* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: The Mad Virus

Date of first publication: 1940

Author: Henry Kuttner (as Paul Edmonds) (1914-1958)

Date first posted: Mar. 24, 2021

Date last updated: Mar. 24, 2021

Faded Page eBook #20210365

This eBook was produced by: Alex White & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

This file was produced from images generously made available by Internet Archive/American Libraries.

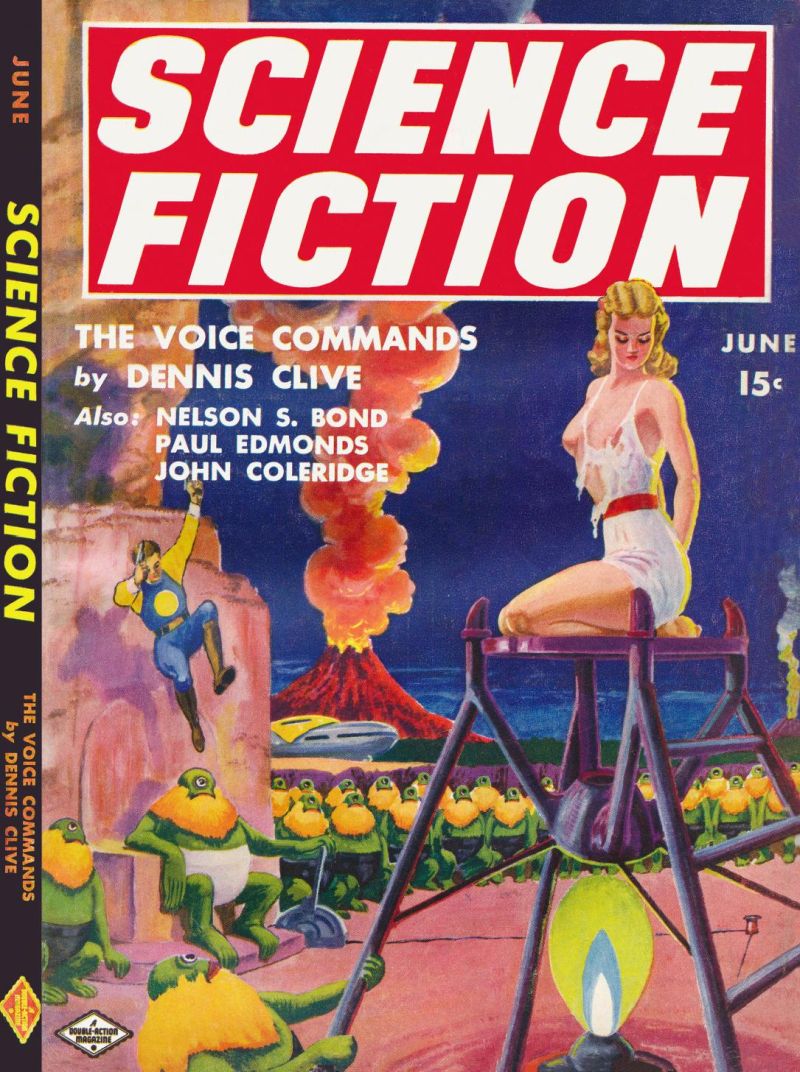

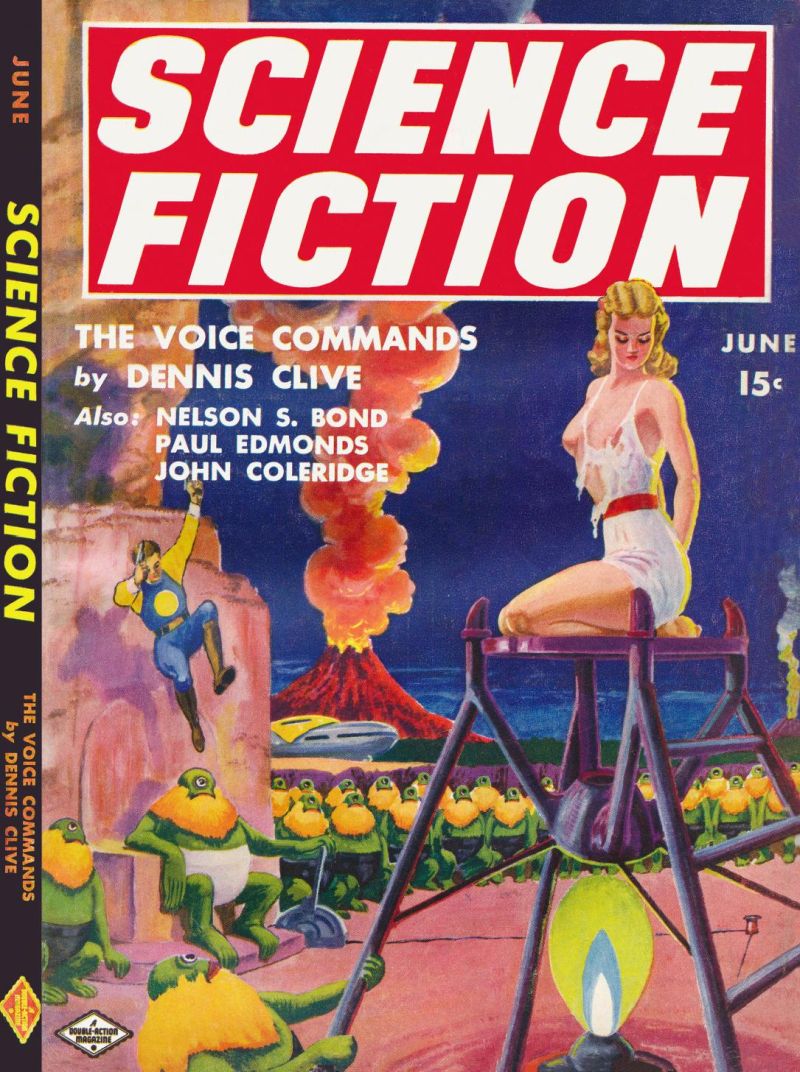

THE MAD VIRUS

by Henry Kuttner

Writing under the pseudonym Paul Edmonds.

