* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Trapped in the Jungle!

Date of first publication: 1945

Author: Frederick Sadleir Brereton (1872-1957)

Date first posted: Jan. 23, 2021

Date last updated: Jan. 23, 2021

Faded Page eBook #20210161

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, John Routh & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

TRAPPED IN THE JUNGLE!

By

Lt.-Col. F. S. BRERETON, C.B.E.

Illustrated by

VERNON SOPER

HOLLIS AND CARTER LTD.

25 ASHLEY PLACE

LONDON

S.W.1

First published in 1945

Printed by Jarrold & Sons, Ltd., Norwich

Trapped in the Jungle!

Mystery floats across the broad bosom of the gigantic reaches of the Pacific Ocean. But it would be safe to say that no greater mystery was ever presented to the wondering eyes of man than that which suddenly and unexpectedly raised its head at dawn of day on a certain December morn in the year of grace 1941.

A white yacht floated, as yet a mere misty shape, for the day had not yet broken, though an eastern glow heralded the coming morn. She rolled and wallowed gently from side to side, heaving as the vast ocean lifted and fell. She might have been a living thing, still asleep under the disappearing stars, yet stirring from her all-night slumber, slowly awakening to greet the rising sun.

And as the eastern glow—a purple mist it appeared—broadened and brightened, changing from purple to golden-orange, banishing the inky blackness of a tropic night which had been relieved by such glimmering from the stars as is to be seen only in far eastern places, she seemed to awaken into life, to throw off all lassitude, to rub her shapely eyes as it were, and to start into active life. She surged forward, propelled by a strong puff of wind which filled the tiny foresail under which alone she had passed the hours of darkness.

There were figures on her deck, a tall man, whose athletic frame became clearer as the light brightened, two youths, one unusually tall, and a native boy of as yet uncertain nationality. All but the native were clad in swimming-trunks and stood at the rail waiting to take their usual morning plunge.

It was at that precise moment, when dawn swept the ocean with that same suddenness with which darkness falls in the tropics, that this mysterious affair happened. Not a ship was in sight. The myriad coral islets which stud the wide Pacific, with their waving palms and their still lagoons flashing beneath the sun, were far away, many of them hundreds of miles. Honolulu, dream island of this ocean, home of the Pacific fleet and chief garrison of the United States in those waters, was too far distant to be seen. There were three smudges of smoke on the far horizon which probably denoted ships, and it seemed that birds of unusual size were hovering and darting to and fro in that direction. But there was no sound, save for the gentle lap of water soughing against the sides of the yacht and the two succeeding splashes as the two youths dived into the ocean.

A great ugly shape reared itself as if it were some marine monster, and rose beside the yacht, the swirl it made rocking the vessel. First appeared a periscope, through which no doubt the submarine commander had kept the yacht under observation. Then the conning-tower heaved above the surface, followed by the long deck from which a flood cascaded. There was the sound of some metal latch being operated. A dome-shaped hood swung upward, and in a few moments a swarm of dusky, stocky figures tumbled out and stood at attention on the deck.

At that moment, too, a swarthy figure erected itself behind the rail of the conning-tower and shouted a sharp order. Instantly a grappling-iron or some similar sort of instrument was heaved across the narrow space separating the two vessels, and as the tall man aboard the yacht gaped and gasped and the native cowered, the yacht was dragged to the side of the submarine. The crew boarded her as another sharp order was given, and in a trice the tall man, owner of the yacht perhaps, was seized and hurried across the deck and was dragged aboard this pirate underwater vessel.

It was an astounding affair. The two young fellows who had plunged into the sea for their usual morning swim hardly grasped the situation. Indeed, it was difficult to believe that anything out of the ordinary had happened, or even could have happened. For the yacht was there, as trim and neat and graceful as ever. The figure of the native servant could be seen. Only the owner of the craft had disappeared, while beside the vessel floated the ugly form of a submarine.

“Wa-al, I never!”

“What’s—it’s a sub,” gasped the other youth, shaking the water from his eyes.

“You’ve said it,” came the drawled response. “A sub. A Jap sub.”

“But—I say, what have they done to Mr. Baines? This is a hold-up.”

“That fellow,” shouted the one who had first spluttered his astonishment. “Look at him on the bridge. The son of a gun!”

The swarthy officer who had shouted his orders reared his head again above the rail of the conning-tower and waved. An order again snapped from his lips, while the members of the crew who had swarmed aboard the yacht and had abducted the owner, hustled him to the conning-tower and then forced him to descend into the interior of the vessel. Three of the crew leaped the space between the two ships and dived into the interior of the yacht. A minute later they came racing on deck again and once more gained the deck of the submarine.

“It is done,” the leader reported. “The bomb is placed and the fuse lighted. In less than five minutes the yacht will disappear.”

An electric hooter screeched. Men of the submarine still on her deck swarmed into the conning-tower and disappeared. A solitary figure remained for only a few seconds, sweeping the surface of the ocean to make sure that he was not observed. His gaze fell on the two bobbing heads just beyond the yacht and his right hand felt for the revolver at his hip.

“In less than two minutes,” called his junior. “Perhaps——”

Casting a last swift and malicious glance at the two youths treading water within so few feet of him, the commander of this pirate submarine waved to them ironically. Then he dived into the interior of his vessel. The hood clanked to with a resounding bang, and within a few moments the subdued sound of a motor broke the silence. The smooth waters of the Pacific were churned into foam at the after end of the submarine, and gathering way with incredible speed, she suddenly dived, her slippery deck dipped beneath the surface, her conning-tower disappeared in fantastic fashion, and in a trice even the periscope had been swallowed.

“Of all the cheek,” growled one of the youths, he of the drawling, American voice.

“It’s a kidnapping affair,” gasped his companion. “A Jap submarine commander seizes the person of a prominent and wealthy American citizen, and in peace-time, mark you.”

“Peace-time!” spluttered the other. “Peace-time, eh? You say that! Why America and Japan are on the very edge of war. It might happen to-morrow.”

“Watch Chu,” shouted his friend, and then choked and coughed to get rid of the flood of salt water which had filled his mouth.

They saw the only remaining figure aboard the yacht racing towards the stern. He bent low and disappeared below the shelter of the rail. Then he appeared again, and springing on to the rail took a header into the sea. It was all too astonishing. The sudden appearance of that sinister submarine, the abduction of the owner of the yacht, and the equally precipitate disappearance of this Japanese pirate—for Japanese she was without a doubt—would provide subject for gossip and even for heated debate for days to come. But Chu was adding to the mystery. This Chinese “boy,” boon companion of the two young fellows paddling to keep their heads above the swelling surface of the immense Pacific, was abandoning the ship.

“Why?” demanded one of the swimmers.

“Why? Wa-al—Now—say David, that gets me.”

“Saw him cutting the dinghy loose,” cried the other, trying to lift himself higher out of the water so as to obtain a better view of his surroundings. “Perhaps——”

