* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Mike Mullins of Boston Crick

Date of first publication: 1953

Author: Owen Templeton Garrett (O. T. G.) Williamson (1883-1968)

Date first posted: Dec. 16, 2020

Date last updated: Dec. 16, 2020

Faded Page eBook #20201239

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, John Routh & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

O. T. G. WILLIAMSON

Mike Mullins

of

Boston Crick

The Ryerson Press—Toronto

Copyright, Canada, 1953, by

THE RYERSON PRESS, TORONTO

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced

in any form (except by reviewers for the public

press), without permission in writing from the publishers.

Published February, 1953

PRINTED AND BOUND IN CANADA

BY THE RYERSON PRESS, TORONTO

TO

Marjorie

The most notable production of Northern Ontario has not been its silver or its gold, its sawlogs, pulp and paper or its fertile farms. Great as all these have been and much as they have added to the wealth and stability of Canada, they are out-classed as distinctive achievements by the people of the country. These are truly a product of the North Country. It took them as they came, a heterogeneous crew, and, rejecting the unfit through lack of spirit and lack of hardihood, moulded them to its heart’s desire. It was a stern school which demanded courage, dogged fortitude and a strong measure of gaiety from all its pupils. There were hardships, discouragements and many forms of death to face and overcome. Good men died in its holocausts. Lonely graves are marked with a twelve-inch blaze at the foot of its rapids. The lakes took their toll and so did falling timber and premature explosions. But, through it all, they persisted and, millionaire or railway navvy, they finally received the accolade that dubbed them as true Northerners. They are a special race of men, these Northerners and the hall mark of their guild is still plainly to be seen.

In the beginning, they were a heterogeneous crew. They hailed from the four corners of the earth and from all its seven seas. Settlers came, by boat up the long stretch of Lake Temiskaming, from abandoned southern farms and straight from England. Railway construction crews came from wherever jobs were scarce and many stayed as section-men along the line. With the Cobalt rush, came miners from the hard-rock counties of Eastern Ontario, from the Yukon, British Columbia and Nova Scotia. They came from Butte, Nevada and New Mexico, from Kalgoorie, the Rand, South China and the Malay States. There were Cousin Jacks, Scots and Englishmen, with Irish from the North and South. There were French, Finns and Scandinavians; navvies, mule skinners, muckers, miners, axemen, river drivers, sawyers, blacksmiths and men whose only stock-in-trade were strong backs and optimism. Very notably, they came from Renfrew, Pembroke and Calabogie.

The Northland took them all and taught them its own code of ethics. It was simple and it was adequate. A man learned to stand on his own feet and he learned to help his fellow in distress. The latter was imperative regardless of danger, self-interest or inconvenience. For all that there was claim-jumping on occasion, a man’s personal property was inviolable in the bush. Food, canoes and snowshoes, on which life might depend, could be cached with the full assurance that they would be found intact when wanted. Yet a well-stocked cache of food could be drawn on in dire necessity but such loans were always scrupulously repaid. They were all good fellows or they did not last. The land that could not break them taught them to love it with a deep passion which seldom found expression.

For all that the Northland minted them with its own stamp, they remained rugged individualists. Jack Munro, Mayor of Elk Lake and heavy-weight contender, wore no man’s strait-jacket. Bob Potter, with fifty-four years of the North behind him, is still the Northerner par excellence. Kindly, humorous and straight, he has the same optimism which led him as a boy to Lake Temiskaming in ’98. Smith Ballantyne, whose prodigious packing feats are legendary, still works, after fifty years of work, for the land he loves. There is Ken Ross, of Varsity football fame, who ranged the country far and wide from the turn of the century, surveying, prospecting and building transmission lines. He too was moulded by its code. Their name is legion. Humble men with honoured names and human frailties; Hollinger, Gillies, Wilson, Preston, McIntyre and Horne. Then there were characters like Father Paradis, who drained Frederick House Lake with a shot or two of dynamite. This act caused more than raised eyebrows in official circles and Father Paradis’ attempt to colonize the arid silt exposed did nothing to avert their censure. Frederick House Lake today reflects the blue skies for miles on the way to Timmins but Father Paradis is forever part of the Northland’s story.

The rush to the Northland of Ontario began in earnest fifty years ago. Though much remains, the memories of those days are dying fast. Since folk-lore, the most ephemeral of essences, supplies the high-lights which make history a vital story, it was felt that some at least of the feeling of those days should be preserved. An attempt has been made in these stories to record something of the gaiety of those fading times. They are not tales of heroism or of high emprise. The Northerner was a hard-working man who could not have worn a hero’s bays with any degree of comfort. Rather they attempt to recall the flavour of the times. If some of the incidents are true, it is hoped that they are none the worse for that. Those that are invention pure and simple conform in general pattern with incidents which did take place.

If it is asked whether Mullins is a real person, it may assist to recall that an old timer at Kirkland Lake said that he could not remember his being at Boston Creek. Since the old timer was notoriously forgetful, this might be taken as proof positive. I can only say that I have lived with him during the past seven years and he is as real as I can make him. You will find him today, under half-a-dozen names, at lonely stations along the line, in little country stores, in cookhouses at lumber camps and at mine bunk-houses in the bush. Annie, a bit shrewder than Mike, is the Northern woman, all honour to her, who shared adversity and disaster with her man and won through to a placid life, looking back without regret. O’Rourke may do a bit of bootlegging on the side but he is a good fellow for all that. And so are they all who observe the Northland’s code.

If Mullins serves the purpose of giving some amusement, he will ask no better. For my part, if he has succeeded in recording something of the life of Northern Ontario in those old formative days, I am content.

—O.T.G.W.

North Bay, September 24, 1952

This is le mot juste, since what follows is purely introductory. Candour forces me to say that I did not meet Mullins at Cobalt in 1907 although, on his own admission, he was at the Kerr Lake Mine that year. My first knowledge of him came from Old John, when he related the pig shipment episode. Old John, otherwise John Doyle, is a T. & N.O. Agent who has been in retirement for the past ten years. A close friend of Mullins, he outranks him on the Seniority List by about two minutes, which, together with his masterful attitude, has permitted him to dominate the situation whenever they are together My first actual contact with Mike came when, still indignant because of the notoriety thrust upon him by the publication of his Big Moment, he told me about the measles epidemic up at MacDougall Chutes. Since these constituted my introduction, they must serve as well to introduce the reader to Mike Mullins.

For those who are not content to paint their own mental pictures, it may be said that Mullins is a plain man of medium height and breadth of shoulder. He would pass unnoticed in a crowd but even a casual glance might be arrested by his eyes. They are eyes which smile even when his lips are set; eyes which, while they may be no asset in a poker game, are peep holes to the inner man. Mike sticks his chest out occasionally when he feels that he has pulled off something good, which distinguishes him from Old John whose chest is always distended. A masterful man is Old John with plenty of self-assurance but with a heart of gold.

O’Rourke? There’s a man. Fifty years ago in Southern Ontario, his blood-brothers might have been seen in half a hundred pleasant, well-kept bars, sliding beer mugs half their length and accepting cigars for many a proffered drink. His moustache is of the proper weight and curl and he would be a museum piece except for the subtle variations forty years of Northern Ontario have imposed. The ruddiness and pleasing plumpness of the authentic type has been replaced by a weather-beaten tan and a certain muscular stringiness but he still radiates hospitality and is a good fellow according to his lights.

Annie is a sweet woman, one of the best. You may picture her with eyes of the deepest blue and a kind and understanding smile. If her face is now lined, the lines are an honourable accumulation of good marks conferred for forty years of backing up her man and smiling through the vicissitudes of pioneering. She lets Mike talk, when a word from her might puncture one of his rosiest dreams. She is a motherly woman and Mike thrives on it.

For the others, if you come to Northern Ontario, you will find them all the way from North Bay to Moosonee. Not at all heroic, still they are part of the warp and woof of the pattern and fabric of Northern life.

Mike Mullins of Boston Crick

It all happened long ago at a little bush station south of Matheson. Much of it came to me second hand and what I had from Mike himself was so larded with talk about organization and organizing ability—his presumably—that it only tended to confuse the issue. Anyway, from one source or another, the incident worked out as near as may be like this.

Mike Mullins was in a quandary. His big moment had come and he feared that it might be too big for him to cope with single-handed. “There’s glory in it for sure,” thought Mike, “but more kicks than kisses if I don’t pull it off.” A voice over the telephone had informed him that in three days there would be a shipment of a thousand pigs to handle. Mike was alone. The Agent, for two days, had been fighting the thousand devils that torture a man in a severe bout of ’flu. No help could come from that quarter. It was sink or swim and Mike decided to take the plunge. Never before had pigs been shipped from that point and Mike was determined to share none of the glory of such a shipment with the Chief Despatcher.