First published in Science Fiction, June 1940.

Kedrick and his mad band of gangsters seize Dr. Morgan and force him to reveal a great scientific secret that the criminal plans to use to bring horrible death to his enemies! Teague, the reporter, is about to inform the authorities and thus save a city from disaster—but Kedrick is too quick!

When Bill Teague, Pineville correspondent for the Los Angeles Blade, strolled into the bank, everything seemed normal, at first sight. It was just after eleven. A blond youngster was making out a check at a desk. Only one teller was visible, and he seemed engrossed in the counter before him. Teague came over and said:

“Hi, there. Is President Malley in yet?”

The teller didn’t look up. He leaned on the marble counter, slumped over, his shoulders sagging beneath a wrinkled coat. Teague noticed that the man’s clothes seemed much too large for him.

The reporter’s lean, dark face was puzzled. About to repeat his question, he turned as a door opened and hurried footsteps sounded. President Malley popped out of his office, a wiry, wrinkle-faced, gray-haired oldster. The blond youth at the desk looked up, saw the president, and waved a cheery hand.

The change in Malley was fantastic. Into his furtive eyes came an expression of panic fear; he brought out a bundle of bills from his pocket, ran over, and pushed the currency into the other’s hands. The boy stood staring in amazement. Teague felt a little warning throb tingle inside his brain.

He didn’t realize, then, what lay behind Malley’s actions. He couldn’t. The Chief of Police had tipped him off that morning that the bank president had received an extortion note, and Teague had promptly come down to interview Malley. Now he hurried forward as the president ran toward his office.

“Mr. Malley, wait a minute!”

The other cast a terrified glance over his shoulder. He gasped something indistinguishable. Teague caught up with him.

“I’d like—” he began quickly—and then paused, wide-eyed, as President Malley thrust something into his hands—a bundle of currency! On top was a thousand dollar bill.

Malley was trembling uncontrollably, his wrinkled face twitching. “Take it!” he gasped. “Don’t hurt me—don’t!”

The next moment a flash of panic came into the bank president’s eyes. He whirled, raced into his office, and slammed the door. Teague heard his footsteps receding into the distance.

He turned around, met the amazed stare of the other customer, the blond youngster.

“Holy smoke!” the boy gulped. “He’s gone slap-happy. Are yours grand notes, too?”

Teague thumbed through them and nodded. He looked around. The bank was empty, save for the motionless teller behind the barred window. Teague went over, spoke to the man again. No answer. He reached out and touched the teller’s shoulder.

The fellow seemed to collapse. He fell down and disappeared behind the counter. Teague had a glimpse of a shrunken, withered face, midget-small, atop which the hair seemed like an incongruously large wig.

The reporter whirled. “Phone the police,” he snapped. “Pronto!”

The youngster swallowed convulsively, nodded, and hurried to a phone. Teague pushed his bundle of thousand-dollar bills carefully across the counter and raced after President Malley.

The man’s office was deserted. A phone was ringing somewhere, shrill and insistent. Teague hesitated.

The roar of a motor jerked him toward a door. He flung it open, stared out into a parking lot at the back of the bank. Malley, in a light coupe, was driving toward the street. Teague yelled.

Malley didn’t hear. The coupe rolled on. Teague sprinted after it, hoping to see a taxi or a car he could commandeer.

The bank president’s automobile sprang ahead, swerved out into the street, with a grinding of gears. It accelerated swiftly—and drove—into disaster.

Two blocks away Teague could see the car, rocketing along like mad. Another automobile appeared, coming in the opposite direction. There was plenty of room for the two vehicles to pass. But apparently Malley didn’t think so.

Teague saw the coupe swing around with a scream of skidding tires. The car, driven at a dangerous speed, went out of control. It rolled over, smashed into a telephone pole, and came to rest with its wheels spinning. The noise of the crash died.

Teague gave a low whistle and sprinted toward the wreck. A crowd was collecting swiftly. He pushed through it, saw Malley’s body, a twisted, bleeding thing, on the sidewalk, the man’s head propped up on somebody’s overcoat, policeman was giving first aid as Teague squatted down beside the bank president.

“Get back, you,” the officer grunted. “Give him air.”

“I saw the wreck,” Teague explained swiftly. “I’m from the Blade.”

Malley’s eyes opened. In them was the same frightful look of ghastly fear. The blood-smeared, pasty features writhed and twisted.

Malley whispered, “The virus—” and died.

Teague waited a moment, and then slowly got up. He dropped back into the crowd. He had no intention of being held as a witness. Malley’s last words had opened a little shutter of memory in his brain. Faintly he heard the officer’s voice:

“... fourth one we’ve had this morning. They all seemed to go crazy. They’re down in the emergency hospital now ...”

