* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Three Years' War for Peace

Date of first publication:

Author: Basil Joseph Mathews (1871-1951)

Date first posted: Mar. 12, 2022

Date last updated: Mar. 12, 2022

Faded Page eBook #20220319

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, John Routh & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

This file was produced from images generously made available by Internet Archive/American Libraries.

THREE YEARS’ WAR

FOR PEACE

BY

BASIL MATHEWS, M.A.

NEW YORK

GEORGE H. DORAN COMPANY

TO

ERNEST BRAITHWAITE

Second-Lieutenant

14th Royal Warwickshire

Regiment

Missing, believed killed: July 22nd,

1916

“He was last seen leading his men into action under heavy fire.”

“It is for us . . . to bring increased devotion to that cause for which these honoured dead have given the last full measure of devotion.”—Abraham Lincoln at Gettysburg.

To-day we are all asking the same question.

The miner as he flings down his pick, slings his coat over his shoulder and makes for home; the sweating steel-worker as he staggers back from the blaze of his furnaces; the girl with yellowing skin as she leaves her work in the high explosive factory; the city man opening his “War Final” in the suburban train at night; the mother at home, quivering with her dread of the ring at the door and the buff telegram of death—we all ask “How long? . . . When will the boys come home? When shall we win back to the days and ways of peace?”

And some ask further. “Why must we go on with the war? At home we have now been at the tension of time and overtime for years. And the boys at the Front and on the high seas. . . . Is it worth the treasure of life that we are pouring out daily? Why not stop now?”

The spirit of the answer to that question came in a letter from a brother of mine at the Front. His whole life is bound up with his home—his wife and three splendid children. His longing to be back with them is on him all the time. He loathes war with a daily increasing rebellion. Yet in his latest letter home he writes: “It must seem strange—and I hope you will not misunderstand—but I don’t want to be home out of this business until we have put it through.”

The answer to the question, “Why not stop now?” is there. The whole issue can be packed into a sentence which sums up the faith of our armies—the wildest and roughest of our men and the most sensitive alike: We must go on with the War because we do not want our children and grandchildren to have to wade afresh through all this blood and muck.

We, who still live on, look back now across the three most tremendous years in all the history of man. The fourth year will determine the destiny of mankind for a thousand years to come. The foul Thing that made the War is still in the saddle. It must be felled to the ground. The lives of all our children—of the world’s children to all time—are to be made or marred by what we do or fail to do. If, then, having put our hand to this plough, we now turn back, our shame will go down from generation to generation without end.

Can we, however, begin to see where the long dreadful furrow will end? We are in the midst of the dust and toil, the blood and sweat of it all. Vision is blurred—and without the vision our ideals and our passion perish. The landmarks are hidden in the smoke of the battle. The great Voices are drowned in the clamour of our forges and the clatter of our looms.

With aching hands and bleeding feet

We toil and dig, lay stone on stone;

We bear the burden and the heat

Of the long day and wish ’twere done.

We shall “toil and dig” better if we can for a moment stand erect and get a glimpse of the goal.

This book is an effort to do that, to see, across the smoke and turmoil of the battle after three years of war, the fortunes of the day and the promise of to-morrow. To focus so vast a field in one picture eliminates a myriad details that are quite momentous in themselves; but the view may be no less true for that.

The book is not an argument, nor a detailed record. It is rather a moving picture of great events thrown on the screen—“lest we forget.” Taking the answer to that question: “Why go on with the War?” as its goal, it looks back over the origin and trend of the War; tries to estimate the measure of the amazing transformation of our life to meet the War’s demands; and stands reverently before the miracle of the sacrifice already made; it attempts to give a true “relief map” of the situation as a whole as it is, and to refresh our tired eyes with a forward view of the new world toward which we strain, that world for which our honoured dead have given their lives and for which our living have surrendered those whom they loved even more than life itself.

BASIL MATHEWS.

| CONTENTS | |

| CHAPTER I | Into the Breach |

| CHAPTER II | The Transformation of Britain |

| CHAPTER III | The Service of the Empire |

| CHAPTER IV | The Sea-Scape |

| CHAPTER V | The War on the Land |

| CHAPTER VI | Why Must We Go On? |

It is not easy even now to grasp the grim, tremendous fact that we are making greater history than we can read.

As we look right across the history of man through all recorded time there is no moment that stands as peer to that in which the clock struck on August 4th, 1914, and the twelve days of fate ended.

In that hour the old world was broken up and melted down. From the Orkneys across Europe and Asia to New Guinea and Samoa, from the Yangtse across two oceans through America to the Zambesi and the Tigris, every land and people saw their familiar life shattered. For each a new epoch had opened. All future human life—labour, capital, commerce; government, social life, national being; our inter-racial relations—all date a new world from that midnight. Time itself was in travail.

The world-fire was kindled by three shots from a Browning pistol. In that sense the right hand of Prinzip (the Serb student of Austrian nationality who on June 28th, 1914, assassinated the Archduke Francis Ferdinand, heir to the Throne of the Austrian Empire, with his wife, when at Serajevo visiting the newly annexed provinces of Bosnia and Herzegovina) has already slain its million men. But this murder, though it was made the immediate occasion of the War, was not its cause. The causes of the War were political, racial, diplomatic, and intellectual.

If any one political event above another led the Central Empires to precipitate war at that time it was that the Balkan War, by reviving a free Serbia, had thrown a mighty dam across the Eastward movement of the Germanic race. Serbia cut the Berlin-to-Bagdad line. She strangled the Hamburg-to-Basra land route to the East. Politically, then, this baulked passion of Germany for dominion in the Near East, as a decisive step in a struggle for world-empire, was the cause of the War. If we seek its racial origin we find that in the antagonism of Slav and Teuton. Diplomatically, as Sir Edward Grey said, war became inevitable through “the absence of good-will in Berlin.”

But, in the last resort, as Lord Acton declared, “Ideas are the cause and not the result of public events.” In that ultimate sense the cause of war was a philosophy of force and of “will-to-power,” issuing in an ethic of savagery. That philosophy became incarnate in a centralised, despotic government in which the Army is supreme, and was propagated through a splendid educational system. It created as its tool a mighty scientific war-machine which, in the hand of the General Staff, is the true master of Germany. Its exponent of supreme power was Nietzsche. The historian who applied its principles to the State was Treitschke. It was reduced to military theory by men like von Bernhardi. Its origin was in Germany. But its missionaries were everywhere.

The whole trend of the diplomacy of Austria and Germany through the fateful “Twelve Days” from July 24th to August 4th deepens the conviction of their “will to war” into moral certainty.

On July 23rd, almost a month after the assassination, the Austrian Empire presented its drastic Note making demands on Serbia that would have reduced her to a vassal of Austria, which would thus automatically extend its rule to the borders of Greece and Bulgaria. That Note meant the absorption of a Slav people by a Teutonic Government. An answer was ordered within forty-eight hours. Germany, through her Ambassadors in London, Paris and Petrograd, declared her agreement with the terms of the Austrian Note. Russia, appealed to by Serbia as the greatest Slav Power, advised agreement to every demand, save two which meant national suicide. On July 25th, within an hour or so of receiving the Serbian reply, the Austro-Hungarian Minister left Belgrade, which four days later was being bombarded by Austrian guns. Through the twelve days Sir Edward Grey “toiled terribly,” first to secure peace, then to localise the conflict. He invited Germany to call a Conference and was refused. He tried every door and heard the key of rejection grate in all. In return England was invited to stand aside while France was smitten to the ground and robbed of her colonies, and while Belgian neutrality was broken. The infamous suggestions were rejected.

In 1911, 1913 and on July 31st, 1914, Germany through responsible Ministers had declared that she would observe the Treaty of 1839 to respect Belgian neutrality. Yet on August 2nd the Minister (who three days earlier, on July 31st, had declared, in reply to an inquiry from the Belgian Government, that he was certain that Germany adhered to her pledges) presented a Note to the Belgian Government demanding a passage through Belgium for the German Army on pain of instant declaration of war. On the evening of August 3rd the German troops crossed the frontier.

The Imperial Chancellor, Bethmann-Hollweg, in the Reichstag engraved on eternal brass the infamy of Germany:—

“We are now in a state of necessity, and necessity knows no law. . . . We were compelled to override the just protest of the Luxemburg and Belgian Governments. The wrong—I speak openly—that we are committing we will endeavour to make good as soon as our military goal has been reached. Anybody who is threatened, as we are threatened, and is fighting for his highest possessions, can have only one thought—how he is to hack his way through.”

