* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: First Things in Acadia, "The Birthplace of a Continent"

Date of first publication: 1936

Author: John William Regan (as John Quinpool) (1873-1945)

Date first posted: May 14, 2021

Date last updated: May 14, 2021

Faded Page eBook #20210527

This eBook was produced by: Mardi Desjardins, Howard Ross & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

Reproduction by kind permission of the artist, from the painting by Ernest Board, R.O.I., R.W.A., now in Bristol, Eng. Municipal Art Gallery.

Discovery of America—Departure of John and Sebastian Cabot, from Bristol, Eng., May 2, 1497, in ship “Matthew.” They landed in Nova Scotia (Acadia) June 24, 1497.

FIRST THINGS

In Acadia

“The Birthplace Of A Continent”

(NOVA SCOTIA, NEW BRUNSWICK, PRINCE EDWARD

ISLAND, PARTS OF MAINE, QUEBEC, NEWFOUNDLAND)

By

JOHN QUINPOOL

Copyright 1936. All rights Reserved

FIRST THINGS PUBLISHERS LIMITED

Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada

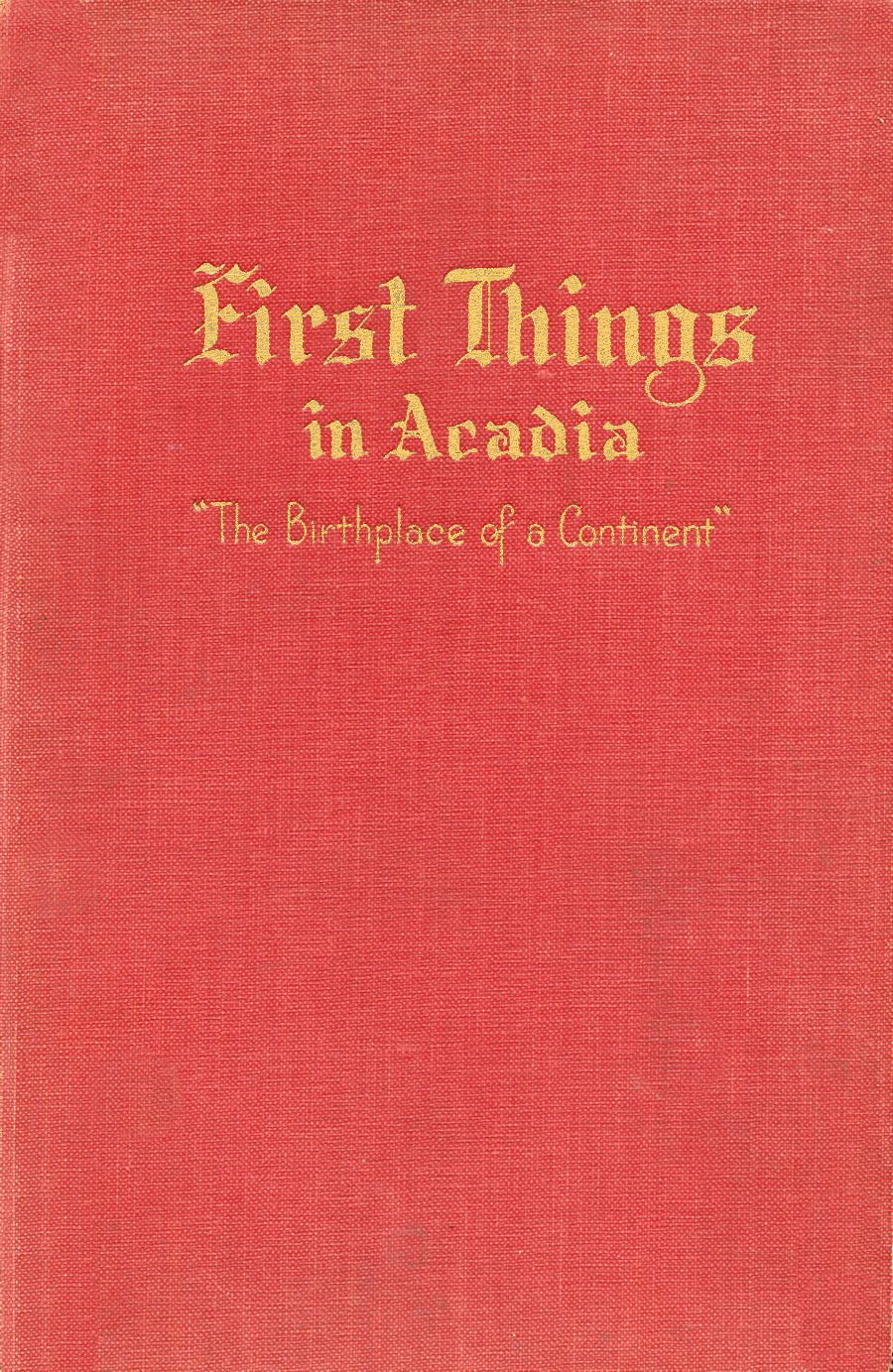

Map of North Atlantic Ocean,—Voyages of Cabot and Columbus are shown—An inset in lower right-hand corner is an enlargement of a section of Sebastian Cabot’s world map, 1544, with the legend “Prima Tierra Vista”, the first land seen, near Cape North, Cape Breton, “Acadia.”

This Volume

is dedicated by permission to

His Excellency The Right Honourable

Lord Tweedsmuir

G.G.M.G., C.H.

Governor-General of Canada.

