* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Adventure Bound

Date of first publication: 1955

Author: Capt. W. E. (William Earl) Johns (1893-1968)

Date first posted: Aug. 28, 2021

Date last updated: Aug. 28, 2021

Faded Page eBook #20210865

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, akaitharam, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

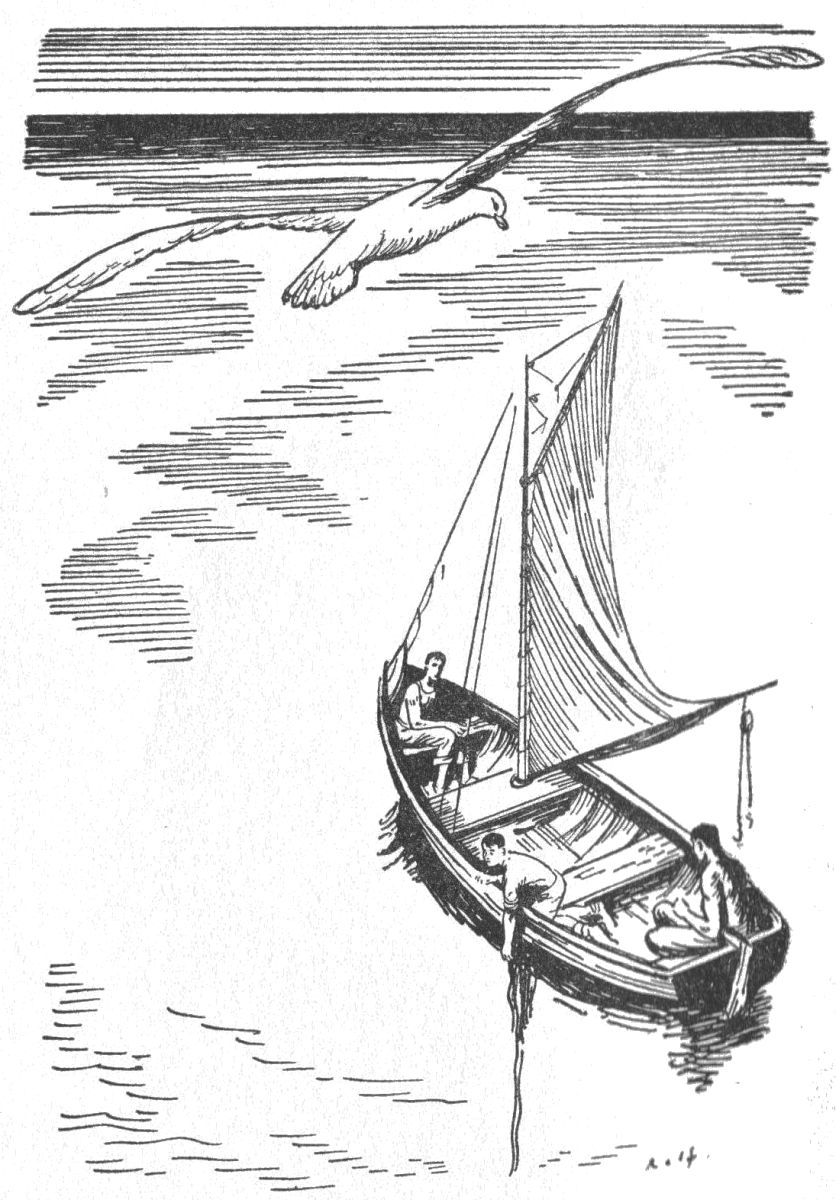

The ship’s lifeboat floated motionless

ADVENTURE BOUND

by

CAPTAIN W. E. JOHNS

Illustrated by Douglas Relf

THOMAS NELSON AND SONS LTD

LONDON EDINBURGH PARIS MELBOURNE

TORONTO AND NEW YORK

THOMAS NELSON AND SONS LTD

Parkside Works Edinburgh 9

36 Park Street London W1

312 Flinders Street Melbourne C1

218 Grand Parade Centre Cape Town

Thomas Nelson and Sons (Canada) Ltd

91-93 Wellington Street West Toronto 1

Thomas Nelson and Sons

19 East 47th Street New York 17

Société Française d’Editions Nelson

25 rue Henri Barbusse Paris Ve

———

First published 1955

ADVENTURE BOUND

THE ship’s lifeboat floated motionless on a sea that shimmered with all the hues of mother-of-pearl under a dome of palest turquoise. Around it and above, as far as the eye could probe the misty dawn, only one thing moved: a snow-white albatross that swung low on rigid wings, the undersides reflecting faintly the colours of the water as the great bird skimmed with effortless ease the placid surface of the ocean.

There were three men in the boat—or, to be strictly correct—two men and a boy. None was properly dressed. All were heavy-eyed, with a powdering of salt encrusting hair and eye-brows. It would have been difficult to find a more ill-assorted trio.

One, the oldest, sat in the stern, an arm resting on the tiller, as, chin in hand, he gazed steadily into the pitiless distances. Judged by features alone he was an ugly man, but, as sometimes happens, this was more than counterbalanced by an expression of amiability and content. He was about forty years of age, broad and heavily built. He was naked to the waist, and when he moved the muscles of his massive torso rippled under a skin that was heavily tattooed in a wonderful variety of designs—dragons, anchors, palm-trees, lovers-knots and names. The word ‘mother’ was entwined in a laurel wreath, and ‘Pompey,’ on a life-belt, occupied the centre of his chest.

The second member of the party, in order of seniority, sat in the bows. He was a lean, long-limbed, sun-tanned fellow of early middle age. His eyes, now brooding over the waste of water, were so brightly blue as to be particularly noticeable. His hair was flaxen. Clean-shaven, what little flesh he carried on his face was moulded to prominent bones, and this, with a firm-lipped mouth, gave him, except when he smiled, a somewhat hard appearance. He was scantily dressed in a vest, and a pair of grey flannel trousers held up by a many-pocketed belt.

The third occupant of the boat was a boy who, half reclining on his seat and fidgeting constantly, dangled his fingers in the water as if to admire the limpid drops that fell from them. He looked about fifteen, but would not have passed as a first-class specimen of that age. He was thin; his face was pale and inclined to be pinched; but his eyes were clear and his expression alert. He wore a khaki shirt and shorts, much stained, and a pair of gym shoes that had seen better days.

The lean man, who from time to time had glanced at him with slight disapproval, broke the silence. ‘You’ll lose your hand in a minute, kid, if you go on playing that game. I can see two shadows—and there’s only one bird.’

The boy withdrew his hand with alacrity. ‘What’s the other shadow?’

‘Shark.’

The boy stood up to look.

‘Sit down before you fall in,’ ordered the lean man curtly.

‘All right,’ said the boy in a hurt voice. ‘Don’t be grumpy. I’ve never seen a shark. This is my first adventure.’

‘Make the most of it,’ invited the lean man grimly. ‘If we don’t soon get a breeze it’s likely to be your last.’

The tattooed man shifted the piece of tobacco that he was chewing from one side of his mouth to the other and spat reflectively into the sea. ‘Don’t worry, son,’ he said cheerfully, speaking with a curious accent. ‘If your time’s come it’s come, and there ain’t nothin’ you can do about it. If it ain’t come, it ain’t. I’ve been in worse spots than this. It could have been wusser. We’ve got a boat. We might have been swimmin’.’ He threw a meaning glance at a triangular fin that was keeping the boat company.

‘What did we hit—a mine?’ queried the boy.

‘Guess so. A ship don’t blow her guts out for no reason, not even an old sea-cow like the Midas.’

‘Was there time to send out an S O S do you think? If so, planes might be out looking for us.’

‘Not a hope, son. She went down too fast. Never had a ship sink under me faster. If the forr’d hatch hadn’t been open I’d still be in her.’

‘This boat is the one that stuck when they tried to lower her. That’s when the oars dropped out. Afterwards she fell in, or I wouldn’t be here.’

‘That’s what I mean. Our time hadn’t come.’

‘Whatever happens now I’ve had an adventure, and a jolly good one,’ stated the boy, almost with enthusiasm.

‘What’s good about it?’ growled the lean man.

‘Everything. I got what I was looking for.’

‘Adventure, eh?’

‘Yes.’

‘Is that why you were going to Trinidad?’

‘Is that where we were going?’

‘Didn’t you know?’

‘No. I didn’t ask. It was all the same to me. I hoped we were going to a foreign country, the wilder the better.’

The big man began to laugh loudly, but broke off abruptly. ‘How come you on board if you didn’t know what port we was bound for?’

‘I was a stowaway.’

‘In that case I ought to throw you overboard.’

‘Not while the shark’s there.’ The boy looked startled.

‘Seeing as how we may need you to help bale if we ship a sea I’ll let you stay aboard,’ decided the big man confidentially.

The lean man stepped into the conversation. ‘Suppose we quit fooling and get down to hard facts. With strict rationing we’ve food and water for a week. If we don’t get a breeze in that time we shall still be where we are now.’

‘Couldn’t we be drifting somewhere,’ suggested the boy hopefully.

‘We could, but we’d have to drift a long way before we got anywhere.’ The lean man looked at the big man. ‘What’s your idea of our position?’

‘I figure we’re close on four hundred miles from the nearest land, which’d be the top end of South America. The Midas was thirteen days out. Reckoning we made a hundred miles before that south-west wind died on us makes us about where I said. Don’t worry. We’ll get a breeze. We’re in the trades and they come from the east. Failing that we oughta pick up that fast current that runs north up the coast of South America. And now, seeing as how we’re likely to be shipmates for a bit, what about getting to know each other. What’s your name, son?’

