* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please check with a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. If the book is under copyright in your country, do not download or redistribute this file.

Title: Bering's Voyages: An Account of the Efforts of the Russians to Determine the Relation of Asia and America Vol. I

Date of first publication: 1922

Author: Frank A. Golder (1877-1929)

Date first posted: Mar. 15, 2021

Date last updated: June 16, 2022

Faded Page eBook #20210337

This eBook was produced by: Howard Ross & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

AMERICAN GEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY

RESEARCH SERIES NO. 1

W. L. G. Joerg, Editor

BERING’S VOYAGES

An Account of the Efforts of the Russians to

Determine the Relation of Asia and America

BY

F. A. GOLDER

IN TWO VOLUMES

VOLUME I:

The Log Books and Official Reports of

the First and Second Expeditions

1725-1730 and 1733-1742

WITH A CHART OF THE SECOND VOYAGE

BY

ELLSWORTH P. BERTHOLF

AMERICAN GEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY

BROADWAY AT 156TH STREET

NEW YORK

1922

COPYRIGHT, 1922

BY

THE AMERICAN GEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY

OF NEW YORK

Reprinted 1935

CONDÉ NAST PRESS

GREENWICH, CONN.

Reprinted from plates by the

LORD BALTIMORE PRESS, BALTIMORE, MD.

TO

PROFESSOR EDWARD CHANNING

OF

HARVARD UNIVERSITY

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| Preface | ix | |

| Part I | ||

| The First Expedition, 1725-1730, and Its Setting | ||

| I | The Geographical Knowledge of the North Pacific Ocean at the Beginning of the Eighteenth Century | 1 |

| II | Bering’s First Expedition, 1725-1730 | 6 |

| III | Gvozdev’s Voyage to America in 1732 | 21 |

| Part II | ||

| The Second Expedition, 1733-1742 | ||

| IV | Bering’s Second Expedition, From Its Inception to the Beginning of the Sea Voyage | 25 |

| V | The Log Book of Bering’s Vessel, the “St. Peter,” and of Her Successor, the Hooker “St. Peter” | 36 |

| VI | Lieutenant Waxel’s Report on the Voyage of the “St. Peter” | 270 |

| VII | The Journal of Chirikov’s Vessel, the “St. Paul” | 283 |

| VIII | Chirikov’s Report on the Voyage of the “St. Paul” | 312 |

| IX | The End of the Expedition | 328 |

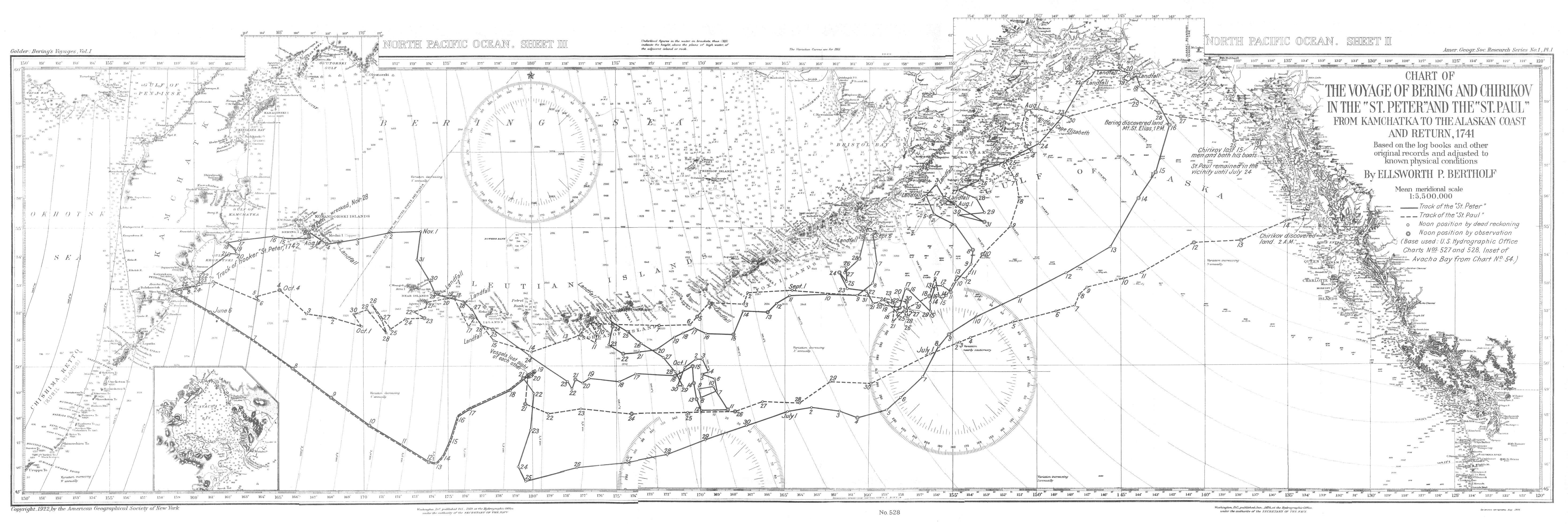

| Note to Accompany the Chart of the Voyage of Bering and Chirikov from Kamchatka to the Alaskan Coast and Return, 1741, by the late Ellsworth P. Bertholf | 330 | |

| Bibliographical Note | 349 | |

| Index to both volumes (originally only in Vol. II.) | ||

| Errata to both volumes (originally only in Vol. II.) | ||

| Fig. | Page | |

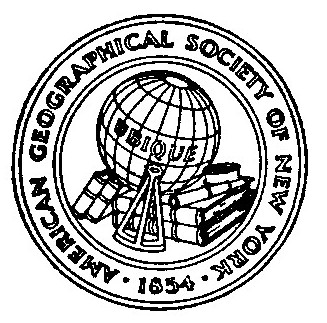

| 1 | Section of a map by Guillaume Delisle, 1714, to illustrate contemporary knowledge of the North Pacific . . . facing | 2 |

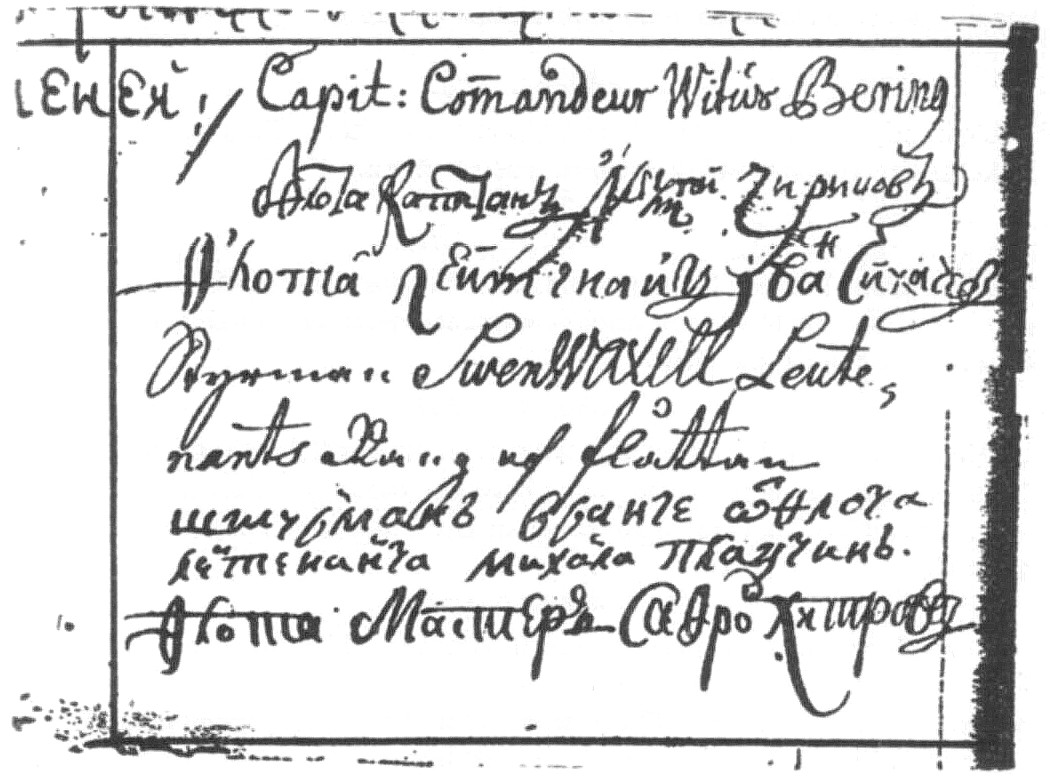

| 2 | Facsimile of part of Peter the Great’s orders for the first expedition, with comments in his own handwriting . . . facing | 7 |

| 3 | Map showing route of the first expedition from St. Petersburg to Bering Strait | 10 |

| 4 | Facsimile of a manuscript map showing the route of the first expedition from Yudoma Cross to Urak near Okhotsk. (Drawing by Spanberg in the Russian archives.) . . . facing | 13 |

| 5 | Copy of the eastern section of the map accompanying Bering’s report on his first expedition. (After Dall’s facsimile.) | 14-15 |

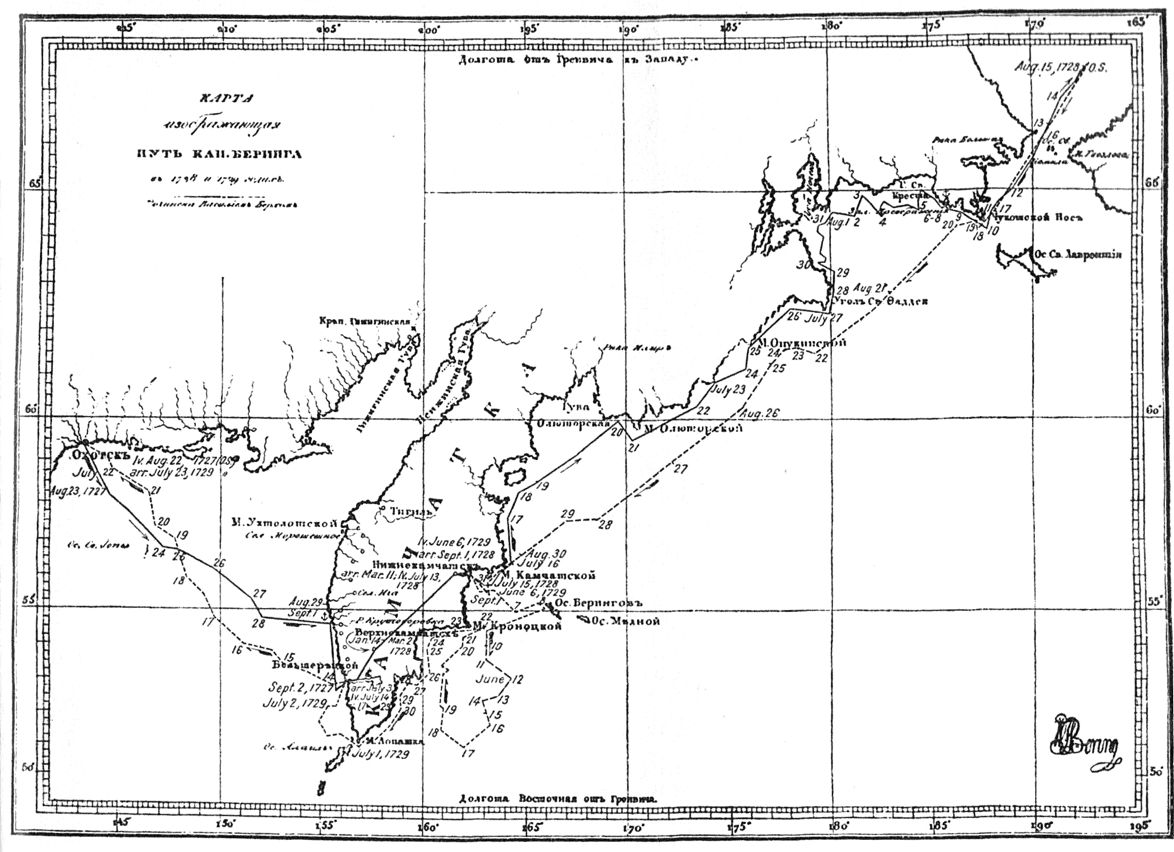

| 6 | Facsimile of Berkh’s map, 1823, showing route of the first expedition from Okhotsk to Bering Strait and return. . . . facing | 20 |

