* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: The Radio Man Returns

Date of first publication: 1939

Author: Ralph Milne Farley (1887-1963)

Date first posted: Mar. 26, 2022

Date last updated: Mar. 26, 2022

Faded Page eBook #20220367

This eBook was produced by: Alex White & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

This file was produced from images generously made available by Internet Archive/American Libraries.

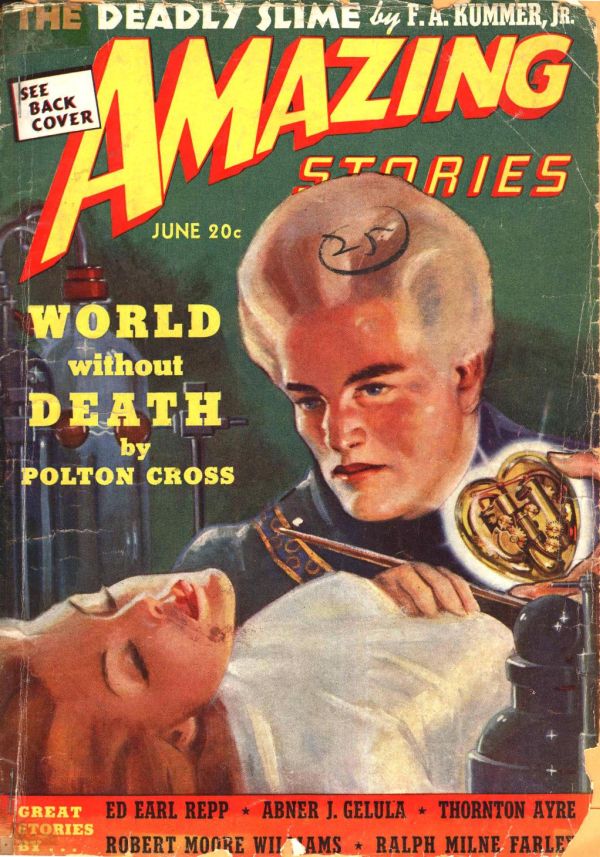

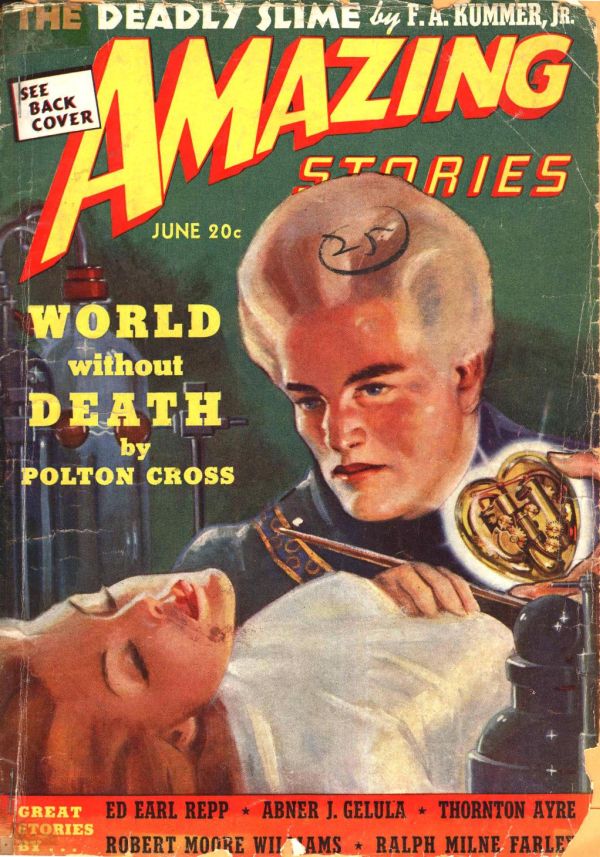

the Radio Man Returns

By RALPH MILNE FARLEY

First published Amazing Stories, June 1939.

Unseen wings menace the President, until the Radio Man returns to pit Venus’ science against invisibility

Imagine my surprise at running across Myles Cabot at my class reunion in June, 1939! The last that I had heard of him, before my interplanetary radio-set went haywire, he had been on the Planet Venus. Yet here he was, seated in the Harvard Union, reading a newspaper, and looking as keen and virile as ever!

“Myles!” I exclaimed, rushing over to him. “What’s the big idea? Trying to win the long distance attendance cup away from Consul Frost of Calcutta?”

“Hello, Farley,” he replied, as casually as though we had seen each other the day before. He arose, and handed over a copy of the Boston Post. “Look at this newspaper! I’ll bet I can tell you how he did it.”

“How who did what? Oh, I see.”

Screaming headlines recounted that a bomb had been dropped on the White House lawn by an invisible airplane, which had been clearly heard, although not seen.