In those words and in the things done in Belgium in obedience to the German High Command, Prussianism in its mailed might assailed the very foundations of free life in the world. The ordinance that bound civilisation together was “rolled up like a scroll that is read.”

“We worked for peace,” declared Sir Edward Grey on August 3rd in the House of Commons, “up to the last moment and beyond the last moment. How hard, how persistently, and how earnestly we strove for peace the House will see from the papers that are before it.[1] But that is over so far as the peace of Europe is concerned.”

It has been argued that immediate explicit decision by Britain to fling in the sword with Russia and France would have given pause to the Central Powers and so prevented war. If so, it would nevertheless merely have postponed war for a few years till Germany was stronger still on land and water. Frustrated though the efforts for peace were, their moral influence was so great that—looked at in perspective—they may prove to have been a determining element in the War. For they had a tremendous power in two directions. First, the rejection of those efforts by Germany, combined with the moral issue of the invasion of Belgium, brought into the War the full passion and weight of the British Empire, whose whole structure was as exclusively organised for peace as Germany was organised for war. Secondly, those efforts won the general confidence of the neutral peoples in the honesty of Britain’s purpose.

No man holds the clue to British policy who looks, in the Continental manner, for a coherent reasoned plan. Through the centuries of our strange record, the clue lies, not at all in a clearly conceived Weltpolitik rigorously followed, but in the spontaneous action of an instinct rooted in a conscience that blends Puritanism, business caution and chivalry. The British have gone wrong—when—as with the North American Colonies—a non-representative ruler (like our North-German drill-sergeant, George III.) has held the reins and driven counter to the national conscience. Our method is blundering, the instinct is sure. The defects of this way of government lie on the surface, like the warts on a giant oak. The strength lies hidden, where the sap flows silently through the tough roots and trunk to the growing branches.

No one of us will ever forget that 3rd of August on which Sir Edward Grey made his statement—the sunny Bank Holiday when the clouds of war massed themselves in a clear sky before our incredulous eyes, and the growl of the distant thunder rolled upon us. At the suddenly unmasked cannon’s mouth instant life-and-death decision was demanded. The world’s future trembled in the balance, though we could not in those early days realise to the full the stupendous issues that were at stake. We loathed the thought of war; but we chilled to the marrow with the dread of a dishonourable peace. By a colossal paradox the Empire as it read Sir Edward Grey’s statement was at once stunned and relieved beyond measure. We stood to lose the whole world—but not our soul.

On the instant the ranks of the Empire closed. The civil war that threatened Ireland was stilled by Germany as Ulsterman and Nationalist mobilised for France. The fierce energy that struggled for Votes for Women turned itself with heroic vigour into the channels of national war organisation. The hot angers of Labour and Capital fused in a glowing concentration against the bully of the world.

The riotous joy of the boulevards of Berlin had no parallel in London. The “dour” quiet of it all deceived even our Allies then and for long after into a wonder whether we really were “all in” for the War. But beneath the surface glowed a determination that, from the outset, meant (as we had shown a hundred years before in face of Napoleon when our allies one by one fell out of the ranks, but we held on) that we ultimately were there to the last man and the last penny. The bulldog is slow to anger and silent, but when the grip has once closed not even death unlocks the grim jaws.

Berlin that day pelted the windows of the British Embassy with stones, and the Emperor William sent a message to our Ambassador which showed that he shared with his Prussian people that curious inability to understand what civilised Europe knew five centuries ago—when the savages of North Germany still offered human sacrifices in their uncouth haunts—and what the true Southern Germany knows full well, the meaning of chivalry, the gentleman’s instinctive treatment of a foe, the gulf fixed between man and the “cad.” While this happened in Berlin, British warships were piloting the German Ambassador (whose departure from London was watched by large and silent crowds) past German mines that were sown in British waters before war had been declared.

Our fleet steamed to its stations. Lord Kitchener was stopped with one foot on the gangway of the vessel that was taking him to Egypt, and was called back to London as Minister of War. Mobilisation was ordered. The smallest and most perfectly trained Army owned by any Great Power in the world concentrated—an army planned, trained and equipped for small border fighting in the remote places of the world. Lord Haldane, by his clear thought and his careful organisation, particularly in guiding Public School and Undergraduate energy into the Officers’ Training Corps, in planning the dispositions of our Expeditionary Corps and their reserves, and in raising the Territorials, had lifted that little Army to a level of efficiency unequalled in its own history and unsurpassed elsewhere. Some 90,000 men with about 15,000 horses and 400 guns were instantaneously available.

Under the curtain of the nights up to August 13th the giant line of transports moved with stern, implacable strength across the grey waters. Their defence lay in the unseen sentinel in the North Sea, the hidden blockade across the Bight of Heligoland. The men who in the twilight caught their last glimpse of the Isle of Wight saw the sun rise blood red over France. The “long ships” of the Empire—a world-commonwealth of free nations—had carried its pioneers into Armageddon.

In each man’s pocket was Kitchener’s message to his troops concluding with the immortal commands:—

“Be invariably courteous, considerate and kind. Never do anything likely to injure or destroy property, and always look upon looting as a disgraceful act. You are sure to meet with a welcome, and to be trusted; your conduct must justify that welcome and that trust. Your duty cannot be done unless your health is sound. So keep constantly on your guard against any excesses. In this new experience you may find temptations in wine and women. You must entirely resist both temptations, and, while treating all women with perfect courtesy, you should avoid any intimacy.

“Do your duty bravely.

“Fear God.

“Honour the King.

“Kitchener, Field-Marshal.”

They swung along the roads singing their song of “Tipperary” and startling France with their thunderous negative to the question, “Are we down-hearted?” The gay people of France had gone grim at the opening of the war; but the Army of the nation that “takes its pleasures sadly” took its war gladly—with a song and a laugh. We are always at our best when things are at their worst.

When our men landed, Belgium and France had already been fighting for ten days. On the very day when the German Ambassador in Brussels declared that his Government would respect Belgian neutrality, three Army Corps in the German field-grey were massing against her frontiers. The swift thunderbolt of Thor was to smash France through Belgium and then to swing back on Russia. Speed was of the first moment to Germany. A day lost might turn the fortunes of the world-war. We must, said the German Chancellor, “hack our way through.”

Liége stood in the path. A scratch force hurriedly swept together manned its defences. Germany flung her men upon it. They were repulsed again and again. In two days the David of Europe had broken the long legend of the Prussian giant’s invincibility. Then the mighty German guns smashed the twelve-foot concrete and the wrought-iron cupolas of the Liége forts like egg-shells. The guns had not been brought up at the outset because arrogant Germany despised her tiny adversary. That pride was a cause of the great fall; for it lost priceless days to Germany. From the south-eastern forts to the city, from the city to the north-west forts, General Leman drew back his men, but still held the gap. At last the heroic General was dragged from the débris of his last fort and the long retreat began.

To recall and record the story of the reign of “frightfulness” in Belgium would be to chronicle the incredible, were not the facts overwhelmingly substantiated in all their details. In that verified record we see, not merely that savagery is reduced to a science, but that the world can never be safe till this new cancer is cut clean out of the body of humanity.

The cold catalogue is enough: a baby crucified with hands and feet outstretched, nailed like a rat to a barn; another baby carried aloft, skewered on a bayonet in a regiment of singing soldiers; girls violated again and again until they died; matrons, old men and priests slaughtered; men mutilated in ways that one man can hardly whisper to another; women and children thrust forward as a screen between “the gallant troops of Germany” and their enemy; organised massacre; the abuse of the Red Cross and the White Flag.[2] Everything that we thought secure among civilised men was defiled and destroyed—fidelity to the pledged word, reverence for age, the sanctity of womanhood, childhood and weakness; standards of honour, of justice and of clean fighting. And they were destroyed, not in an access of passion, but on a deliberate and calculated policy of “frightfulness.” The soldiers who had, when they went to China, been ordered by their Kaiser to emulate the Huns under Attila, now outdistanced their model. The orders of the General Staff and the execution of those commands stand without parallel.

