* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: The Romance of Labrador

Date of first publication: 1934

Author: Sir Wilfred T. Grenfell (1865-1940)

Date first posted: June 5, 2021

Date last updated: June 5, 2021

Faded Page eBook #20210604

This eBook was produced by: Mardi Desjardins, Howard Ross & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

THE ROMANCE OF LABRADOR

BOOKS BY

SIR WILFRED GRENFELL

FORTY YEARS FOR LABRADOR

THE STORY OF A LABRADOR DOCTOR

YOURSELF AND YOUR BODY

WHAT CHRIST MEANS TO ME

THE FISHERMAN’S SAINT

HODDER & STOUGHTON, LTD.

LONDON

Photograph by F. C. Sears

Frontispiece

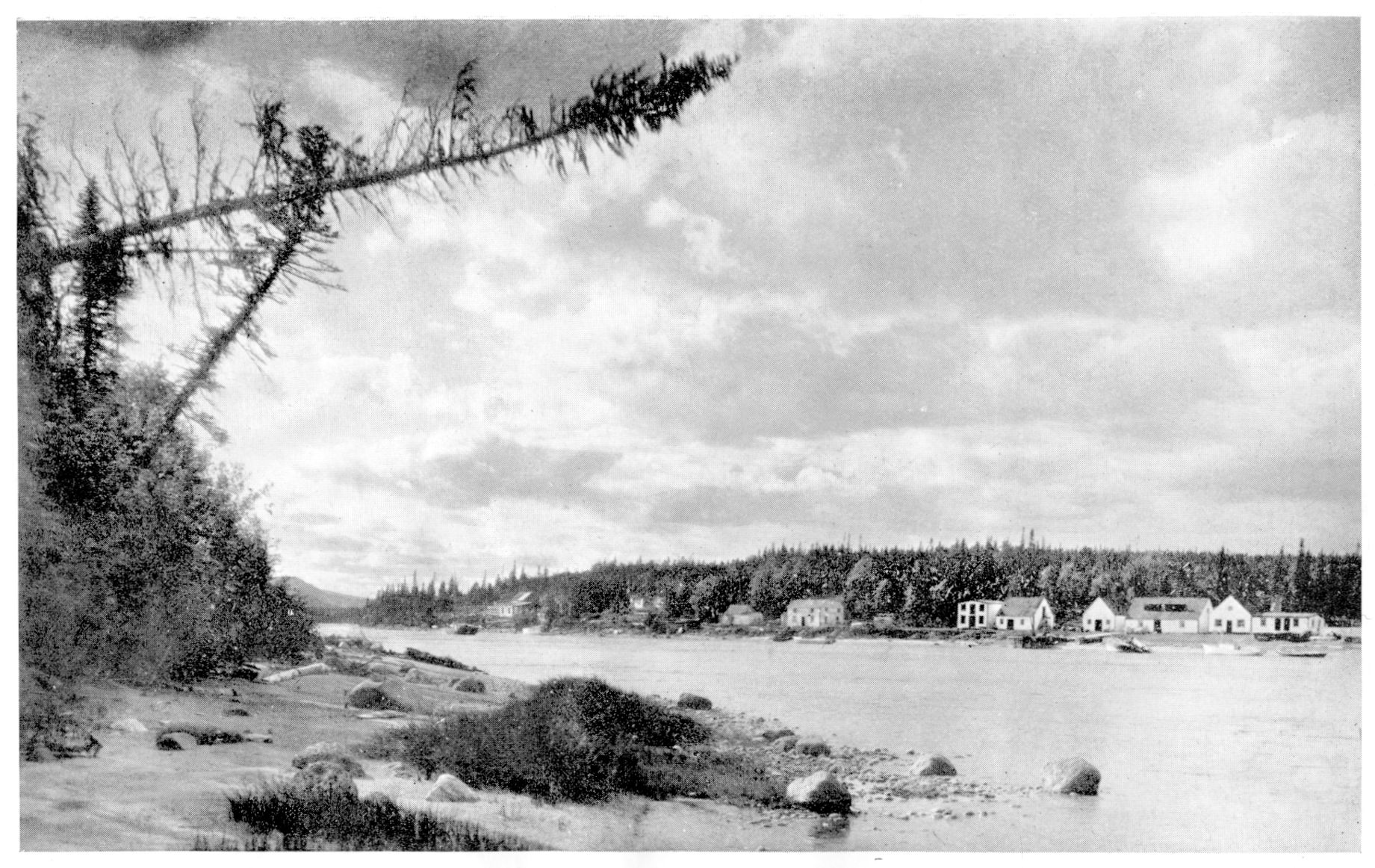

SUNSET AT NORTHWEST RIVER

A LABRADOR VILLAGE

THE ROMANCE

OF LABRADOR

SIR WILFRED GRENFELL

K.C.M.G., M.D., F.R.C.S., etc.

Illustrations by D. Ross

LONDON

HODDER & STOUGHTON LIMITED

1934

Copyright, 1934, by

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY.

All rights reserved—no part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in magazine or newspaper.

Published September 1934

Reprinted December 1934

Made and Printed in Great Britain by

Key and Whiting, Ltd., and The Kemp Hall Press, Ltd.

London and Oxford

“There is a lure to far-away places on the earth’s frontier which only those who have been there can fully understand. It may be the desert, the mountains, Africa, the Orient, the South Sea islands, fever-infested tropical jungles, or barren Arctic wastes. Wherever it may be, and no matter the hardships endured, the lure to go back is always the same, and those who have felt it have truly lived.”

In a previous book called “Labrador: The Country and the People” most of the scientific facts concerning Labrador, up to 1922, have been collated. It was intended for a book of reference rather than for popular consumption; and readers desiring information on special subjects must be referred to it.

I wish here to acknowledge my indebtedness to the following authorities: Dr. E. B. Delabarre, Dr. Charles Townsend, Dr. O. Austin, Dr. Charles Johnson, Mr. John Sherman, Mr. Outram Bangs, Miss Mary Rathbun, Mr. William Cabot, Mr. W. G. Gosling, Professor Fernald, Mr. W. S. Wallace—who have all been among my best helpers. Valuable information has been received also from the books and records of: Dr. Loeber in the Encyclopædia Britannica, Dr. Cranz’s records, Mr. Rolt-Wheeler, Mr. Meade Minnigerode, M. de la Ronciève of Paris, the curators of libraries and museums which I visited in Rouen, Dieppe, Paris, London, New York and elsewhere, to the Hudson’s Bay Company’s magazine, “The Beaver,” Dr. Bryant’s monograph, Mr. Durgin’s letters, Dr. Storer’s observations, Dr. Prowse’s History, Mr. Dillon Wallace, Mr. Hesketh Pritchard, and Mrs. Hubbard.

In “The Romance of Labrador” I owe special debts also to Professor Coleman of Ottawa, Professor Wheeler of Cornell, Mr. Noel Odell of Cambridge, England, and particularly to Dr. Reginald Daly of Harvard, whose monograph written for “Labrador: The Country and the People” I have here largely used again.

The data on which the following chapters are based have been garnered from every source available to an inveterate wanderer, and from more than forty years’ personal experience in the country. It is impossible for the author to acknowledge as he would wish his debt to others. If any feel aggrieved, he trusts that they will accept this expression of sincere gratitude to everyone who has added to the stock of knowledge of “The Romance of Labrador.” All men of science desire to have their contributions to knowledge used to the utmost for the benefit of mankind. Like good coin, the more it is turned over the greater their reward.

