently, “whose meaning you must clearly understand. That’s the word ‘key.’ I wonder if you can give me a definition of it.”

“Do you mean the kind of key that unlocks a door?” Alice asked.

“No,” said the Bass Clef, smiling, “I mean a musical key. And yet they are somewhat alike, after all—only it would be better to say that a musical key is something that locks a door. For a musical key locks the door, so to speak, against all tones except those that belong to the particular scale in which a piece of music is written. You see, ‘key’ means almost the same thing as ‘scale,’ the chief difference being that the tones of a scale always occur in consecutive order, one to each step of the Staff, while the tones of a key may occur in any order you please. When we say that a piece is in the key of C we mean that its tones are those of the scale of C and that all other tones must keep out—unless we send an orderly with an ‘accidental’ Sharp or Flat or Natural to open the door for them. Does that solve the puzzle?”

“It makes it much simpler,” said Alice. “But how do you decide what key to write a piece in?”

“The General decides that. Then Captain Key Signature takes his post on the Staff, just beside me, and indicates by the number of Sharps or Flats he wears which key the General has chosen to use. For example, one Sharp shows that the key is G major or E minor; one Flat indicates F major or D minor, and so forth. If you don’t know the signatures of all the other keys, or how to tell whether the key is in the major or minor mode, you will have to learn those details when you get your Theory textbook, for I haven’t time to explain them now. Here comes the dessert, and after mess I must take you to call on the Commanding Officer. It’s considered good form for all visitors to call on the C. O.—and our C. O. is a great stickler for form. He’s a charming gentleman, though, and I’m sure you’ll enjoy meeting him.”

“Is he the general you’ve mentioned so often?” Alice inquired.

“Oh, dear, no!” said the Bass Clef. “The General is a far more important person. Our C. O. is merely the commandant of this post. His name is Colonel Form.”

“I’m sure he must be very nice,” said Alice; “but I do so want to see the General. Do you s’pose I shall?”

“Perhaps you’ll see him very soon. We never know when he’s going to appear. He’s liable to pop up at any moment, and when he does he makes things hum, I assure you. Now, if you’ve quite finished your dessert we’d better go and call on the Colonel.”

Alice said good-bye to the other officers at her table and then followed the Bass Clef toward the door. Just as they were leaving the mess hall Captain Key’s jolly laugh rang out above the clatter of dishes and the hum of conversation; and again Alice felt inclined to join in his laughter.

“Goodness me!” she exclaimed, “the Captain is in a merry mood, isn’t he?”

“Yes,” said the Bass Clef, “he’s still in the major mode. You see, ‘mode,’ in a sense, means very much the same thing as ‘mood.’ Major mode—glad mood; minor mode—sad mood. There’s no better way than that to describe them.”

RULES AND REGULATIONS

As Alice and the Bass Clef left the mess hall they overtook a number of officers who had finished their lunch and were returning to their various posts of duty. Alice noticed that they walked less rapidly now than when the bugle had summoned them to mess; also, they looked slightly drowsy and a bit puffy in the region of the waist line. “They seem to be a good deal like human beings when it comes to eating,” she reflected. “I shouldn’t be surprised if they’re like human beings in other ways too, when you get to know them. I think they’re nice—specially the Bass Clef. He’s a little cross now and then, but I don’t blame him. I do make him answer lots of questions, and most people hate to answer questions. The other officers are nice too, and they all look splendid in their white uniforms. I wonder whether the Colonel is as nice as the rest of them.”

At this point her speculations were interrupted by the Bass Clef, who said cheerily:

“Here we are. This is Headquarters. I hope the Colonel will have time to see us. He’s a busy man, you know, but he’s very punctilious about receiving visitors, unless it’s quite impossible.”

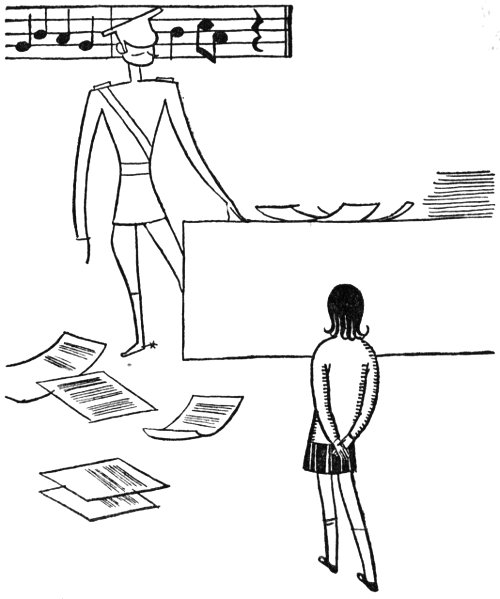

They had entered the little square building near the flagstaff and were in a sort of corridor with rooms on either side. Through the open doors of these rooms Alice could see notes of all kinds working industriously at various tasks. Some were seated at tables, writing or adding up tall columns of figures, while others bustled about with their hands full of important-looking papers.