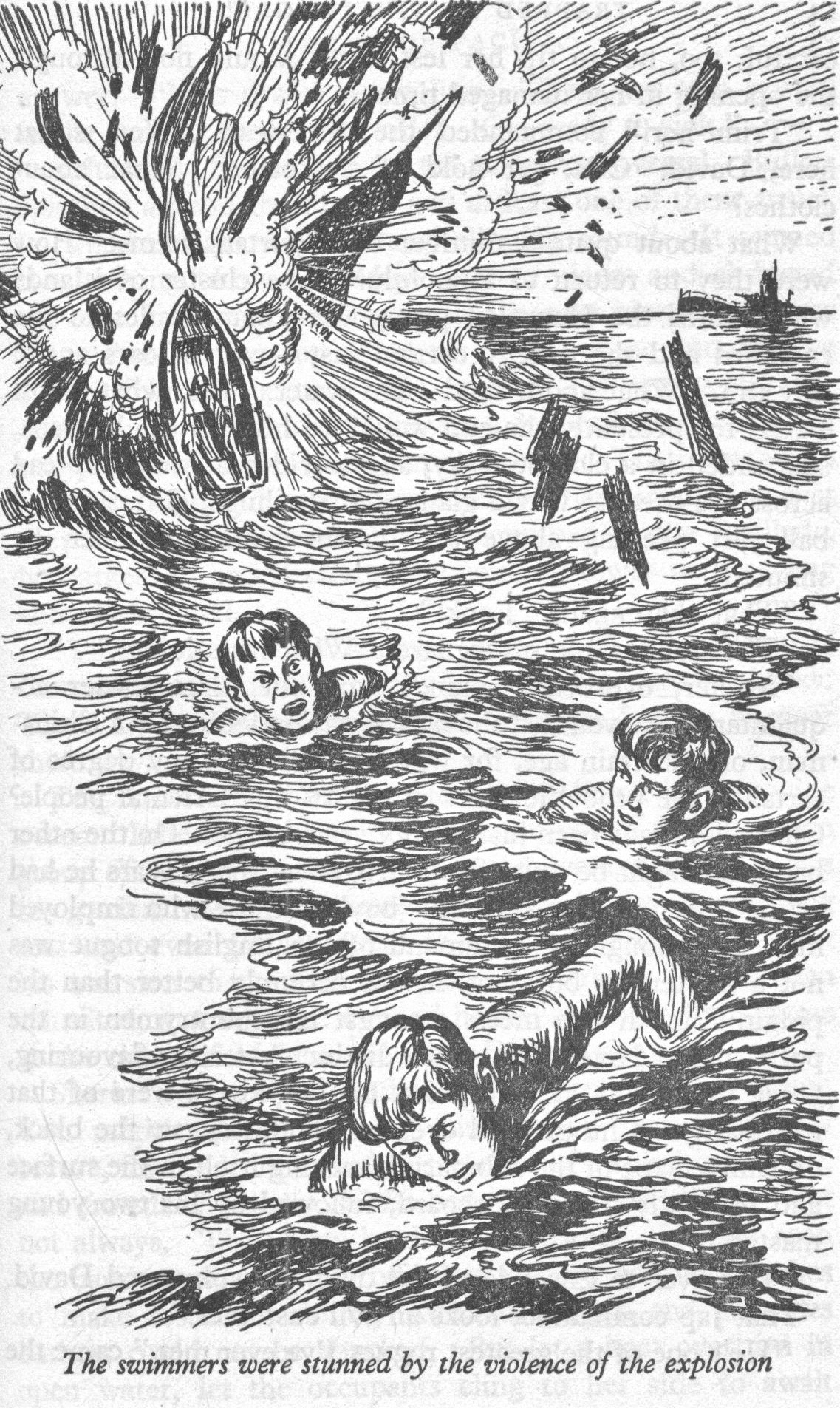

A shattering detonation shook the air. At one moment the graceful Mignonette rolled and heaved ever so gently, as if awaiting their return. And then her single mast shot into the air as if catapulted. Her deck rails burst asunder. The sea around shuddered as her planks were shattered, while the swimmers were partially stunned by the violence of the explosion.

“Masters, duck,” bellowed Chu. “Quick, masters. Under the water.”

Perhaps immersing their heads helped a trifle to minimise the force of the bursting bomb. It may have saved the swimmers from the hail of debris which fell around them, all it seemed that remained of the graceful Mignonette. No, not all, for as the vessel burst asunder and foundered a dinghy floated clear of the wreckage, but not entirely, the boat so much used on fishing excursions or to take them ashore when the yacht lay off some island.

It was a seaworthy little craft which could face Pacific swells with confidence, and which had in fact withstood no little battering when breezes swelled almost to gale proportions and warned those aboard her to head for the yacht or for the shore in case a sudden Pacific tornado should overwhelm them. The dinghy slouched in the water, head down, part of her woodwork shattered and carried away. Not more than four inches of planking kept the water out of her, so that if the wind were to increase and the sea be lashed by something even short of a gale she would run the risk of foundering. Yet she was the only floating object within miles, save for the widely scattered wreckage of the Mignonette.

“We get aboard her,” shouted the American.

“Where’s that submarine?” demanded David, he with the British accent. Not that fashions of speech mattered much at such a moment, or were even to be noted. Still the few sentences which had passed between them, blown from spluttering lips, sometimes half-drowned by water lapping into their mouths, had shown that one of the swimmers was nearly certainly of American origin. Or he might have come from Canada.

His companion on the other hand had without doubt been educated amidst British surroundings. His voice was clear, as clear that is to say, as circumstances permitted, and he possessed that quaint, hardly-to-be-described inflection of voice which one so often encounters from people of British origin, an inflection which at times creates antipathies, even dislike, and which, far oftener, is found so attractive by people of America.

How often had David, the gay-hearted English schoolboy, when travelling across the great spaces of the American continent, been teased about his accent! More than a few times natives of Western America had affected not to be able to understand him, while there was at least one occasion when an American miss seated behind the reception table of an hotel had detained the lad.

“Say, go on talking for a while. My! Isn’t it queer to hear you! And say! Do all the young fellows over there speak as you do?”

“Don’t matter where she is. We get aboard the dinghy and look around. Time to think about that ruffian of a commander when we’ve the dinghy between us and this ocean, not to mention sharks, which shouldn’t be forgotten. You come too, Chu.”

They struck out for the boat and reaching her side hoisted themselves aboard, taking care not to upset the light craft, careful, too, not to tip her lest water should flow through the opening in her damaged timbers.

“Trim her!” commanded the American. “You squat here, David. Chu, get hold of the bailer. What about clothes?”

What about quite a number of important items! How were they to return to Honolulu? The cluster of islands which form the Hawaiian group were many miles to the eastward and the dinghy carried just a pair of oars and a tiny sail. What about food—and water. Yes, what about water, for presently the sun would be high in the heavens, suspended in a cloudless sky, and torrid heat would spread across the ocean. David glanced at the huge, glittering red ball just peeping above the distant horizon. Then he shouted.

“That chap again! Look!”

“The unutterable blackguard. What’s he doing?”

“Master, overboard again,” sang out Chu. Closer acquaintance showed that the native was undoubtedly a Chinaman, of uncertain age, for who can tell with any degree of certainty the probable years of one of this Oriental people? Chu might have been just twenty years of age. On the other hand, he might be quite forty. However many years he had actually seen he was still just “boy” to those who employed him, and though his command of the English tongue was not a matter for boasting, it was certainly better than the pidgin English one meets amongst his countrymen in the ports, and had moreover a quite distinct American flavouring, going to suggest, perhaps, that his employers were of that nationality. Chu glanced over his shoulder, saw the black, ungainly shape of the submarine heaving itself to the surface and promptly dived overboard, followed by his two young masters.

“Get over to this side of the dinghy,” spluttered David. “That Jap commander looks an evil customer.”

“He’s one of the greatest rogues I’ve ever met,” came the answer. “He’s drawn a revolver. There are men posted in the conning-tower with rifles. Get ready to sink.”

Spluttering fire broke from the underwater vessel. Bullets splashed around the dinghy and at least one of them struck its wooden sides with a sharp clipping sound. It seemed that, having blown the Mignonette to pieces and abducted the owner, the commander of this Japanese pirate vessel was determined to destroy all traces of his crime and remove all possible tale-bearers. He emptied his revolver at the dinghy and only ordered his men to cease fire when the magazines of the weapons were emptied. Then, unable to see those who had been aboard her, perhaps imagining that they were still there and had succumbed to the fusillade, he barked an order, closed the conning-tower with a bang and crash-dived.

“Time to get aboard again,” sang out David. “Even if that rascally Jap isn’t here any longer there may be sharks. There are sure to be sharks, eh? Thought I saw a fin over there a while ago.”

The American grunted. He was at home in this wide ocean. Indeed, he knew the surroundings of the Hawaiian group of islands almost as well as the average fellow knows his garden. And there were few places in the surrounding seas and even farther afield that he had not visited. But his aversion to sharks was constant. Perhaps it had been inherited, just as is the natives’ hatred and fear of alligators in the rivers of Malaya and other Eastern parts.

Sharks were to be found in every corner of this ocean. You might take a morning plunge and feel reasonably secure, for the brutes would keep clear of a splashing figure, and crowds of bathers off the beaches overawed them. But not always. They were bold and ferocious. He had seen the bamboo pens erected off some Eastern bathing beaches to make assurance doubly sure, for within the palisades bathers could not be attacked. But let a boat overturn in open water, let the occupants cling to her side to await rescue, and in a twinkling a dozen of the brutes would swirl to the attack.

“Aboard we go,” the American shouted. “Chu, lead the way and then give us a heave. Steady does it. I think the dinghy is lower in the water. The pot shots they took at it will sure have driven holes through the planks and some of them may be low down. Up you come, David.”

With all the care that was possible in such strenuous circumstances they clambered into the dinghy and shifted their positions till she was evenly trimmed.

“And now we repair damages,” said David, shaking the water out of his hair. “Here’s a nice little round hole from a Jap bullet. Their tommy-guns drove quite a wave of spray over us, and if they had turned them directly at the dinghy I reckon they would have cut her into pieces.”

Chu shivered. Not that the Chinese boy lacked courage. But he had had some experience of Japanese tommy-guns and of their ruthlessness. For years now—it seemed for longer than he could remember—these islanders had been attacking his country. Their regiments had overrun miles of it. Millions of his people had been slaughtered or driven from their homes, and the invader was still within China, shooting everywhere, trying to reduce the people to slavery and to make them accept the law of Japan.