Whistling softly, Teague went back to the bank. He let himself in through the rear door. He was remembering something the Chief of Police had said that morning. ... “Doc Morgan’s disappeared. Probably nothing in it. He may have run down to Los Angeles for a spree. But his sister Norma phoned me, said he hadn’t been in all night.”

Doctor Morgan ... wasn’t he the man who’d been experimenting on protein molecules?[1] And Malley had gasped something about a virus—

|

Many of the disease-producing viruses, once thought to be ultra-small bacteria, actually are giant protein molecules, according to Dr. Calvin B. Bridges of Caltech and other biologists. |

Teague glanced around Malley’s office as he went through, but saw nothing unusual. Inside the bank he hesitated. His eye caught a flicker of movement.

There was a stand of bottled spring water in the corner. Paper cups were scattered around it and on the floor, a few feet away, was something which at first Teague did not realize was human.

It had been human once. The reporter went suddenly sick with nausea as he recognized blond hair. It was the boy he had left in the bank—but he was undergoing a metamorphosis that was utterly ghastly. His body seemed to be dissolving, flowing and melting from the bones, seething out through the gaps in the clothing. In a moment it was nothing but a clothed skeleton, lying motionless in a widening puddle of evil-smelling ichor. Teague felt his stomach jump against his throat; he steadied himself against a desk. Good God! What monstrous horror dwelt in this building? What incredible thing could dissolve a man’s body thus? Acid? Teague’s gaze went back to the stand of bottled water. He remembered the dying man’s words—“the virus!”[2]

|

In 1938 Dr. R. B. Bensley of the University of Chicago announced that he had identified the “glue of life,” a binding material which holds together the cells of the human body. This substance, plasmosin, can be compared to the attraction which holds the particles of objects together. The action is reversible. When plasmosin lets go, the cells affected degenerate like toy balloons bursting. It is now known that this was the explanation of the young man’s death. |

Quickly the reporter went behind the counter and examined the corpse of the teller. He jotted down a few notes and then, hearing footsteps, slipped back into Malley’s office. Peering through the door’s crack, he saw several uniformed officers enter the bank.

Teague decided not to wait for them. If his guess were right, he was on the track of the biggest story that ever hit Pineville, Southern California’s “millionaire city.” He had no time to spare in making explanations now. But, thinking swiftly, he took a moment to scribble in blue pencil on Malley’s desk blotter, “The bottled water is poisoned! Analyze it!”

“Maybe I’m wrong,” he thought as he slipped out the back door. “But just in case I’m right, my note will stop ’em from drinking any of that water. And maybe prevent a few more deaths.”

Two officers were coming across the parking lot. They saw Teague, shouted. He dodged nimbly among the parked cars and managed to lose himself, finally, among the pedestrians on the street.

“Now for Doctor Morgan,” he thought. He didn’t know the address. In a drug store he found it in a telephone directory, and jotted it down in his notebook. Then, struck by a thought, he telephoned the city hospital.

“I want some information,” he told the voice that answered him. “On—uh—a glandular disorder.” “Maybe it is,” he added to himself. “I wish I’d studied medicine, though!”

“Hello,” he said presently. “I’m trying to find out the name of a certain disease from the symptoms. What? Oh—I represent the Blade. Yeah. Here it is: the guy’s shrunk tremendously, his bones are smaller, his lower jaw is stuck way out....”

Teague went on to describe the appearance of the dead bank teller. Then he listened for a while, and with a word of thanks, hung up. Whistling softly, he went out of the drug store and hurried to where he had parked his roadster. Tooling it toward Doctor Morgan’s home, he thought things over.

“Hyperarathyroidism,” he pondered, referring to his notebook. “Bones excreting lime salts at an incredible rate. It should take months or years. Apparently it happened in less than an hour.”[3]

|

The famous case of Captain Charles Martell, “the man who shrank,” was caused by a parathyroid tumor. Because of the overactivity of the parathyroid gland, new bone tissue being formed lacked the necessary lime salt to harden it, and the bones became thinner because more calcium was being lost than was being taken in. See The Advance of Science by Watson Davis, Page 225 et seq. |

Teague was still trying to figure things out when he reached Morgan’s house. The place was an isolated stucco building on the outskirts of Pineville. Moved by an indefinable impulse of caution, the operator hid his car among a thick clump of trees before cat-footing toward the doctor’s home.

As it turned out, his action was lucky. There was a dark blue sedan parked in front of the house, with the motor running, though no one was in it. Teague looked around. In this district the homes were far apart, and the nearest was two blocks away. Despite the hot California sunlight, a little chill crept along the hollow of Teague’s back. He sensed something wrong—plenty wrong!

It was a reporter’s hunch, nothing more. But, nevertheless, Teague slid quietly through the bushes, keeping out of sight, till he reached the house. Loud voices came to his ears. He crept from window to window sill at last he found the right one.

He looked into a laboratory. Three men and a girl were there. Two of the men were familiar types—Teague had seen such thugs in the line-up at headquarters. One was a nervous, skinny, bucktoothed man with a tic under his left eye. The other was huge, stolid, dull-faced and quite bald. He held the girl captive in his great arms.

The girl was a red-haired little fury. She fought desperately, hopelessly, her wide blue eyes hot with angry resentment. Suddenly she saw Teague at the window. For a second she stiffened—and then relaxed, looked quickly away. A clever kid, Teague realized.

