* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Hepatica Hawks

Date of first publication: 1932

Author: Rachel Field (1894-1942)

Date first posted: Mar. 11, 2022

Date last updated: Mar. 11, 2022

Faded Page eBook #20220317

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, John Routh & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

Books by Rachel Field

Hitty: Her First Hundred Years

Illustrated by Dorothy Lathrop

Little Dog Toby

Illustrated by the author

Eliza and the Elves

Illustrated by Elizabeth McKinstry

Pointed People

Illustrated by the author

Calico Bush

Decorations by Allen Lewis

Copyright, 1932,

By THE MACMILLAN COMPANY.

All rights reserved—no part of this book

may be reproduced in any form without

permission in writing from the publisher,

except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief

passages in connection with a review written

for inclusion in magazine or newspaper.

Set up and plated. Published October, 1932.

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

For

L. S. B.

This Tale of Odd Sizes

| PICTURES |

| Hepatica with Josh and Molly |

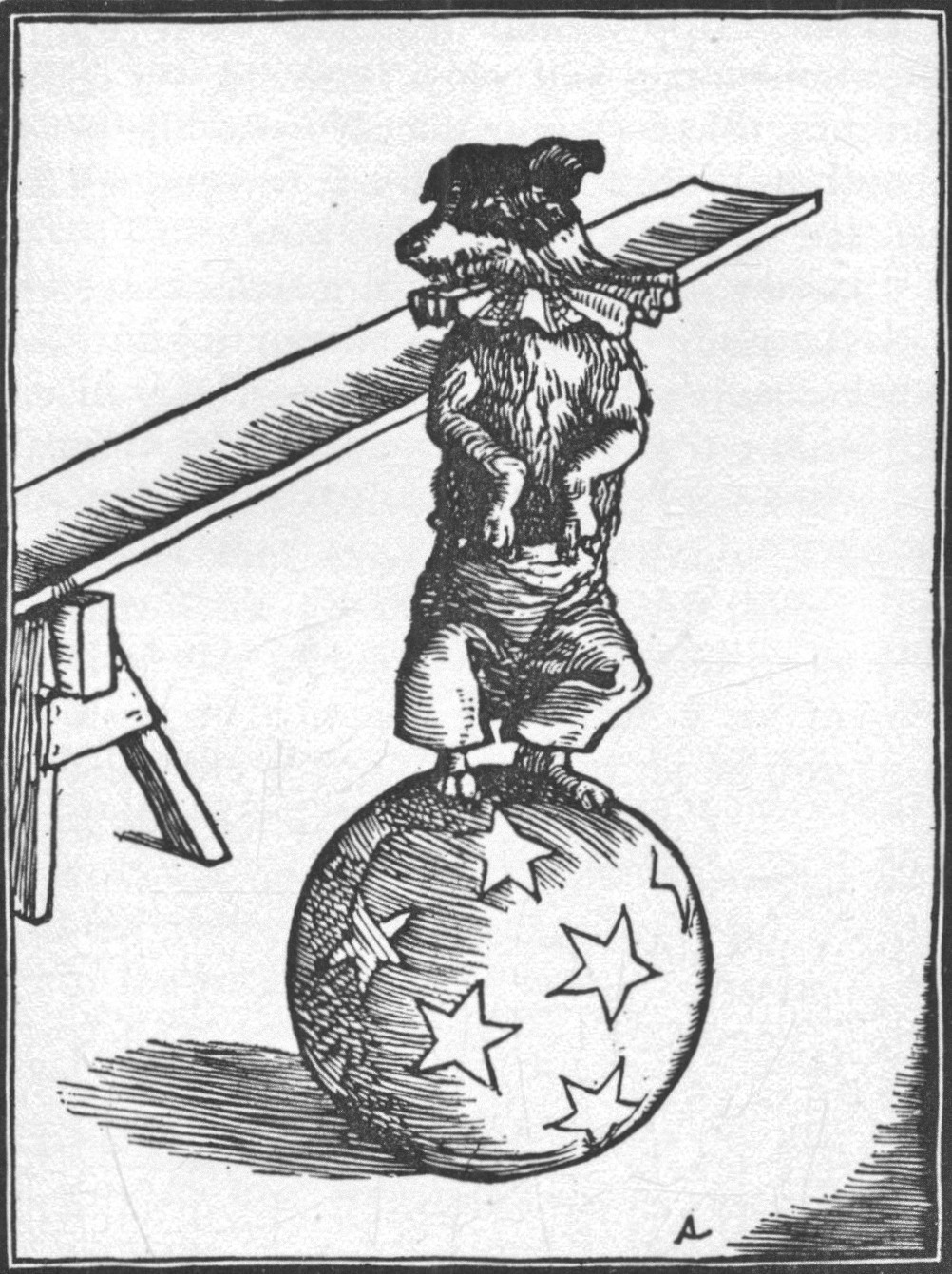

| Chi-Chi himself (this page) |

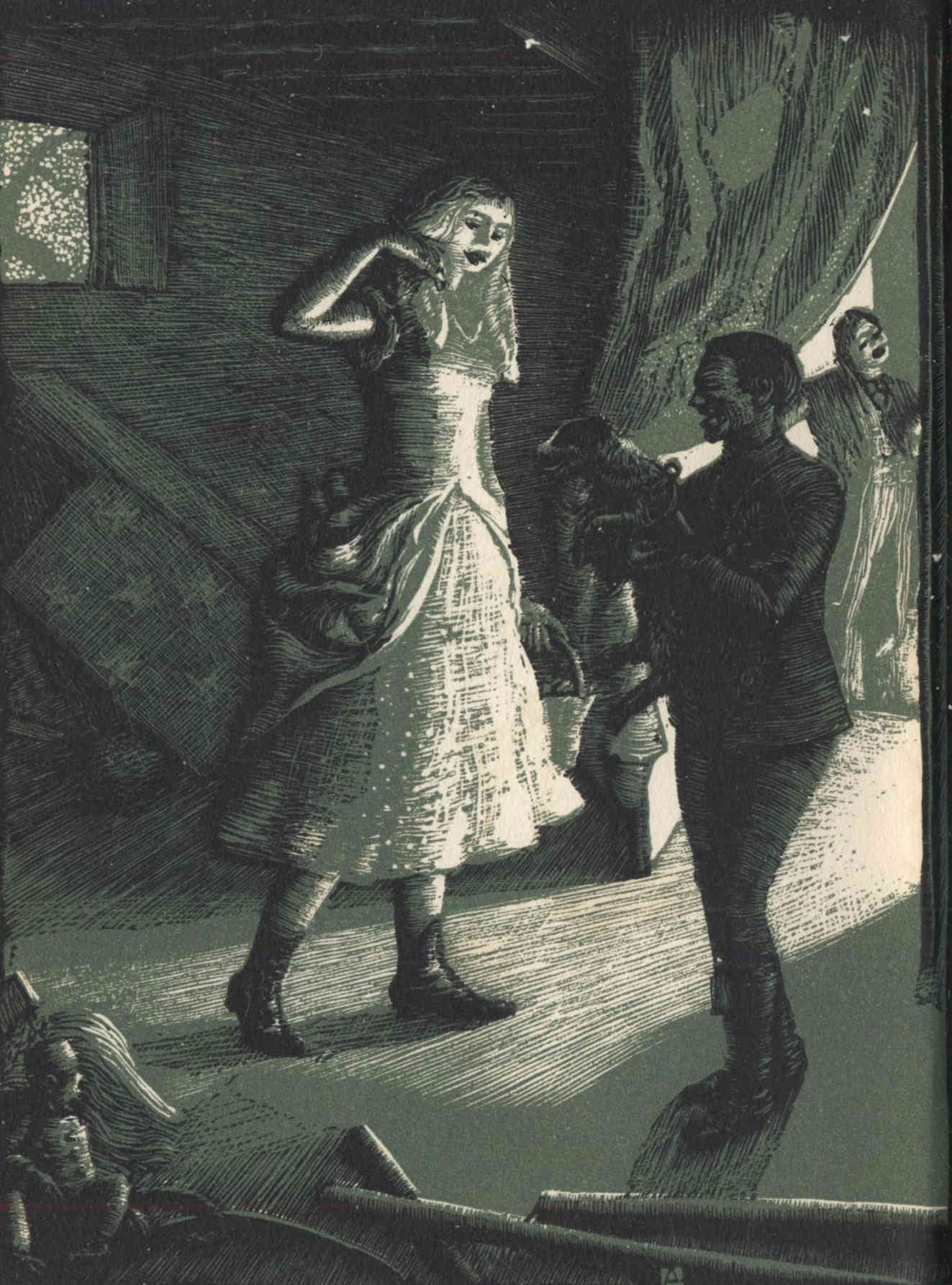

| Molly performs |

| Hepatica helps Miss Titania Tripp, at the Dime Museum |

| “Listen to the mocking bird” |

Hepatica Hawks

“Ladies and Gentlemen, our next number will prove conclusively that the gifts of reason and intelligence are not confined entirely to the human race. . . .”

Hepatica Hawks knew from this and from the tinkle of a bell and three short barks that followed Joshua Pollock’s announcement, that the performing dog and monkey act was about to begin. Molly and Chi-Chi were only just starting their round of tricks. There would still be time for her to take another look at the cherry tree before she must go out to the platform for her turn. She leaned as far out of the window as its narrowness and her tight-fitting blue silk waist would let her.

