* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

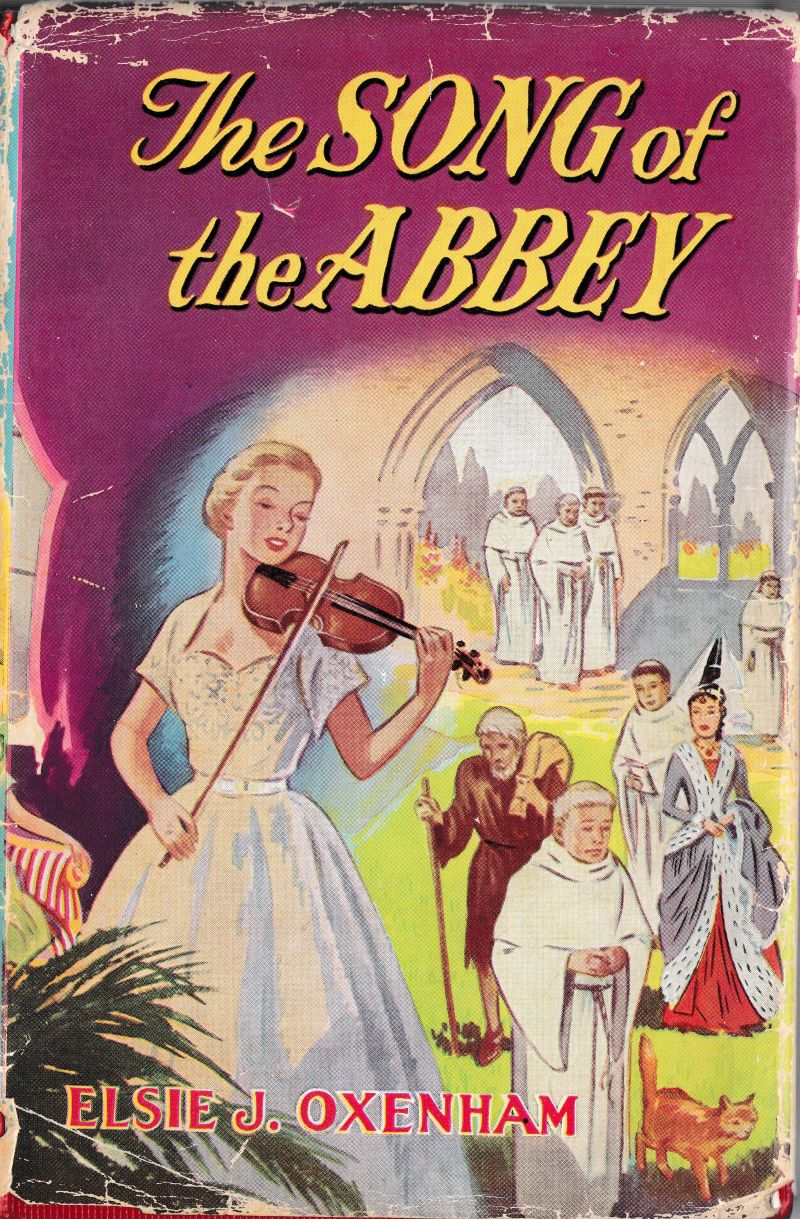

Title: The Song of the Abbey

Date of first publication: 1954

Author: Elsie Jeanette Dunkerley (as Elsie J. Oxenham) (1880-1960)

Date first posted: Oct. 12, 2021

Date last updated: Jan. 18, 2022

Faded Page eBook #20211017

This eBook was produced by: Hugh Stewart, Alex White & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

s.o.a. See Chapter 24

They walked through the garden.

THE SONG OF THE ABBEY

by

ELSIE J. OXENHAM

COLLINS

LONDON AND GLASGOW

This Impression 1959

To

ALICE A. MANNING

with all good wishes

and many thanks

for help

in many ways

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| 1. | Tessa’s Trouble | 7 |

| 2. | Carol Carter | 14 |

| 3. | Jansy Gives Advice | 22 |

| 4. | Nanta Hears the News | 28 |

| 5. | A Hamlet Club Job | 35 |

| 6. | Queens in Council | 42 |

| 7. | The Head Decides | 50 |

| 8. | Standing by Tessa | 60 |

| 9. | Hope for the Club | 68 |

| 10. | The Head’s Way Out | 75 |

| 11. | Queen Theresa | 83 |

| 12. | A Letter to Virginia | 90 |

| 13. | The Hamlet Club Meets | 96 |

| 14. | Damaris Talks of Bridesmaids | 101 |

| 15. | Hostess for Kentisbury | 108 |

| 16. | Patch Tells her Story | 115 |

| 17. | Lieutenant and Mrs. Kane | 123 |

| 18. | Nanta Plans for Patch | 131 |

| 19. | The Crowning of Tessa | 143 |

| 20. | A Ring for Rosalind | 152 |

| 21. | Squashing Carry Carter | 162 |

| 22. | Farewell to a Dancer | 170 |

| 23. | The Tallest Bridesmaid | 180 |

| 24. | A Party for Mary Damayris | 191 |

| 25. | The Song of the Abbey | 203 |

| 26. | A Medal for Theresa | 209 |

| 27. | Thrills for Rachel | 216 |

| 28. | Christmas Presents for Bill | 226 |

| 29. | A Treat for Tessa | 233 |

| 30. | Nanta Plays the Abbey Song | 240 |

| 31. | Nanta is Willing | 248 |

| 32. | A Song of Rainbows | 253 |

“What’s the matter with Tessa?” Nanta asked, as Frost held open the door of the car and the school party crowded in.

She was the reigning May Queen and Tessa was her successor, to be crowned on May-Day. But this was still only March, and Nanta was troubled by the cloud on the face of the Queen-elect.

“Same old thing,” said Jansy Raymond. “I had to take a message to her from the Head, while you orchestra people were hard at it, and Tessa was letting herself go about to-morrow night. She hates being left out.”

“It’s jolly hard on Tessa,” said one Abbey twin, from her corner. “I wouldn’t like it a scrap.”

“I’d be bursting mad,” said the younger twin.

They came together in the car every day, a jolly friendly party. The babes, tucked into the front seat beside the chauffeur, were Rosemary and Michael Marchwood, she aged nearly ten and he almost seven. Rosemary was a dark little person, with smooth short hair and beautiful brown eyes; Mike was big and fair and sturdy and was the life of the Kindergarten class. Their home was at the Manor and their mother, Jen Marchwood, had been the Beech Brown Queen at school fifteen years before.

Next in age, and living next door at the Hall, were their twin cousins, Elizabeth and Margaret Marchwood. Now almost fourteen, they had made their mark at school, both at cricket and in the orchestra. Jansy Raymond had been fifteen at Christmas; her mother and theirs were cousins and Jansy spent her schooldays at the Hall, as her home was in the country. She was very like the twins, with the same beautiful dark red hair, but hers was worn in two plaits, which were growing long, while the younger girls still had bobbed curls.

Nanta, the eldest of the party, nearly nineteen, was the reigning Queen Lavender, a Cookery student, who was leaving school at the end of the term. A tall fair girl, with yellow hair wound round her head in big plaits, she looked grown-up and responsible, and none of the younger crowd would have questioned her authority.

“Not now that she does her hair like that,” Jansy had said one day. “She looks much more grown-up. When she stuck it over her ears in head-phones, it looked as if she’d just rolled it up so that it wouldn’t go into her soup. But when she came back after the Christmas hols, with that big crown like Mother’s—well, we remember now that she’s really Lady Rosalind and we’re properly respectful.”

“I copied your mother’s way of doing her hair,” the victim had retorted. “Virginia has been doing hers this way, and everybody seems to like it. I always want to look like Virginia.”

Her name was Rosalind Atalanta Kane, but Atalanta had been shortened into Nanta by her sisters as soon as they could speak. Their father had been the Earl of Kentisbury for one week before he died, and that week had given a much-disliked title to the girls. Their Aunt Rosamund, the present Lady Kentisbury, had decreed that Nanta must use her first name, as “Lady Atalanta” would be undesirable, so everyone had tried to turn her into Rosalind, and the name was always used at school and when she visited Kentisbury. But at home it had been too difficult and Nanta had kept her nickname.

“I may be half-witted,” said Joy Quellyn, the mother of the twins, “but I keep mixing her up with Rosamund. After all, Ros lived here for eight years! I find myself saying Rosamund all the time. She’ll have to be Nanta.”

“I’d much rather be Nanta,” Rosalind assured her.

“It’s plain laziness with me,” said Jen Marchwood. “I don’t try to remember, because I like Nanta so much better. Nanta she shall be, and Rosamund must put up with it. Nanta can be Rosalind at school and at Kentisbury, but at home it’s too confusing.”

The elder sisters were now married. Virginia, living in Wiltshire, had a baby daughter, to whom Nanta was godmother and in whom she delighted. When she left school she would live with Virginia and Nancy Rose, and she was looking forward to it greatly. Till her school life was over, she, like Jansy, lived at the Hall, with the twins and several babies and their parents, Joy and Ivor Quellyn.

She was knitting her brows over Tessa’s trouble as they drove home that Friday evening. “I wish we could help, but nobody can do anything. Tessa will just have to put up with it,” she said.

“If the show was in Wycombe, I wouldn’t be surprised if Tessa slipped out and went on her own,” Jansy hinted. “She’s so terrifically keen.”

