* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Death of an Ambassador

Date of first publication: 1957

Author: Manning Coles

Date first posted: Apr. 4, 2022

Date last updated: Apr. 4, 2022

Faded Page eBook #20220404

This eBook was produced by: Stephen Hutcheson, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

RECENT CRIME CLUB SELECTIONS

GEORGE BAGBY: DEAD WRONG. A Broadway dancing star, two wealthy cousins, a socialite fiancée, and a batty old lady all had pronounced opinions concerning what might have been an attempted suicide. They pressed them on Inspector Schmidt of Homicide—and it was up to him to decide which ones were right and which ones were “dead wrong.”

$2.95

STEPHEN RANSOME: SO DEADLY MY LOVE. Lynn Griffith spent three fear-suffocated days on a strange beach in the hands of two kidnapers, one gentle and one brutal. Once she heard someone softly whistling a familiar song . . . “Ebbtide.” Returned after payment of a large ransom, Lynn tried to recall some details which would help identify her abductors. Remembrance and recognition struck like a double blow when she arrived home to find her husband impatiently awaiting her, whistling his favorite song . . . “Ebbtide”!

$2.95

CHRISTOPHER LANDON: UNSEEN ENEMY. His tiny three-year-old daughter Margaret was the only important thing in John Stebbings’ dreary life. Then Margaret was kidnaped. When the police gave up, Stebbings went to private detective Harry Kent. Kent, with the help of his attractive wife and journalist friend, began a hunt (in spite of the something Stebbings was hiding) which led him into a vicious racket, a moving love affair, and—he fervently hoped—into the arms of a lost and frightened little girl.

$2.95

SELDON TRUSS: THE TRUTH ABOUT CLAIRE VERYAN. Claire Veryan’s youth and beauty didn’t keep prison doors from closing behind her. Outside her prison walls were friends and foes—all with good, or deadly, reasons for helping her escape. Could an ingenious masquerade unmask a murderer and reveal the whole truth about Claire Veryan?

$2.95

FOR MORE THAN a hundred years readers have been enjoying detective stories; and for more than twenty-five years they have found the best mystery and detective stories in the Crime Club.

Look for the Crime Club gunman who points the way each month to new books of high entertainment value. The partial list of authors of our Crime Club Selections justifies such a claim.

GEORGE BAGBY

MANNING COLES

LESLIE CHARTERIS

FREDERICK C. DAVIS

DORIS MILES DISNEY

RUTH FENISONG

E. X. FERRARS

THE GORDONS

BERT AND DOLORES HITCHENS

KATHLEEN MOORE KNIGHT

PHILIP MACDONALD

STEPHEN RANSOME

GEORGES SIMENON

ARTHUR W. UPFIELD

THE CRIME CLUB

Published by

DOUBLEDAY & COMPANY, INC.

Publishers of Amy Vanderbilt’s

Complete Book of Etiquette

Letterpress U.S.A.

70839

Price, $2.95

Death of

an Ambassador

MANNING COLES

A CRIME CLUB SELECTION

The fatal shooting of the much publicized Esmeraldan ambassador shocked London and gave Scotland Yard a dramatic puzzle to unravel. Immediately the Esmeraldan Embassy complicated the Yard’s work by holding a suspected Frenchman beyond reach of the police.

This sent Tommy Hambledon of the Foreign Office’s intelligence service to Paris and to his old friend Letord in the French Sûreté. Together they set themselves to tracking down the ambassador’s dark past and a murderer’s present whereabouts.

Just how the crisscrossing clues and numerous suspects tied into the ambassador’s death was the big problem to untie before it could snare Hambledon and Letord in new deaths—that could be their own.

Scene: London and Paris.

This novel has not appeared in any form prior to book publication.

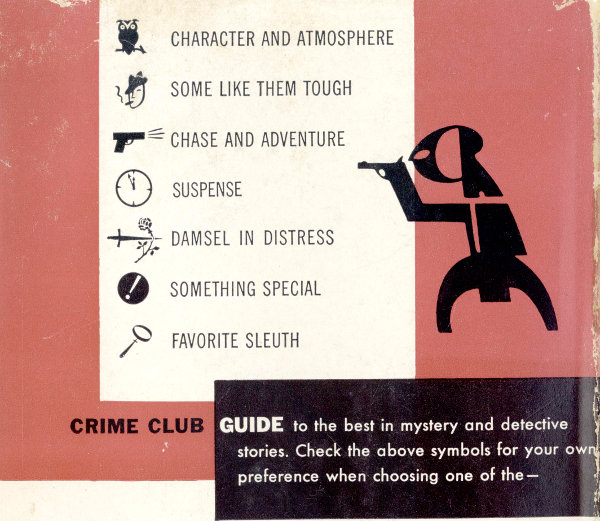

CHECK THIS SYMBOL

ON BACK OF JACKET

JACKET DESIGN BY BOB RITTER

BY MANNING COLES

Novels:

THE FAR TRAVELLER • HAPPY RETURNS

BRIEF CANDLES • THIS FORTRESS

Intrigue and Adventure:

DEATH OF AN AMBASSADOR • BIRDWATCHER’S QUARRY

THE BASLE EXPRESS • THE MAN IN THE GREEN HAT

ALL THAT GLITTERS • ALIAS UNCLE HUGO

NIGHT TRAIN TO PARIS • NOW OR NEVER

DANGEROUS BY NATURE • DIAMONDS TO AMSTERDAM

NOT NEGOTIABLE • AMONG THOSE ABSENT

LET THE TIGER DIE • WITH INTENT TO DECEIVE

THE FIFTH MAN • GREEN HAZARD

WITHOUT LAWFUL AUTHORITY • THEY TELL NO TALES

TOAST TO TOMORROW • DRINK TO YESTERDAY

Books for Boys:

GREAT CAESAR’S GHOST

A CRIME CLUB SELECTION

The fatal shooting of the much publicized Esmeraldan ambassador shocked London and gave Scotland Yard a dramatic puzzle to unravel. Immediately the Esmeraldan Embassy complicated the Yard’s work by holding a suspected Frenchman beyond reach of the police.

This sent Tommy Hambledon of the Foreign Office’s intelligence service to Paris and to his old friend Letord in the French Sûreté. Together they set themselves to tracking down the ambassador’s dark past and a murderer’s present whereabouts.

Just how the crisscrossing clues and numerous suspects tied into the ambassador’s death was the big problem to untie before it could snare Hambledon and Letord in new deaths—that could be their own.

Scene: London and Paris.

This novel has not appeared in any form prior to book publication.

Favorite Sleuth

DEATH OF

AN AMBASSADOR

A

Tommy

Hambledon

Story

BY MANNING COLES

Published for The Crime Club by

Doubleday & Company, Inc.,

Garden City, New York, 1957

To

A. H. G. Hoggarth M.A., F. R. Hist. S.

“Forty Years On.”

All of the characters in this book are fictitious

and any resemblance to actual persons,

living or dead, is purely coincidental.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOG CARD NUMBER 57-10009

COPYRIGHT © 1957 BY DOUBLEDAY & COMPANY, INC.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

FIRST EDITION

| CONTENTS | |

| one | Murder in Mayfair, 9 |

| two | Escape, 17 |

| three | The Predikant of Alkdam, 25 |

| four | Southampton-Le Havre, 32 |

| five | By the Petit Pont, 39 |

| six | Middleweight Undertaker, 46 |

| seven | Dossier of an Ambassador, 53 |

| eight | Darkness in Paris, 61 |

| nine | Scullions’ Entrance, 71 |

| ten | The Policeman’s Story, 78 |

| eleven | Bank Robbery, 85 |

| twelve | The Cat with Four Eyes, 93 |

| thirteen | The Blind Men, 101 |

| fourteen | Eddi the Cabbage, 110 |

| fifteen | The Ladder Dodge, 118 |

| sixteen | Three Lumps of Sugar, 125 |

| seventeen | Gogo the Dwarf, 133 |

| eighteen | Métro to Abbesses, 143 |

| nineteen | Speaking Tube, 153 |

| twenty | Jean Télémaque, 163 |

| twenty-one | Bravo 173 |

| twenty-two | Lament, 181 |

CAST

Pedro Maximilio Teluga, the Esmeraldan Ambassador to the Court of St. James, otherwise Enrigo le Canif

Gaston Dubois of Paris

Thomas Elphinstone Hambledon

Commander Bagshott of the C.I.D.

