* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please check with a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. If the book is under copyright in your country, do not download or redistribute this file.

Title: Poppy Ott Hits the Trail

Date of first publication: 1933

Author: Edward Edson Lee

Date first posted: May 7, 2021

Date last updated: May 7, 2021

Faded Page eBook #20210514

This eBook was produced by: Stephen Hutcheson & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

JUM GOT A CRACK IN THE REAR END THAT KNOCKED HIM CLEAN ACROSS THE CREEK. (Page 123)

BY

LEO EDWARDS

AUTHOR OF

THE POPPY OTT BOOKS

THE JERRY TODD BOOKS

THE TRIGGER BERG BOOKS

THE ANDY BLAKE BOOKS

THE TUFFY BEAN BOOKS

ILLUSTRATED BY

BERT SALG

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS NEW YORK

Copyright, 1933, by

GROSSET & DUNLAP, Inc.

Printed in the United States of America

To

“KAYO” BRADISON

An Earnest Student, a Determined Athlete, a Trustworthy Scout and a Swell Pal

Here is a list of Leo Edwards’

published books:

As soon as the black-bass season opened up, in June, Poppy Ott got out his steel fishing rod and disappeared into the hills north of town. He was gone a whole day. And when he came back that night he had a face a foot long. He was worried about something. And yet he was peculiarly excited too. I could tell by the look in his eyes.

“Say, Jerry,” says he, when I dropped in on him that evening to get the news, “what do you know about law?”

“What kind of law?” says I, helping myself to a banana.

Poppy and his widowed pa are good feeders. They always have stuff sitting around in dishes. And if a fellow doesn’t fill up when he’s there, old Mr. Ott acts offended. Of course, I never offend him myself. Next to my pa I think he’s one of the finest men in the whole state. Yet, when he came to town, he was nothing more than a common tramp. As for Poppy himself, I never saw a more ragged kid in all my born days. But he soon proved that he had good stuff in him. Getting a job, he bought himself some decent clothes. That kind of shamed his pa, I guess. Anyway Mr. Ott decided to do a little work himself, and less loafing. Now he and Poppy (who got his odd nickname from peddling popcorn) have a comfortable home on the east side of town. And they both have the respect of everybody who knows them, which proves that rags are no handicap to an ambitious boy.

I took a shine to Poppy the first time I saw him, ragged as he was. Nor have we ever had a moment’s trouble since. He has his ideas and I have mine. And if I think mine are the best, I tell him so. But usually I have to admit that his are the best. Take that “Stilt” idea, for instance. Then came the famous “Pedigreed Pickles,” and still later the “Freckled Goldfish” and “Tittering Totem.” Very recently he had dipped into pancake flour—or maybe I should say “Prancing Pancake” flour. For that’s the peppy name he gave it. Boy, oh, boy! We sure had a time solving that mystery—for we bumped into a lot of stuff besides flour. Pirate stuff, mind you. Little did I dream, though, as I sat in his parlor eating bananas, with the cat in my lap, that an even crazier mystery was getting ready to jump out at us and grab us by the shins.

Poppy had said something about law. So I asked him again what kind of law he meant.

“The kind,” says he, “that puts people into jail.”

I took time out to search his face.

“Poppy,” says I severely, as I treated another banana to a free ride down my gullet, “have you been fishing in somebody’s private pond?”

“No,” says he truthfully.

“Then what are you afraid of?” says I.

“I’m just wondering,” says he, “if the law would put me in jail for helping a runaway boy.”

A runaway boy!

“Evidently,” says I, as I further searched his sober face, “you saw something up the creek besides scenery.”

“I did,” says he earnestly.

“Well,” says I, “don’t keep me in suspenders.”

“I met a strange boy,” says he. “I never saw him before. And I doubt if you did either.”

“I know a lot of farm boys,” says I. “In fact, the most of the boys in my Sunday-school class live in the country.”

“You never saw this boy in a Sunday-school class. Nor in any other kind of a class.”

“Doesn’t he go to school?”

“No. He never saw the inside of a schoolhouse.”

“But how does he get by with it?” says I, amazed. “I thought every boy had to go to school.”

“He’d like to go to school. He told me so. But his aunt won’t let him.”

“And doesn’t he even know that the earth is round?” I followed up.

“Probably not.”

“How old is he?”

“Thirteen.”

I was so amazed I forgot to reach for another banana.

“Well, I’ll be cow-kicked,” says I. “What do you know about that? And right here in Illinois, too.”

“As I understand it,” Poppy proceeded, “he has three aunts. But the only one I saw was an angular old battle-axe with a face like a granite tombstone. Hard and cruel. You know what I mean. She and her sisters kept him in a closet when he was a baby. But now they let him run wild in the woods.”

“Maybe he’ll turn out to be another Tarzan,” says I, with mounting interest.

“I feel sorry for him, Jerry. And if I can get him out of there, without crossing the law, I’m going to do it.”

“Does he wear pants, like us?” says I, trying to picture him in my mind. “Or does he have hair on him, like a monkey?”

“Please don’t make fun of him, Jerry,” says old sober-sides. “For he’s an object of pity.”

“Where in Sam Hill did you meet him anyway?” I followed up curiously.

“At the foot of Clarks Falls.”

“That’s a good place,” says I, “for a kid to run wild. For the rock piles up there are like young mountains.”

“I never dreamed myself that Illinois had such hills, till I saw them with my own eyes. And the trees? Boy, there’s a forest up there that stretches for miles. A regular Amazon jungle.”

“Don’t overlook the bats,” says I, drawing on my memory, “and the rattlesnakes.”

“I didn’t see any bats. It was the wrong time of day. But I did surprise an old rattler. He was taking an afternoon nap on a big flat stone.”

“What happened when you woke him up?”

“Oh,” came the pleasant reply, “he twiddled his tail, sort of chummy-like, and then tried to bite a hunk out of me.”

“You’re lucky,” I shivered, “that his neck wasn’t as long as he thought.”

“Are there many snakes up there, Jerry?”

“I never saw but two or three myself. I dare say though they’re plentiful.”

“I wanted you to go with me this morning. But I noticed that you weren’t particularly keen about it. So I decided not to coax you.”

“Did you follow the creek all the way to the falls?” says I, speaking of the little stream that trickles into the town from the northern hills.

“Practically all the way. Once I climbed a rock pile and picked up the winding trail on the other side.”

“How long did it take you?”

“Four hours each way.”

“I’d hate to go on a hike like that all alone.”

“It was kind of lonesome,” he admitted. “But it was fun. For everything that I saw up there was new to me. I caught a lot of fish too.”

“Where?—in the pool at the foot of the falls?”

“That’s where I caught the biggest ones. And I made a queer discovery too, Jerry—something that I’m going to follow up. But first I’ve got to rig up a diving suit.”

I was staring at him now.

“A diving suit?” I repeated. “What in Sam Hill are you talking about?”

“Jerry,” he spoke earnestly, “did you know that the early Indians used to mine lead near Clarks Falls?”

“I’ve heard,” says I, “that they got lead some place near here. But who told you about it?”

“An old settler. According to his story this land at one time all belonged to the native Indians—the hills and hollows and everything else. Then the white men came. And the natives were gradually crowded back. Finally the redskins were taken away altogether and put on a government reservation. One of the last to go was a young brave by the name of Crow Foot. It hadn’t taken the new settlers very long to tumble to the fact that the Indians had a lead mine of their own. And so, when only Crow Foot was left, the crafty settlers tried to find out from him where the lead mine was. They needed lead, they said, for bullets. And they offered Crow Foot six ponies if he’d lead them to the secret mine. He might just as well, they said. For he was going away for good. And the hidden mine never would do him any good. Crow Foot, I guess, figured that the white men wanted to make more bullets so that they could kill more Indians. And so, true to his people, he started off alone on his pony. The white men, he said, would never find out where the lead mine was from him. But they did—almost. For that night a trapper found the Indian lying unconscious in the woods. He had fallen from his pony. It took a lot of faithful nursing to save his life. And in gratitude he drew a map for the trapper. If the good white man would go this way and that way, it was all drawn out on the hard ground with a stick, he’d find a hole in the rocks. And deep in this hole was the secret lead mine. The trapper, of course, thought that he was in luck. It would be easy, he figured, to find the hidden mine. It was his intention to sell the lead and get rich. And he told his wife to keep her mouth shut about their sudden good fortune. But the thought of being rich made her dizzy. And she said things to the neighbors that aroused their suspicions. Earlier the whites had tried to follow the redskins when they went after lead. And now the greedy whites tried to follow the trapper. It was learned that he headed for the hilly section near Clarks Falls. And having lost the trail, the spies decided to wait for him and waylay him. But he never came back.”

“That’s almost like the story of the Forty Thieves,” says I. “Remember, Poppy? Ali Baba’s greedy brother was trapped in the treasure cave. He got in all right. But he couldn’t get out. And probably that’s what happened to the trapper too.”

“I’d sooner think, Jerry, that he was killed by a landslide.”

“Well, maybe he was. But what’s that got to do with the strange kid that you met near the falls?”

“Nothing.”

“Then why did you mention it?”

“The point is, Jerry, that I’ve found a new hole near the falls. A hole that you never saw; nor anybody else around here. But I can’t explore it till I fix up a diving suit. For it’s under water.”

