* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a https://www.fadedpage.com administrator before proceeding. Thousands more FREE eBooks are available at https://www.fadedpage.com.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Biggles Hits The Trail

Date of first publication: 1941

Author: Capt. W. E. (William Earl) Johns (1893-1968)

Date first posted: Dec. 3, 2020

Date last updated: Dec. 20, 2020

Faded Page eBook #20201206

This eBook was produced by: Al Haines, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

CAPTAIN W. E. JOHNS

Biggles

Hits The Trail

OTHER BOOKS BY CAPTAIN W. E. JOHNS

BIGGLES FLIES NORTH

BIGGLES FLIES SOUTH

NO REST FOR BIGGLES

© W. E. JOHNS 1941

Biggles Hits the Trail was first published in the U.K. in 1941 by Oxford University Press. This edition was first published in 1962, and was reprinted in 1969, by May Fair Books Ltd, 14 St. James’s Place, London, S.W.1, and was printed in Great Britain by Love & Malcomson Ltd, Brighton Road, Redhill, Surrey, England.

Major James Bigglesworth, better known to his friends as Biggles, pushed his coffee cup aside, rapped on the table sharply with the handle of a spoon, rose to his feet, and looked from one to the other of his two guests with an expression of quiet amusement.

‘What are you going to do?’ inquired Algy Lacey, his comrade of many adventures, who sat on his left.

‘I’m going to make a speech,’ replied Biggles seriously. ‘I’ve never made one before, and I don’t expect I shall ever make another, but I think an occasion like this demands one. It is the first time——’

‘Absolutely, old lad,’ declared Algy, ‘but don’t be too long about it because I want to switch on the wireless. Menovitch is playing the Grieg Concerto at nine o’clock, and I want to hear it.’

Biggles frowned. ‘Whose dinner-party is this, anyway; whose room is it, and who’s making the speech, me or you?’ he inquired, coldly.

‘Go ahead.’

‘Thank you.’ Biggles cleared his throat. ‘Gentlemen——’

‘Ha! Did you hear that, Ginger?’ interrupted Algy, glancing across the table at a sandy-haired, freckle-faced youth. ‘He called us gentlemen——’

‘Will you shut up?’ snapped Biggles. ‘You never could behave like a gentleman, even in Mess. I only called you one as a matter of form; there’s no other way to start a speech.’

‘How about “gallant comrades”?’

‘Where are they?’

Algy looked pained. ‘Did you hear that, Ginger?’ he complained. ‘He’s casting nasturtiums——’

‘I’ll cast the salad bowl if you don’t shut up,’ snarled Biggles.

‘Sorry, old lad, it shan’t happen again.’

‘Gentlemen,’ resumed Biggles, with a withering glance at Algy, ‘I feel I should fail in my duty if I allowed this auspicious occasion to pass without a few words on the reason for this festive gathering tonight. As you are aware, we sent our guest of honour—who, as we are all friends, I will call by his apt if undignified pseudonym, Ginger—to Brooklands Aerodrome for a course of instruction in the art of flying, and its allied subject, ground engineering. Last week he was tested for his Pilot’s ‘A’ Licence, and yesterday notification of its award was made by the Royal Aero Club.’

‘Hear, hear!—hear, hear!’ exclaimed Algy enthusiastically.

‘All right, once was enough; no one asked you to sing a song, did they?’ frowned Biggles. ‘But to continue,’ he went on, taking a letter from his pocket. ‘I have here a letter from Pim Carthorne—I mean Captain Carthorne—his instructor, and in it he speaks highly of the progress made by his pupil. I do not propose to read it, because, while praise is good when taken in small doses, too much is apt to cause a swollen head. Let it suffice that Pim—Captain Carthorne—has been good enough to say that his pupil on this occasion shows more than usual ability in the handling of an aircraft, and should turn out to be a first-class pilot. Further, perhaps on account of his zeal, his knowledge of care and maintenance and aero engines is equal to that of many qualified ground engineers. He concludes, however, by deploring his promiscuous employment of American slang, which he claims is likely to affect adversely any self-respecting British aeroplane.’

Biggles folded the note and put it in his pocket. ‘Before I offer you my heartiest congratulations, Ginger,’ he went on earnestly, turning his keen eyes on the blushing youngster who sat on his right, ‘I am going to give you a word or two of advice—from an old-timer to a beginner, so to speak. It is this. Do not set too great a store on such knowledge as you have acquired, which after all, at present, is very little. You can fly, and have flown, an aeroplane, which means that you are master of a machine. But never, never let your confidence outrun your discretion, for if you do you will be lucky if you live long enough to regret it. Never forget the fact that you are only allowed to visit the world above your earth-tied fellows on sufferance. By your art—call it a trick if you like—you have learned to overcome a great natural force—gravity; and you cannot flout Nature with impunity. Treat Nature with respect and she will tolerate you, even encourage you; but treat her with contempt, and your days are numbered. You know a little now, and when you have six thousand hours logged, as I have, you will know more; but that isn’t everything, and you will still be only a puny mortal at the best. Never forget that.

‘And finally, bear in mind that you owe something to those pioneers who made this great thing possible. Honour the traditions of courage, modesty, and faithfulness in little things that they have set down as a guide for you to follow, and you will always be welcome at any place where airmen meet, for they will know you for what you are, even though they do not speak of it. Fail in those qualities, and you will be less than a pariah slinking around the tarmac for such crumbs of good-fellowship as he can find. And now I am going to ask Algy to stand up and join me in drinking the health of the fledgling who we both hope will be a credit to his machine, to us, and aviation as a whole, in the old R.F.C. toast. Soft landings!’

‘And no dud engines,’ murmured Algy.

‘Ginger!’

‘Ginger!’

Biggles sat down and reached for a cigarette. ‘All right, Algy, you can turn the wireless on now,’ he said. ‘We’ll call on Ginger to reply to the toast presently.’

Algy glanced at the clock and hurried to the instrument. ‘It’s a bit late, I’m afraid,’ he said quickly, as he switched on and waited for the valves to warm up.

A voice, faint at first, but rapidly increasing in volume was speaking . . . ‘few minutes late. Now before we begin here is an S.O.S.’

‘Oh, confound these S.O.S.s,’ grumbled Algy. ‘I’ve never heard of any one answering. . . .’ The words died away on his lips as the voice of the announcer continued.

‘Will Major James Bigglesworth—B-I-double G-L-E-S-W-O-R-T-H, Major James Bigglesworth, last heard of at Brooklands Aerodrome, go at once to Brendenhall Manor, Buckinghamshire, where his uncle, Professor Richard Bigglesworth, is dangerously ill.’

Algy stared at the instrument. ‘Well, I’m——’

‘Shut up—he hasn’t finished,’ snapped Biggles.

‘I am requested to add,’ continued the voice, ‘that if Major Bigglesworth receives this message, and goes to Brendenhall, he is advised to exercise the same caution as on the occasion of his last visit—whatever that may mean. . . . And now we are going over to the Albert Hall for——’

Click! Algy snapped back the switch, and as the voice ended abruptly, swung round on his heel to face his partner. ‘Well,’ he said crisply, ‘what do you make of that?’

Biggles shook his head; a worried frown creased his forehead. ‘Dickpa’s ill, obviously, but there’s more to it than that. I don’t like the sound of that last sentence, and that’s a fact. What was it? “Exercise the same caution as on the occasion of his last visit.” That’s a fair warning, Algy. You remember our last visit—eh?’

‘I’m not likely to forget it.’

‘Why, what happened?’ put in Ginger eagerly.

‘I can’t stop to tell you about it now,’ said Biggles shortly. ‘Dickpa—he’s my uncle—I’ve always called him Dickpa since I was a kid—was having a desperate time with a gang of American desperadoes on account of a secret he held. That message means that he’s in trouble; it can’t mean anything else.’

‘But how did he get word to the B.B.C., if he’s ill? Who told the B.B.C. about it?’

‘I don’t know, but I’ll soon find out.’ Biggles crossed swiftly to the telephone, ran through the pages of the directory until he found the number, and then dialled it. ‘Hello! Hello! Is that the B.B.C.? This is Major Bigglesworth speaking. I’ve just received your S.O.S. Can you oblige me by telling me how you received that information? . . . Thank you.’ He glanced at Algy. They’re putting me through to another department,’ he explained. ‘Yes—Major Bigglesworth speaking,’ he went on quickly, turning again to the instrument. ‘Yes . . . sorry to trouble you, but it may be very serious . . . what’s that? . . . Where? . . . Brendenhall Station. . . . I see. . . . Thanks very much. . . . Thank you. . . . Goodbye.’ He replaced the receiver and turned to the others who were watching him expectantly. ‘The message was sent in by Lord Maltenham,’ he said, curtly.

‘Who the dickens is Lord——?’

‘I have no idea. Not the remotest. It doesn’t really matter, though. What does matter is that he has left a note for us with the station-master at Brendenhall Station; we are to call for it and read it before going on to the house.’