The “frightfulness” was carried out to inspire a terror that would paralyse resistance. But the men of “blood and iron” had no imagination—they lacked elementary brain power in ultimate things. They had forgotten the soul of the world. So they are amazed that instead of inspiring terror they have lighted such a passion for freedom as the world has never known. The world now sees that a truly damned Thing is in the saddle in Germany, and if it is not unseated it will ride mankind, including the German people, with bit and bridle and bloody spur.

So the grey armies of Germany, stretching across the Continent, “hacked a way through.” Backed by a complete system of strategic railways, fitted with a plentiful supply of complete personal equipment, with every form of weapon in profusion from the rifle and the machine-gun to the monstrous cannon drawn by thirteen traction engines, with aircraft ranging from the Taube to the giant Zeppelin, and with a tradition of invincibility, stiffened by fine training and reinforced by great personal courage, it was the mightiest weapon of war that had ever been forged. And it was a weapon in the hand of the Great General Staff in which the finest brains of the specialised military caste were perpetually planning and replanning the very campaigns that were now being put to the test of reality.

The immediate sequel, the story of which has been re-written a thousand times, is one of the most amazing epics on a grand scale in the history, not merely of war, but of civilisation. The miracle is still inexplicable on rational grounds. The David of Belgium had hampered the giant’s stride across Belgium, though the swift and unexpected fall of Namur left the Gideon’s band of the British Expeditionary Force to fend the blow of five German Army Corps. Some 240,000 men converged on our exposed, unsupported, outnumbered ranks at Mons. The British flung back the advance attacks again and again. To have stayed would have made Mons a British Sedan. News came that the French line had been broken on the Sambre on the British right, and that their armies were in retreat. So the perilous withdrawal began, the story of which even to-day leaves a man aching with the anguish of those intolerable fatigues and thrilling with pride at the unbroken spirit of the men. Back to the west and the south the tired troops moved, holding up the foes in the costly battle of Le Cateau, trailing away over the rolling hills and running rivers, and with the enemy always at their heels, till the Eiffel Tower revealed to German eyes the goal they sought. The line-up between the Marne and Paris began.

At that hour the world stood on the tiptoe of suspense and held its breath. From Shanghai and Sydney to Calcutta and Cape Town, from New York and Toronto to Petrograd and Rome, men waited in intolerable expectation of the fall of Paris. General de Castelnau on August 25th took the Germans in flank and won the battle of Grand Couronné. Von Kluck swerved to the centre, believing—it may well be—that the British Army was broken. The French armies and our own were locked in a deadly wrestle with the German line through those early September days—days that will loom larger and larger upon the mind of the world as they grow more distant. There has been no more decisive hour since the Turk was flung back from Vienna by Sobieski nearly two and a half centuries ago. At last the German grip relaxed and they turned their backs upon the Paris which lay so near and yet on that day for ever beyond their grasp. That it was so and is so remains and will remain a miracle.

The allied advance began. We drove the German forces from the Marne across the Aisne into the trenches of that tortuous line from Dunkirk to Belfort which is now engraved with acid on the mind of the world.

The German victory as planned by the General Staff was smashed, although from Tannenberg to the Sambre they had fought successful and resounding battles. Victory in war is to put your opponent out of action either by smashing or containing his forces. Germany could never in this war do that. The Entente had fought for and secured time. It remained to use that time to the full compass of the event.

|

British White Paper. |

|

Report of the Committee on Alleged German Outrages . . . presided over by Lord Bryce. |

The Allies had fought for and had secured time—time so priceless that to waste an hour of it was treachery. Behind the thin line of tested steel in Flanders and France and behind the shield of her Navy, Britain began that transformation of her whole life which stands, without parallel in history.

Britain’s unpreparedness, which stood as an unimpeachable witness to her innocence of planning the War, made the needed change of her entire way of life greater than in any other nation involved in the War. The revolution transformed her social, industrial and political life with a completeness that defies analysis and baffles imagination. The change is not simply, as it were, either mechanical or chemical; it is organic; it goes to the roots of life. The most continuous, unbroken national life in the world has not suffered revolution, but has perpetrated revolution upon itself.

The first and deepest element in that change is the personal[1] dedication of life. There is nothing known to us which we can set up by way of comparison with that voluntary enlistment of over five million men. If the sacrifice of everything for others is the moral principle of religion, the enlistment of these millions of our men stands as the greatest religious act in British history.

The Universities for the first time in their long centuries of history emptied themselves. They did so instantaneously. Irresponsible, high-spirited, pleasure-loving undergraduates swung in without a breath of hesitation, took unspeakable hardships without a murmur, shouldered responsibilities on which great issues hung, lived strenuously and died gallantly. Students who lived for the increase of knowledge and for the service of man; gentle, industrious scholars, whose manliness and grace saturated all their life, went out to endure fatigues and to command men. They surrendered books and music, the flights of thought, the contemplation of history, pictures and all the pleasant warfare of argument, for a life in the mud and strain of the drilling ground and the route march, in all the grind and rasp and elemental brutishness of war. To these men the call that was irresistible lay, not so much in the things for which the superb professional soldier like Kitchener stood, but in the clean, straight policy of Grey. His speech on August 3rd placed the men of our ancient Universities in the Army. They simply accepted the evidence. Their enlistment was the absolute dedication of the young leadership of an empire to a single purpose.

The unanimity was not limited to any class or type. From factory and warehouse, city office and farmyard, schoolhouse and shop-counter; from tram and omnibus, railway and mine, the men poured in till the enlistments of a single day surpassed the pre-war enrolment of a year. The flood of men overwhelmed the military machinery of the country. When the news from Flanders was at its worst, enlistment swelled to its best. In thousands of homes where the advocacy of world-peace had been the genuine absorption of all the thought that was given to foreign affairs, every male member of military age sprang to his place in the new Army.

If that personal enlistment on a national scale was the first and most dramatic element in our revolution, the adoption, with hardly a dissentient voice, of compulsory military service was a stern witness to the national determination to carry the War through to a victorious conclusion. The surrender of personal freedom in ultimate things to military control is as deep a sacrifice and as thorough a break with all historic principle as could be demanded of Britain. It was made, not to coerce the shirker, but to set up a universal standard of reference as to where a man’s true duty lay.

Less conspicuous than the enlistment of the men, but as heroic and complete, was the self-offering of the girlhood and womanhood of the country. To-day women from every walk of life have put aside the dainties and domesticities that grace life, in order to tread the furrows of the farm, stoop over whirling lathes, shovel nitrate of soda, fill shells with high explosive, “man” railway trains, trams and omnibuses, make aeroplane wings, drive motors, mould bricks, crush coal, fire kilns and in a thousand ways to replace the men who have gone. The women of England to-day literally hand out to the armies the guns, shells, cartridges and food without which the Army would wilt in a week. It is not too much to say that the women of England are largely responsible for putting over the bombardment—the barrage that has made each new advance possible at the Front.

This brings the story of transformation to its mechanical and industrial element—the reconstruction that has made Britain one vast armament factory. At the beginning of the War Britain’s ammunition needs were served by three Government factories and a few auxiliary private firms. How often in the early period of the War our gunners sat gloomily by their batteries, being pounded by shells, and with none of their own for a reply!

The story of what has been done here baffles the utmost stretch of the mind. In the spring of 1917 the capacity for producing high explosive was twenty-eight times as great as in the spring of 1915, and the cost was barely one-third per ton of the early War charges. A single section of this one department of the Ministry of Munitions supplies to the Food Production Department, as a by-product, all the artificial manures required for the agriculture of the country.

