* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: The Chiefs of Colquhoun and their Country Vol. I

Date of first publication: 1868

Author: William Fraser (1816-1898)

Date first posted: Mar. 4, 2021

Date last updated: Mar. 4, 2021

Faded Page eBook #20210311

This eBook was produced by: Barbara Watson, David T. Jones, John Routh & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

Among the baronial families of Scotland, the chiefs of the Clan Colquhoun occupy a prominent place from their ancient lineage, their matrimonial alliances, historical associations, and the extent of their territories in the Western Highlands. These territories now include a great portion of the county of Dumbarton.

Upwards of seven centuries have elapsed since Maldouen of Luss obtained from Alwyn Earl of Lennox a grant of the lands of Luss; and it is upwards of six hundred years since another Earl of Lennox granted the lands of Colquhoun to Humphrey of Kilpatrick, who afterwards assumed the name of Colquhoun.

The lands and barony of Luss have never been alienated since the early grant of Alwyn Earl of Lennox. For six generations these lands were inherited by the family of Luss in the male line; and in the seventh they became the inheritance of the daughter of Godfrey of Luss, commonly designated “The Fair Maid of Luss,” and, as the heiress of these lands, she vested them by her marriage, about the year 1385, in her husband, Sir Robert Colquhoun of Colquhoun. The descendant from that marriage, and the representative of the families of Colquhoun and Luss, is the present baronet, Sir James Colquhoun.

The lands and barony of Colquhoun also descended in the male line of the family of Colquhoun for nearly five centuries; and although the greater part of them has been sold, portions still belong to the present representative of the family. No other family in Dumbartonshire has possessed lands in that county so long as that of Colquhoun.

Considering the vicissitudes which have attended other baronial families, their early neighbours in the Lennox, the long continuance of the Colquhouns in their territories is not a little remarkable. The great Earls of Lennox, from whom the Colquhouns originally derived their chief baronies, came to an early and ignominious end—forfeiting at the same time their lands and their lives. The Stuart Earls of Lennox were scarcely less unfortunate than the original race. Mathew, the second Stuart Earl, who was the brother-in-law of Sir John Colquhoun, fell at Flodden. His son and successor was treacherously killed by Sir James Hamilton of Finnart, at the battle fought near Linlithgow in 1526. This Earl deserved a better fate; for, according to the eulogium of the Chief of the Hamiltons, he was the wisest man, the stoutest man, and the hardiest man ever born in Scotland. His son, the Regent Lennox, also fell in an insurrection against his own authority as Regent; while the tragic fate of the Regent’s son, the unhappy Darnley, who also bore, as Regent, the title of Earl of Lennox, is well known. The very name of Lennox seems then to have been ominous of evil to its possessors. The title descended to King James the Sixth, but whether from his natural timidity or from his State policy, he resigned it successively to his nearest collateral kinsmen of the Stuart race. But misfortune still followed this title in the cruel fate of the Lady Arabella Stuart, who was the only daughter of Charles Earl of Lennox, the younger brother of Darnley. Subsequent holders of the title seldom enjoyed it long or successfully, and the great Lennox estates were ultimately sold to strangers.

The Colquhouns, besides their proximity to the ancient Earls of Lennox, who were their early neighbours and contemporaries, were surrounded by several clans, the principal of whom were the Buchanans of that Ilk, the Macfarlanes of Arrochar, and the Macaulays of Ardincaple.

For many centuries these three clans held territories bounding with those of the Colquhouns, and during that period those family feuds, then common to all clans, were of frequent occurrence in the Western Highlands. In the seventeenth century the Buchanans ceased to hold their ancient inheritance on Lochlomond, and in it they were succeeded by the “gallant Grahams,” who proved good neighbours and friends to the Colquhouns. As the Buchanans lost their hereditary domain of Buchanan, so the Macfarlanes and Macaulays also ceased to be the owners of Arrochar and Ardincaple: and these baronies were acquired by the Colquhouns, who added them to their ancient barony of Luss. Thus, of all the principal clans connected with the county of Dumbarton, the Colquhouns alone have been able not only to retain their own, but to acquire the territories of their ancient rivals, who, it is to be regretted, derived no benefit from the liberal and even extravagant considerations paid by the Colquhouns, owing to intermediate parties having purchased those territories at comparatively small prices. The late Mr. Ferguson of Raith, on the re-sale of the barony of Arrochar to the late Sir James Colquhoun, realized a profit of about fifty thousand pounds, or nearly double the price which his father had paid to the Macfarlanes. This large profit, had it been realized by the Macfarlanes, would have rendered them comparatively wealthy.

Although the three clans now mentioned—the Buchanans, the Macfarlanes, and the Macaulays—were all involved in those clan feuds, which were so little calculated for the advancement of civilisation, each of them has the honour to boast of distinguished names. The Buchanans at an early period gave to learning an unrivalled scholar. The Macfarlanes had chiefs renowned for great bravery, and one of them, in the last century, was the most accomplished antiquary of his age. The Macaulays, in still later times, could boast of their noble orator and historian.

Another clan, the Macgregors, although unconnected by territory with the Colquhouns, frequently came into hostile collision with them. After many minor engagements, the feuds between the Colquhouns and the Macgregors culminated in the sanguinary battle of Glenfruin, in which the latter were victorious, although their triumph was dearly bought, their very name being from that time proscribed. From the materials in the Colquhoun Charter-chest, we have been able to give a very complete account of that engagement.

Besides the long-continued possession of their extensive territories, several of the chiefs of the Colquhouns held high offices of State,—such as those of Comptroller of the Exchequer, Great Chamberlain of Scotland, Sheriff-Principal and hereditary Coroner of the county of Dumbarton, and also Governor of the Castle of Dumbarton.

The First Volume contains the personal history of the chiefs of Colquhoun and Luss, from Maldouen of Luss in the year 1150, to his descendant and representative, Sir James Colquhoun, the present Baronet of Colquhoun and Luss. As the history of the family extends over so many centuries, it is often connected with events of a highly stirring character in the history of our country, which are not unfrequently noticed in the Memoirs; and in some instances it will be found that new light is thrown upon those events. Full details are given of the state of the Western Highlands at different periods, particularly of the practical operation of the system of clanship, and of the feuds to which it constantly gave rise. From the great extent of territory which the Colquhouns possessed in Dumbartonshire, and from the part which, from their position in that territory as constituting the debatable land between the Highlands and the Lowlands in the west, they were often called to act in their native county, their history is to a great extent the history of Dumbartonshire, and the history of Dumbartonshire forms an important part of the history of Scotland.

After having given, in the First Volume, a detailed account of the successive chiefs of the Clan Colquhoun, it seemed desirable to describe the territories, interesting in themselves, with which the Colquhouns for so many centuries have been associated. This description has been attempted in the Second Volume. This territorial survey comprehends a large proportion of the county of Dumbarton. The lands and barony of Colquhoun, embracing the estates of Auchentorlie, Dumbuck, Barnhill, and Overtown of Colquhoun, and the Castle of Dunglas on the Clyde, formerly the chief mansion of the Barony of Colquhoun, are first noticed, as having formed the original possessions of the Colquhouns. Then follow accounts of the Barony of Luss, the Castle of Rossdhu, the Churches and Chapels of Luss, and the Sanctuary round the Church of Luss, the Castle of Bannachra, and the Barony of Arrochar, with its mountains, lochs, rivulets, and castles; likewise the ancient Castle and Chapel of Faslane, and other territories, all now forming the Colquhoun Country.

Lochlomond and its Islands, so far as these are connected with the Baronies of Luss and Arrochar, are also fully described. The Correspondence of Lord Jeffrey in reference to Lochlomond, where for many years he passed his summer holidays, is now printed for the first time, and will be found interesting, like all the correspondence of that distinguished man.

As an instance of the imperfect histories of the county of Dumbarton, including even that of the accurate and well-informed author of Caledonia, it may be noticed that the grant by King Robert the Bruce, to his faithful adherent, the Earl of Lennox, of the right of Gyrth or Sanctuary for three miles around the Church of Luss, has never been mentioned in any county, family, parish, or other history. This interesting document in the history of Luss and the Lennox certainly deserves particular notice, and it is now, for the first time, brought to light, printed and lithographed from the original, preserved among the Lennox muniments at Buchanan Castle.

Many of the places described are associated with important historical events. The ancient Castle of Faslane recalls the memory of Sir William Wallace, who, when a visitor there on one of his hazardous exploits, met with a cordial reception from his compatriot, Malcolm fifth Earl of Lennox. The woods of Colquhoun and the mountains of Arrochar are intermingled with deeply interesting scenes in the history of Robert the Bruce. The Castle of Bannachra is memorable for the tragic death of Sir Humphrey Colquhoun of Luss, in a conflict with the Macfarlanes.

The Second Volume includes Memoirs of some of the Branches or Cadets of the Colquhouns of Luss—the Colquhouns of Tillyquhoun, and the Colquhouns of Camstradden, with Pedigrees of other Colquhoun families, including those of Glennis and Kenmure, Garscadden and Killermont, Kilmardinny and Barnhill.

The Second Volume further includes a large selection of the Colquhoun and Luss Charters, of which an Abstract is given, to facilitate reference. The feudal muniments of the family have been carefully preserved, while their epistolary correspondence has been nearly as carefully destroyed. Only a very few letters now exist. The interesting letter from Lady Helen Colquhoun on measures connected with the Rebellion of 1745 was accidentally discovered in another repository, after the memoir of herself and her husband had been printed off. The letter has been carefully lithographed for this work.