“But if you haven’t seen it,” says I, amazed, “how do you know it’s there?”

He picked up his fishing rod.

“Jerry, I had over fifty feet of line on that reel. It was a fine, strong line—plenty strong enough, I figured, to hold anything that I’d hook in Clarks Creek. But I got something in the pool under the falls—probably a big bass—that first took every inch of line that I had, and then snapped it like a cobweb. The pool itself isn’t more than twenty feet deep. I sounded it. And yet I had lost over fifty feet of line! That can be explained in only one way. There’s a submerged natural passageway going back under the falls. And when I get a chance to explore it, I have the feeling that I’ll see things that no white man has ever seen before me—not even the trapper himself. For, as I say, he undoubtedly was killed by the landslide that blocked the canyon and raised the water level in the pool.”

For a moment or two I was too amazed for words. But finally I got my voice back again.

“And do you really think,” says I breathlessly, “that you’ve actually found the Long Lost Indian lead mine?”

Never had I seen him look more earnest.

“I do for a fact, Jerry,” he spoke slowly. Then he added, with shining eyes: “And if I’m right, it not only is going to mean a fortune for both of us, but a decent home for that Saucer child.”

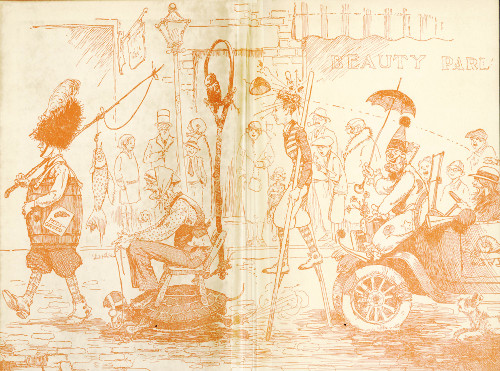

Before I go on with my story, I think I better tell you something about myself and the town in which I live. And as my other chums have a prominent part in the story, I’m going to tell you about them too. Nor must I overlook faithful Davey Jones. Gee! He’s only a sea turtle. But if the time ever comes when animals are awarded hero medals he ought to get one as big as an elephant’s back porch.

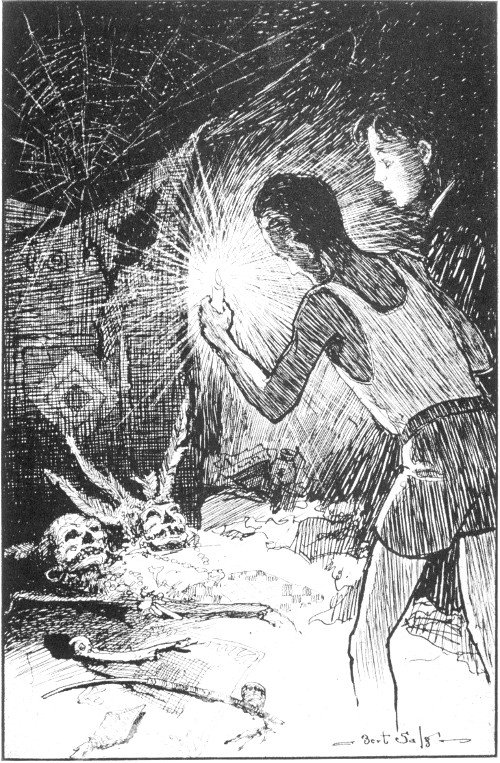

For not only did he let us load him down with our camping truck, as the pictures in this book prove; but later on he actually saved our lives. Like Ali Baba’s greedy brother we got into the treasure cave all right. But we couldn’t get out! And without Davey’s help our bones undoubtedly would have been added to the pile under the air shaft. Those grim whitened bones! They told a strange story. And they further put an end to a still stranger mystery.

But I won’t say any more about the bones here. That part comes later on.

My name is Jerry Todd. And like my swell dad, who owns a brickyard, I was born and raised in Tutter, Illinois. You can tell by the name of our town that it isn’t very big. For “Tutter” doesn’t sound like Chicago or Boston or San Francisco. When you hear the name spoken, or see it in print, you naturally think of cowpaths and hitching posts. That’s us, all right! But I like it. I wouldn’t trade towns with any boy anywhere. Nor would I trade chums. For I think I’ve got the best home, and the best chums, of any boy in the whole United States.

Take my chum Red Meyers, for instance. With his freckles and brick-colored topknot he isn’t much to look at. In fact, it’s generally conceded, even in his own family, that he’s the homeliest kid in the community. But he’s true-blue to his pals. Every time. And what he lacks in size he makes up for in gab. Dad laughingly calls him the little squirt with the big squawk. And can he squawk! Oh, baby!

Red and I live in the same block. He has a swell big barn, where we often put on wild-west shows; and his father runs a moving-picture theatre. Mrs. Meyers and mother belong to the same church societies, mainly the Stitch and Chatter Club, which meets once a week to make fancy hair-curlers for the heathens. In the same way Mr. Meyers and dad attend the same lodges. Red and I in turn often trade meals. He lets me know when his ma is cooking up something special, like fried chicken or liver and onions. And I do the same with him. In that way we both get a double dose of everything.

He further trades meals with Rory Ringer, another member of our gang, who lives at the other end of the block. Rory recently came to America from England. And you should hear his gab! He can’t say “arm” to save his life—at least he never does. With him an “arm” is a “harm.” And a “house” is an “’ouse.” He further calls “hawks” “’awks,” and “owls” “howls.” It sure is funny. One time when he was eating at our house he asked mum to pass him the “kyke.” And then he asked for another “bananah.” It was Red who got him into our gang. I thought myself that the newcomer was kind of small. But I’ve learned since that mere size is unimportant. Grit is the thing that counts. And Rory sure has it in big gobs. In our numerous battles with the tough Stricker gang, he holds his own with the best of us. And can he heave rotten tomatoes! Oh, oh! He hits the bull’s-eye every time.

Older members of our six-cornered gang are big Peg Shaw and Scoop Ellery. As I have written down in my various books, Peg is our best scrapper. But don’t get the idea that he goes around looking for a scrap. Absolutely not! He’s the best-natured kid in town. But he can put aside that big grin of his in a jiffy, let me tell you, if the occasion requires it. And then—oh, boy! He’s a whole battalion in himself. As for Scoop, it’s his swell leadership that has brought us through more than one neighborhood battle with flying colors.

At one time Scoop was our sole leader. But now he shares the leadership of our gang with Poppy Ott. There’s a pair for you! Poppy himself likes to work out clever business schemes. It’s born in him. Scoop in turn is a born detective. In fact, we all have detective badges. We call ourselves the Juvenile Jupiter Detectives of America. And we’ve had the good fortune to bump into some real mysteries too.

First, there was the mystery of the strange “Whispering Mummy.” Then the mysteries of the “Rose-Colored Cat,” the “Oak Island Treasure,” the “Waltzing Hen” and the “Talking Frog.” I’ve put our adventures into a series of books, like this one. And while the titles may sound odd to you, or even childish, don’t get the idea that I write fairy tales. Hardly! Take the “Talking Frog” book for instance. The mechanical frog itself was the clever invention of an odd old man, whose valuable radio device would have been stolen by a crooked toy manufacturer if we hadn’t stepped in. There’s a “ghost” in this exciting story, and a queer “puzzle room.” From beginning to end the book is packed full of fun and mystery. Having put a finish to that adventure, we next solved the crazy mystery of the “Purring Egg,” and after that in turn more mysteries, one of which took us into a strange “Whispering Cave” on Oak Island. While there we played “Pirate” to help a strange boy, who stood in danger of losing his inheritance. Later we found ourselves in charge of a newspaper. I started in as Editor-in-Chief. But I got into so much hot water with my mixed-up editorials (the wonder is that I didn’t get into jail!) that I soon changed my title to “Editor-in-Grief.” Still later we set up a “Caveman” kingdom on Oak Island, a favorite haunt of ours. And now, as I say, we were about to stumble headlong into still another mystery.

Many Illinois towns are surrounded by flat prairies. But Tutter is shut in by big hills, rolled up, thousands of years ago, by the gigantic river that then emptied the Great Lakes into the Gulf of Mexico. There is still a small river in the floor of the valley. But the two streams that give us the most fun in summer are Clarks Creek, as mentioned, and the winding canal into which the creek empties. The land that the creek drains is too hilly for farming. And deep in these northern hills is a remarkable waterfall. In the spring, or in rainy weather, this waterfall is a sight worth seeing. But few people ever get to it. For it’s too wildly located. Some day, I dare say, it will be made into a state park, like Starved Rock, another local point of interest. And then, of course, expensive roads will be built, enabling people to get close to the falls in cars. I suppose that’s all right. As long as the natural beauty is there, the people who make up the state have a right to enjoy it. Yet I hate to see the old wildness disappear. For boys love that kind of stuff. And I’d like to see some of the natural wildness left for the boys who will follow me. The best fun in the world is camping. At least that’s my idea. And there’s no camping that equals wild camping. It’s real fun when you’re in a place where you can roam in all directions without being chased by bulls or confronted by a “keep-off-the-grass” sign. And a camp with electric lights, grocery-store service and running water is no camp at all.

