* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: South with Scott

Date of first publication: 1938

Author: Edward Ratcliffe Garth Russell Evans (as Admiral Lord Mountevans) (1880-1957)

Date first posted: Dec. 29, 2020

Date last updated: Dec. 29, 2020

Faded Page eBook #20201271

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, Howard Ross & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

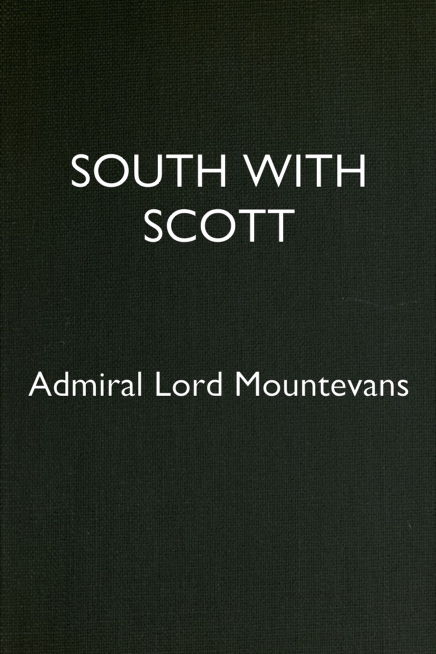

Captain Robert Falcon Scott.

SOUTH WITH

SCOTT

BY

ADMIRAL

LORD MOUNTEVANS

K.C.B., D.S.O.

With 31 photographs by

HERBERT PONTING, F.R.G.S.

COLLINS

LONDON AND GLASGOW

First printed 1938

To

Lashly and Crean

THIS BOOK IS AFFECTIONATELY DEDICATED

PRINTED AND MADE IN GREAT BRITAIN BY

WM. COLLINS SONS AND CO. LTD.

LONDON AND GLASGOW

The object of this book is to keep alive the interest of English-speaking people in the story of Scott and his little band of sailor-adventurers, scientific explorers, and companions. It is written more particularly for Britain’s younger generations.

I have to acknowledge with gratitude the assistance of Miss Zeala Wakeford Cox of Shanghai and Paymaster Lieutenant-Commander Bernard Carter of H.M.S. Carlisle.

Without their help, I doubt if the book would have found its way into print.

Edward R. G. R. Evans.

| Shore Parties. | |

| Robert Falcon Scott | Captain, C.V.O., R.N. (The ‘Owner,’ ‘The Boss’). |

| Edward R. G. R. Evans | Lieut. R.N. (‘Teddy’). |

| Victor L. A. Campbell | Lieut. R.N. (‘The Wicked Mate’). |

| Henry R. Bowers | Lieut. R.I.M. (‘Birdie’). |

| Lawrence E. G. Oates | Captain 6th Inns. Dragoons (‘Titus,’ ‘Soldier’). |

| G. Murray Levick | Surgeon R.N. |

| Edward L. Atkinson | Surgeon R.N., Parasitologist (‘Atch’). |

| Scientific Staff. | |

| Edward Adrian Wilson | B.A., M.B. (Cantab.), Chief of the Scientific Staff, and Zoologist (‘Uncle Bill’). |

| George C. Simpson | D.Sc., Meteorologist (‘Sunny Jim’). |

| T. Griffith Taylor | B.A., B.Sc., B.E., Geologist (‘Griff’). |

| Edward W. Nelson | Biologist (‘Marie’). |

| Frank Debenham | B.A., B.Sc., Geologist (‘Deb.’). |

| Charles S. Wright | B.A., Physicist. |

| Raymond E. Priestley | Geologist. |

| Herbert G. Ponting | F.R.G.S., Camera Artist. |

| Cecil H. Meares | In charge of dogs. |

| Bernard C. Day | Motor Engineer. |

| Apsley Cherry-Garrard | B.A., Asst. Zoologist (‘Cherry’). |

| Tryggve Gran | Sub.-Lieut. Norwegian N.R., B.A., Ski Expert. |

| Men. | |

| W. Lashly | C. Stoker, R.N. |

| W. W. Archer | Chief Steward, late R.N. |

| Thomas Clissold | Cook, late R.N. |

| Edgar Evans | Petty Officer, R.N. |

| Robert Forde | Petty Officer, R.N. |

| Thomas Crean | Petty Officer, R.N. |

| Thomas S. Williamson | Petty Officer, R.N. |

| Patrick Keohane | Petty Officer, R.N. |

| George P. Abbott | Petty Officer, R.N. |

| Frank V. Browning | Petty Officer, 2nd Class, R.N. |

| Harry Dickason | Able Seaman, R.N. |

| F. J. Hooper | Steward, late R.N. |

| Anton Omelchenko | Groom. |

| Dimitri Gerof | Dog Driver. |

| Ship’s Party. | |

| Harry L. L. Pennell | Lieutenant, R.N. |

| Henry E. de P. Rennick | Lieutenant, R.N. |

| Wilfred M. Bruce | Lieutenant, R.N.R. |

| Francis R. H. Drake | Assistant Paymaster, R.N. (Retired), Secretary and Meteorologist in ship. |

| Dennis G. Lillie | M.A., Biologist in ship. |

| James R. Dennistoun | In charge of Mules in ship. |

| Alfred B. Cheetham | R.N.R., Boatswain. |

| William Williams | Chief Engine Room Artificer, R.N., Engineer. |

| William A. Horton | Engine Room Artificer, 3rd Class, R.N., 2nd Engineer. |

| Francis E. C. Davies | Leading Shipwright, R.N. |

| Frederick Parsons | Petty Officer, R.N. |

| William L. Heald | Late Petty Officer, R.N. |

| Arthur S. Bailey | Petty Officer, 2nd Class, R.N. |

| Albert Balson | Leading Seaman, R N. |

| Joseph Leese | Able Seaman, R.N. |

| John Hugh Mather | Petty Officer, R.N.V.R. |

| Robert Oliphant | Able Seaman. |

| Thomas F. McLeod | Able Seaman. |

| Mortimer McCarthy | Able Seaman. |

| William Knowles | Able Seaman. |

| Charles Williams | Able Seaman. |

| James Skelton | Able Seaman. |

| William McDonald | Able Seaman. |

| James Paton | Able Seaman. |

| Robert Brissenden | Leading Stoker, R.N. |

| Edward A. McKenzie | Leading Stoker, R.N. |

| William Burton | Leading Stoker, R.N. |

| Bernard J. Stone | Leading Stoker, R.N. |

| Angus McDonald | Fireman. |

| Thomas McGillon | Fireman. |

| Charles Lammas | Fireman. |

| W. H. Neale | Steward. |

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | SOUTH POLAR EXPEDITION—OUTFIT AND AIMS | 1 |