The third man was a lean, well-dressed greyhound, with a handsome, expressionless face and very cold black eyes. He gripped a cane in bronzed, strong fingers. He pointed with it to a pile of equipment in the corner.

“Carry that out, Baldy. Jevne, get some rope and tie up the girl.”

Teague, at the window, thought swiftly. He knew he couldn’t overcome three men—armed men, he realized, noticing the betraying bulges in their coats. Perhaps, if he waited, some lucky break might come up. Who was the girl? Hadn’t the Chief of Police said something—of course! This was the sister of Doctor Morgan, the vanished scientist!

The girl’s slim figure struggled vainly as she was bound. She was rolled into a corner, and Baldy and the dwarfish, nervous Jevne went to work carrying equipment out to the sedan. Teague crouched lower in the bushes as he watched. Retorts, Bunsen burners, chemicals, a tank of oxygen—microscopes, all kinds of apparatus bundled together apparently without rhyme or reason. At last Baldy entered, shaking his huge body like a dog.

“All through, Kedrick. What now?”

“The girl,” said the lean man, pointing with his cane. “Carry her out.”

Baldy obeyed. Kedrick took a last glance around, nodded as though satisfied, and permitted a slight smile to break the immobility of his bronzed face. White teeth flashed. He sauntered to the door and went out.

Hastily Teague tried the window. It was unlocked. It slid up with a creak, but the roar of a starting motor drowned the noise. The reporter clambered into the laboratory, looking around hurriedly. There was no time to spare.

No papers were visible, nothing that might be a clue. Teague saw a newspaper clipping under a desk; he snatched it up, stuck it in his pocket, and raced back to the window. The sound of the car’s motor was fading in the distance. The reporter sprinted to where he had left his roadster, backed it into the street, and set out to trail his quarry, visible three blocks away.

Teague wished he had a gun with him. But, he thought, it would be easy to pick up a police officer sooner or later. Driving with one hand, he got out the newspaper clipping and scanned it. His lips pursed in a soft whistle.

The clipping shed new light on the problem.[4] “But I’m still in a fog,” Teague thought. He gave his attention to driving. The quarry had not yet discovered they were being trailed; Teague had shadowed men before, and knew how to do it unobtrusively. The sedan slid away from Pineville, through deserted, lonely roads. It began to climb into the hills above the little city. Teague began to get worried. He hadn’t seen a police officer yet. What would happen if the kidnappers discovered him?

|

If both genes and viruses are invisible specks of special protein, it is obvious that these specks are tiny powers which not only determine what we are, but also, while ‘on the loose,’ serve as mighty captains of the hosts of death. It is a mighty power these molecules possess. Besides reproducing themselves they have the magical ability to control and organize the development and activity of every form of life!”—Los Angeles Times, May 15, 1938. |

“Blade reporter found dead in car,” Teague soliloquized, grinning wryly. He began to whistle a funeral melody. The dirt road led up, winding among parched, arid hills. Presently greener vegetation appeared; they were nearing the reservoir that supplied the city with water.

Teague let his car drop far behind. It was the only way to avoid discovery. In about fifteen minutes he caught sight of the kidnappers’ sedan parked near a ramshackle frame house above the road. The blue waters of the reservoir gleamed far down the slope.

Teague kicked the gears into reverse, nearly backed off the road, and finally managed to get the roadster hidden behind a huge rock beside the road. “Ready for a quick getaway,” he said optimistically to himself. “I’m a sap. Why the devil don’t I go after the police?”

But Teague knew why. He was remembering the girl, Norma Morgan, and her wide, frightened blue eyes and the cold, ruthless eyes of Kedrick. The reporter had an idea why Norma had been brought here, and the thought of torture had occurred to him more than once.

He made a wide detour and came around to the back of the ramshackle house. The sun was blazing hot on his head and shoulders. There was no sound but the droning buzz of insects.

Teague waited, half-crouched behind a rock. There were no bushes here to hide his approach.

A harsh voice said, “Don’t move, sucker.”

The reporter’s body jerked convulsively. Teague stood frozen, trying to locate the voice.

“Now lift ’em. Quick!”

Teague raised his hands. The bucktoothed little man came out from behind another rock, the tic under his eye twitching convulsively. He held a gun pointed at the other’s stomach.

Teague tried a smile. “Hello, Jevne,” he murmured. “Hot day, isn’t it?”

“Baldy!” the little man called. The giant came out of the house. He shambled over to Teague and searched him for weapons.

“Nothin’, Jevne,” he grunted. “Not even a shiv.”

“You’re not such a wise guy,” Jevne said to the reporter. “We spotted you miles back.”

“My arms hurt,” Teague said mildly. “And it’s hot. How about asking me inside?”

“Sure. The boss wants to see you, or I’d plug you now. Let’s go.” Jevne nodded toward the decayed back porch. Teague went toward it, with a cold consciousness of the gun’s muzzle aimed unswervingly at his back.

They took the reporter through a dim-lit, stuffy hall into a big front room cluttered with laboratory apparatus. The girl was there, bound to a chair. The bronzed greyhound, leaning on his cane, nodded pleasantly, though his face was immobile as ever.

“All right, Baldy. Get the rest of the stuff in from the car.”

The giant went out. Kedrick said, “Have a chair.”

“Why not?” Teague said, and sat down on a dusty sofa that creaked under his weight. “I suppose it’s no use telling you I’m at a loss to understand this hold-up?”