Morton Rust, a classmate from Wall Street, strolled by. “Watch stocks crash,” he predicted. “The President’s narrow escape will give the market the jitters.”

But the vagaries of the stock market did not interest me. What I wanted to know was how Cabot happened to be back here on Earth again, instead of millions of miles away in space.

“You haven’t told me how you got here,” I objected. “How are things on Venus? How is the Princess Lilia? How is your son, little King Kew? Did the ant-men ever—?”

“Stop! Stop!” he interrupted. “Look here, Farley, aren’t you more concerned with the safety of your own President, than with the welfare of a dynasty on a distant planet?—Don’t look now, but in a minute tell me who is that man with a large shaggy head, standing just behind you. He seems to be snooping on us.”

I swung slowly around. Then turned back and replied, “It’s Sedgwick. Surely you remember him.”

“Mixed up in some foreign government, wasn’t he? I ran across him several times in Detroit, but couldn’t quite place him.—O, Sedgwick!”

But our leonine classmate moved away, not hearing—or pretending not to hear.

“Let’s take a walk through the College Yard,” Cabot suggested, folding the newspaper and cramming it into a pocket of his Norfolk jacket. “I’ve something to tell you, which I don’t wish overheard.”

When we were out on the grass beneath the elms, with no other classday group within fifty feet of us, Cabot continued, with lowered voice, “Ralph, this thing worries me. Oh, I know that the authorities try to laugh it off. They say that there must have been a plane, and that the bomb-dropping must have been an accident. But—mark this—any bomb carried by an Army or Navy plane would be easily identifiable from the fragments, and yet none of the news-dispatches mentions the type-number of the bomb. Doesn’t that seem—?”

In the distance a newsboy could be heard crying an extra: “Read all about it! Invisible plane drops another bomb. Read all about it!”

Cabot stopped abruptly, listened, and then with a sharp “Come on!” led the way out to the Square, where we purchased two papers. As before, the plane had been heard but not seen. And I noticed that the AP dispatch, although mentioning that the fragments had been turned over to the Ordnance experts, gave no intimation as to the type of the bomb.

“Well?” I asked.

“I’m going to Washington,” Cabot announced. “For although I’m a naturalized Cupian, I’m still an American at heart. I’ve seen the same stunt pulled in Cupia, on Venus. We must save the President.”

“We? Then you’ll take me along?”

“Why not!”

“And, now that you’re talking why-nots, why don’t you phone your information to the F. B. I.?”

“Wires may be tapped. I tell you, I’ve been followed and spied upon, ever since I started designing that special car of mine. A big black sedan trailed me here, all the way from Detroit.”

“What special car of yours?”

“It’s a long story. Tell you later.—Look!”

Our shaggy-maned classmate, Sedgwick, had come out of the Yard, and was staring at us frowningly.

“There, you see,” Cabot continued, a worried look in his clear blue eyes. “Are Mrs. Farley and Jacqueline here with you?”

I shook my head. “Still down on the farm at Chappaquiddick.”

“Then come on. We’ll get in my car, as though to go just for a short drive. Not check out, or anything. Of course, we’ll be followed, but maybe we can give them the slip.”

I nodded eager agreement. It was going to be much more exciting to live a story, then just merely to write one. So we strolled casually over to the Church Street Garage, and took out his 1939 Olds.

As we started slowly enough toward the Fresh Pond Parkway, Cabot frowned sadly. “I hate to yield that long distance attendance cup to Frost of Calcutta.—But perhaps they’ll award it to me posthumously.”

“You mean ‘in absentia’,” I answered, shuddering slightly.

“Look back,” said Cabot.

I did so. A car with a New York license was following us.

“Note the number,” my friend commanded.

We drove aimlessly around the pond, then headed back toward Cambridge. The New York car still followed. Then Cabot headed for Highway 1.

In the highway traffic we lost sight of the car. We stopped for lunch. When we came out, there stood the New York car beside ours. From there on, Cabot stepped on the gas. But no one seemed to follow.

We cut over into Connecticut, and had to slow down for their strict speed laws. We took to a back road, paralleling the main highway.

And then it happened!

A totally strange car pulled past us from behind, and then tried to force us into the ditch. The man beside the driver held an automatic out the window.

“Remember, it was self-defense,” Cabot snapped, as he pushed one of a row of buttons on the dashboard.

A double explosion! The other car veered off, and crashed into some trees to the left of the road.

“One-pounder cannon. High explosive shell,” Cabot explained.

I turned and looked back through our rear window. A man with a machine-gun was scrambling out of the wrecked car. Then, with a rattling roar, our rear window became spattered with cobwebby rosettes.

“Bullet-proof glass,” Cabot chuckled.

“But how about your tires?”