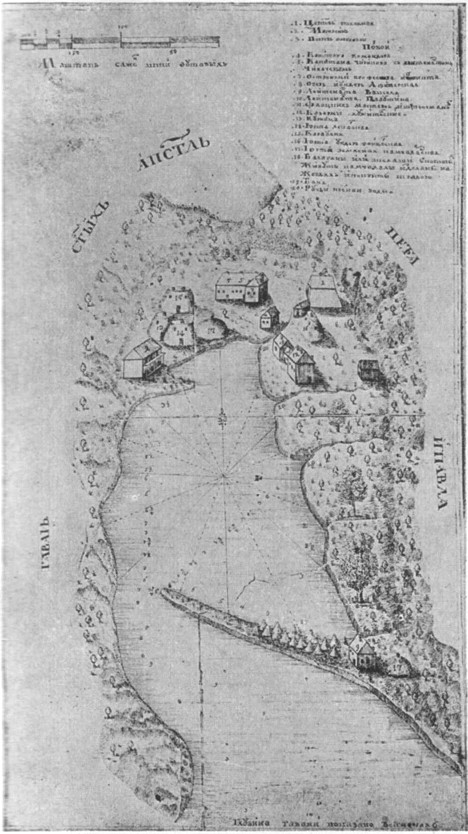

| 7 | Facsimile of a manuscript map of the Harbor of St. Peter and St. Paul (Petropavlovsk), 1740. (Drawing by Elagin in the Russian archives.) . . . facing | 34 |

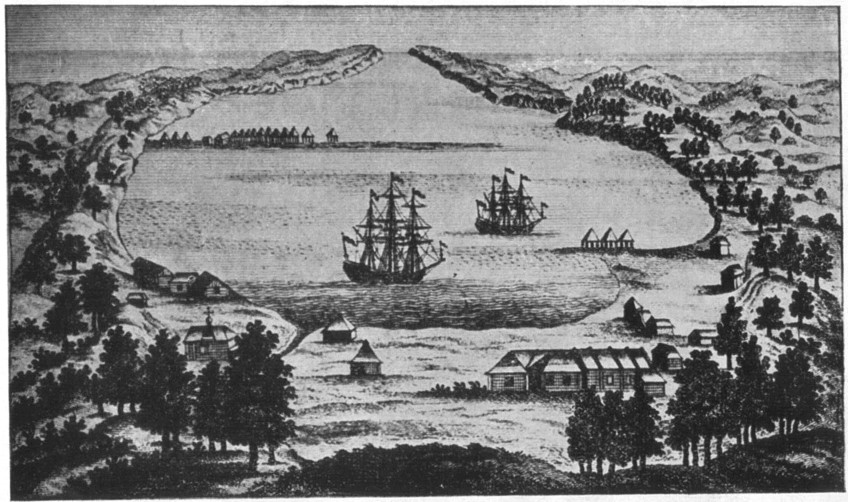

| 8 | The Harbor of St. Peter and St. Paul. (From an old engraving) . . . facing | 35 |

| 9 | Facsimile of signatures of Bering and his officers. (From the log book of the St. Peter: entry of May 4, 1741.) | 39 |

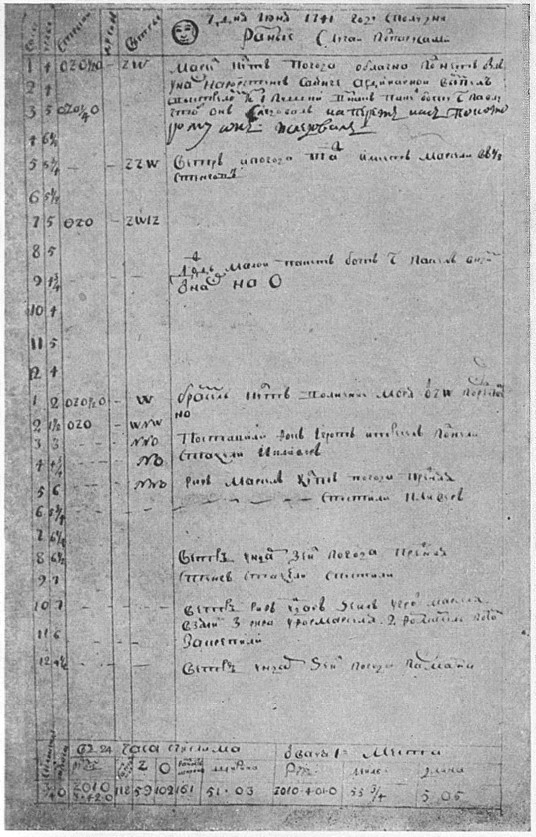

| 10 | Facsimile of a page of the log book of the St. Peter kept by Yushin: entry of June 7, 1741 . . . facing | 52 |

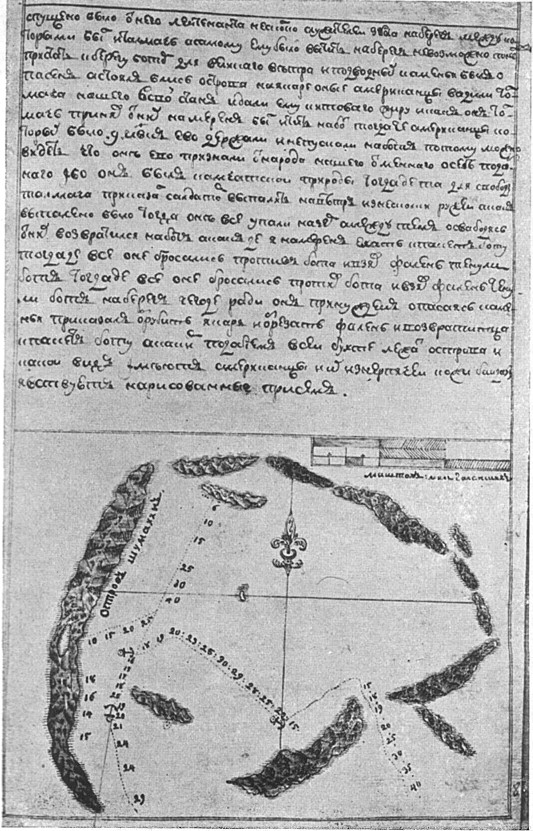

| 11 | Facsimile of a page of the log book of the St. Peter kept by Khitrov: end of entry of September 5, 1741, with map of the Shumagin Islands . . . facing | 148 |