‘Tommy. Tommy Tucker. It’s Jack, really, but I’ve always been called Tommy after the Tommy Tucker who sang for his supper.’

‘We’ll all be a’singing for some supper presently.’ The big man chuckled at his own joke. ‘Go on, Tommy; tell us about yourself.’

‘I’m sixteen and I come from Wapping,’ continued Tommy. ‘Dad and Mum were killed by a bomb in the war. When I left school I tried for the Air Force to see the world, but they said my physical standard wasn’t up to it, so I got a job delivering vegetables for a greengrocer. There didn’t seem to be much hope of finding any adventures in cabbages and cucumbers so I stowed away on the Midas.’

‘What made you choose the Midas?’

‘She looked such a dirty old tramp that I felt sure she went to funny places.’

The big man guffawed. ‘She’s sure gone to a funny place this time.’

‘When I got hungry I gave myself up. The mate gave me a clout and put me into the galley to wash dishes. That’s what I was doing when we blew up. I’ve still got a shilling and my scout’s knife.’

‘A bob, a knife and a bit o’ string, and you’re okay anywhere,’ asserted the big man.

‘That’s all, except I hope I don’t die till I’ve found a treasure or a gold mine.’

‘Tough guy, eh?’

‘What about you?’ questioned Tommy. ‘What’s your name?’

‘It’s writ on me chest. I had it writ big so when my turn came to be washed up they’d know it was me.’

‘But is Pompey your real name?’

‘If I ever had another I’ve forgot it. Nobody’d know me by it so it wouldn’t be no use, would it? From Frisco to Tokyo, Boston to Bombay, I’m Pompey the stoker, the man who keeps the screws a’turning. Shovelled me way round the world, as you might say. If I had a shilling for every ton of coal I’ve shifted I’d be a millionaire.’

‘Are you British?’

‘Well, I wouldn’t say that exactly, although that’s what’s in me Blue Book, and if it suits the owners it suits me. According to my ma I gave my first bleat on a Chilean cargo boat. My father was engineer. Scotch, as my ma told me. She was Spanish. Her father ran a hotel in Valparaiso. They got married, and she sailed with him till a hurricane threw us on the beach near Santa Cruz. That was the last she saw of him. He must have gone down with the ship. She carried me, a kid, to Frisco. Later on she married the skipper of a whaler, and sailed with him. I haven’t seen her since.’

‘You didn’t go with them?’

‘Not me. I hated him as much as he hated me. Sail with a guy who’d cuff a kid every chance he had? Not likely. After that I drifted around on all sorts of ships, mostly flying the Red Duster,[1] till one day, after being torpedoed and picked up by a destroyer, I found myself in Pompey. Next time I sailed and they asked me last port I said Pompey. But one of us must have made a mistake because when I got me Blue Book I found they’d put Pompey in the place where my name should have been. I’ve been Pompey ever since.’

[1] The Red Ensign of the merchant service

‘Where on earth is Pompey?’

The big man looked shocked. ‘You never heard of Pompey? But then, at school I suppose they’d call it Portsmouth.’

‘You must have had some wonderful adventures!’

‘Oh, I just take life as it comes—if that’s what you call adventures.’ Pompey looked at the man in the bows. ‘What about you, mister? I reckon you paid your passage.’

‘I did.’

‘And what would you be doing on an old tub like the Midas?’

‘It happened to be the cheapest way of getting to where I wanted to go.’

‘Tell us the rest,’ requested Pompey.

‘What does it matter?’

‘Come on now, play the game,’ demanded Tommy.

The lean man smiled. ‘I suppose we might as well talk about something. Name, Driscoll—Jim Driscoll; better known on my job as Digger because I’m Australian. Age thirty-five. Went to any school that happened to be handy. My father was a mining engineer, always on the move. Mother died when I was a kid so he dragged me around until he was killed in an accident, when I pushed out on my own to look for my bread, and, with luck, a little butter.’

‘Did you have adventures?’

‘If an adventure is something that happens to knock you flat just when you think you’re on your feet, the answer is yes. A couple of days ago I was bouncing on air. Now, with the reward of eighteen months sweated labour at the bottom of the Atlantic, I’m back where I started. That’s how it goes.’

‘Did you ever find any gold?’

‘None to speak of, although I’ve done a lot of looking. You soon learn there’s no future in that—unless you happen to be the one in ten thousand who strikes lucky. If the gold bug is biting you, my advice is, forget it. It’s a gamble in which the hunter stakes everything—his comfort, his health and his life—on a million to one chance. Most of those who try it eventually come down to the things that aren’t so hard to find. There’s a market for almost everything these days.’

‘What sort of things?’

Digger shook his head. ‘I see I’ve started something. Civilisation clamours for more and more raw materials—metals, chemicals, timber, dyes, medicinal plants, aromatic gums for perfumes, skins, flowers and even bugs and beetles. Of course, the modern prospector has to know about these things—be able to recognise what he sees. My last job was to collect orchids for a millionaire in England. He paid me well. Where’s the money? Gone to Davy Jones.’

‘That was tough.’

‘It’s nothing new. I once spent a year walking about on the bottom of the Timor Sea looking for pearls. Had the luck to find an untouched oyster bed and got a hatful. On my way to port a willy-willy blew my schooner on a reef and I lost pearls, ship and everything else. You might call that an adventure, but if it ever happens to you, my lad, you’ll find another name for it.’

‘Did you ever find any diamonds?’

‘No, but I once struck a vein of peridotite. That’s a kind of rock in which diamonds are sometimes born. Those you find in gravel have had the rock worn away. The crystals are harder than the rock. I was just going to start work when along came a police patrol and arrested me for poaching diamonds in territory that had been closed for prospecting by Government orders. I didn’t know. So instead of diamonds I got a month in gaol.’

‘That was rotten luck.’

‘You learn to take the rough with the smooth.’

‘What was your best find?’

Digger thought for a moment. ‘About a bushel of ginseng.’

‘What’s that?’

‘The root of a plant. You spot it by a ferny leaf and a little red flower. In China it’s worth its weight in gold. The Chinese believe it’ll cure any disease and ensure long life. I was humping the stuff to the coast when I went down with malaria. While I was sick wild hogs ate the lot. That isn’t adventure. It’s heartbreak. Still, you go on. The motto of the prospector is, “where it is, there it is.” ’

‘Did you lose every time?’

‘No. If I had I wouldn’t be here. I’ve made money out of ipecacuanha, sarsaparilla, vanilla, babbasa, guarana, uricuri and ivory nuts.’ Digger laughed at the expression on Tommy’s face. ‘Those are the things the modern explorer looks for,’ he added.

‘But what the dickens are they?’

Digger sighed. ‘Ipecacuanha—the medicine your mother may have given you when you were a toddler—is the root of a Brazilian violet. You get sarsaparilla from the flower you call smilax. Vanilla, the flavouring they put in ice-cream, is the seed pod of an orchid. The other things yield wax which is in big demand in Europe. They use ivory nuts to make buttons. I once took a concession on an area of grass in Burma and sold it for a thousand pounds. It was a pampas grass that makes fine paper. I happened to know that. On my last trip I got some good samples of cinnabar, bauxite and balata gum.’

‘What on earth are they?’

‘Cinnabar is mercury ore. Bauxite is the chief source of aluminium. Balata is a sort of hard rubber used in engineering for coating canvas driving belts. If the samples turn out as good as I hope I shall buy a concession from the Government concerned and sell it to a company that exploits these things. Now stop asking questions.’

‘You know,’ said Tommy earnestly, ‘if they’d teach us these things at school, instead of algebra, for instance, there’d be some sense in it. Chaps would know what to look for while they were waiting for adventures to turn up.’

‘You’re telling me,’ put in Pompey. ‘Coming round the Horn one time we fished out of the sea a great lump of fat. At least, that’s what the skipper thought it was. He made us grease the mast with it. Do you know what it was? Ambergris, worth about five quid an ounce. And we slung it about like it was soft soap. The Old Man drank himself to death when someone told him what he’d done. That’s what comes of not knowing the ropes.’

‘What’s ambergris?’ asked Tommy.

‘I was waiting for you to say that. They say it’s a disease on a whale’s lungs. The whale coughs it up and they put it in scent, so I’m told. And if you’re going to say what’s this and what’s that every time anyone speaks I may have to change my mind and put you overboard after all.’

There was silence for a few minutes. Then Pompey let out a yell and pointed to a ripple that was spreading across the surface of the sea. ‘Here comes the wind,’ he shouted.

For two days the boat ran before those winds which, for their steadiness and reliability, are perhaps the most famous in nautical history; the ‘Trades’ that wafted Columbus, and thousands of ships after him, to the New World.

For the first twelve hours the wind was light; the sea sparkled, and there was nothing more suspicious about the sky than a prospect of rain. Tommy, who was content with this state of affairs, asked more questions, and learned more about his companions. He also learned to like them.

‘There are some things you’ll never get to know in a classroom, laddie, and my job is one of them,’ Digger told him. ‘You have to go places. And what good has it done me, anyway? Fifteen years of slogging through country most people have the sense to avoid and all I possess is my jungle pack.’

‘Where is it?’ asked Tommy, looking surprised.

‘It’s this belt I’m wearing—and you wouldn’t guess what’s in it. I was shipwrecked once on one of those desert islands books rave about. That was the time I lost my schooner. It taught me a lesson. I’d have swapped all the pearls that ever came out of the sea for a box of matches and a fish-hook. I swore that if I was lucky enough to be taken off I’d see that it never happened to me again. From that day to this I’ve never travelled without my belt. At sea I’ve slept in it, which is why I still have it. I’ve never needed it—but I may. Experience can be a hard master—but you don’t forget the lessons it teaches you.’