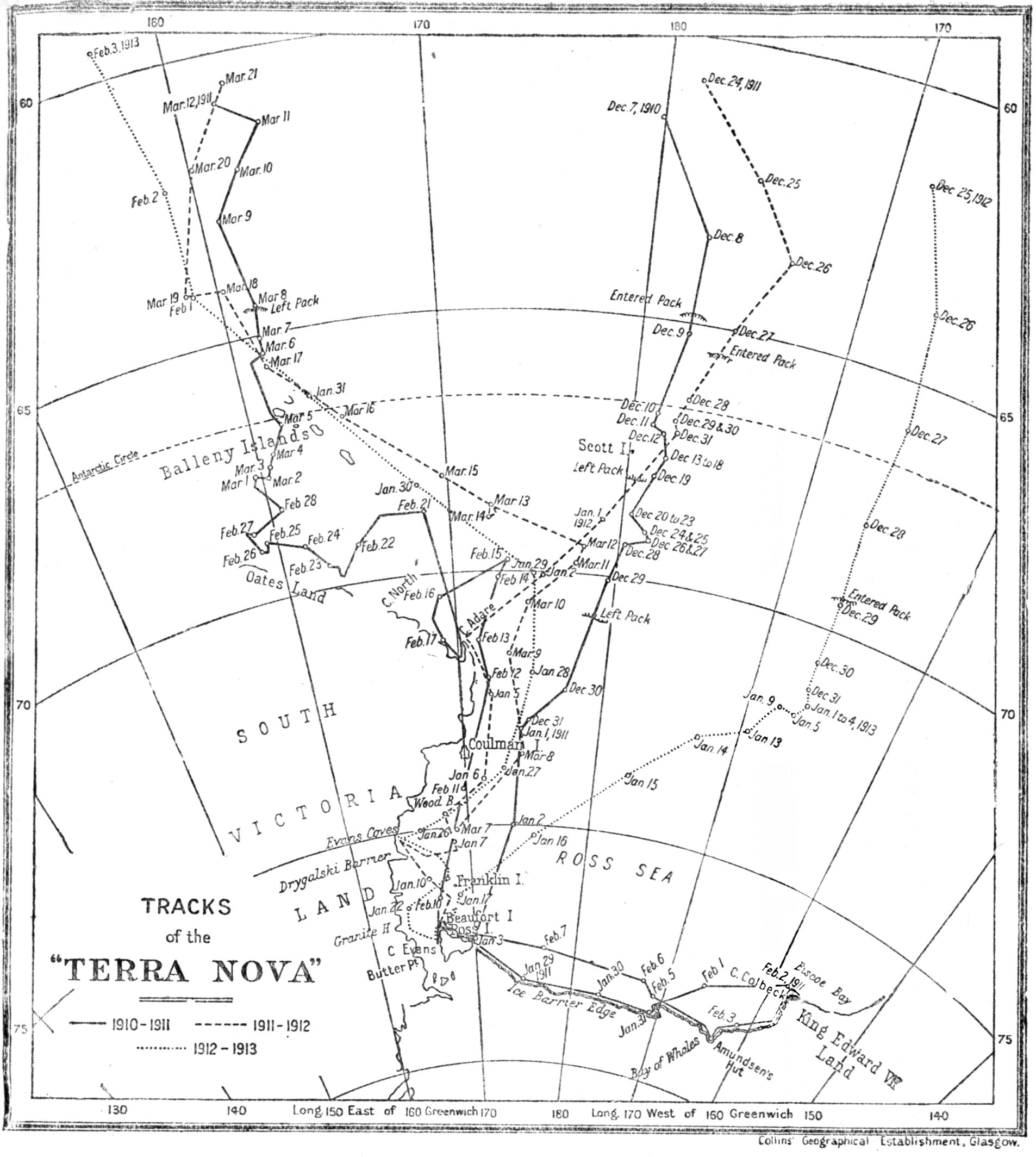

| II. | VOYAGE OF THE ‘TERRA NOVA’ | 11 |

| III. | ASSEMBLING OF UNITS—DEPARTURE FROM NEW ZEALAND | 24 |

| IV. | THROUGH STORMY SEAS | 31 |

| V. | ANTARCTICA—THROUGH THE PACK ICE TO LAND | 38 |

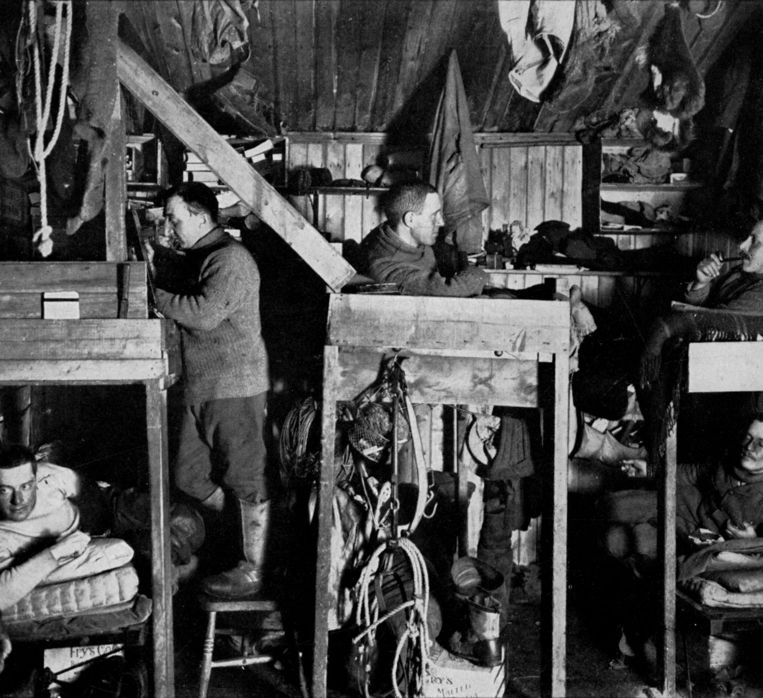

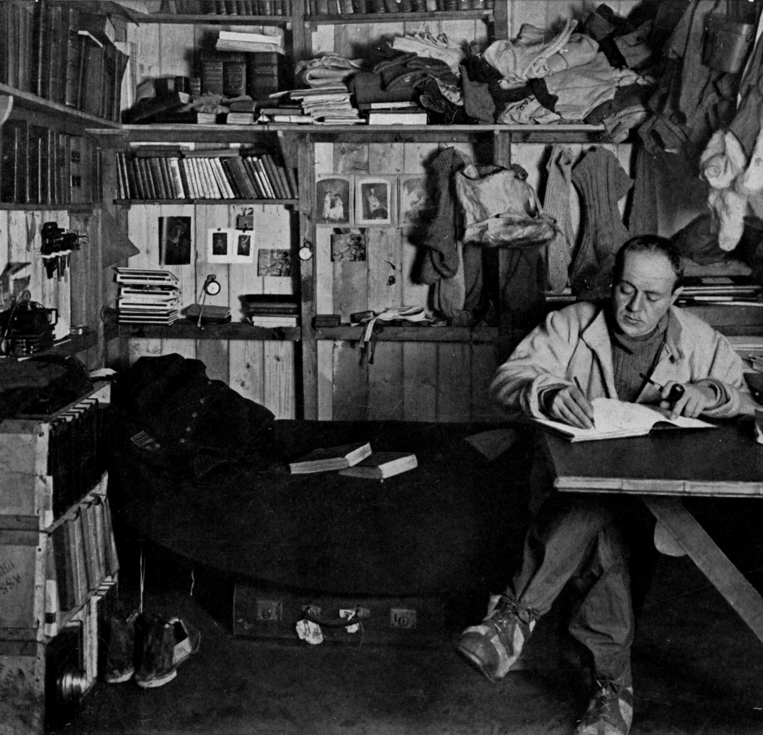

| VI. | SETTLING DOWN TO THE POLAR LIFE | 66 |

| VII. | ARRANGEMENTS FOR THE WINTER | 96 |

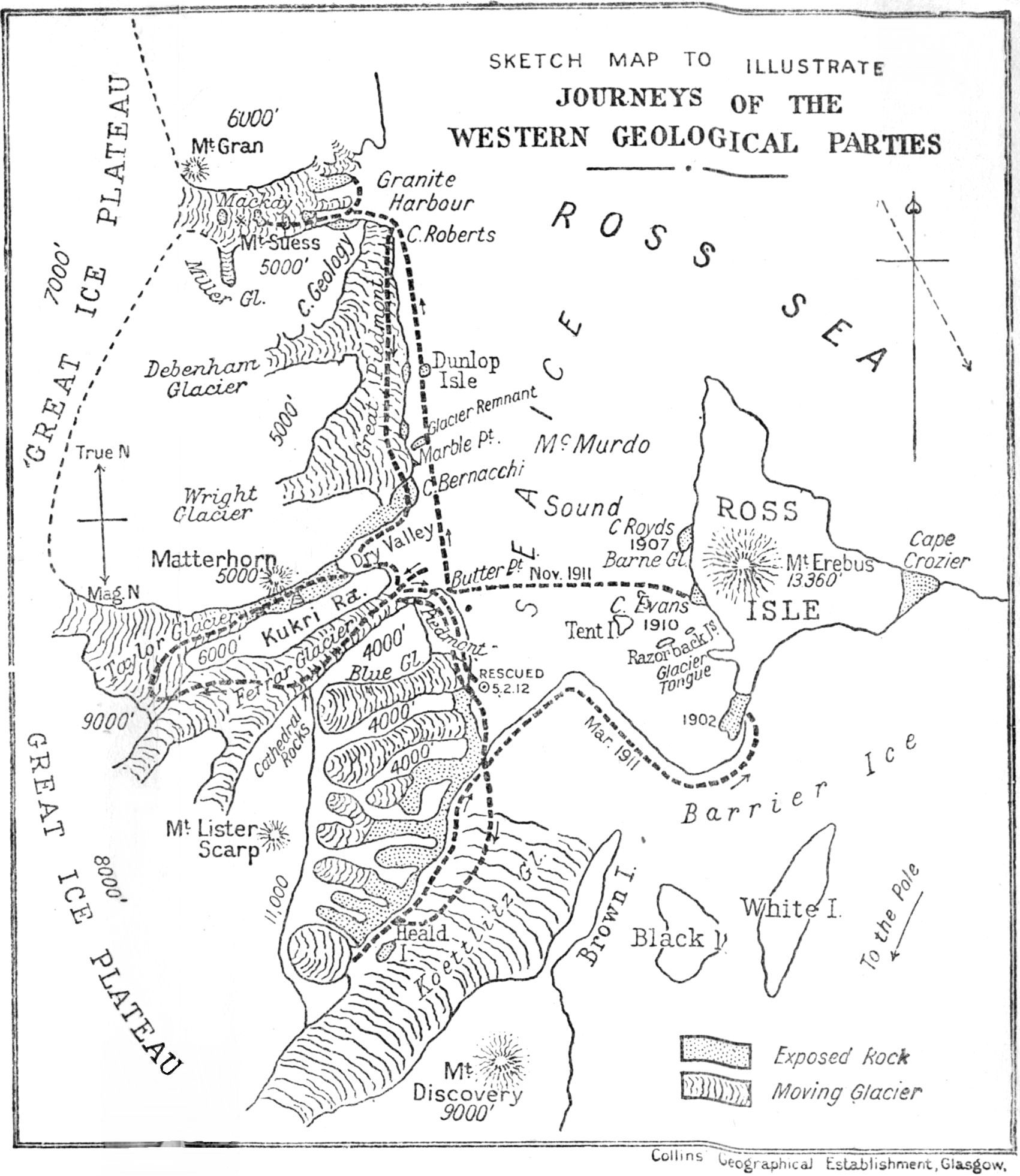

| VIII. | THE WINTER CLOSES IN | 104 |

| IX. | PRELIMINARY EXPLORATIONS | 115 |

| X. | SPRING DEPOT JOURNEY | 129 |

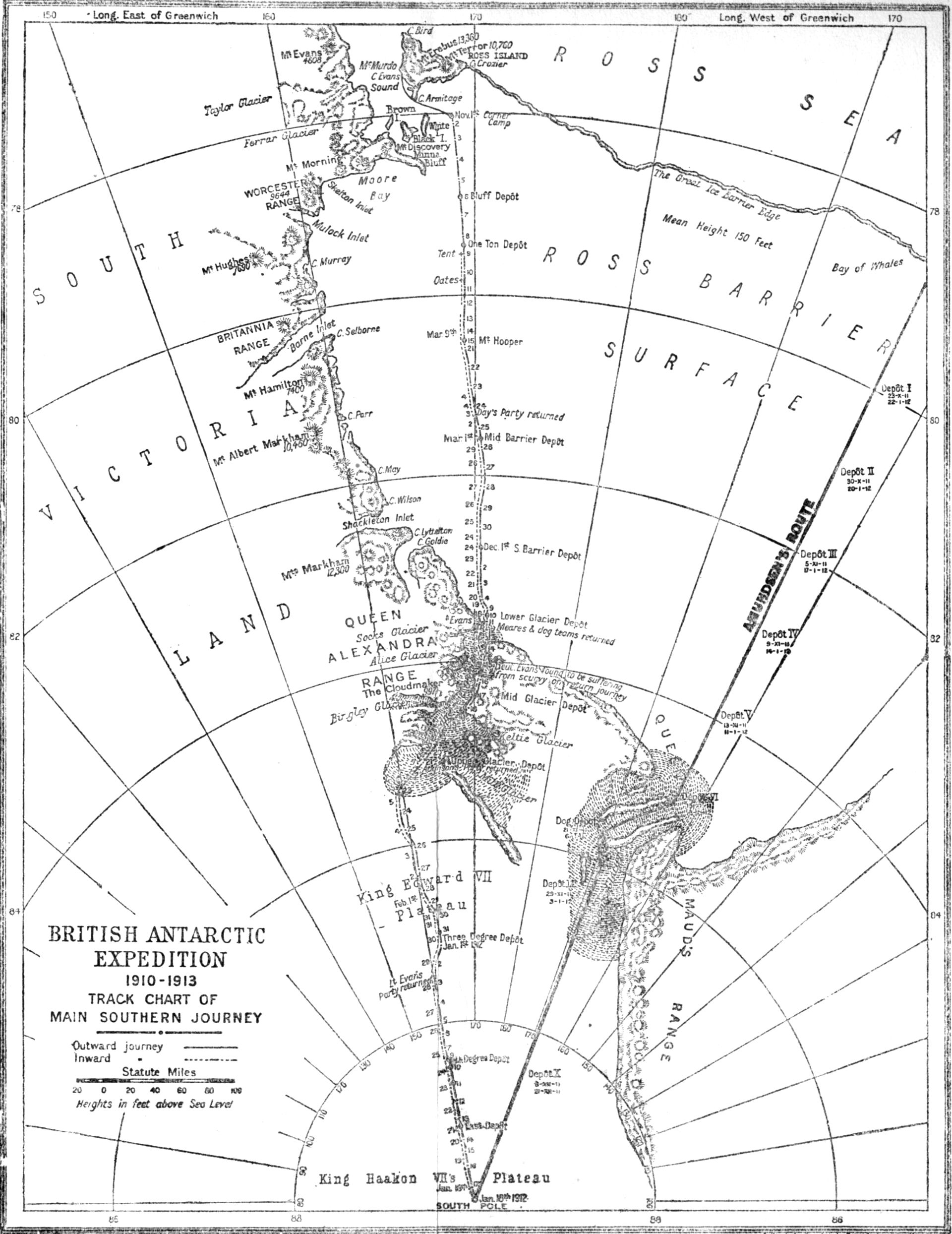

| XI. | PREPARATIONS AND PLANS FOR THE SUMMER SEASON | 137 |

| XII. | SOUTHERN JOURNEY—MOTOR SLEDGES ADVANCE | 166 |

| XIII. | THE BARRIER STAGE | 180 |

| XIV. | ON THE BEARDMORE GLACIER AND BEYOND | 190 |

| XV. | RETURN OF THE LAST SUPPORTING PARTY | 208 |

| XVI. | THE POLE ATTAINED—SCOTT’S LAST MARCHES | 227 |

| XVII. | THE SECOND WINTER—FINDING OF THE POLAR PARTY | 243 |

| XVIII. | ADVENTURES OF THE NORTHERN PARTY | 256 |

| XIX. | NARRATIVE OF THE ‘TERRA NOVA’ | 275 |

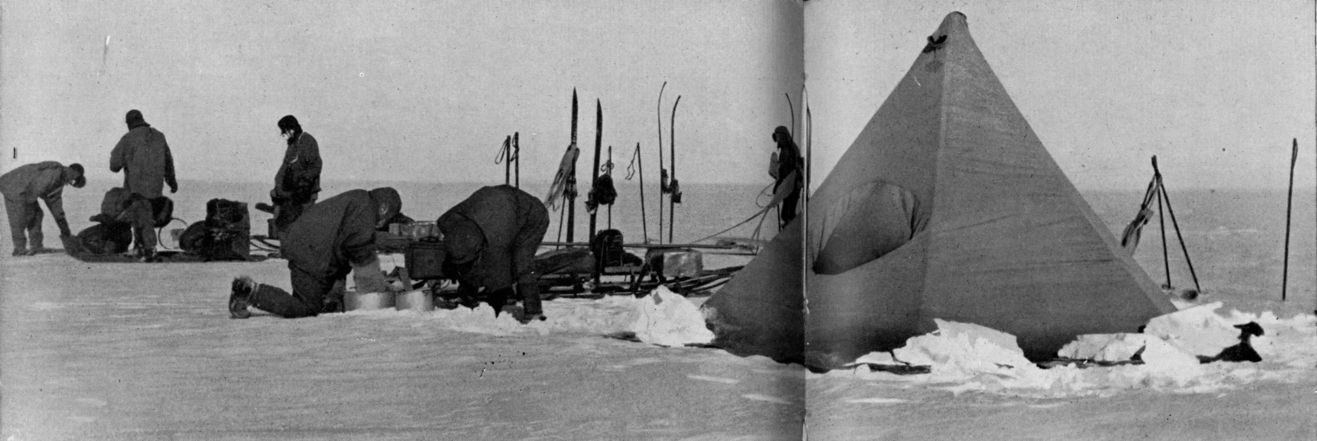

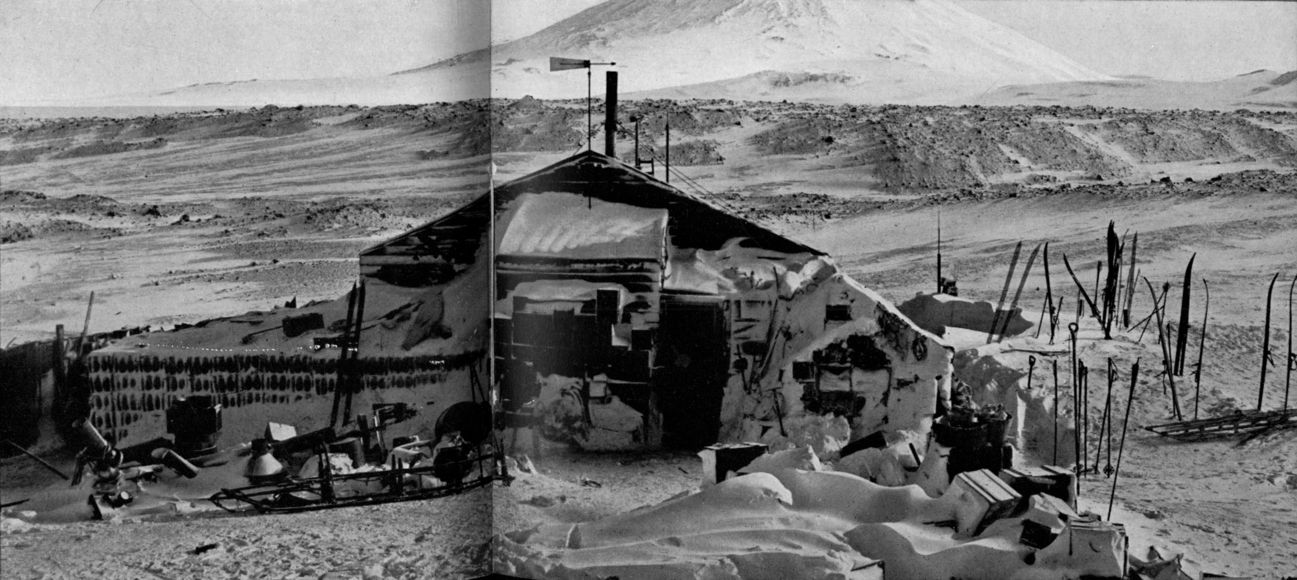

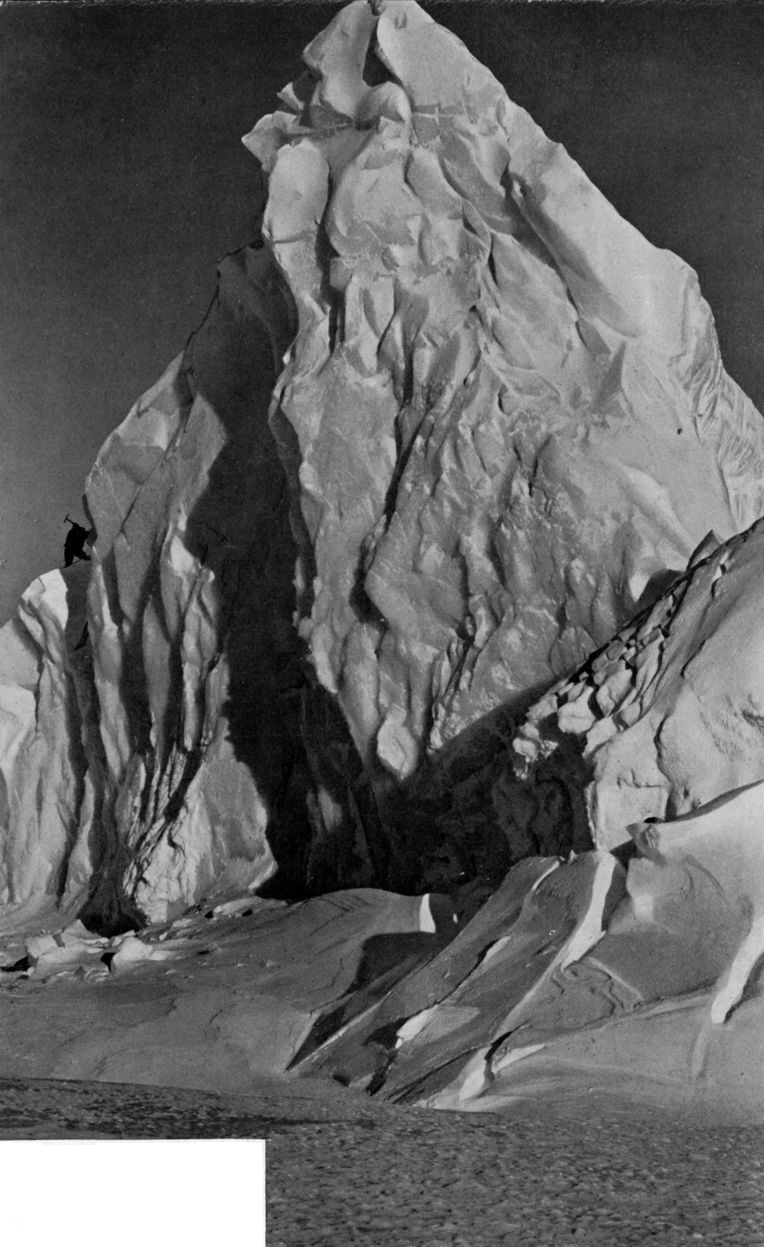

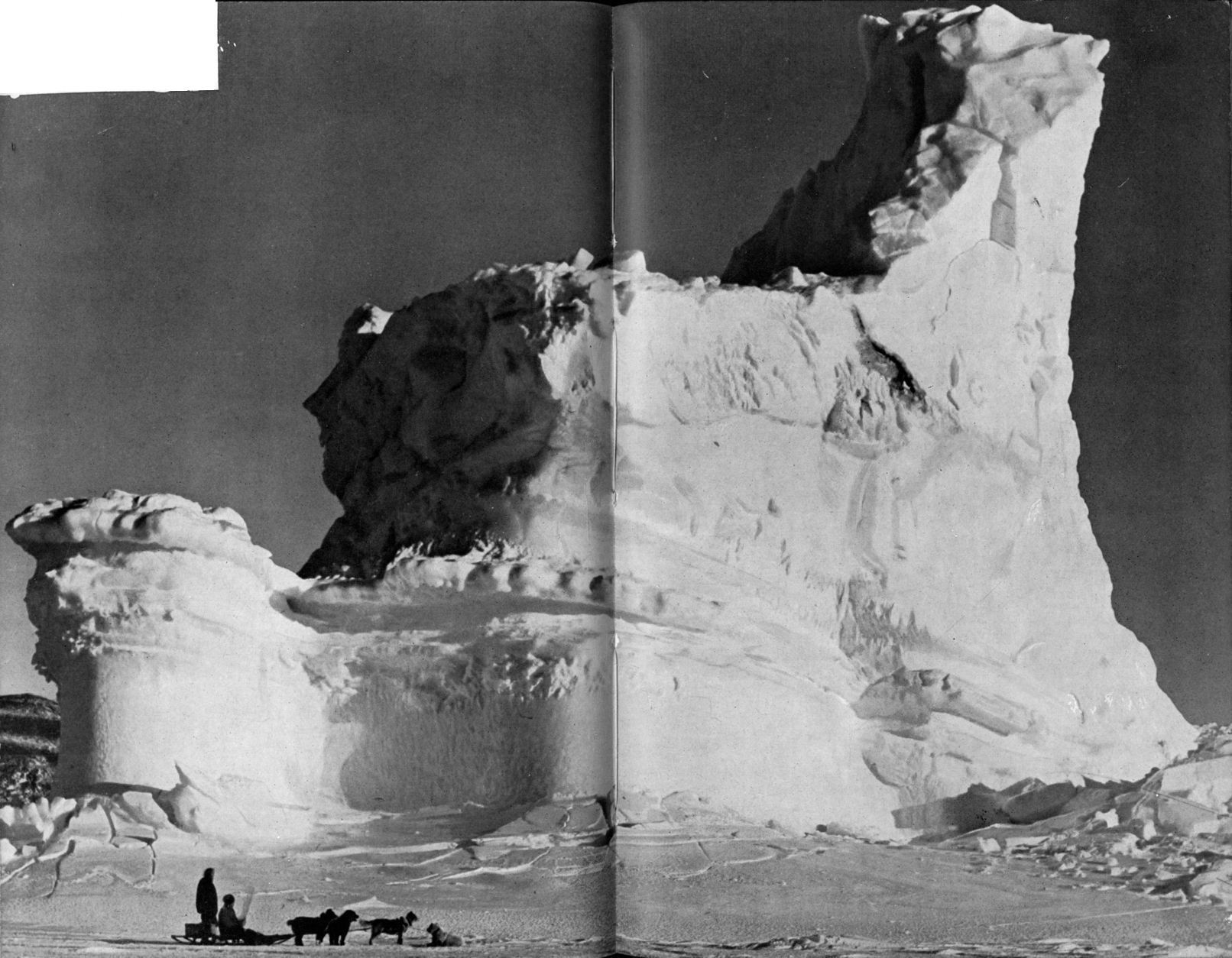

Photographs by Herbert Ponting, British Antarctic Expedition 1910-1913. Copyright, Paul Popper and E.N.A.

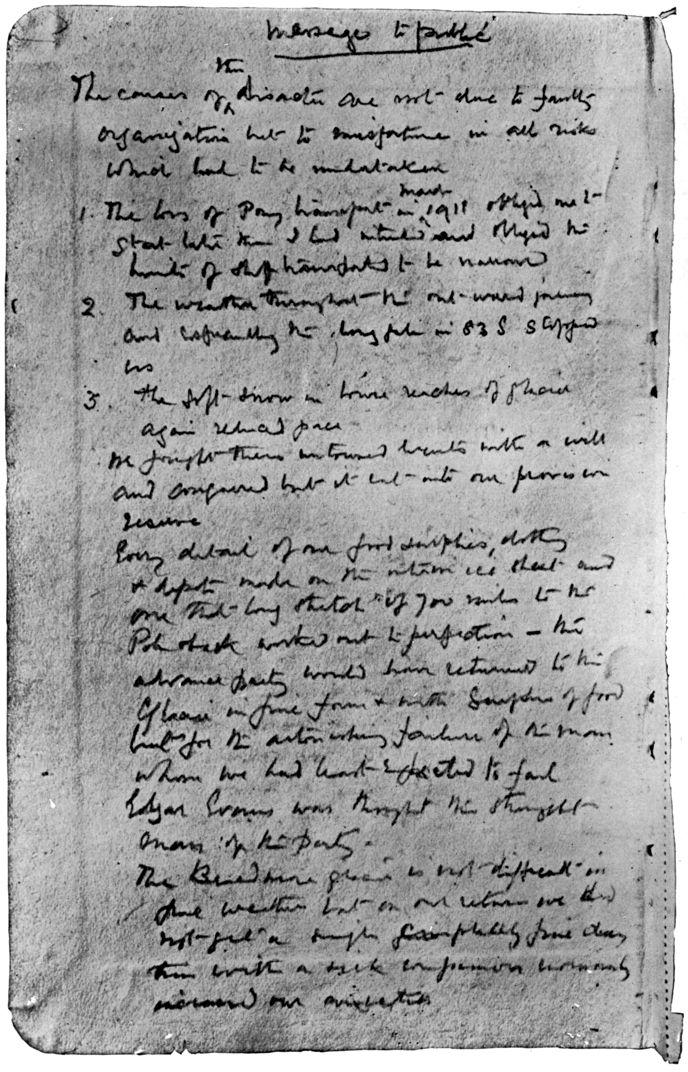

It is nine years since the last supporting party bid farewell to Captain Scott and his four brave companions, whose names are still fresh in the memory of those who were interested in Captain Scott’s last Polar Expedition. The Great War has come and gone and the majority of us wish to forget it, but the story of Scott undoubtedly appeals still to a great number of people. It is a good story, and my only hope is that I can retell it well enough to make my volume worth while reading after so much has already been published concerning the work of the British Antarctic Expedition of 1910.

The main object of our expedition was to reach the South Pole and secure for the British nation the honour of that achievement, but the attainment of the Pole was far from being the only object in view, for Scott intended to extend his former discoveries and bring back a rich harvest of scientific results. Certainly no expedition ever left our shores with a more ambitious scientific programme, nor was any enterprise of this description ever undertaken by a more enthusiastic and determined personnel. We should never have collected our expeditionary funds merely from the scientific point of view; in fact, many of our largest supporters cared not one iota for science, but the idea of the Polar adventure captured their interest. On the other hand, a number of our supporters affected a contempt for the Polar dash and only interested themselves in the question of advanced scientific study in the Antarctic. As the expedition progressed, however, the most unenthusiastic member of the company developed the serious taste, and in no case did we ever hear from the scientific staff complaints that the Naval members failed to help them in their work with a zeal that was quite unexpected. This applies more particularly to the seamen and stokers.

Captain Scott originally intended to make his winter quarters in King Edward VII. Land, but altered the arrangement after the fullest discussion with his scientific friends and advisers, and planned that a small party of six should examine this part of the Antarctic and follow the coast southward from its junction with the Great Ice Barrier, penetrating as far south as they were able, surveying geographically and geologically. This part of the programme was never carried out, owing to the ice conditions thereabouts preventing a landing either on the Barrier or in King Edward VII. Land itself.

The main western party Scott planned to command himself, the base to be at Cape Crozier or in McMurdo Sound, near the site of the Discovery’s old winter quarters at Cape Armitage, the exact position to be governed by the ice conditions on arrival.

Dogs, ponies, motor sledges and man-hauling parties on ski were to perform the Polar journey by a system of relays or supporting parties. Scott’s old comrade, Dr E. A. Wilson of Cheltenham, was selected as chief of the scientific staff and to act as artist to the expedition. Three geologists were chosen and two biologists, to continue the study of marine fauna and carry out research work in depths up to 500 fathoms. The expeditionary ship was to be fitted for taking deep-sea soundings and magnetic observations, and the meteorological programme included the exploration of the upper air currents and the investigation of the electrical conditions of the atmosphere. We were fortunate in securing as meteorologist the eminent physicist, Dr G. Simpson, who is now head of the Meteorological Office in London. Dr Simpson was to have charge of the self-recording magnetic instruments ashore at the main base.

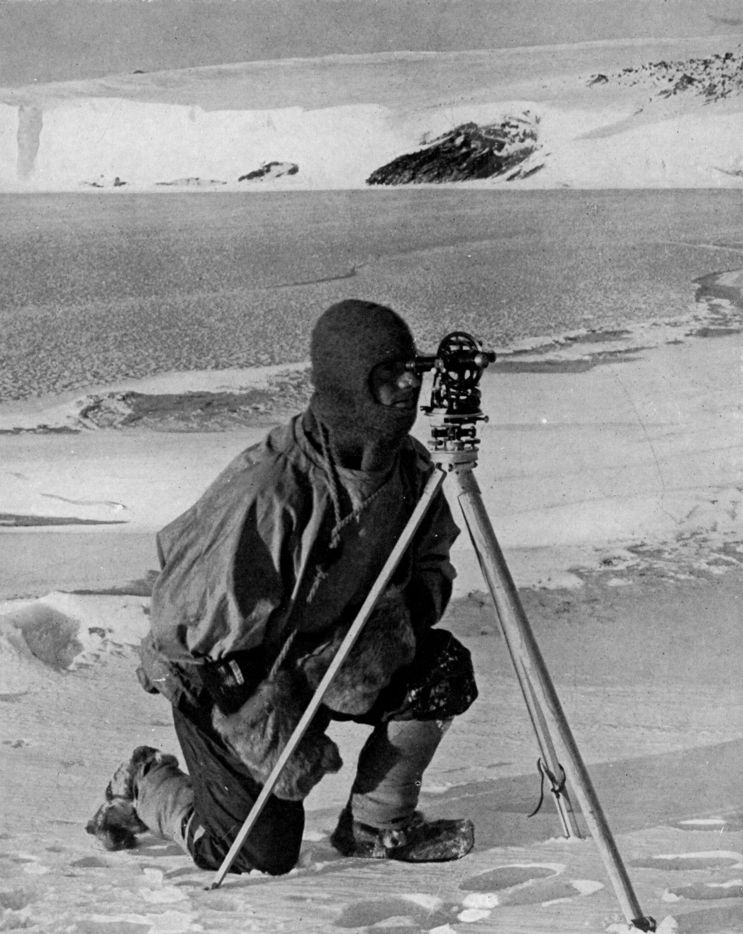

Study of ice structure and glaciation was undertaken by Mr C. S. Wright, who was also assistant physicist. The magnetic work of the ship was entrusted to Lieut. Harry Pennell, R.N., an officer of more than ordinary scientific attainments and a distinguished navigator. Lieut. Henry Rennick was given control of the hydrographical survey work and deep-sea sounding. Two surgeons were lent by the Royal Navy for the study of bacteriology and parasitology in addition to their medical duties, and Mr Herbert G. Ponting was chosen as camera artist and cinematographer to the Expedition.

