* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Graham's Magazine Vol. XXI No. 6 December 1842

Date of first publication: 1842

Author: George Rex Graham (1813-1894), Editor

Date first posted: Apr. 14, 2022

Date last updated: Apr. 14, 2022

Faded Page eBook #20220439

This eBook was produced by: Mardi Desjardins & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

GRAHAM’S MAGAZINE.

Vol. XXI. December, 1842 No. 6.

Contents

| Poetry | |

| The Serenade | |

| Sonnets | |

| Sonnet | |

| Noon | |

| True Affection | |

| The Farewell | |

| The Holynights | |

| The Pastor’s Visit | |

| To the Night-Wind in Autumn | |

Transcriber’s Notes can be found at the end of this eBook.

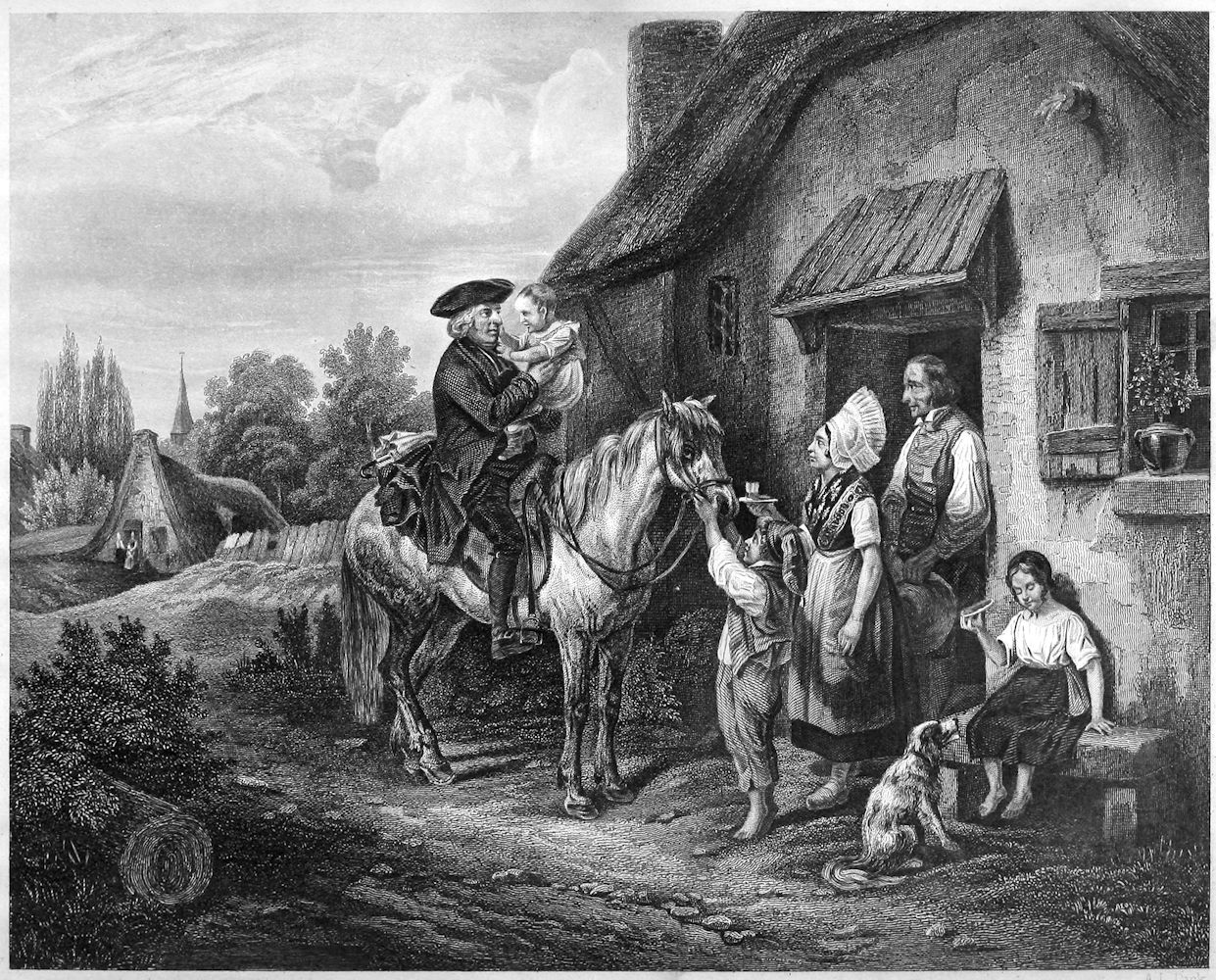

Painted by E. Prentice Engraved by H.S. Sadd

GRAHAM’S MAGAZINE.

Vol. XXI. PHILADELPHIA: DECEMBER, 1842. No. 6.

———

BY J. FENIMORE COOPER, AUTHOR OF “THE SPY,” “THE PIONEERS,” ETC.

———

Among the many brave men who early contributed to render the navy of the republic popular and respectable, the gallant seaman whose name is placed at the head of this article is entitled to a conspicuous place; equally on account of his services, his professional skill, and his personal merit. Although his connection with the marine, created under the constitution of 1789, was of short continuance, it left a durable impression on the service; and, if we look back to the dark period of the Revolution, we find him contending in some of the fiercest combats of the period, always with heroism, and not unfrequently with success. Circumstances, too, have connected his renown with one of the most remarkable naval battles on record; a distinction of itself which fully entitles him to a high place among those who have fought and bled for the independence of their country, in stations of subordinate authority.

Richard Dale was born in the colony of Virginia, on the 6th November, 1756. His birthplace was in the county of Norfolk, and not distant from the well known port of the same name. His parents were native Americans, of respectable standing, though of rather reduced circumstances. His father, dying early, left a widow with five children, of whom the subject of this memoir was the eldest. Some time after the death of his father, his mother contracted a second marriage with a gentleman of the name of Cooper, among the issue of which were two well known ship-masters of Philadelphia.

Young Dale manifested an inclination for the sea at a very early period of life. The distrust of a parental control that has no foundation in nature, and which is apt to be regarded with jealousy, stimulated if it did not quicken this desire, and we find him at the tender age of twelve, or in 1768, making a voyage between Norfolk and Liverpool, in a vessel commanded by one of his own uncles. On his return home, he appears to have passed nearly a twelve-month on shore; but his desire to become a sailor still continuing, in the spring of 1770 he was regularly apprenticed to a respectable merchant and ship-owner, of the borough of Norfolk, named Newton. From this moment his fortune in life was cast, and he continued devotedly employed in the profession until his enterprise, prudence and gallantry enabled him finally to retire with credit, an unblemished name, and a competency.

During his apprenticeship, Dale appears to have been, most of the time, employed in the West India trade. Every sailor has his chances and hair-breadth escapes, and our young mariner met with two, at that period of his life, which may be thought worthy of notice. On one occasion he fell from the spars stowed on the belfry into the vessel’s hold, hitting the kelson, a distance of near twenty feet; escaping, however, without material injury. A much greater risk was incurred on another. While the vessel to which he belonged was running off the wind, with a stiff breeze, Dale was accidentally knocked overboard by the jib sheets, and was not picked up without great difficulty. He was an hour in the water, sustaining himself by swimming, and he ever spoke of the incident as one of more peril than any other in a perilous career.

When nineteen, or in 1775, Dale had risen to the station of chief mate on board a large brig belonging to his owner. In this situation he appears to have remained industriously engaged during the few first months of the struggle for independence; the active warfare not having yet extended itself as far south as his part of the country. Early in 1776, however, the aspect of things began to change, and it is probable that the interruption to commerce rendered him the master of his own movements.

Virginia, in common with most of the larger and more maritime colonies, had a sort of marine of its own; more especially anterior to the Declaration of Independence. It consisted principally of bay craft, and was employed in the extensive estuaries and rivers of that commonwealth. On board of one of these light cruisers Dale was entered as a lieutenant, in the early part of the memorable year 1776. While in this service, he was sent a short distance for some guns, in a river craft; but falling in with a tender of the Liverpool frigate, which ship was then cruising on the Cape Henry station, he was captured and carried into Norfolk. These tenders were usually smart little cruisers, another, belonging to the same frigate, having been taken shortly before, by the U. S. brig Lexington, after a sharp and bloody conflict. Resistance in the case of Dale was consequently out of the question, his capture having been altogether a matter of course.