“In a little while, masters,” he said, speaking in that sing-song voice so many of his race adopt. “To-day, yesterday, almost for always it seems the Japs have been top dog, eh? P’raps they win more. P’raps they try to kill all the Americans and take Honolulu.”

“Kill us! My word! Let ’em try,” shouted the American.

“Yes, master. But presently they will, p’raps. But wait a little bit. You see something good. Everyone not quite so without guns and things such as airplanes same as the poor Chinee. Suppose they attack Honolulu.”

The very mention of such a possibility roused the American youth. He doubled two quite respectable fists and shook them aimlessly in the face of the Chinese boy.

“Let ’em try,” he bellowed. “I’d like to see them do it.”

Would he really? Did Elmer Roach, for that was his name, suspect that the Japanese had such an intention? Pooh! The idea was fantastic. Japan attack America, the mighty United States, the prosperous and highly developed peoples inhabiting those rich lands to west and east of the Rocky Mountains. Fantastic! Impossible! Attack a country possessing no great army it was true, but with a Pacific fleet lying for the most part at Honolulu, with other outlying islands in strategic situations out in the Pacific.

Consider the impossibility of such a dream. From south of the marvellous, land-locked harbour of San Francisco right up to the tip of Alaska, America was in control of most of the Pacific coast of North America, save for that held by Canada, and there was sworn and real friendship with that country. Dutch Harbour in the north was a bastion which might awe the Japanese and, moreover, the world knew that America desired to conquer no one. She wanted peace and good neighbourliness with one and all, even with Japan, greedy, dangerous Japan. Even then, as the Great War in Europe, led by the aggressor Hitler, and aided by his pompous satellite, Italian Mussolini, raged across that continent and Great Britain alone faced those formidable enemies, Franklin Roosevelt, wisest of Presidents, a man gifted with remarkable foresight, desired only peace for his country, and at that very moment was in conference with Japanese delegates come to Washington to discuss peace.

“P’raps. Only p’raps they attack America, master,” said Chu, wagging a wise head.

How could anyone of the three seated in that small, insecure dinghy, imagine that that “perhaps” of Chu’s was in fact a certainty. Could they be expected to guess that even at that moment, as the sun climbed higher into a tropic sky and the day broadened, Honolulu was already under fierce attack? The suggestion seemed more than fantastic. No war had been declared between Japan and America. Delegates were even then discussing friendship in the White House in Washington. Could any nation in such circumstances countenance such a rascally act, such treachery?

Japan could and did. Those smudges of smoke on the distant horizon, glimpsed in the first rays of dawn by the people aboard the Mignonette, came from the funnels of Japanese warships, from her airplane carriers, and even then, as the civilians and garrison of Pearl Harbour, America’s naval base, stirred from their beds, ate their breakfasts and decked themselves for the day, Japanese aircraft were hurtling to and over the place, circling the proud Pacific fleet, bombing ships and shore installations, bombing airfields and planes, sowing destruction and death, operating in fact on a pre-arranged plan designed to kill and to destroy and in particular to cripple the offensive and defensive power of America’s fleet.

What treachery! What terrible scenes of death! How helpless ships and shore against this sudden attack made while peace was under discussion! In a very few hours, when the President broadcast the news, people of America were stunned, aghast, enraged, and then set firm on a purpose. Not to avenge, though surely punishment for such treachery was merited. But to fight this Eastern aggressor, this ruthless, unscrupulous murderer. To rid the world of the growing Japanese menace. To fight for liberty, security, and peace, perhaps to do so at the side of Britain.

Fortunately David and Elmer were ignorant of those terrible happenings at Pearl Harbour. They were out of sight and out of sound of the conflict and, moreover, their own position was sufficiently precarious.

“We take stock,” said Elmer in a business-like tone of voice. “Say, taking stock won’t take much of the day.”

“Item number one,” grinned David, rummaging under the thwarts of the boat. “Plenty of sea water at our feet, but none for drinking purposes. Not a can. Not a keg.”

“Ah!” grunted Elmer. “That’s tough. No water, and these the tropics. We’ll have to get shade. Suppose we rig the sail as an awning. There’s practically no breeze, so we shall lose nothing. And shade will help our thirst. Jingo! I feel thirsty already. Swallowing salt water doesn’t help any. What about grub?”

David began to realise the difficulty of their condition. It was with anything of a smile that he reported that there was no store of food aboard.

“Not a crust,” he said. “No drink. No food.”

They sat for a while staring rather moodily at one another. And who could blame them? For the swelling Pacific stretched everywhere, endlessly it seemed, unbroken by even a ripple, just swelling now and again, heaving, as if in deep sleep. They were alone in that waste. A cockleshell lay between them and destruction and how were they to exist and for how long could they hold out hoping for rescue?

So much had happened in so short a space of time that, coupled with the acute need for self-preservation, it is not to be wondered at that David and Elmer and Chu, the Chinese boy with such sparkling, squinting eyes, set seemingly at an absurd angle, had little opportunity to consider matters outside their own immediate surroundings. Vaguely at the back of their minds they were wondering what fate had befallen their friend, Mr. Baines, abducted by that raucous, stunted, unprepossessing Japanese commander.

“This water question is a teaser,” growled David, peering up into the sky and shading his eyes from the glare of the sun. “It’s hot now. We shall be roasted.”

“Then we rig the sail as I said,” cried Elmer. “Lend a hand. Here’s a bit of rope, and with that we may be able to make a job of it. Gee, I’m famished too. Think of it, aboard the Mignonette we’d now be sitting down to breakfast. Hot coffee, you know.”

“Porridge, perhaps,” grinned David. “Bacon and egg if Chu was clever. And jam.”

It is one of the peculiarities of the white man that he will, so far as he is able, continue the customs he followed at home however far he be removed from it. True, some wisdom has been learned. The diet chosen in the tropics is usually lighter than that partaken of in England or America. But bacon and egg is a favourite and a common dish throughout the world occupied by the white man, and from Calcutta to Bombay, even in far hotter Madras, in many parts of the Malay peninsula, in New York, Washington, Seattle and thousands of other cities and townships and country places the well-known British egg and bacon is a favourite.

“Jam,” echoed Elmer wryly. “Jam. Butter too. And—wa-al, no use grumbling. We’ve got to face matters. But about Uncle Ted. That Jap always had a grudge against him. Ever heard of Hato, Japanese naval officer, the fellow who appears to have commanded the submarine?”

David shook his head vigorously. “Never!” he grunted. “But I’d pick him out from fifty other Japs, and what’s more I mean to.”

“Him spy,” declared Chu, laconically, picking at the frayed edge of his clothing. “Him one of the thousands of officers sent to America, to Canada, to Singapore and other little places to watch.”

“As barbers, tinsmiths, photographers, anything or any trade you care to suggest. They were at Honolulu. You could have your hair cut——”

“Or get a shave,” interrupted David, grinning, for not so much as a hair adorned his chin.

“Yes, buddy, shaved, shaved all the way through the Panama Canal, shaved and photoed in any port between San Francisco and Dutch Harbour in the north. The Japs have been spying on the white man in every corner of the East. And why?”

“Getting ready,” suggested David.

“You’ve hit it first time. Getting all set to tackle the white man, to throw him out of these parts, to drive him from the Pacific, yes, even from North America.”

“And why then should this commander fellow, Hato, abduct your uncle?” asked David.

“That’s telling. That’ll have to wait for another day, for talking makes me that thirsty,” grumbled Elmer. “And what’s more, buddy, I don’t grip the whole of the yarn. It’s sort of complicated. There’s a bit of the personal hatred of Uncle Ted by Hato. Then there’s the great secret the Jap nation is after. That’ll have to wait. What do you guess has happened to uncle?”

How could anyone answer that question, that is anyone save the commander known as Hato? The sudden surfacing of the submarine, the abduction of Mr. Baines and the obvious intention of the Japanese to destroy all who witnessed this outrageous action must have some sinister meaning. As the Pacific closed for the second time over the periscope of the pirate vessel it created an even greater mystery. Why had this thing happened to peaceful yachting people? What was the object of the abduction? And where would Mr. Baines be taken?

Actually he had been hustled to the foot of the ladder leading from the conning-tower and two armed sentries were posted before and behind him.

“Move and they shoot,” growled Hato. “Tell me, who were the boys? One is Elmer, eh?”

Alfred Baines regarded the Japanese officer coldly and made no answer.