‘But how the dickens did he know that you would ring up the B.B.C.?’ inquired Algy.

‘He didn’t know it, but I expect he hoped I would. After all, it was a pretty obvious thing to do. The B.B.C. say that they were asked not to broadcast the message about the note at the station, but if I rang up they were to tell me. This fellow Maltenham’s no fool apparently. It sounds to me as if there’s some dirty work going on. Come on; let’s be getting along.’

‘You mean to Brendenhall?’

‘Of course; where else? Sorry we can’t finish the party. Ginger, but this is urgent. We’ll finish it another day. You haven’t met Dickpa, of course. He’s a grand chap—explorer. You may remember my telling you about our treasure hunt in the Matto Grosso, in South America. Well, he’s the chap we took—here, where are you off to?’

‘To get my hat and coat,’ replied Ginger, instantly. His face was flushed with excitement and his eyes sparkled. ‘I’m coming with you, aren’t I?’ he asked anxiously.

Biggles hesitated. ‘Yes, I suppose you can come,’ he muttered slowly. ‘Be careful what you’re up to, though; I’ve got a feeling there’s trouble ahead.’

‘That’s what I thought, otherwise I shouldn’t be so anxious to come,’ returned Ginger, coolly.

‘I thought that was what you were thinking,’ declared Biggles. ‘All right. What’s the time? Nine-thirty. My car’s in the garage round the corner. It’s a straight run down to Brendenhall, and provided it keeps fine we should do it in an hour. Just a minute.’ He crossed to the desk, took out a service Webley revolver, loaded it from a packet of cartridges that lay beside it, and dropped it into his pocket. ‘It’s always as well to be on the safe side,’ he observed, carelessly. ‘Come on, then; let’s get away.’

Exactly fifty-five minutes later Biggles’s Bentley pulled up with a groaning of brakes outside the small country station of Brendenhall. Two oil lamps cast a dim, yellow radiance on the platform, and a single lighted window revealed the booking-office.

‘Well, here we are,’ he observed, as he opened the door and stepped out. ‘You might as well come in with me and we’ll see what Maltenham has to say in his note.’ He led the way to the booking-office pigeon-hole. ‘I’m Major Bigglesworth,’ he told the clerk behind the grille. ‘You have a message for me, I believe?’

‘Here you are,’ replied the man immediately. ‘A gentleman left it about an hour and a half ago; he said you might be calling, but he couldn’t stop.’ He passed over the envelope.

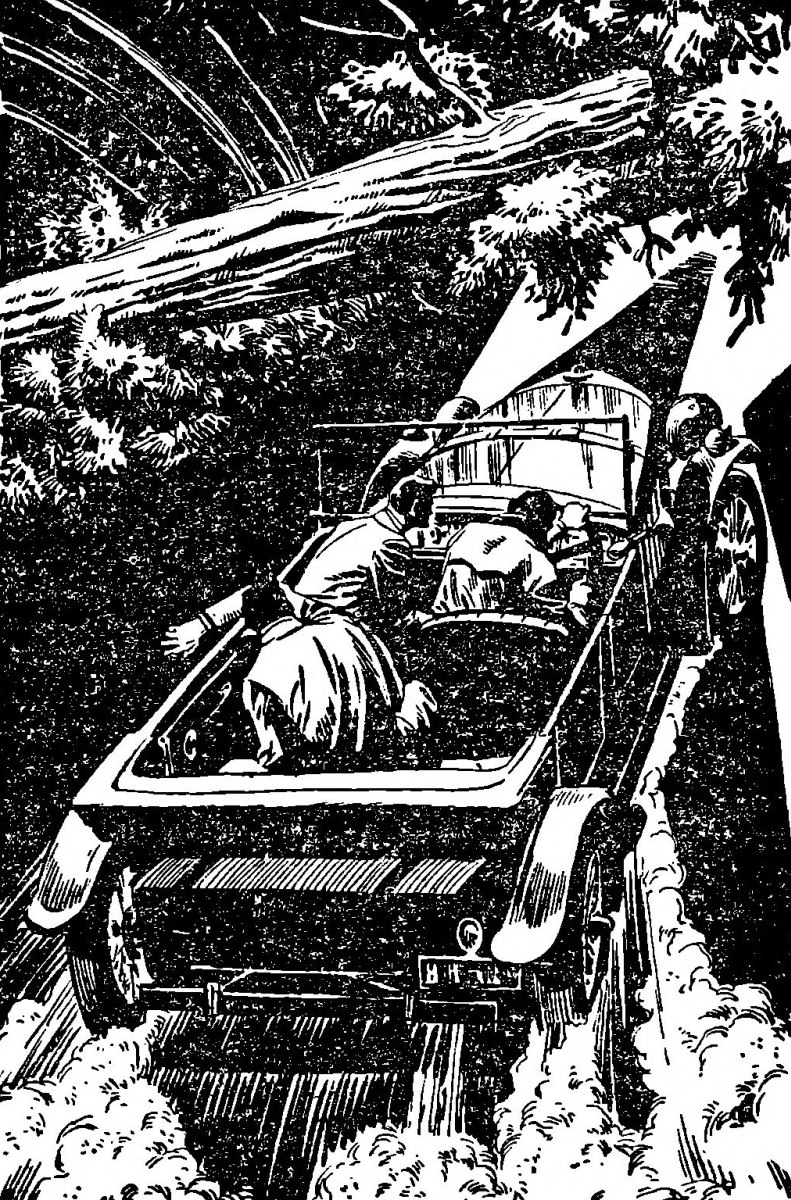

The car swerved to avoid the tree across the road

‘Thanks.’ Biggles tore it open impatiently as he walked quickly to one of the outside lamps. ‘I’ll read it aloud,’ he said. ‘Dear Bigglesworth, Get up to the Hall as quickly as you can, but watch your step; there are some funny people about in the park. If you are driving, go slow and keep your eyes open. If you see a blue light, go for dear life. Your uncle has been hurt, so I must get back to him. He’s alone, and I’m afraid. I’ll tell you the rest when I see you. For God’s sake be careful. Yours, Maltenham.’

There was a moment’s silence when Biggles finished reading.

‘Not so good, eh?’ murmured Algy softly. ‘I suppose there isn’t any chance of this lad Maltenham being off his rocker?’

‘That letter sounds sane enough to me,’ replied Biggles grimly, ‘but it’s thundering mysterious,’ he added. ‘I wonder what this blue light is that he talks about—but there, it’s no use guessing. Let’s go. Algy, you take my gun; if any skunk takes a crack at us let him have it, but shoot low. We don’t want any inquests if we can possibly prevent it. Ginger, you keep your eyes skinned, but keep your head down if there’s any trouble.’

‘O.K., chief,’ agreed Ginger. ‘How far’s this Hall place, anyway?’

‘A couple o’ miles or so. The last mile is up a private drive,’ answered Biggles, as the car shot forward into the night. He ran on his side-lights only until he reached the drive, but as he turned slowly into the narrow entrance he flicked on the powerful headlights. They blazed like twin searchlights through a long avenue of horse-chestnuts, backed by heavy pinewoods, but there was not a sign of life as far as they could see, although a bend in the road a quarter of a mile ahead hid the house from view.

‘Watch out,’ ordered Biggles tersely.

‘See anything?’ asked Algy quickly.

‘No, but I expected to. I’ve never turned into this drive before at night without seeing one or two rabbits scuttle across it. There’s somebody about, I fancy.’ Biggles slowed down to a steady twenty miles an hour, but as nothing occurred his apprehension wore off and he increased the speed to thirty-five. He reached the corner, and with the old Elizabethan house now in view, he was about to put his foot down on the accelerator when a yell of warning broke from Ginger’s lips.

‘Look out—the tree!’ he shouted, and with his hands over his face, flung himself on the floor of the car.

Biggles saw it at the same moment. A great elm that flanked the drive fifty yards ahead was moving; with a slowness that was awful in its deliberation, it was falling straight across the road. There was no time to think, and he acted instinctively with the same speed that had more than once saved his life in the air. His heel crushed down the foot-brake while he grabbed the hand-brake and flung his weight on it. Instantly all four wheels locked. Fortunately the road was dry, but even so the heavy car skidded wildly as the wheels bit into the yielding gravel with a grinding scream that was lost in the mighty roar of sound as the huge tree struck the ground.

From first to last the whole thing was a matter of perhaps three seconds. It was touch and go. Carried on by its own volition, the big car swung sickeningly, and it was only due to the fact that the left side wheels went off the road and sank into the turf, dragging the car round to the left, that the party escaped annihilation. As it was, there was a splintering crash as a branch struck the bonnet and sheered through the windscreen in a cloud of flying splinters. The lights went out. Then all was silent.

Biggles was on the ground first, crouching forward, eyes probing the darkness ahead, behind, and aside. ‘Give me that gun, Algy—quick,’ he snapped. ‘Either of you hurt?’