I’m going to tell you about a real camp!

The Stricker gang that I mentioned lives in Zulutown, which is the name that the Tutter people have for the tough west-side section beyond my dad’s brickyard. The two parts of town are divided by a raised switch-track. This track is the danger line. And if we go beyond it, any time of the day or night, we sensibly arm ourselves with rocks and clubs.

Bid Stricker, the leader, hates the ground we walk on. And nothing pleases him any better than to corner us singly and plaster us with mud. He’s jealous too because we have the best ideas. If we put on a show he tries his best to break it up. And in the same way he followed us to Oak Island one time and stole our scow. That was the time we played “Pirate.” And did we ever fix him in the end! Oh, baby! I’m glad he’s in this book. For I want to show you how we handle him when he gets too fresh.

Other members of the gang that you’ll meet in the following pages are Jimmy Stricker, Bid’s cousin, Jum Prater (whose mouth is so big that he has to put clothespins on it when he yawns to keep from turning inside-out) and the two Milden brothers, Chet and Hib.

Before Rory and Poppy came along, to join forces with us, Bid had us outnumbered. But now the situation is reversed. So, whenever a battle starts, we’re pretty certain how it will end, if we’re all together. And even if we’re shy a warrior or two, we can usually hold our own if Peg himself is on hand.

But let’s get on with my story.

Poppy had just told me about his amazing discovery at Clarks Falls. He had every reason to believe, he said, that he had actually located the entrance to the Long Lost lead mine, as worked, years ago, by the native Indians. I had often hunted for the mine myself. But it never had occurred to me, or to the hundreds of other boys who had similarly searched for it, that the entrance was submerged.

I had heard it said that a landslide in the vicinity of the falls had undoubtedly blocked the hidden cave, which was further believed to contain all kinds of native Indian trinkets. But now it would seem that instead of covering up the cave direct, as suspected, the landslide instead had caused the water under the falls to back up and do the concealing.

Which in itself was odd. But even odder was the manner in which the cave had just been rediscovered. A captive bass had done the trick!

And now the successful young explorer was walking on air.

“Yes, sir, Jerry,” says he, with dancing eyes, “we’re going to be rich. For the lead in that cave is worth a fortune. And probably we’ll find a lot of valuable Indian pottery too.”

“But how are you going to get at it,” says I, “if it’s covered up with water?”

“First of all I’m going to make a diving suit, to explore the cave. And if it turns out to be the cave I suspect, we’ll buy a pumping outfit and pump the pool dry. Then we can go into the cave just like the Indians did.”

“You’ll need a pretty big pump,” says I, “if it works faster than the falls itself.”

“Shucks! We haven’t had a drop of rain for weeks. And the falls is almost all dried up.”

I did some heavy thinking.

“Poppy,” says I, at length, “had it occurred to you that there might be a curse on that mine?”

“What do you mean?” says he, searching my face.

“Well,” says I, “you say yourself that the trapper was killed by a landslide before he could get into the cave. That looks suspicious. And I’d sure hate to have a similar landslide get chummy with me.”

“I’ll take a chance,” says he daringly.

Then he added:

“By the way, Jerry, didn’t you tell me the other day that Red Meyers had rigged up some kind of a diving outfit to hunt for lost golf balls?”

“Sure thing,” says I. “But I know what’ll happen to you if you start out to explore a submerged cave with that goofy contraption. For poor Red himself almost suffocated the afternoon that he and Rory tried it out in their cistern.”

“Maybe I can perfect it.”

“All it is,” says I, “is a pail turned upside-down, with a rubber hose fastened to it. There are glass eyeholes in the pail, and a rubber neckband to keep the water out. With Rory pumping air into the hose with an auto pump, Red thought sure that he could go any place under water. But the place he came nearest to was the local hospital. And his mother tells the story that he still drips water out of his ears when he sneezes.”

Poppy laughed.

“I’m sorry I missed that.”

“Red and Rory are caddying this summer. And they found out that the big water hazard in the golf course is literally plastered with lost golf balls. That’s what gave them the idea for the submarine outfit. But so far as I know to the contrary, the water-logged golf balls are still there.”

“Nevertheless,” persisted Poppy, “I’d like to see their outfit. For we’ve got to have something like that.”

Here a peculiar scraping sound occurred at the front door.

“What’s that?” says I, startled.

Laughing, Poppy opened the door. And in waddled a huge turtle.

It was old Davey Jones himself!

If you have read my book about the “Prancing Pancake” you’ll need no introduction to old Davey, the educated sea turtle. He was brought to town by one of the book’s main characters, who at one time owned a complete animal circus.

The first time I saw Davey he scared the wits out of me. I stumbled upon him in the weeds in Happy Hollow, just outside of town. His odd master was feeding him bits of raw liver. And it was then that I heard his history.

He came from Boot Island, in the tropics. And it was generally conceded by scientists that he was hundreds of years old. Anyway he was the biggest thing of his kind that I ever had set eyes on. So, when he took after me, on those powerful legs of his, with outstretched neck, it isn’t to be wondered at that I screeched bloody murder. I thought then that he was going to chaw a hole in my back porch. But I learned later that this was his way of having fun. When spoken to, by his odd master, he looked up at me as meek as a kitten. And when instructed, he even offered me one of his front flappers. That was his way of “shaking hands.”

He had earlier saved his master’s life. That’s why he was retained when all of the other performing animals in the show were sold.

Called away, on important business, the retired showman had left his unusual pet with old Cap’n Tinkertop in Zulutown. But it was nothing uncommon for the turtle to get out of his pen and wander around town. At first he caused a sensation. But the people soon learned that he was harmless. And now he frequently carried small children on his back.

Some of the kids, of course, thought it was smart to poke sticks at him. But he soon put a stop to that! And did I ever hoot the day he took after Bid Stricker. Gosh! Bid’s eyes stuck out like halved onions. To save himself he climbed a tree. Nor did the turtle let him come down till ten o’clock that night.

“Who are you looking for, Davey?” says Poppy, as the big turtle lumbered from room to room.

“Maybe he misses his master,” says I.

“Let’s take him home,” suggested Poppy.

So we started down the street in the gathering dusk, the intelligent turtle following at our heels. Pretty soon we came to the corner of School and Elm Streets, where old Mrs. Glimme lives in a rambling wooden house.

A very wealthy woman, Mrs. Glimme helps support her extravagant daughter-in-law in Chicago. There’s a grandson too. When he comes to Tutter he runs around with Bid Stricker. And once the two of them cornered me in an alley and turned my pants inside-out. Even worse they tied my hands. So I had to go home that way. I never would run down any kid simply because he came from the city. I’d be silly to do that. For there’s just as many good boys in the city as in the country. But I’ve got to confess that I can’t bear the sight of Reginald Glimme. He’s a snob and a bully. Because he has money he thinks he can run everybody. But he can’t run me. That’s why he dislikes me.

There was a farm carriage in his grandmother’s private drive. And just as Poppy and I turned the corner, thus getting a full view of the big yard, a tall angular woman got out of the shabby looking rig and mounted the steps to the front door.

I never had set eyes on her before. And probably I wouldn’t have given her a second glance if Poppy hadn’t suddenly clutched my arm.

He was peculiarly excited.

“Wait here, Jerry,” says he, in a low voice.

And without another word he darted into the shadowy bushes and silently wormed his way to the waiting carriage. I saw him look inside. And somehow his manner suggested to me that he was disappointed. Then I saw him tiptoe toward the house.

Turning, I observed too that Davey Jones had similarly disappeared into the shadowy yard.

Mrs. Glimme at one time had a lot of servants. But now she has the big house all to herself. For she likes to be alone. The kindly neighbors often worry about her. For she keeps out of sight for days at a time. They watch her chimneys in the winter and her bedroom light in the summer. If they fail to see smoke on time, or a light, they call her up on the telephone. And if that fails to arouse her, they knock directly on her doors. Once they found her unconscious at the foot of her cellar stairs. She had a fractured hip. But nobody in the neighborhood ever learned what caused her to trip and fall.

The town gossips say she’s too close-mouthed. They’d like to have her do more talking about her troubles and her secrets. And because she won’t, they run her down, hinting even that she herself helped to put her son out of the way. But I never took any stock in that theory. For I know how my ma loves me. And I don’t believe that any mother, unless she was totally crazy, would deliberately harm her only child.

Besides, Bardwell Glimme, at the time of his mysterious disappearance, was a man grown, with a wife and a baby boy.

I’ve never seen Reggie Glimme’s mother. But I’ve been told that all she cares about is pretty dresses and gay parties. In the winter time she lets the servants take care of her son. And when summer comes she dumps him onto his grandmother. But he never stays in Tutter any longer than he has to. For he takes after his restless mother. And that big house at the corner of School and Elm Streets is too blamed quiet to suit him.

Yet his grandmother always tries to make his visits pleasant. When he was small, she even bought hickory nuts and sprinkled them on the ground for him to find, so that he could go back to Chicago and tell his chums that he went “nutting” while he was in the country. In the same way she once buried Indian arrowheads for him to find. And how he bragged about that arrowhead collection of his! The city boys got the idea from his talk that nuts and arrowheads were as common in the country as mosquitoes. But that isn’t true at all.