The little bush station had a twenty-car siding. A two mile spur stabbed off into the bush to serve a now long-forgotten mill. Trains stopped for flags and devil a bit else. It was a peaceful spot. Rather too peaceful for the amount of business now in sight.

“Pigs is it,” thought Mike, “and one thousand of them. Where they’re coming from ’tis hard to say but shipped they’ll be and nothing short of murder’s going to stop me. One thousand pigs and how big would a pig be now?” It seemed to Mike that they came in assorted sizes and big pigs would take more cars than little pigs. “How big was a big pig?” That was the question. Memories of fat pigs from his youth made them appear enormous. “Not a black-fly’s eyebrow less than six feet long they be, for certain, and two feet across the beam at the very least. One thousand of the creatures! Sure, ’tis big business I’m engaged in and one of those days it will be Mr. Mullins, General Freight Agent, no less.”

This bright vision faded abruptly when Mike realized that the thousand had to be reduced to terms of stock cars. Arithmetic in its simplest form was higher mathematics to Mr. Mullins. Sums that required no more than his ten fingers for their solution were well within his compass but calculations involving lead pencils and furrowed brows were quite another matter. However, he went to it.

“One thousand pigs is it and each of the creatures two feet across the back of him.” He plunged deep into the problem. Slightly blown, some minutes later, he came up with the answer. “If you stand them side by side along the track, they’ll make a procession sideways two thousand feet no less and that’ll bring more than half of them out on the main line. Anyway standing them up like a lot of soldiers will never do. ’Tis into stock cars, bad cess to them, I’ll have to pack them.” With grim determination, Mike went at it again with pencil and maledictions against every pig that wasn’t already reduced to bacon.

Fifty stock cars was the answer. Try as he would, there was no other and the siding would take twenty. “The saints be with me but they may be little pigs but, big or little, ’tis twenty cars they’ll get. Worry enough I’ve had already to be giving thought to the comfort of a pig. Crowd in, you devils, and lucky you are to be riding at all, at all.” Twenty cars and Mike looked along a siding as empty as the main line streaking away into the bush.

A man can only stand so much and Mike needed rest. It is doubtful if he got it. Years later Mike asked if counting sheep would make one sleep. When assured it would, all he said was, “Counting pigs won’t work. I’ve tried it.” However each day brings its problems and, tired as he was, Mike was up with the crack of dawn. There on the siding, blank the day before, as if in answer to prayer, were ten stock cars. “ ’Tis leprechauns I’ll be seeing next. Sure, and I must be living right.” Half his problem was solved because a way-freight in the night had dropped them to make a passing farther up the line. All day they stood there and no one made a pass at them. Ten cars and he needed twenty. In the morning the pigs would arrive and big or little they must be shipped. It was a worrying day for Mike and the temptation to call in the Chief Despatcher was strong but resisted. This was Mike’s show and he would see it through alone.

Night was falling and there were still only ten cars. The barometer of Mike’s feelings was falling fast and pointed strongly to foul weather when a toot from the sawmill switch engine made it jump a point or two. The dinkey rumbled out of the bush with a string of a dozen boxcars ahead of it. Spotting these on the spur near the main line switch, it uncoupled and chugged its way back to the mill. “Tempting a decent man, is it? ’Tis piracy on the high seas or pigs rampaging in the ticket office and I has no choice. I’ll do it and may the saints protect me.”

A car mover was his only tool and it’s far less handy than a 300-class locomotive. Fortunately the spur was on just the suspicion of a grade. Setting all brakes, Mike cut loose the first car and started pumping. It was a night of toil and backache, pumping the mover, throwing switches and hopping up to brake wheels. At last it was done in the first streaks of early dawn and Mike, exhausted, croaked, “Bring on yer pigs.”

He had not long to wait. Around a curve in the road, the first wagon appeared and a car, passing it at high speed, drew up to the station. A burly man hopped out, glanced at the siding and almost raced up to Mike. “Man, man,” he cried, “I’m lucky. I’ll need the lot and a hundred more.”

“The lot of what?” said Mike.

“The cars, man, the cars,” he roared. “Here’s the boom at the pulp mill gone and all the logs hightailing it to James Bay. The chippers are eating into the stock pile like twenty beavers at a poplar. We’ll save the situation. There’s twenty thousand cords of pulpwood waiting for your cars and you’d better be ordering more at once.”

“The cars is bespoke,” said Mike, grandly, and turned to greet the man on the first wagon.

“You’re the pig man, I take it,” said Mike, “and when will the pigs be coming?”

“Sure they’re here,” said the man. “Can’t you see them on the wagon?”

“What’s here?” said Mike.

“The sow and pigs,” said the man, “and perhaps you’ll help the crate on to the platform.”

Mike stared, but it was too much for his jaded nerves. “One sow and pigs! One thousand pig! And ten thousand ring-tailed devils.” He caught the pulp man as he was stepping into his car. “The cars is yours,” he said, “Sure and I couldn’t see you stuck. I’ve rearranged my shipments and you can start loading at once. It’s all along of my organizing ability.”

Pigs is it and Old John indeed. Him that hasn’t wore out his first set of store teeth yet! There’s plenty the same man could learn from pigs if he had the mind to do it. But no, it’s blacken a man’s character he’s after doing until every grinning engine-driver grunts to me as he drills by. Or it’s, “Mr. Mullins, have you any stock cars on the siding? There might be a bit of pulpwood to be loading in the morning.” ’Tis me that could be telling how he come to be drove out of Galway, no less, if I had a drop of his black blood coursing in my veins. Sure, I’m not one to be telling tales on him but—

It was the winter of ’34 and times was hard all over. MacDougall Chutes was hit hard like all the rest. Of course people was eating, for none ever starve in the North Country, but it was slim pickings at the best. There was little ready money and not much of anything in the store. All through November, the wood piles took an awful beating and every house was banked with snow right up to the sills. Come December and there was mornings when you couldn’t tell the time of day on any thermometer in the village. It was cold and no mistake and the snow kept coming.

The school was open and Nora, the school mistress, as pretty a girl as ever you’ll see outside of Ireland and always with a smile for me and John, was hard put to it to gather any sort of a class about her. The village children made the grade, except the littlest of them, but them that came in from the country stayed at home. We’d see them ploughing through the drifts, wrapped up like Eskimos and their little noses red when they wasn’t white with frost bite. I’m thinking that Nora was undressing them and thawing of them out and getting them ready to go home the most of the time.

One day we’re watching the children bucking through the drifts, when John says, “Mike, what day is it?”

“Sure,” I says, “it’s the eleventh of December.”

“And what will it be two weeks from now?” he says.

“It will be the twenty-fifth,” I says, for I’m quick at figures.

“And what day is that?” he keeps on like I’m one of Nora’s pupils.

“Bedad,” I says, “I was near forgetting. It’s my woman’s birthday and I’ll have to be after getting her a present.”

“You’re no better than a heathen,” says John, “not to be knowing that ’tis Christmas Day.”

“Sure, it’s no matter,” I says, “and me without chick nor child.”

“Take shame to you,” says John. “You see them kids. What kind of Christmas will they be having, with their dad’s not working and most of them living under the black shame of relief?”

By the powers, when he put it that way, it looked pretty slim and hopeless but, at the moment, we both cocked an ear at the schoolhouse right across the way. Bedad, if Nora and the kids wasn’t singing as if their little hearts would burst. “Good King Wenceslaus,” it was and they followed up with “O Little Town of Bethlehem” and “Silent Night.” I’m damned if John, the old fool, wasn’t crying, not that I could see the tears of him for there was a kind of a mist about.

“Well,” says John, when the singing stopped, “What are we going to do about it?”

For the life of me, I didn’t know and I waited for John to give the lead.

“I’ll tell you what we’re going to do about it,” he says. “We’re going to be Sandy Claus to those kids and give them a Christmas like they never seen before. There’ll be a tree in the schoolhouse, with candles on it and fixings like an Orangeman on parade, bad cess to all of them. There’ll be ice-cream and candy canes and animals and hot drinks and cakes and pies. And there’ll be a present for every blessed one of them and a big one for Miss Nora.”

“Where’ll it all come from?” I says. “Devil a bit of it is there in MacDougall Chutes, except the Christmas tree and it might be cakes and pies.”