‘We’re both all right,’ replied Algy in a tense whisper.

‘Good—stand fast.’

Silence, a brooding uncanny silence, fell, and Biggles slowly straightened his back. ‘Could it have been a fluke—an accident?’ he muttered.

‘I don’t know,’ replied Algy. ‘What’s this coming—look!’

There was no need to point. From a spot some little distance ahead a cold blue radiance appeared. There was no central point to the light, which appeared to have no beginning and no end; rather was it like a beam of phosphorescent mist creeping slowly through the night air in their direction. For a moment or two they watched it, fascinated by the phenomenon, and then Biggles sprang back in alarm. ‘It’s blue,’ he gasped. ‘It’s the blue light. Run for it—this way,’ He dashed off into the trees with the others at his heels.

At the first sound of their footsteps the light had increased in intensity and probed feelingly towards them. Biggles stopped suddenly and swung round with an angry snarl. ‘I’m not going to bolt from a confounded light,’ he grated, and jerking up the revolver, sent three shots crashing in quick succession in the direction of the beam. As the third spurt of flame leapt from the muzzle the light jerked suddenly and came to rest on his upraised arm, which remained motionless, picked out in lines of blue fire.

The others heard him catch his breath spasmodically, saw his fingers jerk open convulsively and the revolver fall to the ground. Then he sprang back and dashed past them. ‘Run,’ he cried in a curious high-pitched voice. ‘Run for your lives, and don’t stop.’

Side by side, stumbling and tripping over unseen obstacles, striking their faces on low-hanging branches, they tore through the wood. ‘This way—bear round to the right—let’s try and make the house,’ panted Biggles, as they raced on.

For what must have been half a mile they ran as they had never run before, and then, after a glance behind, they began to slow down.

‘What the——’ began Algy.

‘Don’t talk—keep going,’ snapped Biggles, and it struck Algy that he had never seen him so shaken. ‘This way,’ he went on. ‘I used to birds-nest in this park when I was a kid, so I know every inch of it. There should be a footpath about here—yes, here it is. Good! This will take us up by the back of the gardener’s cottage to the house. I think we’ve given them—or it—the slip, but keep your eyes open.’

‘What about the car?’ asked Algy anxiously.

‘I can’t help that. I wouldn’t go back to that place for fifty cars—not now, anyway. Quietly now; if these blue-light merchants have decided that we’ve got away they might make straight for the house to prevent us from getting in; they must know that’s where we were bound for.’

‘I suppose we shall be able to get in?’

‘I’m hoping Malty—this Lord chap—will be there to open the door for us. Here we are; quietly does it.’ Biggles stopped and peered ahead intently, listening, with every nerve taut.

Immediately in front of them, at a distance of thirty or forty yards, loomed the black mass of the old house. Not a light showed anywhere. The track they were on diverged a few paces ahead, one path turning to the left through a thicket of sombre, evergreen shrubs, and the other joining the weed-covered main drive where it swung round in a wide circle before the front door.

‘Let’s get a move on,’ muttered Algy irritably. ‘I’m getting the willies standing here. This is the sort of place where anything might happen—anything.’

‘You’ve sure said a mouthful,’ agreed Ginger. ‘Come on Biggles, let’s go.’

‘Right,’ snapped Biggles. ‘Run for it.’ Suiting the action to the word, he broke cover, and with the others close behind, sprinted for the front door. Reaching it, he twisted the old wrought-iron handle and put his shoulder against the massive oak portal, but it did not budge an inch. Casting all attempts at secrecy to the winds, he beat upon the panels with his fists. ‘Maltenham! Maltenham!’ he yelled. ‘It’s me—Bigglesworth. Open the door.’

There was no reply. Silence, utter and complete, hung over the place like a pall, and he felt a thrill of apprehension run through him. Frantically he kicked the lower panel with the toe of his boot. ‘Maltenham—Dickpa, open the door!’ he shouted again.

The ringing echo of his voice floated back eerily from the woods, but there was still no sound from the house. He moistened his lips and turned to the others. ‘I don’t like this,’ he muttered, turning again to peer into the gloom to left and right. ‘Either they’re not here or else——’ He did not finish the sentence.

‘Well, let’s break in, for heaven’s sake,’ exclaimed Algy. ‘Either my nerves are not what they used to be, or else there’s a blight on the place; I feel that if a mouse squeaked I should scream.’

‘For goodness’ sake, pull yourself together,’ Biggles told him angrily. ‘It’s no use trying these lower windows: they’re barred, as you know. We’d better try that side pantry window—the one—My heavens, what’s that!’

Shrill and clear through the still night air from somewhere in the wooded heart of the park came the long-drawn scream of a man in mortal fear. It rose to a high, palpitating falsetto and then ended abruptly.

It was so horrible that for a moment the three airmen remained rooted to the ground; Ginger was unashamedly clutching Algy’s arm, while Biggles, his face deathly pale in the wan star-light, peered into the darkness in the direction of the sound. For an instant or two he hesitated, and then threw up his hands in a helpless gesture. ‘Sounds like murder being done,’ he muttered harshly, ‘but we can’t do anything in the dark, and unarmed. Pray heaven it isn’t Dickpa. Come on, let’s get inside. Keep close.’ He led the way round to the side of the house and halted under a small square window. ‘I’d better go in because I know the way,’ he went on. ‘When I’m inside you slip round to the front door and I’ll let you in. Give me a leg up, Algy.’

He took out a box of matches, held them between his teeth, seized the window-sill in his hands and vaulted up. There was a tinkle of falling glass as he shoved his elbow through the pane. The window swung open and his lithe body disappeared through the small aperture. For a moment his face showed dully white in the black opening. ‘O.K.,’ he breathed. ‘Get round to the front door.’

He struck a match and hurried down the corridor that gave access to the breakfast room, from which a door opened directly into the huge hall. On his way he picked up a heavy silver statuette from a small table, and holding it by the head, swung it as a weapon; but he reached the front door without incident and threw back the chains and bolts.

Algy and Ginger literally leapt inside. ‘Get a light on the scene, for the love of Mike,’ implored Algy.

Biggles crossed swiftly to a large oil lamp that stood on the centre table, lighted it, and looked around swiftly. ‘My gosh! there’s been trouble here all right. Look at all this,’ he said. ‘The place looks like an arsenal.’

Right across the table lay an enormous double-barrelled elephant gun. Beside it was a hammerless twelve-bore, a .410 collector’s gun, and a small rifle. Leaning against the window that overlooked the drive was an Express rifle. Several broken boxes of cartridges were scattered about. A number of spears and cutlasses that normally decorated the walls had been taken down and were standing or lying in handy positions.

Biggles picked up the elephant gun and snapped open the breach. ‘Loaded,’ he said laconically, as he closed it again and replaced it on the table. ‘Where’s Dickpa? That’s the first and most important matter to attend to. Lock that door, Algy, and we’ll go upstairs; I know where his room—hark!’ The last word was a high note of warning. He snatched up the elephant gun and made a dash for the door. ‘Sounds like somebody coming,’ he added tersely.

‘And in a hurry,’ put in Algy, picking up the twelve-bore.

Footsteps were coming down the drive; they were those of a man running in stark terror, and if confirmation of this were needed, the loud gasping sobs for breath of the runner supplied it.

‘Look out—the light!’ cried Ginger.

‘You stand by to guard the door,’ yelled Biggles, and dashed into the open in the direction of the approaching footsteps. Dimly through the gloom he could just make out the dark form of a man who swayed from side to side as he raced towards the house. Behind him, silent, yet dreadful in its ghostly deliberation, danced a stream of blue mist. Biggles brought the gun to his shoulder. ‘Halt! who goes there?’ he roared.

The runner threw up his hands. ‘Shoot! Shoot!’ he screamed. ‘I’m——’ He stumbled and pitched face downwards on the gravelled drive.

Biggles’s lips parted in a mirthless smile as his fingers tightened over the triggers. He did not take aim for the simple reason that there was no mark to aim at except the uncertain light. Two long streaks of orange flame leapt from the twin barrels as the gun thundered out its heavy charges in a quick left and right. The blue light disappeared instantly. Bang! Bang! Algy’s twelve-bore blazed into the darkness, the spraying shot rattling on the bushes like hail. Crack! A flash came from the doorway, and a bullet ricocheted up from the road with a shrill whe-e-e.

‘Careful with that rifle, Ginger,’ shouted Biggles. ‘Come on, Algy—take his feet.’ He bent over the fallen man and seized him by the collar. Half dragging and half carrying, they managed to get the prostrate form into the hall, where they dropped him on to the hearthrug.

‘Shut that door, Ginger, bolt it and re-load the guns,’ ordered Biggles. ‘Algy, pass me that decanter off the sideboard. I believe this is Maltenham, and he looks in a bad way.’