The small yard on which the window opened was green and quiet. Already the soft dusk of a spring evening had begun to gather there. By half closing her eyes Hepatica could make the trunk and branches of the one-sided cherry tree fade into the dimness. The pale bloom seemed to hang in air, like fountain spray caught in the moment of tossing. It was the crookedest tree she had ever seen, but somehow in spring these were prettier than straight ones. She decided that if Joshua Pollock had gone in for collecting trees instead of people for his “Freaks and Fandangos” this was exactly the sort he would have chosen.

She rested her bare arms on the sill and sniffed at the freshness that came to her from grass and white petals. Behind her the hall smelled of varnish and oil lamps. The space between the wall where she leaned and the painted canvas was cluttered with boxes and belongings. She could see her father’s old ulster hanging over the back of a chair, with T.T.’s garland of artificial flowers on the seat; Flossie’s ukulele and Hawaiian grass were spilling out of a battered portmanteau. All these things were familiar to her in every twist and fold, but the springing green outside the window only made them seem limp and inadequate in contrast.

Queer how spring could make you feel, Hepatica thought, her ears straining for the click of the castanets that would mean the act was nearing its close—as if one also must put out green shoots. Too bad one couldn’t. New straw hats, or old ones trimmed over, were far less satisfactory. But perhaps other people didn’t feel that way. Perhaps it was only because she was an outsize, and hats always came so much too small, and it took such yards and yards for a new dress. She sighed, remembering she must begin to let down the hem of her sprigged challis to-morrow. Still, to-morrow was her birthday. She would wait till the day after. It was going to seem queer to be fifteen. But birthdays were like that. One day you were one age and the next another. She never got over the surprise of it. Then, too, a fifteenth birthday had an importance all its own, for there you were, right in the middle of your teens with being grown up just round the corner.

“I must remember to be very surprised about the blue poplin,” Hepatica told herself, “and not let on I’ve seen Flossie and Mabel sewing on it, and I do hope I’ll be pleased enough when T.T. gives me the gold beads. I mustn’t act as if I’d guessed she was going to.”

Sometimes it was quite a responsibility being pleased enough on birthdays and Christmas, especially when the troupe was traveling and quarters were cramped.

There! hands were clapping out beyond the platform. Molly was barking her acknowledgment, and Jerry tossed the paper hoop into a corner to let Hepatica know it was her turn. She moved away from the window, smoothing out the blue folds of her skirt. Mechanically she pulled a long fair curl over either shoulder before she took up the basket with the rose petals on top and the packet of her photographs underneath.

“And now, Ladies and Gentlemen,” she heard Joshua Pollock’s voice booming out with the words she knew so well, “we come to one of the most remarkable features of our entertainment. You have seen fire eating and sword swallowing. You have witnessed the astounding feats of Chi-Chi, the African monkey, and Molly, the performing dog. The mysteries of the future and necromancy have been revealed. Venomous snakes have twined their deadly coils about bare flesh. You have seen and heard Leta, the Hawaiian Belle reared beneath palms and flaming tropical volcanoes. You have stared in amazement while Hallelujah Hawks, the Human Pike’s Peak, unfolded his eight feet four of living brawn and bone before you, tossing as feathers weights that would have confounded the efforts of Samson himself, but now, Ladies and Gentlemen, prepare yourselves for a still more astonishing phenomenon—Hepatica Hawks will appear in person to prove to you that she is indeed her father’s daughter.”

Hepatica picked her way carefully between boxes over to the side of the painted canvas tree. Jerry, in his red jersey tights crowded past her, holding Molly under his arm. He grinned at her and the little spotted dog put out a pink tongue in greeting as they went by.

“Unique of her kind,” the voice was going on, “an Amazonian wonder from birth. At the tender age of two years this child overtopped seven, eight and even ten-year-olds. A veritable mountain of childhood, Ladies and Gentlemen, and now . . . now at the threshold of her teens, or as a well-beloved bard has so fittingly expressed it, ‘standing with reluctant feet where the brook and river meet’ she measures six feet four and a quarter inches in her stockings. In her stockings, mind you, with proportions on an equally generous scale, and to prove that she is not lacking in the feminine graces she will dance for you and sing. Then, to further prove her genuineness she will step down and mingle with the audience. Do not miss the opportunity to measure yourself and your children alongside this youthful wonder. Ladies and Gentlemen, I have the honor of presenting to you the Giant’s Daughter, Miss Hepatica Hawks.”

Hepatica was used to the murmurs and startled “ohs” that greeted her when she stepped to the center of whatever platform they happened to be occupying. Even on pleasant afternoons like this when there were only a few stragglers in the front rows, she never failed to rouse interest and admiration, and she waited, as her father and Pollock had taught her, till they were quiet again before beginning the first steps of her polka.

“She’s real light on her feet considering her size,” a woman in the second row remarked to the little girl beside her in a voice Hepatica could hear above the tinkle of the music box.

“Is it all her, Ma? Honest?” The child’s mouth was fixed in a round O of amazement.

“Ain’t so bad looking, for a freak.” An old man with an ear trumpet confided in a shrill whisper to his companion, “Never saw one with yellow hair before. But she looks older’n he said.”

“Ssh,” the elderly woman next him spoke into the ear trumpet, “she’s going to sing now.”

Hepatica had made the polka as brief as she dared. The older she grew the less she liked going through the dancing part of her act, and this platform had the most creaking, uneven boards she had ever known. There were still a few more bars for the music box to play before it tinkled into “The Last Rose of Summer,” but that would give her a chance to catch her breath. She had told Joshua Pollock only yesterday how hard it was to sing right on top of a polka, and he had said it didn’t matter what you sounded like as long as you made a noise. There, it was swinging into the next tune. Hepatica advanced to the edge of the platform and, holding her basket in both hands, waited for the first notes. The lamps in their tin sockets below her made her ankles uncomfortably warm. A woman halfway back was fanning herself vigorously, without the least regard for the music. Hepatica fixed her eyes on a distant point of light that came through a half-drawn shutter, and began:

“ ’Tis the last rose of summer

Left blooming alone,

All her lovely companions . . .”

People shifted and shuffled at first, but then they grew quiet. Hepatica heard her voice going up and down easily. She could feel the notes coming out of her, yet she never seemed to be doing it exactly, not even the high part where Flossie always went into a squeak.

Now she was nearly at the end. Her right hand burrowed into the basket and brought up a fistful of the paper petals. In a quick gesture she tossed them out into the front row. Some even fell as far as the second and third. The little girl beside her mother stood up to catch them and two other children held out their hands in eagerness. When there were more people she threw out another handful, but one was plenty this time. Hepatica had learned when to be saving.

The hands were clapping quite hard, and the old lady next to the deaf old gentleman was nodding her head approvingly.

“That’s a nice song,” she said into the ear trumpet, “and she sung it real pretty.”

Joshua Pollock had stepped out again, his silk hat under his arm. Hepatica gave him one of her hands and he led her down the rickety steps into the hall. Mechanically she took out one of her photographs from the bottom of the basket.

“Buy a picture of Hepatica Hawks,” Pollock was urging, “a little memento of this extraordinary child. Posed singly or with her famous parent. Ten cents, Ladies and Gentlemen, none sold elsewhere.”

The little girl wanted her mother to get one, but she wouldn’t. However, the woman who had fanned so hard did, and the old man with the ear trumpet seemed interested. Hepatica was sure he would have done so if he had been alone. He peered at her closely with his little sharp eyes and pinched her arm when Pollock brought her over. She was used to pinches and pokes. It would have been a very poor day indeed without them.

“Genuine, I should say she is!” Pollock was explaining as they went about, his voice very loud to hide the noise they were making behind the curtain as they trundled out the little blue booth with the gilt stars scattered over it.

“All right, Patty,” Pollock whispered to her as the music box sounded again in signal that T.T.’s act was ready. “No more till the ‘grand finale.’ ”

She slipped through a curtain at the side while he took his place by the footlights once more and began his next introduction.

“Ladies and Gentlemen,” she could hear him saying as she put down her basket and went to join Jerry and the animals on a trunk, “there are times when that nearly always regular dame, Mother Nature, plays fantastic tricks which astonish the learned world and confuse all mankind. I am about to introduce you to one of her most startling variations of the human pattern. It is not often that a public is privileged to see two giants and a pygmy for the price of a single admission. But Joshua Pollock is one who believes in good measure and spares no pains to secure the greatest variety in freaks for his patrons. It is therefore my pleasant privilege to present to you a midget whose miniature proportions would put to shame the famous Tom Thumb. I refer to Miss Titania Tripp, Ladies and Gentlemen, unrivaled for smallness in two hemispheres. She was born in the state of Rhode Island, a significant fact, since this is also the smallest state in the Union. Less than the height of an ordinary yardstick, measuring thirty-two and one-half inches from top to toe, tipping the scales at twenty-six pounds, and wearing slippers that her illustrious namesake might have envied, she will perform for you her impersonation of the Vanishing Circassian Dwarf. Miss Titania Tripp.”