Tommy had assumed, naturally, that all they had to do was to make a landfall, but he was disillusioned by Pompey, who informed him that it was one thing to sight land but another matter to set foot on it. Many a lifeboat, declared the sailor, had been lost with all hands trying to get ashore through heavy surf after surviving a thousand miles of open water. The fact that there were no oars in the boat was not likely to make getting ashore any easier.

On the second day the wind freshened and blew up a short choppy sea, that not only caused Tommy some alarm but gave him his first pangs of sea-sickness. He no longer asked questions. Praying that they might soon see land he watched Pompey shorten sail. To the south the sky now presented an uncanny appearance, and Pompey looked at it so often that it was evident he did not like it. However, he said nothing. The foaming crests of the waves that now surrounded them began to break into the boat, and Tommy, scared and miserable, helped to bale.

‘Still enjoying your adventure?’ Digger asked him slyly.

Tommy didn’t answer. It was dawning on him that adventures might, after all, be more enjoyable in an armchair than in reality. Once, when a big sea broke aboard and threw the boat on its beam ends, he thought it was the finish; but by some miracle Pompey managed to keep them right side up although knee-deep in water. He baled furiously.

Towards evening, with surprising suddenness, the wind abated, and the sea fell to a long oily swell. The sky, no longer blue, turned to an ominous sickly yellow, casting an evil light on the heaving ocean. Tommy mustered the courage to ask Pompey how far he thought they were from land.

Pompey said he thought they were close; too close; he would have preferred more sea-room. There was, he opined, a pampero on the way.

Tommy didn’t know what a pampero was, and, as it was obviously something unpleasant, he refrained from asking to be enlightened. Just how unpleasant a pampero could be he was soon to learn. He noticed the albatross had disappeared.

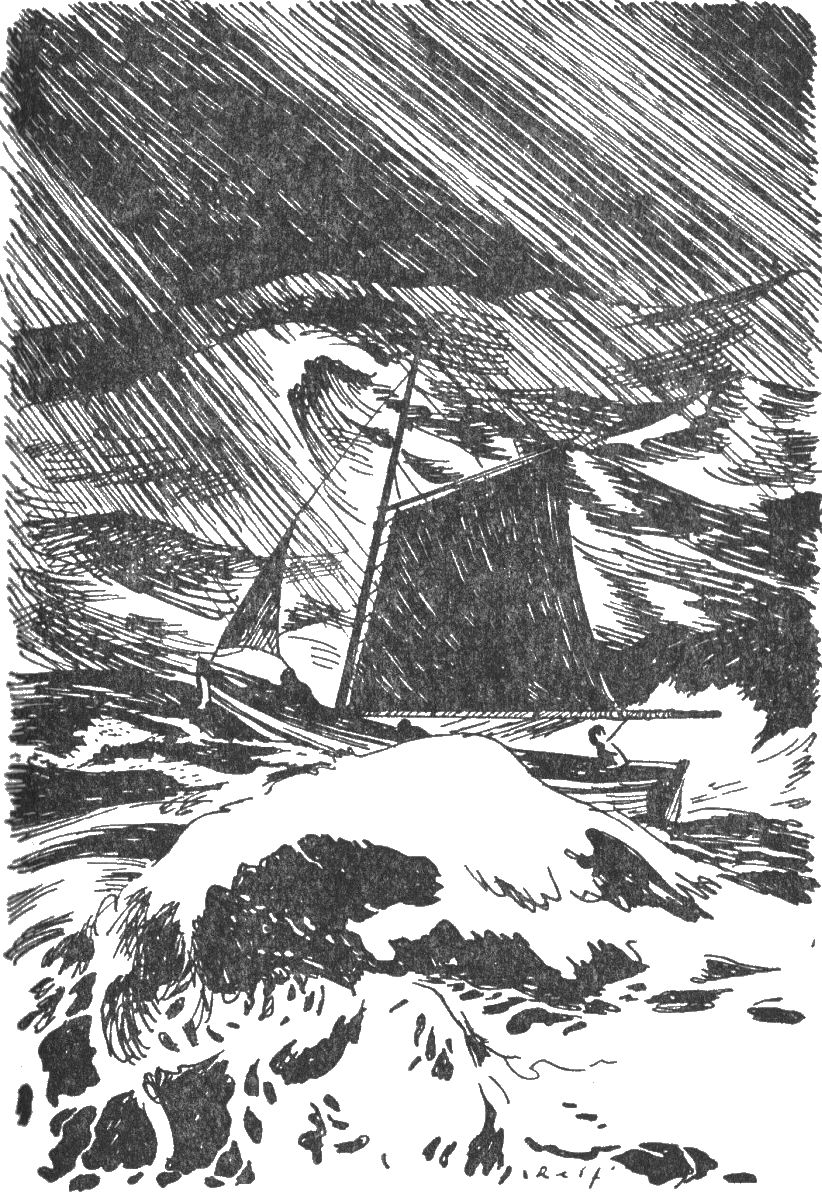

Presently, far away over the port bow, a purple smudge appeared. ‘Here she comes,’ announced Pompey calmly. A moment later Digger sang out that he could see land. Tommy was overjoyed, but Pompey received the information without enthusiasm. He said he daren’t try to turn. ‘When she hits us, mates,’ he advised, apparently referring to the pampero, ‘keep your heads down and hang on.’

The purple smudge rose swiftly until it covered half the sky. It was now dim twilight. Digger said he thought he could see a light on the shore. Tommy wished heartily that he was with it.

Ten minutes later the pampero hit the boat. It arrived with a roar, tearing the surface off the sea and throwing a great deal of it into the boat, which heeled over under the shock. The sail disappeared in a blur of spray. Tommy, unprepared for an onslaught so violent, gasped and clung to his seat. The boat rolled sickeningly, and his stomach rolled with it.

The pampero hit the boat

The wind had begun blowing in tremendous gusts, piling up seas into which the boat plunged, shipping water. Tommy, baling madly as the boat dropped into a trough, was sure it could not recover in time to top the next curling crest. Yet in some amazing way it did. Weary with the strain of holding on and baling, half blinded by the salt in the stinging spray, to Tommy the ordeal became a nightmare.

How long these conditions persisted he did not know. Time had ceased to have meaning. He baled mechanically. Yet with it all there was born in him a strange jubilation. He was battling with nature in her most ferocious mood. There was something inspiring about it. He wanted to shout. Instead, he was horribly sick.

Darkness hid the raging water, darkness utter and complete. There was no moon. Not a star showed in the heavens. The wind moaned. The sea snarled. The boat rocked, helpless, at its mercy.

Some time during the night the wind fell. But not the sea. Still it snarled. Still the boat rose and fell at its whim.

The end was as sudden as it was unexpected, for not a light showed anywhere. The boat seemed to stop abruptly, as if brakes had been applied to check its motion. It rose like a lift, and came down with a crash. A mountain of water poured over it and in an instant Tommy was struggling for his life. Unseen hands seemed to be dragging him down—down—down. Little specks of light began to dance before his eyes and he knew that he was drowning. He had to breathe or die. He opened his mouth. Air poured into his lungs. But the respite was brief. Again he was dragged down. His struggles became feeble and he knew his strength was failing. So this, he thought dimly, was the end of his adventures. He hoped it would soon be over.

Then his movement seemed to change. Instead of being dragged down he was being thrust forward. It was as though he were on an enormous toboggan. It crashed with a roar like thunder, hurling him on to something solid; but before he could clutch it he was being dragged back at terrifying speed. Again he was flung forward. He felt stones in his hands, and he dug his fingers into them to stop the ghastly slide. The whole world seemed to be sliding, and he with it.

Suddenly, to his amazement and relief, he found he could breathe. Sucking in air in great gasps he tried to stand; but he was still on a sliding world, and in spite of his efforts to cling to it he was torn away. His endeavours to regain it became frenzied when from somewhere near there came a mighty roar, as if an avalanche was overtaking him. Something struck him with the speed of an express train and swept him into a world that was torn by lightning and noises beyond imagination; a world that ended in a void into which he fell, leaving behind the uproar.

He seemed to be falling for a long time. The sensation was not unpleasant but he wished it would end. He could see the bottom now, a misty plain where all was silent. He threw out his hands to break his fall. As he struck it, it exploded in a sheet of scarlet flame that faded quickly to crimson, to purple, and finally, to black.

He returned to the world he knew without being immediately aware of it. He did no more than open his eyes and gaze unseeingly at a dawn sky; a canopy of egg-shell blue feathered with pink; but for a little while it conveyed no message to his brain. Then, slowly at first, but presently with a rush, memory returned, and he sat up, not without difficulty, for he was stiff and sore from the pounding he had received from the giant combers that had flung him on a shelving shingle beach. He removed from his neck a ribbon of slimy kelp, and as he did so he became aware that he was the centre of attraction for an army of crabs, such crabs as he had never seen before, creatures with waving antennae and ridiculous stilt-like legs. Now that he had moved they were retiring, clicking their disappointment. He picked up a stone and threw it to hasten their departure.

This exertion served a useful purpose, for it caused him to evacuate a prodigious amount of sea water. The spasm passed and he felt more normal, able to think reasonably clearly. His first thought was, naturally, wonderment that he was still alive. He realised, of course, what had happened. Next he thought of Pompey and Digger, hoping they had been as lucky. He could see no sign of them. He got unsteadily to his feet and looked around.