Algy dashed to the sideboard and returned to where Biggles was removing the unconscious man’s collar. ‘That’s the idea,’ muttered Biggles, as they managed to get some of the liquid through his lips. ‘Not too much—we don’t want to drown him. Hello, what now?’ They both sprang to their feet as a new sound reached them. Standing at the foot of the stairs, hanging on to the banister, was a white-robed figure that held an automatic unsteadily in its right hand.

‘Dickpa!’ Biggles’s joyful shout eased the tension. ‘Be careful with the gun—it’s me, Biggles,’ he added quickly.

‘Thank God you’ve come,’ whispered the Professor fervently. ‘Great heavens! what’s happened? Don’t tell me they’ve got poor Maltenham!’

‘So it is Maltenham.’

‘Yes. Poor fellow, is he hurt?’

‘I don’t think so. It’s only shock and exhaustion I fancy. They were after him, but we managed to get him inside just in time. But what’s the matter; you look ill?’

‘I am. I shouldn’t have got up really, but I heard the noise. How did you get in? I must have been in a dead sleep; neither Maltenham nor I have slept for days.’

‘Well, you get back to bed,’ Biggles told him. ‘We’ll bring Maltenham round, and then perhaps you’ll tell us the meaning of this unpleasant state of affairs.’ Biggles turned to Algy. ‘See Dickpa up to his room,’ he ordered. ‘And you, Ginger, watch the drive through that window and let me know if you see anything unusual.’

‘O.K.,’ replied Ginger obediently.

Half an hour later the Professor, propped up in bed, told his story while Biggles, from a box-seat in the window, kept a watchful eye on the front door. Algy and Ginger sat on guard by the other window, while Lord Maltenham, little the worse for his adventure, reclined in an armchair near the bed. He was a delicate-looking young man of not more than twenty-one or twenty-two years of age, with a high, intellectual forehead and rather sad, dreamy eyes. A long upper lip betrayed the thinker, rather than the man of action, and Biggles was wondering how his uncle had become associated with him when the Professor began to speak.

‘I suppose you must be wondering what is going on here,’ he observed. ‘And why I—or perhaps it would be more accurate to say we—should have to resort to the desperate expedient of sending for you by the radio.’

‘Yes, naturally I have wondered,’ replied Biggles readily. ‘I expected to find you desperately ill, but as far as one may judge, there doesn’t seem to be very much the matter with you, if I may say so.’

‘True. To be quite frank, there is little wrong with me at the moment except weakness, and nerve trouble brought on by the experiences I am about to relate. I am afraid Maltenham exaggerated my illness to the B.B.C. officials, but we wanted you here, and we didn’t know your address so there was nothing else for it. In any case, it is as well for you to know about the strange things that have happened, because if anything tragic occurred—well, neither Maltenham nor I is unknown to the world, and questions might be asked.’

‘I shouldn’t talk like that, Dickpa. Let us hope——’

‘Oh, quite—quite. I merely remarked—But let me tell the story, then you’ll understand what we are up against. Speaking from memory, it must be nearly two years since we last saw each other. You were anxious to go off on a flying trip, while I was equally anxious to pursue my studies in other directions, or, to be more precise, in the Far East, a locality that has always interested me intensely.

‘Well, I had booked my passage and made all the necessary arrangements when, two days before I was due to sail, I had a visitor. It was the son of my old friend, the Earl of Maltenham, and he was in great trouble.’ Dickpa threw a glance in the direction of the subject of his conversation. ‘May I tell them?’ he asked.

‘By all means,’ replied Maltenham, without hesitation.

‘Good,’ continued the Professor. ‘As I was saying, Roger—that’s Maltenham’s Christian name, by the way—came to see me. At that time he was a medical student. His father had recently died, leaving him a large sum of money, but that could not help him. To be quite frank, he had, like many medical men before him, discovered the deplorable properties of certain drugs to which he had access, and from casual curiosity he had rapidly acquired a taste which he was well aware would ultimately destroy him. Realizing his danger, he asked me to save him by taking him with me, where he knew he would be beyond the reach of temptation. In short, he suggested abandoning his medical career, which was not of real importance, and coming with me to China. Naturally, I agreed, and we went.

‘Six months later we were far in the heart of Western China, on the borders of Tibet. Few people realize the size of Tibet. To tell you it covers a million square miles would mean little, because the brain fails to grasp what that really means. You are airmen, so let me explain in your own way. The country is as long as from London to Constantinople, and as wide as from London to Gibraltar. Which means that you could get most of Europe into it quite comfortably. An area of roughly a quarter of that vast expanse of land is uninhabited—or is supposed to be. Europeans have barely touched upon the fringe of it, possibly because there is not a railway within four hundred miles of its frontiers, which in turn is no doubt due to the fact that it lies at an altitude of between thirteen thousand and sixteen thousand feet above sea-level. So much for Tibet. I merely mention this in order that you may better understand what is to follow.

‘Now while we were on the western frontier of China, which is also the eastern frontier of Tibet, we heard a curious native rumour of a mountain, known as the Mountain of Light, which according to report held some strange properties. For example, people who dwelt near it never suffered from any form of illness, and lived to a great age. At first we discountenanced these tales, but as they persisted, and no matter where we went the natives always pointed in the same direction, we were forced to conclude that there must be some foundation of truth in them. Having decided that, it will not surprise you to learn that we attempted to verify the story by personal experience. And that was the beginning of our troubles, for of all the unusual circumstances that thereafter attended us, one fact alone was clear, and that was that the mountain was guarded by powers against which we could do nothing.

‘It would take me too long to tell you now of all the dangers that beset us. But they were real, very real, and ultimately we fled, thinking that with our departure our perils would cease; but in that we were mistaken, sadly mistaken, as we were soon to learn. The fact that we were willing to depart evidently did not satisfy those who, for want of a better name, we will call the guardians of the mountain. No! The fact that we knew of the existence of the mountain was sufficient to jeopardize our lives, and I am convinced that we only escaped death by a merciful Providence, in the shape of a snowstorm which caused us to lose our way, and instead of trekking to China as we intended, we finally forced our way over the Himalayan passes and then through the jungle to India, or rather, Burma. Our presence in India was noted in the newspapers, and forthwith the persecution started afresh. Again, I cannot tell you of the many narrow escapes we had. On one occasion we were the innocent cause of two planters losing their lives. The rest-house was full, so we gave our rooms up to them because they were both very tired. In the morning they were both dead—without a mark on their bodies. The murders were a mystery to every one except us, for we knew that the fate that had overtaken them should have been ours.

‘And now I come to the most alarming incident of all, and one that may open your eyes to the mysterious forces that surrounded us, and still do surround us, if it comes to that. We were followed right across India, but when we finally sailed from Bombay on the Calamore Castle we thought, naturally, that our troubles were at an end. Again we were mistaken. Now I want you to listen to me very carefully, but kindly reserve your remarks until I have finished.

‘The first night out from Bombay, Roger and I were lying in our stateroom, trying to go to sleep. We had booked rather late, so we could only get a double-berthed cabin; not that it mattered. In fact, as it turned out it may have been a good thing. Roger was already half asleep and I was just dozing off when I saw the lid of my cabin trunk slowly opening. I may mention that it was still quite light in the cabin, because I am not a good sailor and I had deliberately left one light burning in case I had to get up. Now I am not nervous, and for some seconds I watched the trunk with a sort of detached curiosity, thinking perhaps it was a trick of the eyes, or an illusion caused by the movement of the boat. But when I saw that the lid was quite definitely opening I knew without doubt or question that somebody was inside it. Cabin trunks do not open themselves—at least, not those we are accustomed to in England.

‘As soon as I realized this I reached for the small automatic I had bought in India, which was in my jacket pocket, and then jabbed Roger in the back to wake him up. This movement was evidently seen by the fellow in the trunk, for the lid closed again quickly with a very definite click. I heard it, mark you, as well as saw it. I leapt out of bed with a shout and sprang on the lid of the box to keep it shut while Roger came to my assistance. Now it looked as if we were in for a fine old row, so to be on the safe side I told Roger to ring the bell while I remained on the box. A steward answered the summons, but I told him that as we had a potential murderer in the room he had better fetch an officer. He did. Still sitting on the box, I explained to both of them what had happened, and asked the officer to take the man in charge.

‘With that I got off the trunk and the officer invited the occupant to come out in no uncertain terms. There was no response, so he opened the lid and looked inside.’ Dickpa coughed and looked at his nephew apologetically. ‘Biggles,’ he said evenly, ‘believe me or believe me not when I tell you that the trunk was empty. By empty I mean that there was not a man in it. There were two other objects: a nasty-looking dagger and a small bottle made of very curious glass.’

Biggles nodded understandingly. ‘You had a nightmare, eh?’ he suggested.

‘I was prepared for you to say that,’ observed Dickpa. ‘No, I did not have a nightmare. I——’

‘But wait a minute,’ interrupted Biggles, ‘I don’t get the hang of this. You say the box was empty. Well, that’s that: why make a fuss about it?’