“Not a bit,” Kedrick agreed. His cane swung up, pointed at Teague’s eyes. “Not after we found you snooping around the back of the house. Who are you?”

“He’s a reporter. I found this in his pocket,” said Jevne, handing Teague’s press card to Kedrick.

Baldy came in, grunting under the weight of the oxygen tank. Jevne’s furtive eyes flicked toward it. Teague read fear in them.

“Want to help?” Baldy said with a touch of malice. Jevne licked his thin lips, shook his head.

“The stuff won’t hurt you,” the giant jeered. Kedrick’s cold face turned toward the man. Silently he pointed his cane toward the door. Grinning, Baldy went out, his bare skull gleaming with sweat.

“I’ll take the gun,” Kedrick said. “Tie him up, Jevne.”

Teague made no resistance as the little man obeyed. It would have been useless, anyhow. He flashed a glance of reassurance at the girl, and she smiled at him shakily. Her red hair was tumbled in ringlets about her shoulders, and her face, despite a smudge of dirt across one cheek, was very pretty indeed.

Kedrick said gently, “I hope you have no injudicious ideas of acting the hero. I want some information from you, and I am in no mood to play melodramatic games.” He twisted the cane’s head and slipped out a glistening steel blade. “I want to know what brought you up here.”

The sword-cane’s point steadied a few inches from Teague’s right eye. Kedrick went on, “I am not bluffing. If I catch you in a lie, I will blind you.”

“Okay,” Teague said. “Fair enough. I’ve got no objection to spilling what I know.”

“Wise of you.” Kedrick’s voice was sardonic, though his face did not change. “Go ahead.”

Teague did. He held nothing back. There was no point in doing so. He told of what he had seen at the bank, his visit to Doctor Morgan’s home, and his witnessing the girl’s abduction.

“So I trailed you up here,” the reporter finished. “That’s the whole thing.”

Kedrick brushed imaginary dust from his sleeve. “Then we have no need for this,” he observed, sheathing the sword-cane’s blade. “You say no one else knows of our—er—hideout?”

“I didn’t have a chance to spill the news,” Teague grunted. “Your trained apes nabbed me.”

Baldy, lounging at the door, rumbled an oath. Kedrick jerked his head.

“Baldy—Jevne—come with me.” He glanced at Teague and the girl. “I advise you not to try to escape. I think you know my threats aren’t bluffs.” His cold gaze dwelt on the two; then he followed the others out and closed the door gently. Teague drew a deep breath.

“A nice guy,” he observed. “A very nice guy. Yeah. It looks like we’re in a spot, Miss Morgan.”

The girl tried a smile that didn’t quite succeed. “I—I’m afraid so. I heard your story—Mr.—”

“Bill. Bill Teague.”

“Bill, then. Thanks for trying, anyway. I’m sorry you got into this mess.”

Teague tested the ropes that bound him. They were tight. Nevertheless he started to work on them as he talked.

“Now that I’m in it, suppose you give me the low-down. Just what’s the angle?”

Norma Morgan’s blue eyes were worried. “My brother—Kedrick has him a prisoner up here. He told me as we drove . . . Stephen has been working on the protein molecule. He created a new virus—a mutant.”[5]

|

“Already it has been shown that both genes and viruses are subject to evolutionary change. They have been observed to change in their natural environment and also have been changed artificially in the laboratory. A virus, for example, may thus gain the ability to produce a disease its ancestor could not cause.”—Los Angeles Times, May 15, 1938. |

“I see,” Teague said, remembering the deaths at the bank. “What sort of virus is it?”

“Something completely new. It’s self-selective. It doesn’t affect all people alike, but ferrets out the weakest parts of an individual organism. Man’s very specialized, you know—and the virus finds the loopholes in his armor, the flaws in each organism.”

Teague said, “Then those deaths at the bank—”

“I can guess. The teller’s weak spot was his parathyroid gland. The virus worked on that. It’s incredibly fast in its effects, Bill. And Malley, the president—it affected his brain. Phobia—fear.”

“Exactly,” a cold voice broke in. Kedrick sauntered into the room, swinging his cane. “Since you seem so interested, Mr. Teague, I shall gratify your curiosity. I heard of Doctor Morgan’s experiments. I visited him—wormed my way into his confidence, to use a cliché. I saw the effects of his virus on animals—and I decided to make use of the virus as a weapon.”

“I get it,” Teague said grimly. “A shakedown.”

“A shakedown. Nothing crude—but Pineville, as you know, is full of millionaires. They’ll pay up, under threat of death. I’m going to inoculate them with the virus, and charge them a certain sum each to cure them. There is an antidote, you know.”

Norma nodded. “There’s an antitoxin. It’s made easily enough and builds up antibodies that make the victims immune.”

“Your brother is stubborn, Miss Morgan. We took a small amount of the virus from his laboratory, but he refused to make more. He said he had no apparatus—so we procured some just now. His own. However, we first tried out what we had on President Malley. We introduced the virus into a bottle of spring water in the bank, and threatened Malley with death if he didn’t pay.”

Light broke on Teague. “So that was why he gave me the money! The virus developed his secret weakness—fear!”

“I think you’re right. I have a better plan now. The virus was too strong. But if it’s introduced into the reservoir, it’ll be diluted sufficiently. The whole city will get a mild attack. That will save time—they’ll pay after that! And we can collect and leave sooner than I’d hoped.”