| Chap. | Page | |

| Prologue | xiii | |

| I. | The Pageant of the Rocks | 1 |

| (The Stage is Set) | ||

| II. | The Pageant of the Indians | 16 |

| (The Curtain Rises) | ||

| III. | The Pageant of the Eskimo | 32 |

| (The “Innuit” Arrive) | ||

| IV. | The Pageant of the Vikings | 51 |

| (“Winged Hats and Dragon Ships”) | ||

| V. | The Pageant of the Big Four | 68 |

| (The Kaleidoscope Shifts) Columbus, Cabot, Cortereal, and Cartier. | ||

| VI. | The Pageant of the French | 96 |

| (“Le coq se trouve dans le nouveau monde”) | ||

| VII. | The Pageant of the English Occupation | 114 |

| (The Lion’s Share) | ||

| VIII. | The Pageant of the Unitas Fratrum | 139 |

| (Peaceful Penetration) | ||

| IX. | The Undersea Pageant | 155 |

| (“Oh, Ye Whales and all that Move in the Waters”) | ||

| X. | The Pageant of the Three Kings | 181 |

| (Of Sub-Arctic Waters) | ||

| XI. | The Pageant of the Soil | 204 |

| (Phanerogams and Cryptogams) | ||

| XII. | The Pageant of the Animals | 223 |

| (“The ‘Little Brothers’ of the ‘Labourer’s Land’”) | ||

| XIII. | The Pageant of the Air | 255 |

| Νίκη Πτερωτός (Winged Victory) | ||

| XIV. | The Pageant of Forty Years and After | 283 |

| (Apologia Pro Vita Mea) |

| Sunset at Northwest River. A Labrador Village | Frontispiece |

| Page | |

| Cape Uivuk | 18 |

| Cape Blow-me-Down | 19 |

| The Contorted Crust of the Earth near Cape Mugford | 34 |

| The Kiglapeits, or Dog-toothed Mountains | 35 |

| The Great Kaumajets (Shining Tops) | 50 |

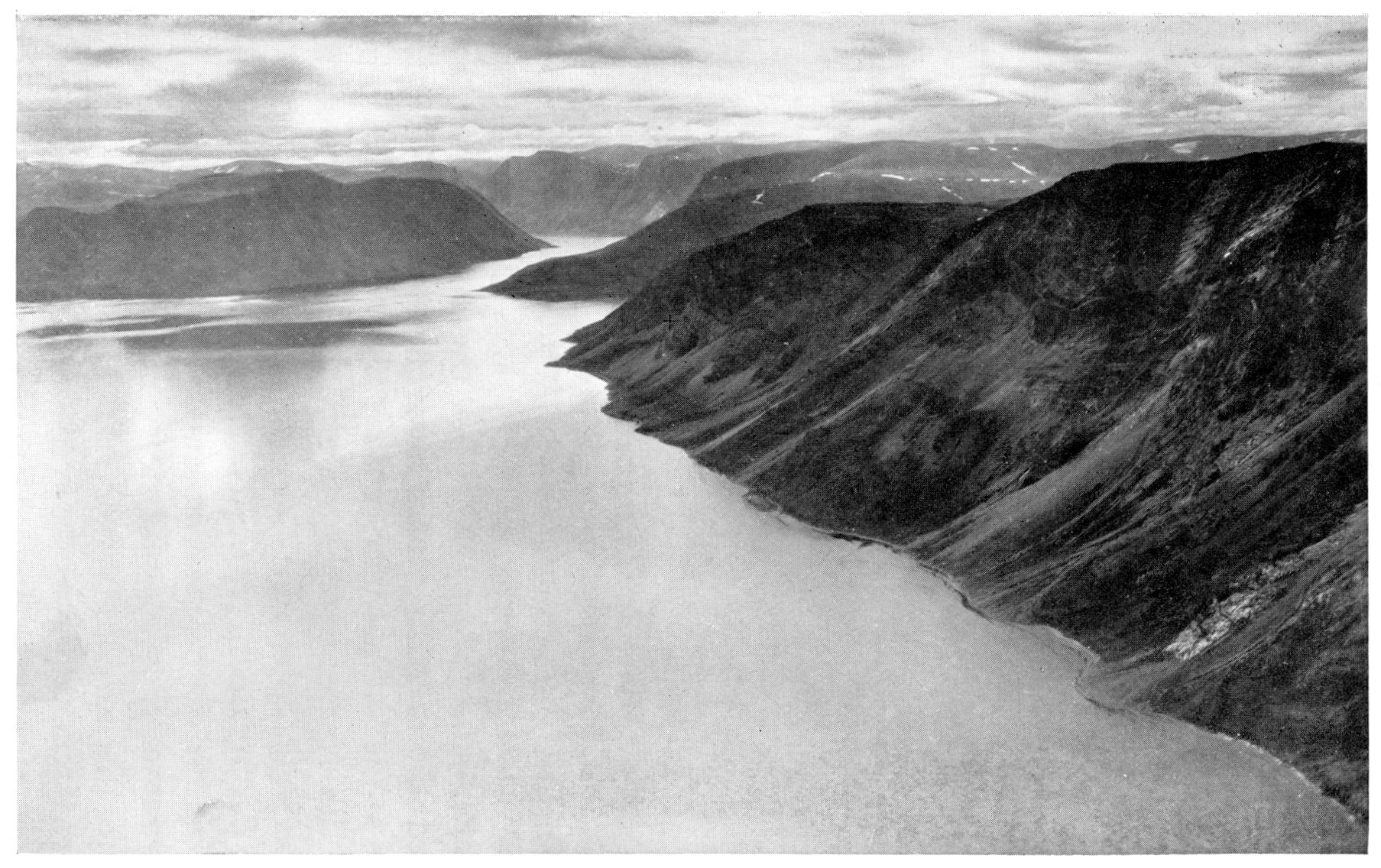

| Saeglek Fjord, an old Ice Channel | 51 |

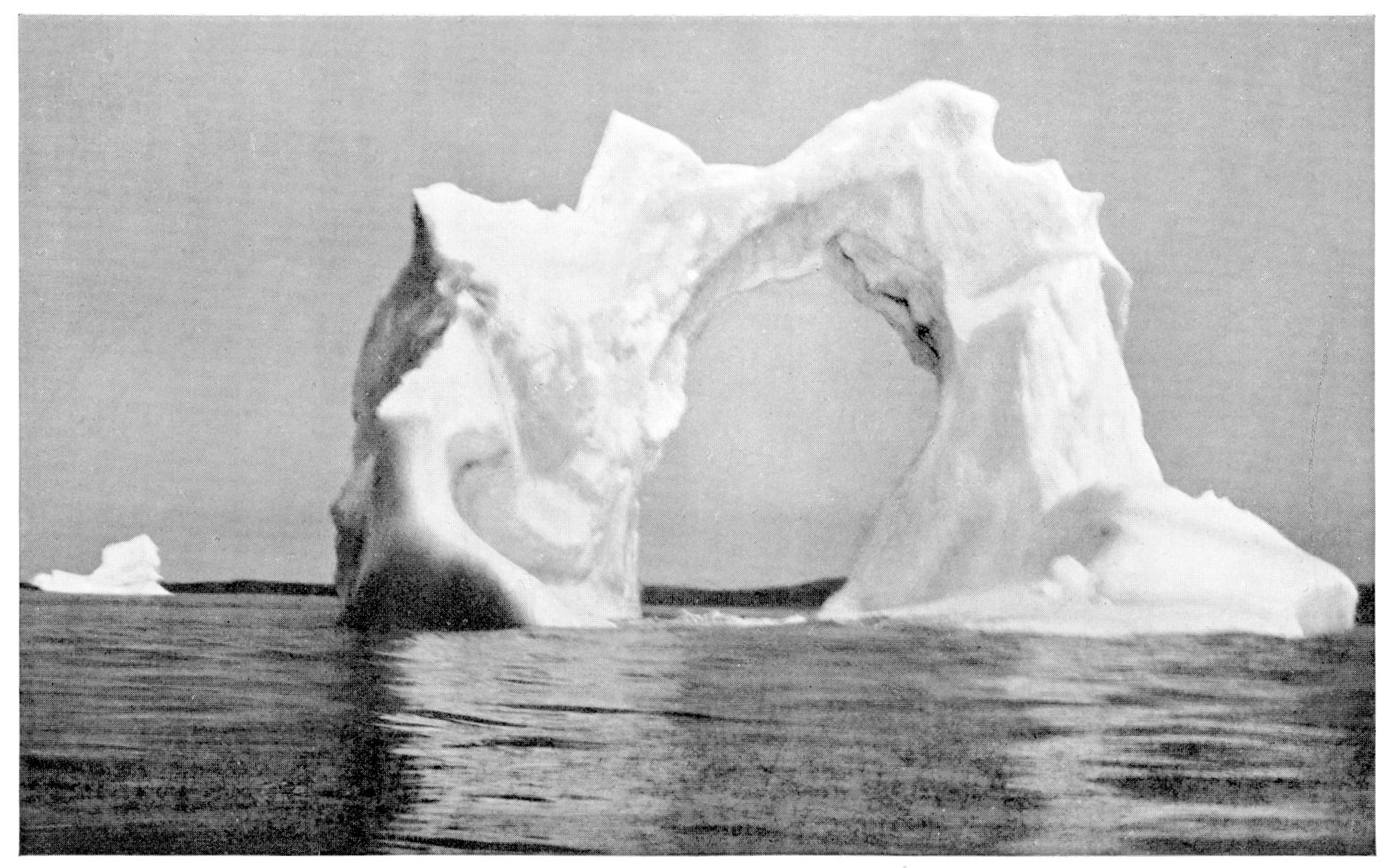

| Labrador Gothic | 66 |

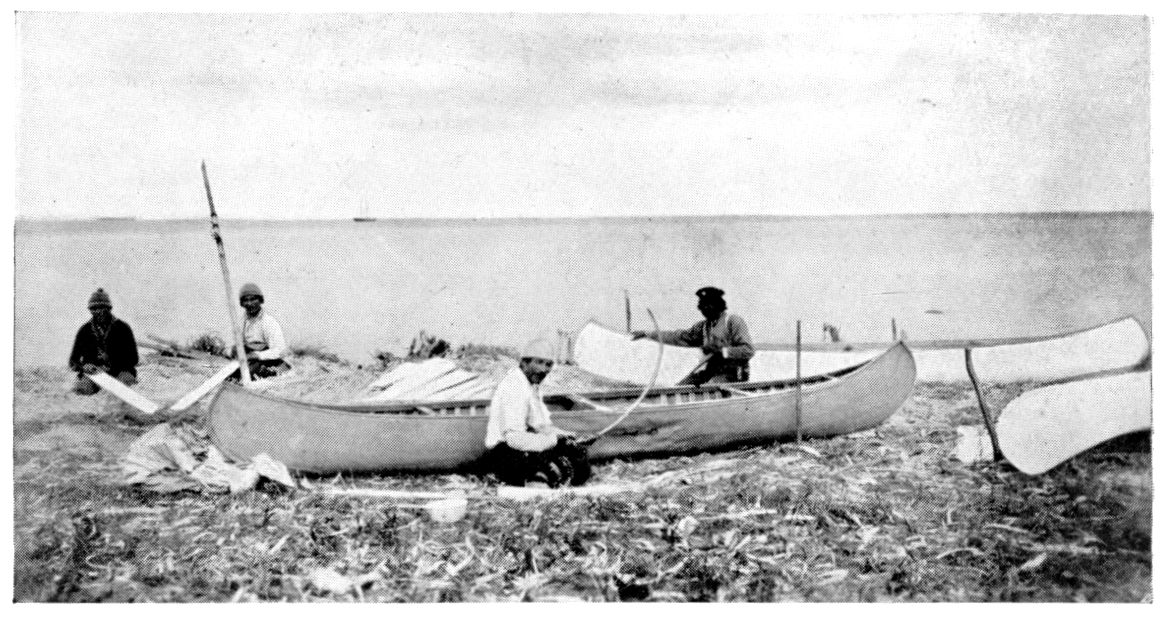

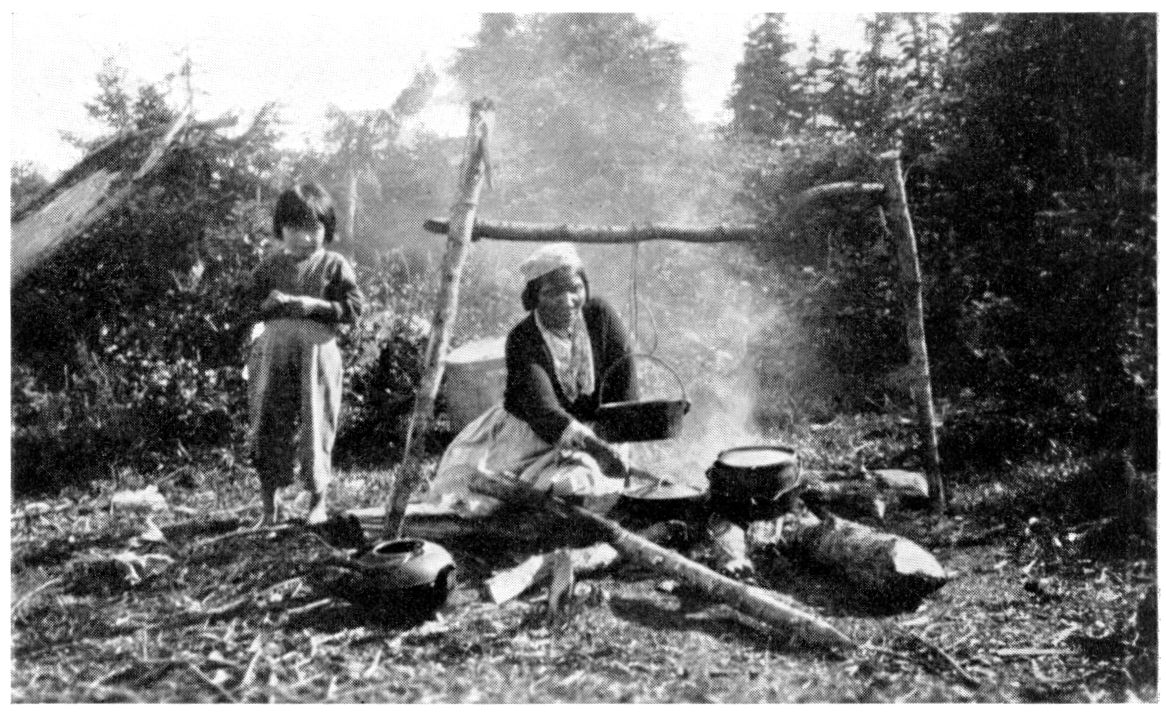

| Labrador Indians—the Nascopies. Breakfast | 67 |

| Eskimo Grave | 98 |

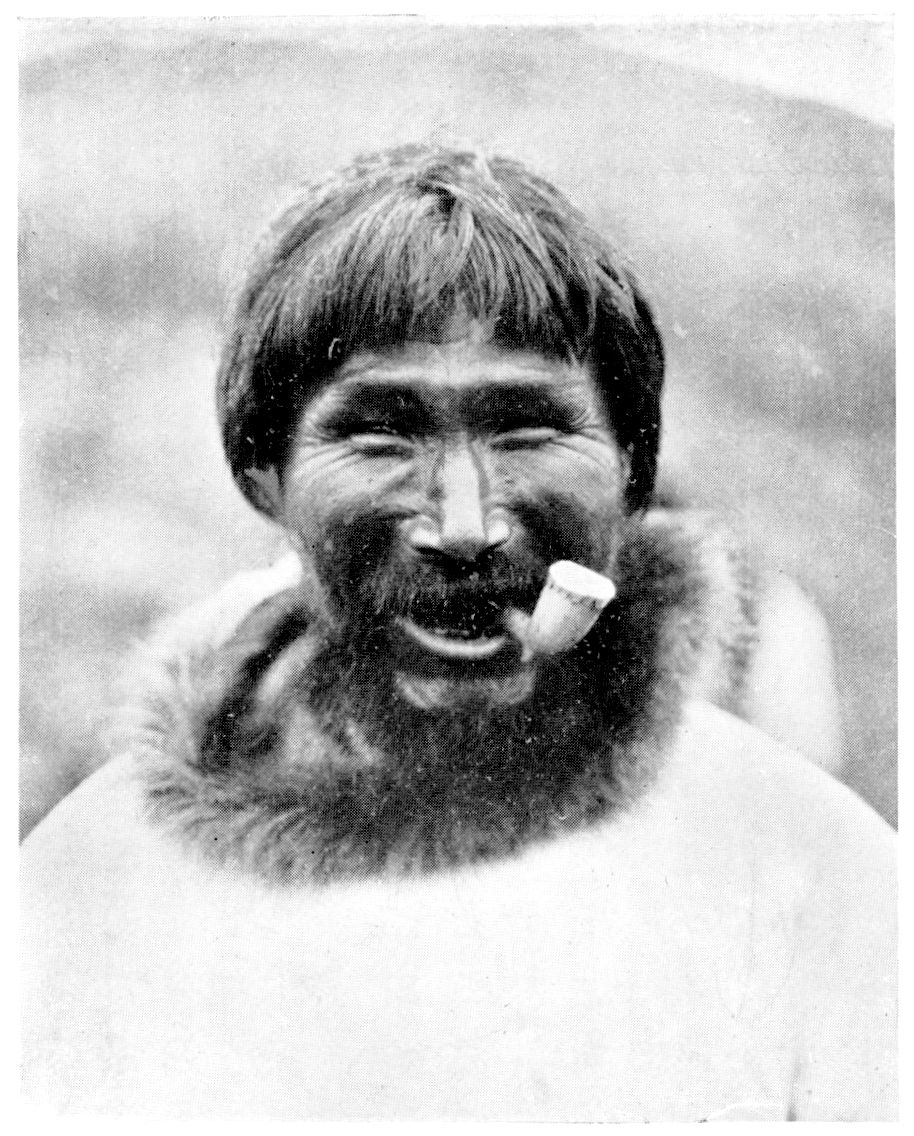

| North Labrador Eskimo. Eskimo at Moravian Station | 99 |

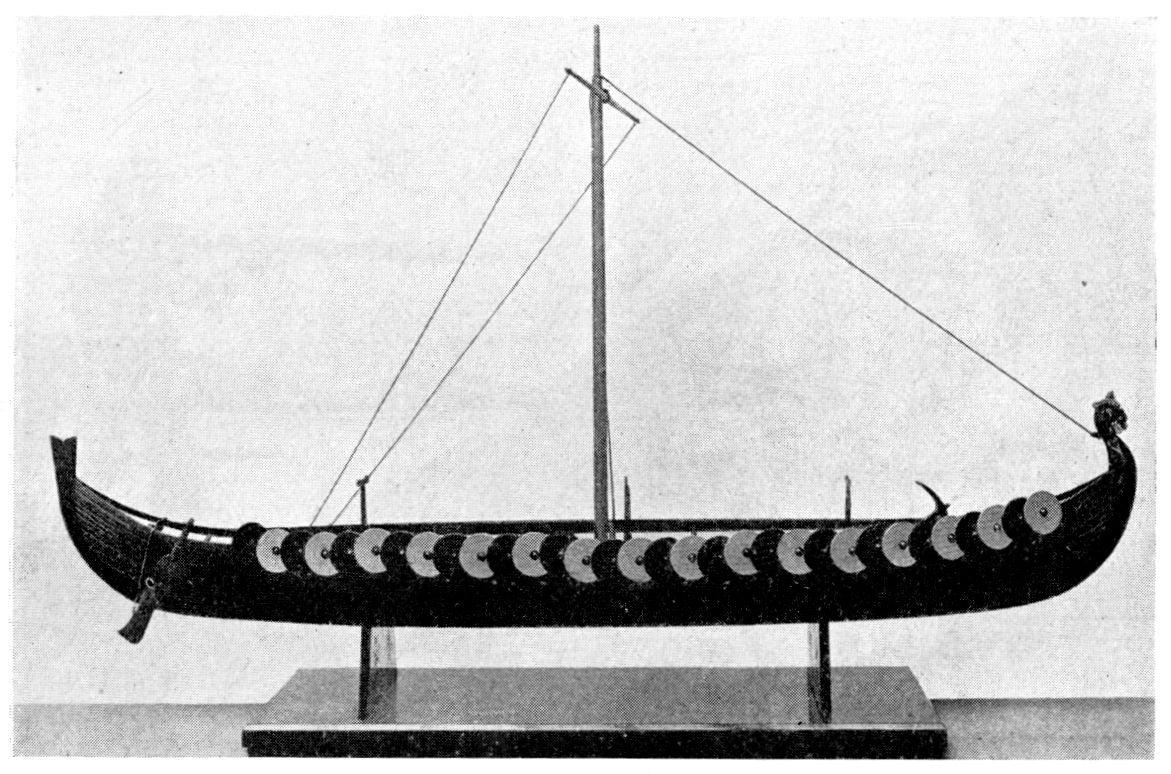

| Viking Ship (8th to 10th Century) | 114 |

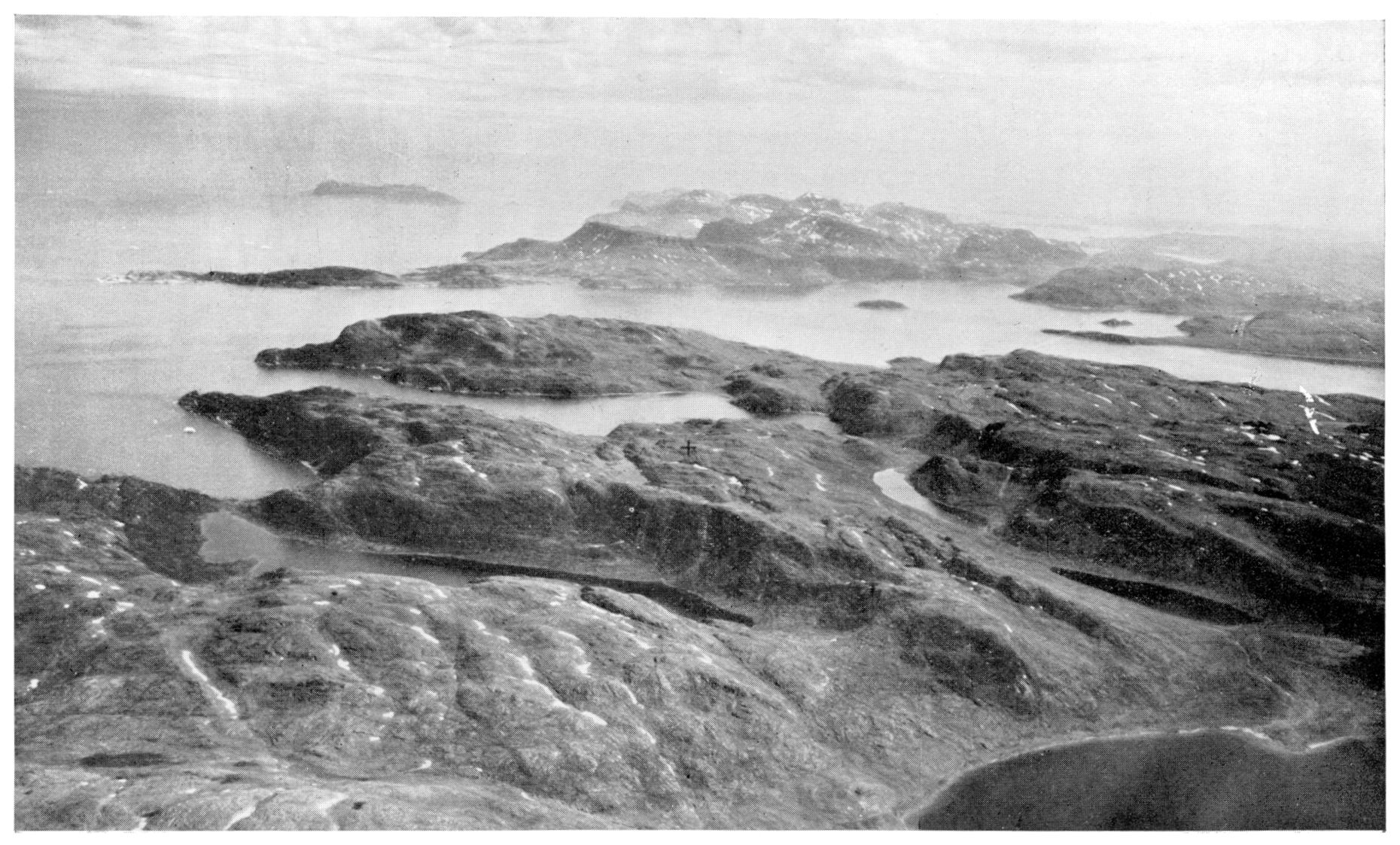

| As the Vikings saw It | 114 |

| “I will call this land Helluland—the Land of Flat Stones” | 115 |

| A Piece of Helluland | 115 |

| The Bishop’s Mitre | 130 |

| The Canyon of the Grand Falls | 131 |

| Rapid Transit | 146 |

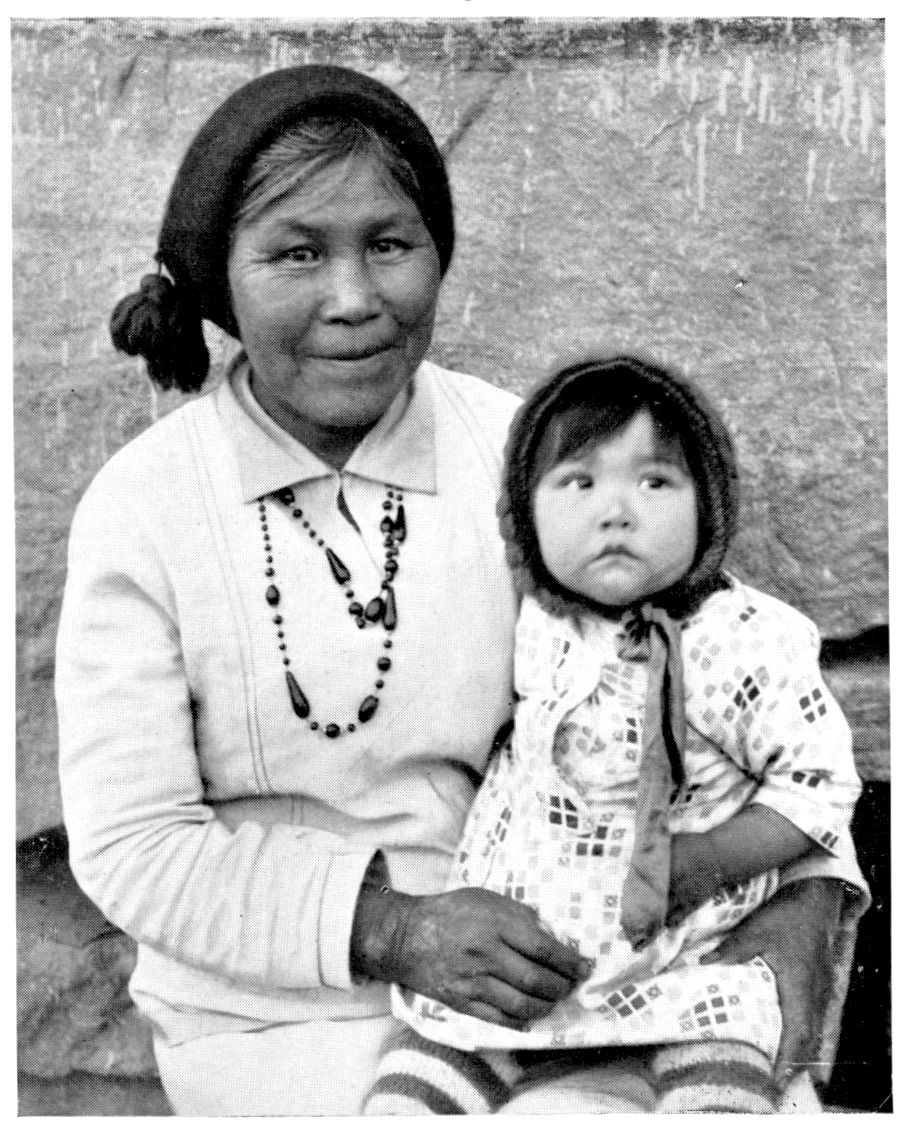

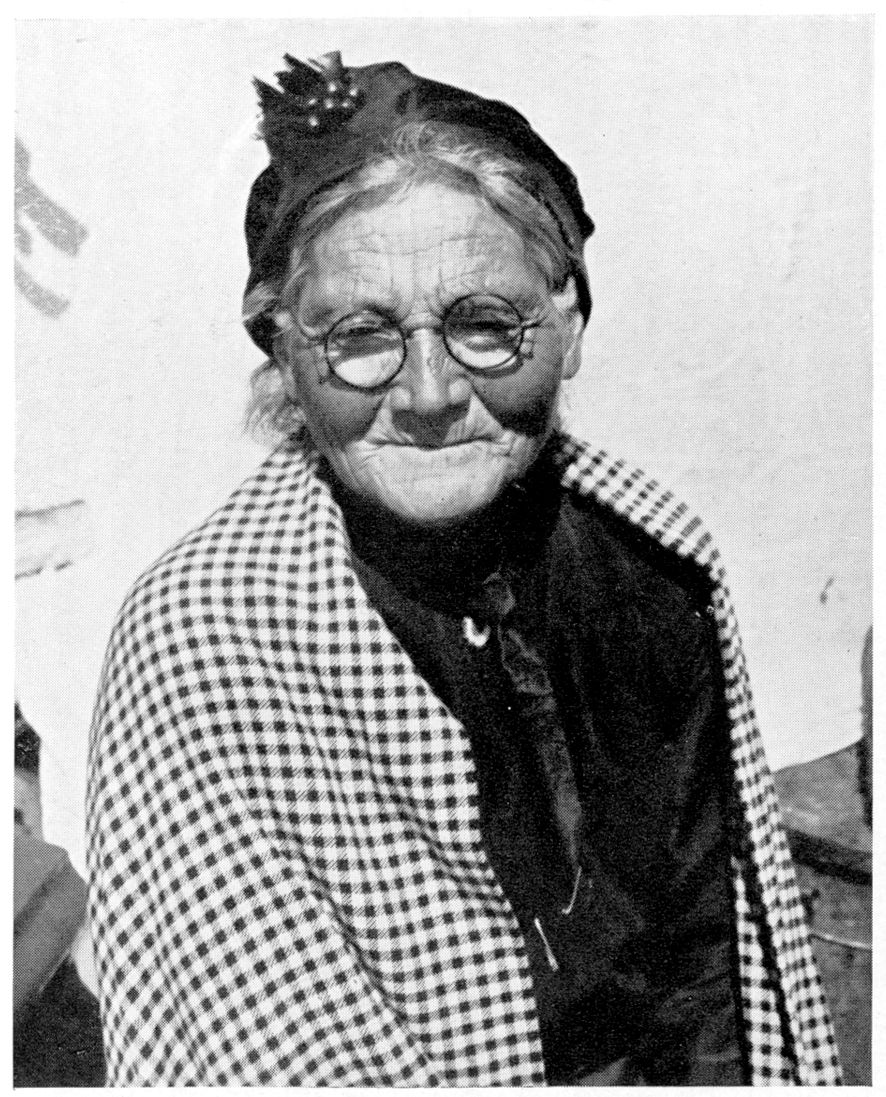

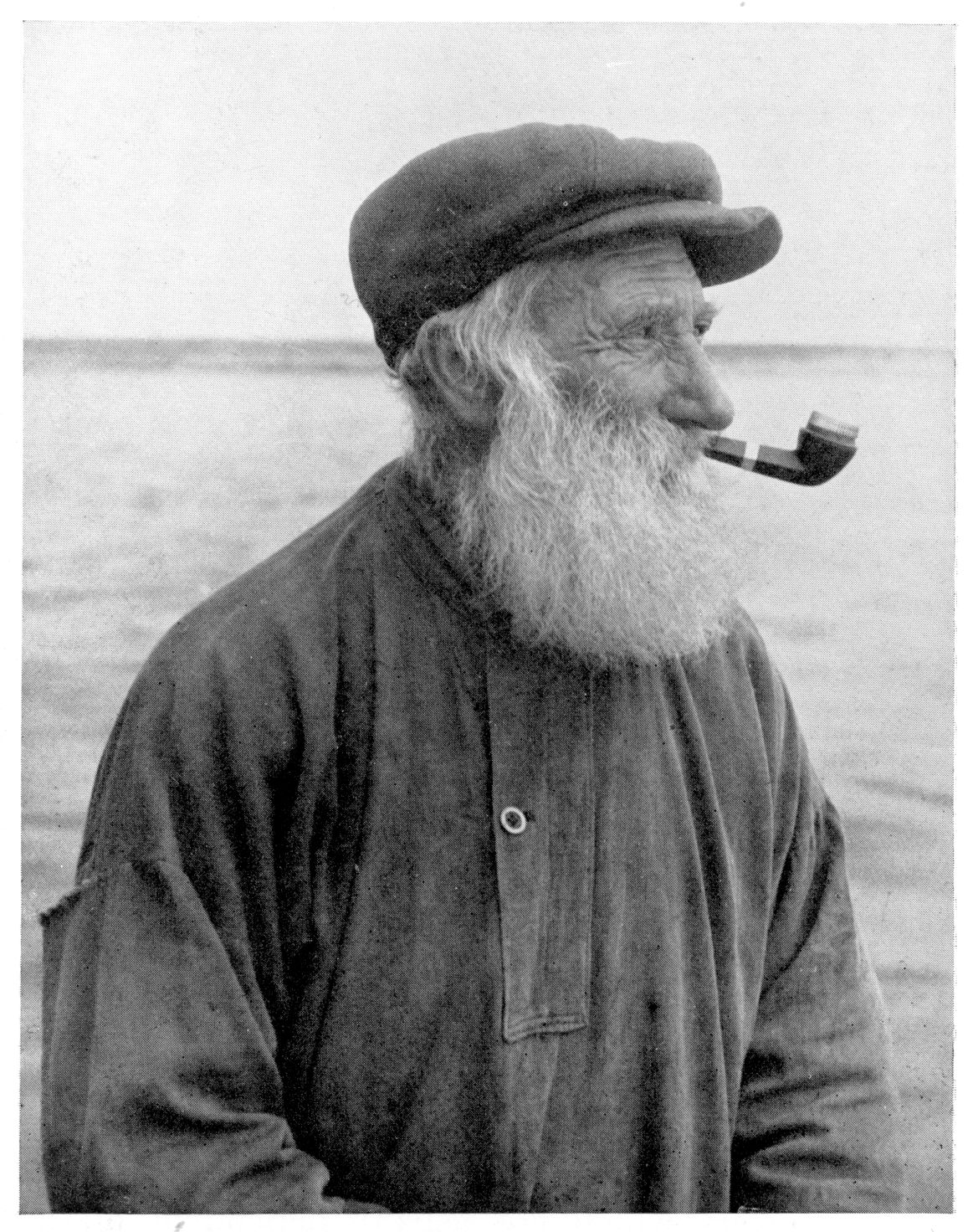

| A Mother in Israel | 147 |

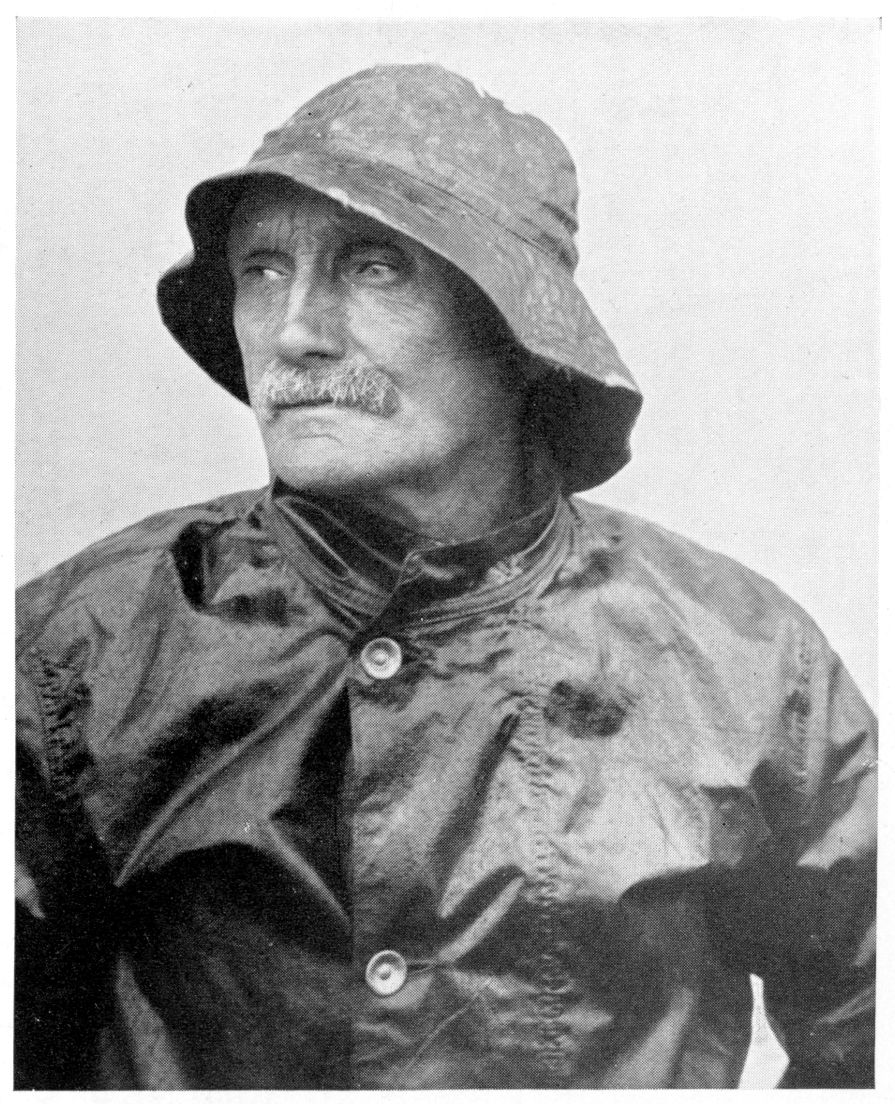

| Abe, the Mate of Sir Wilfred’s Hospital Boat | 147 |

| “The Land God Gave to Cain” | 178 |

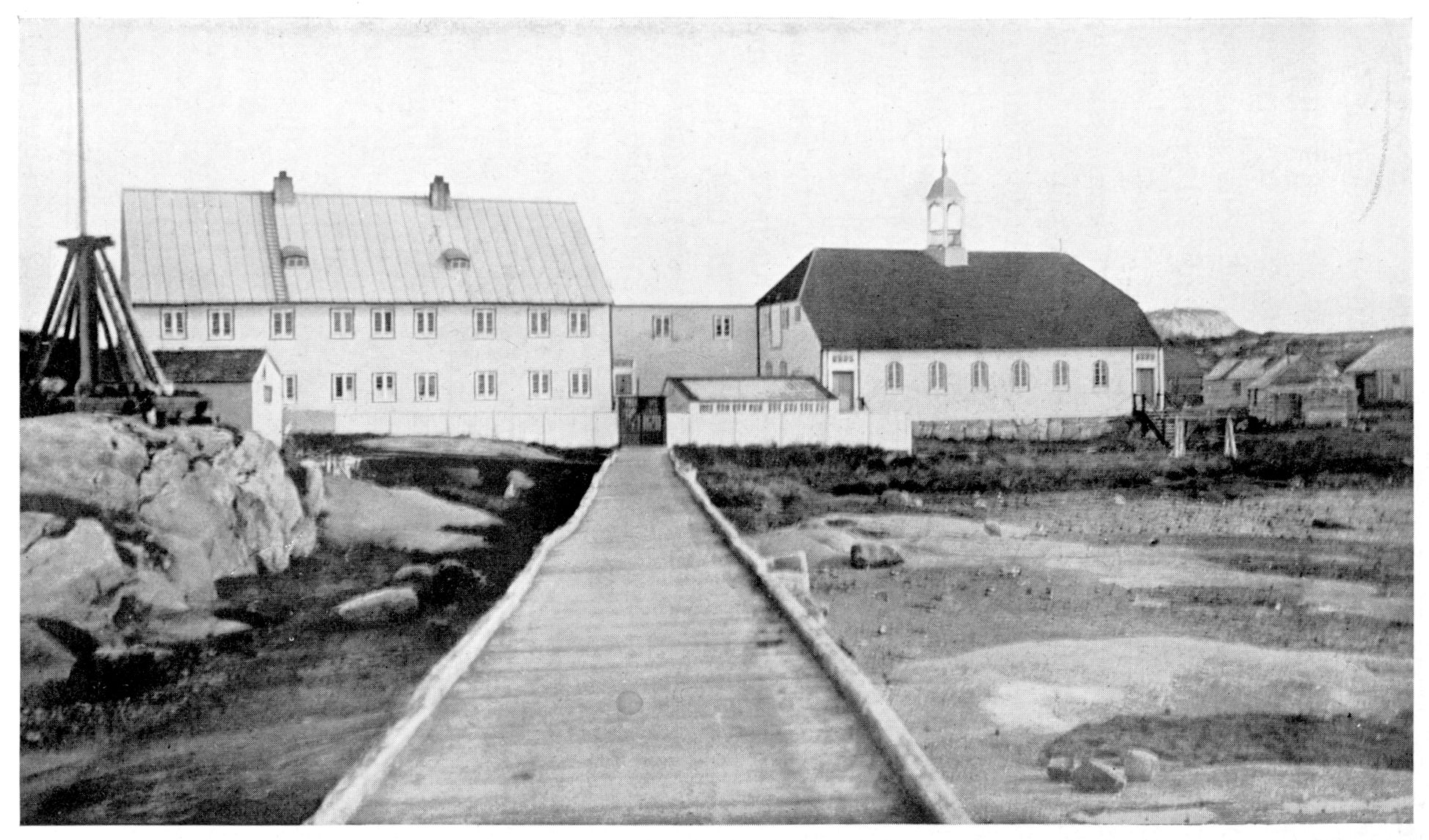

| “Hopedale,” the Moravian Mission Station among the Eskimo | 179 |

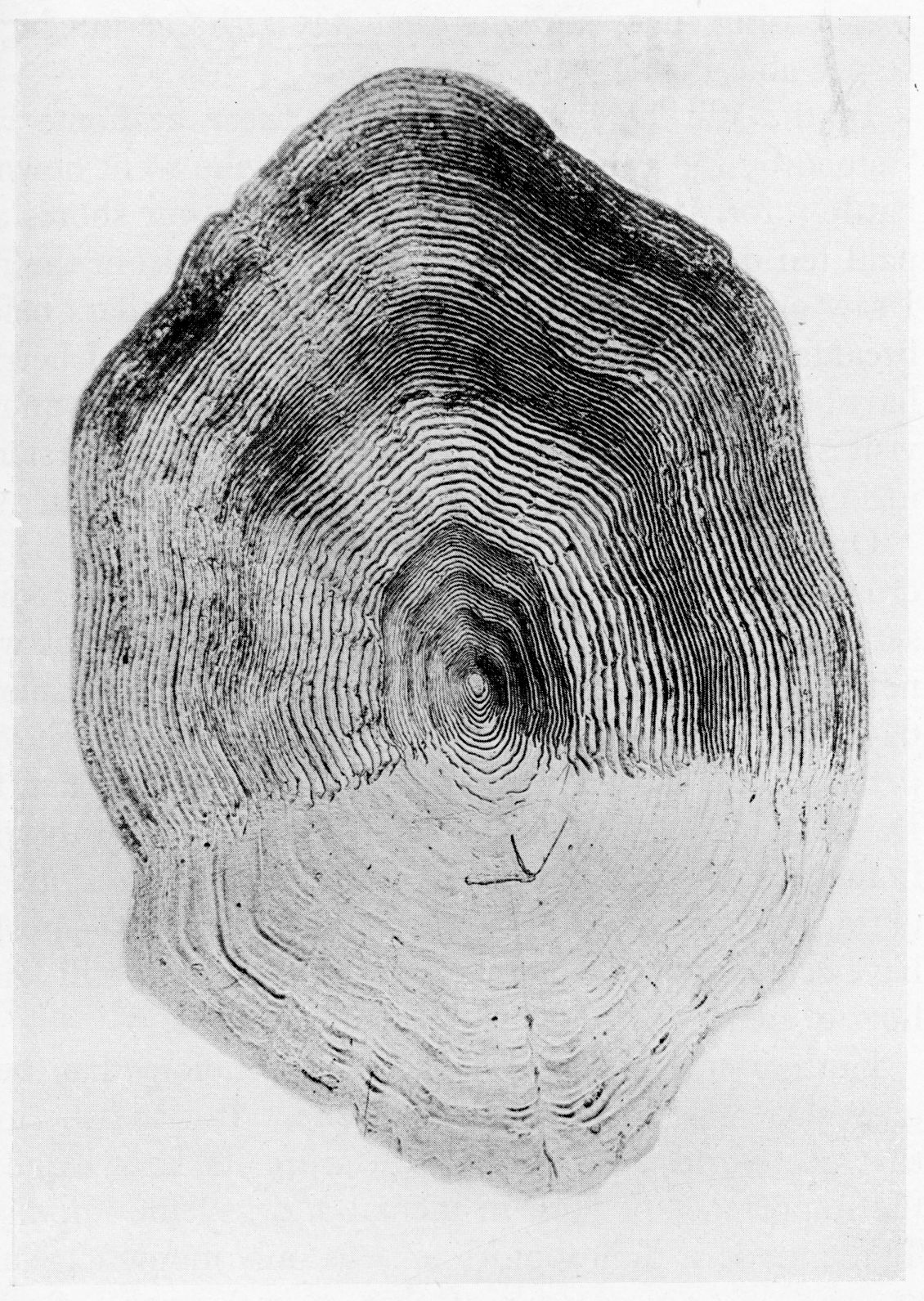

| Salmon Four Years in River | 194 |

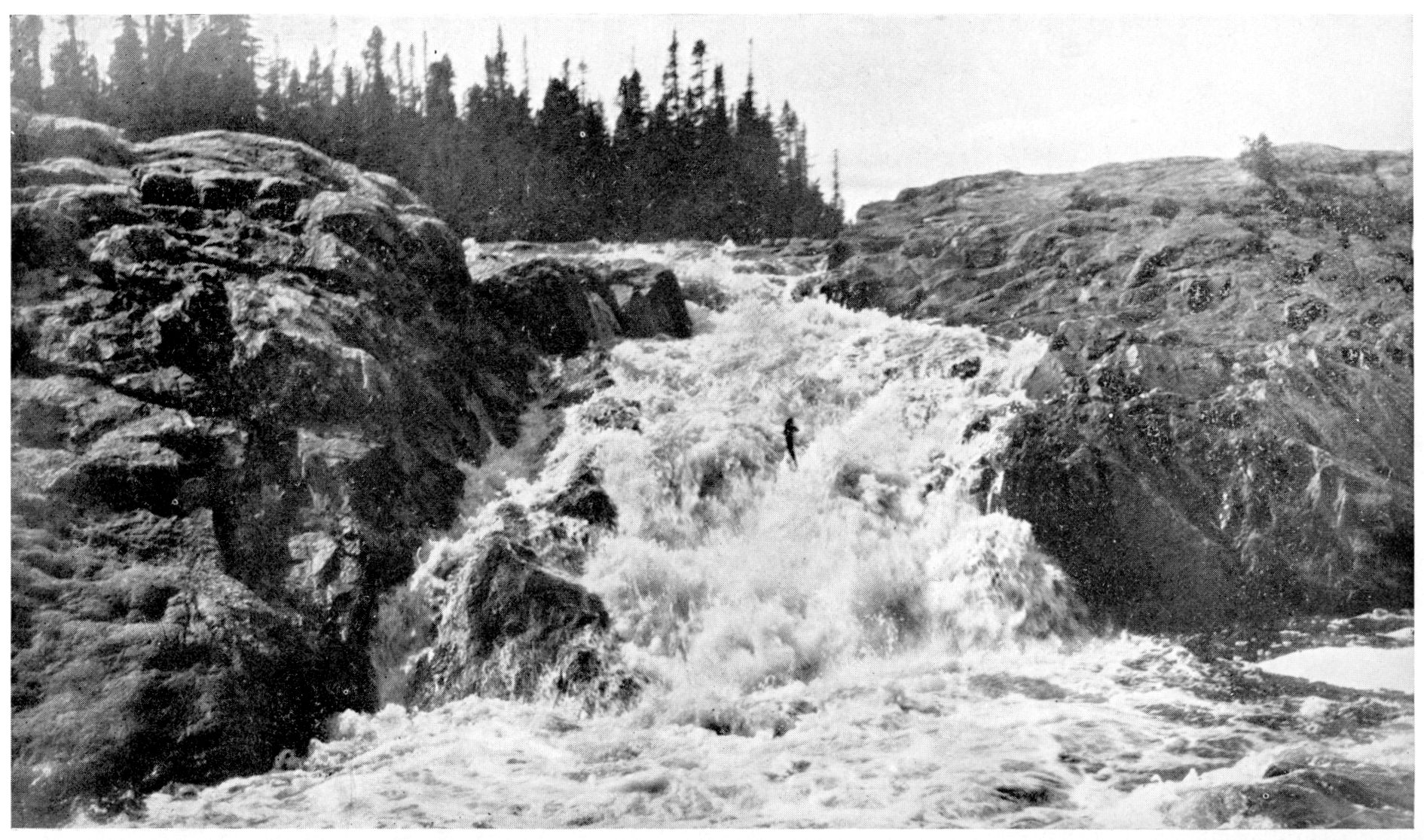

| One of the Three Kings—Salmon seen Jumping up Falls | 195 |

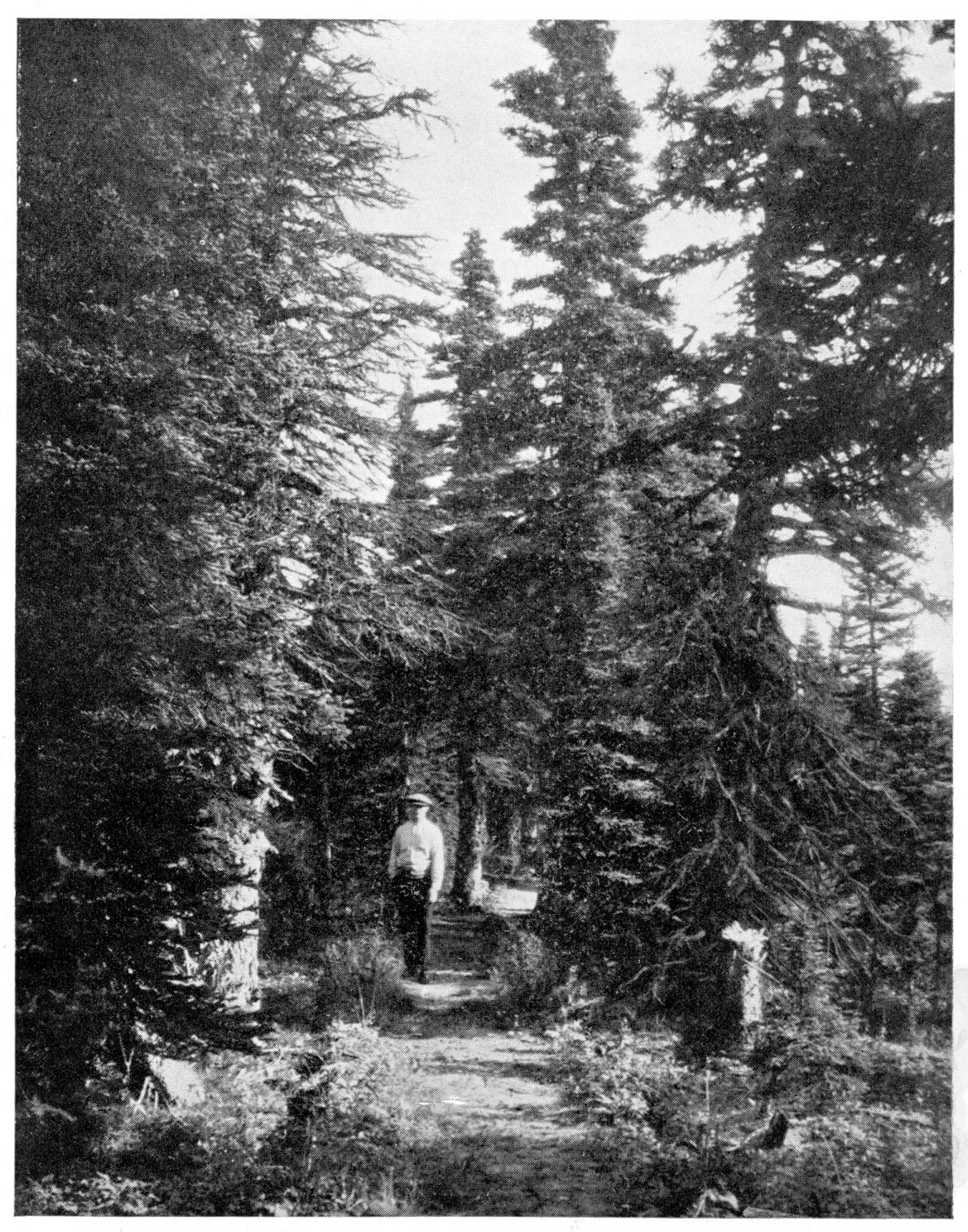

| A Modern Apostle | 210 |

| A Northern Neighbour | 211 |

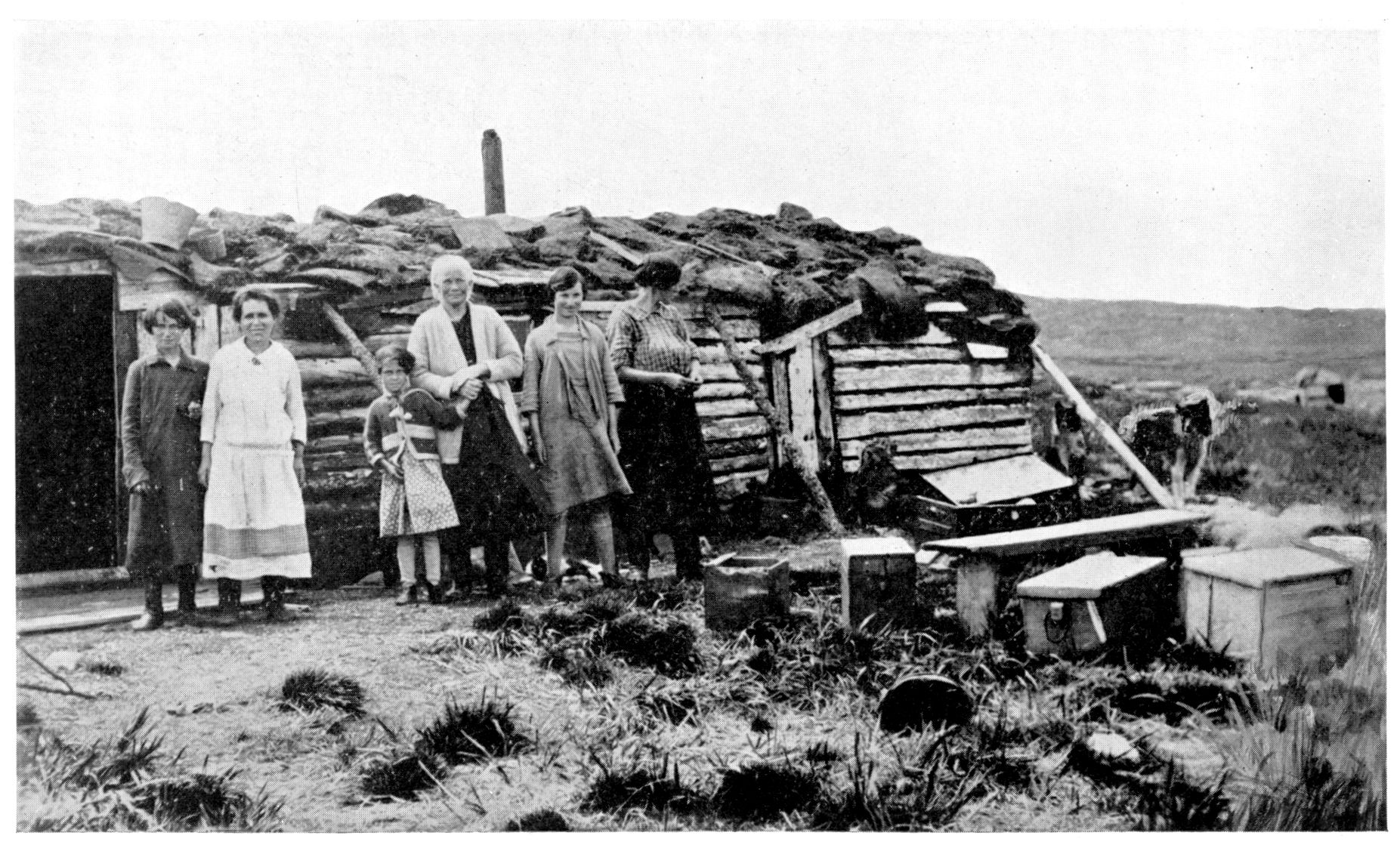

| Labrador Summer Fishing Shack | 226 |

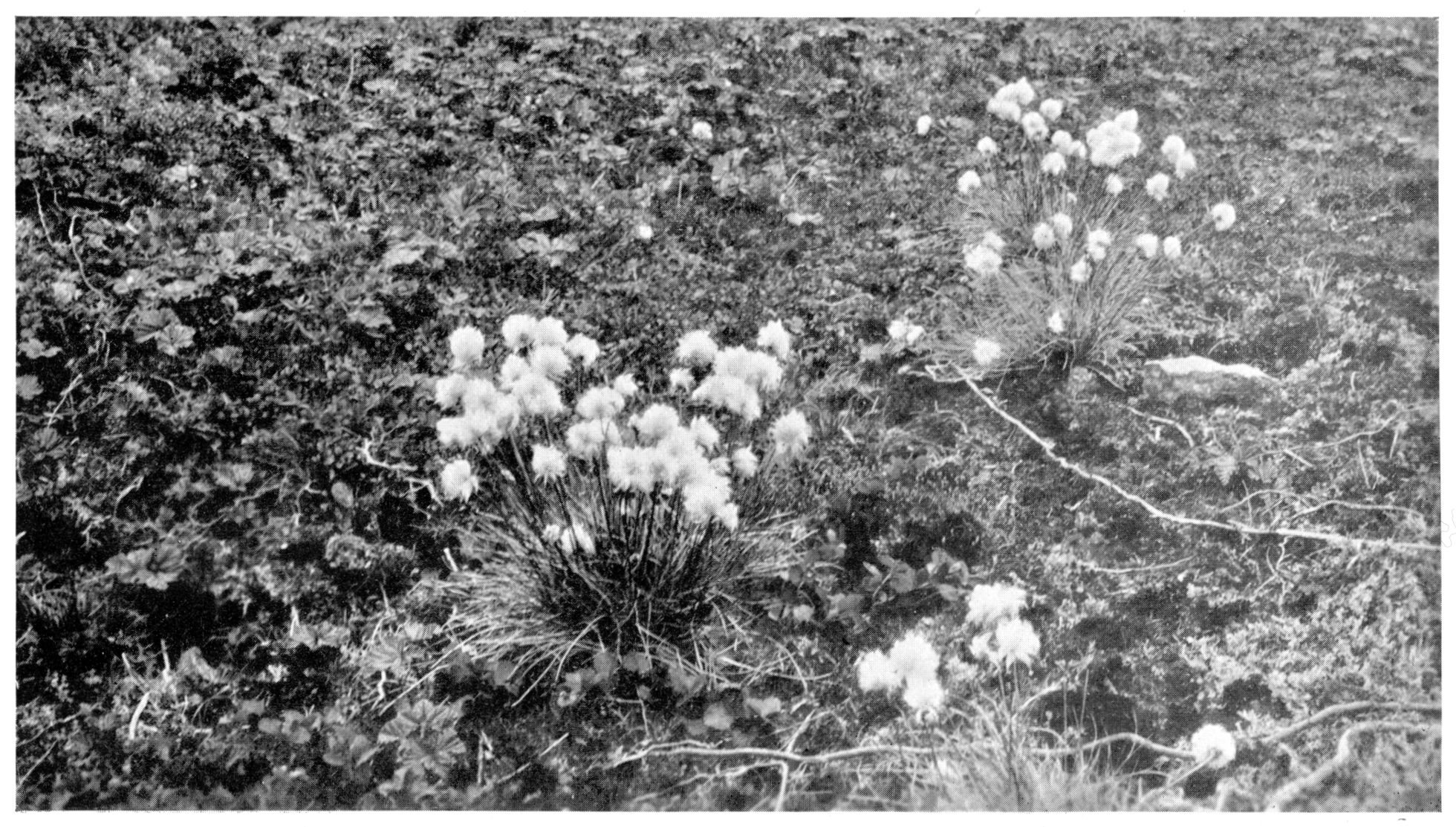

| Wild Cotton | 227 |

| Reindeer | 258 |

| Cape White Handkerchief | 259 |

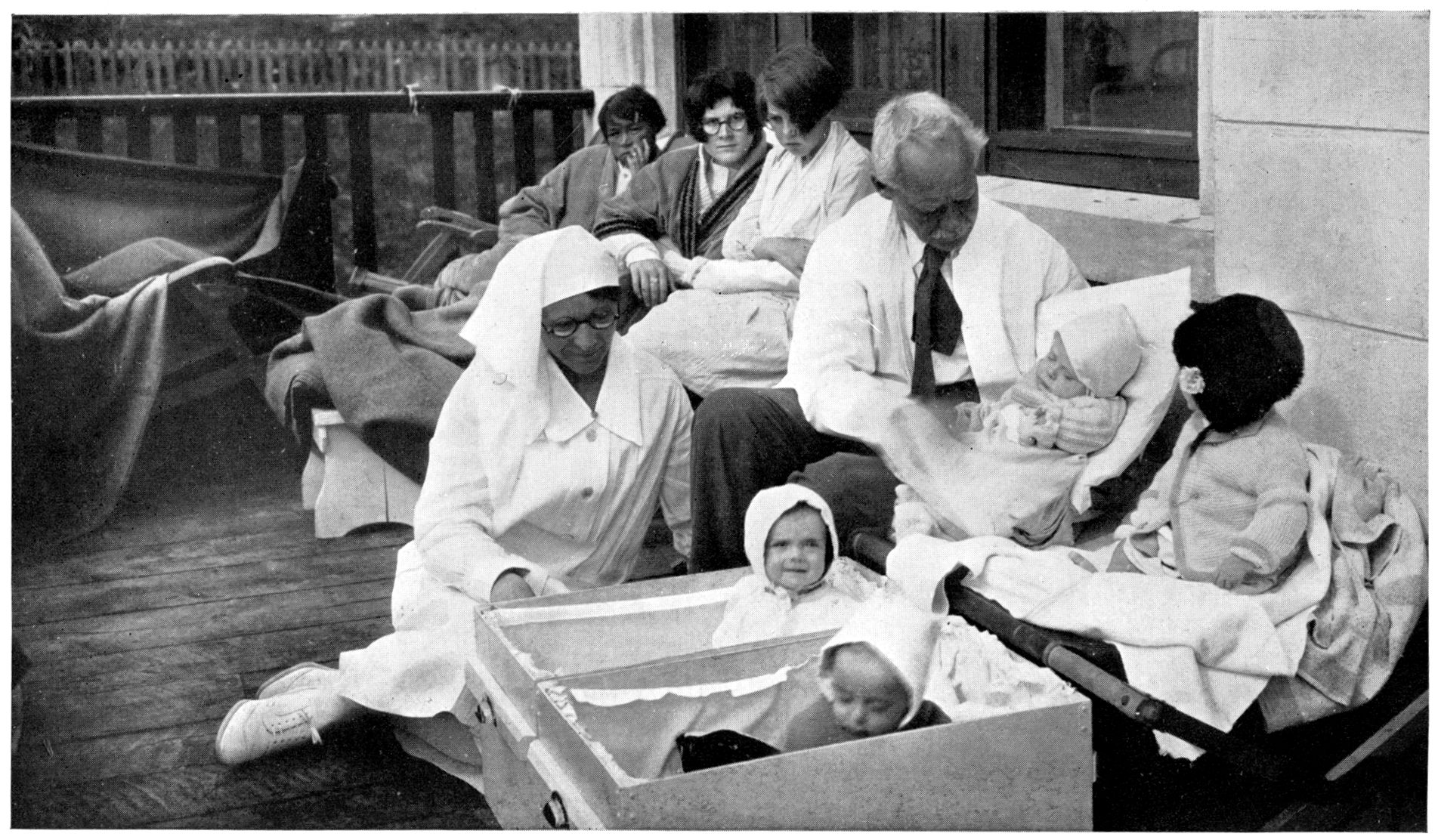

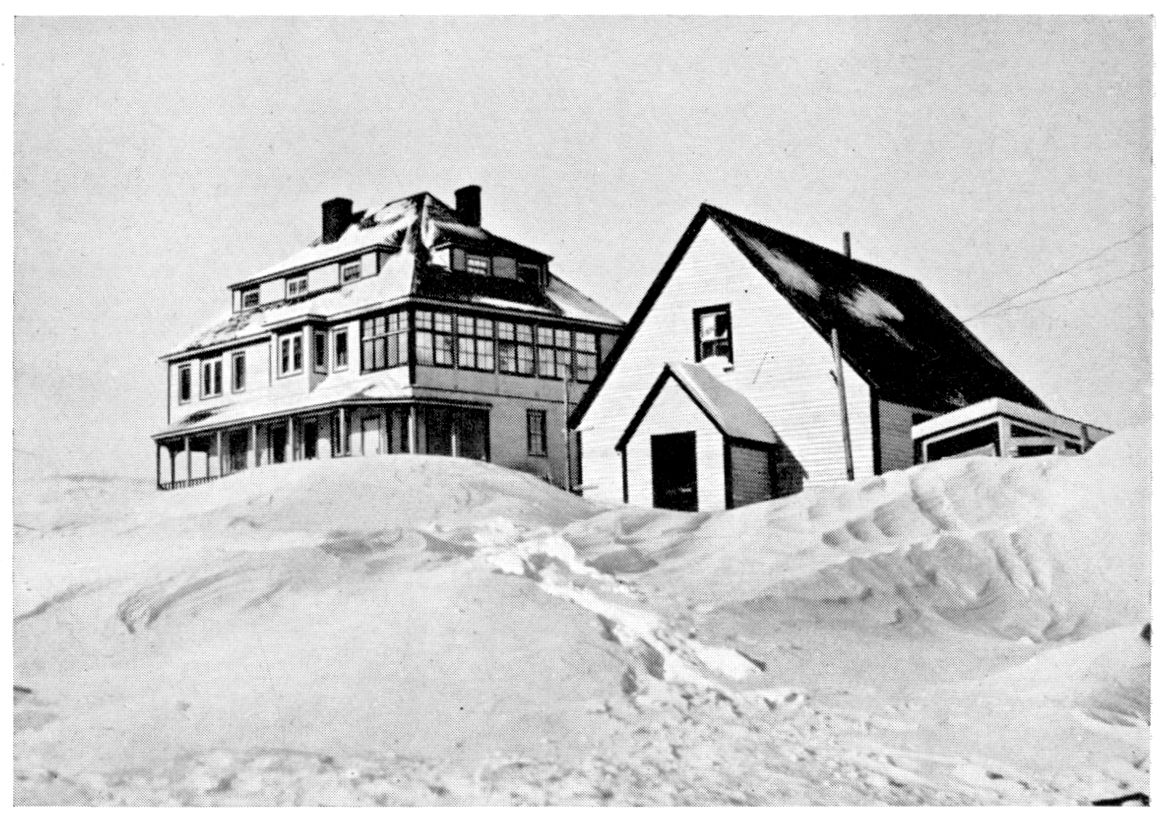

| The Sunning Balcony—St. Anthony Hospital | 274 |

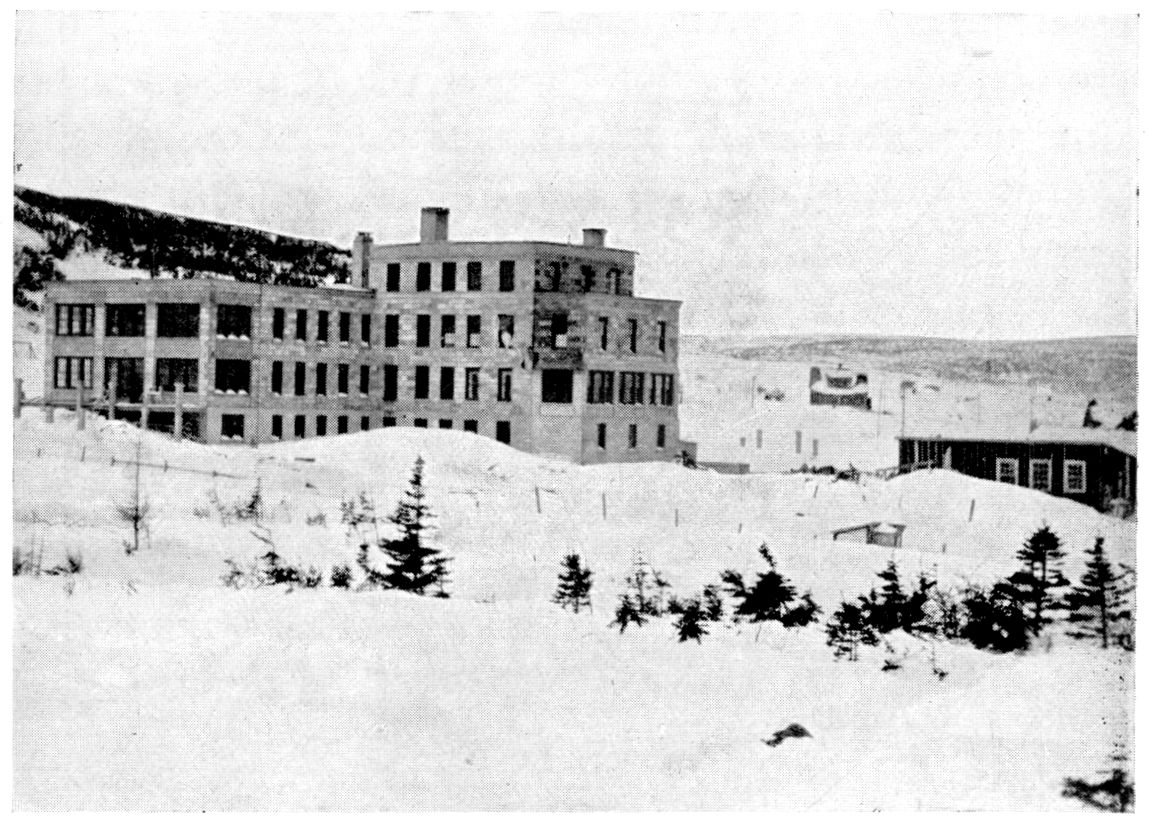

| Harrington Hospital of the International Grenfell Association | 275 |

| St. Anthony Hospital | 275 |

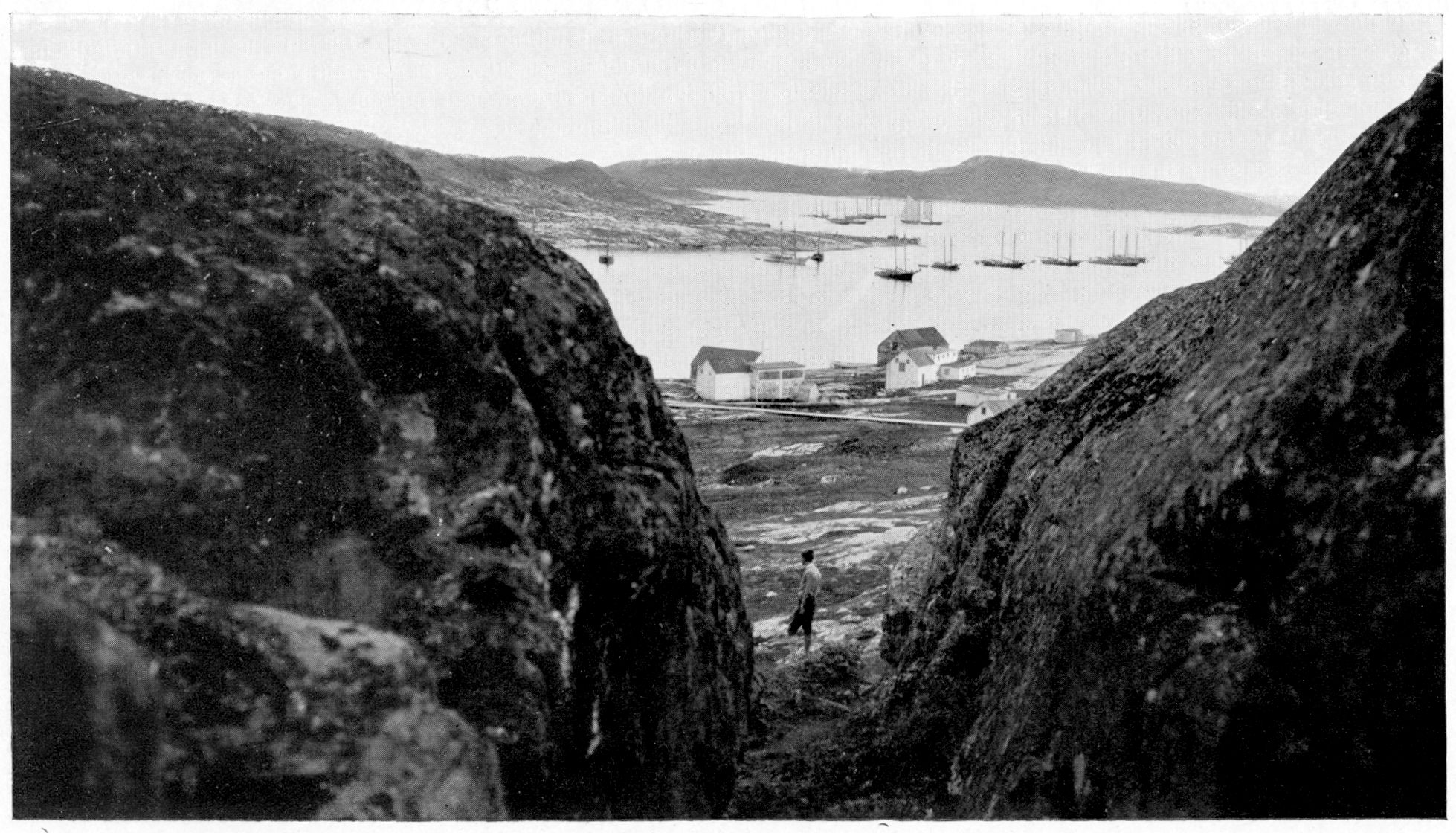

| Indian Harbour | 298 |

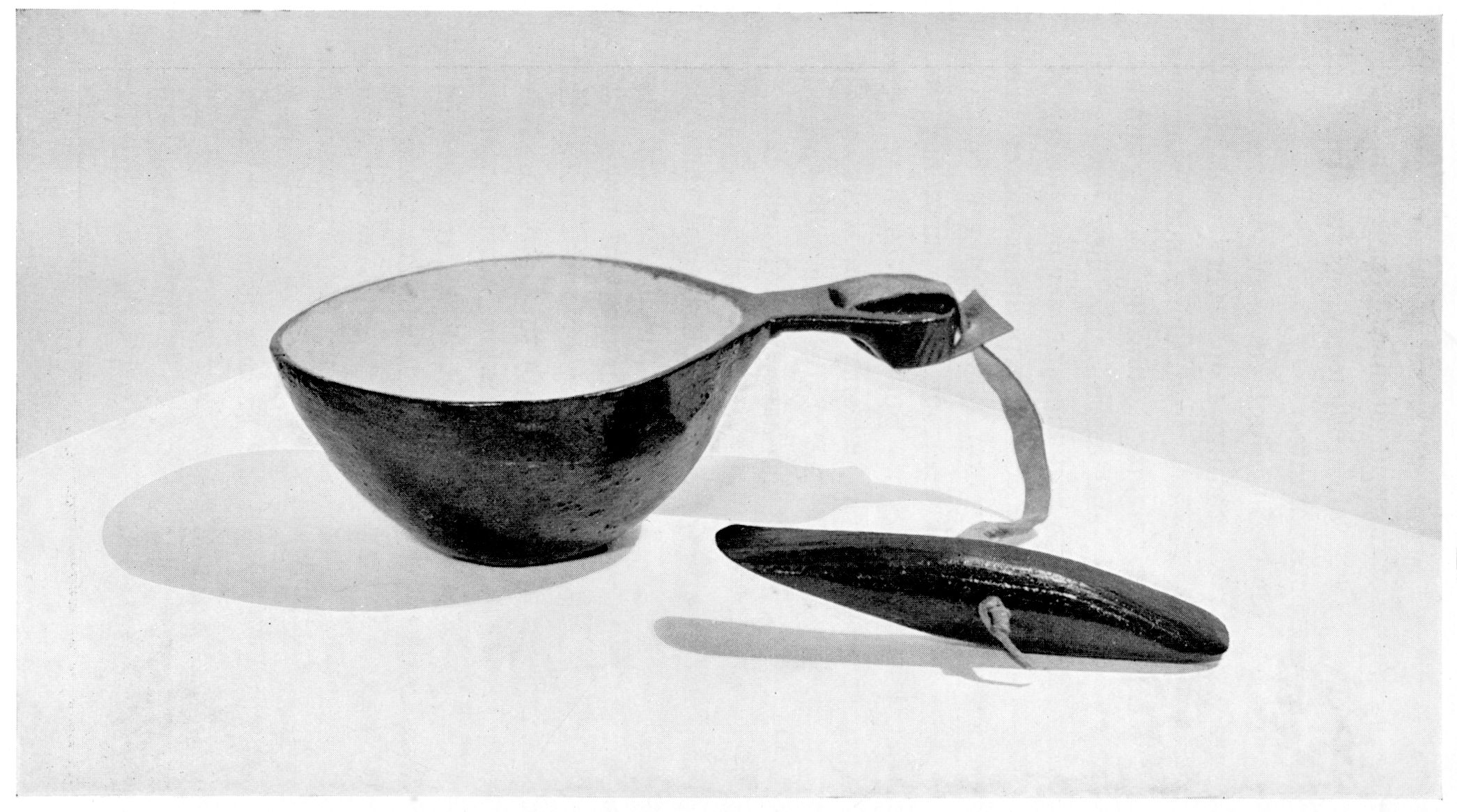

| Viking Drinking Cup—Birch Knob | 299 |

