* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Nothing Can Rescue Me

Date of first publication: 1943

Author: Elizabeth Daly (1878-1967)

Date first posted: Aug. 22, 2021

Date last updated: Aug. 22, 2021

Faded Page eBook #20210848

This eBook was produced by: Alex White & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

Nothing Can Rescue Me

Henry Gamadge #5

Elizabeth Daly

First published 1943 by Farrar & Rinehart

| ONE | Some Silly Game |

| TWO | Chapter Nine |

| THREE | Being of Sound Mind |

| FOUR | Mouse in the Attic |

| FIVE | Planchette |

| SIX | Explosive |

| SEVEN | Lull in the Storm |

| EIGHT | Elemental |

| NINE | Defence Programme |

| TEN | All Nice Folks |

| ELEVEN | Percy Rejects an Alibi |

| TWELVE | A Garden Not So Lovesome |

| THIRTEEN | Lightning |

| FOURTEEN | Last Will |

| FIFTEEN | Slacks |

| SIXTEEN | Yew Hedges |

| SEVENTEEN | Evidence |

| EIGHTEEN | End of Planchette |

| NINETEEN | Mania |

| TWENTY | Case History |

The plump little man leaned over Gamadge’s shoulder and squeaked in his ear: “Who am I?”

“Hutter!”

“It’s a wonder you knew me.” Sylvanus Hutter circled Gamadge’s chair, pulled one up for himself, and sat down. He smiled and rubbed his knees. “That last reunion was in 1927.”

“Good Heavens.” Gamadge had laid aside his magazine, to gaze benevolently at his old classmate. “ ’27 from ’42 leaves fifteen.”

“That’s New York for you! But of course I’m always on the wing; or was,” his face fell, “until recently. Life will be different for awhile, I suppose.”

“Plenty of things to see on our continent.”

“I don’t suppose I shall have time to see them. As for digging! Good-bye to the digs for the duration.”

“Perhaps you’ll have time to get out another handsome book. I see them, if I don’t see you.” Gamadge added: “Nice of you to tap me.”

“I was going to call you up. Lucky to find you at the old club.”

“I shouldn’t be here if my wife weren’t away.”

“Oh, is she? That’s too bad. Florence and I hoped you’d both be able to come up to Underhill to-morrow for over Sunday. We’ve never met Mrs. Gamadge—too absurd.”

“She’s in the West; her aunt’s ill there, and needed her.”

“But you’ll come, Gamadge, old man?”

Gamadge, as he considered the question, thought that fifteen years had not made much difference in Sylvanus Hutter. He was old for thirty-six—his lightish hair was thinning, his pinkish face had developed creases that would soon be wrinkles; but he was still as neat as a pin, and still punctilious—if he had dressed for a solitary dinner at the club; his yellow-brown eyes were still unable squarely to meet the eyes of the person he was talking to; his manner, in spite of a touch of nervousness, was as deliberate as of old. Sylvanus had never caught trains; he had advanced upon them with quiet purpose, ignoring their clamour and the rush of the crowd.

The round eyes besought Gamadge, and shifted away. “Florence will be disappointed if you can’t manage the week-end—what’s left of it.” He added: “Dine with me and think it over.”

“Awfully sorry, I’m meeting some men for bridge and dinner. Wish I were not; I’m straight from the office.”

“You in an office?”

“Bit of a war job. I’d like to go up to Underhill; I haven’t seen Florence for five years—since her wedding. You don’t see much of people at their weddings.”

“I wasn’t at the wedding. Couldn’t get home for it.” Hutter was still rubbing his plump knees, “I was laid up abroad.”

“So you were.” Gamadge remembered a theory, current at the time, that if Sylvanus had not been stranded in Rome with a broken leg his Aunt Florence would never have rushed into, and gone through with, her unsuitable marriage.

“Florence says you really must come to-morrow; I mean, you really must.” Hutter’s straying eyes rose from Gamadge’s tie to his face, and remained there. “It’s—it’s a case, you know.”

“A case?”

“For you. At least, Florence thinks it is. I don’t as yet agree with her. I still think it may be some silly game.”

“I have no time for cases, Syl; my assistant’s in camp, my own job’s shot to pieces, and I’m up to my ears in war work.”

“Surely you could give us to-morrow and Sunday?”

“I’d have to leave on Sunday afternoon. I must be in that office by nine on Monday morning.”

“You could probably clear the whole thing up overnight. We know,” said Hutter, smiling, “what a great man you are.”

This was a joke—a Hutter joke. Greatness, even to the present sophisticated generation of Hutters, meant an ability to make a great deal of money; except in the case of a few persons, most of whom had been dead a long time.

“Don’t tease me,” begged Gamadge.

“Tease you? We’re only thankful we know a fellow like you. The matter’s confidential, very ticklish, Florence is upset. She needs a man of sense to confer with.”

“Her husband doesn’t qualify?” Gamadge, remembering Tim Mason the cheerful idiot, the muscular sportsman, who had succeeded at last where other, wiser fortune hunters had failed, asked the question with raised eyebrows.

Hutter laughed, “I think you know Tim Mason!”

“I knew him once—slightly. I haven’t seen him since the wedding, either.”

“Well, he’s sixteen years younger than Florence, and you can guess that she didn’t marry him because he was sensible.”

“He must be forty now.”

Hutter wagged his head. “He’s no help in a matter of this kind. He won’t take it seriously.”

“You say you don’t take it seriously, whatever it is.”

“Well; I—at first I didn’t. Now I’m beginning to wonder whether it oughtn’t to be looked into after all.”

“What’s it all about, anyway?”

“I’m ashamed to say that it seems to be all about spooks.” Hutter laughed without much heartiness.

“I’m no authority on them, my dear boy.”

“Poor Florrie thinks she is. She took up automatic writing, and planchette, and all the rest of it, some time ago. Sally Deedes got her into it—you remember Sally? She’s been in a state of distraction for a great while, what with her marriage going to pieces, and her shop, and taxes, and the war. To tell you the truth, Gamadge, I ask myself whether Sally isn’t doing the things herself; unconsciously, of course. I ask myself whether Florence isn’t!”

Gamadge was irritated. “What things? What things?”

“Don’t ask me; it’s all above my head. I’d only confuse you and myself if I attempted to explain. You must come and get it straight from Florence, you really must.”

Gamadge sat back to study Florence Mason’s nephew with knitted brows. If Syl’s complacence had been disturbed, something very disagreeable must be going on at Underhill. Gamadge would not have been surprised to hear that trouble had followed the Mason marriage, but he would not have expected the trouble to proceed from the spirit world.

He thought of Florence’s wedding. She had carried it off well, with the childlike confidence that disarms criticism, and the cool determination that overrides it. She had looked younger than her fifty-one years, if a trifle haggard in her smart bridal gown and veil. She had been fluttery, emotional, triumphant. Mason, thick-shouldered and blond, the picture of satisfaction and good humour, had crushed the bones of Gamadge’s hand. “Isn’t she a wonderful girl, old man?” And Florence had embraced Gamadge, had cried, had shown him Syl’s lovely cable from Rome.

“Henry darling,” she had quavered, “why don’t you get married?”

Gamadge had benignly wished them luck. Now he passed the imbecile query on to Sylvanus Hutter: “Why don’t you get married, Syl?”

“Me?” Hutter was almost resentful. “Why should I get married? I’m perfectly happy as I am—or was, until this wretched war stopped my work. I don’t even know what will happen to my new book—the Mexican book. The fellow who was helping me with the text—clever boy—has gone off to fight.”

Gamadge respected the taste, the industry, and the knowledge that went into Hutter’s art-and-travel books, published at his own expense in luxurious style, and illustrated for the most part with photographs of places and objects taken by Hutter himself. And Hutter collected things, too. Gamadge asked: “Did you bring much stuff home with you?”

“Oh, no; that isn’t my field, you know; my field is closed. And my collecting wasn’t ever to be taken seriously, in any case; I hadn’t the money to buy much of anything really good. But Florence was worried about our best things—she has some nice silver and glass, you know; she insisted on having it all crated—waterproof crating—and bringing it up to Underhill. She thinks we might bury it.”

“No, really?”

“Florence wouldn’t stay in New York after the air wardens began to come around. She was frightened.”

“I wondered how you all happened to be in Underhill in February.”

“We went up on the first, for the duration.”

“Dear me! I had no idea people were evacuating themselves.”

“Oh, Florence was determined to go. We closed the New York house, and we’ve taken a little apartment. We all run down, now and then. This is the twentieth, isn’t it? We’ve been up at Underhill nearly three weeks.”

“What on earth does Mason find to do with himself at Underhill?”

“Oh, he’s quite happy. He has his horses, and he’s planning a nine-hole golf course across the stream. He comes to town a good deal, runs about, follows the races. Florence keeps the house full of people, you know. We’re very gay.” But Sylvanus did not look gay.

“She always did love a houseful.” Gamadge smiled, remembering Underhill in former days.