“Dreadful hot back here, ain’t it?” whispered Jerry, moving over to make room for Hepatica beside him. “Wish’t we could have got that other hall, but Pollock says the Christian Endeavorers are having a May festival there. I expect that means slim business to-night.”

“I expect so,” she agreed. The small, spotted dog thrust a pointed nose into her hand, licking her fingers daintily and wagging that fraction of tail.

“Molly acts thirsty to me, Jerry,” she went on. “Can’t you get her a drink?”

“She’s had three already, but I suppose another wouldn’t hurt her.” Jerry rose good naturedly. “You hold Chi-Chi while I see if there’s any left in the dipper.”

The monkey made no protest at being transferred. He settled down quietly in Hepatica’s lap, one of his tiny hands fastening supple fingers about her thumb. Chi-Chi was a small, gentle monkey, his coat a soft grayish-brown except where it shaded into silver-white round his grave, puckered face. Hepatica took off his little green cap to scratch behind his ears. It was a favorite spot and he leaned against her with a contented sigh. At least Chi-Chi didn’t mind the heat. It was cold and wet weather that set him shivering and coughing. Hepatica remembered how sick he had been winter before last when they had all taken turns sitting up with him and giving the medicine in drops every fifteen minutes. He was such a good monkey, even the veterinary had said he was almost too human. One of the brass buttons on his little green cloth jacket was hanging by a thread. Hepatica pulled it tight and knotted it underneath. She must remember to sew it fast before the evening show. He blinked up at her, his small eyes bright under wrinkled lids.

Jerry came back with Molly, and the rest of the troupe began to gather for the last act. Flossie had changed into her pink gauze and she was hooking Mabel Pollock into the peacock-blue satin with the signs of the zodiac, while Mabel held her breath and shifted her two hundred and sixty-seven pounds from one foot to the other. Adam Crump, Flossie’s husband, stood near by in his toreador outfit, trying to read a newspaper in the dim light with his swords and fire bucket beside him. Over in a corner Hepatica could see her father slowly uncoiling himself, dusting off his green tights and shaking back the lock of hair that always fell into his eyes. Then he reached up to an overhanging beam, knocked the ashes out of his pipe and put it there beside his tobacco pouch for safe-keeping.

“I’m dreaming now of Hallie,

Sweet Hallie, in the valley . . .”

T.T. was singing while the music box carried the tune under her shrill pipings, and the tap-tap of her heels sounded on the floor of the little booth.

“She’s tired,” Hepatica thought as she listened critically, “she’s way behind the music and her breath’s going to give out before she gets to the mocking bird and the grave.”

“Listen to the mocking bird,

The mocking bird . . .”

It was barely a whisper now, but the little heels went on clicking. Flossie looked up from Mabel’s blue satin back and signaled frantically. She might have spared herself the trouble. Hepatica had stepped over to the canvas wings again and taken up the refrain.

“And the mocking bird is singing o’er her grave.”

It wasn’t the first time Hepatica had finished it for T.T. No one would notice out front. They would be too busy watching the tiny figure in canary yellow disappearing behind the curtains, the little feet in the high-heeled red slippers pointing and twinkling to the last.

Thump. Thump. The curtain was down now and Pollock making his final announcement.

“Ladies and Gentlemen. I thank you. Miss Titania Tripp, the Vanishing Circassian Dwarf, thanks you from the bottom of the smallest heart on record. We thank you, one and all. And now a last glimpse of Joshua Pollock’s Famous Freaks and Fandangos. A tableau vivant to remember us by . . .”

They were all busy now back of the curtain. In a single gesture Hallelujah Hawks lifted the midget from her place and shoved the blue booth out of the way. Hepatica reached out her arms to receive T.T. while her father and Jerry rolled the wooden stands deftly into position. Mabel made for her throne at the left. Adam seized his bucket and swords and took his place beside her. Flossie caught up the ukulele and knelt on one knee with her pink skirts in a gauzy circle about her. Jerry set Chi-Chi on his shoulder, took up a fresh paper hoop and stationed himself at the right with Molly waiting impatiently to do her jump. Hallelujah balanced his heaviest weight in the back center, and Hepatica advanced to the middle with T.T. perched doll-like in the crook of her arm.

“Whew!” the midget wheezed, screwing up her face into innumerable fine wrinkles where the powder and rouge had a way of settling. “I didn’t count on my breath givin’ out so soon. Thanks for comin’ in on the tune, Patty.”

“That’s all right,” Hepatica answered, smoothing the diminutive folds of the yellow taffeta skirt, “only I guess you need to take another asthma pill before to-night.”

“Mercy no, child, it’s nothing but that stitch in my side again. Tell Hallelujah to wind the music box quick or it won’t last through.”

There was just time for his long arm to follow her directions before the curtains parted once more. The platform was small and they had to be careful not to get in one another’s way as they went through their parts. Hepatica always felt glad hers was a more or less passive rôle, merely holding T.T. carefully while the midget leaned out kissing her finger tips to the audience and waving a red paper rose and the music box ground out “Good Night, Ladies” with Molly jumping in and out of the hoop.

“And so, Ladies and Gentlemen, we bid you farewell till to-night’s performance. . . .”

The green baize curtain rattled down again, thumping the wooden boards and showering them all with dust as they scampered to the wings.

“Whew!” Titania Tripp protested with a loud sniff. “Just look at that, will you? No wonder I get wheezin’. I don’t believe this place has had a dusting, let alone a scrubbing, since Garfield was assassinated.”

Hepatica set T.T. down carefully by the curtained space that did duty for ladies’ dressing room. Flossie and Mabel were already there before them, struggling out of their costumes and trying to hide something blue spread on a chair. It looked suspiciously like the new poplin and Hepatica knew she must contrive not to see it. They must have been working on it while she was out doing her turn to have it ready for the party to-night. Hepatica’s heart warmed at all the trouble they were taking.

Ever since she could remember, except when it came on a Sunday, they had celebrated her birthday by making a party of supper the night before. She knew exactly how it would be as well as she knew her act. First her father would invite her to go for a walk to get her out of the way while the others hurried to have everything set out and ready when they returned. There would be cold chicken and biscuits instead of the usual ham sandwiches and coffee between shows, and ice cream that Jerry had been out to get at the nearest confectioner’s, and of course the cake, candles and all. Hepatica could remember clear back to the time when there had been four candles on a little round cake. Her father had asked why there were four and T.T. had explained that one was “to grow on.” He hadn’t seemed pleased about that extra one.

“I know too much about growing,” he had protested.

Hepatica could understand better now what he had meant. Of course the candles hadn’t really had anything to do with her size, but she had certainly more than fulfilled expectations.

“Come on, Patty,” she heard him calling to her. “Want to stretch your legs with me a bit before supper?”

“Yes, Pa,” she told him. “I’ll be out in a minute.”

She turned to a square of mirror hung up in one corner and began to get out of her blue silk. T.T. and Flossie were whispering in the other corner. She tried not to hear what they were saying as she wiped the make-up off and washed her hands and face at the tin basin. It wasn’t the thing forty-odd years ago to wear paint and powder on the street, and Joshua Pollock was very careful that his troupe observed the proprieties.

“You couldn’t find a more decent, first-class set of freaks anywhere,” he boasted on all occasions.

Hallelujah Hawks was waiting in his ulster and cap when his daughter met him at the side door. She had put on her old dark cashmere, and a knitted tam was pulled down over her long curls. She looked almost her real age now, though her cheeks were so round and very red from scrubbing.

“Well, Patty,” he smiled at her, his big mouth turning up in a slow pleasant way under the drooping ends of his fair mustache.

“Have you seen the cherry tree, Pa?” Hepatica asked him as they went down the steps together. “It’s an awful pretty one.”

They stopped a moment by the little yard to look at it, but neither of them said anything. Words never came easily to Hallelujah, though he could muster them on occasion. Hepatica was rather like him in that way, but perhaps it was because T.T. was talkative enough for all of them.

“Worse’n a canary, she is,” Joshua Pollock would complain sometimes. “Yes, it’s the little birds always make the most noise.”

It was still quite light on the streets though a man on a bicycle was going from lamp post to lamp post turning up jets of gas. As Hepatica and Hallelujah turned a corner they came full upon their own pictures with T.T. and the rest staring from a poster announcing that “Joshua Pollock’s World Famous Freaks and Fandangos” would be performing in Masonic Hall on the afternoon and evening of April 30, 189-. Rain had made the colors run, and the paste no longer held the lower corners to the board fence. It flapped in the spring air, as if their picture selves were waving a greeting. But neither of the two gave this more than a glance. They were used to meeting themselves on fences and billboards.

Children playing in front yards stopped to watch them go by, eyes and mouths round with wonder. Sometimes they pointed, or ran to call others from indoors.

“Lookee!” shrilled a boy from his front steps to a playmate across the street. “Look at what’s goin’ by.”

A very small child swinging on a gate they passed looked up and burst into a terrified roar. In panic at their approach she lost hold and rolled almost under Hallelujah’s feet. He stooped down and picked her up with the same detached gentleness that circus elephants use toward their keepers, swinging her over the fence to the grassy lawn.

“There now, Sissy,” he said, “don’t you cry.”

But her roars followed them for a long way.

