* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Tarzan and the City of Gold

Date of first publication: 1933

Author: Edgar Rice Burroughs (1875-1950)

Date first posted: Feb. 6, 2021

Date last updated: Feb. 6, 2021

Faded Page eBook #20210239

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, Jim Blanchard, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

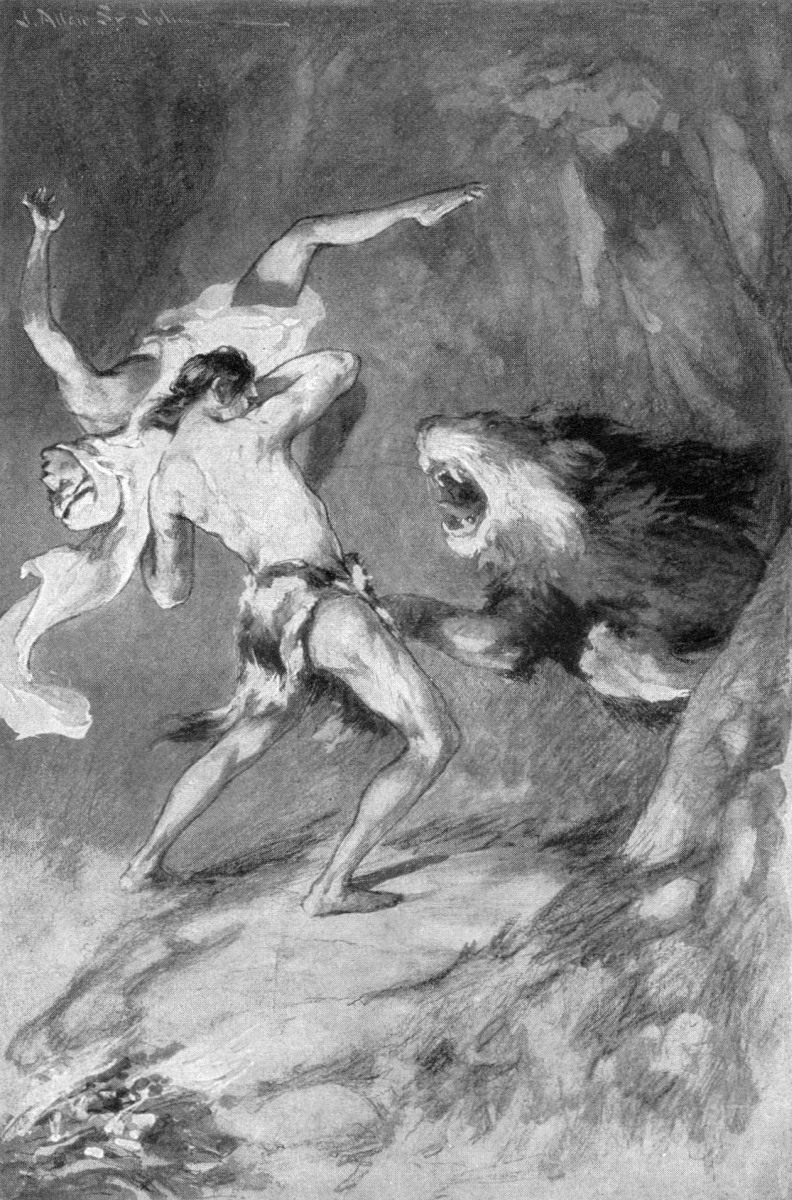

Tarzan lifted him high above his head and hurled him into the face of Numa.

TARZAN AND THE

CITY OF GOLD

By

EDGAR RICE BURROUGHS

Illustration by

J. Allen St. John

EDGAR RICE BURROUGHS, Inc.

Publishers

TARZANA CALIFORNIA

Copyright in the United States of America, 1933, by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc. Copyright in the Dominion of Canada, Great Britain, and the Pan-American Union, 1933

by

Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.

All Rights Reserved

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

| CHAPTERS | ||

| PAGE | ||

| I | Savage Quarry | 9 |

| II | The White Prisoner | 19 |

| III | Cats by Night | 34 |

| IV | Down the Flood | 50 |

| V | The City of Gold | 64 |

| VI | The Man Who Stepped on a God | 80 |

| VII | Nemone | 96 |

| VIII | Upon the Field of the Lions | 111 |

| IX | “Death! Death!” | 125 |

| X | In The Palace of the Queen | 139 |

| XI | The Lions of Cathne | 160 |

| XII | The Man in the Lion Pit | 174 |

| XIII | Assassin in the Night | 191 |

| XIV | The Grand Hunt | 209 |

| XV | The Plot That Failed | 227 |

| XVI | In The Temple of Thoos | 240 |

| XVII | The Secret of the Temple | 260 |

| XVIII | Flaming Xarator | 276 |

| XIX | The Queen’s Quarry | 290 |

TARZAN AND THE CITY OF GOLD

TARZAN AND THE

CITY OF GOLD

Down out of Tigre and Amhara upon Gojam and Shoa and Kaffa come the rains from June to September, carrying silt and prosperity from Abyssinia to the eastern Sudan and to Egypt, bringing muddy trails and swollen rivers and death and prosperity to Abyssinia.

Of these gifts of the rains, only the muddy trails and the swollen rivers and death interested a little band of shiftas that held out in the remote fastnesses of the mountains of Kaffa. Hard men were these mounted bandits, cruel criminals without even a vestige of culture such as occasionally leavens the activities of rogues, lessening their ruthlessness. Kaficho and Galla they were, the offscourings of their tribes, outlaws, men with prices upon their heads.

It was not raining now; and the rainy season was drawing to a close, for it was the middle of September; but there was still much water in the rivers, and the ground was soft after a recent rain.

The shiftas rode, seeking loot from wayfarer, caravan, or village; and as they rode, the unshod hoofs of their horses left a plain spoor that one might read upon the run; not that that caused the shiftas any concern, because no one was looking for them. All that anyone in the district wished of the shiftas was to keep out of their way.

A short distance ahead of them, in the direction toward which they were riding, a hunting beast stalked its prey. The wind was blowing from it toward the approaching horsemen; and for this reason their scent spoor was not borne to its sensitive nostrils, nor did the soft ground give forth any sound beneath the feet of their walking mounts that the keen ears of the hunter might detect during the period of concentration and mild excitement attendant upon the stalk.

Though the stalker did not resemble a beast of prey, such as the term connotes to the mind of man, he was one nevertheless; for in his natural haunts he filled his belly by the chase and by the chase alone; neither did he resemble the mental picture that one might hold of a typical British lord, yet he was that too—he was Tarzan of the Apes.

All beasts of prey find hunting poor during a rain, and Tarzan was no exception to the rule. It had rained for two days, and as a result Tarzan was hungry. A small buck was drinking in a stream fringed by bushes and tall reeds, and Tarzan was worming his way upon his belly through short grass to reach a position from which he might either charge or loose an arrow or cast a spear. He was not aware that a group of horsemen had reined in upon a gentle rise a short distance behind him where they sat in silence regarding him intently.

Usha, the wind, who carries scent, also carries sound. Today, Usha carried both the scent and the sound of the shiftas away from the keen nostrils and ears of the ape-man. Perhaps, endowed as he was with supersensitive perceptive faculties, Tarzan should have sensed the presence of an enemy; but “Even the worthy Homer sometimes nods.”

However self-sufficient an animal may be it is endowed with caution, for there is none that has not its enemies. The weaker herbivora must be always on the alert for the lion, the leopard, and man; the elephant, the rhinoceros, and the lion may never relax their vigilance against man; and man must always be on guard against these and others. Yet one may not say that such caution connotes either fear or cowardice; for Tarzan, who was without fear, was the personification of caution, especially when he was far from his own stamping grounds as he was today and every creature a potential enemy.

The combination of ravenous hunger with the opportunity to satisfy it may have placed caution in abeyance as, oftentimes, a certain recklessness born of pride in his might did; but, be that as it may, the fact remains that Tarzan was wholly ignorant of the presence of that little knot of villainous bandits who were quite prepared to kill him, or anyone else, for a few poor weapons or for nothing at all.