1936

| Page | |

| Editor’s Introduction, Page 10; Acknowledgments | 304 |

| “Acadia,” origin of name | 48 |

| Agriculture, its birthplace in North America | 266 |

| Agricultural Fair, Windsor, N. S., first in Canada | 105 |

| A Lost North Atlantic Continent is confirmed | 20 |

| “America,” source of name is in doubt | 16 |

| America, Discovery of the Continent in “Acadia” | 24 |

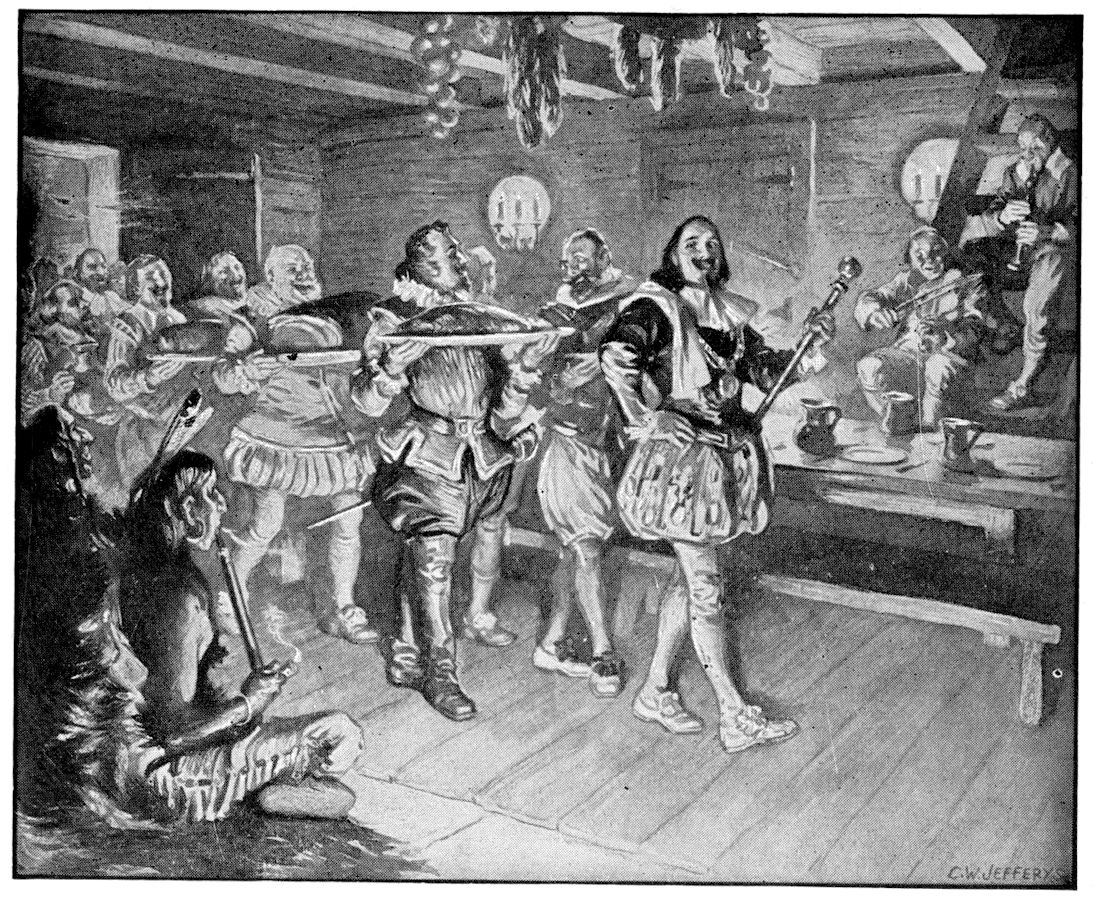

| America’s First “Social” clubs, pp. 107 and | 61 |

| American “Royalty” in London | 74 |

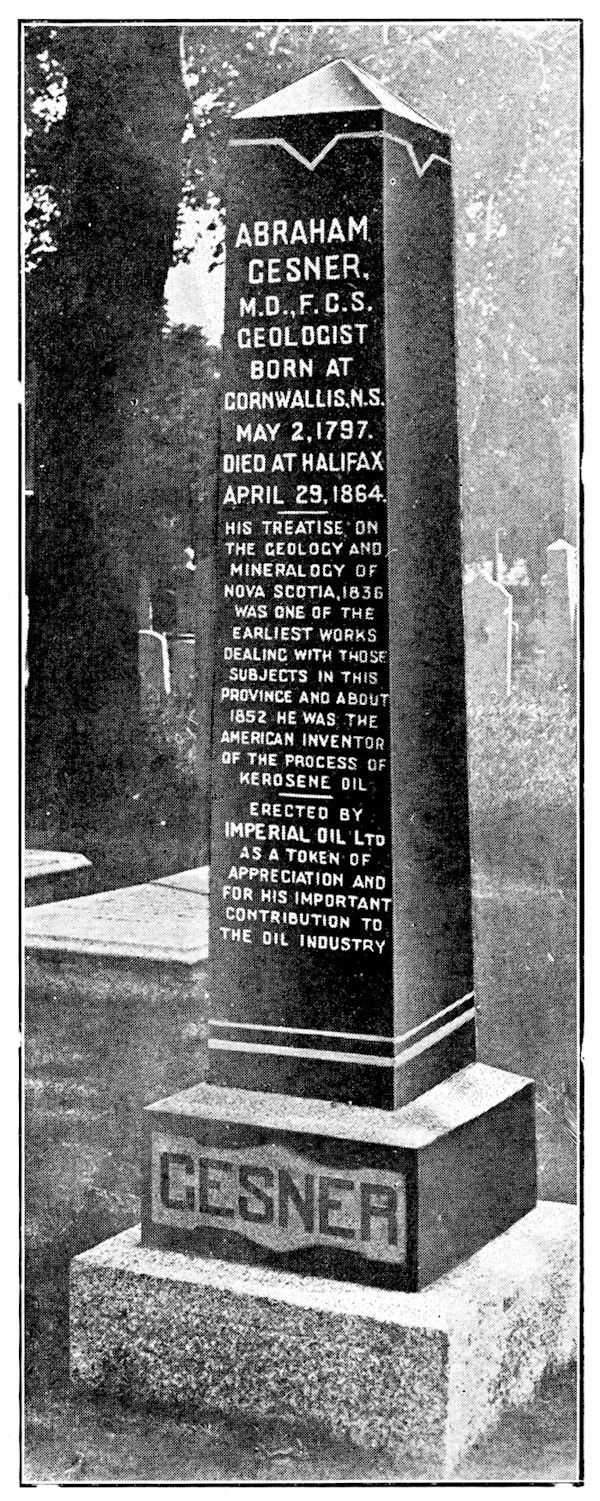

| America’s First Oil Industry Monument, Gesner | 229 |

| Anglican Bishop in North America, the first | 285 |

| Anglican Colonial See, first in British Empire | 190 |

| Anti-Slavery Proclamation, the first liberation | 278 |

| Apple Orchards of “Evangeline,” first in N. A. | 259 |

| “Associated Press” Firsts, were in Nova Scotia | 125 |

| Aviation, first in the British Empire | 202 |

| Baptist Church, first in Dominion of Canada | 88 |

| Baptist University, the pioneer in Canada | 104 |

| Baptism of Indian Nation commenced in “Acadia” | 219 |

| Beaver’s Appearance in Heraldry in Scotland | 213 |

| Bible Society, First in North America | 91 |

| Board of Trade, Halifax, oldest in North America | 115 |

| Boundaries of “Acadia,” first that were definite | 42 |

| Buddhist Pacific Migration was anticipated | 25 |

| Canadian Casualty in Boer War, first to fall | 132 |

| Cartier’s Primary “Acadian” Landfall | 270 |

| “Cathedral City,” Fredericton, First in North America | 80 |

| Chocolate factory, first Canadian production | 84 |

| Coal in North America, first discovered in “Acadia” | 137 |

| Columbus’ voyages summarized | 26 |

| Covered Ice Rink, the first and source of hockey | 83 |

| Curling on Ice, “Firsts” in the Scottish game | 85 |

| Deathless Song, Home, Sweet Home, linked to “Acadia” | 288 |

| Distillery in Canada, first was in Halifax | 245 |

| Divorce Court, first in Canada in Nova Scotia | 242 |

| Domestic Animals, dogs, chickens, sheep first reported | 75 |

| “Empire Premier,” first was Andrew Bonar Law | 141 |

| “Empire Day,” first officially approved in Nova Scotia | 152 |

| English Governor of “Acadia,” first a Scot, Col. Vetch | 282 |

| Explorers, chronology of early American navigators | 39 |

| First Air Conditioning devised by Simon Newcomb | 289 |

| First American Zoo was in Nova Scotia | 273 |

| First American Abolitionist, W. L. Garrison | 73 |

| First Dry Land in the Western Hemisphere | 19 |

| First “Monroe” Doctrine cut through “Acadia” | 82 |

| First Nova Scotia London Agent, a dramatist | 275 |

| First U. S. Consulate in British North America | 71 |

| First Winter Marching in New Brunswick | 23 |

| First Shots in a Long War, 1613-1763 | 74 |

| Fur Trade and Fisheries of N. A., first century of | 107 |

| Gold from South Africa minted in Canada | 153 |

| Halifax Explosion, 1917, Boston first to respond | 153 |

| Horses and cattle, first in North America in “Acadia” | 76 |

| Incorporated City, Saint John, first in Canada | 68 |

| Insurance, first Fire and Marine business | 114 |

| Iron Bridges, first made in Canada at Dartmouth | 72 |

| Iron and Steel, first Canadian production in Nova Scotia | 253 |

| Libraries, first in North America in “Acadia” | 111 |

| Life Insurance, first President a Nova Scotian | 112 |

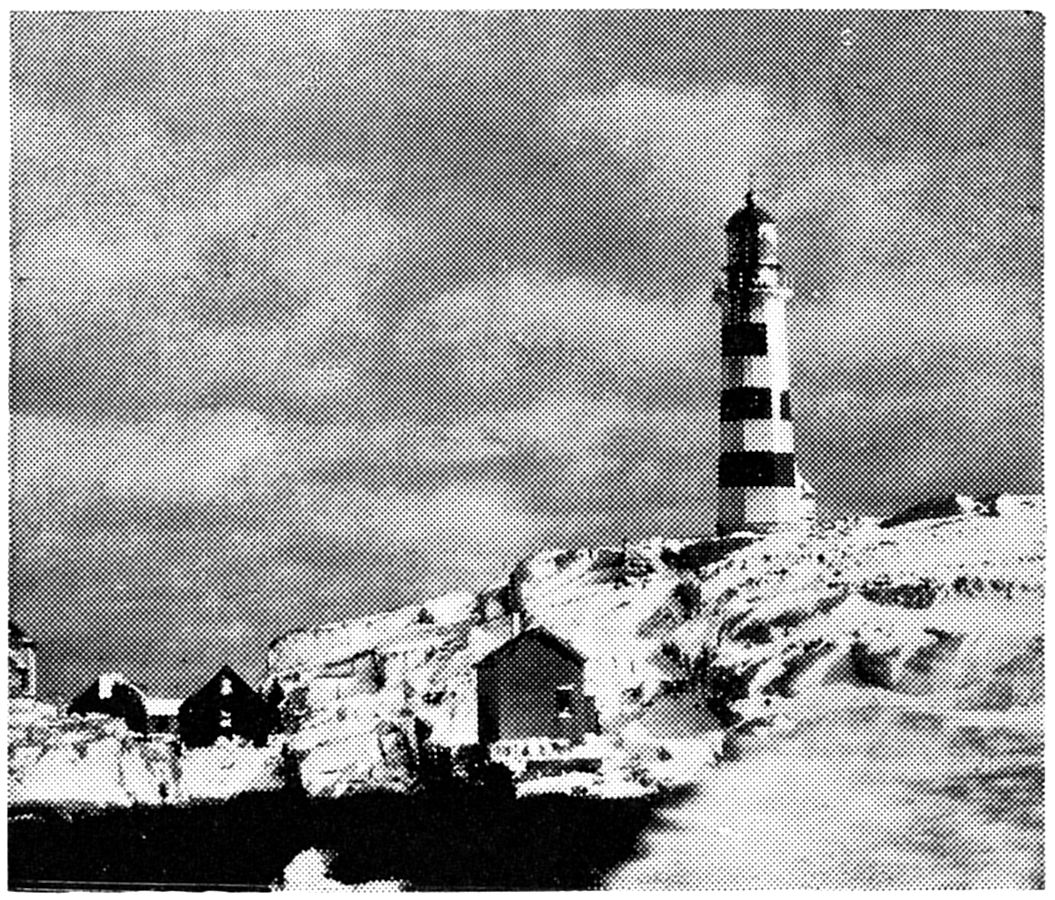

| Lighthouse, first in Canada at Louisburg, 1731 | 271 |

| Lobsters, world’s finest, first in the West in “Acadia” | 250 |

| Longfellow in “Acadia”, poet visited Cape Breton | 224 |

| Lotteries, first authorized in Dominion of Canada | 79 |

| Lutheran Church, the first in Canada | 95 |

| Mass in the Air, first in the “Acadian” zone | 222 |

| Methodist Church in Canada, first was at Halifax | 98 |

| Military Events, first British regulations in Canada | 86 |

| Military Monument, first in Canada, has disappeared | 269 |

| Missionaries, first Canadians sent to Foreign Fields | 89 |

| Missionary, the first in America, Leif Eiriksson | 34 |

| Miscellaneous “Firsts”, 150 separate items | 144 |

| Moose River Mines assigned to oldest formation | 19 |

| National Societies, first in Canada | 81 |

| Negro V. C., a Nova Scotian the first in the world | 236 |

| Newspaper, oldest in North America | 120 |

| Newspaper, first in Prince Edward Island | 122 |

| Oldest Dissenting Congregation in B. N. A. | 89 |

| Overseas Judge, first Colonial on the British Bench | 241 |

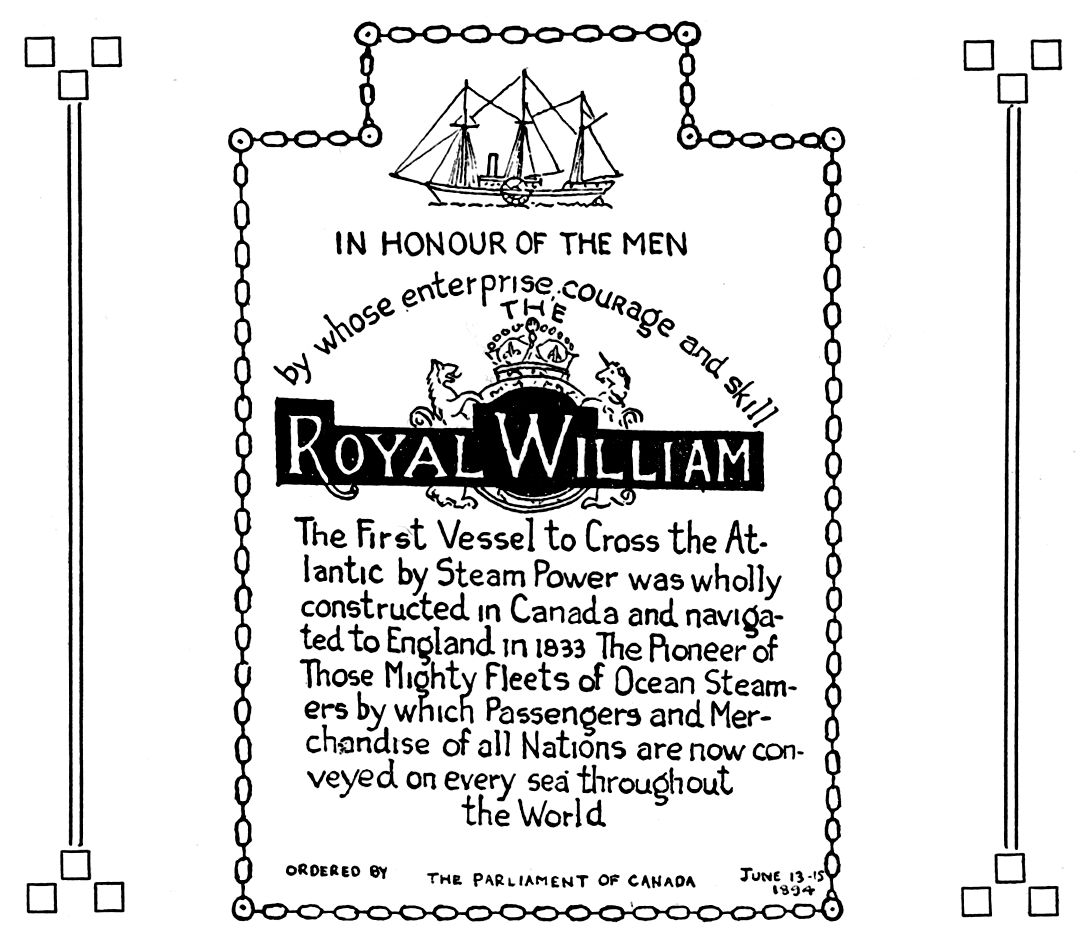

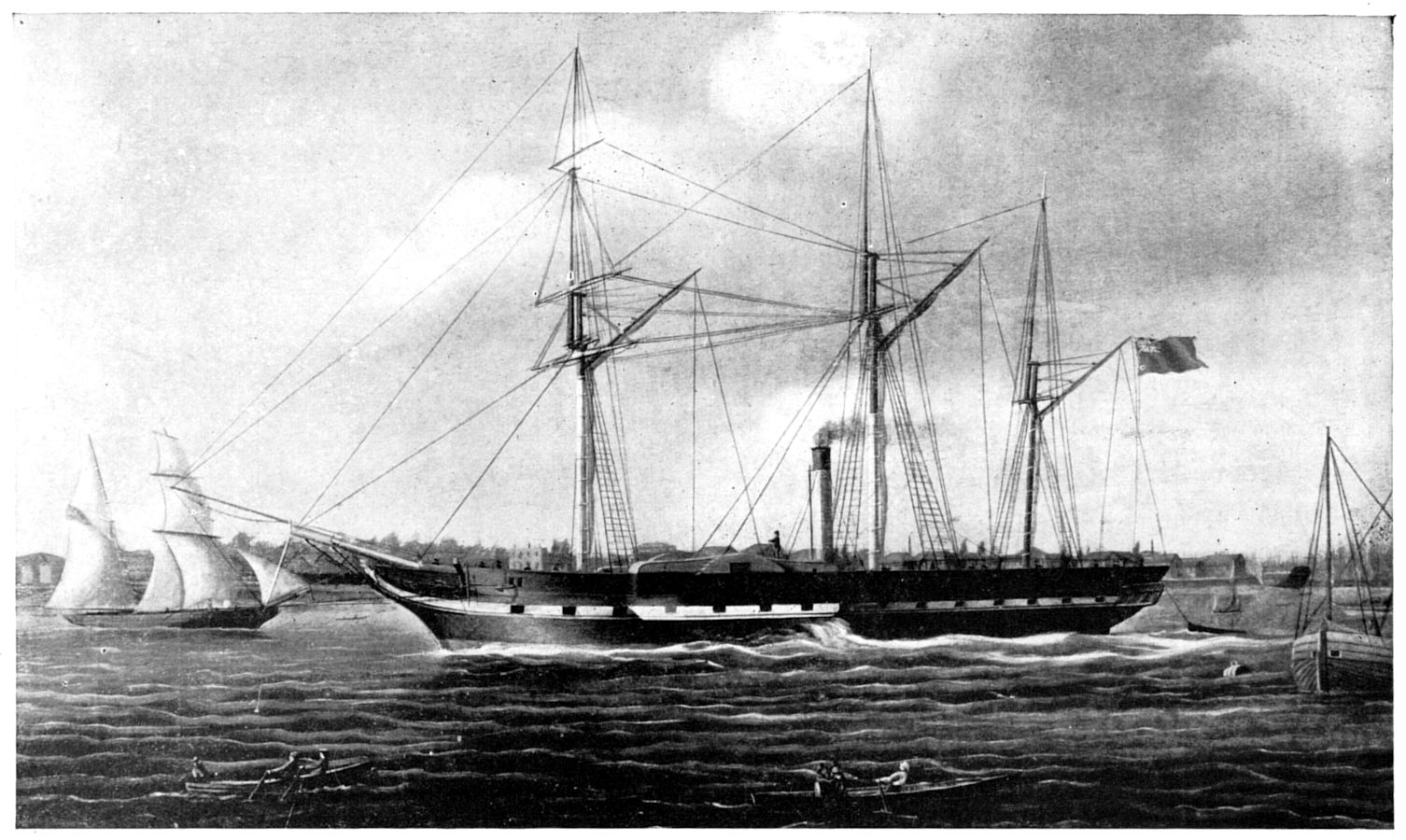

| Pioneer of Mighty Fleets, “Royal William” | 184 |

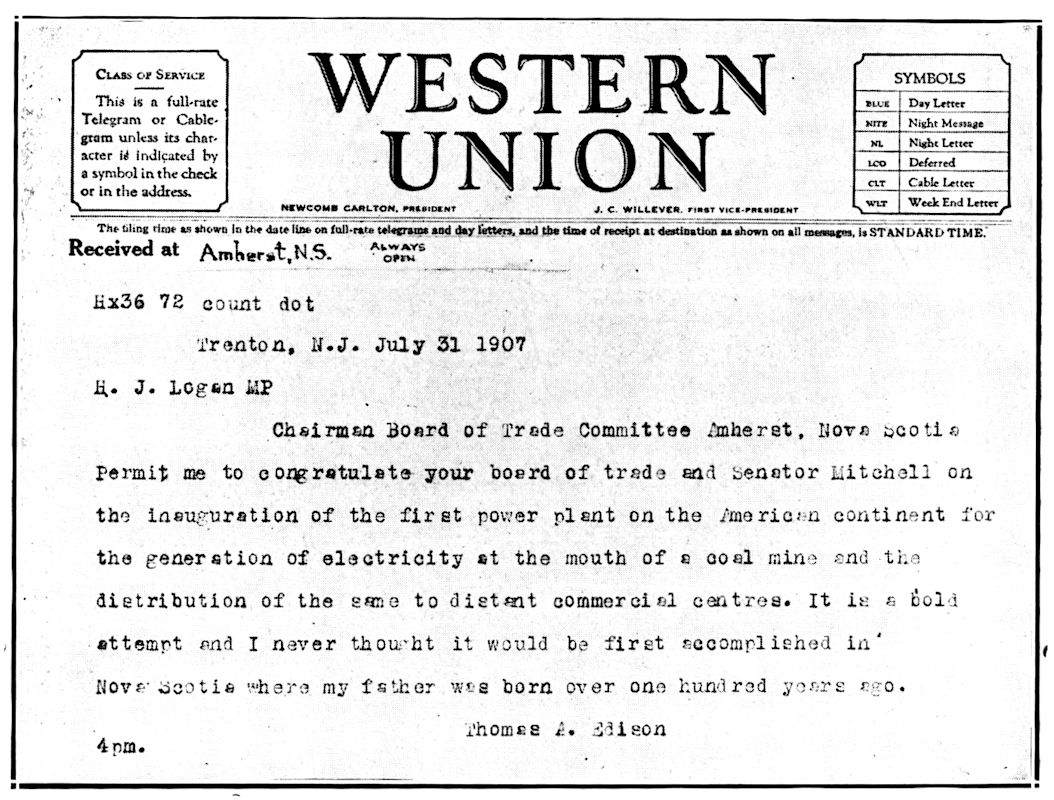

| Pit-mouth Coal-Electric, first in North America | 226 |

| Polar Wireless, the first in 1909 | 159 |

| Post Office, first Canadian office at Halifax | 117 |

| Press Association, first operated in Nova Scotia | 127 |

| Printed Book, first in Canada in Nova Scotia | 124 |

| Priest, first “Acadian” to be ordained | 216 |

| Printing Press, first in Canada | 129 |

| Prime Minister, first British Executive to visit Canada | 281 |

| Presbyterian Services, first in Canada were Huguenot form | 63 |

| Protestant Church, oldest in Canada, St. Paul’s | 193 |

| Quakers in Canada, first were in Nova Scotia | 93 |

| Quintuplets, first reported in Canada at Pictou, N. S. | 151 |

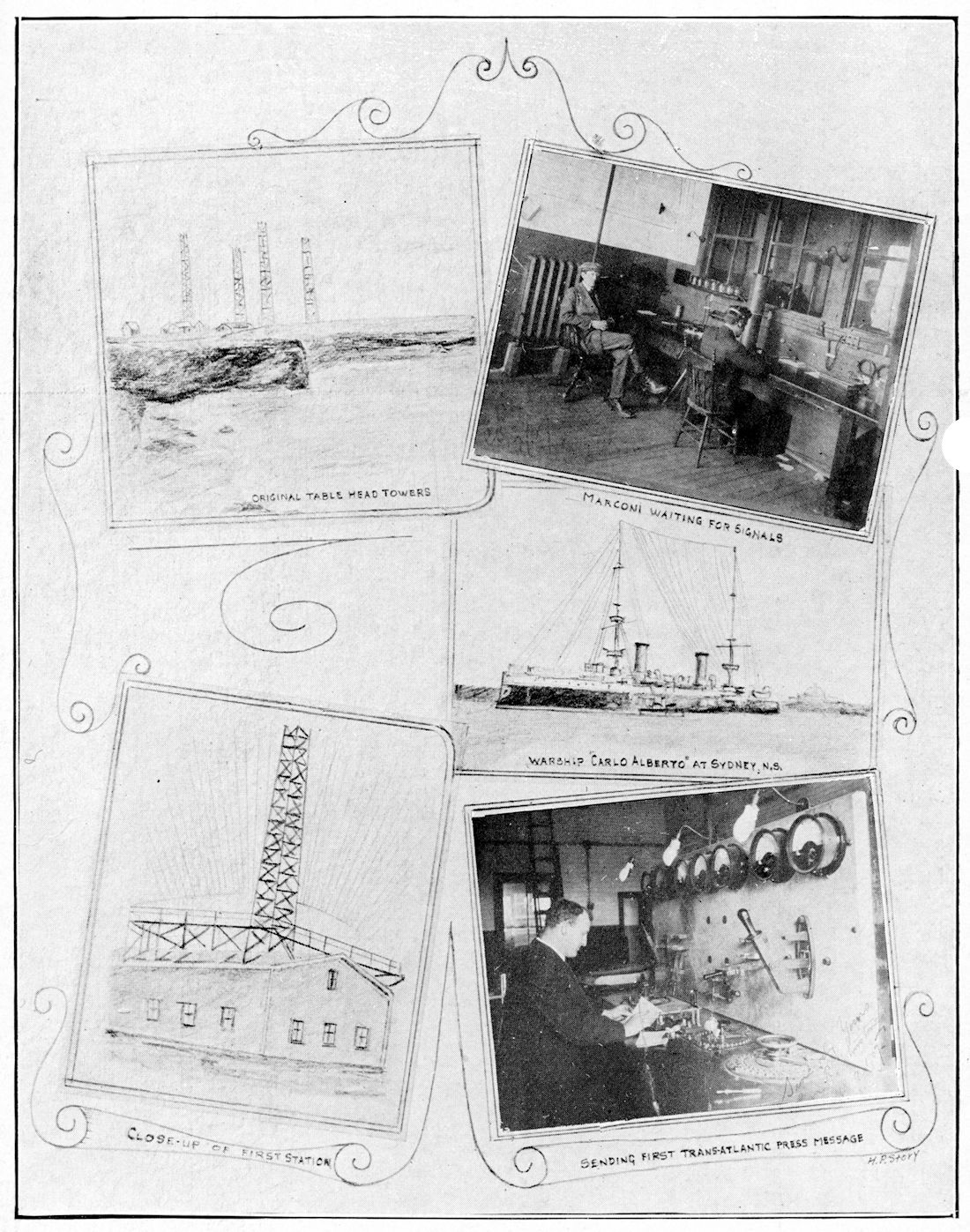

| Radio, first transatlantic station in Cape Breton | 161 |

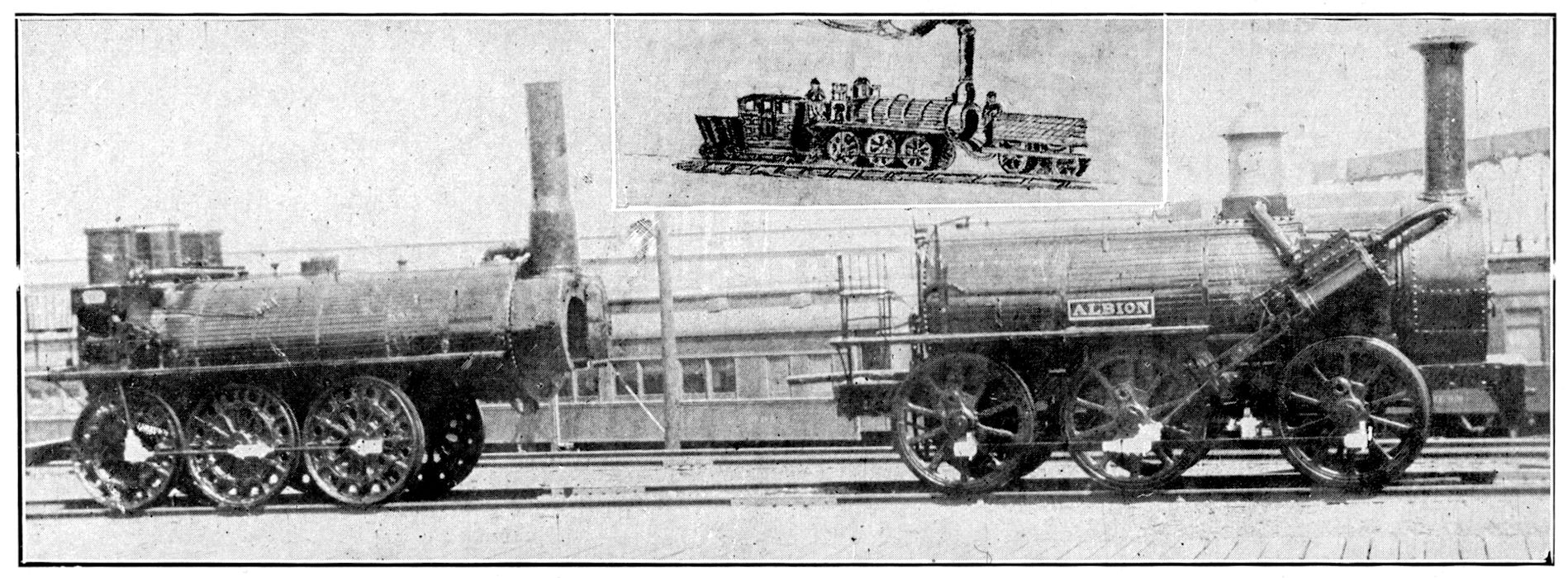

| Railways and all-iron rails, first Canadian | 262 |

| Rail and Telegraph “Firsts” in “Acadia” | 51 |

| Responsible Government commenced in Nova Scotia | 232 |

| Round-the-world messages, the first efforts | 157 |

| Royalty Visits to North America, a complete list | 53 |

| Savings Bank, first Government institution | 109 |

| Sable Island, first accounts give 100 miles length | 76 |

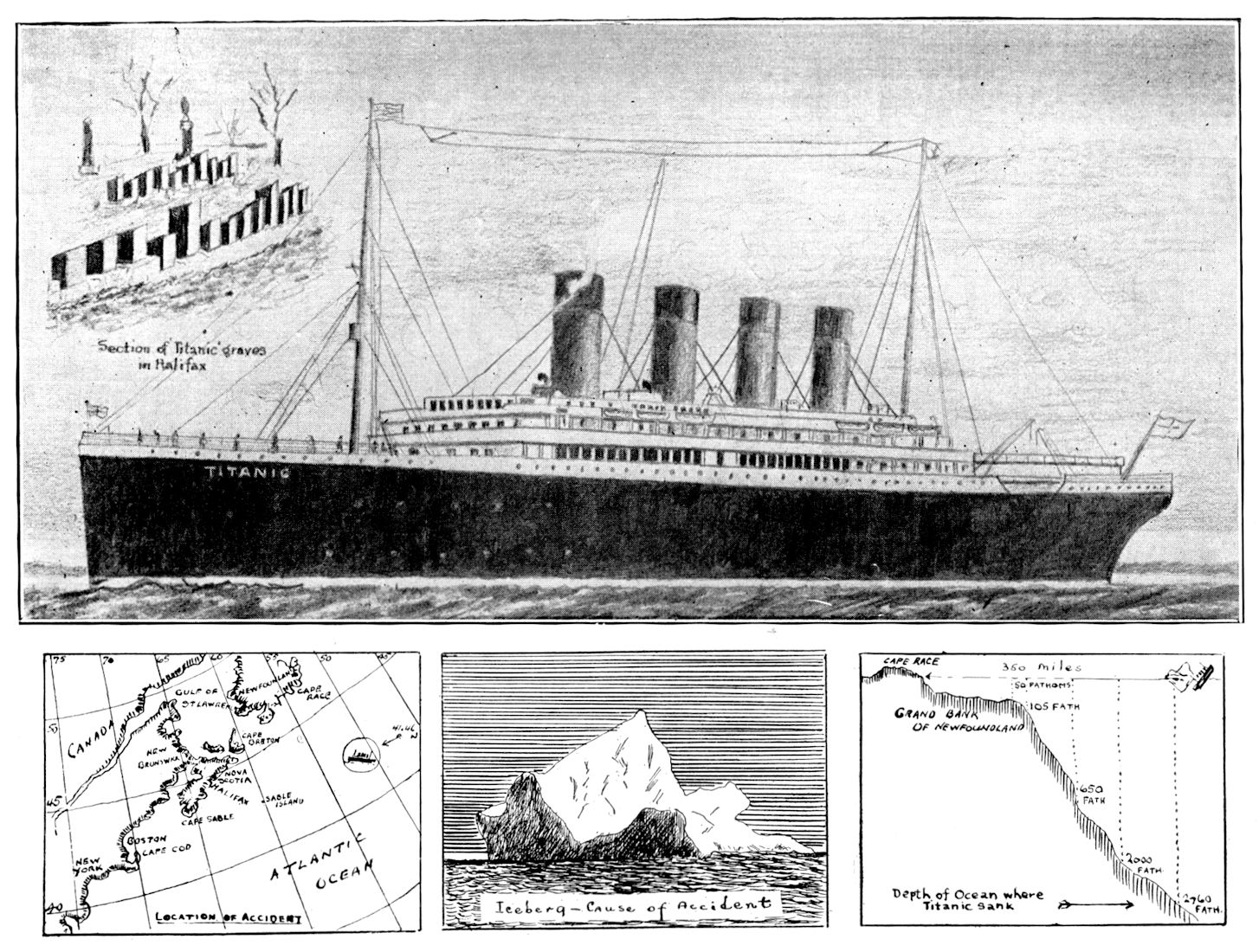

| “Sea Gave up the Dead,” Titanic disaster | 134 |

| Sedition Deportee, the first was a printer | 84 |

| Settlement, the oldest mainland colonization | 210 |

| Shipbuilding, earliest attempts in North America | 254 |

| Spring Skates, first in the world | 78 |

| Square and Compasses, first Canadian Masonry | 256 |

| Steamship, first Cunard, S. S. “Unicorn” | 176 |

| Standard Time commenced in Nova Scotia | 151 |

| Submarine Telegraph, first in North America | 155 |

| Supreme Court, first in British Empire | 239 |

| Swedenborgians, first branch in Canada | 94 |

| Telephone, first commercial system in the world | 170 |