The author is indebted to F. C. Sears for many of the photographs.

This book is an attempt to record the scientific and historic facts about Labrador, as far as they are known. It is the “audi alteram partem” of a medical man, who has spent much of the past forty years on those coasts, and who admires greatly Mussolini’s dictum, “We must not be proud of our country for its history, but for what we are making of it to-day.”

When the word “Labrador” is mentioned, men shrug their shoulders and shiver as automatically as, when the definition of a spiral staircase is asked, they twist their right forefinger up into ascending whirls.

Quite recently, a university graduate coming to Labrador in June to help me for his summer holidays, unblushingly walked up the wharf carrying a pair of boots with skates screwed on them. Practically no part of Labrador is north of Scotland, and three out of our five hospitals are south of the latitude of London.

The records by which Labrador has been judged are those of disappointed adventurers, of genuine explorers who condemned that which they did not understand how to adapt, of those who in a new era of man’s power over Nature have never personally seen the country, and of men who have become so dependent upon the luxuries of so-called modern civilization that they have neither the grit nor the vision to-day for the venture of converting its raw materials to man’s use. So far it has been the men who judged it, and never the land itself, which have been “of no use.” No stories of the peoples who have passed across the world’s stage bring home as vividly the reasons why, under man’s hand, the progress of civilization is often deplorably delayed.

We have no fear of being listed in the days to come as among the “false prophets.” There is no “dump-heap”—unless it is we, who are free to become such. In God’s economy there is no waste.

“Lo, the book exactly worded

Wherein all hath been recorded:

Thence shall judgment be awarded.”

“The Labrador Coast is still one of the most bold and rugged in the whole world,” said a famous geologist. “The bareness of the rocks, their freedom from obscuring forest and turf, helps the long coast to tell its own geological story. Mother Nature has there taken off more than the usual amount of clothing which she is wont to bestow on the land elsewhere; and the autographed story of the ages is so imprinted on her naked bones that those who run may read its thrilling pages, and the wayfaring man can enjoy the conceit of being for a while a veritable Sherlock Holmes. To know Labrador is to know her geology. Seldom elsewhere is the explorer’s mind so forced to think of the very beginning of things. One day the scientific study of Labrador will bring a rich store to our knowledge of the whole earth.”

To follow the story, however, the reader must keep thinking of a thousand years as but a day. The mountains we look at now do not seem to alter one iota in our lifetime, yet whole series of mountain ranges have grown up and then been worn away in the earth’s lifetime by the same forces that are acting to-day.

The bedrocks of Labrador are for the most part of remote antiquity and belong to the very foundation of the whole continent of North America, the “oldest series” of rocks. These “Archæan” formations constitute a complex mixture of rocks of different ages, a veritable jumble-box of underground history, and yet may be regarded as a vast geological unit, stretching all across from the coast to Hudson’s Bay and then on to the Pacific and to Mexico. The whole is often called the “Basement Complex.” It bears no fossil remains of animals or plants.