The materials for these volumes have been derived mainly from the family muniments at Rossdhu. The information thus acquired is of undoubted authenticity, and becomes especially valuable when it delineates and records transactions of remote times. But while these family muniments are the principal authority for the Memoirs, other sources have been drawn on for the history of the Clan Colquhoun. In particular, this work is indebted to His Grace the Duke of Montrose, who has on this, and on so many other occasions, made accessible, in the most liberal and unrestricted manner, his invaluable family muniments. From the frequent references to these, it will be seen how much these Memoirs are indebted to his liberality.

Other proprietors in the Lennox have also afforded the use of their muniments. Sir Robert Gilmour Colquhoun, K.C.B., now of Fincastle, the representative of the family of Camstradden, whose branch forms a prominent section of the Second Volume, kindly communicated the ancient muniments of Camstradden.

To him who is most interested in this work, the Chief and representative of the ancient race which it records, these Volumes are indebted for much important information, which could only be supplied from his accurate knowledge of the history of his Clan and their Country.

WILLIAM FRASER.

32 Castle Street, Edinburgh,

December 1869.

| CONTENTS OF VOLUME FIRST. | |

| PAGE | |

| TITLE-PAGE | i |

| PRESENTATION PAGE | iii |

| PREFACE | v |

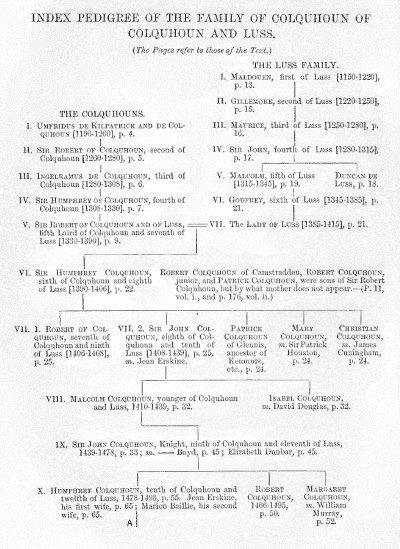

| INDEX PEDIGREE OF THE FAMILY OF COLQUHOUN | xxiv |

| ILLUSTRATIONS IN VOLUME I. | xxviii |

| HISTORY OF THE FAMILY OF COLQUHOUN OF COLQUHOUN AND LUSS | 1-416 |

| ORIGIN OF THE FAMILY OF COLQUHOUN. | |

| Traced back to 13th century—Assigned by fabulous accounts to the 9th century—Originally named Kilpatrick—St. Patrick, the Apostle of Ireland, connected with parish of Kilpatrick—Kirkpatricks of Closeburn—Family and Lands of Kirkpatrick | 1-4 |

| I.—UMFRIDUS DE KILPATRICK, First of Colquhoun [1190-1260]. | |

| Obtained Charter of Lands of Colquhoun, cir. 1246—Translation of Charter—Name changed to Colquhoun, | 4-5 |

| II.—SIR ROBERT OF COLQUHOUN [1260-1280]. | |

| Probably the son of Umfridus—Acted in an Inquest as to the heirs of Dufgullus, brother of Maldouen Earl of Lennox, | 5-6 |

| III.—INGELRAMUS OF COLQUHOUN [1280-1308]. | |

| Witnessed a Charter by Malcolm fifth Earl of Lennox—Received a Charter from King Robert Bruce of the Lands of Salakhill (Sauchie), | 6-7 |

| IV.—SIR HUMPHREY OF COLQUHOUN [1308-1330]. | |

| Received from King Robert Bruce a Charter of the Barony of Luss in 1309—Robert Wishart, Bishop of Glasgow, absolved Bruce for the slaughter of Comyn—Was rewarded by a grant of Lands—Sir Humphrey at the Battle of Bannockburn—Obtained a Charter of Sauchy, | 7-9 |

| V.—SIR ROBERT OF COLQUHOUN AND OF LUSS [1330-1390]. | |

| Probably the son of Sir Humphrey—Married the Heiress of Luss, | 9-12 |

| FAMILY OF LUSS OF LUSS. | |

| Their high antiquity, but origin obscure—Their descent derived by tradition from the Earls of Lennox—Can be traced back to 1150, | 12-13 |

| I.—MALDOUEN, First of Luss [1150-1220]. | |

| Dean of Levenax—Received from Alwyn Earl of Lennox a Charter of the Lands of Luss—Boundaries of said Lands described—Maldouen not the son of Earl Alwyn, | 13-15 |

| II.—GILLEMORE, Second of Luss [1220-1250]. | |

| Son of Maldouen—Obtained two Charters of Luss between 1225 and 1270, | 15 |

| III.—MAURICE, Third of Luss [1250-1280]. | |

| Witnessed several Charters by Maldouen Earl of Lennox and others—Granted to the Church of Glasgow the right of cutting timber from the woods of Luss for the Steeple of the Cathedral—His two sons, | 16-17 |

| IV.—SIR JOHN, Fourth of Luss [1280-1315]. | |

| High in favour with Malcolm fifth Earl of Lennox—Privileges granted by the latter to Sir John—His two sons, | 17-19 |

| V.—MALCOLM, Fifth of Luss [1315-1345]. | |

| Received Charter of Confirmation of the Lands of Luss—Translation of said Charter—Received Charter of part of the Lands of Glyne—and royal grant of part of the teinds of Luss—Witnessed several Charters between 1333-1364, | 19-20 |

| VI.—GODFREY, Sixth of Luss [1345-1385]. | |

| Was Witness to a Charter by Duncan Earl of Lennox—The latter executed at Stirling in 1425—Godfrey’s only daughter, the “Fair Maid of Luss,” | 21 |

| VII.—THE FAIR MAID OF LUSS [1385-1415]. | |

| Married Sir Robert of Colquhoun—Their family took the name of Colquhoun, | 21 |

| VI.—SIR HUMPHREY COLQUHOUN, Sixth of Colquhoun and Eighth of Luss [1390-1406]. | |

| Witnessed several Charters of Duncan Earl of Lennox—Granted to his brother Robert the Lands of Camstradden—Impression of his Seal, and ancient description thereof—His children, | 22-24 |

| VII. (1.)—ROBERT DE COLQUHOUN, Seventh of Colquhoun and Ninth of Luss [1406-1408]. | |

| Obtained, in 1407, from William Wallas, Lord of Cragy, a Confirmation of all the Lands held of the Granter—Terms of the Confirmation—Died circa 1408, | 25 |

| VII. (2.)—SIR JOHN COLQUHOUN, Eighth of Colquhoun and Tenth of Luss [1408-1439], married Jean Erskine. | |

| Bound himself by Letters-Patent to marry Margaret, daughter to Duncan seventh Earl of Lennox, widow of Robert Menteith of Rusky, on certain conditions—Translation of Requisition by the Earl to Sir John to implement that obligation—Sir John Colquhoun appointed by King James I. Governor of Dumbarton Castle—Patron of Luss—Member of Parliament—Character of King James I.—His Death—Disturbances during the Regency—Vigorous and patriotic conduct of Sir John Colquhoun—His tragical Death—Appointment of Justice Aires or Circuit Courts, | 25-32 |

| VIII.—MALCOLM COLQUHOUN, Younger of Colquhoun and Luss [1410-1439]. | |

| A youth of high promise—Died young, during his father’s lifetime—Left a son, John, who succeeded his grandfather in Colquhoun and Luss, | 32 |

| IX.—SIR JOHN COLQUHOUN, Knight, Ninth of Colquhoun and Eleventh of Luss [1439-1478], married, first, —— Boyd; second, Elizabeth Dunbar, Countess of Murray. | |

| An eminent Statesman, and a royal favourite—Knighted for his public services—Obtained Charters of the Barony of Luss, the Free Forest of Rossdhu, lands of Saline, Kilmerdony, Nisbet, Tulyechil, Roseneath, Strone, tenements in the Canongate, etc. etc.—Death of King James II.—Sir John, Comptroller of the Exchequer under the Queen Regent—A Member of Parliament—A Commissioner for concluding the marriage of King James III. and the Princess Margaret of Denmark—Appointed Principal Sheriff of Dumbarton—Great Chamberlain of Scotland—Commissioner Plenipotentiary for the Marriage of Prince James of Scotland with the Princess Cecilia of England—Sir John appointed Governor of Dumbarton Castle—Killed at Siege of Dunbar Castle, | 33-54 |

| X.—HUMPHREY COLQUHOUN, Tenth of Colquhoun and Twelfth of Luss [1478-1493], married, first, Jean Erskine; second, Marion Baillie, Dowager Lady Somerville. | |

| His Infeftment in tenements in Canongate, and in the lands of Bordland of Saline—Imprisonment and Death of John Earl of Mar—Humphrey obtained from King James III. the third of the ward lands of Granton and Stanehouse, and remission of the relief duties of his lands, on account of his father having fallen at the Siege of Dunbar Castle—Litigation respecting the lands of Galmore, etc.—Lawsuits between Humphrey and Lady Elizabeth Dunbar, his stepmother, and Buchanan of that Ilk and others—Battle of Sauchie—Death of King James III.—Death of Humphrey in 1493, | 55-70 |