The circumstances that brought Tarzan northward into Kaffa are not a part of this story. Perhaps they were not urgent, for the Lord of the Jungle loves to roam remote fastnesses still unspoiled by the devastating hand of civilization and needs but trifling incentive to do so. Still unsated with adventure, it may be that Abyssinia’s three hundred fifty thousand square miles of semisavagery held an irresistible lure for him in their suggestion of mysterious back country and in the ethnological secrets they have guarded from time immemorial.

Wanderer, adventurer, outcast, Greek phalanx, and Roman legion, all have entered Abyssinia within times chronicled in history or legend never to reappear; and it is even believed by some that she holds the secret of the lost tribes of Israel. What wonders, then, what adventures, might not her remote corners reveal!

At the moment, however, Tarzan’s mind was not occupied by thoughts of adventure; he did not know that it loomed threateningly behind him; his concern and his interest were centered upon the buck which he intended should satisfy the craving of his ravenous hunger. He crept cautiously forward. Than he, not even Sheeta, the leopard, stalks more silently or more stealthily.

From behind, the white-robed shiftas moved from the little rise where they had been watching him in silence, moved down toward him with spear and long-barreled matchlock. They were puzzled. Never before had they seen a white man like this one; but if curiosity were in their minds, there was only murder in their hearts.

The buck raised his head occasionally to glance about him, wary, suspicious; and when he did so, Tarzan froze into immobility. Suddenly the animal’s gaze centered for an instant upon something in the direction of the ape-man; then it wheeled and bounded away. Instantly Tarzan glanced behind him, for he knew that it had not been he who had frightened his quarry but something beyond and behind him that the alert eyes of Wappi had discovered; and that quick glance revealed a half dozen horsemen moving slowly toward him, told him what they were, and explained their purpose; for, knowing that they were shiftas, he knew that they came only to rob and kill—knew that here were enemies more ruthless than Numa.

When they saw that he had discovered them, the horsemen broke into a gallop and bore down upon him, waving their weapons and shouting. They did not fire, evidently holding in contempt this primitively armed victim, but seemed to purpose riding him down and trampling him beneath the hoofs of their horses or impaling him upon their spears. Perhaps they thought that he would seek safety in flight, thereby giving them the added thrill of the chase; and what quarry could give the hunter greater thrills than man!

But Tarzan did not turn and run. He knew every possible avenue of escape within the radius of his vision for every danger that might reasonably be expected to confront him here, for it is the business of the creatures of the wild to know these things if they are to survive; and so he knew that there was no escape from mounted men by flight. But this knowledge threw him into no panic. Could the requirements of self-preservation have been best achieved by flight, he would have fled; but as they could not, he adopted the alternative quite as a matter of course—he stood to fight, ready to seize upon any fortuitous circumstance that might offer a chance of escape.

Tall, magnificently proportioned, muscled more like Apollo than like Hercules, garbed only in a narrow G string of lion skin with a lion’s tail depending before and behind, he presented a splendid figure of primitive manhood that suggested more, perhaps, the demigod of the forest than it did man. Across his back hung his quiver of arrows and a light, short spear; the loose coils of his grass rope lay across one bronzed shoulder; at his hip swung the hunting knife of his father, the knife that had given the boy-Tarzan the first suggestion of his coming supremacy over the other beasts of the jungle on that far gone day when his youthful hand drove it into the heart of Bolgani, the gorilla; in his left hand was his bow and between the fingers four extra arrows.

As Ara, the lightning, so is Tarzan for swiftness. The instant that he had discovered and recognized the menace creeping upon him from behind and known that he had been seen by the horsemen he had leaped to his feet, and in the same instant strung his bow. Now, perhaps even before the leading shiftas realized the danger that confronted them, the bow was bent, the shaft sped.

Short but powerful was the bow of the ape-man; short, that it might be easily carried through the forest and the jungle; powerful, that it might send its shafts through the toughest hide to a vital organ of its prey. Such a bow was this that no ordinary man might bend it.

Straight through the heart of the leading shifta drove the first arrow, and as the fellow threw his arms above his head and lunged from his saddle four more arrows sped with lightninglike rapidity from the bow of the ape-man, and every arrow found a target. Another shifta dropped to ride no more, and three were wounded.

Only seconds had elapsed since Tarzan had discovered his danger, and already the four remaining horsemen were upon him. The three who were wounded were more interested in the feathered shafts protruding from their bodies than in the quarry they had expected so easily to overcome; but the fourth was whole, and he thundered down upon the ape-man with his spear set for the great bronzed chest.

There could be no retreat for Tarzan; there could be no side-stepping to avoid the thrust, for a step to either side would have carried him in front of one of the other horsemen. He had but a single slender hope for survival, and that hope, forlorn though it appeared, he seized upon with the celerity, strength, and agility that make Tarzan Tarzan. Slipping his bowstring about his neck after his final shot, he struck up the point of the menacing weapon of his antagonist, and grasping the man’s arm swung himself to the horse’s back behind the rider.

As steel-thewed fingers closed upon the shifta’s throat he voiced a single piercing scream; then a knife drove home beneath his left shoulder blade, and Tarzan hurled the body from the saddle. The terrified horse, running free with flying reins, tore through the bushes and the reeds into the river, while the remaining shiftas, disabled by their wounds, were glad to abandon the chase upon the bank, though one of them, retaining more vitality than his companions, did raise his matchlock and send a parting shot after the escaping quarry.

The river was a narrow, sluggish stream but deep in the channel; and as the horse plunged into it, Tarzan saw a commotion in the water a few yards downstream and then the outline of a long, sinuous body moving swiftly toward them. It was Gimla, the crocodile. The horse saw it too and, becoming frantic, turned upstream in an effort to escape. Tarzan climbed over the high cantle of the Abyssinian saddle and unslung his spear in the rather futile hope of holding the reptile at bay until his mount could reach the safety of the opposite bank toward which he was now attempting to guide him.

Gimla is as swift as he is voracious. He was already at the horse’s rump, with opened jaws, when the shifta at the river’s edge fired wildly at the ape-man. It was well for Tarzan that the wounded man had fired hurriedly; for simultaneously with the report of the firearm, the crocodile dove; and the frenzied lashing of the water about him evidenced the fact that he had been mortally wounded.

A moment later the horse that Tarzan rode reached the opposite bank and clambered to the safety of dry land. Now he was under control again; and the ape-man wheeled him about and sent a parting arrow across the river toward the angry, cursing bandits upon the opposite side, an arrow that found its mark in the thigh of the already wounded man who had unwittingly rescued Tarzan from a serious situation with the shot that had been intended to kill him.

To the accompaniment of a few wild and scattered shots, Tarzan of the Apes galloped toward a nearby forest into which he disappeared from the sight of the angry shiftas.

Far to the south a lion rose from his kill and walked majestically to the edge of a nearby river. He cast not so much as a single glance at the circle of hyenas and jackals that had ringed him and his kill waiting for him to depart and which had broken and retreated as he rose. Nor, when the hyenas rushed in to tear at what he had left, did he appear even to see them.

There were the pride and bearing of royalty in the mien of this mighty beast; and to add to his impressiveness were his great size, his yellow, almost golden, coat, and his great black mane. When he had drunk his fill, he lifted his massive head and voiced a roar, as is the habit of lions when they have fed and drunk; and the earth shook to his thunderous voice, and a hush fell upon the jungle.

Now he should have sought his lair and slept, to go forth again at night and kill; but he did not do so. He did not do at all what might have been expected of a lion under similar circumstances. He raised his head and sniffed the air, and then he put his nose to the ground and moved to and fro like a hunting dog searching for a game scent. Finally he halted and voiced a low roar; then, with head raised, he moved off along a trail that led toward the north. The hyenas were glad to see him go; so were the jackals, who wished that the hyenas would go also. Ska, the vulture, circling above, wished that they would all leave.

At about the same time, many marches to the north, three angry, wounded shiftas viewed their dead comrades and cursed the fate that had led them upon the trail of the strange white giant; then they stripped the clothing and weapons from their dead fellows and rode away, loudly vowing vengeance should they ever again come upon the author of their discomfiture and secretly hoping that they never would. They hoped that they were done with him, but they were not.

Shortly after he had entered the forest, Tarzan swung to an overhanging branch beneath which his mount was passing and let the animal go its way. The ape-man was angry; the shiftas had frightened away his dinner. That they had sought to kill him annoyed him far less than the fact that they had spoiled his hunting. Now he must commence his search for meat all over again, but when he had filled his belly he would look into this matter of shiftas. Of this he was certain.