To my mind the outfit and preparation were the hardest part of our work, for we were not assured of funds until the day of our departure. This did not lighten Scott’s burden. The plans of the British Antarctic Expedition of 1910 were first published on September 13, 1909, but although Scott’s appeal to the nation was heartily endorsed by the Press, it was not until the spring of 1910 that we had collected the first £10,000. Personally, I was despatched to South Wales and the west of England to raise funds from my Welsh and west country friends. Scott, himself, when he could be spared from the Admiralty, worked Newcastle, Liverpool, and the North, whilst both of us did what we could in London to obtain the money necessary to purchase and equip the ship. It was an anxious time for Scott and his supporters, but after the first £10,000 had been raised the Government grant of £20,000 followed and the Expedition came properly into being. Several individuals subscribed £1000 each, and Government grants were subsequently made by the Australian Commonwealth, the Dominion of New Zealand and South Africa. Capt. L. E. G. Oates and Mr Apsley Cherry-Garrard were included in the donors of £1000, but they gave more than this, for these gallant gentlemen gave their services and one of them his life. An unexpected and extremely welcome contribution came from Mr Samuel Hordern of Sydney in the shape of £2,500, at a time when we needed it most. Many firms gave in cash as well as in kind. Indeed, were it not for the generosity of such firms it is doubtful whether we could have started. The services of Paymaster Lieut. Drake, R.N., were obtained as secretary to the Expedition. Offices were taken and furnished in Victoria Street, S.W., and Sir Edgar Speyer kindly consented to act as Hon. Treasurer—without hesitation I may say we owe more to Sir Edgar than ever we can repay.

We were somewhat limited in our choice of a ship, suitable for the work contemplated. The best vessel of all was of course the Discovery, which had been specially constructed for the National Antarctic Expedition in 1900, but she had been acquired by the Hudson Bay Company, and although the late Lord Strathcona, then High Commissioner for Canada, was approached, he could not see his way to obtaining her for us in view of her important employment as supply ship for the Hudson Bay Trading Stations. There remained the Aurora, Morning, Björn, Terra Nova, Shackleton’s stout little Nimrod, and one or two other old whaling craft. The Björn, a beautiful wooden whaler, would have served our purpose excellently, but, alas! she was too small for the enterprise and we had to fall back on the Terra Nova, an older ship but a much larger craft. The Terra Nova had one great defect—she was not economic in the matter of coal consumption. She was the largest and strongest of the old Scotch whalers, had proved herself in the Antarctic pack ice and acquitted herself magnificently in the Northern ice-fields in whaling and sealing voyages extending over a period of twenty years. In spite of her age she had considerable power for a vessel of that type.

After a preliminary survey in Newfoundland, which satisfied us as to her seaworthiness in all respects, the Terra Nova was purchased for the Expedition by Messrs David Bruce & Sons for the sum of £12,500. It seems a high price, but this meant nothing more than her being chartered to us for £2000 a year, since her owners were ready to pay a good price for the ship if we returned her in reasonably good condition at the conclusion of the Expedition.

Captain Scott handed her over to me to fit out, whilst he busied himself more with the scientific programme and the question of finance. We had her barque-rigged and altered according to the requirements of the expedition. A large, well-insulated ice-house was erected on the upper deck which held 150 carcasses of frozen mutton, and, owing to the position of the cold chamber, free as it was from the vicinity of iron, we mounted here our standard compass and Lloyd Creek pedestal for magnetic work. Our range-finder was also mounted on the ice-house. A new stove was put in the galley, a lamp room and paraffin store built, and store-rooms, instrument, and chronometer rooms were added. A tremendous alteration was made in the living spaces both for officers and men. Twenty-four bunks were fitted around the saloon accommodation, whilst for the seamen and warrant officers hammock space or bunks were provided. It was proposed to take six warrant officers, including carpenter, ice-master, boatswain, and chief steward. Quite good laboratories were constructed on the poop, while two large magazines and a clothing-store were built up between decks, and these particular spaces were zinc-lined to keep them damp-free. The ship required alteration rather than repair, and there were only one or two places where timber had rotted and these were soon found and reinforced.

I shall never forget the day I first visited the Terra Nova in the West India Docks: she looked so small and out of place surrounded by great liners and cargo-carrying ships, but I loved her from the day I saw her, because she was my first command. Poor little ship, she looked so dirty and uncared for and yet her name will be remembered for ever in the story of the sea, which one can hardly say in the case of the stately liners which dwarfed her in the docks. I often blushed when admirals came down to see our ship, she was so very dirty. To begin with, her hold contained large blubber tanks, the stench of whale oil and seal blubber being overpowering, and the remarks of those who insisted on going all over the ship need not be here set down. However, the blubber tanks were withdrawn, the hold spaces got the thorough cleansing and whitewashing that they so badly needed. The bilges were washed out, the ship disinfected fore and aft, and a gang of men employed for some time to sweeten her up. Then came the fitting out, which was much more pleasant work.