“You’ll get them,” says John, “and I’ll tell you how.”

I knew it would be so, for he is a masterful man when it comes to giving orders to the likes of me.

“You’ll go this day and collect the money,” he says. “Here’s what I have on me for a starter.”

“Sure,” I says, “I’m working steady myself and I matches you dollar for dollar.”

“ ’Tis a start,” says John. “Now go to it.” And I did.

Before night, I had a roll would fill a boxcar. The lads at the mill come through handsome. The section gang wasn’t a bit behind. The store and the hotel kicked in with what they could. If it wasn’t much, it was worth more for the way they gave it. ’Twas done secret. No kid was to know anything about it. Him at the big house, that had known hard times hisself, just asked what we had and doubled it. I was scared, we had so much.

John had been working himself. Every good cook in the village, with an extra bit of flour in the barrel, was pledged to be mum and give a thumping contribution to the feast. John and me worked late that night. There was fifty kids and Nora to look after. An order went out to the big city for the lot of them. Something warm for everyone and something foolish. Drums and horns and games, dolls and sleighs and hockey sticks. I disremember all of it but it was sure enough and there was a red coat and white whiskers for John to play Sandy Claus.

School was out two days before Christmas. The bales and boxes was in the freight shed and as pretty a tree as you ever see was set up in the schoolhouse that very night. John’s woman and mine and a dozen others was all over it. You never see its equal. There was red and blue and white running every which way and, bedad, sparkly stuff like icicles hanging down all over. There was candy canes and animals, like John said, and stars and shiny balls. I just stood back and stared and I’m damned if my old woman didn’t kiss me in a corner. ’Twas all ready by midnight and not a kid the wiser. All the people in the country had been told and everything was set for the big day.

And what a day it was. An even zero with every flake of snow a diamond and it crunching and squeaking underfoot. Never was so many sleighbells in MacDougall Chutes when the teams started coming in. At seven o’clock the doors was opened. Every kid in town was there, except little Dinny Dixon and him down with measles right forninst the school. There was singing and Nora led such carols as you never heard. Old Rafferty was there with his fiddle and Pete Coture danced jigs and hornpipes like his legs was rubber. That slick young feller from the mill did tricks with cards and, easy as spitting, he’d take things out of the air I never would have thought was there. He took Bob Potter’s watch and smashed it with a hammer and there it was next minute safe in Mr. Potter’s pocket. You can bet, I kept my hand tight on my own. Then there was eating and it was good to see those kids dig in.

Long around ten o’clock, the big time came. John ducks out to dress hisself over at the station. When next I see him, what with the magic tricks and dancing and the carols still ringing in my ears, I didn’t know him. For me, he was just Sandy Claus, with his red coat and whiskers, a great bulging pack and a twinkle in his eye. I met him at the back door near the tree.

“ ’Tis fine,” I says, “but I can’t help thinking about little Dinny Dixon.”

“Give him never a thought,” says John. “When I come across, there he was, with his ma and pa, and their noses like putty on the window pane. So in I goes and Dinny thinking that I’m straight from the North Pole. He’s got his skates and his sweater and he’s as happy as a kitten with two tails.”

“ ’Tis well,” I says. “The fun can now go on.”

And fun it was as every little gaffer and his sister comes up and gives a bob and gets their presents. Sure, they believed in Sandy Claus that night. Nora comes last. For her, we had a deerskin parka, lined with rabbit skins and trimmed with wolf fur. She put it on and the pretty face of her, framed in the grey softness of it, was prettier than anything I ever hope to see. She made a little speech. At least, she started one and then she cried and kissed the only bit of John’s face that wasn’t whiskers. All in all it was a grand night. As they straggled home, they was all singing. It was “Hark! The Herald Angels Sing” and, bedad, I’m not so sure that some of the angels wasn’t singing with them.

That’s the end of it—almost. But just to show you what a lunkheaded, ornery derail Old John really is, within a week every house in the town that had a kid was placarded with a red measles sign and old Doc. Macintosh was like to have a nervous breakdown. Pigs is it. Let him talk to me of pigs.

It was last week that one of the old timers dropped in and at once we were swapping yarns about the early days. He had travelled the line when Cobalt was a pup and stumps were still standing on Third Avenue in Timmins. Varied and vivid were the tales he told and there was more than one about Mike Mullins. Harry McGee knew everyone and there was little about the railway that had escaped his notice.

It was therefore in a mood for reminiscence that I greeted Mike when he breezed in close on Harry’s departing heels.

“The best of everything to you, sir,” said Mike, “and a grand job you did with my yarn about Old John and him spreading the measle bugs all over MacDougall Chutes. The ribbing he’s been getting from the lads has clear put the pigs out of their silly heads. ’Tis sorry I’d be for him if I could forget the tales the same John has told about myself.”

“Forget and forgive, Mike,” I said, “It’s all good fun and not a bit of venom in the lot of it. Spring’s here and that’s a time for forward thinking.”

“Right you are, sir, but I can remember a spring when looking ahead didn’t seem to do much good. ’Twas the year after the big fire. That would be in ’17 and the whole country burnt out right from Cochrane to New Liskeard.” Mike paused and looked me in the eye. Reassured by a bit of green in it, he went on. “Devil a bit of anything was left. I mind the beaver was using cakes of ice to build their dams, a thing never seen before nor since. However, as you say, spring is here and pretty it looked as I come along. The crick’s nudging and eating into its banks and singing a tune that puts heart into a man. All the little birds is chirping as if there wasn’t three feet of snow into the bush.”

“I can see you have quite a love for music, Mike,” I said. “Wasn’t it the carols that time got you and John to playing Santa Claus?”

“ ’Twas that and more fun I never had. Yes, music of all kinds is good and the Irish pipes is best of all. Piannys is good too when the pipes is lacking.”

“Do you mean to tell me that you play one?” I said, for by this time I was prepared for anything.

“Devil a bit,” said Mike, “but any of them things sort of strums the heart strings of me and puts a tingle in my feet. No, I don’t play none but once I sort of acted as an impresario, I thinks you calls them.

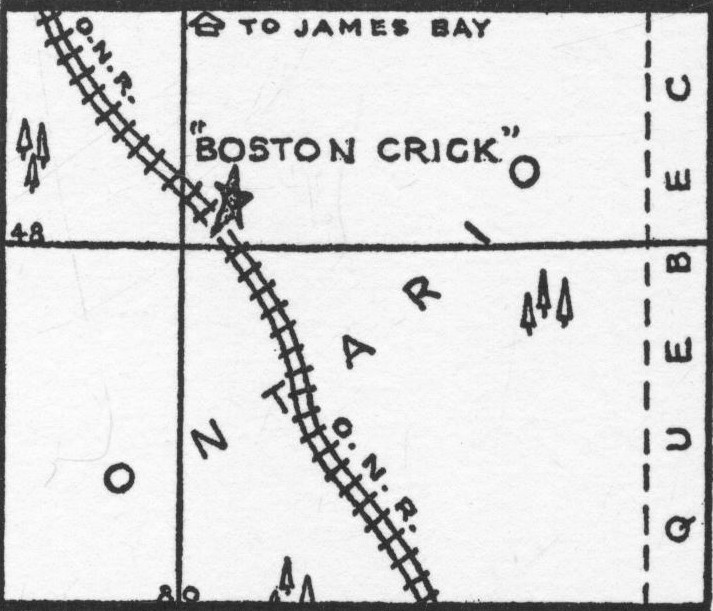

“ ’Twas this way. In them days, I was the Agent up at Boston Crick. There was some claims about that was being worked though they has played out since. We was busy enough with mine hoists and boilers, pumps and drill steel. Lots of outfits got their chuck then through the Crick and men was coming and going all the time. The little town was pretty active too. All in all times was good right there. Then one day what should come in but a pianny, one of them high kind in a crate like six coffins stuck together. Well we rustled it into the shed and I see by the billing that it’s going to a claim ten miles back in the bush. They had been having trouble holding their men and I guess they thought a little music might liven up the camp.

“Anyway there it was just at the tail end of winter and the road, which was no more than a snow track through the bush, was breaking fast. A week before and taking it in would have been as easy as spitting over a log. Now it was impossible. That pianny was good for a month or two right where it lay. So we shoved it into a corner and that was that.