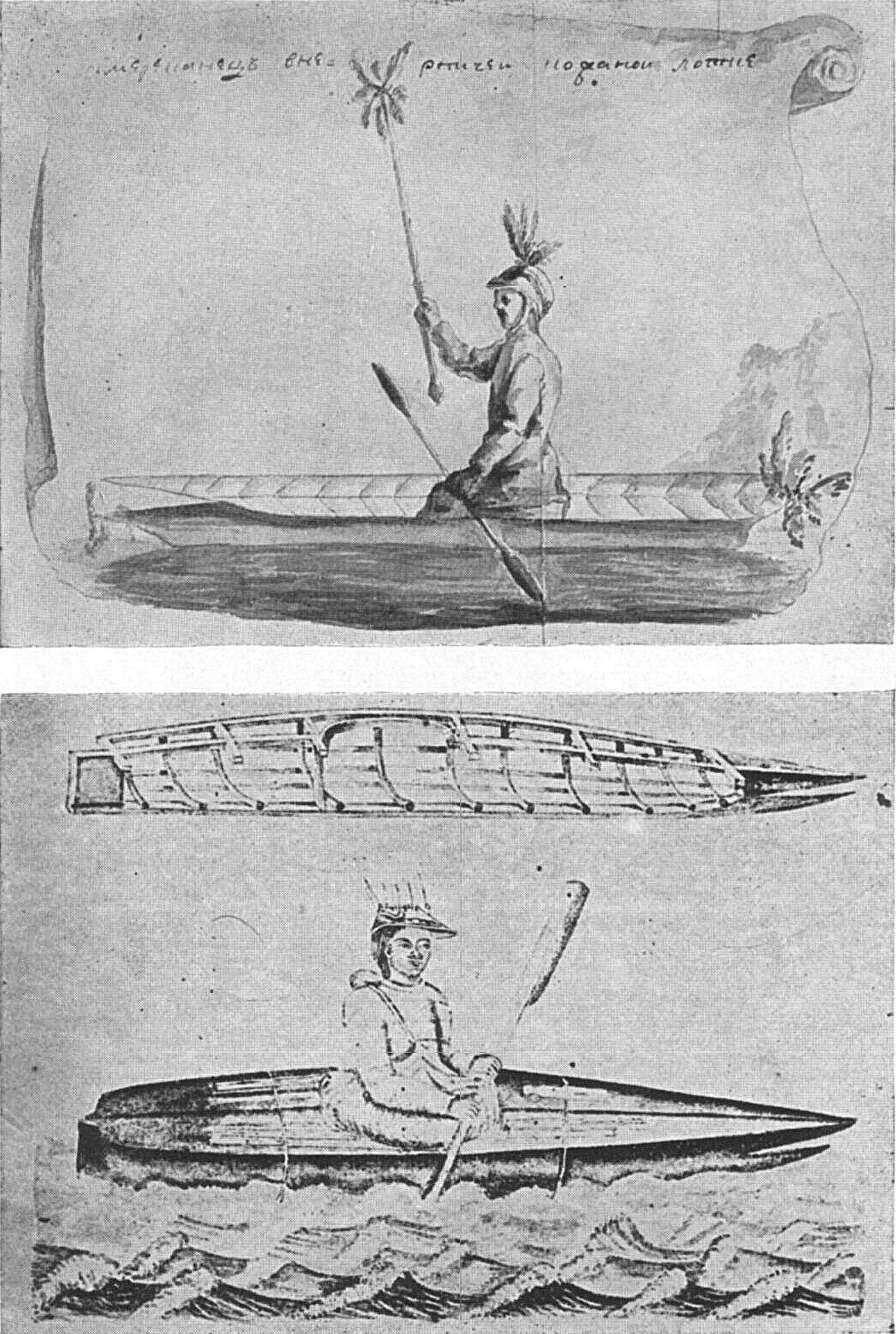

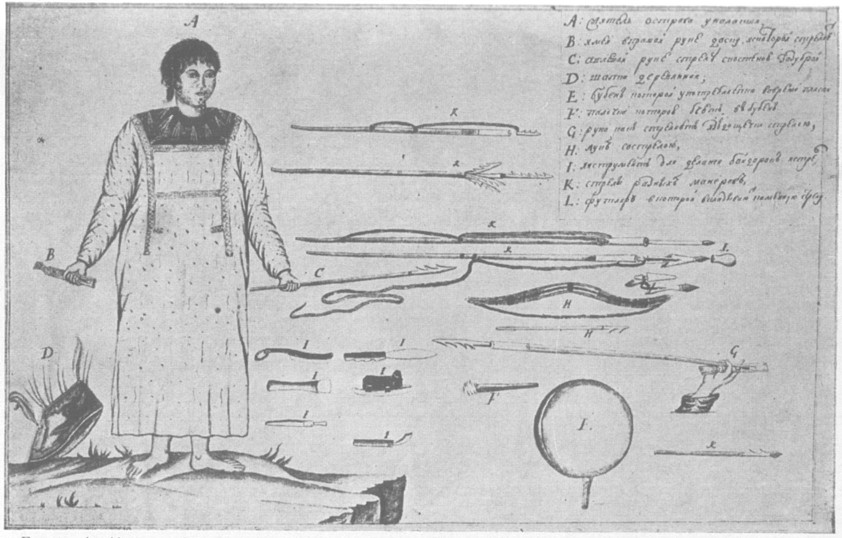

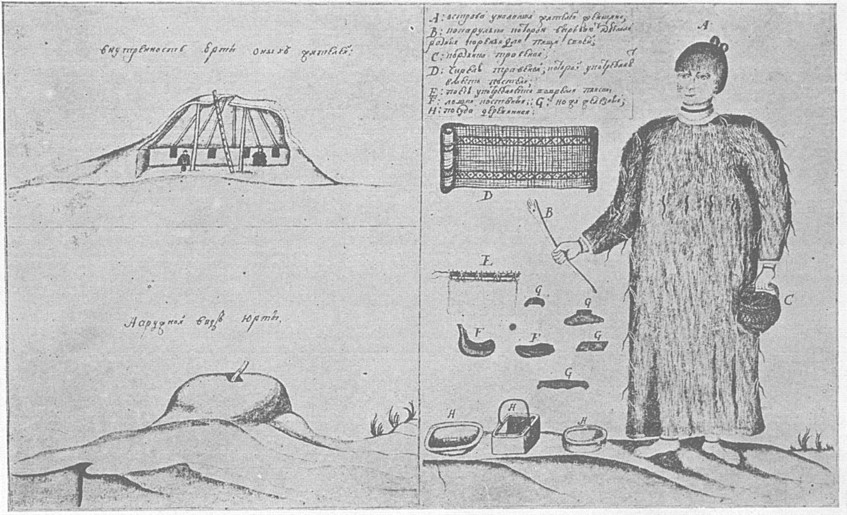

| 12 | Upper: An Aleut in his baidarka, or skin boat. (Drawing on the chart of the voyage of the St. Peter by Waxel and Khitrov in the Russian archives.) | |

| Lower: A native of Unalaska in a baidarka. (Drawing by Levashev in the Russian archives.) . . . facing | 149 | |

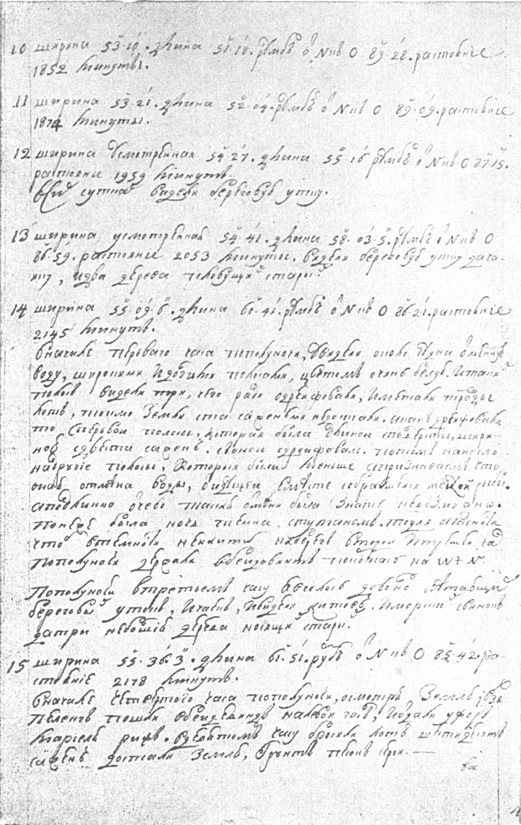

| 13 | Facsimile of a page of the journal of the St. Paul: entries of July 10-15, 1741 . . . facing | 290 |

| 14 | A man of Unalaska. (Drawing by Levashev.) . . . facing | 304 |

| 15 | Left: Inside and outside views of native hut, Unalaska. | |

| Right: A native woman of Unalaska. (Drawing by Levashev.) . . . facing | 305 | |

| Pl. | ||

| 1 | Chart of the voyage of Bering and Chirikov in the St. Peter and the St. Paul from Kamchatka to the Alaskan coast and return, 1741, based on the log books and other original records and adjusted to known physical conditions. Mean meridional scale, 1:5,500,000. By Ellsworth P. Bertholf . . . facing | 348 |

The discovery of the northwest coast of America by the Russians deserves far more consideration than it has yet received. Our information on the subject is very fragmentary—a chapter here and a chapter there in the histories of the Russian Far East and the American Far West. This neglect is due not so much to lack of interest as to lack of material and to the peculiar problems which the handling of the material presents. But these difficulties are gradually disappearing, and it is now possible to undertake a task that twenty years ago seemed out of the question. In this work the author has made the actors tell their own story of the discovery of the northwest coast of America. It would have been worth while to bring together all the interesting material relating to the subsidiary voyages of Bering’s second expedition—the voyages of Spanberg to Japan and the explorations along the Arctic coast—but neither time nor space permitted it.

Volume 1 includes an account of the log books and reports of the navigators, and Volume 2 deals with the journal of Steller, which throws much light on the second expedition and furnishes valuable scientific data. In the translation the terminology of the navigators has been retained and their ideas faithfully rendered in so far as it was possible, considering that their penmanship was not always legible, nor their language grammatical, nor their expressions intelligible. With these original data before him the reader is in a position to form an independent conclusion respecting the controversies raging around this voyage. This book is not the last word on the subject, and it is hoped that other investigators will use its material to make further studies in the field.

The late Captain E. P. Bertholf, until within two years of his death in 1921 Commandant of the U. S. Coast Guard, and an authority on the waters and shores of Bering Sea and the North Pacific Ocean, has made a distinct contribution to science by plotting out scientifically the tracks and landfalls of the {p. x} St. Peter and the St. Paul. In addition he read the manuscript and suggested improvements. Lieutenant Raymond Burhen, U.S.N., and Captain Sam Hoyt, of Seattle, have helped in the matter of nautical expressions. To all these gentlemen the author is sincerely grateful. He takes this occasion also to testify publicly to the courtesy and genuine good will of the Russian archivists and scholars of the old régime with whom he had contact in Petrograd and Moscow in his search for material. They were ever ready to inconvenience themselves to help him in his work. Some of these men have been forced from their position and their country, and others, like Professor Lappo-Danilevski, have died of starvation. They were real scholars and true gentlemen, and it is with a feeling of reverence and gratitude that this tribute is paid to them.

The numerous naval expeditions of the sixteenth century in search of a short passage to Asia gave the geographers a fairly good idea of the waters and shores of the Atlantic and of those parts of the Arctic that were nearest to Europe and European settlements. Equally helpful in making the Indian and the South Pacific waters familiar to the educated world were the voyages via the Cape of Good Hope route to the Indies, China, and Japan, the annual voyages of the Spanish naval officers between Mexico and the Philippines, and the occasional raids of the English freebooters along the Spanish-American coast. From the early years of the seventeenth century onward more or less reliable maps existed for the Pacific Ocean south of the parallel which runs through Cape Mendocino and the northern part of the main island of Japan, but for the vast region north of that line not a single map that could in any way lay claim to accuracy was to be found before the time of the Bering voyages. It was not even known whether the North Pacific area was all land or all water, whether Asia and America were separated or united (Fig. 1).

There were many reasons for believing that islands or a continent were to be found in that northern region. When the Jesuits came to Japan in the middle of the sixteenth century they learned that north of Japan proper there was a body of land called Yezo, but they could not fully inform themselves as to its shape and size. A somewhat similar report reached Europe from another quarter. Richard Cocks, an English merchant in Japan, in a letter written in 1611, made mention of “an island called Yedzo, which is thought to be rather some part of the continent Tartaria.”

But this was not the only vague information the cartographers had to go on. The credulous were as eager as ever to hear of islands with golden streets, and they accepted as a fact every baseless rumor which helped to confirm them in their belief. One of these rumors was that in the year 1582, or thereabouts, a Spanish vessel in going from Manila eastward ran into a storm which drove her to an island situated in latitude 37° 30′ N. and some 400 miles east of Japan. The inhabitants of this island were hospitable and rich to such an extent that even the pots and pans were made of gold and silver.

The Spanish government attached enough importance to current gossip to send Sebastian Vizcaíno from Mexico in search of the rumored El Dorado. He spent the autumns of 1611 and 1612 in cruising north, south, and east of Japan without, however, being able to locate the prize. In the meantime the Dutch traders heard the story, and they in turn became interested. In 1639 the Dutch East India Company instructed Mathijs Quast and Abel Janszoon Tasman to find the gold island, but all their efforts were in vain. Four years later the company sent another expedition in command of Maerten Gerritszoon Vries. He sailed north and east of Japan, sighting the island of Yezo without, however, being able to determine either its shape or its size, and came among (what are now known as) the Kurile Islands. The two southernmost of these, Kunashiri and Itorup, he thought were one island, which he named State Island and the other, Urup (which he thought to be part of the American continent), Company Land. But neither gold nor silver did Vries find, though he sailed north to Sakhalin, south to Formosa, and east 460 miles from Japan. The Vries discoveries were put on the map by Jansson in 1650. The preceding year (1649) another cartographer, Texeira by name, published a map on which he marked the discoveries (in the early part of the seventeenth century) of a certain Juan de Gama just about where Vries placed his Company Land, that is to say between latitude 40° and 45° N. (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1—Section of a map of the northern hemisphere by Guillaume Delisle, July, 1714, to illustrate the contemporary knowledge of the North Pacific. Note the “Terre de la Compagnie” and the “Côte découverte par Dom Jean de Gama.”

It is no wonder that these three reports, that of the Jesuits, Vries, and Texeira, of the three poorly described territories, Yezo, Company Land, and Gama Land, bewildered the cartographers. They were at a loss to know whether the lands in question were islands or continents, whether they were parts of America or of Asia, whether they were three distinct lands or one and the same. On the maps of the second half of the seventeenth and the early part of the eighteenth century all these views, and many others besides, found expression. Johann Baptist Homann of Nuremberg, on his map of about 1712, suggested that Terra Esonis was probably the northwest coast of America and the same land that Gama discovered; on the other hand Guillaume Delisle, in a memoir which he read before the Paris Academy of Sciences in 1720, made the statement that Yezo was a part of Asia and that Japan was a peninsula of it. The difference in the point of view of these two men gives an idea of the confusion on the subject that existed at the beginning of the eighteenth century. There was only one way of clearing up these difficulties, and that was by actual investigation.

During the century and a half that the cartographers were losing themselves in their speculations and paper explorations of the North Pacific the Russian trappers, traders, tribute gatherers, and missionaries were wandering over the length and breadth of Siberia and pushing their discoveries to the “Eastern” Ocean. They had not, however, a clear idea of what they were doing; they had not even a very good mental picture of the land they discovered.

By actual navigation they had learned that the Ob, Yenisei, and Lena emptied into the “Icy” Sea, that the Amur, Ud, and Okhota flowed into the Eastern Sea; but they were ignorant as to whether there existed a passage between these two seas. They {p. 4} knew that one could go by water from the mouth of the Ob to the mouth of the Lena, from the mouth of the Amur to the mouth of the Okhota, but they did not know whether one could navigate from the mouth of the Lena to the mouth of the Okhota. They were not agreed among themselves whether there was land to the north and east of the two last-named rivers. Many of these Siberian hunters believed that not far from the mouth of the Kolyma River a large continent (bolshaya zemlya) extended northward and that the Asiatic mainland stretched out indefinitely to the eastward. Something was also said and known of the Anadyr and Kamchatka Rivers, but they were supposed to discharge their waters into the Arctic. According to some curious Siberian maps of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries eastern Asia ended somewhere near the mouth of the Okhota River and northern Asia close to the Yana River, and the two parts together, where they joined, formed a right angle. The areas which now go by the name of Kamchatka and the Chukchi Peninsula were then unnoticed. This may have been due to the Siberians’ ignorance of the country or to their ignorance of the science of map making.

