* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: A Diary Kept While with the Peary Expedition of 1896

Date of first publication: 1897

Author: Benjamin Hoppin (1851-1923)

Date first posted: Nov. 23, 2021

Date last updated: Nov. 23, 2021

Faded Page eBook #20211142

This eBook was produced by: Mardi Desjardins, John Routh & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

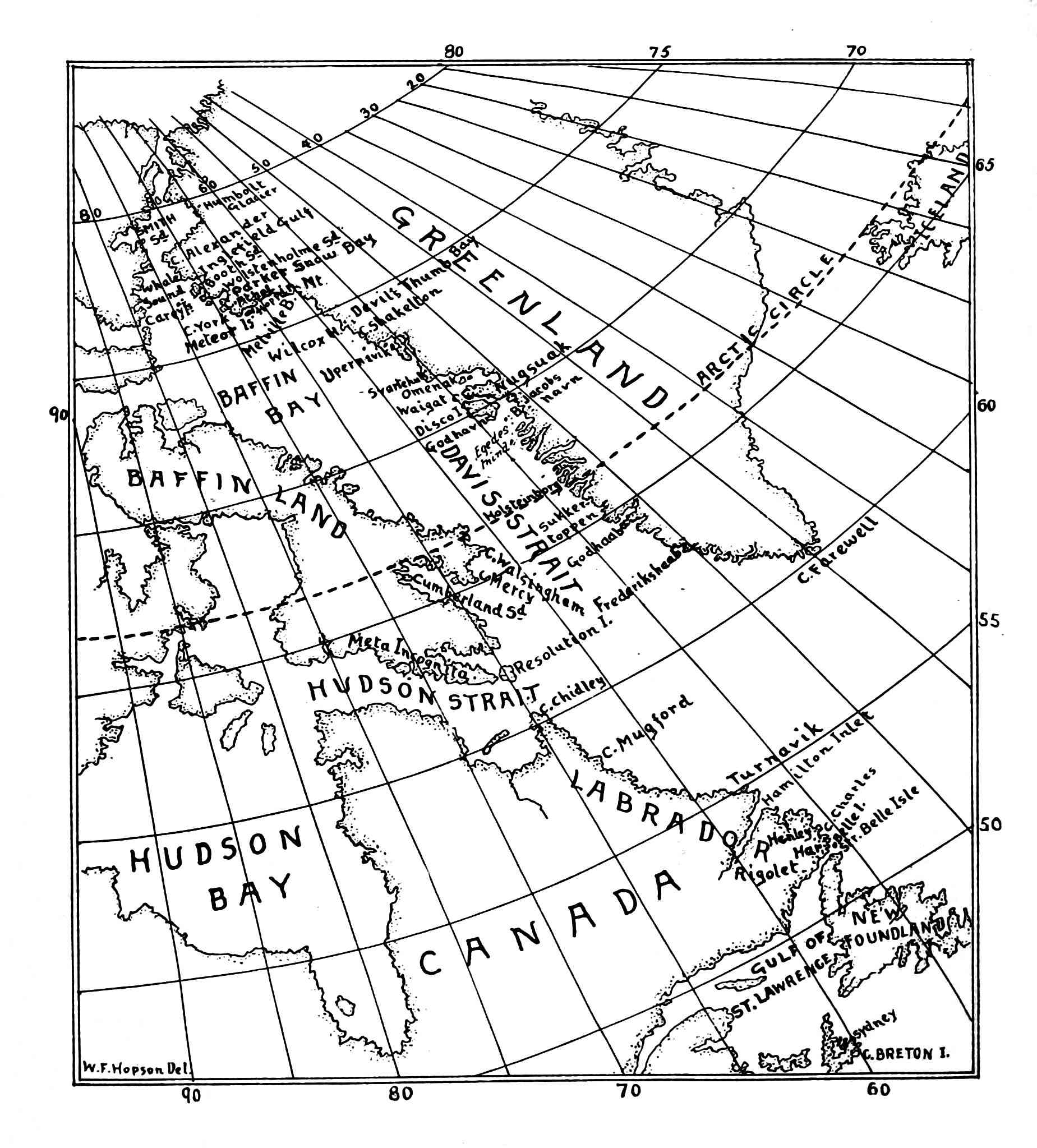

The Peary Arctic Expedition of 1896 had been arranged for, and the place and date of sailing had been fixed upon (Sydney, Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia), perhaps as early as the evening of Sunday, July 12th. Some of the party had come to Sydney by Thursday, July 9th, and our immediate party had come from Baddeck, Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, on the night of July 10th. Some of the baggage of this party had come to Sydney nearly a week before, on July 6th and 7th. Those of the party who came previously were Mr. Russell W. Porter, Jr., Mr. Putnam of Washington, D. C., of the U. S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, who had been detailed by the U. S. government to make pendulum observations; and Mr. Hugh Lee of Meriden, Conn., who had been with Lieut. Peary on a former trip.

The weather had been warm and the foliage of the country around Sydney was fully out, strawberries were in bearing, and the evergreens were dark. On Sunday the 12th July we went and found a spring in a meadow said to have curative powers.

The baggage of the party from Cornell University was in Sydney, stored in a building on Harrington’s wharf, and the party itself came soon afterwards. Professor Tarr was in charge, Professor Gill, assistant, and students Mr. Watson, Mr. Kindle, Mr. Martin and Mr. Bonesteel.

The School of Technology of Boston was represented by Professor Alfred Burton, Prof. George Barton and Mr. Russell W. Porter; besides these were Mr. Phillips, of Harvard University, and Mr. Dodge of New Hampshire.

The chief officers of the Expedition were Lieut. R. E. Peary, U. S. N. commanding, and Captain John Bartlett, of Brigus, Newfoundland, in command of the steamer Hope. Mr. Operti, an artist of New York, also accompanied the Expedition, and Mr. M. A. Hansen, of the American Museum of Natural History, Central Park, New York, a colored gentleman of African connections who had been to the Arctic Regions twice before with Lieut. Peary, and Mr. Hugh J. Lee, of Meriden, Ct., who had been with Lieut. Peary before. From Baddeck, Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, came Mr. Alexander H. Sutherland; Mr. George Hollifield, of Halifax; and Mr. Benjamin Hoppin, of New Haven, Conn.

The Expedition had interest taken in it by the American Museum of Natural History, New York, Central Park, 77th St. and 8th avenue, and was aided by Mr. Morris K. Jessup, President of the Museum.

The elections had just passed in Canada, the parties had met in an interesting manner.

The Sydney time could be found at Sydney. There was a heavy rain on one of the first days of the week, but fair weather had set in.

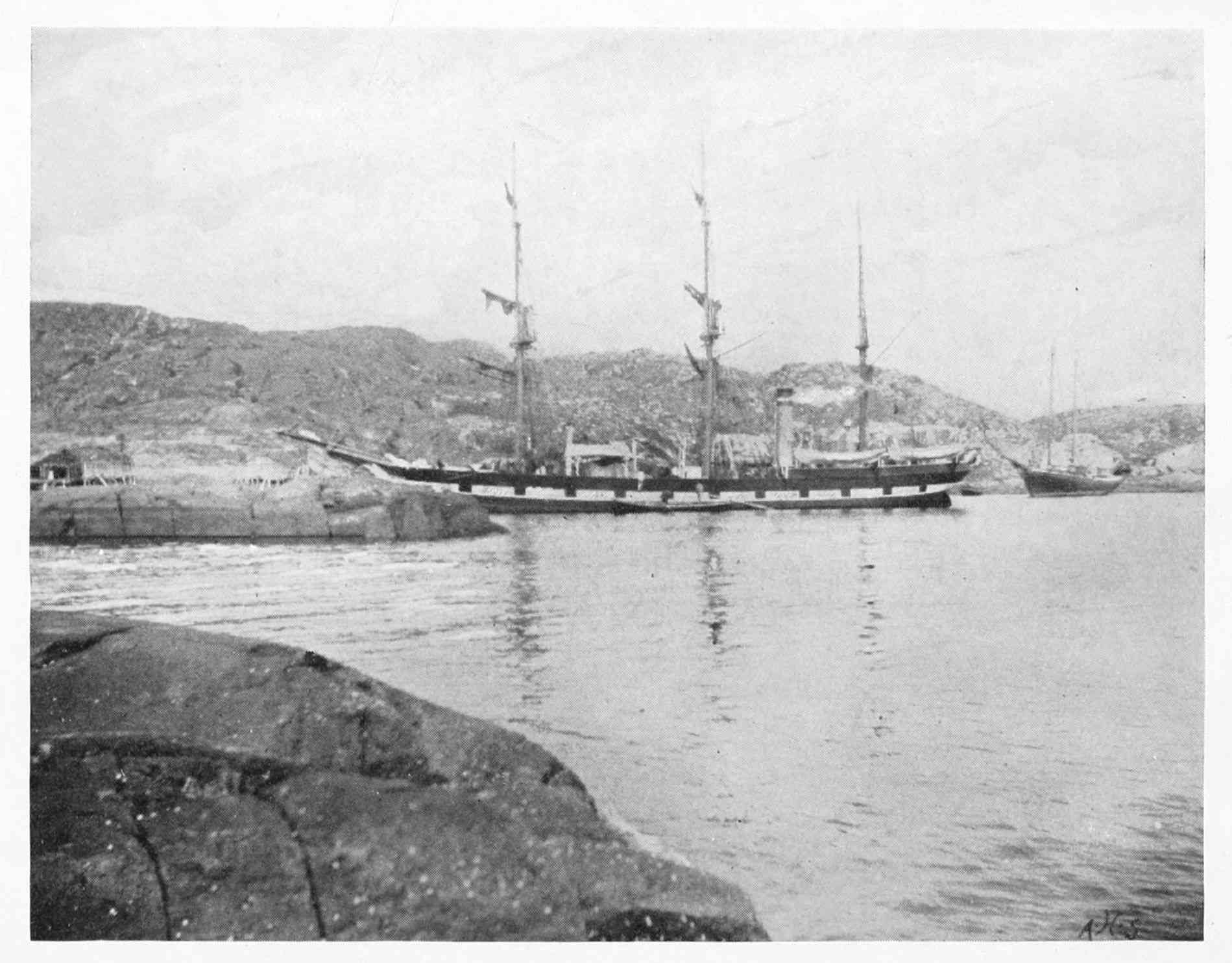

One object of the Expedition was the obtaining of a meteorite known since 1816. It is said also that this had been seen by Captain Parry some time before. The party was to have a steam vessel called the Hope, which had been at St. John’s, Newfoundland.

