* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please check with a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. If the book is under copyright in your country, do not download or redistribute this file.

Title: Jerry Todd and the Talking Frog

Date of first publication: 1925

Author: Edward Edson Lee (as Leo Edwards)

Date first posted: Aug. 11, 2021

Date last updated: Aug. 11, 2021

Faded Page eBook #20210828

This eBook was produced by: Stephen Hutcheson & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

MR. RICKS ABSENT-MINDEDLY POURED THE SYRUP DOWN THE BACK OF HIS NECK AND SCRATCHED HIS PANCAKE!—(Page 12)

BY

LEO EDWARDS

Author of

THE JERRY TODD BOOKS, ETC.

ILLUSTRATED BY

BERT SALG

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS : : NEW YORK

Made in the United States of America

Copyright, 1925, by

The Methodist Book Concern,

Cincinnati, Ohio

Copyright, 1925, by

GROSSET & DUNLAP

When I started writing this book, I thought of calling it: JERRY TODD AND THE PUZZLE ROOM MYSTERY. But Scoop told me that wasn’t the proper title. “There is more in the book about the talking frog than there is about the puzzle room,” he pointed out. “So why don’t you call it JERRY TODD AND THE TALKING FROG?”

So it was our leader, you see, who gave this book its title.

Like my other books, this is a fun-mystery-adventure story. The “fun” part is where we peddle the spy’s beauty soap. Bubbles of Beauty, let me tell you, was very wonderful soap! At first we couldn’t believe that it would do all of the amazing things that Mr. Posselwait claimed for it. But that is where we got a surprise!

There is a ghost in this story. B-r-r-r-r! At midnight it comes to the old haunted house, walking on the porches. Creepy, I’ll tell the world. We kept the doors locked. For we were all alone in the brick house, Scoop and I and Peg and our new chum, Tom Ricks. It was to help our new chum that we braved the perils of the haunted house. You see, a puzzle maker had met with a strange death in the brick house, and that is what made it haunted.

“Ten and ten.” That was the Bible’s secret. What was “ten and ten”? Why did the ghost come nightly to the inventor’s home? We found out, but it took us many exciting days to solve the mystery.

Yes, if you like a spooky, shivery, mysterious story, you surely will enjoy this book, my fifth one.

Here are the titles of my five books in their order:

My sixth book will be JERRY TODD AND THE PURRING EGG. This dodo egg, taken from King Tut’s tomb, was more than three thousand years old. The Tutter newspaper called it the “million-dollar egg.” Could it be rejuvenated? One man said so. The story of what happened when the egg was “rejuvenated” makes mighty good reading for a boy who likes a book packed full of chuckles and mysterious tangles. Your friend, Jerry Todd.

When I started writing books for boys (this is Leo Edwards speaking) I was practically unknown in the story-writing world. Never having heard of me, boys didn’t know whether to buy my books or not. The titles, featuring Whispering Mummies and Purring Eggs, seemed kind of silly to a lot of young readers. But to-day hundreds of thousands of boys look forward to my new titles. If the books are slow in coming, a goodly portion of these hundreds to thousands of “fans” write and tell me about it. Also they jack me up if things aren’t so-so. And, happier for me, they pat me on the back (verbally) if they like my stuff. I never tire of reading these bully good letters. And I was tickled pink when my publisher told me that I could incorporate a few of these letters in a “Chatter-Box.” An experiment, the first “Chatter-Box” appeared in my sixteenth book. And so popular has this department become (it is made up almost wholly of letters, poems and miscellaneous contributions from boys and girls who read my books) that now I have been given the pleasing job of supplying my earlier books with brief “Chatter-Boxes.” Writers of accepted poems, built around the characters in my books, or featuring some boyish interest, win prizes. And, of course, it is pleasing to other boys to see their letters in print. If you have written me a letter I may have used it in another “Chatter-Box.” Or if you are contemplating a letter, why not write it to-day? It may be just the letter I need for one of the big “Chatter-Boxes” in my new books. It may even give me an idea, for my books, which will bring millions of added laughs into the world.

“I have read every book you published, including the Trigger Berg books,” writes Philip Horsting of Brooklyn, N. Y., “and I like them all. Trigger Berg can get into mischief faster than any boy I know. I think that the ‘Chatter-Box’ is a very good idea and while I’m writing this letter my aunt is reading the latest ‘Chatter-Box’ right now.”

“I just read Andy Blake’s Secret Service,” writes Bill Hopwood of Primos, Pa., “and there’s something in the book I don’t understand. When Eddie Garry’s uncle, with whom Eddie was living, told Andy that the latter’s father was his younger brother, and Eddie’s father’s twin, how come that Andy’s name is Blake and Eddie’s name is Garry? Did Andy’s father go under a false name?”

Yes, Bill, when Andy’s father ran away from home, determined never to have anything more to do with his own people, he dropped the name of Garry and took the name of Blake. By rights, we should call Andy by his true name. But he prefers to keep the name he has known all his life. So we’ll continue to speak of him as Andy Blake instead of Andy Garry.

“Not long ago,” writes Dub Moritin of Dallas, Texas, “I was reading one of your Jerry Todd books and I saw where you had a Freckled Goldfish club. Gee, Mr. Edwards, I sure would like to join! The boys call me Dub. If you want to call me that, it’s OK with me. I have six Todd and two Ott books. I save my weekly spending money and if I haven’t enough Mom gives me the rest. For both Mom and Dad are crazy about your books. I am sending the two two-cent stamps to join your club.”

“I am trying to get another boy besides myself to join the Freckled Goldfish club,” writes Charles F. Spiro of Yonkers, N. Y. “I told him what an honor it was to be a Freckled Goldfish. The kids living near me use the number thirteen for a danger cry just like Jerry and his gang.”

“Some day I’m going to break a rotten egg to see how it smells,” writes John F. McIntyre of Natchez, Miss. “Then I can prove it to my brother who is a dummy and said Jerry and Poppy wasn’t any account. Gr-r-r-r-r! I feel like biting his head off. If I did it wouldn’t be anything gone. Is it very easy to write a book? If so, would you please tell me how to do it? I am joining the Freckled Goldfish lodge to get my name in the big book.”

Well, John, I don’t know what you’re going to prove by breaking a rotten egg. But if you’ll gain anything by it, in proving to your older brother that Jerry and Poppy are worth-while pals, go ahead. I assure you that it would be very hard indeed for a small boy to write a book. We have to live a good many years, and learn a lot about the world and its ways, before we can write interesting books. But if you want to get some pointers on story writing see my first “Chatter-Box” in Poppy Ott and the Tittering Totem.

“The boys around my neighborhood were always talking about how spooky and funny your books were,” writes Carl A. Swanson of Minneapolis, Minn. “I never had read one of your books. But I decided to read one to see if it was as good as my friends had said. Boy, was it ever hot! It was Poppy Ott and the Freckled Goldfish. I just got Poppy Ott and the Tittering Totem Saturday and I laughed so much Sunday reading it that both my grandmother and my dad started reading it.”

“I would like to join the Secret and Mysterious Order of the Freckled Goldfish,” writes Mortimer A. Stiller of New York, N. Y. “Jerry, Poppy and Trigger are my best pals. I agree with whoever said. ‘He that loveth a book will never want a faithful friend,’ only, of course, I find more than one friend in your books. Your latest idea of having a ‘Chatter-Box’ in each book is great. As I live in the city the only thing that I can do that you mention is to start a local Goldfish chapter, so please send me the necessary booklets.”

“I have just finished reading Andy Blake’s Comet Coaster,” writes Jack Pattee of Chicago, Ill. “I liked the book very much but I like Jerry Todd better. Before I read Andy Blake I read Trigger Berg and His 700 Mouse Traps. That was a swell book, only it didn’t have a mystery. I have a friend, Jerry O’Neil, and he told me that he wrote to you and you are going to put his letter in the ‘Chatter-Box’ in Jerry Todd, Editor-in-Grief. I am a Freckled Goldfish and I read most of your books. I have a small black dog named Gertie who likes gumdrops, candy and chocolate doughnuts.”

Out of my book, Poppy Ott and the Freckled Goldfish, has grown our great Freckled Goldfish lodge, membership in which is open to all boys and girls who are interested in my books. Thousands of readers have joined the club. We have peachy membership cards (designed by Bert Salg, the popular illustrator of my books) and fancy buttons. Also for members who want to organize branch clubs (hundreds are in successful operation, providing boys and girls with added fun) we have rituals.

To join (and to be a loyal Jerry Todd fan I think you ought to join), please observe these simple rules:

(1) Write (or print) your name plainly.

(2) Supply your complete printed address.

(3) Give your age.

(4) Enclose two two-cent postage stamps (for card and button). (5) Address your letter to

Leo Edwards,

Cambridge,

Wisconsin.

To help young organizers we have produced a printed ritual, which any member who wants to start a Freckled Goldfish club in his own neighborhood can’t afford to be without. This booklet tells how to organize the club, how to conduct meetings, how to transact all club business, and, probably most important of all, how to initiate candidates.