| XI.—SIR JOHN COLQUHOUN, Knight, Eleventh of Colquhoun and Thirteenth of Luss [1493-1536], married, first, Lady Elizabeth Stewart of Lennox; and second, Margaret Cunningham of Craigends. | |

| His Infeftment in his father’s lands—Litigation respecting the lands of Bordland—His Marriage with Lady Elizabeth Stewart—Obtained with her the lands of Auchingache, Larg of Glenfruin, Auchenvennel, Stuckiedow, and Blairhangane, in liferent—Lands of Garscube—Ballernick-mor—Corsragul, Chapeltoun and Schelis—Letterwald-mor and Stuckinduff—Ardinconnel, Finnard, Portincaple, Forlinebrek—Sir John a Lord of Privy Council—Acquired the lands of Tullichintaull, Forlingearoche and Blairwardane—Infefted in an annual-rent from Restalrig, on precept by “Hector Boece”—Lands of Strone, Mamore and Mambeg, Easter Kilbride, Little Drumfad, Rachane and Altermony—Death of James IV. at Flodden—Attempted usurpation of the Regency by John Duke of Albany—Surrender of Dumbarton Castle—King James V. grants a pardon to Sir John Colquhoun for seizing the said Castle—John Earl of Lennox slain near Linlithgow—Humanity of the Earl of Angus—Sir John acquired the lands of Finnard, Portincaple, Forlingbrek, and Little Drumfad—Obtained from the King a gift of the bygone rents of the Bordland of Saline—Acquired the half lands of Borland—Was a Member of Parliament and Privy Councillor—His character—Acquired the lands of Letterpeyne, Peywinauthir, Cloudnocht, and Auchinadde—His death in 1536, | 71-102 |

| XII.—HUMPHREY COLQUHOUN, Twelfth of Colquhoun and Fourteenth of Luss [1536-1537], married Lady Catherine Graham (Montrose). | |

| His infeftment in the lands of Salachy and Kirkmichael-Buchanan, Letterpeyne, Peywinauthir, Cloudnocht, and Auchinadde, Saline—His death in 1537, | 103-108 |

| XIII.—SIR JOHN COLQUHOUN, Knight, Thirteenth of Colquhoun and Fifteenth of Luss [1538-1574], married, first, Christian Erskine; and second, Agnes Boyd. | |

| Feuds between the Macgregors and the Colquhouns—His infeftment in the lands of Ballernick-mor, Kilmardinny, Barony of Luss, etc.—Colquhouns of Barnhill—Feud between the Macfarlanes and the Colquhouns—Sir John infefted in the lands of Stukintebert, Glenloyng, Tullichintaull—Patronage of office of Clerk of the parish of Luss—Sir John’s right of entertainment in a tenement in the Canongate—Purchased the lands of Finnard, Portincaple, and Forlinbrek; lands of Porterfield, Ardmernock, Strone, Garscadden—Acquired from Kilmardinny his right to lands of Durling, Stroneratan, Stukinduff, Blairvaddoch, and others—Assault on Hamilton of Cochno—Death of Christian Erskine—Her Testament—Dispensation for Sir John’s marriage with Agnes Boyd—He acquired the lands of Glen, Kirkmichael-Buchanan, and was infefted in Wester Kilbride—Marriage of Queen Mary to Henry Lord Darnley—Death of Henry Lord Darnley—The lieges of Dumbarton summoned by Sir John to muster at Hill of Ardmore—“The Casket Letters”—Marriage of Queen Mary with Bothwell—Her resignation of the Crown to her son, King James VI.—The Earl of Murray made Regent—Rendezvous of the Regent’s army at Maxwellheuch, near Kelso—Sir John fined for non-attendance thereat—Obtained a remission—Fought for the Regent at Langside—Colquhoun of Balvie, of the Queen’s party, made prisoner there—Sir John infefted Agnes Boyd, his wife, in liferent, in Easter and Middle Kilbryde and others—Barony Court of Luss at Port of Rossdhu—Alexander Master of Mar appointed guardian of the person of King James VI.—Sir John Colquhoun one of his cautioners—The Bond of Caution—Bond between Sir John and the minister of Luss relative to the manse of the latter in Glasgow—His death in 1574-5—His character and times—Death of Agnes Boyd, his second wife, in 1584—Account of her testament dative—Their five children, | 109-139 |

| XIV. (1.)—SIR HUMPHREY COLQUHOUN, Knight, Fourteenth of Colquhoun and Sixteenth of Luss [1574-1592], married, first, Lady Jean Cunningham (Glencairn); and second, Dame Jean Hamilton. | |

| Succeeded his father when ten years old—Robert fourth Lord Boyd obtained from the Crown a gift of the non-entries of the Barony of Luss, and of the marriage of the heir—Humphrey served heir to his father in his lands of Ballernick-mor, etc.—Example of the transfer of Roman Catholic revenues to the support of the Reformed Clergy—Humphrey acquired the heritable office of Coroner of the shire of Dumbarton—Humphrey infefted as heir of his father in the Barony of Luss, etc.—Purchased from Smollett of Kirktown the non-entries of the lands of Finnart, Portincaple, etc.—Death of Lady Jean Cunningham—Sir Humphrey married, secondly, Jean Hamilton, daughter of Lord John Hamilton, afterwards Marquis of Hamilton—Terms of their Marriage-Contract—Letters of Protection by the Duke of Lennox to Sir Humphrey when about to visit the Continent—Served heir to his father in his lands in Fife—Put to the horn for non-payment of his taxation, and for being implicated in the slaughter of William Brisbane of Barnishill—Gift of his escheat to Robert Chirnside of Over Possill—Sir Humphrey infefted his wife in liferent in the Bordlands of Saline—Disordered state of the Highlands—Feud between the Colquhouns and the Macfarlanes—Bond of Manrent between Sir Humphrey and Earl of Huntlie—Feud between George Earl of Huntlie and James third Earl of Murray—Assassination of the latter by the former at Donibristle—Feud between the Colquhouns and the Macgregors—The Macfarlanes and Macgregors besiege the Castle of Bannachra—Sir Humphrey slain—Murder of Robert Colquhoun of Tillichintaull at the battle of Bannachra—Contract between Alexander Colquhoun of Luss and Malcolm Macfarlane—The “Traitor Colquhouns”—Ward and non-entry of Sir Humphrey’s lands granted to the Commendator of Blantyre, | 140-166 |

| XIV. (2.)—ALEXANDER COLQUHOUN, Fifteenth of Colquhoun and Seventeenth of Luss [1592-1617], married Helen Buchanan (of Buchanan). | |

| Served heir to his brother in the Barony of Luss, etc.—Purchased the ward and non-entry of the Lordship of Luss from the Commendator of Blantyre—Retonred heir to Jean Colquhoun, his niece—Appointed by the King tutor to Margaret and Agnes Colquhoun, his nieces—Feud between the Colquhouns and the Galbraiths—Commission of Justiciary granted to Galbraith of Culcreuch for pursuing the Clan Gregor—Complaint made by Alexander Colquhoun and Macaulay of Ardincaple to the Privy Council anent the said Commission—Obligation by Alexander Colquhoun not to reset Buchanans, Macgregors, or Macfarlanes—The Macfarlanes become bound to answer to the Duke of Lennox for their depredations committed on the lands of Luss—Alexander Colquhoun obtained Letters of Inhibition against them—Alexander summoned to appear before the King at Holyrood with reference to the removal of “Feuds”—Bond by John Earl of Mar for the peaceable behaviour of the Macfarlanes towards him and his tenants—Counter bond granted by him to the Macfarlanes—Duke of Lennox appointed Commissioner of Justiciary, for punishing theft in the Highlands—The Lairds of Luss, Buchanan, and others, ordained to find caution to him, for themselves and their servants—Macfarlanes ordained to find caution—Lawsuit between Ludovick Duke of Lennox and Alexander Colquhoun of Luss and his nieces—Presentation to the parsonage and vicarage of Luss—Goods wrongously taken by the Macfarlanes—Colquhoun obtain decreet against Macfarlanes of Arrochar—Bond of Reconciliation between Alexander Colquhoun and Malcolm Macfarlane, heir of Gartanartane, etc.—Depredations of the Clan Macgregor—Origin of the animosity between them and the Colquhouns—Earl of Argyll became bound for the good behaviour of the Macgregors—Laird of Luss and his tenants authorized by the King to wear offensive weapons—Luss’s complaint of the conduct of Argyll in permitting the Clan Gregor to commit outrages upon him—Raid between the Macgregors and the Colquhouns at Glenfinlas—Alexander Colquhoun appeared to complain before the King at Stirling—Obtained from the King a Commission of Lieutenancy for repressing such crimes—The Macgregors roused by this circumstance—Order by the Town Council of Dumbarton to the burgesses to provide themselves with armour—Alaster Macgregor of Glenstra, and the Clans Gregor, Cameron, and Anverich, advance into the territory of Luss—The Laird of Luss prepares to repel them—Battle of Glenfruin (the Glen of Sorrow)—Resentment of the Government against the Clan Gregor—Proceedings against Macaulay of Ardincaple for abetting the Macgregors—Diet against him deserted through the influence of Lennox—Act of the Privy Council for abolishing the name of Macgregor—Execution at Edinburgh of many who had taken part in the battle of Glenfruin—Government proceeds against the Campbells for resetting the Macgregors after Glenfruin—Alexander Colquhoun apprehends three of the Clan Gregor—Apprehension, trial, and execution of Allaster Macgregor of Glenstra and his four accomplices—John Colquhoun, fiar of Camstradden, captures two Macgregors, and delivers them to the Privy Council—Argyll commissioned to grant respites and remissions to such of the Macgregors as renounced their surnames, and adopted others—Argyll rewarded for his services by a grant of Kintyre—Macfarlanes accused of having been art and part in the slaughters at Glenfruin—Complaint of Alexander Colquhoun to the King against the Macgregors—Stringent measures adopted by the Government in consequence—The Macgregors fortify the island of Loch Katrine—Alexander Colquhoun and others engage to the Privy Council to fight the Clan Gregor at their own charges for a month—“Overtour for transplanting the bairnis of Clangregour”—Disputed presentation to the Kirk of Luss—Contests between the patron and the incumbent—Litigation between Alexander Colquhoun and the Inhabitants of Dumbarton—Colin Campbell of Lundy and James Campbell of Lawers present a petition to the Lords of Secret Council to stop execution of a charge of horning raised by Alexander Colquhoun against some of the Clan Gregor—The Laird of Luss requested to be present at the meeting of the Council—Regulations of the Privy Council relative to the upbringing of the children of the Clan Gregor—Subsequent fate of that Clan—The tocher of Dame Jean Hamilton, wife of Humphrey—Alexander Colquhoun obtains from Macaulay of Ardincaple a charter of the lands and isle of Inchvanik, in Lochlomond—Trial of Patrick Earl of Orkney for treason—Laird of Luss one of the Assize—His death in 1617—His Testament, | 176-238 |