Antoine Letord, Chief Superintendent of the Sûreté in Paris

Madame Dubois

The Reverend Nicolaas van Leyst of Alkdam, Holland

Inspector Georges Guernan of the Sûreté

François de Montargent de la Sainte Croix

Robert Écritet, a criminal lawyer in Paris

Paul Joseph, an art dealer in Paris

Gogo, a dwarf

Jean Saucisse, Jacques le Delicat, Fréchant, Veron, Pepi l’Agneau, Eddi le Chou and others, all crooks

Police, café proprietors, etc.

SCENE, Paris

TIME, the present day

The sun was going down upon a gloriously hot June day; level rays came over the roofs of the terraced houses upon the west side of Whatmore Street, Mayfair, to shine directly into the attic windows of the similar terrace of houses upon the east side. Whatmore Street runs from Curzon Street into Piccadilly and, like its neighbours upon either hand, Stratton Street and Bolton Street, is a road of the most impeccable dignity.

There were a number of people strolling slowly along the pavements, in twos and threes, in the cool of the evening; as they passed one of the tall houses in the middle of the west side the passers-by glanced interestedly at it, for this was the new Esmeraldan Embassy. The house had recently been repainted white from roof to pavement level and all the woodwork was a deep emerald green. There were three steps up to the front door, which had a pillared portico; over the portico was a flagstaff leaning forward, from which hung the emerald-green flag of Esmeralda, the small Central American state which, under an energetic and enlightened President, was making such strides in the world of progress.

The passers-by were hoping, vaguely, that something amusing would happen, for although the Esmeraldan Embassy in London had only been open a matter of weeks, the high spirits of the pleasure-loving Spanish American staff had already caused comment in the West End.

There was not much to interest the strollers on this June evening except the lights in the open, uncurtained windows of the Ambassador’s drawing-room. Three magnificent glittering chandeliers hung from the ceiling of this room; they were all lit up and displayed plainly the large looking glasses upon the green walls and the expensive furniture recently installed by a well-known firm. Also displayed was the Ambassador.

He was a young man to hold such a post, not more than thirty or so, one would say, but already beginning to run to seed a little round the jaw and under the eyes. He wore a moustache and a small pointed beard and was in full evening dress; he was talking in the most animated manner with a small man in a lounge suit. They were both, it seemed, arguing vehemently; their words were not audible in the street, but their gestures spoke for themselves.

The three adjoining houses opposite to the Esmeraldan Embassy were thrown together in 1883 by one Euphemia Morley on her retirement as housekeeper in the Bishop’s Palace of a west-country diocese. She knew exactly what was wanted in the way of quiet respectable accommodation for country clergy and their ladies when visiting the metropolis; such accommodation was practically non-existent in 1883 and Euphemia supplied a real need. It is no longer quite so exclusive as it was in Euphemia’s lifetime, nor is it so inexpensive, but its name is still the first to rise in the minds of provincial clergy when planning a visit to London.

The door of Morley’s was standing wide open upon this fine evening. A Canon from one of the remoter dioceses, pleasantly replete and mildly excited on the first evening of one of his rare visits to London, came out of the door and stood upon the top step to look happily about him.

His attention was claimed by the lighted windows of the Embassy opposite, especially those of the room with the sumptuous chandeliers. There were two men arguing visibly. They danced about, gesticulating widely, and occasionally shook their fists at each other, and the Canon could not but be entertained. He watched for a few minutes and was then seized in conscience for window peeping.

“These foreigners,” he murmured gently, “so excitable always. The Latin temperament.”

He was on the point of going on his way when the smaller of the two men raised both arms in the air and shook his fists above his head as though appealing to heaven to remedy some injustice. At precisely the same moment the younger and taller of the two leaned suddenly forward and fell to the ground out of the Canon’s sight.

“That man,” said the Canon, half aloud, “has had some kind of seizure.”

The smaller man uttered a loud cry which was audible in the street, and instantly the scene changed. People came running into the lighted room from both sides at once, some of them bent over the fallen man while others seized the smaller one by both arms and dragged him back. A man in green livery rushed to the windows, unhooked the curtains and drew them close. The scene was over.

A quarter of an hour later, every blind was drawn down in the Esmeraldan Embassy and next morning the emerald flag was hanging dismally at half-mast. His excellency, the Esmeraldan Ambassador to the Court of St. James, had been rudely hustled to the company of his ancestors.

The news came out too late for any edition of the evening papers but it was in time for the last news summary of the B.B.C. “We regret to announce,” said the measured voice, “that His Excellency, Señor Pedro Maximilio Teluga, the Esmeraldan Ambassador, died suddenly this evening at the Esmeraldan Embassy in Whatmore Street.” The announcement issued from the Embassy had stated bluntly that Teluga had been shot dead by a man whom he was interviewing, but the B.B.C. does not broadcast sensational stories until they have been officially confirmed. In any case the Canon was in bed and sound asleep long before that news was broadcast.

The editor of the Daily Wire, however, was not—far from it. This was the sort of thing he liked; good meaty stuff with plenty of thrills and not too much grief, well situated in the middle of London’s West End and well timed in a period when as a rule there is precious little news to be had. He lifted an office telephone and said: “Send in Biggs, now.”

Biggs was his star reporter, a thin sallow man with a nose for news like that of a bloodhound who has just been offered a murderer’s boot.

“Biggs, the Esmeraldan Ambassador’s been murdered. Shot dead by a man visiting him; at least, that’s what they say.”

“Man get away?”

“No, the staff collared him.”

“I wonder what they’ll do with him. I suppose they could hold on to him. Extra-territorial, embassies,” said Biggs. “Bit awkward. British nationality?”

“No details. You know the place?”

“Oh yes. In Whatmore Street, opposite The Dog-Collar.”

“The what?”

“Morley’s. Where all the parsons go.”

“Oh yes, of course. Biggs, if you can’t do anything at the Embassy, you’d better take a front room at Morley’s and keep an eye on the place. I’ll send a photographer up to keep you company.”

Biggs glanced at his watch. “There’s half an hour. Morley’s locks up at midnight.” He left the room and borrowed a suitcase on his way out. One does not arrive at Morley’s without luggage.

There was no crowd in Whatmore Street, since the news was not yet public; the street was, in fact, almost deserted except for two metropolitan policemen on duty at the front door of the Embassy. Biggs went up to the door, one of them stopped him and he said: “Daily Wire.”

“No good,” said the policeman. “No admission, no interviews, no statements, no callers.”

“No hawkers,” said Biggs, “no circulars, no nothing.”

“That’s right.”

“Want to keep it all to themselves, do they? What happens if I walk up and ring the bell?”

“They don’t open. They ring up Scotland Yard and ask why the two muttonheaded dummies outside the door—that’s us—are letting tiresome people ring their bell.”

“How do you know they’d do that?”

“Because they’ve done it twice already.”

“Looks as though I’m wasting my time,” said Biggs, who knew finality when he met it.

“That’s right. Come back in the morning; they’ll open up sometime, I suppose.”

“I suppose so. Well, thanks very much. Good night.”

Biggs took his hat off, brushed it with his sleeve, straightened the brim and put it on again, after which he pulled his coat tidily into place, stowed his fountain pens away out of sight, straightened his tie and crossed the road to ring the front-door bell of Morley’s. After a short pause it was opened and he walked straight in.

“Good evening. I shall want a room here for a couple of days, I hope very much that you have a vacancy.”

“Well, sir,” said the night porter doubtfully, “we are very full up at the moment on account of this Conference on Parochial Duties and Privileges as is being held in London at the moment, sir.”

Biggs smiled.

“That is why I am here,” he explained. “I am the clerk to one of the principal Organizing Secretaries and my chief thinks it would be as well if I were here, at Morley’s, where so many of our delegates are staying.”

“I see, sir,” said the night porter, who was turning over the pages of the register. “Well, it looks as though you were going to be lucky, sir, if I may so put it. One of the delegates ’ad—had—to go back home on account of illness and he clocked out—that is, sir, he left the hotel late this evening and there is his room vacant, if that would suit you, sir. Number 17, first floor front.”

“Providential, indeed,” said Biggs, and meant it.

“I’ll take you up, sir,” said the porter, taking a key off the hook.

“I may have to make a number of telephone calls—”

“Bless you, sir, you can sit in your own room and talk on the telephone all day and all night if you so wish. There’s a telephone in every room besides the ’ouse—house telephones, sir.”

“Splendid. Admirable,” said Biggs, and did not repeat “Providential” only because he did not wish to overdo it.