| Tennis, first in Canada had unusual results | 198 |

| Thanksgiving in English, the first in Canada | 195 |

| Theological Seminary, Pine Hill, Halifax, a pioneer | 102 |

| Transoceanic Cable, first was promoted in “Acadia” | 292 |

| “Union Jack,” was a Scottish King’s decree | 12 |

| University Charter, first in Canada, King’s, N. S. | 101 |

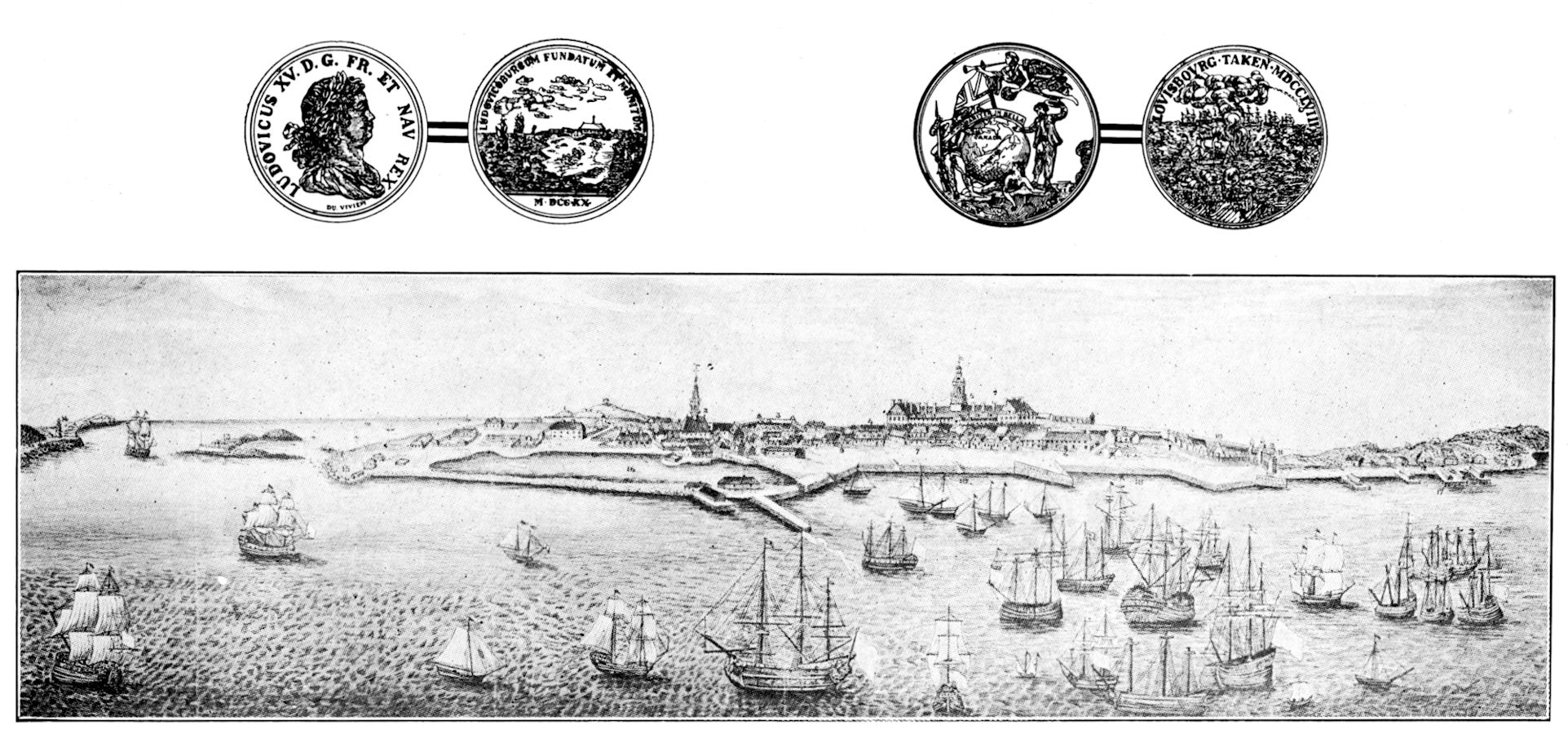

| Walled City, Louisburg, first in North America | 274 |

| Walrus Fishery has become extinct in our time | 87 |

| Washington’s First Portrait by Gilbert Stuart | 81 |

| What’s in a name?, query re North-East America | 301 |

| Wireless Operator, the first regular despatcher | 167 |

| Women College Graduates, the first in Canada | 103 |

| Women College Graduates, the first R. C., in N. A. | 223 |

| Yacht Squadron; Quoit Club; first and oldest | 71 |

| At Page | |

| Acadians, first priest and church after “Expulsion” | 161 |

| Agricultural Fair, first in Canada | 105 |

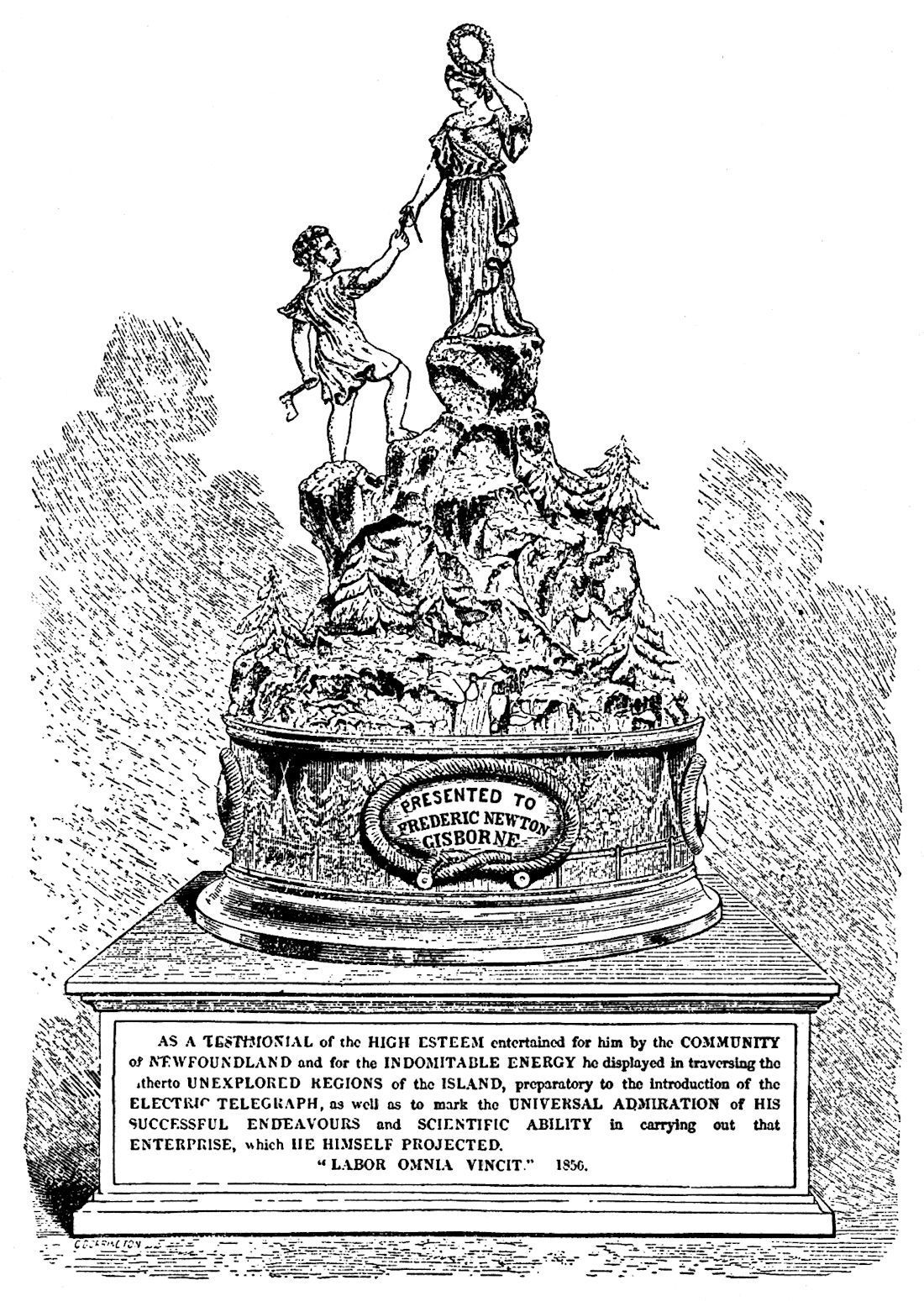

| Atlantic Cable statuette presented F. N. Gisborne | 300 |

| Astronomy, Simon Newcomb memorial | 290 |

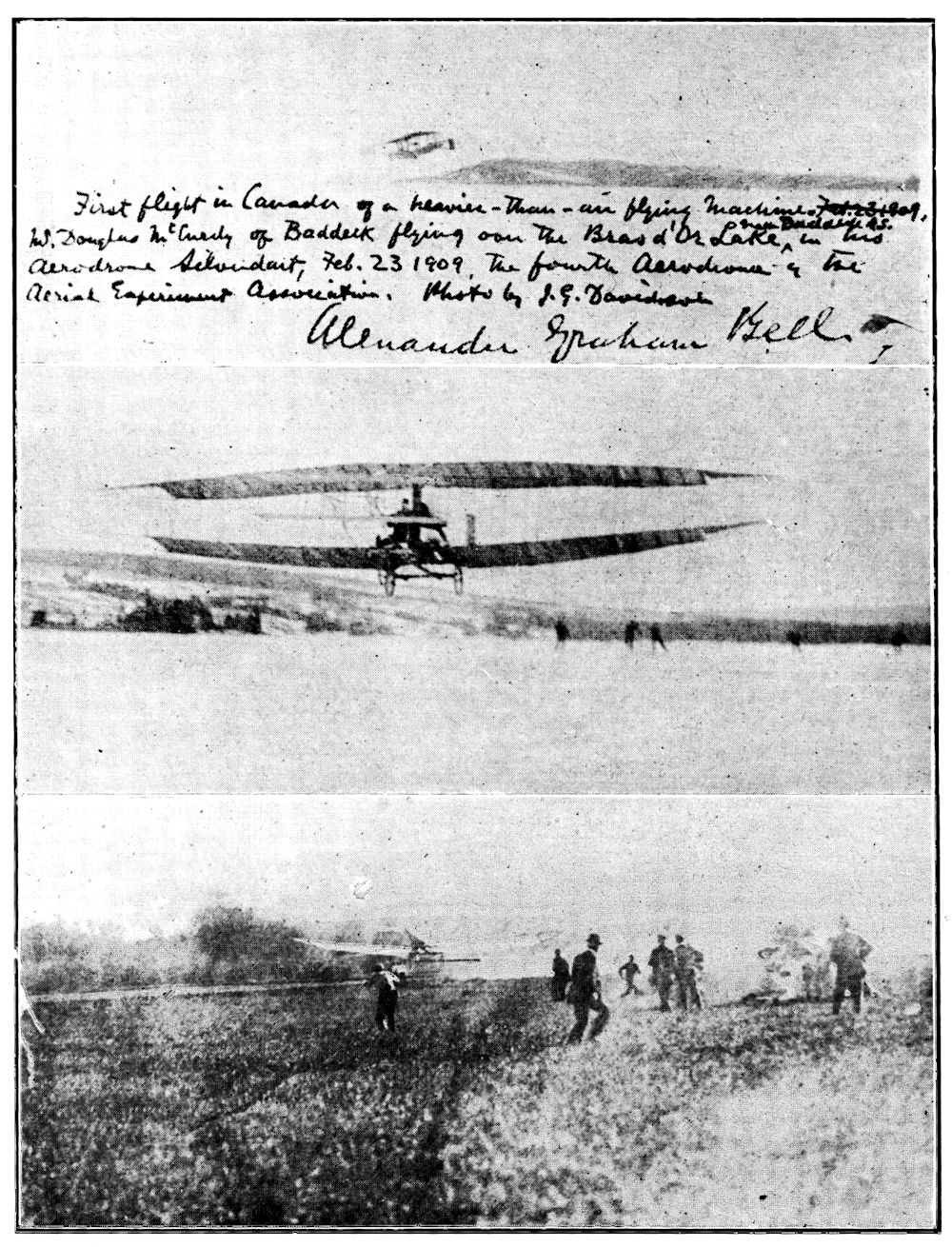

| Aviation, Prof. Bell’s record telegram | 203 |

| Aviation, First Flights, two pictures, at pages 224 and | 225 |

| Baptism of Indian Chieftain and family in Acadia | 220 |

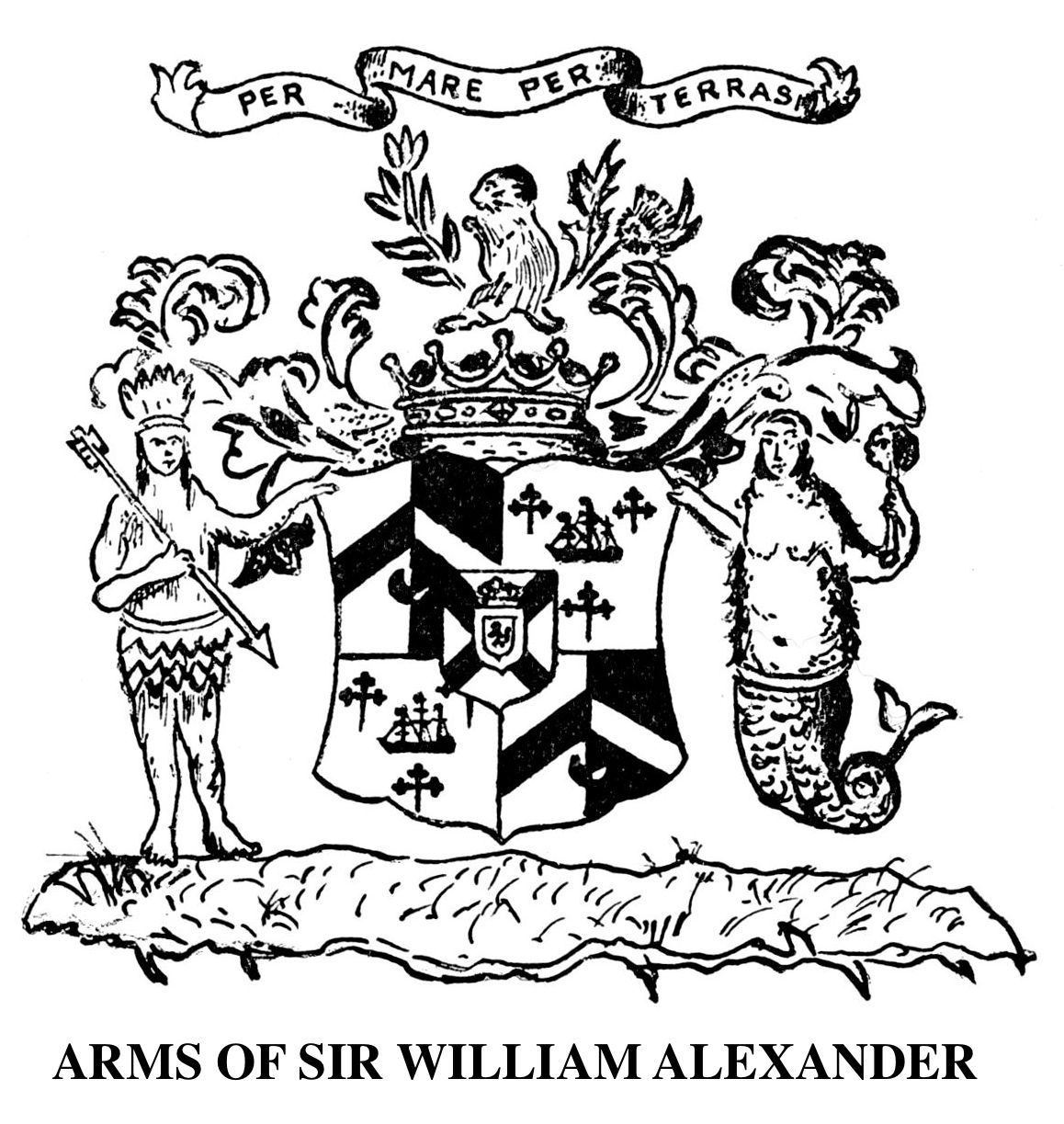

| Beaver Crest, first use in European heraldry | 215 |

| Belcher, Hon. Jonathan, first Chief Justice | 288 |

| Black, Rev. (Bishop) William, Apostle of Canadian Methodism | 240 |

| Boundary Mark, Perry, Maine | 67 |

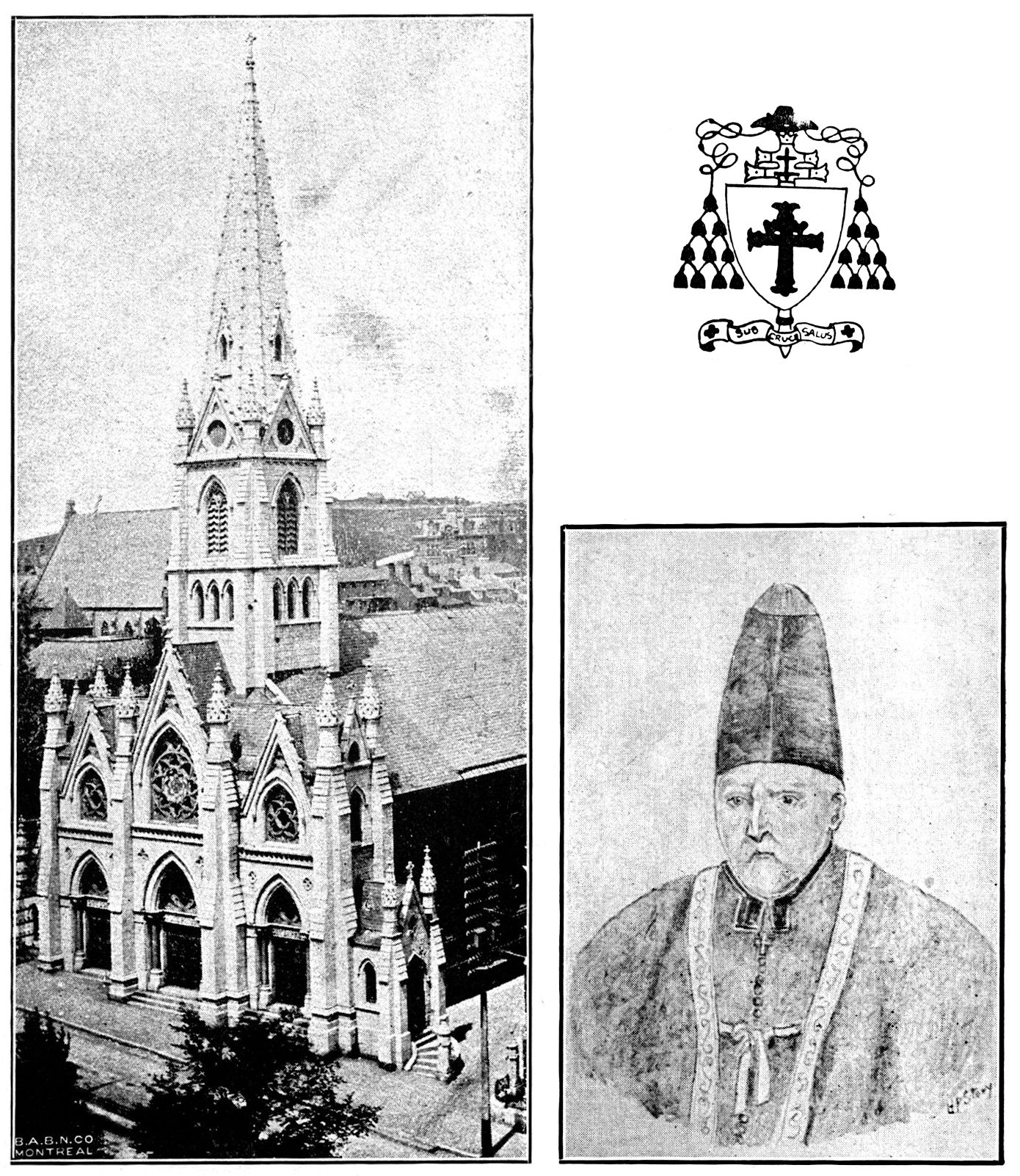

| Burke, Rt. Rev. Edmund, first English speaking R. C. Bishop | 160 |

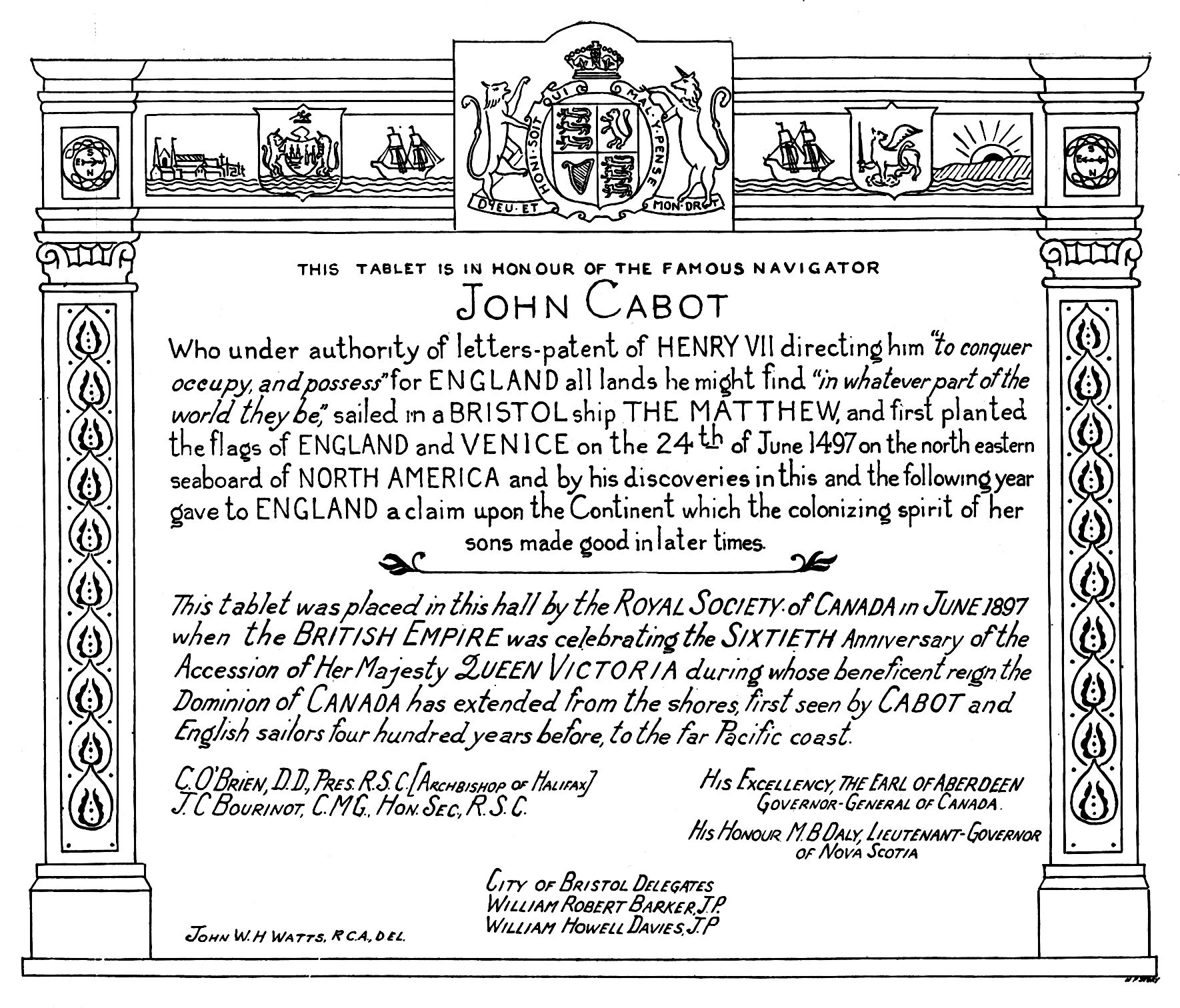

| Cabot Tablet, Halifax | 32 |

| Cabot, sailing from Bristol Colored Frontispiece | |

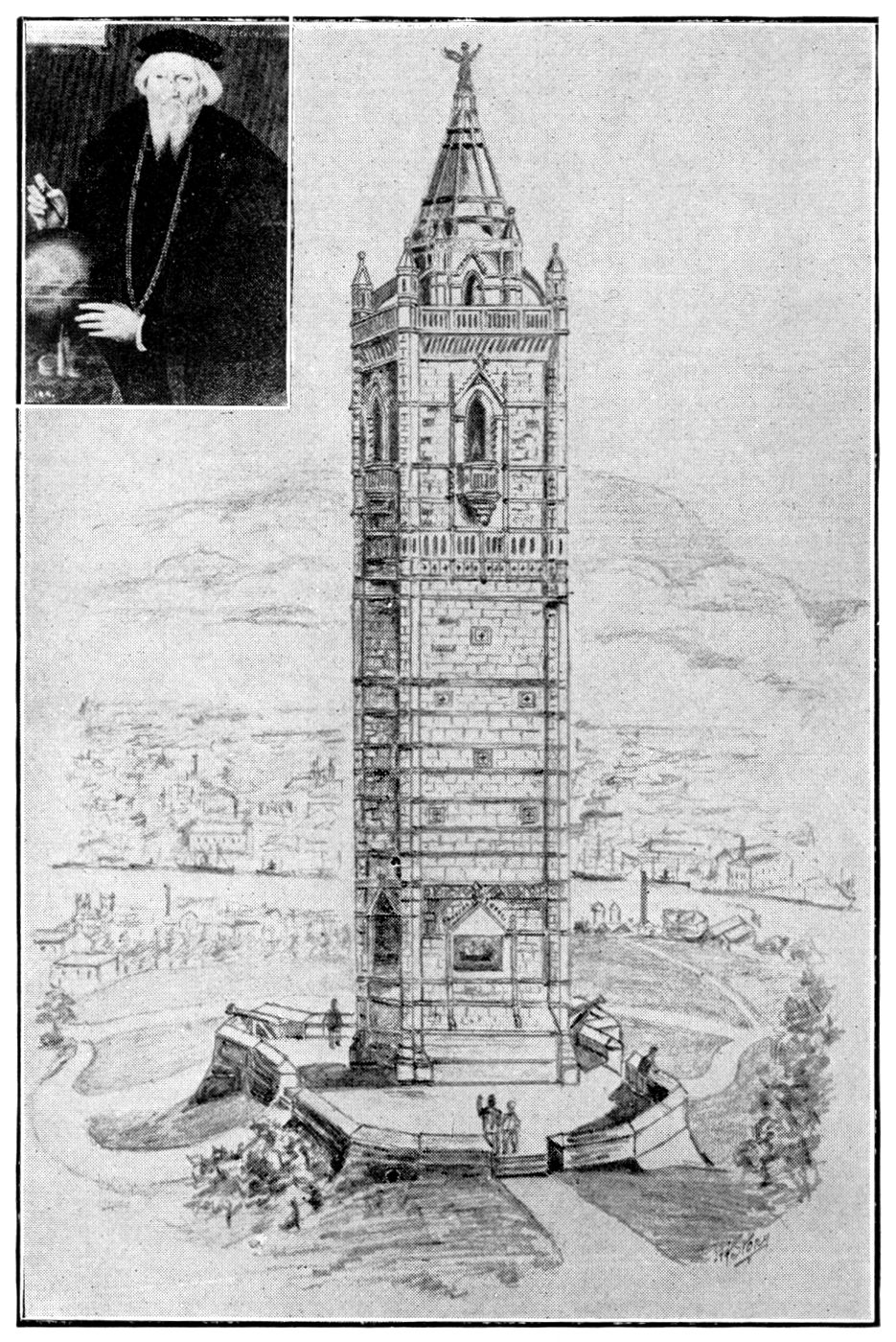

| Cabot, Sebastian | 33 |

| Cabot ship “Matthew” | 131 |

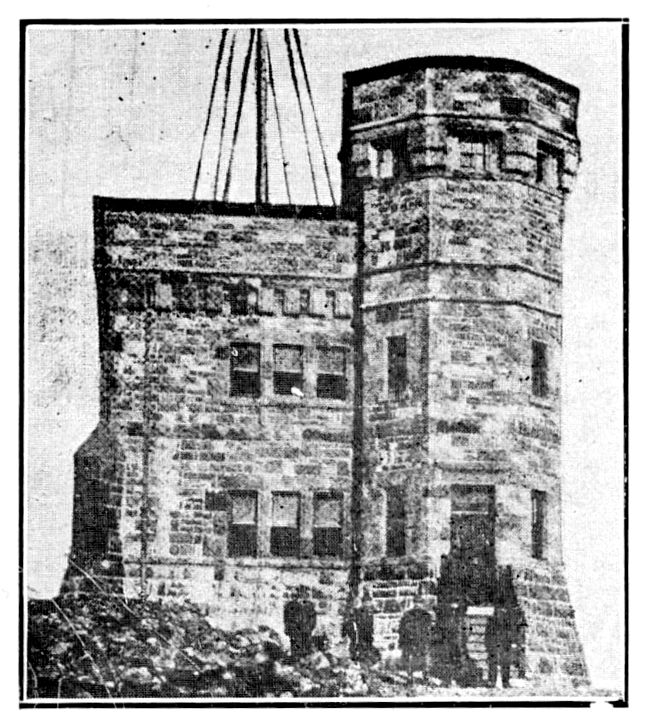

| Cabot Towers, Bristol and St. John’s, Nfld., at pages 33 and | 194 |

| Cartier’s Acadian Landfall | 129 |

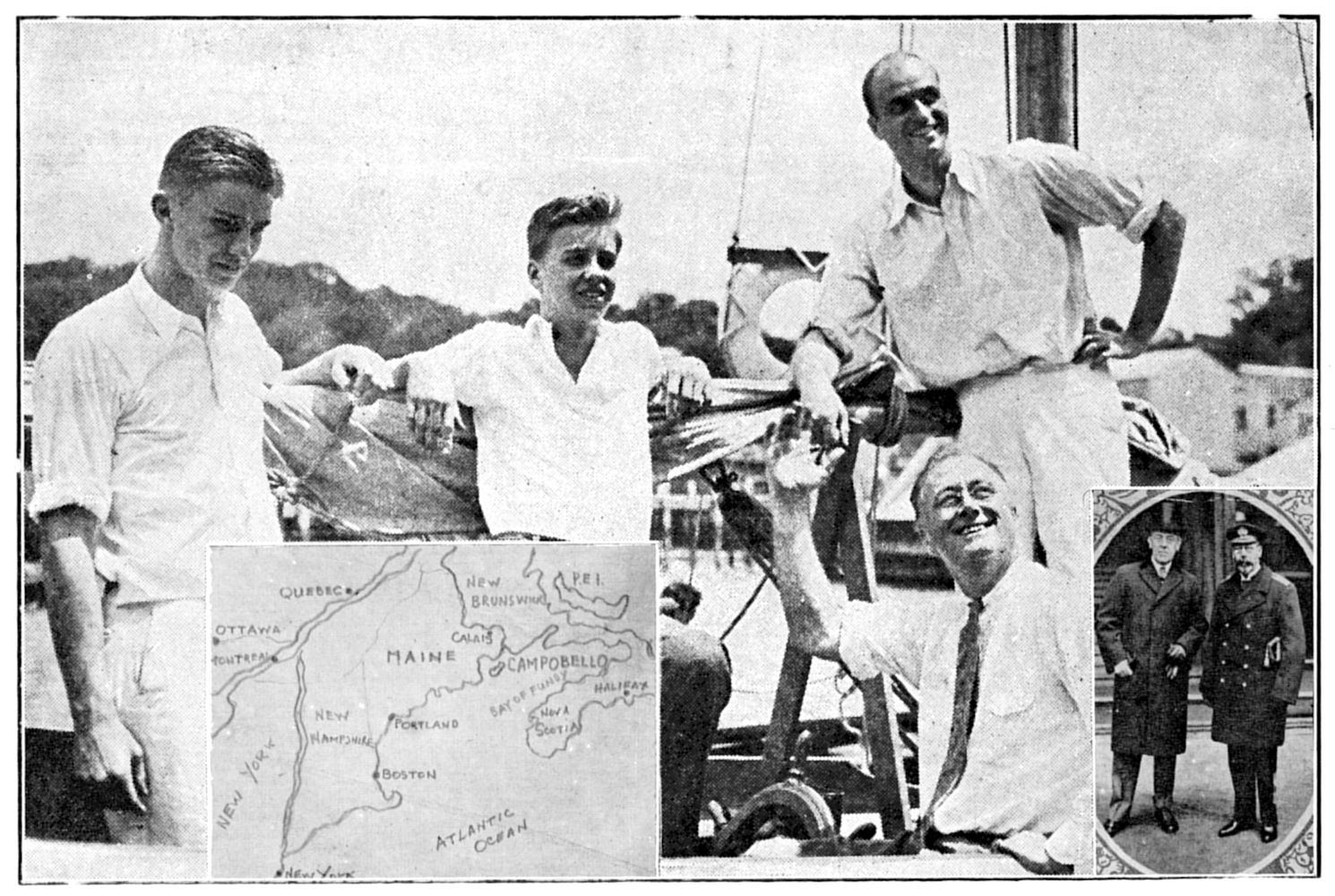

| Campobello, President Roosevelt’s “Acadian” summer home | 64 |

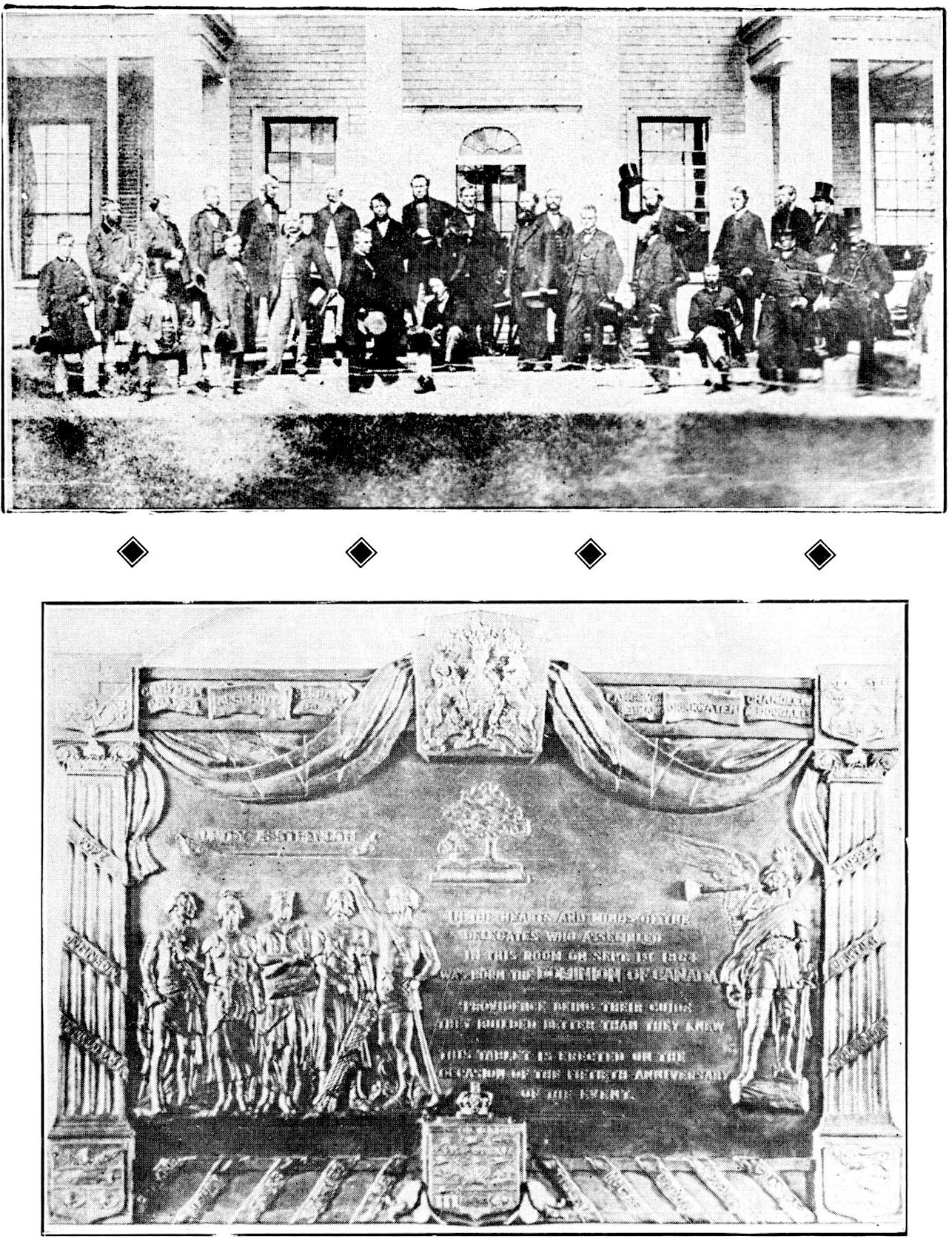

| Canadian Confederation, Golden Jubilee, Charlottetown | 282 |

| Courts of Law, first in Canada in “Acadia” | 244 |

| Confederation of Canada, first conference in P. E. I. | 209 |

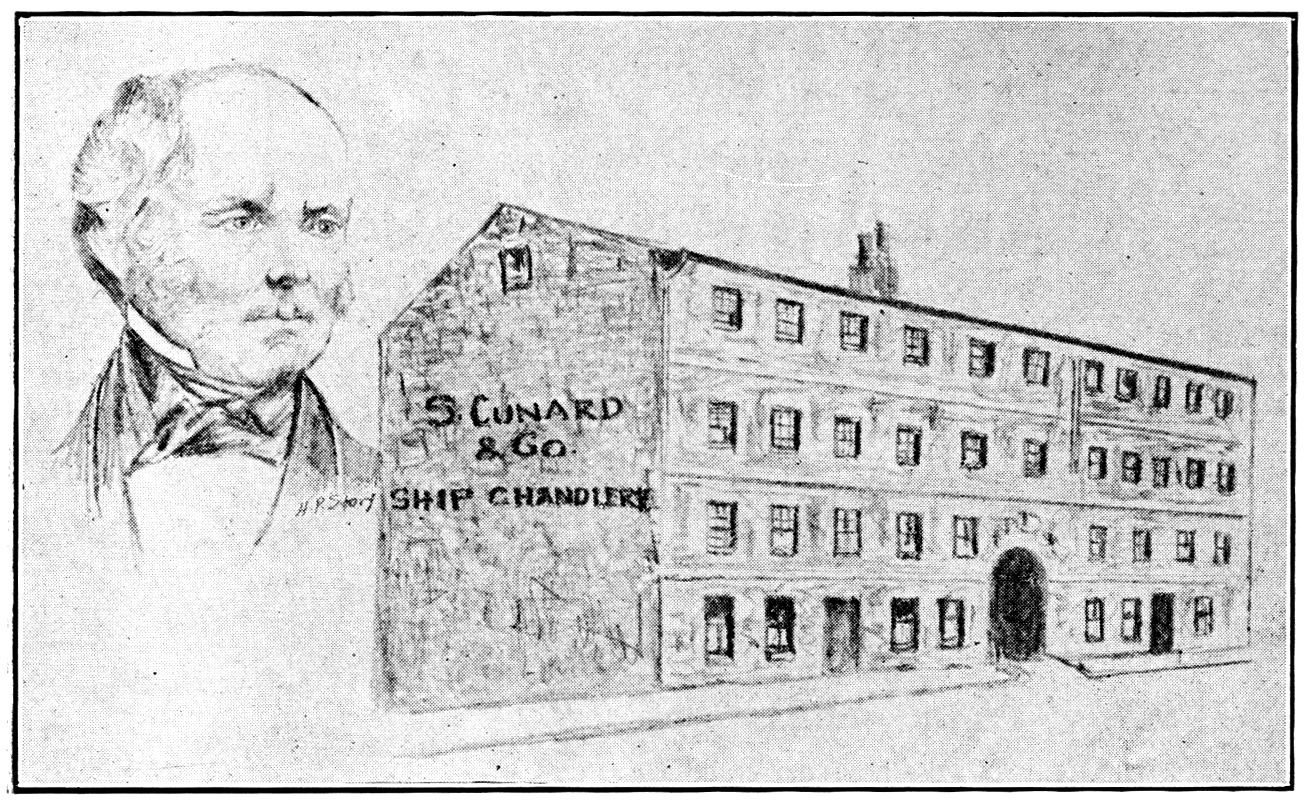

| Cunard, Sir Samuel, with Office Building and first ocean liner | 112 |

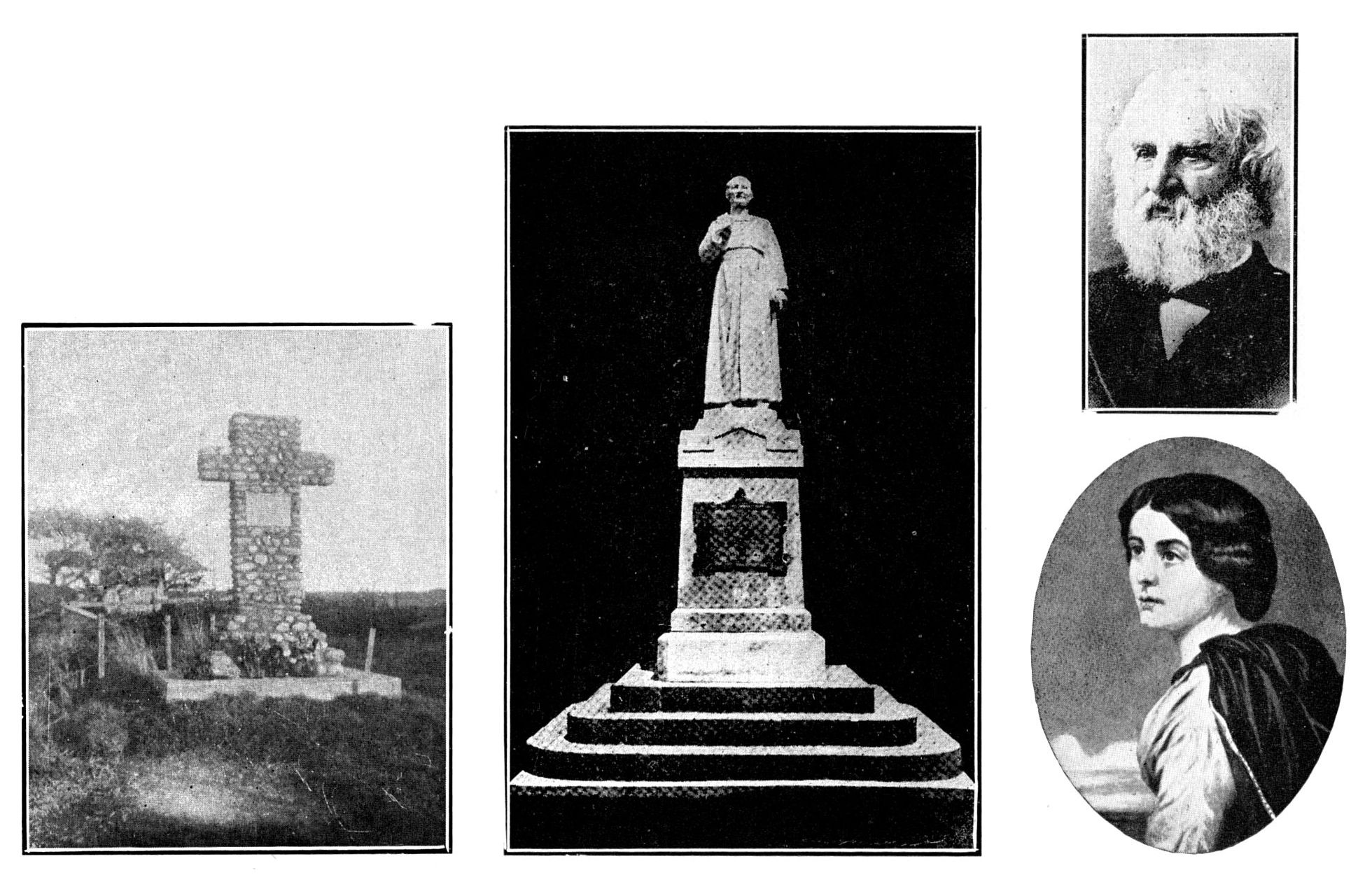

| De Mont’s Monument at Annapolis Royal | 144 |

| De Mont’s Tablet, St. Croix Island, Maine | 66 |

| Discovery of America, by John Cabot | 131 |

| Doge’s Palace, Venice | 48 |

| Edison, T. A. and father Samuel Edison, born in “Acadia” | 113 |

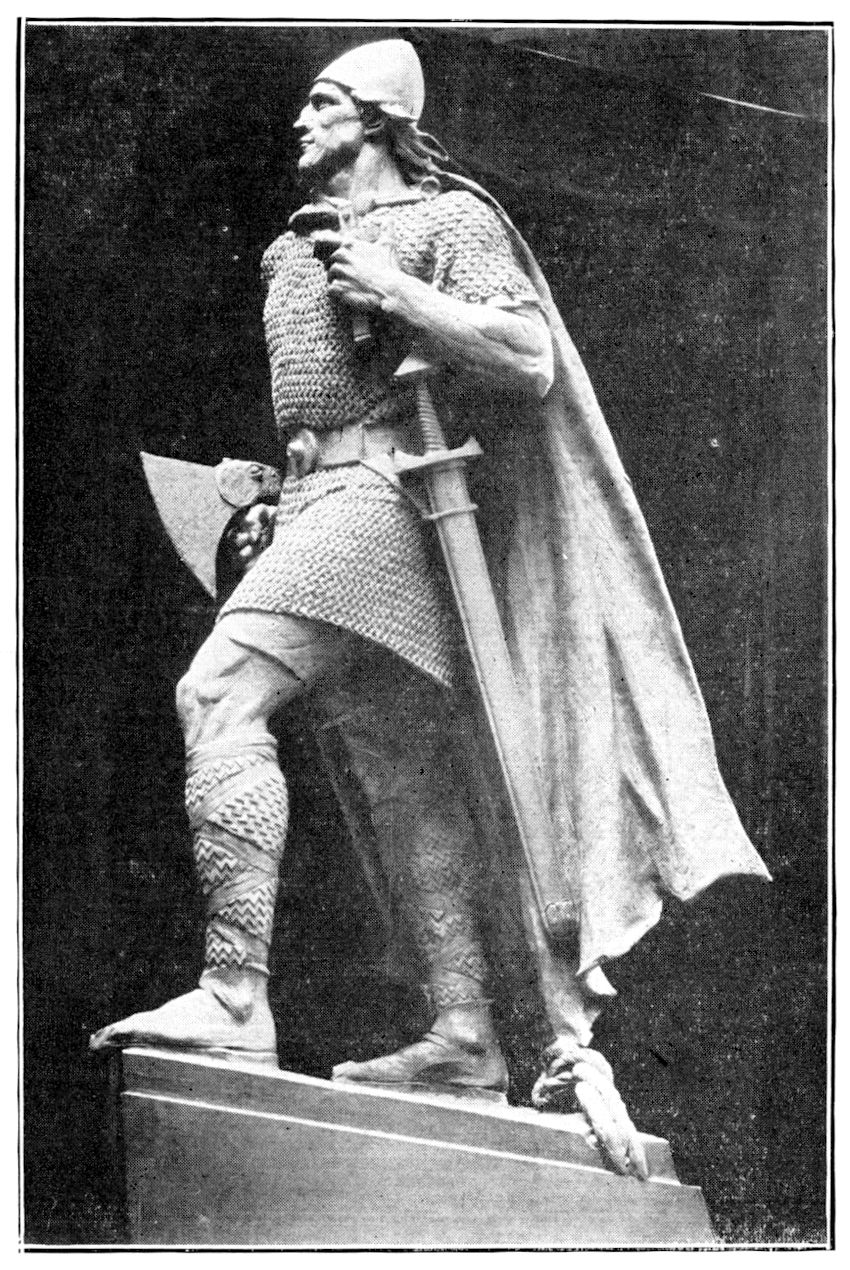

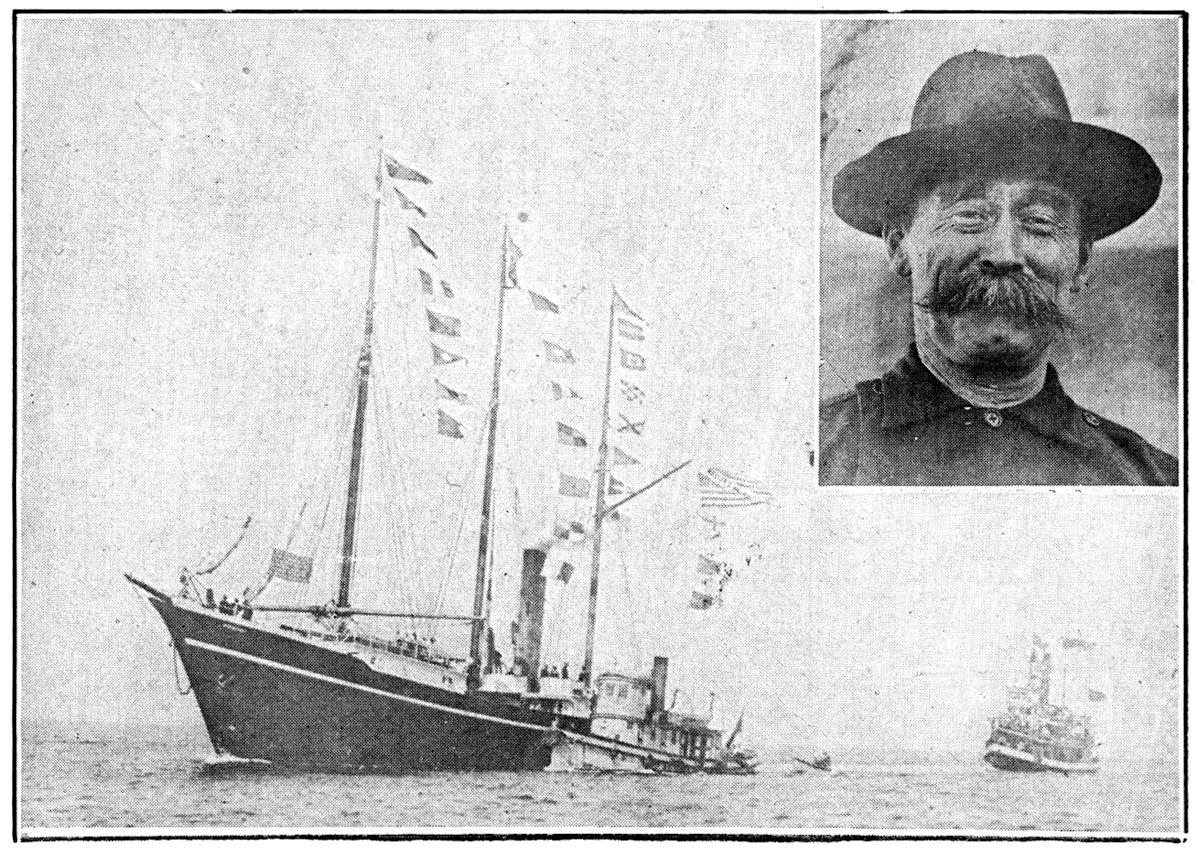

| Eiriksson, Leif, statue and Iceland schooner | 128 |

| Elephants, prehistoric, trumpeted through “Acadia” | 49 |

| Gisborne, Frederic N., Atlantic Cable projector | 288 |

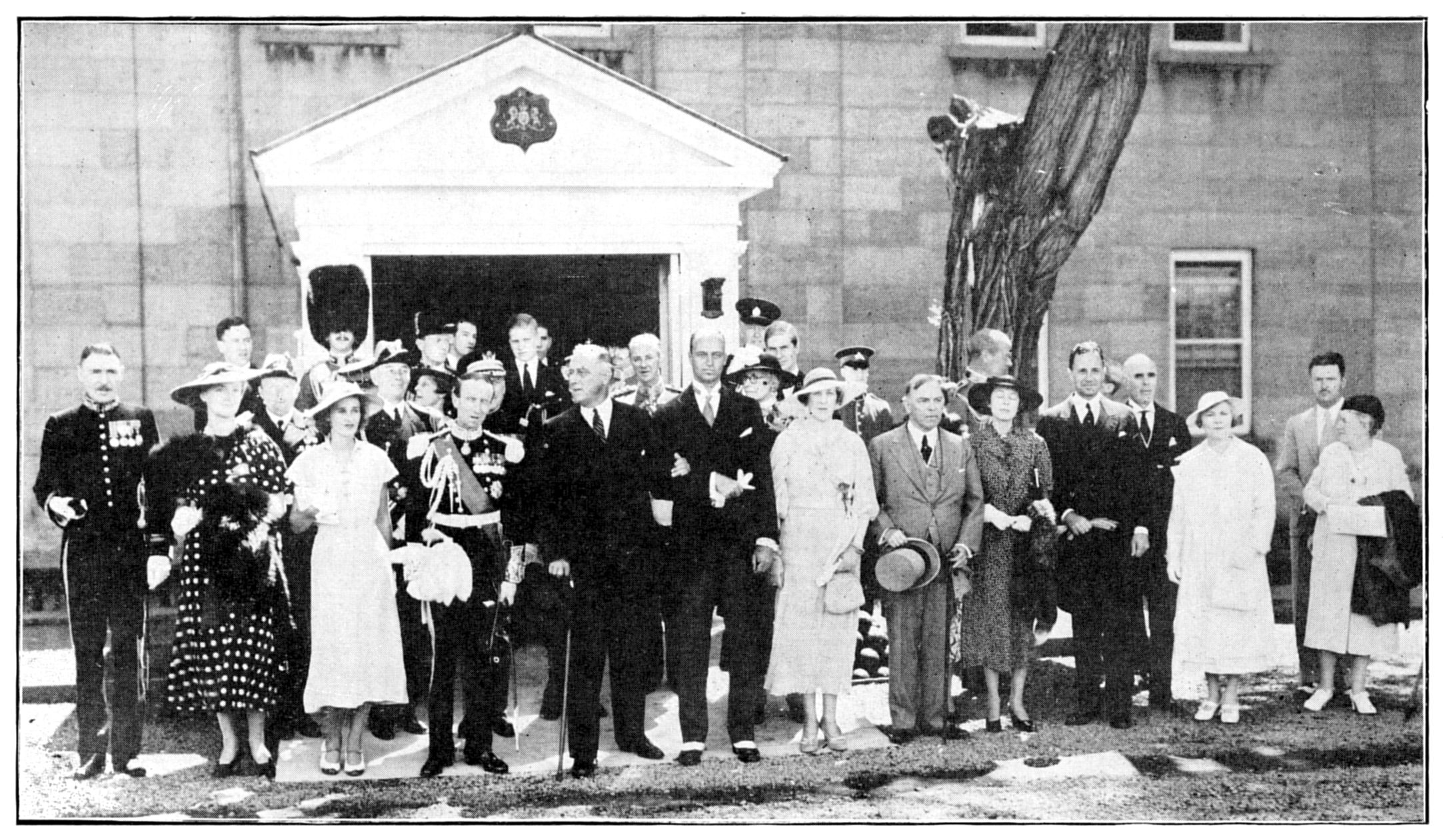

| Governor General of Canada and Lady Tweedsmuir | 65 |

| Harding, Rev. Theodore, Canadian Baptist pioneer | 240 |

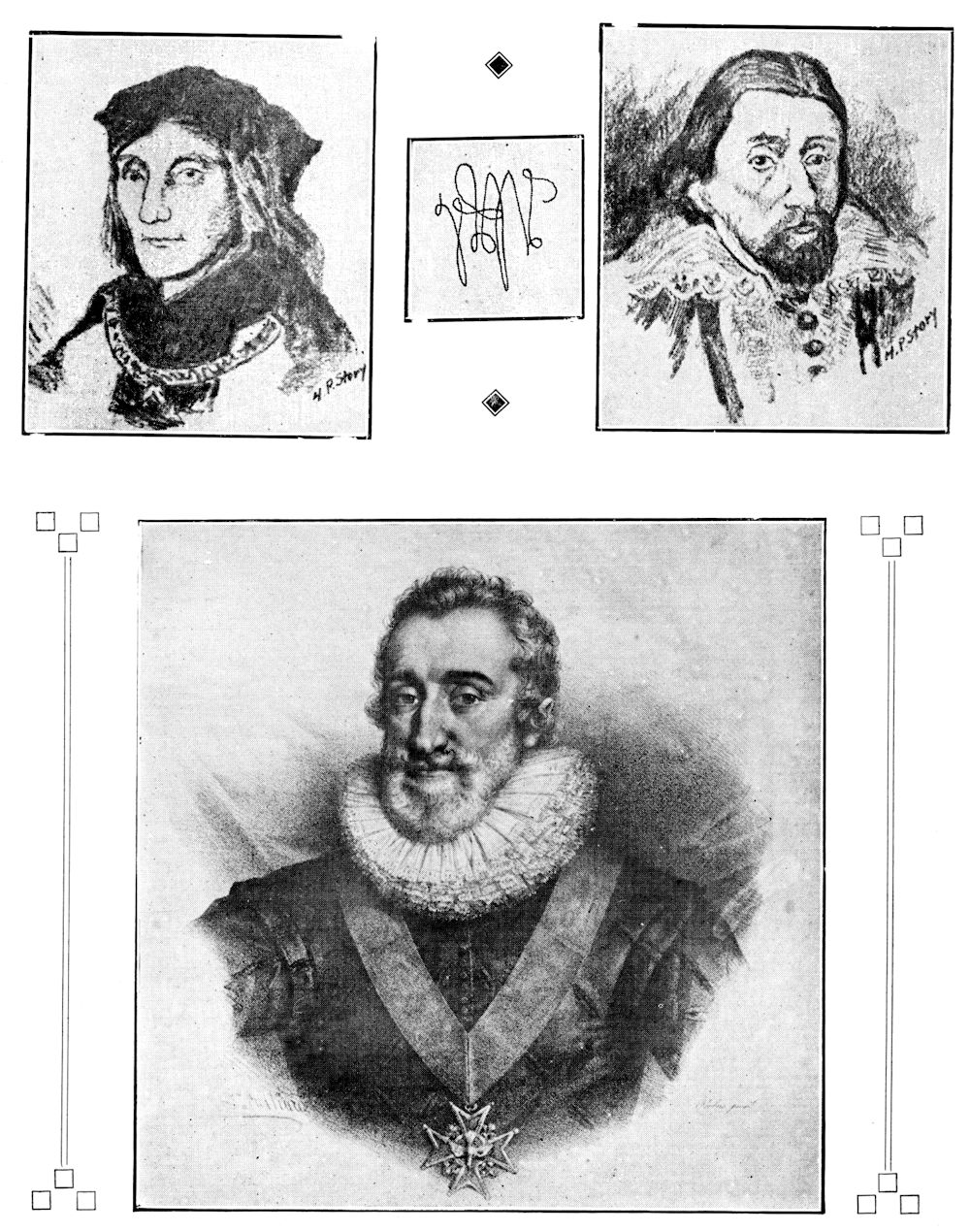

| Henri IV, France, founder of French “Acadia” | 176 |

| Henry VII, England, and the cipher of the rich monarch | 176 |

| Inglis, Rt. Rev. Charles, first Anglican colonial bishop | 81 |

| James I (England) or VI (Scotland) son of Mary Stuart | 176 |

| King, Rt. Hon. W. L. Mackenzie, Canadian Prime Minister | 65 |

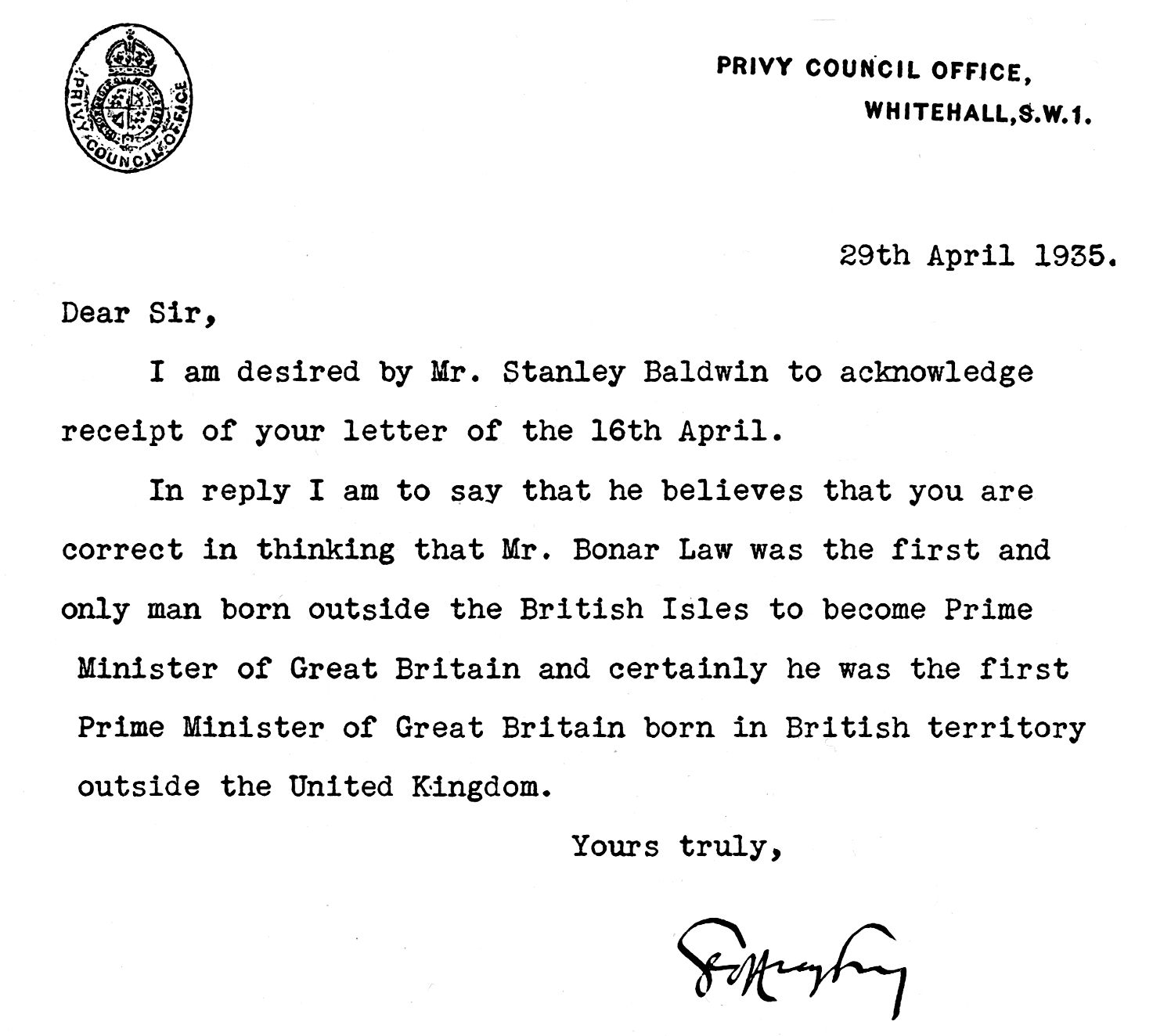

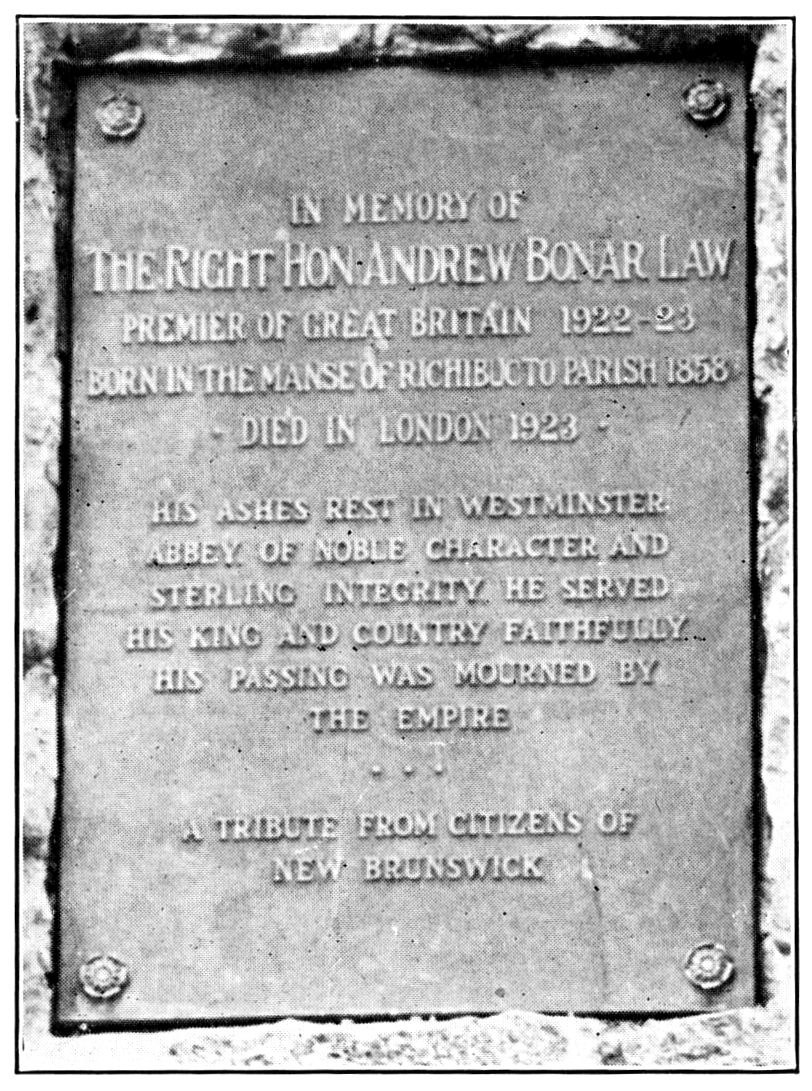

| Law, Rt. Hon. A. Bonar, Privy Council letter | 142 |

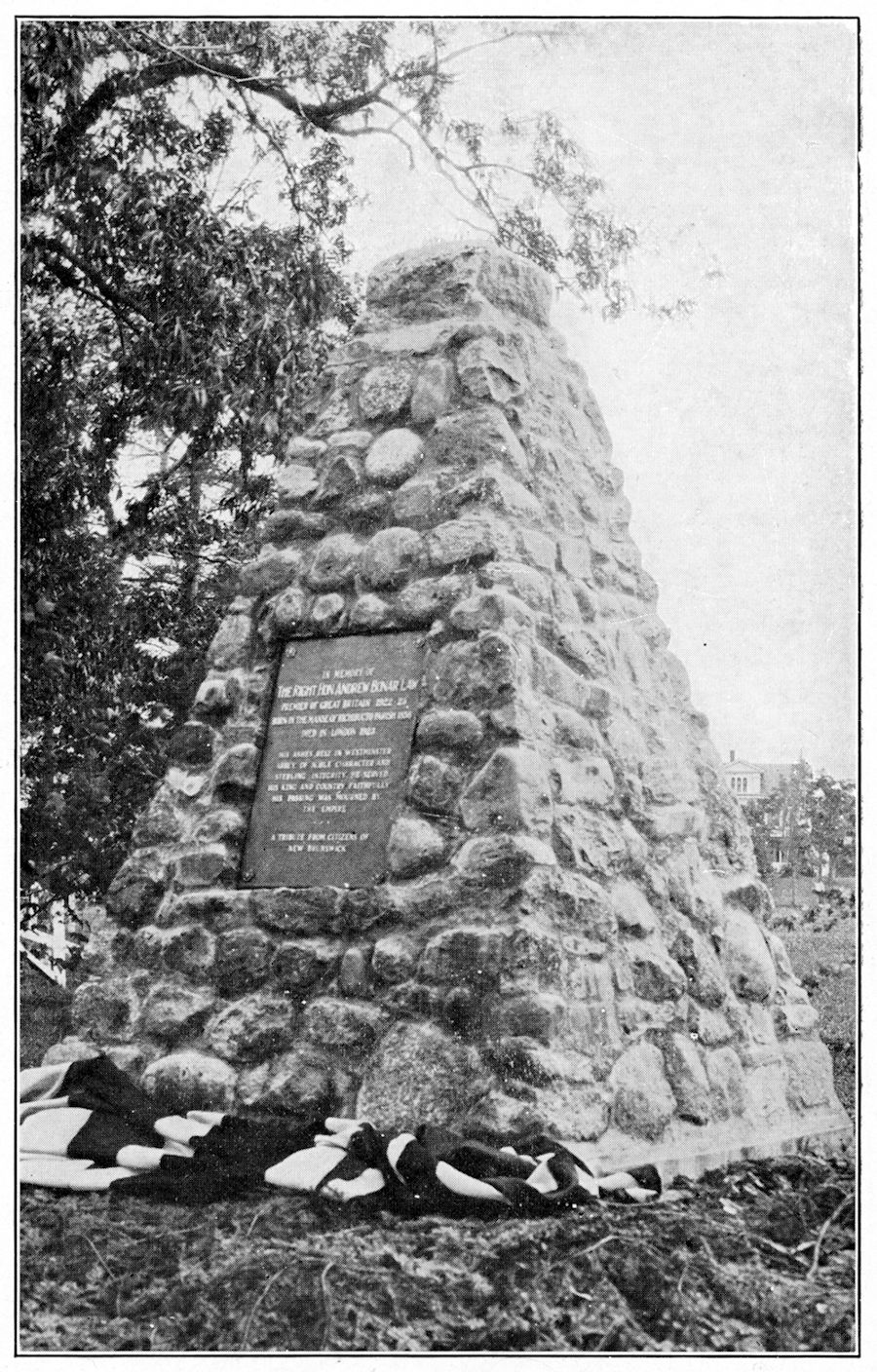

| Law, Rt. Hon. A. Bonar, cairn and tablet, pages 192 and | 193 |

| Lighthouse, Sambro, oldest English built in Canada | 289 |

| Longfellow, Henry W., American poet | 161 |

| Louisburg, view of America’s first walled city, 1731 | 80 |

| Map of North Atlantic ocean with routes of explorers | 2 |

| McCulloch, Rev. Thomas, first president Dalhousie University | 240 |

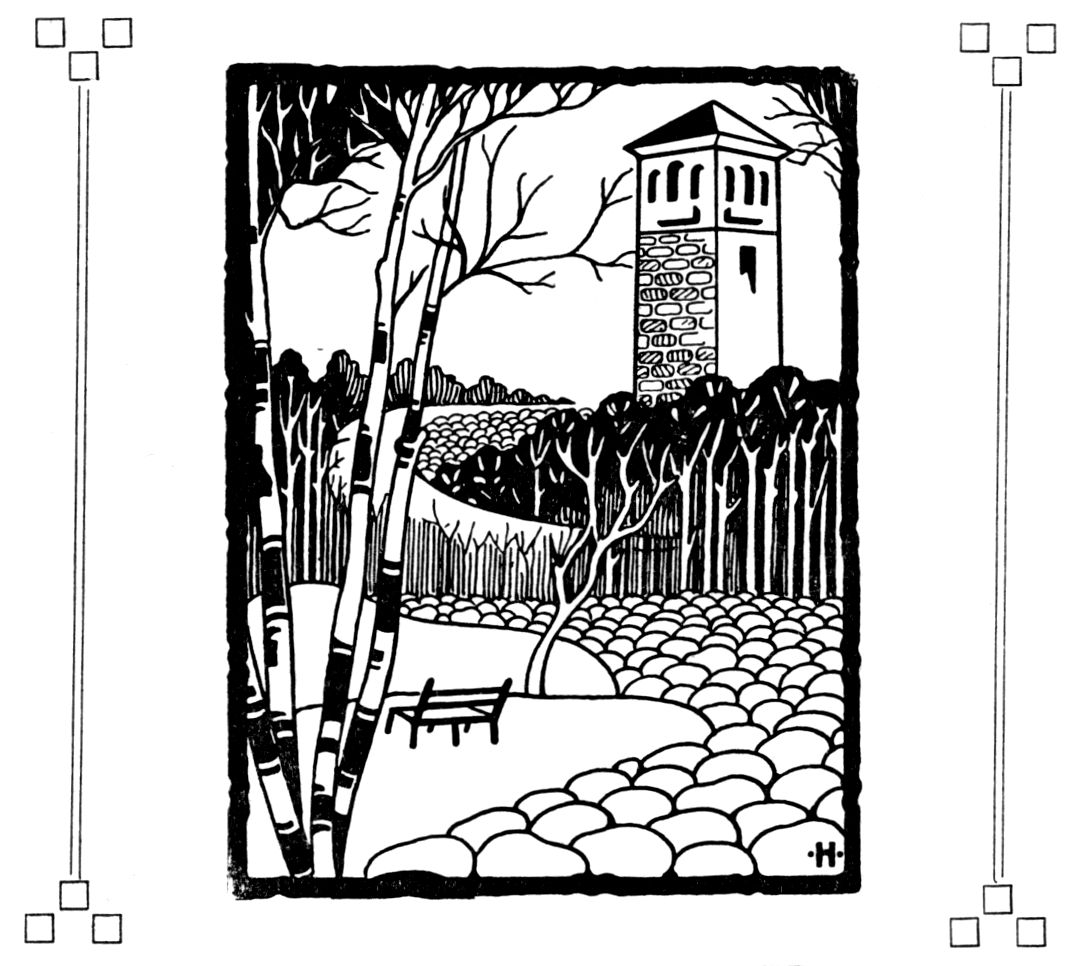

| Memorial Tower, Halifax, commemorates an Imperial system | 233 |

| Nicolas Denys’ grave in New Brunswick | 139 |

| North Pole Discovery by Admiral Peary | 289 |

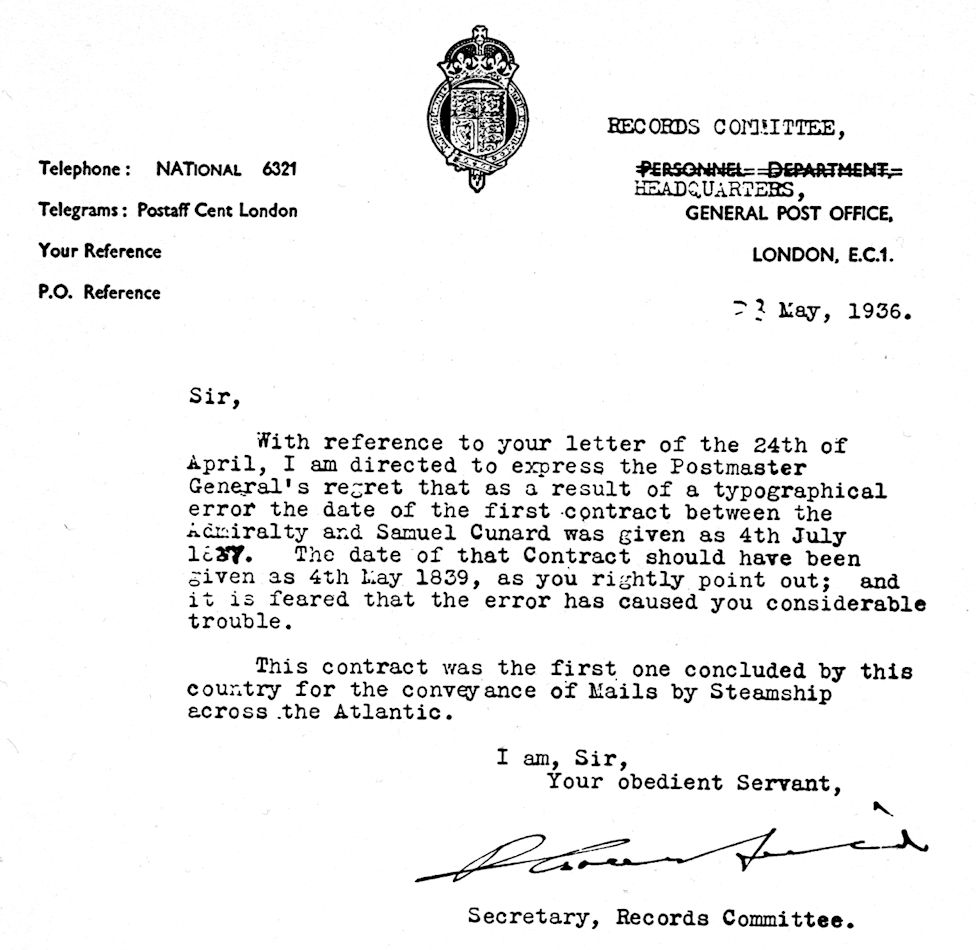

| Ocean Mail Contract by steam, the first and P. O. letter | 181 |

| Oil Monument, Gesner, the first in the American industry | 241 |

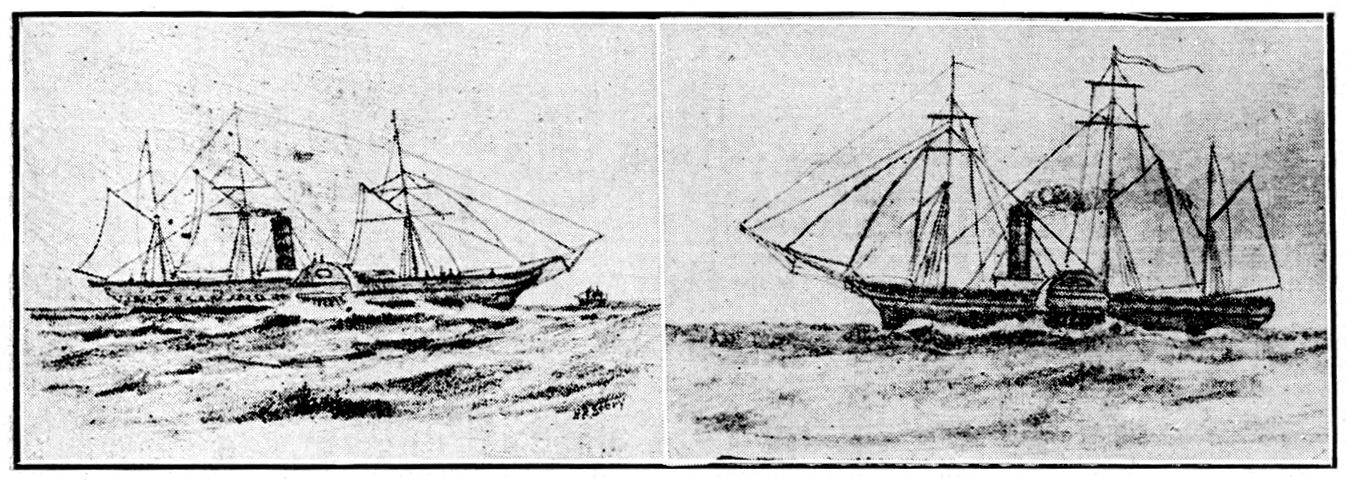

| Pioneer steamship, “Royal William,” at pages 96 and | 184 |

| Printing Press, first in Canada, in Acadia | 120 |

| Railways and iron rails, first in Canada in Nova Scotia | 273 |

| Responsible Government, First in Canada; tablet | 235 |

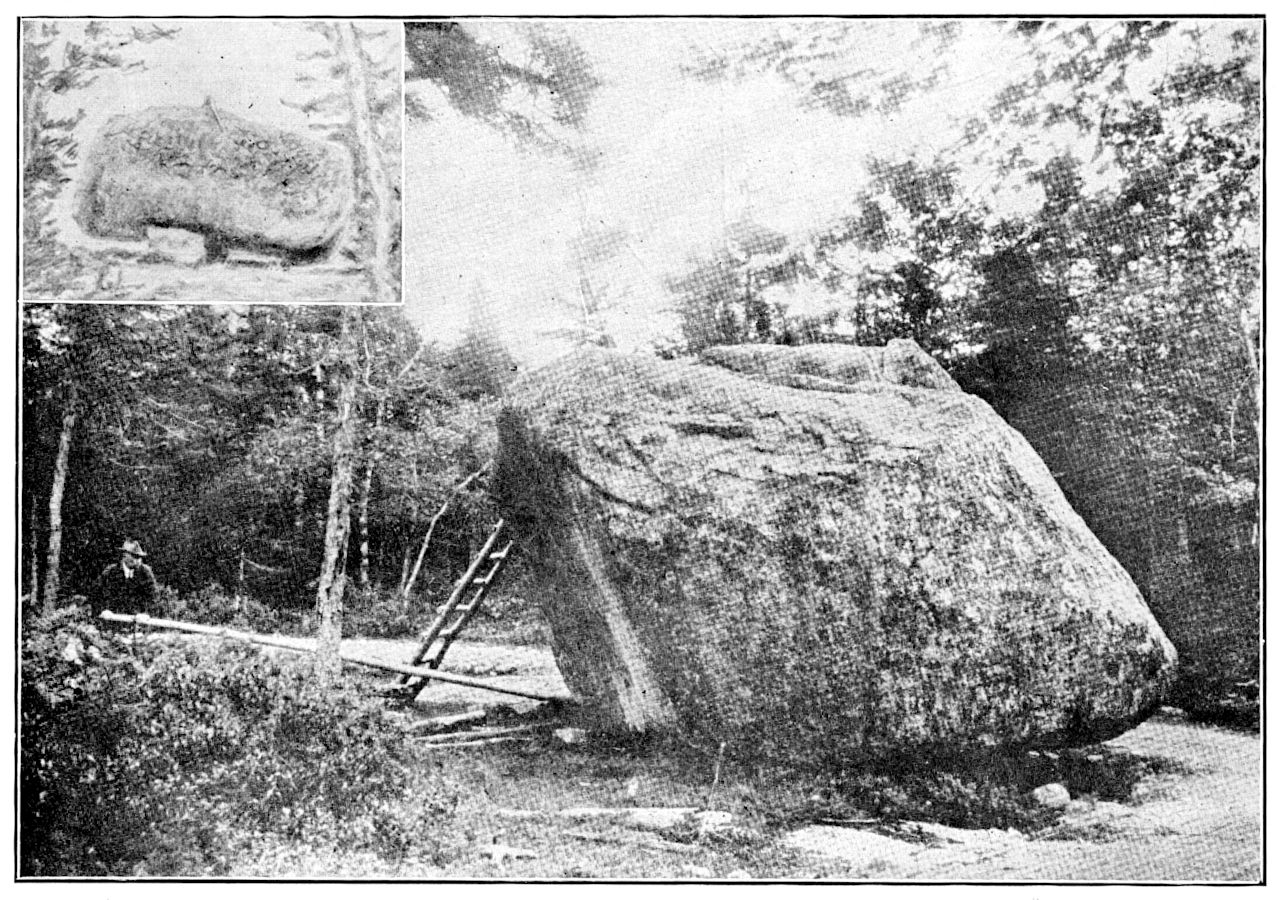

| Rocking Stone, “largest in world” at Spryfield | 208 |

| Royal Standard, first flag in the West; colored | 256 |

| Roosevelt, F. D., First President to officially visit Canada | 65 |

| Seabury, Rt. Rev. Samuel, first Anglican Bishop in America | 81 |

| Social Club, America’s First weekly lunch meeting | 145 |

| St. Croix Island, “Isle de Saincte Croix” | 145 |

| Submarine Telegraph, first saltwater cable in America | 156 |

| Telephone, first commercial system, Works and Mines letter | 173 |

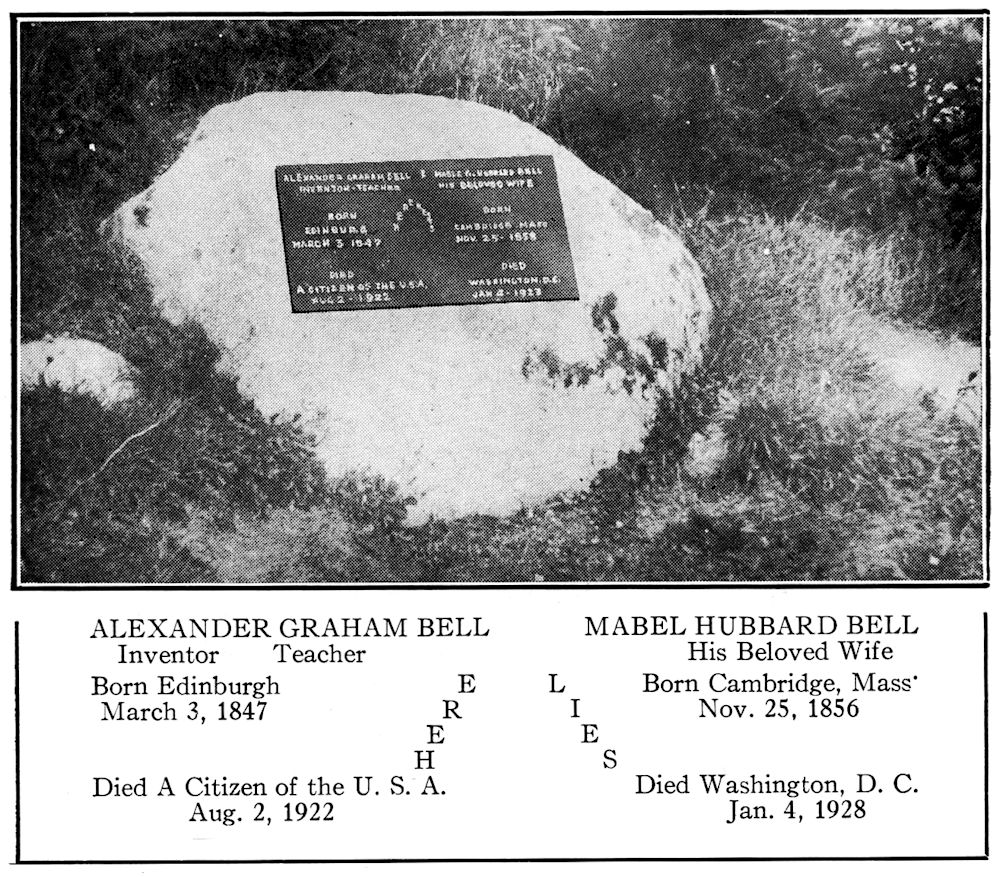

| Telephone, the grave of Prof. and Mrs. Graham Bell | 240 |

| “Titanic” disaster, first of kind in marine annals | 97 |

| Wheat milling, first in North America | 266 |

| Wireless, first transatlantic messages, pages 166 and | 272 |

| William IV, England, first of royalty to cross the Atlantic | 177 |

n initial effort has been made to sift and assemble under

one cover, many important “FIRST THINGS,”

largely of National or Continental character, which

distinguish northeast sections of United States and

Canada, a district known to fame as the “Acadian” area,

which is the memorable site of John Cabot’s Discovery of

the Mainland of the Western Hemisphere. Instead of following

the usual continuous-narrative type of historical composition,

the convenient plan of independent short chapters

has been adopted in this instance, in order to cater to popular

circulation. At the same time, there has been strict regard

for accuracy, as far as that is possible, to render the volume a

welcome and dependably handy reference for schools, libraries,

newspapers, travel and government agencies. An index is

included, but a book of the short-story type has the special