On reaching Norfolk, our young officer was thrown on board a prison-ship. Here he found himself in the midst of those whom it was the fashion to call “loyal subjects.” Many of them were his old school-mates and friends. Among the latter was a young man of the name of Bridges Gutteridge, a sailor like himself, and one who possessed his entire confidence. Mr. Gutteridge, who it is believed subsequently took part with his countrymen himself, was then employed by the British, in the waters of the Chesapeake, actually commanding a tender in their service. The quarrel was still recent; and honorable, as well as honest men, under the opinions which prevailed in that day, might well be divided as to its merits. Mr. Gutteridge had persuaded himself he was pursuing the proper course. Entertaining such opinions, he earnestly set about the attempt of making a convert of his captured friend. The usual arguments, touching the sacred rights of the king—himself merely a legalized usurper, by the way, if any validity is to be given to the claims of hereditary right to the crown—and the desperate nature of the “rebel cause,” were freely and strenuously used, until Dale began to waver in his faith. In the end, he yielded and consented to accompany his friend in a cruise against the vessels of the state. This occurred in the month of May, and, hostilities beginning now to be active, the tender soon fell in with a party of Americans, in some pilot boats, that were employed in the Rappahannock. A warm engagement ensued, in which the tender was compelled to run, after meeting with a heavy loss. It was a rude initiation into the mysteries of war, the fighting being of a desperate, and almost of a personal character. This was one of those combats that often occurred about this period, and in those waters, most of them being close and sanguinary.

In this affair, Dale received a severe wound, having been hit in the head by a musket ball; with this wound he was confined several weeks at Norfolk, during which time he had abundance of leisure to reflect on the false step into which he had been persuaded, and to form certain healthful resolutions for the future. To use his own words, in speaking of this error of his early life, he determined “never again to put himself in the way of the bullets of his own country.” This resolution, however, it was necessary to conceal, if he would escape the horrors of a prison-ship, and he “bided his time,” fully determined to take service again under the American flag, at the first fitting opportunity.

In the peculiar state of the two countries at the time, and with the doubtful and contested morality of the misunderstanding, there was nothing extraordinary in this incident. Similar circumstances occurred to many men, who, with the best intentions and purest motives, saw, or fancied they saw, reasons for changing sides in what, in their eyes, was strictly a family quarrel. In the case of Dale, however, the feature most worthy of comment was the singleness of mind and simple integrity with which he used to confess his own error, together with the manner in which he finally became a convert to the true political faith. No narrative of the life of this respectable seaman would be complete, without including this temporary wavering of purpose; nor would any delineation of his character be just, that did not point out the candor and sincerity with which he, in after life, admitted his fault.

Dale was only in his twentieth year when he received this instructive lesson from the “bullets of his countrymen.” From that time, he took good care not to place himself again in their way, going, in June or July, to Bermuda, on a more peaceable expedition, in company with William Gutteridge, a relative of his beguiling friend. On the return passage, the vessel was captured by the Lexington, the brig just mentioned, then a successful cruiser, under the orders of Capt. John Barry; an officer who subsequently died at the head of the service. This occurred just after the Declaration of Independence, and Dale immediately offered himself as a volunteer under the national flag. He was received and rated as a midshipman within a few hours of his capture. This was the commencement of Dale’s service in the regular navy of his native country. It was also the commencement of his acquaintance with the distinguished commander of the Lexington, whose friendship and respect he enjoyed down to the day of the latter’s death. While the brig was out, our midshipman had another narrow escape from death, having, together with several others, been struck senseless by lightning during a severe thunder storm.

Barry made the capture just mentioned near the end of his cruise, and he soon after went into Philadelphia, which place Dale now saw for the first time. Here Barry left the Lexington to take command of the Effingham 28, a ship that never got to sea, leaving our new midshipman in the brig. Capt. Hallock was Barry’s successor, and he soon rated Dale, by this time an active and skilful seaman, a master’s mate. Early in the autumn, the Lexington sailed for Cape François, on special duty. On her return, in the month of December, she fell in with the Pearl frigate,[1] and was captured without resistance, carrying an armament of only a few fours.

As it was blowing very fresh at the moment this capture was made, the Pearl took out of the prize four or five officers, threw a small crew on board, and directed the brig to follow her. By some accounts Dale was left in the Lexington, while by others he was not. A succinct history of the events of his life, written by a connection under his own eye, and which is now before us, gives the latter version of the affair, and is probably the true one. At all events, the remaining officers and crew of the Lexington rose upon the captors in the course of the night, retook the brig, and carried her into Baltimore.[2]

The English landed several of their prisoners on Cape Henlopen, in January, 1777, under some arrangement that cannot now be explained, though probably it was connected with an exchange for the men taken and carried away in the prize. Among these was Dale, who made the best of his way to Philadelphia, when he received orders to proceed to Baltimore; which he obeyed, and rejoined his brig, the command of which had now been transferred to Capt. Henry Johnston.

The next service on which the Lexington was employed was in the European seas. In March, she sailed from Baltimore for Bordeaux, with despatches. On her arrival, this brig was attached to a small squadron under the orders of Capt. Lambert Wickes, who was in the Reprisal 16, having under his command also the Dolphin 10, Capt. Samuel Nicholson. This force of little vessels accomplished a bold and destructive cruise, making the entire circuit of Ireland, though it was eventually chased into a French port by a line-of-battle ship. Its object was the interception of certain linen-ships, which it missed; its success, however, in the main, was such as to excite great alarm among the English merchants, and to produce warm remonstrances to France, from their government.

At this time France was not at war with England, although she secretly favored and aided the cause of the revolted colonies. The appearance of American cruisers in the narrow seas, however, gave rise to so many complaints, as to induce the French government, in preference to pushing matters to extremities, temporarily to sequester the vessels. The Lexington was included in this measure, having been detained in port more than two months; or, until security was given that she would quit the European seas. This was done, and the brig got to sea again on the 18th September, 1777.[3]

It is probable that the recent difficulties had some effect on the amount of the military stores on board all three of the American vessels. At all events, it is certain that the Lexington sailed with a short supply of both powder and shot, particularly of the latter. The very next day she made an English cutter lying-to, which was approached with a confidence that could only have proceeded from a mistake as to her character. This cutter proved to be a man-of-war, called the Alert, commanded by Lieutenant, afterward Admiral Bazely, having a strong crew on board, and an armament of ten sixes.

In the action that ensued, and which was particularly well fought on the part of the enemy, the Americans were, in a measure, taken by surprise. So little were the latter prepared for the conflict, that not a match was ready when the engagement commenced, and several broadsides were fired by discharging muskets at the vents of the guns. The firing killed the wind, and there being considerable sea on, the engagement became very protracted, during which the Lexington expended most of her ammunition.

After a cannonading of two hours, believing his antagonist to be too much crippled to follow, and aware of his own inability to continue the action much longer, Capt. Johnston made sail, and left the cutter, under favor of a breeze that just then sprung up. The Lexington left the Alert rapidly at first, but the latter having bent new sails, and being the faster vessel, in the course of three or four hours succeeded in getting alongside again, and of renewing the engagement. This second struggle lasted an hour, the fighting being principally on one side. After the Lexington had thrown her last shot, had broken up and used all the iron that could be made available as substitutes, and had three of her officers and several of her men slain, besides many wounded, Capt. Johnston struck his colors. The first lieutenant, marine officer, and master of the Lexington were among the slain.

By this accident Dale became a prisoner for the third time. This occurred when he wanted just fifty days of being twenty-one years old. On this occasion, however, he escaped unhurt, though the combat had been both fierce and sanguinary. The prize was taken into Plymouth, and her officers, after undergoing a severe examination, in order to ascertain their birthplaces, were all thrown into Mill Prison, on a charge of high treason. Here they found the common men; the whole being doomed to a rigorous and painful confinement.