“You say nothing? Very well. Wait! Wait till I have dealt with them. Ah! There is the bomb. Return to the place,” he cried, snapping the order at his junior while he gripped the ladder and made ready to swarm into the tower again.

Alfred Baines shivered. Not that he was cold, though be it remembered he was still clad only in swimming-trunks. Indeed, it was hot in the operations room of the submarine. But he had a lively memory. He knew the Japanese, and had reason to remember Hato.

“Pretended to be a clerk,” he told himself. “Got a job in my office as such, and quite accidentally gave away the fact that he knew something of naval matters and more about metallurgy. He was fired for spying. Yes, spying. What now is he after?”

What indeed, for Alfred Baines was not the man to confide in any but the most trustworthy, and even to his oldest friends he was generally a trifle taciturn, apt to change the conversation if it reached a point beyond which he thought it unwise to go, and capable of suppressing any individual whom he deemed to be curious. Not that he himself was a man of mystery, one of those inscrutable persons known to few if to any, who hide their thoughts under a cloud of silence. He could be excellent company, and had made a host of friends as he travelled to and fro about the world. Alfred Baines had in fact visited a majority of the countries with which we are familiar, and had often stepped aside from the beaten tracks to journey in out-of-the-way places.

To his intimates he was known as a pleasant if somewhat reserved native of Honolulu, where he supervised a pineapple plantation and spent many happy hours in the endeavour to improve that luscious fruit. His father had ploughed the first stretch of land to be put under pineapples, and like Alfred had been a wanderer. But he too was a scientist, just as was Alfred. Years before Alfred had been born he had prospected parts of the great chain of Rocky Mountains in an endeavour to discover an outcrop of the famous Californian lode. Fortune had rewarded him. The Baines gold mine became notorious for the richness of its returns, and the wealth thus created had enabled him to indulge his scientific bent to the full, and as failing health and advancing age made change of air and of scene and more leisure desirable, he had sailed for Honolulu, which thereafter became his home and his headquarters.

What more natural than that Alfred, the son, should follow in his father’s footsteps? The Californian mine provided him with dollars. The pineapple plantation gave pleasant employment and diversion, while the wonderful climate of that sunny and salubrious spot agreed with him amazingly. But the quest for metals, rare metals, took him from the slopes of the Rockies to Chili and Peru, to the vast Ural range in Russia, to the snow-bound slopes of the Himalayas, even to the centre of China, and once, somewhat daringly, to the heart of Japan. Alfred had become an authority in respect of the rarer metals. He was already credited with an epoch-making discovery. Could that be the reason for his abduction? Had his investigations led to the uncovering of a metallurgical secret which might affect the course of the great war now raging throughout Europe, and the exploitation of which might give certain victory to the nation which possessed it? Japan had waged an aggressive war against China for some years and had failed to defeat her. Only a few moments ago she had flung all the might of her air fleet against the unready and still trusting Americans at Pearl Harbour, and even at this moment the world outside Japan was ignorant of this news, of the monstrous act of treachery which had been perpetrated by a nation even then discussing peace between herself and America.

Alfred Baines winced and shivered again. This scandalous act of piracy on the high seas, leading to his abduction, to the destruction of the Mignonette—for he had felt rather than heard the detonation of the bomb—must have some sinister meaning. He was well aware that war between Japan and America was a possibility, even a probability, though to attack the mighty United States seemed to him and to the world in general an act of sheer lunacy. Yet Japan, too, was powerful, immensely powerful and dangerous, with fanatical millions eager and willing to carry out the orders of their war lords, determined to spread the sway of Japan throughout the East, worshippers of the Mikado who would leave no stone unturned, hesitate at no act of treachery however monstrous, and seize every and any object or person which promised to aid success.

“I think I see their design,” thought Alfred. “This means that they are determined on war against my country. It means that my secret must be wrested from me.”

His face hardened. The lips closed firmly together and his frame stiffened.

He heard the conning-tower hatch crash to, following the rattle of rifles. Then a sharp order was issued, and as Hato clambered down to the operations room the vessel dived.

“That is the end of the yacht,” snapped the Japanese. “She has been blown to pieces.”

Alfred regarded him stoically. “And the three who were my companions aboard?” he asked.

“Gone. Sunk. They will never speak again,” declared Hato, a malicious grin spreading across his broad face. Hato was not one of those highly educated Japanese one meets in European universities, come to suck learning from the white man, those polished, well-mannered individuals so anxious to curry favour with their fellows. Indeed, the politeness of the Jap in our midst has become a byword. They are punctilious, extremely formal, often good companions, given over much to bobbing and bowing. And often enough their features are straight and only their dusky complexion and their stunted figures declare them to have come from Nippon. But Hato was of Mongolian cast of countenance. Broad and short, he was like a powerful baboon, his jet-black hair tending to stand on end, his prominent cheek-bones declaring his origin, his eyes aslant, a mat of untidy, bristly hair adorning his upper lip. There was nothing attractive about this commander. Rather, there was something which repelled.

“Disappeared,” he added. “They were shot through and through. Sorry!”

“For what?” asked Alfred coldly.

“For disturbing your trip,” grinned Hato. “For destroying the yacht. For the young fellows. But you are saved. Good! That is a great reward. Presently we will discuss affairs. Now I shall see to your comfort. You need clothes. Well, perhaps there are some aboard which will fit you, though few Japanese are of your height. Still, you must be clothed. Then, when you have eaten and have had time to think things over you will speak. Yes, you will tell the whole story to our intelligence department. After that you will be set free. That is a bargain, eh?”

The cool, calculating reserve of the American made Hato wilt. He knew him well, had watched him during the time he had been masquerading in his employ and had learned that he was a man of determination as well as a scientist of no mean attainment. Even now, when Alfred was firmly in his hands, and would soon be facing a group of Japanese determined to unravel any secret he might possess, Hato doubted whether they would succeed.

“Pooh!” he thought, regarding the American askance and noting the firm lines about his face. “He will speak. They will make him. They have ways. Yes, ways of making the most obstinate and the most silent eager to talk.”

One of the crew appeared carrying an armful of clothes, and selecting the most likely handed them to Alfred. They were not exactly elegant, and the trousers were ridiculously short, while the sleeves of the loose naval jacket scarcely reached beyond the elbows. Still, they were clothes, and an improvement on the slender bathing garment he was wearing. Moreover, clad in these strange, ill-fitting garments he felt more at ease, better able to endure his position, better able in fact to resist any blandishments and inducements the rascally Hato might put before him. Clothes do not make the man, as the saying argues, but they do help towards his equanimity. His swimming garb had in these strange surroundings tended towards a feeling approaching inferiority. Now he felt himself again and smiled.

“You are pleased?” asked Hato.

“Precisely.”

“And you would eat. A little breakfast perhaps, for it is still early morning.”

Alfred nodded. “Exactly so,” he answered. “I am hungry.”

“Then come.”

Hato led his prisoner to the tiny wardroom of the submarine and called the mess servant.

“Coffee,” he ordered. “And perhaps an egg. Or jam. You will forgive if there are not aboard here all the foods to which you are accustomed. Rice is the staple diet of crew and officers, with little beside. Still, there are a few such luxuries as eggs. Please give your commands.”

Alfred Baines was not exactly a stoic. But he was a severely practical man and given to accepting facts where they were inevitable.

“I’m a prisoner,” he said to himself as he crammed his long frame into the cramped quarters between the wall of the wardroom and the tiny mess table. “There is trouble ahead. Stormy days one would imagine. The best thing to do is to eat and rest and make ready. But I’m troubled about those boys. I’ve had my day. But they are mere youngsters. It is horrible, ghastly to think that they have possibly been murdered by this scoundrel Hato.”

Well might his thoughts be occupied with the fate of Elmer and David, to say nothing of Chu. For dangerous though his own position was in that submarine, he was infinitely safer for the time being than they were. Thrusting forward under water for a while, and later on the surface, the vessel gave security as it sped forward to some destination as yet unknown to him. But contrast that condition with that of David and his American chum, adrift in the wide Pacific, in a cockleshell of a boat which because of the damage it had suffered was decidedly unseaworthy, and which, moreover, was as bare as any Mother Hubbard’s cupboard.

They were indeed a forlorn little party of castaways. Huddling beneath the sail rigged from mast to thwarts, for a red-hot sun sent its blazing rays down upon them, they sat and watched and pondered.

“Ships,” said Elmer after a while, pointing eastward. “Several of ’em.”

Far away on the horizon were more smudges of smoke. Not the clouds one might expect from coal-burning steamers, but a wispy, smoky haze given off by the funnels of oil-burners.

“Jap warships, shouldn’t wonder,” he ventured. “Are those birds?”

“Airplanes, master,” declared Chu, shading his eyes.