advantage that it may be opened and enjoyed at practically

any point, whenever ten minutes reading time happens to be

available.

n initial effort has been made to sift and assemble under

one cover, many important “FIRST THINGS,”

largely of National or Continental character, which

distinguish northeast sections of United States and

Canada, a district known to fame as the “Acadian” area,

which is the memorable site of John Cabot’s Discovery of

the Mainland of the Western Hemisphere. Instead of following

the usual continuous-narrative type of historical composition,

the convenient plan of independent short chapters

has been adopted in this instance, in order to cater to popular

circulation. At the same time, there has been strict regard

for accuracy, as far as that is possible, to render the volume a

welcome and dependably handy reference for schools, libraries,

newspapers, travel and government agencies. An index is

included, but a book of the short-story type has the special

advantage that it may be opened and enjoyed at practically

any point, whenever ten minutes reading time happens to be

available.

The first normal reaction to perusal of a novel and authentic “First Things” summary, is appreciation that the world is an everlasting debtor to the vision and service of pioneers. It is a privilege to be the first publication to point out the unusual quota of major “First Things” that has been forged in the American “Acadian” zone, the product undoubtedly of sharply epic clashing conditions, somewhat on the same lines that beautiful gems are a crystalization of intense upheaval and consequently not mined in every hayfield. Central geographical location also has been a factor in “Acadian” historical pre-eminence. Early settlers, prior to the advent of railroads, refused to leave the security of water communication and seaboard situations and for 200 years, rival powers staged a battle royal for North American key supremacy in the “Acadian” Maritime Zone.

Similar to twin faces carved on an old Roman New Year divinity, there are two sides to modern historical research work, but one of them, relating to the future, is habitually overlooked. While it is quite generally recognized that printing and archive collections and public memorials have been instrumental in defeating Father Time’s ancient tendency to consign poor mortals to the limbo of the lower orders and forgotten things, it may not be as fully understood that historical information is constructive as well as preservative, and is capable of being utilized for considerable practical value. One of the driving lessons of history is the dynamic reminder that nothing is final and that a constant stream of fresh enterprise is necessary to take up the slack and keep the wheels of progress harmoniously humming.

With few and poor tools, “Acadian” and “Nova Scotian” pioneers have handed on a remarkable North American “First Things” inheritance and it is up to posterity to enlarge and extend the sphere of human knowledge. It is an incentive to effort, that through the medium of typography and art, the memory and accomplishments of people may be handed on into the indefinite future.

“First Things in Acadia” contains 100 chapters and upwards of 250 primary occurrences. Subjects have been carefully checked, but in a multiplicity of tricky “Firsts,” there are bound to be errors, and corrections and additions are cordially invited. Opinions differ as to scope of items that should be admitted and several matters have been temporarily excluded. In a popular publication, it is not practicable to insert copious footnotes, but supporting material has been filed and will be gladly placed at disposal of interested inquirers. There has been a lot of correspondence and kind assistance, which is gratefully acknowledged on another page. Incidentally, the book is a polite tribute to pioneers at large, who help ever so little to push back the interior limits of the big unknown universe, that surrounds the world’s small clearing. Orderly social readjustment is another extensive field that calls for volunteers.

“All the past we leave behind,

We debouch upon a newer, mightier world, varied world,

Fresh and strong the world we seize,

World of labor and the march,

Pioneers! O Pioneers!”

J. Q.

Halifax, Nova Scotia

October 10, 1936

A compiler of “First Things” in North-East America (Acadia) is favored with a double advantage that the area to be surveyed is compact, and the period to be reviewed is short, dating from the advent of European explorers at the close of the 15th century.

At the Discovery of America by John Cabot in “Acadia,” the western continent was hailed as a “promised land,” ideal for occupation by Europeans, with the added glamor of distance, which, in this case, did not peter out. Emigrants eventually flocked to American homes and overran the whole continent, but with little or no fusion with native strains. The basis of American civilization is wholly imported.

A complete hiatus separates present American and Canadian society from the profound and mysterious past of the New World. Corn, potatoes, tomatoes, cocoa have been welcome additions to the world’s menu, the western tobacco habit has become universal, but American mythological deities and heroes have not been canonized in films or literature.

Down to the hour of passing in 1506, dying Columbus murmured the illusion that at least he had reached the shores of the Grand Khan in purpling Asia, which, luckily is not correct. He had not seen the Pacific Ocean and did not know a New Hemisphere intervened. In large degree the American and “Acadian” prehistoric story of a billion years is a sealed blank book, that may not always remain a stupendous void, but just now is fortunately outside of the scope of this inquiry.

For literary purposes the high-speed drama of American growth, from Stone Age usage to 20th century efficiency, is conveniently crowded into the relatively brief interval of 440 years, which contrasts with unnumbered centuries that Old World communities had to plod through trials and tribulations to acquire even the rudiments of refinement.

The devolution of the alphabet from ancient hieroglyphics and symbolical picture writing down the aisles of time to eventuate in simple phonetic A. B. C.’s, that children can comprehend and that can be made the vehicle of lofty expression, is typical of the long trail the fathers trod, starting no person knows where, but it probably commenced at knot-tying and sticknotching by cave-men ancestors.