Scott originally intended to leave England with most of the members of the Expedition on August 1, 1910, but he realised that an early start from New Zealand would mean a better chance for the big depot-laying journey he had planned to undertake before the first Antarctic winter set in. Accordingly the sailing date was anticipated, thanks to the united efforts of all concerned with the fitting out, and we made June 1 our day of departure, which meant a good deal of overtime everywhere.

The ship had to be provisioned and stored for her long voyage, having in view the fact that there were no ship-chandlers in the Polar regions, but those of us who had ‘sailed the way before’ had a slight inkling that we might meet more ships, and others who would lend us a helping hand in the matter of Naval stores.

Captain Scott allowed me a sum with which to equip the Terra Nova; it seemed little enough to me but it made quite a hole in our funds. There were boatswain’s stores to be purchased, wire hawsers, canvas for sail-making, fireworks for signalling, whale boats and whaling gear, flags, logs, paint, tar, carpenter’s stores, blacksmith’s outfit, lubricating oils, engineer’s stores, and a multitude of necessities to be thought of, selected, and not paid for if we could help it. The verb ‘to wangle’ had not then appeared in the English language, so we just ‘obtained.’

The Expedition had many friends, and it was not unusual to find Petty Officers and men from the R.N.V.R. working on board and helping us on Saturday afternoons and occasionally even on Sundays. They gave their services for nothing, and the only way in which we could repay them was to select two chief Petty Officers from their number, disrate them, and take them Poleward as ordinary seamen.

It was not until the spring of 1910 that we could afford to engage any officers or men for the ship, so that most of the work of rigging her was done by dock-side workers under a good old master rigger named Malley. Landsmen would have stared wide-eyed and open-mouthed at Malley’s men with their diminutive dolly-winch had they watched our new masts and yards being got into place.

Six weeks before sailing day Lieut. Campbell took over the duties of Chief Officer in the Terra Nova, Pennell and Rennick also joined, and Lieut. Bowers came home from the Indian Marine to begin his duties as Stores Officer by falling down the main hatch on to the pig iron ballast. I did not witness this accident, and when Campbell reported the matter I am reported to have said, ‘What a silly ass!’ This may have been true, for coming all the way from Bombay to join us and then immediately falling down the hatch did seem a bit careless. However, when Campbell added that Bowers had not hurt himself my enthusiasm returned and I said, ‘What a splendid fellow!’ Bowers fell nineteen feet without injuring himself in the slightest. This was only one of his narrow escapes and he proved himself to be about the toughest man amongst us.

Quite a lot could be written of the volunteers for service with Scott in this his last Antarctic venture. There were nearly 8000 of them to select from, and many eligible men were turned down simply because they were frozen out by those who had previous Antarctic experience. We tried to select fairly, and certainly picked a representative crowd. It was not an all-British Expedition because we included amongst us a young Norwegian ski-runner and two Russians; a dog driver and a groom. The Norwegian has since distinguished himself in the Royal Air Force—he was severely wounded in the war whilst fighting for the British and their Allies, but his pluck and Anglophile sentiments cost him his commission in the Norwegian Flying Corps.

Dr Wilson assisted Captain Scott in selecting the scientific staff, while the choice of the officers and crew was mainly left to myself as Commander-elect of the Terra Nova.

Most Polar expeditions sail under the Burgee of some yacht club or other. We were ambitious to fly the White Ensign, and to enable this to be done the Royal Yacht Squadron adopted us. Scott was elected a member, and it cost him £100, which the Expedition could ill afford. However, with the Terra Nova registered as a yacht we were able to evade those Board of Trade officials who declared that she was not a well-found merchant ship within the meaning of the Act. Having avoided the scrutiny of the efficient and official, we painted out our Plimsoll mark with tongue in cheek and eyelid drooped, and, this done, took our stores aboard and packed them pretty tight. The Crown Preserve Coal Co. sent us a quantity of patent fuel which stowed beautifully as a flooring to the lower hold, and all our provision cases were thus kept well up out of the bilge water which was bound to scend to and fro if we made any quantity of water, as old wooden ships usually do. The day before sailing the Royal Geographical Society entertained Scott and his party at luncheon in the King’s Hall, Holborn Restaurant. About 300 Fellows of the Society were present to do us honour. The President, Major Leonard Darwin, proposed success to the Expedition, and in the course of his speech wished us God-speed. He congratulated Captain Scott on having such a well-found expedition and, apart from dwelling on the scientific and geographical side of the venture, the President said that Captain Scott was going to prove once again that the manhood of our nation was not dead and that the characteristics of our ancestors who won our great Empire still flourished amongst us.

After our leader had replied to this speech Sir Clements Markham, father of modern British exploration, proposed the toast of the officers and staff in the most touching terms. Poor Sir Clements is no more, but it was he who first selected Captain Scott for Polar work, and he, indeed, who was responsible for many others than those present at lunch joining Antarctic expeditions, myself included.

Sailing day came at last, and on June 1, 1910, when I proudly showed Scott his ship, he very kindly ordered the hands aft and thanked them for what they had done.

The yards were square, the hatches on with spick-and-span white hatch covers, a broad white ribbon brightened the black side, and gold leaf bedizened the quarter badges besides gilding the rope scroll on the stern. The ship had been well painted up, a neat harbour furl put on the sails, and if the steamers and lofty sailing vessels in the basin could have spoken, their message would surely have been, ‘Well done, little ’un.’

What a change from the smudgy little lamp-black craft of last November—so much for paint and polish. All the same it was the Terra Nova’s Indian summer. A close search by the technically expert would have revealed scars of age in the little lady, furrows worn in her sides by grinding ice floes, patches in the sails, strengthening pieces in the cross-trees and sad-looking deadeyes and lanyards which plainly told of a bygone age.

But the merchant seamen who watched from the dock side were kind and said nothing. The old admirals who had come down to visit the ship were used to these things, or perhaps they did not twig it. After all, what did it matter, it was sailing day, we were all as proud as peacocks of our little ship, and from that day forward we pulled together and played the game, or tried to.

Lady Bridgeman, wife of the first Sea Lord, and Lady Markham hoisted the White Ensign and the Burgee of the Royal Yacht Squadron an hour or so before sailing. At 4.45 p.m. the visitors were warned off the ship, and a quarter of an hour later we slipped from our wharf in the South-West India Docks and proceeded into the river and thence to Greenhithe, where we anchored off my old training ship, the Worcester, and gave the cadets a chance to look over the ship. On the 3rd June we arrived at Spithead, where we were boarded by Captain Chetwynd, Superintendent of Compasses at the Admiralty, who swung the ship and adjusted our compasses. Captain Scott joined us on the 4th and paid a visit with his ‘yacht’ to the R.Y.S. at Cowes. On the 6th we completed a series of magnetic observations in the Solent, after which many officers were entertained by Captain Mark Kerr in the ill-fated Invincible. We were royally looked after, but I am ashamed to say we cleared most of his canvas and boatswain’s stores out of the ship. Perhaps a new 3½-inch hawser found its way to the Terra Nova; anyway, if the Invincible’s stores came on board the exploring vessel she made good use of them and saved them their Jutland fate. We left the Solent in high feather on the following day.

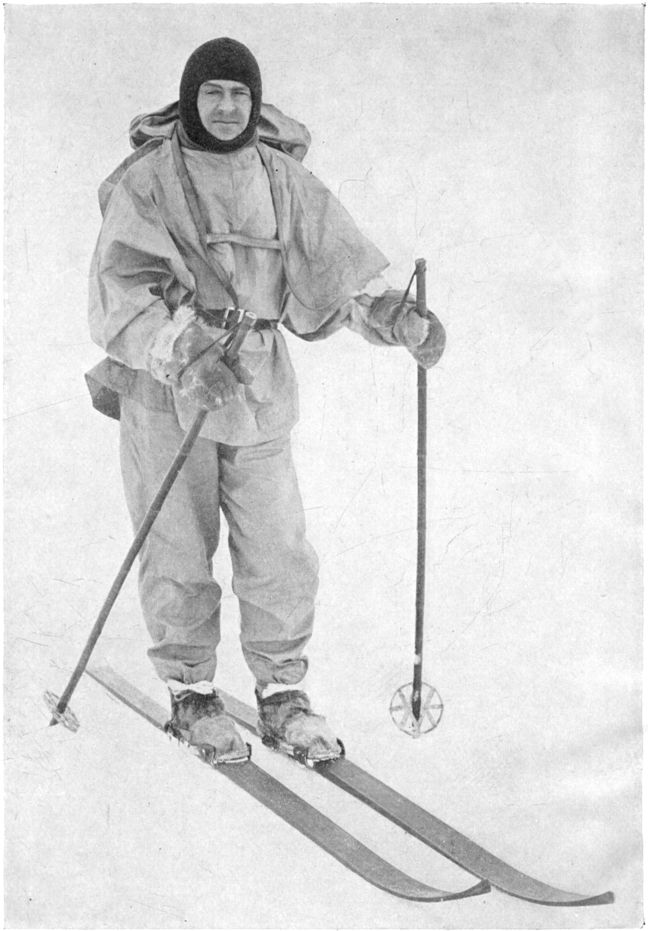

“Under sail!”—the Terra Nova, heeling to a gale on her journey south, and——

The Sea Horse took us in tow to the Needles, from whence H.M.S. Cumberland, Cadets’ Training Ship, towed us to Weymouth Bay. This was poor Scott’s last Naval review. He had landed at Portsmouth and busied himself with the Expedition’s affairs and rejoined us at Weymouth in time to steam through the Home Fleet assembled in Portland Harbour. We steamed out of the ‘hole in the wall’ at the western end of Portland Breakwater and rounded Portland Bill at sunset on our way to Cardiff, where we were to be received by my own Welsh friends and endowed with all good things. We were welcomed by the citizens of the great Welsh seaport with enthusiasm. Free docking, free coal, defects made good for nothing, an office and staff placed at our disposal, in fact everything was done with an open-hearted generosity. We took another 300 tons of patent fuel on board and nearly 100 tons of Insole’s best Welsh steaming coal, together with the bulk of our lubricating oils. When complete with fuel we met with our first setback, for the little ship settled deeply in the water and the seams, which had up till now been well above the water-line, leaked in a way that augured a gloomy future for the crew in the nature of pumping. With steam up this did not mean anything much, but under sail alone, unless we could locate the leaky seams, it meant half an hour to an hour’s pumping every watch. We found a very leaky spot in the fore peak, which was mostly made good by cementing.

——journey’s end: the Terra Nova in the icy vastness of the Antarctic.

On the 15th June we left the United Kingdom after a rattling good time in Cardiff. Many shore boats and small craft accompanied us down the Bristol Channel as far as Breaksea Light Vessel. We hoisted the Cardiff flag at the fore and the Welsh flag at the mizen—some wag pointed to the flag and asked why we had not a leek under it, and I felt bound to reply that we had a leak in the fore peak! It was a wonderful send-off and we cheered ourselves hoarse. Captain Scott left with our most intimate friends in the pilot boat and we proceeded a little sadly on our way.

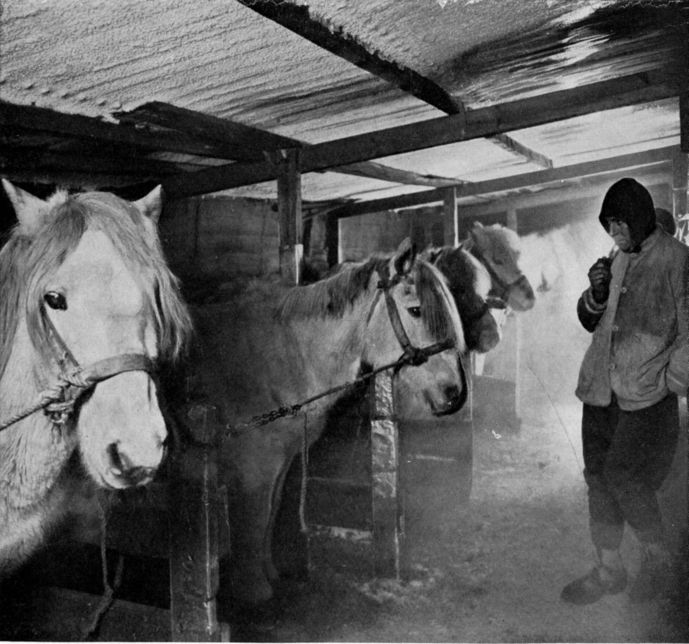

“All the ponies were white”—above, a part of the British Antarctic Expedition’s stables. Below, one of the dogs indulges a taste for music.

After passing Lundy Island we experienced a head wind and the gentle summer swell of the Atlantic. In spite of her deeply-laden condition the Terra Nova breasted each wave in splendid form, lifting her toy bowsprit proudly in the air till she reminded me, with her deck cargo, of a little mother with her child upon her back.

Our first port of call was Madeira, where it was proposed to bunker, and we made good passage to the island under steam and sail for the most part. We stayed a couple of days coaling and taking magnetic observations at Funchal, then ran out into the north-east Trades, let fires out, and became a sailing ship.

Whilst lazily gazing at fertile Madeira from our anchorage we little dreamt that within two months the distinguished Norseman, Roald Amundsen, would be unfolding his plans to his companions on board the Fram in this very anchorage, plans which changed the whole published object of his expedition, plans which culminated in the triumph of the Norwegian flag over our own little Union Jack, and plans which caused our people a fearful disappointment—for Amundsen’s ultimate success meant our failure to achieve the main object of our Expedition: to plant the British Flag first at the South Pole.

Under sail! Quite a number of the scientists and crew had never been to sea in a sailing ship before, but a fair wind and a collection of keen and smiling young men moving about the decks were particularly refreshing to me after the year of fund collecting and preparation.

We learnt to know a great deal about one another on the outward voyage to New Zealand, where we were to embark our dogs and ponies. The most surprising personality was Bowers, considering all things.

Officers, scientists, and the watch worked side by side trimming coals and restoring the ’tween decks as cases were shaken and equipment assembled. The scientific staff were soon efficient at handing, reefing, and steering. Every one lent a hand at whatever work was going. Victor Campbell was christened the ‘Wicked Mate,’ and he shepherded and fathered the afterguard delightfully.

Wilson and I shared the Captain’s cabin, and when there was nothing afoot he made lovely sea sketches and water-colour drawings to keep his hand in. Certainly Uncle Bill[1] had copy enough in those days of sunlit seas and glorious sunrises. He was up always an hour before the sun and missed very little that was worth recording with his artistic touch. Wilson took Cherry-Garrard under his wing and brought him up as it were in the shadow of his own unselfish character. We had no adventures to record until the last week in July beyond the catching of flying-fish, singing chanties at the pump, and Lillie getting measles. We isolated him in the dark room, which, despite its name, was one of the lightest and freshest rooms in the ship. Atkinson took charge of the patient and Lillie could not have been in the hands of a better or more cheery medico.

Not all of the members of the Expedition had embarked in England, although the majority came out in the ship to save expense.

Captain Scott had remained behind to squeeze out more subscriptions and to complete arrangements with the Central News, which he was making in order to give the world’s newspapers the story of the Expedition for simultaneous publication as reports came back to civilisation in the Terra Nova. He also had finally to settle magazine and cinematograph contracts which were to help pay for the Expedition, and lastly, our leader, with Drake and Wyatt, the business manager, were to pay bills we had incurred by countless items of equipment, large and small, which went to fill up our lengthy stores lists. Thankless work enough—we in the ship were much better off with no cares now beyond the handling of our toy ship and her safe conduct to Lyttleton. Cecil Meares and Lieut. Bruce were on their way through Siberia collecting dogs and ponies. Ponting was purchasing the photographic and cinematographic outfit, Griffith Taylor, Debenham, and Priestley, our three geologists, and Day, the motor engineer, were to join us in New Zealand, and Captain Scott with Drake at Capetown.