‘But I saw and heard it open and shut.’

Biggles shook his head. ‘I give it up,’ he confessed; ‘I’m no good at conundrums. Either there was some one in the box, or there wasn’t. You say there was no one in it. If that was so——’

‘Just a minute, let me finish,’ broke in Dickpa. ‘Naturally, I was flabbergasted, and felt a bit of a fool, particularly as the officer looked at me in a condescending way that said as clearly as words that he suspected I had been drinking. Then I happened to examine the cabin trunk and found that it was not my trunk at all. Mine had been pushed under the bunk, while Roger’s, which is one of the wardrobe sort, was standing on end against the wall with the door open. Neither of us had ever seen the third trunk before. Briefly, I told the officer that I would not be responsible for it, and moreover I would not have it in my room in any circumstances whatever. I helped him to rope the thing up, and then he took it away, both he and the steward grumbling at the weight of it.

‘We heard no more about it, and had pretty well forgotten about the whole affair by the time we reached England; but as we were about to leave the boat at Southampton we were sent for by the captain. I must tell you, however, that as the Calamore Castle steamed into Southampton Water she ran into a dense fog and collided with a Norwegian tramp that was going out. The Calamore Castle was damaged below the waterline, and was leaking badly, but not dangerously, when she docked. You may have read about it in the papers. The water got into the hold, so the luggage was pulled out and put on deck, where it was examined by the Customs people before being released. When they came to the trunk that had been in my room no one claimed it, so they cut the cords and opened it.’ Dickpa paused to let the words sink in.

‘Go on,’ said Biggles impatiently. ‘What did they find in it? A cage of white mice?’

‘No; they found the body of a Chinese coolie,’ replied Dickpa steadily.

‘Dead?’

‘Of course. The trunk had been submerged and the fellow had evidently been drowned.’

‘But you said the trunk was empty.’

Dickpa shrugged his shoulders. ‘I did,’ he admitted.

‘But you can’t have it both ways,’ declared Biggles. ‘Either the box was empty or it had a man in it. It couldn’t be empty and have a coolie in it at the same time. What are you trying to tell me?’

‘I am not trying to tell you anything. I’ve merely stated what happened.’

‘A stowaway, perhaps—crawled into the trunk himself,’ suggested Biggles.

‘And then roped it up on the outside with my special knots? No, that won’t do.’

‘Are you asking me to believe that the trunk was corded up exactly as it had been when you last saw it?’

‘My knots had not been undone, I’ll swear to that. The ropes were the first thing I looked at.’

Biggles frowned. ‘Have you had a touch of fever lately, Dickpa?’ he inquired.

The Professor smiled. ‘I’ll forgive you for a natural, if rather pointed, remark,’ he said. ‘No, I haven’t had a touch of fever for some time.’

‘Then the fellow must have crawled through the keyhole,’ declared Biggles emphatically. ‘There was no other way in.’

‘You wouldn’t have thought so if you had seen him,’ returned Dickpa. ‘He was a hulking great brute. But let me go on; we won’t discuss possible solutions until you’ve heard the whole story.’

‘My goodness! You’re not going to tell me that you’ve any more stories like the last one, I hope.’

‘The next one is worse, if anything. At any rate, it’s just as inexplicable.’

‘Then for goodness’ sake fire away and let’s get it over,’ invited Biggles. ‘Nothing less than chloroform will make me sleep tonight, if you go on like this.’

‘I will pass on then to the time we reached home,’ continued Dickpa. ‘For some days nothing happened. Roger and I were kept busy looking after ourselves, keeping the place ship-shape and going over maps, with a view——’

‘To going back to China, eh?’ put in Biggles shrewdly.

‘Precisely.’

‘Is that why you didn’t engage any staff, servants?’

‘To be quite truthful, it is. There seemed to be no point in it. But don’t interrupt; let me get on with the story. The day before yesterday I was sitting here by the open window writing up my field notes. Roger had gone for a stroll, taking the forty-four rifle with him in order to try to get something for the pot. I suppose I must have dozed, but suddenly I was alert, conscious of danger; that’s the only way I can explain it. I could have sworn some one was in the room, but I could see nobody, so I sat down again, blaming myself for letting my nerves get into such a state. Then I saw something. It appeared to be a sort of blue light, a ray that began at an indefinable point near the door and shone across the room in my direction. At the same time I became aware of an unpleasant numbing sensation, and the room began to grow dark.

‘I fancy my symptoms were almost exactly those of what is commonly called a stroke, and to be quite candid I thought for a moment or two that that was what had happened to me. My eyes were failing fast, and there is no doubt whatever that I was succumbing to a form of paralysis. I tried to shout in the hope that Roger was somewhere close at hand, but I couldn’t utter a sound. I tried to lift my arms, but they were as lifeless as leaden weights. And all the time the light was growing stronger. I must admit that at that stage I gave myself up for lost.

‘At that moment Roger walked through the door. I could just see him, faintly, through what appeared to be a deep purple mist that was rapidly closing in on me. He has since told me that it was broad daylight, so obviously my eyes were at fault. He also told me that I looked so dreadful that at first he thought I was dead. Then he saw the ray, and something more. He says he is convinced that he saw a shadowy form behind it. He still had the rifle in the crook of his arm but, of course, he had unloaded when he came into the house. Fortunately he still had some cartridges in his pocket, so he slipped one into the breach and let drive at the vague form behind the light.

‘I remember hearing the shot, but it was no louder than the crack of an eggshell. Then I lost consciousness. When I came round Roger was pouring some sal volatile between my lips. I could move, but only just. I seemed to have been stricken with chronic rheumatism in every limb. Well, to make a long story short, Roger got me to bed, and there I have been ever since, with Roger on guard. There is only one other point, but it is an interesting one. When Roger went back to the spot where he thought he had seen the figure he found something that supplied a real clue to what was going on.’

‘What was that?’

‘Bloodstains. There were bloodstains on the floor. A thin trail led to the door and out into the garden.’

‘Splendid!’ cried Biggles, with a sigh of relief.

‘What makes you say that?’

‘Because in my limited experience I know that what can bleed can feel; and what can feel can be tackled with good honest powder and shot. If you had asked me to help you to keep a gang of spooks at bay, you wouldn’t have seen me for a cloud of dust and small pebbles. But the bloodstains make it a different proposition. From your accounts, these lads from the wide open spaces have some funny tricks, but if, as it seems, a lead slug can make a hole in one of them, then it shouldn’t be beyond our power to settle any argument to our own satisfaction.’ He turned to Maltenham. ‘Tell me,’ he said, ‘what happened to you tonight?’

‘I was the victim of a similar attack to that made on your uncle, but it was not so severe,’ replied the young earl. ‘You see, I felt I couldn’t keep awake indefinitely. While your uncle and I were fit we could take turns to mount guard, but with your uncle out of action it all fell on me. He saw I was cracking up under the strain, and suggested I should try to get in touch with you. I thought of the B.B.C., and went off to the village to telephone.

‘After I had rung them up I started off back, but was attacked in the drive by this infernal ray. I saw nobody, of course. When the light suddenly appeared in front of me I dashed into the wood and got hopelessly lost; as a matter of fact it was the lights of your car that gave me my bearings. I struck the drive near the house, but no sooner was I on it than I could feel—things—around me in the darkness. It was horrible. Then I saw the light again and I am afraid I panicked. I just sprinted for home for dear life. The ray followed me, and actually shone on me once; it produced a sort of numbing shock.’

‘I know,’ nodded Biggles; ‘I’ve felt it, too.’

‘You have! Where?’

‘Tonight, in the drive. The ray caught my arm and half paralysed it. It made me drop my revolver. It was not unlike an electric current shooting through my fingers.’

‘Exactly.’

‘Well, what are you going to do about it?’ inquired Biggles. ‘You can’t go on like this indefinitely. Sooner or later something serious is bound to happen to one or the other of you.’

‘I’m afraid that’s only too true,’ admitted Dickpa. ‘I hate the idea of being run out of my own house by a lot of savages, but I think the sooner we find a place——’

‘Savages? Who said they’re savages?’ asked Biggles quickly.

There was a moment’s silence, and then the Professor nodded slowly. ‘I see what you mean,’ he said in a low voice. ‘You mean——’

‘I mean that people who have learned to control a deathray, or a ray that can produce paralysis, at the same time making themselves invisible, can hardly be classed as savages.’

‘Invisible!’

‘There’s no other solution, bar a miracle, and miracles don’t happen nowadays. Obviously that fellow in your trunk was there all the time, but you couldn’t see him. You could see the weapon with which he proposed to kill you, and the bottle may have contained the dope that produced invisibility—we’ll call it that for want of a better name. That’s why the box was so heavy when the steward had to carry it. After death the fellow returned to normal form. Then again, the fellow in the room here. Malty says he saw a vague shadowy form—that’s right, isn’t it?’