The names of the Captain and crew of the S. S. “Hope” were:

| John Bartlett | Brigus, | Newfoundland | Captain. |

| William Smith | Cupids, | ” | 1st officer. |

| John Pomeroy | Catalina, | ” | 2d officer. |

| James Bradbury | St. John’s, | ” | Chief Engineer. |

| Frederick Martin | ” | ” | Second Engineer. |

| Henry W. Perry | Brigus, | ” | Chief Steward. |

| Thomas Chalker | ” | ” | Seaman. |

| Frank Hall | St. John’s, | ” | ” |

| James Way | ” | ” | ” |

| Aubrey Hicks | Catalina, | ” | ” |

| John Walsh | St. John’s, | ” | ” |

| William Roust | ” | ” | Oiler. |

| Thomas Shepherd | ” | ” | Fireman. |

| George Pike | ” | ” | ” |

| William Bryan | Outer Cove, | ” | ” |

| Ananias King | St. John’s, | ” | Assistant Steward. |

| Caleb Ladrew | ” | ” | Carpenter. |

| William Godley | ” | ” | Cook. |

The names of the party were as follows:

Lieut. R. E. Peary, Washington, D. C., Commanding.

Albert Operti, New York City, Artist.

J. D. Figgins, Falls Church, Va., Taxidermist.

Hugh J. Lee, Meriden, Conn., Interpreter.

Matthew A. Hansen, American Museum of Natural History, New York City, assisting.

Alexander Hugh Sutherland, Baddeck, Cape Breton Island, Photography.

George Hollifield, of Halifax, Nova Scotia, and Baddeck, Cape Breton, Photography.

Benjamin Hoppin, New Haven, Conn., Mineralogy.

Party from Cornell University going to near Devil’s Thumb Bay, North Greenland:

R. S. Tarr, Professor of Dynamic Geology and Physical Geography, Commanding, Ithaca, N. Y.

A. C. Gill, Professor of Mineralogy and Petrography, Assistant in Command, Ithaca, N. Y.

T. L. Watson, student (Geology), Ithaca, N. Y.

E. M. Kindle, ” (Palaeontology), Franklin, Indiana.

J. A. Bonesteel, ” (Geology), Franklinville, N. Y.

J. O. Martin, ” (Entomology), Ithaca, N. Y.

Party from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology going to Omenak, near the Noursoak Peninsula, North Greenland:

Alfred E. Burton, Professor Mass. Institute of Technology, Boston, Mass.

George H. Barton, Professor Agriculture Mass. Institute of Technology, Boston, Mass.

Russell W. Porter, student Architecture, Mass. Institute of Technology, Springfield, Vt.

Besides these:

G. R. Putnam, U. S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, Washington, D. C.

John E. Phillips, student in Harvard College (Geology), North Beverly, Mass.

Arthur M. Dodge, Hampton Falls, N. H.

A party was to be landed at Hudson Strait for prospecting for mica—by White Strait, S. W. coast of country near Cockburn Land, or Baffin Land—consisting of:

| George Bartlett | Brigus, | Newfoundland | Commander. |

| Samuel Breaker | Brigus, | ” | Cook. |

| Patrick White | Brigus, | ” | Assistant. |

| Michael Leary | Turk’s Gut, | ” | |

| Aaron Reed | Salmon Cove, | ” | |

| Mr. Taylor | St. John’s, | ” | |

| John Eddie | St. John’s, | ” | |

| A. Penny | Bull Cove, | ” |

Samuel Breaker afterwards came on to the North with the Cornell party.

Mr. George Bartlett’s party was fitted out by his father (Captain Bartlett of S. S. Hope), to find mica which was reported at Hudson Strait. He expected to take Esquimaux to show him the places where it lies, but there were none there, and mica could not be found in such a great country without guides, so the search was given up. It was a great disappointment as well as loss. Mr. Bartlett went instead to Atanikerdluk, near the Waigat Strait, Disco Island, to gather fossils, where he found and brought home some tons of them.[1]

| July 15th, Wednesday | Went on board S. S. Hope. The ship set sail under favorable auspices, with cheers and good wishes from many gathered on the wharf. |

| July 16th, Thursday | Passed Cape Ray Light. |

| July 17th, Friday | Fine day—got along the Newfoundland coast to a little south of Cow Head or Port au Choix—comparing chronometers—one gentleman, Mr. Operti, got up to see the sun rise—it was quite cold in the morning—we are about 20 miles west of Newfoundland coast, near the Bay of Islands. |

| July 18th, Saturday | A pleasant day in the morning. Passed Amour Light—saw the pasturage with the Lighthouse, near where was the wreck of the “Lily”—about noon eight small icebergs in sight, on the starboard side toward the bow. Passed Belle Isle—patches of snow on the mountains of Labrador. Wind from the southwest. Ship quite steady. All at dinner. Talked of vitascope, kinetoscope, and photography. It would be interesting to observe solidity of ice at the bottom of glaciers. |

| July 19th, Sunday | Off Labrador—we were two hours in the ice. Bright day—some parts of the Labrador coast visible, rather dark colored rocks, spotted I should think, with lighter colored rocks—at 7.30. Passed through ice from about 9½ o’clock to 11 or so—came not far from Hamilton Inlet at 11 o’clock; we were about fifteen miles from the coast.[2] |

| July 20th, Monday | Arrived at Turnavik about 9½ o’clock—a small fishing station—Mr. William Bartlett. The mail steamer sometimes stops here, giving an opportunity to send letters. We forwarded some. Left here about 12 o’clock. |

| July 21st, Tuesday | Along the coast of Labrador—Cape Mugford—going through a good deal of ice. |

| July 22d, Wednesday | Labrador coast—at noon, N. Latitude 59° 22″. |

| July 23d, Thursday | In the morning near Cape Chidley. Saw bears early in the day, one female and two small cubs—Professor Tarr saw them first about daylight—several of our men fired shots—she got over a ridge of ice with her cubs. They licked the wounds of the mother and she slid into the water, but was secured and brought on board afterwards. The cubs were lassoed and drawn on to the ship. The cubs were carried on the ship all the way to the north and back to Sydney, C. B. They were then sent to the Zoölogical Garden at Washington, D. C., U. S. A. They had grown to be pretty good sized young bears. |

| July 24th, Friday | The steamer worked through the ice in Hudson Strait, which about this time was rather thick in some places, then reached open water. |

| July 25th, Saturday | At about 9 o’clock got to Big Island, or the largest of the Upper Savage Islands—Professor Burton, Messrs. Porter, Phillips, Putnam, Dodge, Watson and Bonesteel, went ashore for two days. A house on Big Island—one formerly used by persons surveying for a steamer line from England to Port Churchill. |

| Went to north shore of White Strait in the evening—some of us went on shore—saw ridges of hills—Mr. Operti and Mr. Hugh Lee made a cairn, an American man as it is called, on a hill—the hills mostly stony and rocky—some vegetation, lichens, mosses, and a few grasses and some flowers, the flowers in bloom.[3] | |

| Rocks on the shore. Small lakelets back, looking as if they were continuations of the sea. The sea was pleasant and mild, the sun was bright until about 9 o’clock several times. | |

| July 26th, Sunday | At White Strait—on shore in the morning and evening—all had rest. Passed a rock in the middle of White Strait with four fathoms of water on it at high water, 1 p.m. |

| July 27th, Monday | Came to the shore at Ashe Inlet, at Big Island—found the party we had left there safe. Some observations had been taken. It was foggy in the morning. Some rain falling. Thermometer not very high. Barometer about stationary. |

| Terra Nivea or Meta Incognita lies on the northern side of Hudson Strait. It was probably first visited by the Portuguese or possibly a fisherman, the Portuguese discoveries in this neighborhood dating perhaps about the time of the Cortoreal, after Columbus. Before this there had been interest in navigation and discovery. The Azores had been discovered and added to Portugal. The ideas or maps of a geographer called Pomponius Mela had been studied. The early fisheries of the French may have embraced the banks of Newfoundland. The steamer Arctic was lost near here. The entrance of Hudson Strait is about thirty miles or something more wide in the narrowest part. The shores of Resolution Island rising to the north of the Strait are rather bold—the other shores not quite so high. At Big Island where we came first there was not much ice. Near Big Island there were some eider ducks. The male of the eider duck, the king eider, has a black head and whitish body. The female seemed to be of a color approaching a brownish black. It is said that the male bird separates from the female bird after breeding time, and that the males go in coveys. | |

| The voyage of Henry Hudson in 1610, A.D., followed the Portuguese—the old name of Hudson Bay or Ungava Bay was the Baia de Mosotros. There seems to be a current of one or two knots an hour setting to the south off the coast of Labrador, and it is said that there is food for codfish there, and that the cod run in shoals in this current. In the southern part of Labrador the cod, the green ones, are sometimes in shoals almost mingled with black fish or rock fish. The cod come along in shore often. | |