To one side was the sea, the waves still spreading lace curtains on a beach that stretched away on either hand in a sweeping crescent. Debris along the high-water mark told him what had happened to the boat. Behind, and not far away, the wall of a forest rose sheer for a hundred feet, dark, mysterious, menacing. Dimly in its twilit depth the liana-festooned boles of giant trees faded into a tangle of foliage. At one spot, in contrast with the sombre background, a spray of scarlet flowers sprang like a flame from a low-hanging branch. It looked as if his wish had been fulfilled, and he had landed in a wild country. It was rather wonderful, but a little bit frightening. The forest looked the sort that would conceal wild beasts and savages.

Still trembling from shock he moved a little farther away from it and sat on a heap of seaweed. He felt sick, weak and thirsty—very thirsty indeed. The inside of his mouth was rough with dryness, and his lips were stiff with salt.

The snapping of a twig in the forest brought him to his feet, heart thumping with apprehension. Pompey appeared, carrying what appeared to be one half of an enormous orange. This turned out to be part of the shell of a strange fruit. It was nearly full of muddy water.

‘Have a drink,’ invited Pompey.

Tommy drank the water gratefully. It tasted foul, but he was in no state to be particular. ‘Do you know what happened to Digger,’ he asked.

‘He’s all right,’ was the reassuring answer. ‘Trying to find something to eat. We found you, pulled you up clear of the water and then looked round for some water with less salt in it. How are you feeling?’

‘Not so bad.’

‘That’s swell.’ Pompey grinned. ‘How’s the adventure going?’

‘Fine. After all, we’re still alive, that’s the main thing. Do you know where we are?’

‘America, I guess.’

‘Not on an island?’

‘If it is it’s a big ’un. No, I reckon we’re on the mainland.’

‘What part? America is a big place.’

‘Sure is. Your guess is as good as mine. Mebbe if we walk along the beach we’ll come to some place. Then we can ask where we are. Here comes Digger.’

Digger appeared, carrying a small bunch of green bananas. ‘This is the best I can do,’ he announced. ‘Lucky to find these. Got them in a patch by an abandoned hut a bit along. Indian shack, I think.’

‘Is there no fruit in the forest?’ asked Tommy in a surprised and disappointed voice.

‘Could be, but we’re not likely to get it. The birds and monkeys get what’s growing, and any that falls is grabbed by the ants. Forget what you’ve read in your story books. The easiest place to starve to death is in a tropical forest, which is mostly sweat, thorns, rotten leaves and mosquitoes. If we want to eat we’d better start walking.’

They set off along the beach.

They had not gone far when a large brilliantly coloured butterfly whirled past them. Digger jerked a thumb at it. ‘Collectors in London and New York will pay ten pounds for that sort.’

Pompey frowned. ‘Aw shucks! Why worry about money?’

‘Don’t you?’

‘Me? No. I don’t worry about nothin’. What’s the use. Living at all is a risky racket, but I shan’t go before my time and nor will you. When our time comes we shall go, and nothin’ won’t stop us, so what’s the use o’ worrying. There might be a bunch of Indians round the corner waiting to stick us full o’ spears. So what? Right now we’re alive, and that’s enough to go on with.’ Pompey’s tone of voice changed suddenly. ‘Say, what’s all this?’

From round the bend in front of them had appeared a long straggling column of men, not fewer than a hundred. The leaders were mounted. The rest marched. Some limped, or walked with difficulty. Dressed in a variety of garments, some colourful, all carried weapons. A wagon brought up the rear.

‘Now we shall know where we are!’ exclaimed Tommy.

‘Sure,’ murmured Pompey dubiously. ‘Sure we shall know where we are. Mebbe we shall wish we didn’t.’

‘What do you mean?’ asked Tommy. ‘I call this a perfect end to my adventure.’

‘If you was to ask me, Tommy lad, I’d say your adventure’s just about to start,’ said Pompey soberly. ‘If ever I saw a crew of hombres I didn’t like the look of, it’s right here. Don’t forget this ain’t the first time I was in South America.’

‘That goes for me too,’ put in Digger. ‘I can smell trouble from here.’

The motley mob advanced. Some horsemen galloped forward.

It was some minutes before Tommy could get an inkling of what was happening. He could only stand silent and bewildered in the centre of what seemed to be a furious argument. One or two things were clear, however. The first was, Pompey and Digger had been correct in their judgment of the situation. Trouble, serious trouble, was uncomfortably evident. The second was, the marching men were troops, soldiers of some sort, or bandits. A number of wounded suggested that there had been an engagement, and this party was the remnant of the side that had been defeated. This was in fact the case, as he was soon to learn.

For a time the altercation raged, words flying in threats and expostulations. There were moments when blows seemed imminent. Pompey, vehement, pointing at the sea, was obviously explaining who and what they were. Digger backed him up, but with little effect. So much could be followed by the fierce gesticulations, but to Tommy the actual words conveyed nothing. It came as a surprise to him that both Pompey and Digger could speak the language used. Then he recalled that Pompey’s mother had been Spanish, and supposed that to be the tongue he now employed with a fair degree of fluency.

At last Pompey threw up his arms in resignation or despair and turned to Digger. ‘It’s no use,’ he muttered savagely in English. ‘It’s either do what they say or have our throats cut. That won’t get us no place.’

Digger agreed. ‘We’d better go with them,’ he decided.

Rifles were put in their hands, cartridges in their pockets, and the march was resumed.

‘Would you mind telling me what all that was about?’ asked Tommy, as they trudged along with the rest.

Pompey answered: ‘It seems like we’ve got tangled up in a revolution. I’d say this lot have had a smack in the eye and are now collecting men to have another go. No use arguing with ’em. Mebbe we’ll get a chance to skip presently.’

‘But we’re British,’ protested Tommy. ‘If they killed us there’d be a row.’

‘And what good would that do you if you was under the ground pushing up the daisies?’

‘We shall have to slip away before we get mixed up in a battle,’ said Digger. ‘I was caught up in one of these local rows once before. We shall have to be careful how we go; if they catch us bolting they’ll shoot us on the spot. If the other side wins we shall be shot for fighting against them.’

‘That’s a cheerful look-out, I must say,’ observed Tommy bitterly.

‘I hope this lot have got some grub with ’em, that’s all,’ said Pompey. ‘Don’t scoff it all. Keep a bit by for a get-away.’

Tommy strode on in a daze, wondering if this could really be happening.

After marching for some miles without pause a river was reached. It was forded. On the far bank was a village, with a mixed population of whites, mulattoes and Indians. The people ran out cheering, carrying food.

‘We seem to be on the popular side, anyway,’ remarked Tommy.

‘Don’t you believe it,’ dissented Digger sarcastically. ‘It would have been the same had the other side come along. People bring out their grub because if they didn’t it would not only be taken but the place burnt down. They’re trying to put the best face on a bad job. This will probably ruin them.’

To say that the food was distributed would be to give a false impression. It was a case of snatch and grab, every man for himself. Pompey, who was not backward in moving forward, may have got more than his share, but he divided it generously and they all had a reasonable meal. In less than half an hour a bugle sounded and the march was resumed.

‘I reckon the enemy must be close behind us or we wouldn’t be pushing on so fast,’ opined Pompey. ‘In this part of the world people usually have forty winks after dinner; but not today; and that can only mean one thing. Some of the wounded are dead on their feet, but they keep going because they know what’ll happen if the other side catches up with ’em.’

The march was continued until dusk. Only the fear of death kept Tommy on his feet, for he was near the limit of his endurance. Pompey carried his rifle. To make matters worse the last part of the march crept up a narrow track that was not only steep but sticky with mud. It ended on a plateau dotted with outcrops of rock and growths of cacti. Here the army halted.

Some pigs that had been taken from the village were now slaughtered and the meat issued. Maize meal was doled out from the wagon, each man getting his share. Tommy, who had sunk down from sheer exhaustion, would not have bothered with it; but Pompey insisted that he went for his ration, pointing out that his life might depend upon it.

Camp fires sprang up on all sides. So strange and wild was the scene that Tommy was now sure he was dreaming, or in a delirium.

Pompey nudged him. ‘How’s your adventure going, Tommy?’ he chaffed, impaling some strips of meat on a stick and holding them in a fire he had lighted.

Tommy smiled wanly. ‘It’s going a bit too fast for me to keep up with it.’ He yawned. ‘I’m so tired I can’t think.’

‘Aw shucks! Don’t say that. A bit of meat and a night’s sleep’ll make a new man of yer. Sorry we ain’t got no apple sauce.’

A coarse but satisfying meal was just concluded when a young man, tousle-headed and unshaven, came and squatted beside them. ‘I saw them pick you up,’ he said in English. ‘You’re British or Americans, ain’t you?’

Digger said they were British.

‘I’m glad to have somebody to talk to at last,’ rejoined the newcomer.

‘Who are you?’ inquired Digger.

Digger said they were British

‘Joe Batson’s the name. Batty they called me in the Army, and batty I must have been to come to this loonybin. They picked me up a week ago. Crumbs! What a time I’ve had! And all I was doing was having a quiet drink at a cantina in their cockeyed town.’

‘What country’s this?’ asked Pompey.

‘Rioguiana.’

‘What’s going on?’

‘Revolution. Bloke named Don Enrique Avenida tried to bump off the president and grab the country, but somebody blew the gaff and the plot went off at half cock. Now he’s on the run. He’s the good-looking fellow on the grey horse. Seems a decent sort of chap. Plenty of guts. In the thick of it all the time. The rest are mostly a lot of drips. Ran like rabbits at the first bang. We got a pasting. This bunch is all that’s left of about five hundred. Another five hundred didn’t turn up at all. Lot o’ skunks.’