‘Quite right,’ agreed Maltenham. ‘It was a spectral shape—the sort of thing one imagines a ghost to be.’

‘Yet the human body was there all the time; the presence of the blood proves that. Spooks don’t bleed—at least, I’ve never heard of one that did. But what nonsense am I talking?’ he concluded angrily. ‘We should have to believe in fairy tales to consider such things seriously.’

‘I don’t think so.’ It was the Professor who spoke. ‘I think you’ve spoken nothing less than the truth. I begin to suspect that the whole thing is far deeper and more sinister than we at first suspected. And after all, these people came from the Mountain of Light. Light! Mark the word. How can a mountain produce light? I’ll tell you what I think. I believe that this mountain exists, and that its remarkable properties can be attributed to large radium deposits. I’ve always had a half-formed idea in the back of my mind that such might be the case. Radium would account for the curative properties. Good heavens! why, nobody knows the full power of radium yet, and there’s no knowing what extraordinary things these people could do if they had radium in quantities. One grain is sufficient——’

He broke off abruptly as a loud knock came on the front door.

‘Ginger,’ cried Biggles, springing to his feet, ‘have you been watching the drive?’

‘No; I am sorry, but I’m afraid I got carried away by the Professor’s story,’ admitted Ginger frankly.

‘I see,’ snapped Biggles. ‘Come on, Algy—and you, Ginger. You’d better come too, Malty. Our friends seem to be in a hurry,’ he added, as the knocking broke out afresh.

He ran quickly downstairs into the hall with the others close behind. ‘Maltenham, take the twelve-bore and post yourself at the foot of the stairs,’ he ordered. ‘Ginger, take the rifle and cover me.’ He picked up the elephant gun. ‘Algy, open the door and stand clear. I shall be interested to see the man who can take a left and right in the breadbasket from this baby and still stand on his feet,’ he added grimly. With the weapon at the ready, he took up a position about three yards from the door, facing it.

Algy drew the bolts, turned the handle, and sprang clear.

‘Come in,’ called Biggles in a steady voice.

The massive oak door swung slowly inwards on its hinges. There was an instant’s silence, charged with tense expectancy, and then a short hysterical laugh broke from Biggles’s lips. The others stared in mute astonishment as a police-sergeant, followed by a constable, entered.

‘Why, what’s all this?’ asked the sergeant, looking from one to the other in amazement.

‘Er—we were expecting some friends,’ explained Biggles.

‘Friends!’ ejaculated the sergeant incredulously. ‘Is this how you usually greet your friends?’

‘Well, not exactly perhaps,’ replied Biggles rather lamely. ‘But what can we do for you, sergeant? You’ve come up about my car, I suppose?’

‘So it’s your car in the tree, is it?’ said the sergeant suspiciously. ‘Looks like you’ve had a close squeak, young man.’ He stroked his chin reflectively. ‘And it also looks to me as if you gentlemen have been having an evening on the spree,’ he added, winking significantly.

‘Is that what you’ve come here to tell us?’ inquired Biggles, rather coldly.

‘No, sir, it’s something much more serious than that,’ answered the sergeant quickly. ‘I’ve come to ask you if you can throw any light on this affair of the dead man that’s been found in the park.’

Biggles stared. ‘Dead man?’ he repeated foolishly. ‘No—but sit down, officer. Let me offer you some refreshment. Algy, close the door and bolt it. Maltenham, fetch the decanter and a couple of glasses.’ He laid the elephant gun on the table and sat down opposite the sergeant. ‘Now! what’s this about a dead man?’ he asked. ‘Who is it?’

‘That’s what we’re trying to find out. He’s a foreigner, though. Looks to me like a Chinaman, though the Inspector says he’s a Jap. Naked as a new-born babe, too, that’s the funny part of it.’

‘How did he die?’

‘Shot. Shot right through the chest. A single gun-shot wound. The sort of hole you’d expect a rifle about that size to make,’ he observed slowly, pointing to the forty-four.

Biggles caught Maltenham’s eye and flickered an eyelid. ‘Who found the body?’ he asked.

‘Bert Dalton. Maybe you’ve heard of him. No? Ah, well, he’s a poacher. We know him all right. He was poaching when he found it. He don’t deny it. His story is that he stumbled on something in the dark, so he slips his torch across it to see what it was. He let out a yell, he says, when he saw it was a stiff ’un and made for the police-station as fast as his legs would carry him, which was the best thing he could have done. Lucky for him he’d only got his old twelve-bore, so we know he didn’t do the shooting.’

‘Where’s the body now?’

‘We took it to the mortuary, and then the Inspector suggested that it might be a good thing if I slipped along here to see if you knew anything about it.’

‘No,’ said Biggles slowly. ‘I’m afraid we can’t help you.’

‘Funny. You’ve been doing a bit of shooting up here tonight, haven’t you? People don’t often shoot after dark—except people like Bert Dalton.’

‘How did you know we’d been shooting?’

‘Dalton told us. He heard the shots.’

‘Quite right,’ admitted Biggles. ‘But that was after he’d found the body, so we couldn’t have shot your man.’

‘How did you know it was afterwards?’ asked the sergeant in surprise.

‘Because I know exactly when Dalton found the body. I heard his yell of fright, although, of course, I didn’t know what it was then, or who it was.’

‘I see, sir,’ said the sergeant slowly. ‘No, I wasn’t suggesting you had anything to do with the shooting of this Chink, or whatever he is. The doctor says he’s been dead some time, twelve hours or more. The bullet was fired at pretty close range, he says.’

Biggles nodded. ‘Between you and me, sergeant, we’ve seen some funny people about in the park this last day or two; we thought they were gipsies. They may have fallen out amongst themselves. As you may know, Professor Bigglesworth, who, by the way, is my uncle, has been abroad, and there has been no one here to look after things, so people could pretty well come and go as they pleased on the estate. It might be a good thing if you had a thorough look round as soon as it gets daylight.’

‘The Professor’s at home now, isn’t he?’

‘Yes, but he’s ill in bed.’

‘I see, sir. Then we’ll leave him out of the proceedings if we can, but there’s bound to be an inquest, and he may be asked to attend.’

‘Very well, sergeant, you know best. And I’ll tell you what. While these strangers are about I should be glad if you would ask one of your men to have a look round here, say once a day, until further notice. Tell him to come up to the house to make sure everything is all right.’

‘Very good, sir, I’ll see if it can be arranged,’ agreed the sergeant, rising. ‘Good-night, sir.’

‘Good-night, sergeant.’

As the door closed behind the police officers Biggles looked at the others soberly. ‘Malty,’ he said, ‘I’m afraid you killed that cove.’

‘It looks like it, I must admit.’

‘I don’t think there’s any doubt about it.’

‘What had I better do?’

‘Nothing at present. Let’s get back to Dickpa and tell him what’s happened.’

They returned to the bedroom, where they told the Professor what had transpired.

The early hours of the morning found them still deep in discussion.

‘Well, I’m getting tired,’ announced Biggles at last. ‘The point you’ve got to decide is, what are you going to do about this whole business?’

‘I don’t know how other people feel about it, but I know what I should like to do,’ replied the Professor.

‘What’s that?’

‘Go back to China, or rather Tibet, and get to the truth of the thing.’

‘Sounds crazy to me,’ observed Biggles. ‘You’re not by any chance thinking of asking me to fly you there, are you?’ he added suspiciously.

‘I was.’

Biggles frowned, but there was a twinkle in his eye as he looked his uncle straight in the face. ‘Do you know, Dickpa,’ he said reproachfully, ‘I believe you’ve had that idea all along. Really, if you’d admit the truth, that’s why you sent for me.’

A faint smile spread over the Professor’s face. ‘You’re quite right,’ he admitted.

‘Do you realize what such an expedition would cost, quite apart from the risks?’ inquired Biggles.

‘A lot of money, I expect, but Roger——’

Biggles swung round to face Maltenham. ‘So that’s it, is it!’ he observed. ‘You’re in the plot, too.’

‘I’m afraid I am,’ confessed Maltenham. ‘That is, I’m prepared to finance it, provided I can come.’

‘You’ve still got an aeroplane, Biggles, haven’t you?’ asked Dickpa.

‘Yes, I’ve still got the old “Vandal”, but I don’t think she’s up to an affair of this sort. She’s obsolete, and the engine’s getting a bit shaky, which isn’t surprising considering the number of hours it’s done. No; if we went we should need a new machine.’

‘I suppose you know what sort you’d select, if you had to get one specially for this trip?’ inquired Maltenham.

Biggles thought for a moment. ‘Yes,’ he said, ‘there’d be no difficulty about that; but aeroplanes cost a lot of money, particularly amphibians, which is the type I should use, because we could then get down on either land or water in emergency.’

‘How much would you require altogether, do you think?’

‘The machine, fuel, oil, and all the rest of the things we should need would leave no change out of thirty thousand pounds.’