Either from policy or cupidity, the treatment received by the Americans, in this particular prison, was of a cruel and oppressive character. There is no apology for excessive rigor, or, indeed, for any constraint beyond that which is necessary to security, toward an uncondemned man. Viewed as mere prisoners of war, the Americans might claim the usual indulgence; viewed as subjects still to be tried, they were rightfully included in that healthful maxim of the law, which assumes that all are innocent until they are proved to be guilty. So severe were the privations of the Americans on this occasion, however, that, in pure hunger, they caught a stray dog one day, skinned, cooked and ate him, to satisfy their cravings for food. Their situation at length attracted the attention of the liberal; statements of their wants were laid before the public, and an appeal was made to the humanity of the English nation. This is always an efficient mode of obtaining assistance, and the large sum of sixteen thousand pounds was soon raised; thereby relieving the wants of the sufferers, and effectually effacing the stain from the national escutcheon; by demonstrating that the sufferers found a generous sympathy in the breasts of the public. But man requires more than food and warmth. Although suffering no longer from actual want and brutal maltreatment, Dale and his companions pined for liberty—to be once more fighting the battles of their country. Seeing no hopes of an exchange, a large party of the prisoners determined to make an attempt at escape. A suitable place was selected, and a hole under a wall was commenced. The work required secrecy and time. The earth was removed, little by little, in the pockets of the captives, care being had to conceal the place, until a hole of sufficient size was made to permit the body of a man to pass through. It was a tedious process, for the only opportunity which occurred to empty their pockets, was while the Americans were exercising on the walls of their prison, for a short period of each day. By patience and perseverance they accomplished their purpose, however, every hour dreading exposure and defeat.

When all was ready, Capt. Johnston, most of his officers, and several of his crew, or, as many as were in the secret, passed through the hole, and escaped. This was in February, 1778. The party wandered about the country in company, and by night, for more than a week; suffering all sorts of privations, until it was resolved to take the wiser course of separating. Dale, accompanied by one other, found his way to London, hotly pursued. At one time the two lay concealed under some straw in an out-house, while the premises were searched by those who were in quest of them. On reaching London, Dale and his companion immediately got on board a vessel about to sail for Dunkirk. A press-gang unluckily took this craft in its rounds, and suspecting the true objects of the fugitives, they were arrested, and, their characters being ascertained, they were sent back to Mill Prison in disgrace.

This was the commencement of a captivity far more tedious than the former. In the first place they were condemned to forty days’ confinement in the black hole, as the punishment for the late escape; and, released from this durance, they were deprived of many of their former indulgences. Dale himself took his revenge in singing “rebel songs,” and paid a second visit to the black hole, as the penalty. This state of things, with alternations of favor and punishment, continued quite a year, when Dale, singly, succeeded in again effecting his great object of getting free.

The mode in which this second escape was made is known, but the manner by which he procured the means he refused to his dying day to disclose. At all events, he obtained a full suit of British uniform, attired in which, and seizing a favorable moment, he boldly walked past all the sentinels, and got off. That some one was connected with his escape who might suffer by his revelations is almost certain; and it is a trait in his character worthy of notice, that he kept this secret, with scrupulous fidelity, for forty-seven years. It is not known that he ever divulged it even to any individual of his own family.

Rendered wary by experience, Dale now proceeded with great address and caution. He probably had money, as well as clothes. At all events, he went to London, found means to procure a passport, and left the country for France, unsuspected and undetected. On reaching a friendly soil, he hastened to l’Orient, and joined the force then equipping under Paul Jones, in his old rank of a master’s mate. Here he was actively employed for some months, affording the commodore an opportunity to ascertain his true merits, when they met with something like their just reward. As Dale was now near twenty-three, and an accomplished seaman, Jones, after trying several less competent persons, procured a commission for him from the commissioners, and made him the first lieutenant of his own ship, the justly celebrated Bon Homme Richard.

It is not our intention, in this article, to enter any farther into the incidents of this well known cruise, than is necessary to complete the present subject. Dale does not appear in any prominent situation, though always discharging the duties of his responsible station, with skill and credit, until the squadron appeared off Leith, with the intention of seizing that town—the port of Edinburgh—and of laying it under contribution. On this occasion, our lieutenant was selected to command the boats that were to land, a high compliment to so young a man, as coming from one of the character of Paul Jones. Every thing was ready, Dale had received his final orders, and was in the very act of proceeding to the ship’s side to enter his boat, when a heavy squall struck the vessels, and induced an order for the men to come on deck, and assist in shortening sail. The vessels were compelled to bear up before it, to save their spars; this carried them out of the firth; and, a gale succeeding, the enterprise was necessarily abandoned. This gale proved so heavy, that one of the prizes actually foundered.

This attempt of Jones, while it is admitted to have greatly alarmed the coast, has often been pronounced rash and inconsiderate. Such was not the opinion of Dale. A man of singular moderation in his modes of thinking, and totally without bravado, it was his conviction that the effort would have been crowned with success. He assured the writer, years after the occurrence, that he was about to embark in the expedition with feelings of high confidence, and that he believed nothing but the inopportune intervention of the squall stood between Jones and a triumphant coup de main.

A few days later, Jones made a secret proposal to his officers, which some affirm was to burn the shipping at North Shields, but which the commanders of two of his vessels strenuously opposed, in consequence of which the project was abandoned. The commodore himself, in speaking of the manner in which this and other similar propositions were received by his subordinates, extolled the ardor invariably manifested by the young men, among whom Dale was one of the foremost. Had it rested with them, the attempts at least would all have been made.

On the 19th September occurred the celebrated battle between the Serapis and the Bon Homme Richard. As the proper place to enter fully into the details of that murderous combat will be in the biography of Jones, we shall confine ourselves at present to incidents with which the subject of this memoir was more immediately connected.

The Bon Homme Richard had finally sailed on this cruise with only two proper sea-lieutenants on board her. There was a third officer of the name of Lunt, who has been indifferently called a lieutenant and the sailing-master, but who properly filled the latter station. This gentleman had separated from the ship in a fog, on the coast of Ireland, while in the pursuit of some deserters, and never rejoined the squadron. Another person of the same name, and believed to be the brother of the master, was the second lieutenant. He was sent in a pilot-boat, accompanied by a midshipman and several men, to capture a vessel in sight, before Jones made the Baltic fleet coming round Flamborough Head. This party was not able to return to the Bon Homme Richard, until after the battle had terminated. In consequence of these two circumstances, each so novel in itself, the American frigate fought this bloody and arduous combat with only one officer on board her, of the rank of a sea-lieutenant, who was Dale. This is the reason why the latter is so often mentioned as the lieutenant of the Bon Homme Richard, during that memorable fight. The fact rendered his duties more arduous and diversified, and entitles him to the greater credit for their proper performance.

Dale was stationed on the gun-deck, where of course he commanded in chief, though it appears that his proper personal division was the forward guns. Until the ships got foul of each other, this brought him particularly into the hottest of the work; the Serapis keeping much on the bows, or ahead of the Bon Homme Richard. It is known that Jones was much pleased with his deportment, which, in truth, was every way worthy of his own. When the alarm was given that the ship was sinking, Dale went below himself to ascertain the real state of the water, and his confident and fearless report cheered the men to renewed exertions. Shortly after, the supply of powder was stopped, when our lieutenant again quitted his quarters to inquire into the cause. On reaching the magazine passage he was told by the sentinels that they had closed the ingress, on account of a great number of strange and foreign faces that they saw around them. On further inquiry, Dale discovered that the master at arms, of his own head, had let loose all the prisoners—more than a hundred in number—under the belief that the ship was sinking. Dale soon saw the danger which might ensue, but finding the English much alarmed at the supposed condition of the ship, he succeeded in mustering them, and setting them at work at the pumps, where, by their exertions, they probably prevented the apprehended calamity. For some time, at the close of the action, all his guns being rendered useless, Dale was employed principally in this important service. There is no question that without some such succor, the Richard would have gone down much earlier than she did. It is a singular feature of this every-way extraordinary battle, that here were Englishmen, zealously employed in aiding the efforts of their enemies, under the cool control of a collected and observant officer.