When Peter the Great came into power he took deep interest in the activities of his energetic Cossacks and tried to give them intelligent guidance. He sent many of his Swedish prisoners of war into Siberian ports to teach his subjects to build sea-going vessels, to use nautical instruments, and to construct modern maps. Between 1700 and 1715 Kamchatka and the Kurile Islands were discovered and explored, and the terra incognita in Asia was pushed still farther eastward. Reports of these discoveries reached the scientific men of Western Europe, and when Peter came among them in 1716 and 1717 they discussed with him the question of the North Pacific and urged him to settle once for all the problem whether Asia and America were united. Peter accepted for himself and for his country the honor and the {p. 5} responsibility, and carried the undertaking through successfully, although at the time his success was somewhat doubted. When Bering’s second expedition came to an end in 1749, Bering Strait had been discovered, the Arctic coast of Asia from the White Sea to the Kolyma River had been charted, and the North Pacific coast of America from Cape Addington to Bering Island had been placed on the map. This was Russia’s share in the work of discovery and exploration, and a very important contribution to geographical knowledge it was.

On his return to his capital in 1718 Peter the Great went to work at once on the problem of the relation of Asia to America. He ordered two of his officers, Fedor Luzhin and Ivan Evreinov, to proceed to Asia to make certain investigations for him and “to go to Kamchatka and farther, as you have been ordered, and determine whether Asia and America are united; and go not only north and south but east and west, and put on a chart all that you see.”[1] They left Russia in 1719, reached Kamchatka in 1720, cruised among and explored the Kurile Islands in 1720 or 1721, returned to St. Petersburg in 1722 or 1723, and made a verbal report to the emperor. Just what they reported is not known, but it is certain that they did not “determine whether Asia and America are united.”

This failure did not discourage Peter; it probably convinced him that in order to be successful the undertaking would have to be maintained on a larger scale than he had contemplated in 1718. The time was more favorable now than before for such work; the Peace of Nystad gave him the leisure and the peace of mind for planning great things. Unfortunately his health began to fail, and, as he realized that he had not long to live, he made more haste. On December 23, 1724,[2] he set matters in motion by drawing up the following orders:

|

Polnoe Sobranie Zakonov Rossiiskoi Imperii, Vol. 4. Doc. 3266. |

|

In the present work the dates are according to the old style, at that time eleven days behind the new style. |

Fig. 2—Facsimile of paragraphs 3 and 4 of Peter the Great’s orders of December 23, 1724, for Bering’s first expedition, with comments in his own handwriting. For translation, see the text, p. 7. This document is found in the Archives of the Ministry of Marine: Papers of the Admiralty Council, 1724, No. 29, Petrograd.

| Peter’s Orders | Reports |

| 1. To find geodesists who have been in Siberia and have returned. | The Senate learns that the following named geodesists have been in Siberia: Ivan Zakharov, Peter Chichagov, Ivan Evreinov, who died,[4] Fedor Luzhin, Peter Skobeltsyn, Ivan Svistunov, Dmitri Baskakov, Vasili Shetilov, Grigori Putilov. |

| 2. To find among the deserving naval lieutenants or sub-lieutenants such as could be sent to Siberia and Kamchatka. | Admiral Sievers and Rear Admiral Senyavin recommend among the naval lieutenants Stanberg,[5] Zverev, or Posenkov; among the sub-lieutenants Chirikov or Laptev. It would be advisable to have over them as commander Captain Bering or Fonverd. Bering has been in the East Indies and knows conditions, and Fonverd has had experience as navigator. |

| 3. To find among the apprentices or assistant master builders one who could build there a deck ship along the lines of the big ships here. For that purpose there should be sent with him young ship carpenters, such instruments as may be needed, one quartermaster, and eight sailors. | The student of shipbuilding, Fedor Koslov, is able to build either decked or open ships if he is furnished with a plan. It is very necessary to have as navigator or assistant navigator one who has been in North America. |

| 4. Likewise to forward from here one and a half* sets of sails; blocks, cables, and such like; four falconets with the necessary ammunition; and one or two sailmakers. | Rigging is being sent. *Two sets. The rest is all right. |

| {p. 8} | |

| 5. If there are no such navigators in our navy, a letter should be dispatched at once to Holland that two men be sent who know the sea in the north and as far as Japan. These men should come by the admiralty post. | Vice-Admiral Sievers has written that he has among our men navigators who know the sea and that he will send them without delay. |

December 23, 1724.

|

Archives of the Ministry of Marine: Papers of the Admiralty Council, 1724, No. 29, pp. 129-130. In the left-hand column are Peter’s instructions, in the right is the report of the Senate or the Admiralty Council. The lines in italics are comments on the report by Peter made in his own handwriting (see Fig. 2). |

|

In 1720 or 1721 Evreinov and Luzhin, as stated above, went to the Kurile Islands at the order of Peter. Soon after their return Evreinov died. |

|

I.e. Spanberg. |

We are sending to Siberia Fleet-Captain Vitus Bering with assistants to undertake a naval expedition and to carry out such instructions as he has from us. When he comes to you and asks help of one kind and another for the expedition you are to give it to him.

January, 1725.

On the strength of the recommendations of the Senate and the Admiralty Council the tsar selected Vitus Bering[7] to lead the expedition and gave him as lieutenants Martin Spanberg[8] and Alexei Chirikov. In the early part of January, 1725, he also drew up and signed the instructions;[9] but, owing to his failing health, he had to leave the execution of them to his friend Count Apraksin.[10] The death of Peter on January 28, 1725, did not in the least {p. 9} disturb the plans of the undertaking. Catherine was determined to carry out all the policies and ambitions of her husband. Already, on January 24, the vanguard of the party had left the capital, but Bering and several others did not leave until February 5, the day the instructions were handed to him, as may be read in the report of Bering which follows.

|

Archives of the Ministry of Marine: Papers of the Admiralty Council, 1724, No. 29. |

|

Vitus Bering was born at Horsens, Denmark, in the year 1681. As soon as he was old enough he went to sea and in 1703 made a voyage to the East Indies. In 1704 he joined the Russian navy with the rank of sub-lieutenant. He rose gradually in the service, being made lieutenant in 1707, lieutenant-captain in 1710, captain of the fourth rank in 1715, captain of the third rank in 1717, captain of the second rank in 1720, and captain of the first rank in 1724, when he was put in charge of the expedition. For a fuller account of Bering’s life the reader is referred to Peter Lauridsen’s “Vitus Bering,” transl. by J. E. Olson, Chicago, 1889. |

|

Spanberg was a Dane and Chirikov a Russian. |

|

Printed below, pp. 10-11, in Bering’s report. |

|

Nartov’s account of the last days of the monarch (Razskazi Nartova o Petre Velikom, edited by L. N. Maikov, St. Petersburg, 1891, p. 99) shows how important the latter regarded the expedition: “In the beginning of January, 1725, Peter was realizing that he had not long to live, yet his unconquerable spirit was busily at work for the good of the country. With his own hand he drew up the instructions relative to the Kamchatka expedition, which should determine the relation between Asia and America. He also selected the officers for this work—Vitus Bering, Martin Spangenberg [this was the usual way of writing it at this period], and Alexei Chirikov. “I was then almost constantly with the Emperor and saw with my own eyes how eager His Majesty was to get the expedition under way, being, as it were, conscious that his end was near. When all had been arranged he seemed pleased and content. Calling the general-admiral [Count Apraksin] to him he said: ‘Bad health has obliged me to remain at home. Recently I have been thinking over a matter which has been on my mind for many years, but other affairs have prevented me from carrying it out. I have reference to the finding of a passage to China and India through the Arctic Sea. On the map before me there is indicated such a passage bearing the name of Anian. There must be some reason for that. In my last travels I discussed the subject with learned men, and they were of the opinion that such a passage could be found. Now that the country is in no danger from enemies we should strive to win for her glory along the lines of the arts and sciences. In seeking such a passage who knows but perhaps we may be more successful than the Dutch and English, who have made many such attempts along the American coast. I have written out these instructions and, on account of my health, I entrust the execution of them, point by point, to you, Feodor Matveyevich.’ ” |

To the Most Enlightened, August, and Great Empress of All the Russias [is submitted] a short account of the Siberian Expedition undertaken by Her Imperial Majesty’s humble servant. Fleet Captain V. I. Bering.[12]

On February 5, 1725, I received from Her Imperial Majesty the Empress Catherine Alexeyevna,[13] of illustrious and immortal memory, the instructions drawn up by the hand of His Imperial Majesty Peter the Great, of deserving and eternal fame, a copy of which follows:

1. Build in Kamchatka or in some other place in that region one or two decked boats.

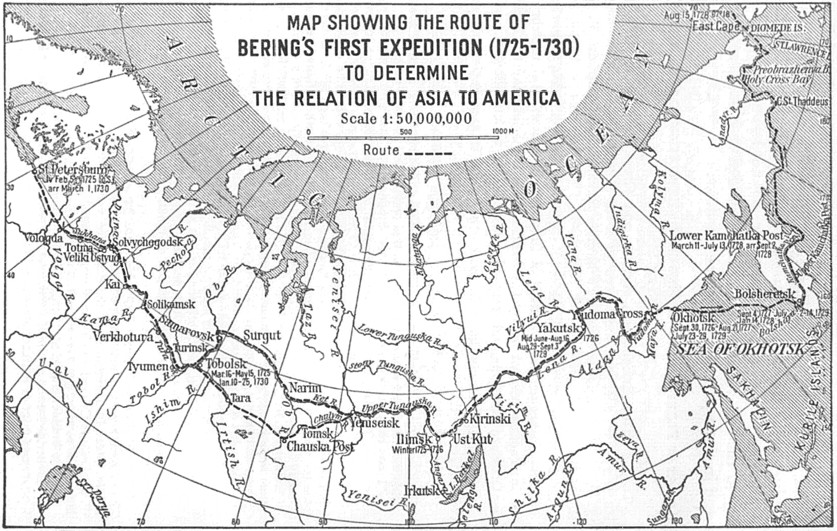

Fig. 3—Map showing the route of Bering’s first expedition. Scale 1:50,000,000. Of the land journey, between St. Petersburg and Okhotsk, both the outward and the return routes are shown; of the sea voyage, between Okhotsk and Bering Strait (overland across Kamchatka), only the outward route is shown. (Based, for the land journey, on the text herewith and the tables (see bibliography) of Bering’s report, and, for the sea voyage, on the map, reproduced in Fig. 6, accompanying Berkh’s work of 1823 (see bibliography), which is based on the log book kept by midshipman Peter Chaplin.)

2. Sail on these boats along the shore which bears northerly and which (since its limits are unknown) seems to be a part of America.

3. Determine where it joins with America, go to some settlement under European jurisdiction; if you meet a European ship learn from it the name of the coast and put it down in writing, make a landing to obtain more detailed information, draw up a chart and come back here.[14]

In the orders given me by General-Admiral Count Apraksin[15] it was stated that I was to ask for mechanics and supplies from the provincial government at Tobolsk and that I was to make monthly reports to the Admiralty College.[16]

On January 24, before I received the instructions, there was dispatched by the Admiralty College in the interest of the expedition one of my lieutenants with 26 men and 25 wagonloads of materials. Altogether there were under my command 33 men, and they were sent by way of Vologda. From St. Petersburg to Tobolsk we passed en route the following cities: Vologda, Totma, Veliki Ustyug, Solvychegodsk, Kai, Solikamsk, Verkhotura, Turinsk (also called Epanchin), and Tyumen.[17]

On March 16 Tobolsk was reached and there we remained until May 15 because of the cold weather. During the stay I requisitioned the necessary material for the expedition. On May 15 we started down the Irtish to Samarovsk in four boats, known in Siberia as doshcheniki.[18] They were loaded with supplies brought from St. Petersburg as well as other things gathered at Tobolsk. In the last-named city there were added to my company, at my request, a monk, a commissar, petty officers, and soldiers to the number of 34.