“I wouldn’t blame her,” Margaret Marchwood remarked.

“Oh, Margaret! Of course you would,” Nanta cried. “She couldn’t go behind her aunt like that!”

“She can’t, as it’s in London. Tessa’s sometimes a bit mad,” said Elizabeth darkly, “but she’s not as mad as that. She couldn’t go to London on her own at night.”

“Tessa isn’t mad any more, now that she’s been chosen Queen,” Nanta said quickly. “It’s made all the difference. She used to do mad things, but she’s quite sensible now.”

“All the same, I’m glad the show isn’t any nearer home. Tessa knows we’re all going, even Rosemary. She’s raging at being left out. It’s partly because she’s the new Queen,” Jansy added. “She’s been feeling important; you know she has, Nanta Rose! This has been a horrible shock to her.”

Nanta looked at her severely. “Will you never forget my baby name, Lob?”

“Never,” Jansy, the Lobelia Queen of a year ago, said cheerfully. “I like it. I always think of you as Nanta Rose.”

“Then please stop! Nanta is babyish enough, without anything tacked on to it.”

“It’s not babyish, only friendly. I couldn’t possibly stop; I shall always call you Nanta Rose. I remember not to do it at school,” Jansy urged. “I’ll call you ‘my lady’, if you like it better. Oh well, I won’t!” she said hurriedly, at the look Nanta gave her. “I promised Tessa we’d tell her every single thing about to-morrow night,” she went on. “But it didn’t cheer her up at all.”

“Did you expect it would?” Nanta asked grimly. “Tessa wants to be there, not to hear about it afterwards.”

“She wants to be able to say she was there,” Margaret said. “She doesn’t want to feel left out.”

“Because she’s the next Queen,” Elizabeth agreed. “I’d feel just the same myself.”

It was very hard on Tessa, and everyone was full of sympathy. Saturday night was to be a great occasion. Two and a half years before, the dancer, Mary Damayris, had met with an accident, and her career in ballet had seemed ended. She had recovered from the injury to her hip, but had been unable to dance again; with her sister Rachel she had come to the old Abbey which belonged to Jansy’s mother, to take the place of their aunt, who had been the caretaker. Putting away all thoughts of ballet, she had dropped her stage name and had become once more Damaris Ellerton, and had bravely built up a new life, making a beautiful garden round the gate-house of the Abbey, while Rachel acted as guide to the ruins. As Guardians of the Abbey they had been happy enough, but to Damaris this had been only second-best, and she had always kept the longing for ballet and the theatre.

Then, one wonderful night—the night of Nanta’s crowning as Queen Lavender—she had announced that she was going to dance again, to be Mary Damayris once more. The power she had lost had come back, and all the excitement and glamour of the theatre would be possible to her. Months of training had followed, but now, at last, she was ready, and on Saturday night she was to make her triumphant come-back to the stage.

Everyone would be there. Even little Rosemary was to be allowed to go. It would be a night of joy and thrills and thanksgiving. Mary Damayris would have an overwhelming greeting from the crowd who had loved her.

Tessa had written to her mother, who was in the South of France, recovering from a bout of influenza, begging to be allowed to go. Her mother had been perfectly willing, if the aunt who was taking charge at home consented. If not, she said, she would take Tessa herself, as soon as she returned. But that, to Tessa, would not be the same thing at all. It was the wonderful first night that attracted her, when Mary Damayris would be welcomed by the crowd.

And Aunt Edith had objected; had flatly refused to go herself or to send Tessa with anyone else. She did not care for ballet, and she felt it was unsuitable for a schoolgirl. No pleading had been any use; she would not go, and Tessa must not go either. What her mother did on her return was no business of Aunt Edith’s, but for herself she would have nothing to do with the project.

It was no wonder Tessa was in despair. Many of her school friends would be there, and especially all the crowd from the Abbey. Nanta and Jansy, the two Queens before her, were going, and she, the next Queen, must stay at home.

She was desperately unhappy and very angry. At school everybody heard of her trouble. At home she was silent, and Aunt Edith was hard and determined.

“And what’s the matter with Tessa?” A fair-haired smartly-dressed woman stopped the Queen-elect on her way home from school. “You look extremely grim, my dear! What’s up? Has the school found another Queen? I thought you were ready to jump over the moon because you’d been chosen.”

Tessa looked at Carol Carter, who was an acquaintance, though not a close friend, of her mother’s. Carol was about thirty-seven, unmarried, smart and lively, and she seemed to spend her life, from what Tessa had heard, at bridge-parties, dances, and the theatre. She appealed strongly to the reckless side of Tessa, which had been in evidence when she first changed over from ordinary school work and became a half-grown-up Cookery student, but which had been suppressed after a hint from Nanta that it was likely to hinder her chance of election as Queen. Tessa wanted to be Queen of the Hamlet Club more than anything in the world; she had eagerly subdued her wilder side, and the Club had joyfully chosen her as Queen.

“Well, what’s the trouble?” Miss Carter asked again.

Tessa boiled over, pouring out her story, as she had done at school.

“And I know her; Mary Damayris! Her sister lives in the Abbey, and I’ve been there to tea. The last time I went home with Jansy and Rosalind we went into the Abbey and she was there, Mary Damayris herself, and the man she’s going to marry in June, when she leaves the stage for good. He’s awfully nice and she’s as jolly as anything. She said she’d try to come to my crowning. And—and I can’t go to her first night! It’s filthy! It’s foul! I loathe Aunt Edith! She’s a stick!”

Carol Carter looked at her thoughtfully. “How brutal of your aunt! It won’t be at all the same thing to go in a fortnight, when your mother comes back.”

“Not a scrap the same.” Tessa’s voice broke. “They’ll all have been by that time. It’s the first night I want to see.”

“Yes, of course. She’ll have a wild welcome. Your aunt doesn’t understand. Can’t you make her see?”

“I’ve talked till I’m tired. She gets grimmer and grimmer and then she shuts me up.”

“You’re sure your mother would have let you go?”

“She said so. But it made no difference to Aunt Edith.”

“Come in here with me,” Carol said abruptly, and turned in to a tea-shop and ordered tea and cakes. “I won’t keep you long. Now listen, child!”

Tessa did not like being called “child,” but she listened, with widening eyes.

“I have two seats for to-morrow night,” said Carol Carter. “I was taking a young cousin, but it doesn’t matter so much to her as to you. She doesn’t know any of these people and she has never seen ballet. I could take her next week. Could you slip out and join me? I’d have my car by the church at six o’clock, and I’d bring you home to your own gate. Would you like to risk it? What about Aunty?”

Why she did it she hardly knew. She was sorry for the girl’s disappointment and she liked her. She did not question her own action more deeply than that. But far down in her mind was the thought that if Tessa found herself in trouble it would make difficulties for the Club, who had chosen her as Queen. And Carol Carter did not like the Hamlet Club.

Tessa did not stop to think of the Club or her future crown. “Would you?” she cried. “You couldn’t be so kind! To-morrow! I may be there, after all! Oh, Miss Carter, would you really? Would your cousin mind?”

“My cousin will put up with it. But what about your aunt?”

“I don’t care about her,” Tessa said recklessly. “Mother said I might go. That’s all that matters. I could slip out easily. There’ll be a row when I get back, but I don’t mind that.”

“Leave a note on your pillow to say you are quite safe and that I’m taking you in my car. Then she won’t be worried, though she may be mad.”

“She will be mad!” Tessa laughed excitedly. “But I don’t care. It’s her own fault.”

“Yes, she is very unreasonable. I don’t see that you will be committing a great crime. You have your mother’s approval.”

“Mother said, if Aunt Edith was willing.” Tessa had an honest side and it forced her to the admission. “She didn’t mean me to go without telling anybody.”

“But she will feel that your aunt was unreasonable too,” Carol pointed out smoothly.

Tessa, only too eager to be persuaded, accepted the specious argument and plunged joyfully into plans for the great event.

“Our seats are in the stalls, so you’ll have to dress,” said Carol. “Don’t meet your aunt on your way out! You could hardly pretend you were going for a walk.”

Something jarred on Tessa; the secrecy—“You could hardly pretend.” She thrust away the thought. “I’ll be very careful, Miss Carter.”

“Oh, call me Carol! We’re going to have an adventure together. We’ll have a little dinner somewhere, before going to the theatre.”

Tessa’s face glowed. This was an adventure, indeed! “You are a jolly good sort!” she exclaimed.

Carol smiled. “I hope you’ll enjoy it,” she said graciously. “I shall enjoy having your company. You’ll be much more thrilled about it than my cousin.”

Tessa went home treading on air. “Suppose I hadn’t met her to-night? It’s wonderful!”

She was at the appointed spot in good time, her yellow frock covered by a big coat, a scarf over her short dark curls. Her eyes were very bright and her cheeks were pink. So were Carol Carter’s, but Tessa’s fine colour was entirely natural.

“Any difficulties?” Carol asked gaily. “Did you creep down the back stairs? Or did you bribe the maids?”

Tessa’s happy face clouded. “I didn’t need to. Aunt Edith had a telegram; her daughter has been taken ill. She rushed away this afternoon; she won’t be back till Monday.”

“Oh, good luck! Then you had no trouble.”

“It’s odd,” Tessa said doubtfully. “I don’t understand why, but I’d rather it hadn’t happened. I’d feel better if I’d had to dodge Aunt Edith.”