Presently they left stores and streets for more open country. The houses had bigger yards and more trees round them, till soon they sat in fields, with patches of wood and orchard between. A river, swift and noisy with spring rains, was going by green banks where willows grew, and at the foot of the road an old covered bridge loomed in a dark shape with an oblong of light at the other end.

“How about sitting here a spell before it’s time to turn back?” Hallelujah suggested.

They found a place on one of the wooden beams and sat together in the deepening dusk, watching lights spring up in houses along the way they had come.

“Well, Patty,” her father said, pulling at the pipe he had been busy lighting, “to-morrow’s the first of May.”

“I know, Pa.”

“Seem’s if it comes round faster every year,” he went on. “I couldn’t hardly believe it this morning when T.T. said you’d be fifteen. But she’s right. I counted it up to make sure.”

They were quiet again for a long while. Under the bridge the water rushed in a furious torrent of sound. A bat swooped where the rafters met in the dimness above them. Hepatica could barely make out her father’s face though his pipe glowed faintly. She liked to smell the spicy fragrance of his tobacco, all mixed up as it was with the cool freshness of running water and grass and leaves. Soon, she knew, he would begin to talk about her mother. He always did on the night before her birthday.

“Yes,” he was saying, “I expect it wouldn’t seem so queer to me if Myra had lived. Your getting born and her dying on the first of May gets me all mixed up in my feelings kind of.”

“I know, Pa.”

“I’m going to give you that ring she used to wear. I’ve brought it along in my pocket. Someway I didn’t want to give it to you with the rest looking on.” He felt for her hand. “I had a piece put in to make it bigger. She wasn’t like us, just regular size, Myra was.”

“I know, Pa.” Hepatica drew closer to him, her cheek was against the sleeve of his ulster. “But are you sure you’d ought to? Won’t you miss it from your watch chain?”

“No, I want you to have it now you’re getting so big. She didn’t have so many things of her own. I wish I’d got her more. I was going to . . .”

She felt him slip it on her finger and though it was too dark to see she knew just how blue the little turquoise in the middle of the two gold leaves looked.

“I’ll be real careful of it. Thank you, Pa.”

Hepatica seldom thought about her name, though she knew it was a queer one. It was part of her, and every spring her father reminded her of how she had come by it. She knew the story by heart, almost word for word, as she knew the printing on Joshua Pollock’s handbills and the way the red curls were ranged on either side the parting of T.T.’s wig. He was beginning to tell her now about that other spring hillside where he had waited fifteen years ago on the afternoon that she was born. That was farther north, in Massachusetts or Connecticut. He never could remember which, though the hillside and the houses below it stayed by him clearly. Even after all these years he could see again just how the trees grew on the higher ridges of the hills, how the windows in the town gave back the sun in little bright squares, and how the chimney of the particular house he watched sent up a wavering blue thread of smoke. He remembered how tired his eyes had grown staring for a sign from the doorway below. T.T. had promised to wave a towel when they wanted him. Sometimes he had had to look away they blurred so with watching. That was how he had come to notice the little clump of blue flowers in the grass beside him. Ordinarily he would have been too far away to see them, but then his face had been almost on a level with their hairy stems and faintly tinged petals. Their blueness had astonished him. It was not like the color of sky or water or even other blue flowers he had seen.

“They made me feel funny,” he was telling Hepatica. “I was most afraid to breathe for fear of hurting them.”

It had seemed as if they meant something. . . . Hepatica sat very still beside him, waiting for him to get to the part about the children. She knew he would tell her about them in a minute, because they came next. There had been three of them, a boy and two little girls with baskets of flowers. “May baskets,” they had told him after they had recovered from their fright at finding a giant stretched across their path. The boy and the older girl had been curious and friendly, peering at him with round eyes and asking a question or two. But the smallest girl had hung back, with both hands pressed to the front of her dress. Hallelujah had liked her best. He could see some of those same blue flowers between her fingers. He had pointed to them and asked her their name.

“Hepatica,” she had told him, her voice so small he had had to strain his ears to catch her whisper.

And then T.T. had waved her signal and he had gone crashing down through the underbrush with a little bunch of blue flowers that the child must have thrust in his hands.

“Yes, that’s how you come to be called Hepatica,” Hallelujah Hawks told his daughter for at least the tenth time that she could remember, and with as much wonder as if it were the first recital, “and it never seemed queer to me.”

From the town a clock struck the half-hour and they rose.

“We’d better be going back,” said Hepatica. “It’ll be nearly seven by the time we get in.” They could just make out the ruts of the road ahead though it seemed almost light to their eyes after the darkness of the covered bridge. “I hate to leave the river behind.” Hepatica sighed as they walked toward the clustered lights. “I expect there wouldn’t be time to come again before the train goes to-morrow.”

“No, I guess not.” Her father puffed at his pipe, his long legs moving, shadowy and enormous, beside her.

In nearly all the houses they passed people were eating supper. Hepatica liked to look in at windows where the curtains were up and people gathered round their tables. It was rather like the theater—these little lighted stages, only the people on them were playing at being themselves. They didn’t know they were actors, or that they had an audience out there in the dark.

Now they were back in the center of the town again, another corner to turn and they would find themselves by Masonic Hall. They passed by the other hall, the one Jerry had said they ought to have had. Inside the May Festival was going at full tilt. Through open doors and windows Hepatica could see the long tables spread with white cloths and people sitting or moving about. The smell of fried chicken and coffee came out to them, and the pleasant clatter of crockery and many voices talking together.

“Seem to be having quite a time of it in there,” her father said.

“Yes,” Hepatica answered, “it’s the Christian Endeavorers.”

Just as they went by a group of young people flocked out of the doorway. The light, full dresses of the girls showed plainly against the dark suits of the boys who followed them. They had brought plates of ice cream to eat there on the steps, and they made a gay commotion as they settled themselves. They laughed a great deal and elbowed and shuffled one another about with easy familiarity.

“Don’t you shove so, Dick,” a girl’s voice came shrilly. “No fair crowding in.”

Some of the girls sat close together, their skirts and sashes mingling in bright patches. More often though there were boys between, making a sort of pattern; a pattern Hepatica was beginning to notice more and more as she grew older. She found herself wondering what it would feel like to be part of a group like that, eating ice cream on just such steps, talking to some boy beside her. But, of course, she wouldn’t know what to say. She had never known anyone her own age, not even the winter they had stopped in Philadelphia for three whole months. No one in the show had ever expected her to. It was only lately that she had thought of it herself. Several of those girls looked even younger than she, but then they were regular size. She could hear one of them laughing as she and her father turned the corner. It was the kind of laugh she was sure she could never give, but she liked to hear it.

“Patty,” Hallelujah spoke suddenly as if he were with difficulty pulling some thought out of a far place in his mind, “you don’t mind being a freak, do you?”

He had never spoken so to her before, and she felt suddenly shy and embarrassed, as if he were looking at her in that way he had done sometimes of late.

“Goodness, no,” she answered, quickening her steps as they came in sight of their hall, “why should I?”

“I just wondered.” They were turning in at the door. “It’s different from when you were little, and I thought, maybe if you did . . .”

“But I don’t, Pa.”

“Well, if you did, I thought I’d ought to do something about it maybe.”

“Hey, there,” Jerry sang out from the window above them. “It’s about time you two showed up. Here they be.” They could hear him calling to the rest inside as they mounted the wooden steps.

Every member of the troupe had given Hepatica a present, and with the exception of the birthday cake and candles she had them all on. The freaks went in for finery, and so besides the blue poplin dress from Flossie and Mabel, there were flowered hair ribbons from Adam, a silver locket in the shape of a heart from Joshua Pollock, and an Irish lace collar from Jerry. Then there were T.T.’s gold beads in the worn morocco leather case they had lived in for years and years. Hepatica had hardly been able to eat any supper for trying to concoct proper thank-yous beforehand. All the while she watched the others eating their chicken and biscuits and ice cream she turned over possible phrases in her mind. Then, when the beads had been brought out, to distract her while Mabel was fixing candles on the cake in the ladies’ dressing room, she hadn’t been able to say any of the things she had planned.

“Oh, T.T.,” she had almost groaned as the midget stood on tiptoe beside her to present them, “not your gold beads? You hadn’t ought to. I . . . I can’t—”

“Yes, you can too.” T.T.’s tiny face quickened with pleasure under the make-up she had been too busy to remove between performances. “It’s a lucky thing they were always long for me. Let’s try ’em right on.”

This was gone through with great ceremony. T.T. had to be lifted on a chair, while Hepatica bent forward on hers, and all the others gathered round to watch. The gold beads had belonged to Titania Tripp’s grandmother and mother before her, and on the occasions when she had worn them they had hung halfway to her waist. But they fitted close to Hepatica’s throat. “As if they had been made for her,” the rest agreed, admiring the effect.

“Look out, T.T.” Hepatica cried, catching at her just as she almost toppled off the chair, gathering her into her lap and kissing her small powdery face. She looked tired, Hepatica noticed, and her hands felt very hot. She hoped T.T. had remembered to take her pills so she wouldn’t have a bad night with her asthma. But perhaps she only looked more tired than usual because she had taken off her wig and her grayish wisps of hair were drawn back so tight. “Oh, the beads are so beautiful.” Hepatica sighed. “Had I better wear them for my turn to-night or only keep them for extra special?”