“Well, about this time there was talk of doings in the village. ’Twas in wartime, you mind, and all the lads of fighting age and some that wasn’t was overseas. They was Engineers and Highlanders mostly for the McKloskeys and the Murphys and the Indians all took a liking for the kilts. These fighting men was boys and ’twas well known that they’d fight the easier if they knew their home folks was backing of them up. So parcels was being sent as often as they could be got together and the letters from the lads was common property. Everybody worked together and the ways of raising money stopped at nothing short of blowing safes. This time ’twas to be a concert and I’m busy with my freight and passengers so I have no part in the arrangements.

“First I know, they was sticking printed posters on the station. Never had the Crick done anything so grand. There was to be singers and comic fellers, a fiddler and a magician, musical glasses and two pianny players. One of them was little Katie Doherty and the other was Ole Swenson, shift boss at the Whatahope. Nothing as big had ever been done north of the Bay. I’m reading the first of them and, I’ll not deny it, sticking my chest out because we could do so well, when who should come along but Father Walsh and the Consolidated minister.

“ ‘Good day to you, your Reverence and Mr. Jones,’ I says, ‘ ’Tis a fine doings for the lads we do be having.’

“ ‘’Tis that, Mike,’ says his Reverence, ‘but I’m thinking that we’ll have to cancel the whole affair.’

“ ‘Sure, there’s never been a fire in the schoolhouse,’ I says.

“ ‘Not the least taste of it, Mike,’ says Father Walsh, ‘and every artist is raring to go. The joke, if you can call it that, is sure on us. Mr. Jones and me, we arrange the whole thing and get the posters printed and then, bedad, we remember that in all the Crick there’s nary a pianny.’

“I’m just getting ready to tell him that ’tis sorrow I’m feeling for them when I looks hard at Father Walsh. Then I feels sorry for myself. Everybody knows, including Father Walsh, that I have a pianny in the shed.

“ ‘You’d never do it to me now,’ I says, ‘You know they’d chop me into little pieces and I’d lose my job besides if it was ever to come out.’

“ ‘Mike, Mike,’ says his Reverence, ‘I’m ashamed. Don’t you ever give a thought to the lads in the mud of the trenches? I mind, when Tim Conlan goes away, you said there was nothing you wouldn’t do for him.’

“ ‘And,’ says Mr. Jones, ‘do you know about the Thirty-nine Articles and Runnymede and St. Bartholomew’s Eve?’

“Of course I didn’t and I see that I was licked.

“ ‘Gentlemen,’ I says, ‘Mike Mullins is your man and may all the shamrocks wither at Killarney if I don’t see it through. You’ll handle it like your baby sister and you’ll have it back in its box in the morning. I have my methods,’ I says, plucking up a bit of courage, ‘and, at least, ’tisn’t as bad as a burying I once went through.’

“So that afternoon the pianny went to the schoolhouse and I took steps to consolidate my position as the soldier boys would say. First I hopped into the pianny box with a hammer and a fistful of nails. I spiked it down as solid as the floor itself. Then I closed the box all neat and comfortable. Having taken my precautions, I went to the concert that night with my conscience as easy as any uncaught burglar. Everybody there patted me on the back and I sure felt good. If it hadn’t been for Michael Mullins there would have been no concert and well they knew it. Father Walsh opened the proceedings and when he thanked me for my public spirit was when he called me a impersario. Bedad, I was even sitting on the platform beside the instrument.

“The concert started with a comic song and Mrs. Jones, as light-fingered a lady as I ever want to see, was playing the accomp’niments. When the applause was nicely going, I looks at the door and there was Harry McGee, the Travelling Auditor. For all his crinkly smiles, he was the auditor, and me sitting on the platform right forninst the pianny I had pinched. I’m telling you, I suffered and it kept getting worse. The musical glasses comes next and a song was after. Then little Katie Doherty comes up to do her piece. I see right away by the hands of her that she’d been eating candy bars. The chocolate was sticking to her fingers. So up I gets pretending to fix the stool for her and gave them a wipe on my handkercher. It did some good because, when I wiped the sweat off my forehead, there was brown streaks across it.

“How I lived through the rest of it, I’ll never know. It seemed to go on for hours. Big Ole Swenson played ‘The Battle of the Baltic’ and the pianny took an awful beating. Mr. McGee sat through it all. Finally it came to an end with Mr. Jones announcing a collection of three hundred dollars and, praise the saints, there was no more praise for Mr. Mullins. Down I goes to Mr. McGee, for I figures them’s the tactics that’ll see me through and, sure enough Mrs. Jones comes rushing up.

“ ‘We owe it all to you, Mr. Mullins,’ she says, ‘Without—’

“ ‘Think nothing of it,’ I says, breaking in. ‘Sure, we all did our best for the fine collection,’ and I got Harry out of the school. We talk a bit about this and that, the fine crowd, the songs and the pianny playing and then he says,

“ ‘Been riding all day on Number 9 and I’ll turn in for I’m tired but I’ll have a word with you in the morning and we’ll check things up.’

“Well, there I was. No chance of moving the pianny before daylight and everything in the shed would be checked. I dreamed that night with battles and chocolate bars all mixed up together but, bright and early, I was at the station. About eight o’clock, Harry McGee comes down.

“ ‘Well, Mike, let’s go to it,’ he says, ‘for I’m taking the speeder north when I get the low down on your stuff.’

“I didn’t like the way he said it, me not being easy in my mind but I took the bills and we started in. There wasn’t much in the shed. We checked a bit of drill steel and a few oil drums. There was some odds and ends of furniture and then we come to the pianny.

“ ‘Mike,’ says he, ‘I think this’d be better at the other end. Let’s give it a shove.’

“ ‘Sure, you’re right, Harry,’ I says, ‘but think of the heft of it. I wouldn’t have you straining yourself. I’ll just get a few of the boys in here when we are done.’

“ ‘Why I could move it myself,’ he says.

“ ‘Of course you could with them big strong arms of yours but it wouldn’t be dignified for you to do it and I’ve a bit of a sore back myself. Would you be looking at this barrow now and it with a broken handle. ’Twas the way it come to us,’ and I got him to thinking of other things. By and by, he goes away on the speeder and Mike Mullins had scored again.”

When I next saw Harry, I grinned at him. “Mike Mullins certainly put one over you in the piano business up at Boston Creek. I thought you always got your man.”

“He sure did,” said Harry, “with me facing a foot-square shipping tag tacked to the back of it through the whole of the performance.”

“Fishing is it,” said Mike apropos a remark about a thirty-pounder caught in Lake Temagami. “I don’t hold with it. Not that I won’t eat the creatures on a fast day but, by the powers, I won’t play games with them.”

“Why the bitterness, Mike?” I said, surprised at his vehemence. “Fishing, of all sports, is designed for the contemplative soul attuned to Nature in her happiest mood.”

“Is it now,” said Mike darkly. “That ain’t the way it looked to me the only time I tried it.”

“Here’s my pouch. Fill your pipe and let’s have the story.”

With his briar drawing nicely, Mike looked thoughtful for a moment before he spoke.

“This was the way of it. ’Twas in 1908 it happened, the time I’m going to Gowganda to make my fortune. Them days I’m a young feller just out from the Old Country and full of ambition to see what makes the world go round. Well, I drifted up to Toronto doing this and that and I’m working on a track gang with the old Grand Trunk. One day the lads is talking about a place called Cobalt and one of the right sort named Murphy says he’s turning in his check and trying his luck up there come pay day.

“ ‘What’s there,’ I says, ‘and where is Cobalt at?’

“ ‘Sure, ’tis away up north,’ says Murphy, ‘and ’tis where the silver comes from. They has it in chunks as big as boxcars and anyone that finds it can have it. There’s so much they even makes sidewalks of it.’

“Well, I thinks to myself, I’d admire to see a sidewalk made of silver, so I tells Murphy that I goes along with him. ’Tisn’t more than a week later Murph and me steps off the train at Cobalt and starts looking round. Devil a bit of silver could we see. The sidewalks, what there was of them, is wood perched up on posts to keep them out of the mud but ’twas a bustling place with half the town always on the move. Getting a job was easy and I’m lugging mine timbers on the surface out at the Kerr Lake. The lad was right about the silver sidewalk and many a time I’ve scraped the heel of my foot across it to help the shine of it. The silver was there all right but of course the whole country’s staked and devil a bit of it was there for Mullins.

“Come spring, I hear them talking about Gowganda which is a country with silver sticking out of the rocks like promises at an election rally. So what do I do but chuck up my job and go along, for I’m bound to have a silver mine. Down to Latchford I goes and up the Montreal on the Booth boats and me knowing no more about prospecting than I does about ashtronomy. ’Tis the tail end of the evening when we arrives at Elk Lake and the rapids and the river and the bush is giving me thoughts about the bunk-house at the Kerr Lake. Well, I has a bit of money, for I’m never one for the blind pigs and such, and I gets bunked down at the King Edward right up from the landing stage. Next morning, I’m mooching round and I run into a feller and him looking for a partner. Right away, we hooks up and I’m an Orangeman if it don’t turn out to be Old John that was to be in the hair of me for forty years.