The complete initiation is given word for word. Naturally, these booklets are more or less secret. So, if you send for one, please do not show it to anyone who isn’t a Freckled Goldfish. Three chief officers will be required to put on the initiation, which can be given in any member’s home, so, unless each officer is provided with a booklet, much memorizing will have to be done. The best plan is to have three booklets to a chapter. These may be secured (at cost) at six cents each (three two-cent stamps) or three for sixteen cents (eight two-cent stamps). Address all orders to Leo Edwards, Cambridge, Wisconsin.

“We have eleven members in our Pool,” writes Gold Fin Samuel Ferguson of Philadelphia, Pa., “and at almost every meeting we have visitors. I am enclosing a cipher code that we use in writing secret messages.”

Also it is Sam’s suggestion that we have a booklet printed giving an official Freckled Goldfish secret code, then members can write to one another in secret. How many members of our club would like to possess such a booklet? Let me know as soon as possible. And if there is sufficient demand, we may produce one. But you fellows have got to show me that there is a demand for the booklet before we go ahead with it. Another boy suggested that we have such a booklet and then print part of “Our Chatter-Box” in code. How does that strike you?

“We now have a Freckled Goldfish song, yells, a jazz band composed of tin cans and our Pool is decorated swell,” writes Gold Fin Francis Smith of Chambersburg, Pa. “Also we have two goldfish, named Leo and Freckles.”

I suppose I ought to send my namesake a present. What do you want, Francis, a box of goldfish food or an angleworm?

Nancy Hannemann of Chicago, Ill., is, I think, our youngest member. Giving her age as two, she confesses that the letter of application was written by her Brother, also a Freckled Goldfish.

“I have been a Freckled Goldfish for several months,” writes C. B. Andrews of Oklahoma City, Okla. “It is a secret and mysterious order, but nothing secret and mysterious has been done yet. So I suggest that you write to each member, telling him to join with other local members and do mysterious good turns. For example, suppose some poor old lady in your neighborhood has a birthday. Early in the morning before she is up and around, leave a couple of goldfish at her door with a card reading: ‘With the compliments of the Secret and Mysterious Order of the Freckled Goldfish.’ That would be pleasantly mysterious.”

Which, I think, is a corking good suggestion.

The three happiest boys in Yankton, South Dakota, are Dan Schenk (G. F.), Joe Dowling (S. F.) and Bob Seeley (F. F.). Not only have these boys organized a successful Pool, but they have swell rotographed letterheads. The reproduction of the “fish” is almost as good as Salg could do himself. Dan advises that the Pool has its meetings in an attic. Boy, I bet they have fun!

“Our Freckled Goldfish club,” writes Ernest Smith of Alhambra, Calif., “has an orchestra consisting of a violin, saxophone, a jazzophone and a harmonica. All of the boys playing in the orchestra are Freckled Goldfish.”

And had you heard, gang, about the marvelous piece of “art” that you can get by sending ten cents in stamps to Grosset & Dunlap, 1140 Broadway, New York, N. Y. Yah, the “art” referred to is Leo’s picture—and what a wonderful bargain! Only ten cents for such a marvelous picture!

Here is a complete list of Leo Edwards’ published books:

I got into the bushes quick as scat. Biting hard on my breath, sort of. For right there in front of our eyes was a regular old gee-whacker of a dinosaur. Bigger than the town water tower and the Methodist Church steeple put together. I tell you it was risky for us.

My chum got ready with his trusty bow and arrow.

“Do you think you can hit him in the heart?” I said, excited-like, squinting ahead to where the dinosaur was dragging his slimy body out of the pond.

Scoop Ellery’s face was rigid.

“Got to,” he said, steady-like. “If I miss, he’ll turn on us and kill us both.”

“It’s a lucky thing for Red and Peg,” I said, thinking of my other chums, “that they aren’t in it.”

“They’ll miss us,” said Scoop, “if we get killed.”

My thoughts took a crazy jump.

“Why not aim for a tickly spot in his ribs,” I snickered, pointing to the dinosaur, “and let him giggle himself to death?”

“Sh-h-h-h!” cautioned Scoop, putting out a hand. “He’s listening. The wind is blowing that way. He smells us.”

“What of it?” I grinned. “We don’t smell bad.”

“Keep still,” scowled Scoop, “while I aim.”

Bing! went the bow cord. My eyes followed the arrow. It struck. The old dinosaur angrily tooted his horn. But he didn’t drop dead. For his hide was sixteen inches thick.

We were lost! Scoop said so. And without arguing the matter I went lickety-cut for a tree.

“Come on!” I yipped over my shoulder. “He’s after us.”

Up the tree I went monkey-fashion. And when I straddled a limb and squinted down, there was the old dinosaur chewing my footprints off the tree trunk.

“How much longer have we got to live?” I panted.

“Two minutes and fifteen seconds,” informed Scoop, who, of course, had followed me into the tree.

“I can’t die that quick,” I told him. “For I’m all out of wind.”

But he was squinting down at the dinosaur and seemed not to hear me.

“He’s got his trunk coiled around the tree,” he said. “Feel it shake! He’s pulling it up by the roots.”

“Wait a minute; wait a minute,” I said, motioning the other down. “You’re getting things muddled. A dinosaur hasn’t got a trunk. This must be a hairy elephant.”

“Climb higher,” cried Scoop. “He’s reaching for us!”

So up we went.

All of a sudden I heard some one go, “Hem-m-m!” And what do you know if there wasn’t another boy in the top of the tree! A stranger. About our age.

“You had me guessing,” he said, grinning good-natured-like. “I thought at first you were crazy.”

Staring, I finally managed to get my tongue unhooked.

“Where’d you come from?” I bit off, letting my face go dark. For he didn’t belong in our dinosaur game. And I wanted him to know it.

Instead of answering, he inquired pleasantly:

“Was that a cow that chased you up the tree?”

“Huh!” I grunted, letting myself go stiff. “Do you suppose we’d run from a cow?”

“It made a noise like a cow,” he grinned, “when you shot it with your toy bow and arrow.”

“It’s a dinosaur,” I scowled.

His grin spread wider.

“And it was a dodo bird,” he said, “that picked me up by the seat of the pants and dropped me in the top of this tree.”

Well, that kind of took my breath. And I glared at him for a moment or two. Then his steady, friendly grin put me to laughing.

“I saw you coming through the woods,” he said after a moment. “I couldn’t quite figure out what you were doing. So I climbed up here to watch.”

Something poked a green snout from the stranger’s right-hand coat pocket.

“Are you after frogs, too?” he inquired, following my eyes.

“Frogs?” I repeated, staring harder at the squirming pocket.

He pointed down to the pond in the ravine.

“It’s full of frogs,” he told me. “Big fellows. See?” and producing an old lunker of a bullfrog he held it up.

“Hello!” he said.

“K-k-kroak!” responded the frog.

The boy laughed.

“Perfect,” he said, patting the frog on the head. “Now say it in Chinese. Hello!”

“K-k-kroak!”

The grinning eyes looked into mine.

“Would you like to hear him say it in Yiddish?”

“I’d like to make a meal of his fried legs,” I returned.

“You can have him,” the other offered. Then, without another word, he let himself down limb by limb, scooting in the direction of town, a mile away.

Scoop gave a queer throat sound and came out of his thoughts.

“That’s the new kid,” he said.

“You talk like you know him.”

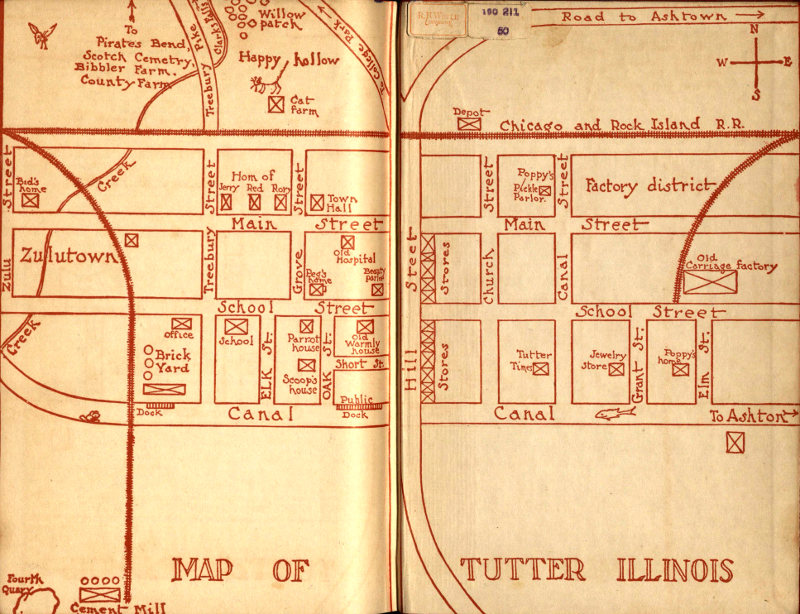

“I know of him. He belongs to the new family in the old Matson house. Ricks is the name on the mailbox. There’s a man and a woman and this boy in the family—only the woman is a Miss Polly Ricks, and not the boy’s mother. The mother is dead, I guess.”

Then my chum told me how his pa was the administrator of the Matson estate; and, of course, it was through Mr. Ellery, a Tutter storekeeper, that the new family had rented the long-vacant house where Mr. Matson, a queer old man, had been murdered for his money. It is a lonely brick house on the edge of town. The front yard is full of pine trees, just like a cemetery. And when the wind blows the pines whisper strange stories about the murder and about the vanished body.