| The temperature of Hudson Strait was, in July, about 30 degrees or so. The presence of ice might have added chilliness to the atmosphere. The bears spoken of above were about 8 miles or so off the shore, quite close to the ship, on a pan of ice. They are said to swim quite well. They have a kind of long silvery fur. The paws are large. The eyes of the one killed seemed to have almost a mild expression. | |

| The cakes of ice seen here are ten feet or so in thickness, while the anchor or shore ice seems now to be about 15 or 20 feet thick. In some places near the shore at “Hope Harbor,” there are floating pieces of ice. The shore ice is much honey-combed and not very tough. The long ridges of hills come down to the shore, running rather north and south in direction. There are some small islands off the coast. We lay in White Strait on Saturday, and the western side of the Strait was not free from fog all the way. Wind W. to W.S.E. The whistle was blown on Sunday as a signal to come on board early. | |

| The party came out about noon, having endeavored to get an observation of the sun. We saw the house left by the party that surveyed for the proposed line of steamers to Port Churchill. The house is on the east side of the inlet, Ashe Inlet. Ashe Inlet is on the south side of Big Island, near its east point. The party we left had had a storm and their boat, a whale boat, had one rope with which it was fastened, loosened and been thrown against the rocks, some planks being broken. Professor Burton had incurred some danger in saving the boat. They had seen a deer, reindeer?, with a fawn, with gold color. Walrus and deer bones were found, also an Esquimau skeleton. They left a mark at the position of observing, and writing on the walls of the house. The ceiling had been taken away by the first occupants—they passed some time in exploration and saw some eider ducks. Ashe Inlet seemed to be a good place for a steamship to go into and come out of. There was almost no snow near the shore, but stretches of it on the hills, while on the north shore of White Sound there was an ice-foot nearly all the way, and anchor ice, a good deal of anchor ice—on Sunday evening a cake about 75 feet long came down on the ship, and the ship moving her engine we escaped. There was another smaller piece of ice also there, and more pieces near the shore of the strait about ten feet high out of the water, some moving on, and some aground. Also pans of ice more stationary. | |

| Left Big Island in the morning or near noon. In the evening we stopped at Noodla, where were six families of Esquimaux counting 33 people. | |

| July 28th, Tuesday | At noon we were off the south part of Meta Incognita or off Resolution Island. |

| July 29th, Wednesday | Off the eastern shore of Resolution Island, I think, not far from Cape Warwick. A bold cliff or bluff about 200 feet high was seen, reddish in color. |

| July 30th, Thursday | In the afternoon sighted probably Lady Franklin Island, apparently opposite the land, about two miles long, with heavy ice bluffs in front and not very far from it. Had snow off the mouth of Cumberland Gulf. |

| July 31st, Friday | In the morning about 6 o’clock, saw Cape Mercy, the southern point of Cumberland Peninsula and the northern limit of Cumberland Sound—we passed along the side of the ice pack; but could not get in, the ice making a large ice floe, with bergs about fifty feet long. On the east of Cape Mercy we passed through some ice about twenty feet thick, blue on the bottom. Heavy ice all the way. |

| August 1st, Saturday | On this day about 7 o’clock in the evening crossed the Arctic Circle. Father Neptune came on board, a man dressed with a hump on his back with a dipper of some soft substance. The land, Baffin Land, was not very far distant on the left. It was foggy, but it did not interfere with our progress, the fog toward the southwest being the heaviest. The vessel was steaming along at a pretty good rate, perhaps 8 knots or so—last night or the night before, it lay to for the first time—no ice or icebergs to-day. The clouds covered over almost everything in the distance. There were some grampuses in sight, and about this time or before a walrus was said to have been seen. The weather not very cold, thermometer about 38 degrees in the afternoon—the evening before it was about 32 or 34 degrees. It was 39° near the Arctic Circle. Some ice in the morning. Tried an observation with artificial horizon. 10 o’clock evening—temperature of air 39°, water 33°. |

| August 2d, Sunday | At noon near the district of Egedesminde. Ice. In the afternoon about 5 o’clock came to Godhavn, on Disco Island, the capital of North Greenland. An Inspector resides here. The Inspector is Herr Andersen. |

| Before the ship reached the harbor Governor Almquist, an assistant of Inspector Andersen, came on board. At Godhavn many of our party were introduced to Inspector Andersen, his wife, and others of the family—Fired a salute.[4] | |

| August 3d, Monday | In the morning Prof. Tarr, Prof. Gill, with students of Cornell University and others, went about three miles on the Island of Disco—zeolytes to be found. Prof. Burton, and others, also went on shore at one time. Capt. Bartlett was here before and made a cairn of stones still to be seen above the village. There were then rolling stones which came near, but were stopped or avoided. Some of the cliffs opposite Godhavn were called the twelve apostles—one pinnacle only is now left. A ship or steamer, the Castor, was looked for from Denmark. Another boat came later. Temperature of the water near the entrance of the Waigat Strait or Channel, between the island of Disco and the mainland, 8½ o’clock in the evening, about 42 degrees. Left Disco at about three in the afternoon. There was fog in the morning, which detained us. Our course was to the south of Godhavn. There were many icebergs in the sea near to the entrance of Waigat Sound. Seventy were counted in the evening. I counted forty near Waigat Strait. |

| August 4th, Tuesday | Stopped for a time at Sarkak and went on. This morning we saw a beautiful line of coast, reddish clay with the water reddish in the distance near the Waigat, about a mile or so south of Atanikerdluk. There were icebergs in the channel. There is quite a high mountain to the S.E. of Atanikerdluk, while a little peninsula stretches out in the Waigat, making a small harbor. The isthmus is about an eighth of a mile across. We left Mr. George Bartlett and his party there, arriving at Atanikerdluk about 8 o’clock in the morning. Two tents were left with him, and about twelve Esquimaux came there and helped him somewhat in gathering fossils. I walked to the south of the peninsula and found small fossils. At a height the soil became friable with fresh pieces of coal. The whistle of the steamer called all aboard. Temperature of the water near the entrance of the Waigat strait or channel between the island of Disco and the mainland at 8½ o’clock in the evening, 42°. |

| August 5th, Wednesday | Waigat Strait has high shores on both sides. On the right going north are places named on the chart, Ate, etc. The left of the Waigat (going north) has mountains with snow on the tops of them. It is said there are seals in this channel. The ice glistened in the sun as we approached the north, and a kind of bright, white light rested on the tops of the mountains. Then at 5 p.m. we reached Omenak or Umanak Bay, Jacob’s Bay, or North East Bay. When we passed Niakornat about seven kayaks came near the ship and the ship slowed. One kayaker was taken on board as pilot. As we came to the eastern side of the peninsula of Niakornat people appeared on the cliffs. Governor Hendricksen, of Niakornat, came in a boat and made a visit to the ship, and courtesies were exchanged. Articles of interest were bought, of antiquity or curiosity. Fish, birds and a haunch of venison also.[5] |

| August 6th, Thursday | At Omenak is a settlement of that name where we left Prof. Burton and Mr. Porter, the party from the School of Technology, Boston, also Messrs. Putnam, Phillips and Dodge, engaged a house. The assistant Governor of Umanak and the Captain of the Brig Constantia of Copenhagen, which was lying here, came on board. Weighed anchor 9.45 a.m., taking Brig Constantia in tow, and parted with her at 10.30. At Omenak an iceberg came near the stern of our ship, and the boats on the side were taken out of its way. When we first came to Omenak we made fast to an iceberg, but afterward went inside the harbor as the ice was dangerous. Extensive glaciers here. |

| August 7th, Friday | At Upernavik—passing close to an island with a beacon on it—Governor Herr Knudsen and the Assistant Governor, Herr Ohlsen, came on board the Hope and were most cordial and kind, and afterwards we went ashore and breakfasted with them. Upernavik is the most northern settlement of the Danish Government, and is the farthest north of any inhabited part of the civilized world. Prof. Tarr engaged two Danes or Danish half-breeds, and two Esquimaux for his station at Devil’s Thumb Bay. We left Upernavik about 1 o’clock and went north along the high and rocky coast, passing through much heavy ice and icebergs forty or fifty feet square and high, with pans or pieces of icebergs and drift ice all around us. We found a harbor with thirteen fathoms of water at the entrance, and we could look down the shore for half a mile from the entrance. The Cornell party were landed on the further, east, side near Sugar Loaf Bay on a rocky beach, with small bay, with a lake of water behind it—it is three or four miles from Wilcox Head—there were large pieces of ice at the side of the harbor, sometimes covered with mud or dust, and slight traces of vegetation I believe, also a glacier near. The party landed were Prof. Tarr, Prof. Gill, Mr. Watson, Mr. Martin, Mr. Bonesteel and Mr. Kindle. It has been proposed to call the harbor Hope Harbor—we left about 4 o’clock in the morning. When about sixty miles from Wilcox Head we shot a polar bear—it was seen swimming in the water—the bear secured. |