“Inflated sponge-rubber inners.” He pushed a second button on the dash. Only one explosion this time. “Missed him!” A second explosion far to the rear.

Cabot pushed a third button, then turned off into a side road. Behind us hung a thick pall of smoke, obscuring our detour.

We reached the next town without event, and pulled into a garage, where Cabot inspected the rear tires. Badly ripped they were, but still holding up. Cabot asked to have them changed.

While this was being done, another car of the same model as ours came in for some minor adjustment. It bore New Hampshire plates, was covered with Dartmouth banners, and contained two very personable looking young men.

The garage attendants finished with both cars at about the same time. Cabot beckoned to me, and we walked to the front of the shop and peered out, up and down the street. Just beyond the garage stood the New York car, which we hadn’t seen since morning.

“Um,” said Cabot, and his blue eyes narrowed. Then he strode back to the two Dartmouth men, and drew them into a corner. “Where are you headed for, fellows?” he asked.

“What’s it to you?”

Cabot grimly drew a card out of his pocket, and flashed it at them.

“Oh!” And their jaws dropped.

“You haven’t done anything.” Cabot smiled engagingly. “But I and this other G-man here want some help.” They brightened eagerly. “We are being followed by a New York car containing criminals. You’ve heard of The Man on Long Island?” They nodded. “Well, they’re henchmen of his. I want you to change numbers with us, go out of here and head south. They’ll follow you, and we’ll follow them. When they stop you, we’ll take them by surprise. Are you game?” They nodded again. “But it will better fit my plans if you can elude them entirely; only don’t get pitched for speeding.”

While they were changing the number-plates—and shifting their college flags onto our car—Cabot drew the garage man aside, and flashed his card again. “As soon as both our cars have left, phone the local police, give them the Michigan number which is being put on these young fellows’ car, and tell them that a New York car—my friend here will give you the number—full of gangsters is after the Michigan one. Tell the police to follow it, and arrest the gangsters. But, don’t, on your life, mention my car or where I’ve gone.”

The Dartmouth men warmly shook hands with us, and departed. From the front of the shop, we saw the New York car start up in pursuit. We hurried to our own car—and Cabot backed it out the rear door of the garage.

“But you said—,” I began.

“—that I’d follow and protect them? Yes. But the local police can do that for me. Meanwhile we’ll be giving the enemy the slip.”

“You never told me that you were a G-man!”

“I’m not. That card is merely a night pass to the Federal Bureau of Investigation. I counted on the Dartmouth fellows reading only the heading on it.”

Now that we were temporarily free of our pursuers, I again queried Cabot as to how come he was here on Earth instead of still on Venus. We compared notes, as we drove along.

Toward the end of 1938, I had received a letter from the Radio Corporation of America, informing me that a patent application of theirs had been rejected by the U. S. Patent Office on the strength of a complete description of identically the same apparatus in one of my three published novels about Cabot’s adventures on the planet Venus.[1]

|

In spite of the inviolate rule of secrecy which enshrouds the U. S. Patent Office, we have good evidence to believe that this statement is an actual fact. Holland’s patent on his submarine was similarly invalidated on the strength of Jules Verne’s “Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea.”—Ed. |

This letter from the R. C. A. had gone on to inquire whether there actually was such a person as Myles Cabot, and whether his recorded adventures on Venus were the truth. Of course, I had answered yes to both questions.

The next development had been a visit from a group of R. C. A. engineers at my Chappaquiddick Island farm off the Massachusetts coast. They wanted to see the remains of the huge radio set which Cabot had built there, and which he had used to transmit himself back to Venus, and with which I had kept in touch with him for a short while after his return, until it had inexplicably ceased to function.

The outcome of their visit had been their purchase from me of the remains of the set, and all the notes and blueprints which Cabot had left. I had felt rather guilty about having messed-up their patent, and so let them have all the junk for a mere song. Furthermore my barn needed repairing.

Then I had dismissed Cabot from my mind until I had unexpectedly run across him yesterday morning at the class reunion.

He now explained that the Radio Corporation had repaired the radio set which they had bought from me, had thus reopened communication with Venus, and had finally persuaded him to transmit himself to earth again.

After some research work for the R. C. A. in the early spring of 1939, Cabot had gone over to General Motors to help them design a special car for the Federal Bureau of Investigation, which was the car he now was driving.

Hence the bullet-proof glass, the one-pounder cannons, the sponge-rubber inner tubes, and the smoke-screen, all of which had come in so handy in our encounter with the ruffians who had attacked us.

Cabot’s ruse of interchanging the number-plates proved highly successful—at least so far as we were concerned. We drove all night, and reached Washington intact the next morning. The newspapers carried an account of the car which we had shot up, but no mention of any similar occurrence in that vicinity; so we concluded that the Dartmouth two had avoided trouble. Probably they had been followed clear to their homes, before their pursuers discovered the impersonation. A later check-up verified this.