Norma said desperately, “You can’t control the virus! Stephen doesn’t know enough about its properties yet. If you poison the reservoir, you may kill everybody in Pineville.”

Kedrick smiled. “A very poor attempt to frighten me, Miss Morgan. Your brother will estimate the right proportions.”

He turned, called a command. Through the door came Baldy, pushing before him a slight, bedraggled figure. Norma caught her breath in a little sob.

“Steve! What have they done to you—”

Stephen Morgan looked older than his thirty-odd years. Grey hair frosted his temples. His thin, scholarly face was worn and haggard.

“God, Norma,” he whispered. “Kedrick said they’d got you, but I didn’t believe him!”

Kedrick said smoothly, “The oldest tricks are often the best. No doubt you’ll prepare the virus rather than see your sister tortured.”

Morgan’s lips twitched. He said, “You won’t—”

“I am mild by nature,” Kedrick murmured. “I could not bring myself to hurt the girl. But Baldy is less sensitive.”

The giant licked thick lips. His tiny eyes dwelt on Norma’s slim body. She shuddered against the ropes that bound her.

“Damn you!” Morgan said tonelessly. “I’ll make the virus. I—I’ve got to.”

“No, Steve—don’t!” Norma said, her voice unsteady. “I can—”

Without looking at his sister Morgan snapped, “What are we waiting for? Come on!”

Kedrick followed Baldy and his captive out of the room. The door shut. Teague again went to work on the ropes that bound his wrists. They were loosening slightly, he thought.

Norma was crying softly. Teague said, “Cheer up. I’ll be loose pretty soon.”

Her eyes widened. “What? Oh, Bill! If we could get hold of a gun—”

Teague shrugged and continued his efforts. But it was twilight before he neared the end of his struggle. Twice Morgan, guarded by Baldy, had entered the room, selected apparatus, and left without speaking. And now Kedrick came in. He had a hypodermic syringe in his hand, and a vial of yellowish liquid.

Baldy, Jevne and Morgan entered. Kedrick turned to them, said, “I’ve got the antitoxin. Since we’re working around this stuff, it’s a good idea to make ourselves immune. You’re sure this is the right dope. Morgan?”

The scientist nodded wearily.

“Good. Then I’ll try it on your sister first. That all right?”

“Yes,” Morgan said. “I knew you’d do that. It’s the real antitoxin, Kedrick.”

Nevertheless, Kedrick carefully sponged off Norma’s forearm and injected the fluid. “That’s the right amount, eh?”

“Yes.”

Teague winced as the needle dug into his flesh. He said, “You’d make a lousy doctor, Kedrick. That’s no way to make an injection.”

“It’ll do,” the other said emotionlessly, and, refilling the syringe, shot the antitoxin into Morgan, Baldy and Jevne in turn. Then, with a nod of satisfaction, he went out, rolling up his own sleeve in preparation.

“Jeepers!” Jevne said, the tic under his eye jerking. “I’d rather work around dynamite any day.”

Baldy grinned. “Yeah, half-pint. You got a yellow streak down your back a yard wide.”

The little man flushed. He turned to Morgan, said, “Come on, guy! Back to your lab!”

The three went out. Teague said to the girl, “Do you think that was really the antitoxin?”

“Oh, yes. The virus would have been transparent, not yellowish. Steve wouldn’t—I wish he had!” she cried suddenly. “If he’d poisoned us all, it might have been better!”

It was getting dark. Teague freed his hands after five minutes of final struggle. Hastily he released the rest of the ropes.

Norma said, “Bill! The window—”

Teague looked out. Silhouetted against the sky he made out a small figure hurrying along, a bulky object in his hand. The reporter’s face went white.

“The reservoir!” Norma whispered. “Jevne’s gone to pour the virus in—”

The door opened without warning. It was Baldy, carrying an oil lamp. In the yellow glow his face looked gargoylish. He didn’t notice at once that Teague was free.

The reporter dived forward. His shoulder smashed into Baldy’s legs. The giant went back, toppling across the threshold, the lamp crashing to the floor, and, luckily, going out. Baldy wasn’t unconscious though.

Monstrous strength surged in the giant’s muscles. His great arms came up, trying to drag Teague into their crushing embrace. The reporter dug his knee into Baldy’s stomach, heard an explosive curse. An iron-hard fist thudded into his shoulder, sent him reeling back.

Baldy was surging upright, a black colossus in the gloom. Teague looked around for a weapon. He saw a bottle of some liquid on the table nearby, and caught it up.

Baldy lunged forward. A gun snarled viciously. Teague heard the bullet thud against the wall.

He threw the bottle, with all his strength, at the giant’s head.

There was a tinkling crash and a hoarse scream of rage and pain. The gun roared again. Baldy toppled to the floor, bellowing.

Footsteps sounded, racing closer. Teague sprang to the girl’s side, tried to unbind her. The knots were difficult in the dark.

She said urgently, “Don’t wait, Bill! Stop Jevne before he poisons the reservoir.”

And, as Teague hesitated—“You’ve got to stop him!”

Baldy was still thrashing around in the dimness. The door slammed open as Teague got to the window and flung it up. A bullet screeched past his head. He dived out, rolled over and over on the ground, and scrambled to his feet. Bending low, he ran down the steep slope to the road.

