* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: The Family Compact

Date of first publication: 1920

Author: William Stewart Wallace (1884-1970)

Date first posted: Apr. 21, 2022

Date last updated: Apr. 21, 2022

Faded Page eBook #20220455

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

This file was produced from images generously made available by Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries.

This book is dedicated to the memory of our dear colleague

James ‘jimmy’ Wright

who worked tirelessly and cheerfully with his friends at DPC despite great hardship

CHRONICLES OF CANADA

Edited by George M. Wrong and H. H. Langton

In thirty-two volumes

24

THE FAMILY COMPACT

BY W. STEWART WALLACE

Part VII

The Struggle for Political Freedom

Click on image for high resolution colour version

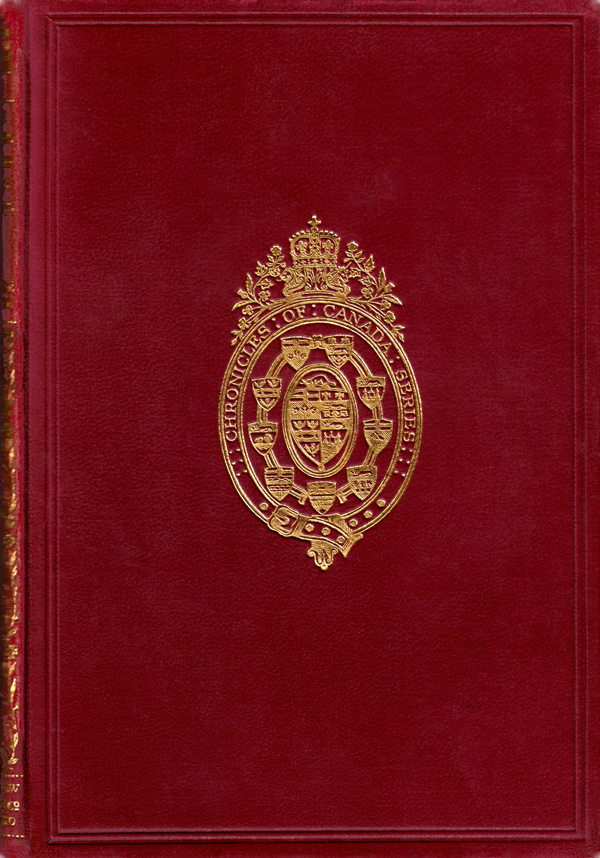

THE FIGHT AT MONTGOMERY’S FARM, 1837

From a colour drawing by C. W. Jefferys

THE

FAMILY COMPACT

A Chronicle of the Rebellion

in Upper Canada

BY

W. STEWART WALLACE

TORONTO

GLASGOW, BROOK & COMPANY

1920

Copyright in all Countries subscribing to

the Berne Convention

Press of The Hunter-Rose Co., Limited, Toronto

TO

MY FATHER

| CONTENTS | ||

| Page | ||

| I. | A LOCAL OLIGARCHY | 1 |

| II. | THE ‘JACOBINS’ | 8 |

| III. | THE BANISHED BRITON | 27 |

| IV. | THE MAITLAND RÉGIME | 43 |

| V. | A REFORM ASSEMBLY | 66 |

| VI. | ‘ONE OF THE MEMBERS FOR THE COUNTY OF YORK’ | 74 |

| VII. | THE SEVENTH REPORT | 93 |

| VIII. | THE ‘TRIED REFORMER’ | 100 |

| IX. | ‘REBEL BLOOD’ | 114 |

| X. | THE OUTBREAK | 128 |

| XI. | THE AFTERMATH | 149 |

| BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTE | 161 | |

| INDEX | 165 | |

| ILLUSTRATIONS | |||

| THE FIGHT AT MONTGOMERY’S FARM, 1837 | Frontispiece | ||

| From a colour drawing by C. W. Jefferys. | |||

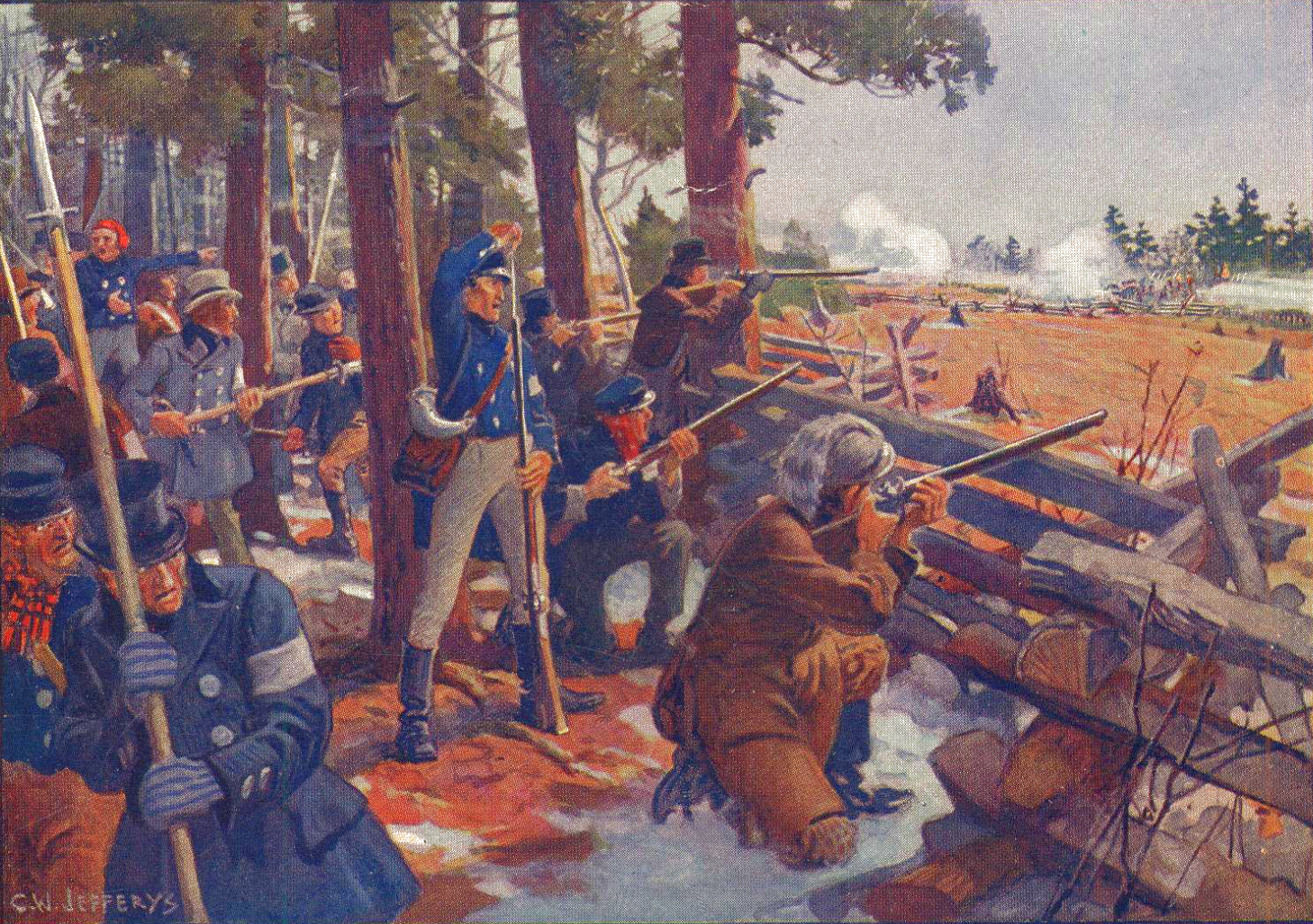

| JOHN STRACHAN | Facing page | 30 | |

| From a painting; in the Department of Education, Toronto. | |||

| SIR PEREGRINE MAITLAND | ” | 44 | |

| From the John Ross Robertson Collection, Toronto Public Library. | |||

| WILLIAM LYON MACKENZIE | ” | 48 | |

| From the painting; by J. W. L. Forster. | |||

| SIR JOHN COLBORNE, LORD SEATON | ” | 66 | |

| From an engraving in the Dominion Archives. | |||

| SIR FRANCIS BOND HEAD | ” | 100 | |

| From an engraving in the Château de Ramezay. | |||

| WILLIAM WARREN BALDWIN | ” | 112 | |

| From the John Ross Robertson Collection, Toronto Public Library. | |||

| JOHN ROLPH | ” | 138 | |

| From a steel engraving in Dent’s ‘Upper-Canadian Rebellion.’ | |||

| ROBERT BALDWIN | ” | 146 | |

| From the John Ross Robertson Collection, Toronto Public Library. | |||

| SIR JOHN BEVERLEY ROBINSON | ” | 154 | |

| From a painting In the Department of Education, Toronto. | |||

| MARSHALL SPRING BIDWELL | ” | 156 | |

| From a photograph In the Collection of the Lennox and Addington Historical Society, Napanee, Ontario. | |||

