* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

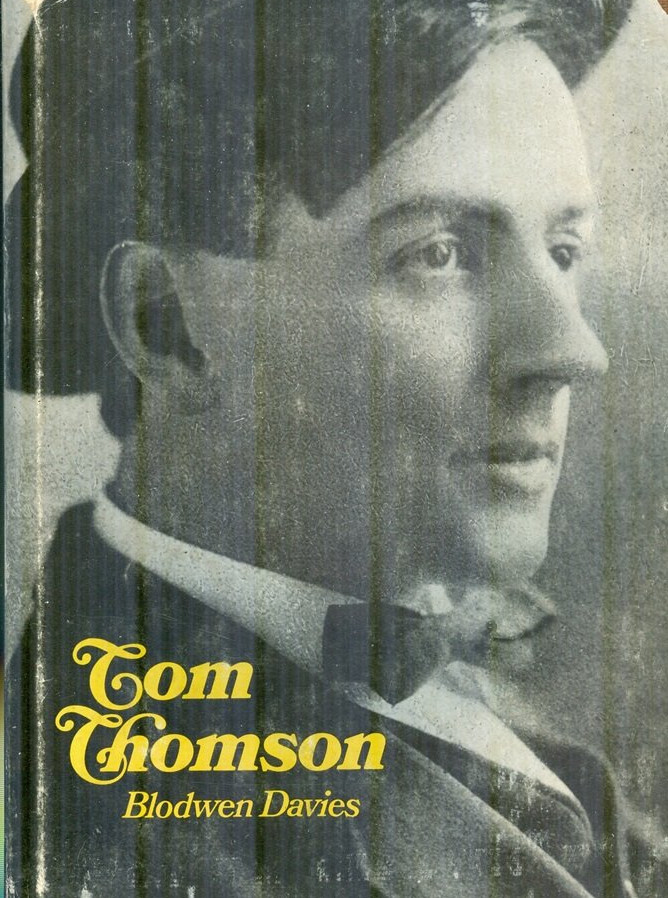

Title: Tom Thomson: The Story of a Man Who Looked for Beauty and for Truth in the Wilderness

Date of first publication: 1935

Author: Blodwen Davies (1897-1966)

Date first posted: Jan. 21, 2022

Date last updated: Jan. 21, 2022

Faded Page eBook #20220122

This eBook was produced by: John Routh & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

THE STORY OF A MAN WHO LOOKED FOR BEAUTY AND FOR TRUTH IN THE WILDERNESS

By BLODWEN DAVIES

Foreword by A. Y. Jackson, R.C.A.

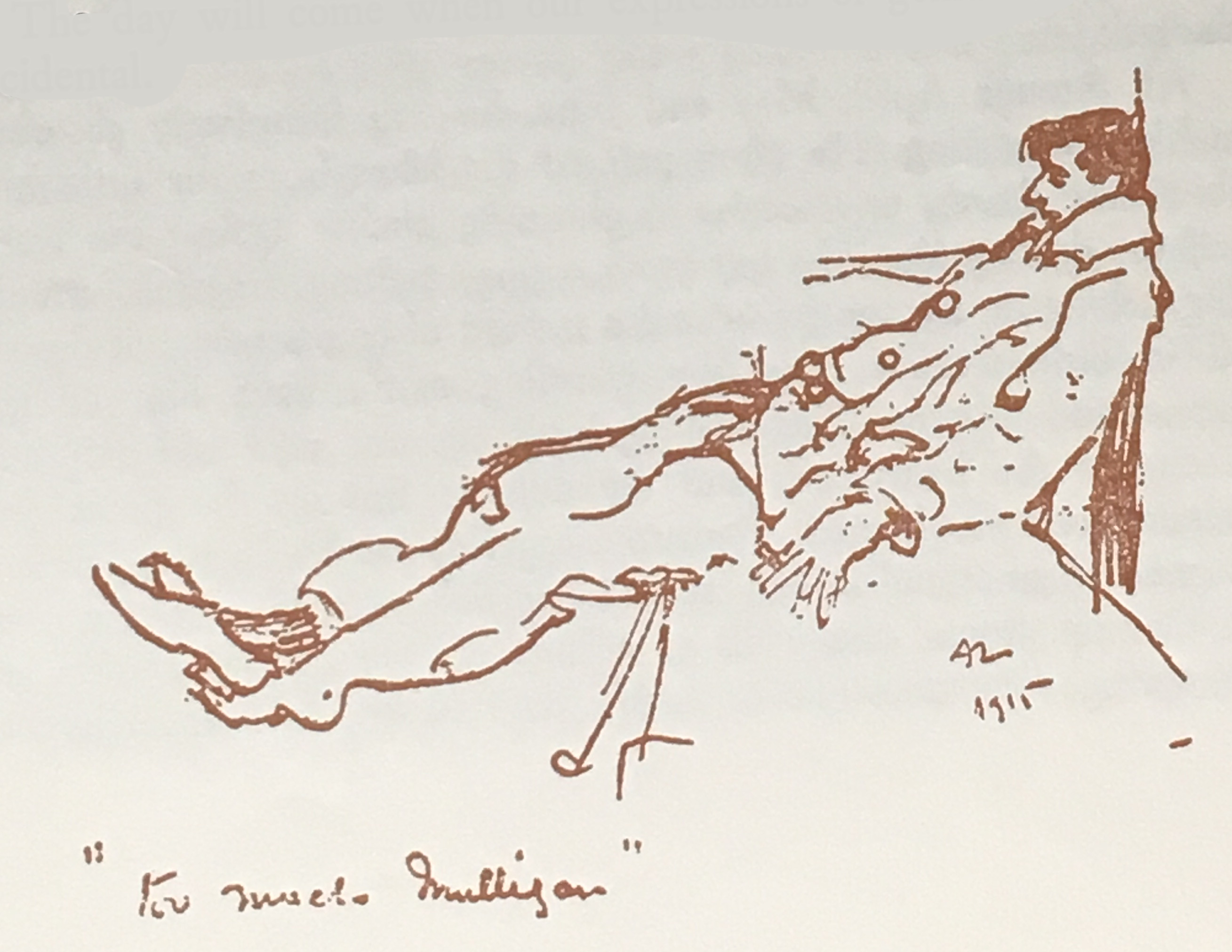

Sketches by Arthur Lismer, R.C.A.

MITCHELL PRESS LIMITED Vancouver, Canada

A revised memorial edition of the limited

and privately printed first volume by

the author, the late Miss Blodwen Davies

Designed and printed at Vancouver, Canada

as the

Centennial Project

of the publishers

Mitchell Press Limited

Copyright, 1967

“Work is love made visible.

And if you cannot work with love

but only with distaste, it is better

that you leave your work

and sit at the gate of the temple

and take alms of those

who work with joy.”

From The Prophet

by Kahlil Gibran

Truth has its rights and its privileges, but it has to fight for them against the prevailing human weakness for embellishment and decorative effects. The simplicity of truth is something for which the artist and the philosopher alike must struggle, for man has a strange, overwhelming desire to complicate simplicity and elaborate truth into attenuated half-truth. So it is that since his death in 1917, the legend that has grown up around Tom Thomson, the artist, has been allowed to obscure the character of the man. Tom Thomson was not a genius who flashed, full-fashioned, into the sphere of Canadian thought. He acquired nothing easily and what he achieved was done by devotion and concentration, and in the spiritual struggle that marks any work of value to the race. His genius would never have flowered untended.

Thomson was not an untrained artist. For five or six years before he joined the sketching group at Grip Ltd., in Toronto, he supported himself as a commercial artist. Thomson was a very proficient draftsman. Before he abandoned commercial work he was considered the best letter man in the country and one of the best all-round men in the business.

When Thomson began seriously to turn his attention to painting, he was at the ripest period of his adult life. At thirty-five he was at the peak of his physical development and also mentally and spiritually mature. The mind he then applied to the technicalities of his art was keen and aware. He was highly sensitive and capable of great concentration. He was able, therefore, to absorb much more from his new associates than an adolescent student. His friends among the artists were men keenly interested in him as a personality. They were never casual. The professional teacher must, of necessity, divide his interest among the members of a class. Still unconscious of his true significance, Thomson’s friends were all anxious to hasten his development as a craftsman.