What now? If he had Norma and Doctor Morgan with him, he might have tried to escape in his car. As it was, Teague went plunging perilously downward toward the reservoir, his eyes slowly accustoming themselves to the gloom. The moon had not yet risen, but a faint glow still hung above the hills in the western sky.

Teague was sweating and gasping when he saw before him the slight figure of Jevne, stooping on the brink of a low bluff that overhung the reservoir. The water was a dull leaden color in the dusk. A cold wind blew up from it.

Jevne jerked erect. His hand fumbled in his coat, came up swiftly. But Teague was charging down like a mad bull. Jevne had no time to fire; the gun was knocked from his hand, and he was sent toppling back under the impact of the reporter’s body.

The little man wavered on the edge of the bluff. He clawed the air, yelling—and went over. His cry was cut off by a splash.

Feet pounded closer. Teague glanced up, saw a bulky form lumbering toward him. Baldy!

The reporter hesitated, braced himself. Light glinted on a metallic object near by—the gun Jevne had dropped. Teague dived at it, heard Baldy’s weapon bark. A bullet creased his arm with white-hot agony. Lying on his side on the ground, Teague swung up his arm and fired at the looming shape a few yards away.

Baldy let out his breath in an explosive groan. The big form folded up, crashed down almost on top of Teague. Then another gun snarled, and the reporter felt a stunning blow smash down on his head. The lights went out.

Teague woke up with a dull, throbbing ache in his skull. His brain felt as though it was trying to crawl through the sutures. He opened his eyes, wincing, and stared up at a familiar ceiling. He was lying flat on his back, bound, in the same front room of the hideout. The oxygen tank stood beside him. Apparatus cluttered the floor.

An oil lamp splashed yellow gleams on the walls. A toneless voice was speaking swiftly. Teague listened.

“... strange epidemic seems to have affected Pineville only. Medical aid is being brought from Los Angeles. The Governor has been advised to throw a cordon of National Guardsmen around the city to prevent spread of the infection. Stand by for the next news-flash.”

Music came. Teague realized that he was listening to a radio. He looked around. Norma was bound to a chair, asleep, her red hair tumbled about her face. Jevne, shivering a little, crouched in a sofa beside a portable radio. He gripped an automatic. The man’s face was flushed a deep red, and occasionally his body shook convulsively. He saw Teague, tried to speak, but a dry, hacking cough racked him.

“Pneumonia,” the reporter thought. He said aloud, “What time is it?”

“You’re awake, are you?” Jevne snarled. “I ought to smash your face. You killed Baldy—know that?”

“Glad to hear it,” Teague said, wishing his head would stop aching. “You crawled out of the reservoir, eh?”

“Yeah,” said Jevne, his flushed face twisted in a bitter grin. “After Kedrick shot you. And I poured in the virus, too. It’s starting to work. Listen!”

The music halted; a voice said:

“Volunteers are wanted at the Main Hospital. Do not use your cars. Automobiles are ordered off the streets. If you live near the Main Hospital and wish to volunteer, telephone Doctor Ferguson at Palm 1300. Otherwise remain in your homes.” The voice hesitated, went on, “A correction. Palm 1200. Palm 1200. We have been working for hours here at the station, and we’re pretty tired. However, we’ll keep on the air till things get better. The list of dead has risen to thirty-four. The driver of a bus leaving Pineville died at the wheel and the vehicle ran off the road into a dirt embankment. Two passengers were killed; the rest escaped with minor injuries. Stay off the streets! This is important! Stand by for more news flashes.”

Teague felt sick. He said, “Nice going, Jevne. There won’t be a soul alive in Pineville pretty soon. What time is it?”

“Four o’clock.” Jevne’s breathing was hurried and uneven. His nervousness was increased almost to hysteria. “God, that damned poison! I always knew—”

The girl had awakened. She said, “Is the antitoxin finished yet?”

“Yeah,” Jevne muttered. “Morgan finished it half an hour ago.”

“If that’s poured in the reservoir—” Norma began.

“Shut up!” Jevne said viciously. “Kedrick knows what he’s doing.” But there was a queer expression on the man’s flushed face.

Teague’s eyes widened. He opened his mouth and closed it without speaking. As the radio voice came again Jevne turned toward the window, and the reporter hastily wormed his way toward the cylinder of oxygen. Could his bound hands reach the valve?

No—but Teague shoved himself half upright against the wall. Silently he pressed his lips against the stop-cock, managed to turn it with his teeth. He let himself down quietly as Jevne looked around.

“The Governor has ordered a cordon of National Guardsmen thrown around Pineville,” said the radio excitedly. “No one is permitted to leave the city. It can be entered only with a permit. The death list has risen to more than fifty—Chief of Police Haggard is among the dead. Doctor Ferguson reports by telephone that all the red blood cells in his body were destroyed by some unknown agency. Chief Haggard died for want of oxygen. Many have gone insane.”

The valve hissed. Teague hoped Jevne wouldn’t notice it. But the little man was too ill to hear the escaping gas.

Norma had seen the reporter’s action. Her blue eyes watched him, puzzled. He winked at her warningly.

Teague waited. A queer, heady exhilaration began to mount in his brain. His respiration increased. The effect on Jevne was even more pronounced. He was a shaking bundle of nerves.

At last Teague said to the girl, “Norma, do you feel—funny?”

She hesitated, trying to understand. “I—”

“My God!” the reporter broke in harshly. “That damned virus!”