The next morning the news broke with a roar like a collapsing dam and the only people who did not appreciate it were Scotland Yard, which is the headquarters of the Metropolitan Police, and, presumably, the Esmeraldans. A murder in an embassy and they were holding the accused as prisoner.

Scotland Yard, in the person of one of its highest officials, rang up the Esmeraldan Embassy to convey the respectful condolences of the Metropolitan Police upon this unparalleled outrage and to offer any assistance in their power in unravelling the crime.

The First Secretary was most grateful for the condolences but needed no help in unravelling the crime. They had the assassin in custody. With renewed thanks, good morning.

Commander Bagshott of Scotland Yard rang up Thomas Elphinstone Hambledon of Foreign Office Intelligence.

“I say, Hambledon, could you come round here? You’ve heard that somebody’s shot the Esmeraldan Ambassador——”

“I saw headlines in my morning paper,” said Hambledon. “Why? Does anybody mind?”

“Now don’t stall. This is right up your street, come on.”

Hambledon walked into Bagshott’s office ten minutes later, threw his hat into the IN tray and said: “What is all this and why worry me?”

“Because you know the Esmeraldans and they’ll remember you. After all, it was your lottery winnings that financed the revolution which chased out President Massimo and put this lot in——”

“I know. I am very pained that no statue of me has yet been erected in St. Martin. Never mind, they may do it someday. Well?”

“They’ve got a prisoner in the Embassy accused of the murder and they won’t give any information about him. The Commissioner himself, no less, rang them up this morning and they hung up on him. So I went round myself to interview somebody and was not admitted.”

“And there wasn’t a darn thing you could do about it,” said Hambledon. “Too disrating. Go on.”

“We don’t know who this fellow is they are holding; he may be a British subject. Teluga is said to have been shot, but all the windows were wide open and nobody in the street outside heard a shot fired. The——”

“Perhaps the assassin used a catapult.”

Bagshott sighed and tried again.

“The Commissioner’s compliments and as you’re about the only man in London likely to be persona grata at the Esmeraldan Embassy, would you be so good as to pay a formal call of condolence and see what you can get out of them?”

“What? Claw-hammer coat, striped trousers and a top hat?”

“And a tie,” said Bagshott.

An hour later a glittering Daimler drew up at the Embassy door and Mr. Hambledon, in the garments of ceremony, alighted. The Embassy had been advised of the Señor Hambledon’s coming, and the green door, with long black ribbons tied to the knocker, opened to admit him.

Hambledon went in and was received by the First Secretary in a small room at the back of the hall. After the exchange of stately courtesy on both sides, Hambledon got down to business. He was empowered, he said, to offer all the facilities of the British Courts of Justice for the trial of the accused with the utmost rigour of the Law.

The First Secretary was overcome with gratitude for the noble offer but pointed out that the crime had been committed within Embassy precincts, which were, as his distinguished visitor was well aware, extra-territorial. “This,” said the First Secretary, tapping an exuberant Turkey carpet with the toe of a patent-leather shoe, “is the sacred soil of Esmeralda.”

Hambledon agreed enthusiastically, but asked if, for their records, the British Government might know who the accused man was. Was he, for instance, a member of the Embassy staff?

The First Secretary exhibited horror and said that no true-born Esmeraldan would ever etc, etc.

A long and juicy list of Esmeraldan assassinations within the past fifty years slid through Hambledon’s mind, but he only said that naturally that would be so. It was, in fact, on that account that he had come to ask a few particulars such as the name, address, and nationality of the accused.

“The point is this,” he added. “If the man was resident in Britain, the police here could obtain authority to search his dwelling and obtain, perhaps, evidence of the motive which inspired so dreadful a deed.”

The First Secretary was most grateful but said that it seemed that the prisoner had come to Britain merely in order to commit this crime. He did not appear to have resided here.

“And his name?”

“Alas! We have good reason to believe that the name he gave us is not really his. An alias, esteemed sir, a transparent alias.”

“And his nationality?”

“One of those unfortunate creatures who are known as Stateless Persons, to the best of our knowledge.”

“And he was staying in London?”

“If he is to be believed, he spent one night on a grassy bank in your most beautiful Hyde Park,” said the First Secretary with a bland smile. “Believe me, this, your visit, adds but one more item to the long list of benefactions which your immense kindness has showered upon Esmeralda. I cannot express our deep sense of the obligations we owe you. Come again, respected Señor Hambledon, upon a happier occasion.”

“So I came away,” said Tommy, reporting to Bagshott. “It is my considered opinion that they have made up their minds to erect a gallows in the Embassy back yard and hang him and I don’t know what you can do to stop them.”

The rest of the afternoon passed slowly. Biggs suffered acutely from boredom, as did the photographer whose unhappy lot it was to share his vigil.

The houses in Whatmore Street, all alike, had flat-fronted façades of white-painted stucco, topped by a row of small dormer windows. Most of these attic windows had bars across them, including those of the Esmeraldan Embassy.

Biggs and the photographer were playing cards, smoking incessantly and drinking whisky to pass the time between meals. It was Biggs’s deal and the photographer stood up to stretch his legs, strolled across to the window and looked out.

“Nice evening,” he remarked. “Another fine day tomorrow, I shouldn’t wonder, it’s a nice clear sk——” His voice broke off.

“What’s the matter?” asked Biggs, getting up hastily.

“That left-hand attic window. Blind’s gone up and there’s——”

“Someone’s wrenching at the bars——”

“The prisoner——” they said in unison, and the photographer dashed for his camera.

“He’s got two of the bars away——”

“And there goes the third,” said Biggs.

“He’s got out.” The camera swung into position and the operator focussed carefully. Click.

The dormer windows were a foot or so back from the edge of the roof and the man’s movements were not yet visible from the street below.

“He’ll go along the roofs, I suppose.”

“I don’t think so,” said Biggs. “The Esmeraldans had barbed-wire entanglements put up where their roof joins the next-door houses. Don’t want bombs through skylights.”

“Who would?” asked the photographer indignantly. “This is London. He’s crawling along the edge—ugh! Makes my spine creep——”

“He’s making for a down pipe from the gutter—he’s reached it.”

The man on the roof raised himself, and the camera clicked again and again.

“He’s climbing down over the edge,” said Biggs, and even his voice sounded breathless. “He’ll get a grip on the top of that down pipe if it doesn’t break away——”

A few of the crowd below saw the two faces at the window staring upwards and themselves looked up, their neighbours looked up also; seen from above, a forest of hats became a forest of faces, and even the faces grew paler. There came a low murmur from the crowd, instantly stilled as the man on the roof got a grip of the top of the pipe and very slowly let himself slide over the edge. That is, the movement started slowly and ended with a sudden slip and a jerk.

“I shall be sick in a minute,” said the photographer, but he did not cease operating.

“Keep at it,” said Biggs. “You may get one of him turning over in mid-air yet.”

Apparently the same thought occurred to the police also, for they began hurriedly to clear a space below the pipe.

The man must have shifted his grip, for he slid down the pipe until brought up by the first tie which held it to the wall. A short pause and another slide, another pause. There was a deathly silence in the street, broken by a gasping sob from somebody. Another slide and a stop.

“Nearly there,” said Biggs, “nearly there.”

Three of the police stepped forward; the man turned his head, looked down and slithered the last ten feet into their welcoming arms.

“A—ah,” said the crowd.

“You,” said the police, “are coming with us, please.”

“Messieurs,” said the man, clinging tightly to a sergeant’s coat sleeve, “it is precisely that which I most desire.”

A series of signals was passed from one policeman to another, which resulted in a taxi whirling up from Piccadilly. As it came to a stop, a loud and angry cry floated down from the top storey of the Embassy. Once more the crowd looked up to see an angry face leaning from the top window and a furious fist being shaken to the accompaniment of words in the Spanish tongue.

The prisoner paused with one foot on the step of the taxi, looked up and made one of those gestures which transcends the barriers of language. He then stepped in with an escort, the door slammed and with a ragged cheer from the crowd the taxi drove away.

Biggs threw himself upon the telephone.

A few moments later the door of the Embassy opened and a man stood on the threshold. He beckoned to the nearest policeman, who strode up and saluted smartly.

“The assassin,” said the Esmeraldan carefully, “has evacuated himself by window. Kindly arrest and restore to our judica—justica—judification. Prestissimo.”

“Sforzando,” said the policeman, who came of a musical family. He saluted again, about turned and marched away. The Esmeraldan front door slammed.