“What an odd point of view!” Carol laughed lightly. “I should have thought you’d be glad. Unless the maids give you away, your aunt needn’t know anything about it.”

“Unless I tell her, when she comes back.”

Carol looked at her in amusement. “You couldn’t be such a little ass, surely!”

Tessa’s cheeks flamed and she said no more, but felt she had been childish and silly.

Carol saw it and changed the subject. “I like your frock. Pretty colour!”

Tessa was herself again in a moment, the touch of discomfort thrust aside. “I love lemon yellow. It’s the colour I’ve chosen for my May Queen train. My flowers will be lupins, and I’m having great spikes of them, in blue and rose and apricot, reaching out from the corners.”

“On lemon yellow? That will suit you, with your dark hair and eyes. You’ll be a fine spot of colour!”

“The procession needs brightening up,” Tessa explained happily. “I’m going to do it. We’ve had a lavender Queen, who is very demure, and a lobelia Queen, who looks regal but sober; and a rosemary Queen, in quiet colours too. It’s time we had a vivid Queen.”

“You’ll look lovely as the vivid Queen,” Carol told her. “I was nearly Queen once. Did you know?”

Tessa turned to her eagerly. “No, what happened? I knew you’d been to our school. Why were you only ‘nearly Queen’?”

“A split vote. Half of them wanted me, but half didn’t.”

“Oh, hard lines! Weren’t you fearfully upset?”

“I was, at the time. But it might have been a nuisance. I certainly shouldn’t have wanted to keep on dressing up as Queen, year after year, as they do. It’s time those married people dropped out. Some of them are so old that their daughters are Queens. Absurd, I call it!”

“Oh, but we like them to come! We want to see them, and we like the long procession!”

“That’s all right. But it wouldn’t appeal to me.”

“Did they choose the other person as Queen?”

“That wouldn’t have been fair. I had as many votes as she did.”

“Then what did they do?” Tessa asked, enthralled by this early history of the Club.

“They turned us both down and chose the newest member, who had only joined that evening. It was mad, of course, and a fearful risk; she might have been too awful for words. But it worked out quite well.”

“Who was she? Which Queen? Oh, please tell me—Carol!”

“Not shy of me any longer? All right, I’ll tell you. She was Joy Shirley, and she was a jolly pretty kid, in those days. She’s Lady Quellyn now. I suppose you’ve seen her at the Hall?”

“Oh yes! I know her twins, Elizabeth and Margaret—but their name’s Marchwood, isn’t it?”

“She married twice; the twins are the first family. She got the crown I ought to have had.”

“It was hard lines on you,” said Tessa. “Tell me more about those days!”

“No, you tell me about meeting Mary Damayris and her fiancé. What is he like?” and Carol kept the conversation firmly away from her schooldays.

“Where’s Rosalind?” Tessa burst into the cloakroom on Monday morning and looked wildly round. “I saw the car from the Hall. I want Rosalind!”

“You can’t have her till this afternoon,” Jansy said. “She went to Kentisbury yesterday, to tell them about Saturday night; Aunty Ros couldn’t be there because of the new baby. So Rosalind went to tell her more than she could say by phone. What’s up, Tessa?”

“I want to talk to her. I think I’m in a fearful mess.”

“Don’t you know?” jeered somebody. “I usually know only too well!”

“What’s the matter, Tessa?” Jansy saw that the trouble was serious.

Tessa flung off her hat and coat and seized the ex-Queen by the arm. “Perhaps you’ll do. I must tell somebody; I feel horrible. You’re only a kid, but you have been Queen. It ought to count for something.”

“I’ll do anything I can,” Jansy said patiently. “If you’d only tell me what’s the matter, I’d know if I could help.”

“Look here, Jansy! I went to that show on Saturday night. I saw you and all the Abbey crowd, but you didn’t see me. We were three rows behind you, and we slipped out quickly.”

“Oh, Tessa! Did your aunt relent at the last minute? I am glad! Wasn’t it marvellous? But how did you get tickets? We heard they were all sold days before.”

“Aunt didn’t know. She doesn’t know yet. I went with Miss Carter; she’s a friend of Mother’s. I’ve known her for some time,” Tessa said defiantly.

Jansy was staring at her blankly. “But—how do you mean? Did you say your aunt——?”

“She had to go away for the week-end; somebody had been taken ill. She won’t be back till this afternoon.”

“And you went, without asking her?” Jansy said slowly.

“I met Miss Carter on the way home from school on Friday, and I told her how bad I was feeling. She had tickets, and she offered to take me. We went in her car; it was perfectly safe. There was nothing wrong in it. But——”

“Only that you cheated your aunt,” Jansy told her unhappily.

“I felt she’d been unfair,” Tessa urged. “Mother said I could go. I suppose I’ll have to tell her.”

“Who? Your mother? Or your aunt?”

“Both,” Tessa retorted. “I meant Aunt Edith. I’ve written to Mother, of course.”

“I wish you hadn’t done it,” Jansy said. “It wasn’t quite—oh well!”

“What were you going to say?” Tessa demanded.

“It doesn’t matter. You know, or you wouldn’t be so keen to tell Rosalind.”

Tessa gave her a quick look. “Not straight? Not good enough for a Queen?”

“I didn’t say so. Why did you tell me?” Jansy asked indignantly.

“Because there’s something more. You haven’t heard it all yet. As we were coming out, the most awful thing happened. We ran right into the Head! I never dreamt she’d be there. She knew how much I’d wanted to go, so she smiled, and was just frightfully sweet, and said how glad she was that my aunt had arranged for me to come, after all. I didn’t know where to look or what to say; then she disappeared into the crowd, and I couldn’t get near her again. Now I feel I’ve cheated her as well as Aunt Edith. And do you think Rosalind will say I ought to go to Miss Raven and tell her I was there without leave?”

Jansy was gazing at her in horror. “Oh, Tessa, what frightfully bad luck! If she hadn’t been there—well, I don’t know. But when she spoke to you, and said that about your aunt, it’s almost like telling her a lie, isn’t it?”

“It’s letting her believe what isn’t true,” Tessa admitted. “But I didn’t tell her a lie!”

Jansy shook her head. “It will seem to her as if you had.”

“I want to know what Rosalind thinks.”

Jansy, overwrought and very much afraid of trouble for everybody, exploded suddenly. “Why do you want to put it on to her? Can’t you decide for yourself? Why should she tell you what to do? It’s jolly hard on Nanta Rose!”

“She’s the Queen,” Tessa muttered. “I’ll do it, if she says I must.”

“Well, I think it’s mean! Make up your own mind! You won’t like it, when you’re Queen—if you’re Queen——!”

“What do you mean?” Tessa exclaimed, a lurking fear, rigidly suppressed, leaping to the surface of her mind. “Why ‘if’? I’ve been chosen by the Club!”

“I know, and I want you to be Queen. But I’ve a ghastly idea—oh, can’t you see it for yourself?”

Tessa looked at her, wide-eyed and white. “You think the Club will say I’m not good enough to be Queen?”

“Not the Club. We all want you. But they might, if—oh, Tessa, go and tell the Head! Don’t wait for Rosalind—go now! It will make all the difference with the Club!”

“I don’t understand.” Tessa stared at her.

“They may feel you were mad to do it, but they’ll say—at least, you were honest and owned up,” Jansy explained breathlessly. “I know that’s how they’ll feel! And suppose your aunt tells the Head, Tessa?”

Tessa gave her a horrified look. “She couldn’t be such a rotter! But—yes, she could. She’ll be wild, and she might do it. Thanks, Jansy! I’ll go—now at once.”

She raced away to the Head’s study, her courage screwed up to top pitch.

Jansy gazed after her; then she went gloomily to her own classroom.

“What’s wrong with our future Queen? I saw her just now, looking like nothing on earth,” cried Phyl, Tessa’s chum, meeting Jansy on her way.

“She’ll tell you. I can’t.”

“Has she made an ass of herself again?” asked Sandra.

“I’m afraid perhaps she has.” Jansy, very unhappy, wished for Nanta as fervently as Tessa had done.

In a corner of the tennis court, at break, Tessa told the story to Phyl. “And whether you’ll ever be my maid-of-honour, is more than I can say, my dear,” she finished.

“Tessa, you are an ass! Why did you do it?” Phyl cried.

“Tessa, what did the Head say?” Jansy interrupted the conversation. “Sorry to butt in, but you ought to tell me; you shoved the trouble on to me!”

“Yes, it’s only fair.” Tessa’s face was full of foreboding. “The good Head was properly shocked; said I’d gone behind Aunt Edith and it wasn’t decent—in other words, of course! Said she was glad I’d told her and not left her to find out for herself. And said she’d have to think it over and decide what to do about it.”

“What did she mean by that?” Phyl demanded. “It’s nothing to do with school. She can’t give you lines or marks for what you did at the week-end!”

“I’m not so sure of that,” Jansy said sturdily. “If the Head saw any of us fooling about in the streets, being noisy, or larking with boys, she’d do something about it, however much out of school it was.”

“I’m afraid she means to do something,” Tessa said unhappily. “I wish I hadn’t been such an ass!”

“Didn’t she give you any hint?” Phyl asked anxiously.

Tessa kicked at the grass and stared at her feet. At last she faced Phyl and Jansy desperately.

“She said one thing. Said she didn’t feel I was trustworthy enough to be Queen. She’s going to talk to Rosalind.”

“Oh!” Phyl groaned. “But she couldn’t mean——”

“That’s what I’ve been afraid of,” Jansy wailed. “I’ve been dreading it all along. Oh, Tessa, why were you such an idiot?”