It is no place for people to live. Everybody in Tutter says so. And I wondered why this new Ricks family had picked out such a lonely, spooky home.

It was a queer move for them to make.

We talked it over and exchanged opinions on the way into town. And when we came to the grove of pine trees, Scoop took me through a hole in the hedge and pointed out a brand new lock on the barn door.

A queer, droning sound weighted the air. I called the other’s attention to it.

“Machinery,” said Scoop, nodding toward the east wing of the big barn. “Not farm machinery,” he explained, “but lathes for turning steel, and drillers. Pa helped unload the truck.”

“Mr. Ricks must be a machinist,” I said.

“I have a hunch,” said Scoop, “that he’s an inventor.”

The following Monday morning the new boy started to school, entering our grade. And in the days that immediately followed I came to like Tom Ricks a lot. For he was the right sort. And soon we were visiting back and forth, playing in my yard one night and in his the next.

Scoop, of course, shared in our games, as did Red Meyers and Peg Shaw, my other chums. For I never would throw down an old friend for a new one. And it was during one of our trips to the old Matson place that we learned about the talking frog.

For Mr. Ricks, an inventor as Scoop had surmised, was working on a very wonderful radio toy. Tom called it an electro-mechanical frog.

We had promised our new chum that we wouldn’t breathe a word about the talking frog to any one else. For a Chicago radio company had spies searching for Mr. Ricks. These people knew that the inventor was working on a radio toy, and it was their evil intention to steal the invention, the same as they had stolen a simplified radio transmitter that Mr. Ricks had designed and built in his little Chicago workshop. It was to save the new invention from being stolen from him that he was now hiding in our inland town, where he could work undisturbed.

“A Milwaukee company is interested in Pa’s invention,” Tom told us, “and if he can make the frog say, ‘Hello!’, or make it repeat any other single word, they’ll pay him twenty-five thousand dollars for the idea and develop it in their laboratories.”

Grinning, he added:

“So you can see what I had in my mind that day in the tree. I frequently get frogs for Pa, to guide him in tuning the tone bars. For the toy, of course, must sound like a real frog or it won’t be a complete success.”

“And you say the mechanical frog actually talks?” said Scoop, who had been eagerly taking in each word.

“Sometimes it does,” said Tom. “But you can’t depend on it. You see it isn’t perfected.” There was a short pause. “I tell you what: Come out to-night after supper and I’ll try and coax Pa to let you see it. I’ll explain to him that he can trust you to keep his secret.”

“Hot dog!” cried Peg Shaw, thinking of the fun we were going to have listening to the talking frog.

This was on Friday. And directly after supper Scoop and I and Peg headed for Tom’s house. Red couldn’t go. He had queer spots all over his back. Not knowing whether it was scarlet fever or mosquito bites, his mother was keeping him in the house until the doctor had seen him.

“You fellows are lucky,” he told us, when we called for him.

“You will be lucky,” his mother told him sharply, “if you escape an attack of scarlet fever. For there’s dozens of cases over in Ashton. And you were there last week.”

“Aw! . . . I haven’t got a fever. Please let me go, Ma.”

“You’ll go to bed,” his mother threatened, “if you don’t keep still.”

We had met Aunt Polly in the times that we had been at Tom’s house, but never had we seen Mr. Ricks until to-night. He was considerably taller than his sister, and older, with stooped shoulders and faded blue eyes that looked meekly at one over the top of small, steel-rimmed spectacles.

Tom introduced us. But he had to speak to his father several times and shake him by the shoulder to make the old gentleman put aside his book. It was a book on inventions, I noticed.

“Oh, yes; yes, indeed,” said Mr. Ricks, vague-like, giving us a limp handclasp without actually seeing us. “Very glad to meet you. Very glad, of course. Um. . . . Now whar did I leave off?” and plunk! went his nose into the big book.

Later we came to know how very absent-minded he was, and how queer in a lot of his actions; but I am going to tell you about it here, before I go deeper into my story, else you might not fully understand what follows.

For instance, he never seemed able to quit thinking about his inventions. Even while eating his meals an idea would come to him, and there he would sit with his fork halfway to his mouth, his eyes making invisible drawings of things in the air. And you would be talking with him about the weather, or about fishing, and right in the middle of a sentence he would mumble: “Now if I file the end sharp, I bet it’ll work easier an’ won’t bind,” or, “Um. . . . I bet I’ve got one tooth too many in that thar gear.”

I guess he wouldn’t have known enough to stop working at mealtime and bedtime if Aunt Polly, in her bustling capable way, hadn’t kept tab on him. And he needed some one like that to give him sharp attention. For I’ve seen him absent-mindedly hang his handkerchief on the towel rack and stuff the towel in his pocket. And once, going to church, he got as far as the front gate before his watchful sister discovered that he had on one shoe and one slipper. Golly Ned! It would have been fun to see him come into church dressed like that.

Peg tells the story, which he made up, I guess, that one time when he was eating breakfast at Tom’s house, Mr. Ricks absent-mindedly poured the syrup down the back of his neck and scratched his pancake!

To-night Aunt Polly bustled from window to window, drawing the shades.

“Now,” she nodded sharply to the inventor, who was pottering at her heels, book in hand, “you can bring it in.”

The lowering of the window shades had filled me with uneasiness. For the precaution, suggested the near-by presence of possible prying eyes. And I didn’t like to think of the shadowy pines as holding such hidden dangers.

Then my nervousness melted away in the moment that the talking frog was placed on a small table in the middle of the room. Made of metal and properly shaped and painted, it squatted five inches high, which was considerably larger than a live frog, but it had to be oversize, Tom explained, because of the many gears, magnets and tone bars that his father had designed to go inside.

We had our noses close. And no movement of the inventor’s escaped us as he wound a spring here and turned a knob there. It was a pretty fine invention I thought. And I realized that Mr. Ricks, with all of his queer forgetful ways, was a very smart man. He was what you would call a genius. I guess that is the right word.

Presently the worker straightened, sort of satisfied-like, so we knew that the frog was ready to perform.

“Hello!” he said, talking into the green face, his chin thrust out.

The vibration of his voice tripped the machinery and put the wheels into motion. The big hinged mouth opened in a natural way. But other than a dull rumbling of gears, no sound came out.

“Jest you wait,” puttered Mr. Ricks. “I hain’t got it ’justed quite right.”

We watched him.

“Hello!” he said, after a moment.

“R-r-r-r!” responded the frog.

Aunt Polly laughed good-naturedly.

“Laws-a-me! It sounds as though it had a bad pain in its tin stomach.”

“Indigestion,” grinned Peg, his big mouth stretching from ear to ear.

“We should have brought along some charcoal tablets,” laughed Scoop.

The disappointed inventor did some more puttering. But all that he could get out of the tin frog was, “R-r-r-r!”

“It did better than that last night,” Tom told his father.

“I know it, Tommy. I know it. Um. . . . Calc’late the new tone bar that I made to-day hain’t improved it none.”

He puttered with the frog for maybe an hour. Finally Aunt Polly took up her knitting and told him to put the frog in the kitchen cupboard. She had noticed, I guess, that he was getting nervous.

“Mebby,” he countered, fidgety-like, “I better put it in the barn.”

I grinned. For I saw in a moment what he was up to. He wanted to keep on tinkering, and he would have that chance if he could get the frog into his workshop.

But Aunt Polly read the other’s thoughts.

“I said to put it in the kitchen cupboard,” she repeated firmly.

The blue eyes offered meek protest.

“It’ll be safer in the barn, Polly.”

“It’ll be safe enough in the kitchen,” said Aunt Polly, jabbing with her needles.

“Yes, of course; of course. But I’ve got a burglar ’larm on the barn door. Mebby, Polly——”

“And I’ve got a burglar alarm on the kitchen door,” cut in Aunt Polly, making her needles fly.

A domino game failed to draw our thoughts from the talking frog; and Tom told us how the Milwaukee company was planning to get out a complete line of talking toys—this in the event that Mr. Ricks’ experiments were successful.

“It seems to me,” said Scoop, out of his thoughts, “that twenty-five thousand dollars isn’t enough money for such a big idea.”

“Twenty-five thousand dollars,” spoke up Peg, whose folks are poor, “is a fortune, I want to tell you!”

“Of course,” nodded Scoop. “But an invention like this ought to be worth more than twenty-five thousand dollars to the man who thought it up. A hundred thousand, I should say. Or half a million.”

“I forgot to tell you,” Tom said, “about Pa’s royalty.”

“Royalty?” I repeated.

“It’s this way,” Tom explained. “Pa’ll get twenty-five thousand dollars cash money for the idea; then the company will develop and apply the idea, and Pa’ll get a royalty on each talking toy sold.”

I asked what a royalty was.

“It’s a written agreement,” Tom told me, “under which Pa’ll get a certain part of every dollar that the company takes in. The money is his pay, as an inventor, for letting them use his idea. For instance, if they sell a million dollars’ worth of talking toys, Pa’ll get fifty thousand dollars. That’s five per cent.”

“Crickets!” I said, regarding my new chum with quickened interest. “You’re going to be rich.”

He sobered.