The first forty years of the nineteenth century saw in Upper Canada a political struggle which culminated in armed rebellion. This struggle was, in the main, constitutional: its roots lay in the constitution which William Pitt gave Upper Canada in 1791. The Constitutional Act seemed on the surface a very liberal measure. It gave the people of Upper Canada a Legislative Assembly elected on a wide basis. But what it gave with one hand, it took away with the other. The actual work of government it threw into the hands of a lieutenant-governor and an Executive Council, who were wholly independent of popular control, and who were responsible only, in a vague and nominal way, to the distant secretary of state at Westminster. And even the work of legislation was placed partly in the control of the lieutenant-governor and his advisers. For there was an upper chamber, known as the Legislative Council, which was able to block any measures passed by the popular Assembly; and the power of nominating the members of this upper chamber was virtually placed in the hands of the lieutenant-governor. Under these arrangements, human nature being what it is, there sprang up inevitably in Upper Canada a governing clique, prone to administer the affairs of the province at its own pleasure, and sometimes in its own interest.

This clique came to be known as the Family Compact. The term, drawn from the alliances between the crowned heads of Europe during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, was not only absurd as applied to Canadian party politics, but was even less appropriate than party designations usually are. ‘There is, in truth,’ confessed Lord Durham, ‘very little of family connection among the persons thus united.’ The Rev. John Strachan, for instance, one of the leading spirits in the Family Compact for many years, had no family relationships in York until his son married in 1844 the daughter of John Beverley Robinson. Nor was there the nepotism among the Family Compact that has been commonly imagined. ‘My own sons,’ testified John Beverley Robinson, ‘have never applied, and I have never applied for them, to the Government for any office of any kind, and they none of them receive a shilling from the public revenue of the country in which I have served so long.’ But however inappropriate the term Family Compact may be, it has become part and parcel of Canadian history; and in the following pages it is used to denote, without offence, the governing class of Upper Canada from 1800 to 1841.

Just when the name first came into use is not certain. Its origin has generally been attributed to William Lyon Mackenzie, who in his Sketches of Canada and the United States, published in 1833, gave a list of thirty public men in the colony between whom a relationship could be traced, and asserted that ‘this family compact surround the lieutenant-governor and mould him like wax to their will.’ This, however, was certainly not the first use of the term. As early as the year 1828 it occurs in a letter written by Marshall Spring Bidwell to Dr William Warren Baldwin. ‘I think it is probable,’ wrote Bidwell, ‘that I shall have the pleasure of paying my respects to you at York in Michaelmas Term, and I shall be happy to consult with yourself and Mr Rolph on the measures to be adopted to relieve this province from the evils which a family compact have brought upon it.’[1]

[1] Toronto Public Library MSS., B 104, p. 153.

Just when the Family Compact may be said to have taken form is hard to decide. It has been usual to trace its origin to the second period of Francis Gore’s régime, when its influence was used to crush Robert Gourlay. But there are good reasons for placing it earlier than this. If it were necessary to put one’s finger on the point at which, more than any other, the Family Compact may be said to have come into existence, that point might reasonably be the end of General Hunter’s administration in 1805, when an element among the public officials secured the selection of Alexander Grant as president and administrator of the province over the head of Peter Russell, who had been president from 1796 to 1799.[2] It was this element which those in opposition to the government denominated ‘the Scotch faction’ or ‘the clan.’ The lieutenant-governor, wrote Robert Thorpe in 1806, is ‘surrounded with the same Scotch pedlars, that had insinuated themselves into favour with General Hunter, and that have so long irritated and oppressed the people; there is a chain of them linked from Halifax to Quebec, Montreal, Kingston, York, Niagara and so on to Detroit—this Shopkeeper Aristocracy has stunted the prosperity of the Province and goaded the people until they have turned from the greatest loyalty to the utmost disaffection.’ In another letter he described the lieutenant-governor as ‘surrounded by a few half-pay Captains, men of the lowest origin with every American prejudice and every idea of military subjection, and directed by half a dozen storekeepers, men who have amassed wealth by the plunder of England, by the Indian Department and every other useless Department, by a Monopoly of Trade and extortion on the people; this shopkeeper aristocracy who are linked from Halifax to the Mississippi, boast that their interest is so great in England that they made Mr Scott (their old Attorney) Chief Justice by their advocate Sir Wm. Grant, that they will keep Lt. Governor Gore in his place, drive me away, and hold the people in subjection.’ When every allowance is made here for partisan exaggeration, it is still clear from these statements that there already existed in 1806 in Upper Canada something strongly resembling the Family Compact of later times.

[2] Between the departure of one lieutenant-governor and the arrival of his successor there was often an interregnum, during which a ‘President and Administrator’ was appointed.

The principle upon which admission to the charmed circle of the Compact was determined, is indeed a mystery. Birth and family were no ‘open sesame.’ Charles Burton Wyatt, whose brother was private secretary to the Duke of Wellington, was excluded; while Thomas Scott, who had been a ‘Methodist preacher,’ and John M’Gill, who had risen from the carpenter’s bench, were the moving spirits of the administration. Later, John Walpole Willis, who was married to the daughter of an earl, was given the cold shoulder; while John Strachan, the son of an Aberdeenshire quarryman, sat in the seats of the mighty. The Baldwins, father and son, were as well-born, as wealthy, and as able as any member of the Family Compact; yet from first to last they were in the ranks of opposition. Not even John Beverley Robinson was a sounder statesman or truer gentleman than Marshall Spring Bidwell, the leader of the moderate wing of the Opposition; and Allan MacNab and James FitzGibbon, the commanders of the governmental forces at Montgomery’s Farm, were tyros in the art of war by the side of the rebel commander, Anthony Van Egmond. All that can be said about the Family Compact is that it was a local oligarchy composed of men, some well-born, some ill-born, some brilliant, some stupid, whom the caprices of a small provincial society, with a code all its own, had pitch-forked into power.

On October 7, 1804, there occurred on Lake Ontario a marine tragedy which had an important effect upon the political history of Upper Canada. The government schooner Speedy, bound for the assizes in the Newcastle district, foundered on that day with all on board forty miles east of York (now Toronto). Among those lost were Thomas Cochran, one of the judges of the court of King’s Bench, and Angus Macdonell, the member of the Legislative Assembly for the constituency of Durham, Simcoe, and East York. The vacancies thus created in the judicial bench and the parliamentary representation of the province were filled respectively by two men, Robert Thorpe and William Weekes, who may be described as the founders of the Reform party in Upper Canada.

William Weekes was an Irish barrister who had spent some time in New York in the law office of the famous Aaron Burr. He went to Upper Canada in 1798, and was admitted (‘rather hastily and unadvisably,’ wrote Francis Gore later) to the provincial bar. He seems to have plunged immediately into provincial politics. In the summer of 1800 he was, according to Richard Cartwright, the chief agent in securing the election of Mr Justice Allcock to the Legislative Assembly. In 1804 Weekes himself came forward for election as the member for Durham, Simcoe, and East York. ‘I stand,’ he said in his electoral address, ‘unconnected with any party, unsupported by any influence, and unambitious of any patronage, other than the suffrages of those who consider the impartial enjoyment of their rights, and the free exercise of their privileges, as objects not only worthy of the vigilance of the legislator, but also essential to their political security and their local prosperity.’ He was defeated by Angus Macdonell; but a few months later Macdonell went down on the Speedy, and in the by-election, which was held in February 1805, Weekes was elected in his place.