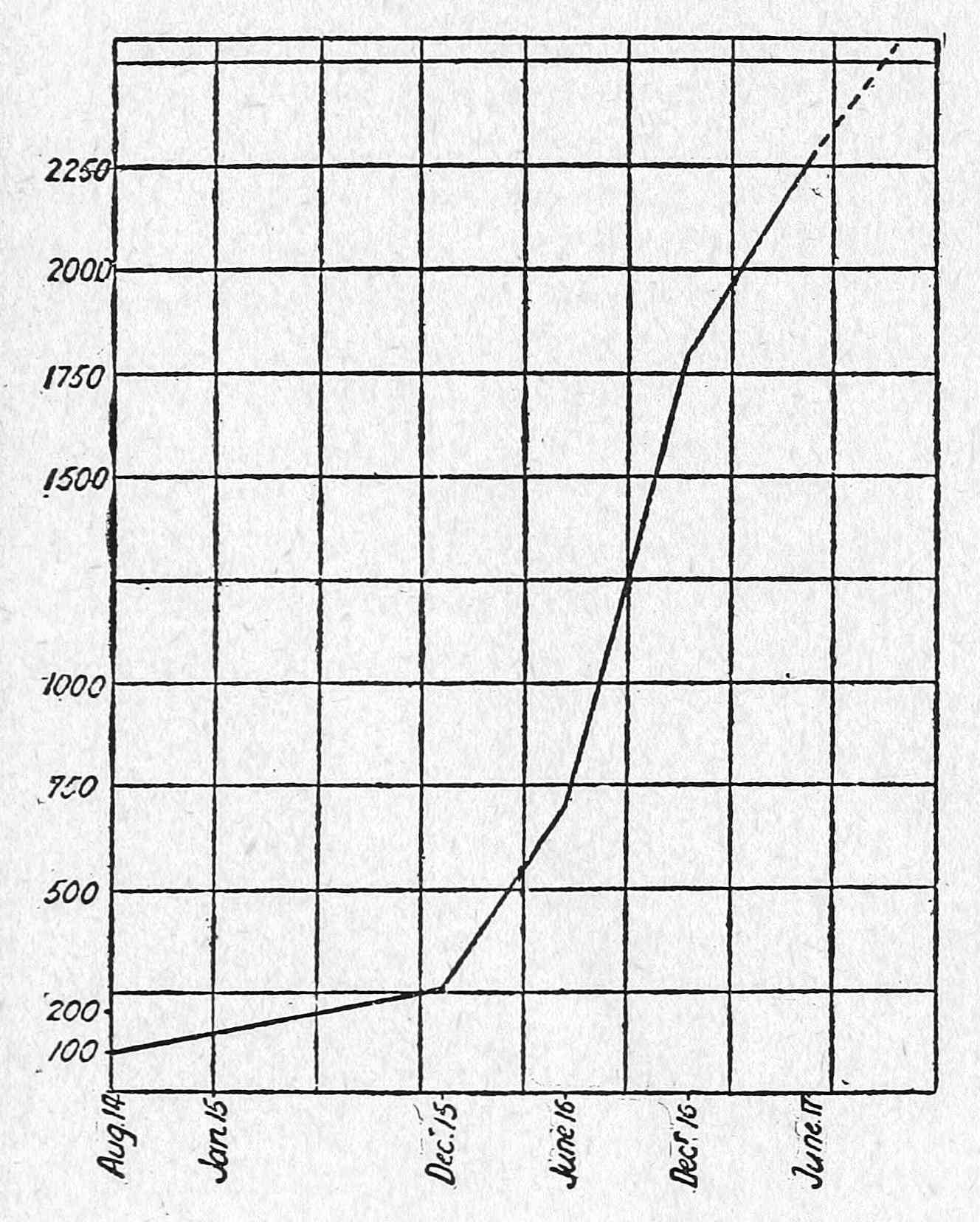

Weekly Output Chart

The curve of weekly output here reproduced will indicate graphically the change that has taken place in the production of completed gun ammunition. New explosives have been discovered, all the technical difficulties of their manufacture eliminated, the supply speeded up, and as a result our soldiers have moved on to the ridges of Vimy and Messines from which the Germans had pounded them with shell for more than thirty dreadful months.

These guns and this ammunition roar from the Italian and Russian fronts as well as in Flanders and France, in the Balkans and in Palestine, on the banks of the Tigris and in the jungle of Africa.

Over and above these things, whereas at the beginning of the War we could only make 10 per cent. of the glass for optical instruments that we required for ourselves, we can now do all that we need and provide substantial assistance to our Allies. Our entire and paralysing dependence on Germany for potash has been broken by a discovery which puts the supply of more than all our needs into our own hands.

Tanks and super-tanks, with still more yet unrevealed inventions to follow; railway engines and railway lines for the immense network of new strategic lines behind the Front; a myriad motor lorries; agricultural implements for widening the range of harvest; these have all been provided by the Army behind the Army, the industrial array of Britain. The supply of aeroplanes has been doubling every six months. From abroad some 1,500,000 tons of munition supplies come every month with an average loss, since the beginning of the “ruthless submarine campaign”—as Dr. Addison informed us on June 28th, 1917—of at the most 5.9 per cent. by submarine warfare. The annual output of British steel has risen from seven million tons to ten millions and is still increasing.

To state the industrial revolution that followed the bitter munitions lesson of the second Battle of Ypres, we can take another series of concrete instances, holding in mind the product of the whole of the first year of war as the unit for comparison. The British arsenals put out in 1917 as many heavy Howitzer shells in a single day as in the whole first year of war, as many medium shells in five days, and as many field-gun shells in eight days. In high explosives and in heavy guns every three days in 1917 produced the total output of the first year of war. The new national projectile factories in 1917 had a total length of over fifteen miles of an average breadth of forty feet, with more than ten thousand machine tools driven by seventeen miles of shafting with an energy of twenty-five thousand horse-power and a weekly output of over ten thousand tons weight of projectiles. The increase of output continues steadily and shows no sign of reaching its limits. What is more, Britain is so instinctively true to her history that in all planning of new arsenals the thought of turning them into productive industrial centres, when war is over and peace returns, is held steadily in mind.

We reach perhaps the deepest and most difficult of all elements in the British transformation when we discover that of the five hundred different processes in munition work upon which women are engaged some three hundred and fifty had never been performed by a woman before 1915. The significance there lies, not primarily in the swift training of women to these difficult technical tasks, nor in their readiness to undertake the work. It lies in the fact that the millions of men who through decades of travail have built up a trade union system in defence of their own rights, have surrendered their hardly won positions for the purposes and for the period of the War. The acceptance by the trade unions of extensive dilution of labour, involving the influx of women and non-union workers into exclusive and privileged categories of skilled industry, fills us with something of the astonishment which would hail the break-up of Indian caste. It is a corporate and deliberate sacrifice on a national scale. And without that sacrifice the whole Alliance would inevitably have been defeated in the War. We owe a debt of honour to those men which must be recognised in action after the War.

We had before us this task, “to improvise the impossible.” The miracle is not that we made a score of blunders, but that the impossible came true, the incredible happened. England became a new people, just because “England to herself was true.”

So when men ask “What is England doing in the War?” we ask from the bottom of our hearts, “What is she not doing?” A nation wedded to peace, a people that never wished for or expected war with Germany—a country not invaded, and sheltered by an invincible fleet—a land with an immemorial tradition against compulsory military service, materially wealthy, with everything to lose and little enough to gain—what has she done?

Her Fleet, with a vastly increased strength, and its personnel increased from 136,000 before the War to something approaching 400,000, has swept the seas free of the enemy on the surface, and is in incessant war upon her foe beneath the sea. Her Fleet and her heroic Merchant Service have borne year in, year out, from the ends of the earth to her Allies and herself, the supplies without which Germany would have triumphed before the Christmas of 1914.

By July, 1915, two million men had voluntarily enlisted. Britain, at length, surrendered her birthright of freedom, and accepted compulsory service. To-day her armies hold the foe in three continents and on six fronts, and are co-operating with her Allies on two others. Her guns confront the enemy on the whole vast steel circuit of this colossal siege. Her tens of thousands lie in their graves from the Tigris, the Ægean and the Zambesi, to the Somme, the Aisne and the Yser, and still the dreadful daily toll of life is taken.

Her women have flung aside without a thought all the happy pre-occupations of peace, and from the hospital ward to the munitions shed, from the milk-cart to the motor-’bus, have given themselves without stint to ungrudging and brilliantly successful labour, while their hearts are broken by the loss of the men who have made their world.

Her whole industrial life has been revolutionised. Her skilled labour in the shipyards, the arsenals, the factories and the mines; at the loom, the lathe, the desk and the forge, has given its right arm, and put aside its most treasured privileges. England has poured out her wealth for the allied effort by thousands of millions. She has drawn her products from every habitable place on earth, and thrown them into the pool.

She has indeed flung into the breach for the freedom of the world, not her possessions simply, but herself, her immemorial heritage, her treasured citizenship, the commonwealth of nations that constitute her empire—her heart and mind and soul!

|

The Imperial contribution is dealt with in a separate chapter. |

“Can you think of the British Empire,” cried Burke, “without a Sursum Corda?”