“You keep them on, Patty,” Joshua Pollock decided, “and I’ll see if they make you look any older from out front. Mustn’t have you getting too grown up, you know, or I can’t pull that part about the brook and river meeting. No, sir, you’ve got to stay twelve awhile longer even if you have got to be fifteen.”

“Seems just yesterday she was three, don’t it, Hallelujah?” the midget was saying, her eyes fond and shining under beaded lashes.

“Your ice cream’s most melted,” Jerry was saying on Hepatica’s other side, “ain’t you going to eat it?”

“Oh, yes, all the presents made me forget. It’s nice, Jerry, chocolate and vanilla, too.”

“I thought you’d like two kinds.” He was beaming as he fed some of the melted part to Chi-Chi. “I went clear over to the May Festival place to get it.”

Hepatica took up her spoon resolutely. She couldn’t help thinking how queer it was that she should be eating the same ice cream as those girls and boys on the steps they had passed. She wished Jerry hadn’t reminded her of them somehow.

“Glory Hallelujah!” she heard her father exclaim in the way that earned him his name. “Just look at that, Patty!”

Mabel Pollock was bringing the birthday cake from the dressing room. Its wavering candles lighted up her broad face, making her body appear more than ever clumsy and waddling in her old flowered wrapper. She set it down in triumph before Hepatica while the rest clustered round to watch her surprise over it. The candles were pink on white icing. They made a soft, clear light on the faces gathered about the table. All their eyes held little bright points that were reflections of the candle flames, even Chi-Chi’s and Molly’s were more shining than usual.

“It’s lovely,” Hepatica admired, “especially the candles.”

“They’d ought to be,” chuckled Flossie. “Adam most held up the show this afternoon he took so long finding ’em.”

“Yes, sir,” grinned Adam, “you come near having to do without your candles this year.”

“Sixteen of ’em, you see,” Titania Tripp tapped at Hallelujah’s knee to remind him, “we’ve never forgot that extra one, not once. Remember, Hallelujah, how I’d tell her ‘one to grow on,’ and she’d say it after me? And how you always kind of shook your head, and—”

“Hey, now, T.T. quit gabbing,” Joshua Pollock ordered good naturedly, “it’s time to clear up here and get ready for the show.”

“Come on, Patty, make your wish and cut it.” Mabel Pollock was already gathering up things at her end of the table.

Hepatica stared hard at the sixteen little flames before her. She had always taken the wishing part very seriously. Perhaps it was foolish, but she couldn’t help half believing there was something in this ceremony. Several times before her wishes had come true, though of course lots of other times they hadn’t. Still one must be careful not to wish the wrong thing, just in case. “Well, then,” she thought, puckering her lips to be ready to blow, “I wish I had someone to be friends with—someone different. . . .”

“Hurry up, Patty!”

“Hey, just one wish, you must be making a whole string of ’em.”

“All right, I’ve made it. Pfff.” Hepatica puffed her cheeks out like balloons and with one breath the yellow tips changed to blackened ends of wick. The lovely light died from all the faces that had held it. There was only a faint bitter smell of smoke as Hepatica plunged a knife into the frosting.

The birthday party had taken so long that they had to hurry to be ready for their turns. Hepatica helped Flossie into her snake charmer’s costume because she came first, and then struggled with the top buttons of Mabel’s boots.

“I know I hadn’t ought to have taken them off between shows,” Mabel said as she added more make-up, “but this spring heat and hurrying so just played the mischief and all.” Off flew a pearl button and Hepatica went crawling after it. “Isn’t that the worst luck? Well, I’ll just have to go on without it.”

“No, I’ll sew it, Mabel.” Hepatica reached for a needle and thread from the bristling pin cushion. “There’ll be time. I just heard Adam carrying out the swords and bucket.”

“You’re certainly a handy one.” Mabel resigned herself to Hepatica, one leg extended, her body stiff as a Chinese idol in rolls of fat. “Be sure you fasten it tight, though, it’s no joke when they go pop in the middle of the act and maybe hit someone in the front row.”

After Mabel left she turned her attentions to T.T. She always helped her with the two back hooks her short arms could never reach. T.T.’s preparation for her part was a lengthy and elaborate process, but Hepatica knew every step of it as well as Titania. Her earliest memories were connected with these little jars and bottles and brushes ranged on the shelf under the mirror. It was a legend in the troupe that Hepatica had held the rabbit’s foot in her fist before she was a week old.

A calico apron covered the midget’s shoulders to keep the powder from where it wasn’t supposed to be, and the smearing and patting and rouging and penciling had already begun. As well as she knew every motion of this Hepatica never lost her amazement at this queer sort of game which could so miraculously hide wrinkles and little lines and make eyes and cheeks so very bright.

For T.T.’s cheeks always emerged redder than the rose she wore pinned at the point of her fitted waist. Last of all came the wig. It was T.T.’s most cherished possession and when not in place, it lived in state in a flowered bandbox. Hepatica watched critically till she saw it safely on, the red fringes just touching the penciled eyebrows, and the curly part behind so firmly anchored down with pins that not a wisp of the grayish knot underneath showed.

“I’d never be able to get through my act and face the public without it,” T.T. had confided to her once long ago when she was a child. “It’s my fascination.”

Hepatica had thought that was another name for the wig and had called it so for years. She knew better now, though she still clung to the name from force of habit.

“Your fascination’s a little bit over one ear to-night,” she told her now. “Here, I’ll fix it.”

“Don’t sound’s if there was many out front,” the midget remarked as a faint pattering of applause came to them, followed by the boom of Joshua Pollock’s voice.

“It’s that May Festival, I guess.”

“Yes, I guess so. Joshua’s run into a lot of things like that lately. Well, maybe there’ll more turn up for our acts. I wish it wasn’t so hot back here. Seems like this first spring heat takes the gimp out of me more’n it used to.”

Hepatica picked up a newspaper and began to fan her absently. Outside the green curtains she could hear the music box playing “My Old Kentucky Home” and the creaks and thumps that meant her father was setting up Flossie’s throne for the snake charming. That wouldn’t take long, she knew, and Pollock never encouraged his audience to draw closer as he did for the other acts. There was good reason for this. Those smooth, dark snakes that Flossie twined so fearsomely about her arms and throat while onlookers shuddered or peered in fascinated dread, were cunningly fashioned of rubber, the only sham part of Pollock’s “Freaks and Fandangos.” He wasn’t proud of them, but where was the harm in one little trick in a whole two hours of acts by genuine freaks?

“You know, Patty,” T.T.’s voice was going on beside her as she fanned, “I think Joshua ought to do something to liven things up more. The music box is all right for you to sing and me to dance to, but it ain’t the novelty it was when he got it twelve years ago. Folks want more noise nowadays. I’ve told him so plenty of times, but you know how stubborn he is. Besides he grudges an extra penny.”

“I know. Did you take your asthma pills, T.T.?”

“What? Oh, them—well, maybe I did forget. I declare, Patty, you keep after me worse’n a mother hen with one chick. Nobody’d think it used to be the other way round and not so long ago either.”

She smiled fondly at Hepatica who had come back with a cup of water and was counting out the pills from a little bottle. There was a queer bond between the two that made them like to be alone together. Even when T.T. had scolded and punished Hepatica long ago, they had always felt close and sure of each other. Perhaps it was their very difference in size that made this so. Hepatica seldom gave it much thought, only she knew that next to Pa she mattered most to the midget. It was T.T. who had sat up nights with her through croup and whooping cough and measles and the time she had caught diphtheria and they had had to stay for three weeks in a ramshackle town in the prairies.

Once she had seen a painted target at a shooting gallery, with lots of different colored circles growing smaller and smaller till they reached the bull’s eye in the middle. She had thought then that her own feelings were something like that, with her father and T.T. in the closest ring. After them she placed the rest of the troupe in varying stages of nearness. Joshua Pollock went in the farthest one, not that she had anything special against him, only somehow she couldn’t help being fonder of Jerry and the trained animals.

“I believe I’ll rest me here for a bit,” Titania Tripp was telling her. “Flossie’ll be around to let me know when it’s time for my turn. I guess it’s the spring bothers me,” she added apologetically as Hepatica turned anxious eyes upon her. “No, I ain’t got that stitch in my side any more.”

“You’re sure?” Hepatica questioned, fixing a place for her on one of the trunks, rolling her jacket to make a pillow. “Watch out these buttons don’t catch your curls when you go to get up.”

She lingered a moment, her hands straightening T.T.’s costume, then reaching out to the little bit of forehead that showed between the midget’s eyebrows and the wig’s red fringes. With firm fingers she pressed the wrinkled skin, smoothing it toward the temples lightly. T.T. sighed and let her eyelids drop.

“I’m all right, Patty,” she said. “You go on out and stop fussin’ over me.”

Hepatica threaded another needle and went back to the wings. Molly’s stump of a tail began to thump on the trunk at sight of her, and the monkey blinked bright eyes from Jerry’s shoulder. She went to them, picking her way carefully over creaking boards and strewn paraphernalia.

“Give me Chi-Chi, Jerry,” she whispered. “I want to sew the top button on his coat.”