In the House Weekes lost no time in making his influence felt. The very day after he took his seat he gave notice of motion ‘that it is expedient for this House to enter into the consideration of the disquietude which prevails in the Province by reason of the administration of Public Offices.’ The motion was lost on division; and the next day the lieutenant-governor, General Hunter, prorogued the House. But when the House reassembled a year later, Weekes once more took up the attack. In the interval which had elapsed General Hunter had died, and a junto of officials, headed by John M’Gill, the inspector-general, and Thomas Scott, the attorney-general, had placed in the presidency of the province a nominee of their own, Alexander Grant. Grant was a weak man, and it was expected that he would be the tool of his friends. These facts doubtless added edge to the vigour of Weekes’s attack. In the first place, he obtained his committee on the state of the province. In it he attacked the administration of the land-granting department, and championed the cause of those United Empire Loyalists and military claimants who found it difficult to get justice in the allotment of lands. He advocated improved communications. He took up the cudgels on behalf of the Methodists and Quakers, who at that time in Upper Canada were under legal disabilities. He attacked the Alien Bill of 1804, which made a residence in the province of seven years necessary before the franchise could be obtained. But his greatest achievement was the discovery of some irregularities in the public accounts. He found that moneys amounting to £617, 13s. 7d. had been paid out of the provincial treasury. It was not charged that there was any corrupt motive in this ‘misapplication’ of the public funds; but the House voted that there had been a violation of its rights and privileges, and when Francis Gore assumed the administration of affairs in 1806 he thought it well to replace the money in the provincial treasury.

In this course of opposition to government Weekes did not want for support. He had behind him in the House a little knot of men, foremost among whom were David M’Gregor Rogers and Philip Dorland, the representatives of the Loyalists of the Bay of Quinté district, and Benajah Mallory, a Methodist preacher who in 1812 went over to the American cause. Outside the House he was aided and abetted by Robert Thorpe, the successor of Cochran as one of the justices of King’s Bench, and by Charles Burton Wyatt, the surveyor-general.

Thorpe and Wyatt, like Weekes, were both Irishmen. Thorpe was a barrister who had been appointed in 1802 a puisne judge in Prince Edward Island; but his relations with the islanders had not proved happy, and when word reached the Colonial Office of the loss of the Speedy and of the death of Cochran, Thorpe was ordered to proceed to Upper Canada to fill his place. He reached York in September 1805. He had not been long in the province before he discovered the existence of some discontent. ‘From a minute inquiry for five months,’ he wrote to England, ‘I find that Govr. Hunter has nearly ruined this province.’ When the provincial parliament met in the beginning of February 1806, Thorpe lent his support to those who were agitating against the government. Although he was not at this time a member of the Assembly, he even aimed at guiding the deliberations of the House. ‘In a quiet way I have the reins so as to prevent mischief,’ he wrote, ‘though like Phaeton I seized them precipitately.’ He was constantly within the bar of the House, and Weekes and his friends were in the habit of leaving their seats to consult him. On one occasion, when the clerk of the Executive Council refused to answer questions relative to transactions in the Council, Thorpe actually rose uninvited and announced to the House that the clerk could be compelled to answer.

Wyatt was hardly less backward in supporting the popular cause. In his administration of the surveyor-general’s office, to which he had come out in 1805, he had fallen foul of the Executive Council; and he was only too ready to air before the Legislative Assembly the grievances which he nourished and the abuses of which he complained. He even went the length of producing for the examination of the Assembly’s committee, without the permission or knowledge of the president, his commission and the books of his office.

In this course of action Thorpe and Wyatt were probably impelled partly by a genuine desire for reform. Their establishment of an Agricultural and Commercial Society for Upper Canada in the winter of 1805-6 showed that they had the interests of the province at heart. But they were actuated also by personal feelings. They had not received a warm welcome from the Government House set. Moreover, in the summer of 1806, news arrived that the ‘Scotch party’ had succeeded in putting their attorney-general, Thomas Scott, into the chief justiceship, a position which Thorpe had confidently counted on getting. When the news arrived, Thorpe’s annoyance knew no bounds. ‘A being has been put over my head, and made Chief Justice,’ he wrote, ‘who has neither talent, learning, nor manner.’

Such was the state of affairs when Francis Gore arrived in the province as lieutenant-governor in August 1806. Gore was a retired cavalry officer who had had one year’s experience of civil government as lieutenant-governor of Bermuda. His ideas were those of the average English gentleman of his time. ‘I have had the King’s Interest only at Heart,’ he wrote a year after his arrival in Upper Canada, ‘and I have [contended] and ever will contend against Democratic principles.’ In view of this fact, it was almost a foregone conclusion that he would be repelled by Thorpe’s appeal to popular rights. Moreover, when Gore arrived in York, Thorpe was away on circuit, and before he returned the members of the Executive Council had had an excellent opportunity to gain the lieutenant-governor’s ear, and to poison his mind against Thorpe and his friends.

Only a few days before Thorpe and Gore had their first interview, the political struggle, for the first time in Upper Canada, bore tragic fruit. William Weekes, while arguing a case before Thorpe at the assizes at Niagara, allowed himself to descend, apparently, to a political harangue against the government. He described General Hunter, for instance, as a ‘Gothic Barbarian whom the providence of God had removed from this world for his tyranny and iniquity.’ To all this Thorpe listened ‘with the greatest composure.’ At the conclusion of Weekes’s speech, however, William Dickson, one of the counsel engaged in the case with him, rose and objected to Weekes’s language as ‘disrespectful in the highest degree to a Court of Justice.’ The result of this reproof was that Weekes challenged Dickson to a duel with pistols. At dawn on the 10th of October the two men, with their seconds, met on the eastern side of the Niagara river, behind the American fort. Shots were exchanged, and Weekes fell, mortally wounded.

Thorpe was much blamed for having allowed in court the intemperate language which brought about the duel; and he was even accused of having instigated the challenge. Certainly, the incident did not improve his standing with Gore. When, on his return to York, he called on Gore at Government House, he met with a reception that was far from conciliatory. The charges and complaints which Thorpe, with indiscreet frankness, brought against the executive government were copied down by the lieutenant-governor’s secretary; and the remarks which Gore appended to the interview for the benefit of the secretary of state show that he was already bitterly prejudiced against Thorpe and his party. Nor was Thorpe’s opinion of Gore flattering. ‘In our first interview,’ he wrote, ‘I found him imperious, self-sufficient, and ignorant, impressed with a high notion of the old system.’

The death of William Weekes created a vacancy in the constituency of Durham, Simcoe, and East York. Hardly had Thorpe reached York before a requisition was addressed to him by a meeting of the freeholders, asking him to stand for the vacant seat. Without a moment’s hesitancy he accepted the invitation. The lieutenant-governor represented to him ‘the impropriety of a Judge becoming a candidate for a seat in a popular assembly’; but Thorpe pointed out to him, what was then an undoubted fact, that there was no rule preventing judges from sitting in the legislature, either in England or in Canada, and he declined to alter his decision. The election was bitterly contested. A government candidate was nominated, and every effort was made to have him elected. ‘The Lt. Governor and Storekeepers,’ wrote Thorpe, ‘worked with all their force against the people, every species of undue influence, bribery, coercion and oppression, was used by them, the Lt. Governor himself demeaned by trying to seduce both high and low.’ On the other hand, Gore charged that Thorpe and his friends went to the poll under the banner of the Irish rebels, a harp without the crown, and that they made seditious references to the American Revolution and the fate of Charles the First. Thus for the first time we find the governor’s party employing against the Reformers that weapon which was later to become so familiar and so deadly, the charge of disloyalty.

The result of the poll was the triumphant election of Thorpe. This rebuff to the lieutenant-governor was the signal for strong measures on his part. He seems at this time to have made up his mind that the Opposition must be crushed. In the first place, he denied the ‘Jacobins,’ as Thorpe’s party now came to be called, the freedom of the press. He allowed to be printed in the Upper Canada Gazette and Oracle a post-election address of Thorpe’s opponent charging Thorpe and his friends with disloyalty; but when Thorpe’s friends sent an answer rebutting this charge, it was refused admission to the paper by order of the lieutenant-governor’s secretary. In the second place, he dismissed or suspended from office two of the government officials who had supported Thorpe’s candidature. These two officials were Surveyor-General Wyatt and Joseph Willcocks, sheriff of the Home district.

The charges against Wyatt were several. He was charged with having taken the books of the surveyor-general’s office before a committee of the House without the government’s permission, and with having defended his action on the ground that ‘the House of Assembly was omnipotent and it was his duty to obey it.’ He was accused of having substituted his own name for that of another in the books of the surveyor-general’s office, with the object of getting a favourable grant of land—an action which, though perhaps irregular, he explained later to the satisfaction of the secretary of state. And he was accused of having dismissed the chief clerk in the surveyor-general’s office because he had voted for Thorpe’s opponent—a charge which Wyatt easily disposed of, as he had recommended the clerk’s dismissal a month before the election took place. The truth is that the head and front of Wyatt’s offending was his support of the Thorpe party while he was an officer of government.