In 1497 North America emerged from unfathomable obscurity, to inherit a world of ready-made information—a “First Thing” accounted the second big event of the Christian Era—which was communicated all at once like the mechanics of a movie production, where time and action are reduced to a couple of fascinating hours, by manipulation of a pair of scissors and the elimination of superabundant details.

At “Acadia” in 1497, John Cabot automatically sponsored calendar reckoning on the western strand—the first American calendar “salesman.” Untold generations had come and gone and mound-building successors had slumbered through an infinite round of seasons, without the need of an alarm clock, the prototype of Rip Van Winkle. In the twinkling of an eye a different sunrise occurred, a curtain was stripped away in “Acadia” and the Western Continent stepped into the floodlights, a beneficiary of the labors of forgotten multitudes in Europe and the dim East. Immense dormant resources, waited only the Midas touch of intelligence to unlock and disgorge the greatest and most varied treasure trove the earth has known. This is the Cinderella summary of Canadian and American expansion, with John Cabot the fairy godfather, or Moses, of the scenario.

* * *

It is mainly the swift alchemy since 1497, whereby North America has risen from primitive flint and bone gadgets to chrome steel precision, to traffic in the clouds and to distant voice transmission, which supplies the background for accompanying pages.

In marine matters, for instance, “Acadian” First Things arch the centuries from Cabot’s Landfall, 1497, to the winged-mercury east-west solo performance of Beryl Markham, 1936. Cabot sailed “blind” 53 days into the western “darkness” of ancient Atlantic superstition and Markham sped “blind” 25 hours into the swifter sunset, just missing calling it a day. It is a coincidence that these trail-blazers, Cabot and Markham, landed at the same involuntary destination in Nova Scotia (Acadia), though separated by four centuries in time. The contrasting differences in crew, construction, speed and native element of the two craft epitomize the world’s onward sweep.

In viking days, approaching a strange coast, Norsemen tossed overboard wooden seat pillars, rune-carved with images of Odin and Thor and it was left to pagan gods to point out a landing place. The warriors usually waded to the attack, where the house-beams drifted ashore. Kindlier influences possibly functioned in directing Cabot’s ship “Matthew” and Markham’s plane “Messenger” through perils and fog-banks to peaceful anchorage at an American “Land of First Things.”

It may not be appreciated that the original “Acadian” grant in 1604 extended from Washington to Ottawa on the seaboard and “as far inland as they may go,” probably the first intimation of a coast to coast objective. On crested parchment the French official term, “Acadia,” comprehended most of North America, but in practice the style was restricted to Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, with parts of New England, Maine, Quebec, Newfoundland and Labrador alternately added or subtracted, depending on whose ox was gored in the course of boundary disputes. “California” was mentioned in one of Sir William Alexander’s Scottish grants and the Moon seems about the only place that was not included in these omnibus documents. One hundred years slipped away after Cabot’s Discovery before practical colonization was undertaken.

* * *

To a Scot and a Stuart, James I of England, goes the credit of being the first to emphasize a British claim to all territory from Florida to Labrador, by right of Cabot’s landfall in “Acadia” and by succeeding exploration. Broad charters were issued by King James for Virginia, New England and Nova Scotia. The rugged motto assigned Nova Scotia—Munit Haec et Altera Vincit—illustrated by a mailed hand and the business end of a bunch of thistles, is significant of the Caledonian Monarch’s determination to defend British overseas title, as the basis of a revamped Imperial policy, conceived in Scottish pride and traditional love of adventure.

James I magnified the union of the two crowns of Scotland and England and immediately ordered an elaborate double encrusted Stuart diadem. On October 20, 1604, contemporary with the founding of French “Acadia” and eighteen months after the death of Elizabeth, last of the Tudors, the son of ill-fated and attractive Mary of Scotland, swept aside all objections of courtiers and off his own bat, proclaimed the united countries should henceforth be known as Great Britain.

Consolidated coins appeared with the epigraph, “J. D. G., Mag. Brit. F. et H. Rex.” It was commanded also there should be a new flag. The heraldic crosses of St. Andrew and St. George were combined. The energetic and pedantic prince signed the flag decree “Jacques,” so the public unofficially labelled the bunting, “Union Jack,” a mixture of French and Jacobite paternity that has been a meteoric success.

* * *

At the “Discovery of America” in 1497, two nations, Peru and Mexico were using bronze, building highways and temples and making progress. Maize, tobacco, potatoes, bananas were cultivated in various sections in a primitive way, but generally speaking, American aborigines were 1,000 years behind the times. In effect, events that are listed are high-spots in the transfer of European culture, piece-meal, to a New World, a task in transitional stages succeeding feudalism and preceding democracy, which Kings alone had the money and power to set in motion. The panorama of millions moving across the “Red Sea” of the Atlantic to found Commonwealths, a connection which great shuttling fleets presently maintain, is part of the spectacle that is sought to be sketched in popular fashion.

The First “Cross” on the mainland of the Western Hemisphere, destined to be continuous, was planted by explorer John Cabot at the “Acadian” portals of the Western world.

The apparent location is a point not far from bluff Cape North, adjudged one of the world’s oldest headlands, which has witnessed the rise and fall of changing shore-lines. This is the genuine American “Hill of the Cross” where the translation of Christianity to the west was definitely commenced. Hamlet suggests that “a divinity shapes our ends” and it is curious that the first American Cross was the product of a “wandering” voyage of nearly two months, one of the longest unbroken sea-voyages of record and without a good compass, yet Cabot’s handful of British seamen were rewarded with a bloodless domain larger in area than accumulated Viking conquests scored in Norse battle-axe progress across Europe, from an Aryan cradle in Asia.