At length the cheerful intelligence was received that the enemy had struck. Dale went on deck, and immediately demanded Jones’ permission to take possession of the prize. It was granted, and had he never manifested any other act of personal intrepidity, his promptitude on this occasion, and the manner in which he went to work, to attain his purpose, would have shown him to be a man above personal considerations, when duty or honor pointed out his course. The main-yard of the Serapis was hanging a-cock-bill, over the side of the American ship. The brace was shot away, and the pendant hung within reach. Seizing the latter, Dale literally swung himself off, and alighted alone on the quarter-deck of the Serapis. Here he found no one but the brave Pierson, who had struck his own flag; but the men below were still ignorant of the act. We may form an opinion of the risk that the young man ran, in thus boarding his enemy at night, and in the confusion of such a combat, for the English were still firing below, by the fact that Mr. Mayrant, a young man of South Carolina, and a midshipman of the Bon Homme Richard, who led a party after the lieutenant, was actually run through the thigh by a boarding pike, and by the hands of a man in the waist below.

The first act of Dale, on getting on the quarter deck of the Serapis, was to direct her captain to go on board the American ship. While thus employed, the English first lieutenant came up from below, and finding that the Americans had ceased their fire, he demanded if they had struck. “No, sir,” answered Dale, “it is this ship that has struck, and you are my prisoner.” An appeal to Capt. Pierson confirming this, the English lieutenant offered to go below and silence the remaining guns of the Serapis. To this Dale objected, and had both the officers passed on board the Bon Homme Richard. In a short time, the English below were sent from their guns, and full possession was obtained of the prize.

As more men were soon sent from the Bon Homme Richard, the two ships were now separated, the Richard making sail, and Jones ordering Dale to follow with the prize. A sense of fatigue had come over the latter, in consequence of the reaction of so much excitement and so great exertions, and he took a seat on the binnacle. Here he issued an order to brace the head yards aback, and to put the helm down. Wondering that the ship did not pay off, he directed that the wheel-ropes should be examined. It was reported that they were not injured, and that the helm was hard down. Astonished to find the ship immovable under such circumstances, there being a light breeze, Dale sprang upon his feet, and then discovered, for the first time, that he had been severely wounded, by a splinter, in the foot and ankle. The hurt, now that he was no longer sustained by the excitement of battle, deprived him of the use of his leg, and he fell. Just at this moment, Mr. Lunt, the officer who had been absent in the pilot-boat, reached the Richard, and Dale was forced to give up to him the command of the prize. The cause of the Serapis’ not minding her helm was the fact that Capt. Pierson had dropped an anchor under foot when the two ships got foul; a circumstance of which the Americans were ignorant until this moment.

Dale was some time laid up with his wound, but he remained with Jones in his old station of first lieutenant, accompanying that officer, in the Alliance, from the Texel to l’Orient. In the controversy which ensued between the commodore and Landais, our lieutenant took sides warmly with the first, and even offered to head a party to recover the Alliance, by force. This measure not being resorted to, he remained with Jones, and finally sailed with him for America, as his first lieutenant, in the Ariel 20, a ship lent to the Americans, by the King of France.

The Ariel quitted port in October, 1780, but encountered a tremendous gale of wind off the Penmarks. Losing her masts, she was compelled to return to refit. On this occasion Dale, in his responsible situation of first lieutenant, showed all the coolness of his character, and the resources of a thorough seaman. The tempest was almost a hurricane, and of extraordinary violence. The Ariel sailed a second time about the commencement of the year 1781, and reached Philadelphia on the 18th February. During the passage home, she had a short action, in the night, with a heavy British letter-of-marque, that gave her name as the Triumph; and which ship is said to have struck, but to have made her escape by treachery. Jones, who was greedy of glory, even fancied that his enemy was a vessel of war, and that he had captured a vessel of at least equal force. This was not Dale’s impression. He spoke of the affair to the writer of this article, as one of no great moment, even questioning whether their antagonist struck at all; giving it as his belief she was a quick-working and fast-sailing letter-of-marque. He distinctly stated that she got off by out-manœuvring the Ariel, which vessel was badly manned, and had an exceedingly mixed and disaffected crew. It is worthy of remark that, while two articles, enumerating the services of Dale, have been written by gentlemen connected with himself, and possessing his confidence, neither mentions this affair; a proof, in itself, that Dale considered it one of little moment.

The account which Dale always gave of the meeting between the Ariel and Triumph—admitting such to have been the name of the English ship—so different from that which has found its way into various publications, on the representation of other actors in that affair, is illustrative of the character of the man. Simple of mind, totally without exaggeration, and a lover, as well as a practicer, of severe truth, he was a man whose representations might be fully relied on. Even in his account of the extraordinary combat between the Richard and Serapis, he stripped the affair of all its romance, and of every thing that was wonderful; rendering the whole clear, simple and intelligible as his own thoughts. The only narratives of that battle, worthy of a seaman, have been written rigidly after his explanations, which leave it a bloody and murderous fight, but one wholly without the marvelous.

On his arrival at Philadelphia, after an absence of four years, more than one of which had been spent in prison, Dale was just twenty-four years and two months old. He was now regularly put on the list of lieutenants, by the marine committee of Congress; his former authority proceeding from the agents of the government in Europe. It is owing to this circumstance that the register of government places him so low as a lieutenant. Dale now parted from Paul Jones, with whom he had served near two years; and that, too, in some of the most trying scenes of the latter’s life. The commodore was anxious to take his favorite lieutenant with him to the America 74; but the latter declined the service, under the impression it would be a long time before the ship got to sea. He judged right, the America being transferred to the French in the end, and Jones himself never again sailing under the American flag.

The name of Dale will inseparably be connected with the battle of the Richard and Serapis. His prominent position and excellent conduct entitle him to this mark of distinction, and it says much for the superior, when it confers fame to have been “Paul Jones’ first lieutenant.” We smile, however, at the legends of the day, when we recall the account of the “Lieutenants Grubb” and other heroes of romance, who have been made to figure in the histories of that renowned combat, and place them in contrast with the truth-loving, sincere, moral and respectable subject of this memoir. The sword which Louis XVI. bestowed on Jones, for this victory, passed into the hands of Dale, and is now the property of a gallant son, a fitting mark of the services of the father, on the glorious occasion it commemorates.[4]

Dale was employed on board a schooner that was manned from the Ariel, after reaching Philadelphia, and sent down the Delaware to convoy certain public stores. The following June, he joined the Trumbull 28, Captain Nicholson, as her first lieutenant. The Trumbull left the capes of the Delaware on the 8th August, 1781, being chased off the land by three of the enemy’s cruisers. The weather was squally and night set in dark. In endeavoring to avoid her pursuers, the Trumbull found herself alongside of the largest, a frigate of thirty-two guns, and an action was fought under the most unfavorable circumstances. The Trumbull’s fore-topmast was hanging over, or rather through her forecastle, her crew was disorganized, and the vessel herself in a state of no preparation for a conflict with an equal force; much less with that actually opposed to her. The officers made great exertions, and maintained an action of more than an hour, when the colors of the American ship were struck to the Iris 32, and Monk 18. The former of these vessels had been the American frigate Hancock, and the latter was subsequently captured in the Delaware, by Barney in the Hyder Ally.

This was the fourth serious affair in which Dale had been engaged that war, and the fourth time he had been captured. As he was hurt also in this battle, it made the third of his wounds. His confinement, however, was short, and the treatment not a subject of complaint. He was taken into New York, paroled on Long Island, and exchanged in November.

No new service offering in a marine which, by this time, had lost most of its ships, Dale obtained a furlough, and joined a large letter-of-marque called the Queen of France, that carried twelve guns, as her first officer. Soon after he was appointed to the command of the same vessel. In the spring of 1782, this ship, in company with several other letters-of-marque, sailed for France, making many captures by the way. The ship of Dale, however, parted from the fleet, and, falling in with an English privateer of fourteen guns, a severe engagement followed, in which both parties were much cut up; they parted by mutual consent. Dale did not get back to Philadelphia until February of the succeeding year, or until about the time that peace was made.