Tarzan had considered the gastronomic potentialities of the bandit’s horse, but had discarded the idea. On several occasions in the past he had been forced to eat horse meat, but he had not liked it. Although he was hungry, he was far from famished; and so he preferred to hunt again until he found flesh more palatable, nor was it long before he had made his kill and eaten.

Satisfied, he lay up for a while in the crotch of a tree, but not for long. His active mind was considering the matter of the shiftas. Here was something that should be looked into. If the band were on the march, he need not concern himself about them; but if they were permanently located in this district, that was a different matter; for Tarzan expected to be here for some time; and it was well to know the nature, the number, and the location of all enemies. Furthermore, he felt that he could not let them escape without some additional punishment for the inconvenience they had caused him.

Returning to the river, Tarzan crossed it and took up the plain trail of the shiftas. It led him up and down across some low hills and then down into the narrow valley of the stream that he had crossed farther up. Here the floor of the valley was forested, the river winding through the wood. Into this wood the trail led.

It was almost dark now; the brief equatorial twilight was rapidly fading into night; the nocturnal life of the forest and the hills was awakening; from down among the deepening shadows of the valley came the coughing grunts of a hunting lion. Tarzan sniffed the warm air rising from the valley toward the mountains; it carried with it the odors of a camp and the scent spoor of man. He raised his head, and from his deep chest rumbled a full-throated roar. Tarzan of the Apes was hunting too.

In the gathering shadows he stood then erect and silent, a lonely figure standing in solitary grandeur upon that desolate hillside. Swiftly the silent night enveloped him; his figure merged with the darkness that made hill and valley, river and forest one. Not until then did Tarzan move; then he stepped down on silent feet toward the forest. Now was every sense alert, for now the great cats would be hunting. Often his sensitive nostrils quivered as they searched the air; no slightest sound escaped his keen ears.

As he advanced, the man scent became stronger, guiding his steps. Nearer and nearer sounded the deep cough of the lion; but of Numa Tarzan had little fear at present, knowing that the great cat, being up wind, could not be aware of his presence. Doubtless Numa had heard the ape-man’s roar, but he could not know that its author was approaching him.

Tarzan had estimated the lion’s distance down the valley and the distance that lay between himself and the forest and had guessed that he would reach the trees before their paths crossed. He was not hunting for Numa, the lion, and with the natural caution of the wild beast, he would avoid an encounter. It was not food either that he hunted, for his belly was full, but man, the archenemy of all created things.

It was difficult for Tarzan to think of himself as a man, and his psychology was more often that of the wild beast than the human, nor was he particularly proud of his species. While he appreciated the intellectual superiority of man over other creatures, he harbored contempt for him because he had wasted the greater part of his inheritance. To Tarzan, as to many other created things, contentment is the highest ultimate goal of achievement, and health and culture the principal avenues along which man may approach this goal. With scorn the ape-man viewed the overwhelming majority of mankind which was wanting in either one essential or the other, when not wanting in both. He saw the greed, the selfishness, the cowardice, and the cruelty of man; and, in view of man’s vaunted mentality, he knew that these characteristics placed man upon a lower spiritual scale than the beasts, while barring him eternally from the goal of contentment.

So now, as he sought the lair of the man-things, it was not in the spirit of one who seeks his own kind but of a beast which reconnoiters the position of an enemy. The mingled odors of a camp grew stronger in his nostrils, the scents of horses and men and food and smoke. To you or to me, alone in a savage wilderness, engulfed in darkness, cognizant of the near approach of a hunting lion, these odors would have been most welcome; but Tarzan’s reaction to them was that of the wild beast that knows man only as an enemy—his snarling muscles tensed as he smothered a low growl.

As Tarzan reached the edge of the forest the lion was but a short distance to his right and approaching; so the ape-man took to the trees, through which he swung silently toward the camp of the shiftas. Numa heard him then and roared, and the men in the camp threw more wood upon the beast fire.

To a tree overlooking the camp, Tarzan made his way. Below him he saw a band of some twenty men with their horses and equipment. A rude boma of branches and brush had been erected about the camp site as a partial protection against wild beasts, but more dependence was evidently placed upon the fire which they kept burning in the center of the camp.

In a single quick glance the ape-man took in the details of the scene below him, and then his eyes came to rest upon the only one that aroused either interest or curiosity, a white man who lay securely bound a short distance from the fire.

Ordinarily, Tarzan was no more concerned by the fate of a white man than by that of a black man or any other created thing to which he was not bound by ties of friendship; the life of a man meant less to Tarzan of the Apes than the life of an ape. But in this instance there were two factors that made the life of the captive a matter of interest to the lord of the jungle. First, and probably predominant, was his desire to be further avenged upon the shiftas for their wanton attack upon him, which had frightened away his intended kill; the second was curiosity, for the white man that lay bound below him was different from any that he had seen before, at least in so far as his apparel was concerned.

His only garment appeared to be a habergeon made up of ivory discs that partially overlay one another, unless certain ankle, wrist, neck, and head ornaments might have been considered to possess such utilitarian properties as to entitle them to a similar classification. Except for these, his arms and legs were naked. His head rested upon the ground with the face turned away from Tarzan so that the ape-man could not see his features but only that his hair was heavy and black.

As he watched the camp, seeking for some suggestion as to how he might most annoy or inconvenience the bandits, it occurred to Tarzan that a just reprisal would consist in taking from them something that they wanted, just as they had deprived him of the buck he had desired. Evidently they wished the prisoner very much or they would not have gone to the trouble of securing him so carefully; so this fact decided Tarzan to steal the white man from them. Perhaps curiosity also had a considerable part in inducing this decision, for the strange apparel of the prisoner had aroused within the ape-man a desire to know more concerning him.

To accomplish his design, he decided to wait until the camp slept; and settling himself comfortably in a crotch of the tree, he prepared to keep his vigil with the tireless patience of the hunting beast he was. As he watched, he saw several of the shiftas attempt to communicate with their prisoner; but it was evident that neither understood the other.

Tarzan was familiar with the language spoken by the Kafichos and Gallas, and the questions that they put to their prisoner aroused his curiosity still further. There was one question that they asked him in many different ways, in several dialects, and in signs which the captive either did not understand or pretended not to. Tarzan was inclined to believe that the latter was true, for the sign language was such that it could scarcely be misunderstood. They were asking him the way to a place where there was much ivory and gold, but they got no information from him.

“The pig understands us well enough,” growled one of the shiftas; “he is just pretending that he does not.”

“If he won’t tell us, what is the use of carrying him around with us and feeding him?” demanded another. “We might as well kill him now.”

“We will let him think it over tonight,” replied one who was evidently the leader, “and if he still refuses to speak in the morning, we will kill him then.”

This decision they attempted to transmit to the prisoner both by words and signs, and then they squatted about the fire and discussed the occurrences of the day and their plans for the future. The principal topic of their conversation was the strange white giant who had slain three of their number and escaped upon one of their horses; and after this had been debated thoroughly and in detail for some time, and the three survivors of the encounter had boasted severally of their deeds of valor, they withdrew to the rude shelters they had constructed and left the night to Tarzan, Numa, and a single sentry.

The silent watcher among the shadows of the tree waited on in patience until the camp should be sunk in deepest slumber and, waiting, planned the stroke that was to rob the shiftas of their prey and satisfy his own desire for revenge. As he patiently bided his time, there came strongly to his nostrils the scent spoor of Numa, the lion; and he guessed that the carnivore, attracted by the presence of the horses, was coming to investigate the camp. That he would enter it, he doubted, for the sentry was keeping the fire blazing brightly; and Numa seldom dares the fearful mystery of flames unless goaded by extreme hunger.

At last the ape-man felt that the time had come when he might translate his plan into action; all but the sentry were wrapped in slumber, and even he was dozing beside the fire. As noiselessly as the shadow of a shadow Tarzan descended from the tree, keeping well in the shadow cast by the beast fire.

For a moment he stood in silence, listening. He heard the breathing of Numa in the darkness beyond the circle of firelight, and knew that the king of beasts was near and watching. Then he looked from behind the great bole of the tree and saw that the sentry’s back was still turned toward him. Silently he moved into the open; stealthily, on soundless feet, he crept toward the unsuspecting bandit. He saw the matchlock across the fellow’s knees; and for it he had respect, as have all jungle animals that have been hunted.