“Yes. She was fairly happy until this wretched business came along. Somebody’s been playing tricks. Until yesterday, though, I hoped that if we paid no attention the nonsense would stop. Yesterday—to be frank with you, I was disturbed; I let Florence persuade me that we’d better call you in. Miss Wing was inclined to wait a little.”

“Miss Wing?”

“Florence’s secretary.”

“Florence has a secretary, has she?”

“Oh, yes. She’s had several. She needs somebody to do her cheques and her social correspondence, get the household bills straight, that kind of thing. As a matter of fact, I’ve often been glad of someone to do my own accounts when I’m busy. And Miss Wing is a very highly educated girl, and she’s been indispensable,” said Hutter, smiling a little, “since Florence began to write.”

“Florence is writing? Splendid.” Gamadge himself refrained from smiling.

“For a year or so she tried plays, but she seemed to have a good deal of trouble with them, so she decided to attempt a novel. She started it as soon as she got to Underhill, and she’s been at it tooth and nail.”

“Good for Florence.”

“It was just what she needed to keep her busy up there. Miss Wing was invaluable—gave her her head, and did all the hard work. She’s a most cultivated, accomplished girl, a cousin of Sally Deedes. Has a bachelor’s degree, fell on hard times. Florence is devoted to her. She’s lasted,” said Hutter simply, “four years.”

“It sounds as if she had plenty to do.”

“She earns her salary, but you know Florence—how extremely good she is to people she likes. Miss Wing hoped at first that she’d be able to get to the bottom of this trouble we’ve been having—clear it up herself. But Florence and I think it’s gone too far; it ought to be stopped.”

“How long has it been going on?”

“A couple of weeks.”

“Who’s been in the house while it was going on?”

“That’s the worst of it—that’s why Florence is so badly upset. Eliminating the servants—and we can eliminate them, as you will see—”

“Tell me now why we can eliminate them.”

“They’re mentally incapable of such a trick. Besides—ridiculous! You remember dear old Thomas, and Florence’s Louise; devotion itself. The others—well, they’re out of the question. When you hear the story you’ll know what I mean.”

“I hope so.”

“Just take my word for it that the thing needed brains, brains and a debased kind of imagination. You know, Gamadge, that I have very little imagination myself; I take things coolly, I don’t go off the handle. But this business has given me a very queer feeling; unless Florence or Sally has quite gone off her head, hang it all, there’s something ugly in the house. Bad feeling, I mean.”

“Who was there besides the servants, Syl?” asked Gamadge patiently.

“Mason and myself, Sally Deedes, Miss Wing, Susie Burt, and a young fellow named Percy. Did you ever know Susie Burt? She would have been a child when you used to stay at Underhill.”

“I remember a beautiful Mrs. Burt.”

“That was Susie’s mother, Florence’s best friend. She died, her husband died, and Susie’s their only child. Susie’s had practically no income for some years. Florence took her on, tried to make her into a secretary just before she married Mason. It didn’t work; Susie’s not up to it. She stays with us a good deal—awfully pretty, very good company when she wants to be—and she has had various jobs from time to time here in town. None of them was very solid or lasting. Florence thinks she’s forward with men, but of course the poor girl wants be married. I never saw any great harm in her myself.”

“Who’s Percy?”

“He’s an old friend of Susie’s, charming fellow, been coming to Underhill with the Burts since he was a child. Great favourite with Florence; has no people, writes or something, lots of personality. Mason thinks he’s affected, but it’s only his way. He’s from Georgia originally, but he now lives in New York.”

“Do all these people know about the unpleasantness, whatever it is?”

“Oh, yes. Florence talked of nothing else. Now she’s talking about nothing else but you.”

“You say it may be some silly game. Miss Wing more or less agrees?”

Sylvanus, rather uncomfortably, said she did.

“How do the others react?”

“Mason declares it’s a stupid joke, meant to tease Florence; that’s more or less what I think and Miss Wing thinks, but he’s amused and we’re not; his sensibilities aren’t too fine, you know. Susie Burt has no opinion—her mind’s a blank on the subject. Percy won’t express himself at all—but then he’s out of it—no axe to grind. I mean—” Hutter coughed. “He’s too intelligent to do such a thing, if you know what I mean; just as Susie isn’t intelligent enough.”

“I don’t in the least know what you mean; you won’t tell me.”

“He’s too intelligent. Wouldn’t bother. Sally says it’s the spirits.”

“Says the spirits are playing a trick on Florence?”

“She’s really not herself since her divorce from Bill.”

“And you occasionally wonder whether she or Florence isn’t playing the trick in some trance?”

“Only because any other theory seems so incredible. Florence is badly upset, Gamadge.” He looked suddenly piteous.

“I’ll come if she needs me.”

“Needs you? She begs you to come. She implores you to come.”

Gamadge’s mind travelled back through the years; to school and college vacations when his mother and father had been far away, and he had been invited to Underhill. He remembered the glorious food, the parties, the winter sports, the camping and fishing, the pretty girls. He remembered Miss Florence Hutter presiding over the household and spoiling Syl’s friends; lively, affectionate, kind, but subject to sudden tempers and jealousies, easily bored with her protégés, easily made suspicious of their loyalty. Domineering—too domineering to marry while she was young. She had always seemed to Gamadge extraordinarily vulnerable in spite of her shrewdness.

“Well, I shan’t be able to stay long enough to do much good,” he said. “As I told you, I must go back on Sunday.”

Hutter, expelling a long breath, seemed also to expel care. He instantly got to his feet, gently shook one leg and then the other, and spoke with all his normal serenity: “Thank goodness. Mason and I are driving up to-night in his two-seater, but the big car’s in town being overhauled, and I’ll have Smith pick you up to-morrow morning. Will nine be too early? It will get you up to Underhill in time for a talk with Florence before lunch.”

“I’ll be ready.”

“And I’ll telephone Florence now. Take a load off her mind.” Sylvanus hesitated, and assumed the look that Hutters assumed when they were about to discuss money. “By the way, Florence expects you to accept a fee.”

“Very nice of her.”

“People sting her awfully, but she knows you won’t. We don’t know the proper fee for consultation, but Florence thought she might suggest what she pays her specialist for a visit—a hundred.”

“Well, I don’t know,” said Gamadge, enjoying himself. “Let’s say no remuneration unless I exorcise the spirits from Underhill; and if I do, she can pay me what she pays Macloud—if he’s still her lawyer—for exorcising some of the decimals out of her supertax.”

“Oh, good God, my dear fellow!” Hutter looked frightened.

“That or nothing,” smiled Gamadge.

“Talk it over with Florence; and Smith shall drive you home on Sunday.”

Sylvanus shook hands warmly, and trotted off. Gamadge mounted to a vast brown room, on an upper floor, and sought a lean man who was reading in a corner. “Hi,” he said.

“Hi.”

“Nobody here—we can talk.”

“No, we can’t. I’m busy.”

“I want to know how Nahum Hutter left his money, and how much he left.”

Mr. Robert Macloud raised his saturnine visage from the Law Journal, but maintained a grip on it. He said: “Nahum left about ten millions. Florence and Sylvanus have the use of the income, share and share alike, until one of them dies. The survivor—presumably Syl—then gets the whole capital, and can spend it.”

“You don’t say.” Gamadge let himself down into the depths of a leather chair.

“Nahum fixed it that way for his two children, Florence and Washington; Washington and Mrs. Washington died, and Nahum transferred the arrangement to Florence and Syl—Washington’s only child.”

“What income do Florence and Syl struggle along on?”

“About a hundred thousand apiece, taxes paid; that’s what they have now.”

“No provision for heirs, if any?”

“None. Old Ben Hutter didn’t make his fortune from railroads until Nahum was grown. Nahum was born and brought up in something like poverty on the original Hutter farm. He seems to have made up his mind that Florence and Syl should be comfortable as long as they lived; I suppose he thought that the survivor would have so much money he or she simply couldn’t lose it.” He added after reflection: “And I suppose he thought Florence wouldn’t marry—she was forty when he died, and had turned all fortune hunters down. Very funny; there must be something about Mason that I missed.”

“I faintly remember Nahum as quite a terror.”

“A pet, compared to old Ben. Nahum was rather proud of his children; he liked their social success; but Ben Hutter cast his other son, Joel, into outer darkness because he wanted to stay home and fish in the stream. They had a frightful row; Ben didn’t leave him a cent.”

“Did he mind?”

“Don’t know; but he died.”

“Would it be indiscreet of me to ask if Florence and Syl have made wills?”

“You mean you want to know what’s in ’em. No secret about Syl’s; he hasn’t much to leave. So far he’s lived well up to his income, you know how—travel, financing excavations, putting out his books. What he has goes to museums.”

“Queer situation, in a way; both of ’em as rich as Solomon, and neither can make an impressive will until the other dies.”