‘You talk like you was on the side of this Don Whatsisname,’ observed Pompey.

‘Not me. I’ve no axe to grind. But it made me mad to see these rats walk out on their leader when things got hot. Went against the grain somehow. Well, it’s all over bar the hangings and shootings and Don Enrique knows it. The troops must have seen me so I’m for the high jump if we’re caught. That’s why I’m heading for the border with the rest.’

‘What border?’

‘Some say Brazil, some say Venezuela. It’s all the same to me. I never was much good at geography.’

‘How come you to be in this part of the world?’ asked Pompey.

Batty Batson smiled sheepishly. ‘It sounds a joke, but I came here looking for a half a ton of gold. I must have been nuts.’

Tommy, who had nearly fallen asleep, sat up at the word gold. ‘Gold!’ he ejaculated. ‘Do you really know where there’s some gold?’

‘Yes. And there’s not much doubt about it being there. It’s a long story.’

‘Go ahead,’ invited Digger. ‘There’s always time to listen to a tale about a half a ton of gold even if it’s all lies.’

‘There’s no lie about this lot,’ declared Batty. ‘It was there, even if it isn’t there now.’

‘Where?’

‘I’ll come to that in a minute. Do you remember a German light cruiser named the Ronstadt being caught and sunk off the coast of South America by our lads in the war?’

‘Perfectly well.’

‘There was more to it than that, although I reckon few people know about it. This was how the story came my way. I don’t mind you knowing because if I get scuppered in the next scrap—but we’ll talk about that in a minute. When I was called up for National Service I was sent to Germany—army of occupation, you know. My lot were in Hamburg. I was billeted on an old German lady named Frau Lowenhardt. Nice old lady. Lived alone. Husband and only son were both killed in the war, she told me. Some things were still short in Germany so I used to take her anything I could scrounge. Maybe that’s why she took a fancy to me. She got like she was my own mother. Then one day I was posted to Korea. The night before I was due to leave she called me into her room. She had something to tell me, she said. This is what it was.’ Batty took the short end of a cigarette from his cap, lit it with a glowing stick, and continued:

‘It seems her son was a sailor. He was on the Ronstadt when she was sunk. At the time her job was to fetch a load of gold that had been pinched from somewhere earlier in the war. The ship that had actually pinched the gold dumped it. Where and why I don’t know. It doesn’t matter. The point is, the Ronstadt got it, and was on her way home when she got word that our lads were after her; whereupon she bolted into a Rioguianan river called the Olarayo. The skipper, seeing he was trapped, and reckoning he’d be lucky to get home, hid the gold again. The British Government didn’t know anything about the gold, of course, and the skipper of the Ronstadt was going to see we didn’t get it whatever happened. As I say, he took it ashore and buried it again. It’s in bars, by the way. Afterwards he made a dash for home, but he was out o’ luck. Our chaps caught him and down he went. There were only a few survivors, and the old girl’s son, Karl, was one of them. Now according to Karl there was only one other fellow amongst those who were saved who knew where the gold had been hidden—a petty officer named Dostler. What happened to him I don’t know. Karl didn’t know. This, you understand, is what Karl told his mother when he got back to Germany, before he went back to sea and got drowned. Before he went, though, he made a map of the place where the gold was hidden and gave it to his mother to take care of. Maybe he had an idea of getting the gold himself one day—but I don’t know about that. Anyway, he didn’t get a chance. Well, the old girl said she didn’t want the map. It was no use to her, so as I’d been kind to her she gave it to me, thinking it might do me a bit of good.’

‘Have you still got it?’ asked Digger.

‘You bet your life I have,’ asserted Batty. ‘As soon as my time was up I decided to have a go at it. I’d got my gratuity. My idea in the first place was to see if the stuff was still there, bearing in mind that this bloke Dostler might have got there first. It was no use deciding what to do about it if it wasn’t there.’

‘Why didn’t you report this to the Government?’ inquired Digger.

‘What Government? The Rioguianans? Ha! They’d have seen it wasn’t there. And if I’d told the British Government all they could have done was approach the Rioguianans, so it would have come to the same thing. No, I wanted to get my hands on a bit of the stuff myself—naturally.’

‘What happened?’ asked Tommy eagerly.

‘Well, I had to wait some time for a permit to land in Rioguiana, but I got here all right. Landed at Los Ricas, the capital, a bit down the coast. Found a little place where I could stay, parked my pack and went out to get my bearings. I was sitting at a cantina—one of those places where you sit on the path—having a cup of coffee when, blow me down! if bullets didn’t start whizzing. Then, before you could say Jack Robinson, up comes a bunch of toughs. They make signs I’ve got to fight—or else. So I fought. Actually, I couldn’t do anything else, because by this time the other side was shooting at me and I had to defend myself or I’d had it. After they’d seen me shooting at ’em my only chance was to stick to this lot! Several people got roped in like I did, but until you came along I was the only Britisher in the party.’

‘What do you reckon to do now?’ asked Pompey.

‘Hang on till we get to the border and then skip.’

‘What about the gold?’

Batty looked dubious. ‘I don’t know. If I come back and they cop me I’m for the high jump.’

‘How did you intend to get to this place where the gold was hidden?’ asked Digger curiously.

‘Walk, of course.’

‘Walk! By yourself?’

‘Why not? I’ve marched hundreds of miles in my time—in full marching order.’

‘What about grub?’

‘I had my old army pack with enough iron rations in it to last me for two or three weeks, and a little money to buy stuff on the way, so I wasn’t worried on that score. The trouble is, I’ve lost my pack, and unfortunately my passport was in it. I left it in my lodging, and after what’s happened I wouldn’t dare to go back for it.’

‘When you talk about half a ton of gold, do you mean that literally?’

Batty smiled apologetically. ‘Well, not exactly. I was sort of keeping it in round figures. Actually, Karl told his mother there were thirty ingots of five kilograms each. I worked that out to be roughly three hundred and thirty odd pounds as we should weigh it. Say, three hundredweights.’

Digger did some quick mental arithmetic. ‘Worth around fifty thousand pounds at today’s prices.’ He grinned. ‘You were going to have a nice job shifting that lot single-handed.’

‘After humping sandbags up and down trenches that didn’t frighten me. But I’m dashed if I know what I’m going to do about it now.’

‘You’d better stick to us,’ declared Pompey. ‘We’re all in the same boat.’

‘But these people wouldn’t dare to touch us,’ protested Tommy. ‘If they did the British Government would have something to say about it.’

‘In these parts they shoot first and talk afterwards,’ observed Pompey cynically.

‘We’d better see about some sleep,’ advised Digger. ‘We look like having another stiff day tomorrow.’ He looked at Tommy. ‘How’s your adventure going, kid?’

‘Fine,’ answered Tommy, without conviction. ‘But I wish it wouldn’t go quite so fast.’

All around, the camp-fires were burning low. The early noise and bustle, and the mutter of conversation, had died to a strange uneasy silence.

Using his shoes for a pillow Tommy stretched himself out on the hard earth, and within a minute was sound asleep.

Tommy opened his eyes the next morning to a world of noise and confusion that was all the more bewildering because the plateau was shrouded in a clammy grey mist that made it impossible to see beyond a few yards. The time, he judged, was not long after daybreak. Pompey, Digger and Batty were on their feet, attitudes tense, staring into the murk. Figures loomed up, running, panting, distraught, to vanish again in the fog. A medley of noises indicated panic.

‘What’s going on?’ asked Tommy anxiously.

Pompey answered. ‘Sounds to me like the Government troops have caught up with us.’

Hardly had the words left his lips than some shots were fired. A bugle pealed. Voices yelled. A ragged volley crashed, to be followed by sinister whistlings in the air.

‘Let’s get out of this,’ pleaded Tommy urgently.

‘Sure—but how?’ answered Pompey. ‘Which way do we go? Running into the enemy won’t help us any.’

A man, waving a drawn sword, rushed past, yelling.

‘He says fight or die,’ translated Digger. ‘What he really meant was fight and die.’

‘What’s Don Avenida up to?’ muttered Batty. ‘Why doesn’t he get his mob together instead of letting ’em run wild?’

‘How can he give orders with everyone bawling his head off?’ inquired Pompey in a voice heavy with disgust.

There was now a steady crackle of musketry. Bullets whined as they glanced off the rocks or slashed through fleshy cactus leaves.

‘If we stand here one of us is going to stop something in a minute,’ said Digger calmly. ‘Let’s try to find out which way the attack is coming from.’

‘Sounds like they’re all round us,’ observed Pompey, biting the end off his coil of tobacco.

They all moved forward slowly, across the pampa. A man lay in a grotesque position across their path. He was dead. Tommy shrank away, his mouth suddenly dry, at his first sight of a man killed in action. On all sides, now, was the dreadful clamour of battle. Tommy knew that had he been alone he would have fled, panic-stricken. Only the casual behaviour of the others prevented him from obeying the impulse. He was terrified, and he was afraid his face would reveal it.

‘You wanted adventure, kid, and by gosh, you’re getting it,’ observed Pompey grimly. ‘Don’t waste your time ducking. You don’t hear the smacker that gets you.’

‘Tough luck, running into a madhouse like this,’ said Digger sympathetically.

‘Enough to scare the daylights out of anybody,’ declared Batty. ‘This not being able to see a blooming thing. . . .’

A large dark shadow loomed in front of them. It turned out to be about twenty men who had formed a square and were shooting blindly into the fog. Don Avenida, his horse dead at his feet, was there, sword in one hand and revolver in the other.