Here and there in the Labrador Peninsula the worn-down surface of the Complex is veneered with nearly horizontal beds of much younger limestones, shales, sandstones, and hardened gravels, some of which enclose fossils of some of the earliest known organisms. Elsewhere in the continent this veneer covers still larger patches and so obscures the true majesty of the Basement Complex, which in reality is continuous underground from the Arctic Ocean to the Isthmus of Panama and from Labrador to California. In Labrador the veneer over three-quarters of the Peninsula has been gnawed away through endless ages by weather, rain, and ice sheets. This ancient surface has thus been resurrected and to-day presents an astonishingly flat surface. Amazing it is when one compares the simplicity of the plain-like relief over most of Labrador with the infinite turmoil through which its constituent rocks passed when the contortions of the crust of the young earth prepared the structure we call the Basement Complex.

Most of the Basement rocks were once molten. They froze into crystalline masses, composed of minerals like those in the familiar granite. These include quartz, glass-clear and without planes of cleavage; feldspar, cleaving in two sets of planes; mica, cleaving in scales; horn-blende with its own peculiar cleavages and other properties. In varied combination these minerals formed to make different kinds of granite and, more rarely, such rocks as syenite, diorite, and other species familiar to the geologist. Intermixed with those dominant rocks are lavas and other volcanic products of the old time of storm and stress, and also limestones formed at intervals during the early invasions of the ocean into what we now know as Labrador.

Granites, syenites, lavas, and limestones were all gripped in the vice that made mountain structures, and in this process new molten masses were squeezed up into the writhing mass of older rocks and themselves were cooled to form younger granites and the like. Again and again this kind of thing happened. With each paroxysm of the crust of the earth the rocks were heated by friction and by the temperature of the newer, invading “melts.” At the same time, the solid rocks were pressed with unimaginable force, so that their original minerals were flattened and re-crystallized into new flat forms. The result was a general layering of the rocks, of whatever nature originally. The process of this mighty change is technically called metamorphism; the Basement Complex is very largely composed of metamorphic rocks.

The Peninsula is only now being mapped in detail, but studies already made by geologists suggest that one of the main chains of mountains, generated when the Basement Complex was formed, trended along the north-east coast. It seems, then, that well before the earliest known fossil was entombed in the earth’s rocks—more than five hundred million years ago—north-eastern Labrador underwent tremendous pressure from the north-east, with a great mountain structure as the result. There is some reason to think that the roots of this structure, though greatly worn down, can be detected all the way from Belle Isle Strait to Cape Chidley, Labrador’s Land’s End.

Dr. Robert Bell discovered in Baffin’s Land what looks like another ripple of this same range, in which case it would extend more than thirteen hundred miles. The old Labrador range and the others of the great Appalachian Mountain system, meet at the Straits of Belle Isle. The Labrador range locates one of the most ancient (pre-Cambrian) formations in America; the other is much younger (post-Carboniferous).