They said of the Chinaman that he could see farther than anyone they had yet encountered, and perhaps he was right. The birds, they had seen half an hour earlier swarming about the distant smudges of smoke might have been, and probably were, Japanese airplanes.

“Heard gun-fire too, masters,” said Chu. “Listen now. There! Bang, bang, bang! You hear?”

Very faintly across the wide stretch of water came the sharp, staccato notes of what appeared to be heavy gun-fire, and as the minutes passed and those distant airplanes so much resembling birds swarming above what must be ships became more clearly visible, one swooped into the sky with black smoke trailing behind it.

“That proves the case,” gasped David. “There’s fighting going on.”

“Honolulu,” growled Elmer. “They’re attacking Pearl Harbour. What do you think of that now? Attacking America, and only yesterday we heard on the Mignonette’s radio that Jap envoys were talking peace to the President at Washington. Yep, talking peace. And—there she goes. That plane’s dived right into the sea.”

“What’s it all mean?” gasped David. “It can’t be——”

“You’ve said it,” drawled Elmer. “It’s war, red war between America and the Nips. I’d give a lot to know what has happened at Pearl Harbour. The people there hoped for peace. They had no thought of an attack and felt safe, at least while peace talks were in progress. But supposing they’ve been attacked. Gee!”

He ended the sentence with a shrill whistle. Well he might, for that morning had indeed brought sudden disaster to Pearl Harbour. The place, the garrison, the ships and their crews and a peaceful, unsuspecting population had been mangled.

“Let’s hope they don’t spot us, if those ships are really Japanese,” said David. “Say, Elmer, about this question of drink and food. I put drink first, for a fellow can get along without food for a time. But no drink, with all this salt water round us too. Not so good, eh?”

It was anything but good. It was a desperate situation, which had been faced already in this stupendous war by very many shipwrecked people, by the crews of vessels torpedoed by German and Italian submarines. This was a war to the knife. Ships were not called upon to surrender. They were sunk out of hand and crews which might escape into their few surviving boats were left to fend for themselves. Sometimes even they were hooted and reviled by the crews of the submarines, surfacing after the torpedo had struck home and sent the ship to the bottom. War to the knife, yes. War against women and children, for many a boatload of men, women, and children, had put off from a sinking vessel and had faced the perils of the open ocean, with little food aboard perhaps, a slender supply of water, and no rescue within sight. A ghastly band had perished.

“Wa-al, it’s just bad, that’s all there is to it,” growled Elmer, his brow knotted as he pondered the situation. He sat there on the thwart, in the shade of the awning, staring at the distant smudges of smoke and at the airplanes still circling about their carriers. Elmer was a gallant-looking fellow. Even though only so slenderly clad he was a fine figure of youthful manhood. Or perhaps the very absence of clothes displayed his elegant and powerful proportions to greater advantage. Perhaps he was close to his eighteenth birthday, a tall, broad-shouldered, athletic-looking American. He was fair, and the tan on his face made him appear still fairer.

“Got this yellow hair from a Scandinavian ancestor,” he’d say with a delightful grin when the subject was mentioned. “Good enough for him. That goes with me, too.”

Elmer might be nearly six feet in height, upstanding, light on his feet, narrow at the hips, quick in movement but given to rather drawling speech. His sunny features and his ready and friendly smile helped to provide him with many chums, who soon learned that beneath the easy manners and the happy outlook of their friend there was character, a sturdiness and a staunchness which went well with his slowness of speech.

Elmer liked to sit back as it were and debate a matter carefully, to scrutinise the pros and cons. But present him with a sudden crisis and he became a man of action. In fact he was not unlike his uncle Alfred. He was just a younger edition of that cool, calm, reflecting individual, with the same friendly outlook on life, unspoiled by his fortunate position and wise beyond his years because of the many opportunities which wide travel had given.

David was an altogether different sort of person, though to be sure his slenderly garbed exterior helped as in the case of Elmer to show to advantage his active figure. But he was lightly built by comparison, not so broad of shoulder nor so tall as yet, for he was only just turned seventeen years of age, and whereas Elmer was unusually fair, David was dark. But he had the English bloom in his cheeks, was in fact a most attractive youngster, and was withal gay and lighthearted when times were good and prosperous, and was no coward, as recent events had proved, when disaster threatened or suddenly overtook them.

“Just bad, that’s all there is to it,” grunted Elmer.

“Lots of folks have had to face the same position,” reflected David. “It might rain, eh? We’d be able to catch water in our awning.”

“Sure,” grunted Elmer. “But it don’t rain so much hereabouts, except sometimes, and then it comes down fit to drown you. It’s no water one second and oceans of it next. Yes, we could catch some in the awning and fill ourselves with as much as we can take. There’s no can aboard to store it. But there—rain—don’t look like it, does it?”

Chu sat in the stern of their rickety craft, watching, listening, now and again interjecting a remark, still picking at the frayed edge of the loose blouse he was wearing. It was of brilliant red colour, for bright things, like toys, please the happy minds of the Chinese. Presently he unravelled a brilliant strand and held it up for inspection.

“Perhaps that provide the water. P’raps food too,” he laughed.

“Now, see here, Chu——” began Elmer.

This flippant behaviour of the Chinese boy irritated him. Besides, in times of adversity, when danger threatens, it helps to soften the situation if one can indulge in sharp words.

“This thing means life and death. See? If there’s no water we’re next door to done. You get that?”

“Just a second or so,” said David, and there was a note of excitement in his voice. “This fellow Chu is up to something useful. He’s not a fool, and not the one to joke when we’re all in a tight corner. What’s up, Chu?”

The Chinaman’s eyes rolled. He smiled indulgently at his two young masters and then, turning his back on them bent and fumbled beneath the stern board. A moment or so later he turned again and once more displayed the scrap of brilliant cotton he had unravelled.

“See, masters,” he gurgled in his sing-song voice. “No water. No food. But fishing-lines on board. But no bait. Well, in China boys tie scarlet cotton to their hooks and fish. Supposing we do the same. Same as you see here. P’raps fish bite and come on board. Then there is food, eh? Food and drink. You no believe that p’raps. But it’s all true. Fish give food and drink and will keep us plenty good till someone finds us.”

The fellow proved a genius. To the highly sophisticated perhaps the eating of raw fish causes a shudder. Yet our Scandinavian friends devour iced, uncooked herring with gusto. It is a luxury they delight in. Chu showed the way to David and Elmer. He had no scruples and no hesitation; and, moreover, he was a masterly fisherman. This Pacific was packed with fish, and the brilliant strip of cotton attracted them as though it were a magnet. Then, once the first feelings of revulsion were overcome, this raw fish diet proved both refreshing and palatable, and it instantly satisfied their thirst.

The clever Chu had in fact given the whole party a new lease of life. But, artful and clever though he was, he could not lessen the danger of their situation. They were still adrift in a boundless ocean, with a shallow, rickety cockleshell between them and destruction, and days might pass, even weeks, before succour could reach them.

“Boat ahoy! Sit up, me hearties. Ahoy, there! Ahoy!”

Chu sat upright and rubbed the sleep from his eyes.

“Masters!” he gasped. “Masters! Masters!”

Unceremoniously he kicked David, who lay on the flimsy bottom boards of the boat, his tousled head on his arms, sunk in deep sleep. The lanky Elmer was right aft, curled up under the stern seat, his skin ebony, thanks to long exposure to the sun, three weeks’ growth of luxuriant, youthful beard on his chin.

“Ahoy! Ahoy, me lads!! Stand by to be taken aboard.”

Was it a dream? Was that really a ship surging slowly towards them so that in a few minutes she would be alongside? Her bows made hardly so much as a ripple, for she was going dead slow, and already her propeller was reversing so that Pacific foam swept along her side towards the bows, frothing and heaving and already making the boat rock. David and Elmer were on their feet in a moment, gripping the gunwale, balancing the craft carefully, for long habit had now taught them to be always wary of their movements and to take infinite trouble to trim their cockleshell.

“A ship!” shouted David.

He too was as brown as any berry, burned almost black in fact, and though no luxuriant beard graced his youthful chin, flimsy, glistening hairs were budding absurdly from his lip and chin, promise perhaps of better things to come.

“Now what do you say to that,” yelled Elmer. “Hooroosh! A ship!”

“All fast asleep here,” said Chu, as if he were chiding them. “An’ no one keep watch.”

“That’s me,” shouted Elmer. “I’m the fellow to blame. Say, it was that hot yesterday and last night that I couldn’t keep an eye open. Oh, yes, I know, David did his go and called me to take my watch. But—but—wa-a-al, what’s it matter now? It’s a real live ship. Those are real men aboard her, and, say, those are the first voices besides our own we’ve heard these three weeks or more. Three weeks did I say?”