Now we look back upon Thomson’s career from the vantage point of historical position. Thomson’s friends looked upon him from an entirely different point of view. To us he is the past. To them he was the intimate present. In 1914 when Thomson was for the first time installed in a studio of his own he was naively unaware of any significance in his work other than the personal. A. Y. Jackson said of him at this time that “he did not realize he possessed a large store of knowledge he was not using.”

Beyond cavil now is the fact that some of the men who were associated with him, unknown and apparently unimportant at the time, were individuals of vast significance to the creative life of Canada. They were potential directors of creative thought. If, as some of Thomson’s most reluctant admirers and his friends’ most bitter critics again and again stated, Thomson was the chief figure in the movement that characterized his time, his was the motive power actuating the change in the art expression of his day,—if this was true, what would have happened when his influence was withdrawn? Surely the movement would have collapsed.

If Thomson alone had been imbued with the new mood then manifesting, his associates would have sunk comfortably into mediocrity, safe from the barrage of vilification which has been directed at their work during the last twenty years. But it was only after the death of Thomson that the modern movement in art in Canada actually took shape. Thomson never heard the phrase The Group of Seven. It was coined three years after his death.

Thomson’s obscure friends were helping an obscure and eccentric individual to find an outlet for his spiritual fire, for it burned even in his earliest work, as a discerning eye could see. His chief need was a technique in painting. The leading artists would have scoffed at the thought that a thirty-five-year-old commercial artist could make a significant contribution to the fine arts. None of Thomson’s friends had any lofty eminence from which to look down upon his amateur efforts. They liked Thomson as a man and they had faith in him as an artist. Nobody knew what Thomson was or might become. If his genius had been obvious, anyone would have been glad to discover him. However, only those on the same spiritual trails can travel together.

It would be equally unfair and untrue to imply that Thomson became a great artist because he encountered the companionship of the men who offered him an opportunity to paint. The group of young artists who were associated in the budding art movement twenty years ago included many whose very names are today almost forgotten, and others who journeyed a little way and wearied of the trail-breaking. External influences are important only insofar as they strike a response from the inner life. Thomson might have lived shoulder to shoulder with his new friends for decades without ever breaking through the crust of habit if he had not had striking power from within.

There was nothing accidental about the career of Tom Thomson. Inevitably he moved into the pattern which his contribution was to co-ordinate. Every experience of Thomson’s from childhood added something to his equipment. His knowledge, his assurance, his integrity were as important as a medium and a technique.

The Thomson of the familiar legend was a rough and simple woodsman, with a woodsman’s trappings and ways. A new generation interpreted his life as crude and undirected. Thomson lived a simple life, it is true, because it was the only life he could live and maintain his physical and spiritual independence. Freedom was essential. He could sacrifice the material but never the spiritual necessities. Thomson’s simple life was lived deliberately, under economic pressure. He knew that the few dollars he would ever earn would go so far and no further. It remained for him to decide how they would be spent. His was a cheerful and philosophical adaptation of circumstances. What the uninitiated did not realize was that there was in his work a profundity and significance that did not proceed from the soul of an unevolved individual fumbling his way through life. In Thomson’s history there are all the evidences of a personality driven by a cosmic urge to fulfil that part of a plan with which he had been entrusted in this life. The man was never intellectually conscious of the plan nor of his part in it but he was intuitively loyal to the creative principle within him.

The Thomson of the legend created in the classrooms and the studios, where Thomson himself was unknown, was a romantic man of genius, moody and solitary, who dashed off an occasional masterpiece when inspiration roused him from his inertia. The legendary Thomson was careless, eccentric. The legend gave birth to an unfortunate point of view among young artists who preferred dreamy waiting for inspiration to the steady stoking of the creative fire and who wasted many precious years waiting for genius to burn.

Thomson in real life was a most capable, level-headed and dependable individual. In whatever circumstances he might find himself, he was quite able to provide himself with food and shelter. He instinctively escaped the devitalizing effect of the industrial age and remained always the positive man. He was an excellent craftsman, woodsman and fisherman, a good cook, an attractive companion, and a musician. Though he was unconventional he was never incompetent or irresponsible. Most people regard a man of genius as inconvenient because he does not accommodate himself to the second-hand standards of life that satisfy them. The genius makes his own standards of life and they are so different to the tattered acceptances of his contemporaries that they call him queer, eccentric, if not quite mad. A man of Thomson’s type can regard the commonplace, conforming life with pity and concern. Thomson could give things their proper values. For the most part he acted intuitively, trusting the inner promptings. Towards the end of his life he divested himself more and more of the paraphernalia of city life. He would not allow his days to be cluttered with inconsequential friends or occupations. The creative worker must be ruthless with himself and with others in order to be discriminating with his time. Time is limited but the urge and necessity to create is unlimited. Thomson was quite capable of making unwelcome visitors realize their intrusion. He was most truly unhappy when he was forced by circumstances into uncongenial company. It was only when Thomson let down his guard against those predatory influences that beset genius that he became involved in the circumstances that lead up to his death.

Thomson must sometimes have known the inertia that from time to time steals upon the artist but it was never a physical inertia. His long months alone in the North with his canoe proved him active and resourceful. In town, while others slept, Thomson was hiking, afoot in summer, on snow shoes in winter, through the outskirts of Toronto. He knew intimately every season of the year and every hour of the day and night in the natural world he loved so well. This was the stuff from which he shaped his work and he was no laggard in the gathering of it.

In the company of the immortals walks this lover of the wilderness and its mysteries. Unconscious of his own significance, he went up alone into the North and brought out the sword that cut the bonds of tradition in Canada. It was his Excalibur, the sword out of the stone, that proved his authority. He was not the first to paint the North but he was the first to set its moods and message down on canvas in an unmistakable symbolism that even the uninformed could read. It was Thomson’s faculty for simplifying an experience to its essentials that made him an expressionist of his era.

Tom Thomson was a manifestation which came at the appointed and crucial time in the development of the spiritual life of Canada. He was a portent to show a sceptical people that there could be an expression of Canadian aspirations in an untraditional form. There is no birth without pain, and it was out of suffering—acute spiritual suffering—that Tom Thomson produced his work. The urge for a native expression in the arts in Canada was an important part in the achieving of national self-consciousness and self-reliance. Canada became differentiated from her neighbors and her sister dominions and began to feel, like any newly self-conscious individual, “I think, therefore I am.” Once Canada is wholly aware of herself through her creative leaders in the arts and sciences, in industry and economics, she will relate herself to the self-consciousness of humanity as a whole, which is striving for an expression of the spirit and aspiration of Man just as, in a lesser way, Canadians seek expression for the Canada of which they form a part.

Eight or nine months of every year in the cloister of the wilderness gave him time and opportunity to develop his genius, but it was difficult for the inarticulate Thomson to adjust himself and his ideals to a material-minded world. His only expression, his only protest, was in paint. That is why Thomson painted so passionately, so feelingly, in the brief years of his painting career. Only for the last three years of his life did Thomson have the technical skill to manifest the truth that burned within him, the power to paint his joy in elemental beauty and elemental conflict. At thirty-five he was unknown; at forty, acknowledged first of all Canadian painters; in death, a legend.

Tom Thomson was a man with a message. He might have been a musician, a poet or a dramatist. What he had to say had to be said. Circumstances of environment turned him towards form and color. Thomson was not a man with a medium seeking adequate objects for his brush. He was a man with the theme innate within him, groping about for seven-eighths of his life for a medium. And Canada, in her spiritual childhood, needed the graphic form of art above all others.

B.D.

Tom Thomson’s family history was Scottish on both sides of the house; and through both channels he inherited the pioneer strain.

Thomas Thomson, the first of the name to settle in Canada, was born in St. Fergus, Aberdeenshire, in Scotland, in 1806. He was a man of no formal education, who boasted that he had “never filed six-penny worth of paper in any school.” He was, however, a literate man, self-educated; he had good, strongly-marked characteristics and a natural force of personality. He was sufficiently eccentric to be a township character and he is still vividly recalled by men and women, now old in their turn, who knew him when they were young. “Tam”, as he was called, came to Canada endowed with nothing but head and hands; he made himself a prosperous farmer and left his heirs a comfortable patrimony.

“Tam” Thomson came to Canada as an immigrant in the eighteen-thirties. It was a decade of rapid expansion in Ontario. There were many people then living who had come into Upper Canada, as it was called, when the colony was founded for refugee Loyalists. It was still very much the pioneer state when he arrived.