From Samarovsk I sent ahead my marine guard,[19] who carried with him orders from the provincial government of Tobolsk to the towns along the way to have boats prepared at Yeniseisk and Ust-Kut,[20] but {p. 12} he himself was to proceed to Yakutsk. After leaving Samarovsk we went up the Ob to Surgut and to Narim, thence up the river Ket to Makovska Post.[21] Along the course that we followed from Tobolsk to Makovska live the Ostyaks,[22] who were formerly idolaters but through the labors of Metropolitan Philophei[23] of Tobolsk were converted to Christianity in 1715. We proceeded overland from Makovska to Yeniseisk and there went aboard four boats and worked our way up the rivers Yenisei and [Upper] Tunguska to the mouth of the Ilim River. On the Tunguska there are three rapids (poroga) and several rocky shoals (shkver). In the rapids there are large submerged rocks across the whole width of the stream so that a boat can get through in only one or two places; the shoals likewise have rocks above and below the surface but they [the shoals] are not very large. The shoals differ from the rapids in that the former have little water and continue for a verst or two at a stretch, which causes some trouble in getting over them. At Yeniseisk I took for my service, in accordance with instructions from Tobolsk, 30 carpenters and blacksmiths. The rapids and shoals made it impossible to go up the Ilim to Ilimsk, and on that account there were sent out from that town smaller craft. On these the heavier materials were taken to Ilimsk, but the lighter were transported to the same place in the course of the winter.

Lieutenant Spanberg with 39 men, carpenters and laborers, was sent overland to Ust-Kut, where, during the winter, they constructed 15 barges for taking the men and supplies down the Lena to Yakutsk. With the other members of the party I wintered at Ilimsk because there were not enough accomodations for all at Ust-Kut and we could not go through to Yakutsk owing to the snow and cold, the lack of teams, and the uninhabited country. According to orders from Tobolsk we were to receive our food supplies from Irkutsk and Ilimsk, as no grain grows at Yakutsk. During the winter I went from Ilimsk to Irkutsk to consult with the voivode[24] of that city, who formerly held a similar position at Yakutsk, about that country, of which we knew very little, and to find out the best way of going from there to Okhotsk and Kamchatka. Towards the end of the winter I took over to Ust-Kut {p. 13} my whole company, which included 20 carpenters and blacksmiths from Irkutsk and two coopers from Ilimsk.

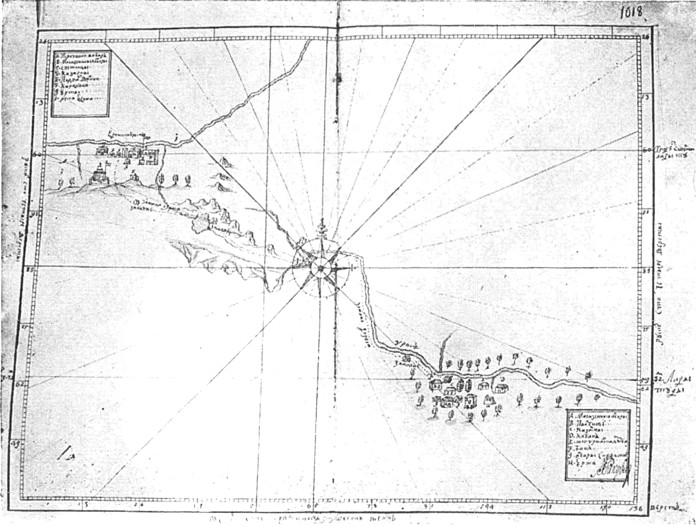

Fig. 4—Facsimile of map showing the route of Bering’s first expedition across the Stanovoi scarp from Yudoma Cross by way of the Urak River to Urak near Okhotsk. (Drawing by Spanberg found among the Bering Papers No. 24 in the Archives of the Ministry of Marine in Petrograd.)

Translation of key: Upper left (village of Yudoma Cross): A, powder house; B, warehouse; C, living quarters; D, barracks; E, underground room (cellar?); F, guardhouse; G, native huts; J, Yudoma River.

(Dotted lines indicate winter route. In summer goods were portaged from Yudoma Cross to the headwaters of the Urak.)

Lower right (village of Urak): A, warehouse; B, cemetery; C, barracks; D, tavern; E, pilot’s house; F, bathhouse; G, storerooms of employees; H, native huts.

Along the Tunguska, Him, and Lena Rivers, as far as the Vitim,[25] live the idolatrous Tungus who have deer for riding, but those who have no deer make their homes along the banks of streams and subsist on fish and get about in birch canoes.

In the spring of 1726 we left Ust-Kut in 15 barges and went down the Lena to Yakutsk. From the Vitim down along the Lena, on both banks, live the Yakuts and a small number of Tungus. The Yakuts have many horses and cattle which supply them with food and clothing, but those that have but few of these animals live on fish. They are idolaters; they worship the sun and the moon and, of the birds, the swan, the eagle, and the raven. They hold in high respect their priests, whom they call shamans, who keep in their possession small idols (bolvanov) known to them as shaitany. They claim to be of Tatar origin.

On arriving at Yakutsk I called for help to assist my men on the barges, and, as soon as they came, I dispatched Lieutenant Spanberg in 13 of the boats that were built at Ust-Kut and drew but little water down the Lena to the Aldan and from there up the Maya and the Yudoma. These barges were loaded with materials which could not be transported overland, besides other naval and land stores. I had hoped that this freight could be taken by water as far as Yudoma Cross,[26] a much cheaper way than sending it by horses. That same summer I, with a small number of my men, went from Yakutsk to Okhotsk on horseback, taking with us a pack train, each horse carrying only a five-pood[27] load, and in this manner we brought over sixteen hundred poods of provisions. It was impossible to make use of wagons owing to the mud and the hills. At Okhotsk Post there are only ten Russian dwellings. Lieutenant Chirikov was left behind to winter at Yakutsk with the understanding that he was to come overland to Okhotsk in the spring.

Towards the end of December, 1726, I received word from Lieutenant Spanberg that his boats were ice-bound in the Gorbea River,[28] about 450 versts from Yudoma Cross, and that he had made sleds and was hauling on them the most needed material. I made up a party from my own men and those of the ostrog and gave them dog teams and supplies, and sent them to the relief of the lieutenant. He arrived with his company about the first part of January, 1727, without, however, bringing in any of the material, which he left in four different places along the uninhabited trail. They had been on the road ever since November 4 and during that time had suffered greatly from hunger, having been compelled to eat the dead horses that had dropped by the wayside, the harness, their leather clothing, and boots. Fortunately they found at Yudoma Cross the 150 poods of flour which we had left behind when some of our horses gave out.

Fig. 5—The eastern section of the map accompanying Bering’s report of his first expedition. Reproduced from W. H. Dall’s facsimile (Appendix No. 19, U. S. Coast and Geodetic Survey Rept. for 1890, Pl. 69) of a copy of the map prepared for use in Sweden, with transliteration of the Russian names, in 1889 in the collection of Baron Klinckofström. Compare with Bering’s route and the coast outlines on Figs. 3 and 6.

Along the Aldan and Maya live the same kind of Yakuts as those on the Lena; but on the Yudoma, that part which is near Okhotsk Post, are the wandering coast Tungus, or Lamuts, as they call themselves. They have many deer, on the backs of which they ride summer and winter and which, as well as the wild deer, supply them with their food and clothing. Here, too, are to be seen the pedestrian Tungus who live near the sea and along the banks of the streams and depend on fish for their sustenance. They have the same religion as the Yakuts.

About the first part of February I gathered 90 men and several dog teams and gave them to Lieutenant Spanberg with orders to bring in whatever was left on the Yudoma. He himself returned during the first days of April, but some of his men did not come in until the middle of the month. Even then they failed to bring in everything, and it was necessary to send another party of 27 men to Yudoma Cross, which stayed away until May but brought in all the material on pack horses. In these regions people never go in winter from Yakutsk to Okhotsk or other far-off places on horseback; they go on foot, dragging behind them sleds—the kind we used between the Gorbea and Okhotsk—with such things as are needed, each sled carrying from 10 to 15 poods. A trip like this takes from eight to ten weeks. The snow here is sometimes seven feet deep, and in places even deeper, and people who travel in winter dig their way through the snow to the ground and there pass the night.

On June 30, Lieutenant Spanberg sailed for the mouth of the Bolshaya River on his newly built ship[29] which was loaded with all the materials. He had orders to discharge the cargo, send one of the petty officers with carpenters to Kamchatka to prepare ship timber, and return himself to Okhotsk.

Lieutenant Chirikov came from Yakutsk July 3, bringing with him in accordance with my instruction 2,300 poods of flour. We loaded the flour on Spanberg’s ship, which had returned, and on an old boat,[30] which had come in from the Bolshaya River, and sailed with my company for Bolsheretsk Post on August 21. The supplies that were still in the boats on the Gorbea I sent back to Yakutsk in charge of the pilot and the men who had been detailed to watch over them, with orders to get a receipt for them and then hasten back with some part of the {p. 17} supply of iron and tar and join me in Kamchatka in 1728. At the mouth of the Bolshaya River we had to discharge the cargo into small boats and take it to Bolsheretsk. This post had only 14 Russian houses. The heavier materials and part of the supplies were loaded into small boats and sent up the Bystra River,[31] a stream with a swift current, to within 120 versts of the Upper Kamchatka Post. That same winter we left Bolsheretsk on dog teams for the Upper and Lower Kamchatka Posts. Each evening we made a camp in the snow and covered over the opening. This country has some bad blizzards, called purgas,[32] and if a person is hit by one of them in an open place without having time to construct a shelter he is in danger of being snowed over and freezing to death. In the upper ostrog there are 17 houses; in the lower, 50; and in the other place, where the church is, there are 15 more. In all three places there lived, during our stay, not more than 150 persons [Russian]; their chief occupation is collecting tribute. The natives who drove the teams that brought us over from Bolsheretsk prepared 300 poods of whale blubber from a whale that had been washed ashore in the fall. In place of money they [the natives] were given Chinese tobacco. In southern Kamchatka live the Kurils, in the northern the Kamchadals. They have a common language, but there are a few minor differences. A small number of these people are idolaters. The others do not believe in anything and are strangers to all good customs (i chuzhdi vsiakykh dobrykh obychaev). Neither the natives of Kamchatka nor the Russians who live there sow any grain. Of domestic animals they have only the dog, which is used for driving, hauling, and for furnishing clothing. The food of the natives consists of fish, roots, berries, wild birds, and sea animals in season. In the neighborhood of the Yakutsk monastery, which is about a verst from the Kamchatka church, there are raised at the present time oats, hemp, and radishes. Turnips are cultivated in all three ostrogs, and they reach such a size as is seldom seen in Russia, four of them making a pood. I took over to the monastery above mentioned some rye and barley and had it sown, but whether it matured or not I cannot tell, for sometimes early frosts kill the crop. In cultivating the soil the people are handicapped by lack of draft animals.

From all aborigines under Russian jurisdiction tribute in fur is collected. The natives have many evil practices. If a woman or a beast gives birth to twins one of them must be killed at once. Not to do so {p. 18} is a great sin. It is a practice among the Kamchadals, if one of them is very sick, even a father or a mother, to take him out into the forest and leave him there, be it summer or winter, with just enough food to last a week, and as a result many die. The homes of the dead are not again occupied, and the dead themselves are not buried but are thrown into the woods, where the dogs devour them.[33] The Koryaks burn their dead; this custom is now forbidden, but the law is not strictly enforced.