“Little did I know, as the lad says in the dunce’s cap, what was to come of it. However, there we was partners and us sitting on the edge of the Post Office verandah talking things over. Not that there was much to talk about for John was as green as me. For all that, we’re getting acquainted, with John talking pretty big about how he has handled boats ever since he was a little lad, him having been reared on a bit of the coast in the Old Country. To hold my end up, I’m telling him what a swimmer I am and how I swam the Shannon at its widest, though I never saw the stream and did my bit of swimming in the Liffey.

“By and by, two sports come along and plumps theirselves down beside us. You could tell they was sports by the clothes of them and the fishing taykle. Well, these gents was talking loud and we could hear that they was making bets. They’d bet on anything. Whether anyone would go in the Post Office before anyone would come out and how many people was going which way on the bridge or any other thing that took their fancy. Soon a crowd was gathered round listening to the fun and some of them starts making bets theirselves. Then one of the gents looks at me and John and he says:

“ ‘These gentlemen has the look of dead game sports. I’m thinking, if they’re agreeable, we could fix them up with fishing taykle and stage a fishing Derby on the bridge. To start the thing, I puts twenty dollars on the big one.’

“ ‘I covers your twenty,’ says his friend, ‘and I has twenty more if any of the gents in the crowd would like to try their luck.’

“Soon the bets is flying thick and fast and near the whole town is milling round placing their money. John and me can’t spoil sport like that so we says we is agreeable and I even bets ten dollars at two to one on myself.

“Well, you must know the bridge in them days was nothing more than a plank walk riding on barrels with a bit of a railing on both sides. About four feet wide it was, for there was devil a horse or cart in the country. The Montreal’s wide and deep with a nice easy current. So the crowd ropes off a bit of the bridge near the middle for me and John, and the gent gets out two poles joined together that they says is casting rods. They has little windlasses on them for to roll the line up and there’s a ugly little critter on the end of the line full of hooks that they calls a plug. The idea, they says, is that we throws the plug out and, when a fish takes hold, we works him in with the little windlass. ’Tis agreed by all that once we starts there’s to be no interfering. So out we goes to the middle of the bridge and someone fires a gun and we’re off.

“It don’t go so good because John hooks me and I hook John the first time we tries to throw the plugs. When we gets untangled, we moves a bit and things goes better. We gets so we can throw the plugs about twenty feet or so, John upstream and me the other way. We throws them out and we winds them in and nothing happens but the crowd is still making bets and the odds change every time a plug hits the water. Then I hear a roar from the crowd and, out of the corner of my eye, I see that John has got a fish with his windlass singing like it’s mad. But, bedad, I pays no more attention to him with my ten dollars to protect and all my backers howling at me from the bank. I cast again and gets a good one and I’m just winding in when something hits my plug and away it goes with me trying to grab a hold on my windlass. Just then, about fifty feet away, up comes the biggest fish I ever hope to see. It jumps clear into the air and I’m damned if it doesn’t seem to have two lines on it. ‘Lunge’ yells someone from the bank but I don’t know what it means and anyway I’m too busy for such trifles, with me winding hard for the fish is coming right for me but deep in the water. I hear John winding too. Then this devil of a fish dives under the bridge and my line runs out again and saws against a barrel.

“I hears John yell, ‘The creature’s my side of the bridge. D’you want to ruin the good fishing taykle? For the love of Heaven, under the bridge you go and we’ll get him on this side.’

“Well, I don’t like the idea so much but just then the fish jumps again and there’s a roar from the crowd so in I goes. ’Tis a hard swim with my clothes and all and the fish tugging at the line but I makes it with my breath near gone. When I comes up with my pole in my hand, John’s winding hard again and the crowd’s cheering and laughing fit to kill. I’m just starting to climb out, when John yells, ‘Back you goes. He’s making for your side.’

“ ‘Go yourself,’ I yells, ‘He’s as much yours as mine.’

“ ‘If I could only swim,’ says John, sorry like. ‘In you go,’ he says. ‘Do you want to be losing the biggest fish ever seen in Elk Lake?’

“So I takes a big breath and down I goes with the current fine to help me. I’m half way through, like as not, when something hits me on the shoulder. ’Tis the fish, for I opens my eyes as he streaks by, and I’m scared for he’s a wicked looking devil. So I swims hard but I makes no headway with something tugging at my shoulder. I’m near done but there’s nothing for it but turning back. ’Tis easier going then and, when I’m like to bust, up I pops clear of the barrels. I grabs hold, breathing hard, and there’s John laughing so he can hardly stand with his pole almost in my face and his plug hooked tight in my collar. There’s no sign of the fish and anyway I’ve lost all interest. There was a good deal of arguing but finally all bets is called off when I offers to fight any two of them if they decides what John caught was fish. As I says, since that time I don’t mind eating the creatures but devil a game will I play with them.”

“And what happened to the partnership?” I said. “Did you go to Gowganda and stake a claim?”

“Sure, I never got past Elk Lake, nor John neither. Me and John got jobs with the T. & N.O. up around North Cobalt and we’ve been with the road ever since.”

“Too bad John never learned to swim,” I said. “It was a one-sided show he made you put on.”

“Swim, you says. The cunning devil. That same summer he wins a hundred dollars for swimming across Lake Temiskaming from Ville Marie to Haileybury. Bedad, he was more like to catch that fish with his bare hands than with any pole and windlass.”

Mike Mullins came into the office and flopped down in his accustomed chair. His lack of greeting made me glance up from what I was doing to see the grandfather of all black eyes assuming new tints of maroon and purple.

“For the love of Heaven,” I said, “have you been in a collision?”

Mike grinned with a sort of modest pride.

“Sure, ’twas a big Swede down by the shops and him, you might say, almost out of reach barring a step ladder. But I asked for it.”

“A wise man stays in his own class,” I said, “but what was it all about?”

“Well, this Oleson,” said Mike, “a quiet hunk of a man in general but forty wildcats when roused, was giving Old John the rough side of his tongue and John not there. So I stepped into him and later, when I come to, Oleson is gone and the lads is pouring water on my head.”

“But surely,” I said, “Old John has ridden you enough for you to enjoy someone putting the spurs into him.”

“ ’Tis easy to see, sir, you’re new in these parts. All the lads knows that one word against John and they has to fight Mullins. If there’s any blaggarding to do, I can do it myself.” And I knew that Mike meant it.

“It’s all a riddle to me,” I said. “I’ve heard about the pigs and the fishing at Elk Lake and I can see nothing in either to make you take a black eye for John. What’s the story behind it all.”

“It’s like this. Me and John is friends for forty years and all the shiners in the world will never pay for what I owes him. I never told you, sir, about the lad I lost. Me and Annie, that’s my woman, had five years of dreaming and thirty years of sorrow for him and Old John has shared the lot. Perhaps you don’t know the black hours in the night when you wake up thinking you’ll see him and, when you remember, the cold grips your heart. No matter. ’Twas long ago and the memory of the little lad is sweet when the sun is shining.

“We was all, John and me and his woman and Annie, up the line together from New Liskeard. ’Twas a little station with John the Agent and me about everything else. There wasn’t so many trains them days and we had time on our hands. Little Micky, as soon as he could toddle, was in and out most of the time. John called him the General Manager and ’twas fine to see him riding John’s shoulder with the sun in the gold hair of him. All the train crews knew him and he knew the lot of them. Sure, if they could have spoiled the lad, they would have done it, for hardly a train went through without something from the crew for Micky. There was lead soldiers, I mind, and we has some of them yet and him lining them up for battles on the floor behind John’s chair. Good as gold, he was and never in the way, with a cheery word for everyone.

“So it went for five years and him coupled to the hearts of us like the tug of fifty box cars down at Jocko. Saving our money, we was, against the time he goes to college and John and his woman saving too for they never has a child and Micky was as much theirs as ours. We’d talk about whether Micky would be a engineer, a doctor or a lawyer and we’d settled on a engineer when the black diptheriar struck. ’Twas all over in two days. The railway doctor hightailed it through on an engine from the Bay, but ’twas too late and we buried little Micky and the hearts of us under some white birch trees in the graveyard.