| It was a male and the dimensions were: | ||

| Nose to end of body, 6 feet 11 inches. | ||

| Tail, 6 inches. | ||

| Girth of the neck, 2 feet 8 inches. | ||

| Girth of ankle, 1 foot 5½ inches. | ||

| Height of fore shoulder, 3 feet 8 inches. | ||

| Girth of leg above elbow, 2 feet 1½ inches. | ||

| Waist, 4 feet 9 inches. | ||

| Girth of flank, 5 feet 6 inches. | ||

| Breadth of fore foot, 8½ inches. | ||

| Breadth of hind foot, 7⅜ inches. | ||

| Nose to center of hip joint, 5 feet 11 inches. | ||

| Weight of one fore quarter, 58 pounds. | ||

| Weight of other fore quarter, 50 pounds. | ||

| Weight of one hind quarter, 64 pounds. | ||

| Weight of skin, perhaps 100 pounds. | ||

| Total weight, perhaps 800 pounds. | ||

| The skin was taken off for mounting. | ||

| At Melville Bay—Much ice—stuck fast but backed out. | |

| August 8th, Saturday | Saw the cliff of Cape York rising before us. The second fastest trip made across Melville Bay—the fastest was made by Lieut. Peary in a previous year, but in 1891 he was three weeks in crossing the bay. Went up the mountain where we found birds in great numbers—much ice—one berg is half a mile long—made the ship fast to the main or floe ice and went ashore—high peaks rising from snow-capped mountains—glaciers and icebergs glistening in the sunshine—beautiful warm weather, have had the midnight sun for some time—Cape York appears to be quite high, of dark stone, sometimes covered with a kind of lichen like seaweed, tripe de roche perhaps, with white flowers and many birds hovering about in clouds, the little auks with heads large for the body. Two young auks shot. Many ducks flew about or skimmed on the water. Ice pack close to us—seals are found here, and a large animal, perhaps a seal, is seen—Esquimaux on the ship with clothes of bear and deer and seal skins. A large glacier extends to the eastward of the settlement of Cape York into the sea, a part near it being apparently broken off, then a tongue, then apparently another broken portion. |

| August 9th, Sunday | Cape York. In the morning temperature 70° in the sun; in the evening, air 32°. Temperature of the water, 28¼°. At 12.30 this morning midnight sun made the brightness of day—beautiful weather—scenery very fine—immense glaciers, snow-capped mountains, icebergs, land cliffs, colored rocks, all combined—there was a partial eclipse of the sun at midnight—on the lower half one-fifth obscured—went partly up the hillside—saw about ten or twelve Esquimaux and seven tents and about twenty dog’s, one puppy having a collar of fur on his neck. In Melville Bay the icebergs are high, one being like a castle with two turrets. |

| August 10th, Monday | Left Cape York at midnight, but really in broad daylight, reached Conical Rock about 5 a.m. We shot 80 ducks and gulls at Parker Snow cliffs from a boat; icebergs in sight. Great numbers of birds, baccalieu, auks, guillemots away up the cliffs, which are of white quartz with reddish color on the outside, perhaps like hematite rocks—these cliffs are perhaps 700 feet high; anchored in eleven fathoms in a little bay, one glacier coming in from the east, and another running out into the sea on the south—the cliffs have ledges or benches, and they are called loomeries, from the immense multitude of birds which cover them—the baccalieu birds or turrs are not very large, black and white with black webbed feet. The cliffs are weathered by the sea, dark towards the bottom, descending directly into the water. They seem to be entirely of gneiss with one vein of dark stone near the water, above four feet broad, with half crystalline front almost like coal. Our second officer, who steered our boat, gave me three eggs, gull eggs, the ice gull, perhaps the kittywake gull—as many as 200 birds in all were taken. This gentleman says that he has been let down seventy fathoms—he went up about 150 feet on the rocks; the rope is liable to untwist, the man spinning around like a top—one man was killed in this way. A barrel of eggs was to be obtained and he offered to get them—it was near Turnavik in Labrador; he had a fish line to guide him, but he fell into a ledge fifty feet below—he was drawn up but did not recover from the accident. |

| Conical Rock is dark red—red and black rocks mixed, hill about 700 feet high. Stopped at Parker Snow Bay. Two glaciers nearly to the water’s edge—there are five tupiks at Parker Snow Bay. The hills on the north have small lines of quartz, about 3 inches through, dip about 45° to the north, but the top layer of red rock about 30° dip to the northward. To the west the dip of the rocks is 45°. Beyond is a seam of rock-like slate 40 feet broad, and running up 100 feet. At one point the black rock is veined with white. The valley is about a mile broad. Petowik glacier can be seen outside of Parker Snow Bay—it is several miles broad, a grand sight. | |

| Dalrymple Rock, quite high, steep with sharp points, Cape Athol and Omenak follow in rapid succession—the shore off Booth Bay is low, with ice; some young eider ducks and eggs and nests were taken here—one nest had four eggs in it. | |

| August 11th, Tuesday | Near North Star Bay, at a bay north of Mount Dundas—Reddish cliffs around Mount Dundas—the tops of the cliffs formed a sort of wall—Wolstenholme Island or Saunders Island in front, Cape Athol near on other side—high cliffs all the way from Cape York. The ice was young, not very thick—it forms in spikes or pieces and the wind piles them together in heaps—no whaling ships had stopped there—must have gone west. We anchored at Omenak or Ominooe and some of us went ashore, with Esquimaux. The tide rises seven feet here. About a hundred yards away there are two places of settlement, a winter and a summer one, with skin tents or tupiks at the latter one; one was oblong; and lying about were rolls of skin, sledges, bird spear, pieces of meat. One sledge was 7½ feet long, 20 inches broad and 5½ inches high—the runners shod with pieces of ivory about four inches long, one inch wide and a quarter of an inch thick, bound on to the bottom of the runner with thongs countersunk in the runner. Walrus tusks were used for strengthening the side of a sledge, and one sledge had a runner composed of pieces of wood bound together, lengthened out with a piece of bone. A piece of one with iron was seen here, at the summer settlement, which was perhaps from the North Star, an English vessel which was lost near here. The iron was about 2½ inches round on top, with beveled corners. It appeared as if cut off with a sharp instrument. Near by were Esquimaux graves covered with stones. |

| The rocks seemed here to have no regular cleavage but were sometimes near the water broken into square lines of fracture. The igloos for winter were on the west—they are stone huts, but the tupiks for summer are skin tents. | |

| At this summer settlement are four Esquimau families, four tupiks, four sledges and a good many dogs. A party of us went ashore at the winter settlement of Omenak. It has seven igloos, made of stone, lying along the shore, one construction consisting of two or three igloos together. There are little dog houses made with covered tops. The owner of one of the houses had died. He was buried within the house. The kayak of the owner of the sledge and tent poles were left near the house, also in the house a stone lamp with blubber in it, and outside of the house a fine walrus head with pair of tusks, which was brought to the ship. A hat and coat which Lieut. Peary had given the owner of the house before. The owner of the house was a Nalegaksoak, the best hunter at Omenak. He had once come out in his kayak ten miles to meet a steamer on which Lieut. Peary was. | |

| August 12th, Wednesday | In the morning went across the Sound to Esquimau settlement of Kikertarsuak, perhaps Manson Island. From there went towards the mouth of the Sound. Saw two walruses diving—backs quite high out of water. Was in a boat away from the ship. Two walruses were on a pan of ice near an iceberg. Had a fine sight of the walruses within about fifty yards. Walruses dark slate or stone color, with black marks on heads. The boat rose and fell on the waves. One walrus rose as the boat came up and stood about five feet high. A shot was fired at the body of one; he leaned over a little to the left towards the water and then plunged into it with the other one; the shot seemed to have no effect if it struck him. The pan of ice was several feet high from the water and had been discolored by the walruses. An island which we passed, Agpat, Saunders Island, I think, is about 1000 feet high, perhaps, with rocks in layers red, white and red—the dip about 20 degrees to the eastward. It stands in bastions and layers—one of them green. One broad band of sandstone ran in about the middle of the cliff. Tried for walrus—walrus caught—harpooned by Esquimau—the kayak struck against the ice and the Esquimau was overturned, but he was rescued by other Esquimaux who were with him and then brought on board the ship by a boat. This Esquimau was seen some time ago nearly 20 miles from Cape York living in a cave with two dogs tied in front of it, with pieces of meat, seal or perhaps walrus. The ice turned after the walrus was struck—the piece of wood in front of the seat in the kayak on which the Esquimaux (in Whale Sound) rest their paddles was broken. It was mended with gut or skin line afterward—the walrus took the float attached to the harpoon under the water. |

| The measurements were: | ||

| Walrus—9 feet 7¾ inches long—(it was a male.) | ||

| Girth of belly, 8 feet 4 inches. | ||

| Length of front flipper, inside measurement, 1 foot 8¼ inches. | ||

| Girth of front flipper, 2 feet 1½ inches. | ||

| Length of back flipper, 2 feet 1 inch. | ||

| Girth of back flipper, 1 foot 10½ inches. | ||

| Breadth of front flipper, no need of spreading it, 11 inches. | ||

| Breadth of back flipper spread, 2 feet 3½? inches. | ||

| Afterward in the evening another walrus was harpooned. | ||

| Walrus—length 8 feet 2½ inches. | ||

| Girth of waist, 7 feet 8 inches. | ||

| Inside measurement of front flipper, 1 foot 9 inches. | ||

| Girth of front flipper, 1 foot 9 inches. | ||

| Length of back flipper from center of body to end of toe inside, 1 foot 9½ inches. | ||

| Girth of back flipper, 1 foot 7 inches. | ||

| Breadth of front flipper, 10½ inches. | ||

| Mr. Operti and I were in the crow’s nest. | |

| By glass salinometer salinity of water east of north part of Saunders Island 1/8 less than 2/32, salinometer line temperature of 190°. | |

| Temperature of air, evening, 37°. Temperature of water 34°?. | |

| Number of bands in the strata on the north side of Saunders Island, fifty-seven. The island is 5 miles broad and 13 miles long. | |

| August 13th, Thursday | At Kikertuomey or Kikertarsuak again—five tupiks, five meat houses—one a small one—four columns for drying meat, one column of wood. Seal skins staked down, several old places for meat. Winter igloos to the west. The village is on a kind of promontory of dark-colored rock, friable, worn in bastions towards the east about 100 feet apart. Many dogs at the settlement, nine of large size, the rest of them puppies—one quite white with dark head; most of them were dark-colored. The rocks were brownish, sloping back from the settlement and were about 1200 feet high. |