When I reached Lower Kamchatka Post the timber for our ship was in large part ready. We went to work on her April 4, 1728, and with the help of God had her completed by July 10.[34] The timber we hauled on dog teams. Tar, since we had not brought any with us and the natives had none on hand as they did not know how to make it, we manufactured out of a tree known there as listvennik.[35] For lack of anything better to take along on the sea voyage, we distilled liquor from grass by a process known in that country;[36] salt we boiled out of sea water; butter we made from fish oil; and in place of meat we took salt fish. We had on board enough provisions to last 40 men a year. On July 14 we sailed from the mouth of the Kamchatka River out to sea and followed the course laid down by the instructions of His Imperial Majesty Peter the Great and here marked on the chart.

On August 8, when we were in latitude 64° 30′ N., eight men who claimed to be Chukchi (a people known for a long time to the Russians of the country) rowed to us from the shore in a leathern boat and, when near, asked who we were and why we came. On being invited on board, they put one man over, who, with the help of large inflated seal bladders, swam over to have a talk with us. A little later the boat moved up to us and the men in it told us that large numbers of Chukchi live along the shore, that a short distance from here the coast turns to the west, and that not far ahead of us is an island. We located this island, which we named St. Lawrence, in honor of the day, and found on it a few huts but no people, although I twice sent the midshipman to look for them.

By August 15 we came to latitude 67° 18′ N. and turned back because {p. 19} the coast did not extend farther north and no land was near the Chukchi or East Cape and therefore it seemed to me that the instructions of His Imperial Majesty of illustrious and immortal memory had been carried out. Had we gone on and met with unfavorable winds we might have been prevented from returning to Kamchatka that season, and to have wintered where we were would not have been wise because there was no wood of any kind and the native population does as it pleases, is not under Russian control, and has nothing to do with the Russian tribute collectors.[37]

From the mouth of the Kamchatka River to the point from which we turned back the coast is mountainous, almost as straight as a wall, and covered with snow even in summer.

On August 20 there came to our ship four boats containing 40 Chukchi like those who had visited us before. They offered for sale meat, fish, {p. 20} water, about 15 red and white fox skins, four walrus tusks—all of which they disposed of to the crew for needles and such like articles. They told us that their relatives go to the Kolyma on deer and not by boat, that farther along the coast live some of their people, that they had known the Russians for a long time, and that one of their number had been at Anadyrsk Post to trade. The rest of their conversation did not differ greatly from what was said by those who had been to see us before. On September 2 we sailed into the mouth of the Kamchatka River and passed the winter in the Lower Kamchatka Post.

Having repaired the ship, which had been laid up, we left the mouth of the Kamchatka River on June 5, 1729, and set an easterly course, because the inhabitants of Kamchatka said that in clear weather land could be seen across the sea. We made a careful search for it over a distance of 200 versts but could not find it. We circumnavigated and charted the southern part of Kamchatka, which up to this time had not been surveyed, and then sailed to the mouth of the Bolshaya River and from there to Okhotsk Post. At the request of the authorities at Yakutsk I left with the government officials in charge of the posts of Lower Kamchatka and Bolsheretsk 800 poods of flour, dried meat, salt, and groats.

It was July 23 when we reached the mouth of the Okhota River, where I handed over the ship and all that went with it to the officer in command. We hired horses and went to Yudoma Cross, and from there we proceeded by boats and rafts down the Aldan to the portage (belskoi perepravy) and lower, where we again took horses and rode on to Yakutsk. From Okhotsk to Yakutsk it took us from July 29 to August 29 and to September 3.[38] On September 10 we went in two boats up the Lena and proceeded until October 1, when we were blocked by ice and therefore spent a part of the autumn in the village of Peleduye.[39] By October 29 there was sufficient snow on the ground, and the banks of the Lena were firm enough on account of the ice to permit us to go on. We followed the [Upper] Tunguska and the Yenisei to Ilimsk and Yeniseisk, passing Russian settlements on the way. From Yeniseisk to Tomsk we continued along the river Chulym,[40] meeting with more Russian settlements and villages of newly converted Tatars. Between Tomsk and Chauska Post[41] we passed through other Russian settlements. From Chauska to Tara we crossed the Barabinsk Steppe, from Tara to Tobolsk we followed the river Irtish and met with Tatar villages. At Tobolsk we arrived January 10, 1730, and left there on the 25th of the same month for St. Petersburg, going over the same country as on the outward journey to Tobolsk. On March 1 we reached St. Petersburg.

|

Zapiski Voenno-Topogr. Depo, Vol. 10, pp. 69-75, St. Petersburg, 1847. The original report in manuscript is in the Archives of the General Staff, Section X, No. 566. [A translation of the published version appeared (pp. 135-143) in W. H. Dall: A Critical Review of Bering’s First Expedition, 1725-30, Natl. Geogr. Mag., Vol. 2, 1890, pp. 111-169.—Edit. Note.] |

|

Vitus Ivanovich Bering. Bering’s father’s name was Jonas. |

|

Catherine I, second wife of Peter, who succeeded him to the throne on February 8, 1725, and reigned until her death on May 6, 1727. |

|

Polnoe Sobranie Zakonov Rossiiskoi Imperii, Vol. 7, Doc. 4649. |

|

Feodor Matveyevich Apraksin (1671-1728), one of Peter’s right-hand men. See also footnote 10. |

|

The Admiralty College was created in 1718 and became a Ministry in 1802. |

|

For the route of the expedition, see map, Fig. 3. Most of the towns named, from Kai eastwards, were posts and stopping places for Siberian hunters and traders. Verkhotura (Upper Tura) was founded in 1598, Tyumen in 1586, and Tobolsk in 1587. Turinsk was also called Epanchin because a Tatar chief of that name lived here before the Russians came. |

|

A doshchenik “is built of boards without a keel, flat-bottomed, about 35 to 40 feet long; rows and steers with long sweeps, two men to each; is furnished with a mast, and one square sail, and named from dosok, a board.” (Martin Sauer: An Account of a Geographical and Astronomical Expedition to the Northern Parts of Russia, . . . by Commodore Joseph Billings . . . , London, 1802, p. 20, footnote.) |

|

Peter Chaplin. |

|

Ust-Kut (Mouth of the Kut), where the Kut falls into the Lena and marks the head of navigation. |

|

Built as a palisaded fort (ostrog) in 1619. |

|

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries they made trouble for the Russians, but they are of no importance now. In 1911 the total number of Ostyaks in Siberia was 20,000. |

|

Philophei (Leszczynski) (1650-1727). In 1702 Peter put him in charge of the Siberian missions, and it is recorded that through his efforts 40,000 natives were converted to Christianity. |

|

Mikhaelo Izmailov, voivode from October, 1724, to April, 1731. In the Annals of Irkutsk (V. P. Sukachev: Pervoe stolyetie Irkutska, St. Petersburg, 1902, pp. 133-134) it is recorded that Spanberg and “Ivan Bering” were there in the course of this winter. |

|

The Vitim is a right branch of the Lena flowing into it in 113° E. (see Fig. 3) and is known for its fine sables. In 1911 the Tungus, including the Lamuts, numbered 75,204; the Yakuts 245,406. |

|

At the headwaters of the Yudoma, where navigation ceases, there was erected a cross, hence the name Yudoma Cross. For this part of the route, see map. Fig. 4. |

|

A pood is about 36 pounds. |

|

A left tributary of the Yudoma near its mouth. Probably the Derbi River of today. |

|

The Fortune. |

|

The Lodiya. |

|

The Bystra (Swift), a branch of the Bolshaya, is full of rapids and shoals and is difficult to navigate. From Bolsheretsk to Lower Kamchatka Post the distance is 883 versts. |

|

“The poorga raged with redoubled fury; the clouds of sleet rolled like a dark smoke over the moor, and we were all so benumbed with cold that our teeth chattered in our heads. The sleet, driven with such violence, had got into our clothes and penetrated even under our parkas, and into our baggage.” (Peter Dobell: Travels in Kamchatka and Siberia, 2 vols., London, 1830; reference in Vol. I, p. 102.) |

|

A fuller and better account of the natives is to be found in S. P. Krasheninnikov’s “History of Kamchatka,” St. Petersburg, 1755, and G. W. Steller’s “Beschreibung von dem Lande Kamtschatka,” Frankfort and Leipzig, 1774. |

|

She was christened St. Gabriel. |

|

Larch. |

|

According to Steller the liquor is made in the following manner: “Der Brandtewein wird aber folgendermassen angesetzt. Man gieset auf 2 Pud süsses Kraut 4 Eimer warmes und laues Wasser, leget zum Ferment entweder was von der Destillation übrig geblieben hinein, wovon er aber einen üblen Geruch oder Geschmack bekommt, oder Beeren von Schimalost [“Shimalost” is the Kamchatka honeysuckle bush (Lonicera caerulea) which bears delicious blue berries.—L. Stejneger.] wovon er sehr stark, angenehmer wird, und mehr Brandtewein giebet, oder man fermentiret ihn mit eingesauertem Mehl; nach Verlauf 24 Stunden wird er destilliret, und bekommt man einen Eimer Brandtewein.” (“Beschreibung von dem Lande Kamtschatka,” p. 86.) |

|

On August 13, having reached 65° 30′, Bering called his officers together to discuss the question whether to go on or turn back. He said to them: “Since we have come to latitude 65° 30′ N. and according to my opinion and the statements of the Chukchi, we have reached and passed the most easterly point of their land, the question is now, shall we go farther north? If so, how far? When should we begin to look for harbors? Where does it seem best—looking at it from the point of view of best serving our country—to go for the winter in order to protect men and ship?” The officers were divided in opinion. Spanberg, the senior officer, said: “Having come as far north as we have, and since on the Chukchi coast there are no harbors nor wood . . . so that we could preserve ourselves in such winter weather as we have in this region; and since these natives are not peaceful . . . I suggest that after we have gone on the course we are on until the sixteenth of this month, and if by that time we are not able to reach sixty-six degrees, we should then in God’s name turn about and betimes seek shelter and harbor on the Kamchatka River, whence we came, in order to save men and ship.” Chirikov made this argument: “As we have no positive information as to the degree of north latitude Europeans have ever reached in the Arctic Ocean on the Asiatic side we can not know with certainty whether America is really separated from Asia unless we touch at the mouth of the Kolyma, or at least the ice, because it is well known that there is always drift ice in the Arctic Ocean. Therefore it seems to me that according to your instructions we ought to sail without questioning—unless we are hindered by the ice, or the coast turns to the west—to the mouth of the Kolyma, as your instructions demand [a place under European jurisdiction?] But should the land continue still farther to the north, it would be necessary on the twenty-fifth of this month to look for winter quarters in this neighborhood, and above all opposite Chukotski Cape, where, according to the accounts of the Chukchi through Peter Tatarinov, there is a forest. And if up to that time winds are contrary, then look there by all means for a place to winter.” (Zapiski Hydrogr. Depart., Vol. 8, pp. 550-552, St. Petersburg, 1850.) [For details on the sea voyage, the most important part of the expedition, which Bering in this report deals with only briefly, the main source of information is the midshipman Peter Chaplin’s log book, an abridged version of which, with map (cf. Fig. 6), was published by Berkh in 1823 and translated by Dall in 1891. Polonskii’s discussion of the first expedition, from which the above quotation is taken, is likewise of value. A narrative based on Berkh and Polonskii will be found in F. A. Golder’s “Russian Expansion on the Pacific,” pp. 140-147. For the references, see the bibliography.—Edit. Note.] |

|

Not clear. Possibly August 29 represents the break in the journey at the portage. |