In order to get another series of magnetic observations and to give the staff relief from the monotony of the voyage as well as an opportunity for doing a little special work, we stopped at the uninhabited island of South Trinidad for a couple of days, arriving on July 26.

Trinidad Island looked magnificent with its towering peaks as we approached it by moonlight. We dropped anchor shortly after dawn, the ship was handed over to the Wicked Mate and Boatswain, who set up the rigging and delighted themselves with a seamanlike refit. Campbell had a party over the side scrubbing the weed off, and many of the ship’s company attempted to harpoon the small sharks which came close round in shoals and provided considerable amusement. These fish were too small to be dangerous. After breakfast all the scientists and most of the officers landed and were organised by Uncle Bill into small parties to collect birds’ eggs, flowers, specimens, to photograph and to sketch. A good lunch was taken ashore, and we looked more like a gunroom picnic party than a scientific expedition when we left the ship in flannels and all manner of weird costumes. Wilson, Pennell, and Cherry-Garrard shot a number of birds, mostly terns and gannets, and climbed practically to the top of the island, where they could see the Martin Vaz islets on the horizon. Wilson secured some Trinidad petrels, both white breasted and black breasted, and discovered that the former is the young bird and the latter the adult of the same species. He found them in the same nests. We collected many terns’ eggs; the tern has no nest but lays its eggs on a smooth rock. Also one or two frigate birds were caught. Nelson worked along the beach, finding sea-urchins, anemones, and worms, which he taught the sailors the names of—polycheats and sepunculids, I think he called them. He caught various fishes, including sea-perches, garfish, coralfish, and an eel, a small octopus and a quantity of sponges. Trigger-fish were so abundant that many of them were speared from the ship with the greatest of ease, and Rennick harpooned a couple from a boat with an ordinary dinner fork. Lillie, who had recovered from measles, was all about, and his party went for flowering plants and lichens. He climbed to the summit of the island—2000 ft.—and gave it as his opinion that the dead trees strewn all round the base of the island had been carried down with the volcanic debris from higher altitudes. It was also his suggestion that the island had only recently risen, the trees which originally grew on the top of the island having died from unsuitable climate in the higher condition. Gran went up with Lillie and took photographs. ‘Birdie’ Bowers and Wright were employed collecting insects, and, with those added by the rest of us, the day’s collection included all kinds of ants, cockroaches, grasshoppers, mayflies, a centipede, fifteen different species of spider, locusts, a cricket, woodlice, a parasite fly, a beetle, and a moth. We failed to get any of the dragonflies seen, and, to the great sorrow of the crews who landed with us, missed capturing a most beautiful chestnut-coloured mouse with a fur tail. Land crabs, a dirty yellow in colour, were found everywhere, the farther one went inland the bigger were the crabs. The blue shore crabs were only to be seen near the sea or along the coast and water courses. Several of these were brought off to the ship for Dr Atkinson to play with, and he found nematodes in them, and parasites in the birds and fish.

During the afternoon a swell began to roll in the bay and those on board the ship hoisted the warning signal and fired a sound rocket to recall the scattered parties. By 4.30 we had reassembled on the rocks where we had landed in the forenoon, but the rollers, being fifteen feet high, it was obviously unwise to send off cameras and perishable gear, and since it was equally inadvisable to leave the whole party ashore without food and sufficient clothing and the prospect of an inhospitable island home for days, we all swam off one by one, the boat’s crew working a grassline bent to a lifebuoy. The boat to which we swam was riding to a big anchor a hundred feet from the shore, just outside the surf. There were a few sharks round the whaler, but they were shy and left us alone. Rennick worked round the boat in a small Norwegian pram and scared them away. Many trigger-fish swallowed the thick vegetable oil which the boat’s crew ladled into the sea to keep the surf down, and I think this probably attracted the sharks, though it was not very nice to swim through. None of us were any the worse for our romp ashore, but the long day and the hot sun tired us all out. Nearly all the afterguard slept on the upper deck that night, and, but for the dismal roar of the swell breaking on the rocks and the heavy rolling of the Terra Nova, we spent quite a comfortable night. Dr Atkinson and Brewster had been left ashore with the gear, but they got no sleep because all night the terns flew round crying and protesting against their intrusion. The wail of these birds sounds like the deep note of a banjo. The two men mostly feared the land crabs, but to their surprise they were left in peace.

Next day about 9 a.m. I went in with Rennick, Bowers, Oates, Gran, and two seamen to the landing place, taking a whaler and pram equipped with grass hawser, breeches buoy, rocket line, and everything necessary to bring off the gear. We had a rough time getting the stuff away undamaged by the sea, but the pram was a wonderful sea-boat and we took it in turns to work her through the surf until everything was away.

At the last, when nearly everything had been salved and got to the whaler, the collections in tin boxes, wooden cases and baskets, and the two men, Atkinson and Brewster, were on board, a large wave threw the pram right up on the rocks, capsizing her and damaging her badly. Her two occupants jumped out just before a second wave swept the boat over and over. Then a third huge roller came up and washed the pram out to sea, where she was recovered by means of a grapnel thrown from the whaler. The two on the rocks had to face the surf again but were good swimmers, and with their recovery our little adventure ended. It was a pity we had bad weather, because I intended to give the crew a run on the island when Campbell had finished with them.

We remained another day under the lee of Trinidad Island owing to a hard blow from the south-east—a dead head wind for us—because I felt it would be useless to put to sea and punch into it. We were anchored one mile S. 4° E. (magnetic) from the Ninepin Rock, well sheltered from the prevailing wind. We left Trinidad at noon on the 28th, well prepared for the bad weather expected on approaching the Cape of Good Hope.

Whilst clearing the land we had an excellent view of South West Bay and saw a fine lot of rollers breaking on the beach. I was glad we kept there that day, as, in my opinion, our anchorage was really the only fair one off the island. By noon on the 29th we had left South Trinidad out of sight, the wind had freshened again and we could almost lay our course under sail for the Cape. This next stage of the voyage was merely a story of hard winds and heavy rolls. The ship leaked less as she used up the coal and patent fuel. All the same we spent many hours at the pump, but, since much of the pumping was done by the afterguard—as were called the officers and scientists—we developed and hardened our muscles finely. In the daytime the afterguard were never idle; there is always plenty to do in a sailing ship, and when not attending to their special duties the scientists were kept working at everything that helped the show along. Whilst on deck they were strictly disciplined and subordinate and respectful to the ship’s executive officers, while in the ward-room they fought these same officers in a friendly way for every harsh word and every job they had had imposed on them.

Campbell was a fine seaman; he was respected and admired by such people as Oates and Atkinson, who willingly pocketed their pride and allowed themselves to be hustled round equally with the youngest seaman on board. The Wicked Mate generally had all the afterguard under the hose before breakfast, as washing water was scarce and the allowance meagre on such a protracted voyage.

In the hotter weather we nearly all slept on deck, the space on top of the ice-house and in the boats being favourite billets. There was no privacy in the ship and only the officers of watches and lookout men were ever left with their thoughts. One or two of the younger members confessed to being homesick, for the voyage was long and it was not at all certain that we should all win back to ‘England, home, and beauty.’

Those who were not sailor men soon acquired the habit of the sea, growing accustomed to meeting fair and foul weather with an equally good face, rejoicing with us sailor men at a fair wind and full sail and standing by top-gallant and topsail halyards when the prospects were more leaden coloured and the barometer falling. We numbered about forty now, which meant heaps of beef to haul on ropes and plenty of trimmers to shift the coal from the hold to the bunkers. One or two were always stoking side by side with the firemen, and in this fashion officers, seamen, and scientific staff cemented a greater friendship and respect for one another.

On August 7, after drinking to absent friends, Oates, Atkinson, and Gran, ‘the three midshipmen,’ were confirmed in their rank and a ship’s biscuit broken on the head of each in accordance with gunroom practice, and after this day, during good and bad weather, these three kept regular watch with the seamen, going aloft, steering, and taking all the usual duties in their turn.

From the start Pennell, who was to relieve me in command of the ship on her arrival at the Antarctic base, showed an astounding knowledge of birds, and Wilson took the keenest interest in teaching him about bird-life in the Great Southern ocean and giving him a preliminary idea of the bird types to be met with in Antarctica.

Reflecting back to these days one sees how well we all knitted into the places we were to fill, because a long sea-voyage searches out hidden qualities and defects, not that there were many of the latter, still one man developed lung trouble and another had a strained heart. One of these, to our great regret, was forced to leave the expedition before the ship went south, while the other had to be ruled out of the shore party—an awful disappointment to them both.

We reached Simon’s Town on August 15, and here the Naval authorities gave us every assistance, lent us working parties and made good our long defect list. We were disappointed on arriving to find that Captain Scott was away in Pretoria, but he succeeded in obtaining a grant of £500 from the South African Government and raised another £500 by private subscription. When Captain Scott came amongst us again he wrote of the Terra Nova party that we were all very pleased with the ship and very pleased with ourselves, describing our state of happiness and overflowing enthusiasm exactly.

Those who could be spared were given leave here; some of us went up-country for a few days and had a chance to enjoy South African scenery. Oates, Atkinson, and Bowers went to Wynberg and temporarily forgot the sea. Oates’s one idea was a horse, and he spent his holiday as much on horseback as he possibly could. In a letter he expressed great admiration for the plucky manner in which Atkinson rode to hounds one day at Wynberg. These two were great friends, but it would be hard to imagine two more naturally silent men, and one wonders how evident pleasure can be obtained with a speechless companion.

Scott now changed with Wilson, who went by mail steamer to Australia in order to organise and finally engage the Australian members of our staff. Our leader was without doubt delighted to make the longer voyage with us in the Terra Nova and to get away from the hum of commerce and the small talk of the many people who were pleased to meet him—until the hat was handed round—that awful fund-collecting.

|

Dr Wilson’s nickname. |

The trip from Simon’s Town to Melbourne was disappointing on account of the absence of fair winds. We had a few gales, but finer weather than we expected, and took advantage of the ship’s steadiness to work out the details for the sledge journeys and depot plans. The lists of those who were to form the two shore parties were published, together with a skeleton list for the ship. The seamen had still to be engaged in New Zealand to complete this party.

A programme was drawn up for work on arrival at winter quarters, a routine made out for McMurdo Sound or Cape Crozier, if it so happened that we could effect a landing there, weights were calculated for the four men sledging units, sledge tables embellished with equipment weights, weekly allowances of food and fuel, with measures of quantities of each article in pannikins or spoonfuls, provisional dates were set down in the general plan, daily ration lists constructed, the first season’s depot party chosen, and, in short, a thoroughly comprehensive handbook was made out for our guidance which could be referred to by any member of the Expedition. Even an interior plan of the huts was made to scale for the carpenter’s edification.

It was an enormous advantage for us to have our leader with us now, his master mind foresaw every situation so wonderfully as he unravelled plan after plan and organised our future procedure.

Meantime, the seamen were employed preparing the sledge gear, sewing up food bags, making canvas tanks and sledge harness, fitting out Alpine ropes, repair bags, thongs, lampwick bindings, and travelling equipment generally. Gran overlooked the ski and assigned them to their future owners, Petty Officer Evans prepared the sewing outfits for the two shore parties, the cooks assembled mess-traps and cooking utensils, and Levick and Atkinson, under Dr Wilson’s guidance, assembled the medical equipment and fixed up little surgical outfits for sledge parties. By the time we arrived at Melbourne, our next port of call, a great deal had been accomplished and people had a grasp of what was eventually expected of them.

Scott left us again at Melbourne and embarked on yet another begging campaign, whilst I took the ship on to Lyttelton, where the Terra Nova was dry-docked with a view to stopping the leak in her bows. The decks, which after her long voyage let water through sadly, were caulked, and barnacles six inches long were taken from her bottom and sides. Whilst in New Zealand all the stores were landed, sorted out and restowed. On a piece of waste ground close to the wharves at Lyttelton the huts were erected in skeleton in order to make certain that no hitch would occur when they were put up at our Antarctic base. Davis, the carpenter, with the seamen told off to assist him, marked each frame and joist, the tongued and grooved boards were roughly cut to measure and tied into bundles ready for sledge transport in case it happened that we could not put the ship close to the winter quarters. Instruments were adjusted, the ice-house re-insulated and prepared to receive the 150 frozen sheep and ten bullocks which were presented to us by New Zealand farmers. Stables were erected under the forecastle and on the upper deck of the Terra Nova, ready for the reception of our ponies, and a thousand and one alterations and improvements made. The ship was restowed, and all fancy gear, light sails, and personal baggage put ashore. We took on board 464 tons of coal and embarked the three motor sledges, petrol, and paraffin.

We spent four weeks in Port Lyttelton, four weeks of hard work and perfect happiness. Our prospects looked very rosy in those days, and as each new member joined the Expedition here he was cordially welcomed into the Terra Nova family.

Mr J. J. Kinsey acted as agent to the Expedition, as he had done for the National Antarctic Expedition of 1901-4, and, indeed, for every Polar enterprise that has used New Zealand for a base.

New Zealanders showed us unbounded hospitality; many of us had visited their shores before and stronger ties than those of friendship bound us to this beautiful country.

When we came to Lyttelton, Meares and Bruce had already arrived with nineteen Siberian and Manchurian ponies and thirty-four sledge dogs, and these were now housed at Quail Island in the harbour; All the ponies were white, animals of this colour being accepted as harder than others for snow work, and the dogs were as fine a pack as one could select for hard sledging and rough times. Meares had had adventure in plenty when selecting the dogs and told us modestly enough of his journeys across Russia and Siberia in search of suitable animals. Scott was lucky to get hold of such an experienced traveller as Meares, and the Terra Nova gained by the inclusion of Lady Scott’s brother, Wilfred Bruce, in the Expedition. Wilfred Bruce was christened ‘Mumbo,’ and, although a little older than the rest of the officers, he willingly took a subordinate place, and Pennell, writing of him after the Expedition was finished, said that he withheld his advice when it was not asked for and gave it soundly when it was.

Lieut. Bruce joined Meares at Vladivostock, and he must have thought he was joining a travelling circus when he ran into this outfit. Meares crossed by Trans-Siberian Railway to Vladivostock, thence made preparation to travel round the Sea of Okotsk to collect the necessary dogs. He started off by train to Kharbarovsk, where he got in touch with the Governor-General of Eastern Siberia, General Unterberger, who helped him immensely, got him a good travelling sledge for the trip down the Amur River to Nikolievsk, and wrote a letter which he gave Meares to show at the post-houses and whenever in difficulties. The Governor-General ordered frozen food to be got ready for Meares’s journey. A thousand versts[1] had to be traversed, and this only took seven days; the going was interesting at times, and Meares had good weather on the sledge journey to Nikolievsk, although the cold was intense and sometimes the road was very bad. The sledges were horse-drawn between the post-houses.

Mr Rogers, the English manager of the Russo-Chinese Bank at Nikolievsk, helped Meares considerably in securing the dogs. Most of them were picked up in the neighbourhood of that place, but were not chosen before they had been given some hard driving tests. In one of the trial journeys the dogs pulled down a horse and nearly killed it before they could be beaten off. Some of them have a good deal of the wolf in their blood.

A settlement of ‘fish-skin’ Indians was visited in the dog search, and Meares told us of natives who dressed in cured skins of salmons. These people were expert hunters who trekked weeks on end with just a pack of food on their backs, their travelling being done on snowshoes.