The prisoner was taken to Scotland Yard and Bagshott, warned in advance by telephone, awaited him eagerly. Tommy Hambledon, who could run when he wanted to, came cantering up Whitehall and turned the corner into Great Scotland Yard at the same moment as the taxi.

Hambledon came into Bagshott’s office and found the Commander alone. Tommy looked round the room.

“What?” he said. “Don’t tell me I’ve beaten the taxi on the last lap, or has the prisoner been abducted even from your august corridors?”

“He’s having a wash and brush up, free,” said Bagshott. “He not only needed it but even asked for it.”

“Did he crawl out of a drain?”

“No. He got out of an attic window and slid down a rain-water pipe into the custody of the police. He seemed delighted to be among them.”

“Slid three storeys down by a pipe? He must be an athlete.”

“Or a cat burglar,” said Bagshott.

“Same thing. Do the Esmeraldans know they’ve lost him?”

“Oh yes, indeed they do. They want him back, they have been ringing up the Commissioner about him. He is to be returned instantly, whole and alive, and the police who carried him off under their very eyes are to be arrested and dismissed the Force.”

Bagshott’s telephone rang. He lifted the receiver, said: “Right. Send him up,” and replaced the receiver. “Our visitor.”

The next moment the man was shewn in; a small, dark, sinewy man with long arms for his height and large, powerful hands. He was given a chair and encouraged to explain himself.

“You speak English?”

“A little, but so slow and careful, you know? I speak French.”

“Then we will speak French,” said Bagshott. “What is your name, please?”

“Gaston Dubois.”

“Nationality?”

“French.” Dubois added an address in Paris, “for I am of Paris, monsieur, I was born there.” He grinned cheerfully and settled himself comfortably in his chair.

“How long ago?”

“In 1915, monsieur.”

“Thank you,” said Bagshott. “Now, would you like to explain to me why you were climbing down a rain-water pipe of the Esmeraldan Embassy half an hour ago?”

“But, with the greatest pleasure in the world, monsieur. You see, if I stay they are for hanging me in the yard at the back. Messieurs”—Dubois beamed upon Hambledon and Bagshott impartially—“messieurs, I am of those who have a conscientious objection to capital punishment when applied to me, so I came away. You applaud the decision, yes? Messieurs, they were erecting a gallows.”

“Oh, were they,” said Bagshott grimly.

“Did they hold a trial?” asked Hambledon. “I assume they did; who conduc——”

“Oh no, monsieur,” said Dubois. “They said there was no need. The Ambassador was shot while I, who speak to you, was so unlucky as to be alone in the room with him, so it stands to reason that it was I who shot him. I attempted to argue with them. I said, ‘But, messieurs, if I have shot him where is the gun?’ They say, ‘You throw it out of the window.’ I say ‘Very good, then. Ask of the concourse outside if any person saw a gun thrown from the window,’ for there were many in the street at that time. They say, ‘It is useless, for you threw it to an accomplice who caught it. You shall die.’ So they take me up to that high room and every time one brings me a meal he tells me how the gallows is getting on.”

“I see,” said Bagshott. “Tell me, what really happened, in your opinion? Was the Ambassador really shot or did he have a stroke or——”

“Oh yes, monsieur, he was shot, for there was a little hole in his head just here”—Dubois put his finger tip just above his left ear—“and a little blood came out, but not much, monsieur, for you will understand the fellow was immediately dead.”

Hambledon noticed the contemptuous epithet, but before he could speak Bagshott went on:

“If that is so, where do you suggest the bullet could have come from?”

Dubois’s shoulders went up to his ears.

“The windows were wide open—no blinds—he had the lights on to show the English that Esmeralda could afford to buy those so expensive chandeliers; that is true, he said so himself when he switched them on. There are houses opposite with many windows all open that hot evening; how should I know where the bullet came from?”

“And what did you go to see him about?”

“Money. He had owed me money since five years when he left Paris to go back to Esmeralda, where he was born. Now that he is so rich and I am so poor, I think he can repay what he owes to an old comrade.”

“Did he agree to do so?”

“Him? Enrigo le Canif agree to pay what he owed?”

“You call him by a strange name,” said Hambledon. “I understood that his name was Pedro Maximilio Teluga.”

“That may well be, monsieur. Many small children have pretty names chosen for them by their mothers, but when they grow up and their characters are formed,” said Dubois, hissing his sibilants, “their associates give to them a name which is more appropriate. Pedro Maximilio—heaven help us!—Teluga was a bad smell and a dose of poison, but I did not kill him, messieurs.”

“You seem to know a good deal about him,” said Hambledon, and for some reason the remark stopped Dubois dead.

“I have heard stories,” he said sullenly, and would say no more about Teluga. He asked if he could go and was told that he could not, for the present. He had been seen breaking out of the Embassy and his story had not yet been confirmed.

“I want to go home.”

“Back to Paris?”

“Back to Paris, precisely.”

“I’m afraid we can’t let you leave the country just—”

“But I am innocent!”

“Look here,” said Bagshott, “I don’t know what experience you have had of the operation of the law——”

Dubois started nervously and Hambledon grinned.

“—but you must know that there is a charge of murder laid against you by the Esmeraldans and that your defence to that charge will require to be proved. What are you worrying about? We don’t hang people in back yards without trial, and you will be safe with us. The Esmeraldans are after you, you know. Are you——”

“Very well. I will stay a few hours, at least.”

Bagshott touched a bell and Dubois was removed to a safe place. The door opened again and a constable came in with a visiting card which Bagshott read.

“Bring him in, then. No, don’t go, Hambledon. This is a parson who is staying at Morley’s, opposite the Embassy, and he says he’s got something to tell us. Nice, for once, to hear a story one can believe, I assume that canons of the Church of England are usually truthful?”

“I imagine so,” said Hambledon, rather amused. “They vary, like other men, but normally their statements are reliable.”

The door opened and the Canon was shown in.

“So good of you to see me. You will please tell me at once if what I have to say is of no interest to you, as the last thing I would wish to do is to waste the time of a busy man like you. Gentlemen, it is impossible that that man could have shot the Ambassador. I saw it all.”

“This,” said Bagshott, “is the sort of evidence which policemen pray for. Please go on. Tell me, first, where exactly were you when it happened?”

The Canon explained that he was standing at the front door of Morley’s, “which, as no doubt you know, is raised three steps above pavement level; also I am, as you have seen, a tall man.” He had permitted himself to be amused by the pantomimic gestures of two men within the Embassy who were plainly at odds with each other. “Gentlemen, I rebuked myself for peeping, but if they desired to be private they would surely have drawn the curtains. Now this is the point; it was at the exact moment when the smaller man was shaking both fists in the air above his head, like this, that the taller man bent forward and fell to the floor where I could no longer see him. The smaller man uttered some kind of exclamation, a number of people rushed into the room and somebody drew the curtains. You see my point, gentlemen. If it had been said that the smaller man threw a knife, I might have believed it, but to shoot with a pistol, no, no. Impossible.”

“Tell me, sir,” said Bagshott. “Would it, in your opinion, be possible for this man to have been shot from the street?”

“From the street. Not without the assassin being observed; there were people about. You mean, perhaps, from a car or van, but there was no vehicle of any kind standing or passing at that moment.”

“Did you hear a shot fired, or any sound which might have been a shot fired?”

The Canon hesitated momentarily and then looked up.

“I did hear, not a shot in the ordinary sense, but a noise like ‘piff-ff!’ It reminded me of a pump-up air-gun I had when I was a boy, dear me, many years ago. But an air-gun pellet would not, I am sure, penetrate the skull of a grown man at that range. It might, I suppose, stun him—I am no expert on these matters——”

“And the sound came from—where?”

“I thought, from somewhere above my head, but I must have been mistaken. The sound must have come from somewhere else.”

“But,” began Bagshott——

“My dear sir,” said the Canon, a little testily, “we clergy are hardened, or at least accustomed, to being the cockshy for all sorts of wildly absurd accusations, but no one has hitherto alleged that we shoot ambassadors.”

Bagshott made deprecatory noises and explained that what he had in mind was that one, at least, of the hotel guests was not in Holy Orders. “In any case, do you in fact all know each other personally?”

“Apart from the Organizing Secretary, I do not suppose that any one of us knows every single one of the others, but each of us severally would be known to one or more. I hope I make myself clear.”

Bagshott said, abundantly so, and began to express his thanks, which the Canon cut short.