“What?” Jevne glared down at the bound man, his face a twisted mask. “What d’you say?”

“The virus,” Teague said tonelessly. “Your friend Kedrick’s infected us, that’s all.”

“You’re crazy,” Jevne jerked out. A storm of trembling shook him.

“Those hypodermic injections,” Teague went on. “They weren’t the antitoxin. Kedrick didn’t use the stuff himself, did he?”

“He went outside—” Jevne said.

“Yeah—so he could use the real antitoxin on himself. He’s killing us off, Jevne—all of us. We’re no good to him now. He’ll collect the shakedown money and beat it without splitting with you or anybody else. Baldy was lucky I killed him!” Teague said grimly. “He died quickly. This virus isn’t quick.”

“You’re crazy!” Jevne almost screamed. “Kedrick wouldn’t pull a thing like that on me!”

“Do you believe that?” Teague asked. “Kedrick’s out for himself. He doesn’t give a damn about you or anybody else. Listen, Jevne—you’ve got a gun. Do me a favor. Use it on me. And on Norma. For God’s sake, kill us! I can feel the virus starting to work on me already, I tell you!”

Norma understood. She said to Teague, “I remember now. It wasn’t the antitoxin Kedrick gave us. It would have had an entirely different effect. You’re right; we’ve all got the virus in our bloodstream.”

Jevne lurched to his feet. His oxygen-excited brain, already half delirious with incipient pneumonia, was insane with terror. Teague said, “Remember Malley, the bank president? He went crazy with fear. The toxin found his secret weakness—”

“Fear!” Jevne shrilled. “It’s true—Kedrick shot that poison into me!” He stumbled forward, brandishing the gun. His eyes were glaring and mad. Fear ruled Jevne’s mind as surely as though the virus had actually been administered.

“Kedrick!” the man mouthed. “God, I’ll kill him! I’ll kill him!”

He lurched to the door, flung it open. Teague heard his footsteps moving unsteadily away. The reporter pushed himself up, managed to turn off the oxygen with his teeth.

He hopped laboriously toward a table, pushed a beaker to the floor. It shattered. Teague let himself down again and fumbled for a sharp-edged bit of glass.

“To the left a few inches,” Norma said breathlessly. “There!”

Grunting with satisfaction, Teague rolled toward the girl. He propped himself up against the chair, and, guided by Norma’s instructions, managed to slice through some of the cords that bound her. After that it was easier. The girl freed herself, and then released Teague.

Bullets crashed nearby. Teague said, “Wait here, Norma!” He raced out into the hall, hurried along it. From an open doorway pale lamplight streamed.

Within the room Stephen Morgan was bound to a chair, his haggard face grimly set. Two men were struggling on the floor—Jevne and Kedrick. Blood was pumping from Jevne’s breast. On the floor beside him lay a filled hypodermic syringe.

Kedrick had a gun in his hand. He lifted it, smashed it down viciously on Jevne’s head. The little man’s clawing hand touched the hypodermic. He gripped it, swung it up, drove it into Kedrick’s face. Blood sprang out from dozens of tiny cuts.

Kedrick put all his strength into a blow that crushed Jevne’s skull like cardboard.

Teague realized that he had waited too long. He sprang forward—and Kedrick leaped up, lifting his gun. The man’s once-handsome face was a crimson ruin.

He snarled, “Get back! Hear me?”

Teague hesitated, heard a soft cry behind him. Norma!

“Don’t move, or I’ll kill the girl.”

Teague stood motionless, his muscles tensed. By a miracle the splinters of glass had missed Kedrick’s eyes. The man’s face was drawn in a grin of agony.

“I think—I think I’ll kill you anyway,” he said, and for the first time Teague heard Kedrick’s incisive voice thick and hoarse. “Both of you. And Morgan ...”

The gun’s muzzle steadied, pointing at Teague’s heart. Kedrick’s finger tightened on the trigger.

The reporter looked intently into Kedrick’s eyes. Just before the man fired there would be a signal there.

But—why didn’t Kedrick shoot? He was standing quite still, and in his eyes there was growing a look of stark, frightful fear.

He screamed.

And his flesh—changed!

It seethed and bubbled and dropped from his bones in dreadful disintegration. The virus in the hypodermic syringe had entered Kedrick’s bloodstream through the cuts in his face. And the plasmosin, the “glue of life,” was being destroyed by the poison.

The cells of Kedrick’s body degenerated, no longer held together. Once more Kedrick screamed, his voice knife-edged with agony—and then he sank down, writhing and struggling, as the framework of his flesh failed.

The reporter stood watching grimly until the last semblance of life and movement had departed from the horror on the floor.

Then Teague freed Morgan. As the last rope fell from him, he sprang up, hurried to a table and caught up a bottle.

“The antitoxin, Teague,” he said. “We’ve got to put this in the reservoir. It’ll stop the plague, destroy the virus.”

He paused at the door. “But we’d better hurry down to Pineville afterward. I’ll save some of this antitoxin, in case it’s needed—and I can make more in an hour.”

Without waiting for a reply, Morgan went out. Norma and the reporter followed him. Glancing at the girl’s bright curls, Teague felt a pleasant exhilaration.

“You know,” he observed, “things have been happening so fast we haven’t really had time to get acquainted.”

“That’s right,” Norma agreed, “but there’ll be plenty of time from now on, Bill!”

[The end of The Mad Virus by Henry Kuttner (as Paul Edmonds)]