“You’re quite wrong; Florence can make a very good will indeed. She never financed digs; in the good old days she took her savings and went on the market. Just like her father, has the Midas touch. She made half a million.”

“Be a good scout and tell me how she’s leaving it.”

“What are you, that you should be told?”

“It wouldn’t be ethical of me to say.”

“You have no monopoly on ethics. And even if I did tell you, the information might cease to be of value any day. Florence, I am sorry to say it, has become a will-shaker.”

“Has she, though?”

“You been seeing them of late years?”

“Not for fifteen, except that glimpse I had of her at her wedding.”

“That wedding was her Rubicon.”

“She seemed pretty much then as she had always been, except that her poor face had been lifted.”

“She’s turned despot, and is surrounded by slaves. Even Syl, who’s financially independent of her, must do as he’s told, or he’d have to go—the house wouldn’t hold him.”

“Mason?”

“I’m not quite sure how much influence Mason still has, and I shall have no further opportunities for observation. They’ve fired me.”

“Syl and Florence have? What on earth for?”

Macloud made a face. “For sending in a bill, I suppose. They have a failing which they share with some other rich persons—they think paupers ought to work for them for love.”

“I’m going up there to-morrow on a job.”

Macloud removed his cigar to glance alertly at his friend. “Job? Books? Papers? Autographs? Didn’t know Syl bothered with them.”

“He didn’t really say what the job was.”

“Nothing in the criminological line, I presume? Ah, well; get the amount of your honorarium down in writing first, my boy, and take my blessing with you.”

“I’m doing whatever it is on spec.”

“Heaven help you.”

Gamadge, frowning, lighted a cigarette. “Florence was awfully good to me when I was young,” he said. “My father had to travel for his health, and my mother naturally went along; the Hutters took me in for holidays. Florence was awfully kind.”

“She’s still kind; sometimes too kind. Then she gets tired of people, or suspicious of them, or something, and it’s all off. The set-up there isn’t too healthy, I sometimes think.”

“That’s what I thought, from what Sylvanus told me to-night.”

“Well, I’m out of the picture now, thank goodness. Go away and leave me in peace, why don’t you?”

Gamadge went away, but only to the opposite corner of the room. He got some books out of a glassed case, and settled down to read everything he could find on automatic writing, with special reference to the use of planchette.

But his thoughts would wander to Underhill in the old days; he remembered sitting in the Gothic dining-room at meal-times and wondering, as he listened to the homilies of Nahum Hutter, that Florence and Sylvanus were as decent as they were; for Nahum’s homilies were variations upon one theme—that we live, after all, by our pockets, and that the man or woman who has something to give away must never hope to possess entirely disinterested friends.

After crossing the Hudson at Poughkeepsie the big Hutter car travelled north-west. It followed an excellent highway through the town of Bethea, and then bore off to the left and rolled sixteen miles into mountain country. Beyond the village of Erasmus (fourteen houses, a store, a church, and a handsome library) it turned left again, to proceed with due caution along a dirt road harrowed by winter storms. Gamadge looked out at the landscape that he had once known so well; at the hillsides covered with immemorial hemlock, the later growths of beech and maple in the valleys, the rocky fields and brown streams. Strange, wild country; haunted country in the past, when no Indian would camp where the hemlocks made day into night. Haunted country still, legend declared, on the mountains.

Three miles above Erasmus the Hutter house stood on its ridge, with a view to the south-west of Catskill ranges. It was sheltered on the east by a towering slope of hemlock, the hill that had given it its present name; a stream ran below the grounds to the west, and beyond it were cultivated fields and pastures. Long ago Underhill had been the Hutter Farm, but old Ben Hutter had come back to it in triumph after he made his fortune, and rebuilt it of field stone into a fine large house, a typical summer residence of the ’eighties. It was a kind of villa, like the villas that old Hutter was now invited to outside New York; he admired them very much, and saw no reason why one of them should not be set down among the hemlock forests. It was weather-tight, three stories high, and almost square, with a lawn and a carriage house. It had a bathroom, but water did not run in the house. It had no plumbing. Large fires burned on its hearths on all but a few summer evenings, and it was lighted by kerosene. It was not meant to be lived in during cold weather.

At the turn of the century when old Hutter died, his son Nahum allowed his children to modernize the house. They christened it Underhill, and introduced another bathroom, hot and cold running water, and sanitation. The grounds were landscaped, and there was a library.

By the time Nahum died—in 1925—Underhill made its own electricity, had an oil burner in the cellar and lost slices from its bedrooms; the slices became individual baths. Florence and Sylvanus came up at all seasons of the year, and steadily refused to do anything about the three miles of bad road from Erasmus; they were only too glad to be cut off from the tourist traffic.

By February 1942, when Gamadge stepped out of the car and looked at Underhill, it had encountered decorative art. The field stone had been filled in with stucco, and washed a delicate pink; a tracery of ironwork surrounded its roof and climbed up its walls; its pointed windows were now arches, and its porch had been shaved away. Gamadge stood upon shallow front steps and gazed at it. He feared for the once stately interior, but he ought to have trusted Florence and Syl and their decorator; when he had greeted old Thomas affectionately and entered the hall he was delighted. Underhill’s dignity had been preserved, but its grimness was gone.

“Well, Thomas,” he said, “I’m glad to be walking on the old black-and-white marble again, and I must say it looks better than it ever did before.”

“Yes, sir. All the white does brighten up the house. But it’s a dark house, sir.”

“So it is. These high, narrow windows.”

“Mrs. Mason would like to see you upstairs, sir. It’s very nice to have you with us again.”

“Very nice to be here.”

Sylvanus popped from the library on the left. “Gamadge—this is splendid. Florence wants to see you, but will you have something to warm you up first? You must have had a cold journey.”

“Warm as toast. Not a thing, thank you, Syl.”

“I’ve put you in your old room, the one next to mine. Hope you don’t mind sharing my bath?”

“Of course not.”

“I’ll see you when you come down.”

Gamadge was glad that a stalwart Scandinavian maid possessed herself of his bag. He followed the ancient Thomas up to the second floor and along its wide corridor to the back of the house. Thomas knocked at an end door, opened it, and stood aside.

Underhill might be a dark house, but Florence Mason had contrived a bright room for herself by having partitions removed and securing an outlook to the north, south and west. She sat beside the crackling fire in what seemed a flood of sunlight, although the February sun was pale; sat among her light-blue draperies, on a tufted chaise-longue, and held out her arms to him.

“Henry, darling Henry, I’m so glad you could come!” Gamadge went over and hugged her. “Of course I came.”

“You haven’t changed a bit.” She kept both his hands in a nervous grip when he straightened to look down at her. He couldn’t say the same; she had changed a good deal. Whatever her maid Louise could do had been done for her, but Florence herself had ceased to take an interest in herself. Her hair, dyed a bright brown, had not been carefully rearranged for him as it would have been in earlier days, and she had painted a purplish-red mouth crookedly over her own. She had aged greatly since her marriage; her round hazel eyes had lost all their brightness. She looked as though she no longer cared to be young, and had no idea how to be old.

“Dear Florrie,” said Gamadge.

Her ringed hands jerked at his. “I was so frightfully disappointed when Syl told me your wife was away, Henry. Why did you marry her in Arizona or somewhere? I’ve never laid eyes on the child.”

“I’ll bring her up to see you when she gets home.” He looked about him, pulled up a satinwood chair, and sat down. “I’m not at all sure that I like the idea of your staying up here indefinitely. You’ll be bored, and that’s not good for you or anybody.”

“We often go to town. I got so upset with the blackouts and everything that I couldn’t stay in New York. Even if we blackout here, it won’t seem so close to the war. I feel so safe here. I mean I did feel so safe, till these things happened. At first I was just angry.”

“And aren’t you now?”

“No. I’m frightened. Henry—” she clutched at his hand again—“Henry—I’m not doing the things myself. I’m not crazy.”

“Definitely you’re not.”

“Tell them so! Tell everybody I’m not doing the things myself!”

“You must first tell me all about it, Florrie; that’s what I’m here for.”

She sat back against her blue-satin pillows. “I know you won’t laugh and say it’s a joke. That’s what Tim says.”

“Perhaps he’s just trying to reassure you. Tell me about it.”

“Well, you see, I began to write a novel. I can hardly bear to think of it now.”

“Oh, why? It seemed to me so sporting of you.”

Mrs. Mason’s face brightened a little. “I liked doing it, Henry. I was never so surprised in my life—it wasn’t hard at all!”

“What a clever girl you are.”

“I know they say there’s a story in everyone’s life, if we could only write it.”

“If.”

“And of course the story in my life was Tim and me. Our affair. I thought I’d write it, making myself of course very much younger. So that it would be more popular, you know.” She looked at him anxiously.

“One makes these concessions to the tastes of the larger public.”

“Our affair, Tim’s and mine, was so interesting and so unusual. Of course the romance doesn’t last.”

“Doesn’t it?”