“I hope so, Jerry. I’d like to know what it seems like to be rich. We’ve been poor all my life. And I’ve got a hunch that Aunt Polly won’t be able to stretch our money over very many more months. Yes, if Pa doesn’t hurry up and make his frog talk, I suspect that we’re likely to move over to the county poorhouse.”

It was now after nine o’clock and time for Scoop and Peg and me to go home. So we got our caps. But in the moment that we started for the front door a fearful racket came from the kitchen. Bing! Crash! BANG! It sounded as though a million tin pans had been upset in a heap. I pretty nearly jumped out of my skin.

“My burglar alarm!” screeched Aunt Polly, throwing her knitting into the air. And like a flash she disappeared fearlessly into the hall, heading for the back room.

Squeezing the stutter out of my nerves, I followed Tom and my chums into the kitchen. The back door was ajar. Some one had picked the lock. But in opening the door the unknown prowler had not reckoned on Aunt Polly’s homemade burglar alarm—a dozen or more pots and pans balanced nicely on a wabbly stepladder.

“Um. . .” mumbled Mr. Ricks, pottering into the room, book in hand. “Did I hear a noise?” Looking over his glasses, he got his eyes on the pans and stared at them blankly. “Now how did all them pans come to fall down? An’ whar in Sam Hill did they fall from?” Mouth open, he stared at the ceiling, moving in a small circle.

Aunt Polly caught him as he stumbled over a pan.

“Shut the door,” she told Tom crisply, “and lock it.” Then she took the pottering inventor by the arm and led him from the room. “Go back to your book,” she ordered. “We don’t need you here.”

“But, Polly——”

She got him out of the kitchen. Then she sort of went to pieces.

“Oh, Tommy!” she cried, trembling, her eyes filled with fear. “It’s one of Gennor’s spies. You know how they’ve been searching the country for your pa. They’ve come to steal his invention. What shall we do?”

“I wish I knew,” said Tom, looking dizzy.

Scoop’s eyes were snapping.

“Why,” he spoke up, taking the lead, sort of, “the thing for us to do is to save the frog.”

Aunt Polly gave a gesture of despair.

“We might as well give up,” she cried, sinking into a chair. “For we stand no chance against Gennor.”

Scoop wanted to know who Gennor was.

“Mr. Felix Gennor,” Tom informed, “is the president of the Gennor Radio Corporation of Chicago.”

“The name sounds big,” said Scoop. “He must have a lot of money.”

“Millions,” informed Tom, gloomy-like.

“Which means,” said Scoop, sizing up the situation in his quick way, “that it’s going to be a hard fight to lick him.”

Aunt Polly was wringing her hands.

“We stand no chance,” she repeated, shaking her head. “For money always wins out.”

“Money won’t win out this trip,” declared Scoop.

After a bit the conversation slowed up and we told Aunt Polly that she had best go to bed and get some rest.

Scoop did the talking.

“You mustn’t worry,” he told her, as she started up the stairs with a hand lamp, “for there’s no immediate danger. And by to-morrow morning we’ll know what to do to save Mr. Ricks’ invention.”

It was his scheme for the four of us to stand guard till daybreak. So, when Aunt Polly and Mr. Ricks were in bed, I ’phoned to Mother, explaining that I would spend the night with Tom. Then Scoop and Peg ’phoned in turn to their folks.

Making sure that the doors and windows were locked, we took the talking frog from the cupboard and buried it in a wooden box in the cellar’s dirt floor. We intended, as guards, to see that no one entered the house without our knowledge; but, as Scoop sensibly pointed out, it was just as well to play safe and keep the invention under cover.

In the next hour our leader sifted his thoughts for a plan to outwit the Chicago manufacturer. And finally he waggled, as though having come to certain satisfactory conclusions.

“One time,” he said, “my Uncle Jasper invented a percolating coffee pot and got it patented in Washington. The patent prevented any one else from stealing his invention. . . . Is your pa’s talking frog patented?” he inquired, looking into Tom’s face.

“Of course not. It isn’t perfected yet.”

“Everything seems to work all right except the tone bars.”

“Yes.”

“Well, let’s get a patent on the parts that work. For that is what Gennor would immediately do if he got his hands on the frog. If we get to Washington first with our patent application he’ll be licked.”

Tom’s eyes snapped.

“You’re right. I’ll tell Pa about it the first thing in the morning.”

“Yes,” waggled Scoop, “your pa is the one to see about the patent. And the sooner he starts for Washington the better. There’s a train into Chicago at five o’clock. And from Chicago he can go directly to Washington. The people in the patent office will tell him how to get his drawings registered. And while he’s doing that, we’ll have some fun with mister millionaire.”

“A thing I can’t understand,” mused Tom, “is how Gennor traced Pa to this town.”

“Maybe,” I spoke up, giving Scoop and Peg the wink, “it was a ghost that picked the lock, and not a spy as you suppose.”

“Ghost?” repeated Tom, staring.

“Mr. Matson’s ghost,” I followed up.

“Who’s Mr. Matson?” he wanted to know.

“Haven’t you heard about the murder?” I countered, surprised.

He shook his head.

“Mr. Matson,” I told him, “was a queer old codger. A puzzle maker. Didn’t believe in banks. Kept his money in the house. One night robbers came. The old man was murdered. But the body never was found. That’s the strange part. The robbers either buried it or took it away with them.”

“Then how do you know there was a murder?”

“Because the cellar stairs and the kitchen floor were covered with blood. Big puddles of it. And the money and the ten-ring puzzle were gone.”

Torn scratched his head.

“But I don’t get you,” he said, puzzled. “Even if there was a murder, why should the old man’s ghost come here?”

“Because,” I said, putting my voice hollow, “right here in this kitchen is where they cut his throat. This was his home.”

Tom’s eyes bulged. And noticing this, Scoop laughingly clapped a hand on the frightened one’s shoulders.

“Jerry’s trying to scare you, Tom. No one ever saw the old man’s ghost around here.”

“Old Paddy Gorbett did,” I reminded quickly.

“Shucks! Any one who knows old Paddy always believes the opposite to what he tells.”

Tom shrugged and gave a short laugh.

“I’ve read stories about ghost houses, but I never thought I’d live in one.”

“There’s no such thing as a ghost,” declared Scoop.

“Of course not,” agreed Tom. “But just the same we had better keep this story from Aunt Polly’s ears. It would make her nervous. And she has plenty of worries as it is. If Pa goes to Washington, she won’t sleep a wink till he gets back. She’ll imagine him getting into all kinds of trouble.”

We thought naturally that the mysterious prowler would make further attempts to enter the house. But daybreak came without a single disturbing sound.

At four o’clock Tom awakened his aunt. She readily admitted to the wisdom of getting the talking frog drawings registered in the patent office at Washington; but the thought of sending her absent-minded brother so far from home worried her.

“I just know that something awful will happen to him,” she declared.

But Tom won her over. And then between them they made the dazed inventor understand what was expected of him.

It was daylight when we went with Mr. Ricks to the depot. I was on needles and pins, sort of, expecting any second to have a spy jump out and grab the old gentleman before we could get him on the cars. Therefore I drew a breath of relief when the train pulled out.

But a shock awaited us when we ran up the path to the house.

“He didn’t get the right papers at all,” Aunt Polly cried from the front porch. “His drawings are in there on the table. And what he has is a roll of my dress patterns.”

Well, we were struck dumb, sort of. For, with Mr. Ricks aboard the speeding train, what chance had we to exchange the useless dress patterns for the needed drawings? None. Our helplessness made me sick.

“He’ll discover the mistake when he gets to Washington,” Scoop said finally, “and wire us. Then we can mail the drawings, registered. It will delay matters; but it’s the best thing that we can do under the circumstances.”

“Tom’s pa never sent a telegram in all his life,” waggled Aunt Polly. “He won’t know how.”

Nevertheless a telegram came that afternoon. Scoop read it aloud. There was a dead silence. Then Tom went in search of his relative.

“Aunt Polly,” he said, “you’ve got to get ready for a trip.”

“Laws-a-me!” gasped the old lady, suspecting the truth. “What awful thing has happened to your pa?”

“He took the wrong train out of Chicago. And how he ever happened to get off at Springfield, Illinois, I don’t know. But he’s there—the telegram says so. And the dress patterns have come up missing.”

“Gennor’s work!” cried Aunt Polly, acting as though she was ready to collapse.

Tom nodded grimly.

“Pa is no match for the crooks. And you’ve got to go to him and help him. They won’t get the real drawings away from you. And you can stay in Washington till the drawings have been registered in the patent office.”

“But why don’t you go?” Aunt Polly wanted to know, with a troubled look.

Tom regarded her steadily.

“I have a hunch,” he said, “that I’m going to be needed here.”

“But I don’t like to go away and leave you alone.”

Scoop came into the conversation with an easy laugh.

“Don’t let that worry you, Aunt Polly. For he won’t be alone. We’re going to stand by him. Hey, gang?”

“Easy,” said Peg.

“How about you, Jerry?”

“Easy,” I said, copying after Peg.

I tried to act chesty about it. But I didn’t succeed very well. For I was thinking about the man with the million dollars.

Aunt Polly put her railroad ticket into her handbag.