| Got water from an iceberg; the water trickling in small streams would run into sidelong clefts in the ice—a pump was put on the iceberg, a fire built, the ship lying close to the berg, and a hose put from the ship to the iceberg, the force pump carrying the water to the ship. I went to the top of the berg, perhaps 50 feet high or more—the day was warm, over 48° in the sun. | |

| The land sloping behind Mt. Dundas was free from snow for some distance inland. A glacier with hills on both sides of it is at the head of Wolstenholme Sound, the glacier running back to the inland ice. Horizon foggy. The northern part of Smith Sound or Kane Sea has been known since the time of Capt. Inglefield, 1852. Baffin did not distinguish it. The shore was quite free from ice in the early part of August, 1896. Some icebergs in the water. The tide runs at about three knots or over at Kikertarsuak, where we now are, at the north side of Wolstenholme Sound. Near Kikertarsuak two or more icebergs or ice islands broke with a noise like thunder—one breaks now. There is a small duck here called sometimes a bull bird. At St. John’s, Newfoundland, a year ago last winter many of these birds were driven into the harbor by the ice—the harbor was full of them. The water at the back of our ship measures 22 fathoms. There are now on board the Hope about twelve Esquimaux and four Esquimau women and some children, the men doing a good deal of labor, and the women dressing and sewing the skins of the birds and animals we have taken. | |

| A bearded seal was caught about two miles beyond the settlement of Omenak in the morning, and brought to the ship in the afternoon—it was an ookgook seal, a square flipper. It was harpooned in the water as he was going to dive, and towed over with a bladder, about ten miles from Omenak—he had a small head with black eyes and his beard was white; his coat was dark with short silvery hair. The ookgook seal is one of the largest animals near here. It occurs also in Repulse Bay near Hudson’s Bay. Took mercurial for spirit thermometer. | |

| The stratification of the land is not so marked here. From Parker Snow Bay specimens of red granite and red sandstone baked like a brick, and a bluish and red fine dark sandstone, and a kind of substance, gypsum probably, with long crystals apparently, found by members of the party. | |

| At Kikertarsuak a blue stone with white veins, small, about one-sixth of an inch with cleavage is found. The forms in which the snow rests in the top of a mountain on the south side of Omenak Fjord, near Disco, in a large hollow is something like the filaments of a large leaf with eight or nine ribs like a palm and some feathery lines like the lines of a Sequoia leaf or bunch of pine needles. | |

| The current at Kikertarsuak appears to be quite strong near the shore. Some good-sized pieces of ice passed us, going to the eastward. The glacier is quite solid to the east. One gentleman of the party was in an igloo and the stones tumbled on him, but Lieut. Peary helped him out. Outside the Sound there was a kind of fog, but the sun was high at 7 o’clock, p.m. The Esquimaux helped in getting water—channels were made on the iceberg. In the evening skins were brought out. When icebergs meet they crash together and in breaking make loud reports. | |

| In the afternoon went into Smith Sound, passing Granville Bay. Granville Bay on the south point—dark rock with dip about 20° to the S.W. On shore in the evening, at a small bay north of Granville Bay, a glacier at the head of bay, limestone rocks; saw a red-throated diver and two reindeer, one a buck. A little house of stones was on the end of the point, probably an Esquimau stopping-place, with bones around. | |

| Near the N.W. point of Granville Bay, north of the small bay just spoken of, is a mountain called by the Esquimaux Oobloodatingwah, the Sunlight Rock, so called because the sun just touches the top of it when it disappears in the last days of the fall. | |

| Temperature of the air at 12 o’clock 36°, water 36°, mercurial thermometer about 40°. | |

| August 14th, Friday | Passed Cape Parry, Cape Pawlett, and Cape Trautwine, and stopped at 11 a.m. near the village of Ittibloo (Iteplik) on Whale Sound. We went ashore, seeing a glacier near us. Five tupiks here, one with a light burning in it. The village is surrounded with grass on a sloping piece of ground at the foot of a mountain with a glacier and stream to the southwest. Oong-we, an Esquimau, died here last fall and was buried in the middle of the village in skins with stones piled above and two stones on the body. About ten or twenty pretty good-looking dogs. Near Ittibloo is a mountain, Kavidtluassuak or Falcon Mountain. Went hunting reindeer in the afternoon with an Esquimau. We stayed out till 2 o’clock next morning by the midnight sunlight. Shot at deer. Six p.m., anchored at Olric’s Bay. |

| August 15th, Saturday | In Olric’s Bay, near Salmon River; young ice formed in the night. Started at midnight and came around toward Kangerdluksuak and anchored in the morning in Inglefield Gulf. |

| August 16th, Sunday | At Kangerdluksuak went reindeer hunting with Mr. Hollifield and an Innuit to a lake and meadow, with a stream in it, about five miles away—stayed out till one o’clock next morning, in bright sunshine. Temperature of air 11 a.m. 40°—found spirit compass of value. |

| August 17th, Monday | Left Kangerdluksuak towards noon. Came to Hurlburt Glacier, with a row of pinnacles stretching about 500 feet into the sea, the height being 200 feet; a moraine on the east; an Esquimau house near and stones for lamps. The Esquimaux come here in summer and get the stones to make lamps. Came across to Bowdoin Bay and saw Anniversary Lodge, where Lieut. Peary and party were—one of their two houses here was burned and another torn down. Took some things from there. Went near Bowdoin Bay glacier. Soundings 123 fathoms. |

| August 18th, Tuesday | Went back to Kangerdluksuak—took up Mr. Lee. Stopped at Karnah. Obtained one narwhal from near Karnah. Three walruses taken. |

| Measurement of one walrus: | ||

| Length, 9 feet 7½ inches. | ||

| Girth of waist, 8 feet 4 inches. | ||

| Girth of belly, 8 feet 9½ inches. | ||

| Inside of front flipper, length, 2 feet ½ inch. | ||

| Girth of front flipper, 1 foot 10 inches. | ||

| Length inside of back flipper, 2 feet. | ||

| Girth of back flipper, 1 foot 8½ inches. | ||

| Breadth of flipper, 10½ inches. | ||

| Two more walruses taken, one trying to get into the boat from the pan of ice; he put his tusks over the gunwale and knocked off a splinter—the other, a cow walrus, rolled off the ice pan. Captured nineteen walruses, one of them, a young one, alive. There were twenty in all, one got away. In the evening returned to Cape Karnah, where we had been in the morning. We left there the Esquimaux and the walrus meat, of which there were many tons; it had filled one side of the deck, making it list over. Lieut. Peary had supplied the Esquimaux last year also with walrus meat, sufficient for a winter’s use. | |

| August 19th, Wednesday | Went to Robertson Bay in the morning and saw about ten tupiks near the head of the bay. Left Mr. Hansen with a tent to see about walrus meat. Saw the Verhoeff glacier, which is much broken by the grinding of the moraine. |

| Saw the ice cap with a cloud over it that looked like a second icecap. Wind from N.E. Temperature of the air about 40°—spirit thermometer. Went to the north, seeing Cape Cleveland, a reddish promontory with a glacier coming down to the sea, joining another glacier, making an ice-foot. Passed Cape Alexander, with the Crystal Palace glacier on the north side. Looked at the ice in Smith Sound, which seemed to stretch completely from shore to shore. Reached latitude 78° 24′ N. We did not attempt to pass through ice and turned to the right, coming to the place of “Polaris House.” At Life Boat Cove the water is moderately deep; saw land stretching far upwards, rocky. Saw Port Foulke, Dr. Hayes’ winter quarters. At August Sontag’s grave we reset the stone, which had fallen. He was the astronomer of the party. There was not much ice in sight to the westward. Cape Isabella is a round mountain with a snow-clad summit, about 2,000 feet high, and beyond on a lower point is Cape Sabine. The Polaris is sunk a little to the north of Littleton Island. Sutherland Island is small with light reddish rock broken almost like basalt on the west. Cape Ohlsen is a rather long point in the water, of light reddish rock also broken. The Polaris House is some 500 yards or so to the northeast of the rugged beach where the Polaris was run ashore. Lieut. Peary found one handle of a hand-pump with two handles, about five feet apart, and a broken letter press. We got a piece of a musk ox skull, apparently from Thank God Harbor, and the dial of the steam gauge with the name H. A. Ashcroft, Boston, on it. A good many pieces of iron, nails, screw eyes, etc., were lying about, and one piece that looked like a part of the gunwale, three feet long and six inches through, with a rounded end; also locks and hinges and small pieces of rope and canvas much weathered. We passed the bay on which is the settlement of Etah, but this year no Esquimaux are there. Port Foulke is small with land rising on all sides of it, rocky, with a little brook coming in at the head of the bay. Three or four small islands lie to the north of the entrance called by Dr. Hayes, The Youngsters, Knorr, Starr and Radcliffe. On the hills were Arctic hares, and multitudes of young ducks were catching shrimps in the harbor. Ice too heavy towards Cape Sabine and Smith Sound to pass. Near this was our highest point north latitude, 78° 24′. We turn south at 9 p.m. | |

| August 20th, Thursday | At Robertson Bay—the settlement has twelve or more tupiks, with fifty-four Esquimaux. Mr. Hollifield and I went up the hill to the east and walked towards the “Verhoeff” glacier. The glacier comes low quite quickly. A high dome of inland ice was visible to the southeast. An Arctic hare was in the field on top of the hill. Snow banks and small glaciers were near the summits of the hills or gorges—a little snow or rain this morning. Near Herbert Island about 9.30 p.m. Temperature of air 38°. Dogs were at the settlement. Stopped at Igludahomey, Peteravik, and got a white whale, about fifteen feet long; its tail fin stiff like a propeller, the outside white and smooth; it is said to fall off, on cutting up, leaving the skin underneath. |