After taking great pains, thirty-four fine dogs were collected, all used to hard sledge travelling, and these Meares shipped on board steamer which took him and his menagerie by river to Kharbarovsk. The journey to Vladivostock was by train. The Russian officials allowed him to hitch on a couple of cattle trucks containing the dogs to the mail train for that part of the journey.

Russian soldiers and Chinamen were detailed by the Governor-General to assist the procession through the streets of Vladivostock to their kennels here. A slight upset was caused by a mad dog rushing in amongst them, but fortunately it was killed before any of our dogs were bitten. Some of them were flecked by the foam from the mad dog’s jaws, but none were any the worse after a good carbolic bath. After the dogs were settled and in good shape the ponies were collected and brought from up-country in batches. On arrival at the Siberian capital they were examined by the Government vet., after which Meares and an Australian trainer picked the best, until a score were purchased. Horse boxes were obtained now and feed tins made for the voyage and, after minor troubles with shipping firms, Meares, Bruce, and three Russians sailed from Vladivostock in a Japanese steamer which conveyed them to Kobe. Here they transhipped into a German vessel that took them via Hong-kong, Manila, New Guinea, Rockhampton, and Brisbane, to Sydney. There the animals were inoculated for the N’th time and a good deal of palaver indulged in before they were again shifted to the Lyttelton steamer. The poor beasts suffered from the heat, particularly the dogs, although they had been close-clipped for the long and trying voyage.

At Wellington, New Zealand, Meares was compelled to tranship the animals to yet another steamer. When the travelling circus was safely installed in Quail Island our dogs and ponies had undergone shipments, transhipments, inoculations and disinfectings sufficient to make them glad to leave civilisation, and we had to thank Meares for his patience in getting them down without any losses.

We sailed from Lyttelton on November 25 for Port Chalmers, had a tremendous send-off and a great deal of cheering as the ship moved slowly away from the piers. Bands played us out of harbour and most of the ships flew farewell messages, which we did our best to answer.

Some members went down by train to Dunedin and joined us at Port Chalmers. We filled up here with what coal we could squeeze into our already overloaded ship and left finally for the Great Unknown on November 29, 1910.

Lady Scott, Mrs Wilson, and my own wife came out with us to the Heads and then went on board the Plucky tug after saying good-bye. We were given a rousing send-off by the small craft that accompanied us a few miles on our way, but they turned homeward at last and at 3.30 p.m. we were clear with all good-byes said—personally I had a heart like lead, but, with every one else on board, bent on doing my duty and following Captain Scott to the end. There was work to be done, however, and the crew were glad of the orders that sent them from one rope to another and gave them the chance to hide their feelings, for there is an awful feeling of loneliness at this point in the lives of those who sign on the ships of the ‘South Pole trade’—how glad we were to hide those feelings and make sail—there were some dreadfully flat jokes made with the best of good intention when we watched dear New Zealand fading away as the spring night gently obscured her from our view.

|

Roughly 660 miles. |

After all it was a relief to get going at last and to have the Expedition on board in its entirety, but what a funny little colony of souls. A floating farmyard best describes the appearance of the upper deck, with the white pony heads peeping out of their stables, dogs chained to stanchions, rails, and ring-bolts, pet rabbits lolloping around the ready supply of compressed hay, and forage here, there, and everywhere. If the Terra Nova was deeply laden from Cardiff, imagine what she looked like leaving New Zealand. We had piled coal in sacks wherever it could be wedged in between the deck cargo of petrol. Paraffin and oil drums filled up most of the hatch spaces, for the poop had been rendered uninhabitable by the great wooden cases containing two of our motor sledges.

The seamen were excellent, and Captain Scott seemed delighted with the crowd. He and Wilson were very loyal to the old Discovery men we had with us and Scott was impressed with my man, Cheetham, the Merchant Service boatswain, and could not quite make out how ‘Alf,’ as the sailors called him, got so much out of the hands—this little squeaky-voiced man—I think we hit on Utopian conditions for working the ship. There were no wasters, and our seamen were the pick of the British Navy and Mercantile Marine. Most of the Naval men were intelligent petty officers and were as fully alive as the merchantmen to ‘Alf’s’ windjammer[1] knowledge. Cheetham was quite a character, and besides being immensely popular and loyal he was a tough, humorous little soul who had made more Antarctic voyages than any man on board.

The seamen and stokers willingly gave up the best part of the crew space in order to allow sheltered pony stables to be built in the forecastle; it would have fared badly with the poor creatures had we kept them out on deck on the southward voyage.

A visit to the Campbell Islands was projected, but abandoned on account of the ship being unable to lay her course due to strong head winds on December 1. We therefore shaped to cross the Antarctic Circle in 178° W. and got a good run of nearly 200 miles in, but the wind rose that afternoon and a gale commenced at a time when we least could afford to face bad weather in our deeply-laden condition. By 6 p.m. I had to heave the ship to under lower topsails and fore topmast staysail. Engines were kept going at slow speed to keep the ship under control, but when night fell the prospect was gloomy enough. Captain Scott had consented to my taking far more on board than the ship was ever meant to carry, and we could not expect to accomplish our end without running certain risks. To sacrifice coal meant curtailing the Antarctic cruising programme, but as the weather grew worse we had to consider throwing coal overboard to lighten the vessel. Quite apart from this, the huge waves which washed over the ship swamped everything and increased the deck weights considerably. Ten tons of coal were thrown over to prevent them from taking charge and breaking petrol cases adrift. In spite of a liberal use of oil to keep heavy water from breaking over, the decks were continually swept by the seas and the rolling was so terrific that the poor dogs were almost hanging by their chains. Meares and Dimitri, helped by the watch, tended them unceasingly, but in spite of their combined efforts one dog was washed overboard after being literally drowned on the upper deck. One pony died that night, Oates and Atkinson standing by it and trying their utmost to keep the wretched beast on its feet. A second animal succumbed later, and poor Oates had a most trying time in caring for his charges and rendering what help he could to ameliorate their condition. Those of his shipmates who saw him in this gale will never forget his strong, brown face illuminated by a hanging lamp as he stood amongst those suffering little beasts. He was a fine, powerful man, and on occasions he seemed to be actually lifting the poor little ponies to their feet as the ship lurched heavily to leeward and a great sea would wash the legs of his charges from under them. One felt somehow, glancing into the ponies’ stalls, which Captain Scott and I frequently visited together, that Oates’s very strength itself inspired his animals with confidence. He himself appeared quite unconscious of any personal suffering, although his hands and feet must have been absolutely numbed by the cold and wet.

In the middle watch Williams, the Chief Engineer, reported that his pumps were choked and that as fast as he cleared them they choked again, the water coming into the ship so fast that the stokehold plates were submerged and water gaining fast. I ordered the watch to man the hand pump, but that was soon choked too. Things now looked really serious, since it was impossible to get to the pump-well while terrific seas were washing over the ship and the afterhatch could not be opened. Consequently we started to bail the water out with buckets and also rigged the small fire-engine and pumped with this as well.

The water in the engine room gradually gained until it entered the ashpit of the centre furnace and commenced to put the fires out. Both Williams and Lashly were up to their necks in water, clearing and re-clearing the engine room pump suctions, but eventually the water beat them and I allowed Williams to let fires out in the boiler. It could not be otherwise. We stopped engines, and with our cases of petrol being lifted out of their lashings by the huge waves, with the ponies falling about and the dogs choking and wallowing in the water and mess, their chains entangling them and tripping up those who tried to clear them, the situation looked as black and disheartening as it well could be.

When dawn broke the greater part of the lee bulwarks had been torn away and our decks laid open to the sea, which washed in and out as it would have over a rock. The poor old ship laboured dreadfully, and after consultation with Captain Scott we commenced to cut a hole in the engine room bulkhead to get at the hand pump-well.

Meanwhile I told the afterguard off into watches, and, relieving every two hours, they set to work, formed a chain at the engine room ladder way and bailed the ship out with buckets. In this way they must have discharged between 2000 and 3000 gallons of water. The watch manned the hand pump, which, although choked, discharged a small stream, and for twenty-four hours this game was kept up, Scott himself working with the best of them and staying with the toughest.

It was a sight that one could never forget: everybody saturated, some waist-deep on the floor of the engine room, oil and coal dust mixing with the water and making every one filthy, some men clinging to the iron ladder way and passing full buckets up long after their muscles had ceased to work naturally, their grit and spirit keeping them going. I did admire the weaker people, especially those who were unhardened by the months of physical training of the voyage out from England.

When each two-hour shift was relieved, the party, coughing and spluttering, would make their way into the ward-room where Hooper and Neale, the stewards, mere boys, supplied them with steaming cocoa. How on earth the cooks kept the galley fires going I could never understand: they not only did this, but fed us all at frequent intervals.

By 10 p.m. on the 2nd December the hole in the engine room bulkhead was cut completely. I climbed through it, followed by Bowers, the carpenter, and Teddy Nelson, and when we got into the hold there was just enough room to wriggle along to the pump-well over the coal. We tore down a couple of planks to get access to the shaft and then I went down to the bottom to find out how matters stood. Bowers came next with an electric torch, which he shone downwards whilst I got into the water, hanging on to the bottom rungs of the ladder leading to the bilge. Sitting on the keel the water came up to my neck and, except for my head, I was under water till after midnight passing up coal balls, the cause of all the trouble. Though, of course, we had washed out the bilges in New Zealand, the constant stream of water which leaked in from the topsides had carried much coal dust into them. This, mixed with the lubricating oil washed down from the engines, had cemented into buns and balls which found their way down and choked both hand and engine pump suctions. I sent up twenty bucketfuls of this filthy stuff, which meant frequently going head under the unspeakably dirty water, but having cleared the lower ends of the suction pipe the watch manning the hand pump got the water down six inches, and it was obvious by 4 o’clock in the morning that the pump was gaining. We therefore knocked the afterguard off bailing, and the seamen worked steadily at the pump until 9 a.m. and got the water right down to nine inches, so we were able to light fires again and once more raise steam. We made a serviceable wire grating to put round the hand pump suction to keep the bigger stuff from choking the pipes in future. It was days before some of us could get our hair clean from that filthy coal-oil mixture.

One more pony died during the gale, but when the weather moderated early on the 3rd, the remaining seventeen animals bucked up and, when not eating their food, nonchalantly gnawed great gaps in the stout planks forming the head parts of their stalls. At last the sun came out and helped to dry the dogs. Campbell and his seamen cleared up the decks and re-secured the top hamper in the forenoon, we reset sail, and after tea Scott, Oates, Atkinson, and a few more of us hoisted the two dead ponies out of the forecastle, through the skylight, and over the side. It was a dirty job, because the square of the hatch was so small that a powerful purchase had to be used which stretched out the ponies like dead rabbits.

We only made good twenty-three miles that day and, although the gale had abated, it left us a legacy in the shape of a heavy uncomfortable swell. Most of the bunks were in a sad state, the ship having worked so badly that the upper deck seams opened everywhere and water had literally poured into them.

Looking at the fellows’ faces in the ward-room at dinner that night there was no trace of anxiety, worry, or fatigue to be seen. We drank to sweethearts and wives, it being Saturday evening, and those who had no watch were glad to turn in early.

More fresh wind next day but finer weather to follow. Gran declared he saw an iceberg on the 5th December, but it turned out to be a whale spouting. Our runs were nothing to boast of, 150 miles being well above the average, but the lengthening days told us that we were rapidly changing our latitude and approaching the ice.

|

Sea phrase for sailing ships. |

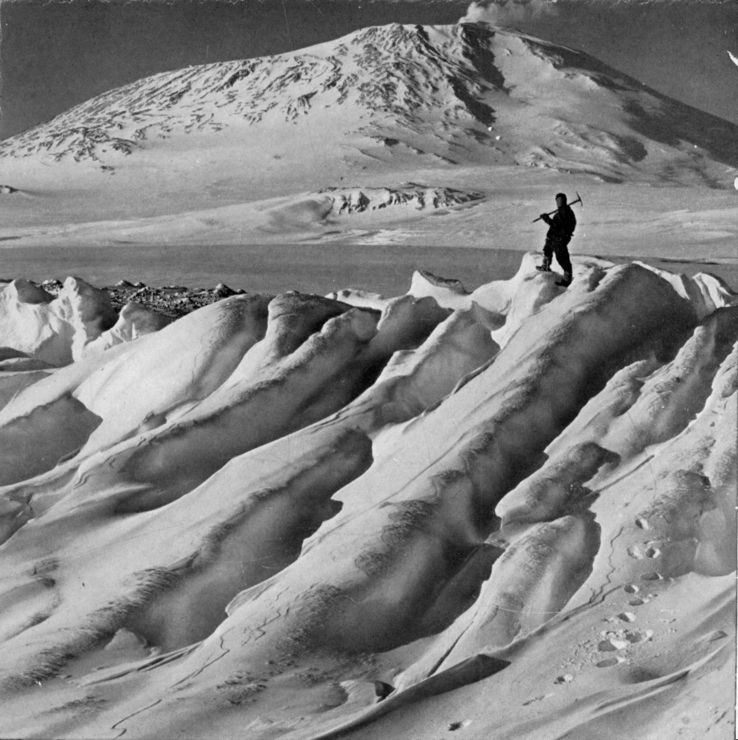

We sighted our first iceberg in latitude 62° on the evening of Wednesday, December 7. Cheetham’s squeaky hail came down from aloft and I went up to the crow’s-nest to look at it, and from this time on we passed all kinds of icebergs, from the huge tabular variety to the little weathered water-worn bergs. Some we steamed quite close to and they seemed for all the world like great masses of sugar floating in the sea.

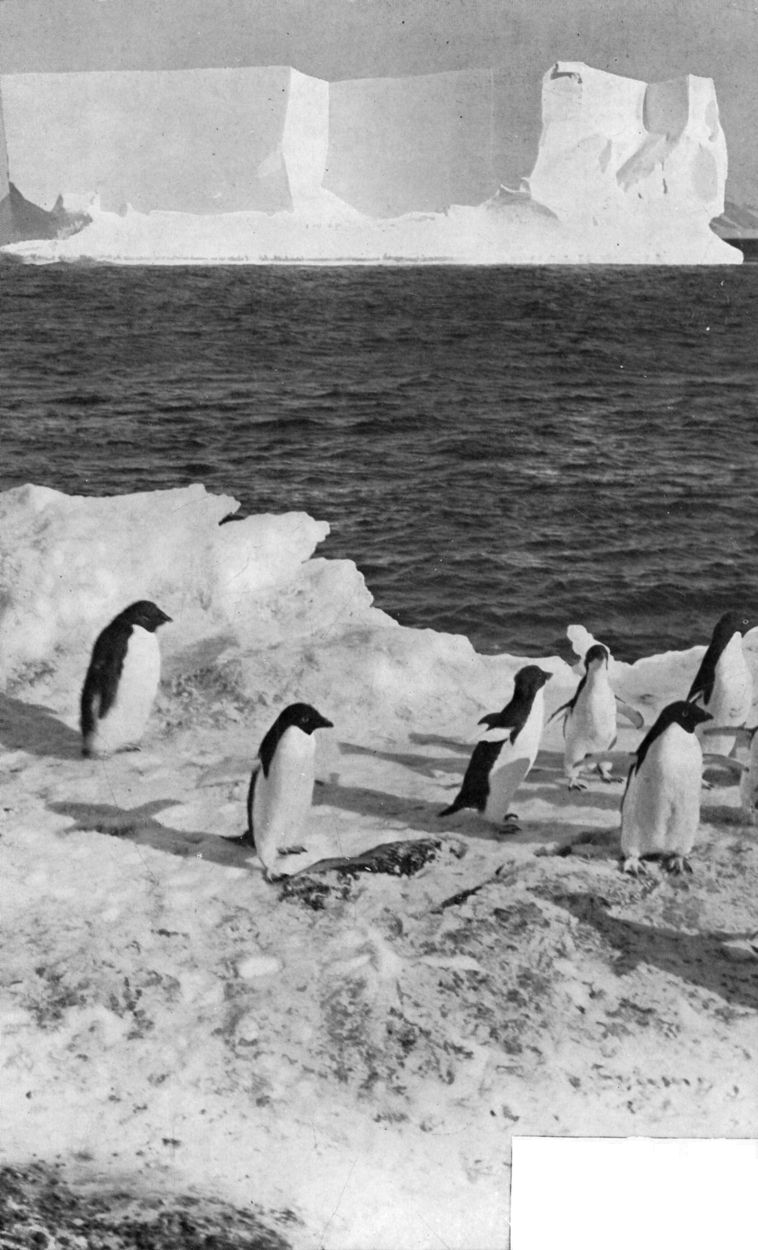

From latitudes 60° to 63° we saw a fair number of birds: southern fulmars, whale birds, mollymawks, sooty albatrosses, and occasionally Cape-pigeons still. Then the brown-backed petrels began to appear, sure precursors of the pack ice—it was in sight right enough the day after the brown-backs were seen. By breakfast time on December 9, when nearly in latitude 65°, we were steaming through thin streams of broken pack with floes from six to twelve feet across. A few penguins and seals were seen, and by 10 a.m. no less than twenty-seven icebergs in sight. The new-comers to these regions were clustered in little groups on the forecastle and poop sketching and painting, hanging over the bows and gleefully watching this lighter stuff being brushed aside by our strong stem.