Cabot reported at once to head G-man J. Edgar Hoover at the Department of Justice Building, and turned over the car. Then the two of us set out for the White House.

On the Avenue in front of the Justice Building, whom should we run across but our financier friend, Morton Rust!

“Fancy meeting you two here!” he exclaimed, holding out his hand.

“Why aren’t you still at the reunion?” I inquired.

“I might ask the same of you. But the fact is I received a sudden call from the Treasury Department about helping to swing a new issue of short-term notes. And you?”

“You don’t happen to have seen our classmate Sedgwick around here, do you?” Cabot interjected.

“No. Why?”

“Oh, merely that he seems to be the most ubiquitous member of our Class,” Cabot laughed. “But, look here, Rust. I’ve got an idea which I’ve been mulling over in the back of my mind all the way down here. It was suggested by your remark in the Harvard Union yesterday morning about the effect of the White House bombings on the stock market. Farley and I are on our way to the White House right now by special invitation to discuss the matter. Would you mind coming with us? It’s just a hunch, but I believe you could help.”

The eyes of our stock-broker friend glowed eagerly. “Would I! It would be killing two birds with one stone: helping to solve the mystery of the invisible plane, and perhaps giving me a drag with the Secretary of the Treasury. Sure I’ll come.”

“There’ll be more than birds killed, if we don’t hurry,” Cabot commented grimly, as he hailed a taxi.

The President was awaiting us in the Blue Room, and with him were several experts from the Air Corps and the Technical Staff of the Ordnance Department. Of course, they had all heard of Myles Cabot the Radio Man, greatest scientist of two worlds, but had always regarded him as more or less of a myth—like Burroughs’s Tarzan. Even after actually meeting him and shaking hands with him, they still kept glancing at him incredulously and furtively throughout the entire conference.

As soon as the introductions were over, Cabot waved aside all compliments, and got down to business. First he asked if the bomb fragments had indicated that the bombs were of government make. On receiving the expected negative answer, he told of the two cars which had followed us, one of which we had so successfully shot up, and of their accurate track of our whereabouts, until we had given them the slip by swapping license-plates with the Dartmouth men. This seemed to indicate that a rather far-flung organization was behind the bombings.

“Which rules out the hypothesis of a crazy scientist,” the President commented. “Do you suppose that it is the work of some foreign power, or of some subversive organization?”

“I rather think not, Sir,” Cabot replied, pursing up his lips and narrowing his eyes. “You have not received any threats on your life, or any specific demands, have you?”

“Yes, I have.” The President handed over a typewritten note. “This just came in by mail this morning.”

Cabot frowned, as he took the piece of paper. He read aloud:

“Mr. President, I am concerned with your safety. Leave the White House at once, making public statement that you have done so. If you stay, I shall bomb the White House, and this time I shall not miss. If you leave, and omit to publish the fact, I shall follow you and destroy you. Only by obeying my orders, can you be saved. (Signed) Wings over Washington.”

Cabot brightened as he finished reading.

The President smiled a wry smile. “I am something like a ship-captain, gentlemen. Of course, I cannot leave the bridge.”

“Is America sinking?” Morton Rust asked with a slightly malicious tinge to his tone.

The President flashed him a quick glance of annoyance.

I hastily interposed, “Don’t mind Morton, Sir. He’s an economic royalist.”

The President’s booming laugh relieved the situation.

“It all fits in with my theory,” Cabot announced. “That’s why I brought Mr. Rust here. Morton, tell them how this latest development will affect the stock market.”

“Well—um—you may not all agree with my theories, but I’ve a reputation as a fairly successful trader. When it becomes known that his Excellency does not intend to leave the White House—”

“It will not become known,” the President testily interjected.

“Begging pardon, but it will. There is a leak here somewhere. Undoubtedly the contents of that quaint billet-doux which Mr. Cabot has just read to us is already known on the Street. Well, as I was saying, when it leaks out that the President is not going to leave the White House, the market will drop. When he announces it, the market will rise.”

“I don’t get the first,” said one of the Army officers, “but the second seems natural enough. Of course, the market will be reassured by our President’s courage.”

“Quite the contrary. Market-shaking events, unless wholly unforeseen, always have an effect exactly opposite to what an amateur would suppose; for the full effect of the news has already been discounted by insiders. Then, just before the news becomes public, and the lambs rush in and try to profit by the news, the insiders unload or load up, as the case may be, and the market moves just the opposite from what one would think it would.”

“Well,” said the President, “even assuming that there is a leak in my official family, how does that help us solve the mystery of the bombings?”