| XV.—SIR JOHN COLQUHOUN, First Baronet of Nova Scotia [1617-1647], married Lady Lilias Graham (Montrose). | |

| Obtained in 1602 Crown Charter of the baronies of Colquhoun and Luss—Received from his father the liferent of the altarages in the Kirk of Luss and the Chaplaincy of Rossdhu—Received also a Crown Charter of the lands of Auchintorly and Dunnerbuck, recognosced from Robert Lord Boyd—Disputes with the Minister of Luss—Refused to augment the stipend of Luss—Travelled abroad after the death of his father—Returned to Scotland—Acquired the lands of Balvey Logan, Gartconnell, Fergustoun Logane, Ledcamroch Logane, and Bannachtane Logane—Sold Balvey to his brother Humphrey in 1629—Was a member of the Parliament of 1621, which ratified the General Assembly’s “Five Articles”—King Charles I. grants to him part of the region of Nova Scotia, in free regality, to be called the Barony of Colquhoun, and conferred on him and his heirs-male the dignity of Baronet, | 239-254 |

| XVI. (1.)—SIR JOHN COLQUHOUN, Second Baronet [1647-1676], married Margaret Baillie, Heiress of Lochend. | |

| Educated at the University of Glasgow—Put in possession of the family Estates, during his father’s lifetime, by his uncle, Sir Humphrey, who had acquired them—Married Margaret Baillie, daughter of Sir Gideon Baillie of Lochend—Anecdote respecting Sir John and Margaret Baillie—Letter from Sir John Crawford of Kilbirnie, her stepfather, and Magdalene Carnegie, her mother, to Sir John Colquhoun, her husband—Their marriage celebrated without due proclamation of banns—Minister of Luss deposed for having celebrated it—Deliverance of the Presbytery of Dumbarton thereanent—Renewing of the Covenant in the Kirk of Luss—Margaret Baillie retoured heir to her father, Sir Gideon, in the lands of Woodhall, and others, in Berwick—Also retoured heir to her sister, Jean Baillie, in the half of the Barony of Lochend, and other lands—Postnuptial Contract between her and her husband, Sir John Colquhoun—Infefted in liferent in the lands of Garscube, mains of Colquhoun, lands of Connoltoun and Dunglas, also in Dunnerbuck and Auchintorlie—Margaret Baillie became bound to infeft Sir John in all the lands of Lochend—Destination of the said lands—Lands of Arrochar disjoined from Luss, and erected into a separate parish—Letter from the Marquis of Argyll to Sir John respecting the holding of various lands—The latter appointed by the Parliament a Commissioner of War for the shire of Dumbarton—Struggles between Cromwell and the royalists for the possession of the Castle of Rossdhu—Sir John included in Cromwell’s “Act of Grace,” but fined for his adherence to the royalist party—Order for modifying his fine—Archibald Lord Lorne excluded from Cromwell’s indemnity—Sir John Colquhoun became one of the sureties for his Lordship’s good behaviour—Purchase of the lands of Balloch by Sir John—Infefted in the lands of Blairvaddoch, Stuckiedow, Letrualt-mor, Faslane, Garelochhead, and others—Sold Easter Tullychewen—Appointed a Commissioner for the Visitation of the University of Glasgow—Appointed by Parliament a Commissioner for the preparing of Overtures for advancing trade, etc.—Execution of James Marquis of Montrose, Sir John’s uncle, at Edinburgh—His honourable interment—Protest taken by Sir John that the establishment of the Justiciary Court should not prejudice his office of Coroner of the shire of Dumbarton—Became bound to the Privy Council for the peaceable behaviour of his tenants, vassals, etc., of his name and clan; and received a counter bond from his tenants, etc.—Purchased the lands of Cameron, Darleith’s Spittell, and the teinds of Bonhill—Obtained a gift of the ward, etc., of the land of Bannachra—Sold the estate of Lochend—Curious Notarial Instrument connected with the sale of these lands—Sir John’s death in 1676—His Testament, | 255-289 |

| XVII.—SIR JAMES COLQUHOUN, Third Baronet [1676-1680]. | |

| Obtained possession of the Estates in 1676, during his minority—Has been omitted in previously published histories of the family—Obtained a gift of the ward and non-entry of the lands of Fergustoun-Logan, and others, his father’s lands—Also obtained a Charter of Drumfad, Tullichintaull, Cameron, Finnart, Craigerostan, Balloch, etc.—Threatened raid by the Macdonalds—Sir James died at Glasgow in 1680, while still a minor—Account of his Funeral Expenses—Was succeeded by his uncle, James Colquhoun of Balvie, | 290-293 |

| XVII. (2.)—SIR JAMES COLQUHOUN, Fourth Baronet [1680-1688], married Penuel Cunningham. | |

| Succeeded his nephew in the title of Baronet, and also in the Barony of Luss—Was infefted in Balvie in 1679—Order by Sir James for the removal of troops quartered on Auchindinnane—Visit of James Duke of York to Dumbarton—Sir James charged to enter heir to his deceased nephew—Purchased from Alexander Colquhoun of Tullychewen the ward, etc., of the lands of Bannachra—Appointed one of the Commissioners for uplifting the King’s Cess—Infefted in the lands of the Mains of Balvie-Logan, lands of Craigrostan, and others—Actions of Reduction and Improbation of an alleged Bond of Taillie, and a nomination as to the succession of heirs to the Estates of Luss—The Revolution of 1688—Earl of Perth’s Letter to Sir James—Earl of Perth imprisoned in Stirling Castle—Death of Sir James in 1688, | 294-301 |

| XVIII.—SIR HUMPHREY COLQUHOUN, Fifth Baronet [1688-1718], married Margaret Houston. | |

| Educated at Glasgow University—Appointed one of the Commissioners for the suppression of nonconformity—Obtained from King James VII., in 1685, a Charter of the Baronies of Luss and Colquhoun—Obtained Charter of Mains of Balvie-Logan and others—Infefted in Craigrostan, etc.—Sold the lands of Balvie in 1688—A warm supporter of the Revolution Government—Lieutenant-Colonel of the Militia of Argyll, Dumbarton, and Bute—Commissioner for uplifting the sum imposed upon the shires and burghs by the Act of Convention of Estates—Disponed the lands of Craigintuy, Portincaple, and Forlingbrek—Purchased the lands of Letrault-mor and part of Strone—Sold to John Colquhoun of Garshake, the lands of Chapleton and Chaplecroft, Middleton and the Overtouns—Disponed also the lands of Glenmulichane and Inverbeg—Sold part of his lands of Miluetoun of Colquhoun and Carcastoun, reserving the fishings of Lochlomond and coble fishings in the Clyde—Obtained four annual fairs and a weekly market for Luss, with the tolls, customs, and duties thereof—Lands of Silverbanks and Dunnerbuck feued to John Colquhoun—Purchased from John Colquhoun of Camstradden the lands of Camstradden, Auldachlay Hill and the Slate Crag, excepting Auchingaven—Sat in Parliament in 1703—Joined in the protest against the Act for allowing the importation of wines and foreign liquors—A Commissioner of Supply in 1704—Settled the Barony of Luss, failing his own sons to be born, on his only daughter Anne and her husband, James Grant of Pluscardine, and their heirs-male—Resignation and regrant of the Colquhoun Baronetcy of Nova Scotia in 1704—Title and Estates descended, on the death of Sir Humphrey in 1718, to James Grant, who was designated Sir James Colquhoun of Luss, Baronet—Terms of a Bond of Taillie granted by Sir Humphrey in 1706—Provision therein that the Estate of Luss should never be held by the Laird of Grant—Took an active part in opposing the “Treaty of Union”—The “Lochlomond Expedition”—Sir Humphrey died in 1718—Buried in the Chapel at Rossdhu, | 302-327 |