“Not at all,” he said. “Not good of me at all, it was my duty. That poor little man—I assume you will now be able to induce the Esmeraldan Embassy to release him?”

“He is no longer there, he escaped this evening.” Bagshott permitted himself an amused smile. “In fact, he slid down a rain-water pipe and landed safely in the street in full view of Morley’s. You did not see the performance?”

The Canon’s face fell. “No, did he? No, I did not see it. Slid down the pipe, did he? Dear me, I hope it is not wrong to wish I had seen it. What a lot I shall have to tell when I reach home again. But I must not keep you from your work.”

“If you could spare a few moments while the statement is typed and then sign it——”

“Certainly, with pleasure. Shall I have to give evidence for the accused at a trial——?”

“There will be no trial, thanks to your evidence.”

“Dear me, how singularly fortunate I am——”

The Canon burbled gently out and the door closed behind him.

Bagshott said that he was going to Morley’s himself. He deprecated, he said, a too prevalent idea that the more senior ranks at Scotland Yard merely sit in their offices awaiting and collating reports while the junior ranks go out on the job. For one thing, said Bagshott, it isn’t true; for another, it ought not to be, and finally, why should mere superintendents and/or inspectors have all the fun?

They were ushered into the manager’s office and Bagshott proceeded to extract information with the practised ease of an experienced housewife shelling beans. Yes, the manager had been at Morley’s for many years; yes, it followed that his personal acquaintance with members and clergy of the Church of England was extensive indeed. Yes, it would be a simple matter to supply the names of all those who were occupying rooms in the front of the hotel. The register was at the porter’s desk, just a moment——

The manager dived out to get it and returned immediately with a large flat book.

“Now, how far back do you wish me to go?”

“Yesterday,” said Bagshott, “only yesterday.”

“Oh. That is fortunately simple.” The manager proceeded to read out a string of room numbers, attaching a name to each: “Archdeacon Grantly from the diocese of Barchester and Mrs. Grantly; the Reverend John Chisholm, Vicar of Billberry, a New Forest parish; the Reverend——”

The list went on and on until the manager came to “The Reverend Predikant Nicolaas van Leyst of the parish of Alkdam, Holland. Now there is someone who is new to me,” said the manager, taking off his spectacles to look at his visitors. “He is a minister of the Lutheran Church and I understand that he is attending this Conference on Parochial Duties and Privileges merely as a spectator, in order to study what one might call the domestic organization of the Church of England. He wrote from Holland to book a room; here is his letter on his own paper. Yes, yes, he is the only one who was not known to me previously and who had a room in the front of the hotel until late last night.”

“He is no longer here, then?”

“Oh no. No, he came to me in some distress because he had had a message to say that his wife was ill and he must get back at once. He was all in a rush; he paid his bill while my porter fetched him a taxi in an endeavor to catch the boat train from Liverpool Street for Harwich and the Hook. Poor man, I hope he caught it, he had none too much time.”

“So his room is now empty——”

“Oh no. No, it was let again late last night, at nearly midnight in fact, to a young Englishman, not in Holy Orders, who is a clerk to one of the Organizing Secretaries. His name is Hereward Biggs.”

“Room number 17,” said Bagshott.

“Number 17, exactly.”

“I wonder whether Mr. Biggs would mind our just having a look at his room.”

“I will ring up to him and ask,” said the manager, picking up the telephone. “You wish me to announce you by name?”

“No, don’t ring,” said Bagshott hastily. “We will just walk up and announce ourselves, if he is there. I think I know Mr. Biggs. Well, thank you very much, Mr. Er-er——”

“Snook.”

“Mr. Snook. You have been most helpful.”

“But,” said Snook, “you do not wish for any information about the other guests?”

“Are there any more in the front rooms?”

“Not in the front rooms, no——”

“Thank you, then we need not trouble you. Number 17 is on the first floor?”

“That is so, yes. Up the stairs and turn left and it is on your right.”

“He had not a glimmering,” said Hambledon as they walked up the stairs, “of what all this is about.”

“Not a spark, but I suppose that everyone still thinks that Dubois did the shooting. Tell me, Hambledon, is the clerical manner infectious?”

“Certainly it is. Highly. Here’s the room.”

Bagshott tapped at the door; a voice inside told them to come in and they did so. The two young men inside were sitting at a table, playing cards; the room was blue with smoke; an overflowing ash tray was on the seat of a chair and the dressing-table carried two whisky bottles, one empty, and some used glasses.

The photographer glanced up but, not recognizing the visitors, he said nothing; Biggs did not even look up.

“Put it down somewhere,” he said, “there’s a good girl. On the bed will do.”

Bagshott laughed and Biggs whirled round.

“I thought it was probably you here,” said Bagshott, “when the manager told me the name was Biggs. Do you really do spare-time work for the Conference on Duties and Privileges? I knew the Wire had someone on the spot here somewhere; your despatches have the authentic eyewitness flavour.”

“Do sit down,” said Biggs, hurling things off chairs on to the bed. “And it’s Mr. Hambledon, isn’t it? Won’t you have a drink?—George, wash two tumblers for the gentlemen.”

“It’s very good of you, but we didn’t come here to drink your whisky. We came——”

“To ask a few questions,” said Biggs.

“You came here, when was it? Late last night?”

“Just scraped in before the place closed at midnight.”

“Yes. Has the room been turned out and cleaned today?”

“Now, does it look it? A young woman in a checked apron made the bed, but when she proposed to disturb us further we told her to scram.”

“And last night? Do you know if anything had been done to it before you came in?”

“Only clean sheets. There was a motherly old dear in a white apron tottering around the corridors when I came in. She said she’d remade the bed but she’d turn out the room in the morning, if that would do.”

“Do you mind if I have a look round now?”

“Not at all,” said Biggs in a puzzled voice. “Please help yourself. The only things here that are mine are the shaving things on the washstand; the luggage there in the corner is camouflage.”

Bagshott nodded and began by pulling out the drawers in the chest of drawers one after the other; there was nothing in any of them, although he pulled out the drawer paper and looked underneath it. Hambledon opened the wardrobe door and found nothing inside, nor in the drawer under the hanging space.

“Have I missed something?” asked Biggs.

“You didn’t find anything, did you, which the previous tenant had left behind? Any rubbish—a crumpled envelope, a train ticket——”

“No.” Biggs’s puzzled look was slowly giving place to a dawning idea and he looked across the road at the Embassy windows opposite. “No, nothing. But then, I didn’t look.”

Hambledon crossed to the dressing-table and pulled out both small drawers under the table top. He made a small grunting sound and Bagshott came to look. There was a card lying in the drawer, the sort of small card which hotels give their clients to remind them of their room number. It was face upwards, and gave the name and address of the hotel, the name of the proprietor and the room number written in ink. Bagshott picked up the card by its edges and turned it over, on the back was a note of an address: “127 Southgate Street, Lambeth,” and the upright stem of the figure seven had a stroke across it in the manner used by foreigners to distinguish a seven from a figure one.

Bagshott took an envelope from his pocket, slipped the card into it, put it in his wallet, and went on searching with Hambledon, but there seemed to be nothing else. Hambledon looked round the room; there was a piece of decorative carving along the top of the wardrobe. He took a chair across the room and stood on it to enable him to see over the top. There was a moment’s pause.

“Bagshott,” said Hambledon.

Bagshott snatched another chair, stood on it, peering, and said: “Dear me.” By this time Biggs and friend were dancing on the bed but they leapt off it again when the Commander very carefully and slowly lifted down a rifle of the folding variety, hinged to allow the barrel to lie back along the stock. The gun was fitted with a silencer. Bagshott stepped off the chair and laid the rifle on the table among the playing cards.

Biggs burst into speech. “Have I spent thirty-six hours in the same room as the murder weapon and not found it? Oh, Lord, I’ll never live it down.”

The Esmeraldan Embassy were informed by telephone from Scotland Yard that there was good reason to believe that their lamented Ambassador had been shot from a window on the opposite side of the street. In order to prove whether or not this was the case, would the Embassy be so good as to permit an autopsy to be held in order that the bullet might be recovered? A police surgeon, experienced in these cases, would be sent from Scotland Yard to perform the autopsy; a microscopic examination by ballistic experts would then confirm or disprove certain evidence in the hands of Scotland Yard.

The Embassy said that they demanded as their right the immediate return of the assassin who had escaped from their custody.

Scotland Yard replied that that was impossible, since the man who had escaped from Embassy premises was not the Ambassador’s assassin but completely innocent of that crime. If an autopsy were permitted, further steps could then be taken to discover and apprehend the guilty person.