“Those,” said the Bass Clef, “are the regimental clerks. They do the ‘paper work’ of the post—that is, they keep records and accounts, make copies of the General’s campaign plans, write letters, and make out the orders that are issued from Headquarters. It keeps them busy, as you can see. Now we shall find out whether the Colonel can receive us. This is his office.”

They had reached the last door on the left of the corridor. Entering it, they found themselves in a small room furnished only with three or four chairs and a bench on which an orderly was sitting. The orderly sprang to attention, and the Bass Clef said:

“Find out whether the Colonel will see Major Bass Clef and a visiting civilian.”

“Yes, sir,” said the orderly. “Will the Major and the visitor be seated?”

They sat down, and the orderly vanished through a door marked

COMMANDING OFFICER—PRIVATE

“Goodness!” Alice exclaimed. “I shall never get these musitary terms straight.”

“What’s the matter now?” demanded the Bass Clef.

“Why, that sign on the door—it says the Commanding Officer is a private, and you said he was a colonel.”

The Bass Clef laughed. “That’s a good one! Who ever heard of a private soldier commanding a regimental post? No, my dear, that sign means that the door leads to the Colonel’s private office.”

“Oh, of course!” said Alice, blushing. “I might have known that. How stupid of me!”

“Never mind,” the Bass Clef consoled her. “Musitary language and customs are always confusing to civilians at first. You’ll get the hang of them after a bit.”

Just then the door marked “Private” opened, and the orderly reappeared.

“The Colonel’s compliments, sir,” he said, “and the Colonel will be pleased to receive the Major and the visitor at once.”

“Good!” said the Bass Clef. “Come along, young lady,” and he ushered Alice into the private office.

It was a comfortable room, furnished with armchairs, a sofa, and a large flat-topped desk. Here, as in the mess hall, everything was snowy white except some maps of the Great Staff, drawn in black, which hung on the walls.

As they entered a rather severe-looking officer rose from his seat behind the desk to greet them. He wore no insignia on his breast, but on each of his shoulders was a silver eagle.

“Good-afternoon, Major,” he said, in a voice that sounded to Alice rather cold and formal. “I trust you are well. This young lady, I presume, is our civilian guest, whom I am happy to welcome on behalf of the regiment. Pray be seated; and excuse me a moment, I beg, while I sign these reports. They must be forwarded to General Headquarters at once.”

He resumed his place at the desk and began to write furiously, apparently having quite forgotten the existence of his visitors. They sat down on the sofa, and Alice whispered in her friend’s ear:

“I don’t believe he’s very glad to see us. Maybe we ought not to have interrupted him.”

“Don’t worry,” the Bass Clef Whispered. “He always seems stiff and formal at first. His name, you remember, is Form, and his job is to see that all campaigns are carried out along the exact lines specified by the General; so it’s not surprising that he’s grown to be rather precise and rigid in his manner. When you get to know him better you’ll find that he’s really very pleasant and hospitable. Anyhow, he’s an enormously important officer. It would be impossible to carry out any kind of campaign without him.”

“There!” suddenly exclaimed the Colonel, laying down his pen and gathering his papers into a neat sheaf. “Those matters are attended to. Now my time is at your disposal until half-past two, when I have to make an inspection of the artillery.”

“Oh,” said Alice, “have you got guns and things?”

“We have no rifles or machine guns,” the Colonel replied. “Those are destructive weapons for which we have no use; but we have some very fine canons.”

“Aren’t cannons destructive weapons too?” Alice asked.

“Ours are not,” said the Colonel. “They are musical canons.”

“But don’t they shoot?”

“No, indeed. Why should they?”

“Well,” said Alice, “I don’t see what good they are if they don’t shoot. I shouldn’t think you could do much fighting with them.”

“We don’t have to,” said the Colonel. “Our army never fights. That is why it is better than the ordinary kind of army.”

“Oh,” said Alice doubtfully. “I s’pose it is better not to fight if you can help it. Anyhow, I do wish I could see those cannons.”