With the strange history of the big house running through my head, I watched Poppy worm his way through the shadowy bushes to the front door, where the tall angular visitor was still waiting impatiently for admittance. Then the door opened. I could see Mrs. Glimme against the lighted background; she seemed peculiarly small and frail; and I could detect the murmur of voices.

Poppy had told me to wait on the sidewalk. But I couldn’t see any sense in that. Besides I was curious to learn what the women were talking about. So I did some pussy-footing myself. And with each guarded step the voices grew plainer.

“But the money isn’t due,” Mrs. Glimme spoke in a troubled trembling voice.

In contrast, the visitor’s harsh voice made me think of spikes going through a corn sheller.

“I want the money to-night,” she said.

“I’ll get it for you to-morrow. But I can’t pay you to-night. It’s impossible. For I haven’t that much money in the house.”

“You heard what I said,” an added sharpness appeared in the visitor’s harsh unrelenting voice. “I want my money to-night. And if you know what’s good for you, Anne Glimme, you’ll get it for me without further argument.”

Mrs. Glimme trembled with agitation.

“Have you no heart at all, Rachel Saucer? Do you propose to hound me to my very grave?”

“HAVE YOU NO HEART AT ALL, RACHEL SAUCER?”

Rachel Saucer! I saw now why Poppy was so excited. Saucer, I recalled, was the name of the strange boy that he had met that afternoon at Clarks Falls—the kid who never had seen the inside of a schoolhouse. And this tall bony woman evidently was the mentioned “battle-axe.”

Boy, she sure was a “battle-axe,” all right!

Her voice rasped with hatred. And she seemed to take a cruel delight in taunting the weaker woman in the lighted doorway.

“Heartless am I?” she began. “Well, maybe I am. But I’m exactly what you made me, Anne Glimme. When I was a girl you snubbed me. You were rich and I was poor. I wasn’t good enough to associate with you then. I wasn’t even good enough for you to wipe your feet on. Trash! That’s what you called me. Trash! And later, when you learned that your precious son was in love with my younger sister, you did everything in your power to separate them. Finally you succeeded. And what happened then? Shall I tell you, Anne Glimme? Shall I tell you to your face, right here on your own doorstep? Shall I? Or do you want to buy me off as usual? It’s for you to decide. And I don’t propose to wait either. Either I get my money to-night, in gold, or the truth about you and your son will be on everybody’s tongue to-morrow morning.”

“Rachel! Rachel!” came the pitiful begging cry. “Please.”

There was a harsh grating laugh, which more than ever revealed the visitor’s cruel unrelenting nature.

“How times have changed!” she spoke tauntingly. “A Glimme begging favors from a Saucer! Ha, ha, ha!” Then the voice changed. It was full of fury now. “But you’ll get no favors from me. I want my money. And I want it now.”

I thought that poor Mrs. Glimme would collapse in the doorway.

“Please come inside,” she begged weakly. “I’ll give you what money I have on hand. And I’ll send the rest to you to-morrow morning, as soon as the bank opens.”

Poppy had caught sight of me in the bushes. And as the two women disappeared into the house he joined me.

“I thought maybe I’d find the Saucer kid in the buggy,” he told me. “And I was going to coax him to jump out and beat it. But evidently his aunt came to town alone.”

“You certainly hit the mark,” says I, “when you called her an old battle-axe.”

“That’s the way she went at the kid this afternoon. As hard as nails. I wondered why he acted so timid. All the time he was talking to me he kept peeking over his shoulder. Sort of fearful-like. And finally he told me the truth. He had an aunt, he said, who knocked him around like a dog. He had been told never to talk to anybody outside of the family. If he saw anybody in the woods he was supposed to run and hide, like a groundhog. But he disobeyed orders when he saw me. That’s why his aunt beat him.”

“Someone ought to beat her,” I spoke angrily.

“We were sitting on a log beside the pool,” Poppy proceeded. “He was just telling me how he’d love to go to school and have boy friends like me. When all of a sudden something grabbed him from behind. And there she stood! Gosh, Jerry! I can’t begin to describe the look on her hatchet-like face. Nobody but the devil himself could look that way. And I doubt if even the devil could do it, unless he had a pain in his stomach. Holding the kid with one muscular hand, she switched him with the other till his bare legs were raw. Then she drove him ahead of her in the direction of their home. I later saw the place. It’s a log house set into the rocks. I bet it’s a hundred years old at the very least. And how anybody gets out of there with a carriage is a mystery to me. But evidently there’s a road of some sort.”

“If we’re going back to help the kid,” says I quickly, “we can’t follow the course that you took to-day. That’s too winding. We need a more direct course. So let’s find out where that road is.”

“How?”

“By following the woman home, of course.”

“By George!” cried Poppy. “That’s an idea.”

We could tell by the looks of the old farm horse that it wasn’t a fast traveler. It probably would walk all of the way home. Or even if it broke into an occasional trot we felt that we could keep up with it. Nor would it be hard, we agreed, to keep out of the driver’s sight.

Our plans thus made, Poppy stood guard near the waiting carriage while I skinned down the street to Wheeler’s drug store and called up mother. I had a big job on my hands, I said; and I might not get home till midnight. She didn’t like that a little bit. But when I explained to her that a friend of Poppy’s was in trouble, and needed my help, she gave in. For she realizes that boy chums owe a duty to one another.

Then who should percolate through the store door but freckled Red Meyers himself.

“Have you seen him, Jerry?” came the quick inquiry.

“Who?” says I shortly, eager to get away.

“The Indian.”

“What Indian?”

“The rain-maker.”

“Who are you talking about?” says I, puzzled.

“There’s a rain-maker in town. A real Indian. He got permission to pitch his wigwam in the public park. And to-morrow he’s going into the hills, where his ancestors used to hunt wild game, to make it rain.”

I thought of Poppy’s plan.

“Who wants it to rain?” I grunted.

“The farmers, of course.”

“I don’t,” says I bluntly.

Red grinned.

“What’s the matter?” says he. “Have you decided to put off your regular midsummer bath till next year?”

I had heard of scientists dynamiting clouds to produce rain. But I couldn’t make myself believe that an Indian could do it with magic charms, as Red now declared. And giving him the horselaugh, I left him in the drug store, with a big gob of ice cream in front of him, and quickly retraced my steps to the corner house.

But in the brief time that I had been away the carriage had vanished. So had Poppy. I was peculiarly disappointed.

Then, to my added surprise, a sleek little roadster drove into the yard. It was the Glimme kid! And beside him sat Bid Stricker.

“Hi, Gram,” greeted the new arrival, when his grandparent met him at the front door.

“Why, Reginald!” came the amazed cry. “What a pleasant surprise. How did you get here?”

“In my new car.”

“In your new car? Do you mean to tell me that you have a car of your own?”

“Sure thing. Didn’t mum tell you about it in her last letter?”

“No.”

“It took a lot of coaxing, Gram, but I finally got it.”

“I didn’t think that you were old enough to drive a car.”

The newcomer didn’t like that.

“Humph! To hear you talk, anybody would think that I was an infant.”

“But I’m sure you aren’t sixteen,” the grandparent persisted.

“Well, keep it to yourself, Gram. For as yet they haven’t found out about it down in Springfield, where the auto licenses are made out.”

Bid then called from the car.

“Hey, Glimme! Shall I bring in your bags?”

“Sure thing. But don’t touch that stuff on the runningboard.”

“What is it?”

“A tent and surveying instruments.”

Mrs. Glimme peered in the lighted car.

“Who is the other boy?” she inquired.

“Oh, one of your town kids. I picked him up down the street.”

“But what are you doing with a tent and surveying instruments?”

“I’m going camping.”

“Where?”

“Up in the hills, near Clarks Falls.”

A sudden change came over the woman.

“Oh, no!” she cried imploringly. “Don’t go there. You must not. For if Rachel found out who you were——”

And there she stopped, later retreating into the house, with increased agitation, when Bid stumbled up the porch steps with two huge traveling bags.

“Here you are,” sang out the luggage carrier, relieving himself of the load.

The grandson stood with a puzzled look on his face.

“My grandmother gets queerer every day,” says he.

“Is she sick?”

“Not that I know of.”

“She looked kind of white to me.”

“She got that way when I told her that I was going camping.”

“Boy! I wish I could go with you.”

“Well, why not?”

“Can I?—honest?”

“Sure thing. Get your stuff together to-night. And I’ll pick you up in the morning. But you’ve got to work.”

Bid began to cool off.

“What do you mean?” he grunted.

“I’m going to do some prospecting as well as camping. And I want you to do the digging.”

“Prospecting?” Bid repeated. “What do you expect to find up there? Gold?”

“No,” young Glimme spoke shortly. “Lead.”

Young Gummy, as we called him, had a big opinion of himself. And having inherited a piece of land in the northern hills, near Clarks Falls, it was his intention to survey the tract himself. He was dead sure, he told Bid, as I further hugged the near-by bushes, that the Long Lost lead mine was on his property. For he had found an old map among his father’s papers. And he had every reason to believe, he concluded, that it was an exact copy of the map that the Indian had drawn on the ground for the trapper.