“Now,” she told Tom, fumbling nervously with the handbag’s metal clasp, “try and keep yourself nice and neat while I’m away and wash behind your ears and don’t be late to school and feed the canary and the goldfish and wind the clock Sunday night.”

“I’ll remember,” Torn grinned.

“There’s plenty of baked stuff in the pantry and half of a ham and you know how to fry potatoes and boil eggs. So I warrant you won’t starve. But in lighting fires be careful with your matches and don’t burn down the house.”

Torn waggled, still grinning.

“And feed the cat,” his aunt continued, “and don’t let the sun shine through the windows on the parlor carpet and——”

Here the train for Springfield rumbled into the station.

“Good-by, Aunt Polly,” said Tom, as the excited little old lady went briskly up the car steps.

Pausing, she bent over and gave him a kiss on the mouth. Then her forehead puckered.

“There was something else I wanted to tell you,” she said, thoughtful-like, “but it’s plumb slipped my mind.”

“All aboard!” called the conductor.

“Oh, yes,” screeched Aunt Polly, as the train got into motion, “it’s my rubber plant. Water it every day and put dish water on it once a week and——”

In the silence that followed the train’s departure, Tom grinned at us and drew a deep breath.

“She forgot to tell me to keep the ice box door closed and not to let the cat sleep on the parlor sofa.”

Then he sobered.

“But Aunt Polly’s all right. And I don’t want you to think that I’m making fun of her. Ginks! I’ll miss her like sixty. And I’ll be glad when this patent office business is over with so that she and Pa can be home again.”

As we turned to leave the station the Stricker gang scooted by us. We haven’t any time for the Strickers. Bid and Jimmy are cousins and one is just as mean and as tricky as the other. That part of Tutter beyond Dad’s brickyard is called Zulu-town, and it is in this tough neighborhood that the Strickers and their followers have their homes. Because we won’t do the mean things they do they have it in for us.

“Aunty has gone away on the choo-choo,” hooted Bid, “and left her ’ittle boy home all alone.”

“And she gave him a nice juicy kiss,” jeered Jimmy.

“Right on the mouth,” another member of the gang put in.

Tom took after them, chasing them away.

It was darkening fast, so we started back to the brick house. First, though, I ran home and explained the situation to Mother. She immediately wanted to know why Tom couldn’t come to our house and stay. I told her that it would be more fun living at his place—sort of like camping. She shook her head and said that boys were queer creatures.

“Did you know,” she told me, “that Donald Meyers is sick in bed?”

“Scarlet fever?”

“The doctor hasn’t said that it is scarlet fever—at least he hasn’t put up a quarantine sign. But nobody is allowed to go into or out of the house.”

“Poor Red,” I murmured, sorry for my chum.

Here the other fellows whistled to me, so I ran into the street. They were talking about the sick one.

“It doesn’t seem right,” said Scoop, “not to have Red with us.”

“He’s ornery,” grunted Peg, “but when he isn’t around you miss him.”

Hurrying, we shortly came within sight of the whispering pines. On the moment they looked fearfully grim and spooky to me. I shivered a bit as I followed my chums up the path.

It came ten-eleven-twelve o’clock.

“Midnight!” grinned Peg. “Now listen for the ghost.”

I held my breath. In the deep silence I could hear the rubbing of my fidgety fingers. Then from without the kitchen door came a faint pat! pat! pat! Some one was crossing the porch on tiptoes. The doorknob turned—slowly, with scarcely a sound.

Gosh! I don’t mind telling you that I was scared stiff.

“The spy!” breathed Scoop.

Five-ten minutes passed.

“He heard us in here,” said Tom, “and beat it.”

Evidently this was the case. For the outside world within range of our ears was a well of silence into daybreak.

Tom got breakfast. And when the dishes were washed and put away, we went outside and covered every inch of the yard. But the midnight prowler had dropped no clews.

We had dinner; then we played games in the front yard. Darkness came. And again we heard the mysterious prowler on the back porch. But this was the night’s only disturbance.

Scoop, I noticed, was pressing hard on his thinker.

“If ever there was a time when I wanted to skip school,” he said to us at breakfast, “it’s to-day.”

I knew what was worrying him. He was afraid that while we were in school the spy would break into the unguarded house and dig up the talking frog.

Yes, it was risky leaving the frog in the house without a guard. We talked it over.

“If you don’t want to leave the frog here,” I said to our leader, “why don’t you carry it along with you to school?”

“It won’t go in my pocket.”

“Put it in a lunch box. You can keep the lunch box in your desk. Miss Grimes won’t know what you’ve got in it. She’ll think it’s full of sandwiches and pickles.”

Miss Grimes is our teacher. I suppose she’s all right. But I don’t like her. She’s too cranky.

We went to the cellar and dug up the talking frog. But before we put it in the lunch box that Tom had provided we wound it up and turned the small knobs the way we had seen Mr. Ricks do.

“Hello!” said Scoop, grinning into the tin face.

Nothing happened. He tried it again; then gave the frog a shake.

“R-r-r-r!” rumbled the frog, waking up, sort of.

“Let me do it,” I cried, pushing the others aside. Getting my mouth down close, I yelled:

“Rats!”

“R-r-r-a-s!” said the frog.

“Why,” said Tom, excited-like, “that’s the best it ever did.”

“Maybe,” I said, with a snicker, “if we jiggle it some more it will talk perfect.”

“Nothing like experimenting,” grinned Scoop, and he gave the frog another shake.

“Rats!” he yelled.

“R-r-r-a-t-s!” rumbled the frog. “R-r-r-a-t-s! R—r-r-a-t-s!”

Scoop laughed.

“Wait a minute; wait a minute,” he said, trying to hush the frog up. “You’re talking out of your turn. You mustn’t say it more than once.”

“R-r-r-a-t-s!” rumbled the frog. “R-r-r-a-t-s! R-r-r-a-t-s!”

We pretty near died, we laughed so hard. Then the school bell rang and we dumped the invention into the lunch box and started on the run for the schoolhouse. And every time we jiggled the lunch box the frog would rumble at us: “R-r-r-a-t-s! R-r-r-a-t-s!”

“To-night,” grinned Scoop, “we’ll try it out on some hard words like ‘cat’ and ‘bat.’”

I had to stay in at recess that morning. For there was a music memory test and, as usual, I got the names of the pieces all mixed up. I’m no good at music.

Maybe all public schools haven’t music memory contests, so I’ll write down what it is. You see, each room has a talking machine. And at the beginning of the school year the board of education picks out twenty or thirty records. Not easy pieces like, “Yes, We Have No Bananas,” but a lot of hard truck that is called classical. These records are played over and over again by the teacher. And at the end of the school year we are supposed to be able to write down all of the names of the pieces when the teacher plays them and give the names of the musicians who made them up. . . . It’s all right for a fellow who has an ear for music.

“Now,” Miss Grimes told me at recess, shoving some records at me, “here are the first four pieces. Take them, one at a time, and play each one over and over again till you know it.” Then she went out of the room, closing the door behind her.

It was fun at first. But I got sick of it. The old pieces were no good. So I hunted up something snappy. A band piece with a lot of loud toots in it. And at the first toot, what do you know if the tin frog didn’t come to life! “R-r-r-a-t-s!” it rumbled in Scoop’s desk, sort of muffled-like. Then the record gave another loud toot and the frog sassed it back. Say, it was bully! There is some sense to that kind of music.

I took the frog out of the lunch box and put it on a chair in front of the talking machine. Mr. Ricks had told us that it was the sound waves that tripped the machinery inside of the frog. I don’t understand about sound waves. But I saw right off that it was the loud toots that did the business. And I decided to do some experimenting.

Our talking machine has a cloth front where the music comes out. But one day Bid Stricker skidded and rammed his elbow through the cloth, breaking the bracketwork. And now I discovered that by making a slightly larger hole in the cloth I could squeeze the frog inside.

This worked fine. And I was having a high old time when the door opened and in came Miss Grimes. I thought I’d catch it. But she was complaining to another teacher about something and didn’t notice what I was up to. Then the bell rang and the kids all came in.

When school was called, Miss Grimes said to me:

“How many times did you play ‘The Maiden’s Prayer’?”

“Six times,” I guessed, wondering which one of the pieces was that.

“And are you sure that you will recognize it the next time that you hear it?”

“Yes, ma’am,” I said, getting fidgety. What worried me was the talking frog. It was still shut up in the talking machine. I was afraid that something would happen.

So I was glad when a knock sounded on the door. And who should come walking into the schoolroom but old Deacon Pillpopper, the man who invented the big community incubator that I told about in my first book, JERRY TODD AND THE WHISPERING MUMMY. If you have read this book you will remember that the Strickers locked me in the incubator, making me think, through a trick note, that the stolen mummy was there. But I got even with them in the end!

We like the friendly deacon. For he’s kind of queer. He makes up riddles and puzzles and on his visits to the school he springs the riddles on us, often giving us money if we guess the answers.

Miss Grimes was very polite to the visitor, for he is a member of the county board or something. And directly after reading class she gave him a chance to show off.

“I can see, Mr. Pillpopper,” said she, smiling at the old gentleman, “that the boys and girls are all on edge wondering if you have a few new riddles.”

And the deacon looked awfully pleased with himself, like a purring cat, sort of, and said:

“Um. . . . Kin I use your blackboard, Miss Grimes?”