“I shall be happy to show them to you at the proper time,” said the Colonel, “but they’re rather complicated, and I doubt whether you could understand them just now. If you’ll allow me, I’ll first explain some of our regulations, which will help you to understand the mechanism of the canons.”

The Colonel laid his hand on a row of books, handsomely bound in white sheepskin, that stood on his desk.

“These volumes,” he said, “contain the rules and regulations for all forms of musitary drill, tactics, and strategy. The first is called Manual of Theory. It treats of rhythm, notes, scales, and all the elementary subjects. The next is the Manual of Harmony, which gives the rules for combining tones to form chords and for using the chords to the best advantage. The third book, the Manual of Counterpoint, deals with the same subject as the Manual of Harmony, but in a different way. This one we need not consider for the present. The fourth volume is the Manual of Musical Form. It tells how to construct a musical composition. In other words, it tells how to take a motive, which is the germ of a musical idea, and develop it into a complete composition, such as a minuet, a waltz, a rondo, or a sonata.”

“Oh!” cried Alice, “that’s just what I’ve been wanting to know. Can I get a book like that in my country?”

“Certainly,” said the Colonel, “and I hope you will when the time comes. But first you must learn the rules of Theory and Harmony, or you will not understand the Manual of Form.”

“Oh, dear!” Alice exclaimed ruefully. “Does it take long to learn all those other rules?”

“To learn them thoroughly requires a considerable amount of time and effort; but if you will spend the rest of the day with us I think we can explain enough about them to enable you to understand how music is composed, though, of course, it would take much longer to teach you to compose it. You will have to keep your ears and eyes wide open, though, if you want to learn even the little that we shall attempt to teach you.”

“I will!” Alice promised eagerly; “and I’ll try to remember everything I see and hear. I’ve already learned about the Great Staff and the clefs, and a little about intervals. And I know what ‘key’ means, and the difference between minor mode and major mode, and—” she glanced slyly at her companion on the sofa—“and Major Bass Clef.”

“Do you indeed?” said the Colonel, taking no notice of Alice’s little joke. “Major, I presume that you are responsible for this young lady’s rapid progress. I compliment you. You’re a credit to the Service.”

The Bass Clef bowed modestly. “You’re very kind, sir,” he said, “but I’ve done nothing out of the ordinary. The young lady is an apt pupil.”

Alice flushed with pleasure, and the Colonel said:

“That is very gratifying—very gratifying indeed. It is a pleasure to know that we are not wasting our time when we attempt to explain our duties and our regulations to a civilian. So few civilians seem to realize the importance of regulations—or, at least, of obeying them. Perhaps, however, that is because they have so many regulations nobody can remember them.”

“Why,” said Alice, “we haven’t nearly so many as you have. You’ve got four books full of regulations, right there on your desk.”

The Colonel smiled. “The regulations of your country,” he said, “would fill a hundred books larger than these. Practically everything you do is governed by regulations. The food you eat, the clothes you wear, the houses you live in, are all supposed to conform to certain laws. When you drive through the streets in your motor car you are supposed to obey rules that say how fast you may go, when you must stop, where you may park your car, and so on. Why, your traffic regulations alone would fill a good-sized book; and yet some of you complain that our regulations are too numerous and too hard to learn. And the worst of it is that you don’t always obey your regulations as we obey ours. How often, when I’ve been in your country, I’ve seen people in motor cars drive past a red traffic light—if there was no policeman at the crossing.”

“That’s true,” Alice admitted; “I’ve seen them do it heaps of times. But doesn’t anybody ever break the rules in your country?”

“Nobody except the General. He can break them whenever he likes.”

“Doesn’t he ever get arrested for breaking them? My father got arrested once for parking too long and had to pay a fine.”

“That is what would happen to anyone except the General if he broke our rules; but the General can break them without penalty, because he makes them. He’s the highest authority in our country; consequently there would be nobody to punish him even if he did wrong. But he never does wrong, even when he breaks a rule, for he never breaks one without a good reason. If he did he wouldn’t be a general!”

Alice pondered a moment and then asked:

“How does the General decide what rules to make?”

“The General,” replied the Colonel, “is what we call a musitary genius. He has a kind of sixth sense that always helps him to do the right thing. Some people call it ‘inspiration.’ The old Greeks used to believe that inspiration came from the Muses, who were goddesses that presided over the arts. No one knows where inspiration really comes from, but the General always has it; otherwise he wouldn’t be a general. At any rate, with the aid of his inspiration he’s constantly discovering new ways of doing things—combining tones, moving troops from chord to chord, planning campaigns, and so forth; and when people see how successful those ways are they call them rules. Then, after a time, the General finds still better ways of doing things; and so the old rules are broken and new ones take their place.