I expected next to hear the chesty young prospector say something about a cave under the falls. But he didn’t. And was it ever a relief to me when he finally admitted to his chum that the map was incomplete.

“But I’m positive,” he wound up, “that the lead mine is somewhere near the falls. For that’s where the trail leads to. And that’s where the trapper was killed by a landslide.”

“Evidently,” says Bid, “the trapper must have made two copies of the ground map. For he needed a copy himself, to tell him where to go. And if he was killed by a landslide, as you say, the paper must have been buried with him.”

“I think his wife copied the ground map too,” young Gummy gave his head a wise wag. “But evidently a shower came up before she finished it. For the map suddenly ends just at the most important part.”

“And do you really believe that you can find the lead mine?” Bid spoke excitedly.

“Why not? I’ve got a better chance than anybody else.”

(So he thought!)

“Gee, you sure are a lucky guy!”

“What have you been doing all winter?” Gummy then inquired sociably.

“Oh, fooling around,” Bid shrugged.

“Is Jerry Todd and his gang still on earth?”

“Sure thing. But I hardly ever see them any more. For they’ve learned that it’s wise to keep out of my way.”

“Yes,” Gummy spoke meanly, matching his words with a dark look, “and if they know what’s good for them they’ll continue to keep out of your way. And mine too. For I don’t care to have them snooping around on my property. And that’s what they’d do, all right, if they got wise to my plans.”

“They’ll never find out anything from me,” Bid promised faithfully.

“Jerry thinks that the woods are free. But when I get my signs up I’ll show him that there’s one part of the woods that isn’t free.”

Bid leaned forward eagerly.

“Can you have him arrested for trespassing?”

“Absolutely.”

“Boy, I hope he does butt in on us. For I’d like to see you put him behind the bars. That would take him down a peg or two.”

“Does he still chum around with that big Shaw boy?”

“Sure thing.”

“How about Scoop Ellery?”

“He’s still in the gang. In fact, they’ve got one more in their gang than I have in mine.”

“But you can still lick ’em, huh?”

“Easy,” Bid lied.

And did I ever want to laugh!

“I know very well what will happen,” Gummy proceeded, “if Jerry finds out that I’m fencing in the falls. And until I can complete the survey, and get my signs up, I have no legal right to order him away. But I don’t want him hanging around at any time. So the thing for us to do, I guess, is to round up your whole gang. Then, if he shows up, we can put him out by force.”

“Hot dog!” cried Bid.

“I have one tent in the car. But we’ll probably need another.”

“How about the eats?”

“I’ll furnish the grub. But you’ve got to bring your own bedding.”

“I’ll have everything ready by six-thirty to-morrow morning,” promised Bid.

“Make it ten-thirty. For I’ll need time to buy the grub.”

“Do you know anything about the country up there?”

“Not much.”

“There’s a log cabin near the falls. And the people who live there drive in and out. They’re friends of my grandmother’s. So I can fix it up with them to take care of the car.”

“Who are they?”

“Three old maids by the name of Saucer.”

“Saucer! Haw, haw, haw! Some name. They ought to marry three brothers by the name of Cup. Then there’d be three Cups and Saucers.”

Bid thought that was awfully funny.

“And what would their children be?” he hee-hawed. “Pie plates?”

“Salt and pepper shakers, of course.”

“How many will your car carry?” Bid then inquired.

“As many as we’ve got to put in it.”

“The fellows will yip their heads off when I tell them about this.”

“Well, tell them not to do their yipping in front of Jerry Todd and his gang. We’re going prepared. But I’d just as soon have the woods to myself for a couple of weeks.”

Mrs. Glimme had gone to the kitchen to prepare a lunch for the newcomer. I could see her moving about in the lighted house. And now she called her grandson inside.

Bid started for the street, but stopped abruptly, and then screeched bloody murder, when a huge ungainly object crossed his path.

It was old Davey!

I later took the turtle home. And then I went back to Poppy’s house. Surely, I told myself, he’d be home by midnight. And wondering what he’d do, when he learned of young Glimme’s plans, I settled myself on the front porch.

I had time now to think of that odd conversation between the two women. And I found myself wondering what Mrs. Glimme had done that made it necessary for her to buy the other woman’s silence. There had been mention of a love match between the Glimme boy and the Saucer woman’s younger sister. This match seemingly had been opposed by the wealthy Tutter woman. She finally separated the pair. And then something had happened.

I knew, of course, that the Glimme boy had disappeared. But I still didn’t believe that his own mother had secretly put him out of the way—not even to separate him from an undesirable girl. For at the time of his disappearance he was married! It stood to reason that the mentioned separation had occurred long before that. No, I told myself, Bardwell Glimme’s disappearance was a puzzle in itself. There might be a crime there. But it wasn’t the thing that the mean country woman had referred to. There was something else. And slowly it percolated into my bean that whatever that “something else” was, it led directly to the unhappy boy that Poppy had met at the falls.

The boy’s aunts were getting hush money from Mrs. Glimme. I knew that to be a fact. And maybe, the conclusion formed itself in my head, the money was pay for keeping the poor kid out of sight.

It didn’t seem possible that Mrs. Glimme would do a thing like that. Yet the facts of the case were against her. And I found an ugly feeling toward her growing up inside of me. I’m a boy myself. I want a square deal. I want other boys to have a square deal. And in this particular case I was ready to fight for the boy who wasn’t getting a square deal.

Mrs. Glimme’s money wouldn’t save her. If she was selfishly ruining the country boy’s life, I intended, with Poppy’s help, to expose her. And then the law could take care of her.

But granting that my theory was correct, who could the boy be? And what would Mrs. Glimme benefit by keeping him out of sight?

It sure was a puzzle, all right.

I grew sleepy as the lights around me went out one after another. And finally I lit out for home, figuring that when I woke up in the morning, at the regular time, Poppy would be there to tell me his story.

“Is that you, Jerry?” came sleepily from mum’s bedroom, when I tiptoed up the stairs.

I stopped to give her a good-night kiss.

“I hope,” says she, “that you won’t feel compelled to stay up many nights like this to accommodate your new chum.”

“I haven’t seen him yet,” I confessed.

“Who is he?” she spoke curiously.

“His name is Saucer,” says I.

And then I asked her if she knew anything about the three old maids who lived near the falls. She had heard of them, she said. But she acted kind of funny when I told her that they had a boy in the family. He couldn’t be a real nephew, she declared, for none of the sisters had a husband. Which gave me something more to think about.

Maybe, I considered, as I got into bed, the boy had been left at their house in a basket. Such things do happen. Or possibly they had gotten him at some orphans’ asylum.

But why should they take him out of an asylum and then hide him in the woods? That was the part that stumped me.

My thoughts then jumped to the cave under the falls. And a queer tingle stole over me as I pictured its probable riches. Good old Poppy! It was like him, I told myself, to want to share his good fortune with me. And yet, the troubled thought shoved itself at me, we were liable to lose everything if young Gummy’s survey turned out as he anticipated.

His unexpected appearance on the scene didn’t help our case a-tall. And I found myself wondering what Poppy would do when he learned of the rich kid’s intentions. Would we race the cocky young surveyor to the falls? And would we later drive him off? That would be fun. But if he really owned the land we’d be the losers in the end. For once he had proved his claim to the tract, he could drive us off and keep us off.

Gosh! There was need for prompt action, all right. I could see that. And for a moment or two I was tempted to get quietly out of bed and go back to Poppy’s house. But I finally decided to stay where I was, hopeful that my chum would show up early in the morning.

Mum got me out of bed at six-thirty.

“Did you know,” says she, as she put out a clean shirt for me, “that Poppy Ott has disappeared?”

“Huh?” says I sleepily, unable at first to comprehend what she was talking about.

Then, as I got my wits together, I gave the bed covers a throw.

“Isn’t Poppy home yet?” I inquired excitedly.

“No. And if you have any idea where he is, you better get up and talk with Mr. Ott. For he just telephoned. And he’ll be here in a minute or two.”

Poppy had a bad woman to deal with. I realized that. And I wondered, with a sinking heart, if he had gotten into trouble. He had set out to do the rescuing act. But it wasn’t improbable, I told myself, that he needed rescuing himself.

Mr. Ott came in grumbling.

“Hen scratchin’,” he spoke in his odd sputtering way. “Nothin’ but hen scratchin’. An’ him stayin’ out all night too. Humph! I ought to use a switch on him.”

“Jerry himself was out till midnight,” mum informed.

“Thar you be, Miz Todd!” the old man spoke triumphantly. “Thar you be! They’re two of a kind. One stays out till midnight. An’ the other stays out all night. We ought to switch the both of ’em.”

Mum smiled. For she knew very well that the old man’s savageness was all put on. As a matter of fact he thinks that the sun rises and sets in his son. And I doubt if Poppy ever got a switching in all his life. Instead of switching him, as threatened, Mr. Ott backs him up in everything he does.

Now the glowering old man handed me a paper.

“Hen scratchin’,” says he again. “Nothin’ but hen scratchin’.”

I gave an excited cry.

“It’s a note from Poppy.”

“The farmer I buy milk from found it tied to his back door when he got up this morning at daybreak to milk his cows. It had my name on it. So he got me out of bed to deliver it.”

Mum glanced over my shoulder.

“It does look like hen scratching,” she declared.