Another of the most marvellous underground events occurred very late in the building of the Complex. For fifty miles north from Ford’s Harbour and for many miles inland, a vast body of molten rock displaced the old formation. This then crystallized under the pressure of the cover of overlying strata, which have since absolutely worn away. This has left the “intruder” visible over hundreds of miles. This rock is called gabbro. In composition it is like basalt, which is the commonest kind of lava or rock erupted from volcanoes. It has an especially dark colour like basalt and it dominates the island cliffs and mainland mountains all around Nain. These high lands are bare of soil and vegetation, and their black slopes afford a sense of sombre majesty.

Most of this gabbro is a wonderfully beautiful variety of feldspar, called “Labradorite,” one of the abundant constituents of the world’s crust. In Square Islands and on Mt. Pikey there are other large masses of the mineral. Owing to the peculiar internal structure of this variety of Labradorite, white light penetrating its glassy surface is broken up into its coloured components. Some the mineral absorbs, but some, reflected from myriads of microscopic particles, flash like flame out of the iridescent crystals. Purples, blues, and violets are the predominant colours, but orange, red, green, and yellow are not uncommon.

The finest Labradorite crops out in those ledges. As a gem it is difficult to polish, being cleavable, but from it letter weights, table tops, and pendants of flashing, living beauty have been made, and command a steady market.

After the old mountain structure around Nain was essentially completed, it was broken by countless cracks that reached down to the earth’s depths where basalt was kept molten by heat. Into these fissures the basalt was squeezed upward and there it crystallized, set like cement, and so knit the whole range together again.

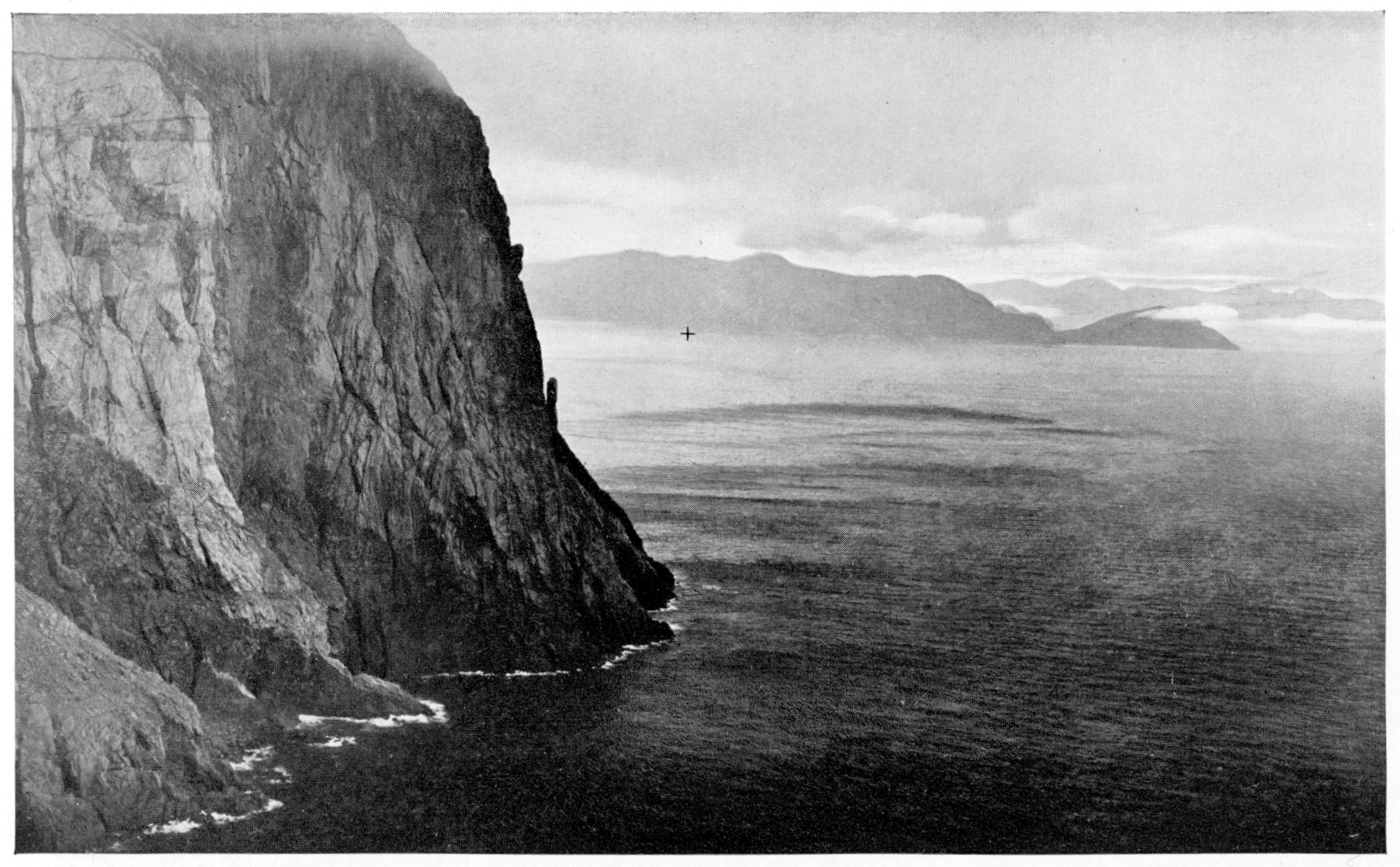

These frozen “ribs” greatly strengthened the ridge against the onslaughts of weather. All up and down the Coast the grey cliffs and slopes are seamed with these thousands of fissure-fillings, the so-called “dykes of trap rock”—excellent examples of which are seen at Indian Harbour and Ice Tickle. In Cape Uivuk and Cape White Pocket Handkerchief, which rise perpendicularly from the sea, are huge dykes running the whole way up the cliffs—fifteen hundred feet in height. They afford invaluable landmarks whenever one happens to be trying to make a harbour on a coast still without any artificial aids to navigation.

The dykes of basalt or trap rock, being more resistant to weather than the older rock, stand up as palisades across islands, as if these marked abandoned fortifications of cyclopean battlefields. Curiously, however, it resists the assaults of the sea less well than do the granites, so that near the shore thick dykes crop out on the floors of long chasms slicing the land. On Mt. Blow-Me-Down are dykes one hundred to four hundred feet in width, exposed on its face for thousands of feet. Conspicuous for many miles offshore, these dykes compel the voyager to wonder at the stupendous force which so clove the mountains to their mysterious depths, suggesting gigantic preparations for earth’s final Armageddon. All this clearly shows that the present-day contour of the land is due much more to the age-long sculpturing by weather and waves, than to the original upheaval of the earth’s crust.