| XVIII. (1.)—ANNE COLQUHOUN, Heiress of Luss [1718-1724], married James Grant of Pluscardine, afterwards Sir James Colquhoun, Sixth Baronet [1718-1719]. | |

| Anne and her husband succeeded to the family estates, and the latter to the title of Baronet, under the name of Colquhoun, in 1718—His father, Ludovick Grant of that Ilk, and the family of Grant—Sir James’s brother, General Alexander Grant, who had succeeded to the estates of Grant in 1717, having died in 1719, Sir James succeeded to these estates, when he resumed his paternal name of Grant, and dropped the name and arms of Colquhoun of Luss—Ludovick, his second son, became possessor of the estate of Luss, and bore the name and arms of that family—Subsequent history of Sir James Grant—His death in 1747—His character—Anne Colquhoun, his wife, died at Castle Grant in 1724—Her numerous children by Sir James, | 328-333 |

| XIX. (1.)—SIR LUDOVICK COLQUHOUN, Seventh Baronet of Nova Scotia [1719-1732], married, first, Marion Dalrymple; and second, Lady Margaret Ogilvie. | |

| Succeeded to the Estates of Luss when twelve years old—Studied law, and was admitted to the bar in 1728—Succeeded to the Grant estates—Landing of Prince Charles in Lochaber—Intention of Ludovick Grant to join Sir John Cope and to defend the country against the enemies of Government—His proposal coldly received by the President—General Cope defeated at Prestonpans—Ludovick marches about 700 men to garrison Lord Findlater’s house at Cullen, against Lord Lewis Gordon’s attack—Movements of the Laird of M’Leod, and his rout at Inverury by Prince Charles’s forces—Victory gained by the insurgents at Falkirk—Ludovick Grant proffers his services to the Duke of Cumberland—Was accepted, and, with 200 men, joined the Duke’s army—Defeat of Prince Charles at Culloden—Lord Balmerino captured by the Grants, and delivered to the Duke of Cumberland—Energetic conduct of Ludovick Grant—Surrender and ultimate fate of the rebels in the north—Sir Ludovick died at Castle Grant in 1773—Poetical tribute to his memory, | 334-343 |

| XIX. (2.)—SIR JAMES COLQUHOUN, Eighth Baronet of Nova Scotia, created Baronet of Great Britain [1732-1786], married Lady Helen Sutherland. | |

| The fourth son of Anne Colquhoun, succeeded his elder brother Ludovick in the Luss estates when the latter succeeded to Grant—Fought, as a Captain, at the battle of Dettingen, in 1743—Promoted to be Major of the famous “Black Watch”—Prevented from bad health from taking part in the battle of Fontenoy—Returned to Scotland prior to 1745—Prince Charles appeared in Scotland—Routed the King’s troops at Prestonpans—Gained the battle of Falkirk—Duke of Cumberland arrived in Scotland—Advanced to Aberdeen—Major Colquhoun unable to join him on account of bad health—Lord Milton greatly assisted in restoring tranquillity by Major Colquhoun—Battle of Culloden—Duke of Cumberland’s proclamations relative to the rebels—Letter from Sir James on behalf of the Clan Macgregor—Lord Milton’s favourable reply thereto—Four letters from Sir James to Lord Milton on the subject of receiving the surrenders of persons who had held commissions under Prince Charles—Meeting between Rob Roy and Sir James Colquhoun on the island of Inchlonaig, in Lochlomond—Diligence of Sir James in searching out and apprehending concealed rebels—Sir James retires from the army in 1748—Three letters from Sir James to Lord Milton requesting his lordship’s influence on behalf of friends—Sir James created a Baronet of Great Britain—Numerous additions made by him to the estate of Luss—The burgh of barony of Helensburgh—Present mansion of Rossdhu commenced to be built about 1774—Habits of Sir James in his old age—His high personal character—His death in 1786—Death of Lady Helen in 1791—Both interred in the Chapel of Rossdhu—Lady Colquhoun in connexion with the management of her domestic affairs—Dr. Samuel Johnson’s visit to Sir James at Rossdhu Castle—Disposition and codicil thereto, by Lady Helen, respecting legacies to her children, | 344-384 |

| XX.—SIR JAMES COLQUHOUN, Second British Baronet [1785-1805], married Mary Falconer. | |

| Made Sheriff-depute of Dumbartonshire and one of the Clerks of Session—Purchased various lands—Proposed purchase of Camstradden—His correspondence with Horace Walpole—His collection of paintings, etc.—His character, | 385-394 |

| His fifth son, John Campbell Colquhoun, Advocate, Sheriff of Dumbartonshire, | 395-397 |

| XXI.—SIR JAMES COLQUHOUN, Third British Baronet [1805-1836], married Janet Sinclair (Ulbster). | |

| M.P. for Dumbartonshire—His reconciliation with the Macgregors—Improvement of his Estates—Purchases Arrochar for £78,000—Acquires other lands—His death, | 398-405 |

| Janet Sinclair, Lady Colquhoun, | 405-412 |

| XXII.—SIR JAMES COLQUHOUN, Fourth and present British Baronet, succeeded 1836, married Jane Abercromby (of Birkenbog). | |

| His improvement of the Luss estates—Purchased Ardincaple and salmon-fishings in the Leven and Clyde—M.P. for Dumbartonshire from 1837 to 1842—Appointed Lord Lieutenant of Dumbartonshire, | 413-415 |

| XXIII.—JAMES COLQUHOUN, Younger of Colquhoun and Luss. | |

| Made a Justice of the Peace for the county of Dumbarton—Appointed Deputy-Lieutenant of that county, | 415-416 |

| ILLUSTRATIONS IN VOLUME FIRST. | |

| Title-page: on each side a Sauch Tree, the Badge of the Colquhouns, having thereon their Armorial Shield, with Crest and Motto at the top and their Slogan at the foot. | |

| Facsimile of Confirmation by William Wallace, Lord of Cragy, to Robert of Colquhoune, Lord of Luss, 30th June 1407 | |

| Portraits— | |

| Sir John Colquhoun, Second Baronet, “The Black Cock of the West,” | |

| Margaret Baillie, heiress of Lochend, his wife | |

| Anne Colquhoun, heiress of Luss | |

| Sir James (Grant) Colquhoun, her husband | |

| Sir James Colquhoun, First British Baronet | |

| Lady Helen Sutherland, his wife | |

| Facsimile of Letter by Lady Helen Sutherland, Lady Colquhoun. 5th January 1745 | |

| Armorial Bearings of “Colquhoun of Luss,” from the Book and Register of Arms by Sir David Lindesay, Knight, Lyon King of Arms, A.D. 1542 | |

| Armorial Bearings of Sir James Colquhoun of Colquhoun and Luss, Baronet, on the side of each Volume. [Not available. ed.] | |

In tracing the history of the family of Colquhoun of Colquhoun and Luss, the origin and remote ancestry of two distinct families—Colquhoun of Colquhoun and Luss of Luss—require to be investigated. Both these families are of high antiquity, and they merged into one in the reign of King David the Second, by the intermarriage of Sir Robert Colquhoun, who was the fifth Laird of Colquhoun, with the daughter of Godfrey of Luss, the sixth Laird of Luss. That lady was heiress of the estate of Luss, and she was commonly called “the Fair Maid of Luss.”

The earliest surname under which the family of Colquhoun is traced is that of Kilpatrick. In the reign of King Alexander the Second, which was from the year 1214 to 1249, Umfridus de Kilpatrick obtained from Maldouen third Earl of Lennox a charter of the lands of Colquhoun, situated in the parish of Old or West Kilpatrick, within the earldom of Lennox and shire of Dumbarton. On acquiring the lands of Colquhoun, Umfridus dropped his original surname of Kilpatrick, and adopted that of Colquhoun. The adoption of surnames from lands successively acquired was a common practice in the time of King Alexander the Second, when surnames were less fixed than they came to be in later times. Umfridus is thus the earliest ancestor of the Colquhoun family who is vouched by the testimony of an authentic charter.

Not content, however, with such a satisfactory foundation, several writers on the family of Colquhoun have attempted to find their origin in the younger son of Conoch, a king of Ireland, who, it is said, came to Scotland in the reign of Gregory the Great, King of Scotland, that is, between the years 882 and 893, and obtained from King Gregory a grant of lands in the shire of Dumbarton, to which he gave the name of Conochan; a name which gradually became corrupted into Cochon, which afterwards became Colquhoun.[1] But it is easy to show that such a theory is utterly fabulous. It has often been the mischance of ancient families to have their early history perversely shrouded in fable and romance, and the story which represents the younger son of the Irish King Conoch as the founder of the family of Colquhoun is a fair specimen of the straining after similarities of names, in the absence of authentic memorials, to account for the origin of families. The inventors of this theory overlook the fact that the earliest surname of the Colquhouns was Kilpatrick, which has no similarity to Conoch or Conochan. To prove its probability they would require to show that the progenitors of Umfridus de Kilpatrick were Conochs or Conochans or Colquhouns; but of this there is not the slightest evidence.