“Very simple, Mr. President,” the stockbroker replied, “and I believe that this is what Mr. Cabot has in the back of his mind. Have the F. B. I. check-up on all large buying and selling orders (say, of over a thousand shares) of all rapidly fluctuating stocks, and trace these to their source. My own firm will be glad to cooperate, and I shall be glad to keep in touch with you.”

Cabot nodded emphatically.

The President fixed Morton with an intense but disarming stare. “Of course,” he boomed, “you will give me your word that you and your associates will keep out of the market yourselves, so long as you are in touch with us.”

“Certainly, Mr. President,” Morton replied in an aggrieved tone.

“And now, Mr. Cabot,” the President continued, “I understand that you have a theory as to how these bombings are being accomplished. Something fourth-dimensional, I suppose?”

“Not at all,” Cabot laughed. “Something much more simple than that.”

“But what?”

“Please, Sir, let me combat it first, and explain it afterwards.”

“All right! All right!” a bit testily. “What are your plans?” Then, grinning engagingly, “Remember, I’m to be killed tomorrow afternoon, I believe.”

“In view of the White House leak, Mr. President, I prefer to discuss them with you and Ralph here, alone.”

So the President waved the others out of the Blue Room, and the three of us got down to business.

“Did you know,” Cabot promptly began, “that sound travels with the speed of light?”

“Does it?” The President frowned, removed his glasses with his left hand, and pinched and massaged the top of his nose with the thumb and forefinger of his right. Then, from the inexhaustible storehouse of his memory, there came, “It seems to me that I was taught at college that light travels at 186,000 miles per second, whereas sound travels only 1,100 feet. Isn’t that why one sees the lightning before one hears the thunder?”

“Yes. But there is also a little-known scientific principle that every sound wave has two phases, like for example, the electrostatic and the electromagnetic phases of a radio wave. Only, whereas both phases of a radio wave travel at the same rate of speed, the two phases of a sound wave travel at two utterly different rates. We are all accustomed to the phase which we pick up with our ears. The other has only recently been discovered by Cupian scientists on Venus—perhaps it is not yet known on Earth. It is electrical in its nature, and hence travels with the velocity of light. The situation is just as though there were a microphone and a radio transmitting set located at the source of the sound; we would pick up the audio-frequency long before the sound itself reached us.”

“Very interesting, I am sure,” the President drily remarked, “but just where is that getting us?”

Cabot held up one hand in mild protest. “Ordinary Army sound-detectors aren’t very satisfactory to locate an unseen plane; because, first, you can’t get an accurate intersection due to the slow speed of sound, and besides there are different distances between the two or three receivers and the source. Secondly, even if you did get an accurate intersection, the plane would be quite somewhere else by the time we got it located. But, with my device for picking up the speed-of-light phase of the sound wave, we can get an instantaneous location of the plane just as though we were training telescopes on it.”

“Sounds fishy to me,” said the President. “Well, Mr. Cabot, what do you propose?”

“Give us a room here in the White House as a work-shop. Keep our presence here a secret. I’ll make out a list of supplies which I need; get them just as quickly as you can, for we’ll have to work fast. Provide a secret-service escort for my friend here and me. We’ll put up at the Hotel Washington, and rest up from last night’s ride until you phone us that everything is ready. Meanwhile, have the F. B. I. check up on the stock market—and on the whereabouts and activities of our classmate Sedgwick.”

“What have we got to lose?” laughed the President, genially, holding out his hand.

We left the White House under escort. But, before turning in for a nap at the hotel, we took a taxi to the garage of the Department of Justice, and removed the door-lock from Cabot’s car. Then bought some pajamas and toilet things.

Morton Rust took a room near ours on the same floor, and was likewise assigned a Secret Service escort.

I was dog-tired. It seemed as though I had scarcely hit the pillow in our double room at the hotel, when the phone rang. We had slept for five hours, and our supplies were ready for us at the White House.

Snatching a brief lunch in the Coffee Shop, during which we read in the afternoon papers that the stock market had taken an unexplained dip, we hastened to our new laboratory. The G-men reported that Sedgwick could not be located.

Cabot’s first act was to remove the lock from the door of our workshop, and substitute the lock which he had taken from his car. “Another gadget,” he explained. “A fanciful conception of my own. Note these two keys: one is full-length and the other lacks the tip—looks as though it were broken off. Either will unlock the door, but the long one will also release a flood of sleeping-gas. I’ll give you one of the long ones.” Then, as I raised my eyebrows, his blue eyes twinkled and he added, “But, of course don’t ever use it.”