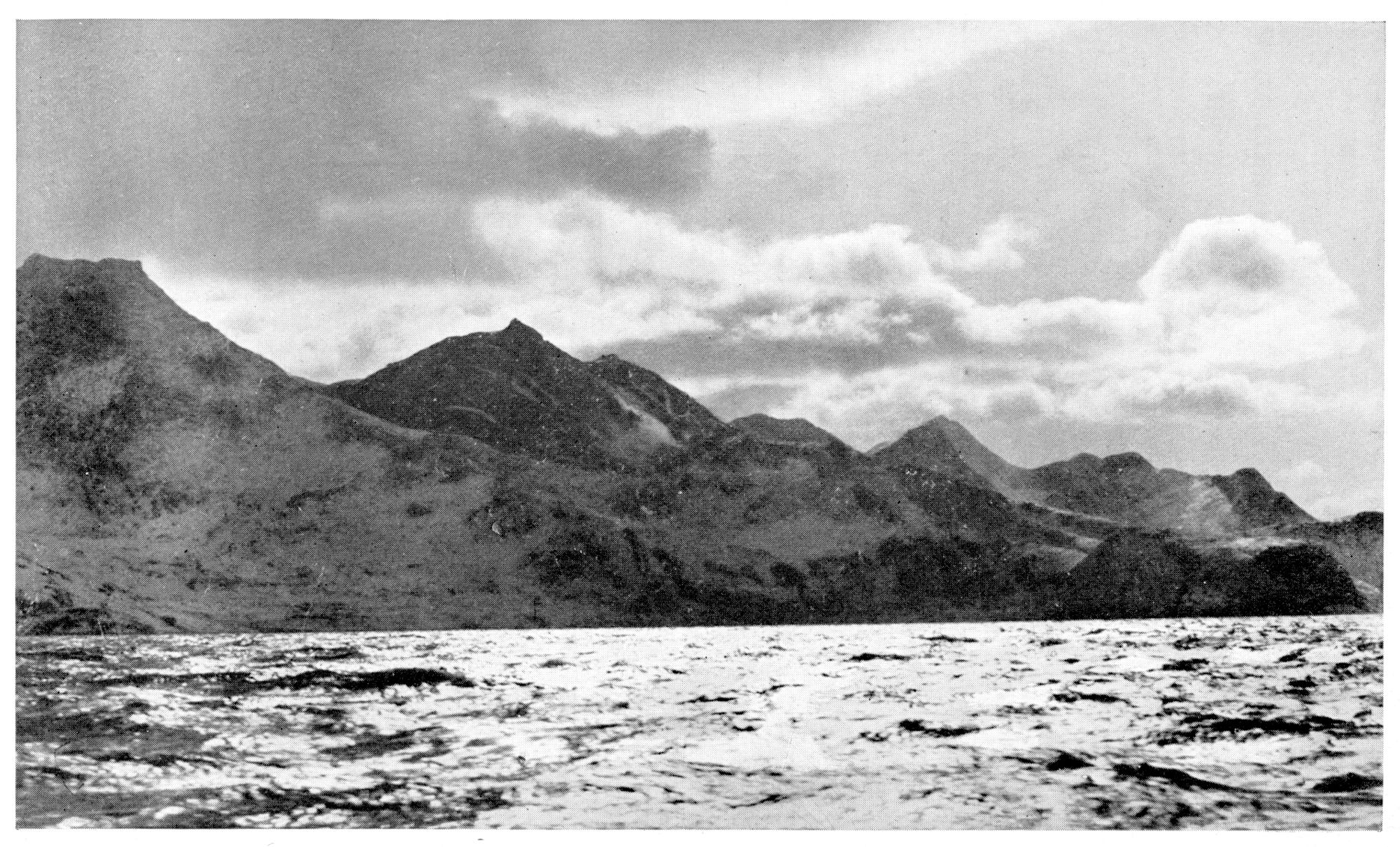

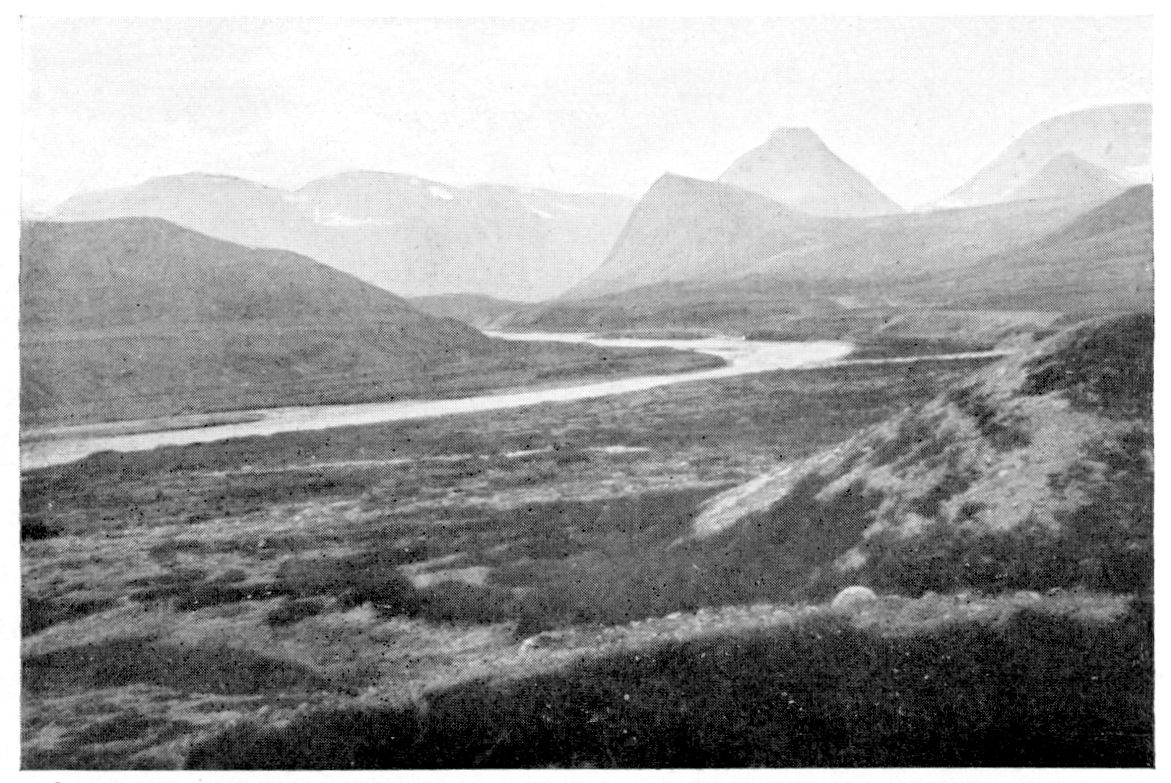

In comparatively recent geological times the Basement was lifted bodily, so that the streams have had to cut through thousands of feet of rock. It was this action which created the present coast relief for one hundred and fifty miles south of Cape Chidley, rivalling in grandeur, though not in height, the Alps or the Selkirks. These “reconstructed” mountains are called the Torngats, which means “devils.” Their bare, jagged peaks, springing abruptly thousands of feet from the fjords or the ocean, are like the forbidding horns of the well-known chief himself. The dark shadows, made the more startling by the brilliance of the high lights of the northern sun or the eerie loneliness of their naked crags under a ghostly, whispering aurora, people these fastnesses with spirits sinister for the savage mind.

Nakvak Bay is one of the great portals to this region of the “Devils.” Its narrow entrance, flanked by sheer cliffs two thousand feet in height and usually supporting a ceiling of clouds, suggests to the visitor that he is Jack, timorously entering the Giant’s Gateway. One passes along mile after mile between its lofty walls rising abruptly from Stygian water sometimes to lone peaks towering nearly four thousand feet in the air. On the northern side the serrated skyline, caused by what is aptly dubbed the Razor Backs, bristles with cyclopean teeth. Mr. Noel Odell points out that these consist of rare granite of unusual formation and resistance called Charnockite, which occurs also in southern India and has close kinsmen on the north side of two other near-by fjords in Labrador, called Komaktovik and Kangalaksiorvik. Between the enamelled teeth immense gullies gouged out in the last ice age end in flat-floored hanging valleys with perpendicular sides. The whole suggests the ferocious jaws of Cerberus, guarding the entrance to Hades.

Here and there are high cornices, huge ice-filled cirques and “glacierettes,” reaching about half a mile in maximum length, with occasional glacial lakes of exquisite blue and green tints. On the northern slopes of Mt. Tetragona, so named by Professor Coleman after the beautiful wild heath flower, great precipices, twenty-five hundred to three thousand feet in height, fall perpendicularly to the glacier below.

Twenty odd miles from the mouth a nearly vertical precipice three thousand feet high marks a salient angle where two branches of Nakvak Fjord meet. Its head is twice the height of Cape Eternity in the famous Saguenay River, while from its sides numerous waterfalls tumble from high hanging valleys into the abyss below. Here rise the highest mountains, directly from the sea, between Baffin’s Land and Cape Horn. Nothing else in eastern American scenery approaches the ruggedness of the Torngats of Labrador.

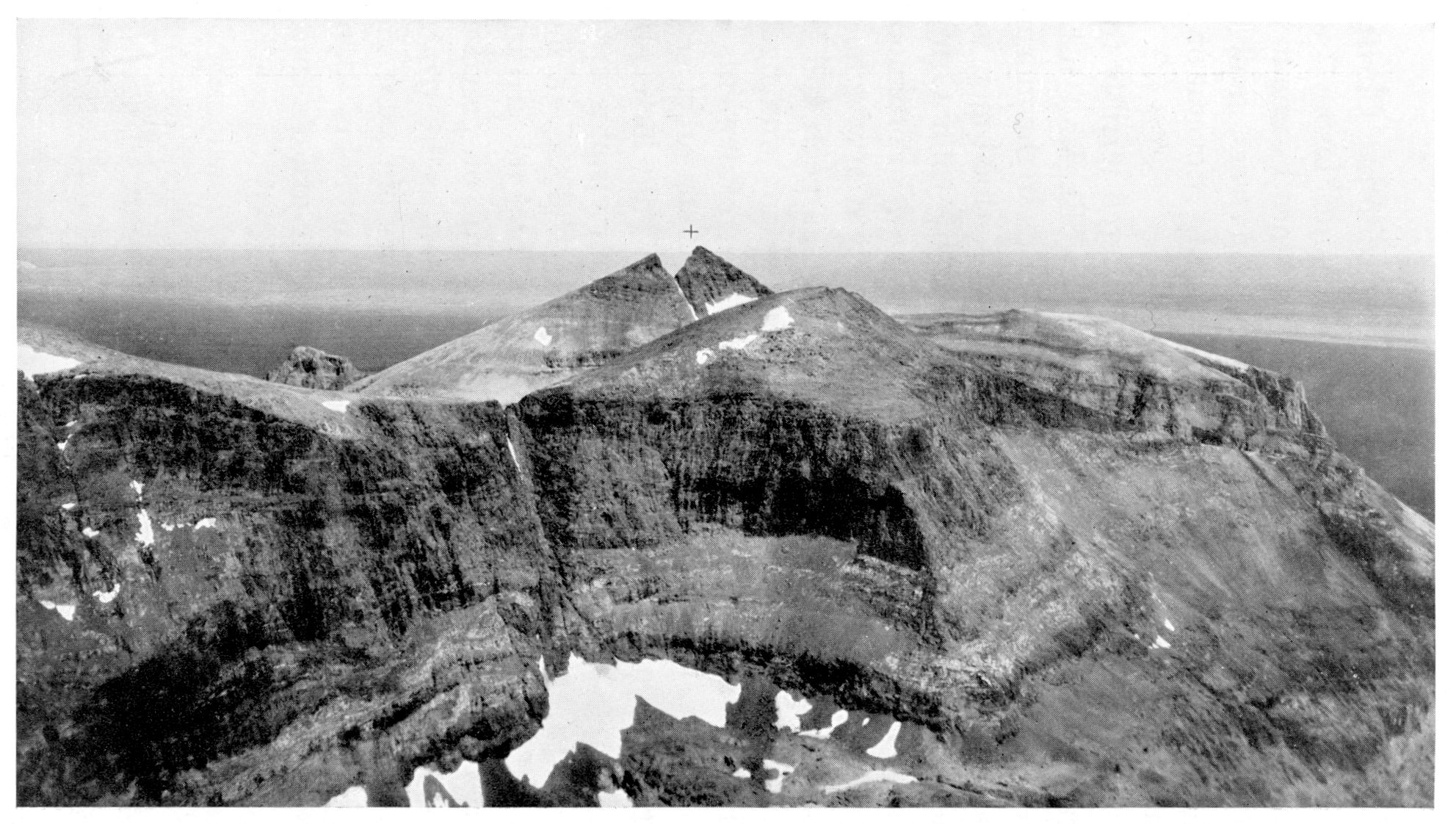

Fifty miles south of Hebron is another wholly new element appearing in the landscape. Not only is it new among the wonderful mountain forms of the Labrador Coast, but it possesses unique and imposing features in its architecture. It consists of a range of mountains covering some three hundred square miles, called by the Eskimo the Kaumajet or Shining Tops, which is the exact equivalent of the Hindu Himalaya. Even in summer the Kaumajets always wear caps of snow.

One titanic cleft through this range is used by numbers of craft, both as a centre for fishing and as a short cut to the north. It is about two miles wide and both sides rise almost perpendicularly in great terraced bastions of pink rock, three thousand feet high, the whole tipped and lined by green ledges. Especially when the snow outlines the ridges it is a perfect picture of beauty. Here and there over the sides leap sparkling cascades. A large one takes one leap of seventy feet.

It was my privilege to witness that rare phenomenon, a thunderstorm, in this Tickle, which bears the name of a famous man called Mugford. “Tickle” on the Labrador means a ticklish place to sail through—as this unquestionably is. The flashes of lightning gave an even more thrilling effect than the scintillating colours of the Aurora Borealis in the fall, while the rolling cadences of the thunder suggested that old Boreas had seized the hammer of Thor to demolish us puny mortals.

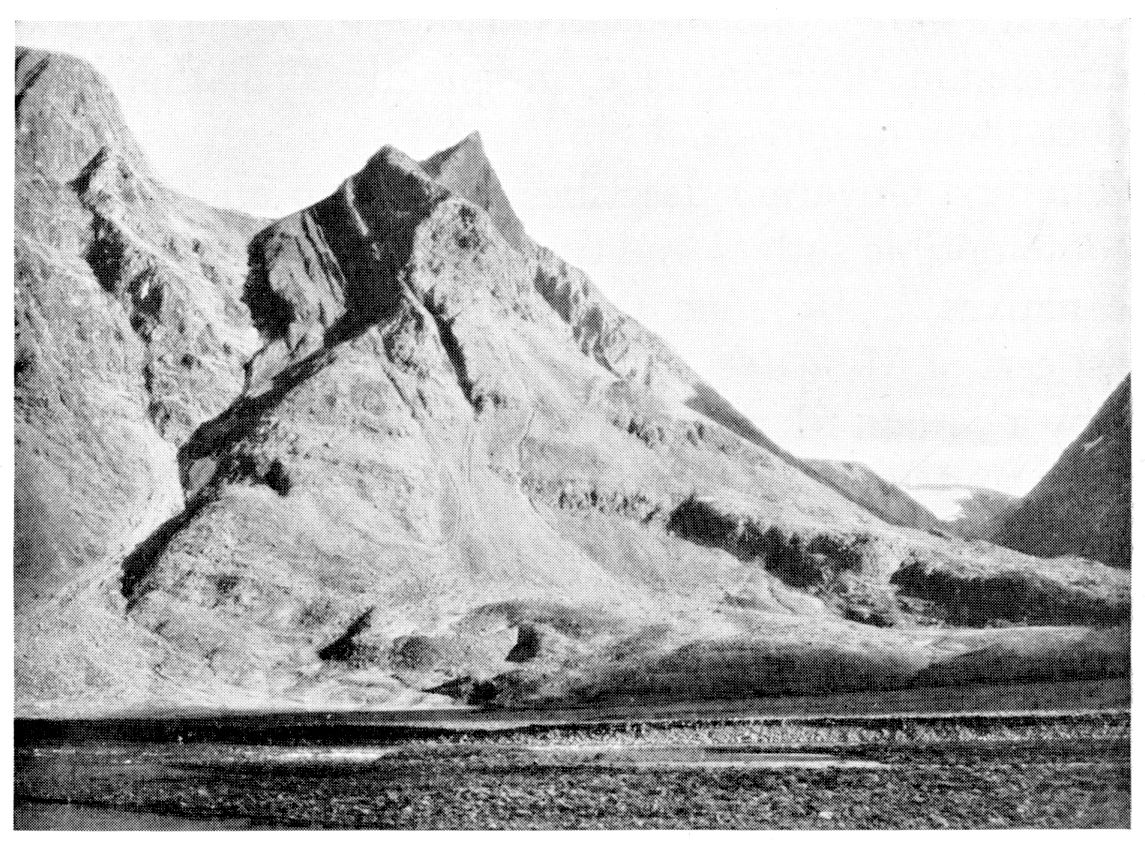

Here is the geological story of this weird region. This section of the well worn-down mountain roots, which, here formed the earth’s crust, for some reason sank down into the sea, due to some wrench, some pressure, some strain. Then on its back were deposited through long ages under water, mud, sand, gravel, lavas, or volcanic ash, until finally they reached thousands of feet in thickness. Then once more the writhing earth bent its back, carrying the whole up out of the water for thousands of feet, in the form of slates, sandstones, conglomerates, and quartzites, all welded together as before by ribs of trap rock. Here was an entirely new variety of raw material. In shape it was like a series of dromedary humps, yet so vast as to be over half a mile in thickness, fifteen hundred feet of which are volcanic formations. For before the subsidence under the sea, during countless millions of years volcanoes had been belching out enormous volumes of ash and debris, coarse and fine, in violent explosions—witness to which is the fact that still, bedded in the lava, one can see some of the perfectly rounded bombs, which froze as they spun through the air from the mouth of Nature’s cannon.

Once again the whole was given over to the “secular arm” of frost and other weathering agents, and the still more destructive action of water streams, patient and resistless. To-day only comparatively small patches of these ancient sea bottoms remain in the superb walls of the great gorges and canyons which now form these appalling waterways and harbours, and in the large islands of Ogualik (cod) and Naunautot (white bear) which rise directly from the ocean, thousands of feet in the air.

This region has well been described as a huge geographic fossil, which was once entirely hidden by the generous covering spread over it; but now that that has been so largely torn off, it lies an open book for all to read.

The range is capped by two massive rock towers, each soaring about eight hundred feet above the ridge. They stand a quarter of a mile apart. Sudden slopes fall full eighteen hundred feet, and then there is a sheer drop into the sea. The aeroplanes of the Grenfell-Forbes Survey Expedition found peculiar pleasure in flying between these ancient sentinels when taking the picture here shown. The light grey colour of the Basement in contrast with the black of the stupendous masonry above gives to the perfect symmetry the impression that the whole is the work of giants with the brains of men.

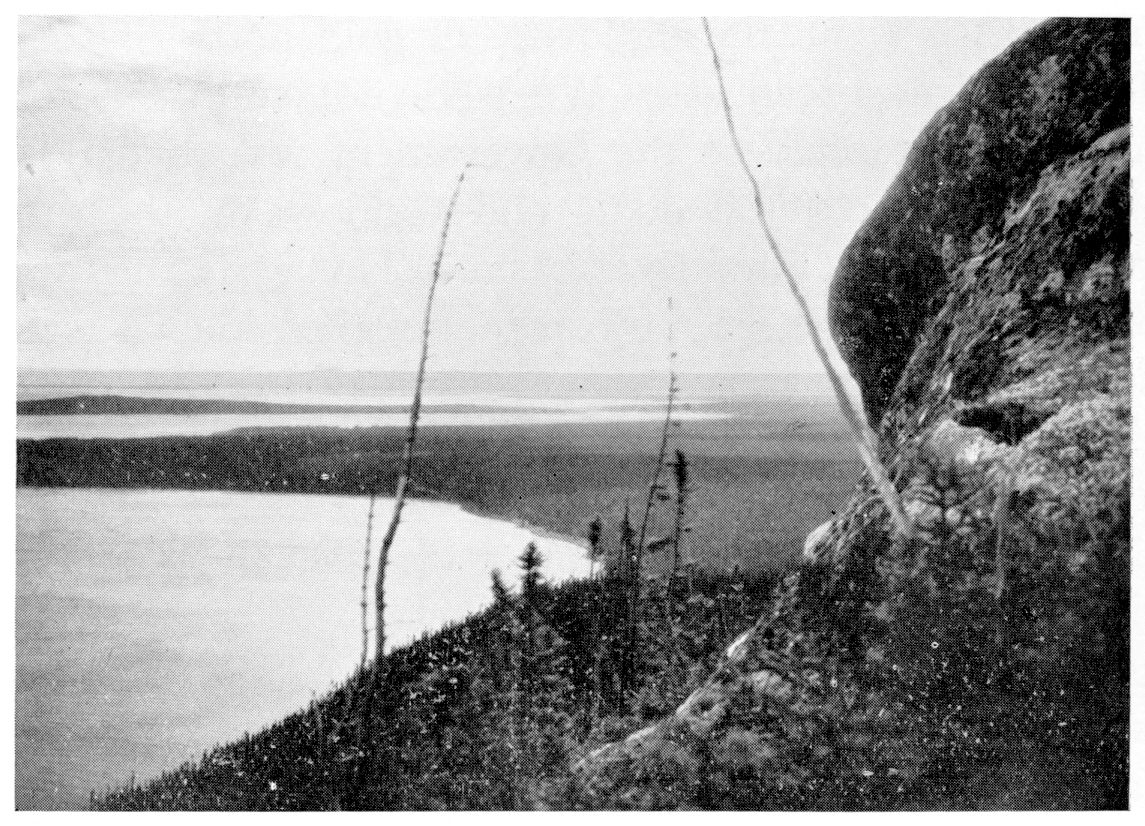

Yet another of the “high places” of the Labrador is the Kiglapeit or Dog Tooth range. It is a great sierra, again an island, some fifty miles south of the Kaumajets, which in solemn loneliness rears its rocky and giant vertebrae, ten in number, over two thousand feet above the sea. It is like a monster reptile, thirty miles in length, left stranded on the shore. Oddly enough, this time it lies east and west, with its head jutting out towards the Atlantic. Mt. Thoresby, the actual head of this petrified dinosaur, is of sombre gabbro, looming twenty-seven hundred feet into the air.

From this point the mainland, stretching for three hundred and fifty miles to the Straits of Belle Isle, is girt with islands, forming a plateau about five hundred feet in height. The general skyline is so strikingly level that it could scarcely be more so if some titanic shovel had filled in all the hollows. This flatness sweeps right away inland as far as Lake Winnipeg. This is the “almost plain” to which the Archæan Mountains have been reduced by wasting.

None of the younger sedimentary deposits, representatives of the lifetime of the earth, have yet been found on the north-east coast. Only far away to the south and west are there sea bottoms of geological epochs, consisting of accumulated mud, sand, and gravels—many miles in thickness—which now constitute the emerged continent known to all of us as North America. But if there was ever more veneer on the Basement Complex than that now remaining in the limited Kaumajet region, it has yet to be discovered. Thus for millions of years Labrador has been above the sea, during which time the onslaught of Nature’s forces has laid bare throughout its length and breadth the very foundations of the world. The only remains of Labrador’s constructive evolution are the Kaumajet deposits of geological yesterday, called the Glacial Period, and of this morning, the post-Glacial Epoch.

Long years ago an ice cap accumulated in North America, like that of Greenland to-day. It was thickest between the St. Lawrence River and James Bay. Slowly, like other major glaciers, this ice flowed in all directions—out to the seaboard of this long coast, literally ploughing the floor as it moved along.