To us this word is more filled with light than it was even to the orator who spoke it. For, indeed, there has never been an hour when we could cry “lift up your hearts” as we could in the day when out of the horrible night of the War’s origin,

“Black as the pit from pole to pole,”

came the flaming response of a world-wide Empire to the need of the Mother-country.

The secret of the rally which amazed us all, stunning the Central Empires with its staggering and unexpected blow, and thrilling Britain and the Allies with its swift and deliberate loyalty, lies hidden in that word “Mother-country.” Our men from the Dominions, the Crown Colonies, and the Dependency of India are sons, not subjects, of the Home-land.

The tie of Empire was loose—the strands were of silk and would snap at the strain of war. The Dominions would stand aside to save themselves. India would leap at the chance of rebellion when Britain’s hands were more than full in Europe. So the German publicists argued—those leaders who have lost their war, not from failure in military preparation, but from the lack of simple elementary imagination—from blindness to realities that were freely revealed to babes.

The word “Empire” sent the German leaders to their text-books. They saw the Egyptian, the Assyrian, the Babylonian, the Greek, the Roman, the Spanish Empires based on military domination. They rooted their own theory and practice of Empire in the idea of rule thrust upon unwilling subjects. But the British Empire eludes that definition. It is not in that sense an Empire, but is rather a league of self-governing nations, blended with Dependencies that are in training for self-rule—a colossal experiment in international government with a minimum of compulsion and a maximum of freedom.

So the silk strands did not snap. They were stronger than the iron bands of Germany. Germany did not destroy the British Empire; she gave it a new revelation of itself. She expected disruption or at least apathy, and she discovered young nations shoulder to shoulder in one unbreakable rank. She proclaimed our decadent softness—and whole armies of conquering virility sprang upon her. There is a grim poetic justice in the historic fact that it was Canada at Ypres which broke the last German efforts to reach the coast of Calais and menace the British shores.

The Central Empires deserve our undying gratitude for initiating by their challenge a new era of unspeakable possibility for the Empire. Among the elements of the new world that sprang into being in August, 1914, none is more dramatic or of greater moment than the flame that fused our Commonwealth and Nations into one. The hammer of Thor in the hands of the Teuton has welded the Empire’s noble metal into a single sword of tempered steel. She is now compact of—

“Iron dug from central gloom,

And heated hot with burning fears,

And dipt in baths of hissing tears,

And battered with the shocks of doom

To shape and use.”

The miracle of what has already happened to the Empire in the War is only surpassed by the wonder that the future holds.

We look first at the story of the three years that now are history.

The call of the great adventure for the defence of the Empire, for the freedom of small nations, for those principles of loyalty to the given word, of even-handed justice and of personal liberty which are the secret of the British Raj, had no sooner sounded than every province of the Empire sprang to arms. English and Boers, Scots and Canadians, Irish and Indians, men of Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland and Africa, even the little island peoples of Fiji and Niué and the Cook Islands, offered their lives.

Within eight weeks of the declaration of War Canada had concentrated, equipped and embarked from Quebec a voluntary army of 33,000 men—the largest force that had ever crossed the Atlantic at one time. These were the men who bore the brunt of that first diabolical gas attack. Lord French has told us of that day; “The Canadians held their ground with a magnificent display of tenacity and courage; and it is not too much to say that . . . these splendid troops averted a disaster which might have been attended with the most serious consequences.” That force, as has been truly said, “at Langemarck barred the way to the advancing Germans and saved the day for the Empire, the Allies and the world.”

Canada’s recruiting went steadily on. No sooner had the First Division sailed, than a second was organised. From her new-born cities, from the shores of her lakes and the banks of her splendid rivers, from her lumber camps, her wheat-fields, her mining camps and her industrial centres, men of every province rallied, trained, sailed and fought. By the spring of 1917 over 400,000 men had enlisted in the Canadian Forces. At Neuve Chapelle, Ypres, Festubert, Givenchy and on Vimy Ridge, in every place where the call has come, their splendid manhood has lifted modern war to a higher level of clean, heroic sacrifice. Similarly, her wealth has been given in supplies of grain, cheese, horses, salmon, munitions, clothing, even submarines for the use of the Allies; and she has lavished money and service in hospital work. Before the War no shells had been made in Canada outside the Dominion arsenal at Quebec. By August, 1916, over 20,000,000 shells had been shipped to Europe. They have more than won the twenty-three V.C.’s and numerous other distinctions that have been awarded to them.[1]

The smallest of our self-governing Dominions, Newfoundland, has sent its regiment which heroically won its hill-top nearer to Constantinople than any other effort in the tragic experiment of Gallipoli, while its Naval force has patrolled the Ægean and the North Sea. Newfoundland has made her offerings for the supplies of the troops and even equipped and dispatched her aeroplanes for the Front.

The strong-limbed, clean-cut, high-tempered breed of Australia has thrown into the War an army almost as great as that put into the field for the South African War by the whole Empire, and twice as large as our initial Expeditionary Force of August, 1914. Alongside that army, which volunteered for foreign service, came the battle cruiser Australia and the three smaller cruisers, Melbourne, Sydney and Brisbane, with flotillas of submarines, torpedo-boats and destroyers. The Commonwealth has equipped, armed and transported its own men and has met the costs of commissariat and medical supplies, beside shipping and maintaining many thousands of her famous horses. In the Navy, the infantry, cavalry, artillery, mechanical transport, camel corps, and miners’ corps and in new munition factories in her different States, Australia has undertaken every kind of war-service open to her.

Right across the entire breadth of the world, New Zealand with its passion for freedom thrilled with response to the need of Belgium. From a population equal only to one of England’s great provincial cities, her fiery breed of men have thrown themselves into the fray with clear vision of the issues at stake and of the sacrifices demanded. General Smuts has told us that of her total population of one million, about one hundred thousand entered military service in the War—men who, coming from the newest and least traditional of lands, shed their first blood within range of Sinai, and as they recuperated, faced the inscrutable features of the Sphinx. The gifts of over three million pounds from a million people, over and above War Loans of over thirty millions, and vast contributions of food-stuffs, reveal the steady spirit in which civilian New Zealand backs up the efforts of its troops.

The Australians and New Zealanders together created and baptised in sacred blood a new name that stands for the most glorious heroism of the War—the name of “Anzac,”[2] associated for all time with the adventure of Gallipoli. Their long and ever-growing list of military distinctions represents but barely their heroic courage.

The first task of the South African Government, under its soldier statesman, General Botha, was to reduce a miniature rebellion which had broken out under the stimulus of bribery and intrigue. She then turned to the conquest of German South-West Africa. A British South African Army of 58,000 conquered this area of a third of a million square miles, and then garrisoned the country. Some of the South African Army joined the Rhodesian and East African colonists, together with English, Australian, Canadian and Indian troops, to reduce German East Africa, now almost completely subdued. These vast territories when completely reduced will, with the Kamerun country conquered largely by the West African Frontier force, place some million square miles in the hands of the Allies.

Some seven thousand men have crossed to England from South Africa for the fighting in Europe, with a general hospital, ambulance and aviation squadron complete. Over 40 per cent. of the adult male white population of Rhodesia are enlisted in African forces, while many from all over the sub-continent have come home to enlist in England itself. The great chiefs like Khama, Lewanika and Griffith have sent money and offered men for war, while many thousands of African Negroes are working in the ports of France to help our Ally there.

The mere catalogue of the imperial service given by the smaller outposts is endless. From Malta, Hongkong and Shanghai, from Zanzibar, Mauritius, Sierra Leone, from Fiji, and other islands of the Pacific, from Aden, from Guatemala (where out of a total population of eighty-two, forty volunteers travelled to England at their own costs—£65 per head—to volunteer), from the Argentine, men have come in spontaneous homage to give what service is in their power. The strangely potent appeal of the cause is illustrated curiously in Malaya, where contributors to a squadron of sixteen aeroplanes include British, French, Dutch, Jews, Armenians, Chinese, Japanese, Indians (of numerous races) and Malays.

But when all is told the strangest story of all remains—one that reads like an Arabian Night’s romance, yet is the solid history of our own day. No one living can have remained unmoved by, or will ever forget, the thrill of emotion that quickened the pulse of England when India offered herself with Oriental lavishness.