“Thus, you see, our rules and regulations have grown out of experience. They represent what the wisest heads consider the best ways of doing things. When we do a thing a certain way it’s not merely because some rule says we shall, but because we know that it’s the best way yet found in which to do it. Take, for instance, the rule of Harmony regarding parallel fifths. I don’t suppose you know What that is, now, but you will soon learn all about it when you study your Manual of Harmony. For the present I will merely say that it was once strictly forbidden by regulations for two notes standing on steps a perfect fifth apart to move an equal number of steps in the same direction. Now, why do you suppose that was forbidden? Simply because somebody decided that there ought to be a rule against it?”

“N—no,” said Alice, “I s’pose not.”

“Certainly not,” said the Colonel. “It was because we had learned from experience that such a progression didn’t sound well. Therefore a rule was made about it to save others the trouble of having to learn it from experience for themselves—which always takes a long time.”

“Why!” Alice exclaimed, “rules are really to make things easier, aren’t they?—not harder. I never thought of that before.”

“Then,” said the Colonel, “you’ve learned a valuable lesson. And now,” he went on, glancing at the watch on his wrist, “it’s nearly time for rhythmic drill. You must not miss that, so we’d better hurry.”

The Colonel buckled on his sword, picked up his cap and gloves, and then, with slightly exaggerated courtesy, held open the door for Alice to pass. But as the Bass Clef was about to follow her the Colonel stepped in front of him—for a colonel takes precedence over a major; and the Commanding Officer was a great stickler for form.

BETWEEN THE BARS

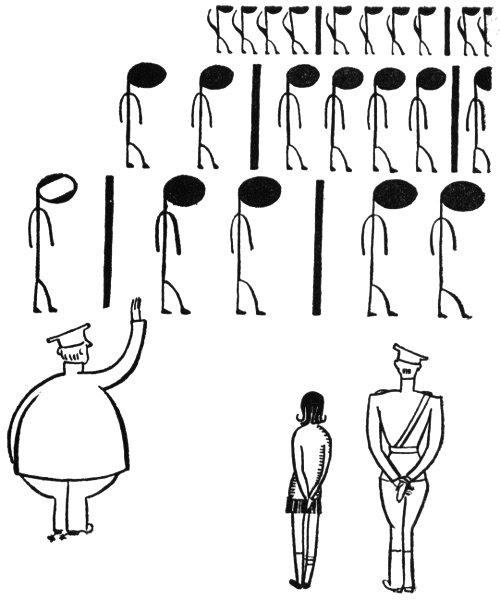

As Alice, accompanied by the Colonel and the Major, left Headquarters she saw that a row of black posts had been set up in the middle of the Parade Ground. These posts were about six feet tall and stood some twelve feet apart. Beyond them, drawn up in line formation and standing at ease, was a company of notes of all denominations—whole notes, half notes, quarter notes, and so on, down to sixty-fourth notes with four tails. Standing in front of the company, talking to the First Sergeant, was Lieutenant Rhythm.

At the edge of the Parade Ground, almost directly in front of Headquarters, was a small reviewing stand composed of several tiers of wooden seats, rising one above the other.

“Let us sit here,” said the Colonel. “The seats are rather hard, but young people don’t mind that, and soldiers are used to it; and from here we shall have a good view of all that happens on the Parade Ground.”

“Aren’t we going back to the Great Staff?” Alice inquired.

“Not yet,” said the Colonel. “The Staff is not necessary for the rhythmic drill, since rhythm is quite independent of pitch; and it’s more convenient to hold the drill here on the Parade Ground. All we have to do is mark off distances to represent measures of musical time. That is easily done by setting up those black posts to take the place of bars.”

The Colonel was silent for a few moments, staring thoughtfully into the distance and drumming with his fingers on the railing of the stand. Then he said:

“I wonder if you know what ‘rhythm’ is?”

“Well,” said Alice, “I think I know, but I’m not sure that I could explain it.”