“They say not. But when I began to write, it all came back to me. The ideas seemed actually to flow!”

“Did they?” Gamadge’s eye wandered rather apprehensively to a sheaf of manuscript on a table at Mrs. Mason’s elbow.

“I dictate to my secretary, Evelyn Wing. Then she types out what we’ve done, and next day we discuss it. If it needs revising, she types it again.”

“What I call an ideal arrangement.”

“I have no trouble at all. Evelyn looks up things for me, and makes such excellent suggestions. She’s very highly educated, you know, so I don’t have to worry about making mistakes.”

“You seem to have a paragon there.”

“Oh, I couldn’t live without her now! It’s not only that she’s clever; she’s so good to me. So kind. I regard her as one of my best and dearest friends.” Mrs. Mason looked at him with what seemed a touch of bravado.

“Why not?”

“She runs the household, she does our cheque-books and answers invitations, and when I had flu last year she sat up all night until Dr. Burbage sent a nurse. She isn’t silly about men, and she doesn’t fly into a temper if I get nervous.”

“You’re not getting too dependent on her, Florrie? These young people move on; they have their own lives to lead.”

“Evelyn won’t leave me while I need her. You know—I get cross, sometimes, Henry.” She gave him a sidelong look. “People are so provoking.”

“They are.”

“Instead of taking offence she just sits quietly and waits for me to get over it. Even Sally Deedes takes offence sometimes, when I rage to her about Bill.”

“Sally found this treasure for you?”

“Yes, Sally’s her cousin—much older, of course. Evelyn’s people all died, and she had no money, and she went through a dreadful time. Sally told me; Evelyn never talks about it.”

Gamadge silently agreed that Miss Wing must have had a dreadful time.

“I’ve made Father’s den into an office for her. You remember the den?”

Gamadge remembered it, and the rather wolfish old gentleman who had growled in it.

“Evelyn typed my novel in the den every night. Then she took the page she had got to out of the typewriter and left it on top of the pile of script.” Mrs. Mason turned to pick up the clipped sheaf of papers from the little stand beside her. “We were on Chapter Nine; here’s all we’ve done of it.” She handed him the sheets, and suddenly there was stark terror in her eyes. “Please look at Page 83.”

Gamadge looked at her, and then turned to Page 83.

“Now begin at the marked paragraph.”

Gamadge found the marked paragraph, and read aloud:

Gloria buried her yellow curls in the cushion, and beat her small clenched fist against the back of the sofa. Sobs shook her slender body. Roy was beside her in two strides. He crushed her in his arms.

“Go away,” she choked.

Roy held her closer. “I won’t go,” he said huskily, “until you listen to me.”

LISTEN TO ME, SAID THE DEMON, AS HE PLACED HIS HAND UPON MY HEAD.

Gamadge stared, looked up at Mrs. Mason, and stared again. “What on earth?” he at last demanded.

Mrs. Mason’s lips were pressed tightly together. “Somebody wrote that in?” he asked.

“There it was, all in big capitals, when Evelyn went and got the script the next morning. A week ago yesterday.”

“Friday, the thirteenth?”

“Friday, the thirteenth.”

“That was overdoing it.”

“I never noticed the date at the time, I was so annoyed. It seemed like such a silly kind of joke, and nobody would own up to it. And it sounded so wicked, somehow. Not like a joke at all. I don’t see how anybody thought of it. It’s too senseless. It’s too strange.”

“Poe is considered rather strange at times,” said Gamadge.

“Poe!”

“Yes. E. A. Poe. It’s a quotation from Poe.”

“Well, I must say I’m glad to hear it; it makes everything a little less uncanny, even the other ones.”

“Are there other ones?”

“Wait until you see them. This is nothing.”

“And you say nobody in the house realized that it was a quotation from anybody?”

“No. Ought they to have recognized it? Of course I shouldn’t.”

“I don’t think the average person would recognize it; I do, because I just happen to know the piece it comes from: ‘Silence—A Fable.’ It’s a good deal more sinister in this context than it is in its own. Miss Wing seems to have gone on from it as if it were part of the text.”

“She wanted to throw the page away and say nothing about it; she was annoyed, because it seemed to be poking fun at me, in a way; at my book.”

“Queer way to go at it.”

“Too queer. I wouldn’t let her touch it! I wanted to leave it right in the page, just as it was. We found it that Friday, as I said, and on Saturday morning we found—look at Page 89.”

She watched him as he did so. He read the marked passage:

Gloria told herself again and again that she would never get over it. She whispered to herself that she would be unhappy always. And she had been so carefree, so happy and busy, until Roy came into her life.

YOU SHALL FULLY KNOW

THAT YOUR ESTATE

IS OF THE TWO THE FAR MORE DESPERATE.

Gamadge communed with this for a moment in silence. Then he looked up at Mrs. Mason. “Surely,” he said, “you all realized that this is a quotation.”

“No, we didn’t.”

“Syl didn’t? Miss Wing didn’t?”

“Nobody did. We just thought it was queer—like the other.”

“It isn’t queer like the other. It’s from George Herbert; it’s from a poem called ‘A Paradox.’ Lovely thing.”

“I never heard of it, and I don’t remember ever having heard of George Herbert, either.”

“Did you still think that somebody was playing a peculiar joke on you?”

“I was sure they were making fun of my novel. I made an awful fuss. Is it so funny?” asked Mrs. Mason, with a wistful look at him. “It seems to me to be just like what I read.”

“It’s not the kind of thing that’s exactly in my line, but I should say you were making a very good job of it. What does Miss Wing say about your work?”

“She won’t criticize anything but the grammar and punctuation and that sort of thing. She says she never can get any perspective on the work of people she knows.”

“She seems to be a person of great intelligence indeed.” Gamadge looked down at Page 89, and said: “I see that you and she went sternly on, in spite of these curious additions to the text.”

“We certainly did go on. I told everybody that if the jokes went on I should find out who was doing it, and I’d never forgive them. It would be the end. Now Page 92—we hadn’t the heart to do more than three pages on Saturday. See what we found on Sunday morning.”

Gamadge read:

Gloria laughed until the tears came. Roy begged: “Don’t laugh at me, sweetheart! I can stand anything else, but please don’t laugh!”

“But you’re so funny, Roy! A great big man like you on his knees!”

LADY! LAUGH, BE MERRY; TIME IS PRECIOUS.

When Gamadge looked up from this, his face was grave. Mrs. Mason said quickly: “That’s the way Evelyn looked when she saw it.”

“She noticed a change of tone?”

“It—it seems to warn me.”

“There is an implied threat. Here—keep calm, Florrie; don’t go off the handle, now; I need your co-operation.”

Mrs. Mason tore at her handkerchief. “We decided to sit up and watch, at least Evelyn did. Nothing happened, of course; it’s impossible to do anything in this house without everybody else knowing about it. I couldn’t work on Sunday or Monday, but I did a few pages on Tuesday, and I absolutely forced myself to do some more on Wednesday! I had to know what was coming! But on Thursday morning I couldn’t stand it; I made Syl get hold of you.”

On the last page but one Gamadge read:

“Oh, it’s such fun just to be alive!” Gloria threw herself into Roy’s arms, and buried her face on his shoulder. “I’m glad we’re both alive,” he murmured into her ear.

THOU ART BUT DEAD; IF THOU HAVE ANY GRACE, PRAY.

Mrs. Mason, anxiously waiting until he had finished, burst out in a wail: “What is it from, Henry? What is it from?”

“Play by John Ford; and so’s the other—unless I’m much mistaken.” Gamadge lifted angry eyes to hers. “Keep calm, Florrie. They may very well just be tasteless fooling with your text.”

“Look at the last one.” Mrs. Mason’s tone was the quiet tone of one who is reconciled to the worst. “Look at the last one, and then say it’s tasteless fooling!”

“Now, don t forget that they’re all quotations; I should have thought anybody would know that, just to glance at them.”

“I didn’t know it; and that lets me out, Henry; and besides, I can’t even type!”

Gamadge turned to the last page. He read Mrs. Mason’s harmless lines, and then the great and terrible words that followed them:

“But I’m so lonely, Roy, in this great big house.” Gloria clung to him, “People think I have everything, but I’m so lonely!”

“Just you give me a ring, day or night, and I’ll come,” he promised tenderly. “I don’t care if it’s three in the morning, I’ll come, and you can talk to me out of the window.”

“Oh, it’s wonderful to know that you’re there!”

WHATSOEVER NOISE YE HEAR, COME NOT UNTO ME, FOR NOTHING CAN RESCUE ME.

Gamadge, rearranging the pages of Chapter Nine, said in a voice of cold disgust: “Marlowe; Doctor Faustus.”

A glimmer of satisfaction could be observed in Mrs. Mason’s eye; she had sampled her Compendium of Useful Knowledge, was sure that it contained the answers to all her problems, and now prepared to buy it: “Henry, you know everything. I’ll give you five thousand dollars if you’ll find out who put those quotations into my book, and why they did it.”