Then we plunged into work building a sort of combined telescope and radio receiving set hooked up with an ordinary sound-ranger. I never did quite master the details. All that Myles would say in explanation was, “The sound-ranger will give us the general direction—or, should I say, ex-direction, of the plane. Then we can advance the telescope, and pick up the fast phase of the plane’s sound. I must build three of these. Then if we hitch them up to the ordinary Sperry fire-control apparatus of a battery of anti-aircraft guns, just as though they were ordinary telescopes, we can bag the plane just as though we could see it.”

“But why can’t we see it?”

“I have my theory. But it really isn’t pertinent to our present problem, and I don’t care to risk my reputation with prophesying. We’ll check, when I shoot it down.”

We worked all night, and half completed one of the new instantaneous sound-rangers. In the morning papers, Walter Winchell’s column announced the following: “A certain exalted individual, who is mortally afraid of having eggs laid on him, is said to have called into consultation a crack-pot swami (who claims to have come from another planet). Swami thinks he can catch hen. Government by hunch, we call it.”

Stocks rose. Our market expert, Morton Rust, grinned knowingly as he explained to our little inside group at the White House, “The swami yarn was all over Wall Street yesterday, demoralizing the market. Then, when Winchell sprung the story, there came the inevitable reaction. Fundamental principle of stock-speculation: bark always worse than bite.”

An anti-aircraft battery was moved onto the White House grounds. Shortly after they had unlimbered their equipment, the sound of an invisible plane could be heard. I ran up out of the laboratory to see the show, but Cabot kept on working. Frantically the old-fashioned sound-rangers, with their four huge funnels, were traversed and laid to pick up the sound. The keenest officer minds of the Coast Artillery and Technical Staff trained their blind telescopes by guesswork on the vacant blue ahead of the apparent source of the sound. The batteries opened fire, with well calculated dispersion, on absolutely nothing.

Then from above a bomb dropped with exact precision upon one of the guns, wiping out it and its crew. The invisible bomber passed on to the northward.

Stocks crashed. A letter arrived at the White House, ordering the President to get rid of Myles Standish Cabot at once, or face the consequences. And, although no one but the President, Cabot, and I knew of this latest communication, stocks dipped still lower.

“This seems to eliminate both Rust and the supposed White House leak,” said Cabot, as he redoubled his efforts.

“What! You suspect Rust?” I asked.

“I did. But this leak must have come from the bomber himself. I’m afraid the President is in for it. For it’ll take at least two more days to complete my other two sets.”

“Couldn’t he leave secretly, and pretend to be still here?” I hazarded.

But Cabot shook his sandy head. “If there is a White House leak, it would do no good.” Suddenly he stiffened, his face lit up, and his blue eyes sparkled. “By the Lost Religion!” he exclaimed. “I have it!”

“What?”

“I’ll catch him with one set of apparatus. Listen here. There are always slight sound-variations in the purr of a motor, no matter how carefully it is tuned up. We’ll get a two-pen chronograph and record the sound tracks of both phases. Wherever we see a characteristic break in the track, we can make a micrometer measurement on the two recorded tracks. Knowing the constant difference between the velocity of each of the two phases, this will give us the exact distance of the plane. We have its instantaneous direction from the radio-telescope. Distance and direction uniquely determine position. We’ve got ’em licked with one apparatus. Come on.”

He hastily scratched out a bill of materials. “Send this over to the Technical Staff,” he commanded. “And tell the President that, by late tomorrow, the White House will be impregnable. I hope that this leaks out, and reassures the country.”

It did, and stocks rose again.

That evening, with the new apparatus still uncompleted, Cabot insisted on a rest. His hands were shaking, and he appeared very nervous. So, in spite of all that was at stake, I did not argue with him. We returned to the Hotel, had supper, and went right to bed. I promptly passed out, and did not open my eyes again until it was broad daylight.

Cabot was gone from his bed! My first thought was: “Kidnapped!”

Without bothering even to shove my feet into my slippers, I rushed into the adjoining room, where slept our Secret Service body-guard. Instantly one of them covered me with his automatic.

Then laughed, “Oh, it’s you, Mr. Farley.”

“Where’s Myles?” I demanded.

The man grinned. “No cause for alarm. He left for the White House before daybreak.”

“Under guard, I hope.”

“Certainly.”

I sank into a chair. Then rising and dressing as hurriedly as I could, I rushed to the White House. They said that Cabot was in our laboratory.

But, when I reached the place, it was locked. No one answered to my rap on the door, and my call of Cabot’s name. I snatched out my key.

Then remembered.

Something hard and round dug into my ribs from behind, and a harsh voice rasped in my ear, “Don’t make a move or a sound.”

I tensed myself, and my mind began to race. “You wouldn’t dare to shoot. The guards would come running.”

“Oh, no, they wouldn’t.” My unseen captor laughed harshly. “My rod has a perfect silencer. Be quick about it! Open the door!”