The story was all over the school by midday. Tessa made no secret of it, and finding that she was talking freely, Jansy answered questions among the younger girls as well as she could.

“Nanta Rose won’t like that,” Elizabeth Marchwood said gloomily. “For two pins the Head won’t let Tessa be Queen.”

“The Head can’t interfere. It’s the Hamlet Club’s job to choose the Queen and we’ve chosen Tessa,” her friend Diana argued.

“I think like Elizabeth does,” Margaret-Twin said firmly. “The Head won’t care about the Hamlet Club.”

“You two have only got one voice between you,” Diana scoffed.

“ ’Tisn’t true!” Margaret shouted. “We fight like anything, if we want to! But I know the Head won’t care what we think, and so does Lizbeth.”

“I’m afraid she’ll care so much that she won’t want us to have a Queen who might let the Club down,” Jansy said sombrely.

“Tessa wouldn’t ever do it again. She wouldn’t do it after she’s Queen,” Diana urged.

That was a very general view among the members of the Club. Tessa had been an idiot, but she had had a horrible shock and she would never do such a thing again. They were positive she would not fail, if she were Queen.

Jansy was not so sure. Tessa’s reckless side had shown before and it might break out again. Was that how Miss Raven felt?

“Besides,” Ann and Jennifer, friends of Diana and the twins, spoke together, “it was really that other person’s fault. She oughtn’t to have taken Tessa to town. She knew there’d be a row.”

“She’s a snake and a serpent,” Margaret said bitterly. “She tempted Tessa, and look what’s happened!”

“And Tessa was soft,” Elizabeth groaned. “It’s an awful pity.”

On that everyone was agreed, and on another point also. The Queen would be distressed when she heard the story. Her return was awaited anxiously by everybody, from Tessa down to Rosemary Marchwood and her friend Hermione Rose.

Nanta was quietly happy as the Kentisbury car brought her back for afternoon classes. Her reign had been peaceful and would, she felt, be looked back upon with pleasure by the school. She knew she would receive a thick crown of forget-me-nots when she gave place to Tessa on May-Day, a sign of her popularity with the Club. She had hardly a month more of school, but she would come back often, for coronations, and would wear her shining lavender train to welcome new Queens. Some day she hoped to see the Abbey twins crowned, and later on perhaps Rosemary and Hermione also.

She was looking forward to the summer, however. The sister who had mothered her had a beautiful home in the country and a fascinating baby girl of a year old. Nanta was to live with them and see as much as she wanted of Nancy Rose, her god-daughter. Virginia’s husband was attending lectures on agriculture in Bristol and was often away for a whole day; Virginia, hoping for a son and heir in the autumn, would spend a quiet summer, and she definitely wanted Nanta’s company. It was all arranged very happily.

The car set the Queen down at the school gate and she went in, carrying her violin.

On every side girls were lying in wait. They swooped down on her in an excited crowd.

Nanta thrust her violin into Margaret Marchwood’s hands. “Hold that for me! Be careful! What is the matter with you all?”

“Well, listen! We want to tell you! The most awful thing——”

“I can’t listen to you all at once! Oh—Jansy! What is this row about?”

The crowd made way for the ex-Queen, who thrust them aside ruthlessly. “Tessa’s in a fearful mess,” she said bluntly. “We don’t know what’s going to happen.”

Nanta looked down at her. “What is it? Oh, not Tessa!” she wailed.

“She went to the show on Saturday night without leave from her aunt, and the Head saw her there. Tessa’s been to her to own up.”

Nanta took her arm and led her out of the crowd. “Don’t come, all you lot. Jansy will tell me. I can’t say anything till I know more. I simply don’t understand. Take care of my fiddle, Margaret-Twin! Now, Jan! Tell me quickly!”

In a corner of the playground Jansy hurriedly gave the details. “Tessa’s hanging about, wanting to speak to you. But she said she’d let us tell you the worst.”

“Everybody knows, then?”

“Oh yes! She isn’t making any secret of it. Nanta Rose, what do you think the Head will do?” Jansy asked piteously.

They looked at one another, Jansy hopeful of comfort from someone so much older.

“I can’t imagine,” Nanta said. “But she’ll do something.”

“She won’t say Tessa mustn’t be Queen, will she?” Jansy voiced her great fear. “It would make dreadful trouble. The girls have been talking about it. They say the Head can’t interfere with the Club.”

“I’m afraid the Head will feel she can,” Nanta said unhappily. “She’ll say she must do what is best for the school. An untrustworthy Queen wouldn’t be good for either the school or the Club. I don’t say Tessa’s untrustworthy; she doesn’t think, that’s all. But it’s what the Head will say.”

“There’ll be a fearful row, if she butts in and takes away the Queen we’ve chosen, Nanta Rose.”

“Then it will be up to you and me to make the Club see sense!” Nanta spoke without hesitation. “We’re Queens. We have to stand by the Head. You will, won’t you, Jan?”

“I’ll stand by you through thick and thin,” Jansy vowed. “But I’m not looking forward to it.”

“That’s putting it very mildly! I’m terrified of what’s coming,” Nanta said gloomily. “We’re partly to blame, I’m afraid. We chose too soon; or we told Tessa too soon. A Queen has never been chosen in January before; we ought to have waited. But we were so sure, and we wanted Tessa so much. There’s the bell! I’ll speak to Tessa as I go in.”

Tessa was waiting for her near the door. “Rosalind, I’m so fearfully sorry! I’ve been an awful idiot. Do you loathe me too utterly?”

“Not a bit, but you were an ass, Tessa. I’m sorry, too, but I know how you felt. I’m glad you saw the show—if only you had gone in a different way.”

“I know. I can’t be altogether sorry, because it was so marvellous. That wonderful welcome, when Mary Damayris first came in! I’m glad I didn’t miss that. No other performance will be quite the same. Was it so very awful of me to go with Miss Carter?” Tessa asked wistfully. “You know how keen I was.”

“It was awful of Miss Carter to ask you. She understood, didn’t she?”

“Oh yes! She knew all about it. She said Aunt Edith was being brutal. We went in her car; we were quite safe,” Tessa urged.

“I wish you’d stood out against her, but I see how difficult it was for you,” Nanta said gravely. “I blame Miss Carter quite as much as you. But I don’t know what the Head is going to say. You’ve seen her, Jansy said?”

“Oh yes! I felt I was cheating her by letting her think I’d gone in a proper way, so I rushed off and told her.”

“I’m glad you did. You didn’t go quite in a proper way, did you?”

“No, it was sneaky,” Tessa burst out. “If Aunt Edith had been at home I’d have had to creep out of the house. Oh, I cheated, of course; there’s no getting away from it.”

“I can’t tell you not to feel bad about it,” Nanta said soberly. “I’m terribly sorry you did it. But I know how you were feeling and how that person got round you. I don’t suppose I can do much to help, but if there’s anything I can do I’ll do it. I’ll stand by you, and so will Jansy and the Club.”

“You’re an angel!” Tessa said fervently, as they went in together. “I’ve been afraid of what you’d say. I don’t feel quite so bad now.”

“I feel bad, though,” Nanta said to herself, as she went to the cloakroom to change her shoes and hang up her coat.

Her French class suffered that afternoon, for her thoughts were busy. Her violin lesson, which followed, was not really a lesson at all, for she played quite as well as her teacher. But it was good practice and they played together and discussed the music, and both felt benefit from the lessons. To-day, however, Nanta could not concentrate, and she begged to be excused the last few minutes, saying she wanted to see the Head.

“It’s all I can do. It may be no use, but I can try,” she thought, as she put away her fiddle. “Perhaps she’ll tell me what she’s going to do. At least I can put in a word for Tessa.”

And feeling very anxious she went to the Head’s study. As the reigning Queen she was a privileged person and she was admitted at once.

“Come in, my dear. I was just wondering if I should send for you,” said Miss Raven.

“You have heard what has happened?” Miss Raven looked at the tall girl who stood beside her desk. “Sit down, my dear. Perhaps you can help me to think this out.”

“Miss Raven, I am so sorry about it!” and Nanta broke into eager pleading for Tessa, urging her desperate longing to see the show and not to feel left out, and her sudden yielding to temptation. “At the last moment, when she had given up hope, it was really very hard to be offered what she wanted so much! She’d have had to be very firm and brave to refuse.”

“Yes, yes, I see that. But is she fit for the great responsibility you girls are giving her next term? That is what is troubling me.” The Head went straight to the point.

“I’m sure Tessa will be a good Queen. She’ll be careful what she does when she’s Queen,” Nanta pleaded.

“I don’t feel at all sure of it. Tessa has shown herself weak in this matter. She may allow herself to be tempted again.”

“She was honest about it. She came and owned up,” Nanta urged.

“Yes, I am glad she did. If she had tried to conceal the truth I should have had no doubts on the matter. I shall have to think it over carefully. Come to me again to-morrow afternoon; I may have more to say then. And don’t look so unhappy, my dear! The Club has plenty of time before May-Day to choose another Queen.”

“Oh, but they want Tessa! We couldn’t turn her down now!” Nanta cried. “Oh, please, Miss Raven! It would break Tessa’s heart! Miss Lane is making her Queen’s train; it’s half finished, I know. And everyone knows she has been chosen. It would be dreadful to have to explain.”