“Fair enough.” Gamadge laid Chapter Nine on his knees, gave Mrs. Mason a cigarette, and lighted it and his own. “But I never may find out, you know. Crime in the family circle—it often goes unpunished, you know. I’m certain of one thing, Florrie; you didn’t do it. All these authors didn’t lie buried in your unconscious.”

“Do you think automatic writing is just what is in your mind all the time?” She asked it wistfully.

“I do. Many people disagree with me.”

“Sally Deedes is sure it’s spirits; but she’s psychic, and I’m not.”

Gamadge frowned. “What has transformed that once sceptical and frivolous creature? She used to be as materialistic as anybody I ever knew in my life.”

“She’s had so much trouble, Henry; with Bill, you know. I managed to make her divorce him at last, but she’s still broken-hearted. After a year! The occult takes her mind off him.”

“Let her take the medicine that agrees with her, but let her not hand it on to you. That medicine doesn’t agree with everybody.” He added, removing his cigarette to look at her sharply: “You don’t think the spirits annotated your script, do you?”

“Sometimes I hardly know what to think; I’d rather think that than think other things! Since Thursday—” she cast a glance at her bewitched novel, and looked away from it again—“I have been dreadfully nervous at night. These doors are all so thick, and they fit so tight; I don’t believe anybody would hear me if I did—make a noise.”

“Don’t let this joker undermine your morale. The thing was meant to scare you, you know; let’s give our anthologist a bit of a disappointment. Why are you so marooned at night? Have you no bell?”

“No, I’ve never needed Louise in the night-time. I’m only too glad to get rid of her. You know what she’s like—practically on top of me all day.”

“Er—what about Mason?”

“Tim has his own room—that little one that used to be Father’s dressing-room, beyond the bath.”

Gamadge looked over his shoulder at a closed door in the east wall. “Why don’t you and he keep the communicating doors open?”

“He likes them shut.”

“Let him forget what he likes,” said Gamadge indignantly. “I never heard such stuff.”

“It’s on my account,” explained Mrs. Mason. “He doesn’t like to disturb me. He gets up early, and sometimes he comes in late.”

“Tell him you wish to be disturbed, at least until you get to the bottom of this foolery. It’s a damned shame that you should be left alone at night to scare yourself into fits.”

“I won’t ask favours of him.” She seemed likely to burst into tears. “I have some pride left.”

Gamadge, rather perturbed, considered her in silence. He said at last: “I’ll have a word with Mason.”

“No, Henry; I forbid you!” Her round eyes gleamed at him through tears. “I absolutely forbid you.”

“Well, I’m not sure that I don’t think you’re right. Much better to have Louise in with you than one of the suspects.” He patted her arm as she began to sob. “Now, please, Florrie! If we’re to investigate; we must do it properly. If you want to find out who played this horrid game with you, you must go right at it like a policeman; leave no loopholes. That’s the only way. Have Louise in with you at night.”

She dried her eyes. “All right, I will. I’m sorry, but it’s all so miserable. I’ve done so much for them all. I give Sally her clothes—not my old ones, you know; I dress her. Susie Burt comes here whenever she likes, and I make her a little allowance for her rent in New York—fifty dollars a month. I settled a hundred thousand on Timothy when we married.”

“He’s probably spent that long ago. You can’t play polo and fly aeroplanes and travel de luxe for nothing.”

“Tim’s given up lots of things. He’s getting very economical.”

“Who’s paying for that private golf course?”

“It’s just in case we have to give up using the cars, Henry!” She added, as he smiled at her, “People must have a little fun.”

“You’re mighty good to him, and I dare say to them all.”

“They don’t know how good!” She looked suddenly like the more formidable Florence of the old days.

“They don’t know, but they may guess.” He studied her for a moment, and then said briskly: “Now let’s tackle this curious problem you’ve given me.” He crossed his knees, and turned the pages of Chapter Nine. “Who in the house does a neat job of typing, and also has a more than nodding acquaintance with literature?”

Her face clouded. “That’s it. Nobody here types as well as Evelyn, and she knows more about books than any of them, even Glen Percy.”

“So far as you know. I must go into the matter myself, of course. Now as to why the thing was done. Malice, as your husband seems to insist? For if it’s a joke it’s a malicious one, and in fact it takes us into the field of morbid psychology; I mean that no balanced person runs the risk of losing favours present and to come by gratifying petty spite. I’m inclined to reject the theory of petty spite, anyway. It would merely have tried to make your book sound funny—much funnier than these quotations do. They’re not funny at all. They’re ominous.”

“They were meant to frighten me.”

“And that means hatred.”

“If anybody hated me,” said Mrs. Mason, her lip quivering, “I should know it.”

“People often don’t know it; tragedy is full of people who didn’t know it. Assume that you’re right, though, and that nobody in your house deeply hates you; there must have been some reason for playing this game, and a good reason too. Was some other effect upon you intended? Was some other effect achieved?” As she was silent, he went on: “Did anybody suggest that a special person had the means and the ability to play the trick? Suggest, in fact, that Miss Evelyn Wing had been tampering with her own typescript?”

Mrs. Mason, looking very angry, tossed her head.

“Mason insisted that it was a practical joke, meant to humiliate you. Did he say it must have been done by Miss Wing?”

“I knew Evelyn Wing wouldn’t do a thing like that—especially if it pointed right to herself!”

“But did you know it immediately? Were you shaken at first? Do be frank with me, Florrie.”

“Just at first I didn’t know what to think.”

“And then you had the subtle notion that it all pointed too directly to her to have been done by herself. Did you have the notion?” He looked her at sceptically. “Do you trust her absolutely, Florence?”

She hesitated, and then said sombrely: “There’s only one person I know that I can trust absolutely; but I trust Evelyn Wing better than to—”

“Who is the person that told you Evelyn Wing couldn’t have done it?”

Mrs. Mason, rather flushed, said nothing.

“Well, at least we have a point or two for the record. Mason suggested that the trick had been played by Miss Wing, out of malice.”

“I’ll never forgive him!”

“Mason, therefore, presumably wants to get rid of her.”

“It was so small of him!”

“We have been told that a favourite has no friends. Our second point is that some person—not Miss Wing—argued you out of the idea by showing you—what? That if Miss Wing were the guilty party she would have botched the job, misspelled words, interpolated something less literary? Convinced you, in fact, that the whole thing was a plot to eliminate your secretary.”

“I believe it was!”

“And what did you do about it? Or haven’t you done anything yet?”

“I did do something, I can tell you! I made a new will.”

“Did you indeed?” Gamadge allowed a match to go out on its way to his cigarette.

“Yes, I did. But it’s temporary—until we find out who put the things in my book.”

“Well, Florrie, you’ve been a trifle precipitate.”

“This last thing was the last straw. Henry! You don’t know what I’ve had to put up with from people. I’ve been meaning to make a new will for ever so long.”

“When did you make the new one?”

“On Thursday afternoon.”

“Quick work!”

“I’d had time to see that last awful quotation, and hear what Tim had to say, and realize that it wasn’t true. I had to do something. I should have burst if I hadn’t made that will.”

“Did Bob Macloud draw this new will up for you?”

“No, he fussed so over the telephone that I just told him he needn’t do anything for us ever again, and that I was through. When I think of the bills he sent in!”

“Bob’s very discreet, Florrie,” said Gamadge, smiling.

“You can carry that kind of thing too far. I told him to destroy my other will, and I just drew up the new one myself. I know exactly how, and I got the telephone man and his assistant to witness it for me. They’re very nice boys, local boys; I’ve known them since they used to bring berries around.”

“You know how to make wills, Florrie?”

“Yes, I do. I’ve had plenty of practice.”

“I suppose you made one after you were married.”

“Yes, I did. I left everything to Tim, and Bob Macloud fussed me and fussed me until I made another, a much more sensible one, about three years ago.”

“Poor Bob.”

“I’m quite willing to admit that it was more sensible. You know I haven’t much to leave, Henry; only about five hundred thousand dollars. You know how our money’s tied up?”

“You and Syl have the income.”

“Until one of us dies, and of course I shall die first. So I’ll never have more to leave than this five hundred thousand, which—as I keep reminding Bob—is absolutely my own to do as I like with. I earned it myself!”

“Playing the market?” Gamadge smiled at her.

“Yes, and it was hard work, I can tell you! I read the financial pages every day, and I spent hours at my broker’s, sitting in front of one of those blackboards, with a lot of men.”

“I bet you had a glorious time.”

“It was glorious to make the money, and have something to put in a will. I never can save much out of my income now, and I don’t suppose that I’ll ever be able to earn much that way again. Do you?”

Gamadge said he feared not.