The Labradorian, or Laurentian, ice cap extended over two million square miles, to the plains of the upper Mississippi and the North-west Territories of Canada, and as far south as New York City. Even Mt. Washington, six thousand, two hundred and ninety-three feet in height, was covered by the flooding ice. To the north-west Hudson’s Bay had an ice cap all to itself, called Keewatin, while Newfoundland boasted also a private white night-cap.

For reasons unknown, the ice caps disappeared. Not one acre was left on the mainland, unless the Grinnell Glacier in Baffin’s Land could be counted a last remnant of it. The bared back of Labrador shows marks which glaciers etched there not long ago. For exactly as rivers do, the ice stream tears up its bed at the upper end and carries it along with it until it drops the debris or drift material of its load as it slows down near the end, where the glacier’s moraine corresponds to the river’s delta. And here we may remember that rivers, like glaciers, have often disappeared, such as the one which the Italians have recently rediscovered in the Libyan Desert.

In the glacial period the outer edges of the ice cap lay far out under the ocean, where the material which the great mill was grinding was then deposited. This vanished ice cap was no idler in its moulding of the present Labrador architecture. One sees endless examples of its work; for Dame Nature often surprised it at its task and forced it to throw down and leave some huge rock after it had just been moved from its still self-evident bed—exactly as at Assuan, where a great granite monolith was being hammered out of the solid rock for the Pharaoh of three thousand years ago, by a hundred thousand workmen tapping incessantly around it with granite stones, held in the hand as hammers. They had almost removed the obelisk by hammering dry, wooden wedges into the holes they had made, and then wetting them, when they, too, were surprised by enemies and fled, throwing down their implements, which are there to this day to show how with almost equally incredible tools, sufficient numbers of puny men, working long enough, achieved impossible results. Just so a glacier uses rocks for crowbar and crane as well as for gouge and chisel.

It was normal cutting by streams long before glacial days which produced most of the grand features of the Labrador sculpture.

Glaciers, like rivers, write indelible records with veritable graving tools too deeply to be denied. Labrador’s glaciers have left grooves a foot deep in soft rocks. They did it by dragging frozen-in boulders over the rock faces of their beds. Occasionally to-day one sees off the Labrador Coast some capsized but triumphant iceberg, aggressively holding aloft just such a graving tool frozen into its now upper surface. The striae record for all time the direction of the ancient ice streams.

Some five thousand feet up on the top of the highest peaks of the central range Odell discovered just such marks, showing that presumably, from the extensive weathering of the near-by summits, in the far older pre-Pleistocene Ice Age the whole of Labrador was buried under the cap. However, all agree that the jagged devil peaks of the Torngats probably maintained their impish heads high above the latest of the four devastating ice floods, the streams from which, with resistless force, tore their way through the central and coast ranges of the north, right into the Atlantic Ocean. The whole for a long period, says Odell, formed a rocky archipelago in the glacial mer-de-glace, which, when it once more disappeared, left the contour of northern Labrador as it exists to-day.

The half million square miles between the Atlantic and Pacific are one vast complex of pre-Cambrian rocks, which have furnished, farther west in its better-known parts, immense deposits of valuable minerals. Iron and copper have been found in the Lake Superior district, magnetic iron ores in the Adirondack regions, gold in those of Porcupine, silver and cobalt in those of Cobalt, copper and nickel in Sudbury, and some of the richest gold mines in the world in the famous Hollinger, Timmins, and Flin Flon mines.

Some fine work done by Dr. Low, of the Canadian Geological Survey, showed vast deposits of magnetite in the neighbourhood of the Grand Falls. Also near them, one grant of forty square miles has recently been made for gold mining, since prospecting has been made easier by aeroplane. Gold was discovered “in situ” in the Mealy Mountains some years ago, and a fine iron pyrites mine was begun in Rowsell’s Harbour and only discontinued because of the difficulty of transportation.

The latitude of Labrador is that of Britain. The scrubbing of the ice cap and the cold bath in which she lies only partly explain her scanty vegetation. The uplift of her coast-line helped further to deprive her of the extra garment of fertile clay or till that was deposited, and still remains in the valleys and prairies farther west.

The distance between Labrador and Greenland does not seem to be getting gradually wider, yet it probably is, for Mother Earth is not rigid, but still a whirling, mobile mass, ever whirling round at a terrific speed as she hurtles through space, and wrinkles on her face keep altering with her age. Thus the Gully, known now as the Gulf of St. Lawrence, is just a smile dimple filled with rich blessings for her children.

The split in the earth’s surface between Europe and America left, during the process, Greenland and Iceland as fragments of the ancient bridge between the continents, just as the Aleutian Islands are parts of the old band that once united America and Asia—for the slip tendency is ever to the westward.

All along the Atlantic seaboard of the Americas, from Labrador to Patagonia, runs an undersea shelf, attributed once to the vast debris of the lost continent of Atlantis. However, with the lapse of time, the steep edges of the great cracks naturally sagged and wore down, while the bottoms of the great cracks filled with lava from below and sediments from above.

The soil and rocks torn from the surface of the land by weather, by rivers, or by brutal ice were not lost, but deposited on the growing shelf. The ocean all the while added its quota of remains of animal life. The whole, as well as the great extension known as the Grand Banks, off Newfoundland, has been a veritable nursery of fish through the centuries—a priceless food supply for mankind.

The Labrador Peninsula, like some diffident virgin, is still wrapped in garments of isolation, having turned away her wooers. But there can be no reasonable doubt that, untouched in the thousands of square miles of the Labrador terrain, as well as in her waters, lie vast treasures yet to be wrested from her for the benefit of the world.

There are still three or four thousand Indians remaining in Labrador’s hinterland, feathers in Canada’s cap, while the still existing Eskimo are the best tribute to the Moravian missionaries. Labrador has been kinder to the Indians than anywhere else in America, not excluding Puritan New England, judging by the much larger proportion of them to the whites which still exists in the Northland.

The original Indians of North America, like her Eskimo, are Mongoloid in type. Still to-day the eastern Asiatic tribes and the North-eastern Indians have so many traits in common with Eastern Siberians that there is little doubt of their common origin.

No remains of palæolithic instruments, or human remains, associated with those of animals of pre-glacial days or in rocks of those ages, have ever been discovered in North or South America as they have in Europe, Asia, Africa, and Oceania.[1] Moreover, the cultural traits of the rest of the world, except perhaps the ability to make fire and use bows and arrows and harpoons, never reached the American Indian previous to the Russian invasion. The same is true of all the important domesticated animals and plants except the dog.

The toilsome march of Homo Bimana from the Cradle of the Race in the Euphrates Valley to America was therefore probably on foot, and made before “our mobile earth” burned her last land bridges which had connected America with Europe by way of what is now Behring Sea, and so after she (America) had received the Indian contribution.

The Indians of the Labrador unquestionably came from farther south and west, for they are all branches of the great Algonquins who have left their names in endless places from the Atlantic to the Mississippi and the Rocky Mountains, and from the Carolinas and the Gulf of Mexico to Hudson’s Bay. Beyond were their enemies, the Indians of the plains to the south, and the Athabascans to the north-east.

History tells us that the Labrador Indians were attacked by the “bloodthirsty” Iroquois and driven north. Though comparatively few pursued, it was with such “relentless ferocity” that they fled as far as Hudson’s Bay and the very northern end of the land. In 1660 the Iroquois raided the country around Lake Tamagami as far as Ottawa. There are pictographs on the surrounding cliffs, supposed to commemorate these raids. Even to-day the Indian mother uses the name “Iroquois” to frighten her children, as the Spanish did that of Francis Drake. Probably it is on this account that the Labrador Indians received the name Nascopies, which is indifferently translated as “ignorant,” “heathen,” or “unworthy.” Whatever its exact meaning, it was certainly not intended to be complimentary. This Indian invasion in turn drove back the Eskimo to the seaboard, except in the peninsula between Ungava and Hudson’s Bay, which is still Eskimo country.

The northern section of these remaining Indians no longer go south in spring to the Gulf. They remain in North Labrador, where they trade around Davis Inlet, with Nain or even with Port Chimo. They are now called “Montagnais” or mountaineers, and speak only a dialect of the great Cree language. The southern branch of the Indians can still understand them, a fact which holds true right across to the Rockies—the original language being the same all the way. The Gulf of St. Lawrence, however, has been a barrier between them and their New England relatives, and when an Abnaki sees a Nascopie on the Labrador on a winter trail, they have to speak in French or in sign language.

CAPE UIVUK

Dr. Cabot says that the language is without any “r” sound, which has been attributed to the difficulty of facial muscles rendered stiff with cold articulating it. He claims that the Scotch clerks of the Hudson’s Bay Company are better able to speak Algonquin than the English, being accustomed from birth to being “stiff with cold.”

CAPE BLOW-ME-DOWN SHOWING RECENT GLACIAL ACTION

Less than half the Labrador Indians can speak any language but their own. Another branch of the Indians in Labrador is known as the Barren Ground Indians. They hunt around St. George’s River and they, too, trade at Fort Chimo, or Whale River, or Mistassini. The Nascopies called themselves “Nenenot,” which means the “ideal” or true people; just as the Eskimo, whose name signifies “raw meat eaters,” call themselves with even less modesty “Innuit,” or simply “The People.” This optimism is the evil of nationalism. The Israelites, who exterminated so many peoples in Palestine of old, always regarded themselves root and branch as “The Chosen People.” Every nation at heart succumbs to this temptation. “We are the people and wisdom shall die with us.”[2] It is this kind of patriotism which lies at the root of most wars.

It is not inspiring to remember that until the white folk came to the St. Lawrence, Labrador provided liberally for its original owners. When Europeans began to settle the St. Lawrence basin, vast forests spread from the Gulf to the Arctic prairies, except on the highest plateaux. Not till then did the devastating forest fires occur which swept the Coast from the Saguenay to Romaine, and from the Gulf to the Height of Land. They destroyed the game, the timber, and even the soil, and drove the unfortunate Indians from their healthy highlands to the few swampy parts which had escaped the flames, or back to the low ground near the coast, where tuberculosis and other troubles found them an easy prey. Possibly wandering hunters were less careful to observe the rigid fire code of the Indians in other territory than their own.

The Nascopies were first heard of in Europe when Cortereal’s sailors captured a lot of them in Hamilton Inlet for the benefit of His Most Christian Majesty, the King of Portugal. They were “tall, strong, and tattooed.”

The Nascopies, though without any written code, have a system of their own which includes a central meeting ground in the region of the Great Lakes, and a grapevine telegraph which circulates the news of the families, who still go every year all the way south by canoe to meet their priests and sell their catches of fur. The high plateau has always been a home for the caribou, which has afforded the northern Indians an easier existence. However, endless fish, speared and netted in every river and lake, will always be their standard staff of life. This fish diet is supplemented by eggs, berries, and birds, and even mammals—small and large, from a squirrel to a deer. It was this sufficiency which accounted for the fact that many ceased to roam so far and wide to earn a livelihood by trapping. As a result, however, now that modern firearms and traps have reached them, they are destroying, like children, their own sources of supplies, and they are themselves disappearing more rapidly than their southern cousins. This is perhaps the more remarkable since the latter suffer more from contact with the whites of the St. Lawrence shore, where social diseases, easy access to “firewater,” and the less dramatic nemesis of proximity to specific contagious diseases and epidemics take a larger toll. These results are noticeable even in the size of the Indians and their bodily framework. The northerners are practically useless for the heavy work of guides and porters. The more active life, aided possibly by a mixture with the Scotch fur traders’ and the French “Habitants’ ” blood, render the latter far better risks for any adventurers succumbing to “the lure of the Labrador wild.”

On the contrary it is equally true that given a mixed group of Eskimo from north of Cape Chidley and those from the south, nurtured around the Moravian Mission stations and relying on flour and “civilized” diets, it would be possible for any intelligent stranger to separate them correctly, simply by the differences in their physique. The northerners are sturdier, livelier, and have a real red colour in their cheeks.

The introduction of reindeer into Alaska made the natives there happily self-supporting. For Labrador, nothing constructive has been attempted for the Indians. There has been no conservation of forests, or of animals, like the buffalo in Canada or the reinstatement of the fur seal in the Pacific. How could it be otherwise than a simple corollary that the Indians of the Labrador are steadily vanishing, if only by a slower process, than if the sea had not prevented their farther flight when the Iroquois were pursuing them so many generations ago?

Everywhere in Labrador the physically weakest still go to the wall. No white man is yet able to make a home in the interior, where the only law is still the immemorial code of the hunting ground. The high interior, scrubbed bare of soil by the ice ages and burned over by the great fires, can only become a white man’s country when the wealth of its minerals justifies the expense of supplying his needs from the outside. The Indians and Eskimo, who die in our environment, can live there happily and can be an asset to human life, which it will take a long time to evolve again once they disappear.

The end of the winter for the Indians is signalized by the sinking of the snow, and by Bruin coming out of his cave after his long sleep. Fur becomes worthless in May. The sun bleaches the bright colours of the hair; the foxes sleeping on the snow, which gets moist during the day, freeze their long hairs to it, and literally pluck themselves. Such pelts are called “trace-galled.” Also all furs begin to lose density in the spring, so the season closes and the Indian migration southward begins.

Indians and even the half-breeds are very strict about not killing fur out of season. The trappers once brought out to us a man caught for the second time taking a silver fox in late September. The offender was bound hand and foot. In our capacity as magistrate we had to warn him and his family to leave the country, as the rest of the men were determined to enforce the law of the forest, and send them by a shorter road to the “happy hunting grounds” if they dared to remain.

Though unfenced, hunting lands or fur paths are held by individual trappers. They descend from father to son, or daughter’s husband. All relations have a right in the hunting lodge and must be taken care of—even widows, orphans, and the incapacitated. It is a kind of modified Soviet arrangement. Whilst crossing another’s land you may kill game for food only. A three-year rotation, hunting only one-third of one’s fur path annually, is the custom. To-day a fur path is roughly one mile wide and of indefinite length.

By June, the Leaf Moon, these Indians are back on their southern reserves. July, St. Anne’s Moon (their patron saint), is spent in receiving spiritual instruction from their priests. When August comes, the Moon of Flight, the families once more leave for the interior.

The flight really applies to the young ducks, who, like the manna of old, make possible the migration of the Indian families. The Indians are then burdened with supplies and the ducks afford easy meat by the wayside, without delaying progress. Dr. Cabot’s description of one such family which he overtook suggests the courage of Abraham. As he got out of his canoe one day, an old, withered Indian woman greeted him on the river bank. Beside her was her still older, totally blind husband, leaning on a staff. The heads of two children peered out through the bushes at the strange canoe. A near-by shot was heard, and a smiling young man carrying a partridge joined the group. This family could not possibly reach their camping ground until the autumn. Yet they were embittered by no worries or regrets. They were perfectly cheerful, though they had none of the frills of life, and though there was only one effective pair of hands to fend for them all. The fact that obstacles are so unending and sources for obtaining supplies so scanty that two American explorers on just such a journey, with a native guide and a perfect equipment, could starve to death, proves that some other than a material factor is necessary to prevent fatalities from being frequent.

Before the white man came the Indians did not have to make these long journeys. There can be no doubt that, although they evolve character, they do tell on the very old, the young, and the feeble. Occasional disasters where whole Indian families have perished of starvation are only too well authenticated. No country is without its tragedies. At the end of a fjord called Nullataktok we ourselves came upon the remains of a camping ground where a dozen or more skulls and other bones told plainly the fate which is never unreasonably far from these Indians. A trader in Fort Chimo said that every year during his long residence there an average of five or six persons had failed to return. Alas, the less the food supply, the farther these Indians must go to seek it. During our own first ten years on the Coast, fifty per cent. of the Indian families were reported to have starved or died through deficiency diseases around Fort Chimo away in the north. There are no doles in the interior.

In the summer of 1931 we saw Indians leaving on their winter trail from near Nain with what seemed to us nothing whatever with which to secure a livelihood. Their tents were in rags, clothing almost absent, ammunition and twine practically nil. Not a few were barefooted; and they did not have enough provisions to last the week out.

Almost always they have a small dog which runs along the bank as they paddle. It barks, treeing birds and small animals which can then frequently be captured merely by a noose on the end of a pole. I have known an Eskimo kill as many as five hundred white partridges in one winter with nothing but his dog whip. The Indians prefer a bow of spruce wood, with a thong or sinew for a string. The arrows are made of spruce with great flat-faced knobs, which strike hard and are easier to hit with than the pointed arrows used by the Eskimo. Moreover, they need no metal tips.

On partridge diet only, however, they cannot keep strong; and “rabbit” starvation is a well-recognized term on the Coast. Both should be accompanied by some flour, or other carbohydrate addition. The great lake trout, or “the fish that swallows anything” as they call it, is their best and most dependable food. It is supplemented by whitefish, pike, salmon, and trout; though the whitefish go into deep water during the winter and are not then available.

In winter neither the Indians nor the trappers use dogs for driving. They haul their supplies and walk themselves. Dog food is heavy. Moreover, their method is quieter for hunting, and requires no trails through the woods or up cliffs. The sledge is very narrow and very light, made of birch or larch which do not “ice up” easily (a serious handicap). Only when the spring sun thaws the snow by day and it freezes at night, are runners attached. No skis are used—only a roundish “bear-paw” snowshoe, which is far better in the woods. Special pairs made very large and with fine meshes are used to run down caribou in deep snow.

The Indians, like the Eskimo, are polygamous. The ability to maintain the family is the only law. It is their custom to put the old and feeble out of the way, the person concerned preferring that to abandonment and freezing to death.

Those who know have described the Nascopies as mean and inhospitable to strangers, and selfish; in fact, very unlike the rest of the Crees.[3] What can we say, however, who give them little without exacting payment? Towards one another, no people show more generosity. A hunter keeps only the head of an animal; the whole of the rest he gives to the others if in need. They in fact exercise a community of food, such even as they buy at the stores seldom remaining in the same hands more than three or four days.

In spite of their Christian affiliations, their old beliefs are by no means extinct. In this respect, too, these poor Indians are very like the rest of us. Their mental machine, uncrowded as ours is by outside impulses, retains old impressions, especially emotional ones, longer than ours does.

In the Indian lodge the spirit of original evil is called a Windigo. Spirits, however, are not malevolent if uninfluenced by human beings; but the nearer they are to being men the less they are to be trusted! A priest can use any spirit for evil purposes! It is popular to laugh at these poor Indians’ conception of the Deity as being anthropomorphic. But whose brain can conceive of God in any other way? At least their great Manitou is wholly good, and these humble folk have even tried to regard him as a trinity—in which the first person gives them what is necessary for life, the second person gives them abundantly more than they need, and the third person that of which they cannot have too much. To an Indian, that of course is fur. Every notable feature in Labrador has its spirit, to the minds of both Indian and Eskimo alike.

So long as the language of the old wilderness life persists, so long will these people continue (as we do) to mix inbred with acquired ideas. The Indians, furnished with calendars and pins, mark up the Saints’ Days and Sundays, which they certainly observe better than does the average European. Along their travelled routes there are many lonely graves marked by our common token of a cross. Passers-by respect them, and camps, tents, wigwams are not pitched too near them so that their peace may not be disturbed.

Among Indians and Eskimo alike many legends exist. It is less easy to collect those of the Indians. Comeau describes their curious habits of “shoulder-bone reading.” As soon as ever a caribou is killed its shoulder-blade must be removed. The meat is cut off as close to the bone as possible, which is then boiled for a few minutes, wiped absolutely clean of all meat, and hung up to dry. That night when all the family in the wigwam are asleep, the neck of the bone is held in a split stick over hot coals for a few seconds, until small cracks spread across the bone. The small burnt spots on the branches indicate not only the distance of game from the camp—which is always the largest burnt black spot—but also the direction in which the hunter must go to find it. The hunter fares forth accordingly, and “no Gospel truth was ever more firmly believed in.”

The Indian, again like the Eskimo, does not fear the bear but his spirit, and will not use the name “bear” if he can help it. Instead he calls it “black animal.” He will talk to the body of a bear in a trap in order that the spirit may not seek vengeance. Women and children never eat the paws of a bear for fear of suffering later from cold feet; just so an Eskimo wears a piece of bearskin sewed on his coat, so that the next bear may see it and keep away from so brave a hunter. He will not even mention the name of an iceberg while passing it, or the name of a dead man until a new man bears his name.

At the Indian Dog Feast, which is especially for their medicine men, the objective is much the same as that of a modern medical college. It is a kind of graduation, intended to turn out efficient practitioners. The course opens with private séances in the tent of the principal doctor. A drum is beaten directly the student enters, and is continued all night for several nights in succession. The door is closely barred and secrets pass continuously between the master and the pupil. The noise which goes on all the time insures that these mysteries do not leak out through uninvited “listeners-in.” When exhaustion is reached and the pupil has held communion with all the spirits, both good and bad—for both are regarded as supreme sources of power—the novice is considered to have graduated. His profession insures him a good living as a rule, and much of the same authority as is accorded to a priest in civilization.