“I don’t suppose you could,” said the Colonel. “It isn’t easy to explain; but I shall try to explain it to you:

“Rhythm is regularity. In a broad sense, anything that is repeated over and over again, in exactly the same way each time, is a rhythm. The return of the seasons each year, the alternation of day and night, the ticking of a clock—all these things are rhythmic because they are regular. In music, rhythm means the regular repetition of an impulse which we call a ‘beat.’ When soldiers march, for instance, the fall of their feet, all together and with perfect regularity, makes a rhythmic sound. A galloping horse also makes a rhythmic sound; but the sound of several horses walking is not rhythmic, because the noises they make are irregular and are not repeated over and over again, always in the same order.

“Rhythm, however, is not something you hear or see, but something you feel. It is usually suggested to you by sounds, such as the hoofbeats of the galloping horse, or by regular movements, such as the swinging of a pendulum; but rhythm itself is something stronger and more mysterious than the sounds or visible motions that suggest it. Suppose you were watching soldiers march by, in a parade—the chances are that you would soon find yourself counting ‘One—two, one—two,’ in time with the sound of their footsteps.”

Alice nodded her head. “Yes,” she said, “I do that every time I see a parade. Somehow I just can’t help it.”

“That shows you have a sense of rhythm,” said the Colonel. “Now, then, while watching a parade, have you ever seen the soldiers change to double time?”

“What is that?” Alice asked.

“Double time is the military term for a sort of jog trot, in which you take twice as many steps in the same length of time as you do in a march.”

“Oh, yes,” said Alice, “I’ve seen them do it in parades when they got left behind and wanted to catch up with the others.”

“Well, then,” said the Colonel, “when the soldiers changed to double time didn’t you find that the ‘one—two’ rhythm was so firmly fixed in your mind that you went on counting ‘one—two,’ even though you heard two footsteps to each count?”

“Yes,” said Alice; “only, when they changed to double time I counted ‘One—and—two—and, One—and—two—and——’ ”

“Which was an excellent idea,” the Colonel approved. “In that way you kept track of the parts of beats as well as of the beats themselves. Now we come to the next important point about rhythm, which is ‘accent.’ Have you ever noticed that one of your shoes generally wears out sooner than the other?”

“Why, yes,” said Alice, “and I’ve often wondered why.”

“It’s because you tread more heavily on one foot than on the other. Everybody does. Consequently, when you walk at a regular pace, one foot comes down a little harder than the other, which makes a stress, or accent, in the rhythm—‘One—two, one—two.’ All rhythms are like that: the first beat is heavier than the other, or others. In music we call the first beat the ‘strong’ beat and the others the ‘weak’ beats.

“Now, in reading music it is convenient to have the rhythms separated from each other in a way that the eye can easily grasp. For that purpose we use ‘bars,’ which are lines drawn vertically across the staff. The space between these bars are called ‘measures,’ and each measure contains exactly one rhythmic unit. By the way, you may sometimes hear the space between two bars referred to as a ‘bar.’ People have a way of saying ‘Three beats in a bar,’ or ‘Two bars’ rest,’ simply because ‘bar’ is a shorter word than ‘measure’; but that often leads to misunderstanding, and I hope you will never do it.”

Alice promised that she would be careful not to confuse the two terms, and the Colonel continued:

“A musical measure, then, contains one rhythmic unit—that is, the exact number of beats of which the rhythm is composed; and, so long as the same rhythm continues, all the measures are of equal length in time. The space a measure occupies on the printed page may be longer or shorter, according to the number of notes it has to accommodate, but the length of time it represents will be the same, whether it contains one note or many.

“Notes, you know, are the signs that indicate

the duration of musical sounds. The standard

note is the whole note, or semibreve. It represents

four beats and is equal to two half notes, or

minims; four quarter notes, or crotchets; eight

eighth notes, or quavers, and so forth. Any one

of these notes may represent a beat. In every piece

of music the kind of note that represents a beat,

as well as the number of beats that go to a measure,

is shown by the rhythm signature at the beginning

of the piece. This rhythm signature—which

is generally called ‘time signature,’ though

that is a misleading name for it—usually appears

as a fraction. The numerator, or upper figure of

the fraction, shows the number of beats that belong

in each measure, and the denominator, or

lower figure, shows the kind of note that constitutes

a beat. For example, the signature  means

that each measure contains four beats and that

each beat has the value of a quarter note.

means

that each measure contains four beats and that

each beat has the value of a quarter note.

“Theoretically, a measure may contain any number of beats, and, as I said before, any kind of note may represent a beat. However, you will seldom find measures that contain more than twelve beats, or beats of smaller value than sixteenth notes, and even those generally occur only in very slow music. Ordinarily, measures consist of two, three, or four beats, and the beats of half notes, quarter notes, or eighth notes. Measures of six eighths, nine eighths, and twelve eighths are compound rhythms and are generally counted as measures of two, three, or four beats, with a triplet of eighth notes to each beat.”