“You’ve wondered why I never went to the war and it’s been a shame to me for all the life of me. ’Twas early in ’15 it happened and, with the black rage in me, to stop a bullet was all I asked for. I see the lads joining up, with the light in their faces, but I couldn’t go with them. ’Twould have been too much for Annie and her arranging and dusting Micky’s toys and smiling over them.

“ ‘Mike,’ she says to me once, ‘you’re dying for to fight. You can go if you must.’

“ ‘Why should I fight?’ I says. ‘Remember Cromwell, woman.’ And me with my own father dead with the Dublins in South Africa.

“However, the morning after the burial, I’m late and dragging my feet to the station. John sees me coming and he’s at the door when I arrives.

“ ‘You’re late, Mullins,’ he says, ‘and you’ll work this day to pay for it.”

“ ‘Sure,’ I says and I got no further.

“ ‘You’re late,’ he says again savage like, ‘and I’ll take no excuses. Into the shed with you and straighten of it up. ’Tis worse than a Connemara pig pen.’

“ ‘All right, my bucko,” I says to myself, ‘if that’s the way you want it,’ and I went on into the shed. ’Twas as neat as a colleen’s ankle, the way we always kept it. There was a raft of package stuff lined up in rows to be got at easy, with some heavy stuff at one end and ten tons of salt at the other. John follows me in.

“ ‘You’ll shift the salt to this end,’ he says, ‘and the machinery to the other,” and out he goes with never another word.

“I’m mad for I sees no sense in it but I says nothing and I goes to work. ’Twas a big job with the shed nigh full and everything needing shifting to work it out. The machines, pumps and the like, was on skids or they would have stayed put for all of me. However, I juggled them the length of the shed with a bar and lugged the salt, two hundred pound bags it were, to make room. Them days I’m in my prime and mad clean through to help me. By the tail of the afternoon, and me with my knees buckling, I’m so tired, the job is done and I’m just taking a breather when John comes in again.

“ ‘You’ve finished, have you,’ he says, ‘and long enough you took. Now you’ll holystone the floor except the salt end. ’Tis a disgrace to the railway.’

“With that, out he stomps and I goes to work once more with black hate shoving at my elbow. By quitting time I’m done and, wreck that I am, I goes to the office to tell Old John a bit of what’s on my mind. I shoves open the door and there he is with his head on the arms of him and him sprawled out on the ticket counter. His back is heaving and sobs is wracking his very heart out. I closes the door and goes away on my toes. I never looked back but, if he saw me through the window, he could see me with my head up but he’d never hear the little song that was playing on my heart strings.”

It was not a time for words but Mike got up and started for the door.

“Sure, you’re not going so soon, Mike,” I said.

“I’m that,” said Mike, “for I have to find that Swede and he can black my other eye and welcome.”

“No, I can’t call to mind any such goings on in the early days. Of course there was blind pigs, or where would the lads have got their licker, and mebbe a bit of moonshine made by a gentleman with a place in the country. The banks was mostly tents in them days but I never heard tell of anyone blasting their way into them with dynamite. Sure, you could hang your watch on a tree and it was safe as churches from an Indian or a white man mebbe.”

All this was apropos a comment on the frequency and boldness of bank robberies as Mike lolled in his accustomed chair.

“I mind the strike at Cobalt. That would be ought seven. A tame affair entirely. I’ve seen more excitement at a Sunday School picnic for all the milling round in Cobalt Square. ’Twas a peaceful country them days, except perhaps for the time I’m held up when I am Agent up at Boston Crick.”

“You don’t mean a gunman stood you up, Mike,” I said.

“I do that. He was a tough customer and had a gun in the ribs of me before I knew what’s happening. If you have the time, I’ll tell you about it. ’Twas along in January, when the Crick was a busy little place thinking it was going to be another Cobalt. I’m on my way to the station after having my dinner, when I sees a feller coming towards me. I notice him because he don’t look quite right somehow. His parka and boots is new and they looks like something you might see in a moving picture. They looked too much like a parka and boots, if you understand me. Anyway, ‘Tenderfoot,’ says I to myself and thinks no more about it. Just as we passes, a couple of kids on the way to school comes up and I hear one of them say, ‘Mr. Mullins, has the money’ and t’other says, ‘Yes, and I betcha it’s a million dollars.’ I recalls this afterwards but it makes little impression at the time.

“Well, I goes on into the station and there’s the money the kids is talking about right in the open on my desk. I’d clean forgot to put it in the safe. ‘Bad luck to you, Mullins,’ I says to myself, ‘you never think of anything.’ So I opens the safe, that has about a thousand dollars of the company money into it, and gets out the sealing wax, for I wants the parcel shipshape before I puts it away. I’m putting big blobs of wax on the parcel and whistling to pass the time when I feels something jabbing me in the ribs.

“ ‘It’s a stick-up, Buddy,’ I hears and who’s behind the gun but me bucko in the parka and boots.

“ ‘Sure,’ I says, ‘You don’t mean you’d rob me.’

“ ‘Enough talking,’ he snarls at me, ‘and hand it over.’

“I know I’m beat and I does it. Anyway, for all his toughness, I see he’s nervous and nervous people and guns is a bad combination. He grabs the parcel and he says, ‘You can keep the change but don’t you make a move for half a hour if you values your life.’ With that, out he ducks and I see from the window that he’s taking a trail away from the village. There’s no one in sight and I’m agin’ tackling a man with a gun in the open.

“However, I’m thinking fast. I figgers this laddie is heading for Tim Conlin’s shack that’s been empty for six months. He’ll hide out there for a hour or two and grab the way-freight where it hits the top of the grade. Of course there’s no roads them days except bush roads to the camps.

“I’ve got to get that money back and I don’t aim to get hurt in doing it. So I gets into my coat and, as soon as he’s out of sight, I hops on the jigger which is standing convenient on the track. ’Tis a long chance. The trail me desperado’s took is hard beat and the going’s good but it ain’t the shortest road to a spot I knows about. It circles round a little valley to miss the hills and comes near as spitting to the track about three miles down. He’ll be doing four to make it that far. I’ll mebbe have half a hour or twenty minutes to do my business, whatever that may be.

“I’m all for action in a emergency, as you might call it, but devil a idea did I have at the start. ’Twas not ’til I’m pumping the jigger for dear life that it comes to me. For there, hanging to the side of it, is a bear trap complete with as fine a set of ugly teeth as you would care to see. One of the section lads was going to take it into the bush that very afternoon. It gave me wings, as the feller says when the bull caught up with him. The record I set for them three miles ain’t been beat unless them people at Salt Lake I read about has done it.

“When I reaches the spot I’m making for, I grabs the bear trap and the padlock off of the jigger and barges into the bush. The trail’s not more than a hundred yards away and it don’t take me fifteen minutes to bury that trap in the right o’ way and padlock it to a convenient tree. I smooths up the snow as natural as paint and takes cover behind some rocks. It’s a long wait of ten minutes, with me anxious and all, and I’m thinking that I haven’t got the right of it when I hears him coming. All he’s thinking about is making speed and bear traps, if he ever heard of them, isn’t in his mind at all, at all. Down he comes, hitting the trail fast and hard, and I hears the bear trap snap and he tumbles on the face of him. I never hears the remarks of a bear in the first moments of his surprise but me bucko had all the appropriate words and music. ’Twas a wonder the spruce trees didn’t shrivel up. ’Twas hurting, you could tell that, and I lets him rave. After a while he starts to work on the trap but they’s harder to get off than any shoepac. When he sees that it’s no use and settles down to cursing a bit more, and I’ll say for the lad that he never repeats hisself, I yells, ‘It’s a stick-up, Buddy, and you’d better make up your mind to like it.’

“ ‘Come into the open,’ he says, ‘where I can see you.’

“ ‘Not likely,’ I says, ‘You’ll first throw your gun this way and then the money.’

“You could see he’s thinking hard and they was tough thoughts with little good in them for Mullins. After a while, he gave up and did it, first the gun and then the money. I watched him close, for them guns might have been travelling in pairs. Then I come out and got the gun and the money.

“ ‘Now me bucko,’ I says, ‘you’ll just stay where you are until I can send some big, strong men to relieve you,’ and with that I goes back to the jigger but I don’t set no records getting back to the Crick.”

“Did he get a stiff sentence?” I said. “Robbery under arms is a pretty serious offence.”

“That’s the queer thing about it,” said Mike. “When we went back to bring him in, he was gone. The trap was a hundred yards down the trail and it looked as if he had walked or crawled with the trap still on his leg. He must have had a pal that helped him out of it. He got that far himself, you see, because I clean forgot the key was tied with a bit of string to the padlock.”