Cartier relates that the Huron Indians, when killing a criminal prisoner, would slash the body and sink it in the river for ten hours, when certain fish which he called “cornibots” would be found in the cuts. These they considered of more value than gold or silver, because they would stop bleeding from the nose! He experimented with some of them and found that the claim was justified. The faith element in healing is a universal human trait.

It is noticeable that Indians rarely intermarry with whites, but though French and English girls have been known to marry Indian men, they never marry Eskimo. The Indian never marries an Eskimo, but cross-breeding between settler men and Eskimo girls is not uncommon.

Jacques Cartier, writing in 1556 from his winter station, says that though he would not have believed it unless he had seen it, the Indians, both male and female, would go naked into the water in winter between the ice-pans in the St. Lawrence, hunting for fish, and apparently did not mind it. They have, alas, lost this physical fortitude long ago, partly because of the doles which they have received.

In South America the Indian race survives. For in spite of our prejudice, “The Spanish Conquest destroyed in order to construct, whereas the Pilgrim Fathers destroyed in order to remove.” So writes W. E. Macleod in “The American Indian Frontier.” The red man has had his passionate apologists in prose and poetry—such varied writers as Fenimore Cooper, Montaigne, Macaulay, Southey, and Byron—as well as his detractors, who accounted him nothing but a common, ferocious beast, and offered a reward for murdering him at sight. General Braddock offered a bounty of five pounds sterling for every enemy’s scalp, “Indian or French,” a special reward of two hundred pounds for the chief Wildcat, and a reward of one hundred pounds for Father Le Loutre, a Jesuit missionary amongst the Indians. The Governor of Pennsylvania in 1756 went further and made special rates, with quotations for female scalps also. Wholesale slaughter of Indians for gold was made legal in 1849. To believe this now is difficult, but the definite policy of extermination was undoubtedly established. One has only to read “A Century of Dishonour” to be convinced of it.[4]

It is an unforgettable fact that Mather, on hearing of a massacre of Indians, thanked God publicly from the pulpit “for sending six hundred more heathen souls to hell.”

The indictment of the reservation system, as administered in the United States, is official and convincing. This story of failure is simply that of this world. No race has yet been long willing to forgo the opportunities of profiting at the expense of a weaker neighbour.[5] The story of Naboth’s Vineyard is no monopoly of the Hebrews. Civilized Greeks and Romans, just as much as Huns and Goths, Kings of France, Spain, and England, every bit as much as the Vikings of Norway and Denmark, were all predatory animals. Neither Kubla Khan nor Emperor William held any monopoly in “coveting their neighbour’s goods.” Students of the Indian side of the problem will find, however, a recent recrudescence of apologists for it, and among them some of their own highly developed people.[6]

The banishment of the Indians to the Bad Lands, which afterwards proved to be rich oil-fields, ended by the American Government having to enforce a law preventing every male adult Indian from having more than a thousand dollars a month. Yet access to everything which money can buy was far from supplying the “elixir vitae” to this race. On the other hand, in the recent endeavour to use them as herders for the reindeer, unlike the Eskimo in the west, they proved a signal failure. The Indian seems to be entirely unwilling to earn his living by any regular work.

Alas, our Indians of the Labrador are equally slow to envisage their real dangers, exactly as when they fought first on one side and then on the other, for no other reward, as it proved, than their own extinction. The good weapons given them only enabled them to destroy the buffalo and other game—their one source of supply of almost everything they needed.

The problem to-day is exactly reversed. The Government no longer considers the Indian a physical menace, but a moral responsibility as the former owner of the country. The survival of any race depends primarily on itself. The Indian has shown himself capable of exhibiting all our virtues as well as our vices. A hundred thousand once warlike Sioux Indians are living happily in Canada, appreciating law and order so well that only a handful of Mounted Police are required amongst them. The Indian beneath his red skin is much the same as we under our white one, but he lacks our background of centuries of education.

The Quebec Government have taken no little trouble to repatriate their Indians on the Côte du Nord. Their endeavours to place him on the land beside the French “Habitants” have, however, so far only confirmed the suspicion that the Labrador Indian is bound for extinction. In spite of the grit of the Montagnais and the Nascopie of the high plateau, firewater, indolence, and other temptations have found them displaying little resistance. The greatest single source of destruction of the Indians has been alcohol. The chiefs of the Aztec Indians, even of the Iroquois, realized this and became the first American prohibitionists; and our traders were the first bootleggers. By the irony of fate, the Latins are to-day returning this compliment to our civilization.

In Labrador the interior seems to offer the only chance left to the Indian. He has never shown any aptitude for competing in sea fisheries. Conservation and adaptation of animal life, coupled with altruistic paternalism, might enable him to hold on there and so justify the Government’s attempts. Naturally the Government feels bound to prevent starvation; but the dole and alcohol destroy the very moral fibre on which the survival of the Indian depends.

|

A. L. Kroeber, Encycl. Brit. |

|

The Bible. |

|

Mackay, “Twenty Years on the Labrador.” |

|

“A Century of Dishonour,” by Helen Hunt Jackson. |

|

“The Problem of Indian Administration,” Institute of Government Research, Baltimore. |

|

“Old Indian Trails,” McIntosh; “The Soul of the Indian,” Eastman; “Indians of the Enchanted Desert,” Crane; “The American Indians and Their Music,” Densmore; “The Downfall of Temlaham,” Barbeau. |

In 1796 Major Cartwright wrote in his famous Journal concerning the Arctic:

“Here the squat-legged Eskimo

Waddle in the ice and snow,

And the playful polar bear

Nips the hunter unaware.”

Of the Labrador he wrote:

“In peace they rove along this pleasant shore,

In plenty live; nor do they wish for more.”

The second race which crosses the Labrador stage is one of thrilling interest. There is little doubt that, like the Indians, the Eskimo came from Asia after the Ice Ages—but probably later, coming in skin boats instead of on foot. No race, Asiatic or European, is to-day quite like them. They can live happily where no other men on earth can exist. They are the world’s best utilitarians. No Eskimo has ever had nervous prostration, and in their simple life they are to-day probably the most contented people on earth. “Me Very Laughing” could well be the legend on their national flag. Their language, called Karalit, is apart from all others; none seems to be related to it. Fifty dialects exist. The words are what one might call “agglutinative,” so that in their poetry or hymns one or two words are all that a line can contain. Thus “merngotorvikangilak” is one line which runs in my memory, as being sung by a dying Eskimo patient who had come south to one of our hospitals. It meant “There will be no sorrow there.”

It is true that they belong to the “great unwashed,” but everyone familiar with them as a medical man will agree with me that it cannot be shown that their physical health suffers in any particular way on that account. In their original snow houses they strip stark naked on account of the heat; and the practice of smearing their bodies with oil and then rubbing it off with birds’ skins, and finally scraping it clean with their “ooloos,” or broad skinning knives, is much easier and more practical than soap and melted ice in their frigid environment. Their habitat is nearer the North Pole than that of any other human beings.

Obliged to be fatalists to a greater or less degree, they are yet individuals as we are. Their love for the family is as “human” as our own. An Eskimo hunter fell ill on the edge of the polar sea just when winter was coming on. To the last he hunted in an heroic endeavour to provide for his wife and little boy. Finally he could do no more. It was obvious that death was near. Day after day, week after week, the wife stayed by and cared for the dying man without thought of herself and child, though she knew that when the end came the nearest spot where help could be obtained lay a hundred miles away. Yet not until she had collected great stones and built a grave and laid her husband in it, together with his clothing and all his belongings, including his rifle, and piled up more stones to protect it from wild animals, did she start with her little son for the almost impossible journey. Though she had four dogs, there was practically no food for them, for the boy had only been able to catch a few foxes in his father’s traps.

Day after day they journeyed, trusting to the dogs to lead them in the right direction. Weaker and weaker they grew. But life is just as sweet near the Pole as near the Equator, and still they struggled on. At last they could go no farther, and apparently had resigned themselves to death when a party from the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Post chanced to find them, “just in time to bring them back to life.” Even to Hudson’s Bay men it was a new vision of the power of love, when they found a tiny, eight months’ baby cooing at the bottom of the sealskin sleeping-bag.[1]

Per contra, two white settlers coming south to the Moravian Mission station for the Easter Feast a few years ago, missed their way in a blizzard and perished. Later it was found that the dogs, which returned after a few days wild with hunger, had eaten the bodies of both the man and the woman.

THE CONTORTED CRUST OF THE EARTH NEAR CAPE MUGFORD

The Eskimo, though racially akin to the Indian, are a much whiter race, the young people being often fair and ruddy. It is quite true that exposure to the weather and the fact that the Eskimo never wash have deceived those who only judge of their natural colour by the older people. Stefansson describes the “blond Eskimo.” Peary’s pictures suggest the same fact. However, there has been much admixture of white blood in some parts of the Arctic.

No study of eugenics can afford to neglect the Eskimo, if only on account of their extraordinary experiment in the extent to which the human body is capable of adaptation. Wherever they came from, their ventures into the Arctic ice-fields are really far more dramatic than was Abraham’s into the Promised Land. Contact with Europeans, our food, clothing, and habits, are found to lower materially the Eskimo’s power of resistance.

Their straight black hair, dark almond-shaped eyes, high cheek-bones and long heads all certify Mongolian origin. It has been said “scratch an Eskimo and find a Tartar,” which in the light of the stories of their retaliation on Europeans was quite credible. In justice, however, it must be remembered that everyone’s hand was against them. Crees and Iroquois drove them to the coast, where the Vikings caught and slew them, as the Sagas tell us. The French pioneers agreed: “L’Esquimau est méchant; quand on l’attaque, il se défend.”

THE KIGLAPEITS, OR DOG-TOOTHED MOUNTAINS

Incidentally, the Eskimo are not all of them small or by any means weak. Only Norse Vikings could refer to them as weaklings, or “Skroelings.” The men are thick-set, very heavy boned, and may be even six feet in height. Early adventurers to Labrador, who carried off all that they caught for slaves, attest that they made excellent manual labourers, when compelled to work.

Once they were spread across forty degrees of latitude and their number estimated to be seventy thousand. In 1891 forty thousand was the total estimate. In 1930 the estimate for all the Eskimo remaining in the world is twenty-eight thousand. In Labrador only about nine hundred remain to-day.

Two thousand years ago there were Eskimo on the west coast of Newfoundland. They had disappeared, however, with few exceptions, before John Cabot arrived in 1497. The last of them, a few half-breeds, left the northernmost point of Newfoundland the year we arrived on the Coast, 1892. That was the fatal year when an American schooner carried off from North Labrador a large party of Eskimo for a side show in the World’s Fair in Chicago. Few returned. One, the little son of the chief, we ourselves picked up two years later, dying of tuberculosis on a stony beach in Nakvak Fjord.

Concurrent with the Eskimo of Newfoundland, who lived by seal hunting, were a race of whale-hunting Eskimo of Hudson’s Bay. Recent discoveries and relics preserved in museums of the Hudson’s Bay Company suggest that three thousand years ago these men used stones in building houses, though without mortar.

Killing whales indicates no small advance in evolution, for it must have been easier to approach a mastodon or a dinosaur on the land, and after launching your attack to escape by hiding, than to pursue “Moby Dick” to his lair in a sealskin boat—a very poor craft in which to be taken for a “Nantucket Sleigh Ride.”

Wood in the extreme north is so scarce that even in Labrador we have seen one of these frail craft with its framework made of fragments of driftwood pegged together with ivory from a walrus tusk. We have also seen bows made of split bone lashed together with deer sinew, coming from Baffin’s Land. The pieces were arched away from instead of towards the hunter, to supply the resiliency of which the bone has none. The arc was kept from breaking by heavy thongs lashed lengthwise both in front and behind the bone.

When they could get it they used the long, drooping horns of the musk-ox, which they split lengthwise and then lashed with thongs in the same way. The bow-string was of sinew. Nothing can be cleverer than the Eskimo hunting weapons. Thus walrus tusks are used to weight their harpoon tops and to carry the iron barbs, when they can get any. Only the barb is attached to the line. It comes loose off the handle directly the animal is struck. The line, which is of seal or walrus hide, runs through a ring, or heavy toggle, attached to the shaft and tusk and prevents their being lost. We brought them out some iron heads from Europe, as they cost so little, but the natives preferred their own brand. The line attached to an inflated sealskin is thrown overboard and easily followed.

Before lines of hemp were brought them they made their own of fine shreds or splits of baleen or whalebone, tied end to end. Their hooks were ivory, weighted with soapstone or with granite tied up in bags woven from the tendons of seals. They also wove nets of the same material and used them to dip up fish, especially capelin, for drying. They would catch ducks and even wild geese with bolas like the Indians of the Pampas, using ivory blocks on the walrus or seal lines. They supplemented the darting stick or spear by clever stone traps put out in the water for trout and salmon.

One of their most ingenious devices is the runner or “shoe” of their sledge. Fine mud is mixed with warm water and plastered on the wooden runner, on to which it instantly freezes. This is smoothed down with a rasp. A piece of bearskin is then moistened and run along it several times until a quarter to a half inch of ice covers the whole length. This enables it to run over snow with almost no friction. If a piece does get knocked off they keep it carefully and freeze it on again.

In my possession I have an arrow made from a bit of driftwood, tipped with a small triangular scrap of rusty iron from the keel of an old wreck, with goose feathers to steady it. With this arrow the owner had walked right up to a polar bear and driven it through his heart. Incidentally this same hunter had drifted for three months on the ice-floe with his family and also that of a friend who had been drowned. There was only himself to provide for the whole number of women and children. They finally landed at Cape Wolstenholme at five o’clock one Sunday night. The Hudson’s Bay Company factor saw them landing and offered to open the store. Extraordinary as it may seem, that Eskimo knew that it was Sunday, and preferred to wait until the next morning to get some supplies. Moreover he and his fellow-voyagers invited the agent to sing a hymn of praise with them on the rocks by the skin tubik as soon as it was pitched. This is another tribute to the Moravians.

“Eskimo” is a name of contempt. In Indian it is “Uskepoo.” In the Cree language “Ashki” means raw and “mow” means meat. Hence the derivation “raw meat eaters.” But although the Eskimo appear to have robust stomachs, it is neither personal preference nor recognition of the superior vitamin values of raw foods which induces them to forgo cooking. More often, as in the case of the Cherub’s explanation to the Archbishop who offered him a seat in the heavenly choir-stall, “Il n’y a pas de quoi.” The Eskimo call us “Kablunak”—the people with the big brow. They consider us inferior animals and think we are descended from the red fox!

On long journeys in his skin oomiak, or women boat, though it allows mighty little spare space, a man will carry three wives (if he can afford them), dogs, a tent, a few seal carcases, and endless other impedimenta! I have seen a wife and children and even dogs being ferried along the Coast both on and in a kayak.

The kayak is the most wonderful boat of its size. It can go through breakers off a flat beach, turn over and come up again, go to windward faster than a four-oared row-boat, jump over another boat, ride almost any kind of sea—and the paddler always faces the way he is going. They are so steady that I have shot geese with a double-barrelled eight-bore gun from one. When you land you pick your craft up and take it home with you on your head. If you are caught in ice you jump on to the floe and pull the kayak up after you.

But to return to the subject of cooking. If we had to substitute a stone lamp for a portable stove, seal oil and moss for alcohol, and instead of using matches had to make a fire by holding the vertebra of an animal in our teeth and with a seal’s rib bow and deer tendon line had to make fire by rotating a dry stick in a rotted bone cavity, would it be long before we preferred to jerk our walrus meat, sun-dry our fish, and eat them raw? I have watched an Eskimo, who had brought a supply of sun-dried walrus meat on board the hospital ship with him, stripping the dry black strips and chewing them with such relish that I tried them myself. I still prefer ham and eggs. As a matter of fact, however, Eskimo do demonstrate that it is correct to say that man is a “cooking animal.” For amongst the very earliest relics of Eskimo life are wonderful stone pots and kettles. Many have been brought to us in Labrador, amazingly hewn out of solid granite blocks, where soft stone has not been available.

Evidence shows that an Eskimo values his large granite kettle as highly as we prize ours of copper or iron. If you or I, with only an Eskimo’s tools, had made such a pot, nothing would have induced us to part with it. Even death failed to part it from an Eskimo owner. Being the most valuable thing he possessed, it was always buried with him, a small hole being bored through it so as to set its spirit free also, so that it might accompany him to the land beyond, which he believed in as naturally and as implicitly as in his home here. What better evidence could be afforded of devotion on the part of his ever-needy family! It is surely more unselfish than the custom of the Chinese of burning only tinsel paper effigies of the belongings of the departed, merely as a symbol of freeing the spirits of the possessions. The similarity of these habits suggests the persistence of a common racial custom.

The best evidence of the value placed on these pathetic tributes to the departed is the fact that to-day, if the kettles are to be taken from ancient graves, something else must be substituted. This is equally true of the stone lamps, stone necklaces, stone knives and arrows, and other tokens of their faith and hope. Their intellects, now that they are Christians, would exempt them from such obligations, but their hearts are in the same place as ours. In graves any distance from the Moravian Mission stations I have seen new rifles, good kayaks, and other valuables still laid in stone caches by the bones of the departed loved one. I once sent two Eskimo to get some old stone kettles from a burial cache inland. We had to supply something to put in the place of the things they took, and happened to be in possession of a number of old razors. As Eskimo do not have hair on their faces these implements seemed scarcely appropriate to appease the spirit even of a good-natured Innuit. But my messengers were perfectly satisfied with them.

Similarly nothing would persuade many of my British neighbours on the Labrador Coast that a seventh son, or the seventh son of a seventh son, cannot cure almost anything; exactly as His Britannic Majesty used to heal “The King’s Evil” by his touch. Indeed, close to one of our hospitals there dwells now just such a seventh son, who is often called in before sending for the doctor, to stop bleeding or “heal an evil.”

On the other hand, in suffering or bereavement, the Eskimo show remarkable fortitude and resignation. On one occasion one of the leading Eskimo at Hopedale had been reloading the cannon with which they welcomed each year the arrival of the Moravian supply-ship Harmony, when it exploded and blew off both his arms. Before I saw him he had lain for a fortnight with practically nothing but cold-water dressings on his wounds. The awful pathos of the man’s suffering led me to try to sympathize with him. With a bright smile he replied, “It is nothing to what my Saviour suffered for me.”

Another time, an Eskimo was showing me the spot where, as he and his brother returned in a very rough sea in their kayaks, his brother capsized and was drowned. “Did you try to rescue him?” I asked. He shrugged his shoulders. “But why not?” “Ajaunamat,” he replied with a further shrug. “Ajaunamat” is their equivalent for “kismet.”

Like all human beings, the Eskimo had certain men to whom to go in times of sickness and trouble. Before the advent of the Moravian Mission these men, called Angekoks, acted as sorcerers. There were no priests among the Eskimo, for though a deeply religious people they had no kind of worship. To them everything had a spirit, even an iceberg or a tobacco pipe. Their gods were many. The mother of all seals lived in the moon, and when properly invoked by the Angekok (who had to be well paid) would drop a seal in their bay to lure others to that harbour. The father of all caribou lived in the centre of the earth, and could be propitiated in the same way. Tongak was the evil spirit of the sea. The story goes that the mother of storms lived in the ocean, whither she had run away to spite her father. In return he had cut off her fingers, which came to life as great animals of the deep.

Comparing the Eskimo of the south with the old whale-hunting Eskimo of the north suggests an evolution which must have occupied a longer period of time than even our most vivid imagination can picture—possibly ten thousand years. There is evidence that the Eskimo did not always follow the sea, though to-day not one of ours lives a hundred miles from it. A race existed in the Barren Lands of Canada which lived chiefly off the vast herds of caribou which fed on the arctic prairies—a multitude which has never been equalled in the world except by the buffalo of the west. Photographs taken as late as 1890 of Eskimo west of Hudson’s Bay, dwelling on these arctic prairies, show them dressed only in skins, without any weapons but flints, living in skin tents, never having had contact with civilization, and apparently unacquainted with anything which could connect them with the world outside.

Polar Eskimo discovered in the present ice cap the “cold-stored” carcase of mammoths which perished in the last glacial period, fully ten thousand years ago. They actually partook of soup made of the flesh, preserved in a manner that is a forerunner of the justly famous Birdseye Frosted Foods process.