And she said:

“Of course, Mr. Pillpopper; of course.”

He went to the blackboard and drew a picture and said:

“The moon’s got two eyes [he put in the eyes] a nose [he put in the nose] and a big, round face,” and he drew a circle around the eyes and the nose. Then he turned and squinted at us. “I’ve got a dime,” he said, “fur the first b’y who kin do that jest like I done it.”

Well, every kid in the room shot up his hand to get first chance; and the lucky one went to the blackboard and drew the moon’s face and turned to the deacon to thank him for the dime. But the old man chuckled and shook his head. Then another kid tried it. And he didn’t do it right. Every boy in the room tried it but me. Whatever the trick was, no one caught on to it. I figured I’d be just as unlucky as the rest. But I drew the eyes and the nose and the circle as best I could. And what do you know if the deacon didn’t hand me the dime! I pretty near fainted, I was so surprised.

“You see,” he told the others, patting me on the head, “Jerry is the only b’y in the room who used his eyes an’ noticed that I done it with my left hand.”

“But he’s left-handed,” Bid Stricker cried, mad as hops to think that I had won the dime.

At this the deacon scratched his head and looked kind of silly.

He had another test for the girls; and when this was over, Miss Grimes motioned to Amelia Didman to play a few pieces on the talking machine. Amelia got the machine wound up and put the needle down. A familiar toot jumped at me out of the hole in the cloth. And right off I knew that I was in for trouble.

If you can imagine the talking machine record and the tin frog fighting each other tooth and nail, that is how it sounded. First the record would sort of swell up and give an angry toot, as though it was determined to make the frog back up and shut up. And then the frog would dig in and screech: “R-r-r-a-t-s!” And that would make the record madder than ever and it would stomp its front feet like a fighting bull and give a still louder toot. And then the frog would lift itself onto its toes and sass the other. Then they would clinch and knock out each other’s false teeth and kick each other in the seat of the pants.

The scholars were laughing fit to kill. Sort of dazed at first, Miss Grimes’ face got red and she hurried to the talking machine to see what was wrong. Then she gave an awful jump. For, as she leaned over the machine, the record and the frog got a strangle hold on each other. Thump! The record smashed the frog on the left ear. And when the frog quit wabbling it gave the other a wallop on the snout.

Being a member of the county board, the deacon tried awful hard to be dignified and set a good example and not laugh. But when the record got a smash on the snout that was too much for the old gentleman. He busted right out. And you could hear him cackling above everybody else.

“I guess,” said Miss Grimes, frosty-like, “that our talking machine needs repairing,” and she shut it off and rapped for order.

As I say, I had expected that I would catch it. But for once I was lucky. And that noon Scoop and I and Tom waited around till the teachers came out of the schoolhouse, then we slipped into the schoolroom and got the frog. I suspect that it is a wonder to Miss Grimes to this day what made her talking machine act up. For when the man came to fix it, he could find nothing wrong with it except the hole in the cloth.

We didn’t take the frog to school that afternoon. We put it back in the wooden box and buried the box in the cellar. For Scoop was convinced that to leave it unguarded in the cellar was less of a risk than taking it to school.

Wednesday morning when we came into the school grounds a number of the kids were yipping and kicking up their heels. Tom was the first one in our gang to grab the good news that was going around among the scholars.

“Hot dog!” he cried. “Teachers’ convention. No school till next Monday.”

We were excited. And right away we began to plan our fun.

“Let’s catch frogs,” suggested Scoop. “We can sell them and make some money. For almost everybody likes fried frog legs.”

So we got a bag and started out. First we tried our luck in the millpond behind the brick house. But what frogs we saw there were small and not worth catching. So we decided to go to the ravine where Scoop and I had played dinosaur.

“Risky,” said Peg, reflective-like.

“What’s risky?” inquired Scoop.

“Leaving the talking frog without a guard.”

“You’re right,” considered Scoop. He fished some matches out of his pocket. “We’ll draw cuts,” he said, getting the matches ready. “The short-match drawer will be the guard.”

“That’s fair enough,” said Tom, drawing.

I drew next, hoping that I would be lucky. I didn’t want to miss the fun of going to the ravine.

Peg got the short match.

“I almost wish,” he said, making a wry face, “that I had kept my mouth shut.”

Scoop laughed.

“We’ll be back by twelve o’clock. So be sure and have dinner ready for us and don’t burn the coffee.”

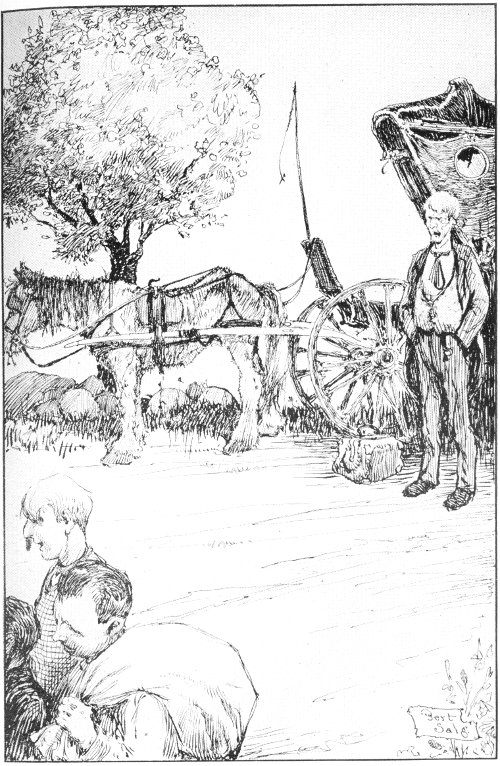

We started off, three abreast. But we hadn’t gone very far along the country road before we came to a horse and buggy, drawn up in the shade of a high hedge. It was the ricketiest buggy I ever set eyes on. The wheels were warped out of true. They made the buggy look as though it had a bad case of bowlegs. The leather top was cracked and shrunken out of shape.

And the horse! Good night! That horse was so skinny that you could have used its ribs for a washboard. It was sway-backed and its hip bones stuck up like chair knobs. It had a big head, and when I got a look into its sober, forlorn-looking face, I had the uncomfortable feeling that it was dying of a broken heart. I don’t know how old horses get to be as a rule. But if some horses live to be fifty years old, this skate was easily sixty-something.

An oldish man was seated in the dilapidated buggy. He had some kind of an iron jigger in his lap. And when he saw us he gave a start, as though he had been caught doing something that he didn’t want us to know about. Kerplunk! Quick as scat the iron thing disappeared under the buggy seat.

He was every bit as queer-looking as his old nag. Yes, sir, they were a good pair. The long face that he had turned to us was thin, like a sunfish. The eyes were black, sort of restless-like, and set close together. The head was bald on top. We could see that it was because the man’s hat was parked on the buggy seat. He wasn’t fat. But he had more stomach than he needed. The way it stuck out in front, like a halved pumpkin, made me think of a lean boa constrictor that had swallowed a dog.

Well, we kind of stared at him, wondering who he was, and he, in turn, squinted back at us.

“Howdy, boys,” he smiled, friendly-like.

“Howdy,” Tom returned.

It struck me on the moment that my new chum’s voice sounded queer. I wondered why. Turning to look at him, to read his thoughts, I found him squinting hard at the old nag. As though he had seen it before and was trying to puzzle out something in his head.

“You boys must be out coonin’ chickens,” the stranger cackled, pointing to the bag that I was carrying.

“No,” I spoke up. “We’re planning to fill our bag with frogs.”

“Frogs?” he repeated, looking at me questioning-like.

“We’re going to sell the hind legs,” I explained, “and earn some money.”

“Um. . . . How would you like to work fur me? The three of you. Calc’late you kin make a lot more money assistin’ me than you kin sellin’ frog legs. I’ve got a real proposition, boys.”

“What’s your line?” I grinned, looking at the four-legged washboard. “Horse trading?”

I was a little bit suspicious of this stranger. For one time an old shyster came to Tutter and stung me for a dollar and a quarter for a membership in his fake detective agency. Since then I have been cautious about taking up with men I’m not acquainted with.

Very gravely the old man reached under the buggy seat and brought out a fancy sign. He hung the sign on the side of the buggy. It read:

BUBBLES OF BEAUTY

The Wonder Soap That Makes All Women Beautiful

I had heard of Ivory soap and Palmolive soap and two or three other kinds of advertised toilet soap. But I never had heard of Bubbles of Beauty. It must be something brand new, I figured.

The man stood up in the buggy and kind of posed, one hand resting on his over-size stomach and the other feeling around in the air above his head. He looked awfully tall. With his lanky arms and legs and thin face and pushed-out stomach he seemed to be all out of proportion. Looking at him, I was reminded of the funny pictures in the Sunday newspapers.

“Boys,” he said, dramatic-like, “I ask you as a disinterested friend, who has done the most for this country, Edison or Gallywiggle?”

I grinned.

“Henry Ford,” the old man questioned further, acting as though he was preaching a sermon, “or Gallywiggle?”

Amused, I wondered who Gallywiggle was. I had heard of Mr. Edison and Mr. Ford, but I never had heard of a Mr. Gallywiggle. Gallywiggle! Wasn’t that a name for you?