The Embassy said that if the shot had indeed been fired from across the street, presumably the man responsible had been harboured by the management of the establishment called Morley’s Hotel and strongly urged that the manager and all the staff should instantly be arrested. “Somebody must have seen the murderer.”

Scotland Yard said that doubtless that would prove to be so, once the evidence only obtainable by an autopsy had been made available. Till then, an indispensable link was missing.

The Embassy sighed in an exasperated manner and said that no doubt extreme pertinacity was a principal ingredient in successful detection, and Scotland Yard agreed that that was so, indeed. The Embassy then said that provided that a surgeon of their own choosing was also present, a police surgeon would be permitted to make the autopsy. At what time——

Scotland Yard said: “At ten o’clock tonight? Thank you very much, that will be most helpful.”

In the meantime, Hambledon having gone home, Bagshott was pursuing his enquiries at Morley’s. There were plenty of descriptions available of the Reverend Nicolaas van Leyst of Alkdam from both staff and guests. He was a man above medium height, with brown hair retreating at the temples, grey eyes, a fresh complexion and a scar across his right cheek rather high up, across the cheekbone. He spoke English very well, though with a marked foreign accent. One of the clergy who had spoken to him said that he was mildly surprised to learn that the man was Dutch, his accent rather suggested that his mother tongue had been French. On the other hand, he did not seem to have said much to anybody; a civil greeting or a remark about the weather and he would pass on his way. He was, said another of the guests, a man who always seemed on the point of going somewhere else. He did not stop, he only paused, as it were. Age? Oh, a man in the forties, not more. Possibly less. No one seemed to be very sure of his age; it was of course on his passport, but the manager had not noticed it, why should he?

Someone suggested that Bagshott should ask a man who had sat at the same table with Van Leyst for one or two meals; they had been observed to be speaking together. “Where is Smith? Oh, sitting in that corner, the thin man with white hair. I’ll take you over. I say, Smith, just a minute——”

After ten minutes of the Reverend Mr. Smith, Bagshott came to the conclusion that Van Leyst had chosen him as a companion because then it would not be necessary for him—Van Leyst—to say anything at all. Mr. Smith’s conversation was of the kind which flows gently and irrevocably on.

“I do remember one thing I said to him one day when we were at lunch together. He said that he rather liked the C. of E. dress, it always looked so well cut and a good fit. I said that it was all a question of going to the right tailor and that did not necessarily mean the most expensive tailor. I am sure you agree with me, Mr.—er—Bagot, is it not? I gave him the address of my own man, down in Lambeth, not far from the Palace, you know, man named Jenkins in Southgate Street, and I remember that he wrote it down.”

Bagshott slipped the room-number card out of its envelope and showed it to Mr. Smith.

“Yes, yes, that is it. I saw him write it down and I noticed that he crossed the seven in the continental manner, I was looking to see if he had it right, the spelling and all, you know.”

Bagshott thanked him gratefully, came up for air and returned to Scotland Yard to put through an enquiry to the Dutch police about the Reverend Nicolaas van Leyst, Predikant of Alkdam. Was there such a man, was he in England or had he just returned therefrom?

The next day the answer came back from Holland. Certainly the Reverend Nicolaas van Leyst was Predikant of Alkdam, but he was equally certainly not in England nor had he recently returned therefrom. He was, in point of fact, in hospital with a broken leg and had been for the past three weeks. This enquiry sounded interesting and if there was any way in which the Dutch police could further assist their English confrères they would be most happy to do so.

“Well, we know a little more about him now, don’t we?” said Hambledon. “We know that he is probably a foreigner, though the accent and the crossed seven could both have been assumed for the purpose. We know that his name is not Leyst although it’s pretty certain that he has some connection with Alkdam. The Predikant’s own note paper, you know, you’ve got it there. He knew the name of the Predikant there and used it in case somebody looked him up in a book, he may even have known that the real Van Leyst could not possibly embarrass him by turning up in London. We have a very detailed description of him and I imagine you have his fingerprints—yes? Any luck?”

“Not in our records,” said Bagshott. “I’m sending them over to Holland on the chance that they may be known there.”

“Send them to the Sûreté in Paris, too. One of your parsons said that he thought the man’s accent was French, not Dutch, and I rather trust that sort of impression. What about the bullet?”

“It was a rifle bullet, a 6.7 mm. I am expecting a report from the ballistics people at any moment.”

“Did your people find anything else in the room?”

“No. Some fingerprints on the top of the wardrobe which matched those on the card. Hambledon, why did he leave his gun behind? He brought it in his luggage, presumably, so he could have taken it away again.”

“Because he didn’t want it any more and it would be an incriminating thing to carry about with him, wouldn’t it? Fancy trying to pass Customs with that in your luggage, that is, if one were trying to pass Customs. Were there any fingerprints on the gun? No, there wouldn’t be. I wonder where X got Van Leyst’s passport from, don’t you? That is, if Van Leyst has one, and if not——”

The telephone rang and Bagshott lifted the receiver, listened to what was said, thanked the speaker and rang off again.

“Ballistics department,” he said. “That bullet was fired from that rifle at Morley’s.”

“Well, that lets out Dubois, doesn’t it? What are you going to do with him?”

“Turn him loose,” said Bagshott. “In point of fact he’s never been in custody, only detained for questioning.”

“He knows more than he’s told us, doesn’t he?” said Hambledon. “If only a few funny stories about the late Ambassador and his possibly colourful past. I mean, there must have been a reason for the shooting unless the executioner is a man with a down on ambassadors as such and just happened to start off with Esmeralda’s. In that case, my poor friend, what an interesting time you’re going to have as the programme continues.”

“You have the most revolting ideas of any man I’ve ever known, though as a matter of fact we’d thought of that one. Precautions are being taken. Let’s have Dubois in and see if we can get anything out of him.”

Dubois was brought in and it was plain at once that he was not nearly so cheerful and happy as he had been the evening before. He looked anxious and fidgeted in his chair.

“We have good news for you, Monsieur Dubois,” began Bagshott. “You have been completely cleared of the charge of having shot Señor Teluga and even the Esmeraldan Embassy is convinced of your innocence.”

“Thank you,” said Dubois, and wound his fingers together. “Tell me, have you got the man who did it?”

“Not yet, but it is established that the shot was fired from a window on the other side of the road. I think you suggested that that was what had happened, did you not?”

“Yes. Yes, I did, but then I had not thought. Last night, you understand, I had just escaped from those brigands. But then when I go to bed I cannot sleep. I lie and think and the thought comes to me that it might so easily have been I who was shot in place of Enrigo le Canif. Or, even, as well as he.”

“I suppose so,” said Bagshott slowly, “but why should anybody shoot you?”

“They shot Teluga,” said Dubois.

“Why did they?”

Dubois’s shoulders went up. “Who knows?”

“Someone who had a grudge against him presumably.”

“Who knows?” repeated Dubois.

“We were hoping that you did, Dubois,” said Hambledon. “Tell me, do you know anyone who has a motive for shooting Teluga? And, possibly, you also?”

“No, no. I do not know anything about Teluga except that in the past I lent him money and yesterday he said that he would not repay. No one would want to shoot me, why should they?”

“You should know,” said Hambledon, and Dubois’s eyes went from side to side, but he did not speak.

“Dubois,” said Bagshott, “I think there is something you could tell us about the man who shot Teluga. If you know nothing, what are you afraid of?”

“It is enough to frighten anyone, to have a man shot dead within arm’s length. Some madman, how should I know? Can I go back to Paris?”

“Certainly you can, though it’s too late to catch the morning train today. You can go tomorrow perfectly well, why not? Stay in London tonight and cross tomorrow.”

“Can I stay here?”

“What? In this building? My dear Dubois, this is the headquarters of the Metropolitan Police, not a hostel. Where did you stay before the Esmeraldans collared you?”

“In an hotel. I am not going back there. I have some luggage—a suitcase—let it go.”

“Dubois, what is the matter with you? What are you afraid of?”

“Nothing. Nothing. It is my nerves which fail me. Can I get my ticket for Paris at the railway station? Do not stare at me like that, I beg you. I know nothing.”

Bagshott considered for a moment.

“About your ticket, it would be better to buy it today at a travel agency and reserve a seat at the same time. Listen. I will send you in a police car to Cook’s office in Pall Mall, that’s the nearest. You will buy your ticket and reserve your seat and then the police car will take you to the Speedwell Hotel at Charing Cross, where you can stay the night. You will be quite safe there. You can send a messenger with a note to collect your luggage from wherever it is and pay the bill if you haven’t done so. In the morning you can take a taxi to Victoria and get into the Paris train. All right?”