The origin of the family of Colquhoun is traced by another theory to a younger son of one of the ancient earls of Lennox.[2] The only evidence on which this theory rests is the similarity of the armorial ensigns borne by the family of Colquhoun to those of the earls of Lennox, the saltier being charged upon the shields of both families. But this heraldic evidence, standing alone, is insufficient to establish the descent of the Colquhoun family from that of Lennox. In early times it was common for families who held lands from powerful earls to adopt the principal armorial ensigns of their lord superior. This was the practice in the earldom of Lennox, as well as in other earldoms. In Moray, the holders of lands under the earls of that name adopted their well-known cognizance of the stars. In Strathearn, the cheverons of the earls of Strathearn were frequently adopted by the families holding lands under them, while in Annandale the families who held lands under the Bruces, as lords of Annandale, very generally adopted their armorial bearings, and these are adopted at the present day by the families of Maxwell, Johnstone, Jardine, and others, all of whom have, with some variations, the well-known saltier of the Bruce. Armorial bearings thus adopted were called arms of patronage. Although the similarity of arms shows in many cases a common descent in families from remote times, such as the Angus lion, which is borne by the family of Ogilvy, in virtue of their descent from the ancient earls of Angus, who carried that cognizance, yet mere heraldic evidence requires corroboration.

The terms of the charter by Maldouen Earl of Lennox to Umfridus de Kilpatrick do not indicate any relationship between them. Had any relationship existed, the probability is that it would have been stated in the charter by the Earl styling Umfridus as his cousin or other relative. The absence of any acknowledgment of relationship between them in the charter leads to the inference that none existed. This negative evidence seems to outweigh any positive testimony that might be afforded by the similarity of charges on their shields.

The great apostle of Ireland, St. Patrick, was closely connected with the parish of Kilpatrick in the Lennox, which is appropriately named after him, because, according to tradition, he was born at Kilpatrick. But the fame of the great saint was far from being local. Other churches and other districts of lands were named after him in different forms. In the stewartry of Kirkcudbright there are the churches of Kirkpatrick-Durham and Kirkpatrick-Irongray, and in Annandale there are the parishes of Kirkpatrick-Juxta and Kirkpatrick-Fleming, and the lands of Rampatrick and Kirkpatrick. These lands of Kirkpatrick can be traced under that name as early as the twelfth century. They appear also to have given a surname to a family of considerable note—the Kirkpatricks of Closeburn in Nithsdale. They are better known by that designation than as Kirkpatricks of Kirkpatrick. Although the lands of Kirkpatrick furnished them with a surname, they appear to have retained them but for a short period, and to have acquired the lands of Closeburn, which became their territorial designation. That family obtained from Robert de Bruce, Lord of Annandale, grants of various lands and fishings in that district. By a charter without date, Robert de Bruis granted to Ivo and his heirs the fishing of Blawad and of Hesther, to be held of the granter, for payment to him annually of one pound of pepper or six pennies.[3]

Ivo, the grantee in this charter, was the progenitor of the family of Kirkpatrick. He was then without a surname, as he apparently had not yet acquired the lands of Kirkpatrick. The charter, although undated, must have been granted between the year 1124, soon after which Robert of Bruce acquired the Lordship of Annandale, and the year 1141 when he died. The grant of the lands of Kirkpatrick to Ivo or his successors has not been discovered. But it must have been made before the end of the same century, as in another charter by Robert of Bruce to Roger Crispin of the lands of Cnoculeran, one of the witnesses is Roger of Kirkepatric.[4] No connection can be traced between Ivo, the progenitor of the Kirkpatrick family, and Umfridus de Kilpatrick or Colquhoun.

|

Nisbet’s Heraldry, edition of 1804, vol. i. p. 133. Buchanan of Auchmar’s Scottish Surnames, Glasgow, 1723, p. 90. Baronage of Scotland, by Sir Robert Douglas, 1764, p. 23. Also Histories of the Families of Colquhoun and Luss, in MS. at Rossdhu. |

|

Sir George Mackenzie’s Heraldry, MS. |

|

Original Charter at Drumlanrig. |

|

Original Charter, ibid. |

Umfridus de Kilpatrick obtained a charter from Maldouen, third Earl of Lennox, of the lands of Colquhoun, to be held for rendering to the Earl, his superior, the third-part of the service of one knight. The charter is undated, but it must have been granted before, or not later than, the year 1246, as the Earl’s father-in-law, Walter, the High Steward of Scotland, who was one of the witnesses to the charter, died in that year.[1] This is the earliest charter extant bearing on the history of the family of Colquhoun, and it may be translated from the Latin as follows:—

To all his friends, and men present and to come, Maldouen Earl of Lennox, greeting: Let all men present and to come know, that I have given, granted, and by this present charter have confirmed to Umfridus de Kilpatrick the whole land of Colquhoun, by its right divisions, with all its just pertinents, to be held by him and his heirs of me and my heirs in feu and heritage, freely, quietly, fully and honourably, in wood and plain, in meadows and pastures, in pools and mills, in fishings, and in all other easements belonging to the foresaid lands; he and his heirs rendering therefrom to me and my heirs the third part of the service of one knight for every service and exaction; before these witnesses, Sir Walter, Steward of our Lord the King, Malcolm my son, Gillaspec Galbraith, Hamelyn, Malcolm, Duncan, my brothers, Malcolm Beg, Doven my chamberlain, Fergus Makcomyng, and many others.

It may be assumed, therefore, that Umfridus was born towards the close of the twelfth or in the beginning of the thirteenth century, that he flourished during part of the reign of King William the Lion and during the whole reign of Alexander the Second, and that he died in the early part of the reign of Alexander the Third. After obtaining this grant, Umfridus, according to a custom common at that time, dropped the surname of Kilpatrick and assumed that of Colquhoun from his lands of Colquhoun.

Umfridus de Kilpatrick was witness to a charter granted in the year 1250 by Maldouen Earl of Lennox, confirming to the monks of the monastery of Paisley some pasture land in Lennox.[2]

The lands of Colquhoun acquired by Umfridus de Kilpatrick, at a period so early, formed a part of the parish of Kilpatrick, the charter probably conveying to him the whole country from the burn to the possessions of the Church of Kilpatrick. The lands of Colquhoun continued to be the property of his descendants for many generations, and the superiority of part of them still belongs to his lineal representative, the present Sir James Colquhoun of Colquhoun and Luss, Baronet. Some of the vassals pay a year’s rental for their entry, and in other cases merely a nominal sum, and in one case it is a pound of pepper.

|

Cartularium Comitatus de Levenax, p. 25; Crawfurd’s Officers of State, p. 318; Crawfurd’s General Description of the Shire of Renfrew, etc., Robertson’s edition, p. 437. |

|

Registrum Monasterii de Passelet, p. 172. |

Sir Robert of Culchon (Colquhoun) appears to have been the next representative of this family, and may be presumed to have been the son of Umfridus de Colquhoun, though no legal evidence to that effect has been preserved. In 1271 he acted on an inquest, the members of which were appointed to inquire whether Maria, wife of John of Wardrobe, and Elena, wife of Bernard of Erth, and Forveleth, wife of Norrin of Monorgund, daughters of the deceased Finlay of Camsy, were the true and lawful heirs of the deceased Dufgallus, brother of Maldouen Earl of Lennox, and who found that they were so, having been descended from Malcolm, who was the brother of Dufgallus and their grandfather, and that Dufgallus had never married.[1] This Laird of Colquhoun was probably born towards the close of the reign of King William the Lion, flourished during the whole reign of Alexander the Second, and died in the end of the reign of Alexander the Third. After the year 1271 his name does not appear in any record of the period which we have met with.

|

Registrum Monasterii de Passelet, p. 191. |

Ingelramus de Colquhoun, who also lived in the reign of Alexander the Third, appears to have succeeded Sir Robert; and although the link of filiation is again wanting, we may venture to regard him as the son of Sir Robert. The first, and indeed almost the only notice of him extant is between the years 1292 and 1333, when he was witness to a charter by Malcolm Earl of Lennox, confirming a charter to Gillemore, son of Maldouen, made on the donation of Maldouen, late Earl of Lennox, to Malcolm of Luss, son and heir of Sir John of Luss, of the lands of Luss. The charter is undated, but from the names of the witnesses and others mentioned therein it may be concluded with certainty that it must have been granted between the years specified.[1] Ingelramus received from King Robert the Bruce a charter of Salakhill [Sauchie], in Stirlingshire, that part of it formerly given to Osbert, son of Forsyth, amounting to 100s., for the service of two bowmen and three suits of court, being reserved. The charter is without date, but it could not have been granted before the 25th of March 1306, when Robert the Bruce began to reign.[2] Ingelramus lived during an exciting period in the history of Scotland—during the reigns of Alexander the Third, of Margaret, Alexander’s grand-daughter, of John Balliol, and the interregnum between 1296 and 1306, when the kingdom was divided by powerful factions, and prostrated by the power of Edward the First of England, the period when Sir William Wallace distinguished himself by his heroic exploits for the independence of his country, and the beginning of the reign of Robert the Bruce.

|

Cartularium de Levenax, p. 24. |

|

Harleian MSS., 4628, 2, British Museum. |

Humphrey of Colquhoun, who flourished in the reign of Robert the Bruce, succeeded Ingelramus about the year 1308, and may be presumed to have been his son. He received a charter of the barony of Luss from King Robert the Bruce in 1308, for his special service, and for never having deserted Bruce’s interest. On the 26th April 1309 he was witness to a charter by King Robert the Bruce, which confirmed to Robert Wischart, Bishop of Glasgow, all the churches, lands, rents, possessions, and goods pertaining to that bishop.[1] In this charter he is designated “Vmfredus de Culchoun, miles.”