The Colonel glanced quizzically at Alice, who appeared slightly dazed.

“All this explanation is frightfully boring, isn’t it?”

“N—not exactly,” said Alice; “but it’s rather confusing. I’m afraid I’m not very good at figures.”

“Never mind,” the Colonel consoled her. “Almost everybody finds them hard at first. When you’ve seen the company perform the rhythmic drill it will all be much clearer to you—and you haven’t long to wait, for they’re about to begin.”

As the Colonel spoke, Lieutenant Rhythm,

having called the company to attention, walked

to the left-hand end of the row of black posts and

took up his position on the side nearer the reviewing

stand, looking down the row of posts. Standing

in this position he faced almost directly toward

Alice, who could see that the breast of his

tunic bore the sign  .

.

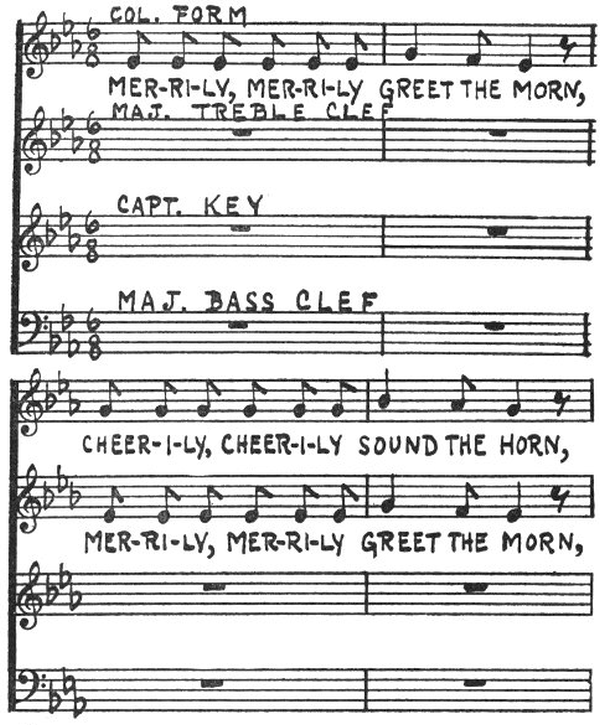

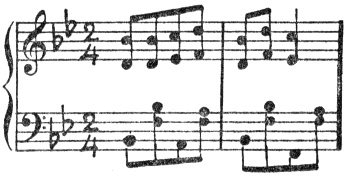

“The drill begins,” and the Colonel, “with two-four rhythm, which means that there are two beats to each measure and a quarter note to each beat. There they go!”

“Quarter notes—Forward—MARCH!” cried the Lieutenant.

A line of notes detached themselves from the company and marched forward. Two paces from the row of posts, at the command of the Lieutenant, they halted. The Lieutenant then gave the order: “By twos—between the bars—MARCH!” Instantly the notes separated into pairs, took two paces forward and halted, a pair of notes in each space between two of the posts.

“Left—FACE!” barked the Lieutenant, and the notes all turned to the left. As they did so they apparently vanished.

“Why!” exclaimed Alice, “they’ve disappeared. Where have they gone?”

“Nowhere,” said the Colonel. “They are still there, but they are so thin that you can’t see them unless they are facing you.”

“Poor things!” said Alice. “I never heard of such thin soldiers. Don’t they get enough to eat?”

“Oh, yes,” the Colonel assured her. “They are well fed, but we keep them thin on purpose, by giving them plenty of exercise. Their thinness is a great advantage, as you’ll see in a moment.”

Again the Lieutenant barked a command:

“Two-four rhythm—Tempo moderato—COUNT OFF!”

“One!” said the first note of the first pair. As he called out his number he faced to the right, suddenly becoming visible again, just as if he had materialized out of thin air. The second note then said, “Two!” and also faced to the right. Then the next pair took up the count, in perfect rhythm, followed by the third pair, and so on—“One—two”—all down the line. At each count a note reappeared at the proper place in his measure, so that when they had all finished counting Alice could see two quarter notes standing between each pair of posts.