Closer and closer he came to his prey. At last he crouched directly behind him. There must be no noise, no outcry. Tarzan waited. Beyond the rim of fire waited Numa, expectant, for he saw that very gradually the flames were diminishing. A bronzed hand shot quickly forward, fingers of steel gripped the brown throat of the sentry almost at the instant that a knife was driven from below his left shoulder blade into his heart. The sentry was dead without knowing that death threatened him, a merciful ending.

Tarzan withdrew the knife from the limp body and wiped the blade upon the once white robe of his victim; then he moved softly toward the prisoner who was lying in the open. For him, they had not bothered to build a shelter. As he made his way toward the man, Tarzan passed close to two of the shelters in which lay members of the band; but he made no noise that might awaken them. When he approached the captive more closely, he saw in the diminishing light of the fire that the man’s eyes were open and that he was regarding Tarzan with level, though questioning, gaze. The ape-man put a finger to his lips to enjoin silence, and then he came and knelt beside the man and cut the thongs that secured his wrists and ankles; then he helped him to his feet, for the thongs had been drawn tightly, and his legs were numb.

For a moment he waited while the stranger tested his feet and moved them rapidly in an effort to restore circulation; then he beckoned him to follow, and all would have been well but for Numa, the lion. At this moment, either to voice his anger against the flames or to terrify the horses into a stampede, he elected to voice a thunderous roar.

So close was the lion that the sudden shattering of the deep silence of the night startled every sleeper to wakefulness. A dozen men seized their matchlocks and leaped from their shelters. In the waning light of the fire they saw no lion; but they saw their liberated captive, and they saw Tarzan of the Apes standing beside him.

Among those who ran from the shelters was the least seriously wounded of Tarzan’s victims of the afternoon. Instantly recognizing the bronzed white giant, he shouted loudly to his companions, “It is he! It is the white demon who killed our friends today.”

“Kill him!” screamed another.

“Kill them both!” cried the leader of the shiftas.

Completely surrounding the two white men, the shiftas advanced upon them; but they dared not fire because of fear that they might wound one of their own comrades. Nor could Tarzan loose an arrow nor cast a spear, for he had left all his weapons except his rope and his knife hidden in the tree above the camp that he might move with the utmost freedom and in silence while seeking to liberate the captive.

One of the bandits, more courageous, probably because less intelligent, than his fellows, rushed to close quarters with musket clubbed. It was his undoing. The man-beast crouched, growling; and, as the other was almost upon him, charged. The musket butt, hurtling through the air to strike him down, he dodged; and then he seized the weapon and wrenched it from the shifta’s grasp as though it had been a toy in a child’s hands.

Tossing the matchlock at the feet of his companion, Tarzan laid hold upon the rash Galla, spun him around, and held him as a shield against the weapons of his fellows. But despite this reverse the other shiftas gave no indication of giving up the battle. They saw before them two men practically defenseless, and now with redoubled shouts they pushed closer.

Two of them rushed in behind the ape-man, for it was he they feared the more; but they were to learn that their former prisoner might not be considered lightly. He had picked up the musket that Tarzan had cast aside and, grasping it close to the muzzle, was using it as a club. The heavy butt struck the foremost bandit heavily upon the side of the head, dropping him like a felled ox; and as it swung again, the second bandit leaped back barely in time to avoid a similar fate.

A quick backward glance assured Tarzan that his companion was proving himself a worthy ally, but it was evident that they could not hope to hold out long against the superior numbers pitted against them. Their only hope, he believed, lay in making a sudden, concerted rush through the thin line of foemen surrounding them, and he sought to convey his plan to the man standing back to back with him; but though he spoke to him in English and in the several continental languages with which the ape-man was familiar the only reply he received was in a language that he himself had never before heard.

What was he to do? They must go together, and both must understand the purpose animating Tarzan. But how was that possible if they could not communicate with one another? Tarzan turned and touched the other lightly on the shoulder; then he jerked his thumb in the direction he intended going and beckoned with a nod of his head.

Instantly the man nodded his understanding and wheeled about as Tarzan started to charge, still bearing the struggling shifta in his grasp; but the shiftas were determined not to let these two escape; and while they could not fire for fear of killing their comrade, they stood their ground with clubbed muskets and with spears; so that the outcome looked dark indeed for the lord of the jungle and his companion.

Using the man in his grasp as a flail, Tarzan sought to mow down those standing between him and liberty; but there were many of them, and presently they succeeded in dragging their comrade from the clutches of the ape-man. Now it seemed that the situation of the two whites was hopeless, for there was no longer anything to prevent the bandits using their matchlocks to advantage. The shiftas were in such a transport of rage that nothing less than the extermination of these two foes would satisfy them; but Tarzan and the other pressed on so closely that the muskets were useless against them for the moment; though presently some of the shiftas withdrew a little to one side where they might have free use of their weapons.

One fellow in particular was well placed to fire without endangering any of his fellows, and raising his matchlock to his shoulder he took careful aim at Tarzan.

As the man raised his weapon to his shoulder to fire at Tarzan, a scream of warning burst from the lips of one of his comrades, to be drowned by the throaty roar of Numa, the lion, as the swift rush of his charge carried him over the boma into the midst of the camp.

The man who would have killed Tarzan cast a quick backward glance as the warning cry apprised him of his danger; and when he saw the lion he cast away his rifle in his excitement and terror, his terrified scream mingled with the voice of Numa, and in his anxiety to escape the fangs of the man-eater he rushed into the arms of the ape-man.

The lion, momentarily confused by the firelight and the swift movement and the shouts of the men, paused, crouching, as he looked to right and left. In that brief instant Tarzan seized the fleeing shifta, lifted him high above his head, and hurled him into the face of Numa; then, as the lion seized its prey and its great jaws closed upon the head and shoulder of the hapless bandit, he motioned to his companion to follow him, and, running directly past the lion, leaped the boma at the very point that Numa had leaped it. Close at his heels was the white captive of the shiftas, and before the bandits had recovered from the first shock and surprise of the lion’s unexpected charge the two had disappeared in the shadows of the night.

Just outside the camp Tarzan left his companion for a moment while he swung into the tree where he had left his weapons and recovered them; then he led the way out of the valley up into the hills. At his elbow trotted the silent white man he had rescued from certain death at the hands of the Kaficho and Galla bandits.

During the brief encounter in the camp Tarzan had noted with admiration the strength, agility, and courage of the stranger who had aroused both his interest and his curiosity. Here, seemingly, was a man moulded to the dimensions of Tarzan’s own standards, a quiet, resourceful, courageous fighting man. Radiating that intangible aura which we call personality, even in his silences he impressed the ape-man with a conviction that loyalty and dependability were innate characteristics of the man; so Tarzan, who ordinarily preferred to be alone, was not displeased to have the companionship of this stranger.

The moon, almost full, had risen above the black mountain mass to the east, shedding her soft light on hill and valley and forest, transforming the scene once more into that of a new world which was different from the world of daylight and from the world of moonless night, a world of strange greys and silvery greens.

Up toward a fringe of forest that clothed the upper slopes of the foothills and dipped down into canyon and ravine the two men moved as noiselessly as the passing shadow of a cloud, yet to one hidden in the dark recesses of the wood above, their approach was not unheralded, for on the breath of Usha, the wind, it was borne ahead of them to the cunning nostrils of the prince of hunters.

Sheeta, the panther, was hungry. For several days prey had been scarce and elusive. Now, in his nostrils, the scent of the man-things grew stronger as they drew nearer. It was the pure scent of man that came to him unvitiated by the hated odor of the flame-belching thunder stick that he feared and hated. Eagerly, Sheeta, the panther, awaited the coming of the men.

Within the forest, Tarzan sought a tree where they might lie up for the night. He had eaten and was not hungry. Whether or not his companion had eaten was his own concern. This was a law of the jungle from which Tarzan might deviate for a weak or wounded companion but not for a strong man able to provide for himself. Had he killed, he would have shared his kill; but he would not go forth and hunt for another.