She carried the monkey to a place on the landing where the steps led down to the side door. It was cooler there and though the only light came from one long beam through a gap in the canvas trees, still, by holding the jacket and needle and thread directly in it she could manage. Chi-Chi nestled in the crook of her arm. She could feel his hot small body pressed close to her side, his tail lax across her lap. Sometimes he made little sighs, but oftener he sat quietly blinking his lids, his fingers in the curling ends of her hair.

“There,” breathed Hepatica to herself and the monkey, “that’s on to stay.”

She shook out the small green jacket, spread it on one knee, and ran the needle into the front of her dress. Below her, halfway up the stairs, a window had been opened. Cool night air blew in refreshingly, and the tinkle of the music box sounded pleasant and far away. Absently she began to rub Chi-Chi’s back in time to “My Old Kentucky Home.” Presently it stopped. Joshua Pollock was beginning his remarks before the necromancy act. Scraps of his speech came to her, but she hardly listened, knowing it already so well.

“And now, Ladies and Gentlemen, the curtains will presently part to reveal not merely Queen Juno herself—you have already seen her in the flesh and marveled, as well you may—but they will open upon the gates of the future. . . . The future, I say, Ladies and Gentlemen, and I say it not lightly but as one who knows. . . . The stars in their courses have whispered their secrets to this marvelous woman. Her eyes pierce easily the veils that hide the future from our sight. Who knows what fortune might be ours to-morrow if we but knew enough to seize it as we burrow blindly in the dark mazes of the present? You have but to ask—Queen Juno will do the rest. And lest there be any among you not wishing to give voice to the questionings that stir your minds and hearts, I may add, I will pass among you these slips of paper and will myself carry them to her majesty. Put on your thinking caps, Ladies and Gentlemen, and take advantage of the powers that possess this extraordinary woman who sits enthroned before you. Note the signs of the zodiac bordering her robe and a crystal ball, symbol of the ancients, in her right hand. Opportunity knocks but once, so have your questions ready. Coming, coming, Ladies and Gentlemen.”

Hepatica could hear the usual rustling and whispering that followed this announcement. She knew that Mabel was out there on the throne, her skirts carefully arranged to cover the places where the gilding was beginning to peel. It sounded as if there would be a good many questions to-night, but even if there shouldn’t be there were always the old ones that Joshua Pollock kept in his pocket in case audiences were shy or slim. The act must always last at least ten minutes to fill out the evening and give Flossie time to change into her Hawaiian costume.

“Our first question,” Joshua Pollock’s voice came again, “seems to be from the fair sex, to judge by handwriting and the sweet fragrance rising from the paper. Ah, I thought so, it is prompted by the ardor of a tender heart. To love or not to love, Ladies and Gentlemen. This lady would know whether a dark man or a fair shall bring her the greatest happiness. How fortunate she is here to-night, with Queen Juno and her crystal ball at her disposal—”

His voice dropped to a more intimate rumble. Hepatica only half listened. She knew Mabel was answering with the speech from the paper-covered book that began, “Beware of dark, swarthy men though they come with honeyed words and gold jingling in their pockets.” Maybe one of those very girls she had seen on the steps eating ice cream had asked that question. Hepatica found herself thinking of those figures at the May Festival. She wished she could put them out of her mind. Why couldn’t she? Such lots of ruffles on their skirts, clear up the waist, and big puffy sleeves that stood out like wings on their shoulders, and their hair in the most beautiful bangs and towering twists. She meant to try doing hers that way. Even if Pollock did make her keep the curls for her act and to look younger, there wouldn’t be any harm in just trying some Sunday when there wasn’t any show. T.T. would show her how maybe, only she felt the same way Pollock did about Hepatica’s looking grown up, though for different reasons.

Something was moving below her on the stairs. She leaned forward, peering into the dimness. There couldn’t be anyone at that door. It only opened from the inside. But the window. Yes, there was someone at it. A shadowy leg came over the sill. A hand gripped the frame, and then a head and body followed, stealthily, with scarcely more than a creak or two. Hepatica heard Chi-Chi stir uneasily and make a faint, apprehensive sound from her lap. Her own heart beat faster under her blue silk waist, but she did not move. Another minute of waiting and a dark head appeared on the steps below. Now it was directly in the shaft of light that came from behind her. She could see a boy’s face distinctly, pale with high cheek bones, and eyes that seemed to be all black pupil, staring into hers. Still, she did not move nor make a sound.

“Hello,” she heard the boy say in a voice that was husky and pleasant, his eyes screwing up at the corners, and his lips parting in a wide grin. “Hello,” he repeated.

Suddenly Hepatica came to. She realized that he was speaking to her, and though she had not told herself to answer, she found her voice doing so.

“Hello,” she said back to him, and all the time her eyes were on his face and her hands keeping their hold on Chi-Chi her thoughts were on her birthday-cake candles and the wish she had so lately made.

His name was Tony Quinn and he was going to belong to the show. Hepatica woke early on her birthday to remind herself of this remarkable fact. She lay very still, partly so as not to disturb T.T. who slept beside her on the other side of the bolster they had put down the middle of the lumpy hotel bed, partly to remember better all that had happened last night. Her heart beat fast now under her cotton nightgown with the Hamburg edging at wrists and neck, because she had been so fearful about asking Joshua to let Tony come. She couldn’t remember how she had gone through her turn at all, thinking of him waiting on the stairs, and she the only one who knew he was there. But her voice had sounded just the same singing “The Last Rose of Summer.” She hadn’t missed a single note, and her hand had been steady as she tossed the rose petals. There had been a lot of pokes and pinches, and three of her photographs sold. All the time she followed Pollock up and down the spaces between the wooden seats, her mind was back on the landing, seeing Tony’s eyes look at her out of the dimness, watching for his sudden, crooked smile, hearing him tell her all about himself and how important it was for him to be part of the Freaks and Fandangos.

“Buy a picture of Hepatica Hawks—a little memento of this extraordinary girl. . . .”

And under the boom of his words, others were pounding in her ears, a desperate echo from somewhere deep inside her.

“Oh, make Joshua take him. Make him. Oh, let me think of the right things to say so he will. He mustn’t let him go back to that place where they beat him and make him kill the pigs. Oh, please, it’s got to come out all right. It’s got to.”

Thinking about it now under the darned, dingy spread with its honeycomb pattern and most of the ball fringing off, she realized that she must have been praying. She hadn’t called it that while she was doing it. She had gone on making her silent petitions all through T.T.’s act and the grand finale. It had seemed the show would never end. But it had.

“Patty, what’s come over you?” the midget had asked as Hepatica set her down and made for the stairs.

She hadn’t stopped to answer. Her cheeks were burning and her fingers felt cold as icicles. Just for a moment she stopped. Perhaps, she had told herself, she had made him up. But, no, there he was waiting, smiling at her halfway up the stairs.

And then they had gone to Joshua Pollock. They were standing there before him, with all the others coming out of the dressing rooms to see what was going on. Mabel had already changed into her flowered wrapper, T.T.’s wig was off, and Jerry hadn’t got out of his tights so that all his beautiful tattoo marks had showed plainly, even the green and red mermaid across his chest. Hepatica remembered now how curious and puzzled her father had looked, and how Joshua Pollock had slammed the lid down on his tin cash box, so none of them could see how much money he had taken in. Maybe, she had thought, even as she had begun her eager petitions, it would be a good thing if the dimes and quarters had come in poorly. That might make a difference about his taking Tony on. It might make him see how much they needed him and the banjo he had brought along in its green cloth cover.

“I can beat a drum too,” Tony had explained. “I used to do it in the boy’s band over at the orphanage before I came to work for old man Hodge.”

“We do need a drum,” Hepatica had joined in, remembering T.T.’s words earlier in the evening and turning to her for help, “don’t we, T.T.? It would save your voice a lot besides,” she had added persuasively.

“Since when did you start worrying about me?” Pollock had answered with a short laugh. “I’ve got enough on my hands without taking on more trouble. Besides,” he had pointed out practically, “this chap’s no freak, and I’ve always made it my policy to deal in genuine, first-class freaks only. I have to be careful of my reputation, heading a show like this.”

“But Jerry isn’t a freak,” Hepatica had reminded him. “At least only his tattoo marks and knowing how to train animals. Tony Quinn could learn tricks, too, and have another act playing the banjo and drum.”

“Yes, sir,” Tony had put in respectfully, his eyes darkening with enthusiasm. “I catch onto things real quick, they all say I do, and you need a sleight-of-hand act in your show. I said so to myself this afternoon when I was watching.”

“Why not take the boy on and give him a try?” T.T. had ventured. “We could do with some young life besides Patty.”

“Good little T.T.,” Hepatica thought now in gratefulness, looking down at the tiny creature asleep beside her, her breath coming short and raspingly in spite of the asthma pills.

But Pollock had had other objections. It would be risky business if that farmer decided to get out a warrant and arrest him for luring his hired boy away. He might follow the troupe to the next town they played. Pollock couldn’t afford to pay fines or get a bad name. No, he had explained, he was sorry, and of course in running away to join the Freaks and Fandangos Tony Quinn had paid them all a great compliment. Hepatica remembered that Pollock had put that part very prettily while she stood twisting her hands, trying desperately to think of something to make him change his mind.