Against Willcocks no specific charges were levelled. He was dismissed merely on account of his general character and his support of Weekes and Thorpe. Gore described him as ‘an United Irishman, who fled from Thomas Street, got on in Upper Canada as a clerk to the Receiver General, was turn’d out by him. Was a sort of upper servant afterwards to Mr Allcock, who to provide for him got him appointed sheriff.’ He seems to have been at heart a republican; and Gore obtained affidavits showing that one evening after dinner, at the house of John Mills Jackson in Yonge Street, he had inveighed bitterly against the governor and ‘his damned Scotch faction.’ Such expressions as ‘Damn the Governor and the Government; push about the bottle,’ and the avowal of republican principles, would not perhaps be regarded to-day as serious offences. But in 1807 the horrors of the French Revolution were still so recent that it is possible to understand how Gore thought it necessary to remove a republican like Willcocks from his official position.

In the spring of 1807 Wyatt returned to England, in company with John Mills Jackson, to lay his case before the authorities. Both men had influence at Westminster. Wyatt expected, through his father and brother, to obtain influence at court and with the ministry, and Jackson’s brother was a member of the House of Commons. Jackson was a very interesting figure. He was a gentleman commoner of Balliol College, Oxford, and a man of some wealth. He had gone to Upper Canada in 1806, but had promptly fallen foul of the government over a grant of land, and had joined hands with the Thorpe party. His republican sentiments had earned him the soubriquet of ‘Jacobin Jackson.’ In England both Wyatt and Jackson had interviews with Lord Castlereagh, who was then in charge of the Colonies; but though it looked for a time as though they might succeed in bringing about Gore’s recall, they found that the wheels of government moved very slowly, and Wyatt had in the end to turn to the law-courts for redress. Jackson caused the question of the administration of Canada to be brought up in the House of Commons; and he published a pamphlet entitled A View of the Political Situation of the Province of Upper Canada, which, on account of some indiscreet statements, was unanimously voted a libel by the Upper Canada Assembly. Many years later Jackson returned to Upper Canada, and took up land on Lake Simcoe: Jackson’s Point, now a popular watering-place, is named after him.

While Wyatt and Jackson were seeking to obtain redress in England, Thorpe and Willcocks were continuing the struggle in Upper Canada. The provincial parliament met in the beginning of February 1807. The session had hardly begun when an attempt was made to upset the election of Thorpe to the Assembly on the ground that judges were not eligible to sit. The Assembly confirmed him in his seat, but it gave him little support during the session. On one occasion he stood alone in a division in the House. There is good reason for believing that a judicious distribution of the loaves and fishes among members of the House had contributed to bring about this result.

In March 1807 Gore wrote to the secretary of state asking that Thorpe should be suspended, and prophesying that the most serious evils would ensue if he were allowed to retain his position. The only charge against him was that of his opposition to the government while retaining a seat on the judicial bench. In July the lieutenant-governor, although he had not received the decision of the secretary of state, left Thorpe’s name out of the commission of assize. Thorpe was already in financial difficulties, owing to his large family and the inadequacy of the emoluments attaching to his position; and this action, which robbed him of his pay as judge on circuit, reduced him to serious straits. In the autumn news reached York through unofficial channels that Thorpe’s suspension had been determined upon by Lord Castlereagh. The news was conveyed to Thorpe by William Dummer Powell, one of his fellow-judges, and he was given to understand that Gore was willing to grant him leave of absence and money to take him back to England before the official notification should arrive. Thorpe, however, declined to put himself under any obligation to Gore; but after publishing an address to the electors of Durham, Simcoe, and East York announcing that he had been suspended as a result of misrepresentation on the part of the lieutenant-governor, he abruptly left the colony. He returned to England, and was there given the post of chief justice of Sierra Leone, a position of nearly twice the value of that of puisne judge in Upper Canada. Both Wyatt and Thorpe brought actions for libel against Gore in the courts in England; and both of them obtained verdicts in their favour, Wyatt for £300, Thorpe for a lesser amount. Gore’s expenses in these suits were, after some demur, paid by the British Treasury.

On the departure of Thorpe, Willcocks was left to fight the battle single-handed. Since the columns of the Upper Canada Gazette were closed to the popular party, Willcocks had founded, in August 1807, a paper entitled the Upper Canada Guardian, or Freeman’s Journal, the first of a long line of party newspapers in Upper Canada. As far as is known, there is only one copy of this paper in existence. It seems to have been printed at first on the American side of the border; and there is reason for believing that Willcocks obtained the funds for carrying it on from the Irish republican leaders in New York. It evidently obtained a good circulation, for in 1809 William Dummer Powell found it in every house as he went on circuit.

In the parliamentary session of 1808 Willcocks entered the Legislative Assembly as one of the members for Lincoln, Haldimand, and West York. It was not long before he embroiled himself with the majority in the Assembly. On January 29 a paragraph in the Upper Canada Guardian, in which it was charged that the members of the Assembly had been bribed by the lieutenant-governor, was brought to the attention of the House. A prosecution of Willcocks was talked of, but was dropped, apparently at the request of Gore; but when Willcocks repeated the statements he had made, he was tried by the House, and was unanimously found guilty of using expressions that were ‘false, slanderous and highly derogatory to the dignity of this House.’ By the speaker’s warrant he was committed to the common jail, and there he languished until the end of the session.

Willcocks remained a member of the Assembly until the War of 1812. He was one of those members who obstructed the government during the session of 1812 in its attempt to suspend the operation of the Habeas Corpus Act. The statement has been made that Willcocks fought on the British side at the battle of Queenston Heights; but this may be doubted. Certainly, early in 1813, he was found in the American ranks. In 1814 he was killed while wearing the uniform of a colonel of the American army at the siege of Fort Erie. On him it is difficult to pass a fair judgment. He was a renegade and a republican, but he had seen little in Ireland or in Upper Canada to commend to him monarchical institutions.

Nothing is more striking about these early opponents of government than the predominance among them of men of Irish blood. Weekes, Thorpe, Wyatt, Willcocks were all Irishmen. There is even reason for believing that racial jealousy between the Scotch and the Irish was one of the roots of the trouble in Upper Canada in 1806. All these men had the defects of the Irish race. They were turbulent, headstrong, and indiscreet. Like the later Reformers, they made grave mistakes. None of them should have attempted to carry on an agitation against the government while in the government’s employ. But they had, in the main, the interests of the common people of Upper Canada at heart. They were not a disreputable or, on the whole, a disloyal party. The fact that they numbered among their supporters at first William Jarvis, the secretary of the province, Dr William Warren Baldwin, the father of Robert Baldwin, and the Rev. Robert Addison, the rector at Niagara, is proof that they were not merely noisy agitators.

The Family Compact was latent in the Constitutional Act of 1791. In 1806 it was just budding. In John M’Gill and Thomas Scott may be recognized the forerunners of the Family Compact of the twenties and thirties; Francis Gore was, in some respects, a prototype of the later lieutenant-governors; and William Weekes, Robert Thorpe, and Joseph Willcocks are the true predecessors of the rebels of ’37.

For ten years after the events of 1806-7 there was no political disturbance in Upper Canada of any moment. It was not until 1817 that Robert Gourlay came into the province. The story of Gourlay is one of the most painful passages in the history of Family Compact rule in Upper Canada. It is so painful that it is difficult to understand, in the light of the twentieth century, the attitude of mind which made it possible for men like Peregrine Maitland, John Strachan, William Dummer Powell, and John Beverley Robinson to play the parts in it which they played.

Robert Gourlay was a Scotsman of good birth, good education, and good intentions. His father had been a writer to the signet in Fifeshire. He himself was a graduate of the University of St Andrews; and the great Thomas Chalmers, who had been his friend and classmate, afterwards described him as ‘one of the ablest of my fellow-students.’ At the age of thirty-seven he was reduced through misfortune to comparative poverty, and he determined to emigrate to America. He settled in Upper Canada, and immediately set up in business as a land-agent. In connection with his business he began to formulate a scheme for systematic emigration from the British Isles to Canada. He had been attached in Great Britain to the commission appointed to inquire into the causes of pauperism; and he believed that systematic emigration to the colonies would relieve the over-population which was thought to be at the root of the economic evils from which Great Britain was suffering, and would at the same time supply Canada with that labouring population of which she stood most in need. It was in pursuit of this scheme that Gourlay first came into conflict with the Family Compact party of that time.