|

Peleduye is at the mouth of the river of the same name, a branch of the Lena. |

|

On the Chaus River, founded in 1713. It is 223 versts from Tomsk. |

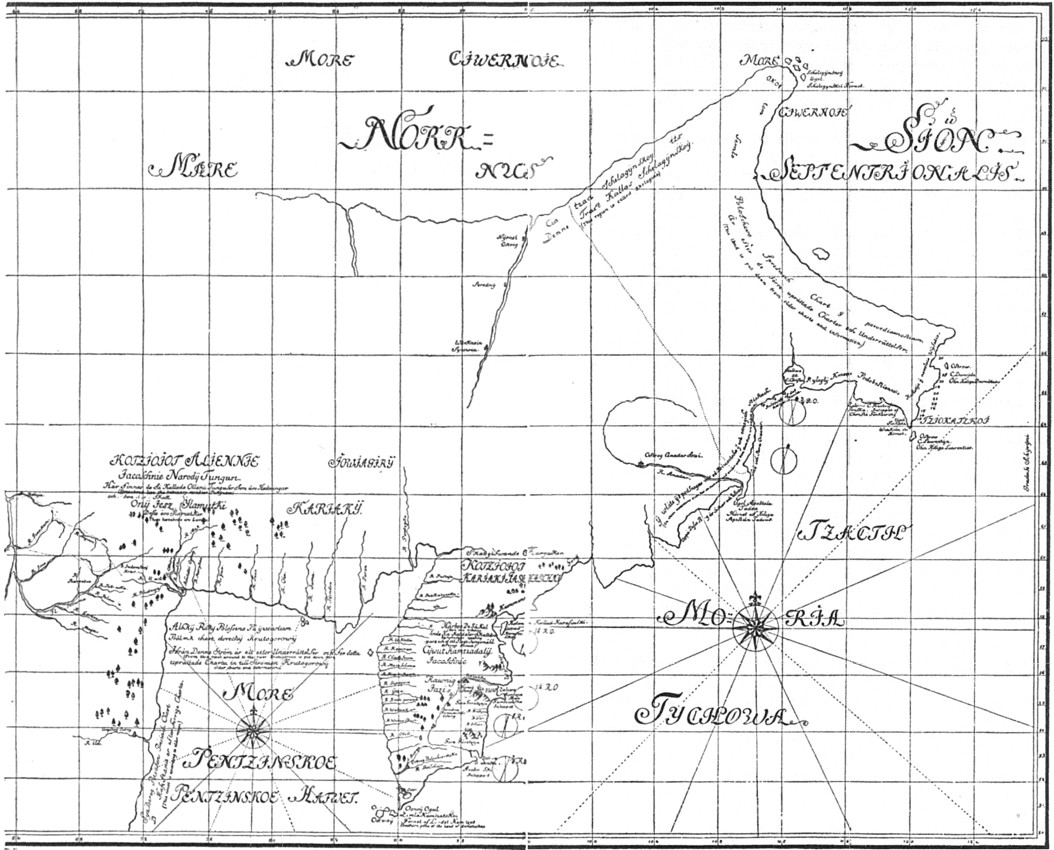

Fig. 6—Facsimile of Berkh’s map of 1823 (see bibliography) showing the route of Bering’s first expedition from Okhotsk to Bering Strait and return. Mean meridional scale 1:16,000,000 (originally 1:9,000,000). The dates have been identified and added from Berkh’s abridged version of midshipman Peter Chaplin’s log book. On sea they represent noon positions. Berkh’s plotting of the ship’s tracks has been slightly modified for August 18-20 and August 29, 1728. It would also seem as if the position of the tracks on August 10, 1728 (Bering’s report implies that a landing was made on St. Lawrence Island, cf. p. 18) and June 10-17, 1729 (Chaplin’s log book) might be susceptible of other interpretation. But otherwise, so far as known, Berkh’s map is the standard, and only modern, reconstruction of the tracks of Bering’s vessels on his first expedition. It does for that expedition what Captain Bertholf’s map (Pl. 1) does for the second.

The vessels in which the several sections of the tracks shown were sailed are: August 22-September 2, 1727, Fortune (Bering and Spanberg) and nameless vessel (Chirikov and Chaplin; it is this vessel’s track that is shown); July 15-September 1, 1728, St. Gabriel; June 6-July 3, 1729, St. Gabriel; July 14-23, 1729, St. Gabriel.

After the Russians had conquered Kamchatka they pushed northward and established trading relations with the natives of East Cape. While they were in that neighborhood the traders heard that across from the cape there was a large country (bolshaya zemlya), and occasionally they saw the inhabitants of that country who were held captive by the Chukchi. The adventurous Cossacks decided to subdue these people, as well as the Chukchi, and force them to pay tribute. One of their leaders, Afanasi Shestakov, went to St. Petersburg to persuade the government to let him undertake this task. On March 23, 1727, the Senate gave him the necessary authority[1] and force for the work in hand. It was Shestakov’s plan to attack by land and sea the Chukchi and other hostile natives on the mainland and when they were conquered to send a force to the land beyond East Cape. With that in view the Cossack leader took possession in 1729 of all the sea-going vessels Bering had left behind him at Okhotsk.

The campaign of 1730 ended disastrously for the Russians. Some of the boats were wrecked, the land forces were either waylaid or defeated in open fight, and in one of these Shestakov lost his life. Out of all this great undertaking only one important thing was accomplished—the sighting of new land opposite East Cape.

|

Polnoe Sobranie Zakonov Rossiiskoi Imperii, Vol. 7, Doc. 5049. |

Shestakov was succeeded in command by Dmitri Pavlutski, captain of dragoons and a well-known Chukchi fighter. In addition to the other information about the “large country,” Pavlutski had received in 1730 the report of one Melnikov on {p. 22} that subject which tended more and more to confirm him in the belief that such a bolshaya zemlya really existed. During the winter of 1731-1732 Pavlutski sent word to the officers of the St. Gabriel who were with the ship at Lower Kamchatka Post to bring him supplies to the Anadyr in the spring and after that go in search of the land opposite East Cape.[2] When the time came for sailing only one of the officers, Michael Spiridonovich Gvozdev was physically fit for duty, and he took command of the ship and set the course for the bolshaya zemlya. His achievement did not impress Pavlutski very much, and it was not until several years later that he was made to write out his report, which, with unimportant sections omitted, runs as follows:[3]

In May, 1732, we received orders from Major Pavlutski, who was at the time at the Anadyr fort, to go aboard the St. Gabriel with the pilot and underpilot and sail around Kamchatka Cape to the mouth of the Anadyr and opposite Anadyrski Cape to what is known as the “large country,” examine and count the islands there, and gather tribute from the inhabitants. On July 23 we left Kamchatka River, and four days later Kamchatka Cape was doubled. We came to Anadyrski Cape August 3 and from there went to the islands to collect tribute. Moshkov told us of an island Bering had discovered, and we sailed about in order to find it. By this maneuvering we reached the southern part of Chukotski Cape, where, on August 5, we anchored three versts from shore. It was calm, and I went on land to examine the coast and fetch drinking water. Close to the shore we observed a small fresh stream into which we pulled. The country seemed uninhabited; but not far from where we stood was a herd of deer, numbering about 150 or more, guarded by two men, who ran away on seeing us. I killed two of the deer, filled two barrels with water, and went on board.

The next day two Chukchi came toward the ship in two baidars but would not approach near enough so that we could enter into conversation with them. When they had looked at us for a time they pulled away. On the morrow I, with nine men, went to the spot from which I had seen the natives issue the day before, but all that we found there were two huts of earth and whalebone. As we started back we caught {p. 23} a glimpse of two men who ran away on seeing us. We got under sail on the 8th, steering for an island on the course suggested by Moshkov. On the following day Fedorov sent me a note saying that in his opinion we had not yet reached the place in question [large country] since we were still south of Chukotski Cape, and asked for my opinion. On the 10th we sailed back to the spot where we had been a few days before and took on fresh water. Two days later we ran into a calm and anchored. On going ashore we saw two huts and people, who, on noticing us, pulled away from the land in three baidaras. We managed to get into conversation with them and asked them for tribute, which they refused to give. Having a fair wind on the 15th we went on our way and on the 17th sighted an island, but on account of the head wind we could not approach it but had to keep close to Chukotski Cape.

Here we saw many Chukchi, with whom we tried to enter into conversation but without much success. When the wind shifted once more to fair we steered again for the northern end of the island [one of the Diomedes]. Our attempt to land was resisted by a shower of arrows, to which we replied with muskets. After a great deal of difficulty the natives told us that they were Chukchi and that some of their people had fought with the other Chukchi against Pavlutski. In cruising about the island, which is about two and a half versts long and a verst wide, we came across other natives, but all refused to pay tribute. We made a landing and examined their homes, and from the island we saw the “large country”. It was near one o’clock of the morning of August 20 when we left the first island, and six hours later we anchored off the second, which is smaller than the first, and about half a mile distant. A ship’s boat and a baidara were sent to the shore, but meeting with an unfriendly reception they returned.

About three o’clock of the afternoon of August 21 at we sailed for the “large country” and anchored about four versts from its shore. It was now Fedorov’s watch, and he, without consulting any one, gave orders to weigh anchor and approach the southern point of the shore. From there we could see huts, but in spite of our best efforts we did not come as close to them as we wished on account of the head wind and the shallow water. The breeze veering to north-northwest, we were obliged to stand out to sea on a southwest course and by doing so came to the fourth island on the 22nd. A strong wind was blowing, and when we tried to approach the shore the sails gave way. The sailors then came to me and asked that we return to Kamchatka because of the lateness of the season and the stormy weather. I referred them to the underpilot without whose consent I could not order such a move. In the meantime there came to us from the island a Chukchi in a leather boat which had room for but one man. He was dressed in a shirt of whale intestines which was fastened about the opening of the boat in such a manner that no water {p. 24} could enter even if a big wave should strike it. He told us that Chukchi lived in the “large country,” where there were forests, streams, and animals. We had no opportunity of going ashore, and from the distance we could not tell whether all that he told us of the “large country” was true or not. When he was gone the sailors spoke to me again about returning to Kamchatka, and I answered them as before. Then they held a council and drew up a petition addressed to me and the underpilot, enumerating many reasons why we should go back. Taking these arguments into consideration we decided to return and entered the mouth of the Kamchatka River September 28.

Outside of the islands enumerated we saw no others, and the reason for not indicating their exact position is that the log book Fedorov and I kept was sent to Okhotsk in 1733. Another reason is that Fedorov when on watch often failed to make any observations in the journal. On returning to Kamchatka I asked his aid in drawing up a map, but he refused to join me; and it was impossible for me to undertake it alone, for the reasons just enumerated.

From his own account it is quite evident that Gvozdev was not aware that he had sighted the American coast. He thought he had discovered an island. He says that after anchoring near the first and second islands he steered for the “large country” [third island] and from there to the “fourth island.” This is all that is known of Gvozdev’s voyage.

|

In the “Lettre d’un officier de la marine russienne,” 1753 (see bibliography), the statement is made that Pavlutski ordered Gvozdev to bring the provisions left by Bering to the country of the Chukchi, whom Pavlutski was fighting. Gvozdev could not find Pavlutski and therefore started back and accidentally ran into the American coast. |

|

Archives of the Ministry of Marine: Papers of Count Chernishev, 1762-1768, No. 367. See also Zapiski Hydrogr. Depart., Vol. 9. pp. 88-103, St. Petersburg, 1851. |

When Bering returned to Russia he made his report to the Empress and to the officers of the Admiralty and the Senate and tried to persuade them that “the instructions of His Imperial Majesty . . . had been carried out.” Some clapped their hands while others shrugged their shoulders. The doubters maintained that as long as the coast and waters between the Kolyma River and East Cape were unexamined the problem of the relation of Asia to America was unsolved. They were not without arguments. They called attention to the numerous Siberian rumors that a large body of land (bolshaya zemlya) existed north of the Kolyma River and another east of East Cape. Were these two or more distinct continents or islands or were they one? Were they part of Asia or part of America? These and such like questions were asked. They were fair questions. Bering was expected to answer them but could not answer them satisfactorily.