This charter, dated at Arbroath, to which Humphrey of Colquhoun, knight, was a witness, is worthy of special notice, from its connection with the history of the times in which he lived, and with events in regard to which he doubtless took a deep interest. Robert Wischart, Bishop of Glasgow, in whose favour it was made, was a strenuous defender of the independence of Scotland. When overpowered by circumstances, he, indeed, repeatedly swore fealty to Edward the First of England; but he, as often as circumstances favoured, took part against that hostile invader of his country, against whom he vehemently incited the people to fight. He was amongst the first to join Wallace when he erected the standard against Edward the First; and he equally supported Robert the Bruce when he raised the old war-cry of Scotland against English domination. He absolved Bruce from the anathema of the Church for the slaughter of Comyn in the Church of Dumfries, and took an active part in the preparations made for his coronation. Wischart, however, was taken prisoner by the English in the Castle of Cupar, which he held against them in 1306. One of the charges brought against him was that he had used the timber which Edward the First of England had allowed him for building a steeple to his cathedral, in constructing engines of war against that King’s castles, and especially the Castle of Kirkintolach.[2]

At the time when the above charter was made in his favour the bishop was still in prison; and in the charter King Robert expresses, in affecting terms, his feelings of commiseration towards him under his long and wearisome imprisonment. “Since,” says he, “it would be a pernicious example, and dissonant to reason, to render evil for good, much more since it is a laudable demonstration of gratitude to show favour to those who have deserved well by a suitable recompense, we, deeply pondering, as we are bound, the imprisonment and chains, the persecutions and wearinesses which the venerable father, Lord Robert, by the grace of God, Bishop of Glasgow, has hitherto constantly endured, and still patiently endures, for the rights of the Church and of our Kingdom of Scotland, we have freely granted to the said Lord Bishop all his churches, lands, rents, possessions, and goods.” The bishop, it may be added, was not released till after the battle of Bannockburn, fought on 24th June 1314, when Bruce’s wife, his sister Christian, his daughter Marjory, the young Earl of Mar, his nephew, and the Bishop of Glasgow, were exchanged for the Earl of Hereford, who, on the capitulation of Bothwell Castle by the English into the hands of the Scots, immediately after that battle, became their prisoner.[3] The bishop had grown blind in prison. He survived his liberation only two years, having died in November 1316.

Humphrey of Colquhoun was in the army of Bruce at Bannockburn; and the valour and skill he then displayed attracted the special notice of his sovereign, who granted him a charter of Sauchy, in Stirlingshire, for his good service performed at that battle.

Sir Humphrey of Colquhoun was also witness to a charter by Malcolm Earl of Lennox to John of Luss, granting him certain privileges and immunities within the bounds of his lands of Luss. This charter is undated, but it was confirmed by King Robert on 6th March 1316, from which it may be presumed that it was granted shortly before that date.[4]

There is a Malcolm Culchone who received from King David the Second (1329-1371) a charter of the lands of Gask, and of 13s. 4d. out of the lands of Balmelyn, in the shire of Aberdeen;[5] but whether he was related to Sir Humphrey of Colquhoun we are unable to determine. In 1329 Malcolme of Culchone, who received annually ten pounds from the royal exchequer till he should be otherwise provided for, was paid by the chamberlain, during the last term of his account for that year, the sum of one hundred shillings.[6] In the year 1357 there was paid by Sir Robert of Pebles, the Chamberlain of Scotland, to Malcolme of Culwone, who is probably the same person as in the preceding account, the sum of £6, 13s. 4d. for the King’s use.[7]

|

Registrum Episcopatus Glasguensis, vol. i. p. 220. |

|

Reg. Episc. Glasguensis, vol. i. p. xxxvi. |

|

Tytler’s Hist. of Scotland, vol. i. p. 292. |

|

Cartularium Comitatus de Levenax, p.22. |

|

Robertson’s Index, p. 61, No. 5. |

|

Accounts of the Great Chamberlains of Scotland, printed at Edinburgh, 1836, vol. i. p. 94. |

|

Ibid. vol. i. p. 351. |

Sir Robert of Colquhoun, Knight, is the next representative of this ancient family that appears on record. We do not find him anywhere called son of Humphrey, though from the time at which he flourished, and the fact that he succeeded him in the lands of Colquhoun, it may be inferred that he was so. “Robert of Colquhoun, knight,” was a witness to a relaxation granted by Malcolm fifth Earl of Lennox to Arthur Galbraith of all the suits which, according to the tenour of his charters, he was bound to make to the Earl for the lands of Bannachra, Keangerloch, and others. He was also a witness to a charter granted by the same Earl to Arthur Galbraith of the lands of Buchmonyn and of Gilgirinane; to another granted by the same Earl to Sir Patrick of Grame of the lands of Auchencloich and Strablane; and to a relaxation of captions on the lands of the said Sir Patrick by the same Earl.[1] All these transactions must have taken place between the years 1292 and 1333, the period during which that Earl held the earldom.

Sir Robert married, in or previous to the year 1368, the daughter of Godfridus, sixth laird of Luss, his only child and heiress. By this marriage he added greatly to his paternal estates, having by it acquired the extensive property of Luss. From this property he afterwards took his designation, and his descendants, who continue in possession of the lands to the present day, retain it.

The commonly received account of the marriage of Sir Robert with the heiress of Luss is, that in the reign of King David the Second he married the daughter and sole heiress of Humphrey of Luss, with whom he acquired the lands of Luss. As, however, no Humphrey of Luss appears on record, and as Godfridus is the last of the Lusses of whom we have any notice, it is probable that Umfridus has by mistake been written for Godfridus, and that it was the daughter and heiress of the latter whom Sir Robert married. No direct evidence of the marriage indeed exists, but the uniform tradition of the family, and the possession of the estates of Luss, leave no doubt on the subject.

After his marriage to the heiress of Luss, Sir Robert took the designation “de Luss” in addition to that of Colquhoun, though her father, Godfridus, was still alive. “Robert of Colfune (Colquhoun), Laird of Luss,” was a witness to an obligation by Malcolm Fleming, Lord of Biggar, in favour of Robert Lord Erskine, warranting the lands of Dalnotar, and others, dated 8th January 1368.[2] In a charter, dated in the same year, he is designated “Robertus dominus de Colquhoun et de Luss,” Lord of Colquhoun and of Luss;[3] and in a charter by Isabella Fleeming of Dalnotar to Sir Robert Erskine, knight, of the lands of Achintorlie, in the Lennox, he is similarly designated.[4] To this latter charter John Lyle, son and heir of Sir John Lyle of Duchal, knight, was also a witness, which shows that it must have been granted about the year 1370.[5] Sir Robert was also a witness under the simple designation “Robertus de Colquhoun,” to a charter, dated 20th August 1373, by Walter of Fosselane, Lord of Lennox, to Walter Lord of Buchanan, of the lands of Auchmar, in Stirlingshire, which belonged to William Boyd.[6] Sir Robert of Colquhoun and of Luss was dead in 1391, when his lands of Mykilsalchy (Meikle Sauchy) were in the hands of the King, the heir not having up to that time obtained infeftment.[7]

By the heiress of Luss, Sir Robert Colquhoun had four sons—

Humphrey Colquhoun, who succeeded him.

Robert Colquhoun, who obtained from his brother, Sir Humphrey, a grant of the lands of Camstradden, part of the estate of Luss. If there was any previous grant of these lands by Sir Robert, the father, no trace of it can now be found.

Robert, junior, to whom, in the grant of the lands of Camstradden quoted below, the lands were destined, failing heirs-male of Robert, to whom the charter was granted. He is designed in the charter “frater junior.”

Patrick, to whom in the same charter the same lands were destined, failing heirs-male of Robert, junior.

The charter grant of the lands of Camstradden now mentioned is written in Latin, and may be thus translated:—

To all who shall see or hear this charter, Humphrey of Colquhoun, Lord of Luss, everlasting salvation in the Lord: Know ye that I have given, granted, and by this present charter have confirmed to my beloved and special brother, Robert of Colquhoun, for his homage and service rendered, and to be rendered to me, my whole lands of Camysradoch and Achigahane, with the pertinents, lying in my lordship of Luss, within the earldom of Levenax; to be held and had, my said lands of Camysradoch and Achigahane, with the pertinents, by the said Robert, my brother, and his heirs-male lawfully begotten, or to be begotten, of his body; whom perhaps failing, by Robert of Colquhoun, my younger brother, and his heirs-male, in the manner before written; whom perhaps failing, by Patrick of Colquhoun, my brother, and his heirs-male, as is before mentioned; whom also perhaps failing, by me and my lawful heirs whomsoever, in feu and heritage for ever, of me and my heirs, freely, quietly, wholly, fully, and peaceably, in wood and plain, in meadows, pastures and pasturages, in roads and paths, in waters and pools, in aviaries and fishings, in fowlings and huntings, in pleas and suits, and in their issues, with escheats, merchets and bludwyts, and with all other liberties, commodities, easements, and just pertinents whatsoever, as well not named as named, as well under the earth as above the earth, belonging to, or that may hereafter in any way belong to, the same lands; for rendering therefrom the said Robert, Robert and Patrick, my brothers, and their heirs, as before mentioned, to me and my heirs, for the common army of our Lord the King, two cheeses from every house in which cheese is made in the said lands of Camysradok and Achigahane, and for rendering for the common assistance of our Lord the King as much as belongs to so much land within the Lordship of Luss for every other service, exaction, or demand. In testimony of which thing, my seal is appended to my present charter at Luss, on the fourth day of the month of July, in the year of our Lord one thousand three hundred and ninety-five, before these witnesses, Sir Nigel of Balnory and Sir Robert Lang, chaplains, William Bukroy, Donald Macroger, and John Balnory, with many others.