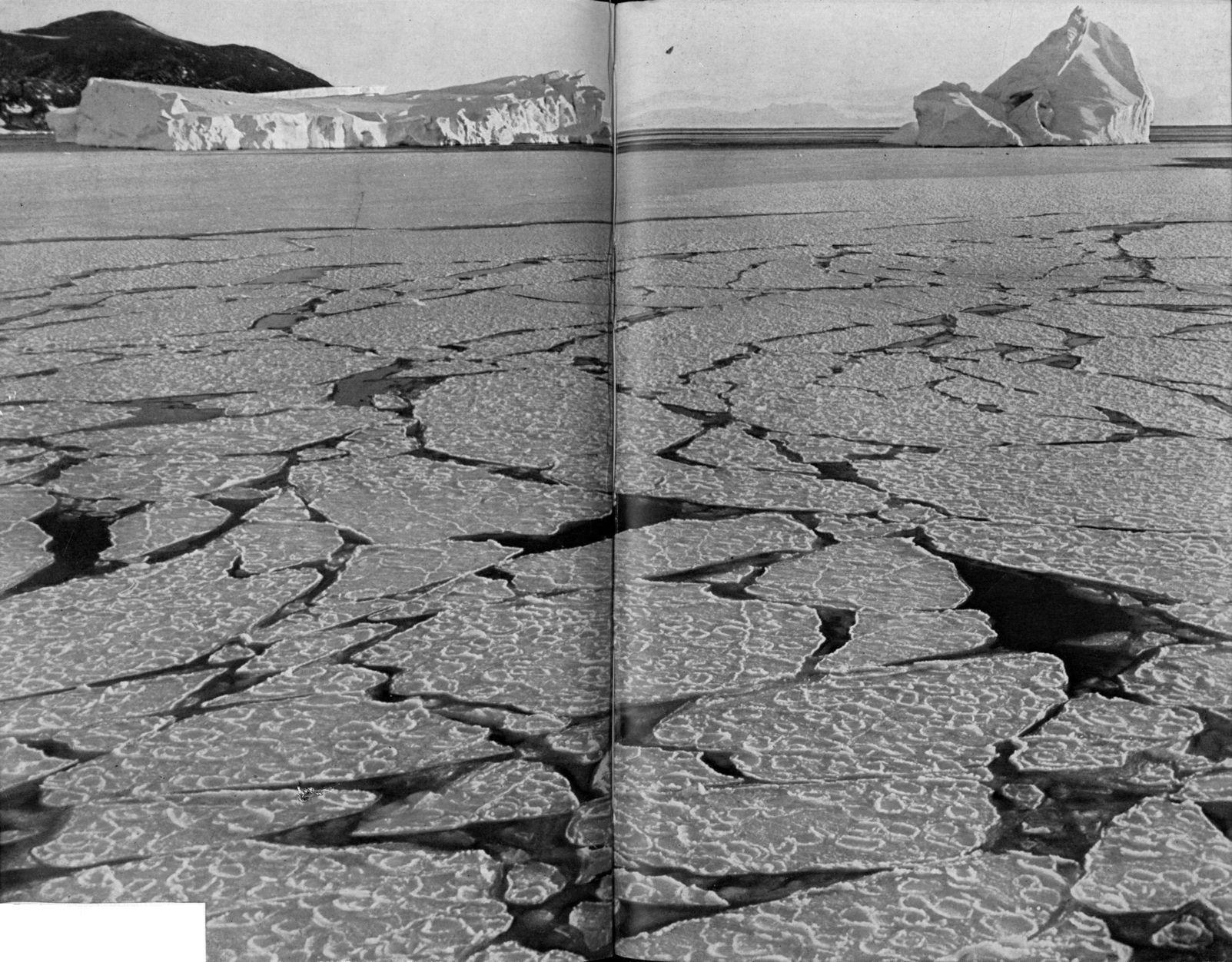

We were passing through pack all day, but the ice hereabouts was not close enough nor heavy enough to stop us appreciably. The ship was usually conned by Pennell and myself from the crow’s-nest, and I took the ship very near one berg for Ponting to cinematograph it. We now began to see snow petrels with black beaks and pure white bodies, rather resembling doves. Also we saw great numbers of brown-backed petrels the first day in the pack, whole flights of them resting on the icebergs. The sun was just below the horizon at midnight and we had a most glorious sunset, which was first a blazing copper changing to salmon pink and then purple. The pools of water between the floes caught the reflection, the sea was perfectly still and every berg and ice floe caught something of the delicate colour. Wilson, of course, was up and about till long after midnight sketching and painting. The Antarctic pack ice lends itself to water-colour work far better than to oils.

When conning the ship from up in the crow’s-nest one has a glorious view of this great changing ice-field. Moving through lanes of clear blue water, cannoning into this floe and splitting it with iron-bound stem, overriding that and gnawing off a twenty ton lump, gliding south, east, west, through leads of open water, then charging an innocent-looking piece which brings the ship up all-standing, astern and ahead again, screwing and working the wonderful wooden ship steadily southward until perhaps two huge floes gradually narrow the lane and hold the little lady fast in their frozen grip.

This is the time to wait and have a look round: on one side floes the size of a football field, all jammed together, with their torn up edges showing their limits and where the pressure is taken. Then three or four bergs, carved from the distant Barrier, imprisoned a mile or so away, with the evening sun’s soft rays casting beautiful shadows about them and kissing their glistening cliff faces.

Glancing down from the crow’s-nest the ship throws deep shadows over the ice and, while the sun is just below the southern horizon, the still pools of water show delicate blues and greens that no artist can ever do justice to. It is a scene from fairyland.

I loved this part of the voyage, for I was in my element. At odd times during the night, if one can call it night, the crow’s-nest would have visitors, and hot cocoa would be sent up in covered pots by means of signal halyards. The pack ice was new to all the ship’s officers except myself, but they soon got into the way of conning and working through open water leads and, as time went on, distinguished the thinner ice from the harder and more dangerous stuff.

On December 10 we stopped the ship and secured her to a heavy floe from which we took in sufficient ice to make eight tons of fresh water, and whilst doing this Rennick sounded and obtained bottom in 1964 fathoms, fora-minifera and decomposed skeleton unicellular organs, also two pieces of black basic lava. Lillie and Nelson took plankton and water bottle samples to about 280 fathoms. A few penguins came round and a good many crab-eater seals were seen. In the afternoon we got under way again and worked for about eight miles through the pack, which was gradually becoming denser. About 2.30 p.m. I saw from the crow’s-nest four seals on a floe. I slid down a backstay, and whilst the officer on watch worked the ship close to them, I got two or three others with all our firearms and shot the lot from the forecastle head. We had seal liver for dinner that night; one or two rather turned up their noses at it, but, as Scott pointed out, the time would come when seal liver would be a delicacy to dream about.

Campbell did not do much conning except in the early morning, as his executive duties kept him well occupied. The Polar sledge journey had its attractions, but Campbell’s party were to have interesting work and were envied by many on board. For reasons which need not here be entered into, Campbell had to abandon the King Edward VII. Land programme, but in these days his mob were known as the Eastern Party, to consist of the Wicked Mate, Levick, and Priestley, with three seamen, Abbott, Browning, and Dickason. Campbell had the face of an angel and the heart of a hornet. With the most refined and innocent smile he would come up to me and ask whether the Eastern Party could have a small amount of this or that luxury. Of course I would agree, and sure enough Bowers would tell me that Campbell had already appropriated a far greater share than he was ever entitled to of the commodity in question. This happened again and again, but the refined smile was irresistible and I am bound to say the Wicked Mate generally got away with it, for even Bowers, the incomparable, was bowled over by that smile.

We crossed the Antarctic Circle on the morning of the 10th, little dreaming in those happy days that the finest amongst us would never recross it again.

We took a number of deep-sea soundings, several of over 2000 fathoms, on this first southward voyage. Rennick showed himself very expert with the deep-sea gear and got his soundings far more easily than we had done in the Discovery and Morning days.

We were rather unfortunate as regards the pack ice met with, and must have passed through 400 miles of it from north to south. On my two previous voyages we had had easier conditions altogether, and then it had not mattered, but all with these dogs and ponies cooped up and losing condition, with the Terra Nova eating coal and sixty hungry men scoffing enormous meals, we did not seem to be doing much or getting on with the show. It was, of course, nobody’s fault, but our patience was sorely tried.

We made frequent stops in the pack ice, even letting fires out and furling sail, and sometimes the ice would be all jambed up so that not a water hole was visible—this condition would continue for days. Then, for no apparent reason, leads would appear and black water-skies would tempt us to raise steam again. Scott himself showed an admirable patience, for the rest of us had something to occupy our time with. Pennell and I, for instance, were constantly taking sights and working them out to find our position and also to get the set and drift of the current. Then there were magnetic observations to be taken on board and out on the ice away from the magnetic influence of the ship, such as it was. Simpson had heaps to busy himself with, and Ponting was here, there, and everywhere with his camera and cinematograph machine. Had it not been for our anxiety to make southward progress, the time would have passed pleasantly enough, especially in fine weather. Days came when we could get out on the floe and exercise on ski, and Gran zealously looked to all our requirements in this direction.

December 11 witnessed the extraordinary sight of our company standing bareheaded on deck whilst Captain Scott performed Divine Service. Two hymns were sung, which broke strangely the great white silence. The weather was against us this day in that we had snow, thaw, and actually rain, but we could not complain on the score of weather conditions generally. Practically all the ship’s company exercised on the floes while we remained fast frozen. Next day there was some slight loosening of the pack and we tried sailing through it and managed half a degree southward in the forty-eight hours. We got along a few miles here and there, but when ice conditions continued favourably for making any serious advance it was better to light up and push our way onward with all the power we could command. We got some heavy bumps on the 13th December and, as this hammering was not doing the ship much good, since I was unable to make southing then at a greater rate than one mile an hour, we let fires right out and prepared, as Captain Scott said, ‘To wait till the clouds roll by.’ For the next few days there was not much doing nor did we experience such pleasant weather.

Constant visits were made to the crow’s-nest in search of a way through. December 16 and 17 were two very gray days with fresh wind, snow, and some sleet. Affectionate memories of Captain Colbeck and the little relief ship, Morning, came back when the wind soughed and whistled through the rigging. This sound is most uncanny and the ice always seemed to exaggerate any noise.

I hated the overcast days in the pack. It was bitterly cold in the crow’s-nest however much one put on then, and water skies often turned out to be nimbus clouds after we had laboured and cannoned towards them. The light, too, tired and strained one’s eyes far more than on clear days.

When two hundred miles into the pack the ice varied surprisingly. We would be passing through ice a few inches thick and then suddenly great floes four feet above the water and twelve to fifteen feet deep would be encountered. December 18 saw us steaming through tremendous leads of open water. A very funny occurrence was witnessed in the evening when the wash of the ship turned a floe over under water and on its floating back a fish was left stranded. It was a funny little creature, nine inches in length, a species of notathenia. Several snow petrels and a skua-gull made attempts to secure the fish, but the afterguard kept up such a chorus of cheers, hoots and howls that the birds were scared away till one of us secured the fish from the floe.

Early on the 19th we passed close to a large iceberg which had a shelving beach like an island. We began to make better progress to the south-westward and worked into a series of open leads. We came across our first emperor penguin, a young one, and two sea-leopards, besides crab-eater seals, many penguins, some giant petrels, and a Wilson petrel. That afternoon tremendous pieces of ice were passed; they were absolutely solid and regular floes, being ten to twelve feet above water and, as far as one could judge, about 50 feet below. The water here was beautifully clear.

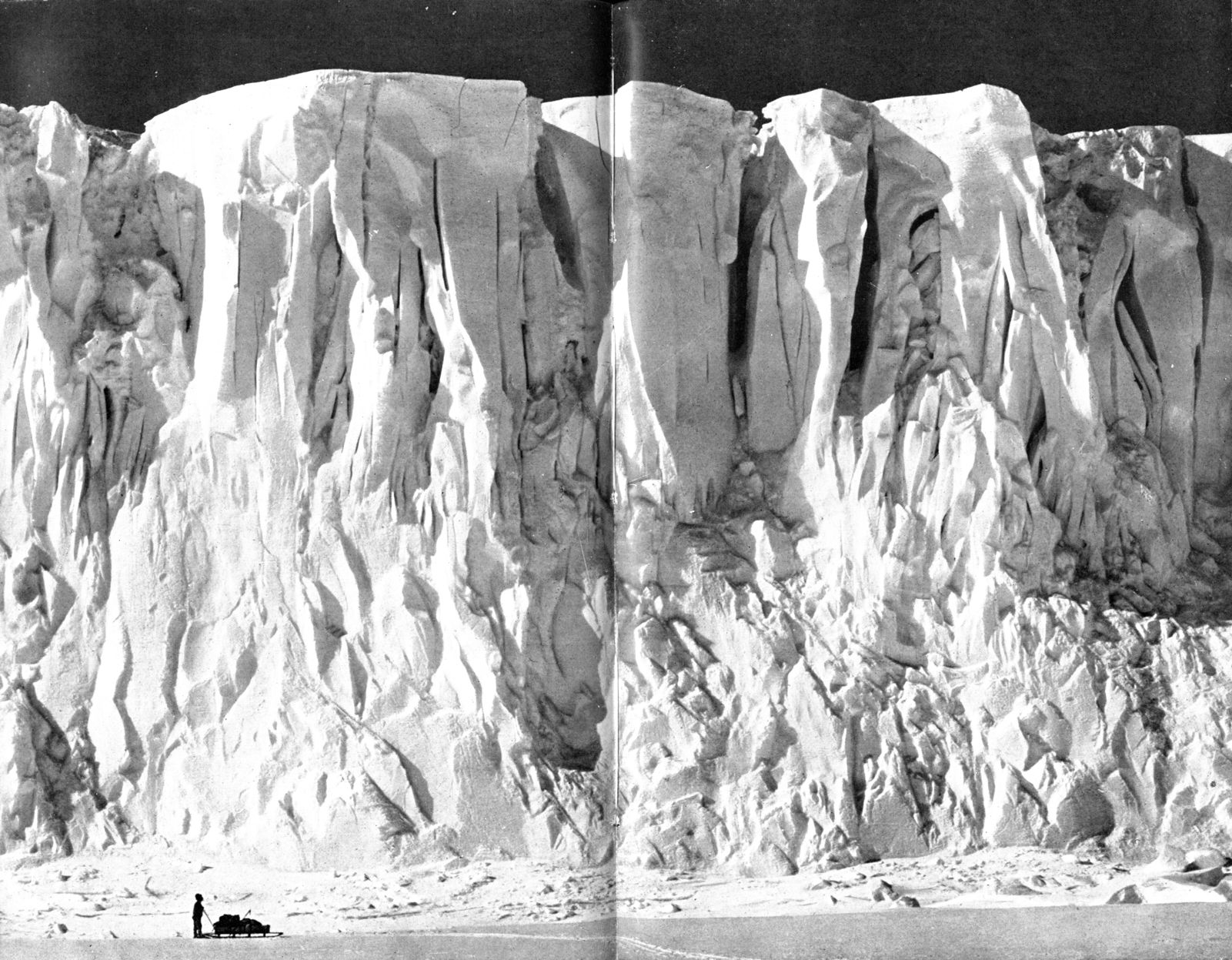

“——like great masses of sugar floating in the sea”—an Antarctic iceberg.