“Mr. Gallywiggle,” the old man went on, sort of warming up, “Mr. Mortimor Hackadorne Gallywiggle, the president of our company an’ the friend of all humanity. The genius who has taken more warts from women’s noses than all of the talkin’ machines an’ all of the automobiles put together. The man who has made millions of sallow skins pink. The man who has turned bushels of blemishes into barrels of blushes. The man, folks, who spent fifty years of his noble, useful life perfectin’ the formula of the greatest gift that science has ever bestowed upon womankind. Bubbles of Beauty! The only toilet soap of its kind in the world. An’ to-night, ladies and gents, to introduce this marvelous beautifier into your homes—for one evening, folks, as a special introductory offer—we are cuttin’ the price of this household necessity down to only a dime, ten cents, a cake.”

Suddenly his voice trailed away. And he looked sort of embarrassed-like. I guess he had forgotten himself. I figured it out that he was a soap peddler and was used to talking this way to street-corner crowds.

“Boys,” he said, holding our eyes with his own, “if you’ll work fur me I’ll make you assistant beautifiers. I need you in my business. For this thing of makin’ women beautiful is a big job. To do it thorough, like our dear departed president, Mr. Gallywiggle, asked me to do, personal, when he signed my territorial contract, I’ve got to have plenty of capable help. Mebby you kin guess how turrible I’d feel to learn that I had passed up some poor, unfortunate woman who wanted to be beautiful an’ who was left homely simply because I was so rushed that I didn’t git around to her with a cake of our marvelous Bubbles of Beauty.”

There was a worn black leather satchel in the buggy. He opened this satchel and took out several small cardboard boxes. Removing the cover of one of the pink boxes, he let us see that it contained three thin cakes of soap. It was swell soap all right. I could tell by the smell.

“As I started to say,” the soap man continued, “my name is Ajax Posselwait. I’m on a’ advertisin’ tour through this section of the country gittin’ folks acquainted with our marvelous Bubbles of Beauty, the wonder soap that makes all women beautiful. To introduce the soap into every home we are offerin’ three cakes for a quarter. In the cities, where thousands of women, yes, millions of women, are usin’ Bubbles of Beauty to keep beautiful with, the reg’lar price is fifty cents. But it’s all a part of our sellin’ plan to put up with a loss in gittin’ established in a new territory. We just charge up the loss to advertisin’.”

He cleared his throat.

“Now, it ain’t goin’ to be no trick at all fur you boys, as assistant beautifiers, to sell a box of our marvelous Bubbles of Beauty into every home in this community. All you’ve got to do is to tell the women how the soap improves the complexion, drives away blotches, transforms wrinkles into dimples. An’ fur every quarter that you take in you keep ten cents, which is your pay, an’ I git fifteen cents.”

I looked at our leader. He had suggested catching frogs as a possible way of earning money. And on the moment it seemed to me that selling this man’s soap was a better money-making scheme than frog-catching. He couldn’t gyp us, like the fake detective did, because we wouldn’t be putting up any money. We were safe.

“Um. . .” said Scoop, thinking.

“You kin make a lot of money workin’ fur me,” the soap man put in, persuasive-like.

“Maybe,” said Scoop.

“It ain’t ordinary peddlin’,” the man went on. “It’s what I call artistic peddlin’. Yes, sir, an assistant beautifier must be an artist to be a success at his job. Absolutely. He’s got to have enough tact to sell somethin’ to a homely woman to make her beautiful without makin’ her feel that he knows that she’s homely an’ needs what she’s buyin’ from him. Doin’ a thing like that successfully is an art, just the same as paintin’ beautiful pictures an’ carvin’ statues. It’s a job that any boy kin be proud of. Fur it calls fur ability. An’, like I say, your profit is a dime out of every quarter.”

“YOUR PROFIT IS A DIME OUT OF EVERY QUARTER!” SAID THE SOAP MAN.

“Fifteen cents,” said Scoop, whose father is one of the shrewdest business men in Tutter.

“Ten cents,” said the soap man, scowling.

“Not enough,” said Scoop. He took my arm and started off. “Come on, gang,” he said. I tried to hold back, but he hissed in my ear to follow him and keep still. He had a scheme, he said.

“Um. . . . Just wait a minute,” the soap man called after us.

We paused and looked back.

“Fifteen cents,” said Scoop.

The older one’s scowl deepened.

“Plain robbery, that’s what! Calc’late though I’ve got to stand fur it.”

Scoop gave me a dig in the ribs with his elbow.

“Fifteen cents,” he whispered in my ear, “is better than ten cents. I figured that we could hook him for the extra nickel.”

We went to the buggy and our new employer gave each of us four boxes of soap, twelve boxes in all. “Bubbles of Beauty” was printed on the covers in gold lettering.

“You ought to have it all sold by noon,” he said.

“Where’ll we find you when we want to settle up?” inquired Scoop.

“You boys live in Tutter, I take it.”

Our leader nodded.

“As you go into town on this road,” the man pointed, “there’s a big red brick house on the right-hand side with a yardful of pine trees.”

“We know the place,” Scoop said quickly, giving Tom and me a look that was intended to shut us up if we had any thought of saying anything.

“Back of the brick house there’s a’ old mill.”

“Yes,” said Scoop.

“Well,” said the soap man, flapping the lines, “when you want to settle up with me that’s where you’ll find me.”

“In the old mill?”

“Exactly. Git up, Romeo.”

We watched the rickety buggy until it had disappeared in the direction of town in a cloud of dust.

Tom was the first one to speak up.

“I was asleep at the switch,” he said, talking more to himself than to us, “not to have suspected it.”

Scoop turned quickly.

“Not to have suspected what?” he inquired.

“Last Friday noon,” our new chum told us, “that man came to our back door peddling books. And that same night some one tried to steal the talking frog. Don’t you see the connection, fellows? The soap man is a spy of Gennor’s. That’s why he’s hanging around here, peddling books one week and soap the next. His peddling is just a blind.”

We were excited.

“For almost two weeks,” Tom told us, “the sway-backed horse has been stabled in the deserted mill. I saw it there and wondered whose animal it was. But I never connected it with the book agent or suspected that its owner, a spy of the enemy’s, was hiding in the upper part of the mill, watching our house.”

Scoop was thinking.

“Posselwait,” he murmured, repeating the soap man’s name. “Ajax Posselwait. Um. . . .” He started down the road under a sudden idea. “Come on, fellows,” he grinned. “We’ll go over to Mrs. Kelly’s house and sell her some Bubbles of Beauty.”

I laughed when he said that. For Mrs. Kelly, who lives in the country, is one of the plainest-looking women you can imagine. She has a fat, freckled face and red hair. Her husband, an old friend of Dad’s, was killed in a runaway the year I started to school.

“Do you think you can make her beautiful?” I inquired, grinning at our leader.

“I can’t see how we can possibly fail,” he laughed, “with such wonderful soap to use on her as this.” He squinted into one of his pink boxes and smelled of its contents. Then he added, serious: “Selling her beauty soap, though, is the least important part of our errand. What I want more than her money is a chance to peep into the old Matson Bible.”

This recalled to my mind that the murdered puzzle maker and Mrs. Kelly had been related, which explains how the family Bible had come into her possession, together with a number of other things that had belonged to the old man.

“What do you want to read her Bible for?” I inquired, puzzled to understand our leader’s motive.

“Well,” he countered, “if the miser had a brother, there would be a record of it in the family Bible, wouldn’t there?”

“A brother?” I repeated.

“Jerry, didn’t you notice anything familiar about the soap peddler?”

“No,” I said.

“Then you better have your eyes tested,” grunted Scoop. “For he looks a lot like old Mr. Matson. The same thin face; eyes set close together. Don’t you remember how the old puzzle maker looked?”

I did remember, for the miser had been dead but two years. And now that Scoop had directed my thoughts to it, I could acknowledge to a distinct resemblance between the soap peddler and the dead man. Certainly, I checked off in my mind, the two men had the same kind of shifting, close-set eyes.

“But the soap man’s name is Posselwait,” I said, bewildered.

“It’s no trick,” said Scoop, “for a man engaged in crooked work, as this man is, to change his name.”

“You think his real name is Matson?”

“It isn’t impossible. Certainly he looks enough like the dead puzzle maker to be his brother.”

“Why do you call the murdered man a puzzle maker?” Tom spoke up.

“Because,” informed Scoop, “puzzle making was his hobby. A queer old duck, he liked to stump people with original conundrums and puzzles. He was smart about it, too. Just before he was murdered he made a ten-ring wire puzzle that no one could solve but himself. Pa tried it. So did Jerry’s pa and half of the men in our town. It was some puzzle, I want to tell you! After the old man had been murdered, people tried to find the ten-ring puzzle. But it had disappeared along with the old man’s money. And it hasn’t been seen or heard of to this day.”

“Maybe,” said Tom, using his thinker, “the puzzle had something to do with the murder.”

Scoop stared, his jaw sagging.

“Why! . . . No one ever thought of that!”

“Queer,” I spoke up, still bewildered, “that the murdered man’s brother should be a spy of the Chicago manufacturer’s. Maybe we’re mixed up on that point.”

“Not on your life,” waggled Tom. “I know that the soap man is a spy. For if he isn’t, why should he be hiding in the old mill?”