“What orders from the King-Emperor for me and my men?” wired the gallant Maharajah of Rewa. The message was symbolic of the spontaneous offer of the Principalities and Powers of that vast and varied congeries of peoples grouped under the name of India.

Germany had recorded her expectation that in a European war, England would need to send additional troops from home to hold down restive India, in the event England called from India more than three-quarters of her British troops and more than a half of her native army. The Nizam of Hyderabad placed £400,000 and his regiment at the disposal of the King-Emperor, the Maharajah of Mysore a third of a million pounds, the Gaekwar of Baroda the whole resources of his State. Maharajahs rivalled one another throughout India in their help; while the Aga Khan, the spiritual head of eighty million Moslems, issued a direction to those millions to serve the Empire, and then volunteered to serve as an infantry private in the Indian Expeditionary Force. And there are few pictures in history like that of Sir Pertab Singh, the aged chivalrous Indian prince-warrior, who had sworn that he would not die in his bed, riding through France at the head of his men. From the “steel-wire” Ghurkhas and from virile Sikhs, from independent border States like Chitral, Nepal, Bhutan and even from Thibet offers came pouring in upon the Viceroy.

The offering of India was first hailed with pelting roses at Marseilles, and was sealed in blood when the Indian troops captured Neuve Chapelle. From that day to this in Gallipoli and Salonika, in Palestine, Mesopotamia and in Africa, India has given of its best in the strange war of the sahibs across the “black water.”

Such a superb epic of spontaneous loyalty, offering its all for the defence of such a heritage, calls for a statesmanship for the future that will lift its conceptions of Empire to the level of the opportunity. In so far as the event has eclipsed our wildest hopes of what the Empire might do, our thought for its future should surpass the conceptions of its past.

Purged by the fire and annealed by the discipline of the War, the Empire is called to realise a deeper freedom within itself, and to help to confer a wider liberty on the world. When our Imperial power endeavoured to quench freedom in America, America smote us back and broke from us—and we learned our first great lesson. To-day, America has joined us once more to help to establish that democratic liberty in all the earth.

When freedom rose again in Africa after the great Boer War, we made a daring experiment in liberty, a precedent that grows the greater as its consequences reveal themselves in history. For, when the history of the War and of the Empire are retold a thousand years hence in the perspective of history, there will be no more arresting or significant figures in the story than those of General Botha and General Smuts. To-day South Africa has rallied to help us, not only by her arms, but through the just and lucid vision that has—in the speeches of General Smuts—raised the whole level of our thought of the War and its issues to a loftier elevation.

New organisation will be needed to meet these new needs and prepare for the building of a still stronger Empire. Imperial Conferences will regularly discuss the principles governing the foreign policy of the Empire. The new strands of union will reveal themselves in the warp and woof of government. But behind and beneath the organisation, creating it and therefore more important than it, is the spirit, the temper that the constituents of the Empire bring to it. And the loftiness and strength of that spirit will grow with the growth of our educated free democracies—and will grow in the measure of the qualities that have called its members into the War, i.e., in the measure of its equal justice, of its fidelity to the given word, and of its peoples’ knowledge of liberty.

The War has knit us closer to incalculable millions of men—far beyond any unity of rule in history; tall, bearded Sikhs and short, sturdy Ghurkas, Indian girls on tea plantations, brown labourers in Bombay factories, Maharajahs in palaces, outcasts in fetid hovels, African men on veldt and in forest, men on the wharves of Hongkong and Singapore, men from the coral islands of the South Pacific to the edge of the Arctic ice, from the limitless plains of Australia to the snows of Klondike, millions who are now irrevocably linked with the destinies of our world-scattered Anglo-Saxon tribe.

The call of such an Empire to-day, in the face of our new experience of unity, is not so much to imitate as to initiate, not to follow precedents, but make them; not to ride easily in the track of the pioneers, but to share their venturesome spirit and go beyond them. For we start where they left off. Their foundations are superb; we should disappoint them if we built no greater than they had dreamed.

There is a scale of plan and action which will make our raj, not a competing Empire in a race for power, but—as it were—a congeries of nations standing everywhere for equal liberty among all peoples—a unit in a world-wide super-national league that will discrown tyranny, heal divisions, cleanse the earth from cruelty, establish knowledge and set up freedom in all the earth.

It may be a distant dream. Yet it is held more fully now than ever in history; and the War by breaking up the past, revealing the possibilities off the future, and by releasing vast spiritual resources, has made it the one object to which men can worthily devote their time and talent.

|

Up to June, 1917. |

|

The Australian and New Zealand Army Corps. |

They come crowding up from the grey horizon; they swing away again over the edge of the world—all day and every day, “come wind, come weather,” some five thousand of them between any Sunday and Sunday.

They are of every size and shape, and of all the nations outside the Central Empires—great, striding cargo liners that tread down the Channel like a City merchant in Cheapside; dingy, reeking “tanks” that flounder heavily through spray and spume; solid cattle-boats, stolid coasters, stiff high-bowed tramps like hay-wagons, and ocean-hounds that fly the seas with a shearing rush.

They carry the variegated supplies of Western Europe and its armies—bringing the needed stuff from every port that trades with man to-day. Their drab hulls are stuffed with more romance than were the argosies of Venice or the square-rigged ships of Tarshish. Those hulls have been loaded by Sudanese, Egyptians, Arabs and Indians; by Greenlanders, Chinese, Japanese and Africans, by Singhalese, Spaniards, Samoans and Papuans.

During the War[1] the Mercantile Marine has successfully carried eight million men and ten million tons of war material. One million sick and wounded have been transported. Fifty million gallons of petrol; over a million horses and mules; one hundred million hundredweights of wheat; seven million tons of iron ore; £500,000,000 worth of goods have been exported. We have lent France about six hundred ships and four hundred to Italy.

Every meal that we eat, every time that we array ourselves with clothes, from our morning coffee to the soap for our bath, from the rubber on our heels to the tie around our neck, we live and move and act only by and with things that have, in the last resort, come to us on the broad backs of these merchant-ships. Through them comes every grain of food that the soldier eats, every garment that he wears, every rifle, gun, cartridge and shell. They have gathered dates and oil from Basra, wheat from the Argentine, rice and cotton from India, rubber, cocoa and precious metals from Southern America and Africa, copra from coral islands. The brain reels and imagination staggers as one tries to visualise the infinite variety, and the world-range of the scope of the merchantman.

But wonder rises to awe when we recall that to-day these men are the target at which the Central Empires are aiming the whole might of their naval power organised with feverish concentration and directed with consummate skill. To slay this merchant-sailor and destroy his works they have invented super-submarines and mine-laying submarines; they have flung overboard all law and humanity; they have alienated what friendship or tolerance was left to them in the neutral world, and have brought up against them the armed wrath and might of America.

And the German instinct here is right in recognising in the merchant-sailor his supreme enemy. From Yokohama and Hongkong, Bombay and Vancouver, the Argentine and Lagos, to Liverpool, Rouen, and Marseilles; Naples, Port Said and Archangel, these men and their ships are the allied line of communication. To destroy them is to cut the jugular vein of our War. The German dread of the merchant-sailor has made them defy the law of nations and of humanity, and follow a path of demoniac indiscriminate destruction in their futile effort to break him. Yet even by defying all restraint of law, they have failed and will fail. Without them the War would be over in a month. But the channel of life-blood is not cut.

These grey-eyed men, with their tanned, seamed faces that know neither fear nor brutal hate, are, it is true, again and again blown into the water by torpedo and mine. But when picked up by a friendly destroyer and brought to port, they straightway sign on in another ship and are out again on the old long trail. So long as there is a ship to sail they will sail, and the shipyards of the world are seeing to it that they shall not be without stout decks under their feet.

It is a curious thing in our history, recurring through its every stage, that this strange breed of high-spirited, hard-handed, far-sighted, cautious, cunning, silent merchant-sailors have been a rock on which our enemies have broken. Under Drake they smashed the Armada; they foiled the Dutch; they baffled Napoleon; they defy the Teuton. We realise how great they were when we remember what they did under Drake. To-day, facing more terrible and hidden foes who strike in the dark without warning, they are just as great in all the essentials of daring, resource, and humanity as were their heroic Elizabethan forbears.