The Head looked thoughtful. Unconsciously Nanta had used an argument which definitely appealed to her. It was only Miss Raven’s second year as Head; she did not want school troubles known throughout the town.

“I agree with you. It would be most unpleasant. But the good of the school must come first,” she said, and dismissed the very unhappy Queen.

“Tell us, Nanta Rose!” Jansy and the twins pleaded, as the car set out for home.

“There’s nothing to say. The Head’s thinking it over, and I’m to go to her again to-morrow afternoon. She wants the best for the school. But she isn’t sure that Tessa ought to be Queen.”

There was a stunned silence. It was broken by a shrill outcry from Margaret. “There’ll be a jolly old row! That won’t be good for the school!”

“She hasn’t any right to butt in! It’s Hamlet Club business,” Elizabeth asserted.

Jansy looked unhappily at Nanta. “It’s no use frowning, Nanta Rose. It’s not only these two. That’s how all the girls are talking. I’ve heard lots of them say it.”

“Then we’re in for trouble,” Nanta said heavily. “Did you squash them?”

“I tried, but it sounded rather feeble,” Jansy admitted. “It’s how I feel myself, you see. This is a Hamlet Club job. That’s what the girls say.”

“But the Club is part of the school; a very important part. And you and I have tried to make it lead the school. We can’t possibly go against what the Head decides.”

“We’ve got to stick to the Club,” Elizabeth urged.

“Couldn’t you tell the Head what’s going to happen, if she goes on like this?” Margaret asked darkly.

“Threaten the Head? Oh, Margaret-Twin, we couldn’t do that!” Nanta laughed in spite of her distress.

“No, but you could warn her,” Elizabeth said. “Tell her how bad we feel, and let her guess the rest. That would be tactful!”

“There’ll be a rebellion,” Margaret began.

“Then you’ll have to reckon with Jansy and me.”

“Do you mean you’d side with the Head against the Club? But you’re the Queen!” Elizabeth gazed at her in horror.

“So I must do what’s best for the Club.”

“A rebellion against the Head could never be best, no matter how bad we feel,” Jansy explained.

“I shall ask Mother what she thinks,” Margaret said. “She was Queen once.”

“We can tell her, can’t we?” Elizabeth asked anxiously. “It doesn’t have to be a secret?”

“It can’t be a secret,” Jansy said. “We’ll have to tell people. They know Tessa’s been chosen.”

“It can’t be a secret,” Nanta agreed. “The old Queens were at the party when we told Tessa. They’ll have to know.”

“Then we can tell Mother,” the twins spoke together.

“And Nanta Rose and I will talk to Rachel,” said Jansy. “Here’s the Abbey—oh, look! There’s Aunty Jen, waiting for us. There’s your mother, Rosemary and Mike!”

“We’ve seen her,” Mike shouted. “Hi, Mother! Come in the car with us!”

“No, you’re coming out of the car with me.” Tall curly-haired Jen Marchwood, as fair as Michael and a complete contrast to dark little Rosemary, had stopped the car at the Abbey gate. “Hop out, all of you! Twins, your mother has asked us three to tea, so you can look after Rosemary and Mike.”

“We’ll have tea with them and the boys and Maidie-Rose,” said Elizabeth, referring to her small half-brothers and the baby girl who had been born in America almost a year before.

“But we want to hear what Mother says about the row,” Margaret cried.

“We’ll do both,” Elizabeth said firmly.

“Row? What’s the matter? What is she talking about, Lavender?” Jen addressed Nanta by her Queen’s name. “Who is in a row?”

“Everybody. The whole Hamlet Club. We’re in a frightful mess, Lady Jen.”

“Then we must certainly hear about it! We wanted your report on Rosamund and the new baby, but perhaps there’s something more urgent.” Jen looked at the Queen keenly. “You’re worried, dear. This won’t do! We can’t have our Fiddler upset.”

“It’s much more urgent,” Nanta agreed. “And I am worried. We want to know what you think.”

“We want to tell you old Queens about it,” said Jansy.

“You might say ‘former Queens’. We’re not so very old,” Jen laughed. “As former Queens we certainly want to know when the Club is in trouble.”

“Well, it is now,” Elizabeth told her.

“It’s in a ghastly mess,” said Margaret. “We’ll tell you and Mother both at the same time.”

“Yes, don’t say any more till we find your mother,” Jen agreed.

The car drove on to the Manor, and the schoolgirls and Jen went through the ancient gate-house and up the drive between flower-beds thick with golden and violet crocus and bushes of sweet-briar.

“Can you still see this as it used to be, when it was just a meadow?” Jen asked, hoping to change the current of Nanta’s troubled thoughts.

“Not very clearly, though I sometimes try.” Nanta gave her a quick smile. “I can’t banish the garden. I can see only flowers.”

“We knew it as a meadow for twenty years,” Jen said. “But the garden is beautiful. Mary Damayris did a good spot of work when she made it; her years away from the theatre weren’t wasted. She has left us the garden as a reminder of those days, and Benedicta is keeping it as beautifully as she did.” And she waved to a girl in khaki smock and breeches, with lint-white hair, who was digging in a far corner.

She waved in reply, but went on with her work, and Jen and the girls went to the inner gate. It was opened for them by the Abbey Guardian, Rachel, the dark-haired sister of the ballet-dancer, who wore a white gown like a monk’s robe as a sign of her position.

“All well?” she smiled, as she held the heavy gate open for the small children.

“No, very ill,” Margaret retorted. “The Queen’s coming to talk to you after tea.”

Rachel looked at Nanta. “What’s the matter?”

“Bad trouble at school, Rachel. May I tell you about it later?”

“Oh, please do! I’m very sorry.”

Queen Lavender’s eyes rested on the quiet garth and the old grey buildings. “It helps, just to come back to this peaceful place. I like to feel we have it behind us. I’m glad we aren’t boarders at school.”

“We’d never get away from the mess,” Jansy added. “I know how you feel, Nanta Rose. We can’t forget the row, but we are out of it once we’re back in the Abbey.”

“It should help you to see things more clearly and put the row in its proper place,” Rachel said. She looked at Jen. “Do you know what it’s all about?”

“I do not, and I’m bursting with curiosity,” Jen said solemnly. “All these hints about rows and messes are so tantalising! Come and tell Joy and me all about it, Jansy and Nanta!”

“Lob and Lavender,” said Jansy. “It’s because we’re Queens that we’re so worried.”

“Then the old Queens must try to help,” Jen told her.

In the big entrance-hall, with its family portraits and stained-glass windows throwing coloured patterns on the polished floor as the sunset light streamed in, Joy, Lady Quellyn, and Jen, Lady Marchwood, listened to the story told as a duet by Nanta and Jansy round the tea-table. On promise of hearing their mother’s verdict later, Elizabeth and Margaret had accepted their duties as hostesses and were upstairs in the nursery, entertaining Rosemary and Mike and playing with David and Richard, who were five and four years old, and Baby Rose, or Maidie-Rose, as they insisted on calling her.

“Just Rose isn’t important enough. It’s such a little name, when I’m Elizabeth and Twin’s Margaret,” Elizabeth had argued, when their mother tried to change her young daughter’s name from Baby to Rose. “As her first name’s Maidlin, for Aunty Maid, we’re going to call her Maidie-Rose.” And “Maidie-Rose” had been adopted by most of the clan, in spite of Joy’s preference for the simpler name.

“You are in a mess, sure enough,” Jen groaned, when she understood the situation. “And I don’t see how to help. It rests with the Head, and we can’t go and plead with her. If it had still been dear old Mackums—I mean Miss Macey! You didn’t know her, Nanta—we might have done something.”

“Carter?” said Joy thoughtfully. “Could that be Carry Carter, who was my maid-of-honour? You remember the fuss with Carry, Jen? No, of course you won’t; it was before your time. Queer to think there were days when we didn’t know Jenny-Wren!”

“I thought we’d always known her.” Jansy grinned.

“I remember hearing the story when I was a quite new kid of thirteen,” Jen said. “She let you down in some way, didn’t she?”

“She read a private note-book which I’d been silly enough to leave lying about, and used what she read to make trouble.”

“Oh, the beast!” Jansy cried. “It sounds like the same person. But Tessa said ‘Carol Carter’.”

“You can’t blame her for making the best of her name,” Joy laughed. “I’d turn into Carol myself if I were unlucky enough to be called Caroline. But she was Carry at school. I saw her for a second in the crowd at the theatre, but I didn’t see Tessa. Of course it’s Carry Carter, turned up again and trying to do a bad turn to the Club because, all those years ago, she wasn’t chosen Queen!”

“She’d have been a jolly bad one,” Jen said. “How have you managed to avoid her all these years?”

“She got herself sent to boarding-school. She’d have liked to be Queen, but when Joan was chosen after me, and Muriel after Joan, Carry gave up hope and went off to school in London. She tried hard to be a friend to me when she came back, grown-up and smart.” Joy smiled. “She wanted to visit here and be a pal. She always was a little snob, and she liked the look of the Hall! But I didn’t want her and I never asked her here. She didn’t like being ignored, so she kept out of my way and never came to crownings or anything at school. I haven’t seen her for years. She’s away from home a great deal, I believe.”

“Could we do anything about this mess?” Jen began. “Could you write to Miss Raven and say you believe Miss Carter was trying to pay off a grudge against the Club, by getting the future Queen into trouble?”

“I could, but it wouldn’t be any use. Miss Raven would merely say Tessa had shown she had no backbone and she was too weak to be Queen.”