Tarzan found a branch that forked horizontally. With his hunting knife he cut other branches and laid them across the two arms of the Y thus formed. Over this rude platform he spread leaves; and then he lay down to sleep, while from an adjacent tree up wind Sheeta watched him. Sheeta also watched the other man-thing on the ground between the two trees. The great cat did not move; he seemed scarcely to breathe. Even Tarzan was unaware of his presence, yet the ape-man was restless. A sense so delicate that he was not objectively aware of its existence seemed to warn him that all was not well. He listened intently and sniffed the air but detected nothing amiss. Below him, his companion was making his bed upon the ground in preference to risking the high-flung branches of the trees to which he was unaccustomed. It was the man upon the ground that Sheeta watched.

At last, his bed of leaves and grasses arranged to suit him, Tarzan’s companion lay down. Sheeta waited. Gradually, almost imperceptibly, the sinuous muscles were drawing the hind quarters forward beneath the sleek body in Preparation for the spring. Sheeta edged forward on the great limb upon which he crouched, but in doing so he caused the branch to move slightly and the leaves at its end to rustle just a little. Your ears or mine would not have been conscious of any noise, but the ears of Tarzan are not as are yours or mine.

He heard; and his eyes, turning quickly, sought and found the intruder. At the same instant Sheeta launched himself at the man lying on his rude pallet on the ground below; and as Sheeta sprang so did Tarzan. What happened happened very quickly; it was a matter of seconds only.

As the two beasts sprang, Tarzan voiced a roar that was intended both to warn his companion and to distract the attention of Sheeta from his prey. The man upon the ground leaped quickly to one side, prompted more by an instinctive reaction than by reason. The panther’s body brushed him as it struck the ground, but the beast’s thoughts were now upon the thing that had voiced that menacing roar rather than upon its intended prey.

Wheeling as he leaped aside, the man turned and saw the savage carnivore just as Tarzan landed full upon the beast’s back. He heard the mingled growls of the two as they closed in battle, and his scalp stiffened as he realized that the sounds coming from the lips of his companion were quite as bestial as those issuing from the throat of the carnivore.

Tarzan sought a hold about the neck of the panther, while the great cat instantly attempted to roll over on its back that it might rip the body of its antagonist to shreds with the terrible talons that armed its hind feet. But this strategy the ape-man had anticipated; and rolling beneath Sheeta as Sheeta rolled, he locked his powerful legs beneath the belly of the panther; then the great cat leaped to its feet again and sought to shake the man-thing from its back; and all the while a mighty arm was tightening about its neck, closing off its wind.

With frantic leaps and bounds the panther hurled itself about in the moonlight while Tarzan’s companion stood unarmed and helpless. Twice he had tried to run in and assist the ape-man, but both times the two bodies had struck him and sent him spinning across the ground. Now he saw a new factor being injected into the battle; Tarzan had succeeded in drawing his knife. Momentarily the blade flashed before his eyes; then it was buried in the body of Sheeta. The cat, screaming from pain and rage, redoubled its efforts to dislodge the creature clinging to it in the embrace of death; but again the knife fell.

Now Sheeta stood trembling upon uncertain feet as once again the knife was plunged deeply into his side; then, his great voice forever stilled, he sank lifeless to the ground as the ape-man rolled from beneath him and sprang to his feet.

The man whose life Tarzan had saved came forward and laid a hand upon the shoulder of the ape-man, speaking a few words in a low voice but in a tongue that Tarzan did not understand though he guessed that it expressed the gratitude that the manner of the man betokened.

What thoughts were in the mind of Tarzan’s companion? Twice within an hour this strange white man had saved him from death. For what reasons, the man could not guess. That sentiments of friendship and loyalty were aroused in his breast would seem only natural if he possessed either honor or gratitude, but of this we can have no knowledge until we know him better. As yet he is not even a name to us; and, following the policy of Tarzan, we shall not judge him until we know him better; then we may learn to like him, or we may have reason to despise him.

Influenced by the attack of the panther and knowing that Numa was abroad, Tarzan, by signs, persuaded the man to come up into the tree; and here the ape-man helped him construct a nest similar to his own. For the balance of the night they slept in peace, and the sun was an hour old before either stirred the following morning; then the ape-man rose and stretched himself.

Nearby, the other man sat up and looked about him. His eyes met Tarzan’s, and he smiled and nodded. For the first time the ape-man had an opportunity to examine his new acquaintance by daylight. The man had removed his single garment for the night, covering himself with leaves and branches. Now as he arose, his only garment was a G string, and Tarzan saw six feet of well-muscled, well-proportioned body topped by a head that seemed to bespeak breeding and intelligence. The man’s features were strong, clear cut, and harmoniously placed; the face was more noticeable for strength and rugged masculinity than for beauty.

The wild beast in Tarzan looked into the brown eyes of the stranger and was satisfied that here was one who might be trusted; the man in him noted the headband that confined the black hair, saw the strangely wrought ivory ornament in the center of the forehead, the habergeon that he was now donning, the ivory ornaments on wrists and ankles, and found his curiosity piqued.

The ivory ornament in the center of the headband was shaped like a concave, curved trowel, the point of which projected above the top of the man’s head and curved forward. His wristlets and anklets were of long flat strips of ivory laid close together and fastened around the limbs by leather thongs that were laced through holes piercing the strips near their tops and bottoms. His sandals were of heavy leather, apparently elephant hide, and were supported by leather thongs fastened to the bottoms of his anklets.

On each arm below the shoulder he wore an ivory disc upon which was carved a design; about his neck was a band of smaller ivory discs elaborately carved, and from the lowest of these a strap ran down to his habergeon, which was also supported by shoulder straps. Depending from each side of his headband was another ivory disc of large size, above which was a smaller disc. The larger discs covered his ears. Heavy, curved, wedge-shaped pieces of ivory were held, one upon each shoulder, by the same straps that supported his habergeon.

That all these trappings were solely for purposes of ornamentation Tarzan did not believe. He saw that almost without exception they would serve as a protection against a cutting weapon such as a sword or battle-ax; and he could not but wonder where the stalwart warrior who wore them had had his genesis, for nowhere in the world, so far as Tarzan knew, was there a race of men wearing armor and ornaments such as these.

But speculation concerning this matter was relegated to the background of his thoughts by hunger and recollection of the remains of yesterday’s kill that he had hung high in a tree of the forest farther up the river; so he dropped lightly to the ground, motioning the young warrior to follow him; and set off in the direction of his cache, keeping his keen senses always on the alert for enemies.

Cleverly hidden by leafy branches, the meat was intact when Tarzan reached it. He cut several strips and tossed them down to the warrior waiting on the ground below; then he cut some for himself and crouching in a crotch proceeded to eat it raw. His companion watched him for a moment in surprise; then he made fire with a bit of steel and flint and cooked his own portion.

As he ate, Tarzan’s active mind was considering plans for the future. He had come to Abyssinia for a specific purpose, though the matter was not of such immediate importance that it demanded instant attention. In fact, in the philosophy that a lifetime of primitive environment had inspired, time was not an important consideration. The phenomenon of this ivory-armored warrior aroused questions that intrigued his interest to a far greater extent than did the problems that had brought him thus far from his own stamping grounds, and he decided that the latter should wait the solving of the riddle of this seeming anachronism that his new-made acquaintance presented.

Having no other means of communication than signs rendered an exchange of ideas between the two difficult, but when they had finished their meal and Tarzan had descended to the ground he succeeded in asking his companion in what direction he wished to go. The warrior pointed in a northeasterly direction toward the high mountains; and, as plainly as he could through the medium of signs, invited Tarzan to accompany him to his country. This invitation Tarzan accepted and motioned the other to lead the way.

For days that stretched to weeks the two men struck deeper and deeper into the heart of a stupendous mountain system. Always mentally alert and eager to learn, Tarzan took advantage of the opportunity provided by time and propinquity to learn the language of his companion, and he proved such an apt pupil that they were soon able to make themselves understood to one another.

Among the first things that Tarzan learned was that his companion’s name was Valthor, while Valthor took the earliest opportunity to evince an interest in the ape-man’s weapons; and as he was unarmed, Tarzan spent a day in making a spear and bow and arrows for him. Thereafter, as Valthor taught the lord of the jungle to speak his language, Tarzan instructed the former in the use of the bow, the spear being already a familiar weapon to the young warrior.