I thought, “Perhaps the gas will get him, too.” So I quickly inserted the key in the lock, and turned it. A sweet pungent odor flooded over me.

As I slumped weakly to the floor of the corridor, I twisted around to observe the effect on my captor.

But he had stepped back out of the range of the gas. Nor could I identify him, for a bandana was tied across his face.

When I came to my senses again, coughing, reeling with nausea, I was lying handcuffed on a couch in the Blue Room, with a Medical Department Major kneeling beside me. Standing by were the President, Morton Rust, and two of my Secret Service body-guard.

The President’s face was grim and set. “Well, Farley,” he said, “I guess we’ve spotted the White House leak at last. Cabot warned me that you were not to be trusted. Why were you trying to enter his laboratory in his absence?”

Still reeling from the effects of the sleeping-gas, I swung my feet around and sat up dizzily on the couch. “I was looking for Cabot,” I moaned.

“A likely story,” Rust cut in harshly.

“Where is Myles?” I demanded.

“I don’t know,” the President replied. “He left the building under guard—destination unnamed.”

“But we’ve got to find him. Some one held me up with a revolver and made me open the laboratory door. Whoever did it, has probably wrecked our almost completed apparatus. The White House is again at the mercy of the invisible bomber, and this time he will probably bomb the White House itself.”

“You ought to know,” Rust grated.

“We’ve got to find Cabot!” I persisted. “There is no time to lose. He will vouch for me.”

“Thinking first of yourself, eh?” Rust laughed grimly.

“This is no laughing matter. Take my key, somebody, and see if my assailant didn’t wreck all our apparatus. I couldn’t have done it, for I fainted from the gas before I got in.”

“And now you want us to be gassed, too?” the President sarcastically asked.

“I’ll open it myself.”

“It would be safer for all concerned,” said the President, “to keep you away from the laboratory. The apparatus is safe, for you didn’t quite reach it. And we’ll leave it strictly alone, until Cabot returns.”

The telephone rang, and the President answered it. I heard him give his version of my arrest. Then, still holding the phone, he turned back to us with, “It’s Cabot. He says he’ll be back in a couple of hours. He seemed relieved that his gas-lock kept you from getting in.”

“Two hours!” I moaned. “Hell will be popping before then. Let me speak to him.”

“You’ll speak to no one,” the President snapped. He hung up.

“Where did Cabot call from?” I persisted.

The President’s face fell. “I didn’t ask.”

“Have it traced! Please! Think of America!” I begged.

“I am thinking of America.” Then, to the two Secret Service men, “Take this fellow over to the State War and Navy Building and lock him up.”

So, kicking, struggling, and protesting, I went. Where was Cabot? Would he return in time? But, even if he returned, what could he do, with our apparatus all smashed?

Yet, such was my confidence in the Radio Man, that I felt he would do something effective, if I could but reach him and give him the facts. His mistrust of me pained me even more than the stubbornness of the Chief Executive.

About an hour and a half later the guards came for me, and told me that the President had sent for me. Perhaps he had seen the light. Perhaps he had gotten in touch with Cabot again. Perhaps it was not too late.

But, as I and my guards entered the driveway of the White House, we heard far to the southward the burring roar of an airplane motor. And the blue sky was devoid of any plane to have caused that noise. The three of us halted and gaped.

Soldiers came piling out of their tents on the White House lawn, whipped the tarpaulin off of a three-inch gun, took their stations, and began swinging the gun around in the general direction of the oncoming invisible menace.

Futile gesture! What could they do without Cabot?

Now the planeless sound was almost over the White House.

“Commence firing!” shouted the Lieutenant in command.

The cartridges began passing rapidly from hand to hand, the nose of each shell being poked into the fuse-setter beside the gun and twisted, just before being inserted in the breech.

“Crack—crack—crack,” came the ear-splitting staccato explosion of the gun, as its barrel slid backward and forward with rhythmic cadence.

With the same cadence a cluster of puffs of cotton-batting smoke began to appear, one by one, in the distant blue above. The putt-putt-putt of these little shell-bursts was wafted down to us.

And then suddenly we saw the shape of a huge bombing-plane, a twisted and torn silvery shape, with parts flying away from it, hanging in mid-air above the White House.

As this mass of wreckage hurtled toward us, we ducked and closed our eyes.

“Cease firing!” shouted the Lieutenant.

Next we heard, as we cowered, the “boom” of the bursting plane—its own not-yet-released bomb had evidently been hit—and then the crash behind us, as the wreck landed on Lafayette Mall.

We sprang to our feet again, and stared around. A crowd of men were running down the front steps of the White House toward us. And among them was Myles Cabot.

The rest rushed past us toward the now-burning pile of wreckage, but Cabot stopped by me.