In “Tam” Thomson’s day immigrants were arriving in the province at the rate of thirty to forty thousand a year, hailing chiefly from Scotland and northern Ireland. It was a journey of two or three months from the United Kingdom to Quebec. There the immigrants transferred to steamboats which took them to Montreal and again transported bundles and hide-bound trunks to Durham boats for the journey up the St. Lawrence to Kingston. There they had the choice of a steamboat to York or stagecoach by the Kingston Road to the capital. Inns and posthouses where stage horses were replaced and passengers refreshed were characteristic of Upper Canada highways of those times.

Thomson reached Canada in the era of plagues that swept the country like prairie fires. In 1833 the first plague-ridden ship reached Montreal. For two decades thereafter Canada wrestled with a problem big enough to overwhelm a small colonial state. Little ships reeking of cholera, typhus and ship’s fever plied the seas with crowded human freights, consigning to the troubled waves the bodies of their victims and debarking the fatherless, the widowed, the helpless and the penniless in scores of thousands every season at St. Lawrence ports. Poverty and despair filled the land with the low wailing of their victims.

In spite of all this “Tam” Thomson was hopeful and humorous. His son, at ninety years, was able to recall some lines of a witty poem his father wrote on his experiences in the quarantine sheds at Montreal.

Pickering township, to which “Tam” Thomson and his unknown bride each turned at about the same time, was still the backwoods. Claremont comprised a store and an inn in a clearing in the woods. It was fifteen years after his arrival that it was named Claremont and a postoffice opened.

Less than a mile from the crossroads was Thomson’s homestead. For a year of service to an older settler he earned a yoke of steers. For supplies he could not get by local barter he walked to Whitby or to Toronto. His life was one of downright facts that demanded every resource of brawn and brain. He cut logs for a cabin he built close to the road and in the cleared spaces roundabout he sowed the first crops between the tree stumps and gathered the harvest by hand. As the roots rotted he hacked and dragged them from the good black loam. Every acre was consecrated by the faith of this brave young Scot.

In 1833 the Brodie family emigrated from Peterhead in Thomson’s native Aberdeenshire. They were rather a remarkable family and among their descendants have been some distinguished men and women. One of the daughters was Elizabeth Brodie who was twenty-one when she arrived in Canada. Thomson must have known her during his earliest years of struggle with the bush. In 1839 they were married.

Elizabeth presided thriftily over the little log cabin but the first year of their married life was a series of disasters. The earnestly religious couple, steeped in a stern Presbyterianism, must have wondered why they were being so harshly dealt with. Their colt died. The cow wandered away into the bush and they found her fast in the tangled undergrowth, dead from hunger and exposure. Neighbors’ dogs killed their sheep. Elizabeth helped with all the farm work as long as she could. When her child was born they called him John. Elizabeth was so ill that for months recovery was uncertain. She had a long, slow convalescence, a tragedy in pioneer life.

They had no other children. As time went by their fortunes improved; forest gave way to fields and their crops flourished. Thomson built a new house of the beautiful rock so plentiful on his land. It was a charming one storey cottage of rose and grey granite, with a sloping roof and broad chimneys. There they lived contentedly.

Young John went to the log school up the road where a succession of drunken schoolmasters held sway. Both his parents were anxious that this son of theirs should have the advantage of a better education. The Thomsons were now prosperous and John a handsome youth. He went to school at Whitby but he was content to be a farmer.

At nineteen he was married. His bride was Margaret Mathewson who was born in Ross in Prince Edward Island, a spot not far from the capital. Her mother was a woman of fine character and gentle ways. Her grandfather was a doctor.

Margaret Mathewson and her family received most of their education from an old uncle who was a local celebrity. In the evenings he gathered together the men, women and children of the community and taught them as the old bards taught, by reading and reciting and discussing the poems and traditions of the race. Ancient history was one of his favorite subjects, but many a branch of learning came within the scope of this wise old man’s teaching.

Her father moved up to Ontario at the close of the American Civil war, in which he had fought for the North. He was a builder, and constructed many fine stone houses that still stand in western Ontario towns.

When John married, his father built him a house, on the brink of the hill, close to the old cottage. Both houses still stand, the older one no longer occupied.

Presently the elder Thomson handed over the management of the farm to John and, still in the prime of life, retired to enjoy his leisure. Now he had time for his pet hobby; all about was rare good fishing and “Tam” loved it to the end of his days. The pioneers, living out a gracious old age in the granite cottage, were now nearing the end of their life span. They were not old people for neither reached the allotted three score years and ten. In August 1874 Elizabeth saw her last harvest and was carried up the road to the village graveyard where so many of their pioneering comrades already lay. For “Tam” the savor had gone out of life. He did not linger long behind her. At the end of March, in 1875, he, too, went up the road for the last time. It was a bright winter’s day and all the neighbors were there to do honor to an old friend.

His namesake was not yet born.

To John and Margaret Thomson were born eleven children. Just before the arrival of the seventh child, Henrietta Mathewson threw in her lot with her sister’s family and, like the traditional maiden aunt, gave unstintedly of her love and service to the offspring of the romance of others. On the fourth of August, 1877, the new child, who was to be called Thomas John Thomson, was put into her arms. That he became a great artist meant little to her compared to the fact that he was always kind to her as she grew old. She had a great love for this child that came to her on the day of his birth.

Only the fact that his parents were there had kept John Thomson in Claremont. He wanted to move north. His approach to the problem was simple and direct for he hitched a horse to a democrat and with his immediate necessities under the seat, he set out for weeks of roving in search of a new farm. On Georgian Bay he found fine country settled largely by Scottish families. At Leith Thomson discovered land to his liking. The farm had a good brick house on the brow of a hill not far from the shores of the Bay. As he had done so often before, he went over the fields with his spade, turning over the soil, fingering it knowingly. He was content with what he found—and there was good fishing in the Bay. He bought Rose Hill and went home to tell his family the news.

The migration from Claremont to Leith began when Tom Thomson was two months old. Along with five sisters and brothers, mother, father and aunt, he travelled northwestward towards his new home in that country of which he was to be both priest and prophet.

At Leith four more children were born. It was a big house but there was no room to spare while the big family were growing up in it. “My sister and I never ate the bread of idleness,” said Aunt Henrietta.

John Thomson believed that the farm was a proper sphere for a man’s labor but none of his sons followed his way of life. Some years before Tom Thomson’s death his father gave up the farm and retired to a small house and a large garden in Owen Sound. John Thomson never lost his love of the outdoors. For many years in his old age he kept a horse and buggy just for his fishing expeditions with his old pal, Colonel Telford. The town, with friendly interest, watched their comings and goings just as Claremont had watched old “Tam” a generation earlier.

Nearly seven decades after her marriage to John, Margaret Thomson died, in January, 1925. A year later, in February, 1926, John Thomson, hale and venerable was married to Henrietta Mathewson who had already been one of his household for nearly half a century. He was eighty-six; she was eighty. So, together, they settled down in the little house to spend the few remaining years of life together. It was a pleasant culmination of long, arduous and loyal lives, spent in common labor for the family group.

They spent the long days in familiar tasks, in labor that went slowly with the declining speed of human life. While he worked in his garden, she worked about the house, as she had done all her long life. They favored a faithful, old-fashioned stove. Before it they sat in long winter evenings, in easy speech or easy silences, just as their moods dictated.

John Thomson died, in his ninety-first year, in September of the year 1930.

Such was the past out of which our artist emerged. It was unsophisticated, gentle, honest and practical. There was a note of joy in his family story, a delight in elemental things, in physical strength and skill, in human relationships, in the outdoor world, in music; and finally, in an orthodox God who punished and rewarded, who protected and disciplined his faithful people. There was the pioneer strain directed to adventuring in a composed, orderly, affectionate family that was progressing by degrees to the place where it was ready to offer to the race the body, brain and emotions of a man fit to strike a new note, to add something to the stature of his kind.

The thing Thomson had to do emanated from the virgin land on which his family lived and worked for three generations. Spiritually they were in tune with its primitive strength and beauty; physically they were adjusted to its seasons and demands. There was no tragedy in the Thomson family life to distort his response to the land; there was no bitterness, no resentment to choke his utterances. His family had toiled and had been rewarded. They had contended with the country’s ruggedness, its heat and its cold and had turned its qualities to their use and comfort. They could rejoice in their ingenuity, in their comfort, in their overcoming, because they had earned the right to the fruits of the earth and those fruits they knew how to enjoy, soberly and lovingly.