“Well, as I say, I felt that this five hundred thousand was my own; so about three years ago, when I made my new will, I did just as I chose in it. I left nice legacies to the servants, and annuities to Thomas and Louise, and a hundred thousand to my church in New York—dear Dr. Stokes-Burgess, I hope he’ll be alive then to distribute it. He’s quite a young man. It’s the Church of SS. Gervase and Protase. And I left a hundred thousand to the Bethea Home for Destitute Children; Mother founded it, and I’ve always been interested in it. I wish I had enough to rebuild it entirely—it’s dreadfully out of date, no laboratory. That left about two hundred and sixty thousand. I left twenty-five thousand apiece to Sally Deedes, Susie Burt, and Evelyn Wing. Tim was my residuary legatee; that meant a hundred and eighty-five thousand, more or less, my personal goods and chattels, and Underhill.”

“Underhill is yours, is it?”

“Oh, yes; didn’t you know? It costs me a fortune, too, and Syl won’t do anything, though he treats it as if it belonged to him too.”

“You brought him up to treat it that way.”

“Well, he ought to help me with the taxes and upkeep. My personal chattels don’t amount to much—I never bought myself jewellery.”

“Didn’t your father buy you jewellery?”

“Just a few things. He hated buying jewellery. He thought it was a poor investment, and I suppose I caught the idea from him. Well, Bob Macloud didn’t make any fuss about the will I made three years ago.”

“It’s not a bad will. But if Miss Wing knows what’s in it, I’m not surprised that she keeps her temper when you lose yours.”

“She doesn’t know anything about her legacy. Nobody knows about my wills. The only will they know anything about is that first one I made after I married; I told everybody I was leaving everything to Tim. Five hundred thousand didn’t seem much for him—then.”

“No; I understand that.”

“But Bob Macloud fussed me about Susie Burt and Sally. I think it was very good of me to leave them as much as I left Evelyn. Susie didn’t keep her temper when she was my secretary; I can tell you; and I told Sally frankly that I shouldn’t leave her anything if I thought she would spend it all on Bill Deedes.”

Gamadge, remembering Bill Deedes’s sweetness and fatal charm, groaned faintly. He murmured: “Poor Sally.”

“When she promised to divorce him, I put her down for twenty-five thousand, as I said. She doesn’t know how much she’s getting, though. And she doesn’t know that when she finally did divorce Bill, I made up my mind to leave her fifty thousand.”

“Good.”

“So on Thursday, when I made my new will, I gave her fifty thousand, and I gave Susie fifty thousand. And,” said Mrs. Mason, looking at him defiantly, “I gave Tim fifty thousand, and I made Evelyn Wing my residuary legatee.”

Gamadge sat back and stared at her. Then he said with restraint: “Let me get this straight. The legacies to the servants, the church, and the Home, stand; Miss Burt, Sally Deedes, and your husband receive fifty thousand apiece; and your secretary gets—how much exactly?”

“It comes to about a hundred and ten thousand, I think, it and Underhill, and my personal belongings. Jewellery and stuff.”

“How much does the jewellery and stuff add up to?” Gamadge glanced around the delicately furnished room.

“My furs and silver and glass and china, and the furniture and things, and my poor little brooches and bracelets and rings are appraised at fifty thousand.”

“Low estimate, I think. Why Underhill to Miss Wing? Why not to Sylvanus?”

“He can buy it from Evelyn, if he wants it. He’ll be rich enough to buy anything, when I die; don’t forget that!”

“I’m not forgetting. Mason will fight, Florence.”

“They say it’s very hard to break a will.” She added, rather pleadingly: “He never came back from Palm Beach when I had flu last winter; we came up here for Christmas, Syl and I, and had a party. And I couldn’t get a nurse for two nights, and Evelyn sat up with me. It was so small of Tim to try to get rid of Evelyn!”

“Some people might not wonder at his trying to get rid of her. So you think he was the one that cooked up that business with the quotations.”

“Oh, Henry, I wish I didn’t think so!”

“Well, my poor, dear girl, I’m awfully sorry.”

“Of course if you find out he didn’t, I’ll make another will.”

Gamadge smiled. “This one is just to shake at Mason if I don’t clear him?”

“He doesn’t know anything about it yet, but he knows I don’t believe Evelyn put the things in my book.”

“And you telephoned Bob Macloud, and dictated this will to him on Thursday, and he cut up rough?”

“He was perfectly wild. Of course he doesn’t know my reasons; he doesn’t know about the things in the book, or what Evelyn means to me.”

“Or that Mason didn’t come back from Palm Beach when you had flu.”

“Or—or anything,” said Mrs. Mason, turning her head away. She looked at Gamadge again to add sharply: “It’s all none of Bob’s business. His business was to follow my instructions.”

Gamadge rose, folded the few pages of Chapter Nine lengthwise, and put them in his pocket. He said: “I’ll see all these people. I’ll hold a conference after lunch from which you will be rigorously excluded. Then I’ll report to you. I suppose you don’t know whether the authors quoted in your script are available here—in the library?”

“No, I don’t.”

“And nobody, not even Syl, admits knowing that the extracts are quotations?”

“No.”

“And Sally blames the spirits.”

“She says a mischievous spirit sometimes gets through. She says it’s a slight risk we run.”

“This was a mischievous spirit indeed.”

“She says it can’t harm me, and that if we pay no attention to it, it will go away. Like a child, you know.”

“She is optimistic. You can discard that theory, Florence; discard it for ever. Poe, John Ford, and Christopher Marlowe may have turned into troublesome ghosts, and they may have entered into a conspiracy to confuse and annoy authors of light fiction; I wouldn’t put it past them; but count George Herbert out of it. He wouldn’t spend eternity like that—he wouldn’t dream of it.”

Mrs. Mason gave him a watery smile. “Oh, Henry, I’m so glad you’re here. You’re not very spiritual, you know, but you can make me laugh.”

“Oblige me by laughing, then.”

She had begun to laugh, rather hysterically, when Timothy Mason emerged from the communicating bathroom. He was in his shirt sleeves. Two small griffons pranced behind him; at sight of Gamadge they exploded in a shrill chorus of barking.

Mason had been working on his thick, light hair with a military brush. As he crossed the room he transferred the brush to his left hand, and flung out the right in a buoyant gesture of welcome.

“Hello, there, Gamadge!” He almost shouted it. “Glad to see you. You’re evidently the doctor my wife needed.”

Gamadge rose, smiled, and held out his own hand; but he stayed where he was. He had no sympathy with the race of griffons—it usually bit him. He allowed his fingers to be crushed again in Mason’s iron paw. “Hope I’ll be of use here,” he said.

“You’ve cheered Florence up—that’s all I ask. Excuse my appearance; I’m changing—had a ride.”

“You look fit.”

Mason looked very fit; he was solid and muscular, with no sign of superfluous fat. His white-yellow hair, lashes and almost invisible eyebrows, his bulldog face—blunt nose and square jaw, sanguine skin and wide mouth—certainly forbade handsomeness, but there was something about him. Life, zest, physical power and durability, easy good humour—these had captivated Florence Mason. They captivated her still. When Mason bent to kiss her lightly on the cheek, and Gamadge saw the look in her eyes, he knew that while her husband troubled to placate her she would never get rid of him. She might scold him, punish him, even hate him, but she would not do without him. Gamadge was sure that her rage at her own weakness was what made her implacable towards Bill and Sally Deedes. They, at least, should part! I could shake her, he thought, and listened to Mason.

“Now we’ll get the mystery solved. Until a couple of days ago I didn’t want you up here on the job, Gamadge—I’ll be frank with you. I always think the less fuss made about these private rows the better. But I didn’t like the tone of that last crack Florence found in her manuscript; the sooner we get rid of the joker now the better I’ll be pleased.”

Gamadge had relaxed into an easy posture, one hand in a trouser pocket and one shoulder drooping, which took an inch off his height; it permitted Mason to look down on him. “Can’t promise results,” he said. “The problem may be insoluble.”

“Oh, don’t give up before you start, old man! I’d hand you a tip to set you going, but Florence doesn’t think much of it.”

“I’ll be glad of it, if you think it’s worth something.” Gamadge avoided Mrs. Mason’s angry eye.

“Well, I’m a dumb sort of feller, only see what’s in front of my nose; but it strikes me the joker is a neurotic. Not entirely responsible. Lots of young people are, and get over it. They write poison-pen letters, and a psychiatrist cures ’em.”

“We’ve been over that, Tim,” said Mrs. Mason coldly. “Mr. Gamadge doesn’t think much of the idea, and he doesn’t think much of Syl’s, either—that I wrote the things in myself.”

“You write ’em in? What nonsense. Just like Sylvanus, though. He’d rather make Florence think she was going crazy, Gamadge, than have trouble in the home.”

“And Henry says those things in my book are all quotations.”

“Quotations?”

“Poe, and Christopher Marlowe, and I don’t know who all.”

Mason laughed heartily. “The spirits must have been taking a course in English Lit. We ought to tell Sally.” He became grave, and added: “I hope to goodness you will clear the mess up, Gamadge; it’s scaring fits out of my wife.”