“Awfully sorry, Ralph,” he panted. “But I had to use you as a decoy. My apparatus was finished early this morning and moved out onto the lawn, and hitched up to the fire-control. We almost caught the fellow who gassed you, but he got away. So we figured that he would make an immediate and final bombing attack, while he thought we were still unprepared. Hence our false accusation of you.”

I grinned with relief. “Glad to have been of service.”

“Well, our job is over.” Then, to my guards, “Take off his handcuffs.”

We entered the White House. Cabot seemed to have lost all interest in the fallen plane, on which fire-engines were now playing streams of water.

The President received us, thanked us warmly, and apologized to me profusely with a twinkle in his eye.

Morton Rust was there. “The stock market will boom,” he announced, “for this is a case of unexpected news, and there was no leak this time. The market had dipped to new lows just before the attack. Too bad the poor fellow who lies burned to a crisp over across the Avenue won’t be able to cash in on the rise.” His voice sounded bitter. Then he grinned. “Sorry, Ralph, that I had to join in the denunciation of you a short while back.”

“You’re a darn good actor!” I exploded.

“Well,” Cabot announced, “I’m going back to the Hotel, and catch up on some sleep. And what a relief not to be dogged by guards any more!”

As Myles and I strolled back alone to the Hotel Washington, I asked, “And now tell me the secret of the plane’s invisibility.”

“Very simple. We used the same stunt on Venus in one war there. The entire surface of the plane was a carefully rounded mirror, so that all one could see when looking at it was the reflection of the sky beyond. That is why the plane only flew in absolutely cloudless weather.”

We bought some special editions—“Extry! Extry! All about the bomber”—and went up to our room. I felt let down, and slumped into a chair. Cabot, too, sat down, but seemed unable to relax—he had been under too much of a strain, I suppose. After all, the responsibility all through had been his, not mine.

For a while we read our newspapers in silence. The market had already begun to soar. The body in the plane had proved absolutely unrecognizable—but had been shipped over to the laboratories of the F. B. I. for measurement of the bones and study of the teeth.

“Was it Sedgwick, I wonder?” I asked.

“We’ll know it was, if he is never seen again,” Cabot replied. “But I rather imagine that the flyer was not the real party at interest. Poor man! He was probably just a tool.”

I snapped out of my lethargy.

“Then why are we sitting here unguarded? We are less safe now than at any time since we left Cambridge!”

“I’m well armed,” Cabot laughed. “My bag of Cupian tricks is not yet exhausted. Suppose you run down to the lobby and buy a late edition. When you return, knock three times and give your name. I’ll sit facing the door, and keep my eyes open.” He took a forty-five out of his pocket, and toyed with it.

“By the way,” I asked, “did the check-up of the Stock Exchange produce any clues?”

Cabot shook his head. “We made the mistake of setting a $1,000 share limit. News of that fact must have leaked, too. The guilty man must have operated under several aliases, and always at lower figures. Now run along and buy your paper. I’ll be all right.”

I returned, reading the paper as I plodded down the hotel corridor. Absent-mindedly I rapped three times on the door of our room.

It was flung open in my face, and I found myself staring into the muzzle of a revolver, around which bulged the vanes of a Cutts silencer. The face behind the weapon was masked. Behind him stood another man, back to us, covering the motionless seated figure of Myles Cabot. Cabot had evidently forgotten his promise to me, for his chair was turned to face the window, and only the top of his head was visible from where I stood.

I wondered if he still held his forty-five, and whether he would risk using it.

“Will you please to step into the room and close the door softly behind you,” commanded a suave voice, quite different from the harsh tones of the man who had trapped me at the laboratory. I did as directed. “And now will you please to stand over there by the window.” I started to obey, keeping a wary eye on the gun which menaced me.

“Get up, damn you, Cabot!” the other intruder rasped. “I told you that once before, and would have shot you by now for disobeying, only I wanted to wait until your friend came back. Stand up, damn you, and stick up your hands.”

By this time I had reached the window, and was standing beside Cabot’s chair, my eyes still glued to the weapon of my captor.

“Anything to oblige,” spoke Cabot’s cool voice, from the closet-door behind the two men—not from the chair where he seemed to sit. “Don’t look now, but I have both of you covered. And I have already rung for the G-men, who have been waiting in the next room. That’s only a clothing-store dummy in that chair. Farley, take their guns.”

I did so.

“Now snatch off their masks.”

I did that, too. The one with the harsh voice was our classmate, Morton Rust. The other was a stranger.

“I suspected you nearly from the start, Morton,” Cabot continued in a level tone, tinged with sadness, as the Federal operatives entered and shackled the two men. “The stock market reacted just a bit too perfectly.”

[The end of The Radio Man Returns by Ralph Milne Farley]