Thus the days and the weeks passed and the two seemed no nearer the country of Valthor than when they had started from the vicinity of the camp of the shiftas. Tarzan found game of certain varieties plentiful in the mountains, and it was he who kept their larder supplied. The impressive scenery that was marked by rugged grandeur held the interest of the ape-man undiminished. He hunted, and he enjoyed the beauties of unspoiled nature, practically oblivious of the passage of time.

But Valthor was less patient; and at last, late one day when they found themselves at the head of a blind canyon where stupendous cliffs barred further progress, he admitted defeat. “I am lost,” he said simply.

“That,” remarked Tarzan, “I could have told you many days ago.”

Valthor looked at him in surprise. “How could you know that,” he demanded, “when you yourself do not know in what direction my country lies?”

“I know,” replied the ape-man, “because during the past week you have led the way toward the four points of the compass, and today we are within five miles of where we were a week ago. Across this ridge at our right, not more than five miles away, is the little stream where I killed the ibex and the gnarled old tree in which we slept that night just seven suns ago.”

Valthor scratched his head in perplexity, and then he smiled. “I cannot dispute you,” he admitted. “Perhaps you are right, but what are we going to do?”

“Do you know in what direction your country lies from the camp in which I found you?” asked Tarzan.

“Thenar is due east of that point,” replied Valthor; “of that I am positive.”

“Then we are directly southwest of it now, for we have travelled a considerable distance toward the south since we entered the higher mountains. If your country lies in these mountains then it should not be difficult to find it if we can keep moving always in a northeasterly direction.”

“This jumble of mountains with their twisting canyons and gorges confuses me,” Valthor admitted. “You see, in all my life before I have never been farther from Thenar than the valley of Onthar, and both these valleys are surrounded by landmarks with which I am so familiar that I need no other guides. It has never been necessary for me to consult the positions of the sun, the moon, nor the stars before; and so they have been of no help to me since we set out in search of Thenar. Do you believe that you could hold a course toward the northeast in this maze of mountains? If you can, then you had better lead the way rather than I.”

“I can go toward the northeast,” Tarzan assured him, “but I cannot find your country unless it lies in my path.”

“If we reach a point within fifty or a hundred miles of it, from some high eminence we shall see Xarator,” explained Valthor; “and then I shall know my way to Thenar, for Xarator is almost due west of Athne.”

“What are Xarator and Athne?” demanded Tarzan.

“Xarator is a great peak the center of which is filled with fire and molten rock. It lies at the north end of the valley of Onthar and belongs to the men of Cathne, the city of gold. Athne, the city of ivory, is the city from which I come. The men of Cathne, in the valley of Onthar, are the enemies of my people.”

“Tomorrow, then,” said Tarzan, “we shall set out for the city of Athne in the valley of Thenar.”

As Tarzan and Valthor ate meat that they had cut from yesterday’s kill and carried with them, many weary miles to the south a black-maned lion lashed his tail angrily and voiced a savage growl as he stood over the body of a buffalo calf he had killed and faced an angry bull pawing the earth and bellowing a few yards away.

Rare is the beast that will face Gorgo, the buffalo, when rage inflames his red-rimmed eyes; but the great lion showed no intention of leaving its prey even in the face of the bull’s threatened charge. He stood his ground. The roars of the lion and the bull mingled in a savage, thunderous dissonance that shook the ground, stilling the voices of the lesser people of the jungle.

Gorgo gored the earth, working himself into a frenzy of rage. Behind him, bellowing, stood the mother of the slain calf. Perhaps she was urging her lord and master to avenge the murder. The other members of the herd had bolted into the thickest of the jungle leaving these two to contest with Numa his right to his kill, leaving vengeance to those powerful horns backed by that massive neck.

With a celerity and agility that belied his great weight, the bull charged. That two such huge beasts could move so quickly and so lightly seemed incredible, as it seemed incredible that any creature could either withstand or avoid the menace of those mighty horns; but the lion was ready, and as the bull was almost upon him, he leaped to one side, reared upon his hind feet and with one massive, taloned paw struck the bull a terrific blow on the side of its head that wheeled it half around and sent it stumbling to its knees, half stunned and bleeding, its great jawbone crushed and splintered. And before Gorgo could regain his feet, Numa leaped full upon his back, buried his teeth in the bulging muscles of the great neck, and with one paw reached for the nose of the bellowing bull, jerking the head back with a mighty surge that snapped the vertebrae.

Instantly the lion was on his feet again facing the cow, but she did not charge. Instead, bellowing, she crashed away into the jungle leaving the king of beasts standing with his forefeet upon his latest kill.

That night Numa fed well; but when he had gorged himself he did not lie up as a lion should, but continued toward the north along the mysterious trail he had been following for many days.

The new day dawned cloudy and threatening. The season of rains was over, but it appeared that a belated storm was gathering above the lofty peaks through which Tarzan and Valthor were searching for the elusive valley of Thenar. The chill of night was dissipated by no kindly warmth of sunlight. The two men shivered as they rose from their rude beds among the branches of a tree.

“We shall eat later,” announced Tarzan, “after a little climbing has put warmth into our blood.”

“If we are lucky enough to find anything to eat,” rejoined Valthor.

“Tarzan seldom goes hungry,” replied the ape-man. “He will not go hungry today. When Tarzan is ready to hunt, we shall eat.”

Down the box canyon they went until Tarzan found a place where they might ascend the precipitous side wall; then they toiled upward, the warrior from Athne confident that each step would be his last as he clung to the steep face of the canyon wall but too proud to reveal his fear to the agile ape-man climbing so easily above him. But he did not fall, and at last the two stood upon the summit of a mighty ridge that led upward toward lofty peaks.

Valthor’s heart was pounding and he was breathing heavily, but Tarzan showed no sign of exertion. He was about to continue on up the ridge, when he glanced at his companion and saw his condition; then he squatted on the ground with a laconic “Rest now”; and Valthor was glad to rest.

All day they moved toward the northeast. Sometimes it rained a little, and always it threatened to rain more. A great storm seemed always to be gathering, yet it never broke during the long day. Tarzan made a kill before noon, and they ate; but immediately afterward they started on again. The cold, damp, sunless air offered them no incentive for tarrying on the way.

It was late in the afternoon when they ascended out of a deep gorge and stood upon a lofty plateau. In the near foreground were no mountains, but at a distance lofty peaks were visible dimly through a light drizzle of rain. Suddenly Valthor voiced an exclamation of elation. “We have found it!” he cried. “There is Xarator!”

Tarzan looked in the direction that the other pointed and saw a mighty, flat-topped peak in the distance, directly above which low clouds were reflecting a dull red light. “So that is Xarator!” he remarked. “And Thenar is directly east of it?”

“Yes,” replied Valthor; “which means that Onthar must be just below the edge of this plateau, almost directly in front of us. Come!”

The two walked quickly over the level, grassy ground for a mile or two to come at length to the edge of the plateau beyond which, and below them, stretched a wide valley.

“We are almost at the southern end of Onthar,” said Valthor. “There is Cathne, the city of gold. See it—in the bend of the river at this end of that forest? It is a rich city, but its people are the enemies of my people.”

Through the rain, Tarzan saw a walled city between a forest and a river. The houses were nearly all white, and there were many domes of dull yellow. The river, which ran between them and the city, was spanned by a bridge that was also a dull yellow color in the twilight of the late afternoon storm. Tarzan saw that the river extended the full length of the valley, a distance of fourteen or fifteen miles, being fed by smaller streams coming down out of the mountains. Also extending the length of the valley was what appeared to be a well-marked road. Near the center of the valley it branched, one fork following an affluent of the main stream with which it disappeared into the mouth of a canyon on the eastern side of the valley. Directly below them and extending to the northern extremity of Onthar was a level plain dotted with trees; across the river, a forest stretched from the farther bank to the steep hills that bounded Onthar on the east and southeast.

Tarzan’s eyes wandered back to the city of Cathne. “Why do you call it the city of gold?” he asked.

“Do you not see the golden domes and the bridge of gold?” demanded Valthor.

“Are they covered with gold paint?” inquired Tarzan.

“They are covered with solid gold,” replied Valthor. “The gold on some of the domes is an inch thick, and the bridge is built of solid blocks of gold.”