I shrugged.

“Search me,” I said.

“His main reason for being in the neighborhood,” Tom went on, sure of himself, “isn’t to make women beautiful. Not so you can notice it! The spiel he gave us about his wonderful soap was bunk, and nothing else but. He can’t string me. For I know that it takes more than soap to drive away warts and things. His soap may be good, but it won’t do all of the wonderful things that he claims for it.”

Scoop grinned.

“We can find out how good the soap is by using it on Mrs. Kelly.”

“If it makes her beautiful,” I laughed, “we ought to get a dollar a cake for it.”

“Easy,” waggled Scoop, his eyes dancing.

He screwed up his forehead.

“Fellows, it doesn’t make any difference to us whether the soap will make women beautiful or not. We’re going to peddle it just the same. For we’ve got to keep an eye on the soap peddler until we get word from Washington and know for sure that the talking frog drawings have been registered and that everything is safe for us. By working for mister spy as assistant beautifiers, we will be able to camp on his trail and no questions asked. See?”

There was sense in that all right.

On our way to Mrs. Kelly’s house we came to the Pederson farm. Mr. and Mrs. Orvil Pederson are Norwegians. When they talk English they get their words twisted up.

“Well,” I grinned, “if we’re going to do any beautifying this morning, we might as well start in here.”

“Sure thing,” laughed Scoop. He patted me on the back. “You’re a good talker, Jerry. Go ahead and show your stuff.”

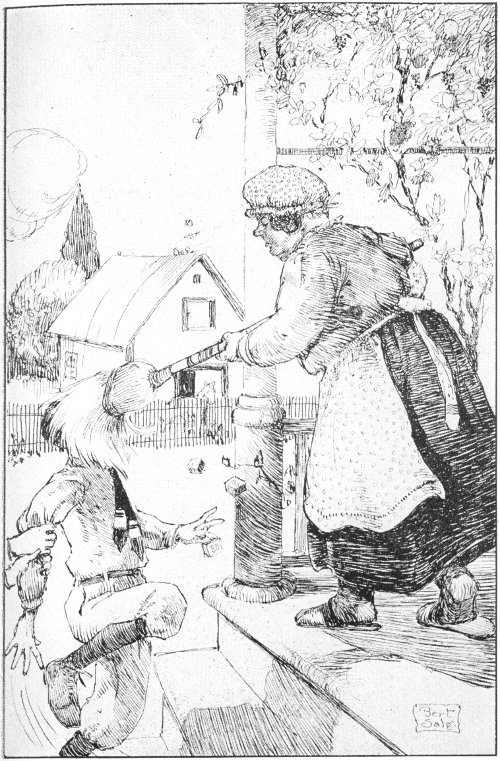

The other fellows followed me to the porch and I knocked, chesty-like, on the kitchen door. Mrs. Pederson was cooking something that smelled awfully good. It was a warm September day. When she came to the door her face was two shades redder than a ripe tomato. Her nose was red, too. She didn’t look very beautiful.

Taking a cake of Bubbles of Beauty from a box, I began:

“Mrs. Pederson, your face tells me that you haven’t been using the right kind of toilet soap.” I showed her the cake in my hand. “This kind of soap,” I told her, “will make you beautiful.”

“What?” she cried, in a shrill voice. “Is it so ugly that I am in my face that you should come here to tell me about it in my own house like a young smart aleck?”

I saw that I had made a bad start.

“I mean,” I said quickly, “that you will become even more beautiful than you are if you will use our marvelous Bubbles of Beauty instead of just ordinary toilet soap. Bubbles of Beauty,” I recited, “has taken more warts from women’s noses than all of the automobiles and talking machines in the world. It changes wrinkles into dimples; blemishes into blushes; makes sallow skins pink.”

You see, I have a good memory!

“Mrs. Pederson,” I went on, getting in some of the soap man’s gestures as I recited his street-corner speech, “let me ask you as a disinterested friend, who has done the most for this country, Mr. Edison or Mr. Pollywiggle?”

“Gallywiggle,” Scoop hissed into my ear.

“Mr. Ford,” I went on, “or Mr. Gallywiggle?”

My customer blinked her eyes and looked dizzy.

“Mr. Mortimor Hackadorne Gallywiggle,” I recited, using my hands, “the president of our company, the friend of all human beings. The man who has turned bushels of blemishes into barrels of—of——”

“Blushes,” prompted Scoop, and I could hear him giggling.

Mrs. Pederson opened the door. I thought that she wanted to take a close look at my soap. So I held it out to her, telling her how it took Mr. Gallywiggle, the friend of humanity, fifty years to learn how to make. I told her how wonderfully beautiful she would be when she had used the new toilet soap for a few days. I told her a lot of things. I guess I told her too much!

Swish! Bang! Down came a broom on my head. It made me see seventeen million stars. I was too dazed in the moment and too surprised to run away. I was too dazed even to understand what she was screeching at me as she jabbed me in the stomach with the broom. Scoop saved my life by dragging me down the porch steps.

SWISH! BANG! DOWN CAME A BROOM ON MY HEAD.

When I got my senses back, sort of, I was standing in the middle of the country road.

“Anything knocked out of kilter, Jerry?” Scoop inquired, grinning.

“I’m about two inches shorter,” I said, feeling of my neck and kind of screwing my head around.

“She gave you some awful wallops.”

I admitted it.

“She had no right to do it,” Scoop went on, his face darkening. “It wasn’t fair. She might have been ladylike and told you to go away if she wasn’t interested in your soap. Your ma and my ma wouldn’t have done a trick like that. No ladylike woman would. . . . She needs a good lesson,” he waggled.

“Go up to the door and scold her,” laughed Tom.

“Better than that,” said Scoop, “I’m going to turn the tables on her and make her coax me to sell her a cake of my soap.”

I had a picture of him doing that!

“If you try it,” I said, “you better make out your will before you start in.”

He grinned at me.

“Jerry, ol’ pal, I don’t want to hurt your feelings or knock on your system, but I’ve got a hunch that your selling spiel needs polishing up. It’s—— Well, to use the soap peddler’s expression, it isn’t artistic. It lacks tact.”

That made me hot.

“I hope that she doesn’t get rheumatism in her arms,” I shot at him, “when she starts after you with her broom.”

I watched him saunter down the farmhouse lane. Then I sat down on a big rock and waited for Mrs. Goliath to get into high gear with her broom. My head hurt something fierce. But I grinned, notwithstanding. Oh, boy, how I grinned! He’d catch it. I was glad. For he was acting altogether too chesty. He needed taking down a peg or two.

I imagined that I could feel the bump on my head getting bigger and bigger as I sat on the rock with my cap in my lap and my four boxes of Mr. Gallywiggle’s beauty soap in my cap.

And when I thought of how the bump came to be there, so big and painful, I said to myself, in just anger over Mrs. Pederson’s unwarranted attack, that I hoped that she would get her pay for banging me up.

For one thing, I hoped that she would become homelier and homelier. She could become as homely as an old mud fence and I wouldn’t let her have a single cake of my beauty soap. No, I wouldn’t! She could stay homely for the next million years for all I cared. I’d let some other woman have my soap to get beautiful with—some deserving woman who was kind to boys and used them in the way that boys should be used—good boys, I mean, like myself.

Then I quit grouching in my mind, sort of, to watch Scoop. He was close to the farmhouse porch, where Mrs. Pederson was still standing, broom in hand. I didn’t want to miss the fun of seeing her land on him. Pretty soon, I told myself, he would be yelping for help. I grinned, forgetful of my bump, in the thought of it.

“Good morning, Mrs. Pederson,” I heard him say. My, he was polite! His voice was all honey and cream. I got up and went closer.

There was a flower bed beside the porch. He let on as though he was awfully surprised and tickled to find the flower bed there. From his actions you would have thought that a flower bed—this flower bed—was the most wonderful and the most important thing in the world.

He ran over and got down on his knees and began touching the flowers as though he was in love with them. He stuck out his nose and smelled of the blossoms with his eyes squinting into the sky. I could imagine from the expression on his face that he was seeing angels. But when I looked up all that I saw was a crow.

“Such beau-utiful geraniums,” he gurgled, letting the word “beautiful” sort of string out, as though it was hard for him to bite off some of the letters. “My,” he said, “it must take a lot of skill and a lot of patience to raise such beau-u-tiful flowers. Ma says it’s a knack. She can’t raise sunflowers, hardly. Isn’t this a Martha Washington?”

“Um . . .” said Mrs. Pederson, thawing out, sort of.

“And I do declare!” Scoop gurgled, acting as though he had just discovered a diamond mine. “If here isn’t a rose geranium—a perfect specimen. Why, it’s got four buds on it! And just look at this blossom!” He raised his eyes. “Mrs. Pederson,” he said, sober, “you ought to go into the flower business. Why, the way you can make flowers grow you’d become rich and famous in no time at all.”

The flattered owner of the flowers left her broom on the porch and came down the steps. Pretty soon she was on her knees beside the flower bed, jabbering about the flowers as though she was crazy. Scoop was jabbering too. It was very disgusting to me. For I saw what he was up to. He was plastering her with soft soap, to get her dime, and she didn’t have sense enough to realize it.