“It’s a guess,” said David. “We just don’t know. But, jingo, it is a ship, at last, the first we’ve seen within miles ever since this business started.”

During the days they had drifted in that cockleshell—how many days not one of the three could guess, for they came and went with monotonous regularity—during those days an occasional smudge of smoke had been seen in the far distance, and once a ship appeared to be steering towards them though still far away. But either she altered course or the brilliant, blinding rays of a tropic sun deceived them. She disappeared in a heat mist and for a while there was dejection on board. But, youthful spirits soon revived. While the weather held all was reasonably well with them. True, the sun was uncomfortably hot. The sail had, however, been a godsend. They sheltered in its shade for part of the day, hoisting it when there was a breeze and the sun cast a shadow over the boat in which they could lie. But why hoist the sail at all?

“Might take us farther and farther from help and oceangoing steamers,” said David.

“Yep,” agreed Elmer, laconically. “We’ve no maps, no compass, no information of our whereabouts. Seems to me that letting the drift carry us is as wise as anything.”

And so they fished and fished, and ate and slept, taking turns to keep watch. Strange that it was during the energetic Elmer’s turn for duty that rescue had arrived. Towering above them was the rail of the steamer. Men were leaning over, and David was sure he caught sight of a girl. A man in his shirt-sleeves, the garment wide open at the neck, was perched on the bridge and was using a megaphone.

“Stand by there to bring ’em aboard,” he shouted.

“Mr. Jennings, drop your ladder and get down on the end of a rope. We’ll hoist ’em aboard. Drop the slings we use when painting ship and smart with it. Stand by, men.”

It was the voice of a Scot, the familiar broad accents declaring the fact without leaving room for doubt. The engine telegraph rang as the order was sent to the men below to shut off steam. At once the propeller ceased to churn, and way having by then been taken off the ship she lay to within a few yards of the drifting boat.

“Put her in closer, lads,” shouted the captain. “Get an oar out.”

The three young fellows had been so startled, so taken aback, so stirred by the appearance of the ship that they were almost dazed. It meant rescue when hopes of rescue had descended almost to zero. It meant security, companionship, home perhaps, an opportunity to search for Elmer’s uncle.

“And it means a change of diet, don’t it,” laughed Elmer, as though he had been thinking aloud, for the amazing change in their fortunes and all that it might mean had been surging through his mind. “Oars, yes, that’s the ticket. Paddle her over.”

Chu had one over the stern already, and David soon had the other dipping in the water. Together they brought their rickety craft close to the towering sides of the vessel.

“Who goes first?” sang out David. “You do, Elmer.”

“Not on your life, my bantam,” shouted the American. “I’m heaps older than you and age gives command, don’t it?”

“Depends,” grinned David. “Commands go to ability first. A spot of age helps, of course.”

“Heave to with that jaw-wabbling,” came from the mate who had caused a ladder to be dropped over the side and had swarmed down it. He was resting there, a rope secured about his waist, standing on the lowest rung, his feet dripping in the swell of the Pacific and then lifting into the dry.

“D’you expect me to hang here all day like a fly while you get to work arguing. Say, who is skipper of this outfit?”

“He’s here,” cried Elmer.

“You! Well, perhaps, but a hair-cut’ll do something to clear up the situation,” grinned the mate. “But you take orders from me, see. Come aboard. Get yourself into this sling.”

“Me! In a sling! Not on your life,” bellowed Elmer, obstinately. He stood to his full height, showing off his athletic figure, while his fair hair now inordinately long, floated about his head and neck like a golden mane. “I’m as fit as any man,” cried the American. “And I don’t get hoisted in any sling, just as if I was a baby. No, sir, I climb.”

Climb he did, reaching the rail in no time; followed by Chu and then by David.

“Been aboard that shell long?” asked the mate, while men crowded round them.

“What’s the date?” asked David.

“Just three days left in December.”

“And when was Pearl Harbour bombed by the Nips?”

“The seventh, early dawn. Why? How’d you hear the yarn?”

“We were almost in it,” cried Elmer. “It’s a heap of a long story. But here it is in short. We were aboard a yacht, the Mignonette, perhaps more than fifty miles from Honolulu, and early that seventh a Jap submarine blew us up. Here’s what’s left of the yacht and its crew.”

“But that’s three weeks ago, neither more nor less,” declared the mate. “Captain, these young fellows say they’ve been aboard that old tub since the seventh of December, the day Japan attacked Pearl Harbour. What do you make of that? Three weeks aboard and look fit, though their clothing isn’t much to boast of.”

That was only too true. Coming so suddenly and unexpectedly back into a busy world as it were they were hardly more than barely decent. Their swimming-trunks had frayed badly, the sun had taken the colour out of them, and here and there the garments were held together precariously by threads picked from the frayed edge and dexterously inserted by Chu’s cunning fingers.

Captain Perkins regarded them closely. Was there something suspicious about their yarn? Care was vitally necessary, especially just now in the Pacific where spies abounded and the Japanese were sweeping the high seas, endeavouring to sink every ship.

“They look the tale all right, Mr. Jennings,” he said. “Hair-cut won’t do ’em any sort of harm, that’s true. But—but three weeks. How did they live? Any stores aboard that boat?”

“Two fishing-lines and nothing more, sir. The thing is as bare as a bone. Just a sail, two oars, a couple of fishing-lines, and many holes in the sides. Seems as if she had been gunned.”

“That’s right,” cried David. “She was. You see, we were just starting our morning swim when the submarine rose and attacked the yacht. How have we lived? Why are we as fit as ever? Because Chu—this is Chu, our Chinese boy—thought up the idea of catching fish as they do in China, with a bright scarlet strand from his togs to attract the fish as bait. It did the trick. We caught the fish every day. Could have done so all day and all night. I begin to hate the thought of eating more raw fish. Excuse me, Captain, but have you any other sort of food aboard, and—and coffee?”

“And some clothes, too. Gee! I’m tired of this sort of theatrical costume,” laughed Elmer. “Of course, it was all right in the tropics. But in the Atlantic it would have meant death, fish or no fish. As to food and drink, it was a brute of a situation. I thought we were bound to sink on that point. But fish are meat and drink. Drink, sir, and that’s what saved us.”

“Come down below. Knock a hole in that boat and sink her, Mr. Jennings. Steward! Where’s the steward?”

He was one of the men crowding about the rescued youths and led the way at once to the deck house.

“Coffee, yes,” he grinned. “It’s smoking hot this instant. Now what would you fellows like? With what can I tempt you?”

“I’d eat horse, if there was nothing better,” roared Elmer. “Say, mister, what really is there?”

“Porridge. Piping hot. Plenty of milk too.”

“Sakes!” shouted Elmer, rubbing his hands.

“And eggs and bacon to follow, eh, steward?” David laughed.

“You’ve hit the right nail. You could have a cut off a joint just to start with, to sort of fill odd corners,” grinned the steward, thoroughly enjoying the situation, of which he was certainly master. “We’ve some bully beef opened. That’s famous stuff. And eggs. Sure! How many of ’em for each? And the Chinee? Does he eat our grub?”

“Try him,” laughed David. “He’s Westernised. He’s had his fill of fish. Chu, what say to breakfast?”

They were a deliriously happy party, for even then they could hardly realise the good fortune which had befallen them. Only those who have been cast adrift in such an immense ocean as is the Pacific, could adequately comprehend what deliverance meant. Day after day David and his companions had shielded their eyes from the all-pervading glare and the terribly hot rays which were reflected from a surface almost entirely clear of ripples. A smooth, oily sheet of glistening water, dull green in colour for the most part but sometimes of a Mediterranean blue, stretched into the distant horizon, with never a ship upon it. Not one airplane came within their vision, and no breeze seemed to ruffle the water. Still, there was a breeze at times, as hot as the exhaust of a furnace, and no doubt tidal movements had swept them from the position in which they were when the Mignonette was sunk.

Indeed, unknown to the castaways, they had drifted very many miles, and at times, at night in particular, when the roasting rays of the sun ceased to beat upon them and black darkness swallowed sea and cranky boat, cool air swept gently across the surface wafting them invisibly and smoothly upon a westerly course.

“You could steam for days through these seas even in peace-time,” said the friendly steward, as he stood in the small saloon, arms akimbo, watching his guests devour their breakfast with appetites which he had seldom witnessed before. “It’s just huge, immense, stretches for thousands of miles and takes days, no weeks, to cross from one port to another. Now that there’s a war on and the Jap fleet is patrolling there are, of course, fewer ships around. We shouldn’t be here save for the fact that we got orders to turn round when bound for Seattle and make for Hong Kong. Perhaps that will be attacked. The old man, our skipper, you know—skippers aboard freighters are always called that—isn’t under any delusion. He knows he won’t be safe till he makes port, perhaps not even then. But he’s a clever old bird. He’s been afloat pretty well all his life, and if anyone can dodge these Nips he’s the boy. More coffee? Does it taste good?”