The governing clique of Upper Canada in 1817 was not greatly different from what it had been in 1807. Thomas Scott had retired from the chief justiceship and the Executive Council; but his place had been taken by William Dummer Powell, long a faithful adherent of the governor’s party. John M’Gill and James Bâby still remained members of the Executive Council, though both were growing old and the reins were slipping from their hands. D’Arcy Boulton, who had been solicitor-general in 1807, was attorney-general in 1817. The new faces among the leaders of the party were those of John Strachan and John Beverley Robinson. Strachan was an Aberdeenshire schoolmaster who had emigrated to Canada as early as 1799, and who had carried on a school at Kingston, at which the sons of many of the leading families in Upper Canada were educated. He had taken orders in the Church of England, and by his great force of character had rapidly risen to importance. In 1812 he had yielded to the solicitations of Gore and Brock, and had accepted the charge of the church at York. In 1815, on the recommendation of Gore, he had been appointed to a seat on the Executive Council; and from the first he had exercised over that body a powerful influence. He was a man of whom it is difficult to form a fair opinion: he had, in his own way, high ideals, but he had also a good idea of feathering his own nest, and his influence on the course of public affairs in Upper Canada was almost uniformly pernicious. John Beverley Robinson was a pupil and protégé of Strachan’s. He was a young man of brilliant abilities and high character, whom Strachan had hailed as ‘a second Pitt.’ In 1817 he had become solicitor-general.

To this ruling party Robert Gourlay first gave offence by addressing a circular letter, containing thirty-one questions, to the various townships of the province. His object was merely to obtain information which would assist him in his immigration schemes. The questions seem nowadays innocent enough; but unfortunately the thirty-first question, which ran, ‘What in your opinion retards the improvement of your township in particular, or the province in general, and what would most contribute to the same?’ was regarded as an attack upon the government. And it so happened that the answers which were received to this question revealed the existence of a considerable amount of discontent in the province. As Robert Thorpe had prophesied ten years before, the administration of the Crown Lands department had begun to bear evil fruit. In every township two-sevenths of the land had been set apart as crown and clergy reserves, and of the rest large blocks were held by speculators and by government officials. Only a fraction of each township, under these circumstances, had been settled; and the townships could not secure a population of sufficient density to maintain roads, schools, and churches. The vacant lands, moreover, were not taxed, and the whole burden of taxation fell on the resident settlers. When John Beverley Robinson in 1818 introduced a bill into the Legislative Assembly proposing to tax vacant lands, the vested interests were strong enough to defeat the bill by an overwhelming majority.

These were real grievances; and if Gourlay had possessed common prudence, he might have effected much good by his inquiries. But, unhappily, common prudence was what he lacked most. Although he had been in the province for only a few months, he rushed into print, and assailed the administration of affairs in language which certainly lacked urbanity. He earned the bitter enmity of Strachan, for instance, by describing him as ‘a lying little fool of a renegade Presbyterian.’ When he had his pen in hand he possessed neither tact nor moderation. ‘With regard to sound principles of emigration,’ he wrote candidly to Wilmot Horton, one of the officials of the Colonial Office, ‘you are as blind as a mole.’ ‘Corruption,’ he announced in one of his pamphlets, ‘has risen to such a height in the province, that it is thought no other part of the British Empire witnesses the like.’

In the spring of 1818 Gourlay brought his agitation to a climax by issuing a call to the ‘resident’ landowners to send up delegates to a provincial convention to be held at York, for the purpose of discussing grievances and of drawing up a petition to be forwarded to the Prince Regent in England. The convention met, and was widely attended. The delegates were mostly men of respectable standing, half-pay officers, militia veterans, and gentlemen-farmers. They drafted an address to the Prince Regent in which their grievances were stated. They complained, in the first place, of the abuses connected with the granting of lands and the settlement of the colony; and they complained also of the failure of the British government to meet the claims for losses sustained by the Canadian militia during the War of 1812. Finally, they prayed that a royal commission should be sent out to inquire into the condition of Upper Canada. This address was published in the American newspapers, and so reached the ears of the public in England. It was largely owing to the attention it created that the British government took up the question of the militia claims the next year, and that a settlement was arrived at.

At the time of this convention Gourlay became a sort of popular hero. ‘He was idolized by the Canadians,’ wrote an Englishman in Canada, ‘as much as ever Bonaparte was by the French.’ It was clear that discontent was gathering head, so much so that Sir John Sherbrooke, the governor-general of Canada, residing in the lower province, actually contemplated a visit to Upper Canada to deal with the situation. The difficulty hitherto had been that Gore had left the province in 1817, and since that time the government had been in the hands of an administrator, Samuel Smith. Smith had been loath to proceed to strong measures against Gourlay, in spite of pressure brought to bear upon him by Strachan; but after the meeting of the convention and the publication of the address to the Prince Regent, Smith agreed to the prosecution of Gourlay for a libel on the government.

It was while this charge was hanging over Gourlay’s head that Sir Peregrine Maitland arrived in Upper Canada as lieutenant-governor. Maitland was an able soldier and a man of charming personality; but he was a reactionary Tory of the type then dominant, not only in England, but all over Europe. It was not to be expected that he would have much in common with a Scotch Radical like Gourlay, and he seems to have accepted the Family Compact view of Gourlay from the first. He had been in the province only a few days when he wrote home describing him as ‘half Cobbett, half Hunt’; and when Gourlay was acquitted at Kingston, on August 15, 1818, of the charge of libelling the government, Maitland wrote home expressing his regret, but announcing his hope that Gourlay would be crippled by a second prosecution to be brought against him shortly for libel upon a private person. His hope was ill-founded, however, for so great was Gourlay’s popularity that it was found impossible to get a jury to convict him.

Defeated in the law-courts, the government turned to other avenues of attack. When the provincial parliament met on October 12, 1818, Maitland told the members that he did not doubt that ‘they would feel just indignation at the attempts which had been made to excite discontent and organize sedition’; and he suggested that such conventions as that which Gourlay had called might be made illegal. The Assembly took up the suggestion; and while they maintained theoretically the right of petition, they denied it practically by resolving that ‘the Commons House of Assembly is the only representation of the people,’ and that such conventions as that which Gourlay had called were unconstitutional. Legislation was actually passed which constituted such public meetings a misdemeanour.

This Act, which remained on the statute-book for only two years, was fearlessly attacked by Gourlay. In the columns of the Niagara Spectator he assailed the action of the legislature in an article entitled ‘Gagged, gagged, by jingo!’ The language of the article was severe, but no severer than leaders which appear every morning and evening in Opposition newspapers to-day. The article was, however, promptly voted by the Assembly to be a libel, and the attorney-general was instructed to prosecute the editor of the Spectator. This unfortunate man, whose name was Bartemus Ferguson, had not really been responsible for the appearance of the article complained of. It had been published, under Gourlay’s name, during Ferguson’s absence and without his knowledge. Yet Ferguson was arrested in his bed, in the dead of night, carried to Niagara, and thence to York, where he had difficulty in finding friends to bail him out; and in the summer of 1819 he was tried at Niagara and sentenced to pay a fine of £50 and to undergo eighteen months’ imprisonment: during the first month of this time he was to stand in the public pillory for one hour a day, and at the end of the eighteen months he was to give and find security for his good behaviour to the amount of £1000.

Gourlay was, however, the chief culprit, and it was not intended that he should get off with impunity. On December 21, 1818, he was arrested and brought before two legislative councillors, William Dickson and William Claus, as an ‘evil-minded and seditious person’ under the meaning of the Alien Act of 1804. The Alien Act was an obsolete law of doubtful constitutionality, directed against the disaffected Irish and American immigrants who had flocked into the colony in early days. It gave authority to certain officials, and among them to members of the Legislative Council, to issue a warrant for the arrest of any person, not having been an inhabitant of the province for the preceding six months, who had not taken the oath of allegiance and who was suspected of sedition. In case the person so arrested failed to establish his innocence, he might be notified to leave the province within a specified time; and if he failed to depart, he was to be imprisoned until the time of the general jail delivery. If found guilty, upon trial, he was to be banished from the province, under penalty of death.

Dickson and Claus had both been friends of Gourlay, but in some unknown way Gourlay had alienated them. Whether their action in arresting Gourlay was taken at the instigation of the government party at York cannot be determined. Maitland, at any rate, seems to have had no hand in it. It is fortunate for his reputation that this is so, for the prosecution was a very reprehensible business. Dickson and Claus both knew that Gourlay was loyal to the British crown, and that he did not come under the provisions of the Alien Act. In order to convict him, perjured evidence was necessary. This was obtained from Isaac Swayzie, a disreputable and illiterate member of the Legislative Assembly, who was a hanger-on of the government. Swayzie swore that Gourlay had been domiciled in the province less than six months, although it was a matter of common knowledge that he had been a resident of Upper Canada for eighteen months. Swayzie also gave testimony that Gourlay was a seditious person. The trial was the veriest farce, and Gourlay was condemned to leave the province within ten days.