| August 21st, Friday | Going towards the south. In the afternoon got to the settlement of Omenak or Oominooe, in Wolstenholme Sound. 10 a.m. temperature air 38°. 10 evening, temperature air 40°. The young walrus that we called Jack and had on board, died. |

| August 22d, Saturday | Went out towards Wolstenholme Island. Got a large walrus about noon. He was harpooned by one of the Esquimaux, after which he was shot twice. The length of his tusks was about one foot. |

| The measurements were: | ||

| Length, 10 feet 8 inches. | ||

| Waist, 10 feet 7 inches. | ||

| Length front flipper, 2 feet 1½ inches. | ||

| Length back flipper, 1 foot 3½ inches. | ||

| Wolstenholme Island seen from the south has a mass of red rock to the east, right hand side, and to the left hand side west, a light brown rock, then the island becomes lower with darker rock or vegetation. 3 o’clock a.m. thermometer 38° above 0—8 o’clock a.m. temperature air 46°. Nineteen walruses were taken in all before this, averaging 1,000 pounds or so, except three small ones, making 16,000 pounds of meat, or over, and one white whale. The walrus obtained is the largest yet taken. It must weigh over half a ton. Stopped at Parker Snow Bay—saw an Esquimau, Illi, ashore with a gun, probably one which Lieut. Peary had given him. During this day at Manson Island. An Esquimau came back to the ship for a gun which he had left. Saw a gun made to fire from the side with a strong piece of iron somewhat springy. Going back to Parker Snow Bay, some went along the shore in a boat. Took a family on board with sledge and ten or twelve dogs, six of them Lieut. Peary’s. | |

| August 23d, Sunday | In the morning at Cape York and at about ten o’clock were at the place of the meteorite. Tied to the rocky shore; the meteorite had not been moved—we put a plank ashore and commenced digging—Mr. Hollifield and I took a walk and made a cairn of stones on a hilltop near by, on the S.E. of the island toward Baffin’s Bay, and on the edge of the ice sheet. Found a piece of wood, some of it fresh, that is woody but decayed, some fossilized—found mica in quartz. It was foggy. Some icebergs to the S.E. One probably grounded. In the evening walked to the middle hill—found the top of a glacier—a gull flew over it—found below the rock an agate-like feldspar—many red stones lying there—a glacier near with several streams running through it—excellent water to drink. 10 p.m. temperature of water 27°—air 20°. |

| August 24th, Monday | Work on the meteorite. Made a road to the ship—pieces of lumber laid from the rail of the ship to the shore—ship ready to be cleaned—some ice in the bay—one piece apparently fifty feet square—cloudy in the morning with some gleams of the sun towards the north. Temperature of air this morning about 38°. Bushnan Island lies to the south of this. The back lower end of the iron, which was about three feet under ground, is now hoisted up clear of the ground about three inches. |

| August 25th, Tuesday | Work on the iron. It is now entirely clear from the ground—an iron wheel and steel chain and the rails are brought up—in the afternoon the end of an iron wire cable is brought—the railroad iron has been laid on two skids—the metal has been placed on the rails and moved ten feet toward the ship. Mr. Sutherland and I took a walk and found a stone about ten feet high and ten feet square with bits of mica in it—walked some on the ice—a little lake is near the center of the island—on the way back found a stone with a vein of greenish stone in it—open water stretching to north and west of the island. The tide rises here about four feet. The island stands near Melville Bay and is called Meteor Island. It is about six miles long and three miles broad. The hill of Sarwiksuak, 500 feet high, lies to the eastward. To the westward are two prominences; the further one, I think, is Cape York. It is said the natives call this Imnanoerne Imnanak. Behind Meteor Island is a smaller one or islet and two glaciers, one on the north and one on the northwest. There are three Esquimau fox traps well preserved on the rocks or stones which lie between the two glaciers which come into the water on the west. The appearance of the rocks on a kind of hill with prominences on the north is singular, and it is like the wings of a bat or leaves of a plant like plantain, which grows in Greenland. Temperature of water about 8.45 a.m. 28°—young ice is formed near the icebergs in the bay. Temperature of the air about 9 a.m. 39°—a little rain in the afternoon. |

| August 26th, Wednesday | About 12 noon temperature of water about 28°—air about 35°—some rain this morning. Iron at top of hill. Temperature 11 p.m. water 28°—air 38°. Iron nearly at foot of hill. |

| August 27th, Thursday | In the morning foggy. Lichens grow freely on the rocks above the water line near the sea. Iron is getting nearer the ship. |

| August 28th, Friday | Walked to end of the point. Temperature, water 29°, air 30°, at 10 p.m. Three of the jack-screws have given out. |

| August 29th, Saturday | Temperature, morning, air 32°, water 27°. Rainy. Height of hill at S.W. of the island where the meteorite is, about 369 feet. At noon Mr. Sutherland and I went to the top of the little hill south of the ship. Ice is forming around our steamer. Cleared in afternoon. Went to a hill at the east of Meteor Island named after a person on the Hope by Lieut. Peary—grand view—counted five glaciers. Putting ballast aboard. |

| August 30th, Sunday | Crew not working on iron to-day. Temperature, about 9.45 a.m., water 29°, air 32°. About 12 p.m., water 27°. |

| August 31st, Monday | About 11 p.m., temperature, air 32°, water 28°. Snow during the day—hills near the ship covered with snow. The iron lies near the ship. Mr. Operti, our artist, has a tent on shore, and a kind of shelter with a sail is made for Mr. Bradbury, who has a forge. He has made a shoe to come on the rail. The iron rests on rails. The sailors from the ship work on it in the day time, and the Esquimaux with others at night. There are about ten Esquimaux. On Saturday ballasting was going on. A heap of stones comes up to the lower hatchway—timbers have been cut and put in to strengthen the edges of the upper main hatchway. Snow—wet snow—but work goes on day and night, preparing to take meteorite on board. |

| September 1st, Tuesday | At Meteor Island—morning—Active work on the iron. It was tried whether the hard wood beams would bear the weight of the iron mass—a heavy part of the mass was brought to bear on one of the beams and it bent it down. Meteor Island and the other side of the bay near by to the east was visited last year by Lieut. Peary, and two masses of iron were brought away from the land, which did not lie so deep in the ground as this mass—one weighed about three tons. It was brought on the ship by aid of a differential pulley. The mass here is said to contain nickel and a little cobalt and something else. The percentage of iron is very large. The tide rises here about four feet. This afternoon it turned at about 6½ o’clock from high water. Some rails are fixed on beams. All timbers available will be needed, it is said, for the bridge from the shore to the ship. The heap of stones is made inside of the starboard quarter and the hold of the boat, and a mass of stones to the edge of the lower hatchway. It has frozen in the bay for some days—at first a mere skimming of ice, perhaps a sixteenth of an inch—now, after the rain it does not seem thick near the ship’s side. The rain has taken away the snow from the hillsides near here. It is raining now. There is a mountain of snow, a dome, to the eastward of us, apparently on the mainland, which has been ascended by a gentleman, and with an aneroid barometer it was calculated to be about 4000 feet high. There are other domes of snow near us, and the Souwallik mountains stretch out into the sea. The more distant ones are said to be 650 or 675 feet high. The mountain jutting into the sea may be Melville Mountain, from 500 to 1000 feet high. There are icebergs to the south of us, not very large, 80 or 100 feet across, thickly scattered about. It seems as if Cape York or open water could be seen to the S.W., a purple ridge. 10.40 p.m., temperature, water 27°, air 36°. |

| September 2d, Wednesday | Temperature of air near 10.40 a.m., about 35°; about 12 o’clock, air 33°, water 28°. Work at the iron stone. A chorus sung by the sailors at work is as follows: |

Oh my Johnny Voker

We will turn this heavy Joker

We will roll and rock it over

We will turn the heavy Joker

Oh my Johnny Voker, Haul!

| Compass in two days moved little if any. |

| Stone measurements: | |||

| Around the mass sideways, 25 feet 2-5/8 inches. | |||

| Around the mass front and back, 19 feet 5-3/8 inches. | |||

| Height of front end, 4 feet 5 inches. | |||

| Height of back end, 4 feet 6 inches. | |||

| Top convex from side to side, 12 feet 2 inches. | |||

| Bottom, from front to back, concave, straight measurement, 6 feet 9 inches. | |||

| Bottom, underside from side measured near back end, 5 feet 9 inches. | |||

| A hollow underneath the mass about six inches high. | |||

| The mass from the edge of the bank from the water, 6 feet. | |||

| One cubic foot of wrought iron weighs 485 lbs; one cubic foot of nickel, 788 lbs., as Lieut. Peary said, about 7 pr. ct. nickel. | |||

| The stone tipped over now, lying upside down on skid 6 feet from the edge of the rock at the sea. Gave up work on the iron, the jack lift proving insufficient. A 100 ton jack and three smaller jacks had given way; besides these we had three or four pulleys to raise 6000 or 8000 lbs. apiece and a steel chain. It would take, it is said, three or four days to put the meteorite on board. It rained heavily. Went with Mr. Sutherland to the top of the hill. Some ice seen in front to the south, with some open water. Quite foggy a short distance from the shore. Came back and took down a tent we had on shore. I left a compass mark at Meteor Island near “Hope Pier,” two small stones under heaps of stones marking a north and south line, (near brow of hill about 300 feet west of “Hope Pier.”) In the evening went and collected stones, spar, etc. Temperature of water about 10½ p.m., 28°. The rain, varying with snow, at Meteor Island, was quite continuous. It rained more or less for five or six days there. Our decks were now moderately free from slush. | |