And so Thomson came to epitomize this love of a land that was wooed in strength and conquered in love; his task was to paint it as it had never been painted before. Tom Thomson had talent that came to be called genius. The situation was one that could develop in pioneering family stock that had remained true to best principles from the day they first set to work in the Canadian bush, until, in the third generation, comfort and education produced men and women fit to pioneer in art, in science, in religion, in education and in many of the foremost fields of human endeavor. The pioneering spirit was thus diverted into intellectual and intuitional pursuits and set itself to fresh tasks for the evolution of humanity.

Tom Thomson’s country, where he spent the impressionable years of childhood, is a beautiful country at any time of the year. Often in winter it has the quality of an etching, with everything reduced to the delicacy of tones in black and white. The lacey, naked elms, the delicate birches, the dark and friendly pines, fringing the skylines, outlining the contours of the hills, filling the hollows, give contrast to houses and barns in homely groups. Fields outlined by picturesque old rail fences give a natural design to this rolling country. There are days when the snow rests upon the shelf-like branches of the pines in strange, sculptural forms. New fields, where woodcutters had been at work, are like giant mushroom beds when every stump has a tam o’ shanter of snow. Or again, under the blazing light of an afternoon sun all this may change and glow with color, as blue and purple shadows serve as foils for the unearthly beauty of the northern snows.

Spring has a tremulous beauty in this windswept land. Against the dark and ancient greens of balsam and cedar and all their kin, the delicacy of early greens is sharply accentuated. The northern spring is abundant and extravagant. It breaks its alabaster box with a recklessness that wipes out the memory of winter’s bleakness at a stroke. Great stores of energy, dormant for months, suddenly are unloosed. The earth breathes the wonder of its own fertility. These months Thomson loved. Summer defies the palette, with its color and intensity. The lakes are jewel-like, the trees as pagan as when the Indians worshipped them as the haunts of beneficent spirits. The very rocks seem to have a curious quality of vitality. Autumn is the best-loved season of the year in Canada. In it the cycle of birth and death comes again to the gates of darkness and nature takes a gallant farewell in a blaze of light and color.

All this had its effect on the impressionable Thomson, nor were his parents unaware of natural beauty. His mother was a remarkable woman who possessed the happy faculty of putting first things first. She never allowed her duties or responsibilities to dull the bright edges of her personality. Her family cannot recall a time when she was too preoccupied with the affairs of the household to read her daily paper and to keep in touch with the events of the years in which she lived. Books were as much a part of her surroundings as curtains on her windows or carpet on her floors. The works of classical poets and novelists were there, archaeological romances, books of science and tales of adventure. Her children, sharing the glamorous adventures of knights and ladies, learned the lilt of beautiful English from the pages of many an old bard.

“She managed that each member of the family,” wrote one of her children, “shouldered a share of the responsibility and work, so that there was always leisure for the finer things of life, such as music, literature and hospitality.”

Hospitality was one of Margaret Thomson’s virtues. Of sympathy and joy she had equally large resources. Sudden needs, bereavements, illnesses, accidents, never found her too busy or too weary to lend a helping hand. Generous and impassive, she shared her rich personality with every one in need, and if the occasion was one of joy, she was ready to laugh with her friends. There was little of importance in the neighborhood of Leith in which the mother of the Thomson household did not share.

“They were all music-minded and liked to have music and musicians around them,” writes an old friend. “Every one of them was a musician of one sort or another. They were the kind of people of whom one carried nothing but pleasant memories in after life. I never knew a family anywhere that was so utterly unselfish and that is a virtue which, like charity, covers a multitude of sins.”

John Thomson, a magnificent figure of a man, even in his nineties, a fine patriarchal type, broad-shouldered, sinewy, bearded and burned, was the parent from whom Thomson inherited his physical characteristics. John Thomson was a man of impeccable principles. His word was as good as his bond and there were no subtleties in his philosophy. Right was right, wrong was wrong. He could be stern but he was just and kind and affectionate. He had a sense of humor his son inherited from him.

“John Thomson was always regarded as a rather unique character at Leith,” contributes another old friend. “He was a gentleman in every sense, but one of the most eccentric men who ever drew the breath of life.”

Any farmer who stood on a hilltop alone at night just to look at the stars, was, of course, decidedly “queer” to his matter-of-fact neighbors.

It was a happy household. In the evenings the father tutored the children in mathematics and grammar while the mother coached them in history and literature. Both parents read aloud to them a great deal. The love of beauty and consideration for one another bred something fine in all the children. The impulse to give was fundamental with Tom Thomson, as man and as artist. He gave richly and generously of whatever he gave. The possessive and acquisitive instincts were in abeyance. Thomson was a man born to give and he fulfilled himself when he learned how to spend his own spiritual wealth. So long as he kept it locked up within his personality he was ill at ease, bewildered and unadjusted. As soon as he found an outlet he became increasingly conscious of his natural destiny. Tom Thomson was one of those rare manifestations in western civilization, a man who completely detached himself from the idea of profit.

As a child, Thomson was a wholesome lad with a zest for active fun and a capacity for getting a great deal more out of small experiences than the average youngster. When he was a small boy his father one day brought him a pair of top boots with red leather trimmings and copper toes. He put them on immediately and ran out into the melting snow of an early spring day to taste the joy of his new possessions. He trudged about till dusk but when he returned home, tired and happy, the red and the polish were all gone. Someone asked him what was wrong with his boots. The child looked down at the ruined decorations with contemplative eyes and then glanced up and said: “I guess they must be shoddy.” The child got down to principles early in life, for nothing ever roused deeper scorn in Tom Thomson than persons or things that masquerade under false colors, and failed him for want of true character.

Young Tom loved the trip back into the sugar bush in early spring. The sugaring-off was an event on the farm, for when the first warm, sunny days of spring came they were followed by frosty nights, and between them they made the sap of the maple trees flow freely into the troughs and pails so carefully set out in the custom of the Indians. The work of gathering and boiling sap was the first spring festival and to young Tom it was a time of wonder. With his mother he watched for returning birds, for pussy willows and swelling buds and the curious shapes of the banked snows shrinking away before the encroaching warmth.

Even as a very small boy Tom Thomson delighted in the fishing around Leith, but not only did he catch his own fish but he also cleaned and cooked them over an open fire to the huge delight of his playmates. Some of them can still recall those outdoor feasts.

From childhood, too, he had the urge to draw. He scratched his first sketches on frosty window panes and there is a cellar door in the old house at Leith still covered with his earliest efforts. A sister writes:

“Sometimes Tom would take a notion to draw such funny caricatures of people we knew. He would keep us all laughing and guessing who they were. Always while he drew he whistled and sang and I can still see the whimsical grin he wore when he got a particularly good caricature.”

As he grew up Tom Thomson longed for a sailing boat and finally his father consented to having the old row boat equipped with sails. With the help of a chum, David Ross, he got the craft ready for “sea.” When the last knot was tied and the last gadget in place, fortune sent them a nice stiff breeze and with the breeze came Joe Coture, a French Canadian fisherman with a reputation as an expert sailor. He had a two-masted sailing boat that had the name of being the fastest on the Bay. “Old Joe” was proud of his boat and his reputation. With the magnificent audacity of youth, the boys headed their little boat out towards the fisherman and flung him a challenge to race them. To their huge delight they skimmed past him in their cockle shell of a boat. The boys felt like young lords of creation and returned home to boast that they had “passed old Joe so fast, he looked as if he was backing up.”

Such were some of the small incidents and adventures of Thomson’s childhood, which bore within them the seeds of a future blossoming—his love of the natural world, his affinity with the elements, his skill and delight in the use of his hands as well as an innate sense of the quality of people and things.

As he stretched out into manhood, his physical strength was unequal to the forces then at work in him and demanding expression in some form then foreign to his environment. Fortunately he was a country boy, so when he showed the first physical signs of the strain he was under, wise parents took him out of school and turned him loose, with a dog and a shotgun, to wander the countryside around the Bay for a year or more. It was excellent treatment for a sensitive, imaginative but, nevertheless, wholesome and happy youth. He had an old felt hat that he soaked in water and shaped to a point over the handle of a broom. Then he decorated it with squirrels’ tails and wildflowers. From under its worn brim his bright, inquiring eyes peered out upon the clean land from which he was one day to extract enough of truth and of beauty to stir the consciousness of a nation. He had the shores of the Bay, the streams that flowed into it, and all the lakes and pools within a day’s journey, to explore. Wider and wider grew the radius of his wanderings in search of haunts of wild birds and animals, rare plants and curious trees. It was then he laid the foundations of his uncanny knowledge of the natural world of the North but never till the day of his death did he end his tireless studies in the great school in which he was so apt a pupil.