“Well, I’ve made a little progress; the spirits aren’t responsible, and Mrs. Mason isn’t responsible, and it wasn’t a joke.”

“Not a joke; you mean it was plain malice?”

“More than malice. I should say a flavour of madness.”

“Oh, come now! If you’re going to be an alarmist I won’t go on thinking that you’re a good doctor for my wife at all.”

“At any rate, I prescribe company at night for her until she’s less nervous.”

Mason stood with his arms hanging at his sides, his brows knitted in what seemed perplexity. “You’re not pretending she’s in any danger, are you?”

“It’s certainly dangerous to lose too much sleep. Of course she worries; so would you, so would I in her place.”

“I wouldn’t. I thought the best thing for Florrie’s nerves would be to make light of the thing. I don’t know why she didn’t lock up her manuscript after that first happening.”

“I’m rather glad that she didn’t dam the flow,” said Gamadge. “It might have burst forth in another place. Your wife oughtn’t to be alone at night just now, Mason.”

“Sally can come in. Unfortunately I’m no good as a cure for insomnia; I snore, I get up at seven, and I can’t sleep a wink myself if my door’s open.”

“How about the faithful Louise?”

“Louise is as nervous as a witch herself. If Florence would have the dogs—” he glanced down at the griffons. They sat side by side, looking from one speaker to the other as if interested in the conversation.

“And listen to them scratching at your door all night?” asked Mrs. Mason crossly. “No, thanks.”

“Have Louise,” said Gamadge.

Mason abandoned the subject without more words. He asked; “How are you going to start the investigation, Gamadge? Are you going to examine the old typewriter for fingerprints?”

“Fingerprints bore me. I’ll begin by having a talk with you all after lunch—all but Florence; she’s to absent herself from the conference, and I’ll report to her afterwards. I might as well know at once where everybody is at night.”

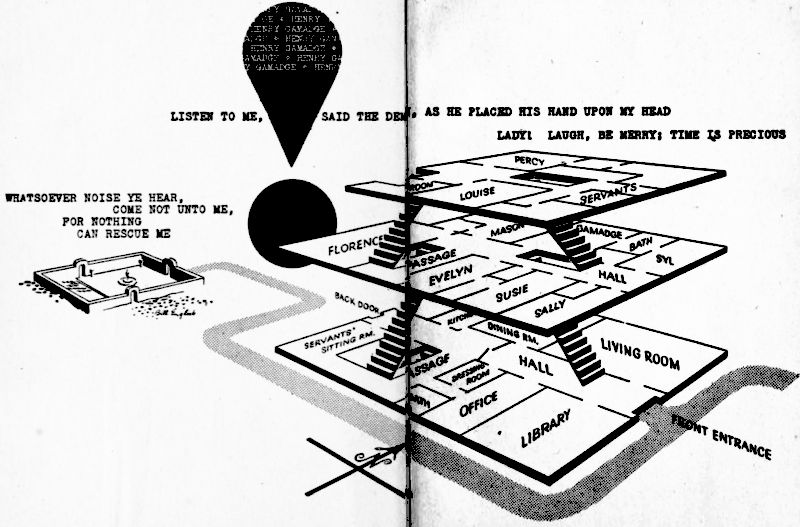

He went and opened the bedroom door. At the other end of the corridor a triple-arched window showed him the bare tops of beeches, a distant ridge of hemlock, a strip of pale, wintry sky. Towards the front of the house the main staircase faced him, rising to the upper floor, and on his immediate left a little passage ran, at right angles, to the back stairs. Four solid doors on the left, five on the right, and between them scenic wallpaper and oak panelling.

“I’m next to Florence, with a bath between,” said Mason. “The next two doors on that side belong to cupboards, and then comes a guest room—yours, I believe—and then Syl’s. There’s a bath connecting them, too. Sally’s across the hall, opposite Syl; her door is just beyond the stairs. She has her own bath, too.”

“Not much like the old days,” said Gamadge, “when we all had our highly decorated bowls and jugs.”

“And splashers,” laughed Mrs. Mason. “There are lots more bathrooms now. Next to Sally is the hall one, and then comes Susie Burt. She shares a bath with Evelyn Wing. Evelyn has the last room on this side, just beyond the back passage.”

“Where is Mr. Percy?”

“Right above our heads,” said Mason, with a look of humorous resignation. “The large north-west room—with bath, of course. He’s well dug in.”

“Now, Tim, you know I always love to have Glen here,” protested Mrs. Mason, “and you know he’ll soon be leaving for his air-force training. He’s just waiting for them to send for him.”

“I hope they’ll let me fly,” said Mason. Florence’s eyes suddenly filled with tears. Gamadge asked hastily: “What does Mr. Percy do for a living, if he does anything?”

“Oh, he does,” said Florence. “He’s not at all well off, poor boy. He writes, I think; doesn’t he, Tim?”

“Advertising copy at present,” replied Mason.

“Who else is upstairs?” asked Gamadge.

“There’s the other little guest room—the south-west one,” said Mrs. Mason, “and all the servants’ rooms, and a big bath. Thomas used to be in the garage, you know, but now we’ve moved him in here; he has the nicest little suite, with his own bathroom.”

“Eight bathrooms; that’s something.”

“Oh, we’re very comfortable now at Underhill.”

Physically, thought Gamadge. He said: “Well, see you at lunch; I think,” he added, pausing with his hand on the door-knob, “that Syl was right; we may eliminate the servants from our problem. Euclid would call them absurd.”

He went into the hall. Mason closed the door after him, but not in time to prevent the griffons from rushing out at his heels. They turned down the back passage, made for the stairs, and began to scramble up them, loudly barking. Gamadge saw that their objective was a young or youngish woman who stood on the top step of the dark and narrow flight.

His first impression—heightened by the fact that she wore a thimble—was definite; that Florence had a visiting seamstress in the house. But the calmness of the prolonged look she gave him, the careless gesture with which, still meeting his gaze, she repressed the bounds of the griffons, and at last something familiar in the shape of her round, bright eyes, made him readjust his ideas. She wore a grey cardigan sweater, a longish brown skirt, brown stockings, and black Oxford ties of unsportsmanlike cut; she was probably a native, but she was apparently a Hutter.

“Excuse me,” said Gamadge. “Would you mind telling me who you are?”

“I’m Corinne Hutter.”

“Stupid of me; I didn’t know there were any Hutters except Florence and Syl.”

“I’m their cousin. I’m the only other one there is.”

Her voice had the regional twang, but it was not unpleasing. There was a note of dry humour in it, and as his eyes grew more accustomed to the dimness of the little hallway and stairs he saw that her smile was dry too. She had a high, domed forehead from which dark hair was drawn tightly back into a topknot; her nose was long, her skin colourless or sallow; she ought to have been plain, she was very nearly plain, but not quite. And she was not insignificant. Gamadge thought that with half a chance to develop it, she would have had a certain distinction that Florence and Sylvanus did not possess.

“Younger branch of the family?” he asked.

“Yes. My father was Joel Hutter.”

“Florence didn’t tell me you were staying in the house.”

“They probably don’t know I’m here to-day. I drive over sometimes to take a walk in the woods.”

“Well! I’ve known the Hutters for twenty years, and I didn’t know they had a cousin in these parts.”

“There’s nothing funny about that,” said Miss Hutter, smiling her dry smile. “I live in Erasmus. I’m one of the librarians in the Erasmus library.”

“Look here; my name’s Gamadge, and I’m up here on some business for Florence Mason. I have to talk to everybody in the house. Shall I see you at lunch?”

“Oh, no. I never eat with the house-parties. I had my lunch before I came over.”

“Can I talk to you now? This may be my only chance.”

“Come on up.”

Gamadge climbed the stairs and followed her into the little south-west corner room. He remembered it well as a cubbyhole into which last-minute guests had often been crammed; a neat little place, with muslin curtains at the windows—one of them now had a long rent in it, near the frill, and Miss Hutter’s needle was sticking in it—and fumed-oak furniture. It was very much as it had been, even to the brass bed with its muslin valance and the blue rag carpet. A small table was laden with magazines, Miss Hutter’s handbag, her driving gloves, and her knitted hat.

She sat down in a rocking-chair. Gamadge took a hard one in front of her, and so small was the floor space that their knees almost touched.

“You were going downstairs when I saw you,” he said. “Had you an errand? I can wait while you do it.”

“Just going down to find Louise and ask her for some finer thread,” she told him. “It can wait.” She took a small sewing kit from her pocket, unrolled it, and got out a spool of white cotton and a minute pair of scissors. While she removed the needle from the curtain and threaded it, Gamadge automatically produced his cigarette case.

“Have one?” he asked, offering it to her, opened.

“I don’t smoke.”

“Mind if I do?”

“Yes; but you can if you want to.”

Gamadge, replacing the cigarette case in his pocket, remarked: “Incredible woman; if you were in my will I’d cut you out of it.”

Miss Hutter looked up at him to ask coolly: “Who’s been talking to you about wills?”