“Scrumptious!” laughed David, emptying his cup. “When you’ve had raw fish for breakfast, with no coffee to wash it down, eh? and raw fish for lunch, with some more thrown in for tea, don’t you know, eh?”

“And then some,” grinned Elmer, shaking his head to sweep his ridiculous yellow mane out of the way of his eyes. “Say, steward, got a barber aboard?”

“Here? On just a freighter! On your life, no! Every man here is a barber. I cut the old man’s hair. It’s a great honour. Also the mate’s. One of the greasers does the job for the engine-room staff, and the deck hands cut one another’s hair. You’d say we make sights of one another. Not a bit of it. It’s like everything else that you set your hand to. You get expert, you know, take a pride in making a man look fancy and sometimes wonder whether you won’t, after all, settle down some day and hang out a barber’s sign. More food for anyone? We’ve heaps of it.”

There is a limit even to the appetite of youth, though he may have been starved of necessary food for quite a while. That could not be said of David and his friends. They were an excellent illustration of what could be done under similar circumstances. Not perhaps in Atlantic seas, where rough weather is common and where fish are, maybe, far less abundant. There is also in those waters the question of exposure. Men who are torpedoed and thrown into the Atlantic do not always succumb to drowning. They are more or less paralysed by the cold, and if left to fight for existence in an open boat with insufficient cover and no means of keeping their clothing dry too often suffer tortures, have their hands and feet frostbitten and succumb.

In the Pacific tropical heat has its dangers and its severe discomforts. But it does not kill so readily, though the heat induces thirst which, if not quenched, makes men drink sea water, and that means madness.

“And now for clothes,” said the steward. “You are the second bunch for whom we’ve had to search our lockers for spare togs.”

“Meaning?” asked Elmer.

“The Nips torpedoed a ship two weeks ago. She was a small freighter on her way to Hong Kong from one of the Solomon Islands. There were seven hands on board, a mate and the old man and his daughter. The explosion killed three, including the skipper. The rest got away in one of the ship’s boats and we picked ’em up two days later. The Japs just left the survivors to drown or die. That’s war.”

“That’s this devilish war,” exclaimed David, horrified.

He was too young to have much knowledge of what was known as the Great War, the intensity of which, and its bitterness and cruelty were already far surpassed by the new war in which he found himself immersed. In that earlier war the Germans, though organised and enormously powerful, were not the formidable people they now were. Their aims were not so far sweeping and grandiose. They desired the world this time. Or rather, they aimed to subdue the greater part of Europe, and had cajoled the upstart Italian Mussolini to join forces with them. But they were not the only nation with ambition to overrun their neighbours. Indeed, Japan had not hesitated to state her case. She desired the East, all of it, for herself. China to begin with. Then the myriad islands dotting the wide Pacific, large and small—and some are enormous. Finally, she had aggressive intentions towards the Malay Peninsula, the Dutch East Indian possessions, even India itself; and rumour and the warnings of those who knew the Japanese war lords and had had perhaps unpleasant experience of the overweening conceit of the nation, indicated that, like the upstart Hitler and his German-speaking supporters, Japan had designs on the whole globe and was determined, however long the struggle might take, to subdue the white man.

David was living in adventurous, momentous times. This was a bitterly cruel war, war to the knife, war which meant life or death, freedom or slavery for Britons and Americans and a host of other nationals. It was a struggle which demanded every ounce of grit and determination and which would test their fighting and organising qualities as never before. What then was the torpedoing of a mere ocean freighter?

“Anyway,” said the steward. “We picked them up, and they, like you, wanted togs. Come along to the old man’s quarters. That’s his order.”

How often during this tremendous struggle have ships’ companies had need to ransack their lockers in search of spare garments for castaways? Generous, good-hearted fellows that they are they vied with one another to provide David and Elmer with suitable clothing. And since the tropics call for no great amount of covering it was not long before they were completely clad. Hair-cutting followed. A burly Irishman, one of the deck hands, took the steward’s place, the latter having other duties, and soon Elmer was seated on a sugar box under the awning slung across the main deck, and with a towel round his neck was submitting himself to the dexterous fingers of Mike.

“And sure it’s himself would be pleased to have a beard same as that,” sang out Mike as he stood back and took stock of the young American. “Sure he would.”

“And who’s himself, eh?” asked Elmer.

“Why, the old man, none other,” laughed Mike. “Begad, it’s a year since he set to to grow one. But is it the one he’d dare to show at home? He’d have all the hooligans of bhoys following him shouting. It’s that spiky he almost pricks his fingers with it, and it just grows in patches. But this—this——”

He stroked Elmer’s chin and fondled the beard which three weeks in an open boat, in a torrid climate, without razor or scissors, had caused to sprout.

“Lay off,” shouted the good-natured Elmer, grinning at some of the deck hands who were lounging near at hand enjoying this break in the monotony of ship life. “Cut the blamed thing and keep a lock of it if you like. I reckon a good bath after the hair-cut will complete the business, for though we often took a dip some fresh water would be sort of refreshing.”

“How’d you young fellows feel about taking your turn on watch,” asked the skipper when at last their hair-cutting, bathing, and general toilet were completed. “This Japanese business has made a lot of difference to the hours of duty. Every man has to do his whack. Even Miss Mary Evans does a good share. Eh, young lady?”

They had been joined by a slim, smiling girl, perhaps she might be termed a young woman. She was barely twenty years of age, petite, decidedly pretty and, one would say, a trifle inclined to be masculine. But then she had lived aboard ship with her father and had more or less roughed it for some years. She knew much about ship customs and the handling of vessels. And she had sailed to many of the ports in the Far East and knew many of the tiny islands dotting the Pacific. She was clad in blue overalls, the only reasonably suitable garment the ship had been able to supply.

“And why not?” she asked, smiling at them. “The day has passed, when a girl just sits and knits. I took a watch on the Saucy Ann before she was torpedoed and I’m glad to do so here. It keeps one from thinking.”

“Then the hours are two on and two off,” said the captain. “We keep a man all day up in the crow’s-nest. From there he gets a long view. Then a man is posted in the bows and the stern, and two more to starboard and port. That’s as much as we can do. Of course, every man knows his duty in case of attack. We’ve a couple of light anti-aircraft guns for’ard and aft. They were fitted when we were last in Hong Kong, where some of the hands were trained to work them. The Navy couldn’t spare any gunners to sail with us. Anyway, lads, that’s our defence against the Nips, that and our constant watching. Mr. Jennings, post these lads to their boats and put ’em wise to all the ropes. Warn ’em not to undress at night, not for the next few nights at any rate, for the Nips are out to blow every white man they can find out of what they think is their sea.”

David and Elmer were thoroughly enjoying themselves. After their long spell in the open boat shipboard life was most interesting and entertaining. They went on watch at regular intervals, stood to their boats when “Boat Stations” were ordered, and were particularly pleased to be chosen as part of the crew of the two guns.

“Just in case,” said the mate. “It’s always well to have reserves of men, you know. And serving these guns is hard work. Though not by any means the latest models, they are useful weapons for they can fire as Ack Ack guns or can be depressed to aim at a ship. That is a mighty good point, for we might get planes attacking us; or it might be a surface vessel. Just recollect that we are in the midst of enemy waters. It’s hard for the old man to decide which way to steer. He was ordered from his course away east and is now dodging down hoping to make a north Australian port, perhaps Darwin. There’s no news yet of the Nips being down there. But this war moves fast and they have their eyes on Australia just as they have on Singapore and the Dutch East Indies.”

David and Elmer studied the map in the captain’s cabin and saw for themselves the actual position of the ship compared with that of the many islands held by the enemy.

“We’ll be almighty lucky if we slip through without being spotted, eh?” grunted David.

“Just anything may happen,” agreed Elmer. “But we’ve had one brush with these Nips and are bound to have others.”

A little after sunrise a few days later the masthead look-out hailed the deck.

“A plane,” he shouted. “Flying this way too, out of the west.”

“Might be from a Philippine base,” said the captain. “Those devils have made a ferocious attack on the Filipinos and the Americans there. Jap sure enough,” he cried a few minutes later, fixing his glasses on the plane. “A reconnaissance plane I’ve little doubt. He’ll be calling up his home base. There’ll be fireworks soon. Every man stand to!” he shouted.