“It’s written in code,” I explained, with continued excitement.

Poppy should have been home hours ago. And the fact that he had written to his father in code (realizing, of course, that the puzzled parent would promptly bring the secret message to me), proved that something unusual had happened, as I suspected.

Mr. Ott hung over me nervously as I deciphered the secret message word for word.

“Evidently,” he grunted, “you an’ Poppy must ’a’ made this up between you.”

I nodded, too busy at the time to tell him that my chum had gotten the simple code out of a book.

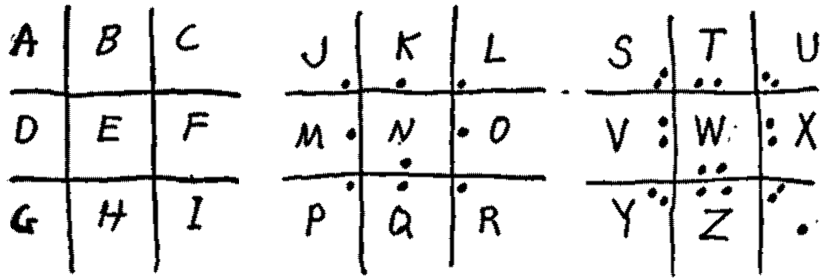

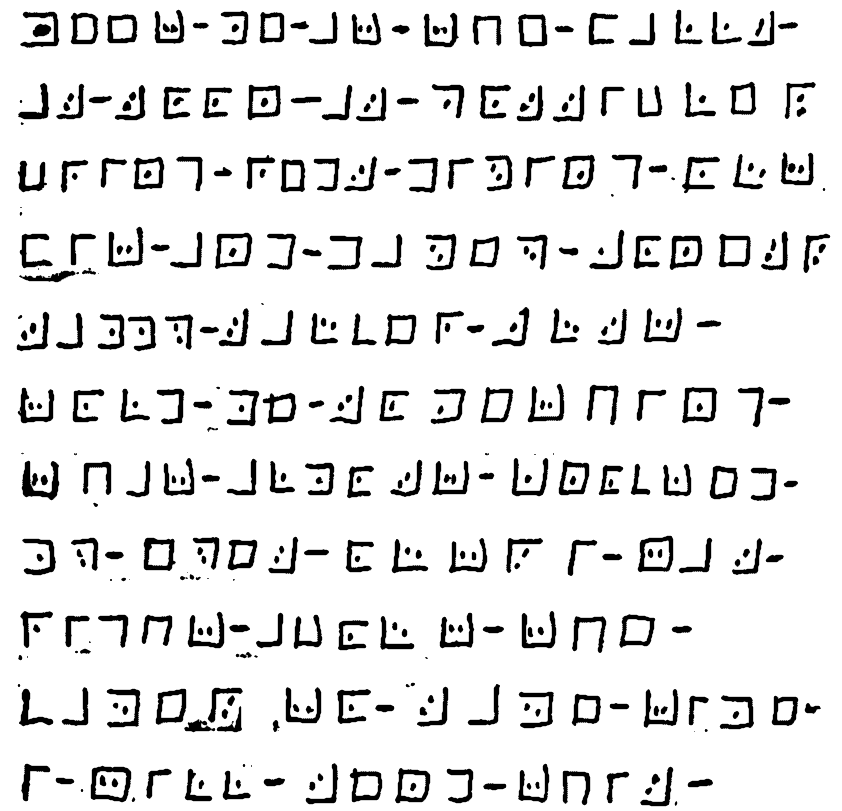

In order to decipher the message I first made three diagrams like this:

Here is the message as it was brought to me:

And here is what I got out of it:

Meet me at the falls as soon as possible. Bring Red’s diving outfit and Davey Jones. Sammy Saucer just told me something that almost knocked my eyes out. I was right about the cave. To save time I will send this note to town with our milkman who lives near here. Tell dad I will be home as soon as possible. Try and get here by noon. Bring Sammy some candy as he never had any. We are hiding from his aunts. If you see them in the woods do not let on to them that you know anything about us. Your excited pal Poppy.

“Whar is he?” Mr. Ott inquired, when the completed note had been read to him.

“At Clarks Falls,” I informed.

“Doin’ what?”

“Searching for the Long Lost lead mine.”

“Fol-de-rol!” the old man sputtered.

“I doubt if I can get there by noon,” I spoke thoughtfully. “But I ought to make it by night.”

“If—” mum put in pointedly.

“If what?” says I, searching her face.

“If your father and I decide to let you go.”

But there was nothing in that to yap over. For I could tell by her manner that she had no intention of keeping me at home. Dear old mum! She just said that to remind me that she had a claim on me.

Mr. Ott started off, still sputtering to himself, but came back to take another look at the deciphered note.

“Divin’ outfit,” says he, scowling at the message. “What does he mean by that?”

“Evidently,” I dropped the hint, “he has to use a diving outfit to get into the lead cave.”

“Humph! They hain’t no lead cave. That’s just a tradition.”

“We may surprise you,” says I.

Mum took the note.

“But what in the world is Poppy going to do with Davey Jones?” she inquired.

“Old Davey,” I spoke nonsensically, “is a diving machine in himself. And who knows but what Poppy is going to teach him to swim into the cave and come out with hunks of lead in his mouth?”

That was too much for old Mr. Ott. And he went off shaking his shaggy head. Boys were a queer mess, he said.

Later he sent a whole raft of camping supplies to the house. Which proved in itself that he had a lot of confidence in us, even if he did think we were queer!

I knew, of course, that Poppy never intended to use old Davey to lift the lead in the submerged cave. My clever chum had some other important use for the unusual turtle.

And I wondered myself what was coming.

I lit out for Red’s house, having telephoned to Scoop and Peg to meet me there as soon as possible. Something big had popped up, I said. And we had to act quick.

Mrs. Meyers met me at the kitchen door with a pancake turner in her hands.

“Laws-a-me!” she grumbled. “I wish you’d take that young son of mine outside and shake some of the appetite out of him. It used to be that I could fill him up with six pancakes. But now it takes ten.”

“Six would be enough,” Red spoke for himself, “if you made ’em big enough.”

“What do you want me to bake them in?” his mother stiffened. “The family wash tub?”

“That’s an idea,” laughed Red, as he got up from the breakfast table rubbing his plump stomach.

His mother stopped him at the door to pick at his ears.

“Goodness gracious!” she further complained. “From the looks of your ears anybody would think that soap cost ten dollars an ounce.”

Red grinned.

“I wish it did,” says he. “For then we couldn’t afford to buy it.”

“Stand still,” came the sharp command, as he started to squirm.

“Ouch!” he squawked. “Good night nurse! If you want to drill for oil, why don’t you go down to Texas?”

I thought he’d dance a jig when he heard about the proposed camping trip. But instead he eyed me curiously.

“What are you going to do?” he quizzed. “Follow the rain-maker into the hills?”

The rain-maker! Gosh! I had forgotten all about him.

“We’ve got more important work to do,” says I, “than following a fake rain-maker around.”

He didn’t like that.

“You may change your mind about him being a fake rain-maker, if you get your shirt-tail dampened this afternoon.”

I looked up at the cloudless summer sky.

“There’s no sign of a rain storm up there,” I declared.

“Well, there’ll be plenty of rain up there when old Pebble-in-the-brook starts to do his stuff.”

Pebble-in-the-brook!

“Is that his real name?” I inquired curiously.

“Sure thing. And he’s a full-blooded Indian too.”

“The mere fact that he’s a real Indian,” says I, “doesn’t prove that he knows how to make it rain.”

But Red was dead sure that the Indians were master magicians.

“They can do some blamed queer things with their charms,” he declared.

“And what would happen if the rain lasted too long?” says I, hiding a grin. “Could he stop it too?”

“Of course,” came the confident reply. “He has charms to make it rain, and others to make it stop.”

“Bunk,” I snorted, showing him how expertly I could turn up my nose.

“Just the same,” he hung on, “if I go camping with you to-day, I’m going to carry my raincoat.”

“Why not wear your overcoat too?” I spoke genially. “For he may get his charms mixed up and start a snow storm instead.”

Rory then weaved into the yard with a long garden hose trailing behind him.

“’Ot dog!” he expressed himself in good old American slang, as he stopped in front of us. “I finally got hit fixed.”

“What?” says I.

“The ’ose,” says he. “It ’olds hair now.”

“’Olds hair?” says I, squinting at him. “Who’s hair. What are you talking about?”

“The ’ose,” says he.

Red laughed.

“Don’t you catch on, Jerry? He’s been patching my diving hose. And it finally holds air.”

“Oh! . . .” says I, as my face broke into a grin. “It ’olds hair, huh?”

“I put hadhesion tape on hit,” beamed Rory.

“Hadhesion tape,” I repeated, laughing. “Boy, I bet it was an awful blow to the king of Hengland when you moved to America.”

“I don’t think the king knew anything about hit,” Rory spoke soberly.

Which made me laugh harder than ever.

“You’re a great little guy,” I told him, messing up his hair.

“Cut it hout,” he squawked, slapping at me with the hose.

And then it suddenly began to spout water.

Red broke into a triumphant dance.

“I told you that old Pebble-in-the-brook could make it rain,” he yipped.