“Tell them about the pigs,” she had heard herself urging Tony as a last resort, “and how he took the strap to you day before yesterday.”

So Tony Quinn had told them, and even Pollock had looked thoughtful and asked a question or two that made hope flare up in Hepatica’s heart again.

“It ain’t that I minded the chores,” Tony had insisted, “though anybody round here’ll tell you he puts ’em on so hard he can’t get a hired man to stay. I wouldn’t of minded the mush and sour milk so much an’ never gettin’ off or havin’ a whole suit, but I won’t slaughter no pig, not for nobody. It’s awful when they run gruntin’ and squeakin’ into a corner of the pen an’ you have to go after ’em with a knife. I done it once an’ I won’t ever again. I don’t care if he did take the strap to me. You can see he did, if you don’t believe me.”

Hepatica closed her eyes again remembering how he had jerked off the cotton shirt he wore, and how ugly and purplish those welts had looked across his scrawny shoulders and back. She had stared at the marks in fascination, but Mabel and Flossie had made little shrieks and T.T. had turned away, clicking her teeth in sympathy. Well, they had done the trick better than words; better than Tony’s eager eyes, or her own insistence. There had been more talk and a good many more objections, but she had known it would come out all right. And it had. When they had packed their things and straggled out to The Cooley House across the street, they had left him behind with Jerry and Chi-Chi and Molly who were going to sleep on benches in the men’s dressing room and be up early to get the baggage to the station before the eight-nineteen train they were taking to Wilsonville.

“Good night,” Tony had said as she had left with Titania, “see you in the morning.” How easy it had been, not the way she had thought it would be talking to someone your own age and not a freak either!

Now it was morning—her birthday, and things would never be the same again. Someone was whistling on the street under their window, “Oh, dear, what can the matter be?” Hepatica smiled to hear the familiar notes coming so briskly from unseen lips, growing fainter every second till they were lost at last and only sparrows in the tree outside kept up their fragmentary conversations. She smiled at the shadows of leaves that patterned the window shade; at the sharp, bright patches of spring sunshine falling on the roses of the Brussels carpet; she smiled to see her scalloped petticoats and the blue poplin dress with its tatting collar waiting for her across a chair, waiting to be part of this new-found friendship that had come so miraculously almost before the wish had left her.

“T.T.,” she cried, sitting bolt upright in bed with such suddenness that its ancient springs rattled none too reassuringly, “wake up! It’s most seven o’clock!”

“Goodness, Patty,” the midget blinked herself awake, “you scared me out of a year’s growth, and I was havin’ the nicest dream too—all about stayin’ at the Murray Hill Hotel, in New York, you know, the one we passed with the marble lobbies and gold furniture. Oh, dear, what a bed,” she thumped the mattress with one small clenched fist, “it’s stuffed with corn cobs I guess. Took me hours to get to sleep last night, and you dead to the world in a minute. But you shouldn’t have worn those beads to bed, dearie. It gives you rheumatism or something. Anyway they’ll tarnish, even real gold ones like these.”

But Hepatica was up and at the window, leaning out to the cool, sweet air.

“It is the first of May,

It is the first of May,

Heigh-ho, the cherry O,

It is the first of May,”

she sang, making up words to fit the tune of a game she had often watched other children playing, hanging as far over the sill as she dared to catch a glimpse of the cherry tree by Masonic Hall. Yes, there it was, a crooked drift of white between the buildings, sunny and shining, but not so eerily lovely as last night in the dusk.

“For pity’s sake, don’t hang out the window in your nightgown!” shrilled T.T. “Anybody’d be scandalized to see you.”

Bacon and eggs and coffee at the station counter with the high revolving stools; Tony Quinn grinning a sly greeting across the waiting room, because Joshua Pollock was taking no chances on his being seen with the troupe.

“Not that I think that farmer’d come after him and make trouble,” he told the rest as they waited for the train, “but it’s just as well to have him get on board and sit by himself. We’ll be out of the state by noon and then it won’t matter. What do you think about his costume, T.T.? Mabel and I kind of thought something in the military line would look nice. Plenty of brass buttons when he beats the drum.”

“Well, you want to be sure it don’t look too much like Chi-Chi’s.” The midget snapped the clasp of her alligator-skin bag, and lifted her left eyebrow. “Wouldn’t do to have folks get ’em mixed up!”

“I guess she must feel pretty good to-day,” thought Hepatica hearing this. “She never talks back to Joshua unless she’s all right.”

The train was a slow local one. It stopped at every smallest wooden-soap-box of a station along the way. There was a wailing baby at one end of the car, and at the other a small boy who went plunging from his seat to the water cooler and back, spilling cups full as he passed. Still, Hepatica didn’t mind. She didn’t even mind about Tony’s not sitting with them, because he would be doing that soon. Now and then she would steal quick looks at him where he sat in a seat at the farther end, reading some papers he had picked up in the station. He looked different by daylight, as different as the cherry tree had, but still the same really. Only this morning his hair didn’t stand up about his thin, palish face in quite such dark disorder. His eyes looked less popping and scared, and it seemed to Hepatica that his shoulders were not hunched so high. Maybe that was because of those welts he had shown them. She shuddered, suddenly remembering how painful they had looked.

The conductor had been kindly disposed toward animals. He wasn’t the sort to make them keep the covers of Chi-Chi’s and Molly’s traveling baskets shut tight.

“Go ahead, take them out,” he had said when Jerry explained what was inside. “This is no weather to be cooped up, only don’t let them make free of the car and scare any old maids. I had that happen once on my route and I ain’t forgot the screechings—they didn’t come from the animals either!”

How they had laughed as he winked and passed up the aisle. Jerry had Molly on the seat beside him, but the monkey wanted to come to Hepatica. He liked the pleasant softness of her lap and the blue poplin. She held him close to the window, wishing it were possible to have it open a crack. But even her father hadn’t been able to budge it.

“Spring, Chi-Chi,” she said under the grinding rumble of the train, and the monkey scratched his ear in solemn approval.

They were rushing through the kind of country she liked best, with newly plowed fields striped in green and brown. Sudden brooks, foaming and tawny, appeared and disappeared in woods that were misty with spring leaves. Such tender, greenish tassels were hung out everywhere and the fiery tips of maples bright as October but much too small to belong to any month but May. Wild chokecherry trees rose now and again in delicate, cloudy white. There were bright green rolls of skunk cabbage wherever brooks flowed through wooded places, and when they came out into sunny clearings or open fields marsh marigolds followed the water in a fringe of living gold. Calves and mottle-coated colts on ridiculously long legs were in pasture; boys fished in flat-bottomed boats; and sometimes men plowing paused to wave as the train sped by. It seemed impossible to Hepatica that she could ever have felt about spring as she had last night.

Titania Tripp sat facing her on the turned-back plush seat. She looked smaller than usual because her feet, struck out straight before her, were still several inches from the edge, let alone dangling over. Sometimes she dozed, her head, in its fluted straw with the bunched violets, lolling to one side; sometimes she peered intently at the country beyond the windowpane, pointing things out to Hepatica that she had already noticed for herself.

“See, Patty, that orchard! My, my, but the trees are pretty. Always put me in mind of pop-corn balls when they’re so full of bloom.” Or again as the train pulled up at another way station, “Mercy, another stop? Call this a town? La Fayette Ville.” She spelled the name aloud scornfully. “I guess if that Frenchman had known what he was comin’ to he’d have stayed home. Still, it might be worse, and that’s a real sweet little house across the field there, just about my size.”

“It’s a smoke house, T.T., must be with that great chimney.”

“Well, I don’t care. I could fix it up with curtains at the window and a garden in front, and . . .”

Hepatica laughed.

“I could never come and visit you,” she pointed out, “at least I’d have to sit outside on the grass if I did. You know even if I doubled over I could never get through that door.”

T.T. was always seeing little houses she wanted and Hepatica was always having to explain their difficulties to her. She had begun doing so when she was barely able to talk. “You’re so practical, you’d ought to go far,” the midget often told her with an affectionate tap of her twiglike fingers.

They had to change trains at noon, and there was half an hour’s wait at a place called Sodom Junction. T.T. made jokes about that name, too, but she pointed out that at least the junction part was something to count on.

“You can always be sure of junctions havin’ a lunch counter,” she remarked as Hallelujah swung her off the steep steps and set her down beside their piled-up baggage and the animals.

Faces pressed close to car windows to see their exodus, and the station stragglers all gathered round with curious interest.

“Say, Sissy,” sang out one of the men lounging on the platform, “what did they give you to grow on?”

He winked at Hepatica with sharp, small eyes, and a neighboring crony spat out tobacco juice and answered with a grin, “Shucks, Sam, can’t you see she swallowed gunpowder when she was a baby an’ it made her shoot right up!”

Hepatica joined in the shouts of laughter that greeted this sally, but she was glad when the train steamed away again and the lumbering mail wagon and station hack rattled off. Several small boys lingered, their snub noses already sprinkled with early freckles, their mouths gaping over the wonders of “Pollock’s Freaks and Fandangos,” their eyes round and blue as berries. The youngest one had a grimy lollypop. He wanted to offer it to Chi-Chi but he was afraid. Hepatica felt sorry for him and took pity on his shyness.