‘Is that all? Then the matter becomes simple,’ declared Maltenham eagerly. ‘I have ten times that amount of money and nothing to do with it. I’m not concerned with making money out of this venture; the financial side doesn’t interest me. I’m only thinking about the good we might do. My governor always wanted me to do something big. He never had a very high opinion of me, and—well, I have a feeling that this is my opportunity.’

‘All right, if that’s how you feel about it,’ answered Biggles.

‘If I can be of some benefit to humanity I shall feel that I have done some good with my life.’

‘From what I can see of it, you’ll be lucky to have a life to do anything with by the time this business is finished,’ declared Biggles. ‘You’re thinking about the radium, of course?’

‘Nothing else. If it is there and we can get some of it, it may help to cure a million poor souls who are now dying of such ghastly diseases as cancer.’

‘Good! Then the sooner we’re out of this place the better.’

‘Then you’ll go?’

‘Of course I’ll go,’ laughed Biggles. ‘To tell you the honest truth, I was hoping for something of the sort when I came here.’

‘You rank hypocrite,’ cried the Professor.

‘You lie quiet and get yourself fit and well, Dickpa,’ Biggles told him seriously. ‘We can’t go until you’re on your feet again. And now where are we all going to sleep?’

‘The greatest danger we have to face is not finding a landing-ground when we get there,’ said Biggles seriously, looking at each of the four members of the party in turn as if seeking confirmation of his opinion.

Six weeks had passed since the S.O.S. message had sent the three airmen post-haste to Brendenhall Manor; they were now sitting on the veranda of the rest-house at Chittagong Aerodrome, which is situated near the frontiers of Bengal, Assam, and Burma. Nothing of importance had happened at Brendenhall after the departure of the police-sergeant. The Professor, as in duty bound, had attended the inquest on the dead native, and the others had escorted him to the court in a police car. After an interview with the Coroner, a non-committal verdict of ‘Death from Misadventure’ had been returned, and there the matter ended. Then the whole party had taken the next train to London without returning to the Hall, Dickpa deciding to leave the place in the hands of a competent agent rather than face the perils that unquestionably existed there.

In London they had sought out an obscure hotel, from where Biggles had quietly conducted the negotiations for the purchase of an aircraft and the preparations for the voyage. After considerable thought, and long and earnest debates with Algy, they had decided upon an all-metal, twin-engined ‘Gannet’ amphibian, one of a type that had recently gone into production for the Royal Air Force. It was, to all intents and purposes, a flying boat, but fitted with a wheel-landing chassis which could be raised or lowered at the will of the pilot. The two ‘Hercules’ air-cooled engines were mounted between the planes, one on either side of the hull, in accordance with orthodox design and practice. Forward were cockpits for two pilots sitting side by side, fully equipped with the latest ‘blind’ flying instruments. A low doorway gave access to the spacious cabin, which, besides having seating capacity for six passengers, contained roomy lockers for stores and equipment. These lockers were important; normally, in Service machines, they were intended for spare parts, in order that the machines could operate at sea as units independent of shore assistance, but they now formed handy receptacles for the compact stowage of the large quantity of food that the uncertain duration of the voyage demanded.

There had been some little trouble over ‘carnets’,—the document without which, in accordance with International Air Regulations, no aircraft may travel abroad—because naturally, Biggles found it difficult to state his destination. Ultimately he had overcome this obstacle by stating that the amphibian was bound for a pleasure cruise down the Australian route, but covered himself against the inquiries that would inevitably result when the aircraft ‘disappeared’, by saying that the party might make local excursions en route. He decided that if difficult questions were asked on their return to civilization, he would have to say that they had got off the track, or had been delayed at an out-of-the-way spot by bad weather.

Finally, the great day came when the Explorer—as the amphibian had been appropriately named—had left Brooklands on the first stage of her long journey. Thereafter they had followed the main trunk route to Karachi, across India, and then on to Chittagong, which had been selected as the jumping-off-place for the unknown, because it was the nearest aerodrome to their final destination. They had arrived on the previous day, and were now engaged in a last council of war.

‘Frankly, this question of finding a landing-ground is the only thing that worries me,’ continued Biggles. ‘You see, in the first place, it isn’t as though we knew exactly where we are going. We don’t, not to within a hundred miles or more. According to Dickpa’s field notes, read in conjunction with such maps of western China as exist, the distance to the approximate position of the mountain, in a straight line, is about eight hundred miles. By jettisoning some of our stores we could carry enough petrol in the tanks to fly there, look round, and if we found nothing, fly back. But I daren’t cut down the stores in case we do find something and want to stay there. Then again, it isn’t as if we had to fly over ordinary country. We’ve got to climb to fourteen or fifteen thousand feet to get over the mountains, and remain at that height over the plateau when we get there. This high altitude flying means loss of efficiency; it means that we shall have to fly most of the time on full throttle, or nearly full throttle, when at lower altitudes we should cruise on half-throttle; consequently, we shall want every drop of petrol we can carry to get up there and back. We’ve got to carry petrol with us, in drums, apart from what we can get in our tanks, including the extra tank I had installed. So we shall be all right as long as we can find a landing-place, because then we can go down, fill our tanks from the reserve supply, scrap the empty drums—which will be so much less weight to carry—and have a reasonably safe margin for getting back. But if we can’t find a landing-place we shan’t be able to refuel, in which case we may find ourselves in the cart. It boils down to this: we can’t get there and back without landing. I thought I’d better warn you.’

‘But surely we shall find a place big enough to land in, in all this vast country?’ put in the Professor.

‘Not necessarily. You said yourself that in all your journey on foot you did not see a single place that might be regarded as an aerodrome. A flat patch is no use if there are rocks and things sticking about. I for one don’t want to have to walk home; walking isn’t in my line: it’s too slow. Water is our best chance. If we can find a lake we shall be O.K., although we may have a job to take off at such a high altitude if the water is dead calm, as it is almost certain to be. In case you don’t know, a marine aircraft of any sort, but a flying boat especially, needs a wave to provide the kick that sends it into the air—particularly if it is heavily loaded, as we shall be. But there, it’s no use looking for trouble. As I said before, I thought I’d better tell you just how we stand, so that if any one thinks better of it there is still time to drop out.’

There was a chorus of protest and Biggles smiled. ‘That’s that, then,’ he observed. ‘We leave the ground tomorrow morning at the crack of dawn.’

‘How long will it take us to reach this place?’ asked Malty, as Maltenham was now called by every one.

‘Eight hours. I could do it in less, but I want to nurse my engines. We’ve got to go a long way up, remember.’

‘Is the machine all ready?’ asked Dickpa.

‘Absolutely on the top line ready for the word go,’ replied Biggles. ‘Algy and Ginger and I have spent the day looking over her, as you know.’

‘Very well, then I’m going to turn in. I am looking forward to tomorrow. I feel it will be one of the high spots in my life.’

‘In more senses than one,’ grinned Biggles, as the party rose to prepare for bed.

The stars were paling in an opal sky the following morning as the Explorer taxied out across the aerodrome into position to take off on her great adventure.

Biggles swung round slowly into the wind, eased the throttle open, and the amphibian raced across the sun-baked earth, leaving a swirling cloud of dust high in the air behind her. His face was set and grim, for the slightest swerve in such a heavily loaded machine might tear a wheel off, with disastrous results. The machine took a long run to ‘unstick,’ but once in the air she climbed steadily and smoothly, and Biggles brought her round gently on a course to the NNE.

Below them lay the virgin jungle, stretching away in all directions as far as the eye could see; away to the left, the distant delta of the Ganges lay like a skein of carelessly dropped grey threads. An hour passed, and the landscape remained unchanged except that straight in front a line of jagged white teeth now rose high into the sky like a mighty wall. It was a wall, in truth; a fourteen thousand feet high wall that through the ages has formed an impassable barrier across the neck of the Indian Peninsula, and held the Chinese hordes in check. In recent years one or two white men have made the journey from China to India on foot, but very few, and those that have got through have had little time to examine the inhospitable country on either side of them.

‘How far are they away?’ asked Algy, nodding towards the distant mountains.

‘The best part of two hundred miles,’ replied Biggles tersely, easing back the joystick as he continued to climb for height in order to surmount the mighty range that lay athwart their path, at the same time watching the towering summits with brooding eyes, for he knew that, as in other mountains, mist forms easily and quickly in the Himalayas, and he had no desire to fly ‘blind’ through the menacing peaks.

The sun rose higher as the day wore on, but with the needle of the altimeter now on the fourteen thousand feet mark, they were too high to feel the heat. Below, the great Brahmaputra river wound a slow, sinuous course towards the Bay of Bengal, as if weary of the titanic struggle in which it had battered its way through the mountains, to fall at last through unfathomable gorges into the plains beneath.