“I suppose the railway made it right with you for your courage in recovering the money,” I said with a new respect for Mike.

“Sure, they never heard anything about it and ain’t to this day. If you was to tell the story now,” said Mike anxiously, “you wouldn’t think that Archie would reach back that far to get me, would you now? You see the stick-up man never had any of the railway’s money. He says, you mind, ‘You can keep the change,’ and it was the change, over one thousand dollars, that was my real worry. The parcel of bills would have done him little good. You see, it was in the war days and we was always doing things at the Crick for the lads that was overseas. This time it was to be a Millionaires’ Night and the parcel was the phoney money.”

Old John dropped in to wish me the compliments of the season and stayed to chat. As I hadn’t seen Mike for a week or more, I asked for news of him.

“Sure, Mullins is in bed with a mustard plaster on his chest,” said John. “It was all along of him being helpful. You see, the ice was on Chippewa Crick and Mike’s down along the tracks when he sees some of the lads trying out their skates. It don’t look too safe to Mullins and so he gallops over to tell the kids. They ain’t impressed and Mullins undertakes to show them. He goes out to the middle and gives a bit of a jump. He’s right about it not being safe and the next thing he knows he’s up to the arm pits yelling bloody murder with the cold. The kids gets him out and it’s been mustard plasters for him ever since.”

“Mike’s got a heart of gold,” I said, “but perhaps he’s a little short on judgment.”

“Impulsive, you might say,” said John. “Why I’ve seen Mullins go right through a fight and, at the heel of the hunt, find he’s been fighting the wrong man. I’ve wore myself out with the man and that’s a fact. Take the time at Boston Crick. He blunders into that with his eyes shut and I don’t suppose he knows the rights of the matter to this day.

“It wasn’t my shift at all, at all but I was there to relieve Mullins, who was Agent them days. He’s going on holidays and it’s then that he’s courting Annie Lavery. Before he gets back he’s married to her and has been for nearly forty years, the poor woman. Anyway, I hops off the van of the up-freight with my bag in my hand and Mike’s going up the trail away from the station. He waves his hand and keeps on going and that’s the last I sees of him for that time. What’s been happening, I learns subsequent, as you might say.

“It seems a few days before I arrives, Mike’s out in the bush aways picking raspberries, in an old burn like as not. Coming home, he’s mooching along the trail when he sees a letter lying in the grass. He picks it up but it’s rained the day before and the writing on it’s run so he can’t read the address. Now Mike ain’t one for reading other people’s letters but something comes over him that makes him bound to look at it. Mike says later it’s instinct or second sight or mebbe the blessed saints that makes him do it. Be that as it may, he opens it and takes a quick squint at it. Right at the top in gold letters is Rita Cholmondeley and a address. It’s been sent to ‘Dearest Ricky’ and it’s signed ‘Rita.’ He sees that much and it tells him nothing. So he takes another gander and right in the middle of it he sees ‘jump Niagara Falls.’ That was all he saw and it was enough for Mike. Impulsive was what he was and always will be. ’Tis the saints for sure has led him to it to save the girl from her rash act. Before he closes the letter, he takes another look at the gold lettering. It’s Rita Cholmondeley right enough and a street and number in Toronto. Mike says he’ll remember that address to his dying day and well he does for by the time he hot foots it to the station, the letter’s nowhere to be found.

“No matter. On the way in he makes up his mind what to do. It ain’t two minutes before a wire is on its way. ‘Don’t make jump Niagara Falls. Ricky desperate. Mullins.’ is what he says. Then he sits back to think. Devil a bit does he know what to do next. He don’t know who Ricky is nor where he’s at. ’Tis on a Tuesday all this happens and he spent the next couple of days investigating. Of course, being Mullins, he don’t tell anyone about it or ask advice. It’s all Mullins, Special Investigator and blood hound on the trail. Of course, it’s a hard trail to follow and it’s not ’til the shank of the evening on the Thursday that he runs into a character that can tell him Ricky goes to some open ground about ten miles east of the Crick. This Ricky is a young feller called Richard Wilson. He’s a tenderfoot with a partner as green as himself but they’re husky lads and packed in a good load of chuck intending to stay put until they makes a strike.

“It’s Mike’s idea he has to get this Ricky out to the telegraph before the girl has made the fatal jump. So he’s on his way when I hops off of the van. As I says, I don’t see him any more at that time and, consequent, I knows nothing about what took place. However, I’m busy picking up the loose ends around the office and, except for the thought that Mike’s starting his holidays in a queer way with Annie down at North Cobalt, I thinks no more about it.

“Number 9’s due about 1.30 and I’m out on the platform when she pulls in. There’s a raft of express and I’m busy right up to the second toot. When I has time to look about me, the platform’s empty except for one gal who’s standing helpless like and looking kind of lost. I goes up to her and asks if there’s anything I can do for her.

“ ‘I’m looking for Mr. Wilson,’ she says, and I see her lips is quivering. She’s a slip of a gal, with a pretty face and a voice that gets right in among you.

“ ‘I’m a stranger here myself, Miss,’ I says. ‘It’s my first morning in the place and I don’t know Mr. Wilson but we’ll see what we can do to find him for you.’

“ ‘Perhaps you know Mr. Mullins then,’ she says.

“ ‘Mullins, is it,’ I says, and I know I’m for it. ‘Of course I knows him. He’s the Agent here when he’s for working.’

“ ‘If I could see him, he would explain,’ she says, ‘for I have a telegram from him.’

“With that I ask her to come into the office and she brings out the telegram. ‘Don’t make jump Niagara Falls. Ricky desperate,’ is what it says. It’s signed Mullins right enough but it don’t make sense to me. So we gets our heads together, in a manner of speaking, and the story comes out something like this.

“The gal’s Rita Cholmondeley all right and she’s a kind of a actress. At least I gathers she dusts the furniture and opens the door and all like that. It appears she learns it in college and keeps right on with a regular company of actors. Ricky, that’s what she calls Wilson, is in college too and he’s just got out. They’re in love, you can see that, but they’re as poor as Hogan’s pig and Ricky’s proud and wants the best for the little woman. So they agrees that Ricky comes north to seek his fortune and Rita takes the job with the actors. When Mullins’ telegram comes, she can’t make it out but she figgers they can get someone else to dust the furniture and she takes the first train north. It’s enough for her that Ricky’s desperate even if she don’t understand the part about jumping Niagara Falls.

“ ‘You wasn’t going to jump over them?’ I says.

“ ‘Heavens, no,’ she says with a kind of squeak. ‘We were going to give the show there.’

“Then I sees that Mullins has been impulsive again but we still don’t know about the letter nor where he gets the information. Anyway we gets a bite to eat and I brings the gal back to the station while we figgers out the next move. It’s along in the middle of the afternoon and we’ve got nowhere when I sees a young feller hot footing it down the trail to the station. He barges in and looks through the ticket window. Then they both lets out a yell and the young feller scrambles through the door into the office. They goes into a clinch and it’s ‘Ricky’ and ‘Rita’ and ‘dearest’ and such so that I sees there’s no place for me in the office. After a while they quiets down and I goes on back in. They’re sitting hand-in-hand just looking at each other kind of dreamy and I sees there’s an organizing job for me. The telegram’s brought out and Rick knows no more about it than the rest of us. However, it appears that Rick and his partner has staked a couple of claims the second day they’re in and Rick has a bag of samples. Free gold, he says, and some rocks he says is good. He comes out to record it down at Haileybury while his partner stands pat because of claim jumpers which has been known in them parts. The long and the short of it is they’re rich to hear Rick tell it and Rita’s there, so what are they waiting for.

“All this takes time, of course, what with one thing and another, and it’s mebbe seven o’clock when I looks out the window and sees Mike straggling down the trail. He’s coming slow with a sag to his shoulders and he’s not happy, you can easy tell that. I tell the lovebirds who he is and they’re ready for him. As he comes in, with the blood of the blackfly bites dried on his face, Rita jumps up and grabs him round the neck and kisses him.

“ ‘You wonderful man,’ she says, ‘You did it all for us, and everything’s all right and we’re going to be married.’

“Mike looks kind of funny for a minute but Rick is pumping his hand and Rita’s hanging on to him. I see Mike kind of straighten up and the devil puts a spark of light into his eyes.

“ ‘Think nothing of it,’ says Mike. ‘I was bound to save you and I did. Sure, I’d do it again, blackflies and all, bad cess to them, for a colleen as pretty as yourself.’