In common with most of the officers of the navy, Lieutenant Dale was disbanded, as soon as the war ceased. He was now in the twenty-seventh year of his age, with a perfect knowledge of his profession, in which he had passed more than half his life, a high reputation for his rank, a courage that had often been tried, a body well scarred, a character beyond reproach, and not altogether without “money in his purse.” Under the circumstances, he naturally determined to follow up his fortunes in the line in which he had commenced his career. He became part owner of a large ship, and sailed in her for London, December, 1783, in the station of master. After this, he embarked successfully in the East India trade, in the same character, commanding several of the finest ships out of the country. In this manner he accumulated a respectable fortune, and began to take his place among the worthies of the land in a new character.

In September, 1791, Mr. Dale was married to Dorothy Crathorne, the daughter of another respectable ship-master of Philadelphia, and then a ward of Barry’s. With this lady he passed the remainder of his days, she surviving him as his widow, and dying some years later than himself. No change in his pursuits occurred until 1794, when the new government commenced the organization of another marine, which has resulted in that which the country now possesses.

Dale was one of the six captains appointed under the law of 1794, that directed the construction of as many frigates, with a view to resist the aggressions of Algiers. Each of the new captains was ordered to superintend the construction of one of the frigates, and Dale, who was fifth in rank, was directed to assume the superintendence of the one laid down at Norfolk, virtually the place of his nativity. This ship was intended to be a frigate of the first class, but, by some mistake in her moulds, she proved in the end to be the smallest of the six vessels then built. It was the unfortunate Chesapeake, a vessel that never was in a situation to reflect much credit on the service. Her construction, however, was deferred, in consequence of an arrangement with Algiers, and her captain was put on furlough.

Dale now returned to the China trade, in which he continued until the spring of 1798. The last vessel he commanded was called the Ganges. She was a fine, fast ship, and the state of our relations with France requiring a hurried armament, the government bought this vessel, in common with several others, put an armament of suitable guns in her, with a full crew, gave her to Dale, and ordered her on the coast as a regular cruiser.

In consequence of this arrangement, Capt. Dale was the first officer who ever got to sea under the pennant of the present navy. He sailed in May, 1798, and was followed by the Constellation and Delaware in a few days. The service of Dale in his new capacity was short, however, in consequence of some questions relating to rank. The captains appointed in 1794 claimed their old places, and, it being uncertain what might be the final decision of the government, as there were many aspirants, Dale declined serving until the matter was determined. In May, 1799, he sailed for Canton again, in command of a strong letter-of-marque, under a furlough. On his return from this voyage he found his place on the list settled according to his own views of justice and honor, and reported himself for service. Nothing offered, however, until the difficulties with France were arranged; but, in May, 1801, he was ordered to take command of a squadron of observation about to be sent to the Mediterranean.

Dale now hoisted his broad pennant, for the first and only time, and assumed the title by which he was known for the rest of his days. He was in the prime of life, being in his forty-fifth year, of an active, manly frame, and had every prospect before him of a long and honorable service. The ships put under his orders were the President 44, Capt. James Barron; Philadelphia 38, Capt. Samuel Barron; Essex 32, Capt. William Bainbridge; and Enterprise 12, Lieut. Com. Sterrett. A better appointed, or a better commanded force, probably never sailed from America. But there was little to do, under the timid policy and defective laws of the day. War was not supposed to exist, although hostilities did; and vessels were sent into foreign seas with crews shipped for a period that would scarcely allow of a vessel’s being got into proper order.

The squadron sailed June 1st, 1801, and reached Gibraltar July 1st. The Philadelphia blockaded the Tripolitan admiral, with two cruisers, in Gibraltar, while the other vessels went aloft. A sharp action occurred between the Enterprise and a Tripolitan of equal force, in which the latter was compelled to submit, but was allowed to go into her own port again, for want of legal authority to detain her. Dale appeared off Tripoli, endeavored to negotiate a little about an exchange of prisoners, and did blockade the port; but his orders fettered him in a way to prevent any serious enterprises. In a word, no circumstances occurred to allow the commodore to show his true character, except as it was manifested in his humanity, prudence and dignity. As a superior, he obtained the profound respect of all under his orders, and to this day his name is mentioned with regard by those who then served under him. It is thought that this squadron did much toward establishing the high discipline of the marine. In one instance only had Dale an opportunity of manifesting his high personal and professional qualities. The President struck a rock in quitting Port Mahon, and for some hours she was thought to be in imminent danger of foundering. Dale assumed the command, and one of his lieutenants, himself subsequently a flag officer of rare seamanship and merit, has often recounted to the writer his admiration of the commodore’s coolness, judgment, and nerve, on so trying an occasion. The ship was carried to Toulon, blowing a gale, and, on examination, it was found that she was only saved from destruction by the skilful manner in which the wood ends had been secured.

The vigilance of Dale was so great, however, and his dispositions so skilful, that the Tripolitans made no captures while he commanded in those seas. In March, 1802, he sailed for home, under his orders, reaching Hampton Roads in April, after a cruise of about ten months. The succeeding autumn, Com. Dale received an order to hold himself in readiness to resume the command from which he had just returned. Ever ready to serve his country, when it could be done with honor, he would cheerfully have made his preparations accordingly, but, by the order itself, he ascertained that he was to be sent out without a captain in his own ship. This, agreeably to the notions he entertained, was a descent in the scale of rank, and he declined serving on such terms. There being no alternative between obedience and resignation, he chose the latter, and quitted the navy. At this time, he was the third captain on the list, and it is no more than justice to say, that he stood second to no other in the public estimation.

Dale never went to sea again. Possessed of an ample fortune, and possessing the esteem of all who knew him, he commanded the respect of those with whom he differed in opinion touching the question which drove him from the navy. With the latter he never quarreled, for, at the proper period, he gave to it his two elder sons. To the last he retained his interest in its success, and his care of mariners, in general, extended far beyond the interests of this life.

Many years previously to his death, Com. Dale entered into full communion with the Protestant Episcopal Church, of which he proved a consistent and pious member. Under the newly awakened feelings which induced this step, he was the originater of a Mariner’s Church, in Philadelphia, attending it in person, every Sunday afternoon, for a long succession of years. He was as free with his purse, too, as with his time; and his charities, though properly concealed, were believed to be large and discriminating. With some it may be deemed a matter of moment, with all it should be a proof of the estimation in which Dale was held by certainly a very respectable part of his fellow citizens, that he was named to be the first president of the Washington Benevolent Society; an association that soon degenerated to serve the ends of party politics, whatever may have been the design that influenced the few with which it originated.

The evening of the life of Dale was singularly peaceful and happy. It was as calm as its morning had been tempestuous. It is true he had to weep for the loss of his first-born son, a noble youth, who died of wounds received in the action between his old ship, the President, and a British squadron; but he had given the young man to his country, and knew how to bear up under the privation. He died, himself, in the seventieth year of his age, in his dwelling at Philadelphia, February 26th, 1826; departing in peace with God and man, as he fondly trusted himself, and as those who survive have every reason to hope.

By his marriage with Miss Crathorne, Com. Dale had several children, five of whom lived to become men and women, viz. three sons and two daughters. Of the former, Richard, the eldest, fell, at an early age, a midshipman on board the President. John Montgomery, the second, is now a commander in the navy, having served with Warrington, in the last English war. This gentleman is married to a lady of the well known family of Willing. Edward Crathorne, the youngest son, is a merchant of Philadelphia. He is married and has children. The eldest daughter, Sarah, married T. M’Kean Pettit, Esq., a judge of the District Court, in Philadelphia, and is dead, leaving issue. Elizabeth, the youngest, is the wife of Com. George Campbell Reed, of the navy, and has no issue.