The love of the gun was a boyish phase, for when he lived alone in the North in later years Thomson never carried a gun nor did he ever kill bird or animal for food or sport.

Those months of solitary rambling in the woods made him unique even in youth. “It seems to me that eighteen, Tom’s age at the time of which I write, is a particularly trying and awkward one for most young people,” writes a friend. “Some of us are filled with unwarranted conceit and enthusiasm; some utterly bewildered and confused in their outlook on life. And yet Tom was always quiet, sensible and manly; the tone of his voice was pleasant; he had an attractive laugh; he never seemed awkward and I cannot now recall a single flippant remark of his.”

Tom’s sense of humor and his quiet philosophy sometimes combined to get him into trouble. The minister of the little church that stood across the road from Tom’s home was a certain erudite and orthodox Scottish doctor of theology who resented Tom’s independent spirit and inquiring brand of intelligence. Tom had been working on a nearby farm with some other lads. They were making their way homeward on a quiet Wednesday, the traditional evening of prayer in the Presbyterian church. Some one of the boys, and it may have been Tom, suggested that they drop into the service. They were in their working clothes, just as they had left the fields. To those of other faiths in other lands there would have been nothing incongruous in turning into a place of prayer in clothing impregnated with the soil upon which they all worked and subsisted, but in Leith and in the eyes of the orthodox Dr. Fraser, as the boys well knew, it was an affront to Deity to worship in one’s working clothes. Moreover, it was an affront to Dr. Fraser. A wise and loving man would have turned the tables on the boys by assuming their sincerity and welcoming them to meditation and communion. Instead of that, he administered a scorching rebuke.

Tom could be grimly humorous in paying off such little debts. Once the minister stayed to supper at a farm on which Tom was working. Tom was told to serve butter to each plate. Impishly he recalled the minister’s weakness for butter, so he served him a very meagre portion. Then he spent the meal hour watching the minister’s plate and in replenishing it in small portions warranted not to last very long. Again and again Tom asked and again and again the minister admitted he needed butter, to the suppressed amusement of all at the table.

Tom’s clashes with Dr. Fraser were of much more than passing interest. They had the effect of stiffening his resistance towards the orthodox mind. His rebellion began with this man who upheld the historic banners of Calvinism in a modern world. Dr. Fraser represented Tom Thomson’s first conflict in the world of ideas. In the antagonism between the two were all the elements of the struggle between the established, the unalterable, and the expansive, progressive principle. It matters little how we approach that problem, where we begin, nor what the incidents of the controversy may be. The principles are constant; the conclusions are important.

It was about twenty years later that Thomson sold his first canvas. He telephoned the news home to his family in Leith. Even in the elation of that astounding event his mind flew back to the conflicts of his youth.

“And by the way,” he concluded, “tell Dr. Fraser I painted it on Sunday.”

Tom, in his turn, was always a challenge to the old minister’s most cherished traditions, and in spite of increasing prestige and the deep sense of shock and regret that Tom Thomson’s death stirred in the hearts of all who knew the man and his work, Dr. Fraser never admitted him to be anything more than “an amateur interpreter of the North.”

That, however—in the truest and best sense of the word “amateur”—Thomson was throughout his painting career.

In his late ’teens Tom Thomson became very restless. The promptings of his spiritual necessities became more and more insistent, although the harassed lad did not know what was afoot. The wanderlust was in his blood. He was straining for change and adventure and a new way of life. The urge expressed itself first in a desire to go sailing on the Great Lakes. He heard adventurous tales from the men of Owen Sound who brought fantastic ice-encased ships home to port through high November seas and the elemental struggle evoked a response in him. However, his parents refused to consider the lakes as a means of livelihood, and Thomson had to look elsewhere for an outlet. He could not reconcile himself to the life of a farmer.

When Thomson came of age he came into possession of a legacy from his grandfather, “Tam” Thomson. That seemed the time for decision and action of some kind. He elected to apprentice himself to a firm of machinists in Owen Sound. This was in the winter of 1898. His experiment ended after eight or nine months, not because of any fault he had to find with the trade but because he could not get on with the foreman. At the age of twenty-two he was again at a loose end.

Years later Thomson still regretted his withdrawal from the machine shop and thought of going back to take up his apprenticeship again. It was a craft that gave him the chance to use his hands and he was always happy when he was doing skilled manual work.

It was harvest time when Thomson returned to the farm and as soon as the harvest work was done he was off on a new tangent. This time he went down to Chatham to enter a business school and prepare himself for office work. His brothers, George and Henry, had already graduated there and Tom decided to follow their example.

His stay in Chatham did him no good, for now he seemed to be drifting. He lacked enthusiasm. The work was uncongenial and Thomson had nothing, in or out of his school, on which to focus his attention.

There were times when Thomson bitterly resented the lack of direction in his life and of educational opportunities. He secretly regretted that he had not gone on through high school to university. He was definitely conscious of some unexpressed power, but he had no contact with what we identify as the “creative life” nor with people who discussed self-expression as either the privilege or the duty of the individual seeking to adjust himself to civilized society. The current trend of orthodox faiths and philosophies made of the young men of the day careerists rather than artists. A young man was expected to “get on in the world” at whatever cost to the secret longings and aspirations which had to be repressed in living up to conventional standards. But while he had none of the pose or jargon of the studios, Thomson had an inner prompting that kept him on his way in search of experience, no matter how much of a laggard or a ne’er-do-well he might appear to be. When the business course was over, Thomson went home only to find himself as much at sea as ever. He was now a tall, vigorous and attractive man of twenty-four, still without a job or the prospect of one, but worse still, in the eyes of his provident family apparently no strong convictions on the subject. An old friend of those days discloses something of Thomson’s mood at the time.

“I discovered,” he writes, “how deeply sensitive he was and how he resented anything like public ridicule. I recall one night at Meaford in 1901 when he unburdened himself, lamenting his lack of success in life in terms that rather astonished me. I began to think that he then realized his power and had secret ambitions.”

His brothers, George and Henry, had gone to Seattle, one of the boom towns of that time. Thomson made up his mind to follow them. He went west in the same year, 1901. A few months later a fourth brother, Ralph, followed.

Thomson made the common error of seeking freedom and a solution for his problems from external circumstances. He hoped, that by some sort of magic, change of scene and associations would satisfy the hunger in his heart. What he truly sought was a change in his inner life, that world of which he knew so little, and he longed for a transformation that would bring order out of chaos and harmony out of discord. Thomson’s state of mind is common to most highly developed individuals at some stage in their unfolding, when the little triumphs and possessions of the average man seem so childish as compared with the elusive memories of struggles and aspirations in some shadowy past. The spirit brooks no turning back, no compromise with the affairs of those who had not travelled quite so far on the spiral path. It is indeed a crucial time for those in whom the creative fire smolders. Fortunately for Thomson, his heritage and his home training saved him from disaster in the testing years. The discipline of his youth, the inherent honesty and sincerity with which he was endowed, were the protective forces that surrounded that fine spiritual necessity for “the good, the true and the beautiful.” It would be impossible to describe what Tom Thomson suffered in those years of inner conflict, but the sensitivity displayed in his work is eloquent of intensity of feeling. To be true to himself and to adjust himself to society was his problem. Outwardly he showed few signs of the conflict, except that he had a gentleness and a consideration for others that was unusual for a man of his age.

Thomson seldom showed anger or excitement and his control may sometimes have been mistaken for indifference. One night in Seattle, Thomson was taking a short-cut home through a vacant lot and suddenly found himself looking into the barrel of a revolver. The young man behind the gun was awkward in his procedure, though he succeeded in getting his victim’s watch and money. Thomson made the remark that he must be new to the business, as he trembled so violently.

“Yes,” said the man, “you are the first.”