‘Where’s the rest of his men?’ wondered Tommy.

‘Bunked, I’ll bet,’ answered Pompey.

‘Lot o’ rats,’ snarled Batty. ‘That’s what they did last time.’

They joined the leader of the lost cause. He saw them, and threw them a smile of gratitude, although he must have known that he was doomed. Soldiers could sometimes be seen vaguely, like phantoms, in the mist. Shots poured in, and Don Avenida’s supporters fell, one after another. The fog began to lift. Rocks and cactus spurted flame. Then Don Avenida went down, and that was the end. With the fall of their leader the last surviving members of his party broke and fled.

‘That’s the pay-off,’ said Pompey tersely. ‘It’s now or never. Come on.’ With that he dashed off, away from the direction of the main attack. A soldier sprang up in front and lunged at him with a bayonet. Pompey shot him.

All this Tommy saw as if he were a detached spectator. The whole thing was less real than if he had been watching a screen play. His movements had become mechanical. His brain seemed numb. Indeed, he was no longer even conscious of his limbs. Only the instinct of self-preservation remained, and under its impulse his one purpose was to get away as quickly as possible from a situation into which he had been thrown by circumstances beyond his control.

The mist had now become a drizzle, but he was scarcely conscious of it. Thorns tore at his legs. He hardly felt them. It was not so much that he actually feared death. He just wanted to escape from one of those nightmares that seem endless, in which one rushes on without getting anywhere. Always in front were rocks and cactuses, and then more rocks and cactuses.

A soldier sprang up in front

Then, at last, the ground began to slope downwards. A few trees appeared, becoming thicker as the ground continued to fall away. Keeping together they hastened on, Pompey and Digger, their rifles held ready for instant use, leading the way. Where they were going Tommy didn’t know. He suspected that none of them knew. It didn’t matter. The thing was to get away from a battle which, judging by screams and yells behind them, had become a massacre. Panting, slipping, sliding, clutching at trees for support, he blundered on. Once he jumped over a snake as it glided across his path. It was the first wild snake he had ever seen, and although he loathed the reptiles, at the time the incident passed almost unnoticed. He remembered it later with a shudder. Digger told him it was a bushmaster, one of the most deadly snakes in the world. He was thankful he didn’t know it at the time.

Slowly, the gruesome din of war faded away behind them. Pompey paused for a moment to say they would have to push on, for now would begin the business of rounding up any surviving rebels. So they went on, to what seemed to Tommy for hours. The ground had continued to fall and they were now in real forest. The heat was suffocating, and Tommy remembered what Digger had said about sweat, thorns and rotting leaves. They moved through a dark-green twilight, under a roof of leaves that dripped water in a steady stream. But there was none to drink, and he needed a drink badly. The only part of him that was dry was his mouth. He told Digger so, whereupon Digger took hold of a liana as thick as his leg, and saying, ‘Hold your hands,’ slashed it with his knife. Clean cool water gushed out, and Tommy drank it gratefully.

‘Never try doing that yourself,’ warned Digger. ‘There’s another liana very much like that one, but it’s poison. Contains strychnine.’

They went on.

The journey seemed interminable, but like all journeys it came to an end, and this was first revealed by a bright light ahead.

They staggered towards it, and there above them was the sky. Before them rolled a broad river.

Now, thought Tommy thankfully, they would have to stop. And so they did; but not for long. Distant calls and whistles made it evident that they were being pursued; and as they must have left a track plain enough for a child to follow they could only push on or be overtaken. They were all in a dreadful state, streaked with mud and hair plastered on their faces. By good fortune they had struck the river at a bend, with the result that a beach had been cast up, although this, when they set off along it, turned out to be mud into which they sank nearly to the knees. The river itself was the colour of mud. An inquiry from Tommy ascertained that no-one knew where they were, or the name of the river, although Batty had made a careful study of a map of the country before starting on his quest. But then, he had been on the march for a week.

Rounding the bend they saw a house—or rather, a shed—in a little clearing. It was a dreary dismal place, and appeared to have been abandoned. Digger said it was, or had been, the home of a rubber collector. Just beyond it the beach lost itself in a hideous tangle of mangrove roots, and to Tommy’s consternation it looked as if they would have to take to the jungle again. It need hardly be said that his mental picture of a tropical forest had by this time been rudely shattered. However, their luck was in, for lying on the bank, half hidden by rushes, they found a canoe. At its best it must have been a primitive affair, consisting simply of a hollowed-out tree trunk; but now it was in the final stages of dilapidation. Still, it appeared to be watertight, as they ascertained by tipping the rain water out of it. Digger found two old paddles lying at the back of the hut; they were in the same worm-eaten state as the boat, but they had to suffice. It could only be hoped that they would last to the far side of the river. It took their combined strength to get the heavy watersoaked craft on the water. Pompey and Digger operated the paddles, taking a course diagonally downstream to lessen the strain on them.

They were only just in time. The river was about two hundred yards wide, and they were not more than half way across when several soldiers appeared on the bank they had just left, reaching the water where they themselves had emerged from the forest. The Government troops had obviously followed their tracks, and it was natural that they should continue to do so, for the marks in the mud were as plain as if they had been made by half a dozen buffaloes. For this reason the canoe was not seen immediately, and by the time a shout announced its discovery it was some way down the river, as well as nearly across. Nevertheless, it was not out of danger, and bullets were soon flicking feathers on the water. Two or three anxious minutes followed before the canoe was driven under some overhanging branches out of sight of the enemy. There it rested. After a while, following a debate, the soldiers moved off downstream and disappeared in the jungle.

. . . bullets were soon flicking feathers on the water

Pompey urged the clumsy craft forward to the bank, where they all got out. Tommy sank down regardless of the slushy state of the ground and mopped his face with a filthy rag that had once been a handkerchief.

‘Let’s hope there isn’t another canoe anywhere near on the other bank,’ he said fervently. ‘I’m about all in.’

‘What! Packing up in the middle of your first adventure!’ chided Pompey. ‘You can’t do that.’

‘I’m sorry about Don Avenida,’ remarked Batty. ‘He seemed a decent sort of chap.’

‘Aw shucks! I shan’t lose any sleep over him,’ declared Pompey. ‘People who start trouble can’t grumble if it trips them up. If there’s anybody to be sorry for it’s the poor saps who backed up his gamble for the president’s chair.’

‘They ran like a lot of rabbits,’ muttered Batty.

‘They knew what was coming to ’em if they got caught. Their trouble was they lost their heads. We got away because we kept together and watched which way we went.’

‘And here we are,’ said Batty.

‘Yes, and where’s that?’ inquired Digger practically. ‘Do you know where we are, because I don’t? We’d better see about finding out. I’ve had some experience of this sort of country so I can tell you we’re a long way from being out of the wood. And I mean that literally as well as figuratively, as you can see for yourselves. We’ve got to eat before the mosquitoes eat us, and unless we can find a village that’s going to be difficult. If we can find a village we might also get an idea of where we are.’

Batty now broke the news that he had a map, as well as the sketch showing where the gold was buried; but when he produced it hope turned to disappointment, for it turned out to be merely a page torn from an atlas, showing the whole of South America, of which Rioguiana is but an infinitesimal part. On a scale so small the map was useless for any practical purpose other than showing the position of the country. Moreover, being wet, the paper had stuck in its folds like pulp, for which reason it had to be handled with the greatest care if it was not to fall to pieces.

‘You know, Batty, you’d have done better to wait for the dry season instead of coming in on the edge of the wet, when everything is waterlogged and bedraggled,’ remarked Digger, trying to unstick the map. ‘Let’s try to work it out this way,’ he went on, pointing with a muddy finger. ‘Here’s Los Ricas. That’s where you say you started from. How long were you on the march?’

‘Five days.’

‘Doing how many miles a day?’

‘It’s hard to say. You see, we started over mountains, and then had some forest to get through in order to reach the coast. After that we must have done about fifty miles. But I can tell you this. When we halted last night we weren’t far from the frontier. I can’t understand why we didn’t stick to the coast.’

‘I can guess the answer to that,’ said Digger. ‘Had we carried on along the coast we should have struck this river at the mouth, with no way of crossing. With the river in front and the government troops behind we should have been trapped; wherefore Don Avenida turned inland to strike the river higher up, where it may be possible to cross. If we weren’t far from the frontier this river may form the boundary. If it is the boundary then it must be the Olarayo, into which the Ronstadt bolted—and hid the gold.’

‘Wait a minute,’ requested Batty. ‘It isn’t as easy as that. Like most of these big rivers the Olarayo has about six mouths—what they call a delta. Karl makes a note of that on his chart. What I’m trying to say is, even if this is the Olarayo we’re on now, it isn’t necessarily the particular mouth into which the Ronstadt bolted. As far as the gold is concerned it doesn’t really matter, because the stuff was hidden above the point where all the different rivers join.’

‘Never mind the gold. What about some grub,’ put in Pompey impatiently. ‘We couldn’t do anything with the gold even if we found it. A couple bars’d sink this crazy canoe. Let’s get out of this mess we’re in.’

Digger agreed. ‘We couldn’t make any headway upstream in this dugout. The only way we can go is down. And we’d better keep near the bank in case it sinks, because there are some nasty beasts in all these rivers. We shall just have to keep going till we come to a village, unless we have the luck to strike a rubber collector’s hut. Not that he’d be likely to help us with grub. It takes these chaps all their time to feed themselves. We’ll keep on this side because of the troops on the other bank. Some of them may have crossed over, of course. In a delta there is seldom a clearly defined frontier. There are usually islands that are a sort of no-man’s-land. It boils down to this. We can’t stay here. There’s no question of walking through the forest. We can’t go upstream so we must go down, and the sooner we’re on our way the better, because if we don’t get somewhere before dark we’re going to have an uncomfortable night. A week of this without mosquito nets and we shall be rotten with malaria.’