Dubois overflowed with thanks.

“This address in Paris which you gave us, we can get in touch with you there, can we?”

“Certainly, certainly. At all times, it is my home where I live.”

Bagshott gave orders for a police car to convey Dubois, who was then shown out, still babbling of unheard-of kindnesses and unexampled courtesy. The door closed behind him and Bagshott looked across at Hambledon.

“No use holding on to him even if we could,” said Bagshott. “He wasn’t going to talk.”

“He wasn’t, no. This is one of those cases where, one feels, the abolition of thumbscrews was a mistake. I think I’ll ring up Letord at the Sûreté; he may know something about Dubois or be better able to induce him to talk than we are. Tiresome man, Dubois. There’s no doubt that, tossing on his wakeful pillow, it suddenly dawned on him who had really shot Teluga and why and it scared him stiff. Poor Teluga, it really was a little hard having one man after his money and another after his life at the same moment.”

“Dubois thought the man with the rifle would be after him, too.”

“Yes, that was very plain.”

“Then why in the name of common sense,” said Bagshott irritably, “couldn’t the fool tell us all about the man and let us deal with him?”

“I simply hate having to point it out,” said Tommy sympathetically, “but the fact is that Dubois has more confidence in X’s capabilities than he has in ours. I may as well ring Letord from here; it is police business after all.”

Letord said that he knew the man called Dubois quite well. He was a high-class cat burglar and he considered murder to be vulgar and crude. However, he must be persuaded to be sensible. “I will send one of my fellows to meet him off that train and bring him here; perhaps he will talk to Papa Letord.”

The night passed and the next day; it was not until seven in the evening that Letord got into touch with Hambledon.

“The man Dubois,” said Letord’s incisive voice. “Where is he, then? Has he changed his mind about coming home? He was not on that train; do you know if he started on it?”

“No, I don’t,” said Hambledon, vaguely uneasy. “He certainly took a ticket and booked a seat on that train; I assume he caught it. We didn’t go and see him off. Why should we?”

“I merely thought that you might have done so, I do not wish to suggest that you should. As a man he is completely valueless, but as a source of information he may have his uses. Shall we continue to look for him here? He has not yet, by the way, arrived home.”

“I’ll see if we can find out anything here,” said Hambledon.

He got into touch with Bagshott, who blasted Dubois in a few appropriate phrases and said that he would send a man round to the Speedwell Hotel.

The Speedwell reception desk said that Mr. Dubois, the French gentleman, had certainly taken a room there in the early afternoon, but had gone out in a taxi at about four o’clock. He had returned before five, cancelled his booking and left in another taxi at about eight-fifteen. The hall porter remembered both occasions perfectly as the gentleman had asked for a taxi to be summoned and, when it came to the door, had rushed across the pavement and leapt into it like a rabbit down its hole. Yes, the taxis both came off a neighbouring rank, the porter always got taxis from there. Yes, he knew the drivers; with any luck they might be there now. They were, and the Scotland Yard man interviewed them. They remembered the agitated Frenchman perfectly well. Got the wind up proper about something, hadn’t he? The first had taken him to Cook’s office in Pall Mall, waited for him and driven him back again. The second had driven him to Waterloo Station and had heard him asking the porter where to find the boat train to Southampton for Le Havre. “So presumably,” said Bagshott, telephoning to Hambledon, “Dubois changed his mind about the Dover-Calais route and went to Paris via Le Havre instead. It got him out of the country twelve hours earlier.”

“It did, yes,” said Hambledon thoughtfully.

“I don’t see that we need to do anything about it. He wanted to go, so he went.”

“Yes,” said Hambledon.

“What’s the matter?”

“I don’t know. I seem to have got something nagging at me but I don’t know what.”

“Try flea powder,” said Bagshott helpfully.

Hambledon went to Cook’s office in Pall Mall on his way to the office in the morning and found the clerk who had attended to Dubois the day before. Yes, the French gentleman. He came in the early afternoon of the day before yesterday and took a ticket and a reservation on the Paris train Dover-Calais, not the Golden Arrow, the ordinary train. At about half-past four or so he came in again looking anxious and upset and asked if there was any other way of getting to Paris except via Dover. The clerk said certainly, there was the Folkstone-Boulogne route and the Newhaven-Dieppe. There was also the route via Southampton and Le Havre but that was a longer sea passage, a night crossing in fact.

“He seemed to like the idea of a night crossing,” said the clerk. “He said, ‘It go tonight, yes?’ and I agreed. He said, ‘Those others, to Boulogne and Dieppe, tonight also?’ I said no, they would be for tomorrow. So he said, ‘I go tonight please, thank you. You alter ticket, yes?’ So I changed the tickets for him and he buzzed off. Oh, he asked about going by air, but I couldn’t get him a reservation at such short notice.”

“Thank you so much,” said Hambledon, and went from there to the Speedwell Hotel at Charing Cross, where he talked to the desk clerk who had dealt with Dubois. She was a sensible and intelligent young woman and said that Dubois had seemed nervous when he first came.

“I can speak French,” she said, “so we got on quite well. He said he wanted a room with a window looking into a light well; he did not wish to look out on the street. I forgot to say he asked me to send a messenger for a suitcase he had left in an hotel in Bloomsbury. When it came I sent it up, and not long after that he came down and went to the bar for a glass of wine. While he was still there the telephone here rang and someone—a man’s voice—asked for Monsieur Dubois.”

“Asked in French?”

“Oh no, in English, but there was just that little trace of foreign accent. So I asked the caller to hold on and I went and fetched Mr. Dubois. I could not, of course, hear what was said from the other end, but after the first sentence I thought Mr. Dubois was going to faint. He gasped and turned a dreadful colour, so I dodged round the counter and gave him a stool to sit on. They were talking French then, at least Mr. Dubois was, and I didn’t get all of it because he talked so fast. He seemed to be denying something. ‘No, no, I did not,’ he kept saying. ‘I was not ever with that gang, indeed no. I do not like their—no, no excuse me, you are quite wrong. I do not know what you mean—please do not talk to me like that.’ I don’t generally listen like that,” added the girl, with an embarrassed laugh, “but he looked so ill that I was watching him. He didn’t say much, only ‘no, no,’ several times and, ‘believe me, you are quite mistaken. Whoever told you that, lies. I went there, yes, but it was nothing to do with them.’ Then he stopped in the middle of a sentence, so I suppose the caller had hung up on him. He leaned on the counter, looking so really ghastly that I asked if I could do anything. He asked for a double brandy, so I got the bartender to give him one. He kept on thanking me for being kind to him and I said I hoped he hadn’t had bad news.”

The girl stopped and looked away.

“What did he say to that?”

“Something rather funny. He said: ‘Mademoiselle is lucky. She has led an innocent life, her past will never overtake her.’ Then he asked Dick, the porter, to get him a taxi and went out for an hour or so. When he came back he said he would not want his room after all as he was going back to France that evening.”

Hambledon spoke to the porter, the waiter, and the bartender, but as none of them could speak French, it was not likely that Dubois, whose English was painfully limited, would have confided his sorrows to them. In any case, he had not.

Hambledon walked round to Scotland Yard in the June sunshine and went in to see Bagshott.

“Of course,” said the Commander. “I can ring up British Railways and get them to check on their tickets; that’ll tell us. You’re afraid something may have happened to him, are you?”

“Yes,” said Tommy Hambledon.

A day or two later Hambledon rang up Letord in Paris.

“About Dubois,” he said. “He changed his mind about travelling Dover-Calais on account of a telephone call he received at his hotel; I don’t know, of course, what was said, but the conversation was in French and it frightened him into sixteen blue fits. He rushed off to Cook’s, changed his tickets and travelled that night via Le Havre. I suppose you haven’t seen him anywhere about?”

“He has not come back to his own place,” said Letord, “but one of my men believes that he saw him walking in the Boulevard Haussmann. You want me to look for him?”

“Odd though it may seem, yes. You see, he is my only link with the man who shot Teluga, for I am perfectly certain that Dubois knows more than he is telling. I don’t even know that he went to Paris, but he certainly reached Le Havre. What I should really like is for him to be, not arrested, but shadowed. I should like to know who are his contacts and I think I will come across myself, probably tomorrow.”