“Your cousin Florence has.”

“You said you never heard of me.”

“When you told me who you were I was immediately struck by the fact that you don’t figure in her will.”

“Or in Cousin Sylvanus’s will, either.” She calmly began to sew up the rent in the curtain.

“Some other financial arrangement?” asked Gamadge diffidently.

“I don’t know why you’re interested,” said Miss Hutter, “but there isn’t any other financial arrangement. My side of the family always got along without Uncle Nahum’s money, and so do I.”

“You still regard it as the late Nahum’s money?”

“Yes, and so does everybody else. Cousin Florence and Cousin Syl just spend it.”

Gamadge said, raising his eyebrows, “Your attitude is unusual—in these times.”

“Our side of the family is kind of independent. I have enough money of my own to live on, and I have my salary.”

“I feel it a privilege to know you, I really do.”

Miss Hutter returned his amused look, and then said: “I was Cousin Florence’s secretary and sort of housekeeper a good while ago—the first she had. Before she was married. It didn’t work.”

“Didn’t it?” asked Gamadge gravely. “Too bad.”

“We never had a fight. I like her, and I like Cousin Syl. I come here whenever I want to, and take walks and a nap. I guess the truth is Cousin Florence and I are too much alike. She wants her own way, and I don’t like to be bossed. Besides, I wasn’t the right person for the job. Cousin Florence needs somebody she can dress up, and show around, and play cards with.”

“Like Miss Susie Burt?”

“Susie Burt isn’t cut out for a secretary.”

“Like Miss Evelyn Wing?”

“I guess Evelyn Wing is just about right for Cousin Florence.”

Gamadge produced Chapter Nine from his pocket. He said: “You may be the disinterested observer I’ve been hoping for. When were you here last, Miss Hutter?”

“Two weeks ago to-morrow; that Sunday it cleared up after lunch. I wasn’t coming, and then I did come. Had a nice walk.”

“If you haven’t been here since, you probably haven’t heard about this tampering with Mrs. Mason’s book.”

“What book?”

“She’s writing a novel.”

For a moment Miss Hutter looked a trifle arch. Then she said: “I didn’t know about it. How was it tampered with?”

“Somebody typed things into it at night, after Miss Wing finished work on it. Here you are; you’ll find them for yourself. Begin at Page 83.”

She fastened off her thread, stuck the needle into the curtain, and took the script from him. By the way she travelled through it, Gamadge saw that she needed no help in seizing the facts. At last she looked up at him. “It’s the craziest thing I ever heard of. When did it start?”

“Middle of last week, ended on Wednesday night; because on Thursday Florence decided that she’d had enough, and yesterday she made Syl get hold of me.”

“Are you a detective?” She looked at him with interest.

“No, just investigate things sometimes.”

“I should think she would have had enough of it by the time she saw this last quotation.”

“Thank Heaven somebody admits to knowing it is a quotation.”

“Of course it’s a quotation. They all are. Who says they aren’t?”

“Not even Miss Wing seems to have said they were.”

She frowned at him, and then at the script. “I don’t know where they’re from.”

“But you immediately knew them for literature. Don’t you agree with me that any educated person ought to know that?”

Miss Hutter considered. Then she said, “Lots of people can’t tell one kind of writing from another. This Demon thing—who wrote that?”

“Poe.”

“I can’t place that poetry, either.”

“George Herbert—A Paradox.”

“The others sound like old plays.”

“Of course they do, and they are from old plays. Ford and Marlowe.”

“I guess I’m like a lot of librarians they tell about—I know more names of books than what’s in ’em.”

“Can you suggest why any person should distress Florence by putting these things into her book?”

She ruminated, and at last inquired: “Who was here those nights?”

“Sylvanus, Mason, Mrs. Deedes, Miss Burt, Miss Wing, and Mr. Percy.”

Again she pondered, turning the leaves of the script.

“There’s something about it,” she said at last, “that looks worse than just spite work. But it might be spite work.”

“You think so?”

“Well—if you’ve known Cousin Florence all that long time you know a good deal about her, don’t you?” She looked up at him.

“A good deal.”

“She likes all these people,” (and Gamadge knew that Corinne Hutter would never come nearer than that to the word “love”), “likes some of them ever so much. But anybody that gets on her nerves, or makes her mad, or even if she’s just feeling mad herself at something else—she’ll take it out on them. She’ll say something mean.”

“How mean?”

“Pretty mean. She works herself up to thinking that they’re out for what they can get, and that they’re making fun of her behind her back.”

“Sylvanus isn’t out for what he can get.”

“No, and I guess she trusts him more than any of them. And I don’t think Glen Percy ever makes her mad, and she wouldn’t say anything mean to him if he did. She can’t get many young men to the house any more. Susie Burt doesn’t go around with young ones much, and Evelyn Wing doesn’t seem to have any.”

“But she takes it out of the others, does she?”

“Yes, and they don’t go.”

“Poor devils, they don’t.”

“They must feel pretty mean themselves, sometimes.”

“Mean enough to do that?” Gamadge indicated Chapter Nine.

“I wouldn’t have said so.” She added: “I’ve heard her say things even to Cousin Sylvanus. When she didn’t think he helped enough with the expenses, and when he fights with Cousin Tim Mason.”

“Does she go for the paragon—Miss Wing?”

“I don’t think she does much. I don’t think Evelyn Wing would stand it. But I did hear her say once that Evelyn Wing needn’t dress up for Cousin Tim Mason, because she wasn’t his type.”

“Heavens!” Gamadge winced.

“I know it sounds pretty bad, but Evelyn Wing had sense; she just lets things like that roll off her back.”

“If I were Miss Wing, and Florence said a thing like that to me, hanged if I wouldn’t hit the ceiling. And if didn’t hit the ceiling I might—” he put a forefinger on Chapter Nine, and looked at Corinne Hutter inquiringly.

She thought it over. At last she said: “I don’t think she’s the kind to do it; and even if she was, she’d do something else. This typing, and these quotations and everything—they point to her. She’s too bright for that.”

Gamadge said in an admiring tone: “You don’t miss much. How about somebody wanting them to point to her?”

Corinne Hutter took this suggestion without surprise; but while she reflected on it she protruded her lower lip. She said at last: “I don’t see much of them; just passing sometimes, and in Cousin Florence’s room when I drop in to see her. I don’t see them the way I used to when I was here all the time. Evelyn Wing wasn’t here then. I don’t know how they feel about her.”

“They might be jealous, perhaps?”

“I don’t know why they should. None of them can handle Cousin Florence, and they know it.”

“Mason can’t?”

“I hardly know him. I like him, though; he’s always pleasant.”

“This job—” Gamadge took back Chapter Nine, refolded it, and stowed it away again—“it’s not a thing anybody could do—without help.”

“Susie Burt couldn’t.”

“Could her friend Percy?”

“He reads a lot, anyway; he comes down to the library in Erasmus, and he sits with his feet up and reads for hours.”

“What does he find to read there that he couldn’t find in the excellent gentleman’s library here at Underhill?”

“We have a fine library at Erasmus,” said Miss Hutter, with some feeling. “It was a donation from some rich people that used to live there, and people give us their books. Somebody died in Bethea a few years ago and left us a thousand books, all old.”

“What does Percy take out?”

“French poets and novelists, Old English poetry, dictionaries, and The Anatomy of Melancholy. He read that all one summer.”

“Not for advertising copy, I am sure.”

Miss Hutter gratified him by laughing.

“Sally Deedes couldn’t do it alone,” he went on, “but of course Miss Wing’s her cousin. And poor Bill Deedes could have helped her, but I don’t see him at it.”

“Besides, they’re divorced now.”

“So they are. Syl could do it, and Mason ought to be able to, unless he’s forgotten that there’s any printed matter outside of Racing Form. He went to a good school and university. And for all we know, somebody may have helped him.”

She said, as he rose, “It’s perfectly terrible to think of Cousin Tim Mason doing such a thing. It’s perfectly terrible anyway. Mrs. Deedes never did it.”

“Do you think she’d boggle at much, if she had an idea she’d be helping Bill?” He added, “Divorce or no divorce.”

“I don’t know why this should help Mr. Deedes. He’s going to marry a rich widow.”

“Well, we must confer about it again. You’re invaluable to me, Miss Hutter.”

“I have got to get back to Erasmus this afternoon.”

“It’s clouding over; don’t miss your walk.”

She cast a glance at an enormous and shining magazine that lay on top of the others. “I want to finish a story, first. We don’t take many periodicals at the library.”

As he reached the door the griffons came whiffing from under the bed. Gamadge, surprised at their emergence, remarked that they seemed to get around faster than the human eye could follow them.

“Just like lightning bugs,” agreed Miss Hutter. “You never know where they’re going to turn up.” She admonished them: “Go down and get your lunch, now.” They galloped past him to make for the front stairs; Gamadge went after them, and descended to the second floor.