To submit to this sentence would have ruined Gourlay’s business. It would have been a tacit acknowledgment of guilt and a denial of his natural allegiance. He determined, therefore, to ignore the verdict. The result was that when the ten days had passed he was arrested and thrown into jail. After some delay he caused himself to be taken, under a writ of habeas corpus, before Chief Justice Powell at York, for the purpose of being either discharged from custody or admitted to bail. He presented excellent evidence to the effect that he had been domiciled in the province for more than six months, that he was a loyal British subject, and that he had taken the oath of allegiance. There could hardly have been a clearer case. But Gourlay’s release at this time would have been regarded as a triumph for him and a defeat for the government. Chief Justice Powell therefore remanded Gourlay to jail, on the technical plea that the warrant of commitment was regular and that the Act made no provision for bail.

Gourlay then attempted to bring actions against Dickson and Claus for false imprisonment; but here, too, he was defeated by legal chicanery. The defendants each obtained an order for security for costs, and Gourlay, lying in jail, with his business going to ruin, was not able to raise this security. The actions therefore lapsed, and Dickson and Claus escaped prosecution.

It was not until August 20 that Gourlay’s trial took place. During the months that intervened he lay in jail at Niagara. The close confinement and the mental distress which he suffered seem to have affected both his mind and his health. During his imprisonment he was attacked frequently by violent headaches, and no attempt seems to have been made to alleviate for him the prison conditions of that time. When he came up for his trial, he was a wreck of his former self and was not in full possession of his faculties. During the progress of the trial he appeared to be only half-conscious of what was going on. He had a written defence and protest in his pocket, but he seems to have forgotten to use it. He does not even appear to have heard the verdict of guilty. And when Chief Justice Powell, who was presiding, asked him if he had any statement to make before judgment should be rendered, he burst into a loud peal of maniacal laughter. It must have been clear to every one in the court-room that Gourlay was not in his right mind. Yet no considerations of mercy seem to have affected the determination of the court officials to secure his conviction. John Beverley Robinson, the attorney-general, who conducted the prosecution, based his case not on the ground of Gourlay’s guilt within the meaning of the Alien Act, but on the technical ground of his having refused to leave the province when ordered to do so. There is reason to suspect that the sheriff packed the jury. And neither Chief Justice Powell nor Sir Peregrine Maitland lifted a finger to see that Gourlay obtained fair play.

The sentence of the court was that Gourlay should leave Upper Canada within twenty-four hours, on pain of death without benefit of clergy. The next day he crossed to the American side of the Niagara river. He went first to Boston, where he published an account of his persecution under the title of The Banished Briton. Thence he went to the British Isles, where he published in 1822 his Statistical Account of Upper Canada, a valuable work which embodies the information he collected in 1818. He proved to be very much a rolling stone. In 1837 he was living at Cleveland, Ohio; and it is interesting to know that at that time, in spite of what he had suffered, his sympathies were still British. After the Union of 1841 his case was taken up by the Canadian parliament, and his arrest and sentence were pronounced ‘illegal, unconstitutional, and without possibility of excuse and palliation.’ In 1856, when an old man of seventy-eight years, he returned to Canada, and a pension of £50 was granted him; but this pension he never drew.

Robert Gourlay had grave defects of character. Like William Lyon Mackenzie, he was a confirmed grievance-monger. He was pugnacious, tactless, and extravagant in his language. But the head and front of his offending was his criticism of the government, and it is not now necessary to remark that criticism of the government is not at English common law a crime. If the leaders of the Family Compact party had remembered this fact in 1818, they would have deserved better at the hands of historians.

Sir Peregrine Maitland was a Tory of the Tories. In our time, when a governor makes no attempt to rule, he might have proved an ideal official, for he performed the ceremonial duties of viceroyalty to perfection. But from 1818 to 1828, when the actual administration of public affairs was in the hands of the lieutenant-governor, his régime was reactionary and autocratic. For this, however, Maitland was not wholly to blame. He had had little experience of civil government, and he leaned heavily on the advice of those about him: probably at no period was the influence of the Family Compact over the lieutenant-governor greater than under his régime. And it should never be forgotten that this was the period when the reactionary ideas of Wellington and Metternich were dominant, not only in England, but in the whole of Europe; and that Maitland and his advisers, in their political views, were merely the children of their time.

Maitland regarded it as incumbent upon him to suppress liberal opinions. The persecution of Gourlay was, of course, the outcome of such a policy; but persecution did not stop with Gourlay. An instructive case was that of the militia officers who had attended Gourlay’s convention in 1818. They were all men who had fought in the War of 1812, and had suffered losses in their support of the British crown. They had attended the convention partly in order to protest against the delay on the part of the British government in granting them compensation; and it was largely owing to their efforts that compensation in the form of grants of land was made in 1819. Yet when Maitland received orders to grant this compensation, he and the Family Compact leaders took it upon themselves to refuse allotments of land to all those who had taken part in the convention.

An attempt was made also to prevent the election to the Legislative Assembly of persons of ‘republican’ views. The Assembly had always tended to be democratic: as early as in 1792 Simcoe had noted a tendency on the part of the people to elect as their representatives men who ‘kept one table’—that is, who ate with their servants. But except for one or two short periods, the executive had been successful in maintaining a majority in the Assembly. Some alarm was felt, however, when in 1821 a by-election occurred in Lennox and Addington. This was a United Empire Loyalist constituency; but the United Empire Loyalists were by no means all supporters of the Family Compact. The member elected was Barnabas Bidwell. Bidwell was a man of unusual ability and superior education: he had been attorney-general of Massachusetts and a member of the United States Congress. In 1810 his political enemies had accused him of misappropriation of public money, and to avoid the consequence of this accusation he had fled to Canada, where, on the outbreak of the War of 1812, he had taken the oath of allegiance. He had been a friend of Robert Gourlay, and was known to be strongly opposed to the policy of the Upper Canada government. When he took his seat in the House his election was promptly challenged, on the ground that he was a person of immoral character and a fugitive from justice, and that he had taken the oath of citizenship in the United States. It appeared in the proceedings that the government had gone so far as to send an agent to Massachusetts to collect evidence against him. Bidwell, for his part, contended that the charges were those of his political enemies, and that the fact of his having at one time been a citizen of the United States was no bar to his admission to the Canadian legislature. A motion for his expulsion was, however, brought forward, and after a long debate it was carried by a majority of one vote. When a new election was ordered, and the son of Barnabas Bidwell, Marshall Spring Bidwell, attempted to take his father’s place, he too was declared ineligible for election, because he had been born in Massachusetts and had never taken the oath of allegiance; and it was only when the election law was amended in 1824 that he was enabled to sit.

In the last parliamentary session which took place before the elections of 1825 a very unwise action was taken by the governing party in regard to religious disabilities. The view which had hitherto obtained was that the Church of England was established by law in Canada. Some colour was lent to this view by the language of the Constitutional Act; and from the earliest times the governing clique had been composed of members of the Church of England. One of the disabilities under which the Methodists and other nonconformists suffered was that their ministers could not solemnize marriages. In the session of 1824 a bill was passed by the Assembly removing this disability, and giving to marriages conducted by Methodist ministers the legality which they had hitherto lacked. But this very just provision was thrown out by the Legislative Council, apparently with the full approval of the government. The Methodists were then, as now, a powerful political element in the province; and apart from the question of religious equality, this discrimination against them was, on the part of the government, a piece of egregious folly.

The result was that the elections of 1825 saw the return to parliament of a number of men strongly opposed to the government. The United Empire Loyalists of Lennox and Addington sent up two advanced reformers in the persons of Marshall Spring Bidwell and Peter Perry. Bidwell was one of the noblest spirits that ever crossed the threshold of Canadian history; Perry was a man of much humbler education, but of real eloquence and common sense. Middlesex sent up John Rolph and Captain John Matthews. Rolph was a young Englishman of great ability and subtlety of mind, who was destined to become one of the founders of modern medical science in Upper Canada, and one of the leaders of rebellion in 1837. Matthews was a retired officer of the royal artillery, who was destined to be the first of that little band to fall a victim to the Family Compact. Dr William Warren Baldwin had had a seat in the previous parliament, but to this House he was not elected. Many years had passed by since Francis Gore had described him as ‘an Irishman ready to join any faction’; yet his interest in the cause of Reform had never faltered, and he was always ready to help the Opposition to the best of his ability. His high public character was a great asset to them: ‘I have frequently heard him named,’ wrote an English visitor, ‘the only honest man in the Province.’