“She was very badly tempted. It was hard on her,” said a voice from the tea-table.

Joy’s friend and secretary, Mary Devine, had been attending to the tea-pot. The four Queens turned to her eagerly, Jen the first to get out her question.

“What do you think about it, Mary-Dorothy? Tell us what to do!”

“I don’t see that you can do anything. I’m very sorry for Tessa, but she has made a bad mistake. You might plead for her and for the Club—all you former Queens. Joan and Rosamund and Maidlin would be glad to help. It will be very hard on the Club if there’s any interference with the coronation, after all these years.”

“Ghastly! The whole town would know,” Jen agreed.

“Beatrice and Grace ought not to be left out of this,” Mary said, speaking of the two nurses in charge of the children upstairs. “They are former Queens; in any Hamlet Club business they should have their share. Shall I send them down? I’ll stay with the babes.”

“Mary-Dorothy, how kind you are!” Joy exclaimed. “Yes, please fetch the girls. But we want your advice too.”

“I can only suggest a petition to the Head, signed by all the former Queens you can find. Maidlin has Queen Honesty in her nursery, and Rosamund has Hyacinth and Lilac. You could have quite a list of signatures.”

“It won’t do any good,” Joy said. “But we can try.”

“It would show Miss Raven how strongly we feel,” Jen began.

Mary paused on her way to the door. “If she thinks you’re trying to interfere, it may do more harm than good. Miss Raven is the one to decide. You mustn’t let her feel you are trying to force her hand.”

“She’d turn against our ideas at once,” Jen admitted, as Mary went upstairs. “You know her better than we do, Nanta and Jansy. How would she react to a petition from the early Queens? She doesn’t really know us.”

“She might be mad and say you were trying to butt in,” Jansy said gloomily.

“It would have to be put to her very carefully,” Joy said. “And while we are preparing our petition she may have made up her mind. If she has once given her verdict she isn’t likely to change for anything we can say.”

“Not if she’s a Head worth having,” Jen assented, with gloom equal to Jansy’s.

“She won’t change her mind,” said Nanta.

The Striped Queen, Beatrice, and Grace, the Garden Queen, came racing down to join the conference, as soon as they heard the Club was in trouble. But neither could make any useful suggestion. Beatrice remembered Carry Carter and asserted that it was just what might have been expected of her, but Gracie had never known her. She was much younger, being the seventeenth Queen, while Queen Bee had been the eighth.

Jen was moved to protest. “I don’t know Carry and I don’t like what I’ve heard of her, but she may have meant this kindly. We’ve no proof that she was trying to hurt the Club. She knew Tessa and she saw how disappointed the girl was. She tried to help. That’s all.”

“Would you have helped in that way?” Joy demanded.

“Of course not. I hope I know what’s decent! But from what you say of Carry Carter, she evidently wasn’t particularly honourable even when she was at school.”

“That’s putting it very mildly,” Joy said grimly.

“Give the woman a chance. She may have tried to be kind, and she seems to have no principles,” said Jen.

Nanta looked up. “The Head will still say Tessa ought not to have gone.”

“That’s what we’re all afraid of,” Joy agreed. “No matter how much Carry Carter may have been to blame, the real trouble is that Tessa didn’t refuse.”

“In fact, Tessa’s principles weren’t any stronger than Carry’s,” Gracie Gray remarked. “If the new Head says she’s too weak to be Queen, you can’t blame her.”

“But Tessa’s nice! You don’t know her,” Jansy wailed. “We all like her. We want her for Queen!”

“We asked her too soon,” Nanta said heavily. “It was our mistake. It was partly because she’s the new Queen that Tessa cared so much. She felt important and excited; we’ve all known that; and she couldn’t bear to be left out. It’s partly our fault.”

“Perhaps you could remind Miss Raven of that, when you see her to-morrow,” Jen suggested.

Nanta sighed. “I’ll try. And I think we might send a petition, signed by all the Queens we can get hold of.”

“We can ask Clover and Wild Rose,” Joy said. “And of course the President and the first Queen. We can find nearly everybody. But it will take a few days. I’m afraid we’ll be too late. The Head will have to decide.”

“I’d like to go and talk to Rachel in the Abbey,” Nanta said wearily. “I know she can’t do anything, but we’ll have to tell her; she knows something is wrong. It helps to talk things over with her.”

“This is hard on you, Lavender,” Jen said gently. “You’ve had such a happy reign.”

Nanta’s lips pinched. “I thought something like that, in the car coming back this afternoon. I felt so good about school; everything seemed to have gone so well. There’s less than a month left now.”

“And Tessa has spoiled everything! It is really very hard,” Jen exclaimed.

“It isn’t Nanta Rose’s fault!” Jansy cried.

“No, but it’s going to fall on her; seeing the Head, and perhaps arguing with the Club,” said Joy, as Nanta went out. “You must back her up, Jansy. We know she’ll accept whatever the Head decides; she has no choice. But she may find herself up against the Club, if they take Tessa’s side, as of course they will. Don’t let Nanta feel she’s alone against the world!”

“I won’t. I’ll stand by her,” Jansy said fervently. “Can’t I go to the Abbey too? I want to hear what Rachel says.”

“Go presently,” Jen advised. “Let Nanta have a few minutes with Rachel first.”

It was closing time in the Abbey. Rachel, seeing Queen Lavender at the door, took off her white gown and put away the manuscript on which she had been working.

“Come along! I’ll light the fire; I don’t need it till the evening. Have you had tea?”

“Yes, thanks, all I want.” Nanta looked round the little parlour, inside the outer walls of the Abbey, with its crimson lamp, gray and blue pictures of the Lake District, and magnificent daffodils and tulips in green jars on the table and bookcases. “Are these some of Mary Damayris’s flowers?”

Rachel, in a blue dress, knelt to coax the fire into life. She smiled up at the Queen. “Yes, aren’t they lovely? She brought them home on Saturday night because they were so beautiful, but she couldn’t take them back to town with her, so I’m getting the benefit. The tulips came from Kentisbury and the daffodils from the Manor. There! That will be all right. Now what has happened at school?”

She drew up a low chair and listened intently while Nanta told her story.

“Oh, poor Tessa! One can understand it, of course. And poor Lavender! What a blow, when you hoped for so much from Tessa!”

“I knew you’d understand,” Nanta said gratefully. “You can’t do anything; but it helps to feel you care. You see how dreadful it is, don’t you? Jansy and I must do what the Head wants; Queens can’t lead rebellions! Margaret is sure there will be what she calls a rebellion. But it will be very difficult, if we can’t make the Club see it.”

“I sympathise most deeply,” Rachel said. “But you must uphold the Head. Perhaps the girls will be reasonable.”

“But the crowning in May, Rachel! I know the Club won’t choose another Queen. They’ll stick to Tessa, now that she knows we want her.”

“Is that the Head’s suggestion? No, I don’t suppose they’ll choose anyone else. But it would be dreadful to have no Queen.”

“I can’t see any way out,” Nanta said drearily.

“There will be a way; there always is,” Rachel told her bracingly. “I don’t say it will be easy, and I can’t guess what it will be, but there will be one way, at least, and you’ll have to go ahead and see what you can make of it. Jansy will back you up.”

“Oh yes! But she’s only fifteen. It’s all the help in the world to have people like you and Mary-Dorothy, and Lady Jen and Lady Joy, at home to talk to. We feel we have you behind us. If we were boarders, alone at school, we couldn’t carry on. Here comes Jansy!”

“Instead of listening while you tell us a school story, we’ve brought the story to you, Rachel,” Jansy proclaimed, squatting on the hearthrug. “Have you talked sense to Nanta Rose? Talk to me too!”

“I’m very sorry about one thing,” Rachel said soberly. “I’m terribly upset that this has happened because of Damaris. She’ll be sorry too.”

“It isn’t her fault.” Jansy and Nanta spoke together.

“No, but she’ll be sorry,” Rachel said again. “I’m ringing her up later, to hear how to-night’s show went, but I shan’t tell her your story till to-morrow. It wouldn’t be fair.”

“No, not after her show. Saturday night was marvellous. Really, I don’t blame Tessa,” Jansy remarked. “She just couldn’t bear to miss it when she was given the chance to go. It was that woman’s fault. I’m going to tell Tessa what Aunty Joy says about her. Then Tessa will loathe her for ever.”

“Tessa won’t trust her again,” Nanta said. “I’m sure she’s had enough of Miss Carol Carter.”

“Carry, or Caroline.” And Jansy looked up at Rachel and repeated the story Joy had told.

Rachel pursed her lips. “Not a good friend for Tessa. What a pity they met that afternoon!”

Nanta rose to go home. “You’ll tell Mary Damayris how much we loved her dancing, won’t you? When is she to be married? Is it fixed?”

“In June. She and Brian have decided definitely now. She wants the twins and Jansy to be bridesmaids.”

“Oh, good! How nice of her! I shall be very willing to oblige her,” Jansy said formally.

“Come home and do your prep. To-morrow’s going to be difficult enough without unprepared work,” Nanta warned her.

“I can’t think about prep. I’m too worried,” Jansy retorted.

That was the usual attitude in the Hamlet Club next day. Work was badly prepared or not done at all. Thoughts were wandering, and the girls were excited, or gloomy, or anxious, according to their temperaments.

“Everything’s horrid,” Hermione Manley confided to her friend, Rosemary Marchwood, and other ten-year-olds.