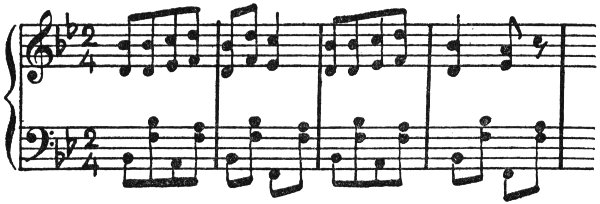

“There,” said the Colonel, “you have a demonstration of the simplest form of duple rhythm—the rhythm of military marches, polkas, and many other kinds of lively music. However, music in two-four rhythm is seldom as simple as this—just one note to each beat. More often there are two or three or four, or even more, notes to some of the beats, and sometimes one note will last for two beats. The next part of the drill will show you how notes of different time value can be used in measures of two-four rhythm.”

As he spoke the quarter notes, at a word from the Lieutenant, about-faced and marched back to their place in the company line. Then the Lieutenant gave another command, and notes of various kinds marched forward and took their places between the posts. When the movement was completed Alice saw that each measure was occupied by a different kind and number of notes. In the first measure was a single half note; in the second, two quarter notes; in the third, four eighth notes; in the fourth, eight sixteenth notes. In the fifth measure were sixteen thirty-second notes, and in the sixth measure was a row of sixty-fourth notes so numerous that Alice hadn’t time to count them, but she guessed that there were thirty-two of them—which, she learned from the Colonel, was correct.

Again the notes faced to the left becoming invisible, and again the Lieutenant gave the command to “count off.” The half note in the first measure counted “ONE—two!” facing to the right at the first count. The quarter notes in the second measure called out their numbers and reappeared, one at each count, as they had done in the first part of the drill. Then came the eighth notes. As each of them represented only half a beat they had to reappear at double the rate of the quarter notes, or one to each half beat. This they did in the following manner: At the count of “one” the first eighth note appeared; then, midway between “one” and “two,” the second appeared, saying “and” as he turned. So they continued throughout the measure—“One—and—two—and,” one note appearing at each word, until all four were visible.

The sixteenth notes in the following measure counted off in a similar manner, except that they appeared at double the rate of the eighth notes, the first note saying “One,” the next three saying “and,” and so on—“One—and—and—and, two—and—and—and.”

The thirty-second notes counted and faced to the right twice as rapidly as the sixteenth notes, which was very fast indeed; but when it came the turn of the sixty-fourth notes to count off they spun around into view with such rapidity that it made Alice dizzy to watch them.

“Goodness gracious!” she cried. “How do they ever turn so quickly—and each one at exactly the right instant! Why, I can’t even count as fast as that.”

“They’ve been doing it for a long time,” said the Colonel, “and practice makes perfect, you know. Now they’re going to give us a demonstration of triple rhythm.”

Once more the notes which had just completed

their drill rejoined the company, and once more

the Lieutenant ordered out a fresh detachment of

various kinds of notes. The rhythm signature on

the Lieutenant’s breast was now  , and at the

command to “count off,” the notes in each measure

counted up to three. When they had finished,

the first measure contained three quarter notes;

the second, six eighth notes; the third, twelve

sixteenth notes; the fourth, twenty-four thirty-second

notes; and the last, forty-eight sixty-fourth

notes.

, and at the

command to “count off,” the notes in each measure

counted up to three. When they had finished,

the first measure contained three quarter notes;

the second, six eighth notes; the third, twelve

sixteenth notes; the fourth, twenty-four thirty-second

notes; and the last, forty-eight sixty-fourth

notes.

The drill now became more and more complicated. In the next exercise, which was in four-four rhythm, the first measure was occupied by a whole note. At the count of “one,” instead of facing to the right, as all the others had done, he remained invisible, but held up, so that it could be seen from the reviewing stand, a small black sign, oblong in shape and suspended from a short black rod. This, the Colonel explained, was a whole note rest.

“A measure, you know, must have its full quota of beats,” said the Colonel, “no matter how many notes it contains. Therefore rests are used to take the place of any note or notes that may be missing. Now, in the second measure we have, first, a half note. He represents two beats. Then there’s a quarter note, representing the third beat. That leaves one beat to be accounted for. It might be represented by another quarter note, by two eighth notes, by four sixteenth notes, by a quarter note rest, or by a combination of notes and rests. In this case, as you see, the last beat is represented by an eighth note, a sixteenth note, and a sixteenth note rest. The sixteenth note rest, you notice, like the note it stands for, has two tails, but it has no head, and the same is true of all the rests, from eighth note rests on down.