It was at this time that William Lyon Mackenzie first attracted attention by his advocacy of Reform in his newspaper. Mackenzie was a Scotsman who had come to Canada in 1820 at the age of twenty-five years. He had begun life in the old country as an assistant in a draper’s shop. In Canada he went into business as a chemist and bookseller, first at York and then at Dundas; but in 1824 he cast aside his prospects of success in business and embarked on the precarious enterprise of publishing a newspaper. The name of the paper was the Colonial Advocate, and it was published first on May 18, 1824, at Queenston. In it he began that propaganda which was to culminate in the events of ’37. He was a born agitator. Fearless even to recklessness, wholly indifferent to his own interest, public-spirited according to his own lights, extravagant in his language, he was precisely the sort of man who was likely to obtain an ascendancy over the common people of Upper Canada at that time. He was not a clear political thinker; he was governed often by personal pique; his utterances were lacking sometimes in tact and good taste. Men like Bidwell and the Baldwins found little in common with him. But his influence was nevertheless great; and his little wiry figure, filled with a veritable St Vitus’s dance of nervous energy, and surmounted by a large head set with burning blue eyes, commanded attention then, as it commands attention now.

The outbreak of a reforming spirit in 1824 brought with it the usual aftermath of persecution by the government. The first victim was Captain Matthews. Matthews, though a half-pay officer, had aligned himself with the Reformers in the House, and had made himself obnoxious to the heads of the government. On New Year’s Eve 1825 he gave the government a chance to strike at him. A company of travelling actors from the United States had been stranded in York, and on New Year’s Eve they gave a performance, under the patronage of the Legislative Assembly, to enable them to leave town. Matthews, who had been dining very well, attended the performance with many other members of the House. The occasion proved very convivial. The band was called upon to play many tunes, among them ‘Yankee Doodle’ and ‘Hail Columbia.’ ‘Hail Columbia’ they were not able to play, but ‘Yankee Doodle’ was rendered amid great enthusiasm. During the performance some one called for ‘hats off,’ and Matthews was one of those who complied with the demand. There is no doubt that his behaviour was prompted by mere hilarity. Yet for this innocent offence of having called for the national anthems of the United States on New Year’s Eve, Matthews had his pension stopped, and was himself ordered back to England. He succeeded in having his pension restored, but he never again set foot on Canadian soil.

One of the most striking features of the persecution to which the Reformers were subjected was its pettiness. Because Charles Fothergill, the king’s printer, had given several votes in the House that did not meet the approval of the government, he was dismissed from his position; because Francis Collins, the official reporter of the House, had attacked the government in his paper, the Canadian Freeman, he was denied the remuneration regularly voted to him by the legislature; and because William Lyon Mackenzie had made himself obnoxious to the lieutenant-governor, he was refused the grant voted to him by the legislature for publishing the debates.

The most famous political incident of this period, however, was the destruction of William Lyon Mackenzie’s printing-press at York on June 8, 1826. The Colonial Advocate, which had not been a financial success, had been moved by Mackenzie from Queenston to York in the preceding November. Its tone had given great offence in government circles. This was due, however, not so much to the political views it contained as to the personal abuse with which those views were accompanied. Mackenzie was never able to dissociate the sin from the sinner. He assailed public men with whom he had no private difference as if they were his bitterest personal enemies. In the early summer of 1826 his newspaper broke into a carnival of abuse of some of the most respectable families of York, abuse so gross that it did not deserve to be noticed. On the evening of June 8, however, when Mackenzie was absent from town, a number of young men, most of them sons or protégés of leading members of the Family Compact party, and one of them the private secretary of Sir Peregrine Maitland, entered the office of the Colonial Advocate and proceeded to demolish the printing-press, to upset the type, and to scatter some of it into the bay. There is no doubt that these young men took this action on their own initiative. It is a mistake to regard the episode as an instance of political persecution on the part of the Family Compact. It was merely an attempt, on the part of a number of well-meaning youths, to teach Mackenzie, as they thought, a much deserved lesson in public manners.

At the same time, it was a grave error in judgment, a fact which the rioters themselves were among the first to recognize. In the first place, it roused sympathy for Mackenzie. He had been out of town when the attack on his press took place, and the scurrility of his paper was either forgotten or condoned in view of the loss he had suffered. It was inevitable, too, that the attack should be given a political complexion. In the second place, the destruction of the press proved the means of setting Mackenzie on his feet financially. When the attack took place he was on the verge of bankruptcy, and it is doubtful if he could have continued the publication of the Advocate much longer. Now, on the advice of his friends, he brought against the rioters not a criminal action, but a civil action for damages. The trial took place in the autumn of 1826. The lawyers for the defence made no attempt to deny the fact of the trespass, and did not, from motives of delicacy, submit to the court all the passages in the Advocate which had given rise to the trespass. The result was that the jury awarded to Mackenzie heavy damages—£625. This was far in excess of the value of the property destroyed, and the verdict must have been due in part to political feeling. The amount was raised by subscription among the members of the Family Compact party; and Mackenzie was launched forth once more, with a new press and a new bank account, on his turbulent journalistic career.

Mackenzie was not the only journalist with whom the governing class had trouble. In 1825 an Irish Roman Catholic named Francis Collins had established the Canadian Freeman in opposition to the government. Collins was a writer who mistook coarseness for vigour, and the general tone of his paper was much lower than that of Mackenzie’s. For three years he was allowed to have his say with impunity: then, in the spring of 1828, two indictments were brought against him by the attorney-general, John Beverley Robinson. One was for libel against the lieutenant-governor, whom he had accused of ‘partiality, injustice, and fraud.’ The other was for libel against the solicitor-general, Henry John Boulton, whom he had accused of murder in connection with a duel in which Boulton had been a second eleven years before.

The case came up on April 11, 1828, before Mr Justice Willis at the York assizes. Willis was an English lawyer who had come to Upper Canada in September of the previous year as one of the puisne judges of the court of King’s Bench. He was a man of good abilities and was well connected: his wife, Lady Mary Willis, was the daughter of the Earl of Strathmore. He had been politely received in York, but he soon found that he was regarded as an interloper. There were a number of men who considered themselves entitled to the position which he had secured. Moreover, Lady Mary Willis does not seem to have made herself a persona grata with Lady Sarah Maitland. And when it became known that Willis was a candidate for the chief justiceship of the province, for which John Beverley Robinson was considered in official circles the proper nominee, the gulf between Willis and the official set appreciably widened.

It was at this juncture that the case of Collins came up at the assizes. As soon as Willis took his seat on the bench, Collins rose and asked for permission to speak. When this was granted, Collins began to attack the attorney-general for partiality in the discharge of his duty, pointing out that Robinson was prosecuting him, whereas he had not prosecuted the destroyers of Mackenzie’s press. At this point Robinson himself entered the court. When he had gathered the drift of Collins’s speech, he rose, and pointing out that it was entirely irregular, expressed the hope that the business of the court would not be interrupted any longer. Collins, however, proceeded with his speech without interruption; and when he had finished, Willis replied, amid the silence of the court: ‘If the attorney-general has acted as you say, he has very much neglected his duty. Go you before the grand jury, and if you meet with any obstruction or difficulty, I will see that the attorney-general affords you every facility.’

The attorney-general rose to defend himself. He pointed out, with perfect self-control, that it was not his business to hunt for indictments. He had followed the practice of proceeding only upon information and complaint, and not of setting the law in operation of his own motion. Willis replied that this merely proved his practice to have been uniformly wrong. At this the attorney-general lost his temper, and answered that he knew his duty as well as any judge on the bench.

‘Then, sir,’ retorted Willis, ‘if you know your duty, you have neglected it.’

Collins took the advice of Willis, and brought his complaints before the grand jury. The result was that two true bills were found, one against H. J. Boulton and J. E. Small for having been accessory to the Jarvis-Ridout duel, and the other against seven young men for participation in the destruction of Mackenzie’s press. The trials took place immediately. Boulton and Small were acquitted of the charge against them; and the ‘type-rioters’ were let off with a nominal fine of five shillings each. But Collins’s vigour in carrying the war into Africa evidently caused the attorney-general to reconsider his course of action. With great good sense Robinson determined to drop the prosecutions against Collins for libel, and to hold over some other actions against Collins which had emanated from the grand jury. ‘I will forbear any further action during the present assizes,’ he said, ‘and in proceeding or not hereafter, I shall be governed in a great measure by the sense which the defendant shall show of his duty and obligations as the conductor of a public newspaper.’