In Seattle, Thomson entered the business college that his brother, George, had started, to put in time until he had a chance to settle down to office work. He was still restless and ill at ease. Then one day he came home to his brothers and announced that he had decided to go into photo-engraving. It was a more important decision than it might have seemed, for it was actually the turning point in his life. Photo-engraving was in its infancy and was linked up with the new age of advertising. Thomson had a gift for fine penmanship and a sense of design, and these he could apply to his work, for advertisers were beginning to realize the importance of design and imagination in their art work. Thomson found in the studio endless outlets for his skill and his imagination and he was happier than he had been since his school days. At last his feet were upon the trail. Even the mechanics of the craft interested him and he found scope for his ingenuity.

Thomson made amazing strides. His self-confidence was naive and boundless. He ignored instructions from his chief and gave his fancy rein. The chief’s irritation soon gave way to discreet co-operation when he discovered that Thomson’s designs were always acceptable to his customers.

Thomson’s unconventionality demonstrated itself in his attitude towards his employer, with whom he lived. One day Thomson was sent on a message to a rival firm and while he waited he began to draw. Absorbed in his sketch, he did not hear the man approach. Thomson looked up some time later and the man asked him how much he was earning at his job. Thomson told him.

“I’ll give you five dollars a week more to work for me.”

Thomson accepted at once, quite casually and went back with the news. He changed studios but he went on living with his former employer.

It was in Seattle that Thomson also began sketching from nature in crayons and water colors. The results were quite simple and commonplace and gave no promise of the boldness of color and design that were to be expressed later.

One more event occurred that completed the cycle of experiences that Seattle had in store for him. He fell in love. Friends and relatives knew next to nothing of the significance of that brief and tragic romance. Thomson was endowed with a depth of feeling that would have been incomprehensible to the inexperienced young woman he would meet in a west coast town many years ago. Nobody knows exactly what happened. Some say that the lady laughed.

Whatever the incidents may have been, the purpose seems apparent. If Thomson had married and settled down in Seattle there would have been no lonely lover of the North, roaming the wilderness and spending the richness of a profoundly passionate love of nature on elemental beauty. His stay in Seattle did three things for Thomson: it adjusted him to society by giving him a craft; it gave him a clue to a method of expression; it opened the floodgates of his emotional life. Briefly, then, he became an adult human being, economically, spiritually and emotionally independent. The true results of the change slowly unfolded as the years went by.

For Thomson Seattle had done its best and its worst. He realized that the place had no real meaning for him. Returned home in 1905, he settled in Toronto.

It was not long after his return that he began to work with oils in a very experimental way that merely indicated his growing feeling for the art of painting. He became a great favorite with children and a sister recalls how he would sit in a big chair “painting ferocious looking lions, just ready to spring out of a tangle of jungle grass, while two children were perched on the arms of the chair and one peered over his shoulder, thrilled and spell-bound”. Children feel the quality of a man. Thomson’s increasing affinity for them and for the things of nature show how his character was broadening and his consciousness expanding to an awareness of others and of the means of contacting and enjoying the unspoiled wonder and faith and happiness of natural things. He was never happier than when amusing children or raptly studying the ways of birds or wild animals.

It is said Thomson took a few lessons about this time, anxious to learn more about his medium, but he never referred to them later among the artists who aroused his genius. When he came to know them he discovered a new world in the creative attitude to life. He realized how he had been fumbling in the dark and he never made mention to them of any early attempts to paint. It is a fact, that he did produce in those years little paintings which he gave away to members of his family.

Thomson passed the years 1905 to 1910 in obscurity at a desk in an engraving house in Toronto and most of his brief life had already been paid out in preparation for a few short years of achievement.

Developments in the world of the creative arts in Canada were now converging to a point where they were to focus the attention of the public upon certain painters as the expressionists of a new era. The events in the life of Tom Thomson could be paralleled in the lives of several of his contemporaries who were also cast to play parts in the drama of that turbulent decade. The career of Thomson was to be the briefest and most dramatic of them all. He was the keystone, perhaps, of the arch which others were so carefully building. Without them Thomson could not have achieved fulfilment and without him, his generation would have missed a rich note of dedication.

Thomson knew nothing of these other men with whom his fortunes were to be linked. Their ways of life had never touched his until the fateful year 1911. One day Tom Thomson walked into the studios of Grip Limited and asked Albert Robson for a place on his staff. Robson was one of the old Art Students League that had made valiant efforts in the Nineties to give art in Canada the true flavor of Canadian thought. There was not only promise but even genius in the group but the public was not ready for them and their work was not spirited and aggressive enough to worry the Royal Canadian Academy or rouse the temper of the public. The enterprise flowered early in the frosty spring of Canada’s consciousness of the arts, but it made its own valuable contribution to a new awareness of environment. The League’s influence became evident years after it had disbanded. The same fine fervor for the native note that later characterized Tom Thomson and his friends had stamped their work, an urge for an underivative expression, but they were largely concerned with subject matter. Thomson’s group took that for granted and fought the issue on technique and interpretation. Robert Holmes was one of the League, and C. W. Jefferys another, a third was Dave Thomson, who later was lost to Canada.

Robson was the man who carried the principles of the League into business and revolutionized commercial art in Canada by raising it from the level of an imitative trade to that of a creative craft. He knew that to compete with the American houses that got all the big railway contracts he had to produce not only the equal of their work but something a little better, in order to overcome the handicap. To do that he built up a staff of adventurous, intelligent young men, including J. E. H. MacDonald, Arthur Lismer, Fred Varley, Tom MacLean, Frank Carmichael and many others who made names for themselves in the fine arts. When Thomson asked for the job, he got it.

A few days later his former employer called Albert Robson in an attempt to dislodge Thomson by accusing him of laziness, incompetence and quarrelsomeness. Robson took the advice for what it was worth. He discovered Thomson was a man in whom generosity of effort was a characteristic. He would often scrap a design and start over again rather than patch up a piece of work to make it do. Thomson’s record gave the lie to every one of the false charges.

MacDonald was head designer in the studio when Tom Thomson joined them. He was a tall, red-headed man, with a slightly dour, slightly shy manner and a deep sense of humor. He was a designer of the very first rank. Later he was one of the original members of the Group of Seven and eventually he became the principal of the Ontario College of Art, the appointment coming shortly before his death. He first became known to the public through the controversy over his canvas, “The Tangled Garden”, which created a storm when it was exhibited at the Ontario Society of Artists’ show in 1916. Born in Durham in England, of Canadian parents, in 1873, he had come to Canada as a small child. All his training and experience were in this country.

At another desk sat Arthur Lismer, tall and lean and whimsical, lately from Yorkshire, and in search of opportunity and spiritual adventure. He had put up a fine effort in his early youth for an education in the arts and worked his way through the Sheffield School of Art and the Academie Royale des Beaux Arts in Brussels. He developed a passionate desire to bring the study of the arts within easy reach of all children. Even when Thomson first knew him Lismer had an excellent philosophy of art—he believed it to be less a profession than a way of life. The appreciation of art is not an esthetic privilege but a means of deepening and enriching the personality. The creation of any form of art sharpened the perceptions, expanded and stimulated the powers of every boy and girl, man and woman. Years after Thomson’s death, Lismer had an opportunity to put his philosophy to work in art education for children and became internationally distinguished for it.

Another of Thomson’s associates was Tom MacLean, who was one of the first to travel the north country seeking sketching material. He had been over the Lake Temiskaming and the Abitibi country. It was MacLean who roused Thomson’s latent interest in the farther north. Thomson knew the Georgian Bay country, but Algonquin, Temagami and the Mettagama country were unknown to him. At MacLean’s suggestion Thomson and H. B. Jackson, still another fellow-worker, tried Canoe Lake for an early summer holiday in 1912. Later on in the same year Thomson and Broadhead went into the Missiassagua country at MacLean’s urging.

With the Grip crowd Thomson found congenial company. There was many a jest to enliven the time for none of them paraded their ambitions or their underlying necessities. They were tradesmen with a fine feeling, a well-directed energy that not only made for good commercial work but which drove them all to making experiments with their own creative work as artists. From the time Thomson began to sketch with his new friends on their Saturday afternoons and holidays, life had quite a new and energizing interest for him. In the evenings he went back to his room at 66 Wellesley Street and sat at his window with his sketch box, painting a corner store, over and over again, struggling with composition and technique. In this room, too, he began to experiment on canvas after his sketching trips in 1912. Frank Carmichael recalls going there one day and finding Thomson at work.