‘Couldn’t we shoot something to eat?’ suggested Tommy tentatively. ‘We’ve still got our rifles.’

‘Certainly, if we have the luck to see anything to shoot at other than alligators, and there will probably be plenty of those,’ answered Digger. ‘Come on.’

The dugout was pushed clear of the trees and started on its journey down the river of doubt.

As the canoe proceeded cautiously down the broad stream Tommy had an opportunity to think calmly for the first time since the Midas’s lifeboat had been cast ashore on Rioguiana; and his dominant sensation was one of disappointment. He felt he had been cheated, misled by the glowing accounts he had read of the tropics. How right Digger had been when he had talked of discomfort, ill-health and death being the portion of the explorer.

That his wish to meet with an adventure had been fulfilled he would not have denied; but this was not the sort of adventure he had visualised, or would have chosen. This one had been forced upon him. But then, he brooded disconsolately, perhaps that was what an adventure really was—something forced upon one, willy-nilly. And without unpleasantness there could be no adventure. In a word, the dreams he had cherished had let him down badly.

He would not have minded being dirty, wet and hungry, had there been compensations; had the scenery lived up to its reputation for sunshine, colour and variety. This horrible sameness was depressing. Where was the sun? The blue sky? The luscious fruit, the gorgeous flowers and the wild animals? Certainly they were not here—or if they were they were not to be seen, so they might as well not have existed. Instead, all was drab monotony, dark and cheerless. And to cap all, the miserable land was beset with strife, murder, sudden death and ferocious insects. There were plenty of insects, and they all seemed to be as hungry as he was.

The dugout, cumbersome and waterlogged, drifted on a turgid yellow stream under an overcast sky from which rain sometimes fell in torrents. On each side the sombre green wall of the forest rose straight from the water, sullen, and in some indefinable way, menacing. The only variation was at the bends, where a beach of mud and debris had been cast on the wide curve. At every turn of the river Tommy looked ahead eagerly for something different. But it was always the same. More water; more forest. Sometimes the canoe overtook dead trees, and islands of floating weeds. On one of these lay a snake. Aside from this reptile, an occasional parrot flapping across the river, or an alligator on a mudbank, were the only creatures he saw to confirm that he was in the wild country of his dreams. The day wore on. They saw no soldiers, which was at least a mercy for which to be thankful.

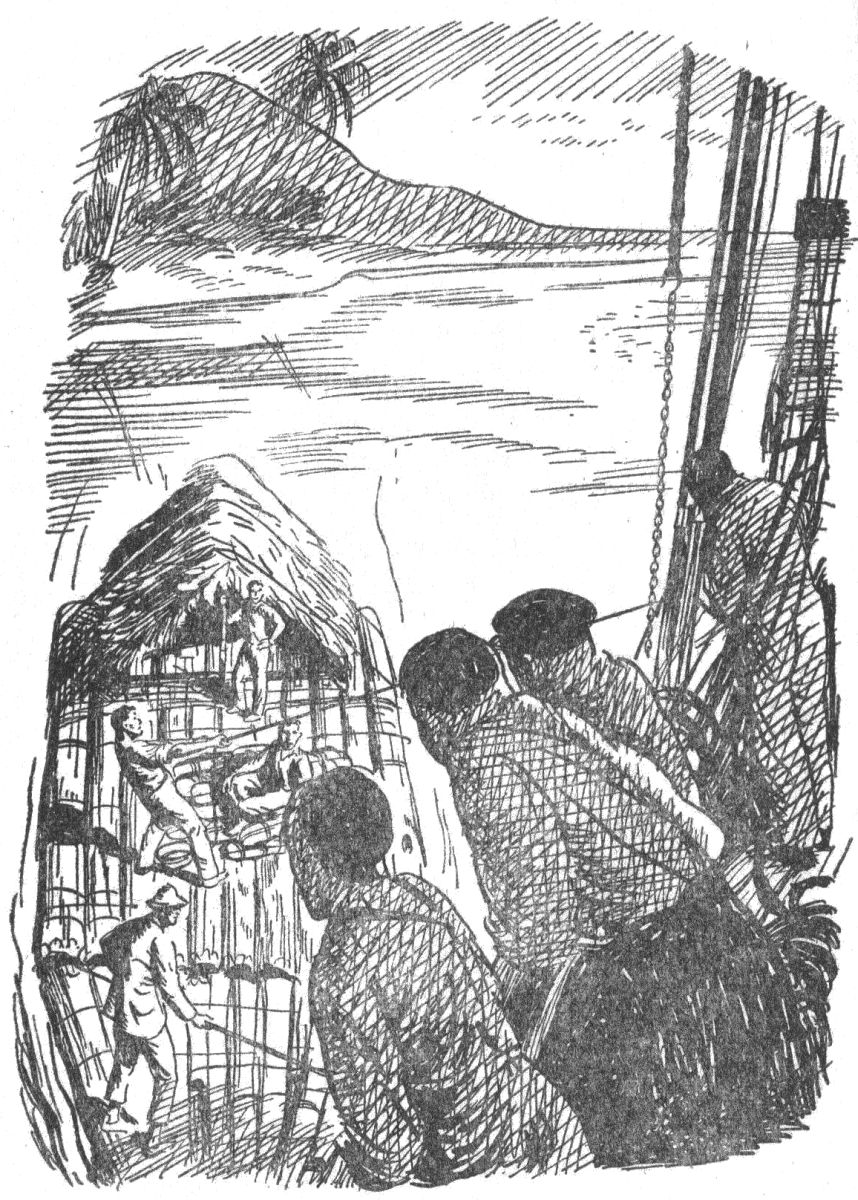

It was dusk when, in a clearing on their side of the river, they came upon a fairly well-built hut, with a palm-thatched shed close by. To call the building a house would be to flatter it. Two almost naked children were chasing some little brown pigs in the mire, watched by a mangy dog. The barking of this animal brought an unhealthy-looking woman to the door. She had a baby in her arms. Pompey called something to her, as if to assure her of their peaceful intentions, as they dragged the canoe clear of the water. Then, in an indescribable scene of squalor, Pompey and Digger engaged her in a conversation which Tommy, of course, was unable to follow. This took place on a sort of platform built outside the hut. It had a roof but no walls. The floor was made of palm-frond spines. It was littered with empty tins and garbage. In places it had broken through into muddy holes in which the pigs had wallowed. Flies were everywhere. The smell was awful.

At the end of the conversation Pompey translated for the benefit of those who had not understood. The woman was the wife of a rubber collector who was away on his rounds. Soldiers had been there looking for four gringos who were on their way down the river. The river was not the Olarayo but a tributary. A jungle track would take them to the village of Sanquitos, on the near bank of the Olarayo, about five miles distant. The woman had no food to spare. The soldiers had taken her chickens. But she could let them have some fruit, and some farofa, which Digger said was a national dish, a sort of porridge made of manioc root. They could spend the night in the shed where the rubber was stored. There were some old hammocks there.

That was all. The woman watched them listlessly as they discussed the matter. Not that there was much to discuss. In the circumstances they were glad to accept any sort of food and shelter for the night. They would make for Sanquitos first thing in the morning. There would, they realised, be some danger in this; but it would be less dangerous than continuing in the dugout. In any case, they were still in no position to choose. The present hand-to-mouth existence could not be maintained indefinitely. Just what they would do when they got to Sanquitos would depend on what they found there. The only member of the party who had any Rioguianan money was Batty, and he hadn’t much. Digger had five English pound notes, and an American twenty-dollar gold piece, in his ‘emergency’ belt; but it was thought there might be some difficulty, and danger, in trying to change these into local currency. Apart from that, their only marketable possessions were the rifles they still carried. But as none of them had a permit to carry firearms the disposal of these weapons would be attended by some risk.

As by this time it was nearly dark, they went into the hut to make preparations for the night. Digger lit a small fire clear of the balls of crude rubber, both to enable them to see what they were doing and to discourage the mosquitoes that were now rising in swarms. The woman brought them some mediocre oranges, and a bowl of farofa which they ate, using broken pieces of gourd for spoons. To Tommy the stuff tasted like a mixture of sawdust and chalk. Moreover, it gummed up his mouth, so that he had some difficulty in getting it down; but it did at least satisfy his appetite, and he felt better for it. Worn out, he climbed into his hammock and was instantly asleep.

The next thing he knew the woman was there, in the sullen red glow of daybreak, wringing her hands, making frantic signals and crying something in a shrill voice.

Pompey was out of his hammock in a flash, ‘Come on,’ he rapped out urgently. ‘Soldiers are coming up the river in a gunboat. The dame wants us out of the way in case they call here.’

Whether or not the soldiers called they never knew, for no further invitation was necessary to send them running down the track which the woman pointed out to them, and that was the last they saw of her. Tommy was upset that they should leave her without recompense, or even thanks, but the circumstances were such that the slightest delay might have cost them all their lives—not excluding their benefactress, who might have been shot for harbouring rebels.

After covering about a mile of heavy going at top speed they stopped to listen, but hearing no sounds of pursuit they steadied the pace; for which Tommy was thankful, for under the great trees the atmosphere was like a turkish bath. His clothing stuck to his body.