He was not altogether discredited; for it was realized that he had done a good piece of work, even if he had not done it as well as he should. That he had ability no one doubted, and it was believed that with his experience and the lesson taught him he would do much better if he were given another chance. Bering, no doubt, desired another chance, and he submitted to the Empress the following propositions[1] which would tend to encourage her to send another expedition.

1. According to my observation the waves of eastern Kamchatka are smaller than in other seas, and I found on Karaginski Island large fir trees that do not grow on Kamchatka. These signs indicate that America, or some other land on this side of it, is not far from Kamchatka—perhaps from 150 to 200 miles. This could easily be ascertained by building a vessel of about 50 tons and sending it to investigate. If this be so [the existence of such a country], a trade might be established between the empire and the inhabitants of those regions.

2. Such a ship should be built in Kamchatka, because the necessary timber could be obtained more easily. The same holds true in the matter of food—fish and game are especially cheap there. Then, again, more help may be had from the natives of Kamchatka than from those of Okhotsk. One other reason should not be overlooked; the mouth of the Kamchatka River is deeper and offers a better shelter for boats.

3. It would not be without advantage to find a sea route from the Kamchatka or Okhota River to the Amur River or Japan, since it is known that these regions are inhabited. It would be very profitable to open trade relations with these people, particularly the Japanese. And as we have no ships there (in the Okhotsk Sea), we might arrange it with the Japanese that they meet us halfway in their boats. For such an expedition a ship about the size of the one mentioned would be needed, or one somewhat smaller might serve the purpose.

4. The cost of such an expedition—not including salaries, provisions, and materials for both boats, which can not be had there and would have to be taken from here and Siberia—would be from 10,000 to 12,000 rubles.

5. If it should be considered wise to map the northern regions of the coast of Siberia—from the Ob to the Yenisei and from there to the Lena—this could be done by boats or by land, since these regions are under Russian jurisdiction.

The question of a second voyage must have been raised even in 1730, for early in 1731 arrangements for the undertaking were already made. The desire to determine the relation of Asia and America was not the only argument advanced in favor of the expedition. Some of the reports on that subject submitted to the Empress pointed out the benefits to be derived from territorial and commercial expansion, additional naval bases, and the discovery of precious metals. No doubt all these reasons had their weight with those in authority.[2]

|

According to Lauridsen’s “Vitus Bering,” Chicago, 1889 (note 40, p. 208), first published in V. Berkh: Zhizneopisaniya Pervykh Rossiiskikh Admiralov, 4 vols., St. Petersburg, 1831-36; later reprinted by Sokolov in Zapiski Hydrogr. Depart., Vol. 9, pp. 435-436, St. Petersburg, 1851.—Edit. Note. |

|

Archives of State, XXIV, No. 8, 1732; No. 9, 1732-1743. |

Another question that came up was how this expedition should be sent—by land or by water. There seems to have been a difference of opinion on that subject. Count Nikolai Golovin[3] and Admiral Sanders submitted separate memoirs to Her Majesty recommending that two ships with naval and other supplies be chartered to go from Russia to Kamchatka by way of Cape Horn and Japan. After discharging their cargoes and resting the crews the ships could proceed on their voyage of discovery in the North Pacific. Count Golovin even offered to lead the expedition in person if the proper support were assured him.

A number of reasons were given why the sea route was preferable to the overland route. In the first place there would be a saving of time. It would take from ten months to a year for the sea voyage from St. Petersburg to Kamchatka and a year or a little more for the work of exploration and the return to Russia; on the other hand it would require two years to transport naval and other stores overland to Kamchatka, two more years to build sea-going vessels, and two more years to make the voyage and bring back the results to St. Petersburg.

Why the propositions of these two prominent men were not accepted is not clear. Perhaps because by 1731 and 1732 the expedition had ceased to be regarded in the light of purely maritime and geographic discovery and had come to be looked upon as one of scientific investigation in the larger sense, both by land and sea, in the Arctic Ocean as well as the Pacific. It had been decided to send along scientists of the newly founded Imperial Academy of Sciences to make a study of the people and the resources and to secure other scientific data about Siberia and the lands to be discovered. Then, too, in order to settle beyond dispute the much-debated question of the relation of Asia to America, it had been determined to survey and chart the Arctic coast from the White Sea to the mouth of the Kamchatka River. It was assumed as a matter of course that the leader of the expedition {p. 28} could supervise its various activities, and therefore it would be necessary for him to be within land reach of the different parties. These may or may not have been the reasons, but the fact remains that Bering and his parties were ordered to proceed overland.

|

Archives of State, XXIV, No. 8, 1732. |

Because of the great distance to the Pacific, the difficulty of transporting material, and the lack of laborers, skilled and unskilled, for the building of sea-going vessels, the naval part of the expedition needed most attention. On July 30, 1731,[4] Grigori Pisarev (who had been appointed commander of the port of Okhotsk on May 10, 1731)[5] was ordered to proceed to his post and make ready for Bering’s coming. Pisarev was told to take, from different regions of Siberia, Russians and Tungus and settle them in the neighborhood of Okhotsk and Yudoma Cross—the Russians to be put to cultivating the soil and the Tungus to watch the flocks of sheep and the herds of horses and cattle which Pisarev would introduce. For the peopling of Okhotsk Pisarev had instructions to pick up at Yakutsk 300 young and strong men from those who were in prison for debt or for other crimes. In addition he was to take from Russia 20 ship carpenters to build four or six ships, under the supervision of naval architects who were to be sent by the Admiralty College, and from Ekaterinburg a number of iron workers to smelt iron and forge anchors and such things.

|

Polnoe Sobranie Zakonov Rossiiskoi Imperii, Vol. 8, Doc. 5813. St. Petersburg. |

|

Ibid., Vol. 8, Doc. 5753. |

The official order for the expedition, in which Bering is mentioned as commander, was announced by the Senate on April 17, 1732,[6] and this was followed up on May 2 of the same year by a general outline of the undertaking.[7] On December 28, 1732, the {p. 29} Senate issued the principal instructions,[8] and a summary of the main articles that relate directly to the voyage to America is here given.

1. The Senate approves of the expedition in the hope that it will really be for the benefit and glory of Russia. It has given orders to the governor of Siberia, to the vice governor at Irkutsk, and to Pisarev to assist Bering. It is sending members from the Academy of Sciences,[9] students from Moscow,[10] assayers from Ekaterinburg, mechanics, and others. It confirms the project to examine not only the waters between Kamchatka and Japan, Kamchatka and America, but also the waters along the Arctic coast.

2. In the instructions which Peter gave to Bering it was evident that Peter desired to determine whether Asia and America were united. Bering says that he went as far as 67° N. and found no connection between these two continents. It may be that north and west of the mouth of the Kolyma the two continents do not join, but no one knows whether this is so or not. In order to settle the relation between Asia and America the Admiralty proposes to send exploring expeditions along the Arctic shores from Archangel to the mouth of the Kamchatka River.

4. It has been reported that opposite the mouth of the Kolyma River there is a large land (bolshaya zemlya), that Siberians have been on it, and have seen the inhabitants. It is ordered that Bering should investigate this matter very thoroughly when he is at Yakutsk. If this is a true report, he should send a sloop to investigate. If it is found that Siberia really joins America so that it is impossible to proceed to Kamchatka, then the investigating party should follow the newly found coast as far as it can to learn in which direction it runs and return to Yakutsk.

If people are found there, they are to be treated kindly; they are to be given presents; they are to be asked the extent of their country and its resources, and they are to be invited to become our subjects and to pay tribute. If they are unwilling to do so, they are to be let alone; and no time should be wasted in arguing with them.

It is not at all likely, but it is possible, that by following the Arctic coast our explorers may come to some European settlement. In that case they should act according to the instructions given to Bering and Chirikov. If the explorers ascertain that Siberia and America are not connected, they should proceed to Kamchatka.

5. In regard to going to America, it was ordered in 1731 that ships for this voyage should be built at Okhotsk. If they are ready, Bering should take two of them and proceed; if they are not finished, he should finish them. If they have not yet been started on, or if they are not seaworthy, the Admiralty College is of the opinion that the ships should not be built at Okhotsk. Bering recommends that Kamchatka, because it has more timber and a better harbor, should be selected as the place for shipbuilding. Bering desires to have two ships for the voyage so that in case of a misfortune to one of them the other would stand by. If one ship is completed at Okhotsk, it would be a good plan to take that and go to the Kamchatka River and there build the other one. Bering is to be in command of one of these vessels and Chirikov of the other. On the voyage they are to keep together, work together, and do all that is in their power to advance naval science. To help them a member of the Academy of Sciences [Louis Delisle de la Croyère] is sent along.

6. A late report of Captain Pavlutski, which was sent from Kamchatka, stated that recently Afanasi Melnikov with a small party returned from Chukchi Cape. This Melnikov was sent from Yakutsk in 1725 to bring the natives [Chukchi] under subjection and make them pay tribute. Melnikov says that in April, 1730, while he was on Chukchi Cape, there came over from an island in the sea two men who had walrus teeth fastened to their own [pieces of walrus ivory in their lips]. These men told Melnikov that it takes a day to go from Chukchi Cape to their island, and another day from there to another island ahead of them, which island is called bolshaya zemlya. On this bolshaya zemlya all kinds of animals are to be had—sables, beavers, land otters, and wild deer. All kinds of green trees grow there. There are many natives on bolshaya zemlya; some of them have deer, and others have not. Although such reports cannot be trusted, yet they should be followed up and a voyage should be made in the direction of the islands. If they are located and people found on them, they should be treated as the instructions in Article 4 indicate. Go on [from there] to America and learn whether there is any continent, or islands, between Kamchatka and America; for, aside from the information furnished by Pavlutski, little is known on that subject. On the map of Professor Delisle a sea is located between Kamchatka and the Spanish province of Mexico in latitude 45° N. If the American coast is discovered, Bering should carry out the instructions given him by Peter in 1725, that is to say, to go to some European settlement. If a European ship is met with, he should learn from it the name of the coast, write it down, make a landing, obtain some definite information, draw a map, and return to Kamchatka. Be always on your guard not to fall into a trap and not to show the people you meet with the way to [Kamchatka].

• • • • •

9. Bering is to take with him 2,000 rubles’ worth of presents to be distributed among the natives. Chinese tobacco, known as “shar log,” is especially worth while because the natives are eager for it.

• • • • •

11. In these voyages search should be made for good harbors and for forests where timber for shipbuilding is to be had. Let mineralogists with a guard go ashore and prospect. If precious minerals are found in some place under Russian jurisdiction, the commander of Okhotsk and the principal officers elsewhere should be notified, and they shall send ships, miners, workmen, instruments, machinery, and provisions and begin working the mines.

12. Geodesists should be sent to examine all the rivers that fall into Lake Baikal from the east in order to find a nearer way to Kamchatka than by Yakutsk.

13. Captain Bering and all the officers in command of ships at sea should keep secret the instructions from the Admiralty College. For Bering, Chirikov, Spanberg, and the officers in command of the sloop which is to go east of the Lena to Kamchatka, special instructions are issued, and these may be made public. These public instructions are to state that at the request of the St. Petersburg, Paris, and other Academies the Emperor Peter the Great, of deserving and eternal fame, sent, out of curiosity, an expedition along his own shores to determine whether Asia and America are united. But the expedition did not settle that point. Now Your Imperial Majesty, influenced by the same reasons, is ordering a similar expedition and for a similar purpose. If you should come to settlements under European or Asiatic jurisdiction or if you should meet with ships of European or Asiatic governments, and are asked the object of your voyage, you may tell them what has just been said. If they demand to see your instructions, show them. This will allay their suspicions, because it is well known that European Powers have sent out expeditions and that the question whether Asia and America are united is still unanswered.

14. In order that the expedition may not be retarded on account of delay in getting provisions and supplies of one kind and another, the Admiralty College should send at once special officers to Yakutsk to build boats and expedite the transportation of materials.