Stripped to the waist, grouped round their guns or at points to which they had been posted, the crew peered out from beneath the awnings or from the open deck, sweeping the horizon and watching the surface of the sea nearer at hand lest a submarine should attack. Another plane presently appeared and for a while the two circled the ship at a distance. Then they turned and were lost in the misty distance.

“That means business,” said the captain, grimly, as he went his way, visiting the gun crews and other parts of the ship. Then he mounted the bridge and megaphone in hand waited for an attack which all were sure was coming, which indeed might be expected at any moment.

This greatest of wars that the world has ever witnessed had already spread from Europe to Africa when David and Elmer were caught up in its toils. The German aggressor had swept through Poland till he was in touch with the Soviet Republics of mighty Russia and, turning, had in the course of a few months launched an attack upon Belgium, France, Holland and Norway, overrunning all four countries. The conquest of the French Republic, sudden and almost unforeseen as it was, had led to the driving backward on to the Channel coast of the British Expeditionary Force, some three hundred thousand of which, hemmed in by Hitler’s armoured panzer forces, had miraculously escaped from Dunkirk, losing guns, tanks, every conceivable item of equipment.

But thanks to the hardihood of hundreds of sailors, some of them members of the Royal Navy but a host just fishermen or yachtsmen—and all the latter volunteers—who crossed the sea to Dunkirk in a huge variety of vessels, some mere open boats, this band of valiant men had reached the shores of England, filled with a spirit of determination to continue the fight when they were rested and re-equipped.

It was at this moment that Italy joined her partner Hitler, and these two members of the Axis Forces prepared to fall upon Britain, who alone stood between them and complete victory in the greater part of Europe.

There was still a third member of the Axis, namely Japan, whose conquests in China in recent years had been alarmingly, not to say dangerously, significant of things to come. Years before she had seized Manchuria, one of China’s greatest provinces, and by a process of infiltration had been penetrating ever deeper into China elsewhere. Japan was fully mobilised for war, and provided with all the latest weapons. China on the other hand was ill-armed or scarcely armed at all and was forced to fall back before the invader, scorching the earth and retiring into the interior of her vast country.

It was Japan’s opportunity for further aggression, for presently, having failed to defeat the British in the air, having indeed suffered a severe reverse in the memorable and momentous Battle of Britain, Hitler and the satellite Mussolini turned their attention elsewhere. The Italians marched through their Libyan possessions against Egypt, with the object of cutting Britain’s life-line with India by way of the Suez Canal, and Hitler, the arch aggressor, the cunning, unscrupulous leader of all Germany, turned upon Russia, with whom she had signed a pact of friendship only a few months earlier.

Japan took full advantage of Russia’s weakness, or supposed weakness, on the borders of Manchuria. There was no love between these two nations, and Russia had already shown Japan that she was well able and fully prepared to protect her eastern provinces. But a formidable German host, millions of men in fact, was pouring into the western parts of Russia, rolling the valiant armies of this new opponent backward, till Moscow, seized once before, and to his undoing, by the great Napoleon, was invested and in greatest danger.

Japan prepared to strike. Her southward infiltration was causing the greatest concern in America, and while war between the two was by no means certain, it became more of a probability because of Russia’s preoccupation elsewhere. Thus the American fleet at Pearl Harbour, American troops in the Philippines and elsewhere in Pacific waters, and her outspoken disapproval of Japanese aggression in China and Asia was a threat to further Japanese conquests. If she desired the East for herself, with all its vast magazine of raw materials—rubber, oil, and a thousand other commodities—she must neutralise America. Cut the claws, in fact, of the mighty United States and thus render achievement of her fullest designs possible.

She entered into peace discussions with Franklin Roosevelt, America’s staunch, far-seeing, courageous President and secretly made ready for war. The hour had arrived when she should strike. That treacherous attack on Pearl Harbour was her method of declaring war. She found America unprepared, organised only for peace and desirous of securing it. In an hour she roused the whole of the United States as they had never been aroused before. They were startled, staggered, but not dismayed. Instantly they made ready to repair the damage to their Pacific fleet while the whole country mobilised for war against the rascally Axis partners. And Britain, hitherto standing alone in a warring world, promptly elected to join in the struggle against Japan beside America.

Elmer, the young American, and David, British to the backbone, found themselves therefore on the morning of 7th December 1941 not only boon companions and friends but allies, caught up so unexpectedly by this opening round in the struggle in the Pacific, a struggle which was to be continued for long and which was to witness a succession of gallant exploits and adventures.

Hours passed as the crew stood by expecting attack, and though they scanned sky and sea, nothing appeared to attract their attention.

“But they’ll come again, sure,” said the mate. “Perhaps they’ll wait till we’re closer to their base, so that they can send their torpedo bombers. What’s their range, sir?”

“I can’t say,” came the answer. “Japanese armaments are at the moment more or less of a secret, though it is thought that they have the latest weapons. Anyway, perhaps the weather will help us. We’ll strip the awnings, Mr. Jennings, for my glass is dropping and I think we may be in for a blow. That might help us to sneak in south towards Port Moresby and so put New Guinea between us and the enemy. The wireless news is none too good. After their attack on Pearl Harbour the Nips bombed Singapore, and are now said to be on their way to Hong Kong. They’re all over the place, hang them!”

It took very little time to strip the ship of her awnings, in which condition she was perhaps in better position to protect herself against airplane attack. Meanwhile clouds were gathering on the horizon, no bigger at first than a man’s hand. But growing, becoming darker and more threatening in appearance every half-hour. A mysterious wind came sweeping across the hitherto smooth expanse of this mighty ocean till presently there was a gentle and slowly increasing swell. It was swelteringly hot, though the glowing ball of the sun was now obscured by mist.

“A tornado, shouldn’t wonder,” said the mate, who had his station with the gun which David and Elmer were helping to man.

Mike, too, was one of the gun’s crew, and the steward, supported by two more of the deck hands. Close at hand, piled in the racks, was a good supply of shells, while a tub of water had been placed in the shade so that it could easily be reached.

“Sure foightin’ and watching makes a man thirsty, that it does,” grinned the Irishman, who seemed to be looking forward to an encounter with the enemy. “Then there might be a fire, and wather’s good for that, too.”

“A plane!” sang out the man aloft. “Two of them. No, three!”

At once all eyes turned to the sky while the gun crews who had been resting beside their weapons took up their several stations. Elsewhere along the deck men on watch swept the ruffled surface of the ocean in search of a periscope.

“They’re not so easy to spot, eh?” asked David, remembering their own encounter with an undersea boat, not so long ago. “It’s true that we had no reason to suspect the presence of a sub, and were not on the look-out.”

“Ay!” one of the hands replied. “That’s their way, youngster. They just sneak up all unbeknownst. Spot you from a long way off, savvy, then submerge, and make a course under water till they judge they’re near enough to send over a torpedo. That’s the moment when the periscope appears. Just a few moments, eh, savvy? Then, bang! You go up sky high if you’re not lucky, women and children, every man jack.”

“And don’t I know it?” shouted Mike. “ ’Tis myself was torpedoed in the Atlantic just a year past, me and the whole ship’s company, the old man, and three women and six childer, begorra! But the devils had no mercy for us. There was a sea runnin’, and when they’d broke the back of the ship and she was foundering just as quick as—well as quick as knife—do ye think they came alongside to help? They just stood off, surfaced then, you understand, and machine-gunned us, shot us up, as we launched a boat and piled into her.”

He was red-hot with indignation. Sweat was pouring down his lined and sunburned face, and at that moment Mike no longer appeared the smiling, happy, jovial Irishman his shipmates knew so well, but a raging, formidable individual, shaking with indignation.

“Say, that’s bad,” ventured Elmer. “Shot you up? They were Germans, I’ll bet, and that’s the sort of devilish thing they’ve done time and again.”

“It’s what they did in the last war,” shouted Mike. “Sure, don’t I know? Shouldn’t I be the one to spake of it, for I was torpedoed then too. Twice, me bhoys.”

“And got saved. That’s fine,” interjected one of the gun crew.

“And went to sea again. That’s better still, Mike,” declared David.

“Betther still, is it?” demanded Mike, still red-hot with indignation. “And wouldn’t any man who’s a man want to sign on again the instant he made port if only to show those devils that he wasn’t afraid? But those Germans machine-gunned us. They stood off with the Atlantic waves washing their deck and sousing against the conning-tower and laughed. Do ye hear? They laughed at us there struggling to save the women and childer. And Ireland, land of me birth, stands neutral. Neutral!” exploded Mike. “Neutral while the rest of the world, all the dacent world that wants peace and freedom and happiness for all stands beside Britain and America and Russia and China, the four biggest Allies.”