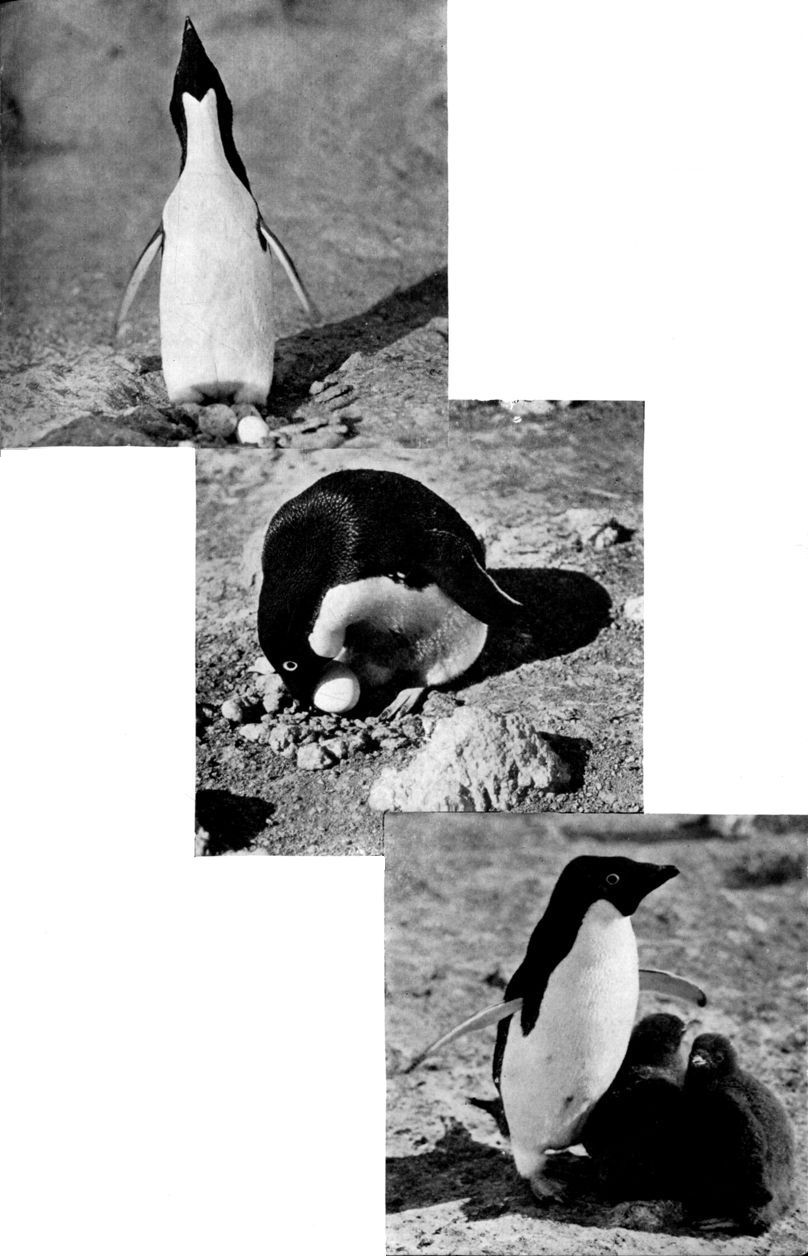

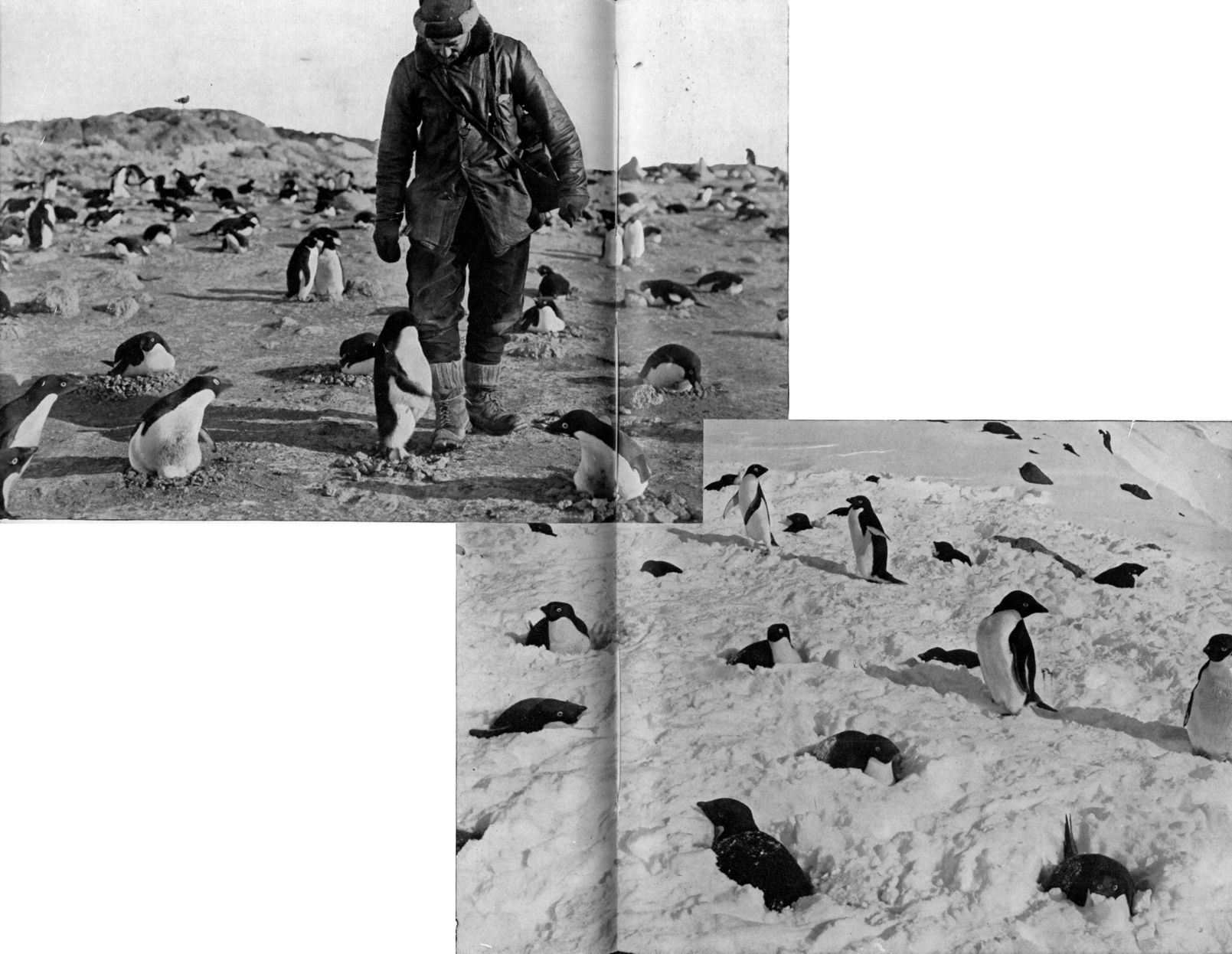

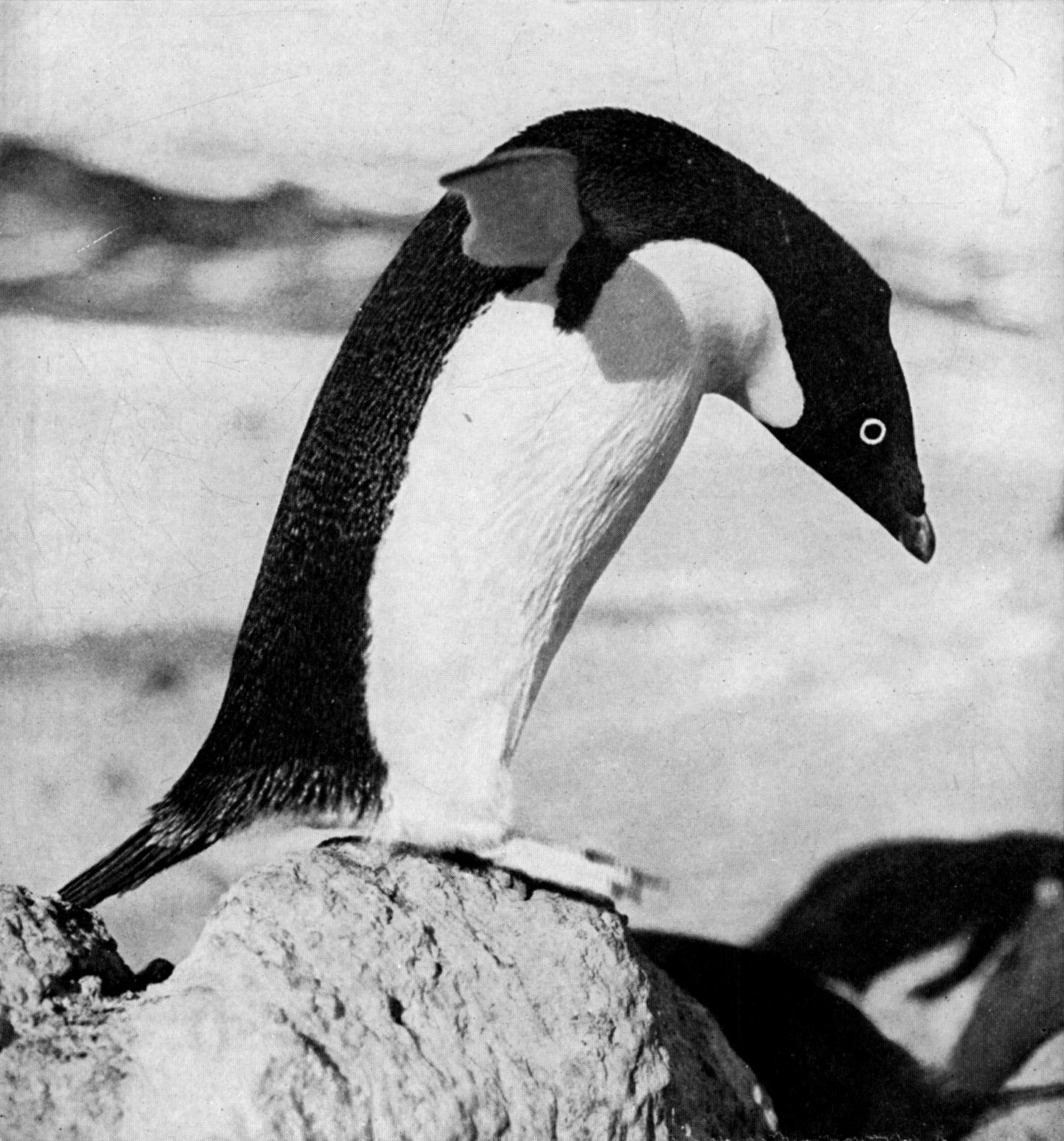

We had now reached latitude 68° and, as penguins were plentiful, Archer and Clissold, the cooks, made us penguin stews and ‘hooshes’ to eke out our fresh provisions. Concerning the penguins, they frequently came and inspected the ship. One day Wilson and I chased some, but they continually kept just out of our reach; then Uncle Bill lay down on the snow, and when one, out of curiosity, came up to him he grabbed it by the leg and brought it to the ship, protesting violently, for all the world like a little old man in a dinner jacket. Atkinson and Wilson found a new kind of tapeworm in this penguin, with a head like a propellor. This worm has since been named after one of us!

We were now down to under 300 tons of coal, some of which had perforce to be landed, in addition to the 30 tons of patent fuel which were under the forward stores. I had no idea that Captain Scott could be so patient. He put the best face on everything, although he certainly was disappointed in the Terra Nova and her steaming capacity. He could not well have been otherwise when comparing her with his beloved Discovery. Whilst in the pack our leader spent his time in getting hold of the more detailed part of our scientific programme and mildly tying the scientists in knots.

We had some good views of whales in the pack. Whenever a whale was sighted Wilson was called to identify it unless it proved to belong to one of the more common species. We saw Sibbald’s whale, Rorquals, and many killer whales, but no Right whales were properly identified this trip.

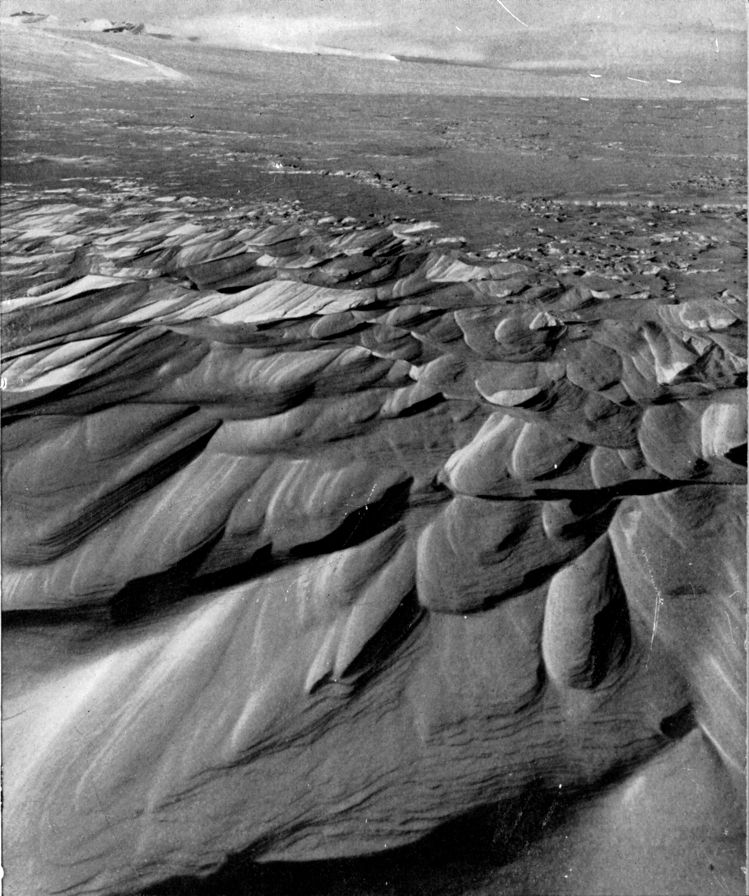

“It is a scene from fairyland”—“pancake” ice in the Antarctic.

I very much wanted to show Scott the island we had discovered in the first Antarctic Relief Expedition and named after him, but when in its vicinity snow squalls and low visibility prevented this.