The line is not cut, again, because of that astonishing miniature Armada of craft of every sort that serves as the fringe of the great fleet. There are thousands of these ships manned by over fifty thousand men. There are Lowestoft and Grimsby trawlers who know every shallow and pit-hole within a score of leagues, men as sea-crafty as a thousand years of sea-blood can make them; men as implacable as death, because, as one of them said, “I see Lusitania sprawlin’ all across the sea all the time.” There are sea-dogs from the ports of the West Country, from Plymouth round to Cardiff, and from the Clyde to the Shetlands, and round to Glasgow and the Irish ports, who know the sea as a gillie knows his moor. Men who have always tracked the herring now hunt the elusive submarine. The word comes in to them that a new nest of mines has been laid and they turn out over the grey waste to divert the traffic of the seas, to sweep up the nest, smash the mines and come back to smoke and yarn on the jetty while the commerce ships “go on their lawful occasions.” They are at this “job” by the shores of Tyre and Rhodes, they see the sun come up over the plain and mountains of Troy, they sweep the seas in which Paul was wrecked and where Ulysses’s galley-men stuffed their ears. These men are blockading Germany, keeping lonely vigil, “tossing on their weary beats,” keeping the seas from the Pentland Firth to the Fjords of Norway and across the Channel, boarding steamers in a high gale when the spray freezes in an icy coat and the sight is blinded by the blizzard, sleeping two hours and on watch twenty, and out for forty days on end.

In the last resort, however, the merchantmen sail in unending procession and the small craft sweep the seas securely because of that dread invisible force on which the freedom, not only of the seas, but of the world depends. Within a week of the opening of war, German ocean-borne commerce did not exist. The dread of our Navy had wiped it off the map. In that unlovely waste of Northern waters the Fleet lies, so powerful that its very presence there in leash holds the German battle fleet, which cost its authors £300,000,000, paralysed in its lair. Line behind line are the Grand Fleet and its attendant craft of every kind that man has conceived for modern war upon the sea, manned by men who have proved under the ultimate test of sea-battle their superb skill and courage, their adequacy to their tremendous responsibility. Again and again, times without number, it issues forth and sweeps the North Sea, looking in vain for an enemy who finds “discretion the better part of valour.”

The British Navy has throughout worked in co-operation with the powerful allied Navies of France, Italy, Russia, Japan. They have later hailed with joy the support, already so powerfully felt, of the American Navy.

These Allies will themselves readily acknowledge that the hazard has ultimately and largely rested on the British Grand Fleet and its auxiliaries. The German Fleet knows that at any hour of the year it can meet our Fleet in the North Sea. The prize that would follow a successful battle is stupendous—the greatest, the most glittering the world has ever offered to any nation, and the prize toward which Germany has pressed these many years. She does not, since her failure at the Jutland fight, attempt to take it. On the contrary, all her above-water ships, whether men of war or merchantmen, are in port; while the British ships take the seas when and where they will. If we fought a uniformly successful battle every morning for the freedom of our sea-traffic—with the loss of, say, three or five merchant-ships, we should be dazzled, and the world would wonder at the miracle. That the result is achieved without the battle, and as a matter of course, is a greater and not a smaller achievement.

It is for this reason that the story of the war at sea is so swiftly told. Within twenty-four hours of the opening of war a situation was established which has continued unchanged, though emphasised and illuminated by battle-incidents and phases of pressure and resistance. The war at sea divides itself roughly into five phases. The phases are (1) the clearing of the seas of German commerce and raiders; (2) battle with the enemy’s home fleet; (3) blockade of the enemy’s ports; (4) securing the lines of communication; and (5) bombardment in amphibious war.

At the very outset German outposts fell like ripe fruit into the hands of the Fleet—Samoa, which was seized to the joy of its inhabitants by the New Zealand expedition; “Neu Pommern” in the Bismarck Archipelago taken by the Australians; the wireless stations in Togoland, South-West Africa, the Caroline and the Pacific Islands and in German New Guinea. Striding the seven seas the Fleet sank Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse and Cap Trafalgar, and captured Spreewald. The Emden—the bravest and most sporting foe that Britain has yet met in the War—was rounded up and shattered off the Cocos Keeling Islands. The Goeben and Breslau by well-contrived flight escaped to Constantinople with dire results on the trend of the War. Von Spee won the only German victory over British ships in the battle that sent Monmouth and Good Hope to the bottom and threw the lightly armoured Glasgow out of the fight. The triumph was short. When Sturdee on December 8th sank the Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, Nürnberg and Leipzig off the Falklands this running chase was practically over. The Dresden was destroyed off Juan Fernandez three months later, while Prinz Eitel Friederich was interned and the Karlsruhe disappeared. The Königsberg, hidden in the windings of the Rufigi river, was smashed by the shallow-draft monitors on July 11th, 1915.

We were severely rapped over the knuckles for the blunder of doing patrol work with cruisers when that brilliant German submarine officer, von Weddigen, with three successive torpedoes, sank Aboukir, Hogue and Cressy in thirty minutes.

Early in the War, on August 28th, 1914, came the sharp, dramatic little fight of the Bight of Heligoland in the very jaws of the enemy’s ports and far from our own base. Heligoland, that triangular little plateau of rock which Lord Salisbury presented to Germany, had been fortified at a cost of ten million pounds as, so to speak, the bows of the German Navy, butting into the North Sea. Behind the sixteen-mile-wide channel that separates Heligoland from the coast lie the ports and anchorages, the submarine, Zeppelin and destroyer bases. The game from our side on that occasion was one of baiting the German Fleet to come out and fight. The Arethusa ran through the haze with her pack of hounds—the swift destroyers—at her heels and sides. German ships began to loom in the grey mist. The fighting was terrific, with the sharp bursts of flame, the roar and shriek and crack of the raging shells, with hits to the credit of both sides. The destroyer Liberty dashed in under the very guns of Heligoland to get at the German cruisers in harbour. At last the Lion, Invincible, New Zealand and Queen Mary rode in, and, while avoiding the enemy submarines, drove the surviving German ships to cover with an enemy loss of three light cruisers, two destroyers and some twelve hundred men, the British losses totalling sixty-nine men.

A second “sea-scrap” of real importance was the Dogger Bank fight which intercepted the third attempted raid on the East Coast. A futile raid on Yarmouth had been followed by a ghastly “tip and run” bombardment of Hartlepool, Whitby and Scarborough with an unholy slaughter of women and children, a wreckage of houses and churches. On January 24th, 1915, Admiral Beatty’s patrolling squadron sighted four German battle cruisers with light cruisers and destroyers making for the British coast. The Germans turned tail and Admiral Beatty gave chase. The Blücher, shattered by shell and rent by torpedo, carried her 15,000 tons to the bottom of the North Sea, while the Seydlitz and the Derfflinger disappeared in the distance in flames.

The one outstanding decisive sea-battle of the War up till the present fell on May 31st, 1915, when Sir David Beatty’s battle cruisers at 2.20 p.m. sighted the enemy out and in force. A sea-plane reported the German battle cruisers falling back—probably on stronger forces. Should Beatty fall back on our Grand Fleet which was out further north, or engage the enemy, who was evidently in superior force? At great risk he determined “to engage the enemy in sight.” For fifty minutes, from 3.48 to 4.38, Beatty was engaged heavily in a running fight south-eastward in which he lost Indefatigable and Queen Mary. Then the German High Seas Fleet appeared and Beatty with Evan Thomas, who had joined him with his four battleships, swung north-west to draw the whole German Fleet toward Jellicoe and the British Grand Fleet.

With the arrival of Jellicoe and his Fleet the range of the battle became so tremendous and its conduct so complex that no eye can really measure it or follow its movements. Its main feature can be put into a sentence. The great battleships, moving southward, maintained a titanic bombardment of each other, screened by squadrons of light cruisers and flotillas of destroyers, while the German Fleet as a whole sought safety in a flight, brilliantly protected by able torpedo tactics. A spreading haze and then nightfall hampered the British pursuit. The black night was pierced by the long white spears of the searchlights under which the destroyers looked like “black beetles on a tin-plate.” Every now and then hell spouted up in the death-blaze of a stricken battleship. When dawn returned all that remained of the German Fleet had crept away to Wilhelmshaven, while the British Fleet scoured the seas in search of the enemy or of the seamen who might be floating on the waves.