Cabot’s company were actually guided to one of few places in 10,000 miles Atlantic frontage of the two Americas, where old Archaen rocks of Northern Cape Breton, members of the most ancient geological system, jut out into the immemorial ocean, so America’s first “Cross” was dramatically placed at one of the oldest neighborhoods of time, where terrain is more venerable than geography of Egypt or the Holy Land.

The path-finding bark which Captain Cabot, afterward styled the “Great Admiral” in London, steered to an “Acadian” harbor, had a biblical name and the day the initial Cross was installed was June 24, feast of John the Baptist.

* * *

With limited available nautical equipment of the 15th century, there was one chance in a thousand of contacting any particular point, which necessitated crossing an uncharted ocean. An example is an expedition of 1492, which ended at a coral isle, one of 3,000 rocks and cays of the Bahamas, 350 miles from the American mainland, that was never reached. The island of San Salvador, or Watlings, the supposed landing place, is one of hundreds—in the Bahamas archipelago, and cannot be positively identified, they all look so much alike.

“So near and yet so far,” the West Indies landfall “out-to-sea” in 1492 has had the effect of transferring the actual finding of the American Continent from the Tropics to temperate “Acadia” and to British seamen. Information of Cabot’s disembarkation at a new continent in Cape Breton electrified the Courts of Europe.

In this instance, the intricate Bahamas, stretching leagues to seaward, play a part in history surpassing classic labyrinths of Greece and Rome. The West Indies completely engrossed the activities of Spanish navigators from 1492 to 1498 and it was not until the latter year that Columbus contacted the South American Main. Twenty years later, the ageing courtier Ponce de Leon, combed the Bahamas network six months, searching for the “Font of Rejuvenation.”

It is a fad for Caribbean excursionists today to organize playful “Ponce de Leon Clubs.” Before separating, members are presented a perpetual health certificate as a souvenir of pleasant holidays and friendships.

Jovial Henry VIII is said to have prompted a somewhat similar token at Hampton Court palace. A famous maze of shrubbery, which beats cross-word puzzles to find the way out, is attributed to bluff Hal’s wish to commemorate the Bahamas intervention that gave England and the Tudor Dynasty the credit of Discovering America, through the medium of John Cabot’s landfall in “Acadia.”

Cardinal Wolsley built and owned Hampton Court residence, designed on lines of Tudor splendor, but found it expedient to present the property, lock, stock and barrel to the covetous King, which however did not prevent Shakespeare writing the prelate’s last, long farewell to greatness, that “hangs upon the favor of princes.”

* * *

The Cape Breton or “Acadian” Cross of 1497—a red letter year in American church annals—was probably made out of a native evergreen—a soughing pine, a stately spruce or fir or a sad hemlock—but in view of subsequent prolific ecclesiastical increase from the land of the midnight sun to the flaming cross of the southern heavens, the proverb of the oak and acorn perhaps better represents extraordinary religious development that governs the New World.

A world religious census records 175 million Christians and 30 million “Miscellaneous” in North and South America in 4½ centuries. Asia and Africa combined are credited with 42 million Christians in One Billion souls in 1900 years. The discrepancy is enormous.

While the Sermon on the Mount is rejected or making slow inroads in Old Lands, the Gospel is paramount in the younger west from Pole to Pole and from Dawn to Dusk, on the “road to Mandalay,” and with surplus funds available for foreign missions. Oriental students are puzzled to understand why militant Buddhists, having swamped Christian Missions in the East in 13th and 14th centuries, should then allow the rich American field to slip through their fingers. Especially as Buddhism was already introduced on the Pacific coast of America and American Indians are palpably Asiatic extraction, while the hazards of North Pacific crossing are negligible compared to Atlantic billows.

Reservation of the Western Hemisphere for Christianity looks like a law of compensation for Moslem interference in Europe and the Near East. The first move, as noted, in the pre-emption of the American mainland for European and Christian ethics was conducted by intrepid John Cabot at “Acadia” in 1497. Cabot’s action was official, not casual.

It was clearly recognized in Europe, that Christianity and Western Civilization required to be closely associated and the same philosophy may be essential in 1936. A condition precedent of Cabot’s Commission, inserted by the shrewd money-loving Henry VII, stipulated that new lands be given religious teaching, hand-in-hand with business administration. It was the King’s wish the “Flag” and the “Cross” should be united, which James, later incorporated in the Union Jack. There had been Bishops in China and Greenland, possibly in Vinland (Acadia), 300 to 400 years before Cabot’s discovery, but they had not been supported and converts lapsed to paganism.

“Acadia,” having been the site of the first permanent Cross on the Western Mainland, this district possesses claims to regard as the “Palestine of the New World,” a potential mecca.

* * *

A score of thought-provoking “First Things” are associated with John Cabot’s epic voyages. It was at Acadia, English explorers first uttered the language of Shakespeare in America. English feet, Cabot and crew, first trod the American mainland, barring natives and traditional voyagers. An English keel, Cabot’s ship “Matthew,” first plowed the waters of the American Main, also excepting unrecorded ventures. Cabot’s crew were pioneers in recorded fishing operations on the Grand Banks; they put down baskets weighted with stones and brought them up miraculously full of fish. Schools of cod were reported so thick at times, the progress of the vessel was interfered with, a fact which drew universal attention to “Baccalaos”, Land of the Cod.

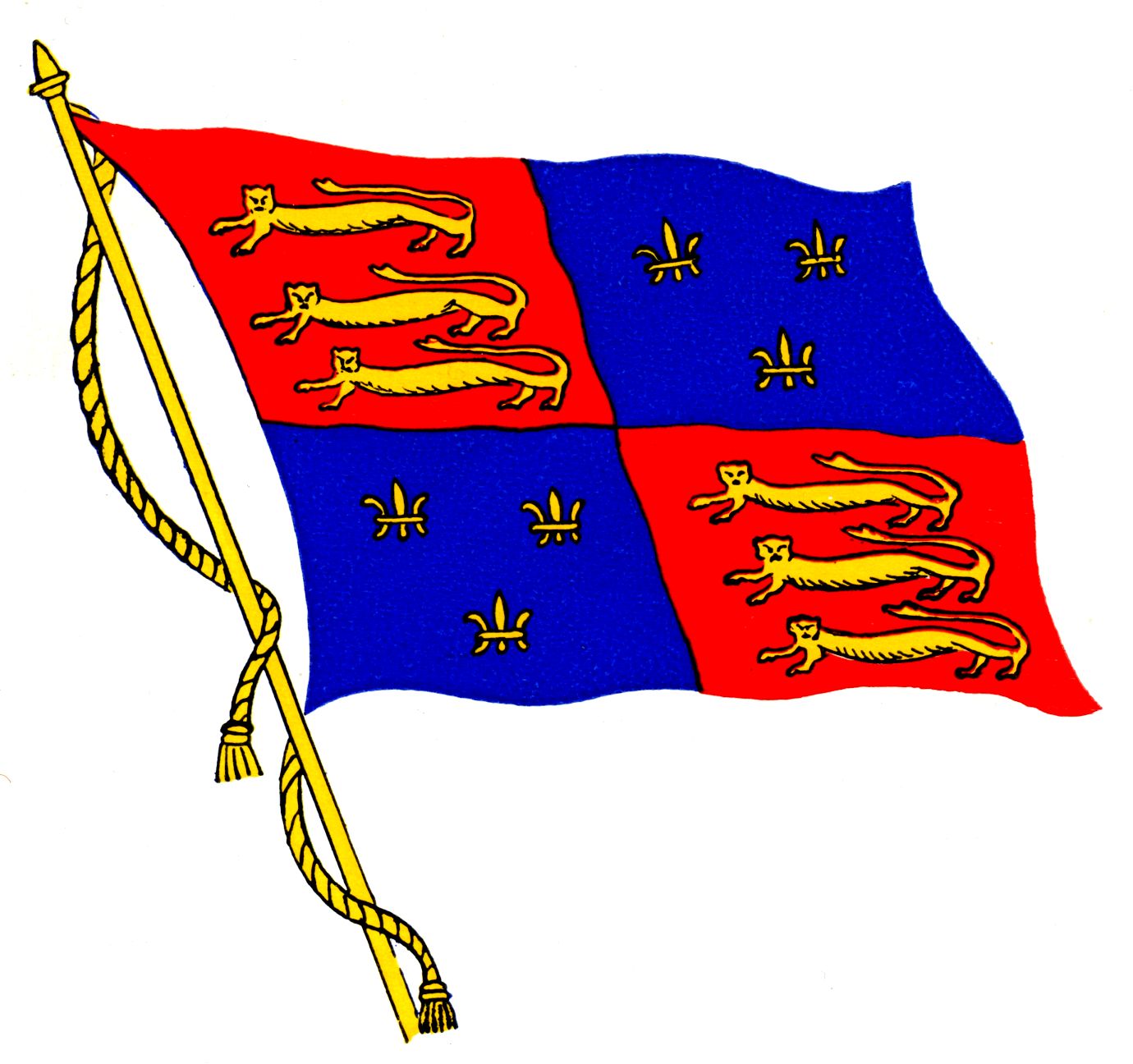

A quartered English flag of lions and lilies and a winged-lion pennant of St. Mark were unfurled by Cabot on an Acadian hillside, to be the first European colors to flaunt the breeze and greet the morning sun on the New World continent.