“The room was thick with smoke and there was Tom with this huge canvas. It was a northern scene, a distant line of shore and a vast expanse of grey and soggy sky.”

The sketching crowd searched for nearby sketching fields and found them at Weston, Lambton Mills and York Mills. One of Thomson’s first experiences in sketching from nature was by Scarlett’s Road near Lambton Golf Club. A friend sketching nearby had a fairly successful time and when Thomson strolled over to see what he had done, he was so disgusted with his own effort that he walked up and down the road a while, thinking intently, and then suddenly pitched his panel whirling into the bush.

As the group made progress with their sketching they roamed farther afield. They spent many happy weekends at Lake Scugog, unconsciously developing a group spirit and an attitude towards a solution of their common problems. Tom Thomson, his friends recall, seemed more “alive” and at ease there than they had ever seen him in town. Shyness and reserve fell from him and he was into all the fun, and his wholehearted and often silent laughter was proof to his friends of the unfolding of his personality. Thomson, with his mandolin, was one of the best loved figures in that adventuring little company.

The year 1912 was a highly significant one in the life of Tom Thomson. Either in the late autumn of 1911 or in the early spring of the new year, Thomson acquired his first real sketch box and began to take painting seriously. But he had not arrived at the point where he could conceive of art as total career. All that winter the group discussed the North as a future hunting ground. Thomson was once more restless and impatient and the lure of adventure was strong upon him. With H. B. Jackson he planned his first trip. His friends gave him a pack sack and a Dutch oven and in May sent him off, full of anticipation.

Thomson and his companion dropped off the train at Canoe Lake station and made the crossing of this lake that ever afterward was to be associated with his name. They did not camp on Canoe Lake but crossed it and paddled into Smoke Lake and then made their way on to Tea Lake Dam, where they camped. It was fine country, traced with old lumber trails through the woods, with countless lakes and streams, rapids and waterfalls. From camp there stretched on the one hand Smoke and Ragged Lakes, and on the other the picturesque length of Oxtongue River, and the vast chain of waterways and portages that lead all over the north country.

Algonquin Park appealed to Thomson from the first. He did little sketching, merely making notes and casual studies, for the passion for paint was not yet on him. It was the first time in years that he had been back to the wilderness and he was excited about fishing. The holiday was all relaxation and delight. Thomson displayed his old skill as a woodsman as he yielded to the lure of spring in the North.

The holiday over, Thomson returned to his desk only to be haunted by dreams of Algonquin. Jackson once recounted his amazing cunning out-of-doors. Twenty years ago jaunts of this kind were rare and considered very venturesome, for the north had not yet been turned into a vast complex of playgrounds for thousands of city dwellers. The trappers and lumberjacks were still lords of the wilderness.

The group at Grip’s felt the trip had been quite an adventure. Thomson was afire with longing to get back to the old Indian travelways and his friends were infected with the wanderlust. One of them, Bill Broadhead, decided to join Thomson on a much longer and more arduous trip that would take them much farther north than Algonquin. The district was New Ontario and their jumping off place was Biscotasing on the Canadian Pacific line. They stocked up with provision at the Hudson’s Bay Company’s store, the time-honored bacon, beans, rice, tea and so on. With tent, blankets, and sketching materials, they had about two hundred pounds of dunnage apiece.

The last week in July they set out in a light Peterborough canoe and paddled the length of Lake Bisco, on into Lake Ramsay and up Spanish River, camping in the sunsets, sketching whenever they found something to intrigue them. Wild life was abundant and the streams abounded with fish. Finally, by leisurely travel, they reached the height of land that divides the flow of waters that reach the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River, from those that flow into the Arctic. On Green Lake they ran into the sterner side of the voyageur life in a torrential storm. Their canoe was swamped and capsized but both men were strong swimmers and were able to save their dunnage. For a while, weather conditions made travel difficult, all the streams being so swollen that landmarks were submerged or distorted. At one portage they discovered a washout and a tent buried under it. Fearful for the life of some fire ranger they stopped to dig but found no one. Finally they reached Mississagua Forest Reserve and found themselves once more on waters flowing south.

On Audinadong River, a branch of the Mississagua, they spent several days, spell-bound with the massive beauty of Aubrey Falls and the gorge through which its waters flow, with its rocky walls higher than those of Niagara River. In spite of bad weather, they sketched a great deal. It was a country of impressive qualities, a virgin world steeped in the spirit of the true North, that lofty, inspirational ideation that is so difficult to convey. Yet it was to this task that Tom Thomson, unskilled and inarticulate, was from this time forward entirely dedicated. In this country they had another accident. When they came to the celebrated rapids called the “forty miles of white water”, they found its turbulence accelerated by long rains. In spite of the raging fury of the river, the two men set their course through the long series of rapids quite nonchalantly. Nearing the end of this swift and dangerous passage, they ran into trouble and capsized. This time they reached shore with difficulty and though they retrieved most of their dunnage, they lost a great many sketches and those they saved were damaged.

At last they reached Squaw Chutes and found Mark Ripley, a quaint, philosophical character, living in peace and solitude with animals he had won as pets and companions. The two men had reached the end of their expedition. They were carried out by road to Bruce Mines and boarded a ship for Midland.

It was now the last week in September and they had been two months vagabonding in the wilderness. Their arrival in Toronto was awaited with a curious expectancy by Thomson’s friends.

The adventurers reached town, lean, brown and exhilarated. Broadhead produced his sketches; they were clever and technically skilled. Thomson, in turn, brought out his work, a series of little panels, dark and tight and immature. However, to their friends there was no doubt about which of the two men had brought home the authentic spirit of the North. Broadhead had facility; Thomson had feeling. Thomson’s work was scrutinized, analyzed and thoroughly discussed, and added fuel to the fires of aspiration and unrest among his friends.

Although Thomson was not concerned with the background of art yet he was inevitably influenced by the circumstances it produced. The creative world in Canada, small and circumscribed as it was twenty-odd years ago, was in the throes of a first class conflict when Thomson painted. It was the old quarrel between the academic, the established, and the pioneer and adventurer. It was a wholesome state of affairs, for it indicated that the newcomers had struck fire. The fire had smouldered in Canada since the seventeenth century when Quebec stood for the fine flavor of the Renaissance and Montreal for the baroque. But never until now had the quarrel hinged on a difference in point of view on a native expression and technique. The first artist to use the native scene as subject matter was Krieghoff, a Bavarian, never a great artist but a sympathetic one, who loved the St. Lawrence country and its people. Contemporary with him was Paul Kane, son of an Irish wine merchant of York. From copying old masters in Europe he had turned to painting Indians in the west. In the eighteen-forties he crossed the prairies and made his way through the Rockies to the coast. Kane was not a great artist either, but in him and in Krieghoff something stirred and responded to the spirit of the wild, new land.

Both these men were still living when the Ontario Society of Artists was formed in 1872. This was a significant event and for nearly a century the Society has served its original purpose of bringing Canadian artists together and introducing new painters to the public.

However, early conflict, when it arose, was between exponents of English or French schools of thought, for Canada was painted either with an English or a French brush. Horatio Walker was another Troyon, Paul Peel another Bouguereau, Homer Watson another Constable and so on. Though they were known abroad, they had little effect on the direction of art at home. Meantime, however, two men were breaking trail, for Suzor Coté and Maurice Cullen, working in Montreal, had devoted themselves to snow, about which Canadians had a curious complex. Painting snow was as bad as rattling the bones of the family skeleton. Both men were determined to paint things as they saw them. They were followed by the first of the moderns, J. W. Morrice, who loved the austere Canadian winter, but his work was too adventurous for his day and he was driven into exile in Paris. Thomson’s friends had a keen admiration for his work. Such, very briefly, was the situation in Canada. There was a considerable body of painters, many of them competent, and many of them sincerely searching for a new note, but the frost was not out of the ground yet—the frost of tradition.

Vital forces were, however, slowly converging; the Canadian genius was stirring and events among Thomson’s friends were one phase only. Into the picture there now stepped another figure, Dr. James MacCallum. He was not an artist, but he was the first to demand from the artists the very note they were striving to sound. He was evidence of the need for an expression of an expansion of consciousness in a northern people. He had conceived the idea of finding an artist who could paint the North as he saw it. He discovered J. E. H. MacDonald and took him and his family to Georgian Bay in 1911.