| September 3d, Thursday | Sailed early in the morning at about 8 o’clock, or earlier. The weather now so dark in the morning that we could not read the thermometer; about 320, I think, at 8 o’clock. Came into Sarwiksuak Bay, lying to the southwest of the projecting ridge of a snowbank, getting 8 fathoms. Went after breakfast in a boat to the shore at the head of the little bay. Found a snowdrift near it to the south with a brook on the north of it. Mr. Sutherland, another, Mr. Hollifield and I passed the snowdrift to the east of us. It had 26 bands of dust or dark streaks on the front. The tenth, eleventh and twelfth from the top were quite near together, then a broad streak of perhaps 15 to 20 feet to the next. The average distance of the dust lines from the top of the glacier each year, from one another, is about 7 or 10 feet perhaps. Passing over the lower part of a snow bank about an eighth of a mile broad we came to a ravine, the isthmus between Sarwiksuak Bay and the next, Prince Regent’s Bay. We found at an elevation above the sea of 300 feet, perhaps, a heap of dark bluish stones, trap, which had been used by the Esquimaux as hammers to detach pieces of iron from the small supposed meteoric mass, brought away last year. The heap was about 20 feet across each way and 6 or 7 feet high. These stones occurred no nearer than the shores of Wolstenholme Sound, 200 miles away. The meteoric stone brought last year had lain in the middle of these, leaving a hole three feet deep. The mass had weighed about three tons—a road had been made some three feet broad and it was dragged along this and across the foot of the snowbank and over the ice to the ship, the Kite, on two poles about six inches through, by Esquimaux. There was another smaller piece of iron near this, perhaps, two or three cubic feet in amount, 24 inches by 18 inches, and one foot thick. This had also been taken away on the Kite. There were Esquimau shelters, three near by and one a little further off, which had been used by the Esquimaux while working at the iron. Could one of these shelters have been a grave? I ascended a hill near by the rock, 500 feet high from the sea, and had a fine view of a glacier of five miles broad running apparently ten or twenty miles back into the land, which filled the bottom of a valley towards Prince Regent’s Bay. It was cut up by crevasses and a river was running to the south of it. There were high snow mountains in the interior, the ridge I was on running back to the summit. On the other side of the valley there were mountains probably about 2000 or 3000 feet high. On returning to the boat I obtained other specimens, one seeming to have a little mica in it and red and white stone, another a red surface, while a third was flat of a dark blue color. In 1894 Lieut. Peary had been to this place with an old Esquimau. The stone was under three feet of snow, and only by looking over the ground much, and by a small piece of blue stone appearing above the snow, could he find it. The pit in the snow was three feet deep to the top of the mass, and after digging around it and standing in it he could not see out. The other stone, the one on Meteor Island, could not be found. In 1895 the bay, Sarwiksuak Bay, had a wall of ice around it, then a strip of open water, then floe ice. Anchor ice in the bottom of the bay. It is shallow near the head of the bay, only ten or twelve feet deep, and has a whitish reflection from the snow and glacier above. A cliff of ice here is about 120 feet high. Lieut. Peary says the knife or knives found by Ross are not in the British Museum, where they would be if in existence. He has two knives, a man’s and woman’s, the woman’s knife with three pieces of iron about the size of a five-cent piece each, set so as to form a cutting edge. The Esquimaux may have spent three days in getting out a piece of iron—no pieces found under the mound of stones. Pieces of pitch pine about 16 inches long and 7 inches square were there, five of them left last year. |

| At 4.28 p.m. temperature of water 29°, air 36-1/10°. At 9.27 p.m. temperature of water 30°, air 39°.10. At 10 p.m. temperature, air 39°. | |

| September 4th, Friday | Bushnan Island. Two points standing out to the east behind the entrance to the bay to the west of the two islands. We had started at 3 or 4 o’clock in the morning. Left Sarwiksuak Bay and came to the north and west of Meteor Island. The channel not very full of ice. We passed to the west of Bushnan Island, which is quite prominent. There is a mountain with its head cloven, at the head of the bay. We came by four or five more promontories going to the west, and several icebergs. On one of these, on the north side, a bear had a hole quite high up. It was shot. It was a female. We arrived near Cape York once more and tied to the glacier about a mile and a half to the eastward of the village and got water. Sledges came to us. I walked over the glacier to the village at the sledge track and had a sledge ride with an Esquimau called Myouk and six dogs. Then I walked up on the glacier again and had a fine view of the island-like cliffs at the edge of the glacier surrounding the bay to the east of Cape York, the glacier stretching lonely towards the north of the sea, with ice to the south. Left Cape York, went near by the western point of the ridge near Cape York, at about 7 o’clock. Temperature of water at 7.40, 28½°. Thermometer about this time 35-9/10°. |

| September 5th, Saturday | Temperature of air 9.40, 32°; water 10.36 a.m., 28°; air, same time, a little under 33°; sounding in front of Bowdoin Bay glacier was about 120 fathoms, and in front of Imnanak (Cape York) glacier, 23 fathoms. Foggy this morning and afternoon. At quarter to 7 no wind. Last night took in sails in the evening. Wind changed to southerly. At 11.06 p.m., water 28°, air at 11.12 p.m., 28°. Melville Bay was quite open after leaving Cape York. We stopped once for the ice in the night of the 4th and 5th. The fog lifted a little at about noon and the horizon was indistinct. I tried an observation. The fog heavy and the air cold during the day. Frost collected on rope, and icicles came on the bridge of the ship. Melville Bay is about 150 or 200 miles across. Bears come out some distance on the floes. |

| September 6th, Sunday | Thermometer at 7.25, air 30°. Cool—ice fell from the rigging on the deck. Got under way about 8 in the morning. Temperature at 7.05, evening, 33° or 34°. |

| September 7th, Monday | In the morning arrived at Sugar Loaf Bay near where the Cornell University party were left. At 7 a.m., water 30°. At “Hope Harbor” the dip is about 25° to the east—reddish rock—limestone. An Esquimau double igloo. Saw a cairn about 4½ feet high with an American flag on a flagstaff over a white cloth, floating a little in the breeze. A bottle was tied to the staff with this note inside—a notice, dated Aug. 31st. “Impossible to land—in camp on the west side of the peninsula, two miles from here. R. S. Tarr.” Two records of the same kind were with the bottle on leaves from a note book. Lieut. Peary took the bottle and breaking the neck read the notice. We went on in the steamer around the point, Lieut. Peary, Mr. S., George and I, looking for the tents. Lieut. Peary saw them first, and said “There they are” (the Cornell party). Thermometer, 7.37 a.m., air 36⅔°. |

| Hill behind the camp 250 feet high, about, and beyond that a mountain; to the east a streak of snow nearly to the summit. An Esquimau igloo on the shore. The party have been about two weeks in camp. They have visited the Duck Islands. Many signs of glaciation are said to occur in Melville Bay as reported by a geologist with a party at Melville Bay. Took aboard Professor Tarr, Professor Gill, Mr. Kindle, Mr. Bonesteel, Mr. Martin, Mr. Breaker and the pilot, with three others—four persons from Upernavik. The party had been in camp near the mountain called the Devil’s Thumb, two miles from it. Professor Tarr had made an excursion with others of about five miles on the inland ice. Rivers about ten or twenty feet across were found, and pot-holes but no crevasses. The Devil’s Thumb was ascended by Professor Gill and Mr. Martin, and a cairn was built at the top of it. The glacier extended into the sea near the Devil’s Thumb, making a loose floating amount of ice; the water froze for three nights in succession. They returned and encamped near (about two miles from) Wilcox Head. They had left the record mentioned above at a little harbor spoken of near the end of Wilcox Head, with the small American flag (about two feet or so) and a white piece of cloth. One of the boats which they had, a dory, was injured by a storm. | |

| Weather pleasant to-day. Left Wilcox Head for the south not far from noon. The waves, a little distance below Sugar Loaf Bay, named from Sugar Loaf Mountain on the island of Omenak, which forms a hill called Sugar Loaf, were covered with a substance on top like oil—perhaps ice on the water. The headlands were high but were pretty free from snow. Some islands stood at some distance out into the water showing a reddish brown; a rather square mass to the south of Sugar Loaf Bay and the little island of Omenak in the centre of it were landmarks. | |

| It strikes me that there must be a good deal of water coming into Melville Bay by springs, icebergs and glaciers. It was said that the Cornell University party had much good water from a stream. Temperature about 9.45 p.m., water 34°, and at 8.30 p.m., air 35⅞°. Mr. Operti took the flag from the cairn made by the Cornell University party. The names of members of this party were subscribed by themselves upon it. There were four assistants from Upernavik with Professor Tarr. | |

| September 8th, Tuesday | In the early morning at 6.30 o’clock, at the Danish Harbor, at Upernavik; at 200 yards from the shore, about 4¾ fathoms—water dark blue. At the harbor two houses and a powder house—one of the houses of stone perhaps. The hill rises to about 450 feet behind; to the east of the houses a rocky hillside. A little rocky islet lies at the mouth of the harbor. One member of the party obtained a pair of Esquimau boots. A light wind in the morning followed by calmer weather. The Danish brig lay in the harbor, it is said, when we were in Upernavik before, this year. A bank of clouds lies to the west, probably over the ice in the bay. Temperature about 7.45 a.m., water 34⅔°; at 8 o’clock a.m., air 39°. Dip to the west and east. Morning. A light breeze is springing up from the N.W. The sun is trying to come out through the clouds. Two islands are in sight in the bay to the west. A patch of snow is lying on the hillside over the houses. There are many promontories coming out. It is possible these are the remains of the world-forming epoch. High mountains behind Upernavik—five houses and a church—a small one fronting the brig. The mountains seem to be about 5000 feet high, behind to the northeast of Upernavik. They are much broken. There is a cliff on an island or point of the mainland south of Upernavik with a somewhat sloped or pyramidal form, with a dike of light stone, gneiss or quartz running perpendicularly towards the sea nearly through the top of it. The dike seems to point east and west. |