“Acadia” was the first part of the American mainland to welcome Europeans. The first European King to exercise jurisdiction on the sunset continent was a Welshman, Henry Tudor, miser and diplomat, who reconciled Red and White Rose factions in England and ended a Civil War. Henry VII celebrated this adjustment with an overseas foothold in “Acadia,” marking John Bull’s matriculation from insular to world career, after ignominious expulsion from France by the Maid of Orleans and total collapse of 300 years dream of Continental Power had left England shut up within the narrow seas. In addition to being the beginning of the greatest Empire in History, Cabot’s Landfall in “Acadia” in 1497 has been the genesis and parent of Brother Jonathan’s progressive republic.

Classic French of Bossuet’s oratory was first pronounced in America in the umbrageous shelter of “Acadian” harbors and it remains the mother tongue of more people in the transatlantic field than in any quarter outside of France. Gallic speech is growing in America.

Folds of the Royal Standard, raised on a staff in “Acadia” by John Cabot, a personal gift of the King, effected a timely shift in western history from the narrow tropics into spacious temperate latitudes further north. The continent that Columbus missed, mainly through mutinous crews, was uncovered by Cabot just beyond sundown. In a second voyage Cabot coasted and mapped 1,800 miles, a prodigious feat of navigation and executive capacity, performed without a base and daily facing hostile tribesmen while seeking nightly shelter, wood and water in the course of months of work in strange and primitive places. As yet there were no firearms superior to Indian archery.

The World’s “Great Admiral” Cabot was not a nameless adventurer, but possibly the premier explorer of all time. Cabot was the first Royal Commissioner, armed with plenary authority, ever to set foot on the American Continent, empowered to proclaim sovereignty and take possession in the right of a King. In the Public Archives at Halifax, Nova Scotia, is a duplicate of the British Standard that was raised on shore in Cape Breton in 1497, and it was the First National Banner unfurled on the mainland of the Western Hemisphere. The fleur de lys is conspicuous of the former claim of English monarchs to be Kings of France. The Halifax flag was donated by ladies of Bristol, England, to the Canadian Club of Halifax, August 14, 1912, in connection with dedication by H. R. H. the Duke of Connaught of a Parliamentary Memorial Tower, at Northwest Arm, Halifax. At the entrance of the Tower are bronze lions, fac similes of Landseer Lions in Trafalgar Square, London, the gift of the Royal Colonial Institute. Inside the unique Empire Tower at Halifax, are mural tablets representing all principal parts of the British Empire, in some cases composed of native stone of the several countries. The first real representative legislature of the British Empire, outside of the United Kingdom, was at Halifax in “Acadia,” which the Northwest Arm Tower is broadly intended to connote.

* * *

Portuguese exploration and settlement in Newfoundland and Nova Scotia (Acadia) 1500-1521, trailed Cabot and was made in conjunction with Ferdinand of Spain. The obvious aim was to erase effects of Cabot’s prior discovery. Portuguese settlements in “Acadia” were probably the earliest genuine colonization projects and in that respect they rival or antedate Mexico and Brazil, where mining received most attention, corresponding to fish and fur activity further north. Through Cabot the British “Broad Arrow,” is the oldest Government property mark in America and it greatly interfered with the plan of Pan-American hegemony which Spanish and Portuguese rulers had arranged to assert and establish in all transatlantic countries.

“Acadian” voyages of blonde Norse sea-rovers and of possible Irish predecessors, 1000 A. D., are beginning to receive more critical examination. “Mikla Garth,” Great Ireland, near Vinland (Acadia) is no longer dismissed as a figment of the imagination. Scholars are probing documents and traditions in “Thule” in a renewed quest for northern information too long neglected.

A philologist contends the name “America” is an old Scandinavian expression, “Am Erika,” the Sea of Erik, signifying part of the western ocean that Greenland colonists navigated while trading back and forth to Vinland, principally for timber, a business still carried on with Nova Scotia, owing to forest scarcity in circumpolar areas. Norse linguists pronounce “Am Erika” a mere coincidence, though strikingly parallel. It is objected that Waldsemuller in 1507 at first only applied the name America to South America, which Vespucci had visited after Columbus, but Spanish authorities, in keeping with prevalent colonial jealousies, had kept secret the fact that Columbus had found a southern continental extension in 1498, one year after Cabot.

While casting about for names to designate western discoveries, cartographers at engraving centres on the border of France, Germany, and Switzerland were undoubtedly familiar with Vinland narrations then current at Hamburg. The style “America” may easily trace to both sources, that is, to the Norse—Acadian, and to the German—Italian, without any conflict. This is possibly what occurred and eventually, draughtsmen in 1557, extended the appellation to include the north continent, which was little if any earlier than the name “Acadia” had appeared on Italian maps, growing out of Verrazano’s report. If the authenticity of “Am Erika” as a Norse phrase of 1200 A.D. is undisputed, it evidently existed in that shape long before Vespucci was born in 1451, at Florence. German spelling is still “Amerika.”

* * *

“Acadian First Things” are not all antiques. The list has kept pace with science and industry. All principal churches in Canada—Episcopalian, Roman Catholic, Baptist, Methodist, Presbyterian, Lutheran—commenced in the “Acadian” field. First steel and chocolate manufacture in Canada, first journalism, book printing, Atlantic cable, wireless, ocean steam navigation began in “Acadian” initiative.

First aviation and Supreme Court in the British Empire, commercial telephones, organized temperance, first distillery in Canada, rail operation, Bible Society, Sunday School, Responsible Government, Order of Daughters of the Empire, libraries, shipbuilding, orcharding, Masonry, Oddfellows, Indian baptism, ice-skating, hockey, school inspection of teeth, iron bridge-building are just a few of the primary matters touched on.

The Associated Press of the United States was organized by New York papers to forward European news, received by steamship at Halifax, to New York and Boston by dashing pony express and pigeon post.

The founding of Cunard Steamship service by a Nova Scotian, precipitated a pretty battle between graceful sailing “Clippers” and side-wheeler “Steam Kettles.” The “Kettles” won and the culmination is palatial “Queen Mary,” with a sister ship, somewhat larger, being planned.

The first Canadian legislature is in Nova Scotia. The Dominion of Canada was launched at a conference in “Acadia” at Prince Edward Island. The first coal discovery in America was in New Brunswick. Andrew Bonar Law, native of New Brunswick, was the first Prime Minister of Great Britain to be born outside of the British Isles, which broke a cast iron tradition against any but a native son filling that post of power.

The first sermons in America by the Bishop of Connecticut, the first Bishop of the United States, were preached in “Acadia.” Franklin D. Roosevelt is the first President of the United States to own a summer home in Canada, which is at Campobello in “Acadia”, although there are indications that George Washington included Nova Scotia in numerous real estate investments.

Port Royal (Annapolis Royal) Nova Scotia, first mainland capital in North America and first capital of “Acadia” changed hands, back and forth, sixteen times in incessant warfare. Captured, pillaged, burned, retaken, surrendered and rebuilt! Following final British occupation in 1710, the wartorn capital was subjected to six more assaults by French and Indian commands, making a grand total of 22 in all, reminiscent of feudal towns of the Middle Ages. The later attacks were 1711, 1724, 1744 (July), 1744 (September), 1745, 1746. In 1781, pretty Annapolis Royal was sacked by American privateers, which Washington disapproved, completing an all-time American battling record of 177 years. Annapolis Royal is now a favorite tourist resort. At Fort Anne Museum there is a valuable collection of souvenirs and the town has many interesting memorials of colonial times.

* * *

At the extreme eastern part of “Acadia” are the ruins of Louisburg, the first scientifically walled city in America. In 1895 the General Society of Colonial Wars, New York, erected an obelisk at Louisburg, commemorative of the 150th anniversary of the capture of the stronghold in 1745 by New England militia, when 1,200 assailants lost their lives, mainly through epidemic. This was the initial considerable mortality of American forces outside of national borders. In 1936, the same organization applied to the Canadian Government for permission to install an imposing granite Cross in the neglected French and American military cemetery at Louisburg, which will be close to the historic site of the First Cross (Cabot) that graced the mainland of the Western Hemisphere in modern times. There is a possibility that King Edward VIII, while on tour in 1937, the President of the United States, the Governor General of Canada, a French Government representative and Canadian public men will attend the “Cross” unveiling at Louisburg. This may also synchronize with dedication of an extensive Canadian National Park about to be established in Northern Cape Breton. The park has not yet been named, but will be the first large national reservation, located in the primary “Acadian-American” zone.

The supplementary cover title, “The Birthplace of a Continent” refers to measureless geological primacy of the “Acadian-Laurentian” section of North America, which invests the “New World” with a mantle of antiquity, more remote than Bible lands or than snow-crowned summits of geography. An interesting outcome of modern investigation, is the discovery that northeast sections of the American continent are the probable central core or zone, around which the two Americas have gradually evolved into existing outlines.

400 years ago the Western Hemisphere was christened the “New World,” having been the last to come under the attention of geographers, and it added one third to known arable acreage, which has been a help in the light of increasing world population. Actually North America is a surprisingly Old World in the geological time-clock.

The Acadian-Laurentian district of northeast America possibly embraces some of the oldest dry land of the globe, when, in a certain morning long ago, a decree was issued:—“Let the waters under the heavens be gathered into one place and let the dry land appear, and it was so.” There is food for thought in the casual speculation that venerable Cape Breton and Laurentian hills may be an unchanged bench-mark, never again submerged, of the “beginning of the world.”

The “Canadian Shield,” renowned for gold, silver, copper and nickel, which extends from Labrador to Minnesota, with an upfold in Newfoundland and Cape Breton and a wedge-shape spur in Maine and Vermont, is Archaen age, sufficient to make even Chronos dizzy.

Before Father Adam, when grain and cotton fields, pampas, ranches, rivers, islands, mountains and volcanoes of the two Americas were still under water, Acadian-Laurentian “islands” were possibly basking in violet rays, the only “summer resort” in the West, which had emerged from the universal ocean.

No approximate epoch can be assigned the unfathomable time, when lowly moss and molluscs gravitated from surrounding seas to institute life on land on the newly-risen, naked, wet, Laurentian and “Acadian” rocks, then devoid of other living things. It is evident the first “garden” of America was not a paradise.

A friend at Stanford University comments that:—“The Rocky Mountains, as features of the landscape, are very young, as are indeed all other high mountains. As a complex system of rock folds under ground, they are not nearly as old as your mountains in Eastern Canada.”

Gold-bearing deposits in the Atlantic coast series of Nova Scotia, including Moose River mines, have recently been placed in the primary Pre-Cambrian or Archaen classification, a general term descriptive of some of the world’s oldest known formations, usually rich in metals.

A theory of technicians is that Nova Scotia auriferous measures, now covered, formerly also rose to lofty dome-folded elevations, containing treasures of yellow ore exceeding flights of imagination. In a monograph, G. A. Young, Geological Survey of Canada, estimates that:—“During the Paleozoic, these quartzites were folded and crumpled into structures so complex, that very high mountains (Alpine) must have resulted.” Afterward the Acadian area was subjected to various glacial movements, when ice sheets, responding to excess weight and pressure, are accused of steam-shoveling into safe-keeping in the Atlantic Ocean, a range of hills that contained more gold than is hoarded in strong boxes of the Great Powers.

There is some compensation in the reflection that the golden “Acadian” hills, which glaciers unceremoniously pushed overboard, helped form inexhaustible off-shore fishing banks, that have supplied world markets with billions of pounds of vitamin sea food—cod, haddock, swordfish, tuna, mackerel, lobsters, halibut, soles, sardines and scallops. In 400 years since Cabot’s discovery, “Acadian” fisheries have yielded billions in piscatorial wealth, harvested by international fleets.

The speediest fishing craft in North Atlantic fishing is the champion Nova Scotia schooner “Bluenose,” which visited Chicago “Century of Progress” Exhibition, Toronto National Fair, Montreal, Regatta at Cowes, Isle of Wight and yachting functions at New York and Boston.

A recent explanation which has been offered for isolation that wrapped the Western Hemisphere in oblivion for thousands of years is an ingenious theory of drifting continents propounded by a German scientist, the idea being that in rotation of the earth, at some remote period, America gaily broke away from Europe—left home so to speak—and has been gradually going west on her own ever since. The possibility is added that the Westward Ho! movement, can be detected and measured, if a system of observation stations were installed in Greenland.

A similar conjecture was made years ago, that the Moon is a tangential fragment from the Pacific coast of North America.

Former American separation is different from the case of Australia, as all continents taper south to nothing, and two-thirds of the dry land of the globe are in the northern hemisphere. Furthermore, there is little or no indication that southern continents ever were linked, whereas there is much information, such as the western migration of old-world mammals, particularly elephants, that land contacts must have long prevailed between North America and other continents, and were interrupted by earthquakes or subsidence.

Omitting the German drift thesis, down to date, most American physiographers appear to have been content to accept the proposition, that a single ancient highway at Behring Straits was the only world communication with North America, and that all prehistoric traffic was confined to the narrow and circuitous polar detour at Alaska, a condition which continued, it is contended, to a date variously estimated at 10,000 to 30,000 years ago, when Behring Isthmus broke down and Old Man America was divorced from dark-eyed Asia. America became an Ishmaelite.

Modern investigations necessitate a revision of this theory as a much fuller American retrospect has been built up. A definite conclusion has been reached in competent circles, that the conception of a single Behring route to and from America is an error and does not meet the requirements of better data that has been assembled. Scientists now incline to the view there must have been a second direct Atlantic land connection between Europe and America and this has been stated in technical literature.

Regarding a former Atlantic land connection between Europe and America, the learned head of McGill University Department of Geology, makes a general comment:—“It is probable that a land bridge connected Europe and America, perhaps with minor breaks, right up to some time in the Tertiary. . . . It is thought that this land mass reached as far south as the British Isles on the East and included Nova Scotia on the Western side.”

Lost Continent long united the British Isles and Canada—This is a new view of scientists and Nova Scotia or “Acadia” may have been the shore-end of the missing “bridge”, over which prehistoric pachyderms reached America, as skeletons have been found in the “Acadian” area. One Cape Breton elephant, it is estimated, stood 12 feet high, second only to “Imperial Mammoth,” restored, 13½ feet, discovered in Nebraska, largest found anywhere, shown in the illustration. (Photo by courtesy American Museum of Natural History, New York).

A casual statement from the Economic Division of Geological Survey, Ottawa, contains the remark:—“Your idea that mastodons arrived from the Old World by way of Greenland appears to me not impossible. . . . It should, in fact, be considered having possibly been the route of migration of large mammals during some part of the late Tertiary time.”

The talented director of Royal Ontario Museum kindly writes: “It is generally accepted by all geologists that there was a continuous land bridge from North America into Europe via Iceland and the Faroe Islands. . . . In the West (mastodons) they reached Great Britain from Africa, from which place by means of an early Miocene land bridge via Shetland Islands, Iceland and Greenland, they reached America.”

There is evidence the vanished North Atlantic continent persisted into the era of “Recent Life” which may or may not include Man. So far anthropology offers no indication that the final collapse occurred in human times, though plant and animal life were well established, but while the prospect that the lost continent was inhabited is remote, it is not impossible.

One of the exhibits in the case is a non-volcanic submarine plateau between Canada and the British Isles, which carries a network of insulated cables across the “submerged tumuli of a drowned world.” 150 million electric words dealing with social, financial and official subjects are annually transmitted. The count would be greater if decoded. Most Atlantic cable traffic lands in “Acadia,” significant of the thought that older parts of Nova Scotia are sections of the bridge-head or shore-end of a lost continent, a faint conception of which is being slowly reconstructed from scientific data.

Cross-sections of the bed of the Atlantic Ocean have discounted the old “Atlantis” fable, that a southerly land between the West Indies and the Azores sank with cities and fields. It has also been asserted that South America and Africa were connected at one time, but it is now more generally believed these legends are largely an echo of the disappearance of a North Atlantic continent, possibly equal to Australia in extent, over which prehistoric elephants wandered to American soil.

Dawson’s “Acadian Geology” notes that bones of a prehistoric elephant of record size were disinterred in Cape Breton (Acadia) more than 100 years ago. Some are in the Provincial Museum at Halifax. It is calculated this monarch was 25 feet in length, 12 feet high at the shoulder and had bowed tusks 9 feet long. The Cape Breton dimensions are second to the “Imperial Mammoth,” the world’s greatest, 13½ feet at the shoulder and 25 feet in length, found in Nebraska in 1858. Elephant remains have been unearthed in every country, except Australia. The pachyderms are interesting because of their wander-lust and intelligence. Progenitors have been traced from Egypt. They circled the earth and frequently lived 100 to 130 years and were able to adapt themselves in hide and teeth to any change of climate or food. Great herds apparently roamed the Americas and it is a deep mystery why they ultimately became extinct, some students say only 1,000 years ago.

A second find of teeth of an elephant was made in Cape Breton at Baddeck. Most intriguing is a skeleton turned up July 4, 1936—Independence Day—at Hillsboro, New Brunswick, the third in the Acadian area. The bones of this native American are in 150 pieces, but perhaps 80 per cent complete and are being carefully restored at New Brunswick Museum, Saint John. This animal is the mastodon type, 9 feet 6 inches tall, somewhat less than modern elephants, and more thick-set. In some countries elephant measurements are to the top of the head and include the trunk. The “Imperial” and “Cape Breton” mammoth specifications, as quoted, exclude the head and trunk, showing the truly magnificent creatures that were developed on the western continent. With head and trunk added to height and length, the Cape Breton giant would be a Great Mogul.

The Hillsboro mastodon discovery was in four feet of blue clay and drift and close to the site of the Battle of Peticodiac, 1755, when an English and New England force attempted to extend the “Expulsion” of Acadians into New Brunswick (present name) and were repulsed with heavy loss. A common grave of the victims was marked by a mound for many years, which has disappeared and the location is now commemorated by a public monument.

At New London, Prince Edward Island, the petrified jaw of a man-eating alligator was exhumed in sandstone, an old beach. Coal measures of Nova Scotia furnish some of the oldest fossils of the globe, being the impressions of primitive creatures that were entombed on the flanks of hoary hills of a pioneer continent.

Legend identifies bold Basques with the missing Atlantic dominion. These hardy fishermen from Northern Spain reputedly crossed the Atlantic to “Acadian” fisheries since earliest times. The Basque nation are of unknown descent and their Iberian dialect unlike any in Europe, with a mixture of American Indian and Mongolian forms. The letter “r,” as in American languages, is not used. Before the Christian Era, a fable relates, Basque Fathers entered into an alliance with Indian tribes in North East America and founded a powerful mixed nation, with important communities and fleets of galleys. Practically the whole people, other than a comparative few that escaped to Spain, are said to have perished, with Queen Irura, of exotic beauty, in an extensive earthquake. The legend runs that native sages foretold the calamity as the doom of fate to punish the “cross” of red and white. “Barzil,” off the “Acadian” coast, a “mythical” large island-remnant of a former lost continent is pictured as the scene of the western Basque Empire annihilation.

The first notable feat in America, in winter marching of troops, was General Benedict Arnold’s American force conducted from Kennebec, Maine, to the fruitless siege of Quebec in the latter part of 1775. 300 men perished through exposure and hardship.

In more severe weather and covering a greater distance, starting February 11, 1813, the 104th regiment, 1,000 strong, raised in New Brunswick, under Major Drummond, travelled from Saint John to Quebec in the remarkable time of sixteen days, without the loss of a man.

In December, 1832, the 43rd British light infantry marched from Fredericton to Quebec, over improved roads and bridges. The Duke of Wellington pronounced it an exceptional military performance, but it actually was less arduous than the 1813 expedition.

In the winter of 1861-62, in connection with the Trent affair, an army of 5,000 picked British troops, with transport and artillery, moved from Saint John to Quebec by road and frozen river. Inhabitants along the way provided sleds. No accidents or delays occurred, but the incident probably hastened construction of an Intercolonial Railway joining the “Acadian” provinces to Canadian provinces and consolidating a Canadian Confederacy.

It is only within living memory, after a lapse of nearly 400 years and largely as a result of documents brought to light in foreign archives, that the mills of the gods have granted probate and approval to John Cabot’s title to fame as the first European explorer, excluding legendary and vanished voyagers, to see and set foot on the mainland of the Western hemisphere.

Measured by extent and magnificence of North American development, the indirect results of Cabot’s, “Discovery of America” easily surpass ancient empires. The Cabot exploit is typical of important events which have transpired in Acadia.

It is related that, “after much wandering fifty-two days,” on June 24, 1497, “at the hour of five, at daybreak,” (hora a sub diliculo), while approaching from sea the hitherto unknown or forgotten Nova Scotia extension of the continent, Captain John Cabot, skilful pilot, scanning the western horizon from the deck of the tossing “Matthew,” a small vessel of 80 tons, glimpsed rising from the ocean brim, the long-visioned outlines of a “New World,” dimly foretold by sages, repeatedly mentioned in Nordic sagas, but overlooked during centuries of preoccupation principally in connection with the Crusades.

June 24, 1497, became the first day in an American calendar, replacing picture writing on stones and trees. Cabot effected a landing at a convenient harbor in Cape Breton “Acadia” and took formal possession of “America” on behalf of the King and Crown of England. A contradiction is presented that the “Acadian” or Nova Scotia section of Eastern Canadian rocks, which were grim with age before the uplift of the Rocky Mountains or Himalayas, should be the first part of the American continent to be contacted and one of the last portions of the world to be chronicled on charts and globes.

That Cabot had discovered an additional continent, which intercepted anticipated water communication with Asia was not realized until 1513, when Balboa beheld the shimmering Pacific Ocean. The new land had been catalogued as part of Asia. Cabot’s feat of finding an extra division of the earth is an occasion of so much greater meaning and grandeur, that nothing comparable to this item in “Acadian” annals can ever again illumine world history.

All Cabot’s personal papers and records have been lost or perhaps suppressed. In the absence of details of an event as important as the “Discovery of America” it is allowable to speculate on some of the circumstances. It was the dawn of present American interests. On a bright June morning in 1497, the same as today, sunrays scattered the fog-cap on Cape Breton hills and exposed to view gloomy wooded recesses of rugged Cape North, Nova Scotia, rising precipitously 1,200 feet from the ocean’s azure depths. A blue sky spanned the firmament. As the mist rose an English cry of “Land! Land!” rang from the masthead lookout. In fancy John Cabot is pictured on the fore-deck, left hand shading steady eyes, and right arm extended pointing to a shore line verging into view. “Prima Tierra Vista,” the first land seen, is engraved on earliest American maps, referring to Cape North, as the Historic Landfall of the Western Continent. Cabot probably coined the phrase, a three-word account of the Discovery of America, classing with “Veni, vidi, vici” and other gems of laconic brevity.

Fifty-two days’ sailing and twenty years’ pursuit of a purpose formed by Cabot at Mecca, holy city of Islam, were crowned with success in “Acadia.” The day was the Feast of John the Baptist. A British Royal Standard, the present of Henry VII, was the first flag unfurled on the western continent. The fleur de lys quarterings are noticeable, referring to the claim of the Kings of England to be Kings of France, which was continued for some years. Between two flags on shore the crew of the “Matthew” erected a tall “Cross.” The carpenters’ tools and nails, which were used, inaugurated the Iron Age on the mainland of the West. Cabot’s limited company consisted of his son, Sebastian, and eighteen mariners. Formal ceremonies of possession were carried out and, in keeping with the spirit of the times and in compliance with the King’s command, a “Cross” was planted on a hillside, expressive of the thanksgiving of sailors and a simple act of consecration of the country to the enduring principles, a “Cross” symbolizes.