“It’s this Hamlet Club bother,” Rosemary agreed. “They don’t know what’s going to happen. The twins can’t talk about anything else, and Jansy and Queen Lavender don’t say a word; they’re too upset. It was horrid in the car this morning.”

Jansy sought Tessa as soon as she reached school, and found her coming to look for Nanta, her face white and set.

“Lavender, I’m sorry. I must say it again. It’s all my fault and I feel frightful. Shall I resign from being Queen? I think it would just about kill me, but I’ll do it, if you say I must.”

“No, don’t do that,” Nanta said quickly. “We do really want you; we know you’ll never do anything like this again.”

“Rather not!” Tessa said, with emphasis.

“We want to see you through. You’re our Queen, and we’re not going back on you. The Club wouldn’t like it, if they lost you now.”

“It wasn’t all your fault,” Jansy cried. “That Miss Carter has been a sneak and a rotter all her life. You’ll never like her again when you hear what she did once.”

Tessa listened, frowning. “She didn’t say anything about that to me. She told me she had nearly been Queen.”

“She wouldn’t tell you it all, of course. Will you like her again, Tessa?”

“No,” Tessa said curtly. “You needn’t have told me. I was an ass to go with her, but she shouldn’t have asked me. I don’t trust her now. Aunt Edith’s been rubbing it in.”

“Has your aunt come back?” Nanta asked.

“Oh yes! There’s the father and mother of a row! I told her; I didn’t want the maids to give me away or Miss Raven to write to her. We had a scene, and we’ll have more yet. She swears she’ll write to the Head and say I’m not fit to be Queen; I said the Head knew that already. And she’s writing to Mother. I was glad I could say I’d written on Sunday.”

“At least you haven’t tried to hush it up,” Jansy said.

“What do they say at the Abbey?” Tessa looked at Nanta. “You told them, I suppose?”

“We couldn’t help it. They’re Queens of the Club; they had to know. They’re terribly sorry. But if they were running the school I think they would give you another chance. They’re very understanding and kind.”

Tessa nodded and turned away hurriedly. Any touch of sympathy would break her down to-day, though she could meet blame or scorn with defiance.

From every class reports went to the Head of inattention and carelessness. Miss Verity could not keep the girls to their French; Miss Honor complained of their maths; Miss Raven herself had difficulty with their literature; the cookery mistress was really annoyed with her senior students.

“They say they’re worried,” said Miss Verity. “The whole school seems to be worried.”

“But the Hamlet girls are the most upset,” said Miss Honor, who had been the Wild Rose Queen in her schooldays. “We shan’t get good work out of them till this affair is settled.”

“I can do nothing with Tessa and Rosalind and the rest,” the cookery mistress added.

“Janice Raymond made a complete mess of her French translation, and she can do it well enough, when she likes,” Miss Verity remarked.

The Head knew that something must be done. Early in the afternoon she sent for Nanta.

“Is there any chance of the Hamlet girls choosing another Queen?” she asked abruptly. “I can’t think Tessa is fit for the position at present.”

Nanta faced her bravely. “They won’t do it, Miss Raven. I’ve heard them talking. They’ve chosen Tessa, and they mean to stick to her.”

“I can’t force them to choose someone else,” the Head said. “You are making it very difficult for me. I can’t accept Tessa as a trustworthy Queen, but I don’t want to break the school tradition of the May-Day crowning. If they would choose somebody else for this year, and if Tessa proved herself to be trusted, by next year I might be able to allow her to be Queen.”

“Miss Raven, if you’d give her another chance!” Nanta pleaded. “She’ll never do such a thing again! She has had a dreadful shock; she’ll be steady enough now. If she hadn’t met that—that friend, this wouldn’t have happened. It wasn’t her own idea. She was tempted by that person. I know she was weak and silly, but that was all.”

“But would a weak and silly Queen be good for the Hamlet Club?”

“I feel the Club is partly to blame.” Nanta spoke with great earnestness, and with courage too. “Perhaps I was more to blame than anyone. We chose Tessa too soon. I urged the rest to do it. We oughtn’t to have told her in January; it has never been done before. It was partly her excitement and her important feeling about being Queen that made her go; she couldn’t bear to be left out. We were to blame, Miss Raven. We were in too much of a hurry. But there seemed to be no one else—and there’s no one else now. I can’t ask the girls to choose again, for they’ll just say ‘Who is there?’ and I haven’t anybody to suggest. Couldn’t you let Tessa try?”

“She might let you down and that would be disastrous for the Club and for the school,” Miss Raven said gravely.

“She wouldn’t do that. She’d feel responsible, if she was Queen.”

“And yet, being Queen-elect, she did this, my dear.”

In despair Nanta stood silent.

The Head looked at her thoughtfully. As Queen, Nanta knew the temper of the girls even better than she and her mistresses did. She guessed fairly well what their attitude must be, from the Queen’s downcast face.

“Have you had a meeting of the Club over this business?” she asked.

“No, Miss Raven. Not a real meeting.”

“Only informal gossip. Call a meeting, then—for this afternoon, if you like—and tell the Club I wish them to choose another Queen. Point out that it will be a great pity if there can be no crowning in May.”

Nanta looked at her in mute despair, but made no comment.

“You think it will be no use? That it is a waste of time?”

“Yes, Miss Raven.”

“All the same, I would like you to try.”

“Very well, Miss Raven.”

“Some new idea may come out of your meeting. Well, what are you thinking, my dear?”

“Must I say, Miss Raven?”

“Certainly. Please tell me what you think.”

“I don’t believe it will be a helpful idea,” Nanta said unhappily. “I think it’s very likely there will be ideas, several of them, but they won’t be ideas that will make things any better. I’d rather not give the girls the chance to put them into words.”

“I see.” The Head looked at her thoughtfully. “You have done your best, anyway. I won’t blame you for what happens.”

In complete despair Nanta went to find her maid-of-honour, Margaret-Twin, and sent her round to each classroom with notices of a meeting to be held after school.

“We must get it over,” she said to herself. “None of us would sleep to-night if it were put off till to-morrow; I know I shouldn’t.”

She went to Tessa and begged her not to come to the meeting. “I’ll tell the Club you have offered to resign. You can’t do any more. I’ll ring you up to-night and tell you what happens. It would only make you feel bad to be there.”

Tessa turned a scared face to her. “She won’t have me for Queen?”

“She wants us to find somebody else. But the Club won’t do it. That’s the trouble, Tessa. They’re going to defy the Head. I don’t know what she’ll do.”

“Gosh!” said Tessa. “I say, Lavender, I’m not worth it. Let me back out! Then it would all blow over. We can’t have a complete school row over me!”

“I’ll tell the girls you’ve offered,” Nanta said again. “But don’t come and say it yourself. That would make us all feel awful. We don’t want the kids in tears.”

“It might be myself in tears,” Tessa said grimly. “Perhaps I’d better not. But tell the Club I don’t want a revolt in the school over this.”

“Right! I will,” Nanta promised. “I said all I could to the Head, you know.”

“You’ve been jolly decent about it,” Tessa said hurriedly, and fled.

The library was in an uproar. The Hamlet Club had come to hear the Head’s decision; their Queen had given it briefly, without comment.

“She won’t have Tessa. We’re to choose someone else. She doesn’t want us to give up the coronation.”

A hubbub broke out. Nanta threw herself back in a big chair and waited.

“There isn’t anybody else! She can’t make us have a Queen we don’t want!”

“She has no right to butt in on our affairs! No Head has ever interfered with the Hamlet Club! It’s our business who is Queen!”

“She can’t have a coronation without a Queen. I say, everybody, she’ll want to have it!” There was a shout of triumph from Elizabeth Marchwood. She sprang on to a chair and managed to make herself heard. “We’ve had crownings for years and years and years. If there isn’t one people will talk, and they’ll say there must be something wrong in the school!”

“Miss Raven doesn’t want them to think that,” Margaret added in delight. “If we won’t choose anybody else, she’ll have to put up with Tessa.”

There was a shout of agreement from the younger members, but the elders looked grave.

“Serves her right, if she finds herself in a hole,” Margaret added, taking advantage of the attention Elizabeth had won. “Interfering with the Hamlet Club! It’s like her cheek!”

“I say, Lavender, can’t you stop this?” asked Sandra, a senior, uneasily.

Nanta was already on her feet. “Margaret! I’m ashamed of you! How dare you speak of the Head like that!”

“But it’s true,” cried Jennifer and Ann together. “No Head butts in on Hamlet Club business! We choose the Queen!”

“Girls!” Nanta ignored the juniors. “I ought to tell you that Tessa has offered to resign her place as chosen Queen, rather than have trouble in the school.”

“But we want her! We’ve chosen her and we’re going to stand by her,” came the quick response from every corner of the room.

“And do you think it will be comfortable, if we insist on having a Queen whom the Head has refused?”

“That’s her look-out,” Elizabeth said instantly. “If she doesn’t like the Queen we choose, she can—she’ll have to put up with it, that’s all.”

“It’s her own fault,” Margaret shouted.

“You two are going to have a jolly time in the car going home,” Jansy observed.

This possibility had not occurred to the twins. While the uproar broke out again, Elizabeth asked anxiously, “Are you going to side with the Head against the Club, you and Nanta?”

“Jansy, you couldn’t be so silly!” Margaret almost wept. “Don’t you want to stand by Tessa, you two?”