The woman was there crying in a shrill voice

The first indication that they were approaching Sanquitos was provided by an area where trees had been felled recently, for red sap still dripped from the cut surfaces. Digger said he thought Sanquitos must be a lumber town. The trees, he told them, were redwoods, the pau brazil that had given Brazil its name. The trees lay in all directions, and they had either to climb over the slippery trunks or work their way round them. When sounds not far ahead warned them that they had nearly reached their immediate destination Digger said it was time they made a plan of action. They sat on a branch to discuss it.

At the end it was resolved that Digger, leaving his rifle behind, should go ahead, alone, and spy out the land. The first and most important thing was to ascertain if soldiers were there, or had been there to warn the population to be on the look-out for four Europeans. Should the coast be clear he would look for a lodging where they could have a clean up, eat some food and decide what they should do next. Taking some of Batty’s money he departed on his mission.

He was away for some time, but his news, when he returned, was good. There were no soldiers in what he described as a small township, engaged in the timber industry, on the right bank of the Olarayo. There were shops and a hotel of sorts. Wood-burning steamers, plying up and down the river, called for fuel and cargo. One was there now. No doubt they would be able to book a passage on it to the coast. Posing as an American reporter, he had changed his twenty-dollar gold piece and taken one room only at the hotel, for himself. He thought it better that the others should do the same, as odd men would be less likely to attract attention than a party of four—particularly as it was known, in the capital at any rate, that four Europeans had been involved in the rebellion. Finally, he had bought a long-sleeved shirt for Pompey, whose tattooed skin, he averred, could hardly fail to identify him as one of the wanted men should descriptions be published. Once in the town they would try discreetly to raise money on the rifles. In such an outpost it should not be difficult to find a buyer.

All this worked out as planned, and with only one slight hitch. They entered the town one at a time. When Tommy’s turn came he saw Pompey talking to an official of some sort. Later Pompey told them it was the local policeman, who had asked him if he had seen anything of a party of four gringos who were travelling together. Pompey had, of course, said no. Thus was the wisdom of Digger’s plan proved, and they took heed of the warning.

To Tommy, Sanquitos was a horrible little town, dirty and untidy, ramshackle without being picturesque. It consisted of nothing more than two rows of one-storied wooden dwellings on either side of an earth road, slippery with mud and littered with rubbish. One end wandered away into the forest; the other end finished at a rough wharf where the river traffic berthed. There were one or two general stores, and a dilapidated structure with bedrooms scattered haphazard round a courtyard, that was known as the hotel.

Apparently the arrival of strangers, mostly recruits for the lumber camps, was nothing unusual. No questions were asked, and by evening they were installed in their rooms, having had a bath and a meal, looking reasonably respectable in the cheap cotton clothes that were worn by the local people—white, black, brown and every intermediate shade. More than half the population was Indian.

Assembled in Digger’s room, the question that now arose was what to do next. On their way down the river and through the forest it had been the general assumption that they would get out of the country as quickly as possible; but now they were feeling better, and no immediate danger threatened, it was inevitable that the subject of the gold should be reintroduced. Batty was still determined to go after it, and even Pompey agreed that it would be a pity, now they were so close to the cache, to go away without so much as ascertaining if the gold was still there.

The big problem, of course, was money, for they would need a boat, digging tools, and, since they would go upstream, food for at least two or three weeks. Should they find the gold, the question would arise, what could they do with it? For more reasons than one it was obviously impracticable to attempt to transport all the gold down the river in a canoe—never mind get out of the country with it. Then there was the matter of the ownership of the gold. To whom did it belong? Batty admitted frankly that he didn’t know. That aspect of the case hadn’t struck him. He had assumed, somewhat casually, that whoever it had belonged to originally must have long ago regarded it as lost. Surely it was now a matter of ‘findings keepings.’

The others were not so sure of this, but Pompey, always practical, squashed the argument by stating that the time to count these particular chickens was after they were hatched. Should they find the gold they could move it to a new cache, and then decide what to do about it. The common sense of this was so apparent that no-one disputed it, so they returned to ways and means of reaching the place where the gold was alleged to have been hidden. Without money they were obviously helpless, so Digger said he would see how much he could raise on the rifles, or at any rate, on three of them, for if they were going up the river they ought to keep one.

With this object he went off again, and after a lengthy absence returned with more encouraging news. He had sold three of the rifles, and most of the cartridges, to a second-hand dealer. He hadn’t got much of a price, but as the deal was under the counter, so to speak, that was only to be expected. But he had enough, he thought, for their purpose. From the same dealer he had bought an old, but river-worthy canoe, with a tarpaulin cover which could if necessary be used as a tent. He had also bought, as part of the deal, a pick and a spade, so all they needed now was food. Not so much would be required as they had originally estimated, for he had arranged for a tow, with the skipper of the steamer then taking on firewood at the wharf, for as far as they needed to go. There would be no difficulty in travelling downstream. It was the upstream journey which, under the power of paddles alone, would take time, and consequently a big supply of food.

Pompey smacked his thigh. ‘Nothing like having a man in the crew who knows his way around,’ he said admiringly.

‘I don’t know,’ answered Digger dubiously. ‘I’ve started on some crazy jaunts in my time, but this is, I think, the craziest.’

‘What time does the steamer cast off?’ asked Pompey.

‘Ten o’clock tomorrow morning, when another steamer, from another arm of the estuary, is due in. That should give us comfortable time to get food aboard, settle up here and get ready for off.’

Tommy grinned. ‘This is beginning to sound more like the sort of adventure I was looking for,’ he declared.

‘I hope you’ll still be thinking so in a week’s time,’ returned Digger soberly. ‘Things have been going well. I’ve learnt from experience to watch out for a snag when things look too rosy.’

The snag, although they did not know it, was even then on its way up the river.

Morning came again under a leaden sky, but an occasional fleeting glimpse of blue foreshadowed the approach of better weather, although there were still frequent and heavy showers.

Tommy made a reconnaissance with Digger to make sure all was well. At the wharf, the steamer that was to tow them up the river was still unloading bags of manioc, which, Digger said, was the staple food of the country, and, incidentally, the root from which tapioca is made. Behind it floated the canoe. There were also some other queer-looking craft, looking like rafts made of logs tied together, or pinned together with skewers, the forward end being brought to a point. Sometimes two or three of these rafts were lashed together. Each raft carried a rough superstructure of canes in the form of a shelter—it could hardly be called a hut.

Digger said these were balsas. When two or three were fastened together the result was called a callapo. These craft were built and used by Indians known as balseros, and their purpose was to bring their produce down the river—balsa logs, rubber and the chicle—another rubber-like latex—that formed the base of chewing gum. Balsa wood, being as light as cork after it had been cut for some time, floated on the top of the water, not in it. The trees grew nearly everywhere in tropical America, always near water. Tommy recalled that it was on account of its lightness that balsa wood was used for making models, particularly model aeroplanes.

‘Why didn’t we have a balsa,’ inquired Tommy. ‘There seems to be more room on one than in a canoe.’

Digger smiled sadly. ‘As you see, the method of propulsion is by pole, and going upstream it takes a bit of handling. In fact, in deep water, to get a balsa upstream at all is a dickens of a job, not to say hard work. Usually three balseros are required to work the raft. Two pull on a tow rope while the other man steers. You may have noticed that at every bend of the river there’s a beach on one bank. Very well. Two men, towing the raft, walk up the beach for as far as they can get. Then they pole to the other bank and haul up the next beach on that side. So they go on up the river, criss-crossing all the time. Of course, coming down is comparatively easy.’

‘That doesn’t sound like fun to me,’ said Tommy seriously.

‘It isn’t,’ agreed Digger. ‘I’d better go and see about the grub.’

Tommy and Batty kept watch on the canoe while Digger and Pompey fetched the stores. No-one took any notice of them.

At ten o’clock the tow rope was made fast and everything was ready—everything, that is, except the steamer, which seemed to be in no hurry to move off. Tommy fretted at the delay, but it made no difference. In a way, this unpunctuality did them a service. Certainly it provided them with some information that was to affect their movements.

What happened was this. While they were waiting, Tommy, tired of squatting in a cramped position in the canoe, got out and sat on the wharf. He was still there, for the steamer showed no signs of departure, when up the river came a small but powerful-looking steam yacht of some fifty or sixty tons. As it neared the wharf, clearly with the intention of tying up, Tommy watched the deck closely. Naturally he thought it might be a Government craft with soldiers on board. This, however, was apparently not the case, for four civilians in smart duck suits came ashore, leaving the craft in charge of a coloured man—presumably the river pilot. The men were, without doubt, Europeans. As, talking, they passed the place where Tommy was sitting, he caught one word of their conversation clearly, possibly because that word struck a chord on his memory. The word was Dostler. This, he recalled with a shock, was the name of the second member of the crew of the ill-fated Ronstadt who knew where the gold was buried. That could only mean one thing. In his haste to get back into the canoe to tell the others what he had heard he nearly upset it.

‘They’re Germans all right,’ muttered Batty, his eyes on the retreating figures. ‘We needn’t wonder what they’re doing here.’

‘There is this about it,’ said Digger. ‘If Dostler is in that party, and they’re on their way up the river, it means that the gold is still where it was buried.’

‘It won’t be there much longer if they get to it first,’ put in Batty bitterly. ‘And here we sit doing nothing.’

At this juncture, to the great relief of everyone in the canoe, the captain of the steamer went on board, and a hoot of the siren promised an early departure.

They passed the place where Tommy was sitting

‘As Dostler, knowing about the gold, is still alive, I wonder why he waited for so long before coming after it,’ said Tommy. ‘I mean, it’s extraordinary that he should arrive at the same time as ourselves.’