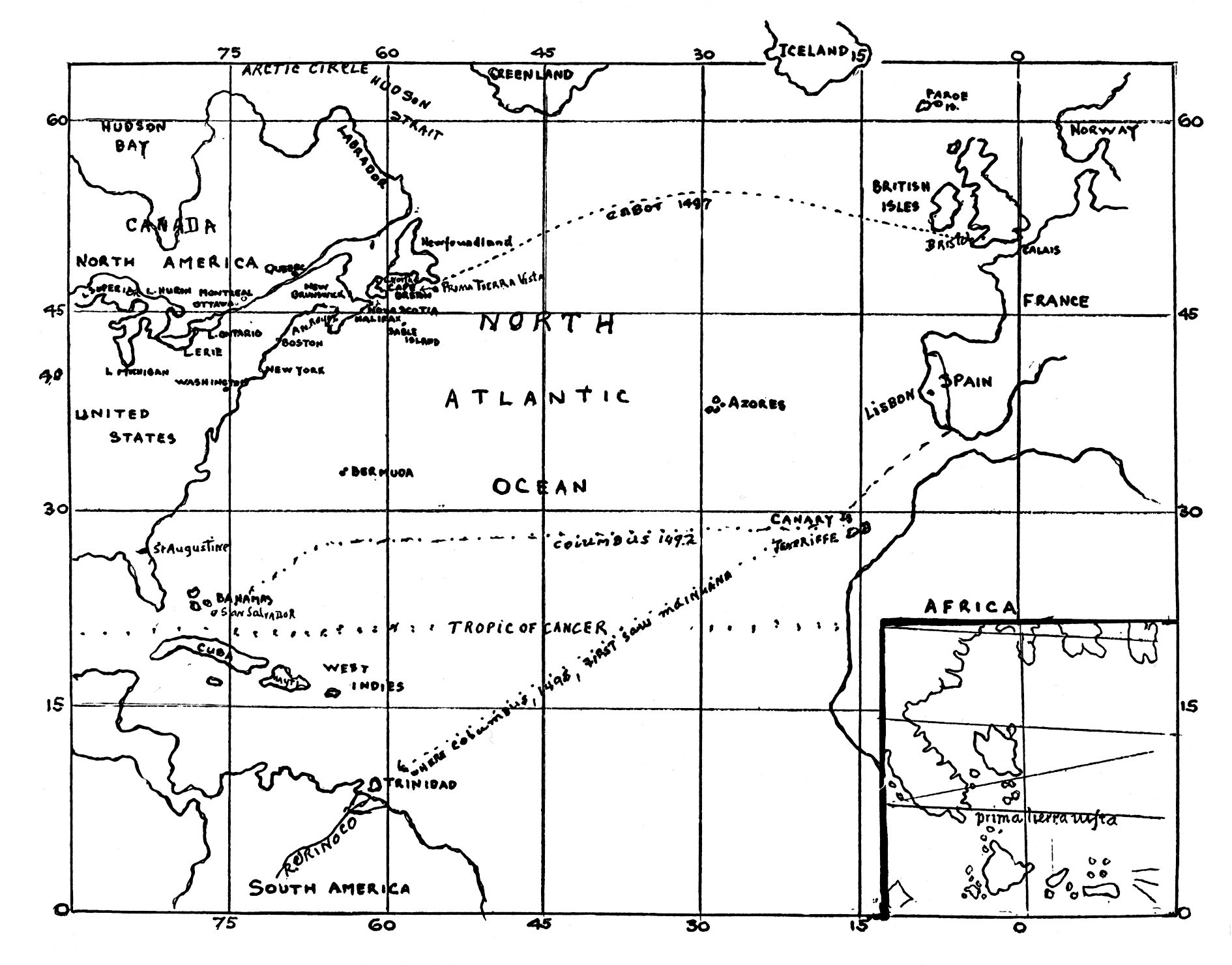

Discovery of America—Artist’s sketch of an immortal picture, the Landing of John Cabot, in Cape Breton, 1497. The Royal Standard of England, first flag on the mainland of a New World, is at the left. Bareheaded, the Commander salutes the Cross. Sebastian Cabot is about to do the same. No firearms are in sight. The arquebus was introduced in 1520, matchlock in 1567, flintlock and musket 1630.

* * *

“A discussion of the several interesting questions relating to the voyage of the Cabots, belongs to another chapter; but assuming here, that the voyage of the ‘Matthew’ from Bristol, England, in the summer of 1497, is beyond controversy, the precedence of the Cabots over Columbus in the Discovery of the Continent may be taken for granted”—Justin Winsor, Harvard Librarian, in “Narrative and Critical History of America.”

“John Cabot was the pioneer of English discovery and colonization. A long life of mercantile adventure had prepared him for the great work; and the experienced old navigator was at least sixty years of age, when he offered his services to Henry VII”—Sir C. B. Markham, K.C.B.

“Labrador, as well as Newfoundland, was discovered by John Cabot in 1497. Discovery of a map made by or under the direction of Sebastian Cabot, proves the honor of being “prima tierra vista” belongs to Cape Breton.”—Britannica.

Dr. S. E. Dawson, Royal Society of Canada, concludes Cabot’s Landfall was in Cape Breton. Among authorities quoted are Mons d’Avezac, Geographical Society of France; Dr. Charles Deane, Boston; Abbe Beaudoin; J. Carson Breevort, Astor Library; Rev. M. Harvey, L.L.D., St. John’s, Nfld., Sir John Bourinot, C.M.G., J. F. Nicholls, City Librarian, Bristol, Eng.

* * *

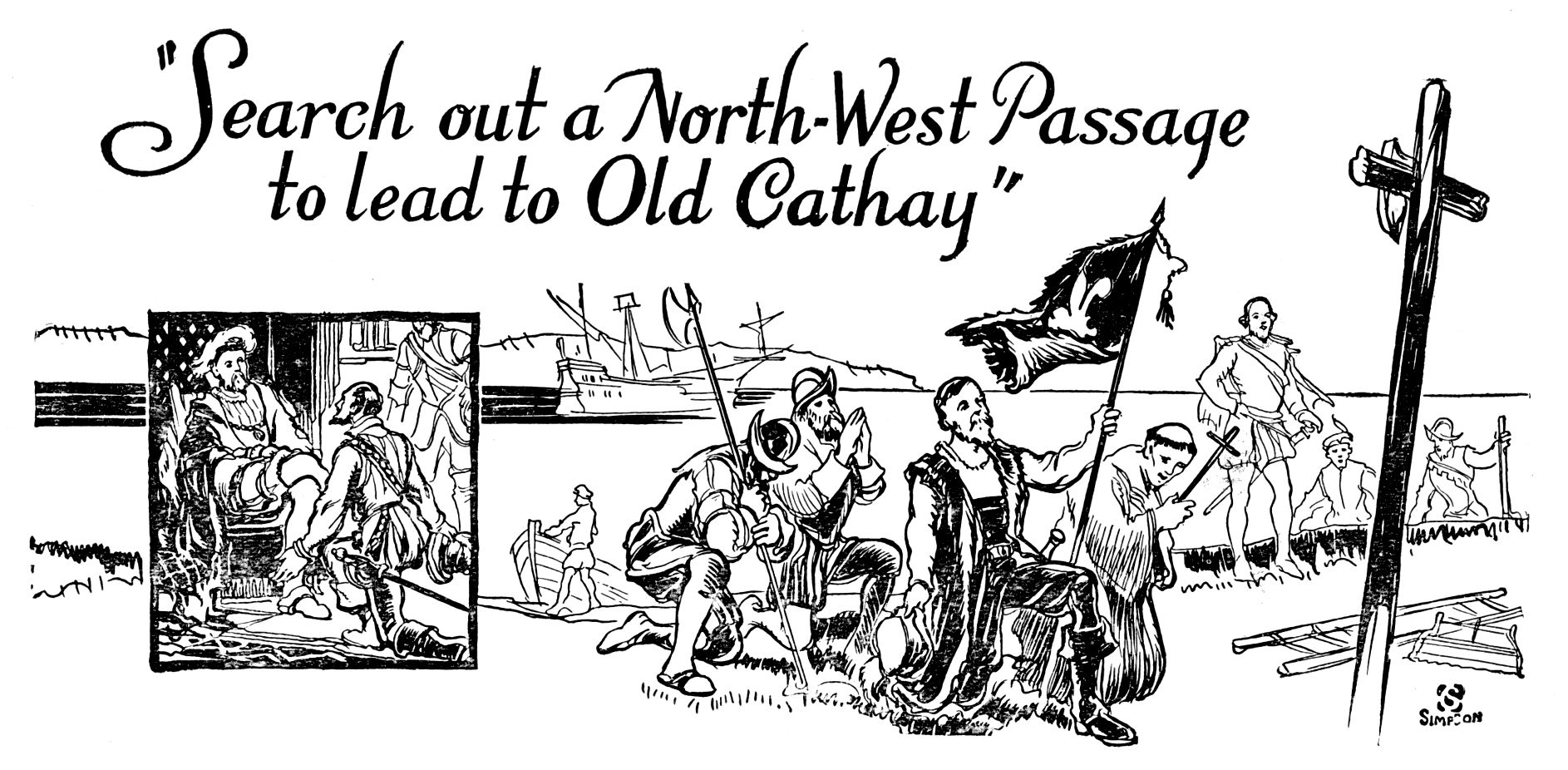

15th century discovery of the American continent possibly averted wholesale Mongolian settlement on the Pacific coast. In a way, the “Discovery of America” is virtually the greatest of the Crusades and presents Cabot in “Acadia” in the unconscious dual role of explorer and successor of Coeur de Lion. For thousands of years barbarous tribes of Eastern Asia knew “America.” Subjects of the Grand Khan regularly crossed the North Pacific to “Fu Sang,” the Chinese name of a beautiful American flower, that was applied to the overseas country. A break then seems to have taken place in the American contact.

Charles G. Leland, (Hans Breitman) in “Fu Sang, The Discovery of America by Buddhist missionaries in the 5th century A. D.,” quotes a French sinologist, Deguiques, that an account of “Fu Sang” is inscribed in annals of the Celestial Empire and is regarded as an important state document. The report was made by Hoel Shin, a Chinese missionary, who returned after a long absence. The direction and distance travelled suggested “America” and ended probably at Mexico. It was a more or less familiar route at a time when hundreds of Buddhist monks were busy with propaganda in various Asiatic districts. The Fu Sang, “America,” narrative is reported transcribed into popular writings and woven into Oriental poetry and romance. Failure to follow up the trans-Pacific project energetically, is attributed to mass conversions that took place in Japan and the adoption of a closed door policy, intended to keep out foreigners and restrain nationals from emigrating.

Mancu Cabak, a Persian Buddhist, is described as another American visitor and as the reputed first Inca Emperor “child of the sun-god,” paralleling the Japanese Emperor’s descent from the Sun Goddess. Some philologists detect echoes of the “Man” syllable in Canadian names “Manitoba” and “Manitoulin.” Cabak and “Kebec” are also linked and the “codiac” termination in Eastern Canada is compared with “Kodiak Island” Alaska, while “Man-Cu” is said to be a Manchurian Deity and a variant of old Baal of Babylon. The Indian title “Manitou” alludes to the “Great Spirit,” but Seattle and Vancouver authorities do not see any significance in the occurrence of the prefix “Man” on both sides of the Pacific. A general migration of Asiatics to America is assigned to periods varying from 2,000 to 15,000 years ago, both before and after Buddha and Confucius. It is conspicuous that the greatest of the dead cities of Central America, discovered 25 years ago, is probably Manchu Picchu, estimated to be at least 2,000 years old, containing extensive ruins of homes, temples and gardens and the evident former centre of a large and progressive population.

A flight of parrots or tropic birds helped deprive Columbus of the distinction of discovering the mainland and existence of a “New World” in the west and it is not often that the migratory instincts of feathered friends have had more extensive consequences. Toscanelli’s chart, the Admiral’s guide, placed Quisnay (City of Heaven), southern capital of Zipango, land of gold and spices, near the 30th parallel, and a due west direction on this line was adhered to for thirty days, following final departure. Columbus’ little fleet cleared from Teneriffe, September 6, 1492.

On October 6, at the advice of Martin Pinzon, captain of the “Pinta” and second in command, an experienced pilot and shipowner who had assisted the financing, Columbus changed the course to southwest. Pinzon saw a flock flying south and birds have been guides to mariners from the “Ark” onwards. Six days later, on October 12, land was discovered in the Bahama Islands, 300 to 400 miles from the mainland of America. The voyage to the continent was not completed.

The oblique alteration of the helm opens the way for controversy. One conjecture is that if Columbus had resisted the counsel of Pinzon, a continuation of the original route and the influence of the Gulf Stream, would have carried the explorers to Cape Hatteras and United States and Canada would now have a Spanish population.

“Not much,” comments one critic, “England would have taken the continent in any case.” Several writers surmise, that as Columbus’ crew were restive, if the voyage had been prolonged to reach the mainland the Admiral would have been forced to turn back, which is not majority sentiment, as both Columbus and Pinzon are believed to have been determined to find land, though the crew may have taken control at the end of the stipulated three days and would have found there were two logs being kept to conceal the true distance from Europe. Columbus had misjudged the circumference of the earth and predicted the shores of “Asia” would be much earlier encountered.

It was not until the third voyage, Wednesday, August 1, 1498, thirteen months after Cabot had landed in Nova Scotia on Saturday, June 24, 1497, that Columbus at Trinidad,—“beheld for the first time, in the mainland of South America, the continent he had sought so long”—(Britannica). During the last voyage, 1502-04, the Admiral, discredited and forbidden to touch at Hispaniola, West Indies headquarters, was ashore at Honduras and Panama, which was Columbus’ first continental landing. Columbus never saw the mainland of North America and at death at Valladolid, old capital of Spain, 1506, was still of the opinion the western continent was the coast of Asia.

* * *

Favored by trade winds in sunny climes Columbus’ ships in 1492 averaged 4.4 knots per hour progress for 36 days from Teneriffe to San Salvador Island. The particular island is a matter of dispute. In the boisterous North Atlantic, Cabot advanced at the slow rate of approximately 2 knots per hour during 52 days from Bristol to Nova Scotia, (Acadia), probably meeting adverse weather, with “much wandering,” but not a word survives. The log of the “Matthew” has been lost. The time, from land to land was nearly 50 per cent greater than Columbus’.

Cabot was familiar with cosmography and on return to London from America in 1497, prepared a map and globe, which with report, have disappeared. Almost all known details of the Cabot voyages are second-hand materials, which have been unearthed in archives of Spain and Italy in correspondence that Ambassadors at the Court of St. James sent respective sovereigns. British archives on Cabot are painfully deficient, outside of the Royal commissions that have been preserved and information relative to granting Cabot a bonus of £10 and payment of a pension of £20 ($1,000 today) to “him that found the new Isle.”

Yet in the language of Hakluyt: “The title which England has to that part of America, which is from Florida to 67 degrees northward is or was derived from the letters patent granted to John Cabot and his three sons,” in 1496. Letters patent for the second voyage, signed by Henry VII, February 3, 1498, confirm the success of the previous year. The indenture refers to: “The land and isles found (were discovered) by the saide John Kabotto, Venecaine.” Sebastian Cabot is not named in the second indenture.

FORMER ROYAL STANDARD OF ENGLAND—The First Flag of record on the Mainland of the Western Hemisphere, was unfurled by Captain John Cabot in “Acadia” (Cape Breton) June 24, 1497. According to ladies of Bristol, Eng., the flag was a personal present of Henry VII., to the explorer. This beautiful banner, now for perhaps the first time specially printed in the West, is probably the victorious crest that waved at or after Crecy, when the Black Prince adapted the triple-feather motto, “Ich Dien.”

Shakespeare has no notice of America or of Cabot’s transcendant performance, other than a casual allusion to the Indies in “The Tempest,” while Henry VII, parsimonious and richest of princes and master diplomat, sometimes styled the “Solomon of the West” is also passed over by Elizabethan dramatists. One unruly author traces the names “Columbus” and “Cabot” to a common Sanskrit stem, “Kapota,” meaning a dove, homing pigeon, ship messenger or explorer, brought from the Far East by Marco Polo. Both American explorers were natives of Genoa and sailed under different flags, other than Italian.

The theoretical objective of Cabot’s masterful voyage was “Cambuluo,” (Peking), northern capital of the Grand Khan, supposedly situated on the 50th parallel, the same as Bristol (or Vancouver and Winnipeg), which was an error, but in addition no allowance could be made for unknown currents.

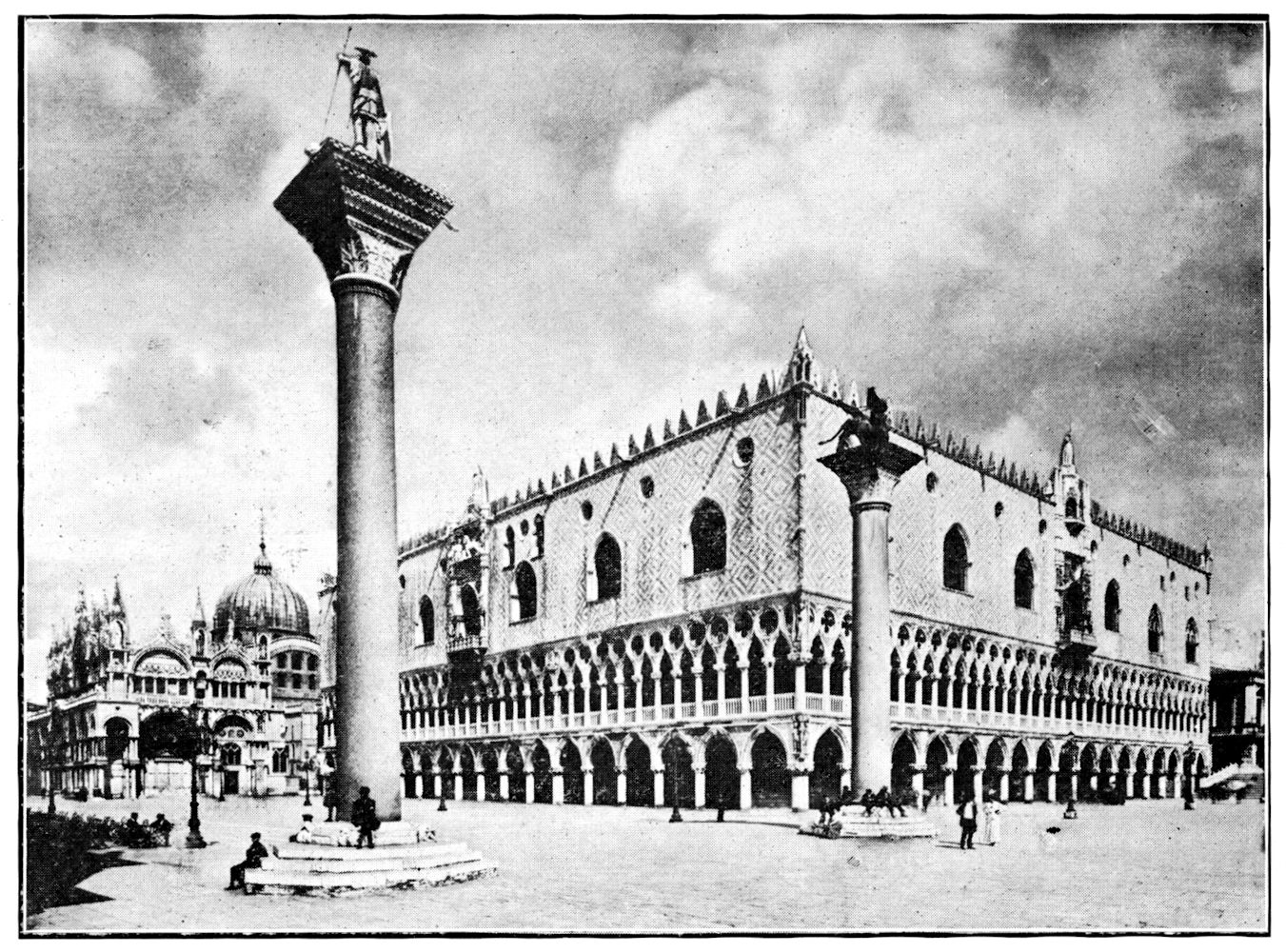

In 1476, after 15 years prescribed residence, Cabot was granted “full” citizenship in prosperous Venice, which permitted foreign trading. At Mecca, a caravan centre, Cabot’s active interest was aroused in the subject of the sphericity of the earth and the possibility of sailing west to Asia as a means of eliminating middle-men and saving time in transporting Eastern products to European capitals. When the Doge of Venice, Andrea Vendramin, addressed John Cabot with the dignified formula of the senate “te nostrum creatus”—we create thee one of us—it was the first step on the road to Mecca and to the heights of Olympus in “Acadia” in the far west.

Palazzo Ducale-Doge’s Palace, Venice—The actual building where John Cabot was created a full citizen of the Republic in 1476, which was the first step on the way to Discovery of America in 1497 at “Acadia” or Nova Scotia.

Ayala, junior Spanish minister at London, represents Cabot having ineffectually sought assistance in Spain and Portugal. Italian Republics were centres of distribution for caravan trade from the East and were unwilling to countenance any diversion likely to interfere with Mediterranean connections. Many Genoese were resident in London and held high positions. One was King’s physician. With other Italians, they met daily in Lombard street and frequented legations maintained by Spain, various Italian Princes and the Republic of Venice. Considerable commerce existed between England, Venice and Genoa. Regular Mediterranean caravels touched at Spanish and Portuguese ports and carried mail and news.

* * *

John Cabot married in Venice and with family, is believed to have removed to Bristol, a growing emporium, about 1486. It was at Bristol in 1477 that Columbus is reported to have embarked for Iceland to inquire about Greenland and other lands in the west formerly colonized by Norsemen. A large trade in fish and merchandise was carried on between Iceland and Bristol and about 1477 the Governor of Iceland was killed by English sailors in a riot, which brought about war between England and Denmark that lasted until 1491. A number of Bristol ships were seized in Danish ports and Cabot is understood to have been a representative of Bristol merchants in securing a settlement of claims.

Bartholomew Columbus, brother of Christopher, was delegated to approach Henry VII to finance Columbus’s western project, but was taken prisoner by pirates while crossing the English Channel and was detained for months. When he reached London, King Henry listened with favor to the proposal, but it was too late, as word came that meantime Christopher Columbus had obtained a second and successful hearing with the Spanish Queen, through the intervention of her confessor, head of Rabida Monastery, where the homeless Columbus stopped for shelter, with a young son by the hand, on the way to England.

Cabot always seems to have been active. In a letter July 25, 1498, writing to King Ferdinand, the diplomat, Ayala, referred to Cabot’s previous work:—“The last seven years Bristol people have sent out every year two, three or four caravels in search of the Island of Brazil and of the Seven Cities according to the fancy of this Genoese (Cabot).”

It is not believed that Cabot accompanied early Bristol expeditions (there was one in 1480), though it is obvious he promoted them as far back as 1491 in the apparent hope of locating traditional islands that could serve as stepping stones for the greater enterprise.

When Henry VII, disappointed at not sponsoring Columbus, appended a peculiar sign manual to England’s first Royal Patent of Discovery, March 5, 1496 in favor of “John Cabotto, citezen of Venice, Lewes, Sebastyan and Soncio, his sonnys” empowering them to seek strange lands and take possession in the King’s name, the canny founder of the Tudor dynasty inserted a proviso that outfitting of “five ships or vessels” should be at “their own proper costs and charges.” Cabot was a poor man, which may explain twelve months’ delay procuring necessary credit for despatching a single bark, the “Matthew,” the first week of May, 1497, on an epic adventure. The personnel of the dauntless British crew of 18 men has not been found. The “Matthew” is supposed to have been Cabot’s own schooner.

“Departure of John and Sebastian Cabot” is the title of a large canvas by the late Ernest Board, R.W.A., in Bristol Municipal Art Gallery, painted for the Corporation. Seamen are hauling on the mainsail of the “Matthew” embroidered with the Royal Arms and the Arms of Bristol. On the harbour steps a clerk is checking a last lot of weapons and armour. Townsfolk are assembled at the quay. Abbot Newland, or Nailheart, waits to give a blessing, while the Mayor bids John Cabot farewell. Young Sebastian holds the Letters Patent from the King, and beside him is his weeping mother to whom a nun offers consolation. Cabot, a commanding figure, notwithstanding 60 years of age, about the same age as Columbus, completes the group in a splendid work of art, reproduced at the front of this hand-book.