In considering the character of Dale, we are struck with its simple modesty and frank sincerity, quite as much as with its more brilliant qualities. His courage and constancy were of the highest order, rendering him always equal to the most critical duties, and never wearying in their performance. Such a man is perfectly free from all exaggeration. As he was not afraid to act when his cooler judgment approved, he had no distrusts to overcome ere he could forbear, as prudence dictated. Jones found him a man ready and willing to second all his boldest and most hazardous attempts, so long as reason showed the probabilities of success; but the deed done, none more thoroughly stripped it of all false coloring, or viewed it in a truer light than he who had risked his life in aiding to achieve it.

The person of Dale was in harmony with his moral qualities. It was manly, seaman-like, and of singularly respectable bearing. Simplicity, good faith, truth and courage were imprinted on his countenance, which all who were thrown into his company soon discovered was no more than the mirror of his mind. The navy has had more brilliant intellects, officers of profounder mental attainments, and of higher natural gifts, but it has had few leaders of cooler judgment, sounder discretion, more inflexible justice, or indomitable resolution. He was of a nature, an experience, and a professional skill to command respect and to inspire confidence, tributes that were cheerfully paid by all who served under his orders. The writer of this article has had extensive opportunities of hearing character discussed among the sea-officers of his country; few escape criticism, of some sort or other, for their professional acts, and fewer still, as men; yet he cannot recall a single instance in which he has ever heard a whisper of complaint against the public or private career of Richard Dale. This total exemption from the usual fortunes of the race may, in part, be owing to the shortness of the latter’s service in the present marine, and to the limited acquaintance of his cotemporaries, but it is difficult to believe that it is not chiefly to be ascribed to the thoroughly seaman-like character of the officer, and to the perfect truth and sterling probity of the man.

|

This ship has been differently stated to have been the Liverpool and the Pearl. We follow what we think the best authorities. |

|

The prize-officer of the Lexington was a young American, of a highly respectable family, then an acting lieutenant in the English navy. His prisoners seized an occasion to rise, at a moment when he had gone below for an instant, in consequence of which he was dismissed the service; living the remainder of his life, and dying, in his native country. |

|

It is a curious feature of the times, that, the French ordering the Americans to quit their ports with their prizes, the latter were taken out a short distance to sea and sold, Frenchmen becoming the purchasers, and finding means to secure the property. |

|

This sword has, quite recently, become the subject of public discussion, and of some private feeling, under circumstances not wholly without interest to the navy and the country. At page 63, vol. 2, of Mackenzie’s Life of Paul Jones, is the following note, viz.: |

“This sword was sent by Jones’ heirs to his valued friend, Robert Morris, to whose favor he had owed his opportunities of distinguishing himself. Mr. Morris gave the sword to the navy of the United States. It was to be retained and worn by the senior officer, and transmitted at his death, to his successor. After passing through the hands of Commodore Barry, and one or two other senior officers, it came into possession of Commodore Dale, and now remains in his family, through some mistake in the nature of the bequest, which seems to require that it should either be restored to the navy in the person of its senior officer, or else revert to the heirs of Mr. Robert Morris, from one of whom the writer has received this information.”

That Captain Mackenzie has been correctly informed as to a portion of the foregoing statement, is as probable as it is certain he has been misled as to the remainder. It would have been more discreet, however, in a writer to have heard both sides, previously to laying such a statement before the world. A very little inquiry might have satisfied him that Commodore Dale could not have held any thing as the senior officer of the navy, since he never occupied that station. We believe the following will be found to be accurate.

Of the manner in which Commodore Barry became possessed of this sword we know nothing beyond report, and the statement of Captain Mackenzie. We understand that a female member of the Morris family gives a version of the affair like that published in the note we have quoted, but the accuracy of her recollections can hardly be put in opposition to the acts of such men as Barry and Dale.

The sword never passed through the hands “of one or two other senior officers,” as stated by Captain Mackenzie, at all. It was bequeathed by Commodore Barry to Commodore Dale, in his will, and in the following words, viz.

“Item, I give and bequeath to my good friend Captain Richard Dale, my gold-hilted sword, as a token of my esteem for him.”

We have carefully examined the will, inventory, &c. of Commodore Barry. The first is dated February 27, 1803; the will is proved and the inventory filed in the following September, in which month Commodore Barry died. Now, Commodore Dale was not in the navy at all, when this sword was bequeathed to him, nor when he received it. Dale resigned in the autumn of 1802; and he never rose nearer to the head of the list of captains, than to be the third in rank; Barry, himself, and Samuel Nicholson, being his seniors, when he resigned.

The inventory of Commodore Barry’s personal property is very minute, containing articles of a value as low as one dollar. It mentions two swords, both of which are specifically bequeathed—viz. “my gold-hilted” and “my silver-hilted sword.” No allusion is made in the will to any trust. Only these two swords were found among the assets, and each was delivered agreeably to the bequest. The gold-hilted sword was known in the family, as the “Paul Jones sword,” and there is not the smallest doubt Commodore Barry intended to bequeath this particular sword, in full property, to Commodore Dale.

Let us next look to the probabilities of the case. The heirs of Paul Jones, who left no issue, gave the sword to Robert Morris, says Captain Mackenzie, as a mark of gratitude. This may very well be true. But Mr. Morris “gave the sword to the navy of the United States,” to be retained and worn by its senior officer. It would have been a more usual course to have lodged the sword in the Navy Department, had such been the intention. That Commodore Barry did not view his possession of the sword in this light, is clear enough by his will. He gave it, without restraint of any sort, to a friend who was not in the navy at all, and who never had been its senior officer. This he did, in full possession of his mind and powers, six months before he died, and under circumstances to render any misconception highly improbable.

Can we find any motive for the bequest of Commodore Barry? It was not personal to himself, as the sword went out of his own family. The other sword he gave to a brother-in-law. “Paul Jones’ sword” was bequeathed to a distinguished professional friend—to one who, of all others, next to Jones himself, had the best professional right to wear it—to “Paul Jones’ first lieutenant.” Commodore Dale did leave sons, and some in the navy; and the country will believe that the one who now owns the sword has as good a moral right to wear it, as the remote collaterals of Jones, and a much better right than the senior officer of the navy, on proof as vague as that offered. His legal right to the sword seems to be beyond dispute.

In the inventory of Commodore Barry’s personals, this sword is thus mentioned, viz.—“a very elegant gold-hilted sword—$300.” The other sword is thus mentioned, viz.—“a handsome silver-hilted, do. $100.”

Beneath a bower, where poplar branches long

Embracing wove Seclusion o’er the abode

Of hermit sage, what time the full moon rode

’Mid spectre clouds her star-paved streets along,

Rose on the listening air a plaintive song,

Sweet as the harmony of an angel’s lyre,

And soft as sweet; breathed heavenward from a quire

Of Beauty, hid the encircling shades among.

Of mysteries high, I ween, that sage had dreamed—

Who now, upstarting, clasps his hands to hear

The mystic notes of Nature’s Anthem clear,

Which holiest bards have heard and heavenly deemed!

’Tis even thus as to that sage it seemed—

’Tis Beauty makes the dreams of Wisdom, dear!

———

BY THE AUTHOR OF “HENRI QUATRE.”

———

’Twas the eve of Newbury fair, and the time near the close of the long reign of Harry the Eighth, after monasteries were suppressed. Reform stalked through the land—all things were turned topsy-turvy—abbots and monks beggared, that poor lords might thrive—priests permitted marriage, and nuns driven from their pleasant retreats, were forced to spin for a livelihood. But amid the greater marvels, the townspeople of Newbury had often leisure to ask why Mistress Avery remained so long a widow.