“Dubois is honoured,” said Letord, “and I shall be delighted.”

“So shall I be, to see you. As regards Dubois, the Esmeraldan Embassy are worrying the Home Office and one really can’t blame them, and the Home Office are worrying me, which, after all, is that for which I am paid. So I’ll see you tomorrow if nothing else crops up.”

Hambledon flew to Paris the following day and went straight to Letord’s office to learn that Dubois had not been seen again. “If, indeed, it was he whom my man saw. We went through his room very thoroughly and, my friend, I do not believe it.”

“What do you not believe?”

“Why, that that is his only place of residence. What, a man like that, always tidily dressed, clothes brushed, shoes polished and a sufficiency of clean shirts, to live only in one grubby little room on the second floor of a tenement in the Rue des Taillendiers? The room looks out upon a blank wall. It is furnished with a bed, a table, a couple of chairs, an oilstove and a frying pan. Nonsense.”

“That is the address he gave us,” said Hambledon.

“I daresay. I should never be surprised to hear that he had a little villa out at Passy, that one, and a wife and two children, one boy and one girl, and that he takes round the collection bag at church on Sundays. He is not a——”

There came a tap at the door and one of Letord’s plain-clothes detectives rushed in.

“Monsieur, I have found Dubois——”

“Where is he?”

“But almost beneath our windows. He is on the quay below us, here, a little further along, between the Petit Pont and the Pont au Double. He is waiting for someone, he walks up and down and looks at his watch, so I thought it safe to come away, messieurs.”

Before the man had finished speaking, Hambledon and Letord were out of the room and running down the stairs.

The Préfecture of the city of Paris is on the Île de la Cité; here also are the great church of Notre Dame, the Palais de Justice, the Sainte Chapelle and many other such places of historic and antiquarian interest as are listed in guidebooks.

One side of the Préfecture faces, across an open square, the west front of Notre Dame; the south side of the square is bordered by a garden with a statue of Charlemagne; below the garden is the river. At the bottom of the walls on both sides of the river there run narrow quays near water level. At either end of the square there are bridges across the river; the Pont au Double by the cathedral, and the Petit Pont by the Préfecture. The detective led Letord and Hambledon upon the Petit Pont and indicated the short stretch of shelflike quay between the two bridges.

“He is still there, messieurs.”

He was, indeed. He had on a felt hat tilted forward over his eyes, but there was no mistaking the simian slope of the shoulders, the unusually long arms which hung a little forward of his body and the big hands, half closed, like a sailor’s. High above his head the trees of Charlemagne’s garden moved gently against the cloudless sky, and long trails of creepers hung down like curtains from the parapet.

“That’s Dubois all right,” said Hambledon. “A peaceful scene, isn’t it? I wonder for whom he waits.”

Dubois took a turn up and down. There is a flight of wide steps at either end of this stretch of quay, leading up by the two bridges; Dubois looked up at one and then turned to look up at the other and Hambledon drew back.

“He cannot recognize us,” said Letord. “He has the sun straight in his eyes if he looks up here. Besides, there are always people on bridges looking over at rivers, why? I do, myself, if I am not in my usual hurry.” Dubois looked at his watch again. “His friend is late, I think.”

Hambledon glanced across at the parapet of the garden, there was someone leaning upon it, a man but barely visible in the shadow of the overhanging trees and between the massed clumps of greenery. The man raised his arm as though to throw something, people are always throwing rubbish into the river, screwed-up paper bags, empty cigarette packets——

Something fell through the air from the parapet; it landed just at Dubois’s feet and burst with a sharp crack and a puff of smoke. As for Dubois, he was a shapeless heap in a pool of blood.

The detective was first off the mark, but he had to run off the bridge before he could see who was behind the parapet; by the time he turned the corner there was no one there. When Hambledon and Letord overtook him he was staring about like a terrier who has unaccountably mislaid a rabbit, and no one else was betraying the slightest interest.

“They would notice nothing, up here, above the noise of traffic,” said Letord, and ran down the steps, followed by Hambledon and the detective.

Dubois was very obviously dead.

“I will ring for an ambulance,” said Letord, “and have this débris removed to the mortuary. My dear Hambledon, how annoying for you. Let us return to my office.”

A man came in with a tray on which were the various things taken from Dubois’s pockets. There were all the usual things one would expect to find in a man’s pockets; a handkerchief, a half-empty packet of cigarettes and some matches, a penknife, a bunch of keys, some loose coins, a wallet containing a little over two thousand francs in assorted notes, the remains of a book of Métro tickets, and a receipted bill for repairs to a chair, made out to Madame Dubois, Rue du Moulin 57c, Avenue Simon Bolivar.

“What did I tell you?” growled Letord. “The wife, here she is.”

“Where is the Avenue Simon Bolivar?”

“Just beyond the Gare de l’Est.”

There was also a folded paper which was not in very good condition since something appeared to have passed through it, tearing a jagged hole.

“The weapon,” said the detective who had brought the things in, “was a hand grenade. We found some of the pieces.”

Letord nodded. He laid the paper down upon his blotter and very carefully unfolded it, flattening out the jagged points with a paper knife. When he had finished the sheet was almost entire; it was a letter.

Dear Dubois,

It is many years since we met; you may have forgotten me. I have but just returned to Paris after a long absence and I should like to see you again. I have, in fact, something to suggest which may be to our mutual advantage.

I cannot give you my address as I am moving about, but if you would be on the lower quay between the Petit Pont and the Pont au Double, on the Île de la Cité side, at about seventeen hours on Thursday next, the fourteenth, the meeting would, I am sure, be profitable to us both.

The signature was not very legible and was also damaged, it looked like C or G Le Gris or Le Gros, and there was no address. The envelope was missing, so that there was no postmark to suggest a place of origin.

“Now we know what took him there,” said Hambledon.

“Perhaps Madame can tell us something about this Le Gros or Gris, let us go and ask her.”

“Very well,” said Hambledon without enthusiasm, and Letord glanced at him.

“I remember,” he said, “you do not like the weeping, do you? Never mind, you are not this time the cause of it. You can employ the time of our journey in composing the effective consolations, can you not? Besides, we do not know, she may be delighted.”

But Letord was wrong. Madame Dubois was a woman in the later thirties, with a pleasant face and a calm manner, and she received the news with a dignity and self-control which did not disguise the fact that her grief was deep.

“My poor Gaston,” she said, and her voice shook.

“Madame,” said Letord, looking down at his boots, “if it is any consolation to you, he was killed instantly and did not suffer even for a moment. I, who speak to you, saw it happen.”

“And yet you could not prevent it.”

Letord explained the circumstances.

“But,” she said, “who could have wished to do such a dreadful thing?”

Letord looked at Hambledon, who took up the story.

“Madame may have read in the papers the story of the assassination of the Esmeraldan Ambassador in London last week. Madame, I do not know whether your husband told you, but he was actually talking to the Ambassador when he was shot from a window across the road. This fact was not discovered until later and the Esmeraldans, in the excitement of the moment, concluded that your husband had shot him. They detained him in their custody at the Embassy, but Monsieur Dubois made his escape and took refuge with the London police, as he had a right to do, being perfectly innocent of the murder. He told you about this?”

She wiped her eyes and smiled faintly.

“He told me that he was going to London on a matter of business, to collect some money that was due. When he returned I asked him whether his journey had been successful. He said that it had not, since the man who had owed the money was now dead. He said no more, messieurs, and I did not ask, for he never spoke to me at all about his business affairs.”

“He came to the police, as I have said, madame,” went on Hambledon, “and I was there when he was interviewed, for it is our duty to find the man who shot the Ambassador if we can. We asked your husband many questions in case he might have seen or heard anything which would help us—you understand, madame. We knew that he was not guilty—we have proof of that—but he was there, an eyewitness. He could not tell us anything at all about the murder; he had seen nothing except the Ambassador fall dead before him, but I formed the opinion that he did know something which he was not telling. In plain fact, madame, I thought he was very seriously alarmed, but he kept his own counsel and left for Paris by the first available train. I came to Paris for the express purpose of seeing him again and imploring him to confide in me, but before I have a chance to speak to him he also is assassinated.”

She had sat perfectly still with her eyes fixed upon Hambledon while he was speaking; when he had ended she looked away out of the window for a few moments before she answered.

“You will understand, messieurs, that when one has received a shock like this, one does not, at first, think very clearly, but it is plain even to me, now, that you think that there is a connection between these two wicked deeds.”

“Yes, madame, that is what I think.”