“Come here, Margaret-Twin,” said Nanta, ignoring the wild talk that was going on all around.

“What for?” Margaret demanded truculently.

“Only that I want to speak to you. I can’t shout against this din.”

“You come too, Betty-Twin,” Margaret said piteously.

Elizabeth climbed down from her chair and put her arm round the younger twin. “Come and see what Lavender wants, Peggy.”

“You’re being very unkind to Jansy and me,” Nanta said quietly. “We want Tessa as much as you do, but being Queens we can’t go against the Head. Perhaps some day you’ll be Queen yourself; you never know! Then you’ll find how difficult girls can make things for you.”

Margaret gazed at her. “I didn’t mean to make it hard for you and Jansy.”

“Sorry!” Elizabeth wailed. “We’re very sorry! But we do want Tessa and we don’t like the Head messing up Hamlet Club business! She does want us to have a crowning, doesn’t she?”

“Yes, I think she does.”

“Then she ought to let us crown who we want to.”

“What dreadful grammar, Elizabeth-Twin!”

“Who cares about grammar? And who could be Queen, if Tessa isn’t?”

“That’s what I can’t tell you,” Nanta admitted.

“There isn’t anybody,” said Margaret stubbornly.

“I rather agree with Margaret,” Sandra remarked. “As no one else seems in the least suitable, we might as well have Tessa.”

Nanta, looking white and tired, suddenly rang a small bell which she had brought from a classroom. Silence fell, as the girls turned to her in astonishment.

“Sorry to startle you, but we aren’t getting anywhere, and it’s late. Girls, let me speak for a moment. I must take some message to the Head from this meeting. We still want Tessa as Queen and we can’t think of anyone else. Is that right?”

“Correct on both points,” said Jansy promptly.

“We’d rather go without a coronation next May. Is that right too?”

“Heaps rather!” There was a defiant shout.

“I don’t know,” Sandra admitted. “It will be awful, after all these years. Isn’t there any other way?”

“It will be horrible having to explain to people, and they’ll talk,” Jansy said unhappily. “It will be bad for the Club.”

“Bad for the school too,” Phyl observed. “But I don’t see anything else for it, Lavender.”

“It will be bad for us as well,” Nanta said grimly. “The Head isn’t going to love the Hamlet Club after this.” She leant forward over the librarian’s desk. “Girls, for the sake of the school, to keep things going happily, couldn’t we give in and find somebody else, for this year? Miss Raven promised she would let Tessa be Queen next year, if she showed herself steady and responsible in the meantime. Couldn’t we?”

There was an immediate change in the atmosphere. The girls had listened, with sympathy for her obvious distress, but now they stiffened into definite opposition.

“No, we couldn’t.” The reply came from every corner.

“Whom could we ask?” Phyl demanded.

“Anybody; you—Sandra—anyone. Just to carry on for a year, to satisfy the Head, and have a coronation.”

“We don’t want to satisfy her. We don’t want her butting into our affairs,” said Diana.

“That’s how we all feel,” Margaret muttered.

“Is that how you all feel?” Nanta put the question directly to the meeting.

“Yes, it is!” The answer was defiant but unanimous.

“Then I must tell the Head.” Nanta leaned on the desk, looking white.

The girls gazed at her, feeling uncomfortable.

“You don’t seem to realise how hard it is for me,” she broke out, her voice unsteady.

“It isn’t fair! You shan’t do it this time!” Jansy sprang on to the dais beside her. “Hamlet Clubbers, we’re shoving everything on to Lavender. It’s mean! We ought to do our share. We’ll send a deputation to the Head, and Lavender mustn’t be on it. We’ll tell the Head she did everything she could to make us be sensible, but that we wouldn’t listen. Now please offer to be on the deputation! Be sports—come on! I don’t want to do it a bit, but I’ll be one, if I have to. We must let Lavender off. She’s not going to do any more.”

“How nice of you, Lob!” Sandra said warmly.

“It’s lovely of you, Jansy, but it’s no use. The Head expects me to bring her a message from the meeting,” Nanta exclaimed.

“You shan’t do any more, Nanta Rose,” Jansy insisted.

“Perhaps I could be the deputation?” said a new voice, from the back of the room.

“Miss Verity!” On every side girls whirled round to face the young French mistress, who had come in unnoticed and had been standing silently near the door.

“Oh, I say, how ghastly! She’ll tell the Head what everybody’s been saying!”

Miss Verity heard the whisper that ran round. She came to the dais and stood by Nanta and Jansy.

“Girls! I am a member of the Club and I have every right to be here. You have been hospitable to me and have received me kindly; now perhaps I have a chance to repay your generous welcome. I shall not betray anything that has been said, of course; but being a sort of half-and-half—Hamlet Club and Staff—I may be able to discuss your difficulty with the Head, as none of you could do. I see her point, and I see yours. We all want to have a coronation. We have to find some way.”

She had come to the school a year and a half before, and was well liked by the girls. Twenty-two years ago, her aunt, Marguerite Verity, had been the third Queen of the Club and one of its original members, and as Queen “Strawberry” she had helped Joy during her first difficult days as Queen. Her niece had been welcomed warmly by all who had known Marguerite; she had been eager to learn English folk-dances, as her life had been spent in France. The Club had accepted her and had taught her; she had danced with the girls at their parties and at Nanta’s crowning.

“Will you let me try what I can do?” she asked.

The girls looked at her doubtfully, and she laughed. “Your consciences are uneasy, and I don’t wonder. I shall merely tell Miss Raven how very strong your feeling is; she can’t know unless she is told, and she would feel Queen Lavender was prejudiced. The only thing I shall repeat is how bravely Rosalind has spoken and how loyal she has been to the Head and to the school. That I shall certainly do.”

“Hear, hear!” Jansy said loudly.

“Oh, please, Miss Verity! Please don’t!” Nanta begged.

“Don’t be mad, Nanta Rose,” Jansy scolded. “I shall do it, if Miss Verity doesn’t. Any deputation must say you’ve done your best.”

“Yes, we must say that,” Miss Verity agreed. “Well, girls? Will you let me try?”

“Yes, please, Miss Verity.” The girls sounded subdued, not liking the thought that their wild talk had been overheard.

“Good! I will see Miss Raven at once. Off you go, all of you! It’s getting late. You shall hear the result to-morrow. Janice, tell Lady Quellyn that Rosalind is to go to bed. She’s tired out.”

“Oh, please, no!” Nanta cried. “I couldn’t sleep!”

“Early, then. You are very tired. You’ll see to it, Janice?”

“Yes, Miss Verity!” Jansy grinned at the Queen. “I’ll put you to bed, Nanta Rose.”

“So you were present at the meeting?” The Head looked at Miss Verity in amusement. “How much can you tell me? I am anxious to know the real feeling in the Club. But I suppose you can’t say very much?”

“They were afraid I was going to betray them wholesale, when they discovered I was there,” Miss Verity laughed. “I can’t do that, of course. But they were going to send a deputation, so I offered to take on the job. I hope you won’t mind, but I’ve sent them all home and told Rosalind Kane to go to bed early. She was quite worn out.”

“I’m sorry. Was the meeting so difficult?”

“For her, yes. The one thing I am requested to tell you is how brave and loyal our Queen was,” and Miss Verity told of Nanta’s guidance and her final pleading speech. “It was for the good of the school and all against her own wishes. She did her best to lead the meeting, but it was almost too much for her. She’s an artist through and through, and she hates trouble.”

“Yes, she is very sensitive. She is a good leader for that reason. I’m glad you sent her home. Tell me what you can, without being unfair to the girls.”

The Head looked grave when she realised the strength of feeling in the Club. “They won’t choose anyone else? They would rather give up the crowning?”

“Yes. But the seniors feel that would be a disaster.”

“A very great pity. The story would be all over the town. We should have enquiries from the local papers—from everyone.”

“It would be tragic,” Miss Verity agreed.

“I can’t go back from the position I have taken as regards Tessa. And I do not wish to do so. She must, at least, have a period of probation before I can allow her to act as Queen. I am glad she offered to withdraw; she has been honest about the affair all through. But I can’t feel she is ready to be Queen. I must abide by what I have said.”

“I had an idea, while the girls were talking,” and Miss Verity leaned forward and spoke urgently. “A small idea, but it might help.”

Miss Raven gazed at her thoughtfully. “Yes, that would do. It’s clever; I could agree to that. Thank you, my dear! I will think over your plan, and in the morning I will talk to Rosalind. I wonder if she would help us? She’s the only one. We can’t ask anything of Janice Raymond next term.”

“No, her exam must come first. Rosalind will be anxious to help the Club, if she can arrange it.” And Miss Verity went home, more hopeful for the morrow.

She rang up the Hall presently and asked if she might speak to Lady Rosalind. “We all completely forget that title,” she laughed, as she waited.

Jansy answered the call. “Rosalind is in the Abbey, Miss Verity. Shall I fetch her for you?”

“No, don’t disturb her. I’m sure she finds the Abbey restful. Tell her I feel more hopeful about the Club. Miss Raven wants to see her to-morrow. That’s all I can say at the moment.”

“Thank you, Miss Verity. It will cheer her up. Was the Head very mad with us?”

“No, not in the least. Why should she be mad?”

“Oh, well! We wouldn’t do what she wanted. But we couldn’t, could we?”

“Choose a new Queen? No, I don’t think you could. Make Rosalind go to bed early, Janice.”

“Yes, I will. Thank you for helping us, Miss Verity.”