I then caught sight of Peg, who, in his fun-loving way, had fastened the other end of the trailing hose to a water faucet.

In the spirited water fight that followed, Mrs. Meyers indignantly took the hose away from us and chased us out of the yard. Later we saw her mopping up the back porch.

“She’ll be glad to get rid of you,” I laughingly told Red.

“But where are we going?” he quizzed.

“Wait till Scoop shows up,” says I, “and I’ll tell you all about it.”

“Here he comes now,” sang out Peg.

Mrs. Meyers in the meantime had disappeared into the house. And when we heard her dusting the piano, in the front room, we scooted through the garden to the barn door, and up the haymow stairs. There was no danger of being overheard here by the snoopy Stricker gang. So I dished out the whole story, starting with Poppy’s fishing trip and ending with the secret note.

Peg took the deciphered note and read it.

“But if Poppy wanted all of us to come to the falls, why didn’t he say so? You’re the only one who’s mentioned.”

“You must remember,” says I, “that Poppy left town before young Gummy showed up.”

“As yet,” I went on, “Poppy doesn’t know you’re needed. But when he learns the truth of the situation he’ll be mighty glad to see you. And if you help us fight for the cave you’ll get your share of the treasure too.”

Peg laughed.

“If I get a crack at young Glimme,” says he, with narrowed eyes, “I’ll feel satisfied.”

“I owe him several cracks myself,” put in Scoop.

“Yes,” spoke up Red, “and I have several that I’ve been saving for Bid Stricker.”

I turned to Rory.

“How about you?” I grinned. “Are you in favor of the camping trip?”

“Hit was my hintention,” says he, “to ’unt for golf balls to-day. That’s why I patched hup the ’ose. But if Red wants to ’unt for lead hinstead, that’s ho-k with me.”

“All right,” says I quickly. “Having settled that matter, the next step, I guess, is to separate and collect our stuff. We’ll need a couple of pup tents. We should have plenty of blankets too.”

“How about the heats?” says Rory.

“Heats?” repeated Peg, mopping his sweaty face. “Suffering cats! This is hot enough to suit me.”

“I didn’t mean that kind of heats,” says Rory.

Peg grinned.

“Oh! . . .” says he. “You mean eats.”

“Sure thing,” says Rory pleasantly.

He used to get sore when we kidded him about his “H’s.” But he takes it good-naturedly now. In fact, he often laughs at himself.

It was our intention, if possible, to beat young Gummy to the falls. Another race, so to speak, between the hare and the tortoise. While he was fooling around in town we’d plug along as fast as we could. Of course, when he once got started he’d cover the ground fast. But, even so, he had considerable walking to do at the very end of the trail. And if the private road that the Saucer women used was as rocky as I had been led to believe—and any road in that section was bound to be rocky—I had the feeling that he might find himself hung up with a broken axle.

Which sure would be swell!

If by any chance we did get to the falls first, it was our further plan to throw up an embankment in regular military style, and hold the others off. To accomplish this we planned to take along several snappy automobile tubes, for giant slingshot rubbers. We got that idea from the “cannon” in the “Pirate” book. Having a bigger gang this time, and more room to work in, we could use several “cannons.” Also we planned to take along several small slingshots.

All enthused now, we separated, it having been agreed that I was to round up old Davey Jones while Red in turn got his diving machine together. It was left to Scoop to get the needed inner tubes. Peg promised to round up the required pup tents. And we all worked together in planning the eats.

When it came time to start out we learned that we had more stuff than we could carry. We talked of using a wheelbarrow. Still, we sensibly agreed, it would be almost impossible to push a loaded wheelbarrow up the rocky gorge that we had to travel in order to reach the falls.

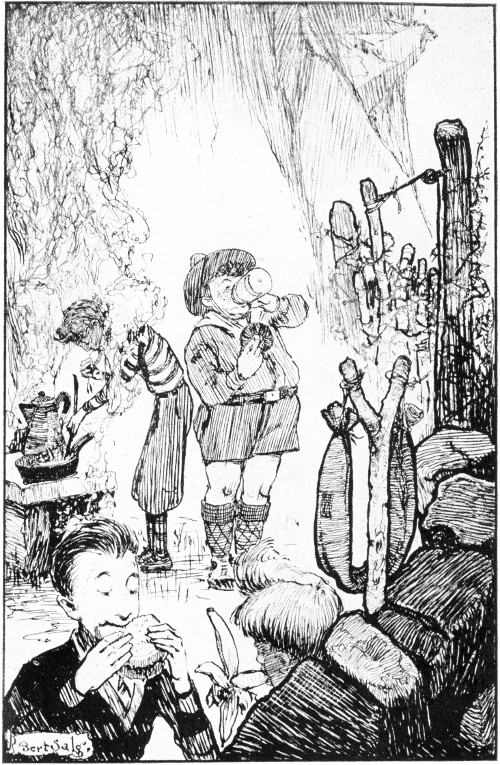

It was then that someone suggested that we hitch old Davey to a cart. He had been taught to pull a cart in the circus of which he had earlier been an important part. And when we tried out the idea he acted as tickled as a kid with an all-day sucker. Not that he pranced around dog-fashion—or anything like that. Turtles can’t prance. But Davey’s funny little eyes always showed when he was feeling good. And they sure danced now.

The harness that we made for him was kind of sloppy. But it did the trick. And having satisfied ourselves that the Strickers were nowhere in sight, we started out. Fortunately we hadn’t far to go before we reached the creek. And from then on we wound in and out among the willows and rocks, Scoop picking the way in true pioneer fashion, and the rest of us following in line, with faithful old Davey midway in the odd procession.

The few people that we met stared at us in open wonderment. It was a new thing for them to see a turtle hitched to a loaded cart. Which isn’t saying though that we let old Davey haul everything. I guess not! I carried one of the pup tents myself and two blankets. Scoop and Peg had similar packs on their backs. Rory had the long garden hose wrapped around his body. It made him look like a snake charmer. Dressed in his Boy Scout suit, Red had enough kitchenware dangling from his belt to stock up a young hardware store. He further carried a roll of sweaters and towels. And you should have heard the racket when he stumbled. Gosh! It sounded like a tin cyclone.

Davey’s load consisted mainly of the stuff that Mr. Ott had bought for us. Nor did we know at the time exactly what the numerous packages contained. Therefore we had many pleasant surprises later on.

At noon we stopped on the bank of the creek and prepared our first outdoor meal. But first we stripped and took a cooling dip in the clear water. It was nice and shady here. In fact we passed through many places that day that the sun never got at. For on both sides of us were towering sandstone ledges.

Peg got out a fishing line.

“We won’t have time to cook fish,” I told him, as he dropped his baited hook into the water.

“Don’t kid yourself,” says he. “These fish aren’t for you—they’re for old Davey.”

And as though he knew exactly what was going on, the eager-eyed turtle waited expectantly at the fisherman’s elbow. I watched Peg catch eleven big shiners in quick succession, all of which disappeared whole down the turtle’s huge gullet. And then I dressed and made a meal myself on warm baked beans, brown bread, greasy butter, ham sandwiches, pie and cake. We had a few bites of Sammy’s candy too. But we didn’t eat much of it. The poor kid! He certainly hadn’t gotten much out of life so far. But if the lead mine turned out as well as we anticipated, he’d have plenty of everything in the future, candy included.

Davey had crawled into a cool hole to take a nap. But he got up cheerfully enough when we started off, though, as the afternoon advanced, it was noticeable that he moved slower and slower.

“What’s the matter with him?” laughed Scoop. “Is he running out of gas?”

“You must remember,” says I, “that it’s a blamed sight harder for him to climb over the rocks than it is for us. So you must not make fun of him.”

“He looks to me,” says Peg, “as though he’s all in.”

“He is all in,” I declared. “And if we don’t ease up on him he’s liable to turn on us and scare the liver out of us. For I know him!”

“Gosh!” growled Scoop. “I don’t want to spend the night here.”

“Why not?” says Peg. “Here’s a dandy spring beside the creek. And here’s a swell place for our tents.”

“But I thought it was agreed that we were to get to the falls as quickly as possible?”

“We probably could make it ourselves,” says I. “But we’ll never get there with old Davey. So take your choice—either do the right thing by him or kiss him good-by.”

“All right,” Scoop gave in unwillingly. “Let’s unpack and get set for the night.”

Peg dropped down beside me on the creek bank.

“How does it look to you, Jerry?” he inquired.

“Kind of wild,” says I.

“Had you noticed how funny your voice sounds down here?”

“Everything seems louder.”

“It’s the high ledges. They act just like a sounding board.”

To prove what he meant, he gave a loud cry, which came back at him with a thousand thundering echoes.

“It’s just like yelling into a rain barrel,” says he.

We had struck a wild spot all right, just as I had said. And I wondered, with a touch of uneasiness, if the coming night would present any dangers. Maybe, I told myself, as I looked around at the rock piles, there were bigger creatures hidden here than rattlesnakes.

A bunch of crows came along and perched in a tree. And when I looked up to see what they were cawing about, there sat Red and Rory on an overhanging sandstone ledge.

“Come on hup,” Rory called down to me from his lofty perch.

“No thanks,” says I. “I’ve done enough climbing for one day.”