“The next measure,” the Colonel continued, “presents a novel feature. Its first note is a quarter, but he is holding up in his left hand a round black disk. That disk is called a ‘dot,’ and it increases the value of the note to the left of it by half. Thus the quarter note with the dot represents a beat and a half, and he and the eighth note which follows him fill up the first two beats of the measure, the other two beats being represented by a half note rest.”

In the next three exercises, which were in six-eight, nine-eight, and twelve-eight rhythm, the dot appeared very often; for, as each beat equalled three eighth notes, a quarter note had to be provided with a dot in order to represent a whole beat. Each of these drills was performed twice, the first time in slow tempo, the second time in fast tempo. In the slow six-eight drill each note had a number to himself, the count being “One—two—three—four—five—six”; but in the fast tempo only the first and fourth notes had numbers, the others saying “and” as they turned, so that the count was “One-and-and, two-and-and.” The nine-eight and twelve-eight drills followed the same system, except that their measures contained nine and twelve eighth notes, respectively.

When these exercises were finished and the notes were all back again in the company formation the Lieutenant gave the command “Rest,” whereupon the notes relaxed their rigid attitude of attention and began to chat and laugh together. Seeing that there was to be a moment’s intermission, Alice seized the opportunity to ask a question that had occurred to her.

“I’ve seen measures of two beats and three beats and four beats and six beats,” she said, “but I haven’t seen any measures of five beats. Aren’t there any measures that have five beats?”

“Yes,” replied the Colonel, “there are; but they are not used nearly so often as the others. Recently the General has begun to use measures of five beats more frequently, and occasionally he even uses measures of seven beats. But those rhythms are so difficult to follow that, if I were you, I shouldn’t try to learn them until I had thoroughly mastered the simpler ones. Now, after the notes have rested for a little while, they will give us a very interesting demonstration—an exercise in syncopation.”

“What is that?” Alice inquired.

“It’s the result of a conflict of accents.”

Alice looked blank, and the Colonel smiled.

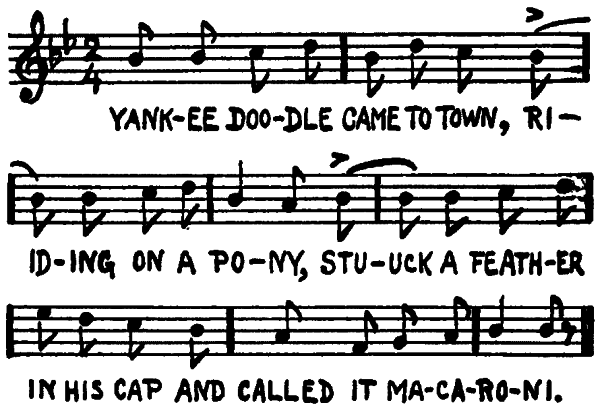

“That isn’t a very clear explanation, is it?” he said. “Well, I’ll try to make it clearer. In music there are two kinds of accents—the rhythmic accent, which is the stress you feel on the strong beat of a rhythm, and the dynamic accent, which is the stress you hear when one tone is sung or played more loudly than another. As a rule, the rhythmic accent and the dynamic accent come together. Take, for example, the song ‘Yankee Doodle.’ If you recite the words without the music you will find that you naturally pronounce certain syllables more strongly than others—thus:

“ ‘YANK-ee Doo-dle CAME to town,

RI-ding on a PO-ny.’

“Now if you sing both the words and the tune, beating time as a conductor does while you sing, you will find that you naturally give a strong down beat as you sing the syllable ‘YANK,’ and a light up beat as you sing ‘Doo’; then another down beat at ‘CAME,’ and another up beat at ‘town,’ and so on. In such a case the two accents—the one you feel and the one you hear—come at the same instant. But sometimes the accent you hear comes on the weak beat instead of the strong one, which causes a conflict between it and the accent you feel. They fight each other, so to speak, to determine which is the more important. That is rather exciting, as fights usually are—which probably accounts for the fact that syncopation is always fascinating and explains why it is used so much in the popular dance music called ‘Jazz.’ And now we are going to see the notes represent syncopated rhythms.”

The Lieutenant called the company to attention and ordered out a detachment of eighth notes, who took their places in the measures by groups of four. The fourth note in each measure, Alice noticed, held in his left hand a curved black object that looked somewhat like the blade of a cavalry sabre. She asked the Colonel what this object was, and he told her it was called a “tie.”

“You will soon see what it is used for,” he added. “Meanwhile, I want to call your attention to the rhythm signature on the Lieutenant’s breast.”

Alice saw that it had changed back again

to  .

.