Sitting in her embowered porch, watching the cavalcade of merchants, buffoons and jugglers, on their way to the encampment and site of the morrow’s revels, she attracted many a longing eye. The merchant, whose wandering vocation led him from ancient Byzantium to the shores of the Thames, who came to Newbury to exchange rich silks and foreign jewelry for broadcloth, as he rode by the capacious square tenement, with its deep, embayed windows of dark chesnut-wood, and caught a glimpse of the fair owner, sighed when contrasting his own desolate, wandering lot with that of the fortunate wooer of the rich, comely widow. Mistress Avery was relict of the richest clothier of Newbury, who, dying, left her in sole possession of looms, lands, tenements and leases. Handsome, young, brisk, with riches unquestionable, she attracted tender regards from all quarters—even the proud gentry of Berkshire, with genealogical tree rooting from Norman marauder, far back as the conquest, disdained not an alliance garnished with broad manors, woods of a century’s growth, and goodly array of tenements, of which our widow held fee-simple. But when pressed successively by belted knight and worshipful esquire, she courteously declined their offers, alleging she was bent on marrying one of her own class in life, (if she should change condition,) one who could take upon himself, without degradation, the task of superintending the looms. High born swains repulsed, the field was open to gallants of lowlier rank. But these faring no better, and incurring the ridicule of neighbors, suitors became shy and reserved, seeking to extract token of favor ere they avowed themselves. If the curate called, ’twas merely an inquiry after her soul’s health—the inquiry perhaps linked to a request that she would, from her stores of boundless wealth, add a trifle to the contributions of the poor’s box. The lawyer had his ever ready and undeniable excuses for visiting—leases there were to sign, indentures to cancel. Nor was the tailor barred his plea—was there not much broadcloth yearly fashioned into apparel for lusty serving-man, active apprentice?

Behind Mistress Avery, as she sat gazing at the straggling pageantry, there loitered in hall and doorway the apprentices and domestic servants of the household. Distinguished amongst his companions, by superior stature, stood John Winehcomb, chief apprentice. To him the widow oft turned with remark on passing stranger; the soft regard thrown into her address would have excused boldness in one far less favored by nature than the apprentice, but his answers were submissive, modest, even bashful. An acute observer might perhaps have detected a shade of discontent on the widow’s handsome features, perhaps, as fancifully, attributed it to the coyness and reserve of young Winehcomb; and, indeed, as revolving months lengthened the period of widowhood, there had not been wanting whispers, that ’Prentice John stood a fairer chance with his mistress than all the knights or reputable burgher citizens and yeomen of the county. His appearance certainly did not gainsay the rumor—he had completed his twentieth year, health flushed his cheeks, honesty and intelligence stamped his looks—the features were bold and decided, though of modest expression. In character, he was one of those gifted youths, in whom strict attention and unvarying promptitude supply the place of experience, and who acquire the management and conduct of business, in ordinary cases, rarely entrusted to men of mature years. The clothier, when dying, recommended his spouse to confide business affairs to John—she had done so; in the factory and with the workmen ’Prentice John was all and everything—from his word ’twas useless to appeal.

But when young Winehcomb’s credit with Mistress Avery was canvassed, the gossips were at a loss to affix on decisive marks of favor or tenderness. ’Tis true, he accompanied her to church, but so did the other apprentices—walked by her side, sat next his mistress during prayers, his arm was accepted, his hand arranged the cushions—but then, was he not chief apprentice, would it not be slighting to prefer the services of a junior? Look narrowly at his conduct—there were none of the characteristics of a favored swain, no semblance of behavior indicating one presumptuous of the honor, nor could the absence of these tokens be attributed to natural timidity in the presence of the sex, for at country meetings and fairs, where hoydenish romping was the usual diversion of youth, John participated in rustic gallantries. Yet, sooth to say, though the gossips were at fault, they were not wrong in their conjectures; the widow was deeply in love with ’Prentice John, for his sake had dismissed high-born suitors, wealthy citizens, and, we need hardly say, (though scrupulously regardful of reputation,) had given him many hints, which, alas! he was slow to understand. It might be inexperience, want of self-confidence, or innate modesty, which withheld the youth from tracing her encouragement to its real motive; but from whatever cause, Mistress Avery, who had a very high opinion of her own personal attractions, knew he must be perfectly well acquainted with her riches, was greatly perplexed with his diffidence, his want of susceptibility, and concluded the apprentice must be in love elsewhere to withstand such allurements.

One while, racked with jealousy, determined in very spite and vexation to accept the offer of the first suitor, the next hour affection gained the ascendancy, and she resolved to declare her love. But pride took fire and caused a tumult in the heart, of which young Winehcomb, the unconscious origin, was little aware. How provoking the calmness of his replies, the quiet gaze which met her impassioned glance! Oft with difficulty she refrained from bestowing a hearty cuff on the cold youth, object of fond desire—as often, and with greater difficulty, did she refrain from tenderer salute. To-morrow shall put this wilful-headed boy to the test! If his heart be engaged, it is more than likely he has made an assignation, which I will frustrate! So thought Mistress Avery, revolving a scheme to bring young Diffidence on his knees, or to a direct confession that he loved another. Under pretence of making inquiries respecting the description of merchandise then passing the house, borne on a long train of pack-horses, under conduct of merchants of foreign aspect, the widow beckoned the apprentice (who was standing at respectful distance, beneath the threshold, with his fellow apprentices) to approach her chair, placed outside the house under cover of the overarching porch.

“John!” said the dame, fixing her large eyes on the youth, “I warrant there is store enough of trinkets and finery in yon bales to satisfy the wants of every maiden in Newbury. Happy the youth whose wages are unspent, for to-morrow, by ’r Lady! he might buy the love of the most hard-hearted damsel. Certes, no swain need die of love, if he have money in his purse!”

“If the love were bought by those foreign pedlar wares, it would not be much for a Newbury lad to boast of,” replied the young man, blushing—for the gaze of his mistress was keen and ardent.

“Are the lads of Newbury then so disinterested, Master John,” exclaimed the widow. “Well! I will put one, at least, to the proof. I must walk through the fair, if only to chat with my tenants’ wives from Spene and Thatcham, and shall need your protection, for these strange foreigners may be rude, and Cicely is such a coward she would run away.”

Mrs. Avery was rather baffled by the result of her own feint; for, contrary to expectation, she could discover neither chagrin nor disappointment; the apprentice answered cheerfully, he should be proud to attend on his honored mistress, and would not forget a good cudgel, more than a match for any foreigner’s steel—nay, to ensure her from insult, he would bring all his fellow apprentices. This was more than the lady desired. She was again puzzled, and declined, rather pettishly, the extra corps of gallants, volunteered by the apprentice, more especially, as she affirmed that it was contrary to the letter and spirit of their indentures, which guaranteed festival and fair-days to be at their own disposal. But they would gladly abandon the privilege to do her service, rejoined the pertinacious and simple youth, with ill-timed assiduity.

“Fool!” muttered the widow between her teeth, but not so indistinctly as to pass unheard by the apprentice, who immediately drew back abashed.

A bright morrow gladdened the hearts of the good folk of Newbury. The morn was occupied in the sale and purchase of commodities—the staple article of the town was readily exchanged for foreign merchandise, or broad Spanish pieces, as suited the inclination of the parties dealing. These were busy hours for young Winehcomb and his associates, but amply redeemed by the gayety and attractive dissipation of the afternoon. In walking through the fair, Mistress Avery leaned on the youth’s arm, an honor envied the apprentice by many an anxious, would-be suitor. Ere growing tired of the drollery of the jugglers, mountebanks and buffoons, or the more serious spectacle of the scenic moralites, they encountered Master Luke Milner, the attorney, who thought the opportunity should not be thrown away of endeavoring to gain the widow’s good graces. Master Luke believed his chance very fair—he was of good family, on the youthful side of thirty, but exceedingly foppish, after the style of the London gallants, but caricatured—too many ribbons on doublet, too many jewels on beaver, shoes garnished with roses large as sunflowers. “The worshipful attorney will never do for me,” thought Mistress Avery! She had often thought so, and was blind to many courtesies and compliments which the learned man ventured to throw in with his legal opinions. But now she had a part to play, a stratagem to practice on the feelings of young Winehcomb. Love, like hunger, will break through every restraint; she scrupled not making the lawyer’s vanity subservient to her policy, and, accordingly, listened to his flattery with more than ordinary attention, keeping an eye, the while, on ’Prentice John, to observe the effect of the legal gallant’s honeyed speeches. Alas! for poor, love-stricken Mistress Avery—no burning jealousy flushed the cheek of John—lightened in his eye, or trembled through his frame! Hearing the conversation grow each moment more interesting and tender, believing himself one too many, he politely retired to a respectful distance. Was he so cold and insensible, the handsome blockhead? soliloquized Mistress Avery, heedless of the lawyer’s flowing speeches—I will break the indentures—banish him the house! The wretch!