Tarzan lifted his eyebrows. As he looked down upon this seemingly deserted and peaceful valley he could not but conjure another picture—a picture of what it would be if word of these vast riches were carried to the outside world, bringing the kindly beneficences of modern civilization and civilized men to Onthar. How the valley would hum and roar then with the sweet music of mill and factory! What a gorgeous spectacle would be painted against the African sky by tall chimneys spouting black smoke to hang like a sable curtain above the golden domes of Cathne!

“Where do they find their gold?” he asked.

“Their mines lie in the hills directly south of the city,” replied Valthor.

“And where is your country, Thenar?” asked the ape-man.

“Just beyond the hills east of Onthar. Do you see where the river and the road cut through the forest about five miles above the city? You can see them entering the hills just beyond the forest.”

“Yes,” replied Tarzan; “I see.”

“The road and the river run through the Pass of the Warriors into the valley of Thenar; a little northeast of the center of the valley lies Athne, the city of ivory; there, beyond the pass, is my country.”

“How far are we from Athne?” inquired Tarzan.

“About twenty-five miles, possibly a little less,” replied Valthor.

“We might as well start now, then,” suggested the ape-man, “for in this rain it will be more comfortable to be on the march than to lie up until morning; and in your city we can find a dry place to sleep I presume.”

“Certainly,” replied Valthor, “but it will not be safe to attempt to cross Onthar by daylight. We should certainly be seen by the sentries on the gates of Cathne, and as these people are our enemies the chances are that we should never cross the valley without being either killed or taken prisoners. It will be bad enough at night on account of the lions, but by day it will be infinitely worse as we shall have both men and lions to contend with.”

“What lions?” demanded Tarzan.

“The men of Cathne breed lions, and there are many at large in the valley,” explained Valthor. “That great plain that you see below us, stretching the full length of the valley on this side of the river, is called the Field of the Lions. We shall be safer if we cross it after dark.”

“Whatever you wish,” agreed Tarzan with a shrug; “it is all the same to me if we start now or wait until dark.”

“It is not very comfortable here,” remarked the Athnean. “The rain is cold.”

“I have been uncomfortable before,” replied Tarzan; “rains do not last forever.”

“If we were in Athne we should be very comfortable,” sighed Valthor. “In my father’s house there are fireplaces; even now the flames are roaring about great logs, and all is warmth and comfort.”

“Above the clouds the sun is shining,” replied Tarzan, “but we are not above the clouds; we are here where the sun is not shining and there is no fire, and we are cold.” A faint smile touched his lips. “It does not warm me to speak of fires or the sun.”

“Nevertheless, I wish I were in Athne,” insisted Valthor. “It is a splendid city, and Thenar is a lovely valley. In Thenar we raise goats and sheep and elephants. In Thenar there are no lions except those that stray in from Onthar; those we kill. Our farmers raise vegetables and fruits and hay; our artizans manufacture leather goods; they make cloth from the hair of goats and the wool of sheep; our carvers work in ivory and wood.

“We trade a little with the outside world, paying for what we buy with ivory and gold. Were it not for the Cathneans we should lead a happy, peaceful life without a care.”

“What do you buy from the outside world, and of whom do you buy it?” asked Tarzan.

“We buy salt, of which we have none of our own,” explained Valthor. “We also buy steel for our weapons and black slaves and occasionally a white woman, if she be young and pretty. These things we buy from a band of shiftas. With this same band we have traded since before the memory of man. Shifta chiefs and kings of Athne have come and gone, but our relations with this band have never altered. I was searching for them when I became lost and was captured by another band.”

“Do you never trade with the people of Cathne?” asked the ape-man.

“Once each year there is a week’s truce during which we trade with them in peace. They give us gold and foodstuffs and hay in exchange for the women, the salt, and the steel we buy from the shiftas, and the cloth, leather, and ivory that we produce.

“Besides mining gold, the Cathneans breed lions for war and sport, raise fruits, vegetables, cereals, and hay and work in gold and, to a lesser extent, in ivory. Their gold and their hay are the products most valuable to us; and of these we value the hay more, for without it we should have to decrease our elephant herds.”

“Why should two peoples so dependent upon one another fight?” asked Tarzan.

Valthor shrugged. “I do not know; perhaps it is just a custom. Yet, though we talk much of wanting peace, we should miss the thrills and excitement that peace does not hold.” His eyes brightened. “The raids!” he exclaimed. “There is a sport for men! The Cathneans come with their lions to hunt our goats, our sheep, our elephants, and us. They take heads for trophies, and above all they value the head of man. They try to take our women, and when they succeed then there is war, if the family of the woman seized be of sufficient importance.

“When we wish sport we go into Onthar after gold and women or just for the sport of killing men or capturing slaves. The greatest game of all is to sell a woman to a Cathnean for much gold and then take her away from him in a raid. No, I do not think that either we or the Cathneans would care for peace.”

As Valthor talked, the invisible sun sank lower into the west; heavy clouds, dark and ominous, hid the peaks to the north, settling low over the upper end of the valley. “I think we may start now,” he said; “it will soon be dark.”

Downward through a gully, the sides of which hid them from the city of Cathne, the two men made their way toward the floor of the valley. From the heavy storm clouds burst a flash of lightning followed by the roar of thunder; upon the upper end of the valley the storm god loosed his wrath; water fell in a deluge of masses wiping from their sight the hills beyond the storm.

By the time they reached level ground the storm was upon them and the gully they had descended a raging mountain torrent. The swift night had fallen; utter darkness surrounded them, darkness frequently broken by vivid flashes of lightning. The pealing of the constant thunder was deafening. The rain engulfed them in solid sheets like the waves of the ocean. It was, perhaps, the most terrific storm that either of these men had ever seen.

They could not converse; only the lightning prevented their becoming separated, as it alone permitted Valthor to keep his course across the grassy floor of the valley in the direction of the city of gold where they would find the road that led to the Pass of the Warriors and on into the valley of Thenar.

Presently they came within sight of the lights of the city, a few dim lights framed by the casements of windows; and a moment later they were on the road and were moving northward against the full fury of the storm. And such a storm! As they moved toward its center it grew in intensity; against the wind that accompanied it they waged a grim battle that was sometimes to them and sometimes to the wind, for often it stopped them in their tracks and forced them back.

For miles they pitted their muscles against the Herculean strength of the storm god; and the rage of the storm god seemed to rise against them, knowing no bounds, as though he was furious that these two puny mortals should pit their strength against his. Suddenly, as though in a last titanic effort to overcome them, the lightning burst into a mighty blaze that illuminated the entire valley for seconds, the thunder crashed as it had never crashed before, and a mass of water fell that crushed the two men to earth.

As they staggered to their feet again foot-deep water swirled about their legs; they stood in a broad, racing torrent that rushed past them toward the river; but in that last effort the storm god had spent his force. The rain ceased; through a rift in the dark clouds the moon looked down, perhaps in wonder, upon a drowned world; and Valthor led the way again toward the Pass of the Warriors. The last storm of the rainy season was over.

It is seven miles from the Bridge of Gold, that is the gateway to the city of Cathne, to the ford where the road to Thenar crosses the river; and it required three hours for Valthor and Tarzan to cover the distance, two hours for the first third and one hour for the remainder; but at last they stood at the river’s brink.

A boiling flood confronted them, tearing down a widened river toward the city of Cathne. Valthor hesitated. “Ordinarily,” he said to Tarzan, “the water is little more than a foot deep. It must be three feet deep now.”

“And it will soon be deeper,” commented the ape-man. “Only a small portion of the storm waters have had time to reach this point from the hills and the upper valley. If we are going to cross tonight, we shall have to do it now.”

“Very well,” replied Valthor, “but follow me; I know the ford.”

As the Athnean stepped into the water the clouds closed again beneath the moon and plunged the world once more into darkness. As Tarzan followed he could scarcely see his guide ahead of him; and as Valthor knew the ford he moved more rapidly than the ape-man with the result that presently Tarzan could not see him at all, but he felt his way toward the opposite bank without thought of disaster.

The force of the stream was mighty; but mighty, too, are the thews of Tarzan of the Apes. The water, which Valthor had thought to be three feet in depth, was soon surging to the ape-man’s waist, and then he missed the ford and stepped into a hole. Instantly the current seized him and swept him away; not even the giant muscles of Tarzan could cope with the might of the flood.