| Left Upernavik at about 8 a.m. Not very far from the mountain called Sanderson’s Hope. The sides of the cliffs are quite steep, about 80°, apparently, and are furrowed in water or snow courses. There is not much ice in sight. Last year is said to have been quite a pleasant one at Upernavik—Danish station. On seaweed brought up from the bottom here are the seed pods of Buccinum, a kind of shell or coral with a little worm coming out, and Bryozoum. The party from Cornell University dredged the shore and found them near Wilcox Head. Some of the Cornell party went to Duck Islands, about ten miles off, in a whale boat. The persons from the Danish settlement knew the way apparently. It was a pleasant day when they went. Graves from whaling ships were found on the islands, and gun shells apparently from whaling boats. The small islets are quite numerous here, and the coast is high. | |

| Sanderson’s Hope may be 3425 feet high. Snow lies on the northern side of the hills—the smoke from the steamer rests in clouds or streaks. | |

| The seaweed was long, about 8 or 10 feet in the harbor, with long stems—and at Devil’s Thumb it was long also—and the same at Upernavik. It is brownish in color, slightly thicker in the middle with crisped edges, sometimes with almost a hole between the edges and the sides. | |

| There are ten grown dogs on board and one puppy belonging to Mr. Hansen, and we have the two bear’s cubs. The top-gallant yard of the fore mast of the ship has been taken down and placed on top of the cook’s galley. There was some rain at Wilcox Head while we were away. The ship goes now with rather an easy motion. There may have been some movement towards the north among the Esquimaux. Much water and fog here. Deer skins to be had on the coast. The fog hangs over the mountains and cuts off the view of the top of them like a knife. The fog is dark. The Greenland ice sheet must contain a great amount of water. The barnacles in the bottom of the sea near Holsteinborg are quite numerous. The termination of many words in the Esquimau language in k is peculiar, like Upernivik, Kinivik, etc. It is thought that Esquimaux may have lived in the houses on Wilcox Head. A double house near Wilcox Head, at the first place we stopped at; and the remains of a house at the camp of the Cornell party, two miles away from it. There is said to be a large number of Esquimau graves—20 or 30 graves—near their camping place—some with five or six bodies perhaps—this is west of Wilcox Head. The different layers in the stones at the camp of the Cornell party, near Wilcox Head, were remarkable. There would sometimes appear to be eight or ten layers. One stone about eight inches thick was black and white—many stones of a reddish color. A gull at Meteor Island kept flying around, sometimes near the island. The configuration of the island would seem to point to its having been connected once with the mainland. There was a good deal of ice near Cape York to judge from the collections of icebergs, one of them a quarter of a mile, or more perhaps, long. This last mentioned iceberg lay near the edge of the glacier, near Cape York. I was interested by the apparent politeness of some of the young men at Cape York. | |

| It is said that a piece of drift wood was seen at or near Duck Islands. Fossils of trees were found in Hudson Strait. Professor Asa Gray was inclined to think, from Arctic fossils, that Greenland had once a warmer climate. The landscape to-day looks dark in the September weather. | |

| The rocks between Upernavik and Cape Cranston, or the Svarte Huk Peninsula, are mostly of a dark formation. It seems almost as if the slaty rocks might be used for building material. Stars were seen last night—Vega and others—hard and cold in appearance. Professor Tarr had no sickness in his camp, and no accident—only one cut finger required iodine, and he had no use for his medicine chest. | |

| We hear that no more boats will come from Denmark this year, and Professor Tarr carries letters. | |

| The coast at Cape York impressed me as being high—unusually so—one becomes used to great heights in Greenland. The Carey Islands are high and rather square masses of land, conforming somewhat to the plateau or cliff-nature of the shores on the east of Smith Sound. There must be some marine life in Baffin’s Bay—perhaps the seaweed may remain as a sign of what occurred at a remote geologic period—it is quite large—some rockweed-seaweed, branching at two or three inches—a part of the branches seen not far from Cape Shackleton, south of Sugar Loaf Bay. The warmer character of the water, if my instrument is correct, may come from the large body of water here with currents. Many whaling vessels must have been here at some time. If Greenland should be found to be an archipelago like a continent in form, it would show that much ice and snow have collected here. Baffin’s Bay must have a great body of ice. | |

| I skated at Meteor Island on a glacier, though it is rather rough and sloping. Meteoric iron occurs in a great many parts of the globe. The land of the Iron Mountains is low as they stretch out into Melville Bay. Some strata seem to have been found in the high Arctic Regions. | |

| Afternoon—The clouds rise somewhat and give a view of the shore. The shore from Svarte Huk is quite bold. The promontory of Tukingasok or Dark Cape stands out; then another point, perhaps the island of Kingatok, is a landmark with almost horizontal strata. | |

| The Arctic part of the journey seemed to form a country by itself. Great stretches of land with ice between, and Baffin’s Bay and Smith Sound penetrating it—Baffin’s Bay in the neighborhood of Upernavik seems broad. There are some icebergs floating on it. At the northern part of it, coming down, we encountered dense fog with icebergs. In the north there was much ice in the bays and small pieces stretching about as far as one could well see from the glacier of Cape York. Captain McClintock was frozen in, 17th August, 1857, near Bushnan Island, and ships have been lost not far from there. There is a pack of ice in the middle of the bay. The ice is said to stop in its northern course around the southern end of Greenland near Holsteinborg or in that neighborhood. The Norwegians are thought to have come as far north as the Women’s Islands of Baffin, not far from Upernavik, and voyagers from Iceland are said to have come to Lancaster Sound. Melville Bay has promontories that stretch into it. By the soundings given on the charts there is a deep place not very far from Bushnan Island of about 420 fathoms—with the ice and icebergs on both ends of it to the north and southeast. The Bergy Hole, a portion of water famous for icebergs, called so on this account, lies to the northwest of the Devil’s Thumb. Persons have been on shore at this mountain. | |

| The centuries seem to have shut in Melville Bay somewhat. | |

| The current on the western shore of Baffin’s Bay sets nearly always to the south. | |

| There have passed through here many expeditions—expeditions in aid of Sir John Franklin; Dr. Kane’s expedition; the expedition in search of him; the expedition of Dr. Hayes; the Polaris expedition; the expedition of Sir George Nares; the Greely expedition, the ship being commanded by Captain Pike; the Greely Relief expeditions; the Peary expeditions, etc. | |

| The sunlight in summer passes, and the Arctic light commences in Smith Sound about the last of September or beginning of October. I felt as if the midnight sun were going around me in the north. The grass in the north is scanty—the blades about six inches high and far between, wither in September—little streams of water in some places running over small stones. A current is said to set towards the south coming from Cape York through Melville Bay. | |

| As the fog lifted this afternoon a mountain top, Sanderson’s Hope, appeared, with a streak of snow coming down from it to the west. A photograph was made by Mr. Sutherland of Sanderson’s Hope. There is an Esquimau tradition that when animals are scarce, or when they do not appear, there is a sorceress or woman who keeps the animals back, and that when an angekok, as he is called, or one who has some authority, like that of a religious person, goes by a quickly-revolving piece of ice and seals, he may be able to free them. A previous expedition of Lieut. Peary passed into Smith Sound visiting the Esquimau settlements, and endeavored to raise the meteoric iron. | |

| The cold of the Arctic regions seemed not to be very great in summer, with the appliances we had for heating, in the steamer. | |

| The food of the whale is said to be small shrimps which occur in the water—said also to be eaten by the little auks, which carry them to their young. The great ice fields which are said to be in Lancaster Sound must send down large quantities of ice into Baffin’s Bay—much ice on the shores of Cumberland Sound, where the temperature is affected by these great fields of ice. | |

| I cannot find much in regard to the expedition of the Swedish naturalists Björling and Calstenius. Mr. Björling, in a former expedition, encamped near the mountain called Devil’s Thumb. | |

| This expedition in the Schooner Ripple went to the shores of the Carey Islands. They met a storm and it is possible that they attempted to go across to Cape Faraday on the opposite side of Smith Sound. There they were thinking of meeting with Esquimaux. The last season was a severe one for dogs in some places on the Greenland shore, and it was severe at Godhavn; the one before may have been so also. The effect of the sun in the evening making the clouds appear red is peculiar in the Arctic regions. Near Wilcox Head I observed in the evening what seemed to be like an effect of the aurora borealis. The great seaweed of the Arctic regions is quite remarkable. There is seaweed in the neighborhood of Whale Sound. Some seaweed was found in the bay north of Mount Dundas near North Star Bay. | |

| The young walrus which we captured seemed to be quite tame. We called him Jack—he sometimes raised his body—he was taken into the ship by a leg. Fine weather and fine sunsets characterized the first part of the journey. The birds on the bird cliffs sat on the ledges in rows and have little nests in the rocks. Many young were found in nests near the water. The birds would almost always sweep down upon the water in flying away, coming down like a fall of snow. The cliffs were sometimes quite high—at Parker Snow cliffs perhaps a thousand feet, with guillemots and kittywake gulls upon them. At Dalrymple Rocks were eider ducks. A nest of the eider duck was obtained made of grass cut from the ground at the west. On one of the islands in the Wolstenholme Sound were cliffs with birds. Ivory gulls may have been found near Wilcox Head by the Cornell University party. | |

| The isolation of the land on the north of Melville Bay with magnificent glaciers, and high peaks with snow caps, is remarkable—a dark fog would seem to be rolling sometimes near the top of the glacier. The land north of Melville Bay might have been flat and then covered with snow. The settlement at Cape York is perhaps the only one on the coast which is always inhabited—skin tents or tupiks with several persons and children—18 large dogs and perhaps ten puppies there. Temperature 8.50 o’clock p.m., water 32° Fahr. | |