But Collins was not a man who learned by experience. He continued in his paper as violent and defamatory as ever. The attorney-general thereupon revived one of the indictments which had been temporarily dropped. But in this case Collins was acquitted by the jury. Then Robinson brought against him an action for libel on his own account. Collins had accused Robinson of ‘native malignancy’ and ‘open, palpable falsehood.’ These expressions, perhaps, would not now be considered libellous, but in 1828 the jury brought in a verdict of guilty. Collins was sentenced to pay a fine of £50, to undergo imprisonment for twelve months, and to find securities for his good behaviour. This was a heavy sentence; but in view of the forbearance which had been shown Collins at first, it should not be described as excessive.

Long before Collins fell under the penalties of the law, his champion, Mr Justice Willis, had left the province for good. Relations between him and the government had reached a climax when he had declined to sit in the court of King’s Bench on the ground that it was improperly constituted. Willis’s action was obviously taken with a view to embarrassing the government. At the same time, the Family Compact were only too glad to find a pretext for getting rid of him. He had begun to associate with the Reform element, ‘who,’ wrote Maitland, ‘are not very respectable in any sense’; and there may have been fears that he would develop into a second Thorpe. The Executive Council therefore recommended his removal, and a writ to this effect was issued on June 26, 1828. A few days later Willis left for England, to lay his case before the Colonial Office. The judgment of the Privy Council went against him, and he was appointed to a judgeship in British Guiana.

The case of William Forsyth created a great deal of attention at that time, and was used as an example of Sir Peregrine Maitland’s tyrannical rule. Forsyth was a tavern-keeper on the Canadian side at Niagara Falls. He had encroached upon the government reserve which ran along the bank of the river, had enclosed it with a fence, and had built a blacksmith’s shop on it. His action was a gross and impudent invasion of the public domain. If recourse had been had to the law-courts, he would have been summarily ejected. But Maitland merely gave orders to the engineer officer of the district to remove the fence and to demolish the building. The fence was removed, but Forsyth replaced it. A second time it was removed. Then Forsyth brought suit against the sheriff and the officer who had performed the task. Both actions, however, failed on technical grounds. Forsyth then appealed for redress to the House of Assembly. The Assembly conceived that there were grounds for an inquiry, since there had obviously been an illegal exercise of force by the military. A committee was appointed, and it proceeded to summon witnesses to give evidence. The adjutant-general of militia and the superintendent of Indian Affairs, when summoned to attend, applied to Maitland for permission. This Maitland refused to grant, and the two officers were imprisoned by order of the speaker for contempt of the House of Assembly. Maitland’s conduct in refusing to allow these officers to testify, and indeed in using military force in the first place, was severely condemned later by the secretary of state, Sir George Murray. But his actions should be regarded as errors of judgment rather than as wilful tyranny. Certainly, William Forsyth should never be entered on the martyr-roll of Reform.

Two more incidents of Maitland’s régime must be noticed. One of these was the publication of the letter and ‘ecclesiastical chart’ which Archdeacon Strachan sent in May 1827 to the Colonial Office. These documents were composed primarily for the purpose of pressing on the home government the claims of the Church of England in Canada. There had grown up in Canada, notably among the members of the Church of Scotland, a strong disposition to dispute the exclusive right of the Church of England to the land reserves which had been set apart in 1791 for the support of ‘a Protestant clergy,’ and Strachan was mainly concerned in combating this view. He argued that the Church of England in Upper Canada was the established church, and should obtain more liberal support from the home government. Unfortunately, he thought it necessary to his argument to blacken the good name of other religious bodies in Upper Canada. ‘The teachers of the different denominations,’ he wrote, ‘with the exception of the two ministers of the church of Scotland, four congregationalists, and a respectable English missionary of a Wesleyan Methodist meeting at Kingston, are, for the most part, from the United States, where they gather their knowledge and form their sentiments. Indeed, the Methodist teachers are subject to the orders of the conference of the United States of America; and it is manifest that the colonial government neither has, nor can have, any other control over them, or prevent them from gradually rendering a large portion of the population, by their influence and instructions, hostile to our institutions, both civil and religious, than by increasing the number of the established clergy.’ These ungenerous imputations were answered by the Rev. Egerton Ryerson, then a young Methodist preacher of only twenty-four years of age, in a pamphlet which he himself described as ‘the first defiant defence of the Methodists, and of the equal and civil rights of all religious persuasions; the first protest and argument on legal and British constitutional grounds, against the erection of a dominant church establishment supported by the state in Upper Canada.’ A storm of indignation broke about the head of Archdeacon Strachan; and from this time dates the beginning of a Methodist agitation against the monopolization of the clergy reserves by the Church of England, an agitation which continued until the reserves were applied to secular purposes in 1854. Sir Peregrine Maitland himself had no share in the preparation of Strachan’s letter and chart, but he was known to be in sympathy with Strachan’s views, and so did not escape some of the obloquy which they called forth. It was, indeed, the fact that the governing clique were, almost to a man, supporters of the Church of England that lent to this religious quarrel its real importance. The cause of the Church of England became identified with that of the Family Compact, and the political quarrel took on some of the bitterness and intensity of the religious quarrel. It will be found that, in what follows, the religious question often affords the clue to the true interpretation of the course of events.

The other incident to be noticed was the agitation over the Naturalization or Alien question. In 1824 the chief justice of England had ruled that any one who had continued to reside in the United States after the peace of 1783 could not possess or transmit British citizenship, and consequently that no such person could inherit real estate in any part of the British Empire. The effect of this judgment upon Upper Canada was to disfranchise and denaturalize a large part of the population; and to render their titles to land invalid. The colonial secretary suggested that a bill should be passed by the parliament of Upper Canada restoring to these persons their civil and political rights. The bill originated in the Legislative Council, and when it came to the Assembly, the members of that body were aghast when they found that it did not pretend to grant full naturalization. This was regarded by the Assembly, and by the great body of American immigrants into Canada, as an attempt on the part of the government to discriminate against them. So far as Maitland is concerned, it should be said that he merely followed the instructions of the Colonial Office. A battle royal over the question continued for several sessions, and in the end the members of the Assembly, after memorializing the home government, had their way. But the action of the provincial government was misconstrued throughout Upper Canada, and many an American immigrant into the colony was driven into opposition by the agitation over the Naturalization Act. The presence of this element in the Reform party was afterwards partly responsible for the charges of republicanism and disloyalty so frequently levied against the Reformers by the Family Compact party.

Sir Peregrine Maitland left Upper Canada in the beginning of November 1828. Before he went, however, the elections for a new Assembly were held. To Maitland the result of these elections must have been a disagreeable pill. The Reformers carried the country by a substantial majority. In the county of York, William Lyon Mackenzie and Jesse Ketchum were returned; elsewhere such men were elected as Marshall Spring Bidwell, John Rolph, Peter Perry, and the elder Baldwin. The reasons for this result are obvious. The motives lying behind the destruction of Mackenzie’s press had been misconstrued; the letter and ‘ecclesiastical chart’ of Archdeacon Strachan had aroused against the government the feeling of the Methodists; the Americans in the colony had been antagonized by what they regarded as an attempt to rob them of their civil and political rights; and many regarded the prosecutions for libel which had taken place through Sir Peregrine Maitland’s régime as an attempt to stifle freedom of speech.

Sir Peregrine Maitland’s successor was Sir John Colborne. Colborne was a distinguished veteran of the Napoleonic wars who had been lieutenant-governor of Guernsey since 1825. He was at this time forty-two years of age. Though not a brilliant man, he possessed mature judgment and steady nerves, and as an administrator he stood head and shoulders above both his predecessor and his successor in office. He had no illusions about the leaders of the Family Compact. Of Archdeacon Strachan he wrote, a few months after his arrival in Canada: ‘I cannot blind myself so far as not to be convinced that the political part he has taken in Upper Canada destroys his clerical influence, and injures to a very great degree the interests of the episcopal church, and, I am afraid, of religion also.’ At first Colborne held himself distinctly aloof from Family Compact influences, and it was only when Reformers like Mackenzie became factious in their opposition to government that he was forced into the Family Compact camp. Colborne was not of a democratic turn of mind. But it is noteworthy that during his period of office there were no persecutions and prosecutions by government such as had taken place under Maitland. The expulsions of Mackenzie from the Assembly were the work of a Tory majority in the House itself, and there is no doubt that Colborne did not wholly approve of their course. His real interest in the welfare of the colony was shown by his founding of Upper Canada College and by his advocacy of good roads. ‘In allowing your roads to remain in their present state,’ he bluntly told the Assembly, ‘the great stimulus to agricultural industry is lost.’ Colborne’s ideal was something very different from the dolce far niente policy of Maitland.