The lord of the jungle fought the swirling waters in an effort to reach the opposite shore, but in their embrace he was powerless. Was the storm god proud or resentful to see one of his children succeed where he had failed? That is a difficult question to answer; for gods are strange creatures; they give to those who have and take from those who have not; they punish whom they love and are jealous and resentful; in which they resemble the creatures who conceived them.

Finding even his great strength powerless and weakening, Tarzan gave up the struggle to reach the opposite bank and devoted his efforts to keeping his nose above the surface of the angry flood. Even this was none too easy of accomplishment, as the rushing waters had a trick of twisting him about or turning him over. Often his head was submerged, and sometimes he floated feet first and sometimes head first; but he tried to rest his muscles as best he could against the time when some vagary of the torrent might carry him within reach of the bank upon one side or the other.

He knew that several miles below the city of Cathne the river entered a narrow gorge, for that he had seen from the edge of the plateau from which he had first viewed the valley of Onthar; and Valthor had told him that beyond the gorge it tumbled in a mighty falls a hundred feet to the bottom of a rocky canyon. Should he not succeed in escaping the clutches of the torrent before it carried him into the gorge his doom was sealed, but Tarzan felt neither fear nor panic. His life had been in jeopardy often during his savage existence, yet he still lived.

He wondered what had become of Valthor. Perhaps he, too, was being hurtled along either above or below him. But such was not the fact. Valthor had reached the opposite bank in safety and waited there for Tarzan. When the ape-man did not appear within a reasonable time, the Athnean shouted his name aloud; but though he received no answer he was still not sure that Tarzan was not upon the opposite side of the river, the loud roaring of which might have drowned the sound of the voice of either.

Then Valthor decided to wait until daylight, rather than abandon his friend in a country with which he was entirely unfamiliar. That the Athnean remained bespoke his loyalty as well as the high esteem in which he held the ape-man, for the dangers that might beset Tarzan in Onthar would prove even a greater menace to Valthor, an hereditary enemy of the Cathneans.

Through the long night he waited and, with the coming of dawn, eagerly scanned the opposite bank of the river, his slender hope for the safety of his friend dying when daylight failed to reveal any sign of him. Then, at last, he was convinced that Tarzan had been swept away to his death by the raging flood; and, with a heavy heart, he turned away from the river and resumed his interrupted journey toward the Pass of the Warriors and the Valley of Thenar.

As Tarzan battled for his life in the swirling waters of the swollen river he lost all sense of time; the seemingly interminable struggle against death might have been enduring without beginning, might endure without end, in so far as his numbed senses were concerned. His efforts to delay the apparently inevitable end were now purely mechanical, instinctive reactions to the threat against self-preservation. The cold water had sapped the vitality of his mind as well as of his body, yet, while his heart beat, neither would admit defeat; subconsciously, without active volition, they sought to preserve him. It was well that they did.

Turnings in the river cast him occasionally against one shore and then the other. Always, then, his hands reached up in an attempt to grasp something that might stay his mad rush toward the falls and death; and at last success crowned their efforts—his fingers closed upon the stem of a heavy vine that trailed down the bank into the swirling waters, closed and held.

Instantly, almost miraculously, new life seemed to be instilled into the veins of the ape-man by the feel of that stout support in his grasp. Quickly he seized it with both hands; the river clutched at his body and tried to drag it onward toward its doom; but the vine held, and so did Tarzan.

Hand over hand the man dragged himself out of the water and onto the bank, where he lay for several minutes; then he rose slowly to his feet, shook himself like some great lion, and looked about him in the darkness, trying to penetrate the impenetrable night. Faintly, as through shrubbery, he thought that he saw a light shining dimly in the distance. Where there was a light, there should be men. Tarzan moved cautiously forward to investigate.

He knew that he had crossed the river but that he was a long distance from the point at which he had entered it. He wondered what had become of Valthor; and determined, after he had investigated the light, to start up the river in search of him; even though he feared that his companion had been swept away by the flood, as he had.

But a few steps from the river Tarzan encountered a wall, and when he was close to the wall he could no longer see the light. Reaching upward, he discovered that the top of the wall was still above the tips of his outstretched fingers; but walls which were made to keep one out also invited one to climb them. The ape-man, filled with the curiosity of the beast, desired now more than ever to investigate the light he had seen.

Stepping back a few paces, he ran toward the wall and sprang upward. His extended fingers gripped the top of the wall and clung there. Slowly he drew himself up, threw a leg across the capstones, and looked to see what might be seen upon the opposite side of the wall.

He did not see much; a square of dim light forty or fifty feet away; that was all, and it did not satisfy his curiosity. Silently he lowered himself to the ground upon the same side as the light and moved cautiously forward. Beneath his bare feet he felt stone flagging, and guessed that he was in a paved courtyard.

He had crossed about half the distance to the light when the retreating storm flashed a farewell bolt from the distance. This distant lightning but barely sufficed to momentarily relieve the darkness surrounding the ape-man, revealing a low building, a lighted window, a deeply recessed doorway in the shelter of which stood a man. It also revealed Tarzan to the man in the doorway.

Instantly the silence was shattered by the brazen clatter of a gong. The door swung open, and men bearing torches rushed out. Tarzan, impelled by the natural caution of the beast, turned to run; but as he did so, he saw other open doors upon his flanks; and armed men with torches were rushing from these as well.

Realizing that flight was useless, Tarzan stood still with folded arms as the men converged upon him from three directions. Perhaps his insatiate curiosity prompted him to await quietly the coming of the men as much as a realization of the futility of flight. Tarzan wanted to see what the men were like and what they would do. He knew that he must be in the city of gold, and his imagination was inflamed. If they threatened him, he could still fight; if they imprisoned him, he could escape; so, at least, thought Tarzan, whose self-confidence was in proportion to his great size and his giant strength.

The torches carried by some of the men showed Tarzan that he was in a paved, quadrangular courtyard enclosed by buildings upon three sides and the wall he had scaled upon the fourth. Their light also revealed the fact that he was being surrounded by some fifty men armed with spears, the points of which were directed toward him in a menacing circle.

“Who are you?” demanded one of the men as the cordon drew tightly about him. The language in which the man spoke was the same as that which Tarzan had learned from Valthor, the common language of the enemy cities of Athne and Cathne.

“I am a stranger from a country far to the south,” replied the ape-man.

“What are you doing inside the walls of the palace of Nemone?” The speaker’s voice was threatening, his tone accusatory. Tarzan sensed that the presence of a stranger here was a crime in itself; but this made the situation all the more interesting; while the name, Nemone, possessed a quality that fired his interest.

“I was crossing the river far above here when the flood caught me and swept me down; it was only by chance that I finally made a landing here.”

The man who had been questioning him shrugged. “Well,” he admitted, “it is not for me to question you anyway. Come! You will have a chance to tell your story to an officer; but he will not believe it either.”

As the men conducted Tarzan toward one of the buildings, he thought that they seemed more curious than hostile. It was evident, however, that they were only common warriors without responsibility and that he might find the attitude of the officer class entirely different.

They conducted him into a large, low-ceilinged room which was furnished with rough benches and tables; upon the walls hung weapons, spears and swords; and there were shields of elephant hide studded with gold bosses. But there were other things in this strange room that compelled the interest of the ape-man far more than did the weapons and the shields; upon the walls were mounted the heads of animals; there were the heads of sheep and goats and lions and elephants. Among these, sinister and forbidding, were the scowling heads of men. The sight of them reminded Tarzan of the stories Valthor had told him of these men of Cathne.

Two men guarded Tarzan in one corner of the room, while another was dispatched to notify a superior of the capture; the remainder loafed about the room, talking, playing games, cleaning their weapons. The prisoner took the opportunity to examine his captors.

They were well set up men, many of them not ill-favored, though for the most part of ignorant and brutal appearance. Their helmets, habergeons, wristlets, and anklets were of elephant hide heavily embossed with gold studs. Long hair from the manes of lions fringed the tops of their anklets and wristlets and was also used for ornamental purposes along the crests of their helmets and upon some of their shields and weapons. The elephant hide that composed their habergeons was cut into discs, and the habergeon fabricated in a manner similar to that one of ivory which Valthor had worn. In the center of each shield was a heavy boss of solid gold. Upon the harnesses and weapons of these common soldiers was a fortune in the precious metal.