The main difference in the general situation created by the Battle of Jutland is that before the battle the British Fleet reigned unchallenged, but challengeable: after the battle it reigned challenged, and—by the issue—now unchallengeable.

The Navy’s help in co-operating with land forces draws the eye whenever it occurs. We have seen brilliant examples of it, largely aided by the flotilla of flat-bottomed torpedo-proof monitors—wallowing gun-platforms—off the Belgian coast, on the shores of Syria and, up in the Adriatic, on the edge of the Carso. But the classic, tragic example is that of Gallipoli, first by brilliant work on the hopeless task of forcing the narrows against land forts, sunk torpedo tubes, floating mines and submarines; and then in co-operation with the landing, fighting and finally withdrawing Anzac forces. The Navy never failed in the whole of that strenuous luckless venture. The defensive lesson of that conflict was the reiteration of the peril, from the action of submarines, in which battleships lie when stationary.

If it is impossible to visualise the work of the Navy itself with its amazing complexity of defence and offence, how will the mind contain, in addition, even the simpler elements of the work that goes to her making and her equipment?

In mile after mile of shipbuilding yards, amid a deafening eternal rat-tat-tat of mighty hammers on colossal plates, the hulls of super-Dreadnoughts tower aloft, overshadowing the lean sinister shapes of growing destroyers and mysterious hybrids that blend venom and speed in terrifying proportions. It is here that a million tons were added to the Navy in the first year of War, and still the total rises as fresh ships are invented to meet the new needs.

For the tale of her equipment, the maze of her factories and stores a whole volume is demanded to do credit simply to the efficiency of production and distribution. When a ship goes to sea she must have on her all that her thousand men can properly need through months of absence.

From the ends of the earth the food, clothes, comforts, the whole equipment and furnishing of the men of all the ships of the Fleets, are brought into a city within a city that hides itself within walls on the banks of a river in Britain. In that place tarpaulins, oil-skins, jumpers, boots hang in unbroken line beyond the range of the eye. The leaf of the Navy’s tobacco is sorted here, and stored in its air-tight tins. Millions of pounds of chocolate are made every year. The machinery for the strengthening and the comfort of the men whose watchful eyes are on sleepless outpost between us and our vigilant enemy radiates from that centre.

Whether we look to the detail upon which this Navy depends or to the world-wide and world-making functions that it performs, or to the way in which it shapes its work to new baffling problems, we find the wonder growing with our knowledge.

We see at the one end her commissariat, complete to the last bootlace, her building yards straining to the last ounce. At the other end we see her submarines nosing their way through Baltic ice and Mediterranean islands, her destroyers ferreting in every creek from Cape Horn to the Zambesi and from the Shetlands to Corfu. We watch her blockade growing sterner and sterner, carried out sleeplessly over stormy, blinding wastes of water. We see her mine-sweepers tirelessly cleansing the ocean ways that the commerce of the world may go by without let or hindrance. We watch her carrying the men and munitions of all the Allied nations. Her rendezvous are at Salonika, Port Said, Dar-es-Salaam, Basra, Toulon, a hundred other centres in all the continents and many of the islands of the world. She “mothers” our liners across the danger zone. She holds the vast arc of the steel siege within her wide arms and by the grip of her tireless fingers. We know that if she failed the British Empire would fall to pieces. And yet we sleep sound in our bed o’ nights!

In her wise, far-sighted brain, her humane chivalrous heart and in her firm grip there lies—as there has lain through these years—the safety of those resources which will, when the War has been brought to a triumphant end, have secured the freedom both of the waters and the lands of the world.

|

Up to July, 1917. |

The forces of fourteen nations, including many millions of men of the European, American, Asiatic and African peoples, are wrestling on the soil of three continents on nine fronts[1] covering thousands of miles.

To attempt the study of such a war in detail numbs the mind by the multiplicity of its factors and the bewildering variety of its forms. Yet the colossal dimensions of the conflict—not only its sheer bulk, but the enormous forces of the human spirit that it has called into action—give it, when looked at in perspective, a certain staggering simplicity. If we climb to some sufficiently lofty ridge of contemplation we get a view in which the details are lost and the outlines become clear; an outlook from which we can determine the main tendencies of the fight, and—it may be—can catch, through the mist and smoke, some sufficiently convincing glimpse of the goal to which it is surely moving.

The true test of the fortune of war does not lie finally in the occupation of territory, the capture of fortresses or the penetration of lines. These things all have their measure of importance. But victory does not rest on geographical facts. Ultimate victory lies in putting the enemy’s armed forces finally out of action. The promise of victory lies in the possession of the instruments that will achieve military decisions of that order.

Germany’s initial plan in the War rested on that sound strategical principle. The scheme was, first, to put the forces of France out of action by a swift, irresistible, decisive blow, and then, to swing round and smite Russia. The plan failed. The Marne broke it. That is why the Marne is the most decisive battle in modern history.[2]

The Aisne witnessed the initiation of the second plan, which was less sound in principle, but was forced on Germany by the situation as a whole. This plan was to break through on the northern sector of the west (while holding the rest of the front) and by a double movement to take Paris from the north and threaten Britain from Calais and her sister ports. Essentially it was a plan to pin the Allies down on the West and the East; and—from behind superior fortifications—by action based on stronger artillery and man-power, to secure a decision by smashing through or turning their lines, and subsequently containing sufficiently large forces. The enormous superiority in munitionment that the Central Empires then held gave sufficient hope of the success of this plan—though at the best, as they knew, victory would come at far greater cost than the initial “hammer-blow” scheme would have entailed.

How near the second plan came to success on the West the Allied peoples were never told, and even now have hardly understood. Only the men who survived the unspeakable strain of the battles of Ypres know—and they cannot express it. The German forces stormed against a British Army of less than a fifth of their own numbers, and with still less adequacy in artillery. Like a thin steel wire the line from Nieuport to Arras curved under the awful onslaught of shell and gas and infantry attack. Monitors came to the rescue on the coast. The waters of the Yser were poured over on the German forces. The tension was so terrible that the line was all but snapped. Yet, by that miracle of spirit which inspires free men in supreme emergency, the high-tempered steel held. We do not yet as a people understand how near we then lay to disaster. But history will carve in immortal relief the record of the glorious heroes who saved us in those days. “Their bodies were our defence while we wrought our defences.”

The Kaiser, who had personally watched this contest with intent interest, put up his field-glasses and turned away. The third phase opened.

Baffled on the West, the German tide—though it covered Belgium and most of industrial France—surged Eastward. The Central Empires threw their strongest forces upon Russia. Smitten at Tannenberg, the sweeping Russian advance in East Prussia and Galicia had been checked, and now ebbed. Hindenburg’s breakers swept Russia from Galicia. Warsaw fell, and with the fortresses went guns that Russia could not spare. By consummate skill, she again and again extricated her armies when it seemed that the German forces had all but gripped them in its giant trap. But Poland was submerged. Russia was constantly in retreat, but a military decision was never actually reached. It did not seem, however, even when Kitchener told an incredulous England that Germany had shot her bolt on the Eastern front, that the unequipped armies of Russia could stay the German forces till they had enclosed Petrograd and Moscow. Yet this happened. Russia at last stood her ground. The third plan had failed.

So there opened the fourth phase, a tremendous and confused wrestle, swaying to and fro, that finally extended in one vast arc in the East from Riga through the Carpathians to the Black Sea.

While that prolonged wrestle between Russia and the Austro-German forces was going on a new phase of the war developed. To grasp its significance involves recalling the objectives that Germany has in the War. These certainly on her own showing included the seizure of French colonies and large and strategically decisive parts of the Near East. Whether Germany ultimately win the War in the West or the East, or, as the evidence leads us to believe, nowhere, her real ambitions lay in the Near and Middle East. They covered that plateau which bridges the stride from Europe to Asia, and, still more, that wonderful plain between the Tigris and Euphrates, which to the eye of the prophetic irrigator waves with potential harvests. But if her hand grasped at the Middle East, her eye ranged farther east across Persia through Afghanistan to Delhi, and down the Euphrates and Tigris to the Persian Gulf. The policy that went under the name of “Central Europe” really planned a road from Antwerp and Hamburg to Alexandretta and Basra, and ultimately overland to Western China and the confines of India.