It was in 1912 that a friend of Dr. MacCallum, Col. Mason, took two nephews on a canoe trip in the Mississagua country. Traversing the forty miles of white water, he made the boys walk a certain portage to investigate before running the rapids. At the end of the portage they found Thomson and Broadhead salvaging their sketches out of the river. On his return home, Col. Mason told the incident. The doctor knew the Mississagua country as a boy, so he decided to look up the artists. He learned the name of the street on which Thomson lived but not the number. One day he set out to find him, and rang the bells from door to door until he found the right place. Thomson was out but the doctor was shown into his room and found it strewn with sketches, which he proceeded to examine carefully. Thomson found him there and though pleased with his interest, he belittled his work and told the doctor to take home any of them he fancied.

After prolonged study of the sketches, Dr. MacCallum believed he had found the man to paint the North to suit him. He could do nothing to further Thomson’s technical ability, but he could do something the artists could not do, and that was to provide financial support.

“A tall, slim, clean-cut young man,” is how he speaks of Thomson as he was then, “quiet, reserved, chary of words. As I looked over his sketches, I realized their truthfulness, their feeling and sympathy with the grim, fascinating northland. Dark they were, muddy in color, tight and not wanting in technical defects, but they made me feel that the North had gripped Thomson, as it had gripped me ever since, as a boy of eleven, I first sailed through its silent places.”

He saw no more of Thomson that winter, but in March he was among those who greeted Thomson’s canvas at the O.S.A. show with sympathetic interest.

As the winter went by, Thomson’s friends had prepared for this annual O.S.A. show, while Albert Robson quietly prodded Thomson into attempting a canvas. He was reluctant, and had plenty of excuses—he did not know enough about canvases, he did not have a place to work, and so on. But Robson was relentless. Thomson could use the workshop on Sundays and paint there.

Finally, Thomson got to work and painted a canvas he called “Northern Lake.” Quiet and unadventurous as it seems now, it was outstandingly bold and vigorous for 1913, and it serves to mark the changes that have taken place in the attitude to interpretation of environment in Canada since then. (For many years it hung in Teacher’s College in Ottawa then it was removed to an office in Queen’s Park.)

Off the canvas went to the hanging committee and to Thomson’s surprise, it was accepted. At that time the Ontario government offered an annual prize of two hundred dollars for a picture of outstanding distinction at the O.S.A., the picture winning the prize becoming the property of the government. Sir Edmund Walker was one of the selection committee. On the night of the pre-view he rose to heights of enthusiasm over “Northern Lake” and walked about the room drawing attention to it. Romantic as it may seem, the prize went to Thomson’s canvas.

When news of the award reached Albert Robson, he went into the workshop and bent over Thomson at his desk.

“Tom, your picture has been bought”, he said.

Thomson did not stir, nor as much as look up from his work, but Robson saw the blood rising under his skin until the back of his neck was scarlet.

“What damn fool did that?” he asked gruffly.

The show was notable for other things, also. Lawren Harris exhibited four canvases, forerunners of a new mood. One was “The Corner Store”. Jackson had four, all from sketches done on his Italian tour. Lismer had “The Clearing”, one of the first in which he brought through the essence of the Canada he knew. MacDonald had six Georgian Bay studies.

If there was a change in the quality of painting in the opening years of the decade, there were also greatly increased numbers of exhibitors and entries. Also, there was change of subject matter. Fergus Kyle, writing in “The Year Book of 1913”, remarked with surprise that “of the ninety-one paintings exhibited, at least ten were subjects distinctly of this country.”

Thomson was a product of this age of gestation. He would never have become an artist if the times had not been ready for him. There was a quickening, of which his experience was a part. The writers of the day all record the new pulsations in the creative life of Canada as so many men and women became increasingly aware of the subjective and real qualities of their own times and own environment.

Meantime, during these significant years, two other young Canadians, unknown to each other and to the Grip crowd, were making their way to the same objective. Lawren Harris was a young man who did not allow his financial independence to stand in the way of his striving for creative achievement. The other man was A. Y. Jackson, who was making his way on savings accumulated by exacting labor at uncongenial tasks.

Both these men had been studying in Europe and both reached home in 1909. They returned with a common hope of finding, somewhere in Canada, the material out of which to create a native expression in painting.

Behind Lawren Harris was Ontario pioneer tradition. He had an untrammelled intellectual zest that promoted experimental thought. He was, even then, interested in the study of occult literature and believed much was possible in the conscious spiritual and esthetic development of man. He was stimulated by A. E. Russell’s work and the Irish Renaissance movement. He was in search of other young Canadians on the same trails.

A. Y. Jackson was a Montrealer. As a boy he hiked about the Quebec countryside and he is still a devotee at the altar of that real Quebec for which he has to search now in more and more remote spots, as the age of standardization creeps over the Laurentian hills. There is little of the north shore from Quebec to the Saguenay that he has not known intimately and on foot. He began work as an office boy in a lithographing plant but when he was discovered putting all his spare time on drawing, he was shifted into the art department. At his next job he worked three days a week and kept the rest of his time for painting. One summer he got to Europe on a cattleboat from Montreal. There was no lack of direction in Jackson. He came home knowing what he wanted and he worked like a galley slave to get it. When he had saved enough, he went across again and at twenty-five he registered at the Julien Academy, an art student for the first time in his life. On his return in 1909, he was determined to make painting his profession.

That winter he went sketching in the Eastern Townships and one of the results was “The Edge of the Maple Wood.” This hung at the O.S.A. in 1911, attracting the attention of the younger group, particularly of Lawren Harris and J. E. H. MacDonald. Who A .Y. Jackson might be, nobody knew.

Jackson was forced back into commercial work so he took two jobs, one a day job, the other evenings, and so saved another thousand dollars and went back to Europe.

On his return from this trip, Jackson and Randolph Hewton, another Montrealer, held an exhibition of their work which was greeted with an all-pervading silence. The critics did not even go to look at it. Bankrupt with the effort, the two men retreated to a small village near Farnham, Quebec, where living was cheap and the sketching was good. Jackson’s faith and hope were strained to the breaking point.

When they left Montreal, the spring show of the Montreal Art Association was on and a visit to it had filled them with dismay. There was no vitality there, nor any modern feeling. But while the young artists slogged away in the country the critics expressed themselves as seriously disturbed over the daring modernism that had invaded the spring show.

During that season of retreat Harris got into touch with Jackson to ask if “The Edge of the Maple Wood” was still for sale. It was, since no one had ever tempted the artist to part with any of his Canadian canvases. Harris bought it, but the appreciation and enthusiasm of the buyer were worth more to Jackson than the cheque, badly as he needed the money.

“The Edge of the Maple Wood” is still a noteworthy painting in addition to being an historical piece, a very fine expression of a typically Canadian subject and mood. If it had not hung at the O.S.A.,—if Harris and MacDonald had missed the show—if Harris had not bought it and so made it possible for Jackson to go to Toronto and Georgian Bay that fateful year, what would have been the difference in the story of Tom Thomson and of Canadian painting? The movement needed Jackson’s energy and inspirational qualities. He was to supply a certain pugnacity and a fine old cavalier propensity for laying about him with brush and pen as if each was a good, bright blade.

That summer Jackson went to Toronto, where he met MacDonald and Lismer, but missed Harris. The latter followed him to Kitchener, however, and urged him to throw in his lot with the Toronto crowd. Jackson went north to think over the idea. The group, almost unconsciously motivated, was drawing together.

One spring day in 1913, Mark Robinson, a ranger in Algonquin Park, paddled down Potter’s Creek to Canoe Lake. He saw a stranger sitting among the alders, sketching. Robinson speculated—sketching was a new dodge. The Park authorities were contending with beaver poachers who used many ingenious methods, but none of them had ever thought of posing as an artist. He approached the newcomer, glanced at his sketch and greeted him.

Thomson liked the look of the ranger. He was sketching an old tree stump around which the marsh grass grew tall and rank. They discussed the character of tree stumps and Thomson told Robinson they were the hardest things in the world to paint. Then he asked suddenly:

“Do you suppose I could get any guiding to do?”

“You might,” said Robinson, cautiously, “but I don’t know anything about you. Park guides have to be licensed by the government.”

Thomson proceeded to explain his business in the Park.

“Well, if you get a chance to take a party out, come over to the shack and I’ll talk it over with you,” he replied.