Not cold, not insensible, Mistress Avery, for see! Even whilst he loiters, there approaches a party from the village of Spene, with whom our apprentice is intimate—he laughs, chats with the young men and maidens, and finally, as the mirth grows more uproarious, salutes a very handsome, fresh colored, smart young damsel. The dame, who witnessed the scene, stung with jealousy, believing her suspicions confirmed, broke off abruptly, whilst Master Luke was at the very acme of his tender theme; leaving the astonished gallant, cap in hand, to the derision of acquaintance, who sarcastically advised him to repair the loss by writ of error.

——

Though the widow took no notice of the incident which aroused her jealousy, John was made sensible he had incurred her displeasure. She walked silent, moody, reserved, scarcely replied to his remarks; her large, dark eye flashed anger, but the apprentice, though awed, was struck with its beauty, more struck than he had ever been. It was a new sensation he experienced. He inwardly deprecated the threatened wrath, wondered by what sad mischance he had incurred it, was more tremblingly alive to her resentment, than when oft-times—during the course of apprenticeship—conscious of deserving it. A strange, uneasy feeling began to haunt him—he was sensible of loss of favor, and though, after taxing memory, unconscious of merited disgrace—was surprised, inquieted, by the deep dejection of spirits under which he labored. It seemed as though he had incurred a loss, of which he knew not the extent till now. His arm trembled, and she snappishly rebuked his unsteadiness; he again encountered her glance—it was wild, angry, fierce, yet he felt he could have looked forever.

They were opposite one of those temporary taverns, erected for the accommodation of the higher classes frequenting the fair—tricked out with gaudy splendor, yet affording delicious viands, choice wines to wearied strollers. It so happened that, passing by the open doorway, their progress was arrested by Master Nathaniel Buttress, the wealthy tanner—mean, avaricious, advanced in years, yet ardently longing to add the widow’s possessions to his own accumulated riches. With studied bow, and precise flourish of beaver, he bade Mistress Avery good day, and followed up the salute by invitation to sip a glass of sack, the fashionable beverage of the time. At fair-season, there was not the slightest impropriety, either in the offer, or its acceptation—it was quite in the usual license of these festivals. But ’Prentice John was doubly surprised; in the first place, that the miserly tanner (his niggardliness was proverbial) should have screwed up courage to treat any one with the high-priced nectar—and that his arm, which he gallantly offered, should have been accepted with alacrity by the fair dame, who, our apprentice was aware, had oft made devious circuits, on many occasions, to elude a meeting. Young Winehcomb found himself, lacquey-fashion, following in the rear. He was deeply mortified—such circumstance had never happened before—yet, though vexed, the annoyance was only secondary to extreme surprise at the character of his own feelings. He had valued highly the good will, kind words, and occasional gifts of the lady, as proofs of favor, founded on his honesty, diligence and promptitude, or, at least, without deeply analizing his feelings, believed that in such spirit he received them. But now, smarting under disgrace, it seemed as though lost favor was dear for its own sake—bereft of smiles to which he had been insensible till the present hour, he was unhappy, miserable. ’Prentice John had great difficulty in withholding his cudgel from the tanner’s back, but though he gave him not a beating, he mentally promised one. Master Buttress, elated with good fortune, was more vain-glorious than cautious; unlike prudent lover, uncertain of continuance of sudden favor, dreading loss of vantage ground, snatched by eager rivals, he escorted the dame to a conspicuous seat, whence they could behold the fair, from whence his favored lot was visible to all. The ready drawers, ere ardor called, hastened to place before the guests a tray laden with costly delicacies, crowned with silver flagon full of the favorite potation. Young Winehcomb, who sat apart, though partaking the dainties, was maddened to behold his mistress listen so complacently to the addresses of the veteran suitor. Could she be serious? And if she were—what then? Was she not absolute mistress of herself, her wealth—and was he so specially concerned in her choice? This self-questioning elicited the conviction, startling though true, that he was deeply, personally concerned. He was, then, undeniably in love with his mistress! Was the passion of sudden growth, the birth of the present hour? Alas! no—it had been long smouldering unconsciously—nay, if he doubted, memory flashed innumerable, though till now, unnoticed facts proving its existence—and he had foolishly let slip the golden chance of wooing till too late—till his advantages were the prey of a successful rival!—his own affection only brought to light by the torch of jealousy. Such was the cruel, torturing position of young Winehcomb. ’Twas aggravated in being obliged to listen to the tanner’s flattery, to witness its favorable reception. Nay, worse—he became conscious that Mistress Avery remarked his inquietude, his ill-suppressed hatred of Master Nathaniel, as her eye was often for a moment bent on him. He was convinced she took pleasure in his torments, for on these occasions her manner—though strictly within the rigid limits of propriety—invariably was more marked and tender toward the detested, fulsome niggard. He had heard, alas! such was the custom of the sex. Often was ’Prentice John resolved on leaving the lovers to their own conversation, but restrained anger on reflecting it was his duty to be present with and protect Mistress Avery, till she quitted the fair and returned home. Nor did he relish the notion of leaving the field altogether to the tanner—jealousy united with sense of duty in detaining the youth.

Master Buttress was in rare good humor; he could not deem otherwise but that he was the fortunate, chosen man, and he found leisure in the intervals of fits of gallantry, to conjure flitting visions of broad manor added to broad manor, tenement to tenement, and to picture the future Master—nay, Worshipful Master Nathaniel Buttress, richest gentleman in the county of Berkshire. The only damp on his high spirits was the present outlay; he had been drawn into expenses far beyond usual habits; had never been guilty of similar extravagance; the veriest prodigal of London could not have ordered a more costly board; and that tall, rosy-cheeked lad imbibed the precious sack with the avidity of a sponge, and never looked a tithe the better humored, but sat grinning menaces at him—the donor of the feast! Well! well! all should soon be remedied, and the disagreeable, lanky apprentice turned adrift.

“But who is that now passing the tavern; is it not Master Luke Milner, the attorney? How enviously he looks! he has the reputation of having pressed hard his own suit, but in vain! If I invite him, he will gladly come—drink the widow’s health—and it will save me half the reckoning!” So reasoned the tanner. The lawyer accepted the invitation, though a slight shade of displeasure, he could not wholly dispel, flushed his brow. Master Luke entered, bowing lowly to the widow. Drawing a chair, near as good manners admitted, to the fair dame, he carefully deposited scented gloves and jeweled beaver on adjoining bench, and, in sitting, showed anxiety to display a trim foot, though rather overshadowed by the large roses. The tanner soon perceived that avarice had induced a grievous oversight, for the widow was not quite won. It was both unaccountable and annoying—how perverse these women are! she seemed now disposed to extend as much favor to Master Luke as she had previously exhibited to Master Buttress. ’Prentice John was pleased and distressed at the scene—glad of the tanner’s discomfiture, he was enraged at the other’s success. The elder suitor had shown indifference to the presence of the apprentice, viewed him as a necessary appendage to the widow’s state, or, at worst, a tax on his purse to the extent of sack imbibed; but our lawyer, nearer John’s own age, and gifted with keener eye than his rival, liked not young Winehcomb’s vicinity, his prying, resolute gaze.

“Mistress Avery,” said the lawyer blandly, “our young friend appears uneasy; nor do I wonder, for more than once, in the fair, did I hear red, pouting lips lament the absence of Jack Winehcomb. I pray thee, suffer the lad to stroll where he lists; Master Nathaniel and your unworthy servant, with permission, will zealously protect the pride and boast of Newbury.”

If John had broken any engagement by attendance on her, replied the dame—and a keen smile, part malicious, part searching, lit up the widow’s features as she gazed on the disconcerted youth—let him seek Cicely, who was not far off, to take his place, and he had full permission to absent himself. ’Prentice John, though vexed and out of countenance, said he had no other engagement than duty enjoined, and he was entirely at his mistress’ command.