This grant of the lands of Camstradden is narrated in a charter of confirmation by Duncan Earl of Lennox, dated at Inchmurrin, 4th July 1395.[8]

The lands of Luss, which Sir Robert acquired by marriage, had for a long time previous been the property of a family of the name of Luss, their surname having been derived from the name of their lands.

As by the marriage of Sir Robert with the heiress of Luss the family of that name became merged with that of Colquhoun, it is proper in this place to give some account of the family of Luss from its earliest representative, so far as now known, to the heiress of Luss whose property Sir Robert inherited, and whose family name he also assumed.

|

Cartularium Comitatus de Levenax, pp. 29, 30, 38, 40. |

|

Original Obligation in Cumbernauld Charter-chest. |

|

Original Charter in Luss Charter-chest. This designation which Sir Robert takes in this charter clearly proves that Buchanan of Auchmar is incorrect in asserting that it was Humphrey, Sir Robert’s son, who married the heiress of Luss. |

|

Crawford’s Officers of State, p. 318. |

|

Vide Douglas’s Peerage, under Lyle, Lord. |

|

Cartularium Comitatus de Levenax, p. 59. |

|

Accounts of the Great Chamberlains of Scotland, ut supra, vol. ii. p. 185. |

|

Cartularium Comitatus de Levenax, p. 77. |

The family of Luss is of high antiquity, but its origin, like that of other ancient families, is involved in obscurity and uncertainty, although their most ancient Christian names would seem to point to a Celtic extraction. Tradition has here also attempted to supply the place of well-attested history by attributing to the family of Luss a descent from the Saxon blood of the Earls of Lennox. But of such a lineage the earliest charters of that house give no indication. The saltier belonging to the armorial ensigns of the houses of Colquhoun and Lennox, which has been adduced to prove that these families have a common ancestry, has been also used, as already shown, as an argument to prove that the family of Luss originated in the same stock. But in the latter case the argument is even of less force than in the former; for that bearing has not been traced to the family of Luss before it merged in that of Colquhoun. The arms of the Colquhouns, it may be presumed, are those of Umfridus, the first of that name, rather than those of the house of Luss. It is, indeed, possible that they may have been those of Luss, as Sir Robert Colquhoun may have adopted them on his marrying the heiress of that house; but it is nothing more than a possibility; for had he adopted her arms, he would probably have quartered them with his own; nor would he have adopted them while he left her name to sink entirely.

The earliest period at which the family of Luss can be traced from authentic records is about the year 1150.

Maldouen, Dean of Levenax,[1] is the first of those ancient lords of Luss that appears on record. He received from Alwyn second Earl of Lennox a charter of the three lower quarters of Luss, viz., Achadhtullech, Dunfin, and Inverlaueran, and another quarter on the west side of Luss.

The charter itself, of the date of which we are ignorant, but which must have been in or before the year 1224,—the Earl who granted it having died before 1225,—is not included in the “Cartularium de Levenax,” nor is it known to be now in existence. But that such a charter was given is certain, from the charter of confirmation or recognition granted by Maldouen third Earl of Lennox to Maldouen, Dean of Luss, and to his son, Gillemore. Maldouen had been illegally kept from possessing these lands by Maldouen third Earl of Lennox, who, after his father’s death, held possession of them for some time, but how long is not stated. At last Earl Maldouen, prompted, as he himself affirms, by penitence for having detained them from the rightful owners, reconveyed to Maldouen, who is designated “formerly Dean of Luss,” and Gillemore, his son, by charter the foresaid lands, with the right of the patronage of the church of Luss, and with all the pleas, prison dues, escheats, etc., of the said lands. These lands are described in the writ as contained within these boundaries, namely, from Ald Suidheadhi and from the Laueran to Lower Duueglas, as Duueglas falls from the mountain into Lochlomond, on the one side, and from the head of the Laueran, across by the summit of the mountains, to the lower just boundary between the land of Luss and the land of Nemhedh (Roseneath), as it descends into Lochlong on the other side; and thence to the burn called Ald Bealech Nascamche as it descends into Lochlong; and from the head of that rivulet right across to the river Duueglas, as it falls into Lochlomond, as said is, and Frechelan and Elan Rosduue, and Ines Domhnoch. A special reservation is made in favour of the granter of the lands contained between Cledhebh and Banbrath (Banry or Bandry), with the islands pertaining thereto.

These lands thus described were to be held of the Earl of Lennox for rendering to him and his heirs, for the common army of the King, two cheeses from every house in the said lands in which cheese was made, for all other services, forinsic as well as intrinsic, customs, exactions, and demands, and giving as much common assistance to the King as belonged to two arrochars of land in the earldom of Levenax.[2]

The leading boundaries described in that charter still form the boundaries of the Luss estates, although from the revolution of names that has taken place since the date of the above charter, it is difficult to identify with perfect accuracy all the names of the boundaries mentioned in the charter.

The reddendo of cheeses for the King’s host stipulated in the grant, as well as in charters of other lands in Luss, would seem to lead to the conclusion that the valleys of Luss, amidst the extensive forest of the Levenax, were famed in those early days for more pasturage, and a more abundant dairy produce, than the present aspect of the country, with so much arable land under tillage, would lead us to suppose. The charter made by Alwyn second Earl of Lennox in favour of Maldouen, seems to have been the first grant of Luss to that family. Soon after this grant was made to them, they were accustomed to take the designation “de Luss;” the territorial name thus supplying their surname. The lands of Luss continued to be possessed by the family till, by the marriage of the heiress of Luss with the Laird of Colquhoun, as already stated, they passed into another family, in which they have continued down to the present day. Some have supposed that this Maldouen was a son of Earl Alwyn; but this is clearly a mistake, as both Maldouen, his son, and Maldouen, Dean of Lennox, were witnesses to the Earl’s charter of the lands of Cochnach to the church of Kilpatrick.[3] Dean Maldouen, however, though not a son, may have been a near kinsman of Earl Alwyn.

|

In the Cartulary of Lennox, p. 12, he is called Dean of Levenax, and at p. 97 he is called Dean of Luss, probably because his church was at Luss. |

|

Cartularium Comitatus de Levenax, p. 97. |

|

Cartularium Comitatus de Levenax, p. 97. |

Gillemore succeeded his father, Maldouen, in the lands of Luss. He obtained from Maldouen third Earl of Lennox two charters of these lands. In these charters, the boundaries, rights, and reddendo of the lands are described as in the charter of them already quoted, granted to his father by the said Earl.[1] Gillemakessoc, son of Gillemore, is a witness to one of these charters, made in favour of his father; but he does not himself seem to have ever possessed the lands of Luss. These charters are undated, but they must have been granted between the years 1225 and 1270, the period during which Maldouen was Earl of Lennox.

|

Ibid. pp. 19, 96, 97. |

Maurice is the next laird of Luss that appears on record. “Mauritius de Luss” was witness to a charter by Maldouen Earl of Lennox to Maurice, son of Galbraith, and the heirs of his marriage with Katharine, daughter of Colpatrick, of a carucate of the land of Cartonvenach; and to another charter by the same Earl in favour of the said Maurice, and Arthur his son, of a fourth part of land in Auchincloich, in exchange for other lands.[1] He was a witness to a charter by the same Earl, in 1250, granting to the monastery of Paisley in pure, free, and perpetual alms, one pasture of land of Levenax, and to the monks thereof the right to hold and possess all other their lands in the earldom of Levenax, as they held them at the time of this grant, or before.[2] He was also a witness to a charter by Engus, son of Duncan, confirming to the monks of Paisley the church of Kyllinan, dated 5th March 1270.[3] He appears again as a witness to a charter by Gillemichell, son of Edolf, to Malcolm his son, of the lands of Gartchonerane, and to two confirmations of that charter, one by Duncan, son of Gillemichel Makedolf, and the other, which is dated 17th November 1274, by Malcolm Earl of Lennox.[4]

On 17th August 1277, Maurice, as Laird of Luss, for a certain sum of money, made a charter, granting to God and the blessed St. Mungo and the church of Glasgow the right of cutting and preparing out of any parts of his woods of Luss whatever should be necessary for the woodwork of the steeple and treasury, which the chapter of the Cathedral of Glasgow, in consequence of its growing wealth and importance, was then in the course of erecting, with free access thereto and egress therefrom, and liberty of pasturage for the horses, oxen, and other animals which should be employed in carrying the wood required.[5] In that age privileges of this description were generally granted gratuitously to the church by the proprietors of the soil from their devotion or their fears; but on the part of this Celtic laird, it was a purely mercantile transaction. In granting this privilege he does not even affect to have been governed by a higher motive than the reception of its value in money; though, in conformity with the language of the time, the charter is said to be granted “to God and the blessed St. Mungo, and the Church of Glasgow.”

Maurice of Luss is said to have had issue—

John, who succeeded him.

William of Luss, designed vicar in a document dated 1313, may have been his son.[6]

|