“As for me, I says nothing then nor since and Rick and Rita plays the cards as they was dealt.

“Next day the Consolidated minister ties them up as tight as ham and eggs and Mike gives the bride away with every blackfly bite standing out on him like candles on a Christmas tree. Every year since on the seventeenth of June me and Mike hears from them. They’re doing fine and Michael Wilson is a big hunk of a man hisself and married years ago.”

It was the day before Christmas when Mike came in to see me. He was muffled up in an overcoat and two sweaters but his cold was practically gone. I asked him about Rick and Rita and he said:

“You know I was all wrong that time. The gal’s name wasn’t Chol-mon-del-ey at all. It was Chumley all the time and t’other was just her stage name. I never knew until I stand up with her before the Minister.”

The exploits of our past, seen through the mist of years, glow with increasing lustre. All our yesterdays are bright with valorous achievements. The faint arthritic twinge, the slowing reflex are of little moment when the tenuous arms of memory probe the glamour of the fragrant years. Some such nostalgic influences stirred Mike to reminiscence.

“The spring always puts the itch in the feet of me. ’Tis when I’d like to be out looking for new things. If there was mountains to be climbed now or new seas to sail on, it would be a fine thing. ’Tis in a manner of speaking, you understand, for I’ve climbed no mountains but ’tis a grand thing to be young and to know your own strength. ’Tis a great country we have with the good air of it blowing up your lungs like bellows. Boy and man, I’ve knowed it for forty years. ’Twas bush mostly when I come, with the grand logs plunging down the rivers in the springtime. Cobalt was a roaring town and the boxcars of silver going south with every train. One man was as good as another and they was all good men.

“There was bush fires that wiped the country clean and took the poor people with them. Then there was ploughing of the good earth and the fine farms and the herds of cattle. I’ve seen it all grow up and the gold towns round the mines and the paper mills with the fine towns and gardens. ’Tis a grand thing to be a part of. Me and John went through it all together and it’s a young man I’d like to be this day to see what another fifty years will do to it.

“ ’Twas ought seven, I come to see the sidewalks made of silver up at Cobalt. Green I was them days but I’ve learned since and there’s not much of the country I haven’t known along the old T.N.O. I’ve even been to Moosonee and I’ll tell you about that.

“ ’Twas in ’37. August it was and John and me gets our holidays together. We’d been talking about this Jameses Bay and how the Eskimos and polar bears floats round there on chunks of ice. Well, one thing leads to another and we makes up our minds to go and see it. Our women is agreeable. Annie says, ‘ ’Twill do you good, Mike, to see them pigging it round in their snow houses. You’ll value your own when you get back.’

“Well, we starts to get organized. We plans to take a camping outfit and get a canoe at Moosonee. Young Harve Fisher, that’s always mucking about in the bush, lends us a tent and Rod McLeod, the devil, gets us two fur parkas against the cold. We collects pots and pans and dishes, blankets and axes and everything a man could need. And food, we sure wasn’t going to starve. A slab of bacon, beans and rice, flour and tea and coffee and a raft of stuff the women folks puts in. We must have lugged two hundred and fifty pounds up to the station when we boarded 49. ’Twas the middle of August and a hot night but we was a grand sight. If you was to look up the Nugget of them days, you’ld see our picture as we boards the train. We wore our socks like lumberjacks over our pants and we had the parkas on because there was no room for them in our packs. Hot we was and no mistake but swaggering a bit because of the adventure of it.

“Well, we gets to Cochrane in the morning and by this time we’re stripped down to our undershirts. We boards the Polar Bear and keeps a sharp lookout for the first ice and snow. We never sees none right to Moosonee but there’s lots else. The grand rivers we cross on the high bridges, the white water in Sextant Rapids and the Moose River, a mile wide at the Crossing. There was Indians at every stop, mostly Scotch Indians if the tartans meant anything, with Indian babies in their baskets.

“Anyway, about dark we pulls into Moosonee and we sticks our tent up and beds down for the night. Next morning, before anyone is stirring, we packs our stuff the half-mile to the river. Here we find a Indian and dickers with him for a canoe. What we wants is to get away fast for we’ve had enough of photographs. We knows where we’re going and we don’t need no advice.

“Everything settled with the Indian, we piles our stuff into the canoe and heads downstream. The current’s running nice and fast and we aims to make short work of it to a likely place for breakfast, for we hadn’t ate at Moosonee. We paddles a bit but mostly lets her run with the current, which we judge is four miles a hour.

“It ain’t what we expects. Devil a bit of ice can we see. There’s not a cloud in the sky and the sun’s beating down hot and strong but prettier country you never see. The river looks to be two miles wide with islands all along the way. The fine trees are growing on them and the water’s clear so that you can see the gravel on the bottom. The air has a tang to it that gets us thinking about breakfast. So we pulls into a gravelly island and beaches the canoe well up the shore. Then we makes our fire and has our breakfast. Like two kids we was with the freedom of it and all. We gets things cleaned up and has a swim and comes ashore and snoozes for an hour or two. We has ten days and so there’s no hurry to see the Bay. ‘Take it easy,’ says John, ‘snow and ice is all right but this sun suits me fine,’ and I agrees.

“When we goes to the canoe, there it is with its stern in the water. ‘Sure, we carried it a length inshore,’ I says. ‘What’s happening?’

“ ‘Must have been rain upstream,’ says John. ‘The river’s rising.’

“ ‘Could be,’ I says and we thinks no more about it.

“ ‘Shove her in the water,’ says John. ‘I feels like fishing.’

“John, you’ll remember, is a fisherman, though I don’t hold with it myself as I tells you before. My dislike of the sport don’t cover eating them so I says I’m agreeable. Right forninst the place where we has lunch is a crick and I paddles over to it. There’s a little bar at the mouth but we slides right over and as nice a crick as you would want to see opens up before us. It’s mebbe seventy feet wide and, by the time John has his pole fixed, we’re right into it. He hasn’t made more than three or four casts when he gets a strike.

“ ‘Trout as sure as you’re a foot high,’ says John and, after a fight with the creature, he brings it into the canoe. A two pound speckled trout with the red spots grand to see. Going along nice and easy, he catches a couple more and then two or three he puts back, for John is no fish-hog, you’ll understand. We has enough for that time so we paddles up, it may be half a mile or so, to where a rapids breaks fast around an Island. We has a general good time exploring like a couple of kids. ’Twas as good as playing hookey.

“By this time, it’s mebbe four o’clock and we heads back to our island to make camp. ’Tis a strange thing but the bar’s sticking out of the water down by the mouth. ‘Sure, the stream’s falling fast,’ says John as we eases through a shallow spot. Anyway, we carries the canoe well ashore, for we’re not trusting them quick floods too much. We gets the tent up with a bed of spruce and balsam boughs and makes our fire down on a rock by the shore.

“ ‘’Tis hungry, I am,’ says John, ‘with nothing to eat since breakfast.’

“ ‘We’ll have the trout and bacon,’ I says, ‘and I’ll cook you a pot of rice and raisins,’ for I elects myself cook, for I figgers that’s easier than rustling firewood. So I hangs a pail with about a pound of rice into it to boil and gets the trout frizzling in the bacon fat. Oh, the grand smell of it with the wood smoke in the nose of you.

“Did you ever cook any rice, sir? ’Tis the most amazing stuff. The fish has just come to a nice brown, when I hears something plopping in the fire. The rice is coming up like a fountain. I takes it off of the fire with a stick and yells for John to bring a bucket. We catches near a pailful before it stops erupting. So much rice, I never see. Every time I puts it on the fire, up she comes a-whooping. Anyway, it makes grand eating with raisins and brown sugar. ’Tis near dark when we finishes and turns into our blankets. I mind we talks a bit about what we’ll see next day down at the Bay and we watches the Northern Lights a-dancing in the sky. Green and pink and silver they was, swooping and cavorting around. They was still at it when we falls asleep.

“Next morning, we’re up with the sun to make a day of it and gets our breakfast. There was rice, I minds. The river’s running hard as ever when we launches the canoe. ‘They let’s it out of the dam at Fraserdale,’ says John. ‘That’s the reason for it.’ Anyway, we paddles hard with the current fine to help us, for we knows we has only ten or twelve miles to go. The river’s changing all the time. There’s narrow channels with the current rippling and tugging at the canoe. Then comes stretches that look like lakes, all wide and lazy like. We goes along for two hours mebbe, making good time, when what does we see but a great river tumbling into the Moose over a rapids. Devil a sight of the Bay is there anywhere about.