Red pulled up a big fern by the roots and tossed it down to me.

“Take it home and plant it under your sweetheart’s bay window,” he yelled.

I had noticed the many ferns that grew in the rocks. And I had wondered too at the trees that had taken root there, mostly pines and cedars. It didn’t seem possible to me that they could get enough moisture to keep them alive. Yet they seemed green and healthy, though some of them, in their determination to cling to the rocks, had grown into some awful shapes. As for the ferns themselves I never had seen bigger ones. Some of them were fully five feet tall. The rocky crevices were full of wild flowers too.

There was no sign of a dry spell here! And it was hard for me to believe that outside of the damp canyon, with its dripping ledges and countless cool springs, everything was drying up. But such was the case.

Red and Rory thought that it would be a feather in their caps if they could climb to the top of the towering ledge. But finding themselves shut off by a perpendicular wall, they finally came down, hot and sweating, carrying between them a roll of green moss as big as a bedspread. They had lifted it from a wet rock, they said. And later, when we took another swim, they draped the moss around them like petticoats.

Then, as the moss began to break up, they started pitching it at us. But they got the worst of it in the end. For we had them outnumbered. And to save themselves they finally had to run down the stream.

Peg took a handful of the moss and rolled it into a ball.

“If I could find some way of holding this stuff together,” says he, “I’d suggest that we use it on young Gummy. For if we could mess him up, and make him stink, that would hurt him a dozen times worse than just peppering him on the shins with rocks.”

Remembering how we fixed up the rotten-egg cannonballs in the “Pirate” book, I took the moss and rolled it in mud.

“There you are,” says I. “Try that out in your big slingshot.”

Scoop made a suggestion.

“I think it would be better still,” says he, “if we rolled it in clay and sort of baked it in the sun for a few hours. That would make it firm. But when it struck, it would splatter like a rotten tomato.”

“That’s what we want,” laughed Peg.

Golly Ned! I sure hoped that we could make it work, even if we had to rig up portable cannons and chase the enemy into their own camp. For young Gummy is a regular dude. Him get dirt on his nice clothes? I should say not. And I could readily imagine how furious he’d be if he suddenly found himself plastered from head to foot with slimy green moss. Boy! It was something to look forward to, all right.

Having noticed a number of scattered strawberry plants in the canyon, Peg set out to see if he could find a worth-while patch. He asked me to go with him. But I had promised Scoop to help him put up the pup tents. This job completed, the leader and I later trailed our big chum up the canyon, where we found him feeding his face in one of the biggest natural strawberry patches that I ever had seen in all my life.

Strawberries of any kind are good. But the wild ones are the sweetest. And these were the swellest tasting berries that I ever ate.

“How about picking some for supper?” says I.

“That’s an idea,” says Peg.

So we got busy and filled our caps.

Red and Rory in the meantime had gathered a small supply of fuel. And when we came back to the camp with our loaded caps we found them cooking supper.

“What are we going to have beside strawberries?” quizzed Peg, as he dumped his berries into a pan.

“Fried heggs,” says Rory, “and peanut-butter sandwiches.”

“How about some soup?” suggested Scoop.

“Ho-k,” says Rory.

No one in the bunch looked any hungrier than old Davey. And was he tickled when I borrowed Peg’s fishing line and started for the creek.

“Come on, Davey,” I called, “it’s time to eat.”

But I needn’t have bothered to call him. For he was already at my heels.

Stopping in a willow patch beside the creek I cut myself a pole, later baiting the hook of the attached line with a grasshopper. I had a cork on the line. And when it bobbed out of sight I gave a quick yank, pulling in a five-inch shiner.

Killing it, I saved a part of its flesh for bait and gave the rest to the waiting turtle. Snap! The fish disappeared in one mouthful. And a dozen more that I caught vanished in the same quick way.

The crows, I guess, felt that I ought to feed them too. For they cawed louder than ever. And when I looked up I could see hundreds of them in the towering trees overhead.

Tiring of the racket, Scoop got out his small slingshot and drove the cawers away.

“If they were blackbirds,” says he, as he stopped beside me on the creek bank, “we’d kill four and twenty of them and make a pie, like the queen in the nursery rhyme.”

“Oof!” says I, turning up my nose. “That doesn’t sound good to me.”

“How about a boiled owl?” he then inquired laughingly.

“You can have it all,” says I.

“I just saw an old owl.”

“Yah,” says I, “and when it starts to get dark you’ll see millions of bats too. For this is the battiest place in the whole United States.”

“Where are they now?” he looked around.

“Hidden in the rocks.”

So far Davey hadn’t given us a moment’s trouble, outside of slowing up our march. Liking us, and having gotten used to us (for we saw a lot of him during the time that we were solving the “Prancing Pancake” mystery), he seemed perfectly willing to follow wherever we led. Now, having been filled up, he let us pen him in for the night, Peg in the meantime having gone off with the pole to fish for bass.

I found him leaning over the edge of a flat-topped rock. And as I followed his line with my eyes I could see dozens of big bass in the lower pool.

But oddly they wouldn’t bite until he jiggled his bait on the surface of the water. And the only thing they’d strike at then was grasshoppers. I watched him pull in three one-pounders. Then, taking the line myself, I pulled in a two-pounder.

“I bet a cookie,” says I, on our way back to camp, “that we could find enough food up here to keep us going the rest of our lives. For we’ve already found strawberries. And the thorny bushes around here prove that there’ll be plenty of raspberries later on. As for the creek itself, it’s fairly alive with fish. And if there’s anything that tastes better than fried fish, I’d like to have you name it.”

“Fried fish are all right,” waggled Peg. “But I dare say we’d get tired of them if we had to eat them three times a day.”

“Don’t overlook the fact,” says I, “that there’s plenty of rabbits here too. I’ve seen dozens of them to-day. And almost every tree has a squirrel in it.”

“You can’t eat rabbits and squirrels in the summer time,” says he.

“True enough,” says I. “But if this was going to be our regular home, we’d make good use of the rabbits and squirrels when winter came.”

Peg looked around with dancing eyes.

“Boy! It sure would be great to spend a winter here. And if we had traps and guns I bet we could make a lot of money too. For there’s hundreds of furry things hidden away in these rocks. I’m dead sure of that.”

“Weazels, huh?”

“Yes, and foxes too.”

“This would be a swell place to raise beavers,” I looked at the creek.

“If the land was ours,” says Peg, “we could raise a lot of things, even buckwheat for our own pancakes. In fact, I can think of nothing I’d like any better than to be left in a place like this and told to take care of myself.”

“You’d never lack for pants,” says I, “as long as there were any wild animals left. And like Robinson Crusoe you could make yourself a goat-skin umbrella too.”

“To start with, I’d want an axe and a saw—for I’d have to cut down the trees and make myself a hut. I’d want a couple of dogs too. Also some chickens and pigeons, a bag or two of grain for seed, and a gun. With that much, I could stay here forever.”

“Oh, boy!” I spoke longingly. “If only we could do it.”

And then, as I caught sight of a sliding tail in the rocks, I jumped seven feet.

“A snake!” I yelled.

“Poof!” says Peg, with an indifferent gesture. “Real pioneers aren’t afraid of snakes.”

Scoop came running.

“Fish!” he yipped, when he saw what we were carrying. “We’re going to have fried fish. Um-yum-yum!”

“Not to-night,” says Peg, as he stopped beside the fire. “I’m going to put them in the spring and cook them to-morrow morning.”

“Well,” says Scoop, “if you expect to keep them alive you better get them into the water right away.”

“And hurry back,” put in Red, as Peg started off. “For supper’s all ready.”

And what a supper it was! Of course, the “heggs” had a slightly burned taste. And when I dipped into the butter, which had been hardened in the spring, I uncovered a grasshopper. But that was nothing to worry about.

We started with soup, in regular banquet style. Then came the “heggs” and peanut-butter sandwiches. We saved the strawberries for dessert. We had cocoa too. And cookies.

In all, it was a feast fit for a king. And somehow I felt like a king, as I sat on a log, with the egg dish on one side of me and the strawberries on the other. We were all kings. This was our kingdom. Here we could do as we pleased. The old life, with its clamoring schoolbells, was gone forever. No more examinations. No more Saturday-night baths. Nothing now but freedom.

That’s the way a fellow usually feels the first day he goes camping. But it wears off in time. And though I had talked to Peg about staying here forever, I knew from experience that after a couple of weeks I’d be just as glad to get back home as I was to leave.

Every fellow was his own dish-washer. So, when the pleasant meal was over, we all went down to the creek and scraped our tinware in the sand.

“And what now?” says Red, when we came back to the camp, where everything had been put in order.

The sun had already disappeared from sight. For you must remember that we were in the bottom of a deep chasm. But according to our watches we still had two hours of daylight. And satisfied that we were within a mile of the falls, Scoop now suggested that we send out a couple of spies to check up on things there.

“I’ll go,” Red and Rory volunteered together.

“Me too,” Peg and I similarly spoke up.

Scoop grinned.

“I’d like to make the trip myself,” says he. “But we can’t all go. So, to be fair, I guess we’ll draw cuts.”

Peg and Red got the deciding straws. And happily shaking hands with each other they lined up for instructions.