“Chi-Chi mustn’t have candy,” she explained kindly, bending down to the little boy. “It might make him sick. But he’s real tame if you want to pet him.”

But he couldn’t bring himself to come any nearer two such extraordinary creatures, and so Hepatica left him still staring and sucking while she rejoined the others at the lunch counter.

Now that they were over the state line Tony could sit with them. He and Titania Tripp had already begun a spirited conversation when Hepatica came in. She could tell this even before she made out any words by the way the violets were wagging on the midget’s hat. She slipped into the empty place between Tony and her father. It seemed to have been saved for her.

“I’ll put Chi-Chi in his basket while we eat,” Jerry said, his mouth already full of stew. “Afterwards we’ll take him an’ Molly over to that meadow across the tracks. There’ll be time to give ’em a sniff of green. The station agent says our train’s most always late.”

Tony Quinn hardly said a word to her all through the meal, but that was because T.T. kept him so busy answering questions. It was pleasant sitting next to him, though, watching the way he made doughnuts and coffee and pie disappear.

“Hey, young feller,” remonstrated Joshua Pollock from across the counter, “watch out you don’t burst that jacket of yours! Acts like he was aiming to rival you, Mabel, don’t he?”

“He’d better not try!” Mabel reached for her third cream puff and added more sugar to her coffee. “A fat lady’s one thing, but fat men freaks don’t have any kind of following.”

“Well, once I get him that show outfit he’ll have to stay the size to fit it,” Pollock announced. “I’m laying enough out on him now to eat up most a month’s profits.”

“You quit talkin’ profits an’ losses, Josh,” T.T. piped up with a grimace, “it’s enough to take away anybody’s appetite to hear you! What’s become of the cheese?”

“There, I guess maybe I ate the last piece,” apologized Hallelujah, sheepishly looking down at the plate he had just cleared. “I didn’t notice till it was all gone.”

“Sorry, m’am,” the lunch-counter man told her. “I’d have laid in more if I’d known you folks was goin’ to stop. Anything else I can get you?”

“Well, I suppose I can try a piece of the apple pie, though ’twon’t be the same.” The midget peered playfully up at him from the edge of the counter which was on a level with her sharp chin. “You know the saying:

‘Apple pie without the cheese,

Is like a kiss without the squeeze!’ ”

Hepatica laughed with the rest, though this wasn’t the first time she had heard T.T.’s little joke. But she wanted to laugh to-day. She wanted to skip and run, too, like Molly when Jerry let her off her leash on the grass across the tracks. She didn’t, of course, because it wouldn’t have been becoming in anyone fifteen years old and her size. But something in her wanted to all the same. She and Tony had gone over there with Jerry and the animals while the rest lolled about on the hard seats of the station and Joshua Pollock sat in the ticket office and swapped stories with the agent. It was so much pleasanter outside Hepatica didn’t see how he could.

They found a nice place half in shade under a willow tree that straddled a bowlder. It wasn’t such a big one, but by sitting close they could all get on it, and Hepatica said they must because the grass did seem to be just a trifle damp. Molly ran sniffing in circles, her pointed nose to the ground, her fraction of a tail tense with pleased importance. Chi-Chi wasn’t allowed such complete liberty because of the damp grass and his sudden dashes up trees, but he had the run of the sunny rock and as far as his long chain would let him explore. Sometimes he brought things back to Hepatica—a dead twig, a dried seed pod, or a hastily pulled handful of new grass, all of which she accepted graciously.

“He likes you a lot, don’t he?” said Tony, watching this pantomime with his one-sided smile.

“Well, he really likes Jerry best,” Hepatica admitted honestly, “but my lap’s more comfortable.”

“He’s mine,” Jerry told them between puffs of his pipe, “I give him his grub an’ he knows it, but he makes for Patty every chance he gets. He’s one that likes the women best, lots of monkeys are that way, an’ I don’t know’s I blame ’em.”

“Wonder if it’s true we all come from monkeys,” Tony went on, absently chewing grass shoots into a cud. “I read that in some papers they had at the place I worked in ’fore I went to Hodge’s. I wouldn’t wonder if there was something in it, the way their hands look, so pink and human. What do you think?”

“Well, maybe,” Hepatica thought. She wouldn’t quite commit herself, it felt a little queer at first having opinions with somebody new and strange. “How old are you?”

“Most seventeen, but I can pass for eighteen any day. How old are you?”

“Fifteen. To-day. Too bad you didn’t come in time for the party. We always have it the night before, a cake and everything.”

“You don’t look that old, not in the face.”

Hepatica felt herself turning red under his sudden scrutiny—she who was so used to curious stares that she always took them as a matter of course.

“It’s my hair, I guess,” she said, pushing back one of the long fair curls that had strayed over her shoulder from the tying behind. “I can’t put it up on account of Pollock wanting me to keep looking twelve for the show.”

“Yellow hair’s nice—for a girl, I mean,” Tony wagged his own dark head approvingly, “but it makes a feller look like a Willy boy.”

“My father has it,” Hepatica pointed out, “and I guess he never looked like a Willy boy.”

“I guess not!” Jerry slapped his knee with a loud guffaw at the notion.

“Well, he’s a giant,” Tony reminded them. “That makes everything different.”

They made willow whistles from the new shoots. At least Tony made them, his fingers very deft and brown as he hollowed out the soft pith with an old jackknife. Hepatica watched in fascination as he cut and pushed and peeled the wood that smelled so keenly of fresh sap. She had never known about willow whistles before.

“Gee,” Tony exclaimed when she told him, “I thought everybody had ’em when they were little. ’Course I ain’t tried my hand at makin’ any for quite awhile. Had too many other things to do.”

He put the first finished one to his lips and worked his fingers along the little holes he had cut; and actually a thin, sweet pipe came out—not quite a tune, and yet there were notes like bubbles or the places in a brook where the water goes over stones with a quick gurgle. Hepatica was enchanted; Molly barked, and Chi-Chi stopped his exploring to listen with his head cocked on one side.

“Say now, that sounds great,” Jerry admired. “I ain’t heard one since I was a little shaver.”

“Oh, let me try.” Hepatica could hardly wait to put her lips to the freshly cut end of wood. But though she puffed her cheeks out and blew with all her breath, she couldn’t make it sound the way Tony had.

“It’s a trick,” he told her, “but you’ll get the hang of it. You blow too hard, and you don’t keep your tongue puckered right.”

He went on whittling another and Hepatica tried to follow his directions, resulting in uncertain squeaks and shrill blasts. All the time she felt happiness streaming over her in clear waves like sunlight and the moist spring air. Something deep inside her stirred. It was an inner screw of sharp, pleasant pain that made her feel light and shaken. She must try to remember it always—this light on grass and gray-green willow leaves; the pale sprinkling of bluets a little way off; Chi-Chi, blinking in the sun, his tail curled like a brownish fern frond; a red-winged blackbird heading for that thicket, its flaming side toward her as the dark wing lifted, and Tony’s quick fingers and puckered lips making a willow shoot give back the spring in a soft, sweet string of little notes.

If only it could last forever, or even just a whole afternoon! But already Hallelujah was sending out a hail from the station platform, and an engine snorted its distant warning.

“It goes like this.” Tony picked the notes out with one finger on the dusty keys of the upright piano in the hall where Jerry and Hallelujah were already unpacking properties behind what passed for scenery. “Dum de, dum da, dum da, da, da . . .”

Hepatica, hanging over the rosewood instrument, frowned softly, trying to fit the printed words of the song to his drumming. She read them over slowly, painstakingly. The little black notes climbing up and down their lines of fencing confused her no matter how hard she tried to connect them with the sounds they stood for. Tony was so quick in everything he did. It made her feel extra slow and clumsy. She didn’t blame him for growing impatient. He was right, though, about making her learn new songs and discarding “The Last Rose of Summer” and the paper rose petals. He was right about everything. Even Joshua Pollock admitted he’d put new life into the Freaks and Fandangos.

“Now come on, let’s try it with the banjo.” His fingers were already tightening the strings. “I’ll play to here,” he tapped the sheet of music, “and when I nod my head you begin.”

The song was called “Annie Rooney” and the man in the music and stationery store had assured them it was the most popular hit in New York. That had decided Tony, though for herself Hepatica had preferred one called “Half Past Nine.” Tony finished his introductory pickings at the strings and she began. It had a nice, easy chorus part that she swung into with gusto, glad to reach it after the more intricate ups and downs of the explanatory verses:

“She’s my sweetheart, I’m her beau!

She’s my Annie, I’m her Joe!

Soon we’ll marry—never to part!

Little Annie Rooney is my sweetheart!”

It was hard at first for her to keep with the banjo. She had grown so used to the music-box accompaniment, and then often Tony put in extra bits on the spur of the moment. The way she went over and over the songs till she had them fixed forever in her mind annoyed him. He was impatient, quick to vary things. He couldn’t understand what made her so plodding.

“You’re slower’n cold molasses,” he said after they had gone through it for the seventh time. “If you make me play that through once more my thumb’ll crack open.”

“But that part in the middle where I have to go high—we kind of don’t keep together right.”

“Well, who cares, long’s we end up without gettin’ too far off key? It’s a pity you can’t pump a pipe organ, you’d never give out.”

“Yes, I got plenty of breath,” Hepatica admitted smiling.