The mountains seemed to be very close now, but Biggles, as his eyes probed the serrated edge for a pass, knew that they were still some distance away, and he continued to climb, glancing from time to time at his engine-revolution indicator. Slowly they drew nearer, and the details of the most awe-inspiring scenery in the world became visible; but Biggles gazed across the scene of stupendous grandeur unmoved. As far as he, as an airman, was concerned, the range was merely an obstacle that had to be overcome, a natural physical feature which he, by his skill and experience, must conquer. Nevertheless, a faint smile played around the corners of his mouth as he caught Algy’s eye after gazing down into a gorge that dropped sheer away below them to a point so deep that its bed was lost in dark, purple shadows. They were among the peaks now, tier after tier of them in a world of snow and ice, like sentinels guarding a new world.

The smile was suddenly replaced by a frown, however, as he caught sight of a white, wraith-like streamer curling away from one of the nearest peaks.

At first he thought it might be snow being blown away by the wind, but a second glance confirmed his suspicions. It was fog, and in a few moments several of the other peaks were half hidden. He looked around anxiously and saw that the mist was not coming from anywhere: it was forming on the mountains themselves; the very atmosphere was becoming opaque, due possibly to a sudden change in the temperature. He glanced to the right and saw that the sun had disappeared.

At that moment he was a good thousand feet above the highest peaks and flying on full throttle, so he eased the stick forward for more speed in the hope of getting clear of the mountains before the mist enshrouded them in its clammy folds. The machine roared on over the silent desolation, but one by one the peaks disappeared from view until only the nearest were visible, and they were but cold white spectres that loomed eerily in the gathering murk.

Biggles turned his eyes to his instruments. ‘Did you see anything ahead that looked as if it were above us?’ he shouted.

‘No, I think we’re over the highest,’ replied Algy, with an assurance he did not feel, for he knew that the lives of the whole party now rested on the engines. If either of them should fail, not all the skill and airmanship in the world could save them.

Biggles grunted and played for safety. Speed could not help them now, so he eased the throttle back a little and started to climb again, very, very slowly. At sixteen thousand feet he was satisfied that he was safe from striking an obstruction, but nevertheless he breathed a sigh of relief when a few minutes later the machine shot out into clear air under a steely blue sky. Below, the mist lay flat, like a white blanket of snow; to the east and west it stretched to the infinite distance, but a few miles ahead it broke off abruptly as if it had been cut with a knife. The phenomenon was not new to him, but he had never before observed it with so much satisfaction. ‘Pass me a sandwich, Algy, will you?’ he said. ‘I think the worst is over.’

And so it proved, for twenty minutes later the earth again came into view, and the white peril drifted away astern. ‘Thank goodness,’ he muttered thankfully, as he looked down with interest on a landscape that he knew had never before been looked upon by Europeans. It was not a pleasant sight. Grim, stark, and utterly lifeless, it was a land of tortured rock; of jagged knife-like ridges and deep forbidding gorges. ‘I hope there isn’t too much of this,’ he shouted, as he gazed below. ‘My goodness, did you ever see such a place! No wonder nobody’s ever tried to conquer the country.’

But his fears were groundless, for the rocky terrain slowly gave way to open plain, a vast wind-swept expanse of sand and shingle dotted here and there with sparse, grey-green herbage. ‘First one extreme and then the other. This looks like the world’s biggest aerodrome,’ observed Biggles, as he gazed across the monotonous waste.

For another two hours they flew on without change of scene. Once they passed a slowly moving line of men, driving heavy, bovine yaks, the animals that are used as beasts of burden on the great plateau; the men threw themselves on the ground as the machine sped over them. It was the first time either Biggles or Algy had seen natives behave in such a fashion, and the incident was sufficient to show that they had never seen an aeroplane before. They could see the details of the strange scene clearly, for although the altimeter registered fifteen thousand feet, Biggles reckoned that they were not more than a thousand feet above the ground. On another occasion they saw, in the distance, a small village of square, stone or mud houses, with thatched roofs; above it, on a slight rise in the ground, a large fort-like structure, built in the Chinese fashion with long overhanging eaves, appeared to be watching over it. They did not circle to examine it, but held on their course over the plain that was now giving way to broken country again. Low rocky hills appeared; they were divided by deep gorges, through which streams rushed in white-lashed pent-up torrents, while some distance ahead gaunt, grey peaks reared their heads far above the inhospitable vista. Beyond the peaks a great mass of rock rose in a series of steppes to a group of formidable mountains.

Biggles felt a sudden sense of disappointment. How on earth were they going to tell which one of them was the Mountain of Light—even supposing that the mountain they sought was in the group? The old saying, ‘looking for a needle in a haystack’, came into his mind. At home the difficulty had seemed trivial, but now, confronted by cold reality, the matter assumed a totally different aspect. Glancing at the watch on the instrument board, he saw that they had been in the air a few minutes less than eight hours. He beckoned to Algy. ‘Take over for a bit,’ he said. ‘I’m going to speak to Dickpa about landing. I don’t feel inclined to face that stuff ahead; we had better come down this side of it.’

Leaving Algy in charge, he went through into the cabin, where he found the three passengers gazing out of the window. The Professor and Malty were in earnest conversation, but they smiled when they saw him. He seated himself next to Dickpa and nodded towards the mountains. ‘I’m going to land this side of them,’ he shouted, above the noise of the engines. ‘We shall never find a landing-place amongst them, and goodness knows what is on the other side. We’ll fly up close to them, have a good look round, and then come down this side of them to refuel.’

‘You do whatever you think best,’ replied the Professor; ‘I leave things absolutely to you.’

Biggles turned from the instrument panel, his face bewildered

‘All right; then that’s what I’ll do,’ answered Biggles; and then started as his practised ears detected a slight change in the note of the engines.

‘What’s the matter?’ asked Dickpa quickly, observing his startled expression.

‘Nothing, I hope,’ replied Biggles casually, but all the same he hurried back to the cockpit. One glance at Algy’s face was sufficient to tell him that something was wrong. Instinctively his eyes flew to the engine-revolution indicators, and he caught his breath sharply when he saw that the revs of both engines had fallen considerably. But the thing that astonished him most was the fact that both had fallen to precisely the same mark. For two engines to fail at the same moment would have been remarkable, but that they should both fall in equal ratio was an even more amazing coincidence. To his consternation he saw that both engines were still losing power, and what was more incredible, the needles of both indicators were falling in perfect unison. They might have been synchronized instead of being separate units. Never could he have imagined such a remarkable state of affairs, and he stared at Algy speechlessly, for once at a loss to know what to do.

‘What do you make of it?’ shouted Algy.

Biggles shook his head. ‘Beats me,’ he replied tersely. ‘Let me have her: I’m going down.’ Curiously enough, neither of the engines appeared to be getting hot, and both oil and pressure gauges were registering normal figures.

He sat down in his seat, took over the joystick, and swung round in a wide circle in order to examine the whole area for the best place to effect a landing; but as he turned away from the mountains the roar of the engines increased in volume, and to his dumbfounded astonishment he saw both rev-counters climbing steadily. He shook his head like a man faced with a problem for which there is no answer, and turned back on his course with the intention of pursuing his original plan. Instantly both engines started to fail again, very slowly, but definitely. They reminded him of a gramophone motor running down. Quite bewildered, he turned away again with his eyes seeking a landing-place.

‘Am I going crazy or are they?’ he shouted to Algy, pointing at the instruments, the needles of which were now creeping back up the dials. In spite of the seriousness of their position, the expression on Algy’s face made him smile; never had he seen his partner so completely taken aback. ‘It’s no use,’ he continued, ‘we can’t go on like this. Something must be wrong; we’ll go down and see if we can find out what it is.’

They were now quite close to the nearest foothills, running along the face of a very steep escarpment from which a stream bubbled and spilt itself on to the plain. Below, the ground was flat, and as far as they could see free from rocks or other obstructions. There was little wind, if any, and with the idea of being as near to fresh water as possible, Biggles decided to land as close as he could to the cliff, in preference to the bleak open plateau, where moreover the machine would be exposed to the mercy of a gale should one arise.

He throttled back and flew low over the prospective landing-ground, subjecting every inch of it to a careful scrutiny before he attempted to land; then, satisfied that the ground was clear, he lowered his wheels and dropped lightly on the coarse grass and shingle that covered the earth at that spot.

A moment later the Explorer had run to a standstill; the roar of the engines ceased abruptly and was succeeded by an overpowering silence as he switched off and jumped to the ground. ‘Well,’ he observed, ‘we’re here, anyway.’

The door in the hull opened and the others stepped out, stretching their limbs after the long spell of enforced inactivity.

‘Well, so far so good,’ cried the Professor. ‘What is the programme, Biggles?’

‘First, all hands to refill the tanks, in case we have to get off in a hurry; second, we shall have to look over the engines; third, a square meal. I can do with one. We can talk about what we are going to do after that while we eat. It’s well on into the afternoon, so we shan’t be able to do much today, anyway. Come on, the sooner we get this spare petrol into the tanks, the happier I shall feel.’